Abstract

Introduction:

The Uncanny Valley Effect (UVE) describes the discomfort users feel when interacting with Embodied Conversational Agents (ECAs) that display human-like features, often resulting in anxiety, disgust, and avoidance. This systematic review investigates how user characteristics and ECA design features influence UVE, aiming to provide insights for improving user engagement.

Methods:

Following PRISMA guidelines, we screened 21,897 papers from ACM Digital Library, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, ProQuest, and Web of Science, with 29 studies meeting the inclusion criteria. These studies focused on the roles of anthropomorphism, attractiveness, and uncanniness in user interactions with ECAs.

Results:

Using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) tool, most studies were rated as having weak to moderate methodological quality. We developed a Checklist for Avoiding the Uncanny Valley Effect in ECAs, offering critical recommendations across key dimensions such as physical appearance, non-verbal and verbal communication, and the incorporation of social and cultural norms. Additionally, our review underscores the need for methodological improvements.

Discussion:

Future studies must address confounding variables with greater precision, provide transparent reporting on participant withdrawal, and employ more robust, standardized measurement tools to generate reliable and actionable findings. Without these advancements, the field risks perpetuating inconclusive and contradictory insights, limiting the development of ECAs that effectively engage users while mitigating the UVE.

Systematic review registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42023426584, identifier: CRD42023426584.

Introduction

Embodied Conversational Agents (ECAs) are revolutionizing education and healthcare, bringing cost-effective, adaptable, and portable solutions to the table (Boian et al., 2024; Kavanagh et al., 2017; Philip et al., 2020; Podina et al., 2023; Podina and Caculidis-Tudor, 2023; Ter Stal et al., 2021). In a nutshell, ECAs are digital entities with anthropomorphic features that facilitate both verbal and non-verbal interactions with users (Liew and Tan, 2021; Loveys et al., 2020a). Their interaction skills are becoming more versatile. ECA can emulate intuitive interactions with people via vocal characteristics, facial expressions, gestures, and, more recently, personality traits (Liew and Tan, 2021; Nass and Moon, 2000; Sebastian and Richards, 2017; Provoost et al., 2017; Ter Stal et al., 2021). In human interactions, research consistently shows that similarity fosters more enjoyable communication and a stronger interpersonal bond (Burleson and Denton, 1992; Philipp-Muller et al., 2020). This principle has influenced the design of ECAs, under the assumption that greater anthropomorphism would lead to more pleasant interaction with ECAs. However, studies have shown a paradoxical effect when it comes to achieving the optimal level of anthropomorphism, known as the Uncanny Valley Effect (UVE), which is an intriguing facet of user psychology that remains conceptually and empirically inconsistent.

In this review, we do not aim to suggest a novel definition, further amplifying the lack of consensus in the literature, but rather to clarify existing ones by organizing them within a coherent conceptual model. We adopt a tripartite model of the UVE that distinguishes between three key components and apply this theoretical framework specifically in the case of ECAs: anthropomorphism, attractiveness, and uncanniness (Diel et al., 2021; Ho and MacDorman, 2017; Mara et al., 2022; Mori et al., 2012; Stein and Ohler, 2017; Zhang et al., 2020): (1) Anthropomorphism refers to the degree to which an ECA resembles users in terms of physical, behavioral, and mental characteristics, (2) Attractiveness is related to the positive appraisal of an ECA, perceived as enjoyable, likeable, intelligent, or friendly, and (3) Uncanniness refers to the negative appraisal of an ECA, perceived as disgusting, ugly, or threatening. We broadened the UVE definitions to encompass the emotions and behavioral reactions of the user. Typically, once an ECA’s anthropomorphism increases, the attractiveness also increases until a threshold of around 65% (Slijkhuis, 2017). Heightened levels of attractiveness in ECAs can trigger emotions like calmness, happiness, enthusiasm, and a greater willingness to engage with the ECA (Diel et al., 2021; Ho et al., 2008). However, beyond that threshold of anthropomorphism, attractiveness decreases and uncanniness increases. At higher levels of uncanniness, users experience emotions like fear, anxiety, or disgust and a willingness to avoid the ECA (Mori et al., 2012; Slijkhuis, 2017; Urgen et al., 2018). The exact point where this shift occurs is still debated, with some research suggesting that UVE is strongest when perceived anthropomorphism is between 10 and 30% or 70–90% (Kim et al., 2020; Mori et al., 2012).

Understanding UVE remains challenging due to the existence of multiple competing hypotheses that try to explain our perception of anthropomorphism in ECAs. These range from the morbidity and movement hypotheses to the category ambiguity (Cheetham and Jancke, 2013; Kätsyri et al., 2015; Pollick, 2010). Among these, the perceptual mismatch hypothesis has received strong empirical support. It suggests that users feel uncanniness when they perceive inconsistencies across different levels of anthropomorphism between ECAse features (Kätsyri et al., 2015; Pollick, 2010). Another influential explanation of the UVE is provided by the Cognitive Expectation Violation Theory (CEVT), which proposes that highly anthropomorphic ECAs may generate unrealistic expectations, which, when unmet, lead to uncanniness (Grimes et al., 2021). However, as ECAs become sophisticated, not only in their appearance, but also in their ability to simulate emotions and mental states, appearance-based theories alone no longer suffice. The Uncanny Valley of Mind (UVM) broadens this perspective by highlighting the role of perceived cognitive and emotional anthropomorphism (Desideri et al., 2021; Di Natale et al., 2023; Gray and Wegner, 2012; Stein and Ohler, 2017). Still, determining an excessive level of anthropomorphism remains difficult, as it is not simply an experimental variable to be manipulated in controlled conditions. Anthropomorphism is also a subjective and context-dependent perception shaped by user characteristics (Dubois-Sage et al., 2023). One such characteristic is Theory of Mind (ToM), which is the ability to attribute emotional states to others in order to understand and predict behaviors (Dubois-Sage et al., 2023; Premack and Woodruff, 1978). ToM is linked to social activity and verbal reasoning of the user (Iglesias-Pazo et al., 2025). These individual differences complicate the efforts to predict outcomes such as attractiveness and uncanniness. To better align theory with the features of next-generation ECAs, this systematic review explores how user characteristics and ECA features may mediate or moderate the relationship between anthropomorphism, attractiveness and uncanniness.

Furthermore, the empirical study of the UVE is hampered by methodological inconsistencies, particularly in how the UVE is measured. A major limitation lies in the over-reliance on subjective self-report instruments, which use binary adjective pairs (e.g., familiar-unfamiliar, inert-interactive) drawn from widely used tools such as the Godspeed Questionnaire (Bartneck, 2023; Ho and MacDorman, 2017; Tobis et al., 2023). However, these scales often lack the nuance needed to capture the emotional ambivalence central to the UVE. Moreover, certain items may be semantically ambiguous: for instance, the term interactive might be interpreted as physically responsive by some users and socially communicative by others, undermining reliability and interpretability. Behavioral measures, such as eye-tracking, are also frequently used but raise interpretive challenges. These responses may reflect perceptual salience or cognitive load rather than affective discomfort (Cheetham and Jancke, 2013; Matsuda et al., 2012), making it difficult to isolate the psychological mechanisms specific to UVE. Similarly, although physiological and neural data (e.g., EEG) are occasionally included, no consistent biomarker has been established across studies or stimulus types (Gorlini et al., 2023). Despite the absence of a clear consensus on UVE in the literature, its real-world financial consequences are undeniable. Disney’s infamous $150 million loss from “Mars Needs Moms” due to unsettling character designs is a stark reminder of how the UVE can severely impact humans (Schwind et al., 2018).

The present paper provides a robust evaluation of past research and offers recommendations for future studies, helping scientists and practitioners develop ECAs that effectively mitigate the UVE while enhancing user engagement. Our systematic review goes beyond previous work by simultaneously examining how user characteristics and ECA features interact to shape perceptions of anthropomorphism, attractiveness, and uncanniness. This approach not only clarifies the underlying mechanisms of the UVE but also offers practical insights for designing ECAs that are better aligned with user expectations. Specifically, we address three central research questions to advance the field: Q1. To what extent is UVE present in user interactions with ECAs? Currently, the presence of UVE in ECA interactions remains uncertain. While there is significant evidence of UVE in human-robot interactions, much less is known about its occurrence in user-ECA interactions; Q2. Which user characteristics are associated with how users perceive the ECA in terms of anthropomorphism, attractiveness, or uncanniness? Examining how user characteristics impact perceptions is important for tailoring a customer profile, which allows for more effective interactions; Q3. What ECA features are connected to how users perceive the ECA in terms of anthropomorphism, attractiveness, or uncanniness? Pinpointing which ECA features shape user perceptions enables us to refine design elements and make ECAs more appealing.

