Abstract

Background:

This systematic review examines the evidence on the use of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) tools for African populations and evaluates their psychometric properties, cultural adaptation, and applicability.

Methods:

A systematic search was conducted across PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and gray literature from January 2015 to January 2025. The review followed PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) and COSMIN (Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments) frameworks. Duplicate screening and study selection were independently performed by multiple reviewers. Eligible studies included the development, adaptation, or validation of HRQoL for African populations. The protocol was submitted for registration to the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under the identification number CRD42025639055.

Results:

Forty studies met the inclusion criteria, with 31 (77.5%) focusing on adults and minimal attention given to the pediatric population. East Africa had the highest representation, with 17 (42.5%), while West Africa accounted for 7 (17.5%). Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha ≥ 0.70) was demonstrated in 33 (97.1%) out of the 34 tools. A total of 34 different HRQoL tools were identified, including 12 generic instruments. The SF-12 and WHOQOL-BREF were the most validated tools, whereas the EORTC QLQ-C30 was the most validated disease-specific tool. Cultural adaptation was a major focus, with 32 (80.0%) of the studies incorporating linguistic modifications to enhance contextual relevance. Most studies, 28 (70.0%), used cross-sectional designs. Overall, most tools demonstrated good reliability and cultural adaptability, although limitations such as small sample sizes, limited geographic coverage, and incomplete reporting of responsiveness and test–retest reliability were common.

Conclusion:

Significant progress has been made in developing and validating HRQoL tools for African populations. However, gaps remain, including the need for longitudinal studies, greater inclusion of children’s HRQoL assessments, and broader geographic representation. Strengthening research capacity will be pivotal in advancing culturally responsive HRQoL tools and integrating them into healthcare decision-making in Africa.

Systematic review registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42025639055, Identifier: CRD42025639055.

Introduction

Health systems that provide good-quality care aim not only to prevent and treat diseases but also to improve the wellbeing and quality of life (QoL) of patients (WHO, 2020a). QoL is a multidimensional concept that refers to an “individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, and standards” and is affected by a person’s physical health and psychological state (The Whoqol Group, 1998).

The improvement of QoL and other outcomes through proper prevention and treatment mechanisms is at the heart of clinical science and all health systems. Outcomes could be economic, clinical, or humanistic. Clinical outcomes in patient care measure the impact of the treatment on the patient, especially their QoL. Hence, the assessment of QoL should consider multidimensional aspects of physical and psychological health (Vagetti et al., 2014).

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL), which is derived from QoL, is a multidimensional concept that reflects an individual’s perception of the impact of a disease state or intervention on their physical, psychological, and social aspects of life (Tran et al., 2012; European Medicine Agency, 2006). HRQoL is essential in inpatient follow-up and monitoring, as it provides valuable feedback from the perspective of patients about a disease condition and its accompanying interventions (Mafirakureva et al., 2016).

The HRQoL measurement has emerged as an essential health outcome in clinical trials, clinical practice improvement strategies, and healthcare services research and evaluation (Varni et al., 2003). Research on HRQoL often explores patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) that can offer valuable insights into therapeutic interventions, health strategies, and health policy development (Brazier et al., 2002; Miller et al., 2021; Conrad and Barker, 2010). This patient-centered exploration of the experience of health is particularly important, as the disjuncture between patients’ subjective experience of treatment and wellbeing and clinical improvements has been observed (Brazier et al., 2002).

HRQoL instruments are commonly grouped into generic and disease-specific measures, each serving distinct purposes in health assessment (Lipton et al., 2013). Generic instruments, such as the SF-36, SF-12, EQ-5D, and WHOQOL-BREF, assess broad domains of functioning, such as physical, emotional, and social, allowing comparisons across diseases and populations (Hand, 2016). These tools are widely used in Africa, and several validation studies report acceptable psychometric properties, particularly in internal consistency and construct validity. For example, the WHOQOL-BREF has demonstrated reliability across multiple African languages; however, cultural discrepancies have been reported regarding items related to social relationships, spirituality, and environmental context (Colbourn et al., 2012; Bowden et al., 2002; Price et al., 2020). These findings suggest that although generic tools are broadly applicable, they may overlook culturally embedded expressions of wellbeing. In contrast, disease-specific instruments—such as the EORTC QLQ-C30 for cancer, the KDQOL for kidney disease, or HIV-specific QoL measures—are tailored to capture symptoms and functional limitations unique to particular conditions (Glover et al., 2011; Namisango et al., 2007). Although these tools generally show stronger clinical sensitivity, many lack extensive validation in African populations. Several studies note inconsistencies in factor structures, challenges in linguistic adaptation, and reduced responsiveness due to cultural variations in symptom reporting (Ngwira et al., 2021; Soto et al., 2015; Crawford, 2012). The distinction between generic and disease-specific tools is, therefore, essential, as their adequacy in Africa varies and depends on rigorous local validation.

However, owing to the need for high-quality, specifically designed questionnaires based on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in clinical practice, the instruments are usually translated into different languages (Ware, 2000; Herdman et al., 2011). Evidence shows that the reliability and validity of an instrument are influenced by socioeconomic factors, such as education, literacy, and rural or urban living, which were often associated with populations’ cultural backgrounds and historical racial inequalities (Wissing et al., 2010; O’Keefe and Wood, 1996; Mullin et al., 2000; Nelson et al., 2020).

The HRQoL can be measured using generic or disease-specific instruments. Generic tools such as the SF-12, SF-36, EQ-5D, and WHOQOL-BREF capture broad aspects of physical, psychological, and social wellbeing and allow comparison across different diseases and populations. However, evidence from African studies shows that although these tools often demonstrate acceptable reliability, several items may not fully align with local cultural norms, particularly in domains related to social relationships, spirituality, and environmental context (Olsen et al., 2013; Gladstone et al., 2008). Disease-specific instruments, such as the EORTC QLQ-C30 for cancer or diabetes-specific QoL scales, provide more clinically sensitive assessments. However, many have undergone limited validation in African settings, with challenges reported in linguistic adaptation, conceptual equivalence, and responsiveness (Naamala et al., 2021; Marsh and Truter, 2021). This distinction matters because the adequacy of each type of tool in Africa depends on rigorous and context-specific validation.

Validating HRQoL instruments typically involves assessing their reliability, validity, and responsiveness, as well as ensuring cultural and linguistic appropriateness. This is especially important in Africa, where cultural norms, language diversity, and shifting health burdens from infectious to chronic non-communicable diseases may influence how individuals interpret and respond to HRQoL items (Marsh and Truter, 2021). Despite increasing use of these tools, synthesized evidence on their validation in African populations is lacking, underscoring the need for a systematic review to map existing instruments, highlight gaps, and guide future adaptation or development.

To support this assessment, this review uses the COSMIN (Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments) framework, which provides internationally recognized criteria for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on PROMs (Mokkink et al., 2016). Although alternative guidelines exist, such as ISOQOL standards or the FDA PRO guidance, COSMIN offers the most comprehensive and structured approach for evaluating psychometric properties, making it particularly suitable for this review (Lorente et al., 2020). Despite the growing use of HRQoL instruments in African health research, there remains limited consolidated evidence on how these tools have been developed, adapted, and psychometrically validated for use across the continent’s diverse cultural and linguistic contexts. No prior systematic review has comprehensively synthesized this evidence, even though such information is essential for ensuring that PROMs are conceptually appropriate, reliable, and meaningful for African populations. Therefore, the objective of this systematic review is to identify and critically appraise all studies that have developed, adapted, or validated generic or disease-specific HRQoL instruments for African populations. Guided by the PROSPERO-registered protocol (CRD42025639055), the review aims to answer the following research question: “Which HRQoL measurement tools have been validated or culturally adapted for use in African populations, and what is the quality of the evidence supporting their psychometric properties and contextual relevance?” This study also seeks to highlight the methodological strengths and limitations of the included studies to inform future research and to promote more robust and culturally appropriate HRQoL measurement across African settings.

Methods

Design

This study was conducted as a systematic review to identify, evaluate, and document HRQoL measurement tools developed or validated for use in African populations. This systematic review assessed the psychometric properties, cultural adaptation, and validation of HRQoL tools across diverse populations in Africa. The review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The protocol was formally registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), registration number CRD42025639055.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria:

-

Studies conducted among children or adult populations residing in Africa.

-

Studies that focused on the development, cross-cultural or linguistic adaptation, or psychometric validation of an HRQoL tool. Adaptation was defined as any modification made to an existing HRQoL instrument to improve its cultural, linguistic, or contextual relevance to an African setting. This includes translation, back-translation, and pilot testing. Validation was defined as the evaluation of one or more psychometric properties of the HRQoL instrument, such as reliability (e.g., internal consistency and test–retest), construct validity, criterion validity, responsiveness, or factor structure, based on the COSMIN guidelines.

-

Quantitative, qualitative, cross-sectional, longitudinal, and mixed-method studies.

-

Peer-reviewed primary studies with sufficient methodological detail from 1 January 2015 to 1 January 2025.

Exclusion criteria

The study’s exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

Studies that exclusively focused on non-human populations.

-

Studies that used HRQoL tools without developing, adapting, or validating them for African populations.

-

Unpublished theses and retrospective analyses of secondary datasets.

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and gray literature sources. Additional sources included the reference lists of relevant articles. The search was designed to retrieve studies published to date, using a combination of MeSH terms and free-text keywords related to HRQoL measurement tools, their development, validation, and use in Africa. Boolean operators (AND/OR) and truncation (*) were applied where necessary to refine the search.

