Abstract

Introduction:

Antenatal classes have increasingly been integrated into healthcare practices in most middle- and high-income countries over recent decades. The aim of the present study was to compare levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms during pregnancy and the postpartum period among (a) women who attended antenatal classes and (b) women who did not participate in antenatal education.

Methods:

We analyzed 9,689 perinatal respondents recruited in eight Italian regions between October 2021 and December 2024. Each participant was assessed once, during their pregnancy (n = 4,169) or their postpartum period (n = 5,520), and completed the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) and Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) scales. The cut-off scores to identify women at risk for depression and anxiety were ≥12 and ≥10 for EPDS and GAD-7, respectively. Propensity scores based on socio-demographic and clinical covariates were estimated with multiple imputations and inverse-probability-of-treatment weighting (IPTW).

Results:

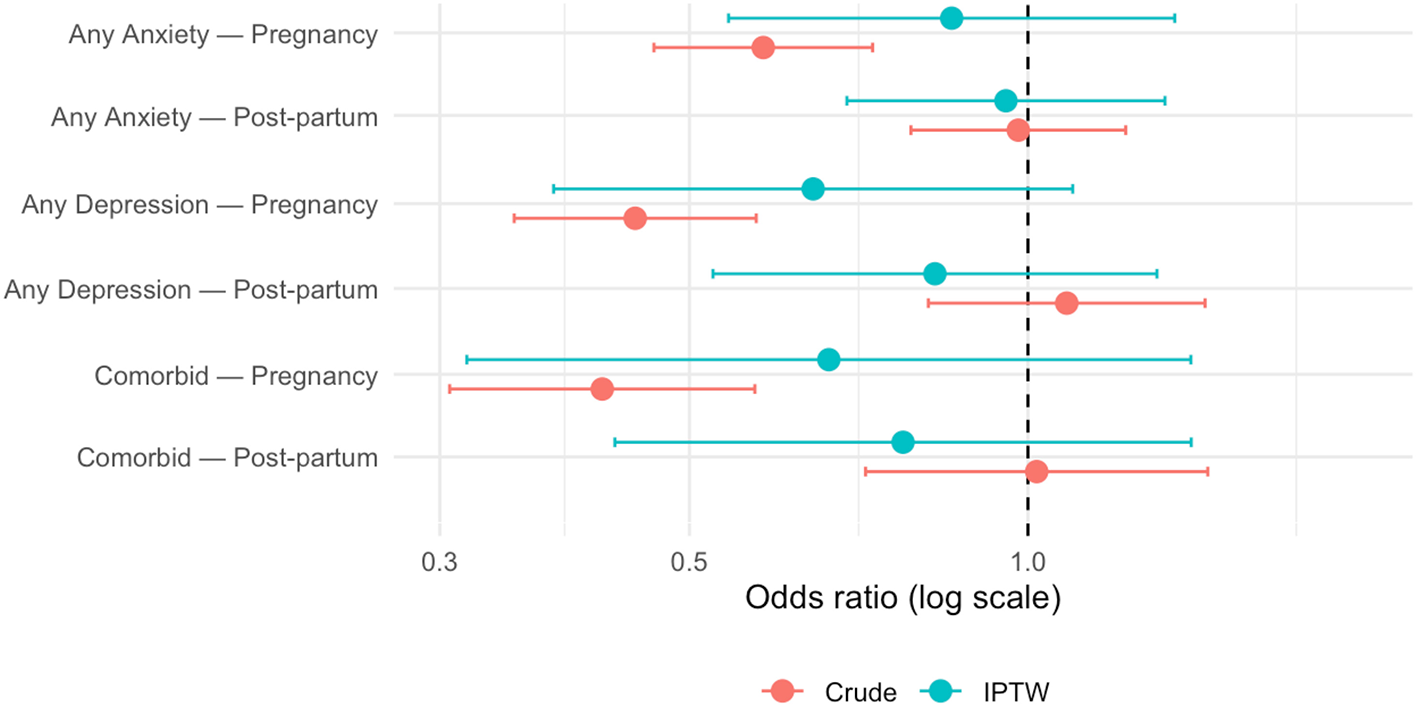

Attendance was frequent (47%). Crude models showed that, during pregnancy, class participants had lower mean scores (ΔGAD = −0.8; ΔEPDS = −1.0) and markedly lower odds of screening positive (OR = 0.58 for anxiety; 0.45 for depression). After IPTW adjustment these associations weakened and became non-significant (pregnancy OR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.54–1.35 for anxiety; 0.64, 0.38–1.10 for depression); all post-partum IPTW estimates were similarly null (ORs 0.96 and 0.83, CIs span 1). E-values (1.9–2.5) indicated that moderate unmeasured confounding could erase the residual pregnancy effects.

Conclusions:

Our results suggest antenatal education classes are modestly effective in reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms during pregnancy. However, these modest prenatal improvements attenuate after adjustment and do not persist into the postpartum period. This indicates a need for standardized, evidence-based antenatal education that is integrated into broader psychosocial support frameworks.

Introduction

Pregnancy and childbirth are characterized by complex hormonal, physical, emotional, and psychological changes in women's lives (Jee and Sawal, 2024; Olza et al., 2018). During pregnancy, expectant mothers often experience anxiety, uncertainty, and fear regarding pregnancy, labor, delivery, and their ability to care for a newborn (Sheen and Slade, 2018; Wilska et al., 2021). Therefore, it is unsurprising that nearly one in four pregnant women experiences symptoms or disorders related to anxiety (Fawcett et al., 2019) or depression (Yin et al., 2021). These conditions frequently co-occur (Ou et al., 2025; Shen et al., 2024) and often increase in prevalence during the postpartum period (Astbury et al., 2025). Antenatal anxiety and mood disorders have been associated with adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes (Runkle et al., 2023), maternal mortality, suicide, self-harm (Howard and Khalifeh, 2020), problematic mother-infant bonding (O'Dea et al., 2023), and psychiatric symptoms in offspring (Chen et al., 2024). Collectively, these findings underscore the importance of early screening and assessment (Weingarten and Osborne, 2024), as well as preventive interventions (Motrico et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2025).

Regarding preventive nonclinical interventions, antenatal education (also known as antenatal classes, expectant parent classes, antenatal parenthood education, prenatal classes, childbirth preparation, or childbirth classes) has increasingly been integrated into healthcare practices in most middle- and high-income countries over recent decades (Downer et al., 2020). The WHO (2018) recommends several context-specific interventions, including (i) childbirth education workshops, covering topics such as childbirth-related fear and pain, pharmacological pain-relief options and their effects, nonpharmacological pain-management strategies, benefits and risks of cesarean vs. vaginal delivery, and indications and contraindications for cesarean sections; (ii) nurse-led applied relaxation programs, including group discussions about pregnancy-related anxiety and stress, the rationale for applied relaxation, and training in deep-breathing and other relaxation techniques; (iii) psychosocial couple-based prevention programs, focusing on emotional self-regulation, conflict resolution, problem-solving, communication skills, and mutual support strategies to promote positive co-parenting; and (iv) psychoeducation sessions led by therapists and midwives that provide information about fear and anxiety, pain and childbirth fears, normalization of individual responses, stages of labor, hospital procedures, the birth process, and pain-relief options.

