Abstract

Fear of failure is often rooted in highly self-critical autobiographical memories that elicit persistent distress and avoidance. Imagery-based interventions aim to reduce the impact of such memories, yet their mechanisms of action remain unclear. In this three-arm parallel group randomised controlled trial, 180 young adults with elevated fear of failure were randomly assigned to imagery exposure, standard imagery rescripting, or imagery rescripting with a 10-min delay designed to disrupt memory reconsolidation. Across four sessions delivered over 2 weeks, outcomes were assessed using self-report measures and physiological markers, with follow-ups at 3 and 6 months. All interventions led to significant and sustained reductions in negative emotions, arousal, and fear of failure, as well as decreased physiological reactivity to autobiographical memories of criticism. Contrary to predictions, delayed rescripting did not show superiority, while planned contrasts suggested more consistent benefits of standard rescripting compared to delayed rescripting and a rebound effect after exposure. Notably, prediction error, operationalised as transient increases in physiological arousal during rescripting, predicted stronger therapeutic change in rescripting but not in exposure. These findings demonstrate that both common therapeutic factors and prediction error contribute to durable improvements in emotional responses to adverse memories, advancing the understanding of mechanisms underlying imagery-based techniques.

Clinical trials registration:

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT07048756, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT07048756.

Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences, such as criticism, neglect, or harsh responses from caregivers, have been consistently linked to long-term impacts on psychological well-being and quality of life in adulthood (Williams et al., 2022). Among these experiences, the way caregivers respond to a child’s mistakes or failures may play a key role in shaping later emotional and cognitive patterns. One possible consequence is fear of failure – the belief that making mistakes leads to rejection or being perceived as less worthy (Balkis et al., 2024). Research suggests that fear of failure may stem from early relational experiences and social learning processes (Deneault et al., 2022; Peterson et al., 2024).

To address earlier adversities, some therapeutic approaches use imagery-based techniques aimed at modifying the emotional meaning of specific autobiographical memories. Two commonly applied techniques are Imagery Exposure (IE) and Imagery Rescripting (ImRs). Both involve the activation of difficult or distressing memories through imagination, but they are based on different therapeutic assumptions and proposed mechanisms of change.

Imagery exposure involves systematic and controlled repeated mental exposure to distressing events which is suggested to result in gradual weakening of emotional reactivity via habituation (Hamlett et al., 2023). Habituation may allow for increased tolerance of distressing content thanks to a better top-down regulation of aversive memory traces, rather than directly updating these traces (Schiller et al., 2013). Clinical evidence shows that imagery exposure produces significant reductions in emotional distress across anxiety- and trauma-related disorders. Randomised and routine-care studies have demonstrated large and sustained effects of IE, confirming that it is an established and effective intervention for anxiety problems (Hoppen et al., 2024; Roth-Rawald et al., 2023).

During ImRS, an individual recalls a distressing childhood memory and then imagines a more supportive or protective outcome (Arntz and Weertman, 1999; Morina et al., 2017). This process was proposed to alter the emotional significance of distressing memories and associated beliefs about the self, others, and the world (Woelk et al., 2022).

Clinical research supports the efficacy of Imagery Rescripting (ImRs) in reducing emotional distress (Woelk et al., 2022; Veale et al., 2015). However, the precise mechanisms underlying its effectiveness remain unclear (Siegesleitner et al., 2020; Kunze et al., 2017). It is hypothesized that ImRs not only reduces emotional responses but also alters the affective meaning of memories. It leads to the hypothesis that the mechanisms of change in ImRs may be memory reconsolidation and/or prediction error, both rooted in neurocognitive models of emotional learning.

Memory reconsolidation is a biological process in which reactivated memories become temporarily labile and modifiable before reconsolidating into long-term storage (Nader et al., 2000; Arntz et al., 2013). Interventions applied during a specific time interval -referred to as the reconsolidation window, starting approximately 10 min after memory activation- can disrupt reconsolidation and induce lasting changes in the original memory trace (Schiller et al., 2013; Germeroth et al., 2017; Agren et al., 2017).

Experimental studies have shown that providing new, non-threatening information in the reconsolidation window during threat exposure eliminates conditioned fear responses rather than merely suppressing them (Schiller et al., 2013). While these findings remain debated (Chalkia et al., 2020), successful applications of disruption of reconsolidation-based interventions have been demonstrated in various domains, including spider phobia (Agren et al., 2017), and imaginal exposure (Agren et al., 2017). Using the reconsolidation window for modifications of aversive memory traces in psychotherapeutic contexts remains a promising yet under-examined area (Bui and Milton, 2023).

Another mechanism increasingly discussed in the context of psychotherapy (also ImRs) is prediction error (PE) – the discrepancy between an individual’s expectation regarding a real (or imagined) and actual ending of events. PE is central to learning theory and expectation violations are thought to promote memory updating (Sinclair et al., 2021; Exton-McGuinness et al., 2015). ImRs may elicit PE by introducing unexpected elements – such as a protective figure in a previously threatening memory – thereby enhancing emotional relearning (Dibbets and Arntz, 2016; Siegesleitner et al., 2019).

Although a few studies have explored the potential role of reconsolidation in therapeutic memory change (Strohm et al., 2021), none have directly compared reconsolidation and its disruption, nor systematically examined the role of prediction error in Imagery Rescripting (ImRs) – particularly in the context of personalised autobiographical memories involving criticism, a theme frequently encountered in clinical work.

To address this gap, we conducted a randomised trial including three active conditions: Imagery Exposure (IE), standard Imagery Rescripting (ImRs), and delayed Imagery Rescripting (ImRs-DSR), in which a 10-min interval between memory reactivation and intervention was introduced to interfere with the reconsolidation process. Each intervention session targeted the same autobiographical memory of parental criticism. This design allowed us to investigate whether disrupting reconsolidation alters the emotional and physiological effects of ImRs, and to test the role of prediction error in therapeutic memory change.

We included participants with high levels of fear of failure - a factor often related to memories of social evaluation (Tariq et al., 2021). We assessed outcomes using self-report questionnaires as well as objective physiological indicators – salivary alpha-amylase (sAA) and skin conductance level (SCL). We also applied behavioral research procedures to test how general and stable the treatment effects were. We did this by evaluating the “renewal effect” – the return of fear in a setting different to the one used during treatment (Broomer and Bouton, 2023), such as an unfamiliar room. To measure the durability of change, we included recall (procedure testing spontaneous recovery, which is delayed return of fear in the same room where the treatment was delivered) and reinstatement (return of fear after re-exposure to a fear-related cue). We tested whether the benefits of each intervention lasted over time. To assess generalisation, we used participants’ autobiographical memories not included in the therapeutic intervention, which we refer to as past and future scenarios of aversive events.

Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1 (treatment short-term efficacy—direct effects)

Participants in all three conditions (IE, ImRs, ImRs-DSR) will show a reduction in emotional and physiological responses to the treated autobiographical criticism scenario following the intervention. However, this reduction will be stronger in the rescripting conditions (ImRs and ImRs-DSR) compared to IE, and strongest in ImRs-DSR due to the hypothesized enhancement of memory updating through reconsolidation disruption.

Specifically, after undergoing ImRs-DSR participants are expected to show the most pronounced reduction in fear of failure as well as lowest skin conductance levels (SCL) and subjective emotional distress (e.g., fear, sadness, guilt) for their treated autobiographical criticism scenarios, and highest increase in positive affect (e.g., relief, calmness), compared to the other two conditions.

Hypothesis 2 (stability and long-term effects)

Treatment effects observed post-intervention will be maintained over time (3- and 6-month follow-ups) in all groups, but more strongly in ImRs and ImRs-DSR compared to IE. The ImRs-DSR condition is expected to show the highest stability of both subjective and physiological treatment gains, including resistance to reinstatement (i.e., return of emotional reactivity after hotspot reactivation).

Hypothesis 3 (generalisation)

Treatment effects will generalise beyond the directly targeted memory to non-treated autobiographical memories (i.e., past and future criticism scenarios), as well as to novel contextual settings (i.e., renewal).

Participants in the ImRs and ImRs-DSR groups are expected to show greater generalisation of emotional regulation (i.e., lower physiological and subjective reactivity) than participants in the IE group. The ImRs-DSR group is expected to exhibit the broadest generalisation due to deeper memory updating.

Hypothesis 4 (prediction error)

Participants in both rescripting conditions (ImRs and ImRs-DSR) will exhibit greater prediction error (PE) during the intervention phase than those in the IE condition, due to the unexpected positive transformation of the memory scene (see Prediction Error section).

Higher PE is also expected to be associated with greater treatment effects (i.e., greater reductions in post-intervention physiological arousal and subjective distress). PE levels are expected to be comparable between ImRs and ImRs-DSR, as the rescripting content is identical.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited between June 2020 and June 2022 via online advertisements, social media, and university mailing lists. A total of 6,349 individuals completed the initial online prescreening survey. Of these, 180 participants met the eligibility criteria following clinical interviews and were randomly assigned to one of three experimental conditions:

-

Imagery Exposure (IE) (n = 60),

-

Imagery Rescripting (ImRs) (n = 60),

-

Imagery Rescripting with a 10-min reconsolidation window (ImRs-DSR) (n = 60)

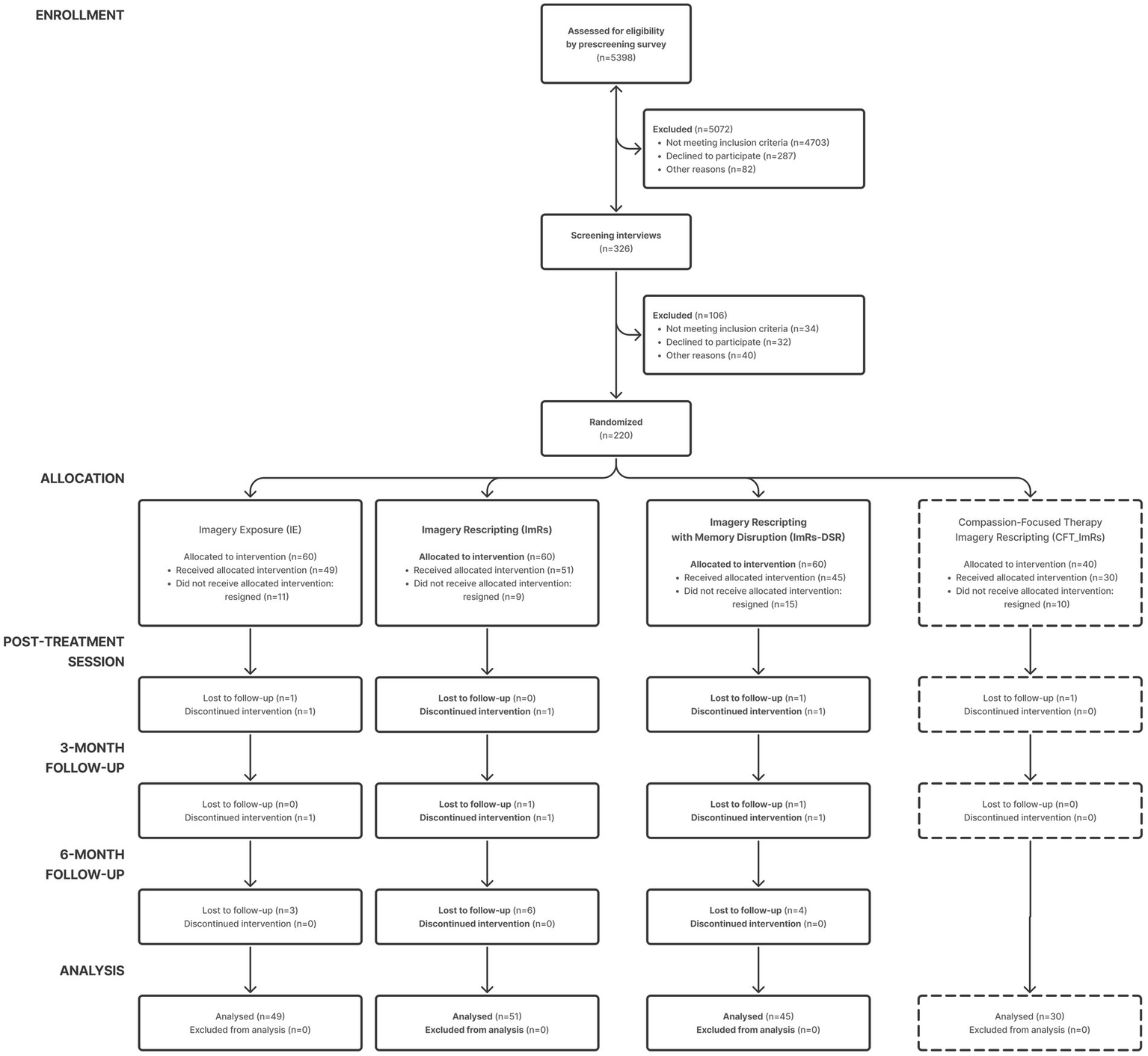

Of the 180 participants in the three conditions, 145 participants that completed at least one time point, were included in the final analyses (IE: 49, ImRs: 51, ImRs-DSR: 45). The full participant flow is depicted in the CONSORT diagram (see Figure 1). Eligible participants were between 18 and 35 years of age, scored at least 1 SD above the mean on the Performance Failure Appraisal Inventory (PFAI; Conroy et al., 2002; Polish adaptation: Golińska, 2017), and were not undergoing psychotherapy or psychopharmacological treatment at the time of the study. Additional exclusion criteria included a history of sexual abuse or severe childhood maltreatment, current affective or anxiety disorders, personality disorders, psychotic symptoms, active suicidality, or substance use disorders.

