Abstract

Introduction:

Based on Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice, this study examines the mechanisms through which family cultural capital influences academic achievement among Chinese college students. While existing research has often fragmented the interplay between capital, habitus, and field, this study integrates these elements into a coherent analytical framework: family cultural capital → habitus → field → academic performance. By addressing gaps in contextualized and integrated analyses, this research explores how familial resources are internalized and transformed within educational settings, with a focus on the unique socio-cultural context of Chinese higher education.

Methods:

A cross-sectional survey was conducted with 2,929 students from 12 Chinese higher education institutions, selected through stratified and convenience sampling. Data were collected via a five-point Likert-scale questionnaire measuring family cultural capital, individual habitus, school field, and self-reported academic performance. Structural equation modeling (SEM) and bootstrap mediation analysis were employed to test the hypothesized chain mediation model.

Results:

The direct effect of family cultural capital on academic performance was significantly negative (β = –0.226, p < 0.001). However, significant positive indirect effects emerged through the mediating roles of habitus (β = 0.368, 95% CI [0.284, 0.470]) and school field (β = 0.084, 95% CI [0.038, 0.146]). More importantly, the sequential mediating effect of family cultural capital on academic performance, sequentially through habitus and field, is statistically significant (β = 0.087, 95% CI [0.044, 0.140]).

Discussion:

The findings indicate that, within the Chinese context, family cultural capital does not directly enhance academic performance. Instead, its benefits are realized indirectly through the development of adaptive habitus and alignment with school field dynamics. This aligns with Bourdieu’s emphasis on field-specific capital valuation and highlights the importance of contextual factors, such as Confucian-influenced parental expectations and institutional environments. The study underscores the need for educational policies that foster habitus development and field integration to mitigate inequities.

1 Introduction

The family, as the basic unit of social structural relations (Reiss, 1965), can provide material resources necessary for daily life and also realize functions such as emotional communication, relationship building, and individual socialization (Bernardes, 1999). No matter what changes occur in the current family organizational form and relationship structure, its social value is irreplaceable (Daly, 2005). Factors of family background, such as family relationship and structure (Lansford et al., 2001; Peterson, 2005), family economy (Lundberg and Pollak, 2007; Spencer and Komro, 2017), and family social status (Hogan and Kitagawa, 1985) exert a strong influence on the growth and development of teenagers. For the influence of family on the development of teenagers, Pierre Bourdieu’s Theory of Cultural Capital goes beyond the perspective of material economy, has strong explanatory power, and has been widely used in research (Davies and Rizk, 2018).

Family cultural capital’s value, the cultural property passed on by different family backgrounds, varies depending on the distance between family education and school education in different educational actions (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1977). Family cultural capital refers to the material cultural resources, cultural activities, cultural atmosphere, cultural space in the family environment, as well as the family cultural relations and structures beyond economic and social factors such as quality and literacy, academic certificates, and educational and parenting activities that can influence family members (Willekens and Lievens, 2014). Family cultural capital affects an individual’s psychology (Lehman et al., 2004), health (Abel, 2007), quality of life (Kim and Kim, 2009), and acquisition of social status (Georg, 2004). Family cultural capital even has an impact throughout the entire span of a person’s life (Georg, 2016).

However, existing research exhibits three limitations: First, most studies have fragmented the interactive ternary relationship among capital, habitus, and field in Bourdieu’s theory of practice, analyzing the effects of individual variables in isolation (Goldthorpe, 2007; Yang, 2014); second, some studies have focused solely on the direct effect or a single mediating effect of family cultural capital on academic achievement (Tan et al., 2019); and third, a few integrated studies have not incorporated the context of Chinese localization, resulting in limited theoretical explanatory power (Davies, 2024).

To address these research gaps, this study combines family cultural capital, habitus, and fields, using Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice system to construct the research framework, which can mitigate the limitation of the single-factor analysis of cultural capital. This novel framework could provide a clearer understanding of the complex influence mechanism of individual educational achievements and further deepen the application of cultural capital theory in the analysis of the influencing factors of college students’ academic performance. In addition, through the data analysis method of chain mediating effect, the theoretical system of educational sociology regarding the relationship between family and education could be expanded in the context of students’ academic achievement, enabling us to have a more comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the role of the mechanism through which family cultural capital influences educational outcomes.

This study utilizes Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice and takes individual habitus and the school field as mediators to examine the influence of family cultural capital on college students’ academic performance. The specific research objectives include: (1) studying the formation of college students’ academic achievements within Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice framework from the dimension of family cultural capital; (2) exploring the influence of family cultural capital on the academic performance of college students; and (3) determining whether habitus and fields mediate the relationship between family cultural capital and academic performance.

2 Theoretical framework and hypotheses development

2.1 Theory of practice

Bourdieu’s systematic exposition of the Theory of Practice first appeared in Outline of a Theory of Practice (1972). Through the analysis of field data in Algeria, Bourdieu put forward the basic viewpoints on the dialectical relationship between institutions and practices, individuals and society, epistemology and strategy, and symbols and social fields (Rasmussen, 1981). Since its conception, Bourdieu began to transcend structuralism and gradually formed his unique Theory of Practice (Acciaioli, 1981). In An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology, Bourdieu and Wacquant (1992), through reflection on the key concepts in his theoretical system, clarified the relationship among three factors (i.e., capital, habitus, and field), and combined them to form a tripartite Theory of Practice. Bourdieu’s ternary framework of capital, habitus, and field cut the “Gordian knot” by offering a more robust methodological toolbox for sociological research (Breiger, 2000). To demonstrate the characteristics of practical actions in different fields, Bourdieu (2015) synthesized the relationship logic between the three factors and the Theory of Practice using the formula:

In the framework of Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice, it is important to properly address the issues of lag—the temporal mismatch between an individual’s cultural capital and the demands or values of a particular field—and adaptation, which refers to the process by which individuals adjust their dispositions and practices to align with the evolving norms and expectations of that field (Bathmaker, 2015).

Family cultural capital does not have a fixed value attribute. Its value is determined by the specific field and the different spaces and stages it is in. When taking family cultural capital as the analytical framework of the influence mechanism and function mode of social behavioral relations, it should be placed in a specific field (Lamont and Lareau, 1988). To better understand the operation mode, power system, and spatial position of the research object of the field, the structural relationship and operation principle of family cultural capital in this field should be analyzed. In addition, it is necessary to clarify the differences and connections between capital and habitus (Roksa and Robinson, 2016).

To better understand the relationship between family cultural capital and the field, it is important to move beyond abstract philosophical debates—such as those that focus solely on individual subjectivity (subject-centered approaches) or overarching structures (structure-centered approaches)—and instead focus on how individuals and structures interact in the distribution of power within the field. Likewise, it is important to not only overcome the constraints of structural philosophy, but also more clearly understand the practical significance of the objective relationship of the field’s structure that acts on the agent and is manifested through the agent.

This study focuses on the correlation among family cultural capital, habitus, field, and academic performance of college students. Therefore, it is assumed that using Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice as the research framework could reveal the correlation among these elements from multiple perspectives, presenting their dynamic changes and interaction processes, which could yield germane results that may inform further in-depth exploration of related issues in college student academic performance.

