Abstract

Introduction:

Camouflaging behaviors in women have been associated with mental health outcomes, like anxiety and suicidality but the mechanisms underlying these relationships remain unclear. This study aimed to examine the relationship between autism, camouflaging and anxiety with suicidal ideation and to investigate the possible mediating role of anxiety in the relationship between camouflaging and suicidal ideation in women.

Methods:

Four hundred and seventy-one women (72 autistic, aged 18–64 years, and 399 non-autistic, aged 18–66 years) participated in this study. The Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q), the General Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) and item 9 of the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) were used to assess camouflaging, anxiety and suicidal ideation, respectively.

Results:

The results showed that autistic women scored higher than non-autistic women on all measures. In addition, anxiety, having a depression diagnosis and the assimilation strategy were significantly associated with suicidal ideation. Furthermore, anxiety mediated the relationship between autism diagnosis and camouflaging with suicidal ideation.

Discussion:

The results highlight the importance of considering anxiety in the relationship between camouflaging and suicidal ideation, particularly among autistic women, and to recognise it as a target for intervention approaches aimed at reducing the likelihood of suicidal ideation.

1 Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by differences in communication and interaction with other people, and by restricted interests and repetitive behaviours that affect functioning in different areas of life (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). Autism is more often diagnosed in boys (Cruz et al., 2024), with possible gender differences in the phenotype of autism contributing to girls being diagnosed later or underdiagnosed (Loomes et al., 2017).

Indeed, a ‘female autism phenotype’ has been proposed, positing that the presentation of autistic women is qualitatively different from the typical presentation of men (Hull et al., 2017), contributing to the diagnostic imbalance between boys and girls (Cruz et al., 2024; Hull et al., 2020). Research still holds the hypothesis toward a male-centered vision of autism that lacks to consider internalizing symptoms, which are more commonly seen in autistic women, potentially leading to misdiagnosis (Beggiato et al., 2017; Cruz et al., 2024; Mao et al., 2024). Autistic women are also associated with increased camouflaging, i.e., the use of social strategies to decrease the visibility of their autistic characteristics to fit in social contexts (Hull et al., 2020). Thus, camouflaging is hypothesized as a contributor to women having higher mental health challenges (e.g., anxiety and depression), compared to non-autistic women with mental health conditions (Dubreucq and Dubreucq, 2021). Moreover, autistic women appear to be at more risk of suicidal ideation (i.e., thoughts of self-harm or of ending one’s life) and suicide history relative to men (Dubreucq J. et al., 2023; Dubreucq M. et al., 2023; Harmer et al., 2024; Newell et al., 2023).

However, more research is needed to understand the interplay between autism, camouflaging, anxiety, and suicidal ideation in women, as these associations remain understudied. In line with this, recent research has highlighted the importance of clarifying the relationship between camouflaging and suicidal thoughts and behaviours, with a particular focus on examining potential mediators of this relationship (Arqueros et al., 2025). Understanding factors associated with suicidal ideation is essential for the development of targeted intervention approaches to reduce suicidal thoughts or behaviours and improve quality of life in this population (Harmer et al., 2024).

1.1 Gender, mental health, and autism in women

Gender is a complex concept that involves psychosocial and cultural aspects and is influenced by social practices, norms, and expectations of others (World Health Organization, 2014). Gender has a significant impact on mental health, with women being particularly vulnerable to mental health problems, especially internalising disorders (e.g., anxiety or depression), in part due to exposure to social (e.g., discrimination), economic (e.g., poverty) and environmental (e.g., inequalities) stressors (Baños and Miragall, 2024; Seedat et al., 2009). Compared to men, women are at higher risk of suicidal ideation, with distinct gender-specific risk factors, such as mental illness or feelings of hopelessness, playing an important role (Shelef, 2021).

These gender-related aspects are also relevant when considering autism in women. Although women have similar core autistic traits to men, they are often misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed in part because their behavioural expression of autism, although similar to the underlying characteristics described in the diagnostic criteria, may differ from the traditional male expression, with less obvious social impairments (Belcher et al., 2023; Kopp and Gillberg, 1992). This may relate to the fact that women typically exhibit more social behaviours than autistic men (Dubreucq and Dubreucq, 2021), which may be explained by gendered social norms or expectations regarding women (Tubío-Fungueiriño et al., 2021). Women’s presentation of autism therefore differs from the typical male presentation in that autistic characteristics may be expressed differently from the traditional criteria. For example, compared to autistic men, autistic women have higher levels of social motivation (e.g., having friendships with others) (Head et al., 2014; Sedgewick et al., 2016), and differences in the profile of restricted and/or repetitive behaviours and focused interests, or their interests may be more in accordance with their age (i.e., more focused on relational aspects) (Allely, 2019).

The fact that autistic women seem to have more social communication/interaction abilities (described as narrow constructs, such as social attention), may be associated with their ability to camouflaging their autistic traits to fit into social environments (Wood-Downie et al., 2021). Camouflaging refers to using social strategies to minimise the visibility of autism or autistic traits to facilitate social integration and peer acceptance (Hull et al., 2020; Lai and Baron-Cohen, 2015; Tubío-Fungueiriño et al., 2021). Camouflaging strategies include assimilation, i.e., the adoption of observed attitudes and/or behaviours to fit into social situations; compensation, i.e., the performance of behaviours to overcome social difficulties associated with autistic traits; and masking, i.e., the concealment/hiding of autistic traits (Hull et al., 2020). Autistic girls identify and learn social behaviours from others (for example, facial expressions, or making eye contact) that are considered ‘appropriate’ behaviours, which are then reinforced by social expectations, increasing their expression (Lai et al., 2017).

However, camouflaging has important psychological consequences for autistic women, as it has been associated with higher anxiety and lower mental wellbeing (Conde-Pumpido Zubizarreta et al., 2025c; Khudiakova et al., 2024) and linked to an increased risk of suicidal ideation (Cassidy et al., 2020). These relationships are partly explained by the fact that efforts to suppress or hide autistic traits require significant cognitive and emotional resources, which may, in effect, contribute to increased levels of internalising disorders (i.e., anxiety and depression) (Hull et al., 2017).

1.2 Suicidal ideation, autism, camouflaging, and anxiety in women

Suicidal ideation refers to thinking about or planning to commit suicide and is closely associated with suicide attempts and deaths and is considered as a significant risk factor for future suicidal behaviours (Harmer et al., 2024). Compared to non-autistic individuals, autistic people are at greater risk, as rates of suicidal ideation in autistic adults are significantly higher than in the general population (Hirvikoski et al., 2020). Within autistic adults, women appear to be a particularly vulnerable group as they show elevated risk factors for suicidal ideation (i.e., thoughts and behaviours) compared with autistic men. One survey reported that 74.3% of autistic adults experienced suicidal ideation in the past year, with male sex linked to lower ideation (Moseley et al., 2022). A systematic review shows a pooled prevalence of 34.2% for suicidal ideation and supported previous evidence that suicidality is more prevalent in autistic women than men (Newell et al., 2023).

Recent research suggests that camouflaging is associated with increased suicidal ideation (Cassidy et al., 2023). A study of 58 adult women, who scored high on broad autistic traits found that camouflaging moderately predicted psychological distress and functional challenges (Beck et al., 2020). Another study of 160 undergraduate students (86.9% of whom were women), showed that camouflaging autistic traits was associated with a higher risk of experiencing thwarted belonging and lifetime suicidality (Cassidy et al., 2020).

