Abstract

Background:

The spouse is the most at risk of developing psychological consequences following the loss of a partner (anxiety, depression, complicated grief) compared to other family caregivers. The principal aim of this study was to investigate the possible implications and bereavement process for those who have lost a spouse following a cancer diagnosis and the implementation of continuous deep sedation (CDS).

Methods:

A scoping review was conducted according to the PRISMA protocol using the following databases: PubMed, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, PsycInfo, Overview, PsycArticles, and PubPsych. The publication period used as a selection criterion was 2010–2023.

Results:

A total of 317 articles emerged from the keywords. However, the research studies focused exclusively on the practice of CDS, and the consequences of bereaved partners did not produce any results.

Conclusions:

The absence of selected articles has revealed various reflections and questions. Is it possible that CDS and its effects on grief are not evaluated because the practice is infrequent? As perceived and symbolically associated with euthanasia, can this lead to moral conflicts where it is illegal, and therefore generate a taboo? Given the results of the following study and the role of the grieving partner, it is essential to conduct further research on this topic and to suggest it.

Introduction

Approximately 40 million people each year require palliative care, an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families. Palliative care aims to prevent and alleviate the pain perceived by the person diagnosed with a profoundly severe and generally terminal disease. Palliative care specialists assess and treat pain and other physical, psychosocial, social, or spiritual problems (World Health Organization, 2020).

Palliative care teams use an interdisciplinary approach, with professionals playing distinct roles: physicians, nurses, support workers, psychologists, paramedics, pharmacists, physiotherapists, and volunteers (World Health Organization, 2020).

According to the World Health Organization (2020), worldwide, 34% of patients who activate and seek palliative care have cancer, the globally second leading cause of death after cardiovascular diseases.

Furthermore, within palliative care regimes, in severe cases, Continuous Deep Sedation (CDS) is used to reduce the suffering caused by symptoms with a sedative effect to induce a deep state of unconsciousness until the moment of death (Bruinsma et al., 2014).

The international literature does not employ a single, universally accepted term to describe sedation practices at the end of life. Various expressions—such as continuous sedation, palliative sedation (PS), terminal sedation, continuous PS therapy, continuous deep sedation, or even slow euthanasia—are used interchangeably, often referring to overlapping but not identical practices (Papavasiliou et al., 2014; Rys et al., 2012; Rietjens et al., 2006; ten Have and Welie, 2014). This terminological heterogeneity complicates the comparison of studies and the identification of relevant evidence within the literature. For this reason, and to ensure clarity and consistency throughout the present article, we adopt the term Continuous Deep Sedation (CDS) to refer to the practice under examination.

Patients are, therefore, suffering from a severe, incurable, life-threatening disease with a short-term prognosis. Patients are presenting with so-called refractory suffering. This refractory suffering must be objectified by a third-party, recognized professional (Pierron, 2020). The High Authority of Health (Haute Autorité de santé) and the French Society of Support and Palliative Care (Société Française d'Accompagnement et de soins Palliatifs) recommendations specify the indications for applying this law (Haute Aut. Santé, 2020; Guirimand et al., 2010). The medications used, the implementation modalities, the technical decision-making tools, and the scales to evaluate the patient's comfort and the depth of sedation are described (Sessler et al., 2002).

Several studies in the scientific literature have examined professionals' subjective experiences when making decisions and establishing a CDS (Vieille et al., 2021; Morita et al., 2019; Camartin and Björkhem-Bergman, 2022; Belar et al., 2022; Abarshi et al., 2014; Lux et al., 2017). Physicians and nurses formulate the need to exchange with the patient and their relatives, anticipate sedation, and discuss with the different health actors (Chazot and Henry, 2016; Salas et al., 2020; Mesnage et al., 2020; Chemrouk and Geniey, 2020; Peyrat-Apicella and Chemrouk, 2022). The National Centre for Palliative and End-of-Life Care's (Centre national des soins palliatifs et de la fin de vie) survey on CDS (Louarn, 2017) shows that sedation is often proposed by the medical team and less frequently requested by the patient. According to Serey et al. (2019), the patient's main motive is a refractory symptom that corresponds to psychological suffering in most cases (69%). Health professionals express the complexity of these moments when the CDS is evoked and implemented.

Regarding families, most report satisfaction and view the treatment positively, particularly regarding the possibility of providing the patient with complete relief from symptoms (Tomczyk, 2018). Others, however, view CDS as emotional stress and discomfort, determined, for example, by the inability to communicate with the patient. They argue that CDS could accelerate death (Shen et al., 2018). Maintaining the bond can also take the form of physical contact. Yet, the longer continuous deep sedation lasts, the harder it becomes for relatives to manage the growing sense of emptiness. Several studies suggest that prolonged sedation increases family distress, with the waiting itself becoming a source of stress (Bruinsma et al., 2014; Raus et al., 2014). This suffering may even lead some families to wish to hasten their loved one's death.

As recalled by Areia et al. (2020), cancer and its treatments affect not only the patient but also the family caregivers, who are, in 85% of cases, spouses or adult children (Clark Paul et al., 2011). Furthermore, the entire social network surrounding the sick person is affected practically and emotionally (Areia et al., 2020).

It is estimated that about 20% to 50% of family caregivers of end-stage cancer patients suffer from adverse psychological sequelae (Areia et al., 2020), including distress, depression (Dionne-Odom et al., 2016; Guldin et al., 2012; Bacqué and Hanus, 2020; Holtslander et al., 2017), insomnia (Holtslander et al., 2017), anxiety (Areia et al., 2020; Rumpold et al., 2016), intensified burden (Areia et al., 2020), high levels of somatization (Dionne-Odom et al., 2016), anticipatory (Rumpold et al., 2016), and complicated grief (Dionne-Odom et al., 2016; Guldin et al., 2012; Bacqué and Hanus, 2020).

