Abstract

Language comprehension is essential to communication, yet understanding varies between literal meaning and verbal irony. While children grasp words' surface meanings, interpreting verbal irony requires them to consider context and infer the speaker's true intent, revealing a deeper layer of meaning. What factors contribute to this complex skill? The current study examined the impact of sex, narrative skills, executive functions (working memory and inhibitory control), theory of mind and emotion comprehension, while controlling for age, on understanding of literal statements and verbal irony in 267 typically developing 4–9-year old children (130 boys). To assess children's irony comprehension, we presented them with cartoon scenarios and asked to choose an emoji to indicate whether a parent's reaction was literal or ironic. A full-null model approach was used to examine the impact of children's cognitive, executive, emotional, and narrative skills on their irony understanding, where the full contained our factors of interest and the null contained only age and sex. The results indicated that age was the only factor related to literal meaning comprehension. In contrast, both age and working memory were significantly related to irony understanding. These findings can be used as a foundation for developing training to enhance non-literal language and pragmatic skills in children.

Introduction

Language comprehension is a fundamental prerequisite for effective social interaction and communication. A particularly important aspect of language comprehension is the ability to grasp non-literal meaning, especially irony. Irony is defined as “the expression of one's meaning by using language that normally signifies the opposite, typically for humorous or emphatic effect” (OED: Oxford English Dictionary, 2025). Ironic statements, or verbal irony, are part of the broader construct of semantic and pragmatic skills. Irony (or verbal irony) involves a second-order meta-representation, meaning that in order to grasp it, the listener must (a) comprehend the utterance and (b) recognize the speaker's dismissive or distancing attitude toward the attributed thought (Köder and Falkum, 2021).

The question of when children begin to understand irony remains a matter of active research and debate. While some studies have found indications of irony understanding as early as ages 3–4 (Loukusa and Leinonen, 2008; Recchia et al., 2010), most research suggests that irony understanding typically emerges at ages 4–5, requiring additional cognitive effort and longer processing time compared to non-ironic utterances (Banasik-Jemielniak and Bokus, 2019). Massaro et al. (2013) conclude that 5-year-olds demonstrate a clear understanding of ironic intent. However, other researchers remain skeptical, showing that even 8-year-olds may struggle with the intended meaning of ironic statements (Nicholson et al., 2013). Some scholars argue for an even later developmental onset, pointing out that even 13-year-olds may not fully grasp implicatures (Demorest et al., 1984). Although the study of irony comprehension in children spans more than 40 years (Fuchs, 2023), the precise roles played by executive functions, Theory of Mind, and linguistic skills remain an open question (Fuchs, 2023). Given the lack of consensus on the developmental trajectory of irony comprehension, the present study aimed to address this question in Russian children aged 4–9.

Additionally, there is a lack of research examining to what extent are the comprehension processes for literal and non-literal (in particular, ironic) utterances similar or different in terms of the psychological characteristics of typically developing children that support them.

Among the most frequently discussed cognitive skills associated with children's processing of literal and non-literal meanings are executive functions, theory of mind, emotion comprehension, and narrative skills. The following sections outline the role of each factor in comprehension of literal and non-literal utterances.

Factors contributing to comprehension of literal utterances in children

According to Fuchs (2023), key contributors to irony understanding in children include executive functions, theory of mind, emotional comprehension, and linguistic skills. It is unclear, however, whether the same factors are involved in understanding literal utterances.

Executive functions (EF) are mental processes that regulate many aspects of cognition and behavior (Miyake et al., 2000). One widely accepted framework for describing executive functions is that of Miyake et al. (2000), which identifies its key components such as cognitive flexibility, inhibitory control, and working memory (both visual and auditory). The role of executive functions in language comprehension can be understood as part of their overall contribution to language processing (Shokrkon and Nicoladis, 2022), supporting language comprehension (Ye and Zhou, 2009), with specific roles of working memory (Gathercole and Baddeley, 2014) and cognitive flexibility (Filipe et al., 2023).

The Theory of Mind (ToM) is understood as “the ability of an individual to make inferences about what others may be thinking or feeling and to predict what they may do in a given situation based on those inferences” (Schlinger, 2009, p. 435). It is related to language comprehension (Antonietti et al., 2006; Zufferey, 2010). Nevertheless, the impact of theory of mind on utterances comprehension, with the factor of age controlled for, has not yet been investigated.

Emotion comprehension (EC), following the approach of Pons and Harris, is defined as the ability to understand “the nature, causes, and consequences of the emotional experience in the self and others” (Pons and Harris, 2019, p. 431). Children's development of EC progresses through several stages (Pons and Harris, 2004, 2005): “External” level (ages 3–5), “Mental” level (ages 4–7), and “Reflective” level (ages 6–10). While the connection between children's EC (and emotional development in general) and language comprehension is well-documented (Beck et al., 2012; Conte et al., 2019), the specific contribution of EC to utterances comprehension has yet to be demonstrated.

