- 1School of Foundation Studies, Xiamen University Malaysia, Sepang, Selangor, Malaysia

- 2Department of Botany and Plant Biotechnology, Postharvest and Agroprocessing Research Centre, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

- 3South African Research Chairs Initiative in Sustainable Preservation and Agroprocessing Research, Faculty of Science, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

- 4China-ASEAN College of Marine Sciences, Xiamen University Malaysia, Sepang, Selangor, Malaysia

- 5Centre of Excellence for Sustainable Technologies for Agricultural Advancement and a Zero-Waste Economy (STARGAZE), Xiamen University Malaysia, Sepang, Selangor, Malaysia

- 6Division of Nutrition, Dietetics and Food Science, School of Health Sciences, IMU University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- 7Department of Food Science and Nutrition, Faculty of Applied Sciences, UCSI University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

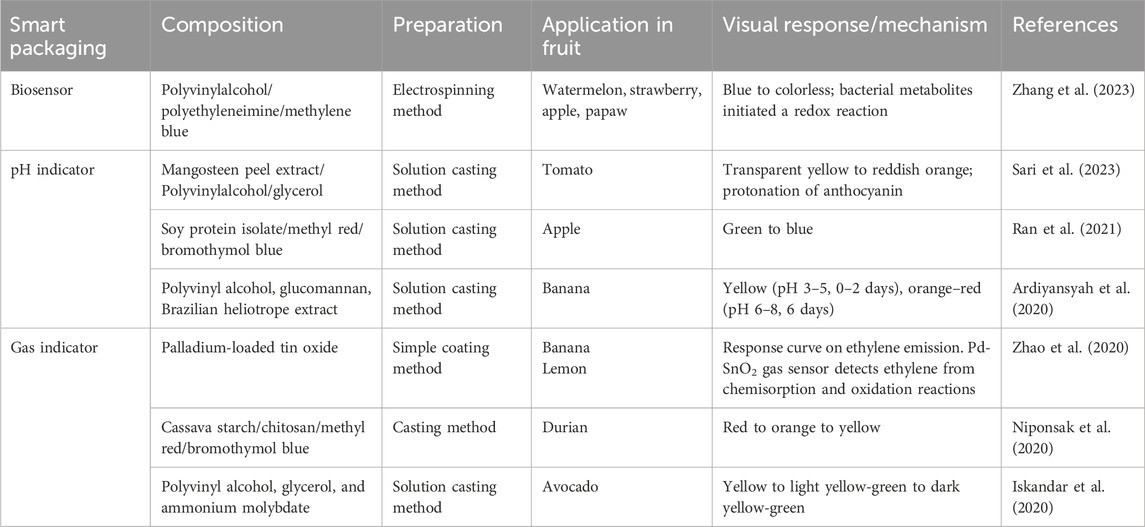

Post-harvest fruit losses result in significant waste problem due to the decline in quality by physiological metabolism and unfavorable environmental conditions. To extend shelf life and mitigate waste and environmental impacts, investigations on innovative fruit packaging technologies such as active, edible, biodegradable, and smart packaging are warranted. Active packaging enhances fruit preservation by ethylene scavengers, controlling fungal growth, regulating moisture, and providing antioxidants through bioactive compounds. A growing trend involves edible and biodegradable packaging made from natural polymers (polysaccharides, proteins, and lipids), which prevents physical, mechanical, and microbiological damage to fruits while also serving as a medium for additives like antimicrobials and antioxidants, thus improving freshness and quality. In addition, smart packaging utilizes biosensors, pH indicators, and gas indicators for live monitoring throughout the supply chain and can be united with other packaging technologies to enhance functionality. Current developments concern on the green and hybrid packaging, particularly to unite biodegradable packaging with active and smart packaging to deliver synergistic functionalities. This can preserve the fruits quality while offering active properties or live monitoring while supporting environmental sustainability. This review provides insights on the current advances and potential future development in innovative active, edible, biodegradable, and smart packaging technologies, while also addressing the current challenges associated with these packaging.

1 Introduction

Fruits are highly perishable agricultural products. At the retail stage, particularly in supermarkets, fruits are usually packaged in commercial plastic films such as trays or bags. During this retail phase, problems such as weight loss, texture decline, microbial growth, and fruits’ off-flavor would negatively affect their shelf life. The short post-harvest lifespan of fruit is largely due to their high moisture content and the ongoing biological processes after harvesting, making them highly susceptible to physical injuries and microbial infections (Xu et al., 2018). This results in significant post-harvest losses, which are exacerbated by the limitations of the conventional packaging, including humidity, temperature fluctuations, and excessive moisture condensation. Therefore, preventing fruit quality deterioration during storage and distribution is a significant challenge from both technical and economic perspectives. Thus, there has been growing attention on research aimed at enhancing fruit packaging to improve quality and safety and preserve nutritional value.

Effective packaging is essential for safeguarding fruits from chemical and microbial contamination, as well as physical damage caused by shock, temperature, and humidity. Leveraging appropriate conventional and innovative packaging technologies can significantly reduce microbiological and chemical hazards, ensuring the freshness of fruits while extending their shelf life. Continuous advancements in fruit packaging are now emphasizing on monitoring or controlling the freshness and ripeness of fruits throughout transportation and distribution. Smart and active packaging have greatly improved fruit quality, safety, consumer acceptance, and public health (Wan et al., 2024).

Utilizing active packaging and smart packaging has emerged as an effective method for maintaining the quality of fruits, aligning with the overall objectives of food packaging systems. Active packaging involves to the incorporation of active compounds into the existing packaging to enhance functionality, such as ethylene scavenging, moisture absorption, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties, oxygen removal, and carbon dioxide absorption. In recent years, rigorous efforts have been made to progress active packaging in grapes, lychees, strawberries, bananas, peaches, blueberries, cherries, and pomegranates by altering the atmosphere and releasing active compounds (Yildirim et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2019; Mahajan and Lee, 2023). Hygroscopic salt, silica gel, and zeolites have been suggested for moisture absorption in active packaging (Dai et al., 2022). Recently, there has been an increasing focus on novel moisture-regulating materials and natural plant extracts or antioxidants in the development of active packaging (Wan et al., 2024). For example, alginate-based film with cactus pear extract with high antioxidant and antimicrobial activities has been developed to incorporate both the functionalities of biodegradable and active packaging (Asiri et al., 2024).

Meanwhile, smart packaging is an innovative technology that employs indicator labels, sensors, and RFID tags to provide live information about the freshness, ripeness, and microbial growth in fruits. This technology can be used as a standalone packaging system or be integrated with other packaging methods. Currently, the application of smart packaging for fruits is still in its early stages, with ongoing research aimed at exploring its commercial potential (He et al., 2022). Recent development emphasizes on the use of natural plant-based pigments to act as freshness indicator to ensure the safety of smart packaging (Sari et al., 2023). At the same time, biodegradable packaging can be incorporated into smart packaging to promote environmental sustainability (Amin et al., 2022). Thus, comprehensive studies on the safety evaluation and real-time monitoring are still continuing, aligning with global goal of circular economy.

Although active and smart packaging technologies are on the rise, the continued use of synthetic plastics raises significant environmental concerns. The use of synthetic plastics, chemicals, and synthetic compounds in conventional packaging systems is increasingly being condemned due to their adverse effect on health and the environment. Consequently, edible and biodegradable packaging has emerged as a sustainable solution, that can both mitigate post-harvest losses in fruits and minimize waste and environmental impact. Edible films and coatings are commonly applied to fruits to slow down respiration and ripening, preserve color and nutritional value, and protect against water loss and physical damage (Sharma et al., 2024). Recently, bacterial biopolymers and nanocrystal cellulose have been given attention due to its superior mechanical property in packaging and it offers non-toxicity, biodegradability, and high bioactivity (Wang et al., 2023; Aziz et al., 2024). Exopolysaccharides, which derived from bacteria can be used as edible coating or film in the preservation of food (Aziz et al., 2024). Given these advantages, edible and biodegradable packaging is a key area for development of sustainable packaging technologies that align with the Sustainable Development Goals.

This review focuses on recent advancements and applications of active, edible, and biodegradable packaging, as well as smart packaging for post-harvest fruits. It also discusses the mechanisms of various packaging systems and the impacts on the physiological changes of fruits, as well as their shelf life while emphasizing the challenges and future prospects in the field.

2 Methodology

This article reviewed research articles that investigated the applications of active packaging, smart packaging, edible and biodegradable packaging in fruits. The analyzed research papers were published in the last 11 years, between 2020 and 2025 and accessed through Google Scholar, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect. The Boolean operators ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ were employed to enhance the search scope. The main keywords used for literature search included ‘active packaging,’ ‘ethylene scavenger,’ ‘bioactive packaging,’ ‘edible packaging,’ ‘edible film,’ ‘biodegradable packaging,’ ‘biodegradable film,’ ‘smart packaging,’ ‘intelligent packaging,’ and ‘application in fruit.’ Synonyms and associated keywords were also used to search for relevant literature. The selected papers were critically reviewed and the evidence presented was analyzed to provide a comprehensive understanding of the topic. The relevant information and analyzed data from the selected literature were extracted and categorized according to the different sections of this article.

