Abstract

North Indian Classical Music (NICM) provides a structured context to examine how improvisational and memory-based skills are developed through oral transmission. While improvisation is central to NICM performance, there is limited research on the pedagogical strategies that support its acquisition, particularly in relation to cognitive processes such as memory, pattern recognition, and schema development. This study analysed audio-visual recordings and fieldnotes from music lessons in both music schools and guru-śiṣya paramparā settings in India. Lessons were coded thematically with attention to instructional techniques, learner responses, and cognitive strategies including repetition, segmentation, and variation. Students were rarely asked to improvise spontaneously. Instead, learning focused on imitation and memorisation of modelled material, with inexact replication often leading to creative recomposition. Teachers used structured sequences of palṭās and tāns to support phrase construction, pitch accuracy, and intensification strategies. These techniques scaffolded both domain-specific (musical) and domain-general (cognitive) skills. Findings suggest that improvisational competence in NICM is developed through memorisation, structured variation, and implicit learning. The study contributes to understanding how oral traditions support cognitive development in music and highlights the need for further interdisciplinary research on learning and memory in non-notated musical systems.

1 Introduction

Cognitive aspects of musical learning have long been of interest to researchers in developmental psychology because of the way in which musical learning and performance use so many areas of the brain in their execution (Kraus and Chandrasekaran, 2010; Habibi et al., 2018). The cognitive processes at work when western musicians perform in a variety of different situations have been explored at length in the music education literature, however a paucity of research on learning, practice, memorisation and performance beyond the Western Classical tradition has been identified (Hallam et al., 2016). Within the field of ethnomusicology there is a growing body of work surrounding the cognitive processes of musicians from oral traditions (Pearce and Rohrmeier, 2012) which highlight the differences in cognitive challenge between performing improvised music when contrasted with memorised music or reading music from written notations. This study seeks to build on and develop these ideas relating to North Indian Classical Music (NICM).

Similarly, in the field of music education, the challenges that western musicians face in developing improvisation skills after they have learnt music using pedagogies common to the western classical style of learning are well documented (Kratus, 1991; Sudnow, 2002; Sawyer, 2007; Shevock, 2018). Hadar and Rabinowitch (2023) propose that factors affecting the ‘tightness’ or ‘looseness’ of improvisation within a musical style can be understood in terms of their varying levels of structural sparseness, flexible social roles, cultural nonconformity and creative freedom resulting in a continuum of overall looseness with free jazz at one end of the spectrum and western classical music at the other. This demonstrates how important contextual aspects are when attempting to understand improvisation within a style of music. The article continues to argue that NICM occupies an area of the spectrum closer to western classical music than free jazz and is an area for western classical musicians to consider when seeking to broaden their pedagogical strategies for the development of improvisation skills.

This study therefore aims to identify what the improvisatory objects and processes being used in the training and performance of NICM are. This will be achieved by reviewing ethnomusicological literature and analysing video recordings of lessons (tālīm). For readers unfamiliar with the context of NICM, the next few sections of the introduction provide a review of what ethnomusicologists have written about improvisation in NICM so far, with a focus on dhrupad, ṭhumrī and ḵẖayāl (vocal music styles). Appendix A provides a glossary of key terms at the end of this article for reference.

2 Materials and methods

The lack of comprehensive contemporary literature reviews on improvisation in North Indian classical music (NICM) necessitates an explanation of the improvisatory objects and processes at work in a performance. Once these have been identified, a short-term, naturalistic, qualitative research design will be employed to identify how these are taught in practice. The theoretical perspective underpinning this research design is interpretivist and it is situated within a social constructivist view of epistemology. The methods of data collection were mainly observations recorded as fieldnotes and videos. Analysis of the data has incorporated aspects of thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2022) leading to schema analysis following the initial coding stages. By looking at these strategies in depth, the aim is to uncover ways that teachers develop the capabilities of their students in relation to the creation of musical performances.

This supports the overall aim to understand the multi-layered complexities of the teaching and learning strategies used using qualitative rather than quantitative methods (Cohen et al., 2018, p. 434). The study seeks to avoid simplifications through the selection of a qualitative methodology to reflect the “contradictions, richness, complexity, connectedness, conjunctions and disjunctions” (Cohen et al., 2018, p. 288) of the social, musical and educational worlds of the research participants.

Researcher positionality requires me to locate my views, values and beliefs in relation to the research process and the research output. To allow me to do this effectively, it was necessary for me to become a learner of NICM so that I could reflect on the activities that I was observing with the insight of a learner (albeit an adult, Western learner). My positionality as a researcher working in an inter-disciplinary way makes it important to ensure that in designing an appropriate methodology and set of methods by which to investigate pedagogical strategies for improvisation in NICM, that the customary approaches of both ethnomusicology and educational psychology were followed. I attempted to carefully manage the issue of me being a white, western educated, middle aged, female teacher-researcher taking my values and biases to modern India. The issues here affect not only the validity and reliability of my research but the ethics of my doing the research in the first place. Three issues in educational research in postcolonial context are highlighted by McKeever:

“Do I, as a white person have any right to research Indian experience? […] The ethics of knowledge production in a country that has experienced colonization and the dangers of conducting research that perpetuates a colonialist ethics.” (McKeever, 2000, pp. 102–103)

There were undoubtedly aspects of my privilege that were unavoidable, but I attempted to mitigate this by presenting myself authentically—as an interested student with a passion for learning from the teachers and students within the music schools, gharānās and gurukuls where I was permitted access. I felt that I had a responsibility to try not to make students or teachers feel uncomfortable due to my presence, and I attempted to convey this through my dress, my manner and responding to any conventions of behaviour that were expected of students.

Data was generated by observing lessons in six urban centres in India (New Delhi, Varanasi, Kolkata, Bhopal, Lucknow, and Mumbai) during the academic year 2016–17 as part of my PhD research. Initially, records of these were kept using written fieldnotes, but this technique progressed to making dual-perspective video recordings at a later stage in the research once codes and themes were becoming clear in the data. This allowed me to focus one camera on student(s)/śiṣya(s) and one camera on teachers/gurus which were later combined within the same frame. The written-up fieldnotes and video observations were imported into NVivo—a Computer Aided Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS) package which allowed me to assign codes to the data, apply classifications and run queries related to the data generated (Lewins and Silver, 2007).

Participants and field sites were selected by ease of access. Whilst this is not an ideal system in terms of obtaining the widest possible spread of teachers/gurus, it did ensure that the collection of data was efficient, and that teachers and gurus were willing to give their consent to be recorded. More selective methods posed challenges, due to the presence of gatekeepers who, without a formal introduction from someone they know and respect would not be willing for me to observe their teaching and talk to their pupils. In many situations I felt that teachers were giving a ‘demonstration lesson’ rather than teaching ‘normally’, and these observations have been excluded from the data corpus. Duran et al. (2011) also experienced these difficulties and resolved them in the same way. I also excluded lessons where errors in my communication had led to me observing instrumental rather than vocal lessons, because I considered that instrumental techniques for improvisation would be different from those used in vocal lessons.

Once the data from ‘demonstration lessons’ and instrumental lessons was excluded, I had 19 h and 4 min of recorded lessons/tālīm. Once themes had been identified and applied to the timestamps on the videos, the CAQDAS package also gave the option of moving between episodes in the video data where themes had been identified, to check and compare the places where a particular feature had been coded for. This brought structure to a previously unstructured set of data, allowed me to keep track of (and review) transcripts of lessons and allowed me to see how far I had progressed with the coding of the dataset, and to make a note of emerging notes on the data as I coded. From this data, two illustrative examples were selected, one from a music school and one from the guru-śiṣya paramparā (GSP—a lineage of teaching and learning where knowledge is imparted through a relationship between guru and śiṣya) from which the illustrative examples for this research article are drawn.

3 The practice of North Indian classical music—its grammar and oral transmission techniques

In performance, NICM shares several conventions with western classical music. Performers tune their instruments on stage at the beginning of a concert and sometimes adjust their tuning during the performance too. They perform for a quiet and seated audience, with or without amplification, depending on the venue’s size. Those seated near the front often have higher social or artistic status and may call out in admiration at particular features of the improvised performance, to which performers may respond (Clayton, 2007; Clayton and Leante, 2015). Performances typically include an accompanying drone played by an instrument such as the tānpūrā and/or an electronic śruti box, which serves as a constant reference point, allowing musicians to focus precisely on intonation during performance, rehearsal, tālīm, and riyāz (practice). A significant emphasis is placed on the accuracy of intonation, which is remarkable given the absence of fixed pitches for tones beyond the natural fourth, fifth, and octave. The other pitches can vary microtonally between rāgs (named melodic frameworks for improvisation) and musicians (Bor, 1999). This complexity demands that performers internalise the notes of the rāg they are to improvise, resulting in the practice of doing rigorous and repetitive exercises focused on intonation during the initial stages of training. These repetitive exercises (known as palṭās) have been extensively described in the literature (Deshpande, 1989; Magriel, 1999), but they can affect the progress and motivation of young students too, particularly when students are reliant on their own auditory perception skills to determine whether they are rehearsing them with accuracy. Rāg is an important concept in NICM which is difficult to define, but usually refers to a combination of the melodic mode and vocal/instrumental colour conveyed by the performer. The melodic mode is known as the thāt and there are many different rāgs in each thāt for example kalyāṇ thāt which broadly corresponds to the Lydian mode and counts yaman, hindol and deś amongst its rāgs.

