Introduction

Orpheus, as an archetypal model of musical performance, enters our cultural consciousness not only as an exemplary performer but also as a figure whose fleeting glance into the visible shattered the magic of creation. Through this metaphor, for three millennia we have (re)interpreted the deeper projection of the conflict between the artistic idea and the performer's inner tension (Partridge, 2014; Blanchot, 1981). The performer's inner tension is partly framed by the constructs of stage fright (Steptoe, 1989) and music performance anxiety (MPA; Kenny, 2011), which empirical research often links to impaired stage performance (Chan, 2011). MPA is consistently associated with lower self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997; Zarza-Alzugaray et al., 2020) and reduced self-esteem (Rosenberg, 2015/2015, Jiang and Tong, 2024), as well as heightened self-monitoring and threat appraisal (Kenny, 2011; Brooks, 2014), perfectionistic concern (Spahn, 2015), and attentional narrowing with a consequent loss of the “big picture” of performance (Clarke et al., 2020). Such processes hinder the optimal flow of performance, understood as a balance between challenge and skill (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990).

Because the myth portrays Orphic performance as technically flawless, the motif of lapse directs us to a dimension that anchors peak performance beyond mere technical execution (Privette, 1983). Privette supplements the apex of creative activity with the notion of peak experience, which brings self-transcendent qualities into performance. Precisely the moment when Orpheus “loses the transcendent thread” entails a breakdown of the performance and its meaning—a motif we subsequently use as a philosophical key for a cautious, empirical dialogue with the analogy of the myth. We ground this dialogue in findings indicating that mindfulness and related contemplative practices may facilitate a shift from an anxious mode to a more optimal performance state (Czajkowski et al., 2020; Paese and Egermann, 2024; Paese and Schiavio, 2025), while understanding the transcendent dimension as both performing at the height of one's abilities and experiencing a sense of belonging to something beyond the individual (Bernard, 2009; Jääskeläinen, 2022).