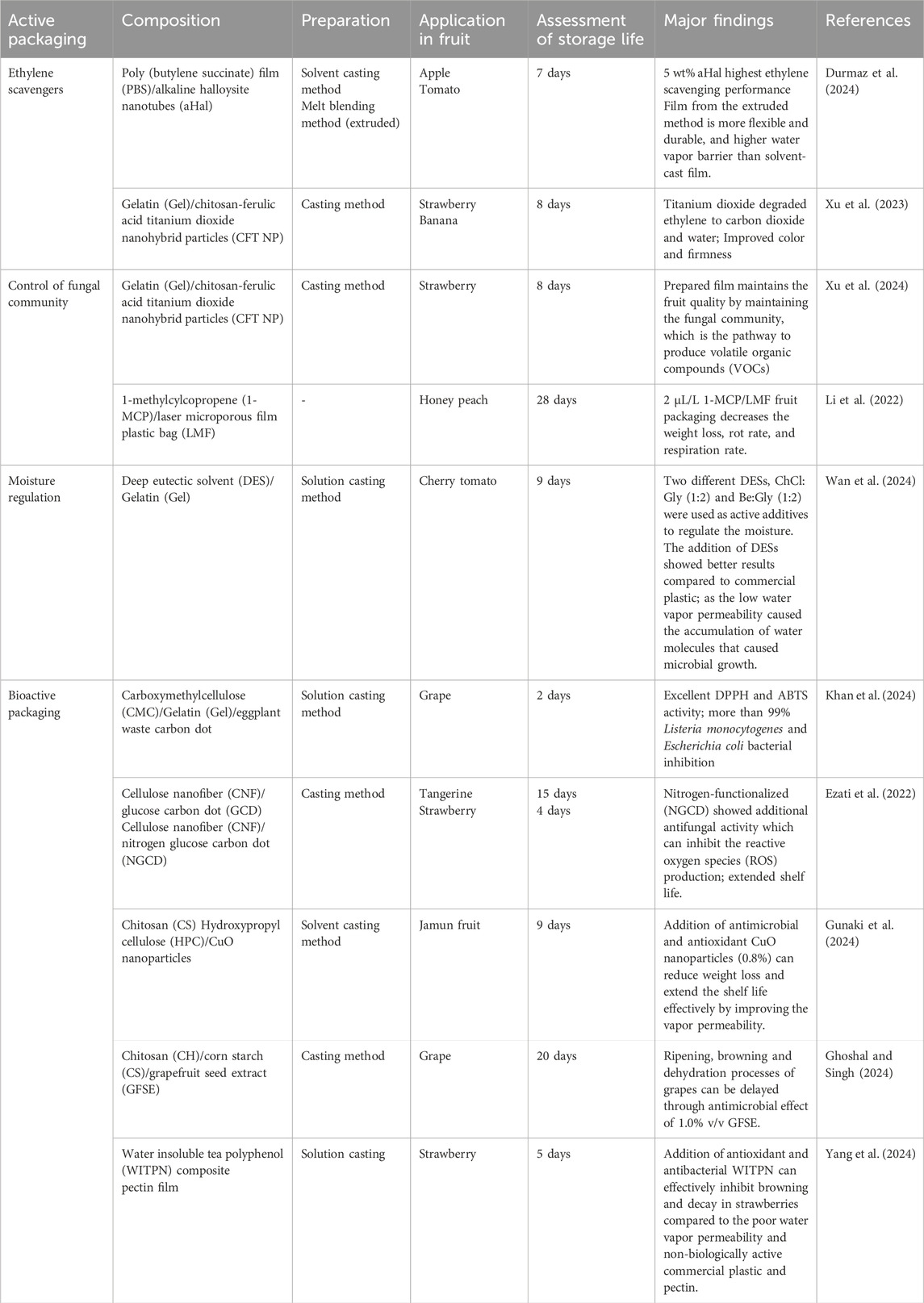

3 Active packaging

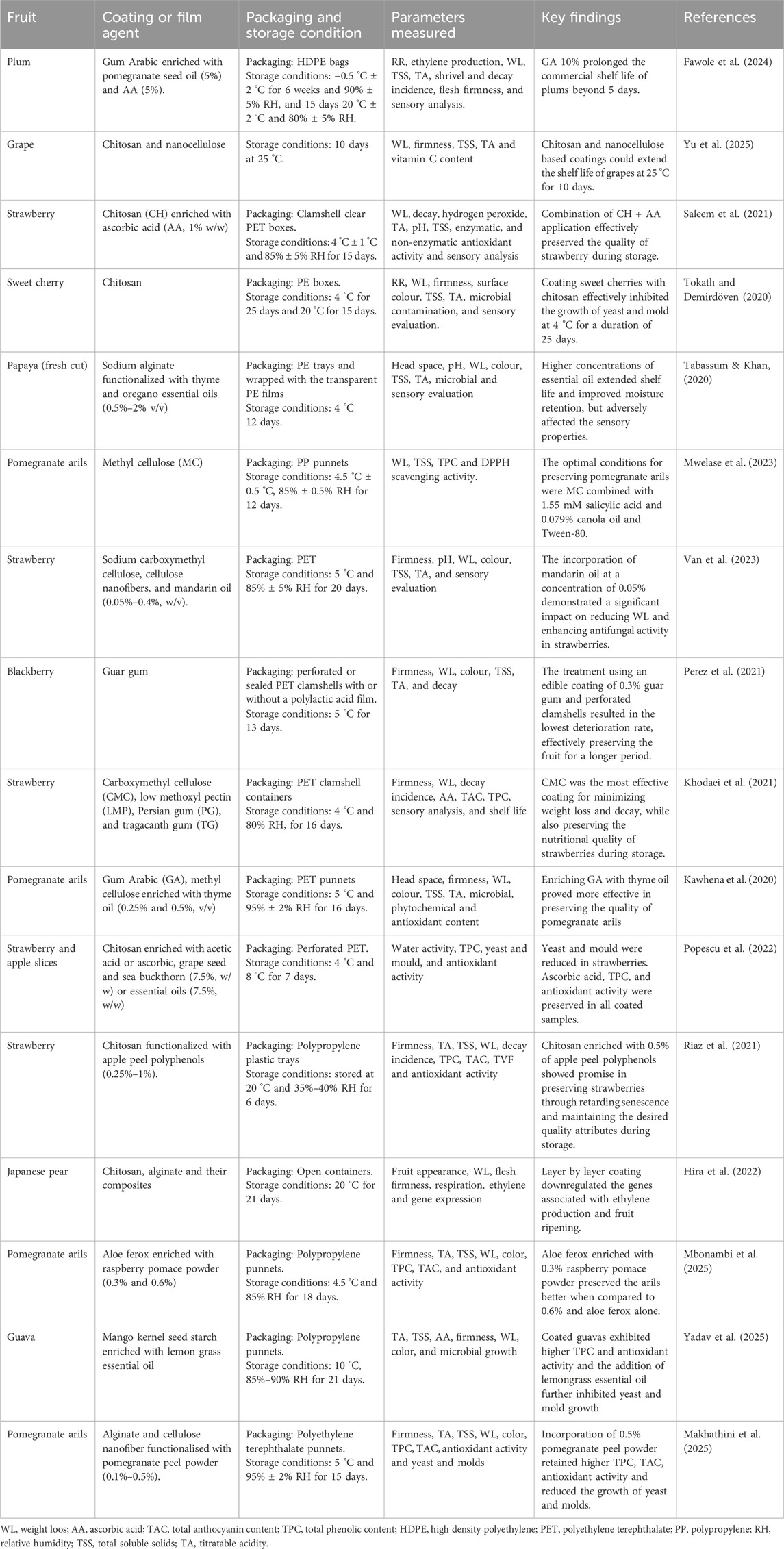

Active packaging is defined as packaging in which subsidiary components are deliberately incorporated into the material to improve its performance (Yam, 2010). It involves packages that can intermingle with the food products, offering a promising alternative to traditional technologies. It offers significant benefits in extending product shelf life and preventing food degradation, addressing concerns within the packaging industry due to the upsurge in online shopping (Alves et al., 2023). Most active packaging systems rely on mechanisms such as ethylene and oxygen scavengers, antioxidants, antimicrobials, carbon dioxide atmosphere, and moisture controllers (Figure 1). These schemes efficiently eliminate undesired molecules, release crucial elements, or control the packaging environment as needed to prolong the food storage life (Tas et al., 2017). When developing and manufacturing active packaging systems, it is important to adhere to the guidelines and standards set by various regulatory bodies, such as the European Food Safety Authority in the EU and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the USA, which establish the legal framework for their proper use, safety, and marketing (Song and Hepp, 2005; Restuccia et al., 2010). From Table 1, it can be seen that the recent works between 2021 and 2025 have particularly evolved toward multifunctional and sustainable systems that focus on greener alternatives by combining biodegradable polymers. This transition indicates the importance of eco-friendly design that progresses both fruit package applications and safety.

Figure 1. Overview of active packaging in fruit preservation (Created in BioRender.com).

3.1 Ethylene scavengers

Ethylene (C2H4) is an organic compound released by climacteric fruits after harvest, and it can function as a phytohormone to promote growth and even at a low concentration of 0.1 μL/L (Wei et al., 2021). It can be either endogenous ethylene, which is released from biological pathways of plants, or exogenous ethylene, which is produced from sources such as plastics, automobile exhaust, and smoke (Keller et al., 2013). Although it can accelerate fruit ripening, ethylene often causes over-ripening and even decay, and shortens the fruit’s shelf life (Martínez-Romero et al., 2009; Kaya et al., 2016). Hence, maintaining ethylene levels in the packaging environment is important for maintaining fruit quality and delaying the detrimental climacteric fruit process. To date, several methods have been suggested to remove ethylene from fruit packaging, including the use of reactive oxygen species (ROS), halloysite nanotubes, and photodegradation (Kaewklin et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2023; Durmaz et al., 2024).

Owing to the high reactivity of the C=C double bond in ethylene, most of the scavenger systems are oxidizers, for example, potassium permanganate (KMnO4), silica, zeolite, and perlite, which are supported by metal catalysts, are available in the form of sachets or film. However, due to the high toxicity, multiple safety concerns were raised regarding the direct usage of KMnO4 and zeolite sachets on food (Janjarasskul and Suppakul, 2018; Alves et al., 2023). Moreover, zeolite has not been approved by the FDA, prompting researchers to seek alternative packaging solutions that effectively eliminate ethylene and are safe for consumer use (Awalgaonkar et al., 2020).

As reported by Durmaz et al. (2024), halloysite nanotubes can adsorb ethylene gas easily owing to their hollow structure, and at the same time, it is FDA approved (Gaikwad et al., 2018). This study demonstrated that the incorporation of alkaline-treated halloysite nanotubes (aHal) into poly (butylene succinate) (PBS) films improved their ethylene scavenging ability, with the best performance observed at 5 wt% aHal content. Biobased PBS is a biodegradable polyester that is environmentally friendly and is in line with the objectives of the European Green Deal. Besides, the FDA has approved biobased PBS for food contact, making it suitable to be used in fruit packaging applications. Both extrusion and solvent casting methods showed ethylene scavenging properties, making these films effective for preserving the freshness of apples and tomatoes for 7 days. The ethylene gas scavenging, water vapor barrier properties, and weight loss of fruits were studied. Between these two methods, packaging from the extrusion method demonstrates better flexibility and durability compared to solvent casting methods (Durmaz et al., 2024).