This systematic review presents several innovative contributions that address critical gaps in the literature on the UVE. Firstly, this review breaks new ground by investigating the behavioral and mental attributes of ECAs that contribute to perceptions of anthropomorphism, attractiveness, or uncanniness—areas that have been largely neglected in favor of a focus on physical appearance (Kätsyri et al., 2015; Mara et al., 2022). Prior studies have disproportionately emphasized the visual resemblance of ECAs to humans, despite evidence that the UVE intensifies when ECAs mimic not just physical traits but also cognitive and emotional characteristics (Jiang et al., 2022; Stein and Ohler, 2017). By shifting the focus to these less explored aspects, this review offers a more nuanced understanding of what makes an ECA feel “human-like” and how this can trigger both positive and negative reactions. Secondly, this review is pioneering in its examination of how the UVE may evolve during active user-ECA interactions. Most studies to date have relied on passive forms of engagement, such as showing participants photos or videos of ECAs, which do not fully capture the complexity of real-time interaction (Santamaria and Nathan-Roberts, 2017). An active type of interaction implies dynamic conversational exchanges between users and ECAs. This review offers a more realistic assessment of how the UVE manifests in everyday settings, where users are not merely passive observers but active participants in the interaction. Finally, the review goes beyond a purely theoretical contribution by offering both methodological and practical recommendations that can guide future research and development. These insights are designed to help scientists improve experimental designs and assist engineers in creating ECAs that are not only more effective but also tailored to individual user traits. This forward-thinking approach emphasizes the need for personalized ECAs that can better accommodate user diversity, enhancing both usability and emotional engagement. In sum, this systematic review provides a much-needed critical analysis of the UVE, addressing its underexplored aspects and offering actionable solutions.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Potentially relevant papers were found after a thorough search of Scopus, Web of Science, ProQuest, IEEE Explore, and ACM Digital Library in July 2024. These databases were selected based on an initial scan of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on user-ECA interactions (Dey et al., 2018; Diel et al., 2021; Jiang et al., 2022; Kätsyri et al., 2015; Kavanagh et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2020; Liew and Tan, 2021; Yao and Luximon, 2020), which revealed that these five sources were the most commonly used. The search strategy was designed to prioritize recall over precision in the initial phase, aiming to capture a broad, interdisciplinary body of literature on the UVE and ECAs, which resulted in over 21,000 records. We cross-checked our results against reference lists from recent reviews and key studies in th field to ensure adequate coverage.

The full search string is provided below:

("uncanny valley" OR "uncanny valley effect" OR user* OR similar* OR real* OR affinity OR familiar* OR warm* OR likab* OR pleas* OR attract* OR appeal* OR friend* OR natural* OR intelligen* OR esthetic OR beaut* OR harm* OR accept* OR valence OR arousal OR eerie OR creep* OR uncann* OR weird OR strange* OR typic* OR comfort* OR threat* OR dominan* OR ugl* OR dull OR freak* OR predict* OR bor* OR shock* OR thrill* OR bland OR emotional OR anomaly OR disgust*) AND (embodied agent* OR embodied conversation* agent OR embodied conversation* OR interface agent* OR embodied social agent* OR embodied virtual agent* OR embodied companion agent* OR embodied computer agent* OR relational agent* OR empathic agent* OR conversation* agent* OR interface agent* OR animated agent* OR computer agent* OR emotion agent* OR exercise agent* OR motivation* agent* OR virtual agent* OR virtual character* OR virtual user* OR virtual coach* OR virtual advisor* OR virtual specialist* OR virtual dialog* agent* OR avatar OR pedagogical agent* OR learning partner* OR virtual tutor* OR social robot*) AND (experience* OR user* OR expectation* OR usability OR understanding* OR bias* OR emotion* OR attitude* OR interact* OR conversation* OR cooperat* OR cognit* OR evaluation OR assessment OR social*).

The search string was meticulously constructed by employing previously defined synonyms for the UVE (Diel et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020), synonyms for the ECA (Loveys et al., 2020a), and for user-chatbot interactions (Rapp et al., 2021).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included research that assessed a minimum of (a) one of the UVE variables (anthropomorphism, attractiveness, or uncanniness), through (b) quantitative data based on (c) dynamic and engaging interactions involving dialogues or interactive gaming experiences (d) between individuals and ECAs. Specifically, we focused on papers that examined (e) how users perceive social interaction with (f) ECA representations that differ from the physical characteristics of the individuals involved. These studies were required to be (g) peer-reviewed and written in (h) English. Finally, the age of the participants wasn’t an inclusion criterion.

We excluded qualitative research without reported data, as well as studies involving individuals with psychological or physical disabilities, such as autism spectrum disorder, dementia, or multiple sclerosis, as the perception of the ECAs might differ (Feng et al., 2018; Olaronke et al., 2017). Moreover, we also excluded studies examining interactions with ECA through images or videos, since they can be considered passive forms of interaction (Coan and Allen, 2007), especially due to the ECA’s inability to respond to user input. Additionally, we excluded research that focused solely on ECA design and development or user performance in a task. Furthermore, we excluded research featuring ECAs with machine-like or pet-like appearances, as these features are expected to lower perceived uncanniness reported by users (MacDorman, 2005). Finally, studies where ECAs shared the same face or body as participants were also excluded, as this choice of representation might lead to higher uncanniness regarding the ECA (Schwind et al., 2017).

Selection of studies

The review protocol has been officially registered on PROSPERO1 under the registration number: CRD42023426584. This review followed the guidelines outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses2.

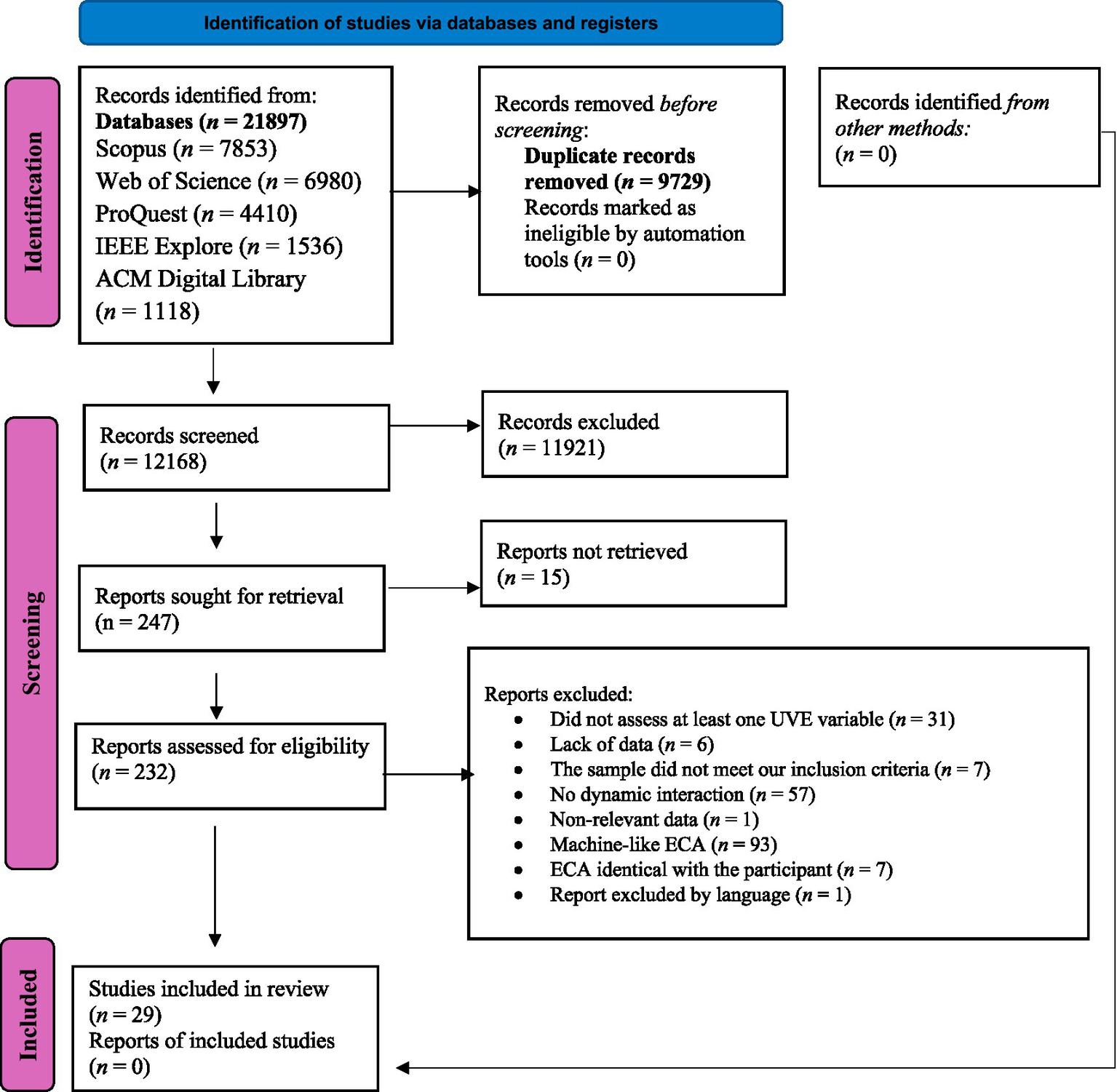

Following an exhaustive search, we initially identified a total of 21,893 online records, as depicted in Figure 1. After removing duplicates, we examined the title and abstracts of the remaining studies to assess their potential relevance. The full text of the remaining 247 articles was analyzed in detail. Our meticulous selection process resulted in the inclusion of 29 studies that rigorously met the predefined criteria. The citations for these included publications are accessible in the Supplementary materials.

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram of the selection process.

