Abstract

Introduction:

This meta-analysis seeks to explore how the complex relationship between loneliness and belongingness in higher education students can be explained by a set of pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic dynamics.

Methods:

A meta-analysis including 56 studies and involving a total of 30,062 participants was conducted, and the review explores direct relations and moderation through age, education, and country.

Results:

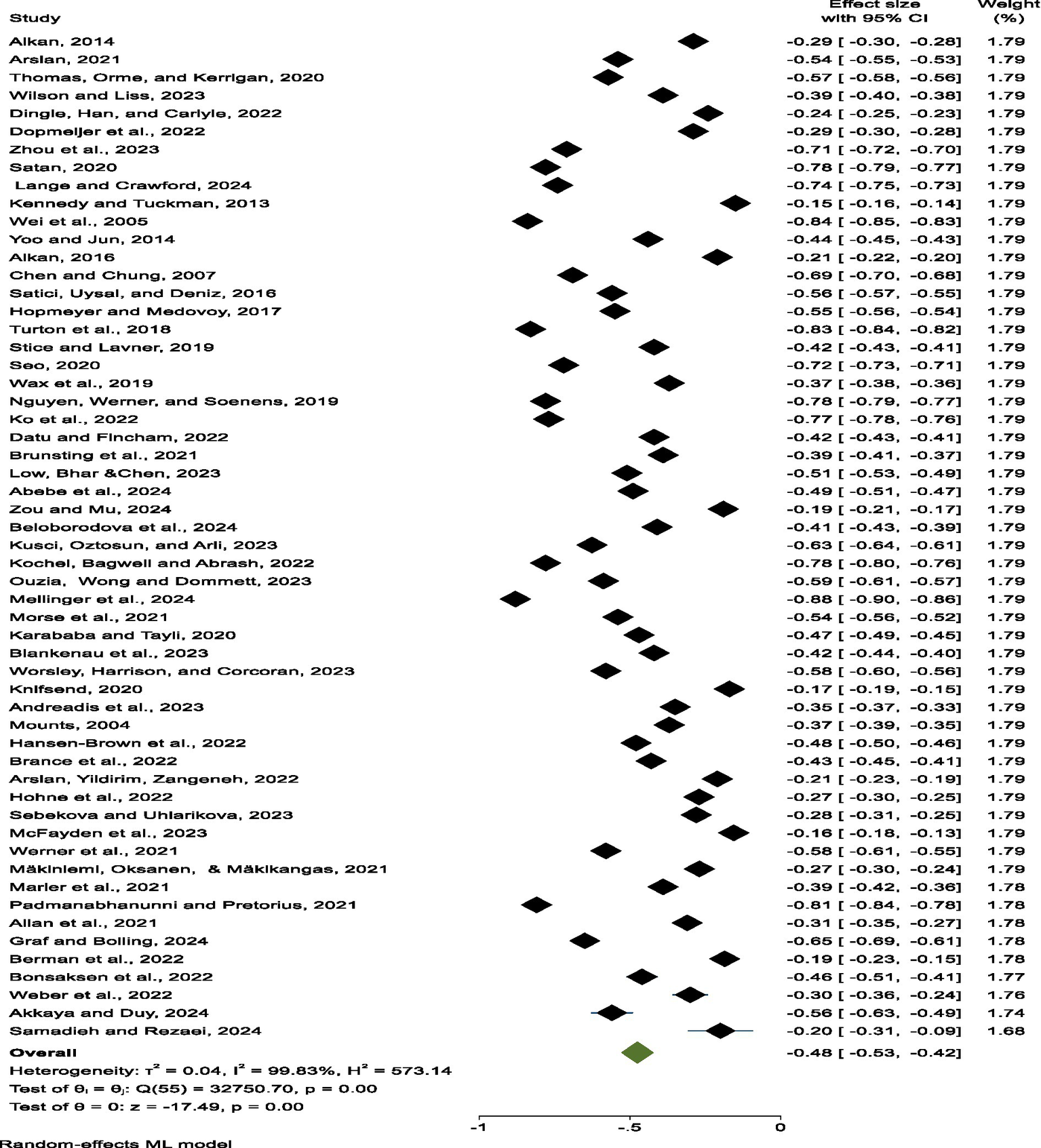

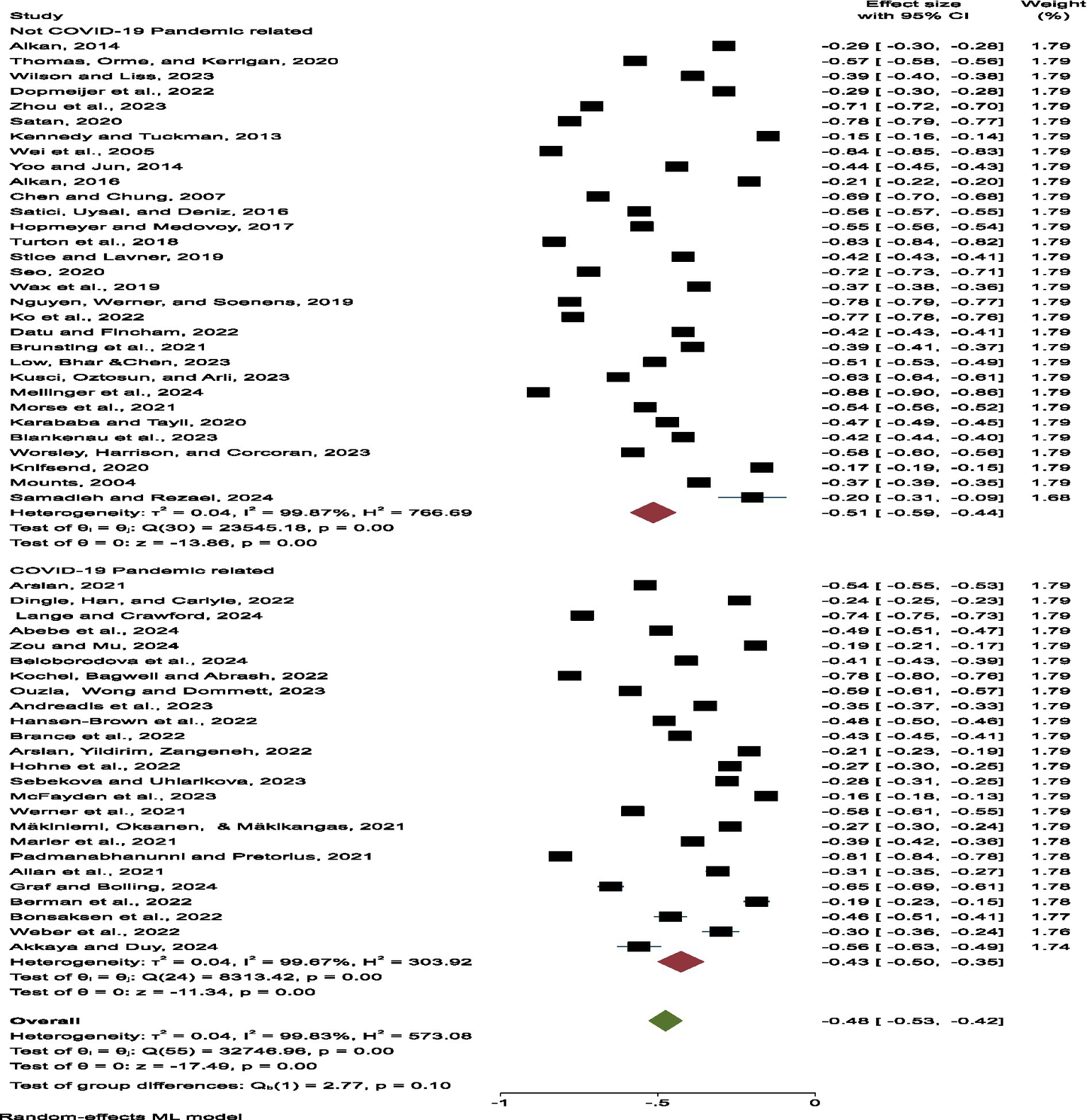

Results indicate a moderate-to-strong negative relationship between loneliness and belongingness (r = -0.48, 95% CI [-0.529, -0.422]), such that a consistent association was found across situations such that increases in one’s level of loneliness is associated with decreases in one’s level of belongingness. Nevertheless, there was no small-degree of inter-study heterogeneity (Q = 1058.86, p < 0.0001, I2 = 94.33%), which is a potential reason for the differences in the study populations and methods, employing a random-effects model to account for these discrepancies. After further scrutiny of the results, location, and year of study, and country did not moderate the effect size, which in turn reflects the stability of the association across context and time. In the subgroup analysis the effect size of the relationship between the level of the Information Technology (IT) usage and the externalisation was lower in the time of the pandemic than in the time preceding the pandemic. The effect size of the pre-pandemic group is -0.515 (95% CI: -0.589 to -0.441, p < 0.001 < 0.001) and the effect size of pandemic group is slightly smaller with -0.427 (95% CI: -0.502 to -0.352, p < 0.001 < 0.001). This means that although the level of loneliness have normalised, there have been a subtonic influence on perceived belonging of the novelty stressor caused by breakdowns in social connection from pandemic-level influences. In addition, no significant publication bias was observed.

