Abstract

A much-cited model by Stodden and colleagues has proposed motor competence to be a 17 promising target for intervention to increase childhood physical activity. Motor competence is thought to influence future physical activity through bidirectional causal effects that are partly direct, and partly mediated by perceived motor competence and physical fitness. Here, we argue that the model is incomplete by ignoring potential confounding effects of age-specific and age-invariant factors related to genetics and the shared family environment. We examined 106 systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses on the Stodden model for the mention of familial confounding. These reviews summarized data from 1,344 primary studies on children in the age range 0–18 on the associations in five bidirectional pathways: motor competence—physical activity, motor competence—perceived motor competence, perceived motor competence—physical activity, motor competence—physical fitness, and physical fitness—physical activity. We show that a behavioral genetic perspective has been completely lacking from this vast literature, despite repeated evidence for a substantial contribution of genetic and shared environmental factors to motor competence (h2 = ♂55%—♀58%; c2 = ♂31%—♀29%), physical fitness (h2 = ♂65%—♀67%; c2 = ♂3%—♀2%), and physical activity (h2 = ♂37%—♀29%; c2 = ♂33%—♀49%). Focusing on the alleged causal path from motor competence to physical activity, we find that the systematic reviews provide strong evidence for an association in cross-sectional studies, but weak evidence of prediction of physical activity by motor competence in longitudinal studies, and indeterminate effects of interventions on motor competence. Reviews on interventions on physical activity, in contrast, provide strong evidence for an effect on motor competence. We conclude that reverse causality with familial confounding are the main sources of the observed association between motor competence and physical activity in youth. There is an unabated need studies on the interplay between motor competence, perceived motor competence, physical fitness, and physical activity across early childhood and into adolescence, but such studies need to be done in genetically informative samples.

1 Introduction

1.1 The importance of physical activity in children and adolescents

The paramount importance of regular physical activity (PA) to enhance children’s health has been extensively documented (Elhakeem et al., 2018; Janssen and Leblanc, 2010; Jose et al., 2011; Kaplan et al., 1996; Leskinen et al., 2009; Wendel-Vos et al., 2004). The well-established effects of physical activity have led to the development of physical activity guidelines for youth, widely adopted across the globe (World Health Organization, 2020). Despite this, and the many active policies supporting an increase in physical activity in various settings, the majority of children and adolescents does not meet recommended physical activity levels (Guthold et al., 2020). Furthermore, as children move through childhood and adolescence towards adulthood, physical activity participation rates tend to further decline (Conger et al., 2022).

Of note, these general epidemiological trends describe what happens to the average child but fail to address the large individual differences in physical activity behaviors. These individual differences have been shown to be remarkably stable throughout the lifespan (Breau et al., 2022; Telama et al., 2005; van der Zee et al., 2019) such that children who start out to be more physically active in childhood tend to remain more active later in life. This ‘tracking’ of physical activity suggests that it would pay off to increase the number of active children to arrive at larger numbers of adolescents and adults meeting the recommended physical activity levels. Not surprisingly therefore, much effort has been spent on identifying modifiable determinants of childhood physical activity. One of the more promising traits investigated is motor competence (Øglund et al., 2015; Øglund et al., 2014). Globally, children (3–10 years) demonstrate “below average” to “average” motor competence levels (Bolger et al., 2021), suggesting that there is room for improvement of this trait by targeted intervention. However, such intervention is only meaningful to increase youth physical activity levels to the extent that motor competence has a causal effect on physical activity.

1.2 The role of motor competence in physical activity: the 2008 Stodden model

Motor competence can be defined as the full complement of a person’s motor abilities needed to execute all forms of goal-directed motor acts necessary to manage everyday tasks (Bolger et al., 2021; Henderson and Sugden, 1992). The potential role of motor competence for physical activity received a large boost with the development of the “Stodden model” by Stodden et al. (2008). The Stodden model identifies motor competence as a main determinant of youth and adolescent physical activity, a basic idea foreshadowed by the earlier work of Hands and Larkin (2002). To be physically active as they grow older, children need fundamental motor skills like running, jumping, catching, and throwing. Children that start out with low actual and perceived motor competence may not engage in sufficient physical activity to develop the motor competence and physical fitness needed to engage in the required level of physical activity during middle and late childhood. This will draw them into a negative spiral of disengagement in which the lower levels of physical activity in turn will amplify their motor skill deficits compared to their more active peers. “This will ultimately result in high levels of physical inactivity and will place these individuals at risk for being obese during later childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. “(Stodden et al., 2008, p. 297).

Three characteristics of the Stodden model turn it into a dynamic but complex model that make it difficult to predict the development of stable physical activity habits as well as moments that would be optimal for change by intervention. First, it adds two mediational pathways, acting through physical fitness and through perceived motor competence, to the direct pathways between motor competence and physical activity. Second, it suggests non-recursive, reciprocal effects in the direct and mediated pathways. Third, the model allows changes in the direction of effects in the pathways as a function of age. While being very complete by incorporating age-moderation, bidirectionality, and mediation, the Stodden model at the same time is undercomplete by solely focusing on the possibility that these pathways reflect causal effects.

1.3 The potential confounding by familial factors in pathways of the Stodden model

In its essence, the Stodden model revolves around a set of five associations between motor competence and physical activity, between motor competence and perceived motor competence, between perceived motor competence and physical activity, between motor competence and physical fitness, and between physical fitness and physical activity (MC-PA, MC-PMC, PMC-PA, MC-Fitness, Fitness-PA). These associations can arise through fundamentally different mechanisms governing the development and the ensuing stability of the associations between the traits as well as the changes in these associations over time. Figure 1 depicts potential sources of the association between motor competence and physical activity at each of three different ages, and how these sources can impact on the stability of these associations across developmental time. To maintain intelligibility, the Figure greatly simplifies the continuous nature of development by using discrete ages 2, 7, and 13, rather than a more fine-grained model that uses steps of, e.g., 2 months. It’s aim is merely to provide an illustration of the complexity of interpreting (longitudinal) associations.

Figure 1

Sources of the association between motor competence and physical activity and its stability over time. Rectangles contain the observed values of the motor competence (MC) and physical activity (PA) traits at the three example ages (2, 7, 13). Ovals contain the set of latent determinants of these traits (DetMC, DetMC2, DetMC7, DetMC13 and DetPA, DetPA2, DetPA7, DetPA13) which may be genetic or environmental determinants. DetMC2, DetMC7, DetMC13 contain the age-specific latent genetic/environmental determinants of motor competence operating on MC at age 2, 7 and 13, respectively. DetMC contains the age-invariant latent genetic/environmental determinants that operate on the traits at all ages. Similar applies to DetPA, DetPA2, DetPA7, DetPA13. Dotted purple arrows from DetMC2, DetMC7, DetMC13 and DetPA2, DetPA7, DetPA13 reflect age-specific effects of these determinants, whereas the solid purple arrows from DetMC and DetPA reflect age-invariant effects of these determinants. Double-headed black arrows indicate correlation of the underlying determinants, which leads to confounding in the MC-PA associations. Red continuous lines indicate the autoregression of the motor competence and physical activity traits across time. Blue arrows indicate true causal effects of motor competence on physical activity, or in reverse, physical activity on motor competence. Blue arrows pointing into age 2 reflect causal effects from earlier ages.

As a major innovation to the Stodden model, Figure 1 adds latent determinants that may act as confounders of the associations between motor competence and physical activity, or its putative mediators, perceived motor competence and physical fitness. Two sets of latent determinants have been repeatedly nominated by the field of behavior genetics to play a role in many developmental traits. The first set of determinants consists of the common or shared environment that contains all factors shared by family members living in the same household, including the physical home environment, family warmth and mutual support, parenting style and example setting, neighborhood characteristics, and socioeconomic status (including education level of the parents). The second set consists of the genetic variance shared by family members which may reflect additive trait effects of the two parental alleles in a gene, or non-additive trait effects due to allelic dominance or allelic interaction (epistasis).

Starting at the top of the model shown in Figure 1, we see that motor competence at age 2 (“MC age 2”) is considered to be influenced by latent determinants (“Det MC2”). These may involve genetic variants that influence sensorimotor brain functioning and neuromuscular control, or differences in motor skill challenges related to the family that children grow up in or other environmental factors such as climate or exposure to structured physical education in school or childcare settings. The influence of these genetic and environmental determinants of motor competence can show substantial stability over time (reflected in the purple arrows emanating from the latent “Det MC” factor that influences motor competence at all ages) because the genetic code does not noticeably change after conception, and influences related to parental rearing styles, and neighborhood or household characteristics can also be stable. However, the influence of some of the latent determinants may be confined to specific ages (reflected in the latent “Det MC2 … Det MC13” factors). For example, parental social support effects may be strong at ages 2 and 7 but become more diluted when children enter secondary school. While some genetic variants may be expressed at all ages, other variants may show age-specific (suppression of) gene-expression as part of maturation. At the bottom of the figure, we see a parallel situation for physical activity, again with both age-invariant and age-specific latent factors influencing physical activity behaviors at the three ages depicted.

At each age, an association between motor competence and physical activity may arise entirely through the correlation of the age-invariant and/or age-specific factors, without the need for a direct causal path between the two traits. For example, part of the many genetic variants that influence motor competence may overlap with those influencing physical activity, creating horizontal genetic pleiotropy when they influence these traits through independent routes (Minica et al., 2020; Minica et al., 2018; Solovieff et al., 2013; Verbanck et al., 2018). Likewise, environmental risk factors like household poverty and parental rearing styles may independently restrict motor competence development and reduce opportunities for regular physical activity. If the effects of genetic or environmental factors change in strength from childhood to adolescence, they may also cause a strengthening or weakening of the associations over time. Such a confounder-induced age-related change in the association would not be discriminable from an age-moderation effect on the putative causal pathway between motor competence and physical activity.

