- 1Institute of Sport Science, Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg, Oldenburg, Germany

- 2Institute of Sport Science, Universität Rostock, Rostock, Germany

Background: Core strength and its control in movement, also called core stability, are crucial for athletic performance. However, there is no consensus in the scientific literature regarding the extent of the relation between core strength, core stability, and athletic performance. According to the functional anatomy of the core, it seems that core stability indirectly influences the relation between core strength and athletic performance.

Objectives: This study aimed to examine the relation between core strength, core stability, and athletic performance.

Methods: Forty-one adult sport students were included in a laboratory study. The subjects participated in two testing sessions. Each testing session started with the Unilateral Landing Error Scoring System (ULESS) test. Single-leg drop jumps were performed on force plates to assess jump height as parameter for athletic performance. Drop jumps were recorded from frontal perspective to analyze kinematic data, i.e., lateral pelvic tilt, lateral trunk lean, and frontal knee angles, to evaluate core stability. A testing session involved either isometric core muscle endurance or maximal core strength and core power measurement in four exercises: flexion, extension, lateral flexion right, and lateral flexion left.

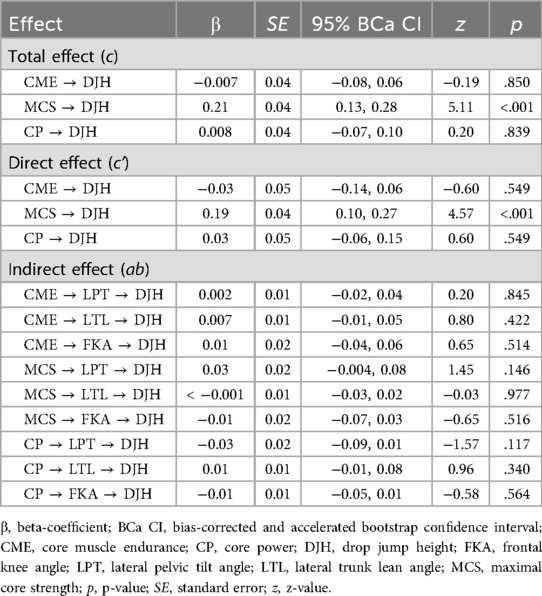

Results: A mediation analysis with multiple predictors and multiple mediators was conducted using standardized z-scores of core strength components as predictors, kinematic parameters of core stability as mediators, and jumping performance as the criterion variable. The mediation analysis revealed no statistically significant indirect effects of the mediators on the relation between core strength and jumping performance. Only a small direct effect [β = 0.19, 95% BCa CI (0.10, 0.27), p < .001] on the relation between maximal core strength and jumping performance was observed.

Conclusions: The results indicate that, at least in our experimental setup, core stability does not appear to mediate the relation between core strength and jumping performance, but maximal core strength shows a relation to jumping performance. Insufficient force transfer of the hip musculature through the kinetic chain of the drop jump may cause the missing mediating effect of core stability. Consequently, hip strength measurement should be included as an additional predictor or mediator alongside core strength or core stability in the mediation model.

1 Introduction

1.1 Core strength and core stability

Core strength or core stability has become important in enhancing sports performance (1–9) and skill acquisition (10, 11), improving physical fitness, balance or postural control (1, 12), and reducing the risk of injury to the upper and lower extremities (13–18) and in daily activities (19, 20). Given that the constructs of core strength and core stability have been widely accepted, it is surprising that no clear distinction is made between these constructs (21). In fact, the terms “core strength” and “core stability” are frequently used synonymously, although they originate from different approaches, bear different definitions, and accomplish different functions from an anatomical point of view (21, 22).

In general, the core is anatomically described as a box with the abdominals in the front, the paraspinal and gluteal muscles in the back, the diaphragm as the roof, and the pelvic floor and hip girdle musculature at the bottom (21, 23). The core represents a crucial element within numerous kinetic chains of sporting movements that enable the transfer of mechanical energy to the upper and lower extremities and therefore efficient movement execution (24–27). Functionally, the core musculature can be classified into local, global, and (axial-appendicular) transfer muscle systems (28–30) that generate forces and work synergistically to achieve proximal stability for distal mobility in athletic movements (26, 31). Thus, core strength can be defined as the ability of a core muscle or a core muscle group to generate muscular force (32). According to this definition, core strength includes different components, such as the maximal core strength, core endurance, and core power (33). Various types of sports or tasks prioritize the mentioned core strength components to different extents (34).

Neuromuscular control of the core muscles is critical for the precise and coordinated execution of muscle activation, which occurs at the right time, for the correct duration, and with the right combination of forces necessary to control the movement or position of the body. Thus, the body can respond to internal and external as well as expected or unexpected perturbations to ensure static and dynamic core stability (13, 26, 31, 35, 36). Consequently, core stability can be defined as a dynamic process that requires optimized core strength (maximal core strength, core endurance, and core power) and neuromuscular control (accurate joint and muscle receptors and neural pathways) that allows efficient integration of external and internal sensory information (13). It seems to be a controlling factor in movement that mediates the direct relation between core strength and athletic performance.

Nevertheless, the distinction between core strength and core stability appears to be ambiguous in the current literature. Accordingly, core muscle endurance tests are predominantly used to represent the construct of core stability or core strength, regardless of their different definitions (21, 34). Few studies have been conducted on the dominant coordinative aspect of core stability in relation to core strength. Small correlations between maximal core strength (e.g., isokinetic) or core muscle endurance (e.g., Biering-Sørensen test, double leg lowering test) and core stability (e.g., sudden loading test, stable and unstable sitting test) were observed (37–39). The findings of these studies revealed that core strength and core stability appear to be distinct components that nevertheless seem to be related to each other. Therefore, different clinical tests should be used to assess the stability and strength of the core. Additionally, it must be considered that specific test performance seems to be associated with the neuromuscular control mechanisms involved in each test (37, 39, 40).

1.2 Relation between core strength, core stability, and athletic performance

Adequate core muscle structure and core muscle control are the basis of the kinetic chain for facilitating the transfer of generated forces and moments between the lower and upper extremities in motor tasks of daily life and various sports (25, 26). From a theoretical perspective, core stability appears to mediate the relation between core strength and athletic performance. Thus, the following assumption could be made: An athlete has a high level of core stability when (1) the coordination and (2) the structure of core muscles are adequate so that the produced core strength is sufficient and can be better transferred to the lower and upper extremities, resulting in increased athletic performance. In contrast, an athlete has slight core stability when (1) the coordination and/or (2) the structure of core muscles are inadequate so that the produced core strength is absorbed or limited by neuromuscular control under unstable conditions. Thus, less force is transformed into work of the lower and upper extremities, resulting in decreased athletic performance (41–45).

