Abstract

Intentionally or not, humans produce rhythmic behaviors (e.g., walking, speaking, and clapping). In 1974, Paul Fraisse defined rhythmic behavior as a periodic movement that obeys a temporal program specific to the subject and that depends less on the conditions of the action (p. 47). Among spontaneous rhythms, the spontaneous motor tempo (SMT) corresponds to the tempo at which someone produces movements in the absence of external stimuli, at the most regular, natural, and pleasant rhythm for him/her. However, intra- and inter-individual differences exist in the SMT values. Even if several factors have been suggested to influence the SMT (e.g., the age of participants), we do not yet know which factors actually modulate the value of the SMT. In this context, the objectives of the present systematic review are (1) to characterize the range of SMT values found in the literature in healthy human adults and (2) to identify all the factors modulating the SMT values in humans. Our results highlight that (1) the reference value of SMT is far from being a common value of 600 ms in healthy human adults, but a range of SMT values exists, and (2) many factors modulate the SMT values. We discuss our results in terms of intrinsic factors (in relation to personal characteristics) and extrinsic factors (in relation to environmental characteristics). Recommendations are proposed to assess the SMT in future research and in rehabilitative, educative, and sport interventions involving rhythmic behaviors.

1. Introduction

Rhythm is an essential human component. “Rhythm is defined as the pattern of time intervals in a stimulus sequence” (Grahn, 2012, p. 586), and the tempo is the rate of the stimuli's onset within a regular sequence (Grahn, 2012). Early in life, rhythm is present in a large number of activities of daily life, such as walking, speaking, chewing, doing leisure activities (dancing, swimming, pedaling, playing a musical instrument, singing, clapping, etc.), or school activities (writing and reading). Some activities require producing a rhythm with a spontaneous tempo (e.g., writing, reading, chewing, walking, speaking, etc.), and some others require synchronizing with a rhythm produced by an external event (e.g., playing a musical instrument, singing, clapping, dancing, etc.). Those activities can have different rhythmic components. For example, speech generally shows a non-isochronous rhythmic structure, but other language skills, such as reading, may also show beat-based patterns (i.e., isochronous patterns based on equal time intervals; see Ozernov-Palchik and Patel, 2018). Writing seems to be linked to isochronous rhythmic production (Lê et al., 2020b), even if it is not yet well-known whether writing shows more beat- or non-beat-based processing. Other activities, such as tapping or clapping, are well-known to show isochronous patterns.

Rhythmic abilities are deficient in various populations, and nowadays, rehabilitative interventions based on rhythmic synchronization are used to improve motor control. This is the case for populations with neurological diseases (e.g., Parkinson's disease, stroke, and cerebral palsy; see Braun Janzen et al., 2021), rare diseases or conditions (Launay et al., 2014; Bégel et al., 2017, 2022a; Tranchant and Peretz, 2020), or neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., dyslexia, developmental coordination disorder, and attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder; Puyjarinet et al., 2017; Bégel et al., 2018, 2022b; Lê et al., 2020a; Blais et al., 2021; Daigmorte et al., 2022). In this context, participants are required to synchronize their movements to an external rhythm, usually with an auditory metronome, to regulate the speed of their gait or manual or verbal responses. The ability to synchronize with an external rhythm is particularly studied during sensorimotor synchronization tasks that consist of the “coordination of a rhythmic movement with an external rhythm” (Repp and Su, 2013, p. 1). The tempo and the sensory modality of the external rhythmic stimuli can modulate the performance of sensorimotor synchronization (see Repp, 2005; Repp and Su, 2013 for extensive reviews of the literature). Sensorimotor synchronization is less accurate and stable when the tempo is slower (Drewing et al., 2006; Repp and Su, 2013) and slower than the spontaneous motor tempo (SMT; Varlet et al., 2012). SMT is the rhythm at which a person produces movements in the absence of stimuli at his/her own most regular, natural, and pleasant rate. Hence, the tempo of the external rhythm has to be adapted to the actual tempo of the participants. Recent studies individualize the parameters of the intervention by adapting the tempo of the metronome to be synchronized (Benoit et al., 2014; Dalla Bella et al., 2017; Cochen De Cock et al., 2021; Frey et al., 2022). This is done by measuring the individual's SMT before an intervention. Rehabilitation is then performed with music at either ±10% of this tempo. Therefore, it seems interesting to evaluate rhythmic abilities, especially spontaneous motor tempo (SMT), to individualize learning and rehabilitation.

It is usually admitted in the pioneering work of Paul Fraisse that the most representative reference value of the spontaneous motor tempo (SMT) is 600 ms in healthy human adults (Fraisse, 1974). However, a growing body of literature about SMT suggests that this value is not universal. Fraisse himself pointed out that, even if the SMT is supposed to be relatively stable in one individual, inter-individual differences are more important and could be related to the instructions, the material of measurement, the body position, the chronological and intellectual development, and the sensory deficits (Fraisse, 1974). Even if these factors have been tested in a few studies, to our knowledge, no updated review of the literature has been made to provide complete and recent knowledge on the range of SMT values in healthy human adults and the factors influencing them. For example, recent studies suggest that age is a major factor modulating the value of SMT. The review by Provasi et al. (2014a) focuses on the spontaneous (and induced) rhythmic behaviors during the perinatal period, with a special emphasis on the spontaneous rhythm of sucking, crying, and arm movements in newborns. The authors indicate that the SMT evolves from newborns to the elderly. Fast rhythmical movements of the arms have been identified in fetuses with a tempo of 3 or 4 movements per second (250–333 ms; Kuno et al., 2001), whereas a tempo of 450 ms has been found during drumming (Drake et al., 2000) or tapping (McAuley et al., 2006) in children around 4 years old and more. The value of the SMT is relatively fixed around 400 ms between 5 and 8 years, even if the variability of the SMT tends to decrease with age (Monier and Droit-Volet, 2019). The SMT is supposed to increase to achieve 600 ms in adulthood (Fraisse, 1974) and to slow down further with age to achieve 700–800 ms in the elderly (Vanneste et al., 2001). In the case of tempo produced with the mouth, the SMT of non-nutritive sucking is around 450 ms in neonates (Bobin-Bègue et al., 2006), whereas the spontaneous crying frequency is between 1,100 and 2,400 ms in newborns (Brennan and Kirkland, 1982). All these results suggest that the relationship between SMT and age is not general and linear. The effector producing the SMT could be a potential factor affecting the relationship between SMT and age.

Some studies focus on the SMT produced with the mouth in a quasi-rhythmic pattern during speech production and in an isochronous repetitive pattern during syllable rate production. The review of Poeppel and Assaneo (2020) reports that the temporal structure of speech “is remarkably stable across languages, with a preferred range of rhythmicity of 2–8 Hz” (125–500 ms; Poeppel and Assaneo, 2020, p. 322). One could suggest that this rhythm is faster than the rhythm supposed to be found in rhythmical movements of the arms (600 ms in adulthood, Fraisse, 1974). However, in the broader context of speech production, we cannot neglect the communicative aspect of speech. The audience for the speech could also influence the SMT (Leong et al., 2017). Thus, it is possible that, in addition to the age previously mentioned, not only the effector but also the communicative goal of the activity may influence the SMT.

Moreover, environmental factors are supposed to influence SMT values. In the review of Van Wassenhove (2022), it is suggested that the manipulation of external landmarks, such as the time of day, can modulate the endogenous temporal representation of time and, as a consequence, the SMT (Van Wassenhove, 2022).

In this context, the objectives of the systematic review are (1) to characterize the range of SMT values found in the literature in healthy human adults and (2) to identify all the factors modulating the SMT values in humans.

2. Materials and methods

We conducted a systematic review according to PRISMA recommendations (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; Page et al., 2021).

2.1. Information sources and search strategy

Studies were identified by searching in the PubMed, Science Direct, and Web of Science databases. These databases were selected because they represent a broad spectrum of disciplines related to motor behavior. The final search was performed on 4 July 2022. There was no restriction on the year of publication; all articles present in the databases at this time point were searched. The search was first conducted in all languages, and then only English and French studies were selected for screening. As the term “spontaneous motor tempo” is not exclusively used, we searched a broad spectrum of synonyms for this term. Filters were also used to identify relevant research depending on the database (Table 1).

Table 1

| PubMed | Science Direct | Web of Science | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Search equation | ((spontaneous motor tempo) OR ((spontaneous OR self-paced OR internally-driven OR internal OR preferred OR internally-guided) AND (motor NOT locomotion NOT locomotor) AND (tempo OR rhythm OR rhythmic OR tapping OR (intertap interval)))) | (‘human') AND ((‘spontaneous motor tempo') NOT (‘locomotion' OR ‘locomotor') | ALL = (human) AND (ALL = ((spontaneous motor tempo) OR ((spontaneous OR self-paced OR internally-driven OR internal OR preferred OR internally-guided) AND (motor NOT locomotion NOT locomotor) AND (tempo OR rhythm OR rhythmic OR tapping OR (intertap interval))))) |

| Applied filters | “Human” and “All type of documents” | “Review articles” and “Research articles” | “All type of documents” |

| Search results | 1,225 | 1,141 | 813 |

Search strategy information.

2.2. Selection of studies and eligibility criteria

We only selected articles and reviews before screening by excluding congress papers, chapters, books, and theses. Reviews identified in databases were just used to find missing original articles about SMT, and they have not been included in the systematic review (reviews not included: Provasi et al., 2014a; Poeppel and Assaneo, 2020; Van Wassenhove, 2022).

