Abstract

Introduction:

The purpose of this study is to empirically investigate the pattern of visitors’ revisiting behavioral intention via the innovational approach of Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and the Expectation Confirmation Theory (ECT).

Methods:

This research was conducted by data collection with structured questionnaires as its instrument, which was distributed among 420 yoga tourism visitors in two destinations, Mysore and Rishikesh in India. Collected data had been processed by confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling.

Results:

The data analysis results showed that the behavioral attitude of yoga tourism visitors can mediate the influence of behavioral intention through the satisfaction. The findings of this study include the following points: (1) the components of attitude, subjective norm and destination image apply a direct effect on the cultural and spiritual experiences of yoga tourism visitors; (2) cultural and spiritual experiences have a direct effect on the expectation confirmation and the satisfaction of yoga tourism visitors; (3) Expectation confirmation has a direct effect on the satisfaction and the behavior intention of yoga tourism visitors; and (4) Satisfaction has a direct effect on the behavior intention of yoga tourism visitors.

Discussion:

This study contributed by examining the satisfaction and revisit intentions of yoga tourism visitors through an integrated study of planning behavior and expectation confirmation models, which might be refilling the scarcity of research in the tourism literature. The result of this study might offer important implications for scholars, marketers, and tourism industry to better serve this emerging niche market.

1. Introduction

Tourists’ intention to return reflects not only their high regard for the destination’s attractiveness but also the destination’s future economic development potential. As a result, revisiting behavior is a frequently studied construct in both industry and academia. The scholars have examined tourists’ willingness to return from a variety of perspectives, including the quality of the tourist destination experience (Jung et al., 2015; Meng and Cui, 2020), the experience of auxiliary facilities within the destination (Prentice and Hsiao, 2021), the interaction between host and visitor (Tabaeeian et al., 2022), and service quality (Tosun et al., 2015). Moreover, some scholars begin their research with tourists’ motivation (Li et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2014). From the time series perspective, the travel experience can be divided into three stages: pre-trip, on-site, and post-experience. Clearly, the majority of existing research on tourists’ revisit intentions (RI) focuses on the on-site stage, especially on the effect of the on-site experience on tourists’ future RIs.

When conducting visitor behavior research, it is critical to take a holistic approach (Leiper, 1979). According to Remoaldo and Cadima Ribeiro (2015), holistic refers to something that emphasizes the whole and its interdependence. Therefore, when considering tourists’ willingness to return, it is necessary to consider the influence and correlation among various stages of the tourism experience. Some researchers have begun to focus on how to comprehensively consider the factors of different stages in order to comprehend the behavioral intention of tourists, such as Li et al. (2020), who divided tourists’ experience into three stages: pre-trip, on-site, and post-trip in order to investigate the interaction among factors before, during, and after tea tourists travel. Li et al. (2022) diverged from conventional research by focusing on tourists’ sharing behavior before travel and its impact on their subsequent travel itinerary and travel experience, rather than sharing behavior during or after travel. The inner mechanisms underlying tourist behavior have been thoroughly elucidated by previous research.

Existing research on tourist revisit behavior generally begins with the experience or experience quality during the tourism process and investigates how it influences the tourists’ intention to return. Few scholars have also considered and incorporated pre-travel stage factors into the framework of their research. In order to predict tourists’ intentions to return, this study will combine the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and the expectation confirmation theory (ECT) to develop a comprehensive theoretical model.

Participants in yoga tourism who traveled to India were the focus of this study. The reasons listed below explain why this particular group was chosen. Yoga tourism was selected as the focus of the study due to its uniqueness and rapid growth. Yoga tourism is a self-discovery journey that has the potential to transform a person’s physical, psychological, spiritual, and social consciousness. They collaborate to unite the mind, body, and spirit (Kelly and Smith, 2009). Yoga tourism is a subset of special interest and wellness tourism (Smith and Kelly, 2006), and its popularity has increased globally in recent years (Sharma and Nayak, 2018), but there is a lack of research on the topic (Cheer et al., 2017). Not only for yoga tourism managers but also for managers of other similar wellbeing tourism, it is of great theoretical and practical importance to investigate the internal mechanism that causes such tourists to return. Due to the integration of the TPB and the ECT, a second significant theoretical contribution of this study is a better understanding of the connotation of yoga tourists’ experience expectations for yoga tourism in India, as well as the factors that influence yoga tourism experience expectations. It is evident that this research will provide a solid theoretical foundation for future yoga tourism researchers.

In summary, this study raises the following three important research questions: (1) What do Indian yoga tourists expect from yoga tourism? (2) What factors influence the formation of experience expectations among yoga tourists? (3) Discuss the revisit behavior of yoga tourists and provide management enlightenment for the development of yoga tourism from the perspective of before, during, and after tourism. In the subsequent content, this research will be subdivided into two sub-studies, the relevant literature will be analyzed, and a research model will be developed, beginning with the theoretical foundation of the research.

2. Theoretical foundation and hypotheses development

Ajzen and Fishbein (1975, 1980) proposed the “Theory of Reasoned Action” (TRA) as a theoretical model for understanding human behavior and psychology. The TRA and its extension, the TPB, are cognitive theories that offer a conceptual framework for understanding human behavior in specific contexts. Ajzen also demonstrated the appliance of the TPB in leisure and tourism studies (Ajzen and Driver, 1992), in which the results show that after increasing the control of perceived behavior, the theoretical model of planned behavior showed the effect of enhancing the predictive ability. Ajzen explained that leisure benefit is the concept of benefit goal that the consumers expect and participate in tourism, and consumers’ expected psychology is more important than the actual perceived benefit. Using the TPB model, it would be helpful to discover the issues of the travel decision-making process. Since the TPB is a rational decision-making model, which has traditionally been used to analyze the decision-making process in many different fields, including tourism (Hamid and Isa, 2015). Actually, the visitors’ intention before travel is also an interpretation and prediction of individual willingness and behavior, which is affected by behavioral attitudes, subjective norms (SNM), and perceived behaviors. Based on the TPB, scholars analyze the visitors’ behavior and deduce that visitors’ behavior will be affected by the attitude of visitors themselves, and the attitude of visitors will affect the visitors’ behavior intention (Taylor and Todd, 1995). Sparks used the TPB model to see whether wine tourism visitors would consider another wine trip within a year of their last visit, by dividing attitude into emotional attitude and attitude toward past wine holidays. The results showed that, apart from emotional attitude, other TPB factors had a direct effect (Sparks, 2007). In general, from most tourism studies using the TPB model, the results lead that the attitudes of tourists in their pre-trip period would affect their on-site behavior intentions.

On the other hand, the TPB model has been widely employed in tourism-related studies of tourist perceptions of one-time visitors, or single-visit tourists, to a particular destination (Bianchi et al., 2017; Soliman, 2019; Hasan et al., 2020). By the current limited study about the revisit behavior by extending the TPB model, the common comments figured out that certain variables may significantly affect the RI of visitors, for instance, satisfaction, destination image (DIM), and perceived value. Visitors’ satisfaction gathered on the previous trip was confirmed as the key mediator to their RI (Abbasi et al., 2021). In another word, visitors’ attitude before their revisit (pre-visit), such as the satisfaction from their previous visit, is the determining factor of their RI. Under this tone, it seems that the pre-visit attitude would determine the RI. However, the mentioned approach seems to ignore the re-visitors’ previous experience earned from their first visit to the same destination. From the current literature about revisit behavior, it is mostly considered that the decision-making of revisit and its behavior are the results of previous experience (Adongo et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2021). In fact, there is no revisit study that has yet been used concerning the pre-visit factors. Since the TPB model has been extended in tourism-related studies of visitors’ behavior, this study attempts to extend the TPB model to discuss how the attitude, perceived behavior control, and SNM affect the revisiting behavior of yoga tourism visitors.

Obviously, tourism is a holistic behavior of visitors, which consists of three stages: pre-trip, on-site, and post-experience. It is necessary to consider the entire stages of the tourists’ behavior as a holistic body when we examine the revisit behavior of tourists to a destination. Previous research on destination loyalty shows that one of the most decisive factors for encouraging tourists’ revisiting to a destination is the visitors’ previous satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their previous stays (Appiah-Adu et al., 2000; Bigne et al., 2001; Yoon and Uysal, 2005; Alegre and Garau, 2010; Prayag and Ryan, 2012; Eusébio and Vieira, 2013). Including satisfaction or dissatisfaction, the experience of tourists from their previous visit to a destination would be one of the key factors to affect the pre-trip attitude of their revisiting the same destination (Hasan et al., 2020).