Narrative skills are children's ability to construct coherent and cohesive stories based on a sequence of episodes. The narratives can be evaluated in terms of their macrostructure (overall organization and logical liens), microstructure (language specific correctness), and the use of internal state terms (lexical units denoting feelings, emotions, perception and other internal states) (Gagarina et al., 2012). While both narrative skills and utterance comprehension are components of language competence, however, it remains unclear which aspect of narrative skills—macrostructure, microstructure, or the use of internal state terms—contributes to utterance comprehension, and whether such a relationship exists at all.

Therefore, while separate pieces of evidence support a relationship between utterance comprehension and other cognitive domains (namely, executive functions, emotion comprehension, theory of mind, and narrative skills), the unique contribution of these domains to comprehension, after accounting for age, has not been investigated.

Factors contributing to comprehension of non-literal utterances, in particular irony, in children

In this section we examine how the aforementioned cognitive abilities contribute to comprehension of non-literal (ironic) utterances.

In the domain of EF, inhibitory control has been found to play a significant role in irony comprehension (Caillies et al., 2014). As for the working memory, research with adults suggests that fluid intelligence, rather than working memory, modulates irony processing (Kyriacou and Köder, 2024). By contrast, Antoniou and Milaki (2021) showed that in bidialectal speakers, working memory substantially facilitates faster irony comprehension. Further studies with adults have likewise reported significant correlations between verbal working memory and the understanding of irony and sarcasm (Godbee and Porter, 2013). Yet, no study examined the role of executive functions on comprehension of ironic utterances in children with the factor of age controlled for.

Turning to the Theory of Mind (ToM), findings indicate that ToM significantly supports irony understanding in autistic children (Song et al., 2024), whereas no such effect has been observed in 5–8 year-old typically developing children (Szücs and Babarczy, 2017).

Evidence regarding the role of emotion understanding in comprehension of non-literal utterances remains mixed. Bajerski (2016), for example, found that in adults, emotional intelligence was negatively associated with irony understanding across several dimensions. In contrast, Nicholson et al. (2013) reported that for 8–9-year-old children, EC makes a substantial contribution to irony understanding.

Thus, although the general theoretical framework (Pexman, 2023) assumes that understanding irony requires linguistic knowledge, working memory, and cognitive flexibility, empirical research specifically on children aged 4–9 remains insufficient.

Another point of debate concerns the relative importance of contextual information vs. vocal intonation in children's irony understanding (Fuchs, 2023). Although considerable evidence advocates for the role of intonation as a key factor (Köder and Falkum, 2021), the issue is not yet settled (Fuchs, 2023). Regarding the comprehension of intonation, research indicates that working memory is a significant predictor of its development (Kuang et al., 2024; Stepanov et al., 2020).

Research relevance and aim

Thus, the impact of EF, EC, ToM, and narrative skills on the comprehension of both literal and ironic utterances in children remains understudied. This research question is highly relevant not only for designing intervention programs for children with ASD and communication disorders but also for supporting the development of social-communicative skills in typically developing children. The aim of the present study is to assess and compare the contributions of EF, EC, ToM, and narrative skills to the comprehension of literal and ironic utterances, as key aspects of pragmatic competence, in children aged 4 to 9 years.

Methods and sample

Sample

The sample consisted of 267 monolingual Russian children aged 4 to 9 years (M = 82 months; SD = 17), of whom 130 were boys. Of these, 109 children attended senior or preparatory preschool groups (ages 51–74 months), while 158 were in the first or second grades of primary school (ages 81–111 months). All children came from families of middle socio-economic status. Children were tested in two sessions. Children who did not complete both testing sessions, as well as those whose parents did not provide written informed consent, were excluded from the study.

Instruments

To assess children's comprehension of ironic and non-ironic utterances we used the tasks developed by Köder and Falkum (2021). The original tasks were used with Norwegian children aged 2 to 8 years, as well with adults. The tasks were translated and adapted for Russian-speaking children. These are 12 illustrated stories in which parents ask their children to perform or not certain actions (e.g., washing hands before eating, playing with a sibling, not soiling the floor). The children either comply with or ignore the request. Then, the parents provide feedback: either in a literal praise (e.g., “Good job, well done!”) or literal criticism (e.g., “That was very bad”). In three out of the 12 scenarios, the child fails to comply with the parent's request, and the parent uses ironic praise “Good job!”, implying criticism. The participants are instructed to choose either a “happy” or a “sad” smile to report the real meaning of a parent's feedback. Each correct answer earns the child one point, so a total score can range between 0 and 9 for the understanding of literal statements, and 0 and 3 for the irony-specific scenarios.

To assess EC, we used the TEC (Test of Emotion Comprehension) (Pons and Harris, 2004). TEC is a tool that allows to capture child emotion understanding and measures its nine components: (1) emotion recognition, (2) external cause, (3) desire, (4) belief, (5) reminder, (6) regulation, (7) hidden, (8) mixed, and (9) morally-based emotions. The test consists of 22 tasks. An accurate answer receives 1 point, and a wrong answer receives a zero. The total raw score is the sum of points for all 22 tasks, ranging from 0 to 22 points. The reliability of this instrument in Russian-speaking children has been demonstrated previously (Bukhalenkova et al., 2024).

