Abstract

Introduction:

Cruelty-free labels have moved from niche certification to mainstream expectation. Yet, little is known about how the multiple cues that accompany these products converge to turn moral intent into action. Addressing this gap, the present study reconceptualizes cruelty-free purchasing as a layered moral performance orchestrated by symbolic, social, and economic stimuli.

Methods:

A mixed-methods design combined a cross-sectional survey of 624 adult consumers framed within a Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) model with partial least squares structural equation modeling and 22 in-depth interviews, which were analyzed thematically.

Results:

Quantitative results show that the logo, influencer advocacy, and perceived corporate social responsibility image each elevate altruistic motivation (β = 0.282–0.539), which, together with ethical concern, explains 74% of the variance in cruelty-free buying. Price fairness moderates this pathway, such that motivation converts to purchase only when the premium is judged acceptable (interaction β = −0.15). Downstream, buying cruelty-free products strongly inspires self-expression (β = 0.843), social bonding (β = 0.745), and behavioral empowerment (β = 0.647). Qualitative themes, ranging from millisecond “ethical sparks” upon spotting the bunny icon to community-building rituals like #crueltyfreehaul, corroborate and enrich these statistical paths.

Discussion:

Together, the findings portray cruelty-free consumption as a script in which logos, parasocial voices, and fair prices jointly ignite compassion, channel it into purchase, and reward it with identity and community pay-offs. Practically, credible certification, authentic influencer partnerships, transparent corporate social responsibility communication, and fair-premium pricing emerge as levers for brands and policymakers seeking to translate compassion from intention to action across the expanding cruelty-free marketplace.

1 Introduction

Recent industry reports and academic analyses converge to show that the cruelty-free (CF) designation has shifted from niche certification to a mainstream purchasing criterion. Across bathroom shelves, kitchen cupboards, and even pet food aisles, the small rabbit emblem has leaped from obscurity to everyday shorthand for compassion. Industry surveys now reveal that nearly three out of four shoppers (73.9%) actively seek CF alternatives whenever possible (Amalia and Darmawan, 2023). The dollars have followed the sentiment: sales of animal-friendly household cleaners reached USD 6.97 billion in 2024 and are projected to grow at more than 11% CAGR through 2030 (Grand View Research, 2024a, 2024b; Statista, 2023). Likewise, CF personal care and beauty lines, which currently constitute a USD 6.2 billion market, are forecast to almost double by 2032 (Fact View Research, 2023). What unites these disparate categories is a shared moral promise: Ordinary consumption can spare non-human animals from harm. This expansion is closely intertwined with regulatory developments: in the European Union and the United Kingdom, comprehensive bans on animal testing for cosmetic products and most cosmetic ingredients, combined with marketing bans on newly animal-tested products, have effectively embedded CF positioning within the mainstream marketplace (European Commission, 2013; Cruelty Free International, 2023). In contrast, the United States has followed a more fragmented path, with a growing number of state-level “cruelty-free cosmetics” laws and ongoing federal debate over the Humane Cosmetics Act (Humane Society of the United States, 2017; Cruelty Free International, 2021). Several Asia–Pacific countries have likewise introduced bans or strong restrictions on cosmetic animal testing or, as in the case of China, relaxed mandatory testing requirements for many “general” products (Government of India, 2014; Eurogroup for Animals, 2019; RSPCA Australia, 2025; Premium Beauty News, 2021). Within this landscape, the Turkish market is not isolated but is continuously exposed to CF standards, labels, and narratives circulating through European regulation and multinational brand strategies, providing a relevant context for examining how ethical values and social drivers shape consumer preferences for CF products.

Despite this commercial momentum, scholarship still treats CF purchasing as a single-factor phenomenon, examining moral identity (Mouat et al., 2019) in one paper and price sensitivity (Curth et al., 2024) in another, leaving unanswered how multiple cues cooperate or compete at the point of choice. Moreover, prior quantitative studies often rely on Likert-type surveys, which are detached from the rapid, sometimes visceral heuristics shoppers deploy in real aisles (Bakr et al., 2023; Suphasomboon and Vassanadumrongdee, 2022), while qualitative work seldom anchors its insights in a formal explanatory model (Talavera and Sasse, 2019).

Parallel to this stream of work, recent studies on moral licensing further clarify how an initial “good” act shapes subsequent ethical consumption decisions. Wen and Hu (2023) show that moral licensing is not a fixed outcome. When individuals publicly share a prior moral behavior on social media, lower moral self-regard can suspend the typical licensing effect and increase the likelihood of engaging in another moral act, particularly in near-term decisions. Building on a broader spillover perspective, Gregersen et al. (2025) distinguish between positive spillover, negative spillover, and (moral) licensing, demonstrating that one ethical choice can either reinforce or undermine later behaviors depending on how it is embedded in social and contextual cues. In a pro-environmental setting, McCarthy (2024) finds that moral licensing can disrupt the standard path from perceived behavioral control to conservation behavior in solar households, as consumers vindicate wasteful energy use after an initial ethical investment, even though social influence remains a key driver of intentions. At the individual level, Shi and Xiao (2023) show that creativity can strengthen moral credentials and thereby increase unethical behavior, underscoring how identity-relevant traits interact with licensing dynamics. These findings portray moral licensing as a malleable, socially embedded process rather than a uniform effect. Within our S–O–R framework, they suggest that earlier cruelty-free choices and identity claims may either spill over into stable CF preferences or, conversely, license a return to conventional products when economic or social constraints are salient. This underscores the need to examine how ethical values, altruistic motivation, perceived consumer empowerment, and social drivers in the Turkish market can support more consistent CF purchasing rather than moral leniency.

Guided by the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S-O-R) paradigm, the present mixed-methods study brings that interplay into focus. We examine four stimuli that routinely co-occupy a CF package or smartphone screen: a certified logo, influencer advocacy, the brand’s perceived corporate social responsibility (PCSR) image, and price fairness (PF). We propose that these cues ignite altruistic motivation (AM) and sharpen ethical concern (EC), which in turn give rise to three response-level outcomes—purchase intention, identity expression, and behavioral empowerment.

Our work advances the field in three ways. First, by modelling symbolic, social, and economic cues simultaneously, we capture the trade-offs consumers face when a moral aspiration collides with a trusted brand name or an unfavorable price tag. Second, we integrate a large-sample PLS-SEM with 22 in-depth interviews, triangulating “cold” structural paths with “hot” narrative details—illustrating, for example, how a rabbit icon can trigger a split-second ethical spark that overrides habitual preferences. Third, we extend S-O-R research by tracing downstream psychological payoffs, self-expression, social bonding, and perceived self-efficacy, which are rarely examined in ethical consumption studies.

For this purpose, this article is organized as follows. Following the introduction, Section 2 develops the theoretical framework by reviewing the S-O-R paradigm (Hwang and Griffiths, 2017) in the context of CF consumption and detailing the symbolic (label), social (influencer), and economic (CSR and PF) stimuli. Section 3 presents the quantitative study, describing the sample, measurement scales, and PLS-SEM results. In Section 4, we outline the qualitative methodology and thematic analysis process, providing in-depth reporting of the seven themes derived from the interviews. Section 5 integrates the quantitative and qualitative findings, interprets them considering prior literature, and discusses the insights that emerge from their convergence. Section 6 summarizes theoretical contributions, practical implications, limitations, and avenues for future research. Finally, Section 7 concludes with overarching takeaways and offers targeted recommendations for both policy and marketing practice.

This study explores how PF and AM jointly influence CF purchasing behavior and its psychological consequences within the S–O–R framework. Despite extensive research on ethical consumption, little is known about how perceptions of fairness interact with moral motives to shape CF behavior, particularly in non-Western, middle-income contexts. Drawing on survey data from consumers in Türkiye, the study examines a moderated sequential mediation process linking PF and AM to CF buying behavior and three types of inspiration: SEI, BEI, and AI. The results identify PF as an economic boundary condition that enables moral intentions to translate into ethical purchasing.

The findings extend S–O–R-based models by conceptualizing PF and AM as interacting stimuli, enrich the organism component by distinguishing SEI, BEI, and AI as meaningful yet temporary outcomes of CF behavior, and contextualize these mechanisms within Türkiye’s socio-economic environment. In response to recent calls for theory-driven, mixed-methods insights into moral decision-making (Arman and Mark-Herbert, 2024; Sun, 2020), we reveal how packaging symbols, parasocial voices, and price tags co-script everyday ethics. We further argue that establishing such a ‘moral script’ is essential for brands and policymakers if compassion is to translate from intention to action across the expanding landscape of CF goods.

2 Study background

During the past 5 years, CF purchasing has emerged as a prominent research topic at the intersection of consumer psychology and sustainability studies. However, the evidence base remains fragmented across product categories, theories, and national settings. Table 1 condenses six recent SSCI-indexed studies that probe why consumers choose CF alternatives. Two broad observations emerge.

Table 1

| No. | Authors (year) | Context/sample /product focus | Method | Principal antecedents tested | Core insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Grappe et al. (2021) | Québec, n = 450/CF cosmetics | Between-subjects experiment PLS-SEM | Claim credibility, animal-welfare concern, subjective norms | External (credibility) and internal (altruism, norms) jointly lift attitude → CF intention. |

| 2 | Bakr et al. (2023) | Canada vs. Kuwait, n = 617/Plant-based/CF meat | Survey PLS-SEM | Env-concern, CF motive, meat attachment, neophobia | CF motive boosts attitude; meat attachment suppresses it; TPB paths stable cross-culturally. |

| 3 | Schuitema and De Groot (2015) | UK/IE labs, n ≈ 200/CF shampoo and moisturiser | Factorial experiment | Price, brand, CF cue, carbon footprint | Green cues sway choice only if price low and brand familiar → CF premium limits uptake. |

| 4 | Amalia and Darmawan (2023) | Indonesia, n = 326/CF personal care | Survey PLS-SEM | Hedonism, env-value, knowledge, TPB | Attitude, PBC, norms predict intention; hedonism and env-value act via attitude. |

| 5 | Suphasomboon and Vassanadumrongdee (2022) | Thailand, n = 423/Green/CF cosmetics | Survey PLS-SEM | Functional, emotional, social value; EC | Functional value → EC → intention; EC strongest direct driver. |

| 6 | (Villena-Alarcón and Zarauza-Castro, 2024) | Spain, n = 300 + 5 influencers/CF beauty on Instagram | Mixed (content + survey) | Influencer credibility, hashtag use | Low hashtag usage; authenticity valued but CF uptake modest → message dilution on social media. |

Overview of SSCI-indexed empirical studies investigating antecedents of CFBB.