Discussion:

Overall, these findings confirm the strong negative association between loneliness and sense of belonging and emphasise the important role in providing community support for students, especially during social disruptions.

1 Introduction

Students with a transition from high school to university in 2020 saw one of the most significant turning points in terms of their education pathway due to the rapid progression of COVID-19 to a pandemic on a global scale. As certain nations saw a rapid increase in the number of infected people, public health officials implemented vital measures to try and slow the virus’s spread. These strategies entailed mandatory containment of positive individuals, a prolonged period of broad self-isolation for symptomatic individuals and rigorous physical distancing procedures, all of which altered the way everyone acted (Ammar et al., 2020). This was not simply a matter of administration; these public health modifications created new spatial profiles that profoundly influenced the emotional and social experiences of relatives, friends, and nearby individuals. As a result of travel restrictions and adjustments to public health, it became virtually impossible for these pupils to attend schools located outside their home countries, thereby rendering it impossible for many students to attend their desired universities. When they could finally enroll, social distancing directions forbidding in-person lecturescaused a sudden increase in online learning. This massive upheaval left students without the traditional university experience of personal lectures, impromptu discussions, campus life (such as social clubs and extra activities) (Elumalai et al., 2021; Lederer et al., 2021; O'Connor et al., 2020). As a result, many students found themselves cut off from important opportunities to build meaningful relationships with faculty staff, department members and peers — relationships that typically develop through informal interaction in an academic environment (Porter et al., 2023). More than academic challenges, the results of these dramatic changes were feelings of loneliness and social disconnect that reached unprecedented level among students. Early research during the pandemic has demonstrated how widespread social wardens had increased loneliness, a process that appeared to be particularly pronounced for higher education students as they acclimatised to this novel environment (Groarke et al., 2020; Leal Filho et al., 2021). This period of self-isolation has shined a spotlight on the importance for all students to have access to robust support services and tools to work through their feelings around this major disruption in their education.

In the higher education context, Dost (2024a, 2024b) recently utilised structural equation modelling (SEM) with 284 female students and 120 male students. The researcher found that stress related to COVID-19 adversely affected both types of belongingness—collegiate community and degree department belonging —while concurrently elevating academic anxiety across diverse demographic groups. Loneliness emerged as a significant mediating variable, with pronounced effects observed among international and male students. Dingle et al. (2022) examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on social connectedness and mental health of first-year students enrolled in a metropolitan university in Australia. The study involved 1,239 students (30.4% international) and used a 3 (cohorts: 2019, 2020, 2021) × 2 (enrolment status: domestic and international) between-group design. Results showed that both loneliness and university belonging were significantly worse during the first year of COVID-19 compared to the year before or after. Contrary to expectation, domestic students were lonelier than international students across all cohorts. The prevalence of mental health problems among United Kingdom university students is estimated to be around 20–25% (Lewis and Stiebahl, 2024; NHS England, 2023). However, since young populations are especially susceptible to mental health problems such as depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic (KCL, 2022), this probably underestimates current prevalence. Depressive and anxiety symptoms are particularly prevalent in the transition to university (Cage et al., 2021) and have been found to rise over the first year of university student life (Campbell et al., 2022). The proportion of home students (UK domiciled) who disclosed a mental health problem to their Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) rose from just under 1% in 2010/11 to 5.8% in 2022/23 (Lewis and Stiebahl, 2025). During the period of 2016/17 to 2022/23, the number of UK undergraduates who reported a mental health condition increased from 6 to 16%, meaning one in six students currently have a mental health problem (King’s College London (KCL) Report, 2023). It was reported by mental health charity Student Minds (2023) that 57% of students claimed that they had previously experienced a mental health issue and 27% that they had been diagnosed with a mental health condition (Farrier et al., 2024). Freshmen and minority students have been especially hit by these problems as highlighted by studies from various countries such as Italy (World Health Organization (2023), Germany (Jungmann and Witthöft, 2020) and the United States (Ettman et al., 2020) that signalled the enhanced risk those groups are exposed to. Furthermore, travel bans also had a negative influence on mental health, in particular for international students who had trouble beginning studies or returning home over break to visit their family and friends (Akiba et al., 2024). Establishing new relationships and a new social network is a significant concern of first year students in the undergraduate course as their friendships become crucial to their psychosocial adaptation to university life (Dost, 2024a). This may in turn erode an individual’s sense of social connectedness, and consequently the peer and faculty/department supports available to them (Burns et al., 2020). This sense of support is necessary to manage the challenges of a successful college or university transition and to feel connected to their university, college, or group.

Studies have focused on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ sense of belonging and feelings of loneliness. For example, McCallum et al. (2021) reported on 1,217 participants aged 18 years or older who completed an online survey from March 28 to 31, 2020. Linear regression models revealed that COVID-19-related work and social adjustment difficulties, financial distress, loneliness, thwarted belongingness, eating a less healthy diet, poorer sleep and being female were all associated with increased psychological distress and reduced wellbeing (p < 0.05). Psychological distress was more elevated for those with high difficulties adjusting to COVID-19 and high levels of thwarted belongingness (p < 0.005). Similarly, as COVID-19-related work and social adjustment difficulties increased, wellbeing reduced. This was more pronounced in those who felt lower levels of loneliness (p < 0.0001). Mooney and Becker (2021) monitored undergraduate computing students’ sense of belonging for over 3 years and found that the COVID-19 pandemic had a larger impact on the sense of belonging of all students. They also found that men and women who do not identify as being part of any minority appear to have had similar downward shifts in their sense of belonging. In addition, men who do not identify as being part of any minority saw the largest statistically significant drop in belongingness post-COVID-19. Zhou et al. (2023) examined loneliness and school belonging as predictors of suicide risk in college students in China in a cross-sectional study. In total, 393 college students participated in the study. The results of hierarchical regression analyses that controlled for age and gender indicated that school belonging buffers the negative effects of loneliness on suicidal behaviour and depression. Evidence of a significant loneliness and school belonging interaction as a predictor of both suicidal behaviour and depression was found. Kusci et al. (2023) conducted research with a sample composed of international students studying in universities in Türkiye. Sense of belonging was found to be in a negative relation with social exclusion and loneliness. Moreover, a positive relationship was observed between social exclusion and loneliness. Finally, it was noticed that social exclusion acts as a mediator of the process towards belonging and loneliness and has a significant impact on loneliness.

The notion of belonging is widely explored in academic literature and is associated with a range of connections to places, experiences and communities (Antonsich, 2010; Dost and Mazzoli Smith, 2023; Dost, 2024a; Dost, 2024b). When considering explicitly loneliness, the most fitting point is social belonging—the subjective bonds and relationships individuals develop with others. Belonging and loneliness are two related constructs that encompass personal experiences that are central to being human, indicative of the ubiquity of social need (Cacioppo and Patrick, 2008). Belongingness, the deep feeling of being connected to something greater than oneself, has long been a key issue in psychological and educational discussion (Allan et al., 2021; Baumeister and Leary, 2017; Dost, 2024a). It can be grounded in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Maslow, 1968). This system lists belonging as one of the most basic emotional needs, third only to food and shelter and safety. A lack of belongingness can result in striking degrees of loneliness, isolation and alienation, illustrating the importance of this need in total wellbeing (Allen et al., 2021). The university social membership is also important for the cultivation of a student identity. When these group affiliations are disrupted (as during the pandemic), identity confusion or alienation leads to greater loneliness. In the wake of profound disruptions in the university in recent years, it is crucial to capture the ways in which students have accommodated working conditions over time and to understand this in relation to other constraints—initially during and post-pandemic. Its unclear whether belongingness and loneliness associations became stronger more generally after the pandemic was declared (e.g., Killgore et al., 2020; Sutin et al., 2020). Studies have found similar (Barringer et al., 2023; Gopalan et al., 2022; Peng and Roth, 2021; Sibley et al., 2020), higher (Kovacs et al., 2021; MacDonald and Hülür, 2021), and lower (Bartrés-Faz et al., 2021; Kelly et al., 2024; Morán-Soto et al., 2022) levels of correlations between loneliness and belongingness. This study is designed to fill this gap in the literature on the link between students’ self-concept of belonging and loneliness before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Understanding the adaptations of university life to pandemic-related institution shutdowns and post-pandemic conditions would enable educational institutions to better comprehend the changing nature of student life and develop more effective strategies to address the next set of challenges. To this end, the present study systematically gathered research and publications from before, during and after the pandemic to discuss the changes in students’ experiences of belonging and loneliness between these different epochs. This argument seeks to add richness to our understanding of how students are traversing their social terrain during an era of dramatic shifts.