For greater specificity in the selection of the studies, inclusion criteria were based on the PICO (population, intervention, comparator, and outcome) strategy (Table 2). For this, we selected studies carried out on human samples producing rhythmic tasks. A control factor or control group was identified as a comparator. Spontaneous motor tempo was identified as the Outcome. Moreover, we selected other exclusion criteria: (1) studies that did not present experimental data; (2) studies that did not present a SMT task (i.e., focusing only on sensorimotor synchronization or on perception of rhythmic stimuli); (3) studies that did not report data on SMT (a SMT task is produced by the participants, but variables studied assess, for example, brain data or relative phases); (4) studies that did not focus on intentional SMT (studies on cardiorespiratory rhythms like breath or heart rate); and (5) studies that focus on walking with displacement (locomotion). We excluded studies on locomotion because locomotion involves spatiotemporal regulation; however, we retained studies on walking on a treadmill because walking on a treadmill involves mainly temporal regulation.

Table 2

| PICO strategy | |

|---|---|

| Description | Component |

| Population | Human |

| Intervention | Rhythmic task |

| Comparator | Control factor or group |

| Outcomes | Spontaneous motor tempo |

Description of the PICO strategy that was used.

All titles and abstracts were screened by one researcher (AD), and if the articles fit the review criteria, they were read in full. The full-text eligibility assessment was conducted by two independent reviewers (AD and JT). Disagreements were resolved by a discussion according to the PICO strategy with a third researcher (EM).

2.3. Data collection process

For tabulation and extraction of data referring to the selected studies, Excel® software spreadsheets were used. After screening the selected studies, we classified them into two categories, i.e., those measuring the SMT values (in general, as a prerequisite for a subsequent rhythmic sensorimotor synchronization task) and those examining the effect of factor(s) on the SMT values.

For studies measuring the SMT values, we extracted study characteristics, demographic variables, methodological variables, and outcome indicators from each study. The extracted characteristics included the authors, the year of publication, and the sample size. Demographic variables included sex, age, and laterality. Methodological variables included the instruction, the task, the effector(s), and the measurement recording. Outcome indicators included SMT values and their units. We finally convert all of the SMT values to milliseconds to be comparable and to provide a range of SMT values.

For studies about factor(s) modulating SMT values, we extracted study characteristics (first author and year of publication), methodological variables (task and effector(s)), and outcome indicators (factor(s) effects, their significance, and their direction on SMT values, i.e., on the mean or median and/or the standard deviation or coefficient of variation). Sometimes, we also extracted other information (e.g., subgroups and specific statistical analyses) to understand and interpret the results.

3. Results

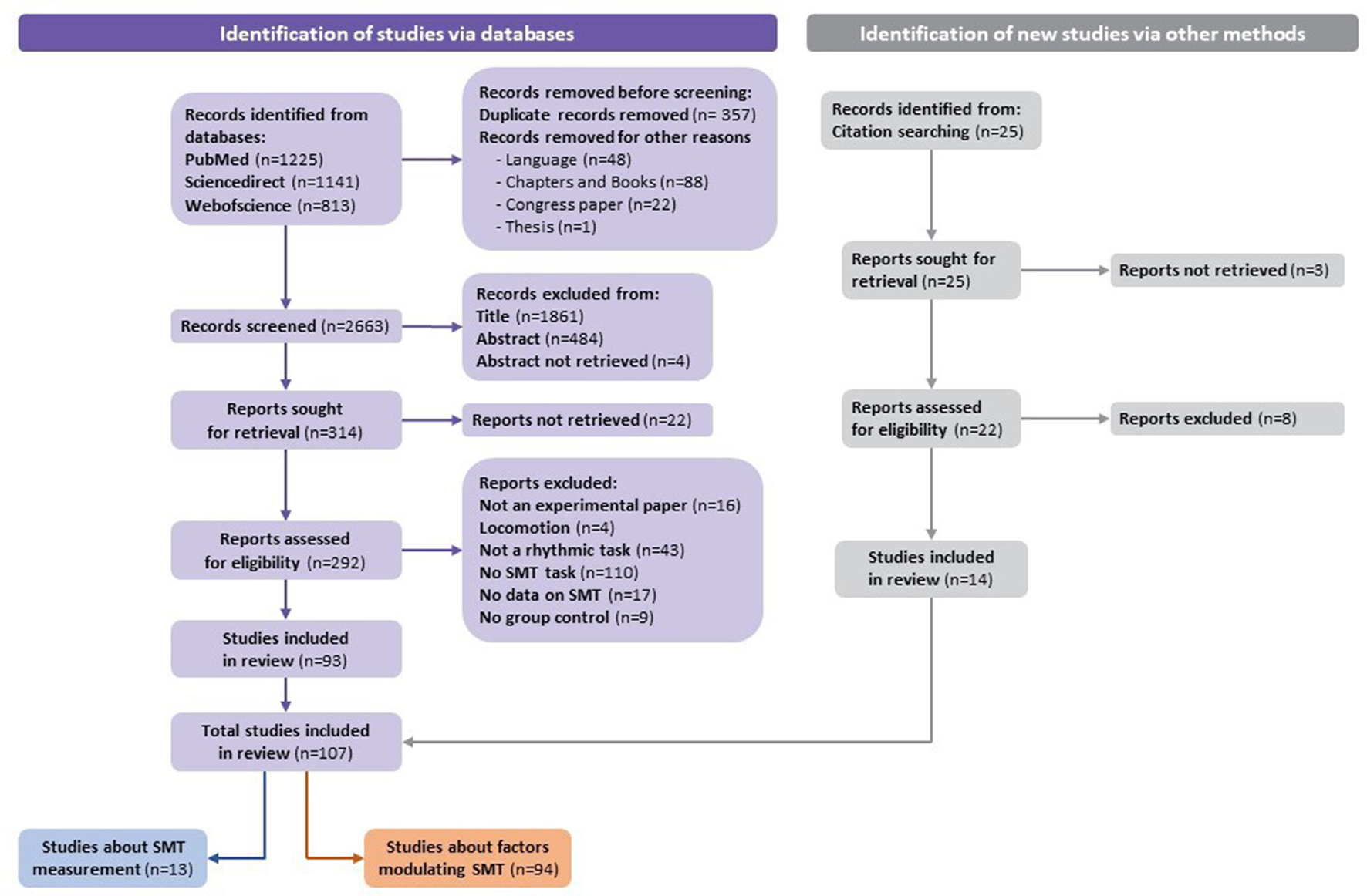

A total of 3,179 studies were identified via databases. Before screening, 357 duplicates and 159 studies were removed (e.g., language, chapters and books, congress papers, or theses). According to the exclusion criteria, 2,349 studies were excluded based on the title or the abstract. After verifying the records left in full, according to the pre-established eligibility criteria, 93 studies from databases were included in the systematic review. Moreover, 14 out of 25 studies identified via citation searching were included. Finally, a total of 107 studies were included in the systematic review. Results from the process for selecting the included articles (following the recommendations of Page et al., 2021) are described in the flowchart (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Flowchart of the identification of studies via databases.

In total, 13 studies provide a SMT value or a range of SMT values in healthy adults (Table 3). Our results reveal that the range of SMT values is from 333 to 3,160 ms. Notably, 94 studies measure the effect of the factor(s) on the SMT values (Table 4). We classified studies according to the type of factors modulating the SMT values: intrinsic factors, in relation to personal characteristics, and extrinsic factors, in relation to environmental characteristics. Concerning intrinsic factors, we have found studies investigating the effects of a pathology (N = 27), age (N = 16), the effector or the side (N = 7), the expertise or a predisposition (N = 7), and the genotype (N = 2). Concerning extrinsic factors, we have found studies investigating the effects of physical training (N = 10), external constraints (N = 7), observation training (N = 5), the time of testing (N = 4), the internal state (N = 3), the type of task (N = 5), and a dual task (N = 2).

Table 3

| References | Participants processed | Paradigm | SMT | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | Sex Age ±SD (years old) Laterality | Instruction | Task | Trial(s) (duration or intervals number) | Measurement recording | Effector | SMT values | Converted SMT values (in ms) | Coefficient of variation | ||||

| Mean, median or range | SD | Unit | Mean, median, or range | SD | |||||||||

| Hattori et al. (2015) | 6 | 2M 4F 27 ± N.S. Not reported |

Not reported | Tapping | 1 (30 times) | Intertap intervals | Fingers | 333–505 | 12.6–23 | ms | 333–505 | 12.6–23 | Not reported |

| Ruspantini et al. (2012) | 11 | Not reported Not reported Not reported |

To periodically articulate the/pa/syllable, mouthing silently, at a self-paced, comfortable rate | Producing a syllable | Not reported | Syllable rate | Mouth/lips | 2.1 | 0.5 | Hz | 476 | 200 | Not reported |

| McPherson et al. (2018) | 20 | 5M 15F 18–26 19 right-handed 1 left-handed |

To hit the drum, sustaining a constant pulse at their own, naturally comfortable tempo | Drumming | 10 (15 s each) | Beats per minute | Hand | 62–122 (one at 189) | Not reported | bpm | 492–968 (one at 317) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Rousanoglou and Boudolos (2006) | 11 | 5M 6F 21.2 ± 0.5 (M) 21.3 ± 0.5 (F) Not reported |