Rather than performing named compositions, each part of a concert programme will focus on one rāg. This intense focus on pitch accuracy highlights another crucial distinction between rāgs and scales. A rāg is not merely a scale or mode; different rāgs may use the same pitches but in varied configurations. The characteristics distinguishing one rāg from another include scale, ascending and descending lines, the number of notes, emphasised notes and register, intonation, obligatory embellishments, and the intended time of performance (Jairazbhoy, 1971; Sorrell and Narayan, 1980). The inventory of melodic ingredients of a rāg involves the arrangement of swars (notes) in ascending and descending orders of pitch, tetrachord configurations, and a hierarchy of melodic importance among the notes. This includes contours and paths for moving through this configuration, the function and aesthetic effect of each swar, and microtones and microtonal inflections (McNeil, 2017).

Musicians ascribe different moods and feelings to specific rāgs, often linked to the lyrical themes of bandiśes (fixed melodic compositions) performed in these rāgs. During improvised sections, performers must evoke the emotion of the rāg rather than focus on individual pitches and their transitions. Performances are constructed in real-time rather than from notation, requiring extensive memorisation of both fixed elements of the composition and key phrases of the rāg. These key phrases, often including distinctive ornamentation, are essential for audience recognition of the rāg. The oral tradition in NICM is organised around these antecedent sets of phrases, and the process of weaving them together with consideration of expansion, increase, extemporisation, and gesture is crucial for producing a compelling improvised performance (Neuman, 2012). This use of set patterns aids memory and facilitates elaboration, although the terminology used by ethnomusicologists to describe this elaboration is inconsistent, and further exploration is needed to understand the cognitive processes at work during performance. For example, Neuman (2012, p. 444) uses the terms pakaḍ, calan, vistār, baṛhat (increase), upaj (extemporisation or variation) and andāz (gesture/conjecture) but these terms are not universally understood by musicians and ethnomusicologists. McNeil (2017) considers that this elaboration works at three levels vadi bheda, chalan bheda and uccharan bheda and conceives of fixed melodic material as ‘seed ideas’ from which improvised materials grow.

3.1 The classicisation of an oral tradition

Colonial efforts to modernise and categorise aspects of Indian culture significantly influenced educational practices in institutions. Reformers like Bhātkande and Paluskar sought to place music education at the heart of cultural education, especially its theoretical aspects (Bakhle, 2005). Bhātkande envisioned a democratised system of music education that would make music instruction common and universal in India (Bhātkhande, 1934). These reforms have left a lasting impact, with the creation of music colleges which continue to follow their ideas. These reformers, who were often English-educated, high-caste, middle-class Hindus, prioritised a national system of music education with a greater focus on explicit theory teaching compared to the traditional guru-śiṣya paramparā (a lineage of teaching and learning where knowledge is imparted through a relationship between guru and śiṣya). Modern music colleges offer qualifications like the Sāṅgīt Vishārad, (equivalent to a Bachelor of Music), which include extensive factual knowledge about NICM and require students to learn numerous rāgs for performance (Pradhan, 2009).

This structured, institutional approach focused on amassing a breadth of knowledge quickly, contrasts with the GSP, where learners might spend months on exercises in a single rāg under close supervision (Deshpande, 1989). Pradhan questions the ability of students at modern music colleges to retain information long-term due to the high number of rāgs included in institutional syllabi (Pradhan, 2009). Teacher training also faces issues, with teaching roles often given as philanthropic gestures rather than appointments being made based on pedagogical expertise. Neuman (1980) also noted that institutional teaching methods differ significantly from the GSP. However, many private music schools today adopt its principles to promote a particular educational ethos. These schools prefer to recruit their own alumni as teachers, ensuring consistency in expectations, syllabus knowledge, and pedagogical strategies. This practice reflects a modern interpretation of paramparā (tradition) where the collective teachings of an institution replace the traditional guru. Music schools often advertise the idea of a gurukul (training institution run by a guru) or GSP as integral to their teaching model. This approach has been highlighted by Krishna as “an ideology rather than a pedagogical reality” (Krishna, 2020, p. 28). In music education, the GSP emphasises enculturation over transmissive strategies, fostering a sense of music as divine rather than a marketable commodity. This approach helps preserve the nature of the tradition and sustainability, ensuring it is passed on to future generations, however the extent to which this ethos is shared by private music schools varies between institutions.

3.2 The improvisatory characteristics of NICM

During a performance, musicians rely heavily on memory to improvise. Nooshin (2003) theorises that memorising models during training teaches compositional principles useful for improvisation and variation. Pressing’s cognitive model of improvisation development emphasises the improved efficiency, fluency, flexibility, error correction, and expressiveness that develops with improvisational competence. This model accounts for inventiveness and coherence through specific cognitive changes:

“Increased memory store: Expanding memory of musical, acoustic, and motor aspects.

Improved memory accessibility: Building redundant relationships and aggregating constituents into larger cognitive assemblies.

Refined perceptual attunement: Enhancing sensitivity to subtle and contextually relevant information” (Pressing, 1988, p. 166).

The relationship between memory and perceptual information selection described here, which develops increasingly efficient neural pathways, is key to developing the ability to create compelling and coherent performances of NICM.

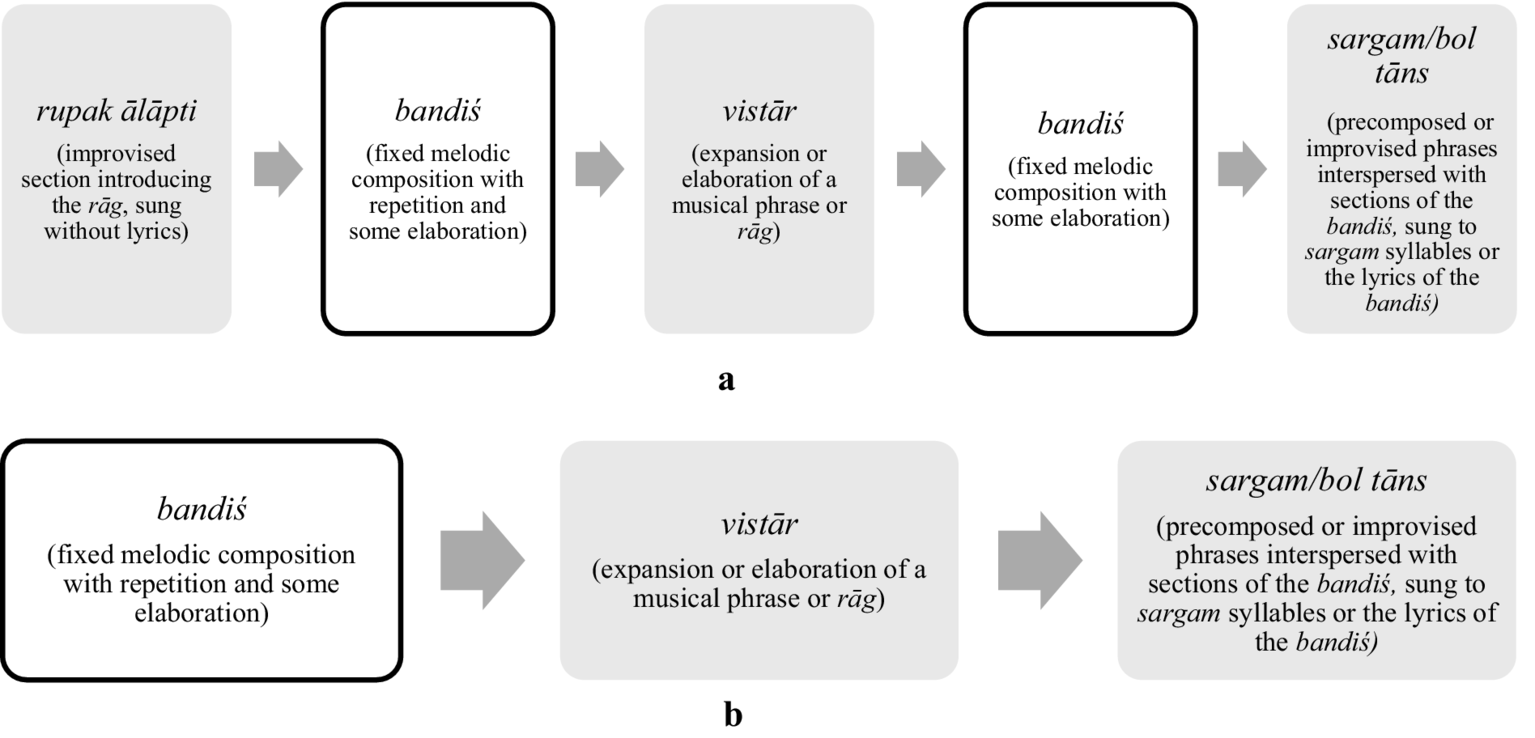

Despite the fact that all phrases are open for embellishment in NICM, a clear distinction is made between the composed and improvised sections of a performance (Nooshin and Widdess, 2006). The precomposed parts (bandiśes), vary melodically and textually between gharānās and have evolved over time, although their themes, lyrics, and rāgs have endured for centuries. Performers still ornament the bandiś, varying the ornamentation each time a phrase is repeated. The structure of a performance has important implications for developing improvisatory competence in NICM where a performance of a rāg can last for 45 min to well over an hour depending on contextual factors. The structure of a ḵẖayāl performance (a style of vocal music whose literal translation is imagination) is shown in Figures 1a,b. These illustrate the pre-composed and improvised sections of a baṛā (long) and choṭā (short) ḵẖayāl.

