- 1Department of Food Science and Technology, Pondicherry University, Pondicherry, India

- 2Biochemistry Division, ICMR-National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad, Telangana, India

This study investigated the effects of gamma-(γ)-polyglutamic acid (γ-PGA) on the physical, structural, and sensory properties of muffins. γ-PGA polymer, extracted from Bacillus valezensis M-E6, was incorporated into muffin batter at concentrations ranging from 0.2% to 1%. The volume index of muffins was increased to 104 with γ-PGA (0.6%) compared to the control muffins (without γ-PGA, 95.3). Textural profile analysis revealed the best texture for muffins containing 0.6% γ-PGA, characterized by the lowest hardness (1508 g), which was half that of muffins without γ-PGA, along with improved cohesion and springiness. The viscosity of control batter was 12648 mPa·s, whereas for γ-PGA batter, it was 14845 mPa·s. Also, a decrease in lightness (L*) and an increase in redness (a*) were observed in muffins with γ-PGA. γ-PGA muffins received higher overall acceptability scores than the control in the sensory evaluation. The antioxidant activity of the muffin increased from 6% to 41% when incorporated with γ-PGA, which makes it a functional muffin. Incorporating γ-PGA improved the physical, textural, and sensorial properties of muffins, making it a promising natural ingredient for enhancing the quality and shelf life of baked products. These results suggest that γ-PGA not only improves the texture and quality of muffins but also benefits moisture retention and shelf life, aligning with consumer preferences for natural and sustainable food ingredients.

1 Introduction

Muffin is a popular sweet quick bread, known for its excellent flavour and delicate texture (porous and spongy with high volume). It resembles a cupcake; however, it is typically less sweet and lacks frosting (Taiyeba et al., 2020). Muffin batter is a complex food system composed of a fat-in-water emulsion. It consists of a continuous phase made up of a mixture of egg, sucrose, and fat. This continuous phase is composed of air bubbles dispersed throughout the flour particles. This structure is achieved by creating a stable batter that contains numerous small air bubbles. The incorporation of these tiny air pockets is essential for developing the desired texture and volume in the final product (Martinez-Cervera et al., 2013). Gamma-polyglutamic acid (γ-PGA) is a natural polymer that has gained significant attention in recent years due to its remarkable properties, such as water holding capacity, water solubility index, oil binding capacity, emulsification activity, thickening potential, flocculation ability, antioxidant, and cryoprotection activity (Bhat et al., 2013; Feng et al., 2018; Fernandes et al., 2023; Insulkar et al., 2018). These properties could lead to its widespread use in the food industry, such as texture stabilizers, thickeners, as a nutritional aid, and food additive (Shih et al., 2004; Ogunleye et al., 2015; Hsueh et al., 2017). This biodegradable and water-soluble polymer is composed solely of glutamic acid residues, making it a unique and versatile material (Shih et al., 2004). While polyglutamic acid can be produced through chemical synthesis, known as α-polyglutamic acid, the microbiological approach involving fermentation by Bacillus species produces γ-PGA. The microbial PGA (γ-PGA) has gained significant attention due to its production with wide range of molecular weights unlike chemical synthesis that produces PGA of less than 10 kDa therefore limiting its applications (Hsueh et al., 2017; Buescher and Margaritis, 2007). Moreover, incorporating γ-PGA into muffins imparts several beneficial functionalities, including enhanced anti-oxidant potential, the ability to moderate postprandial blood glucose responses, thereby contributing to the prevention of hyperglycemia, diabetes, and cardiovascular conditions-as well as serving as an effective calcium supplement due to its superior intestinal absorption rate (Araki et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2018).

Bakers and food scientists have turned to a variety of synthetic texture stabilizers, each with its own unique properties and functionalities. Methylcellulose and carbohydrate-based fat replacements are commonly used stabilizers in baked goods to retain moisture and improve texture (Ren et al., 2020). Methylcellulose is effective in creating soft, tender crumb and preventing staling. Carbohydrate-based fats like inulin and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose improve batter viscosity and texture (Xue and Ngadi, 2007). However, their potential health effects are debated due to their difficulty in digestion.

The potential of γ-PGA in the baking industry is particularly intriguing. The polymer’s ability to modify the rheological properties of dough and baked goods, such as enhancing viscosity, improving texture and increasing shelf-life, has been the subject of extensive research (Jindal and Khattar, 2018). Furthermore, the biodegradable, edible and non-toxic nature alongside Generally Recognised as Safe (GRAS) status (GRN no. 339, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2010) of γ-PGA makes it a desirable alternative to synthetic additives, aligning with the growing consumer demand for natural and sustainable food ingredients (Shih et al., 2004). γ-PGA being a natural polymer has been shown to improve the texture of baked goods including sponge cake and wheat dough (Shyu et al., 2008; Shyu and Sung, 2010).

Earlier, γ-PGA was extracted and characterized from Bacillus sp. M-E6 isolated from white eyed beans. This γ-PGA biomolecule exhibited potent functional properties such as water solubility (100%), water-holding capacity (196.21%), oil binding capacity (104.78%), emulsifying activity (79.33%), antioxidant activity (in vitro), and cryoprotectant properties. This study aims to investigate the application of γ-PGA in the muffin food system. Furthermore, the incorporation of γ-PGA into muffin batter aimed to explore strategies for modifying texture and assess the impact of these changes on various physical and sensory characteristics.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals and raw materials

The muffin ingredients, including refined wheat flour, sugar, milk, eggs, butter, oil, and baking powder, were purchased from the local market in Pondicherry. The IR (Infrared radiation) grade potassium bromide was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, United States. Other chemicals and reagents used were obtained from Hi-Media, India. The γ-PGA was extracted from our culture Bacillus sp. M-E6 was incorporated.

2.2 γ-PGA production

γ-PGA production was performed as described in our previous study (Manika et al., 2025b) using the strain Bacillus sp. M-E6. Briefly, the culture was harvested in the γ-PGA production medium and incubated at 37 °C for 72 h at 180 rpm. The fermented broth was then centrifuged to remove cell biomass at 13,000 x g for 20 min at 4 °C. Subsequently, the supernatant was precipitated by adding three volumes of ice-cold absolute ethanol under refrigeration (4 °C) overnight. The precipitated γ-PGA was centrifuged for extraction, followed by lyophilization, and then powdered for use in the experiment.

2.3 Batter and muffin preparation with γ-PGA incorporation

The muffin ingredients maida (100 g), sugar (36 g), baking powder (3.6 g), butter (22.5 g), olive oil (18 g), eggs (2), salt (1.8 g) and milk (67.5 mL), formulation was followed with some modification suggested by Kaur et al. (2022) and Pruett et al. (2023). Muffins were incorporated with γ-PGA at different concentrations (0.2, 0.5, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0%) and coded as P0.2, P0.5, P0.6, P0.8, and P1.0, respectively. Firstly, γ-PGA (powder), maida, baking powder, and salt were sifted together to make a mix. This was followed by the creaming of sugar, butter, and oil in a separate mixing bowl. Eggs were blended in an electric blender (Philips, Netherlands), then mixed into a creamed mixture (butter and sugar), and finally milk was added. The mixture thus formed is the wet ingredients mix. The dry ingredients mix was gradually added to the wet mix while blending, to avoid any lumps and get a smooth batter of the required consistency. The batter without γ-PGA was used to prepare the control muffin labelled as C-muffin. For baking, 70 g of batter was poured into each muffin mold, greased with butter, having a diameter of 60 mm and a height of 36 mm, arranged in two rows and three columns. The oven was preheated, followed by baking for 20 min at 160 °C (Official methods of analysis, AOAC, 22nd edition 2023). Once prepared, muffins were kept at room temperature for ∼15 min, placed in a cooling rack for 2 h, freeze-dried, powdered, and stored under refrigeration in re-sealable pouches for further analysis.

2.4 Flow properties of dry batter mix

2.4.1 Bulk and tapped density

Ten grams of the dry ingredients batter mix was taken in a 25 mL measuring cylinder, and the volume occupied (Vo) by it was measured before tapping. The net weight of batter (M) and occupied volume were used to calculate the bulk density (A). The cylinder was then tapped for 5 min (30 times per minute) at a height of 3 mm, and the tapped density (B) was calculated as the ratio of the weight of the batter mix taken (M) and the volume occupied by the mix after tapping (Vf). The densities were presented in g/mL (Santhalakshmy et al., 2015).