Data extraction

Table 1 presents the key characteristics of the included studies. Data extraction was guided by a standardized coding scheme developed based on prior reviews (Liew and Tan, 2021; Loveys et al., 2020b) and structured around the PEO model (Population–Exposure–Outcome), which is widely used in systematic reviews to enhance methodological transparency (Hosseini et al., 2024). Additionally, while we calculated inter-rater agreement for the quality appraisal of the included studies, we did not conduct inter-rater reliability procedures during the data extraction phase. Data extraction was performed by one author, with ongoing consultation and consensus discussions with a senior co-author. Nevertheless, the absence of independent double coding means that some degree of individual bias cannot be entirely ruled out, despite our best efforts to ensure accuracy and consistency. To ensure that the template for data extraction captured all relevant information, we piloted it on two studies, as recommended in the best practice guidelines (Büchter et al., 2020; Higgins and Green, 2008). Any discrepancies or uncertainties were discussed and resolved by consensus.

Table 1

| References | UVE Status | ECA type (gender, body motion) | User-ECA interaction | Study characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECA behavior type (scripted, wizard of Oz, autonomous) | User characteristics (age range, mean age, standard deviation) | Type and time of engagement | Sample size (% females) | Randomization | UVE outcomes (assessment method) | Assessment tools (Nr. of items) | |||

| Appel et al. (2012) | Not clear | Female, Half body, Dynamic | NS | Mixed ages, M = 36.2, SD = 12.2 | Structured dialogue, NS | 90 (54%) | Yes | Attractiveness, Uncanniness (Subjective, Behavioral) | RS (24) |

| Bailey and Schloss (2024) | Yes | Female, Full Body, Dynamic | NS | Children, M = 7.92, SD = 1.1 | Game, 20 min | 25 (32%) | Yes | Anthropomorphism, Uncanniness (Subjective, Behavioral) | IDAQ-CF (12) |

| Belda-Medina and Calvo-Ferrer (2022) | Not clear | Female, Half body, Dynamic | Scripted | Young adults, NS, NS | Training, NS | 176 (80%) | No | Attractiveness (Subjective, Behavioral) | CHISM (15) |

| Buttussi and Chittaro (2019) | Not clear | Male, Half body, Dynamic | Autonomous | Young adults, M = 22.0, SD = 1.7 | Training, 30–45 min | 94 (20%) | No | Attractiveness, Uncanniness (Subjective) | APAPQ (26) |

| Conrad et al. (2015) | Yes | Male, Face only, Dynamic | Scripted | Mixed ages, M = 36.8, NS | Structured dialogue, 5–7 min | 75 (50%) | Yes | Attractiveness Uncanniness and Anthropomorphism (Subjective, Behavioral) | NA (11) |

| Creed and Beale (2012) | Not clear | Female, Face only, Dynamic | Scripted | Young adults, NS, NS, | counseling, 10 min | 50 (58%) | Yes | Attractiveness Uncanniness (Subjective) | NA (24) |

| Falcone et al. (2022) | Not clear | Female, Half body, Dynamic | Wizard of Oz and Scripted | Mixed ages, NS, NS | Structured dialogue, 5 min | 36 (44%) | No | Attractiveness, Anthropomorphism (Subjective) | GQS (NS) |

| Hale and Hamilton (2016) | Not clear | Female, Face only, Dynamic | NS | NS, NS, NS | Structured dialogue, NS | 54 (68%) | No | Attractiveness (Subjective, Behavioral) | NA (1) |

| Ham et al. (2024) | Not clear | Female, Half body, Static | NS | Mixed ages M = 31.07, SD = 5.71 | Instagram posts, 0.16 min | 165 (44%) | Yes | Anthropomorphism, Attractiveness, Uncanniness (Subjective) | PEI, PA, ATVI (45) |

| Hao et al. (2024) | Not clear | Female, Half body, Dynamic | Scripted | Mixed Ages, NS NS | Structured dialogue, NS | 354 (32%) | Yes | Attractiveness (Subjective) | NA (1) |

| Lahav et al. (2020) | Not clear | Female, Half body, Dynamic | NS | Young adults, M = 23.24, SD = 2.28 | counseling, 12 min | 42 (57%) | No | Attractiveness, Uncanniness (Subjective) | NA (2) |

| Lisetti et al., 2004 | Not clear | Female, Face only, Dynamic | NS | Young adults, M = 23.04, SD = 3.11 | Structured dialogue | 56 (75%) | No | Attractiveness, Anthropomorphism (Subjective) | NA (8) |

| Luo et al. (2023) | Not clear | Mixed, Half body, Dynamic | NS | Young adults, M = 23.77, SD = 2.95 | Game, NS | 48 (56%) | Yes | Attractiveness, Uncanniness (Subjective) | IEPS (8) |

| Min et al. (2024) | Not clear | Mixed, Half body, Dynamic | Scripted | NS, NS, NS | Structured dialogue, NS | 465 (63%) | Yes | Attractiveness (Subjective) | NA (4) |

| Neumann et al. (2023) | Not clear | Female, Full body, Dynamic | NS | Young adults, M = 24.47, SD = 4.45 | Structured dialogue, 25 min | 36 (58%) | Yes | Anthropomorphism (Subjective) | NA (2) |

| Prendinger and Ishizuka (2001) | Not clear | Male, Full body, Dynamic | Scripted | NS, NS, NS | Structured dialogue, 3 min | 16 (NS) | Yes | Attractiveness (Subjective) | NA (1) |

| Prendinger et al. (2006) | Not clear | Male, Face only, Dynamic | NS | Mixed ages, M = 30, NS | Game, 10 min | 32 (56%) | Yes | Uncanniness | NA (NA) |

| Saad and Choura (2022) | Not clear | NS, NS, Dynamic | NS | Mixed ages, NS, NS, | Structured Dialogue, NS | 1,262 (41%) | No | Anthropomorphism (Subjective) | PRS (12) |

| Sajjadi et al. (2019) | Not clear | Female, Half body, Dynamic | Scripted | Mixed ages, NS, NS, | Structured Dialogue, 15 min | 41 (46%) | Yes | Uncanniness, Attractiveness (Subjective) | GEQ (3) |

| Schouten et al. (2017) | Not clear | Female, Half body, Static | Wizard of Oz | Mixed ages, M = 25.7, SD = 4.4 | counseling, 30 min | 34 (41%) | No | Attractiveness (Subjective, Behavioral, Physiological) | PAQ (3) |

| Song and Shin (2022) | Yes | Male, Face only, Mixed | NS | Young adults, M = 24.2 SD = 6.2, | Structured Dialogue, 0.75 min | 185 (63%) | Yes | Uncanniness (Subjective) | SHM (4) |

| Ter Stal et al. (2021) | Not clear | Female, Half body, Dynamic | Wizard of Oz and Autonomous | Mixed ages, M = 48, SD = 22 | Structured Dialogue, NS | 63 (57%) | Yes | Anthropomorphism, Attractiveness (Subjective) | RS (3) |

| van Pinxteren et al. (2023) | Not clear | Female, Half body, Dynamic | Scripted | Mixed ages, M = 23, SD = 6.5 | Structured Dialogue, NS | 142 (63%) | Yes | Attractiveness (Subjective) | SFVDP (10) |

| Volante et al. (2016) | Yes | Male, Half body, Dynamic | NS | Young adults, NS, NS | Training, NS, NS | 62 (41%) | No | Attractiveness, Uncanniness (Subjective) | NA (3) |

| Wang et al. (2021) | Yes | Female, Half body, Dynamic | NS | Mixed ages, M = 25.3, SD = 7.4 | Game, 2 min | 21 (42%) | Yes | Anthropomorphism, Attractiveness (Subjective) | NA (4) |

| Yin et al. (2021) | Yes | Male, Face only, Static | NS | Young adults, NS, NS | Structured Dialogue, 4 min | 80 (53%) | Yes | Anthropomorphism, Uncanniness (Subjective) | NA (4) |

| Zhang et al. (2024) | Not clear | Female, Half body, Static | NS | Young adults, M = 26.12 NS | Structured Dialogue, NS | 183 (59%) | Yes | Anthropomorphism (Subjective) | NA (4) |

| Zheleva et al. (2023) | Yes | Female, Half body, Dynamic | Scripted | NS, M = 25.6, SD = 11.3 | Game, NS | 44 (100%) | No | Uncanniness (Subjective, Behavioral) | GQS (1) |

| Zibrek et al. (2018) | Yes | Male, Mixed, Dynamic | NS | NS, NS, NS | Structured Dialogue, NS | 222 (NS) | Yes | Anthropomorphism, Attractiveness, Uncanniness Subjective | NA (5) |

Characteristics of the studies included.

NS, Not specified; NA, Not applicable; RS, Rapport Scale; CHISM, Chatbot-User Interaction Satisfaction Model; APAPQ, Animated Pedagogical Agent Perception Questionnaire; GQS, Godspeed Questionnaire Series; PRS, Perceived Realism Scale; GEQ, Game Experience Questionnaire; PAQ, Participant Assessment Questionnaire (affective subscale); SHM, Scale proposed by Ho and MacDorman (subscale Uncanniness); RS, Rapport Scale; IDAQ-CF, The Individual Differences in Anthropomorphism-Child Form; PEI, Perceived emotional intelligence; PA, Perceived anthropomorphism; ATVI, Attitude toward the Virtual Influencer; IEPS, Izard Emotional Perception Scale; SFVDP, scale from Von Der Pütten et al. (2010). Rows highlighted in green indicate significant evidence for the Uncanny Valley Effect. Rows highlighted in yellow indicate inconclusive results regarding the Uncanny Valley Effect.