Figure 1

(a) The structure of a baṛā ḵẖayāl (long ḵẖayāl) in slow-medium tempo demonstrating the improvised sections in shaded boxes and fixed composition sections in bordered boxes. (b) The structure of a choṭā ḵẖayāl (short ḵẖayāl) which will often follow a baṛā ḵẖayāl in performance. The improvised sections are shown in shaded boxes and the fixed composition sections are shown in bordered boxes.

Whilst the length of time spent on each of these sections varies greatly, is clear from these structures that a performer will be improvising for most of the performance. Whether in terms of embellishment of precomposed material or in the creation and recreation of phrases best suited to expressing the sentiment of the rāg. These structures for performance featuring a balance of fixed composition and improvisation form the basis of transmission in NICM. Just as there are a balance of memorised phrases and the rearrangement, combination and creation of new musical ideas in a performance, so this mirrors the pedagogical strategies used to develop improvisatory competence. To the extent that just as a performance will begin with a focus on the drone and slow unfurling of the ālāp (opening section of a baṛā ḵẖayāl) before the more metrically bounded sections of the bandiś, vistār and tāns, the sections of a singing lesson are structured in just the same way.

3.3 Pedagogical strategies used to develop improvisatory competence

Learning bandiśes orally by rote puts the focus on the memory of the sounds rather than the memory of written lyrics or the degrees of the scale. This learning is approached very differently in the GSP where repertoire will be learned aurally which stands in contrast to music school teaching where written lyrics and notation will often be used for support. There are key differences between learning a song aurally and from notation. Aural learning develops strong ‘associative chains’ (Farrell, 2012) where each passage cues the memory of what comes next. This is important not just for the bandiś section of a performance, but also for the improvised sections that are text/rhythm oriented. In these sections, a short section of the bandiś (usually the first phrase, known as the mukhṛā) will be sung, followed by tāns. In some styles of music, this can present a problem, because to ‘reach for’ a specific link in the associative chain a student must start at the beginning. This is not generally an issue in NICM because the first line is returned to many times during the performance and could effectively cue a whole range of different phrases that have been modelled by a teacher and learned by rote. In contrast to this, learning from written notation/lyrics develops a student’s ‘content addressable’ memory (Chaffin et al., 2016) allowing them to answer questions such as ‘how does the second line of the bandiś go?’ without having to sing it in their head from the beginning. These two different ways of accessing memory demonstrate that if a student learns a bandiś using written notation and lyrics, these memories are more likely to be content-addressable and explicit/conscious. Learning a bandiś aurally will construct associative chains that are implicit/unconscious and involve procedural knowledge that cannot be easily expressed in words. This highlights the difference between learning a bandiś and memorising a bandiś, a distinction which appears in Western music but not necessarily in NICM, a context in which, to learn a bandiś a student must also memorise the bandiś.

3.4 Generative and formulaic perspectives on improvisation

The question of whether improvisation in NICM is generative or formulaic is contested within the literature. The generative view suggests that improvisation is driven by associative, moment-to-moment decisions based on preceding material Powers (1980) and Pressing (1988) liken this to language analysis, proposing that improvisation involves stringing together event clusters, akin to constructing a generative grammar for rāgs. Clarke (1988, 1993) supports this by linking improvisation to hierarchical and selective elaboration, evident in the structured progression of phrases during ālāp. He suggests that generative principles underpin both melody and expression, enabling performers to create infinite variations within a finite framework. In contrast to this, Powers and Widdess (2001) highlight that rāg improvisation differs from western tonal systems due to its integration of scale, melodic motifs, and characteristic features (pakaḍ, calan). This complicates generative interpretations, as improvisation often elaborates motifs through techniques like prefixing, suffixing and rhythmic manipulation rather than by assembling notes generatively. Generative elements also appear in vistār, where musicians construct improvisations by expanding pitch ranges and manipulating rhythmic cycles. Slawek (1998) identifies learned ‘programs’ driving this process, exemplified in both tāns and vistār. Performers balance pre-existing schemas with spontaneous adjustments, using freed cognitive resources to focus on expressive nuances.

The formulaic argument posits that improvisation relies on a repertoire of stock phrases and variable strategies adapted to the rāg and performance context. Zadeh (2012) critiques generative models derived from western traditions, emphasising the role of ‘stock expressions’ and ‘variable melodic outlines’ in the genre of ṭhumrī. These formulas, drawn from oral traditions and adapted idiomatically, serve as structural and expressive tools, guiding performers through improvisatory constraints. Ethnomusicological studies of improvisation in NICM such as Zadeh’s have contributed evidence to the formulaic argument by documenting techniques such as transposition, chromatic slides and manipulating the audience’s expectations by delaying resolutions. Magriel (1997) finds that while NICM artists from a particular gharānā share a common ‘dialect’, their individual ‘idiolects’ shape distinctive improvisatory styles. This explains why students often inherit stock expressions from their teachers, reflecting the transmission of formulaic knowledge.

3.4.1 Improvisatory objects: ornaments/embellishments

McIntosh (1993) explores the improvisatory objects and processes involved in embellishing a bandiś, suggesting that improvisatory processes occur through the accumulation of components of various sizes. This process operates at different levels, including the construction of embellishments on a single note. In lessons, teachers may add ornaments, alter the rhythm of the sthāyī, and emphasise specific words through repetition, articulation, or gesture.

Pearson (2016) analyses both musical and physical gestures in performance, examining the relationship between svars (notes) and gamaks (ornaments). She demonstrates how musicians link these musical units coherently, likening it to the way joined-up handwriting uses different linkage patterns depending on the subsequent letter. Widdess (2014) similarly views a melodic pitch as part of a larger event, often linked into an expressive whole by glissando and other ornamentation. Pearson (2016) also introduces the term ‘coarticulation’ to describe this approach, borrowing from phonetics to explain how a phonological segment’s vocalisation is context-dependent and influenced by neighbouring sounds.

3.4.2 Improvisatory objects: palṭās/tāns

Just like the ālāp of a performance, the sections of a performance containing tāns are also initially memorised. Students begin with simple palṭā exercises in bilāval ṭhāṭ (Ionian mode) which develop their memory for regular patterns of notes. They then progress to advanced paḷās with more unpredictable patterns, often in different ṭhāṭs. After mastering these, students copy tāns composed by their teacher. Through practice and familiarity with characteristic phrases of the rāg, students develop strategies to fill in gaps if they cannot remember a teacher’s phrase precisely. This is combined with composing, notating, and memorising their own tāns, leading to the ability to improvise their own. An interview conducted by Nicolas Magriel with guru Devashish Dey and his son Shubhankar Dey demonstrates these strategies and processes, highlighting how they evolve from memorising and practising difficult patterns to focusing on variation. During the interview Nicolas enquires whether the ability to sing difficult patterns relies on continued palṭā repetition:

N: but what about, not just actual tāns but do you ever do this palṭā practice,

D: palṭā practice, yes

N: just some?

D: it depends because in the beginning the student should practice the palṭās more but after that you must deliberately avoid them too, because doing too much of palṭā in higher stage is not only boring but the lustre of the singing is lost something.

N: oh, that’s interesting

D: so, my teacher, Kalvinji guruji, always insisted not to do alaṅkār for long a time and always to make sa sa re ga, sa re re ga, sa re ga ga, re re ga ma, re ga ga ma, re ga ma ma, ga ga ma pa… all of these things [demonstrates this by singing very fast] all these things for the younger students, once upon a time he did a lot of practice like this, two hours or one and a half hours of this kind of thing.

Once you have got that [demonstrates some more of these palṭās with gamak] already you have then to think about how to make it more beautiful rather than to make it powerful. (Dey, 2009).

The memorisation of a palṭā itself makes it a compositional object, but when reaching for a particular phrase, the palṭā training kicks in and allows a musician to grasp it. It is important to note that palṭās are content addressable rather than dependent on associative chains because fragments of palṭās need to be reassembled automatically without conscious thought. Cognitive evidence for the fact that formulaic patterns are processed more quickly and efficiently to random ones is provided by Pawley and Syder (1983).

3.4.3 Improvisatory objects: formulas: stock expressions, variable melodic outlines and musical gestures

Studies of performance in NICM, particularly vocal styles, have explored the connections between spoken language skills and the ability to improvise musical phrases. As outlined in section 3.4, Zadeh (2012) critiques this application to NICM, arguing that formulas from oral literature, everyday speech, and other musical traditions serve as the building blocks of ṭhumrī. She highlights the difference between orality and literacy in performance, noting that formulas provide structural schemes and metrical constraints, much like in oral poetry, enabling poets to draw from a repertoire of conventional phrases rather than creating material from scratch during a performance (Zadeh, 2012, p. 38). In her thesis, Alaghband-Zadeh (2013) provides examples from Rasoolan Bai’s ṭhumrī performances to illustrate her point and identifies stock expressions that consistently appear in Girija Devi’s performances too. Zadeh also notes techniques for manipulating audience expectations by extending or interrupting phrases.

Artists deploy these techniques distinctively, which relates to Magriel’s (1997) ideas about dialect and idiolect, suggesting that while artists conform to dialect rules, they construct their upaj (improvisations on a theme) according to their personal idiolect. Once a phrase is memorised, it becomes easier to create variations and recombine different phrases imaginatively. Alaghband-Zadeh (2013) suggests that the prevalence of these formulas in performance is likely a result of how students were taught. Whether students inherit formulas implicitly or through direct instruction is crucial in analysing learning situations. Training students to listen attentively to phrases they must reproduce supports memorisation and adaptability, enabling them to ‘fill in the gaps’ where necessary. The formulas Zadeh identifies, labelled as “stock expressions,” “variable melodic outlines,” and “musical gestures,” (Alaghband-Zadeh, 2013, p. 67), along with the grand structural schemas of ḵẖayāl, dhrupad, and ṭhumrī performances, constitute improvisatory objects, as do the modal nuclei of ālāp and the pitch ranges of bandiśes (see section 3.4.5 and section 3.4.6).