2.2 Hypotheses development

2.2.1 Family cultural capital

In the sociology of education, family cultural capital has always been a research field of great concern (Davies and Rizk, 2018), since it was used by Bourdieu to study the cultural reproduction process of college students (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1979). Family cultural capital has become an important theory in the fields of equity in higher education and the development of college students. At present, most of the references to the expression of the concept of cultural capital in the literature come from The Forms of Capital (Bourdieu, 1986), in which Bourdieu divided cultural capital into objectified, embodied, and institutionalized forms. This classification has become the most important theoretical lens for researchers to define the category of cultural capital and has been widely used and disseminated (Davies and Rizk, 2018).

Within Pierre Bourdieu’s theoretical framework of cultural capital, the concepts of cultural capital and family cultural capital are frequently conflated. For the purpose of this study, cultural capital and family cultural capital are not coterminous but rather closely related constructs in Bourdieu’s cultural capital framework. In his works, The Inheritors, Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture, and The State Nobility, discussions of cultural capital consistently treat the family-background dimension as a core component. For example, in The State Nobility, a father’s occupational status, the size of the family library, and participation in highbrow cultural activities with parents are all treated as key indicators of cultural capital and mechanisms of social distinction (Bourdieu, 1996). When addressing embodied cultural capital, as mentioned in the book The Forms of Capital:

On the one hand, cultural capital in its objectified state depends above all on the cultural capital possessed by the family as a whole; on the other hand, the conditions for the rapid and easy accumulation of cultural capital are established from the outset by not delaying and not wasting time—an advantage that the offspring of families endowed with substantial cultural capital enjoy to the fullest (Bourdieu, 1986, p. 243).

Drawing on Bourdieu’s formulations, this study defines family cultural capital as the family’s stock of material cultural resources, cultural practices, cultural atmosphere, and cultural spaces, together with the dispositions, educational credentials, and educational upbringing activities that can influence other family members—constituting, beyond economic and social factors, the family’s cultural structure.

Habitus, in Bourdieu’s cultural capital theory, is the materialist path that agents acquire and create from the structure of practical experience in life. In short, habitus is a generative ability existing in the system of disposition tendencies as a skill, which is practiced, structurally constructed and shaped (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992, p. 122). Field can be defined as the objective relationship network or configuration existing among various positions (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992, p. 97).

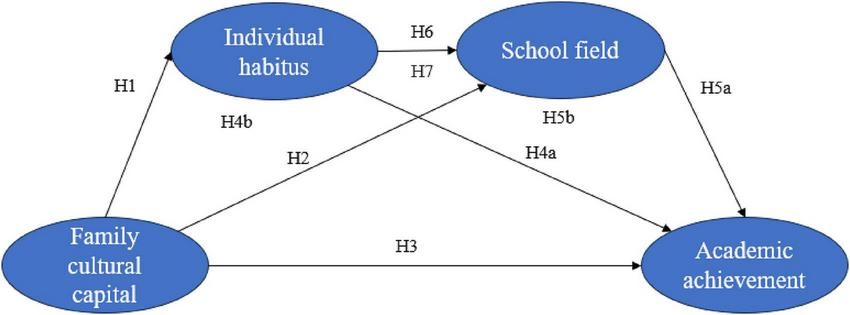

In Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice, habitus and field are closely integrated. As the earliest form of cultural capital individuals encounter, family cultural capital can shape cognition and modes of thinking (Farkas, 2003), influence behavioral tendencies and aesthetic preferences (Hanquinet et al., 2014), and determine values and attitudes toward life (Holt, 1998). These cognitive, affective, and behavioral dispositions constitute components of an individual’s habitus, reflecting the impact of family cultural capital on habitus. Similarly, family cultural capital also defines the entry threshold of the field and influences the power structure within the field (Naidoo, 2004). That is, family cultural capital exerts a profound and complex influence on individual development through the shaping of habitus and its multi-faceted effects on the field. Therefore, this study proposed the following hypotheses:

H1: Family cultural capital has a significant impact on individual habitus.

H2: Family cultural capital has a significant impact on an individual’s position in their respective field.

2.2.2 Influencing factors of college students’ academic achievements

The academic performance of college students is a quantifiable manifestation of their learning achievements at school. The most common way academic performance can show students’ mastery of course knowledge is in the summative form of points or grades (Fenollar et al., 2007). However, the academic performance of a student is the result of the complex interaction of various factors. For instance, factors such as a student’s learning habits, personality traits, teaching effectiveness, and gender differences can have an impact on the academic performance of college students (Arora and Singh, 2017). Since Coleman (1968) pointed out the significant correlation between family background and academic performance, some studies have revealed the educational inequality brought about by family cultural capital (Dumais and Ward, 2010; van de Werfhorst, 2010). Family cultural capital such as school participation, home-school interaction, and tutoring can have an impact on the relationship between families and schools, and thereby affect student’s educational experience (Lareau, 1987). Family cultural capital (Jin et al., 2024; Sullivan, 2001) influences educational achievements (DiMaggio, 1982; Tramonte and Willms, 2010), and educational equity. For college students, it also has an impact on academic performance (Dumais and Ward, 2010; Katsillis and Rubinson, 1990). Therefore, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

H3: Family cultural capital affects the academic achievements of college students.

2.2.3 The mediating role of individual habitus

Family cultural capital can directly influence education through factors such as parental participation or educational investment, and it can also indirectly affect education by influencing students’ motivation. For instance, it can ultimately influence students’ academic performance through mediating factors such as students’ self-efficacy (Radulović et al., 2020), reading behavior (Myrberg and Rosén, 2008), and participation in extracurricular activities (Coulangeon, 2018). For the agent, habitus is a type of generative temperament and quality that emerges from individual practice. Habitus can be shaped by cultural capital and the field, and at the same time, it can also become a component of an individual’s cultural capital in the form of quality. The manifestation of habitus is a characteristic internalized as an individual’s behavioral habits and values, which can affect students’ performance during their schooling. These behavioral manifestations are related to teachers’ educational evaluations of students, and students’ knowledge acceptance during the educational process, both of which can have an impact on the final academic performance. Researchers have long noticed the important mediating role of habitus in Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice system, and have demonstrated this through empirical research (Edgerton et al., 2013; Gaddis, 2013). Therefore, this study proposed the following hypotheses:

H4a: Individual habitus has a direct and significant impact on the academic achievements of college students.

H4b: Individual habitus plays a mediating role between family cultural capital and the academic achievements of college students.

2.2.4 The mediating role of the school field

As a complex field, school factors such as safety, interpersonal relationships, teaching and learning, facilities and infrastructure, and educational policies have an impact on students’ academic performance (Thapa et al., 2013). Consistent with Bourdieu (1986), cultural capital’s value is field-specific; thus, family cultural capital requires adaptation to the school field to yield benefits (Byun et al., 2012). In the process of students achieving excellent academic results, the school field performs the screening and differentiation of family cultural capital by continuously rewarding the family cultural capital with high consistency, and ultimately completes the beneficial distribution of power in the school field. In the process in which family cultural capital influences students’ academic performance, school field factors such as teachers’ educational behaviors (Wildhagen, 2009), teacher-student relationships (Raudenská, 2022), classmate relationships (Chiu and Chow, 2015), school management (Leithwood and Sun, 2018), and school facilities (Durán-Narucki, 2008) can play a mediating role. Therefore, this study proposed the following hypotheses:

H5a: The school environment has a direct and significant impact on college students’ academic achievement.

