- 1Department of Human and Engineered Environmental Studies, Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, The University of Tokyo, Kashiwa, Japan

- 2Research Institute on Human and Societal Augmentation, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST), Kashiwa, Japan

- 3Human Informatics and Interaction Research Institute, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST), Tsukuba, Japan

The Japanese version of the Kenny Music Performance Anxiety Inventory-Revised (K-MPAI-R) has been developed but not yet been validated. This study aims to validate and certify the Japanese version of the K-MPAI-R. Data were collected from 400 participants (250 men, 149 women, and one identifying as other), aged between 18 and 64 years (M = 46.84, SD = 10.45). The sample included 200 professional and 200 amateur musicians, comprising 309 instrumentalists and 91 vocalists. An exploratory factor analysis with promax rotation extracted seven factors that explained 55.8% of the total variance, demonstrating a structure similar to the original version. The scale showed high internal consistency, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.93. Criterion-related validity was supported by correlations with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (r = 0.67) and Performance Anxiety Questionnaire (r = 0.75). These findings indicate that the Japanese version of the K-MPAI-R is a reliable and valid measure of music performance anxiety. This validated instrument enables further investigations into music performance anxiety among Japanese musicians.

1 Introduction

Music performance anxiety (MPA) is the experience of marked and persistent anxious apprehension related to musical performance, typically arising from specific anxiety conditioning experiences (Kenny, 2009b). MPA is accompanied by various symptoms, classified into the following three categories: physiological (e.g., increased heart rate, dry mouth, and sweating), mental (e.g., difficulty concentrating and memory-related issues), and behavioral (e.g., tremors and technical difficulties) (Burin and Osório, 2017; Steptoe, 2001; Salmon, 1990; Irie et al., 2023). MPA is a common issue among musicians (Fernholz et al., 2019) regardless of their cultural or national background. For example, 24% of musicians in Brazil reported experiencing MPA (Barbar et al., 2014). Van Kemenade et al. (1995) have found that 59% of musicians in a Dutch orchestra reported experiencing MPA, and Studer et al. (2011) have revealed that 22% of music students in Switzerland failed an exam because of MPA. Yoshie et al. (2011) have also identified MPA indicators in 64% of both professional and amateur musicians in Japan.

Various questionnaires have been developed to quantify an individual's level of MPA as a stable trait, often including items about physiological and psychological changes experienced in past performance situations (Yoshie and Morijiri, 2024). These questionnaires include the Kenny Music Performance Anxiety Inventory (K-MPAI and K-MPAI-R) (Kenny et al., 2004; Kenny, 2009a), Performance Anxiety Questionnaire (PAQ) (Cox and Kenardy, 1993), Mazzarolo Music Performance Anxiety Scale (Mazzarolo and Schubert, 2022) and Music Performance Anxiety Inventory for Adolescents (Osborne and Kenny, 2005). Some of such questionnaires, including the PAQ (Kobori et al., 2011) and the Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2 for Musicians (Yoshie and Shigemasu, 2006; Yoshie et al., 2009), have been used to measure MPA levels among Japanese musicians. Although each questionnaire offers distinct strengths, the K-MPAI and K-MPAI-R (Kenny et al., 2004; Kenny, 2009a) have been widely adopted in research involving both professional and amateur musicians across various genres, instrumentalists, singers, and ensemble or orchestra participants (Robson and Kenny, 2017; Kenny et al., 2013; Kenny and Ackermann, 2015; Paliaukiene et al., 2018); it has also been translated into 22 languages (Kenny, 2023).

The K-MPAI was developed by Kenny et al. (2004), and is based on Barlow's emotion-based theory of anxiety (Barlow, 2000). Barlow (2000) has described the following three vulnerabilities related to the development of anxiety, anxiety disorders, and emotional disorders: generalized biological vulnerability, generalized psychological vulnerability, and specific psychological vulnerability. Generalized biological vulnerability describes a basic anxiety tendency driven by genetic influences. Generalized psychological vulnerability is shaped by early experiences with uncontrollability, which later amplify stressful events. Specific psychological vulnerability, influenced by early learning experiences, predisposes individuals to focus their anxiety on specific objects or events and influences which object or situation becomes the focus of fear in specific phobias. The K-MPAI comprises 26 items designed to assess such vulnerabilities indicated in Barlow's theory and pre-performance experience, aiming to contribute to the comprehensive conceptualization of MPA and provide an appropriate focus for the development of more suitable treatments (Kenny, 2009a).

Kenny later revised the K-MPAI, incorporating additional factors related to the etiology and maintenance of MPA with a broad focus. This led to the development of the K-MPAI-R with 40 items (Kenny, 2009a). Kenny et al. (2012) explored the factor structure of the K-MPAI-R using a sample of 377 professional orchestral musicians in Australia. A factor analysis identified the following six distinct factors: proximal somatic anxiety and worry about performance; worry/dread (negative cognitions/ruminations) focused on self/other scrutiny; depression/hopelessness (psychological vulnerability); parental empathy; concerns with memory; generational transmission of anxiety; and anxious apprehension and biological vulnerability, a weaker additional factor.