2.4.2 Flowability (CI) and hausner ratio (HR)

The flow characteristics of the dry ingredient batter mix were assessed using variables such as bulk and tapped density. The flow attributes of the batter mix are measured using Carr’s Index (CI) and Hausner ratio (HR), as calculated by the equations provided below (Santhalakshmy et al., 2015).

2.5 Physicochemical properties of wet batter

2.5.1 pH and water activity

The pH of the muffin batter was analyzed using a pH meter (Laboholic, Deluxe pH meter, model no. LH-10). Ten grams of whole batter was mixed with 90 mL of deionized water, followed by dipping a pH probe into the batter solution, and pH was recorded (Alvarez et al., 2017). Water activity of the muffin batter was determined using a water activity meter (Aqualab series, Decagon Devices, Inc., Washington, United States). The measurements were performed in triplicate, considering the samples from the geometric center of the batter (Bhaduri S, 2013).

2.5.2 Specific gravity

The specific gravity (SG) of the raw batter was calculated in accordance with Martinez-Cervera et al. (2012), Martinez-Cervera et al. (2013). Using a graduated beaker, the SG was calculated gravimetrically as the ratio of the weight of a known volume of batter to that of an equal volume of water at 28 °C.

2.6 Physical properties of muffin

2.6.1 Height and weight of muffins

Muffin was kept at a plane surface, and height was measured with a calliper from the highest point to the bottom of the mould. Each formulation was prepared thrice on different days, and the average height was recorded. Muffins were weighed after cooling at room temperature to analyse the difference in weight at different γ-PGA concentrations (Martinez-Cervera et al., 2012).

2.6.2 Moisture content (MC) and water activity (aw)

The moisture content of muffin samples was measured using a moisture analyser (KMA-101, Kinglab, India). Briefly, muffin samples were cut into cross-sections and placed on the moisture analyzer tray, and the moisture content was recorded (Walker et al., 2014).

2.6.3 Volume index

The volume was measured using the AACC template method (AACC, 1983), in triplicate by measuring the height at three different points. The muffins were sliced vertically after baking, and their heights were measured with a ruler at three cross-sectional points (B, C, D). According to this method, the volume index was calculated by the formula given as:

Where, C represents the height of muffin at the center point, and B and D represent the height of muffin at points 2.5 cm away from the center towards the left and right side of the sliced muffins, respectively.

2.6.4 Cooking yield

To determine the cooking yield (CY), muffin batter was weighed before and after baking, once muffins were cooled at room temperature, by the equation given below (Karp et al., 2016).

Where, CY is the cooking yield percentage (%), Wa is the weight of a sample after baking, Wb is the weight of a sample before baking.

2.6.5 Moisture loss during baking

To determine moisture loss during baking, the weight of muffin was compared to the weight of batter (Martinez-Cervera et al., 2012).

2.7 Texture analysis

The texture for the muffins was analyzed using a 5197 TA-HD plus 5,197 Stable Micro Systems analyzer, Texture Exponent Lite software, United Kingdom (UK). The lower, 2.5 cm high portions of the muffins were removed from the mould after being cut horizontally. The crumb sample was cut in 3 × 3 × 3 cm (l × b × h), the flat base cylindrical probe (P/75) with a diameter of 75 mm was used for a double compression test for texture profile analysis. The analysis involved compressing the muffin crumb to 50% of its initial height at a speed of 1 mm/s for 5 s. The pre- and post-test speeds were set at 2 and 30 mm/s, respectively, and the test speed was set at 2 mm/s with a trigger force of 5 g (Kavitake et al., 2020). Texture analysis measured an array of parameters, including hardness, springiness, cohesiveness, and chewiness. The test was performed for all the muffins with varied γ-PGA concentration and muffin without γ-PGA (control muffin).

2.8 Structural properties of muffin

2.8.1 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The structural morphology of muffins was performed using a scanning electron microscope (S-3400, Hitachi, Japan). For analysis, the freeze-dried muffins were powdered and attached to an aluminum stub, then carbon sputtered. The microscopic images were captured with 100–200x magnification (Ahmed et al., 2013).

2.8.2 FT-IR analysis

FTIR analysis was performed to elucidate the presence and interactions between γ-PGA and other ingredients in muffins. Fourier-transform infrared spectra were acquired using an FT-IR spectrophotometer (Thermo Nicolet: 6,700, United States). The freeze-dried muffin samples were powdered with KBr and compressed into pellets for spectroscopic measurements in the frequency range 400–4,000 cm-1 (Kavitake et al., 2020).

2.8.3 Batter viscosity

To measure the viscosity of muffin batter, a rotational viscometer (LMDV-60, Labman digital, India) was used based on the method given by Bhaduri (2013), with slight modifications. The batter was taken in a 500 mL beaker and spindle no. L4 was used at 6 rpm to measure the viscosity. The experiment was performed at room temperature (21.8 °C ± 2 °C), and measurements were recorded immediately.

2.9 Colour analysis

The colour parameters of muffins were examined using a Hunter Lab colorimeter (ColorFlex EZ, United States). Muffin sample selected based on the texture and batter properties were analysed for their colour parameters, i.e., L* (L = 0 [black], L* = 100 [white] indicating lightness, -a* indicating hue on green +a* represents red, = a indicates axis and b* represents yellow colour -b* to yellow (=b*) axis. Additionally, the hue angle (h) and Chroma (C*) are two important components of colour space that are calculated from the colour coordinate values of a* and b*. The term Chroma refers to the purity of colour reflected as a quantitative component (Kane et al., 2003). Muffins with and without γ-PGA were cut horizontally into half along a plane that run parallel to their base and kept on the colorimeter plate to evaluate their L*, a* and b* values of the crumb according to CIELAB colour system. Three slices for each sample were analysed and results were averaged (Matos et al., 2014; Rumiyati et al., 2015). In addition, ΔE (colour difference) was calculated following the equation given below.

The muffin with no γ-PGA was used as the reference for calculating ΔE (Sanz et al., 2009). The following ΔE values were utilized to evaluate whether the total colour difference is perceptible to human eye (Francis and Clydesdale, 1995).

ΔE*<1 colour differences are not readily discernible to the human eye.

1<ΔE*<3 colour differences are not easily appreciated by the human eye.

ΔE*>3 colour differences are readily apparent to the human eye.

2.10 Antioxidant activity

2.10.1 Extraction of bioactive compounds

The extraction of bioactive compounds was performed from finely ground muffin sample using grinder. The sample was subjected to defatting using hexane (1:5 w/v, thrice, 5 min each) followed by drying at 40 °C for 24 h. The dried sample was immersed in methanol (70%, 1:10 w/v) and sonicated in a serological water bath (Sonica- 2200 MH, SOLTECH, Italy) at room temperature for 1 h. Samples were filtered using Whatman filter paper (No. 1) and stored under refrigeration (4 °C) for further analysis (Kaur and Kaur, 2018).

2.10.2 DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) assay

The antioxidant activity of muffin extract was assessed based on the method given by Abdel-Hamid et al. (2019) with some modifications. First, 0.2 mM of DPPH solution was prepared in methanol and 100 µL of this solution was taken. To this, 100 µL of the muffin extract was added and water was used as control. The solution mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min under dark environment. Absorbance was measured at 517 nm followed by calculation of antioxidant activity using following formula:

2.11 Sensory analysis

The sensory analysis of the muffins was carried out with panel consisting of 20 semi-trained people of both genders aged 20–55 years (staff and students from our department), assessed the muffin samples using a 9-point hedonic scale, where 1 indicated “dislike extremely” and 9 signified “like extremely”. The analysis was performed considering attributes like taste, colour, odour, appearance, mouthfeel and overall acceptability. The test was conducted for two muffin samples one without γ-PGA (C-muffin) and one incorporated with γ-PGA (P-muffin), presented on white plates at room temperature under white light. Panellists were served at room temperature with water to cleanse the palate before and during testing. Each panellist received and evaluated both the samples, one at a time, in a sequential manner (Goswami et al., 2015).

2.12 Staling study

The moisture content of the muffin with crust was analysed on 1,3,4,7 and 10th day with storage at room temperature according to the method given by Raffo et al. (2003), with minor modifications. Muffins were stored in perforated plastic packets. Simultaneous texture analysis was done to evaluate the changes occurring in firmness of the muffin as per the method mentioned in the previous Section 2.7.