The confounding genetic or environmental effects may work directly on the two traits themselves, but also make use of an intermediate trait that itself exerts a causal effect on both traits. A first example would be that the same genetic variants that influence motor competence also influence physical activity through their effects on the dopaminergic brain systems that influence motor control as well as exercise reward pathways. A second example of such confounding would be that an obesogenic family environment would increase body mass index (BMI), with BMI having effects on both motor competence and physical activity. In short, cross-sectional associations between motor competence and physical activity at each age can reflect confounding by correlated determinants, which may be genetic or environmental in nature.

However, the effect of the latent underlying factors does not rule out the additional existence of causal effects of motor competence at an earlier age on current physical activity. These causal effects are reflected in the cross-lagged paths of Figure 1. For example, physical activity at age 7 may, in part, depend on the ability to perform basic motor actions at a sufficient level to engage in active play with parents, siblings, or peers at school from age 2 to 7. Conversely, the lagged causal effect may also work in the other direction. Daily engagement in physical activity from age 2 to 7, i.e., playing regular ball games in preschool, may actively contribute to building up motor competence, i.e., lead to increased kicking/throwing skills, at age 7. Such bidirectional causal mechanisms are suggested by the Stodden model as the main cause of the association between motor competence and physical activity in middle and late childhood.

Apart from the mechanisms inducing cross-sectional associations at each age, Figure 1 also depicts the mechanisms that lead to stability of the association of motor competence and physical activity over developmental time. A first mechanism causing stability of the associations between motor competence and physical activity is the autoregression of each of the traits separately. Substantial evidence shows that, even if absolute levels show large maturational changes, the individual differences in both motor competence and physical activity are stable across time (Barnett et al., 2010; Branta et al., 1984; Farooq et al., 2020; Malina, 1990; McKenzie et al., 2002; Pereira et al., 2022; Schmutz et al., 2020). This ‘tracking’ of motor competence and physical activity may arise from direct causal influences of the trait level at a starting age on the trait level at a later age. For example, once a neuromotor skill has been mastered (running, balancing on a beam) it will not be easily lost, and habit formation may solidify physical activity behaviors once these have been taken up in an initial period (Rebar et al., 2024).

Autoregression can be a first source of stability of the association of motor competence and physical activity over time. Once an association has come into existence, e.g., is bootstrapped at age 2 by correlated underlying determinants, it will be propagated across time sheerly by the stability in each of the two traits. A second mechanism that leads to stability of the association of motor competence and physical activity over time are the causal effects of motor competence on physical activity and the reverse causal effects of physical activity on motor competence. Finally, a third mechanism causing stability of the association is a correlation of the age-invariant genetic or environmental determinants of motor competence and physical activity (“Det PA” and “Det MC” in Figure 1). These will not just induce cross-sectional association but also longitudinal associations between motor competence and physical activity.

The Stodden model was created when the associations between the traits in the five pathways (MC-PA, MC-PMC, PMC-PA, MC-Fitness, Fitness-PA) were mostly observed in cross-sectional studies. Cross-sectional studies cannot discriminate between the mechanisms outlined in Figure 1 and outlined above. Nonetheless, if one of the hypothesized associations in the Stodden model is found to be absent, it would at once tell us that no causal effect is likely to exist. In that sense, cross-sectional studies are vital in first demonstrating the primary possibility of a causal association. Longitudinal studies are a step up from cross-sectional studies in that they establish the presence of cross-time (lagged) associations between the traits and can rule out reversed causation. If the assumed causal trait (e.g., motor competence at an early age) is seen to predict the assumed caused trait (e.g., physical activity in adolescence) in the future but in parallel, the association is not seen to hold in the opposite direction this would falsify reverse causation of motor competence by physical activity.

The strongest design to show true causality in the pathways of the Stodden model is the intervention design, where either motor competence or physical activity are manipulated, and it is tested whether the induced changes in one trait led to changes in the other trait. Well-conducted RCTs remain the highest level of evidence for a true causal effect. However, large individual differences can be seen in the response to intervention and it is not always clear what is driving these differences (Kennedy et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2024; Ma et al., 2021; Prochaska et al., 2008). Again familial factors are a potential source of the heterogeneity in responding to intervention. Attempts to increase motor competence and physical activity may fall on more fertile ground in some children compared to others, simply based on their genetic abilities and/or more supportive family environment. So, to further add to complexity, the underlying determinants of motor competence and physical activity in Figure 1 may partly act through their moderating effects of (parental or school-based) attempts to change these traits.

If the genetic and shared environmental determinants independently influence motor competence and physical activity behavior, the size of the causal effects hypothesized to underlie the observed association between motor competence and physical activity behavior would be incorrectly estimated from the size of the association when this confounding is not taken into account. Since the publication of the Stodden model, a very large amount of systematic reviews with or without meta-analyses have been published on one or more of the Stodden pathways. A reasonable expectation, therefore, is that this large volume of work has duly taken the potential of familial confounding into account. Cursory inspection of some highly cited reviews (Barnett et al., 2022; De Meester et al., 2020; Engel et al., 2018; Figueroa and An, 2017) suggested that this might not be the case, but more systematic inspection of the large volume of systematic reviews is needed. In addition, for familial confounding to be a potential issue, it is required that the traits in the Stodden model show substantial variance caused by shared environmental or genetic factors. This requires a review of studies on these traits in the behavioral genetics literature.

1.4 The aims of this narrative review

The first aim of this narrative review is to examine whether and how shared environmental or genetic confounding had been considered, and possibly ruled out, in the large body of literature on the five pathways in the Stodden model. To do so, we inspected all systematic reviews and meta-analysis of primary studies published after 2008 and searched for discussions on potential confounding by genetic and shared environmental factors.

As our second aim, we compare the strength of the evidence and effect sizes obtained for the effect of motor competence on physical activity in cross-sectional and longitudinal designs. This path of the Stodden model is important for intervention studies aiming to increase middle and late childhood physical activity. If familial confounding is present in this main Stodden pathway, we expect cross-sectional associations to be stronger than longitudinal associations. In addition, we expect that interventions on motor competence would not increase physical activity to the degree predicted from the cross-sectional effect sizes.

As a third aim, we explicitly test the potential for familial confounding in the five bidirectional pathways of the Stodden model. This requires that the variance in the traits in the Stodden model in childhood and adolescence are caused by genetic and shared environmental factors. This can be tested in a nuclear family design (e.g., parental, spousal and sibling correlations) or in a wider pedigrees (correlations between, e.g., self-aunt/uncle, self-niece/nephew, etc.), but the strongest design focuses on the comparison of MZ and DZ twin correlations (Knopik et al., 2017; Polderman et al., 2015). We, therefore, review the existing twin studies on the contribution of genetic and shared environmental factors to each of the traits in the Stodden model. Furthermore, we review direct tests of familial confounding that estimate the overlap in genetic and shared environmental factors influencing multiple traits, e.g., between motor competence and physical activity.

In short, our research questions are:

-

To what extent have past systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the pathways of the Stodden model considered unmeasured confounding, in by particular genetic and shared environmental factors?

-

In the main pathway between motor competence and physical activity, are the reported cross-sectional associations stronger than longitudinal associations that in turn are stronger than the effects seen in intervention studies?

-

Do twin studies show that, during childhood and adolescence, genetic and shared environmental factors contribute to individual differences in the traits used in the Stodden model?

2 Method

2.1 Search and selection of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the Stodden model

To address research question 1, a literature search was performed for systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses of the relationships between motor competence, physical activity, perceived motor competence, and physical fitness. Definitions and assessment strategies for these traits can be found in the Supplementary Sections 1, 2. We searched the Pubmed, Web of Science, and EMBASE databases for reviews published after January 1, 2009 (i.e., after the publication of the Stodden model) and before January 15, 2025 (date of final search). The detailed search strategy is shown in Supplementary Methods Section 3’. Of note, for physical activity traits we only extracted results on total physical activity (TPA), moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) or leisure time physical activities (LTPA, including exercise and sports) but discarded light physical activity and sedentary behavior.

The extracted titles and abstracts were initially screened by YZ to identify reports fulfilling the inclusion criteria. Articles were stored in the Endnote citation manager. Full-text reading of selected systematic reviews and meta-analyses was performed independently by YZ and EdG. Discrepancies in article selection were discussed and resolved. References were checked to identify additional systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the traits in the Stodden model.