Figure 1

CONSORT diagram.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were assessed in two stages: first, through an online screening survey with self-report measures, and second, via a clinical interview conducted by CBT-trained clinicians. The diagnostic assessment included the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I. 5.0.0; Sheehan et al., 1998) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Personality Disorders (SCID-5-PD; APA, 2013).

Demographic characteristics were similar across groups. Participants were primarily university students and young female adults, with an average age of approximately 24 years. No significant baseline differences were observed across conditions in terms of age, sex, education level, employment status, or fear of failure scores, however it must be noted that women were overrepresented in the study (see Table 1).

Table 1

| Characteristic | Group | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ImRs-DSR | ImRs | IE | ||

| (N = 45) | (N = 51) | (N = 49) | ||

| Sex, No. (%) | ||||

| Female | 35 (78%) | 42 (82%) | 42 (86%) | 0.478 |

| Male | 10 (22%) | 9 (18%) | 6 (12%) | |

| Prefer not to say/different | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Age, Mean (SD) | 24.53 (3.75) | 24.25 (4.35) | 24.04 (3.80) | 0.836 |

| Employment status, No. (%) | ||||

| Employed | 30 (67%) | 33 (65%) | 29 (59%) | 0.515 |

| Unemployed | 8 (18%) | 5 (10%) | 6 (12%) | |

| Other | 7 (16%) | 13 (25%) | 14 (29%) | |

| University student status, No. (%) | ||||

| Student | 31 (69%) | 33 (65%) | 32 (65%) | 0.899 |

| Not a student | 14 (31%) | 18 (35%) | 17 (35%) | |

| Highest level of education, No. (%) | ||||

| General secondary school | 21 (47%) | 24 (47%) | 25 (52%) | 0.845 |

| University degree (bachelor’s or higher) | 21 (47%) | 22 (43%) | 21 (44%) | |

| Vocational education | 3 (7%) | 5 (10%) | 2 (4%) | |

| Fear of failure, Mean (SD) | 118.74 (11.32) | 120.68 (9.15) | 120.15 (9.18) | 0.629 |

Participants’ demographic characteristics and screening scores.

A priori power analysis using G*Power indicated that at least 51 participants per group were needed to detect medium-sized effects (Cohen’s d = 0.50) with 80% power at α = 0.05. To accommodate an expected dropout rate of up to 25%, the recruitment target was set at 68 participants per condition. Ultimately, 145 participants were enrolled across the three main arms (ImRs, ImRs-DSR, IE). Dropout was lower than expected (≈8% of 145), and 145 were included in analysis.

Study design

This study was conducted as a randomised controlled superiority trial with a between-subjects design and three experimental conditions:

-

Imagery Rescripting (ImRs)

-

Imagery Rescripting with a 10-min reconsolidation break (ImRs-DSR), designed to disrupt memory reconsolidation

-

Imagery Exposure (IE), serving as an active control condition involving emotional imagery without therapeutic modification

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the three groups using computer-generated block randomisation. Allocation was performed by researchers not involved in recruitment or data collection. A double-blind procedure was implemented where feasible: participants and therapists conducting preparatory interviews were blind to condition. All participants listened to audio recordings of autobiographical scenarios, and only the content of the therapeutic segment differed between conditions. However, experimenters delivering the interventions could not be fully blinded, due to structural differences between groups (e.g., presence of a 10-min delay in ImRs-DSR). To minimise potential bias, all scenarios were pre-scripted, pre-recorded, and presented in a standardised format across sessions. A detailed description of the procedure may be found in the Appendix, see Figure 2 and Table 2 for the study design and schedule.

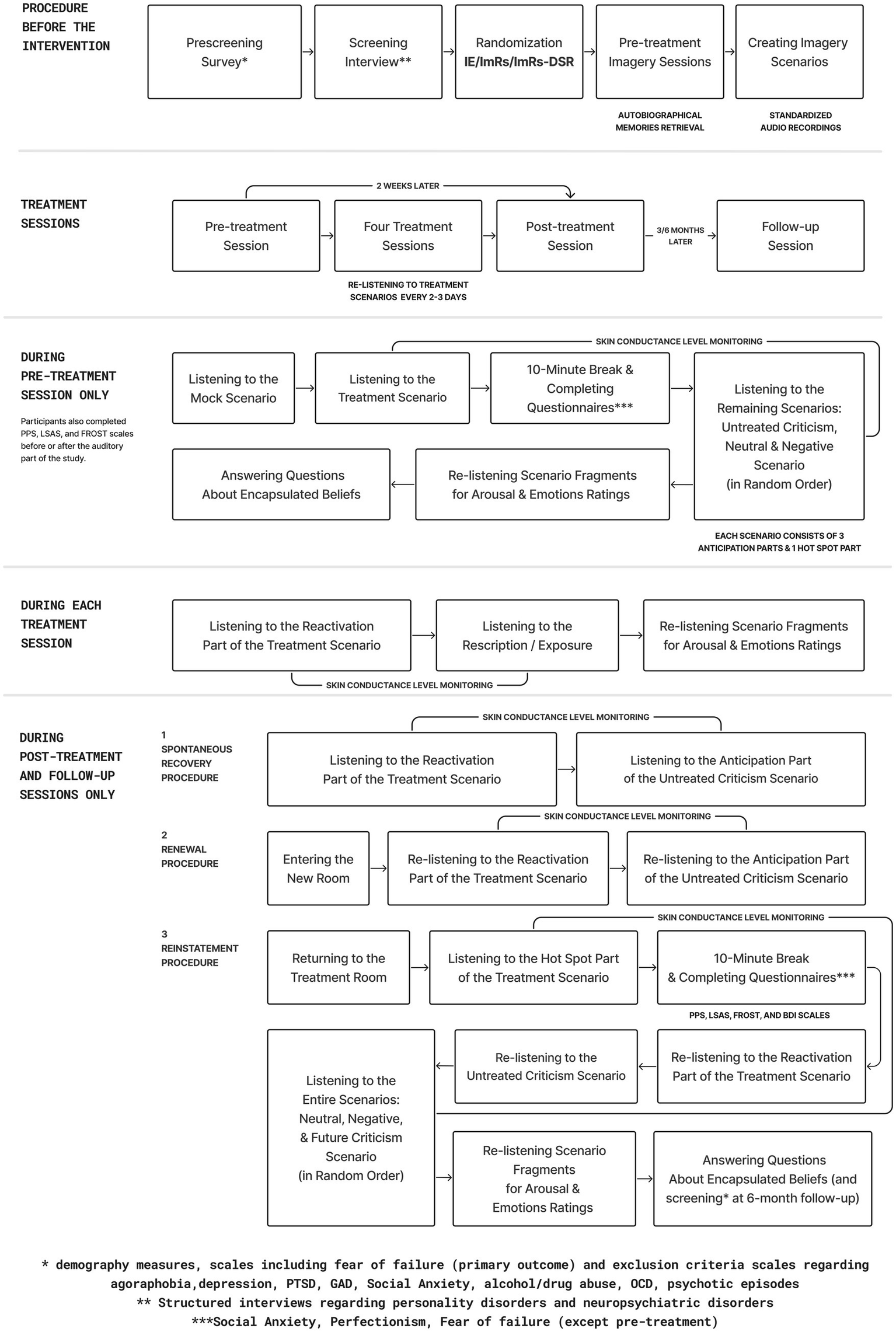

Figure 2

Study design overview.

Table 2

| Study phase | Procedure | Details | Enrollment | Pre-Treatment | Intervention 1 | Intervention 2 | Intervention 3 | Intervention 4 | Post-treatment | 3-month follow-up | 6-month follow-up | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recall | Renewal | Reinstatement | After | Recall | Renewal | Reinstatement | After | Recall | Renewal | Reinstatement | After | |||||||||

| Eligibility | Exclusion Criteria (BDI, YBOCS, AUDIT, DAST, DSM-5 Dimensional Scales) | Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale; Beck Depression Inventory DSM-5 Dimentsional Scales (GAD, Social Phobia, Panic, Agoraphobia, PTSD) Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, Drug Abuse Screening Test |

X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) | Psychiatric disorders (diagnostic interview) | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| SCID-5-PD (Personality Disorders) | SCID-5-PD (Personality Disorders) | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Informed Consent | Informed Consent | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Assessment | LSAS | Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| FROST | Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| PPS | Pure Procrastination Scale | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ratings of emotions / arousal / valence / focus / immersion | All/Treated (Intervention sessions) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Scenario Development | Imagery Interview | Autobiographical memory collection; scenarios development | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Eligibility /Assesment | PFAI (Fear of Failure) | Fear of failure (primary outcome) | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Scenario Presentation | Treated Scenario – Anticipation | Anticipation Phase | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | x | x | |

| Untreated Scenario – Anticipation | Anticipation Phase | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Future Scenario – Anticipation | Anticipation Phase | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Negative Scenario – Anticipation | Anticipation Phase | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Neutral Scenario – Anticipation | Anticipation Phase | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Treated Scenario – Hotspot | Hotspot Phase | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Untreated Scenario – Hotspot | Hotspot Phase | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Future Scenario – Hotspot | Hotspot Phase | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Negative Scenario – Hotspot | Hotspot Phase | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Neutral Scenario – Interaction | Hotspot Phase | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Intervention (Scenario Presentation) | Therapeutic Scenario Playback (ImRs/IE/ImRs-DSR) | Treated | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Physiological | sAA (Baseline/after Hotspot of treated scenario presentation) | Treated | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Skin Conductance Level | All | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

Schedule.

The study involved eight assessment time points per participant, spread across approximately 6 months:

-

Pre-treatment baseline,

-

Four intervention sessions over two weeks,

-

Post-treatment assessment,

-

Follow-up assessments at 3 and 6 months post-treatment.

At each assessment, participants engaged with personalised, audio-guided imagery scenarios, created based on the autobiographical material collected during preparatory interviews and recorded by the psychotherapist assigned to the participant. One scenario (a past criticism memory) was selected as the targeted treatment scenario, while additional scenarios (untreated past criticism, future criticism, neutral, and negative) were used to assess generalisation and specificity of effects. For the sake of clarity, the present manuscript reports results only for criticism-related scenarios (treated, untreated, and future), as these were central to the study hypotheses and intervention rationale.

In addition to baseline listening and imagery of scenarios, the study incorporated behavioral paradigms adapted from basic learning research to test the stability and relapse vulnerability of treatment effects. These included Recall, Renewal, and Reinstatement (see below for further elaboration). These procedures were administered at post-treatment, 3-month, and 6-month follow-ups and applied to both the treated and untreated scenarios.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Law, SWPS University in Poznań (approval no. 2019-03-10). All participants provided written informed consent and received up to 830 PLN (approximately ~224 USD) for full participation.

Note on parallel condition: After study initiation, additional funding was obtained to conduct a fourth condition involving Compassion-Focused Imagery Rescripting (CFT-ImRs). This arm followed a procedure analogous to the other groups but was not included in the current manuscript due to its smaller sample size, lack of long-term follow-ups, and its distinct therapeutic rationale (focus on self-compassion). We mention it here to maintain transparency regarding the full study design.

Imagery scenarios and memory reactivation task

Before treatment, each participant took part in two imagery sessions during which a cognitive-behavioral therapist (CBT) asked him/her to recall three events of being criticized for failures and/or lack of achievements (two past-related and one future-related), one neutral personal event, and one negative event that was not related to failure and criticism. Each imagery session involved only recalling and describing the situation, but no actual intervention. Therapists were supervised, and the recorded imagery sessions were randomly listened to by the supervisor of the experiment as a quality assurance procedure.

Using the information from the two imagery sessions, the following imagery scenarios were developed for each participant: 2 past criticism scenarios, one negative scene without criticism (e.g., an accident), one neutral scenario (e.g., shopping), and one future criticism scenario (e.g., criticism at work). One scenario of past criticism was complemented with a scene of rescripting. Each scenario followed the same framework (see exemplary scenarios in Appendix A) and was audio recorded using the voice of the same therapist who performed the diagnostic and imagery sessions. Each scenario followed a four-part structure, comprising an “anticipation” phase (three segments) and a hotspot phase (the emotionally intense moment in criticism memories, or interaction in other scenarios):

Anticipation phase

Self-Imagery: Description begins with a standardised phrase such as “Imagine yourself as a [age]-year-old girl/boy….” The participant is referred to by their own name as they appear in the memory.

Surroundings Description: The setting is described in the present tense with sensory details (e.g., “You hear...,” “You see...,” “You can smell...”) to enhance immersion and evoke vivid mental imagery.

Person (Critic): A depiction of the person interacting with the participant, typically focusing on a parent or parental figure in the case of criticism-related memories (or other person in non-criticism scenario).

Hotspot phase

Critical Interaction (Hotspot): A detailed narration of the most emotionally intense part of the memory. In the treatment condition, this is the moment of criticism that is later targeted by rescripting. In neutral or negative control conditions, it depicts a routine, emotionally neutral interaction.

This structured scenario framework was used in the Memory Reactivation Task (Strohm et al., 2021), during which participants listened to the audio-recorded scripts and were instructed to imagine each scene as vividly as possible, as if it were occurring in the present moment (See Figure 3 and Appendix for scenario framework and examples).