The K-MPAI-R has been translated into Spanish (Peru) (Chang-Arana et al., 2018), French (Antonini Philippe et al., 2022), Korean (Oh et al., 2020), Portuguese (Dias et al., 2022), Italian (Antonini Philippe et al., 2023), Polish (Kantor-Martynuska and Kenny, 2018), Turkish (Çiçek and Güdek, 2020) and Romanian (Faur et al., 2021), with reliability testing conducted through internal consistency coefficients. In addition, validity testing has been conducted through factor structure examination via exploratory factor analysis (EFA) (Chang-Arana et al., 2018; Antonini Philippe et al., 2022, 2023; Oh et al., 2020; Dias et al., 2022; Kantor-Martynuska and Kenny, 2018; Faur et al., 2021), and correlation analyses with related measures such as the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Chang-Arana et al., 2018; Antonini Philippe et al., 2022, 2023; Oh et al., 2020; Dias et al., 2022; Kantor-Martynuska and Kenny, 2018). Among the factors derived by Kenny et al. (2012), “proximal somatic anxiety and worry about performance”, “depression/hopelessness (psychological vulnerability)”, “parental empathy”, and “concerns with memory” were also observed in a similar form across multiple language versions (Antonini Philippe et al., 2022, 2023; Dias et al., 2022; Faur et al., 2021; Chang-Arana et al., 2018; Oh et al., 2020; Kantor-Martynuska and Kenny, 2018). However, variations in the factor structure have also been found among different language versions of the K-MPAI-R. For example, factors related to “worry/dread (negative cognitions) focused on self/other scrutiny” were only found in French (Antonini Philippe et al., 2022), and Korean (Oh et al., 2020) versions. Factors related to “generational transmission of anxiety” were found only in Italian (Antonini Philippe et al., 2023) and Korean (Oh et al., 2020) versions. These results potentially indicate that differences in languages and/or cultures can influence the factor structure of the K-MPAI-R.

The various language versions of the K-MPAI-R have contributed to a better understanding of MPA, especially personality traits related to MPA. For example, a study conducted on Brazilian musicians found that the group with higher K-MPAI scores had lower self-assessment (Barbar et al., 2014). The K-MPAI-R was also used to evaluate the effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy treatment on MPA management (Juncos et al., 2017).

The development of a Japanese version of the K-MPAI-R would lead to a deeper understanding of the characteristics of MPA among Japanese musicians and allow for comparisons with studies using other language versions. The authors have created the Japanese version of the K-MPAI-R (Kenny, 2023); however, it has yet to be validated. This study aims to develop a validated Japanese version of the K-MPAI-R. Responses from 400 musicians to the Japanese version of the K-MPAI-R were analyzed through the examination of both reliability (e.g., internal consistency) and validity (e.g., EFA). The validity of the Japanese version was assessed by comparing its factor structure with the English version (Kenny et al., 2012) and results from other language versions. Furthermore, its relationships with the STAI (Spielberger et al., 1970) and the PAQ (Cox and Kenardy, 1993) were examined.

2 Method

2.1 Measures

2.1.1 Kenny Music Performance Anxiety Inventory Revised version (K-MPAI-R)

The K-MPAI was developed to assess anxiety symptoms and other associated constructs within the context of music performance. The original version includes 26 items (Kenny et al., 2004), which was later revised and expanded to include 40 items (Kenny Music Performance Anxiety Inventory Revised version: K-MPAI-R) (Kenny, 2009a). The questionnaire is answered on a seven-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 0 (“strongly disagree”) to 6 (“strongly agree”).

The Japanese version of the K-MPAI-R, developed by the authors through a back-translation process, was approved by Kenny (2023); however, it has yet to be validated. A revision of the Japanese version of the K-MPAI-R was conducted to identify any issues overlooked during the translation process and to improve the comprehensibility and cognitive equivalence of the scale. Established guidelines for scale translation recommend that revision processes include cognitive debriefing with multiple individuals from the target population (Wild et al., 2005). We therefore recruited seven musicians from the target population of the K-MPAIR, namely five professionals (a singer, pianist, trombonist, percussionist, and cellist), a university-level music student (a violist), and an amateur musician (a saxophonist), comprising four men and three women, including one bilingual speaker of English and Japanese. Following these interviews, the revisions were made with a focus on consistency with the original version and naturalness in Japanese. During this process, discussions were held among the authors, including experts in music psychology, to determine the final wording. Out of the 40 items, 22 were modified. These items were back-translated again to ensure consistency with the original version. The revised questionnaire is available in the Supplementary Data 1.

2.1.2 State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

The STAI (Spielberger et al., 1970) is a 40-item self-report questionnaire comprising 20 items each for trait anxiety and state anxiety, with responses provided on a four-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 4 (“very much so”). Participants completed the Japanese version of the state scale of the STAI (Hidemi and Kuniharu, 1981). To assess their mental state during musical performances, the following instruction was added: “Imagine the most important performance you have had within the past five years and indicate how much you felt each of the following statements during that time.”

2.1.3 Performance Anxiety Questionnaire (PAQ)

The PAQ (Cox and Kenardy, 1993) comprises 20 statements, with 10 describing cognitive feelings and 10 describing somatizations during musical performances. It measures how frequently participants experience these cognitive and somatic responses across the following three performance settings: practice, group public performances, and solo public performances. Participants rate each statement on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (“Never”) to 5 (“Always”) for each setting. All PAQ items were translated into Japanese through a back-translation process by Kobori et al. (2011). In this study, participants completed the Japanese version of the PAQ, responding to the statements specifically in the context of public performances, without distinguishing between solo and group performances.