To the best of our knowledge, Kaewklin and colleagues made unprecedented findings on the application of chitosan and titanium dioxide (TiO2) composite films as ethylene scavengers in climacteric fruit, utilizing a photodegradation mechanism (Kaewklin et al., 2018). When exposed to UV light, electrons in the TiO2 surface are excited and produce highly reactive species for the degradation of ethylene into CO2 and H2O (Hussain et al., 2011). Even though it could not completely remove all the ethylene, the usage of TiO2 composite film suppressed the concentration of ethylene to a much lower content compared to the one using pure chitosan and the one without any packaging. Other than the ethylene concentration, other properties such as carbon dioxide content, firmness, weight loss, color values, and total soluble solid content were reported. All the results showed that the film prepared can preserve tomatoes’ physiological qualities better than commercially available packaging. In the toxicity aspect, chitosan is a well-known active packaging material due to its biocompatible and nontoxic properties. In addition, TiO2 is chemically inert and extensively used in food and biological products, making this chitosan-TiO2 nanocomposite film safe to be applied to fruits (Kaewklin et al., 2018). Besides, Xu et al. (2023) demonstrated a similar method on strawberries and bananas, where the gelatin/chitosan-ferulic acid titanium dioxide nanohybrid particles packaging film uses water and oxygen to generate reactive oxygen species free radicals to degrade ethylene under sunlight. On the other hand, the free radical produced may attack and damage the cell membrane of the bacterial DNA. The results revealed that using the Gel/CFT NP can maintain the firmness and color of strawberries and bananas for 8 days. Besides, no brown dots were observed in bananas due to the good barrier properties of carbon dioxide and oxygen gas, which decrease the respiratory rate. In this study, a hemolysis assay was conducted to assess the safety of CFT-Gel films, where the relative hemolysis rate is in 0.74%–2.46% (permissible limit = 5%). This observation indicated that the effect of the prepared film on human red blood cells was negligible (Xu et al., 2023).

3.2 Control of the fungal community

The metabolic pathways in fruits produce volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and these pathways can be influenced by various factors, including fruit maturity and the presence of surface fungi (Hou et al., 2023). As fruit ripens, its flavor intensifies, but in overripe fruit, its flavor undergoes significant changes due to the release of certain VOCs and the development of sour, alcoholic, and moldy odors (Kim et al., 2018). Recent studies have shown that pathogenic fungi, which are common in infected fruit, contribute to the formation of VOCs such as esters, alcohols, ketones, and short-chain alkenes (Kim et al., 2018; Gong et al., 2022). The moldy scent of decaying fruit is also a result of fungal metabolism (Hung et al., 2015). Therefore, it is essential to maintain the fungal community balance to preserve the high-quality flavor of fruit in the package.

As reported by Xu et al. (2024), the strawberry flavor is affected by the physiological metabolism and fungal community, which is the pathway producing VOCs. Strawberries without packaging and packed using polyethene (PE) or gelatin (Gel) showed an alcoholic, sour, and moldy flavor. Whereas strawberries packed with gelatin/chitosan-ferulic acid titanium dioxide nanohybrid particles preserved the fruity and fragrance properties for up to 8 days as the fungal community of Mycosphaerella, Botrytis, Papoliotrema, Vishniacozyma, Filobasidium, etc., were maintained and balanced. Besides, Li et al. (2022) demonstrated the usage of 1-methylcyclopropene (MCP) and laser microporous film (LMF) to reduce the abundance of pathogenic fungi such as Streptomyces, Stachybotrys, and Issa sp. in the honey peach packaging. This method improved the relative abundance of antagonistic fungi such as Aureobasidium and Holtermanniella. Owing to the balanced fungi community, the package effectively reduced weight loss and spoilage, consequently extending the storage life of honey peach from 14 days to 28 days at 5 °C.

3.3 Moisture regulation

Traditional fruit packaging often led to water vapor buildup in the packaging due to poor moisture and relative humidity (RH) regulation of materials such as polyethylene and polypropylene. An environment good for microbial growth was created from the condensation of water vapor from the changes in temperature in the packaging (Alabi et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021). Older reported studies focus more on absorbing the water using hygroscopic salts and silica gel in packaging materials, rather than regulating the moisture contents (Gaikwad et al., 2019; Dai et al., 2022). Therefore, there is a need for materials that can control moisture levels in fruit packaging. As described by Wan et al. (2024), low water vapor permeability in commercial cherry tomatoes’ packaging caused the accumulation of water molecules that support microbial growth. However, this problem can be solved by using deep eutectic solvent (DES)/gelatin (Gel)-based packaging, which showed better water vapor permeability, moisture isotherm curve, and moisture absorption-desorption cycle performance. It was suggested that the hydrophilic group in DESs improved the hydrophilicity of the film, leading to a better diffusion rate of the water molecules. Besides, the prepared film was able to capture the water molecule from a higher humidity area and store it to be released in a lower humidity area, thereby regulating the moisture in the packaging, preventing the spoilage, and maintaining the freshness of fruits. This study is the first to report the use of DES@Gel in active packaging for fruit, specifically focusing on the bacterial count, firmness, water content, total soluble solids, pH, and titratable acid of cherry tomatoes after a 9-day period. DES has been commonly used for extracting solvents and detecting food safety solvents in the food industry for the past decades, owing to its non-toxic and eco-friendly properties (Boateng, 2022).

In another study, Rux et al. (2016) reported the moisture absorption kinetics of strawberries and tomatoes using a humidity-regulating tray containing 12% NaCl. Throughout the 16 days, this tray effectively maintained the RH below 97%, reducing condensation and spoilage compared to the commercially available polypropylene (PP) tray. The study showed that inclusion of 12% NaCl in the tray is more effective in tomatoes (1 wt% weight loss), with a lower transpiration rate; while for strawberries, it experienced slightly higher weight loss (3 wt%) due to higher moisture release. The kinetics of moisture uptake was modeled using a Weibull equation.

3.4 Bioactive packaging

Incorporating bioactive compounds in fruit packaging can effectively prolong the fruit’s storage life, as fruit often suffers from microbial infections during the post-harvest period. Depending on the type of packaging material, the bioactive compound can either move into the food matrix or remain on its surface (Peralta-Ruiz et al., 2020). For example, Khan and colleagues developed a film using a combination of strong antioxidant and antibacterial substances from eggplant peel carbon dots, carboxymethyl cellulose, and gelatin. As an antioxidant, the film shows 100% of ABTS and 59.1% of DPPH radical scavenging activities. As an antibacterial, the film can inhibit the growth of Listeria monocytogenes and Escherichia coli by 99.8%. When applied to table grapes, it can maintain firmness, weight, and inhibit total viable colonies for up to 24 days at 4 °C owing to the excellent biological properties of the film. In addition, biomass-derived carbon dots are attractive materials in fruit packaging due to their biocompatibility, stability, and low toxicity (Khan et al., 2024).

Other than that, Ezati et al. (2022) reported that cellulose nanofiber (CNF) composite films using glucose carbon dots (GCD) and nitrogen-functionalized carbon dots (NGCD) showed good antioxidant activity with 99% efficacy against ABTS and 80%–85% against the DPPH assay. While both CNF/GCD and CNF/NGCD composites showed high antimicrobial activity by producing reactive oxygen species (ROS), CNF/NGCD showed additional antifungal activity, extending the shelf life of tangerine and strawberry by 10 and 2 days, respectively. Mold growth was observed in films that did not incorporate CNF/NGCD, as the proliferation of fungi or harmful microorganisms is a primary factor in spoilage (Ezati et al., 2022). In vitro cytotoxicity of the prepared films was studied using the MTT assay. Overall, all the films showed low toxicity (only 10%–20% loss in cell viability) against the mouse fibroblast L929 cell line, displaying a great biocompatibility and high potential to be applied in fruit packaging applications (Ezati et al., 2022). Additional studies on bioactive antimicrobial packaging were demonstrated using grapes (Ghoshal and Singh, 2024; Gunaki et al., 2024).

Furthermore, bioactive packaging can be prepared from cactus pear peel, which contains bioactive compounds. A sodium alginate-based edible active film enriched with cactus pear extract (CPPE) was described by Asiri’s group. The main active phenolic components of antimicrobial and antioxidant agents in CPPE can inhibit microbial growth and slow down oxidation. Besides, a complementary moisture-regulating effect was observed, with an obvious decrease in water vapor permeability due to the hydrogen bonding formation between CPPE’s phenolic compounds and alginate (Asiri et al., 2024).

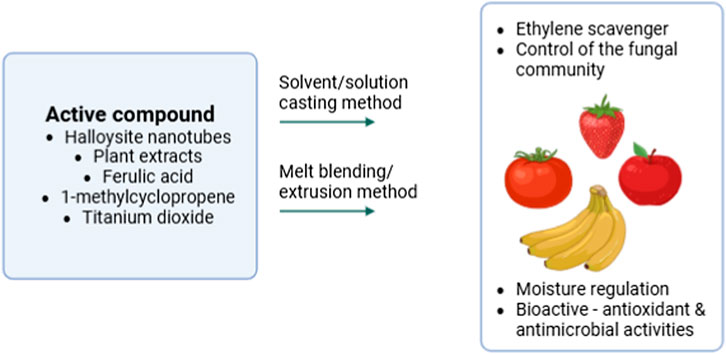

4 Smart packaging

Smart packaging is defined as packaging that can react or provide a signal in a specific way when there are changes, such as alterations in the quality, safety, or ripeness of food (Biji et al., 2015; Alizadeh-Sani et al., 2020). Consequently, these materials can enhance food quality and safety management. In contrast to an active packaging system, a smart packaging system does not release any substances into the food. Instead, it focuses on communicating with the consumer by detecting environmental changes (Restuccia et al., 2010). Additionally, it can also provide support to the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) and Quality Analysis and Critical Control Points (QACCP) systems, which are designed for the on-site management of risky food, detection of latent health risks, and the development of methodologies to minimize or abolish their occurrence (Abedi-Firoozjah et al., 2023). While active packaging alters the packaging environment to prolong fruits’ shelf life, smart packaging supports it by allowing real-time monitoring of the packaging’s environmental changes.