As RI is related to psychological and behavioral mechanisms, it becomes an emerging topic for scholars in tourism research. In order to clarify the relationships between the destination and the antecedents of RI, most of the mentioned studies are based on the factors such as DIM (Marine-Roig and Huertas, 2020; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2021), destination attachment (Isa et al., 2020; Cho, 2021), destination branding (Gupta et al., 2022; Rahman et al., 2022), destination authenticity (Loureiro, 2020; Kumar et al., 2022), destination personality (Jahandide Topraghlou et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2021a), and destination and visitors’ behavior (Abbasi et al., 2021; Šegota et al., 2022). By the repetition in visiting, visitors demonstrate their loyalty to a destination, which becomes support to the sustainability of tourism development (López-Sanz et al., 2021). However, the current study on the mentioned dimension can be insufficient.

Currently, the existing research is more likely to agree that the revisiting behavior of visitors can be considered as the result of the post-experience. It seems more necessary to provide further study by a holistic approach to the factors about the periods of pre-trip, on-site, and post-experience. To reach the mentioned goal, the authors attempt to clarify the impact of prior experience to revisit behavior, by applying the approach of ECT. According to the perspective of ECT, customers’ repurchase intention is determined by their satisfaction with the previous use of the product or service (Oliver, 1980). From this concept, in the context of tourism, the attitude of revisit tourists would be significantly different from the attitude of one-time visitors since the visitors’ experience gained from prior or first-time visits might be a factor to affect their attitude toward revisit behavior.

Regarding culture tourism, the relationship among destination personality, self-congruity, and RI is critical to understanding how tourists decide to revisit a destination (Yang et al., 2021b). Exotic culture is defined as culture shock (Yang et al., 2013). Cultural distance is one of the main mechanisms related to marketing outcomes, especially in terms of tourists’ RIs, which has the potential to exacerbate misunderstandings between hosts and guests as they interpret cues differently (Reisinger and Turner, 2003; Vieira et al., 2021), leading to communication barriers. Tourists’ perception of the external environment may increase their anxiety and uncertainty (Chen et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2021a). Hofstede’s argument is that uncertainty avoidance is more important than any other cultural dimension in predicting travel behavior from a cross-cultural perspective. Uncertainty avoidance is interpreted as the degree to which society perceives itself to be intimidated by any uncertain and ambiguous situation and tries to avoid it. By adopting the cultural dimension approach of Hofstede, it can be seen that the loyalty of visitors across cultures may be predicted by individualism and uncertainty avoidance, and their behavior intention might be evaluated as a determination of tourism internationalization (Yang et al., 2022b).

Many studies explore a destination’s performance by analyzing declared visitor attitude with different aspects of the destination, whether satisfaction or dissatisfaction (Oliver, 1993; Soscia, 2007; Alegre and Garau, 2010; Škoriæ et al., 2021). Some studies talked about the relationship between tourists’ image perception of a tourist destination and a tourist product and their experience expectations (Sharma and Nayak, 2019; Pimtong et al., 2021; Ajay et al., 2022; Carreira et al., 2022; Karakaş et al., 2022; Nautiyal et al., 2022). Based on self-congruity, destination personality is linked indirectly and positively with visitors’ revisit and recommended behavioral intention (Yang et al., 2020). Gender factors might have direct significance among DIM, destination personality, self-congruity, and RI (Yang et al., 2021b). Actual and ideal self-congruity are the mediators among destination personality, DIM, and RI (Yang et al., 2022a). By reviewing the current literature in tourism studies, it is rare to see the application of the decision-making behavior of visitors and the revisit decision-making together with the ECT.

According to the assumption of rational human behavior, there should be a rational decision-making process for the decision-making of visiting behavior, as well as for the decision-making of revisiting behavior. The essence of tourism is an experience (Grappi and Montanari, 2011; Prayag and Ryan, 2012; Prayag et al., 2013; Boo and Busser, 2018; Sharma and Nayak, 2019), which can meet certain expectations of tourists. Although the ECT has been used in the technical field in the past (Oliver, 1980; Anderson and Sullivan, 1993; Patterson and Spreng, 1997; Dabholkar et al., 2000), the ECT can also be one of the angles to explain the rational process of tourist behavior (Bem, 1972; Prayag et al., 2013). However, from the limited studies on RI by the application of the ECT, it was clarifying the increase in visitors’ social return (SR) effects the visit intention to the same destination (Sedera et al., 2017). From the ECT, it is demonstrated the impacts between SR and memorable tourism experience (MTE), as well as the weak link of SR on RI (Mittal et al., 2022).

This study aims to develop an empirical framework to discover the existing black box, in which we would like to demonstrate the key factor of the previous experience earned from their first visit to a certain destination, in affecting the pre-trip attitude. To this end, ECT would be adopted to explain the rational process of visitors’ behavior. In this study, the authors try to adopt the application of ECT to explain the process of yoga tourism visitors’ experience and the process of visitors’ rational decision-making behavior. It would be an innovational application of the ECT, which may verify the expectancy behavior in the pre-trip period, the experience expectation confirmation in the on-site period, and the satisfaction in the post-experience period.

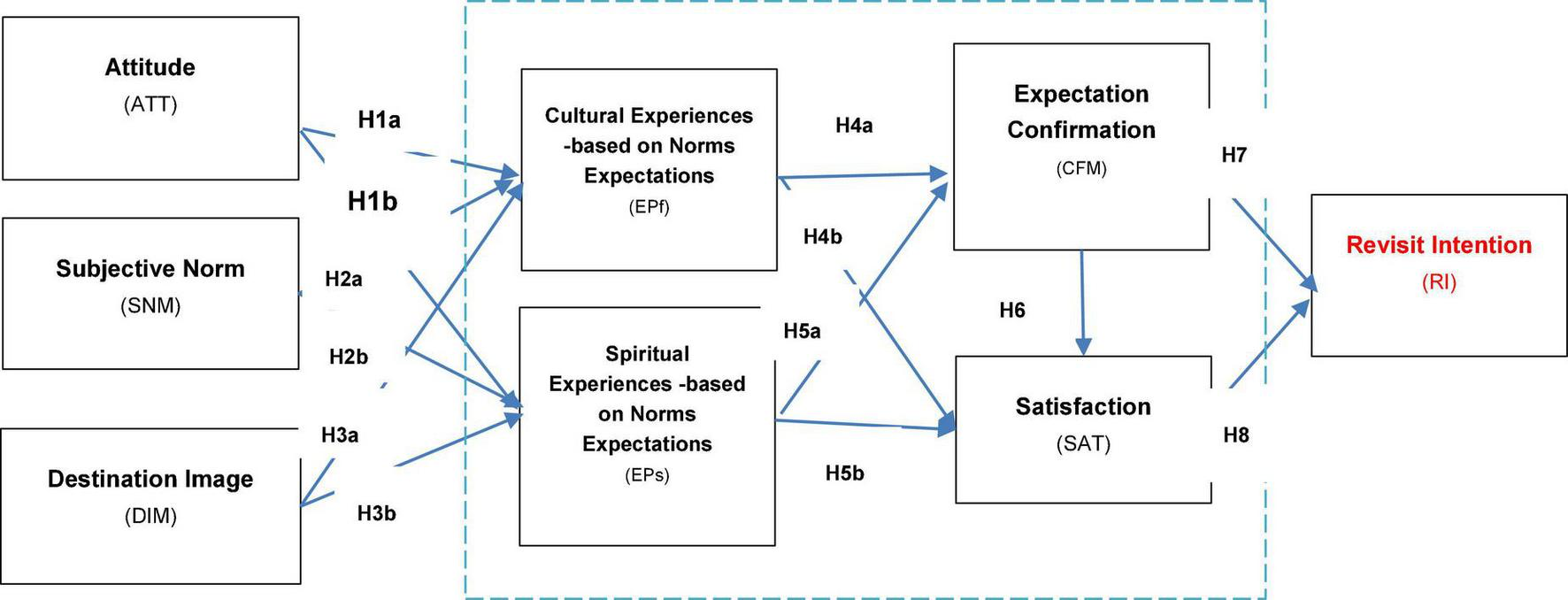

Based upon the previous extensive theoretical foundation, a framework is proposed and constructed accordingly to evaluate the experiential expectation of yoga tourism visitors. There are eight research components in total, including attitude (ATT), SNM, DIM, cultural experience-based on norm expectations (EPf), spiritual experience-based on norm expectations (EPs), expectation confirmation (CFM), satisfaction (SAT), and RI. In view of the specific research objective of this study, attitude, subjective norm, and destination image are deemed as exogenous variable components, while cultural and spiritual experiences, expectation confirmation, satisfaction, and RIs are designated as endogenous variables. Meanwhile, in the consideration of the characteristics of all the research components, these are all deemed latent variables as measured by other observable variables.