To perform two-legged hopping in place at their preferred hopping frequency | Hopping | 2 (15 s each) | Duration of the hopping cycle | Legs | 0.555 | 0.083 | s | 555 | 83 | Not reported |

| Michaelis et al. (2014) | 14 | 7M 7F 18–35 Right-handed |

To tap a response key at whichever rate felt “most comfortable,” to keep a steady pace, and make the spaces between taps as even as possible | Tapping | 4 (30 intertap intervals) | Intertap intervals | Finger | 0.68 | 0.32 | s | 680 | 320 | Not reported |

| Sidhu and Lauber (2020) | 11 | 8M 3F 25.9 ± 3.8 Not reported |

To cycle at a freely chosen cadence | Cycling on a cycle ergometer | 1 (5 min) | Cadence | Legs | 71.6 | 8.1 | rpm | 838 | 95 | Not reported |

| Zhao et al. (2020) | 21 | 13M 8F 26.2 ± 5.4 19 right-handed 2 left-handed |

To perform rhythmic oscillatory movements at their preferred frequency (if he or she can do it all day long) with the amplitude of the participant's shoulder | Performing rhythmic oscillatory movements with a stick | 1 (30 s) | Number of movement cycles | Hand | 17–33 | Not reported | no unit | 909–1,765 | Not reported | Not reported |

| De Pretto et al. (2018) | 14 | 7M 7F 27.7 ± 3.1 Right-handed |

To tap at their most natural pace, at a frequency they could maintain without mental effort, and for a long period of time | Tapping | 3 (40 intertap intervals) | Intertap intervals | Finger | 931 | 204 | ms | 931 | 204 | 5.6 ± 1.3% |

| Eriksson et al. (2000) | 12 | 5M 7F 25–45 Not reported |

Not reported | Opening and closing the jaw Chewing | 2 (12 s each) 2 (12 s each) | Cycle time Cycle time | Jaw Jaw | 2.43 0.86 | 0.86 0.16 | s s | 2,430 860 | 860 160 | Not reported |

| Sotirakis et al. (2020) | 20 | Not reported 27.1 ± 9.15 Not reported |

To perform voluntary postural sway cycles at their own self-selected amplitude and pace | Swaying | 1 (20 cycles) | Cycle duration | Whole body | 3,160 | 530 | ms | 3,160 | 530 | Not reported |

| Malcolm et al. (2018) | 16 | 11M 5F 25.6 ± 4.5 Right-handed |

Not reported | Walking on a treadmill | Not reported | Speed walking | Legs | 3.2–4.5 | Not reported | km/h | Not convertible | Not reported | Not reported |

| LaGasse (2013) | 12 | Not reported 18–35 Not reported |

To repeat the syllable/pa/at a comfortable and steady pace | Producing a syllable | 7 (8 sequential repetitions) | Inter-responses interval | Mouth/lips | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Zhao et al. (2017) | 22 | 12M 10F 26.9 ± 6.6 Not reported |

To tap at a constant and comfortable tempo | Tapping | 6 (30 s each) | Not reported | Finger | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

Summarized results of studies measuring SMT values (N = 13).

The original SMT values reported were converted to milliseconds by the authors (A.D., E.M., and J.T.) to provide a range of SMT values in milliseconds: [333–3,160 ms].

Table 4

| References | Factors modulating the SMT | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Intrinsic factors | |||||||||||

| 1. Pathology | Significance | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or coefficient of variation of SMT) | Other factor(s) | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or coefficient of variation of SMT) | Interaction | Task(s) | Effector(s) | Other information | |

| Amrani and Golumbic (2020) | ADHD vs. Healthy adults | Yes | ADHD faster than Healthy adults | ADHD less stable than Healthy adults (within trial and across sessions) | / | / | / | / | Tapping on an electro-optic sensor | Finger | / |

| Byblow et al. (2002) | Parkinson's vs. Healthy elderly | Yes | Parkinson's is slower than Healthy elderly | Not found | Mode of coordination Side | Inphase faster than antiphase Not found | Not found Not found | No interaction | Producing pronation and supination movements | Forearm | / |

| Delevoye-Turrell et al. (2012) | Schizophrenia vs. Healthy adults | Yes | • Schizophrenia is slower than Healthy adults | • Schizophrenia is less stable than Healthy adults | / | / | / | / | Producing finger down and up rhythmic movements | Finger | / |

| Ultra-High Risk vs. Healthy Younger adults | Yes | • Ultra-High Risk = Healthy Younger adults | • Ultra-High Risk less stable than Healthy young adults • Ultra-High Risk = Schizophrenia |

||||||||

| Flasskamp et al. (2012) | Parkinson's vs. Healthy elderly | Yes | Parkinson's faster than Healthy elderly | Parkinson's less stable than Healthy elderly | / | / | / | / | Producing a syllable | Mouth/lips | Subgroups of Parkinson's (Left-sided vs. Right-sided symptoms) |

| Frankford et al. (2021) | Stammerers vs. Healthy adults | No | Stammerers = Healthy adults | Stammerers = Healthy adults | / | / | / | / | Reading sentences | Mouth/lips | / |

| Häggman-Henrikson et al. (2002) | Whiplash-associated disorders vs. Healthy adults | Yes | Whiplash-associated disorders slower than Healthy adults | Not found | / | / | / | / | Chewing | Jaw | / |

| Horin et al. (2021) | Parkinson's vs. Healthy elderly | Yes | Parkinson's faster than Healthy elderly | Parkinson's = Healthy elderly | Effector | • Finger faster than Gait • Foot faster than Gait |

• Finger = Gait • Foot = Gait |

Interaction Pathology × Effector: Parkinson's faster than Healthy elderly for foot tapping | • Tapping on a keyboard key • Tapping on a pedal |

• Finger • Foot |

Other 5 m walking task |

| Keil et al. (1998) | Schizophrenia vs. Healthy adults | No | Schizophrenia = Healthy adults | Not found | Movement direction | Vertical faster than Horizontal | Not found | Not found | Bimanual coordination task | Fingers | Horizontal and vertical movements |

| Konczak et al. (1997) | Parkinson's vs. Healthy elderly | Yes | • Producing a syllable: Significant effect (no other information) • Tapping: Significant effect (no other information) |

• Producing a syllable: Not found • Tapping: Not found |

Task (Dual vs. Single) | • Producing a syllable: Significant effect (no other information) • Tapping: Not found |

• Producing a syllable: Not found • Tapping: Not found |

Not found | • Producing a syllable • Tapping on a table |

• Mouth/lips • Finger |

Subgroups of Parkinson's (With vs. Without hastening) |

| Kumai (1999) | 2–3.5 vs. 3.6–4.5 vs. 4.6–5.5 vs. 5.6–6.11 vs. 7+ years of mental ages | No | 2–3.5 =3.6–4.5 = 4.6–5.5 = 5.6–6.11 = 7+ years of mental ages | Not found | / | / | / | / | Drumming with a stick | Hand/Forearm | Biological age: 13–23 years old |

| McCombe Waller and Whitall (2004) | Chronic hemiparesis vs. Healthy adults | No | • Paretic limb: Not found • Non-paretic limb: Chronic hemiparesis = Healthy adults |

• Paretic limb: Not found • Non-paretic limb: Chronic hemiparesis = Healthy adults |

Sensorimotor synchronization training in the non-paretic limb (in hemiparesis patients) | Pre faster than Post | Pre = Post sensorimotor synchronization training | Not found | Tapping on keys | Fingers | / |

| Martin et al. (2017) | Alzheimer's vs. Healthy elderly | No | Alzheimer's = Healthy elderly | Not found | / | / | / | / | Tapping on a keyboard key | Finger | / |

| Martínez Pueyo et al. (2016) | Huntington vs. Healthy adults | Yes | Huntington is slower than Healthy adults | Huntington is less stable than Healthy adults | / | / | / | / | Tapping on a keyboard key | Finger | / |

| Palmer et al. (2014) | 2 Beat-deaf vs. Healthy adults | No | 2 Beat-deaf = Healthy adults | 2 Beat-deaf = Healthy adults | / | / | / | / | Tapping on a silent piano key | Finger | / |

| Phillips-Silver et al. (2011) | 1 Beat-deaf (congenital amusia) vs. Healthy adults | Not found (case report) | Not found (case report) | Not found | / | / | / | / | Bouncing | Whole body | / |

| Provasi et al. (2014b) | Cerebellar medulloblastoma vs. Healthy children | Yes | Cerebellar medulloblastoma is slower than Healthy children | Cerebellar medulloblastoma is less stable than Healthy children | Sensorimotor synchronization task Sex | Pre faster than Post Male = Female | Pre = Post sensorimotor synchronization task Female = Male | • Interaction Pathology × Sensorimotor synchronization task: effect of Sensorimotor synchronization on SMT value and its stability is higher in Cerebellar medulloblastoma than in Healthy children. • No interaction Sex × Pathology × Sensorimotor synchronization task |

Tapping on a keyboard key | Finger | / |

| Roche et al. (2011) | DCD vs. Healthy children | Yes | DCD = Healthy children | DCD is less stable than Healthy children | Sensory feedback | Vision+ Audition = No vision + Audition = Vision + No audition = No vision + No audition | Vision+ audition = No vision + Audition = Vision + No audition = No vision + No audition | No interaction Pathology × Sensory feedback | Anti-phase tapping on a table | Fingers | / |

| Roerdink et al. (2009) | Stroke vs. Healthy adults | Yes | Stroke is slower than Healthy adults | Not found | / | / | / | / | Walking on treadmill | Legs | / |

| Rose et al. (2020) | Parkinson's vs. Healthy elderly vs. Younger healthy adults | Yes (in all tasks) | • Finger tapping: Parkinson's = Healthy elderly// Parkinson's faster than Younger healthy adults// Healthy elderly (515 ms) faster than Younger healthy adults • Toe tapping: Parkinson's faster Healthy elderly = Younger healthy adults • Stepping: Parkinson's faster than Younger healthy adults// Parkinson's = Heatlthy elderly// Healthy elederly = Younger healthy adults |

• Finger tapping: Parkinson's = Younger healthy adults// Parkinson's less stable than Healthy elderly// Younger healthy adults less stable than Healthy elderly • Toe tapping: Parkinson's = Younger healthy adults = Healthy elderly • Stepping: Parkinson's = Younger healthy adults = Healthy elderly |

/ | / | / | / | • Tapping on a stomp box • Tapping on a stomp box • Stepping on the spot |