The primary search terms included: (“tool” OR “instrument” OR “scale*” OR “questionnaire*” OR “measure*” OR “assessment tool*” OR “survey*”) AND (“health-related quality of life” OR “HRQoL” OR “QoL” OR “quality of life” OR “health preference*”) AND (“measurement” OR “assessment” OR “evaluation” OR “validation” OR “development”) AND (“Africa” OR “Sub-Saharan Africa” OR “African countries” OR “African region”)**. The search was conducted without language restrictions, but studies had to meet specific eligibility criteria to be included. The full search strategy from gray literature and databases (PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus) is provided in Supplementary File 1.

Study selection and screening

The search results were imported into Rayyan, a web-based tool for systematic reviews, where duplicate records were automatically removed after being assessed by AI. Title and abstract screening were independently conducted by EJU and CNI, with conflicts resolved by the third reviewer, AI. Similarly, full-text screening was performed by EJU and CNI, with discrepancies resolved by AI.

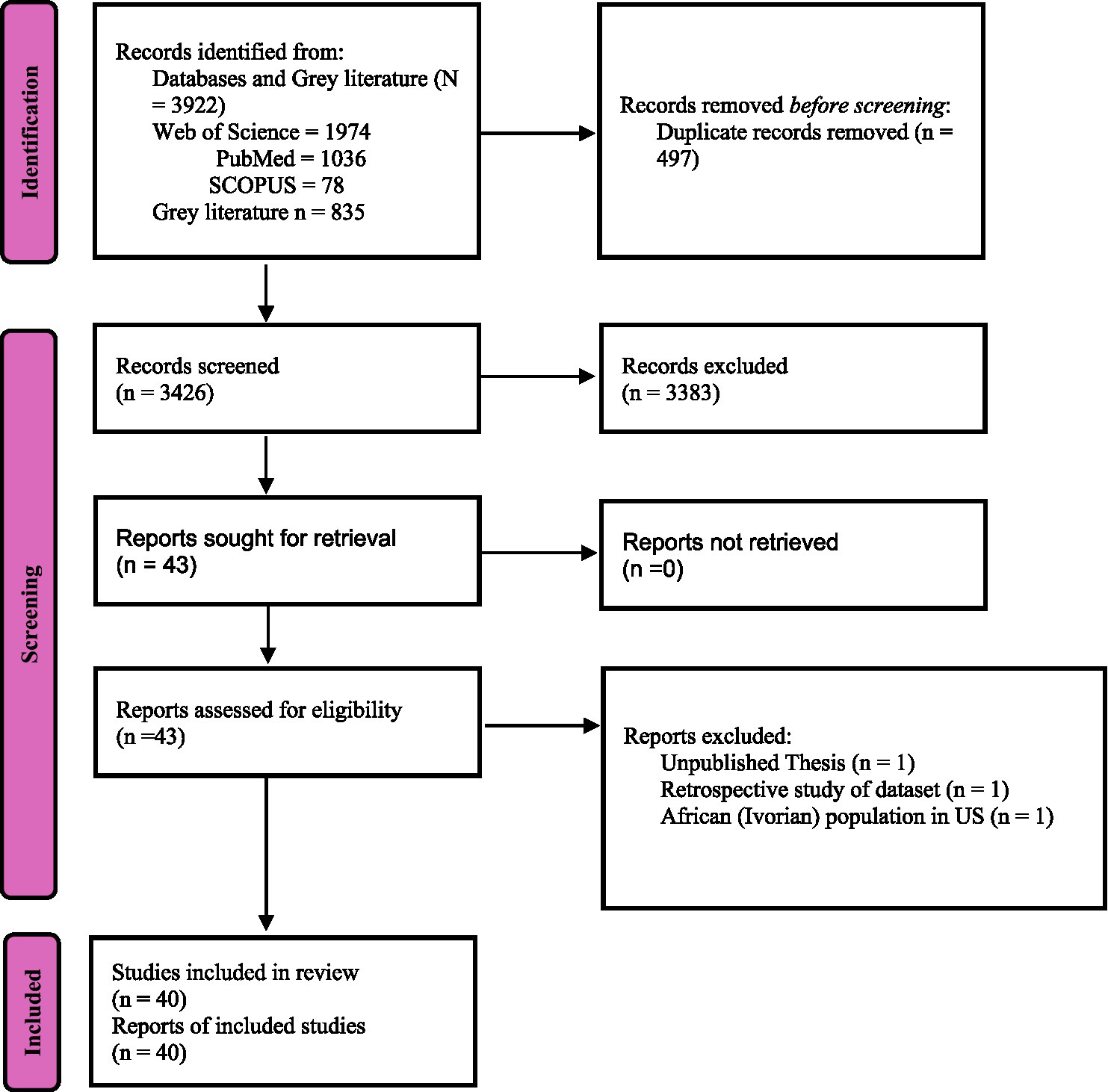

The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1

PRISMA flowchart for HRQoL tools validated for African population.

Data extraction

A structured data extraction form was developed and managed using Microsoft Excel based on the study objectives and COSMIN guidelines. An artificial intelligence (AI) tool was also used to assist in data extraction. Any discrepancies in extracted data were discussed and resolved by consensus. The form was piloted on a random sample of three included studies to ensure clarity and completeness. Necessary revisions were made before full-scale data extraction. Two independent reviewers (EJU and CNI) extracted the following details:

-

Study characteristics (authors, year, country, design).

-

Participant characteristics (sample size, age group, setting).

-

Tool characteristics (name, type, language, mode of administration, domains, validation process).

-

Key findings, psychometric properties, and policy implications.

Any discrepancies in the extracted data were discussed and resolved by consensus, and when needed, a third reviewer (AI) acted as an arbitrator. This dual-coding and consensus-based approach ensured the reliability of the data extraction process. A quality assessment of the 40 included articles was conducted using the 8-item checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies by the Joanna Briggs Institute. Each of the eight questions was used to appraise the articles using the options “yes,” “no,” “unclear,” and “not applicable” (Supplementary File 2).

Data synthesis

A narrative synthesis was conducted to summarize findings across studies. We conducted the synthesis using AI, categorizing the HRQoL tools into generic and disease-specific instruments and identifying trends in validation, adaptation, and psychometric evaluation. Quantitative metrics, including frequency distributions and proportions, were reported to enhance clarity.

Findings were structured according to the characteristics of the measurement tools, the characteristics of the first authors of the included studies, the psychometric properties of the tools, and their application across African settings.

Results

A total of 3,922 records were retrieved from databases, of which 3,425 remained after duplicate removal. After title and abstract screening, 43 articles were retained for full-text review. Three studies were excluded at this stage: one unpublished thesis, one retrospective dataset analysis, and one study on an Ivorian population residing in the United States. Ultimately, 40 studies were included in this systematic review, with the majority (82.5%, n = 33) employing a cross-sectional design alone (Colbourn et al., 2012; Bowden et al., 2002; Namisango et al., 2007; Van Biljon et al., 2015; Reba et al., 2019; Younsi and Chakroun, 2014; Ibrahim et al., 2020; Jikamo et al., 2021; Mbada et al., 2015; Mgbeojedo et al., 2022; Muhye and Fentahun, 2023; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2010; Ehab et al., 2021; Duracinsky et al., 2012; Gqada et al., 2021; Onagbiye et al., 2018; Uwizihiwe et al., 2022; Kidayi et al., 2023; Brandt et al., 2016; Borissov et al., 2022; Kondo et al., 2023; El Fakir et al., 2014a; Olasehinde et al., 2024; Nkurunziza et al., 2016; Farid et al., 2023; El Fakir et al., 2014b; Odetunde et al., 2020; Araya et al., 2019; El Alami et al., 2021; Osman et al., 2018; Smith and Morris-Eyton, 2023; Westmoreland et al., 2018; Guermazi et al., 2012), while only 15% (n = 6) used a longitudinal approach alone (Scott et al., 2017; Ohrnberger et al., 2020; Okello et al., 2018; Owolabi, 2010; Kulich et al., 2008; Getu et al., 2022; Gadisa et al., 2019). Notably, 80.0% (n = 32) of the studies focused on the translation and cultural adaptation of tools to align with local contexts (Colbourn et al., 2012; Bowden et al., 2002; Van Biljon et al., 2015; Reba et al., 2019; Ibrahim et al., 2020; Jikamo et al., 2021; Mbada et al., 2015; Mgbeojedo et al., 2022; Muhye and Fentahun, 2023; Ehab et al., 2021; Duracinsky et al., 2012; Gqada et al., 2021; Onagbiye et al., 2018; Uwizihiwe et al., 2022; Kidayi et al., 2023; Brandt et al., 2016; Borissov et al., 2022; El Fakir et al., 2014a; Olasehinde et al., 2024; Nkurunziza et al., 2016; Farid et al., 2023; El Fakir et al., 2014b; Odetunde et al., 2020; Araya et al., 2019; El Alami et al., 2021; Osman et al., 2018; Smith and Morris-Eyton, 2023; Westmoreland et al., 2018; Guermazi et al., 2012; Kulich et al., 2008; Gadisa et al., 2019).

Geographically, South Africa (Van Biljon et al., 2015; Gqada et al., 2021; Brandt et al., 2016; Scott et al., 2017) and Ethiopia (Reba et al., 2019; Jikamo et al., 2021; Muhye and Fentahun, 2023; Araya et al., 2019; Getu et al., 2022; Gadisa et al., 2019) were the most represented countries, contributing 10.0% (n = 4) and 15% (n = 6) of the studies, respectively. Among studies on disease-specific tools, breast cancer and diabetes (Reba et al., 2019; Ehab et al., 2021; Uwizihiwe et al., 2022; Kidayi et al., 2023; El Fakir et al., 2014a; Olasehinde et al., 2024; Getu et al., 2022; Gadisa et al., 2019) were the most frequently studied conditions, representing 20% (n = 8) of the included studies (Table 1).

