Abstract

Objective:

This meta-analysis investigated the effect of long-term exercise training (ET) including aerobic, resistance, and multicomponent ET on the levels of inflammatory biomarkers in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving healthy subjects.

Methods:

We searched seven databases for articles until May 1st, 2023. A random-effect meta-analysis, subgroup analysis, meta-regressions as well as trim and fill method were conducted using STATA 16.0.

Result:

Thirty-eight studies were included in the meta-analysis, involving 2,557 healthy subjects (mean age varies from 21 to 86 years). Long-term ET induced significantly decreased in the levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) (SMD -0.16, 95% CI -0.30 to −0.03, p = 0.017), C-reactive protein (CRP) (SMD -0.18, 95% CI -0.31 to −0.06, p = 0.005), as well as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) (SMD -0.43, 95% CI -0.62 to −0.24, p < 0.001). Subgroup analysis revealed that Long-term ET conducted for more than 12 weeks and exercise of moderate intensity had greater anti-inflammatory effects. Meta-regression analysis showed that the reduction in CRP level induced by long-term ET was weakened by increasing exercise intensity.

Conclusion:

Long-term ET induced significant anti-inflammatory effects in healthy subjects. Long-term ET-induced anti-inflammatory effects were associated with exercise of moderate intensity and training conducted for more than 12 weeks.

Systematic Review Registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/# myprospero, PROSPERO, identifier CRD42022346693.

Introduction

The global physical inactivity of approximately 27.5% of adults (Guthold et al., 2018) and 81% of teenagers (Guthold et al., 2020) increases 6–10% risk of chronic diseases, premature death (Ozemek et al., 2019) and the risk of dementia (Voss et al., 2019). Lack of physical activity is one of the most common causes of chronic low-grade systemic inflammation, which is related to metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, cardiovascular disease, cancer and other diseases (Furman et al., 2019). Exercise training (ET) is a non-pharmacological tool used to prevent many diseases in which the immune system plays a critical role (Shinkai et al., 1998; Llamas-Velasco et al., 2016; Nieman and Wentz, 2019). Therefore, special attention should be given to investigate the effect of ET on inflammation, which is one of the most important pathological factors for the occurrence and development of various chronic diseases (Rapa et al., 2019; Steven et al., 2019).

Low-grade chronic inflammation is a key physiopathological component of many chronic diseases including cancer (Ritter and Greten, 2019), obesity (Iyengar et al., 2016), type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (Pradhan et al., 2001), atherosclerosis (Hansson, 2005), and Alzheimer’s diseases (Heneka et al., 2015). Theoretically, ET plays an anti-inflammatory role by reducing visceral fat, promoting anti-inflammatory cytokines production from contracting muscle (Pedersen et al., 2001; Petersen and Pedersen, 2005; Pedersen and Febbraio, 2008), and inducing inflammatory cascades by inhibiting the expression of Toll like receptors on monocytes and macrophages (Flynn and McFarlin, 2006). In practice, there is a dose–response relationship between ET and immune response (Garber et al., 2011). For example, exercise of high intensity has a pro-inflammatory effect (de Lucas et al., 2014; Lindsay et al., 2015), while exercise of moderate intensity plays an anti-inflammatory role (Paolucci et al., 2018). Although observational studies (Wannamethee et al., 2002; Majka et al., 2009) strongly support the anti-inflammatory effect of ET, there is no consistency in data obtained from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (Marcell et al., 2005; Irandoust and Taheri, 2018; Irandoust et al., 2022), and results from large-scale RCTs are limited and inconclusive. Therefore, there is need to establish the effect of ET on inflammation as well as the optimum protocols for ET-induced anti-inflammatory effects.

Previous meta-analyzes focused on the effects of ET on inflammatory biomarkers in diseased individuals (Wu et al., 2022; Xing et al., 2022), as well as the acute effects of a single ET on inflammatory biomarkers (Neefkes-Zonneveld et al., 2015), and their research findings might be influenced by specific diseases. As a result, there have been no conclusive reports on the effects of exercise on inflammation in healthy individuals. There is therefore need to conduct comprehensive meta-analysis of existing RCTs to: 1) determine the effect of long-term ET on biomarkers of inflammation [e.g., interleukin 6 (IL-6), C-reactive protein (CRP), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα)] under normal physiological conditions in healthy subjects, 2) investigate how training protocols and characteristics of subjects influence the outcomes, and 3) suggest scientifically proven and credible exercise regimens for healthy people.