According to the literature, the predictors that could negatively influence the psychological course of the end of life correspond to the female gender (Areia et al., 2020), the mental and physical health status of the caregiver (Brazil et al., 2005; Rossi Ferrario et al., 2004), the social support received (Brazil et al., 2010), uncontrolled symptoms and pain, attachment to the patient (Bacqué and Hanus, 2020), and to the circumstances surrounding the death (Shear, 2015). Other factors contributing to bereavement complications include intrinsic factors related to the bereaved person's life course, personality, contextual factors related to the death process, communication with the health care team, and support received by the bereaved (Fasse et al., 2013; Zech, 2019). Furthermore, the risk of co-morbidity increases with the bereaved person's age, especially the presence of depression (Robbins-Welty et al., 2018), the risk of cardiovascular disease, and increased cognitive decline (Atalay and Staneva, 2020). Difficulties in the grieving process increase in cases of assisted suicide or euthanasia (Pott et al., 2011; Diricq, 2017; Ganzini et al., 2009).

Finally, the degree of affection between the bereaved and the deceased is a determining factor in the risk of grief complications, which is more significant following the loss of a partner than, for example, that of a parent or grandparent (Fernández-Alcántara and Zech, 2017; Garrouste-Orgeas et al., 2019; Prigerson et al., 2009). However, despite this notion, there are not many studies on the bereaved spouse in cancer (Rumpold et al., 2016; Fasse et al., 2014; Götze et al., 2014; Egerod et al., 2019; Aoyama et al., 2021). Most research has focused on the practices and attitudes of physicians (Bruinsma et al., 2014) and the consequences on general informal caregivers (Morita et al., 2004) and other family members (Areia et al., 2020). Little is known about the patient's partner and the effects that specific palliative interventions may have on their grief.

For this reason, this study aims to conduct a systematic literature review to investigate the potential consequences and bereavement process for individuals who have lost a spouse to cancer and have undergone deep and continuous sedation. We also aim to assess the quality of research in this field.

The results of this study will provide more information and need for consideration for all those involved in or working with this practice, including researchers, doctors, family caregivers, and healthcare professionals.

Methods

To respond to the research objectives, a literature review was conducted according to the recommendations provided by the PRISMA protocol for scoping a review (Morita et al., 2004). The PRISMA method enables an exhaustive review of all the literature published in the central databases on a theme that will be defined from intersecting keywords.

The databases used were PubMed, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, PsychInfo, Overview, PsycArticles, and PubPsych.

The selection period was limited to 2010–2023 to minimize conclusion bias based on prior findings and those irrelevant to contemporary research. The decision to limit the literature review to studies published from 2010 onwards was made deliberately to ensure that the findings are relevant and applicable to current research. By excluding studies conducted before 2010, the authors aimed to focus on recent advancements (Sani and Bacqué, 2023). They recognized that the rapid evolution of technology and therapeutic approaches in the past decade could make some earlier findings less relevant to the present context.

The research was carried out in English using the following search string: (“deep sedation” OR “continuous deep sedation” OR “palliative sedation”) AND (“partner” OR “spouse” OR “wife” OR “husband”) AND (“grief” OR “bereavement” OR “mourning”) AND “cancer”.

Two researchers (YC, LS) independently reviewed titles and abstracts identified starting from the keywords. Then, in pairs, the researchers independently screened the titles and abstracts of all articles retrieved. In a consultative procedure, consensus on which articles to screen full text was reached by discussion. Next, they independently screened full-text articles for inclusion.

The first selection occurred through the titles and abstracts of the potentially pertinent articles.

Subsequently, duplicates were discarded.

In addition to the studies related to the research objectives and the language of publication, two other inclusion criteria were used, namely:

-

(1) The studies were to be scientific articles.

-

(2) The articles had to appear in peer-reviewed journals.

Finally, all articles concerning children, adolescents, and other literature reviews were excluded.

Therefore, the selection was made by evaluating the topics dealt with in the articles without specifically selecting further criteria such as sensitivity or sensibility.

Starting exclusively from clinical experiences and perceiving missing information at the literature level, the aim was to quantify and present scientific articles published on the psychological consequences of those who have lost a partner following a cancer diagnosis and the activation of sedative practices in the field of palliative care. This analysis, therefore, concerns the presentation of the articles through the name of the authors, the objectives, the methodology, and the results obtained.

