Abstract

Background:

Anxiety is one of the psychological problems that cannot be ignored among many international students. Long-term anxiety has a significant negative impact on the social life and academic achievement of international students. Without timely intervention, it may gradually escalate, induce extreme high-risk behaviors, and seriously threaten the life, health and safety of international students. This study aims to investigate the current situation of anxiety among international students, analyze the influence of perceived social support on anxiety among international students, and explore the mediating role of communicative adaptability.

Methods:

This study was conducted in June 2024, and a convenience sampling method was used to investigate 198 international students in a university in Harbin. Measurements included a general demographic questionnaire, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, and Communicative Adaptability Scale. In this study, SPSS27.0 software was used to conduct descriptive statistical analysis, t test and variance analysis, correlation analysis and regression analysis. Meanwhile, PROCESS plug-in in SPSS27.0 software was used to test the mediation model.

Results:

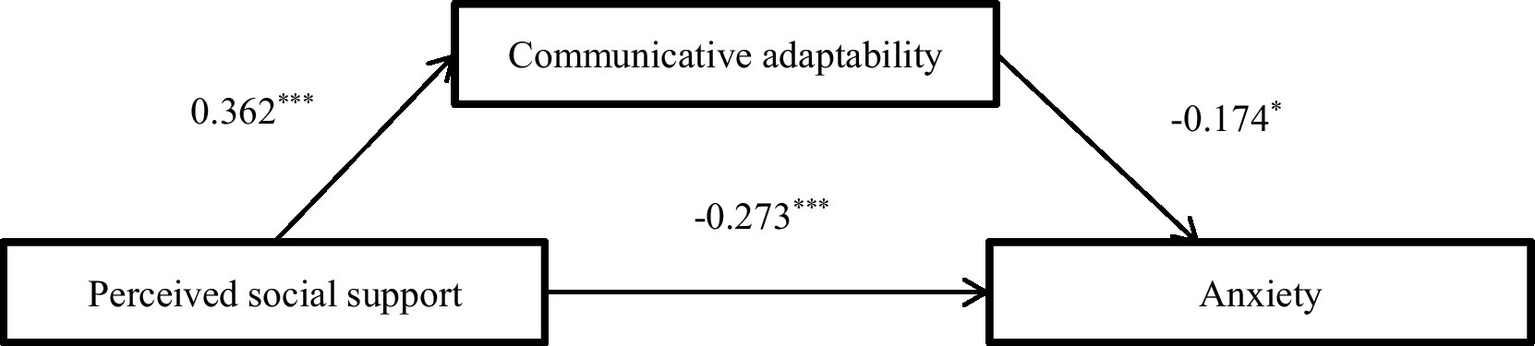

The results of correlation analysis showed that perceived social support was positively correlated with communicative adaptability (r = 0.389, p < 0.01) and negatively correlated with anxiety (r = −0.325, p < 0.01). Communicative adaptability was negatively correlated with anxiety (r = −0.250, p < 0.01). The mediating effect of communicative adaptability was significant in perceived social support on anxiety (95% CI: −0.131 to −0.013).

Conclusion:

Providing more adaptive and targeted social support and cultural adaptation activities may effectively alleviate the anxiety level of international students, and thus maintain and improve the mental health of international students.

1 Introduction

Since the 21st century, globalization has accelerated the development of international educational exchanges, with the number of international students steadily increasing and their backgrounds becoming increasingly diverse. However, students often encounter language barriers, culture shock, and difficulties in social integration during cross-cultural studies, and these stressors significantly impact their mental health (Deb and Miller, 2017; Sirin et al., 2013). Particularly for first-time overseas students, substantial cultural differences, language barriers, and the intertwined emotions of homesickness and loneliness make them more susceptible to psychological issues such as anxiety and depression (Wang et al., 2015). In severe cases, self-harm or suicidal behavior may occur (Chou et al., 2011), not only undermining academic performance and personal development but also posing potential threats to campus stability and social harmony (Araujo et al., 1999).