Table 1

| Ref. No. | Author(s) | Year | Title | Aim of the study | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Van Biljon et al. (2015) | 2015 | A partial validation of the WHOQOL-OLD in a sample of older people in South Africa | Partial validation (i.e., the assessment of the factor structure and the internal consistency reliability) of the WHOQOL-OLD and its shorter versions | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 2 | Smith and Morris-Eyton (2023) | 2023 | Development, validation and reliability of the Smith Toolkit for Integrated Health Related Quality of Life (STI-HRQoL) | Develop a toolkit that could assess the HRQoL in patients with hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease | Cross-sectional (mixed methods) |

| 3 | Reba et al. (2019) | 2019 | Validity and reliability of the Amharic version of the World Health Organization’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOLBREF) in patients with diagnosed type 2 diabetes in Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Ethiopia | Validate the Amharic version of WHOQOL-BREF, which is designed for measuring QoL of people with diagnosed type 2 diabetes in Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 4 | Westmoreland et al. (2018) | 2018 | Translation, psychometric validation, and baseline results of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) pediatric measures to assess health-related quality of life of patients with pediatric lymphoma in Malawi | Translate and culturally validate PROMIS pediatric measures into Chichewa and report on HRQoL at the time of diagnosis among pediatric patients with lymphoma in Malawi | Cross-sectional (mixed methods) |

| 5 | Younsi and Chakroun (2014) | 2014 | Measuring health-related quality of life: psychometric evaluation of the Tunisian version of the SF-12 health survey | Examine the psychometric properties of the Tunisian version of SF-12 in terms of the measurement and conceptual model, sensitivity, “known groups” construct validity, convergent validity, and hence to increase confidence in using the SF-12 in Tunisian studies as an alternative to the more time-demanding SF-36 | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 6 | Ibrahim et al. (2020) | 2020 | The Hausa 12-item short-form health survey (SF-12): translation, cross-cultural adaptation and validation in mixed urban and rural Nigerian populations with chronic low back pain | Translate and cross-culturally adapt the SF-12 into the Hausa language and test its psychometric properties in mixed urban and rural Nigerian populations with chronic LBP | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 7 | Jikamo et al. (2021) | 2021 | Cultural adaptation and validation of the Sidamic version of the World Health Organization Quality-of-Life-BREF Scale measuring the quality of life of women with severe preeclampsia in southern Ethiopia, 2020 | Translate, culturally adapt, and test the reliability and validity of the WHOQOL-BREF when measuring the quality of life of women with severe preeclampsia in southern Ethiopia | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 8 | Mbada et al. (2015) | 2015 | Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation of Yoruba version of the short-form 36 health survey | Cross-culturally adapt the SF-36 into the Yoruba language and determine its reliability and validity | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 9 | Namisango et al. (2007) | 2007 | Validation of the Missoula-Vitas Quality of-Life Index Among Patients with Advanced AIDS in Urban Kampala, Uganda | Explore the validity and reliability of the MVQOLI in terminally ill AIDS patients receiving palliative care in Uganda, Africa | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 10 | Colbourn et al. (2012) | 2012 | Development, reliability and validity of the Chichewa WHOQOL-BREF in adults in Lilongwe, Malawi | Describes the translation from English to Chichewa, adaptation, and piloting process that constitutes the validation of the WHOQOL-BREF in Malawi. | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 11 | Guermazi et al. (2012) | 2012 | Translation in Arabic, adaptation and validation of the SF-36 Health Survey for use in Tunisia | Translate into Tunisian Arabic and validate the SF-36 in a Tunisian population | Cross-sectional (mixed methods) |

| 12 | Mgbeojedo et al. (2022) | 2022 | IGBO version of the Older People’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (OPQOL-35) is valid and reliable: cross-cultural adaptation and validation | Translate, cross-culturally adapt, and psychometrically evaluate the OPQOL-35 among the Igbo older adult population in Enugu State | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 13 | Muhye and Fentahun (2023) | 2023 | Validation of quality-of-life assessment tool for Ethiopian old age people | Translate and validate the WHOQOL-OLD tool for Ethiopian older adults | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 14 | Scott et al. (2017) | 2017 | The use of the EQ-5D-Y health related quality of life outcome measure in children in the Western Cape, South Africa: psychometric properties, feasibility and usefulness – a longitudinal, analytical study | Investigate the psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-Y when used to assess the HRQoL of children with different health states | Longitudinal (cohort study) |

| 15 | Ravens-Sieberer et al. (2010) | 2010 | Feasibility, reliability, and validity of the EQ-5D-Y: results from a multinational study | Examine the feasibility, reliability, and validity of the newly developed EQ-5D-Y | Cross-sectional (quantitative), with additional test–retest procedures |

| 16 | Ehab et al. (2021) | 2021 | Cultural adaptation and validation of the EORTC QLQ-BR45 to assess health-related quality of life of breast cancer patients | Perform cultural adaptation, pilot testing, and assessment of the psychometric properties of the Egyptian Arabic translation of the EORTC QLQBR45 module on Egyptian breast cancer patients | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 17 | Duracinsky et al. (2012) | 2012 | Psychometric validation of the PROQOL-HIV questionnaire, a new health-related quality of life instrument–specific to HIV disease | Showed the psychometric validation of the PROQOL-HIV instrument using data simultaneously collected in eight countries | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 18 | Gqada et al. (2021) | 2021 | Translation and linguistic validation of the EORTC QLQ-PAN26 questionnaire for assessment of health-related quality of life in patients with pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis into isiXhosa and Afrikaans | Translated and validated the EORTC QLQPAN26 questionnaire into isiXhosa and Afrikaans | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 19 | Onagbiye et al. (2018) | 2018 | Validity and reliability of the Setswana translation of the Short Form-8 health-related quality of life health survey in adults | Explored the feasibility and reliability of the Setswana translation of the HRQoL Short Form-8 (SF-8) among Setswana-speaking adults | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 20 | Ohrnberger et al. (2020) | 2020 | Validation of the SF12 mental and physical health measure for the population from a low-income country in sub-Saharan Africa | Computed and validated the SF-12 for the Malawian population | Longitudinal study (quantitative) |

| 21 | Okello et al. (2018) | 2018 | Validation of heart failure quality of life tool and usage to predict all-cause mortality in acute heart failure in Uganda: The Mbarara heart failure registry (MAHFER) | Validated the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) and evaluated its use as a predictor of 3-month all-cause mortality among heart failure participants in rural Uganda | Longitudinal study (quantitative) |

| 22 | Uwizihiwe et al. (2022) | 2022 | Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the Kinyarwanda version of the diabetes-39 (D-39) questionnaire | Translation and cultural adaptation of the Diabetes-39 (D-39) questionnaire into Kinyarwanda and its psychometric properties among diabetic patients in Rwanda | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 23 | Owolabi (2010) | 2010 | Psychometric properties of the HRQOLISP-40: a novel, shortened multiculturally valid holistic stroke measure | Determined the psychometric properties of a shortened version of the HRQOLISP in multicultural transnational populations | Longitudinal study (quantitative) |

| 24 | Kidayi et al. (2023) | 2023 | Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric properties of the Swahili version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-BR45 among breast cancer patients in Tanzania | Determined the validity, reliability, and psychometric properties of the Swahili version of EORTC QLQ-BR45 among women with breast cancer in Tanzania | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 25 | Brandt et al. (2016) | 2016 | Validation of the prolapse quality-of-life questionnaire (P-QoL): an Afrikaans version in a South African population | Validated an Afrikaans version of the P-QoL in a South African population | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 26 | Kulich et al. (2008) | 2008 | Reliability and validity of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) and Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia (QOLRAD) questionnaire in dyspepsia: a six-country study | Documented the psychometric characteristics of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) and the Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia questionnaire (QOLRAD) in Afrikaans, German, Hungarian, Italian, Polish, and Spanish patients with dyspepsia | Longitudinal study (quantitative) |

| 27 | Borissov et al. (2022) | 2021 | Adaptation and validation of two autism-related measures of skills and quality of life in Ethiopia | Culturally adapt and validate two questionnaires for use in Ethiopia: The Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ Family Impact Module | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 28 | Kondo et al. (2023) | 2023 | Validation of Kiswahili version of WHOQOL-HIV BREF questionnaire among people living with HIV/AIDS in Tanzania – a cross-sectional study | Assess the validity and reliability of the Kiswahili version of WHOQOL-HIV BREF among PLWHA in Tanzania | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 29 | El Fakir et al. (2014a) | 2014 | The European organization for research and treatment of cancer quality of life questionnaire-BR 23 breast cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire: psychometric properties in a Moroccan sample of breast cancer patients | Translate and adapt the original version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Breast Cancer-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-BR23) from English to Moroccan Arabic language, to refine its terminology and to adapt it to the Moroccan culture | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 30 | Getu et al. (2022) | 2022 | Translation and validation of the EORTC QLQ-BR45 among Ethiopian breast cancer patients | Translate, validate, and assess the psychometric properties of the EORTC QLQBR45 among breast cancer patients in Ethiopia | Longitudinal study (quantitative) |