• Finger • Toe • Feet |

|

| Rubia et al. (1999) | ADHD vs. Healthy children | Yes | ADHD = Healthy children | ADHD less stable than Healthy children | / | / | / | / | Tapping on a button | Finger | / |

| Schwartze et al. (2011) | Stroke (Basal ganglia lesions) vs. Healthy adults | Yes | Not found | Stroke less stable than Healthy adults | Sensorimotor synchronization task | Not found | Pre less stable than Post | No interaction Pathology × Sensorimotor synchronization task | Tapping on a copper plate | Hand | / |

| Schwartze et al. (2016) | Cerebellar lesion vs. Healthy adults | Yes | Cerebellar lesion = Healthy adults | Cerebellar lesion less stable than Healthy adults | Sensorimotor synchronization task | Pre = Post | Not found | No interaction Pathology × Sensorimotor synchronization task | Tapping on a pad | Finger | / |

| Schellekens et al. (1983) | Minor neurological dysfunction vs. Healthy children | Yes | Minor neurological dysfunction slower than Healthy children | Minor neurological dysfunction less stable than Healthy children | / | / | / | / | Pressing buttons | Hand/Arm | / |

| Volman et al. (2006) | DCD vs. Healthy children | Yes (in both tapping modes) | • In-phase: DCD slower than Healthy • Anti-phase: DCD slower than Healthy |

Not found | Limb combination | • In-phase: Hand-foot ipsilateral = Hand-foot controlateral slower than Hand-hand • Anti-phase: Hand-foot ipsilateral = Hand-foot controlatéral slower than Hand-hand |

• In-phase: Not found • Anti- phase: Not found |

No interaction Pathology × Limb combination (for In-phase and Anti-phase) | In-phase and Anti-phase bi-effectors tapping on a pad | Hand and foot | Limb combinations: - Hand–hand coordination (homologous); - Hand–foot coordination same body side (ipsilateral) - Hand-foot coordination different body side (contralateral) |

| Wittmann et al. (2001) | Adults with Brain subcortical injury left hemisphere without aphasia (LHsub) vs. Brain cortical injury left hemisphere with aphasia (LH) vs. Brain cortical injury right hemisphere (RH) vs. Controls (orthopedic but not brain injury; CTrl) | Yes | LH slower than CTrl LHsub faster than CTrl RH = CTrl | LH = LHsub = RH = CTrl | Side (in controls) | Left = Right | / | / | Tapping on a keyboard key | Finger | / |

| Wurdeman et al. (2013) | Transtibial amputee vs. Healthy adults | No | Transtibial amputee = Healthy adults | Not found | / | / | / | / | Walking on a treadmill | Legs | / |

| Yahalom et al. (2004) | Parkinson's vs. Healthy elderly | No | Parkinson's = Healthy elderly | Parkinson's = Healthy elderly | / | / | / | / | Tapping on a board | Fingers | Subgroups of Parkinson's (Tremor predominant vs. Freezing predominant vs. Akinetic rigid vs. Unclassified) Freezing predominant Parkinson's vs. Unclassified Parkinson's adults significantly different |

| 2. Age | Significance | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Other factor(s) | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Interaction | Task(s) | Effector(s) | Other information | |

| Baudouin et al. (2004) | 21–35 vs. 66–80 vs. 81–94 years old | Yes | 21–35 faster than 66–80 = 81–94 years old | Not found | / | / | / | / | Tapping on a plastic block | Finger | / |

| Drake et al. (2000) | 4 vs. 6 vs. 8 vs. 10 years old children vs. Adults | Yes | Younger faster than Older | Younger more stable than Older | Trial measurement Musical expertise | Trial 1 slower than Trial 5 Non-musicians faster than Musicians | Not found Non-musicians less stable Musicians | No interaction Age × Trial measurement × Musical expertise | Drumming with a stick | Hand/forearm | / |

| Droit et al. (1996) | 31–35 vs. 37–39 weeks of postmenstrual age in brain-damaged and low risks preterm infants | No | 31–35 = 37–39 weeks of postmenstrual age | Not found | / | / | / | / | Kicking | Legs | / |

| Ejiri (1998) | Before vs. After onset of canonical babbling (CB) | Yes | Onset CB faster than Before and After CB | Not found | Audibility of rattles Weight of rattles Sex Side | Audible faster than Inaudible Not found Not found Not found | Not found Not found Not found Not found | Interaction Onset CB × Audibility of rattle: after onset CB, Audible rattle is faster than Inaudible. | Shaking a rattle | Arm | / |

| Fitzpatrick et al. (1996) | 3 vs. 4 vs. 5 vs. 7 years old children | No | 3 = 4 = 5 = 7 years old | Not found | Side Loading | Left = Right Not found | Not found Not found | Interaction Side × Loading: the right limb loaded oscillates faster than the left limb loaded. | Clapping with and without inertial loading limbs | Hands | / |

| Gabbard and Hart (1993) | 4 vs. 5 vs. 6 years old children | Yes | Older faster than Younger | Not found | Sex Laterality | Male = Female Right = Mixed = Left | Not found Not found | No interaction Age × Sex × Laterality | Tapping on a pedal | Foot | / |

| Getchell (2006) | 4 vs. 6 vs. 8 vs. 10 years old children vs. Adults | Yes | 4 faster than 6 = 8 =10 years old = Adults | 4 = 6 = 8 = 10 years old less stable than Adults | Dual task | Single faster than Dual | Dual less stable than Single | No interaction Age × Dual task | Striking cymbals | Hands/forearms | Other walking task (GAITRite) |

| Hammerschmidt et al. (2021) | 7–49 years old | Yes | Younger faster than Older | Not found | Time of day Arousal Long-term stress Musical expertise | Earlier slower than Later Very calm = Rather calm = Neutral = Rather excited = Very excited Low stress = Moderate stress = High stress Non-musicians slower than Musicians | Not found Not found Not found Not found | Not found | Tapping on a keyboard key, or a mouse key, or a touchscreen of a tablet or a smartphone | Finger | Clusters analysis-based on SMT values |

| James et al. (2009) | 6 vs. 10 years old children vs. Adults | Yes | 6 years old faster than Adults | Younger less stable than Older | Support for rocking | Supported = Unsupported | Significant effect (no other information) | Interaction Age × Supported rocking on SMT and its stability: - When the feet were unsupported, only 6 year old were faster than Adults - Only 6 and 10 years old children are more stable with unsupported rocking. | Body rocking | Whole body | / |

| McAuley et al. (2006) | 4–5 vs. 6–7 vs. 8–9 vs. 10–12 years old children vs. 18–38 vs. 39–59 vs. 60–74 vs. 75+ years old adults | Yes | Younger faster than Older | Not found | / | / | / | / | Tapping on a copper plate | Hand | Correlation analysis |

| Monier and Droit-Volet (2018) | 3 vs. 5 vs. 8 years old children vs. Adults | Yes | • In non-emotional context: 3 = 5 = 8 years old faster than Adults • In emotional context: 3 = 5 = 8 years old faster than Adults |

• In non-emotional context: 3 less stable than 5 less stable than 8 years old = Adults • In emotional context: 3 less stable than 5 less stable than 8 years old less stable than Adults |

• Emotional context • Sex |

• High-Arousal faster than Low-Arousal = Neutral • Male = Female |

• High-Arousal more stable than Low-Arousal = Neutral • Male = Female |

No interaction Age × Emotional context | Tapping on a keyboard key | Finger | / |

| Monier and Droit-Volet (2019) | 5 vs. 6 vs. 7 years old children | Yes | 5 = 6 = 7 years old | 5 less stable than 6 less stable than 7 years old | Trial measurement | Trial 1 = Trial 2 = Trial 3 | Trial 1 = Trial 2 = Trial 3 | / | Tapping on a keyboard key | Finger | Linear regression analysis for age |

| Provasi and Bobin-Bègue (2003) | 2½ vs. 4 years old children vs. Adults | Yes | Younger faster than Adults | Younger less stable than Older | Sensorimotor synchronization task | Pre faster than Post | Pre = Post | Not found | Tapping on a computer screen | Hand | / |

| Rocha et al. (2020) | 4–37 months old infants | Yes | Younger slower than Older | Younger less stable than Older | / | / | / | / | Drumming | Hand | Correlation analysis |

| Vanneste et al. (2001) | 24–29 years old adults vs. 60–76 years old elderly | Yes | 24–29 faster than 60–76 years old | 26 = 69 years old | Session measurement | Significant effect (no other information) | Session 1 = Session 2 = Session 3 = Session 4 = Session 5 | Interaction Age × Session measurement: - Session 1 slower than Session 2 = Session 3 = Session 4 = Session 5 in Younger. - Session 1 slower than Session 2 slower than Session 3 = Session 4 = Session 5 in Oldest. | Tapping on a plastic block | Hand | / |

| Yu and Myowa (2021) | 18 vs. 30 vs. 42 months old children | No | 18 = 30 = 42 years old | Not found | / | / | / | / | Drumming with a stick | Hand/forearm | / |

| 3. Effector/side | Significance | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Other factor(s) | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Interaction | Task(s) | Effector(s) | Other information | |

| Byblow and Goodman (1994) | Left vs. Right | No (in both coordination modes) | • Single rhythmic 1:1 coordination: Left = Right • Polyrhythmic 2:1 coordination: Left = Right |

• Single rhythmic 1:1 coordination: Left = Right • Polyrhythmic 2:1 coordination: Left = Right |

Session measurement | • Single rhythmic 1:1 coordination: Session 1 = Session 2 = Session 3 • Polyrhythmic 2:1 coordination: Not found |

• Single rhythmic 1:1 coordination: Session 1 = Session 2 = Session 3 • Polyrhythmic 2:1 coordination: Not found |

Not found (for single and polyrhythmic coordination) | • Single rhythmic 1:1 coordination • Polyrhythmic 2:1 coordination |

