Abstract

Background:

Anxiety and depressive symptoms are highly prevalent comorbidities among patients with myocardial infarction (MI). Although cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a well-established intervention for depression, its efficacy in MI patients remains inconclusive.

Objective:

To evaluate the effects of CBT on anxiety, depressive symptoms, and sleep quality in patients following MI.

Design:

This is a systematic review and meta-analysis. The study followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines for reporting.

Methods:

Nine electronic databases were searched from inception to March 2025 to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating CBT in patients with MI. Two independent researchers screened the literature, assessed study quality, and extracted data based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Random-effects meta-analyses were performed to calculate mean differences, with statistical analyses conducted using Stata 15.0.

Results:

Eleven RCTs involving 1,575 participants were included. The findings showed that CBT led to greater improvements in anxiety and depressive symptoms compared with control interventions. In addition, CBT significantly improved sleep quality among patients after MI.

Conclusion:

CBT is associated with improvements in psychological and sleep outcomes following MI. However, the existing evidence shows high variability and heterogeneity. Further large-scale, high-quality trials are needed to confirm these findings and develop standardized protocols for implementing CBT in this patient population.

Systematic review registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42025636352, identifier CRD42025636352.

1 Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) remains a leading cause of global morbidity and mortality. While advances in revascularization have improved survival, a significant majority of post-MI patients experience clinically relevant anxiety and depression, which are themselves independent risk factors for adverse cardiovascular outcomes and increased mortality (Santos, 2018; Serpytis et al., 2018; Roth et al., 2020; Alpert, 2023). These psychological comorbidities, along with frequently impaired sleep quality, substantially hinder recovery and long-term prognosis (van Melle et al., 2004; Roest et al., 2010; Meijer et al., 2011; Andrechuk and Ceolim, 2016).

The management of post-MI psychological distress is clinically challenging. Although pharmacotherapy is common, concerns about potential cardiovascular side effects persist (Benazon et al., 2005; Fehr et al., 2019). CBT offers a promising non-pharmacological alternative by targeting maladaptive thoughts and behaviors (Zhang et al., 2022). While previous meta-analyses support the efficacy of psychological interventions, including CBT, for broader coronary heart disease populations (Li Y.-N. et al., 2021; Nuraeni et al., 2023), their specific and pooled effects exclusively for MI patients remain inadequately synthesized. Existing evidence is contradictory, with some trials reporting significant benefits of CBT (Zeighami et al., 2018; Nourisaeed et al., 2021; Johnsson et al., 2025) and others showing limited effects (Norlund et al., 2018). Moreover, no meta-analysis has specifically integrated the evidence on CBT’s impact on sleep quality in this population.

To address these gaps, this systematic review and meta-analysis aims to: (1) Quantify the efficacy of CBT in reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients with MI. (2) Evaluate the effect of CBT on sleep quality in this population. (3) Explore potential moderators of treatment efficacy, such as intervention duration. The findings will provide crucial evidence to guide clinical decision-making and optimize psychological interventions in cardiac rehabilitation programs, ultimately improving patient outcomes and quality of life.

2 Materials and methods

This systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42025636352) and has been conducted and reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines (Page et al., 2021).

2.1 Eligible criteria

The selection criteria were established based on the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, and Study design (PICOS) framework. Studies were considered eligible if they met the following criteria: (1) inclusion of patients with MI; (2) incorporation of interventions using CBT or CBT-based approaches, such as mindfulness techniques, cognitive restructuring, and behavioral activation, within the cognitive behavioral therapeutic framework; (3) inclusion of a control group receiving routine care (UC), control care (CC), or other active therapies; (4) reporting of at least one of the following outcomes: anxiety, depression, or sleep quality; and (5) RCTs published in English or Chinese.

Studies involving qualitative studies, animal studies, in vitro studies, observational studies, reviews, letters, conference papers, and study protocols or studies without full-text availability were excluded.

2.2 Search strategies and study selection

Inclusive literature was searched in PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, CINAHL, CNKI, WanFang, and Chinese Biomedical (CBM) databases, from the date of establishment to March 28, 2025. The search terms were developed focused on the keywords “Myocardial Infarction” AND “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy” (Supplementary Appendix 1). Additionally, reference lists of the finalized articles and relevant systematic reviews were manually reviewed to identify any additional eligible studies.

The study selection process followed a pre-defined, multi-stage sampling procedure: (1) De-duplication: Records from all databases were imported into EndNote X9 for duplicate removal. (2) Title/Abstract Screening: Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts against eligibility criteria using Rayyan software. (3) Full-Text Review: Potentially eligible articles were retrieved and independently assessed in full text by the same two reviewers. (4) Consensus and Adjudication: Disagreements at any stage were resolved through discussion. Persistent disagreements were arbitrated by a third senior researcher. This multi-reviewer process constitutes a form of investigator triangulation to minimize selection bias.

2.3 Data extraction and management

A pilot-tested, standardized data extraction form was developed in Microsoft Excel. Data extraction was performed in duplicate by two independent reviewers to ensure accuracy (methodological triangulation). The form captured: (1) study identification details (first author name, publication year, geographic location), (2) participant demographics (sample size, average age, sex composition), (3) intervention characteristics (type, frequency, duration), (4) outcome measures (specific indicators), and (5) supplementary methodological information. Discrepancies in extracted data were reconciled by referring back to the original article and consensus discussion.

2.4 Risk of bias and certainty of evidence assessment

Risk of Bias: The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool (ROB 2.0) (Sterne et al., 2019). This tool was selected for its validation, specificity to RCTs, and detailed domain-based assessment. This comprehensive tool systematically assesses potential bias across five critical domains: (1) randomization process, (2) deviations from intended interventions, (3) missing outcome data, (4) measurement of outcomes, and (5) selection of reported results. Two reviewers independently applied ROB 2.0, judging each domain as “low,” “some concerns,” or “high” risk. Disagreements were resolved as above.

Certainty of Evidence: The quality of evidence for each outcome was assessed using the online version of GRADEpro GDT software (Mendoza et al., 2017). The evaluation was conducted independently by two reviewers. RCTs were initially assumed to provide high-quality evidence, and the certainty of evidence for each outcome was then rated as high, moderate, low, or very low based on five downgrading domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias.

2.5 Data analysis

The analysis employed standard mean differences (SMD) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) to synthesize the data. Effect sizes from individual studies were visually represented using forest plots. Heterogeneity was evaluated using Cochran’s Q test and quantified with the I2 statistic, where values exceeding 50% were considered to indicate substantial heterogeneity. For studies with I2 ≤ 50%, a fixed-effect model was applied; otherwise, a random-effects model was utilized. Publication bias was assessed for outcomes with 10 or more studies through funnel plot examination and Egger’s test. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 15.0, with a significance level set at α = 0.05.

To explore potential sources of heterogeneity, sensitivity analyses were conducted by sequentially removing individual studies and recalculating the overall effect size. Additionally, subgroup analyses were employed to examine the effectiveness of CBT across different delivery methods. These methods included variations in intervention duration, delivery format (internet-based or telephone-based, or face-to-face), and therapy type (traditional CBT vs. third-generation CBT) in addressing anxiety, depression, and sleep quality among MI patients.

When multiple reports were identified from the same study population, we combined them into a single study entry to avoid duplication of participants. For example, Norlund et al. (2018) (Norlund et al., 2018) and Humphries et al. (2021) (Humphries et al., 2021) both described outcomes from the same cohort and were thus treated as one study in the analysis.