1.1 Types of loneliness

Loneliness is a complex emotional state which manifests as a deep feeling of social isolation (Rokach, 2004). It happens when there is a sizeable discrepancy between a person’s real social ties and the connections they hope for. It is essential to differentiate between social isolation and loneliness, as the former does not uniformly predict experiences of the latter; feelings of loneliness are shaped by enduring personal traits (Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017; Svendsen, 2017) and various external factors, including personality characteristics (such as introversion, shyness, and heightened sensitivity) (Buecker et al., 2020), desires for social interaction, and expectations regarding social connections (Akhter-Khan et al., 2023), as well as significant life changes (e.g., transitions like starting college) (Drake et al., 2016; Shaver et al., 1985), along with physical and mental health issues (such as chronic illnesses, disabilities, or physical restrictions) (Maes et al., 2017). Additionally, interactions through digital platforms (where excessive social media usage can sometimes result in superficial relationships) (Nowland et al., 2018) and cultural standards (where different cultures exhibit diverse expectations about social connectedness, family dynamics, and independence) (Lykes and Kemmelmeier, 2014) also play a role. These elements may elucidate the heterogeneous impact of the pandemic on loneliness. For instance, the overall trajectory of loneliness since the pandemic’s onset remains ambiguous, with some studies indicating stable levels (Mund et al., 2020; Peng and Roth, 2021) while others report increases (Kovacs et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2020) or even declines (Bartrés-Faz et al., 2021). Possible contributing factors to these mixed findings include the duration of restriction measures (Bartrés-Faz et al., 2021), as well as variations in sampling and study methodologies. This is relevant, because variables such as the frequency of social contacts, cohabitation, and size of social network which are considered to contribute to real life being socially isolated do not act as sufficient predictors for that type of condition, as it is usually described from mental health research (Nicholson, 2012; Zavaleta et al., 2017). Although these objective dimensions are all factors that can contribute to feelings of loneliness, the experience of loneliness is largely determined by how people subjectively perceive and evaluate their relationships. This is both regarding the level of satisfaction they get from existing relationships and their experiences of social inclusion. As they delve into the complexities of loneliness, Cacioppo et al. (2015, 2016) discerned three main forms of this state of being, which can be seen as encompassing its various dimensions: intimate or emotional loneliness, relational or social loneliness and collective loneliness. Emotional loneliness derives from absence of intimacy with a partner assuring validation, support, and companionship. Emotional isolation refers to a deeper, more intimate emptiness – it means feelings of being disconnected from a partner on an emotional level that is not easily remedied. The implications of emotional loneliness can be even more hazardous as it is positively correlated with increased distress and homicidality, adversely affecting mental wellbeing (Park et al., 2020; Stickley and Koyanagi, 2016).

Relational loneliness is defined as not the availability of a supportive partner, family, or friends, who all together make the interpersonal space as bonds of worth with one another (Cacioppo et al., 2015, p. 240). In contrast to these cases, collective loneliness describes a more general feeling state of disconnectedness with wider social groups and communities. It emphasises the need to be a member of social groups outside the walls of personal relationships. This type of loneliness is associated with participation in voluntary groups and involvement in broader social networks – feelings of hovering on the fringes of real social intercourse. Indeed, some people in the midst of crowds feel even more lonely due to an enhanced sense of both anonymity and lack of intimacy. Moreover, social loneliness is described as the absence of a needed network of peers or friends, suggesting a more broader level of social involvement. Temporal and spatial dimensions can also be used to draw the outline of loneliness, such as two basic dimensions including state and trait loneliness (Tam and Chan, 2019). State loneliness refers to a temporary emotional experience which result due to situational factors, such as life transitions (e.g., moving away for a job, or the ending of personal relationships) that lead to periods where an individual is removed from their usual social support network. Conversely, trait loneliness is a more enduring characteristic (i.e., persisting even when personal circumstances do not warrant such feelings) characterised by an underlying tendency to experience chronic dissatisfaction in and detachment from social relationships. Knowing the differences between them can help us tailor our approach to different needs that people have when they are coping with feelings of isolation.

1.2 Types of belongingness

Humans have an inherent need to establish and maintain lasting and positive relationships with others (Baumeister and Leary, 2017). Rose et al. (2015) note that starting from birth, a person’s wellbeing is closely associated with the nurturing support provided by others. This link is not just about emotional fulfillment; from an evolutionary perspective, a person’s capacity for forming social bonds has had real survival value (Cacioppo and Patrick, 2008; Kenrick and Trost, 2004). People are not only creatures of contact; the nature of belonging is to strive for mutually fulfilling, durable, and supportive relationships (Dost and Mazzoli Smith, 2023). In a comprehensive examination conducted by Dost (2024a), the intricate concept of a general sense of belonging is systematically analysed and categorised into four distinct yet interrelated components: ‘adaptation period sense of belonging’, ‘integration period sense of belonging’, ‘continuum period sense of belonging’, and ‘transition period sense of belonging’. These elements are introduced as part of successive phases within a cumulative cycle, that capture the complexity and progression of belonging. The first component, the “adaptation period sense of belonging,” reflects the starting point of an individual’s journey into a new environment, group, community, or area of study. In this critical phase, participants take on the vital task of making connections and settling into their new surroundings. It is for this reason that this adapting of one utterance by reference to another is vitally important as a basis for subsequent types of interaction and relationship. This is then followed by the ‘integration period sense of belonging’, which is characterised as a more sophisticated and nuanced interactivity among individuals. In this phase, the interactions become more constructive and meaningful, as individuals align their personal values with those resonant within the group or community. It is in this stage that the collaborative spirit flourishes, allowing for the development of social connections that are not only supportive but also conducive to collective learning and growth. The study further elaborates on the ‘continuum period sense of belonging’, which captures the enduring and positive sentiment one maintains toward a particular place, subject matter, or community over an extended period. This stage highlights the importance of maintaining group unity and working toward common goals. It reflects a deep and ongoing expression of support for community, the idea that people feel deeply connected and implicated in relation to their group dynamics. This constant linkage does not only strengthen the individual identity, but also encourages a feeling of responsibility and contribution for the wellbeing of the group. Lastly, the ‘transition period sense of belonging’ emerges as an emotional and psychological experience encountered during intervals between two stable states. This is the critical juncture, it’s one of those transitional phases in our personal journey, prompting necessary preparatory adjustments for what lies ahead. Whether adjusting to new routines, learning new skills or dealing with unexpected circumstances, this period of change is vital both for personal growth and for the development of collective identities.

1.3 Study protocol

The current meta-analysis was constructed and executed in accordance with the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement detailed by Moher et al. (2010). This approach promotes clarity and guidance for systematic reviews and meta-analyses, supports rigorous methods throughout all aspects of the research process.

1.4 Selection of studies

To ensure a comprehensive review of the literature, a systematic search was undertaken across a range of well-known databases such as Web of Science, Scopus, ERIC, APA PhysicsInfo and the British Education Index. Articles from these digital resources cover a wide variety of academic fields but especially in the areas of social sciences, health, and education. The search was conducted on 12 June 2024. The searches were initially limited to peer reviewed articles published in English with a focus on articles examining belongingness and loneliness across three temporal stages, i.e., before the pandemic, during the pandemic, and post the pandemic. This temporal lens was crucial to understanding the changing politics of these issues in higher education. The reference lists of all articles that met the prespecified inclusion criteria were also manually checked, in addition to the database searches. This was important in order to find any new and relevant studies that might have missed initially and to have a broad and robust pool of data set for analysis.

1.5 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The first criteria set for the inclusion of studies in this study were excellent enough to ensure the relevance and methodological strongness of the selected literature. In general, inclusion criteria stipulated that: (a) participants sampled in the studies needed to be enrolled in accredited institutions of higher education, ensuring the findings applied to a valid academic context, (b) data collection methods needed to be conducted in environments that were directly related to higher education or done through established online platforms that were recognised for scholarly research, (c) the utilisation of a quantitative research methodology was required, which allowed for the extraction of numerical data for statistical analysis, (d) the studies had to specifically evaluate the topic of loneliness and belonging, which are key elements related to student experiences, (e) belonging needed to be treated as a dependent variable, which narrowed the focus to how loneliness is tied to students affiliation, and (f) an effect size had to either be explicitly reported in the studies or be derivable from the analyses reported in peer-reviewed journals, which provided a measure of the strength of the relationship between loneliness and belonging.

