Abstract

Introduction:

In the era of artificial intelligence, information literacy is a crucial skill for teachers, enabling the effective integration of technology into pedagogy. This study examines the psychological factors influencing the information-empowered teaching engagement of university English teachers.

Methods:

A cross-sectional survey was conducted with 224 university English teachers in Southeast China. Data were collected using a composite questionnaire measuring information literacy self-efficacy, teacher emotion (both positive and negative), and information-empowered teaching engagement. The data were analyzed via SmartPLS to test the proposed mediation model.

Results:

The findings indicate that university English teachers experience a mix of positive and negative emotions when applying information technology. Information literacy self-efficacy was identified as a primary factor promoting teaching engagement. Both positive and negative emotions were found to play substantial and parallel mediating roles between self-efficacy and engagement.

Discussion:

The study highlights the complex emotional landscape accompanying technology integration. It proposes the design of hybrid professional development programs for technology-rich environments. These programs should concurrently provide emotional support and technical training to enhance teachers’ information literacy self-efficacy and, consequently, their information-empowered teaching engagement.

1 Introduction

The advancement in information technology represented by Large Language Models (LLM) and artificial intelligence (AI) in recent years has changed the way of acquiring knowledge (Cohen et al., 2020). AI tools tend to present knowledge in an authoritative way, yet whether and how much we can trust the information provided remain questionable. It depends on the users’ accurate evaluation of the information, which is fundamentally about information literacy. Information literacy refers to the ability to understand, construct, and create new knowledge, as well as to discover, analyze, and solve problems, including components like information awareness, information knowledge, information application skills, and information ethics and security (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, 2021). The critical importance of these competencies is powerfully illustrated in specialized fields such as engineering education, where critical thinking, data analysis, and ethical decision-making, ensuring reliability and rigor in professional practice are underpinned (Tripon, 2025). The rapid development of AI tools gives rise to higher requirements for information literacy (Chen et al., 2023). In this regard, information literacy has emerged as one of the essential competences for language teachers in the context of educational informatization, enabling them to effectively use the vast resources offered by information technologies.

Language teachers’ information literacy, or digital literacy, a similar construct gaining winds at the very recent years due to the upcoming of the AI era, is always one of the popular topic in the study of applied linguistics. The construct itself and its essential components have been discussed in the existing body of research (Wang, 2022; Qin and He, 2009). Liu et al. (2017) explore the landscape of information literacy and discuss the potential path for its enhancement from a technical standpoint. However, information literacy is not about the possession of skills only. Researchers argue that it should be about the appreciation of information as well (Bruce, 1997), and the importance of psychological factors like self-efficacy and academic motivation in the development of information literacy skills should be acknowledged (Diliello et al., 2011; Ross et al., 2016). These findings underscore the fact that information literacy is multifaceted, and that psychological aspects are as critical as theoretical and technical components.

Even though information literacy has been extensively studied, the psychological dimension of it is still neglected by researchers. In addition, although existing studies have discussed teachers’ attitude toward (e.g., Yang et al., 2021) and emotion about (e.g., Azzaro and Martínez Agudo, 2018) information technology, the discussion about the relationship between these two psychological aspects and teachers’ teaching engagement is few. Therefore, this study intends to address this gap by focusing on the relationship between information literacy self-efficacy, teacher emotion, and information-empowered teaching engagement. Special attention will be paid to examine self-efficacy perceived and emotions experienced by university English teachers in applying information technology to their teaching.

2 Literature review

2.1 Information literacy

With the development of modern educational technology, the professional development of English teachers requires continuous improvement of professional knowledge, teaching skills and professional attitude through various means in the information technology environment (Jiao et al., 2009; Motteram and Dawson, 2025). Therefore, educational informatization requires English teachers not only to possess the “information teaching literacy” that combines information literacy with teaching ability (Chen, 2010; Jiang, 2024) and also maintain a positive emotional attitude toward information technology (Azzaro and Martínez Agudo, 2018; Beaudry and Pinsonneault, 2010; Wong et al., 2013). Correspondingly, Jia and Zhang (2023) proposed that information is a comprehensive concept emphasizing the characteristics of the times, while literacy emphasizes the emotions and values formed through acquired experience. This viewpoint offers the latest interpretation of information literacy that it not only encompasses the dimension of technical capabilities but also the dimension of emotions, emphasizing the comprehensiveness of information literacy.

However, existing research primarily discusses the definition, current status, enhancement strategies, evaluation criteria, and influencing factors of information literacy from the perspectives of traditional technological development and teaching capability enhancement (Wang and Bu, 2022). Although some studies have explored topics related to psychological constructs such as teacher self-efficacy in technological environments (Drossel et al., 2017; Garzon and Garzon, 2023) and teacher identity (Hanell, 2017; Zhang et al., 2023; Su, 2023), there remains a lack of micro-empirical research on the psychological aspect of information literacy, which deserves the attention of the academic community.

2.2 Teaching engagement, self-efficacy, and teacher emotion

Teaching engagement indicates the extent to which teachers commit themselves physically and mentally in teaching practice. It encompasses not only the explicit investment of teachers’ time and energy but also the implicit investment of their experiences and emotions (Kirkpatrick and Johnson, 2014; Mou et al., 2020). In the contemporary era of AI, this concept has evolved to encompass more specialized forms of practice. Specifically, we propose that information-empowered teaching engagement refers to a professional practice process in which teachers, within information-based teaching environments, proactively utilize informational data, tools, and digital resources to carry out teaching across the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional dimensions. This evolution aligns with existing frameworks, such as that of Klassen et al. (2013), who formulated a framework of teacher engagement including physical, cognitive, emotional and social engagement.

Such classifications indicate the inherent relationship between teaching engagement and teacher emotion. Khammat (2022) reports that people who are deeply engaged in their job are more likely to demonstrate better performance, and greater resilience (a positive emotion determining the ability to sustain a long-term career through the challenges of the profession). Similarly, higher job engagement can generate stable and dedicated positive emotional experiences or emotional states (Hemami, 2024; Inceoglu and Warr, 2011). Empirical studies have also shown a strong correlation between teachers’ work engagement and their professional wellbeing. Work engagement represents a positive mental state (Qu et al., 2025), and high levels of engagement is beneficial to fostering teachers’ psychological health (Greenier et al., 2021). However, there is a relative scarcity of research regarding the influence of teacher emotion on their teaching engagement.

Self-efficacy is viewed as a person’s beliefs in their capacity to successfully fulfill certain task (Bandura, 1978). With regard to its correlation with teacher emotion, existing studies has centered on its influence on stress, a negative emotion which further affects burnout, job satisfaction and teacher attrition (Troesch and Bauer, 2017). However, the role of self-efficacy in predicting teacher emotions (positive ones and negative ones) as a hole has been understudied (Wang and Pan, 2023). As a construct of positive self-assessment, self-efficacy reflects an individual’s ability and perception to control and successfully influence the environment (Burić and Macuka, 2018; Hobfoll et al., 2003). Likewise, teacher self-efficacy, which refers to teachers’ beliefs about what they can do in terms of a particular teaching task or instructional context, has been shown to influence motivational and behavioral processes (Landrieu, 2024; Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998), especially when their teaching behaviors interact with personal and external impact factors (Wang et al., 2024). In short, previous studies have indicated that higher teacher self-efficacy correlates with superior teaching quality compared to those with lower self-efficacy (Hoy et al., 2009; Landrieu, 2024; Zee and Koomen, 2016), yet its correlation with emotion is not thoroughly studied.

