- 1Centre for Corpus Research, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, China

- 2Shanghai International Studies University, Shanghai, China

Drawing on a corpus-driven discourse analysis approach, this paper examines the discursive strategies adopted by the spokespersons of China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs during regular press conferences regarding a public health crisis. The analysis reveals that (1) the spokespersons actively used communicative discursive strategies to articulate China's stance and international cooperation initiatives while also employing offensive discursive strategies to counter criticisms from Western countries and media regarding the virus and the pandemic; (2) Interestingly, a juxtapositional discursive strategy was observed, by which China, together with other countries, was represented as the positive majority, whereas the US and the UK's media BBC as the negative minority, reinforcing the rationality of China's policies. It is argued that the spokespersons' use of discursive strategies can be attributed to China's geopolitical dynamics with the West and the influence of traditional Chinese culture on China's diplomatic policies.

1 Introduction

There has been growing interest in examining the features of spokespersons' discourse in recent years (Marakhovskaiia and Partington, 2019; Mao and Zhao, 2020; Liu, 2022; Wu, 2023; Zhang and Tang, 2024; Zhang et al., 2025). For example, Wu (2021) analyzed the argumentative styles used in the discourse of the spokespersons of China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs (CMFA), revealing that a confrontational style was frequently adopted when addressing critics of China or those holding views considered unacceptable by the Chinese government. Parallel to this, Cai and Xu (2023) conducted an analysis of 126 texts from CMFA's regular press conferences focusing on the origin tracing of COVID-19. Their findings indicate that the spokespersons predominantly employed a “seeking similarity” discursive strategy, often by adeptly citing authoritative sources like scientists and the World Health Organization to persuade international audiences to align with China's position. Examining COVID-19-related tweets from the CMFA spokespersons, Wu and Feng (2023) also found that offensive strategies were utilized to rebut US accusations.

However, previous research on CMFA spokespersons' discourse has mainly focused on the features of their discursive strategies, with limited attention to the factors shaping these characteristics, especially during COVID-19 and the period when they were labeled as “wolf warrior diplomats” in Western politics and media (Martin, 2021; Huang, 2022; Dai and Luqiu, 2022). Moreover, studies are also needed on how particular social reality is discursively represented internationally by the spokespersons in an era when China proactively strives for discursive power in the international arena.

Outbreaking in late 2019, COVID-19 quickly became a global health crisis, generating a multitude of discourses characterized by different voices (Breeze, 2021; Jaworsky and Qiaoan, 2021; Breeze and Gintsburg, 2023; Chan and Yu, 2023; Zhang, 2024; Heimo et al., 2025; Murry, 2025). Particularly, the discursive controversy surrounding COVID-19 between China and the West has led to extensive discussions and research. For example, Pietrzak-Franger et al. (2022) found that stigmatization strategies are skillfully used to blame China for COVID-19 in all the three Western newspapers (the UK, Germany, and Austria). They also argued that China was targeted as a scapegoat in narrating the pandemic mainly because of the West's anxieties over China's potential rise to world dominance. Phillips and Cassidy (2024) examined the ways in which COVID-19 was discursively constructed by the media from China and the UK and found that British media adopted a pessimistic and sensational tone by accenting the virus' unknown nature, whereas Chinese reports presented a more optimistic tone by highlighting local success. Though the data were retrieved from the Nexis database, the results rely on a qualitative analysis of only 12 news reports. While these studies are based on a limited amount of data, their results highlight the dialectical relationship between language use and social reality, demonstrating that discourse not only reflects but also shapes social reality.

Discourse on COVID-19 has been produced in other various contexts apart from news media, such as speeches by governmental leaders, think tank reports, and press conferences. Particularly in press conferences, spokespersons for a country's Ministry of Foreign Affairs use discursive strategies to articulate their nation's stance, shaping international perceptions. Cai and Xu (2023, p. 479) argue that the regular press conferences of CMFA are “an authoritative channel for the world to understand China's voice and a frontline for constructing China's discursive power in diplomacy”. Thus, examining the CMFA spokespersons' discourse provides valuable insights into the discursive strategies frequently employed by diplomatic spokespersons to construct national narratives and convey official stances.

This paper aims to examine the discursive strategies adopted by the CMFA spokespersons with a case study of their discourse during regular press conferences regarding COVID-19. Specifically, it addresses the following questions: (1) How did the spokespersons discursively represent “病毒” (virus) and “疫情” (pandemic), two typical lexical items related to COVID-19, in the regular press conferences of CMFA? (2) what discursive strategies were used by CMFA spokespersons in the discursive context of COVID-19? (3) What are the factors, institutional or social, that underpin the spokespersons' choice of different discursive strategies?

