- 1Business Administration Department, ESIC University, Madrid, Spain

- 2Humanities Department, ESIC University, Madrid, Spain

- 3Business Administration and Law Department, ESIC University, Madrid, Spain

- 4Business Administration Department, Rey Juan Carlos University, Madrid, Spain

Introduction: The objective of this article is to develop and validate a metric for assessing gender lens investing (GLI) practices within organizations. The validation of these measurement items constitutes a methodological innovation, responding to calls in the literature for the exploration of novel approaches in comparative studies.

Methods: To achieve this objective, the development of the measurement items was informed by a comprehensive literature review, and their content validation was conducted through a Delphi study.

Results: The primary outcome of this research is the recommendation and validation of a tool designed to measure various dimensions of GLI practices, from both an academic standpoint and the perspective of expert evaluators.

Implications: The application of this tool is expected to facilitate the integration and generalization of diverse perspectives on GLI. As Investment Fund Agencies and companies increasingly invest in GLI initiatives, there is a growing demand for robust instruments to effectively assess their impact.

1 Introduction

Gender lens investing (GLI) practices refer to a movement that, for ethical reasons, establishes or capitalizes funds and companies supporting women as leaders and throughout society (Roberts, 2016). The idea that women should have access to training and jobs in all areas of work, receive equal pay, be able to reconcile work and family life on equal terms with men, and that companies should be organized not only by men but also by women who understand the diverse needs of consumers, aligns with key objectives in organizational psychology. According to Chmiel et al. (2017), in ‘organizational psychology’, psychology plays a central role, as it pertains not only to management but also to how managers lead, how coworkers interact, and how organizations function. In this sense, measuring the effectiveness of GLI policies in companies means assessing whether organizational psychology accounts for gender diversity.

Initial measurements focused on economic impact and risk distribution (Criterion Institute, 2020). Indeed, similar to environmental, social, and governance funds (ESG), investing with a gender lens has proven advantageous for companies. This approach not only fosters a sense of safety and inclusion among but also leads to better long-term economic results (Subramanian, 2022). In fact, numerous reports have demonstrated the importance of this concept, including “Just Good Investing: Why Gender Matters to your Portfolio and What You Can Do about it” (Calvert Impact Capital, 2019), “Gender Lens Investing Landscape. East & Southeast Asia” (2020), “Gender Lens Investing: Legal Perspectives” (2021), which discusses the incorporation of gender considerations in loans and in equity investment, and the “Gender Lens Investing Report” (2021), among others. All these reports reference projects funded by investment funds (equity or public), yet it is reasonable that the portfolios themselves are not publicly disclosed. Nonetheless, private investment in such funds is on the rise, and therefore, some companies are mentioned as business cases (Sasakawa Peace Foundation, Catalyst at Large, and SAGANA, 2020).

However, the initial initiatives to develop a tool for measuring investment with a gender lens seem not to have studied the earlier attempts at measurement. These initiatives either focus on different aspects to be measured, use different metrics, or address different fronts such as investment funds, small businesses, entrepreneurship, governance, etc. Among the most recent initiatives, Sustainable Finance Geneva suggested five infrastructures along with their respective tools for measuring GLI criteria (2021):

1. EDGE (Economic Dividends for Gender Equality). It assesses the gender balance within organizations across their talent pipeline, examines pay equity, evaluates the effectiveness of policies and practices aimed at fostering equitable career progression, and examines the inclusivity of their organizational culture.

2. UN Women and UN Global Compact. It establishes the Women’s Empowerment Principles (WEPs): This operational framework helps private companies promote gender equality and women’s empowerment within their organizations or community. Rather than measuring, it generates GLI criteria to influence public opinion internationally.

3. The IRIS+ System evaluates social and environmental factors, as well as gender equality. However, this evaluation system is aimed only at investment funds (not at individual companies or entrepreneurs) and therefore focuses on risks and returns in investment decisions.

4. The Small Assistance Fund (SEAF) Gender Equality Scorecard assesses six factors: pay equity, workforce participation, leadership in governance, benefits or professional development, workplace environment, and women-powered value chains. However, these measurements are aimed only at small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

5. The 2X Criteria was launched to help investors assess gender-smart businesses, targeting both funds and companies equally. They measure risk and impact on the one hand and gender aspects on the other. The criteria have been globally adopted and supported by IRIS+, HIPSO (Harmonized Indicators for Private Sector Operations), the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD), UN Women’s WEPs. They have also been adopted by the International Finance Corporation (IFC).

To our knowledge, Small Enterprise Assistance Funds (SEAF) has generated the first tool to identify small businesses founded by women, through which diversity can be promoted via private funds. This identification is based on the six vectors aforementioned (2020). The inception of GLI focuses on female entrepreneurship because it stimulates aggregate demand, enhances the consumption of final goods and services, and contributes to economic and social development, thereby fostering more equitable societies by empowering women to secure their own livelihoods (Aljarodi et al., 2021).

The economic independence of women can pose significant challenges, especially for those who are single mothers or of foreign origin (Yin et al., 2023). Therefore, it is crucial to undertake the implementation of the commitments established in the 2030 Agenda, the most comprehensive global action plan worldwide, by all subscribing countries, to ensure the respect for the rights of women and girls. Although not the primary focus of this article, the support for female entrepreneurship is instrumental in integrating economically dependent family members into society, such as elderly relatives, as explored in the “Silver Economy” (Argentum, 2024) or dependent minors (Becker, 1991).

Following SEAF, the social enterprise Pro Mujer was founded in 1999 to help women develop their economic potential in Latin America. Together with Deetkeen and with the support of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), they developed a document called “Tools for Investing with a Gender Perspective” (2021). These tools are divided into four sub-lenses that structure the topics of the yearly GLI Latam forums from 2020 to 2024, namely: (1) Women in leadership; (2) Equality in the workplace; (3) Products and services that benefit women and girls; (4) Equality in the value chain and advocacy practices. This document marked the initial comprehensive endeavor to measure gender equality within a company, alongside its gender-oriented investment strategy. “Tools for Investing with a Gender Perspective” assesses internal management policies and collaboration with civil society, as well as other local or global organizations. The document evaluates the efforts of organizations or funds to offer integrated services, including financial assistance, health, and educational loans, to low-income women in Latin America and the Caribbean.

A condensed version of this document, titled “Self-diagnosis of Gender Approach in Management,” has also been developed by Pro Mujer in partnership with Deekten Impact in their joint fund, the Ilu Women’s Empowerment Fund. This fund represents the first gender lens investing fund aimed at empowering women and advancing gender equality in Latin America and the Caribbean (Ilu Women's Empowerment Fund, 2021). Unlike the comprehensive assessment, this self-diagnosis tool focuses solely on evaluating a company’s management of gender lens investing rather than its investment actions in civil society. Its aim is to categorize a company as meeting the GLI criteria for receiving gender lens investments. The purpose of this exercise is to enable organizations to make informed decisions, prioritize actions, and effectively implement their commitment to gender equality. The results of the assessment outline three possible levels of advancement (basic, intermediate, or advanced) and recommend referring to the tools available for each lens.

Two years later, the PNC Financial Services Group, introduced six criteria to gender lens investors: gender diversity, women in leadership, women founders and fund managers, women-majority enterprise, gendered policies and practices, and products and services tailored to meet the needs of women (2023). “Diversity” appears to be the only aspect not explicitly addressed in the sub-lenses of the Ilu Women’s Empowerment Fund questionnaire, but it is a theme that emerges when discussing the second lens (“equality”).

EDGE auditing provides EDGE Certification, recognized as the leading global standard for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DE&I) (EDGE Certified Foundation, 2024). The EDGE Standards and the Certification System are built on four pillars:

1. Representation at all levels of the organization, with particular emphasis on boards of directors and senior management.

2. Pay equity.

3. Effectiveness of policies and practices to ensure equitable career progression, including equal pay for equivalent work, recruitment and promotion processes, leadership development training and mentoring, flexible working arrangements, and organizational culture.

4. Inclusiveness of the culture, as indicated by employees’ ratings regarding career development opportunities (EDGE, 2024). Although the self-diagnosis developed by the Ilu Women’s Empowerment Fund in 2021 does not explicitly mention “culture,” it is implicitly considered within the metrics of “value chain and advocacy practice.” Like the Ilu Women’s Empowerment Fund, EDGE aims for equity at the workplace; specifically, a minimum of 30% female representation at all levels of companies. However, achieving this 30% threshold poses a greater challenge in boards of directors and senior management (reports from the national securities market commission).

Regarding the 2X Criteria, it can be utilized by any entity to establish their own benchmarks for new business and portfolios, as well as for self-reporting. Specifically, the 2X Criteria aids in identifying eligible investments through four criteria focused on the company itself: (1) entrepreneurship; (2) leadership; (3) employment; and (4) consumption of products and services for women (2X Challenge, 2024). Additionally, it incorporates an indirect criterion, “investments through financial intermediaries.” Therefore, it aligns with SEAF’s emphasis on small businesses and women entrepreneurs, as well as with the Ilu Women’s Empowerment Fund’s four sub-lenses, while also incorporating aspects such as “diversity” (PNC), “culture” (EDGE), and frameworks developed by the IRIS+ System and WEPS. Notably, the 2X Criteria is regarded as the global standard for gender finance.

Female participation and involvement in decision making processes is a component of a “virtuous circle” that brings economic and social benefits to new generations, particularly emphasizing young women (Daher et al., 2022). In Spain, an innovative program has been implemented to promote gender equality and bolster female leadership in the professional realm. Known as “Destino Talento” this initiative is the result of an agreement between Closingap and 50&50 GL, aimed at mentoring young women to achieve specific objectives (50&50 Gender Leadership, 2023). The primary objective of this program is to enhance women’s self-esteem and self-confidence, focusing on digital transformation and the values society needs, in line with the #ODS hashtags.