To assess EF, the NEPSY-II assessment battery was used (Korkman et al., 2007). The NEPSY battery was used because, on the one hand, it allows for the assessment of the relevant cognitive skills in children aged 3 to 16.11 (Davis and Matthews, 2010), and on the other hand, it has been adapted and validated for Russian-speaking children (Almazova et al., 2019). Research has also shown that this battery is suitable for children as young as 4 years (Veraksa et al., 2023). Using this instrument, the following components were assessed in children: inhibitory control and working memory (both visual and auditory). To assess inhibitory control, the Inhibition subtest (NEPSY-II) was used. Tasks performance correctness and time were assessed. Working memory was assessed through Sentence repetition (auditory working memory, maximum score-−34) and Memory for designs (visual working memory, maximum score-−120). The test had been translated into Russian, adapted for use with Russian-speaking children aged 5 to 8 years and showed high reliability (Veraksa et al., 2020).

To assess narrative skills, we used pictures from the MAIN (Multilingual assessment instrument for narratives) (Gagarina et al., 2012). The child was shown a sequence of six pictures bound into a booklet with three episodes. After examining the pictures, the child was instructed to tell what has happened there so it becomes a real story. Children's narratives were evaluated on the narrative's macrostructure: coherence with the narrative structure and the adequacy of the story (scored 2–20 points); and on the narrative's microstructure: lexical and grammatical quality of the narrative (scored 2–20 points) and the number of Internal State Terms (IST). Each IST earned the child one point, with no upper limit.

Theory of Mind (ToM) was assessed using a subtest of NEPSY-II, that included 21 emotion, social, false belief and second-order false belief tasks. The maximum score for the test was 28 points (several tasks give 2 or 3 points, all the other give 1 point). The test includes tasks on emotion recognition, false-belief tasks and tasks on metaphor comprehension.

Procedure

The assessment was conducted by trained testers, individually with each child, in a quiet and bright room of the children's kindergarten. Two sessions were organized with each child, lasting 15–20 min each. Children were free to stop the test at any time. All methods were presented to the children in the same established order: at the first session, children performed the narratives, the TEC, and the Memory for Designs subtest; at the second session, they performed the Inhibition and the Sentence repetition subtests and the tasks for understanding of ironic and literal utterances. Prior to the study, the testers completed specialized training sessions on the administration and scoring procedures of the specified methods.

All the parents were informed about the study goals and gave written consent for their children's participation in the research. The study was carried out in those educational institutions with which cooperation agreements were concluded, and parental consent was collected with the help of the educators working in the groups attended by the children.

Statistical analysis

We conducted all analyses using R (R Core Team, 2020). To examine the role of EF, EC, ToM, and narrative skills in children's comprehension of ironic and literal utterances, we used a full–null model comparison approach (a statistical method to compare two models to see if your main predictor variable is meaningfully improving the model's ability to explain the data), which minimizes type I errors by addressing the problem of multiple testing (Forstmeier and Schielzeth, 2011). For both literal and ironic utterances, we compared a model that included our predictors of interest with a respective null model that did not, using likelihood ratio tests. The null models contained only age and sex. The full models included, in addition, EF (visual working memory, auditory working memory, inhibitory control), EC (total score), ToM (total score), and narrative skills (macrostructure, microstructure, and use of internal state terms). The dependent variable was accuracy (1 = correct, 0 = incorrect) for each of the 9 non-ironic and 3 ironic scenarios per child. If the full–null comparison was significant, fixed effects were derived using the Anova function from the car package (Fox and Weisberg, 2018). p-values were obtained via the lmerTest package using Satterthwaite's approximation (Kuznetsova et al., 2017). Age was z-transformed.

Results

Role of executive functions, emotion understanding, and narrative skills on literal utterances understanding

The null model examining the impact of age and sex on accuracy of non-ironic statement understanding revealed a significant positive effect of age [β = 1.66, OR = 1.66, 95% CI [1.24, 2.22], p = 0.001]. Sex was not significant (OR = 1.48, p = 0.166).

The full-null model comparison showed that the full model did not provide a significantly better fit to the data than the simpler age-and-sex model, i.e., the null [χ2(8) = 11.74, p = 0.163]. The Marginal R2 and Conditional R2 were 0.034 and 0.594, respectively, indicating that once age is accounted for, the individual differences in cognitive and language skills do not add in predicting variance in children's comprehension of literal language (see Table 1).

Table 1

| Predictors | Accuracy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratios | CI | p | |

| (Intercept) | 184.43 | 14.44–2355.92 | < 0.001 |

| z age | 1.44 | 0.96–2.15 | 0.079 |

| Sex [2] | 1.45 | 0.81–2.61 | 0.212 |

| Visual working memory | 0.99 | 0.97–1.00 | 0.097 |

| TEC | 1.21 | 0.98–1.48 | 0.073 |

| ToM | 1.04 | 0.94–1.15 | 0.436 |

| Narratives (macro) | 0.92 | 0.82–1.03 | 0.163 |

| Narratives (micro) | 0.97 | 0.84–1.12 | 0.686 |

| Inhib control | 0.98 | 0.93–1.02 | 0.278 |

| IST | 1.08 | 0.93–1.25 | 0.337 |

| Auditory working memory | 1.05 | 0.96–1.15 | 0.284 |

| Random effects | |||

| σ2 | 3.29 | ||

| τ00ID | 0.46 | ||

| τ00irony_item | 4.13 | ||

| ICC | 0.58 | ||

| N ID | 266 | ||

| Nirony_item | 9 | ||

| Observations | 2,394 | ||

| Marginal R2/conditional R2 | 0.063/0.609 | ||

Regression model of literal utterances understanding.