3 Results

3.1 Literature search results

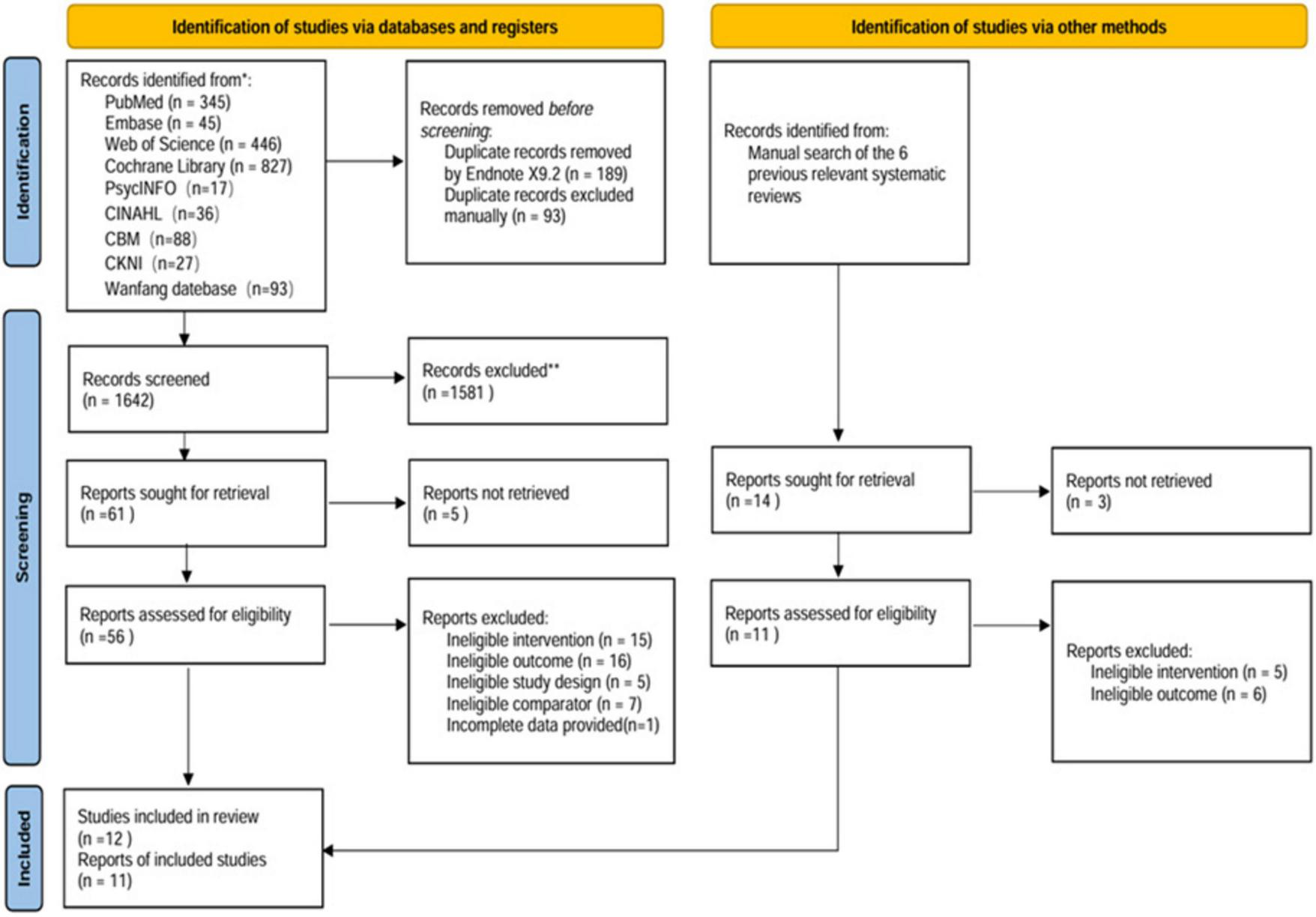

The systematic search across nine databases initially identified 1,924 potentially relevant articles. Following the removal of 282 duplicate records, 1,586 articles were excluded based on title and abstract screening. Subsequent full-text review led to the exclusion of 44 additional articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria. In addition, 14 potentially relevant studies were identified through manual searching of previous relevant systematic reviews, but all were excluded after full-text screening as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Ultimately, 12 articles reporting on 11 distinct studies were selected for inclusion in the meta-analysis. The detailed flow of the literature screening process is illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1

Flowchart of the literature search strategy.

3.2 Basic characteristics of the included literature

The systematic review included 11 studies published between 1993 and 2025, encompassing a total of 1,575 MI patients. The psychological interventions implemented in the included studies encompassed a range of therapeutic approaches: CBT (Wang et al., 2011; Ghiasi et al., 2018; Norlund et al., 2018; Humphries et al., 2021; Ning and Wei, 2023; Li et al., 2024), behavioral therapy (BT) (Brown et al., 1993), rational emotive behavioral therapy (Wang et al., 2022), cognitive behavioral stress management (Chen et al., 2024), mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) (Spruill et al., 2025), and mediated positive stress reduction (MBSR) (Liang et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2023). For intervention format, 2 studies were conducted online or by telephone (Norlund et al., 2018; Humphries et al., 2021; Spruill et al., 2025), while nine studies were delivered in a face-to-face format (Brown et al., 1993; Wang et al., 2011; Ghiasi et al., 2018; Liang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2022; Ning and Wei, 2023; Wu et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2024; Li et al., 2024). The mean intervention duration was 7 weeks, with six trials having an intervention duration of less than 7 weeks (Wang et al., 2011; Liang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2022; Ning and Wei, 2023; Wu et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024). The median study mean age was 59.72 years, with an interquartile range of 57.94–60.84. Detailed information on the characteristics of the included studies is shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| Author year | Country | Characteristics of study participants (EG/CG) | Interventions | Duration of the intervention | Forms of the intervention | Outcome indicator | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | Age (mean ± SD) | Gender (male : female) | Experimental group | Control group | |||||

| Norlund et al. (2018) | Swedish | 117/122 | 58.4 ± 9.0/60.8 ± 7.8 | 73:44/86:36 | CBT | UC | 14 weeks | Online | HADS-A HADS-D |

| Humphries et al. (2021) | Swedish | 117/122 | 58.4 ± 9.0/60.8 ± 7.8 | 73:44/86:36 | CBT | UC | 14 weeks | Online | HADS-A HADS-D |

| Chen et al. (2024) | China | 125/125 | 62.8 ± 10.2/63.6 ± 9.7 | 87:38/95:30 | CBSM | CC | 12 weeks | Face to face | HADS-A HADS-D |

| Wu et al. (2023) | China | 50/50 | 59.72 ± 6.43/60.42 ± 7.12 | 37:13/35:15 | MBSR + CR | CR | 5–7 days | Face to face | SAS SDS |

| Wang et al. (2022) | China | 86/86 | 62.10 ± 6.39/61.32 ± 6.66 | 52:34/55:31 | REBT | UC | 3 weeks | Face to face | SAS SDS |

| Wang et al. (2011) | China | 91/90 | 62 (all) | 102:79 (all) | CBT | UC | During hospitalization | Face to face | PSQI |

| Ning and Wei (2023) | China | 55/55 | 56.44 ± 7.24/56.98 ± 2.33 | Unknown | CBT | UC | 28 days | Face to face | HADS-A HADS-D PSQI |

| Brown et al. (1993) | America | 20/20 | 63.55 ± 7.43/57.65 ± 7.82 | 11:9/18:2 | BT | UC | 12 weeks | Face to face | BDI |

| Spruill et al. (2025) | America | 67/63 | 60.2 ± 12.2/59.4 ± 13.5 | All female | MBCT | UC | 8 weeks | Online (by telephone) | HADS-A PHQ-9 |

| Ghiasi et al. (2018) | Iran | 15/15 | 56.60 ± 5.82 (all) | 9:6/7:8 | CBT | UC | 8 weeks | Face to face | GHQ-28 |

| Liang et al. (2019) | China | 58/58 | 55.12 ± 6.17/55.41 ± 6.25 | 33:25/32:26 | MBSR | UC | 7 days | Face to face | SAS SDS PSQI |

| Li et al. (2024) | China | 70/78 | 58.3 ± 9.3/59.9 ± 9.5 | 60:10/67:11 | VR-CBT | Standard mental health support | 7 days | Face to face | HAMA PHQ-15 PSQI |

Detailed information about the included literature.