2 Corpus-driven method and data collection

A corpus-driven method was adopted to achieve the stated objectives. This methodological approach follows a path where “observation leads to hypothesis leads to generalization leads to unification in theoretical statement” (Tognini-Bonelli, 2001, p. 85). It emphasizes an inductive analysis of linguistic patterns emerging directly from the corpus data/discourse, rather than relying on prior theoretical frameworks. It allows categories, collocations, and discourse patterns to be identified empirically through systematic observation of the corpus itself. This bottom-up method is particularly suited for exploring unfamiliar or evolving discursive practices—such as those used by government spokespersons during times of crisis—where new discursive strategies may emerge.

The corpus under investigation comprises transcripts of CMFA's regular press briefings from January 2020 to December 2021, the first 2 years of COVID-19. All corpus data are publicly available at https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/xw/fyrbt/. Two considerations account for the selection of these data. Firstly, COVID-19 exerted a far-reaching impact, with global debates and discussions on the pandemic emerging as the focus of international attention since its outbreak. Secondly, amid unprecedented global changes, some studies have shown that the CMFA spokespersons grew increasingly aggressive in their discourse and were described as “wolf warrior diplomats” (Martin, 2021; Huang, 2022; Dai and Luqiu, 2022). It is thus worthwhile to examine the actual characteristics of this particular discourse by CMFA spokespersons within the diplomatic context of press conferences.

The corpus data excludes journalists' questions and retains only the spokespersons' responses, since the study focuses on their discourse. For data retrieval, all Chinese response data was segmented using SegmentAnt_jieba, an essential step because Chinese characters have no space in-between, making them incompatible with corpus processing tools like WordSmith, AntConc. After auto-segmentation, we also conducted a manual check to ensure accuracy. The final CMFA spokespersons' responses corpus consists of 782,593 Chinese words. For generating collocates, WordSmith (8.0) was selected for its capacity to compute collocational relationships through statistically comparing with the corpus under investigation and a reference corpus, using measures such as MI3. Torch2019, a balanced corpus containing one million Chinese words, was used as the reference corpus for these calculations.

3 Discursive representation of “病毒”(Virus) and “疫情”(Pandemic)

Using WordSmith (8.0), we extracted all concordance lines for the search items “病毒” and “疫情” respectively. As “discourse is also constructed through collocations” (Gu, 2019), we also generated collocate lists for both items within a five-word span (left and right of the search items). The collocates of the two search items were then ranked respectively in descending order based on the MI3 scores, and their frequencies were marked. Based on the context of the concordance lines, all collocates for “病毒” and “疫情” were categorized according to their thematic properties.