Figure 3

Imagery scenarios framework and examples (A) Framework of criticism scenario (B) Framework of neutral scenario (C) Framework of Imagery Exposure scenario (D) Framework of Imagery Rescripting (E) Framework of Imagery Rescripting with Reconsolidation Disruption Scenario (F) Criticism scenario example (anticipation + hotspot) (G) Imagery Rescripting scenario example (H) Imagery Exposure scenario example.

As mentioned above, we decided to treat the hotspot as an unconditioned stimulus (UCS), similar to the previous study performed by Siegesleitner et al. (2020). In our study, the experience of criticism was considered as the one eliciting automatic aversive responses and having the potential to change the meaning of originally neutral stimuli (Ehlers et al., 2004). For example, recollection of the classroom can have a neutral connotation of everyday classes, or even a positive one, when associated with friends. However, once the criticism (hotspot) takes place, neutral scenery begins to be associated with the aversive experience. This poses some difficulty, as in psychotherapy hotspot is often presented along anticipation (i.e., “late” rescripting, see Discussion). However, considering the hotspot as UCS in our experiment required us to separate it from the rest of the scenario for the sake of the Reinstatement procedure. Furthermore, this translation from behavioral studies has some limitations that pose difficulty in later interpretation, for example, criticism not only evokes fear but also more complex emotions such as guilt or shame (Grey et al., 2001). Yet, we aimed to optimise our research, by treating Hotspot as UCS, which allowed conducting behavioral procedures such as reinstatement. We believe that both behavioral researchers can benefit from testing procedures on more ecologically valid stimuli, as well as psychotherapeutic research can benefit challenging interventions in a laboratory setting using verified behavioral procedures.

Interventions

During the 2 weeks between pre- and post-treatment, participants participated in four imagery intervention sessions, in which they listened to an audio-recorded treatment scenario. The treatment scenario started in the same way as one of the criticism scenarios, with the anticipation phase. However, the imagery of the critic, instead of the hotspot, was followed by the intervention part. In Imagery Rescripting conditions:

-

The therapist enters the scene and prevents the criticism

-

The therapist addresses a critic and points out the child’s needs

-

The therapist addresses the child and acknowledges their needs

-

The therapist suggests to the child to perform an activity that would meet their needs (see Figure 3 and Appendix A).

The rescripting part was presented immediately after the imagery of the critic (ImRs group; see Figure 3D) or after a 10-min break, to provide intervention in the reconsolidation disruption window (ImRs-DSR group; See Figure 3E). During the break, subjects were watching a neutral documentary (Schiller et al., 2013).

In the Imagery Exposure (IE) condition, the treated criticism scenario continued without rescripting but four additional segments were inserted to promote focused exposure. After the appearance of the critic, participants were instructed to focus on their bodily sensations, expectations, and on the image of the critic (see Figure 3). This condition aimed to facilitate emotional processing through focused exposure without altering the original memory content.

Recall, renewal, and reinstatement procedures

At pre-treatment, participants listened to scenarios of criticism, neutral, and negative situations (see Memory Reactivation Task & Imagery Scenarios). At post-treatment and follow-up sessions, criticism scenarios were presented using behavioral procedures: recall (listening to scenarios in the familiar treatment room), renewal (listening to scenarios in an unknown room), and reinstatement (back to the original room, listening to the hotspot and then scenarios) (see Appendix for further elaboration).

Prediction error

In the present study, prediction error (PE) was conceptualised as a moment of surprise – when the content of the scenario unfolded differently than what might have been expected by the participant. In the rescripting conditions (ImRs and ImRs-DSR), criticism was replaced by a positive therapist intervention, potentially violating participants’ expectations. As no self-reported ratings of surprise were collected, PE was not measured directly. Instead, it was operationalised indirectly through the recording of skin conductance level (SCL) as a physiological index of arousal. An increase in SCL observed immediately after the expected moment of criticism - which, according to the scenario structure, was supposed to occur but was replaced by the therapist’s intervention - may indicate a reaction associated with a violation of expectation. A similar arousal pattern has been described in studies on emotional learning and memory updating, where prediction error is linked to transient increases in physiological activity (e.g., Stemerding et al., 2022).

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measures

Primary outcomes were selected to evaluate the emotional and physiological effects of the interventions.

Self-reported fear of failure was assessed using the Performance Failure Appraisal Inventory (PFAI; Conroy et al., 2002; Polish adaptation: Golińska, 2017), a 25-item scale measuring beliefs about the aversive consequences of failure. This measure served as a primary indicator of cognitive-affective change following the intervention.

Physiological reactivity was captured through two complementary indicators:

Skin Conductance Level (SCL): SCL was recorded during imagery exposure to experimental scenarios using Biopac Systems (MP160 EDA-MRI; sampling rate: 2000 Hz; Ag/AgCl electrodes placed on the index and middle finger of the non-dominant hand). Signals were resampled to 1,000 Hz, smoothed (median over 100 samples), and filtered with a high-pass 1 Hz filter. Baseline SCL was calculated from the 3 s preceding the first scenario fragment. Normalised reactivity was computed as (Sugimine et al., 2020):

For analyses, SCL was extracted separately for anticipation and hotspot (emotional peak) phases. SCL is a well-validated marker of sympathetic nervous system arousal and emotional activation (Dawson et al., 2007).

Salivary alpha-amylase (sAA): sAA was used as a non-invasive marker of acute sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) activation. Saliva samples were collected using cotton rolls or Salivette collection tubes, chewed for 1 min. Samples were obtained immediately before and after the scenario presentation, stored at 4 °C, and later analysed at the Institute of Human Genetics (Polish Academy of Sciences). sAA is considered a reliable biomarker of short-term physiological stress responses (Nater and Rohleder, 2009).

Subjective emotional response was also included as a primary outcome: Participants rated each scenario fragment on valence, arousal, immersion, and basic emotions (sadness, guilt, fear, anger, disgust) using a 9-point Likert scale.

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcomes included a broader range of self-report measures assessing comorbid traits and symptoms, collected for exploratory purposes and to contextualise individual differences in treatment response. These were:

-

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996; Zawadzki et al., 2009) – depressive symptoms,

-

Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS; Liebowitz, 1987) - social anxiety,

-

Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (Frost MPS; Frost et al., 1990; Piotrowski and Bojanowska, 2021) - trait perfectionism,

-

Pure Procrastination Scale (PPS; Steel, 2007; Polish translation: Stępień and Cieciuch, 2013) – procrastination tendencies.

All questionnaires were administered at pre-treatment and post-treatment. LSAS, PPS, and Frost MPS were additionally repeated at 3-month and 6-month follow-ups (Table 3).

Table 3

| Analysis | Time | Group | Time x Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | Effect Size (η2p) | F | p | Effect Size (η2p) | F | p | Effect Size (η2p) | |

| SCL anticipation treated criticism recall | 57.750 (2.537,342.519) | <0.001 | 0.3 | 1.529 (2,135) | 0.221 | 0.022 | 1.972 (5.074,342.519) | 0.081 | 0.028 |

| SCL anticipation treated criticism reinstatement | 98.901 (2.112,285.096) | <0.001 | 0.423 | 2.347 (2,135) | 0.100 | 0.034 | 1.050 (4.224,285.096) | 0.384 | 0.015 |

| SCL anticipation treated criticism renewal | 108.084 (2.327,314.189) | <0.001 | 0.445 | 1.948 (2,135) | 0.147 | 0.028 | 1.087 (4.655,314.189) | 0.366 | 0.016 |

| SCL hotspot treated criticism reinstatement | 18.160 (2.597,35.546) | <0.001 | 0.119 | 3.045 (2,135) | 0.051 | 0.043 | 1.684 (5.193,35.546) | 0.135 | 0.024 |

| SCL anticipation untreated criticism recall | 3.708 (2.806,375.986) | 0.014 | 0.027 | 0.255 (2,134) | 0.775 | 0.004 | 0.855 (5.612,375.986) | 0.522 | 0.013 |

| SCL anticipation untreated criticism reinstatement | 0.861 (2.855,382.552) | 0.457 | 0.006 | 1.348 (2,134) | 0.263 | 0.02 | 0.791 (5.710,382.552) | 0.571 | 0.012 |

| SCL anticipation untreated criticism renewal | 0.704 (2.972,398.307) | 0.549 | 0.005 | 3.105 (2,134) | 0.048 | 0.044 | 0.743 (5.945,398.307) | 0.614 | 0.011 |

| SCL anticipation future criticism | 35.541 (1.488,184.558) | <0.001 | 0.223 | 2.155 (2,124) | 0.120 | 0.034 | 0.783 (2.977,184.558) | 0.504 | 0.012 |

| SCL hotspot future criticism | 52.141 (1.285,159.401) | <0.001 | 0.296 | 3.123 (2,124) | 0.048 | 0.048 | 1.236 (2.571,159.401) | 0.298 | 0.02 |

| Treated criticism anticipation arousal | 3.159 (1.948,27.766) | <0.001 | 0.178 | 0.580 (2,139) | 0.561 | 0.008 | 0.441 (3.896,27.766) | 0.774 | 0.006 |

| Treated criticism anticipation disgust | 24.085 (2.033,282.643) | <0.001 | 0.148 | 1.309 (2,139) | 0.273 | 0.018 | 0.836 (4.067,282.643) | 0.505 | 0.012 |

| Treated criticism anticipation fear | 82.538 (1.795,249.478) | <0.001 | 0.184 | 1.127 (2,139) | 0.327 | 0.008 | 1.116 (3.590,249.478) | 0.347 | 0.005 |

| Treated criticism anticipation guilt | 76.635 (1.557,216.363) | <0.001 | 0.355 | 1.718 (2,139) | 0.183 | 0.024 | 1.764 (3.113,216.363) | 0.153 | 0.025 |

| Treated criticism anticipation sadness | 101.711 (1.587,22.644) | <0.001 | 0.423 | 0.510 (2,139) | 0.601 | 0.007 | 3.409 (3.175,22.644) | 0.016 | 0.047 |

| Treated criticism reactivation anger | 36.818 (2.095,291.206) | <0.001 | 0.209 | 0.911 (2,139) | 0.404 | 0.013 | 0.732 (4.190,291.206) | 0.576 | 0.01 |

| Treated criticism hotspot anger | 29.513 (1.989,276.470) | <0.001 | 0.175 | 0.933 (2,139) | 0.396 | 0.013 | 1.139 (3.978,276.470) | 0.338 | 0.016 |

| Treated criticism hotspot arousal | 18.481 (2.047,284.506) | <0.001 | 0.117 | 1.400 (2,139) | 0.250 | 0.02 | 2.103 (4.094,284.506) | 0.079 | 0.029 |

| Treated criticism hotspot disgust | 3.937 (2.233,31.350) | <0.001 | 0.182 | 1.499 (2,139) | 0.227 | 0.021 | 0.797 (4.465,31.350) | 0.540 | 0.011 |

| Treated criticism hotspot fear | 7.831 (2.040,283.491) | <0.001 | 0.338 | 0.187 (2,139) | 0.830 | 0.003 | 0.621 (4.079,283.491) | 0.651 | 0.009 |

| Treated criticism hotspot guilt | 83.091 (2.102,292.151) | <0.001 | 0.374 | 0.781 (2,139) | 0.460 | 0.011 | 0.607 (4.204,292.151) | 0.666 | 0.009 |

| Treated criticism hotspot sadness | 106.990 (2.220,308.537) | <0.001 | 0.435 | 0.373 (2,139) | 0.689 | 0.005 | 0.336 (4.439,308.537) | 0.871 | 0.005 |

| Future anticipation anger | 154.739 (1.529,197.211) | <0.001 | 0.545 | 3.179 (2,129) | 0.045 | 0.047 | 0.804 (3.058,197.211) | 0.495 | 0.012 |

| Future anticipation arousal | 36.434 (2.092,269.814) | <0.001 | 0.22 | 1.213 (2,129) | 0.301 | 0.018 | 0.862 (4.183,269.814) | 0.491 | 0.013 |

| Future anticipation disgust | 66.927 (1.561,201.351) | <0.001 | 0.342 | 4.814 (2,129) | 0.010 | 0.069 | 1.254 (3.122,201.351) | 0.291 | 0.019 |

| Future anticipation fear | 73.228 (1.669,215.362) | <0.001 | 0.362 | 0.423 (2,129) | 0.656 | 0.007 | 0.384 (3.339,215.362) | 0.786 | 0.006 |

| Future Anticipation Guilt | 266.145 (1.789,23.746) | <0.001 | 0.674 | 1.333 (2,129) | 0.267 | 0.02 | 1.759 (3.577,23.746) | 0.145 | 0.027 |

| Future anticipation sadness | 413.148 (1.858,239.714) | <0.001 | 0.762 | 1.849 (2,129) | 0.162 | 0.028 | 1.631 (3.716,239.714) | 0.171 | 0.025 |

| Future criticism hotspot anger | 11.410 (2.320,299.282) | <0.001 | 0.081 | 1.168 (2,129) | 0.314 | 0.018 | 1.291 (4.640,299.282) | 0.270 | 0.02 |

| Future hotspot arousal | 8.960 (2.247,289.811) | <0.001 | 0.065 | 0.389 (2,129) | 0.679 | 0.006 | 1.030 (4.493,289.811) | 0.397 | 0.016 |

| Future hotspot disgust | 7.824 (2.351,303.282) | <0.001 | 0.057 | 3.578 (2,129) | 0.031 | 0.053 | 0.411 (4.702,303.282) | 0.831 | 0.006 |