Results

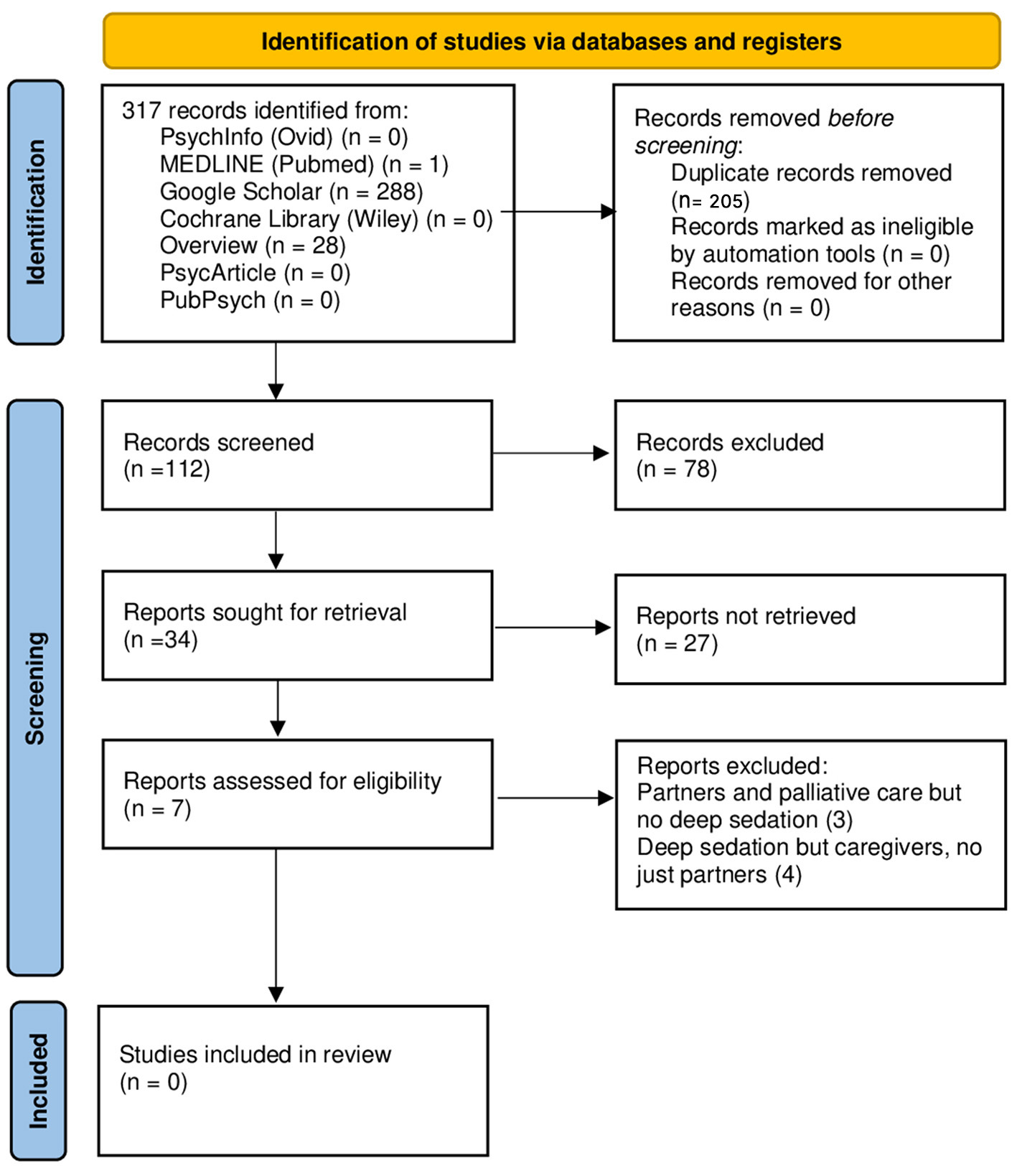

The literature review process is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram.

Through the keywords listed above, the two authors analyzed 317 articles.

Starting from the comparison between the 288 articles found on Google Scholar, the 28 on Overview, and the article on PubMed, 205 were duplicates.

Table 1 shows the 34 articles selected based on their title and abstracts.

Table 1

The 34 articles selected by title and abstracts categorized according to their topic.

They are related to palliative care provided following a cancer diagnosis. The table indicates the authors and whether each article considers deep sedation, bereaved partners, or family members/informal caregivers.

Table 2 shows the percentages of 34 articles. Seven articles were chosen for eligibility. Three articles (8.8%) were found not dealing with deep sedation but with partners and palliative care (Fasse et al., 2014; Egerod et al., 2019; Jones et al., 2022), of which two were literature reviews (Fasse et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2022).

Table 2

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Palliative care | 34 | 100 |

| Continuous deep sedation until death (CDSUD) | 4 | 11.8 |

| Partner | 3 | 8.8 |

| General informal caregiver | 31 | 91.2 |

| Combination | ||

| Palliative care—continuous deep sedation until death (CDSUD) | 4 | 11.8 |

| Palliative care—partner | 3 | 8.8 |

| Palliative care—general informal caregiver | 31 | 91.2 |

| Continuous deep sedation until death (CDSUD)—partner | 0 | 0 |

| Continuous deep sedation until death (CDSUD)—general informal caregiver | 4 | 11.8 |

Percentages of the topics of the 34 articles selected.

Four other articles (14.3%) dealt with deep sedation for informal caregivers (i.e., spouses and children) (Bruinsma et al., 2014, 2016; Shen et al., 2018; Imai et al., 2022).

These articles demonstrate several interesting aspects concerning bereaved loved ones:

While most loved ones thought sedation had contributed to a “good death” for the patient, many expressed concerns. These included concerns about the patient's well-being, their well-being, and questions about whether continuous sedation had shortened the patient's life or whether another approach would have been better (Bruinsma et al., 2014).

This article compares practices in the Netherlands, Belgium, and the UK (Bruinsma et al., 2014).

In the Netherlands and Belgium, several relatives reported that the start of sedation had enabled them to plan a moment of “goodbye.” In contrast, British relatives did not discern an explicit start of sedation or a specific moment of farewell.

Most relatives reported being generally comfortable with the use of palliative sedation; nevertheless, a proportion of them experienced notable distress during the sedation period, highlighting the coexistence of acceptance and emotional burden (Bruinsma et al., 2016).

