Abstract

Objective:

The mental health of rural adolescents is a critical public health issue, with perceived social support acting as a key buffer against depression. However, the specific patterns of this support and their differential effects remain underexplored. This study aimed to identify latent profiles of perceived social support among adolescents using latent profile analysis, examine the distribution characteristics of depressive symptoms across different profiles, and explore demographic factors influencing these profiles, providing empirical evidence for mental health interventions targeting adolescents.

Methods:

A stratified random cluster sampling method was used to survey 1,017 rural adolescents aged 12–18 years in the Wuling Mountain area. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale assessed depressive symptoms, and the Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale measured perceived social support. Latent Profile Analysis was conducted using Mplus 8.3 to identify latent profiles of perceived social support. Chi-square tests analyzed demographic differences across profiles, and multinomial logistic regression examined the association between perceived social support profiles and depressive symptoms.

Results:

Four latent profiles of perceived social support were identified: High perceived social support (43.7%), High Family Support (16.2%), Moderate perceived social support (30.4%), and Low perceived social support (9.7%). Gender and school stage significantly influenced profile distribution, with females more likely to belong to the High perceived social support (Odds Ratio = 21.76) and High Family Support (OR = 9.81) groups, and high school students more likely to fall into the Low perceived social support group. Compared with the Low perceived social support group, the Moderate group was more likely to exhibit no depression (OR = 5.81) or subthreshold depression (OR = 2.65). Both the High Family Support (OR = 8.44) and High perceived social support (OR = 4.86) groups showed significant protective effects against depression.

Conclusion:

Perceived social support among adolescents is heterogeneous, with family support playing a particularly strong protective role against depressive symptoms. Social support interventions should especially target male and high school student populations, offering differentiated strategies based on adolescents’ profile characteristics. Strengthening family support systems is critical for improving the mental health of rural adolescents.

1 Introduction

Depressive symptoms are among the most common emotional disorders in adolescents and are recognized as a major public mental health concern worldwide (McGrath et al., 2023). Based on the dimensional model of depressive symptoms, they can be classified into three stages: no depression, subthreshold depression, and clinical depression (Costello et al., 2003). Clinical depression is typically defined as a mood disorder characterized by a significant and persistent low mood resulting from various causes (Ayuso-Mateos et al., 2010). Subthreshold depression refers to a psychological subclinical state in which individuals exhibit certain depressive symptoms but do not meet the diagnostic criteria for clinical depression. It represents a transitional condition between mental health and clinical depression (Zhang et al., 2022).

Studies have shown that depressive symptoms of varying severity can exert a lasting impact on adolescents’ academic performance and social relationships. Moreover, as depressive symptoms worsen, individuals may become more prone to self-injury, suicidal behavior, or other socially harmful behaviors such as aggression or deliberate injury (Kroenke, 2017; Tuithof et al., 2018). Adolescence is a critical period for personality development and is also marked by frequent psychological conflicts. Without timely and effective intervention, these unresolved issues may lead to the onset of mental health problems or even psychiatric disorders. These outcomes not only disrupt academic and daily functioning but may also compromise physical and psychological well-being and cause serious consequences for families (Ayuso-Mateos et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2023).

Identifying protective factors for adolescent depressive symptoms is essential for early detection and prevention of mental health issues. Perceived social support—an individual’s subjective evaluation and emotional experience of the emotional or instrumental support they receive—reflects how much they feel respected, cared for, and understood within their social relationships (Hou and Chen, 2016; Norris and Kaniasty, 1996). The protective role of social support against depressive symptoms is primarily explained by two classic theoretical models: the stress-buffering hypothesis and the main effect model (Cohen and Wills, 1985). The stress-buffering hypothesis posits that social support acts as a protective shield, mitigating the negative psychological impacts of stressful life events. In the context of adolescence, stressors such as academic pressure, peer conflicts, or family discord can trigger or exacerbate depressive symptoms. Perceived social support can buffer these effects by providing emotional comfort, offering tangible assistance, and enhancing an individual’s coping resources, thereby reducing the likelihood of a stressor leading to a depressive episode (Thoits, 2011). Conversely, the main effect model suggests that social support has a direct, beneficial impact on mental health, regardless of the level of stress. By fostering a sense of belonging, stability, and self-worth, a strong support network can enhance an individual’s overall emotional well-being and resilience, making them less susceptible to depression from the outset (Rueger et al., 2016a). A substantial body of empirical evidence supports these theories, consistently demonstrating that higher levels of perceived social support are associated with a lower incidence and reduced severity of depressive symptoms in adolescents (Huang et al., 2023; Lin et al., 2024; Rueger et al., 2016a; Tian et al., 2024; Zhou et al., 2020).