3.1 Discursive representation of “病毒”(virus)

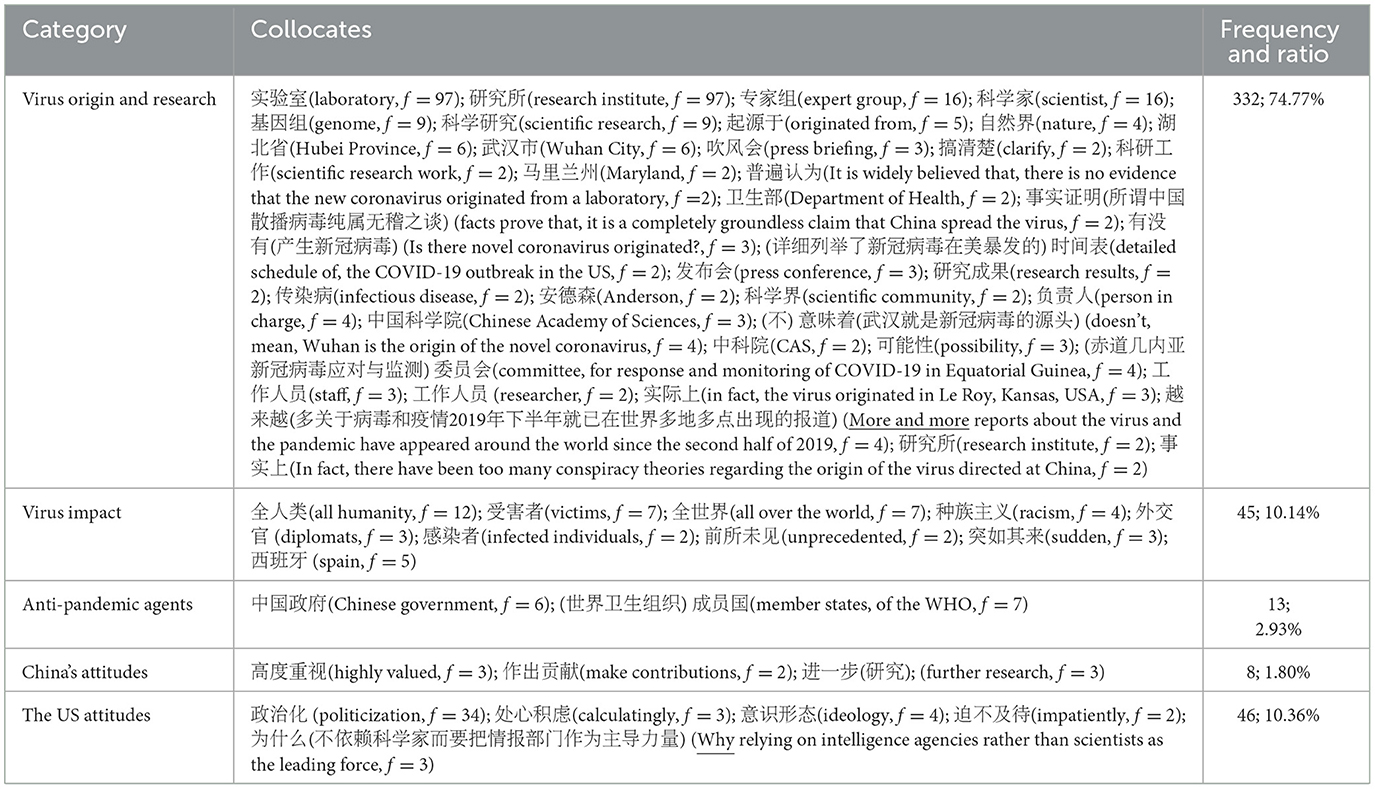

Of the 59 collocates generated for “病毒”, we manually removed four collocates related to question sequences and time (“第一个”[first), “第二个”[second), “下半年”[second half of the year), “近年来”[in recent years]), resulting in 55 remaining collocates. Thematically, these 55 collocates were classified into five categories as detailed in Table 1.

As Table 1 illustrates, the first category, “virus origin and research”, primarily focuses on scientific investigations into the origin of the novel coronavirus, particularly the debate over whether it emerged naturally or via laboratory leakage. This includes discussions on the roles of laboratories and research institutes, the participation of scientists, references to genomes and research findings, and debates on whether the virus originated from the city of Wuhan in Hubei Province. This category of collocates constitutes the highest proportion, accounting for 74.77%. This indicates the spokespersons' primary focus on the issue of virus origin and the attempts by foreign politicians and media to smear China with labels such as “Chinese virus”. Besides, the spokespersons also emphasized the scientific nature of virus tracing, frequently referring to scientific research organizations such as “institutes”, “Chinese Academy of Sciences”, “research academies”, “research community”, and mentioning “scientists” as well as specific researchers like “Anderson”.

The second category, “virus impact”, which addresses the global ramifications of the novel coronavirus, is also a focal point for the spokespersons, accounting for 10.14% of the total. By highlighting the virus' sudden onset, severity, and rapid spread (e.g., “sudden emergence”, “unprecedented intensity”), the spokespersons emphasized its widespread impact on “the entire world” and “all humanity”, including social issues such as “racism”. Notable examples include statements like “Diplomats have immunity due to their posts, but the virus does not know that” (April 3rd, 2020).

As the third category shows, the collocates also reveal that the two primary agents engaged in virus combat are the Chinese government and some World Health Organization member states. This indicates that the spokespersons did not foreground other agents involved in the fight against the virus, because few were specifically mentioned apart from China. However, this could also indicate that virus-combating agents were not a priority in their discourse; instead, the emphasis was placed on such aspects as the attitudes and positionings of involved agents toward the virus.

Turning to the fourth category, the analysis reveals a positive representation of China's anti-virus stance, with spokespersons emphasizing that “The Chinese government attaches high importance to COVID-19 vaccine R&D” (January 15th, 2021). In contrast, the fifth category indicates a negative representation of the US stance, where the spokespersons criticized that “the US politicization of COVID-19 origins tracing is repeating the history of the ‘Spanish Flu”' (August 17th, 2021). Interestingly, the frequency of negative representations of the US stance far exceeds that of positive representations of China's stance (46 vs. 8).

The pattern identified above aligns with the discursive strategies observed in the spokespersons' tweets regarding COVID-19 (Wu and Feng, 2023), where offensive strategies are favored over defensive ones. For instance, one spokesperson stated, “We hope the US will reflect upon its behaviors, eliminate its political virus of ideological bias, and stop vilifying the CPC and Chinese media” (March 20, 2020), a clear manifestation of such offensive strategies.