As more investors seek transparency regarding the criteria for selecting Gender Lens Investing (GLI) within portfolio companies, there is an increasing urgency to develop an integral tool for measuring and evaluating GLI policies and practices. Efforts to measure investment through a gender lens so far appear to complement one another; in fact, many of these initiatives have been supported by public funding from the UN (e.g., UN Women, UN Global Compact, and the 2X Criteria), which seem to advocate for an international tool that can assist their Supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs). However, no existing tool currently combines the strengths of the methods mentioned above. Therefore, the primary objective of this research is to propose a tool for self-assessing the impact of Gender Lens Investment (GLI) within companies, addressing the gaps left by previous measurement methods. Several organizations have already aimed to measure investment through a gender lens; however, to our knowledge, no academic metrics validated by both company and academic experts in Gender Lens Investing (GLI) have been identified.

Considering this, the purpose of this study is to develop a tool that will assist large national and international companies in measuring their organizational practices with a gender lens to establish a metric. This will facilitate their identification by investment fund consultants and inclusion in portfolios sought by investors with a gender lens. To accomplish this goal, a comprehensive review of prior tools, in collaboration with a board of experts, has provided critical insights into: (a) the dimensions to be incorporated in a metric designed to identify exemplary organizational practices in Gender Lens Investing (GLI); (b) the specific aspects of GLI organizational practices that merit particular emphasis; and (c) the prioritized importance of these identified dimensions based on expert evaluation.

As demonstrated, the objectives of the aforementioned organizations in measuring Gender Lens Investing (GLI) have been varied, encompassing legal compliance, support for women facing exclusion, the promotion of women-led small businesses, and enabling companies to self-assess their management practices and social investments in women-supportive activities. Consequently, firms should adopt proactive organizational mechanisms to empower and reinforce gender balance, considering the established benefits associated with this approach (Saeed et al., 2023).

Given these diverse dimensions, managers, mid-level professionals, and gender experts should combine efforts to develop a standardized metric applicable to both medium-sized and large enterprises. In this context, the Delphi method serves as a structured approach to address the current lack of consensus on such a metric.

After this introduction, the second section outlines the Delphi methodology, and the sequential phases employed to validate the questionnaire based on the identified dimensions, Part 3 describes the results and in section discussion and conclusions are presented.

2 Materials and methods

The Delphi is a widely used method in the context of research, especially in the field of Business and Social Sciences (Cabero Almenara and Infante Moro, 2014; Reguant-Alvarez and El Torrado-Fonseca, 2016). Many studies have shown its effectiveness to collect an expert view on different topics (Guldenmund, 2007; Fife-Schaw, 2020).

It is a valuable tool to assess the rigor and relevance of the items of a questionnaire based on the opinion of a group of experts through repeated consultations as they have several opportunities to give and revise their opinion (Giannarou and Zervas, 2014). It is an iterative process (López Gómez, 2018), controlled, guaranteeing the anonymity of the experts who receive statistical feedback of the overall response of the participants derived from the different rounds (Reguant-Alvarez and El Torrado-Fonseca, 2016) and allows consensus to be obtained avoiding direct confrontation between them, groupthink (Holeman et al., 2024) or that a few dominate the process (Boulkedid et al., 2011) and other types of influences or biases (Santaguida et al., 2018). Ultimately, it is characterized by anonymity, iteration and controlled feedback (Cuhls, 2023). These characteristics allow obtaining a balanced group response based on statistical data.

2.1 Delphi stages

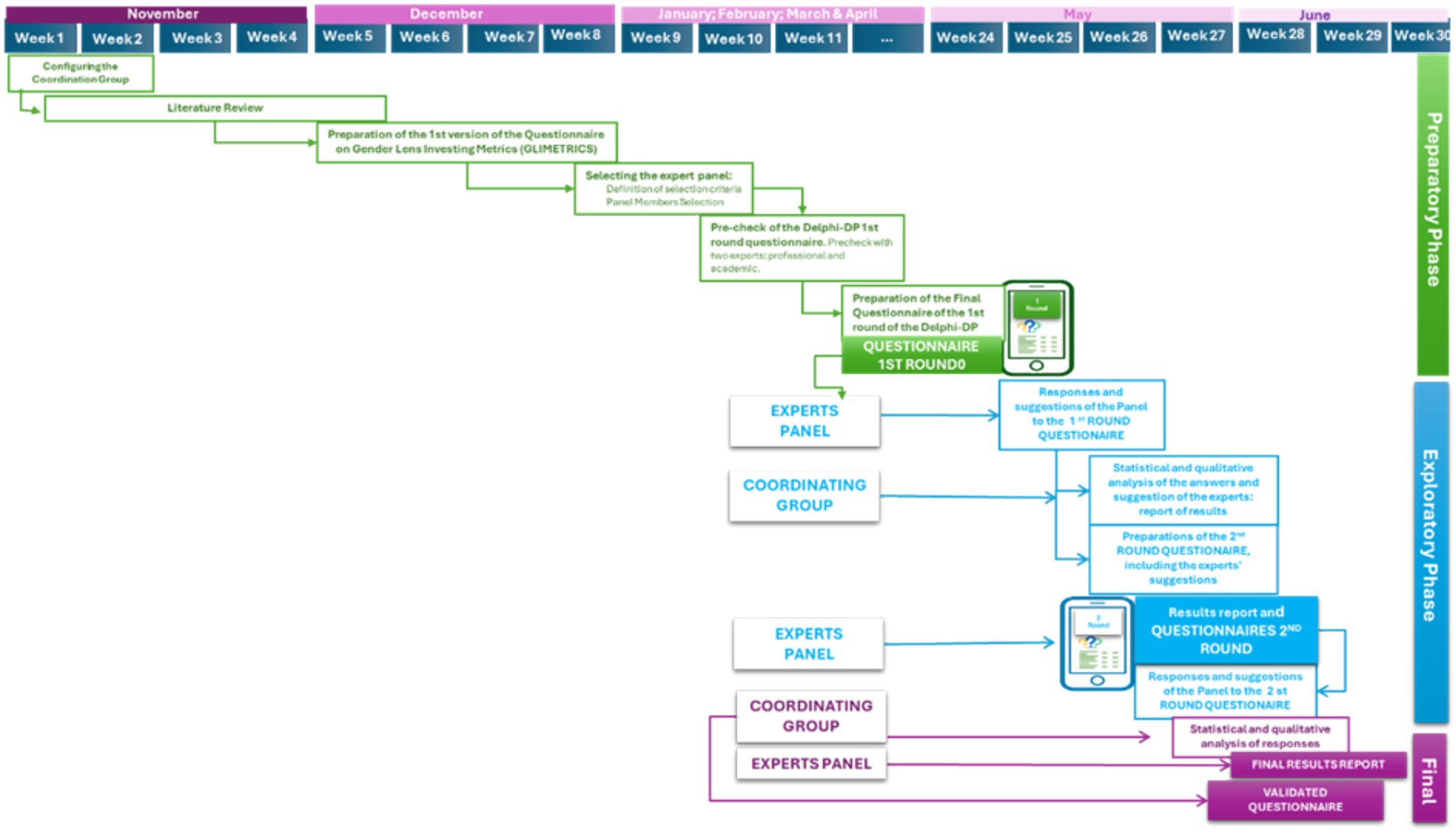

In the context of the preparation and execution of a Delphi study, a series of steps are deployed that are often grouped into different stages. The number and names of these stages vary according to the literature consulted. Within the framework of this research (Bravo Estévez and Arrieta Gallastegui, 2005), three fundamental phases have been identified: preparatory, exploratory and final.

2.2 Preparatory phase

The following tasks were carried out during the first phase, preparatory:

• Configuring the Coordination Group: it is composed of the four authors who participated in the research.

• Literature review: an exhaustive search was conducted for papers related to ways of measuring the impacts of LIGs. The literature review made it possible to recognize the particularities of isolated recommendations on how to measure LIGs. For this reason, a set of items was included in the expert survey.