• Forearm • Forearm |

No comparison between the 2 modes of coordination |

| Getchell et al. (2001) | Right finger tapping in-phase; right finger tapping antiphase; arms clapping alone; lead leg galloping alone; lead leg galloping with clapping; arms clapping with galloping; right leg crawling | Tasks not compared | Not found (tasks not compared) | Not found (tasks not compared) | / | / | / | / | • Tapping on a key • Clapping • Galloping |

• Finger • Arms • Legs |

Correlation analyses between tasks |

| Kay et al. (1987) | Left vs. Right | No | • Single: Left = Right • Bimanual: Left = Right in Mirror and Parallel |

• Single: Left = Right • Bimanual: Left = Right |

• Mode of production • Session measurement |

• Single = Mirror faster than Parallel • Session 1 = Session 2 |

• Single = Mirror = Parallel • Session 1 = Session 2 |

Not found | • Producing single flexion and extension • Producing bimanual flexion and extension |

• Wrist • Wrist |

/ |

| Rose et al. (2021) | Finger vs. Foot vs. Whole body | No | Finger = Foot = Whole body | Not found | Age | Younger = Older | Not found | No interaction Effector × Age | • Tapping on a stomp box • Tapping on a stomp box • Stepping on the spot |

• Finger • Foot • Whole body |

/ |

| Sakamoto et al. (2007) | Arm vs. Leg | Yes | Arms slower than Legs | Not found | / | / | / | / | • Pedaling • Pedaling |

• Arms • Legs |

/ |

| Tomyta and Seki (2020) | 1 Finger vs. 4 Fingers vs. Hand/Forearm | No | Not found | 1 Finger = 4 Fingers = Hand/Forearm | / | / | / | / | • Tapping on (a) keyboard key(s) • Drumming with a stick |

• Finger(s) • Hand/ Forearm |

/ |

| Whitall et al. (1999) | Left vs. Right | No | Left = Right | Not found | Mode of tapping | In-phase faster than Anti-phase | In-phase less stable than Anti-phase | Not found | Tapping on keyboard keys | Fingers | / |

| 4. Expertise/predisposition | Significance | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Other factor(s) | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Interaction | Task(s) | Effector(s) | Other information | |

| Assaneo et al. (2021) | High vs. Low synchronization skill | Yes | High faster than Low | Not found | / | / | / | / | Producing a syllable | Mouth/lips | / |

| Bégel et al. (2022c) | Musicians vs. Non- musicians | Yes | Musicians = Non-musicians | Musicians more stable than Non-musicians | / | / | / | / | Tapping on a pad | Finger | / |

| Loehr and Palmer (2011) | Musicians vs. Non- musicians | No | Musicians = Non- musicians | Not found | / | / | / | / | Playing (one hand) a melody on a piano | Fingers | / |

| Scheurich et al. (2018) | Musicians vs. Non-musicians | Yes | Musicians slower than Non- musicians | Musicians more stable than Non- musicians | Trial measurement | Trial 1 slower than Trial 2 and Trial 3 | Trial 1 = Trial 2 = Trial 3 | No interaction Musical expertise × Trial measurement | Tapping a melody on one piano key | Finger | / |

| Scheurich et al. (2020) | Musicians vs. Non- musicians (experiment 2) | No | Musicians = Non-musicians | Not found | Trial measurement | Trial 1 slower than Trial 2 slower than Trial 3 | Not found | No interaction Musical expertise × Trial measurement | Tapping on a force sensitive resistor | Finger | Percussionists excluded |

| Slater et al. (2018) | Musicians vs. Non- musicians | Yes | Not found | Musicians more stable than Non-musicians | / | / | / | / | Drumming | Hand | Percussionists |

| Tranchant et al. (2016) | High vs. Low synchronization skill | Yes | • Bouncing: High = Low synchronization skill • Clapping: High = Low synchronization skill |

• Bouncing: High more stable than Low synchronization skill • Clapping: High = Low synchronization skill |

Type of task | • In High synchronization skill: Clapping faster than Bouncing • In Low synchronization skill: Not found |

• In High synchronization skill: Clapping more stable than Bouncing • In Low synchronization skill: Not found |

/ | • Bouncing • Clapping |

• Whole body • Hands |

/ |

| 5. Genotype | Significance | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Other factor(s) | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Interaction | Task(s) | Effector(s) | Other information | |

| Suzuki and Ando (2018) | Monozygotic vs. Dizygotic twins | No | Monozygotic = Dizygotic | Monozygotic = Dizygotic | Sex | Male = Female | Male = Female | Not found | Striking cymbals | Forearms/ Hands | Significant correlation between the tempo level of each Monozygotic twin but not between each Dizygotic twins |

| Wiener et al. (2011) | A1+ vs. A1- polymorphism Val/Val vs. Met+ polymorphism | • Yes • No |

A1+ slower than A1 - Val/Val = Met+ | A1+ = A1 - Val/Val = Met+ | / | / | / | / | Tapping on a keyboard key | Not found | Subgroups of polymorphism [DRD2/ANKK1-Taq1a (A1–, A1+); COMT Val158Met (Val/Val, Met+); BDNF Val66Met (Val/Val, Met+)] |

| II. Intrinsic factors | |||||||||||

| 1. Physical training | Significance | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Other factor(s) | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Interaction | Task(s) | Effector(s) | Other information | |

| Byblow et al. (1994) | Pre vs. Post sensorimotor synchronization | Yes | Pre slower than Post | Not found | Mode of coordination Side | Not found Not found | Not found Not found | Not found | Producing pronation and supination coordination | Forearms | / |

| Carson et al. (1999) | Pre vs. Post sensorimotor synchronization | Yes | Pre slower than Post | Pre = Post | Weighted coordination Side Mode of coordination | Heavy weight slower than No weight = Light weight Right slower than Left In-phase slower than Anti-phase | Heavy = No weight = Light weight Right = Left In-phase = Anti-phase | Not found | Coordinating flexing and extending elbow and wrist joints | Arm | / |

| Collyer et al. (1994) | Pre vs. Post sensorimotor synchronization | No | Pre = Post | Not found | Trial measurement Session | Pre: Trial 1 slower than Trial 2 = Trial 3 Post: Trial 1 slower than Trial 2 = Trial 3 Session 1 = Session 2 = Session 3 = Session 4 = Session 5 = Session 6 = Session 7 = Session 8 | Not found Not found | Not found | Tapping on a plastic box | Finger | / |

| Dosseville et al. (2002) | Pre vs. Post physical exercise of pedaling | Yes | Pre slower than Post | Not found | Trial measurement Time of day | Pre: Trial 1 = Trial 2 = Trial 3 = Trial 4 Post: Trial 1 = Trial 3 6 pm faster than 6 am, 10 am and 10 pm//6 am slower than 2 pm | Not found Not found | Not found | Tapping on a table | Finger | / |

| Hansen et al. (2021) | Cadence of physical training: 50 rpm vs. 90 rpm vs. Freely chosen | Yes | 50 rpm slower than Freely chosen 90 rpm faster than Freely chosen | Not found | / | / | / | / | Pedaling | Legs | / |

| Robles-García et al. (2016) | Pre vs. Post vs. 2 weeks Post imitation and motor practice vs. Motor practice alone in elderly with Parkinson's disease | No | Pre = Post = 2 weeks Post | Pre = Post = 2 weeks Post | Type of physical training Laterality | Imitation and motor practice = Motor practice alone Not found | Imitation and motor practice = Motor practice alone In Pre physical training: Dominant more stable than Non-dominant hand | No interaction Training × Type of physical training | Tapping | Finger | / |

| Rocha et al. (2021) | Pre vs. Post passive walking in non-walking infants | Yes | Pre = Post | Not found | Passive walking frequency | Fast = Slow | Not found | Interaction Training × Passive walking frequency: - Infant SMT in the Fast walking frequency became faster from pre to post training. - Infant SMT in the Slow condition became slower from pre to post training. | Drumming | Hands | / |

| Sardroodian et al. (2014) | Pre vs. Post 4 weeks of heavy strength training | No | Pre = Post | Not found | / | / | / | / | Pedaling | Legs | / |

| Turgeon and Wing (2012) | Pre vs. Post sensorimotor synchronization and continuation | No | Pre = Post | Pre = Post | Age | Younger faster than Older | Younger more stable than Older | Not found | Tapping on a mouse key | Finger | Linear regression analysis for age |

| Zamm et al. (2018) | Pre vs. Post faster or slower sensorimotor synchronization | No | Pre = Post | Not found | Time of day Age Sex | Earlier = Later Younger = Older Not found | Not found Not found Not found | Not found Not found Not found | Playing a melody on a piano | Fingers | Pianists Correlation analysis for age |

| Bouvet et al. (2019) | Ascending vs. Descending rhythmic stimuli (listening while trying not to synchronize) vs. Without rhythmic stimuli | Yes | Ascending faster than Descending rhythmic stimuli and Without rhythmic stimuli | Ascending stimulus less stable than Descending and Without rhythmic stimuli | Time of testing | Significant effect (no other information) | Significant effect (no other information) | Interaction Value modulation of stimuli time intervals × Time of testing: - Ascending more stable than Without rhythmic stimuli at the beginning of testing. - Ascending and Descending more stable than Without rhythmic stimuli at the end of testing. | Air tapping task (flexion and extension) | Finger | / |

| 2. External constraints | Significance | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Other factor(s) | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Interaction | Task(s) | Effector(s) | Other information | |

| Bouvet et al. (2020) | One vs. Two vs. Three times the spontaneous motor tempo value as time intervals between stimuli (listening while trying not to synchronize) | Yes | One faster than Two and Three times the spontaneous motor value | One = Two = Three times the spontaneous motor value | Accentuation pattern Session Trial measurement | Unaccented = Binary accented = Ternary accented Session 1 = Session 2 Trial 1 = Trial 2 = Trial 3 | Unaccented = Binary accented = Ternary accented Session 1 = Session 2 Trial 1 = Trial 2 = Trial 3 | • No interaction Value of stimuli time intervals × Accentuation pattern • No interaction Session × Trial measurement |