2.13 Statistical analysis

All the experiment were conducted in triplicate, and the results were expressed as mean ± SD. The results were statistically analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2013 and IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 20). One-way ANOVA test (Duncan’s test) was applied to compare the data and find out the significant difference (P < 0.05). The colour analysis and staling study was employed with t-test (independent samples) for comparison of data and statistical difference.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Muffin preparation and γ-PGA incorporation

γ-PGA was incorporated into muffins at varying concentrations (0.2%–1% w/w), designated as P0.2, P0.5, P0.6, P0.8, and P1.0 to evaluate its influence on textural properties in comparison to control muffins (C-muffin), as illustrated in Figure 1. The figure demonstrates a progressive change in muffin colour with increasing γ-PGA concentration. While C-muffins exhibited numerous pores that were irregularly distributed, the addition of γ-PGA resulted in a more uniform pore distribution. Among the samples, P0.2, P0.5, P0.6, and P0.8 displayed optimal pore profiles. Notably, P0.8 exhibited the highest number of small, round, and evenly distributed solid pores, indicative of a well-aerated and uniformly structured muffin core (Sopotenska and Chonova, 2019).

Figure 1. Muffins prepared with different concentrations of γ-PGA. (a) C-muffin, (b) P0.2, (c) P0.5, (d) P0.6, (e) P0.8, and (f) P1.0.

3.2 Flow properties of dry batter mix

3.2.1 Bulk and tapped density

The flow characteristics of a material, particularly its bulk and tapped densities, determine how the particles are packed and arranged, as well as how much material is compacted (Sopotenska and Chonova, 2019). The flow properties of the batter are shown in Table 1. The bulk densities of muffin batters with and without γ-PGA exhibited minimal variation. The bulk density of the batter with γ-PGA was found to be slightly higher than the batter without γ-PGA, probably due to the presence of γ-PGA particles easing them to accommodate into the spaces between batter particles (Ferrari et al., 2012). The bulk density increased with γ-PGA concentration up to 0.6%. However, at higher concentrations of 0.8% and 1% γ-PGA (P0.8 and P1.0, respectively), a slight reduction was observed. Meanwhile, the tapped densities of the samples both with and without γ-PGA, ranged from 0.66 to 0.67 g/mL, indicating no significant differences (P < 0.05) between them, as presented in Table 1. Similar findings have been observed in the study on exopolysaccharide-based flavour emulsion for muffins (Kavitake et al., 2020).

3.2.2 Flowability (CI) and hausner ratio (HR)

The relative flowability of a powdered substance is an important attribute and is expressed as Carr Index (CI). The CI of the batter samples ranged between 33% and 35%, with no significant difference among the dry batter samples, as shown in Table 1. The control and P0.5, P0.2 and P0.6, and P0.8, P1.0 exhibited flowability indices of 34, 33% and 35% respectively. The values of CI in case of control and samples with γ-PGA indicates fair flowability having no statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). This may be attributed to variation in the structure, shape and size of the particles in the powdered sample, smaller the particles lower the flowability. The cohesive force or static electrical attraction between particles increases adherence and results into reduced flowability (Pooja et al., 2022).

This behaviour may be associated with the preparation of better batter consistency formed in samples P0.8 and P1.0 having the highest value due to low flowability. Cohesiveness, which is expressed as Hausner ratio (HR), of the batter powders was ranged as 1.49 to 1.54 with no significant difference (P < 0.05). According to Santhalakshmy et al. (2015), these values represent high cohesiveness levels in the batter powders may be aiding into the complex formation between γ-PGA and the batter ingredients. Similar results have been obtained by (Arifin et al., 2019) where pumpkin puree was used as butter replacer in muffins.

3.3 Physico-chemical properties of wet batter mix

3.3.1 pH and water activity of the batter

The pH value of control batter (without γ-PGA) was 7.2, however for batter incorporated with γ-PGA it was reduced to 6.76, 6.68, 6.63, 6.56, and 6.74 as per concentrations P0.2, P0.5, P0.6, P0.8, and P1.0 respectively (Table 2). The addition of γ-PGA in batter resulted in slight reduction of pH values due to the influence of the γ-PGA. The result shows similarity with the pH of batter reported by Bhaduri (2013). Water activity (aw), a measure of availability of water molecules for biological and physicochemical processes, plays a vital role in determining the growth of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and mold, as well as the mobility and behaviour of various components within the product (Jager et al., 2016). The aw of batter was found to increase slightly with increasing concentrations of γ-PGA, as indicated in Table 2. This enhancement is attributed to the excellent water retention properties of γ-PGA (Shyu et al., 2008). An increase of 2%–4% in aw was observed in batters containing γ-PGA and those without it. Notably, the muffin incorporated with 1% γ-PGA recorded the highest aw as 0.89, whereas the control muffin showed the lowest aw as 0.86.

3.3.2 Specific gravity

The batter’s ability to hold air is indicated by its specific gravity (SG) values; a lower SG value indicates greater air incorporation and a higher ability to retain air bubbles in batter (Gujral et al., 2003). This characteristic factor ultimately leads to a greater volume post baking with a spongier, soft product, which is an appealing trait for consumer acceptability and the product marketing. According to the results presented in Table 2 no significant difference (P < 0.05) was observed in the specific gravity of different samples. However, specific gravity of P0.6 shown to have the lowest value, i.e., 0.92 which indicates greater air incorporation during mixing compared to other samples with varied γ-PGA concentration. Similar results have been observed by Martinez-cervera et al. (2013), when starch was used as fat replacer, an increase in starch concentration showed a reduction in specific gravity. An increase in batter density and specific volume in muffins was also reported on addition of solid-state fermented cassava flour with significantly improved softness and enhanced protein content (Khurshida et al., 2025).

3.4 Physical properties of muffin

3.4.1 Height and weight of the muffin

The results for the height and weight of the muffin are shown in Figure 2. The height of muffins showed a linear increase from 0.2% to 0.5% γ-PGA (Figure 2). Here, the presence of γ-PGA might be aiding in the muffins’ rise, thus resulting in an increase in height. The muffins at higher γ-PGA concentrations showed a reduction in height, the reason may be the abundant concentration of γ-PGA required to raise during baking. Also, the muffins were observed to be soggy probably due to the adhesive nature of γ-PGA which might have increased the active functional groups linkage (Ho et al., 2006) with the muffin ingredients when used at higher concentrations. Muffin sample, P0.6 showed the maximum height and C-muffin, the lowest which is 51.3 and 41.3 mm respectively. Masmoudi et al. (2020), formulated muffins with acorn flour as a gluten free alternative along with three hydrocolloids (xanthan gum (X), carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) and k-carrageenan (k-C)). They found an increase in height with 26.8% X, 50.5% CMC and 22.7% κ-C, aligning with our study which showed an increase in height when added with γ-PGA. For the weight of muffins, the highest weight 66.93 g was observed in P0.8 muffins as compared to the lowest, 63.96 g (Figure 2) in P0.5 muffins. There was no significant difference in weight observed in the muffins with and without γ-PGA.

Figure 2. Physical properties of muffins at varied concentrations of γ-PGA. P0.2, P0.5, P0.6, P0.8, and P1.0 are the samples with 0.2, 0.5, 0.6, 0.8, and 1% of γ-PGA, respectively.

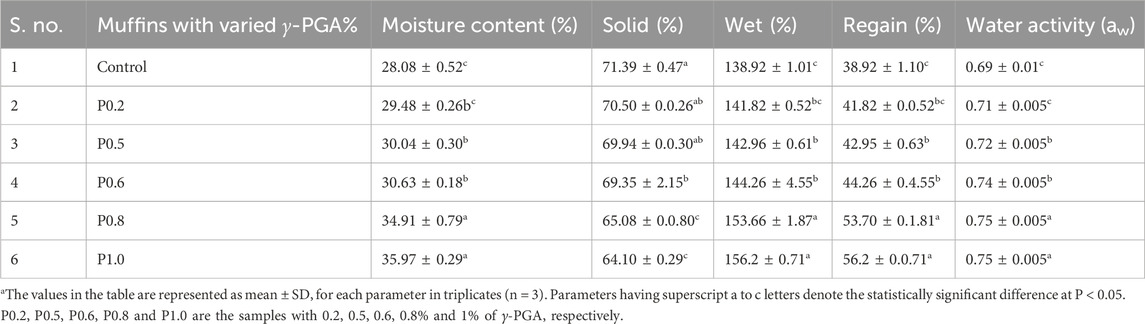

3.4.2 Moisture content and water activity (aw)

The moisture content of muffins is a crucial factor in determining their overall texture, shelf-life and consumer appeal (Samokhvalova et al., 2020). The moisture content of the muffins with γ-PGA was observed to be increased with an increase in γ-PGA concentration. The muffins without γ-PGA exhibited the lowest moisture content of 28%, whereas those containing 1% γ-PGA showed the highest value of 35%. Table 3 presents these results along with other related moisture parameters, including solid content, wet basis moisture, and moisture regain percentage of the muffins. Similar findings were observed in the study performed by Rahman et al. (2015) and Mala et al. (2018) when incorporated muffins with wheat grass and pumpkin powder respectively. The probable reason for such linear increase in moisture content may be the good water binding ability of γ-PGA (Xie et al., 2024).