Although antenatal education programs vary nationally and internationally in content and delivery methods, they typically serve the dual purpose of familiarizing women and their partners with essential aspects of pregnancy and childbirth and preparing them for newborn care [National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2021; WHO, 2016]. The importance of antenatal education in enhancing understanding and supporting women's transition and adaptation to motherhood has also been highlighted in a recent umbrella review and framework (Matvienko-Sikar et al., 2025). Additionally, the need for standardization of these educational programs, while allowing room for personalization to avoid scenarios lacking evidence-based recommendations, has been emphasized (AlKhunaizi et al., 2025; Ferri et al., 2024).

Regarding the effectiveness of antenatal education, meta-analytic findings demonstrate that these programs improve childbirth self-efficacy (Demirci et al., 2023; Zaman et al., 2025; Zanetti et al., 2024), decrease fear of childbirth (Alizadeh-Dibazari et al., 2023; Zaman et al., 2025), reduce rates of planned cesarean sections (Hooper et al., 2025; Zaman et al., 2025; Zanetti et al., 2024), and decrease pain intensity during labor (Alizadeh-Dibazari et al., 2023). Regarding mental health outcomes, particularly anxiety and depression, insufficient evidence exists due to the small number of studies, high heterogeneity in interventions and outcomes, and elevated risk of bias (Alizadeh-Dibazari et al., 2023; Brixval et al., 2015; Hong et al., 2021). Nevertheless, recent non-meta-analytic reviews suggest antenatal education effectively reduces anxiety levels during pregnancy, especially in primigravidas (Athinaidou et al., 2024; Rahmawati et al., 2025). Evidence from psychoeducational prenatal classes indicates reductions in anxiety and improvements in self-efficacy, supporting a plausible pathway for perinatal adjustment (Diotaiuti et al., 2022).

The present study aimed to compare levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms during pregnancy and the postpartum period among (a) women who attended antenatal classes and (b) women who did not participate in antenatal education, within a large perinatal sample. Analyses controlled for maternal age, education, economic status, employment, marital status, past psychiatric diagnosis, current psychotropic medication use, perceived social support, pregnancy trimester, pregnancy planning, assisted conception, parity, and survey period.

Methods

Procedures

This ongoing study (initiated in 2021) is organized by the Center for Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health at the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (Italian National Institute of Health; ISS). In September 2021, the ISS launched the Italian Network for Perinatal Mental Health to track anxiety and depression throughout the perinatal period, and to examine associated risk and protective factors. The Network comprises 16 sites (including obstetrics and gynecology units, psychiatric hospitals, and maternal–child health centers) across eight Italian regions. Recruitment occurred voluntarily during gynecological or obstetric routine appointments. Each participant received a full explanation of the study's aims and procedures and provided written informed consent, with the right to withdraw at any time without affecting their medical care. Each participant was assessed once, at any time during their pregnancy (n = 4,169 pregnant women) or their postpartum period (n = 5,520 new mothers). The protocol received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the ISS (Protocol No. 0024542, 21 June 2021) and adhered to the principles stated in the “Declaration of Helsinki.” The data analyzed in this article were collected between October 2021 and December 2024.

Antenatal education classes

Antenatal education classes are programs designed for expectant couples, led by professionals such as midwives, psychologists, gynecologists, and pediatricians. They generally aim to provide practical and psychological tools to help women navigate pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period with greater awareness. In Italy, the sessions typically address topics related to a woman's physical and mental wellbeing, nutrition, the stages of labor, and pain management techniques, both pharmacological and natural, with particular attention to the partner's role. Newborn care, breastfeeding, and adjusting to a new family are also addressed, with practical exercises such as breathing, relaxation, and baby massage. The courses are held in small groups to encourage sharing experiences and typically consist of 5–10 sessions lasting between an hour and a half and 2 h, typically beginning between the twenty-third and thirty-second week of pregnancy. Participants in the present study attended prenatal courses organized by various institutions; although these courses followed general guidelines for antenatal education, differences in structure and content may have existed, for which detailed data were not available. We also lacked data on the number of days/weeks between the final class and the assessment.

Measures

A structured patient questionnaire (Mirabella et al., 2016) was used to collect sociodemographic, clinical, and pregnancy-related data (e.g., age, marital status, psychiatric history, and perceived social support, recourse to medically assisted procreation). The instrument has been employed in previous perinatal studies (e.g., Cena et al., 2020, 2021a,b,c, 2022), which consistently found that several of these variables were independently and statistically significantly associated with the severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms, after adjustment for potential confounders.

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Cox et al., 1987), a self-report measure that evaluates mood and anhedonia symptoms over the preceding 2 weeks. Although two-factor models showed the best fit for the EPDS in both antepartum and postpartum groups (Stefana et al., 2024), the most reliable score variance derives from a general factor for each scale (Stefana et al., 2023). Each item is scored from 0 to 3, resulting in a total score from 0 to 30. A cut-off of ≥12 indicates clinically relevant depressive symptomatology in perinatal populations (Benvenuti et al., 1999; Camoni et al., 2023). In our sample, the EPDS showed strong psychometric performance, with Cronbach's alpha = 0.90 in both pregnancy and postpartum and McDonald's omega total = 0.93 in pregnancy and 0.92 in postpartum. Moreover, in the Italian validation study (Benvenuti et al., 1999), the EPDS demonstrated sensitivity of 0.86 and specificity of 0.78 for identifying probable depression.

Anxiety severity was measured using the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006), which assesses the frequency of anxiety-related symptoms over the prior 2 weeks on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = “not at all” to 3 = “nearly every day”). Total scores range from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety severity; a threshold of ≥10 suggests clinically significant anxiety (Spitzer et al., 2006). In our sample, the GAD-7 showed high internal consistency, with Cronbach's alpha = 0.90 and McDonald's omega total = 0.93 in pregnancy and 0.88 and 0.92, respectively, in postpartum. The Italian version of the GAD-7 demonstrates strong psychometric properties and measurement invariance between antepartum and postpartum samples (Stefana et al., under review).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted in R 4.5.1 (R Core Team, 2025). We retained 9,689 records with non-missing antenatal-class-attendance status. Twelve prespecified socio-demographic and clinical covariates (Supplementary Table 1) were entered as potential confounders; continuous covariates were mean-centered.

Item-level missingness was < 6%. We applied multivariate imputation by chained equations (m = 10) using predictive mean matching for numeric and logistic regression for binary variables. The imputation model contained all covariates and relevant outcome.

Separate linear regressions predicted EPDS and GAD-7 total scores. Logistic models predicted binary risks (depression: EPDS>12; anxiety: GAD-7 > 8). A multinomial-logit model predicted a four-level symptom profile (None, Depression-only, Anxiety-only, Comorbid). Each model included antenatal-class attendance (Yes vs. No), period, their interaction, and the covariate block. For binary outcomes we report odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs; for the multinomial outcome, relative-risk ratios (RRRs). Estimated marginal means were obtained with emmeans; risk differences (RDs) and numbers-needed-to-treat (NNT = 1/|RD|) were derived on the probability scale. Model assumptions (linearity, homoscedasticity, and normality or deviance residuals) were verified graphically.