| Future hotspot fear | 29.787 (2.195,283.209) | <0.001 | 0.188 | 0.229 (2,129) | 0.795 | 0.004 | 1.262 (4.391,283.209) | 0.283 | 0.019 |

| Future hotspot guilt | 4.302 (2.283,294.566) | <0.001 | 0.238 | 0.444 (2,129) | 0.642 | 0.007 | 0.660 (4.567,294.566) | 0.640 | 0.01 |

| Future hotspot sadness | 67.590 (2.025,261.216) | <0.001 | 0.344 | 0.430 (2,129) | 0.652 | 0.007 | 0.680 (4.050,261.216) | 0.608 | 0.01 |

| Untreated anticipation anger | 59.576 (1.978,274.881) | <0.001 | 0.3 | 1.067 (2,139) | 0.347 | 0.015 | 1.245 (3.955,274.881) | 0.292 | 0.018 |

| Untreated anticipation arousal | 37.047 (1.923,267.233) | <0.001 | 0.21 | 0.506 (2,139) | 0.604 | 0.007 | 0.541 (3.845,267.233) | 0.698 | 0.008 |

| Untreated anticipation disgust | 38.278 (2.054,285.505) | <0.001 | 0.216 | 2.311 (2,139) | 0.103 | 0.032 | 0.999 (4.108,285.505) | 0.410 | 0.014 |

| Untreated anticipation fear | 115.634 (1.666,231.514) | <0.001 | 0.454 | 0.595 (2,139) | 0.553 | 0.008 | 0.485 (3.331,231.514) | 0.713 | 0.007 |

| Untreated anticipation guilt | 132.129 (1.559,216.763) | <0.001 | 0.487 | 1.677 (2,139) | 0.191 | 0.024 | 0.400 (3.119,216.763) | 0.760 | 0.006 |

| Untreated anticipation sadness | 168.716 (1.609,223.649) | <0.001 | 0.548 | 1.008 (2,139) | 0.368 | 0.014 | 1.677 (3.218,223.649) | 0.169 | 0.024 |

| Untreated hotspot anger | 37.973 (2.404,334.092) | <0.001 | 0.215 | 0.965 (2,139) | 0.384 | 0.014 | 1.423 (4.807,334.092) | 0.217 | 0.02 |

| Untreated hotspot arousal | 19.068 (2.105,292.546) | <0.001 | 0.121 | 0.245 (2,139) | 0.783 | 0.004 | 0.802 (4.209,292.546) | 0.530 | 0.011 |

| Untreated hotspot disgust | 16.912 (2.172,301.856) | <0.001 | 0.108 | 2.409 (2,139) | 0.094 | 0.034 | 1.489 (4.343,301.856) | 0.201 | 0.021 |

| Untreated hotspot fear | 65.302 (2.093,29.974) | <0.001 | 0.32 | 0.169 (2,139) | 0.845 | 0.002 | 0.556 (4.187,29.974) | 0.703 | 0.008 |

| Untreated hotspot guilt | 85.918 (2.043,283.933) | <0.001 | 0.382 | 2.379 (2,139) | 0.096 | 0.033 | 0.392 (4.085,283.933) | 0.818 | 0.006 |

| Untreated hotspot sadness | 109.211 (2.258,313.804) | <0.001 | 0.44 | 0.596 (2,139) | 0.552 | 0.009 | 0.277 (4.515,313.804) | 0.911 | 0.004 |

ITT analysis intention-to-treatment analysis results.

Screening measures

To determine eligibility for participation, a comprehensive screening battery was used:

-

Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M. I. N. I. 5.0.0; Sheehan et al., 1998; Polish translation: Masiak and Przychoda, 1998) – Axis I disorders,

-

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Personality Disorders (SCID-5-PD; APA, 2013; Polish translation: Popiel et al., 2019),

-

Brief symptom checklists for anxiety, PTSD, OCD, panic, and agoraphobia (APA, 2013; back-translated version),

-

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10).

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted following the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle using a last observation carried forward (LOCF) approach for missing data imputation (analysed sample consisted of 145 participants). To verify the robustness of the findings, additional per-protocol (PP) sensitivity analyses were conducted and are reported in the Supplementary material (sample differs depending on modality of measure).

To assess treatment short- and long-term efficacy and stability (H1, H2), we conducted a series of 3 (Group: ImRs, ImRs-DSR, IE) × 4 (Time: Pre-treatment, Post-treatment, 3-month follow-up, 6-month follow-up) mixed ANOVAs with repeated measures on the Time factor. These analyses were conducted separately for each outcome variable and each experimental context (recall, renewal, reinstatement), with focus on both subjective and physiological measures (self-reported arousal and emotions, skin conductance level [SCL], and salivary alpha-amylase [sAA]). All time points were analysed simultaneously, using Bonferoni correction at post-hoc, to control multiple comparisons. For each outcome, effect sizes (η2p) are reported. Where relevant, Greenhouse–Geisser corrections were applied.

Importantly, physiological reactivity was analysed separately for the anticipation phase (the first three segments of the audio script), which was present in all procedures (recall, renewal, reinstatement), and the hotspot phase (the emotionally intense segment), which was included only in the reinstatement procedure and only for SCL recordings. As labelling emotions during the imagery task could distort the emotional experience (see Torre and Lieberman, 2018), subjective emotional ratings were collected exclusively at the end of each procedure (i.e., post-treatment, 3-month and 6-month follow-ups), and therefore reflect retrospective evaluations of emotional experience during scenario imagery.

To test our specific hypotheses regarding treatment effects over time, we additionally performed planned contrasts focused on interaction effects. Specifically, we compared change from pre- to post-treatment, pre- to 3-month follow-up, and pre- to 6-month follow-up between selected pairs of groups:

-

ImRs > IE, Pre > Post, to test the therapeutic superiority of rescripting over exposure

-

ImRs-DSR > ImRs, Pre > Post, to test the added value of reconsolidation disruption

The generalisation and stability of treatment effects (H3) was examined by comparing physiological and subjective responses to untreated past criticism scenarios and future criticism scenarios, presented in contexts different from the treatment setting (i.e., renewal and reinstatement procedures). To obtain pre-treatment SCL and rating values for the future scenario, we averaged the data from criticism scenarios at pre-treatment (both treated and untreated). These analyses followed the same 3 groups × 4 time points mixed ANOVA structure, with planned contrasts testing for between-group differences in generalisation.

Mediation analyses examined prediction error (PE) as a potential mechanism of change (H4). PE was operationalised as a physiological arousal shift (increase in SCL) immediately following the expected hotspot (replaced by rescripting) during the first intervention session. We used binary Group factor- both rescripting conditions collapsed into one, and IE as a second. We also operationalised Therapy Efficacy as a difference between pre- versus post-treatment in Skin Conductance Level during hotspot phase. Our model tested whether binary Group predicted Therapy Efficacy, and whether this relationship is mediated by PE.

All statistical analyses were conducted using JASP (v0.19). The significance threshold was set at α = 0.05. Sensitivity analyses using the per-protocol approach are reported in the Supplementary materials.

Results

Treated criticism scenario—physiological response (ITT analysis, summary)

Physiological responses to the treated criticism scenario were examined using repeated-measures ANOVAs across four time points and three intervention groups (IE, ImRs, ImRs-DSR),separately for recall, renewal and reinstatement.

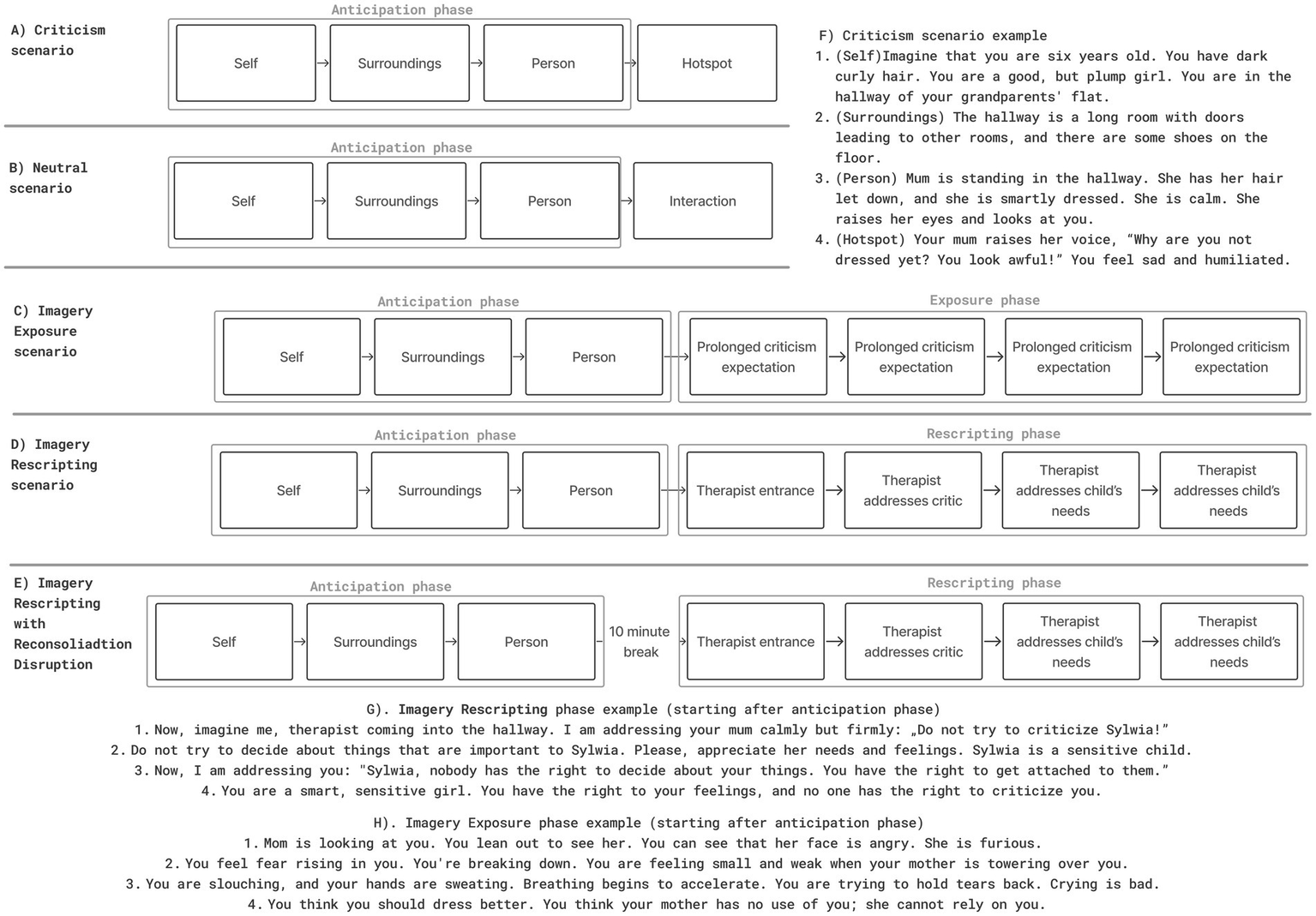

During the anticipation phase, significant main effects of time were observed across all three experimental procedures – recall (F = 57.75, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.30), renewal (F = 108.08, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.45), and reinstatement (F = 98.90, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.42) – indicating substantial and consistent reductions in anticipatory arousal following treatment. Time × Group interactions were non-significant or only marginally approached significance, suggesting comparable improvement across groups, although contrast analyses revealed some differences in SCL reduction over time between groups (see Contrast analysis section).

In the hotspot phase, reflecting peak emotional reactivity, SCL also decreased significantly over time, F(2.60, 342.52) = 18.16, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.119. Although the Time x Group interaction was not statistically significant (p = 0.135), descriptive data suggested slightly greater reductions in the ImRs group, while the IE group showed a modest rebound at follow-up.

Overall, the ITT analyses demonstrated robust and sustained reductions in physiological arousal across time and procedures, with comparable benefits observed across all three intervention types.

Levels of salivary alpha-amylase (sAA) did not show consistent evidence of treatment-related change. A main effect of time was not significant, F(2.67, 338.70) = 1.02, p = 0.378, η2p = 0.008, and no group or time × group interaction effects emerged (all ps > 0.23). This indicates that the intervention procedures had no measurable impact on physiological stress reactivity as indexed by sAA across the study period (see Figure 4 for SCL results and Tables 3, 4).

Figure 4

SCL results during anticipation phases of Recall, Renewal, Reinstatement and during Hotspot at Reinstatement for each group at different follow ups (bars represent 95% CI).