| 31 | Olasehinde et al. (2024) | 2024 | Translation and psychometric assessment of the mastectomy module of the BREAST-Q questionnaire for use in Nigeria | Translate and assess the psychometric properties of the mastectomy module of the BREAST-Q for use in Nigeria | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 32 | Nkurunziza et al. (2016) | 2016 | Validation of the Kinyarwanda-version Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire and Short-Form Nepean Dyspepsia Index to assess dyspepsia prevalence and quality-of-life impact in Rwanda | Develop and validate Kinyarwanda versions of the Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire (SF-LDQ) and the Short-Form Nepean Dyspepsia Index (SF-NDI) to measure the frequency and severity of dyspepsia and associated quality-of-life impact in Rwanda | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 33 | Farid et al. (2023) | 2023 | Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of a self-reporting tool to assess health-related quality of life for Egyptians with extremity bone sarcomas in childhood or adolescence | Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the pediatric Toronto Extremity Salvage Score (pTESS) and Toronto Extremity Salvage Score (TESS) to assess the functional outcome for Egyptian children and adult survivors following surgeries of extremity bone sarcomas | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 34 | El Fakir et al. (2014b) | 2012 | Validation of the Skindex-16 questionnaire in patients with skin diseases in Morocco | To translate and adapt the original version of the Skindex-16 questionnaire from English to Moroccan Arabic language, refining its terms and adapting it to Moroccan culture | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 35 | Odetunde et al. (2020) | 2020 | Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Igbo language version of the stroke-specific quality of life scale 2.0 | Cross-culturally adapting and assessing the validity and reliability of the Igbo version of the SS-QoL | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 36 | Araya et al. (2019) | 2019 | Reliability and validity of the Amharic version of European Organization for Research and Treatment of cervical cancer module for the assessment of health-related quality of life in women with cervical cancer in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | Assess the psychometric properties of the tool among Ethiopian cervical cancer patients | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 37 | El Alami et al. (2021) | 2021 | Psychometric validation of the Moroccan version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 in colorectal Cancer patients: cross-sectional study and systematic literature review | Assess the validity and reliability of the Moroccan Arabic Dialectal version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Core Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) in patients with colorectal cancer | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 38 | Gadisa et al. (2019) | 2019 | Reliability and validity of Amharic version of EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 modules for assessing health-related quality of life among breast cancer patients in Ethiopia | Assess the psychometric properties of the tools among Ethiopian breast cancer patients | Longitudinal Study (quantitative) |

| 39 | Osman et al. (2018) | 2018 | Validation and comparison of the Arabic versions of GOHAI and OHIP-14 in patients with and without denture experience | Compare and assess the validation of two quality of life measures, the Oral Health Impact Profile-14 (OHIP-14) and Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI), in patients with and without previous denture experience | Cross-sectional (quantitative) |

| 40 | Bowden et al. (2002) | 2002 | Methods for pre-testing and piloting survey questions: illustrations from the KENQOL survey of health-related quality of life | develop a culturally relevant generic measure of ‘health’ to measure the impact of interventions designed to reduce disease and/or improve health in Kenya | Cross-sectional (qualitative) |

Descriptive characteristics of the included studies in the review.

WHOQOL-OLD, World Health Organization quality of life for older adults; STI-HRQoL, Smith Toolkit for Integrated Health-Related Quality of Life; WHOQOL-BREF, World Health Organization Quality of Life (brief version); HRQoL, health-related quality of life; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; SF-12, 12-item short-form health survey; SF-36, 36-item short-form health survey; MVQOLI, Missoula-Vitas Quality of-Life Index; AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; OPQOL-35, Older People’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (35 items); LBP, lower back pain; QoL, quality of life. EQ-5D-Y, EuroQol Group 5-dimension for children and adolescents; EORTC QLQ-BR45, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer—quality of life questionnaire for breast cancer patients (45 items); PROQOL-HIV, Patient-Reported Outcomes Quality of Life–HIV questionnaire; EORTC QLQ-PAN26, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer—quality of life questionnaire for patients with pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis (26 items); D-39, Diabetes (39 items); HRQOLISP-40, health-related quality of life in stroke patients (40 items); P-QoL, prolapse quality-of-life questionnaire; GSRS, Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale; QOLRAD, Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; SF-8, 8-item short-form survey. WHOQOL-HIV BREF, World Health Organization quality of life for HIV patients; EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer—quality of life questionnaire for Colorectal cancer patients (30 items); GOHAI, Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index; OHIP-14, Oral Health Impact Profile-14; QLQ-C30, Quality of Life Core Questionnaire in patients with colorectal cancer (30 items); SS-QoL, stroke-specific quality of life scale; pTESS, Toronto Extremity Salvage Score; TESS, Toronto Extremity Salvage Score; SF-LDQ, Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire; SF-NDI, Short-Form Nepean Dyspepsia Index; BREAST-Q, Breast Questionnaire; KENQOL, Kenyan quality of life.

Quality assessment of the included articles using the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist

The vast majority of studies demonstrated robust practices, with 34 (85%) clearly defining their inclusion criteria (Colbourn et al., 2012; Namisango et al., 2007; Van Biljon et al., 2015; Reba et al., 2019; Younsi and Chakroun, 2014; Ibrahim et al., 2020; Jikamo et al., 2021; Mbada et al., 2015; Mgbeojedo et al., 2022; Muhye and Fentahun, 2023; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2010; Ehab et al., 2021; Onagbiye et al., 2018; Uwizihiwe et al., 2022; Kidayi et al., 2023; Brandt et al., 2016; Borissov et al., 2022; Kondo et al., 2023; Olasehinde et al., 2024; Nkurunziza et al., 2016; Farid et al., 2023; El Fakir et al., 2014b; Odetunde et al., 2020; Araya et al., 2019; El Alami et al., 2021; Osman et al., 2018; Smith and Morris-Eyton, 2023; Scott et al., 2017; Okello et al., 2018; Owolabi, 2010; Kulich et al., 2008; Getu et al., 2022; Gadisa et al., 2019) and 33 (82.5%) providing a detailed description of the study subjects and setting (Colbourn et al., 2012; Namisango et al., 2007; Van Biljon et al., 2015; Reba et al., 2019; Younsi and Chakroun, 2014; Ibrahim et al., 2020; Jikamo et al., 2021; Mbada et al., 2015; Mgbeojedo et al., 2022; Muhye and Fentahun, 2023; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2010; Ehab et al., 2021; Onagbiye et al., 2018; Uwizihiwe et al., 2022; Kidayi et al., 2023; Brandt et al., 2016; Borissov et al., 2022; Kondo et al., 2023; Olasehinde et al., 2024; Nkurunziza et al., 2016; Farid et al., 2023; El Fakir et al., 2014b; Odetunde et al., 2020; Araya et al., 2019; El Alami et al., 2021; Smith and Morris-Eyton, 2023; Scott et al., 2017; Okello et al., 2018; Owolabi, 2010; Kulich et al., 2008; Getu et al., 2022; Gadisa et al., 2019). Measurement and analysis were particularly strong, as nearly all studies, 37 (97.5%), reported measuring outcomes in a valid and reliable way and employing appropriate statistical analysis (Colbourn et al., 2012; Bowden et al., 2002; Namisango et al., 2007; Van Biljon et al., 2015; Reba et al., 2019; Younsi and Chakroun, 2014; Ibrahim et al., 2020; Jikamo et al., 2021; Mbada et al., 2015; Mgbeojedo et al., 2022; Muhye and Fentahun, 2023; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2010; Ehab et al., 2021; Duracinsky et al., 2012; Gqada et al., 2021; Onagbiye et al., 2018; Uwizihiwe et al., 2022; Kidayi et al., 2023; Brandt et al., 2016; Borissov et al., 2022; Kondo et al., 2023; Olasehinde et al., 2024; Nkurunziza et al., 2016; Farid et al., 2023; El Fakir et al., 2014b; Odetunde et al., 2020; Araya et al., 2019; El Alami et al., 2021; Osman et al., 2018; Smith and Morris-Eyton, 2023; Scott et al., 2017; Ohrnberger et al., 2020; Okello et al., 2018; Owolabi, 2010; Kulich et al., 2008; Getu et al., 2022; Gadisa et al., 2019). However, the handling of confounding factors was a notable exception. Of the 33 studies for which this criterion was applicable, only 8 (24.2%) adequately identified potential confounders (Van Biljon et al., 2015; Reba et al., 2019; Ibrahim et al., 2020; Mbada et al., 2015; Borissov et al., 2022; Osman et al., 2018; Smith and Morris-Eyton, 2023; Getu et al., 2022) (see Supplementary Tables 2a–c).