To address self-selection for the binary outcomes (any anxiety, any depression, comorbid), we estimated ATE propensity scores with WeightIt using a main-effects logistic regression of attendance on period + the 12 covariates (method = “ps,” estimand = “ATE”). We applied the resulting unstabilized inverse-probability-of-treatment weights in survey-weighted GLMs (svyglm, quasi-binomial link) with robust (sandwich) standard errors. No weight stabilization or trimming/truncation was performed. IPTW models were fit in each imputed dataset and pooled with MIcombine following Rubin's rules.

Using the same covariate set and ATE IPTW, moderation was tested with survey-weighted linear models including Class × Support/Parity/Education interactions; simple effects were obtained with emmeans. Mediation was evaluated with mediate using weighted models for the mediator and outcome, with 1,000 non-parametric bootstraps for CIs.

As a sensitivity analysis, E-values (VanderWeele and Ding, 2017) quantified the minimum unmeasured-confounding strength (risk-ratio scale) required to fully explain observed associations.

Results

Participants

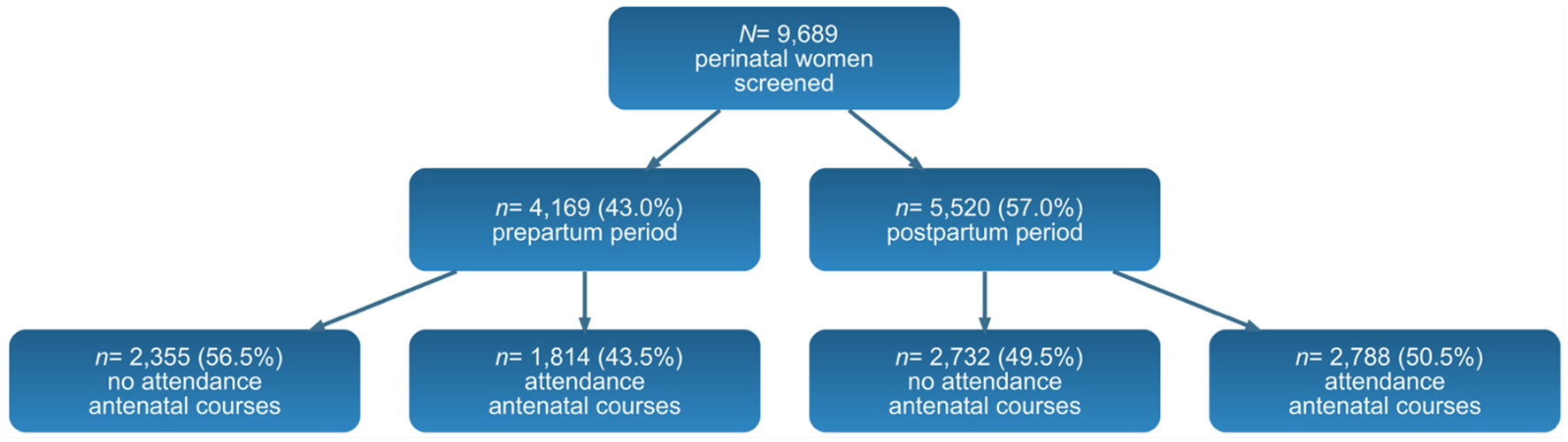

The sample comprised N = 9,689 perinatal women. Of these, 4,169 (43.0%) were assessed during pregnancy [no attendance n = 2,355 [56.5%]; attendance n = 1,814 [43.5%]] and 5,520 (57.0%) during the postpartum period [no attendance n = 2,732 [49.5]; attendance n = 2,788 [50.5%]] (see Figure 1). During pregnancy, antenatal class attenders were significantly more likely to be Italian nationals, hold tertiary education, and be employed, compared with non-attenders. They were less likely to have previous children, report an unplanned pregnancy, or be taking psychotropic medication. Attenders also reported higher social support (all p < 0.001). A similar pattern was observed postpartum: class attenders were again more often Italian, tertiary educated, and employed, and less likely to have other living children or report unplanned pregnancies. They showed higher partner and family support and lower psychotropic medication use (p < 0.05). Participant characteristics are detailed in Supplementary Tables 1, 2.

Figure 1

Flow chart from screening to antennal courses analyzed by perinatal period.

Prevalence of Antenatal-Class Attendance

Attendance was reported by 43.5% of women who were still pregnant (n = 1,814) and 50.5% of those surveyed after delivery (n = 2,788).