First, we extracted publication details, including the author(s) details and year of publication. Second, population characteristics such as total sample size, gender distribution, and average age with standard deviations. Third, we extracted information about the exposure to ECAs, including whether the study used a randomized or non-randomized design, ECA Behavior Type (Scripted, Wizard of Oz, Autonomous), the ECA’s gender, body type (e.g., face-only, half-body without legs, or full-body with legs), type of motion (e.g., static, capable of gestures, or full-body movement), and time of exposure (in minutes). We also examined the type of engagement involved, specifically what the users and ECAs did during the interaction. Here, we differentiated between simple scripted conversations (e.g., structured dialogues), more complex interactions requiring adaptability from the ECA, such as counseling (e.g., for health-related guidance) or training (e.g., educational tasks). Finally, we coded the outcomes assessed, specifying the type and number of outcome measures used. We differentiated between subjective ratings (e.g., Godspeed indices), behavioral responses (e.g., reaction times), and physiological measures (e.g., EEG). We also noted whether measurement tools were standardized or developed ad hoc, and whether the study reported significant results related to the Uncanny Valley Effect (UVE).

Quality assessment

The assessment of the risk of bias and overall quality of the included studies was performed using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) guidelines (Armijo-Olivo et al., 2014, Sievers et al., 2018). While UVE is not traditionally a public health topic, many of the psychological and emotional factors explored in UVE research overlap with public health studies, particularly in terms of understanding human behavior and wellbeing. The decision to use EPHPP in the present systematic review was based on its versatility in evaluating various study designs and offering a structured approach to judging evidence quality.

The EPHPP guidelines provide a consistent, and comprehensive framework of critical methodological aspects of each study across several dimensions: (a) selection bias, (b) research design, (c) controlling for confounders, (d) blinding, (e) data collection methods, and (f) withdrawals and dropouts (Thomas et al., 2004).3 Two independent evaluators assessed each criterion as either strong, moderate, or weak, resulting in an overall quality rating for each study. Each reviewer received identical training and guidance documents for utilizing the tools, ensuring uniformity in their approach. A study was categorized as strong if it received at least four strong ratings and no weak ratings. Studies with less than four strong ratings and no more than one weak rating were assigned a moderate overall rating, whereas studies with at least two weak ratings were classified as weak overall quality (Sievers et al., 2018). The inter-reviewer agreement was strong, with a coefficient of k = 0.85 for the overall study quality. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion until a complete consensus was reached. A study classified as strong indicates a lower risk of bias, whereas a study coded as weak suggests a higher risk of bias (see Table 2).

Table 2

| Study ID | Selection | Design | Confounders | Blinding | Data collection | Withdrawals | OVERALL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appel et al. (2012) | Weak | Strong | Weak | Strong | Strong | Weak | Weak |

| Bailey and Schloss (2024) | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| Belda-Medina and Calvo-Ferrer (2022) | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate |

| Buttussi and Chittaro (2019) | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Moderate |

| Conrad et al. (2015) | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| Creed and Beale (2012) | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Falcone et al. (2022) | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak |

| Hale and Hamilton (2016) | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| Ham et al. (2024) | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Weak |

| Hao et al. (2024) | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak |

| Lahav et al. (2020) | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Moderate |

| Lisetti et al., 2004 | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Weak |

| Luo et al. (2023) | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Min et al. (2024) | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Neumann et al. (2023) | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Prendinger and Ishizuka (2001) | Weak | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak |

| Prendinger et al. (2006) | Weak | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Weak |

| Saad and Choura (2022) | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Moderate |

| Sajjadi et al. (2019) | Strong | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Schouten et al. (2017) | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Weak |

| Song and Shin (2022) | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Strong | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| Ter Stal et al. (2021) | Weak | Strong | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Weak |

| van Pinxteren et al. (2023) | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| Volante et al. (2016) | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Moderate |

| Wang et al. (2021) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| Yin et al. (2021) | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| Zhang et al. (2024) | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak |

| Zheleva et al. (2023) | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Zibrek et al. (2018) | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

Quality assessment results following the usage of the EPHPP instrument.

, Strong quality;

, Strong quality;  , Moderate quality;

, Moderate quality;  , Weak quality.

, Weak quality.

Results

Study characteristics

A substantial portion of the studies included in our systematic review have been published in recent years. The trend in this research area spans over two decades. Notably, up to five studies (17%) were published in 2024, and four studies (13%) were published in 2023, which demonstrates the current importance of the UVE.

The present systematic review encompassed a total of 4,153 users, exhibiting a broad age range from 5 to 88 years old, with a slightly higher representation of females. Regarding ECA features, many studies opted for female-gendered ECAs (18 papers, 62%), and half-body ECAs (17 papers, 58%). The predominant choice among the studies was three-dimensional ECAs exhibiting dynamic movement capabilities (24 papers, 82%) and lacking customization options. More than half of the included studies did not clearly specify what type of behavior had the ECA (16 papers, 55%), but most of the studies that clearly specified it, used ECAs with a scripted behavior. Finally, when it comes to interaction, the average user-ECA interaction duration across studies was 11 min. Unfortunately, most of the studies did not specify the exact engagement time between users and ECAs. Notably, all participants were actively engaged in the interaction with the ECAs. The primary user engagement observed was structured dialogue (17 papers, 58%), followed by interactive games involving both users and ECAs (5 papers, 17%). The remaining studies employed ECA-delivered training sessions (3 papers, 10%), and counseling sessions facilitated by the ECA (3 papers, 10%).

Shifting the focus to the characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. In terms of study characteristics, the prevailing design among the included papers was between-subject (18 papers, 62%), followed by within-subject design (7 papers, 24%), and cross-sectional design (3 papers, 15%). Only one study employed a within-subject design (1 paper, 5%). No study within our review explored the UVE in user-ECA interactions through a longitudinal design, tracking changes over time. Notably, more than half of the included studies randomized participants between conditions (19 papers, 65%). Moreover, a minority of studies measured simultaneously all 3 outcomes of the UVE (3 papers, 15%), and the most extensively studied outcome among these papers was the attractiveness of the ECA (21 papers, 72%). All studies utilized subjective measurements (29 papers, 100%), evaluating UVE through questionnaires or single-itemrevisi questions. However, some studies also used behavioral (7 papers, 24%), including metrics such as gaze time or the count of user-initiated interactions. Additionally, a smaller portion utilized physiological measures (1 paper, 3%), employing metrics such as skin conductance. Half of the studies created their own subjective measurements for the UVE with either singular or multiple items (15 papers, 52%), while the remaining studies used questionnaires to measure the UVE outcomes (14 papers, 48%).

Interestingly, a diverse range of data collection techniques was observed, including behavioral measures like word count, usage of pause-fillers (e.g., “erm,” “hm”), frequency of broken words (e.g., “I was in the bib… library”), time spent interacting with the ECA, and gaze time, as well as acknowledgement through channel utterances such as “okay,” “all right,” “got it,” “thank you” (Appel et al., 2012; Bailey and Schloss, 2024; Buttussi and Chittaro, 2019; Min et al., 2024). Additionally, physiological measures including skin conductance, electromyography, and photoplethysmography were employed in some studies (Lahav et al., 2020; Min et al., 2024). Additionally, several studies in our review included qualitative interviews. These interviews aimed to gather in-depth user feedback, asking questions such as: “What did you like most about the ECA?” and “What did you like least about the ECA?” (Volante et al., 2016). This qualitative approach provided valuable insights into user preferences and experiences with the ECA.

Methodological quality of included studies

A quality appraisal using the EPHPP tool (Armijo-Olivo et al., 2014) revealed that most of the included studies were rated as either weak (17 studies, 59%) or moderate (12 studies, 41%) in overall methodological quality (see Table 2). This indicates a high risk of bias across the evidence base, limiting the reliability and generalizability of findings related to the UVE.

To begin, a notable strength was that most studies (21 studies, 72%) reported using randomized designs and therefore received a strong rating for study design. However, few studies clearly described the randomization process, such as how the allocation sequence was generated and whether allocation was concealed. Without this information, the risk of selection bias remains, despite claims of randomization. Moreover, no studies reported whether randomization accounted for relevant sample characteristics (e.g., gender, age, familiarity with technology), which are likely to influence user responses to ECAs.

In terms of data collection methods, fewer than half of the studies (13 studies, 44%) employed established instruments such as the Godspeed scale. While this tool has its own limitations, it is nonetheless a recognized standard in the field. In contrast, a substantial number of studies relied on ad hoc instruments, meaning that items or scales were created specifically for a single study without prior validation or theoretical grounding. Moreover, a particularly concerning issue is the widespread use of subjective rating scales without reporting internal consistency (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha) or construct validation procedures. The lack of psychometrically proven tools seriously undermines the interpretability and comparability of outcomes.

Most studies were rated as moderate in terms of participant selection (23 studies, 79%), primarily due to unclear recruitment procedures and limited information on sampling frames. Although many studies used appropriate populations (e.g., adults interacting with ECAs), the absence of details on consent processes, recruitment settings, and inclusion/exclusion criteria limits generalizability and replicability.