However, the mechanism linking camouflaging and suicidal ideation is not yet clear. One possible explanation for this association is that camouflaging is strongly associated with greater symptoms of anxiety (Hull et al., 2021; Khudiakova et al., 2024), which in turn are strongly associated with increased suicidal ideation (Doering et al., 2024). Thus, the relationship between camouflaging and suicidal ideation may be mediated by anxiety. Camouflaging is often reported to be exhausting and stressful (Conde-Pumpido Zubizarreta et al., 2025a; Hull et al., 2017; Tierney et al., 2016), which can lead to feelings of being misunderstood or overlooked (Cage et al., 2018). Camouflaging is related to autistic burnout, as is shown by Benatov et al. (2025) that found that that autistic burnout may be a partial mediator between self-reported camouflaging behaviours and depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9, Kroenke et al., 2001).

As autistic women are more likely than autistic men to use camouflaging strategies (Hull et al., 2017; Milner et al., 2023), and as they report higher rates of anxiety (Somerville et al., 2024), it is possible that autistic women are at increased risk of higher levels of anxiety and suicidal ideation, which may partly explain the increased psychological distress observed in this group. It is therefore important to clarify the mediating role of anxiety in the relationship between camouflaging and suicidal ideation in women. Clarifying these relationships will help to inform intervention programmes and gender-sensitive approaches.

1.3 Current study

Given that women often report higher rates of anxiety and depression, and that autistic women are at greater risk for mental health problems and more likely to use camouflaging, it is important to clarify the relationships between autism, camouflaging, anxiety and suicidal ideation in autistic and non-autistic women. The aim of this study is twofold: (i) to examine the contribution of autism diagnosis, camouflaging and anxiety to suicidal ideation, and (ii) to investigate the mediating role of anxiety in the relationship between camouflaging and suicidal ideation in women. Therefore, the present study includes both autistic and non-autistic women as a comparison group because we hypothesise that autistic women will report higher levels of camouflaging, anxiety, and suicidal ideation than non-autistic women. Furthermore, we expect that a diagnosis of autism, camouflaging and anxiety will be significantly and positively associated with suicidal ideation. We also expect anxiety to significantly mediate the association between camouflaging and suicidal ideation in autistic women.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

A total of 471 women, 461 Spanish and 10 of other nationalities but living in Spain, participated in this study. Of these, 72 were autistic, aged 18–64 years (M = 36.06; SD = 10.79), and 399 were non-autistic, aged 18–66 years (M = 34.14; SD = 11.08). Table 1 provides detailed information on the participants’ level of education and co-occurring mental conditions.

Table 1

| Educational level/clinical conditions | Autistic | Non-autistic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Level of education | ||||

| No studies | – | – | 1 | 0.3 |

| Elementary education | – | – | 2 | 0.5 |

| Secondary education | 6 | 8.3 | 33 | 8.3 |

| Degree | 46 | 63.9 | 264 | 66.2 |

| PhD | 3 | 4.2 | 56 | 14 |

| Higher vocational training | 5 | 6.9 | 15 | 3.8 |

| Vocational training | 12 | 16.7 | 28 | 7 |

| Self-reported clinical conditions | ||||

| High abilities | 23 | 31.9 | 17 | 4.3 |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 17 | 23.6 | 15 | 3.8 |

| Developmental coordination disorder | 1 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Specific learning disorder | 6 | 8.3 | 5 | 1.3 |

| Epilepsy | 0 | - | 1 | 0.3 |

| Bipolar disorder | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | – |

| Eating disorder | 9 | 12.5 | 24 | 6 |

| Anxiety | 39 | 54.2 | 76 | 19 |

| Depression | 24 | 33.3 | 49 | 12.3 |

| Sleeping disorder | 15 | 20.8 | 18 | 4.5 |

| Other | 11 | 15.3 | 9 | 2.3 |

Level of education and self-reported clinical conditions for the autistic and non-autistic groups.

Inclusion criteria for both groups were age 18 years or older, Spanish nationality or residence in Spain, and capacity to consent and complete the self-report measures. For the autistic group, inclusion criteria also included having a formal diagnosis of autism (conducted by a health professional, such as psychiatrist or psychologist). Of note, the mean age of diagnosis of the participants was 32.88 years (age range = 6–58), with three women (4.2%) diagnosed before the age of 10, five (6.9%) between the ages of 13 and 19, 21 (29.2%) between the ages of 20 and 29, 22 (30.5%) between the ages of 30 and 39, and 21 (29.2%) between the ages of 40 and 58. Those who were suspected of having an ASD diagnosis but had not received a formal diagnosis were not included in this study.

2.2 Measures of dimensions assessed

2.2.1 Sociodemographic information

Participants completed a sociodemographic questionnaire to collect information on gender, age, nationality, level of education, mental health (i.e., self-reported clinical conditions), and diagnosis of autism.

2.2.2 Suicidal ideation

To assess suicidal ideation, we used the item 9 (‘Thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself’) of the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9), Spanish version (Diez-Quevedo et al., 2001). This is a clinically validated screening tool used to assess and monitor the severity of depression based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition (DSM-IV, American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria. It consists of nine items (e.g., ‘Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless’), answered on a Likert scale from 0 (‘not at all’) to 3 (‘almost every day’), which ask respondents how often they have been ‘bothered by any of the following problems’ in the last two weeks. The items cover sleep, energy, appetite and other possible symptoms of depression. The total score is calculated by adding up all the items and indicates how often a person experiences these feelings, with higher scores reflecting more severe symptoms. The PHQ-9 total score showed strong internal consistency and convergent validity in autistic and non-autistic adult samples (Arnold et al., 2020). Additionally, other studies find item 9 as a valid measure of suicidal ideation in autistic and non-autistic participants (Hedley et al., 2018; Simon et al., 2013).

In this study, we considered a score of 0 (‘not at all’) on item 9 as “absence of suicidal ideation,” and a score of 1 (‘several days’), 2 (‘more than half of the days’), or 3 (‘nearly every day’) as “presence of suicidal ideation.”

2.2.3 Anxiety

To assess anxiety symptoms, we used the General Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7), Spanish version (García-Campayo et al., 2010). GAD-7 is a widely used instrument that measures the severity of generalised anxiety disorder. It consists of seven items that measure the frequency of various anxiety symptoms over the past two weeks (e.g., ‘Worrying too much about different things’). Respondents answer each item on a Likert scale from 0 (‘not at all’) to 3 (‘nearly every day’).

The GAD-7 total score is obtained by summing up all the items and this value was used in the analysis. Higher scores indicate greater severity of anxiety symptomatology. Excellent internal consistency results were observed (α = 0.92).

2.2.4 Camouflaging

To assess camouflaging behaviours, we used the Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire, Spanish version (CAT-Q-ES) (Conde-Pumpido Zubizarreta et al., 2025b). The CAT-Q-ES is a self-report measure that assesses social camouflaging behaviours. This questionnaire consists of 25 items (e.g., ‘When I am interacting with someone, I deliberately copy their body language or facial expressions), rated on a Likert scale from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 7 (‘strongly agree’). Three subscales – compensation (i.e., imitating social behaviours), masking (i.e., suppressing natural reactions) and assimilation (i.e., using coping strategies to manage social interactions) – and a total score are obtained. Higher scores indicate a higher level of camouflaging. Excellent internal consistency results were observed for the total score (α = 0.95), and for the compensation (α = 0.93) and assimilation (α = 0.92) subscales. The masking subscale showed acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.79).

In this study, the subscales and total scores were used to test for group differences. Only the three subscales were used in the regression analysis, as they are highly correlated with the CAT-Q-ES total score, and the CAT-Q-ES total score was used in the mediation analysis.

2.3 Procedure

This study is part of a broader project aimed at validating the CAT-Q in the Spanish population (accepted for publication). Data was collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) tools hosted at Fundación Pública Galega de Medicina Xenómica (Harris et al., 2009; Harris et al., 2019). REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies, providing (1) an intuitive interface for validated data capture; (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (4) procedures for data integration and interoperability with external sources.