Smart packaging is often applied to climacteric fruit groups such as apples, pears, tomatoes, bananas, mangoes, papayas, kiwis, etc. that can undergo ripening even after being detached from the plant. These fruits are also known to undergo a significant increase in the respiration rate and ethylene production (Paul et al., 2012). When picked at an earlier stage, these fruits can ripen perfectly after storage and along the supply chain (Dirpan et al., 2018). However, long-distance transportation in the absence of cold storage often caused excess ripening and deterioration of fruits (Fan et al., 2011; Dirpan et al., 2018). Therefore, a smart packaging that allows easy visual observation and provides consumers with immediate indicators of a fruit’s condition is much needed. Such packaging typically detects pH, gas levels, temperature, light, and humidity as shown in Table 2 (Firouz et al., 2021; Sani et al., 2021; Sari et al., 2023).

4.1 Biosensor

A biosensor is usually used to monitor fruit freshness, pesticide residues, and biological contamination by detecting allergens and bioanalytes. Foodborne pathogenic bacteria and fungi, such as Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella typhimurium, Musa sapientum, Penicillum oxalicum, Asperigillus nigger, Fusarium oxysporum, etc. are normally the species that cause the deterioration of fruits and pose an adverse health effect (Udoh et al., 2015; He et al., 2022). A polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)/PEI/MB nanofiber was prepared via the electrospinning method by Zhang et al. (2023) for direct monitoring of watermelon, strawberry, apple, and papaw freshness. Methylene blue (MB), shows blue color under an oxidized state and colorless under a reduced state, which is useful in the smart food packaging field (Jarupatnadech et al., 2022). Polyethyleneimine (PEI), is a high-density polycationic polymer which able to disrupt the bacterial cell membrane (Gao et al., 2017). PVA, known for its high-water solubility and excellent film-forming properties, was added to address the challenges of forming nanofibers from the high-viscosity components MB and PEI (Huang et al., 2020). In bacterial infection and actual fruit application experiments, high concentrations of Escherichia coli and S. aureus completely decolorise the blue film’s color, together with the dropping of hue values (Zhang et al., 2023).

4.2 pH indicator

Detecting pH changes in fruit packaging is important for ensuring food safety, preserving fruit quality, and reducing waste (Alam et al., 2021). The pH changes are often associated with the fruit’s metabolic and enzymatic activities after ripening or spoiling. A fruit packaging that allows naked-eye observation provides a non-invasive and real-time indication of fruit freshness. A smart pH indicator fruit packaging was developed by Dirpan’s group through a solution casting method, where the Acetobakter xilinum bacterial cellulose membrane was treated with 5% NaOH and immersed in bromophenol blue (BPB) solution. As the mango ripens, pH value increases caused by enzymatic and microbial activities that decrease the total acid content and increase soluble solids in the fruit. The indicator in the packaging changes color from blue (around pH 3.5) to green (around pH 4.7) over a 10-day storage time (Dirpan et al., 2018). A similar pH indicator for fruit packaging was developed by Ran et al. (2021), using soy protein isolate (SPI) combined with bromothymol blue (BB) and methyl red (MR) in a solution-casting preparation method for apple packaging. During apple storage, the indicator displayed an obvious color change from green to blue as the pH increased, due to the release of volatile basic compounds during spoilage.

On the other hand, Sari et al. (2023) reported a pH-sensitive smart label using mangosteen peel, which is a natural product that shows color change under different pH conditions. Anthocyanins from mangosteen peels was extracted via maceration in ethanol and cast into a film together with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and glycerol as a plasticizer. The label changes color from yellow (neutral pH) to orange-red (acidic pH), and it is suitable for monitoring tomatoes’ freshness. Data from 13 days of storage showed changes in color intensity due to the increase in acidity from the tomato’s metabolic activity, which was detected by the pH-sensitive anthocyanin from the mangosteen peel extract.

4.3 Gas indicator

Ethylene (C2H4) is a colorless and odorless plant hormone that can indicate fruit maturity (Caprioli and Quercia, 2014). Immature fruits release low concentrations of ethylene, ranging from 10 ppb to 10 ppm, which can trigger the ripening process. As the fruit matures, ethylene emission increase to over 100 ppm. Excessive ethylene can hasten respiratory rates and spoil the fruit (Janssen et al., 2014). Therefore, developing a gas indicator capable of detecting low concentrations of C2H4 is crucial.

Zhao et al. (2020) presented an ethylene sensor based on palladium (Pd)-loaded tin oxide (SnO2) using a simple coating method, which may work at a temperature of 250 °C and RH of 51.9%. Compared to pristine SnO2, Pd-loaded SnO2 offers 3 times higher response (11.1 Ra/Rg), shorter response time (1 s), good sensitivity (0.58 ppm−1), and low detection limit down to ppb level (50 ppb) owing to the effect of Pd nanoparticle. It was applied to various fruits such as bananas, lemons, apples, and pears. Studies on the emission of ethylene by bananas and lemon for 15 days revealed that ethylene emission could be used as an indicator to estimate the coloration, texture, and flavor of fruits (Zhao et al., 2020).

Other than ethylene, gases such as aldehyde from apples (Kim et al., 2018) and sulfur compounds from durian (Niponsak et al., 2020) can be used as an indicators of freshness of packaged fruit As described by Kim et al. (2018), aldehyde releases from apples can be detected by filter paper associated with several types of pH indicators via inkjet or silk-screen printing. When apples ripen, the emission of aldehyde detected from the Cannizzaro reaction causes a pH change and triggers a color change from yellow to orange to red after 9 days. A similar detection method was demonstrated by Niponsak et al. (2020) using a starch/chitosan/pH indicator matrix for sulfur compounds released from durian. Different color changes were used to describe the freshness of durian throughout 5 days, where red color for onset; orange color for ripe; and yellow color for over-ripe.

4.4 Radio frequency identification tag (RFID)

RFID technology has been expanded to fruit packaging technology to detect freshness, temperature, and humidity management. RFID can be used to monitor the fruit quality throughout transportation and distribution, as their ongoing physiological activity will affect the quality. Vergara et al. (2007) developed a miniature RFID reader incorporated with a metal oxide semiconductor gas sensor to monitor the gas composition during the storage and transport of apples. Thus, the apples’ quality can be monitored by adjusting the operating temperature of the gas sensor. However, limited studies have applied RFID tags to fruit packaging, as the high cost of RFID technology would increase the packaging costs. Therefore, future work should focus on the development of economically and environmentally friendly sensors for scalability applications in fruit packaging.

5 Edible and biodegradable packaging

Edible and biodegradable packaging is a sustainable, third-generation packaging alternative designed to minimize waste and environmental impact. Produced from animal- or plant-based polymers, this type of packaging can be consumed along with the product, eliminating the need for traditional waste management processes (Zhao et al., 2023). As traditional packaging from synthetic plastic polymers poses significant harm to the planet, edible packaging serves as an innovative solution to reduce plastic waste, generation of microplastics, carbon emissions, conserve resources, and manage waste from food processing (Kaseke et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023). Edible and biodegradable packaging, while initially more costly than synthetic alternatives, presents a cost-effective solution in the long term. This is largely due to the potential utilization of byproducts from food processing, which can significantly reduce production costs (Abdulla et al., 2024; Kumar et al., 2025). Edible coatings can either be applied directly to the fruit surface or as preformed films that wrap around the fruit, whole fruit, or minimally processed fruits (Mwelase et al., 2023; Van et al., 2023). To be considered edible, coatings and films applied to foods must be Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS), completely digestible, non-allergic, nontoxic, and stable during processing and storage (Sharma et al., 2024).

5.1 Types of edible coatings and films

Edible packaging formulation typically consists of biopolymers derived from natural sources that can be categorized into hydrocolloids (polysaccharides and proteins), lipid colloids (fatty acids, acylglycerol, and waxes), and composites based on their physicochemical properties (Liyanapathiranage et al., 2023; Sharma et al., 2024). The biopolymer, which is usually formed from the base, is mixed with plasticizers, which are commonly sugars such as mannitol, xylitol, glycerol, sorbitol, sucrose, monoglyceride, etc., to impart softness and flexibility, and other additives (antioxidants, antimicrobials, browning inhibitors) depending on the desired properties of the coating or film (Sharma et al., 2024).

Edible coatings and films have received prominence as sustainable options to traditional plastic packaging polymers such as polyethylene and polypropylene due to their potential to reduce both plastic waste and food losses (Kawhena et al., 2020; Saleem et al., 2021; Liyanapathiranage et al., 2023). Hydrocolloids, which are mainly characterized by a hydrophilic functional group, can be completely or partially dispersed in water, depending on their molecular weight. This group includes polysaccharides, proteins, and their isolates, which can be further divided into animal-based, plant-based, or modified hydrocolloids (Sharma et al., 2024). Plant-based hydrocolloids consist of a broad variety of polymers that include pectin, starch, mannan, different types of gums (guar gum, locust bean gum, gum Arabic, and gum Ghatti), agar, tragacanth, alginates, and carrageenan, while animal-based hydrocolloids mainly consist of gelatin and chitosan (Morodi et al., 2022). Modification of hydrocolloids is commonly performed to enhance their quality, safety, stability, and nutritional qualities (Liyanapathiranage et al., 2023). For instance, cellulose, pectin, and starch, with improved functionality such as gelling, thermal, and textural properties, can be produced from polysaccharides. Meanwhile, cellulose can be specifically manipulated to produce nanofabricated cellulose, carboxymethyl cellulose, nanocrystalline cellulose, methylcellulose, hydroxyethyl cellulose, and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, which have found a wider application in the food industry (Aziz et al., 2022). This highlights the ongoing advancements in biopolymers and the expansion of their roles within the food systems.

Unlike the hydrocolloids, lipid colloids, which are mainly fatty acids, glycerides, and waxes, are characterized by hydrophobic functional groups and emulsion formation. The lipid-water interface of lipid hydrocolloids is a highly active surface that provides an effective moisture transfer barrier (Kaseke et al., 2025). Liposomes, micelles, nanoemulsions, microemulsions, and solid lipid nanoparticles are among the commonly used lipid hydrocolloids in edible coatings and films and are largely desired for being non-toxic, physiochemically stable, surface-reactive, easy to absorb in the human digestive system, and having excellent emulsion properties (Liyanapathiranage et al., 2023; Kaseke et al., 2025).