The aw of baked goods, such as muffins and other bakery products, is a crucial factor that impacts their quality, shelf-life, and microbial stability (Jager et al., 2016). The aw of the muffins was observed to be slightly increased with the increase in γ-PGA concentration as shown in Table 3 owing to the good water holding capacity of γ-PGA. The values showed a difference of 3%–6% in aw of the control muffins and γ-PGA muffins. Similar observations were recorded when muffins were incorporated with wheat grass powder (Rahman et al., 2015).

3.4.3 Volume index

The volume index of baked goods is a crucial indicator for their overall quality and consumer appeal (Kohajdova et al., 2012). Muffins incorporated with γ-PGA were observed to have noticeably higher volume index as compared to their no γ-PGA counterpart (Figure 2). The volume index of muffins was observed to be increased with the increase in γ-PGA concentration from 0% to 0.6%, the reason may be the addition of γ-PGA resulting in an increase in volume due to the improved interaction of free active functional groups of γ-PGA with the batter ingredients. However, there was no significant increase at 0.8% and 1% γ-PGA, probably because of the higher water-holding ability of γ-PGA, which increased the density and thus prevented the rise in the muffins. The volume index of muffins with no γ-PGA was 95.3 and with γ-PGA it ranged between 99 and 104 (Figure 2), P0.6 being the highest. Similar results have been recorded in studies where muffins were supplemented with pomegranate peel (Topkaya and Isik, 2019) and apple skin powder (ASP) at different concentrations (Vasantha Rupasinghe et al., 2009).

3.4.4 Cooking yield

Cooking yield is a key factor that influences the quality of muffins, or the amount of product that is obtained from a given recipe. The cooking yield can impact various physical and sensory properties, including the crust colour, texture, and sensory properties of the muffin (Heo et al., 2019). According to the results shown in Figure 2, the cooking yield of the samples showed no significant difference from the one with no γ-PGA to the ones with different concentration of γ-PGA. The values for cooking yield of all the samples are comparable (Figure 2). The highest value 91.45% was shown by P0.8 muffin whereas the lowest 88.81% was shown by control muffin. The water content that escapes during baking results in the final product formation, is the key element affecting this parameter. There are previous reports that suggest that intermediate oven temperature, between 140 °C and 220 °C, can lead to a more porous, aerated and soft crumb texture, with desirable overall acceptability. This is likely due to the balance between optimal moisture loss and starch gelatinization during the baking process (Karp et al., 2016). Geetanjali et al. (2025), reported a reduction in baking loss and thus increased cooking yield when replaced fat with ultrasonicated corn starch in muffins. In contrast, Cabuk (2021), presented an increased cooking yield when incorporated grasshopper powder to prepare protein rich muffins.

3.4.5 Moisture loss during baking

There is significant difference (P < 0.05) in moisture loss% of the control and the muffin with γ-PGA, as shown in Figure 2. Moisture loss decreases with an increase in concentration of γ-PGA. This indicates that the muffins with incorporated γ-PGA have lower moisture loss compared to the muffins with no γ-PGA (Khouryieh et al., 2005). The values for moisture loss ranged between 8.5% and 11%, control muffin being the highest and P0.8 the lowest. The moisture loss of muffins seems to be gradually decreased with an increase in γ-PGA concentration (Figure 2). According to Marchetti et al. (2018), these traits are important in industry because lower baking loss leads to a higher yield and, consequently, a heavier product. Weight loss as a result of water released from the product during baking has a direct relation with the ability of ingredients to hold water. The remarkable hydrophilic property of γ-PGA has been attributed to its ability to form strong hydrogen bonds with water molecules, thereby reducing moisture loss and enhancing hydration (Guo et al., 2022). Therefore, addition of γ-PGA might be a reason of holding water molecules together and a reduction in moisture loss. Similar results have been observed for the muffin supplemented with spinach powder (Koc et al., 2019).

3.5 Texture analysis

The parameters used in the texture profile study, which are summarised in Table 4, include hardness, springiness, cohesiveness, chewiness, and gumminess. The hardness of the muffins incorporated with γ-PGA was observed to be reduced linearly with an increase in concentration of γ-PGA. The control muffin shows the maximum hardness, i.e., 3654.29 g, and P0.6 the lowest, that is, 1505.88 g, which is 50% less when compared to the control muffin. This was followed by an improvement in cohesion and springiness, which is related to fresh, aerated products. Similar findings have been reported in xanthan gum-infused low-fat muffins, which were shown to be considerably less chewy and hard than the ones without it (Khouryieh et al., 2005). The result of this analysis aligns with the objective of this study, demonstrating a significant reduction in muffin firmness when γ-PGA is incorporated.

However, Kaur and Kaur (2018) reported increased hardness and chewiness in muffins when incorporated with apple peel powder. Additionally, study by Mohammadi et al. (2022), represents the addition of bioactive peptides from lentil protein enhancing the nutritional profile but not affecting the texture of the muffins. High-quality muffins exhibit more springiness, indicating that the sample has recovered from deformation (Sanz et al., 2009). As shown in Table 4, the P0.6 muffin sample exhibits the best attributes for muffin texture compared to the control and other concentrations of γ-PGA. Specifically, the hardness is lowest at this concentration, thus achieving the primary objective of this study. The springiness, cohesiveness, gumminess, and chewiness of control and γ-PGA muffins are in the range of (0.88–0.95), (0.83–0.76), (2494.02–1368.37 g), and (3222.91–1111.29 g), respectively. A reduction in springiness observed with an increase in γ-PGA concentration could potentially be linked to a decrease in muffin hardness (Table 4). These results show that the incorporation of γ-PGA is probably a reason of texture enhancement in muffin and muffin at 0.6% γ-PGA was chosen for further studies (structural study, colour analysis, sensory and staling studies) based on the texture results. Control muffin sample is coded as C-muffin, whereas with 0.6% γ-PGA (P0.6) is coded as P-muffin.