2.2 Participants

A total of 400 individuals participated in this study. Among the participants, 250 were men, 149 were women, and one individual identified as other. The participants were between 18 and 64 years old, and their mean age was 46.84 years (SD = 10.45). All participants were native speakers of Japanese. Eligibility criteria required that participants be currently engaged in musical performance activities, specifically playing a musical instrument (n = 309) or singing (n = 91), and have given a public performance within the past five years. Public performances included situations where the performance was subject to evaluation, such as in music exams, competitions, or auditions, as well as performances before general audiences; however, it excluded performances limited to family, close friends, daily practice, classes, or lessons. The sample was evenly divided between professional (n = 200) and amateur (n = 200) musicians. The criteria for being classified as a professional were either (a) earning income from music or (b) having studied music at a university or specialized music school. This category also included school teachers with a music teaching license for junior high or high school or those who taught music as a specialized subject in elementary school.

2.3 Procedure

An online survey was conducted. The participants were recruited through an online panel maintained by a marketing research firm. Before participating, they read an explanation of the study and provided their informed consent. Those who consented were asked to complete the K-MPAI-R, STAI, and PAQ.

The study was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology.

2.4 Data analysis

All participants answered all questions, and there was no missing data. Some items (1, 2, 9, 17, 23, 33, 35, 37) were reversed following Kenny (2009a). For the 40 items, means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis were calculated. To assess the adequacy for factor analysis, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was calculated, and Bartlett's test of sphericity was conducted. An EFA with a maximum likelihood and promax rotation was conducted to examine the factor structure of the data. The results of the parallel analysis and Minimum Average Partial (MAP) were used as a reference for determining the number of factors. To assess the model fit, the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were calculated. To assess scale reliability, the internal consistency coefficient, specifically Cronbach's alpha, was used. The procedures were developed by drawing on the methods of Antonini Philippe et al. (2022, 2023).

We calculated means and standard deviations for the STAI and PAQ. The items 1, 2, 5, 8, 10, 11, 15, 16, 19, and 20 were reversed for the STAI-state following Spielberger et al. (1970). The items 4 and 8 were reversed for the PAQ. To evaluate the reliability of the scales, we performed correlation analyses to investigate several key relationships. We calculated the correlations for the following using Pearson's correlation coefficient: the total scores of the K-MPAI-R and STAI; each factor score of the K-MPAI-R with the total score of the STAI; the total scores of the K-MPAI-R and PAQ; and each factor score of the K-MPAI-R with the total score of the PAQ.

Data analysis was conducted using R Core Team (2024) and psych package (v4.4.1; William Revelle, 2024).