Beyond these foundational models, recent research illuminates the complex interplay between social support and a wide array of psychosocial factors influencing overall well-being. Social support has been shown to be a critical mediator that can buffer the negative mental health effects of modern stressors, such as problematic social media use (Çiçek et al., 2024) and pandemic-related fears and loneliness (Koçak et al., 2025). The source of this support is paramount; positive childhood experiences and strong parental factors serve as a fundamental defense against anxiety and depression (Şanlı et al., 2024; Alshehri et al., 2020), whereas family conflict can exacerbate these risks, a relationship often mediated by the adolescent’s sense of social connectedness (Çiçek and Yıldırım, 2025). Furthermore, social support does not operate in isolation but often functions by bolstering internal resources. It can foster resilience, which in turn mediates the link between external threats like cyberbullying and psychological distress (Korkmaz et al., 2025), and also enhances psychological flexibility and self-efficacy in the face of uncertainty and future anxiety (Green et al., 2024; Öztekin et al., 2025). This protective network of support, resilience, and meaning in life collectively mitigates psychological distress and loss of motivation (Yıldırım et al., 2025; Aslan et al., 2025). Even among adults, the mental health impact of external stressors is mediated by internal cognitive styles like optimism and pessimism, which are themselves nurtured by social environments (Yıldırım and Cicek, 2022). This body of work collectively demonstrates that social support is a pivotal hub in a network of psychosocial variables that promote mental health.

1.1 The present study

However, most existing studies have adopted variable-centered approaches, focusing primarily on linear associations between the total score of perceived social support and depressive symptoms. This narrow focus may fail to capture the heterogeneous patterns of support adolescents perceive from different sources (e.g., family, friends, significant others) and may limit the precision and effectiveness of intervention strategies (Howard and Hoffman, 2018). To address this gap, the present study employs Latent Profile Analysis (LPA), a person-centered approach, to identify distinct subgroups of adolescents based on their patterns of perceived social support (Su et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2023; Tompson et al., 2017). By doing so, we aim to answer the following research questions:(1)What are the distinct latent profiles of perceived social support among adolescents?(2)How are adolescents with different levels of depressive symptoms (no depression, subthreshold depression, and clinical depression) distributed across these support profiles?(3) Which demographic factors predict membership in these different support profiles? Answering these questions will provide crucial empirical evidence to inform the development of more targeted and effective mental health interventions.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants

After excluding invalid responses, 1,017 valid questionnaires were retained, yielding an effective response rate of 94.34%. Participants ranged in age from 12 to 18 years (M = 15.82), with 505 male students (49.66%) and 512 female students (50.34%). The sample included 391 junior high school students (38.45%) and 626 senior high school students (61.55%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Flowchart of sample inclusion and exclusion.

2.2 Procedure

Between March and April 2025, this study employed a stratified random cluster sampling method to collect data from four regions within the Wuling Mountain area: Xiangxi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture in Hunan Province, Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture in Hubei Province, Tongren Region in Guizhou Province, and Xiushan Tujia and Miao Autonomous County in Chongqing. From each region, one rural junior high school and one rural senior high school were randomly selected. Within each selected school, one to two classes from grades 7 to 12 were randomly chosen, resulting in a total of 32 classes and 1,078 students who completed the questionnaire (Figure 1).

This study was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Jishou University (Approval No. JSDX-2023-0034). All data collected were used exclusively for academic research. Prior to data collection, the research team contacted the administrative departments of participating schools to explain the study’s objectives, procedures, and ethical considerations, and obtained written approval from the relevant authorities. In accordance with ethical guidelines for research involving minors, both students and their parents were fully informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, and confidentiality measures. Informed consent was obtained from all student participants and their parents or legal guardians.

2.3 Measure

2.3.1 Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) was used to assess participants’ depressive symptoms over the past week (Wen et al., 2023). The scale consists of 20 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = “rarely or none of the time,” 4 = “most or all of the time”). Total scores are calculated by summing all item scores, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. Following criteria used in previous studies, participants with a total CES-D score < 24 were categorized as No Depression, those with scores between 24 and 28 (inclusive) were classified as having subthreshold depression, and those with scores ≥ 29 were classified as having clinical depression (Su, Zhang, Yu, et al., 2015; Wang and Hanges, 2011). In this study, the CES-D demonstrated good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.88.

2.3.2 Multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MPSSS)

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MPSSS) (Cosco et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2009), was used to assess adolescents’ perceived social support. The scale consists of 12 items covering three dimensions: family support, peer support, and significant others. Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “very strongly disagree,” 7 = “very strongly agree”), with higher scores indicating greater perceived social support. In this study, the MPSSS demonstrated good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.86 for the total scale.

2.4 Statistical methods

Latent Profile Analysis (LPA), a person-centered statistical approach, was employed to identify unobserved subgroups or ‘profiles’ of individuals based on their patterns of responses across the dimensions of perceived social support (Collins and Lanza, 2010; Muthén and Muthén, 2000). Unlike variable-centered approaches (e.g., linear regression) that examine the average relationship between variables across an entire sample, LPA is uniquely suited to uncover population heterogeneity by identifying distinct clusters of individuals who share similar support characteristics. This approach provides a more nuanced understanding of how social support is experienced differently within the population.

Specifically, LPA was conducted using Mplus 8.3 with the robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimator, which yields standard errors and chi-square tests (χ2 test) robust to the non-normality of observed variables. To determine the optimal number of latent profiles, we estimated a series of models (from one to five profiles) and selected the best-fitting model based on a combination of statistical criteria and theoretical interpretability. These criteria included (Nylund-Gibson and Choi, 2018): (1) lower values for the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and sample-size adjusted BIC (aBIC) indicating better model fit; (2) significant Lo–Mendell–Rubin adjusted Likelihood Ratio Test (LMR-LRT) and Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) (p < 0.05), suggesting the k-profile model is superior to the k-1 profile model; and (3) a high entropy value (close to 1.0, with > 0.80 being acceptable) indicating high classification accuracy.

