Abstract

Creative performance drives innovation, problem-solving, productivity, and competitiveness of organizations. This research comprehensively reviews existing studies on employees’ creative job performance and integrates findings on individual factors that are associated with creative behavior. Examining 82 empirical studies of creative performance, 79 personal factors grouped into eight categories has been identified: demographic factors, personality, cognitive ability, motivation, emotions, self-efficacy, other performance dimensions, and a miscellaneous category. The most relevant personal factors associated with creative performance include educational level (rw = 0.19, 95% CI [.12, .27], p < 0.001; I² = 55.66%), and moderate to strong positive associations for openness (rw = 0.46, 95% CI [0.33,0.59], p < 0.001; I² = 93.76%), intrinsic motivation (rw = 0.39, 95% CI [0.28, 0.50], p < 0.001; I² = 93.37%), creative process engagement (rw = 0.52, 95% CI [0.23, 0.80], p < 0.001; I² = 97.39%), positive affect (rw = 0.31, 95% CI [0.18, 0.43], p < 0.001; I² = 81.53%), and creative self-efficacy (rw = 0.45, 95% CI [0.34, 0.56], p < 0.001; I² = 95.30%). The findings enhance the nomological network of creative performance, offer directions for future research, and suggest improvements for human resource processes, including employee selection, training, and performance assessment.

1 Introduction

Driving innovation is critical to the long-term survival of today’s organizations (Akbari et al., 2021). Creativity is the driving force of innovation and is an essential quality for a company’s long-term success (Peng and Chen, 2023). As the business environment’s competitiveness increases, professional, managerial, and administrative tasks become more complex and knowledge-intensive, and employers expect employees to become more creative (Aleksic et al., 2016). Therefore, creativity is a valuable outcome that should be cultivated and encouraged within organizations through effective human resource management practices (Villajos et al., 2019).

Creativity is a term that has avoided precise definitions owing to its inherently elusive nature, which encompasses the ability to generate novel and valuable ideas, solutions, or expressions that extend beyond conventional boundaries (Zhou and Hoever, 2023). In the work setting, being creative can be considered part of the job performance dimensions (Harari et al., 2016). When employees exhibit creative performance, they produce novel and potentially useful ideas about the organization’s products, practices, services, and procedures (Shalley et al., 2004).

Although prior research has analyzed how creative performance relates to various organizational outcomes, the personal factors associated with it remain insufficiently understood (Zhang et al., 2021). The assessment and analysis of creative performance as a component of job performance is essential for organizational processes, including personnel selection, compensation, and professional development (DeNisi and Murphy, 2017). This study reviews the existing literature on individual-level factors associated with creative performance, synthesizing current findings to clarify how this outcome is characterized within the field of Human Resource Management (HRM). To generate insights that inform both researchers and practitioners, the present work conducts a systematic review aimed at identifying the personal correlates of creative performance.

2 Job performance and creative performance

Job performance is a multidimensional construct that encompasses behaviors under workers’ control that contribute to organizational goals (Campbell and Wiernik, 2015). It is a product of individual factors, work environment, and their interplay (Yang et al., 2022). Research has consistently highlighted the multifaceted nature of performance (Lievens et al., 2021), comprising three key aspects: task performance, which pertains to in-role behaviors; contextual performance (also called Organizational Citizenship Behavior or OCB), which refers to behaviors that foster a positive organizational environment; and counterproductive work performance, which encompasses any negative behavior directed towards individuals or the organization. However, other domains such as adaptive performance (Park and Park, 2019) and creative performance (Zhou and Hoever, 2014) have been proposed in recent years. Organizations often underestimate the importance of creative performance for its subjective value despite its prominent role in achieving organizational success (Al-Madadha et al., 2023). This paper focuses on creative performance to emphasize the value of displaying creative-related behaviors at work.

Creative performance refers to the observable outcomes of employees’ creative behaviors, specifically the extent to which the generate ideas, products, services, or processes that meet two criteria: (1) they are original or novel, and (2) they hold potential value for or applicability within an organization (Oldham and Cummings, 1996; Zhou and Hoever, 2014). Creative performance is related to other constructs, such as creativity and innovation.

Amabile (1996) considered creativity a complex and diffuse construct arising from a combination of individual and environmental factors, resulting in the generation, development, and expression of innovative and original ideas, solutions, or artistic creations. Creativity involves thinking unconventionally and establishing connections between diverse concepts to produce something novel and beneficial (Shalley et al., 2004). On the other hand, creative performance refers to behaviors aimed at generating original ideas and innovative solutions that manifest creativity in action as the tangible result of creative thinking and problem-solving applied to organizational challenges and opportunities (Zhou and Hoever, 2023). The distinction between creative job performance and creativity is also referred to as creative performance behaviors vs. creative outcome effectiveness (Montag et al., 2012). In this framework, creative performance refers to the behavioral antecedent of creativity, encompassing the observable and cognitive actions individuals enact when approaching nonalgorithmic tasks within the creative process (Lubart, 2001). In contrast, creativity denotes the outcomes produced, which emerge from the interaction of individual capacities and contextual factors that support the generation of original and useful ideas (Hennessey, 2017). Regardless of the term used, it mimics the distinction between behavior and outcomes that appear in the job performance literature (Marques-Quinteiro et al., 2015). Thus, creative performance captures the behavioral expression of the creative process, whereas creativity reflects the quality of the resulting ideas (Zhou and Hoever, 2023).

Innovation, another construct related with creativity, refers to the successful implementation of new or improved ideas, products, and services or processes that transform practices, whereas creative performance focuses on the behaviors that generate these novel ideas, often seen as the initial stage of innovation (Anderson et al., 2014). Hughes et al. (2018) state that not all creative performance leads to innovation, and not all innovative behavior requires employees to be creative before they can be innovative. Therefore, the two concepts are related but not as deeply intertwined as traditionally thought.

Creative performance is key for organizations because it helps solve problems and fosters innovation, productivity, and competitiveness. Hence, more effort is needed to predict the creative performance of employees in organizations (Zhou and Hoever, 2023). By viewing creative performance as a behavioral phenomenon, we can better understand the fundamental processes and mechanisms by which employees operate. The analysis and prediction of job performance dimensions considerably impact organizational processes (Dalal et al., 2012). Following Ployhart (2021), we can outline at least three aspects: (1) it allows us to gain insights into the factors that influence productivity, efficiency, and effectiveness within a work environment; (2) research on organizational performance helps identify areas of improvement, and this knowledge can be instrumental in developing strategies to enhance employee satisfaction, reduce turnover, and boost morale; and (3) performance research is valuable for promoting employee development and well-being, as organizations can identify training and development needs, provide targeted support to employees, and foster a culture of continuous improvement.

Given the relevance of predicting creative performance, we want to explore the personal correlates of creative performance. It is necessary to understand which factors are the most relevant and how they can be categorized (Xu et al., 2018; Zhou and Shalley, 2003), because doing so may allows researchers to move beyond isolated findings and develop more comprehensive frameworks that extend the literature on the personal factors associated with creative performance.

3 The present study

Understanding the personal correlates of creative performance provides insights into how individual characteristics relate to innovation within organizations, as well as employee productivity and effectiveness (Anderson et al., 2014). Despite the topic’s relevance, there is no clear delineation of the personal factors related to creative performance.

To our knowledge, the main effort to combine the cumulative research on the topic is the meta-analysis conducted by Xu et al. (2018). They analyzed 22 studies and found 25 determinants of creative performance between personal factors (e.g., positive and negative affect, motivation) and contextual factors (e.g., time pressure, supervisor support). The personal factors they examined included constructs related to emotions (e.g., PANAs), motivation (e.g., intrinsic motivation), and personality (e.g., need for autonomy). They reported an overall association of 0.551 between these 25 factors and creative performance. However, they also recognized that further research is needed, particularly to examine the specific contribution of each factor.

Despite the relevance of the findings of Xu et al. (2018), we found some limitations in their study that led us to perform our own study. First of all, they reported data from workers and students, which can bias the results. Second, Xu et al. (2018) based their studies on relatively restrictive databases (i.e., the Chinese databases CNKI, Wan, and ScienceDirect and SpringerLink), which probably do not account for all creative performance research. Broader databases, like Web of Science (Wos) or Scopus probably achieve more results. Third, they only considered direct effects, leaving a gap in understanding how mediating or moderating factors may influence the overall dynamics.

Taking into account the aforementioned limitations, we propose to conduct a systematic review which: (1) analyzes the studies that report workers’ data; (2) focuses on the main current databases (WoS and Scopus); and (3) considers direct and indirect effects on creative performance.

4 Materials and methods

4.1 Inclusion criteria

Only articles published before January 2024 in peer-reviewed journals were included. There were no restrictions on participant population or geographic or cultural origin. Five criteria were established for inclusion in the review: (1) studies had to be written either in English or Spanish; (2) participants had to be workers; (3) the study design had to be quantitatively oriented; (4) the study must include a measure of creative performance; and (5) the studies had to establish a relationship between some personal construct and creative performance, where the personal construct is proposed as an antecedent of creative performance.