2.1.1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

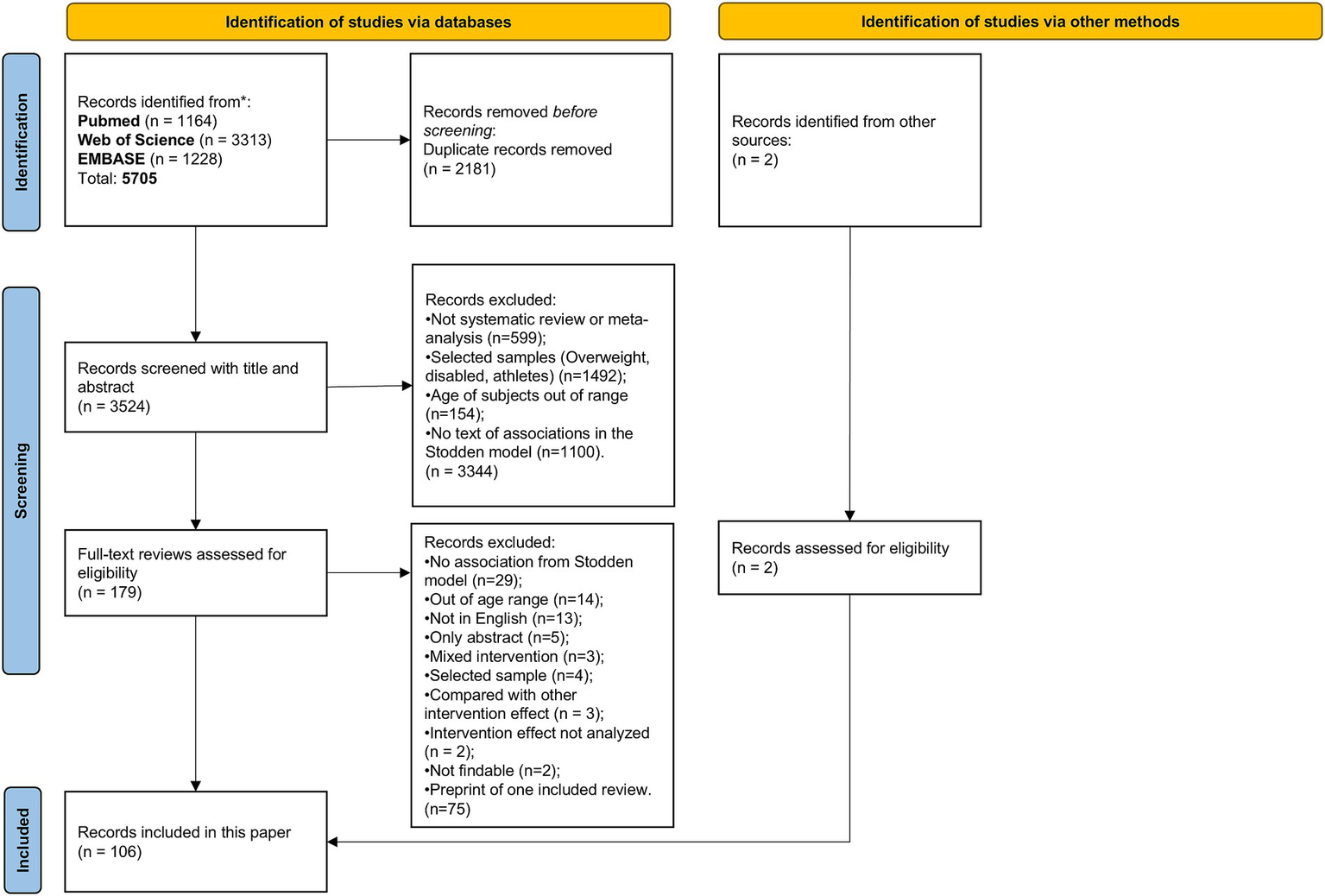

We included peer-reviewed systematic reviews or meta-analyses of observational or interventional studies in humans that assessed the association between any two of the four traits. Only reviews published in English with a focus on participants younger than 18 years old were included. We excluded reviews where the traits from the Stodden model were not among the primary outcomes, or were no association statistics or intervention effects were reported. We excluded reviews on special populations such as youth athletes, children with medical problems or psychiatric conditions. Figure 2 provides a flow diagram describing the selection of the reviews included in the data extraction and analysis step.

Figure 2

Flow diagram describing the selection of the systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the core pathways of the Stodden model.

2.1.2 Data extraction

We extracted the authors of the systematic reviews, year of publication, presence of a meta-analysis, period covered by the search used, age range of the target population, number of primary studies included in the review, and the study design of the primary studies, i.e., (cluster) randomized controlled trial, non-randomized interventional studies, longitudinal, or cross-sectional studies (see Table 1). We then scrutinized the text of the discussion and conclusion sections of the reviews for mention of concerns about unmeasured confounding in general, and more specifically about genetic and shared environmental confounding. This process was repeated by both authors, and an automated text search for the keywords ‘risk of bias’, ‘confound*’, ‘familial’, ‘environment*’, ‘genetic*’ and ‘heritab*’ was used to verify our manual inspection. All information was extracted separately for all pathways (e.g., motor competence and physical activity, perceived motor competence and actual motor competence, motor competence and fitness, etc.) and ordered by age within each pathway.

Table 1

| No. | Review | Type of review | Age range (years) | Trait 1 | Trait 2 | Primary studies on trait 1 and 2 (RCT/ INT/ LON/ CSS) | Confounding mentioned | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | Environ mental effects | Genetic effects | |||||||

| MC and PA (44 reviews included) | |||||||||

| 1 | Øglund et al. (2015) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 0–2 | Motor development | PA | 3 (0/0/2/1) N = 13,534 |

√ | √ | X |

| 2 | Santos et al. (2023) | Systematic review | 0–3 | MC | PA (aquatic activities) | 6 (0/3/2/3) N = 215 |

√ | X | X |

| 3 | Carson et al. (2017) | Systematic review | 0–4 | PA | Motor development | 22 (6/6/1/10) N = 5,380 |

√ | X | X |

| 4 | Timmons et al. (2012) | Systematic review | 0–4 | PA | MC | 4 (3/1/0/0) N = 802 |

√ | X | X |

| 5 | Bingham et al. (2016) | Systematic review | 0–6 | MC | TPA | 11 (0/0/1/10) N = 12,338 |

√ | X | X |

| 6 | Hesketh et al. (2017) | Systematic review | 0–6 | Motor skills | PA | 10 (7/3/0/0) N = 3,204 |

X | X | X |

| 7 | Grady et al. (2025) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 0–6 | PA (school and care-based PA) | FMS | 16 (16/0/0/0) N = 4,905 |

√ | X | X |

| 8 | Behringer et al. (2011) | Meta-analysis | 0–18 | PA (strength training) | Jump, run, throw | 34 (0/34/0/0) N = 1,432 |

X | X | X |

| 9 | Chen et al. (2024) | Meta-analysis | 2–6 | PA | FMS | 23 (22/1/0/0) N = 4,068 |

√ | X | X |

| 10 | Barnett et al. (2022) | Systematic review | 2–18 | MC | PA | 30 (2/0/26/3) N = 15,900 |

√ | √ | √ |

| 11 | Figueroa and An (2017) | Systematic review | 3–5 | Motor skills | PA | 11 (6/0//5) N = 2,157 |

√ | X | X |

| 12 | Engel et al. (2018) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3–5 | FMS | TPA | 11 (8/3/0/0) N = 3,023 |

√ | X | X |

| 13 | Barnett et al. (2016) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3–5 | Locomotor skills | PA | 13 (1/0/4/8) N = 6,556 |

√ | √ | X |

| 14 | Van Capelle et al. (2017) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3–5 | PA | MC | 20 (11/9/0/0) N = 4,245 |

√ | X | X |

| 15 | Veldman et al. (2021) | Systematic review | 3–5 | MVPA | Motor development | 11 (4/6/1/1) N = 1,341 |

√ | X | X |

| 16 | Xin et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 3–6 | FMS | PA | 26 (0/0/2/24) N = 4,851 |

√ | √ | X |

| 17 | Xu et al. (2024) | Systematic review | 3–6 | FMS | MVPA | 21 (0/0/4/18) N = 26,275 |

X | X | X |

| 18 | Jones et al. (2020) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3–6 | FMS | MVPA | 19 (0/0/5/15) N = 3,690 |

X | X | X |

| 19 | Liu Y. et al. (2023) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3–6 | FMS | MVPA | 11 (0/0/3/8) N = 2,514 |

√ | X | X |

| 20 | Wang and Zhou (2024) | Meta-analysis | 3–6 | PA (MC-focused) | Gross motor skills | 23 (23/0/0/0) N = 2070 |

√ | X | X |

| 21 | Li et al. (2022) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3–7 | PA (extra PE) | FMS | 23 (17/6/0/0) N = 2,258 |

√ | X | X |

| 22 | Sinclair and Roscoe (2023) | Systematic review | 3–11 | PA (swimming) | FMS | 10 (3/7/0/0) N = 611 |

√ | X | X |

| 23 | Johnstone et al. (2018) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3–12 | PA (active play) | FMS | 2 (2/0/0/0) N = 193 |

√ | X | X |

| 24 | Liu et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 3–12 | PA (active video games) | FMS | 9 (6/3/0/0) N = 478 |

√ | X | X |

| 25 | Hassan et al. (2022) | Systematic review and network meta-analysis | 3–12 | PA (aerobic exercise) | Gross motor skills | 13 (13/0/0/0) N = 1,109 |

√ | X | X |

| 26 | Oppici et al. (2022) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3–12 | PA (exergame) | FMS | 9 (6/3/0/0) N = 783 |

√ | X | X |

| 27 | Sun and Chen (2024) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3–12 | PA (sports) | FMS | 12 (12/0/0/0) N = 1701 |

√ | X | X |

| 28 | Zhang et al. (2024) | Systematic review | 8–17 | PA | FMS | 26 (11/15/0/0) N = 1,133 |

X | X | X |

| 29 | Lorås (2020) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3–13 | PA (extra PE) | MC | 20 (10/10/0/0) N = 4,190 |

√ | X | X |

| 30 | Holfelder and Schott (2014) | Systematic review | 3–18 | FMS | PA | 22 (0/0/4/18) N = 10,107 |

√ | X | X |

| 31 | Logan et al. (2015) | Systematic review | 3–18 | FMS | PA | 13 (0/0/1/12) N = 10,534 |

X | X | X |

| 32 | Lubans et al. (2010) | Systematic review | 3–18 | FMS | PA | 18 (0/0/4/14) N = 8,981 |

X | X | X |

| 33 | García-Hermoso et al. (2020) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3–18 | PA (extra PE) | FMS | 15 (11/4/0/0) N = 7,177 |

√ | X | X |

| 34 | Zeng et al. (2017) | Systematic review | 4–6 | PA | Motor skills | 10 (10/0/0/0) N = 1,602 |

