- 1The International Federation of Esports Coaches (IFoEC), London, United Kingdom

- 2Department of Psychology, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden

- 3Institute of Health and Wellbeing, Federation University Australia, Berwick, VIC, Australia

- 4Physical Activity, Sport and Exercise Research Theme, Faculty of Health, Southern Cross University, Gold Coast, QLD, Australia

1. Introduction

There has been increasing interest in esports from participation, spectator, and academic perspectives. Concerning the latter, there have been discussions about whether esports can be classified as a sport and its definition (1). A range of academic disciplines have started investigating the esports industry [e.g., Business, Sport Science, Law, Cognitive Science; see (2)], and have provided several differing definitions for esports. We believe that within these definitions, there is a need to consistently distinguish between individuals who play the various esports titles as a form of leisure compared to those who play them competitively. A commonly adopted definition of esports was proposed by Pedraza-Ramirez et al. (3), who view esports as “the casual or organized playing of competitive computer games facilitated through in-game ranking systems or organized competitions” (p. 6).

Studies examining whether esports can be called “sports” provide compelling evidence that this is the case. Campbell et al. (4) suggest that sports sit on a continuum between those which are predominantly physical (e.g., weightlifting) and those which are more cognitively focused (e.g., chess). Esports generally meet the criteria of various definitions of sports (5). The clear distinction between the two domains (sports and esports) lies in the fact that performance is enacted through different mediums, most esports do not adhere to the definition of “sport” presented by Connor (6) “a sport is a game involving physical exertion” (pg 15) whereas, in esports performance is conducted through electronic systems where the use controls an avatar. However, esports and sports share similarities in the sense, that in most cases there are organised teams, there is an element of competition (i.e., winners and losers), and with the professionalisation of esports, counters hours are dedicated to training and refining skill for competetitve success (7). Hence, many of the characteristics attributed to sports also apply to esports (2, 8).

Generally, the term “athletes” refers to those who participate in sports. However, when referring to competitors of specific sports (especially team sports), athletes are also referred to as players (e.g., football, hockey players). We will argue in this paper that a similar hierarchical structure of naming individuals engaging in esports should be adopted in esports research to facilitate clarity on the sample and enhance comparisons across (e)sports.

As esports are widely considered sports, we seek to establish clarity about which term should be used regarding individuals who participate within the vast esports ecosystem. Having consistent terminology that differentiates between the recreational gamer and competitive gamer is an important issue for several reasons. Firstly, this reduces the confusion that might occur across the esports literature. Secondly, it allows comparisons with sports and exercise literature. Thirdly, it allows for a more accurate description of the different groupings of esports participants.

Developing a clearer understanding of how we define those who play video games competitively will allow more targeted research and comparisons. For example, this would allow for research to explore how esports athletes differ from games in terms of health behaviours like physical exercise, nutritional practices, smoking, and drinking as well as psychosocial characteristics like social support and self-regulation.

2. Key terminology within esports literature

Across the range of literature, there is a clear incongruence in the terms used to describe esports athletes (see Table 1). Terms such as esports player, esports athlete, gamer, and video game players can all describe the individuals who interact within the vast esports ecosystem in any competitive manner (i.e., ranked play or structured competition). At times, when referring to the more formal and organized categories, terms may be prefaced, such as “elite” e-athletes, “professional” video gamers, and “competitive” esports players. Due to the nature of esports, and following the definition provided by Perdraza-Ramierez et al. (3), all esports feature some in-game or external ranking system that categorizes players into various rankings indicative of their skill. For example, League of Legends (LoL) features a ranking system that spans from Iron (the lowest) to Challenger (the highest). With a majority of the player base placed between Silver and Gold, and with ∼1% of the participants populating the Master, Grandmaster and Challenger tiers (24). However, not everyone within these tiers participates for a ranking or within a structured and competitive system. Many align themselves with content creation or streaming, providing high-quality live or on-demand entertainment for a larger audience. Cases like this are not exclusive to LoL but feature across almost all prominent esports titles, further highlighting the need to create clear terminology between athlete, entertainer, and player to avoid future ambiguity as the scientific literature within esports develops.