H5b: The school field plays a mediating role between family cultural capital and the academic achievement of college students.

2.2.5 Sequential mediating effects of individual habitus and school fields

In Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice, human action—or practice—results from the dynamic interaction among capital, habitus, and field (Mouzelis, 2008). Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice is based on the concept of initiative. For the theory of practice, each individual is an agent, and they are active participants in the formation of the social world. Therefore, when we discuss the relationship between family cultural capital and school education, we must regard students as active actors (Clegg, 2011), and to a certain extent, students can influence and control their relationships and behaviors at school. In the field of higher education, students can formulate appropriate learning strategies and action plans through a detailed understanding of their experiences, backgrounds, and educational processes to help them achieve excellent academic results (James et al., 2015).

An individual’s habitus will determine how they utilize resources and interact with others in the school environment. For instance, students’ characteristics, positive and negative experiences, as well as cultural similarities, influence the establishment of relationships between students and teachers (Mallik, 2023). Students with proactive learning habits can actively participate in the teaching activities organized by teachers and are more likely to establish good relationships with classmates, thereby creating a positive micro-environment in the school field (David et al., 2024).

In An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology, Bourdieu and Wacquant (1992) emphasizes that habitus serves as the mediating link between individuals and fields. Individuals first develop stable dispositions through family cultural capital, then, guided by these dispositions, participate in field interactions, thereby adapting to or influencing the field’s rules. Habitus thus constitutes a prerequisite for the interplay between family cultural capital and the field; only by forming a congruent habitus can individuals access resources and gain recognition within the school field. This study posits the chained mediation pathway as “family cultural capital → habitus → field → academic achievement,” which aligns with the core logic of Bourdieu’s theory of practice. Therefore, this study proposed the following hypotheses:

H6: Individual habitus has a direct and significant impact on the school field.

H7: Individual habitus and the school field mediate family cultural capital and college students’ academic achievement.

Figure 1 shows the conceptual model of this study’s hypothesis development.

FIGURE 1

Conceptual model.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Measurement

The questionnaire in this study was scored using a five-point Likert scale (1 indicated strong disagreement, and 5 indicated strong agreement). The measurement of family cultural capital in the questionnaire items adopted the scale items of Tan (2017), Tan et al. (2019), and Yuan et al. (2016), covering three dimensions: Family relationship, family support, and family interaction respectively. The measurement of individual habitus-taking was derived from the scale items of Tan and Liu (2022) and Gaddis (2013), including three dimensions: Personal expectations, learning engagement, and learning strategies. The measurement of the school field was adapted from Greenwald et al. (1996), Hampden-Thompson and Galindo (2017), and Sengul et al. (2019), covering two aspects: the teacher-student relationship and the classmate relationship. The measurement of college students’ academic performance adopted the self-reporting model commonly used by previous researchers, including measurement items such as academic performance, competition awards, and scholarships. This study’s questionnaire also contained demographic data, such as gender, age, year of study, type of school, and major. In addition, as some of the questionnaire items were in English, the research team also invited native English speakers to translate the relevant items to improve the questionnaire’s content validity.

3.2 Data collection

This study took China as the research site. China currently has 3,074 higher education institutions, with a total enrollment of 47.63 million students across all forms of higher education (Ministry of Education, 2024). In the specific implementation process of the research, due to limitations in time and funding, random sampling was not employed as the only sampling procedure. The combination of convenience sampling and stratified random sampling was deemed a reasonable method to obtain a large amount of data in this study (Hedt and Pagano, 2011). Data collection was conducted with traditional paper questionnaires.

Through the collaborative network of the researcher’s institution, contact was made with 12 higher education institutions (9 four-year undergraduate universities and 3 vocational colleges) across five provinces/municipalities–Beijing, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Henan, and Inner Mongolia. Within each institution, stratified sampling was conducted based on academic discipline categories, year of study, and gender to recruit volunteer participants, ensuring sample diversity. The main study employed a postal survey method, mailing paper questionnaires to volunteer participants selected through convenience sampling from the target institutions. Following the principles of stratified random sampling, the distribution and collection of paper questionnaires were conducted upon obtaining informed consent from the participants and ensuring compliance with academic ethics regulations.

A pilot test was conducted in October 2024, and a total of 128 valid questionnaires were collected. The pilot test was carried out at Hangzhou Normal University and Tourism College of Zhejiang, where the researchers are affiliated. A prior sample size calculation was carried out to estimate the number of participants required by the model. After the preliminary analysis of the pilot test data, the standardized Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.932, which was higher than 0.8, indicating that the reliability of the scale items was high.

Subsequently, the main study questionnaire was conducted from November 2024 to February 2025. A total of 3,000 questionnaires were distributed, and 2,929 valid questionnaires were retrieved, with an effective return rate of 97.63%. The demographic information of the valid questionnaire respondents is shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| Variable | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 1,257 | 42.92 |

| Female | 1,672 | 57.08 | |

| Year of study | Freshman | 703 | 24.00 |

| Sophomore | 690 | 23.56 | |

| Junior | 926 | 31.61 | |

| Senior | 610 | 20.83 | |

| Major | Science and technology | 493 | 16.83 |

| Literature and history | 782 | 26.70 | |

| Economics and management | 809 | 27.62 | |

| Agriculture, forestry, and Medicine | 105 | 3.58 | |

| Others | 740 | 25.26 | |

| School type | 4-Year undergraduate university | 2,038 | 69.58 |

| Higher vocational college | 891 | 30.42 |

Demographic profile of the questionnaire participants.

N = 2,929.

4 Results

4.1 Measurement properties

Data analysis and model measurement were conducted using SPSS 25.0 and AMOS 24.0 software. First, skewness and kurtosis tests were conducted on the sample data to evaluate the normality of the collected data. In this study, the skewness of each item was between –0.698 and 0.28, and the kurtosis of each item was between –0.157 and 0.89, indicating that the data exhibited a normal distribution (Joanes and Gill, 1998). Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted for 9 factors and 40 analysis items. The effective sample size was 2,929, which was 10 times more than the number of analysis items, so the sample size was appropriate.

After validity analysis, the common degree values corresponding to the questionnaire items in this study were all higher than 0.4, indicating that the information of the questionnaire items could be effectively extracted. The validity was verified using the KMO and Bartlett tests. The KMO value was 0.935, which was > 0.8. The KMO test assesses sampling adequacy for factor analysis, providing strong support for the construct validity of the questionnaire items. In addition, the variance explanation rate values of the 9 factors were 14.107, 7.559, 7.496, 7.284, 6.578, 6.477, 6.197, 5.765, and 5.371%, respectively. The cumulative variance explanation rate after rotation was 66.83%, > 50%. This meant that the amount of information from the questionnaire item could be effectively extracted.

Subsequently, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to examine whether the correspondence between the measurement factors and the measurement items was consistent with the researchers’ predictions, enhancing the validity and reliability of the data. After analysis, the model fitting indicators were as follows: GFI = 0.914, RMSEA = 0.049, RMR = 0.026, CFI = 0.922, NFI = 0.912, NNFI = 0.914. Among them, χ2/df = 7.908. Because the chi-square value expands with the increase of the sample size, when the sample size is large, the representativeness of the chi-square value/degree of freedom index is weak (Bearden et al., 1982; Powell and Schafer, 2001). Therefore, all the indicators of the data in this study were within an acceptable range. According to the factor loading coefficient values, there was a strong correlation between the latent variables and the bound variables in this study. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted for 9 factors and 40 analysis items. The AVE values corresponding to the 9 factors were all > 0.5, and the CR values were higher than 0.7, indicating that the data had good convergent validity (see Table 2).