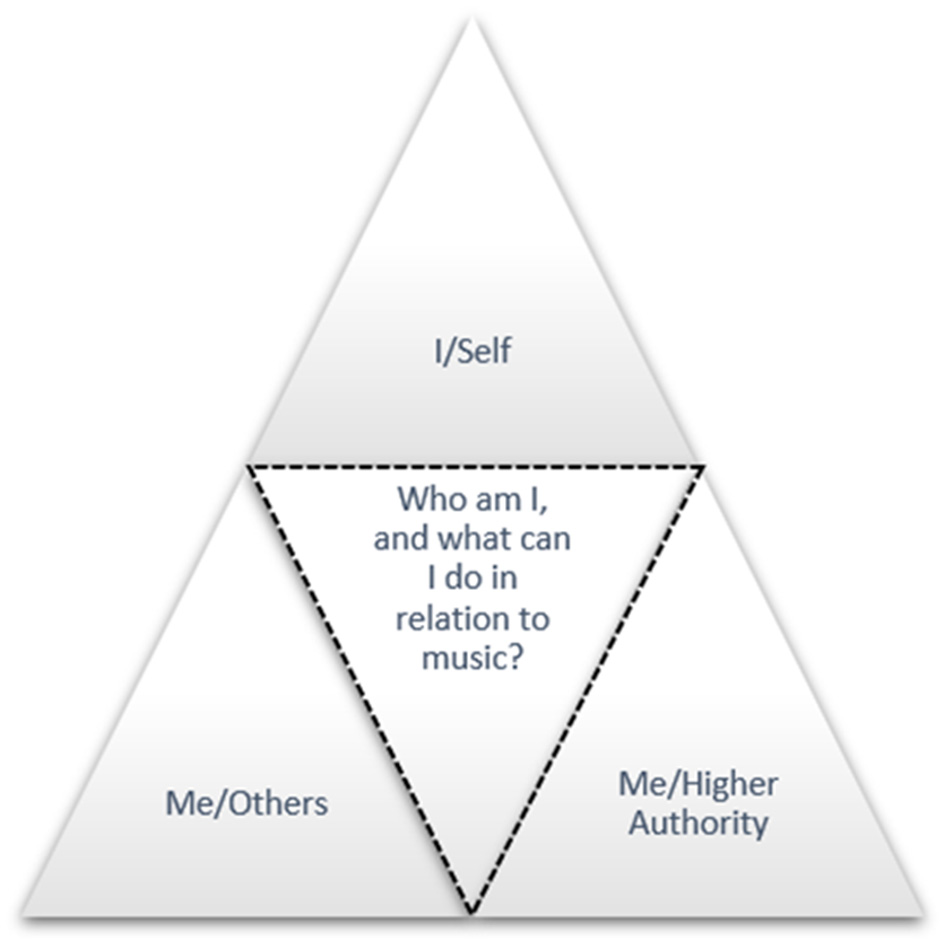

In this article, we argue that, given the overarching motive of musical creation, approaches to MPA should be extended beyond the I/self and Me/others dimensions to the transcendent dimension, focusing on contexts such as rituality, community, valuation, mindfulness, and the search for higher meaning in music performance. In education, this means intentionally cultivating practices in which the performer, alongside balance with self and audience, also seeks a universal meaning—the third vertex of our triangle—as a protective ring against MPA.

Self-concept and musical manifestation

“… not conceptual speech, but music rather, is the element through which we are best spoken to by mystical truth.” (James, 1902/2004, p. 328)

In the above quotation, the philosopher and psychologist William James uses the word mystical in relation to music. In strictly empirical approaches—focused on quantitative testing and applicability—such terminology appears only rarely. Instead, it is more often invoked in philosophy and the psychology of religion, or replaced with more measurable concepts such as transcendental experience, absorption, flow, or aesthetic chills. Yet it was precisely William James (James, 1890) who laid the foundations for an empirical investigation of the unseen but essential source of human meaning—the soul, a concept already central to Plato's philosophy (Plato, 2004). In The Principles of Psychology (1890), James ascribed to this entity a stream of directed consciousness that one devotes to oneself. In this way, he established the concept of self , thereby relocating the domain of the soul, or the thinking self (Descartes, 1966), into the realm of cognitive interpretations of personality. This marked the beginning of a systematic psychological delineation of the individual, which (James 1890), (1902) framed through bodily, material, social, and spiritual dimensions of perception. Were he writing today, he would likely call out the persistent elusiveness that clings to the spiritual stratum within self-concept research (see Hattie, 2003).

Since the 1980s, the musical self-concept and, consequently, musical identity have attracted growing attention among music psychologists (Asmus, 1986; Frith, 1981; Hargreaves, 1986; Schmitt, 1979; Svengalis, 1978). The most comprehensive account was provided by Maria Spychiger, who explained it from a philosophical and psychological perspective (Spychiger, 2010; Spychiger and Hechler, 2014; Spychiger, 2017b) as well as from a music education perspective (Spychiger, 2017a, 2021), while also describing its empirical basis and measurement procedures (Spychiger et al., 2009; Spychiger, 2017b).

Based on the ideas, perceptions, and evaluations reflected in an individual's diverse understandings of their musical activities, the self-concept is divided into an academic dimension and a non-academic dimension (Shavelson et al., 1976; Spychiger et al., 2009). The academic dimension encompasses domains of knowledge and skills such as singing, playing an instrument, auditory abilities, and composition. The non-academic dimension comprises physical, emotional, social, cognitive, and spiritual aspects of the musical self-concept. According to Spychiger, the musical self-concept represents a non-hierarchical and multidimensional psychological construct of the individual, which, during adolescence—in both social and developmental terms—evolves into musical identity. This psychological construct connects personal perceptions with social roles and acts as a key regulator of musical development and experience (MacDonald et al., 2002).

The self-portrait of the musician, as captured by the MUSCI (Musical Self-Concept Inquiry) Scale (Fiedler and Spychiger, 2017), extends beyond the emotional, social, or ability-related aspects of previously established measures, as it enables an understanding of musical functioning through the spiritual and transcendent horizon of artistic experience. The scale includes methodological items such as: “For me, making music is a special kind of prayer; I make music in order to feel the divine; I like to make music which promotes spiritual experience; With my music I can elicit change in people.” (Spychiger, 2017b)

The MUSCI scale thus operationalizes an entity that is not the person him or herself, but rather the product of his or her relationship with the irrational (Spychiger, 2019). Such multifacetedness shapes musical manifestations that, in an individual's relationship (i), with him or herself (ii), with others, and (iii), with an entity that transcends or complements the individual and society, raise the fundamental question: Who am I, and what can I do in relation to music? (Spychiger, 2017b). Within this framework, internal reflection, interpersonal interaction, and a broader connection to the transcendent are formed, which—as shown in Figure 1—is illustrated by a triangular scheme of three vertices.