However, few studies have examined the associations between core strength, core stability, and athletic performance. Prieske et al. (2) listed in their systematic review 15 correlation studies that revealed small relations between core strength and physical performance measures. Bauer et al. (46) reported a small correlation between core muscle endurance and throwing velocity in male handball players. Okada et al. (47) indicated small correlations between core muscle endurance measures and backward medicine ball throw performance. Moreover, several reviews (1–3, 5–9) in recent years regarding the efficacy of core strength or core stability training on athletic performance have reported conflicting results. While Reed et al. (3), Prieske et al. (2), and Saeterbakken et al. (1) revealed small to large effects of core strength or core stability training on physical fitness and moderate effects on sport-specific performance, Dong et al. (6) reported that core training has a large effect on core muscle endurance and general physical fitness parameters of athletes but has a small effect on sport-specific performance. Most correlation and intervention studies include assessment techniques or training programs that focus on the endurance component of the core muscles but do not consider other core strength components, such as maximal core strength and core power, or coordination in core musculature (1, 2, 5, 6, 46, 47). This may be a possible reason why the shared variance between core strength or core stability and athletic performance is only small or why core training has only small effects on sport-specific performance. Consequently, it seems reasonable to consider the core muscular demands (maximal strength, power, and endurance) of a specific sport or task in core strength and core stability assessment and training to improve athletic performance rather than incorporating stimuli that target only the endurance component of the core muscles (6, 34, 38, 48, 49). For example, isometric measurement methods, which assess all core strength components in the same exercise (33, 50, 51), are advisable due to the high standardization of the test conditions. Various studies have suggested that core muscles have a stabilizing function in jumping tasks (e.g., countermovement jumps, drop jumps) (52–55). Moreover, core stability is frequently discussed as a potential risk factor for lower and upper extremity injuries. It is regarded as a crucial element in ensuring the correct positioning of the lower and/or upper extremities (13, 16, 36, 43, 54, 56–59). A comprehensive core strength measurement approach, which considers all components of core strength (33) and a core stability measurement referring to a specific task or sporting movement, is indicated (44).

1.3 Aim and hypothesis

The current scientific literature shows conflicting evidence regarding the extent of the relations between core strength, core stability, and athletic performance. Consequently, it has been suggested that core strength or core stability may play a minor role in athletic performance and/or that the assessments used for measuring core strength or core stability may not have been specifically selected for athletic performance requirements. On the basis of the functional anatomy of the core, it is assumed that the core muscles generate core strength, which must be controlled depending on the sporting movement or task to ensure core performance. Consequently, adequate core stability is an intermediary component that leads to increased athletic performance. Following up, we hypothesize that core stability mediates the effect of core strength on athletic performance.

2 Materials and methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the local Ethics Committee of the Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg, Germany, approved to the protocol (EK/2020/035-08).

2.1 Participants

An a priori power analysis using the formula by Giraudeau and Mary (60) resulted in a sample size of N = 40 participants (see supplementary materials, Sample size calculation). In a randomized controlled study, forty-four adult sports students participated, whereas three subjects were excluded from further analysis for technical reasons. A total of forty-one subjects (nfemale = 20, nmale = 21, age: 24.0 ± 2.9 years, body height: 178.9 ± 9.9 cm, body mass: 75.2 ± 12.8 kg, body fat: 18.3 ± 6.7%) were included in the final data analysis. The subject had no injuries in the trunk area or the upper or lower extremities at the time of measurement and in the previous twelve months, nor were they receiving treatments. The participants represent a diverse range of athletic backgrounds (N = 26 different sports; e.g., handball, soccer, gymnastics, volleyball). A limited number of subjects (n = 15) engaged in targeted core strength training (49.7 min ± 51.1 min) every week. The determination of leg dominance (nright = 20, nleft = 21) was based on the question of which leg is used for take-off in the long jump (dominant leg = jumping leg, nondominant leg = swinging leg).

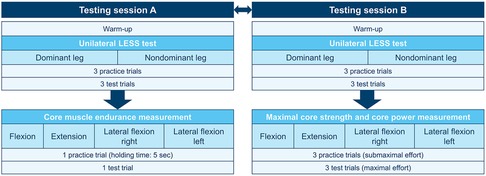

2.2 Procedures

All subjects participated in two testing sessions (see Figure 1), each lasting 90 minutes, in a controlled laboratory environment. Before the commencement of the experimental procedure, the subjects were duly informed about the methodology and provided written consent to participate in the study. In the first of the two testing sessions, the subjects completed a questionnaire that included personal information, sports background, and injury history. The participants were similarly recovered at the beginning of both testing sessions. Anthropometric measurements (body mass, body height, and body fat) were performed via the Inbody270 (Inbody Co., Seoul, Korea) and a stadiometer (Seca GmbH & Co. KG, Germany). Both testing sessions began with a five-minute warm-up to activate the entire musculature of the body, with particular attention to the core. The Unilateral Landing Error Scoring System test (ULESS test) (61) was subsequently conducted to evaluate the core stability and athletic performance data. The order of the starting leg (dominant or nondominant) in the ULESS test was randomized but consistent across both testing sessions. Following the core stability assessment, one of the two testing sessions was performed: Testing session A included the core muscle endurance measurement, and testing session B included the measurement of maximal core strength and core power. The order of the testing sessions was randomized. There were at least seven days between the two testing sessions.

2.3 Instruments

2.3.1 Core stability and athletic performance measurement

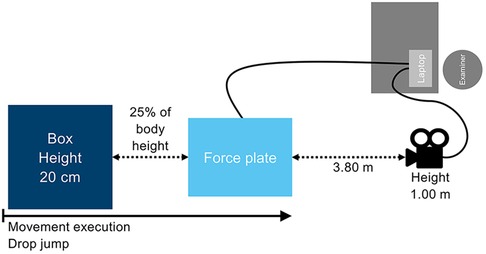

The subjects were asked to perform the ULESS test, which is regarded as a reliable tool for the qualitative assessment of movement kinematics (61, 62). The ULESS test was used to assess both core stability and athletic performance in a sport-specific manner. Single-leg jumps are common in various sports. On the one hand, they are important for athletic performance, and on the other hand, they represent a central injury situation that is considered in injury prevention (15). The subjects stood on a 20 cm high box with both feet pointing forward, approximately at shoulder width. The box was placed at a distance of 25% of the individual's body height from a force plate (Kistler AG, type 9260AA6, frequency 400 Hz, Winterthur, Switzerland). The experimental set-up of the ULESS test is shown in Figure 2.

The subjects were instructed to perform a horizontal drop from the box toward the force plate with a bilateral take-off, landing unilaterally on the force plate, and jumping with the same leg vertically and as high as possible immediately after ground contact. Following the completion of the vertical jump, a bilateral landing was permitted on the force plate. The arms had to be placed on the hips during the whole task (61). To familiarize themselves with the task, the subjects had three practice trials for each leg. Afterwards, three test trials were conducted for each leg, with a 30-second rest interval between trials. A two-minute rest interval was observed during the transition to the other leg. Trials were considered successful when the subjects (1) performed symmetrical bilateral take-off from the box, (2) landed completely and unilaterally on the force plate, (3) and performed a vertical, unilateral jump in fluid motion, and landed with both feet on the force plate. The performances were recorded in the frontal plane using a high-speed camera (VCXU-50C, 100 Hz sampling frequency, Baumer Holding AG, Frauenfeld, Switzerland). The frontal camera was positioned at a distance of 3.80 m from the force plate and at a height of 1 m. The 2D video data were processed by movement analysis software TEMPLO® (Version 2022.1, Contemplas GmbH, Kempten, Germany).