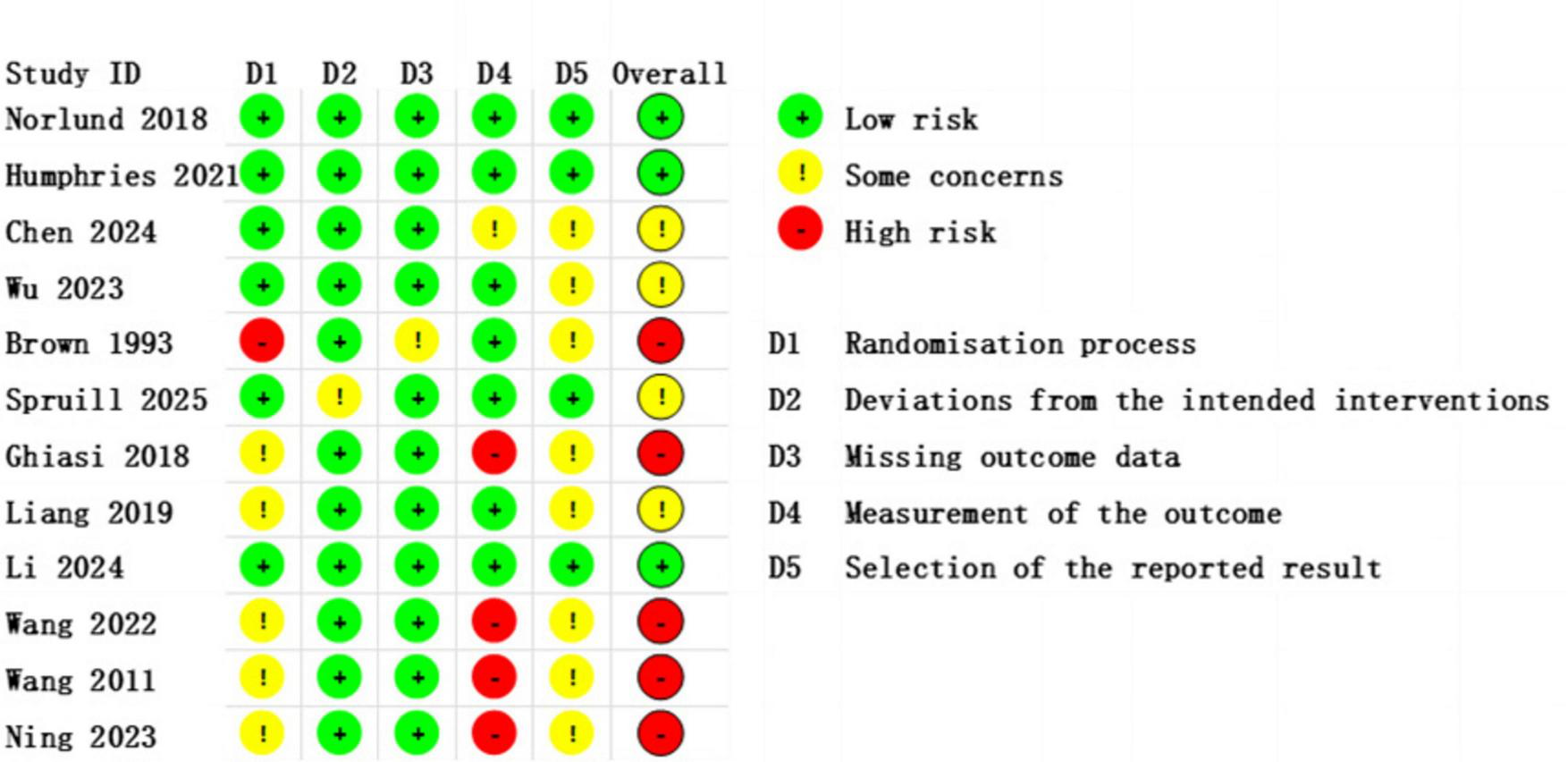

3.3 Risk of bias assessment of the included literature

This study assessed the risk of bias in the included studies using the ROB 2 tool (Supplementary Appendix 1). The results indicated that most studies were judged to have a low or some concerns regarding risk of bias, while only a few exhibited some or high risk of bias, particularly in the domains of blinding implementation and outcome measurement. These methodological limitations may affect the robustness of the overall conclusions. A detailed summary of the risk of bias across all domains for each study is presented in Figures 2, 3.

FIGURE 2

Risk of Bias Assessment traffic light plot, showing the evaluation results of individual studies across different domains.

FIGURE 3

Bar chart of overall distribution across bias domains, displaying the percentage of studies rated as low risk, some concerns, or high risk for each predefined domain (D1–D5).

3.4 Results of the meta-analysis

3.4.1 Primary outcomes

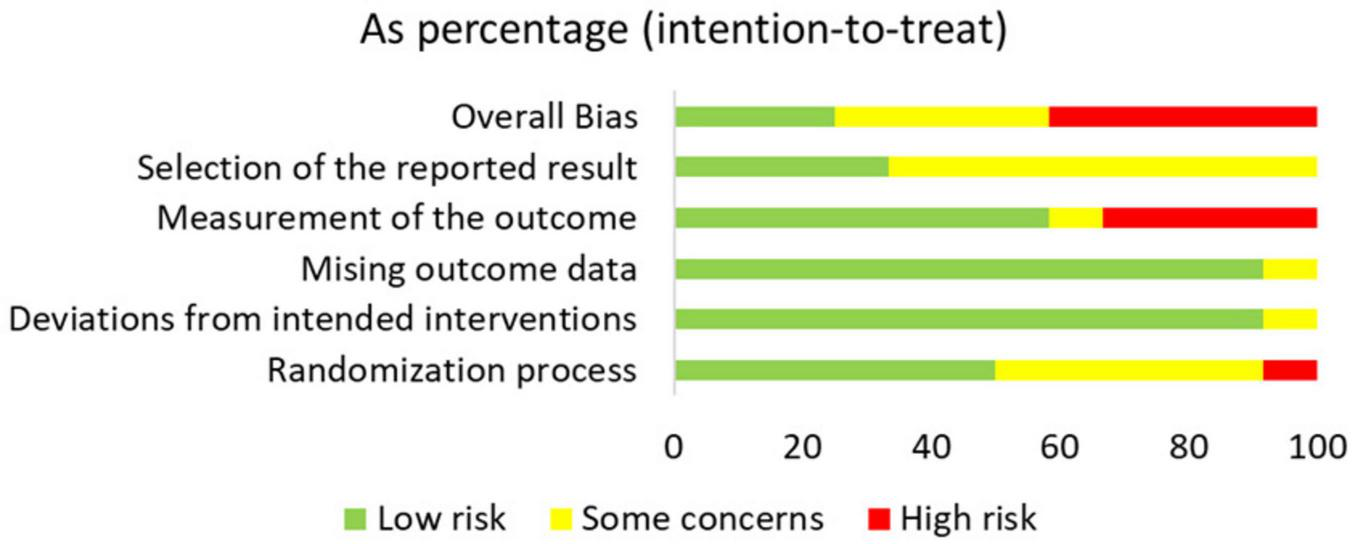

3.4.1.1 Anxiety

Nine independent RCTs of the included trials investigated the efficacy of CBT in alleviating anxiety among patients with MI, encompassing a total of 1,295 participants (Ghiasi et al., 2018; Norlund et al., 2018; Liang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2022; Ning and Wei, 2023; Wu et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2024; Li et al., 2024; Spruill et al., 2025). The pooled results demonstrated that CBT yielded a statistically significant improvement in anxiety symptoms with CBT compared to conventional treatment [SMD = −0.95, 95% CI (−1.48, −0.43), P < 0.001, I2 = 94.8%] (Figure 4). However, high heterogeneity between studies was observed.