Air tapping task (flexion and extension) | Finger | / |

| Hansen and Ohnstad (2008) | 200 m real vs. 3,000 m simulated altitude with loading on the cardiopulmonary system (experiment 1) | No | 173 W at 200 m real = 173 W at 3,000 m simulated = 224 W at 200 m real | Not found | / | / | / | / | Pedaling | Legs | / |

| Hatsopoulos and Warren (1996) | 0 kg vs. 2.27 kg vs. 4.55 kg external added mass | Yes | 0 kg faster than 2.27 kg faster than 4.55 kg | Not found | Session External spring stiffness | Session 1 = Session 2 0 N/m slower than 47.34 N/m slower than 94.68 N/m slower than 142.02 N/m | Not found Not found | Interaction External added mass × External spring stiffness (no more information) | Arms swinging | Arms | / |

| Sofianidis et al. (2012) | No contact vs. Fingertip contact | Yes | No contact slower than Fingertip contact | Not found | Dance expertise | Expert dancers = Novice dancers | Not found | No interaction Contact interaction × Dance expertise | Body rocking | Whole body | / |

| Verzini de Romera (1989) | Quiet vs. Noisy environment | Yes | Noisy environment faster than Quiet | Not found | / | / | / | / | Not found | Not found | / |

| Wagener and Colebatch (1997) | 0.35 Nm vs. 0.18 Nm vs. 0.26 Nm extension vs. 0.09 Nm vs. 0.18 Nm flexion torque load vs. without external load | No | 0.35 Nm = 0.18 Nm = 0.26 Nm extension = 0.09 Nm = 0.18 Nm flexion = Without external load | Not found | / | / | / | / | Flexion and extension | Wrist | / |

| 3. Observation training | Significance | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Other factor(s) | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Interaction | Task(s) | Effector(s) | Other information | |

| Aridan and Mukamel (2016) | Pre vs. Post passive observation of a rhythmic action | Yes | Pre slower than Post (only in subjects with “slower” spontaneous motor tempo at Pre training) | Not found | / | / | / | / | Tapping on keys | Fingers | Subgroups of spontaneous motor tempo profile in Pre training: Slow (slowest spontaneous motor tempo) vs. Fast (fastest spontaneous motor tempo) |

| Avanzino et al. (2015) | Pre vs. Post passive observation combined with Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation | Not found | Not found | Not found | Type of observation training (Passive observation of a rhythmic action vs. Passive observation of a landscape) | Not found | Not found | Interaction Passive observation training × Type of observation: Pre slower than Post only for Passive observation of a rhythmic action. | Performing an opposition sequence | Fingers | / |

| Bisio et al. (2015) | Pre vs. Post passive observation of a rhythmic action | Not found | Not found | Not found | Type of observation training (Passive observation of a rhythmic action vs. Passive observation of a rhythmic action combined with peripherical nerve stimulation vs. Peripherical nerve stimulation vs. Passive observation of a landscape) | Not found | Not found | Interaction Passive observation training × Type of observation: Pre slower than Post only for Passive observation of a rhythmic action combined with peripherical nerve stimulation. | Performing an opposition sequence | Fingers | / |

| Bove et al. (2009) | Pre vs. Post passive observation of a rhythmic action (after 45 min and 2 days) | No | Pre = Post 45 min = Post 2 days | Not found | Instruction Type of passive observation | Not found Not found | Not found 1 Hz more stable than 3 Hz rhythmic action and Landscape | • Interaction Type of Passive observation × Instruction: With instruction faster than without instruction only for passive observation of a 3 Hz rhythmic action. • Interaction Pre-Post × Type of observation: Pre less stable than Post only for passive observation of a 3 Hz rhythmic action |

Performing an opposition sequence | Fingers | / |

| Lagravinese et al. (2017) | Type of passive observation: Passive observation of a rhythmic action vs. Passive observation of a metronome | Not found | Not found | Not found | Session | In Pre training: Session 1 slower than Session 2 slower than Session 3 = Session 4 = Session 5 | Significant effect (no other information) | Interaction Type of passive observation × Session: - Day 5 faster than Day 1 only for Passive observation of a rhythmic action. - Day 5 more stable than Day 1 only for Passive observation of a metronome. | Performing an opposition sequence | Fingers | / |

| 4. Time of testing | Significance | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Other factor(s) | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Interaction | Task(s) | Effector(s) | Other information | |

| Hansen and Ohnstad (2008) | Week 1 from Week 12 (experiment 2) | No | • Pedaling: No change across Weeks • Tapping: No change across Weeks |

• Pedaling: Not found • Tapping: Not found |

/ | / | / | / | • Pedaling • Tapping on a pad |

• Legs • Finger |

/ |

| Moussay et al. (2002) | 6 am vs. 10 am vs. 2 pm vs. 6 pm vs. 10 pm | Yes | • Tapping: 6 am slower than 6 pm//6 pm faster than 10 pm • Pedaling: 6 am slower than 10 am, 2 pm, 6 pm, and 10 pm |

• Tapping: Not found • Pedaling: Not found |

/ | / | / | / | • Tapping on a table • Pedaling |

• Finger • Legs |

Cyclists |

| Oléron et al. (1970) | Wake-up vs. Morning vs. Midday vs. Early afternoon after nap vs. Middle afternoon vs. Evening vs. Bed time | Yes | Wake-up slower than Morning | Not found | Staying in a cave | Beginning of staying in a cave slower than Ending of staying in a cave (linked to circadian rhythm modification) | Not found | Not found | Tapping on a Morse key | Finger | Significant effect only reported between Wake up and Morning |

| Schwartze and Kotz (2015) | Time 1 (Target) vs. Time 2 (Control) | Yes | Time 1 (Target) = Time 2 (Control) | Time 1 (Target) more stable than Time 2 (Control) | Age | Younger = Older | Younger = Older | Not found | Tapping on a pad | Finger | Correlation analysis for age |

| Wright and Palmer (2020) | 9 am vs. 1 pm vs. 5 pm vs. 9 pm | Yes | 9 am slower than 1 pm, 5 pm and 9 pm//1 pm slower than 9 pm | 9 am less stable than 5 pm and 9 pm//1 am less stable than 9 pm | Familiar melody | Familiar slower than Unfamiliar | Familiar more stable than Unfamiliar | No interaction Time of testing × Familial melody | Playing (one hand) a melody on a piano | Fingers | Pianists |

| 5. Internal state | Significance | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Other factor(s) | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Interaction | Task(s) | Effector(s) | Other information | |

| Boulanger et al. (2020) | Increasing vs. Decreasing gravity | Yes (but descriptive data) | Larger linear relationship with gravity in Increasing gravity than in Decreasing gravity (higher energetic cost in high gravity for a given change in frequency) | Not found | Session | Session 1 = Session 2 | Not found | Not found | Performing upper arm movements | Arm | Mathematical data representing spontaneous motor tempo |

| Dosseville and LaRue (2002) | Apnea vs. No apnea | Yes | Apnea slower than No apnea | Not found | / | / | / | / | Tapping on a metal plate | Finger | / |

| Murata et al. (1999) | Mental stress vs. No mental stress | Yes | Mental stress faster than No mental stress | Mental stress less stable than No mental stress | Trial measurement (3 Trials with Mental stress) | Not found | Not found | Not found | Tapping a key | Finger | / |

| 6. Type of task | Significance | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Other factor(s) | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Interaction | Task(s) | Effector(s) | Other information | |

| Forrester and Whitall (2000) | In-phase vs. Anti-phase | Yes | In-phase faster than Anti-phase | In-phase = Anti-phase | Fingers pairing | Index only slower than Middle only | Index only = Middle only = Index + Middle | No interaction Type of task × Fingers pairing | Bimanual tapping on keys | Fingers | / |

| Pfordresher et al. (2021) | Finger tapping vs. Playing a melody vs. Reciting a sentence (experiment 1) | Yes | Finger tapping slower than Playing a melody slower than Reciting a sentence (experiment 1) | Reciting a sentence more stable than Playing a melody and Finger tapping (experiment 1) | / | / | / | / | • Playing (one hand) a melody on a piano • Tapping on a piano key • Reciting a sentence |

• Fingers • Finger • Mouth/lips |

Correlations analyses on consistency across trials |

| Playing a melody vs. Reciting a sentence (experiment 2) | Yes | Playing a melody slower than Reciting a sentence (experiment 2) | Reciting a sentence more stable than Playing a melody (experiment 2) | ||||||||

| Scheurich et al. (2018) | Tapping a melody vs. Playing a melody (experiment 1) | No | Tapping a melody = Playing a melody | Not found | Trial measurement | Trial 1 slower than Trial 2 slower than Trial 3 | Not found | No interaction Type of task × Trial measurement | • Tapping a melody on one piano key • Playing (one hand) a melody on a piano |

• Finger • Fingers |

Correlations analyses on consistency across melodies |

| Tajima and Choshi (1999) | Polyrhythmic vs. Single rhythmic task | Yes | • Left hand: Polyrhythmic slower than Single rhythmic task (Trial 1, 2 and 3) • Right hand: Polyrhythmic slower than Single rhythmic task (Trial 1 and 2) |

• Left hand: Polyrhythmic less stable than Single rhythmic task (Trial 1 and 2) • Right hand: Polyrhythmic less stable slower than Single rhythmic task (Trial 1, 2 and 3) |

Sex | Male = Female | Male = Female | Not found | Tapping on Morse keys | Fingers | Differences reported separately for the right and the left hands and across trials |

| Zelaznik et al. (2000) | Tapping vs. Drawing | Yes | Tapping faster than Drawing | Drawing more stable than Tapping | / | / | / | / | • Tapping on a desk • Drawing a circle on a paper |

• Finger • Fingers/Wrist |

/ |

| 7. Dual task | Significance | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Other factor(s) | Direction of the effect (on mean or median of SMT) | Direction of the effect (on the SD or Coefficient of variation of SMT) | Interaction | Task(s) | Effector(s) | Other information | |

| Aubin et al. (2021) | Selective vs. Divided vs. Sustained attentional conditions | No | Selective = Divided = Sustained | Selective = Divided = Sustained | / | / | / | / | Legs swinging | Legs | Dual task |

| Serrien (2009) | Single motor task vs. Dual motor and verbal counting task | Not found | Not found | Not found | Side (Left vs. Right vs. Bimanual) | Not found | Not found | Interaction Dual task × Side: In Bimanual mode, Dual slower than Single | Tapping on a keyboard | Finger(s) | / |

Summarized results of studies investigating the effects of factors on the SMT values (N = 94).