3.6 Structural properties of muffin

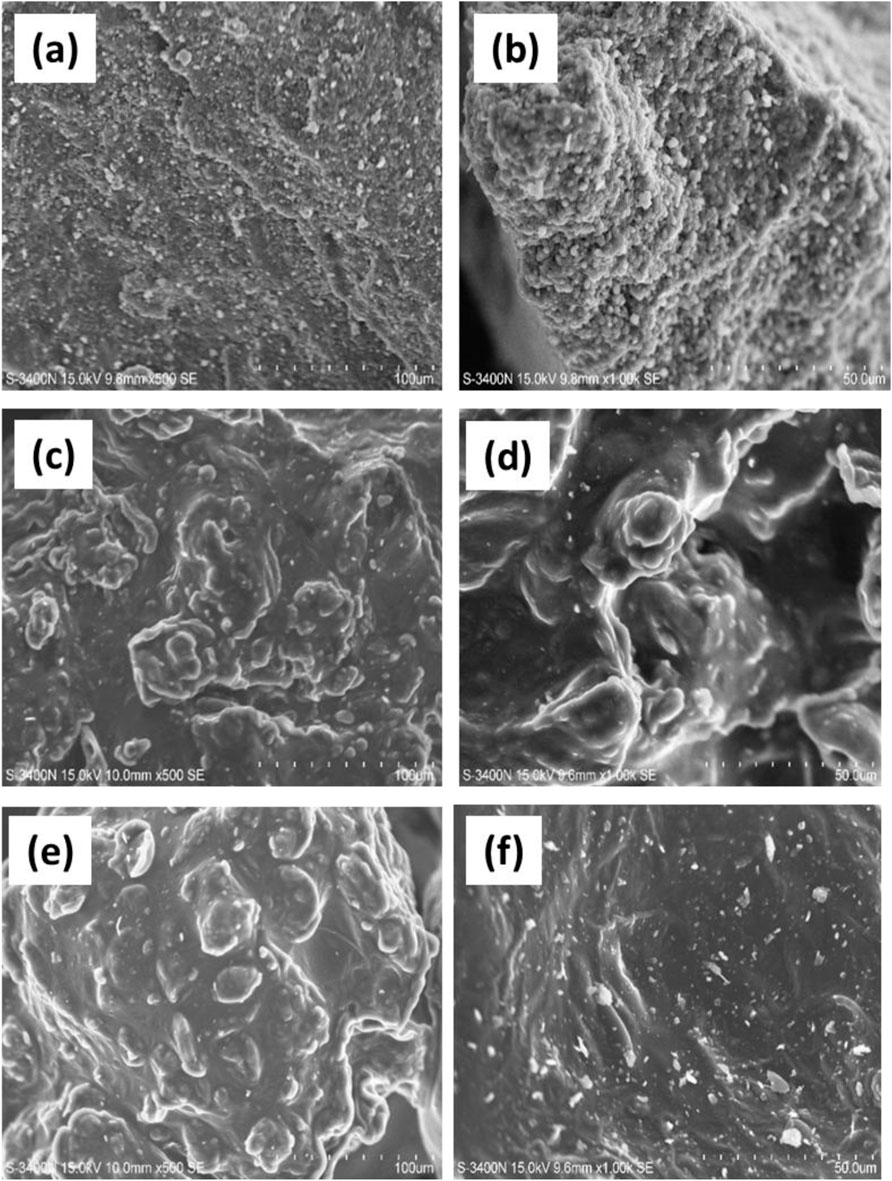

3.6.1 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The morphological structures for γ-PGA biomolecule, C-muffins, and P-muffins (Figure 6) were observed by SEM at different magnifications. The micrograph of γ-PGA shows a clear globular structure with both rough and smooth surfaces (Figure 3a). At higher magnification (1,000x) (Figure 3b), it reveals a detailed microstructure, consisting of thin, porous layers composed of sponge-like granules. SEM images of the C-muffin micrographs at 500x magnification (Figure 3c) show the muffin granules. In addition, Figure 3d shows the same at higher magnification, i.e., 1,000x. The structures in the micrographs representing P-muffin at 500 and 1000x magnification (Figures 3e,f) were observed to have γ-PGA granules attached to thick wall structures of the muffin. Similar to the γ-PGA (P0.6) muffin, a thick-walled, pleated structure was observed in earlier studies for sponge cakes incorporated with commercial γ-PGA by Shyu and Sung (2010).

Figure 3. Scanning electron micrographs of muffins at 500 and 1000 x magnification, γ-PGA (a,b); C-muffin (c,d); P-muffin (e,f)

3.6.2 FTIR analysis

To investigate the impact of γ-PGA on the physico-chemical and functional properties of muffins, the FTIR spectroscopy was employed, a powerful analytical technique capable of providing detailed insights into the molecular composition and structural changes within the muffin matrix (Mildner-Szkudlarz et al., 2016; Harastani et al., 2021). The results of the FTIR analysis revealed distinct changes in the spectral profiles of muffins as a function of γ-PGA concentration. The FTIR spectrum of muffin (Figure 4) exhibits a characteristic absorption band at 1,649.26 for C-muffin and 1,652 cm-1 for P-muffin corresponding to the C=O of amide-I bending. The amide-II stretching band appears at 1,556.41 and 1,559.45 for C-muffin and P-muffin, respectively. Additionally, the C-N stretching vibration of the amide group can be observed at 1,467.32 in C-muffin and 1,463.90 cm-1 in P-muffin (Shih et al., 2004). The presence of a carboxyl group is typically indicated by a broad absorption band in the range of 3100–3700 cm-1. This corresponds to the O-H stretching vibration, indicated by a sharp peak at 3421.27 cm-1 in C-muffin and 3416.92 cm-1 in P-muffin, respectively.

The presence of peaks at 2852.85 and 2850.69 cm-1 indicates the C-H stretching vibrations for C- and P-muffin, respectively. The formation of pyroglutamic acid, a cyclized form of glutamic acid, can be detected through the presence of a characteristic absorption band around 1741.80 and 1744.30 cm-1 for C- and P-muffin, respectively, corresponding to the C=O stretching vibration of the five-membered lactam ring (Mucchetti et al., 2000). The presence of all these functional groups confirms the γ-PGA in P-muffins.

3.7 Batter viscosity

Based on the above results, the batter properties of P0.6 were found to be better; therefore, viscosity can have a profound impact on the final texture and structure of a baked product (Bhaduri, 2013). Muffins are typically prepared with a batter composed of wheat flour, sugar, oil, egg, milk and other aromatic ingredients. The interactions between these components, particularly the gluten proteins, wheat starch and lipids, contribute to the formation of a viscoelastic nature of batter, which is crucial for the development of muffin’s structure. The viscosity of the muffin batter can be influenced by various factors, such as the moisture content, addition of fibers or other ingredients, and the batter mixing process, shear thinning and shear thickening (Bhaduri, 2013). A fine quality muffin should exhibit uniform aeration throughout the baked product. The processes of air incorporation, retention, bubble stability and the formation of convection currents during baking are all closely linked to the initial viscosity of the batter. Consequently, the viscosity of the muffin batter is directly associated with the texture and appearance of the final baked product (Bhaduri, 2013). The viscosity of batter was observed to be increased with an addition of γ-PGA. The viscosity of C-muffin batter was 12,648 mPa s which increased to 14,845 mPa s for P0.6. This change in viscosity is likely attributed to the water absorption properties of γ-PGA, which promote gelation and subsequently enhance the viscosity of the mixture (Shearer and Davies, 2005).

3.8 Colour analysis

Colour analysis is an integral part of bakery products, such as muffins, as their colour can serve as an indicator of the manufacturing process and storage conditions. The CIELAB, colour system was followed for quantifying colour characteristics, a three-dimensional space representing lightness (L*), red-green (a*), and blue-yellow (b*) attributes. The addition of γ-PGA resulted in a reduction of L* or lightness value (Table 5) due to the colour of γ-PGA (brownish) incorporated. Due to the same reason, the redness or a* value of P-muffin was found to be increased slightly. The b* value of the C-muffin is a little higher than the P-muffin, i.e., inclining more towards the yellow scale. The ΔE value was above 3 for P-muffin in comparison to C-muffin, indicating that this difference would be perceptible to the human eye (Martinez-Cervera et al., 2012). The hue angle of 76° for C-muffin corresponds to a yellowish-green colour, while for P-muffin it is 80°, a slightly more green-leaning shade (Granville, 1994). The chroma values of 21 and 20, for C-muffin and P-muffin, respectively, indicate a moderate level of colour intensity [69]. Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that no unusual colours were observed. Similar results have been observed by Kavitake et al. (2020) when comparing control EPS muffins with vanilla-flavoured emulsion muffins.

3.9 Antioxidant activity

Antioxidant activity was assessed using DPPH assay and result of the C-muffin and P-muffins are shown in Figure 5. As depicted, the DPPH assay showed an increase in antioxidant activity of P-muffin when compared to C-muffin. This increase in P-muffin was probably observed due to the addition of γ-PGA, possessing antioxidant activity of its own (Lee et al., 2014a; Lee et al., 2014b; Lee J. M. et al., 2020; Manika et al., 2025b). Similar results were observed by Bazsefidpar et al. (2024), when 6% brewer’s spent grain protein isolate was incorporated as functional ingredient in muffins. In addition, at higher concentration (14%) it resulted in reduced hardness. Kaur and Kaur (2018), also showed to have an increase in antioxidant activity when replaced 10% of wheat flour with flaxseed powder adding functional characteristic to it. Studies report the benefits of antioxidant metabolites as antiageing, anticarcinogenic, antimicrobial and elimination of free radicals thus results in enhancement of health promoting properties of food in which it is incorporated (Alves Ramos et al., 2025).

3.10 Sensory analysis

The sensory ratings for the C-muffin and P-muffin for their colour and appearance, odour, taste, mouthfeel, texture, and overall acceptability are shown in the radar graph (Figure 6). The overall acceptability of P-muffin was greater than that of the C-muffin. According to the results of the sensory evaluation conducted by sensory panelists, the C-muffin received the lowest ratings for taste, mouthfeel, and texture compared to the other evaluated parameters. Moreover, for P-muffins, there is a slightly lower rating on odour and texture. According to the statistical results the overall acceptability of the P-muffins is better than the C-muffins. There is significant difference in results of the colour and appearance of the muffin in which the C-muffin scored 8.1 and P-muffin 8.6 according to the panellists. There is a notable difference in the results for sensory attributes like odour, taste, mouthfeel, and texture. C-muffins scored 7.6, 7.3, 7.5, and 7.3, and P-muffins as 8.3, 8.9, 8.6, and 8.4, respectively. Therefore, it is seen that the score of the C-muffin is significantly lower than the P-muffins, which shows P-muffins have better sensory attributes than the C-muffins. Khouryieh et al. (2005), reported similar results in low-fat muffins.