FIGURE 4

Meta-analysis results for anxiety.

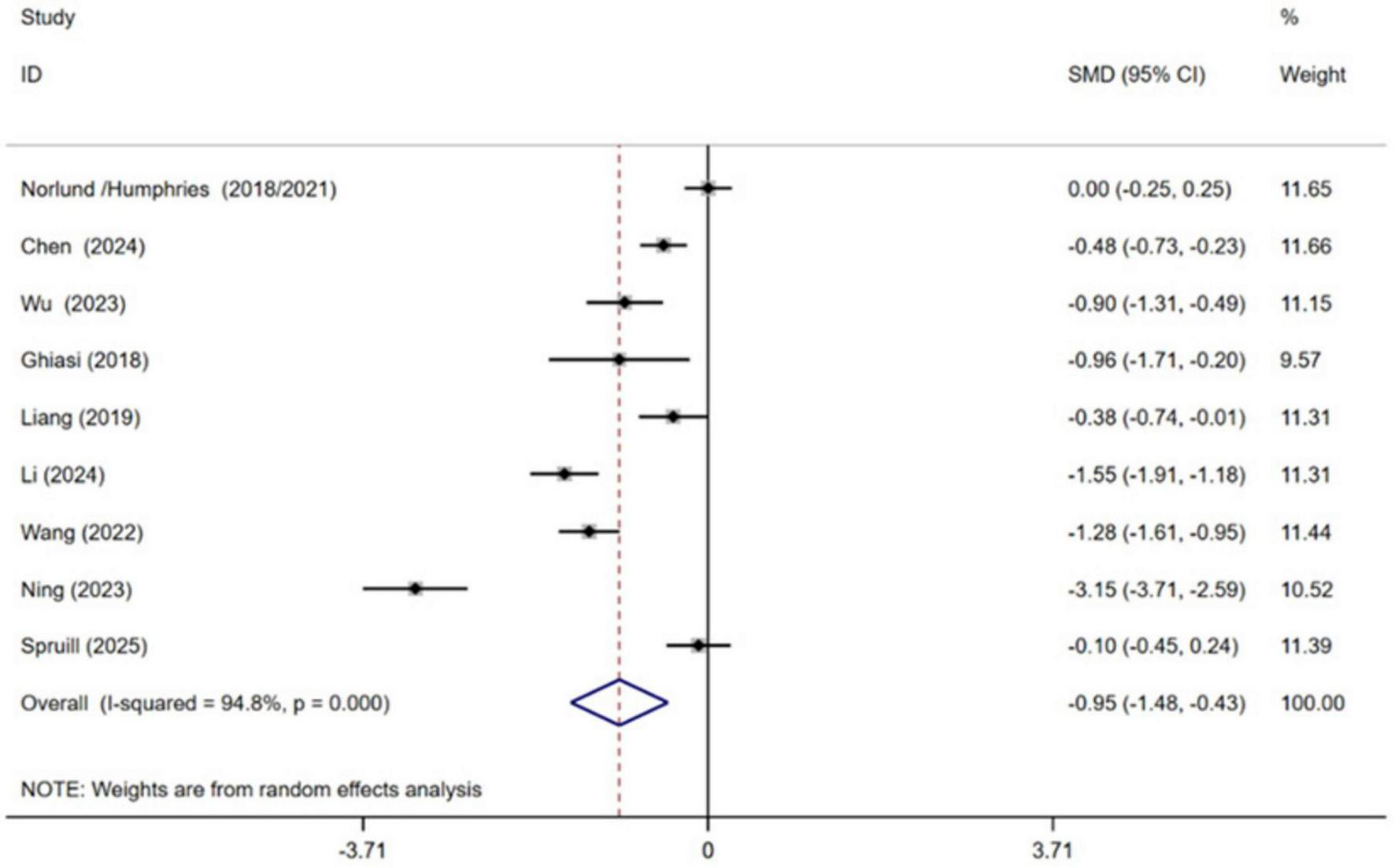

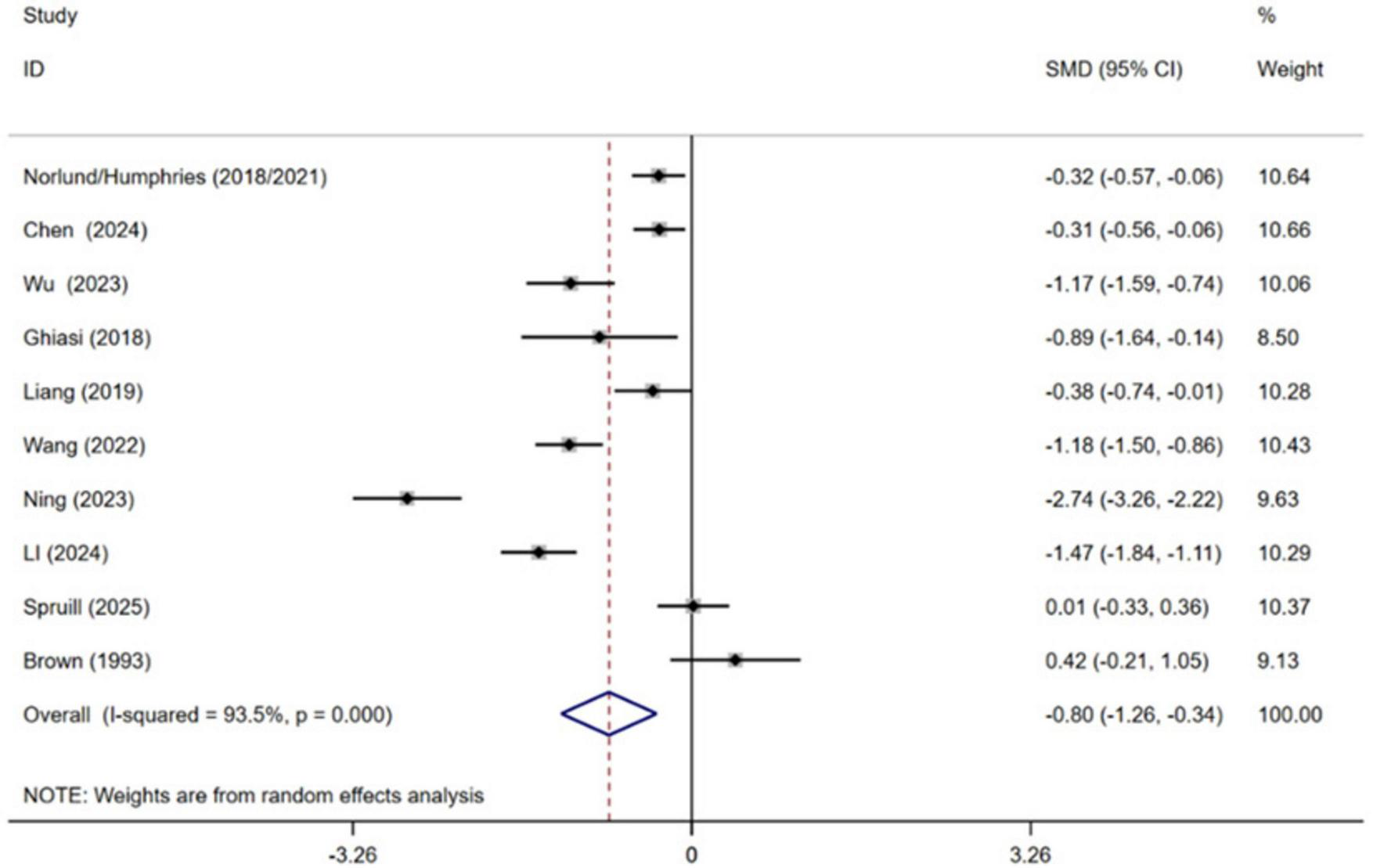

3.4.1.2 Depression

Ten independent RCTs of the included trials evaluated the effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on managing depression in MI patients, comprising a total of 1,335 participants (Brown et al., 1993; Ghiasi et al., 2018; Norlund et al., 2018; Liang et al., 2019; Humphries et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022; Ning and Wei, 2023; Wu et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2024; Li et al., 2024; Spruill et al., 2025). Pooled effect sizes indicated that receiving CBT contributed to lower levels of depression in MI patients compared with conventional treatment [SMD = −0.80, 95% CI (−1.26, −0.34), P = 0.001, I2 = 93.5%] (Figure 5). High heterogeneity between studies was observed.

FIGURE 5

Meta-analysis results for depression.

3.4.2 secondary outcomes

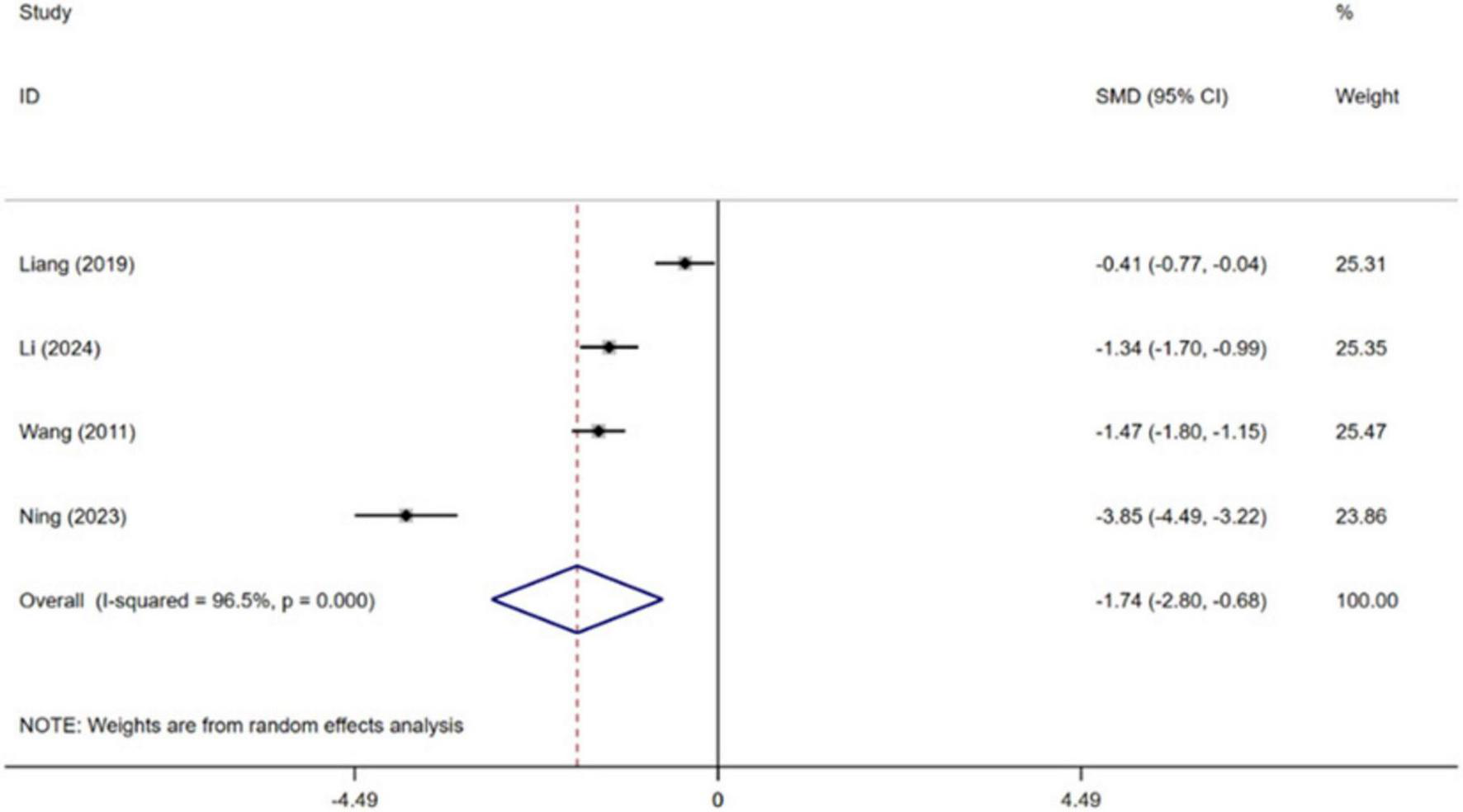

3.4.2.1 Quality of sleep