Blinding was inconsistently addressed. While over half of the studies mentioned participant blinding (16 papers, 55%), few provided information about whether evaluators or technical personnel were blinded to the study hypotheses or conditions. This omission is especially problematic for studies relying on behavioral responses, where observer bias and expectancy effects can influence results.

Two domains were consistently weak: confounder variables (18 papers, 62%) and the withdrawal of participants (14 papers, 48%). Across studies, control for potential confounding variables was generally inadequate. Few investigations accounted for individual differences likely to modulate the UVE, such as prior exposure to ECAs or baseline trait anxiety. The omission of these variables limits the ability to interpret whether observed effects are attributable to the experimental manipulations or to uncontrolled participant characteristics.

Similarly, reporting on participant attrition was often insufficient. In nearly half of the studies, dropout rates were either missing or superficially addressed, leaving it unclear whether participants could withdraw due to technical issues, lack of engagement, or the UVE. Without transparent documentation of participant flow and reasons for withdrawal, it is difficult to assess whether the final samples remained representative of the target population.

Main results

Half of the studies measured user-ECA engagement through structured dialogue, where ECAs asked questions like “How can I assist you?” or interacted with users by administering surveys with questions related to housing or jobs. Almost all ECAs were dynamic, utilizing gestures or facial expressions. Gender representation was balanced, with half of the ECAs depicted as female and the other half as male, and approximately 50% featured half-body representations. The sample sizes in the studies varied, ranging from 21 to 222 participants, predominantly younger, mixed-gender individuals.

Examination of user characteristics related to the UVE outcomes

In our systematic review, a limited number of studies (6 papers, 20%) investigated the role of user characteristics in interactions between users and ECAs (see Table 3). Notably, gender of the users emerged as a key sociodemographic factor (4 papers, 13%), indicating that females generally perceive ECAs as more attractive than males. Female users generally exhibited higher levels of empathy and reported less tension and annoyance toward the ECA (Belda-Medina and Calvo-Ferrer, 2022; Lahav et al., 2020; Lisetti et al., 2004; Sajjadi et al., 2019). Age also played a significant role, with younger participants finding ECAs more attractive (Lisetti et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2024). Another noteworthy factor is the flow state, which appears when users become deeply immersed and fully engaged in an interaction with the ECA, experiencing a high level of focus and reduced awareness of time or external distractions. Specifically, the flow state of the users positively predicted the perceived anthropomorphism of the ECA in one study rated with a moderate overall methodological quality (Saad and Choura, 2022). Despite similar access to technology, Polish users reported more positive attitudes and a greater perceived ease of use toward ECAs for learning compared to Spanish users, suggesting that ease of use may be linked to overall user attitudes. One possible explanation for the less positive attitudes among Spanish participants is their broader familiarity with advanced conversational agents like Alexa, Siri, Cortana, Google Assistant, and Watson. This familiarity may lead to higher expectations and quicker disappointment due to the habituation effect, reducing curiosity and novelty during interactions with simpler ECAs (Belda-Medina and Calvo-Ferrer, 2022). Interestingly, students from the Faculty of Social Sciences perceived the ECA delivering career counseling as more attractive and were more likely to recall its recommendations, compared to students from the Faculty of Exact Sciences. One possible explanation given by authors is that students in Exact Sciences may have less time or interest in engaging with such activities outside their core studies (Lahav et al., 2020). A research investigation focused on how user personality traits, as characterized by the Big Five Model, affected perceived attractiveness (Lisetti et al., 2004). Participants exhibiting higher levels of openness to experience tended to find the ECA more attractive (Lisetti et al., 2004). However, the study was rated with a weak overall methodological quality.

Table 3

| Factor | Main finding | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| User characteristics | ||

| Gender | Female participants showed greater interest in customizing the ECA’s features compared to male participants (Belda-Medina and Calvo-Ferrer, 2022). In other studies, female users were particularly more satisfied with the visual appearance of the ECA and reported significantly more that they would recommend the ECA compared to males (Lahav et al., 2020; Lisetti et al., 2004). Lastly, female users generally exhibited higher levels of empathy and reported less tension and annoyance toward the ECA compared to male users (Sajjadi et al., 2019). | ↑ Attractiveness |

| Education background | When asked if they would take a recommendation from their interactions with ECA into the future, users in social sciences and humanities were significantly more likely to respond positively compared to users in exact sciences, medicine, and engineering (Lahav et al., 2020). | ↑ Attractiveness |

| Personality | Openness to experience was a personality trait that was associated with the higher perceived attractiveness of ECA. Users more open to experience had a more positive view of the ECA than those less open to experience (Lisetti et al., 2004). | ↑ Attractiveness |

| Age | Younger participants perceived the ECA as more attractive (Lisetti et al., 2004; Prendinger et al., 2006). | ↑ Attractiveness |

| Flow | Users who experienced a flow state, characterized by deep involvement in an activity, reported a positive impact on their perception of the ECA’s realism (Saad and Choura, 2022). | ↑ Anthropomorphism |

| Expectations | Users had significantly higher affective expectations of the high anthropomorphic ECA compared to the low anthropomorphic ECA. They anticipated that the ECA would better understand and respond to their emotions (Yin et al., 2021). Therefore, the more the ECA expresses concern or care, the less likely it is to violate the user’s expectations. This relationship was even stronger for ECAs that are highly anthropomorphic, as users tend to expect ECA to be more (Yin et al., 2021). | ↑ Attractiveness ↑ Uncanniness |

| Social norms | Uncanniness did not significantly predict a reduction in eye gaze during user-ECA interactions. Even when users perceived the ECA as uncanny, they continued to maintain eye contact, suggesting that the sense of uncanniness does not strongly disrupt social norms (Zheleva et al., 2023). | ↑ Uncanniness |

| Exposure | Users were more accepting of ECAs displaying emotions after interacting with the ECA than they were beforehand. Specifically, their acceptance of ECAs showing positive emotions increased, and they also became more comfortable with an ECA expressing frustration or anger when faced with obstacles (Luo et al., 2023). | ↑ Attractiveness |

| Familiarity with the ECA | The ECA with a celebrity appearance in a hyper-realistic condition was perceived as less uncanny compared to the ECA with a cartoonish appearance (Song and Shin, 2022). | ↑ Uncanniness |

| Proximity | No significant association was found between perceived proximity to the ECA and feelings of uncanniness. Notably, participants found the ECA interesting and came closer to investigate the details of the ECA. | ↑ Uncanniness |

| ECA features | ||

| Social cues | ECA featuring eye blinking, breathing, posture shifts, and head nods resulted in more favorable perceptions and increased attention from users, in contrast to a text-based conversational agent (Appel et al., 2012). | ↑ Attractiveness |

| Visual representation | Research indicates that the visual appearance of ECAs significantly affects user perceptions and emotional responses. An anthropomorphized Muppet, which did not resemble a human or an existing animal, elicited the most negative emotions and led users to maintain the greatest interpersonal distance, suggesting discomfort with its unfamiliar design (Bailey and Schloss, 2024). In contrast, an ECA dressed casually in a blue t-shirt, green shorts, and multicolored shoes was perceived as more attractive, indicating that familiar and approachable appearances positively impact user perception (Bailey and Schloss, 2024). Similarly, another study found that users preferred an ECA with supermodel-like features, such as idealized facial traits, symmetry, and a polished appearance, over an ECA with more average and relatable physical traits, which was rated less attractive (Hao et al., 2024). These findings highlight that users tend to favor ECAs with visually appealing, idealized aesthetics. Moreover, ECAs that appeared more realistic were perceived as more conscious and alive compared to cartoon-like ECAs, further emphasizing the impact of realism on user engagement and perception (Volante et al., 2016). | ↑ Anthropomorphism ↑ Uncanniness |

| Customization | Approximately 75% of users valued the ability to customize the ECA’s name, race, and gender, including the option for non-binary identities. | ↑ Attractiveness |

| Data privacy | More than half of the users expressed privacy concerns because ECA frequently requested access to social networks and permission for video calls. Many participants were worried about data storage and manipulation, leading them to deny such requests. | ↑ Uncanniness |

| Gender | Among users, 78% of male participants preferred creating a female ECA, while female users showed more diverse preferences: 59% created a female ECA, 37% chose a male ECA, and 4% opted for a non-binary ECA. | ↑ Attractiveness |

| Communication style | Research shows that ECAs designed to engage emotionally or socially tend to evoke more positive responses from users. For instance, an ECA that used humor, making witty remarks and playful comments about healthy eating, was rated as more attractive and improved users’ moods compared to a non-humorous ECA that delivered directly the factual information (Buttussi and Chittaro, 2019; Hao et al., 2024). Similarly, ECAs that expressed emotions were perceived as significantly more anthropomorphic and emotionally intelligent than those that remained emotionally neutral. Positive messages, characterized by more words, fewer negative terms, and increased use of exclamation marks (e.g., “I’m happy to help!”), further enhanced user perceptions of attractiveness and emotional intelligence (Ham et al., 2024; Ter Stal et al., 2021). Moreover, an ECA using empathic, supportive comments like “You did a good job! Please relax a bit. Then let us continue,” was perceived as more enthusiastic and engaging compared to a task-oriented ECA that simply delivered instructions such as “Next question” (Min et al., 2024). Similarly, a social-oriented ECA, which incorporated personal statements such as “Hello,” and “Have a nice day,” was rated more attractive than a task-oriented ECA that used a more straightforward communication style (van Pinxteren et al., 2023). Interestingly, an ECA that conveyed happiness through captions and emojis was found to enhance perceived emotional intelligence more than the same one expressing emotions like lust, love, or sadness (Ham et al., 2024). Together, these findings suggest that ECAs fostering emotional or social engagement, particularly through humor, positive messaging, and empathetic communication, are consistently rated more attractive, emotionally intelligent, and engaging by users. | ↑ Attractiveness ↑ Anthropomorphism ↑ Uncanniness |