TABLE 2

| Construct/items | Factor loading | Cronbach’s α | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family relationship | 0.871 | 0.630 | 0.872 | |

| Family relations are harmonious | 0.793 | |||

| Get along well with my father | 0.812 | |||

| Get along well with my mother | 0.795 | |||

| The relationship between parents is harmonious | 0.774 | |||

| Family support | 0.829 | 0.619 | 0.830 | |

| Support participation in extracurricular activities | 0.778 | |||

| Support participation in sports activities | 0.79 | |||

| Support participation in art activities | 0.792 | |||

| Family interaction | 0.840 | 0.569 | 0.841 | |

| Exchange school matters | 0.766 | |||

| Communicate matters related to friends | 0.775 | |||

| Exchange worries or troubles | 0.743 | |||

| Exchange about life development | 0.735 | |||

| Personal expectation | 0.854 | 0.595 | 0.854 | |

| Higher academic qualifications | 0.739 | |||

| Higher social status | 0.787 | |||

| Higher economic status | 0.789 | |||

| Higher personal achievements | 0.769 | |||

| Learning engagement | 0.911 | 0.533 | 0.911 | |

| When studying, I am energetic | 0.758 | |||

| Even if my learning doesn’t go smoothly, I won’t be discouraged and I can persist | 0.737 | |||

| When studying, I am full of energy | 0.758 | |||

| Learning is challenging | 0.711 | |||

| Be passionate about learning | 0.751 | |||

| The learning purpose is clear and very meaningful | 0.742 | |||

| When studying, time passes quickly | 0.709 | |||

| When studying, I focus on it | 0.713 | |||

| When studying, I feel happy | 0.691 | |||

| Learning strategy | 0.809 | 0.516 | 0.810 | |

| In the process of learning, I will consciously think, organize and process the learning content | 0.692 | |||

| In the learning process, goals will be set and self-monitoring will be carried out | 0.733 | |||

| Have an autonomous consciousness in learning | 0.753 | |||

| I can feel the value of learning | 0.693 | |||

| Teacher-student relationship | 0.885 | 0.660 | 0.886 | |

| Communicate emotional confusion with the teacher | 0.775 | |||

| Communicate with teachers about academic studies | 0.842 | |||

| Communicate with the teacher about daily life | 0.819 | |||

| Communicate with the teacher about life planning | 0.812 | |||

| Classmate relationship | 0.809 | 0.514 | 0.809 | |

| I Have good friends at school | 0.703 | |||

| The atmosphere in the class is very good | 0.704 | |||

| The atmosphere in the dormitory is very good | 0.707 | |||

| My interpersonal relationships at school are very good | 0.754 | |||

| Academic achievement | 0.798 | 0.507 | 0.801 | |

| My comprehensive academic performance ranks high in the class | 0.544 | |||

| I participate in professional and subject-related competition activities | 0.799 | |||

| I participate in cultural and sports competitions and activities | 0.796 | |||

| I obtain a scholarship | 0.68 |

Confirmatory factor analysis results.

Table 3 presents the discriminant validity analysis results for each construct. The square roots of the average variance extracted (AVE) for all factors exceeded the absolute values of their correlation coefficients with other factors, demonstrating adequate discriminant validity.

TABLE 3

| Dimension | Family relationship | Family support | Family interaction | Personal expectation | Learning engagement | Learning strategy | Teacher-student relationship | Classmate relationship | Academic achievement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family relationship | 0.794 | ||||||||

| Family support | 0.521 | 0.787 | |||||||

| Family interaction | 0.514 | 0.563 | 0.755 | ||||||

| Personal expectation | 0.334 | 0.358 | 0.331 | 0.771 | |||||

| Learning engagement | 0.324 | 0.368 | 0.48 | 0.423 | 0.73 | ||||

| Learning strategy | 0.324 | 0.388 | 0.43 | 0.414 | 0.636 | 0.718 | |||

| Teacher-student relationship | 0.333 | 0.325 | 0.421 | 0.247 | 0.469 | 0.399 | 0.812 | ||

| Classmate relationship | 0.419 | 0.384 | 0.411 | 0.393 | 0.449 | 0.425 | 0.542 | 0.717 | |

| Academic achievement | 0.108 | 0.175 | 0.252 | 0.168 | 0.382 | 0.357 | 0.376 | 0.222 | 0.712 |

Discriminant validity: Pearson correlation with the AVE square root value.

The bold numbers on the diagonal lines represent the square root values of AVE.

4.2 Assessment of the structural model

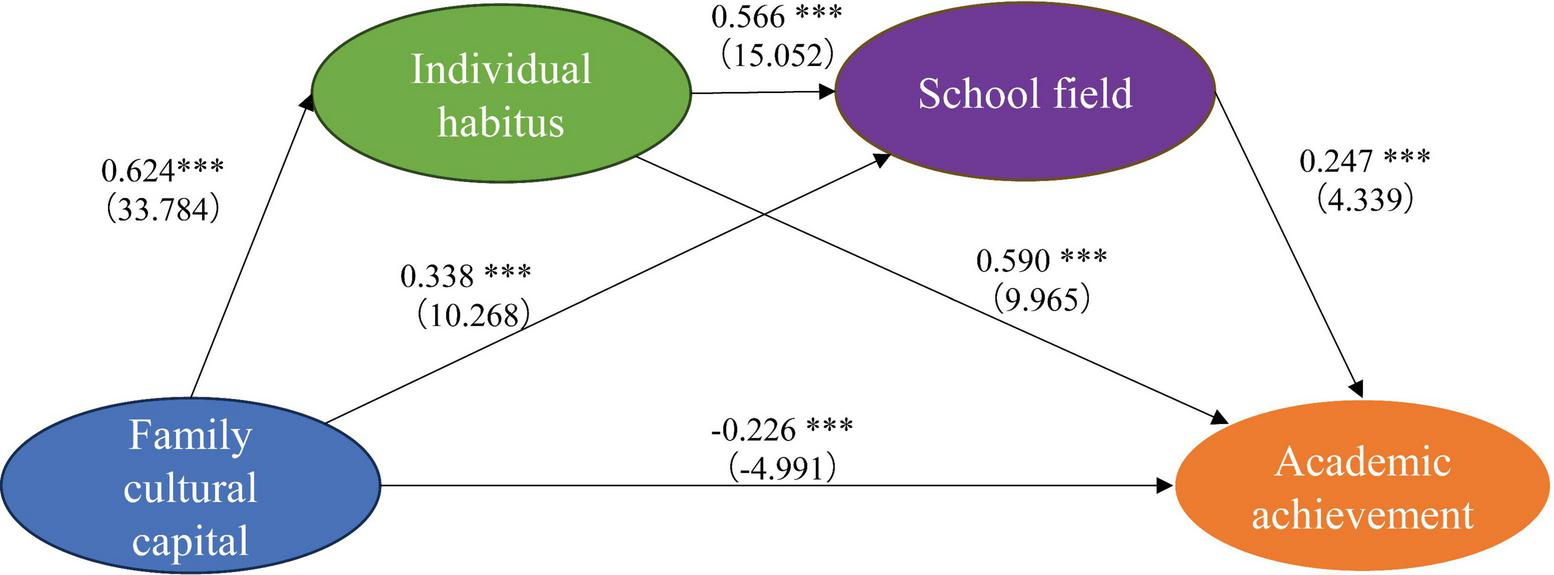

The structural equation model was modeled in AMOS to obtain the model fitting results. Among them, χ2/df = 8.38, GFI = 0.898, RMSEA = 0.050, RMR = 0.041, CFI = 0.910, NFI = 0.899. These values are within a reasonable range. Therefore, the goodness of fit is relatively high in this model (see Figure 2 and Table 4).