In a comparative study assessing relatives' experiences with continuous deep sedation until death vs. transient sedation (Bruinsma et al., 2016), no statistically significant differences emerged in the overall evaluation of the dying phase. Levels of concern, satisfaction, and perceived balance between symptom relief and preserved communication were comparable across groups. Conversely, several indicators of care quality—such as interactions with medical staff, nursing care, coordination of care, and procedural consistency—were rated significantly higher in the continuous deep sedation group. Overall, relatives' experiences of continuous deep sedation were not inferior to those associated with transient sedation and were, in some domains, evaluated more positively.

Discussion

Using the six search engines previously described, the keywords generated an initial set of 317 articles. Considering the breadth of databases consulted and the 12-year time frame (2010–2023), this number appears relatively limited. As already mentioned, the selection process did not yield any studies specifically examining the psychological consequences experienced by bereaved partners after the use of continuous deep sedation (CDS). Although several studies have explored sedation practices or general family experiences, none addressed the particular situation of spouses—despite evidence identifying them as the relatives at highest risk for grief-related complications (Fernández-Alcántara and Zech, 2017; Garrouste-Orgeas et al., 2019; Prigerson et al., 2009).

Of the 34 articles retained after preliminary screening, only 4 (11.8%) addressed CDS (see Table 2). The scarcity of research on this topic is striking, especially given that partners are consistently reported to be the most vulnerable group in bereavement, notably in the context of cancer (Rumpold et al., 2016; Fasse et al., 2014; Götze et al., 2014; Egerod et al., 2019; Aoyama et al., 2021; Jadhav and Weir, 2018; Fagundes et al., 2019; Siflinger, 2017). This discrepancy suggests that, while bereavement in spouses has been investigated, the specific intersection between CDS and partner grief remains largely unexplored.

In reviewing the broader literature, several possible explanations emerge. First, research in palliative care rarely distinguishes between different categories of relatives: partners, adult children, and other family members are often treated as a single group, which may obscure the specific experiences of spouses (Bruinsma et al., 2014, 2016; Shen et al., 2018). Second, the variability in terminology and clinical practices surrounding sedation—ranging from “palliative sedation” to “terminal sedation,” “continuous deep sedation,” or even “slow euthanasia” (Papavasiliou et al., 2014; Rys et al., 2012; Rietjens et al., 2006; ten Have and Welie, 2014)—complicates literature searches and may contribute to inconsistent indexing of studies. This conceptual heterogeneity could partially explain why the search did not identify more targeted research.

Third, CDS may be used relatively infrequently in some healthcare contexts, making it challenging to collect sufficiently large samples to study bereavement outcomes in partners. In addition, the symbolic and ethical implications of CDS may discourage empirical investigation. As highlighted by Claessens et al. (2008), CDS may be perceived as closely related to euthanasia, particularly in countries where assisted dying is illegal. Such associations may create moral discomfort for clinicians and researchers, resulting in fewer studies addressing the psychosocial implications of sedation. Moreover, previous research indicates that while relatives often view CDS as contributing to a “good death,” they may also experience distress linked to communication loss, uncertainty, or unanticipated events during the dying process (Bruinsma et al., 2014; Peyrat-Apicella and Chemrouk, 2022; Raus et al., 2014). These emotionally complex situations may make it more challenging to recruit bereaved spouses for research participation.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the lack of studies on partners' bereavement after CDS is not merely an absence of data but a reflection of broader structural, methodological, and ethical challenges. This gap is clinically significant: given the heightened vulnerability of spouses, targeted research is essential to understand their experiences better, anticipate potential risks for complicated grief, and guide tailored support interventions in palliative care.

Limitations

Finally, this article also presents some limitations. The methodology itself entails certain constraints. The scoping review approach was deliberately chosen to explore an under-researched topic and to map all potentially relevant evidence; however, it does not allow for a systematic assessment of study quality, a formal risk-of-bias evaluation, or a quantitative synthesis of results. Moreover, the absence of a universally recognized terminology for sedation practices, combined with heterogeneous clinical applications of CDS across countries, further limits the comparability of the retrieved studies.

At the same time, these limitations highlight an important strength of our work. The scarcity of studies identified through this comprehensive search points to a substantial and previously overlooked gap in the international literature. This gap underscores the need for further empirical research specifically addressing the experiences and psychological outcomes of bereaved partners of patients who underwent continuous deep sedation until death. The novelty of this topic underscores the relevance and timeliness of exploring it in greater depth.

Conclusion

In conclusion, no articles emerged from the literature search concerning deep and continuous sedation until death and bereavement for spouses of cancer patients. It is essential to broaden research interests to the role and experience of the partner to better understand what is at stake for the relatives of a patient who has died under sedation. It is also advisable to disseminate this research on sedation, including other caregivers (formal and informal) who accompany the patient. Sedation and its symbolic and psychic effects have been evaluated in relatives, demonstrating a scientific and clinical interest in this hypothesis. Nevertheless, the effects of deep and continuous sedation until death on mourning, i.e., on the process considered a temporality, has not been studied.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

YC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PG: Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. M-FB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was funded by the French National Cancer Institute (INCA_15908).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abarshi E. A. Papavasiliou E. S. Preston N. Brown J. Payne S. EURO IMPACT. (2014). The complexity of nurses' attitudes and practice of sedation at the end of life: a systematic literature review. J. Pain Symptom Manage.47, 915–925.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.06.011

2

Aoyama M. Sakaguchi Y. Fujisawa D. Morita T. Ogawa A. Kizawa Y. et al . (2020). Insomnia and changes in alcohol consumption: relation between possible complicated grief and depression among bereaved family caregivers. J. Affect. Disord.275, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.023