Table 4

| Analysis | tp1 | tp6 | tp7 | tp8 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IE | ImRs | ImRs-DSR | IE | ImRs | ImRs-DSR | IE | ImRs | ImRs-DSR | IE | ImRs | ImRs-DSR | |

| SCL anticipation treated criticism recall | 1.932 (13.482) | 6.866 (16.444) | 9.094 (17.826) | −8.735 (9.892) | −9.444 (10.805) | −11.232 (10.604) | −8.855 (9.815) | −4.900 (9.511) | −10.500 (12.211) | −11.231 (10.401) | −10.021 (11.742) | −9.316 (10.988) |

| SCL anticipation treated criticism reinstatement | 1.932 (13.482) | 6.866 (16.444) | 9.094 (17.826) | −13.102 (10.461) | −11.514 (9.911) | −10.136 (10.410) | −14.938 (9.651) | −15.753 (12.001) | −13.252 (10.787) | −12.997 (10.895) | −15.072 (11.871) | −11.897 (8.995) |

| SCL anticipation treated criticism renewal | 1.932 (13.482) | 6.866 (16.444) | 9.094 (17.826) | −14.377 (12.043) | −14.437 (10.976) | −13.589 (10.799) | −16.393 (10.555) | −16.063 (12.201) | −14.955 (9.950) | −14.617 (11.359) | −16.558 (12.294) | −12.119 (8.419) |

| SCL hotspot treated criticism reinstatement | −1.269 (17.063) | 4.313 (24.876) | 11.409 (24.246) | −9.159 (18.481) | −13.355 (15.902) | −6.914 (19.828) | −9.100 (15.701) | −13.104 (17.190) | −8.684 (16.084) | −3.457 (27.945) | −13.176 (20.579) | −5.251 (29.474) |

| SCL anticipation future criticism | −1.101 (6.986) | 0.690 (10.986) | 2.804 (11.755) | 7.511 (4.848) | 7.783 (5.472) | 8.595 (5.153) | 6.829 (4.785) | 5.764 (4.899) | 7.217 (5.072) | 5.803 (4.270) | 6.020 (4.525) | 7.356 (4.655) |

| SCL anticipation untreated criticism recall | −5.664 (11.090) | −7.404 (12.488) | −6.620 (7.580) | −1.010 (12.280) | −3.335 (10.080) | −3.143 (10.318) | −8.529 (10.678) | −5.936 (9.482) | −4.492 (9.724) | −6.157 (15.838) | −4.560 (14.467) | −3.719 (12.210) |

| SCL anticipation untreated criticism reinstatement | −5.664 (11.090) | −7.404 (12.488) | −6.620 (7.580) | −7.882 (9.519) | −7.591 (8.727) | −5.806 (9.064) | −9.198 (10.633) | −6.172 (11.120) | −5.731 (9.931) | −10.166 (10.514) | −8.440 (10.862) | −6.408 (9.123) |

| SCL anticipation untreated criticism renewal | −5.664 (11.090) | −7.404 (12.488) | −6.620 (7.580) | −9.121 (9.314) | −9.150 (10.461) | −5.278 (9.933) | −9.399 (12.451) | −9.785 (13.052) | −5.827 (11.759) | −9.576 (11.708) | −7.507 (10.417) | −4.561 (12.018) |

| SCL anticipation future criticism | −1.101 (6.986) | 0.690 (10.986) | 2.804 (11.755) | 7.511 (4.848) | 7.783 (5.472) | 8.595 (5.153) | 6.829 (4.785) | 5.764 (4.899) | 7.217 (5.072) | 5.803 (4.270) | 6.020 (4.525) | 7.356 (4.655) |

| SCL hotspot future criticism | −4.818 (10.484) | −3.037 (16.326) | 1.350 (13.333) | 7.417 (4.516) | 7.608 (5.129) | 9.112 (5.086) | 6.536 (4.480) | 5.941 (4.976) | 7.215 (5.025) | 5.865 (4.231) | 5.980 (4.420) | 7.329 (4.565) |

| Rating of anticipation phase treated criticism arousal | 4.490 (1.835) | 4.850 (1.923) | 4.284 (1.984) | 3.271 (1.710) | 3.640 (1.787) | 3.489 (1.900) | 3.063 (1.841) | 3.280 (1.896) | 3.261 (1.927) | 3.115 (1.877) | 3.430 (1.974) | 3.307 (1.989) |

| Rating of anticipation phase treated criticism disgust | 2.146 (1.574) | 2.540 (1.937) | 2.523 (1.923) | 1.344 (0.716) | 1.310 (0.782) | 1.784 (1.480) | 1.479 (0.805) | 1.580 (1.239) | 1.875 (1.343) | 1.510 (1.044) | 1.770 (1.679) | 1.739 (1.251) |

| Rating of anticipation phase treated criticism fear | 3.729 (1.822) | 4.170 (2.212) | 3.875 (2.038) | 2.104 (1.225) | 2.130 (1.151) | 2.455 (1.524) | 1.896 (1.180) | 1.980 (1.160) | 2.477 (1.772) | 1.906 (1.266) | 2.200 (1.669) | 2.398 (1.797) |

| Rating of anticipation phase treated criticism FOC | 6.625 (1.468) | 7.100 (1.317) | 6.886 (1.156) | 6.667 (1.674) | 6.030 (1.931) | 6.250 (1.999) | 6.010 (1.867) | 5.510 (2.069) | 5.795 (1.960) | 5.979 (1.984) | 5.560 (2.152) | 5.455 (2.347) |

| Rating of anticipation phase treated criticism guilt | 3.792 (2.324) | 4.290 (2.699) | 3.693 (1.905) | 1.635 (0.892) | 1.940 (0.978) | 2.409 (1.395) | 1.906 (1.119) | 2.200 (1.374) | 2.432 (1.535) | 1.813 (1.040) | 2.150 (1.575) | 2.330 (1.529) |

| Rating of anticipation phase treated criticism IMM | 6.698 (1.620) | 7.000 (1.351) | 6.886 (1.151) | 7.010 (1.655) | 6.460 (1.720) | 6.511 (1.978) | 6.458 (1.747) | 5.910 (2.087) | 6.170 (2.051) | 6.240 (1.919) | 5.810 (2.215) | 5.977 (2.295) |

| Rating of anticipation phase treated criticism sadness | 3.833 (1.790) | 4.300 (2.378) | 3.534 (1.515) | 1.906 (1.055) | 2.030 (1.012) | 2.500 (1.479) | 1.969 (1.205) | 1.920 (0.986) | 2.273 (1.264) | 1.948 (1.107) | 2.170 (1.288) | 2.125 (1.206) |

| Rating of anticipation phase treated criticism anger | 2.708 (1.688) | 2.870 (1.681) | 2.614 (1.667) | 1.448 (0.753) | 1.530 (0.752) | 1.784 (1.374) | 1.438 (0.719) | 1.810 (1.328) | 1.739 (1.009) | 1.542 (1.224) | 1.870 (1.622) | 1.705 (0.904) |

| Rating of anticipation phase future criticism anger | 2.739 (1.351) | 2.707 (1.220) | 2.744 (1.423) | 1.543 (0.900) | 1.734 (1.010) | 1.526 (0.924) | 1.446 (0.717) | 1.915 (1.431) | 1.872 (1.613) | 1.413 (0.702) | 1.862 (1.087) | 1.590 (0.993) |

| Rating of anticipation phase future criticism arousal | 4.592 (1.605) | 4.585 (1.643) | 4.199 (1.715) | 4.424 (1.963) | 4.564 (1.935) | 4.385 (1.801) | 3.598 (2.056) | 4.138 (1.820) | 3.641 (2.173) | 3.522 (1.903) | 3.989 (1.804) | 3.705 (2.095) |

| Rating of anticipation phase future criticism disgust | 2.033 (1.260) | 2.590 (1.616) | 2.635 (1.654) | 1.370 (0.627) | 1.809 (1.509) | 1.679 (1.259) | 1.337 (0.700) | 2.011 (1.699) | 1.718 (1.281) | 1.326 (0.634) | 1.947 (1.537) | 1.769 (1.063) |

| Rating of anticipation phase future criticism fear | 3.908 (1.705) | 4.059 (1.756) | 3.910 (1.732) | 3.272 (1.905) | 3.543 (2.103) | 3.077 (1.979) | 2.783 (1.772) | 3.160 (2.038) | 2.936 (1.759) | 2.620 (1.799) | 3.053 (1.926) | 2.833 (1.615) |

| Rating of anticipation phase future criticism guilt | 3.826 (1.733) | 4.027 (1.817) | 4.071 (1.515) | 2.435 (1.672) | 2.894 (1.936) | 2.077 (1.485) | 2.337 (1.626) | 2.819 (1.831) | 2.154 (1.582) | 1.989 (1.327) | 2.638 (1.744) | 2.333 (1.515) |

| Rating of anticipation phase future criticism sadness | 3.957 (1.385) | 3.957 (1.572) | 3.840 (1.485) | 1.989 (1.108) | 2.553 (1.623) | 1.859 (1.262) | 1.957 (1.277) | 2.574 (1.827) | 2.051 (1.642) | 1.891 (1.229) | 2.426 (1.460) | 2.000 (1.318) |

| Rating of anticipation phase untreated criticism anger | 2.724 (1.344) | 2.750 (1.245) | 2.636 (1.392) | 1.427 (0.686) | 1.555 (0.678) | 1.807 (1.430) | 1.422 (0.675) | 1.790 (0.960) | 1.801 (1.039) | 1.500 (1.116) | 1.800 (1.030) | 1.642 (0.808) |

| Rating of anticipation phase untreated criticism arousal | 4.604 (1.607) | 4.705 (1.681) | 4.136 (1.757) | 3.641 (1.604) | 3.805 (1.722) | 3.597 (1.829) | 3.156 (1.725) | 3.270 (1.792) | 3.114 (1.718) | 3.120 (1.804) | 3.410 (1.771) | 3.182 (1.829) |

| Rating of anticipation phase untreated criticism disgust | 2.021 (1.244) | 2.520 (1.598) | 2.551 (1.603) | 1.318 (0.633) | 1.350 (0.720) | 1.710 (1.429) | 1.411 (0.689) | 1.625 (0.947) | 1.790 (1.229) | 1.401 (0.716) | 1.685 (1.196) | 1.665 (0.937) |

| Rating of anticipation phase untreated criticism fear | 3.849 (1.699) | 4.085 (1.737) | 3.858 (1.664) | 2.172 (1.058) | 2.350 (1.101) | 2.335 (1.328) | 2.010 (1.059) | 2.135 (1.212) | 2.313 (1.373) | 1.906 (0.994) | 2.195 (1.464) | 2.267 (1.393) |

| Rating of anticipation phase untreated criticism guilt | 3.781 (1.716) | 4.095 (1.911) | 3.955 (1.511) | 1.771 (0.863) | 2.115 (1.009) | 2.290 (1.304) | 1.922 (1.011) | 2.210 (1.316) | 2.216 (1.279) | 1.818 (0.858) | 2.100 (1.372) | 2.278 (1.358) |

| Rating of anticipation phase untreated criticism sadness | 3.901 (1.410) | 4.025 (1.599) | 3.727 (1.446) | 1.922 (0.845) | 2.180 (0.983) | 2.426 (1.298) | 1.922 (0.975) | 2.145 (0.992) | 2.176 (1.142) | 1.839 (0.824) | 2.235 (1.093) | 2.102 (1.178) |

| Rating of hotspot phase treated criticism anger | 4.063 (2.462) | 4.980 (2.810) | 4.091 (2.380) | 2.646 (1.918) | 3.020 (1.964) | 2.795 (1.995) | 2.667 (1.982) | 3.220 (2.324) | 3.091 (2.044) | 2.729 (2.322) | 2.740 (1.882) | 2.977 (2.226) |

| Rating of hotspot phase treated criticism arousal | 5.333 (2.244) | 6.180 (2.106) | 4.636 (2.677) | 4.271 (2.050) | 4.720 (2.241) | 4.614 (2.345) | 4.083 (2.277) | 4.440 (2.476) | 4.114 (2.470) | 3.979 (2.302) | 4.460 (2.435) | 4.068 (2.500) |

| Rating of hotspot phase treated criticism disgust | 3.063 (2.338) | 3.640 (2.827) | 4.000 (2.795) | 1.875 (1.734) | 1.840 (1.419) | 2.591 (2.149) | 2.271 (2.008) | 2.280 (2.071) | 2.705 (2.226) | 2.146 (1.774) | 2.080 (1.988) | 2.455 (2.017) |

| Rating of hotspot phase treated criticism fear | 5.188 (2.367) | 5.320 (2.759) | 5.136 (2.557) | 3.167 (2.272) | 3.080 (2.098) | 3.455 (2.118) | 3.271 (2.359) | 3.000 (2.449) | 3.227 (2.371) | 2.958 (2.324) | 2.660 (2.096) | 3.227 (2.271) |

| Rating of hotspot phase treated criticism guilt | 5.917 (2.616) | 6.180 (2.716) | 6.205 (2.288) | 3.292 (2.163) | 3.280 (2.080) | 4.091 (2.291) | 3.708 (2.423) | 3.700 (2.682) | 4.068 (2.618) | 3.500 (2.388) | 3.300 (2.501) | 3.886 (2.335) |

| Rating of hotspot phase treated criticism sadness | 6.063 (2.177) | 6.320 (2.386) | 6.432 (1.910) | 3.771 (2.076) | 3.560 (1.831) | 3.955 (2.382) | 3.833 (2.504) | 3.640 (2.248) | 4.068 (2.225) | 3.604 (2.439) | 3.360 (2.136) | 3.705 (2.278) |

| Rating of hotspot phase future criticism anger | 4.261 (2.203) | 4.926 (2.226) | 4.167 (1.941) | 3.348 (2.253) | 3.936 (2.230) | 4.308 (2.319) | 3.239 (2.330) | 3.596 (2.300) | 3.846 (2.323) | 3.130 (2.166) | 3.553 (2.114) | 3.308 (2.041) |

| Rating of hotspot phase future criticism arousal | 5.457 (1.840) | 5.819 (1.909) | 4.872 (2.430) | 5.500 (2.229) | 5.638 (2.048) | 5.487 (2.050) | 4.652 (2.273) | 4.936 (2.068) | 4.897 (2.583) | 4.543 (2.168) | 4.809 (2.007) | 4.795 (2.577) |