3.2 Discursive representation of “疫情”(pandemic)

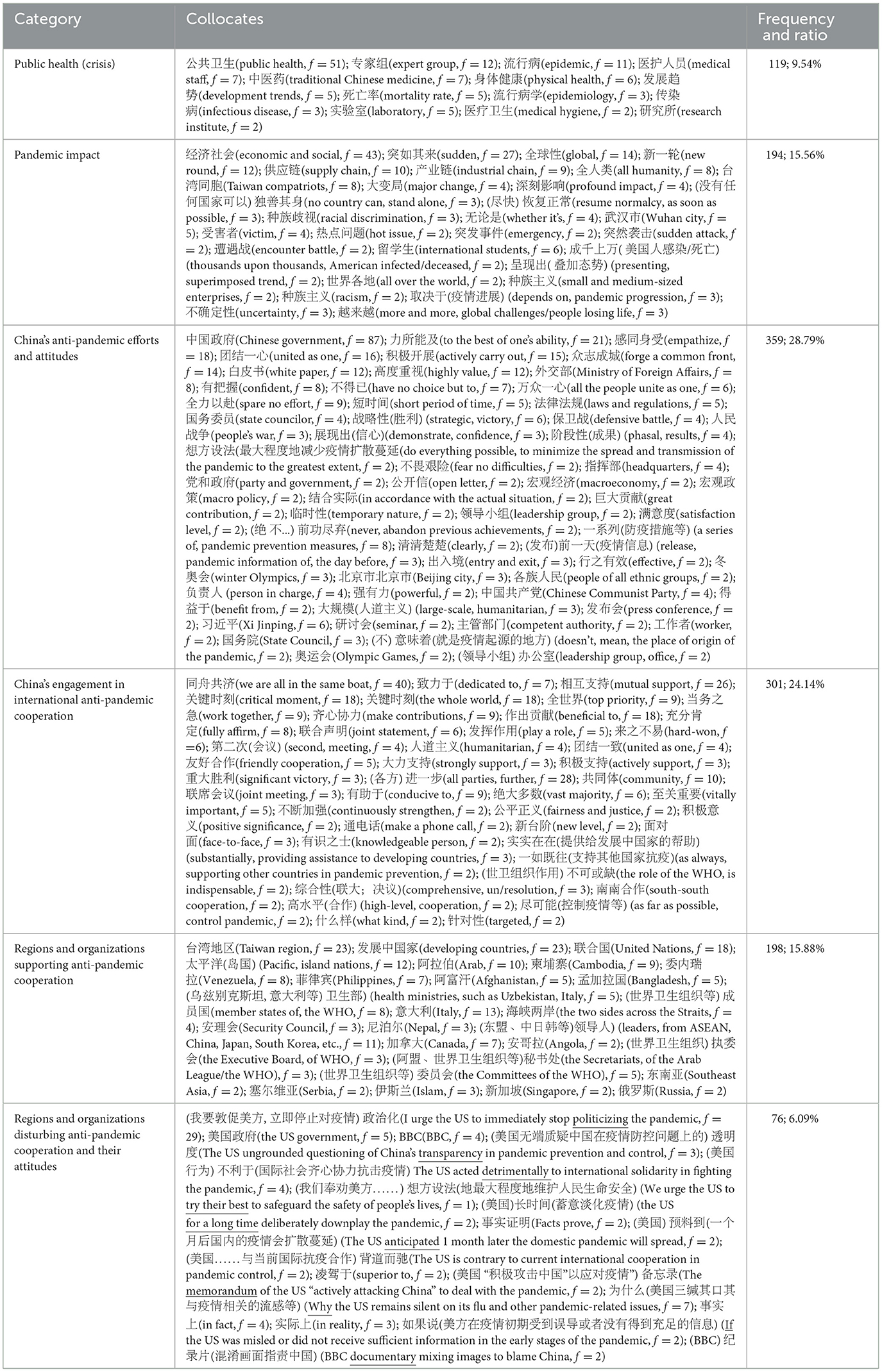

For “疫情”, a total of 190 collocates were generated, and we manually removed seven collocates related to question sequences and time (“第一个”[first], “第二个”[second], “一段时间”[a period of time], “上半年”[first half of the year], “下半年”[second half of the year], “一个月”[one month], “与此同”[meanwhile]). In addition, the collocate “想方设法”(trying every possible means) was grouped into two categories in two different contexts. As a result, 184 collocates were included for analysis, which were classified into six categories thematically as presented in Table 2.

The first category “public health (crisis)” primarily centers on health, medical service, and scientific research related to COVID-19. Particularly, it emphasizes the pivotal role of scientists and medical personnel in pandemic prevention and control, while also mentioning the efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine in COVID-19 prevention. However, the proportion of this category is relatively low, accounting only for less than 10%.

The collocates in the second category “pandemic impact” indicate the profound influence of COVID-19 on the global economy. The sudden outbreak of COVID-19 has triggered a new wave of economic shocks and instability in supply and industrial chains, affecting adversely not only the small and medium-sized enterprises, but also the livelihoods of all people worldwide. For example, “[W]hen tens of thousands of American people are struggling against COVID-19, the two parties are attacking each other ferociously and putting their own political interests above people's life and health” (August 20th, 2021). Similar to the collocates in the “virus impact” category as discussed in Section 3.1, those in the “pandemic impact” category also highlight other social issues brought about by COVID-19, such as “racism” and “uncertainty” of the international situation, all of which pave a solid foundation for the formulation of discourse on global cooperation in pandemic prevention.