√ | X | X |

| 35 | Comeras-Chueca et al. (2021) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 4–15 | PA (active video game) | Motor competence | 10 (8/2/0/0) N = 979 |

√ | X | X |

| 36 | Graham et al. (2022) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 5–11 | FMS | MVPA | 19 (15/4/0/0) N = 10,412 |

√ | X | X |

| 37 | Moon et al. (2024) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 5–12 | PA (extra PE) | MC | 27 (10/17/0/0) N = 13,281 |

√ | X | X |

| 38 | Norris et al. (2016) | Systematic review | 5–15 | PA (active video game) | Motor skills | 8 (4/4/0/0) N = 1,063 |

√ | X | X |

| 39 | Dudley et al. (2011) | Systematic review | 5–18 | PA (extra PE and school sport) | MC | 4 (3/1/0/0) N = 3,196 |

√ | X | X |

| 40 | Collins et al. (2019a) | Meta-analysis | 5–18 | Strength training | Throw, sprint, squat, and jump | 20 (0/20/0/0) N = 1,028 |

√ | X | X |

| 41 | McDonough et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 6–12 | PA (active video games) | Motor skills | 25 (25/0/0/0) N = 4,325 |

√ | X | X |

| 42 | Rico-González (2023) | Systematic review | 6–12 | PA (extra PE) | FMS | 4 (4/0/0/0) N = 1,235 |

√ | √ | X |

| 43 | Poitras et al. (2016) | Systematic review | 7–15 | Motor skills | TPA | 9 (1/1/1/6) N = 5,013 |

√ | X | X |

| 44 | Burton et al. (2023) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 11–17 | MC | PA | 30 (1/0/10/19) N = 17,702 |

√ | X | X |

| MC and PMC (4 reviews included) | |||||||||

| 10 | Barnett et al. (2022) | Systematic review | 2–18 | MC | PMC | 11 (0/2/3/6) N = 3,187 |

√ | √ | √ |

| 32 | Lubans et al. (2010) | Systematic review | 3–18 | FMS | PMC | 3 (3/0/0/0) N = 1,288 |

X | X | X |

| 45 | De Meester et al. (2020) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3–24 | MC | PMC | 32 (1/0/3/29) N = 7,959 |

√ | X | X |

| 44 | Burton et al. (2023) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 11–17 | MC | PMC | 58 (3/0/10/45) N = 22,256 |

√ | X | X |

| PMC and PA (5 reviews included) | |||||||||

| 46 | Wang and Zhou (2023) | Systematic review | 4–12 | PA (MVPA) | PMC | 3 (0/0/1/2) N = 1,464 |

X | X | X |

| 47 | Craggs et al. (2011) | Systematic review | 4–18 | PMC | PA | 8 (0/0/8/0) N = 2,768 |

X | X | X |

| 48 | Babic et al. (2014) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 5–20 | PMC | PA | 46 (0/2/12/34) N = 32,438 |

√ | X | X |

| 49 | Zamorano-Garcia et al. (2023) | Meta-analysis | 7–18 | PA | Perceived sport competence | 10 (1/9/0/0) N = 3,626 |

√ | √ | X |

| 50 | Collins et al. (2019a) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 10–16 | Resistance training | Perceived sport competence | 7 (2/5/0/0) N = 460 |

√ | √ | X |

| MC and Physical fitness (10 reviews included) | |||||||||

| 10 | Barnett et al. (2022) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2–18 | MC | Physical fitness | 16 (2/0/13/1) N = 6,039 |

√ | √ | √ |

| 51 | Hui et al. (2024) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3–10 | MC | Physical fitness | 23 (0/23/0/0) N = 2007 |

√ | √ | X |

| 52 | Liu C. et al. (2023) | Systematic review | 3–16 | FMS | CRF | 16 (0/0/1/15) N = 14,336 |

X | X | X |

| 32 | Lubans et al. (2010) | Systematic review | 3–18 | FMS | Physical fitness | 18 (0/0/4/14) N = 8,981 |

X | X | X |

| 53 | Cattuzzo et al. (2016) | Systematic review | 3–18 | MC | CRF | 38 (0/0/7/31) N = 35,189 |

X | √ | X |

| 54 | Utesch et al. (2019) | Meta-analysis | 4–20 | MC | CRF | 19 (0/0/0/19) N = 15,984 |

X | X | X |

| 55 | Lang et al. (2018) | Systematic review | 5–17 | MC | CRF | 4 (0/0/0/4) N = 2,670 |

√ | √ | X |

| 56 | Lin et al. (2022) | Systematic review | 6–10 | Neuromuscular training | Physical fitness | 4 (0/4/0/0) N = 346 |

X | X | X |

| 57 | Jiang et al. (2024) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 7–14 | MC | CRF | 2 (0/0/0/2) N = 4,932 |

√ | √ | X |

| 44 | Burton et al. (2023) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 11–17 | MC | Physical fitness | 7 (1/0/1/5) N = 1,146 |

√ | X | X |

| Physical fitness and PA (54 reviews included) | |||||||||

| 58 | Henriques-Neto et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 0–18 | Commuting PA | CRF and muscular strength | 11 (1/1/1/8) N = 18,592 |

√ | √ | X |

| 59 | Smith et al. (2019) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 1–25 | PA (extra PE) | Muscular fitness | 17 (16/1/0/0) N = 1,653 |

√ | X | X |

| 60 | Garcia-Hermoso et al. (2020) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3–6 | PA | CRF | 9 (9/0/0/0) N = 4,006 |

√ | X | X |

| 61 | Szeszulski et al. (2019) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3–7 | PA (school and care-based PA) | CRF | 10 (8/2/0/0) N = 3,061 |

X | √ | X |

| 24 | Liu et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 3–12 | PA (active video games) | Physical fitness | 5 (5/0/0/0) N = 304 |

√ | X | X |

| 62 | Pozuelo-Carrascosa et al. (2018) | Meta-analysis | 3–12 | PA (extra PE) | CRF | 20 (20/0/0/0) N = 7,287 |

√ | X | X |

| 63 | Stojanović et al. (2024) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3–18 | PA | CRF | 3 (0/0/0/3) N = 605 |

X | X | X |

| 64 | Garcia-Hermoso et al. (2021) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3–18 | VPA | CRF | 4 (0/0/4/0) N = 565 |

√ | X | X |

| 33 | García-Hermoso et al. (2020) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 3–18 | PA (extra PE) | CRF | 20 (17/3/0/0) N = 4,485 |

√ | X | X |

| 65 | Breslin et al. (2023) | Systematic review | 4–12 | PA (The Daily Mile) | Physical fitness | 9 (1/8/0/0) N = 5,581 |

X | X | X |

| 66 | Anico et al. (2022) | Systematic review | 4–12 | School-based run/walk | CRF | 7 (0/5/2/0) N = 5,024 |

√ | √ | X |

| 67 | Gutierrez-Garcia et al. (2018) | Systematic review | 4–14 | PA (Judo) | Physical fitness | 4 (0/4/0/0) N = 403 |

X | X | X |

| 35 | Comeras-Chueca et al. (2021) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 4–15 | Active video game | CRF | 6 (3/3/0/0) N = 1,005 |

√ | X | X |

| 68 | Villa-González et al. (2023) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 5–13 | PA (extra PE) | Muscular fitness | 17 (16/1/0/0) N = 1,653 |

√ | √ | X |

| 69 | Duncombe et al. (2022) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 5–17 | HIIT | CRF | 30 (24/6/0/0) N = 3,026 |

√ | X | X |

| 70 | Larouche et al. (2014) | Systematic review | 5–17 | Commuting PA | CRF | 10 (0/0/2/8) N = 26,948 |

√ | X | X |

| 71 | Wu et al. (2023) | Systematic review and network meta-analysis | 5–18 | PA (extra PE) | Physical fitness | 63 (48/15/0/0) N = 7,226 |

X | √ | X |

| 72 | Zhou et al. (2024) | Systematic review | 5–18 | PA | Physical fitness | 30 (24/7/0/0) N = 6,494 |

X | X | X |

| 73 | Bauer et al. (2022) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 5–18 | HIIT | CRF | 8 (0/8/0/0) N = 867 |

X | X | X |

| 74 | Eather et al. (2022) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 5–18 | HIIT | CRF and muscular fitness | 11 (3/8/0/0) N = 1,011 |

X | X | X |

| 75 | Lubans et al. (2011) | Systematic review | 5–18 | Commuting PA | CRF | 5 (0/0/1/4) N = 13,604 |

√ | √ | X |

| 76 | Sun et al. (2013) | Systematic review | 5–18 | PA (extra PE) | CRF | 11 (11/0/0/0) N = 2,694 |

√ | √ | X |

| 77 | Wu et al. (2021) | Meta-analysis | 5–18 | Resistance training | Muscle strength | 42 (42/0/0/0) N = 1728 |

X | X | X |

| 78 | Moran et al. (2018) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 5–18 | PA | Muscular fitness | 21 (21/0/0/0) N = 2,267 |

X | X | X |

| 79 | Hanna et al. (2023) | Systematic review | 6–11 | PA (The Daily Mile) | Physical fitness | 5 (0/5/0/0) N = 2,700 |

X | √ | X |

| 80 | Errisuriz et al. (2018) | Systematic review | 6–11 | PA (extra PE) | CRF | 8 (4/4/0/0) N = 12,977 |

X | X | X |

| 42 | Rico-González (2023) | Systematic review | 6–12 | PA (extra PE) | Physical fitness | 8 (8/0/0/0) N = 5,710 |

√ | √ | X |

| 81 | Beets et al. (2009) | Meta-analysis | 6–12 | PA (after-school program) | Physical fitness | 6 (6/1/0/0) N = 4,686 |