Publications meeting the defined inclusion criteria were subjected to further detailed review in stage 2 of the search process, and publications failing to meet these criteria were systematically eliminated. The search did not include any publications that were considered to be unavailable for review. During qualitative assessment, any additional series of exclusion criteria were then implemented to further refine the studies that were included in the pool of studies accepted into the review: (a) studies that were theoretical papers, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and/or qualitative studies were excluded from this process to keep the focus fully on quantitative studies; (b) any paper that did not directly assess both belongingness and loneliness in higher education students was excluded to maintain relevance; (c) studies that did not have available full text, and/or for which the authors could not provide us with a copy upon our request, were removed from the pool to ensure transparency and rigorous examination of the pool; (d) any paper that did not report or could not provide statistical information on the relationship found between loneliness and belonging were excluded to keep all data included self-derived; and (e) any duplicated papers (e.g., from different databases) and/or book chapters that were the same as a paper that had been retrieved in the journal articles were excluded, as journal articles typically offered more in-depth and comprehensive analysis.

After compilation of the publications following the initial criteria, the researcher used a set of criteria to further refine the studies selected for the subsequent meta-analysis (stage 3). These stringent inclusion criteria were designed to secure the quality of the inclusion and were as follows: (a) only papers that reported at least one aspect of intervention loneliness and belongingness among higher education students with underlying statistical evidence were included; (b) studies that conducted a rigorous assessment of participants’ levels of loneliness and belonging were given higher priority, and studies that provided sufficient quantitative data to calculate effect sizes were included; and (c) studies that discussed the correlation between loneliness and belongingness among higher education students were included. By rigorously applying these more stringent criteria the researcher hoped to build a solid and relevant synthesis to the literature on these important issues to higher education of loneliness and belonging and to offer some new thoughts and reflections to the field.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study selection

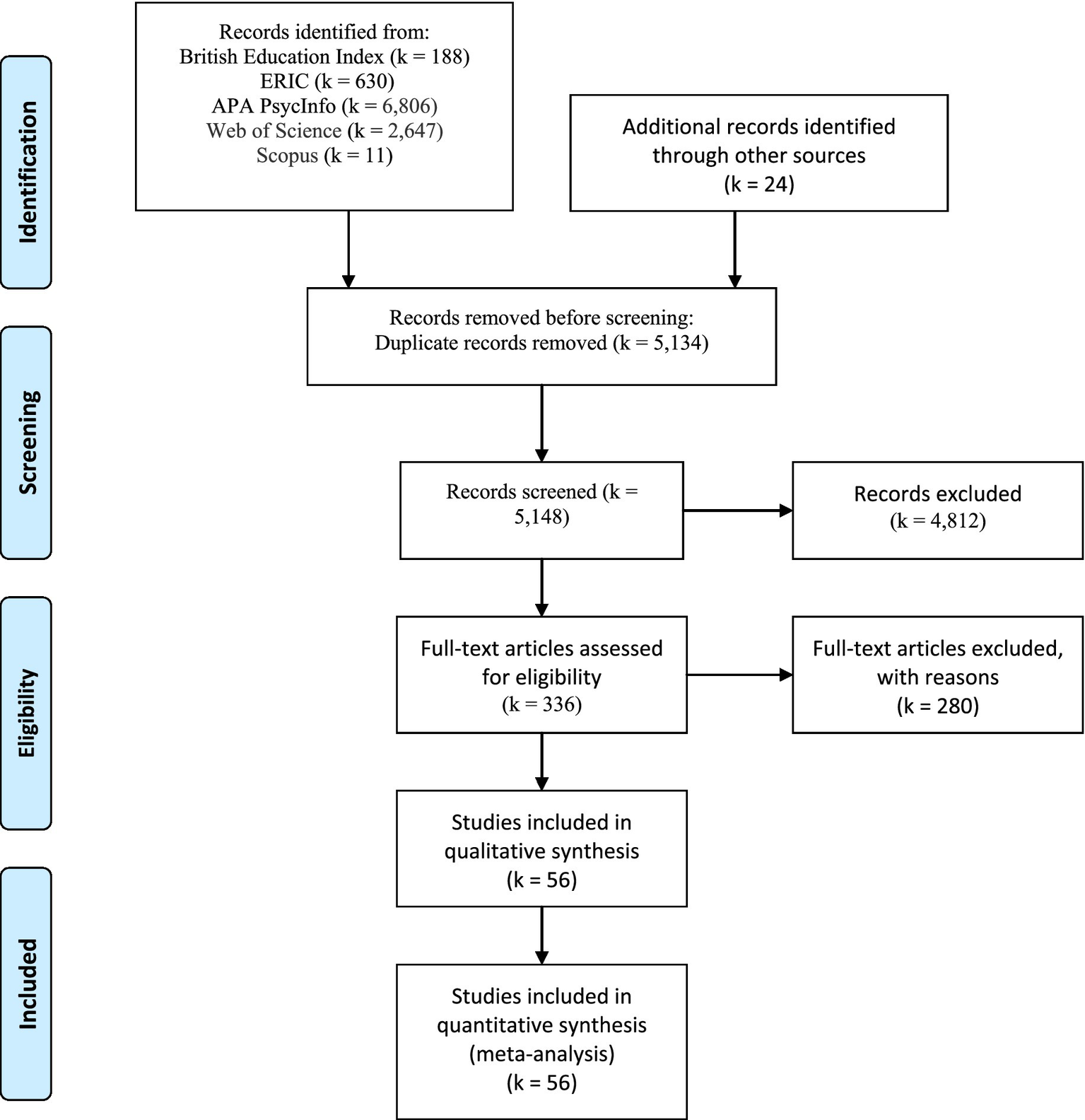

Pilot selection procedure was carried out on a random sample of studies before formal screening. Figure 1 demonstrates the flow of study selection according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2010). An initial pool of 10,282 papers was discovered, which were then screened (see Figure 1). After removing duplicates, all the studies obtained in the search phase were reviewed through their title and abstract using inclusion and exclusion criteria as below. Moreover, after obtaining full-text articles, all articles were hand-searched to identify their eligibility and eligible articles were chosen based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. The researcher first screened studies by sample age and method being in the quantitative form and written in English and from English-speaking countries. Thus, 4,812 articles were excluded due to this first screening. Four, a closer examination of the analysis and statistical results revealed studies in which one or more themes were identified as independent variables and those which identified dependent variables, for which effect sizes were present or could be computed. This resulted in the exclusion of 280 records. A final review resulted in the elimination of studies due to absent data or inadequate measurement, culminating in a final total of 56 studies.

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram showing the result of the search and screening process. From: Moher et al. (2010).

Search string: ‘University belong*’ OR ‘college belong*’ OR ‘higher education belong*’ OR ‘tertiary education’ AND ‘belong*’ OR ‘college belong*’ OR ‘undergraduate belong*’ OR ‘University attach*’ OR ‘college attach*‘OR ‘higher education attach*’ OR ‘tertiary education attach*’ OR ‘college attach*’ OR ‘undergraduate attach*’ OR ‘University bond*’ OR ‘college bond*’ OR ‘higher education bond*’ OR ‘tertiary education bond*’ OR ‘college bond*’ OR ‘undergraduate bond*‘OR ‘University connect*’ OR ‘college connect*’ OR ‘higher education connect*’ OR ‘tertiary education connect*’ OR ‘college connect*’ OR ‘undergraduate connect*’ OR ‘University relate*’ OR ‘college relate*‘OR ‘higher education relate*’ OR ‘tertiary education relate*’ OR ‘college relate*’ OR ‘undergraduate relate*‘OR ‘University engag*’ OR ‘college engag*’ OR ‘higher education engag*’ OR ‘tertiary education engag*’ OR ‘college engag*’ OR ‘undergraduate engag*’ AND ‘loneliness’ OR ‘social isolation’ OR ‘social exclusion’ OR ‘lonely or aloneness’ OR ‘solitude’ or ‘lack social interaction’ OR ‘alienation’ OR ‘psychological distance’ OR ‘social deprivation’ OR ‘solitariness’ OR ‘social withdrawal’ OR ‘covid-19’ OR ‘coronavirus’ OR ‘2019-ncov’ OR ‘sars-cov-2′ v ‘cov-19’ OR ‘2019 pandemic’ OR ‘pandemic’ OR ‘lockdown’ AND ‘belongingness’ OR ‘connectedness’ OR ‘belonging’ OR ‘community’ OR ‘sense of community’ OR ‘sense of belongingness’ OR ‘belong*’ AND ‘higher education’, OR ‘university’, OR ‘undergraduate’, OR ‘undergraduate students’, OR ‘university students’.

2.2 Data extraction and coding

The author categorised all studies in a comprehensive spread sheet. The following information was extracted from each study: year of the study, location (i.e., the country from which data was collected), the sample size, the range of participants’ age, mean scores for belonging, mean scores for loneliness; standard deviations (SD) for belonging and loneliness scores, the length of follow-up, if any; and the measures used to assess loneliness and belonging as well as the mean and standard deviation calculated on the sample; and bivariate correlation (Pearson’s r) or alternative effect size measures of the relationship between belonging and loneliness.