The collocates in the third category of “China's anti-pandemic efforts and attitudes” are mainly about China's efforts and stance toward pandemic prevention, accounting for the highest proportion of 28.79%. The collocates involve many agents in pandemic prevention from the President Xi Jinping to people of all ethnic groups nationwide, as well as various levels of Party committees and governments. This demonstrates that the entire population highly value pandemic prevention. In this context where combating the pandemic was described as a war that must be won, the Chinese people faced challenges without fear, united as one to make concerted efforts to carry out the defensive battle and ultimately achieved a strategic victory. These collocates strongly praise China's efforts and attitude in pandemic prevention. This also indicates that regarding the collocates of “pandemic”, the spokespersons discursively tended to adopt communicative strategies, aiming to promote “their own concepts, practices, emotions to express China's attitude and position, and to uphold China's good image internationally” (Wu and Feng, 2023, p. 73).

The collocates in the fourth category “China's engagement in international anti-pandemic cooperation” highlight China's collaboration with other international entities in combating COVID-19, and China's attitude toward cooperative efforts in pandemic prevention. The use of these collocates potentially indicates that China was trying to show their dedicated efforts for global pandemic control through high-level cooperation with other countries and international organizations. China also provided substantial assistance and tangible support to developing countries, upholding fairness and justice. Furthermore, China also valued international mechanisms for cooperative pandemic control, supporting the comprehensive roles of institutions such as the United Nations and the World Health Organization and promoting South-South cooperation channels. For instance, statements, like “China will continue to do the right thing, provide assistance to others as its capacity permits, and work with the international community to secure the final victory against the pandemic” (April 22nd, 2020), showcase China's commitment to international cooperation in pandemic control.

The fifth category “regions and organizations supporting anti-pandemic cooperation” also reflect, to a certain degree, China's approach and attitude toward pandemic control. The purpose of classifying this category is to compare those countries/regions and organizations that support international cooperation and those that do not. When the frequencies are combined, the total frequency of China and other actively participating entities in pandemic control reaches 660, accounting for 52.93% of the total. This far exceeds the ratio of 6.09% for the US and the BBC, which are shown to disrupt international cooperation. The result further highlights that China's advocacy for international cooperation aligns with international common interests. Furthermore, apart from China as the main participant in international cooperation, there are as many as 27 countries/regions or organizations involved, including major developed Western countries. This is evidenced by statements such as “China and Canada have been cooperating and giving each other valuable support during the difficult fight against COVID-19” (September 18th, 2020). In contrast, there are only two entities that are specifically mentioned as disrupting pandemic control, i.e., the US and the BBC. The sharp disparity in numbers again reaffirms that China stands with the majority of the international community dedicated to striving for the good of all humans.

On the one hand, the collocational patterns identified regarding the fifth and the sixth categories demonstrate that China's proactive advocacy for international cooperation in pandemic control had been widely embraced by many countries/regions and organizations, who represent the mainstream of the international community. In contrast, the smears against China's pandemic response by the US and the UK, coupled with their own ineffective pandemic control measures, constituted a minority standpoint globally. On the other hand, the total frequency of collocates representing the 27 entities participating in cooperative efforts is 198, accounting for 15.88% of the total. In contrast, the total frequency of collocates representing the US and the BBC is 76, taking up only 6.09%. If the BBC's frequency of 6 is excluded, the frequency of negative representations attributed to the US reaches as many as 70 times. This indicates that the spokespersons adopted a variety of offensive discursive strategies, rather than the previously adopted passive approach of prioritizing harmony, to counter the US' attempts to discredit China and to criticize the US's own ineffective anti-pandemic response.

To summarize, the CMFA spokespersons used communicative discursive strategies to articulate China's stance and international cooperation initiatives while also employing offensive discursive strategies to counter criticisms from some Western countries and media regarding COVID-19. They also interestingly adopted a juxtapositional discursive strategy by which China, together with other countries, was represented as the positive majority, whereas the US and the UK's media BBC as the negative minority, reinforcing the rationality of China's policies.

As Marakhovskaiia and Partington (2019) argue, spokespersons' discourse is a genre regularly employing forced lexical priming (Duguid, 2009) that refers to the deliberate and frequent repetition of certain lexical forms to “flood” the discourse with strategically framed messages. Such forced priming of collocational patterns involving “virus” and “pandemic” by the CMFA spokespersons was strategically employed and intended to ensure that both the media in press conference contexts and wider audiences internalize China's official stances.

4 Discussion

Discourse, as a form of social practice, is intrinsically tied to power and ideology. “In every society the production of discourse is at once controlled, selected, organized and redistributed by a certain number of procedures … to gain mastery over its chance events” (Foucault, 1981, p. 52).

To further explore how power and ideology manifest through discourse, van Dijk (1998, p. 6) emphasizes discourse's critical role in shaping ideological structures and argues that examining the regular patterns within discursive practices is essential to understanding how ideologies emerge, evolve, and persist. Specifically, van Dijk's (1998, p. 267) Ideological Square model provides a robust analytical framework by outlining a discursive structure of positive self-presentation and negative other-presentation. Importantly, the Ideological Square model is characterized by two core features: firstly, it emphasizes the group-based nature of ideology; secondly, ideology is inherently self-serving (van Dijk, 1998, p. 68–69).