TPB, Theory of Planned Behavior; PBC, Perceived Behavioral Control.

First, symbolic and social signals, such as certified labels, altruistic concern, and perceived subjective norms, can enhance consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions, but their influence is highly conditional. Research in Québec cosmetics (Grappe et al., 2021) and Indonesian personal care (Amalia and Darmawan, 2023) demonstrates that certified claims, altruistic concern, and subjective norms positively influence attitudes and intentions. However, Spanish Instagram research finds that when influencers post CF content only sporadically, uptake is modest despite high follower trust (Villena-Alarcón and Zarauza-Castro, 2024). Together, these studies suggest that logo credibility and influencer advocacy serve as necessary but insufficient triggers; they require consistent signaling and supportive context to translate into actual behavior.

Second, economic pragmatism often eclipses moral aspiration. A factorial experiment conducted in the United Kingdom and Ireland reveals that CF cues increase product selection only when price parity and brand familiarity are maintained; even modest price premiums undermine this effect (Schuitema and De Groot, 2015). A comparable dynamic is observed in the plant-based meat category, where CF motives elevate attitudes, but meat attachment and price heuristics suppress intention (Bakr et al., 2023). Extending this argument, Suphasomboon and Vassanadumrongdee (2022) demonstrate that functional value, rather than social admiration, most robustly predicts EC, which in turn drives purchasing behavior.

3 Theoretical background and hypothesis development

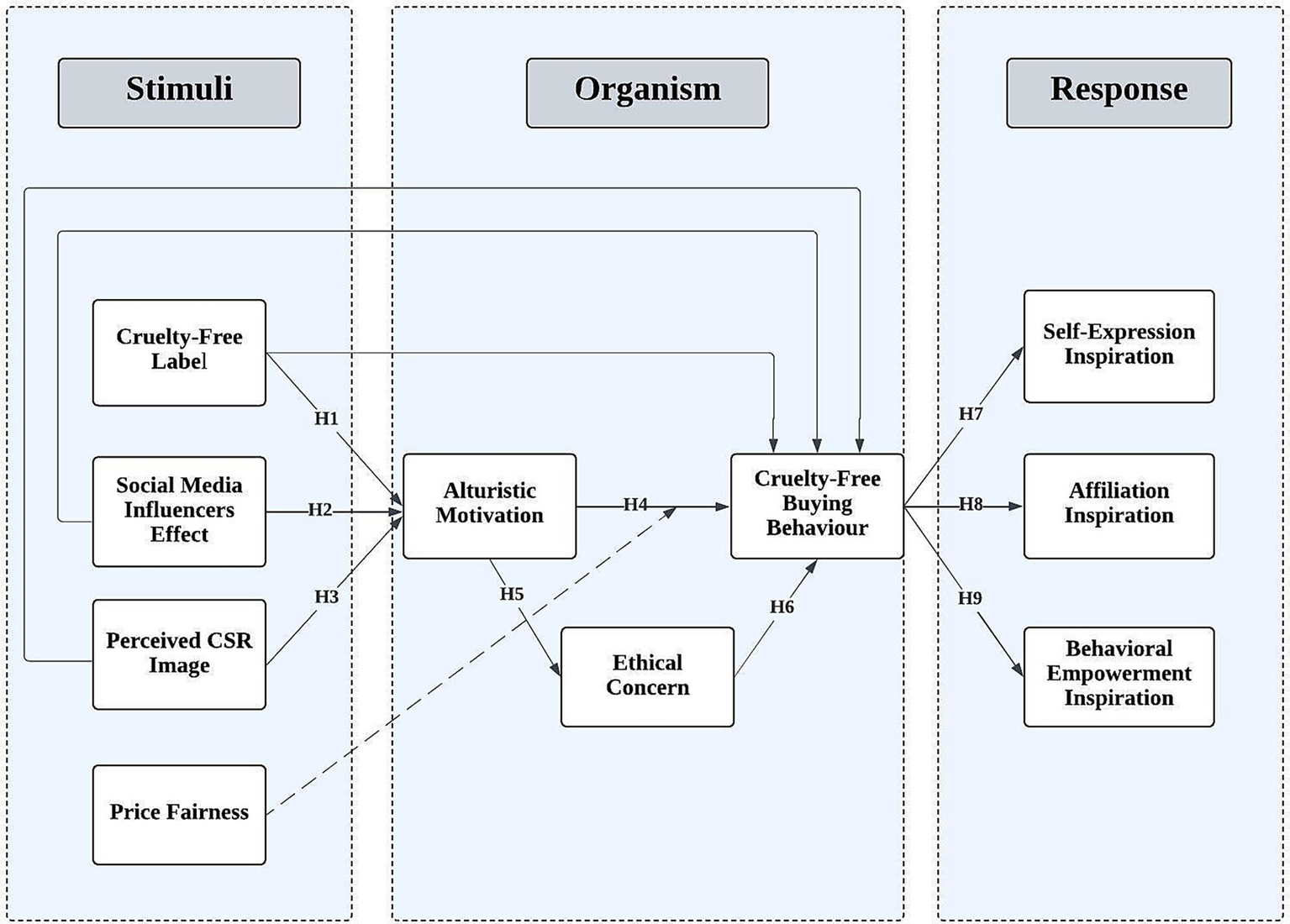

Drawing on the S-O-R paradigm, we organize the literature review and hypothesis development around three layers. First, we examine marketplace stimuli that cue an ethical decision (certified CF label, influencer advocacy, PCSR image, and PF). Second, we discuss two organism-level mediators, AM and EC, that translate those cues into internal readiness to act. Third, we consider response-level outcomes comprising the focal behavior (CF buying) and its post-purchase psychological pay-offs (self-expression, affiliation, empowerment). Figure 1 depicts the resulting conceptual model.

Figure 1

Conceptual framework grounded in the S-O-R paradigm.

3.1 Stimulus-level antecedents

3.1.1 Cruelty-free label and altruistic motivation

CF labeling is an instantly recognizable moral cue, signaling that no animal suffered during the product’s development and appealing to consumers’ other-regarding concerns (Winders, 2006). Empirical research consistently demonstrates that this signal resonates with individuals who value animal welfare intrinsically. In cosmetics, for instance, respondents who notice a CF logo not only form more favorable attitudes but also report stronger purchase intentions, an effect that Wuisan and Februadi (2022) attribute to the importance that such consumers attach to safeguarding animals. Similar evidence is presented by Grappe et al. (2021), who demonstrate that CF logos harmonize ECs with self-presentation motives, yielding a distinctly positive affective response. (Munteanu and Pagalea, 2014; Lewis et al., 2016).

These findings accord with moral-heuristic theory: when shoppers face time or information constraints, they rely on easily processed “ethical shortcuts.” (De Pelsmacker et al., 2005). Sheehan and Lee (2014) show that a CF icon serves precisely this purpose, enabling quick alignment between the act of buying and the buyer’s moral identity. Such alignment is fundamentally altruistic because the primary beneficiary is a non-human other.

More broadly, sustainable consumption studies confirm that the desire to act in the interest of others—whether humans, animals, or the ecosystem—constitutes a pivotal motive behind ethical purchases (Waris et al., 2021; Schuitema and de Groot, 2015). Accordingly, a CF label should do more than enhance product appeal; it should kindle AM by reminding consumers that their choice can prevent harm to sentient beings.

H1. A CF label positively affects consumers' AM.

3.1.2 Social media influencer advocacy and altruistic motivation

Influencers constitute a new class of value transmitters whose authenticity, narrative intimacy, and algorithm-enabled reach make them unusually effective at mobilizing other-regarding motives. Parasocial-relationship theory predicts that when a trusted content creator publicizes an ethical stance, followers are primed to adopt that stance as part of their own moral identity; recent work confirms the prediction across multiple contexts. For green cosmetics, social-media advocacy elevates subjective norms and, through them, AM to support CF brands (Pop et al., 2020). In a broader sustainability context, altruistic—as well as egoistic—motives mediate the effect of influencer messages on purchase intentions (Kumar and Pandey, 2023). Studies in high-credibility contexts show that trust in the messenger amplifies this moral contagion (Chavda and Chauhan, 2024).

The persuasive arc does not end with mere attitude change: altruistically motivated followers go on to circulate ethical content themselves, extending the influencer’s reach through peer sharing (Plume and Slade, 2018). Such network effects help explain why influencer campaigns are now a cornerstone of socially responsible branding strategies (Lokithasan et al., 2019). They also clarify why altruistic concern predicts online purchase intention for ethically positioned products, especially among digital-native cohorts (Traymbak et al., 2022). This evidence supports the proposition that influencer advocacy catalyzes AM, turning moral sentiment into market behavior.

H2. SMIs positively influences consumers’ AM.