| Facial expressions | Users reported feeling less comfortable and found ECAs with more facial expressions to be less natural (Conrad et al., 2015). However, an ECA displaying emotions such as happiness, warmth, and empathy was perceived as more likeable and caring compared to an unemotional ECA, though there was no significant difference in perceived trustworthiness or intelligence between emotional and neutral-faced ECAs (Creed and Beale, 2012). An ECA that mimicked the user’s head and torso movements with a delay of 1–3 s was not rated as more attractive (Hale and Hamilton, 2016). Trust in ECAs varied depending on the emotions they expressed. Users generally lacked trust in an ECA displaying disgust, while an ECA expressing happiness made them feel more at ease and increased their willingness to cooperate (Luo et al., 2023). Interestingly, reactions to happy ECAs were mixed—while over half of participants viewed them as friendlier, more cooperative, and cordial, others found them insincere, describing them as having a “fake smile” or being “too enthusiastic to be trustworthy.” Most participants were distrustful of ECAs showing negative expressions, often characterizing them as “angry,” “uncooperative,” or “aggressive,” although a small group associated these negative expressions with professionalism and seriousness, finding them more trustworthy. Smiling ECAs were generally perceived as warmer and more cheerful compared to non-smiling ECAs (Min et al., 2024). Lastly, while there were no subjective differences in user perceptions between a flat-faced ECA, an ECA that mimicked user expressions, and one with emotionally adaptable expressions, participants spent more time interacting with the ECA displaying emotionally adaptable facial expressions (Wang et al., 2021). |

? Attractiveness ↑ Uncanniness ↑ Anthropomorphism |

| Non-verbal features | Users with an ECA with many non-verbal features reported greater enjoyment and rated the ECA as more autonomous, personal, less distant, and more sensitive compared to those interacting with less non-verbal features (Conrad et al., 2015). Non-verbal features included adaptive behaviors such as waiting for eye contact, pausing if the respondent stopped looking, offering help when needed, and addressing interruptions immediately (Conrad et al., 2015). | ↑ Attractiveness |

| Voice | Approximately, 68% of users in the No-Emotion condition criticized the ECA’s “irritating, bland voice tone” and described it as “sounding patronizing.” | ↑ Uncanniness |

| Agency | An ECA was perceived as less anthropomorphic than a human partner when collaborating on a shared task (Falcone et al., 2022). However, when users were informed that the ECA’s interactions were controlled by a real human, they found the ECA to be more realistic, humanlike, and helpful compared to when they believed it was controlled by a computer algorithm (Neumann et al., 2023). Interestingly, ECAs with self-oriented mentalization abilities—such as expressing their own feelings (e.g., feeling their own hunger) - evoked stronger feelings of uncanniness compared to ECAs with other-oriented mentalization abilities, which focused on understanding the user’s feelings (e.g., recognizing the user’s hunger) (Yin et al., 2021). The self-oriented focus of these ECAs can appear unsettling and contribute to the UVE (Yin et al., 2021). | ? Anthropomorphism ↑ Uncanniness |

| Ethnical similarity | The ECA that shared ethnic similarity with the user was not perceived as more attractive (Hale and Hamilton, 2016). | ? Attractiveness |

| Personality | The extroverted ECA, which initiated conversations with users, was rated as more natural and agreeable compared to the introverted ECA (Prendinger and Ishizuka, 2001). Additionally, users reported a stronger sense of social presence when interacting with the extroverted ECA. This was likely influenced by the extroverted ECA maintaining direct eye contact 90% of the time, while the introverted ECA only made eye contact 30% of the time during the interaction (Saad and Choura, 2022). | ↑ Attractiveness ↑ Anthropomorphism |

| Emotion recognition | Users initiated more interactions with an ECA that provided emotion recognition, but it was not rated as more attractive (Schouten et al., 2017). | ? Attractiveness |

| Emotional congruence | In a game scenario where the ECA was programmed to lose and the participants to win, a notable increase in participants’ stress levels was observed when the ECA exhibited expressions of joy rather than sadness (Prendinger et al., 2006). | ↑ Uncanniness |

Evidence status summary of included studies in the systematic review.

Examination of embodied conversational agent features related to the UVE outcomes

In our review, we observed that ECAs studied were female, half-body, and dynamic in approximately one-third of the cases. Full-body ECAs generally elicited higher levels of anthropomorphism but were also more prone to triggering the uncanniness feelings, especially when their motion was dynamic (Buttussi and Chittaro, 2019). Conversely, half-body and face-only ECAs, while less anthropomorphic, received lower uncanniness ratings (Conrad et al., 2015). The most studies included in the systematic review (18 papers, 62%) examined how various features of the ECA influence user perceptions, such as physical features, facial expressions, communication style, and personality factors (Table 3). Among these features, the facial expressions (6 papers, 20%), and communication style of the ECA were the most extensively explored (6 papers, 20%), but the findings were mixed. A customizable ECA proved to be more attractive, offering users the flexibility to change its gender, race, and name (Belda-Medina and Calvo-Ferrer, 2022). The customisation feature seems to be more important to female users. Overall, users of both genders showed a preference for a female ECA, though choices also included male and non-binary ECAs. Interestingly, an ECA that resembled the user ethnically did not necessarily enhance attractiveness. Furthermore, one study with a good methodological quality found that an ECA with a celebrity appearance in a highly anthropomorphic condition was perceived as less uncanny than the same celebrity represented with a cartoonish appearance (Song and Shin, 2022). When familiar faces are presented in low-anthropomorphism styles, they may trigger stronger feelings of uncanniness, likely because users expect a more realistic physical features when the ECA is based on a real person.

While some research indicated that ECAs with a range of facial expressions were considered more attractive than those without any expressions, the results were not uniform. Eye gaze alone cannot induce uncanniness (Zheleva et al., 2023), probably because more facial features are required in order to induce uncanniness. ECAs with facial expressions were rated higher in terms of perceived compassion and intelligence, and they seemed to encourage more interactions initiated by users (Luo et al., 2023; Min et al., 2024). Moreover, participants spent more time interacting with the ECA displaying emotionally adaptable facial expressions (Wang et al., 2021). However, inconsistencies arose within the same studies. For instance, users did not consistently rate the ECA with facial expressions as more attractive (Conrad et al., 2015; Hale and Hamilton, 2016). Furthermore, the presence of facial expressions in the ECA did not necessarily lead to perceptions of increased friendliness when compared to an ECA without facial expressions (Creed and Beale, 2012). Interestingly a slightly higher number of studies concentrated on positive emotions such as happiness and joy, but some studies examined the effect of negative emotions such as disgust. Users generally perceived positive facial expressions as being more friendly and trustworthy. In contrast, negative expressions were generally associated with lower trust, with users often describing such ECAs as unfriendly or unapproachable (Luo et al., 2023). However, around 60% of users said ECAs with positive expressions looked the friendliest, whereas only 3% did so for those displaying disgust. Interestingly, a small number of users perceived the disgusted ECA as more professional (Luo et al., 2023). Fearful expressions were found to increase fear among users, especially those who had received prior safety training (Buttussi and Chittaro, 2019). These findings suggest that emotional expressions influence user perceptions and emotional responses, but their impact may depend on context, user expectations, and task relevance, with no universally optimal emotional strategy.

In addition to non-verbal cues, the systematic review also explored the role of verbal communication in ECAs. The findings suggest that ECAs with enhanced verbal communication skills are often perceived as more user-like and attractive. Specifically, an ECA expressing joyful messages is regarded as more attractive and helpful compared to an ECA neutral messages (Buttussi and Chittaro, 2019; Ham et al., 2024; Hao et al., 2024). ECAs that used personal greetings like ‘Hello,’ and “Have a nice day,” were rated as more attractive than those with a more straightforward communication style (van Pinxteren et al., 2023). Notably, ECAs that conveyed happiness through captions and emojis were perceived as having greater emotional intelligence than those expressing other emotions like lust or sadness (Ham et al., 2024). Joyful messages were characterized by the use of more words, positive affect terms, and expressive punctuation, like exclamation marks (e.g., “I am happy to help!”). Humor such as amusing stories can enhance the perceived attractiveness of an ECA (Hao et al., 2024). Furthermore, an ECA that engages in friendly communication, evidenced by initiating conversations and employing phrases such as “I’m sorry,” was typically perceived as more attractive. This perception remains consistent regardless of the ECA being represented as male, which was a less-used gender representation in the present review (Prendinger and Ishizuka, 2001). Beyond the quality of information received from ECAs, socio-emotional capabilities were also valued. The ECA could recognize and reflect the user’s emotional state with messages like “It seems you are facing some challenges” and put these feelings into a broader context by saying: “Many people may encounter these difficulties” (Schouten et al., 2017). Additionally, the ECA’s social skill of not interrupting the user during a conversation can make users initiate more interactions (Schouten et al., 2017). Expressions of verbal encouragement, blending affirmation and motivational feedback, such as “Keep going, you are doing well!” can help alleviate user stress (Neumann et al., 2023). This effect supports the extension of the Buffering Stress Theory, traditionally applied to interpersonal relationships, to interactions between humans and ECAs.