With the topics in research on language teaching and learning shifting toward the emotional dimension (Martínez Agudo, 2018), language teacher emotion has gradually attracted scholars’ attention (Chen and Cheng, 2022). Early studies primarily focused on negative emotions experienced in English teaching, such as work stress, professional burnout, and anxiety, without considering teacher emotion as an important factor affecting teaching itself (Zembylas, 2003). Over the past decade, studies on language teacher emotion have mainly concentrated on the emotional experiences of language teachers in different teaching contexts (Xie and Jiang, 2023), and some have indicated a significant correlation between teacher self-efficacy and their emotions (Burić et al., 2020; Hascher and Hagenauer, 2016). Similarly, Lo (2023) posits emotion as a bridge that connects cognitive belief (such as self-efficacy and self-concept) to behavioral engagement. In terms of the relationship between language teacher emotion and teaching engagement, Cowie (2011) believes that language teacher emotion is an important variable affecting teaching behavior, an idea partially supported by Azari Noughabi et al. (2022) who argue that English teachers’ positive emotions influence their work engagement. Dilekçi et al. (2025) draw a similar conclusion that teachers’ positive emotions are critical antecedents and a strong predictor of their work engagement. Lo and Punzalan (2025) further explain that teachers participating in Positive Psychology (PP) interventions generally reported significant improvements in such positive emotions as optimism, which are directly related to higher work engagement, manifested as increased commitment to teaching tasks and active participation in professional development. Overall, despite the existing studies recognizing the connections from self-efficacy to emotion and onward to engagement, the exact mediating mechanism of emotions within this pathway remains a “black box,” necessitating further research.

In summary, the existing literature on teaching engagement, self-efficacy, and teacher emotion has to a certain extent informed us the interrelationship among them. Studies have also consistently highlighted the importance of self-efficacy in language teaching. However, several gaps remain in the current understanding of this topic. Specifically, there is scarce research on the pathway of self-efficacy’s influence on teaching engagement and the impact of teacher emotion on teaching engagement, which deserves a close examination.

3 Research methodology

3.1 Research questions

The study is anchored by three pivotal research questions designed to explore the psychological dynamics underpinning the engagement of university English teachers in information-empowered teaching environments:

-

What are the features of emotions experienced by university English teachers in the information-empowered teaching context?

-

What is the relationship between information literacy self-efficacy, teacher emotion, and information-empowered teaching engagement?

-

Do positive and negative emotions mediate the relationship between university English teachers’ information literacy self-efficacy and information-empowered teaching engagement? If so, what is the magnitude and significance of the mediating effect?

3.2 Subjects

This study employed a convenience sampling method to recruit subjects from universities of various levels in Southeast China. A total of 224 university English teachers participated in the project voluntarily and filled out the questionnaire, which was distributed to them through Wenjuanxing,1 a popular online questionnaire website, in October 2024. The questionnaire link was sent out via faculty WeChat groups, professional networks of the research team, and academic social media communities specializing in English language teaching. The online survey platform mandated responses to all items, thus eliminating missing data. Subsequently, all submissions were manually screened by the researchers to disqualify eight invalid responses, resulting in a final sample of 224 valid questionnaires and an effective response rate of 96.6%.

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the final sample. There were 151 female teachers (67%) and 73 male teachers (33%), a distribution that aligns with the general gender composition observed in the field of English language teaching in Chinese universities. In terms of the age, the participants fell into four age groups, with the majority of them aged 31–40 and 41–50, collectively constituting 76% of the sample. This indicates that the data primarily reflects the perspectives of teachers who were in the core stages of their academic careers. Regarding institutional representation, the sample achieved a relatively balanced distribution across National Key Universities (31%), Provincial Key Universities (28%), and Local Colleges (41%). This distribution helps to capture teaching experiences from varying academic environments and resource levels. At last, the sample included Lecturers (43%), Associate Professors (41%), and Professors (16%), mirroring the pyramidal structure typical of the academic hierarchy in Chinese higher education.

Table 1

| Variable | Gender | Age | School type | Academic title | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | ≤30 | 31–40 | 41–50 | 51–60 | National Key University | Provincial Key University | Local college | Professor | Associate professor | Lecturer | |

| Quantity | 73 | 151 | 5 | 63 | 108 | 48 | 70 | 62 | 92 | 35 | 92 | 97 |

| Percentage | 33% | 67% | 2% | 28% | 48% | 22% | 31% | 28% | 41% | 16% | 41% | 43% |

Demographic information of the subjects (N = 224).

3.3 Instruments

Drawing on the research by Yang et al. (2021), the Composite Questionnaire of Information Literacy for University English Teachers (see Supplementary Appendix 1) was developed. The three scales included in this composite questionnaire were developed through a rigorous process of adaptation and contextualization to suit the specific research context. During the development phase, a pilot study was conducted with 30 university English teachers who were not included in the main survey sample. These teachers were also asked to offer constructive feedback on the content of the questionnaire. With their insights, particularly regarding the clarity and comprehensibility of the language used in the questionnaire, the items were refined to ensure that they were both precise in wording and easily understood, thereby enhancing the overall quality and effectiveness of the questionnaire.

The questionnaire consists of three independent scales, which are specifically introduced as follows:

-

University English Teacher Emotion Scale. Given the lack of well-established scale for measuring teacher emotions in information technology-related contexts, most frequently reported emotions from existing literature (Azzaro and Martínez Agudo, 2018; Xie and Jiang, 2023) were chosen to develop this scale. All statements were well written after referring to the literature and consulting to one expert specialized in studying emotions. The scale is a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = Strongly Disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = Neutral; 4 = Agree; 5 = Strongly Agree. It contains 7 items, with 3 items assessing positive emotions and 4 items assessing negative emotions. As is shown in Table 2, both emotion sub-scales demonstrated strong psychometric properties. Positive Emotion showed excellent reliability (α = 0.877, CR = 0.924) and convergent validity (AVE = 0.802), while Negative Emotion also showed good reliability (α = 0.845, CR = 0.895) and convergent validity (AVE = 0.680), with all metrics exceeding their respective thresholds (Hair et al., 2022).

-

Information Literacy Self-Efficacy Scale. It was developed based on the existing literature, primarily drawing on the 13-item scale translated and validated by Atikuzzaman and Zabed Ahmed (2023). The original 13-item scale was adapted through a process of systematic translation, back-translation, and cultural adaptation. First, one researcher produced an initial translation, which was then reviewed by a subject specialist to align with the context of university English teaching in China. Second, back-translation and multiple rounds of revision were conducted to ensure conceptual consistency. A specific example is the transformation of the original item “Select information most appropriate to the information need” into “I can screen out important information from online resources based on teaching needs,” where back-translation confirmed conceptual equivalence while successfully contextualizing it for the English teaching environment. Third, culturally irrelevant items, such as using traditional library catalogs, were removed, and the focus was narrowed from general information literacy to the acquisition and evaluation of digital teaching resources. For instance, “Create bibliographic records and organize the bibliography” was replaced with “I can integrate existing and new information to expand the English teaching resource database” (see Supplementary Appendices 1, 2) The final scale emerged as an 8-item contextually refined 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = Strongly Disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = Neutral; 4 = Agree; 5 = Strongly Agree. It showed excellent reliability (α = 0.930, CR = 0.942) and good convergent validity (AVE = 0.671), with all values exceeding their thresholds (see Table 2).