3.1.3 Perceived CSR image and altruistic motivation

CSR initiatives serve as moral signals that help consumers assess a firm’s alignment with their ethical standards (Sen and Bhattacharya, 2001; Chen and Kim, 2019). When the signal is interpreted as authentic and other-focused, the firm is reclassified from a market actor to a “moral in-group” partner, prompting a self-transcendent desire to advance shared prosocial aims—an archetypal form of AM (Bhattacharya and Sen, 2004). Crucially, this motivational lift hinges on perceived sincerity rather than the mere presence of a CSR program: high-fit, proactively communicated initiatives strengthen moral identification, whereas low-fit or transparently profit-driven efforts erode it (Becker-Olsen et al., 2005). Empirical work corroborates the mechanism across sectors: Consumers who ascribe altruistic motives to CSR in services and retailing report warmer brand evaluations and a stronger intention to reward the firm (Pérez and Bosque, 2015). Authentic, other-oriented messaging elevates moral emotions and measurably heightens AM (Wong and Dhanesh, 2017; Ji and Jan, 2019); influencer-mediated CSR endorsements likewise increase followers’ readiness to emulate prosocial behavior (Cheng et al., 2021). Meta-analytic evidence further shows that congruence between a consumer’s altruistic values and a focal CSR cause amplifies attitudinal and behavioral outcomes (Ribeiro et al., 2022). Together, these findings suggest that a credible CSR image operates as a psychological catalyst, converting ethical appreciation into an intrinsic willingness to act for the welfare of others.

H3. PCSR image positively influences consumers’ AM.

3.1.4 Price fairness as boundary stimulus

PF sets the economic “permission structure” that determines whether moral motives can be enacted in the marketplace. Building on dual-entitlement theory, consumers simultaneously evaluate (a) their own right to a reference price and (b) the firm’s right to a reasonable profit (Kahneman et al., 1986). When a CF option is priced within this reference zone—or only slightly above it as a justifiable “moral premium”—the economic cost of acting ethically is perceived as tolerable, preserving the intrinsic warm-glow reward that follows prosocial choices (Curth et al., 2024). Equity-based appraisals then remain neutral or positive, allowing symbolic and social cues (such as a logo, influencer advocacy, or CSR) to reach the motivation stage unimpeded. If, however, the price breaches the entitlement boundary, the transaction is re-framed from “shared virtue” to “moral surcharge,” shifting attention from animal welfare to self-protection and heightening loss-aversion concerns (Bolton et al., 2003).

Crucially, fairness evaluations operate upstream, filtering how strongly AM translates into downstream cognitive and behavioral processes. Neuro-imaging work shows that prices deemed unjust extinguish reward-system activation triggered by prosocial cues long before a purchase decision is finalized (Chang et al., 2011). Survey and diary studies also reveal that consumers confronted with perceived overpricing quickly downgrade their moral intent to mere approval, preserving their self-concept while withholding action (Xia and Monroe, 2010; Chong et al., 2021; Maxwell, 2005). In short, PF functions as a boundary stimulus, not because it directly sparks or suppresses compassion, but because it modulates the pathway through which existing altruistic motives become concrete, CF purchases. This boundary role provides the conceptual scaffold for the moderated-mediation hypotheses (H13–H15) developed later in the paper without pre-empting their specific outcome-focused logic.

3.2 Organism-level mediators

3.2.1 Altruistic motivation and cruelty-free buying

Altruistic motivation (AM)—defined as an internalized concern for the welfare of others—activates personal moral norms and a felt obligation to reduce harm (Stern et al., 1995). When such motivation is salient, CF labels become powerful moral affordances, enabling consumers to align marketplace choices with their prosocial values (Schuitema and de Groot, 2015; Magano et al., 2022). Experimental and survey evidence converge on this mechanism: psychosocial values that prioritize animal well-being enhance attitudes toward CF cosmetics and, in turn, purchase intentions (Grappe et al., 2021; Wuisan and Februadi, 2022). Longitudinal and cross-sectional studies further show that these attitudinal gains translate into behavior; altruistic concern predicts both stated intent and verified CF purchases across food, apparel, and beauty contexts (Jaiswal and Kant, 2018; Yazdanpanah and Forouzani, 2015; Prakash et al., 2024). Within the Theory of Planned Behavior, altruism serves as a core antecedent of pro-environmental attitudes (Huang et al., 2018), while value–belief–norm research suggests that moral obligation mediates the transition from intent to action (Chaudhary, 2018). Marketplace studies echo the finding that brands that embed altruistic cues in their positioning elicit stronger engagement and loyalty (Boccadoro et al., 2021). Additionally, social media communities amplify altruistic motives through peer endorsement and normative reinforcement (Kumar and Pandey, 2023). The evidence portrays altruistically motivated consumers as viewing CF products not merely as functional goods but as vehicles for enacting and reinforcing their ethical identity (Aggarwal et al., 2024), thereby increasing the likelihood—and persistence—of CF buying.

H4. AM positively influences consumers’ CFBB.

3.2.2 Altruistic motivation and ethical concern

Altruistic orientations have a positive and significant impact on consumers’ attitudes toward ethical consumption (Oh and Yoon, 2014). This effect arises because individuals committed to altruistic values tend to internalize ethical consumption as part of their self-concept (Culiberg and Bajde, 2013; Chi, 2022; Bae and Yan, 2018). Even when deliberative processes obscure altruistic motives, intuitive, other-regarding reactions often yield ethically favorable decisions (Zhong, 2011). Accordingly, when consumers act on altruistic goals—such as reducing harm to animals or protecting vulnerable beings—their EC is likely to intensify (Le-Hoang, 2025; Chang and Chuang, 2020). They not only perceive cruelty-free options as preferable but also experience a stronger affective response to any potential moral transgressions (Schwartz, 1977). These insights lead us to the following hypothesis:

H5. AM positively influences consumers’ ECs.

3.2.3 Ethical concern and cruelty-free buying behavior

Ethical concern (EC)—the cognitive-affective appraisal that one’s consumption choices carry moral consequences for sentient beings—acts as a pivotal catalyst in CFBB. Laboratory and field studies demonstrate that when empathy is considered in the decision-making process, consumers consistently prioritize products that prevent animal harm (Grappe et al., 2021; Michaelidou and Hassan, 2007; Fox and Ward, 2008). This effect is particularly pronounced among individuals with a pronounced internal locus of control, who are more likely to act when they believe their purchase can influence ethical outcomes (Lim et al., 2019; Dasunika and Gunathilake, 2021; Dissanayake, 2022). Experimental evidence further indicates that prompting moral reflection increases preference for ethically marketed goods (Peloza et al., 2013), while information on animal cruelty redirects demand toward CF options (Gunther et al., 2023). Collectively, these findings position EC as a behavioral driver rather than a mere attitude.

H6. EC positively influence consumers’ CFBB.

3.3 Response-level outcomes

3.3.1 Cruelty-free buying behavior and self-expression inspiration

Choosing CF products enables consumers to establish a value alignment that extends beyond utilitarian exchange and serves as a symbolic self-presentation (White and Argo, 2011). Identity-based consumption theory posits an inspiration sequence: a brief “being inspired by” affective spark on recognizing a value match, followed by a “being inspired to” motivation to display that value publicly (Thrash and Elliot, 2003; Reed et al., 2012). In CF purchases, the act itself signals “I care about animal welfare,” supplying a potent “inspiration-by” trigger. Empirical evidence confirms that value-laden consumption catalyzes visual and behavioral self-expressions: admirers of ethical brands convert their purchases into identity markers that reinforce personal narratives and social images (Schau and Gilly, 2003; Schuitema and de Groot, 2015; van der Westhuizen and Kuhn, 2024). Likewise, Magano et al. (2022) demonstrate that altruism- and responsibility-based attitudes toward CF cosmetics encourage consumers to utilize their purchasing decisions as a platform for ethical advocacy. Together, these findings support the expectation that CFBB elicits SEI.

H7. CFBB positively influences SEI.

3.3.2 Cruelty-free buying behavior and affiliation inspiration

Affiliation inspiration (AI) describes the brief but intense sense of “we-ness” that arises when an individual’s action resonates with a shared ethical norm or community identity (Schau et al., 2009). According to social identity theory, internalizing group values strengthens one’s sense of belonging (Bhattacharya and Sen, 2003). By choosing a CF product, consumers visibly signal membership in an “animal-friendly” community, igniting their AI. Moreover, generative cues—such as imagery emphasizing benefits for future generations—reinforce this communal bond by conveying that “our actions today serve the well-being of tomorrow’s members” (Ma and Xing, 2024). The resulting warm-glow effect further amplifies collective responsibility and the desire to unite with like-minded others (Tezer and Bodur, 2020). Taken together, these processes support the following hypothesis:

H8. CFBB positively influences AI.

3.3.3 Cruelty-free buying behavior and empowerment inspiration

Psychological empowerment theory frames behavioral empowerment as the momentary surge of competence and agency that follows an act perceived as personally efficacious (Zimmerman, 1995). At its core are three mutually reinforcing routes—cognitive, emotional, and behavioral—through which an action nurtures intrinsic motivation (Thomas and Velthouse, 1990). CF purchasing activates each route. Cognitively, the shopper apprehends concrete animal welfare gains, imbuing the choice with meaning and personal relevance. Emotionally, the “warm-glow” effect accompanying prosocial action fortifies moral self-confidence (Chen et al., 2020). Behaviorally, enacting an ethical preference confirms one’s ability to effect change, thereby elevating self-efficacy and encouraging sustainable decisions in the future (Bandura, 1997). Empirical work shows that such empowerment experiences arise whenever technology or information grants users new capacities, whether through e-government portals (Li and Gregor, 2011) or peer-generated reviews that expand choice autonomy (Hu and Krishen, 2019). Accordingly, CF consumption should reliably kindle BEI by informing, energizing, and mobilizing consumers in a single, self-reinforcing episode.

H9 CFBB positively influences BEI.

3.4 Sequential mediations

The CF logo operates as a high-diagnostic moral heuristic: its instantly recognizable imagery short-circuits elaborate information processing and evokes an automatic empathic response toward potential animal victims (De Pelsmacker et al., 2005; Sheehan and Lee, 2014; Greenwald et al., 2002). Neuroimaging research shows that such “no-harm” symbols activate the anterior insula and other regions associated with moral emotion, thereby foregrounding prosocial values at the point of choice (Feng et al., 2022). When this affective trigger aligns with a consumer’s self-schema, it intensifies social–moral identity salience and elevates AM—the felt obligation to act for others’ welfare (Connelly et al., 2011; Park and Lin, 2020a, 2020b; Shaw et al., 2016).