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive analysis

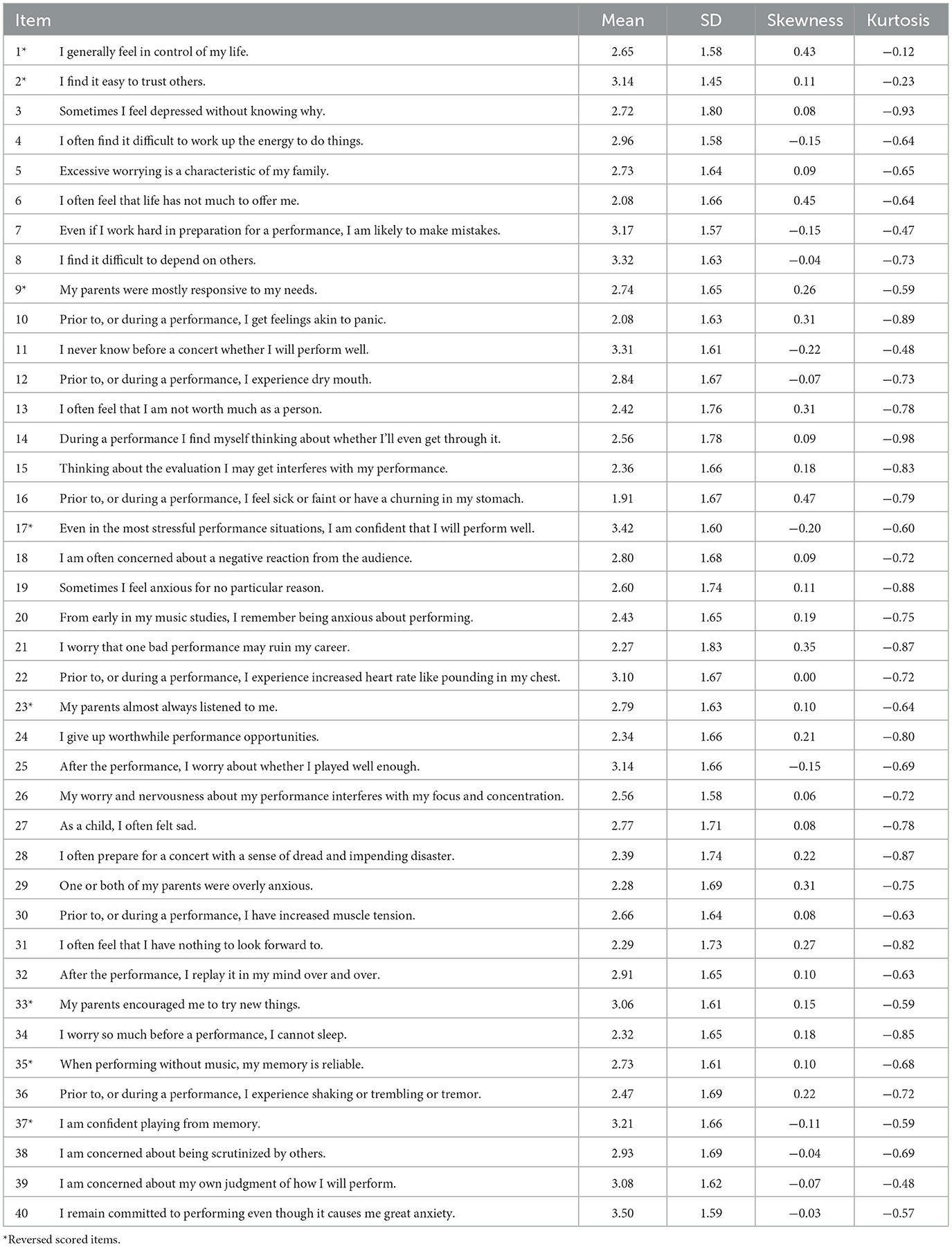

The mean values and standard deviations for each item of the K-MPAI-R are shown in Table 1. Skewness and kurtosis coefficients were calculated for all 40 items. According to Tabachnick and Fidell (2007), skewness and kurtosis coefficients should be within ±1.5 when performing factor analysis on items measured using a Likert scale. The analysis indicates that all 40 items met this criterion.

3.2 Exploratory factor analysis

The KMO assesses sampling adequacy. The KMO value was 0.93, indicating excellent adequacy. Furthermore, the KMO values for each item were above 0.6, confirming the suitability of the data for factor analysis. Bartlett's test of sphericity also confirmed the data's adequacy, with χ2(780) = 9, 593.6, p < 0.001.