FIGURE 2

AMOS output results of the proposed model. The path coefficients for family cultural capital and academic performance (β = −0.226, p < 0.001), family cultural capital and habitus (β = 0.624, p < 0.001), family cultural capital and field (β = 0.338, p < 0.001), habitus and academic performance (β = 0.590) (p < 0.001), field and academic performance (β = 0.247, p < 0.001), and habitus and field (β = 0.566, p < 0.001), presented significant results. Therefore, H1, H2, H3, H4a, H5a, and H6 in the research hypotheses were supported.

TABLE 4

| Hypothesis | Path | Standardized coefficient | T-value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Family cultural capital → habitus | 0.624 | 33.784*** | Supported |

| H2 | Family cultural capital → field | 0.338 | 10.268*** | Supported |

| H3 | Family cultural capital → academic achievement | −0.226 | −4.991*** | Supported |

| H4a | Habitus → academic achievement | 0.590 | 9.965*** | Supported |

| H5a | Field → academic achievement | 0.247 | 4.339*** | Supported |

| H6 | Habitus → field | 0.566 | 15.052*** | Supported |

Structural model assessment and hypothesis test results.

***p < 0.001.

4.3 Assessment of mediation effects

The estimators of mediation analysis are highly sensitive to situations that deviate from the normality assumption. To test the reliability of the mediation effect, the bootstrapping method was used (Alfons et al., 2022). As many as 5,000 bootstrap replications are generally sufficient to stabilize the confidence intervals of mediation effects. Bootstrapping tests were conducted on sensitive data, such as outliers, including heavy tails or the skewness of the observed distribution that may have threatened the proposed mediating mechanism, In Table 5, the total effect of family cultural capital on college students’ academic performance [95% CI (0.252, 0.376)], and the direct influence of family cultural capital on college students’ academic performance [95% CI [–0.338, –0.123)] are presented. The indirect influence of family cultural capital on college students’ academic performance through individual habitus (95% CI [0.284, 0.470]), and the indirect influence of family cultural capital on college students’ academic performance through the school field (95% CI [0.03.8, 0.146]) are also shown. These results indicate that family cultural capital has an indirect influence on college students’ academic performance successively through individual habitus and the school field [95% CI (0.044, 0.140)], and their confidence intervals do not include zero values. Therefore, a significant mediating effect was revealed.

TABLE 5

| Estimation | Bootstrapping 5,000 | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | Percentile 95% CI | |||

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Total effect | ||||

| 0.313 | 0.252 | 0.376 | 0.000 | |

| Direct effect | ||||

| −0.226 | −0.338 | −0.123 | 0.000 | |

| Indirect effect | ||||

| H4b: Family cultural capital → Habitus → Academic achievement |

0.368 | 0.284 | 0.470 | 0.000 |

| H5b: Family cultural capital → Field → Academic achievement |

0.084 | 0.038 | 0.146 | 0.000 |

| H7: Family cultural capital → Habitus → Field → Academic achievement |

0.087 | 0.044 | 0.140 | 0.000 |

Path mediation results.

5 Discussion

5.1 Conclusion

This study investigated the relationship among family cultural capital, individual habitus, school field, and academic performance among Chinese college students. The findings support the influence of family cultural capital on college students’ academic performance mentioned in previous studies (Dumais and Ward, 2010), as well as the mediating role played by habitus and field in this process (Chiu and Chow, 2015; Edgerton et al., 2013; Gaddis, 2013; Raudenská, 2022). In addition, the significant chain mediating effect among family cultural capital, habitus, school field, and academic performance also bolsters the research applicability of Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice.

Three findings warrant further discussion. First, the research results showed that the direct impact of family cultural capital on the academic performance of Chinese college students is significantly negatively correlated. This phenomenon, which is inconsistent with the original assumption of Bourdieu’s theory of cultural capital, confirms that not all cultural capital can directly have a favorable impact on students’ academic performance (Tan et al., 2019). That is, the value of cultural capital in studies focusing on academic performance is not that salient (Byun et al., 2012; Yamamoto and Brinton, 2010). This study utilized the data of Chinese college students to illustrate that in higher education, the direct influence of family cultural capital on academic performance has certain limitations. Especially in Chinese society, family cultural capital is deeply influenced by Confucian culture (Hu, 2023). An environment with high family cultural capital may lead to overly high expectations from parents. It is possible these high parental demands can make some Chinese college students develop a rebellious mentality, which could negatively affect their academic performance.

Second, the results showed that individual habitus and the school field have a significant positive impact on Chinese college students’ academic performance. This study took personal expectations, learning engagement, and learning strategies as latent variables for measuring individual habitus, confirming the important mediating role of self-factors between family cultural capital and academic performance. This result supports the mediating role of habitus factors such as achievement goals and self-efficacy on academic performance (Fenollar et al., 2007). This suggests that a significant influence of Chinese college students’ initiative on their academic performance can be a factor. Similarly, this study takes the teacher-student relationship and the classmate relationship as the latent variables for measuring the school field, confirming that the relationship structure in the school, such as the educational and teaching methods, can have an impact on Chinese college students’ academic performance. In other words, the mediating effect of the school field suggests that cultural capital needs to be linked to the field in which it functions to form value (Davies, 2024).

Third, this study found that, among the sampled Chinese college students, family cultural capital has an indirect positive impact on academic performance through the sequential path of individual habitus and the school field. This indicates that for advantageous family cultural capital to be transformed into excellent academic achievements, it must undergo capital transformation and adaptation to align it with the requirements of school education. This finding supports Bourdieu’s discussion on the original meaning of cultural capital (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1977). This chain-like mediating effect reveals the distinctive features between cultural capital and economic capital. Unlike economic capital, cultural capital cannot be directly passed on to the next generation. It must go through a long period of accumulation, transformation, and field adaptation to gain benefits in a specific field.

5.2 Implications for theory

The findings of this study not only enrich the tenets of Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice, but also promote the transformation of the application of cultural capital theory from resource analysis to relationship analysis and process analysis, providing a referable theoretical integration paradigm and methodological innovation path for subsequent research. The theoretical contributions are reflected in three aspects: an innovative application of Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice system, an expansion of the theoretical framework, and a novel interpretation of the core issues of educational sociology.