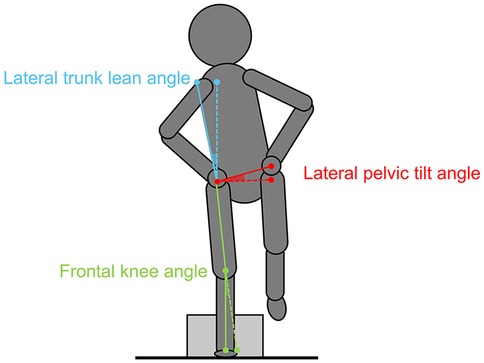

2.3.2 Core stability analysis

Different studies have shown a relation between various biomechanical variables of the core kinematics and lower limb kinematics during jumping tasks (14, 15, 57, 58). It has been proposed that the control of the vertical axis of the upper body, the knee, and the horizontal axis of the pelvis in unilateral movements should be key parameters for assessing core stability (see Figure 3). Therefore, the lateral trunk lean, lateral pelvic tilt, and frontal knee angles in the first ground contact of the drop jump at the moment of maximal knee flexion of the jumping leg (63–65) were determined using movement analysis software (Kinovea, version 0.9.5) (61). The frame at peak knee flexion was visually identified for 2D video analysis (63). The lateral trunk lean angle (blue angle in Figure 3) is formed by the lateral shoulder joint center and the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) of the jumping leg side. A line connects these landmarks, and the angle of the frontal plane is determined (66). The difference between the baseline lateral trunk lean angle in the standing position before jumping and the lateral trunk angle at the time of the first ground contact was calculated. A negative value characterized a lateral trunk leaning toward the jumping leg, and a positive value characterized a lateral trunk leaning toward the swinging leg. For the frontal knee angle (green angle in Figure 3), a line was drawn from the ASIS to the center of the patella and from the patella to the center of the ankle joint of the jumping leg. The angle of the frontal plane was calculated (64). Positive values indicate a valgus knee position, and negative values indicate a varus knee position. The lateral pelvic tilt angle (red angle in Figure 3) was determined through the height difference between the left and right ASIS. The ASISs were connected with a horizontal line starting at the ASIS of the jumping leg. The angle of the horizontal plane was defined (63). A positive value represented a contralateral pelvis rise, whereas a negative value represented a contralateral pelvis drop. Absolute values of the core stability variables were determined under the assumption that core stability decreases with increasing distance from zero degrees in the vertical axis of the spine (lateral trunk lean angle) and knee (frontal knee angle) and the horizontal axis of the pelvis (lateral pelvic tilt angle), regardless of the direction.

2.3.3 Athletic performance analysis

The jump height and ground contact time at the first ground contact of the drop jump in the ULESS test were automatically calculated by movement analysis software TEMPLO® (Version 2022.1, Contemplas GmbH, Kempten, Germany). Therefore, the ground reaction force signals of the force plate for the drop jumps were synchronized and automatically transformed into jump height and ground contact time values. Jump height values were used for the statistical analysis, while the ground contact time was taken to control the stretch-shortening cycle of the participants.

2.3.4 Core strength measurement

All strength components (endurance, maximal strength, and power) of the core muscles were measured in a lying position via the abdominal flexion test (anterior abdominal muscles), the Biering-Sørensen test (back muscles), and the lateral flexion test (oblique muscles) (33, 50, 51). The order of tests remained consistent for all participants following a prescribed sequence for technical reasons: abdominal flexion, back extension, lateral flexion right, and lateral flexion left (33). The positions in each test were standardized and controlled manually using a goniometer. The parameters of holding time, maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVC), and peak rate of force development (pRFD) were measured in each of the four exercises. The instruction provided to the participants within the holding time measurement was to maintain the different test positions for as long as possible. A stopwatch was used by the examiner to record the holding time in seconds. The participants performed one familiarization trial for a maximum duration of five seconds, followed by a test trial in each test position (flexion, extension, lateral flexion right, and lateral flexion left). Five minutes of rest between the test positions was permitted. In MVC and pRFD measurement, the participants were instructed to pull from a light preload as hard and fast as possible on the force sensor for a duration of five seconds (67, 68). Three practice trials with submaximal effort were permitted for each test position, followed by three test trials with maximal effort. The participants rested one minute between each test trial in a single test position and two minutes during transition between positions. The processing of the force-time curves was undertaken using MuscleLab software (Version 10.200.90.5097, Ergotest Innovation AS, Stathelle, Norway) with a sampling rate of 1 kHz (68). The MVC values were extracted as a 20-millisecond moving average from the raw data for each test trial. Moreover, the pRFD values were also determined by a 20-millisecond moving average in force-time curves. The mean MVC and pRFD values of the three test trials in each position were used for further analysis. A comprehensive description and further details of the test setup of the core strength component measurements have been provided by Schulte et al. (33).

2.4 Statistical analysis

The data were statistically analyzed using JASP (version 0.18.3, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands). First, the data were checked with the Shapiro–Wilk test for normal distribution and further examined for skewness, kurtosis, and unimodality (69). The means and standard deviations of core strength variables, core stability variables, and drop jump heights were calculated for each testing session and pooled for the dominant and nondominant legs. The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for the core strength variables, core stability variables, and the drop jump height were calculated to determine test-retest reliability (2-way mixed effects, absolute agreement, multiple raters or measurements). The test-retest reliability of core stability variables and drop jump height was determined by the three ULESS test trials in the first testing session. Test-retest reliability of MVC and pRFD variables was determined using the three test trials for maximal core strength and core power measurement. The ICC values were interpreted according to Koo and Li (70) as poor (< 0.50), moderate (0.50–0.75), good (0.75–0.90), or excellent (> 0.90). Moreover, the standard error measurement (SEM) was computed as (71), and the coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated as to evaluate the degree of variation between measurements. All CV values < 10% can be considered acceptable according to Cormack et al. (72). The interrater and intrarater reliability (2-way mixed effects, consistency of multiple raters or measurements and 2-way mixed effects, absolute agreement, multiple raters or measurements, respectively) of core stability variables (lateral trunk lean, frontal knee, and lateral pelvic tilt angles) were quantified using the ICCs following the recommendations of Koo and Li (70). Two raters screened and rated a selection of 82 recordings (one random trial of each subject for the dominant and nondominant legs). The values of the core stability variables of the two raters were summarized for the dominant and nondominant legs and compared to compute interrater reliability (.83 ≤ ICC ≥ .99). Moreover, one rater re-rated the same 82 recordings a second time, at least one week apart, to calculate intrarater reliability (.88 ≤ ICC ≥ .99) combined for both the dominant and nondominant legs (see supplementary material Table 1). Inter- and intrarater reliability separated for both the dominant and nondominant legs are represented in Supplementary material Table 2.