Following the identification of the latent profiles, descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages) were calculated using SPSS 26.0, and group differences were examined using the chi-square test. Subsequently, a multinomial logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess the association between depressive symptom status (the outcome) and the identified latent profiles of perceived social support (the predictor). Demographic variables that were significant in univariate analyses were included as covariates. To ensure the robustness of our model, we performed preliminary checks for multicollinearity and data separation; no issues were detected. A significance level of α = 0.05 was adopted for all statistical tests.

To verify the stability and generalizability of the identified latent profiles, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. Given that LPA solutions can sometimes be driven by sampling idiosyncrasies or local maxima rather than true population heterogeneity, it is crucial to assess whether the extracted profiles are robust to sampling variations. We employed a bootstrap LPA approach (with 1,000 resamples) because it allows for a rigorous examination of model stability without reducing the effective sample size, which is superior to split-half validation methods. In each resample, the number of profiles and the patterns of conditional means were re-estimated to determine if the four-profile structure consistently emerged.

3 Results

3.1 Common method bias test

As this study relied on self-reported data, the possibility of common method bias (CMB) was considered. To assess its impact, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted (Zhou and Long, 2004). The results revealed that five factors had eigenvalues greater than 1, and the first factor accounted for 29.49% of the total variance—below the commonly accepted threshold of 40%. This indicates that no substantial common method bias was detected.

3.2 LPA results and labeling of adolescents’ perceived social support

Using the 12 items of the MPSSS as observed variables, LPA was conducted to identify potential subgroups. Six latent profile models were sequentially estimated, and model fit indices were examined to determine the optimal solution. The results showed that AIC, BIC, and aBIC values decreased progressively with the addition of classes. Notably, the four-class model (Model 4) had the highest entropy value, and the LMR and BLRT tests were both statistically significant (p < 0.05) across all class comparisons (Table 1). Therefore, Model 4 was selected as the best-fitting model.

Table 1

| Model | AIC | BIC | aBIC | Entropy | LMRT (p) | BLMR (p) | Class probabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50647.948 | 50766.138 | 50689.912 | ||||

| 2 | 39240.490 | 39422.701 | 39305.186 | 1.000 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.56/0.44 |

| 3 | 36952.066 | 37198.296 | 37039.492 | 0.972 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.29/0.28/0.43 |

| 4 | 34484.633 | 34794.884 | 34594.790 | 0.989 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.10/0.30/0.16/0.44 |

| 5 | 33910.453 | 34282.723 | 34043.341 | 0.981 | 0.057 | 0.061 | 0.22/0.09/0.16/0.44/0.09 |

| 6 | 33407.566 | 33845.857 | 33563.185 | 0.976 | 0.041 | <0.001 | 0.08/0.10/0.16/0.15/0.07/0.44 |

Fit indices for LPA of perceived social support.

AIC, Akaike information criterion; BIC, Bayesian information criterion; aBIC, sample-size adjusted BIC; LMR, Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test; BLRT, bootstrap likelihood ratio test.