Four independent RCTs of the included trials evaluated the effect of CBT on sleep quality in patients with MI, encompassing a total of 555 patients (Wang et al., 2011; Liang et al., 2019; Ning and Wei, 2023; Li et al., 2024). Pooled effect sizes indicated that CBT significantly improved patients’ sleep quality compared with conventional treatment [SMD = −1.74, 95% CI (−2.80, −0.68), P = 0.001, I2 = 96.5%] (Figure 6). High heterogeneity was observed between studies.

FIGURE 6

Meta-analysis results for sleep quality.

3.4.3 Subgroup analysis

3.4.3.1 Duration of the intervention

Subgroup analyses were conducted based on intervention duration, categorizing studies into two groups: those with interventions lasting less than or longer than 7 weeks. The results showed that CBT was effective in improving levels of anxiety [SMD = −1.43, 95% CI (−2.17, −0.69), P < 0.001, I2 = 94.4%] and depression [SMD = −1.37, 95% CI (−2.01, −0.72), P < 0.001, I2 = 92.7%] in MI patients receiving shorter-duration interventions (< 7 weeks). In contrast, CBT did not show yield statistically significant improvements in anxiety [SMD = −0.29, 95% CI (−0.62, 0.03), P = 0.079, I2 = 72.7%] and depression [SMD = −0.20, 95% CI (−0.47, 0.06), P = 0.130, I2 = 59.5%] among patients receiving longer-duration interventions (≥ 7 weeks) (details are shown in Table 2).