The research team created a survey on REDCap that was distributed through internal dissemination within autism associations, institutions, federations and clinical units, as well as autism-related research networks and social media. The survey was launched in February 2023, and the last response was received in March 2024. A total of 1,292 people participated. Of these, 709 surveys were fully competed; however, 19 of these participants had only completed the parental version of the CAT-Q-ES and were therefore excluded from this study. Although the survey requested that participants answer all questions, it was possible to proceed without responding.

The primary section of the survey provided information about the study and included an informed consent form. In this section, participants were asked about their clinical diagnosis of autism and how it was obtained (e.g., diagnosis performed by a psychologist). Autistic participants were also asked about the formal clinical diagnosis of other comorbidities associated with autism (for example, other neurodevelopmental conditions, bipolar disorder, or anxiety/depressive conditions). Non-autistic participants were asked if they had any other neurodevelopmental and/or psychiatric diagnoses.

After completing the sociodemographic questionnaire, participants proceeded to complete the other questionnaires (PHQ-9, GAD-7 and CAT-Q-ES). The completion of the survey lasted approximately 15 to 20 min.

2.4 Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using jamovi software (version 2.7, 2025) (The Jamovi Project, 2025).

As the assumption of normality was not met (Shapiro-Wilks test < 0.05 for all variables), we conducted non-parametric tests. Following the recommendations of Fife-Schaw (2006), we also computed the equivalent parametric tests, as parametric methods can remain reasonably robust with non-normal continuous data when sample size guidelines are met (e.g., two groups with more than 15 participants; Banga and Fox, 2013). Because the pattern of results was consistent across both approaches, we report the parametric test results for ease of interpretation and comparability, noting that these tests are generally robust even under moderate violations of normality.

Descriptive statistics were computed for all the measures included in this study (item 9 of the PHQ-9, GAD-7 total score), and CAT-Q-ES questionnaire – compensation, masking, and assimilation subscales – and CAT-Q-ES total score. Then, an Independent-Samples T-Test was performed to test group differences regarding all dimensions, except the Item-9 of the PHQ, in which group differences were tested using Chi-Square (χ2) test.

A logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the associations between anxiety (GAD-7), camouflaging (CAT-Q-ES compensation, masking, and assimilation subscales; the total score was not included give the high correlation with the subscales) and age on suicidal ideation, controlling for autism diagnosis and having and anxiety and/or depression diagnosis.

A mediation analysis was conducted to test the mediating role of anxiety in the relationship between camouflaging and suicidal ideation. Standard errors were calculated using nonparametric resampling via the percentile bootstrapping method, and missing data were treated using the FIML method (Dong and Peng, 2013). A path model in general linear model (GLM) mediation model (using the jAMM module for mediation models) with Maxiumum Likelihood Estimation was used to test the hypothesis of anxiety (i.e., GAD-7 total score) in the role of mediating the relationship between camouflaging (i.e., CAT-Q-ES total score) and suicidal ideation (i.e., item 9), controlling for autism and depression diagnosis (i.e., autistic or non-autistic).

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive and group difference analyses

Regarding suicidal ideation, and considering all participants, the response distribution to the item 9 of the PHQ was as follows: 0 = 318 (68%), 1 = 81 (17%), 2 = 34 (7%), 3 = 38 (8%). The skewness was 1.58 (standard error = 0.11) and the kurtosis was 1.27 (standard error = 0.22), indicating a positively skewed distribution consistent with less frequent suicidal ideation. When dichotomized (i.e., 0 = no suicidal ideation, 1 = suicidal ideation), in the autistic group, 23 (31.9%) women reported no suicidal ideation, compared to 49 (68.1%) who reported having suicidal ideation. In the non-autistic group, 295 (73.93%) women indicated no suicidal ideation, while 104 (26.07%) indicated having suicidal ideation. For the autistic group, the skewness was −0.79 (standard error = 0.28) and the kurtosis was −1.41 (standard error = 0.56), indicating a negatively skewed and relatively flat distribution, with responses clustering toward the higher end of the scale. In contrast, for the non-autistic group the skewness was 1.09 (standard error = 0.12) and the kurtosis was −0.81 (standard error = 0.24), indicating a positively skewed and relatively flat distribution, with most responses falling at the lower end of the scale.

Table 2 shows the mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) of the item 9 of the PHQ, GAD-7 total score, as well as the CAT-Q-ES – compensation, masking and assimilation subscales and total score –, for the autistic and non-autistic groups, as well as the t-test and the χ2 results. Overall, the autistic group scored statistically significantly higher on all dimensions, particularly large effects for anxiety and all CAT-Q-ES subscales (Cohen’s d = 0.82–1.58), indicating that autistic women report greater suicidal ideation, anxiety, and camouflaging strategies compared to non-autistic women (Table 2).

Table 2

| Measures | Autistic | Non-autistic | χ2 (df) or t (df) | p | Cramer’s v or Cohen’s d | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | M(SD) | Range | M(SD) | Lower | Upper | ||||

| PHQ-9 | 0–3 | 1.29 (1.16) | 0–3 | 0.43 | 49.04 (1) | <0.001 | 0.32 | ||

| GAD-7 total score | 0–21 | 14.50 (5.07) | 0–21 | 9.38 (5.62) | −7.23 (469) | <0.001 | −0.93 | −1.18 | −0.67 |

| Compensation | 12–63 | 47.24 (10.84) | 9–60 | 27.45 (12.75) | −12.38 (469) | <0.001 | −1.58 | −1.85 | −1.31 |

| Masking | 8–52 | 41.83 (6.63) | 8–56 | 34.41 (9.42) | −6.40 (469) | <0.001 | −0.82 | −1.08 | −0.56 |

| Assimilation | 15–56 | 45.74 (6.99) | 8–56 | 31.29 (12.39) | −9.61 (469) | <0.001 | −1.23 | −1.49 | −0.97 |

| CAT-Q-ES total score | 35–162 | 134.81 (19.47) | 30–161 | 93.16 (30.72) | −11.10 (469) | <0.001 | −1.42 | −1.69 | −1.25 |

Mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) values for the autistic and non-autistic women and groups differences in all variables.

3.2 Association of autism, anxiety, camouflaging, and age with suicidal ideation

A logistic regression analysis was conducted to test the associations between anxiety, camouflaging strategies (i.e., compensation, masking, and assimilation) and age with suicidal ideation, controlling for autism diagnosis and for having an anxiety and/or depression diagnosis. The model was significant, χ2 (8) = 192.64, p = <0.001, and explained 32% (McFadden R2 = 0.32) of the variability of suicidal ideation. When controlling for autism and having an anxiety and/or depression diagnosis, higher anxiety and depressive symptoms, as well as increased assimilation were statistically significantly associated with suicidal ideation. Autism diagnosis, anxiety and/or depression diagnosis, as well as compensation, masking and age were not significantly associated with suicidal ideation (Table 3).

Table 3

| Predictive variables | Coefficients | Collinearity values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | z | p | VIF | Tolerance | |

| Depression diagnosis | 1.03 | 0.35 | 2.92 | <0.05 | 1.15 | 0.87 |

| Anxiety diagnosis | 0.06 | 0.31 | 0.19 | 0.85 | 1.24 | 0.81 |

| Autism diagnosis | 0.60 | 0.37 | 1.64 | 0.10 | 1.27 | 0.79 |

| GAD-7 total score | 0.15 | 0.03 | 5.65 | <0.001 | 1.19 | 0.84 |

| Compensation | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.22 | 0.83 | 2.52 | 0.40 |

| Masking | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.47 | 0.64 | 1.88 | 0.53 |

| Assimilation | 0.07 | 0.02 | 4.55 | <0.001 | 1.84 | 0.54 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | −1.30 | 0.19 | 1.04 | 0.96 |

Unstandardized beta, z, and p values of the predictive variables of suicidal ideation.

SE = standard error; VIF = variance inflation factor.