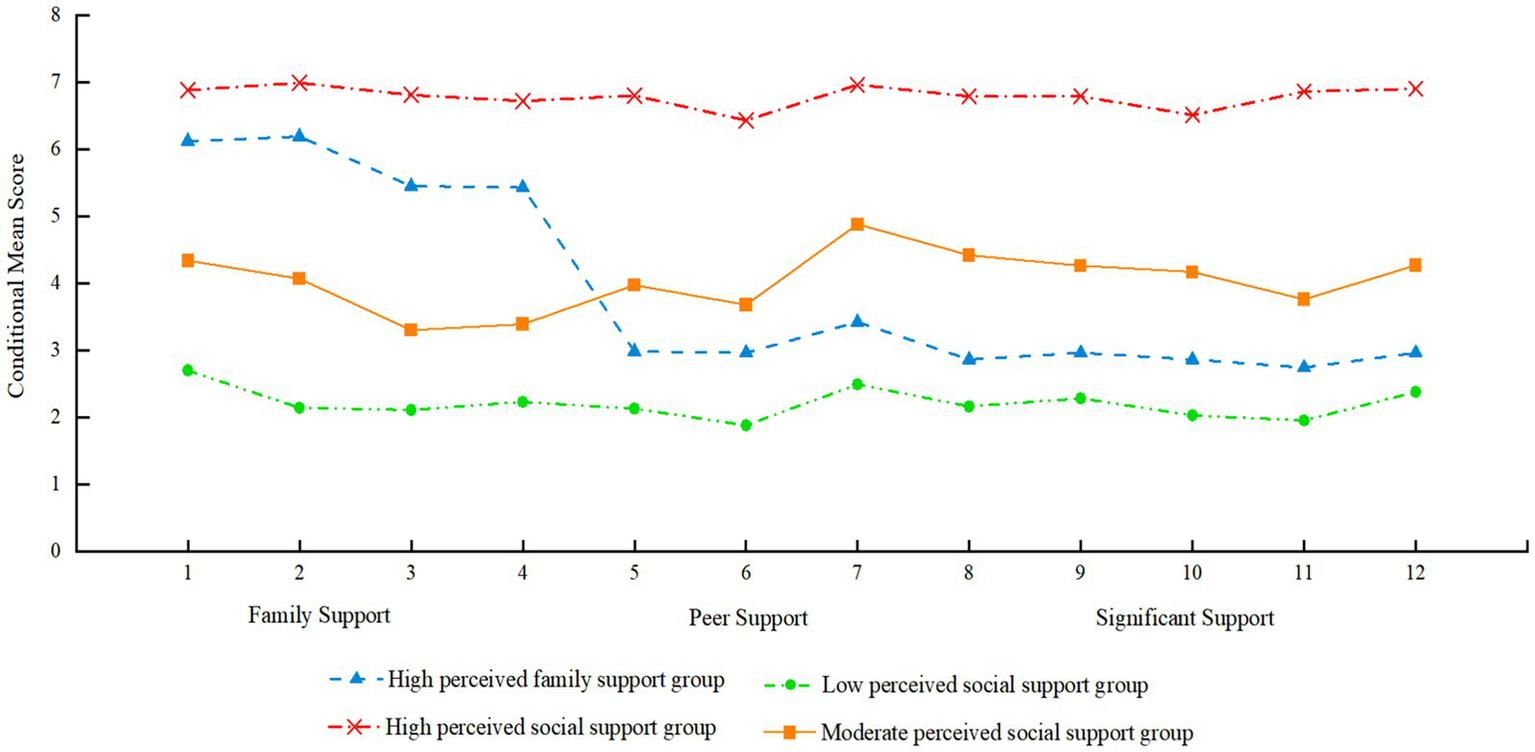

The four latent classes exhibited distinct patterns in the conditional means across the 12 items representing the three dimensions of perceived social support. Class 1 showed the highest conditional means across all three dimensions—family support, peer support, and support from others—and accounted for 43.7% of the total sample; based on its scoring profile, this class was labeled the “High perceived social support” group. Class 2 demonstrated relatively high scores in family support but significantly lower scores in peer support and support from others, comprising 16.2% of the participants, and was thus labeled the “High perceived family support” group. Class 3 displayed moderate scores across all three dimensions and made up 30.4% of the sample, leading to its classification as the “Moderate perceived social support” group. Class 4 had the lowest scores on all dimensions and accounted for 9.7% of the participants; it was designated as the “Low perceived social support” group (Figure 2).

Figure 2

LPA of perceived social support: Four-class solution.

The bootstrap sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of the four-profile solution. Across 1,000 resamples, the four-profile model was consistently identified as the optimal solution (reproduction rate > 95%). Furthermore, the conditional mean patterns of the indicator variables in the resampled solutions closely mirrored those of the original full-sample solution. The consistent reproduction of the distinct profiles (high support, high family support, moderate support, and low support) suggests that the identified latent structure is stable and not an artifact of sampling error.

3.3 Demographic characteristics of adolescents’ perceived social support patterns

To examine the influence of demographic variables on the four latent classes of perceived social support among adolescents, chi-square tests were conducted to compare the distribution differences across demographic factors. Furthermore, multinomial logistic regression was employed to assess the predictive effects of gender and school stage on class membership. Chi-square test results indicated significant differences in the distribution of perceived social support classes by gender [χ2(3) = 386.391, p < 0.001] and school stage [χ2(3) = 10.296, p = 0.016], as shown in Table 2. Using the “Low perceived social support” group (Class 4) as the reference category, multinomial logistic regression analysis revealed that both gender and school stage significantly predicted class membership.

Table 2

| Characteristic | Low perceived social support group | Moderate perceived social support group | High perceived family support group | High perceived social support group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall proportion | 98 (9.7%) | 310 (30.4%) | 165 (16.2%) | 444 (43.7%) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 78 (79.6%) | 276 (89.0%) | 25 (15.2%) | 126 (28.4%) |

| Female | 20 (20.4%) | 34 (11.0%) | 140 (84.8%) | 318 (71.6%) |

| χ2 | 386.391 | |||

| P | <0.001 | |||

| OR (95%CI) | 1 (ref) | 0.48 (0.26–0.88)* | 9.81 (5.74–16.75)*** | 21.76 (11.34–41.77)*** |

| School level | ||||

| Junior high | 23 (23.5%) | 125 (40.3%) | 66 (40.0%) | 177 (39.9%) |

| Senior high | 75 (76.5%) | 185 (59.7%) | 99 (60.0%) | 267 (60.1%) |

| χ2 | 10.296 | |||

| P | 0.016 | |||

| OR(95%CI) | 1 (ref) | 0.45 (0.27–0.76)** | 0.47 (0.26–0.85)* | 0.47 (0.28–0.80)** |

Demographic characteristics across perceived social support profiles among adolescents.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ref, reference group; χ2, Pearson’s Chi-squared test statistic.*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

In terms of gender, compared to boys, girls were significantly more likely to be in the “High perceived social support” group [OR = 21.76, 95% CI (11.34–41.77), p < 0.001]. To examine robustness of the High vs. Low comparison, we applied Firth’s penalized logistic regression, which yielded an adjusted estimate of OR = 9.87 (95% CI: 3.12–31.25). The effect remained statistically significant, though attenuated compared with the original estimate. Girls were also significantly more likely to be in the “High perceived family support” group [OR = 9.81, 95% CI (5.74–16.75), p < 0.001] and significantly less likely to be in the “Moderate perceived social support” group [OR = 0.48, 95% CI (0.26–0.88), p < 0.05]. These results suggest that girls generally tended to perceive higher levels of social support.