2.3 Quality assessment

The quality of full-text articles was critically appraised using the Sieve Quality Assessment Criteria, a unique methodology of appraisal created by Gorard et al. (2020) (see Table 1). The Sieve criteria highlight the complexities involved in research and analytic designs (e.g., education and the social sciences). The methodological quality and the topical relevance of the studies were assessed in detail by the researcher in order to identify the best quality studies. The evaluation process was systematic and multidimensional, considering every paper on the basis of a number of well-specified dimensions. With respect to the diligence of the review, the researcher considered the precision of the research questions, the adequacy of the methods that were used, the trustworthiness and validity of the data collection methods, and the transparency of the data analysis. In order to filter articles not meeting pre-specified quality criterions but including only articles presented through rigorous and transparent research methodologies the study aspired at the use of these specific indications. Each study considered in this analysis was also subjected to a second review of the security of its evidence, based on what Gorard (2024) calls the ‘sieve’ and reflecting consideration of five key criteria: (a) the research design and its fit with the study question, for example, whether the study is an Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) with random assignment, a matched comparison, a longitudinal cohort study; (b) the scale of the study, in particular the smaller size in any substantive comparison; (c) the level of attrition or study drop out; (d) the quality of the outcome measurement, whether it was based on self-reports, use of administrative data, standardised assessments, or evaluations related to the intervention; and (e) other potential threats to validity, such as compromised randomisation or conflicts of interest.

Table 1

| Design | Scale | Dropout | Outcomes | Other threats | Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fair design for comparison (e.g., RCT) | Large number of cases per comparison group | Minimal attrition with no evidence that it affects the outcomes | Standardised pre-specified independent outcome | No evidence of diffusion or other threat | 4* |

| Balanced comparison (e.g., Regression Discontinuity, Difference-in Difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Comparison with poor or no equivalence (e.g., comparing volunteers with non-volunteers) | Very small number of cases pr comparison group | Substantial imbalance or high attrition | Outcomes with issues of validity and appropriateness | Strong indication of diffusion or poorly specified | 1* |

| No report of comparator | A trivial scale of study (or N unclear) | Attrition not reported or too high for comparison | Too many outcomes, weak measures or poor reliability | No consideration of threats to validity | 0 |

Quality appraisal ‘sieve’ (for causal studies) adapted from Gorard et al. (2020).

This rigorous process of evaluation was fundamental to guaranteeing that the results and recommendations of the research were based firmly on the quality and reliability of the evidence available. In order to have a good evaluation of evidence base, this study developed a scoring system based on stringent criteria. Each study was scored by one of the researcher using a modified scoring system ranging from 0 to 4 for topic relevance. A score of 0 indicates that this study is not qualified to be included in this meta analysis and 1* is the minimal score for a study for inclusion in the review. A score of 4* indicates the strongest degree of causal evidence achievable from real world studies (high reliability and validity) while 0 identifies the weakest. This score serves as a tool for assessing the safety and reliability of the evidence derived from the studies included. The rating system helps determine which studies are the best suited for making causal claims about the phenomenon(s) in question. As Gorard et al. (2017) have stressed, research designs vary in their degree of rigour, and are often organised in a hierarchy. For example, randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which are widely considered the most rigorous study design because they have the greatest potential to minimise bias, are given the highest rating of 4*. The studies which utilise convenient comparison groups are scored as 1*. In contrast, quasi-experimental designs, which are intermediate between the other two types of designs, mostly fall between 2* and 3*, indicating moderate rigour and trustworthiness. The results showed that 21 studies were scored 2* of a maximum of four, which suggested moderate quality and relevance of those studies examined (see Table 2). In addition, 24 studies scored 3* indicating of greater importance or rigour. Eleven studies met the highest quality and rigour criteria (score 4*). Such systematic analysis helped in over categorisation of the studies and depicting the overall contribution and impact of these studies on the field.

Table 2

| Author/s | Year | Design | Scale | Dropout | Outcomes | Other threats | Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkan | 2014 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Arslan | 2021 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Thomas, Orme, and Kerrigan | 2020 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Wilson and Liss | 2023 | Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Dingle, Han, and Carlyle | 2022 | Fair design for comparison (e.g., randomised controlled trial) | Large number of cases per comparison group | Minimal attrition with no evidence that it affects the outcomes | Standardised pre-specified independent outcome | No evidence of diffusion or other threat | 4* |

| Dopmeijer et al. | 2022 | Fair design for comparison (e.g., randomised controlled trial) | Large number of cases per comparison group | Minimal attrition with no evidence that it affects the outcomes | Standardised pre-specified independent outcome | No evidence of diffusion or other threat | 4* |

| Zhou et al. | 2023 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Satan | 2020 | Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Lange and Crawford | 2024 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Kennedy and Tuckman | 2013 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Wei et al. | 2005 | Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Yoo, Park and Jun | 2014 | Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Alkan | 2016 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Chen and Chung | 2007 | Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Satici, Uysal, and Deniz | 2016 | Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Hopmeyer and Medovoy | 2017 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Turton et al. | 2018 | Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Stice and Lavner | 2019 | Fair design for comparison (e.g., randomised controlled trial) | Large number of cases per comparison group | Minimal attrition with no evidence that it affects the outcomes | Standardised pre-specified independent outcome | No evidence of diffusion or other threat | 4* |

| Seo | 2020 | Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Wax et al. | 2019 | Fair design for comparison (e.g., randomised controlled trial) | Large number of cases per comparison group | Minimal attrition with no evidence that it affects the outcomes | Standardised pre-specified independent outcome | No evidence of diffusion or other threat | 4* |

| Nguyen, Werner, and Soenens | 2019 | Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Ko et al. | 2022 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Datu and Fincham | 2022 | Fair design for comparison (e.g., randomised controlled trial) | Large number of cases per comparison group | Minimal attrition with no evidence that it affects the outcomes | Standardised pre-specified independent outcome | No evidence of diffusion or other threat | 4* |

| Brunsting et al. | 2021 | Comparison with poor or no equivalence (e.g., comparing volunteers with non-volunteers) | Very small number of cases pr comparison group | Substantial imbalance or high attrition | Outcomes with issues of validity and appropriateness | Strong indication of diffusion or poorly specified approach | 1* |

| Low, Bhar & Chen | 2023 | Comparison with poor or no equivalence (e.g., comparing volunteers with non-volunteers) | Very small number of cases pr comparison group | Substantial imbalance or high attrition | Outcomes with issues of validity and appropriateness | Strong indication of diffusion or poorly specified approach | 1* |

| Abebe et al. | 2024 | Fair design for comparison (e.g., randomised controlled trial) | Large number of cases per comparison group | Minimal attrition with no evidence that it affects the outcomes | Standardised pre-specified independent outcome | No evidence of diffusion or other threat | 4* |

| Zou and Mu | 2024 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Beloborodova et al. | 2024 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Kusci, Oztosun, and Arli | 2023 | Comparison with poor or no equivalence (e.g., comparing volunteers with non-volunteers) | Very small number of cases pr comparison group | Substantial imbalance or high attrition | Outcomes with issues of validity and appropriateness | Strong indication of diffusion or poorly specified approach | 1* |

| Kochel, Bagwell and Abrash | 2022 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Ouzia, Wong and Dommett | 2023 | Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Mellinger et al. | 2024 | Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Morse et al. | 2021 | Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Karababa and Tayli | 2020 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Blankenau et al. | 2023 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Worsley, Harrison, and Corcoran | 2023 | Fair design for comparison (e.g., randomised controlled trial) | Large number of cases per comparison group | Minimal attrition with no evidence that it affects the outcomes | Standardised pre- specified independent outcome | No evidence of diffusion or other threat | 4* |

| Knifsend | 2020 | Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Andreadis et al. | 2023 | Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Mounts | 2004 | Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Hansen-Brown et al. | 2022 | Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Brance et al. | 2022 | Comparison with poor or no equivalence (e.g., comparing volunteers with non-volunteers) | Very small number of cases pr comparison group | Substantial imbalance or high attrition | Outcomes with issues of validity and appropriateness | Strong indication of diffusion or poorly specified approach | 1* |

| Arslan, Yildirim, Zangeneh | 2021 | Comparison with poor or no equivalence (e.g., comparing volunteers with non-volunteers) | Very small number of cases pr comparison group | Substantial imbalance or high attrition | Outcomes with issues of validity and appropriateness | Strong indication of diffusion or poorly specified approach | 1* |

| Hohne et al. | 2022 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Sebekova and Uhlarikova | 2023 | Comparison with poor or no equivalence (e.g., comparing volunteers with non-volunteers) | Very small number of cases pr comparison group | Substantial imbalance or high attrition | Outcomes with issues of validity and appropriateness | Strong indication of diffusion or poorly specified approach | 1* |