Different types of biopolymers can be combined utilizing their specific advantages to produce tailor-made composites with distinct properties. For instance, composites of proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids, which can be applied as single or bilayers, have been studied where lipids function to lessen water transmission, while proteins offer mechanical stability, and carbohydrates regulate the exchange of gasses, further advancing innovation in edible coatings and films development and application (Kawhena et al., 2020; Esfandiari et al., 2025). For instance, Shi et al. (2024) developed a composite of nisin, cellulose nanofiber, and egg protein that extended the shelf life of bananas by more than 6 days at 20 °C while maintaining the appearance, firmness, and nutrient qualities of the fruit during storage, demonstrating the enhanced functionality of the coatings by the various types of biopolymers composited. Advancements in biopolymer production continue with the emergence of new sources, such as plant and seed mucilage, which can functionally compete with conventional biopolymers while being obtained at lower costs (Shinga et al., 2025). However, the successful integration of new biopolymers into the food system necessitates additional research on their safety, effectiveness across different food types, interactions with other compounds, and overall optimization.

5.2 Preparation and characterization of edible coatings and films

While an edible coating is coated directly on the fruit surface via spraying, dipping, or spreading methods, an edible film is first formed by either solvent casting or extrusion, which are the two most common methods (Suhag et al., 2020). Extrusion mainly involves processes that sequentially include formulation, melt blending, extrusion, cooling, and storage. The extruder temperature and operating parameters are largely affected by the characteristics of the polymer that include rheology and thermal properties, with biopolymers exhibiting thermoplastic properties highly desired in this type of film production (Suhag et al., 2020; Weng et al., 2025). Polymer melting can be assisted by aids and plasticizers, while the quality of the film largely depends on the degree of crystallinity of the polymers and the cooling rate. The extruder parameters can be adjusted to the desired film quality attributes, making the process versatile and user-friendly. Certain setbacks, such as errors in the formulation, may result in phase separation, non-uniform distributions, and irregularities in thickness (Liyanapathiranage et al., 2023).

Solvent casting, which is a low-temperature casting method, involves dissolving biopolymers in a solvent to create a film-forming solution, which is then allowed to cast and dry (Liyanapathiranage et al., 2023; Sharma et al., 2024). It is the most preferred method for film development because it is cheaper and simple. Some of the advantages of this method are that it produces a homogenous, fewer defects, optically pure, transparent, flat, and isotropically oriented film. However, solvent casting is associated with disadvantages that include limited moulding shapes, prolonged drying time, conversion into the industrial scale, and denaturation of heat-sensitive compounds (Suhag et al., 2020). In addition, it is associated with variation in film properties attributed by the changes in processing parameters like temperature, evaporation level, etcetera, and trapping of toxic solvent into the biopolymer matrix (Liyanapathiranage et al., 2023; Sharma et al., 2024). Consideration of the physiochemical properties of the components, number of layers, coating thickness, viscosity, and solution solids is critical to ensure that films of the desired qualities, such as strength, barrier, and solubility, are produced. A plasticizer is often added to strengthen the flexibility and durability of the film. In addition, emulsion stabilizers and surfactants are added to promote mixing together with wetting, levelling, and defoaming agents to control the characteristics of the films.

After casting, the films are dried using hot air, steam, or infrared drying and then peeled off. Other methods such as lamination, dipping, and spraying have been explored with their advantages and disadvantages governing their application at either the laboratory or commercial level (Liyanapathiranage et al., 2023; Sharma et al., 2024). Developed films can be characterized based on their mechanical properties like thickness, bursting strength, moisture content, transparency, water solubility, water vapor permeability, tensile strength, elongation, and physical properties such as color, surface morphology, and chemical composition and structures (Ribeiro et al., 2021).

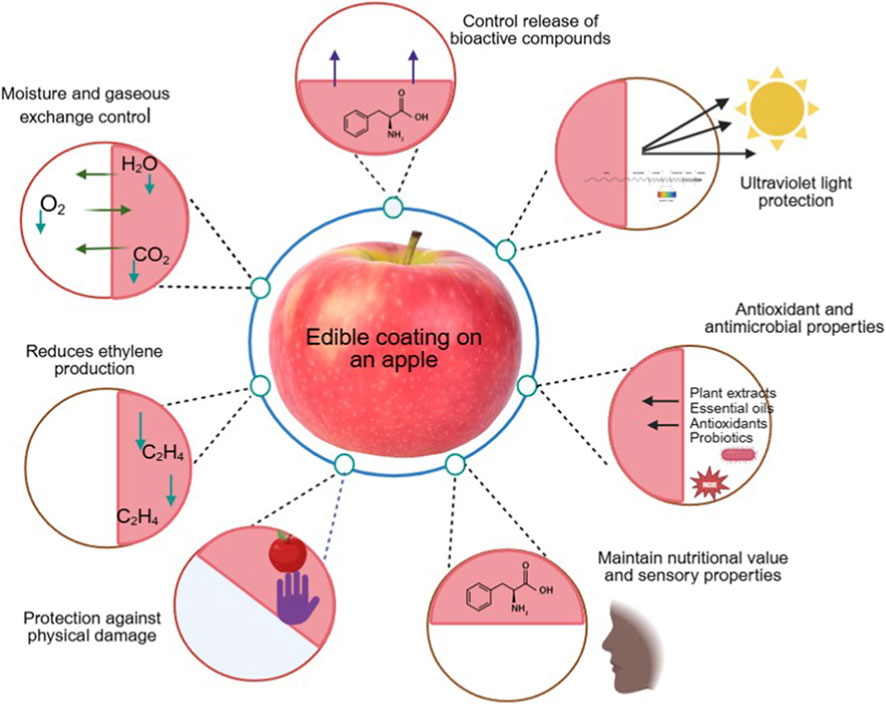

5.3 Application of edible and biodegradable packaging for fruit preservation

Edible and biodegradable packaging for fruits acts as a protective and semipermeable barrier with a thickness of not more than 300 µm that creates a modified atmospheric environment (Sharma et al., 2024). This helps in controlling gaseous, water vapour exchange and physiological processes such as respiration rate (RR), ethylene production, and moisture loss, which in turn enhances the shelf life of the fruit (Figure 2). In addition, edible coatings can assist to mitigate physical, mechanical, and microbiological damage of the fruit as well as acting as carrier for additives such as antimicrobials, and antioxidants further contributing to the enhancement of the fruit’s freshness and quality (Sharma et al., 2024; Shinga et al., 2025). The antioxidants suppress reactive oxygen species formation, either by stopping enzymes or by chelating trace elements preventing lipid oxidation and delaying off-flavors development, while antimicrobials inactive the genetic material and enzyme (Ahmed et al., 2024).

Figure 2. Main functions and mechanisms of action for edible coatings on fruits (Created in BioRender.com).

Evidence from literature has shown that edible coatings and films applied to fruits, either whole or minimally processed, are growing, particularly on highly perishable fruits such as berries, pome and stone fruit, grapes, pomegranates, and apples (Table 3). The biopolymers have been applied either individually or as composites with or without additives and accompanied by either ambient or low-temperature storage, and positive results have been reported. Quality parameters that include physiological processes such as water loss (WL), RR, ethylene production, physical parameters such as color, texture/firmness, decay counts, and chemical parameters like total soluble solids (TSS), titratable acidity (TA), phytochemicals, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity, and sensory evaluation have been studied to assess the efficacy of edible coatings on fruits (Mwelase et al., 2023; Esfandiari et al., 2025; Shinga et al., 2025). The application of guar gum and candelilla wax alone or combined with Bacillus subtilis HFC103, chitosan enriched with ascorbic acid, sodium carboxymethyl cellulose, cellulose nanofibers, and mandarin oil, carboxymethyl cellulose, low methoxyl pectin, Persian gum, and tragacanth gum on strawberries have been reported. The strawberries were stored at temperatures ranging between 4 °C and 25 °C and RH around 80% and significant reduction in WL, fungal, and bacterial growth and decay were reported contributing to the increased shelf life of the fruit (Khodaei et al., 2021 Saleem et al., 2021; Van et al., 2023). Optimization studies of edible coating compositions are vital but still lacking in the literature, especially for novel biopolymers, due to the intricate interactions between the various components involved. Shinga et al. (2025) developed an improved banana coating by optimizing glycerol and cellulose nanofiber levels in a pomegranate peel functionalized Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage. This new formulation effectively preserved bananas during storage, through the reduction of weight loss, water vapor transmission rate, firmness loss, decay, and respiration rate, while also reducing ethylene production. However, the effect of edible coatings of fruit significantly varies with cultivar, harvest maturity, fruit tree management, fruit-grown area, and other factors. Consideration of these factors when interpreting the effect of edible coatings on fruits is therefore important.

Table 3. Recent studies on the application of biodegradable and edible coatings or films to preserve fresh fruit (2020–2025).

Coatings such as chitosan, nano-chitosan, pectin, sodium alginate with or without antimicrobial agents have also been applied to whole or minimally processed fruits such as grapes, nectarines, papaya and apples. In vitro studies revealed that the antimicrobial agents (clove oil, coffee husk, Mimusopsis comersonii seed extracts, thyme and oregano essential oils) inhibited the growth of foodborne pathogens such as S. aureus, Listeria monocytogenes and S. cerevisiae, Salmonella typhimurium and E. coli. When the antimicrobial agents were incorporated into edible coatings they prevented the growth of aerobic microorganism, yeast and mould, without compromising the sensory properties of the fruits (Tabassum and Khan, 2020; Lima et al., 2022; Divyashri et al., 2024; Prieto-Santiago et al., 2025). These findings demonstrate the potential of edible coatings in preserving the quality and safety of fruits, reducing food waste, and improving customer satisfaction. Additional studies demonstrating the impact of edible coatings on fruit quality and safety are presented in Table 3. With the edible packaging market projected to be worth USD 2.14 billion by 2030 with a compound annual growth rate of 6.79%, the future of edible coating packaging is quite promising. However, the future of edible coating in food packaging is dependent on how issues of sustainability, safety and regulation, standardization, and commercialization are addressed (Kumar et al., 2022).