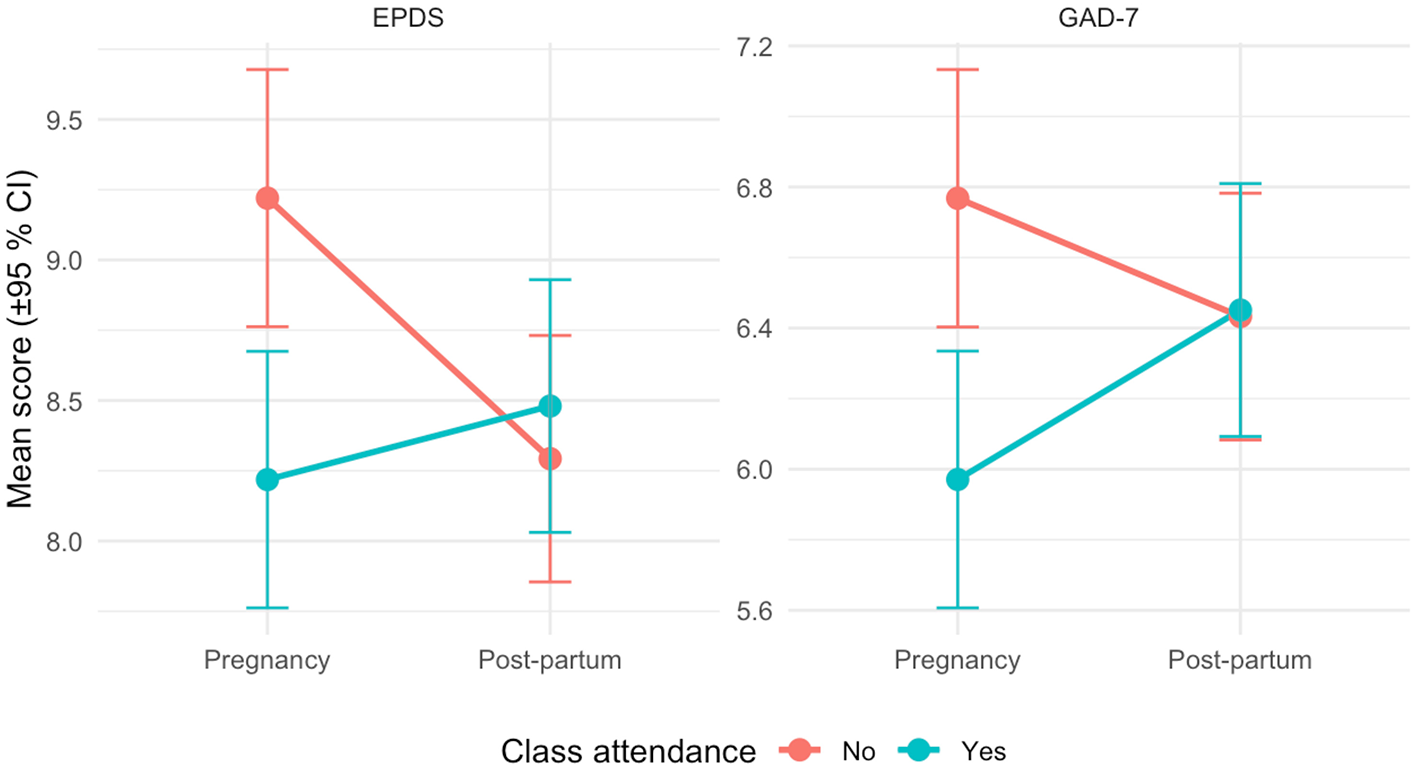

Primary outcomes: symptom severity and binary screening

For anxiety, women who attended antenatal classes during pregnancy recorded GAD−7 scores that were, on average, 0.80 points lower than those of non-attendees (B = −0.80, 95% CI −1.04 to −0.56, p < 0.001); in parallel, their odds of screening positive were 42.0% lower (OR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.46–0.73). In the post-partum period, however, the strong attendance by period interaction (β = 0.82, p < 0.001) essentially erased this benefit, yielding a derived post-partum OR of 0.98, with virtually no difference between groups. Figure 2 displays the predicted mean GAD-7 and EPDS scores for these two periods by attendance status.

Figure 2

Predicted EPDS and GAD-7 mean symptom scores (±95% CIs) by antenatal-class attendance and period.

A similar pregnancy-specific pattern emerged for depressive symptoms. Class attendance was linked to a 1-point reduction in EPDS scores (B = −1.00, 95% CI −1.30 to −0.70, p < 0.001) and a 55.0% decrease in the odds of screening positive (OR = 0.45, 95% CI 0.35–0.57). Yet the interaction term (β = +1.19, p < 0.001) nullified this advantage after birth, producing a post-partum OR of 1.08.

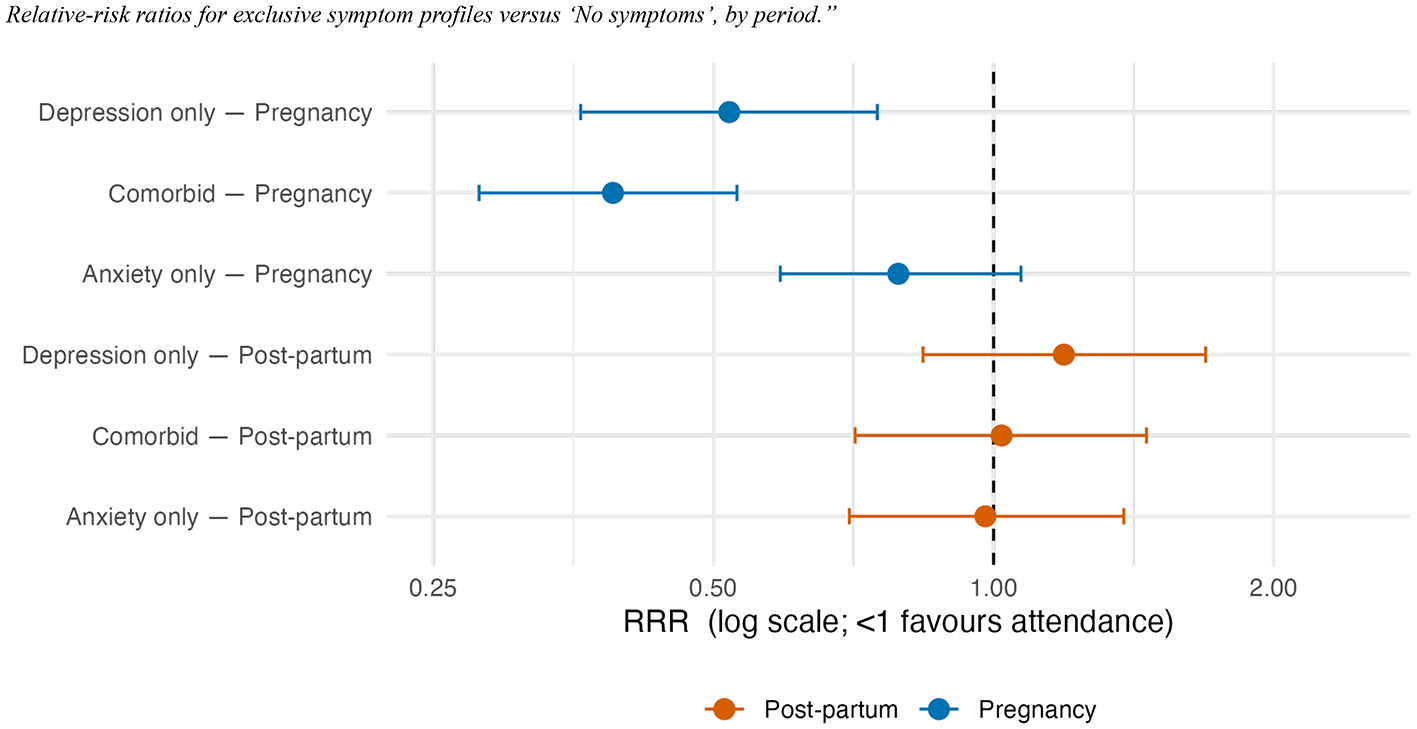

Symptom-profile outcome

Relative-risk ratios (vs. No symptoms) showed lower risks for depression-only (RRR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.36–0.75) and comorbid depression and anxiety (RRR = 0.39, 0.28–0.53), but no clear change in the anxiety-only profile (RRR = 0.79, 0.59–1.07). None of these differences was observed in the post-partum sample. Figure 3 visualizes these profile-specific RRRs and their 95% CIs.

Figure 3

Relative-risk ratios for exclusive symptom profiles vs. “No symptoms,” by period.

