- Academy of Education, Vytautas Magnus University, Vilnius, Lithuania

This study explores how self-efficacy is developed and expressed in prospective music teachers through singing-related coursework in Chinese higher education. Using a qualitative research design, data were collected through semi-structured interviews with eight university music educators who had experience teaching solfeggio, vocal music, choir, and Chinese opera. Qualitative content analysis revealed that self-efficacy in prospective music teachers is closely related to confidence, emotional regulation, collaboration, adaptability, and other essential skills for professional growth. Educators highlighted the importance of designing manageable singing tasks, encouraging peer observation, providing targeted feedback, and fostering a supportive and emotionally safe learning environment. The findings suggest that by systematically integrating self-efficacy enhancement strategies into music education curricula, educators can promote the holistic development of prospective music teachers. These insights contribute to practical implications for curriculum design, teacher preparation, and the ongoing advancement of music education in the context of contemporary challenges.

Introduction

Over the past decade, music and arts education has undergone notable shifts in pedagogy and course design, including wider integration of digital tools and reconfiguration of ensemble and studio practices, with implications for motivation and self-efficacy (Schiavio et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2021; Gill et al., 2022; Zhao and Cao, 2023). Therefore, since ‘teaching’ is framed not merely as conveying ideas but as preparing culturally responsive, inclusive practitioners through authentic immersive experiences (Achieng, 2023; Fuelberth and Woody, 2023). Rather than being framed as mere transmitters of knowledge, contemporary teachers are expected to facilitate learning and foster students’ self-regulated learning and emotion management, with pedagogical choices informed by self-efficacy considerations (Zhu, 2020; Regier, 2022; Muñoz, 2021). In such a context, teachers are challenged with requirements of a more advanced level of professional confidence, flexibility in pedagogy, self-regulation, and reflective practice needs, which, in turn, justifies the necessity of modern teacher education programmes to make their priorities of developing these capacities explicit (Tschannen-Moran and Hoy, 2001; Āboltiņa et al., 2024).

In this changing context of education, the concept of self-efficacy that was initially propounded by Bandura (1977, 1986) has taken a central position in teacher development studies. Self-efficacy is embedded in the social cognitive theory of Bandura (1977), which refers to the confidence of an individual in terms of performing a set of activities that can deliver desired outcomes (Zimmerman, 2000; Farmer et al., 2021). Similarly, the empirical evidence in teacher education demonstrates that strong self-efficacy leads to higher levels of motivation, more positive emotionality, greater commitment in terms of cognitions, and behavioural perseverance (Tschannen-Moran and Hoy, 2001; Sun, 2022). Teachers with higher self-efficacy tend to use unconventional teaching approaches, encourage classroom dynamics, embrace student initiative, and make them resilient to failure-related setbacks (Seçkin and Başbay, 2013; Shah, 2023). Conversely, lower self-efficacy is associated with higher anxiety, avoidance of challenging tasks, and increased risk of burnout (Ma et al., 2021).

These performance-based platforms provide the nurturing environment in which Bandura’s four sources of self-efficacy are activated. Self-efficacy is shaped by four interconnected sources: mastery experiences; vicarious experiences; verbal persuasion, and physiological/emotional states (Bandura, 1977; Usher and Pajares, 2008; Scoloveno, 2018). Mastery experience is often considered the primary source of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977; Royo, 2014; Warner and Schwarzer, 2017; Hier and Mahony, 2018). That is, successfully overcoming challenges and repeatedly building confidence, which supports further action (Clark, 2019; Bhati and Sethy, 2022). In turn, vicarious experiences concern learning based on the observation of successes and failures of others; they are particularly effective among novice teachers or students who lack their personal records of previous success (Warner and Schwarzer, 2017; MacAfee and Comeau, 2020). Self-efficacy increases when trusted individuals provide specific, positive feedback. Conversely, it may be diminished (Clark et al., 2014; Waters, 2020; Legette and Royo, 2021). Finally, subjective assessment of physiological and emotional conditions of people (such as anxiety, excitement, or tiredness) also influences efficacy beliefs and directs them to respond to the teaching or learning problem (Brooks, 2014; Sander, 2020; Han et al., 2022).

Rather than acting independently, the four sources operate as interacting processes. Vicarious experience and verbal persuasion frame how students interpret their mastery attempts (perceived attainability, standards), physiological/emotional states moderate the impact of modelling and feedback, and mastery outcomes then feedback to recalibrate the credibility of models and feedback, forming a ‘forethought-performancereflection’ cycle through singing-related coursework (Bandura, 1977; Usher and Pajares, 2008; Lu and Suo, 2020; Liu, 2021).

The importance of self-efficacy in teacher education has been widely documented. Teachers with strong self-efficacy become highly involved in their professional growth. They are more open to the changes in education applied, and foster positive student outcomes (Klassen and Chiu, 2010; Biasutti et al., 2020; Doménech et al., 2024). This relationship is reciprocal: a teacher with the feeling of self-efficacy develops student motivation and resilience, and vice versa, the positive engagement of students makes a teacher more confident in his or her skills (Björklund et al., 2020; Bergee and Grashel, 2002; Cohen and Panebianco, 2020). In this article, “educators” refers to university music teachers (our interview informants), whereas “prospective music teachers” refers to the target group. We analyse educators’ narratives to understand how these students’ self-efficacy is expressed and developed in singing-related coursework; we do not directly measure students’ self-efficacy. Teachers’ self-efficacy is discussed only as an antecedent shaping feedback, demonstration, and task sequencing. Building on this reciprocal pattern, research shows that teachers’ self-efficacy is positively correlated with their emotional well-being, job satisfaction, and professional identity (Xu, 2022; Zelenak, 2020; Concina, 2023; Ma et al., 2021).

Within music education, self-efficacy is of distinctive importance. As opposed to most fields of studies, music education cannot exist without public performance, emotional expression, and cooperative artistic creation (Hallam, 2010; Burnard et al., 2018; Paolantonio et al., 2023). Since the process of music education occurs in a naturally performative, affective, and social environment, students (prospective teachers) are frequently exposed to performance anxieties, recover from setbacks, and seek to find confidence in their musical voices (Fancourt and Finn, 2019; Wang, 2022; Morgan, 2019; Vaizman and Harpaz, 2022). Therefore, it is up to music teachers to develop not only technical skills and mastery of concepts but also creativity, emotional resilience, and cooperation skills needed in an ensemble (Osborne and McPherson, 2018; Sander, 2020; Gill et al., 2022). These skills both depend on and reinforce self-efficacy, operating through mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion, and physiological/emotional states (Bandura, 1977; Schunk and DiBenedetto, 2021).

In Chinese higher music education, singing-related coursework (Solfeggio, Vocal Music, Chinese Opera and Choir) places prospective teachers in performative and affect-laden settings (Guan, 2023; Wang, 2022). Typical challenges include breath support at higher phrases, smooth register transitions, intonation/timing/blend in choir, language-specific diction, and juried-exam/recital anxiety (Liu, 2018; Yang and Welch, 2023).

This study has its theoretical background in the social cognitive theory developed by Bandura, which defines self-efficacy as one of the key constructs that determine motivation, learning strategies, and persistence in the profession (Bandura, 1977; Schunk and Pajares, 2009; Michaud, 2023). Special attention was paid to Bandura’s four sources of self-efficacy (mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion, and physiological/emotional states), as the canonical lens in music teacher education (Tschannen-Moran and Hoy, 2001; Pan, 2020). Guided by this framework, we used a theory-informed interview guide to ensure coverage in questioning, while coding and categorization were conducted inductively; the theoretical lens is used for interpretation rather than as a coding frame.

According to the Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China (2006) curriculum scheme for the undergraduate Music Education (teacher-training) major, singing-related courses (Solfeggio, Vocal Music, Chinese Oprea, and Choir) account for approximately 36% of required courses (4/11), 40% of total contact hours (414/1,170), and 38% of total credits (23/60), which underscores their curricular centrality. These courses also provide frequent public-performance opportunities (e.g., recitals, juried exams, outreach concerts), increasing students’ exposure to evaluative feedback, peer collaboration, and emotional self-regulation. As a result, singing coursework concentrates Bandura’s four sources of self-efficacy: sustained practice and stage performance (mastery), observing lecturers and peers (vicarious experience), targeted feedback (verbal persuasion), and managing arousal on stage (physiological/emotional states; Tian, 2019; Wang, 2020; Wei, 2023; Xu, 2025). These are precisely the conditions in which self-efficacy is expressed and developed; hence singing is an apt domain for the present inquiry.

Research question: How the expression and development process of prospective music teachers’ self-efficacy skills occurs in university studies that facilitates their engagement in the singing practice.

Aim of the research: To theoretically and empirically reveal the possibilities for developing prospective music teachers’ self-efficacy skills in singing activity.

Objective of the research: To reveal and systematise the methods for developing self-efficacy skills of prospective music teachers in singing activity during their university studies.

Although the significance of self-efficacy as a central factor in the formation of music teachers is fairly well known, the processes in which self-efficacy is cultivated in a singing-related lecture setting remain insufficiently explored. Over the past several years, the literature has focused on limited post-hoc quantitative surveys or self-report instruments, neither of which is effective enough to capture the dynamic, context-specific, and interpersonal factors at play in actual classroom and rehearsal settings (Legette and Royo, 2021; Paolantonio et al., 2023; Wang, 2022). Recent scholarship has been committed to redirecting empirical investigation towards qualitative contextually sensitive forms of investigation that explicate the process by which self-efficacy occurs, manifests and persists through the lived experiences of students, teachers and peers (Pan, 2020; Ye, 2023; Sander, 2020).

To address these gaps, the present study uses semi-structured interviews with eight educators from normal universities in China, each possessing extensive experience in teaching core singing-related courses. This study explores how educators perceive and nurture self-efficacy in prospective music teachers during singing-related classes. It examines the behavioural and emotional signs of self-efficacy, the key factors that influence it, and the effective teaching strategies educators use. Through qualitative analysis, the research aims to deepen theoretical understanding and offer practical insights for improving curriculum design and teacher education.

Methodology

Study design

This study was carried out using a qualitative research design in order to understand the process of developing and expressing self-efficacy among prospective music teachers in Chinese higher education with respect to singing-related lectures. Participants were eight university music educators (key informants) who teach core singing-related lectures (Solfeggio, Vocal Music, Chinese Opera, Choir) with the eight. The empirical data were collected via semi-structured interviews with eight university music educators. The semi-structured guide covered typical domains in singing coursework: (i) opportunities for progress and public performance, (ii) teacher/peer demonstration and modelling, (iii) feedback and affirmation practices, and (iv) strategies for managing performance arousal. These domains ensured coverage in questioning; they did not constrain the inductive coding.