6 Challenges and future perspectives

Different biopolymers are investigated to explore their functionality in creating active packaging with strengthened mechanical stability and efficient delivery of active compounds in active packaging. Natural bioactive compounds, such as plant extracts and antioxidants, have antimicrobial and ethylene scavenging activities. However, bioactive compounds are heat-sensitive and have low bioavailability, which may hinder their applications in active packaging for fruit preservation. Different technologies, such as high-pressure homogenization, encapsulation, electrospun film, and others, can help to improve the surface area, controlled release behavior, and bioavailability of these bioactive compounds (Cui et al., 2024). This can help to improve the performance of active packaging for fruit preservation.

Edible and biodegradable packaging can improve the functionality of fruit packaging system, but their stability and prolonged usage still hinder their commercial applications. Innovative technologies, such as high-pressure homogenization, encapsulation, and ultrasonication can be used to develop edible and biodegradable packaging with improved stability and interactions between packaging and fruit for a longer time (Kumar et al., 2022). On the other hand, the selection of the right biopolymers and coating methods is important in the development of effective edible and biodegradable packaging.

The use of smart packaging is increasingly growing as it provides accurate information from the production to the final-end supplier and consumer. However, safety evaluation is one of the concerns for smart packaging. The potential migration of chemical dyes from pH indicators to the food product and interaction between smart packaging and food systems still require in-depth studies to provide comprehensive safety assessment. On the other hand, the use of non-toxic or natural indicators is one of the trends in smart packaging to ensure safety. High costs of smart packaging technology, especially RFID tags hinders its commercial applications. The price of smart packaging should not exceed 10% of the total price of the food product (He et al., 2022). Thus, future studies on cost benefit analysis and designing of cost-effective smart packaging are still warranted.

To further improve the quality and safety of fruits, different packaging technologies can be combined to offer synergistic effects of functionalities. Innovative packaging technology should focus on the regulation of physiological metabolism in fruit preservation, safe and efficient delivery of function, real-time monitoring to provide accurate information, and green environmental protection to support sustainability.

7 Conclusion

This paper reviewed the applications of active packaging, edible and biodegradable packaging, as well as smart packaging in fruit preservation. Active packaging and edible and biodegradable packaging are effective packaging technologies to maintain the freshness and quality of fruits by reducing water loss, regulating gas transmission and water transpiration, and inhibiting microbial growth. Active packaging has been widely used in fruit preservation by ethylene scavenging, control of the fungal community, moisture regulation, and offering antioxidant and antimicrobial activities by incorporation of bioactive compounds. Thus, active packaging can effectively reduce the ripening process of fruits and extend its shelf life. Edible and biodegradable packaging can assist in mitigating physical, mechanical, and microbiological damage to the fruit as well as acting as a carrier for additives such as antimicrobials, and antioxidants further contributing to the enhancement of the fruit’s freshness and quality. Edible and biodegradable packaging uses natural polymers which can reduce plastic waste and carbon emissions from conventional packaging. Green packaging technology should be supported to minimize environmental impacts and support environmental sustainability. Smart packaging is emerging as it provides real-time monitoring of fruit quality from the production to the supply chain. Accurate information can be provided throughout the journey which can increase public acceptance in the market. Smart packaging can always incorporate with other packaging technologies to offer synergistic functionalities of the packaging system. Future research should focus on the green and hybrid packaging system in regulating physiological metabolism for fruit preservation, ensuring safe and effective delivery of functions, enabling real-time monitoring for precise information, and promoting environmental sustainability.

Author contributions

WC: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization. TK: Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Methodology. SC: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Formal Analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation. YN: Formal Analysis, Data curation, Writing – review and editing, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization. KN: Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Methodology.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdulla, S. F., Shams, R., and Dash, K. K. (2024). Edible packaging as sustainable alternative to synthetic plastic: a comprehensive review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 1–15. doi:10.1007/s11356-024-32806-z

Abedi-Firoozjah, R., Salim, S. A., Hasanvand, S., Assadpour, E., Azizi-Lalabadi, M., Prieto, M. A., et al. (2023). Application of smart packaging for seafood: a comprehensive review. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 22 (2), 1438–1461. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.13117

Ahmed, M., Saini, P., Iqbal, U., and Sahu, K. (2024). Edible microbial cellulose-based antimicrobial coatings and films containing clove extract. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 6 (1), 65. doi:10.1186/s43014-024-00241-9

Alabi, K. P., Zhu, Z., and Sun, D. W. (2020). Transport phenomena and their effect on microstructure of frozen fruits and vegetables. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 101, 63–72. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2020.04.016

Alam, A. U., Rathi, P., Beshai, H., Sarabha, G. K., and Deen, M. J. (2021). Fruit quality monitoring with smart packaging. Sensors 21 (4), 1509. doi:10.3390/s21041509

Alizadeh-Sani, M., Mohammadian, E., Rhim, J. W., and Jafari, S. M. (2020). pH-sensitive (halochromic) smart packaging films based on natural food colorants for the monitoring of food quality and safety. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 105, 93–144. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2020.08.014

Alves, J., Gaspar, P. D., Lima, T. M., and Silva, P. D. (2023). What is the role of active packaging in the future of food sustainability? A systematic review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 103 (3), 1004–1020. doi:10.1002/jsfa.11880

Amin, U., Khan, M. K. I., Maan, A. A., Nazir, A., Riaz, A., Khan, M. U., et al. (2022). Biodegradable active, intelligent, and smart packaging materials for food applications. Food Packag. Shelf Life 33, 100903. doi:10.1016/j.fpsl.2022.100903

Ardiyansyah, M. F., Kurnianto, B. P., Wahyono, A., Apriliyanti, M. W., and Lestaro, I. P. (2020). Monitoring of banana deteriorations using intelligent-packaging containing brazilien extract (Caesalpina sappan L.). IOP Conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci. 411, 1755–1315.

Asiri, S. A., Matar, A., Ismail, A. M., and Farag, H. A. S. (2024). Sodium alginate edible films incorporating cactus pear extract: antimicrobial, chemical, and mechanical properties. Ital. J. Food. Sci. 36 (4), 151–168. doi:10.15586/ijfs.v36i4.2675

Awalgaonkar, G., Beaudry, R., and Almenar, E. (2020). Ethylene-removing packaging: basis for development and latest advances. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 19 (6), 3980–4007. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12636

Aziz, T., Farid, A., Haq, F., Kiran, M., Ullah, A., Zhang, K., et al. (2022). A review on the modification of cellulose and its applications. Polym 14 (15), 3206. doi:10.3390/polym14153206

Aziz, T., Li, Z., Naseeb, J., Sarwar, A., Zhao, L., Lin, L., et al. (2024). Role of bacterial exopolysaccharides in edible films for food safety and sustainability. Current trends and future perspectives. Ital. J. Food Sci. 36 (4), 169–179. doi:10.15586/ijfs.v36i4.2690

Biji, K., Ravishankar, C., Mohan, C., and Srinivasa Gopal, T. (2015). Smart packaging systems for food applications: a review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 52, 6125–6135. doi:10.1007/s13197-015-1766-7

Boateng, I. D. (2022). A critical review of emerging hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents’ applications in food chemistry: trends and opportunities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 70 (38), 11860–11879. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.2c05079

Caprioli, F., and Quercia, L. (2014). Ethylene detection methods in post-harvest technology: a review. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 203, 187–196. doi:10.1016/j.snb.2014.06.109

Cui, X., You, Y., Ding, Y., Sun, C., Liu, B., Wang, X., et al. (2024). Improving the function of electrospun film by natural substance for active packaging application of fruits and vegetables. LWT 191, 115683. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2023.115683

Dai, M., Zhao, F., Fan, J., Li, Q., Yang, Y., Fan, Z., et al. (2022). A nanostructured moisture-absorbing gel for fast and large-scale passive dehumidification. Adv. Mater. 34 (17), 2200865. doi:10.1002/adma.202200865

Dirpan, A., Latief, R., Syarifuddin, A., Rahman, A., Putra, R., Hidayat, S., et al. (2018). The use of colour indicator as a smart packaging system for evaluating mangoes Arummanis (Mangifera indica L. var. Arummanisa) freshness. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Env. Sci. 157, 012031. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/157/1/012031

Divyashri, G., Swathi, R., Murthy, T. K., Anagha, M., Sindhu, O., and Sharada, B. (2024). Assessment of antimicrobial edible coatings derived from coffee husk pectin and clove oil for extending grapes shelf life. Discov. Food 4 (1), 181. doi:10.1007/s44187-024-00236-y

Durmaz, B. U., Nigiz, F. U., and Aytac, A. (2024). Active packaging films based on poly (butylene succinate) films reinforced with alkaline halloysite nanotubes: production, properties, and fruit packaging applications. Appl. Clay Sci. 259, 107517. doi:10.1016/j.clay.2024.107517

Esfandiari, Z., Hassani, B., Sani, I. K., Talebi, A., Mohammadi, F., Zomorodi, S., et al. (2025). Characterization of edible films made with plant carbohydrates for food packaging: a comprehensive review. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 11, 100979. doi:10.1016/j.carpta.2025.100979

Ezati, P., Rhim, J. W., Molaei, R., Priyadarshi, R., and Han, S. (2022). Cellulose nanofiber-based coating film integrated with nitrogen-functionalized carbon dots for active packaging applications of fresh fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 186, 111845. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2022.111845

Fan, L., Song, J., Forney, C. F., and Jordan, M. A. (2011). Fruit maturity affects the response of apples to heat stress. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 62 (1), 35–42. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2011.04.007

Fawole, O. A., Riva, S., Silue, Y., and Opara, U. L. (2024). Evaluating commercial viability of gum Arabic-based edible coatings for enhancing shelf life of'African delight™'plum under simulated packhouse conditions. South Afr. J. Bot. 174, 902–915. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2024.10.005

Firouz, M. S., Mohi-Alden, K., and Omid, M. (2021). A critical review on intelligent and active packaging in the food industry: research and development. Food Res. Int. 141, 110113. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110113

Gaikwad, K. K., Singh, S., and Lee, Y. S. (2018). High adsorption of ethylene by alkali-treated halloysite nanotubes for food-packaging applications. Env. Chem. Lett. 16, 1055–1062. doi:10.1007/s10311-018-0718-7

Gaikwad, K. K., Singh, S., and Ajji, A. (2019). Moisture absorbers for food packaging applications. Env. Chem. Lett. 17 (2), 609–628. doi:10.1007/s10311-018-0810-z