Figure 1

Vertices of the musical manifestation.

Let us imagine a child who, during instrument lessons, has learned to play a melody that he knows well—it is a folk song that his mother sang to him. When learning a melody on an instrument, he will face challenges related to his knowledge and skills, physical capacity, and emotional experience. This involves triggering cognitive processes that guide the understanding and processing of musical material, as well as social aspects that stem from interactions with the teacher, peers and audience. Learning and performing a simple song will thus provoke self-reflection, socially reciprocal dialogue, and the musical manifestation itself will also reflect a relationship to a higher entity—in this case, to national belonging, which transcends both the child and his perception of others. The melody, as a musical message, will take on the symbolic power of national belonging and music heritage, and the child will thereby assume the role of bearer of this important message. At the same time, the child will undergo a complex musical experience in which s/he will also articulate the spiritual purpose of creation.

In this triangular schema MPA is expected in areas where the burden exceeds the regulatory abilities of self-concept; empirical studies often perceive this as lower self-efficacy and/or lower self-esteem (Bandura, 1997; Chan, 2011; Dobos et al., 2019; Rosenberg, 2015/2015). When self-concept is stronger, it is easier to absorb stage pressure—higher self-esteem and especially musical self-efficacy are associated in research with lower MPA and better performance control (Castiglione et al., 2018; Jiang and Tong, 2024; Zarza-Alzugaray et al., 2020; Wang and Yang, 2024). This is also revealed by the symptoms that occur with MPA: emotions are exacerbated, the whole body reacts, cognitive resources are narrowed, and the social context intensifies judgment. However, the existing literature is dominated by a discourse in which therapy for the relief of MPA is framed in terms of I/self and Me/others relations, while the connection to the transcendent (e.g., Bernard, 2009; Jääskeläinen, 2022) has received comparatively less sustained attention.

To the transcendent: Future steps for coping with music performance anxiety

In the I/self dimension of our triangular schema, MPA is managed with relaxation, gradual exposure, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and beta-blockers have been used as adjuncts to treat physical symptoms (Kenny, 2011; Kinney et al., 2025; Nicholl and Abbott, 2025; Spahn, 2015; Szeleszczuk and Fraczkowski, 2022). More modern CBT practices—especially Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)—do not just address symptoms, but also strengthen the relationship to one's own experiences and values. In a group or “coaching” setting (Clarke et al., 2020; Juncos and Markman, 2016) this brings us somewhat closer to the Me/others dimension. Psychodynamic relational approaches explicitly explore early relationships, transference, and the context of performance (Kenny et al., 2016), which directly affects the Me/others dimension. Guided mentoring and social support strengthen bonds with teachers, peers, and audiences and indirectly increase self-efficacy (Huawei and Jenatabadi, 2024), which is associated with lower MPA; brief reappraisal strategies—e.g., “rewrite anxiety into excitement”—are also helpful before and during a performance (Brooks, 2014; Jamieson et al., 2013; Zarza-Alzugaray et al., 2020; Uphill et al., 2012).

We enter the transcendent dimension of performance through the latent analogy of Orpheus and his creative identity—an archetype that opens the cracks of the sacred within the secular in music (Partridge, 2014). He represents the ideal of artistic interpretation, since his singing and playing of the lyre were so powerful “…that even the wild animals were stilled, trees and stones moved to the rhythm of his music…” (Apollodorus, 2008, 1.3.2; Ovid, 2004, 11.1–5). Yet Orpheus cannot fully own his artistic potential, which is woven into his musical identity as a singer, instrumentalist, composer, musical mentor, therapist, and liturgist. The mythical origin of Orpheus' excellence is attributed to his mother, the goddess Calliope, and the god Apollo, who gave him the lyre and taught him to play (Apollodorus, 2008, 1.3.2).