3.4.4 Improvisatory objects: cadential features and overall structural conventions

Cadential features such as tihāi (a polyrhythmic technique where a phrase is repeated three times, often used to conclude a section or performance) are also considered to be an important improvisatory object to be learnt. The strategies used to teach these are not discussed in the literature, beyond examples of students learning tihāis by rote and teachers composing them for their students to learn (Clayton, 2000).

Having explained that the structure of a performance contains a balance of fixed composition and improvisation, the literature also highlights how these musical structures are reflected in the structure of each lesson (tālīm). Where a guru will usually focus on the skills required for each section of the performance sequentially. For performers, having a mental map of the whole performance is crucial if one is to be able to sustain a compelling presentation of the rāg over 45 min or more (Snyder, 2016). The process of memorisation is expedited by the fact that whatever comes next is heavily constrained by what precedes it. Music is made easier to learn by the number of constraints placed on it, and these combine to make memory reconstruction easier. The capacity to memorise quickly improves over time (Ginsborg and Sloboda, 2007), and therefore children who have been listening to and learning these songs since childhood will find them easier to learn aurally as they get older (Magriel, 1997; McNeil, 2017; Faber and McIntosh, 2020). Sanyal and Widdess (2004) calls this concept ‘recreative ability’:

“Accustomed from birth to the sounds of his father and other family members singing and playing in the home, the young musician acquires the instinctive ability to recreate those sounds with the aid of whatever materials he has learned formally. This process of tālīm encourages the development of this recreative ability, which can also be acquired by non-family disciples, and underlies the phenomenon of ‘improvisation’ in Indian music. Recreative ability is a fundamental link between the realms of tradition and performance in Indian music: it is the mastery of processes of improvisation as well as the memorisation of fixed repertory.” (Sanyal and Widdess, 2004, p. 130)

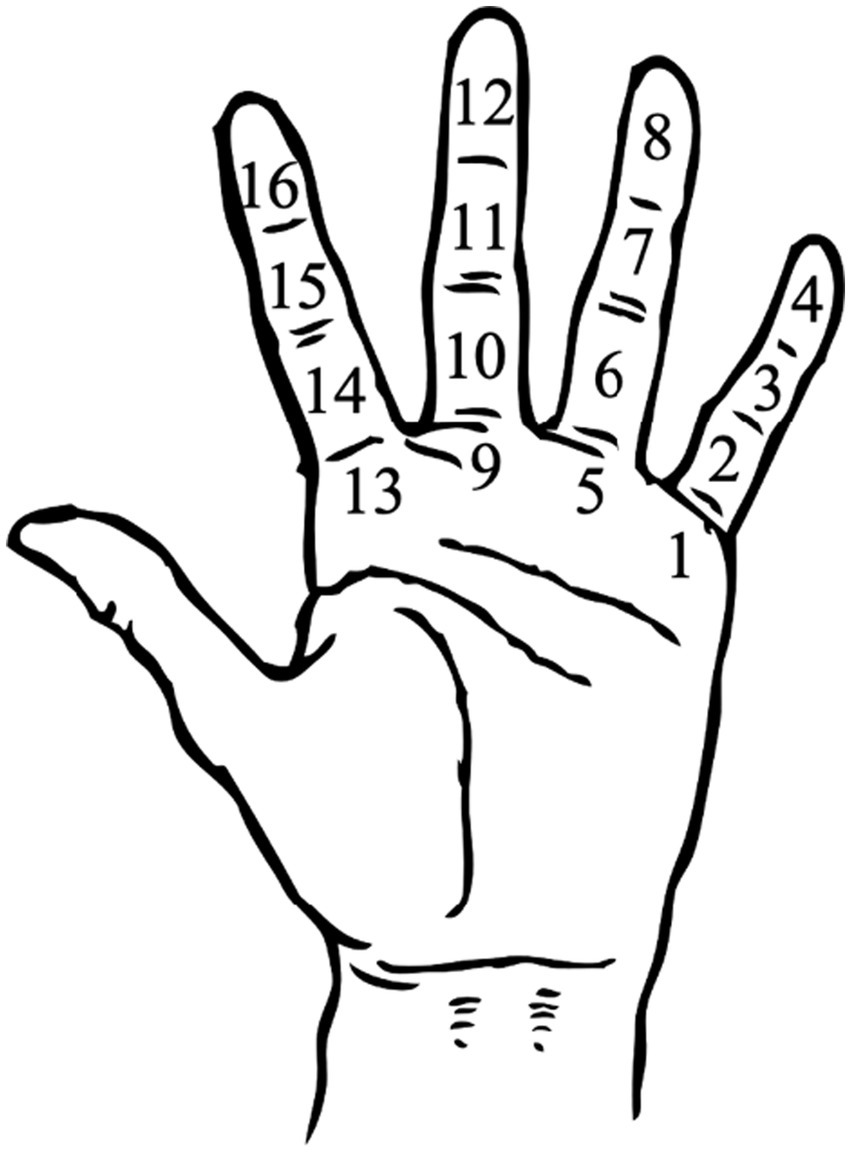

The ability to embellish phrases idiomatically therefore improves over time and with repeated exposure to the performances of gurus. The aspect of a composition that will not vary, however, is the metrical position of the beginning of the mukhṛā. If the bandiś begins on the 13th beat of a 16 beat (tīn tāl) cycle, the performer will always ensure that it begins at that point, even if the variation on the previous repetition of the mukhṛā lasted a few beats longer. This is because, during a performance, a great deal of importance is attached to the arrival of the sam (first beat of the cycle), and musicians attach a high degree of importance to ensuring that improvised phrases ‘come in tāl’ (finish on the sam). This makes keeping track of the metric cycle within a performance a very important feature of children’s learning and explains why teachers ensure that students learn how to count the metric cycle on the joints of their left hand, using their left thumb to keep their place (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Diagram illustrating the areas of the left hand where each beat is signified with a tap from the left thumb.

During lessons, this strategy will be used in a variety of ways, sometimes modelled by the teacher with the addition of saying the numbers out loud, but quite often it is used spontaneously and silently by students during tāns to ensure that the phrase they are constructing will conclude at the start of the next metric cycle. Teachers also ensure that students learn the cheironomy of metric cycles. This is the system by which each vibhāg (duration of rhythmic phrasing within a tāl) is marked by a clap or a wave. Students will use this technique during lessons, and in performance. During lessons, it can be helpful for a student who is improvising to see these points in time marked out by their classmates. It is also common to see members of an audience in a concert setting replicating these gestures. By creating structures of this type for improvisation, students are provided with a fixed point in time when they can return to the material from the start of the associative chain, freeing up their working memory to think about the next improvisatory process or object to deploy.

The implication of tālīm being structured in this way means that it becomes virtually indistinguishable from performance. Zadeh describes how the structure of improvisation was taught by her teacher:

“When I was learning to sing Indian classical music, this overall pattern would inform not only the pieces my teacher taught me, but even the way she structured my lessons. We would start with long, slow exercises focusing on sa, then explore lower register, and then start a series of exercises which reached ever higher notes while increasing in speed and complexity. By learning in this way, this overall structural progression came to seem perfectly natural to me.” (Alaghband-Zadeh, 2013, p. 34)

This makes the learning process within NICM highly efficient, as there are essentially no ‘easy pieces’ that must be mastered before a student is allowed to embark on professional repertoire. This is not to say that a student will be producing professional performances from the beginning of their training, and some rāgs are considered more difficult to learn than others, or not suitable for very young students due to the challenges of conveying the bhāva (emotion) connected with the rāg.