Gao, J., White, E. M., Liu, Q., and Locklin, J. (2017). Evidence for the phospholipid sponge effect as the biocidal mechanism in surface-bound polyquaternary ammonium coatings with variable cross-linking density. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9 (8), 7745–7751. doi:10.1021/acsami.6b14940

Ghoshal, G., and Singh, J. (2024). Study of coating effectiveness of grape fruit seed extract incorporated Chitosan/cornstarch based active packaging film on grapes. Food Chem. Adv. 4, 100651. doi:10.1016/j.focha.2024.100651

Gong, D., Bi, Y., Zong, Y., Li, Y., Sionov, E., Prusky, D., et al. (2022). Characterization and sources of volatile organic compounds produced by postharvest pathogenic fungi colonized fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 188, 111903. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2022.111903

Gunaki, M. N., Masti, S. P., D'souza, O. J., Eelager, M. P., Kurabetta, L. K., Chougale, R. B., et al. (2024). Fabrication of CuO nanoparticles embedded novel chitosan/hydroxypropyl cellulose bio-nanocomposites for active packaging of jamun fruit. Food Hydrocoll. 152, 109937. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2024.109937

He, Y., Xiao, Q., Bai, X., Zhou, L., Liu, F., and Zhang, C. (2022). Recent progress of nondestructive techniques for fruits damage inspection: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62 (20), 5476–5494. doi:10.1080/10408398.2021.1885342

Hira, N., Mitalo, O. W., Okada, R., Sangawa, M., Masuda, K., Fujita, N., et al. (2022). The effect of layer-by-layer edible coating on the shelf life and transcriptome of ‘Kosui’Japanese pear fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 185, 111787. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2021.111787

Hou, X., Jiang, J., Luo, C., Rehman, L., Li, X., Xie, X., et al. (2023). Advances in detecting fruit aroma compounds by combining chromatography and spectrometry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 103 (10), 4755–4766. doi:10.1002/jsfa.12498

Huang, J., Yu, H., Abdalkarim, S. Y. H., Marek, J., Militky, J., Li, Y., et al. (2020). Electrospun polyethylene glycol/polyvinyl alcohol composite nanofibrous membranes as shape-stabilized solid–solid phase change materials. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2, 167–177. doi:10.1007/s42765-020-00038-8

Hung, R., Lee, S., and Bennett, J. W. (2015). Fungal volatile organic compounds and their role in ecosystems. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 99, 3395–3405. doi:10.1007/s00253-015-6494-4

Hussain, M., Bensaid, S., Geobaldo, F., Saracco, G., and Russo, N. (2011). Photocatalytic degradation of ethylene emitted by fruits with TiO2 nanoparticles. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 50 (5), 2536–2543. doi:10.1021/ie1005756

Iskandar, A., Yuliasih, I., and Warsiki, E. (2020). Performance improvement of fruit ripeness smart label based on ammonium molibdat color indicators. Indonesian Food Sci. Technol. J. 3 (2), 48–57. doi:10.22437/ifstj.v3i2.10178

Janjarasskul, T., and Suppakul, P. (2018). Active and intelligent packaging: the indication of quality and safety. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 58 (5), 808–831. doi:10.1080/10408398.2016.1225278

Janssen, S., Schmitt, K., Blanke, M., Bauersfeld, M. L., Wöllenstein, J., Lang, W., et al. (2014). Ethylene detection in fruit supply chains. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phy. Eng. Sci. 372 (2017), 20130311. doi:10.1098/rsta.2013.0311

Jarupatnadech, T., Chalitangkoon, J., and Monvisade, P. (2022). Colorimetric oxygen indicator films based on β-cyclodextrin grafted chitosan/montmorillonite with redox system for intelligent food packaging. Packag. Technol. Sci. 35 (6), 515–525. doi:10.1002/pts.2648

Kaewklin, P., Siripatrawan, U., Suwanagul, A., and Lee, Y. S. (2018). Active packaging from chitosan-titanium dioxide nanocomposite film for prolonging storage life of tomato fruit. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 112, 523–529. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.01.124

Kaseke, T., Lujic, T., and Cirkovic Velickovic, T. (2023). Nano-and microplastics migration from plastic food packaging into dairy products: impact on nutrient digestion, absorption, and metabolism. Foods 12 (16), 3043. doi:10.3390/foods12163043

Kaseke, T., Chew, S. C., Magangana, T. P., and Fawole, O. A. (2025). Elucidating the microencapsulation of bioactives from pomegranate fruit waste for enhanced stability, controlled release, biological activity, and application. Food Bioprocess Technol. 18 (5), 4222–4250. doi:10.1007/s11947-024-03689-2

Kawhena, T. G., Tsige, A. A., Opara, U. L., and Fawole, O. A. (2020). Application of gum Arabic and methyl cellulose coatings enriched with thyme oil to maintain quality and extend shelf life of “acco” pomegranate arils. Plants 9 (12), 1690. doi:10.3390/plants9121690

Kaya, M., Česonienė, L., Daubaras, R., Leskauskaitė, D., and Zabulionė, D. (2016). Chitosan coating of red kiwifruit (Actinidia melanandra) for extending of the shelf life. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 85, 355–360. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.01.012

Keller, N., Ducamp, M. N., Robert, D., and Keller, V. (2013). Ethylene removal and fresh product storage: a challenge at the frontiers of chemistry. Toward an approach by photocatalytic oxidation. Chem. Rev. 113 (7), 5029–5070. doi:10.1021/cr900398v

Khan, A., Riahi, Z., Kim, J. T., and Rhim, J. W. (2024). Carboxymethyl cellulose/gelatin film incorporated with eggplant peel waste-derived carbon dots for active fruit packaging applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 271, 132715. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.132715

Khodaei, D., Hamidi-Esfahani, Z., and Rahmati, E. (2021). Effect of edible coatings on the shelf-life of fresh strawberries: a comparative study using TOPSIS-shannon entropy method. NFS J. 23, 17–23. doi:10.1016/j.nfs.2021.02.003

Kim, S. M., Lee, S. M., Seo, J. A., and Kim, Y. S. (2018). Changes in volatile compounds emitted by fungal pathogen spoilage of apples during decay. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 146, 51–59. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2018.08.003

Kim, Y. H., Yang, Y. J., Kim, J. S., Choi, D. S., Park, S. H., Jin, S. Y., et al. (2018). Non-destructive monitoring of apple ripeness using an aldehyde sensitive colorimetric sensor. Food Chem. 267, 149–156. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.02.110

Kumar, A., Hasan, M., Mangaraj, S., Pravitha, M., Verma, D. K., and Srivastav, P. P. (2022). Trends in edible packaging films and its prospective future in food: a review. Appl. Food Res. 2 (1), 100118. doi:10.1016/j.afres.2022.100118

Kumar, V., Ram, D. K., Sahu, G., Sahu, N. K., and Verma, S. K. (2025). Sustainable modifications in food packaging: a comprehensive review of biodegradable material revolutions. Appl. Food Res. 5, 101385. doi:10.1016/j.afres.2025.101385

Li, X., Peng, S., Yu, R., Li, P., Zhou, C., Qu, Y., et al. (2022). Co-application of 1-MCP and laser microporous plastic bag packaging maintains postharvest quality and extends the shelf-life of honey peach fruit. Foods 11 (12), 1733. doi:10.3390/foods11121733

Lima, E. M. F., Matsumura, C. H. S., Da Silva, G. L., Patrocínio, I. C. S., Santos, C. A., Pereira, P. A. P., et al. (2022). Antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of apricot (Mimusopsis comersonii) phenolic-rich extract and its application as an edible coating for fresh-cut vegetable preservation. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022 (1), 8440304. doi:10.1155/2022/8440304

Liyanapathiranage, A., Dassanayake, R. S., Gamage, A., Karri, R. R., Manamperi, A., Evon, P., et al. (2023). Recent developments in edible films and coatings for fruits and vegetables. Coatings 13 (7), 1177. doi:10.3390/coatings13071177

Mahajan, P. V., and Lee, D. S. (2023). Modified atmosphere and moisture condensation in packaged fresh produce: scientific efforts and commercial success. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 198, 112235. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2022.112235

Makhathini, N., Kumar, N., and Fawole, O. A. (2025). Enhancing circular bioeconomy: alginate-cellulose nanofibre films/coatings functionalized with encapsulated pomegranate peel extract for postharvest preservation of pomegranate arils. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 309, 142848. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.142848

Martínez-Romero, D., Guillén, F., Castillo, S., Zapata, P. J., Valero, D., Serrano, M., et al. (2009). Effect of ethylene concentration on quality parameters of fresh tomatoes stored using a carbon-heat hybrid ethylene scrubber. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 51 (2), 206–211. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2008.07.011

Mbonambi, N. P., Seke, F., Mwelase, S., and Fawole, O. A. (2025). Improving quality management of ‘ready-to-eat’ pomegranate arils using aloe ferox-based edible coating enriched with encapsulated raspberry pomace. Food Sci. Nutr. 13 (7), e70636. doi:10.1002/fsn3.70636

Morodi, V., Kaseke, T., and Fawole, O. A. (2022). Impact of gum Arabic coating pretreatment on quality attributes of oven-dried red raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) fruit. Processes 10 (8), 1629. doi:10.3390/pr10081629

Mwelase, S., Kaseke, T., and Fawole, O. A. (2023). Development and optimization of methylcellulose-based edible coating using response surface methodology for improved quality management of ready-to-eat pomegranate arils. CyTA-J. Food 21 (1), 656–665. doi:10.1080/19476337.2023.2274942

Niponsak, A., Laohakunjit, N., Kerdchoechuen, O., Wongsawadee, P., and Uthairatanakij, A. (2020). Novel ripeness label based on starch/chitosan incorporated with pH dye for indicating eating quality of fresh–cut durian. Food Control. 107, 106785. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.106785

Paul, V., Pandey, R., and Srivastava, G. C. (2012). The fading distinctions between classical patterns of ripening in climacteric and non-climacteric fruit and the ubiquity of ethylene—an overview. J. Food Sci. Technol. 49, 1–21. doi:10.1007/s13197-011-0293-4