Regarding school stage, compared to junior high school students, senior high school students were significantly less likely to be in the “Moderate perceived social support” group [OR = 0.45, 95% CI (0.27–0.76), p < 0.01], the “High perceived family support” group [OR = 0.47, 95% CI (0.26–0.85), p < 0.05], and the “High perceived social support” group [OR = 0.47, 95% CI (0.28–0.80), p < 0.01]. These findings suggest an overall decline in perceived social support among senior high school students, likely due to increased academic pressure and developmental demands.

3.4 The relationship between different depressive symptoms and perceived social support in adolescence

To explore the relationship between different levels of depressive symptoms and perceived social support during adolescence, demographic variables found to be significant in univariate analyses were included as control variables. The four latent classes of perceived social support served as independent variables (with the “Low perceived social support” group as the reference), and depressive symptom categories were the dependent variables (with “Depression” as the reference). Multinomial logistic regression analysis showed that, compared with the “Low perceived social support–Depression” group, the “Moderate perceived social support” group acted as a protective factor against both no depression and subthreshold depression during adolescence (B = 1.759 and 0.975, respectively, p < 0.01). Both the “High perceived family support” group and the “High perceived social support” group were protective factors for the no depression condition in adolescence (B = 2.133 and 1.581, respectively, p < 0.01), with the “High perceived family support” group showing a particularly strong protective effect against no depression (OR = 8.442). Detailed results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3

| Latent profile group | Depressive symptoms status | B | Standard error | OR | OR value 95%CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate perceived social support | No depression | 1.759 | 0.302 | 5.807 | 3.312–10.499 | <0.001 |

| Subthreshold depression | 0.975 | 0.358 | 2.650 | 1.314–5.342 | 0.006 | |

| High perceived family support | No depression | 2.133 | 0.371 | 8.442 | 4.082–17.460 | <0.001 |

| Subthreshold depression | 0.038 | 0.514 | 1.038 | 0.379–2.842 | 0.941 | |

| High perceived social support | No depression | 1.581 | 0.274 | 4.860 | 2.842–8.314 | <0.001 |

| Subthreshold depression | 0.288 | 0.339 | 1.333 | 0.686–2.593 | 0.396 |

Multinomial logistic regression of depressive symptoms and latent classes of perceived social support during adolescence.

B, unstandardized regression coefficient; SE, standard error; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; P, P-value.

4 Discussion

This study employed LPA to identify distinct latent classes of perceived social support among adolescents. Furthermore, it examined the predictive effects of demographic variables (gender and school stage) and depressive symptoms on class membership. The findings revealed heterogeneity in adolescents’ perceived social support, offering new insights into understanding adolescent mental health.

4.1 Latent classes of perceived social support during adolescence

The LPA results identified four distinct latent classes of perceived social support among adolescents: the High perceived social support group, the High perceived family support group, the Moderate perceived social support group, and the Low perceived social support group, with significant differences in social support scores across various dimensions among these groups. This finding indicates that adolescents’ perception of social support is not unidimensional but shows marked individual variability (Thoits, 2011).

First, the High perceived social support group, accounting for 43.7% of adolescents, reported high levels of support from family, peers, and other sources, reflecting a comprehensive and balanced social support network. Studies suggest that adolescents in this group typically demonstrate stronger psychological resilience and positive coping strategies, enabling them to effectively utilize multiple channels for emotional comfort and tangible assistance (Yang et al., 2024; Fergus and Zimmerman, 2005). This multi-source support pattern provides a multilayered protective barrier, effectively reducing the risk of mental health problems (Uchino, 2006).

Second, the High perceived family support group, comprising 16.2% of adolescents, mainly experienced strong family support, whereas support from peers and other sources was relatively low (Zhao et al., 2015). This uneven support structure may reflect differences in family cultural backgrounds, particularly in rural China where the family remains the primary source of reliance for adolescents. Although these adolescents may face certain limitations in peer interactions, the family as the core support system still offers stable and reliable psychological security (Uchino, 2006).

Third, the Moderate perceived social support group, accounting for 30.4%, perceived moderate support across all dimensions, indicating a relatively balanced but not outstanding social support network (Uchino, 2006). Adolescents in this group generally receive basic support from family, peers, and other social relationships, though the depth and quality of support may require enhancement. While this moderate level of social support is not ideal, it can still provide some psychological protection, especially when facing mild to moderate stressors (Rueger et al., 2010).

Finally, the Low perceived social support group, making up 9.7% of adolescents, reported low perceived support across all dimensions, suggesting they may concurrently face challenges such as family estrangement, insufficient peer interaction, and lack of social resources (Rose and Rudolph, 2006). This group is considered high-risk for mental health problems; lacking effective buffering support systems, they are more prone to psychological maladjustment when encountering life stress and developmental tasks (Wang et al., 2018). Approximately one-tenth of adolescents in this study belong to this group, highlighting an urgent need for attention and intervention from families, schools, and society. Different types of social support may have varying effects on adolescent mental health, emphasizing the necessity of providing personalized support and interventions tailored to the specific needs of different adolescent groups.

4.2 Effects of demographic variables on latent classes of perceived social support during adolescence

Regarding gender differences, the present study revealed a distinct pattern wherein females were significantly more likely than males to belong to the High perceived social support and High perceived family support profiles. These gender differences align with gender socialization theories. Specifically, females are often encouraged to express emotions and maintain close interpersonal relationships (Rose and Rudolph, 2006), which may lead them to be more active in building social networks. Conversely, male adolescents may display lower emotional sensitivity or a reluctance to seek help due to traditional masculinity norms (Gariépy et al., 2016). Therefore, when promoting adolescent social support systems, it is crucial to address the specific needs of male adolescents, encouraging them to challenge traditional gender stereotypes and become more open to seeking support.