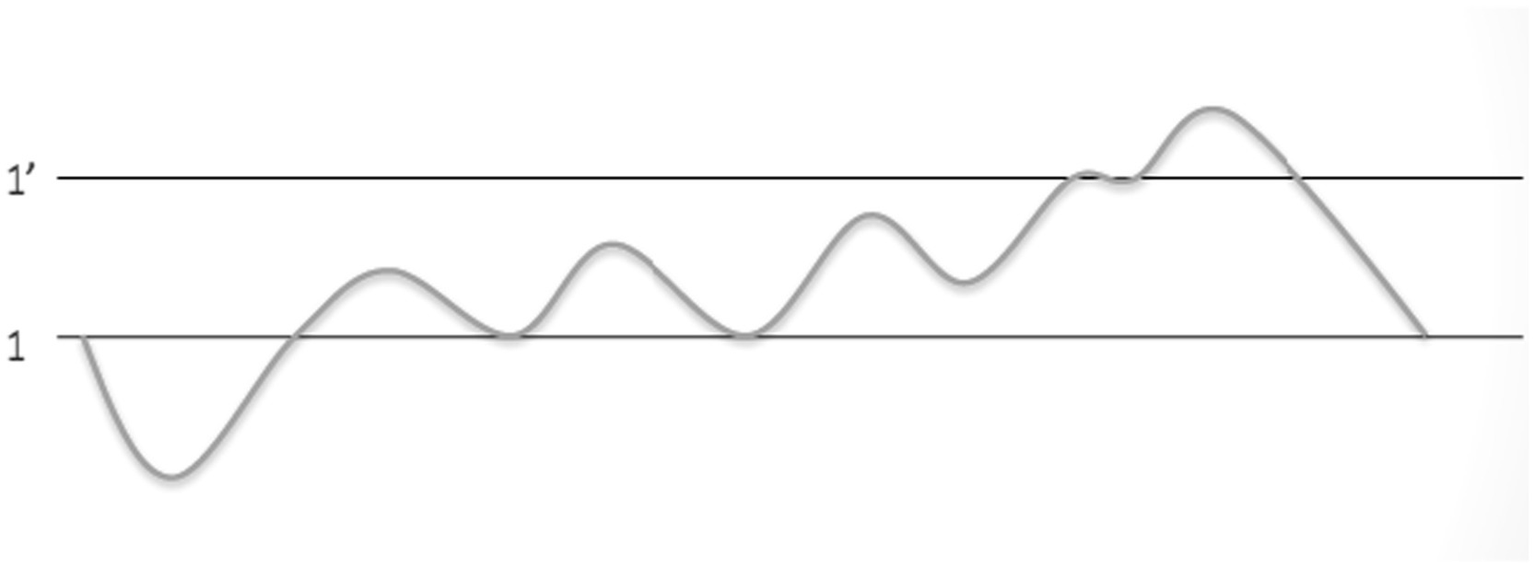

3.4.5 Improvisatory objects: modal nuclei

Modal nuclei are improvisatory objects which contribute to the constraints within which performers improvise. In the sequential phrases of the ālāp (the first section of a ḵẖayāl performance) pitches tend to lie within a specific range, developing according to a particular pattern. This strategy of using modal nuclei gradually reveals the rāg, ensuring that all features unique to the rāg are highlighted in the ālāp (Powers, 2001). Structuring the ālāp in terms of these pitch ranges also creates a teachable model for students. The ālāp progresses from the lowest to the highest register of a singer’s voice, with different scale degrees revealed sequentially. This progression is illustrated in Figure 3 in a diagram created by Widdess (2017), where the ‘sa’ of the middle octave and the ‘sa’ of the higher octave are represented by 1 and 1′.

Figure 3

Example of the pitch range used in melodic expansion of the ālāp from a lecture given by Widdess (n.d.).

Rather than indicating a single melody line, each section of the line in this diagram can be divided into phases. Within each phase, a singer produces several idiomatic phrases within the specific pitch range before moving to the next phase. The diagram shows that the ‘sa’ of the middle register is frequently returned to until the phrases approach the upper ‘sa’, and at the end of the ālāp, there is a return to ‘sa’ in the middle octave. This map of pitch contours provides students and performers with yet more constraints within which to improvise.

3.4.6 Improvisatory objects: pitch conventions of bandiśes

The idea that with practice, material becomes easier to learn because it conforms to expectations of other music that has been heard before is an important feature of learning in NICM because it also cultivates melodic expectations for rāgs. The idea of learning via exposure is not unique to NICM, and has been explored as one of the possible universal processes involved in learning music beyond the Western tradition. Stevens and Byron note that within a particular culture, perception becomes “attuned to or constrained by the culture-specific regularities and conventions (statistical structures, probabilities) of that environment” (Stevens and Byron, 2016, p. 26). Śiṣyas must develop melodic expectations for the bandiś to expedite aural learning of melodically complex material. Very early in training a student will become aware that the melody of the sthāyī (first section of a bandiś) moves in both the lower tetrachord of the middle octave and the lower octave. They will also develop an expectation that the antarā (second section of the bandiś) will rise to the upper tetrachord of the middle octave and the upper octave (Clayton, 2000, p. 114). Widdess refers to this as the antarā formula (Widdess, 1981, p. 161) and finds few exceptions to it in the published compositions and recorded performances examined.

To support students’ logical understanding of the shape of a melody, oral notation is frequently used to scaffold aspects of learning, including the bandiś. This oral notation is one of the transmissive strategies identified as part of the classicisation of the oral tradition in section 3.1, where teachers sing the note names of a bandiś in sargam (where pitches are referred to as sa, re, ga, ma, pa, dha, and ni) to help a student reproduce them accurately. This strategy can be linked to the concept of notational audiation (inner hearing of notated music). Woody (2012) found that this strategy helped musicians to perform on their instrument, with or without a score.

Morris (2005, pp. 52–55) considers that an important factor in developing students’ improvisatory capabilities is the number of bandiśes that a student knows in a particular rāg. He estimates that, whilst a student might know 3–6 bandiśes in each rāg, an established performer will know something like 10–30. This means that the task of learning compositions over the course of a learning and performing career, will lead to performers developing a repertoire of between 400 and 1,500 bandiśes. The more familiar a student is with the process of learning a bandiś, the faster they will be learnt, and experienced students have been known to pick up the lyrics and melody of a composition after only 4–5 listens. A teacher will usually break the composition down into sections and get the student to repeat each section until they are able to reproduce them accurately, before reassembling the sections until the whole sthāyī and antarā can be sung entirely. This strategy undoubtedly develops a student’s musical ear for the intricate details and nuances of a melody, and teachers are careful to ensure that students pick up these melodies and sing them accurately and with precise intonation. The extent to which a teacher’s rendering of a bandiś is consistent from lesson to lesson can be an issue for learners. Some teachers insist that they always sing the bandiś in the same way, in opposition to their students’ assertions (Morris, 2005, p. 61).

These discrepancies could be attributed to a natural part of the creative process, it is not uncommon for performers to forget lyrics or small parts of a composition and to consult other performers or recorded performances of the bandiś for clarification (see example in section 4.2). Given that musicians are used to constructing phrases to fill gaps or joining pieces of melodic material together to create improvisations, it is not too much of a leap to consider that this may also occur in the remembering of a bandiś. Morris provides an excerpt from an interview with Sharadchandra Arolkar in which he asserts “A ḵẖayāal song is not a frozen thing; it’s a fluid sculpture…The substance should be there - the expression, the meaning - but [it’s] not like tracing. You have to create, not to trace by memory” (Morris, 2005, p. 67). This example demonstrates that there are two ways in which learning compositions helps develop students’ improvisation strategies. Firstly, it improves their memories for complex melodic material and their competence in singing ornaments. Secondly, it increases a student’s understanding of the rāg and the quantity of improvisational objects that they can draw on to manifest the rāg in performance. Having a large stock of bandiśes can be seen as an alternative strategy to learning the grammar of the rāg through the memorisation of the ascending and descending grammar of each rāg where certain notes may be omitted or emphasised in ascent or descent.

In pedagogical terms, the impact of the development of sargam for use by teachers and students is highly significant to all sections of performance, including the bandiś. By creating strong associations between the name of the note and the pitch of the note, teachers are not only developing singers who can sight read the basic shape of a bandiś from notation (as in Kodály pedagogy), but they are also building the foundations for pupils who can perform their own precomposed or improvised ālāps and tāns sung in sargam. For pupils who struggle to pick up phrases from their teacher by ear, compositions notated in this form provide important visual cues for the musical material that comes next.

3.4.7 Improvisatory processes: successive variation strategies, compositional strategies, transposition strategies and subverting the audience’s expectations

The idea of syntax of musical units supports a generative view of improvisation in that a performer can string together musical units in novel ways if they conform to the conventional syntax of the musical style. Implicit understanding of melodic syntax is also vital if a listener is to enjoy a performance of Indian music, and if a performer is to use that understanding to reinforce or subvert expectations of how a particular phrase will progress. A musical event that signals that a phrase will be ending warns the listener to expect closure. And, in the same way, musical units can also fulfil a beginning or middle function. Explains that, when formulas are repeated according to the ‘successive variation strategy’ that she has defined, their function is to remind the listener of their previous occurrences, creating a sense of familiarity with the material that can then be varied in order to add interest and a sense of development to the performance. The formulas themselves delineate the structure of a particular section of the music and create a sense of musical syntax.

Compositional strategies of the type identified by Alaghband-Zadeh (2013) and Clayton (2000) have been identified in the literature that analyses performances, but the strategies used to teach them are not fully understood. There is a greater representation of the strategies used by teachers to develop the process of successive variation strategies and the literature also highlights the prevalence of transposition strategies (Manuel, 1989; Nooshin and Widdess, 2006; Alaghband-Zadeh, 2013). These are often presented to emphasise the role that listening to professional performances by gurus and others must play in learning phrases that can be appropriately transposed into different rāgs. It is likely that this strategy extends to the way in which students learn the process of subverting the audience’s expectations, for example by extending a phrase past the conventional closing figure.

3.4.8 Improvisatory processes: khaṇḍadmēru

At the stage of learning to sing palṭās, a process called khaṇḍamēru is often introduced to students. This involves a mathematical process of singing all the possible combinations of notes in groups (usually 3 or 4). Table 1 demonstrates the permutations for the groups of three notes. Degrees of the scale have been given as numbers as well as the first letter of the sargam syllable (S = sa, R = re, G = ga, M = ma, P = pa, D = dha, N = ni). Students will sing these phrases column by column.