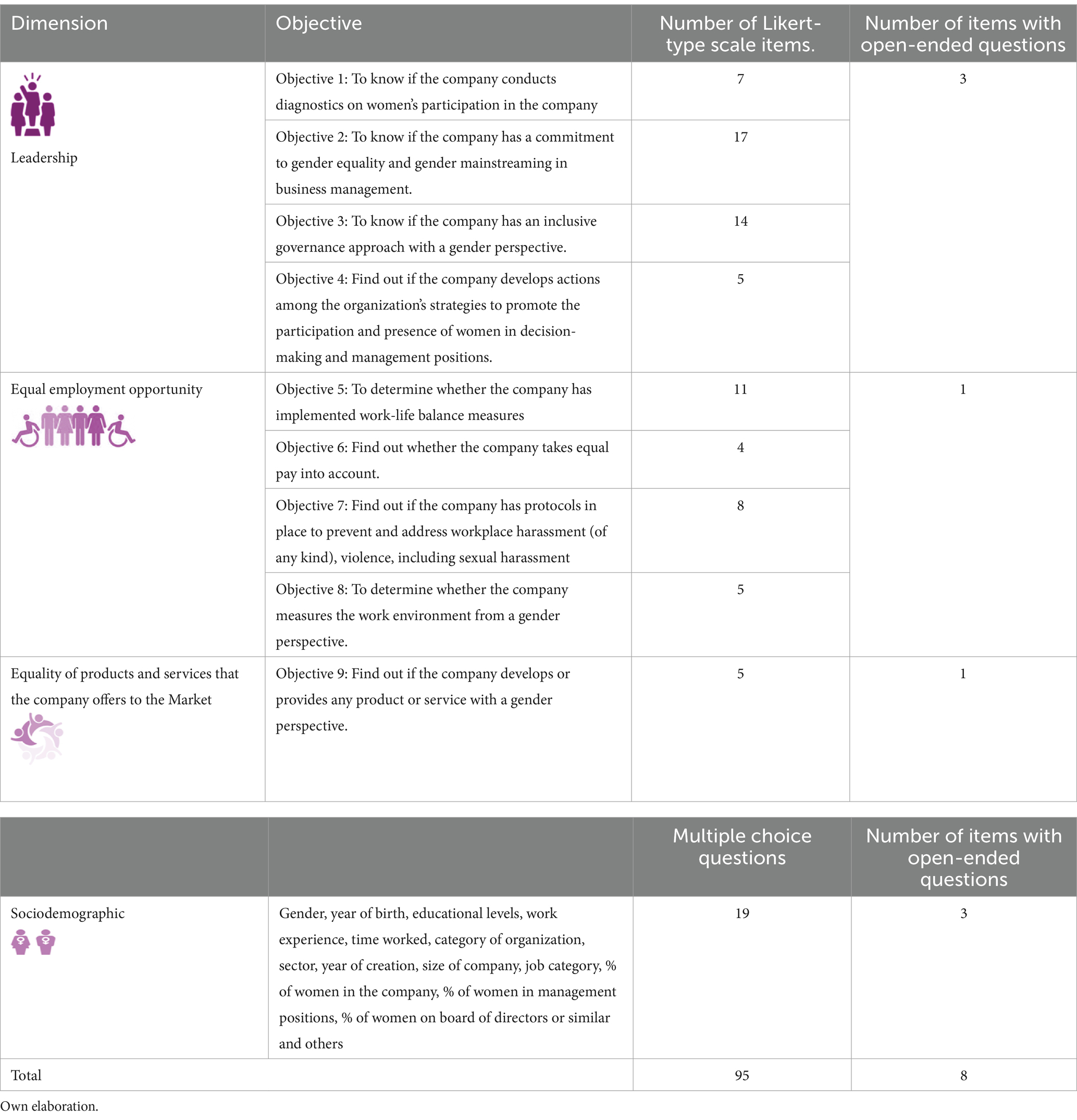

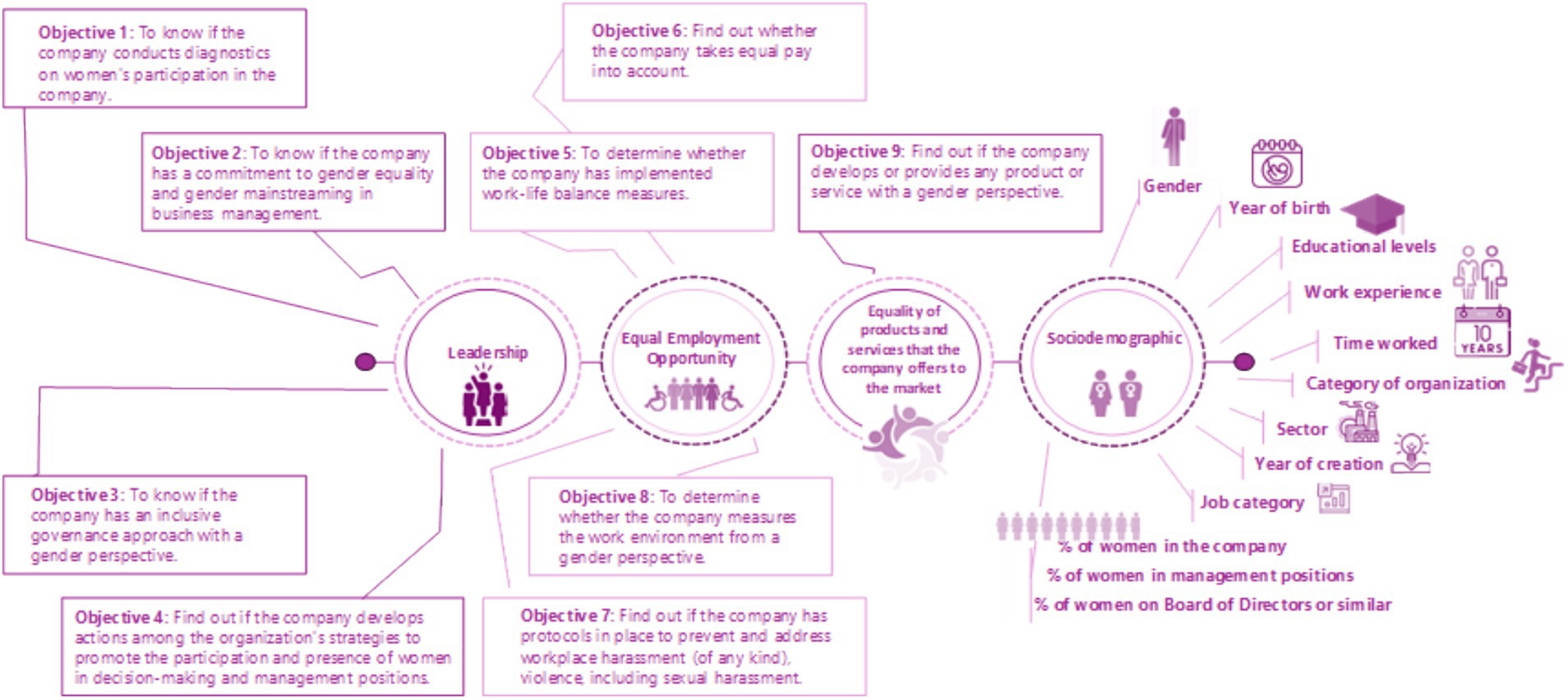

• Elaboration and revision of the GLI questionnaire for its validation. The coordinating team prepared the questionnaire, and, after its revision, 3 dimensions related to each of the GLI variables and 1 dimension with sociodemographic data were included (see Image 1). Each dimension included different objectives with a 6-point Likert scale, where 1 was totally disagree and 5 was totally disagree, 6 was do not know/no answer, open questions because they offer very valuable information (Hung et al., 2008, p. 197) and multiple response questions (See Table 1).

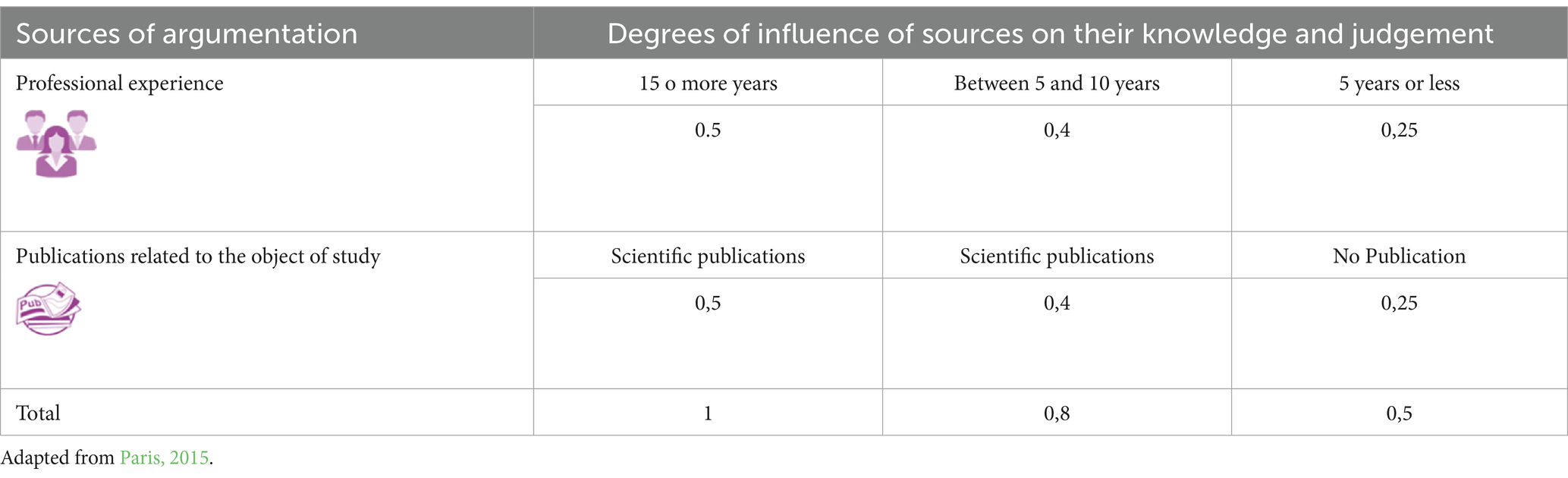

To evaluate the expertise of these two GLI experts, the Competence Coefficient (Kcomp) proposed by García-Martínez et al. (2012, p. 212) was applied, which is calculated as follows:

In this expression, Kc is obtained from the self-assessment made by the experts, and Ka is obtained from the professional experience and the number of publications (See Table 2). Both experts obtain scores above 0.8; therefore, they can be considered as valid because their level of competence is high.

The items of first draft of questionnaire were submitted for evaluation through the Delphi technique during the month of January 2024.

• Elaboration of the questionnaire for the first round of the Delphi:

The questionnaire sought the experts’ opinions on the clarity and relevance of the items related to each of the dimensions considered in GLI and their corresponding measurement scales (Table 1).

Figure 1 presents the dimensions and objectives that, once considered most outstanding antecedents, our proposed questionnaire to measure practices centered on gender lens investing should include in any company.

• Selection of the panel of experts:

The selection of experts was one of the key aspects for the validity of the Delphi results. In this sense, the criteria for the selection of experts and the number of experts selected depended on the topic to be addressed and the objective to be achieved with the application of the Delphi method (appointments) and to avoid a high number of experts, since in this case the “dropout and rejection rate” is higher (Reid and Reid, 1988; Ortega Mohedano, 2008). According to Varela-Ruiz et al. (2012), this technique makes it possible to congregate knowledge increased by the concurrence of various experts.