-

Information-Empowered Teaching Engagement Scale. It was primarily derived from Yang et al. (2021). To achieve a more focused measure, the ‘belief in curriculum standard’ dimension from the original instrument was removed and the retained items were reorganized and refined to form a cohesive scale. This scale is a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = Strongly Disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = Neutral; 4 = Agree; 5 = Strongly Agree. It contains 12 items, including three dimensions, namely emotional engagement (3 items), behavioral engagement (5 items), and cognitive engagement (4 items). Table 2 indicated that the scale demonstrated excellent reliability (α = 0.956, CR = 0.972) and convergent validity (AVE = 0.920).

Table 2

| Dimension | Cronbach’s alpha | Overall reliability (rho_a) | Overall reliability (rho_c) | Mean variance extraction (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative emotion | 0.845 | 0.865 | 0.895 | 0.680 |

| Positive emotion | 0.877 | 0.877 | 0.924 | 0.802 |

| Self-efficacy | 0.930 | 0.931 | 0.942 | 0.671 |

| Teaching engagement | 0.956 | 0.958 | 0.972 | 0.920 |

Structural reliability and validity verification.

SmartPLS was employed to perform exploratory factor analysis (EFA). By using principal component analysis, EFA extracted four factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and the first factor accounted for 38.949% of the total variance. As shown in Table 3, these four factors collectively accounted for 74.130% of the total variance. After varimax rotation, the variances of 4 components were redistributed as 29.749, 15.580, 15.149, and 13.391%, respectively. This clear and interpretable factor structure demonstrated the sound construct validity of the composite questionnaire.

Table 3

| Component | Initial eigenvalues | Extraction sums of squared loadings | Rotation sums of squared loadings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % of variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of variance | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 7.011 | 38.949 | 38.949 | 7.011 | 38.949 | 38.949 | 5.380 | 29.889 | 29.889 |

| 2 | 2.557 | 14.207 | 53.156 | 2.557 | 14.207 | 53.156 | 2.792 | 15.514 | 45.403 |

| 3 | 2.403 | 13.347 | 66.504 | 2.403 | 13.347 | 66.504 | 2.716 | 15.086 | 60.489 |

| 4 | 1.373 | 7.626 | 74.130 | 1.373 | 7.626 | 74.130 | 2.455 | 13.640 | 74.130 |

| 5 | 0.527 | 2.929 | 77.059 | ||||||

| 6 | 0.495 | 2.750 | 79.809 | ||||||

| 7 | 0.463 | 2.570 | 82.379 | ||||||

| 8 | 0.431 | 2.395 | 84.774 | ||||||

| 9 | 0.411 | 2.285 | 87.059 | ||||||

| 10 | 0.379 | 2.104 | 89.163 | ||||||

| 11 | 0.353 | 1.964 | 91.126 | ||||||

| 12 | 0.319 | 1.772 | 92.899 | ||||||

| 13 | 0.312 | 1.731 | 94.629 | ||||||

| 14 | 0.290 | 1.610 | 96.239 | ||||||

| 15 | 0.242 | 1.343 | 97.582 | ||||||

| 16 | 0.217 | 1.206 | 98.789 | ||||||

| 17 | 0.120 | 0.667 | 99.455 | ||||||

| 18 | 0.098 | 0.545 | 100.000 | ||||||

Results of EFA: total variance explained by initial and rotated factors.

Factor analysis was conducted to examine the cross-loadings of each measurement item on its designated and non-designated factors. The results indicated that all items demonstrated satisfactory discriminant validity. Specifically, each item loaded highly on its intended factor (with all absolute values exceeding 0.754, see Supplementary Appendix 1). For instance, factor loadings were as follows: teaching engagement (0.762–0.849), self-efficacy (0.754–0.842), negative emotions (0.774–0.832), and positive emotions (0.845–0.879). This distinct pattern of loadings confirmed that the latent factors were well differentiated, and the four constructs measured by the scale were independent and clearly distinct from one another.

The discriminant validity of the constructs was also tested by using the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations. Table 4 shows that all HTMT values were substantially below 0.85, a conservative threshold suggested by Henseler et al. (2015), demonstrating that the constructs were empirically distinct from one another. Notably, the value between negative emotion and positive emotion was the lowest (0.073), while the highest value was observed between teaching engagement and self-efficacy (0.460). These results overtly showed the discriminant validity, confirming that the four constructs, despite being correlated, were distinct from each other, thereby robustly supporting the discriminant validity of the measurement model employed in this study.

Table 4

| Variable | Negative emotion | Positive emotion | Self-efficacy | Teaching engagement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative emotion | ||||

| Positive emotion | 0.073 | |||

| Self-efficacy | 0.303 | 0.304 | ||

| Teaching engagement | 0.391 | 0.402 | 0.460 |

HTMT ratio for discriminant validity.

The KMO measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (see Table 5) were also examined. The results presented that the KMO measure was 0.897, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant, with an approximate chi-square value of 2747.978 (p < 0.001). As a result, the composite questionnaire was suitable for factor analysis.

Table 5

| KMO | 0.897 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | Approximate Chi-square | 2747.978 |

| df | 153 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 | |

KMO and Bartlett’s tests of sphericity.

3.4 Data collection and analysis

In addition to the aforementioned statistical remedies employed, procedural measures were also adopted in the data collection process to further mitigate the potential for common method bias. These measures, aligned with the guidelines of Podsakoff et al. (2003), included respondent anonymity, the use of reverse-coded items, and randomization of question order.

Following preliminary analyses that included descriptive statistics and correlation analysis, the hypothesized relationships and mediation mechanisms were examined within a structural equation modeling (SEM) framework. All analyses were carried out with SmartPLS 4 software. This analytical approach was chosen because it allowed for the simultaneous estimation of all direct and indirect paths while controlling for measurement error. The significance of the mediation effects was tested using the bias-corrected bootstrap method with 5,000 resamples.

4 Results

4.1 Emotional experiences of university English teachers in information-empowered teaching

To explore the emotional experiences of university English teachers in the process of information-empowered teaching, descriptive analysis and normality tests on the relevant variables were conducted.

According to Table 6, the mean score of positive emotions among university English teachers was 12.07, which fell within the higher end of the scale (12–15). This indicated that these teachers reported a level of positive emotions that exceeded 80% of the maximum score; conversely, the mean score of negative emotions was 10.55, placing it in the medium range (4–12), suggesting that the level of negative emotions experienced by university English teachers were lower than 60% of the maximum score (Shao et al., 2013). The results demonstrated the predominance of positive emotional responses of university English teachers toward the integration of information technology in their teaching practices.