4.2 Literature search

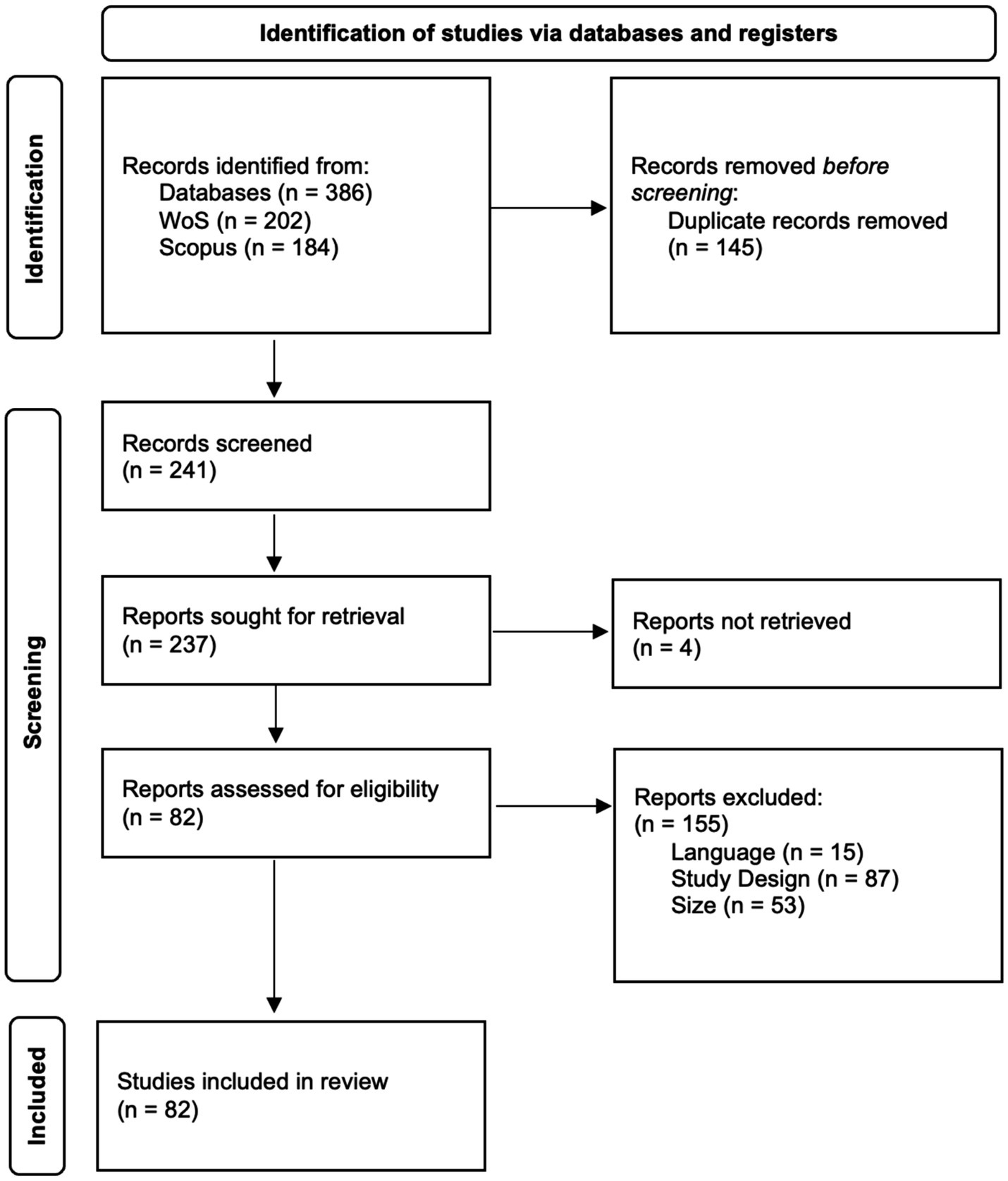

We followed the PRISMA statement for this review (Page et al., 2021) using the Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus databases for literature research. The specific syntax used for the WoS was [“creative performance”] in the “title” field and [“work” or “job” or “organization” or “employee”] in the “topic” field. The specific syntax used for Scopus was [“creative performance”] in the “article title” field and [“work” or “job” or “organization” or “employee”] in the “abstrac” field. The search was performed in January 2024. A total of 386 articles were retrieved, of which 145 (37.6%) were duplicates.

A total of 241 full-text articles were reviewed, of which 82 (34%) were included in the final study. Fifteen articles (6.2%) were excluded due to the publication language. Eighty-seven articles (36.1%) did not meet the research objectives analyzed in this systematic review (i.e., to establish relationships between personal factors and determine whether they are associated with creative performance in organizations; some articles did not measure participants’ creative performance). Fifty-three articles (22%) were excluded because the sample did not comprise employees performing a job in an organization. Four articles (1.7%) were not accessible to the research team. The PRISMA flow diagram can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram.

5 Results

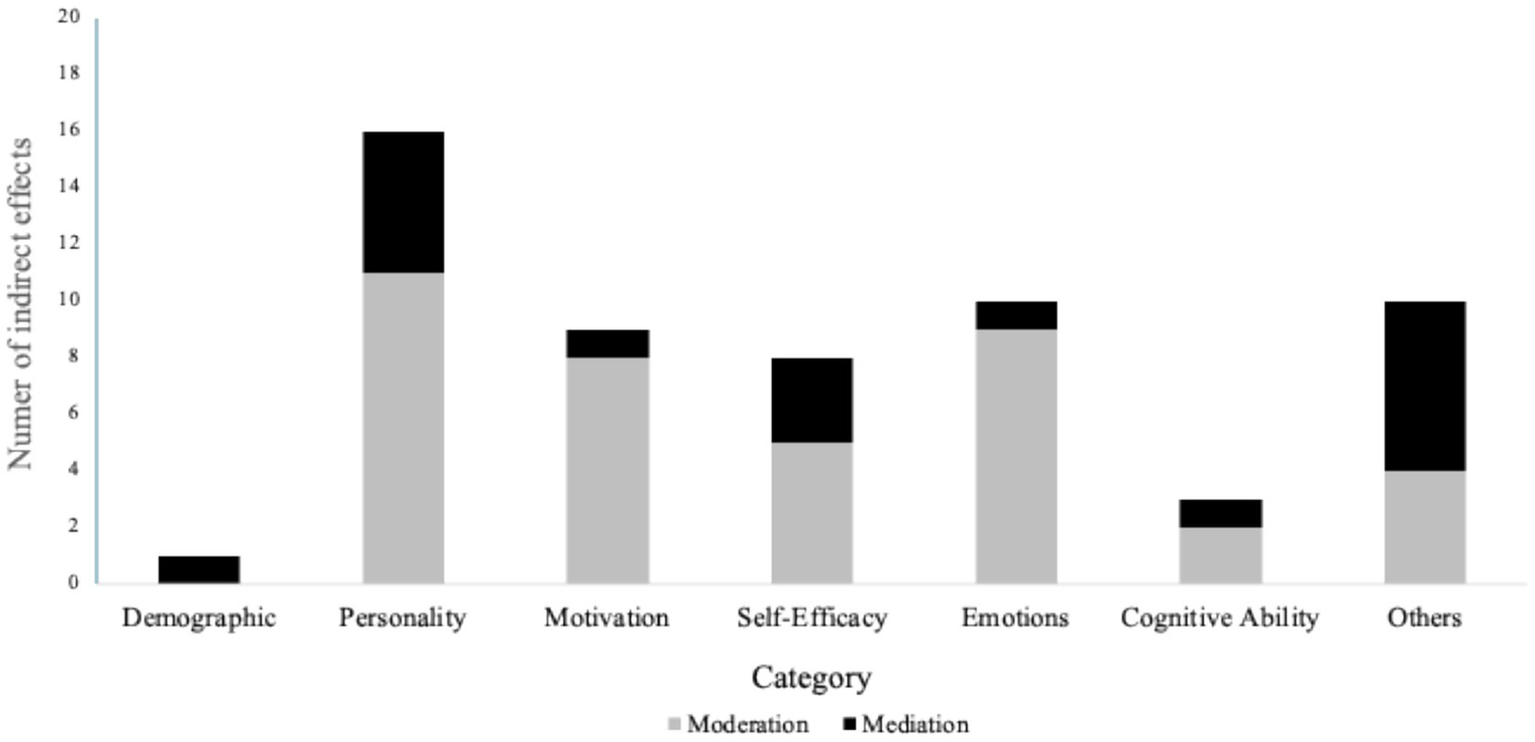

Our review comprises 82 studies. Of them, the analysis revealed 79 direct effects and 57 indirect effects related to personal characteristics influencing creative performance. Of the indirect effects, most were moderations (N = 39; 68.4%), and the remaining were mediations (N = 18; 31.6%), as illustrated in Figure 2. Regarding study design, most followed a cross-sectional design (N = 60; 73.2%). There was consistency in the measurement of employee creative performance. Supervisor ratings were used in 44 studies (53.7%), self-reports in 35 studies (42.7%), coworker ratings in 2 studies (2.4%), and a combination of self-reports and supervisor ratings in only 1 study (1.2%). Given space limitations, indirect effects are also detailed in Supplementary material. Thus, the following sections focus on the main effects.

Figure 2

Moderated and mediated effects of personal correlates on creative performance.

The personal correlates of creative performance identified in the systematic review were categorized into eight different categories: (1) demographic factors, (2) personality, (3) cognitive ability, (4) motivation, (5) emotions, (6) self-efficacy, (7) other performance dimensions, and (8) others. These categories were developed inductively after identifying the full set of personal factors across the reviewed studies, allowing conceptually similar variables to be grouped together. The amount of papers detailing each personal characteristic and the papers that support them are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

| Category | Construct | Reference | Country | Measurement | Industry | N (%F) | r | p | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Gender | Aleksic et al. (2016) | Slovenia | Self-report and supervisor-report | (1) Casual sector (2) Manufacturing |

129 (59%) 165 (34%) |

— −0.10 |

— <0.05 |

CS |

| Cheung and Zhang (2021) | China | Supervisor-report | (1) Knowledge-based (2) Professional services |