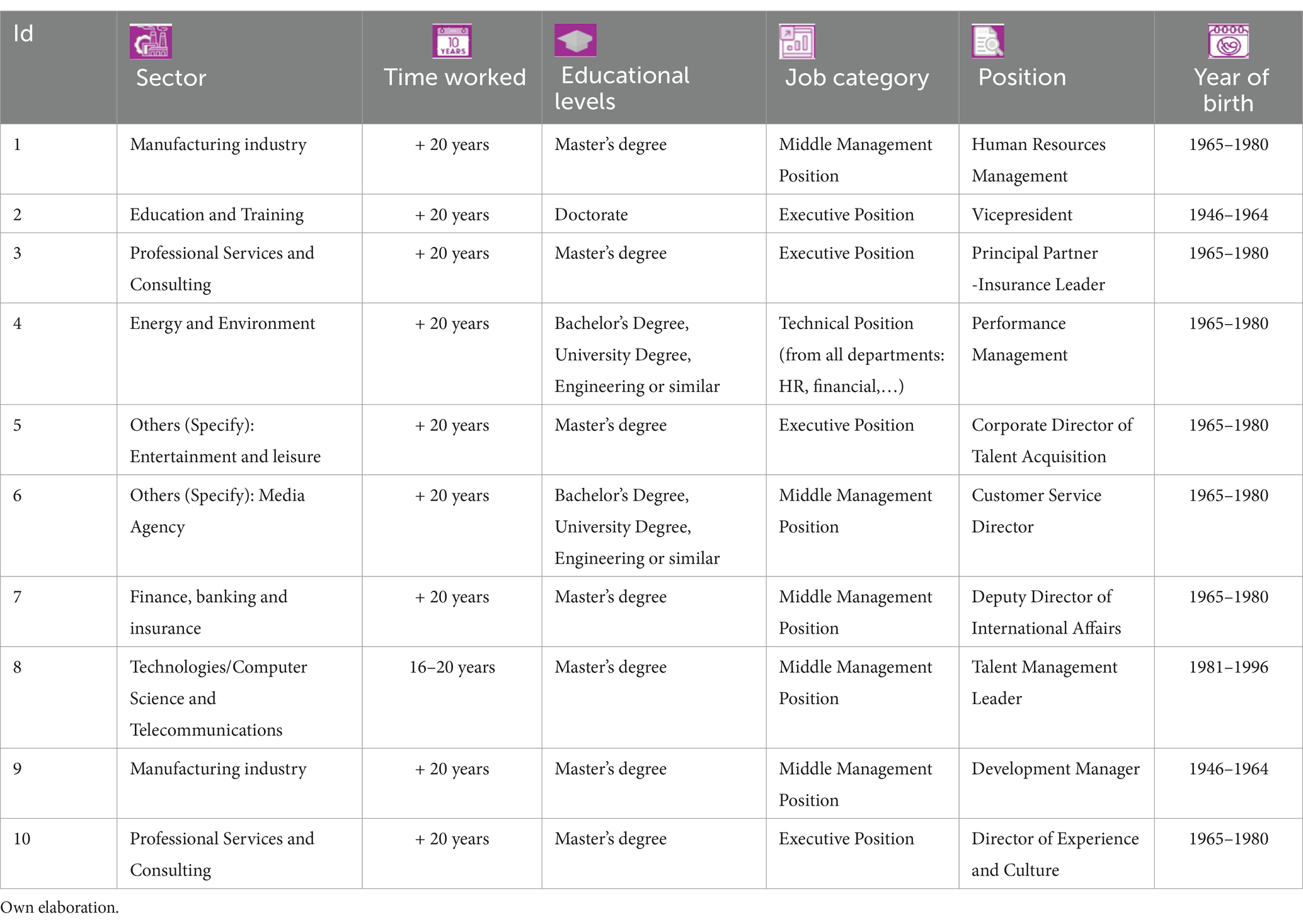

Given the specificity of the object of study and the lack of previous studies, a small panel of experts was chosen. The coordinating team invited 20 potential experts who met the selection criteria. Ultimately, 10 of them agreed to participate in the study. The size of the panel is appropriate, given that, although there are clear discrepancies in the academic community as to the optimal number of panellists (minimum 5, maximum 30), it is within the parameters of representativeness (Zartha Sossa et al., 2019).

In this phase, the aim is to obtain a collective and diverse view of the experts on GLI through successive rounds of questions.

The objective criteria for the selection of the panellists (see Table 3) were as follows:

• Gender: Priority was given to the participation of women.

• Work Experience: Panellists with more than 15 years of experience were considered.

• Educational level: At least a bachelor’s degree was required and, preferably, higher education (master’s or doctorate).

• Age: Representatives of generations Z, Y, X and Baby Boomers were included.

• Professional category: Diversity was sought, from technical to managerial or middle management positions.

• Position: many panelists are employed in roles that entail diversity and gender responsibilities, or in human resources department.

• Professional recognition: through participation in scientific or professional publications, some of the panelists are members of relevant professional associations.

• Sector: Panellists were selected from organizations belonging to different economic activities.

• Preparation of the final questionnaire for the first round of the Delphi:

In this phase, two experts (a university professor and a manager of a multinational company in the financial sector, both with extensive knowledge and experience in gender) were asked to propose improvements to the questionnaire.

Their suggestions involved including some questions (Example: 6.4. Salaries are equal for men and women in identical job profiles; 7.11. In my company, people who take advantage of reconciliation measures have the same career development opportunities as the rest of the staff) and that we included the alternative Do not know/No answer.

The above suggestions were incorporated into the questionnaire that was finally sent to the panel of experts. Before sending the questionnaire, the coordinating team sent an email describing the objective, the process, a QR code and an electronic link to the Microsoft Forms questionnaire.

2.3 Exploratory phase

During this exploratory phase, two rounds of expert consultations were carried out to reach a consensus on the appropriateness and validity of the GLI items and its measurement scale.

• First round: the questionnaire proposed by the coordinating team was sent to the 10 experts so that they could give their opinion on the suitability of the items chosen for measuring the GLI. The questionnaire was divided into 10 blocks corresponding to the 3 dimensions of GLI. In each block, the expert is asked to indicate whether he/she considers that these questions correctly measure the aspects they are intended to measure. If he/she considers that the question is inadequate, he/she is asked to propose an alternative question and/or to make any suggestions or appreciations he/she may have in this regard. At the end of each section of the questionnaire, the expert was asked if, based on his or her professional experience, he or she could identify other aspects of GLI not covered by the study. This first round was carried out during week 3 of the month of January and February 2024.

• Second round: after processing the responses and analysing the overall results of the first round, the coordinating team prepared a report with the results obtained in the first round. Table 4 shows the level of consensus during the rounds.

After analyzing the comments and suggestions made by the experts, the questionnaire to be sent out in the second round was prepared, including information on the degree of agreement on each question and most of the suggestions revolving around the terminology used. This second round was carried out during the month of June 2024.

In this second round, the experts were asked to re-evaluate their responses considering the new information obtained in the first round in search of consensus.

2.4 Final phase

At the end of second round, a statistical analysis was carried out to quantify the responses, aggregate values and obtain a score that reflects the consensus among the experts. As a result of the whole process, the definitive and validated GLI items were generated and incorporated into the GLI metrics questionnaire. Figure 2 shows an outline of the steps followed in the 3 phases that have been carried out in this study.