First, based on Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice, this study constructed an integrated analysis framework of capital–habitus–field interaction, overcoming the limitation of a single-factor analysis strategy. This framework incorporates the core concepts in Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice into a unified analytical tool. Through empirical testing, this study examined the chain mediating effect of family cultural capital on academic performance among Chinese college students in a multi-factor method, moving beyond the single-factor analysis of cultural capital in traditional research. This tripartite theoretical framework not only retains the core logic in Bourdieu’s theory that capital relies on the field to exert its value (Bourdieu, 1986), but also extends the mechanism of interdependence and entanglement among the three constructs (capital–habitus–field) in the Theory of Practice system (Breiger, 2000). This novel capital–habitus–field framework provides empirical support for understanding the potential mechanism by which cultural capital is internalized through individual habitus and adapted to the field to be transformed into academic advantages. In sum, this tripartite interaction framework appears to provide a more comprehensive theoretical analysis tool for research in educational sociology in the Chinese context.

Second, in contrast to the prevailing assumptions about cultural capital theory, this study reframes it by highlighting field specificity and localized context. This study’s findings suggest that the direct impact of family cultural capital on academic performance among Chinese colleges students is significantly negatively correlated, challenging the traditional perception that cultural capital necessarily promotes educational achievements. This reveals that in China—due to the differences in educational fields, examination models, and social mechanisms—the types of cultural capital and the operation mechanisms of the fields that can affect academic achievement are different from those outside China (e.g., North America and Europe) (Davies, 2024). In addition, in the Chinese context, this significant negative direct effect may stem from the rebellious psychology of students caused by overly high expectations from families under Confucian culture, as well as the low adaptability of the East Asian examination system to refined cultural capital (e.g., museum visits, attending concerts, and theatrical performances), suggesting that the value of cultural capital is determined by the specific field. This interpretation aligns with Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice and provides preliminary evidence for its explanatory power in the socio-cultural paradigm of Chinese higher education.

Third, this study reveals the micro-interaction mechanism between habitus and field, expanding the theoretical implications of educational equity research in China. The mediating role of individual habitus factors such as learning strategies, learning engagement, and self-expectations, as well as school field factors such as teacher-student relationships and classmate interactions in the transformation of cultural capital was found in this study. The discovery of this mechanism is similar to Randall Collins’ micro-interactive ritual theory and represents a theoretical refinement to Bourdieu’s cultural capital theory (Davies and Rizk, 2018). Specifically, habitus serves as a bridge between objective structures and subjective actions, both of which are not only shaped by family cultural capital but also actively influence individuals’ behavioral strategies in the school field. This research conclusion contradicts the limitations of the traditional view that family resources determine the acquisition of educational outcomes. It also deepens the connection between family background and academic achievements into a dynamic process analysis of capital transformation → habitus generation → field interaction, providing a new perspective for understanding the complex causes of educational inequality in China.

5.3 Implications for education practice

This study provides multi-dimensional application value for Chinese higher education policy-making, educational practice, and family education by revealing the dynamic relationship among family cultural capital, habitus, field, and academic performance. This dynamic relationship is reflected in the following three implications for education practice.

First, in the formulation of educational policies, this application value promotes a reformulation of family cultural capital and the school field. In the process of formulating educational policies in the Chinese government, the home–school collaboration mechanism can be optimized. In response to the possible negative impact on academic performance caused by expectation mismatch in families with high cultural capital, families can be guided through parent education programs to transform cultural capital into supportive habitus cultivation rather than directly transmitting refined cultural capital, such as artistic cultivation and elite values (Kim, 2022). During the policy-making process, in light of the disadvantages of families with low cultural capital, habit-empowering policies such as learning strategy training and psychological efficacy improvement can be formulated. The strong mediating effect of habitus shown in the results of this study can be utilized to make up for the disadvantages of family resources by promoting families and students to adapt to the rules of the school environment through positive individual habitus.

Second, in the practice of higher education in China, a dual intervention system of habitus cultivation and field optimization should be constructed. In the formulation of teaching strategies in schools, emphasis should be placed on the improvement of habitus (Wong and Liao, 2022). To achieve this, teachers can provide differentiated guidance by evaluating students’ learning strategies, goal expectations, and other habitual classroom indicators. For instance, students with high family cultural capital could be guided by their teachers to transform family advantages into innovative abilities. On the other hand, teachers could strengthen basic learning strategies to directly improve academic performance among students with low family cultural capital. Chinese universities and colleges should also improve the micro-social network on campus. By building an equal teacher–student interaction and peer support network, the relationship structure of the school field could be optimized. This optimization would reduce the exclusion caused by the mismatch of family cultural capital, and enable students from different backgrounds to accumulate beneficial habitus through positive interactions with their teachers and peers on campus.

Third, in family education in China, emphasis should be placed on shifting from the transmission of capital to the empowerment of habitus. To start, Chinese parents need to adjust their role positioning in the family. That is, families with high cultural capital should try to avoid cultural coercion. They can cultivate children’s active learning habitus through democratic discussions, independent decision-making, companionship, mentoring, and guidance. On the contrary, families with low cultural capital can focus on non-material investment and take advantage of the shaping effect of habitus on the field to enhance their children’s adaptability at school. Finally, the initiative of individual students should also be cultivated. Personalized guidance can help students identify their strengths, formulate action strategies suitable for the school field, and indirectly transform family cultural capital into academic advantages.

In conclusion, by recognizing and harnessing the chain-like intermediary nexus between habitus and field—regardless of the level of family cultural capital—students’ adaptability to the school field can be enhanced by cultivating positive habitus, and the impact of family cultural capital on educational inequity can be mitigated in Chinese society.

5.4 Limitations

Through empirical analysis, this study revealed the concatenating mediating effect of individual habitus and the school field between family cultural capital and Chinese college students’ academic performance. The research results provide a fresh lens to see beyond the traditional limitations of family cultural capital theory and can contribute to a more equitable development of Chinese education in multiple aspects, creating a fairer and more effective educational field for students.

However, our study also has certain limitations. First, due to the complexity of family cultural capital theory and challenges in its measurability, the theoretical framework and variable measurement were simplified, which may have introduced some measurement error. Second, the study employed cross-sectional data, which precludes capturing the dynamic evolution of family cultural capital, habitus, and field over time. Third, owing to constraints in sample collection, the research was conducted in a selection of Chinese higher education institutions; therefore, caution should be exercised when generalizing the findings to universities in other countries and regions or to other stages of education.

In future research, several directions merit further exploration to deepen the understanding of the relationship between family cultural capital and student academic performance: (1) Theoretical integration should be enhanced to bridge existing frameworks and offer more comprehensive explanatory power; (2) More dynamic and diverse samples are needed to reflect varying educational contexts and social backgrounds; (3) Key variables related to cultural capital and academic achievement require further refinement and operationalization; (4) Greater emphasis should be placed on contextualizing the transformation of cultural capital within the specific trajectory of China’s educational reform; and (5) Incorporating formative evaluations through qualitative research methodologies—such as interviews, focus groups, and case studies—can yield deeper insights into the nuanced mechanisms through which family cultural capital affects student outcomes and academic performance.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Academic Committee of Department of General Education in Tourism College of Zhejiang (Grant No. ZLYGGJXBXS-2024-002, Approval Date: September 9, 2024). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MJ: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. DG: Data curation, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. HZ: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. YG: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This article was supported by the Major Humanities and Social Sciences Research Projects in Zhejiang Higher Education Institutions (Grant No. 2024QN134).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abel T. (2007). “Cultural capital in health promotion,” in Health and modernity, edsMcQueenD. V.KickbuschI.PotvinL. (New York, NY: Springer). 10.1007/978-0-387-37759-9_5