| Rating of hotspot phase future criticism disgust | 2.783 (1.876) | 3.691 (2.566) | 4.013 (2.553) | 2.261 (1.769) | 3.064 (2.363) | 2.974 (2.121) | 2.196 (1.572) | 2.809 (1.930) | 2.974 (2.345) | 2.304 (1.645) | 3.000 (2.303) | 2.846 (2.277) |

| Rating of hotspot phase future criticism fear | 5.261 (2.076) | 5.213 (2.166) | 5.167 (2.374) | 4.087 (2.374) | 4.319 (2.314) | 3.359 (2.378) | 3.435 (2.218) | 3.617 (2.299) | 3.692 (2.525) | 3.239 (2.272) | 3.660 (2.362) | 3.590 (2.702) |

| Rating of hotspot phase future criticism guilt | 6.011 (2.112) | 6.138 (2.317) | 6.436 (1.957) | 4.609 (2.745) | 5.128 (2.281) | 4.615 (2.662) | 4.130 (2.680) | 4.383 (2.410) | 4.615 (2.642) | 3.826 (2.719) | 4.149 (2.587) | 4.462 (2.594) |

| Rating of hotspot phase future criticism sadness | 6.304 (1.638) | 6.340 (2.124) | 6.692 (1.680) | 4.500 (2.373) | 4.915 (2.205) | 4.462 (2.360) | 3.935 (2.361) | 4.362 (2.540) | 4.051 (2.449) | 3.826 (2.407) | 4.340 (2.434) | 3.846 (2.651) |

| Rating of hotspot phase future criticism anger | 4.458 (2.518) | 5.120 (2.370) | 4.068 (2.172) | 2.833 (1.971) | 3.200 (1.761) | 3.182 (2.160) | 2.917 (1.998) | 3.120 (1.945) | 3.159 (2.134) | 2.708 (2.133) | 3.260 (2.058) | 2.841 (2.112) |

| Rating of hotspot phase future criticism arousal | 5.521 (1.989) | 5.720 (2.138) | 5.091 (2.541) | 4.521 (2.183) | 4.960 (2.407) | 4.886 (2.274) | 4.458 (2.240) | 4.460 (2.451) | 4.386 (2.563) | 4.188 (2.275) | 4.460 (2.332) | 4.182 (2.789) |

| Rating of hotspot phase future criticism disgust | 2.604 (2.181) | 3.740 (2.679) | 4.068 (2.823) | 1.979 (1.523) | 2.300 (1.821) | 2.773 (2.301) | 2.333 (1.950) | 2.620 (2.194) | 2.818 (2.326) | 2.208 (1.924) | 2.580 (2.269) | 2.682 (2.133) |

| Rating of hotspot phase future criticism fear | 5.125 (2.438) | 5.280 (2.391) | 5.295 (2.681) | 3.500 (2.297) | 3.780 (2.427) | 3.568 (2.491) | 3.250 (2.302) | 3.080 (2.266) | 3.545 (2.565) | 2.771 (2.224) | 2.960 (2.303) | 3.227 (2.560) |

| Rating of hotspot phase future criticism guilt | 5.958 (2.405) | 6.160 (2.444) | 6.705 (2.319) | 3.792 (2.250) | 4.080 (2.538) | 4.682 (2.494) | 3.708 (2.518) | 3.520 (2.620) | 4.568 (2.636) | 3.375 (2.358) | 3.380 (2.364) | 4.318 (2.595) |

| Rating of hotspot phase future criticism sadness | 6.417 (1.944) | 6.560 (2.082) | 6.841 (1.879) | 4.146 (2.212) | 4.440 (2.251) | 4.727 (2.224) | 3.917 (2.431) | 3.820 (2.439) | 4.295 (2.184) | 3.792 (2.333) | 4.020 (2.317) | 4.091 (2.504) |

| Beck depression inventory | 14.936 (6.370) | 13.380 (5.646) | 15.000 (6.094) | 12.723 (8.200) | 12.860 (6.007) | 11.465 (6.957) | 12.191 (7.655) | 12.140 (5.990) | 13.047 (7.518) | 9.340 (7.530) | 10.200 (6.518) | 11.651 (9.240) |

| Frost multidimensional perfectionism scale | 3.062 (0.637) | 3.251 (0.578) | 3.128 (0.617) | 2.965 (0.649) | 3.126 (0.616) | 3.135 (0.596) | 3.088 (0.610) | 3.144 (0.608) | 3.130 (0.590) | 3.062 (0.701) | 3.099 (0.651) | 3.082 (0.647) |

| Leibowitz social anxiety scale | 2.073 (0.533) | 2.059 (0.456) | 2.008 (0.493) | 2.072 (0.496) | 2.037 (0.447) | 2.010 (0.513) | 2.036 (0.535) | 2.007 (0.461) | 1.974 (0.555) | 1.984 (0.561) | 2.026 (0.490) | 1.935 (0.546) |

| Performance failure appraisal inventory (fear of failure scale) | 120.149 (9.184) | 120.680 (9.155) | 118.744 (11.320) | 111.723 (21.251) | 115.880 (18.721) | 111.535 (22.183) | 112.149 (23.605) | 115.760 (20.346) | 113.442 (16.836) | 108.638 (27.182) | 111.760 (22.091) | 106.279 (23.054) |

| Pure procrastination scale | 2.877 (1.051) | 2.978 (0.955) | 2.709 (0.952) | 2.783 (1.025) | 3.067 (0.996) | 2.782 (0.848) | 2.857 (1.026) | 2.926 (0.987) | 2.742 (0.841) | 2.830 (1.082) | 2.892 (1.012) | 2.820 (0.933) |

| Salivary alpha amylase | 140.527 (91.230) | 111.418 (76.090) | 139.882 (89.356) | 138.194 (91.869) | 101.254 (70.448) | 126.414 (90.184) | ||||||

| PTSD DSM-V scale | 0.412 (0.588) | 0.507 (0.868) | 0.447 (0.699) | 0.343 (0.687) | 0.288 (0.621) | 0.310 (0.609) | ||||||

| General anxiety disorder | 1.945 (0.538) | 1.898 (0.540) | 1.881 (0.566) | 1.689 (0.556) | 1.744 (0.518) | 1.758 (0.471) | ||||||

| Panic disorder DSM-V scale | 1.283 (0.376) | 1.280 (0.421) | 1.323 (0.514) | 1.213 (0.416) | 1.170 (0.343) | 1.233 (0.343) | ||||||

| Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale | 13.170 (5.787) | 12.280 (6.111) | 10.930 (5.663) | 10.957 (6.963) | 11.500 (5.733) | 10.884 (6.695) | ||||||

ITT descriptive intention-to-treatment descriptive analysis.

Subjective response during treated criticism scenario (ITT analysis)