3 Results

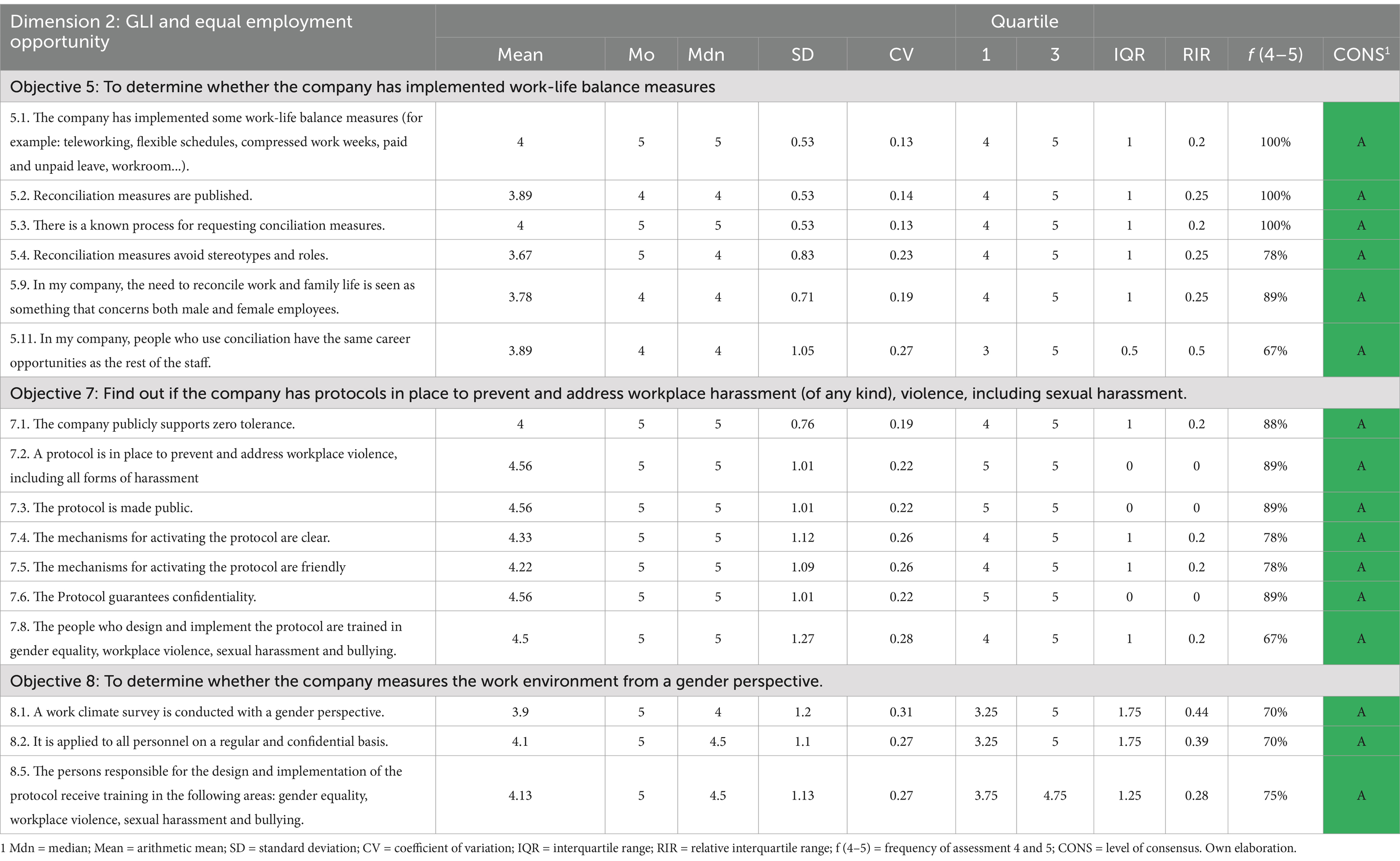

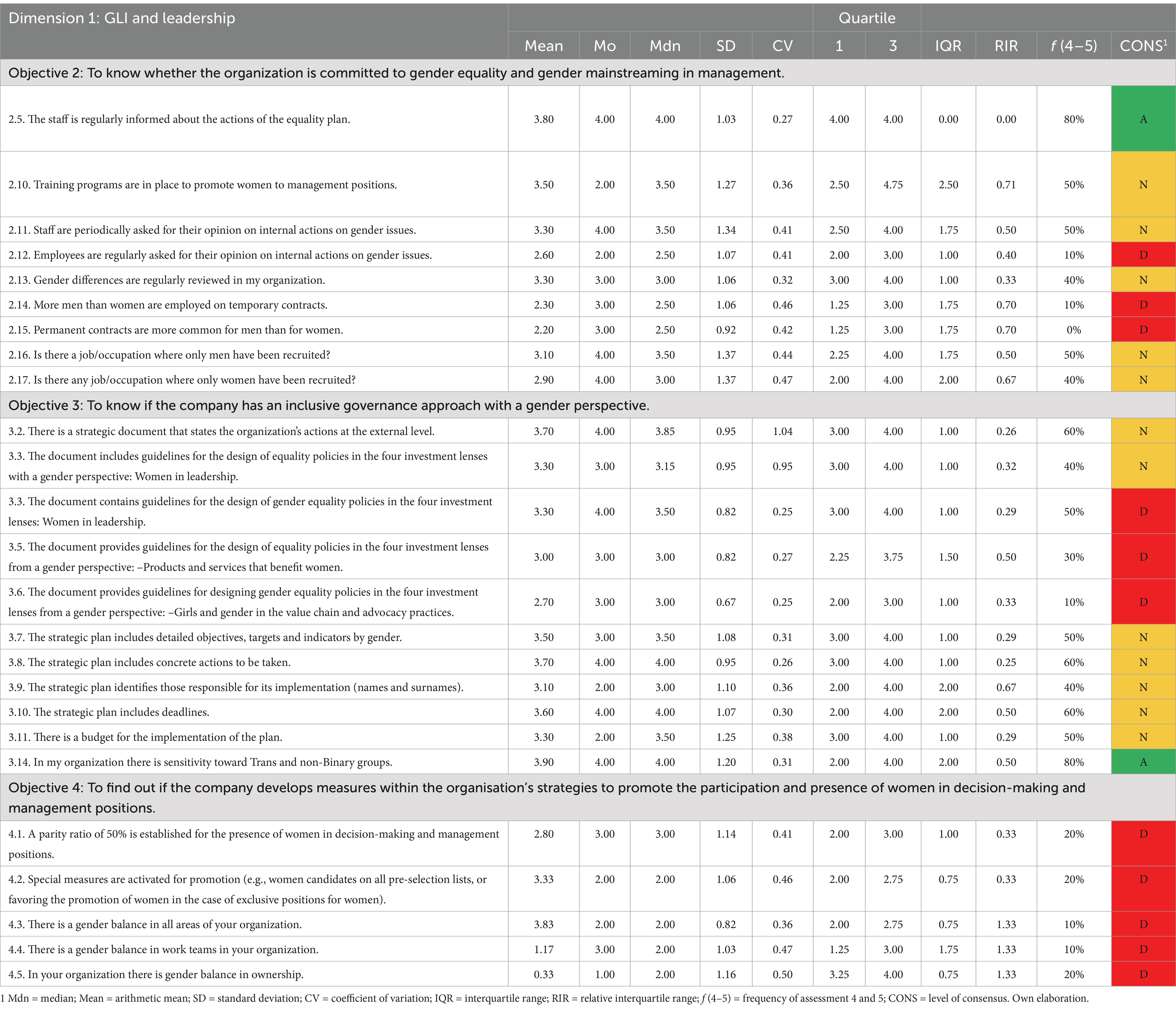

Once the information from the first round was collected, the responses of the 10 experts were analyzed on 76 items grouped into 11 objectives around each of the 3 dimensions identified, GLI and leadership, GLI and labor equality, and GLI on Equality of products and services offered by the company to the market, and on 19 items related to socio-demographic variables and gender. The experts responded on a Likert scale of 1 to 5, where 1 was strongly disagree, 2 was disagree, 3 was neither agree nor disagree, 4 was agree, and 5 was strongly agree.

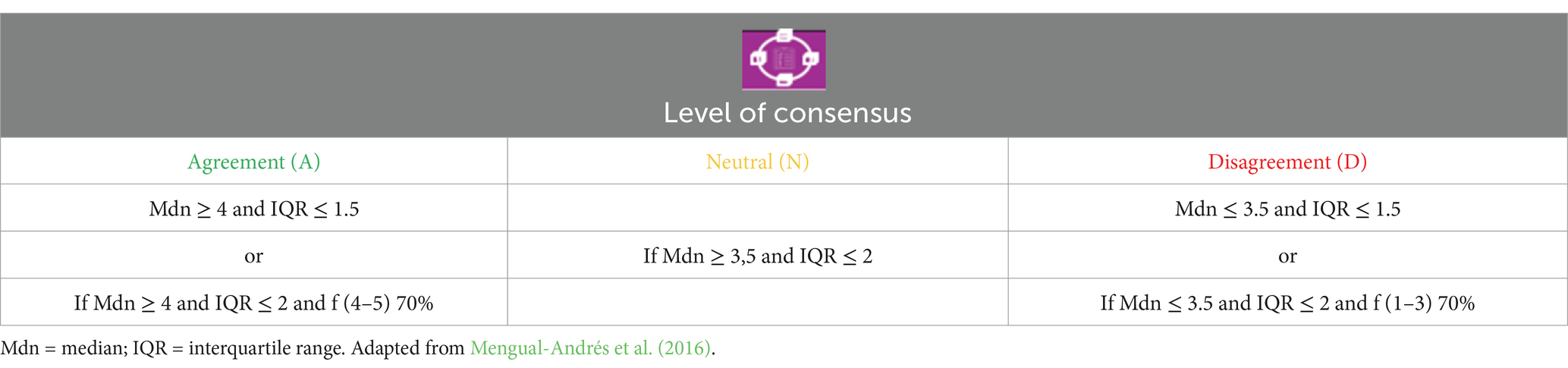

Although there is no single way of determining when a consensus is reached among the different experts consulted in the Delphi, in this study it is understood to be reached under the criteria established by Mengual-Andrés et al. (2016) and López Gómez (2018). The median was chosen as the indicator of central tendency, supported by the interquartile range (IQR) (López Gómez, 2018; Margherita et al., 2021). Furthermore, the median value is very close to the mean, indicating that the distribution is approximately symmetrical.

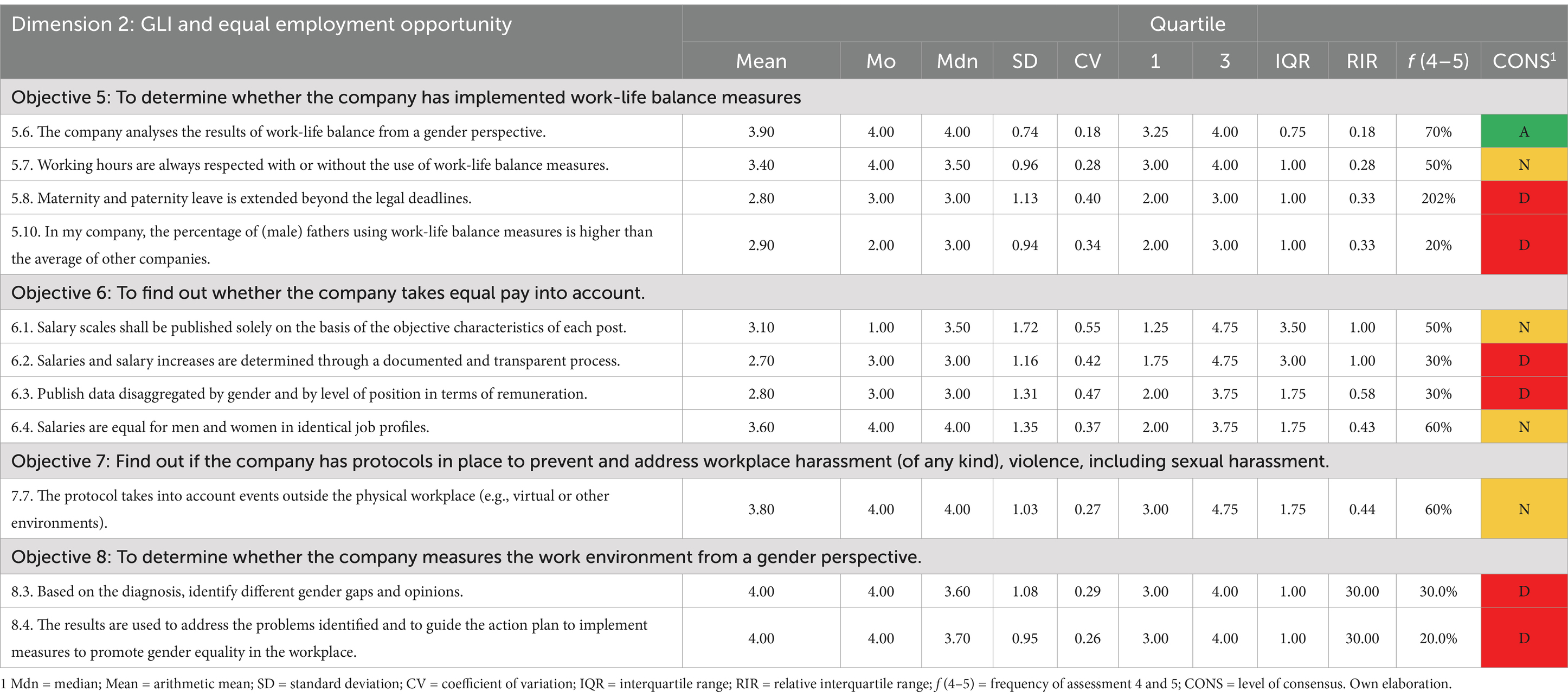

Several studies have used 70% as the cutoff point (Lee et al., 2013; Campbell et al., 2018). Taking this into account, approximately 70% of GLI and Leadership were agreed, excluding the following items: 2.5, 2.10, 2.11, 2.12, 2.13, 2.14, 2.15, 2.16, 2.17, 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, 3.5, 3.6, 3.7, 3.8, 3.9, 3.10, 3.11, 4.1, 4.2, 4.3, 4.4, and 4.5. Tables 5–7 shows the results of the first round of the Delphi.