Few ECAs were not limited to scripted interactions but could actively recognize and adapt to the user’s emotional states, analyzed through valence-arousal mapping of emotions (Prendinger et al., 2006). Emotional states of the user were detected based on physiological data, including skin conductance (i.e., measured via electrodes on the index and small fingers of the dominant hand of the user) and facial electromyography (i.e., with sensors placed on the use’s left cheek). This input allowed the ECA to classify emotional states based on valence (positive–negative) and arousal (low or high). For example, the emotion “relaxed” has a positive valence and a low arousal (Lang, 1995). Another similar framework, PAD, classifies the emotional states based on three dimensions: Pleasure (vs. displeasure), Arousal (vs. sleepiness), and Dominance (vs. submissiveness) (Becker-Asano, 2008; Kshirsagar, 2002; Russell and Mehrabian, 1977). This framework allowed the ECA to express 18 emotional states including: hopeful, peaceful, bored, annoyed, neutral, depressed, sad, happy, surprised, anxious, angry, overwhelmed, afraid (Sajjadi et al., 2019). These emotions were used to simulate personality traits based on Big Five model (Digman, 1997). For instance, the extraverted ECA expressed emotions that were high in dominance. Such an ECA was sociable, assertive, and maintained direct eye contact for 90% of the interaction time with the user (Sajjadi et al., 2019). In another study, an extroverted ECA, which initiated communication and showed positive emotions such as gratitude, was perceived by the users as attractive (Hao et al., 2024). However, an extroverted ECA can also show anger, manifested through mild frown eyebrows, direct eye contact, shoulders up and sideway posture (Sajjadi et al., 2019). In contrast, an introverted ECA was characterized by emotions low in dominance. Such an ECA was more submissive, showed lower assertiveness, and expressed more negative valanced emotions such as sad, overwhelmed and afraid, with the latter conveyed through slightly raised eyebrows, avoided eye contact, dropped shoulders, and a hand placed on legs (Sajjadi et al., 2019). An introverted ECA maintained eye gaze only 30% of the interaction time with the user, compared to 60% during a neutral emotional state, and it was perceived as more unsettling. While extraversion has received more attention in ECA design, other personality traits have been less frequently explored. For example, only one study focused on the agreeableness personality factor, where an ECA perceived as helpful and forgiving was also considered more attractive by users (Prendinger and Ishizuka, 2001). However, traits such as neuroticism, openness to experience, and conscientiousness were largely neglected in user-ECAs interactions.

Furthermore, most of the included studies have focused on the perceived attractiveness of the ECA, probably because this dimension closely mirrors patterns observed in human social interactions. In contrast, the experience of uncanniness is less well understood, particularly because we lack well-established theories of the UVE in interpersonal contexts. As a result, researchers are still working to interpret and reconcile the often inconsistent findings related to this phenomenon. In the reviewed studies, the ECA perceived as most uncanny was also rated highest in anthropomorphism, specifically in terms of both physical and mental features. One plausible explanation is that users tend to expect ECAs to behave in a mechanical, task-oriented manner. When an ECA displays a high degree of autonomy, such as planning, expressing emotions, or demonstrating independent reasoning, this may conflict with users’ expectations and elicit discomfort (Yin et al., 2021). To counteract this effect, some researchers propose designing ECAs to appear more dependent on human guidance and less capable of fully autonomous behavior. However, the relationship between anthropomorphism and user perception is not straightforward. While greater anthropomorphism may increase the risk of uncanniness, it simultaneously raises users’ emotional expectations. For instance, ECAs with highly human-like appearances are often expected to be more emotionally attuned and responsive (Zhang et al., 2024). When such ECAs successfully express empathy or concern, they tend to be perceived as more attractive. This alignment between anthropomorphic appearance and high emotional features can reduce feelings of uncanniness. Conversely, when emotionally expressive expectations are unmet, users may react more critically, especially toward ECAs that appear highly human.

Summary of the main findings

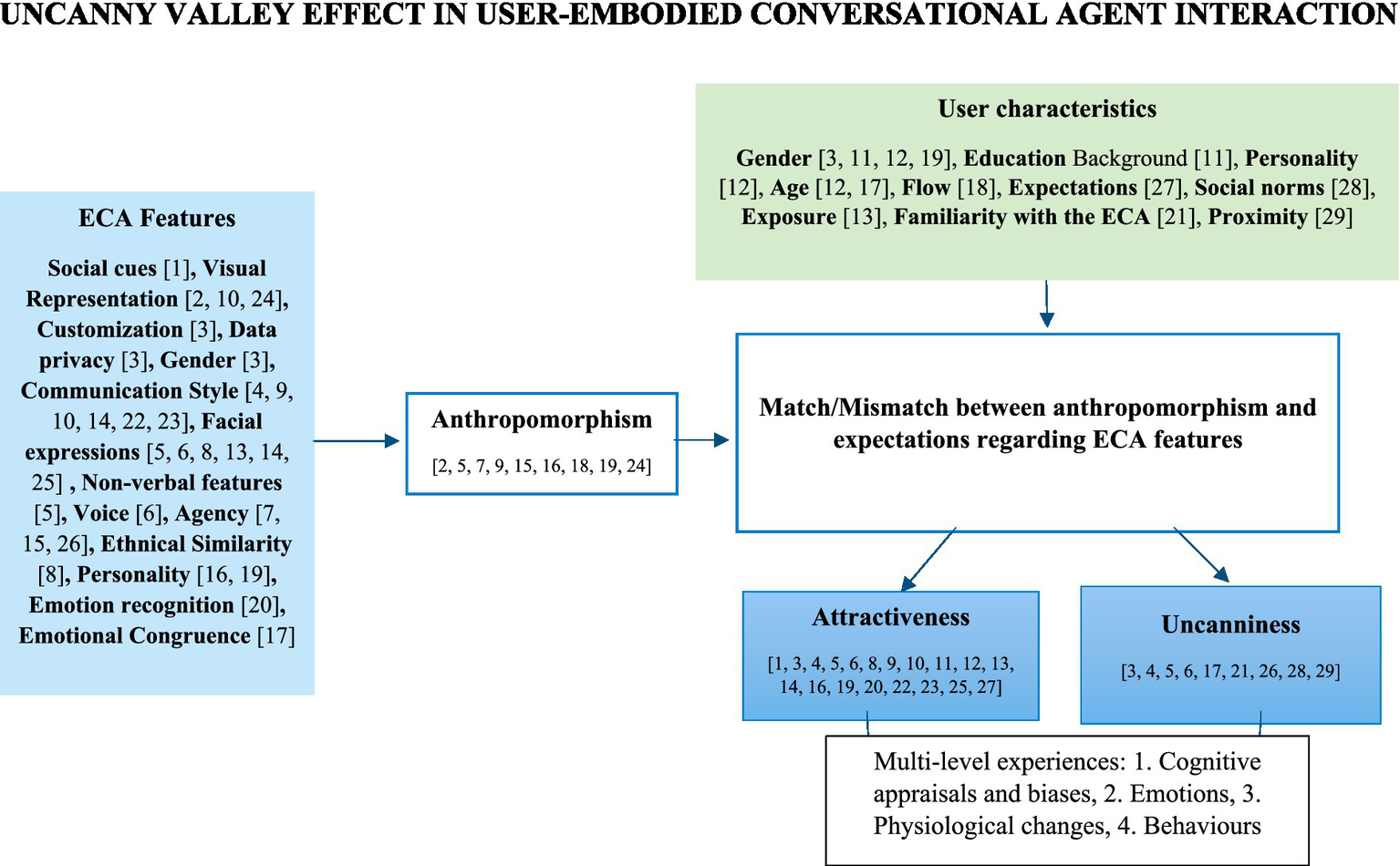

In Figure 2, we present a synthesized overview of the evidence related to factors associated with the UVE outcomes in the studies reviewed. The figure is partially data-driven, based on the findings from the included studies that examined either ECA features or user characteristics. The summary figure draws inspiration from previous work (Loveys et al., 2020a). Our analysis revealed significant relationships between several user characteristics, such as gender and age, and perceived attractiveness of the ECA. We found a significant association between UVE outcomes and various ECA features, including non-verbal features, customization options, humor, friendliness, ECA familiarity. However, we did not find any significant associations between ethnical similarity of the ECA and UVE outcomes. Importantly, the evidence displayed inconsistencies, particularly regarding the relationship between facial expressions exhibited by ECAs and UVE outcomes. Figure 2 not only summarizes the most important results in the included studies but also tries to extend them based on previous theories that can leverage our understanding of user-ECA-interaction.

Figure 2

Proposal for an integrative model regarding factors contributing to the UVE in user-ECAs interactions.