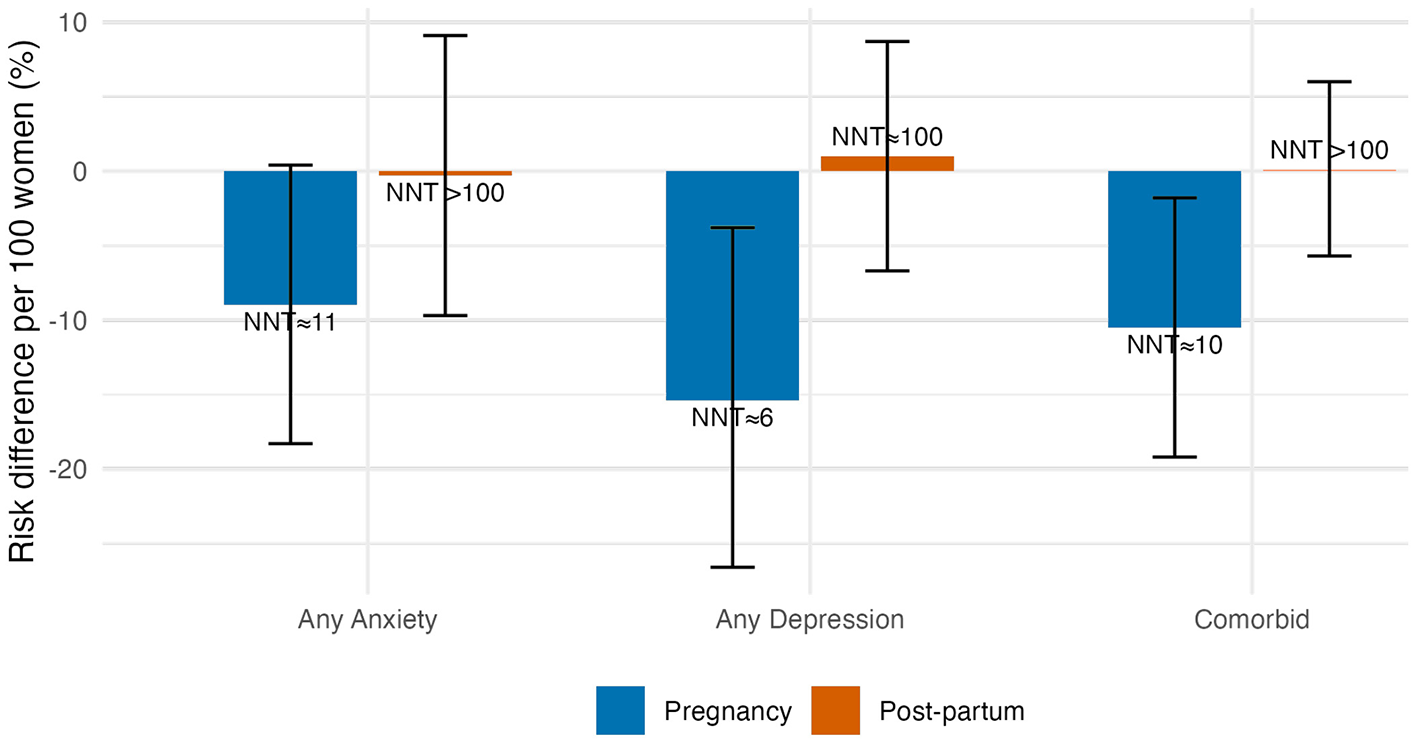

Absolute risk reduction

During pregnancy, attendance was associated with 9 fewer risk of anxiety cases (RD = −0.09, 95% CI −0.183 to +0.004; NNT ≈ 11) and 15 fewer risk of depression cases (RD = −0.154, −0.27 to −0.04; NNT ≈ 7) per 100 women. Post-partum risk differences hovered around zero, yielding NNTs > 100. This means that even under best-case assumptions, only one extra anxiety case would be prevented for roughly every 11 pregnant attendees, and benefits vanish in post-partum. These absolute differences and NNTs are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Risk differences per 100 women (bars ± 95% CIs) and implied number-needed-to-treat. Negative bars = risk reduction.

Propensity-score weighted (IPTW) analyses

Balancing on all covariates attenuated the pregnancy associations to non-significance: for women who were still pregnant, the IPTW OR for anxiety was 0.86 (95% CI 0.54–1.35), while the OR for depression was 0.64 (0.38–1.10). Adding the interaction term to obtain post-partum estimates yielded ORs of 0.96 (0.46–1.97) for anxiety and 0.83 (0.34–1.99) for depression, confirming no benefit after delivery. In other words, after inverse-probability weighting balanced the observed covariates, the associations attenuated and became non-significant, indicating that the crude advantages largely reflected baseline differences between women who did and did not enroll. Figure 5 juxtaposes these IPTW odds-ratios with the corresponding crude estimates, illustrating the attenuation.

Figure 5

Crude and IPTW odds-ratios for antenatal-class attendance predicting anxiety, depression, and comorbidity, stratified by period. Dashed line = null effect.

Sensitivity to unmeasured confounding

E-values indicated that an unmeasured factor associated with both class attendance and outcome by a risk ratio of ≈2 could fully explain the residual pregnancy associations (anxiety RR = 0.76, E-value = 1.95; depression RR = 0.67, E-value = 2.35; comorbid RR = 0.65, E-value = 2.47). These E-values show the pregnancy effects are only moderately robust: an unmeasured factor that roughly doubles both class attendance and mental-health status could wipe them out.

Exploratory moderation and mediation analyses

The following results should be read as hypothesis-generating.

Among pregnant women who felt under-supported, classes were linked to clearly lower anxiety (ΔGAD ≈ −0.80, 95% CI −1.30 to −0.30). When perceived support was average or high, the anxiety difference shrank to essentially zero. For depression, the class gap was small and imprecise at all perceived support levels. These results suggest that women who are short on support seem to experience the most anxiety relief.

Primigravidas recorded a −0.5-point EPDS difference (95% CI −0.90 to −0.10), but the gap vanished for mothers who already had children. No parity pattern appeared for anxiety.

Low, medium, and highly educated individuals displayed similar effects; at most there was a non-significant trend toward a slightly larger anxiety benefit in the highest-education band.

In brief, antenatal classes appear to soothe prenatal anxiety only for women who feel short on partner- or friend-support; those with average or high support gain nothing extra. Depressive symptoms show a small benefit confined to first-time mothers, while parity is irrelevant for anxiety. Educational level does not meaningfully alter any effect. All subgroup findings are exploratory and should be viewed as hypothesis-generating.

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of antenatal education classes, as an adjunct to routine obstetric and gynecological care, on anxiety and depressive symptoms among pregnant and postpartum women. It examined a large cohort of Italian and Italian-speaking women by comparing symptom levels between women who attended antenatal classes and those who did not. Widely used and validated self-report scales measured anxiety and depressive symptoms. Results indicate that participation in antenatal class provides a statistically significant but clinically modest effect in reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms during pregnancy. However, these benefits diminish significantly when differential selection is accounted for through propensity weighting and do not persist into the postpartum period. Specifically, while antenatal classes might offer protection against complex depressive and, especially, anxiety states during pregnancy, their effectiveness does not extend postpartum. The cross-sectional design, distinct pregnancy/postpartum cohorts, and moderate E-values suggest that the observed associations are likely not causal. Although routine antenatal classes may provide short-term psychological benefits during pregnancy, they are unlikely to prevent postpartum anxiety and depressive disorders without additional interventions.

The modest reductions in prenatal anxiety and depressive symptoms among attendees detected in our study are consistent with prior studies suggesting antenatal educational interventions can mitigate pregnancy-specific anxiety (Madhavanprabhakaran et al., 2017; Stoll et al., 2018) and improve childbirth-related outcomes like self-efficacy and pain management (Demirci et al., 2023; Alizadeh-Dibazari et al., 2023). Furthermore, the limited and transient psychological effects is consistent with recent reviews (Athinaidou et al., 2024; Rahmawati et al., 2025). The observed reduction in anxiety during the antepartum period confirms previous findings on the protective role of antenatal education (Rahmawati et al., 2025), particularly for primiparous women facing greater uncertainty about pregnancy risks, medical complications, and childbirth (Lafontaine et al., 2024; Khajehei et al., 2020). However, our result indicating no postpartum benefit in terms of depressive symptom severity contrasts preliminary meta-analytic findings (k = 3; N = 367) suggesting antenatal education may reduce postpartum depression (Alizadeh-Dibazari et al., 2023). Our findings are consistent with psychoeducational approaches reporting reduced anxiety and enhanced self-efficacy in prenatal settings (Diotaiuti et al., 2022), although adjusted estimates in our study suggest attenuation over time and limited persistence postpartum.