X | X | X |

| 82 | Burns et al. (2018) | Meta-analysis | 6–12 | PA | CRF | 20 (13/10/0) N = 10,779 |

X | X | X |

| 83 | Braaksma et al. (2018) | Systematic review | 6–12 | PA | CRF | 23 (23/0/0/0) N = 7,071 |

X | X | X |

| 84 | Reyes-Amigo et al. (2017) | Systematic review | 6–12 | HIIT | CRF | 10 (6/4/0/0) N = 330 |

X | X | X |

| 85 | Gäbler et al. (2018) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 6–18 | PA | Physical fitness | 15 (0/15/0/0) N = 595 |

X | X | X |

| 86 | Neil-Sztramko et al. (2021) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 6–18 | PA (extra PE) | Physical fitness | 41 (41/0/0/0) N = NR |

X | √ | X |

| 87 | Li et al. (2024) | Multivariate and Network Meta-analysis | 6–18 | PA | Physical fitness | 36 (0/0/NR/NR) N = 2,658 |

√ | X | X |

| 88 | Gralla et al. (2019) | Systematic review | 6–18 | VPA | CRF | 16 (0/0/0/16) N = 8,041 |

X | X | X |

| 89 | Cibinello et al. (2023) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 6–18 | Pilates | Flexibility and muscle strength | 10 (0/0/NR/NR) N = 804 |

√ | √ | X |

| 90 | Behringer et al. (2010) | Systematic review | 6–18 | PA | Muscular fitness | 77 (1/1/12/63) N = 1728 |

X | X | X |

| 43 | Poitras et al. (2016) | Systematic review | 7–16 | PA | CRF | 38 (6/3/1/28) N = 26,865 |

√ | X | X |

| 91 | Lei and Jun (2022) | Systematic review | 7–17 | PA (Taekwondo Poomsae training) | Physical fitness | 15 (0/15/0/0) N = 536 |

X | X | X |

| 92 | Pinho et al. (2024) | Meta-analysis | 7–17 | PA | Physical fitness | 80 (0/0/NR/NR) N = 5,769 |

X | X | X |

| 93 | Clemente et al. (2022) | Systematic review | 7–18 | PA (soccer training) | Physical fitness | 13 (0/13/0/0) N = 2,794 |

√ | X | X |

| 94 | Woodforde et al. (2022) | Systematic review | 7–18 | PA (extra PE) | Physical fitness | 4 (2/2/0/0) N = 444 |

X | X | X |

| 95 | Cox et al. (2020) | Meta-analysis | 8–18 | Resistance training | Muscle strength | 11 (0/0/NR/NR) N = 253 |

√ | √ | X |

| 96 | Peralta et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 8–19 | PA (extra PE) | CRF | 24 (0/15/2/7) N = 15,159 |

X | X | X |

| 97 | Zhao et al. (2023) | Meta-analysis | 10–12 | PA (jumping rope) | Physical fitness | 15 (15/0/0/0) N = 1,048 |

√ | √ | X |

| 98 | Ferreira et al. (2024) | Systematic review | 10–15 | PA (swim exercise) | Physical fitness | 5 (0/5/0/0) N = 459 |

√ | X | X |

| 99 | Ramirez-Campillo et al. (2023) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 10–16 | PA (Plyometric training) | Physical fitness | 11 (0/0/??/??) N=NR |

X | X | X |

| 100 | Garcia-Banos et al. (2020) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 10–18 | PA (extra PE) | Muscular fitness | 11 (3/8/0/0) N = 1,161 |

X | X | X |

| 101 | Minatto et al. (2016) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 10–19 | PA (extra PE) | CRF | 40 (23/17/0/0) N = 19,970 |

√ | √ | X |

| 102 | da Silva Bento et al. (2022) | Systematic review | 10–19 | HIIT | CRF | 14 (14/0/0/0) N = 664 |

X | X | X |

| 103 | de Andrade Gonçalves et al. (2015) | Systematic review | 11–19 | PA | Physical fitness | 6 (0/0/1/5) N = 7,599 |

X | √ | X |

| 104 | Singh et al. (2022) | Systematic and meta-analysis | 11–19 | PA (jump rope training) | CRF | 13 (2/11/0/0) N = 538 |

X | X | X |

| 105 | Costigan et al. (2015) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 13–18 | HIIT | CRF | 15 (9/6/0/0) N = 1,110 |

X | X | X |

| 106 | Behm et al. (2017) | Systematic review | 13–18 | PA (extra PE) | Muscular strength | 8 (0/0/NR/NR) N = 3,297 |

X | X | X |

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the core pathways in the Stodden model (2008).

CRF = Cardiorespiratory fitness; CSS = Cross-sectional Studies; FMS = Fundamental Movement Skills; HIIT = High-intensity interval training; INT = Non-randomized intervention studies; LON = Longitudinal studies; MC = Motor competence; MVPA = Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; NR = Not reported; PA = Physical activity; PE = Physical Education; RCT = (Clustered) Randomized Controlled Trials studies; PMC = Perceived motor competence; RCT = (Clustered) Randomized Controlled Trial studies; TPA = total physical activity; VPA = Vigorous physical activity.

2.1.3 Strength of evidence and effect sizes in the motor competence—physical activity pathway

To address research question 2, we extracted additional data on the overall strength of evidence and average effect sizes reported by the included reviews on the main bidirectional pathway of the Sodden model between motor competence and physical activity (see Table 2). The information was separately provided per study design, ordered by age groups (early childhood ~2–5 years of age; middle childhood ~6–12 years of age; and adolescence ~13–18 years of age), and further by the subdomains of the traits (e.g., for motor competence, subdomains like object control skills or balancing skills).

Table 2

| Review | Type of review | Publication year (search period) | Age range (years) | Trait 1 (MC domain) | Trait 2 (PA domain) | # of studies on trait 1 and 2 (RCT/INT/LON/CSS) | Overall findings | Strength of evidence* | Effect size ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional–early childhood | |||||||||

| Santos et al. (2023) | Systematic review | 2023 (until 2022.12.22) | 0–3 | MC | PA (aquatic activities) | 6 (0/3/2/3) N = 215 |

All six studies (100%) found a significant association between swimming activities and motor development. | + | Not specified |

| Bingham et al. (2016) | Systematic review | 2016 (until 2016.09) | 0–6 | MC | TPA | 9 (0/0/1/8) N = 1,202 |

Nine out of 23 analyses (37%) identified motor competence as associated with total physical activity. | ? | Not specified |

| Bingham et al. (2016) | Systematic review | 2016 (until 2016.09) | 0–6 | MC | MVPA | 10 (0/0/1/9) N = 1809 |

Eleven out of 26 analyses (42%) identified motor competence as associated with moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. | ? | Not specified |

| Figueroa and An (2017) | Systematic review | 2017 (until 2015.03.31) | 3–5 | MC (Motor skill competence) | PA | 11 (6/0/0/5) N = 2,157 | Eight out of 11 studies (72.7%) reported a significant association. The effect size was not specified but noted to differ by gender, physical activity intensity, motor skill type, and day of the week (weekdays versus weekends). | + | Not specified |

| Xin et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 2020 (2000.01–2020.04) | 3–6 | MC (fundamental movement skills) | PA | 26 (0/0/2/24) N = 4,851 | Sixteen out of 26 studies (61.5%) reported a significant association between MC and any PA trait (r = 0.10–0.46). | + | Small to moderate |

| Xu et al. (2024) | Systematic review | 2024 (until 2022.07) | 3–6 | MC (fundamental movement skills) | MVPA | 19 (0/0/4/18) N = 26,275 | Across 19 studies, fifteen out of 23 (82.6%) analyses found a significant association between FMS and MVPA (r = 0.25, 95%CI: 0.22 ∼ 0.27). | + | Small |

| Xu et al. (2024) | Systematic review | 2024 (until 2022.07) | 3–6 | MC (fundamental movement skills) | MVPA | 12 (0/0/2/11) N = 6,561 | Across 12 studies, seven out of 14 (50%) analyses found a significant association between FMS and TPA (r = 0.23, 95%CI: 0.19 ∼ 0.27). | ? | Small |

| Jones et al. (2020) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2020 (until 2019.04) | 3–6 | MC (fundamental motor skills) | MVPA | 12 (0/0/0/12) N = 2,578 | Eight of 12 analyses (67%) reported a significant association. Meta-analysis showed a small effect (r = 0.20, 95%CI: 0.13–0.26). Heterogeneity: τ value of ±0.089 from a random effect model. | + | Small |

| Liu Y. et al. (2023) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2023 (until 2023.08) | 3–6 | MC (fundamental motor skills) | MVPA | 3 (0/0/1/2) N = 260 | Three datasets examined the association between total MC and MVPA. Meta-analysis showed a large effect (β = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.38–0.75, p = 0.001). No heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, p = 0.99) from a random effect test. |

? | Large |

| Xin et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 2020 (2000.01–2020.04) | 3–6 | MC (fundamental movement skills) | MVPA | 16 (0/0/1/16) N = 2,617 | Eleven out of 16 studies (69%) found a significant association between MC and MVPA. | + | Small to moderate |

| Jones et al. (2020) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2020 (until 2019.04) | 3–6 | MC (fundamental motor skills) | TPA | 12 (0/0/0/12) N = 1903 | Ten out of 12 analyses (83%) found a significant association. Meta-analysis showed a small effect (r = 0.20, 95%CI: 0.12–0.28). Heterogeneity: τ value of ±0.113 from a random effect model. |

+ | Small |

| Xin et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 2020 (2000.01–2020.04) | 3–6 | MC (fundamental movement skills) | TPA | 12 (0/0/0/12) N = 2,152 |