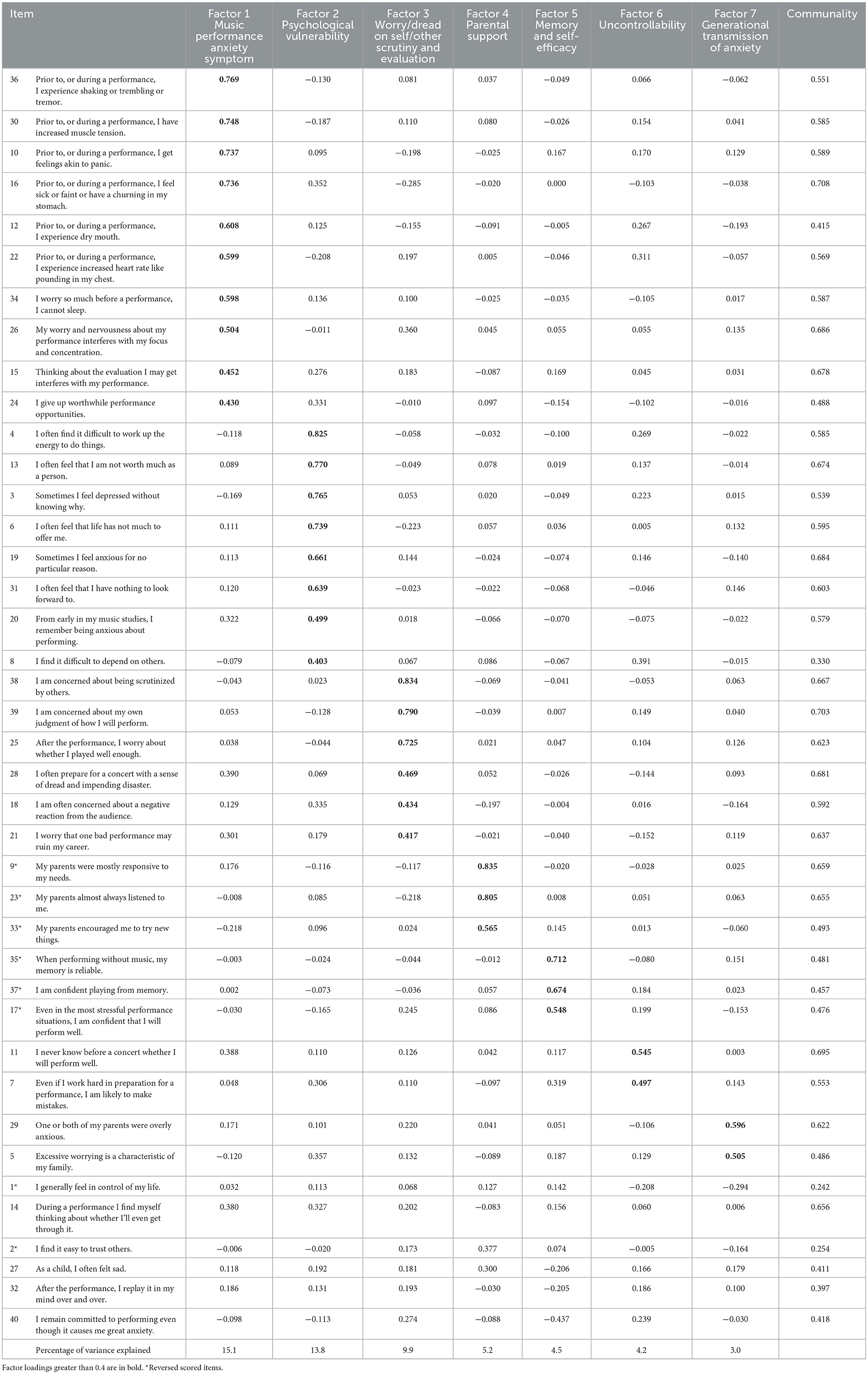

A factor analysis using maximum likelihood estimation and promax rotation was performed on the 40 items of the K-MPAI-R. To determine the number of factors, both parallel analysis and the MAP criterion were used. The parallel analysis suggested a seven-factor solution, while the MAP criterion recommended five factors. Accordingly, EFA was conducted for the five-, six-, and seven-factor models. The fit indices for the models were as follows: for the five-factor solution, χ2(590) = 1, 508.05, p < 0.001, ratio χ2/df = 2.56, TLI = 0.86 and RMSEA = 0.062; for the six-factor solution, χ2(555) = 1, 283.15, p < 0.001, ratio χ2/df = 2.31, TLI = 0.88 and RMSEA = 0.057; and for the seven-factor solution, χ2(521) = 1, 127.42, p < 0.001, ratio χ2/df = 2.16, TLI = 0.90 and RMSEA = 0.054. A TLI value above 0.90 and RMSEA value below 0.08 are generally considered acceptable (Bader and Moshagen, 2022). Considering both the fit indices and content of each factor, the seven-factor solution was determined to be the most appropriate.

The factors were named based on the items with factor loadings of 0.40 or higher.

F1: Music performance anxiety symptoms (10 items: 10, 12, 15, 16, 22, 24, 26, 30, 34, 36; α = 0.91);

F2: Psychological vulnerability (8 items: 3, 4, 6, 8, 13, 19, 20, 31; α = 0.89);

F3: Worry/dread focused on self/other scrutiny and evaluation (6 items: 18, 21, 25, 28, 38, 39; α = 0.89);

F4: Parental support (3 items: 9, 23, 33; α = 0.79);

F5: Memory and self-efficacy (3 items: 17, 35, 37; α = 0.67).

F6: Uncontrollability (2 items: 7, 11; α = 0.75).

F7: Generational transmission of anxiety (2 items: 5, 29; α = 0.67).

We calculated Cronbach's alpha to measure internal consistency. The alphas for factors 1 through 7 were 0.91, 0.89, 0.89, 0.79, 0.67, 0.75, and 0.67, respectively, indicating good reliability for each factor. The overall scale had a reliability of α = 0.93.

The seven factors explained 55.8% of variance (Table 2). The correlations between the seven factors are provided in the Supplementary Figure 1.

The six items with factor loadings of less than 0.4 (1, 2, 14, 27, 32, and 40) were not included in any factor. Similarly to previous literature (Antonini Philippe et al., 2023), we used the total score of all 40 items in the subsequent analyses, rather than refining the scale by removing items.

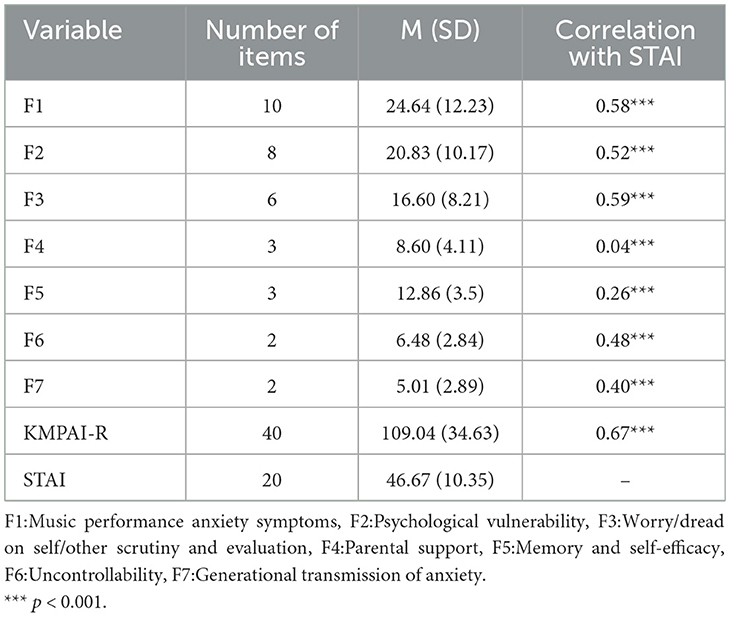

3.3 K-MPAI-R and STAI

The average score of the STAI-state was 46.67 (SD = 10.35) and Cronbach's alpha was 0.89. The K-MPAI-R scores were positively correlated with the STAI score (Table 3).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and correlations between K-MPAI-R factors (seven factors and total score) and STAI.