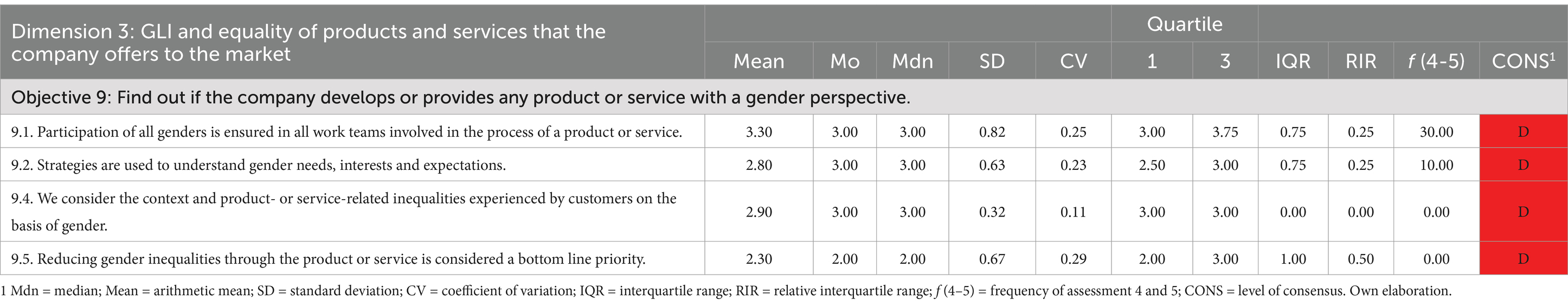

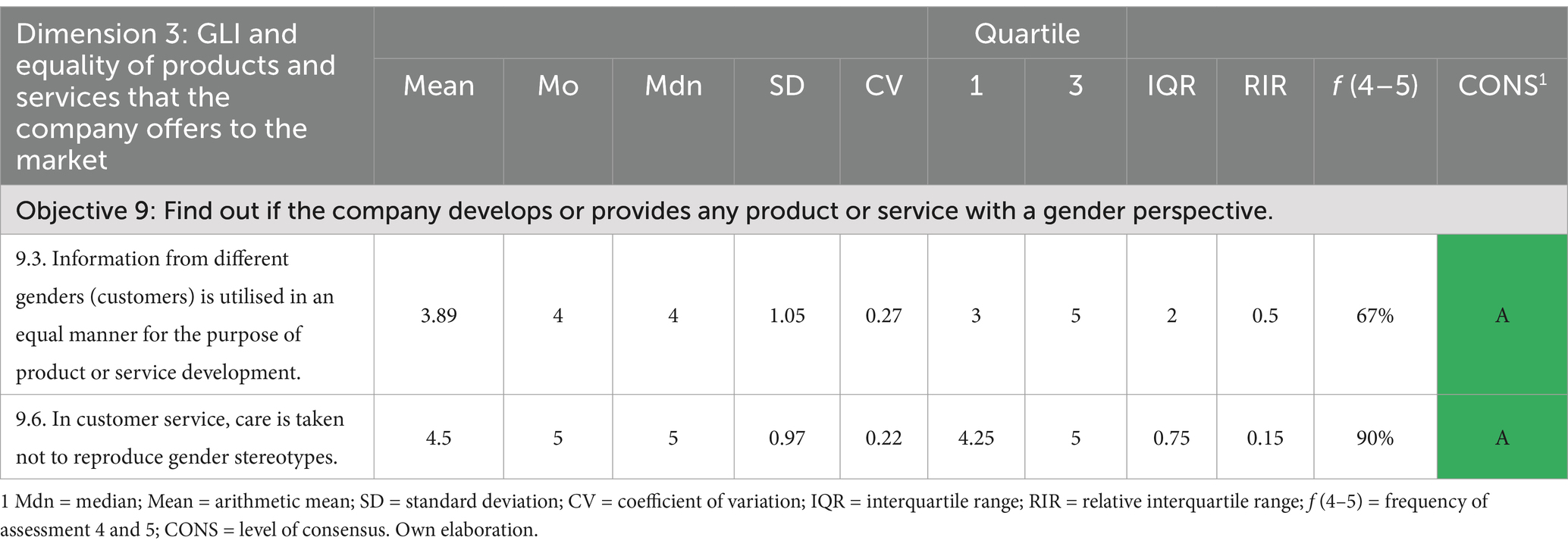

Table 7. Round I Delphi results: GLI and equality of products and services that the company offers to the market.

As it can be observed in Tables 5–7, the results demonstrate a high level of consensus among participants with regard to the identification of gender gaps, the implementation of measures designed to promote equality and reconciliation, and the existence of anti-harassment protocols. The median score for these items on the first Delphi round questionnaire is 4 or above, indicating agreement. This value remains constant in the second and third quartiles, indicating that the majority of responses are concentrated in Likert scale scores 4 or 5. This confirms a relatively symmetrical distribution. The interquartile range (IQR) reaches a maximum value of 2 (≤ 1.5), indicating a low dispersion of responses. Moreover, the proportion of ratings 4 and 5 (agree, strongly agree) is at least 70% (≥ 70%), reaching 100% in some cases. Except for items 3.12, 3.13, 5.11 and 7.8, which were included with 67% of ratings 4 and 5. The remaining items were included because they met the other conditions and were close to the 70% level of agreement.

The data presented above indicates that a consensus has been reached among the experts participating in the initial round of the Delphi study with respect to the appropriateness and clarity of the GLI items illustrated in Tables 5–7. For items related to GLI Leadership, and GLI Quality of products and services that the company offers to the market, the frequency of ratings 4 and 5 on the Likert scale is 79%, and for GLI Equal Employment Opportunity 83%. Applying the acceptance criteria, we observe that, for all items, the median ≥ 4 and IQR ≤ 1.5 are met. Subsequent to the aforementioned conclusions, the coordinating group proceeded to conduct a second round of questioning, encompassing those items which were identified as exhibiting discrepancies of opinion and failing to satisfy the requisite conditions:

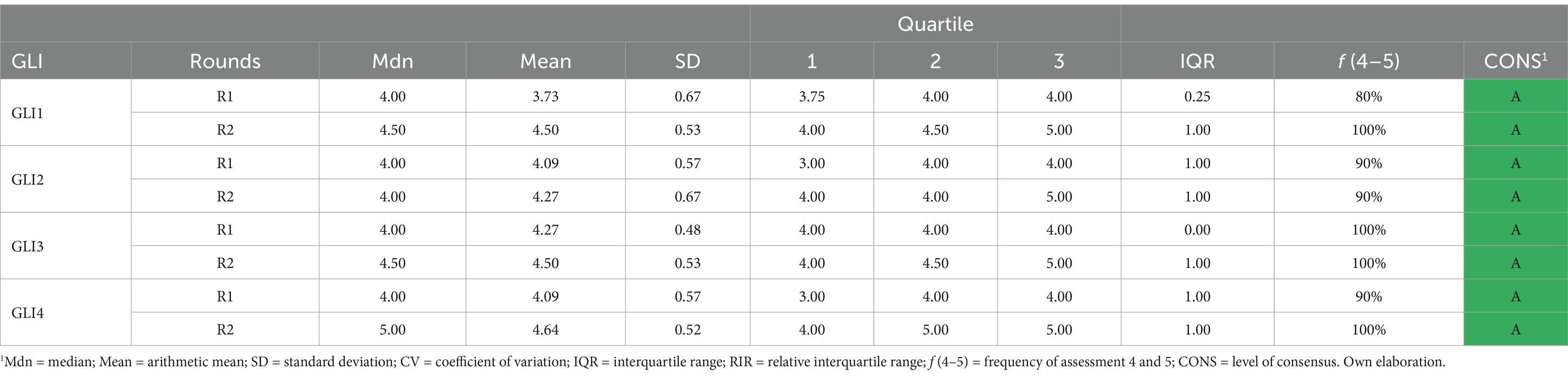

As illustrated in Table 4, the medians (4 and 5) indicate a predominantly positive perception of the assessed areas, while the interquartile ranges (IQRs) vary, demonstrating a divergence in consensus among respondents. The data demonstrate a slight positive skewness. This is characterized by a mean that is lower than both the median and mode. However, there are instances where the mean, median and mode are almost equivalent. This suggests that the distribution is more symmetrical. In round II, all experts who participated in the first round participated too. The results of the second round are shown in Tables 8–10.

As shown in Table 9, the values of all statistical parameters improve with respect to the previous round, indicating that the redrafting of the questions following the suggestions of the experts has strengthened the degree of consensus among them. For items related to GLI and Leadership, the frequency of ratings 4 and 5 on the Likert scale is 38%; GLI and Equal Employment Opportunity 57% and for GLI and Equality of Products and Services that the company offers to the Market 10%. Applying the acceptance criteria, we observe that for all items, the median ≥ 4 and IQR ≤ 1.5, are met.