Factors are classified as intrinsic and extrinsic. Significance is reported as YES if one of the dependent variables (mean, median, standard deviation, or coefficient of variation of SMT) is significantly different between modalities of the main factor studied. The effectors used to perform the task are reported. Other information is reported if mentioned in the studies, particularly the effects of other secondary factors or interactions. The directions of effects of the main and other factors on the dependent variable(s) are reported. The directions of effects are reported as Not found when no statistics were performed on the dependent variable, when the dependent variable was not studied, or when the direction of the effect or the interaction was not explicitly reported.

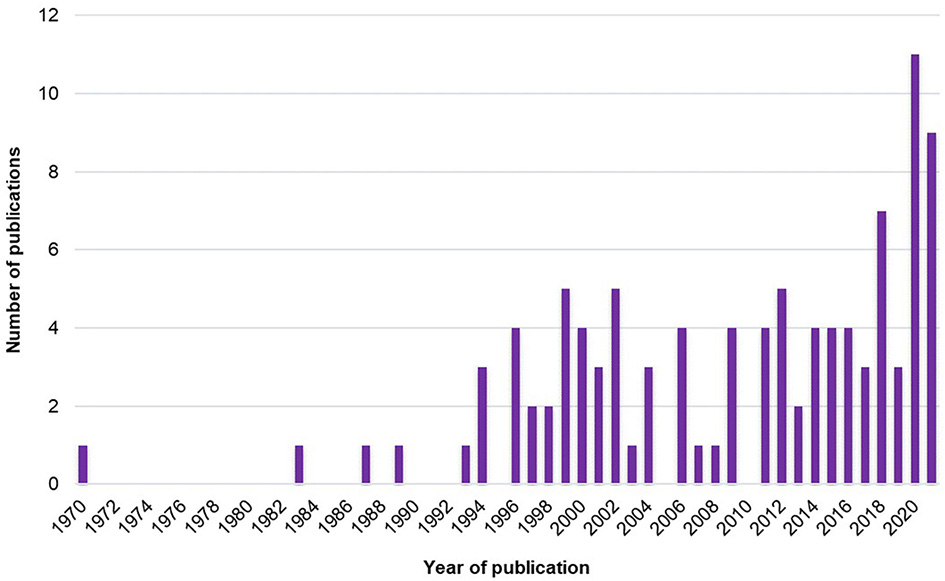

The number of studies exploring the SMT across years is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Number of studies exploring the SMT across years.

4. Discussion

The present systematic review aimed to (1) characterize the range of SMT values found in the literature in healthy human adults and (2) identify all the factors modulating the SMT values in humans.

First, it is interesting to note that the global number of studies has grown since the early 1970's (Figure 2). The increase in studies about SMT actually started in the mid-1990's and has grown non-linearly to reach a peak in 2020. Thus, interest in SMT is old but has recently increased.

Second, our results highlight that (1) the reference value of SMT is far from being a common value of 600 ms in healthy human adults, but a range of SMT values exists and (2) many factors modulate the SMT values. We discuss these factors according to a classification as intrinsic factors, in relation to personal characteristics, and extrinsic factors, in relation to environmental characteristics. We also provide recommendations to measure, report, and use the SMT values for future studies on rhythmic production and perception.

4.1. Range of SMT values in healthy human adults

Regarding the range of SMT values, we have selected the studies that propose an SMT task as a baseline, followed by a second task that is usually a sensorimotor synchronization task, without comparison between factors or conditions (Table 3). However, no value of SMT is reported in some studies (N = 2/13). Hence, it is important to measure the SMT as a baseline before any rhythmic task and to report the SMT values in order to interpret the results with regard to this baseline.

The number of studies measuring the SMT as a baseline for a rhythmic task (to adjust the tempo of the rhythmic task) is rather low (Table 3), compared to those testing the effects of variables on the SMT values (Table 4). This may be due to the fact that the terminology used to designate the spontaneous motor tempo is heterogeneous. Although the SMT was clearly defined by Fraisse (1974) as the speed that the subject considers most natural and pleasant (p. 50), this terminology is not unanimous. Although some authors use the term “spontaneous motor tempo” (Drake et al., 2000; McPherson et al., 2018; Amrani and Golumbic, 2020), others use different terms, such as “preferred motor tempo” (Michaelis et al., 2014), “preferred rate” (McCombe Waller and Whitall, 2004), “preferred frequency” (Volman et al., 2006; Bouvet et al., 2020), “internal clock” (Yahalom et al., 2004), “spontaneous production rate” (Wright and Palmer, 2020), “motor spontaneous tempo” (Dosseville and LaRue, 2002; Moussay et al., 2002), “spontaneous movement tempo” (Avanzino et al., 2015; Bisio et al., 2015), “freely chosen cadence” (Sidhu and Lauber, 2020; Hansen et al., 2021), or “personal tempo” (Tajima and Choshi, 1999). In the same vein, the term “self-paced” is not used with a consensual definition. Sometimes, this term relates to an intentional spontaneous motor behavior without a rhythmic component, even if authors use the term “self-paced tapping” (e.g., Bichsel et al., 2018, not included in the present review), and sometimes it relates to an intentional spontaneous rhythmic motor behavior when “self-paced” is followed by “tempo” (Serrien, 2009; Hattori et al., 2015). For future studies measuring the SMT, we recommend using the terminology “spontaneous motor tempo” when the participant is invited to produce a rhythmic motor task not induced by external stimuli specifying a required tempo. The term “spontaneous motor tempo” should be preferred to the term “self-paced” to define the task. To increase the visibility of studies implying SMT, the term “spontaneous motor tempo” and its acronym “SMT” should appear in the title or keywords of the articles.

The tasks used to measure the SMT are also very heterogeneous. Even if Fraisse (1974) declared that SMT is commonly measured during a manual task (Fraisse, 1974), our results reveal that studies exploring SMT also measure other effectors apart from manual ones. Some studies use self-paced tapping with one or two effectors; others use drumming, hopping, pointing, cycling, swaying, and producing syllables; and another uses jaw opening-closing and chewing (Table 3). Regarding the SMT values, participants seem to be slower when the whole body or the jaw is required, compared to manual responses. Thus, the heterogeneity of effectors (finger, arm, leg, whole body, mouth/lips, and jaw) used to produce the SMT could explain the heterogeneity of results. This hypothesis could be in accordance with the results of Sakamoto et al. (2007), highlighting that the SMT is effector-dependent (Sakamoto et al., 2007), but we recommend to carry out further studies to test the impact of effectors on SMT.

The range of SMT values (from 333 to 3,160 ms) is far from being a common value of 600 ms, as first reported by Fraisse (1974). More specifically, it is important to note that studies reporting the slowest SMT values involve cyclical movements compared to the discrete isochronous movements of tapping or clapping. Regarding finger tapping, SMT appears to be faster (from 333 to 931 ms). Bouvet et al. (2020), who investigate the effect of accents and subdivisions in synchronization, performed a measurement of SMT during finger-tapping with a large number of taps in several trials. They also find a faster value around 650 ms. The heterogeneity of results can be explained by the heterogeneity in the paradigm applied to measure the SMT in the studies. We provide such examples in the following paragraphs.

First, the characteristics of participants are not homogeneously reported, particularly their level of musical experience. In some studies listed in Table 3, authors report that participants have no musical training. Note that some studies mix musicians and non-musicians in their samples (e.g., Michaelis et al., 2014; De Pretto et al., 2018). However, three studies reported in Table 4 show an effect of music expertise (Drake et al., 2000; Slater et al., 2018; Hammerschmidt et al., 2021). Information about musical expertise is particularly important, including the expertise of listening to music, given that it is possible that participants could present amusia or a deficit in rhythm production or perception (Stewart et al., 2006; Clark et al., 2015; Peretz, 2016; Sarasso et al., 2022). To have a better overview of the range of SMT values in healthy adults without musical expertise, we recommend reporting a general level of musical experience, that is, both the level of expertise in music/rhythm production and music/rhythm exposure.

Second, the characteristics of participants are also heterogeneous across studies in terms of age, sex, and laterality. Regarding the age, participants are from 18 to 45 years old (Table 1). Despite the fact that the age range is representative of healthy young adults, the range of SMT values varies in five studies about manual responses from 333 to 1,100 ms (Michaelis et al., 2014; De Pretto et al., 2018; McPherson et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2020). Regarding the sex repartition, only two studies recruit an equal number of women and men (Michaelis et al., 2014; De Pretto et al., 2018); the others recruit either more women or more men. As reported in Table 4, the effect of sex on SMT has not been extensively studied, given that only one study addresses this question and reports no significant results (Suzuki and Ando, 2018). Regarding the laterality, the majority of studies do not report the laterality of participants (Table 3, N = 8/13). The other studies generally recruit right-handed participants (Table 3, N = 3/5). Some studies include one or two left-handed participants (Table 3, N = 2/5). In Table 4, no study investigates the effect of laterality on the SMT values. In the absence of clear results about laterality, we recommend specifying the laterality of the participants by means of a laterality questionnaire (e.g., Oldfield, 1971) in the case of a SMT task performed with a lateralized effector (hand or leg). More globally, to have a better overview of the range of SMT values in healthy adults, we recommend reporting the age, sex, and laterality of participants and specifying, if possible, whether the SMT differs according to these variables.