AM then feeds the value–belief–norm (VBN) sequence by converting empathic concern into an internalized sense of moral duty (Stern, 2000). Meta-analytic evidence across ethical-consumption domains confirms that AM is the most potent precursor of EC and that concern, in turn, predicts both stated and revealed purchasing after controlling for price and quality perceptions (Schamp et al., 2023; Fan et al., 2022). EC functions as a cognitive dissonance regulator: acting on it preserves moral self-consistency and thus lowers the psychological cost of paying a potential price premium (Schwartz, 1977; Griskevicius and Tybur, 2010). Field experiments corroborate the chain: removing the CF logo diminishes AM, suppresses ECs, and cuts CF sales by up to 30% (Tully and Winer, 2014).

H10. The presence of a certified cruelty-free label (CFL) increases CFBB via the sequential mediators AM and EC.

Social media influencers (SMIs) translate personal ethics into public scripts that combine the intimacy of peer talk with the reach of mass communication. Their strategic self-disclosure and perceived authenticity create parasocial bonds that prime followers to accept the influencer as a credible moral model (De Veirman et al., 2017). The social-cognitive theories propose that observing such a model triggers vicarious learning, whereby individuals internalize both the desirability and the efficacy of the behavior being modeled (Bandura, 1986). Experimental work corroborates the mechanism: value-congruent influencer endorsements significantly raise AM—measured as willingness to sacrifice personal gain for animal welfare—and this motivational lift mediates the effect on purchase intent for CF products (Lou and Yuan, 2019). Large-sample survey evidence supports the finding that perceived influencer authenticity elicits moral elevation, which in turn predicts intentions to adopt sustainable goods (Ki et al., 2020). A recent meta-analysis of cause-related marketing confirms that communicator–cause value fit systematically amplifies both attitudinal and behavioral outcomes across 85 independent samples (Fan et al., 2022). Once aroused, AM feeds the value–belief–norm cascade by crystallizing into EC (Stern, 2000). This proximal cognitive driver aligns behavior with moral self-standards, thereby facilitating CF purchasing (Schwartz, 1977). Collectively, the evidence supports a serial pathway in which influencer advocacy heightens AM, which then solidifies into EC, ultimately propelling CF buying.

H11. SMI advocacy increases CFBB through the sequential mediators AM and EC.

A persuasive CSR track record can do more than burnish a brand’s reputation—it offers consumers a concrete proof point that their own moral compass and the firm’s ethical stance are pointing in the same direction. Signaling theory shows that such “other-regarding” cues cut through marketplace noise by conveying costly commitment; social-identity research further demonstrates that consumers readily absorb committed firms into their moral in-group, experiencing the company’s prosocial aims as personally relevant (Bhattacharya and Sen, 2004). This perceived value match sparks AM, a motivational state that expands the self to include vulnerable out-groups such as laboratory animals. In the value–belief–norm cascade, AM solidifies into EC—the cognitive conviction that sparing animal suffering is a non-negotiable moral duty (Stern, 2000). Empirical work confirms the chain: longitudinal panel data reveal that heightened EC predicts not only stated intentions but also verified spending on CF cosmetics even after controlling for price sensitivity and brand familiarity (Pérez and Bosque, 2015). Neuroeconomic studies provide convergent validity, demonstrating that CSR endorsements consistent with a consumer’s core values increase activity in brain regions associated with altruistic reward, which in turn predicts actual purchasing (Lee et al., 2021). Acting on that concern protects moral self-integrity, nudging consumers toward CF options when trade-offs arise (Schwartz, 1977).

H12. PCSR image increases CFBB by sequentially elevating AM and then EC.

3.5 Moderated indirect effects

Price perceptions set the economic stage on which moral motives play out. When a CF option is priced within a range consumers deem “fair,” the cognitive cost of acting on altruistic motives collapses, allowing those motives to steer choice (Xia et al., 2004; Habel et al., 2016). Fair prices signal that the firm is not monetizing empathy, thereby sustaining the warm-glow reward that typically follows prosocial action (Tully and Winer, 2014; Jeong, 2024). Laboratory evidence shows that even highly other-regarding consumers curtail ethical purchases once they sense exploitative mark-ups, whereas price-parity scenarios nearly double uptake (Schuitema and De Groot, 2015). Field experiments in green retailing replicate this pattern: AM predicts actual basket share only when perceived PF is present; when fairness is questioned, moral intent stalls at the attitudinal stage (Haws et al., 2014).

Consumers who perceive prices as fair and choose animal-friendly brands grounded in ethical values simultaneously nourish both altruistic (societal benefit–oriented) and self-expressive motivations (Kennedy and Kapitan, 2022; Hamilton et al., 2020). Such choices enable individuals to articulate and signal their identities through ethical behavior (Achar et al., 2025). When altruistic motivations converge with a propensity to purchase cruelty-free products, ethical consumption acquires personal significance and becomes a vehicle for self-representation (Rangel-Lyne et al., 2021). Moreover, prior research shows that perceptions of price fairness enhance consumer trust, thereby reinforcing this process and deepening the self-expressive dimension of ethical consumption (Li et al., 2025; Heidary and Pluut, 2025).

Once the price hurdle is cleared and the CF product is bought, the act becomes a tangible artefact for identity work. Moral identity theory argues that enacting a cherished value in public space generates “symbolic self-completion,” a surge of SEI that invites consumers to display who they are and what they stand for (Aquino and Reed II., 2002; White and Argo, 2011). Purchases that spare animals from harm are especially potent self-signals because they merge compassionate intent with visible marketplace behavior (Berger and Heath, 2007). Neuroaffective studies confirm that fair-priced, ethical choices activate reward circuits linked to self-relevant meaning, whereas overpriced “ethical luxuries” trigger counterfactual regret and dampen identity expression (Pombo and Velasco, 2021).

H13. The interaction of PF and AM enhances SEI through the mediating role of CF buying behavior.

The consumer-empowerment theory argues that perceiving one’s action as efficacious and morally meaningful triggers a short-lived yet intense surge of behavioral empowerment—an affective state that reinforces future self-directed change (Zimmerman, 1995; Thomas and Velthouse, 1990). When AM is already high, a fair price acts as a catalytic cue, confirming that the firm is not exploiting consumers’ compassion and thereby sustaining the intrinsic “warm-glow” reward associated with prosocial choice (White and Peloza, 2009). Under such conditions, the CF purchase functions as a concrete micro-arena for exercising agency: consumers see their choice as a deliberate intervention in the marketplace rather than a passive response to marketing stimuli. This sense of “voting with one’s wallet” not only validates existing altruistic motives (Shaw et al., 2006; Moraes et al., 2011; Papaoikonomou and Alarcón, 2017) but also encourages consumers to generalize their perceived efficacy to future decisions in adjacent ethical domains, thereby laying the groundwork for more durable BEI.

Neuro-affective evidence suggests that fair-priced, ethical purchases activate ventral-striatal circuits linked to agency; however, identical products priced at a perceived surcharge blunt this signal and suppress post-purchase empowerment (Granato et al., 2022). Field data from sustainable apparel further indicate that only when PF is perceived do altruistically motivated consumers report a heightened sense of control and intention to leverage their buying power for broader social causes (Habel et al., 2020). In summary, PF amplifies the translation of AM into a CF purchase, and that purchase, in turn, inspires behavioral empowerment.

H14. The interaction of PF and AM enhances BEI through the mediating role of CFBB.

AI arises when an action visibly aligns the self with a valued moral community, producing a brief but potent “we-ness” sensation (Bhattacharya and Sen, 2003). A fair price makes this communal signal possible: it reassures altruistically inclined shoppers that joining the CF community does not entail economic exploitation, thereby preserving the social legitimacy of the act (Xia et al., 2004). Beyond this diffuse sense of belonging, affiliation-based inspiration is strengthened when consumers see that their CF choices are noticed, discussed, and endorsed by significant others. Research on ethical consumers and social customer journeys shows that shared experiences, conversations, and co-consumption episodes turn individual ethical purchases into relational events that affirm group membership and mutual commitment to moral goals (Hamilton et al., 2020; Kennedy and Kapitan, 2022). In settings where moral communities or cause-based groups are explicitly signaled, ethical labels can even invite consumers to align themselves with broader solidarity movements and to express support for stigmatized or underserved communities (Achar et al., 2025). Warm-glow studies show that fair-priced, ethical choices evoke stronger feelings of social connectedness than overpriced counterparts, even when the objective savings are identical (Tezer and Bodur, 2020). Large-scale survey evidence from plant-based food markets confirms that PF moderates the link between altruism and purchase; only under fair-price conditions does the purchase elevate perceived group identity and peer approval (Jia et al., 2023). Thus, fair pricing functions as a boundary condition that allows altruistic motives to materialize in a CF purchase, thereby sparking inspiration for affiliation.

H15. The interaction of PF and AM enhances AI through the mediating role of CF purchasing behavior.

4 Materials and methods

Given the study’s objective to estimate a multi-construct S–O–R model that includes an interaction term (PF × AM), multiple indirect paths, and three distinct post-purchase inspiration outcomes (SEI, BEI, AI), we employ an explanatory mixed-methods design. The quantitative phase tests the complete nomological network and the moderated-sequential mediation structure using PLS-SEM, which is well-suited for prediction-oriented modeling with multiple latent constructs and for assessing interactions and indirect effects via bootstrapping. The qualitative phase complements these tests by eliciting consumers’ interpretations of CF cues and price (un)fairness in real purchase narratives, thereby clarifying mechanisms, surfacing boundary conditions (e.g., scepticism toward claims or influencers), and strengthening interpretive validity. Together, the two phases provide a coherent justification for the methodological approach and enable triangulation of statistical patterns with lived accounts of CF decision-making.