With this premise, how should we view contemporary society, which is far from unified in its worship of God or deities, and which can no longer be addressed en masse with either the Matthew Passion or gospel? We thus witness new forms of belief as believers—understood here as devotees ascribing sacred significance to emblematic figures—venerate so-called secular saints (Rojek, 2001). On the basis of a subjective and transcendent experience with, say, Whitney Houston, these devotees then undertake contemporary pilgrimages to digital shrines, the grave, and memorial sites—through which the singer's widely mediated vocal presence functions as a spiritual authority and an institution outside ecclesial settings, especially online (Chidester and Linenthal, 1995; McCutcheon et al., 2002). The contemporary spiritual landscape therefore offers, in addition to the sediments of traditional religions and the confusion and dilemmas related to them, a range of other powerful ideas, encrypted and fragmented within secular entities (Partridge, 2014). From this perspective, spirituality should not be sought solely within religious contexts and acts of worship, but also in secularized spiritualized entities that are not themselves human yet exert significant influence on humans (Spychiger, 2019).

Secularized sources of veneration may manifest as political ideas or movements, but they can equally be attributed to entities such as recording contracts, the position of concertmaster, or even a self-idealized status as a virtuoso, conceived as a network of spiritual purposes and goals. This amounts to privileging certain cognitive concepts of music manifestation over others. If we consider further the individual who idealizes personal virtuosity, career ambitions, or technical perfectionism, research shows that such factors are associated with greater vulnerability to MPA (Castiglione et al., 2018; Dobos et al., 2019; Kenny, 2011).

The analogy we deepen with Orpheus's lapse tells us the same: an inflated dimension of the self can lead to the disintegration of a holistic artistic identity. The excessive desire for earthly love—for Eurydice, or, in modern terms, the all-encompassing lust for success—conceals a creative trap. The ancient myth predicts the artist's disintegration, and the fall of his mission; our reality, along with certain modern myths, points to similar fates of great performers.

It may therefore be a task for future researchers to strengthen this premise and treat MPA as a symptom of a broader imbalance, as intimated by Leech-Wilkinson (2018), Skoogh and Frisk (2019), and Perdomo-Guevara (2014), rather than as a standalone disorder (see Fernholz et al., 2019; Sousa et al., 2016) that burdens us with a series of superficial, unmanageable ailments.

Music performance anxiety as a symptom of asymmetry of the vertices of musical manifestation

In the field of musical identity—as a developmental and social consequence of the musical self-concept—since 2002 a range of musical practices has been reconsidered through the lens of personal and social coherence, reciprocity, and meaningfulness (MacDonald et al., 2002). We identify the latter as emotional wellbeing (Saarikallio, 2017), economic and personal musical synchronicity (Gaunt et al., 2021), optimal musical development (Taruffi, 2017; Evans and McPherson, 2015; Lamont, 2017; O'Neill, 2002), and activities in which a therapeutic (Bradt et al., 2013) or humanitarian and connecting meaning is increasingly indicated (Hess, 2019). Musical identity cannot therefore be the property of an individual, but is created by the common dynamics of coexistence in which the needs of society are outlined. Thus, in the field of education and performance practices, Lukowska (2024) emphasizes the triple mission of the musician as composer, performer, and teacher, and warns that focusing solely on virtuosity creates discrepancies in professional identity and pedagogy. These are reflected in the literature as phenomena of vulnerability and conflict in the identity of the musician (Pellegrino, 2009).

Hargreaves et al. (2003) also focuses on the individual's identity as a regulatory instrument in musical activity, which we must take into account in educational processes as a concept of socially meaningful development of the musician. Such global concepts may also offer a kind of “release from suffering” for those who, even during learning, free themselves from self-perceptive patterns that produce tension rather than wellbeing, and self-absorption rather than creative community. In this way, the “uncalled” will not be unduly burdened by excessive technical overemphasis, constrained bodily expression, or social categories that fail to address their musical self. However, a mere structural step toward oneself and others does not yet bring the full meaning of music performance. The “gods of the underworld” must be addressed with an elaborate system of values and an equivalent creative language, which is not necessarily Orpheus' artful melody but can be a simple folk song that elevates national consciousness. Encouragingly, studies attribute the transformation of anxiety into creative power to transcendent experiences. Alberici (2004), Bernard (2009), and (Jääskeläinen 2022) report that musicians experience such moments as healing and at times even “divine,” as they transcend not only performance stress but also the burdens of everyday life. One participant defined transcendent performance as “the experience of rising above normal physical and mental fears and concerns to a peak experience that is remembered and sought after again and again” (Alberici, 2004, p. 22).