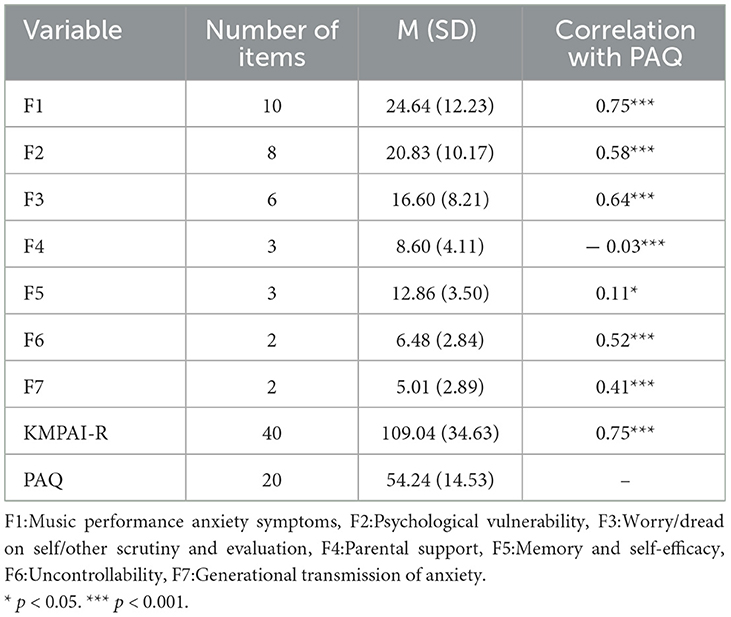

3.4 K-MPAI-R and PAQ

The average score of PAQ was 54.24 (SD = 14.53) and Cronbach's alpha was 0.94. The K-MPAI-R scores were positively correlated with the PAQ score (Table 4).

Table 4. Descriptive statistics and correlations between K-MPAI-R factors (seven factors and total score) and PAQ.

4 Discussion

This study developed a validated Japanese version of the K-MPAI-R. The results demonstrated that the developed questionnaire is reliable for measuring MPA. This conclusion is supported by a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.93, which indicates strong internal consistency.

The Japanese version of the K-MPAI-R showed a moderate level of correlation with the STAI-State (r = 0.67, p < 0.001), indicating its construct validity. The results are consistent with previous studies that showed moderate levels of correlations (r = 0.52 − 0.79) between other language versions of the K-MPAI-R and STAI-State (Antonini Philippe et al., 2022, 2023; Dias et al., 2022). The Japanese version of the K-MPAI-R also showed a moderate level of correlation with the PAQ (r = 0.75, p < 0.001). Since the PAQ measures the frequency of cognitive and somatic responses experienced during musical performances, its correlation with the K-MPAI-R further reinforces its criterion-related validity. The correlation was particularly strong for factors directly related to public performance, such as F1 and F3. These findings highlight the positive relationships between the K-MPAI-R and other measures of anxiety, strengthening the instrument's validity.

The factor structure of the Japanese version of the K-MPAI-R was derived through EFA. Factor 1, “Music Performance Anxiety Symptoms,” includes both somatic symptoms (Items 36, 30, 16, 12, and 22) and cognitive symptoms (Items 15, 26, 34, and 10) that appear before or during a performance. Factor 2, labeled “Psychological Vulnerability,” includes items related to low self-esteem (Items 6 and 13), lack of energy or motivation (Items 4 and 31), vague or unexplained anxiety (Items 3 and 19), performance-related anxiety (Item 20), and difficulty depending on others (Item 8). Factor 3, titled “Worry/Dread Focused on Self/Other Scrutiny and Evaluation,” contains items reflecting traits related to a general concern about being evaluated by others (Items 18, 38, and 39) and behaviors or emotions driven by the fear and worry associated with scrutiny (Items 21, 25, and 28). Factor 4, “Parental Support,” concerns whether parents were supportive and responsive, specifically regarding their responsiveness to needs, active listening, and encouragement for trying new things. Factor 5, “Memory and Self-Efficacy,” reflects a sense of confidence in one's memory and ability to perform well, even in stressful environments. Factor 6, “Uncontrollability,” expresses uncertainty about performance outcomes and the likelihood of making mistakes, regardless of effort or preparation. Factor 7, “Generational Transmission of Anxiety,” comprises items 5 and 29.

The factor structure of the Japanese version of the K-MPAI-R was generally consistent with other language versions, including English (Kenny, 2009a; Kenny et al., 2012), Spanish (Peru) (Chang-Arana et al., 2018), French (Antonini Philippe et al., 2022), Korean (Oh et al., 2020), Portuguese (Dias et al., 2022), Italian (Antonini Philippe et al., 2023), Polish (Kantor-Martynuska and Kenny, 2018) and Romanian (Faur et al., 2021). Among the extracted factors, Factors 1, 2, 4, and 5 were globally shared across multiple language versions. In addition, for the remaining factors, each had corresponding factors in other language versions (Supplementary Table 1). There were no factors derived only in the Japanese version. These findings suggest a consistency in the factor structure of the K-MPAI-R across languages. Overall, the factor structure of the Japanese version of the K-MPAI-R is closely aligned with that identified by Kenny et al. (2012). A comparison of the factors and the items they include can be found in the Supplementary Table 2.

This study involved 400 participants, including 309 musical instrument players and 91 singers, with an equal distribution between professional and amateur musicians. The results obtained from this diverse sample showed that the internal consistency, factor structure, construct validity, and criterion-related validity of the K-MPAI-R were all sufficient, demonstrating the reliability of the Japanese version of the K-MPAI-R. However, this study has several limitations. First, the Japanese version of the K-MPAI-R was validated using a sample of adults aged 18–64 years. Therefore, further investigation is needed to determine its applicability for individuals under 18. Second, while the factor structure of the Japanese version was generally consistent with the original English and other language versions, several differences were observed in the identified factors and/or the items included in them (Supplementary Table 2). Similar discrepancies can also be found between the English and other language versions (Supplementary Table 1). Future research should explore the factors underlying these differences, including potential cultural influences. Third, the present study collected responses from a broad sample, including both amateur and professional musicians, as well as instrumentalists and singers. Further research should analyze the K-MPAI-R scores within specific subgroups to explore individual characteristics associated with vulnerability to MPA.