Anxiety is one of the psychological issues that cannot be ignored among many international students. As an instinctive emotional response mechanism, anxiety serves an adaptive functions within a moderate range. However, excessive anxiety may lead to emotional or physical illness. If anxiety symptoms persistently impair daily functioning and lead to abnormal behavior, it constitutes an anxiety disorder requiring intervention and treatment (Dean, 2016). In the face of the challenge of anxiety, international students showed a significant feature, that is, a low willingness to actively seek psychological treatment. Skromanis et al. (2018) found that compared to Australian domestic students, male international students are more vulnerable to mental health issues and significantly less active in seeking psychological assistance. However, long-term anxiety has a significant negative impact on international student’s social lives and academic achievements. Without timely intervention, anxiety may escalate progressively, triggering extreme high-risk behaviors that severely threaten students’ health and personal safety (Pillay, 2021). Therefore, it is particularly important to explore the mechanism of how to effectively intervene and alleviate the anxiety of international students.

The main effects model of social support emphasizes its impact on individual’s physical and mental health (Cohen and Wills, 1985). This model indicates that social support enhances individual adaptability, effectively alleviates stress, and thereby improves physical and mental health. In addition, studies have further confirmed that perceived social support directly predicts negative emotions and alleviates negative emotions to a certain extent (Li et al., 2016). Perceived social support refers to the degree to which an individual feels understood, supported and respected in social interactions, along with the resulting emotional satisfaction and experiences (Dahlem et al., 1991). Studies have shown that intrinsic perceived social support is an important factor affecting college students’ anxiety (Lee et al., 2013). As a positive variable, perceived social support can effectively reduce anxiety (Gündüz et al., 2018). Its positive effect is that when international students face challenges or stress, they can rely on this sense of subjective support to mobilize internal resources and enhance coping abilities, thereby alleviating anxiety triggered by various stressors.

Cross-cultural adaptation refers to profound changes triggered when individuals or groups from different cultures interact, manifesting across emotional, behavioral, and cognitive dimensions (Searle and Ward, 1990). For this unique and highly sensitive group of international students, adaptive capacity is a critical factor in ensuring academic success, social interaction, and psychological well-being. Kim’s (2003) Integrative Communication Theory reveals that cross-cultural adaptation is a dynamic dialectical process of “stress-adaptation-growth,” emphasizing individuals’ functional adaptability and psychological well-being in new environments. Within this adaptation process, challenges such as language barriers and cultural custom differences frequently pose difficulties for international students, often leading to adaptation dilemmas (Chung and Epstein, 2014). Such adaptive issues are regarded as important mediating variables detrimental to international students’ mental health (Berry, 2005). Academic consensus holds that high-intensity cultural adaptation stress often exerts significant negative effects on individual psychological states, with anxiety being a common emotional response. Against this backdrop, the perceived social support experienced by international students during their overseas lives plays a crucial role. Social support not only provides emotional comfort and psychological security but also helps alleviate feelings of uncertainty and loneliness stemming from cross-cultural communication barriers (Albrecht and Adelman, 1984; Adelman, 1988), thereby effectively reducing anxiety experiences. This study proposes the following hypothesis: Communicative adaptability mediates the effect of perceived social support on anxiety among international students.

Therefore, this study aims to investigate the current status of anxiety among international students, analyze and understand the perceived social support on anxiety, and explore the mediating role of communicative adaptability. The study objectives is to provide more precise and effective strategic suggestions for improving the anxiety of international students, thereby enhancing the overall mental health, building a solid psychological defense for their overseas studies, and promoting personal growth and continuous progress.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants and procedures

This study was conducted in June 2024. A convenience sampling method was adopted to investigate all the international students on campus in a certain university in Harbin. The inclusion criteria for the research subjects are: regular international students currently enrolled, at least 18 years old and willing to participate. Exclude exchange students and those who are unable to understand the questionnaire due to language barriers. A total of 230 questionnaires were sent out. After careful screening and sorting (excluding those with incomplete responses, regular responses, and those that failed the lie detector test), 198 valid questionnaires were successfully recovered, with an effective rate of 86.08%. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Harbin Medical University. In the recruitment and data collection stage of participants, we strictly implemented the principle of informed consent.

2.2 Measures

Demographic information was collected, including gender, parental marital status, parental education level and physical activity status.