4.1 Quantitative strand: structural model results

4.1.1 Participants and sampling

A cross-sectional sample of N = 624 adult consumers residing in Türkiye was recruited via a professional online panel provider. We employed a stratified quota sampling strategy to ensure proportional representation across key demographic strata: gender (52% female, 48% male), age (18–24 = 18%, 25–34 = 37%, 35–44 = 29%, 45 + = 16%), and NUTS-1 region (Marmara, Central Anatolia, Aegean, Mediterranean, Black Sea, Eastern, and Southeastern Anatolia). This approach was chosen because purchase motivations, price sensitivity, and social influence cues are known to vary systematically by demographic segment. Stratification reduces sampling error, while quota controls mitigate overrepresentation, thereby enhancing the generalizability of findings to Türkiye’s adult population (Dillman et al., 2014).

Participants were eligible if they (a) purchased personal-care or household products at least once per month and (b) used a smartphone for shopping-related activities—criteria selected to reflect real-life exposure to CF product cues. An a priori power analysis using G*Power 3.1 (f2 = 0.02, α = 0.05, power = 0.95, 10 predictors) indicated a minimum required sample size of 474; the final sample comfortably exceeded this threshold. Of 721 invitations distributed, 654 responses were received (90.7% response rate), and 30 were excluded due to inattentive responding or survey completion times below one-third of the median, resulting in 624 valid responses. As shown in Table 2, sample demographics closely mirror national census figures, further supporting the external validity of the dataset.

Table 2

| Variable | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 324 | 52 |

| Male | 300 | 48 | |

| Age group | 18–24 | 112 | 17.9 |

| 25–34 | 231 | 37 | |

| 35–44 | 181 | 29 | |

| 45 + | 100 | 16 | |

| Education | High-school or lower | 169 | 27.1 |

| Associate/Bachelor’s | 306 | 49 | |

| Master’s/PhD | 149 | 23.9 | |

| Occupation | Student | 48 | 7.7 |

| Public sector employee | 181 | 29 | |

| Private sector employee | 237 | 38 | |

| Self-employed/entrepreneur | 51 | 8.2 | |

| Academic/researcher | 73 | 11.7 | |

| Not currently employed | 34 | 5.4 | |

| Monthly household income | < 22,150 | 68 | 10.9 |

| 22,150–50,000 | 134 | 21.5 | |

| 50,001–80,000 | 143 | 22.9 | |

| 80,001–110,000 | 110 | 17.6 | |

| 110,001–150,000 | 87 | 13.9 | |

| > 150,001 | 82 | 13.1 |

Socio-demographic profile of the sample.

Sample size: N = 624.

4.1.2 Measures and instrument development

All latent constructs were operationalized with multi-item, reflective scales adapted from prior peer-reviewed research. Scale wording was first adjusted to the CF products context, then subjected to a double back-translation procedure (English ↔ Turkish) to secure semantic equivalence. A panel of three marketing scholars and two industry practitioners evaluated the content validity, resulting in minor lexical refinement.

Items for SEI and AI (3 each) were adapted from Schau et al. (2009) and Venn et al. (2017). AM (4 items) was drawn from Goldsmith et al. (2000) and Prakash et al. (2024). The eco-label (CF logo) perception scale (3 items) followed by Nittala (2014) and Song et al. (2020). EC (4 items) relied on Suphasomboon and Vassanadumrongdee (2022). The PCSR image (7 items) was adapted from Achabou and Ho’s environmental CSR scale and tailored to the CF domain (Achabou, 2020; Ho, 2017; Huang et al., 2022). PF (6 items) combined wording from Petrick (2002), Martin et al. (2009), and Chung and Petrick (2013). The five-item SMI credibility scale was customised by De Veirman et al. (2017). CFBB (6 items) was adapted from Khare (2015), and behavioral-empowerment inspiration (3 items) from Speer and Peterson (2000), Christens (2012), and Li et al. (2021). The original scale items are listed in Appendix Table A.

All items were anchored on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”). A pilot test with 80 respondents confirmed readability and yielded satisfactory internal consistency reliabilities (Cronbach’s α ≥ 0.78). Pilot data also showed no cross-loading above 0.30 in an exploratory factor analysis, supporting preliminary discriminant validity. Final measurement properties (indicator loadings, AVE, CR, α) are reported in Table 3 and meet recommended thresholds for PLS-SEM. Common-method bias was assessed ex-ante through proximal item placement and ex-post via the full collinearity VIF test; all latent VIFs were < 3.3, indicating no substantial bias.

Table 3

| Construct | Outer loadings | VIF | Cronbach’ alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cruelty-free label | 0.782 | 0.871 | 0.694 | ||

| CFL1 | 0.871 | 1.942 | |||

| CFL2 | 0.717 | 1.436 | |||

| CFL3 | 0.895 | 1.772 | |||

| Social media influencers | 0.870 | 0.906 | 0.661 | ||

| SMI1 | 0.880 | 2.232 | |||

| SMI2 | 0.915 | 3.115 | |||

| SMI3 | 0.723 | 1.972 | |||

| SMI4 | 0.866 | 2.508 | |||

| SMI5 | 0.702 | 1.718 | |||

| Perceived CSR image | 0.951 | 0.961 | 0.804 | ||

| PCSR1 | 0.907 | 3.442 | |||

| PCSR2 | 0.868 | 2.889 | |||

| PCSR3 | 0.902 | 2.938 | |||

| PCSR4 | 0.876 | 2.077 | |||

| PCSR5 | 0.921 | 2.815 | |||

| PCSR6 | 0.905 | 2.171 | |||

| Price fairness | 0.903 | 0.928 | 0.721 | ||

| PF1 | 0.805 | 1.993 | |||

| PF2 | 0.806 | 2.008 | |||

| PF3 | 0.842 | 2.562 | |||

| PF4 | 0.879 | 2.268 | |||

| PF5 | 0.908 | 2.863 | |||

| Ethical concern | 67,710 | 0.945 | 0.960 | 0.858 | |

| EC1 | 0.947 | 3.372 | |||

| EC2 | 0.945 | 2.440 | |||

| EC3 | 0.914 | 2.689 | |||

| EC4 | 0.900 | 3.222 | |||

| Altruistic motivation | 0.772 | 0.840 | 0.570 | ||

| AM1 | 0.731 | 1.524 | |||

| AM2 | 0.870 | 1.383 | |||

| AM3 | 0.727 | 1.574 | |||

| AM4 | 0.721 | 1.613 | |||

| Behavioral empowerment inspiration | 0.723 | 0.828 | 0.630 | ||

| BEI1 | 0.895 | 1.261 | |||

| BEI2 | 0.925 | 2.018 | |||

| BEI3 | 0.876 | 1.744 | |||

| Affiliation inspiration | 0.969 | 0.980 | 0.942 | ||

| AI1 | 0.970 | 1.406 | |||

| AI2 | 0.980 | 2.174 | |||

| AI3 | 0.963 | 1.160 | |||

| Self-expression inspiration | 0.802 | 0.882 | 0.713 | ||

| SEI1 | 0.822 | 1.722 | |||

| SEI2 | 0.864 | 1.668 | |||

| SEI3 | 0.848 | 1.781 | |||

| Cruelty-free buying behavior | 0.944 | 0.954 | 0.723 | ||

| CFBB1 | 0.880 | 1.956 | |||

| CFBB2 | 0.877 | 2.851 | |||

| CFBB3 | 0.905 | 1.966 | |||

| CFBB4 | 0.751 | 2.611 | |||

| CFBB5 | 0.856 | 2.940 |

Construct-level evaluation of the measurement model.

4.1.3 Measurement model evaluation

As shown in Table 3, all constructs satisfied established reliability and convergent validity benchmarks (Hair et al., 2024). Outer loadings ranged from 0.717 to 0.980, comfortably above the 0.70 guideline, except for two indicators (CFL2 = 0.717; SMI5 = 0.702) that were retained for content coverage. Cronbach’s α coefficients (0.723–0.969) and composite reliabilities (0.828–0.980) exceeded the 0.70 threshold, indicating strong internal consistency (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994). Average variance extracted (AVE) values (0.570–0.942) surpassed the 0.50 criterion, confirming convergent validity. Variance-inflation factors for all indicators (1.26–3.44) fell well below the conservative threshold of 5, suggesting no concerns about multicollinearity (Kock and Lynn, 2012). Collectively, these statistics demonstrate that the measurement model is both reliable and convergent, providing a sound basis for subsequent structural analysis.

4.1.4 Discriminant validity and collinearity diagnostics

As displayed in Table 4, the square roots of AVE values (0.755–0.971; diagonal) exceed every inter-construct correlation, including the largest observed off-diagonal value (0.825 between EC and SMIs). This pattern satisfies the Fornell–Larcker requirement that a latent construct share more variance with its indicators than with any other construct (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2024).

Table 4

| Construct | AI | AM | BEI | CFBB | CFL | EC | PCSRI | PF | SEI | SMI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI | 0.971 | |||||||||

| AM | 0.512 | 0.755 | ||||||||

| BEI | 0.646 | 0.449 | 0.793 | |||||||

| CFBB | 0.732 | 0.494 | 0.656 | 0.850 | ||||||

| CFL | 0.790 | 0.613 | 0.624 | 0.717 | 0.833 | |||||

| EC | 0.737 | 0.641 | 0.708 | 0.712 | 0.710 | 0.927 | ||||

| PCSRI | 0.806 | 0.695 | 0.662 | 0.722 | 0.609 | 0.782 | 0.897 | |||

| PF | 0.716 | 0.586 | 0.641 | 0.757 | 0.668 | 0.741 | 0.793 | 0.849 | ||

| SEI | 0.652 | 0.562 | 0.736 | 0.644 | 0.764 | 0.770 | 0.702 | 0.720 | 0.845 | |

| SMI | 0.678 | 0.607 | 0.598 | 0.660 | 0.733 | 0.825 | 0.701 | 0.728 | 0.714 | 0.813 |

Discriminant validity matrix (Fornell–Larcker criterion).

Diagonal (bold) values are √AVE; other values are correlations between constructs.