The means and standard deviations of core stability and jumping performance variables were further summarized for both testing sessions and both the dominant and nondominant legs. All variables were z-standardized to indicate the relations between core strength variables, core stability variables, and drop jump height in the mediation analysis. Before running the mediation analysis, a principal component analysis (PCA) was used to reduce the dimensionality of the core strength data. The z-standardized values of holding time, MVC, and pRFD variables of the four exercises (flexion, extension, lateral flexion right, and lateral flexion left) in core strength measurement were included in the PCA. Through the orthogonally varimax rotation, the variables were assigned to the component on which they loaded higher than on the other components. The PCA extracted three principal components out of twelve different core strength variables, which explained 73.4% of variance. MVC variables loaded high on one component, pRFD variables loaded high on one component, and holding time variables loaded high on one component. Based on the results of the PCA, the holding time, MVC, and pRFD values in the flexion, extension, lateral flexion right, and lateral flexion left exercises of the core strength measurement were summed into three components: core muscle endurance, maximal core strength, and core power. According to the theoretical hypothesis, core strength variables (maximal core strength, core power, and core muscle endurance) were considered as predictor variables, core stability parameters (lateral trunk lean, frontal knee, and lateral pelvic tilt angles) demonstrated the mediator variables, and the athletic performance variable drop jump height was characterized as the criterion variable in the simplified mediation model (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Mediation model of the relations between core strength, core stability, and athletic performance (ab, indirect effect; c’, direct effect; c, total effect).

Statistical mediation analysis was performed to expand the understanding of how core strength affects athletic performance through the indirect effect of core stability. If the observed relation between the predictor and criterion variables becomes weaker after the inclusion of an objectively measured mediator variable, partial mediation will occur. If the size of the association between the predictor variable and the criterion variable was not significant and the confidence interval of the beta-coefficient included zero after the inclusion of an objectively measured mediator variable, complete mediation would be observed (73). Multiple predictors (core muscle endurance, maximal core strength, and core power) and multiple mediators (lateral pelvic tilt, lateral trunk lean, and frontal knee angles) were included in the mediation analysis which was performed with JASP (version 0.18.3, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands) based on an R package for structural equation modeling of Rosseel (74). The mediation hypothesis test was estimated using a confidence interval by the bootstrapping method with bias-correction and acceleration (95% BCa, 5000 resamplings) (73). The bootstrapping method is a non-parametric approach by Preacher and Hayes (75) to estimate the effect size and hypothesis testing that does not rely on the assumption about the distributions of the variables and applies to small sample sizes. The method is accomplished by creating new samples from the original data, sampling with replacement is conducted, and the indirect effect is computed for each sample (75). The effect size of R2 was determined to assess the explained variance accounted for in the mediation model. Thus, both the total effect and component paths in the mediation model can be evaluated (76). The effect size of R2 was interpreted according to Cohen (77) as small (R2 = .02), medium (R2 = .13), and large (R2 = .26).

3 Results

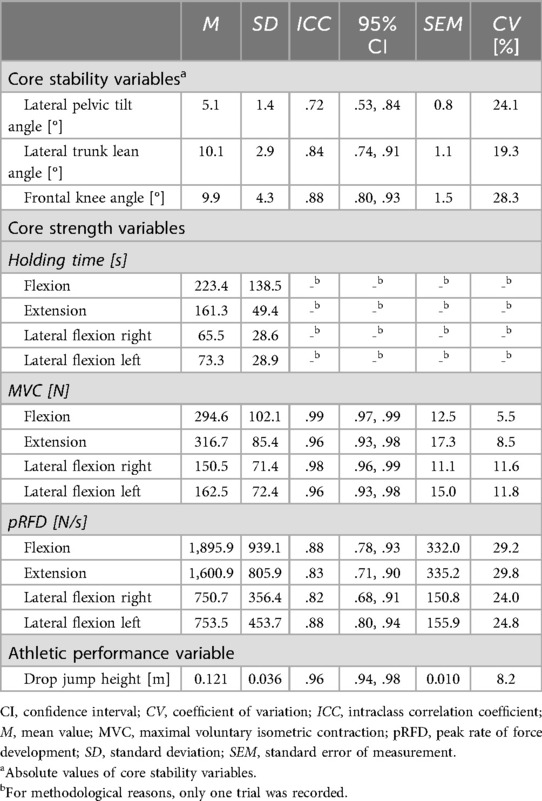

The assumption of normal distribution for all variables can be maintained. Descriptive data, test-retest reliability (ICC), SEM, and CV of the core stability, core strength, and athletic performance variables are presented in Table 1. Test-retest reliability was considered moderate to good (.72 ≤ ICC ≥ .88) for core stability variables, good to excellent (.82 ≤ ICC ≥ .99) for core strength variables, and excellent (ICC = .96) for the athletic performance variable. The SEMs of 0.8–1.5°, 11.1–17.3 N, 150.8–335.2 N/s, and 0.01 m were observed for core stability, MVC, pRFD, and athletic performance variables, respectively. The core stability, MVC, and pRFD variables displayed CV ranges of 19.3–24.1%, 5.5–11.8%, and 24.0–29.8%, respectively. The drop jump height shows a CV of 8.2%. Test-retest reliability separated for both the dominant and nondominant legs is represented in Supplementary material Table 3.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and test-retest reliability of the core stability, core strength, and athletic performance variables.

The total (c), direct (c’), and indirect effects (ab) of the mediation analysis are presented in Table 2. The relations between core strength variables (core muscle endurance, maximal core strength, and core power), core stability variables (lateral pelvic tilt angle, lateral trunk lean angle, and frontal knee angle), and drop jump height showed no statistically significant indirect effects (see Table 2). The direct effect estimated by the mediation model revealed a statistically significant positive relation between maximal core strength and drop jump height [c’ = 0.19, 95% BCa CI (0.10, 0.27), p < .001]. No statistically significant direct effects were observed between core muscle endurance and drop jump height, nor between core power and drop jump height. The total effect of the mediation analysis was statistically significant for the relation between maximal core strength and drop jump height [c = 0.21, 95% BCa CI (0.13, 0.28), p < .001]. There were no statistically significant total effects between core muscle endurance and drop jump height, and between core power and drop jump height. Nevertheless, specific path coefficients of the mediation model were statistically significant (see supplementary material Table 4). The core strength variables together explained. 10 ≤ R2 ≥ .34 of variance in the core stability variables (a paths) and R2 = .52 of variance in jumping height (c paths). The core stability variables together explained R2 = .19 of variance in jumping height (b paths). The core strength and core stability variables together explained a variance of R2 = .57 in the drop jump height (ab paths). In addition, separate mediation analyses were performed for both the dominant and nondominant legs, which yielded similar results (see supplementary material Tables 5, 6).

4 Discussion

This study aimed to examine the relation between core strength, core stability, and athletic performance. The hypothesis was that core stability mediates the relation between core strength and athletic performance (specifically: jumping performance). The main findings indicate that core stability (none of the selected parameters) does not seem to mediate the relation between core strength and athletic performance. In contrast, core strength, particularly maximal core strength, appeared to be directly related to athletic performance with a small effect size (β = 0.19), whereas core muscle endurance and core power did not. Thus, the mediating hypothesis that core stability mediates the relation between core strength and athletic performance could not be verified. According to Zhao et al. (78), these results can be interpreted as direct-only non-mediation.