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) consists of 3 subscales, with a total of 21 items, respectively to investigate the degree of individuals’ experience of depression, anxiety, stress and other negative emotions (Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995). A 4-point scale of 0 to 3 points is used to score, 0 means “Did not apply to me at all,” 3 means “Applied to me very much, or most of the time.” The sum of the seven scores for each subscale is multiplied by 2 to give the subscale score, with higher scores indicating higher levels of depression, anxiety, or stress. Since this study primarily focuses on the anxiety levels of international students, the anxiety subscale was selected. In this study the total questionnaire Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.955, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for anxiety was 0.860. In previous studies, the scale has been demonstrated to be suitable for diverse sample populations, including university students from different countries and international student groups, exhibiting good cross-cultural applicability (Moussa-Chamari et al., 2024; Slaughter et al., 2023).

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) contains 12 items (Zimet et al., 1988), which are divided into three subscales: significant others, family and friend support, and is scored on a 7-point scale (1 means “very strongly disagree,” 7 means “very strongly agree”). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.949. The MSPSS scale has been applied to college students with international student status in previous studies, confirming its applicability within this population (Bokszczanin et al., 2023).

Communicative Adaptability Scale (CAS) consists of 30 items (Worthington and Bodie, 2017), including six dimensions: Social Composure, Social Confirmation, Social Experience, Appropriate Disclosure, Articulation and Wit. The rating scale uses a 5-point scale, with 1 indicating “never true of me” and 5 indicating “always true of me,” and some items require a reverse scoring. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.872. The applicability of the CAS scale has been validated by previous studies and is suitable for the international student population involved in this research (Duran, 1983).

2.3 Statistical methods

This study employed SPSS 27.0 software for statistical analysis, utilizing two-tailed tests with p < 0.05 indicating statistically significant differences. Specific methods included descriptive statistics, t-tests, analysis of variance (ANOVA), correlation analysis, and regression analysis. Prior to mediation analysis, all continuous variables underwent centering to eliminate multicollinearity. The mediation model was tested using Model 4 within the PROCESS plugin.

3 Results

3.1 Demographics

The study primarily involved Asian international students, with India (70 participants), Bangladesh (25 participants), and Indonesia (16 participants) as the main countries of origin. The sample also encompassed a diverse group from 28 countries across the Americas, Europe, and other regions. The majority of participants are enrolled in six-year degree programs, and their native languages are the official or primary languages of their respective countries. There were 105 male students and 93 female students in this study. 6.06% of the students’ parents are divorced; 55.05% of the students’ fathers have a bachelor’s degree or above; 40.91% of the students’ mothers have a bachelor’s degree or above; 38.89% of the students often do sports. See Table 1 for details.

Table 1

| Variable | Number of people | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 105 | 53.03% |

| Female | 93 | 46.97% |

| Parental divorce or not | ||

| Yes | 12 | 6.06% |

| No | 186 | 93.94% |

| Father’s years of schooling | ||

| less than 5 years | 9 | 4.55% |

| 5–9 years (junior high school degree) | 10 | 5.05% |

| 10–12 years (high school education) | 28 | 14.14% |

| 13–16 years (undergraduate / other) | 42 | 21.21% |

| 16 years (bachelor degree or above) | 109 | 55.05% |

| Mother’s years of schooling | ||

| less than 5 years | 18 | 9.09% |

| 5–9 years (junior high school degree) | 15 | 7.58% |

| 10–12 years (high school education) | 44 | 22.22% |

| 13–16 years (undergraduate / other) | 40 | 20.20% |

| 16 years (bachelor degree or above) | 81 | 40.91% |

| Do you often have sports | ||

| Once in a while | 62 | 31.31% |

| Less | 59 | 29.80% |

| Often | 77 | 38.89% |

The basic information of international students in our research (n = 198).

3.2 Scores of anxiety, perceived social support and communicative adaptability of international students

In this study, 38.4% of international students experience anxiety. The students’ anxiety scores were (7.67 ± 8.79), perceived social support scores were (5.17 ± 1.53), and communicative adaptability scores were (100.09 ± 19.24).

3.3 Correlation analysis

The results showed that perceived social support was positively correlated with communicative adaptability (r = 0.389, p < 0.01), and negatively correlated with anxiety (r = −0.325, p < 0.01). There was a significant negative correlation between communicative adaptability and anxiety (r = −0.250, p < 0.01). See Table 2 for details.