Table 5 reports Heterotrait–Monotrait ratios ranging from 0.227 to 0.793, well below the conservative 0.85 threshold and the liberal 0.90 guideline (Henseler et al., 2015; Hair et al., 2024). Hence, every construct remains empirically distinct; even the highest value—between CFL and CFBB—does not threaten discriminant validity.

Table 5

| Construct | AI | AM | BEI | CFBB | CFL | EC | PCSRI | PF | SEI | SMI | PF x AM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI | |||||||||||

| AM | 0.485 | ||||||||||

| BEI | 0.706 | 0.478 | |||||||||

| CFBB | 0.759 | 0.456 | 0.679 | ||||||||

| CFL | 0.676 | 0.681 | 0.698 | 0.793 | |||||||

| EC | 0.669 | 0.642 | 0.763 | 0.748 | 0.712 | ||||||

| PCSRI | 0.441 | 0.701 | 0.709 | 0.757 | 0.605 | 0.629 | |||||

| PF | 0.461 | 0.588 | 0.678 | 0.521 | 0.679 | 0.596 | 0.554 | ||||

| SEI | 0.472 | 0.592 | 0.582 | 0.548 | 0.525 | 0.585 | 0.620 | 0.547 | |||

| SMI | 0.331 | 0.624 | 0.650 | 0.704 | 0.659 | 0.404 | 0.374 | 0.305 | 0.441 | ||

| PF x AM | 0.271 | 0.581 | 0.227 | 0.436 | 0.368 | 0.311 | 0.345 | 0.505 | 0.356 | 0.410 |

Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio matrix for discriminant validity.

Variance-inflation factors for endogenous predictors (Table 6) range from 1.26 to 2.97. The highest values—2.97 for PCSR Image, 2.96 for SMIs, and 2.78 for EC—remain comfortably beneath both the classical ceiling of 5 (Hair et al., 2024) and the stricter lateral-collinearity safeguard of 3.3 (Kock and Lynn, 2012). The interaction term (PF × AM) shows an ideal VIF of 1.58, indicating near orthogonality.

Table 6

| Construct | AI | AM | BEI | CFBB | CFL | EC | PCSRI | PF | SEI | SMI | PF x AM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI | |||||||||||

| AM | 2.153 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| BEI | |||||||||||

| CFBB | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| CFL | 2.071 | ||||||||||

| EC | 2.776 | ||||||||||

| PCSRI | 2.965 | ||||||||||

| PF | 2.644 | ||||||||||

| SEI | |||||||||||

| SMI | 2.962 | ||||||||||

| PF x AM | 1.583 |

Inner model Vif.

4.1.5 Structural model diagnostics

The f2 matrix in Table 7 highlights the model’s parsimony. Large effects (e.g., 0.862, 0.872, 0.706, 0.697) indicate that these predictors explain a substantial proportion of variance in their respective outcomes. Medium contributions around 0.10–0.14 add incremental explanatory power, whereas the near-zero coefficients (0.020, 0.011, 0.009) denote links rendered redundant by full mediation—once the theorized mediator is introduced, the direct path adds no further R2 (Cohen, 1988). This pattern—strong drivers where theory predicts them and trivial direct effects where mediation is posited—confirms the structural model’s coherence and empirical efficiency.

Table 7

| Construct | AI | AM | BEI | CFBB | CFL | EC | PCSR | PF | SEI | SMI | PF x AM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI | |||||||||||

| AM | 0.425 | 0.706 | |||||||||

| BEI | |||||||||||

| CFBB | 0.862 | 0.756 | 0.872 | ||||||||

| CFL | 0.109 | 0.020 | |||||||||

| EC | 0.086 | ||||||||||

| PCSR | 0.137 | 0.011 | |||||||||

| PF | 0.697 | ||||||||||

| SEI | |||||||||||

| SMI | 0.098 | 0.009 | |||||||||

| PF x AM | 0.112 |

Effect-size statistics (f2) for endogenous paths.

The structural model exhibits strong explanatory and predictive power (Table 8). CFBB (R2 = 0.736) and SEI (0.711) approach the “substantial” threshold, while AI (0.556) and AM (0.496) fall comfortably within the “moderate” range. Even the lowest R2 values—BEI (0.418) and EC (0.417)—exceed the 0.25 benchmark, indicating that the model accounts for a meaningful proportion of variance across all endogenous constructs (Hair et al., 2024; Henseler et al., 2015). Complementing this explanatory strength, predictive-relevance diagnostics further support model robustness: Stone–Geisser Q2 values range from 0.421 to 0.808, well above zero, confirming out-of-sample accuracy. Likewise, RMSA coefficients fall between 0.440 and 0.576, reflecting moderate and proportionate residual error relative to construct complexity (Shmueli et al., 2016), thereby affirming the model’s empirical adequacy for both theoretical insight and practical inference.

Table 8

| Endogenous construct | R-square | Q-square | RMSA |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI | 0.556 | 0.670 | 0.576 |

| AM | 0.496 | 0.487 | 0.419 |

| BEI | 0.418 | 0.421 | 0.362 |

| CFBB | 0.736 | 0.808 | 0.440 |

| EC | 0.417 | 0.612 | 0.524 |

| SEI | 0.711 | 0.697 | 0.452 |

| Model fit | |

|---|---|

| Fit index | Estimated model |

| SRMR | 0.084 |

| NFI | 0.878 |

Explanatory power and predictive relevance of endogenous constructs.

Global fit indices reinforce overall adequacy. As shown in Table 8, the model’s SRMR of 0.084 is below the conservative threshold of 0.10, and the NFI of 0.878 approaches the recommended benchmark of 0.90 (Hair et al., 2024), indicating that the reproduced covariance matrix closely matches the observed data.

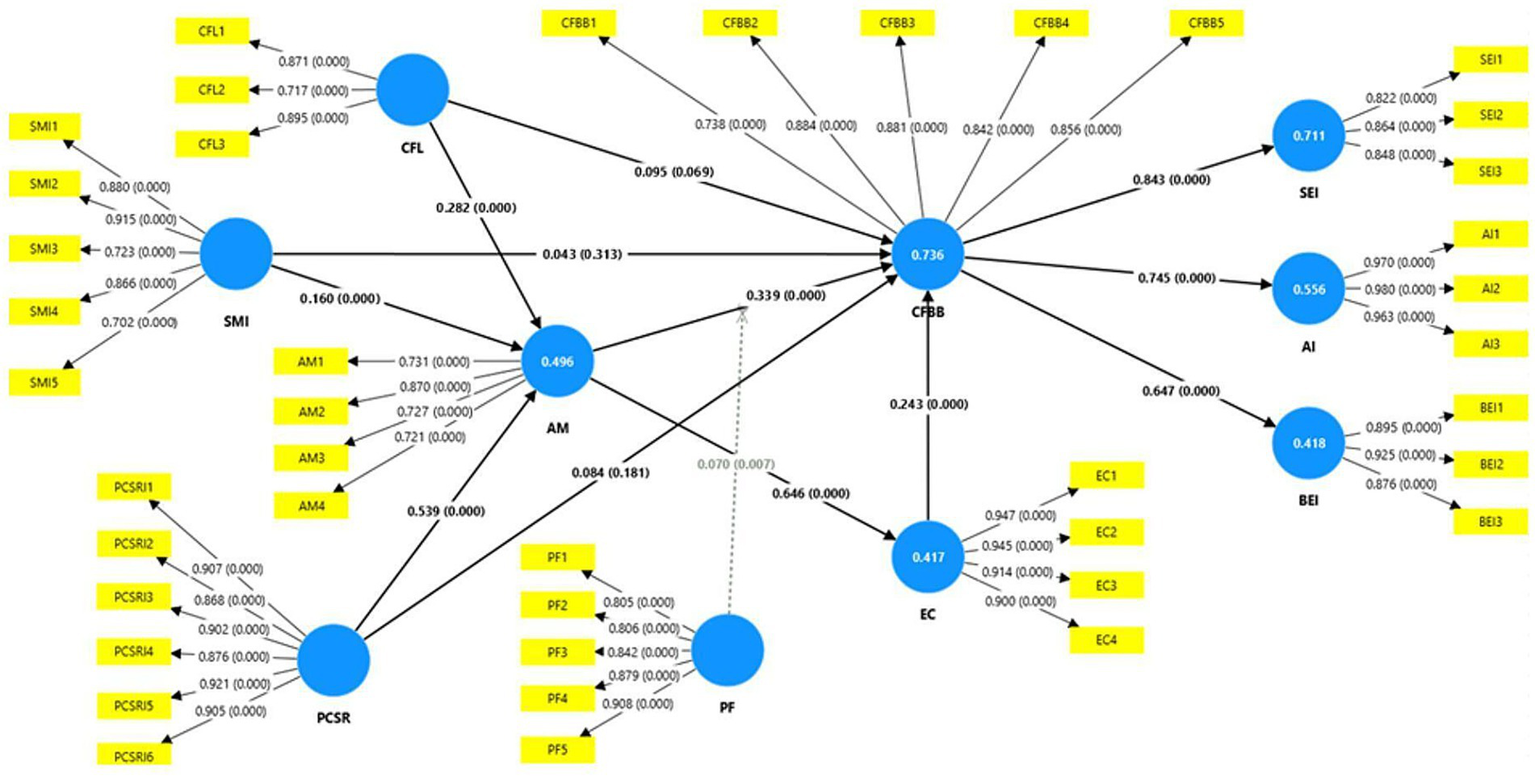

4.1.6 Structural model results

Bootstrapped path estimation (5,000 resamples) produced the coefficient matrix summarized in Table 9 and visualized in Figure 2. Overall, the model accounts for 42–74% of variance across its six endogenous constructs, providing a robust platform for hypothesis testing.