Discussion

With full respect for Orpheus as a possible historical figure (Wroe, 2011) or as an incarnated myth that has left the world priceless artifacts, his story should not be trivialized by pursuing a literal answer to our hypothetical title question. We can, however, understand the turning point—where the mythical figure failed to complete his performance—as an expression of the fragility of his self-concept (Blanchot, 1981), in which stage fright can also be understood as a vulnerability within the realm of narcissism (Gabbard, 1983; Nagel, 2018).

We have therefore examined the archetypal ideal of the musical performer as a prototype of performative (im)perfection that unravels due to identity incoherence (Blanksma, 2024). To that end, we have clarified the internal robustness of the performer's musical manifestation, in which Orpheus embodies, above all, the third vertex—the ritual, the religious, the transcendent (Spychiger, 2019). This dimension is by no means disappearing from our everyday lives. On the contrary, within secular conditions (Partridge, 2014), it grows more colorful, more intricate, and more contested in value. It also shapes musical performance, which, in future research, should approach the emergence of MPA not merely as an individual symptom but as a socially shaped phenomenon (Brooks, 2014; Herman and Clarke, 2023). We hold that its regulation is offered by the self-concept (Hargreaves et al., 2003) and by the formation of musical identity as a shared capital of the individual and society, connected with the higher meaning of musical manifestation.

We must enter that manifestation as beings who have been given a voice, a lyre, and Eurydice—knowing that nothing in it, except the song that, in that very moment, resounds across the living and the dead, is immortal, immutable, or tangible.

Statements

Author contributions

NŠ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Correction note

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the scientific content of the article.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Alberici M. (2004). A phenomenological study of transcendent music performance in higher education (Doctoral dissertation). University of Missouri, St. Louis, MO, United States. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

2

Apollodorus (2008). The Library of Greek Mythology (Trans. R. Hard). Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Original work published ca. 1st−2nd century CE)

3

Asmus E. (1986). Student beliefs about the causes of success and failure in music: a study of achievement motivation. J. Res. Music Educ.34, 262–278. doi: 10.2307/3345260

4

Bandura A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman.

5

Bernard R. (2009). Music making, transcendence, flow, and music education. Int. J. Educ. Arts10, 1–22. Available online at: http://www.ijea.org/v10n14/ (Accessed October 16, 2025).

6

Blanchot M. (1981). The Gaze of Orpheus, and Other Literary Essays (Ed. P. A. Sitney and Trans. L. Davis). Barrytown, NY: Station Hill Press.

7

Blanksma A. (2024). The Orpheus complex: understanding cinema through Maurice Blanchot (MPhil(R) thesis). University of Glasgow. Available online at: https://theses.gla.ac.uk/84697/ (accessed October 16, 2025).

8

Bradt J. Dileo C. Shim M. (2013). Music interventions for preoperative anxiety. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.2013:CD006908. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006908.pub2

9

Brooks A. W. (2014). Get excited: reappraising pre-performance anxiety as excitement. J. Exp. Psychol. General143, 1144–1158. doi: 10.1037/a0035325

10

Castiglione C. Rampullo A. Cardullo S. (2018). Self representations and music performance anxiety: a study with professional and amateur musicians. Europe's J. Psychol.14, 792–805. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v14i4.1554

11

Chan M.-Y. (2011). The relationship between music performance anxiety, age, self-esteem, and performance outcomes in Hong Kong music students (Doctoral thesis). Durham University. Available online at: https://etheses.dur.ac.uk/637 (Accessed September 10, 2025).

12

Chidester D. Linenthal E. T. (eds.) (1995). American Sacred Space. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. doi: 10.2979/1093.0

13

Clarke L. K. Osborne M. S. Kenny D. T. (2020). Examining a group acceptance and commitment therapy intervention for music performance anxiety in student musicians. Front. Psychol.11:881. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01127

14

Csikszentmihalyi M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

15

Czajkowski A.-M. Greasley A. Allis M. (2020). Mindfulness for musicians: a mixed methods study investigating the effects of 8-week mindfulness courses on music students at a leading conservatoire. Musicae Scientiae. 26, 259–279. doi: 10.1177/1029864920941570

16

Descartes R. (1966). Oeuvres et lettres. Paris: Gallimard.