3.11 Staling study

Bakery products, including muffins, are susceptible to various forms of spoilage such as physical, chemical and microbiological deterioration (Smith et al., 2004). The staling studies were performed based on the moisture content and crumb firmness analysed on day 1, 3, 4, 7, and 10 of storage. The results showed that both the muffin samples, i.e., C-muffins and P-muffins did not show a significant difference in moisture reduction from day 1–4 (Table 6).

Muffin staling is commonly perceived by consumers as the crumb becoming noticeably drier, with higher moisture content being linked to a fresher and more desirable crumb texture (Raffo et al., 2003). The moisture content and firmness results are shown in Table 6. The firmness of the samples was analysed on day 3, 7 and 10 of storage. The firmness results showed lower differences up to 10 days into the study, with no significant differences within the sample. However, P-muffin shows noticeable difference when compared to C-muffin in terms of firmness. The growth of moulds over both muffins was observed after day 7. The moisture content of both muffin samples decreased slightly during storage period. C-muffin at the end of 10 days resulted in 3% moisture reduction while P-muffin exhibited 2%. The better moisture retention in P-muffin may be observed due to the good water-holding capacity of γ-PGA (Manika et al., 2025a). Similar results were shown by (Lee E. J. et al., 2020). Therefore, results indicate that both the muffin samples showed a similar trend of moisture loss percentage when stored at room temperature. Though under refrigeration, moisture loss of samples can be prevented which is in line with the research finding stating that refrigeration can effectively extend the muffin’s shelf life mitigating the risks of physical, chemical and microbiological spoilage, thereby preserving the quality and safety of muffins.

4 Conclusion

The incorporation of γ-PGA derived from Bacillus sp. M-E6 has been shown to significantly enhance both textural and sensory attributes in muffin formulations. The findings indicate that batter with γ-PGA exhibited notable flowability and lower specific gravity, which improved its consistency, essential for achieving optimal air entrapment and volume in the muffins. The muffin with γ-PGA exhibited good antioxidant activity which makes them a functional muffin adding benefits to health. The structural characteristics of γ-PGA, as evidenced by SEM analysis, reveal its porous nature, which plays a crucial role in enhancing the crumb structure and height of the muffins, thus aiding in texture enhancement. Sensory evaluation further confirmed that muffins enriched with γ-PGA are more suitable in terms of taste, mouthfeel, and overall acceptability, as they effectively reduce textural flaws commonly associated with traditional formulations. The study confirms the textural application of γ-PGA, with optimal results observed at 0.6% γ-PGA concentration. Additionally, γ-PGA improved the functional properties of muffins by imparting antioxidant activity, along with enhancing various physic-chemical and flow properties of muffin and batter with γ-PGA. These results highlighted the potential of γ-PGA in a certain amount can be incorporated to reduce the textural limitations, in addition to enhancing their functional properties such as antioxidant potential, suppression of postprandial blood glucose, and increased calcium supplementation. Future research may explore the effect of γ-PGA based muffins in animal model system for physiological and overall health improvements. Additional applications of γ-PGA can be taken forward to enhance the physico-chemical and functional characteristics of other baked products. Also, further attention can be given for the production of γ-PGA from waste valorization to align with circular economy principles.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

VM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. PD: Methodology, Writing – review and editing. GR: Writing – review and editing. DK: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization. PS: Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Authors VM, DK, and PD are grateful to the UGC-NFSC-Junior Research Fellowship (F. 40-2/2019 (NET/Fellowships), ANRF - National Post-Doctoral Fellowship (ANRFNPDF/2021/000551), and DST-WISE KIRAN (DST/WOS-A/LS-259/2019 (G) respectively, for the financial assistance.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Central Instrumentation Facility of Pondicherry University and the National Institute of Food Technology, Entrepreneurship and Management, Thanjavur (NIFTEM-T) for providing instrumental facilities.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

AACC (1983). Approved methods of the AACC. Methods of the AACC, methods 10–90, approved October 1976, revised October 1982 and methods 10–91, approved April 1968, revised October, 1982. St Paul, MN. American Association of Cereal Chemists.

Abdel-Hamid, M., Romeih, E., Gamba, R. R., Nagai, E., Suzuki, T., Koyanagi, T., et al. (2012). The biological activity of fermented milk produced by Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393 during cold storage. Int. Dairy J. 91, 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.idairyj.2018.12.007

Ahmed, Z., Wang, Y., Anjum, N., Ahmad, A., and Khan, S. T. (2013). Characterization of exopolysaccharide produced by Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens ZW3 isolated from Tibet kefir–Part II. Food Hydrocoll. 30 (1), 343–350. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2012.06.009

Alvarez, M. D., Herranz, B., Fuentes, R., Cuesta, F. J., and Canet, W. (2017). Replacement of wheat flour by chickpea flour in muffin batter: effect on rheological properties. J. Food Process Eng. 40 (2), e12372. doi:10.1111/jfpe.12372

Alves Ramos, S., Gomes de Moura, D., Eduarda de Laia Queiroz, B., Ferreira de Oliveira, L., Ramalho Silva, M., Amaral, T. N., et al. (2025). Chemical, microbiological, antioxidant activity, phenolic compounds and volatile compounds characterization of melon peel flour (Cucumis melo L.) and its application in pumpkin muffin. J. Culin. Sci. and Technol., 1–20. doi:10.1080/15428052.2025.2497339

Araki, R., Yamada, T., Maruo, K., Araki, A., Miyakawa, R., Suzuki, H., et al. (2020). Gamma-polyglutamic acid-rich natto suppresses postprandial blood glucose response in the early phase after meals: a randomized crossover study. Nutrients 12 (8), 2374. doi:10.3390/nu12082374

Arifin, N., Izyan, S. N., and Huda-Faujan, N. (2019). Physical properties and consumer acceptability of basic muffin made from pumpkin puree as butter replacer. Food Res. 3, 840–845. doi:10.26656/fr.2017.3(6).090

Bazsefidpar, N., Yazdi, A. P. G., Karimi, A., Yahyavi, M., Amini, M., Gavlighi, H. A., et al. (2024). Brewers spent grain protein hydrolysate as a functional ingredient for muffins: Antioxidant, antidiabetic, and sensory evaluation. Food Chem. 435, 137565. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.137565

Bhaduri, S. (2013). A comprehensive study on physical properties of two gluten-free flour fortified muffins. J. Food Process. and Technol. 4 (7), 1–4. doi:10.4172/2157-7110.1000251

Bhat, A. R., Irorere, V. U., Bartlett, T., Hill, D., Kedia, G., Morris, M. R., et al. (2013). Bacillus subtilis natto: a non-toxic source of poly-γ-glutamic acid that could be used as a cryoprotectant for probiotic bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Express 3, 36–39. doi:10.1186/2191-0855-3-36

Buescher, J. M., and Margaritis, A. (2007). Microbial biosynthesis of polyglutamic acid biopolymer and applications in the biopharmaceutical, biomedical and food industries. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 27 (1), 1–19. doi:10.1080/07388550601166458

Cabuk, B. (2021). Influence of grasshopper (locusta migratoria) and mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) powders on the quality characteristics of protein rich muffins: nutritional, physicochemical, textural and sensory aspects. J. Food Meas. Charact. 15 (4), 3862–3872. doi:10.1007/s11694-021-00967-x

Feng, F., Zhou, Q., Yang, Y., Zhao, F., Du, R., Han, Y., et al. (2018). Characterization of highly branched dextran produced by Leuconostoc citreum B-2 from pineapple fermented product. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 113, 45–50. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.02.119

Fernandes, A. R. A. C., Sganzerla, W. G., Granado, N. P. A., and Campos, V. (2023). Implication of organic solvents in the precipitation of γ-polyglutamic acid for application as a sustainable flocculating agent. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 50, 102698. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2023.102698

Ferrari, C. C., Germer, S. P. M., Alvim, I. D., Vissotto, F. Z., and de Aguirre, J. M. (2012). Influence of carrier agents on the physicochemical properties of blackberry powder produced by spray drying. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 47 (6), 1237–1245. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.2012.02964.x

Geetanjali, , Kaur, G., Singh, A., and Khatkar, S. (2025). Effect of ultrasonicated corn starch as a fat replacer on muffin quality and sensory characteristics. J. Food Meas. Charact. 19 (1), 1–11. doi:10.1007/s11694-024-02913-z