| McFayden et al. | 2023 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Werner et al. | 2021 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Mäkiniemi, Oksanen, & Mäkikangas | 2021 | Fair design for comparison (e.g., randomised controlled trial) | Large number of cases per comparison group | Minimal attrition with no evidence that it affects the outcomes | Standardised pre- specified independent outcome | No evidence of diffusion or other threat | 4* |

| Marler et al. | 2021 | Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Padmanabhanunni and Pretorius | 2021 | Matched comparison (e.g., propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified, but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2* |

| Allan et al. | 2021 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Graf and Bolling, | 2024 | Comparison with poor or no equivalence (e.g., comparing volunteers with non-volunteers) | Very small number of cases pr comparison group | Substantial imbalance or high attrition | Outcomes with issues of validity and appropriateness | Strong indication of diffusion or poorly specified approach | 1* |

| Berman et al. | 2022 | Fair design for comparison (e.g., randomised controlled trial) | Large number of cases per comparison group | Minimal attrition with no evidence that it affects the outcomes | Standardised pre- specified independent outcome | No evidence of diffusion or other threat | 4* |

| Bonsaksen et al. | 2022 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Weber et al. | 2022 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Akkaya and Duy | 2024 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

| Samadieh and Rezaei | 2024 | Balanced comparison (e.g., regression discontinuity, difference-in difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3* |

Quality appraisal ‘sieve’ for included studies.

2.4 Effect size extraction

The nature of university students’ loneliness and belonging complexes was explored through an exploratory approach using the correlation coefficient (Pearson r) as the primary survey method. This facilitated an in-depth assessment of the nature and strength of the investigated relationships. The methods employed were N = 54 and varied, but more attention could have been focused on those examining effect sizes (important because these measure not only the relationship but also its direction/consistency across studies) (Deeks et al., 2019). While reading the literature, the author encountered a number of methods used to calculate an effect size, followed by another method (such as an alternative statistical method, such as the F test). Comparisons were made across studies, and due to consistency considerations, the author converted the different effect sizes to r to keep the analysis as homogeneous as possible. For example, the author calculated Pearson’s r correlation coefficients and the separate Packard correlation from the reported means and standard deviations using the Lyons Morris calculator at: www.lyonsmorris.com/ma1/index.cfm, a well-known resource. In contrast, he used the Campbell Collaboration calculator at: www.campbellcollaboration.org/escalc/html/EffectSizeCalculator-R6.php to calculate the associated effect sizes. By using both methods, the researcher was able to refine the analysis and increase confidence in the findings because it allowed us to rely more rigorously on the different study designs.

The researcher followed a detailed protocol to avoid confounding effect sizes that went on to the subsequent phase of analysis. This protocol specified that only one effect size could be derived for any unique sample from a given study. Where studies produced more than one effect size or for the same sample on the exact same analysis, the researcher applied carefully crafted strategic rules to control for any potential dependencies. For example, weight was given to longitudinal effects when both cross-sectional and longitudinal relations were provided, because longitudinal findings provide a more informed picture by observing changes over time. Furthermore, in cases where cross-sectional data were reported at multiple time points but no matched longitudinal analyses were available, pooling of the coefficients was done in a holistic approach in order to obtain a single aggregated effect size. The purpose of this approach was to provide a more complete and relevant representation of the data set. In cases where several independent measurement instruments for the same construct were used (e.g., different questionnaires for anxiety), these measures were pooled to a single effect size. This concatenation also served to decrease redundancy and retain data integrity. When there were more than one longitudinal effect size across two constructs with time lags, then the researcher cumulated across the effect sizes. This approach produced an effect size global in time so that a more general relationship over time was modeled, better capturing the temporal dynamics of the data. The researcher used Cohen (1992) guidelines for interpreting effect sizes, suggesting that values of 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80 for Cohen’s d (or Hedges’ g) represent small, medium, and large effects, respectively; while for Pearson’s r, these values were 0.10, 0.30, and 0.50. In order to accommodate for the diversity in sample characteristics and measurement approaches regarding belonging and loneliness, and average effect size was calculated using a random effects model. This model was particularly appropriate because it assumes that the effect size obtained in the studies refers to different populations and not to the same (homogeneous) population. This yielded that the true effect size from the collected studies was a random variable that contained not only the true effect sizes, but also the variances due to sampling error as well as inter-study variation. Once the true effect size estimate had been computed by the researcher using the random-effects model, the overall Fisher’s z-score was further transformed back into Pearson’s r as the correlation coefficient. This conversion was more than a technical conversion; it greatly improved the interpretation of the data and facilitated communication of the results. Clarity of reporting is critical in particular when considering the subtle interrelations between feelings of loneliness and feelings of belonging among higher education students.

2.5 Data analysis

This research employed random effects models to succinctly capture the variability in true effect sizes across multiple studies. Variation can in turn be attributed to heterogeneity in country-specific populations or to divergent sampling procedures or research designs (Erez et al., 1996). By using this analytical approach, they expected to obtain a more conservative and stable estimate of an average effect, as expressed by Hedges and Vevea (1998). Given the non-independence of effect size estimates within studies and to reduce the risk of model misspecification, the multi-level modelling method was employed along with a robust variance estimator (RVE) (Pustejovsky and Tipton, 2022; Vite et al., 2024). This methodological approach allowed to include more detailed information in an analysis that does not ignore that effect sizes usually do not occur independently and that shared study characteristics can drive their magnitudes. The heterogeneity of effect sizes was examined well using the statistical methods: Q statistics, tau-squared (τ2) and I-squared (I2) (Kabir et al., 2024).

A large Q statistic suggests that the variance in effect sizes is not due to sampling error alone and indicates a need to further examine the reasons behind the heterogeneity (Mikolajewicz and Komarova, 2019). The examination of τ2 and I2 was important to judge how much of the variance could be attributed to between-studies as opposed to within-study sampling error (Lin, 2018). In addition, 95% CIs based on the weighted average effects were calculated following Borenstein et al. (2021). For these confidence intervals, the researcher used cluster robust variance estimation (CRVE) and used small sample degrees of freedom corrections with critical values (Pustejovsky and Tipton, 2018). The factors associated with the variation of correlations between loneliness and belongingness in higher education students. The study additionally investigated the moderators of variance in the correlation between loneliness and belongingness among higher education students through mixed-effects meta-regression models. This study in particular focused on the effect of variables such as publication status, study region, school level, and mean age. Finally, the study evaluated publication bias using a funnel plot asymmetry test, with effect size dependence considered through Egger’s regression test. This meta-analysis not only revealed the evidence of publication bias, but also tested the publication status as a moderator by way of conducting the meta-regression models, which borrowed methodologies from the method developed by Egger et al. (1997) and Rodgers and Pustejovsky (2021). The broad scope of this model made it possible to gain an overview of the factors that might underlie the associations of loneliness and belongingness reported in higher education literature.

Heterogeneity of effect sizes: To test if there was significant unexplained heterogeneity between study effects, the researcher sought to ascertain if the variance in effects across samples was larger than the variance that would be expected in a single sample. Such assessment is important since it guides whether it is reasonable to examine moderators of unexplained heterogeneity that might help understanding the origins of such heterogeneity (Cooper et al., 2009). The analysis was conducted by the researcher was the Q-statistic, a principal statistical measure that examines the null hypothesis. This null hypothesis states that the effect sizes estimated in the different studies are sampled from a single, homogeneous population (Nakagawa and Cuthill, 2007). Conversely, the alternative hypothesis states that the variation in effect sizes is larger than would be expected due to sampling error alone, and that the studies might be sampling different population parameters (Kelley and Preacher, 2012; Cochran, 1954). The researcher also conducted I2 test, in addition to the Q-statistic. This among-study variability metric informs us about the degree of variation across the studies in how the treatment works and helps us to determine how much of that variation can be real (non-artificial) heterogeneity rather than just sampling error (Huedo-Medina et al., 2006; von Hippel, 2015). I2 is the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity and not to chance (Higgins and Thompson, 2002). I2 values of 25% are indicative for low heterogeneity between-study, values of 50% for moderate heterogeneity, and values of 75% for high heterogeneity (Higgins and Thompson, 2002; Melsen et al., 2014). These statistical analyses are important to know the reliability of the combined ES and to check if other factors may be confounding the association between loneliness/social isolation and belongingness. These two statistics allow a comprehensive assessment of the consistency and replicability of the results within studies, serving as the basis for further analyses of potential moderating variables (Sanchez et al., 2024).