17

Dobos B. Piko B. F. Kenny D. T. (2019). Music performance anxiety and its relationship with social phobia and dimensions of perfectionism. Res. Stud. Music Educ.41, 310–326. doi: 10.1177/1321103X18804295

18

Evans P. McPherson G. E. (2015). Identity and practice: the motivational benefits of a long-term musical identity. Psychol. Music43, 407–422. doi: 10.1177/0305735613514471

19

Fernholz I. Mumm J. L. M. Plag J. Noeres K. Rotter G. Willich S. N. et al . (2019). Performance anxiety in professional musicians: a systematic review on prevalence, risk factors and clinical treatment effects. Psychol. Med.49, 2287–2306. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719001910

20

Fiedler D. Spychiger M. (2017). Measuring ‘musical self-concept' throughout the years of adolescence with MUSCI_Youth: validation and adjustment of the Musical Self-concept Inquiry (MUSCI) by investigating samples of students at secondary education schools. Psychomusicol. Music Mind Brain27, 167–179. doi: 10.1037/pmu0000180

21

Frith S. (1981). Sound Effects: Youth, Leisure, and the Politics of Rock'n'roll. New York, NY: Pantheon.

22

Gabbard G. O. (1983). Further contributions to the understanding of stage fright: narcissistic issues. J. Am. Psychoanal. Assoc.31, 423–441. doi: 10.1177/000306518303100203

23

Gaunt H. Duffy C. Corić A. González Delgado I. R. Messas L. Pryimenko O. et al . (2021). Musicians as “makers in society”: a conceptual foundation for contemporary professional higher music education. Front. Psychol.12:713648. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713648

24

Hargreaves D. Marshall N. A. North A. C. (2003). Music education in the twenty-first century: a psychological perspective. Br. J. Music Educ.20, 147–163. doi: 10.1017/S0265051703005357

25

Hargreaves D. J. (1986). Developmental psychology and music education. Psychol. Music14, 83–96. doi: 10.1177/0305735686142001

26

Hattie J. (2003). The status and direction of self-concept research: the importance of importance. Paper presented at the Human Development Conference (13th Biennial Conference of the Australian Human Development Association), Waiheke Island, New Zealand, July.

27

Herman R. Clarke T. (2023). It's not a virus! Reconceptualizing and de-pathologizing music performance anxiety. Front. Psychol.14:1194873. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1194873

28

Hess J. (2019). Music Education for Social Change: Constructing an Activist Music Education. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429452000

29

Huawei Z. Jenatabadi H. S. (2024). Effects of social support on music performance anxiety among university music students: chain mediation of emotional intelligence and self-efficacy. Front. Psychol.15:1389681. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1389681

30

Jääskeläinen T. (2022). Using a transcendental phenomenological approach as a model to obtain a meaningful understanding of music students' experienced workload in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Arts 23. doi: 10.26209/ijea23n6

31

James W. (1890). The Principles of Psychology. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company. doi: 10.1037/10538-000

32

James W. (1902). The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature. New York, NY: Longmans, Green and Co. doi: 10.1037/10004-000

33

Jamieson J. P. Mendes W. B. Nock M. K. (2013). Improving acute stress responses: the power of reappraisal. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci.22, 51–56. doi: 10.1177/0963721412461500

34

Jiang X. Tong Y. (2024). Psychological capital and music performance anxiety: the mediating role of self-esteem and flow experience. Front. Psychol.15:1461235. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1461235

35

Juncos D. G. Markman E. J. (2016). Acceptance and commitment therapy for the treatment of music performance anxiety: a single subject design with a university student. Psychol. Music44, 935–952. doi: 10.1177/0305735615596236

36

Kenny D. T. (2011). The Psychology of Music Performance Anxiety. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199586141.001.0001

37

Kenny D. T. Arthey S. Abbass A. (2016). Identifying attachment ruptures underlying severe music performance anxiety in a professional musician undertaking an assessment and trial therapy of Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy (ISTDP). Springerplus5:1591. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-3268-0

38

Kinney C. Saville P. Heiderscheit A. Himmerich H. (2025). Therapeutic interventions for music performance anxiety: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Behav. Sci.15:138. doi: 10.3390/bs15020138