Methodologically, applying inverse-probability-of-treatment weighting significantly attenuated initial associations, revealing that baseline socio-demographic and psychological differences substantially confound the relationship between antenatal education and psychological outcomes. Moderate E-values further suggest susceptibility to unmeasured confounding, reinforcing caution in interpreting observed psychological benefits as strictly causal. Thus, the attenuation observed after propensity-score weighting suggests selection bias may partly explain previously reported positive outcomes.

Our exploratory moderation analyses provided insights into subgroups potentially benefiting more from antenatal education. Specifically, women reporting low perceived social support showed clearer reductions in anxiety following class attendance. This aligns with strong evidence that perceived social support is critical in buffering anxiety during pregnancy (Cena et al., 2020; McCarthy et al., 2021). The minimal benefits for those with higher perceived social support suggest antenatal education may serve as a compensatory resource, especially beneficial where other supports are lacking. Given that antenatal education in Italy is predominantly delivered in group formats, therapeutic factors specific to group interventions (Yalom and Leszcz, 2020), such as universality (i.e., the recognition that others share similar experiences), may be key mechanisms of action. The moderation observed with depressive symptoms in primiparous women aligns with the understanding that first-time mothers often face heightened vulnerability (Athinaidou et al., 2024; Barimani et al., 2018). Antenatal classes may thus specifically target initial anxieties and depressive symptoms associated with transitioning into motherhood.

Clinical implications

Our findings suggest antenatal education should not be considered a standalone preventive measure for postpartum anxiety and depression. Instead, antenatal classes should be integrated into broader psychosocial support frameworks that emphasize systematic, evidence-based screening/assessment (Cena et al., 2021d) and timely referral for mental health services throughout the perinatal period. Given the observed weakening of effects detected after adjustment for confounders and their moderate robustness to unmeasured biases, refinement of antenatal curricula is recommended. Practical next steps include enhancing and standardizing antenatal programs with evidence-based content, extending educational support into the postpartum period, and integrating antenatal education with postpartum care programs, particularly for those initially benefiting from antenatal classes. Lastly, our exploratory analyses further suggest prioritizing socially isolated and primigravid women.

Limitations and strengths

This study's findings should be interpreted considering some limitations.

The observational design of the study restricts causal inference despite adjustment. Furthermore, the self-reported nature of measures with possible social desirability bias and timing sensitivity, incomplete measurement of adherence to the intervention, limited power for some secondary outcomes and for postpartum follow-up; restricted the generalizability of the study.

Additionally, information regarding program content and delivery formats (e.g., in-person vs. online) was unavailable, highlighting variability in antenatal education programs and reinforcing the need for standardized yet personalized approaches. Despite inverse-probability-of-treatment weighting adjustments, self-selection bias remains, further underscoring the necessity for longitudinal randomized controlled trials to validate findings unequivocally.

However, some strengths can be considered as the large sample size and the use of comprehensive analytical techniques beyond logistic regression, enabling a nuanced understanding of clinical effects.

Conclusion

Antenatal education classes are modestly effective in reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms during pregnancy, particularly benefiting first-time mothers and women with limited perceived social support. The transient nature of these beneficial effects emphasizes the need for standardized, evidence-based interventions integrated into routine perinatal psychological monitoring to achieve and maintain maternal mental health benefits.

Statements

Data availability statement

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by Italian National Institute of Health Ethics Committee (Protocol No. 0024542, 21 June 2021). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

AS: Data curation, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. FM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. AG: Writing – review & editing. GC: Writing – review & editing. LC: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Conceptualization, Formal analysis.

Group members of Perinatal Mental Health Network group

Franca Aceti, Osservatorio Multicentrico per la Depressione Perinatale, Servizio di psicopatologia perinatale, Sapienza Università di Roma, Policlinico Umberto I, Roma, Italy; Ilaria Adulti, Osservatorio Multicentrico per la Depressione Perinatale, Università di Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy; Pietro Bagolan, Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù, Unità Operativa di Psicologia Clinica e diagnosi prenatale, Roma, Italy; Gina Barbano, UOC Infanzia Adolescenza Famiglia e Consultori, Distretto Treviso nord-sede di Oderzo, Azienda ULSS 2 Marca trevigiana, Treviso, Italy; Antonello Bellomo, Osservatorio Multicentrico Depressione Perinatale, UOC Psichiatria, Università di Foggia, Foggia, Italy; Marina Cattaneo, Consultorio familiare di Treviglio, ASST Bergamo Ovest, Bergamo, Italy; Elda Cengia, UOC Ostetricia e Ginecologia Ospedale di Belluno Azienda ULSS 1, Belluno, Italy; Flavia Adalgisa Distefano, UOC di Ginecologia ed Ostetricia dell'Ospedale Cristo Re, Roma, Italy; Angela Fabiano, Divisione Materno Infantile dell'Azienda Ospedaliera di Rilievo Nazionale e di Alta Specializzazione (ARNAS) “Garibaldi”, Catania, Italy; Alice Fent, UOC Ostetricia e Ginecologia Ospedale di Belluno Azienda ULSS 1, Belluno, Italy; Nicoletta Giacchetti, Servizio di psicopatologia perinatale Sapienza Università di Roma, Policlinico Umberto I, Osservatorio Multicentrico per la Depressione Perinatale, Roma, Italy; Laura Giusti, Università degli Studi de L'Aquila, Dipartimento di Medicina Clinica, Sanità Pubblica, Scienze della Vita e dell'Ambiente - MeSVA, L'Aquila, Italy; Antonella Grillo, Divisione Materno Infantile - ASP Catania, Catania, Italy; Teresa Grimaldi, Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù, Unità Operativa di Psicologia Clinica e diagnosi prenatale, Roma, Italy; Loredana Messina, UOC Ostetricia e Ginecologia dell'Ospedale Buccheri La Ferla Fatebenefratelli, Palermo, Italy; Marianna Marra, Osservatorio Multicentrico Depressione Perinatale, UOC Psichiatria, Policlinico A. Gemelli, Roma, Italy; Angelo Marcheggiani, Consultorio di Campobasso - Ambulatorio di Ostetricia e Ginecologia, Campobasso, Italy; Cinzia Niolu, Osservatorio Multicentrico per la depressione perinatale, Università di Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy; Giovanna Picciano, Consultorio di Campobasso - Ambulatorio di Ostetricia e Ginecologia, Campobasso, Italy; Maria Pistillo, UOC Ostetricia e Ginecologia, ASP Enna, Enna, Italy; Rossana Riolo, Ambulatorio genitori senza depressione, ALSS 8-Berica, Vicenza, Italy; Rita Roncone, Università degli Studi de L'Aquila, Dipartimento di Medicina Clinica, Sanità Pubblica, Scienze della Vita e dell'Ambiente - MeSVA, L'Aquila, Italy; Gabriele Sani, Osservatorio Multicentrico Depressione Perinatale, UOC Psichiatria, Policlinico A. Gemelli, Roma, Italy; Melania Severo, Osservatorio Multicentrico Depressione Perinatale, UOC Psichiatria, Università di Foggia, Foggia, Italy; Martina Smorti, Dipartimento di Patologia Chirurgica, Medica, Molecolare e dell'Area Critica, Università di Pisa, Pisa, Italy; Damiana Tomasello, Divisione Materno Infantile - ASP Catania, Catania, Italy.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used ChatGPT o3 to edit the language (grammar, syntax, clarity, and readability) of the original draft. After using this tool, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1724202/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Alizadeh-Dibazari Z. Abdolalipour S. Mirghafourvand M. (2023). The effect of prenatal education on fear of childbirth, pain intensity during labour and childbirth experience: a scoping review using systematic approach and meta-analysis. BMC Pregn. Childb.23:541. doi: 10.1186/s12884-023-05867-0