Goswami, D., Gupta, R. K., Mridula, D., Sharma, M., and Tyagi, S. K. (2015). Barnyard millet based muffins: physical, textural and sensory properties. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 64 (1), 374–380. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2015.05.060

Granville, W. C. (1994). The color harmony manual, a color atlas based on the ostwald color system. Color Res. Appl. 19 (2), 77–98. doi:10.1111/j.1520-6378.1994.tb00068.x

Gujral, H. S., Rosell, C. M., Sharma, S., and Singh, S. (2003). Effect of sodium lauryl sulphate on the texture of sponge cake. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 9 (2), 89–93. doi:10.1177/1082013203009002004

Guo, Y., Shen, Y., Yu, B., Ding, L., Meng, Z., Wang, X., et al. (2022). Hydrophilic poly (glutamic acid)-based nanodrug delivery system: structural influence and antitumor efficacy. Polymers 14 (11), 2242. doi:10.3390/polym14112242

Harastani, R., James, L. J., Ghosh, S., Rosenthal, A. J., and Woolley, E. (2021). Reformulation of muffins using inulin and green banana flour: physical, sensory, nutritional and shelf-life properties. Foods 10 (8), 1883. doi:10.3390/foods10081883

Heo, Y., Kim, M. J., Lee, J. W., and Moon, B. (2019). Muffins enriched with dietary fiber from kimchi by-product: baking properties, physical–chemical properties, and consumer acceptance. Food Sci. and Nutr. 7 (5), 1778–1785. doi:10.1002/fsn3.1020

Ho, G. H., Ho, T. I., Hsieh, K. H., Su, Y. C., Lin, P. Y., Yang, J., et al. (2006). γ-Polyglutamic acid produced by Bacillus subtilis (natto): structural characteristics, chemical properties and biological functionalities. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 53 (6), 1363–1384. doi:10.1002/jccs.200600182

Hsueh, Y. H., Huang, K. Y., Kunene, S. C., and Lee, T. Y. (2017). Poly-γ-glutamic acid synthesis, gene regulation, phylogenetic relationships, and role in fermentation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18 (12), 2644. doi:10.3390/ijms18122644

Insulkar, P., Kerkar, S., and Lele, S. S. (2018). Purification and structural-functional characterization of an exopolysaccharide from Bacillus licheniformis PASS26 with in-vitro antitumor and wound healing activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 120, 1441–1450. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.09.147

Jager, A., Bertmer, M., and Schaumann, G. E. (2016). The relation of structural mobility and water sorption of soil organic matter studied by 1H and 13C solid-state NMR. Geoderma 284, 144–151. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.08.024

Jindal, N., and Khattar, J. S. (2018). “Microbial polysaccharides in food industry,” in Biopolymers for food design (Academic Press), 95–123.

Kane, A. M., Lyon, B. G., Swanson, R. B., and Savage, E. M. (2003). Comparison of two sensory and two instrumental methods to evaluate cookie color. J. Food Sci. 68 (5), 1831–1837. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb12338.x

Karp, S., Wyrwisz, J., Kurek, M., and Wierzbicka, A. (2016). Physical properties of muffins sweetened with steviol glycosides as the sucrose replacement. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 25 (6), 1591–1596. doi:10.1007/s10068-016-0245-x

Kaur, R., and Kaur, M. (2018). Microstructural, physicochemical, antioxidant, textural and quality characteristics of wheat muffins as influenced by partial replacement with ground flaxseed. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 91, 278–285. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2018.01.059

Kaur, M., Kaur, M., and Kaur, H. (2022). Apple peel as a source of dietary fiber and antioxidants: effect on batter rheology and nutritional composition, textural and sensory quality attributes of muffins. J. Food Meas. Charact. 16 (3), 2411–2421. doi:10.1007/s11694-022-01329-x

Kavitake, D., Kalahasti, K. K., Devi, P. B., Ravi, R., and Shetty, P. H. (2020). Galactan exopolysaccharide based flavour emulsions and their application in improving the texture and sensorial properties of muffin. Bioact. Carbohydrates Diet. Fibre 24, 100248. doi:10.1016/j.bcdf.2020.100248

Khouryieh, H. A., Aramouni, F. M., and Herald, T. J. (2005). Physical and sensory characteristics of no-sugar-added/low-fat muffin. J. Food Qual. 28 (5-6), 439–451. doi:10.1111/j.1745-4557.2005.00047.x

Khurshida, S., Muchahary, S., Samyor, D., Sit, N., and Deka, S. C. (2025). Protein enrichment of cassava flour by Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation and development of a muffin. J. Food Meas. Charact. 19 (4), 2438–2448. doi:10.1007/s11694-025-03122-y

Koc, G. C., Erbakan, T., Arici, E., and Dirim, S. N. (2019). Sensory and quality attributes of cake supplemented with spinach powder. J. Food 44 (5), 907–918. doi:10.15237/gida.GD19047

Kohajdova, Z., Karovicova, J., and Jurasova, M. (2012). Influence of carrot pomace powder on the rheological characteristics of wheat flour dough and on wheat rolls quality. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 11 (4), 381–387. Available online at: https://www.food.actapol.net/pub/7_4_2012.pdf.

Lee, N. R., Lee, S. M., Cho, K. S., Jeong, S. Y., Hwang, D. Y., Kim, D. S., et al. (2014a). Improved production of poly-γ-glutamic acid by Bacillus subtilis D7 isolated from doenjang, a Korean traditional fermented food, and its antioxidant activity. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 173, 918–932. doi:10.1007/s12010-014-0908-0

Lee, N. R., Go, T. H., Lee, S. M., Jeong, S. Y., Park, G. T., Hong, C. O., et al. (2014b). In vitro evaluation of new functional properties of poly-γ-glutamic acid produced by Bacillus subtilis D7. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 21, 153–158. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2013.09.004

Lee, E. J., Moon, Y., and Kweon, M. (2020a). Processing suitability of healthful carbohydrates for potential sucrose replacement to produce muffins with staling retardation. LWT- Food Sci. Technol. 131, 109565. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109565

Lee, J. M., Jang, W. J., Park, S. H., and Kong, I. S. (2020b). Antioxidant and gastrointestinal cytoprotective effect of edible polypeptide poly-γ-glutamic acid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 153, 616–624. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.03.050

Mala, S. K., Aathira, P., Anjali, E. K., Srinivasulu, K., and Sulochanamma, G. (2018). Effect of pumpkin powder incorporation on the physico-chemical, sensory and nutritional characteristics of wheat flour muffins. Int. Food Res. J. 25 (3), 1081–1087. Available online at: http://www.ifrj.upm.edu.my/25%20(03)%202018/(27).pdf.

Manika, V., Devi, P. B., Singh, S. P., Reddy, G. B., Kavitake, D., and Shetty, P. H. (2025a). Microbial poly-glutamic acid: production, biosynthesis, properties, and their applications in food, environment, and biomedicals. Fermentation 11 (4), 208. doi:10.3390/fermentation11040208

Manika, V., Devi, B., Majaw, J., Rani, U., Reddy, G. B., Kavitake, D. D., et al. (2025b). Microbial production and functional assessment of γ-polyglutamic acid isolated from bacillus sp. M-E6. Front. Microbiol. 16, 1647287. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2025.1647287

Marchetti, L., Califano, A. N., and Andres, S. C. (2018). Partial replacement of wheat flour by pecan nut expeller meal on bakery products. Effect on muffins quality. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 95, 85–91. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2018.04.050

Martinez-Cervera, S., Sanz, T., Salvador, A., and Fiszman, S. M. (2012). Rheological, textural and sensorial properties of low-sucrose muffins reformulated with sucralose/polydextrose. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 45 (2), 213–220. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2011.08.001

Martinez-Cervera, S., de la Hera, E., Sanz, T., Gomez, M., and Salvador, A. (2013). Effect of nutriose on rheological, textural and sensorial characteristics of Spanish muffins. Food Bioprocess Technol. 6, 1990–1999. doi:10.1007/s11947-012-0939-x

Masmoudi, M., Besbes, S., Bouaziz, M. A., Khlifi, M., Yahyaoui, D., and Attia, H. (2020). Optimization of acorn (Quercus suber L.) muffin formulations: effect of using hydrocolloids by a mixture design approach. Food Chem. 328, 127082. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127082

Matos, M. E., Sanz, T., and Rosell, C. M. (2014). Establishing the function of proteins on the rheological and quality properties of rice based gluten free muffins. Food Hydrocoll. 35, 150–158. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2013.05.007