The interrelationship among the research components in this study is constructed as below: (1) attitude has a direct effect on the cultural and spiritual experiences of yoga tourism visitors; (2) Subjective norm has a direct effect on the cultural and spiritual experiences of yoga tourism visitors; (3) Destination image has a direct effect on the cultural and spiritual experiences of yoga tourism visitors; (4) cultural and spiritual experiences have a direct effect on the expectation confirmation of yoga tourism visitors; (5) cultural and spiritual experiences have a direct effect on the satisfaction of yoga tourism visitors; (6) expectation confirmation has a direct effect on the satisfaction of yoga tourism visitors; (7) expectation confirmation has a direct effect on the RIs of yoga tourism visitors; and (8) satisfaction has a direct effect on the RIs of yoga tourism visitors. In this sense, expectation confirmation has a moderating effect on the relationship between spiritual experiences and satisfaction. In addition, a partial mediating function is performed by satisfaction between expectation confirmation and RIs (refer to Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Research model and hypothesis of the study.

Most previous research has focused on the relationship among experience quality, visitor satisfaction, and behavior intentions (Muhammad et al., 2021). In fact, the quality and content of experience vary not only among customers but also among employees, and the connotation of experience quality varies substantially across industries (Yang et al., 2015). Despite its significance as a component of wellness tourism, the public lacks a comprehensive understanding of the connotation of yoga tourism, particularly yoga tourism in India. Few scholars in the existing literature, including Aggarwal et al. (2008), Ali-Knight and Ensor (2017), and Sharma and Nayak (2019) have conducted an initial discussion on the connotation of the yoga tourism experience. Therefore, a more in-depth discussion of the experience connotation of yoga tourists to India will aid academics and the yoga tourism industry in gaining a more comprehensive understanding of yoga tourism. Similarly, the Service Quality Gap Theory (Parasuraman et al., 1985) recommends that the understanding of experience quality be thoroughly examined from the perspectives of expectations and actual performance. The study of experience necessitates not only the measurement of actual perception, but also an appreciation of experience expectations (Hou et al., 2020). Keeping in mind the aforementioned justification, this study will employ the methods used to develop the scale in order to investigate the experience expectations of yoga tourists visiting India.

3. Methodology and research design

3.1. Study site and context

Yoga is deeply embedded in Indian culture, history, and society and is considered a symbol of Indian cultural identity. The origin of yoga can be traced back to the ancient Indus Valley Civilization (Harappa), which is about 5,000 years ago (Dhyansky, 1987). For the Western audience, yoga was initially considered a practice of the ancient Hindu religious component. Through yoga techniques, people believe that they have changed their lifestyle. Yoga is not only a heritage of India but also has its influence in different countries (Cheer et al., 2017). In Resolution 69/131 adopted by the United Nations on 11 December 2014, it was announced that June 21 was designated as International Yoga Day, which aims to raise the world’s awareness of the many benefits of yoga practice. On 1 December 2016, the UNESCO Intergovernmental Committee for the Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) passed a resolution (ITH/16/11.COM/10.b), including Indian Yoga as item No. 01163 in the ICH List of Humanity. Recognizing that yoga has a wide range of attractiveness with its wellness function for healthcare, yoga practice later spreads in various forms all over the world and becomes more and more popular (Agoramoorthy, 2019).

With its unique universal phenomenon integrating religions, traditions, cultures, color, and nation, yoga tourism is a subset of wellness tourism nurtured across the world, which provide visitors from other countries a reason the “travel to feel well” (Charak et al., 2021). As an indigenous therapy that originated in India, yoga becomes an attraction for visitors, particularly for those yoga fans who are fascinated by this wellness practice and philosophy experiences. Yoga fans visit India to immerse themselves in yoga tourism trusting the authenticity of the country (Rungsimanop and Ashton, 2021). The authenticity of yoga seems to be a reason for yoga fans to their visit and RI to India. India received 17.9 million international arrival visitors in 2019, including many visitors seeking a yoga experience. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the yoga tourism sector generated around USD 6.5 billion yearly (Kathuria, 2020). In the Indian State of Uttarakhand, yoga tourism investment is projected to reach USD 85 billion by 2028, which is over 50% growth forecast reliant on international arrival visitors (McCartney, 2021). However, from the Spring of 2020, yoga tourism went to a standstill ever since the global tourism sector was lockdown by the travel restrictions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (Anand, 2021).

As wellness and spiritual needs are the major desires for yoga-based visitors to India, yoga tourism is an emerging market in India, with great economic potential element in wellness sectors to boost revenue in the tourism and hospitality industries (Dayananda Swamy and Agoramoorthy, 2021). In a related study of yoga tourism in India, it has been explored that destination attractiveness and destination uniqueness were found as significant attributes of visitor experience satisfaction (Singh and Dhakhar, 2022). Due to the historical background of yoga, India being a hub of yoga offers a variety of destinations. In India, there are some yoga-based tourism hotspots, such as Mysore (the origin of Ashtanga Yoga), Bangalore, Goa, Trivandrum, Pune, and Rishikesh (the origin of Indian Yoga) (Ranjan et al., 2022). Considering the geographical location and iconic landscapes, the field investigation of this study was conducted in Mysore and Rishikesh.

3.2. Measurement

This study employs a mixed research approach, with the overall investigation divided into two sub-studies and conducted gradually. The first sub-study aims to establish the connotation of yoga tourists’ experience expectations. This sub-study utilized the methodology proposed by Churchill (1979) and Tsaur et al. (2010). Initially, from June to August 2019, interviews were conducted in China using a snowball sampling technique with individuals who had visited India for yoga tourism the previous year in order to better understand the respondents’ expectations for yoga tourism in India. Between the 26th and 30th interviewees, no new information was found. Consequently, according to this study, the interview data have reached theoretical saturation at this point.

Based on the aforementioned interviews and a few bodies of literature relating to yoga tourism, this study clarifies the expected item bank of yoga tourism experiences. From September to November 2019, the first round of questionnaires was administered on the social platform of yoga enthusiasts, and exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed on the data to determine the fundamental framework of tourists’ yoga tourism experiences. The researchers then traveled to India in January 2020 to administer a second round of data collection questionnaires. The investigation was conducted in Mysore and Rishikesh. Before distribution, the questionnaire was validated for tourists’ purposes. Once confirming the visitors’ purpose to India is for yoga practice, the questionnaires were interpreted and distributed. A non-random sampling method was used, and this study successfully surveyed 402 respondents who were eligible and willing to participate in the survey. To facilitate study 2, that is to build up a more comprehensive interpretation of yoga tourists’ RI based on the integration of TPB and ECM, the second round of questionnaires distributed in India included additional constructs associated with this sub-study. The second sub-study aims to build an integrated TPB and ECM model. This sub-study employed quantitative research methods to validate the previously developed research model and hypotheses, using the aforementioned questionnaire data collected in India.

4. Results

The analytical technique conducted in the main survey of this research is structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis via AMOS 24 software. The first stage is the study of the measurement model, which is used to evaluate whether the measured variables can measure their latent variables correctly in the model. The second stage is the study of the structural model, which analyzes the effect and explanatory power of causality using the structural model (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988).