3

Aoyama M. Sakaguchi Y. Igarashi N. Morita T. Shima Y. Miyashita M. (2021). Effects of financial status on major depressive disorder and complicated grief among bereaved family members of patients with cancer. Psychooncology30, 844–852. doi: 10.1002/pon.5642

4

Aoyama M. Sakaguchi Y. Morita T. Ogawa A. Fujisawa D. Kizawa Y. et al . (2018). Factors associated with possible complicated grief and major depressive disorders. Psychooncology27, 915–921. doi: 10.1002/pon.4610

5

Areia N. P. Fonseca G. Major S. Relvas A. P. (2019). Psychological morbidity in family caregivers of people living with terminal cancer: prevalence and predictors. Palliat. Support Care17, 286–293. doi: 10.1017/S1478951518000044

6

Areia N. P. Góngora J. N. Major S. Oliveira V. D. Relvas A. P. (2020). Support interventions for families of people with terminal cancer in palliative care. Palliat. Support Care18, 269–277. doi: 10.1017/S1478951520000127

7

Atalay K. Staneva A. (2020). The effect of bereavement on cognitive functioning among elderly people: evidence from Australia. Econ. Hum. Biol.39:100932. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2020.100932

8

Bacqué M. F. Hanus M. (2020). Le deuil [The grief], 8th ed.Paris: Presses Universitaires de France - PUF. French.

9

Bajwah S. Oluyase A. O. Yi D. Gao W. Evans C. J. Grande G. et al . (2020). The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of hospital-based specialist palliative care for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.9:CD012780. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012780.pub2

10

Belar A. Arantzamendi M. Menten J. Payne S. Hasselaar J. Centeno C. (2022). The decision-making process for palliative sedation for patients with advanced cancer–analysis from a systematic review of prospective studies. Cancers14:301. doi: 10.3390/cancers14020301

11

Brazil K. Bainbridge D. Rodriguez C. (2010). The stress process in palliative cancer care: a qualitative study on informal caregiving and its implication for the delivery of care. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care27, 111–116. doi: 10.1177/1049909109350176

12

Brazil K. Bedard M. Krueger P. Abernathy T. Lohfeld L. Willison K. (2005). Service preferences among family caregivers of the terminally ill. J. Palliat. Med.8, 69–78. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.69

13

Breen L. J. Aoun S. M. O'Connor M. Johnson A. R. Howting D. (2020). Effect of caregiving at end of life on grief, quality of life, and general health: a prospective, longitudinal, comparative study. Palliat. Med.34, 145–154. doi: 10.1177/0269216319880766

14

Bruinsma S. M. Brown J. van der Heide A. Deliens L. Anquinet L. Payne S. A. et al . (2014). Making sense of continuous sedation in end-of-life care for cancer patients: an interview study with bereaved relatives in three European countries. Support Care Cancer22, 3243–3252. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2344-7

15

Bruinsma S. M. van der Heide A. van der Lee M. L. Vergouwe Y. Rietjens J. A. (2016). No negative impact of palliative sedation on relatives' experience of the dying phase and their wellbeing after the patient's death: an observational study. PLoS ONE11:e0149250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149250

16

Camartin C. Björkhem-Bergman L. (2022). Palliative sedation-the last resort in case of difficult symptom control: a narrative review and experiences from palliative care in Switzerland. Life Basel Switz.12:298. doi: 10.3390/life12020298

17

Chan H. Y. L. Lee L. H. Chan C. W. H. (2013). The perceptions and experiences of nurses and bereaved families towards bereavement care in an oncology unit. Support Care Cancer21, 1551–1556. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1692-4

18

Chazot I. Henry J. (2016). La sédation en soins palliatifs : représentations des soignants et jeunes médecins [Sedation in palliative care: representations of caregivers and young physicians]. Jusqu'à La Mort Accompagner La Vie124, 89–100. French. doi: 10.3917/jalmalv.124.0089

19

Chemrouk Y. Geniey K. (2020). Fin de vie : enquête exploratoire sur l'expérience des soignants en oncologie [End of life: an exploratory survey of caregivers' experiences in oncology]. Psycho-Oncol.14, 61–65. French. doi: 10.3166/pson-2020-0121

20

Claessens P. Menten J. Schotsmans P. Broeckaert B. (2008). Palliative sedation: a review of the research literature. J. Pain Symptom Manage.36, 310–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.10.004

21

Clark Paul G. Brethwaite Drucilla S. Gnesdiloff S. (2011). Providing support at time of death from cancer: results of a 5-year post-bereavement group study. J. Soc. Work End Life Palliat. Care7, 195–215. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2011.593156

22

Coelho A. de Brito M. Teixeira P. Frade P. Barros L. Barbosa A. (2020). Family caregivers' anticipatory grief: a conceptual framework for understanding its multiple challenges. Qual. Health Res.30, 693–703. doi: 10.1177/1049732319873330

23

Coelho A. Roberto M. Barros L. Barbosa A. (2022). Family caregiver grief and post-loss adjustment: a longitudinal cohort study. Palliat. Support Care20, 348–356. doi: 10.1017/S147895152100095X

24

Dionne-Odom J. N. Azuero A. Lyons K. D. Hull J. G. Prescott A. T. Tosteson T. et al . (2016). Family caregiver depressive symptom and grief outcomes from the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J. Pain Symptom Manage.52, 378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.03.014

25

Diricq C. (2017). ≪ Même pas mal ≫, le deuil est un processus intersubjectif [“Even not bad,” grief is an intersubjective process]. Corps En Souffrance Psychismes En Présence 85–102. French. doi: 10.3917/eres.daune.2017.01.0085