2

AlKhunaizi A. N. Alhamidi S. A. Al-Otaibi A. G. AlAbdullah A. A. Alosaif K. S. Zayer M. J. A. (2025). Exploring healthcare providers' perspectives of childbirth education classes for quality of care and positive childbirth experience: an interpretative phenomenological analysis study. BMC Pregn. Childb.25:570. doi: 10.1186/s12884-025-07698-7

3

Astbury L. Pinnington D. M. Milgrom J. Bei B. (2025). The longitudinal trajectory of depression and anxiety across the perinatal period. J. Affect. Disord.370, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.10.080

4

Athinaidou A. M. Vounatsou E. Pappa I. Harizopoulou V. C. Sarantaki A. (2024). Influence of antenatal education on birth outcomes: a systematic review focusing on primiparous women. Cureus16:e64508. doi: 10.7759/cureus.64508

5

Barimani M. Forslund Frykedal K. Rosander M. Berlin A. (2018). Childbirth and parenting preparation in antenatal classes. Midwifery57, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2017.10.021

6

Benvenuti P. Ferrara M. Niccolai C. Valoriani V. Cox J. L. (1999). The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: validation for an Italian sample. J. Affect. Disord.53, 137–141. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00102-5

7

Brixval C. S. Axelsen S. F. Lauemøller S. G. Andersen S. K. Due P. Koushede V. (2015). The effect of antenatal education in small classes on obstetric and psycho-social outcomes - a systematic review. Syst. Rev.4:20. doi: 10.1186/s13643-015-0010-x

8

Camoni L. Gigantesco A. Guzzini G. Pellegrini E. Mirabella F. (2023). Epidemiology of perinatal depression in Italy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Annali dell'Istituto Superiore di Sanita59, 139–148. doi: 10.4415/ANN_23_02_07

9

Cena L. Biban P. Janos J. Lavelli M. Langfus J. Tsai A. et al . (2021d). The collateral impact of COVID-19 emergency on neonatal intensive care units and family-centered care: challenges and opportunities. Front. Psychol.12:630594. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.630594

10

Cena L. Gigantesco A. Mirabella F. Palumbo G. Camoni L. Trainini A. et al . (2021a). Prevalence of comorbid anxiety and depressive symptomatology in the third trimester of pregnancy: analysing its association with sociodemographic, obstetric, and mental health features. J. Affect. Disord.295, 1398–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.015

11

Cena L. Gigantesco A. Mirabella F. Palumbo G. Trainini A. Stefana A. (2021b). Prevalence of maternal postnatal anxiety and its association with demographic and socioeconomic factors: a multicentre study in Italy. Front. Psychiatry12:737666. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.737666

12

Cena L. Mirabella F. Palumbo G. Gigantesco A. Camoni L. Trainini A. et al . (2022). Poor social support is associated with preterm birth rather than maternal prenatal anxiety and depression: a retrospective case-control study. Minerva Pediatr.74, 225–227. doi: 10.23736/S2724-5276.21.06348-5

13

Cena L. Mirabella F. Palumbo G. Gigantesco A. Trainini A. Stefana A. (2020). Prevalence of maternal antenatal anxiety and its association with demographic and socioeconomic factors: a multicentre study in Italy. Eur. Psychiatry63:e84. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.82

14

Cena L. Mirabella F. Palumbo G. Gigantesco A. Trainini A. Stefana A. (2021c). Prevalence of maternal antenatal and postnatal depression and their association with sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors: a multicentre study in Italy. J. Affect. Disord.279, 217–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.136

15

Chen L. M. Pokhvisneva I. Lahti-Pulkkinen M. Kvist T. Baldwin J. R. Parent C. et al . (2024). Independent prediction of child psychiatric symptoms by maternal mental health and child polygenic risk scores. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry63, 640–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2023.08.018

16

Cox J. L. Holden J. M. Sagovsky R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry150, 782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782

17

Demirci A. D. Kochan M. Kabukcuoglu K. (2023). Effect of antenatal education on childbirth self-efficacy: a systematic-review and meta-analysis. Curr. Psychol.42, 11367–11377. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02418-8

18

Diotaiuti P. Valente G. Mancone S. Falese L. Corrado S. Siqueira T. C. et al . (2022). A psychoeducational intervention in prenatal classes: positive effects on anxiety, self-efficacy, and temporal focus in birth attendants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health19:7904. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19137904

19

Downer T. Young J. McMurray A. (2020). Are we still woman-centred? Changing ideologies, a history of antenatal education in Australia. Collegian27, 634–641. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2020.08.008

20

Fawcett E. J. Fairbrother N. Cox M. L. White I. R. Fawcett J. M. (2019). The prevalence of anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period: a multivariate Bayesian meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry80:18r12527. doi: 10.4088/JCP.18r12527

21

Ferri A. Sutcliffe K. L. Catling C. Newnham E. Levett K. M. (2024). Antenatal education - putting research into practice: a guideline review. Midwifery132:103960. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2024.103960

22

Hong K. Hwang H. Han H. Chae J. Choi J. Jeong Y. et al . (2021). Perspectives on antenatal education associated with pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Women Birth34, 219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.04.002

23

Hooper E. Mechkaroff O. Upitis A. Schofield E. Carland J. E. Henry A. (2025). The effectiveness of antenatal education on improving labour and birth outcomes - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Women Birth38:101843. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2024.101843

24

Howard L. M. Khalifeh H. (2020). Perinatal mental health: a review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatr.19, 313–327. doi: 10.1002/wps.20769

25

Jee S. B. Sawal A. (2024). Physiological changes in pregnant women due to hormonal changes. Cureus16:e55544. doi: 10.7759/cureus.55544

26

Khajehei M. Swain J. A. Wen Y. (2020). Primiparous women's narratives of confidence in the perinatal period. Br. J. Midwifery28, 42–50. doi: 10.12968/bjom.2020.28.1.42

27

Lafontaine G. Dubé S. Bédard J. Lehoux A. Brassard A. Lafontaine M. F. et al . (2024). Intolerance of uncertainty, intimacy, and sexual well-being among first-time parents. Can. J. Hum. Sexual.33, 159–171. doi: 10.3138/cjhs-2023-0048