4.1. The connotation of expected yoga tourism experience

Based on a theoretical foundation and interviews, this study categorized 18 items related to the experience expectations of yoga tourists, leaving 11 items after screening by three experts. Through the EFA of 253 valid data obtained from the first round of questionnaires, the results indicated that the first and third items were deleted because the community’s extraction was less than 0.5, and the remaining nine items were subsequently analyzed by the EFA and could be divided into two groups. The content summarizes two dimensions the expectation of functional experience (EPC2, EPC4, EPC5, and EPC6) and the expectation of emotional experience (EPC7, EPC8, EPC9, EPC10, and EPC11). Specific information is provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| Component | ||

| Functional | Emotional | |

| EPC2 | 0.738 | |

| EPC4 | 0.732 | |

| EPC5 | 0.848 | |

| EPC6 | 0.694 | |

| EPC7 | 0.777 | |

| EPC8 | 0.781 | |

| EPC9 | 0.831 | |

| EPC10 | 0.845 | |

| EPC11 | 0.729 | |

Rotated component matrixa (n = 253).

Extraction method: Principal component analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization.

aRotation converged in three iterations.

4.2. Measurement model

The software AMOS 24 is used for the convergence validity and discriminant validity analysis. The convergence validity test is tested by the Standardized Estimate (S.E.), Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of the measurement entry. The results suggest that the number of the remaining latent variables is greater than 0.7, with an exception for the sense of disgust, the number is slightly lower than 0.7. Besides, in case of the exception for the sense of disgust and deprivation, the number of other latent valuables is larger than 0.5. From the specific results of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) are demonstrated as Table 2, it indicates that the data has good convergence validity (Table 2, CFA significant Confirmatory Factor Analysis).

TABLE 2

| Estimate | S.E. | t-value | CR | AVE | Cronbach α | |||

| EPC2 | < — | EPf | 0.678 | 0.824 | 0.539 | 0.829 | ||

| EPC4 | < — | EPf | 0.771 | 0.121 | 12.927 | |||

| EPC5 | < — | EPf | 0.776 | 0.126 | 12.981 | |||

| EPC6 | < — | EPf | 0.708 | 0.104 | 12.090 | |||

| EPC7 | < — | EPs | 0.672 | 0.877 | 0.589 | 0.882 | ||

| EPC8 | < — | EPs | 0.800 | 0.074 | 13.917 | |||

| EPC9 | < — | EPs | 0.755 | 0.068 | 13.265 | |||

| EPC10 | < — | EPs | 0.803 | 0.072 | 13.950 | |||

| EPC11 | < — | EPs | 0.799 | 0.075 | 13.897 |

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) of expected experience.

Table 3 is a matrix of correlation coefficients, showing that fit also meets the criteria of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) (Hu and Bentler, 1999) (Table 3, CFA significant Confirmatory Factor Analysis).

TABLE 3

| Measure | Estimate CFA | Estimate SEM | Threshold | Interpretation |

| CMIN/DF | 2.032 | 2.133 | Between 1 and 3 | Excellent |

| CFI | 0.934 | 0.942 | >0.95 | Acceptable |

| RMSEA | 0.051 | 0.053 | <0.06 | Excellent |

| PClose | 0.394 | 0.205 | >0.05 | Excellent |

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) fitness coefficient.

The results of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) are shown in Table 4. The factors loading or SMC and AVE values of items in every measurement aspect all comply with the reliability test standards (Hair et al., 2010). Table 5 is a matrix of correlation coefficients and discriminative validity coefficients, showing that discriminative validity also meets the standard (Bagozzi, 1981) (Table 4, CFA significant Confirmatory Factor Analysis).

TABLE 4

| Estimate | S.E. | t-value | CR | AVE | Cronbach α | |||

| ATT1 | < — | ATT | 0.732 | 0.888 | 0.570 | 0.890 | ||

| ATT2 | < — | ATT | 0.792 | 0.078 | 15.391 | |||

| ATT3 | < — | ATT | 0.783 | 0.076 | 15.214 | |||

| ATT4 | < — | ATT | 0.766 | 0.087 | 14.879 | |||

| ATT5 | < — | ATT | 0.721 | 0.085 | 13.984 | |||

| ATT6 | < — | ATT | 0.733 | 0.080 | 14.205 | |||

| SNM1 | < — | SNM | 0.721 | 0.744 | 0.500 | 0.763 | ||

| SNM2 | < — | SNM | 0.783 | 0.098 | 10.058 | |||

| SNM3 | < — | SNM | 0.593 | 0.076 | 9.561 | |||

| PBC1 | < — | PBC | 0.700 | 0.808 | 0.587 | 0.856 | ||

| PBC2 | < — | PBC | 0.896 | 0.083 | 12.754 | |||

| PBC3 | < — | PBC | 0.685 | 0.079 | 12.215 | |||

| CFM1 | < — | CFM | 0.847 | 0.855 | 0.664 | 0.859 | ||

| CFM2 | < — | CFM | 0.820 | 0.056 | 18.630 | |||

| CFM3 | < — | CFM | 0.775 | 0.044 | 17.329 | |||

| SAT1 | < — | SAT | 0.785 | 0.868 | 0.688 | 0.873 | ||

| SAT2 | < — | SAT | 0.863 | 0.051 | 18.499 | |||

| SAT3 | < — | SAT | 0.838 | 0.051 | 17.926 | |||

| EPC2 | < — | EPf | 0.678 | 0.824 | 0.539 | 0.829 | ||

| EPC4 | < — | EPf | 0.771 | 0.121 | 12.927 | |||

| EPC5 | < — | EPf | 0.776 | 0.126 | 12.981 | |||

| EPC6 | < — | EPf | 0.708 | 0.104 | 12.090 | |||

| EPC7 | < — | EPs | 0.672 | 0.877 | 0.589 | 0.882 | ||

| EPC8 | < — | EPs | 0.800 | 0.074 | 13.917 | |||

| EPC9 | < — | EPs | 0.755 | 0.068 | 13.265 | |||

| EPC10 | < — | EPs | 0.803 | 0.072 | 13.950 | |||

| EPC11 | < — | EPs | 0.799 | 0.075 | 13.897 | |||

| RI1 | < — | RI | 0.745 | 0.871 | 0.693 | 0.892 | ||

| RI2 | < — | RI | 0.907 | 0.065 | 17.606 | |||

| RI3 | < — | RI | 0.838 | 0.063 | 16.668 | |||

| DIM1 | < — | DIM | 0.817 | 0.711 | 0.554 | 0.736 | ||

| DIM2 | < — | DIM | 0.664 | 0.105 | 9.489 |

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) analysis results.

TABLE 5

| ATT | SNM | PBC | CFM | SAT | EPf | EPs | RI | DIM | |

| ATT | 0.755 | ||||||||

| SNM | 0.124* | 0.707 | |||||||

| PBC | 0.142* | 0.159* | 0.766 | ||||||

| CFM | 0.501*** | 0.118† | 0.227*** | 0.815 | |||||

| SAT | 0.600*** | 0.098 | 0.306*** | 0.807*** | 0.829 | ||||

| EPf | 0.405*** | 0.145* | 0.285*** | 0.464*** | 0.403*** | 0.734 | |||

| EPs | 0.388*** | 0.128* | 0.218*** | 0.519*** | 0.430*** | 0.650*** | 0.767 | ||

| RI | 0.437*** | 0.242*** | 0.291*** | 0.562*** | 0.630*** | 0.478*** | 0.521*** | 0.833 | |

| DIM | 0.618*** | 0.247*** | 0.095 | 0.344*** | 0.400*** | 0.226*** | 0.259*** | 0.424*** | 0.744 |

Discriminant validity.

*Significant in 0.05 level; ***significant in 0.001 level; and †significant 0.000 level. Bold values significant the squared root of AVE.

4.3. Path analysis

Through the application of the software AMOS 24, path analysis of latent variables can be carried out with the involved structural model. The path analysis results are demonstrated in Table 6. Attitude has a significant positive impact on the cultural and spiritual experiences (β = 0.455 and 0.414, p < 0.001), indicating that the higher the attitude evaluation of yoga tourism visitors, the higher the cultural and spiritual experiences they receive. In contrast, the subjective norm has not had a significant positive impact on the cultural and spiritual experiences (β = 0.117 and 0.086, p = 0.063 and 0.158), and the destination image has not had a significant positive impact on the cultural and spiritual experiences (β = −0.078 and 0.016, p = 0.387 and 0.859), indicating that both the subjective norm and destination image evaluation of yoga tourism visitors are not significant with the cultural and spiritual experiences they receive.