TABLE 2

| Outcome | Duration of the intervention |

No. of studies |

Heterogeneity test |

Effects model | Meta-analysis results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | I 2 (%) | SMD | 95% CI | Z | P | ||||

| Anxiety | < 7 weeks | 5 | < 0.001 | 94.4 | Random | −1.43 | [−2.17, −0.69] | 3.77 | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 7 weeks | 4 | 0.012 | 72.7 | Random | −0.29 | [−0.62, 0.03] | 1.76 | 0.079 | |

| Depression | < 7 weeks | 5 | < 0.001 | 92.7 | Random | −1.37 | [−2.01, −0.72] | 4.16 | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 7 weeks | 5 | 0.043 | 59.5 | Random | −0.20 | [−0.47, 0.06] | 1.51 | 0.130 | |

Results of subgroup analysis of the effect of different intervention durations on patients’ levels of anxiety and depression.

3.4.3.2 Forms of intervention

Subgroup analyses were conducted according to different forms of intervention (internet or telephone, face-to-face). The results showed that internet-based or telephone-based forms of intervention did not have a positive effect on anxiety [SMD = −0.04, 95% CI (−0.24, 0.17), P = 0.728, I2 = 0.0%] and depression [SMD = −0.17, 95% CI (−0.50, 0.15), P = 0.293, I2 = 56.7%] levels in patients with MI, whereas face-to-face forms of intervention were effective in reducing anxiety [SMD = −1.22, 95% CI (−1.81, −0.64), P < 0.001, I2 = 93.7%] and depression [SMD = −0.97, 95% CI (−1.52, −0.41), P = 0.001, I2 = 93.5%] symptoms in patients (details are shown in Table 3).

TABLE 3

| Outcome | Forms of intervention |

No. of studies |

Heterogeneity test |

Effects model | Meta-analysis results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | I 2 (%) | SMD | 95% CI | Z | P | ||||

| Anxiety | Internet or telephone | 2 | 0.637 | 0.0 | Random | −0.04 | [−0.24, 0.17] | 0.35 | 0.728 |

| Face-to-face | 7 | < 0.001 | 93.7 | Random | −1.22 | [−1.81, −0.64] | 4.11 | < 0.001 | |

| Depression | Internet or telephone | 2 | 0.129 | 56.7 | Random | −0.17 | [−0.50, 0.15] | 1.05 | 0.293 |

| Face-to-face | 8 | < 0.001 | 93.5 | Random | −0.97 | [−1.52, −0.41] | 3.41 | 0.001 | |

Results of subgroup analysis of the effect of different intervention formats on patients’ anxiety and depression levels.

3.4.3.3 Type of intervention

Subgroup analyses were conducted according to different types of intervention (traditional CBT, third-generation CBT). The results showed that the traditional CBT intervention had a positive effect on both anxiety [SMD = −1.22, 95% CI (−1.97, −0.46), P = 0.002, I2 = 96.3%] and depression [SMD = −0.93, 95% CI (−1.54, −0.31), P = 0.003, I2 = 94.7%] symptoms in patients with MI; the third-generation CBT intervention was effective in reducing patients’ anxiety [SMD = −0.45, 95% CI (−0.89, −0.00), P = 0.048, I2 = 76.5%] levels, while it did not show a statistically significant difference in the effect on patients’ depression [SMD = −0.50, 95% CI (−1.15, 0.15), P = 0.134, I2 = 88.9%] levels; Both types of intervention were effective in improving patients’ sleep quality (details are shown in Table 4).

TABLE 4

| Outcome | Type of intervention |

No. of studies |

Heterogeneity test |

Effects model | Meta-analysis results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | I 2 (%) | SMD | 95% CI | Z | P | ||||

| Anxiety | Traditional CBT | 6 | < 0.001 | 96.3 | Random | −1.22 | [−1.97, −0.46] | 3.16 | 0.002 |

| Third-generation CBT | 3 | < 0.001 | 93.7 | Random | −0.45 | [−0.89, −0.00] | 1.97 | 0.048 | |

| Depression | Traditional CBT | 7 | < 0.001 | 94.7 | Random | −0.93 | [−1.54, −0.31] | 2.97 | 0.003 |

| Third-generation CBT | 3 | < 0.001 | 88.9 | Random | −0.50 | [−1.15, 0.15] | 1.50 | 0.134 | |

| Quality of sleep | Traditional CBT | 3 | < 0.001 | 96.0 | Random | −2.19 | [−3.38, −0.99] | 3.59 | < 0.001 |

| Third-generation CBT | 1 | – | – | – | −0.41 | [−0.77, −0.04] | 2.16 | 0.031 | |

Results of subgroup analysis of the effects of different intervention types on patients’ anxiety, depression, and sleep quality.

3.4.4 Sensitivity analysis

The results of sensitivity analyses suggested that none of the trials would have a disproportionate effect on the overall results, suggesting that the results of the meta-analysis are more robust (Supplementary Appendix 1).

3.4.5 Publication bias

The funnel plot for depression outcomes was approximately symmetric, and Egger’s test indicated no statistically significant publication bias (P = 0.341). Taken together, these results suggest that publication bias among the included studies is unlikely to have substantially affected the pooled estimates (Supplementary Appendix 1).

3.4.6 GRADE assessment

The quality of evidence for all outcomes was assessed using the GRADE approach. The results indicated that the certainty of evidence varied across outcomes. The evidence for anxiety and depression was rated as very low, while the evidence for sleep quality was considered low. The main reasons for downgrading were risk of bias, heterogeneity across studies, and indirectness. Detailed GRADE assessments are presented in Supplementary Appendix 1.

4 Discussion

Anxiety and depression are prevalent psychological comorbidities in patients with MI (Alexandri et al., 2017). This meta-analysis systematically evaluated 11 studies, including 9 studies focusing on anxiety and 10 studies examining depression. The findings revealed that CBT significantly alleviated both anxiety and depressive symptoms in MI patients. These results corroborate previous meta-analytic findings demonstrating CBT’s efficacy in general cardiovascular populations (Reavell et al., 2018). Notably, the effect sizes observed in this study were comparatively smaller than those reported in non-cardiac populations (Wu et al., 2024). This discrepancy may be attributed to the unique psychological profile of MI patients, potentially influenced by factors such as fear of recurrent infarctions or activity avoidance behaviors.

The duration of CBT for managing anxiety and depressive symptoms in MI patients warrants careful consideration. While Zhang et al.’s meta-analysis suggested that extended intervention durations are necessary for CBT effectiveness (Neher et al., 2019), our findings indicate that short-term CBT interventions (< 7 weeks) demonstrate superior efficacy in reducing both anxiety and depressive symptoms compared to longer-term programs (≥ 7 weeks). This discrepancy may stem from a non-linear relationship between the dose of CBT and the therapeutic response. Evidence indicates that short-term, structured CBT can significantly alleviate patients’ symptoms; however, as the intervention duration increases, the incremental therapeutic benefit may plateau or even diminish (Klein et al., 2024). This phenomenon can be explained by several interrelated factors. First, in extended psychological interventions, patient adherence tends to decline over time—a trend particularly pronounced in the post-MI population, where physical limitations and complex healthcare demands often gradually reduce engagement. For example, a recent trial reported suboptimal adherence rates among MI patients participating in a 14-week CBT program, mainly due to waning treatment motivation (Norlund et al., 2018). Second, patients often experience significant anxiety following the acute phase of MI. Implementing structured CBT early during this stage may enhance the relevance and overall effectiveness of the intervention by aligning with patients’ psychological window of need (Tang et al., 2025). Therefore, the key to treatment lies not simply in extending the duration of therapy, but in ensuring the intensity and adherence during the initial phase, followed by personalized support tailored to individual needs.