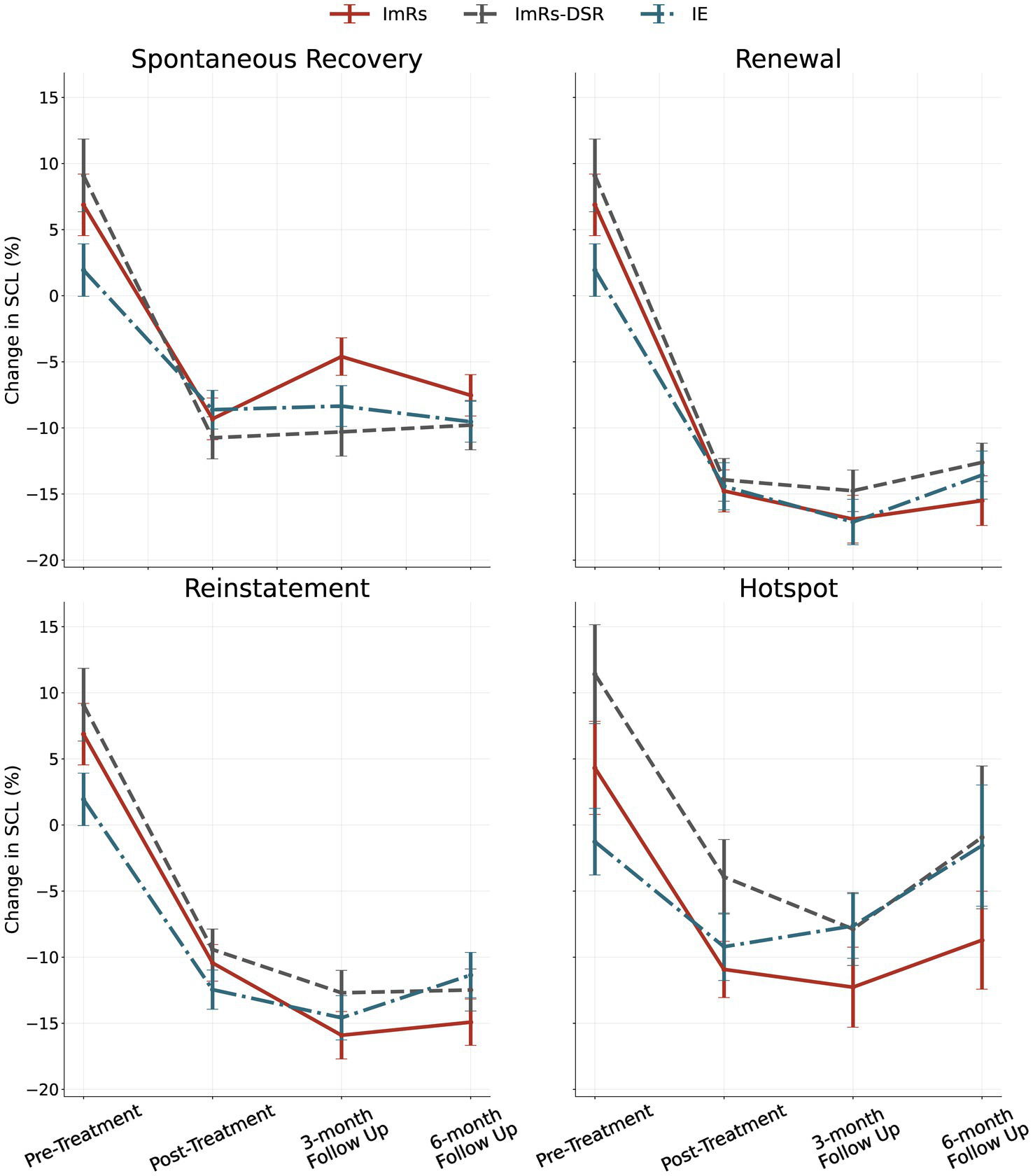

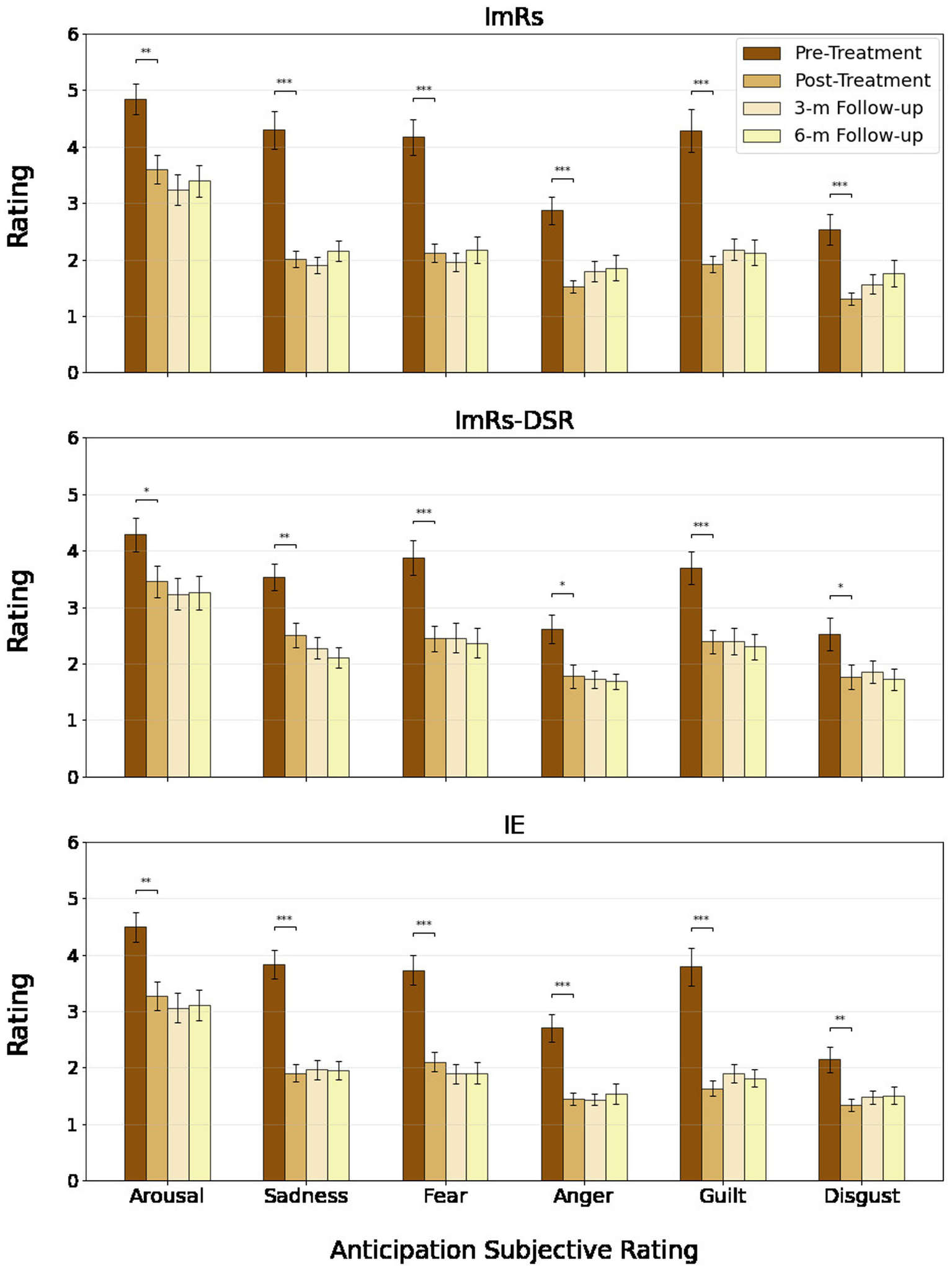

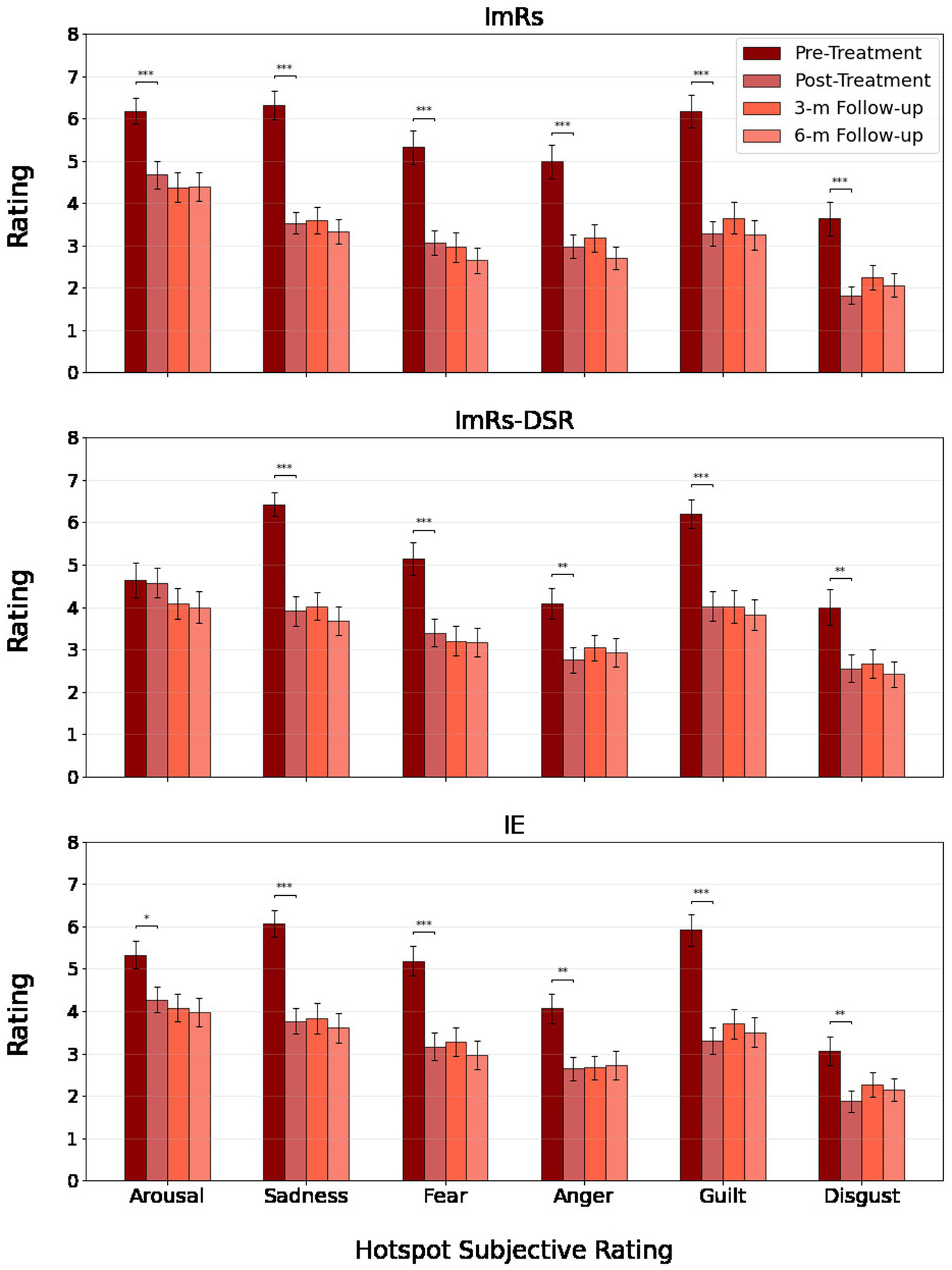

Across both anticipation and hotspot phases, repeated-measures ANOVAs revealed robust main effects of time for all assessed negative emotions, indicating significant and sustained reductions in subjective distress from pre-treatment to post-treatment and across the 3- and 6-month follow-ups (see Figures 5, 6). Effect sizes for time effects ranged from moderate to very large (η2p = 0.12–0.44 in anticipation; η2p = 0.12–0.44 in hotspot). The only significant time × group interaction was observed for sadness during anticipation (η2p = 0.047), reflecting somewhat greater post-treatment decreases in the ImRs and IE groups compared to ImRs-DSR. No other main effects of group or interactions were significant (all ps > 0.07), although contrast analysis revealed interaction for arousal rating (see Contrast analysis section and Figure 6.). Overall, results demonstrate that all three interventions led to durable decreases in subjective negative affect during anticipation and peak emotional reactivity, with improvements remaining stable through follow-up.

Figure 5

Rating of anticipation phase of treated criticism across groups and time points.

Figure 6

Hotspot rating of treated criticism across groups and time points.

Fear of failure results (ITT analysis)

Analyses of the fear of failure (PFAI) did not reveal significant group or time × group interaction effects (all ps > 0.14). A main effect of time was observed, F(2.55, 354.12) = 6.48, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.045, reflecting a small overall reduction in PFAI scores across assessments. Post hoc comparisons indicated that reductions from pre-treatment to post-treatment (ΔM = −3.21, p = 0.009, d = 0.28) and to the 3-month follow-up (tp7; ΔM = −3.85, p = 0.006) were significant, but changes did not remain robust at the 6-month follow-up (tp8, p = 0.087). These results suggest modest improvements in fear of failure following intervention, but without clear differentiation between conditions.

Generalizability and stability SCL—untreated and future criticism (ITT analysis)

For the untreated criticism scenario, physiological responses showed no consistent time effects across anticipation, renewal, or reinstatement phases. Only a weak reduction emerged in the recall procedure (η2p ≈ 0.03), with no lasting changes at follow-ups. No significant group or interaction effects were observed, indicating stable arousal across interventions.

In contrast, future criticism elicited robust increases in physiological arousal over time. Significant main effects of time were found for both anticipation and hotspot phases, with small to medium effect sizes (η2p ≈ 0.20–0.30). SCL rose markedly from pre-treatment to post-treatment and remained elevated across follow-ups, with no differences between groups.

Overall, these findings suggest that interventions did not generalise to untreated autobiographical criticism, consistent across all conditions. They were also associated with heightened reactivity to imagined future criticism.

Generalizability and stability—subjective measures (ITT analysis)

In both the future and untreated criticism scenarios, participants reported significant changes in emotional reactivity during anticipation phase over time (p < 0.001 in all main effects of time), with no significant main effects of condition (all ps > 0.20) or Time × Group interactions (all ps > 0.13). This indicates comparable improvement patterns across intervention groups.

For the future criticism scenario (anticipation and hotspot phase), large time effects were found for sadness (η2p ≈ 0.41–44), fear (η2pl ≈ 0.32–34), and guilt (η2p ≈ 0.23–24), all showing robust decreases from pre-treatment to post-treatment that remained stable through follow-ups. Anger, arousal, and disgust also declined significantly over time, though with smaller effect sizes (η2p ≈ 0.05–0.09).

For the untreated criticism scenario, significant reductions were observed across both anticipation and hotspot phases for most negative emotions. The largest effects were seen for sadness (η2p ≈ 0.41–0.44), fear (η2p ≈ 0.34–0.45), and guilt (η2p ≈ 0.22–0.49), with moderate declines in anger, arousal, and disgust (η2p ≈ 0.09–0.30). Across both scenarios, the absence of significant group differences and interactions suggests that reductions in subjective emotional reactivity were non-specific to treatment type. Worth noting, this finding is contradictory to psychophysiological results, although may be the result of recency effect (see Discussion).

Contrast analysis (ITT and PP analysis)

Although the majority of exploratory contrasts did not reach statistical significance, several noteworthy effects emerged. First, a rebound effect was observed in the IE group compared to ImRs at the 6-month follow-up, reflected in increased SCL responses to the hotspot during reinstatement [t(135) = −2.231, p = 0.027] and, at the trend level, to the anticipation phase during renewal [t(135) = −1.814, p = 0.072] and reinstatement [t(135) = −1.774, p = 0.078]. In addition, analyses demonstrated the superiority of ImRs over ImRs-DSR in reducing subjective ratings of guilt and sadness for the anticipation phase at post treatment [guilt: t(139) = −2.344, p = 0.021; sadness: t(139) = −3.192, p = 0.002]. A consistent pattern further indicated stronger reductions in the arousal ratings of the hotspot phase in the ImRs group relative to ImRs-DSR, both immediately post-treatment and across follow-up sessions [post-treatment: t(139) = −2.665, p = 0.009; 3-month follow-up: t(139) = −2.227, p = 0.028; 6-month follow-up: t(139) = −2.033, p = 0.044; see Figure 6].

Sensitivity analyses using the per-protocol dataset largely confirmed these findings. The rebound effect in IE compared to ImRs was again present at the 6-month follow-up, although here it emerged to be significant during the anticipation phase at reinstatement [t(79) = −2.305, p = 0.024], but not during hotspot [t(76) = −1.279, p = 0.205]. Moreover, the superiority of ImRs over ImRs-DSR in reducing arousal ratings was also observed for these analyses at pre-treatment and at the 3-month follow-up [pre-treatment: t(87) = −2.139, p = 0.035; 3-month follow-up: t(87) = −2.063, p = 0.042] (Table 5).

Table 5

| Analysis | ImRs>IE Pre>Post-Treatment | ImRs>IE Pre-Treatment>3-m F-up | ImRs>IE Pre-Treatment>6-m F-up | ImRs-DSR>ImRs Pre>Post-Treatment | ImRs-DSR>ImRs Pre-Treatment>3-m F-up | ImRs-DSR>ImRs Pre-Treatment>6-m F-up | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t (df) | p | t (df) | p | t (df) | p | t (df) | p | t (df) | p | t (df) | p | |

| SCL anticipation treated criticism recall | −1.495 (df = 135) | 0.137 | −0.244 (df = 135) | 0.808 | −0.970 (df = 135) | 0.334 | 1.039 (df = 135) | 0.301 | 1.902 (df = 135) | 0.059 | 0.387 (df = 135) | 0.699 |

| SCL anticipation treated criticism reinstatement | −0.903 (df = 135) | 0.368 | −1.388 (df = 135) | 0.168 | −1.774 (df = 135) | 0.078 | 0.224 (df = 135) | 0.823 | −0.064 (df = 135) | 0.949 | −0.234 (df = 135) | 0.815 |

| SCL anticipation treated criticism renewal | −1.238 (df = 135) | 0.218 | −1.130 (df = 135) | 0.26 | −1.814 (df = 135) | 0.072 | 0.334 (df = 135) | 0.739 | 0.269 (df = 135) | 0.789 | −0.570 (df = 135) | 0.57 |

| SCL hotspot treated criticism reinstatement | −1.741 (df = 135) | 0.084 | −1.651 (df = 135) | 0.101 | −2.231 (df = 135) | 0.027 | 0.114 (df = 135) | 0.909 | 0.450 (df = 135) | 0.654 | −0.118 (df = 135) | 0.906 |

| SCL anticipation untreated criticism recall | −0.199 (df = 134) | 0.843 | 1.418 (df = 134) | 0.159 | 0.974 (df = 134) | 0.332 | 0.194 (df = 134) | 0.846 | −0.208 (df = 134) | 0.836 | −0.016 (df = 134) | 0.987 |

| SCL anticipation untreated criticism reinstatement | 0.687 (df = 134) | 0.493 | 1.563 (df = 134) | 0.12 | 1.245 (df = 134) | 0.215 | −0.326 (df = 134) | 0.745 | 0.108 (df = 134) | 0.914 | −0.433 (df = 134) | 0.666 |

| SCL anticipation untreated criticism renewal | 0.561 (df = 134) | 0.576 | 0.420 (df = 134) | 0.675 | 1.215 (df = 134) | 0.227 | −0.977 (df = 134) | 0.33 | −0.949 (df = 134) | 0.344 | −0.665 (df = 134) | 0.507 |

| SCL anticipation future criticism | −0.625 (df = 124) | 0.533 | −1.190 (df = 124) | 0.236 | −0.704 (df = 124) | 0.483 | 0.520 (df = 124) | 0.604 | 0.267 (df = 124) | 0.79 | 0.337 (df = 124) | 0.737 |

| SCL hotspot future criticism | −0.544 (df = 124) | 0.588 | −0.794 (df = 124) | 0.428 | −0.574 (df = 124) | 0.567 | 0.956 (df = 124) | 0.341 | 1.009 (df = 124) | 0.315 | 1.014 (df = 124) | 0.312 |