TABLE 6

| Path (hypothesis) | Estimate | S.E. | t-value | P | Support | ||

| EPf | < — | ATT | 0.455 | 0.105 | 5.151 | *** | Yes |

| EPs | < — | ATT | 0.414 | 0.146 | 4.969 | *** | Yes |

| EPf | < — | SNM | 0.117 | 0.028 | 1.856 | 0.063 | No |

| EPs | < — | SNM | 0.086 | 0.04 | 1.413 | 0.158 | No |

| EPf | < — | DIM | -0.078 | 0.059 | -0.865 | 0.387 | No |

| EPs | < — | DIM | 0.016 | 0.084 | 0.178 | 0.859 | No |

| CFM | < — | EPs | 0.423 | 0.091 | 5.255 | *** | Yes |

| CFM | < — | EPf | 0.171 | 0.135 | 2.139 | 0.032 | Yes |

| SAT | < — | EPs | 0.051 | 0.064 | 0.688 | 0.491 | No |

| SAT | < — | EPf | 0.082 | 0.089 | 1.169 | 0.242 | No |

| SAT | < — | CFM | 0.677 | 0.049 | 10.362 | *** | Yes |

| RI | < — | SAT | 0.442 | 0.098 | 5.088 | *** | Yes |

| RI | < — | CFM | 0.230 | 0.072 | 2.747 | 0.006 | Yes |

Path analysis results.

***Significant in 0.001 level.

Cultural and spiritual experiences have a significant positive impact on the expectation confirmation (β = 0.423 and 0.171, p < 0.001 and p = 0.032), indicating that the higher the cultural and spiritual experience evaluation of yoga tourism visitors, the higher the expectation confirmation they receive. On the other hand, cultural and spiritual experiences do not have a significant positive impact on satisfaction (β = 0.051 and 0.082, p = 0.491 and 0.242), indicating that the higher cultural and spiritual experience evaluation of yoga tourism visitors is not significant with the satisfaction they receive.

Expectation confirmation has a significant positive impact on satisfaction (β = 0.677, p < 0.001), indicating that the higher the expectation confirmation evaluation of yoga tourism visitors, the higher the satisfaction they receive. Satisfaction has a significant positive impact on the RIs (β = 0.442, p < 0.001), indicating that the higher the satisfaction evaluation of yoga tourism visitors, the higher the RIs they receive. Expectation confirmation has a significant positive impact on the RIs (β = 0.230, p = 0.006), indicating that the higher the expectation confirmation evaluation of yoga tourism visitors, the higher the RIs they receive.

5. Discussion and conclusion

This study is one of the few studies that explore the experience expectations of yoga tourists. Based on the following process of developing the scale, it can be concluded, from the above study, that the expectations of yoga tourism visitors in India would be figured out as two aspects: functional expectation experience and emotionally expected experience. Meanwhile, by creative integration of the TPB theory and the ECM model within the mentioned study, it would be helpful for better comprehension of the observation to the revisit behavioral intention of yoga tourism visitors. Moreover, the most meaningful contribution of this study can be considered as the exploration of the unexplained gray zone of the TPB model, which has been in place for years, about the interrelationship between attitude and revisit behavioral intention. After a series of empirical research method in this current study, it can be demonstrated that human behavioral intentions can be understood better through the concept integration of two models, the ECM and the TPB.

5.1. Theoretical implications

The findings of this study reveal several intriguing findings. First, the experience expectations of yoga tourism visitors can be divided into two groups: functional experience expectations and spiritual experience expectations. According to the interviews conducted with the respondents of this study, the so-called functional experience expectation refers primarily to the hope that the specific movements of yoga can be enhanced through the yoga experience in India, such as learning more authentic or advanced physical postures, breathing techniques, and body control. As a result of their trip to India, participants are anticipated to gain spiritual relaxation or enlightenment experiences, such as meditation or mind control. Although yoga tourists’ experience expectations are consistent with Ahn and Picard’s (2014) two dimensions of experience, namely, affective experience and cognitive experience, the expectations of yoga tourists are unique. Regarding the anticipated content of the particular experience, additional research is required based on alternative tourism markets. For instance, Öznalbant and Alvarez (2020) divided yoga tourism into three categories: yoga-focused, cultural tourism-focused, and wellness-focused. Clearly, wellness tourism research requires in-depth and targeted investigation. This is the only way to gain a more specific and targeted understanding of tourists’ expectations regarding their tourism experience.

In addition, the TPB theory is incorporated into this research in terms of the factors that influence experience expectations. This study introduced pre-travel images of India as a tourist destination, along with the concepts such as yoga attitudes and subjective behavioral norms. It is expected to provide a more thorough description of the potential factors that influence tourists’ decisions to revisit India. The findings of the study indicated that subjective norms and perceptions of the destination’s image have no significant effect on yoga tourism visitors’ experience expectations. The anticipated experience was significantly influenced solely by one’s attitude toward yoga. In other words, an individual’s inner attitude toward yoga has a larger influence on his or her yoga tourism. This occurs frequently within the yoga community. According to Grover et al. (1987), people’s attitudes toward yoga impact its effects. Moreover, Venkatesh et al. (1994) discovered that yoga practitioners have a significantly more positive opinion of yoga than non-yoga practitioners. This could be due to the distinctive characteristics of yoga tourism products. If a different type of wellness tourism is substituted for the study’s location, the findings of the study may change. Future studies could examine the research framework proposed in this study from a variety of perspectives.

Despite the fact that the attitude toward yoga is more focused on generating functional experience expectations, the path coefficient and t value are greater in terms of spiritual experience expectations in terms of expectation confirmation impact factors. Given that the primary internal logic of this research model is to construct a set of holistic explanations for yoga tourists’ return behavior, the aforementioned conclusions may reveal the transformative power of yoga tourism (Ponder and Holladay, 2013) from a different perspective. Thus, yoga tourists visiting India are initially impacted by their yoga attitudes. Initially, they expected to be able to learn yoga skills from behavior, but during the yoga tourism experience, the expectation of spiritual experience has a greater influence on the confirmation of tourist experience expectations than the expectation of functional experience. In addition, Bowers and Cheer (2017) research on yoga tourism supports the aforementioned viewpoint. All of the above-mentioned scholars acknowledged the transformative power of yoga tourism, but they all explained it in terms of logical deduction. This is the first study to use large sample data collection and empirical analysis to illustrate the transformation process of tourists in the specific model path coefficient, demonstrating that the combination of TBP and ECT would contribute to the existing body of tourism knowledge.

In summary, the finding of the current study demonstrated that expectation confirmation mainly affects satisfaction. Although it also affects revisit behavioral intention, it affects behavior more through the transmission mechanism of satisfaction. It is actually consistent with the theoretical foundation of the hypotheses proposed in this study, the Service Quality Gap Theory (Parasuraman et al., 1985). Only if the expectations are consistent with the actual experience, people will be satisfied and have the revisit willingness. The merely experience expectations do not directly affect consumers’ satisfaction.

5.2. Management implications

In order to explore the unexplained gray zone about the interrelationship between attitude and revisit behavioral intention that was originally ignored, this study combines the TPB and the ECM models and provides a new explanation for understanding the theoretical connotation of TPB. The elements of different stages of tourism, such as subjective norm (pre-visit), destination image (pre-visit), experience expectation (pre-visit), experience confirmation (on-visit), satisfaction (post-visit), and revisit behavior intention (post-visit) can be integrated into one single model. This integrated model can be applied to revisit behavioral study, which can provide a more systematic and holistic understanding of revisit behavior.

From the above study, it can be found that the influence of attitude on functional experience expectations is slightly higher than the influence of emotional experience expectations, which also reflects that yoga tourism is relatively special in contrast to other tourism experiences. At the very beginning of planning and forming expectations before the trip, specific functional expectations are the domination factors for the decision-making. During the evaluation and decision period for RIs, the emotional experience confirmation plays a role as an even more important influencing factor. This seemingly contradictory result just confirms that finding from the on-site interview in India, many yoga tourism respondents expressed that they felt more relaxed after arriving in India. For these yoga tourism visitors, perhaps, one of the initial purposes of going to India was to have more professional and authentic Yoga practice; however, after a period of immersion and washing in India, their attitude and understanding of yoga have been upgraded.