39

Lamont A. (2017). “Musical identity, interest, and involvement,” in Handbook of Musical Identities, eds. R. MacDonald, D. J. Hargreaves, and D. Miell (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 176–197. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199679485.003.0010

40

Leech-Wilkinson D. (2018). The danger of virtuosity. Musicae Scientiae22, 558–561. doi: 10.1177/1029864918790304

41

Lukowska S. (2024). Exploring the composer–performer–teacher role complex in fostering creativity in music education. Convergences J. Res. Arts Educ.17, 105–122. doi: 10.53681/c1514225187514391s.33.242

42

MacDonald R. A. Hargreaves D. J. Miell D. (2002). Musical Identities. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198509325.001.0001

43

McCutcheon L. E. Lange R. Houran J. (2002). Conceptualization and measurement of celebrity worship. Br. J. Psychol.93, 67–87. doi: 10.1348/000712602162454

44

Nagel J. J. (2018). Memory slip: stage fright and performing musicians. Psychoanal. Rev.105, 487–505. doi: 10.1177/0003065118795432

45

Nicholl T. J. Abbott M. J. (2025). Treatments for performance anxiety in musicians across the lifespan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Music. doi: 10.1177/03057356251322655. [Epub ahead of print].

46

O'Neill S. A. (2002). “The self-identity of young musicians,” in Musical Identities, eds. R. A. R. MacDonald, D. J. Hargreaves, and D. Miell (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 79–105.

47

Ovid (2004). Metamorphoses (Trans. D. Raeburn). London: Penguin Classics. (Original work published 8 CE)

48

Paese S. Egermann H. (2024). Meditation as a tool to counteract music performance anxiety from the experts' perspective. Psychol. Music52, 59–74. doi: 10.1177/03057356231155968

49

Paese S. Schiavio A. (2025). Meditating musicians: investigating the experience of music students and professional musicians in a brief mindfulness course to address music performance anxiety. Front. Psychol.16:1567988. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1567988

50

Partridge C. (2014). The Lyre of Orpheus: Popular Music, the Sacred, and the Profane. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199751396.001.0001

51

Pellegrino K. (2009). Connections between performer and teacher identities in music teachers: Setting an agenda for research. J. Music Teach. Educ.19, 39–55. doi: 10.1177/1057083709343908

52

Perdomo-Guevara E. (2014). Is music performance anxiety just an individual problem? Exploring the impact of musical environments on performers' approaches to performance and emotions. Psychomusicol. Music Mind Brain24, 66–74. doi: 10.1037/pmu0000028

53

Plato (2004). Zbrana Dela. Celje: Mohorjeva druŽba.

54

Privette G. (1983). Peak experience, peak performance, and flow: a comparative analysis of positive human experiences. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.45, 1361–1368. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.45.6.1361

55

Rojek C. (2001). Celebrity. London: Reaktion Books.

56

Rosenberg M. (2015). Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton Legacy Library ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1965)

57

Saarikallio S. (2017). “Musical identity in fostering emotional health,” in Handbook of Musical Identities, eds. R. MacDonald, D. J. Hargreaves, and D. Miell (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 602–623. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199679485.003.0033

58

Schmitt M. C. J. (1979). Development and validation of a measure of self-esteem of musical ability (Doctoral dissertation). University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Champaign, IL, United States.

59

Shavelson R. J. Hubner J. J. Stanton G. C. (1976). Self-concept: validation of construct interpretations. Rev. Educ. Res.46, 407–441. doi: 10.3102/00346543046003407

60

Skoogh F. Frisk H. (2019). Performance values—an artistic research perspective on music performance anxiety in classical music. J. Res. Arts Sports Educ.3, 1–15. doi: 10.23865/jased.v3.1506

61

Sousa C. M. Machado J. P. Greten H. J. Coimbra D. (2016). Occupational diseases of professional orchestra musicians from northern Portugal: a descriptive study. Med. Probl. Perform. Art.31, 8–12. doi: 10.21091/mppa.2016.1002

62

Spahn C. (2015). Treatment and prevention of music performance anxiety. Prog. Brain Res.217, 129–140. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2014.11.024

63

Spychiger M. (2010). Das musikalische Selbstkonzept: Konzeption des Konstrukts als mehrdimensionale Domäne und Entwicklung eines Messverfahrens. Final report to the Swiss National Science Foundation. Frankfurt: University of Music and Performing Arts.