Proposal for a new integrative framework of the UVE in user-ECA interaction

This framework builds on the findings of the included studies in the present systematic review (Table 3), which informed our recommendations for reducing the UVE in user-ECA interaction (Table 4). To situate these results within a broader theoretical context, we draw on three key models: Cognitive Violation Theory (CEVT) (Burgoon and Hale, 1988; Burgoon and Walther, 1990; Kätsyri et al., 2015), the ABC model from the Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) (Ellis et al., 2011; Turner, 2016) and the concept of the Uncanny Valley of Mind (UVM) (Gray and Wegner, 2012; Stein and Ohler, 2017). CEVT highlights how mismatches between user expectations and ECA behavior influence user perceptions, while the ABC model from REBT explains how such violations trigger emotional, physiological and behavioral responses from the user. UVM emphasizes the role of mind perception in human ECA-interaction and analyzes the interaction beyond the mere appearance of ECA.

Table 4

| No. | Suggestion | Check |

|---|---|---|

| 1. |

Optimize physical appearance

Design ECAs with polished and aesthetically idealized features, such as symmetrical facial traits, to enhance user perceptions of attractiveness. Users are more likely to respond positively to ECAs with refined, realistic appearances over those with overly simplistic or cartoonish designs. Striking a balance between realism and appeal can reduce feelings of uncanniness while fostering a more engaging interaction. |

□ |

| 2. |

Optimize Non-verbal Features

Focus on incorporating human-like non-verbal behaviors such as gaze direction, body movements, and response timing. ECAs should utilize natural pauses (e.g., waiting for eye contact from the user), which promote social presence. Include gestures like blinking, head nodding, and gaze shifts, which signal attentiveness and engagement. Studies show that these behaviors significantly enhance attractiveness, thus reducing the sensation of uncanniness. Avoid stiff, robotic movements, as constant staring or mechanical gestures increase discomfort and feelings of uncanniness. |

□ |

| 3. |

Include Customization Options

Provide users with options to personalize the ECA’s features (e.g., name, race, gender, and even voice). Customization allows for more user familiarity and relatability, increasing attractiveness and reducing discomfort. Research indicates that female users, in particular, report higher satisfaction when they can customize the ECA’s visual appearance. Offering diverse design options, including male, female, and non-binary ECAs, helps meet individual preferences, further enhancing positive user engagement. |

□ |

| 4. |

Improve Communication Style

ECAs should avoid robotic or overly formal language. Instead, they should use natural, emotionally intelligent communication, incorporating supportive phrases like “You’re doing great!” or “Take your time.” Additionally, the tone of voice is important. Monotone voices are often perceived as patronizing and can increase uncanniness. To mitigate this, ECAs should utilize subtle intonations, appropriate pauses, and a varied vocal range to make their speech more expressive and human-like, fostering greater user comfort and engagement. |

□ |

| 5. |

Avoid Extreme Emotional Incongruence with the Context of Interaction

Ensure that the ECA’s emotional expressions align with the context of the interaction. Incongruent emotions, such as expressing extreme joy when the user is stressed, can amplify the uncanny effect. ECAs should be able to subtly shift their emotional expressions based on the user’s emotional state to maintain alignment with the situation and reduce discomfort. |

□ |

| 6. |

Leverage Familiar Interaction Scenarios

Repeated exposure to ECAs can lead to greater acceptance and comfort over time. Gradual exposure to ECAs in familiar contexts can help users build trust and reduce the UVE. Incorporating familiar settings and interaction scenarios allows users to acclimate more easily, decreasing the likelihood of negative responses. |

□ |

| 7. |

Prioritize Emotional Intelligence and Empathy

ECAs should display emotionally adaptive and consistent expressions. Subtle emotions such as soft smiles, blinking, and empathetic gazes foster trust and relatability. Avoid exaggerated or erratic emotional displays, as emotions like disgust or anger were found to elicit negative reactions. ECAs that show a balanced range of emotional expressions are perceived as more natural and approachable. |

□ |

| 8. |

Incorporate Social and Cultural Norms

ECAs that reflect or are sensitive to the user’s cultural background can enhance feelings of familiarity and trust. Consider incorporating cultural cues, such as language, accent, or behavior, that resonate with the user’s identity. ECAs that are perceived as culturally aligned are less likely to invoke the Uncanny Valley Effect. |

□ |

| 9. |

Expectations and Anthropomorphism

Users generally have higher expectations for highly anthropomorphic ECAs, and when these expectations are not met, the sense of uncanniness can intensify. Therefore, it’s crucial to evaluate user expectations early in the interaction process. ECAs must effectively manage these expectations by demonstrating understanding and empathy toward the user’s concerns. The closer an ECA aligns with user expectations in terms of emotional responsiveness, the less likely users are to experience discomfort or feelings of uncanniness. Meeting these expectations enhances user trust and engagement, helping the ECA to appear more natural and relatable. |

□ |

Checklist for avoiding the Uncanny Valley Effect in ECAs.

To better understand the UVE in user-ECAs interaction, the present framework goes beyond an exclusive focus on the ECA’s features and considers the user’s experience as a central component. We propose a model in which the UVE emerges from the dynamic interplay between ECA features and individual user characteristics based on the results from our included studies on users factors and ECA features (see Figure 2). The interaction begins with a trigger, which is a specific feature of the ECA (e.g., clothing, facial expression, gesture or communication style) as depicted in the studies included in the systematic review (Bailey and Schloss, 2024; Hao et al., 2024; Volante et al., 2016). This trigger activates cognitive appraisals in the user, such as judgments about the ECA’s degree of anthropomorphism: “This ECA is like a human being.” Before the interaction even starts, however, users bring their own factors into the experience. Characteristics such as gender, age, previous experiences, and personality traits were explored in the included studies (Belda-Medina and Calvo-Ferrer, 2022; Lahav et al., 2020; Lisetti et al., 2004; Luo et al., 2023; Prendinger et al., 2006; Sajjadi et al., 2019) shape their expectations and influence how they interpret the ECA’s features. Following the initial appraisal, the user evaluates whether the ECA matches or mismatches their expectations. Given the human brain’s predictive nature, a match typically leads to attractiveness. However, individual traits can moderate this process. Users high in openness to experience may perceive an unexpected or mismatching ECA as both attractive (Lisetti et al., 2004) and uncanny, driven by curiosity (Zibrek et al., 2018). In contrast, users with high trait anxiety may respond to mismatching ECAs with uncanniness, potentially perceiving them as a threat.

It is essential to redefine the outcomes of the UVE across four key levels, grounded in validated theories of Psychology (Ellis et al., 2011). The first and most critical level is cognitive, or how the user thinks about the ECAs. For example, it is important to know whether they perceive it as competent or incompetent, friendly or unfriendly. These cognitive appraisals shape the second level, which is emotional. Here, we assess the user’s emotional response to the ECA, such as feeling relaxed, uncomfortable, surprised, curious, disgusted, or anxious. The third level involves physiological responses, such as changes in skin conductance or heart rate, which indicate levels of stress or relaxation. Finally, the fourth level is behavioral, where we examine how often the user maintains or even initiates the interaction with the ECA. Evaluating outcomes across all four levels is essential for a comprehensive understanding of user experience with ECAs.

In designing and evaluating human-ECA interactions, it is important to consider that users may naturally perceive and respond to ECAs as if they were human partners (Scheele et al., 2015). This opens the door for social cognition to play a role in these interactions with its well-known cognitive biases. One example is the hostile attribution bias, which is the tendency to see unclear behavior as hostile (Birch et al., 2025). In the context of ECAs, an ambiguous response might be misinterpreted negatively, as rude or even aggressive. Another example, anchoring bias causes users to rely too heavily on their first impression of the ECA, even if later behavior is different (Qi, 2024). Lastly, negativity bias means that users give more weight to negative experiences than to positive ones (Vaish et al., 2008). Thus, one awkward moment with the ECA can ruin the entire interaction. These well-known cognitive tendencies come from research on how humans relate to other people. A well-designed ECA should minimize ambiguity, promote trust from the start, and recover gracefully from small mistakes.

Discussion

This study aimed to provide the first comprehensive systematic review to investigate the UVE in user-ECA interaction, with a specific focus on three outcomes: (a) anthropomorphism (9 papers, 31%), (b) attractiveness (29 studies, 65%), (c) uncanniness (9 papers, 31%), with some studies looking simultaneously at more than one outcome (7 papers, 24%). Our review followed the PRISMA guidelines, and we meticulously examined 29 published studies to identify potential three key aspects: (1) user characteristics, and (2) ECA features related to the UVE outcomes. Below, we delve into the key findings derived from our work.

To what extent is the UVE present in user interactions with ECAs?

It is essential to assess the UVE through a comprehensive combination of attractiveness, uncanniness, and anthropomorphism. Focusing solely on attractiveness can offer useful insights into ECA design, but it overlooks the full range of potential discomfort that users might experience. A comprehensive evaluation across all three variables is crucial to better understand and mitigate the UVE.

Approximately one-third of the studies in this systematic review specifically focused on UVE as a primary goal, and these studies successfully confirmed its presence. However, many of the remaining studies only explored UVE-related variables as secondary objectives, with a predominant emphasis on the attractiveness of the ECAs. These studies did not directly examine the transition between attractiveness and uncanniness, which is critical to fully understanding the UVE.