Nine out of 12 studies (75%) supported small to moderate associations between MC and TPA. | + | Small to moderate |

| Barnett et al. (2016) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2016 (1995–2014) | 3–5 | Locomotor skills | PA/Sports | 7 (1/0/0/6) N = 963 |

Five out of 11 analyses (45%) found a significant association between PA/sports and locomotor skills. Heterogeneity was not reported on this association. |

? | Not specified |

| Xin et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 2020 (2000.01–2020.04) | 3–6 | Locomotor skills | TPA | 10 (0/0/0/10) N = 2,144 |

Six out of 10 studies (60%) found a significant association between locomotor skills and TPA. | + | Small to moderate |

| Xin et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 2020 (2000.01–2020.04) | 3–6 | Locomotor skills | MVPA | 16 (0/0/2/15) N = 3,024 |

Nine out of 16 studies (56%) found a significant association between locomotor skills and MVPA. | ? | Small to moderate |

| Liu Y. et al. (2023) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2023 (until 2023.08) | 3–6 | Locomotor skills | MVPA | 5 (0/0/1/4) N = 981 |

Six datasets examined the association between locomotor skill and MVPA Meta-analysis showed no association (β = 0.06, 95% CI: −0.35- 0.47, p = 0.79). Heterogeneity: I2 = 90.26%, (p = 0.001) from a random effect test. |

0 | No association |

| Barnett et al. (2016) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2016 (1995–2014) | 3–5 | Object control skills | PA/Sports | 6 (1/0/0/5) N = 863 |

Five out of 11 analyses (45%) found a significant association between PA/sports and object control skills. Heterogeneity was not reported on this association. |

? | Not specified |

| Xin et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 2020 (2000.01–2020.04) | 3–6 | Object control skills | TPA | 11 (0/0/0/11) N = 2,190 |

Nine out of 11 studies (82%) found a significant association between objective control skills and total physical activity. | + | Small to moderate |

| Xin et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 2020 (2000.01–2020.04) | 3–6 | Object control skills | MVPA | 17 (0/0/1/16) N = 3,024 |

Twelve out of 17 studies (71%) found a significant association between object control skills and MVPA. | + | Small to moderate |

| Liu Y. et al. (2023) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2023 (until 2023.08) | 3–6 | Object control skills | MVPA | 4 (0/0/1/3) N = 855 |

Four datasets examined the association between object control skill and MVPA. Meta-analysis showed a significant, small effect (β = 0.15, 95% CI: 0.02, 0.27, p = 0.02). No heterogeneity (p = 0.15) from a random effect test. |

+ | Small |

| Xin et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 2020 (2000.01–2020.04) | 3–6 | Stability | TPA | 4 (0/0/0/4) N = 1,424 |

Two out of four studies (50%) found a significant association between stability skills and TPA. | ? | Small to moderate |

| Xin et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 2020 (2000.01–2020.04) | 3–6 | Stability | MVPA | 3 (0/0/1/2) N = 1,410 |

One out of three studies reported a significant association between stability skills and MVPA. | ? | Small to moderate |

| Cross-sectional–middle/late childhood | |||||||||

| Holfelder and Schott (2014) | Systematic review | 2014 (2000–2013.06) | 3–18 | MC (fundamental movement skills) | PA | 12 (0/0/2/10) N = 6,071 |

Ten out of 12 studies (83.3%) found a significant association between MC and PA, with r ranging from 0.17 to 0.47. | + | Small to moderate |

| Barnett et al. (2016) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2016 (1995–2014) | 3–18 | MC (skill composite) | PA/ sports | 3 (1/0/1/1) N = 913 |

Three out of four analyses (75%) found a significant association between PA and motor skill composite score. Heterogeneity was not reported for the random effect test on this association. |

+ | Not specified |

| Logan et al. (2015) | Systematic review | 2015 (until 2013.11) | 3–18 | MC (fundamental movement skills) | PA | 13 (0/0/1/12) N = 10,534 |

All studies found at least one significant association between FMS and physical activity. Effect sizes differed across age: small to moderate in early childhood and adolescence and small to large in middle to late childhood. | + | Small to moderate Small to large |

| Lubans et al. (2010) | Systematic review | 2010 (until 2009.06) | 3–18 | MC (fundamental movement skills) | PA | 13 (0/0/2/11) N = 5,187 |

Twelve out of 13 studies (92.3%) found a significant association between MC and at least one domain of PA. | + | Not specified |

| Poitras et al. (2016) | Systematic review | 2016 (until 2015.01) | 7–15 | MC (motor skill development) | TPA | 6 (0/0/1/5) N = 5,179 |

Three out of five (60%) cross-sectional studies found a significant association. | + | Not specified |

| Burton et al. (2023) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2023 (until 2022.08.05) | 11–17 | MC (motor competence) | PA | 8 (1/0/0/7) N = 5,224 |

Eight out of 13 analyses (61%) found a significant association. Meta-analysis showed a small effect (r = 0.21, 95%CI: 0.12–0.30). Very high heterogeneity (I2 = 90.64) from a random effect test. |

+ | Small |

| Holfelder and Schott (2014) | Systematic review | 2014 (2000–2013.06) | 3–18 | Locomotor skills | PA | 5 (0/0/1/4) N = 744 |

All five studies (100%) found a significant, small to moderate association between object control and PA, with r ranging from 0.14 to 0.46. | + | Small to moderate |

| Burton et al. (2023) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2023 (until 2022.08.05) | 11–17 | Locomotor skills | PA | 5 (0/0/2/3) N = 1,443 |

Five out of six analyses (80%) found a significant association. Meta-analysis showed a small effect (r = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.12–0.30). High heterogeneity (I2 = 62.94) from a random effect test. |

+ | Small |

| Holfelder and Schott (2014) | Systematic review | 2014 (2000–2013.06) | 3–18 | Object control Skills |

PA | 6 (0/0/2/4) N = 1824 |

All six studies (100%) found a significant, association between object control and PA. | + | Small to moderate |

| Burton et al. (2023) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2023 (until 2022.08.05) | 11–17 | Object control skills | PA | 6 (0/0/2/4) N = 5,081 |

Eight out of 12 analyses (67%) found a significant association. Meta-analysis showed a small effect (r = 0.26, 95% CI: 0.18–0.33). Moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 38.58) from a random effect test. |

+ | Moderate |

| Burton et al. (2023) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2023 (until 2022.08.05) | 11–17 | Stability/ balance | PA | 5 (0/0/1/4) N = 6,369 |

Eight out of 11 analyses (72.7%) found a significant association. Meta-analysis showed a small effect (r = 0.20,95%CI: 0.13–0.27). Very high heterogeneity (I2 = 86.22) from a random effect test. |

+ | Small |

| Review | Type of review | Publication year (search period) | Age range (years) | Exposure | Outcome | # of studies using LON | Overall findings | Strength of evidence* | Effect size ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal–early childhood—MC - > PA | |||||||||

| Øglund et al. (2015) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2015 (until 2014.09) | 0–2 | MC (motor development) | PA | 3 N = 4,951 |

Two of three studies (66.7%) found that motor development before age 2 predicted physical activity and sport participation in youth with a small effect size. Heterogeneity was not reported for the random effect test on this association. |

+ | Small |

| Jones et al. (2020) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2020 (until 2019.04) | 3–6 | MC (fundamental motor skills) | PA | 5 N = 1,112 |

Three out of five longitudinal studies (60%) showed that MC predicts PA with a small effect size (0.21 < r < 0.28). Heterogeneity was not reported for the random effect test on this association. |

+ | Small |

| Xin et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 2020 (2000.01–2020.04) | 3–6 | MC (fundamental movement skills) | PA | 2 N = 357 |

Two longitudinal studies found that MC did not predict PA. | 0 | No prediction |

| Longitudinal–middle/late childhood–MC - > PA | |||||||||

| Graham et al. (2022) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2021 (until 2017.05) | 5–11 | MC (fundamental movement skills) | MVPA | 19 N = 10,412 |

Only six out of 19 studies showing significant prediction (31.5%). Fourteen of the 19 studies were pooled into a meta-analysis. FMS had a large effect on daily MVPA (13.3 min/day, 95% CI 8.0–18.6; R2 = 0.89). Heterogeneity: τ value of ±7.6 (95%CI: −13 to 21) from a random effect model. |

? | Large |

| Holfelder and Schott (2014) | Systematic review | 2014 (2000–2013.06) | 3–18 | MC (fundamental movement skills) | PA | 7 N = 1936 |

Motor skill competence at baseline significantly explained 5–18% of variance in PA at follow-up in 5 out of 7 studies (71.4%). | + | Small |

| Barnett et al. (2022) | Systematic review | 2022 (until 2019.11.08) | 2–18 | MC (skill composite) | PA | 7 N = 4,167 |

Across seven studies, 71% of the analyses reported a significant prediction of PA by total MC (PA ranging from LPA to VPA, with most studies using MVPA). | + | Small |

| Barnett et al. (2022) | Systematic review | 2022 (until 2019.11.08) | 2–18 | Locomotor, Coordination, Stability skills | PA | 15 N = 6,331 |

Across 15 studies, 42% of the analyses showed locomotor and coordination/ stability skills to predict PA (PA ranging from LPA to VPA, with most studies using MVPA). | ? | Small to moderate |

| Longitudinal–early childhood–PA- > MC | |||||||||

| Jones et al. (2020) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2020 (until 2019.04) | 3–6 | PA | MC (fundamental motor skills) | 2 N = 344 |

Only two studies explored the longitudinal prediction of MC by PA, showing PA to predict balance and locomotor, but not (or a negative effect) for agility and object control. Heterogeneity was not reported on this association. |

? | Small |

| Xin et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 2020 (2000.01–2020.04) | 3–6 | PA | MC (fundamental movement skills) | 2 N = 357 |