4.1 Causes of non-mediating core stability

The absence of mediation could result from an insufficient transfer of force between the core and lower extremities in the kinetic chain (26). Functionally, in addition to the local and global system of the core, the hip musculature (e.g., hip flexors, hip extensors, hip abductors, and hip adductors) is classified as an axial-appendicular musculature that connects the lower extremities to the pelvic girdle of the core and transfers forces through the kinetic chain between the core and the lower extremities during movement (29, 30). Studies investigating the correlations between hip muscle strength and control of the core and lower extremities in single-leg activities (e.g., jumping, step-down task, squat, bridge) have indicated that weak hip abductors may alter muscle activation to control and stabilize the core and lower extremities (79–83). The gluteal muscles (e.g., the gluteus maximus and gluteus medius) appear to play an important role in the frontal plane stability of the pelvis, trunk, and lower extremities during jumping tasks (80, 82). The gluteus maximus is attached to the pelvis and lumbar spine via the thoracolumbar fascia (84). In our study, the hip musculature may have been unable to adequately support the mass of the body during the first ground contact of the drop jump, resulting in compensatory movement of the trunk and/or lower extremities to maintain stability. The hip muscles may not have been able to transfer forces effectively between the lower extremities and core, meaning that the mediating influence of core stability on the relation between core strength and athletic performance of the lower extremities could not be observed. Resende et al. (79) reported that core strength and hip strength predict part of the variability in core stability. Hip strength could be included in an analysis (1) alongside core strength as an additional predictor or (2) alongside core stability as an additional mediator/moderator because of its ability to transfer between the lower extremities and the core. Although no mediating effect of core stability could be indicated, the total mediation model already shows a large effect size (R2 = .57). Extending the mediation model with an additional component may improve the variance accounted for by the component paths (a paths) in the mediation analysis. Further studies could indicate a potentially mediating effect of core stability on the relation of core and hip strength with athletic performance of lower extremities in drop jumps. Alternatively, the potentially mediating effect of core stability and hip strength on the relation between core strength and athletic performance of the lower extremities could be revealed. Despite the absence of a mediating effect of core stability on the relation between core strength and athletic performance in the present study, a distinction was made between the theoretical constructs of core strength and core stability, considering their divergent definitions, in contrast to most previous studies. In accordance with a small number of studies (37, 40), different measurement methods have been employed to quantify (1) isolated core strength, with a focus on the force-generating task of distinct core muscle groups; and (2) core stability, with a focus on the coordination aspect of core muscles during athletic movement. A more thorough examination of the relation between core strength and core stability revealed very small correlations (see supplementary material Table 2). Consistent with our study, similar results have been reported by other studies (37, 40, 85, 86).

In our study, both core stability and athletic performance were determined with drop jump movements to achieve a high degree of representativeness and a potential correlation between core stability and athletic performance following a head-to-toe approach (44). From the perspective of the principle of the kinetic chain (26), poorer athletic performance is expected when the axial stability of the spine, pelvis, and knee in the frontal plane varies in the first ground contact of the drop jump. Nevertheless, in the current study, trivial to small correlations were indicated between core stability and jumping performance (see supplementary material Table 4). Our study partially revealed a weak relation between core stability and athletic performance. In the current literature, there is a paucity of evidence regarding the relation between core stability and athletic performance (87, 88). More evidence is necessary for a comprehensive understanding of how core stability works in the different planes of movement and how it's related to athletic performance (37).

4.2 Relation between core strength and jumping performance

In contrast to most studies, which focus on core muscle endurance in relation with athletic performance (2, 6, 21, 34), our study used a systematic and comprehensive approach to evaluate maximal core strength, core power, and core muscle endurance under highly standardized conditions (33). The results of the present study indicate that maximal core strength is related to jumping performance, whereas core muscle endurance and core power are not. In relation to the jumping performance of the drop jump, it appears that maximal core strength contributes more than core power and core muscle endurance. The single-leg drop jump is a dynamic movement with a high physical load during the initial ground contact. According to the general classification of strength (89), it seems reasonable that maximal core strength, as a basic dimension, was related to jumping performance rather than core muscle endurance and core power. Similar to our study, Prieske et al. (52) revealed positive correlations between maximal core strength of the extensor muscles and drop jump height under stable (r = 0.64) and unstable conditions (r = 0.66). Other studies investigating the relation between core power as well as core muscle endurance and jumping performance, have yielded inconclusive results (41, 53, 90–94).

4.3 Limitations and future directions

Readers should note the following limitations of this study. The kind of muscle action involved in isometric core strength measurements and during drop jumps may not be similar. Thus, dynamic core strength measurements, in addition to isometric core strength measurements, could be considered in further studies (95). The results of this study reveal a relatively high coefficient of variation for certain core power and core stability variables without any systematic biases (e.g., learning or fatigue effects). In future studies, further methodological measures should be taken to improve data quality. The sex and training background of the participants may be potential moderators in the mediation model, which can influence the results. Further studies with larger sample sizes should consider potential sex differences and differences in training background in core strength (96) and biomechanical measurements (e.g., frontal knee angle) (97). Moreover, the current study first of all provides results on core stability in the frontal plane of movement during a drop jump. Further studies should consider biomechanical measurements in different planes of movement to evaluate core stability during movements more precisely and comprehensively in relation to athletic performance.

5 Conclusion

The present study revealed that core stability, with the parameters selected in our study, does not seem to mediate the relation between core strength and jumping performance, but a direct relation between core strength, particularly maximal core strength, and jumping performance was observed. Our current approach suggests that the hip muscles do not adequately transfer forces between the core and lower extremities during the initial ground contact of the drop jump, thereby altering the motor control mechanisms of the core and lower extremities. Future studies should measure hip strength as an additional mediator alongside core stability or as an additional predictor alongside core strength to identify a mediating effect of core stability on the relation of core strength with athletic performance of the lower extremities. A more profound understanding of the interactions between core strength, hip strength, core stability, and athletic performance will facilitate the development of assessments and training that are tailored to the specific demands of different tasks or sports by sport scientists and practitioners.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Kommission für Forschungsfolgenabschätzung und Ethik [Commission for Research Impact Assessment and Ethics], Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg, Oldenburg, Germany. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

SaS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Formal analysis, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization, Data curation. ML: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JB: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. VZ: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. DB: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Open Access Publication Fund of the Library and Information System (BIS; Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg, Oldenburg, Germany) for covering article processing charges.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Nico Bretzler for recording the data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fspor.2025.1669023/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Saeterbakken AH, Stien N, Andersen V, Scott S, Cumming KT, Behm DG, et al. The effects of trunk muscle training on physical fitness and sport-specific performance in young and adult athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. (2022) 52(7):1599–622. doi: 10.1007/s40279-021-01637-0

2. Prieske O, Muehlbauer T, Granacher U. The role of trunk muscle strength for physical fitness and athletic performance in trained individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. (2016) 46(3):401–19. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0426-4

3. Reed CA, Ford KR, Myer GD, Hewett TE. The effects of isolated and integrated ‘core stability’ training on athletic performance measures: a systematic review. Sports Med. (2012) 42(8):697–706. doi: 10.2165/11633450-000000000-00000

4. Zemková E, Zapletalová L. The role of neuromuscular control of postural and core stability in functional movement and athlete performance. Front Physiol. (2022) 13:796097. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.796097