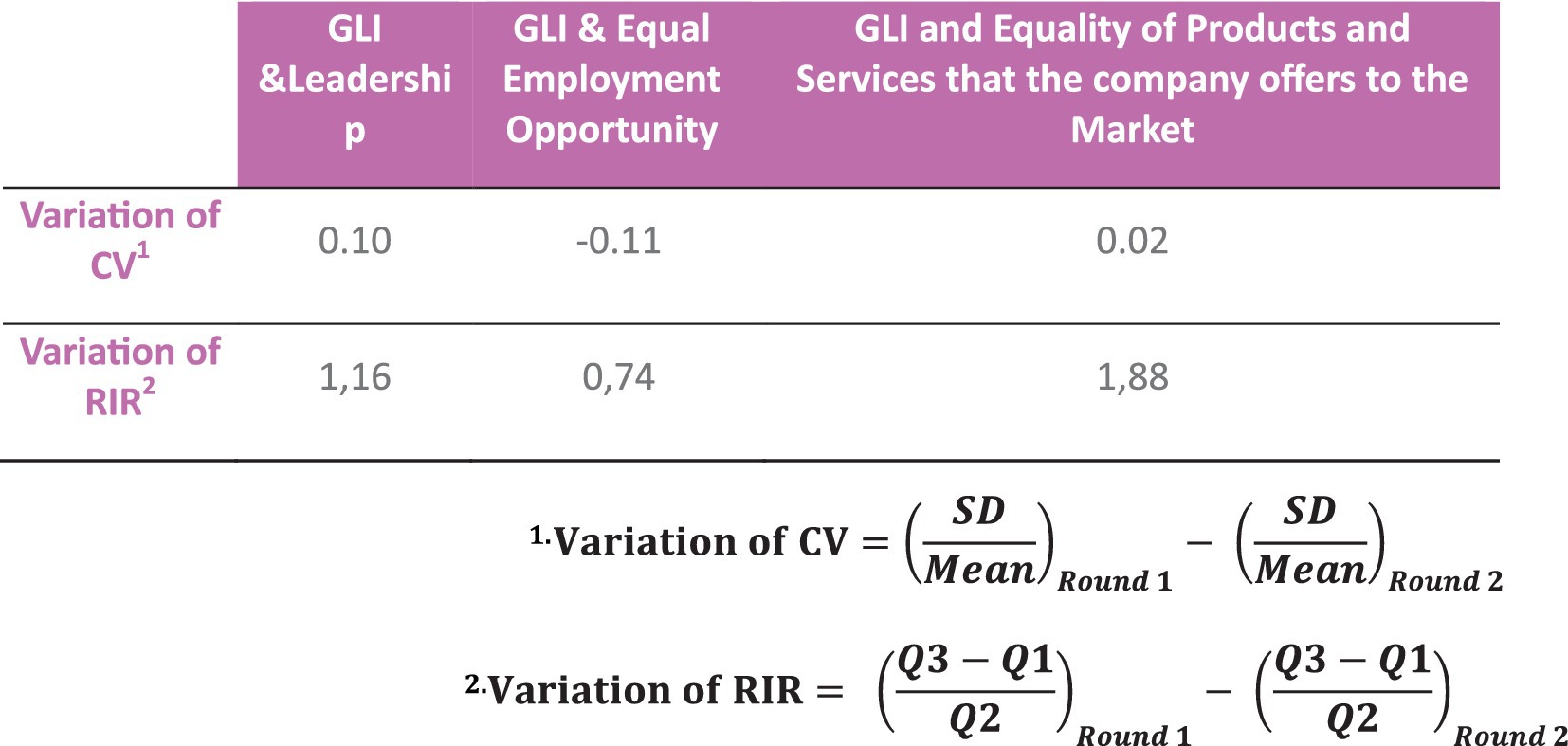

In Table 11, both rounds are compared to find out the stability of the panel, which is understood as the consistency in the experts’ opinions between successive rounds of the Delphi, regardless of their degree of convergence (Pozo et al., 2007). In Table 8, the different parameters analyzed in both rounds are compared, and improvements are shown.

Stability occurs if the variation of the interquartile range between rounds is less than 0.30 and consensus is reached if the variation of the coefficient of variation between rounds is less than 0.40 (Mengual-Andrés et al., 2016) as shown in Figure 3.

Based on the results obtained, the Delphi is closed after the second round, given that the criteria for closing the Delphi are met, as there is a high degree of consensus (median and interquartile range) and great stability in the opinions of the experts between rounds (variation in RIR and CV between rounds).

A comparative analysis of the two rounds revealed notable variation in the coefficient of variation (CV) and relative interquartile range (RIR) across three key dimensions. The dimensions of GLI and Leadership, GLI and Equal Employment Opportunity, and GLI and Equality of Products and Services were examined.

With regard to GLI and Leadership, the CV demonstrated an increase of 0.10 units, thereby indicating a greater dispersion in the second-round data in comparison to the first round. Concurrently, the RIR increased by 1.16 units, indicating a greater degree of relative variability in the distribution of the data. In the domain of equal employment opportunities, the coefficient of variation (CV) decreased by 0.11 units, indicating a reduction in the dispersion of the data. Conversely, the relative interquartile range (RIR) increased by 0.74 units, suggesting greater relative variability. Lastly, with regard to equality in products and services offered by the company, the coefficient of variation (CV) exhibited a modest increase of 0.02 units, while the relative interquartile range (RIR) demonstrated a pronounced surge of 1.88 units, indicating a considerable variability in the distribution between the two rounds.

4 Discussion and conclusion

The primary objective of this study was to develop and validate a comprehensive questionnaire designed to identify and assess the presence and frequency of Gender Lens Investing (GLI) practices within firms, alongside providing recommendations for enhancement. Particular emphasis was placed on three key dimensions of GLI practices as highlighted in the literature and recent influential reports: GLI and leadership, GLI and labor equality, and GLI concerning the equity of products and services offered by the company to the market.

In this regard, it is surprising that Chmiel et al. (2017), when assessing personnel selection and assessment (PSA) processes and the effectiveness of Human Resource Management (HRM) in training, overlook the fact that gender bias acts as a significant ‘barrier to entry’ for certain jobs. Additionally, they fail to address the need for promoting equity within organizations, ensuring equal job opportunities for all. For Chmiel et al. (2017), the gender lens appears more as a problem than a necessity, which stands in contrast to the United Nations’ emphasis on ‘Gender Equality’ in SDG 5. More recent research by Pignault and Houssemand (2021) acknowledges that their study does not consider crucial social, cultural, or individual factors and fails to address gender issues. This omission suggests that occupational psychology has yet to fully integrate gender considerations into its research.

The fact that Sustainable Finance Geneva suggests five infrastructures with their respective measurement methods highlights the lack of consensus on these measurements. Considering the differences between these and later tools: (1) EDGE does not provide a numerical approach but rather an approximate one, and it neglects the needs of female consumers; (2) Sustainable Finance Geneva generates criteria rather than measuring, making it not a tool in itself but rather a set of recommendations for measurement; it explains how to create the tool but does not implement it; (3) The IRIS+ System supports investment fund managers but does not assist companies; (4) SEAF is limited to measuring small and medium-sized enterprises; (5) The 2XCriteria is more focused on measuring economic return than on internal gender policies within companies; and finally, (6) Pro-Mujer, in partnership with Deekten, concentrates on gender policies applicable to any company—whether local, national, or international—but, like the others, it lacks numerical measurement scales, offering only general assessments that would not be useful for evaluating investment funds.

Questionnaire validation prior to its deployment is crucial, as it ensures the quality, reliability, and validity of the data collected, as well as the appropriateness and comprehensibility of the questions for the target population. The Delphi method, widely recognized in both business and social science research, is especially valuable in contexts where information is implicit or biased. In this study, two rounds of expert consultation following the Delphi method were conducted to refine and validate the GLI metrics questionnaire. The statistical analysis of these rounds demonstrated high levels of consensus, stability, and agreement among experts. Following the first round, which showed a substantial level of agreement, experts contributed open-ended feedback and suggestions for improvement. This input allowed for the reformulation of certain items in the second round, incorporating expert insights on specific aspects of GLI organizational practices that warranted particular attention. The validated questionnaire in this study is based on the most developed tool created by the 2XCriteria, incorporating three of its key thresholds: leadership, equality, and products or services for women consumers. Additionally, it draws on key criteria from other relevant literature and aims to serve as an international model tool that consolidates these efforts. The questionnaire is intended to be a reference for Supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs). By providing numerical results that measure management practices and policies across various types of companies, the tool can be easily utilized by both national and international audits for local, national, or global companies within investment fund portfolios.

Through the Delphi stages, the study established the dimensions to be prioritized within the metric and refined the clarity and relevance of the items. Furthermore, the terminology used was adapted to align with language commonly employed by Spanish firms. The validated questionnaire developed through this research offers a new methodological tool with several practical implications: (1) identifying and measuring gender lens investing practices; (2) enabling self-assessment based on the established metric to guide organizational routines; (3) informing decision-making related to gender lens investing; and (4) allowing for the testing of propositions regarding the reciprocal influence between GLI practices and organizational outcomes. In short, this tool is designed to provide evidence of how gender lens organizational practices impact firm performance.

Additionally, the tool offers significant potential for raising awareness. It enables organizations and professional groups to recognize the importance of regularly investing in GLI as part of established organizational practices, which is essential for effectively measuring GLI impact. Furthermore, it provides researchers with a valuable new instrument to support comparative studies, facilitate generalization of case study findings, and explore potential correlations across diverse GLI approaches.

4.1 Limitations

The questionnaire developed in this study has yet to be implemented across multiple companies and, therefore, remains untested in practical organizational settings. This limited application is attributed to the instrument’s novelty, the necessity for further validation, and limited dissemination among organizations that could potentially benefit from its use. Regarding organizational practices, existing literature frequently emphasizes the outcomes of gender lens investments, such as increased female representation in leadership roles or enhanced pay equity indicators. However, there is comparatively less focus on the specific practices companies adopt to realize these outcomes.

4.2 Further research

Adopting a comprehensive approach that accounts for both organizational practices and the outcomes of gender equality investments will be essential. Further, a more rigorous academic analysis of these practices can yield valuable insights into the mechanisms that actively foster gender equality and inclusive leadership.

In conclusion, widespread implementation of the questionnaire across a diverse range of companies, along with a refined academic focus on organizational practices, is critical to advancing the understanding and promotion of workplace gender equality. Broadening the application of the questionnaire will not only allow for its validation but also enable refinement and enhancement of its components, ensuring its relevance across various sectors and organizational cultures. This approach supports comparative analysis and facilitates the potential generalization of findings derived from case studies.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the [patients/participants OR the patients/participants' legal guardians/next of kin] in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

MP-V: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. A-LO-L: Conceptualization, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. M-JB-B: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CD-P-H: Conceptualization, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This article has been financed with funds from OPENINNOVA High Performance Research Group (URJC-V1539).