This research also has certain enlightenment value for the promotion and development of yoga tourism. First, the study carefully discusses the experience of yoga tourism visitors and comes to a relatively stable and reliable conclusion. It is to say that yoga tourism visitors will improve their practice skills on one hand and experience the culture and atmosphere of yoga on the other hand, since these are two key expectations for yoga tourism in India. As the yoga tourism destination, for Mysore and Rishikesh in India, it is more likely to focus on destination promotion as well as destination image branding issues. However, it is necessary to classify the visitors upon their visit history, since the visit behavioral intention of the newcomer visitors would vary from those repeat visitors and their revisit behavioral intention. From the result of the interview, the newcomer visitors may be dominated by utilitarian expectations, but when they decide to visit again the same destination, they become repeat visitors and would be dominated by spiritual or emotional expectation confirmation as their prerequisite. For this reason, the authority of the destination seems to adopt different strategies for newcomer and repeat visitors. In this case, for the authority as well as the industries of the yoga tourism destination, such as the testing sites of this study Mysore and Rishikesh in India, it seems to adopt more actions to consolidate the loyalty of yoga visitors.

5.3. Research limitations and future research prospects

Mixed research of qualitative and quantitative methods was adopted in this current study, and consequently, the obtained results seem relatively valuable. However, certain research limitations do exist. The qualitative research phase of this study was mainly conducted in mainland China. Considering that respondents from different cultural backgrounds may have different experience expectations, the framework of the current yoga tourism experience expectations might be verified by extending to a broader context of cultural background. Besides, most of the sampling methods used in this study are non-probability sampling. For the upcoming future, the sampling methods seem to be optimized to obtain more representative samples, which would be more conducive to the stability of the research conclusions, since the non-random sample has to be treated with great care. Furthermore, from the conceptual/contextual point of view, the RI may be applicable to further research for alternative special interest tourism (SIT), such as wine tourism (Back et al., 2021), coffee tourism (Chen et al., 2021), gastronomy tourism (Widjaja et al., 2020), astrotourism or stargazing tourism (Li, 2021; Rodrigues et al., 2022), volunteer trip (Manosuthi et al., 2020), and suicide travel (Yu et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2022c).

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abbasi A. G. Kumaravelu J. Goh Y. N. Dara Singh K. S. (2021). Understanding the intention to revisit a destination by expanding the theory of planned behaviour (TPB).Span. J. Mark.25282–311. 10.1108/SJME-12-2019-0109

2

Adongo C. A. Anuga S. W. Dayour F. (2015). Will they tell others to taste? International tourists’ experience of Ghanaian cuisines.Tour. Manag. Perspect.1557–64. 10.1016/j.tmp.2015.03.009

3

Aggarwal A. K. Guglani M. Goel R. K. (2008). “Spiritual and yoga tourism: A case study on experience of foreign tourists visiting Rishikesh, India,” in Proceedings of the conference on tourism in india-challenges ahead, (Kozhikode: IIM Kozhikode), 457–464.

4

Agoramoorthy G. (2019). Interdisciplinary science and Yoga: The challenges ahead.Int. J. Yoga1289–90. 10.4103/ijoy.IJOY_9_19

5

Ahn H. I. Picard R. W. (2014). Measuring affective-cognitive experience and predicting market success.IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput.5173–186. 10.1109/TAFFC.2014.2330614

6

Ajay J. Rejikumar G. Ajitha A. A. Mathew S. Chakraborty U. (2022). Destination image and perceived meaningfulness for visitor loyalty: A strategic positioning of Indian destinations.Tour. Recreat. Res.10.1080/02508281.2022.2040294

7

Ajzen I. Driver B. (1992). Application of the theory of planned behavior to leisure choice.J. Leis. Res.24207–224. 10.1080/00222216.1992.11969889

8

Ajzen I. Fishbein M. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research.Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley.

9

Ajzen I. Fishbein M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior.Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

10

Alegre J. Garau J. (2010). Tourist satisfaction and dissatisfaction.Ann. Tour. Res.3752–73. 10.1016/j.annals.2009.07.001

11

Ali-Knight J. Ensor J. (2017). Salute to the sun: An exploration of UK Yoga tourist profiles. Tour. Recreat. Res.42, 484–497. 10.1080/02508281.2017.1327186

12

Anand S. (2021). India’s Yoga capital hit by downward-facing prospects due to Covid-19.New York, NY: The Wall Street Journal.

13

Anderson E. W. Sullivan M. W. (1993). The antecedents and consequences of customer satisfaction for firms.Mark. Sci.12125–143. 10.1287/mksc.12.2.125

14

Anderson J. C. Gerbing D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull.103, 411–423. 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

15

Appiah-Adu K. Fyall A. Singh S. (2000). Marketing culture and customer retention in the tourism industry.Serv. Ind. J.2095–113. 10.1080/02642060000000022

16

Back R. M. Bufquin D. Park J. Y. (2021). Why do they come back? The effects of winery tourists’ motivations and satisfaction on the number of visits and revisit intentions.Int. J. Hosp.221–25. 10.1080/15256480.2018.1511499

17

Bagozzi R. P. (1981). Attitudes, intentions, and behavior: A test of some key hypotheses. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.41, 607–627. 10.1037/0022-3514.41.4.607

18

Bem D. J. (1972). “Self-perception theory,” in Advances in experimental social psychology, ed.BerkowitzL. (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press). 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60024-6

19

Bianchi C. Milberg S. Cúneo A. (2017). Understanding travelers’ intentions to visit a short versus long-haul emerging vacation destination: The case of Chile.Tour. Manag.59312–324. 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.08.013

20

Bigne J. E. Sanchez M. I. Sánchez J. (2001). Tourism image, evaluation variables and after purchase behaviour: Inter-relationship.Tour. Manag.22607–616. 10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00035-8

21

Boo S. Busser J. A. (2018). Tourists’ hotel event experience and satisfaction: An integrative approach.J. Travel35895–908. 10.1080/10548408.2018.1445066

22

Bowers H. Cheer J. M. (2017). Yoga tourism: Commodification and western embracement of eastern spiritual practice.Tour. Manag. Perspect.24, 208–216.

23

Carreira V. González-Rodríguez M. R. Díaz-Fernández M. C. (2022). The relevance of motivation, authenticity and destination image to explain future behavioural intention in a UNESCO world heritage Site.Curr. Issues Tour.25650–673. 10.1080/13683500.2021.1905617

24

Charak N. S. Sharma P. Chib R. S. (2021). “Yoga tourism as a quest for mental and physical wellbeing: A case of Rishikesh, India,” in Growth of the medical tourism industry and its impact on society: Emerging research and opportunities, edsSinghM.KumaranS. (Pennsylvania: IGI Global), 147–169. 10.4018/978-1-7998-3427-4.ch008

25

Cheer J. M. Belhassen Y. Kujawa J. (2017). The search for spirituality in tourism: Toward a conceptual framework for spiritual tourism.Tour. Manag. Perspect.24252–256. 10.1016/j.tmp.2017.07.018

26

Chen A. S. Y. Lin Y. C. Sawangpattanakul A. (2011). The relationship between cultural intelligence and performance with the mediating effect of culture shock: A case from Philippine laborers in Taiwan.Int. J. Intercult. Relat.35246–258. 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.09.005

27

Chen L.-H. Wang M.-J. S. Morrison A. M. (2021). Extending the memorable tourism experience model: A study of coffee tourism in Vietnam.Bri. Food J.1232235–2257. 10.1108/BFJ-08-2020-0748

28

Cho H. (2021). How nostalgia forges place attachment and revisit intention: A moderated mediation model.Mark. Intell. Plan.39856–870. 10.1108/MIP-01-2021-0012

29

Churchill G. A. Jr. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res.16, 64–73.

30

Dabholkar P. A. Shepherd C. D. Thorpe D. I. (2000). A comprehensive framework for service quality: An investigation of critical conceptual and measurement issues through a longitudinal study.J. Retail.76139–173. 10.1016/S0022-4359(00)00029-4

31

Dayananda Swamy H. R. Agoramoorthy G. (2021). The coronavirus pandemic impact on India’s Yoga tourism business.Yoga Mimamsa53145–148. 10.4103/ym.ym_116_21

32

Dhyansky Y. Y. (1987). The indus valley origin of a yoga practice. Artibus Asiae48, 89–108.