Third, how the SMT is measured is not consistent across studies (Table 3). As specified in Table 3, SMT paradigms differ according to the number of trials and their duration, as well as to the instructions provided to the participants. The number and duration of trials vary across studies. Globally, the number of trials is from 1 to 10, and the duration of each trial can be expressed as a range of time (seconds or minutes), a number of responses, or a number of inter-response intervals (Table 3). Two studies do not report any information about trials (Ruspantini et al., 2012; Malcolm et al., 2018). Regarding the instructions, it is important to note that the instructions are not reported in three out of 13 studies (Eriksson et al., 2000; Hattori et al., 2015; Malcolm et al., 2018). When reported, the instructions contain the terms “natural,” “comfortable,” “most comfortable,” “naturally comfortable,” “preferred,” “steady,” “freely chosen,” “own self-selected,” “spontaneously,” “without mental effort,” “do not require much awareness,” “without fatigue,” and “could be performed all day if necessary,” to characterize the manner to produce the SMT (Table 3). Moreover, the tempo itself is characterized as “tempo,” “pace,” “cadence,” “speed,” “rate,” and “frequency.” Even if these terms are supposed to represent the same instruction, we would like to emphasize that the semantics is not a detail. The instruction can modify the participant's behavior depending on the interpretation he/she makes of it. For example, the term “speed” can be interpreted by participants as an instruction to go fast. Thus, to have a better overview of the range of SMT values in healthy adults, we recommend reporting exactly and exhaustively the standardized instructions given to participants. More precisely, we recommend giving priority to the notions of “preferred,” “spontaneous,” and “comfortable tempo,” in the instructions given to the participant. It seems important to avoid the notion of “speed” in order not to induce the idea of performing the task as quickly as possible.

Fourth, how SMT is recorded and computed is not consistent. Regarding the measurement recordings, authors report the inter-response interval, frequency, number of movement cycles during the total duration of the trial, rate, cycle time, speed, or cadence. If reported, the values also have different units (milliseconds, seconds, beats per minute, Hertz, repetitions per minute, or kilometers per hour). Furthermore, the authors usually report the range of SMT values, the SMT mean and/or median, its standard deviation, and/or the coefficient of variation (Table 3). These discrepancies are probably due to the type of task used. Only two studies recording SMT do not report any value for SMT (LaGasse, 2013; Zhao et al., 2017). On this basis, we recommend reporting the SMT values when recorded and homogenizing the measurement recording, the variables, and their units (in milliseconds or Hz). It is, therefore, necessary to report, at least, the SMT values with the median and the range of SMT values with a box plot representing individual values to get access to the distribution of data with the minimal and maximal values. It is also important to specify the methodology to compute the SMT, in particular to report excluded data, for example, the first responses that were performed by the participants, which can be considered warm-up.

4.2. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors modulating SMT values

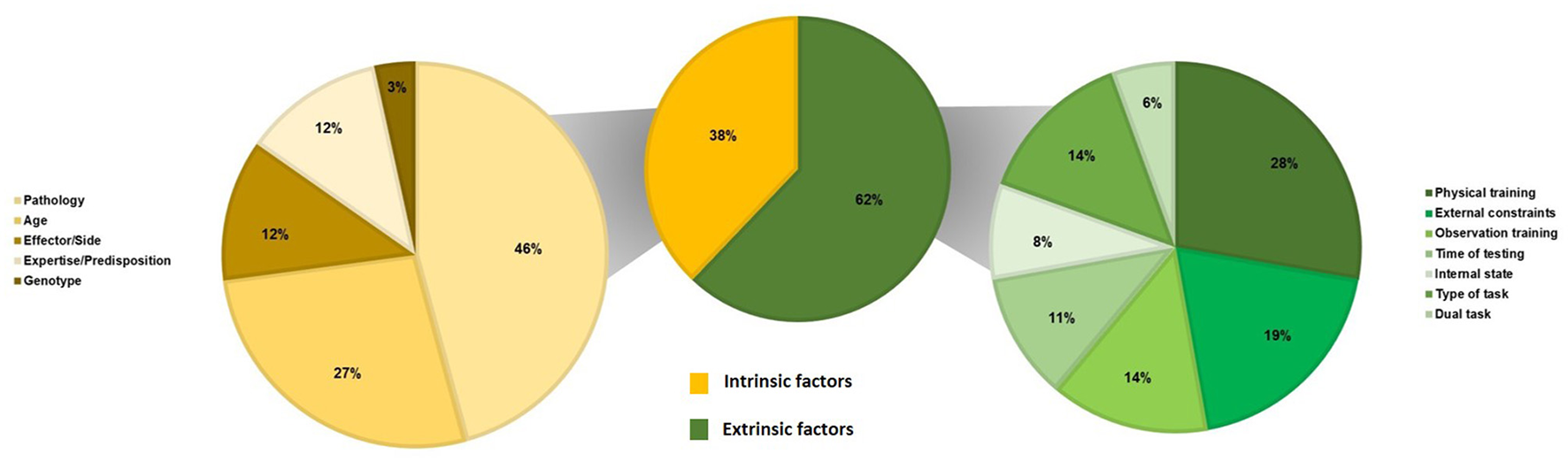

Table 4 summarizes the results of studies about factors that could modulate the SMT values. We classified these factors as intrinsic and extrinsic ones, i.e., factors that could explain inter- and intra-individual variability in SMT values. Figure 3 presents the repartition of studies about the factors modulating the SMT values according to the intrinsic factors (N = 59) and the extrinsic factors (N = 36).

Figure 3

Repartition of studies on the factors modulating the SMT values (N = 94) according to intrinsic factors (N = 59) and extrinsic factors (N = 36).

Regarding the intrinsic factors, our results reveal that the SMT is affected by several factors such as pathology, age, effector, expertise, or genotype (see Table 4). First, our results reveal that several pathologies modify the SMT values. Studies investigate brain lesions (six on Parkinson's, four on stroke, one on Huntington disease, one on Alzheimer's disease, one on Whiplash, and two on cerebellar lesions), neurodevelopmental disorders (two on attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, two on developmental coordination disorder, one on developmental intellectual deficit, one on stuttering, and one on minor neurological dysfunction), and mental disorders (two on schizophrenia). Two studies test the effects of a deficit in music perception (beat deafness, i.e., difficulties in tracking or moving to a beat), and only one study examines the effect of an amputation. Globally, our results show that the most studied pathologies are brain lesions. Results indicate quasi-unanimously that SMT is affected by brain lesions (Table 4, N = 12/15). Studies report that either the frequency or the stability of the SMT differs in brain-injured patients compared to controls. In brain lesions, neurodegenerative disorders are the most studied, such as Parkinson's and Huntington's diseases (both implying a lesion of the basal ganglia) or Alzheimer's disease. Studies on Parkinson's disease report quasi-consistently that SMT is significantly affected in patients compared to healthy elderly individuals (Table 4, N = 5/6), and the study on Huntington's disease reports the same effect (Martínez Pueyo et al., 2016). The only study on Alzheimer's disease does not report any difference between patients and healthy elderly individuals (Martin et al., 2017). Moreover, most of the studies report that SMT is significantly affected in patients with stroke compared to healthy adults (Table 4, N = 3/4). In contrast, results are less consistent for neurodevelopmental and mental disorders. Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder seems to affect the SMT (Table 4, N = 2/2), as does developmental coordination disorder (Table 4, N = 2/2). Only two studies report the effects of beat deafness with no consistent results (Phillips-Silver et al., 2011; Palmer et al., 2014). Based on these results, it is interesting to note that the SMT is affected regardless of the location of the lesion (motor cortex, language areas, basal ganglia, or cerebellum) and regardless of the physiopathology (neurodegenerative vs. neurological vs. neurodevelopmental). Although it seems more likely that focal lesions affect the SMT, future studies are required to better understand if and how the SMT is affected by neurodevelopmental, mental, and sensory disorders.

A second factor modulating the SMT is age. Studies investigate mostly infants (Table 4, N = 14/16). Only three studies investigate the elderly (Vanneste et al., 2001; Baudouin et al., 2004; McAuley et al., 2006). Our results reveal that age modifies the value of the SMT in the majority of studies (Table 4, N = 11/14). In fact, only three out of 14 studies do not find an effect of age in infants or children (Droit et al., 1996; Fitzpatrick et al., 1996; Yu and Myowa, 2021). It is interesting to note that only two studies test the possible effects of age on the SMT in individuals between 18 and 60 years old (McAuley et al., 2006; Hammerschmidt et al., 2021). Anyway, our results suggest that future studies about the SMT should take into account the effect of age bands or include the age of participants as a covariate, especially if participants are infants or elderly individuals.

A third intrinsic factor modulating the SMT is the effector/side used to produce the task. Results are very contradictory, with one study revealing an effect of the effector (Sakamoto et al., 2007) and two studies failing to reveal this effect (Tomyta and Seki, 2020; Rose et al., 2021). It seems that there is no effect of the side of the hand producing the SMT (Kay et al., 1987; Byblow and Goodman, 1994; Whitall et al., 1999). Moreover, it is also possible that SMT differs when it is produced with arms and legs (Sakamoto et al., 2007). Finally, the study of Getchell et al. (2001) reveals a correlation between SMT produced by different effectors. This result suggests that individuals have a general ability to produce their own SMT regardless of the type and number of effectors used (Getchell et al., 2001). Given that only one study reports this finding, further studies are required to confirm this effect.