100 (52.4%) 175 (63.7%) |

0.15 0.17 |

<0.05 <0.05 |

CS | ||

| Eslamlou et al. (2021) | Not reported | Supervisor-report | Aviation | 121 (60.3%) | 0.17 | <0.05 | L | ||

| He et al. (2018) | China | Supervisor-report | Various industries | 335 (15.2%) | 0.15 | <0.05 | CS | ||

| Hu et al. (2022) | Pakistan | Self-report | Manufacturing | 311 (34.7%) | 0.20 | <0.05 | CS | ||

| Hwang et al. (2023) | Korea | Self-report | Manufacturing | 321 (50.2%) | −0.11 | <0.05 | CS | ||

| Leung et al. (2014) | China | Supervisor-report | Education | 189 (45.5%) | 0.19 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Thundiyil et al. (2016) | China | Supervisor-report | Chemical | 459 (46%) | −0.13 | <0.05 | CS | ||

| Wang et al. (2023) | China | Supervisor-report | Manufacturing, finance and internet | 1,384 (43.9%) | −0.09 | <0.05 | L | ||

| Yang et al. (2022) | China | Supervisor-report | Banking | 368 (79.4%) | −0.22 | <0.05 | L | ||

| Educational level | Darvishmotevali et al. (2018) | Cyprus | Self-report | Hospitality | 283 (52%) | 0.13 | <0.05 | CS | |

| Gilmore et al. (2013) | China | Supervisor-report | Pharmaceutical | 212 (74%) | 0.36 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Liu et al. (2019) | China | Supervisor-report | High-tech | 318 (24%) | 0.14 | < 0.05 | L | ||

| Man et al. (2020) | China | Supervisor-report | Medical | 300 (78%) | 0.12 | <0.05 | L | ||

| Thundiyil et al. (2016) | China | Supervisor-report | Chemical | 459 (46%) | 0.18 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Tierney and Farmer (2011) | Not reported | Supervisor-report | Not reported | 145 (68.8%) | 0.24 | <0.01 | L | ||

| Age | Hon et al. (2014) | China | Supervisor-report | High-tech, Manufacturing and Service | 452 (47%) | −0.27 | <0.05 | CS | |

| Hu et al. (2019) | China | Self-report | Casual sector | 275 (70.9%) | 0.13 | <0.05 | CS | ||

| Peng and Chen (2023) | Taiwan | Supervisor-report | Information technology | 413 (75%) | 0.12 | <0.05 | CS | ||

| Thundiyil et al. (2016) | China | Supervisor-report | Chemical | 459 (46%) | 0.18 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Yang et al. (2022) | China | Supervisor-report | Banking | 368 (79.4%) | −0.13 | <0.05 | L | ||

| Job tenure | Hora et al. (2021a) | USA | Supervisor-report | Food manufacturing | 335 (64%) | −0.10 | <0.05 | L | |

| Tierney and Farmer (2002) | Not reported | Supervisor-Report | (1) Consumer Goods (2) High-tech |

502 (−%) 104 (−%) |

0.20 — |

<0.01 — |

CS | ||

| Yang et al. (2022) | China | Supervisor-report | Banking | 368 (79.4%) | 0.07 | <0.05 | L | ||

| Industry type | Hu et al. (2022) | Pakistan | Self-report | Manufacturing | 311 (34.7%) | 0.24 | <0.05 | CS | |

| Marital status | Madjar et al. (2002) | Bulgaria | Supervisor-report | Apparel manufacturing | 265 (97%) | 0.13 | <0.05 | CS | |

| Use of digital platforms | Tonnessen et al. (2021) | Norway | Self-report | Not reported | 237 (50%) | 0.27 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Personality | Openness to Experience | Herbst and Hausberg (2022) | Not reported | Self-report | Not reported | 528 (−%) | 0.45 | <0.001 | CS |

| Shaw and Choi (2023) | USA | Supervisor-report | Consulting | 170 (53.8%) | 0.28 | <0.001 | CS | ||

| Proactive personality | Chen et al. (2015) | Taiwan | Self-report | Manufacturing | 337 (17%) | 0.46 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Choi et al. (2021) | Korea | Self-report | Manufacturing and service | 439 (30.3%) | 0.74 | <0.001 | CS | ||

| Li et al. (2020a) | Taiwan | Supervisor-report | Technology and manufacturing | 125 (46.4%) | 0.45 | <0.01 | L | ||

| Sumaneeva et al. (2021) | Russia | Self-report | Hospitality | 101 (65%) | 0.44 | <0.01 | L | ||

| Creative personality | Audenaert and Decramer (2018) | Belgium | Self-report | Industrial | 213 (36%) | 0.31 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Shalley et al. (2009) | USA | Self-report | Not reported | 1,430 (51%) | 0.16 | <0.05 | CS | ||

| Autonomy orientation | Ye et al. (2014) | China | Supervisor-report | High-tech | 120 (36.7%) | 0.30 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Innovativeness | Chen et al. (2015) | Taiwan | Self-report | Manufacturing | 337 (17%) | 0.49 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Preference for creativity | Aleksic et al. (2016) | Slovenia | Self-report and supervisor-report | (1) Casual sector (2) Manufacturing |

129 (59%) 165 (34%) |

0.66 0.23 |

<0.01 <0.01 |

CS | |

| Conscientiousness | Shaw and Choi (2023) | USA | Supervisor-report | Consulting | 170 (53.8%) | 0.27 | <0.001 | CS | |

| Promotion focus | Liu et al. (2022) | China | Supervisor-report | Retail | 206 (62.6%) | 0.14 | <0.05 | CS | |

| Extraversion | Shaw and Choi (2023) | USA | Supervisor-report | Consulting | 170 (53.8%) | 0.27 | <0.001 | CS | |

| Optimism | Bouzari and Karatepe (2020) | Iran | Supervisor-report | Hospitality | 187 (39.6%) | 0.28 | <0.01 | L | |

| Neuroticism | |||||||||

| Obsessive-compulsive personality | Abukhait et al. (2023) | UAE | Supervisor-report | Hospitality | 252 (49.4%) | −0.28 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Resilience | Eslamlou et al. (2021) | Not reported | Supervisor-report | Aviation | 121 (60.3%) | 0.49 | <0.01 | L | |

| Resistance to Change | Hon et al. (2014) | China | Supervisor-report | High-tech, manufacturing and service | 452 (47%) | −0.34 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Trait positive affectivity | Gilmore et al. (2013) | China | Supervisor-report | Pharmaceutical | 212 (74%) | 0.20 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Cognitive ability | Cultural Intelligence | Hu et al. (2019) | China | Self-report | Casual sector | 275 (70.9%) | −0.62 | <0.01 | CS |

| Innovative cognitive style | De Stobbeleir et al. (2011) | Not reported | Supervisor-report | Consulting | 456 (56%) | 0.23 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Associative cognitive style | Shalley et al. (2009) | USA | Self-report | Not reported | 1,430 (51%) | −0.23 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Perspective Taking | He et al. (2018) | China | Supervisor-report | Various industries | 335 (15.2%) | 0.31 | <0.001 | CS | |

| Motivation | Intrinsic Motivation | Cheung and Zhang (2021) | China | Supervisor-report | (1) Knowledge-based (2) Professional services |

100 (52.4%) 175 (63.7%) |

0.24 0.53 |

<0.01 <0.01 |

CS |

| Glaser et al. (2015) | Germany | Self-report | General population | 830 (34.8%) | 0.28 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Herbst and Hausberg (2022) | Not reported | Self-report | Not reported | 528 (−%) | 0.14 | <0.05 | CS | ||

| Li et al. (2018) | China | Self-report | (1) Information technology (2) Information technology |

141 (31%) 135 (46%) |

0.24 0.41 |

<0.05 <0.01 |

CS | ||

| Liu et al. (2019) | China | Supervisor-report | High-tech | 318 (24%) | 0.18 | <0.01 | L | ||

| Makhija and Akbar (2019) | Pakistan | Supervisor-report | Information technology | 240 (17.5%) | 0.64 | <0.05 | CS | ||

| Malik et al. (2015) | Pakistan | Supervisor-report | Not reported | 181 (14%) | 0.33 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Shaheen et al. (2020) | Pakistan | Supervisor-report | Banking | 303 (33%) | 0.51 | <0.05 | CS | ||

| Shalley et al. (2009) | USA | Self-report | Not reported | 1,430 (51%) | 0.30 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Tonnessen et al. (2021) | Norway | Self-report | Not reported | 237 (50%) | 0.34 | <0.001 | CS | ||

| Xie et al. (2020) | China | Supervisor-report | Not reported | 386 (44.4%) | 0.26 | <0.001 | CS | ||

| Zhang and Bartol (2010) | China | Supervisor-report | Not reported | 367 (34.8%) | 0.66 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Challenge Intrinsic Motivation | Leung et al. (2014) | China | Supervisor-report | Education | 189 (45.5%) | 0.40 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Commitment to creativity | Yoon et al. (2015) | South Korea | Coworker-report | Not reported | 241 (27%) | 0.28 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Intrinsic rewards for creativity | Yoon et al. (2015) | South Korea | Coworker-report | Not reported | 241 (27%) | 0.21 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Extrinsic motivation | |||||||||

| Extrinsic motivation | Herbst and Hausberg (2022) | Not reported | Self-report | Not reported | 528 (−%) | 0.56 | <0.001 | CS | |

| Importance of extrinsic rewards | Malik et al. (2015) | Pakistan | Supervisor-report | Not reported | 181 (14%) | 0.19 | <0.05 | CS | |

| Engagement | |||||||||

| Creative process engagement | Herbst and Hausberg (2022) | Not reported | Self-report | Not reported | 528 (−%) | 0.37 | <0.05 | CS | |

| Khan and Abbas (2022) | Pakistan | Self-report | Service and manufacturing | 303 (27.4%) | 0.69 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Yang et al. (2021) | China | Supervisor-report | Electronics | 347 (33.1%) | 0.13 | <0.05 | L | ||

| Zhang and Bartol (2010) | China | Supervisor-report | Not reported | 367 (34.8%) | 0.70 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Zheng et al. (2022) | China | Supervisor-report | Not reported | 292 (47.3%) | 0.33 | <0.001 | L | ||

| Work engagement | Li et al. (2021) | China | Supervisor-report | High-tech | 237 (39.7%) | 0.39 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Peng and Chen (2023) | Taiwan | Supervisor-report | Information technology | 413 (75%) | 0.55 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Sumaneeva et al. (2021) | Russia | Self-report | Hospitality | 101 (65%) | 0.43 | <0.01 | L | ||