The delivery format moderates CBT’s efficacy. Face-to-face delivery was associated with significant improvements in anxiety and depression, whereas internet- based or telephone-based formats showed no significant benefit. This contrasts with evidence supporting digital CBT in broader cardiac populations (Andersson and Cuijpers, 2009; Kwek et al., 2025), a discrepancy potentially explained by the older age profile and associated digital engagement challenges in our MI cohort, as well as the limited number of remote studies analyzed. Future implementation of digital CBT for MI patients should integrate therapist support to address emotional needs and facilitate engagement (Beck, 1963; Andersson and Cuijpers, 2009; Lau et al., 2017).

This study examined CBT interventions that included both traditional CBT, which emphasizes cognitive restructuring and behavioral activation (Kabat-Zinn, 2003), and mindfulness-based CBT (i.e., MBI—a third-wave modality focused on cultivating non-judgmental awareness of present-moment experience) (Li J. et al., 2021). Subgroup analyses indicated that both approaches significantly reduced anxiety levels in MI patients, with traditional CBT potentially offering additional benefit for depressive symptoms, likely due to its direct focus on illness-related cognitions (Abdelaziz et al., 2024). The efficacy of CBT in improving sleep quality was also supported, though evidence remains limited. The considerable heterogeneity observed highlights that CBT should not be regarded as a uniform intervention; future trials should therefore explicitly compare standardized protocols varying in format, dosage, and therapeutic modality.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

This study systematically searched and integrated relevant literature from multiple databases, and all included studies underwent rigorous quality assessment, ensuring the reliability of the data and the robustness of the conclusions.

This study has several limitations. First, the relatively small number of included studies, combined with clinical heterogeneity arising from variations in intervention duration, specific protocols, and control conditions across trials, may limit the generalizability of our findings. Second, the assessment of primary outcomes (anxiety and depression levels) relied on measurement tools with inherent subjectivity, which could introduce measurement bias and affect the comparability of results across studies. Third, the included studies were mainly conducted in Sweden, China, the United States, and Iran, with limited evidence from regions such as Africa, South America, and parts of Southeast Asia, which may further constrain the global applicability of the findings. Finally, the substantial heterogeneity observed among the included studies warrants a cautious interpretation of the pooled effect estimates, highlighting the need for further validation through large-scale RCTs.

5 Conclusion

This meta-analysis demonstrates that CBT effectively alleviates anxiety, depressive symptoms, and sleep problems in patients with MI. An important and nuanced finding is that the therapeutic benefits of CBT are not uniform but are significantly influenced by intervention characteristics. Specifically, short-term (< 7 weeks), face-to-face, and traditionally structured CBT protocols were associated with the most pronounced improvements, particularly in anxiety and depression.

These findings challenge the conventional view that longer interventions are invariably superior and underscore the importance of optimizing the “dose” and delivery of CBT in this medically vulnerable population. To translate these insights into reliable clinical guidance, future research should move beyond verifying overall efficacy and prioritize large-scale, pragmatic RCTs. Such trials should directly compare optimized short-term versus long-term protocols, evaluate hybrid delivery models to balance accessibility and engagement, and standardize core intervention components and outcome measures to reduce heterogeneity.

For clinical practice, this synthesis suggests that integrating structured, short-term CBT early into cardiac rehabilitation pathways may effectively address acute psychological distress following MI. Ultimately, refining how CBT is delivered can enhance psychological support and overall quality of life for MI survivors, making such care more effective, scalable, and person-centered.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

XW: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LF: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. HL: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. ZH: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. XL: Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to all researchers whose work contributed to this meta-analysis. We acknowledge their invaluable efforts in advancing the evidence base that made this synthesis possible.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2026.1713464/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Abdelaziz A. Hafez A. H. Roshdy M. R. Abdelaziz M. Eltobgy M. A. Elsayed H. et al (2024). Cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of insomnia in patients with cardiovascular diseases: a meta-analysis with GRADE analysis.J. Behav. Med.47819–827. 10.1007/s10865-024-00490-6

2

Alexandri A. Georgiadi E. Mattheou P. Polikandrioti M. (2017). Factors associated with anxiety and depression in hospitalized patients with first episode of acute myocardial infarction.Arch. Med. Sci. Atherosclerotic Dis.2e90–e99. 10.5114/amsad.2017.72532

3

Alpert J. S. (2023). New coronary heart disease risk factors.Am. J. Med.136331–332. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2022.08.002

4

Andersson G. Cuijpers P. (2009). Internet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: a meta-analysis.Cogn. Behav. Therapy38196–205. 10.1080/16506070903318960

5

Andrechuk C. R. S. Ceolim M. F. (2016). Sleep quality and adverse outcomes for patients with acute myocardial infarction.J. Clin. Nurs.25223–230. 10.1111/jocn.13051

6

Beck A. T. (1963). Thinking and depression. I. Idiosyncratic content and cognitive distortions.Arch. Gen. Psychiatry9324–333. 10.1001/archpsyc.1963.01720160014002

7

Benazon N. R. Mamdani M. M. Coyne J. C. (2005). Trends in the prescribing of antidepressants following acute myocardial infarction, 1993-2002.Psychosom. Med.67916–920. 10.1097/01.psy.0000188399.80167.aa

8

Brown M. A. Munford A. M. Munford P. R. (1993). Behavior therapy of psychological distress in patients after myocardial infarction or coronary bypass.J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prevent.13:201. 10.1097/00008483-199305000-00009

9

Chen B. Wen J. You D. Zhang Y. (2024). Implication of cognitive-behavioral stress management on anxiety, depression, and quality of life in acute myocardial infarction patients after percutaneous coronary intervention: a multicenter, randomized, controlled study.Ir. J. Med. Sci.193101–9. 10.1007/s11845-023-03422-6

10

Fehr N. Witassek F. Radovanovic D. Erne P. Puhan M. Rickli H. (2019). Antidepressant prescription in acute myocardial infarction is associated with increased mortality 1 year after discharge.Eur. J. Internal Med.6175–80. 10.1016/j.ejim.2018.12.003

11

Ghiasi F. Jalali R. Paveh B. Hashemian A. H. Eydi S. (2018). Investigating the impact of cognitive-behavioral therapy on the mental health status of patients suffering from myocardial infarction.Ann. Trop. Med. Public Health3:S15.

12

Humphries S. M. Wallert J. Norlund F. Wallin E. Burell G. von Essen L. et al (2021). Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for patients reporting symptoms of anxiety and depression after myocardial infarction: U-CARE heart randomized controlled trial twelve-month follow-up.J. Med. Internet Res.23:e25465. 10.2196/25465

13

Johnsson A. Ljótsson B. Liliequist B. E. Skúladóttir H. Maurex L. Boberg I. et al (2025). Cognitive behavioural therapy targeting cardiac anxiety post-myocardial infarction: results from two sequential pilot studies.Eur. Heart J. Open5:oeaf020. 10.1093/ehjopen/oeaf020

14

Kabat-Zinn J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future.Clin. Psychol.10144–156. 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016

15

Klein T. Breilmann J. Schneider C. Girlanda F. Fiedler I. Dawson S. et al (2024). Dose-response relationship in cognitive behavioral therapy for depression: a nonlinear metaregression analysis.J. Consult. Clin. Psychol.92296–309. 10.1037/ccp0000879

16

Kwek S. Q. Yeo T. M. Teo J. Y. C. Seah C. W. A. Por K. N. J. Wang W. (2025). Effectiveness of therapist-supported internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy interventions on depression, anxiety and quality of life among patients with cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs.24860–870. 10.1093/eurjcn/zvaf084

17

Lau Y. Htun T. P. Wong S. N. Tam W. S. W. Klainin-Yobas P. (2017). Therapist-supported internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms among postpartum women: a systematic review and meta-analysis.J. Med. Internet Res.19:e138. 10.2196/jmir.6712

18

Li J. Cai Z. Li X. Du R. Shi Z. Hua Q. et al (2021). Mindfulness-based therapy versus cognitive behavioral therapy for people with anxiety symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis of random controlled trials.Ann. Palliat. Med.107596–7612. 10.21037/apm-21-1212

19

Li Y. Peng J. Yang P. Weng J. Lu Y. Liu J. et al (2024). Virtual reality-based cognitive–behavioural therapy for the treatment of anxiety in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a randomised clinical trial.Gen. Psychiatr.371–8. 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101434

20

Li Y.-N. Buys N. Ferguson S. Li Z.-J. Sun J. (2021). Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy-based interventions on health outcomes in patients with coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis.World J. Psychiatry111147–1166. 10.5498/wjp.v11.i11.1147

21

Liang H. Liu L. Hu H. (2019). The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the mental states, sleep quality, and medication compliance of patients with acute myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention.Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med.1213514–13523.