Peralta-Ruiz, Y., Tovar, C. D. G., Sinning-Mangonez, A., Coronell, E. A., Marino, M. F., Chaves-Lopez, C., et al. (2020). Reduction of postharvest quality loss and microbiological decay of tomato “Chonto”(Solanum lycopersicum L.) using chitosan-e essential oil-based edible coatings under low-temperature storage. Polym 12 (8), 1822. doi:10.3390/polym12081822

Pérez, D. A., Gómez, J. M., and Castellanos, D. A. (2021). Combined modified atmosphere packaging and guar gum edible coatings to preserve blackberry (Rubus glaucus Benth). Food Sci. Technol. Int. 27 (4), 353–365. doi:10.1177/1082013220959511

Popescu, P. A., Palade, L. M., Nicolae, I. C., Popa, E. E., Miteluț, A. C., Drăghici, M. C., et al. (2022). Chitosan-based edible coatings containing essential oils to preserve the shelf life and postharvest quality parameters of organic strawberries and apples during cold storage. Foods 11 (21), 3317. doi:10.3390/foods11213317

Prieto-Santiago, V., Miranda, M., Aguiló-Aguayo, I., Teixidó, N., Ortiz-Solà, J., and Abadias, M. (2025). Antimicrobial efficacy of nanochitosan and chitosan edible coatings: application for enhancing the safety of fresh-cut nectarines. Coatings 15 (3), 296. doi:10.3390/coatings15030296

Ran, R., Wang, L., Su, Y., He, S., He, B., Li, C., et al. (2021). Preparation of ph-indicator films based on soy protein isolate/bromothymol blue and methyl red for monitoring fresh-cut apple freshness. J. Food Sci. 86 (10), 4594–4610. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.15884

Restuccia, D., Spizzirri, U. G., Parisi, O. I., Cirillo, G., Curcio, M., Iemma, F., et al. (2010). New EU regulation aspects and global market of active and intelligent packaging for food industry applications. Food Control. 21 (11), 1425–1435. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2010.04.028

Riaz, A., Aadil, R. M., Amoussa, A. M. O., Bashari, M., Abid, M., and Hashim, M. M. (2021). Application of chitosan-based apple peel polyphenols edible coating on the preservation of strawberry (Fragaria ananassa cv Hongyan) fruit. J. Food Process. Preserv. 45 (1), e15018. doi:10.1111/jfpp.15018

Ribeiro, A. M., Estevinho, B. N., and Rocha, F. (2021). Preparation and incorporation of functional ingredients in edible films and coatings. Food Bioprocess Technol. 14, 209–231. doi:10.1007/s11947-020-02528-4

Rux, G., Mahajan, P. V., Linke, M., Pant, A., Sängerlaub, S., Caleb, O. J., et al. (2016). Humidity-regulating trays: moisture absorption kinetics and applications for fresh produce packaging. Food Bioprocess Technol. 9, 709–716. doi:10.1007/s11947-015-1671-0

Saleem, M. S., Anjum, M. A., Naz, S., Ali, S., Hussain, S., Azam, M., et al. (2021). Incorporation of ascorbic acid in chitosan-based edible coating improves postharvest quality and storability of strawberry fruits. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 189, 160–169. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.08.051

Sani, M. A., Azizi-Lalabadi, M., Tavassoli, M., Mohammadi, K., and McClements, D. J. (2021). Recent advances in the development of smart and active biodegradable packaging materials. Nanomater. 11 (5), 1331. doi:10.3390/nano11051331

Sari, V. I., Susi, N., Putri, V. J., Rahmah, A., and Rizal, M. (2023). Smart labels as indicators of tomato freshness using mangosteen peel extract. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Env. Sci. 1177, 012049. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/1177/1/012049

Sharma, S., Nakano, K., Kumar, S., and Katiyar, V. (2024). Edible packaging to prolong postharvest shelf-life of fruits and vegetables: a review. Food Chem. Adv. 4, 100711. doi:10.1016/j.focha.2024.100711

Shi, B., Liu, S., and Wang, Y. (2024). Nisin/cellulose nanofiber/protein bio-composite antibacterial coating for postharvest preservation of fruits. Prog. Org. Coatings 194, 108634. doi:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2024.108634

Shinga, M. H., Kaseke, T., Pfukwa, T. M., and Fawole, O. A. (2025). Optimization of glycerol and cellulose nanofiber concentrations in Opuntia ficus-indica mucilage films functionalized with pomegranate peel extract for postharvest preservation of banana. Food packag. Shelf Life 47, 101428. doi:10.1016/j.fpsl.2024.101428

Song, Y. S., and Hepp, M. A. (2005). US food and drug administration approach to regulating intelligent and active packaging components. Innov. Food Packag. 475–481. doi:10.1016/b978-012311632-1/50058-9

Suhag, R., Kumar, N., Petkoska, A. T., and Upadhyay, A. (2020). Film formation and deposition methods of edible coating on food products: a review. Food Res. Int. 136, 109582. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109582

Tabassum, N., and Khan, M. A. (2020). Modified atmosphere packaging of fresh-cut papaya using alginate based edible coating: quality evaluation and shelf life study. Sci. Hortic. 259, 108853. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2019.108853

Tas, C. E., Hendessi, S., Baysal, M., Unal, S., Cebeci, F. C., Menceloglu, Y. Z., et al. (2017). Halloysite nanotubes/polyethylene nanocomposites for active food packaging materials with ethylene scavenging and gas barrier properties. Food Bioprocess Technol. 10, 789–798. doi:10.1007/s11947-017-1860-0

Tokatlı, K., and Demirdöven, A. (2020). Effects of chitosan edible film coatings on the physicochemical and microbiological qualities of sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.). Sci. Hortic. 259, 108656. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2019.108656

Udoh, I. P., Eleazar, C. I., Ogeneh, B. O., and Ohanu, M. E. (2015). Studies on fungi responsible for the spoilage/deterioration of some edible fruits and vegetables. Adv. Microbiol. 5 (4), 285–290. doi:10.4236/aim.2015.54027

Van, T. T., Phuong, N. T. H., Sakamoto, K., Wigati, L. P., Tanaka, F., and Tanaka, F. (2023). Effect of edible coating incorporating sodium carboxymethyl cellulose/cellulose nanofibers and self-produced mandarin oil on strawberries. Food Packag. Shelf Life 40, 101197. doi:10.1016/j.fpsl.2023.101197

Vergara, A., Llobet, E., Ramírez, J. L., Cañellas, N., Zampolli, S., Scorzoni, A., et al. (2007). “An RFID reader with gas sensing capability for monitoring fruit logistics,” in Graduated student meeting on electronic engineering, 43.

Wan, H., Zhu, Z., and Sun, D. W. (2024). Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) films based on gelatin as active packaging for moisture regulation in fruit preservation. Food Chem. 439, 138114. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.138114

Wang, J., Wang, H., Liu, Z., Shi, D., Bai, Y., and Liu, Y. (2023). Chitosan-nanocrystal cellulose composite coating could inhibit fruit decay rate and maintain the texture parameters of fruit in okra (Abelmoschus esculentus [L.] Moench). Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 15 (2), 20–31. doi:10.15586/qas.v15i2.1208

Wei, H., Seidi, F., Zhang, T., Jin, Y., and Xiao, H. (2021). Ethylene scavengers for the preservation of fruits and vegetables: a review. Food Chem. 337, 127750. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127750

Weng, S., Marcet, I., Rendueles, M., and Díaz, M. (2025). Edible films from the laboratory to industry: a review of the different production methods. Food Bioprocess Technol. 18 (4), 3245–3271. doi:10.1007/s11947-024-03641-4

Wilson, M. D., Stanley, R. A., Eyles, A., and Ross, T. (2019). Innovative processes and technologies for modified atmosphere packaging of fresh and fresh-cut fruits and vegetables. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 59 (3), 411–422. doi:10.1080/10408398.2017.1375892

Xu, D., Qin, H., and Ren, D. (2018). Prolonged preservation of tangerine fruits using chitosan/montmorillonite composite coating. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 143, 50–57. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2018.04.013

Xu, H., Quan, Q., Chang, X., Ge, S., Xu, S., Wang, R., et al. (2023). A new nanohybrid particle reinforced multifunctional active packaging film for efficiently preserving postharvest fruit. Food Hydrocoll. 144, 109017. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.109017

Xu, H., Quan, Q., Chang, X., Ge, S., Xu, S., Wang, R., et al. (2024). Maintaining the balance of fungal community through active packaging film makes strawberry fruit pose pleasant flavor during storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 211, 112815. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2024.112815

Yadav, A., Kumar, N., Upadhyay, A., Pavlic, B., Kumar, A., and Kaushik, N. (2025). A sustainable approach to turning mango kernel waste starch into edible coating with lemongrass essential oils for shelf-life extension of guava fruits. Starch-Stärke 77 (10), e70107. doi:10.1002/star.70107

Yang, W., Zhang, S., Feng, A., Li, Y., Wu, P., Li, H., et al. (2024). Water-insoluble tea polyphenol nanoparticles as fillers and bioactive agents for pectin films to prepare active packaging for fruit preservation. Food Hydrocoll. 156, 110364. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2024.110364

Yildirim, S., Röcker, B., Pettersen, M. K., Nilsen-Nygaard, J., Ayhan, Z., Rutkaite, R., et al. (2018). Active packaging applications for food. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 17 (1), 165–199. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12322

Yu, K., Yang, L., Zhang, S., Zhang, N., Zhu, D., He, Y., et al. (2025). Tough, antibacterial, antioxidant, antifogging and washable chitosan/nanocellulose-based edible coatings for grape preservation. Food Chem. 468, 142513. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.142513

Zhang, W., Ma, J., and Sun, D. W. (2021). Raman spectroscopic techniques for detecting structure and quality of frozen foods: principles and applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 61 (16), 2623–2639. doi:10.1080/10408398.2020.1828814

Zhang, W., An, H., Sun, X., Du, H., Li, Y., Yang, M., et al. (2023). Dual-functional smart indicator for direct monitoring fruit freshness. Food packag. Shelf Life 40, 101192. doi:10.1016/j.fpsl.2023.101192

Zhao, Q., Duan, Z., Yuan, Z., Li, X., Si, W., Liu, B., et al. (2020). High performance ethylene sensor based on palladium-loaded tin oxide: application in fruit quality detection. Chin. Chem. Lett. 31 (8), 2045–2049. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.04.032

Keywords: ethylene, bioactive, coating, film, biosensor, indicator