Regarding school stage, high school students demonstrated a lower likelihood of belonging to high support groups compared to middle school students, which contrasts with preliminary expectations. This phenomenon may reflect that as academic demands intensify, high school students often experience reduced social interaction time while simultaneously seeking greater autonomy, leading to a perceived distance from external support systems (Wang and Eccles, 2012). Moreover, the heightened pressure of future planning in high school may result in a subjective feeling of insufficient support, particularly when the environment fails to meet their evolving needs (Stice et al., 2004). Thus, educators should recognize that while high schoolers seek independence, they still require robust, albeit different, forms of support.

4.3 Relationship between perceived social support and depressive symptoms during adolescence

Our analysis confirmed a robust association between social support profiles and the severity of depressive symptoms. First, adolescents in the Moderate perceived social support group were significantly more likely to be free of depressive symptoms compared to the Low support group. This suggests that even moderate levels of social support serve as a substantial buffer against depression (Gariépy et al., 2016). This finding holds important practical implications: ensuring a basic threshold of social support can effectively reduce the risk of severe mental health issues, even if comprehensive support is unavailable.

Notably, the High perceived family support group demonstrated the strongest protective effect against clinical depression, surpassing even the High (comprehensive) support group. Although this group reported relatively lower peer support, the intense family support appeared sufficient to compensate for these deficits. This result likely reflects the cultural context of the participants; in Chinese culture, the family remains the central source of resilience and emotional security for adolescents (Zhang and Wang, 2022). While peer relationships become important during adolescence, a strong family foundation appears to be the critical “safety net” preventing severe psychopathology (Uchino, 2006).

Furthermore, while the comprehensive High perceived social support group also exhibited a significant protective effect, the magnitude was slightly lower than that of the family-centric group. This suggests that the quality and source of support (specifically from parents) may be more pivotal than the mere quantity or breadth of support sources in preventing clinical depression among this demographic.

4.4 Implications

This study expands current understanding of perceived social support in adolescents by identifying four distinct latent profiles, showing that social support varies considerably among individuals rather than being a single uniform construct. The multidimensional perspective, covering family, peers, teachers, and others, provides a clearer framework for future research on how different types of support relate to adolescent mental health.

Practically, recognizing these profiles allows for more targeted interventions. Adolescents with low overall support may need broad-based programs focusing on family and peer support, while those with uneven support (e.g., high family but low peer support) could benefit from efforts to strengthen peer relationships. Schools and mental health professionals can tailor strategies based on these profiles to better address the specific needs of adolescents, improving prevention and intervention outcomes related to depressive symptoms and resilience.

4.5 Limitations and future research

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design prevents establishing causal relationships between perceived social support and depressive symptoms. Future research could adopt longitudinal tracking designs to explore the dynamic interplay between these variables. Second, the sample was limited to rural adolescents in the Wuling Mountain area, whose regional and cultural particularities may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Third, this study relied on self-report questionnaires, which may be subject to social desirability bias and common method variance. Future studies should consider incorporating objective measurement methods and multi-informant reports to enhance the reliability and validity of assessments.

Despite these limitations, this study holds significant theoretical and practical value. It reveals the heterogeneity in adolescents’ perceived social support and offers new perspectives for understanding adolescent mental health. Future research can be further expanded in the following areas: (1) investigating the relationship between different types of perceived social support and the developmental trajectories of depressive symptoms; (2) examining the differential effects of specific social support content (e.g., emotional support, instrumental support) on depressive symptoms; (3) exploring how individual traits (such as attachment styles and personality characteristics) moderate the protective effects of social support on depression; and (4) developing and validating tailored intervention programs based on social support types to provide more targeted practical guidance for promoting mental health among rural adolescents.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study moves beyond a monolithic view of social support by revealing its heterogeneous nature among rural adolescents. By identifying four distinct support profiles, our findings underscore that it is not merely the quantity but the specific pattern of support that shapes mental health outcomes. The powerful protective effect of family-centered support, in particular, highlights a critical leverage point for intervention in this specific cultural context. Ultimately, these person-centered insights provide a more precise roadmap for families, schools, and policymakers to develop targeted strategies that effectively bolster the well-being of at-risk youth.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study has received approval from the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Jishou University (Approval No. JSDX-2023-0034). Permission was obtained from the participating schools, and informed consent was acquired from both the subjects and their parents. Data collected from the follow-up investigation will be used solely for academic analysis and research purposes. Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians, and participating students also provided verbal assent before participation. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

LT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZZ: Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. FZ: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CY: Data curation, Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing. ZC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the Western Project of the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant No. 22XTY003); the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Project for Young Scholars of the Ministry of Education (Grant No. 23YJC890059); and the Hunan Provincial Education and Teaching Reform Research Project (Grant No. 2025JY009).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the schools for approving our baseline survey and the intervention study and thank all the students who participated in our study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Translation and polishing.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1647562/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Alshehri N. A. Yildirim M. Vostanis P. (2020). Saudi adolescents’ reports of the relationship between parental factors, social support and mental health problems. Arab J. Psychiatry31, 130–143. doi: 10.12816/0056864