3.3 Mediating role of anxiety in the relationship between camouflaging and suicidal ideation

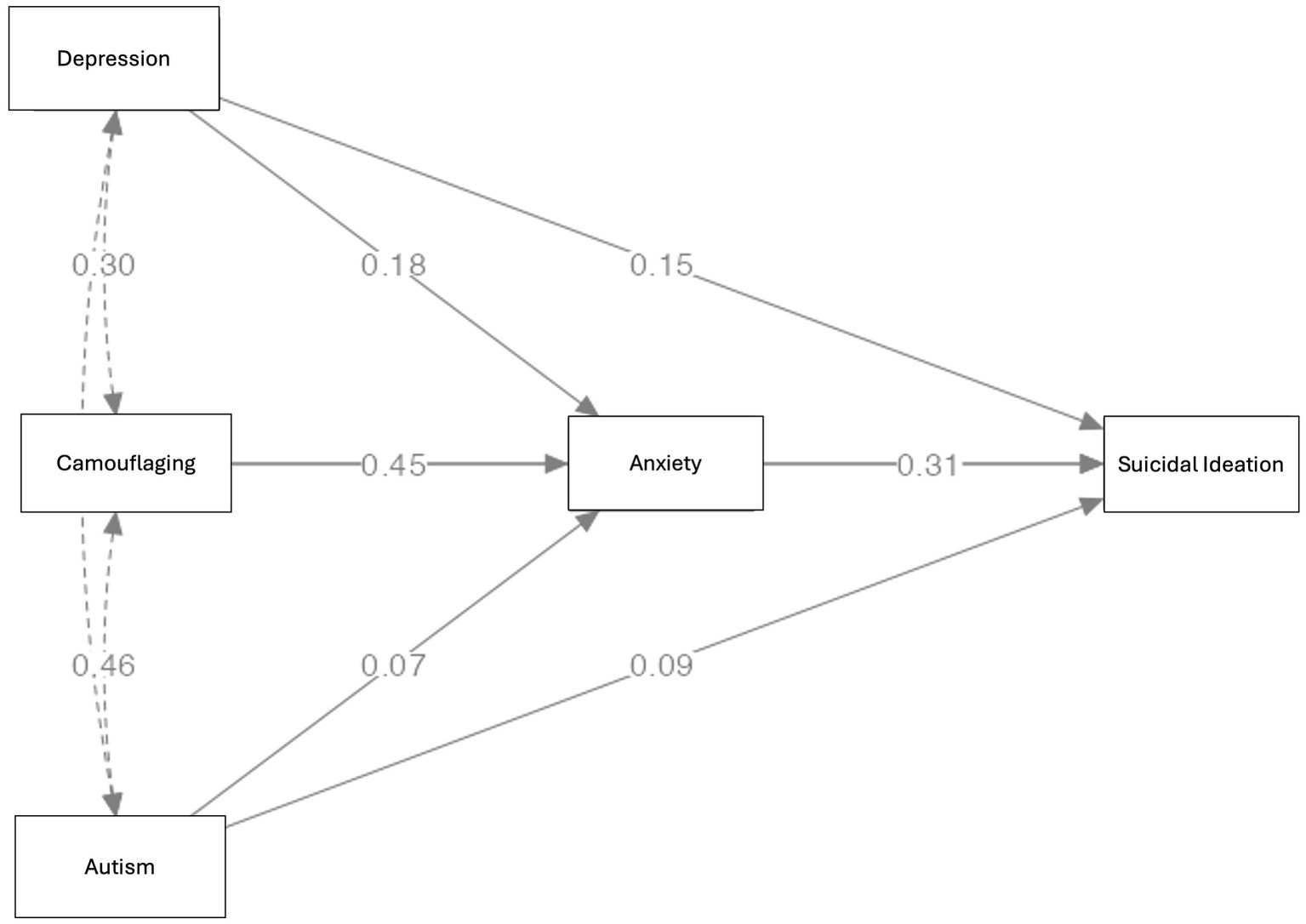

A mediation analysis was conducted to examine whether the statistical association between camouflaging and suicidal ideation was indirectly explained by anxiety, controlling for autism and depression diagnosis. The results are depicted in Figure 1 and Table 4. Positive and statistically significant indirect effects were observed, consistent with the hypothesis that anxiety accounted for part of the association between camouflaging and suicidal ideation (β = 0.14, p < 0.001). Specifically, we observed a positive and statistically significant association between anxiety and suicidal ideation (β = 0.31, p < 0.001), camouflaging and anxiety (β = 0.45, p < 0.001) and between depression diagnosis and anxiety (β = 0.18, p < 0.001). A statistically significant positive direct effect was found between autism and suicidal ideation (β = 0.10, p = 0.02) in the mediation analyses.

Figure 1

Mediation role of anxiety in the relationship between autism, camouflaging and suicidal ideation.

Table 4

| Effect | Estimate | SE | 95% C. I. | β | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| (indirect) Autism → anxiety → suicidal ideation | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 1.63 | 0.10 |

| (indirect) Camouflaging → anxiety → suicidal ideation | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 5.64 | <0.001 |

| (indirect) Depression diagnosis → anxiety → suicidal ideation | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 3.77 | <0.001 |

| Autism → anxiety | 1.15 | 0.69 | −0.20 | 2.50 | 0.07 | 1.67 | 0.09 |

| Anxiety → suicidal ideation | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.31 | 6.71 | <0.001 |

| Camouflaging → anxiety | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.45 | 10.41 | <0.001 |

| Depression diagnosis anxiety | 2.91 | 0.64 | 1.66 | 4.17 | 0.18 | 4.55 | <0.001 |

| (direct) Autism → suicidal ideation | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 2.22 | 0.03 |

| (direct) Camouflaging → suicidal ideation | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 4.54 | <0.001 |

| (direct) Depression diagnosis → suicidal ideation | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 3.82 | <0.001 |

| (total) Autism → suicidal ideation | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.12 | 2.62 | 0.01 |

| (total) Camouflaging → suicidal ideation | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.36 | 7.87 | <0.001 |

| (total) Depression diagnosis → suicidal ideation | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0.21 | 5.07 | <0.001 |

The mediating role of anxiety in the relationship between camouflaging and suicidal ideation.

Models were analyzed using 95% bootstrap (percentiles) confidence intervals (CI). Betas are completely standardised effect sizes.

4 Discussion

Women are a particularly vulnerable group to mental health problems, and autistic women are at even greater risk, as camouflaging may be an additional burden on top of increased mental health problems such as anxiety and suicidal ideation. However, relationships between autism, anxiety, and camouflaging remain poorly studied, so their contribution to suicidal ideation in women is far from clear. Therefore, this study aimed (i) to examine the contribution of autism, camouflaging and anxiety to suicidal ideation, and (ii) to investigate the mediating role of anxiety in the relationship between camouflaging and suicidal ideation.

4.1 Group differences in camouflaging, anxiety and suicidal ideation

As expected, autistic women reported using more camouflaging strategies than non-autistic women. This is in line with other evidence showing that autistic adults or adults who report having high autistic traits use more camouflaging strategies, particularly women (Cook et al., 2021). Autistic women often use camouflaging as a coping mechanism to conceal their autistic traits to facilitate their adjustment to social environments and be accepted by peers (Tubío-Fungueiriño et al., 2021). Thus, our findings are consistent with other literature suggesting that autistic women tend to use more camouflaging to display behaviours that are considered more ‘appropriate’, perhaps to be accepted in social settings (Lai et al., 2017).

However, little evidence exists on how autistic and non-autistic women differ in using camouflaging. To the best of our knowledge, only one study has reported on the use of camouflaging comparing autistic and non-autistic women and no group differences were found (Hull et al., 2020). Thus, our findings contribute to the existing literature on camouflaging gender differences by showing that autistic women camouflage more compared to non-autistic women, but camouflaging differences in autistic and non-autistic women need further investigation. It is therefore important that future studies address this issue, as more evidence is needed to better understand possible camouflaging differences between neurodivergent and non-autistic women.