Role of executive functions, emotion understanding, and narrative skills on ironic utterances comprehension

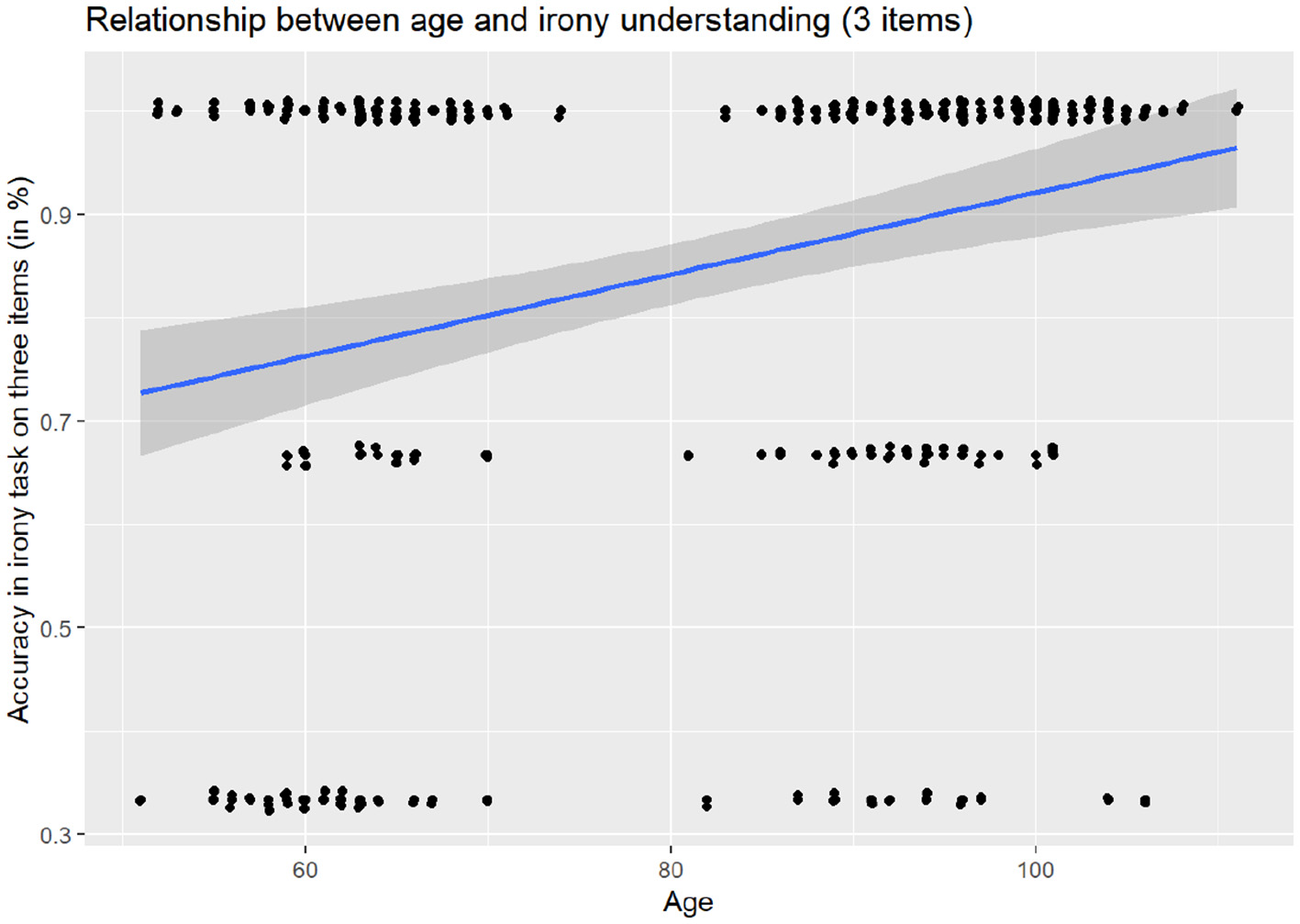

For the three irony-specific items, the null model showed a strong and significant effect of age [β = 4.52, OR = 4.52, 95% CI [2.03, 10.07], p < 0.001], see Figure 1. Sex was again non-significant (OR = 1.51, p = 0.477).

Figure 1

Relationship between accuracy in irony task understanding and age.

A full-null model comparison was marginally significant [χ2(9) = 16.69, p = 0.054], indicating that including the target factors showed an improvement in the fit over the age-only model.