It is noteworthy that as a key element of China's diplomatic practices, spokespersons' discourse is ideologically charged and strategically constructed. The repeated discursive choices–such as the collocational patterns of “virus” and “pandemic”—reveal underlying ideological positions influenced by China's geopolitical relations with the West and by its diplomatic philosophy rooted in distinct cultural and historical contexts.

4.1 Geopolitical relations and diplomatic ideology in the spokespersons' discourse

In its diplomatic discourse, China highlights its guiding principles in developing relations with other countries—principles rooted in peace, development, cooperation, and mutual benefit. Particularly to the US, the Chinese officials, from Chinese President to the CMFA spokespersons, consistently highlight the importance of the China-US relations to the stability and prosperity to the world and seek for cooperations rather than competitions. This commitment is most evident in its promotion of the diplomatic concept of building “a community with a shared future for mankind” (Hu, 2012; Xi, 2015; Nathan and Zhang, 2022).

However, China and the US have in recent years experienced geopolitical tensions and clashes of interest, particularly in the context where the US politicians started trade wars, imposed restrictions on Chinese enterprises, and portrayed China as both a threat and a competitor in their public rhetoric. For example, the Trump administration (2017–2021) reinforced this stance by officially designating China as a “strategic competitor” in documents such as The National Security Strategy Report, The National Defense Strategy Report, and The Nuclear Posture Review, emphasizing that the competition between the two countries is strategic, long-term, and all-encompassing. Such geopolitical relation tension between the US-led Western countries and China was reflected in the CMFA spokespersons' discourse in the context of the global COVID-19 pandemic.

During the pandemic, the US-led Western countries continuously demonized China, propagated the “Chinese virus” narrative, questioned China's pandemic measures, and accused China of using its assistance to other nations for political gain. In response, the CMFA spokespersons drew on communicative discursive strategies to highlight the scientific basis of the novel coronavirus's origin, showcasing China's collective efforts and determination in combating the pandemic. They also emphasized China's promotion of international collaboration in pandemic prevention, reinforcing the diplomatic principle of “a community with a shared future for mankind”.

Interestingly, they simultaneously utilized a juxtapositional discursive strategy of presenting China, together with some other countries, as the positive majority (frequency accounting for 52.93%) while portraying the US and the UK's media BBC as the negative minority (frequency accounting for only 6.09%) to further justify the rationality of China's policies. This aligns with Danziger and Schreiber's (2021) argument that, similar to individual interaction, a country's international communication involves projecting its values and norms through discourse to win support in the global community. This result also provides partial evidence for van Dijk's Ideological Square model, while also expanding the conventional boundaries of “Self” and “Others”, positioning the “Self” among the positive majority and the “Others” among the negative minority.

Meanwhile, China also advocates for a new model of international relations founded on mutual respect, fairness and justice. Regarding the unjust allegations without respect, China has tried responses with a spirit of struggle. This is manifested in Chinese President Xi Jinping's speech at the opening ceremony of a training class for officials at the Party School of the CPC Central Committee September 1, 2021, which states,

“It is unrealistic to always want peaceful days and avoid struggle. We must abandon illusions, be brave in struggle, stand firm on principle, and never yield an inch with unprecedented determination and resolve when defending the sovereignty, security, and development interests of our country.”

This explains that the spokespersons actively participated in a tit-for-tat struggle on the diplomatic frontline by adopting offensive discourse strategies in response to the smears and accusations against China by the US-led Western countries regarding the virus and the pandemic. Motivated by this ideological stance, they resolutely rebutted unfounded allegations and criticized the ineffective and irresponsible handling of the pandemic by the Western countries. This is reflected in Poh and Li (2017) finding that both the academic and political fields have increasingly acknowledged China's steady strengthening of its voice on matters concerning its diplomatic and security interests in recent years.

4.2 Traditional Chinese culture and contemporary China's diplomacy

In the context of the CMFA spokespersons' responses, the diverse representations of other countries' images also find their roots in traditional Chinese culture, particularly Confucianism, which has long shaped China's political, social, and ethical values and provided a foundational framework for China's contemporary diplomatic discourse (Xing, 2015; Lajčiak, 2017). As a classic in Confucianism, Analects of Confucius–Xian Wen contains a philosophical concept that influences the construction of interpersonal and, by extension, international relationships. The concept can be perceived in the dialogue between Confucius and his disciples:

Someone asked, “What about repaying evil with kindness?” Confucius said, “How then will you repay kindness? Repay evil with justice, and repay kindness with kindness”.