26

Egerod I. Kaldan G. Shaker S. B. Guldin M. B. Browatski A. Marsaa K. et al . (2019). Spousal bereavement after fibrotic interstitial lung disease: a qualitative study. Respir. Med.146, 129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2018.12.008

27

Fagundes C. P. Brown R. L. Chen M. A. Murdock K. W. Saucedo L. LeRoy A. et al . (2019). Grief, depressive symptoms, and inflammation in the spousally bereaved. Psychoneuroendocrinology100, 190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.10.006

28

Fasse L. Sultan S. Cecile F. (2013). Expérience de pré-deuil à l'approche du décès de son conjoint : une analyse phénoménologique interprétative [Pre-mourning experience at the approach of the death of one's spouse: an interpretative phenomenological analysis]. Psychol. Fr.58, 177–194. French. doi: 10.1016/j.psfr.2013.02.001

29

Fasse L. Sultan S. Flahault C. Mackinnon C. J. Dolbeault S. Brédart A. (2014). How do researchers conceive of spousal grief after cancer? A systematic review of models used by researchers to study spousal grief in the cancer context. Psychooncology23, 131–142. doi: 10.1002/pon.3412

30

Fernández-Alcántara M. Zech E. (2017). One or multiple complicated grief(s)? The role of kinship on grief reactions. Clin. Psychol. Sci.5, 851–857. doi: 10.1177/2167702617707291

31

Fringer A. Hechinger M. Schnepp W. (2018). Transitions as experienced by persons in palliative care circumstances and their families – a qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Palliat. Care17:22. doi: 10.1186/s12904-018-0275-7

32

Ganzini L. Goy E. R. Dobscha S. K. Prigerson H. (2009). Mental health outcomes of family members of Oregonians who request physician aid in dying. J. Pain Symptom Manage.38, 807–815. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.026

33

Garrouste-Orgeas M. Flahault C. Poulain E. Evin A. Guirimand F. Fossez-Diaz V. et al . (2019). The Fami-life study: protocol of a prospective observational multicenter mixed study of psychological consequences of grieving relatives in French palliative care units on behalf of the family research in palliative care (F.R.I.P.C research network). BMC Palliat. Care18:111. doi: 10.1186/s12904-019-0496-4

34

Götze H. Brähler E. Gansera L. Polze N. Köhler N. (2014). Psychological distress and quality of life of palliative cancer patients and their caring relatives during home care. Support Care Cancer22, 1075–1082. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2257-5

35

Guirimand F. Dauchy S. Laval G. (2010). Quelques précisions et commentaires du Comité scientifique de la SFAP à propos des recommandations sur la sédation en soins palliatifs [Some clarifications and comments from the SFAP Scientific Committee regarding the recommendations on sedation in palliative care]. Méd. Palliat. Soins Support Accompagnement Éthique9, 214–217. French. doi: 10.1016/j.medpal.2010.07.004

36

Guldin M. B. Vedsted P. Zachariae R. Olesen F. Jensen A. B. (2012). Complicated grief and need for professional support in family caregivers of cancer patients in palliative care: a longitudinal cohort study. Support Care Cancer20, 1679–1685. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1260-3

37

Hamano J. Morita T. Igarashi N. Shima Y. Miyashita M. (2021). The association of family functioning and psychological distress in the bereaved families of patients with advanced cancer: a nationwide survey of bereaved family members. Psychooncology30, 74–83. doi: 10.1002/pon.5539

38

Haute Aut. Santé . (2020). Comment mettre en œuvre une sédation profonde et continue maintenue jusqu'au décès? [How to implement deep and continuous sedation maintained until death?]. French. Available online at: https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/c_2832000/fr/comment-mettre-en-oeuvre-une-sedation-profonde-et-continue-maintenue-jusqu-au-deces (accessed November 4, 2022).

39

Hayashi Y. Sato K. Ogawa M. Taguchi Y. Wakayama H. Nishioka A. et al . (2021). Association among end-of-life discussions, cancer patients' quality of life at end of life, and bereaved families' mental health. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care38:1071–1081. doi: 10.1177/10499091211061713

40

Hiratsuka R. Aoyama M. Masukawa K. Shimizu Y. Hamano J. Sakaguchi Y. et al . (2021). The association of family functioning with possible major depressive disorders and complicated grief among bereaved family members of patients with cancer: results from the J-HOPE4 study, a nationwide cross-sectional follow-up survey in Japan. J. Pain Symptom Manage.62, 1154–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.06.006

41

Hirooka K. Otani H. Morita T. Miura T. Fukahori H. Aoyama M. et al . (2018). End-of-life experiences of family caregivers of deceased patients with cancer: a nation-wide survey. Psychooncology27, 272–278. doi: 10.1002/pon.4504

42

Holtslander L. Baxter S. Mills K. Bocking S. Dadgostari T. Duggleby W. et al . (2017). Honoring the voices of bereaved caregivers: a metasummary of qualitative research. BMC Palliat. Care16:48. doi: 10.1186/s12904-017-0231-y

43

Imai K. Morita T. Mori M. Yokomichi N. Yamauchi T. Miwa S. et al . (2022). Family experience of palliative sedation therapy: proportional vs. continuous deep sedation. Support Care Cancer30, 3903–3915. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06745-1

44

Jadhav A. Weir D. (2018). Widowhood and depression in a cross-national perspective: evidence from the United States, Europe, Korea, and China. J. Gerontol. Ser. B73, e143–e153. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx021

45

Jones K. Boyle G. Garcia R. Vseteckova J. Methley A. (2022). A systematic review of the effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy for managing grief experienced by bereaved spouses or partners of adults who had received palliative care. Illn. Crisis Loss30, 596–613. doi: 10.1177/10541373211000175