Characteristics of first authors of the included studies

Among the 40 included studies, 22 (55%) of the first authors were men (Colbourn et al., 2012; Bowden et al., 2002; Younsi and Chakroun, 2014; Ibrahim et al., 2020; Jikamo et al., 2021; Mbada et al., 2015; Muhye and Fentahun, 2023; Duracinsky et al., 2012; Uwizihiwe et al., 2022; Kidayi et al., 2023; Borissov et al., 2022; Kondo et al., 2023; Olasehinde et al., 2024; Nkurunziza et al., 2016; El Alami et al., 2021; Guermazi et al., 2012; Ohrnberger et al., 2020; Okello et al., 2018; Owolabi, 2010; Kulich et al., 2008; Getu et al., 2022; Gadisa et al., 2019), while 13 (32.5%) were women (Namisango et al., 2007; Mgbeojedo et al., 2022; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2010; Ehab et al., 2021; Brandt et al., 2016; El Fakir et al., 2014a; Farid et al., 2023; El Fakir et al., 2014b; Odetunde et al., 2020; Osman et al., 2018; Smith and Morris-Eyton, 2023; Westmoreland et al., 2018; Scott et al., 2017), indicating a gender disparity in authorship of HRQoL research in Africa. The majority of the first authors (n = 32, 80.0%) were affiliated with African institutions (Colbourn et al., 2012; Namisango et al., 2007; Van Biljon et al., 2015; Reba et al., 2019; Younsi and Chakroun, 2014; Ibrahim et al., 2020; Jikamo et al., 2021; Mbada et al., 2015; Mgbeojedo et al., 2022; Muhye and Fentahun, 2023; Ehab et al., 2021; Gqada et al., 2021; Onagbiye et al., 2018; Kidayi et al., 2023; Brandt et al., 2016; Kondo et al., 2023; El Fakir et al., 2014a; Olasehinde et al., 2024; Nkurunziza et al., 2016; Farid et al., 2023; El Fakir et al., 2014b; Odetunde et al., 2020; Araya et al., 2019; El Alami et al., 2021; Osman et al., 2018; Smith and Morris-Eyton, 2023; Westmoreland et al., 2018; Guermazi et al., 2012; Scott et al., 2017; Okello et al., 2018; Gadisa et al., 2019), while 7 (17.5%) were affiliated with institutions outside Africa (Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2010; Duracinsky et al., 2012; Uwizihiwe et al., 2022; Borissov et al., 2022; Ohrnberger et al., 2020; Kulich et al., 2008; Getu et al., 2022; Bowden, 2002). The United Kingdom (Borissov et al., 2022; Ohrnberger et al., 2020; Bowden, 2002) (n = 3, 7.5%) and France (Duracinsky et al., 2012) (n = 1, 2.5%) were represented among non-African affiliations. South Africa (Van Biljon et al., 2015; Gqada et al., 2021; Onagbiye et al., 2018; Brandt et al., 2016; Smith and Morris-Eyton, 2023; Scott et al., 2017) (n = 6, 15.0%), Nigeria (Ibrahim et al., 2020; Mbada et al., 2015; Mgbeojedo et al., 2022; Olasehinde et al., 2024; Odetunde et al., 2020; Owolabi, 2010) (n = 6, 15.0%), and Ethiopia (Reba et al., 2019; Jikamo et al., 2021; Muhye and Fentahun, 2023; Araya et al., 2019; Gadisa et al., 2019) (n = 5, 12.5%) had the highest representation of first-author institutional affiliations. Dual institutional affiliations were observed in 14 (35.0%) of the studies, reflecting interdisciplinary and cross-institutional research collaborations (Colbourn et al., 2012; Ibrahim et al., 2020; Jikamo et al., 2021; Mbada et al., 2015; Mgbeojedo et al., 2022; Duracinsky et al., 2012; Gqada et al., 2021; Uwizihiwe et al., 2022; Olasehinde et al., 2024; El Alami et al., 2021; Westmoreland et al., 2018; Guermazi et al., 2012; Okello et al., 2018; Getu et al., 2022) (see Supplementary Tables 3a–c).

Descriptive characteristics of sample sizes and populations whose HRQoL were assessed

Most studies (77.5%, n = 31) focused on adult populations aged 18 years and above (Colbourn et al., 2012; Namisango et al., 2007; Reba et al., 2019; Younsi and Chakroun, 2014; Ibrahim et al., 2020; Jikamo et al., 2021; Mbada et al., 2015; Ehab et al., 2021; Duracinsky et al., 2012; Gqada et al., 2021; Uwizihiwe et al., 2022; Kidayi et al., 2023; Brandt et al., 2016; Kondo et al., 2023; El Fakir et al., 2014a; Olasehinde et al., 2024; Nkurunziza et al., 2016; Farid et al., 2023; El Fakir et al., 2014b; Odetunde et al., 2020; Araya et al., 2019; El Alami et al., 2021; Osman et al., 2018; Smith and Morris-Eyton, 2023; Guermazi et al., 2012; Ohrnberger et al., 2020; Okello et al., 2018; Owolabi, 2010; Kulich et al., 2008; Getu et al., 2022; Gadisa et al., 2019). In comparison, only 7.5% (n = 3) included children and adolescents alongside the adult population (Mgbeojedo et al., 2022; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2010; Westmoreland et al., 2018), suggesting a significant emphasis on adult HRQoL in African settings.

Sample sizes varied considerably, with 80.0% (n = 32) of studies enrolling fewer than 300 participants (Namisango et al., 2007; Van Biljon et al., 2015; Ibrahim et al., 2020; Jikamo et al., 2021; Mgbeojedo et al., 2022; Muhye and Fentahun, 2023; Ehab et al., 2021; Onagbiye et al., 2018; Uwizihiwe et al., 2022; Kidayi et al., 2023; Brandt et al., 2016; Borissov et al., 2022; Kondo et al., 2023; El Fakir et al., 2014a; Olasehinde et al., 2024; Nkurunziza et al., 2016; Farid et al., 2023; El Fakir et al., 2014b; Odetunde et al., 2020; Araya et al., 2019; El Alami et al., 2021; Osman et al., 2018; Smith and Morris-Eyton, 2023; Westmoreland et al., 2018; Guermazi et al., 2012; Scott et al., 2017; Okello et al., 2018; Owolabi, 2010; Kulich et al., 2008; Getu et al., 2022; Gadisa et al., 2019; Gqada et al., 2021), and only 7.5% (n = 3) involving cohorts exceeding 1,000 participants (Younsi and Chakroun, 2014; Mbada et al., 2015; Ohrnberger et al., 2020).

Recruitment settings were predominantly hospital-based (Colbourn et al., 2012; Namisango et al., 2007; Van Biljon et al., 2015; Reba et al., 2019; Ibrahim et al., 2020; Jikamo et al., 2021; Mbada et al., 2015; Ehab et al., 2021; Duracinsky et al., 2012; Uwizihiwe et al., 2022; Kidayi et al., 2023; Brandt et al., 2016; Borissov et al., 2022; Kondo et al., 2023; El Fakir et al., 2014a; Olasehinde et al., 2024; Nkurunziza et al., 2016; Farid et al., 2023; El Fakir et al., 2014b; Odetunde et al., 2020; Araya et al., 2019; El Alami et al., 2021; Osman et al., 2018; Smith and Morris-Eyton, 2023; Westmoreland et al., 2018; Okello et al., 2018; Owolabi, 2010; Kulich et al., 2008; Getu et al., 2022; Gadisa et al., 2019; Gqada et al., 2021) (77.5%, n = 31), with only 22.5% (n = 9) conducted in community settings (Bowden et al., 2002; Younsi and Chakroun, 2014; Mgbeojedo et al., 2022; Muhye and Fentahun, 2023; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2010; Onagbiye et al., 2018; Guermazi et al., 2012; Scott et al., 2017; Ohrnberger et al., 2020), indicating a potential bias toward healthcare facility-based populations.

Regional distribution revealed East Africa as the leading contributor (Colbourn et al., 2012; Bowden et al., 2002; Namisango et al., 2007; Reba et al., 2019; Jikamo et al., 2021; Muhye and Fentahun, 2023; Uwizihiwe et al., 2022; Kidayi et al., 2023; Borissov et al., 2022; Kondo et al., 2023; Nkurunziza et al., 2016; Araya et al., 2019; Westmoreland et al., 2018; Ohrnberger et al., 2020; Okello et al., 2018; Getu et al., 2022; Gadisa et al., 2019) (42.5%, n = 17), with West Africa (Ibrahim et al., 2020; Mbada et al., 2015; Mgbeojedo et al., 2022; Duracinsky et al., 2012; Olasehinde et al., 2024; Odetunde et al., 2020; Owolabi, 2010) (17.5%, n = 7) contributing the least proportion of studies. Gender-specific studies were limited, with only 17.5% (n = 7) exclusively targeting women, highlighting a notable gap in gender-focused HRQoL research (Jikamo et al., 2021; Kidayi et al., 2023; Brandt et al., 2016; El Fakir et al., 2014a; Olasehinde et al., 2024; Araya et al., 2019; Osman et al., 2018) (see Table 2).