Table 6

| Variable | Score range | Mean | SD | Median | Mode | Minimum | Maximum | Skewness (standard error) | Kurtosis (standard error) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive emotion | 3–15 | 12.07 | 2.32 | 12 | 12 | 3 | 15 | −0.687 (0.163) | 0.422 (0.324) |

| Negative emotion | 4–20 | 10.55 | 3.34 | 11 | 10 | 4 | 25 | 0.184 (0.163) | 0.044 (0.324) |

Levels of positive and negative emotions.

Furthermore, this study also examined the relationship between demographic variables and teachers’ emotional experiences, conducting multiple regression analysis with gender, age, school type, and academic title as independent variables, and positive and negative emotions as dependent variables. The results showed that demographic variables did not have a statistically significant impact on university English teacher emotions in information-empowered teaching (p > 0.05).

4.2 Correlation between information literacy self-efficacy, teacher emotions, and engagement in information-empowered teaching

In order to examine the correlations among college English teachers’ information literacy self-efficacy, teacher emotion, and information-empowered teaching engagement, this study conducted a descriptive analysis before a Pearson correlation analysis.

As shown in Table 7, significant correlations between the information literacy self-efficacy of university English teachers and various aspects of their teaching experience were found. There was a positive relationship between the university English teachers’ self-efficacy and their positive emotion (r = 0.274, p < 0.001), as well as a substantial link with their teaching engagement (r = 0.435, p < 0.001). On the flip side, an inverse relationship was observed between their self-efficacy and negative emotions (r = −0.269, p < 0.001). These findings implied that as these teachers’ confidence in applying information technology in English teaching grows, their level of information-empowered teaching engagement also rises, accompanied by an increased likelihood of experiencing positive emotions and a reduced possibility of experiencing negative emotions.

Table 7

| Variable | Mean | SD | Median | Self-efficacy | Negative emotion | Positive emotion | Teaching engagement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | 3.843 | 0.691 | 3.875 | 1 | |||

| Negative emotion | 2.637 | 0.907 | 2.500 | −0.269*** | 1 | ||

| Positive emotion | 4.022 | 0.812 | 4.000 | 0.274*** | −0.046 | 1 | |

| Teaching engagement | 3.686 | 0.777 | 3.731 | 0.435*** | −0.352*** | 0.368*** | 1 |

Results of descriptive analysis and correlation analysis.

***p < 0.001.

Table 7 also showed the relationship between university English teachers’ information-empowered teaching engagement and their emotional experiences. A robust positive correlation between teaching engagement and positive emotion (r = 0.368, p < 0.001), and a significant negative correlation with their negative emotional experiences (r = −0.352, p < 0.001) were demonstrated. This indicated that the more positive emotions teachers experienced during the teaching process, the more they engaged in information-based teaching, and vice versa.

4.3 Main effect and mediation analysis

4.3.1 Multicollinearity test

Prior to conducting SEM analysis, rigorous diagnostics for multicollinearity among variables was performed to ensure the robustness of the analytical framework. The diagnostic examination included calculating both variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance indices for all variables (see Table 8).

Table 8

| Variable | VIF | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | 1.287 | 0.777 |

| Negative emotion | 1.179 | 0.848 |

| Positive emotion | 1.195 | 0.837 |

| Teaching engagement | 1.469 | 0.681 |

Results of multicollinearity diagnosis.

Following established methodological guidelines (Hair et al., 2022), VIF less than 10 and tolerance greater than 0.1 indicate no serious multicollinearity problems. In this study, the assessment of multicollinearity revealed that all VIFs ranged from 1.179 to 1.469, well below the conservative cutoff of 10; meanwhile, tolerance values ranged from 0.681 to 0.848, exceeding the threshold of 0.1. These results proved that the linear associations among predictor variables were within acceptable limits and confirmed the absence of substantial multicollinearity. Thus, these results supported the robustness of the subsequent SEM analysis.

4.3.2 Measurement model evaluation

The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed to examine the reliability and validity of the measurement model. A common latent factor (CLF) was incorporated into CFA. As shown in Table 9, the results demonstrated a good model fit for the measurement model (χ2/df = 1.008, RMSEA = 0.006, SRMR = 0.034, GFI = 0.921, AGFI = 0.921, NFI = 0.954, TLI = 0.989, CFI = 0.977, and IFI = 0.989). Most indices met the recommended thresholds, supporting the structural validity of the constructs. Nevertheless, the potential for residual method bias inherent in the cross-sectional self-report design had to be acknowledged as a study limitation.

Table 9

| Fit Indices | χ2/df | RMSEA | SRMR | GFI | AGFI | NFI | TLI | CFI | IFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model results | 1.008 | 0.006 | 0.034 | 0.921 | 0.921 | 0.954 | 0.989 | 0.977 | 0.989 |

CFA model fit indices.