Table 1

| In the khaṇḍamēru process, students will sing each of these phrases column by column starting in the top left | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Permutations of SRG | 2 Permutations of RGM | 3 Permutations of GMP | 4 Permutations of MPD | 5 Permutations of PDN | 6 Permutations of DNṠ | 7 Permutations of NṠṘ | 8 Permutations of ṠṘĠ | ||

| Each row shows a different permutation of the three degrees of the scale specified by each column | a | SRG 123 |

RGM 234 |

GMP 345 |

MPD 456 |

PDN 567 |

DNṠ 67 |

NSṘ 7 |

ṠṘĠ |

| b | RSG 213 |

GRM 324 |

MGP 435 |

PMD 546 |

DPN |

NDṠ 76 |

ṠNṘ 7 |

ṘṠĠ |

|

| c | SGR 132 |

RMG 243 |

GPM |

MDP 465 |

PND 576 |

DṠN 67 |

NṘṠ |

ṠĠṘ |

|

| d | GSR 312 |

MRG 423 |

PGM |

DMP 645 |

NPD |

ṠDN |

ṘNṠ |

ĠṠṘ |

|

| e | RGS 231 |

GMR 342 |

MPG |

PDM 564 |

DNP |

NṠD |

ṠṘN |

ṘĠṠ |

|

| f | GRS 321 |

MGR 432 |

PMG |

DPM 654 |

NDP |

ṠND |

ṘṠN |

ĠṘṠ |

|

Example of permutations of 3 notes when khaṇḍamēru process is applied.

Once students can sing this combination of notes fluently, teachers will add challenges to apply ornamentation to the permutations of notes. These units of three or four notes can also be combined vertically to produce longer patterns. Tables 2, 3 demonstrate two different formulas by which the khaṇḍamēru passages are commonly combined.

Table 2

| Passages sung by students which combine khaṉḏamēru phrases | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st sung phrase | 2nd sung phrase | 3rd sung phrase | 4th sung phrase | 5th sung phrase | 6th sung phrase | |

| sargam | SRG, RGM | RSG, GRM | SGR, RMG | GSR, MRG | RGS, GMR | GRS, MGR |

| Degrees of the scale | 123, 234 | 213, 324 | 132, 243 | 312, 423 | 231, 342 | 321, 432 |

| Formula using figures from Table 1 | 1a + 2a | 1b + 2b | 1c + 2c | 1d + 2d | 1e + 2e | 1f + 2f |

Example of khaṉḏamēru patterns combined horizontally.

Or combined vertically:

Table 3

| Passages sung by students which combine khaṇḍamēru phrases | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st sung phrase | 2nd sung phrase | 3rd sung phrase | 4th sung phrase | 5th sung phrase | 6th sung phrase | 7th sung phrase | 8th sung phrase | |

| sargam | SRG RSG | RGM GRM | GMP MGP | MPD PMD | PDN DPN | DNṠ NDṠ | NṠṘ ṠNṘ | ṠṘĠ ṘṠĠ |

| Degrees of the scale | 123 213 | 234 324 | 345 435 | 456 546 | 567 657 | 67 76 | 7 | |

| Formula using figures from Table 1 | 1a + 1b | 2a + 2b | 3a + 3b | 4a + 4b | 5a + 5b | 6a + 6b | 7a + 7b | 8a + 8b |

Example of khaṇḍamēru patterns combined vertically.

This process of developing students’ mental agility for all possible combinations of notes supports the development of both memory for precomposed tāns and the ability to improvise melodic material in sargam. By strengthening the indexical link between the production of the note and the phoneme for notes that do not just follow in step but also contain wider intervals, the tāns that students are able to memorise will include greater variety as time goes on. Learning by rote is the pedagogical strategy by which the process of khaṇḍamēru is learned, but when deployed in the context of a performance can be incorporated creatively within an improvisation.

3.4.9 Improvisatory processes: behlāvā

Another technique used by teachers to develop their students’ improvisatory processes is behlāvā: decorating the words of the composition with notes that are different from the ones formerly used. By repeating the same phrase, several times, the potential for variation in a single phrase and with a limited range of notes explored. This again demonstrates how teachers set parameters for improvisation in order to support students’ creative thinking. McIntosh (1993) explains that another restriction imposed on behlāvā is that the improvised phrase should only take one or two metric cycles before returning to the composition, in order to prevent behlāvā from losing its artistic effect. Behlāvā is an improvisational strategy that lends itself to being taught within the GSP, because it is an exploratory process that can be engaged in during tālīm by both guru and śiṣya concurrently.

3.4.10 Improvisatory processes: intensification strategies

Intensification is a concept referenced in much of the literature as the overarching process by which improvisation occurs in Indian classical music (Clayton, 2000; Henry, 2002; Nooshin and Widdess, 2006; Zadeh, 2012). Clayton considers that the process of intensification during a performance occurs across a number of musical continua—tempo, register and complexity (Clayton, 2000). Nooshin and Widdess (2006) agree that rhythmic intensification through the gradual increase of tempo or rhythmic density is a fundamental process of development in improvisation. Building on the work of Kramer (1988), Clayton considers that the structural aspects of intensification are linear (deductive and sequential), but that, rather than leading to a precise musical climax when the upaj is seen as complete (a teleological strategy), it instead intensifies cumulatively, up until the point at which the limit of a performer’s technical ability has been reached, the point at which the time allowed for their performance is almost up (and in some cases exceeded) or until a performer becomes bored with the process. This suggests that the overall impression gained by the listener is of a non-linear, holistic, and continuous process. Clayton links this improvisatory process to cultural ideologies, asserting that, whilst there is a Western tendency to theorise and attempt to demonstrate logical organisation and coherence within the cultural phenomenon of music, Indian music theorists are much more likely to assert music’s attributes as a state of being. “Thus, a rāg simply is: the performer’s task is to bring the rāg to the listeners’ consciousness and allow us to focus our attention on the rāg’s qualities” (Clayton, 2000, p. 26). The implication of this for learners is that it highlights the teacher’s role in pitching their modelling of intensification at an appropriate level for a student to be able to replicate. It also supports the strategy of seeing rāg as a more complex musical entity than can be grasped by memorisation of the ascending and descending phrases of the rāg. For students, learning characteristic phrases sung by their teacher therefore helps to develop the precise dialectic and idiolectic sensibilities needed to construct fluent performances.

3.5 A note on the transcriptions

This next section of the article uses numerical notation in place of sargam (syllables used to name the notes of a scale in a rāg); hence ‘sa re ga ma pa dha ni’ is written ‘1 2 3 4 5 6 7’. Presenting degrees of the scale as numbers helps to demonstrate patterns more clearly to readers less familiar with the sargam system. Upper and lower octaves (saptaks) are denoted by a dot above or below the number (for example, 7̣, ). If the scale has been altered from the bilāval scale/ṭhāt (or Ionian mode) then this is denoted by a line above or below the number to demonstrate if the note (svar) has been raised (tīvră) or flattened (komal). Hence the ascending bhairav scale/ṭhāṭ (double harmonic major scale) is notated ‘1 2 3 5 7 ’ and the kalyāṇ ṭhāṭ (Lydian mode) is notated ‘1 2 3 5 6 7 ’. Where there is a rest, or a note has been held for twice as long in the pattern, this has been transcribed as –.

4 Illustrative examples

The differences between teaching in the GSP and in music schools are identified in section 3.1; however, the way these differences present themselves on a lesson-to-lesson basis in these specific cases is identified through analysis of the video data from observations. Learners are referred to as śiṣyas in the GSP context and students in the music school context. This section begins with an analysis of the pedagogical strategies used in two recorded observations: one from a music school and one from the GSP. Following this, a thematic discussion presents the implications for understanding the pedagogical strategies used to develop improvisation skills in NICM. Illustrative example 1 takes place in a music school in Varanasi with a female teacher and eight beginner students. The styles they are learning are ḵẖayāl and ṭhumrī and they cover rāg yaman kalyāṇ, malkauns and bilāval during the lesson. Illustrative example 2 also takes place in Varanasi at the home of a male guru with four experienced śiṣyas aged 14–17. The styles they are learning are also ḵẖayāl and ṭhumrī and they cover rāg yaman kalyāṇ during the tālīm.

4.1 Music school teaching

This lesson took place on the evening of March 20, 2018, at a music school in Varanasi. Starting at 6 pm and lasting just over an hour as the sky transitioned from daylight to darkness. The atmosphere was relaxed, with some chatter and laughter among the teacher, students, and parents, yet there was also a clear emphasis on maintaining focus. This session involved only women and children; unlike other lessons I had observed in the music school where the chairman was also present. The class consisted of five girls and three boys aged 7–11, with two mothers sitting at the back, occasionally chatting with the teacher. As a customary practice, students left their shoes in the exterior corridor, touched the teacher’s feet upon entering, and had their heads touched by the teacher before sitting. They sat cross-legged in a semicircle with the teacher at the front, boys on one side and girls on the other, although it was unclear if this seating arrangement was enforced or habitual.

The lesson began with the teacher singing a long, slow “sa,” joined by the students, followed by “pa.” After several repetitions, the students were split into groups of two and three to sing 1,234,567654321 in sargam and ākār (singing pitches to the syllable ‘aa’), with a focus on intonation. Older and more confident students demonstrated better intonation and smoother transitions, as well as greater ease with the faster palṭās compared to younger students, who struggled with the phonemes at higher speeds. The pattern 1122334455, 123323443455 (familiar to the group) was sung in sargam and ākār, with the teacher only needing to start each variation for the students to anticipate the next sequence. Following this, the pattern of singing palṭās in sargam and ākār is illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4

| palṭās sung by students during illustrative example 1 (presented using degrees of the scale) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ascending phrases of the palṭās sung by students | Descending phrases of the palṭās sung by students | |

| 1st palṭā | 1233, 2344, 3455, 4566, 5677, 67 | 766, 7655, 6544, 5433, 4322, 3211 |

| 2nd palṭā | 121233, 232344, 343455, 454566, 565677, 6,767 | 7766, 767655, 656544, 545433, 434322, 323211 |

| 3rd palṭā | 1-32132132121321, 2-43243243232432, 3-54354354343543, 4-65465465454654, 5-7-6576576565765, 6-76767,67676 | 5-76576576565765, 4-65465465454654, 3-54354354343543, 2-43243243232432, 1-32132132121321 |

| 4th palṭā | 13, 24, 35, 46, 57, 6 | 6, 75, 64, 53, 42, 31 |

Examples of palṭās sung in sargam and ākār from illustrative example 1 (music school teaching).