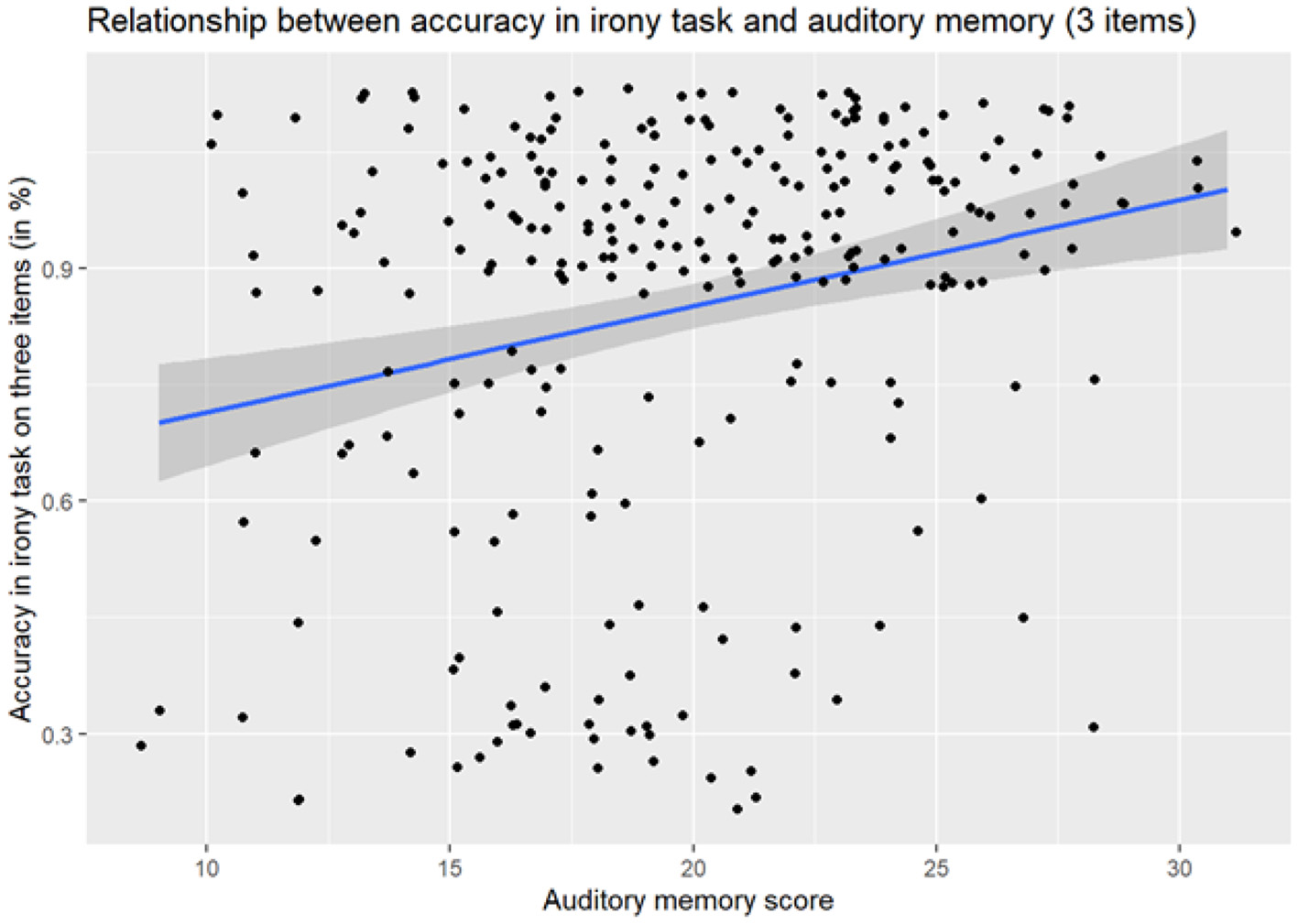

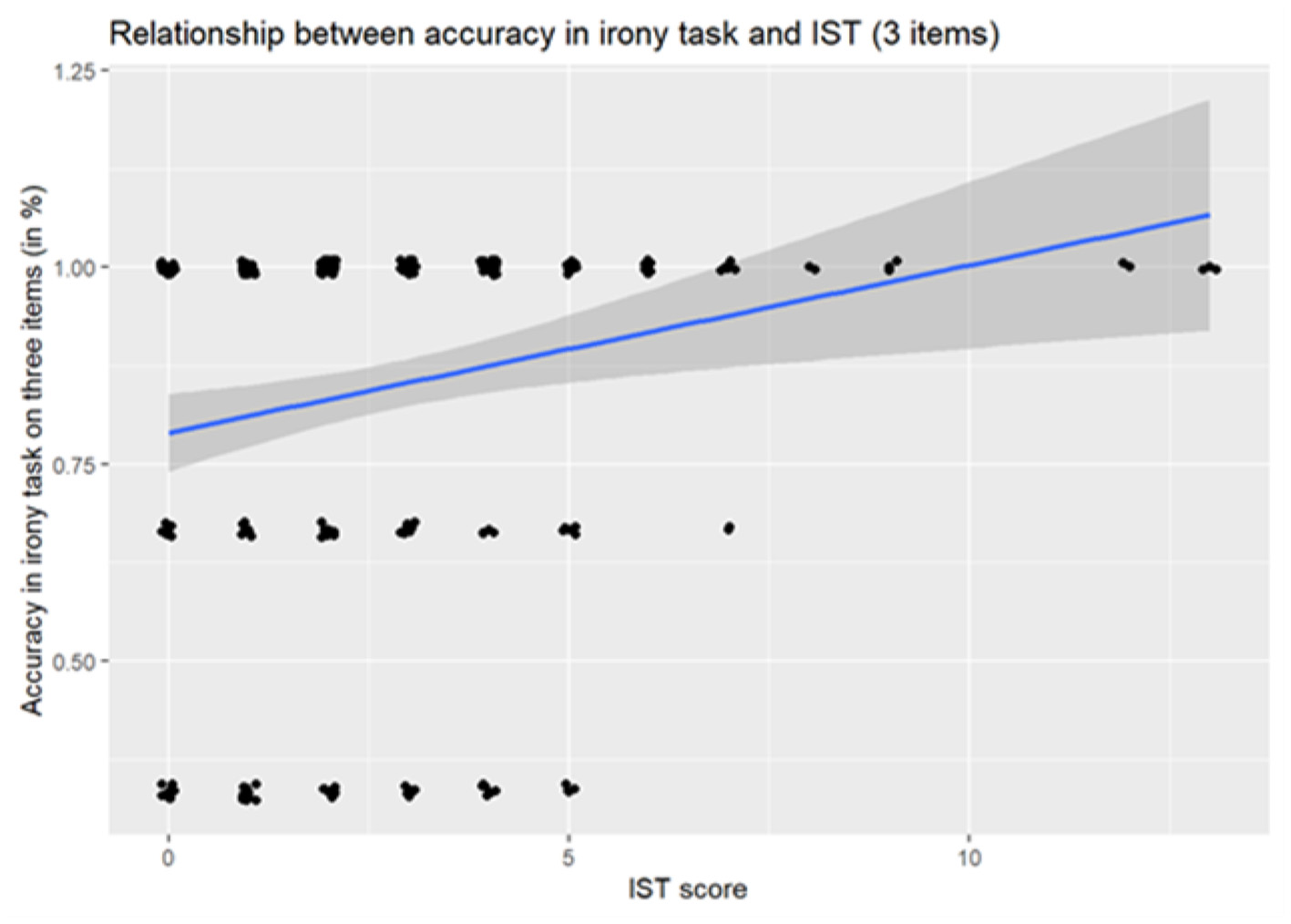

A subsequent reduced model (after removing non-significant factors of p > 0.1 from the full model) revealed that the accuracy on ironic items was significantly predicted by: Age [OR = 2.24, 95% CI [1.02, 4.91], p = 0.044], internal state terms in narratives [OR = 1.38, 95% CI [1.01, 1.88], p = 0.041] and Auditory Working Memory [OR = 1.19, 95% CI [1.02, 1.40], p = 0.032] (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Relationship between accuracy in irony task understanding and verbal working memory.

A visual inspection of the IST scores indicated that the effect of IST in narratives was driven by a small number of high-performing outliers (n = 9), see Figure 3. When these participants were removed, the effect of IST was no longer significant (OR = 1.28, p = 0.149). However, the effect of auditory working memory remained significant [OR = 1.20, 95% CI [1.02, 1.41], p = 0.029] alongside the effect of age.

Figure 3

Relationship between accuracy in irony task understanding and usage of internal state terms in narration.

Discussion

The first of our two main research aims was to examine whether, factors such as EF, EC, ToM, and narrative skills contribute to the comprehension of literal utterances in typically developing 4–9-year-old children, when controlling for age. In a sample of 267 children, we found that when age is included in the analyses, none of these skills was related to literal comprehension. Thus, contrary to expectations based on previous research, neither EF, nor EC, nor ToM, nor even narrative skills contributed significantly to literal comprehension. This effect may be due to the fact that, in our study, a ceiling in the comprehension of literal utterances was reached quite early: by the age of five, almost all children were already giving correct answers to all tasks. Therefore, more complex situations may be needed to obtain similar results.