Table 9

| Hypothesis and structural path | β | Std dev. | T-value | P values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1. CFL → AM | 0.282 | 0.055 | 5.240 | 0.000 |

| H2. SMI → AM | 0.160 | 0.057 | 3.284 | 0.000 |

| H3. PCSR → AM | 0.539 | 0.068 | 7.985 | 0.000 |

| H4. AM → CFBB | 0.339 | 0.040 | 3.043 | 0.000 |

| H5. AM → EC | 0.646 | 0.021 | 30.118 | 0.000 |

| H6. EC → CFBB | 0.243 | 0.060 | 4.324 | 0.000 |

| H7. CFBB → SEI | 0.843 | 0.014 | 61.181 | 0.000 |

| H8. CFBB → AI | 0.745 | 0.020 | 36.974 | 0.000 |

| H9. CFBB → BEI | 0.647 | 0.025 | 26.309 | 0.000 |

| H10. CFL → AM → EC → CFBB | 0.111 | 0.017 | 3.141 | 0.002 |

| H11. SMI → AM → EC → CFBB | 0.107 | 0.016 | 2.946 | 0.005 |

| H12. PCSR → AM → EC → CFBB | 0.148 | 0.022 | 3.681 | 0.000 |

| H13. PF x AM → CFBB → AI | 0.102 | 0.019 | 2.716 | 0.002 |

| H14. PF x AM → CFBB → BEI | 0.115 | 0.017 | 3.283 | 0.001 |

| H15. PF x AM → CFBB → SEI | 0.197 | 0.022 | 4.714 | 0.000 |

Hypothesis testing results.

Figure 2

Bootstrapped PLS-SEM model with standardized path coefficients and R2.

The empirical results align closely with the study’s theorization. First, the three exogenous cues—CF labeling, SMI advocacy, and PCSR image—each exerts a positive, significant, and theoretically coherent impact on AM (H1–H3). Among them, CSR is the most potent predictor (β = 0.539, p < 0.001), which is consistent with the stakeholder-identification view that consumers internalize socially responsible signals as moral self-relevance (Bhattacharya and Sen, 2004). The smaller but meaningful coefficients for labeling (β = 0.282) and SMIs endorsement (β = 0.160) suggest that tangible on-pack cues and parasocial persuasion work in tandem. However, corporate deeds weigh more heavily than words or badges.

AM, in turn, operates exactly as posited: it promotes EC (β = 0.646). It directly encourages CF buying (β = 0.339), supporting value-belief-norm logic and the moral extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991). EC partially carries this effect forward (H6; β = 0.243), yielding a layered motivational pathway that culminates in purchase. The strength and significance of these links validate H4–H6 and justify the sequential-mediation tests. Downstream, CF buying acts as a springboard for three post-purchase inspirations—self-expression (H7, β = 0.843), affiliation identity (H8, β = 0.745) and behavioral empowerment (H9, β = 0.647)—all far exceeding the “large-effect” benchmark in PLS-SEM.

The sequential mediations (H10–H12) are all significant (p ≤ 0.05). Each indirect chain, from the three upstream cues through AM and EC to buying behavior, registers, demonstrating that the cues work primarily by elevating moral motives, rather than bypassing them. This finding reinforces the argument that CF consumption is less an impulse purchase than a moralized decision requiring internalized justification.

The moderated-mediation hypotheses (H13–H15) are supported: the interaction of PF with AM strengthens the indirect effect of buying behavior on all three inspiration outcomes. Fair pricing, therefore, helps motivated consumers translate moral intent into action and, in turn, derive richer psychological rewards.

Every hypothesis is statistically upheld, and effect sizes follow theoretical expectations—strongest for value-based links, moderate for informational cues, and weakest (yet still significant) for direct shortcuts explicitly treated as mediated. The pattern reinforces the coherence and practical relevance of the proposed causal chain from corporate and social signals to individual motives, behavior and identity-building outcomes.

4.2 Qualitative strand: thematic insights from participant narratives

The thematic analysis reported in this section serves a dual purpose: It humanizes the statistical paths uncovered by the S-O-R model and probes for latent meanings that quantitative indicators alone cannot reveal. By foregrounding consumers’ narratives—how a rabbit logo triggers an “ethical spark,” how influencer advocacy shapes moral affiliation, or how PF collides with a “clear conscience”—the qualitative phase illuminates the everyday reasoning, emotions, and identity work that ultimately translate abstract stimuli into CF purchasing acts. In doing so, it provides a textured interpretive layer that validates and elaborates upon the PLS-SEM findings, ensuring that the voices behind the choice fully integrate into the study’s overall explanation of CF consumption.

4.2.1 Participants and interview procedure

The qualitative phase grounded in in-depth interviews complemented the quantitative PLS-SEM findings developed within the S-O-R framework. Recruitment, scheduling, and completion of the interviews took 3 months (March–May 2025). We initially aimed for 20–25 in-depth interviews to balance analytic depth with diversity in CF involvement, age, gender, and occupational background. Participants were recruited purposively to capture variation in exposure to CF products and ethical consumption discourse (e.g., long-term CF users, occasional CF buyers, and consumers who were only recently aware of CF labels). Saturation was tracked iteratively across this heterogeneous sample: after 20 interviews, no substantively new codes emerged, and two additional interviews were conducted with participants from underrepresented profiles, confirming the stability of the thematic structure, resulting in a final sample of 22 interviews. Using purposeful sampling, 22 participants—drawn from diverse socio-demographic backgrounds and exhibiting varying levels of experience with CF consumption—took part in semi-structured interviews lasting 45–75 min each (Patton, 2015). The semi-structured interview guide comprised 14 questions addressing the study’s focal stimuli (CFL presence, SMI advocacy, PCSR image, PF), organism-level mediators (AM, EC), and response-level outcomes (CFBB, SEI, AI, BEI); the full guide is available in Appendix Table B.

Table 10 summarises the demographic and experiential profiles of the 22 interviewees. The ages ranged from the early 20s to the early 40s, and the sample achieved an intentionally balanced gender representation—fourteen women and eight men—reflecting the slight female tilt typically reported in CFproduct markets. Educational attainment ranged from high school diplomas to doctoral degrees. At the same time, occupations included knowledge-intensive roles (e.g., UX designer, data analyst, university lecturer, beauty specialist) and service-sector positions (e.g., barista, retail manager). This breadth ensured the inclusion of consumers with disparate disposable incomes and workplace cultures, factors that influence ethical purchase priorities.

Table 10

| ID | Gender | Age | Education | Occupation | Experience with CF products* | Self-reported purchase frequency | Interview length (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P01 | Female | 24 | Bachelor’s | Student | High (≥ 5 yrs) | Weekly | 58 |

| P02 | Male | 31 | Master’s | Software Dev. | Moderate (2–4 yrs) | Monthly | 46 |

| P03 | Female | 27 | Bachelor’s | Graphic designer | Low (< 1 yr) | Occasionally | 54 |

| P04 | Female | 35 | PhD | Lecturer | High | Weekly | 64 |

| P05 | Male | 29 | Bachelor’s | Sales Rep. | Moderate | Monthly | 49 |

| P06 | Female | 22 | Assoc. Degree | Barista | Low | Rarely | 45 |

| P07 | Female | 40 | High school | Retail Manager | High | Weekly | 57 |

| P08 | Male | 33 | Bachelor’s | Marketing Exec. | Moderate | Every 2 wks | 51 |

| P09 | Female | 26 | Master’s | Research Asst. | Low | Occasionally | 48 |

| P10 | Male | 38 | Bachelor’s | Accountant | Moderate | Monthly | 47 |

| P11 | Female | 30 | PhD | Post-Doc | High | Weekly | 59 |

| P12 | Female | 44 | High school | Homemaker | Low | Rarely | 50 |

| P13 | Male | 28 | Master’s | UX Designer | High | Weekly | 55 |

| P14 | Female | 23 | Bachelor’s | Intern | Moderate | Monthly | 45 |

| P15 | Male | 36 | Bachelor’s | Project Manager | Low | Occasionally | 62 |

| P16 | Female | 32 | PhD | Veterinarian | High | Weekly | 52 |

| P17 | Male | 41 | Associate | Technician | Moderate | Monthly | 46 |

| P18 | Female | 25 | Bachelor’s | Journalist | Low | Rarely | 49 |

| P19 | Male | 34 | Master’s | Data analyst | High | Weekly | 56 |

| P20 | Female | 29 | Bachelor’s | Beauty Specialist | High | Weekly | 73 |

| P21 | Female | 27 | Bachelor’s | Interior architect | High | Weekly | 55 |

| P22 | Female | 37 | Master’s | HR Specialist | Low | Occasionally | 50 |

Participant characteristics.

4.2.2 Thematic analysis strategy and validation

The qualitative dataset comprised verbatim transcripts totaling approximately 132,000–135,000 words, all of which were imported into MAXQDA 2022 for systematic analysis. We followed Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase thematic analysis protocol, beginning with familiarization and inductive line-by-line coding. To preserve conceptual alignment with our quantitative model, coding remained sensitized to pre-specified constructs (deductive) while allowing novel insights to emerge organically (inductive) (Nowell et al., 2017).

Saturation was tracked iteratively; after 20 interviews, no novel first-order codes appeared across two consecutive transcripts, yet two additional interviews were conducted to confirm redundancy (Malterud et al., 2016). The initial pool of 148 open codes was refined through code reconciliation and merged into 63 focused codes. These were then organized into 21 sub-themes and synthesized into seven integrative analytical themes (see Table 11). Together, these themes furnish a rich narrative that deepens understanding of how CF purchasing decisions emerge from the interplay of situational cues, moral motivations, and identity-driven outcomes.