33

Eusébio C. Vieira A. L. (2013). Destination attributes’ evaluation, satisfaction and behavioural intentions: A structural modeling approach.Int. J. Tour. Res.1566–80. 10.1002/jtr.877

34

Grappi S. Montanari F. (2011). The role of social identification and hedonism in affecting tourist re-patronizing behaviours: The case of an Italian festival.Tour. Manag.321128–1140. 10.1016/j.tourman.2010.10.001

35

Grover P. Varma V. K. Verma S. K. Pershad D. (1987). Relationship between the patient’s attitude towards yoga and the treatment outcome.Indian J. Psychiatry29:253.

36

Gupta S. Priyanka Mishra O. N. (2022). Why do tourists revisit a destination? The key roles of destination brand love.Anatolia33289–292. 10.1080/13032917.2022.2028171

37

Hair J. Black W. Babin B. Anderson R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis, 7th Edn.Hoboken, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

38

Hamid M. A. Isa S. (2015). The theory of planned behaviour on sustainable tourism.J. Biol. Environ. Sci.5, 84–88.

39

Hasan K. Abdullah S. K. Islam F. Neela N. (2020). An integrated model for examining tourists’ revisit intention to beach tourism destinations.J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour.211–22. 10.1080/1528008X.2020.1740134

40

Hou H. C. Lai J. H. Edwards D. (2020). Gap theory based post-occupancy evaluation (GTbPOE) of dormitory building performance: A case study and a comparative analysis.Buil. Environ.185:107312. 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107312

41

Hu L. T. Bentler P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives.Struct. Equ. Model.61–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118

42

Isa S. M. Ariyanto H. H. Kiumarsi S. (2020). The effect of place attachment on visitors’ revisit intentions: Evidence from Batam.Tour. Geogr.2251–82. 10.1080/14616688.2019.1618902

43

Jahandide Topraghlou M. Zarei G. Asgarnrzhad Nuri B. (2020). The effect of destination brand image on revisit intention: The mediator role of destination personality, memorable tourism experiences and destination satisfaction.Urban Tour.7129–142.

44

Jung T. Tom Dieck M. C. Lee H. Chung N. (2015). “Effects of virtual reality and augmented reality on visitor experiences in museum,” in Proceedings of the international conference information and communication technologies in tourism 2016, edsInversiniA.ScheggR. (Berlin: Springer). 10.1007/978-3-319-28231-2

45

Karakaş H. Çizel B. Selçuk O. Coşkun Ö. Ceylan D. (2022). Country and destination image perception of mass tourists: Generation comparison.Anatolia33104–115. 10.1080/13032917.2021.1909087

46

Kathuria K. (2020). The business of yoga sees an upsurge in the pandemic. Available online at: https://bwdisrupt.businessworld.in/article/The-Business-of-Yoga-sees-an-upsurge-in-the-Pandemic/26-10-2020-335774/(accessed October 26, 2020).

47

Kelly C. Smith M. (2009). “Holistic tourism: Integrating body, mind, spirit,” in Wellness and tourism: Mind, body, spirit, place, edsBushellR.SheldonP. (Teaneck, NJ: Cognizant), 69–83.

48

Kim Y. Ribeiro M. A. Li G. (2021). Tourism memory characteristics scale: Development and validation.J. Travel Res.61, 1308–1326. 10.1177/00472875211033355

49

Kumar V. Kaushal V. Kaushik A. K. (2022). Building relationship orientation among travelers through destination brand authenticity.J. Vacat. Mark.10.1177/13567667221095589

50

Lee S. Lee S. Lee G. (2014). Ecotourists’ motivation and revisit intention: A case study of restored ecological parks in south Korea.Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res.191327–1344. 10.1080/10941665.2013.852117

51

Leiper N. (1979). The framework of tourism: Towards a definition of tourism, tourist, and the tourist industry.Ann. Tour. Res.6390–407. 10.1016/0160-7383(79)90003-3

52

Li M. Cai L. Lehto X. Huang Z. (2010). A missing link in understanding revisit intention—The role of motivation and image.J. Travel Tour. Mark.27335–348. 10.1080/10548408.2010.481559

53

Li Q. Li X. Chen W. Su X. Yu R. (2020). Involvement, place attachment, and environmentally responsible behaviour connected with geographical indication products.Tour. Geogr.10.1080/14616688.2020.1826569

54

Li T. (2021). Universal therapy: A two-stage mediation model of the effects of stargazing tourism on tourists’ behavioral intentions.J. Dest. Mark. Manag.20:100572. 10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100572

55

Li X. Xie J. Chen S. X. (2022). Cannot wait to share? An exploration of tourists’ sharing behavior during the ‘traveling to the site’ stage.Curr. Issues Tour.253640–3656. 10.1080/13683500.2022.2106192

56

López-Sanz J. M. Penelas-Leguía A. Gutiérrez-Rodríguez P. Cuesta-Valiño P. (2021). Rural tourism and the sustainable development goals. A study of the variables that most influence the behavior of the tourist.Front. Psychol.12:722973. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.722973

57

Loureiro S. M. C. (2020). How does the experience and destination authenticity influence “affect”?Anatolia31449–465. 10.1080/13032917.2020.1760903

58

Manosuthi N. Lee J. S. Han H. (2020). Predicting the revisit intention of volunteer tourists using the merged model between the theory of planned behavior and norm activation model.J. Travel Tour. Mark.37510–532. 10.1080/10548408.2020.1784364

59

Marine-Roig E. Huertas A. (2020). How safety affects destination image projected through online travel reviews.J. Dest. Mark. Manag.18:100469. 10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100469

60

McCartney P. (2021). Where does India stand when it comes to Yoga tourism?.New Delhi, DL: The Wire.

61

Meng B. Cui M. (2020). The role of co-creation experience in forming tourists’ revisit intention to home-based accommodation: Extending the theory of planned behavior.Tour. Manag. Perspect.33:100581. 10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100581

62

Mittal A. Bhandari H. Chand P. K. (2022). Anticipated positive evaluation of social media posts: Social return, revisit intention, recommend intention and mediating role of memorable tourism experience.Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res.16193–206. 10.1108/IJCTHR-12-2020-0287

63

Muhammad D. Shabbir S. Mahmood A. Kazemi E. (2021). Investigating the role of experience quality in predicting destination image, perceived value, satisfaction, and behavioural intentions: A case of war tourism.Curr. Issues Tour.243090–3106. 10.1080/13683500.2020.1863924

64

Nautiyal R. Albrecht J. N. Carr A. (2022). Conceptualising a tourism consumption-based typology of yoga travelers.Tour. Manag. Perspect.43:101005. 10.1016/j.tmp.2022.101005

65

Oliver R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions.J. Mark. Res.17460–469. 10.1177/002224378001700405

66

Oliver R. L. (1993). Cognitive, affective, and attribute bases of the satisfaction response.J. Consum. Res.20418–430. 10.1086/209358

67

Öznalbant E. Alvarez M. D. (2020). A socio-cultural perspective on yoga tourism.Tour. Plan. Dev.17260–274. 10.1080/21568316.2019.1606854

68

Parasuraman A. Zeithaml V. A. Berry L. L. (1985). A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research.J. Mark.4941–50. 10.1177/002224298504900403

69

Patterson P. G. Spreng R. A. (1997). Modelling the relationship between perceived value, satisfaction and repurchase intentions in a business-to-business, services context: An empirical examination.Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag.8414–434. 10.1108/09564239710189835

70

Pimtong T. Hailin Q. W. Lancy Tsang C. Rachel L. (2021). The influence of smart tourism applications on perceived destination image and behavioral intention: The moderating role of information search behavior.J. Hosp. Tour. Manag.46476–487. 10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.02.003

71

Ponder L. M. Holladay P. J. (2013). The transformative power of yoga tourism.Transform. Tour. Tour. Perspect.198–108. 10.1079/9781780642093.0098

72

Prayag G. Ryan C. (2012). Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to Mauritius: The role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction.J. Travel Res.51342–356. 10.1177/0047287511410321

73

Prayag G. Hosany S. Odeh K. (2013). The role of tourists’ emotional experiences and satisfaction in understanding behavioral intentions.J. Dest. Mark. Manag.2118–127. 10.1016/j.jdmm.2013.05.001

74

Prentice C. Hsiao A. (2021). Travel deterrents to regional destinations.J. Retail. Consum. Serv.58:102292. 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102292

75

Rahman M. S. Bag S. Hassan H. Hossain M. A. Singh R. K. (2022). Destination brand equity and tourist’s revisit intention towards health tourism: An empirical study.Benchmarking291306–1331. 10.1108/BIJ-03-2021-0173

76

Ranjan R. Sujay V. S. Himanshu S. Vaibhav K. C. (2022). Factors influencing yoga tourism in Uttarakhand: A case study of Patanjali Yogpeeth.Int. J. Trend Sci. Res. Dev.6292–298.