Table 2

| Scales | M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived social support | 5.17 ± 1.53 | 1 | ||

| Communicative adaptability | 100.09 ± 19.24 | 0.389** | 1 | |

| Anxiety | 7.67 ± 8.79 | −0.325** | −0.250** | 1 |

The correlation of perceived social support, communicative adaptability and anxiety.

**p < 0.01.

3.4 The relationship between perceived social support and anxiety: the mediating role of communicative adaptability

The results showed that perceived social support was negatively correlated with anxiety (β = −0.273, p < 0.05), communicative adaptability was negatively correlated with anxiety (β = −0.174, p < 0.05), and perceived social support was positively correlated with communicative adaptability (β = 0.362, p < 0.05). After controlling for demographic variables including gender, parental marital status, parental education level, and physical activity status, mediation analysis revealed that the mediation effect was significant (95% CI: –0.131 to –0.013). The direct effect of perceived social support on anxiety was also significant (95%CI: −0.418 to −0.128). It is suggested that the influence of perceived social support on anxiety is mediated by direct and indirect communicative adaptability pathways. Relevant data are detailed in Tables 3, 4, with the mediation model illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 3

| Variable | B | SE | T | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived social support on anxiety | −0.336 | 0.069 | −4.860 | <0.001 |

| Perceived social support on communicative adaptability | 0.362 | 0.066 | 5.501 | <0.001 |

| Communicative adaptability on anxiety | −0.174 | 0.075 | −2.320 | 0.021 |

| Perceived social support on anxiety | −0.273 | 0.074 | −3.709 | <0.001 |

Mediation analysis of communicative adaptability on the relationship between perceived social support and anxiety.

Table 4

| Effect | Effect size | SE | LL95%CL | UL95%CL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | −0.336 | 0.069 | −0.472 | −0.200 |

| Direct effect | −0.273 | 0.074 | −0.418 | −0.128 |

| Indirect effect | −0.063 | 0.031 | −0.131 | −0.013 |

Bootstrap results for the mediation analysis.

Figure 1

The mediation model of perceived social support → anxiety. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

4 Discussion

In this study, 38.4% of international students have anxiety, previous studies have also pointed out that there is widespread anxiety among international students (Mahihu, 2020; Wang et al., 2023). The reason can be attributed to the fact that some students are immersed in a new cultural environment, where they encounter different cultural and social backgrounds, which often hinders their rapid integration into the local society. This shift requires a redefinition of their identity and values, leading to deep internal reconstruction, often accompanied by conflict, which greatly exacerbates their state of anxiety. In addition, academic pressure becomes a key factor to be concerned about; The high academic demands of studying abroad, with homework, exams and attendance standards often extremely rigorous, further exacerbate anxiety levels.

This study examines the relationship between international students’ perceived social support and anxiety, revealing a significant negative correlation between the two. Specifically, perceived social support serves as a negative predictor of anxiety within this population. These findings hold significant implications for understanding the mental health challenges faced by international students. Upon first arriving in a foreign country, international students often experience fear and unease when confronting unfamiliar academic and living environments. Perceived social support plays a crucial role in facilitating their adaptation process. It encompasses the understanding, respect, and assistance individuals receive from others—forming a positive emotional experience that enhances psychological resilience while significantly alleviating ruminative thinking (Abela et al., 2004; Flynn et al., 2010). Additionally, perceived social support can motivate international students to engage in social interactions and build meaningful relationships, thereby reducing anxiety levels. Over time, perceived social support exerts a profound impact on mental health: it not only fosters positive self-perception, enhances self-confidence and self-esteem, but also facilitates emotional expression and regulation (Tabatabaei et al., 2018; Wirtz et al., 2006). This psychological reinforcement mechanism helps international students better adapt to life abroad and reduces psychological issues stemming from maladjustment.

Communicative adaptability can negatively predict the anxiety of international students. Social anxiety is a prevalent psychological issue among international students, which is mainly manifested as nervousness, unease and fear of rejection in social situations. Group anxiety theory holds that when individuals interact with members outside their own group, they are more prone to anxiety reactions due to concerns about potentially triggering negative evaluations or behavioral consequences (Fang et al., 2016). Insufficient language proficiency and cultural differences may exacerbate this self-doubt and psychological burden. Furthermore, strong communication adaptability not only facilitates social integration but also positively impacts academic performance. By interacting with local students, international students can access learning resources, master efficient study methods, and adjust their learning strategies based on feedback, thereby alleviating anxiety stemming from academic pressure (Finch and Vega, 2003; Mak and Kim, 2011; Durlak and Weissberg, 2011). Furthermore, gender exerts a significant influence on an individual’s cross-cultural adaptation. Berry’s research indicates that male immigrants typically demonstrate stronger psychological adaptation, while females exhibit relative advantages in sociocultural adaptation, reflecting the differential impact of gender factors across different dimensions of adaptation (Berry, 2005).