2

Aslan Y. Koçak O. Kaya A. B. Alkhulayfi A. M. A. Gómez-Salgado J. Yıldırım M. (2025). Roles of loneliness and life satisfaction in the relationship between perceived friend social support, positive feelings about the future and loss of motivation. Acta Psychol.259:105315. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2025.105315,

3

Ayuso-Mateos J. L. Nuevo R. Verdes E. Naidoo N. (2010). From depressive symptoms to depressive disorders: the relevance of thresholds. Br. J. Psychiatry196, 365–371. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.071191,

4

Chen Z. Yang X. Li X. (2009). Trial application of the CES-D among Chinese adolescents. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol.17, 443–448. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3674.2009.04.015

5

Çiçek İ. Emin Ş. M. Arslan G. Yıldırım M. (2024). Problematic social media use, satisfaction with life, and levels of depressive symptoms in university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: mediation role of social support. Psihologija57, 177–197. doi: 10.2298/PSI220914002C

6

Çiçek İ. Yıldırım M. (2025). Exploring the impact of family conflict on depression, anxiety and sleep problems in Turkish adolescents: the mediating effect of social connectedness. J. Psychol. Couns. Sch.35, 130–146. doi: 10.1017/jgc.2023.23

7

Cohen S. Wills T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull.98, 310–357. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

8

Collins L. M. Lanza S. T. (2010). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: John Wiley & Sons.

9

Cosco T. D. Lachance C. C. Blodgett J. M. Lachance L. C. (2020). Latent structure of the CES-D in older adults: a systematic review. Aging Ment. Health24, 700–704. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2019.1566434,

10

Costello E. J. Mustillo S. Erkanli A. Keeler G. (2003). Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry60, 837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837,

11

Fergus S. Zimmerman M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: a framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu. Rev. Public Health26, 399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357,

12

Gariépy G. Honkaniemi H. Quesnel-Vallée A. (2016). Social support and protection from depression: systematic review of current findings in Western countries. Br. J. Psychiatry209, 284–293. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.169094,

13

Green Z. A. Çiçek İ. Yıldırım M. (2024). The relationship between social support and uncertainty of COVID-19: the mediating roles of resilience and academic self-efficacy. Psihologija57, 407–427. doi: 10.2298/psi220903002g

14

Hou J. Chen Z. (2016). The trajectories of adolescent depressive mood: identifying latent subgroups and influencing factors. Acta Psychol. Sin.48, 957–968. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2016.00957

15

Howard M. C. Hoffman M. E. (2018). Variable-centered, person-centered, and person-specific approaches: where theory meets the method. Organ. Res. Methods21, 846–876. doi: 10.1177/1094428117744021

16

Huang X. C. Zhang Y. N. Wu X. Y. Jiang Y. Cai H. Deng Y. Q. (2023). A cross-sectional study: family communication, anxiety, and depression in adolescents: the mediating role of family violence and problematic internet use. BMC Public Health23:1747. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-16637-0,

17

Koçak O. Yıldırım M. Şimşek O. M. Çevik O. (2025). Understanding the relationships between fear of COVID-19, depression, loneliness, and life satisfaction in Türkiye: testing mediation and moderation effects. Nurs. Open12:e70204. doi: 10.1002/nop2.70204,

18

Korkmaz Z. Çiçek İ. Buluş M. Şanlı M. E. Yıldırım M. (2025). The role of resilience in the relationship between cyberbullying and depression, anxiety, and stress in adolescents. Brain Behav.15:e70916. doi: 10.1002/brb3.70916,

19

Kroenke K. (2017). When and how to treat subthreshold depression. JAMA317, 702–704. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0233

20

Lin Y. Jia G. Zhao Z. Li M. Cao G. (2024). The association between family adaptability and adolescent depression: the chain mediating role of social support and self-efficacy. Front. Psychol.15:1308804. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1308804,

21

McGrath J. J. Al-Hamzawi A. Alonso J. de Jonge P. Demyttenaere K. Hu C. et al . (2023). Age of onset and cumulative risk of mental disorders: a cross-national analysis of population surveys from 29 countries. Lancet Psychiatry10, 668–681. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(23)00193-1,

22

Muthén B. Muthén L. (2000). Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: latent profile and latent class analysis. Multivar. Behav. Res.7, 543–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb02070.x

23

Norris F. H. Kaniasty K. (1996). Received and perceived social support in times of stress: a test of the social support deterioration deterrence model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.71, 498–511. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.71.3.498,

24

Nylund-Gibson K. Choi A. Y. (2018). Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci.4, 440–461. doi: 10.1037/tps0000176

25

Öztekin G. G. Gómez-Salgado J. Yıldırım M. (2025). Future anxiety, depression and stress among undergraduate students: psychological flexibility and emotion regulation as mediators. Front. Psychol.16:1517441. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1517441,

26

Rose A. J. Rudolph K. D. (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychol. Bull.132, 98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98,

27

Rueger S. Y. Malecki C. K. Demaray M. K. (2010). Relationship between multiple sources of perceived social support and psychological and academic adjustment in early adolescence: comparisons across gender. J. Youth Adolesc.39, 47–61. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9368-6,

28

Rueger S. Y. Malecki C. K. Pyun Y. Aycock C. Coyle L. D. (2016a). A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. J. Adolesc.49, 124–133,