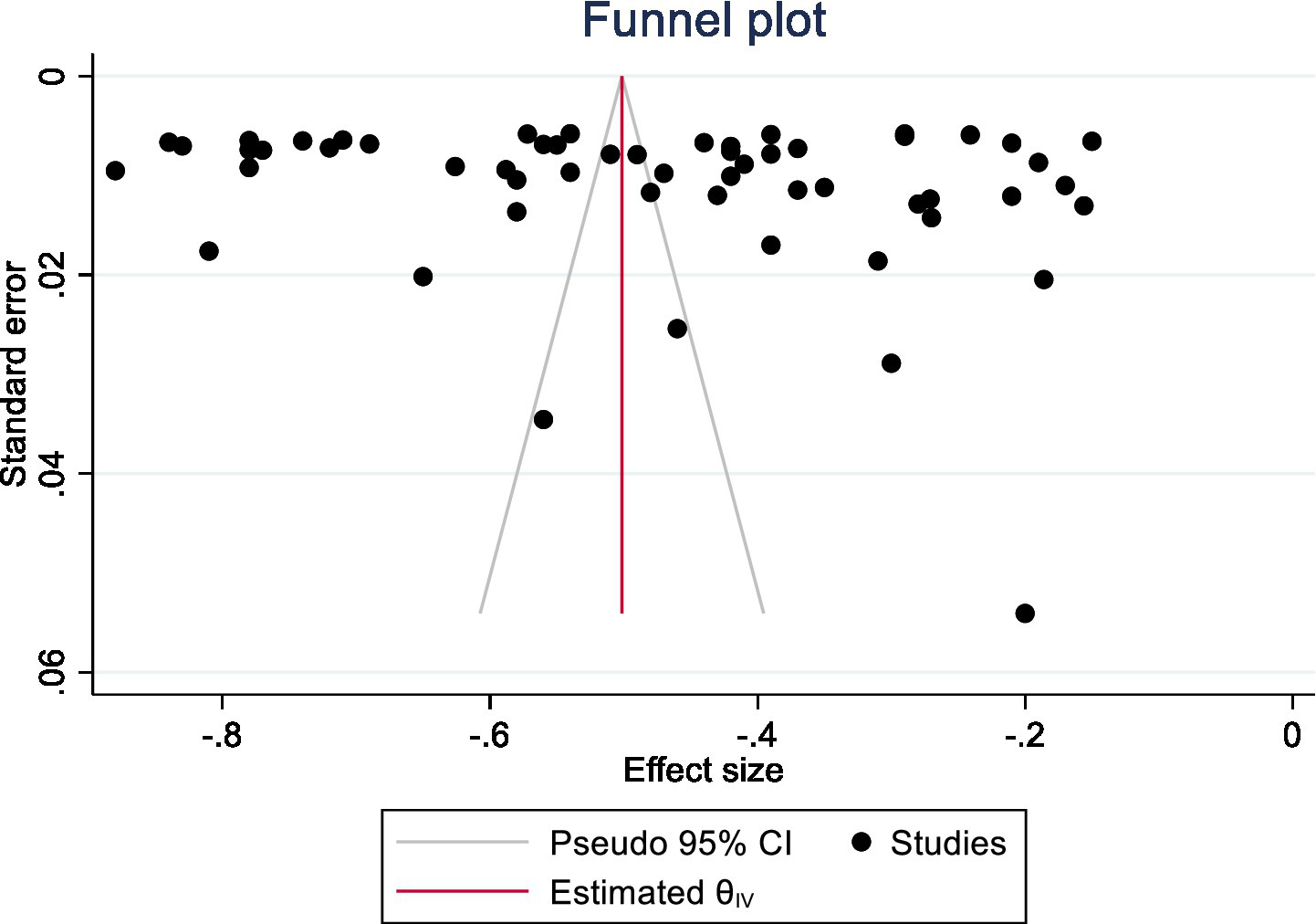

Publication bias: The publication bias was thoroughly investigated using a battery of indices on a wide array of studies by the researcher. The first part of this step-by-step approach was a comparative analysis that sought to compare effect sizes from published studies against those coming from unpublished ones. The analysis sought to detect major differences in correlation findings (and thus the potential effect of publication status on findings in the literature). After this initial examination, the researcher, then, examined the spread of effect sizes within the meta-analytic sample. The researcher sought to identify whether these effect sizes were evenly distributed on both sides of the overall average, making a condition for a balanced representation of the results. On the other hand, an asymmetrical pattern of distribution may suggest bias, which in turn reflects a distorted presentation of the results (Patton, 2004). The comprehensive strategy combined the visual and statistical approach, with particular emphasis on discrepancies between the effect sizes from larger versus smaller-sample studies (Edmonds and Kennedy, 2016; Morris and DeShon, 2002). Finally, it is important to emphasise that analyses with smaller numbers of studies are often subject to greater publication bias (Begg and Berlin, 1988). These smaller studies are often published only if they find a statistically significant result, while studies with larger samples are more likely to be published regardless of whether their results were positive or negative (O’Mara-Eves et al., 2015). A funnel plot was generated by the researcher (a plot of each effect size against its standard error) (see Figure 2). Plots are weighted using number of individual studies with different sample sizes. In a perfect funnel plot one would ideally observe a symmetrical spread of effect sizes centered around the true population effect size (Schwarzer et al., 2015). As power increases, these effect sizes should be narrower and the plot more precise appearing (Ellis, 2010). If the funnel plot introduces evidence of possible publication bias, this could imply the negative findings (those reflected by either weak or even positive relationship scores with loneliness to belonging) are more likely to occur in conjunction with relatively large standard errors, and consequently cluster in a plot’s lower half areas (Song et al., 2002; Tang and Liu, 2000). ‘Egger test’ was performed to further scrutinise the statistical intricacies of publication bias (Figure 2). The present meta-regression analysis was more sophisticated and used the precision of the effect sizes (i.e., the standard errors) as an important predictor of the correlation coefficients in a multilevel modelling context (Egger et al., 1997; Hagger, 2022; Nakagawa et al., 2023). Such a summary result of this meta-regression would be that the intercept of the dependent variable (the correlation coefficient) was significantly different from zero. Such a discovery would mean that the effect size distribution was not symmetrically distributed about the true population effect size, adding weight to concerns about bias in the published literature. Finally, the researcher used the trim-and-fill procedure with the effect sizes in the meta-analytic sample. This advanced method was implemented to improve the estimated average effect size, to determine if it was statistically significant, and to compensate for any apparent funnel plot asymmetry and exclusion of influential outliers (Duval and Tweedie, 2000). Through the use of this multi-method analysis, the researcher aims to develop a more complex and complete picture of publication bias in the literature on the effect sizes for loneliness and belonging.

Figure 2

Funnel plot of meta-analysis of published studies. Each plotted point represents the standard error and effect size difference between loneliness and belongingness among higher education students before and during/after the pandemic. The white triangle represents the region where 95% of the data points would lie in the absence of a publication bias. The vertical line represents the average effect size difference of −0.48 found in the meta-analysis.

2.6 Statistical analysis

3 Results

3.1 Overall study characteristics

A total of 61 studies were included in the analysis. Information about the studies and their effect sizes is summarised in Table 3. The studies were published between 2004 and 2024, with sample sizes ranging from 20 to 2,782 participants, resulting in a total sample size of 30,062. Research was conducted in 18 countries: Australia (k = 3, N = 1,397), Canada (k = 2, N = 576), China (k = 2, N = 904), Finland (k = 1, N = 1,463), Germany (k = 3, N = 1,302), Greece (k = 2, N = 385), Norway (k = 1, N = 61), USA (k = 26, N = 13,779), UK (k = 4, N = 1,750), Philippines (k = 1, N = 504), Slovakia (k = 1, N = 169), South Africa (k = 1, N = 337), South Korea (k = 2, N = 605), Turkey (k = 9, N = 3,312), Taiwan (k = 1, N = 319), Iran (k = 1, N = 345), and the Netherlands (k = 1, N = 3,134). All studies documented a statistically significant negative association between loneliness and belongingness. Individual effect sizes ranged from r = −0.15 to r = −0.83, with most effects classified as moderate in size.