Understanding MPA and its related factors in Japanese musicians using the K-MPAI-R may provide insights into both globally shared and Japanese-specific mechanisms underlying MPA. The Japanese version of the K-MPAI-R would lead to a deeper understanding of the prevalence and characteristics of MPA among Japanese musicians, contributing to the development of more effective interventions and support systems tailored to their needs.

Data availability statement

The deidentified questionnaire data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding authors upon request. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ST: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. MY: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by an internal grant of the AIST and JST PRESTO (Grant Number JPMJPR23IC).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Dianna T. Kenny for the kind assistance in translating the original version into Japanese and for providing valuable comments.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1543958/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

K-MPAI-R, Kenny Music Performance Anxiety Inventory-Revised; MPA, music performance anxiety; K-MPAI, Kenny Music Performance Anxiety Inventory; PAQ, Performance Anxiety Questionnaire; EFA, exploratory factor analysis; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; KMO, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin; MAP, Minimum Average Partial; TLI, Tucker-Lewis index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation.

References

Antonini Philippe, R., Cruder, C., Biasutti, M., and Crettaz Von Roten, F. (2023). The Kenny Music Performance Anxiety Inventory-Revised (K-MPAI-R): validation of the Italian version. Psychol. Music 51, 565–578. doi: 10.1177/03057356221101430

Antonini Philippe, R., Kosirnik, C., Klumb, P. L., Guyon, A., Gomez, P., and Crettaz Von Roten, F. (2022). The Kenny Music Performance Anxiety Inventory-Revised (K-MPAI-R): validation of the French version. Psychol. Music 50, 389–402. doi: 10.1177/03057356211002642

Bader, M., and Moshagen, M. (2022). Assessing the fitting propensity of factor models. Psychol. Methods. 30, 254–270. doi: 10.1037/met0000529

Barbar, A. E. M., De Souza Crippa, J. A., and De Lima Osório, F. (2014). Performance anxiety in Brazilian musicians: prevalence and association with psychopathology indicators. J. Affect. Disord. 152–154, 381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.09.041

Barlow, D. H. (2000). Unraveling the mysteries of anxiety and its disorders from the perspective of emotion theory. Am. Psychol. 55, 1247–1263. doi: 10.1037//0003-066X.55.11.1247

Burin, A. B., and Osório, F. L. (2017). Music performance anxiety: a critical review of etiological aspects, perceived causes, coping strategies and treatment. Rev. Psiquiatr. Clın. 44, 127–133. doi: 10.1590/0101-60830000000136

Chang-Arana, A. M., Kenny, D. T., and Burga-León, A. A. (2018). Validation of the Kenny Music Performance Anxiety Inventory (K-MPAI): a cross-cultural confirmation of its factorial structure. Psychol. Music 46, 551–567. doi: 10.1177/0305735617717618

Çiçek, V., and Güdek, B. (2020). Adaptation of the music performance anxiety inventory to turkish: a validity and reliability study. JASSS. 13, 153–163. doi: 10.29228/JASSS.45980

Cox, W. J., and Kenardy, J. (1993). Performance anxiety, social phobia, and setting effects in instrumental music students. J. Anxiety Disord. 7, 49–60. doi: 10.1016/0887-6185(93)90020-L

Dias, P., Veríssimo, L., Figueiredo, N., Oliveira-Silva, P., Serra, S., and Coimbra, D. (2022). Kenny music performance anxiety inventory : contribution for the Portuguese validation. Behav. Sci. 12:18. doi: 10.3390/bs12020018

Faur, A. L., Vaida, S., and Opre, A. (2021). Kenny music performance anxiety inventory: exploratory factor analysis of the Romanian version. Psychol. Music 49, 777–788. doi: 10.1177/0305735619896412

Fernholz, I., Mumm, J. L. M., Plag, J., Noeres, K., Rotter, G., Willich, S. N., et al. (2019). Performance anxiety in professional musicians: a systematic review on prevalence, risk factors and clinical treatment effects. Psychol. Med. 49, 2287–2306. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719001910

Hidemi, S., and Kuniharu, I. (1981). State trait anxiety questionnaire Japanese version. Jpn. J. Educ. Psychol. 29, 348–353. doi: 10.5926/jjep1953.29.4_348

Irie, N., Morijiri, Y., and Yoshie, M. (2023). Symptoms of and coping strategies for music performance anxiety through different time periods. Front. Psychol. 14:1138922. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1138922

Juncos, D. G., Heinrichs, G. A., Towle, P., Duffy, K., Grand, S. M., Morgan, M. C., et al. (2017). Acceptance and commitment therapy for the treatment of music performance anxiety: a pilot study with student vocalists. Front. Psychol. 8:986. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00986

Kantor-Martynuska, J., and Kenny, D. T. (2018). Psychometric properties of the Kenny-Music Performance Anxiety Inventory modified for general performance anxiety. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 49, 332–343. doi: 10.24425/119500

Kenny, D., and Ackermann, B. (2015). Performance-related musculoskeletal pain, depression and music performance anxiety in professional orchestral musicians: a population study. Psychol. Music 43, 43–60. doi: 10.1177/0305735613493953

Kenny, D., Driscoll, T., and Ackermann, B. (2012). Psychological well-being in professional orchestral musicians in Australia: a descriptive population study. Psychol. Music 42, 210–232. doi: 10.1177/0305735612463950

Kenny, D. T. (2009a). “The factor structure of the revised kenny music performance anxiety inventory,” in International Symposium on Performance Science (Utrecht: Association Européenne des Conservatoires), 37–41.