In this lesson, all palṭās were sung with tablā accompaniment set at 160 mātrās (beats) per minute, which is on the cusp between drut lāya (fast tempo) and madhya lāya (medium tempo), with each svar lasting half a mātrā. Despite some students struggling with this tempo, the teacher emphasised the importance of mastering these palṭās at this speed in both sargam and ākār. This approach ensures that students internalise these patterns well enough to recite them fluently at any speed during improvisation, representing an efficient drill method. The melodic features of the palṭās include repetition and variation, akin to the tāns used in performance. Although the palṭās are simple and in the bilāval scale/ṭhāṭ (ionian mode), the strategy of internalising these patterns for future use in improvisation is evident. The ascending and descending phrases of the palṭās, confined to a narrow pitch range (no greater than a third), also reflect how tāns are constructed in performance.

In this lesson, the teacher uses body language and non-verbal cues to indicate satisfaction with students’ accuracy during palṭās. When correcting errors, she would repeat a short segment to improve students’ ability to copy phrases by rote. Although students sing more confidently in unison, this does not necessarily improve their accuracy. The teacher segments challenging palṭās for struggling students, modelling an effective practice strategy of breaking down longer phrases into manageable chunks. She speaks very little during the lesson, except for a short section where she tests students’ ability to recognise different tāl patterns.

Two-thirds of the way through the lesson, students sing a pre-composed bhajan (devotional song) in rāg yaman kalyāṇ, set to rūpak tāl (a 7 beat cycle). This scale/ṭhāṭ differs from the earlier palṭā activity. After rehearsing the bhajan, students move on to a choṭā ḵẖayāl. The teacher begins by asking students to sing the ārōh (ascending pattern) and avarōh (descending pattern) of rāg malkauns. Initially, students struggle with the pitches due to the lingering memory of the kalyāṇ scale/ṭhāṭ from the bhajan. The teacher then sings the ārōh and avarōh slowly with correct pitches (1-3̲-4-6̲-7̲---7̲-6̲-4-3̲-4-3̲-1), which students repeat. Once this scale/ṭhāṭ has been established, students repeat the ālāp phrases shown in Table 5.

Table 5

| ālāp phrases sung by students during illustrative example 1 (presented using degrees of the scale) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st ālāp phrase | 6̱̣-7̲̣-1-4--- | 6th ālāp phrase | 4-6͟-7̲-7̲-6̲- |

| 2nd ālāp phrase | 4----3̲- | 7th ālāp phrase | 3̲-46̲-7̲---- |

| 3rd ālāp phrase | 3̲-4-3̲-1- | 8th ālāp phrase | ̲--7̲--6̲- |

| 4th ālāp phrase | 6̲̣-7̲̣-1-4---4----3̲-3̲-4-3̲-1--- | 9th ālāp phrase | 7̲-6̲-7̲-7̲-6̲-4--- |

| 5th ālāp phrase. | 1-3̲-4-6̲- | 10th ālāp phrase | 3̲-4-6̲-3̲-4-3̲-7̲̣-6̲̣-1--- |

Examples of ālāp phrases sung by the teacher and repeated by the students in illustrative example 1 (music school teaching).

This sequence demonstrates how the teacher develops students’ memories for characteristic phrases that follow the grammar of the rāg (unlike palṭās). For instance, phrase 4 is a combination of phrases 1, 2, and 3, effectively establishing both memory for phrases and the technique of stringing phrases together incrementally. Key features of the ālāp phrases include mostly stepwise motion and small jumps (e.g., intervals of a third and fourth in phrase 10) that involve ornamentation to create a more stepwise route through the ālāp phrases. The pitch ranges are characteristic of a ḵẖayāl ālāp, starting low and expanding upwards (up to ) before descending back to 1.

Following a long-held 1 at the end of phrase 10, the class transitions to singing the bandiś of the choṭā ḵẖayāl. The teacher adds a tihāi based on the first word of the sthāyī for students to follow, exemplifying how traditionally improvisatory aspects are composed by the teacher and memorised by students in a music school context. Notably, there is no section for vistār in this choṭā ḵẖayāl, and students are not expected to copy the improvisatory phrases demonstrated by their teacher, likely due to their current skill level rather than their age.

4.2 Guru-śiṣya paramparā tālīm

This episode of tālīm, conducted on 13th January 2018 at 8:00 pm, takes place in the guru’s home. The four male śiṣyas are dressed in thick western attire due to the cold and were seated on a raised dais facing their guru. The itabla app provided drone and tablā accompaniment during the lesson, which followed the structure of a full performance of rāg yaman kalyāṇ. The session began with the ālāp section, where śiṣyas repeated phrases sung by the guru in ākār as a group. The guru repeated intricate phrases with verbal explanations to highlight specific expressive features, sometimes singing alongside the śiṣyas for support. Head gestures were used by both the guru and śiṣyas to indicate the accuracy and mastery of the phrases.

Following the ālāp, the lesson focused on perfecting a very slow precomposed bandiś in vilambit ektāl (a slow, 12 beat cycle). The guru began by singing the first phrase of the bandiś without tablā accompaniment, which the śiṣyas copied as a group. After starting the itabla app, the guru had to reset the tablā accompaniment due to a rhythmic issue. He consulted a book of notated bandiśes to verify the correct tāl, then restarted the tablā, and the group continued singing the sthāyī in unison. The use of notated bandiśes, both printed and handwritten, highlights a distinctive feature of this tālīm. While some gurus rely solely on memory, in this instance, śiṣyas had access to printed materials to aid their learning.

Once the ālāp section concluded, the guru and śiṣyas rehearsed aspects of vistār. The guru started by singing lengthy phrases that śiṣyas struggled to remember, necessitating reminders and breaking the phrases into smaller chunks. Sometimes, the guru sang along with the students for support, while at other times he listened and corrected them by interjecting. In the second part of the vistār section of the baṛā ḵẖayāl, individual śiṣyas sang their own improvisations interspersed with the first phrase of the sthāyī. The guru listened and provided musical suggestions, modelling and explaining as needed. When one śiṣya missed the correct beat of the tāl to start the sthāyī, the guru demonstrated an alternative phrase before moving on to the next student. The śiṣyas recorded their tālīm on their phones, allowing them to review the improvisations later. Each student incorporated aspects of the guru’s phrases into their improvisation, and all listened intently to each other.

In the next section of the baṛā ḵẖayāl vistār, the guru modelled variations on the sthāyī, which śiṣyas repeated either as a group or individually. Sometimes, the guru focused on a single word of the lyrics, constructing phrases for individual śiṣyas to repeat. The individual sections were interspersed with the sthāyī, and some phrases were repeated as a group. Those not singing paid close attention to each other’s phrases, sometimes shaping the air with hand gestures to reflect the melodies. As the lesson developed, the pitches expanded into the upper register, continuing into the higher octave and including the characteristic long-held high sa. The śiṣyas copied their guru’s phrases in unison using the text of the first line of the antarā. The format continued with the group singing the sthāyī of the baṛā ḵẖayāl bandiś in ākār, interspersed with variations on the antarā, and finished with the first line of the sthāyī.

The next section of the tālīm focused on sargam and bol tāns as part of the baṛā ḵẖayāl. The tāns shown in Table 6 are demonstrated by the guru and copied in unison by all śiṣyas. Later tāns in the sequence are focused on individual śiṣyas, but for the purpose of this analysis, that detail has been omitted from the transcription below.

Table 6

| tāns sung by students during illustrative example 2 (presented using degrees of the scale) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st tān | 3-23217̣6̣7̣23- | 13th tān | 54̅3234̅67654̅64̅534̅2321 |

| 2nd tān | 7̣237̣27̣323217̣23--- | 14th tān | 54̅3234̅67654̅64̅534̅23217̣6̣7̣234̅3 |

| 3rd tān | 7̣237̣27̣32321--- | 15th tān | 76765 |

| 4th tān | 4̅4̅34̅32, 332321, 7̣6̣7̣234̅3----- | 16th tān | 5767, 5645, 34̅2321---- |

| 5th tān | 7̣234̅3- | 17th tān | 333, 777, , 77, 654̅654̅34̅234̅324̅321 |

| 6th tān | 4̅4̅34̅32, 332321, 7̣6̣7̣234̅3----- | 18th tān | 7̣234̅32, 7̣234̅54̅32, 34̅6777 |

| 7th tān | 7̣234̅54̅32, 34̅54̅32, 34̅654̅3234̅3----- | 19th tān | 4̅6764̅64̅7655654̅34̅2321 |

| 8th tān | 7̣234̅54̅32, 7̣234̅654̅32, 7̣234̅54̅3234̅3--- | 20th tān | 154̅534̅2321 (x3) |

| 9th tān | 34̅7654̅32321 | 21st tān | 76756564̅34̅321 (x2) |

| 10th tān | 54̅3234̅6765764̅64̅534̅2321 | 22nd tān | 7̣234̅3-, 76756564̅34̅321 |

| 11th tān | 4̅67464767654̅654̅2323--- | 23rd tān | 333, 777, , 77, 654̅654̅34̅234̅324̅321 |

| 12th tān | 34̅323-23217̣6̣7̣23--- | 24th tān | 7̣234̅54̅, 234̅567, 7654̅, 654̅34̅2321 |

bol tāns sung as part of the baṛā ḵẖayāl from illustrative example 2 (GSP tālīm).