Table 2

| Ref. no. | Age group | Sample size | Facility | Country | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Older adults | 176 | Hospital | South Africa | South |

|

Adults | 257 | Hospital | South Africa | South |

|

18 years and above | 344 | Hospital | Ethiopia | East |

|

Children between 5 and 18 years | 54 | Hospital | Malawi | East |

|

18 years and above | 3,582 | Community | Tunisia | North |

|

18–70 years | 200 | Hospital | Nigeria | West |

|

Adult women | 264 | Hospital | Ethiopia | East |

|

18–70 years | 1,087 | Hospital | Nigeria | West |

|

18–64 years | 200 | Hospital | Uganda | East |

|

Adults | 309 | Hospital | Malawi | East |

|

16–80 years | 130 | Community | Tunisia | North |

|

Older adults >65 years | 115 | Community | Nigeria | West |

|

60 years and above | 180 | Community | Ethiopia | East |

|

Adolescents (13–18 years) | 224 | Community | South Africa | South |

|

Children and adolescents | 258 | Community | South Africa (+5 non-Africans) |

South |

|

18 and 65 years | 74 | Hospital | Egypt | North |

|

Adults | 791 | Hospital | Senegal (+7 non-Africans) |

West |

|

Adults | 13 | Hospital | South Africa | South |

|

35–65 years | 60 | Community | South Africa | South |

|

15 years and older | 2,838 | community | Malawi | East |

|

13 years or greater | 195 | Hospital | Uganda | East |

|

Patients aged 21–80 years | 309 | Hospital | Uganda | East |

|

Adults | 200 (Nigeria) | Hospital | Nigeria (+1 non-African) |

West |

|

Adult women aged 18–70 years | 422 | Hospital | Tanzania | East |

|

Women 18–90 years | 39 | Hospital | South Africa | South |

|

Adults | 108 (SA) | Hospital | South Africa (+5 non-African) |

South |

|

Children between 2 and 9 years of age | 300 | Hospital | Ethiopia | East |

|

Aged 18 and above | 73 | Hospital | Tanzania | East |

|

At least 18 years | 105 | Hospital | Morocco | North |

|

18 years and above | 248 | Hospital | Ethiopia | East |

|

Women of different age categories | 21 | Hospital | Nigeria | West |

|

>17 years | 200 | Hospital | Rwanda | East |

|

Adult and children 8 years and above | 233 | Hospital | Egypt | North |

|

Above 18 years | 120 | Hospital | Morocco | North |

|

18 years and above | 50 | Hospital | Nigeria | West |

|

18 years and above | 171 | Hospital | Ethiopia | East |

|

18 years and above | 120 | Hospital | Morocco | North |

|

Above 18 years | 146 | Hospital | Ethiopia | East |

|

40 years and above | 69 | Hospital | Sudan | North |

|

Adults | 550 | Community | Kenya | East |

Descriptive characteristics of the participants in the included studies.

Characteristics of the HRQoL tools

A total of 34 tools were reported in the included studies. Of the 12 generic HRQoL instruments used in the studies, SF-12 (Younsi and Chakroun, 2014; Ibrahim et al., 2020; Ohrnberger et al., 2020) and WHOQOL-BREF (Colbourn et al., 2012; Reba et al., 2019; Jikamo et al., 2021) were reported in three studies each. Among the 22 disease-specific instruments, the different versions of the QoL in cancer tool, the EORTC QLQ, were validated in seven studies (Ehab et al., 2021; Kidayi et al., 2023; Araya et al., 2019; El Alami et al., 2021; Getu et al., 2022; Gadisa et al., 2019; Gqada et al., 2021), with the EORTC QLQ-C30 accounting for four of the studies (Kidayi et al., 2023; Araya et al., 2019; El Alami et al., 2021; Gadisa et al., 2019), emphasizing their widespread use in African health research. Most studies (82.5%, n = 33) translated tools into local languages, including Afrikaans, Chi Chew, Igbo, Yoruba, and Arabic, ensuring linguistic and cultural appropriateness (Colbourn et al., 2012; Bowden et al., 2002; Namisango et al., 2007; Van Biljon et al., 2015; Reba et al., 2019; Younsi and Chakroun, 2014; Ibrahim et al., 2020; Jikamo et al., 2021; Mbada et al., 2015; Mgbeojedo et al., 2022; Ehab et al., 2021; Duracinsky et al., 2012; Gqada et al., 2021; Onagbiye et al., 2018; Uwizihiwe et al., 2022; Kidayi et al., 2023; Brandt et al., 2016; Borissov et al., 2022; Kondo et al., 2023; El Fakir et al., 2014a; Olasehinde et al., 2024; Nkurunziza et al., 2016; Farid et al., 2023; Odetunde et al., 2020; Araya et al., 2019; El Alami et al., 2021; Osman et al., 2018; Westmoreland et al., 2018; Guermazi et al., 2012; Ohrnberger et al., 2020; Kulich et al., 2008; Getu et al., 2022; Gadisa et al., 2019). Administration methods varied, with 45% (n = 18) of the included studies adopting self-administration of 13 tools (Mgbeojedo et al., 2022; Gqada et al., 2021; Onagbiye et al., 2018; Kondo et al., 2023; El Fakir et al., 2014a; Olasehinde et al., 2024; Nkurunziza et al., 2016; Farid et al., 2023; Odetunde et al., 2020; Araya et al., 2019; Smith and Morris-Eyton, 2023; Westmoreland et al., 2018; Guermazi et al., 2012; Scott et al., 2017; Okello et al., 2018; Owolabi, 2010; Kulich et al., 2008; Gadisa et al., 2019), while 30.0% (n = 12) adopted interviews in data collection using 10 tools (Colbourn et al., 2012; Bowden et al., 2002; Namisango et al., 2007; Reba et al., 2019; Younsi and Chakroun, 2014; Ibrahim et al., 2020; Jikamo et al., 2021; Duracinsky et al., 2012; Borissov et al., 2022; El Fakir et al., 2014a; Osman et al., 2018; Ohrnberger et al., 2020), reflecting differences in participant literacy and accessibility. Validation efforts demonstrated robust reliability, with internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) exceeding 0.70 in the majority of the tools (see Table 3).

Table 3

| S/no | Tools (authors) | Type | Language | Mode of administration | Domains of HRQoL | Scoring system | Development | Validation (yes/no) | Cultural adaptation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | WHOQOL-OLD (Van Biljon et al., 2015; Muhye and Fentahun, 2023) | Generic | English (Van Biljon et al., 2015) and Amharic (Muhye and Fentahun, 2023) | Self-administered (Van Biljon et al., 2015) and interview (Muhye and Fentahun, 2023) | Sensory abilities; autonomy; past, present, and future activities; social participation; death and dying; and intimacy | Each item is scored on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 5, with higher scores representing greater QoL | No | Yes | No (Van Biljon et al., 2015) and yes (Muhye and Fentahun, 2023) |

| 2. | STI-HRQoL long form 37 items (Smith and Morris-Eyton, 2023) | Specific | English | Self-administered and interview | Physical health, mental health, and socioeconomic health | Agreement scores on a scale of 0 to 1 | Yes | Yes | No |

| 3. | STI-HRQoL—short form 25 items (Smith and Morris-Eyton, 2023) | Specific | English | Self-administered and interview | Physical health, mental health, and socioeconomic health | Agreement scores on a scale of 0 to 1 | Yes | Yes | No |

| 4. | WHOQOL-BREF (Colbourn et al., 2012; Reba et al., 2019; Jikamo et al., 2021) | Generic | Amharic (Reba et al., 2019), Sidamic (Jikamo et al., 2021), and Chichewa (Colbourn et al., 2012) | Interview | Physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environmental health | Each of these items was scored from 1 to 5 on a response scale, which is agreed as a 5-point Likert scale | No | Yes | Yes |

| 5. | PROMIS-25 (Westmoreland et al., 2018) | Generic | Chichewa | Self-administered or proxy | Mobility, anxiety, depressive symptoms, fatigue, peer relationships, and pain interference | A 5-point Likert scale is used. Additionally, a single-item pain intensity measurement was scored from 0 to 10 | No | Yes | Yes |

| 6. | SF-12 (Younsi and Chakroun, 2014; Ibrahim et al., 2020; Ohrnberger et al., 2020) | Generic | Tunisian (Younsi and Chakroun, 2014), Hausa (Ibrahim et al., 2020), and Chi Chewa, Chi Yao or Chi Tumbuka (Ohrnberger et al., 2020) | Interview | Physical functioning, role limitation due to physical problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitation due to emotional problems, perceived mental health | Response for raw scores for some items ranges from 1 to 6. The eight-scale scores range from 0 (the worst) to 100 (the best) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 7. | SF-36 (Mbada et al., 2015; Guermazi et al., 2012; Okello et al., 2018) | Generic | Yoruba (Mbada et al., 2015), Tunisian Arabic (Guermazi et al., 2012), English (Mbada et al., 2015; Okello et al., 2018) | Self-administered (Guermazi et al., 2012) and interview (Okello et al., 2018) | Physical and mental health components with eight subscales: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health | Standard SF-36 scoring (0–100 scale, higher scores indicate better health) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 8. | MVQOLI (Namisango et al., 2007) | Generic | Luganda and English | Self-administered and interview | Symptoms, functional status, interpersonal relations, emotional wellbeing, and transcendence | A 5-point Likert scale is used, with domain scores and a total score formula; the lowest score indicates the least desirable situation and vice versa | No | Yes | Yes |

| 9. | I-OPQOL (Mgbeojedo et al., 2022) | Generic | Igbo | Self-administered and interview | Life overall; health; social relationships; independence control; home and neighborhood; psychological and emotional wellbeing; financial circumstances; religion and culture | Each participant was expected to answer “YES” or “NO” for each item and response option | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 10. | EQ-5D-Y (Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2010; Scott et al., 2017) | Generic | Afrikaans (Scott et al., 2017) and English (Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2010) | Self-administered | Mobility, looking after myself, doing usual activities, pain or discomfort, and worried, sad, or unhappy | Each participant is required to fill in a visual analog scale (VAS), which ranges from 0, the worst health state imaginable, to 100, the best health state imaginable | No | Yes | NO |

| 11. | EORTC QLQ-BR45 (Ehab et al., 2021; Kidayi et al., 2023; Getu et al., 2022) | Specific | Egyptian Arabic (Ehab et al., 2021), Swahili (Kidayi et al., 2023), and Amharic (Getu et al., 2022) | Interview (Ehab et al., 2021; Kidayi et al., 2023) and Self-administered (Getu et al., 2022) | The EORTC QLQ-BR45 comprises four functional scales (body image, sexual functioning, sexual enjoyment, and future perspective) and five symptom scales/items (systemic therapy side effects, breast symptoms, arm symptoms, and upset by hair loss) | These tools use a 4-point scale from 1 = not at all, to 4 = very much, and a scoring scale of 0–100, with a high score indicating better functioning and severity for high symptoms/item scale | No | Yes | Yes |