64

Spychiger M. (2017a). “Teaching toward the promotion of students' musical self-concept,” in Creativity and innovation (European Perspectives on Music Education), Vol. 7, eds. M. Stakelum and R. Girdzijauskiene (Innsbruck: Helbling), 133–146.

65

Spychiger M. (2017b). “From musical experience to musical identity: musical self-concept as a mediating psychological structure,” in Handbook of Musical Identities, eds. R. MacDonald, D. J. Hargreaves, and D. Miell (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 267–288. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199679485.003.0015

66

Spychiger M. (2021). “Motivation and developing a musical identity,” in Routledge International Handbook of Music Psychology in Education and the Community, eds. A. Creech, D. A. Hodges, and S. Hallam (London: Routledge), 254–268. doi: 10.4324/9780429295362-22

67

Spychiger M. Gruber L. Olbertz F. (2009). “Musical self-concept: presentation of a multi-dimensional model and its empirical analyses,” in Proceedings of the 7th Triennial Conference of the European Society for the Cognitive Sciences of Music (ESCOM 2009), Jyväskylä, Finland, eds. J. Louhivuori, T. Eerola, S. Saarikallio, T. Himberg, and P. S. Eerola (Jyväskylä: ESCOM), 503–506. Available online at: https://jyx.jyu.fi/handle/123456789/20934 (Accessed September 10, 2025).

68

Spychiger M. Hechler J. (2014). “Musikalität, Intelligenz und Persönlichkeit,” in Der musikalische Mensch: Evolution, Biologie und Pädagogik musikalischer Begabung, eds. W. Gruhn and A. Seither-Preisler (Wiesbaden: Verlag), 23–69.

69

Spychiger M. B. (2019). “The sacred sphere: its equipment, beauty, functions, and transformations under secular conditions,” in Music, Education, and Religion: Intersections and Entanglements, eds. A. A. Kallio, P. Alperson, and H. Westerlund (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press), 142–156. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvpb3w6q.12

70

Steptoe A. (1989). Stress, coping and stage fright in professional musicians. Psychol. Music17, 3–11. doi: 10.1177/0305735689171001

71

Svengalis J. N. (1978). Music attitude and the preadolescent male (Doctoral dissertation). University of Iowa, Iowa, IA, United States.

72

Szeleszczuk Ł. Fraczkowski D. (2022). Propranolol versus other selected drugs in the treatment of various types of anxiety or stress, with particular reference to stage fright and post-traumatic stress disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23:10099. doi: 10.3390/ijms231710099

73

Taruffi J. (2017). “Building musical self-identity in early infancy,” in Handbook of Musical Identities, eds. R. MacDonald, D. J. Hargreaves, and D. Miell (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 197–213. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199679485.003.0011

74

Uphill M. A. Lane A. M. Jones M. V. (2012). Emotion regulation questionnaire for use with athletes. Psychol. Sport Exerc.13, 761–770. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.05.001

75

Wang Q. Yang R. (2024). The influence of music performance anxiety on career expectations of early musical career students: self-efficacy as a moderator. Front. Psychol.15:1411944. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1411944

76

Wroe A. (2011). Orpheus: The Song of Life. London: Jonathan Cape.

77

Zarza-Alzugaray F. J. Casanova O. McPherson G. E. Orejudo S. (2020). Music self-efficacy for performance: an explanatory model based on social support. Front. Psychol.11:1249. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01249

Summary

Keywords

music performance anxiety (MPA), musical self-concept, musical manifestation, transcendence, Orpheus

Citation

Šimunovič N (2025) Did Orpheus have stage fright? To oneself, to the other, to the transcendent: steps for coping with music performance anxiety. Front. Psychol. 16:1706198. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1706198

Received

15 September 2025

Revised

22 October 2025

Accepted

24 November 2025

Published

17 December 2025

Corrected

13 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Michiko Yoshie, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST), Japan

Reviewed by

Stephen Lim, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Serena Paese, University of York, United Kingdom

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Šimunovič.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Natalija Šimunovič, simunovicna@ag.uni-lj.si

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.