China's diplomatic orientation in dealing with international relations is deeply rooted in this traditional philosophy. As an illustration, when he was invited to give a speech in Berlin on 28th March, 2014, the Chinese President Xi Jinping remarked that, “[W]e do not provoke trouble, but we are not afraid of it. We will firmly defend China's legitimate rights and interests”, which embodies well the idea that “repaying evil with justice and repaying kindness with kindness”.

As an alternative to Western approaches, China advocates resolving conflicts through dialogue, pursues mutually beneficial solutions via peaceful means, and promotes the establishment of a new type of international relations. However, China remains unswerving in defending its national interests and will spare no efforts to counter any attempts to smear or suppress it in its diplomatic practices. During the COVID-19 pandemic, CMFA spokespersons drew on various discursive strategies in regular press conferences to address misunderstandings and counter negative representations of China driven by Western countries' zero-sum mentality. By contrast, toward friendly nations like Russia, the spokespersons actively fostered positive representations in their diplomatic discourse.

5 Conclusion

By a corpus- driven analysis of the collocational characteristics of the terms “病毒” and “疫情” in the CMFA spokespersons' responses during the regular press conferences, this paper tried to identify the discursive strategies by the spokespersons. It is found that the spokespersons employed communicative discursive strategies to highlight the scientific nature of virus origin-tracing and promote international cooperation against COVID-19 as a global challenge and at the same time they adopted offensive discursive strategies to refute smears and accusations from the US-led Western countries by criticizing their ineffective policies against Corvid-19 and their hegemonic intervention in the internal affairs of other countries. It is argued that the collocational characteristics of “病毒” and “疫情” are closely tied to ideological factors underpinning China's diplomacy, which are a result of the joint influence of China's geopolitical dynamics with the West and the impact of traditional Chinese culture on its diplomatic practices.

This study contributes to the expanding body of research on corpus-driven analyses of diplomatic discourse, particularly in the Chinese context and the identification of the juxtapositional discursive strategy in this study also helps extend the current Ideology Square model as a framework for discourse analysis. However, further research is needed to broaden the scope of investigation. For instance, a comparative analysis of the collocational patterns of COVID-19-related terms in the diplomatic discourse of China with that of the US or with Western media discourse could provide more valuable insights. It would also be interesting to further examine the discursive strategies in the diplomatic discourse of China and the US from a diachronic perspective.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://github.com/lt0806/Data.git.

Author contributions

TL: Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Resources. FP: Writing – review & editing, Software, Conceptualization, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This is part of the Research Project of Humanities and Social Sciences of the Ministry of Education (23YJA740017) and Shanghai Pujiang Talent Program (24PJC045).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Breeze, R. (2021). Claiming credibility in online comments: popular debate surrounding the COVID-19 vaccine. Publications 9:34. doi: 10.3390/publications9030034

Breeze, R., and Gintsburg, S. (2023). “Exploiting the crisis: populists, migration, minorities and Covid-19,” in Remedies Against the Pandemic: How Politicians Communicate Crisis Management, eds. N. Thielemann and D. Weiss (John Benjamins Publishing Company), 276–298. doi: 10.1075/dapsac.102.10bre

Cai, X. X., and Xu, Y. C. (2023). On the generated discourse themes in foreign ministry spokespersons' stance expression from the perspective of appraisal theory. Mod. Foreign Lang. 46, 478–489.

Chan, T. F., and Yu, Y. (2023). Building a global community of health for all: a positive discourse analysis of COVID-19 discourse. Discourse Commun. 17, 522–537. doi: 10.1177/17504813231163078

Dai, Y., and Luqiu, L. R. (2022). Wolf warriors and diplomacy in the new era: an empirical analysis of China's diplomatic language. China Rev. 22, 253–283.

Danziger, R., and Schreiber, M. (2021). Digital diplomacy: face management in MFA Twitter accounts. Policy Internet, 13, 586–605. doi: 10.1002/poi3.269

Duguid, A. (2009). “Insistent voices: government messages,” in Corpus-Assisted Discourse Studies on the Iraq Conflict, eds. P. Bayley and J. Morley (Routledge), 234–260.

Foucault, M. (1981). “The order of discourse,” in Untying the Text: A Post-Structuralist Reader, ed. R. Yong (Routledge Kegan Paul Ltd), 51–78.

Gu, C. (2019). (Re) manufacturing consent in English: a corpus-based critical discourse analysis of government interpreters' mediation of China's discourse on PEOPLE at televised political press conferences. Target 31, 465–499. doi: 10.1075/target.18023.gu

Heimo, L., Alasuutari, P., Ferrer, L. P., and Ulybina, O. (2025). Evoking ‘other countries' in media discourses: the case of the Covid-19 pandemic in six countries. Discourse Context Media 63:100847. doi: 10.1016/j.dcm.2024.100847

Hu, J. T. (2012). Report of Hu Jintao to the 18th CPC National Congress. Available online at: http://www.china.org.cn/china/18th_cpc_congress/2012-11/16/content_27137540.htm (Accessed January 05, 2025).