This approach was chosen because educators, as instructors of core singing-related lectures, possess unique insights into the pedagogical processes, challenges, and opportunities associated with fostering self-efficacy in prospective music teachers (Bresler, 2021; Marques and Mateiro, 2024). We analysed educators’ accounts and limited our claims to educators’ perspectives; we did not directly measure students’ self-efficacy. Bandura’s sources guided the interview protocol only; no a priori theory-driven categories were imposed during coding.

Qualitative inquiry was chosen on the basis of its capacity to reflect the multifactorial and subject-situational character of self-efficacy formation, the applicability of which to artistic, performative, and emotionally loaded spheres like music education is evident (Tracy, 2020; Goodman-Scott et al., 2024; Makateng and Mokala, 2025). By collecting and analysing reflective narratives of educators, the present study explores the behavioural and emotional aspects of self-efficacy development in prospective music teachers, as understood from the perspective of teacher interviewees in the context of singing-related lectures.

Participants

Eight educators from eight normal universities in China were interviewed using the purposive sampling. All participants actively taught fundamental singing-related lectures (Solfeggio, Vocal Music, Chinese Opera, and Choir) and had significant experience in dealing with and training prospective music teachers, ensuring both depth of pedagogical knowledge and contextual relevance. The gender distribution included both male and female teachers. All interviewees were assigned codes (E1-E8), which are used to present direct quotations and findings. Inclusion criteria were: (i) teaching at least one core singing-related lecture; (ii) ≥ 10 years of university-level teaching; and (iii) responsibility for lecture design and assessment (e.g., juries/recitals) across multiple cohorts. We interviewed educators as key informants because the study aimed to identify how prospective music teachers’ self-efficacy is developed in singing-related coursework; these instructors design and enact the relevant practices across multiple cohorts, providing a broader comparative view than single-student self-reports. This type of selection strategy guaranteed that the data could be pedagogically important and based on actual educational practice (Etikan, 2016; Bouncken et al., 2025).

The present study focused on third- and fourth-year undergraduate students (prospective music teachers) enrolled in music teacher education programmes. This period is a critical transition in which students move from learners to novice educators, integrating advanced musical expertise with pedagogical training and school practicum (Fisher et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022). By Years 3–4, prospective music teachers typically undertake capstone juries/recitals, ensemble leadership, and practice-teaching (students’ own micro-teaching and school practicum or internship), and are expected not only to refine artistic skills but also to consolidate a professional identity as music educators. Consequently, the expression and development of self-efficacy are more observable at this stage: juries/recitals and successful run-throughs provide mastery experiences; studio and ensemble work afford vicarious modelling; mentor/peer calibrated feedback supplies verbal persuasion; and public performance requires arousal regulation (physiological/emotional states). Early-year cohorts have more limited exposure to these performance- and practicum-based contexts and were therefore not the analytic focus of this study.

Sample size followed information power and saturation principles: recruitment ceased at eight when iterative analysis indicated no new codes or subthemes (thematic redundancy).

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews with eight educators from eight universities were used in the research to explore how prospective music teachers develop self-efficacy in singing-related lectures. A semi-structured interview is a well-established qualitative method that is based on open-ended questions and a flexible framework, which allows for an in-depth exploration of research participants’ thoughts, feelings, and experiences (Adeoye-Olatunde and Olenik, 2021; Buys et al., 2022; Ruslin et al., 2022).

The interview guide was constructed using four sources of self-efficacy by Bandura, and previous research findings in music teacher education (Bandura, 1977; Butler, 2024; Ge, 2024). Semi-structured interviews followed six core prompts: 1. How educators define and understand the concept of self-efficacy in prospective music teachers; 2. Based on the educators’ experiences, the factors that most influence the self-efficacy of prospective music teachers; 3. How they design tasks to help prospective music teachers build self-efficacy during their lectures (Solfeggio, Vocal, Chinese Opera, Choir); 4. How they promote prospective music teachers’ self-efficacy by allowing them to observe the educators’ modelling in their courses; 5. How verbal encouragement can be used to increase prospective music teachers’ self-efficacy; 6. How they help prospective music teachers maintain positive emotional and physiological states. Questions were flexibly sequenced with probes as needed. The full interview guide is provided in Appendix S1.

Before data collection, all participants were informed about the purpose of the research, assured of confidentiality, and provided written consent. The interviews were conducted in China. Interviews were in Mandarin and verbatim-transcribed by the first author; a bilingual assistant audited a subset and English excerpts. We used a bilingual codebook (Mandarin→English) for team analysis; the second author reviewed the English materials, and differences were resolved by discussion. Face-to-face or secure online channels were selected based on the participants’ availability. Each session lasted between 35 and 55 min. All interviews were conducted with the consent of the participants and recorded and transcribed for analysis.

To ensure depth and authenticity, the interviewer participants reflected on specific classroom practices, provided descriptive examples, and explained their pedagogical rationale and emotional connection to their students. Questions were flexibly sequenced, and then probe questions were asked depending on the response of the participants. The non-rigid structure permitted probing and flexibility to the environment and teaching philosophies of each interviewee which contributed to supplementing the data with a realistic educational knowledge base and efficacy experiences.

This statement clarifies the researchers’ neutral relationship with participants and the use of ethical safeguards. It was added to ensure transparency, reflexivity, and trustworthiness, addressing reviewer concerns about possible conflicts of interest or undue influence.

This clarification specifies that, while no institutional ethics committee approval was obtained, the study complied with ethical standards in qualitative research by securing voluntary informed consent, ensuring confidentiality, and using pseudonyms. It was added to enhance ethical transparency in response to reviewer concerns.

Participants were invited through departmental contacts and professional networks. The first author personally identified and selected experienced educators to ensure relevance. Participation was voluntary and uncompensated.

Data analysis

In this study a qualitative content analysis was applied to analyse and organise the data drawn after semi-structured interviews. Patterns, categories, and meanings in textual data were identified through a systematic method called qualitative content analysis. It can help researchers understand manifest and latent matter in communication processes (Strecher et al., 1986; Rampin and Rampin, 2021). Such an approach is particularly well-suited for educational and psychological studies as it accommodates rich, complex data without undermining the contextual meaning of the participants’ narratives (Bingham, 2023; Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2023; Nicmanis, 2024).

The first author conducted inductive qualitative content analysis following Mayring’s (2021) rule-guided procedures. The author read the transcripts repeatedly, assigned open codes to meaningful segments, compared and merged similar codes, and grouped them into subthemes and broader themes. No a priori theory-driven categories were imposed; all categories were data-driven.

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were then segmented into meaning units (sentences/clauses expressing a single idea). The first author retained segments that spoke directly to the research question, such as: (a) educators’ understanding of self-efficacy; (b) factors influencing prospective music teachers’ self-efficacy; (c) educators’ practices (modelling, feedback/affirmation, task design); and (d) singing-lecture contexts (rehearsals, run-throughs, juries/recitals). Small talk and logistical remarks were excluded. No a priori theory-based filters were applied; disconfirming/negative cases were retained and coded. This procedure focuses the analysis on relevant themes while minimising selection bias (Song et al., 2021; Ackermann and Merrill, 2022; Ningi, 2022).

Codes were compared within and across interviews; near-duplicates were merged, overly broad codes split, and boundaries refined. Conceptually related codes were grouped into subthemes and then elevated to a small set of overarching themes with inclusion/exclusion rules. Coding was conducted by the first author; given the inductive, reflexive design, no inter-coder agreement statistics were computed. Dependability was enhanced via a code-recode check on two interviews (with refinements to code definitions as needed) and co-author peer-debriefing at two checkpoints (after interviews 3 and 6), reviewing the codebook and theme map.

The first author maintained (i) a dated code log (code name, definition, exemplar quotation, interview ID), (ii) decision memos documenting merges/splits/renaming and inclusion rules, and (iii) a versioned theme map with timestamps. The first author ran internal checks after each transcript, at two checkpoints (after interviews 3 and 6), and a final pass before write-up; no external auditor was engaged. Typical boundary issues (e.g., targeted feedback vs. affirmation; teacher vs. peer modelling) were resolved by refining definitions and, where appropriate, dual-coding overlapping excerpts (Nowell et al., 2017; O’Kane et al., 2021).

Results

This study collected the experiences of 8 educators from 8 normal universities. These experiences covered the teaching process from vocal teaching, choir, solfeggio and Chinese opera. The primary intent of this study was how to promote the self-efficacy of prospective music teachers with a focus on the strategies educators use to strengthen their students’ self-efficacy during their various teaching activities and practices.