4.3.3 Structural model and hypothesis testing

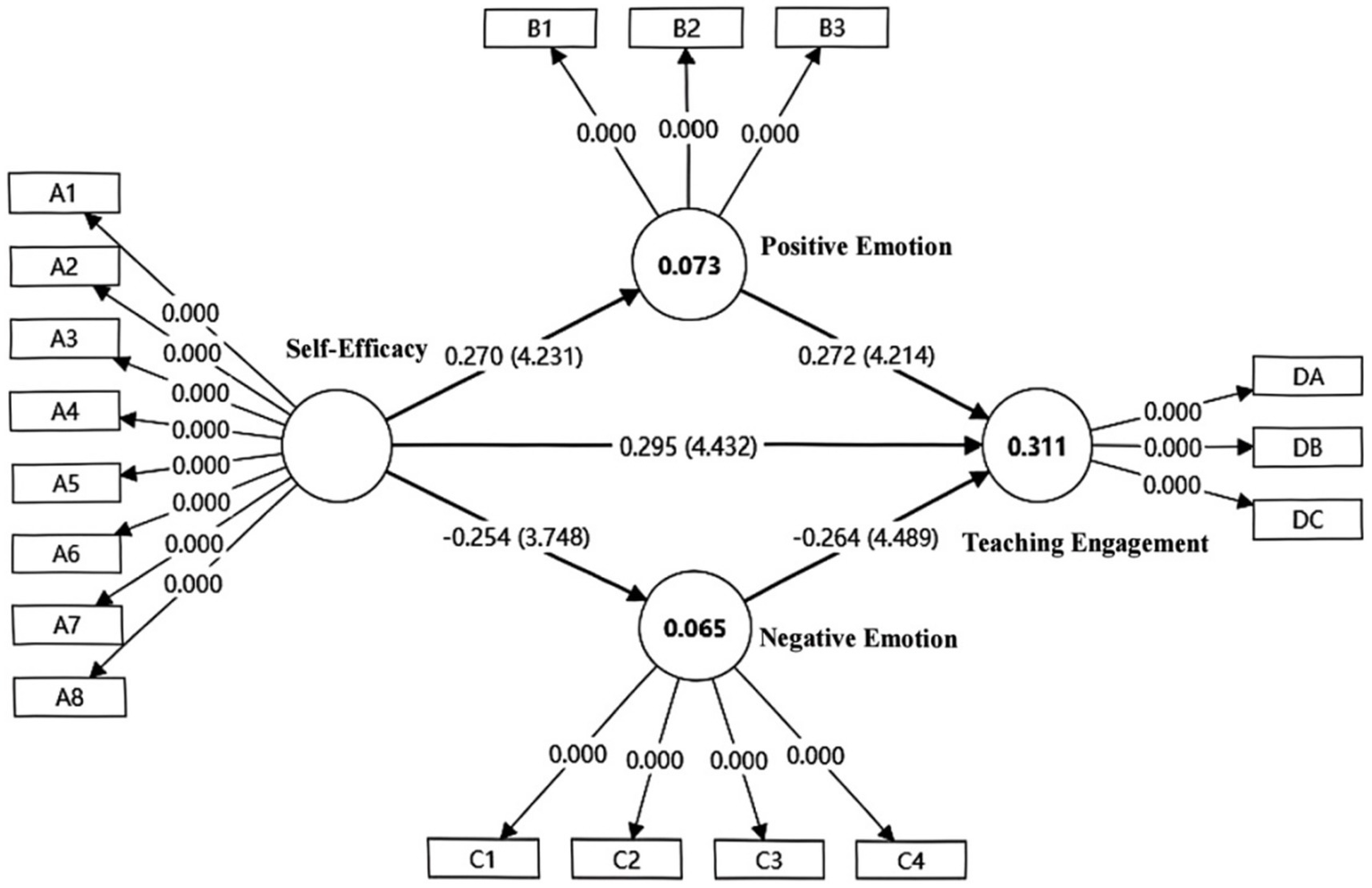

Building upon the validated measurement model, maximum likelihood estimation was used to examine the path coefficients of the structural model. The statistical significance of all paths was verified through Bootstrap method (5,000 samples). Figure 1 shows the mediation model generated by SmartPLS 4 software.

Figure 1

The mediating role of positive and negative emotions between information literacy self-efficacy and information-empowered teaching engagement.

Path analysis revealed that all theoretically hypothesized paths reached statistical significance (see Table 10). Self-efficacy demonstrated a significant positive direct effect on teaching engagement (β = 0.295, t = 4.432, p < 0.05), while simultaneously showing significant negative prediction of negative emotion (β = −0.254, t = 3.748, p < 0.05) and significant positive prediction of positive emotion (β = 0.270, t = 4.231, p < 0.05). Negative emotion exhibited a significant negative effect on teaching engagement (β = −0.264, t = 4.489, p < 0.05), whereas positive emotion demonstrated a significant positive promoting effect on teaching engagement (β = 0.272, t = 4.214, p < 0.05).

Table 10

| Path relationships | β | SD | T-values | p-values | 95% CI [low/high] |

f 2 | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy → teaching engagement | 0.295 | 0.068 | 4.432 | < 0.05 | [0.148, 0.417] | 0.109 | 0.302 |

| Self-efficacy → negative emotion | −0.254 | 0.068 | 3.748 | < 0.05 | [−0.402, −0.139] | 0.069 | 0.060 |

| Self-efficacy → positive emotion | 0.270 | 0.063 | 4.231 | < 0.05 | [0.154, 0.399] | 0.079 | 0.069 |

| Negative emotion → teaching engagement | −0.264 | 0.054 | 4.489 | < 0.05 | [−0.383, −0.168] | 0.094 | |

| Positive emotion → teaching engagement | 0.272 | 0.065 | 4.214 | < 0.05 | [0.145, 0.399] | 0.099 |

Results of structural model path coefficient analysis.

The effect sizes were assessed by the model’s f2. According to Cohen (1988), values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 represent small, medium, and large effects, respectively. As shown in Table 10, all f2 values ranged from 0.069 to 0.109, falling within the range of small effects. Notably, the path from self-efficacy to teaching engagement demonstrated the largest effect size (f2 = 0.109) within the model. Although comparatively small, the effect sizes for the paths from positive emotion (f2 = 0.099) and negative emotion (f2 = 0.094) to teaching engagement were very similar, indicating that both emotional pathways contributed to the prediction of teaching engagement with nearly identical strength. Similarly, the effect sizes for the paths from self-efficacy to positive emotion (f2 = 0.079) and to negative emotion (f2 = 0.069) were closely aligned.

Finally, the model’s overall explanatory power was assessed by the R2. The structural model explained 30.2% of the variance in teaching engagement, indicating a substantial prediction of this core outcome. For the mediating variables, the model accounted for 6.9% of the variance in positive emotion and 6.0% in negative emotion. These results established that the model provided a meaningful account of the key constructs, with particularly strong explanatory power for teaching engagement.

4.3.4 Parallel mediation analysis

To deconstruct the mechanisms underlying self-efficacy’s influence, a parallel mediation analysis was conducted (see Table 11). The bootstrap results confirmed a significant total indirect effect, which accounted for 34.8% of the total effect of self-efficacy on teaching engagement. Crucially, the analysis revealed that the two emotional pathways operated with nearly identical effect sizes. The specific indirect effects via both positive and negative emotion were significant and almost equal in magnitude, a finding formally supported by an equality constraint test [Δχ2(1) = 0.012, p = 0.913]. This pattern demonstrated that the influence of self-efficacy on teaching engagement was partially mediated through two distinct yet equally important emotional channels: the promotion of positive emotions and the alleviation of negative ones.

Table 11

| Effect type | Effect value | SD | 95% CI [low/high] |

Effect proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | ||||

| Self-efficacy → teaching engagement | 0.295 | 0.068 | [0.148, 0.417] | 65.2% |

| Specific indirect effects | ||||

| Via positive emotion | 0.077 | 0.024 | [0.034, 0.129] | 17.5% |

| Via negative emotion | 0.076 | 0.025 | [0.033, 0.129] | 17.3% |

| Total Indirect effect | 0.153 | 0.040 | [0.080, 0.235] | 34.8% |

| Total effect | 0.440 | 0.075 | [0.293, 0.587] | 100% |

Results of parallel mediation analysis.

5 Discussion

5.1 Emotional experience of university English teachers in information-empowered teaching

Participants in this research have highlighted that incorporating information technology into the classroom has significantly improved university English teachers’ experience of positive emotions. By leveraging instant feedback tools Tecent QQ and WeChat, and online teaching platform like ketangpai,2 teachers can foster better student interactions, tailor lessons to individual interests, and adapt their teaching methods to enhance students’ overall learning experience. This has evoked positive emotions of English teachers and a warm reception of technology in English teaching and learning (Liu et al., 2017; Azzaro and Martínez Agudo, 2018). However, Yang et al. (2021) noted a starkly different reaction among primary and secondary school English teachers, who were more skeptical, if not outright negative, about the application of information technology in English teaching.

There are two main reasons for this difference. First, English teaching in university emphasizes the importance of critical thinking, which is consistent with technology convergence goals of college English teaching in China (Guo, 2012), while primary and secondary schools pay more attention to fundamental knowledge and exam preparation, which makes the application of technology inferior to the traditional teaching methods like mechanical vocabulary memorization and grammar drills. Second, according to the Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1986), adoption of technology is dependent on perceived convenience and utility. In China, the impetus for English teaching reform often originates from the frontier research of university English teachers. More often than not, primary and secondary English teachers attend programs about information technology and receive training from experts or researchers from universities. In addition, Chinese universities are usually equipped with more abundant teaching resources, providing a broader application scenario for university English teachers. This enables them to be more acutely aware of the convenience and utility of information technology in English teaching, and thus they are more proactive in integrating it into their daily teaching practices.