| 12. | PROQOL-HIV (Duracinsky et al., 2012) | Specific | French | Interview | PROQOL-HIV has 11 themes: general health perception, social relationships, emotions, energy/fatigue, sleep, physical and daily activity, coping, future cognitive functioning, symptoms, and treatment. The remaining three non-HRQL items concerned satisfaction with HIV healthcare services, financial difficulties due to HIV, and concerns about having a child | PROQOL-HIV domain is on a 5-point scale ranging from 0—never to 4—always, except for one item whose response scale is 0—very good to 4—very poor. For the EQ-5D, the domain is on a 3-point scale and a 100-point visual analog scale (VAS), ranging from best to worst imaginable health state of self-perceived general health | No | Yes | Yes |

| 13. | EORTC QLQPAN26 (Gqada et al., 2021) | Specific | isiXhosa and Afrikaans | Self-administered and interview | Seven multi-item symptom scales in the QLQ-PAN26, namely pancreatic pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, altered bowel habits, hepatic, body image, healthcare satisfaction, and sexuality | A 4-level Likert scale for the languages from previous translations was used | No | Yes | Yes |

| 14. | SF-8 (Onagbiye et al., 2018) | Generic | South African English and Setswana | Self-administered | Physical functioning, role limitation due to physical problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitation due to emotional problems, perceived mental health | The scoring in SF-8 was based on this two-component summary and was calculated by weighting each SF-8 item using a norm-based procedure in the instrument guidelines | No | Yes | Yes |

| 15. | KCCQ (Okello et al., 2018) | Specific | Not stated | Self-administered | KCCQ has physical limitation, symptom stability, symptom frequency, symptom burden, self-efficacy, quality of life, and social limitation. The SF-36 questionnaire covers physical functioning, physical limitation, emotional limitation, bodily pain, general health, mental health, social functioning, energy fatigue, and physical health |

Both were measured using a Likert scale, but the KCCQ was also measured with two summary subscales: the overall KCCQ score and the clinical summary score. The scores for both ranged from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better health status | No | Yes | No |

| 16. | D39 (Uwizihiwe et al., 2022) | Specific | Kinyarwanda | Interviews | It consists of 39 items grouped into five dimensions: Energy and mobility, diabetes control, social burden, anxiety and worry, and sexual functioning | Each item can be answered using a 7-point scale ranging from 0.5 (not affected at all) to 7.5 (extremely affected) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 17. | HRQOLISP (Owolabi, 2010) | Specific | English and German | Self-administered and interview | It comprises two spheres and seven domains. The physical sphere includes physical, psychological, cognitive, and ecosocial domains, whereas the spiritual sphere consists of soul, spirit, and spiritual interaction domains | The domain scores were transformed into a scale with a maximum score of 100 (best health) each | No | Yes | No |

| 18. | EORTC QLQ-C30 (Kidayi et al., 2023; Araya et al., 2019; El Alami et al., 2021; Gadisa et al., 2019) | Specific | Swahili (Kidayi et al., 2023) Amharic (Araya et al., 2019; Gadisa et al., 2019) Moroccan Arabic (El Alami et al., 2021) |

Interview (Kidayi et al., 2023; El Alami et al., 2021) and self-administered (Araya et al., 2019; El Alami et al., 2021) | It is sub-grouped into 15 domains, including five functional subscales (physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, and social functioning); three multi-item symptom subscales (fatigue, nausea/vomiting, and pain); global health status/QoL subscale; and six single items addressing various symptoms and perceived financial impact | The item scoring procedure for the EORTC QLQ-C30 was managed according to the EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. After the scoring procedures, the score was transformed into a 0–100 scale | No | Yes | Yes |

| 19. | BREAST-Q questionnaire (Olasehinde et al., 2024) | Specific | Yoruba | Self-administered | Quality of Life (including psychosocial wellbeing, sexual wellbeing, physical wellbeing of the chest, and adverse effects of radiation) and Satisfaction (including satisfaction with breasts, surgeons, the medical team, and office staff). The psychosocial wellbeing, sexual wellbeing, physical wellbeing of the chest, and satisfaction with breast domains are applicable in the preoperative setting, while all the domains can be used postoperatively | BREAST-Q scores are transformed onto a scale from 0 to 100 | No | Yes | Yes |

| 20. | SF-NDI (Nkurunziza et al., 2016) | Specific | Kinyarwanda | Self-administered | The SF-NDI evaluates tension/ anxiety, interference with daily activities, disruption of usual eating/drinking, knowledge of/control over disease symptoms, and interference with work/study with 2-item 5-point Likert scales, with a total score calculated as the mean of the five subscale scores | Each item is assigned a numerical score that is summed into a total score; scores >14 | No | Yes | Yes |

| 21. | Modified pTESS (Farid et al., 2023) | Specific | Arabic | Self-administered | Modified versions of pTESS included the same additional mental domain, which involved six questions that were adopted from the pediatric anger, fatigue, cognitive, and depression domains of the NeuroQOL system, as well as the mental component of SF-36 | 5-point Likert scale | No | Yes | Yes |

| 22. | Modified TESS (Farid et al., 2023) | Specific | Arabic | Self-administered | Modified versions of TESS included the same additional mental domain, which involved six questions that were adopted from the pediatric anger, fatigue, cognitive, and depression domains of the NeuroQOL system, as well as the mental component of SF-36 | 5-point Likert scale | No | Yes | Yes |

| 23. | EQ-5D-3L (Duracinsky et al., 2012; El Fakir et al., 2014b) | Generic | Moroccan Arabic (El Fakir et al., 2014b), English (Duracinsky et al., 2012) | Interview | Mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression | Scores for the emotional, functioning, and symptom scales are expressed in a linear scale, varying from 0 (no effect on QoL) to 100 (maximum effect on QoL) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 24. | Skindex-16 (El Fakir et al., 2014b) | Specific | Moroccan Arabic | Interview | It is composed of 16 items grouped under three components: symptoms (four items; nos. 1–4), emotions (seven items; nos. 5–11), and functioning (five items; nos. 12–16) | Scores for the emotional, functioning, and symptom scales are expressed in a linear scale, varying from 0 (no effect on QoL) to 100 (maximum effect on QoL) | No | Yes | Yes |

| 25. | SS-QoL 2.0 (Odetunde et al., 2020) | Specific | Igbo | Self-administered | Cognitive | Descriptive statistics of mean and standard deviation were used to analyze domains and overall scores on SS-QoL | No | Yes | Yes |

| 26. | EORTC QLQ-CX24 (Araya et al., 2019) | Specific | Amharic | Self-administered | Physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, and social functioning, three multi-item symptom subscales (fatigue, nausea/vomiting, and pain); global health status/QoL subscale; and six single items addressing various symptoms and perceived financial impact, body image domain, and four items with the sexual/vaginal functioning domain | The standard scoring algorithm recommended by the EORTC was used to linearly transform all scales and item scores to a 0–100 scale | No | Yes | Yes |

| 27. | Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia (QOLRAD) (Kulich et al., 2008) | Specific | Afrikaans | Self-administered | Five dimensions: emotional distress, sleep disturbance, vitality, food/drink problems, and physical/social functioning | The questions are rated on a 7-point graded Likert scale; lower values indicate a more severe impact on daily functioning | No | Yes | Yes |

| 28. | Prolapse quality-of-life questionnaire (P-QoL) (Brandt et al., 2016) | Specific | Afrikaans | P-QOL domain includes general health, prolapse impact, role limitations, physical limitations, social limitations, personal relationships, emotional problems, sleep/energy disturbances, and prolapse severity | All asymptomatic participants were stage 0 on the POP-Q system, and the symptomatic participants were at stages III and IV | No | Yes | Yes | |

| 29. | PedsQL™ FIM (acute version) (Borissov et al., 2022; Farid et al., 2023) | Generic | Ethiopia | Interview | The scale comprises 36 items across eight subscales: physical functioning (6 items), emotional functioning (5 items), social functioning (4 items), cognitive functioning (5 items), communication (3 items), worry (5 items), daily activities (3 items), and family relationships (5 items) | PedsQL™ FIM total score, all items are reverse-coded and rescaled to 0, 25, 50, 75, and 100 | No | Yes | Yes |

| 30. | WHOQOL-HIV BREF questionnaire (Kondo et al., 2023) | Specific | Kiswahili | Self-administered | Physical, psychological, level of independence, social relationships, environment, and spirituality/religion/personal beliefs domains | Each domain has different facets, which were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated a negative perception and 5 indicated a positive perception. The original English WHOQOL-HIV BREF questionnaire was used to assist with scoring and coding | No | Yes | Yes |

| 31. | EORTC QLQ-BR-23 (El Fakir et al., 2014a; Gadisa et al., 2019) | Specific | Moroccan Arabic (El Fakir et al., 2014a) Amharic (Gadisa et al., 2019) |

Self-administered | Two multi-item functional scales (body image and sexual functioning), three symptom scales (systemic side effects, breast symptoms, and arm symptoms), and three single-item scales on sexual enjoyment, future perspectives, and upset by hair loss | Each item was scored on a 4-point Likert scale [“not at all” (WHO, 2020a), to “very much” (Tran et al., 2012)], and the time frame was “during the past week,” except for the sexual items (“during the past 4 weeks”). In summary, 0–100 scale | No | Yes | Yes |

| 32. | GOHAI (Osman et al., 2018) | Specific | Arabic | Interview | Satisfaction with retention, comfort, stability, ability to speak, and overall satisfaction with maxillary and mandibular complete dentures | “Satisfied,” “regular,” or “dissatisfied” scores of 2, 1, or 0 | No | Yes | Yes |

| 33. | OHIP-14 (Osman et al., 2018) | Specific | Arabic | Interview | Satisfaction with retention, comfort, stability, ability to speak, and overall satisfaction with maxillary and mandibular complete dentures | “Satisfied,” “regular,” or “dissatisfied” scores of 2, 1, or 0 | No | Yes | Yes |

| 34. | KENQOL (Bowden et al., 2002) | Generic | Kikamba | Interview | Positive and negative aspects of health that comprised “contentment,” “cleanliness,” “corporeal capacity,” “co-operation,” and “completeness” | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Characteristics of the health-related quality of life tools.