Kenny, D. T. (2009b). “Negative emotions in music making: Performance anxiety,” in Handbook of Music and Emotion: Theory, Research, Applications, eds. P. Juslin, and J. Sloboda (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Kenny, D. T. (2023). The Kenny Music Performance Anxiety Inventory (K-MPAI): scale construction, cross-cultural validation, theoretical underpinnings, and diagnostic and therapeutic utility. Front. Psychol., 14: 1143359. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1143359

Kenny, D. T., Davis, P., and Oates, J. (2004). Music performance anxiety and occupational stress amongst opera chorus artists and their relationship with state and trait anxiety and perfectionism. J. Anxiety Disord. 18, 757–777. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.09.004

Kenny, D. T., Fortune, J. M., and Ackermann, B. (2013). Predictors of music performance anxiety during skilled performance in tertiary flute players. Psychol. Music 41, 306–328. doi: 10.1177/0305735611425904

Kobori, O., Yoshie, M., Kudo, K., and Ohtsuki, T. (2011). Traits and cognitions of perfectionism and their relation with coping style, effort, achievement, and performance anxiety in Japanese musicians. J. Anxiety Disord. 25, 674–679. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.03.001

Mazzarolo, I., and Schubert, E. (2022). A short performance anxiety scale for musicians. Front. Psychol. 12:781262. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.781262

Oh, S., Yu, E.-R., Lee, H.-J., and Yoon, D.-U. (2020). Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Kenny Music Performance Anxiety Inventory. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 59:250. doi: 10.4306/jknpa.2020.59.3.250

Osborne, M. S., and Kenny, D. T. (2005). Development and validation of a music performance anxiety inventory for gifted adolescent musicians. J. Anxiety Disord. 19, 725–751. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.09.002

Paliaukiene, V., Kazlauskas, E., Eimontas, J., and Skeryte-Kazlauskiene, M. (2018). Music performance anxiety among students of the academy in Lithuania. Music Educ. Res. 20, 390–397. doi: 10.1080/14613808.2018.1445208

R Core Team (2024). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

Robson, K. E., and Kenny, D. T. (2017). Music performance anxiety in ensemble rehearsals and concerts: a comparison of music and non-music major undergraduate musicians. Psychol. Music 45, 868–885. doi: 10.1177/0305735617693472

Salmon, P. G. (1990). A psychological perspective on musical performance anxiety: a review of the literature. Med. Probl. Perform. Art. 5, 2–11.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., and Lushene, R. E. (1970). STAI Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (“Self-Evaluation Questionnaire”). Washington, DC: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Steptoe, A. (2001). “Negative emotions in music making: the problem of performance anxiety,” in Music And Emotion (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 291–308.

Studer, R., Gomez, P., Hildebrandt, H., Arial, M., and Danuser, B. (2011). Stage fright: its experience as a problem and coping with it. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 84, 761–771. doi: 10.1007/s00420-010-0608-1

Tabachnick, B. G., and Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using Multivariate Statistics. Boston: Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education, 5th edition.

Van Kemenade, J. F. L. M., Van Son, M. J. M., and Van Heesch, N. C. A. (1995). Performance anxiety among professional musicians in symphonic orchestras: a self-report study. Psychol. Rep. 77, 555–562. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1995.77.2.555

Wild, D., Grove, A., Martin, M., Eremenco, S., McElroy, S., Verjee-Lorenz, A., et al. (2005). Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (pro) measures: report of the ispor task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health 8, 94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x

William Revelle. (2024). psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University.

Yoshie, M., Kanazawa, E., Kudo, K., Ohtsuki, T., and Nakazawa, K. (2011). “Music performance anxiety and occupational stress among classical musicians,” in Handbook of Stress in the Occupations, eds. J. Langan-Fox and C. Cooper (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 409–425.

Yoshie, M., and Morijiri, Y. (2024). A research overview on music performance anxiety. Jpn. J. Res. Emot. 31, 28–40. doi: 10.4092/jsre.31.1_28

Yoshie, M., and Shigemasu, K. (2006). “Effects of state anxiety on performance in pianists: Relationship between the Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2 subscales and piano performance,” in Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Music Perception and Cognition (Bologna), 394–401.

Keywords: music performance anxiety, K-MPAI, factor analysis, validation, anxiety inventory, musician

Citation: Takagi S, Yoshie M and Murai A (2025) Validation of the Japanese version of the Kenny Music Performance Anxiety Inventory-Revised. Front. Psychol. 16:1543958. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1543958

Received: 12 December 2024; Accepted: 24 April 2025;

Published: 18 June 2025.

Edited by:

Andrea Schiavio, University of York, United KingdomReviewed by:

Noah Henry, University of Amsterdam, NetherlandsYuko Arthurs, Goldsmiths University of London, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Takagi, Yoshie and Murai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sakie Takagi, c2FraWUudGFrYWdpQGFpc3QuZ28uanA=; Michiko Yoshie, bS55b3NoaWVAYWlzdC5nby5qcA==

Sakie Takagi

Sakie Takagi Michiko Yoshie

Michiko Yoshie Akihiko Murai

Akihiko Murai