| Salivary alpha amylase | −0.826 (df = 123) | 0.411 | 0.330 (df = 123) | 0.742 | ||||||||

| Rating of anticipation phase treated criticism arousal | 0.019 (df = 139) | 0.985 | −0.297 (df = 139) | 0.767 | −0.094 (df = 139) | 0.925 | −0.890 (df = 139) | 0.375 | −1.112 (df = 139) | 0.268 | −0.901 (df = 139) | 0.369 |

| Rating of anticipation phase treated criticism disgust | −1.274 (df = 139) | 0.205 | −0.857 (df = 139) | 0.393 | −0.382 (df = 139) | 0.703 | −1.430 (df = 139) | 0.155 | −0.892 (df = 139) | 0.374 | 0.039 (df = 139) | 0.969 |

| Rating of anticipation phase treated criticism guilt | −0.436 (df = 139) | 0.664 | −0.441 (df = 139) | 0.66 | −0.336 (df = 139) | 0.737 | −2.344 (df = 139) | 0.021 | −1.744 (df = 139) | 0.083 | −1.586 (df = 139) | 0.115 |

| Rating of anticipation phase treated criticism sadness | −0.906 (df = 139) | 0.367 | −1.322 (df = 139) | 0.188 | −0.606 (df = 139) | 0.545 | −3.192 (df = 139) | 0.002 | −2.805 (df = 139) | 0.006 | −1.747 (df = 139) | 0.083 |

| Rating of anticipation phase treated criticism anger | −0.225 (df = 139) | 0.822 | 0.617 (df = 139) | 0.538 | 0.422 (df = 139) | 0.673 | −1.412 (df = 139) | 0.16 | −0.530 (df = 139) | 0.597 | −0.225 (df = 139) | 0.822 |

| Rating of anticipation phase future criticism anger | 0.731 (df = 129) | 0.466 | 1.408 (df = 129) | 0.162 | 1.518 (df = 129) | 0.131 | 0.770 (df = 129) | 0.443 | 0.213 (df = 129) | 0.831 | 0.932 (df = 129) | 0.353 |

| Rating of anticipation phase future criticism arousal | 0.313 (df = 129) | 0.755 | 1.060 (df = 129) | 0.291 | 0.933 (df = 129) | 0.353 | −0.421 (df = 129) | 0.674 | 0.205 (df = 129) | 0.838 | −0.192 (df = 129) | 0.848 |

| Rating of anticipation phase future criticism disgust | −0.350 (df = 129) | 0.727 | 0.307 (df = 129) | 0.759 | 0.177 (df = 129) | 0.86 | 0.488 (df = 129) | 0.626 | 0.855 (df = 129) | 0.394 | 0.598 (df = 129) | 0.551 |

| Rating of anticipation phase future criticism fear | 0.225 (df = 129) | 0.822 | 0.447 (df = 129) | 0.656 | 0.557 (df = 129) | 0.578 | 0.571 (df = 129) | 0.569 | 0.143 (df = 129) | 0.887 | 0.135 (df = 129) | 0.893 |

| Rating of anticipation phase future criticism guilt | 0.584 (df = 129) | 0.561 | 0.668 (df = 129) | 0.505 | 1.060 (df = 129) | 0.291 | 1.861 (df = 129) | 0.065 | 1.611 (df = 129) | 0.11 | 0.790 (df = 129) | 0.431 |

| Rating of anticipation phase future criticism sadness | 1.478 (df = 129) | 0.142 | 1.499 (df = 129) | 0.136 | 1.324 (df = 129) | 0.188 | 1.449 (df = 129) | 0.15 | 0.943 (df = 129) | 0.347 | 0.732 (df = 129) | 0.465 |

| Rating of anticipation phase untreated criticism anger | 0.348 (df = 139) | 0.729 | 1.245 (df = 139) | 0.215 | 0.936 (df = 139) | 0.351 | −1.219 (df = 139) | 0.225 | −0.444 (df = 139) | 0.658 | 0.148 (df = 139) | 0.882 |

| Rating of anticipation phase untreated criticism arousal | 0.159 (df = 139) | 0.874 | 0.031 (df = 139) | 0.975 | 0.445 (df = 139) | 0.657 | −0.879 (df = 139) | 0.381 | −0.974 (df = 139) | 0.332 | −0.782 (df = 139) | 0.436 |

| Rating of anticipation phase untreated criticism disgust | −1.769 (df = 139) | 0.079 | −1.082 (df = 139) | 0.281 | −0.750 (df = 139) | 0.455 | −1.219 (df = 139) | 0.225 | −0.495 (df = 139) | 0.622 | 0.175 (df = 139) | 0.861 |

| Rating of anticipation phase untreated criticism fear | −0.177 (df = 139) | 0.86 | −0.318 (df = 139) | 0.751 | 0.141 (df = 139) | 0.888 | −0.633 (df = 139) | 0.528 | −1.129 (df = 139) | 0.261 | −0.780 (df = 139) | 0.437 |

| Rating of anticipation phase untreated criticism guilt | 0.089 (df = 139) | 0.929 | −0.071 (df = 139) | 0.944 | −0.086 (df = 139) | 0.932 | −0.904 (df = 139) | 0.368 | −0.394 (df = 139) | 0.694 | −0.853 (df = 139) | 0.395 |

| Rating of anticipation phase untreated criticism sadness | 0.467 (df = 139) | 0.641 | 0.331 (df = 139) | 0.741 | 0.873 (df = 139) | 0.384 | −1.852 (df = 139) | 0.066 | −1.074 (df = 139) | 0.285 | −0.516 (df = 139) | 0.606 |

| Rating of hotspot phase treated criticism anger | −1.046 (df = 139) | 0.297 | −0.617 (df = 139) | 0.538 | −1.497 (df = 139) | 0.137 | −1.250 (df = 139) | 0.213 | −1.258 (df = 139) | 0.21 | −1.818 (df = 139) | 0.071 |

| Rating of hotspot phase treated criticism arousal | −0.754 (df = 139) | 0.452 | −0.917 (df = 139) | 0.361 | −0.661 (df = 139) | 0.51 | −2.665 (df = 139) | 0.009 | −2.227 (df = 139) | 0.028 | −2.033 (df = 139) | 0.044 |

| Rating of hotspot phase treated criticism disgust | −1.336 (df = 139) | 0.184 | −1.142 (df = 139) | 0.255 | −1.326 (df = 139) | 0.187 | −0.833 (df = 139) | 0.406 | −0.127 (df = 139) | 0.899 | −0.029 (df = 139) | 0.977 |

| Rating of hotspot phase treated criticism fear | −0.454 (df = 139) | 0.651 | −0.763 (df = 139) | 0.447 | −0.815 (df = 139) | 0.416 | −1.130 (df = 139) | 0.26 | −0.760 (df = 139) | 0.449 | −1.389 (df = 139) | 0.167 |

| Rating of hotspot phase treated criticism guilt | −0.540 (df = 139) | 0.59 | −0.472 (df = 139) | 0.637 | −0.823 (df = 139) | 0.412 | −1.510 (df = 139) | 0.133 | −0.584 (df = 139) | 0.56 | −0.976 (df = 139) | 0.331 |

| Rating of hotspot phase treated criticism sadness | −0.987 (df = 139) | 0.325 | −0.893 (df = 139) | 0.373 | −0.975 (df = 139) | 0.331 | −0.583 (df = 139) | 0.561 | −0.613 (df = 139) | 0.541 | −0.442 (df = 139) | 0.659 |

| Rating of hotspot phase future criticism anger | −0.138 (df = 129) | 0.89 | −0.524 (df = 129) | 0.601 | −0.439 (df = 129) | 0.661 | −1.956 (df = 129) | 0.053 | −1.644 (df = 129) | 0.103 | −0.892 (df = 129) | 0.374 |

| Rating of hotspot phase future criticism arousal | −0.427 (df = 129) | 0.67 | −0.144 (df = 129) | 0.886 | −0.179 (df = 129) | 0.858 | −1.451 (df = 129) | 0.149 | −1.591 (df = 129) | 0.114 | −1.639 (df = 129) | 0.104 |

| Rating of hotspot phase future criticism disgust | −0.206 (df = 129) | 0.837 | −0.540 (df = 129) | 0.59 | −0.374 (df = 129) | 0.709 | 0.766 (df = 129) | 0.445 | 0.272 (df = 129) | 0.786 | 0.799 (df = 129) | 0.426 |

| Rating of hotspot phase future criticism fear | 0.464 (df = 129) | 0.644 | 0.414 (df = 129) | 0.679 | 0.808 (df = 129) | 0.42 | 1.449 (df = 129) | 0.15 | −0.209 (df = 129) | 0.835 | 0.039 (df = 129) | 0.969 |

| Rating of hotspot phase future criticism guilt | 0.726 (df = 129) | 0.469 | 0.217 (df = 129) | 0.829 | 0.337 (df = 129) | 0.737 | 1.437 (df = 129) | 0.153 | 0.108 (df = 129) | 0.914 | −0.025 (df = 129) | 0.98 |

| Rating of hotspot phase future criticism sadness | 0.734 (df = 129) | 0.465 | 0.688 (df = 129) | 0.493 | 0.810 (df = 129) | 0.419 | 1.493 (df = 129) | 0.138 | 1.116 (df = 129) | 0.266 | 1.373 (df = 129) | 0.172 |

| Rating of hotspot phase untreated criticism anger | −0.665 (df = 139) | 0.507 | −0.909 (df = 139) | 0.365 | −0.223 (df = 139) | 0.824 | −2.279 (df = 139) | 0.024 | −2.115 (df = 139) | 0.036 | −1.255 (df = 139) | 0.212 |

| Rating of hotspot phase untreated criticism arousal | 0.538 (df = 139) | 0.591 | −0.399 (df = 139) | 0.691 | 0.146 (df = 139) | 0.884 | −1.218 (df = 139) | 0.225 | −1.096 (df = 139) | 0.275 | −0.684 (df = 139) | 0.495 |

| Rating of hotspot phase untreated criticism disgust | −1.858 (df = 139) | 0.065 | −1.704 (df = 139) | 0.091 | −1.530 (df = 139) | 0.128 | −0.322 (df = 139) | 0.748 | 0.255 (df = 139) | 0.799 | 0.443 (df = 139) | 0.658 |

| Rating of hotspot phase untreated criticism fear | 0.300 (df = 139) | 0.765 | −0.619 (df = 139) | 0.537 | 0.066 (df = 139) | 0.948 | 0.533 (df = 139) | 0.595 | −0.837 (df = 139) | 0.404 | −0.473 (df = 139) | 0.637 |

| Rating of hotspot phase untreated criticism guilt | 0.177 (df = 139) | 0.86 | −0.704 (df = 139) | 0.482 | −0.370 (df = 139) | 0.712 | −0.115 (df = 139) | 0.909 | −0.889 (df = 139) | 0.375 | −0.724 (df = 139) | 0.471 |

| Rating of hotspot phase untreated criticism sadness | 0.357 (df = 139) | 0.722 | −0.492 (df = 139) | 0.623 | 0.171 (df = 139) | 0.865 | −0.015 (df = 139) | 0.988 | −0.390 (df = 139) | 0.697 | 0.413 (df = 139) | 0.68 |

| Beck depression inventory | 1.372 (df = 137) | 0.172 | 1.165 (df = 137) | 0.246 | 1.486 (df = 137) | 0.14 | 2.386 (df = 137) | 0.018 | 0.540 (df = 137) | 0.59 | 0.101 (df = 137) | 0.919 |

| Frost multidimensional perfectionism scale | −0.389 (df = 137) | 0.698 | −1.592 (df = 137) | 0.114 | −1.683 (df = 137) | 0.095 | −1.855 (df = 137) | 0.066 | −1.304 (df = 137) | 0.195 | −1.164 (df = 137) | 0.246 |

| Leibowitz social anxiety scale | −0.411 (df = 137) | 0.682 | −0.232 (df = 137) | 0.817 | 0.825 (df = 137) | 0.411 | −0.476 (df = 137) | 0.635 | −0.278 (df = 137) | 0.781 | 0.582 (df = 137) | 0.562 |

| Performance failure appraisal inventory (fear of failure scale) | 0.881 (df = 137) | 0.38 | 0.824 (df = 137) | 0.411 | 0.575 (df = 137) | 0.566 | 0.572 (df = 137) | 0.568 | 0.100 (df = 137) | 0.921 | 0.769 (df = 137) | 0.443 |

| Pure procrastination scale | 1.635 (df = 137) | 0.104 | −0.251 (df = 137) | 0.802 | −0.231 (df = 137) | 0.817 | 0.139 (df = 137) | 0.889 | −0.669 (df = 137) | 0.505 | −1.167 (df = 137) | 0.245 |

| PTSD DSM-V scale | −1.123 (df = 137) | 0.264 | −0.596 (df = 137) | 0.552 | ||||||||

| General anxiety disorder | 0.882 (df = 137) | 0.379 | −0.262 (df = 137) | 0.794 | ||||||||

| Panic disorder DSM-V scale | −0.468 (df = 137) | 0.641 | −0.222 (df = 137) | 0.825 | ||||||||

| Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale | 1.506 (df = 137) | 0.134 | −0.753 (df = 137) | 0.453 | ||||||||

ITT contrast analysis.

Secondary outcomes (ITT analysis)