| Green creative process engagement | Hu et al. (2022) | Pakistan | Self-report | Manufacturing | 311 (34.7%) | 0.35 | <0.001 | CS | |

| Motivation to goals | |||||||||

| Goal self-concordance | Zhang et al. (2017) | China | Supervisor-report | Industrial | 162 (41.4%) | 0.29 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Learning goal | Liu et al. (2019) | China | Supervisor-report | High-tech | 318 (24%) | 0.18 | <0.01 | L | |

| Need for achievement | Hon (2012) | China | Self-report | Hospitality and service | 219 (42%) | 0.35 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Need satisfaction | Martinaityte et al. (2019) | Lithuania | Supervisor-report | Banking and cosmetics | 329 (96%) | 0.53 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Motivation (Others) | |||||||||

| Green motivation | Hu et al. (2022) | Pakistan | Self-report | Manufacturing | 311 (34.7%) | 0.29 | <0.05 | CS | |

| Growth need strength | Shalley et al. (2009) | USA | Self-report | Not reported | 1,430 (51%) | 0.28 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Job embeddedness | Karatepe (2016) | Cameroon | Supervisor-report | Hospitality | 212 (48%) | 0.16 | <0.05 | CS | |

| Motivation (General) | Tonnessen et al. (2021) | Norway | Self-report | Not reported | 237 (50%) | 0.34 | <0.001 | CS | |

| Wisdom | Kalyar and Kalyar (2018) | Pakistan | Self-report | Service and manufacturing | 753 (14.1%) | 0.19 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Emotions | Positive dimension | ||||||||

| Positive affect | Gong and Zhang (2017) | China | Supervisor-report | Various industries | 264 (49.2%) | 0.41 | <0.01 | L | |

| Madjar et al. (2002) | Bulgaria | Supervisor-report | Apparel manufacturing | 265 (97%) | 0.20 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Qian and Jiang (2023) | China | Self-report | Various industries | 107 (54.2%) | 0.48 | <0.01 | L | ||

| Thundiyil et al. (2016) | China | Supervisor-report | Chemical | 459 (46%) | 0.18 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Xie et al. (2020) | China | Supervisor-report | Not reported | 386 (44.4%) | 0.25 | <0.001 | CS | ||

| Eudaimonic wellbeing | Villajos et al. (2019) | Spain | Self-report | Various industries | 209 (60.8%) | 0.40 | <0.001 | L | |

| Zhang and Zhao (2021) | China | Self-report | Not reported | 288 (44.8%) | 0.43 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Thriving at work | Bhatti et al. (2022) | Malaysia | Self-report | Information technology | 227 (21.1%) | 0.90 | <0.05 | CS | |

| Christensen-Salem et al. (2021) | Taiwan | Supervisor-report | Public sector | 795 (34%) | 0.49 | <0.01 | L | ||

| Happiness | Khan and Abbas (2022) | Pakistan | Self-report | Service and manufacturing | 303 (27.4%) | 0.59 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Hedonic wellbeing | Zhang and Zhao (2021) | China | Self-report | Not reported | 288 (44.8%) | 0.59 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Negative dimension | |||||||||

| Negative affect | Gong and Zhang (2017) | China | Supervisor-report | Various industries | 264 (49.2%) | 0.50 | <0.01 | L | |

| Stress | Kalyar and Kalyar (2018) | Pakistan | Self-report | Service and manufacturing | 753 (14.1%) | −0.27 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Emotion regulation | |||||||||

| Emotional intelligence | Cai et al. (2022) | Pakistan | Self-report | Education | 237 (43.5%) | 0.70 | <0.05 | CS | |

| Darvishmotevali et al. (2018) | Cyprus | Self-report | Hospitality | 283 (52%) | 0.43 | <0.001 | CS | ||

| Self-efficacy | Creative self-efficacy | Abdullah et al. (2017) | Pakistan | Self-report | Casual sector | 322 (37%) | 0.51 | <0.05 | CS |

| Aleksic et al. (2016) | Slovenia | Self-report and supervisor-report | (1) Casual sector (2) Manufacturing |

129 (59%) 165 (34%) |

0.57 — |

<0.01 — | CS | ||

| Chiang et al. (2022) | Taiwan | Self-report | Education | 341 (74.5%) | 0.54 | <0.01 | L | ||

| Choi et al. (2021) | Korea | Self-report | Manufacturing and service | 439 (30.3%) | 0.67 | <0.001 | CS | ||

| Christensen-Salem et al. (2021) | Taiwan | Supervisor-report | Public sector | 795 (34%) | 0.44 | <0.01 | L | ||

| Hora et al. (2021a) | USA | Supervisor-report | Food manufacturing | 335 (64%) | 0.12 | <0.05 | L | ||

| Li et al. (2018) | China | Self-report | Information technology | 135 (46%) | 0.40 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Li et al. (2020b) | China | Supervisor-report | High-tech | 346 (27.7%) | 0.05 | <0.05 | L | ||

| Liu et al. (2019) | China | Supervisor-report | High-tech | 318 (24%) | 0.31 | <0.01 | L | ||

| Malik et al. (2015) | Pakistan | Supervisor-report | Not reported | 181 (14%) | 0.28 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Man et al. (2020) | China | Supervisor-report | Medical | 300 (78%) | 0.19 | <0.01 | L | ||

| Nwanzu and Babalola (2022) | Nigeria | Self-report | Public and private sectors | 148 (54.7%) | 0.63 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Putra et al. (2023) | Indonesia | Self-report | Software development | 253 (22%) | 0.76 | <0.05 | CS | ||

| Simmons et al. (2014) | USA | Supervisor-report | Not reported | 128 (42%) | 0.57 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Tang and Sun (2021) | China | Supervisor-report | Not reported | 186 (52.7%) | 0.22 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Thundiyil et al. (2016) | China | Supervisor-report | Chemical | 459 (46%) | 0.17 | <0.01 | CS | ||

| Tierney and Farmer (2002) | Not reported | Supervisor-report | (1) Consumer Goods; (2) High-tech |

502 (−%) 104 (−%) |

0.17 0.24 |

<0.01 <0.01 |

CS | ||

| Tierney and Farmer (2011) | Not reported | Supervisor-report | Not reported | 145 (68.8%) | 0.29 | <0.01 | L | ||

| Torner (2023) | Colombia | Self-report | Electrical manufacturing | 448 (39.1%) | 0.58 | <0.001 | CS | ||

| Wadei et al. (2021) | Ghana | Supervisor-report | Service industries | 512 (38.7%) | 0.74 | <0.01 | L | ||

| Yulianti et al. (2022) | Indonesia | Self-report | Education | 200 (61%) | 0.37 | <0.05 | CS | ||

| Yulianti and Usman (2019) | Indonesia | Self-report | Media | 154 (−%) | 0.32 | <0.05 | CS | ||

| Self-efficacy | Ishaque et al. (2019) | Punjab | Supervisor-report | Education | 302 (−%) | 0.32 | <0.05 | CS | |

| Torner (2023) | Colombia | Self-report | Electrical manufacturing | 448 (39.1%) | 0.46 | <0.001 | CS | ||

| Performance | Organizational citizenship behavior | Al-Madadha et al. (2023) | Jordan | Self-report | Telecommunication | 344 (55.9%) | 0.77 | <0.05 | CS |

| Chuang et al. (2019) | Taiwan | Coworker-report | Education | 135 (81%) | 0.53 | <0.01 | L | ||

| He et al. (2018) | China | Supervisor-report | Various industries | 335 (15.2%) | 0.62 | <0.001 | CS | ||

| Performance approach goal | Liu et al. (2019) | China | Supervisor-report | High-tech | 318 (24%) | 0.17 | <0.01 | L | |

| Task performance | Yang et al. (2022) | China | Supervisor-report | Banking | 368 (79.4%) | 0.78 | <0.01 | L | |

| Others | Knowledge sharing | Ren et al. (2021) | China | Supervisor-report | Not reported | 387 (51.2%) | 0.34 | <0.01 | CS |

| Wang et al. (2023) | China | Supervisor-report | Manufacturing, finance and internet | 1,384 (43.9%) | 0.41 | <0.01 | L | ||

| Psychological capital | Gupta and Singh (2014) | India | Self-report | Public research | 496 (25%) | 0.69 | <0.001 | CS | |

| Ozturk and Karatepe (2019) | Russia | Supervisor-report | Hospitality | 159 (67.9%) | 0.28 | <0.01 | L | ||

| Voice behavior | Hwang et al. (2023) | Korea | Self-report | Manufacturing | 321 (50.2%) | 0.77 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Song et al. (2017) | China | Self-report | Not reported | 752 (53.7%) | 0.47 | <0.001 | CS | ||

| Creativity-oriented high-performance work systems | Martinaityte et al. (2019) | Lithuania | Supervisor-report | Banking and cosmetics | 329 (96%) | 0.57 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Diversity ideology | Cheung and Zhang (2021) | China | Supervisor-report | (1) Knowledge-based; (2) Professional services |

100 (52.4%) 175 (63.7%) |

0.23 0.25 |

<0.01 <0.01 |

CS | |

| Employee voice | Karkoulian et al. (2023) | Lebanon | Self-report | Banking | 301 (46%) | 0.76 | <0.001 | CS | |

| Environmental uncertainty | Darvishmotevali et al. (2018) | Cyprus | Self-report | Hospitality | 283 (52%) | 0.31 | <0.001 | CS | |

| Explicit knowledge contribution | Mohammed and Kamalanabhan (2019) | India | Self-report | Information technology | 401 (31.2%) | 0.42 | <0.01 | CS | |

| External digital knowledge sharing | Tonnessen et al. (2021) | Norway | Self-report | Not reported | 237 (50%) | 0.40 | <0.001 | CS | |

| Knowledge acquisition behavior | Sun et al. (2020) | China | Self-report | Not reported | 365 (57.4%) | 0.63 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Knowledge provision behavior | Sun et al. (2020) | China | Self-report | Not reported | 365 (57.4%) | 0.64 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Mindfulness | Khan and Abbas (2022) | Pakistan | Self-report | Service and manufacturing | 303 (27.4%) | 0.47 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Perceived organizational support | De Stobbeleir et al. (2011) | Not reported | Supervisor-report | Consulting | 456 (56%) | 0.16 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Prohibitive voice behavior | Prince and Kameshwar Rao (2022) | India | Self-report | Information technology | 285 (71.2%) | 0.39 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Promotive voice behavior | Prince and Kameshwar Rao (2022) | India | Self-report | Information technology | 285 (71.2%) | 0.47 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Tacit knowledge seeking | Mohammed and Kamalanabhan (2019) | India | Self-report | Information technology | 401 (31.2%) | 0.42 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Use of knowledge management systems | Herbst and Hausberg (2022) | Not reported | Self-report | Not reported | 528 (−%) | 0.62 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Voice toward peers | Li et al. (2022) | China | Supervisor-report | Manufacturing | 206 (20.4%) | 0.52 | <0.01 | L | |

| Work values: comfort | Ren et al. (2021) | China | Supervisor-report | Not reported | 387 (51.2%) | −0.31 | <0.01 | CS | |

| Work values: competence | Ren et al. (2021) | China | Supervisor-report | Not reported | 387 (51.2%) | 0.26 | <0.001 | CS | |

| Work-life balance | Bouzari and Karatepe (2020) | Iran | Supervisor-report | Hospitality | 187 (39.6%) | 0.14 | <0.05 | L | |

Personal correlates directly associated with creative performance.