Definitions and understandings of self-efficacy

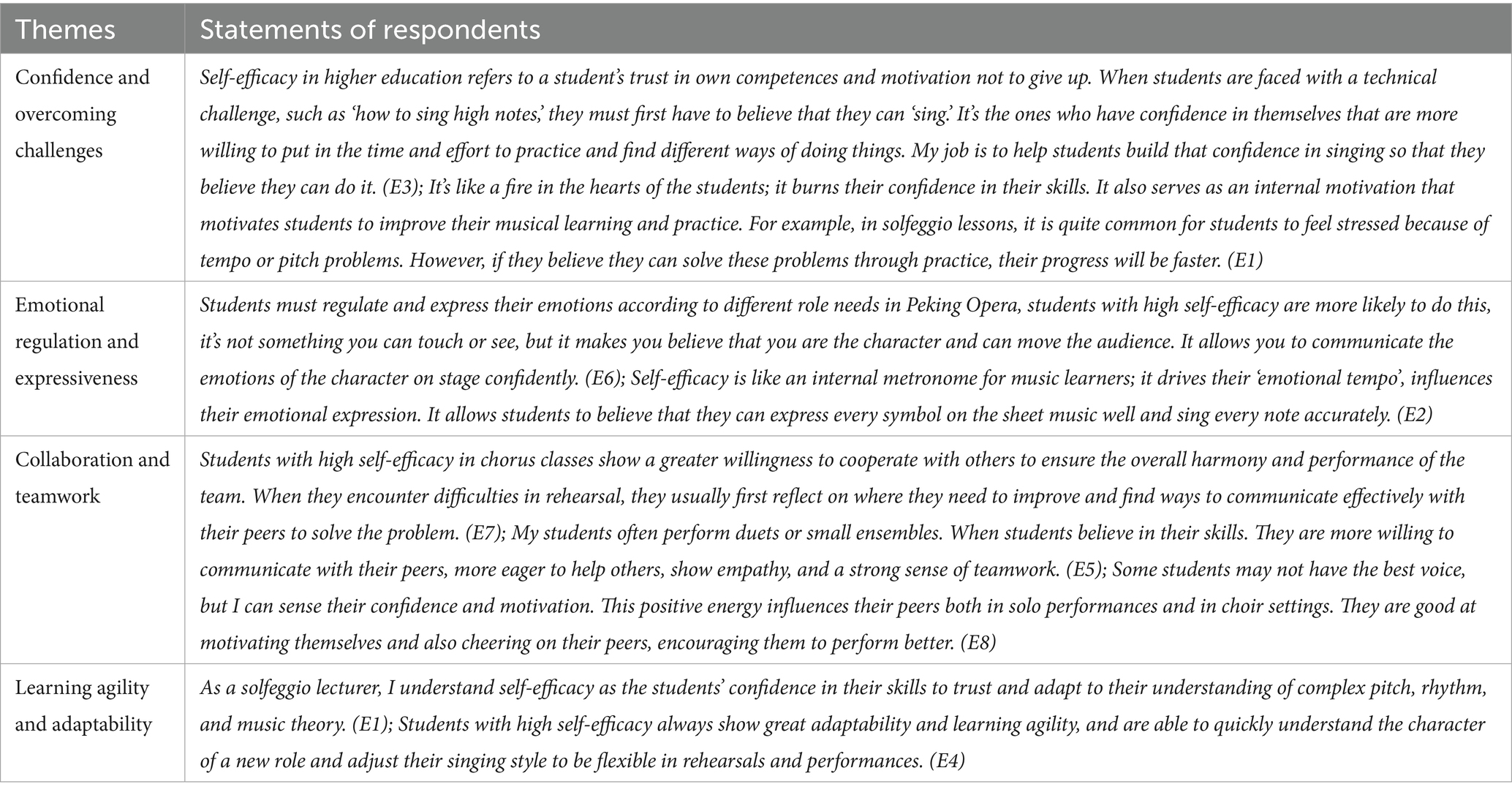

At the beginning of the interview, it was important to identify how educators define and understand the concept of self-efficacy in prospective music teachers. Respondents noted that self-efficacy plays a central role in helping prospective music teachers overcome challenges and build confidence. Educators noted that a high level of self-efficacy influences emotional well-being and expressiveness, helping to develop the adaptability and collaboration necessary for prospective music teachers to succeed in learning and performing.

Table 1 shows that the self-efficacy of prospective music teachers refers to the students’ confidence in their skills to face challenges, adapt to different types of music, and take on various roles in performances. It also emphasises their collaboration skills with others while more effectively managing and expressing their emotions and musical skills. As Educator E5 mentioned, students in higher education already have a basic foundation in music, and self-efficacy is a key factor in helping them get to the next level. It is common for students to feel pressure when they encounter difficulties in learning and performance, such as ‘complex rhythms’ in solfeggio or ‘high notes’ in vocal practice. Self-efficacy helps students build confidence in their skills to face these challenges and encourages them to say to themselves ‘I can do it.’ Such an attitude motivates a student to seek alternative options to find a solution to problems and move at a more increased pace achieved by relentlessly engaging in practice. Educators also emphasise that their task is to make students gain this confidence through practice so that they become successful in their future musical careers.

Self-efficacy is also extremely significant where emotion regulation and expression are concerned. Educator E2 likened it to an ‘internal metronome’ that controls one’s ‘emotional rhythm.’ Music students face various pressures during the performance, such as different performance environments, different audiences, personal status on the day of the performance, or unexpected during the performance. They need to believe in their skills to control and regulate their emotions to better and more freely express the feelings the composer wants to convey.

In terms of teamwork, prospective music teachers’ self-efficacy is understood by Educator E8 as a positive energy and motivation. These students may not have the best voice or the best musical skills, but their self-confidence and positive attitude affect others in the team. The interviewees noted that students with high self-efficacy are more willing to collaborate with others, including showing empathy and teamwork, self-reflection, and encouraging their peers. They believed in their skills to help themselves and their peers improve their performance.

Last the educators highlighted the fact that self-efficacy plays an important role in developing learning agility and adaptability. As prospective music teachers, students should be flexible in terms of new music and styles, complex rhythms, and varying performance demands. As Educator E4 mentioned, students with high self-efficacy show more adaptability and learning agility during practices and performances. The concept of self-efficacy is known to teachers as an important consideration for prospective music teachers, and their goal is to help students improve their self-efficacy to prepare them for their future careers as music educators.

Factors influencing self-efficacy

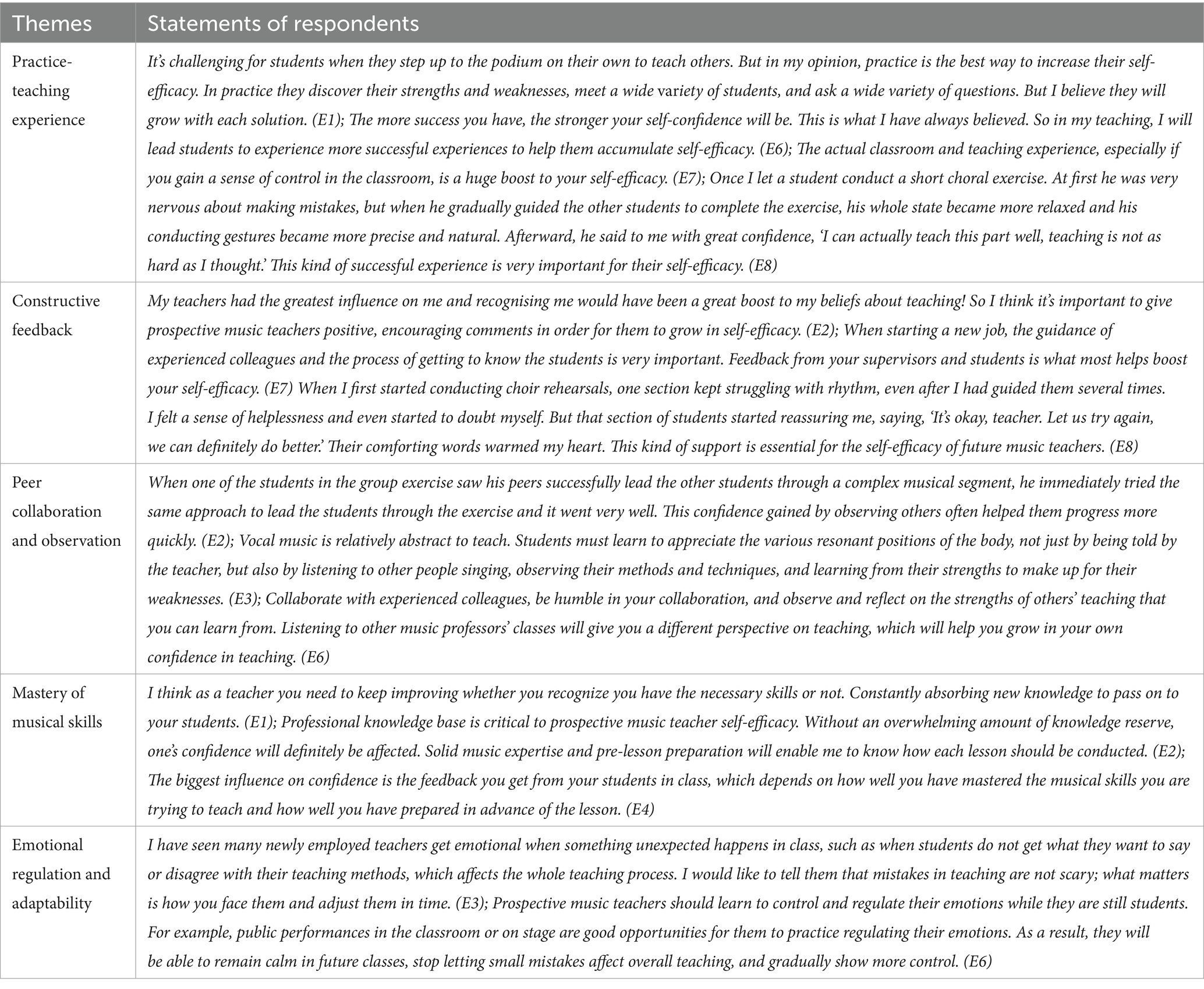

After understanding how music professors define the self-efficacy of prospective teachers, the second interview question was to explore, based on the educators’ experiences, the factors that most influence the self-efficacy of prospective music teachers. Respondents state that practice-teaching experience, peer collaboration, constructive feedback, and the mastery of musical skills are key contributors to building self-efficacy.

Table 2 shows that the interviewed educators suggested important factors affecting prospective music teachers’ self-efficacy based on their own experiences. These are practice-teaching experience, constructive feedback, peer collaboration and observation, mastery of musical skills, and emotional regulation and adaptability.

Almost all educators mentioned the first factor of practice-teaching experience in their responses, that is teaching experience, especially successful teaching experience and noted that this was critical to their self-efficacy. They gained one of the most direct experiences in successful teaching, which allowed them to experience the various situations in the teaching process. As Educator E1 pointed out, there are various problems, various types of students that the teacher has to face in the teaching process. Then the problem-solving process to find their own strengths and weaknesses, so as to improve to grow. Practice is the best way to test what you have learnt, and the teachers mentioned that their self-efficacy increases every time a problem is solved.

The role of mentor feedback, colleagues, family and students feedback is critical in enhancing self-efficacy. Encouraging and positive responses help warm up teachers and feel supported, making them and more confident as far as their own teaching skills are concerned. Educator E2 emphasised the importance of encouragement from the prospective teachers’ own instructors, suggesting that positive and supportive comments help develop their self-efficacy. Similarly, Educator E8 recalled an anecdote of a student giving him a soothing word that allowed him to overcome the feelings of frustration after a challenging choir rehearsal. Such experience implies a positive impact of positive feedback related to music teacher’s self-efficacy.

Another factor that educators referred to frequently was peer collaboration and observation. A significant number of the interviewees explained how much they have learnt by observing their means of teaching through their colleagues, and this has helped them in their practice. Educator E2 remembered that the confidence they received by observing others usually allowed them to advance. Educator E6 pointed out the need to collaborate with more experienced peers and consider their pedagogical assets and to be humble, which will eventually help to induce growth in the sense of self-efficacy building. Being surrounded by others and learning through observation not only grant practical ways of doing things but also reinforce the belief that people can achieve similar successes.