3. Current research and definitions

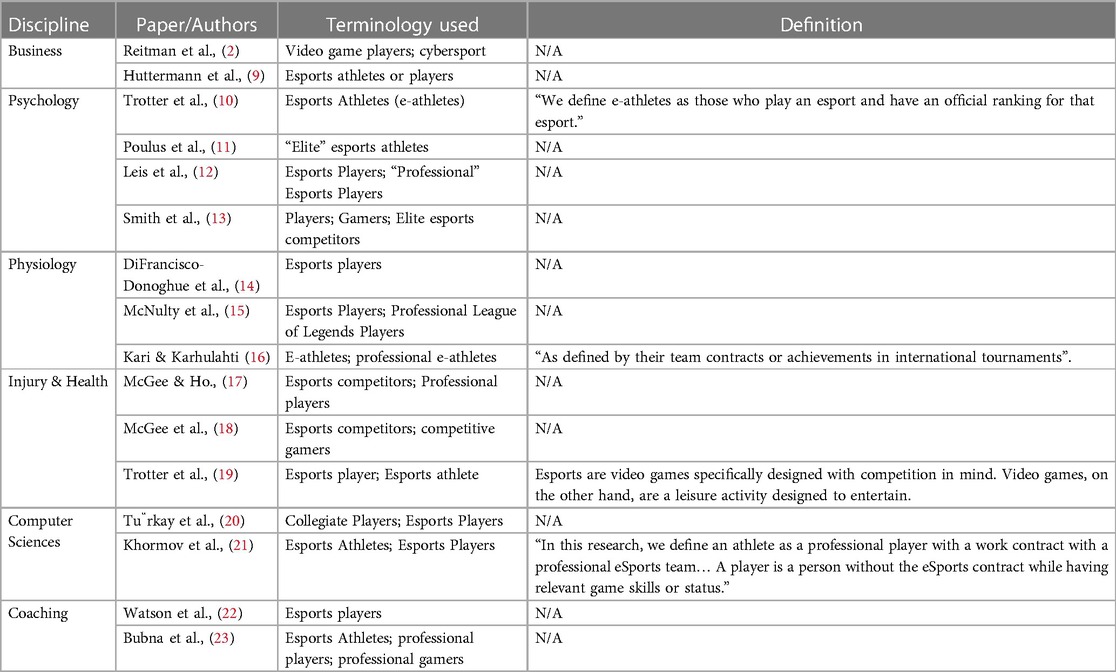

As mentioned previously, many academic domains have started to pay attention to the world of esports. In doing so, they have created a range of definitions and terminology. Although not an exhaustive list, Table 1 briefly explores the current literature available across various academic fields (i.e., business, psychology, physiology, injury & health, computer sciences, and coaching) to evidence the terminology used.

4. Critique of current terminology

When examining Table 1, it is clear that many papers interchangeably use the terms athletes, competitors, and players when discussing esports. This further highlights the need for clarity within the terminology, with considerations taken to define what is considered aligned to an esports athlete and who is encapsulated when discussing the casual gamer. Secondly, out of the sixteen papers outlined within the table, only four papers explicitly define their population, further emphasizing the need to understand the specific distinctions between them.

5. Discussion

We argue that esports athlete (or e'athlete as an abbreviation) is a suitable term that encapsulates individuals who compete in any esports to achieve an in-game ranking or who compete in a formalized competition. Esports athlete (e'athlete) should be used similarly to the umbrella term “athlete”, broadly referring to the players of all types of sports (25). Furthermore, the term “player” can be used when referring to players within a specific esports title [e.g., LoL player, Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (CS:GO) player]. Standardising this terminology across each academic discipline will help differentiate and offer clarification between esports-specific research (competitive games) and video game research (non-competitive games).

An example comes from studies by Trotter et al. (19, 26). In their 2020 study, they compare the health and psychical activity behaviours of e'athletes with those of normative data. Future research could compare e'athletes with gamers, athletes, or normative values. Similarly, the study by Trotter et al. (11) explored the efficacy of a school-based esports program. Future studies could examine how e'athletes would benefit from esports-specific interventions to enhance health behaviours (e.g., physical activity; see 27).