The statistics of descriptive analysis also indicate that university English teachers experienced negative emotions like anger, disappointment, and anxiety. These emotions typically arose in specific pedagogical contexts, such as when they faced technical glitches or encountered the complexities inherent in educational technology systems. In addition, when teachers struggled with new technologies, they experienced helplessness and frustration. The technological anxiety could be particularly pronounced among older teachers. These findings supplement a series of recent studies on teacher emotions concerning AI. For instance, teachers may experience such negative emotions as fear, frustration and anxiety due to a lack of AI knowledge and literacy, adequate resources to support the use of AI in teaching (Shen and Guo, 2024), and confidence (Ci and Jiang, 2025). Collectively, all these studies, together with the present one, show that technical defects, low information literacy, lack of institutional support and self-efficacy are significant contributors to teachers’ negative emotions.

Therefore, it is necessary for institutions to set up a long term technology support system, carry out specialized training regularly, and update the teaching facilities, so as to reduce the technical burden for teachers. However, it is far from enough for institution administrators to provide technology support only, because a very recent research has pointed out that although professional training can enhance teachers’ technical skills to a certain extent, it does not significantly help them deal with the negative emotions that arise when using technologies such as AI in teaching (Ayanwale et al., 2024). A better solution, as Lo (2023) rightly suggests, is to move beyond purely technical training by implementing institutional supports such as hybrid professional learning communities, blended training with emotionally supportive design, and ongoing coaching. These programmatic levers are essential to amplify teachers’ positive emotions and strengthen their self-efficacy within technology-rich environments.

5.2 Self-efficacy in information literacy as a main factor driving engagement in information-empowered English teaching

Statistical analysis reveals a robust correlation between teachers’ information literacy self-efficacy and their teaching engagement. This relationship significantly intensified by the mandatory shift to online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic (Gobbi et al., 2021). At that time, teachers who possessed a high degree of technological self-efficacy were more likely to be confident in on-line teaching and to embrace information technology as a transformative tool in their classroom teaching practice (Skantz-Åberg et al., 2022). Moving beyond correlation, the heightened self-efficacy serves as a critical psychological resource (Bandura, 1978; Bandura, 1989). It empowers teachers to reframe technology integration from a potential threat into an achievable challenge, thereby reducing the cognitive load and anxiety associated with digital tools. This reduction frees teachers’ mental resources for pedagogical innovation rather than mere technical operation, as evidenced by the increased flexibility in instructional design, classroom management, and the enrichment of student learning experiences observed among confident and experienced teachers (Wang et al., 2021).

Consequently, these teachers are more likely to experiment with advanced tools and refine their instructional strategies, a transformation of engagement from quantitative time investment to qualitative pedagogical exploration. This aligns with the findings of Gong (2023) who affirms that such self-efficacy is instrumental in cultivating innovative techniques. Therefore, enhancing information literacy self-efficacy transcends basic skill training, and it constitutes a foundational psychological intervention that builds teachers’ adaptive capacity and innovative potential. Ultimately, this development is not merely a reaction to technological trends but a crucial pathway to enhancing the efficacy and quality of English education in the digital age.

5.3 The mediating role of teacher emotions

In this research, the mediating effect of teacher emotion on the relation between information literacy self-efficacy and the information-empowered teaching engagement is also observed. Path analysis shows that the mediating effects of positive and negative emotions are of comparable strength, suggesting that the absence of negative emotions is just as critical as the presence of positive ones for sustaining teacher engagement in the context of technology integration.

The significant role of positive emotions (e.g., enjoyment, pride) aligns with the broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson, 2001). Positive emotions like enjoyment and pride broaden teachers’ thought-action repertoires, fuel enthusiasm and foster the exploration and innovation necessary for deep engagement with information-empowered teaching, ultimately leading to the improved teaching quality and more productive learning experience (Romo-Escudero et al., 2023). Conversely, the equally powerful role of negative emotions (e.g., anxiety, frustration) is decisively explained by the control-value theory (Pekrun, 2006). In the rapidly evolving environment of current information-empowered language teaching, a perceived lack of control over technology or doubts about its pedagogical value can trigger potent negative emotions. These emotions are not merely transient feelings but actively constrict cognitive resources, divert attention toward threat management, and can lead to avoidance behaviors, such as a retreat to familiar traditional methods, thereby severely curtailing teaching engagement.

This finding highlights the importance of implementing PP interventions within the socio-cultural context of higher education in East Asian. The emphasis on this context is crucial, because prevailing Western-centric PP approaches, which often prioritize individualistic expression and self-enhancement, may not fully align with the collectivistic values, hierarchical relationships, and nuanced emotional expression, commonly found in many East Asian academic settings. Therefore, responding to the call by Lo and Punzalan (2025), it is important to design culturally responsive programs that integrate technical and emotional support. Such initiatives can be structured around the concept of the emotional bridge (Lo, 2023), which posits that cognitive beliefs are linked to behavioral engagement through emotional states. To institutionalize this connection, programmatic mechanisms should be established, including hybrid professional learning communities, blended training with emotionally supportive design, and ongoing coaching. These mechanisms are vital not only for amplifying positive emotions and strengthening self-efficacy but also for actively intervening to mitigate the impact of negative emotions. By reducing anxiety and frustration through structured and culturally attuned support, such interventions can disrupt the negative emotional pathway, thereby fostering a sustainable and adaptive teaching environment.

6 Conclusion

This study, based on the empirical investigation, examines the role of university English teachers’ self-efficacy and emotional experiences in shaping their teaching engagement within information-empowered teaching contexts. The findings demonstrate that enhanced self-efficacy, along with the cultivation of positive emotions, predicts higher levels of teaching engagement. Both positive and negative emotions are found to play equally substantial mediating roles between self-efficacy and teaching engagement. These findings underscore the crucial role of psychological factors in technology-rich teaching environments.

Based on these findings, we recommend that educational institutions including primary, secondary, and higher education establishments should implement a dual support system integrating both technical and psychological assistance. On the one hand, institutions should regularly update teaching facilities and organize technological training; on the other hand, developing hybrid professional development programs incorporating emotional support should be emphasized, so as to intentionally enhance teachers’ positive emotions and effectively alleviate negative emotions. This institutionalized support framework not only helps strengthen teacher self-efficacy but also effectively promotes deep engagement in information-empowered teaching through emotional regulation.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the sample was drawn only from Southeast China, and thus the results may not fully represent university English teachers from central or western China where educational resources and teaching environments differ. Second, the gender imbalance in the sample suggests the findings may be more representative of female teacher populations. Future research could employ stratified sampling methods to expand sample coverage and further develop longitudinal or experimental studies to examine the effects of PP interventions on enhancing positive emotions, as well as the roles of hybrid engagement-oriented professional development in the relationship between self-efficacy, emotion, and teaching engagement. This would provide more contextually appropriate theoretical foundations and practical solutions for teacher professional development within East Asian educational contexts.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants or participants legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

XX: Validation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – original draft. JC: Writing – review & editing. CD: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. HZ: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This article was part of the research project “The Interaction between English Teacher Identity and Emotion from the Perspective of Complex Dynamic Systems Theory,” supported by the Fujian Provincial Association for Social Sciences (Grant No: FJ2023BF020).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1696627/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Atikuzzaman M. Zabed Ahmed S. M. (2023). Information literacy self-efficacy scale: validating the translated version of the scale for use among Bangla-speaking population. J. Acad. Librariansh.49:102623. doi: 10.1016/j.acalib.2022.102623

2

Ayanwale M. A. Adelana O. P. Molefi R. R. Adeeko O. Ishola A. M. (2024). Examining artificial intelligence literacy among pre-service teachers for future classrooms. Comput. Educ. Open6:100179. doi: 10.1016/j.caeo.2024.100179

3

Azari Noughabi M. Ghonsooly B. Jahedizadeh S. (2022). Modeling the associations between EFL teachers’ immunity, L2 grit, and work engagement. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev.45, 3158–3173. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2022.2088766

4

Azzaro G. Martínez Agudo J. D. (2018). “The emotions involved in the integration of ICT into L2 teaching: emotional challenges faced by L2 teachers and implications for teacher education” in Emotions in second language teaching: theory, research and teacher education. ed. Martínez AgudoJ. D. (Cham: Springer), 183–203.