The fourth factor is the mastery of musical skills, which is the basis for developing confidence in teaching. Being a teacher, a solid foundation is needed to constantly improve oneself by absorbing new knowledge and setting an example for students. The educators agreed that a solid foundation of musical knowledge and technical skills was vital for prospective music teachers. Educator E4 emphasised that instructors’ strong musical command and thorough preparation enable more specific, timely, and encouraging feedback, thereby more effectively enhancing students’ self-efficacy.

The educators also pointed at emotional control and flexibility as the important ones in retaining self-efficacy. They discussed their life experiences in coping with unpredictable circumstances, controlling their emotions during stress, and how to adjust to new surroundings. Educator E3 stated that prospective music teachers should learn to face mistakes with a positive mindset and make timely adjustments. Educator E6 added that it is important to seize the opportunity of public performances to exercise to learn to regulate emotions when they are students.

Task-design strategies to build self-efficacy

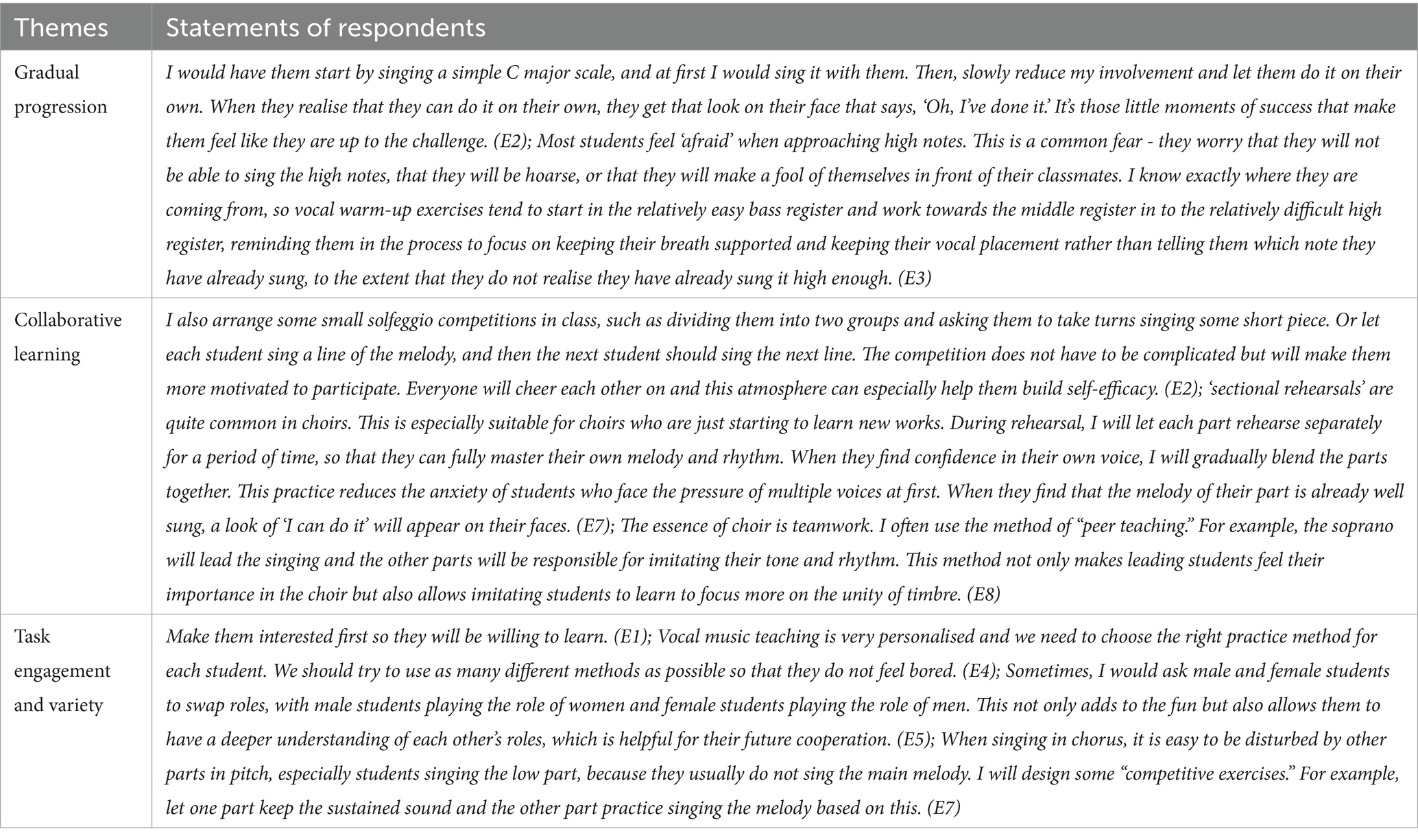

Having explored the factors influencing prospective music teachers’ self-efficacy, educators were asked how they design tasks to help prospective music teachers build self-efficacy during their lectures (Solfeggio, Vocal, Chinese Opera, Choir). Their responses highlighted the importance of designing tasks that start with minimal demands and gradually increase, allowing students to build on small successes. They also emphasised the value of group learning and maintaining task variety to boost student engagement.

Table 3 shows how music teachers design tasks in their courses to build prospective music teachers’ self-efficacy. Most educators mentioned that ‘gradual progress’ is the core idea of task design. Educators break down difficult tasks such as complex rhythmic, big melody jumps, or singing ‘high notes’ into small, more manageable parts, and gradually increase their complexity as students gain more mastery and understanding. This gradually increases the student’s confidence in their skills. Just like what Educator E2 did in the solfeggio class, he led students to start with simple scales and sang with them to support them, then gradually reduced his participation and let students sing on their own. The accumulation of these ‘small successes’ made students realise that they are capable of handling complex music tasks on their own, increasing their self-efficacy. Educator E3 shared his experience as a vocal teacher, where many of his students had a fear of ‘singing high notes’. Faced with this situation, E3 would start practicing with the lower and middle vocal registers, which not only cultivated students’ stability in the middle range but also did not make them feel frustrated because it was too difficult. Sometimes, students unknowingly reach high notes naturally. These methods allow students to feel their progress after completing each small task and gradually improve their self-efficacy.

The educators highlighted the advantages of group learning. Educator E2 described the joyful and supportive learning atmosphere created by students from different groups during group competitions. Such group exercises are most common in choral rehearsals. Educator E8 stated that the essence of choral singing is teamwork. Therefore, more collective factors should be considered when designing tasks. For example, ‘sectional rehearsals’ and ‘peer teaching’ allow students to better master the melody and rhythm of their own parts, so that they believe that their voices are in the team, thereby strengthening their self-efficacy.

The participants also pointed out that increasing task variety helps keep students interested in learning activities, which improves their engagement and contributes to the development of self-efficacy. E1 and E5 shared examples from their solfeggio and Chinese opera classes, such as rhythmic clapping exercises and role-swapping activities. Educator E7 stated that he designed a ‘competition exercise’ based on the situation that low-voice students tend to be out of tune and frustrated in choir rehearsal. These diverse and personalised exercises designed by educators for different students increase students’ motivation to participate in learning tasks, which is crucial to maintaining students’ enthusiasm for learning.

Modelling and vicarious learning

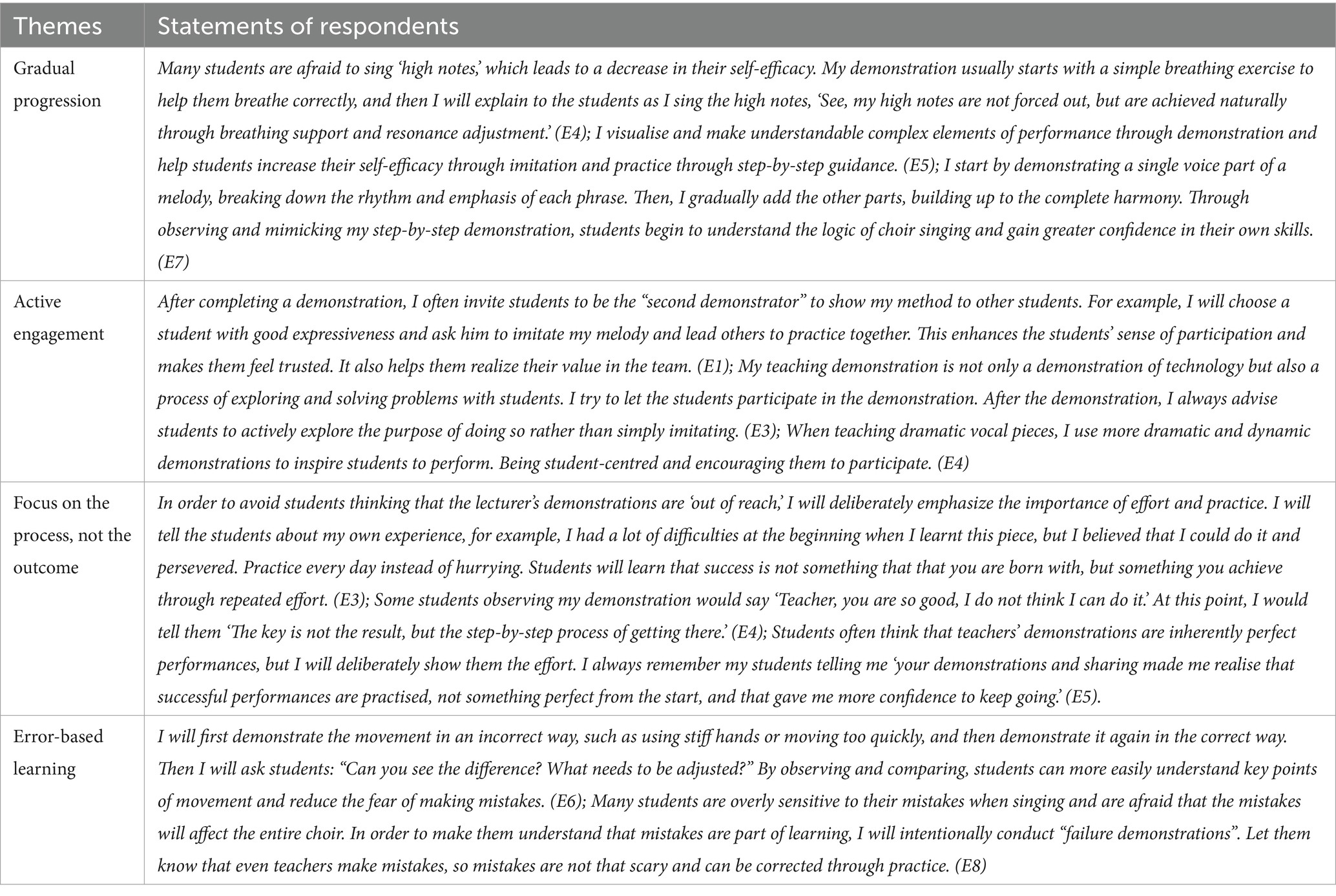

An important source of self-efficacy is vicarious experiences that involve observational learning. Educators were asked how they promote prospective music teachers’ self-efficacy by allowing them to observe the educators’ modelling in their courses. Respondents indicated that creating a supportive environment that combines multiple forms of modelling through dynamic demonstrations from easy to difficult, realistic failure demonstrations, and various forms of teacher-student interaction. Successful demonstration of a teacher provides students with a clear and specific role model to follow which is very motivating, encourages students to be better confident of their strengths and offers vicarious experiences to increase their self-efficacy.