Two longitudinal studies found that PA was a significant predictor for MC (β = 0.07–0.26). | ? | Small |

| Longitudinal–middle/late childhood–PA- > MC | |||||||||

| Barnett et al. (2022) | Systematic review | 2022 (until 2019.11.08) | 2–18 | PA | MC (Motor competence) | 11 N = 5,528 (2 trials were included) |

Eleven longitudinal studies investigated the pathway from PA to any form of MC, with no evidence to support an association, with only 8% analyses significant. Both interventions did not show a significant effect. | 0 | No effect |

| Barnett et al. (2022) | Systematic review | 2022 (until 2019.11.08) | 2–18 | PA | Locomotor, Coordination, Stability skills | 11 N = 4,586 |

Across 11 studies, 24% of the analyses supported a pathway from locomotor/ coordination/ stability skills to PA (ranging from LPA to VPA, with most studies using MVPA). | 0 | No effect |

| Barnett et al. (2022) | Systematic review | 2022 (until 2019.11.08) | 2–18 | PA | Object control skills | 5 N = 2,200 |

Across five studies, 38% analyses supported a pathway from object control skills to PA (ranging from LPA to VPA, with most studies using MVPA). | ? | Small |

| Review | Type of review | Publication year (search period) |

Age range (years) | Intervention | Outcome | # of RCT/INT studies | Overall findings | Strength of evidence* | Effect size ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention–early childhood–MC - > PA | |||||||||

| Hesketh et al. (2017) | Systematic review | 2017 (until 2015.10) | 0–6 | MC (motor skills) | PA | 10 (7/3) N = 3,204 |

Out of 10 RCT/INT studies, five (50%) reported motor skills training had a positive effect on time spent on PA. | ? | Not specified |

| Engel et al. (2018) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2018 (until 2017.7.20) | 3–5 | MC (fundamental motor skills) | TPA | 7 (6/1) N = 1,623 |

Three out of seven (42.9%) studies found a significant effect of MC intervention on the total amount of PA. Meta-analyses showed a small improvement in total PA (SMD = 0.32; 95% CI: 0.09–0.54; p = 0.006). Very high heterogeneity (I2 = 76%, Chi2p = 0.0004) from a random effect test. |

? | Small |

| Engel et al. (2018) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2018 (until 2017.7.20) | 3–5 | MC (fundamental motor skills) | MVPA | 7 (7/0) N = 1,531 |

One out of seven (14.3%) studies found a significant effect of MC intervention on MVPA. Meta-analyses showed a small improvement in MVPA (SMD = 0.21; 95% CI: 0.01–0.40; p = 0.03). High heterogeneity (I2 = 63%, Chi2p = 0.01) from a random effect test. |

0 | Small |

| Intervention–middle/late childhood–MC - > PA | |||||||||

| Engel et al. (2018) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2018 (until 2017.7.20) | 5–12 | MC (fundamental motor skills) | TPA | 3 (2/1) N = 414 |

None of three studies (0%) found a significant effect of MC intervention on the total amount of PA, while meta-analysis showed a small significant improvement in total PA (SMD = 0.23; 95% CI: 0.03–0.42; p = 0.02). No heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, Chi2p = 1) from a random effect test. |

0 | Small |

| Engel et al. (2018) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2018 (until 2017.7.20) | 5–12 | MC (fundamental motor skills) | MVPA | 3 (0/3) N = 348 |

One out of three (33.3%) studies found a significant effect of MC intervention on MVPA. Meta-analysis showed a small significant improvement in MVPA (SMD = 0.29 95% CI: 0.08–0.51; p = 0.007). High heterogeneity (I2 = 63%, Chi2p = 0.01) from a random effect test. |

? | Small |

| Intervention–early childhood–PA - > MC | |||||||||

| Timmons et al. (2012) | Systematic review | 2012 (until 2011.03) | 0–4 | PA | MC | 4 (3/1) N = 802 |

All four intervention studies found that PA significantly improved MC. | + | Not specified |

| Carson et al. (2017) | Systematic review | 2017 (until 2016.4.14) |

0–4 | PA | MC (motor development) | 12 (6/6) N = 5,245 |

Ten out of 12 intervention studies (83.3%) found that PA improved MC. | + | Not specified |

| Grady et al. (2025) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2025 (2014.09–2022.10) | 0–6 | PA (early childhood education and care-based PA) | MC (fundamental movement skills) | 16 (16/0) N = 4,905 |

Early childhood education and care-based PA was found to significantly improve FMS (SMD = 0.544, 95%CI: 0.1–0.98, p = 0.015). Very high heterogeneity (I2 = 95.8%) from a random effect test. |

+ | Moderate |

| Chen et al. (2024) | Meta-analysis | 2024 (until 2023.11.01) | 2–6 | PA (MC-focused exercise training) | MC (fundamental motor skills) | 23 (22/1) N = 4,068 |

All 23 intervention studies (22 RCT) found that motor skills-focused exercise training significantly improved FMS compared to the control group, with structured intervention the most effective (Hedge’s g = 1.29, p < 0.001). No heterogeneity (I2 < 25%) from a random effect test. |

+ | Large |

| Wang and Zhou (2024) | Meta-analysis | 2024 (until 2024.03) | 3–6 | PA (MC-focused exercise training) | MC (gross motor skills) | 23 (23/0/0/0) N = 2070 |

Twenty out of 23 studies were included in the meta-analysis. Of these, 17 (85%) showed significant improvement by motor skills-focused exercise training on gross motor skills as compared to active control (Cohen’s d = 1.53). Very high heterogeneity (I2 = 93%, p < 0.01) from a random effect test. |

+ | Large |

| Veldman et al. (2021) | Systematic review | 2021 (until 2019.11.21) | 3–5 | MVPA | MC (motor development) | 11 (4/6) N = 1,281 |

All ten intervention studies (100%) found a positive effect of MVPA on motor development (either total score, a specific component, or an individual skill). | + | Not specified |

| Van Capelle et al. (2017) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2017 (until 2016.03.30) | 3–5 | PA | MC (fundamental motor skills) | 21 (6/15) N = 4,245 |

Restricting to teacher-led interventions, the meta-analysis across 13 analyses indicated that PA intervention led to a trivial but significant improvement in MC (SMD = 0.13, 95%CI: 0.03–0.22, p = 0.008) in only 4 analyses (30.7%). Very high heterogeneity (I2 = 84%, p < 0.00001) from a random effect test. |

? | Small |

| Zeng et al. (2017) | Systematic review | 2017 (2000.01–2017.07) | 4–6 | PA | MC (motor skills) | 10 (10/0) N = 1,602 |

Eight out of 10 RCTs (80%) reported that increasing PA led to significant improvements in motor performance. | + | Not specified |

| Van Capelle et al. (2017) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2017 (until 2016.03.30) | 3–5 | PA | Object control skills | 7 (5/2) N = 558 |

Restricting to teacher led interventions the meta-analysis across eight analyses indicated a small but significant improvement in object control skills (SMD = 0.47, 95%CI: 0.15–0.80, p = 0.004) in 6 analyses (75%). Very high heterogeneity (I2 = 89%, p < 0.00001) from a random effect test. |

+ | Small |

| Van Capelle et al. (2017) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2017 (until 2016.03.30) | 3–5 | PA | Locomotor skills | 5 (4/1) N = 602 |

Restricting to teacher led interventions the meta-analysis across seven analyses indicated a small significant improvement in locomotor skills (SMD = 0.44, 95%CI: 0.16–0.73, p = 0.002). High heterogeneity (I2 = 57%, p = 0.06) from a random effect test. |

+ | Small |

| Li et al. (2022) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2021 | 3–7 | PA (physical education) | MC (fundamental movement skills) | 23 (17/6) N = 2,258 |

Meta-analysis showed a significant improvement of extra physical education on any form of MC (SMD range:1.38–1.56, I2 = 59.2–93.8%). Very high heterogeneity (I2 = 89.7%, p = 0.0000) from a random effect test. |

+ | Large |

| Johnstone et al. (2018) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2018 (until 2016.12) | 3–12 | PA (active play) | MC (fundamental movement skills) | 2 (2/0) N = 193 |

Both studies showed a significant effect of active play interventions on children’s FMS quotient score and one-leg balance. Meta-analysis could not be conducted with two studies. |

? | Not specified |

| Liu et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 2020 (until 2020.10) | 3–12 | PA (active video games) | MC (fundamental movement skills) | 5 (3/2) N = 340 |

Across five studies, two (40%) reported that active video games significantly improved FMS compared to a control manipulation. | ? | Not specified |

| Zhang et al. (2024) | Systematic review | 2024 (2000–2023) | 8–17 | PA | MC (fundamental motor skills) | 26 (11/15) N = 1,133 |

Across 26 studies, 16 out of 17 (94.1%), ten out of ten (100%), and two out of two studies (100%) found significant effect of PA on locomotor, balance, and object control skills, respectively. | + | Not specified |

| Oppici et al. (2022) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2022 (2007–2022) | 3–12 | PA (exergaming) | MC (fundamental movement skills) | 9 (6/3) N = 783 |

Across nine studies, seven out of 14 analyses (50%) found that exergaming had significant improvements in MC as compared to the control (r = 0.24, 95%CI: 0.11–0.36). Heterogeneity from a random effect test was not reported. |

? | Small |

| Sun and Chen (2024) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2024 (2001–2022) | 3–12 | PA (sports game) | MC (fundamental motor skills) | 12 (12/0) N = 1701 |

All 12 studies (100%) found that sports game interventions had a significant effect on MC (SMD = 0.30, p < 0.0001). No details on the meta-analytic test approach were reported. |