46

Kagawa-Singer M. (2011). Impact of culture on health outcomes. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol.33, S90–S95. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318230dadb

47

Kissane D. W. McKenzie M. Bloch S. Moskowitz C. McKenzie D. P. O'Neill I. (2006). Family focused grief therapy: a randomized, controlled trial in palliative care and bereavement. Am. J. Psychiatry163, 1208–1218. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.7.1208

48

Kissane D. W. McKenzie M. McKenzie D. P. Forbes A. O'Neill I. Bloch S. (2003). Psychosocial morbidity associated with patterns of family functioning in palliative care: baseline data from the Family Focused Grief Therapy controlled trial. Palliat. Med.17, 527–537. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm808oa

49

Louarn C. (2017). Innovations cliniques en soins palliatifs : nouvelles perspectives de réflexion quant aux modalités du souffrir soignant [Clinical innovations in palliative care: new perspectives on the modalities of caregiving]. Rev. Int. Soins Palliatifs32:84. French. doi: 10.3917/inka.173.0084

50

Lux M. R. Protus B. M. Kimbrel J. Grauer P. (2017). A survey of hospice and palliative care physicians regarding palliative sedation practices. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med.34, 217–222. doi: 10.1177/1049909115615128

51

Mesnage V. Bretonniere S. Goncalves T. Begue A. Bernardin G. Brette M. et al . (2020). Enquête du centre national des soins palliatifs et de la fin de vie sur la sédation profonde et continue jusqu'au décès (SPCJD) à 3 ans de la loi Claeys-Leonetti [National Center for Palliative and End-of-Life Care survey on deep and continuous sedation until death (DCSD) at 3 years from the Claeys-Leonetti law]. Presse Méd. Form.1, 134–140. French. doi: 10.1016/j.lpmfor.2020.04.010

52

Milberg A. Liljeroos M. Krevers B. (2019). Can a single question about family members' sense of security during palliative care predict their well-being during bereavement? A longitudinal study during ongoing care and one year after the patient's death. BMC Palliat. Care18:63. doi: 10.1186/s12904-019-0446-1

53

Miyashita M. Aoyama M. Nakahata M. Yamada Y. Abe M. Yanagihara K. et al . (2017). Development the care evaluation scale version 2.0: a modified version of a measure for bereaved family members to evaluate the structure and process of palliative care for cancer patient. BMC Palliat. Care16:8. doi: 10.1186/s12904-017-0183-2

54

Morita T. Ikenaga M. Adachi I. Narabayashi I. Kizawa Y. Honke Y. et al . (2004). Family experience with palliative sedation therapy for terminally ill cancer patients. J. Pain Symptom Manage.28, 557–565. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.03.004

55

Morita T. Kiuchi D. Ikenaga M. Abo H. Maeda S. Aoyama M. et al . (2019). Difference in opinions about continuous deep sedation among cancer patients, bereaved families, and physicians. J. Pain Symptom Manage.57, e5–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.11.025

56

Papavasiliou E. Payne S. Brearley S. (2014). Current debates on end-of-life sedation: an international expert elicitation study. Support Care Cancer22, 2141–2149. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2200-9

57

Peyrat-Apicella D. Chemrouk Y. (2022). Sédation profonde et continue jusqu'au décès : qu'en vivent les soignants? - Enquête exploratoire qualitative en oncologie [Deep and continuous sedation until death: what do caregivers experience? - A qualitative exploratory study in oncology]. Psycho-Oncol.22, 63–70. French. Available from: https://pson.revuesonline.com/articles/lvpson/abs/first/lvpson_2022_sprpsycho000830/lvpson_2022_sprpsycho000830.html (accessed November 12, 2022).

58

Pierron J. P. (2020). Éthique et soin: Les pratiques sédatives. La sédation profonde et continue est-elle encore un soin? [Ethics and care: Sedative practices. Is deep and continuous sedation still care?]. Jusqu'à Mort Accompagner Vie140:91. French. doi: 10.3917/jalmalv.140.0091

59

Pott M. Dubois J. Currat T. Gamondi C. (2011). Les proches impliqués dans une assistance au suicide [Relatives involved in assisted suicide]. Rev. Int. Soins Palliatifs26, 277–286. French. doi: 10.3917/inka.113.0277

60

Prigerson H. G. Horowitz M. J. Jacobs S. C. Parkes C. M. Aslan M. Goodkin K. et al . (2009). Prolonged grief disorder: psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Med.6:e1000121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000121

61

Raus K. Anquinet L. Rietjens J. Deliens L. Mortier F. Sterckx S. (2014). Factors that facilitate or constrain the use of continuous sedation at the end of life by physicians and nurses in Belgium: results from a focus group study. J. Med. Ethics40, 230–234. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2012-100571

62

Rietjens J. A. van Delden J. J. van der Heide A. Vrakking A. M. Onwuteaka-Philipsen B. D. van der Maas P. J. et al . (2006). Terminal sedation and euthanasia: a comparison of clinical practices. Arch. Intern. Med.166, 749–753. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.7.749

63

Robbins-Welty G. Stahl S. Zhang J. Anderson S. Schenker Y. Shear M. K. et al . (2018). Medical comorbidity in complicated grief: results from the HEAL collaborative trial. J. Psychiatr. Res.96, 94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.09.017

64

Rossi Ferrario S. Cardillo V. Vicario F. Balzarini E. Zotti A. M. (2004). Advanced cancer at home: caregiving and bereavement. Palliat. Med.18, 129–136. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm870oa