Table 4 presents the strategies educators use to improve the self-efficacy of prospective music teachers by allowing them to observe and engage in their modelling. Responses were classified into four subcategories: gradual progression, active engagement, focus on the process, and error-based learning. Educators usually demonstrate the reduction of difficulty in steps so that students understand that even difficult techniques can be broken down and achieved step by step. As Educator E4 explained, students gradually overcome their fear of ‘high notes’ and build up their confidence in completing the task by observing teachers breaking down a complex task into manageable steps. Similarly, Educator E7 gave an example of how a simple voice of a melody should be learnt at first and then only the complete harmony is introduced starting with one voice. All these structured ways help to make things easier and to gain confidence in skills of students.

The participants noted the importance of being student-centred and encouraging their active participation in observation and experimentation. Educators encourage students to repeat their demonstrations or lead other peers in practice, As Educator E1 mentioned, this enhances student engagement and makes them feel trusted. Educator E3 also pointed out that it is not only a demonstration of technology, but also a process that encourages students to explore and solve problems together. Participants also emphasised effort and progress rather than focusing on perfect results. They observed that during their demonstrations they would tell the students that successful demonstrations do not happen overnight but are achieved through long-term practice. Educator E3 shared his own difficulties and experiences in practicing and his perseverance encouraging the students to believe that they can succeed and should keep working hard.

The respondents concluded by encouraging the students to learn from the failures they observed. They also made deliberate mistakes and then corrected them. This was done in order to show ways that mistakes are commonly made, and then the educator showed the correct method, prompting students to analyse and adapt their own approach. This approach reduces the fear of failure and the notion of improvement based on the number of attempts taken, giving students more assurance that they can deal with challenges.

Verbal persuasion and feedback practices

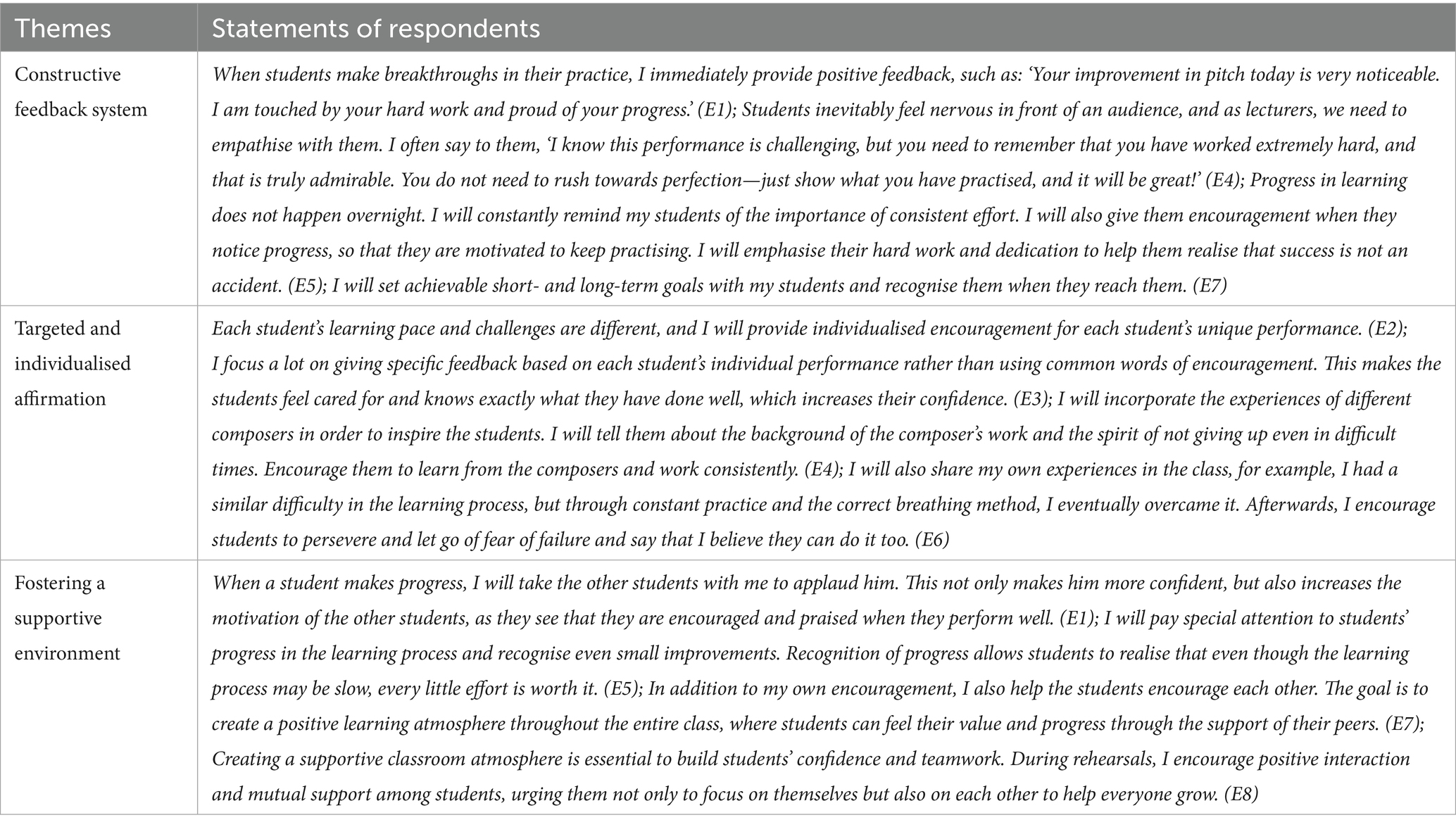

Verbal persuasion is one of the sources of self-efficacy according to Bandura’s theory. Positive verbal encouragement can be effective in increasing self-efficacy. Educators were asked how verbal encouragement can be used to increase prospective music teachers’ self-efficacy. The interviewees stated that singing classes give students enough opportunities to participate in practice, so it is important to evaluate the students’ performance. Respondents emphasised that it is crucial to approach feedback from an encouraging perspective, providing students with positive, constructive evaluations to promote and improve their self-efficacy.

Table 5 shows the strategies educators use to increase the self-efficacy of prospective music teachers through verbal persuasion. Respondents indicated that verbal persuasion is commonly used to increase self-efficacy in the classroom, rehearsals, and performances. These strategies can be divided into three categories: constructive feedback system, targeted and individualised affirmation, and fostering a supportive environment. Educators emphasised the importance of having the right feedback mechanisms in place, for example, Educator E7 stated that students should set achievable goals, Educators E1 and E3 highlighted the importance of timely praise when students make progress, and Educators E4 and E5 added that focusing on the process helps students understand that success is not achieved overnight, but rather through consistent and diligent effort over time.

The participants mentioned the importance of targeted and individualised affirmations for self-efficacy. Emphasis was placed on specific student achievements rather than general praise. As pointed out by Educator E2, each student has a different learning pace and needs targeted affirmations to help students recognise their progress, and Educators E3 and E8 also mentioned that pointing out specific details of what a student has done well and giving positive feedback instead of using common words of encouragement makes students truly cared for and recognised. This is not only verbal encouragement, but also emotional communication, which helps students build up a deeper sense of self-confidence and allows them to express themselves more courageously. Educators E4 and E6 used their personal experiences and background as composers and encouraged students to persevere and believe that through hard work. Through these different ways of encouragement, teachers helped the students build their self-efficacy in their studies and made them feel supported and cared for, so that they would not give up easily when faced with more challenges and would have more confidence and motivation to cope with them.

The other common practice of educators is to create a positive and supportive environment, particularly when it comes to group work. Educator E8 stated the necessity of a positive atmosphere during the rehearsal to unite all the people in a choir, encouraging students to help each other and interact positively. Such a positive and stress-free environment makes students feel safe and respected, which is essential for building self-confidence and increasing teamwork. Educator E5 stated that giving encouragement to students for even small improvements makes them realise that their efforts are worthwhile. The educator encourages students to face challenges and provides continuous support, emphasising the process of effort rather than the pursuit of a perfect result. Educators E1 and E7 mentioned that not only do they encourage the students themselves, but they also bring the rest of the class together to applaud those who do well. Students receive affirmation from the teacher and peers, increasing their self-efficacy. Finally, the teacher educator stressed that feedback should be a two-way dialogue, involving questions about what students are doing, thinking and feeling. It is important to ensure that feedback supports students’ self-efficacy without undermining their confidence.