5. Oyama S, Palmer TG. Effectiveness of core exercise training programs designed to enhance ball-throwing velocity in overhead athletes: a systematic review. Strength Cond J. (2023) 45(2):177–87. doi: 10.1519/ssc.0000000000000738

6. Dong K, Yu T, Chun B. Effects of core training on sport-specific performance of athletes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Behav Sci. (2023) 13(2):148. doi: 10.3390/bs13020148

7. Rodríguez-Perea Á, Reyes-Ferrada W, Jerez-Mayorga D, Chirosa Ríos L, Van den Tillar R, Chirosa Ríos I, et al. Core training and performance: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Biol Sport. (2023) 40(4):975–92. doi: 10.5114/biolsport.2023.123319

8. Rodríguez S, León-Prieto C, Rodríguez-Jaime MF, Noguera-Peña A. Effects of core stability training on swimmers’ specific performance: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Bodyw Mov Ther. (2025) 42:1063–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2025.03.005

9. Ma S, Soh KG, Japar SB, Liu C, Luo S, Mai Y, et al. Effect of core strength training on the badminton player’s performance: a systematic review & meta-analysis. PLoS One. (2024) 19(6):e0305116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0305116

10. Luo S, Soh KG, Soh KL, Sun H, Nasiruddin NJM, Du C, et al. Effect of core training on skill performance among athletes: a systematic review. Front Physiol. (2022) 13:915259. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.915259

11. Luo S, Soh KG, Zhao Y, Soh KL, Sun H, Nasiruddin NJM, et al. Effect of core training on athletic and skill performance of basketball players: a systematic review. PLoS One. (2023) 18(6):e0287379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0287379

12. Shetty S, Neelapala YVR, Srivastava P. Effect of core muscle training on balance and agility in athletes: a systematic review. Kinesiol Rev. (2024) 13(3):383–403. doi: 10.1123/kr.2023-0002

13. Silfies SP, Ebaugh D, Pontillo M, Butowicz CM. Critical review of the impact of core stability on upper extremity athletic injury and performance. Braz J Phys Ther. (2015) 19(5):360–8. doi: 10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0108

14. Song Y, Li L, Dai B. Trunk neuromuscular function and anterior cruciate ligament injuries: a narrative review of trunk strength, endurance, and dynamic control. Strength Cond J. (2022) 44(6):82–93. doi: 10.1519/SSC.0000000000000727

15. Song Y, Li L, Hughes G, Dai B. Trunk motion and anterior cruciate ligament injuries: a narrative review of injury videos and controlled jump-landing and cutting tasks. Sports Biomech. (2021) 22(1):46–64. doi: 10.1080/14763141.2021.1877337

16. Zazulak B, Medvecky MJ. Trunk stability for injury prevention: the core of evidence. Sports Med. (2019) 83(9):443–50.

17. Smrcina Z, Woelfel S, Burcal C. A systematic review of the effectiveness of core stability exercises in patients with non-specific low back pain. Int J Sports Phys Ther. (2022) 17(5):766–74. doi: 10.26603/001c.37251

18. Cope T, Wechter S, Stucky M, Thomas C, Wilhelm M. The impact of lumbopelvic control on overhead performance and shoulder injury in overhead athletes: a systematic review. Int J Sports Phys Ther. (2019) 14(4):500–13. doi: 10.26603/ijspt20190500

19. Granacher U, Lacroix A, Muehlbauer T, Roettger K, Gollhofer A. Effects of core instability strength training on trunk muscle strength, spinal mobility, dynamic balance and functional mobility in older adults. Gertontol. (2013) 59(2):105–13. doi: 10.1159/000343152

20. Granacher U, Gollhofer A, Hortobágyi T, Kressig RW, Muehlbauer T. The importance of trunk muscle strength for balance, functional performance, and fall prevention in seniors: a systematic review. Sports Med. (2013) 43(7):627–41. doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0041-1

21. Enoki S, Hakozaki T, Shimizu T. Evaluation scale and definitions of core and core stability in sports: a systematic review. Isokinet Exerc Sci. (2024) 32(3):291–300. doi: 10.3233/IES-230177

22. Hibbs AE, Thompson KG, French D, Wrigley A, Spears I. Optimizing performance by improving core stability and core strength. Sports Med. (2008) 38(12):995–1008. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838120-00004

23. Akuthota V, Nadler SF. Core strengthening. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2004) 85:86–92. doi: 10.1053/j.apmr.2003.12.005

24. Adeel M, Lin B-S, Chaudhary MA, Chen H-C, Peng C-W. Effects of strengthening exercises on human kinetic chains based on a systematic review. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. (2024) 9:22. doi: 10.3390/jfmk9010022

25. Carvalho D, Ocarino JM, Cruz A, Barsante LD, Teixeira BG, Resende RA, et al. The trunk is exploited for energy transfers of maximal instep soccer kick: a power flow study. J Biomech. (2021) 121:110425. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2021.110425

26. Kibler WB, Press J, Sciascia A. The role of core stability in athletic function. Sports Med. (2006) 36(3):189–98. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200636030-00001

27. Orishimo KF, Kremenic IJ, Mullaney MJ, Fukunaga T, Serio N, McHugh MP. Role of pelvis and trunk biomechanics in generating ball velocity in baseball pitching. J Strength Cond Res. (2023) 37(3):623–8. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000004314

28. Bergmark A. Stability of the lumbar spine: a study in mechanical engineering. Acta Orthop Scand. (1989) 60:1–54. doi: 10.3109/17453678909154177

29. Colston MA. Core stability, part 1: overview of the concept. Int J Athl Ther Train. (2012) 17(1):8–13. doi: 10.1123/ijatt.17.1.8

30. Behm DG, Drinkwater EJ, Willardson JM, Cowley PM. The use of instability to train the core musculature. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2010) 35:91–108. doi: 10.1139/H09-127

31. Wirth K, Hartmann H, Mickel C, Szilvas E, Keiner M, Sander A. Core stability in athletes: a critical analysis of current guidelines. Sports Med. (2017) 47(3):401–14. doi: 10.1007/s40279-016-0597-7

32. Siff MC. Biomechanical foundations of strength and power training. In: Zatsiorsky VM, editor. Biomechanics in Sport. Champaign: Blackwell (2000). p. 103–39.