Measurement indicates the type of assessment used for creative performance. r refers to the Pearson correlation coefficient.

The demographic factors found in the literature are gender, age, educational level, job tenure, industry type, marital status, and use of digital platforms. In terms of gender, the results were mixed, with five showing that women scored higher in creative performance on average than men (Aleksic et al., 2016; Cheung and Zhang, 2021; Eslamlou et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2022; Leung et al., 2014) while in five studies men obtained higher scores (He et al., 2018; Hwang et al., 2023; Thundiyil et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2022). Educational level appears to be positively associated with creative performance (Darvishmotevali et al., 2018; Gilmore et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2019; Man et al., 2020; Thundiyil et al., 2016; Tierney and Farmer, 2011). Time-related outcomes, such as age or job tenure, are inconclusive. Three studies reported that younger individuals scored higher on creative tasks (Hon et al., 2014; Thundiyil et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2022), whereas two studies found that older individuals obtained higher scores (Hu et al., 2019; Peng and Chen, 2023). Regarding job tenure, two studies reported a positive association between job tenure and creative performance scores (Tierney and Farmer, 2002; Yang et al., 2022). However, one study found that employees with less work experience scored higher (Hora et al., 2021a). Three other demographic factors have been examined in relation to creative performance: industry type, marital status, and use of digital platforms. Hu et al. (2022) observed differences by industry type, as employees in the manufacturing sector were more motivated by innovative ideas and solutions than employees in the service sector. Married individuals demonstrated greater creativity than their unmarried counterparts (Madjar et al., 2002). The use of digital platforms (e.g., tools for video meetings, enterprise social media, file-sharing, etc.) positively correlated with creative performance (Tonnessen et al., 2021).

Personality-related factors associated with creative performance were classified according to the Big Five, a model that describes five broad traits of personality—openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism—that are widely accepted in the workplace (Salgado and De Fruyt, 2017). Among these traits, openness shows the strongest empirical support (Herbst and Hausberg, 2022; Shaw and Choi, 2023). Several personality facets also show consistent positive associations with creative performance, including creative personality (Audenaert and Decramer, 2018; Shalley et al., 2009), autonomy orientation (Ye et al., 2014), innovativeness (Chen et al., 2015), and preference for creativity (Aleksic et al., 2016), with a special emphasis on the proactive personality (Chen et al., 2015; Choi et al., 2021; Li et al., 2020a; Sumaneeva et al., 2021). Associations for facets related to conscientiousness (Liu et al., 2022; Shaw and Choi, 2023) and extraversion (Bouzari and Karatepe, 2020; Shaw and Choi, 2023) align with findings from other performance research, with both traits showing positive relationships with creative performance. In fact, openness, conscientiousness and extraversion were the only personality constructs with empirical evidence supporting their association with creative performance at the trait level. Neuroticism is characterized by the tendency to experience unfavorable emotions. Constructs that can be comprised within neuroticism, like obsessive-compulsive personality (Abukhait et al., 2023) and resistance to change (Hon et al., 2014), show negative associations, as expected from the literature. Consequently, traits such as resilience (Eslamlou et al., 2021), which opposes neuroticism, and trait positive affectivity (Gilmore et al., 2013) are positively associated with creative performance. Agreeableness is the only trait that does not show associations in terms of creative performance.

Four personal factors were included in cognitive ability. Hu et al. (2019) observed that cultural intelligence is positively associated with employees’ creative performance. Innovative cognitive style shows a positively association with creative performance (De Stobbeleir et al., 2011). Similarly, perspective-taking is positively related to creative performance (He et al., 2018). However, an associative cognitive style is associated with lower creative performance, a pattern that may reflect its reliance on existing connections, which could relate to lower levels of novelty in idea generation (Shalley et al., 2009).

Evidence shows that motivation is consistently associated with creative performance. The constructs have been categorized as intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, engagement, and others. Concerning intrinsic motivation, intrinsic motivation itself (Cheung and Zhang, 2021; Glaser et al., 2015; Herbst and Hausberg, 2022; Li et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019; Makhija and Akbar, 2019; Malik et al., 2015; Shaheen et al., 2020; Shalley et al., 2009; Tonnessen et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2020; Zhang and Bartol, 2010), challenging intrinsic motivation (Leung et al., 2014), commitment to creativity (Yoon et al., 2015), and intrinsic rewards for creativity (Yoon et al., 2015) show positive associations with creative performance. Regarding extrinsic motivation, constructs such as extrinsic motivation itself (Herbst and Hausberg, 2022) and the importance of extrinsic rewards (Malik et al., 2015) are positively related to creative performance. Another motivational construct related to creative performance is engagement, defined as employees’ commitment to their organizational roles (Reig-Botella et al., 2024). The results show that creative process engagement (Herbst and Hausberg, 2022; Hu et al., 2022; Khan and Abbas, 2022; Yang et al., 2021; Zhang and Bartol, 2010; Zheng et al., 2022) and work engagement (Li et al., 2021; Peng and Chen, 2023; Sumaneeva et al., 2021) are positively associated with creative performance. Similarly, motivation for goals is positively associated with creative performance (Hon, 2012; Liu et al., 2019; Martinaityte et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2017). Other more specific constructs are also associated with creative performance, such as green motivation (Hu et al., 2022), growth need strength (Shalley et al., 2009), job embeddedness (Karatepe, 2016), general motivation (Tonnessen et al., 2021) or wisdom (Kalyar and Kalyar, 2018).

Personal constructs related to emotions have been classified into three categories: positive dimension, negative dimension, and emotion regulation. Within the positive dimension, constructs such as positive affect (Gong and Zhang, 2017; Madjar et al., 2002; Qian and Jiang, 2023; Thundiyil et al., 2016; Xie et al., 2020), eudaimonic well-being (Villajos et al., 2019; Zhang and Zhao, 2021), thriving at work (Bhatti et al., 2022; Christensen-Salem et al., 2021) and happiness (Khan and Abbas, 2022), hedonic well-being (Zhang and Zhao, 2021), had a positive association with creative performance. However, in the negative dimension, negative affect (Gong and Zhang, 2017) and stress (Kalyar and Kalyar, 2018) are negatively related to creative performance. In addition, within the emotion regulation category, emotional intelligence (Cai et al., 2022; Darvishmotevali et al., 2018) is positively associated with creative performance.

Self-efficacy shows a positive relationship with creative performance (Ishaque et al., 2019; Torner, 2023). However, most studies report that creative self-efficacy is positively associated with creative performance (Abdullah et al., 2017; Aleksic et al., 2016; Chiang et al., 2022; Choi et al., 2021; Christensen-Salem et al., 2021; Hora et al., 2021a; Li et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020b; Liu et al., 2019; Malik et al., 2015; Man et al., 2020; Nwanzu and Babalola, 2022; Putra et al., 2023; Simmons et al., 2014; Tang and Sun, 2021; Thundiyil et al., 2016; Tierney and Farmer, 2002, 2011; Torner, 2023; Wadei et al., 2021; Yulianti et al., 2022; Yulianti and Usman, 2019).

Studies also investigate the relationship between creative performance and other dimensions of job performance. As expected, there is a positive relationship between creative performance and the dimensions of organizational citizenship behavior (Al-Madadha et al., 2023; Chuang et al., 2019; He et al., 2018) and task performance (Yang et al., 2022). Similarly, performance-approach goal orientation is positively related to creative performance (Liu et al., 2019). As part of the broader job performance construct, these findings should not be interpreted as evidence of a causal relationship, but rather as indicating covariation among performance dimensions.

A total of 23 personal factors were grouped under the “others” category (e.g., knowledge sharing; psychological capital). These factors are conceptually heterogeneous and do not align within the broader categories that were developed inductively after examining the set of reviewed studies. Because of their specificity and limited recurrence across the literature, a detailed discussion of each factor is beyond the scope of this review. Readers interested in any of these variables may consult the corresponding primary studies for a fuller examination.