Regulating emotional/physiological states

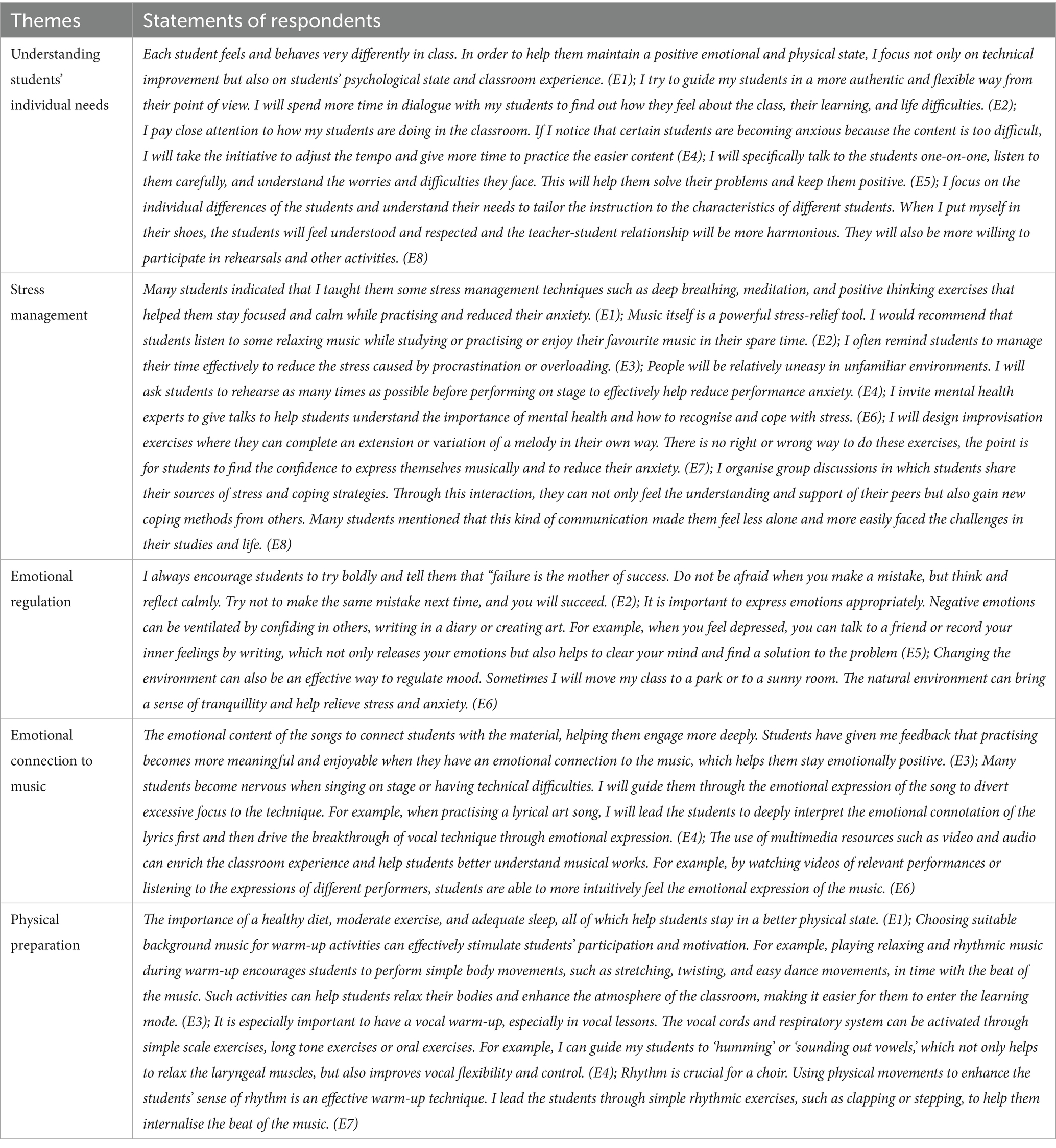

Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy states that emotional and physiological states are also important factors affecting self-efficacy. In the context of music, prospective music teachers face numerous challenges that one goes through like the pressure to learn hard music pieces, daily practice and performing or presenting in front of the audience, this necessitating them to be in a good mood in order to handle the pressure. Educators were asked how they help prospective music teachers maintain positive emotional and physiological states.

The respondents highlighted that psychological issues, such as tension and anxiety, are common at different stages of development for prospective music teachers. They need the support of society, family, peers and lecturers. However, educators often struggle to recognise the psychological states of their students, emphasising the importance of providing more care and communication.

Table 6 categorises the strategies used by the educators to strengthen the positive emotional and physiological states of the students into five main subcategories: understanding individual needs, stress management, emotional regulation, emotional connection to music and physical preparation. Understanding of individual needs of students was mentioned most frequently, that is, genuine concern for the ideas and needs of students. Educator E1 and E8 highlighted that each student is unique and should receive personalised support and guidance tailored to their individual needs and characteristics. Empathising with students, actively listening to their thoughts and concerns, and giving them your full attention and understanding are essential practices. Educators E2 and E5 noted that the additional time spent in conversations facilitates this strategy. Listening to the students helps establish trust with them and make them feel respected and safe, which is critical to establishing self-efficacy.

In the area of stress management, educators shared a variety of effective ways to help students reduce anxiety. Educator E1 mentioned using techniques such as deep breathing and meditation to help students relax, while Educator E2 pointed out that ‘music itself’ is a good stress relief tool and suggested that students relieve stress listening to music they like. Educator E4 invited mental health experts to provide guidance on stress management to students, which can help students better cope with stressors in their studies and lives. Educator E8 mentioned that by allowing students to share each other’s coping strategies through group discussions, it can not only establish a mutually supportive learning atmosphere, but it can also make students feel that they are not alone, thereby increasing their confidence in coping with challenges.

Emotion regulation focuses on teaching students how to manage and express emotions in positive ways. Prospective music teachers are under pressure to learn and perform, as well as teach in the future, and mood swings are inevitable. How to adjust in times of negative emotions is an important part of promoting their mental health and academic success. Educator E2 and E4 both stated that they encouraged students not to be afraid of making mistakes, not to be frustrated by mistakes but to be calm and learn from them, and not to overvalue the results but to emphasise the importance of the process of working hard. Educator E5 suggested that students find appropriate outlets to express their emotions, such as writing in a journal or confiding in friends and family. Educator E6 fully agreed and added that changing the environment is also an effective way to regulate emotions.

The emotional connection to music is the relevant method to make students learn the process of learning music and enjoy it at a more recent level, and in that way, it is an important strategy to improve their understanding and motivation. Educator E3 shared that by guiding students to explore the emotional connotations of the songs, the practice becomes more meaningful and enjoyable. Educator E4 observed that students sometimes focus too much on the technical aspects and neglect the emotional expression, so he led the students to interpret the emotional connotation of the lyrics first, and then push the breakthrough of vocal technique through emotional expression, while Educator E6 mentioned that the use of multimedia technology, such as video and audio, enriched the content of the classroom, and also helped students intuitively understand the expression of the emotions of the musical works. The participants indicated that this emotional connection improved the students’ musical expression and reduced their anxiety about technical challenges.

Finally, respondents indicated that a good physical condition is the foundation of everything. The importance of preparatory physical activities was emphasised. Educator E1 promotes a healthy lifestyle. In music teaching, warm-up movements not only help students activate their physical state but also improve their mood and concentration. The educators will lead the students through a simple physical and vocal warm-up before formal singing. For example, Educator E3 mentioned simple body movements accompanied by rhythmic music such as stretching, twisting, and easy dance movements, and Educator E7 led students to perform simple tempo exercises such as clapping or stepping before rehearsals according to the choir’s characteristics for the need for tempo. Body movements are used to help them internalise the music and enhance students’ sense of tempo. Educator E4, as a vocal educator, emphasises the importance of a vocal warm-up. These help prospective music teachers develop good habits and maintain a healthy and active state to cope with various challenges.

Inductive analysis of participants’ responses to the six interview prompts identified six themes central to the development of prospective music teachers’ self-efficacy: definition & understanding, influencing factors, task design, educator modelling, verbal encouragement, and emotional regulation. These themes provide practical guidance for fostering self-efficacy in teacher-education contexts.

Discussion

This research aimed to provide insights into the processes of building self-efficacy among prospective music teachers in the Chinese higher education system in the light of the views of experienced university educators. The results contribute to a body of literature growing on self-efficacy as a primary psychological construct underlying successful teacher education and professional practice (Bandura, 1977; Schunk and Pajares, 2002; Gill et al., 2022). Although the role of self-efficacy in general teacher education is clear based on previous research (Tschannen-Moran and Hoy, 2001; Michaud, 2023), this study expands the concept to the situation of singing-related activities in the training of music teachers. This context often involves emotional expression, ensemble collaboration, and performance anxiety, which have been under-examined in relation to efficacy development (Osborne and McPherson, 2018; Hallam, 2010; Hendry et al., 2022).

The conclusion made by all the educators in the interviews was that self-efficacy is a central factor in prospective music teachers’ skills to learn, perform, and teach. Respondents noted that students with high self-efficacy were more willing to persevere in practice, find solutions when faced with technical difficulties, and demonstrated higher levels of emotional regulation and resilience in the teaching and learning process. Respondents agreed that classroom practice-teaching is the best way to increase self-efficacy among prospective music teachers, and Schunk and Pajares (2009) also indicated that practice-teaching experience is a determining factor in educators’ self-efficacy. Respondents indicated that prospective music teachers must have solid professional skills or they will have difficulty building confidence in their teaching, and Concina (2023) study also indicated that the acquisition of music skills is highly self-efficacy related, and that prospective teachers’ skills to perform, conduct and deliver choral music training has a direct impact on their confidence in the classroom. The respondents emphasised that feedback from tutors and peers can greatly enhance students’ confidence in teaching. Students’ belief that “I can do it too” can be strengthened by observing the success stories of their peers (Bandura, 1977). The respondents noted that music teachers must learn to manage stress and adapt to different teaching environments. The study by Biasutti and Concina (2017) suggests that self-efficacy in music education is closely related to stress management skills and appropriate regulation of emotions reduces anxiety in the classroom and improves teaching quality.

Based on the results of the interviews, the educators proposed a variety of strategies to promote self-efficacy among prospective music teachers: (1) the educator adopted the ‘simple to complex’ teaching strategy to help students gradually build up their confidence; (2) the educator demonstrated the correct playing techniques and asked students to imitate them so as to nurture their self-confidence; (3) the educator adopted the ‘peer teaching’ model to allow students to coach each other and enhance their sense of teamwork; (4) the educator encouraged students to record their classroom performance and review and analyse it after the class. Although identified within Chinese higher music education, these strategies map onto Bandura’s four sources of self-efficacy (mastery, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion, physiological/emotional states) and are therefore mechanistically generalisable beyond China. Their enactment, however, depends on assessment stakes and classroom norms (e.g., how public correction and peer feedback are used), so context-sensitive adaptation is warranted.