The second aim was to investigate whether, the same factors contribute to the comprehension of ironic utterances in 4–9-year-old, when controlling for age. In the same sample, we found that, in addition to age, only EF—specifically auditory working memory—made a stable contribution to variance in irony comprehension. This finding aligns with Baddeley's working memory theory (Baddeley, 2017), according to which irony comprehension can be explained as the construction of a mental (situational) model. The child's working memory holds key elements (subjects, actions, objects) and integrates them with each other. This allows the child to analyze the situation depicted and the parent's words, and on this basis to infer whether the utterance is literal or ironic. Children with higher auditory working memory capacity demonstrated stronger irony comprehension skills, suggesting that irony understanding might depend on children's ability to retain in working memory both the conversational context and the preceding utterance to which the ironic remark refers.

Verbal working memory has repeatedly been shown to contribute to the processing of intonational contours. Intonation, together with context, plays a central role in irony comprehension (Köder and Falkum, 2021). Thus, based on our findings, one may argue that intonation contributed most strongly in the present study, since if situational interpretation (depicted in the picture) had played a larger role, one would expect a greater contribution of visual working memory.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated a clear distinction in the contributions of cognitive and language skills to the comprehension of literal vs. ironic utterances in typically developing children. Specifically, while only age significantly predicted comprehension of literal utterances, both age and verbal working memory significantly predicted irony understanding. These findings may contribute to the development of educational and intervention programs aimed at enhancing children's understanding of non-literal meaning, thereby improving their working memory and executive functions in general.