This study found that communicative adaptability mediates the relationship between perceived social support and anxiety. Specifically, high anxiety among international students is often closely linked to their perceived lack of social support, which further intensifies the impact of communicative adaptability on anxiety. Perceived social support provides individuals with both informational and emotional assistance. Particularly among friends from the same cultural background who share similar experiences, their targeted assistance fosters a sense of belonging, effectively alleviating anxiety (Adelman, 1988). Simultaneously, perceived social support helps reduce psychological stress, boost self-confidence, and promote cultural understanding, thereby enhancing communicative adaptability (Kim and Stoner, 2008). According to cross-cultural adjustment theory, international students’ cultural adaptation is a dynamic process involving the modification of existing cultural patterns and the internalization of new cultural norms (Berry, 1980). During this process, students can effectively reduce barriers in cross-cultural interactions and enhance social identification and belonging by consciously adjusting verbal or nonverbal behaviors and adopting strategies such as convergence and accommodation. Such behaviors not only facilitate deeper social support and the formation of high-quality cross-cultural friendships but also create more opportunities to employ adaptive emotional regulation strategies (e.g., emotional seeking, cognitive coping) through expanded social support networks. Ultimately, this positive adaptation process significantly alleviates international students’ anxiety by enhancing their sense of self-efficacy (Schimmack, 2005). Therefore, it can be argued that perceived social support indirectly reduces anxiety among international students by promoting communicative adaptability. This mediating effect reveals the profound impact of perceived social support on international students’ mental health and provides an effective pathway for alleviating their anxiety.

Based on the research findings, the following interventions and policy recommendations are proposed to further enhance international students’ cross-cultural adaptation: First, it is essential to integrate faculty, peer, and volunteer resources to establish a sustained and effective support network, ensuring international students receive timely, multi-source understanding and assistance in both academic and daily life. Second, actively create opportunities for cross-cultural interaction. Organize and encourage international students to participate in regular cultural exchange activities such as local festivals, cultural lectures, and language corners. This promotes deeper engagement with local residents, thereby enhancing their understanding of and identification with the host country’s culture. Additionally, universities and relevant institutions must prioritize the critical adaptation phase during the initial enrollment period. Specialized cultural adaptation training courses should be offered to international students, systematically introducing local social norms, behavioral customs, and interpersonal etiquette. This approach will mitigate feelings of cultural shock and accelerate their integration process.

4.1 Limitations and suggestions for future research

This study is mainly based on self-reported questionnaires, which leads to a certain subjectivity of the results, limiting the objectivity and accuracy of the conclusions. Second, because this study was cross-sectional, it is not possible to directly determine cause and effect. To gain a deeper understanding of the mechanisms affecting anxiety conditions, future research could use longitudinal data to explore causality. Furthermore, we did not control for potential confounding variables, such as age, academic level, socioeconomic background, or local social networks, which might influence the observed outcomes. Lastly, the generalizability of our results is constrained by the single-center sampling strategy, and future studies involving multi-center or diverse populations are warranted.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study reveals the close correlation between international students’ anxiety and perceived social support, especially emphasizing the mediating role of communicative adaptability. The high anxiety level of international students may be due to the fact that international students feel less social support, which intensifies the influence of adaptability on anxiety. Therefore, providing more adaptive and targeted social support and cultural adaptation activities may effectively alleviate the anxiety level of international students, and thus maintain and improve the mental health of international students.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to zhaojy@hrbmu.edu.cn.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Harbin Medical University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

LS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CP: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YH: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JW: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JZ: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the students who generously contributed their invaluable time to participate in this study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abela J. R. Z. Vanderbilt E. Rochon A. (2004). A test of the integration of the response styles and social support theories of depression in third and seventh grade children. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol.23, 653–674. doi: 10.1521/jscp.23.5.653.50752