22

Meijer A. Conradi H. J. Bos E. H. Thombs B. D. van Melle J. P. de Jonge P. (2011). Prognostic association of depression following myocardial infarction with mortality and cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis of 25 years of research.Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry33203–216. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.02.007

23

Mendoza C. Kraemer P. Herrera P. Burdiles P. Sepúlveda D. Núñez E. et al (2017). [clinical guidelines using the GRADE system (grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation)].Rev. Med. Chile1451463–1470. 10.4067/s0034-98872017001101463

24

Neher M. Nygårdh A. Nilsen P. Broström A. Johansson P. (2019). Implementing internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for patients with cardiovascular disease and psychological distress: a scoping review.Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs.18346–357. 10.1177/1474515119833251

25

Ning X. Wei J. (2023). Effect of cognitive behavioral pathway intervention on psychological emotions and sleep quality in patients with myocardial infarction.Guizhou Med. J.471665–1666. 10.3969/j.issn.1000-744X.2023.10.092

26

Norlund F. Wallin E. Olsson E. M. G. Wallert J. Burell G. von Essen L. et al (2018). Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety among patients with a recent myocardial infarction: the U-CARE heart randomized controlled trial.J. Med. Internet Res.20:e88. 10.2196/jmir.9710

27

Nourisaeed A. Ghorban-Shiroudi S. Salari A. (2021). Comparison of the effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy and dialectical behavioral therapy on perceived stress and coping skills in patients after myocardial infarction.ARYA Atheroscler.171–9. 10.22122/arya.v17i0.2188

28

Nuraeni A. Suryani S. Trisyani Y. Sofiatin Y. (2023). Efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy in reducing depression among patients with coronary heart disease: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs.Healthcare11:943. 10.3390/healthcare11070943

29

Page M. J. McKenzie J. E. Bossuyt P. M. Boutron I. Hoffmann T. C. Mulrow C. D. et al (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews.BMJ372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71

30

Reavell J. Hopkinson M. Clarkesmith D. Lane D. A. (2018). Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for depression and anxiety in patients with cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Psychosomat. Med.80742–753. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000626

31

Roest A. M. Martens E. J. Denollet J. de Jonge P. (2010). Prognostic association of anxiety post myocardial infarction with mortality and new cardiac events: a meta-analysis.Psychosomat. Med.72563–569. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181dbff97

32

Roth G. A. Mensah G. A. Johnson C. O. Addolorato G. Ammirati E. Baddour L. M. et al (2020). Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: update from the GBD 2019 study.J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.762982–3021. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010

33

Santos J. M. T. D. (2018). Anxiety and depression after myocardial infarction: can inflammatory factors be involved?Arq. Bras. Cardiol.111684–685. 10.5935/abc.20180233

34

Serpytis P. Navickas P. Lukaviciute L. Navickas A. Aranauskas R. Serpytis R. et al (2018). Gender-based differences in anxiety and depression following acute myocardial infarction.Arq. Bras. Cardiol.111676–683. 10.5935/abc.20180161

35

Spruill T. M. Park C. Kalinowski J. Arabadjian M. E. Xia Y. Shallcross A. J. et al (2025). Brief mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in women with myocardial infarction: results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial.JACC Adv.4:101530. 10.1016/j.jacadv.2024.101530

36

Sterne J. A. C. Savović J. Page M. J. Elbers R. G. Blencowe N. S. Boutron I. et al (2019). RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials.BMJ366:l4898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898

37

Tang X. Liu G. Zeng Y. J. (2025). Anxiety disorders following percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction: A comprehensive review of clinical manifestations and interventions.World J. Psychiatry15:110290. 10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.110290

38

van Melle J. P. de Jonge P. Spijkerman T. A. Tijssen J. G. P. Ormel J. van Veldhuisen D. J. et al (2004). Prognostic association of depression following myocardial infarction with mortality and cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis.Psychosomat. Med.66814–822. 10.1097/01.psy.0000146294.82810.9c

39

Wang H. Li F. Kang H. (2011). Effects of cognitive behavioral intervention on sleep quality in hospitalized patients with acute myocardial infarction.Chin. Nurs. Res.2544–45. 10.3969/j.issn.1009-6493.2011.01.018

40

Wang H. Tian Q. Liu Y. Guo J. Zang S. (2022). Impact of rational emotive behavior therapy on psychological status, fear of progression questionnaire-short form (FoP-Q-SF) scores, and prognosis in acute myocardial infarction patients in the ICU.Chin. J. Health Psychol.301510–1514. 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2022.10.014

41

Wu K. Wan M. Zhou H. Li C. Zhou X. Li E. et al (2023). Mindfulness-based stress reduction combined with early cardiac rehabilitation improves negative mood states and cardiac function in patients with acute myocardial infarction assisted with an intra-aortic balloon pump: a randomized controlled trial.Front. Cardiovasc. Med.10:1166157. 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1166157

42

Wu X. Shi M. Lian Y. Zhang H. (2024). Cognitive behavioral therapy approaches to the improvement of mental health in parkinson’s disease patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis.BMC Neurol.24:352. 10.1186/s12883-024-03859-x

43

Zeighami R. Behnammoghadam M. Moradi M. Bashti S. (2018). Comparison of the effect of eye movement desensitization reprocessing and cognitive behavioral therapy on anxiety in patients with myocardial infarction.Eur. J. Psychiatry3272–76. 10.1016/j.ejpsy.2017.09.001

44

Zhang L. Liu X. Tong F. Zou R. Peng W. Yang H. et al (2022). Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in cancer survivors: a meta-analysis.Sci. Rep.12:21466. 10.1038/s41598-022-25068-7

Summary

Keywords

anxiety, cognitive behavioral therapy, depression, meta-analysis, myocardial infarction, sleep quality

Citation

Wei X, Fu L, Liu H, Huang Z and Lu X (2026) Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on anxiety and depression in patients with myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 17:1713464. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2026.1713464

Received

26 September 2025

Revised

24 January 2026

Accepted

26 January 2026

Published

17 February 2026

Volume

17 - 2026

Edited by

Senthil Kumaran Satyanarayanan, Hong Kong Institute of Innovation and Technology, Hong Kong SAR, China

Reviewed by

Ahmad Zain Sarnoto, Institute PTIQ Jakarta, Indonesia

Li Liu, Wuhan Asia Heart Hospital, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Wei, Fu, Liu, Huang and Lu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhihong Huang, 949464832@qq.comXiaoqian Lu, 574800038@qq.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.