Similarly, autistic women reported more suicidal ideation as well as more anxiety and depression symptoms than non-autistic women. The present findings are consistent with previous evidence indicating that autistic people are at elevated risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviours compared to non-autistic people (Brown et al., 2024; Kirby et al., 2024; Newell et al., 2023) being autistic women at higher risk of internalizing disorders than autistic men (Green et al., 2019). The present findings also support the hypothesis that autistic women may be more vulnerable to internalising symptoms and psychiatric conditions due to their position as a doubly minoritised population (Grzeszak and Pisula, 2025). Several social factors may exacerbate this vulnerability, including adverse workplace experiences and job instability (Hayward et al., 2018), as well as various forms of victimization. These include bullying related to not conforming to gender norms, and relational and sexual violence, which have been associated with anxiety symptoms in autistic girls compared to boys (Cazalis et al., 2022; Greenlee et al., 2020). Other relevant social factors include internalised stigma for not conforming to social norms (Wilson et al., 2023), gender roles, feelings of being an “impostor” following diagnosis (Harmens et al., 2022) and camouflaging. The latter has been linked to an emotional burden, stigma, identity loss, and a lack of support (Jones et al., 2025). These experiences may contribute to an increase in internalising symptoms and then associated with a higher risk of suicidal ideation. Clinicians should explore the impact of social pressures, particularly those related to gender expectations and female stereotypes, on autistic women’s histories of victimisation and internalised stigma, and how these factors contribute to an increased risk of suicidal ideation.

4.2 Variables associated with suicidal ideation

As expected, our results showed that, when we consider the autism diagnosis and anxiety and depression diagnoses, anxiety and depressive symptoms and assimilation were associated with increased suicidal ideation. The present results suggest that suicidal ideation may be partly explained by internalising symptoms and the camouflaging strategy of assimilation. Once the co-occurrence of anxiety and depression conditions is controlled, the diagnosis of autism itself does not increase suicidal ideation.

In addition, higher anxiety levels were associated with increased suicidal ideation, which is in accordance with a large body of evidence suggesting that mental health problems, particularly anxiety, are strongly associated with increased suicidal thoughts or behaviours, making it a potential risk factor for suicidal ideation (Bentley et al., 2016; Nepon et al., 2010). The present results suggest that autistic and non-autistic women who tend to report higher internalising symptoms may be at greater risk for thinking about or planning to commit suicide.

Camouflaging was also associated with suicidal ideation, consistent with other evidence suggesting that camouflaging is linked to mental health outcomes (Beck et al., 2020; Cook et al., 2021; Somerville et al., 2024). However, our results showed that only assimilation strategies were associated with suicidal ideation. Assimilation refers to the adoption of observed attitudes and/or behaviours of others to fit into social environments (Hull et al., 2020), which may reflect women’s motivation to be accepted by others by meeting societal expectations (Hull et al., 2017). This may involve additional mental effort, placing greater psychological demands on women and being asssociated with increased suicidal ideation. Indeed, evidence shows that assimilation is associated with greater feelings of loneliness and emotional distress (Hull et al., 2017) and lower psychological well-being (Perry et al., 2022), which may be related to increased suicidal thoughts and behaviours. Some aspects of camouflaging behaviours are shared across neurotypes, and practitioners should consider underlying trauma and stigma experiences that may have led to the development of these social coping strategies in autistic and non-autistic women (Ai et al., 2022; Miller et al., 2021).

The lack of an additional effect of an autism diagnosis on suicidal ideation when considering anxiety and depressive disorders supports the evidence showing that women are a vulnerable group and at higher risk for internalizing symptoms, regardless of diagnosis (Asher et al., 2017; McLean et al., 2011). The literature suggests that several factors may contribute to women’s increased vulnerability to internalising disorders, including psychological factors, such as gender role expectations (i.e., femininity or female stereotypes), low self-esteem, problems in interpersonal relationships (Farhane-Medina et al., 2022), or increased exposure to social (e.g., discrimination), economic (e.g., poverty) and environmental (e.g., inequalities) stressors (Baños and Miragall, 2024; Seedat et al., 2009).

In addition, these findings emphasise the link between internalising symptoms and suicidal thoughts and behaviours, particularly among autistic women. Miranda-Mendizabal et al. (2019) identified depression as a risk factor for suicide attempts in women, particularly during adolescence and young adulthood. Doering et al. (2024) found that individuals with anxiety symptoms close to the time of suicide were more likely to be women, and that anxiety was more common among younger adults than older adults. As autistic women are at an increased risk of experiencing different types of victimisation and stigma than non-autistic women, these factors may potentially exacerbate anxiety and depressive symptoms, thereby contributing to the development of suicidal thoughts and behaviours more than an autism diagnosis itself.

Suicidal ideation has been proposed as an avoidance or decision-making bias to escape painful emotions (Millner et al., 2019). Therefore, our findings suggest that it is possible that women that have higher levels of anxiety and depression and use more assimilation strategies may experience greater psychological distress, and that suicidal ideation may be a potential avoidant strategy to cope with this distress. The present results highlight the need to address internalising symptoms, as well as socio-emotional motivations and coping strategies, in psychological interventions with women. However, it is necessary to determine the strength of this empirical information, and therefore future studies exploring these relationships are needed.

4.3 The mediating role of anxiety

Our results showed that anxiety helped explain part of the relationship between camouflaging and suicidal ideation. As expected, we found those who camouflage more tend to report increased anxiety which may, in this context, relate to greater suicidal ideation. Thus, this result suggests that the association between camouflaging and suicidal ideation may be partly explained by increased anxiety underlying this association, and this is particularly relevant for autistic women.

Research shows that camouflaging autistic traits is associated with increased anxiety in women, who often report that using such strategies is exhausting and stressful, as it requires significant cognitive and emotional resources (Hull et al., 2017; Tierney et al., 2016). These increased anxiety levels may be related to greater social isolation, reduced quality of life and altered functioning outcomes (Bentley et al., 2016). Such difficulties may contribute to autistic women feeling misunderstood or overlooked, which in turn has been associated with more suicidal thoughts and behaviours (Cage et al., 2018). This is consistent with other evidence suggesting that camouflaging may be an anxiety-related experience, associated with poorer mental health. For example, a mixed-methods systematic review of 4,808 autistic people (the majority of whom were white, female sex, and late-diagnosed autistic adults) found that camouflaging is related to social pressure from non-autistic people, the need for social acceptance and self-esteem (the need to fit in and belong), but at a great cost to their well-being, including increased anxiety (Zhuang et al., 2023). Accordingly, camouflaging appears to be associated with increased feelings of anxiety, which may thereby be linked to feelings of being overlooked, unsupported and burnout, negatively impacting on social relationships and identity, and potentially contributing to increased suicidal ideation.

Notably, anxiety also accounted for part of the relationship between a depression diagnosis and suicidal ideation, but not between autism diagnosis and suicidal ideation. The finding that anxiety levels partly explain the risk of suicidal ideation in people with a depression diagnosis is consistent with the high co-occurrence of anxiety and depression disorders, as well as their combined effect on suicidality (Sanches et al., 2022). The present study suggests that suicidal ideation in autistic women may not be directly related to their diagnosis, but rather to the high prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms and diagnoses. These results indicate a complex interplay of factors. Being a woman is associated with a higher risk of anxiety and depression, both of which are independently linked to suicidal ideation. In particular, autistic women are at greater risk of victimisation, which can lead to a range of internalising symptoms and elevated suicidal ideation compared to non-autistic women. Finally, camouflaging, which is associated with stigma and an emotional burden, appears to be relevant for both autistic and non-autistic women. Overall, these findings highlight the importance of considering potential factors underlying camouflaging in autistic women. Importantly, it shows that anxiety may be an important aspect to consider in the relationship between camouflaging and suicidal ideation and to target in gender-sensitive psychological intervention approaches.