2

Adelman M. B. (1988). Cross-cultural adjustment: a theoretical perspective on social support. Int. J. Intercult. Relat.12, 183–204. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(88)90015-6

3

Albrecht T. L. Adelman M. B. (1984). Social support and life stress. Hum. Commun. Res.11, 3–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.1984.tb00036.x

4

Araujo K. Ryst E. Steiner H. (1999). Adolescent defense style and life stressors. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev.30, 19–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1022666908235,

5

Berry J. W. 1980 Acculturation as varieties of adaptation. In: Padilla, A., Ed., Acculturation: Theory, Models and Findings, Westview, Boulder, 9–25.

6

Berry J. (2005). Acculturation: living successfully in two cultures. Int. J. Intercult. Relat.29, 697–712. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013

7

Bokszczanin A. Gladysh O. Bronowicka A. Palace M. (2023). Experience of ethnic discrimination, anxiety, perceived risk of COVID-19, and social support among polish and international students during the pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health20:5236. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20075236,

8

Chou P. C. Chao Y. M. Yang H. J. Yeh G. L. Lee T. S. (2011). Relationships between stress, coping and depressive symptoms among overseas university preparatory Chinese students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health11:352. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-352,

9

Chung H. Epstein N. B. (2014). Perceived racial discrimination, acculturative stress, and psychological distress among Asian immigrants: the moderating effects of support and interpersonal strain from a partner. Int. J. Intercult. Relat.42, 129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2014.04.003

10

Cohen S. Wills T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull.98, 310–357. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310,

11

Dahlem N. W. Zimet G. D. Walker R. R. (1991). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support: a confirmation study. J. Clin. Psychol.47, 756–761. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199111)47:6<>3.0.co;2-l,

12

Dean E. (2016). Anxiety. Nurs. Stand.30:15. doi: 10.7748/ns.30.46.15.s17,

13

Deb S. Miller N. A. (2017). Relations among race/ethnicity, gender, and mental health status in primary care use. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J.40, 233–243. doi: 10.1037/prj0000230,

14

Duran R. L. (1983). Communicative adaptability: a measure of social communicative competence. Commun. Q.31, 320–326. doi: 10.1080/01463378309369521

15

Durlak J. A. Weissberg R. P. (2011). Promoting social and emotional development is an essential part of students education. Hum. Dev.54, 1–3. doi: 10.1159/000324337

16

Fang K. Friedlander M. Pieterse A. L. (2016). Contributions of acculturation, enculturation, discrimination, and personality traits to social anxiety among Chinese immigrants: a context-specific assessment. Cultur. Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol.22, 58–68. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000030,

17

Finch B. K. Vega W. A. (2003). Acculturation stress, social support, and self-rated health among Latinos in California. J. Immigr. Health5, 109–117. doi: 10.1023/a:1023987717921,

18

Flynn M. Kecmanovic J. Alloy L. B. (2010). An examination of integrated cognitive-interpersonal vulnerability to depression: the role of rumination, perceived social support, and interpersonal stress generation. Cogn. Ther. Res.34, 456–466. doi: 10.1007/s10608-010-9300-8,

19

Gündüz N. Üşen A. Aydin Atar E. (2018). The impact of perceived social support on anxiety, depression and severity of pain and burnout among Turkish females with fibromyalgia. Arch. Rheumatol.34, 186–195. doi: 10.5606/ArchRheumatol.2019.7018,

20

Kim Y. S. 2003 Host communication competence and psychological health: A study of crosscultural adaptation of Korean expatriate employees in the United States International Communication Association. Symposium conducted at the meeting of the Conference Papers--International Communication Association. In Annual Meeting San Diego CA Retrieved on April (Vol. 12, p. 2009).