+ | Small |

| Intervention–Middle/Late Childhood–PA - > MC | |||||||||

| Moon et al. (2024) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2024 (until 2021.11) | 5–12 | PA (physical education) | MC | 27 (10/17) N = 13,281 |

Twenty-six studies were included in meta-analyses with 22 (84.6%) showing statistically significant effect on MC (Hedges’ g = 0.71; 95% CI = 0.60–0.81; p < 0.001). Very high heterogeneity (I2 = 78.4%) from a random effect test. |

+ | Large |

| Rico-González (2023) | Systematic review | 2023 (until 2022.02) | 4–12 | PA (school-based physical education) | FMS | 4 (4/0) | Across four studies, three (75%) showed significant effects of PA (school-based physical education) on FMS. | + | Not specified |

| Norris et al. (2016) | Systematic review | 2016 (until 2015.05) | 5–15 | PA (active video game) | MC (motor skills) | 3 (2/1) N = 805 |

Across three studies, two (66.7%) showed significant effects of PA (active video game) on MC as compared to control. | + | Not specified |

| García-Hermoso et al. (2020) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2020 (until 2019.10) | 3–18 | PA (physical education) | FMS | 7 (5/2) N = 3,870 |

All seven studies (100%) showed significant effects of PE-based PA interventions on FMS (Hedges g = 0.38; 95% CI, 0.27–0.49). High heterogeneity (I2 = 73.4%, p = 0.02) from a random effect test. |

+ | Small |

| Dudley et al. (2011) | Systematic review | 2011 (1990.01–2010.06) | 5–18 | PE and school sport | MC | 4 (3/1) N = 3,196 |

Across four studies, all analyses supported an effect of school sports on MC. | + | Not specified |

| Sinclair and Roscoe (2023) | Systematic review | 2023 (until 2023.02) | 3–11 | PA (swimming) | MC (fundamental movement skills) | 10 (3/7/0/0) N = 611 |

All ten studies found that swimming significantly improved at least one domain of MC. | + | Not specified |

| Hassan et al. (2022) | Systematic review and network meta-analysis | 2022 (Until 2022.05) | 3–12 | Aerobic exercise | MC (gross motor skills) | 13 (13/0) N = 1,109 |

Network meta-analysis showed that aerobic exercise training was an effective treatment for the total gross motor skills (ES: 7.49, 95% Cl: 0.1 to 15.7). Bayesian random-effects modeling was used and no heterogeneity was found. |

+ | Large |

| Hassan et al. (2022) | Systematic review and network meta-analysis | 2022 (Until 2022.05) | 3–12 | PA (exergaming) | MC (gross motor skills) | 13 (13/0) N = 1,109 |

Network meta-analysis showed that exergaming was not an effective treatment for the total gross motor skills (ES: −0.17, 95% Cl: −12.8 to 12.4). Bayesian random-effects modeling was used and no heterogeneity was found. |

0 | No effect |

| Hassan et al. (2022) | Systematic review and network meta-analysis | 2022 (Until 2022.05) | 3–12 | Aerobic exercise training | Locomotor skills | 11 (11/0) N = 1,021 |

Network meta-analysis showed that aerobic exercise training was not an effective treatment for locomotor skills (ES: 4.12, 95% Cl: −1.4 to 9.4). Bayesian random-effects modeling was used and no heterogeneity was found. |

0 | No effect |

| Hassan et al. (2022) | Systematic review and network meta-analysis | 2022 (Until 2022.05) | 3–12 | PA (exergaming) | Locomotor skills | 11 (11/0) N = 1,021 |

Network meta-analysis showed that exergaming was an effective treatment for locomotor skills (ES: 12.50, 95% Crl: 0.28 to 24.50). Bayesian random-effects modeling was used and no heterogeneity was found. |

+ | Large |

| Hassan et al. (2022) | Systematic review and network meta-analysis | 2022 (Until 2022.05) | 3–12 | Aerobic exercise training | Object control skills | 16 (16/0) N = 1,515 |

Network meta-analysis showed that aerobic exercise training was an effective treatment for object control skills (SMD: 6.90, 95% Cl: 1.39 to 13.50). Bayesian random-effects modeling was used and no heterogeneity was found. |

+ | Large |

| Hassan et al. (2022) | Systematic review and network meta-analysis | 2022 (Until 2022.05) | 3–12 | PA (exergaming) | Object control skills | 16 (16/0) N = 1,515 |

Network meta-analysis showed that exergaming was not an effective treatment for object control skills (SMD: −0.4, 95% Cl: −10.2 to 8.9). Bayesian random-effects modeling was used and no heterogeneity was found. |

0 | No effect |

| McDonough et al. (2020) | Systematic review | 2020 (2000–2020) | 6–12 | PA (18), exergaming (7) |

MC (motor skill development) | 25 (25/0) N = 4,325 |

Out of 25 RCTs, 20 (80%) that used various PA interventions led to significant improvements children’s motor skill development. | + | Not specified |

| Lorås (2020) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2020 (2002–2020) | 3–13 | PA (physical education) | MC | 20 (10/10/0/0) N = 4,190 |

Sixteen out of 23 analyses (69.6%) found that physical education intervention had significant effect on overall motor competence (g = −0.69, 95%CI: −0.91 to-0.46, p < 0.001). Very high heterogeneity (I2 = 92.74%) from a random effect test. |

+ | Moderate |

| Carson et al. (2017) | Systematic review | 2016 (until 2015.01) | 7–15 | PA | MC (motor skill development) | 2 (1/1) N = 203 |

Neither of the two intervention studies found effects on motor skill development. | ? | No effect |

| Behringer et al. (2011) | Meta-analysis | 2011 (until 2009.08) | 0–18 | Strength training | Jump, run, throw | 34 (0/34) N = 1,432 |

Meta-analysis indicated that strength training led to a significant improvement in combination of jumping, running, and throwing ES = 0.52 (95%CI: 0.33–0.71). No heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) from a fixed effects model. |

+ | Moderate to large |

| Comeras-Chueca et al. (2021) | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2021 (until 2021.03) | 4–15 | Active video game | Motor competence | 10 (8/2) N = 979 |

Seven out of 10 (70%) studies found that active video game had a significant improvement on motor competence. Heterogeneity wasn’t reported for the random effect test on the PA-MC association. |

+ | Not specified |

| Collins et al. (2019a) | Meta-analysis | 2019 (until 2017.06) | 5–18 | Strength training | Throw, sprint, squat-, standing-long-, and vertical jump | 22 (0/22) N = 943 |

Significant intervention effects were identified in 33 analyses on sprint (Hedges’ g = 0.292,95% CI: 0.017 to 0.567, p = 0.038), squat jump (Hedges’ g = 0.730, 95% CI: 0.374 to 1.085, p = < 0.001), standing long jump (Hedges’ g = 0.298, 95% CI 0.096 to 0.499, p = 0.004), throw (Hedges’ g = 0.405, 95% CI 0.094 to 0.717, p = 0.011) and vertical jump (Hedges’ g = 0.407, 95% CI 0.251 to 0.564, p = < 0.001) ability. High heterogeneity for squat jump (I2 = 59%), and noor moderate heterogeneity for other outcomes (I2 = 0–35%). |

+ | Moderate to large |

Design characteristics and main findings from the reviews on the association between motor competence and physical activity.

* Strength of evidence was categorized into three types: “0,” no association (0–33% of studies supporting a significant association, or no significant meta-analytic effects across four or more studies). “?,” indeterminate/inconsistent association (34–59% of studies and less than four studies supporting a significant association, or a non-significant meta-analytic effect or a significant meta-analytic effect across less than four studies). “− “or “+” strong association (≥ 60% of studies and four or more studies supporting a significant association, or a significant meta-analytic effect across four or more studies). ** Effect size was categorized into three types: Small, Correlation: 0.10 < r < 0.30; Hedges’g, or Cohen’s d/SMD values of 0.2 to 0.5; standardized β 0.10–0.19. Moderate, Correlation: 0.30 < r < 0.50; Hedges’g, or Cohen’s d/SMD values of 0.5 to 0.8; standardized β 0.20–0.29. Large, Correlation: r > 0.50; Hedges’g, or Cohen’s d or SMD values > 0.8; standardized β > = 0.30. Heterogeneity classification based on I2: No: 0–25%; moderate 26–20%; high 51–75%; very high 76–100%. CI = Confidence interval; Crl = Credible intervals; CSS = Cross-sectional studies; ES = effect size; FMS = Fundamental Movement Skills; INT = Non-randomized intervention studies; LPA = Light physical activity; LON = Longitudinal studies; MC = Motor competence; MVPA = Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; PA = Physical activity; RCT = (Clustered) Randomized Controlled Trial studies; SMD = Standardized mean differences; TPA = Total physical activity; VPA = Vigorous Physical activity.

The rating for the level of evidence in support of a pathway was based on an adaptation of the methodology developed by Sallis et al. (2000) and later revised by Barnett et al. (2022). Based on the percentage of findings in the primary studies supporting the association according to the systematic review, a pathway was classified as a non-significant (coded as “0”) when only 0 to 33% of studies reported a significant association, or when no significant meta-analytic effects across four or more studies were found. A pathway was classified as an inconsistent or indeterminate (coded as “?”) association when between 34 and 59% of the primary studies reported a significant association or when less than four primary studies in total reported a significant association. Also, a significant meta-analytic effect across less than four primary studies was considered indeterminate. A pathway was classified as strong (coded as “+” or “-”, depending on the direction of the association) when ≥60% of four or more primary studies supporting a significant association, or a significant meta-analytic effect across four or more primary studies was found. The ≥60% criterion to consider evidence “strong” may appear strict but takes into account that there is considerable concern about publication bias towards significant results in sports science in general (Pesce, 2012) and in the specific domain of motor development/physical activity studies (Barnett et al., 2022).