5

Bandura A. (1978). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Adv. Behav. Res. Ther.1, 139–161. doi: 10.1016/0146-6402(78)90002-4

6

Bandura A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am. Psychol.44, 1175–1184. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175,

7

Beaudry A. Pinsonneault A. (2010). The other side of acceptance: studying the direct and indirect effects of emotions on information technology use. MIS Q.34, 689–710. doi: 10.2307/25750701

8

Bruce C. (1997). The seven faces of information literacy. Adelaide, SA: Auslib Press.

9

Burić I. Macuka I. (2018). Self-efficacy, emotions and work engagement among teachers: a two wave cross-lagged analysis. J. Happiness Stud.19, 1917–1933. doi: 10.1007/s10902-017-9903-9

10

Burić I. Slišković A. Sorić I. (2020). Teachers’ emotions and self-efficacy: a test of reciprocal relations. Front. Psychol.11:1650. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01650,

11

Chen J. L. (2010). Integration of computer networks and foreign language courses: a study based on college English teaching reform. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.

12

Chen J. Cheng T. (2022). Review of research on teacher emotion during 1985-2019: a descriptive quantitative analysis of knowledge production trends. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ.37, 417–438. doi: 10.1007/s10212-021-00537-1,

13

Chen M. Zhou C. Man S. Li Y. (2023). Investigating teachers’ information literacy and its differences in individuals and schools: a large-scale evaluation in China. Educ. Inf. Technol.28, 3145–3172. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11271-6

14

Ci F. Jiang L. (2025). “Teacher emotion and AI: current status, theories, and prospects” in Encyclopedia of educational innovation. eds. PetersM. A.HeraudR. (Singapore: Springer), 1–6.

15

Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd Edn. New York: Routledge.

16

Cohen A. Nørgård R. T. Mor Y. (2020). Hybrid learning spaces—design, data, didactics. Br. J. Educ. Technol.51, 1039–1044. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12964

17

Cowie N. (2011). Emotions that experienced English as a foreign language (EFL) teachers feel about their students, their colleagues and their work. Teach. Teach. Educ.27, 235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.006

18

Davis F. D. . (1986). A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: theory and results [doctoral dissertation], Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/15192 (Accessed May 20, 2025).

19

Dilekçi Ü. Limon İ. Manap A. Alkhulayfi A. M. A. Yıldırım M. (2025). The association between teachers’ positive instructional emotions and job performance: work engagement as a mediator. Acta Psychol.254:104880. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2025.104880,

20

Diliello T. C. Houghton J. D. Dawley D. (2011). Narrowing the creativity gap: the moderating effects of perceived self-efficacy. J. Psychol.145, 151–172. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2010.548412

21

Drossel K. Eickelmann B. Gerick J. (2017). Predictors of teachers’ use of ICT in school–the relevance of school characteristics, teachers’ attitudes and teacher collaboration. Educ. Inf. Technol.22, 551–573. doi: 10.1007/s10639-016-9476-y

22

Fredrickson B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol.56, 218–226. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218,

23

Garzon J. Garzon J. (2023). Teachers’ digital literacy and self-efficacy in blended learning. Int. J. Multidisc. Educ. Res. Innov.1, 162–174. doi: 10.17613/cmjv-1386

24

Gobbi E. Bertollo M. Colangelo A. Carraro A. di Fronso S. (2021). Primary school physical education at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic: could online teaching undermine teachers’ self-efficacy and work engagement?Sustainability13:9830. doi: 10.3390/su13179830

25

Gong L. (2023). How can college teachers’ information literacy empower their innovative teaching behaviors under the background of informatization?PLoS One18:e0294593. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0294593,

26

Greenier V. Derakhshan A. Fathi J. (2021). Emotion regulation and psychological well-being in teacher work engagement: a case of British and Iranian English language teachers. System97:102446. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2020.102446

27

Guo Y. (2012). On the role and implementation of educational informatization in modern foreign language teaching. Mod. Distance Educ.4, 47–52.

28

Hair J. F. Hult G. T. M. Ringle C. M. Sarstedt M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

29

Hanell F. (2017). Teacher trainees’ information sharing activities and identity positioning on Facebook. J. Doc.73, 244–262. doi: 10.1108/JD-06-2016-0085

30

Hascher T. Hagenauer G. (2016). Openness to theory and its importance for pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy, emotions, and classroom behaviour in the teaching practicum. Int. J. Educ. Res.77, 15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2016.02.003

31

Hemami H. G. . (2024). Studying the model of psychology of working theory among teachers in Portugal: Predictors and outcomes of decent work [doctoral dissertation], Universidade de Coimbra. Available online at: https://baes.uc.pt/handle/10316/115762#:~:text=The%20present%20thesis%20applied%20the%20“Psychology%20of%20Working,outcomes%20of%20decent%20work%20among%20teachers%20in%20Portugal (Accessed May 11, 2025).

32

Henseler J. Ringle C. M. Sarstedt M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci.43, 115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

33

Hobfoll S. E. Johnson R. J. Ennis N. Jackson A. P. (2003). Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.84, 632–643. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.632

34

Hoy A. W. Hoy W. K. Davis H. A. (2009). “Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs” in Handbook of motivation at school. eds. WentzelK.WigfieldA. (New York: Routledge), 627–653.

35

Inceoglu I. Warr P. (2011). Personality and job engagement. J. Pers. Psychol.10, 177–181. doi: 10.1027/1866-5888/a000045

36

Jia F. Zhang H. Y. (2023). The impact of teaching resources development on foreign language teachers’ information literacy. Technol. Enhanc. Foreign Lang. Educ.5, 82–87+113.

37

Jiang B. (2024). Enhancing digital literacy in foreign language teaching in Chinese universities: insights from a systematic review. Teach. Teach. Educ.154:104845. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2024.104845

38

Jiao J. L. Wang X. D. Qin D. (2009). Technology enhanced teacher professional development: literature reviews in China. J. Distance Educ.27, 18–24.