The aim of this piece was to briefly discuss the various terms used in academic research to describe esports participants and highlight the need for consistent terminology across academic research. The absence of a cohesive naming convention or terminology poses a challenge within the field, hindering researchers' ability to consolidate existing literature and derive significant, cross-study conclusions. This issue becomes particularly evident when conducting systematic reviews or meta-analysis, where the lack of a unified approach complicates the synthesis process.

Looking towards sporting research, the use of “athlete” is generally a broader term used to describe athletes across any range of sports, however, in sports, athletes are often categorized by their level of eliteness (28), expertise (29) and competition level (i.e., national/international, county, university, and club; see (25). However, due to the infancy of the esports industry and esports research, no guidelines exist to help delineate between eliteness, expertise, or competition standards, which leads to the generalization of populations within the ranking system. Further research is still required to understand the appropriate adjectives used to delineate the expertise of esports athletes (i.e., amateur, semi-professional, professional and elite), which can help researchers be more specific within their sampling across the various disciplines that have started to investigate esports.

Author contributions

KB: writing original draft preparation. KB, MT, RP, and DP: writing—review and editing and project administration. MT, RP, and DP: supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Formosa J, O'Donnell N, Horton EM, Türkay S, Mandryk RL, Hawks M, et al. Definitions of esports: a systematic review and thematic analysis. Proc ACM Hum-Comput Interact. (2022) 6(CHI PLAY):1–45. doi: 10.1145/3549490

2. Reitman JG, Anderson-Coto MJ, Wu M, Lee JS, Steinkuehler C. Esports research: a literature review. Games Cult. (2020) 15(1):32–50. doi: 10.1177/1555412019840892

3. Pedraza-Ramirez I, Musculus L, Raab M, Laborde S. Setting the scientific stage for esports psychology: a systematic review. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. (2020) 13(1):319–52. doi: 10.1080/1750984X.2020.1723122

4. Campbell MJ, Toth AJ, Moran AP, Kowal M, Exton C. Esports: a new window on neurocognitive expertise? Prog Brain Res. (2018) 240:161–74. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2018.09.006

5. Holden JT, Kaburakis A, Rodenberg RM. Esports: children, stimulants and video-gaming-induced inactivity. J Paediatr Child Health. (2018) 54(8):830–1. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13897

7. Jenny SE, Manning RD, Keiper MC, Olrich TW. Virtual (ly) athletes: where eSports fit within the definition of “sport”. Quest. (2017) 69(1):1–18. doi: 10.1080/00336297.2016.1144517

8. Ferrari S. Esport and the human body: foundations for a popular aesthetics. DiGRA conference (2013).

9. Huettermann M, Trail GT, Pizzo AD, Stallone V. Esports sponsorship: an empirical examination of esports consumers’ perceptions of non-endemic sponsors. J Glob Sport Manag. (2020) 8(2):1–26. doi: 10.1080/24704067.2020.1846906

10. Trotter MG, Coulter TJ, Davis PA, Poulus DR, Polman R. Social support, self-regulation, and psychological skill use in e-athletes. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:722030. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.722030

11. Poulus DR, Coulter TJ, Trotter MG, Polman R. A qualitative analysis of the perceived determinants of success in elite esports athletes. J Sports Sci. (2022) 40(7):742–53. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2021.2015916

12. Leis O, Raue C, Dreiskämper D, Lautenbach F. To be or not to be (e) sports? That is not the question! why and how sport and exercise psychology could research esports. Ger J Exerc Sport Res. (2021) 51(2):241–7. doi: 10.1007/s12662-021-00715-9

13. Smith MJ, Birch PD, Bright D. Identifying stressors and coping strategies of elite esports competitors. Int J Gaming Comput-Mediat Simul. (2019) 11(2):22–39. doi: 10.4018/IJGCMS.2019040102