33. Schulte S, Bopp J, Zschorlich V, Büsch D. The multi-component structure of core strength. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. (2024) 9(4):249. doi: 10.3390/jfmk9040249

34. Zemková E. Strength and power-related measures in assessing core muscle performance in sport and rehabilitation. Front Physiol. (2022) 13:861582. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.861582

35. Borghuis J, Hof AL, Lemmink KAPM. The importance of sensory-motor control in providing core stability. Sports Med. (2008) 38(11):893–916. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838110-00002

36. Zazulak B, Cholewicki J, Reeves NP. Neuromuscular control of trunk stability: clinical implications for sports injury prevention. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. (2008) 16(9):497–505. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200808000-00011

37. De Los Ríos-Calonge J, Barbado D, Prat-Luri A, Juan-Recio C, Heredia-Elvar JR, Elvira JLL, et al. Are trunk stability and endurance determinant factors for whole-body dynamic balance in physically active young males? A multidimensional analysis. Scand J Med Sci Sports. (2024) 34(3):e14588. doi: 10.1111/sms.14588

38. Barbado D, Barbado LC, Elvira JLL, Dieën J, Vera-Garcia FJ. Sports-related testing protocols are required to reveal trunk stability adaptations in high-level athletes. Gait Posture. (2016) 49:90–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.06.027

39. Vera-Garcia FJ, López-Plaza D, Juan-Recio C, Barbado D. Tests to measure core stability in laboratory and field settings: reliability and correlation analyses. J Appl Biomech. (2019) 35(3):223–31. doi: 10.1123/jab.2018-0407

40. Barbado D, Lopez-Valenciano A, Juan-Recio C, Montero-Carretero C, van Dieën JH, Vera-Garcia FJ. Trunk stability, trunk strength and sport performance level in judo. PLoS One. (2016) 11(5):e0156267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156267

41. Shinkle J, Nesser TW, Demchak TJ, McMannus DM. Effect of core strength on the measure of power in the extremities. J Strength Cond Res. (2012) 26(2):373–80. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31822600e5

42. Hank M, Miratsky P, Ford KR, Clarup C, Imal O, Verbruggen FF, et al. Exploring the interplay of trunk and shoulder rotation strength: a cross-sport analysis. Front Physiol. (2024) 15:1371134. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2024.1371134

43. De Blaiser C, De Ridder R, Willems T, Vanden Bossche L, Danneels L, Roosen P. Impaired core stability as a risk factor for the development of lower extremity overuse injuries: a prospective cohort study. Am J Sports Med. (2019) 47(7):1713–21. doi: 10.1177/0363546519837724

44. Zemková E. Perspective: a head-to-toe view on athletic locomotion with an emphasis on assessing core stability. Sports Med Health Sci. (2025). doi: 10.1016/j.smhs.2025.07.001

45. Kornecki S, Zschorlich V. The nature of the stabilizing functions of skeletal muscles. J Biomech. (1994) 27(2):215–25. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90211-9

46. Bauer J, Gruber M, Muehlbauer T. Correlations between core muscle strength endurance and upper-extremity performance in adolescent male sub-elite handball players. Front Sports Act Living. (2022) 4:1050279. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2022.1050279

47. Okada T, Huxel KC, Nesser TW. Relationship between core stability, functional movement, and performance. J Strength Cond Res. (2011) 25(1):252–61. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b22b3e

48. Palmer T, Uhl TL, Howell D, Hewett TE, Viele K, Mattacola CG. Sport-specific training targeting the proximal segments and throwing velocity in collegiate throwing athletes. J Athl Train. (2015) 50(6):567–77. doi: 10.4085/1062-6040-50.1.05

49. Helm N, Prieske O, Muehlbauer T, Krüger T, Retzlaff M, Granacher U. Assoziationen zwischen der rumpfkraft und judospezifischen anriss-leistungen von judoka [associations between trunk muscle strength and judo-specific pulling performances in judo athletes]. Sportverletz Sportschad. (2020) 34(1):18–27. doi: 10.1055/a-0677-9608

50. Saeterbakken AH, Fimland MS, Navarsete J, Kroken T, Van den Tillaar R. Muscle activity, and the association between core strength, core endurance and core stability. J Nov Physiother Phys Rehabil. (2015) 2(2):28–34. doi: 10.17352/2455-5487.000022

51. Bucke J, Mattiussi A, May K, Shaw J. The reliability, variability and minimal detectable change of multiplanar isometric trunk strength testing using a fixed digital dynamometer. J Sport Sci. (2024) 42(9):840–6. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2024.2368785

52. Prieske O, Muehlbauer T, Krueger T, Kibele A, Behm DG, Granacher U. Role of the trunk during drop jumps on stable and unstable surfaces. Eur J Appl Physiol. (2015) 115(1):139–46. doi: 10.1007/s00421-014-3004-9

53. Nesser TW, Huxel KC, Tincher JL, Okada T. The relationship between core stability and performance in division I football players. J Strength Cond Res. (2008) 22(6):1750–4. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181874564

54. Guo L, Zhang J, Wu Y, Li L. Prediction of the risk factors of knee injury during drop-jump landing with core-related measurements in amateur basketball players. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. (2021) 9:738311. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2021.738311

55. Curi G, Costa F, Medeiros V, Barbosa VD, Santos TRT, Dionisio VC. The effects of core muscle fatigue on lower limbs and trunk during single-leg drop landing: a comparison between recreational runners with and without dynamic knee valgus. Knee. (2024) 50:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2024.07.017

56. Leetun DT, Lloyd Ireland M, Willson JD, Ballantyne BT. Mc clay davis I. Core stability measures as risk factors for lower extremity injury in athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2004) 36(6):926–34. doi: 10.1249/01.Mss.0000128145.75199.C3

57. Zazulak BT, Hewett TE, Reeves NP, Goldberg B, Cholewicki J. Deficits in neuromuscular control of the trunk predict knee injury risk: prospective biomechanical-epidemiologic study. Am J Sports Med. (2007) 35(7):1123–30. doi: 10.1177/0363546507301585

58. Hewett TE, Myer GD. The mechanistic connection between the trunk, hip, knee, and anterior cruciate ligament injury. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. (2011) 39(4):161–6. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3182297439

59. Laudner K, Wong R, Evans D, Meister K. Lumbopelvic control and the development of upper extremity injury in professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. (2021) 49(4):1059–64. doi: 10.1177/0363546520988122

60. Giraudeau B, Mary JY. Planning a reproducibility study: how many subjects and how many replicates per subject for an expected width of the 95 per cent confidence interval of the intraclass correlation coefficient. Stat Med. (2001) 20:3205–14. doi: 10.1002/sim.935

61. De Blaiser C, Roosen P, Vermeulen S, De Bleecker C, De Ridder R. The development of a clinical screening tool to evaluate unilateral landing performance in a healthy population. Phys Ther Sport. (2022) 55:309–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2022.05.012

62. Padua DA, Marshall SW, Boling MC, Thigpen CA, Garrett WE, Beutler AI. The landing error scoring system (LESS) is a valid and reliable clinical assessment tool of jump-landing biomechanics: the JUMP-ACL study. Am J Sports Med. (2009) 37(10):1996–2002. doi: 10.1177/0363546509343200

63. Straub RK, Powers CM. Utility of 2D video analysis for assessing frontal plane trunk and pelvis motion during stepping, landing, and change in direction tasks: a validity study. Int J Sports Phys Ther. (2022) 17(2):139–47. doi: 10.26603/001c.30994

64. Munro A, Herrington L, Carolan M. Reliability of 2-dimensional video asssessment of frontal-plane dynamic knee valgus during common athletic screening tasks. J Sport Rehabil. (2012) 21(1):7–11. doi: 10.1123/jsr.21.1.7

65. Morooka T, Yoshiya S, Tsukagoshi R, Kawaguchi K, Fujioka H, Onishi S, et al. Evaluation of the anterior cruciate ligament injury risk during a jump-landing task using 3-dimensional kinematic analysis versus the landing error scoring system. Orthop J Sports Med. (2023) 11(11):23259671231211244. doi: 10.1177/23259671231211244

66. DiCesare CA, Bates NA, Myer GD, Hewett TE. The validity of 2-dimensional measurement of trunk angle during dynamic tasks. Int J Sports Phys Ther. (2014) 9(4):420–7.25133070

67. James LP, Talpey SW, Young WB, Geneau MC, Newton RU, Gastin PB. Strength classification and diagnosis: not all strength is created equal. Curr Eye Res. (2023) 45(3):333–41. doi: 10.1519/ssc.0000000000000744

68. Maffiuletti NA, Aagaard P, Blazevich AJ, Folland J, Tillin N, Duchateau J. Rate of force development: physiological and methodological considerations. Eur J Appl Physiol. (2016) 116(6):1091–116. doi: 10.1007/s00421-016-3346-6

69. West SG, Finch JF, Curran PJ. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: problems and remedies. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. California, USA: Sage (1995). p. 56–75.

70. Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. (2016) 15(2):155–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012

71. Weir JP. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J Strength Cond Res. (2005) 19(1):231–40. doi: 10.1519/15184.1

72. Cormack SJ, Newton RU, McGuigan MR, Doyle TLA. Reliability of measures obtained during single and repeated countermovement jumps. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. (2008) 3(2):131–44. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.3.2.131

73. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis - A Regression-Based Approach. 3rd edn. New York: The Guilford Press (2022).

74. Rosseel Y. Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Soft. (2012) 48(2):1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02

75. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. (2004) 36(4):717–31. doi: 10.3758/BF03206553

76. Fairchild AJ, Mackinnon DP, Taborga MP, Taylor AB. R2 effect-size measures for mediation analysis. Behav Res Methods. (2009) 41(2):486–98. doi: 10.3758/brm.41.2.486

77. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd edn. Hillsdale, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates (1988).

78. Zhao X, Lynch JG Jr., Chen Q. Reconsidering baron and kenny: myths and truths about mediation analysis. J Consum Res. (2010) 37(2):197–206. doi: 10.1086/651257

79. Resende RA, Jardim SHO, Filho RGT, Mascarenhas RO, Ocarino JM, Mendonça LDM. Does trunk and hip muscles strength predict performance during a core stability test? Brazil J Phys Ther. (2020) 24(4):318–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2019.03.001

80. Boling MC, Padua DA. Relationship between hip strength and trunk, hip, and knee kinematics during a jump-landing task in individuals with patellofemoral pain. Int J Sports Phys Ther. (2013) 8(5):661–9.24175145

81. Zipser MC, Plummer HA, Kindstrand N, Sum JC, Li B, Michener LA. Hip abduction strength: relationship to trunk and lower extremity motion during a single-leg step down task in professional baseball players. Int J Sports Phys Ther. (2021) 16(2):342–9. doi: 10.26603/001c.21415

82. Popovich JM, Kulig K. Lumbopelvic landing kinematics and EMG in women with contrasting hip strength. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2012) 44(1):146–53. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182267435

83. Stickler L, Finley M, Gulgin H. Relationship between hip and core strength and frontal plane alignment during a single leg squat. Phys Ther Sport. (2015) 16(1):66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2014.05.002

84. Neumann DA. Kinesiology of the hip: a focus on muscular actions. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. (2010) 40(2):82–94. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2010.3025

85. Martinez AF, Lessi GC, Carvalho C, Serrao FV. Association of hip and trunk strength with three-dimensional trunk, hip, and knee kinematics during a single-leg drop vertical jump. J Strength Cond Res. (2018) 32(7):1902–8. doi: 10.1519/jsc.0000000000002564

86. Baldon R, Piva SR, Scattone Silva R, Serrão FV. Evaluating eccentric hip torque and trunk endurance as mediators of changes in lower limb and trunk kinematics in response to functional stabilization training in women with patellofemoral pain. Am J Sports Med. (2015) 43(6):1485–93. doi: 10.1177/0363546515574690

87. Chaudhari AM, McKenzie CS, Borchers JR, Best TM. Lumbopelvic control and pitching performance of professional baseball pitchers. J Strength Cond Res. (2011) 25(8):2127–32. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31820f5075

88. Butcher SJ, Craven BR, Chilibeck PD, Spink KS, Grona SL, Sprigings EJ. The effect of trunk stability training on vertical takeoff velocity. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. (2007) 37(5):223–31. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2007.2331

89. Schmidtbleicher D. Strukturanalyse der motorischen kraft. Leichtathlet: Unabhäng Z. (1984) 35(50):1785–92.

90. Clayton MA, Trudo CE, Laubach LL, Linderman JK, De Marco GM, Barr S. Relationships between isokinetic core strength and field based athletic performance tests in male collegiate baseball players. J Exerc Physiol Online. (2011) 14(5):20–30.

91. Sharrock C, Cropper J, Mostad J, Johnson M, Malone T. A pilot study of core stability and athletic performance: is there a relationship? Int J Sports Phys Ther. (2011) 6(2):63–74.21713228

92. Sousa da Silva D, Sousa RMC, Willardson JM, Santana H, Brandão Pinto de Castro J, De Oliveira F, et al. Correlation between lower limb and trunk muscle endurance with drop vertical jump in the special military forces. J Bodyw Mov Ther. (2022) 30:154–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2022.02.024

93. Santos MS, Behm DG, Barbado D, DeSantana JM, Da Silva-Grigoletto ME. Core endurance relationships with athletic and functional performance in inactive people. Front Physiol. (2019) 10:1490. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01490

94. Tomčić J, Šarabon N, Marković G. Factorial structure of trunk motor qualities and their association with explosive movement performance in young footballers. Sports. (2021) 9(5):67. doi: 10.3390/sports9050067

95. Behm DG, Daneshjoo A, Alizadeh S. Assessments of core fitness. ACSM’S Health Fitness J. (2022) 26(5):68–83. doi: 10.1249/fit.0000000000000801

96. Spudić D, Vodičar J, Vodičar M, Hadžić V. Isometric trunk strength assessment of athletes: effects of sex, sport, and low back pain history. J Sport Rehabil. (2022) 31(1):38–46. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2021-0002

Keywords: ULESS test, trunk, kinematics, diagnostics, lower limb, jumping performance

Citation: Schulte S, Lukas M, Bopp J, Zschorlich V and Büsch D (2025) Relation between core strength, core stability, and athletic performance—a mediation analysis approach. Front. Sports Act. Living 7:1669023. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2025.1669023

Received: 18 July 2025; Revised: 12 November 2025;

Accepted: 17 November 2025;

Published: 28 November 2025.

Edited by:

Erika Zemková, Comenius University, SlovakiaReviewed by:

Mokhtar Chtara, University of Sharjah, United Arab EmiratesBanafsheh Amiri, Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovakia

Luis Arturo Gómez-Landero, Pablo de Olavide University, Spain

Copyright: © 2025 Schulte, Lukas, Bopp, Zschorlich and Büsch. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarah Schulte, c2FyYWguc2NodWx0ZTFAdW5pLW9sZGVuYnVyZy5kZQ==

Sarah Schulte

Sarah Schulte Matthias Lukas1

Matthias Lukas1 Jessica Bopp

Jessica Bopp Volker Zschorlich

Volker Zschorlich Dirk Büsch

Dirk Büsch