29

Rueger S. Y. Malecki C. K. Pyun Y. Coyle L. D. (2016b). A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychol. Bull.142, 1017–1067. doi: 10.1037/bul0000058,

30

Şanlı M. E. Cicek I. Yıldırım M. Çeri V. (2024). Positive childhood experiences as predictors of anxiety and depression in a large sample from Turkey. Acta Psychol.243:104170. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104170,

31

Stice E. Ragan J. Randall P. (2004). Prospective relations between social support and depression: differential direction of effects for parent and peer support?J. Abnorm. Psychol.113, 155–159. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.155,

32

Su B. Zhang J. Yu C. Du B. (2015). Identifying psychological and behavioral problems among college students: based on latent profile analysis. Psychol. Dev. Educ.31, 350–359. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2015.03.13

33

Thoits P. A. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J. Health Soc. Behav.52, 145–161. doi: 10.1177/0022146510395592,

34

Tian G. Wang J. Zhu J. Hu H. Hao Y. (2024). Associations of family support and loneliness with underlying depression in Chinese children and adolescents. BMC Public Health24:2524. doi: 10.1186/s12889-025-23771-4,

35

Tompson M. C. Sugar C. A. Langer D. A. Robin L. A. (2017). A randomized clinical trial comparing family-focused treatment and individual supportive therapy for depression in childhood and early adolescence. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry56, 515–523. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.018,

36

Tuithof M. Ten Have M. van Dorsselaer S. de Graaf R. (2018). Course of subthreshold depression into a depressive disorder and its risk factors. J. Affect. Disord.241, 206–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.010,

37

Uchino B. N. (2006). Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J. Behav. Med.29, 377–387. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5,

38

Wang M. T. Eccles J. S. (2012). Social support matters: longitudinal effects of social support on three dimensions of school engagement from middle to high school. Child Dev.83, 877–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01745.x,

39

Wang M. Hanges P. J. (2011). Latent class procedures: applications to organizational research. Organ. Res. Methods14, 24–31. doi: 10.1177/1094428110383988

40

Wang J. Mann F. Lloyd-Evans B. Ma R. Johnson S. (2018). Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry18:156. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1736-5,

41

Wang H. Zhang S. Wu J. Guo W. (2023). Perceived social support and its association with bullying protective behavior and depressive symptoms among middle school students. Chin. J. Sch. Health44, 237–241. doi: 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2023.02.018

42

Wen Z. Xie J. Wang H. (2023). Principles, procedures, and applications of latent class models. J. East China Normal Univ.41, 1–15. doi: 10.16382/j.cnki.1000-5560.2023.01.001

43

Yang X. Xue M. Pauen S. Yang L. (2024). Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag.17, 2233–2241. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S463245,

44

Yıldırım M. Aksoy Ş. Öztekin G. G. Alkhulayfi A. M. A. Aziz I. A. Gómez-Salgado J. (2025). Resilience, meaning in life, and perceived social support mediate the relationship between fear of happiness and psychological distress. Sci. Rep.15:34270. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-16486-4,

45

Yıldırım M. Cicek I. (2022). Optimism and pessimism mediate the association between parental coronavirus anxiety and depression among healthcare professionals in the era of COVID-19. Psychol. Health Med.27, 1898–1906. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2021.1966702,

46

Zhang S. Sang B. Pan T. Ma F. (2022). Emotion regulation choice of intensity and valence in adolescents with different depressive symptoms. Psychol. Sci.45, 574–583. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20220309

47

Zhang Y. Wang K. (2022). Effect of social exclusion on social maladjustment among Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model of group identification and parent–child cohesion. J. Interpers. Violence37, NP2387–NP2407. doi: 10.1177/0886260520934444

48

Zhao J. Liu X. Wang M. (2015). Parent-child cohesion, friend companionship and left-behind children’s emotional adaptation in rural China. Child Abuse Negl.48, 190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.03.002

49

Zhao J. Shen J. Liu X. (2008). Social support network, self-esteem, and interaction initiative among left-behind adolescents: a variable-centered and person-centered perspective. Psychol. Sci.31, 827–831.

50

Zhou H. Long L. (2004). Statistical testing and controlling of common method bias. Adv. Psychol. Sci.12, 942–950. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2004.00942

51

Zhou X. Wu X. An Y. (2020). Perceived social support and depression in Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model of self-esteem and peer relationships. J. Affect. Disord.265, 519–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.076,

52

Zhu F. Zhu X. Bi X. Du S. Yu X. Zhao G. (2023). Comparative effectiveness of various physical exercise interventions on executive functions and related symptoms in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front. Public Health11:1133727. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1133727,

Summary

Keywords

adolescents, depressive symptoms, latent profile analysis, mental health, perceived social support

Citation

Tanming L, Zhou Z, Zhang S, Zhang F, Yan C and Chen Z (2026) Latent profiles of perceived social support among adolescents and their relationship with depressive symptoms. Front. Psychol. 16:1647562. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1647562

Received

24 June 2025

Revised

23 December 2025

Accepted

23 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Murat Yildirim, Ağrı İbrahim Çeçen University, Türkiye

Reviewed by

Muflih Muflih, Universitas Respati Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Shouchuang Zhang, Peking University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Tanming, Zhou, Zhang, Zhang, Yan and Chen.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zeng Zhou, 216023@csu.edu.cn; Ziyi Chen, 1094130962@qq.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.