Mildner-Szkudlarz, S., Bajerska, J., Gornas, P., Segliņa, D., Pilarska, A., and Jesionowski, T. (2016). Physical and bioactive properties of muffins enriched with raspberry and cranberry pomace powder: a promising application of fruit by-products rich in biocompounds. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 71, 165–173. doi:10.1007/s11130-016-0539-4

Mohammadi, M., Salami, M., Yarmand, M., Emam-Djomeh, Z., and McClements, D. J. (2022). Production and characterization of functional bakery goods enriched with bioactive peptides obtained from enzymatic hydrolysis of lentil protein. J. Food Meas. Charact. 16 (5), 3402–3409. doi:10.1007/s11694-022-01416-z

Morriss, R. H., Dunlap, W. P., and Hammond, S. E. (1982). Influence of chroma on spatial balance of complementary hues. Am. J. Psychol. 95, 323–332. doi:10.2307/1422474

Mucchetti, G., Locci, F., Gatti, M., Neviani, E., Addeo, F., Dossena, A., et al. (2000). Pyroglutamic acid in cheese: presence, origin, and correlation with ripening time of grana padano cheese. J. Dairy Sci. 83 (4), 659–665. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(00)74926-5

Ogunleye, A., Bhat, A., Irorere, V. U., Hill, D., Williams, C., and Radecka, I. (2015). Poly-γ-glutamic acid: production, properties and applications. Microbiology 161 (1), 1–17. doi:10.1099/mic.0.081448-0

Pooja, B. K., Sethi, S., Bhardwaj, R., Joshi, A., Bhowmik, A., and Grover, M. (2022). Investigation of physicochemical quality and textural attributes of muffins incorporated with pea pod powder as a source of dietary fiber and protein. J. Food Process. Preserv. 46 (10), e16884. doi:10.1111/jfpp.16884

Pruett, A., Aramouni, F. M., Bean, S. R., and Haub, M. D. (2023). Effect of flour particle size on the glycemic index of muffins made from whole sorghum, whole corn, brown rice, whole wheat, or refined wheat flours. Foods 12 (23), 4188. doi:10.3390/foods12234188

Raffo, A., Pasqualone, A., Sinesio, F., Paoletti, F., Quaglia, G., and Simeone, R. (2003). Influence of durum wheat cultivar on the sensory profile and staling rate of altamura bread. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 218, 49–55. doi:10.1007/s00217-003-0793-1

Rahman, R., Hiregoudar, S., Veeranagouda, M., Ramachandra, C. T., Nidoni, U., Roopa, R. S., et al. (2015). Effects of wheat grass powder incorporation on physiochemical properties of muffins. Int. J. Food Prop. 18 (4), 785–795. doi:10.1080/10942912.2014.908389

Ren, Y., Song, K. Y., and Kim, Y. (2020). Physicochemical and retrogradation properties of low-fat muffins with inulin and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose as fat replacers. J. Food Process. Preserv. 44 (10), e14816. doi:10.1111/jfpp.14816

Rumiyati, R., James, A. P., and Jayasena, V. (2015). Effects of lupin incorporation on the physical properties and stability of bioactive constituents in muffins. Int. J. Food Sci. and Technol. 50 (1), 103–110. doi:10.1111/ijfs.12688

Samokhvalova, O., Kucheruk, Z., Kasabova, K., Oliinyk, S., and Shmatchenko, N. (2020). Manufacturing approaches to making muffins of high nutritional value. Technol. Audit Prod. Reserves 6 (3), 47–51. doi:10.15587/2706-5448.2020.221095

Santhalakshmy, S., Bosco, S. J. D., Francis, S., and Sabeena, M. (2015). Effect of inlet temperature on physicochemical properties of spray-dried jamun fruit juice powder. Powder Technol. 274, 37–43. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2015.01.016

Sanz, T., Salvador, A., Baixauli, R., and Fiszman, S. M. (2009). Evaluation of four types of resistant starch in muffins. II. Effects in texture, colour and consumer response. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 229, 197–204. doi:10.1007/s00217-009-1040-1

Shearer, A. E., and Davies, C. G. (2005). Physicochemical properties of freshly baked and stored whole-wheat muffins with and without flaxseed meal. J. Food Qual. 28 (2), 137–153. doi:10.1111/j.1745-4557.2005.00004.x

Shih, I. L., Van, Y. T., and Shen, M. H. (2004). Biomedical applications of chemically and microbiologically synthesized poly (glutamic acid) and poly (lysine). Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 4 (2), 179–188. doi:10.2174/1389557043487420

Shyu, Y. S., and Sung, W. C. (2010). Improving the emulsion stability of sponge cake by the addition of γ-polyglutamic acid. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 18 (6), 14. doi:10.51400/2709-6998.1948

Shyu, Y. S., Hwang, J. Y., and Hsu, C. K. (2008). Improving the rheological and thermal properties of wheat dough by the addition of γ-polyglutamic acid. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 41 (6), 982–987. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2007.06.015

Smith, J. P., Daifas, D. P., El-Khoury, W., Koukoutsis, J., and El-Khoury, A. (2004). Shelf life and safety concerns of bakery Products—A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 44 (1), 19–55. doi:10.1080/10408690490263774

Sopotenska, I., and Chonova, V. (2019). Image analysis of gluten free muffins’ porosity. Sci. Works Univ. Food Technol. 66, 43–48. https://uft-plovdiv.bg/site_files/file/scienwork/scienworks_2019/docs/1-6.pdf.

Taiyeba, N., Gupta, A., and Verma, T. (2020). Utilization of sweet potato peels and potato peels for the department of value added food products. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 9 (10), 546–553. doi:10.20546/ijcmas.2020.910.065

Topkaya, C., and Isik, F. (2019). Effects of pomegranate peel supplementation on chemical, physical, and nutritional properties of muffin cakes. J. Food Process. Preserv. 43 (6), e13868. doi:10.1111/jfpp.13868

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2010). GRAS notices inventory, GRN no. 339. Available online at: https://www.cfsanappsexternal.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/index.cfm?set=GRASNotices&id=339&sort=GRN_No&order=DESC&startrow=1&type=basic&search=339.

Vasantha Rupasinghe, H. P., Wang, L., Pitts, N. L., and Astatkie, T. (2009). Baking and sensory characteristics of muffins incorporated with Apple skin powder. J. Food Qual. 32 (6), 685–694. doi:10.1111/j.1745-4557.2009.00275.x

Walker, R., Tseng, A., Cavender, G., Ross, A., and Zhao, Y. (2014). Physicochemical, nutritional, and sensory qualities of wine grape pomace fortified baked goods. J. Food Sci. 79 (9), S1811–S1822. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.12554

Xie, X., Zhang, B., Zhang, B., Zhu, H., Qi, L., Xu, C., et al. (2024). Effect of γ-polyglutamic acid on the physicochemical properties of soybean protein isolate-stabilized O/W emulsion. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 30 (7), 671–679. doi:10.1177/10820132231158278

Xu, T., Zhan, S., Yi, M., Chi, B., Xu, H., and Mao, C. (2018). Degradation performance of polyglutamic acid and its application of calcium supplement. Polym. Adv. Technol. 29 (7), 1966–1973. doi:10.1002/pat.4305

Keywords: γ-polyglutamic acid, muffin, texture analysis, sensory, cooking yield, staling study, antioxidant

Citation: Manika V, Devi PB, Reddy GB, Kavitake D and Shetty PH (2025) Microbial γ-polyglutamic acid (γ-PGA) incorporation into muffins: Impact on physico-chemical, functional, and textural properties. Front. Food Sci. Technol. 5:1683686. doi: 10.3389/frfst.2025.1683686

Received: 11 August 2025; Accepted: 30 October 2025;

Published: 02 December 2025.

Edited by:

Maria Gabriela Bello Koblitz, Rio de Janeiro State Federal University, BrazilReviewed by:

Barbara la Gatta, University of Foggia, ItalyPui Khoon Hong, Universiti Malaysia Pahang Al-Sultan Abdullah, Lebuh Persiaran Tun Khalil Yaakob, Malaysia

Copyright © 2025 Manika, Devi, Reddy, Kavitake and Shetty. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Digambar Kavitake, ZGlnYW1iYXJrYXZpdGFrZUBnbWFpbC5jb20=; Prathapkumar Halady Shetty, cGtzaGFsYWR5QHlhaG9vLmNvLnVr

Verma Manika

Verma Manika Palanisamy Bruntha Devi

Palanisamy Bruntha Devi G. Bhanuprakash Reddy

G. Bhanuprakash Reddy Digambar Kavitake

Digambar Kavitake Prathapkumar Halady Shetty

Prathapkumar Halady Shetty