4.4 Limitations and future studies

This study has some limitations. Firstly, our sample is imbalanced in terms of autism diagnosis status because the group of autistic women was smaller than the non-autistic group. Therefore, to replicate these results, future studies should examine the link between autism diagnosis, camouflaging and suicidal ideation in a larger and heterogeneous group of participants. Additionally, participants were recruited and invited to take part in this study online. Online studies may be biased toward people with a particular interest in the topic (such as women with late-diagnosed autism), higher cognitive ability and higher levels of education. Bjelland et al. (2008) reported that adults aged 20 years and above with a higher educational level experienced fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression, suggesting an accumulating protective effect of education throughout life. However, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis (Chi et al., 2023) highlighted a high risk of anxiety disorder among postgraduate students without significant differences between pre- and post-COVID. Although age was not significantly associated with suicidal ideation in this study, evidence suggests an interaction between age, education, and anxiety that should be considered in future studies. Therefore, the generalisation of these results to women with lower educational levels or intellectual disabilities is limited. Although the PHQ-9 item 9 may indicate suicidal ideation in autistic and non-autistic groups, relying solely on this item has several limitations. Firstly, it has not been specifically validated in autistic adults. Secondly, it conflates passive suicidal ideation with risk of self-harm. Thirdly, it only considers frequency, leaving aspects such as intensity, planning, and impulse control unassessed. Furthermore, Na et al. (2018) observed that the PHQ-9 suicide item exhibited poor validity when compared to the gold standard definition of suicidal ideation, and that it must be used in conjunction with a suicide-specific measure. Another limitation of this work is that it does not include overall depressive symptoms, due to their substantial overlap with the suicidal ideation measure. In addition, this study only considered symptoms of generalised anxiety and did not measure symptoms of other anxiety disorders, such as social anxiety, which has also been linked to camouflaging (Hull et al., 2021). Future studies should assess depressive symptoms and other internalising disorders (e.g., social anxiety) with standardised measures to clarify their role in the relationship between camouflaging and suicidal ideation. In view of the absence of suicide-specific measures that have been validated in Spanish autistic individuals, the development of new measures would be a significant step toward a better understanding suicidality in Spanish autistic women.

4.5 Conclusion

This study highlights the complex interplay between autism, camouflaging, anxiety, and suicidal ideation in women and reinforces the importance of considering anxiety as a mechanism contributing to the association between camouflaging and suicidal ideation, especially in autistic women. Additionally, the present work suggests that a greater risk of co-occurring internalising disorders explained suicidal ideation better than autism diagnosis itself in women. However, more research is needed to clearly understand possible factors underlying suicidal ideation in this group, particularly in autistic women. A clear understanding of these factors is crucial for the design of sensitive and targeted interventions and preventive approaches. Although our study highlights the important relationships between camouflaging, anxiety and suicidal ideation in autistic women. Studies of gender differences must help to understand and address the increased risk of suicidal ideation, behaviour and death in autistic and non-autistic people across genders.

4.6 Community involvement

The recruitment process for this study was supported by the dissemination of the survey through autism associations, institutions, federations, clinical units, autism-related research networks, and social media. Additionally, autistic individuals contributed to the cultural adaptation of the Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q-ES) to the Spanish context, ensuring its relevance and appropriateness for the target population.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to montse.fernandez.prieto@usc.es.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Santiago de Compostela (Protocol: USC 26/2023). All participants accepted the participation. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants, as per institutional requirements.

Author contributions

SC-PZ: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. SC: Formal analysis, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MPR: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. JSR: Software, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. ADH: Writing – review & editing. AC: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Project administration. MTF: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology, Data curation. MFP: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Investigation, Project administration, Conceptualization, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by Fundación María José Jove. This investigation has received financial support from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI22/00208). SC-PZ and MPR were supported by a predoctoral fellowship by Xunta de Galicia. SC is supported by national funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P., under the R&D Unit: UID/04810/2025 – William James Centre for Research. Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Spain) (PI22/00025). Xunta de Galicia (Programa de Consolidación y Estructuración de Unidades de Investigación Competitivas) GAIN (GRC- IN607A2025/01).

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants for their participation in this study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Ai W. Cunningham W. A. Lai M.-C. (2022). Reconsidering autistic ‘camouflaging’ as transactional impression management. Trends Cogn. Sci.26, 631–645. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2022.05.002,

2

Allely C. (2019). Exploring the female autism phenotype of repetitive behaviours and restricted interests (RBRIs): a systematic PRISMA review. Adv. Autism5, 171–186. doi: 10.1108/AIA-09-2018-0030

3

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th Edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

4

American Psychiatric Association 2022 Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5th ed., Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing

5

Arnold S. R. C. Uljarević M. Hwang Y. I. Richdale A. L. Trollor J. N. Lawson L. P. (2020). Brief report: psychometric properties of the patient health Questionaire-9 (PHQ-9) in autistic adults. J. Autism Dev. Disord.50, 2217–2225. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-03947-9,

6

Arqueros M. Jamett-Cuevas V. Pulgar-Vera V. Santander-Gonzalez R. Pemau A. Álvarez-Cabrera P. (2025). Camouflaging and suicide behavior in adults with autism spectrum condition: a mixed methods systematic review. Res. Autism121:202540. doi: 10.1016/j.reia.2025.202540,

7

Asher M. Asnaani A. Aderka I. M. (2017). Gender differences in social anxiety disorder: a review. Clin. Psychol. Rev.56, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.05.004,

8

Banga S. J. Fox G. D. (2013). A graphical multiple comparisons procedure for several standard deviations. College, PA: Minitab Inc.

9

Baños R. M. Miragall M. (2024). Gender matters: a critical piece in mental health. Span. J. Psychol.27:e28. doi: 10.1017/SJP.2024.29,

10

Beck J. S. Lundwall R. A. Gabrielsen T. Cox J. C. South M. (2020). Looking good but feeling bad: ‘camouflaging’ behaviors and mental health in women with autistic traits. Autism24, 809–821. doi: 10.1177/1362361320912147,

11

Beggiato A. Peyre H. Maruani A. Scheid I. Rastam M. Amsellem F. et al . (2017). Gender differences in autism spectrum disorders: divergence among specific core symptoms. Autism Res.10, 680–689. doi: 10.1002/aur.1715,

12

Belcher H. L. Morein-Zamir S. Stagg S. D. Ford R. M. (2023). Shining a light on a hidden population: social functioning and mental health in women reporting autistic traits but lacking diagnosis. J. Autism Dev. Disord.53, 3118–3132. doi: 10.1007/s10803-022-05583-2,

13

Benatov J. Sarel-Mahlev E. Bar Yehuda S. (2025). Camouflage, burnout-exhaustion, and depression in autistic adults. Autism Adulthood. doi: 10.1089/aut.2024.0147

14

Bentley K. H. Franklin J. C. Ribeiro J. D. Kleiman E. M. Fox K. R. Nock M. K. (2016). Anxiety and its disorders as risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev.43, 30–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.11.008,

15

Bjelland I. Krokstad S. Mykletun A. Dahl A. A. Tell G. S. Tambs K. (2008). Does a higher educational level protect against anxiety and depression? The HUNT study. Soc. Sci. Med.66, 1334–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.019,

16

Brown C. M. Newell V. Sahin E. Hedley D. (2024). Updated systematic review of suicide in autism: 2018–2024. Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep.11, 225–256. doi: 10.1007/s40474-024-00308-9

17

Cage E. Di Monaco J. Newell V. (2018). Experiences of autism acceptance and mental health in autistic adults. J. Autism Dev. Disord.48, 473–484. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3342-7,

18

Cassidy S. A. Gould K. Townsend E. Pelton M. Robertson A. E. Rodgers J. (2020). Is camouflaging autistic traits associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviours? Expanding the interpersonal psychological theory of suicide in an undergraduate student sample. J. Autism Dev. Disord.50, 3638–3648. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04323-3,