65

Rumpold T. Schur S. Amering M. Kirchheiner K. Masel E. K. Watzke H. et al . (2016). Informal caregivers of advanced-stage cancer patients: every second is at risk for psychiatric morbidity. Support Care Cancer24, 1975–1982. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2987-z

66

Rys S. Deschepper R. Mortier F. Deliens L. Atkinson D. Bilsen J. (2012). The moral difference or equivalence between continuous sedation until death and physician-assisted death: word games or war games?: a qualitative content analysis of opinion pieces in the indexed medical and nursing literature. J. Bioethical Inq.9, 171–183. doi: 10.1007/s11673-012-9369-8

67

Salas S. Bigay-Gamé L. Etienne-Mastroianni B. (2020). Des soins palliatifs précoces et intégrés à la sédation en fin de vie: Early palliative care, end-of-life, sedation. Rev. Mal. Respir. Actual.12, 2S259–2S268. doi: 10.1016/S1877-1203(20)30106-3

68

Sani L. Bacqué M. F. (2023). Online psychodynamic psychotherapies: a scoping review. the case of bereavement support. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 11, 2–19. doi: 10.13129/2282-1619/mjcp-3933

69

Serey A. Tricou C. Phan-Hoang N. Legenne M. Perceau-Chambard É. Filbet M. (2019). Deep continuous patient-requested sedation until death: a multicentric study. BMJ Support Palliat. Care9:e2. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001712

70

Sessler C. N. Gosnell M. S. Grap M. J. Brophy G. M. O'Neal P. V. Keane K. A. et al . (2002). The Richmond Agitation-Sedation scale: validity and reliability in adult ICU patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med.166, 1338–1344. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107138

71

Shear M. K. (2015). Complicated grief. N. Engl. J. Med.372, 153–160. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1315618

72

Shen H. S. Chen S. Y. Cheung D. S. T. Wang S. Y. Lee J. J. Lin C. C. (2018). Differential family experience of palliative sedation therapy in specialized palliative or critical care units. J. Pain Symptom Manage.55, 1531–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.02.007

73

Siflinger B. (2017). The effect of widowhood on mental health - an analysis of anticipation patterns surrounding the death of a spouse. Health Econ.26, 1505–1523. doi: 10.1002/hec.3443

74

ten Have H. Welie J. V. M. (2014). Palliative sedation versus euthanasia: an ethical assessment. J. Pain Symptom Manage.47, 123–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.03.008

75

Thomas K. Hudson P. Trauer T. Remedios C. Clarke D. (2014). Risk factors for developing prolonged grief during bereavement in family carers of cancer patients in palliative care: a longitudinal study. J. Pain Symptom Manage.47, 531–541. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.05.022

76

Tomczyk M. (2018). Sédation continue, maintenue jusqu'au décès : un traitement vraiment efficace? Étude qualitative internationale auprès de professionnels de santé [Continuous sedation, maintained until death: a really effective treatment? An international qualitative study of healthcare professionals]. Rev. Int. Soins Palliatifs33, 129–136. French. doi: 10.3917/inka.183.0129

77

Ullrich A. Theochari M. Bergelt C. Marx G. Woellert K. Bokemeyer C. et al . (2020). Ethical challenges in family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer – a qualitative study. BMC Palliat. Care19:70. doi: 10.1186/s12904-020-00573-6

78

Ventura de M. (2016). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. São Paulo Med. J. Rev. Paul. Med.134, 93–94. doi: 10.1590/1516-3180.20161341T2

79

Vieille M. Dany L. Coz P. L. Avon S. Keraval C. Salas S. et al . (2021). Perception, beliefs, and attitudes regarding sedation practices among palliative care nurses and physicians: a qualitative study. Palliat. Med. Rep.2, 160–167. doi: 10.1089/pmr.2021.0022

80

Wiese C. H. Morgenthal H. C. Bartels U. E. Vossen-Wellmann A. Graf B. M. Hanekop G. G. (2010). Post-mortal bereavement of family caregivers in Germany: a prospective interview-based investigation. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr.122, 384–389. doi: 10.1007/s00508-010-1396-z

81

World Health Organization (2020). Palliative Care. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care (accessed December 15, 2022).

82

Zech E. (2019). Accompagner les membres d'une famille endeuillée : avec toujours plus de présence, respect, chaleur, compréhension empathique et authenticité [Accompanying the members of a bereaved family: with ever greater presence, respect, warmth, empathetic understanding and authenticity]. Méd. Palliat.18, 239–242. French. doi: 10.1016/j.medpal.2019.03.003

83

Zordan R. D. Bell M. L. Price M. Remedios C. Lobb E. Hall C. et al . (2019). Long-term prevalence and predictors of prolonged grief disorder amongst bereaved cancer caregivers: a cohort study. Palliat. Support Care17, 507–514. doi: 10.1017/S1478951518001013

Summary

Keywords

cancer, grief, partner, review, sedation, spouse

Citation

Chemrouk Y, Sani L, Ducos M, Gauthier P and Bacqué M-F (2026) Effects of sedative practices on grief in the spouse of a patient who has died of cancer. An international systematic review. Front. Psychol. 16:1603194. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1603194

Received

31 March 2025

Revised

05 December 2025

Accepted

12 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Anja Mehnert-Theuerkauf, University Hospital Leipzig, Germany

Reviewed by

Dennis Demedts, Vrije University Brussels, Belgium

Anne-Kathrin Köditz, University Hospital Leipzig, Germany

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Chemrouk, Sani, Ducos, Gauthier and Bacqué.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yasmine Chemrouk, chemrouk.yasmine@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.