The study is based on the music education system of the China Normal University, but the results may not apply to other countries or regions. Findings reflect educators’ perspectives (single-source, indirect data); future work will triangulate with student self-reports/interviews and naturalistic classroom observations to corroborate and extend these process accounts. To capture development more directly, future studies should adopt longitudinal, observational, mixed-methods designs: combine repeated student self-efficacy measures (e.g., pre-mid-post semester and pre/post practicum) with video-based observation and coding of micro-teaching and juries mapped to Bandura’s four sources, plus brief diary/experience-sampling of arousal and feedback. Linking these time-varying exposures to within-person change would triangulate and extend the educator-reported processes. The study focused on the specific university and classrooms and could be extended to a wider range of educational settings in the future. Although the music education system of the China Normal University was the basis for the study, the development of self-efficacy of prospective music teachers can vary between cultures. Future research could make cross-national comparisons to explore the effects of different educational systems on prospective music teachers’ self-efficacy. Digital technologies such as online teaching platforms, artificial intelligence feedback systems, and virtual-reality tools of music-teaching related to self-efficacy of music teachers are also the resources that can be used in the context of the study of how the process of approaching the music teacher self-efficacy is informed and impacted by such advances. This study refines how Bandura’s four sources operate in the Singing lecture, extending the framework’s applicability to music at the mechanism level without altering its core.

Conclusion

Research advances the understanding of how self-efficacy is cultivated in prospective music teachers within the unique context of Chinese higher music education. Drawing on the reflective expertise of experienced university educators, the study demonstrates that the effective development of self-efficacy depends not only on the mastery of musical skills, but also on deliberate pedagogical strategies that support emotional regulation, collaboration, and adaptability. These findings highlight the need to integrate self-efficacy enhancement into music teacher training programmes to prepare future educators for the complex challenges of modern classroom and performance environments. The research contributes to theory and practice by offering concrete recommendations to promote self-efficacy through singing-related coursework. Moving forward, continued research in diverse educational contexts will be essential for developing comprehensive models of teacher education that address the evolving demands of music education worldwide.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by He Nan Normal University; Xin Yang Normal University; Luo Yang Normal University; Shang Qiu Normal University; Nan Yang Normal University; Zheng Zhou Normal University; An Yang Normal University; Zhou Kou Normal University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

GB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Resources. AR: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Āboltiņa, L., Lāma, G., Sarva, E., Kaļķe, B., Āboliņa, A., Daniela, L., et al. (2024). Challenges and opportunities for the development of future teachers’ professional competence in Latvia. Front. Educ. 8. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1307387

Achieng, A. E. (2023). Cultural diversity and 21st century music teacher education. Int. J. Res. Cultural, Aesthetic, Arts Educ. 1, 6–9. doi: 10.31244/ijrcaae.2023.01.01

Ackermann, T., and Merrill, J. (2022). Rationales and functions of disliked music: an in-depth interview study. PLoS One 17:e0263384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263384

Adeoye-Olatunde, O. A., and Olenik, N. L. (2021). Research and scholarly methods: semi-structured interviews. J. American College of Clin. Pharmacy 4, 1358–1367. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351885497_Research_and_scholarly_methods_Semi-structured_interviews

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bergee, M. J., and Grashel, J. W. (2002). Relationship of generalized self-efficacy, career decisiveness, and general teacher efficacy to preparatory music teachers’ professional self-efficacy. Missouri J. Res. Music Educ. 39, 4–20.

Bhati, K., and Sethy, T. (2022). Self-efficacy: theory to educational practice. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 10, 1123–1128. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359929249_Self-Efficacy_Theory_to_Educational_Practice

Biasutti, M., and Concina, E. (2017). The effective music teacher: the influence of personal, social, and cognitive dimensions on music teacher self-efficacy. Music. Sci. 22, 264–279. doi: 10.1177/1029864916685929

Biasutti, M., Concina, E., Deloughry, C., Frate, S., Kalarus, A., Mangiacotti, A., et al. (2020). The effective music teacher: a model for predicting music teacher’s self-efficacy. Psychol. Music 49, 1498–1514. doi: 10.1177/0305735620959436

Bingham, A. J. (2023). From data management to actionable findings: a five-phase process of qualitative data analysis. Int J Qual Methods 22. doi: 10.1177/16094069231183620

Björklund, P., Daly, A. J., Ambrose, R., and Van Es, E. A. (2020). Connections and capacity: an exploration of preservice teachers’ sense of belonging, social networks, and self-efficacy in three teacher education programs. AERA Open 6. doi: 10.1177/2332858420901496

Bouncken, R. B., Czakon, W., and Schmitt, F. (2025). Purposeful sampling and saturation in qualitative research methodologies: recommendations and review. Rev. Manag. Sci. 59, 1461–1479. doi: 10.1007/s11846-025-00881-2

Bresler, L. (2021). Qualitative paradigms in music education research. Visions Res. Music Educ. 16:10. Available online at: https://digitalcommons.lib.uconn.edu/vrme/vol16/iss3/10/

Brooks, A. W. (2014). Get excited: reappraising pre-performance anxiety as excitement. J. Exp. Psychol. 143, 1144–1158. doi: 10.1037/a0035325

Burnard, P., Minors, H., Wiffen, C., Shihabi, Z., and Van Der Walt, S. J. (2018). Mapping trends and framing issues in higher music education: changing minds/changing practices. Lond. Rev. Educ. 15, 457–473. doi: 10.17863/CAM.18682

Butler II, E. T. (2024). Examining the perspectives of rural secondary students who are and are not considering music education as a collegiate major, New York, NY, USA: Routledge.

Buys, T., Casteleijn, D., Heyns, T., and Untiedt, H. (2022). A reflexive lens on preparing and conducting semi-structured interviews with academic colleagues. Qual. Health Res. 32, 2030–2039. doi: 10.1177/10497323221130832

Clark, C. J. (2019). The relationships among teacher self-efficacy for music, singing, and adolescent voice change instruction [Doctoral dissertation, University of Iowa] doi: 10.17077/etd.005176

Clark, T., Lisboa, T., and Williamon, A. (2014). An investigation into musicians’ thoughts and perceptions during performance. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 36, 19–37. doi: 10.1177/1321103x14523531

Cohen, S., and Panebianco, C. (2020). The role of personality and self-efficacy in music students’ health-promoting behaviours. Music. Sci. 26, 426–449. doi: 10.1177/1029864920966771

Concina, E. (2023). Effective music teachers and effective music teaching today: a systematic review. Educ. Sci. 13:107. doi: 10.3390/educsci13020107

Doménech, P., Tur-Porcar, A. M., and Mestre-Escrivá, V. (2024). Emotion regulation and self-efficacy: the mediating role of emotional stability and extraversion in adolescence. Behav. Sci. 14:206. doi: 10.3390/bs14030206

Etikan, I. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 5:1. doi: 10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

Fancourt, D., and Finn, S. (2019). What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being?: A scoping review. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 67.

Farmer, H., Xu, H., and Dupre, M. E. (2021). “Self-efficacy” in Encyclopedia of gerontology and population aging. eds. D. Gu and M. E. Dupre (Cham: Springer), 13812–13815.

Fisher, R. A., Summitt, N. L., Koziel, E. B., and Hall, A. V. (2021). Influences on teacher efficacy of preservice music educators. International Journal of Music Education 39, 394–409. doi: 10.1177/0255761420986241

Fuelberth, R. J., and Woody, R. H. (2023). Inclusive music teacher education: valuing breadth and diversity through authentic immersive experiences. Int. J. Music. Educ. 43, 243–255. doi: 10.1177/02557614231199251

Ge, X. (2024). Music teachers' perceptions of creativity in the context of twenty-first century Chinese education: A qualitative study on the influence of experience and policy on primary school music and piano teachers. Doctoral dissertation, University of Glasgow.

Gill, A., Osborne, M. S., and McPherson, G. E. (2022). Sources of self-efficacy in class and studio music lessons. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 46, 4–27. doi: 10.1177/1321103x221123234

Goodman-Scott, E., Perez, B. M., Taylor, D. D., and Belser, C. T. (2024). Youth-centred qualitative research: strategies and recommendations. J. Child Adolesc. Couns. 10, 66–84. doi: 10.1080/23727810.2024.2360681

Guan, W. (2023). Analysis of music education management mode in colleges and universities in China. Front. Educ. Res. 6, 127–148. doi: 10.25236/fer.2023.060525

Hallam, S. (2010). The power of music: its impact on the intellectual, social and personal development of children and young people. Int. J. Music. Educ. 28, 269–289. doi: 10.1177/0255761410370658

Han, S., Li, B., Wang, G., Ke, Y., Meng, S., Li, Y., et al. (2022). Physical fitness, exercise behaviours, and sense of self-efficacy among college students: a descriptive correlational study. Front. Psychol. 13:932014. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.932014

Hendry, N., Lynam, S., and Lafarge, C. (2022). Singing for wellbeing: formulating a model for community group singing interventions. Qual. Health Res. 32, 1399–1414. doi: 10.1177/10497323221104718

Hier, B. O., and Mahony, K. E. (2018). The contribution of mastery experiences, performance feedback, and task effort to elementary-aged students’ self-efficacy in writing. Sch. Psychol. Q. 33, 408–418. doi: 10.1037/spq0000226

Klassen, R. M., and Chiu, M. M. (2010). Effects on teachers’ self-efficacy and job satisfaction: teacher gender, years of experience, and job stress. J. Educ. Psychol. 102, 741–756. doi: 10.1037/a0019237

Kuckartz, U., and Rädiker, S. (2023). Qualitative content analysis: Methods, practice and software. 2nd Edn: SAGE Publications doi: 10.4135/9781036212940

Lee, D., Allen, M., Cheng, L., Watson, S., and Watson, W. (2021). Exploring the relationships between self-efficacy and self-regulated learning strategies of English language learners in a college setting. J. Int. Stud. 11, 567–585. doi: 10.32674/jis.v11i3.2145

Legette, R. M., and Royo, J. L. (2021). Pre-service music teacher perceptions of peer feedback. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 43, 22–38. doi: 10.1177/1321103x19862298

Liu, P. (2018). Research on the innovation of vocal music teaching in colleges and universities-comment on “new visions of vocal music teaching in general colleges and universities”. News Writing 5, 126–130.

Liu, B. (2021). Analysis of problems in vocal music singing and performance teaching in China's colleges and universities and the corresponding countermeasures. Advan. Vocational Technical Educ. 3, 83–86. doi: 10.23977/avte.2021.030417

Lu, M. Y., and Suo, Q. Q. (2020). Children’s academic self-efficacy and its improvement strategies. Development of Educational Science 2, 61–63. doi: 10.36012/sde.v2i5.2109

Ma, K., Chutiyami, M., Zhang, Y., and Nicoll, S. (2021). Online teaching self-efficacy during COVID-19: changes, its associated factors and moderators. Educ. Inf. Technol. 26, 6675–6697. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10486-3

MacAfee, E., and Comeau, G. (2020). The impact of the four sources of efficacy on adolescent musicians within a self-modelling intervention. Contrib. Music. Educ. 45, 205–236.