19

Cassidy S. McLaughlin E. McGranaghan R. Pelton M. O’Connor R. Rodgers J. (2023). Is camouflaging autistic traits associated with defeat, entrapment, and lifetime suicidal thoughts? Expanding the integrated motivational volitional model of suicide. Suicide Life Threat. Behav.53, 572–585. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12965,

20

Cazalis F. Reyes E. Leduc S. Gourion D. (2022). Evidence that nine autistic women out of ten have been victims of sexual violence. Front. Behav. Neurosci.16:852203. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2022.852203,

21

Chi T. Cheng L. Zhang Z. (2023). Global prevalence and trend of anxiety among graduate students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav.13:e2909. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2909,

22

Conde-Pumpido Zubizarreta S. Isaksson J. Faresjö Å. Faresjö T. Carracedo A. Fernández Prieto M. et al . (2025a). The impact of camouflaging autistic traits on psychological and physiological stress: a co-twin control study. Mol. Autism.16:59. doi: 10.1186/s13229-025-00695-9,

23

Conde-Pumpido Zubizarreta S. Lois-Mosquera M. Tubío-Fungueiriño M. Alemany-Navarro M. Hull L. Carracedo A. et al . (2025b). Camouflaging autistic traits questionnaire: cultural adaptation, reliability, and validity in autistic and non-autistic adults from Spain. Autism Adulthood. doi: 10.1089/aut.2024.0003

24

Conde-Pumpido Zubizarreta S. Tubío-Fungueiriño M. Pozo-Rodríguez M. Carracedo A. Cernadas E. Fernández-Delgado M. et al . (2025c). Predicting autistic traits, anxiety and depression symptoms using camouflaging autistic traits questionnaire (CAT-Q-ES): a machine learning study. Res. Autism128:202712. doi: 10.1016/j.reia.2025.202712

25

Cook J. Hull L. Crane L. Mandy W. (2021). Camouflaging in autism: a systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev.89:102080. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102080,

26

Cruz S. Zubizarreta S. C. Costa A. D. Araújo R. Martinho J. Tubío-Fungueiriño M. et al . (2024). Is there a bias towards males in the diagnosis of autism? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev.35, 153–176. doi: 10.1007/s11065-023-09630-2,

27

Diez-Quevedo C. Rangil T. Sánchez-Planell L. Kroenke K. Spitzer R. L. (2001). Validation and utility of the patient health questionnaire in diagnosing mental disorders in 1003 general hospital Spanish inpatients. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr.29, 207–213. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00021

28

Doering S. Probert-Lindström S. Ehnvall A. Wiktorsson S. Palmqvist Öberg N. Bergqvist E. et al . (2024). Anxiety symptoms preceding suicide: a Swedish nationwide record review. J. Affect. Disord.355, 317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.03.118,

29

Dong Y. Peng C. Y. (2013). Principled missing data methods for researchers. Springerplus2:222. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-222,

30

Dubreucq J. Coutelle R. Lajnef M. Godin O. Amestoy A. Atzori P. et al . (2023). Gender differences in psychosocial function and self-reported health status in late-diagnosed autistic adults: results from the FACE-ASD national cohort. Psychol. Med.53, 5674–5684. doi: 10.1017/S0033291722002902,

31

Dubreucq M. Dubreucq J. (2021). Toward a gender-sensitive approach of psychiatric rehabilitation in autism Spectrum disorder (ASD): a systematic review of women needs in the domains of romantic relationships and reproductive health. Front. Psych.12:630029. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.630029,

32

Dubreucq M. Ycart B. Dubreucq J. (2023). Examining mental and physical health between autistic women and women with serious mental illness. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord.104:102148. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2023.102148

33

Farhane-Medina N. Z. Luque B. Tabernero C. Castillo-Mayén R. (2022). Factors associated with gender and sex differences in anxiety prevalence and comorbidity: a systematic review. Sci. Prog.105:368504221135469. doi: 10.1177/00368504221135469,

34

Fife-Schaw C. (2006). Levels of measurement. in Res. Methods Psychol. 3rd edn. eds. G. M. Breakwell, S. Hammond, C. Fife-Schaw, and J. A. Smith (Sage Publications, Inc.). 3, 50–63.

35

García-Campayo J. Zamorano E. Ruiz M. A. Pardo A. Pérez-Páramo M. López-Gómez V. et al . (2010). The assessment of generalized anxiety disorder: psychometric validation of the Spanish version of the self-administered GAD-7 scale. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment.3, 139–144. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-114

36

Green R. M. Travers A. M. Howe Y. McDougle C. J. (2019). Women and autism Spectrum disorder: diagnosis and implications for treatment of adolescents and adults. Curr. Psychiatry Rep.21:22. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-1006-3,

37

Greenlee J. L. Winter M. A. Marcovici I. A. (2020). Brief report: gender differences in experiences of peer victimization among adolescents with autism Spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord.50, 3790–3799. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04437-z,

38

Grzeszak A. Pisula E. (2025). Experiences of females on the autism spectrum through the perspective of minority stress theory: a review. Front. Psych.16:1578963. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1578963,

39

Harmens M. Sedgewick F. Hobson H. (2022). Autistic women’s diagnostic experiences: interactions with identity and impacts on well-being. Womens Health18, 1–11. doi: 10.1177/17455057221137477,

40

Harmer B. Lee S. Rizvi A. Saadabadi A. (2024). Suicidal Ideation. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

41

Harris P. A. Taylor R. Minor B. L. Elliott V. Fernandez M. O'Neal L. et al . (2019). The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform.95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208,

42

Harris P. A. Taylor R. Thielke R. Payne J. Gonzalez N. Conde J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform.42, 377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010,

43

Hayward S. M. McVilly K. R. Stokes M. A. (2018). “Always a glass ceiling.” gender or autism; the barrier to occupational inclusion. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord.56, 50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2018.09.001

44

Head A. M. McGillivray J. A. Stokes M. A. (2014). Gender differences in emotionality and sociability in children with autism spectrum disorders. Mol. Autism.5:19. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-5-19,

45

Hedley D. Uljarević M. Foley K. R. Richdale A. Trollor J. (2018). Risk and protective factors underlying depression and suicidal ideation in autism Spectrum disorder. Depress. Anxiety35, 648–657. doi: 10.1002/da.22759,

46

Hirvikoski T. Boman M. Chen Q. D’Onofrio B. M. Mittendorfer-Rutz E. Lichtenstein P. et al . (2020). Individual risk and familial liability for suicide attempt and suicide in autism: a population-based study. Psychol. Med.50, 1463–1474. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719001405,

47

Hull L. Lai M.-C. Baron-Cohen S. Allison C. Smith P. Petrides K. et al . (2020). Gender differences in self-reported camouflaging in autistic and non-autistic adults. Autism24, 352–363. doi: 10.1177/1362361319864804,

48

Hull L. Levy L. Lai M. C. Petrides K. V. Baron-Cohen S. Allison C. et al . (2021). Is social camouflaging associated with anxiety and depression in autistic adults?Mol. Autism.12:13. doi: 10.1186/s13229-021-00421-1,

49

Hull L. Petrides K. V. Allison C. Smith P. Baron-Cohen S. Lai M. C. et al . (2017). "putting on my best Normal": social camouflaging in adults with autism Spectrum conditions. J. Autism Dev. Disord.47, 2519–2534. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3166-5,

50

Jones S. Sharpe B. T. King R. Waldeck D. Tyndall I. (2025). Putting on a disguise to fit in: a mixed methods study of experiences in autistic camouflaging. Res. Neurodiversity1. doi: 10.1016/j.rin.2025.100004