28

Madhavanprabhakaran G. K. D'Souza M. S. Nairy K. (2017). Effectiveness of childbirth education on nulliparous women's knowledge of childbirth preparation, pregnancy anxiety and pregnancy outcomes. Nurs. Midwifery Stud.6:e32526. doi: 10.5812/nmsjournal.32526

29

Matvienko-Sikar K. Dijk W. V. Dockray S. Leahy-Warren P. (2025). Modifiable and vulnerability factors for maternal stress and anxiety in the first 1000 days: an umbrella review and framework. Women Birth38:101941. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2025.101941

30

McCarthy M. Houghton C. Matvienko-Sikar K. (2021). Women's experiences and perceptions of anxiety and stress during the perinatal period: a systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis. BMC Pregn. Childb.21:811. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-04271-w

31

Mirabella F. Michielin P. Piacentini D. Veltro F. Barbano G. Cattaneo M. et al . (2016). Efficacia di un intervento psicologico rivolto a donne positive allo screening per depressione post partum [Effectiveness of a postnatal psychological treatment for women who had screened positive for depression]. Riv. Psichiatr.51, 260–269. doi: 10.1708/2596.26728

32

Motrico E. Bina R. Kassianos A. P. Le H. N. Mateus V. Oztekin D. et al . (2023). Effectiveness of interventions to prevent perinatal depression: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry82, 47–61. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2023.03.007

33

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2021). Antenatal Care. [E] Antenatal classes. NICE Guideline, No. 201.

34

O'Dea G. A. Youssef G. J. Hagg L. J. Francis L. M. Spry E. A. Rossen L. et al . (2023). Associations between maternal psychological distress and mother-infant bonding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Womens Mental Health26, 441–452. doi: 10.1007/s00737-023-01332-1

35

Olza I. Leahy-Warren P. Benyamini Y. Kazmierczak M. Karlsdottir S. I. Spyridou A. et al . (2018). Women's psychological experiences of physiological childbirth: a meta-synthesis. BMJ Open8:e020347. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020347

36

Ou L. Shen Q. Xiao M. Wang W. He T. Wang B. (2025). Prevalence of co-morbid anxiety and depression in pregnancy and postpartum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med.55:e84. doi: 10.1017/S0033291725000601

37

Rahmawati R. Hidayat A. Koni Suryaningsih E. (2025). Effectiveness of prenatal class participation on maternal anxiety: a scoping review. J. Promosi Kesehatan Indonesia20, 228–242. doi: 10.14710/jpki.20.3.228-242

38

Runkle J. D. Risley K. Roy M. Sugg M. M. (2023). association between perinatal mental health and pregnancy and neonatal complications: a retrospective birth cohort study. Women's Health Issues33, 289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2022.12.001

39

Sheen K. Slade P. (2018). Examining the content and moderators of women's fears for giving birth: a meta-synthesis. J. Clin. Nurs.27, 2523–2535. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14219

40

Shen Q. Xiao M. Wang B. He T. Zhao J. Lei J. (2024). Comorbid anxiety and depression among pregnant and postpartum women: a longitudinal population-based study. Depress. Anxiety2024:7802142. doi: 10.1155/2024/7802142

41

Spitzer R. L. Kroenke K. Williams J. B. Löwe B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med.166, 1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

42

Stefana A. Cena L. Trainini A. Palumbo G. Gigantesco A. Mirabella F. (2024). Screening for antenatal maternal depression: comparative performance of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Annali dell'Istituto Superiore di Sanità60, 55–63. doi: 10.4415/ANN_24_01_08

43

Stefana A. Langfus J. A. Palumbo G. Cena L. Trainini A. Gigantesco A. et al . (2023). Comparing the factor structures and reliabilities of the EPDS and the PHQ-9 for screening antepartum and postpartum depression: a multigroup confirmatory factor analysis. Arch. Womens Mental Health26, 659–668. doi: 10.1007/s00737-023-01337-w

44

Stefana A. Mirabella F. Gigantesco A. Camoni L . the Perinatal Mental Health Network group (under review). Factor structure measurement invariance, clinical change benchmarks of the GAD-7 in pregnancy postpartum. J. Anxiety Disord.

45

Stoll K. Swift E. M. Fairbrother N. Nethery E. Janssen P. (2018). A systematic review of nonpharmacological prenatal interventions for pregnancy-specific anxiety and fear of childbirth. Birth45, 7–18. doi: 10.1111/birt.12316

46

VanderWeele T. J. Ding P. (2017). Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Ann. Intern. Med.167, 268–274. doi: 10.7326/M16-2607

47

Weingarten S. J. Osborne L. M. (2024). Review of the assessment and management of perinatal mood and anxiety disorders. Focus22, 16–24. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20230023

48

WHO (2016). WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. World Health Organization.

49

WHO (2018). WHO Recommendations Non-Clinical Interventions to Reduce Unnecessary Caesarean Sections. Geneva: World Health Organization.

50

Wilska A. Rantanen A. Botha E. Joronen K. (2021). Parenting fears and concerns during pregnancy: a qualitative survey. Nurs. Rep.11, 891–900. doi: 10.3390/nursrep11040082

51

Wu Y. Wang H. Hui X. Qian Z. Wang M. Fenfen E et al . (2025). Efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions for the prevention of antenatal depression: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.172:106088. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2025.106088

52

Yalom I. D. Leszcz M. (2020). The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, 6th Edn. Basic Books.

53

Yin X. Sun N. Jiang N. Xu X. Gan Y. Zhang J. et al . (2021). Prevalence and associated factors of antenatal depression: systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Clin. Psychol. Rev.83:101932. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101932

54

Zaman A. Fadlalmola H. A. Ibrahem S. E. Ismail F. H. Abedelwahed H. H. Ali A. M. et al . (2025). The role of antenatal education on maternal self-efficacy, fear of childbirth, and birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Midwifery 9. doi: 10.18332/ejm/200747

55

Zanetti M. R. D. Sosa C. Foster T. Rossello J. L. Serruya S. De Múcio B. (2024). What are the benefits of antenatal education as a maternal health promotion tool? A systematic review with meta-analysis. ABCS Health Sci.49:e024305. doi: 10.7322/abcshs.2022150.2213

Summary

Keywords

anxiety, childbirth classes, depression, expectant parent classes, prenatal education

Citation

Camoni L, Mirabella F, Gigantesco A, Calamandrei G, Stefana A and Perinatal Mental Health Network group (2026) Effects of antenatal education on maternal anxiety and depression in pregnancy and postpartum period in Italy: modest and transient symptom reductions. Front. Psychol. 16:1724202. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1724202

Received

13 October 2025

Revised

25 November 2025

Accepted

02 December 2025

Published

12 February 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Mohammadreza Shalbafan, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Reviewed by

Stefania Mancone, University of Cassino, Italy

Christina Papapetrou, American College of Greece, Greece

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Camoni, Mirabella, Gigantesco, Calamandrei and Stefana.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alberto Stefana, alberto.stefana@iss.it

ORCID: Laura Camoni orcid.org/0000-0001-9007-6479; Fiorino Mirabella orcid.org/0000-0001-8090-9465; Antonella Gigantesco orcid.org/0000-0001-9262-7756; Gemma Calamandrei orcid.org/0000-0003-3762-3132; Alberto Stefana orcid.org/0000-0002-4807-7184

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.