2

Acciaioli G. L. (1981). Knowing what you’re doing: A review of Pierre Bourdieu’s outline of a theory of practice.Canberra Anthropol.423–51. 10.1080/03149098109508599

3

Alfons A. Ateş N. Y. Groenen P. J. (2022). A robust bootstrap test for mediation analysis.Organ. Res. Methods25591–617. 10.1177/10944281219990

4

Arora N. Singh N. (2017). Factors affecting the academic performance of college students.J. Educ. Technol.1447–53. 10.26634/jet.14.1.13586

5

Bathmaker A. M. (2015). Thinking with Bourdieu: Thinking after Bourdieu. Using ‘field’ to consider in/equalities in the changing field of English higher education.Camb. J. Educ.4561–80. 10.1080/0305764X.2014.988683

6

Bearden W. O. Sharma S. Teel J. E. (1982). Sample size effects on chi square and other statistics used in evaluating causal models.J. Mark. Res.19425–430. 10.1177/002224378201900404

7

Bernardes J. (1999). We must not define “the family”!Marriage Fam. Rev.2821–41. 10.1300/J002v28n03_03

8

Bourdieu P. (1986). “The forms of capital,” in Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education, ed.RichardsonJ. G. (New York, NY: Greenwood Press), 241–258.

9

Bourdieu P. (1996). The state nobility: Elite schools in the field of power.Cambridge: Polity Press.

10

Bourdieu P. (2015). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste.Beijing: The Commercial Press, 169.

11

Bourdieu P. Passeron J. C. (1977). Reproduction in education, society and culture.London: Sage, 46.

12

Bourdieu P. Passeron J. C. (1979). The inheritors: French students and their relation to culture, trans. R. Nice. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

13

Bourdieu P. Wacquant L. J. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology.Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

14

Breiger R. L. (2000). A tool kit for practice theory.Poetics2791–115. 10.1016/S0304-422X(99)00026-1

15

Byun S. Y. Schofer E. Kim K. K. (2012). Revisiting the role of cultural capital in East Asian educational systems: The case of South Korea.Sociol. Educ.85219–239. 10.1177/0038040712447

16

Chiu M. M. Chow B. W. Y. (2015). Classmate characteristics and student achievement in 33 countries: Classmates’ past achievement, family socioeconomic status, educational resources, and attitudes toward reading.J. Educ. Psychol.107152–169. 10.1037/a0036897

17

Clegg S. (2011). Cultural capital and agency: Connecting critique and curriculum in higher education.Br. J. Sociol. Educ.3293–108. 10.1080/01425692.2011.527723

18

Coleman J. S. (1968). Equality of educational opportunity.Integr. Educ.619–28. 10.1080/0020486680060504

19

Coulangeon P. (2018). The impact of participation in extracurricular activities on school achievement of French middle school students: Human capital and cultural capital revisited.Soc. Forces9755–90. 10.1093/sf/soy016

20

Daly M. (2005). Changing family life in Europe: Significance for state and society.Eur. Soc.7379–398. 10.1080/14616690500194001

21

David L. Biwer F. Crutzen R. de Bruin A. (2024). The challenge of change: Understanding the role of habits in university students’ self-regulated learning.High. Educ.882037–2055. 10.1007/s10734-024-01199-w

22

Davies S. (2024). Cultural capital—field connections for three populations of Chinese students: A theoretical framework for empirical research.Chin. Sociol. Rev.56261–284. 10.1080/21620555.2024.2307480

23

Davies S. Rizk J. (2018). The three generations of cultural capital research: A narrative review.Rev. Educ. Res.88331–365. 10.3102/003465431774842

24

DiMaggio P. (1982). Cultural capital and school success: The impact of status culture participation on the grades of US high school students.Am. Sociol. Rev.47189–201. 10.2307/2094962

25

Dumais S. A. Ward A. (2010). Cultural capital and first-generation college success.Poetics38245–265. 10.1016/j.poetic.2009.11.011

26

Durán-Narucki V. (2008). School building condition, school attendance, and academic achievement in New York City public schools: A mediation model.J. Environ. Psychol.28278–286. 10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.02.008

27

Edgerton J. D. Roberts L. W. Peter T. (2013). Disparities in academic achievement: Assessing the role of habitus and practice.Soc. Indic. Res.114303–322. 10.1007/s11205-012-0147-0

28

Farkas G. (2003). Cognitive skills and noncognitive traits and behaviors in stratification processes.Annu. Rev. Sociol.29541–562. 10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100023

29

Fenollar P. Román S. Cuestas P. J. (2007). University students’ academic performance: An integrative conceptual framework and empirical analysis.Br. J. Educ. Psychol.77873–891. 10.1348/000709907X189118

30

Gaddis S. M. (2013). The influence of habitus in the relationship between cultural capital and academic achievement.Soc. Sci. Res.421–13. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.08.002

31

Georg W. (2004). Cultural capital and social inequality in the life course.Eur. Sociol. Rev.20333–344. 10.14301/llcs.v7i2.341

32

Georg W. (2016). Transmission of cultural capital and status attainment–an analysis of development between 15 and 45 years of age.Longitud. Life Course Stud.7106–123. 10.1093/esr/jch028

33

Goldthorpe J. H. (2007). “Cultural capital”: Some critical observations.Sociologica21–23. 10.2383/24755

34

Greenwald R. Hedges L. V. Laine R. D. (1996). The effect of school resources on student achievement.Rev. Educ. Res.66361–396. 10.3102/003465430660033

35

Hampden-Thompson G. Galindo C. (2017). School–family relationships, school satisfaction and the academic achievement of young people.Educ. Rev.69248–265. 10.1080/00131911.2016.1207613

36

Hanquinet L. Roose H. Savage M. (2014). The eyes of the beholder: Aesthetic preferences and the remaking of cultural capital.Sociology48111–132. 10.1177/0038038513477935

37

Hedt B. L. Pagano M. (2011). Health indicators: Eliminating bias from convenience sampling estimators.Stat. Med.30560–568. 10.1002/sim.3920

38

Hogan D. P. Kitagawa E. M. (1985). The impact of social status, family structure, and neighborhood on the fertility of black adolescents.Am. J. Sociol.90825–855. 10.1086/228146

39

Holt D. B. (1998). Does cultural capital structure American consumption?J. Consum. Res.251–25. 10.1086/209523

40

Hu A. (2023). Cultural capital and higher education inequalities in contemporary China.Sociol. Compass17:e13102. 10.1111/soc4.13102

41

James N. Busher H. Suttill B. (2015). Using habitus and field to explore access to higher education students’ learning identities.Stud. Educ. Adults474–20. 10.1080/02660830.2015.11661671

42

Jin M. Zhao H. Gootjes D. C. (2024). The influence of family cultural capital on higher vocational school admission opportunities: A case study in China.Equity Educ. Soc.10.1177/27526461241306117[Epub ahead of print].