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our gratitude to the experts for their valuable insights and feedback on the initial version of the questionnaire.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1534355/full#supplementary-material

References

2X Challenge. (2024). 2X Criteria Reference Guide. Available online at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b180402c3c16a6fe0001e45/t/65e72c44689786427b5b0889/1709648967612/2X+Criteria+Reference+Guide_February+2024.pdf (Accessed November 5, 2024).

50&50 Gender Leadership. (2023). Somos. Available online at: https://www.5050gl.com/somos/ (Accessed November 5, 2024).

Aljarodi, A., Rialp, A., and Urbano, D. (2021). Female entrepreneurial activity in emerging economies: a systematic literature review. Revista Econ. 921, 83–99. doi: 10.32796/ice.2021.921.7269

Argentum. (2024). Competencies for silver economy. Available online at: https://argentum.biz/ (Accessed December 5, 2024).

Boulkedid, R., Abdoul, H., Loustau, M., Sibony, O., and Alberti, C. (2011). Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One 6:e20476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020476

Bravo Estévez, M., and Arrieta Gallastegui, J. J. (2005). El método Delphi. Su implementación en una estrategia didáctica para la enseñanza de las demostraciones geométricas. Revista Iberoamericana Educ. 36, 1–10. doi: 10.35362/rie3672962

Cabero Almenara, J., and Infante Moro, A. (2014). Empleo del método Delphi y su empleo en la investigación en comunicación y educación. Edutec. Revista Electrón. Tecnol. Educ. 48:a272. doi: 10.21556/edutec.2014.48.187

Calvert Impact Capital. (2019). Just good Investig: Why gender matters to your portfolio and what can you do about it? Available online at: https://assets.ctfassets.net/4oaw9man1yeu/2X1gLdNUrUPFhRAJbAXp1q/205876bdd2d7e076fce05d5771183dfe/calvert-impact-capital-gender-report.pdf (Accessed December 15, 2024).

Calvert Impact Capital, and New York University School of Law International Transactions Clinic. (2021). Gender Lens investing: Legal perspectives: How investors incorporate gender considerations into Deal documentation. Available online at: https://assets.ctfassets.net/4oaw9man1yeu/3cpyAZ81zUCR2YcKC7Bn7d/8b03748646283ccea887506c5a44368c/genderlensinvesting_legalperspectives_2021.pdf (Accessed December 16, 2024).

Campbell, M., Katikireddi, S. V., Sowden, A., McKen-Zie, J. E., and Thomson, H. (2018). Improving the con- duct and reporting of quantitative data narrative synthesis (ICONS-quant) reports: protocol for a mixed methods study to develop a guideline report. BMJ Open 8:e020064. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020064

Chmiel, N., Fraccaroli, F., and Sverke, M. (2017). An introduction to work and organizational psychology: An international perspective. New York: Wiley.

Criterion Institute. (2020). Process metrics that analyze power dynamics in investing. Available online at: https://www.criterioninstitute.org/resources/process-metrics-that-analyze-power-dynamics-in-investing (Accessed December 17, 2024).

Cuhls, K. (2023). “The Delphi method: an introduction” in Delphi methods in the social and health sciences. 3–27. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-38862-1_1

Daher, M., Rosati, A., and Jaramillo, A. (2022). Saving as a path for female empowerment and entrepreneurship in rural Peru. Prog. Dev. Stud. 22, 32–55. doi: 10.1177/14649934211035219

EDGE. (2024). EDGE standards and certification framework. Available online at: https://www.edge-cert.org/dei-framework/ (Accessed January 15, 2025).

EDGE Certified Foundation. (2024). EDGE standards and certification. Available online at: https://www.edge-cert.org/dei-certification/ (Accessed January 15, 2025).

García-Martínez, V., Aquino-Zúñiga, S. P., Guzmán-Salas, A., and Medina-Meléndez, A. (2012). Using the Delphi method as a strategy for the assessment of quality indicators in distance education programs. Revista Electrón. Calidad Educ. Superior 3, 200–222. doi: 10.22458/caes.v3i1.439

Giannarou, L., and Zervas, E. (2014). Using Delphi technique to build consensus in practice. Int. J. Business Sci. Appl. Manag. 9, 65–82. doi: 10.69864/ijbsam.9-2.106

Guldenmund, F. W. (2007). The use of questionnaires in safety culture research – an evaluation. Saf. Sci. 45, 723–743. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2007.04.006

Holeman, I., Citrin, D., Albirair, M., Puttkammer, N., Ballard, M., DeRenzi, B., et al. (2024). Building consensus on common features and interoperability use cases for community health information systems: a Delphi study. BMJ Glob. Health 9:e014001. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2023-014001

Hung, H.-L., Altschuld, J. W., and Lee, Y.-F. (2008). Methodological and conceptual issues confronting a cross-country Delphi study of educational program evaluation. Eval. Program Plann. 31, 191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2008.02.005

Ilu Women's Empowerment Fund. (2021) Self-diagnosis of gender approach in business management. Available online at: https://iluwomensempowermentfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Self-Assesment.docx (Accessed December 18, 2024).

Lee, Y. K., Shin, E. S., Shim, J.-Y., Min, K. J., Kim, J.-M., and Lee, S. H. (2013). Developing a scoring guide for the appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation II instrument in Korea: a modified Delphi consensus process. J. Korean Med. Sci. 28:190. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.2.190

López Gómez, E. (2018). The Delphi method in current educational research: a theoretical and methodological review. [the Delphi method in current educational research: a theoretical and methodological review]. Education XX1 21, 17–40. doi: 10.5944/educXX1.15536

Margherita, A., Elia, G., and Klein, M. (2021). Managing the COVID-19 emergency: a coordination framework to enhance response practices and actions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 166:120656. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120656

Mengual-Andrés, S., Roig-Vila, R., and Mira, J. B. (2016). Delphi study for the design and validation of a questionnaire about digital competences in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 13:12. doi: 10.1186/s41239-016-0009-y

Ortega Mohedano, F. (2008). El método Delphi, prospectiva en Ciencias Sociales a través del análisis de un caso práctico. Revista Escuela Admin. Negocios 64, 31–54. doi: 10.21158/01208160.n64.2008.452

Paris, G. (2015). Professionals in vocational training for employment: Competencies and professional development. (Doctoral Thesis). Lleida: Universitat de Lleida.

Pignault, A., and Houssemand, C. (2021). What factors contribute to the meaning of work? A validation of Morin’s meaning of work questionnaire. Psicologia 34, 2–16. doi: 10.1186/s41155-020-00167-4

Pozo, M. T., Gutierrez, J., and Rodríguez, P. (2007). El uso del método delphi en la definición de los criterios para una formación de calidad en animación socio-cultural y tiempo libre. Rev. Investig. Educ. 25, 351–366.

Reguant-Alvarez, M., and El Torrado-Fonseca, M. (2016). Método Delphi. REIRE Rev. Innovació Recer. En Educ. doi: 10.1344/reire2016.9.1916

Reid, M., and Reid, M. A. (1988). Undergraduate algebraic geometry, vol. No. 12. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, A. (2016). The limitations of transnational business feminism: the case of gender lens investing. Soundings 62, 68–83. doi: 10.3898/136266216818497776

Saeed, A., Riaz, H., and Baloch, M. S. (2023). Pursuing sustainability development goals through adopting gender equality: women representation in leadership positions of emerging market multinationals. Eur. Manag. Rev. 20, 273–286. doi: 10.1111/emre.12532

Santaguida, P., Dolovich, L., Oliver, D., Lamarche, L., Gilsing, A., Griffith, L. E., et al. (2018). Protocol for a Delphi consensus exercise to identify a core set of criteria for selecting health related outcome measures (HROM) to be used in primary health care. BMC Fam. Pract. 19:152. doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0831-5

Sasakawa Peace Foundation, Catalyst at Large, and SAGANA. (2020). Gender Lens Investing Landscape. Tokyo: East and South Asia. Available online at: https://www.spf.org/en/global-image/units/upfiles/144596-1-20211027152614_b6178f10669fe9.pdf (Accessed December 20, 2024).

Subramanian, T. M. (2022). Evolving the gender analysis in gender lens investing: moving from counting women to valuing gendered experience. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 12, 684–703. doi: 10.1080/20430795.2021.2001300

Varela-Ruiz, M., Díaz-Bravo, L., and García-Durán, R. (2012). Description and uses of the Delphi method in health care research. Revista Investig. Educ. Médica 1, 90–95.

Yin, H.-T., Chang, C.-P., Anugrah, D. F., and Gunadi, I. (2023). Gender equality and central bank independence. Econ. Anal. Policy 78, 661–672. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2023.04.006

Keywords: gender lens investing (GLI), Delphi method, gender issues, value creation, gender metrics

Citation: Palomo-Vadillo M, Ortega-Larrea A-L, Bordonado-Bermejo M-J and De-Pablos-Heredero C (2025) Developing an index for measuring gender lens investing in organizations: the GLIMETRICS framework. Front. Psychol. 16:1534355. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1534355

Edited by:

Carlos Francisco De Sousa Reis, University of Coimbra, PortugalReviewed by:

Santiago Gutiérrez-Broncano, University of Castilla-La Mancha, SpainHasanain A. J. Gharban, Wasit University, Iraq

Copyright © 2025 Palomo-Vadillo, Ortega-Larrea, Bordonado-Bermejo and De-Pablos-Heredero. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carmen De-Pablos-Heredero, Y2FybWVuZGVwYWJsb3NAdXJqYy5lcw==

Maite Palomo-Vadillo

Maite Palomo-Vadillo Ana-Lucia Ortega-Larrea

Ana-Lucia Ortega-Larrea María-Julia Bordonado-Bermejo

María-Julia Bordonado-Bermejo Carmen De-Pablos-Heredero

Carmen De-Pablos-Heredero