In order to demonstrate the number of times that key fragments are repeated within the improvised bol tāns, Table 7 records the number of repetitions of key phrases within illustrative example 2. This demonstrates how melodic material is being repeated in the bol tāns of both the baṛā and choṭā ḵẖayāl.

Table 7

| Common note combinations in the bol tāns | Number of times phrase is repeated in the bol tāns of the baṛā ḵẖayāl | Number of times phrase is repeated in the bol tāns of the choṭā ḵẖayāl | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common note combination 1 | 323217̣6̣7̣23 | 4 | 10 | 14 |

| Common note combination 2a and 2b | 64̅534̅2321 and 654̅34̅2321 | 6 (4 and 2) | 0 | 6 (4 and 2) |

| Common note combination 3a and 3b | 3217654̅32 and 7654̅32 | 0 | 12 (8 and 4) | 12 (8 and 4) |

| Common note combination 4a, 4b and 4c | 7̣234̅3 and 7̣234̅5 and 72354̅ | 11 (6 and 5 and 0) | 8 (3 and 2 and 3) | 19 (9 and 7 and 3) |

| Common note combination 5a and b | 34̅2321 and 32321 | 14 (7 and 7) | 13 (1 and 12) | 27 (8 and 19) |

| Common note combination 6 a and b | 54̅3234̅ and 234̅67 | 15 (11 and 4) | 10 (6 and 4) | 25 (17 and 8) |

| Common note combination 7a, b and c | 654̅654̅ and 654664 and 654645 | 6 (6 and 0 and 0) | 6 (3 and 2 and 1) | 12 (9 and 2 and 1) |

| Common note combination 8a, b, c and d | 654̅23 or 654̅32 or 64̅534̅ or 654̅34̅ | 12 (1 and 3 and 4 and 4) | 23 (0 and 17 and 5 and 1) | 35 (1 and 20 and 9 and 5) |

The number of times that common note combinations are repeated during two sections illustrative example 2 (GSP tālīm).

In this example, the guru used a method of constructing improvisations with increasing intensity that closely resembled aspects of a ḵẖayāl performance. This approach involved the repetition of small melodic fragments and entire tāns, creating familiar patterns. Key techniques included reusing previously sung tāns within longer tāns and employing specific phrases for syntactic functions, such as ending or beginning motifs. For instance, baṛā ḵẖayāl tān 1 (323217̣6̣7̣23) appeared within tān 4, 6 and 12, while tān 2 (7̣237̣27̣32321) reappeared in tān 3. Tān 4 (4̅4̅34̅32, 332321, 7̣6̣7̣234̅3-----) is repeated within tān 6. Furthermore, certain phrases seem to fulfil specific syntactic functions for example, tān 5 (7̣234̅3-) is repeated within tān 4, 6, 14, 18 and 22 as a motif by which to end the phrase. As well as tāns that end idiomatically, there are motifs that are frequently used at the beginnings too. For instance, tān 10, 13 and 14 start in similar ways (although they are not identical) but they do end in the same way (64̅534̅2321). Tān 11 and 19 start in the same way (4̅6764̅64̅76) as do tān 17 and 23 (333,777,).

Variation was another strategy used, for example, tān 7 and 8 were similar but not identical, with tān 8 developing the phrase from tān 7 while maintaining the same ending. This technique of combining or altering phrases allows for expressive possibilities and increased intensity in the improvisation. Advanced śiṣyas apply these ideas in different contexts, such as within the bol tāns of the choṭā ḵẖayāl. The tāns maintained a consistent fast speed and showed little rhythmic variation, indicating that the śiṣyas had mastered slower speeds and were now developing their skills at a higher tempo. The pitch range expanded throughout the sequence, mirroring the ālāp and intensifying the improvisation. The tāns typically ended on 1, 5, or 3, with only one exception (18), which upon closer inspection, was part of a longer phrase ending on 1.

Following the sargam tāns, the work was consolidated through the ākār tāns, reinforcing the strategies and techniques learned during the session. This methodical approach highlighted the importance of both repetition and variation in developing śiṣyas’ improvisational skills.

5 Results and discussion

The illustrative examples from music school and GSP highlight strategies for developing improvisation skills in students at both early and advanced stages of training. In music schools, lessons for younger students are divided into smaller sections, allowing frequent repetition of characteristic rāg phrases to aid long-term memorisation. As described by Sanyal and Widdess (2004) and Alaghband-Zadeh (2013), lessons are structured to mirror performances, helping students form expectations and schemas which comply with conventions such as pitch ranges and phrase variation. High expectations for focus and respect are common across teaching settings, whether in music schools or in the GSP in line with the conventions observed by Kippen (2008, p. 131). Students are expected to listen silently and learn from others and their teacher, without asking questions. If students struggle, teachers use repetition, segment material or adjust the pace.

More experienced students improvise their own tāns, balancing repetition and variation to avoid unstructured phrases, a strategy that is discussed by teachers and recorded in an archive recording (Dey, 2009) but does not appear in the literature. Strategies for tāns include maintaining pitch range parameters, using melodic and rhythmic variations, and rearranging note combinations like khaṉḏamēru (Qureshi, 2007, p. 92). Imitation of modelled phrases is the predominant teaching strategy (Mirza Maqsud Ali cited in Qureshi, 2007, p. 190). Even advanced students rarely demonstrate spontaneous improvisation, focusing instead on memorising long phrases. This practice helps them eventually create their own phrases. Advanced students develop the ability to improvise through familiarity with the repertoire and understanding the construction principles of patterns, rather than just memorising note sequences (Powers, 1980; Neuman, 2012; McNeil, 2017). Teachers demonstrate the expansion of phrases in ālāp and tāns, showing students how to develop and extend phrases. While palṭās act as maps of tonal space (Magriel, 1999), the ālāp and tāns enable performers to explore both familiar and new pathways through the tonal space, ultimately guiding students towards independent improvisation.

5.1 The foundational skills of simple scale exercises

The simple scale exercises observed in music schools serve multiple functions in musical training, such as developing students’ voice control, precise intonation, breath control, and secure positioning of svars in memory. These exercises help create an indexical link between the notes and their names within the sargam system and support the development of simple alaṅkārs (ornaments), where repeating notes often leads to the natural addition of gamak to embellish each note (Magriel, 2002). Intonation is particularly challenging for young vocal music students, so secure positioning of svars within a child’s comfortable singing range is emphasised from the first lesson. This involves drilling palṭās alongside singing long, slow notes while focusing on listening to the tānpūrā drone or śruti box to check intonation. Palṭās are efficient in training pitch control due to the wide range of note permutations within a scale. The repetitive nature of these drills allows teachers to assess whether students have internalised the pitches and can accurately reproduce them in any order, even when their minds wander during the exercises.

5.2 Transition from scale exercise to palṭās

Once students/śiṣyas have mastered simple scale exercises, the introduction of palṭās further develops their voice control, internalisation of complex pitch patterns, ability to transpose pitch patterns, and cognitive mapping of scale structures, independently of rāg. Palṭās are initially sung slowly in sargam, then in ākār, before speeding up, showing the precise strategies used for internalising these patterns over time. By incorporating palṭās with different leaps over a sequence of lessons, and expecting practice between lessons, students develop precise intonation of various intervals. Once the routes to svars become automatic, students gain ease in sequencing and varying melodic material, a crucial skill for fluent improvisation. As students internalise numerous patterns, they can recall them and produce or link specific musical phrases. These patterns, useful for starting, linking, or ending phrases, are vital tools for memorisation in preparation for performance (Magriel, 1999).

In a ḵẖayāl performance, the final section which incorporates tāns, relies heavily on a performer’s ability to improvise. Teachers use various strategies to develop students’ skills to compose and improvise tāns that are complex yet conform to the rāg’s grammar. The basic skills for performing tāns, both compositional and technical, are taught through palṭās. In advanced training, students learn to memorise, compose, and eventually improvise tāns that retain many features of the earlier palṭās and reflect the rāg’s grammar. This progression illustrates how the strategy evolves from a pedagogical drill to a key feature of improvisation.

5.3 Memorising bandiśes supports improvisational competence

The bandiś material is crucial for students to internalise key phrases of a particular rāg, whilst capturing the expressive nuances of melodic and rhythmic phrases. Teachers and gurus emphasise the accurate rendering of the bandiś, including ornamentation and pronunciation, ensuring precise knowledge construction (Morris, 2005). While variation in performance is valued, the faithful reproduction of bandiśes as taught by the guru is prioritised. This reflects the respect for gurus and the cultural values associated with musical learning.

Students develop schema-based expectations for the pitch direction of bandiśes through enculturation. They learn early that the sthāyī melody moves in the lower tetrachord of the middle and lower octaves, while the antarā rises to the upper tetrachord and upper octave (Widdess, 1981; Clayton, 2000), aiding efficient learning. Although classificatory knowledge of the rāg is less prioritised in the GSP than in music schools, modern GSP teaching often includes theoretical aspects. Gurus may publish and print bandiśes they learned and share performances online, blending traditional aural learning with modern resources.