39

Khammat A. H. (2022). Investigating the relationships of Iraqi EFL teachers’ emotion regulation, resilience and psychological well-being. Lang. Res. Rev.13, 613–640. doi: 10.52547/LRR.13.5.22

40

Kirkpatrick C. L. Johnson S. M. (2014). Ensuring the ongoing engagement of second-stage teachers. J. Educ. Change15, 231–252. doi: 10.1007/s10833-014-9231-3

41

Klassen R. M. Yerdelen S. Durksen T. L. (2013). Measuring teacher engagement: development of the engaged teachers scale (ETS). Frontline Learn. Res.1, 33–52. doi: 10.14786/flr.v1i2.44

42

Landrieu L. C. . (2024). Implicit bias toward students with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the influential role of teacher self-efficacy [doctoral dissertation], University of Northern Colorado. Available online at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations/1094/ (Accessed February 10, 2025).

43

Liu H. Lin C. H. Zhang D. (2017). Pedagogical beliefs and attitudes toward information and communication technology: a survey of teachers of English as a foreign language in China. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn.30, 745–765. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2017.1347572

44

Lo N. P.-K. (2023). Emotional bridge in higher education: enhancing self-efficacy and achievement through hybrid engagement. ESP Rev.5, 7–23. doi: 10.23191/espkor.2023.5.2.7.

45

Lo N. P.-K. Punzalan C. H. (2025). The impact of positive psychology on language teachers in higher education. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract.22, 1–19. doi: 10.53761/5ckx2h71

46

Martínez Agudo J. D. D. (2018). Emotions in second language teaching: theory, research and teacher education. Cham: Springer.

47

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China . (2021). Norms for the construction of digital campuses in colleges and universities (trial). Available online at: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A16/s3342/202103/t20210322_521675.html (Accessed December 17, 2024)

48

Motteram G. Dawson S. (2025). What’s changed in English language teaching? A review of change in the teaching and learning of English and in teacher education and development from 2014–2024. London: British Council.

49

Mou Z. J. Su X. L. Yan D. H. (2020). Research on the modeling of teacher teaching engagement based on teaching behavior in classroom settings. Mod. Distance Educ.3, 61–69.

50

Pekrun R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev.18, 315–341. doi: 10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9

51

Podsakoff P. M. MacKenzie S. B. Lee J. Y. Podsakoff N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol.88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879,

52

Qin M. J. He G. K. (2009). Discussion on the connotation of college English teachers’ information literacy. Foreign Lang. World5, 18–25+41.

53

Qu J. Wang M. Xin Y. (2025). The role of resilience and perseverance of effort among Chinese EFL teachers’ work engagement. Porta Linguarum43, 11–28. doi: 10.30827/portalin.vi43.28309

54

Romo-Escudero F. Guzmán P. Romo J. (2023). “Teachers’ emotions: their origin and influence on the teaching-learning process” in Affectivity and learning: Bridging the gap between neurosciences, cultural and cognitive psychology. eds. FossaP.Cortés-RiveraC. (Cham: Springer), 351–375.

55

Ross M. Perkins H. Bodey K. (2016). Academic motivation and information literacy self-efficacy: the importance of a simple desire to know. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res.38, 2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lisr.2016.01.002

56

Shao K. Yu W. Ji Z. (2013). An exploration of Chinese EFL students’ emotional intelligence and foreign language anxiety. Mod. Lang. J.97, 917–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2013.12042.x

57

Shen Y. Guo H. (2024). I feel AI is neither too good nor too bad: unveiling Chinese EFL teachers’ perceived emotions in generative AI-mediated L2 classes. Comput. Hum. Behav.161:108429. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2024.108429

58

Skantz-Åberg E. Lantz-Andersson A. Lundin M. Williams P. (2022). Teachers’ professional digital competence: an overview of conceptualisations in the literature. Cogent Educ.9:2063224. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2022.2063224

59

Su Y. (2023). Delving into EFL teachers’ digital literacy and professional identity in the pandemic era: technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) framework. Heliyon9:e16361. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16361,

60

Tripon C. (2025). “Information literacy in engineering education” in Digital equity and literacy. eds. SerpaS.SantosA. I. (London: IntechOpen), 1–24.

61

Troesch L. M. Bauer C. E. (2017). Second career teachers: job satisfaction, job stress, and the role of self-efficacy. Teach. Teach. Educ.67, 389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.07.006

62

Tschannen-Moran M. Hoy A. W. Hoy W. K. (1998). Teacher efficacy: its meaning and measure. Rev. Educ. Res.68, 202–248. doi: 10.3102/00346543068002202

63

Wang H. X. (2022). Explorations into the framework and core construct of college English teachers’ information literacy. Technol. Enhan. Foreign Lang. Educ.6, 31–38.

64

Wang Y. Bu L. Z. (2022). The current situation, hot spots and enlightenment of teacher information literacy research—bibliometric analysis based on CNKI and web of science from 2000 to 2021. J. Qilu Norm. Univ.37, 1–12.

65

Wang Y. Pan Z. (2023). Chinese EFL teachers’ self-efficacy and resilience on their work engagement: a structural equation modeling analysis. SAGE Open10, 1–15. doi: 10.1177/21582440231214329

66

Wang W. Yan H. B. Huang X. R. (2021). How far is OMO teaching: the breakthrough of online teaching from the perspective of teachers’ self-efficacy. Mod. Distance Educ.1, 48–55.

67

Wang Y. Yonezawa T. Yamasaki A. Ko J. Liu Y. Kitayama Y. (2024). Examining the changes in the self-efficacy and pedagogical beliefs of preservice teachers in Japan. Front. Educ.9:1322409. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1322409

68

Wong K.-T. Teo T. Russo S. (2013). Interactive whiteboard acceptance: applicability of the UTAUT model to student teachers. Asia Pac. Educ. Res.22, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s40299-012-0001-9

69

Xie Jiang G. Y. (2023). A review on research topics of EFL teacher emotions. J. Jimei Univ24, 54–61.

70

Yang S. S. Shu D. F. Chen H. J. (2021). ICT-integrated teaching in primary and secondary English education: a large-scale survey of EFL teachers in Shanghai. Foreign Lang. Educ. China4, 26–35+93. doi: 10.20083/j.cnki.fleic.2021.03.004

71

Zee M. Koomen H. M. Y. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: a synthesis of 40 years of research. Rev. Educ. Res.86, 981–1015. doi: 10.3102/0034654315626801

72

Zembylas M. (2003). Emotions and teacher identity: a poststructural perspective. Teach. Teach.9, 213–238. doi: 10.1080/13540600309378

73

Zhang S. Gu M. Sun W. Jin T. (2023). Digital literacy competence, digital literacy practices and teacher identity among pre-service teachers. J. Educ. Teach.50, 464–478. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2023.2283426,

Summary

Keywords

information literacy, parallel mediation, self-efficacy, teacher emotions, teaching engagement

Citation

Xie X, Du C, Cheng J and Zhang H (2026) From believing to behaving: Unpacking teacher emotion as the mediator between information literacy self-efficacy and information-empowered teaching engagement. Front. Psychol. 16:1696627. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1696627

Received

01 September 2025

Revised

01 December 2025

Accepted

03 December 2025

Published

07 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Sereyrath Em, University of Cambodia, Cambodia

Reviewed by

Noble Lo, Lancaster University, United Kingdom

Cristina Tripon, Polytechnic University of Bucharest, Romania

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Xie, Du, Cheng and Zhang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Haiyan Zhang, zhanghaiyan@jmu.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.