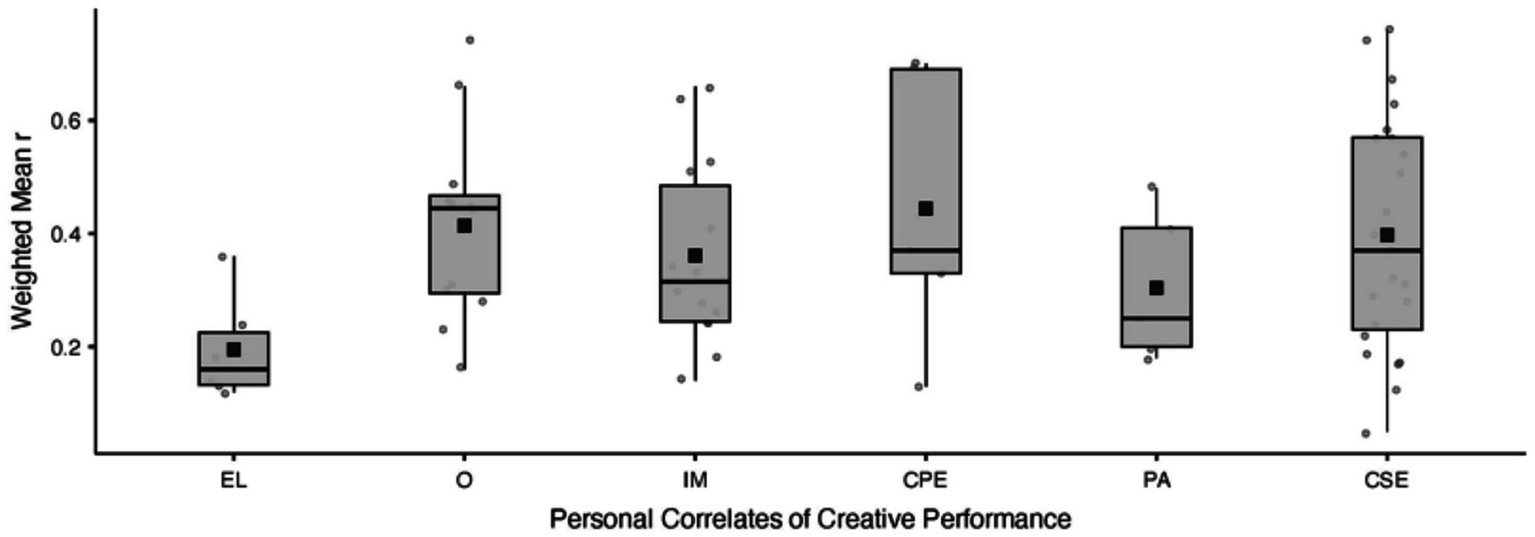

Finally, we aimed to identify which personal factors are most consistently associated with creative performance in the literature. Given the distribution of the papers reporting this relationship (M = 1.96, SD = 2.87), we focused on constructs with five or more studies (+1 SD) examining their association with creative performance. On this basis, six personal factors were retained. Weighted arithmetic means showed a small but significant positive association for educational level (rw = 0.19, 95% CI [0.12, 0.27], p < 0.001; I2 = 55.66%), and moderate to strong positive associations for openness (rw = 0.46, 95% CI [0.33, 0.59], p < 0.001; I2 = 93.76%), intrinsic motivation (rw = 0.39, 95% CI [0.28, 0.50], p < 0.001; I2 = 93.37%), creative process engagement (rw = 0.52, 95% CI [0.23, 0.80], p < 0.001; I2 = 97.39%), positive affect (rw = 0.31, 95% CI [0.18, 0.43], p < 0.001; I2 = 81.53%), and creative self-efficacy (rw = 0.45, 95% CI [0.34, 0.56], p < 0.001; I2 = 95.30%). Given the very high heterogeneity observed for most constructs, these weighted mean correlations should be interpreted with caution and regarded primarily as summary indicators of the central tendency of the reported associations. As illustrated in Figure 3, the variability of effect sizes across studies is substantial, underscoring the need to consider contextual and methodological differences when interpreting these findings.

Figure 3

Key factors on creative performance. Note. EL: Educational Level; O: Openness; IM: Intrinsic Motivation; CPE: Creative Process Engagement; PA: Positive Affect; CSE: Creative Self-Efficacy.

6 Discussion

The present paper aims to identify the main personal correlates of creative performance. For this purpose, we performed a systematic review of the literature. The personal factors identified across studies show substantial heterogeneity in both conceptual focus and empirical findings. In addition to the direct associations summarized in this section, the review also identified a substantial number of indirect effects (39 moderations and 18 mediations) reflecting the complex interplay among personal factors and their links to creative performance. Given the heterogeneity and volume of these results, they are presented in detail in the Supplementary material. Nevertheless, our results suggest that six personal factors are most consistently associated with creative performance. We will now present the implications of these results.

The weighted arithmetic means revealed substantial heterogeneity for most personal factors (I2 ranging from 56 to 97%), indicating that the strength of these associations varies markedly across studies. This variability can be explained by differences in how creative performance was measured (self-reports, supervisor-report, or coworker-report), the diversity of industries represented, and cultural contexts that shape how creativity-related constructs operate. Together, these factors suggest that creative performance is highly context-dependent, and that personal correlates should be interpreted with caution and in relation to the settings in which they were examined.

First, education has been consistently associated with higher levels of creative performance by providing individuals with new knowledge, skills, and perspectives that can expand their creativity and help them generate innovative ideas (Amabile, 1996; Liu et al., 2019). Moreover, it can teach individuals how to think critically and develop problem-solving skills that are essential components of creativity. Specifically, a higher educational level was associated with a slightly higher level of creative performance (Tierney and Farmer, 2011). This may be because people with higher educational levels have more knowledge and skills to draw from when engaging in creative work.

Second, openness was identified as the most relevant Big Five dimension associated with creative performance. Individuals who score high on openness tend to be more imaginative and open-minded, which can lead to increased creativity in their work (George and Zhou, 2001). This result is interesting compared with other performance dimensions such as contextual performance or adaptative performance, where conscientiousness and agreeableness tend to display higher associations than openness (Ramos-Villagrasa et al., 2022).

Third, intrinsic motivation is consistently associated with higher levels of creative performance because individuals driven by an internal need to provide meaning to their work find the task inherently enjoyable and challenging (Amabile, 1997). When intrinsically motivated, employees tend to question conventional work methods, exhibit a greater desire to acquire knowledge, and think innovatively about new work processes (Dewett, 2007).

Similarly, the review also underscores the influence of creative process engagement (CPE) as a motivational factor. CPE is the cognitive process employees engage in to produce creative outcomes (Amabile and Pillemer, 2012). Zhang and Bartol (2010) propose that CPE fosters creativity by enabling employees to more effectively define problems, integrate information, and explore new ideas. Following Yang et al. (2021), individuals who display CPE tend to develop a more precise understanding of the issue at hand, which, in turn, allows them to offer more useful and distinctive solutions. Second, when employees seek information from a variety of sources, they can reassess the status quo with new perspectives and develop novel ideas by integrating this new information with their existing knowledge. Thirdly, the generation of new ideas through exploration facilitates the emergence of originality, as creativity frequently emerges from the generation of a multitude of alternatives through the interconnection of disparate sources of information. Highly engaged employees tend to exhibit high levels of energy and enthusiasm, are deeply involved in their work, and feel strongly connected to their tasks (Bakker and Demerouti, 2014).

Five, concerning positive affect, it is a part of dispositional affectivity and characterizes excited, joyful, enthusiastic, and exhilarate people (Cropanzano et al., 1993). Individuals with high positive affect typically adopt a broad cognitive processing style (Thundiyil et al., 2016). The efficacy of strategies for enhancing creative performance may vary depending on how individuals regulate their affect (Gong and Zhang, 2017).

Lastly, creative self-efficacy (CSE) reflects an individual’s belief in their ability to successfully engage in creative tasks, revealing their confidence in generating new ideas, finding creative solutions, and performing creatively within a specific domain (Hu et al., 2018; Nwanzu and Babalola, 2022). This result is expected because self-efficacy should be studied in relation to specific domains of functioning and particular contexts (Bandura, 1997). CSE, as an individual’s self-confidence in the creation of novel products, is a specific facet of self-efficacy (Tierney and Farmer, 2002), namely one’s perceived ability to succeed in specific tasks (Bandura, 1997). These findings indicate that conceptualizing CSE as a foundation for creative endeavors is paramount. CSE enables individuals to discern opportunities within challenges and persevere in adversity (Tierney and Farmer, 2011). When professionals demonstrate a profound mastery of their field of expertise and the requisite skills, they exhibit a higher CSE, enabling them to conceptualize innovative solutions (Capron-Puozzo and Audrin, 2021). However, it is important to note that many studies examining the association between CSE and creative performance rely on self-report measures for both constructs. This measurement approach may inflate the observed correlations due to common method variance, particularly when creativity ratings are collected from the same source as CSE. Therefore, although the association between CSE and creative performance is robust, it should be interpreted with caution, and future research would benefit from incorporating multi-source or multi-method assessments to reduce potential bias.

6.1 Research implications

This study makes two theoretical contributions to the literature. First, the findings of this research have allowed us to identify the personal factors most consistently associated with creative performance. This contribution helps to clarify the nomological network of creative performance and its integration within the multidimensional job performance perspective. We wanted to focus on personality and cognitive ability. These constructs are among the personal factors most consistently associated with job performance (Sackett et al., 2022), but the present review highlights some differences between creative performance and other performance dimensions. Concerning personality, the most relevant trait for creative performance is openness, not conscientiousness or neuroticism. However, more research is needed to consider the remaining traits (Shaw and Choi, 2023). Cognitive ability does not emerge as one of the primary personal factors associated with creative performance, largely because its role has been examined only in a limited number of studies. Nevertheless, individuals with higher cognitive ability typically learn faster, solve problems more effectively, and adapt better to new situations (Sternberg and Sternberg, 2012). This is especially relevant in jobs that require problem-solving, decision-making, and continuous learning skills (Shalley et al., 2009).