Huang, Z. A. (2022). “Wolf Warrior” and China's digital public diplomacy during the COVID-19 crisis. Place Brand. Public Diplomacy 18, 37–40. doi: 10.1057/s41254-021-00241-3

Jaworsky, B. N., and Qiaoan, R. (2021). The politics of blaming: the narrative battle between China and the US over COVID-19. J. Chin. Polit. Sci. 26, 295–315. doi: 10.1007/s11366-020-09690-8

Lajčiak, M. (2017). China's cultural fundamentals behind current foreign policy views: heritage of old thinking habits in Chinese modern thoughts. J. Int. Stud. 10, 9–27. doi: 10.14254/2071-8330.2017/10-2/1

Liu, K. (2022). The rise of China's Zhao Lijian diplomacy: a time series analysis. Asian Int. Stud. Rev. 23, 191–218. doi: 10.1163/2667078x-bja10018

Mao, Y. S., and Zhao, X. (2020). A discursive approach to disagreements expressed by Chinese spokespersons during press conferences. Discourse Context Media 37:100428. doi: 10.1016/j.dcm.2020.100428

Marakhovskaiia, M., and Partington, A. (2019). National face and facework in China's foreign policy: a corpus-assisted case study of Chinese foreign affairs press conferences. Bandung J. Glob. South 6, 105–131. doi: 10.1163/21983534-00601004

Martin, P. (2021). China's Civilian Army: The Making of Wolf Warrior Diplomacy. Oxford University Press.

Murry, V. M. (2025). Seizing the moments and lessons learned from the global response to COVID-19 pandemic: creating a platform to shape the scientific and public discourse of research on adolescence. J. Res. Adolescence 35:e13020. doi: 10.1111/jora.13020

Nathan, A. J., and Zhang, B. (2022). 'A shared future for mankind': rhetoric and reality in Chinese foreign policy under Xi Jinping. J. Contemp. China 31, 57–71. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2021.1926091

Phillips, P., and Cassidy, T. (2024). Social representations and symbolic coping: a cross-cultural discourse analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic in newspapers. Health Commun. 39, 451–459. doi: 10.1080/1042023, 2169300.

Pietrzak-Franger, M., Lange, A., and Söregi, R. (2022). Narrating the pandemic: COVID-19, China and blame allocation strategies in Western European popular press. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 25, 1286–1306. doi: 10.1177/13675494221077291

Poh, A., and Li, M. J. (2017). A China in transition: the rhetoric and substance of Chinese foreign policy under Xi Jinping. Asian Secur. 13, 84–97. doi: 10.1080/14799855.2017.1286163

Wu, P. (2021). The uncompromising confrontational argumentative style of the spokespersons' replies at the regular press conferences of China's ministry of foreign affairs. J. Argumentation Context 10, 26–45. doi: 10.1075/jaic.20026.pen

Wu, P. (2023). Responding to Questions at Press Conference: Confrontational Maneuvering by Chinese Spokespersons. John Benjamins. doi: 10.1075/aic.21

Wu, Y. Z., and Feng, D. Z. (2023). Digital public diplomacy discourse during the COVID-19 pandemic: an impression management perspective. Mod. Foreign Lang. 46, 69–82. doi: 10.2478/ngoe-2023-0003

Xi, J. P. (2015). Working together to create a new mutually beneficial partnership and community of shared future for mankind. Available online at: https://en.people.cn/n/2015/1130/c90000-8983620.html (Accessed January 05, 2025).

Xing, L. J. (2015). Traditional Chinese Culture and China's Diplomatic Thinking in the New Era. China Int. Stud. 3, 33–50.

Zhang, C., Liu, G., and Zhang, S. (2025). Chinese perceptions and refutations of face-threatening impoliteness regarding diplomatic press conferences. J. Politeness Res. doi: 10.1515/pr-2023-0045

Zhang, X., and Tang, Y. (2024). Digital diplomacy and domestic audience: how official discourse shapes nationalist sentiments in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 11, 1–12. doi: 10.1057/s41599-024-02669-3

Keywords: press conference, discursive strategy, spokesperson, diplomatic discourse, public health crisis

Citation: Li T and Pan F (2025) Constructing diplomatic discourse: a corpus-driven analysis of the discursive strategies by the spokespersons of China's ministry of foreign affairs during a public health crisis. Front. Psychol. 16:1635767. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1635767

Received: 27 May 2025; Accepted: 08 July 2025;

Published: 05 August 2025.

Edited by:

Antonio Bova, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, ItalyReviewed by:

Xujun Tian, Shanghai Lixin University of Accounting and Finance, ChinaChenxia Zhang, Shanghai University of International Business and Economics, China

Rongcheng Pan, China University of Mining and Technology, China

Copyright © 2025 Li and Pan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Feng Pan, MjAyNDAwM0BzaGlzdS5lZHUuY24=

Tao Li1

Tao Li1 Feng Pan

Feng Pan