Makateng, D. S., and Mokala, N. T. (2025). Understanding qualitative research methodology: a systematic review. E-J. Humanit. Arts Soc. Sci. 6, 327–335. doi: 10.38159/ehass.2025637

Marques, M., and Mateiro, T. (2024). Methodological combinations in qualitative research in music education: autobiography and grounded theory. Qual. Rep. 29, 2486–2501. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2024.7651

Mayring, P. (2021). Qualitative content analysis: A step-by-step guide. London, United Kingdom: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Michaud, E. G. (2023). Rural music teacher self-efficacy: Source influence and commitment. Doctoral dissertation, Boston University.

Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China. (2006). National Undergraduate Program Guidance for music education (teacher education) compulsory courses. Available online at: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A17/moe_794/moe_624/200611/E20061129_80346.html

Morgan, H. (2019). An investigation into how the development of musical improvisation skills impacts year 7 girls’ self-efficacy as performers of sub-Saharan African music. J. Trainee Teacher Educ. Res. 10, 275–306. doi: 10.17863/CAM.84718

Muñoz, L. R. (2021). Graduate student self-efficacy: implications of a concept analysis. J. Prof. Nurs. 37, 112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2020.07.00

Nicmanis, M. (2024). Reflexive content analysis: an approach to qualitative data analysis, reduction, and description. Int J Qual Methods 23. doi: 10.1177/16094069241236603

Ningi, A. I. (2022). Data presentation in qualitative research: the outcomes of the pattern of ideas with the raw data. International Journal of Qualitative Research 1, 196–200. doi: 10.47540/ijqr.v1i3.448

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., and Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/1609406917733847

O’Kane, P., Smith, A., and Lerman, M. P. (2021). Building transparency and trustworthiness in inductive research through computer-aided qualitative data analysis software. Organ. Res. Methods 24, 104–139. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335325754_Building_Transparency_and_Trustworthiness_in_Inductive_Research_Through_Computer-Aided_Qualitative_Data_Analysis_Software

Osborne, M. S., and McPherson, G. E. (2018). Precompetitive appraisal, performance anxiety and confidence in conservatorium musicians: a case for coping. Psychol. Music 47, 451–462. doi: 10.1177/0305735618755000

Pan, X. F. (2020). Research on the cultivation of applied talents in choral conducting in colleges and universities. Modern Educ. Prac. 2, 9–10.

Paolantonio, P., Cavalli, S., Biasutti, M., Eiholzer, E., and Williamon, A. (2023). Building community through higher music education: a training program for facilitating musical engagement among older adults. Front. Psychol. 14.

Rampin, R., and Rampin, V. (2021). Taguette: open-source qualitative data analysis. J. Open Source Software 6:3522. doi: 10.21105/joss.03522

Regier, B. J. (2022). High school jazz band directors’ efficacious sources, self-efficacy for teaching strategies, and pedagogical behaviours. J. Res. Music. Educ. 70, 92–108. doi: 10.1177/00224294211024530

Royo, J. (2014). Self-efficacy in music education vocal instruction: A collective case study of four undergraduate vocal music education majors (doctoral dissertation). Pro Quest Dissertations and Theses.

Ruslin, R., Mashuri, S., Rasak, M. S. A., Alhabsyi, F., and Syam, H. (2022). Semi-structured interview: A methodological reflection on the development of a qualitative research instrument in educational studies. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education 12, 22–29. doi: 10.9790/7388-1201052229

Sander, L. (2020). The music teacher in the mirror: factors of music student-teacher self-efficacy. Visions Res. Music Educ. 37. Available online at: https://digitalcommons.lib.uconn.edu/vrme/vol37/iss1/6

Schiavio, A., Küssner, M. B., and Williamon, A. (2020). Music teachers’ perspectives and experiences of ensemble and learning skills. Front. Psychol. 11:291. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00291

Schunk, D. H., and DiBenedetto, M. K. (2021). “Self-efficacy and human motivation” in Advances in motivation science, ed. A. J. Elliot (New York, NY, USA: Routledge), vol. 8, 153–179.

Schunk, D. H., and Pajares, F. (2002). “The development of academic self-efficacy” in Development of achievement motivation. eds. A. Wigfield and J. S. Eccles (Academic Press), 15–31. doi: 10.1016/B978-012750053-9/50003-6

Schunk, D. H., and Pajares, F. (2009). “Self-efficacy theory” in Handbook of motivation at school, eds. F. Pajares and T. C. Urdan (Charlotte, NC, USA: Age Publishing) 35–53.

Scoloveno, R. L. (2018). Resilience and self-efficacy: an integrated review of the literature. Ijsrm.Human 9, 176–192.

Seçkin, A., and Başbay, B. (2013). Investigate of teacher’s self-efficacy beliefs of physical education and sport teacher candidates. Int. Periodical Lang., Literature and History of Turkish or Turkic 8, 253–270. Available online at: https://turkishstudies.net/DergiTamDetay.aspx?ID=5305

Shah, D. (2023). Teachers’ self-efficacy and classroom management practices: a theoretical study. J. Educ. Res. 13, 8–26. doi: 10.51474/jer.v13i1.661

Song, Y., Ballesteros, M., Li, J., García, L. M., De Guzmán, E. N., Vernooij, R. W. M., et al. (2021). Current practices and challenges in adaptation of clinical guidelines: a qualitative study based on semi-structured interviews. BMJ Open 11:e053587. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053587

Strecher, V. J., DeVellis, B. M., Becker, M. H., and Rosenstock, I. M. (1986). The role of self-efficacy in achieving health behaviour change. Health Educ. Q. 13, 73–92.

Sun, J. (2022). Exploring the impact of music education on the psychological and academic outcomes of students: mediating role of self-efficacy and self-esteem. Front. Psychol. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.841204

Tian, M. L. (2019). The importance of vocal music in music education. Song of the Yellow River 5, 77–80.

Tracy, S. J. (2020). Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact. New York, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Tschannen-Moran, M., and Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: capturing an elusive construct. Teach. Teach. Educ. 17, 783–805. doi: 10.1016/s0742-051x(01)00036-1

Usher, E. L., and Pajares, F. (2008). Sources of self-efficacy in school: critical review of the literature and future directions. Rev. Educ. Res. 78, 751–796. doi: 10.3102/0034654308321456

Vaizman, T., and Harpaz, G. (2022). Retuning music teaching: online music tutorials preferences as predictors of amateur musicians’ music self-efficacy in informal music learning. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 45, 397–414. doi: 10.1177/1321103x221100066

Wang, F., Wang, L., Yu, W., Xia, F., Zhang, E., and Su, B. (2022). “Research on the teaching of music education in colleges and universities under the reflective teaching dimension” in Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Information and Education Innovations (ACM), 77–83. doi: 10.1145/3535735.3535744

Wang, S. K. (2020). The teaching and practice of vocal music education in colleges and universities under the perspective of contemporary culture. Chin. Music. 3, 14–20.

Wang, X. (2022). Psychology education reform and quality cultivation of college music major from the perspective of entrepreneurship education. Front. Psychol. 13:843692. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.843692

Warner, L. M., and Schwarzer, R. (2017). “Self-efficacy” in The SAGE encyclopedia of abnormal and clinical psychology, ed. A. Bandura vol. 7 (London, UK.: SAGE Publications), 3036–3038.

Waters, M. (2020). Perceptions of playing-related discomfort/pain among tertiary string students: a thematic analysis. Music. Educ. Res. 22, 257–269. doi: 10.1080/14613808.2020.1765154

Wei, Z. L. (2023). The development and application of vocal music skills: a case study of Chinese vocal learners: development and application of vocal skills: case study of Chinese singing students. Highlights Art Design 4, 66–68. doi: 10.54097/hiaad.v4i3.18

Xu, J. (2022). Reflections on the existing quality of music education and countermeasures. Music Educ. 10, 199–223.

Xu, K. (2025). Examining the relationships among self-efficacy, intrinsic motivation, and self-worth of adolescent singers in structural equation modeling. Psychology of Music. doi: 10.1177/03057356251315690

Yang, Y., and Welch, G. (2023). A systematic literature review of Chinese music education studies during 2007 to 2019. Int. J. Music. Educ. 41, 175–198. doi: 10.1177/02557614221096150

Ye, W. (2023). Research on improving the teaching level of choir conducting courses in higher normal universities. Scientific Management 5, 161–164. Available online at: https://cn.usp-pl.com/index.php/kygl/article/view/157075

Zelenak, M. S. (2020). Developing self-efficacy to improve music achievement. Music. Educ. J. 107, 42–50. doi: 10.1177/0027432120950812

Zhao, S., and Cao, C. (2023). Exploring relationship among self-regulated learning, self-efficacy and engagement in blended collaborative context. SAGE Open 13. doi: 10.1177/21582440231157240

Zhu, W. N. (2020). Research on the cultivation of autonomous learning ability in primary school music teaching. Int. Educ. Forum 2:130.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Self-efficacy: an essential motive to learn. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25, 82–91. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1999.1016

Appendix S1

Semi-structured interview guide (6 items).

This appendix lists the six core prompts used in the semi-structured interviews. Questions were asked flexibly with follow-up probes as needed.

1. How educators define and understand the concept of self-efficacy in prospective music teachers?

2. Based on the educators’ experiences, the factors that most influence the self-efficacy of prospective music teachers?

3. How they design tasks to help prospective music teachers build self-efficacy during their lectures (Solfeggio, Vocal, Chinese Opera, Choir)?

4. How they promote prospective music teachers’ self-efficacy by allowing them to observe the educators’ modelling in their courses?

5. How verbal encouragement can be used to increase prospective music teachers’ self-efficacy?

6. How they help prospective music teachers maintain positive emotional and physiological states?

Note. These prompts align one-to-one with the six subsections in the Results.

Keywords: self-efficacy, prospective music teachers, singing activities, emotional regulation, teacher education

Citation: Bi G and Rauduvaitė A (2025) Development of self-efficacy skills of prospective music teachers in singing activity: insights of educators. Front. Psychol. 16:1685205. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1685205

Edited by:

Enrique H. Riquelme, Temuco Catholic University, ChileReviewed by:

Huihua He, Shanghai Normal University, ChinaMichael S. Zelenak, Alabama State University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Bi and Rauduvaitė. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Asta Rauduvaitė, YXN0YS5yYXVkdXZhaXRlQHZkdS5sdA==; Guanhua Bi, Z3Vhbmh1YS5iaUB2ZHUubHQ=

Guanhua Bi

Guanhua Bi Asta Rauduvaitė

Asta Rauduvaitė