Secondly, our review revealed some gaps in the existing research, suggesting a need for further investigation. More research is needed to delve into sociodemographic variables, as the findings regarding gender, age, and job tenure are inconclusive or mixed. Regarding gender, according to the meta-analysis conducted by (Hora et al., 2021b), evidence indicates a minor yet statistically significant gender difference in creative performance, with men slightly outperforming women. The study attributes this disparity to societal factors, including gender roles and cultural variables. However, it also suggests that initiatives to promote equality could diminish or eradicate this gap in creative performance. (Hora et al., 2021a) find that CSE is a potential explanatory mechanism for the peculiar association between gender and creative performance. To some extent, the observed gender gap may be associated with women’s lower self-confidence in their capacity for creative performance. The study indicates that, despite evolving societal stereotypes and changing working conditions, women may still encounter gender-based biases that can diminish their confidence in their creative abilities and restrict their creative performance. Moreover, further research is required to determine the influence of age and job tenure on creative performance. In clarifying how these variables influence creativity, valuable insights can be gained into how employees’ experiences and life stages affect their capacity to generate innovative ideas and solutions. Further investigation in this domain will assist organizations in developing strategies to enhance creative performance across diverse age groups and career stages.

6.2 Practical implications

In organizational settings, creative performance emerges from the combined influence of individual characteristics, the work environment, and the dynamic interaction between both. From a practical perspective, identifying the personal factors associated with creative performance and understanding which are the most consistently in the literature can guide human resource practices that influence organizational performance (Villajos et al., 2019). One relevant consideration for practitioners is the (relative) stability or variability of the personal factors associated with creative performance over time. Positive affect, personality traits, and intrinsic motivation are relatively stable attributes. In contrast, educational level, creative self-efficacy, and creative engagement may be more amenable to change, depending on the situation or intervention. This information can guide human resource practices by indicating which personal factors may be more relevant to consider in different process.

One of these processes is personnel selection. Suppose we are hiring people who need to display creative performance in their jobs. In that case, we might consider applicants with a high level of education and a strong openness to new experiences.

Another process is training and development. Training programs can immerse employees in diverse scenarios involving critical aspects of creative tasks, thereby providing opportunities to enhance their creative performance. This aligns with Bandura (1997) four sources of self-efficacy. First, mastery experiences can be fostered by providing employees with opportunities to successfully complete challenging creative tasks, thereby strengthening their belief in their creative abilities. Second, vicarious experiences can be cultivated by exposing employees to role models or peers who demonstrate creative success, allowing them to learn and gain confidence through observation. Third, social persuasion involves providing employees with encouragement and positive feedback that reinforces their creative potential. And four, addressing physiological states means creating an environment that reduces stress and anxiety, helping employees feel more capable and confident about their creative behaviors.

Furthermore, training programs could also increase employees’ engagement in the creative process by immersing them in diverse, challenging scenarios that stimulate creative behaviors. This training may be based on three basic dimensions: (i) identifying a problem; (ii) processing information; and (iii) generating an idea to solve the identified problem (Zhang and Bartol, 2010). By engaging in structured activities and real-world problem-solving tasks, employees are encouraged to actively participate in each stage of the creative process, from initial brainstorming to final implementation. Training programs to foster positive affect could enhance creative performance by boosting employees’ mood and emotional state. Positive affect has been shown to enhance employees’ willingness to take risks and explore innovative ideas, which, in turn, can lead to improved creative output (Qian and Jiang, 2023). Career management is related to training and development, where trying to guide workers into positions that match their intrinsic motivation can lead to improved creative performance.

The last process where we can outline the implications of our review is performance appraisal systems. Given that some personal factors are consistently associated with creative performance and that not all are stable over time, differences in employees’ creative performance may emerge and should therefore be examined periodically.

6.3 Limitations and further research

As with any study, the present research has some limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, although we considered the Web of Science and Scopus databases, which are well-known for their comprehensive research coverage, we may have unintentionally excluded relevant studies not indexed within these platforms. Future research could gain from expanding the inclusion criteria or using other databases to reduce the likelihood of missing important information. Secondly, the systematic literature review used publication as an inclusion criterion, a common practice that may introduce publication bias. Because only published studies were included, studies with non-significant or weaker associations may be underrepresented, which could lead to an overestimation of the magnitude of the reported relationships. Thirdly, the current study’s methodology is limited to a systematic literature review. This method is useful for identifying trends and themes across studies, but future research may employ meta-analytic techniques to extend our results. Additionally, as our research is focused only on quantitative research, further research should also consider qualitative studies to improve the scope of the present review. Moreover, because many of the studies included in this review relied on cross-sectional designs, the direction of the observed associations cannot be established, and reverse causality remains possible.

Our review also leads to proposing some ideas for further research. First, we believe that a systematic review focused on the contextual factors associated with creative performance could complement the present research. In addition, an analysis of the measures of creative performance, their functioning, and their limitations might help advance future research on the construct. We also suggest that examining creative performance jointly with the remaining dimensions of job performance would lead to better insights about what each dimension has (and does not have) in common with the others. Furthermore, the systemic nature of creativity imposes important constraints on an individual-centered approach. The effects of personal characteristics on creative performance may be strengthened, attenuated, or obscured by contextual conditions such as team dynamics, leadership, organizational climate, or task structure (Amabile and Pillemer, 2012). In real organizational settings, it is therefore essential to consider these additional influences, as focusing solely on individual factors may underestimate the extent to which person–context interactions shape creative behavior.

Statements

Author contributions

JC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PR-V: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation, Government of Spain, under grant PID2021-122867NA-I00; and by the Department of Innovation, Research and University of the Government of Aragon (Group S31_23R).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1727094/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Abdullah M. I. Ashraf S. Sarfraz M. (2017). The organizational identification perspective of CSR on creative performance: the moderating role of creative self-efficacy. Sustainability9:2125. doi: 10.3390/su9112125

2

Abukhait R. Shamsudin F. M. Bani-Melhem S. Al-Hawari M. A. (2023). Obsessive–compulsive personality and creative performance: the moderating effect of manager coaching behavior. Rev. Manag. Sci.17, 375–396. doi: 10.1007/s11846-022-00528-6

3

Akbari M. Bagheri A. Imani S. Asadnezhad M. (2021). Does entrepreneurial leadership encourage innovation work behavior? The mediating role of creative self-efficacy and support for innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag.24, 1–22. doi: 10.1108/EJIM-10-2019-0283,

4

Aleksic D. Cerne M. Dysvik A. Skerlavaj M. (2016). I want to be creative, but ... Preference for creativity, perceived clear outcome goals, work enjoyment, and creative performance. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol.25, 363–383. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2015.1077809

5

Al-Madadha A. Shaheen F. Alma'Ani L. Alsayyed N. Adwan A. A. (2023). Corporate social responsibility and creative performance: the effect of job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior. Organ56, 32–50. doi: 10.2478/orga-2023-0003

6

Amabile T. M. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to the social psychology of creativity. New York, US: Routledge.

7

Amabile T. M. (1997). Motivating creativity in organizations: on doing what you love and loving what you do. Calif. Manag. Rev.40, 39–58. doi: 10.2307/41165921

8

Amabile T. M. Pillemer J. (2012). Perspectives on the social psychology of creativity. J. Creat. Behav.46, 3–15. doi: 10.1002/jocb.001

9

Anderson N. Potočnik K. Zhou J. (2014). Innovation and creativity in organizations: a state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. J. Manage.40, 1297–1333. doi: 10.1177/0149206314527128

10

Audenaert M. Decramer A. (2018). When empowering leadership fosters creative performance: the role of problem-solving demands and creative personality. J. Manage. Organ.24, 4–18. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2016.20

11

Bakker A. B. Demerouti E. (2014). Job demands–resources theory well-being1–28. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

12

Bandura A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, US: Henry Holt & Co.

13

Bhatti M. A. Khan N. R. Hussain S. Ghaleb M. M. S. (2022). LMX, thriving at work and creative performance: mediating effect of knowledge hiding. Przestrzen Spoleczna22, 196–225.

14

Bouzari M. Karatepe O. M. (2020). Does optimism mediate the influence of work-life balance on hotel salespeople’s life satisfaction and creative performance?J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tourism19, 82–101. doi: 10.1080/15332845.2020.1672250

15

Cai B. Shafait Z. Chen L. (2022). Teachers’ adoption of emotions-based learning outcomes: significance of teachers’ competence, creative performance, and university performance. Front. Psychol.13:812447. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.812447,

16

Campbell J. P. Wiernik B. M. (2015). The modeling and assessment of work performance. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav.2, 47–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111427

17

Capron-Puozzo I. Audrin C. (2021). Improving self-efficacy and creative self-efficacy to foster creativity and learning in schools. Think. Skills Creat.42:100966. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100966

18

Chen M.-H. Chang Y.-Y. Chang Y.-C. (2015). Entrepreneurial orientation, social networks, and creative performance: middle managers as corporate entrepreneurs. Creat. Innov. Manag.24, 493–507. doi: 10.1111/caim.12108

19

Cheung M. F. Y. Zhang I. D. (2021). The triggering effect of office design on employee creative performance: an exploratory investigation based on Duffy’s conceptualization. Asia Pac. J. Manag.38, 1283–1304. doi: 10.1007/s10490-020-09717-x

20

Chiang H.-L. Lien Y.-C. Lin A.-P. Chuang Y.-T. (2022). How followership boosts creative performance as mediated by work autonomy and creative self-efficacy in higher education administrative jobs. Front. Psychol.13:853311. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.853311,

21

Choi S. B. Ullah S. M. E. Kang S.-W. (2021). Proactive personality and creative performance: mediating roles of creative self-efficacy and moderated mediation role of psychological safety. Sustainability13:12517. doi: 10.3390/su132212517

22

Christensen-Salem A. Walumbwa F. O. Hsu C. I.-C. Misati E. Babalola M. T. Kim K. (2021). Unmasking the creative self-efficacy-creative performance relationship: the roles of thriving at work, perceived work significance, and task interdependence. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag.32, 4820–4846. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2019.1710721

23

Chuang Y. Chiang H. Lin A. (2019). Helping behaviors convert negative affect into job satisfaction and creative performance the moderating role of work competence. Personnel Rev.48, 1530–1547. doi: 10.1108/PR-01-2018-0038