21

Kim H. Stoner M. 2008 Administration in social work burnout and turnover intention among social workers: effects of role stress, job autonomy and social support. Administration in Social Work, 32, 5–25. doi: 10.1080/02699930541000020

22

Lee R. B. Maria M. S. Estanislao S. Rodriguez C. (2013). Factors associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms among international university students in the Philippines. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health44, 1098–1107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002548

23

Li J. Theng Y. L. Foo S. (2016). Predictors of online health information seeking behavior: changes between 2002 and 2012. Health Informatics J.22, 804–814. doi: 10.1177/1460458215595851,

24

Lovibond P. F. Lovibond S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav. Res. Ther.33, 335–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u,

25

Mahihu C. (2020). Prevalence of depression, anxiety among international students in the health professions at southern medical university, P. R. China. Open J. Soc. Sci.8, 161–182. doi: 10.4236/jss.2020.812014

26

Mak A. S. Kim I. (2011). Korean international students' coping resources and psychological adjustment in Australia. OMNES J. Multicult. Soc.2, 56–84. doi: 10.15685/omnes.2011.06.2.1.56

27

Moussa-Chamari I. Farooq A. Romdhani M. Washif J. A. Bakare U. Helmy M. et al . (2024). The relationship between quality of life, sleep quality, mental health, and physical activity in an international sample of college students: a structural equation modeling approach. Front. Public Health12:1397924. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1397924,

28

Pillay J. (2021). Suicidal behaviour among university students: a systematic review. S. Afr. J. Psychol.51, 54–66. doi: 10.1177/0081246321992177,

29

Schimmack U. (2005). Response latencies of pleasure and displeasure ratings: further evidence for mixed feelings. Cogn. Emot.19, 671–691. doi: 10.1080/02699930541000020

30

Searle W. Ward C. (1990). The predictions of psychological and sociocultural adjustment during cross-cultural transitions. Int. J. Intercult. Relat.14, 449–464. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(90)90030-Z

31

Sirin S. R. Ryce P. Gupta T. Rogers-Sirin L. (2013). The role of acculturative stress on mental health symptoms for immigrant adolescents: a longitudinal investigation. Dev. Psychol.49, 736–748. doi: 10.1037/a0028398,

32

Skromanis S. Cooling N. Rodgers B. Purton T. Fan F. Bridgman H. et al . (2018). Health and well-being of international university students, and comparison with domestic students, in Tasmania, Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health15:1147. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15061147,

33

Slaughter L. Sie L. Breakey N. Macionis N. Zhang J. (2023). Can we buffer them? Supporting healthy levels of stress and anxiety in first year international students. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ.32:100438. doi: 10.1016/j.jhlste.2023.100438,

34

Tabatabaei S. A. Abro A. H. Klein M. (2018). With a little help from my friends: a computational model for the role of social support in mood regulation. Cogn. Syst. Res.47, 133–146. doi: 10.1016/j.cogsys.2017.09.001,

35

Wang C. C. Andre K. Greenwood K. M. (2015). Chinese students studying at Australian universities with specific reference to nursing students: a narrative literature review. Nurse Educ. Today35, 609–619. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2014.12.005,

36

Wang Y. Wang X. Wang X. Guo X. Yuan L. Gao Y. et al . (2023). Stressors in university life and anxiety symptoms among international students: a sequential mediation model. BMC Psychiatry23:556. doi: 10.1186/s12888-023-05046-7,

37

Wirtz P. H. von Känel R. Mohiyeddini C. Emini L. Ruedisueli K. Groessbauer S. et al . (2006). Low social support and poor emotional regulation are associated with increased stress hormone reactivity to mental stress in systemic hypertension. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.91, 3857–3865. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2586,

38

Worthington D. L. Bodie G. D. (2017). Communicative adaptability scale (CAS). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

39

Zimet G. D. Dahlem N. Zimet S. G. Farley G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Pers. Assess.52, 30–41. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

Summary

Keywords

anxiety, perceived social support, communicative adaptability, international students, mental health

Citation

Song L, Peng C, Hai Y, Wang J and Zhao J (2026) The influence of perceived social support on anxiety among international students: the mediating role of communicative adaptability. Front. Psychol. 16:1498261. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1498261

Received

18 September 2024

Revised

28 October 2025

Accepted

10 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Changiz Mohiyeddini, Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine, United States

Reviewed by

Faiswal Kasirye, Bowling Green State University, United States

Luis Fernando Hernandez Zimbron, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico

Cátia Vaz, Polytechnic Institute of Bragança (IPB), Portugal

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Song, Peng, Hai, Wang and Zhao.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jingya Wang, 1621234036@qq.com; Jiyang Zhao, zhaojy@hrbmu.edu.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.