A key limitation of our study is that, following Köder and Falkum's paradigm, we presented children with only 3 ironic utterances out of 12. As a result, the possible score range for irony comprehension was restricted (0–3), limiting variability. Regarding literal utterances, the task was too simple for the children, leading to a ceiling effect, which may also have constrained our findings. Future research needs to develop material that has more items to test irony comprehension (and across more situational contexts) that might potentially capture infants' variability in the task better.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The study and consent procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Faculty of Psychology at Lomonosov Moscow State University (the approval no: 2024/32). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

EO: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NK: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The research was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (number 24-18-00437).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Almazova O. V. Bukhalenkova D. A. Veraksa A. N. (2019). Assessment of the level of development of executive functions in the senior preschool age. Psychol. J. High. Sch. Econ.16, 94–109. doi: 10.17323/1813-8918-2019-2-302-317

2

Antonietti A. Sempio O. L. Marchetti A. (eds.). (2006). Theory of Mind and Language in Developmental Contexts. Springer Science and Business Media. doi: 10.1007/b106493

3

Antoniou K. Milaki E. (2021). Irony comprehension in bidialectal speakers. Modern Lang. J.105, 697–719. doi: 10.1111/modl.12724

4

Baddeley A. (2017). Exploring Working Memory: Selected Works of Alan Baddeley.London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315111261

5

Bajerski M. (2016). “I Understand You, So I'll Not Hurt You with My Irony”: correlations between irony and emotional intelligence. Psychol. Lang. Commun.20:235. doi: 10.1515/plc-2016-0015

6

Banasik-Jemielniak N. Bokus B. (2019). Children's comprehension of irony: studies on Polish-speaking preschoolers. J. Psycholinguist. Res.48, 1217–1240. doi: 10.1007/s10936-019-09654-x

7

Beck L. Kumschick I. R. Eid M. Klann-Delius G. (2012). Relationship between language competence and emotional competence in middle childhood. Emotion12, 503–514. doi: 10.1037/a0026320

8

Bukhalenkova D. Veraksa A. Guseva U. Oshchepkova E. (2024). The relationship between vocabulary size and emotion understanding in children aged 5–7 years. Lomonosov Psychol. J.47, 150–176. doi: 10.11621/LPJ-24-44

9

Caillies S. Bertot V. Motte J. Raynaud C. Abely M. (2014). Social cognition in ADHD: irony understanding and recursive theory of mind. Res. Dev. Disabil.35, 3191–3198. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.08.002

10

Conte E. Ornaghi V. Grazzani I. Pepe A. Cavioni V. (2019). Emotion knowledge, theory of mind, and language in young children: testing a comprehensive conceptual model. Front. Psychol.10:2144. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02144

11

Davis J. L. Matthews R. N. (2010). NEPSY-II review: Korkman, M., Kirk, U., and Kemp, S. (2007). NEPSY—Second Edition (NEPSY-II). San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment. J. Psychoeduc. Assess.28, 175–182. doi: 10.1177/0734282909346716

12

Demorest A. Meyer C. Phelps E. Gardner H. Winner E. (1984). Words speak louder than actions: understanding deliberately false remarks. Child Dev.55, 1527–1534. doi: 10.2307/1130022

13

Filipe M. G. Veloso A. S. Frota S. (2023). Executive functions and language skills in preschool children: the unique contribution of verbal working memory and cognitive flexibility. Brain Sci.13:470. doi: 10.3390/brainsci13030470

14

Forstmeier W. Schielzeth H. (2011). Cryptic multiple hypotheses testing in linear models: overestimated effect sizes and the winner's curse. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol.65, 47–55. doi: 10.1007/s00265-010-1038-5

15

Fox J. Weisberg S. (2018). An R Companion to Applied Regression.Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. doi: 10.32614/CRAN.package.carData

16

Fuchs J. (2023). 40 years of research into children's irony comprehension: a review. Pragmat. Cogn.30, 1–30. doi: 10.1075/pc.22015.fuc

17

Gagarina N. V. Klop D. Kunnari S. Tantele K. Välimaa T. Balčiuniene I. et al . (2012). MAIN: multilingual assessment instrument for narratives. ZAS Papers Linguist.56:155. doi: 10.21248/zaspil.56.2019.414

18

Gathercole S. E. Baddeley A. D. (2014). Working Memory and Language.London: Psychology Press. doi: 10.4324/9781315804682

19

Godbee K. Porter M. (2013). Comprehension of sarcasm, metaphor and simile in Williams syndrome. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord.48, 651–665. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12037

20

Köder F. Falkum I. L. (2021). Irony and perspective-taking in children: the roles of norm violations and tone of voice. Front. Psychol.12:624604. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.624604

21

Korkman M. Kirk U. Kemp S. L. (2007). NEPSY II. Administrative Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