24

Cropanzano R. James K. Konovsky M. A. (1993). Dispositional affectivity as a predictor of work attitudes and job performance. J. Organ. Behav.14, 595–606. doi: 10.1002/job.4030140609

25

Dalal R. S. Baysinger M. Brummel B. J. LeBreton J. M. (2012). The relative importance of employee engagement, other job attitudes, and trait affect as predictors of job performance. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol.42, 295–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.01017.x

26

Darvishmotevali M. Altinay L. De Vita G. (2018). Emotional intelligence and creative performance: looking through the lens of environmental uncertainty and cultural intelligence. Int. J. Hosp. Manag.73, 44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.01.014

27

De Stobbeleir K. E. M. Ashford S. J. Buyens D. (2011). Self-regulation of creativity at work: the role of feedback-seeking behavior in creative performance. Acad. Manag. J.54, 811–831. doi: 10.5465/amj.2011.64870144

28

DeNisi A. S. Murphy K. R. (2017). Performance appraisal and performance management: 100 years of progress?J. Appl. Psychol.102, 421–433. doi: 10.1037/apl0000085,

29

Dewett T. (2007). Linking intrinsic motivation, risk taking, and employee creativity in an R&D environment. R&D Manag.37, 197–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9310.2007.00469.x

30

Eslamlou A. Karatepe O. M. Uner M. M. (2021). Does job embeddedness mediate the effect of resilience on cabin attendants’ career satisfaction and creative performance?Sustainability13:5104. doi: 10.3390/su13095104

31

George J. M. Zhou J. (2001). When openness to experience and conscientiousness are related to creative behavior: an interactional approach. J. Appl. Psychol.86, 513–524. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.513,

32

Gilmore P. L. Hu X. Wei F. Tetrick L. E. Zaccaro S. J. (2013). Positive affectivity neutralizes transformational leadership’s influence on creative performance and organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Organ. Behav.34, 1061–1075. doi: 10.1002/job.1833

33

Glaser J. Seubert C. Hornung S. Herbig B. (2015). The impact of learning demands, work-related resources, and job stressors on creative performance and health. J. Pers. Psychol.14, 37–48. doi: 10.1027/1866-5888/a000127

34

Gong Z. Zhang N. (2017). Using a feedback environment to improve creative performance: a dynamic affect perspective. Front. Psychol.8:1398. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01398,

35

Gupta V. Singh S. (2014). Psychological capital as a mediator of the relationship between leadership and creative performance behaviors: empirical evidence from the Indian R&D sector. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag.25, 1373–1394. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2013.870311

36

Harari M. B. Reaves A. C. Viswesvaran C. (2016). Creative and innovative performance: a meta-analysis of relationships with task, citizenship, and counterproductive job performance dimensions. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psy.25, 495–511. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2015.1134491

37

He C. Gu J. Liu H. (2018). How do department high-performance work systems affect creative performance? A cross-level approach. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour.56, 402–426. doi: 10.1111/1744-7941.12156

38

Hennessey B. A. (2017). Taking a systems view of creativity: on the right path toward understanding. J. Creat. Behav.51, 341–344. doi: 10.1002/jocb.196

39

Herbst T. D. Hausberg J. P. (2022). Linking the use of knowledge management systems and employee creative performance: the influence of creative process engagement and motivation. Int. J. Innov. Manag.26. doi: 10.1142/S1363919622500475

40

Hon A. H. Y. (2012). When competency-based pay relates to creative performance: the moderating role of employee psychological need. Int. J. Hosp. Manag.31, 130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.04.004

41

Hon A. H. Y. Bloom M. Crant J. M. (2014). Overcoming resistance to change and enhancing creative performance. J. Manage.40, 919–941. doi: 10.1177/0149206311415418

42

Hora S. Lemoine G. J. Xu N. Shalley C. E. (2021a). Unlocking and closing the gender gap in creative performance: a multilevel model. J. Organ. Behav.42, 297–312. doi: 10.1002/job.2500

43

Hora S. Badura K. L. Lemoine G. J. Grijalva E. (2021b). A Meta-analytic examination of the gender difference in creative performance. J. Appl. Psychol.107, 1926–1950. doi: 10.1037/apl0000999,

44

Hu X. Khan S. M. Huang S. Abbas J. Matei M. C. Badulescu D. (2022). Employees’ green Enterprise motivation and green creative process engagement and their impact on green creative performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health19:5983. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19105983,

45

Hu W. Wang X. Yi L. Y. X. Runco M. A. (2018). Creative self-efficacy as moderator of the influence of evaluation on artistic creativity. Int. J. Creat. Problem Solv.28, 39–55.

46

Hu N. Wu J. Gu J. (2019). Cultural intelligence and employees’ creative performance: the moderating role of team conflict in interorganizational teams. J. Manage. Organ.25, 96–116. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2016.64

47

Hughes D. J. Lee A. Tian A. W. Newman A. Legood A. (2018). Leadership, creativity, and innovation: a critical review and practical recommendations. Leadersh. Q.29, 549–569. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.03.001

48

Hwang C. Y. Kang S.-W. Choi S. B. (2023). Coaching leadership and creative performance: a serial mediation model of psychological empowerment and constructive voice behavior. Front. Psychol.14:1077594. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1077594,

49

Ishaque S. Khalid M. Irshad S. Khakwani M. S. Luqman R. (2019). Reward, a driver to creativity: mediating role of appraisals of reward between self efficacy and creative performance. Amazon. Invest.8, 15–28.

50

Kalyar M. N. Kalyar H. (2018). Provocateurs of creative performance: examining the roles of wisdom character strengths and stress. Pers. Rev.47, 334–352. doi: 10.1108/PR-10-2016-0286

51

Karatepe O. M. (2016). Does job embeddedness mediate the effects of coworker and family support on creative performance? An empirical study in the hotel industry. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tourism15, 119–132. doi: 10.1080/15332845.2016.1084852

52

Karkoulian S. Kertechian K. S. Balozian P. Nahed M. B. (2023). Employee voice as a mediator between leader-member exchange and creative performance: empirical evidence from the Middle East. Int. J. Process Manag. Benchmarking14, 311–328. doi: 10.1504/IJPMB.2023.131256

53

Khan S. M. Abbas J. (2022). Mindfulness and happiness and their impact on employee creative performance: mediating role of creative process engagement. Think. Skills Creat.44:101027. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2022.101027

54

Leung K. Chen T. Chen G. (2014). Learning goal orientation and creative performance: the differential mediating roles of challenge and enjoyment intrinsic motivations. Asia Pac. J. Manag.31, 811–834. doi: 10.1007/s10490-013-9367-3

55

Li F. Chen T. Lai X. (2018). How does a reward for creativity program benefit or frustrate employee creative performance? The perspective of transactional model of stress and coping. Group Organ. Manag.43, 138–175. doi: 10.1177/1059601116688612

56

Li H. Jin H. Chen T. (2020a). Linking proactive personality to creative performance: the role of job crafting and high-involvement work systems. J. Creat. Behav.54, 196–210. doi: 10.1002/jocb.355

57

Li Y. Li Y. Yang P. Zhang M. (2022). Perceived Overqualification at work: implications for voice toward peers and creative performance. Front. Psychol.13, 835204–835204. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.835204,

58

Li X. Xue J. Liu J. (2021). Linking leader humility to employee creative performance: work engagement as a mediator. Soc. Behav. Personal.49. doi: 10.2224/sbp.10358

59

Li C.-R. Yang Y. Lin C.-J. Xu Y. (2020b). The curvilinear relationship between within-person creative self-efficacy and individual creative performance: the moderating role of approach/avoidance motivations. Pers. Rev.49, 2073–2091. doi: 10.1108/PR-04-2019-0171

60

Lievens F. Sackett P. R. Zhang C. (2021). Personnel selection: a longstanding story of impact at the individual, firm, and societal level. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol.30, 444–455. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2020.1849386

61

Liu F. Li P. Taris T. W. Peeters M. C. W. (2022). Creative performance pressure as a double-edged sword for creativity: the role of appraisals and resources. Hum. Resour. Manag.61, 663–679. doi: 10.1002/hrm.22116

62

Liu Y. Wang S. Yao X. (2019). Individual goal orientations, team empowerment, and employee creative performance: a case of cross-level interactions. J. Creat. Behav.53, 443–456. doi: 10.1002/jocb.220

63

Lubart T. I. (2001). Models of the creative process: Past, present and future. Creativity Research Journal,13, 295–308. doi: 10.1207/S15326934CRJ1334_07

64

Madjar N. Oldham G. Pratt M. (2002). There’s no place like home? The contributions of work and nonwork creativity support to employees’ creative performance. Acad. Manag. J.45, 757–767. doi: 10.5465/3069309

65

Makhija S. Akbar W. (2019). Linking rewards and creative performance: mediating role of intrinsic & extrinsic motivation and moderating role of rewards attractiveness. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Change8, 36–61.

66

Malik M. A. R. Butt A. N. Choi J. N. (2015). Rewards and employee creative performance: moderating effects of creative self-efficacy, reward importance, and locus of control. J. Organ. Behav.36, 59–74. doi: 10.1002/job.1943

67

Man X. Zhu X. Sun C. (2020). The positive effect of workplace accommodation on creative performance of employees with and without disabilities. Front. Psychol.11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01217,

68

Marques-Quinteiro P. Ramos-Villagrasa P. J. Passos A. M. Curral L. (2015). Measuring adaptive performance in individuals and teams. Team Perform. Manage.21, 339–360. doi: 10.1108/TPM-03-2015-0014

69

Martinaityte I. Sacramento C. Aryee S. (2019). Delighting the customer: creativity-oriented high-performance work systems, frontline employee creative performance, and customer satisfaction. J. Manage.45, 728–751. doi: 10.1177/0149206316672532

70

Mohammed N. Kamalanabhan T. J. (2019). Interpersonal trust and employee knowledge sharing behavior creative performance as the outcome. Vine J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst.50, 94–116. doi: 10.1108/VJIKMS-04-2019-0057

71