51

Khudiakova V. Russell E. Sowden-Carvalho S. Surtees A. D. R. (2024). A systematic review and meta-analysis of mental health outcomes associated with camouflaging in autistic people. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord.118:102492. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2024.102492

52

Kirby A. V. Conner C. M. Mazefsky C. A. (2024). Are autistic females at greater risk of suicide? A call for clarity to advance suicide prevention for the whole community. Autism Res.17, 898–905. doi: 10.1002/aur.3120,

53

Kopp S. Gillberg C. (1992). Girls with social deficits and learning problems: autism, atypical Asperger syndrome of a variant of these conditions. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry1, 89–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02091791,

54

Kroenke K. Spitzer R. L. Williams J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med.16, 606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x,

55

Lai M. C. Baron-Cohen S. (2015). Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions. Lancet Psychiatry2, 1013–1027. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00277-1,

56

Lai M. C. Lombardo M. V. Ruigrok A. N. Chakrabarti B. Auyeung B. Szatmari P. et al . (2017). Quantifying and exploring camouflaging in men and women with autism. Autism21, 690–702. doi: 10.1177/1362361316671012,

57

Loomes R. Hull L. Mandy W. P. L. (2017). What is the male-to-female ratio in autism Spectrum disorder? A systematic review and Meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry56, 466–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.013,

58

Mao H. Cheng L. Zhang Y. Zhang F. (2024). Gender differences in autism Spectrum disorder: a systematic review of diagnosis, intervention, and outcomes. Gender Sustain. Global South1, 92–136. doi: 10.1515/gsgs-2024-0007

59

McLean C. P. Asnaani A. Litz B. T. Hofmann S. G. (2011). Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J. Psychiatr. Res.45, 1027–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006,

60

Miller D. Rees J. Pearson A. (2021). “Masking is life”: experiences of masking in autistic and nonautistic adults. Autism Adulthood3, 330–338. doi: 10.1089/aut.2020.0083,

61

Millner A. J. den Ouden H. E. M. Gershman S. J. Glenn C. R. Kearns J. C. Bornstein A. M. et al . (2019). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors are associated with an increased decision-making bias for active responses to escape aversive states. J. Abnorm. Psychol.128, 106–118. doi: 10.1037/abn0000395,

62

Milner V. Mandy W. Happé F. Colvert E. (2023). Sex differences in predictors and outcomes of camouflaging: comparing diagnosed autistic, high autistic trait and low autistic trait young adults. Autism27, 402–414. doi: 10.1177/13623613221098240,

63

Miranda-Mendizabal A. Castellví P. Parés-Badell O. Alayo I. Almenara J. Alonso I. et al . (2019). Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Int. J. Public Health64, 265–283. doi: 10.1007/s00038-018-1196-1,

64

Moseley R. L. Gregory N. J. Smith P. Allison C. Cassidy S. Baron-Cohen S. (2022). The relevance of the interpersonal theory of suicide for predicting past-year and lifetime suicidality in autistic adults. Mol. Autism.13:14. doi: 10.1186/s13229-022-00495-5,

65

Na P. J. Yaramala S. R. Kim J. A. Kim H. Goes F. S. Zandi P. P. et al . (2018). The PHQ-9 item 9 based screening for suicide risk: a validation study of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ)-9 item 9 with the Columbia suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS). J. Affect. Disord.232, 34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.045,

66

Nepon J. Belik S. L. Bolton J. Sareen J. (2010). The relationship between anxiety disorders and suicide attempts: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. Depress. Anxiety27, 791–798. doi: 10.1002/da.20674,

67

Newell V. Phillips L. Jones C. Townsend E. Richards C. Cassidy S. (2023). A systematic review and meta-analysis of suicidality in autistic and possibly autistic people without co-occurring intellectual disability. Mol. Autism.14:12. doi: 10.1186/s13229-023-00544-7,

68

Perry E. Mandy W. Hull L. (2022). Understanding camouflaging as a response to autism-related stigma: a social identity theory approach. J. Autism Dev. Disord.52, 800–810. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-04987-w,

69

Sanches M. Nguyen L. K. Chung T. H. Nestadt P. Wilcox H. C. Coryell W. H. et al . (2022). Anxiety symptoms and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among patients with mood disorders. J. Affect. Disord.307, 171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.03.046,

70

Sedgewick F. Hill V. Yates R. Pickering L. Pellicano E. (2016). Gender differences in the social motivation and friendship experiences of autistic and non-autistic adolescents. J. Autism Dev. Disord.46, 1297–1306. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2669-1,

71

Seedat S. Scott K. M. Angermeyer M. C. Berglund P. Bromet E. J. Brugha T. S. et al . (2009). Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry66, 785–795. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.36,

72

Shelef L. (2021). The gender paradox: do men differ from women in suicidal behavior?J. Mens Health.17, 22–29. doi: 10.31083/jomh.2021.099

73

Simon G. E. Rutter C. M. Peterson D. Oliver M. Whiteside U. Operskalski B. et al . (2013). Does response on the PHQ-9 depression questionnaire predict subsequent suicide attempt or suicide death?Psychiatr. Serv.64, 1195–1202. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200587,

74

Somerville M. MacPherson S. E. Fletcher-Watson S. (2024). The associations between camouflaging, autistic traits, and mental health in nonautistic adults. Autism Adulthood6, 106–113. doi: 10.1089/aut.2023.0018,

75

The jamovi project . (2025). Jamovi (version 2.3) [computer software]. Available online at: https://www.jamovi.org

76

Tierney S. Burns J. Kilbey E. (2016). Looking behind the mask: social coping strategies of girls on the autistic spectrum. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord.23, 73–83. doi: 10.1016/J.RASD.2015.11.013

77

Tubío-Fungueiriño M. Cruz S. Sampaio A. Carracedo A. Fernández-Prieto M. (2021). Social camouflaging in females with autism Spectrum disorder: a systematic review. J. Autism Dev. Disord.51, 2190–2199. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04695-x,

78

Wilson R. B. Thompson A. R. Rowse G. Smith R. Dugdale A. S. Freeth M. (2023). Autistic women's experiences of self-compassion after receiving their diagnosis in adulthood. Autism27, 1336–1347. doi: 10.1177/13623613221136752,

79

Wood-Downie H. Wong B. Kovshoff H. Cortese S. Hadwin J. A. (2021). Research review: a systematic review and metaanalysis of sex/gender differences in social interaction and communication in autistic and nonautistic children and adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry62, 922–936. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13337,

80

World Health Organization . (2014). Social determinants of mental health. Available online at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/112828/9789241506809_eng.pdf?sequence=1

81

Zhuang S. Tan D. W. Reddrop S. Dean L. Maybery M. Magiati I. (2023). Psychosocial factors associated with camouflaging in autistic people and its relationship with mental health and well-being: a mixed methods systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev.105:102335. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2023.102335,

Summary

Keywords

anxiety, autism, camouflaging, suicidal ideation, women

Citation

Conde-Pumpido-Zubizarreta S, Cruz S, Pozo-Rodríguez M, Suárez-Rama JJ, Díaz-Hernández A, Carracedo A, Tubío-Fungueiriño M and Fernández-Prieto M (2026) The association between autism, camouflaging and anxiety with suicidal ideation in women. Front. Psychol. 16:1685845. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1685845

Received

14 August 2025

Revised

11 December 2025

Accepted

22 December 2025

Published

23 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Alejandro De La Torre-Luque, Complutense University of Madrid, Spain

Reviewed by

Karol Konaszewski, University of Białystok, Poland

María Arqueros, Complutense University of Madrid, Spain

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Conde-Pumpido-Zubizarreta, Cruz, Pozo-Rodríguez, Suárez-Rama, Díaz-Hernández, Carracedo, Tubío-Fungueiriño and Fernández-Prieto.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Montse Fernández-Prieto, montse.fernandez.prieto@usc.es

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work and share last authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.