Table 3

| Group | Author/s | Year | Country/ies | N | M (age) | Scale | Types of loneliness | Types of belonging | M (belonging) | SD (belonging) | M (Loneliness) | SD (loneliness) | r (Correlational coefficient) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Alkan | 2014 | Turkey | 164 | 21.67 | Psychological Sense of School Membership (PSSM) Scale (Goodenow, 1993) and UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., 1980; Russell, 1996) | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Sense of School Membership | 3.26 | 0.49 | 2.04 | 0.59 | −0.29 |

| B | Arslan | 2021 | Turkey | 333 | 21.94 | College Belonging Scale (Arslan and Duru, 2017) and UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-8) (Russell et al., 1978) | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | College Belonging | 46.64 | 9.09 | 14.51 | 4.68 | −0.54 |

| A | Thomas, Orme, and Kerrigan | 2020 | UK | 510 | na | Three-Factor Psychological Sense of Community scale (PSC) (Jason et al., 2015) and The 20-item revised UCLA Loneliness scale (Russell et al., 1980) | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Psychological sense of community (Membership, Influence, and Needs Fulfillment) | 3.9 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 0.7 | −0.572 |

| A | Wilson and Liss | 2023 | USA | 372 | 20.61 | The Wake Forest University Well Being Assessment (Brocato et al., 2020; Brocato & Jayawickreme, 2017) (three items sense of belonging subscale, and four items Loneliness subscale) | Subjective, social, and emotional loneliness | Social Belonging | 48.04 | 10.67 | 53.06 | 11.45 | −0.39 |

| B | Dingle, Han, and Carlyle | 2022 | Australia | 1,239 | 20.7 | The three items UCLA Loneliness Scale (Hughes et al., 2004) and the single-item social identity scale (Postmes et al., 2013). | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Social identification (Self-definition and Group attachment) | 3.39 | 0.93 | 4.77 | 1.63 | −0.241 |

| A | Dopmeijer et al. | 2022 | the Netherlands | 3,134 | 21.8 | The De Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale (De Jong-Gierveld and van Tilburg, 2006) and the Sense of Belonging questionnaire (Meeuwisse et al., 2010) | Emotional loneliness and social loneliness | Academic Belonging (Institutional Belonging) and Social Belonging (Peer Belonging) | 3.81 | 0.6 | na | na | −0.29 |

| A | Zhou et al. | 2023 | China | 393 | na | The Chinese version of the Psychological Sense of School Membership (C-PSSM; Cheung and Hui, 2003) and the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell, 1996). | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Psychological Sense of School Membership | 75.37 | 12.71 | 42.72 | 10.52 | −0.71 |

| A | Satan | 2020 | Turkey | 271 | na | UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russel et al., 1980) and Social Connectedness Scale (Sarıçam and Deveci, 2017) | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Social Connectedness (subjective sense of interpersonal closeness and connection with other) | na | na | na | na | −0.78 |

| B | Lange and Crawford | 2024 | USA | 280 | 23.61 | The 8-item Social Connectedness Scale (SCS; Lee and Robbins, 1995) and the UCLA Loneliness Scale is a 20-item scale (Russell, 1996) | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | subjective sense of interpersonal closeness and connectedness with others and society | na | na | na | na | −0.74 |

| A | Kennedy and Tuckman | 2013 | USA | 671 | 18.2 | Social Exclusion Concerns (CSE) (Kennedy and Tuckman, 2013) and the Psychological Sense of School Membership (PSSM) Scale (Goodenow, 1993) | anticipatory distress and hyperawareness of exclusion | Social belonging and Sense of School Membership | na | na | na | na | −0.15 |

| A | Wei et al. | 2005 | USA | 299 | 19.73 | Basic psychological needs satisfaction (Ilardi et al., 1993) and the UCLA scale (Russell, 1996) | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Relational Belonging | na | na | na | na | −0.84 |

| A | Yoo, Park and Jun | 2014 | Korea | 304 | 21.53 | Peer Connectedness Scale developed for the Korea Youth Panel Survey VI (National Youth Policy Institute, 2008) and social isolation scale | Subjective Loneliness | Social belonging and interpersonal well-being | 4 | 0.61 | 2.01 | 0.95 | −0.44 |

| A | Alkan | 2016 | Turkey | 509 | 22.36 | The PSSM Scale (Goodenow, 1993) and UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., 1980; Russell, 1996) | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | School Membership | na | na | na | na | −0.21 |

| A | Chen and Chung | 2007 | taiwan | 319 | na | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale (R-UCLA) (Russell et al., 1980) and Social Connectedness Scale (SCS) (Lee et al., 2001) | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Relational Belonging | 74.29 | 11.84 | 39.97 | 8.58 | −0.69 |

| A | Satici, Uysal, and Deniz | 2016 | Turkey | 325 | 20.96 | UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-8; Hays and DiMatteo, 1987) and Social Connectedness Scale (Lee and Robbins, 1995) | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Relational Belonging | 15.86 | 7.33 | 12.84 | 3.54 | −0.56 |

| A | Hopmeyer and Medovoy | 2017 | USA | 588 | 20.07 | The UCLA Scale (Russell, 1996), and college belongingness (Asher & Weeks, 2014). | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Relational and contextual (academic/social) forms of belonging | 3.85 | 0.9 | 2.37 | 0.6 | −0.55 |

| A | Turton et al. | 2018 | Greece | 281 | 22.28 | The Social Connectedness Scale (SCS; Lee and Robbins, 1995) and the 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3) (Russell, 1996) | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Relational Belonging | 36.64 | 9.9 | 45.31 | 11.4 | −0.83 |

| A | Stice and Lavner | 2019 | USA | 821 | na | The UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell, 1996), a 20-item self and the Cambridge Friendship Questionnaire (close friendship) (FQ; Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright, 2003). | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Relational Belonging (Close-Personal) | na | na | na | na | −0.42 |

| A | Seo | 2020 | South Korea | 301 | 20.95 | The revised UCLA loneliness scale (Russel, Peplau, & Cutrona, 1980) and the belonging subscale of the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL) (Cohen et al., 1985) | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Relational Belonging | 11.94 | 2.36 | 40.16 | 10.23 | −0.72 |

| A | Wax et al. | 2019 | USA | 660 | 20.37 | The UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell, 1996), and the 6-item College Belongingness Questionnaire (Asher & Weeks, 2010). | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Relational Belonging and Institutional Belonging | 3.77 | 0.82 | 2.14 | 0.54 | −0.37 |

| A | Nguyen, Werner, and Soenens | 2019 | Canada | 220 | 18.54 | The Belonging subscale from the Social Support Questionnaire (Sarason et al., 1987) and the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., 1978). | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Relational Belonging | 5.49 | 1.09 | 2.43 | 1.14 | −0.78 |

| A | Ko et al. | 2022 | USA | 518 | 19.24 | The Social Connectedness Scale (Lee and Robbins, 1995) and the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., 1978) | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Relational Belonging | 4.32 | 1.12 | 2.13 | 0.69 | −0.77 |

| A | Datu and Fincham | 2022 | Philippines andthe United States | 1,189 | 19.84 | The 8-item UCLA Loneliness Scale (Hays and DiMatteo, 1987) and Items in the relatedness subscale (N = 8) of the Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction–General Scale (La Guardia et al., 2000) | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Relational Belonging | na | na | na | na | −0.42 |

| A | Brunsting et al. | 2021 | USA | 126 | na | The Three-Item Loneliness Scale (Hughes et al., 2004) and the six-item Student Belonging Scale (Dahill-Brown & Jayawickreme, 2016) | Emotional and social loneliness | Relational and institutional belonging | 3.93 | 0.81 | 2.07 | 0.77 | −0.39 |

| A | Low, Bhar & Chen | 2023 | Australia, | 138 | 21 | The short form of the UCLA scale (Russell, 1996) and The Campus Connectedness Scale (CCS) (Lee & Davis, 2000). | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Relational and institutional belonging | 57.54 | 13.44 | 23.04 | 5.61 | −0.51 |

| B | Abebe et al. | 2024 | USA | 2,782 | 18.2 | The 15-item Social Connectedness Scale (Lee et al., 2008) and UCLA scale (Russell et al., 1980) | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Relational Belonging | 70.25 | 13.27 | 4.82 | 1.67 | −0.49 |

| B | Zou and Mu | 2024 | China | 511 | 21.53 | The Sense of Belonging Instrument (Hagerty and Patusky, 1995) and the Loneliness Scale (He, 2017) | Emotional and Social Loneliness | Emotional and Social Belonging | 65.13 | 15.87 | 14.92 | 6.07 | −0.19 |

| B | Beloborodova et al. | 2024 | USA | 648 | The UCLA Scale (Russell, 1996) and the Sense of Social and Academic Fit Scale (Walton and Cohen, 2011) | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Institutional/Academic and Relational Belonging | 5.01 | 1.14) | 1.67 | (0.56 | −0.41 | |

| A | Kusci, Oztosun, and Arli | 2023 | Turkey | 284 | 21.63 | The UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., 1978) and General Belongingness Scale (Malone et al., 2012) | Emotional Loneliness and Subjective Loneliness | Intrinsic and Relational Belonging | 5.18 | 1.12 | 2.08 | 0.38 | −0.626 |

| B | Kochel, Bagwell and Abrash | 2022 | USA | 517 | 19.52 | The 10-item Loneliness in Context scale to assess feelings of loneliness in college (Asher & Weeks, 2014) and the 8-item ocial Connectedness Scale (Lee & Robbins, 1995). |

Social and Situational Loneliness | Relational Belonging | 3.85 | 1.17 | 2.77 | 0.87 | −0.78 |