22

Kuang C. Chen X. Chen F. (2024). Recognition of emotional prosody in mandarin-speaking children: effects of age, noise, and working memory. J. Psycholinguist. Res.53:68. doi: 10.1007/s10936-024-10108-2

23

Kuznetsova A. Brockhoff P. B. Christensen R. H. (2017). lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw.82, 1–26. doi: 10.18637/jss.v082.i13

24

Kyriacou M. Köder F. (2024). The cognitive underpinnings of irony comprehension: Fluid intelligence but not working memory modulates processing. Appl. Psycholinguist.45, 1219–1250. doi: 10.1017/S0142716424000444

25

Loukusa S. Leinonen E. (2008). Development of comprehension of ironic utterances in 3-to 9-year-old Finnish-speaking children. Psychol. Lang. Commun.12, 55–69. doi: 10.2478/v10057-008-0003-0

26

Massaro D. Valle A. Marchetti A. (2013). Irony and second-order false belief in children: what changes when mothers rather than siblings speak?. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol.10, 301–317. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2012.672272

27

Miyake A. Friedman N. P. Emerson M. J. Witzki A. H. Howerter A. Wager T. D. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychol.41, 49–100. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1999.0734

28

Nicholson A. Whalen J. M. Pexman P. M. (2013). Children's processing of emotion in ironic language. Front. Psychol.4:691. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00691

29

OED: Oxford English Dictionary (2025). Available online at: https://www.oed.com/dictionary/irony_n?tab=meaning_and_use#64966 (Accessed October 02, 2025).

30

Pexman P. M. (2023). “Irony and thought: developmental insights,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Irony and Thought, eds. R. W. Gibbs Jr., and H. L. Colston (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 181–196. doi: 10.1017/9781108974004.015

31

Pons F. Harris P. L. (2004). TEC: Test of Emotion Comprehension.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

32

Pons F. Harris P. L. (2005). Longitudinal change and longitudinal stability of individual differences in children's emotion understanding. Cognit. Emot.19, 1158–1174. doi: 10.1080/02699930500282108

33

Pons F. Harris P. L. (2019). “Children's understanding of emotions or Pascal's “error”: review and prospects,” in Handbook of Emotional Development, eds. V. LoBue, K. Perez-Edgar, and K. A. Buss (Berlin: Springer), 431–449. doi,: 10.1007/978-3-030-17332-6_17

34

R Core Team (2020). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna. Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/ (Accessed October 02, 2025).

35

Recchia H. E. Howe N. Ross H. S. Alexander S. (2010). Children's understanding and production of verbal irony in family conversations. Br. J. Dev. Psychol.28, 255–274. doi: 10.1348/026151008X401903

36

Schlinger H. D. (2009). Theory of mind: an overview and behavioral perspective. Psychol. Rec.59, 435–448. doi: 10.1007/BF03395673

37

Shokrkon A. Nicoladis E. (2022). The directionality of the relationship between executive functions and language skills: a literature review. Front. Psychol., 13:848696. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.848696

38

Song Y. Nie Z. Shan J. (2024). Comprehension of irony in autistic children: the role of theory of mind and executive function. Autism Res.17, 109–124. doi: 10.1002/aur.3051

39

Stepanov A. Kodrič K. B. Stateva P. (2020). The role of working memory in children's ability for prosodic discrimination. PLoS ONE15:e0229857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229857

40

Szücs M. Babarczy A. (2017). The role of Theory of Mind, grammatical competence and metapragmatic awareness in irony comprehension. Pragmat. Interfaces17, 129–147. doi: 10.1515/9781501505089-008

41

Veraksa A. N. Almazova O. V. Bukhalenkova D. A. (2020). Executive functions assessment in senior preschool age: a battery of methods [in Russian]. Psychol. J.41, 108–118. doi: 10.31857/S020595920012593-8

42

Veraksa A. N. Gavrilova M. N. Karimova A. I. Solopova O. V. Yakushina A.A. (2023). Regularly functions in preschoolers aged 4–7: the impact of kindergarten attendance span. Lomonosov Psychol. J.46, 64–87. doi: 10.11621/LPJ-23-39

43

Ye Z. Zhou X. (2009). Executive control in language processing. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.33, 1168–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.03.003

44

Zufferey S. (2010). Lexical Pragmatics and Theory of Mind: the Acquisition of Connectives. John Benjamins B.V. doi: 10.1075/pbns.201

Summary

Keywords

executive functions, irony, irony understanding, pragmatic development, preschool age, test of emotion comprehension

Citation

Oshchepkova E, Kartushina N and Kovyazina M (2025) Understanding of ironic and literal utterances in 4–9-year-old typically developing children: role of age, narrative skills, emotion comprehension and executive functions. Front. Psychol. 16:1718227. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1718227

Received

03 October 2025

Accepted

02 December 2025

Published

17 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Ilaria Grazzani, University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy

Reviewed by

Micaela Guardiano, São João University Hospital Center, Portugal

Carmen Belacchi, University of Urbino Carlo Bo, Italy

Maria Antonietta Pinto, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Oshchepkova, Kartushina and Kovyazina.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ekaterina Oshchepkova, maposte06@yandex.ru

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.