WHOQOL-OLD, World Health Organization quality of life for older adults; STI-HRQoL, Smith Toolkit for Integrated Health-Related Quality of Life; WHOQOL-BREF, World Health Organization quality of life (brief version); PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; SF-12, 12-item short-form health survey; SF-36, 36-item short-form health survey; MVQOLI, Missoula-Vitas Quality of-Life Index; I-OPQOL-35, Igbo version of Older People’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (35 items). EQ-5D-Y, EuroQol Group 5-dimension for children and adolescents; EORTC QLQ-BR45, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer—quality of life questionnaire for breast cancer patients (45 items); PROQOL-HIV, Patient Reported Outcomes Quality of Life–HIV questionnaire; EORTC QLQ-PAN26, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer—quality of life questionnaire for patients with pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis (26 items); SF-8, 8-item short-form survey; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire. D-39, diabetes (39 items); HRQOLISP-40, health-related quality of life in stroke patients (40 items); EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer—quality of life questionnaire for colorectal cancer patients (30 items); BREAST-Q, Breast Questionnaire; SF-NDI, Short-Form Nepean Dyspepsia Index; pTESS, Toronto Extremity Salvage Score; TESS, Toronto Extremity Salvage Score. EQ-5D-3L, EuroQol Group 5-dimension, 3-level instrument; Skindex-16, the 16-item skin disease quality of life tool; SS-QoL, stroke-specific quality of life scale; QOLRAD, Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia; P-QOL, prolapse quality-of-life questionnaire; PedsQL™ FIM, Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ Family Impact Module; POP-Q, Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification. WHOQOL-HIV BREF, World Health Organization quality of life questionnaire for HIV patients; EORTC QLQ-BR23, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer—quality of life questionnaire for breast cancer patients (23 items); GOHAI, Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index; OHIP-14, Oral Health Impact Profile-14; KENQOL, Kenyan quality of life.

Strengths and limitations of HRQoL tools

Many of the HRQoL tools demonstrated strong contextual adaptability, with WHOQOL-BREF, SF-36, and EQ-5D-Y (Colbourn et al., 2012; Reba et al., 2019; Jikamo et al., 2021; Mbada et al., 2015; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2010; Guermazi et al., 2012; Scott et al., 2017; Kulich et al., 2008) validated across multiple African languages and populations, ensuring relevance in diverse settings. Disease-specific instruments such as the EORTC QLQ-BR45 (Ehab et al., 2021; Kidayi et al., 2023; Getu et al., 2022) for breast cancer and the KCCQ (Okello et al., 2018) for heart failure provided highly specialized assessments, capturing condition-specific impacts more accurately than generic tools. Nonetheless, some instruments, such as the D-39 for diabetes (Uwizihiwe et al., 2022) and the EORTC QLQ-PAN26 for pancreatic cancer (Gqada et al., 2021), were lengthy and complex, posing challenges for use in clinical settings with time-constrained patients (see Table 4).

Table 4

| S/no | Tools | Strength | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | WHOQOL-OLD (Van Biljon et al., 2015; Muhye and Fentahun, 2023) | The WHOQOL-OLD can be used for a broad population; it has domains specific to the older population, and being translated to the Amharic version shows it can be contextual to a particular population based on their local language | It lacks disease-specific sensitivity when compared to other HRQoL tools like EQ-5D; it may be too long for older populations to answer all the questions |

| 2. | STI-HRQoL long form 37 items (Smith and Morris-Eyton, 2023) | STI-HRQoL was developed to assess non-communicable diseases [hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (CVD)]. It has the domain that measures physical health, mental health, and socioeconomic health dimensions | It cannot be used for communicable diseases. It is too long to fill |

| 3. | STI-HRQoL short form 25 items (Smith and Morris-Eyton, 2023) | STI-HRQoL was developed to assess non-communicable diseases [hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (CVD)]. It has the domain that measures physical health, mental health, and socioeconomic health dimensions. It is shorter than the 37-item STI-HRQoL | It cannot be used for communicable diseases. It is too long to fill |

| 4. | WHOQOL-BREF (Colbourn et al., 2012; Reba et al., 2019; Jikamo et al., 2021) | These tools were translated into Amharic, Sidamic, and Chichewa, making them contextually relevant for that population. It is ideal for general life assessment. It contains 26 items, which makes it longer than the WHOQOL-100 | It has limited disease-specific sensitivity. It is less detailed |

| 5. | PROMIS-25 (Westmoreland et al., 2018) | PROMIS is more valid, reliable, and responsive than other PRO instruments. The PROMIS instruments can be used for general disease states and administered across several languages and cultural contexts. Its translation to Chichewa made it easier to assess the HRQoL of pediatric patients with lymphoma in Malawi | It is not disease-specific. It does not have emphasis on the environmental factors like the WHOQoL |

| 6. | SF-12 (Younsi and Chakroun, 2014; Ibrahim et al., 2020; Ohrnberger et al., 2020) | The SF-12 is one of the most widely used and well-validated HRQoL. The SF-12 short-form HRQoL is shorter than the SF-36. It has been used in various populations, which proves its strong contextual property | The SF-12 short-form HRQoL is less detailed than the SF-36. It has a complex scoring system |

| 7. | SF-36 (Mbada et al., 2015; Guermazi et al., 2012; Okello et al., 2018) | The SF-36 is one of the most widely used and well-validated HRQoL. It has been used in various populations which proves its strong contextual property | The SF-36 is the longest of the short-form HRQoL, and it has a complex scoring system |

| 8. | MVQOLI (Namisango et al., 2007) | MVQOLI is a tool that is used in advanced illness and palliative care settings. MVQOLI is preferred over other tools because it measures the transcendence/existential domain. It also showed | It is not suitable for the general population. Its scoring system is complex |

| 9. | I-OPQOL (Mgbeojedo et al., 2022) | OPQOL is used in determining the quality of life of the older population. The I-OPQOL covers the population that has a low English literacy level. The OPQOL was translated into different languages, showing a contextual property | It cannot be used for pediatric or adolescent population |

| 10. | EQ-5D-Y (Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2010; Scott et al., 2017) | The EQ-5D-Y is one of the most widely used and well-validated HRQoL instruments in the adolescent population. It has been used in various populations, which proves its strong contextual property. It is shorter than the SF versions | It is not specific to a disease |

| 11. | EORTC QLQ-BR45 (Ehab et al., 2021; Kidayi et al., 2023; Getu et al., 2022) | EORTC QLQ-BR45 can assess more accurately and comprehensively the impact of new treatments on breast cancer patients’ QoL. It has been validated in several countries | It is not suitable for other forms cancers. It takes longer time to complete |

| 12. | PROQOL-HIV (Duracinsky et al., 2012) | PROQOL-HIV is tailored for HIV management, and it is practical and easier to administered | It is specific to HIV |

| 13. | EORTC QLQPAN26 (Gqada et al., 2021) | EORTC QLQPAN26 incorporates several symptom scales relevant to Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and comprises 26 questions that address unique symptoms and treatments | It is only applicable to pancreatic cancer patients. It is long and not focused on comorbidity |

| 14. | SF-8 (Onagbiye et al., 2018) | The SF-8 is one of the most widely used and well-validated HRQoL. The SF-8 short-form HRQoL is shorter than the SF-12 and SF-36. It has been used in various populations, which proves its strong contextual property | The SF-8 short-form HRQoL is less detailed than the SF-12 and SF-36. It has a complex scoring system |

| 15. | KCCQ (Okello et al., 2018) | KCCQ is the most widely used HRQoL for heart failure patients. It has been culturally adapted and translated | It is specific and focuses on symptom reporting |

| 16. | D39 (Uwizihiwe et al., 2022) | The Diabetes-39 (D-39) questionnaire is a widely used self-reporting tool; it measures glycaemic control, adherence to treatment, and complications and has been linked to other associated constructs of QoL | It is not applicable to other forms of disease, and it is too long |

| 17. | HRQOLISP (Owolabi, 2010) | HRQOLISP measures the spiritual spheres of the quality of life of the patients. It was specific to stroke patients. For this study, it was shortened from 104 to 40, and it was contextual | It is disease-specific and cannot be used for other health conditions. Although shortened, it was still too long to be used |

| 18. | EORTC QLQ-C30 (Kidayi et al., 2023; Araya et al., 2019; El Alami et al., 2021; Gadisa et al., 2019) | It is a psychometrically robust, cross-culturally accepted, and most frequently used tool to assess HRQoL in cancer patients. It is also contextual | Specific for cancer patients and long-term |

| 19. | BREAST-Q questionnaire (Olasehinde et al., 2024) | This tool measures the QoL and satisfaction of patients following breast surgery. It has been translated into 30 languages globally | It is used just to assess the QoL and satisfaction after the surgery has been done, not particularly for living with the disease condition |