Table 11

| Analytic theme (7) | Sub-theme | Representative in-vivo codes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Ethical spark—rapid moral triggers | 1A. Instant logo recognition | “Grab it the moment I spot the bunny.” · “Logo = instant trust.” |

| 1B. Awareness shortcut | “Decision in < 5 s.” · “No need to scan the barcode.” | |

| 1C. Affective jolt | “Sudden pang for the lab animals.” | |

| 1D. Reflexive guilt avoidance | “Put the non-logo shampoo back fast.” | |

| 2. Parasocial guidance—influencer affiliation | 2A. Trust transfer | “If she recommends it, I’m in.” |

| 2B. Role-model activism | “Influencer donates shelter profits.” | |

| 2C. Community sharing loop | “Drop the product link in our group chat.” | |

| 3. Fair price ↔ clear conscience—price–altruism trade-off | 3A. Sacrifice threshold | “+€1–2 is fine; +€50 is too much.” |

| 3B. Rational justification | “The cost of compassion makes sense.” | |

| 3C. Transparency demand | “Show me where the extra money goes.” | |

| 3D. Profit-vs-exploitation | “Are they monetising my empathy?” | |

| 4. Identity performance—staging the self | 4A. Visual self-presentation | “Shelfie with the bunny logo facing out.” |

| 4B. Inner consistency | “Walk my talk; buy my values.” | |

| 4C. Value storytelling | “Explain the logo’s story to friends.” | |

| 5. Collective conscience—belonging and community | 5A. Shared moral identity | “Logo feels like a secret handshake.” |

| 5b. Social approval loop | “More likes on cruelty-free posts.” | |

| 5C. Responsibility chain | “Product purchase equals a micro-donation.” | |

| 6. Empowerment through action—behavioral self-efficacy | 6A. Concrete impact belief | “My receipt is a mini-petition.” |

| 6B. Sustained motivation | “I’m a role-model for my kid.” | |

| 7. Ethical scepticism—CSR talk vs. practice | 7A. Authenticity test | “Need a third-party certificate or I skip.” |

| 7B. Transparency demand | “No evidence? I blacklist the brand.” |

Analytic theme hierarchy (condensed version*).

To ensure methodological rigor in line with COREQ guidelines (Tong et al., 2007), we maintained a detailed audit trail documenting every stage of theme development. Reflective memos capture analytical decisions and researcher reflexivity (Nowell et al., 2017). The qualitative dataset comprised verbatim transcripts, which were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis. An initial codebook was collaboratively developed by two researchers, combining theory-informed sensitising concepts with inductive codes derived from a close reading of a subset of transcripts. Researchers independently coded this subset, compared coding decisions, and resolved discrepancies through discussion, resulting in a refined, shared codebook. Inter-coder reliability was assessed by having a second analyst independently code 25% of the transcripts; Cohen’s κ = 0.87 (“almost perfect” agreement; Landis and Koch, 1977) confirmed coding consistency. One researcher then applied this codebook to the full dataset, while the second researcher cross-checked a purposive subset of transcripts to verify consistency in code application. Any remaining disagreements were resolved by revisiting the raw data and clarifying code definitions. This multi-step process, together with an audit trail of coding memos, was designed to enhance credibility and dependability in line with COREQ guidelines. Discrepancies were resolved through adjudicative dialogue before finalizing the codebook. A code–recode procedure, re-coding a random subset 3 weeks later, verified the stability of our analytic framework.

Table 11 presents a hierarchical overview of all 63 codes, 21 subthemes, and the seven overarching themes, along with exemplar in-vivo quotations. For full transparency, Appendix Table C includes a frequency ledger detailing segment and interview counts per code, and Appendix Table D provides the original list of 148 open codes generated during the initial coding process. This rigorous, multi-layered approach provides a rich and credible narrative of how situational cues and moral motivations converge to shape ethical consumption decisions.

4.2.3 Participant narratives and theoretical reflections

The following section weaves together two complementary strands: (i) the voices of participants, presented through carefully curated verbatim excerpts, and (ii) theoretical reflections that situate those voices within the study’s S-O-R framework. We first introduce a concise thematic synopsis for each of the seven analytic themes, then illustrate its texture with one to three emblematic quotations (P01, P02, … P22). Quotations were selected based on representativeness and rhetorical clarity; ellipses indicate minor linguistic smoothing that does not alter meaning.

Immediately after each quotation set, we articulate how the expressed reasoning, affect, or behavioral intent aligns with—or nuances—the quantitative path estimates. Where relevant, we highlight tensions (e.g., price-conscious trade-offs) that complicate the straightforward stimulus–response logic, thereby enriching the explanatory power of the S-O-R model. We maintain analytic transparency by clearly indicating the sub-theme and code from which each excerpt was derived.

4.2.3.1 Theme 1—ethical spark: rapid moral triggers

A pronounced pattern emerged in 18 of the 22 interviews: participants described the CF logo as an immediate, almost reflexive “ethical spark” that obviated the need for lengthy deliberation. Rather than weighing ingredient lists or sourcing claims, they reported a near-instant effective jolt—equal parts empathy for lab animals and relief at making a “morally safe” choice. This rapid appraisal framed the logo as a visual heuristic that collapses complex ethical reasoning into a single cue, consistent with S-O-R logic in which a high-salience stimulus directly activates organism-level AM and EC. Notably, respondents characterized the process as bodily (“gut-punch,” “flash of guilt”) and temporally compressed (“it all happens in seconds”), suggesting that the label functions less as informational text and more as an emotional trigger capable of overriding habitual brand or price considerations.

P16 “Funny how one tiny logo and suddenly the rest of the aisle looks guilty.”

P03 “The moment I see that little bunny stamp, something fires—like, click, that’s the decent choice.”

P14 “I’m in a hurry, but the cruelty-free logo gives me a quick green light; I do not even compare brands.”

P07: “It’s almost a gut-punch—thinking of lab animals gets me to put the other shampoo back, instantly.”

P11 “My brain runs a tiny checklist: ‘bunny? yes; price okay? yes; done.’ It all happens in seconds.”

P19 “If the packaging does not show cruelty-free, I feel a flash of guilt—like I’m funding pain—so I switch.”

These narratives confirm that the CF logo operates as a high-salience stimulus, capable of embedding itself into routine shopping scripts—a “tiny checklist” that can override price considerations and brand loyalties. This qualitative insight aligns seamlessly with the PLS-SEM results, which showed that the presence of a CF label exerted the most substantial total effect on purchase intention—even when controlling PF and influencer advocacy. These findings illustrate how rapid moral triggers translate directly into behavior within the S–O–R framework.

4.2.3.2 Theme 2—parasocial guidance: moral affiliation with influencers

A recurrent strand in 15 of the 22 interviews was the way participants borrow moral certainty from social media figures they follow. The influencer’s stance on animal testing functions as a “trust proxy”: if the creator frames a product as CF and visibly lives by that ethic, followers feel authorized to adopt the same choice with minimal further scrutiny. In S-O-R terms, influencer advocacy amplifies the Stimulus layer. It grafts parasocial intimacy onto AM in the Organism layer, effectively outsourcing part of the consumer’s ethical due diligence.

P04 “I’ve watched her for years; she shows every step of her routine, right down to the recycling bin. When she says, ‘I switched to this bunny-label brand because no animal suffered,’ I feel like the hard research is already done for me. It’s weirdly comforting—almost like having a friend who’s the diligent one in the group project.”

P10 “If my favorite tech reviewer can dig into GPU specs, I assume she’s dug into cruelty-free claims too. Her stamp of approval is enough.”

P01 “Seeing an influencer donate part of the ad revenue to animal shelters makes me believe the brand must be legit—I buy without hunting for certificates.”

These accounts underscore how parasocial bonds collapse epistemic distance: followers treat an influencer’s endorsement as vicarious due-diligence, elevating influencer advocacy from mere marketing stimulus to a moral shortcut embedded in everyday routines.

P12 “I do not have time to read every ingredients list… When he shows his cruelty-free ‘before and after’ on TikTok, it feels personal—I’ve seen him cry over rescue dogs. That sincerity spills over to the products he backs.”

P21 “If the creator is transparent about sponsorship and still says, ‘No animals harmed,’ I click ‘Add to cart’ out of respect for that honesty.”

Emotional authenticity—displayed through rescue-dog stories or transparent sponsorship—creates a moral halo that fast-tracks followers toward CF purchases.

P18 “Honestly, I trust her more than the logo. She showed footage of writing to the company’s lab asking for testing records, and posted the reply. After that, I thought, ‘If she’s satisfied, so am I.’”

A single vivid case demonstrates how an influencer’s investigative labour supplants the consumer’s own fact-finding, embedding moral affiliation directly into the parasocial bond.

Across all versions, the narratives converge on a common mechanism: influencer credibility serves as a moral accelerant, situating CF purchasing within a trusted interpersonal script rather than a detached cost–benefit analysis or abstract certification check. This qualitative insight complements the quantitative result that influencer advocacy exerts a positive indirect effect on purchase intention via heightened AM.

4.2.3.3 Theme 3 – fair price vs. clear conscience: negotiating the price–altruism trade-off

A cost–morality tension appeared in 17 of the 22 interviews. Participants welcomed the idea of paying “a little extra” for CF assurance yet recoiled when the differential felt punitive. The logo thus triggered an inner calculation in which altruistic intent jostled with perceived PF. In S-O-R terms, the stimulus (price tag) can dampen or amplify organism-level motivation depending on whether it is interpreted as a fair sacrifice or exploitative mark-up.

P05 “Five, maybe ten lira more? Fine—I treat it like a tip for the rabbits. But when the gap jumps to fifty, I start wondering if the brand is just cashing in on my conscience.”

P09 “Cruelty-free should mean ethical all round. If they hike the price beyond reach, the ethic feels half-baked.”

P20 “I set myself a rule: if the CF version is under 15% dearer, I’ll switch. over that, I wait for a promotion.”

These quotes reveal a personal fairness threshold: consumers translate their moral willingness-to-pay into concrete cut-offs (e.g., 15%). When the differential exceeds that threshold, AM gives way to scepticism about the brand’s true intentions.

The price cue flips from moral premium to moral surcharge once transparency falters, underscoring how PF and CSR signaling intertwined:

P02 “I was happy paying extra until I discovered the same product cheaper abroad……… It felt like they were monetising my empathy, so I reverted to my old brand until prices levelled.”

P17 “If the mark-up funds genuine cruelty-free research, great. But brands rarely show the breakdown, so I assume profit motive.”

A single poignant admission captures how economic realities can override moral intent, emphasising that AM is necessary but not sufficient for CF adoption when structural affordability is in question.