77

Rasoolimanesh S. M. Seyfi S. Rastegar Hall C. M. (2021). Destination image during the COVID-19 pandemic and future travel behavior: The moderating role of past experience.J. Dest. Mark. Manag.21:100620. 10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100620

78

Reisinger Y. Turner W. (2003). Cross-cultural behaviour in tourism: Concepts and analysis.Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

79

Remoaldo P. Cadima Ribeiro J. (2015). “Holistic approach, tourism,” in Encyclopedia of tourism chapter: Hollistic approach, tourism, edsJafariJ.XiaoH. (Berlin: Springer). 10.1007/978-3-319-01669-6_477-1

80

Rodrigues Á Loureiro S. M. C. Prayag G. (2022). The wow effect and behavioral intentions of tourists to astrotourism experiences: Mediating effects of satisfaction.Int. J. Tour. Res.24362–375. 10.1002/jtr.2507

81

Rungsimanop P. Ashton A. S. (2021). The influence of the components of yoga destination development toward tourist satisfaction and revisit intention.J. Tour. Hosp.13158–179.

82

Sedera D. Lokuge S. Atapattu M. Gretzel U. (2017). Likes–the key to my happiness: The moderating effect of social influence on travel experience. Inf. Manag.54, 825–836.

83

Šegota T. Chen N. Golja T. (2022). The impact of self-congruity and evaluation of the place on WOM: Perspectives of tourism destination residents.J. Travel Res.61800–817. 10.1177/00472875211008237

84

Sharma P. Nayak J. (2018). Testing the role of tourists’ emotional experiences in predicting destination image, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: A case of wellness tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect.28, 41–52. 10.1016/j.tmp.2018.07.004

85

Sharma P. Nayak J. K. (2019). Do tourists’ emotional experiences influence images and intentions in yoga tourism?Tour. Rev.74646–665. 10.1108/TR-05-2018-0060

86

Singh L. Dhakhar D. (2022). “Mediating role of tourist motivation and participation with satisfaction and revisit intention,” in Tourist behavior: Past, present, and future, 1st Edn, edsKumarN.SousaB. B.SharmaS. (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press). 10.1201/9781003282082

87

Škoriæ S. Mikuliæ J. Barišiæ P. (2021). The mediating role of major sport events in visitors’ satisfaction, dissatisfaction, and intention to revisit a destination.Societies11:78. 10.3390/soc11030078

88

Smith M. Kelly C. (2006). Holist tourism: Journeys of the Self?Tour. Recreat. Res.3115–24. 10.1080/02508281.2006.11081243

89

Soliman M. (2019). Extending the theory of planned behavior to predict tourism destination revisit intention.Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Administr.421–26.

90

Soscia I. (2007). Gratitude, delight, or guilt: The role of consumers’ emotions in predicting postconsumption behaviors.Psychol. Mark.24871–894. 10.1002/mar.20188

91

Sparks C. (2007). Globalization, development and the mass media.New York, NY: SAGE10.4135/9781446218792

92

Tabaeeian R. A. Azam Y. Negin M. Atefeh K. (2022). Host-tourist interaction, revisit intention and memorable tourism experience through relationship quality and perceived service quality in ecotourism.J. Ecotour.10.1080/14724049.2022.2046759

93

Taylor S. Todd P. (1995). Decomposition and crossover effects in the theory of planned behavior: A study of consumer adoption intentions.Int. J. Res. Mark.12137–155. 10.1016/0167-8116(94)00019-K

94

Tosun C. Dedeoğlub B. B. Fyallc A. (2015). Destination service quality, affective image and revisit intention: The moderating role of past experience.J. Dest. Mark. Manag.4222–234. 10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.08.002

95

Tsaur S. H. Yen C. H. Chen C. L. (2010). Independent tourist knowledge and skills. Ann. Tour. Res.37, 1035–1054.

96

Venkatesh S. Pal M. Negi B. S. Varma V. K. Sapru R. P. andVerma S. K. (1994). A comparative study of yoga practitioners and controls on certain psychological variables. Indian J. Clin. Psychol.21, 22–27.

97

Vieira C. J. Jordan E. Santos C. (2021). The effect of nationality on visitor satisfaction and willingness to recommend a destination: A joint modeling approach.Tour. Manag. Perspect.39:100850. 10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100850

98

Widjaja D. C. Jokom R. Kristanti M. Wijaya S. (2020). Tourist behavioural intentions towards gastronomy destination: Evidence from international tourists in Indonesia.Anatolia31376–392. 10.1080/13032917.2020.1732433

99

Yang C. C. Cheng L. Y. Lin C. J. (2015). A typology of customer variability and employee variability in service industries.Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell.26825–839. 10.1080/14783363.2014.895522

100

Yang J. Ryan C. Zhang L. (2013). Social conflict in communities impacted by tourism.Tour. Manag.3582–93. 10.1016/j.tourman.2012.06.002

101

Yang S. Isa M. Ramayah T. (2022a). Does uncertainty avoidance moderate the effect of self-congruity on revisit intention? A two-city (Auckland and Glasgow) investigation.J. Dest. Mark. Manag.24:100703. 10.1016/j.jdmm.2022.100703

102

Yang S. Isa M. Yao Y. Xia J. Liu D. (2022b). Cognitive image, affective image, cultural dimensions and conative image: A new conceptual framework.Front. Psychol.13:935814. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.935814

103

Yang S. Isa S. M. Ramayah T. Zheng Y. (2022c). Where does physician-assisted suicide tourism fit in the tourism discipline?Anatolia.10.1080/13032917.2023.2129737

104

Yang S. Isa S. M. Ramayah T. (2020). A theoretical framework to explain the impact of destination personality, self-congruity, and tourists’ emotional experience on behavioral intention.SAGE Open101–11. 10.1177/2158244020983313

105

Yang S. Isa S. M. Ramayah T. (2021a). Uncertainty avoidance as a moderating factor to the self-congruity concept: The development of a conceptual framework.SAGE Open111–10. 10.1177/21582440211001860

106

Yang S. Isa S. M. Ramayah T. Wen J. Goh E. (2021b). Developing an extended model of self-congruity to predict Chinese tourists’ revisit intentions to New Zealand: The moderating role of gender.Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist.341459–1481. 10.1108/APJML-05-2021-0346

107

Yoon Y. Uysal M. (2005). An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model.Tour. Manag.2645–56. 10.1016/j.tourman.2003.08.016

108

Yu C. E. Wen J. Yang S. (2020). Viewpoint of suicide travel: An exploratory study on youtube comments.Tour. Manag. Perspect.34:100669. 10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100669

Summary

Keywords

yoga tourism, theory of planned behavior (TPB), experience expectations, expectation confirmation model (ECM), revisit behavioral intention, revisit intention, behavior intentions

Citation

Leou EC and Wang H (2023) A holistic perspective to predict yoga tourists’ revisit intention: An integration of the TPB and ECM model. Front. Psychol. 13:1090579. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1090579

Received

05 November 2022

Accepted

30 December 2022

Published

15 February 2023

Volume

13 - 2022

Edited by

Wen-Qi Ruan, Huaqiao University, China

Reviewed by

Blend Ibrahim, Istanbul Commerce University, Türkiye; Shaohua Yang, Anhui University of Technology, China; Chun-Liang Lai, Hungkuang University, Taiwan

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Leou and Wang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eusebio C. Leou, chleou@cityu.moHuiqing Wang, wanghuiqing0426@foxmail.com

This article was submitted to Environmental Psychology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Psychology

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.