14. DiFrancisco-Donoghue J, Jenny SE, Douris PC, Ahmad S, Yuen K, Hassan T, et al. Breaking up prolonged sitting with a 6 min walk improves executive function in women and men esports players: a randomised trial. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. (2021) 7(3):e001118. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2021-001118

15. McNulty C, Jenny SE, Leis O, Poulus D, Sondergeld P, Nicholson M. Physical exercise and performance in esports players: an initial systematic review. J Electronic Gaming Esports. (2023) 1:1. doi: 10.1123/jege.2022-0014

16. Kari T, Karhulahti VM. Do e-athletes move?: a study on training and physical exercise in elite e-sports. Int J Gaming Comput-Mediat Simul. (2016) 8(4):53–66. doi: 10.4018/IJGCMS.2016100104

17. McGee C, Ho K. Tendinopathies in video gaming and esports. Front Sports Act Living. (2021) 3:689371. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2021.689371

18. McGee C, Hwu M, Nicholson LL, Ho KK. More than a game: musculoskeletal injuries and a key role for the physical therapist in esports. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. (2021) 51(9):415–7. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2021.0109

19. Trotter M, Coulter T, Davis P, Poulus D, Polman RCJ. The association between esports participation, health and physical activity behaviour. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:7329. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17197329

20. Türkay S, Formosa J, Adinolf S, Cuthbert R, Altizer R. See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil: how collegiate players define, experience and cope with toxicity. Proceedings of the 2020 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (2020). p. 1–13.

21. Khromov N, Korotin A, Lange A, Stepanov A, Burnaev E, Somov A. Esports athletes and players: a comparative study. IEEE Pervasive Comput. (2019) 18(3):31–9. doi: 10.1109/MPRV.2019.2926247

22. Watson M, Smith D, Fenton J, Pedraza-Ramirez I, Laborde S, Cronin C. Introducing esports coaching to sport coaching (not as sport coaching). Sports Coach Rev. (2022):1–20. doi: 10.1080/21640629.2022.2123960

23. Bubna K, Trotter MG, Watson M, Polman R. Coaching and talent development in esports: a theoretical framework and suggestions for future research. Front Psychol. (2023) 14:1–5. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1191801

24. Conroy E, Kowal M, Toth AJ, Campbell MJ. Boosting: rank and skill deception in esports. Entertain Comput. (2021) 36:100393. doi: 10.1016/j.entcom.2020.100393

25. Nicholls AR, Polman R, Levy AR, Taylor J, Cobley S. Stressors, coping, and coping effectiveness: gender, type of sport, and skill differences. J Sports Sci. (2007) 25(13):1521–30. doi: 10.1080/02640410701230479

26. Trotter MG, Coulter TJ, Davis PA, Poulus DR, Polman R. Examining the impact of school esports program participation on student health and psychological development. Front Psychol: Mov Sci Sport Psychol. (2022) 12:807341. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.807341

27. Polman RCJ, Trotter M, Poulus D, Borkoles E. Esport: friend or foe? In: Gobel S, editors. Serious Games: 4th Joint International Conference, JCSG 2018, Darmstadt, Germany, November 7-8, 2018, Proceedings 4. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing (2018). p. 3–8.

Keywords: esports, esports athletes, terminology, definitions, gamer

Citation: Bubna K, Trotter MG, Polman R and Poulus DR (2023) Terminology matters: defining the esports athlete. Front. Sports Act. Living 5:1232028. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2023.1232028

Received: 31 May 2023; Accepted: 11 August 2023;

Published: 25 August 2023.

Edited by:

Mark J. Campbell, University of Limerick, IrelandReviewed by:

Amy Elizabeth Whitehead, Liverpool John Moores University, United Kingdom© 2023 Bubna, Trotter, Polman and Poulus. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michael G. Trotter bWljaGFlbC50cm90dGVyQHVtdS5zZQ==

Kabir Bubna

Kabir Bubna Michael G. Trotter

Michael G. Trotter Remco Polman

Remco Polman Dylan R. Poulus

Dylan R. Poulus