43

Joanes D. N. Gill C. A. (1998). Comparing measures of sample skewness and kurtosis.J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. D47183–189. 10.1111/1467-9884.00122

44

Katsillis J. Rubinson R. (1990). Cultural capital, student achievement, and educational reproduction: The case of Greece.Am. Sociol. Rev.55270–279. 10.2307/2095632

45

Kim S. (2022). Fifty years of parental involvement and achievement research: A second-order meta-analysis.Educ. Res. Rev.37:100463. 10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100463

46

Kim S. Kim H. (2009). Does cultural capital matter? Cultural divide and quality of life.Soc. Indic. Res.93295–313. 10.1007/s11205-008-9318-4

47

Lamont M. Lareau A. (1988). Cultural capital: Allusions, gaps and glissandos in recent theoretical developments.Sociol. Theory6153–168. 10.2307/202113

48

Lansford J. E. Ceballo R. Abbey A. Stewart A. J. (2001). Does family structure matter? A comparison of adoptive, two-parent biological, single-mother, stepfather, and stepmother households.J. Marriage Fam.63840–851. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00840.x

49

Lareau A. (1987). Social class differences in family-school relationships: The importance of cultural capital.Sociol. Educ.6073–85. 10.2307/2112583

50

Lehman D. R. Chiu C. Y. Schaller M. (2004). Psychology and culture.Annu. Rev. Psychol.55689–714. 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141927

51

Leithwood K. Sun J. (2018). Academic culture: A promising mediator of school leaders’ influence on student learning.J. Educ. Adm.56350–363. 10.1108/JEA-01-2017-0009

52

Lundberg S. Pollak R. A. (2007). The American family and family economics.J. Econ. Perspect.213–26. 10.1257/jep.21.2.3

53

Mallik B. (2023). Factors affecting college teacher-student relationship: A case study of a govt college in Bangladesh.Anatol. J. Educ.8161–180. 10.29333/aje.2023.8211a

54

Ministry of Education (2024). Statistical bulletin on the development of national education in 2023.New Delhi: Ministry of Education.

55

Mouzelis N. (2008). Habitus and reflexivity: Restructuring Bourdieu’s theory of practice.Sociol. Res. Online12123–128. 10.5153/sro.1449

56

Myrberg E. Rosén M. (2008). A path model with mediating factors of parents’ education on students’ reading achievement in seven countries.Educ. Res. Eval.14507–520. 10.1080/13803610802576742

57

Naidoo R. (2004). Fields and institutional strategy: Bourdieu on the relationship between higher education, inequality and society.Br. J. Sociol. Educ.25457–471. 10.1080/0142569042000236952

58

Peterson G. W. (2005). “Family influences on adolescent development,” in In Handbook of adolescent behavioral problems: Evidence-based approaches to prevention and treatment, edsGullottaT. P.AdamsG. R. (Boston, MA: Springer), 27–55. 10.1007/0-387-23846-8_3

59

Powell D. A. Schafer W. D. (2001). The robustness of the likelihood ratio chi-square test for structural equation models: A meta-analysis.J. Educ. Behav. Stat.26105–132. 10.3102/10769986026001105

60

Radulović M. Vesić D. Malinić D. (2020). Cultural capital and students’ achievement: The mediating role of self-efficacy.Sociologija62255–268. 10.2298/SOC2002255R

61

Rasmussen D. (1981). Praxis and social theory (review of outline of a theory of praxis).Hum. Stud.4273–278.

62

Raudenská P. (2022). Mediation effects in the relationship between cultural capital and academic outcomes.Soc. Sci. Res.102:102646. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2021.102646

63

Reiss I. L. (1965). The universality of the family: A conceptual analysis.J. Marriage Fam.27443–453. 10.2307/350182

64

Roksa J. Robinson K. J. (2016). Cultural capital and habitus in context: The importance of high school college-going culture.Br. J. Sociol. Educ.381230–1244. 10.1080/01425692.2016.1251301

65

Sengul O. Zhang X. Leroux A. J. (2019). A multi-level analysis of students’ teacher and family relationships on academic achievement in schools.Int. J. Educ. Methodol.5117–133. 10.12973/ijem.5.1.131

66

Spencer R. A. Komro K. A. (2017). Family economic security policies and child and family health.Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev.2045–63. 10.1007/s10567-017-0225-6

67

Sullivan A. (2001). Cultural capital and educational attainment.Sociology35893–912. 10.1177/003803850103500400

68

Tan C. Y. (2017). Conceptual diversity, moderators, and theoretical issues in quantitative studies of cultural capital theory.Educ. Rev.69600–619. 10.1080/00131911.2017.1288085

69

Tan C. Y. Liu D. (2022). Typology of habitus in education: Findings from a review of qualitative studies.Soc. Psychol. Educ.251411–1435. 10.1007/s11218-022-09724-4

70

Tan C. Y. Peng B. Lyu M. (2019). What types of cultural capital benefit students’ academic achievement at different educational stages? Interrogating the meta-analytic evidence.Educ. Res. Rev.28:100289. 10.1016/j.edurev.2019.100289

71

Thapa A. Cohen J. Guffey S. Higgins-D’Alessandro A. (2013). A review of school climate research.Rev. Educ. Res.83357–385. 10.3102/003465431348390

72

Tramonte L. Willms J. D. (2010). Cultural capital and its effects on education outcomes.Econ. Educ. Rev.29200–213. 10.1016/j.econedurev.2009.06.003

73

van de Werfhorst H. G. (2010). Cultural capital: Strengths, weaknesses and two advancements.Br. J. Sociol. Educ.31157–169. 10.1080/01425690903539065

74

Wildhagen T. (2009). Why does cultural capital matter for high school academic performance? An empirical assessment of teacher-selection and self-selection mechanisms as explanations of the cultural capital effect.Sociol. Q.50173–200. 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2008.01137.x

75

Willekens M. Lievens J. (2014). Family (and) culture: The effect of cultural capital within the family on the cultural participation of adolescents.Poetics4298–113. 10.1016/j.poetic.2013.11.003

76

Wong Y. L. Liao Q. (2022). Cultural capital and habitus in the field of higher education: Academic and social adaptation of rural students in four elite universities in Shanghai, China.Camb. J. Educ.52775–793. 10.1080/0305764X.2022.2056142

77

Yamamoto Y. Brinton M. C. (2010). Cultural capital in East Asian educational systems: The case of Japan.Sociol. Educ.8367–83. 10.1177/0038040709356567

78

Yang Y. (2014). Bourdieu, practice and change: Beyond the criticism of determinism.Educ. Philos. Theory461522–1540. 10.1080/00131857.2013.839375

79

Yuan S. Weiser D. A. Fischer J. L. (2016). Self-efficacy, parent–child relationships, and academic performance: A comparison of European American and Asian American college students.Soc. Psychol. Educ.19261–280. 10.1007/s11218-015-9330-x

Summary

Keywords

academic performance, Chinese college students, educational equity, family cultural capital, theory of practice

Citation

Jin M, Gootjes DC, Zhao H and Gu Y (2026) Family cultural capital and academic achievement: the mediating roles of habitus and field. Front. Psychol. 16:1745371. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1745371

Received

13 November 2025

Revised

25 December 2025

Accepted

26 December 2025

Published

15 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Dario Paez, Andres Bello University, Chile

Reviewed by

Jose Mathews, Sacred Heart College (Cochin), India

Olajumoke Olayemi Salami, University of Johannesburg, South Africa

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Jin, Gootjes, Zhao and Gu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ya Gu, zjnu20245551@zjnu.edu.cn

ORCID: Minglei Jin, orcid.org/0000-0003-0753-9992; Dirk Christiaan Gootjes, orcid.org/0009-0008-6413-4338

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.