Materials and methods

Literature search

This study registry on PROSPERO (ID: CRD 42022346693). This meta-analysis was conducted in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021). Relevant articles published between 1980 and May 1st, 2023 were retrieved from PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, Embase, PsycINFO, Cumulated Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and SPORTDiscus, based on the Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome and Study design (PICOS) framework. The following search strategy was used: (“Exercise training” OR “Physical Exercise” OR “Exercise Therapy”) AND (“Inflammation” OR “Interleukins” OR “Tumor Necrosis Factors” OR “Cytokines”) AND “randomized controlled trial.” Detailed search strategies are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Study selection

Two researchers (YHW and JWT) independently screened titles and abstracts, then reviewed full-text for eligibility. The third researcher (MC) arbitrated any discrepancies to reach consensus. We also conducted a manual search for references to included articles and relevant review articles. Research and review articles were included in the study based on the following inclusion criteria: (Guthold et al., 2018) the volunteers were healthy individuals; (Guthold et al., 2020) the intervention of interest was any type of long-term ET of any intensity, frequency; (Ozemek et al., 2019) the comparisons involved ET versus non-exercise control or ET plus other intervention versus other intervention only; (Voss et al., 2019) the outcomes of interest were inflammatory biomarkers in plasma or serum; (Furman et al., 2019) parallel or crossover randomized controlled trials; and (Nieman and Wentz, 2019) articles published after 1980. The exclusion criteria included (Guthold et al., 2018) studies involving sick individuals; (Guthold et al., 2020) The intervention was the acute effect of one-time ET on inflammatory biomarkers; (Ozemek et al., 2019) studies lacking baseline data or data on the final assessment of outcomes in both intervention group and comparators used to calculate mean changes of treatment ± SD.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction and quality evaluation were conducted by two trained researchers (YHW and JWT) independently. The data extracted included the first author’s surname, publication year, study design, study location, sample size, participants age and gender, baseline body mass index (BMI) of participants, ET intervention (duration, type, intensity, frequency), and outcomes of reported biomarkers. Research articles that contained two or more ET intervention strata (e.g., different type, intensity, frequency or duration of ET), were analyzed as separate trials. All types of ET (i.e., aerobic exercise, resistance exercise and multicomponent exercise) were included in this review. Intensity of ET was classified by maximal heart rate (HRmax), maximal oxygen uptake (VO2peak) and repetition maximum (RM) according to the guidelines by American College of Sports Medicine (Haskell et al., 2007). The methodological quality and risk of bias of each included study were evaluated using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale (Maher et al., 2003). External validity (item 1: Eligibility criteria and source), internal validity (items 2 to 9: Random allocation; Concealed allocation; Baseline comparability; Blinding of participants; Blinding of therapists; Blinding of assessors; Adequate follow-up (>85%); Intention-to-treat analysis) and statistical reporting (items 10 and 11: Between-group statistical comparisons; Reporting of point measures and measures of variability) are covered by the PEDro scale’s eleven items. Items were rated yes or no (1 or 0) based on whether the study obviously meets the criterion. The cumulative PEDro score ranged from 0 to 10 and is calculated by adding the ratings of items 2 to 11. The higher the score, the superior the methodological quality, and the PEDro scale’s scores of 4 were considered “poor,” 4 to 5 were considered “fair,” 6 to 8 are considered “good,” and 9 to 10 were considered “excellent” (Cashin and McAuley, 2020).

The Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system was used to assess the evidence level of each outcome (Goldet and Howick, 2013). According to the GRADE guidelines, study design dictates baseline quality of the evidence (RCTs were initially defined as high quality) but other factors could decrease (e.g., unexplained heterogeneity) or increase (e.g., a large magnitude of effect) the quality of the studies (Goldet and Howick, 2013). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion with the third reviewer (MC).

Statistical analysis

There were differences among the included studies in study participants, ET protocols employed and the measurement of biomarkers. As a result, the random effects model was used to pool estimates of net changes (changes of intervention group minus changes of control group) in the concentrations of biomarkers and the results were presented as standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Advanced data extraction was used for studies that did not directly provide either the baseline or final mean and standard deviation (SD) of outcomes, according to the protocol proposed by Wan et al. (2014).

First, a primary meta-analysis was conducted to establish the overall effect of ET on each biomarker. Then sensitivity analysis was conducted by using a leave-one-out meta-analysis (LOOM) to test the robustness of the primary results and the influence of each report on the effect or heterogeneity. Sources of potential heterogeneity were identified by carrying out subgroup analyzes based on region, gender, age of participants, baseline BMI of participants, duration of intervention, type of ET and intensity of ET (only conducted if more than six trials reported the same outcomes), and subgroup stratification was based on the characteristics of the included studies and also referred to the previous meta-analysis stratification method (Schwingshackl et al., 2014; de Souto Barreto et al., 2019). Difference between groups and sources of heterogeneity were tested using meta-regression analysis. Further meta-regression analyzes were conducted to investigate potential moderators and examine the association between moderators and outcomes, with value of p <0.1 being considered as statistically significant. The heterogeneity among studies was tested using Cochrane’s Q test and quantified using I2-statistic (Higgins et al., 2003). Presence of heterogeneity was indicated by I2 > 50% and p value <0.1 for Q test. Begg’s and Egger’s regression tests as well as funnel plots were utilized to assess publication bias, with a value of p <0.05 suggesting the presence of bias (Egger et al., 1997). If publication bias was encountered, the trim and fill method was used to remove extremely small studies and recalculate the pooled effect iteratively until the funnel plot was symmetrical (Duval and Tweedie, 2000). All analyzes were performed using STATA version 16.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, United States), with double data input to avoid input errors. p < 0.05 was deemed as statistically significant unless specified elsewhere.

Results

Flow of study selection

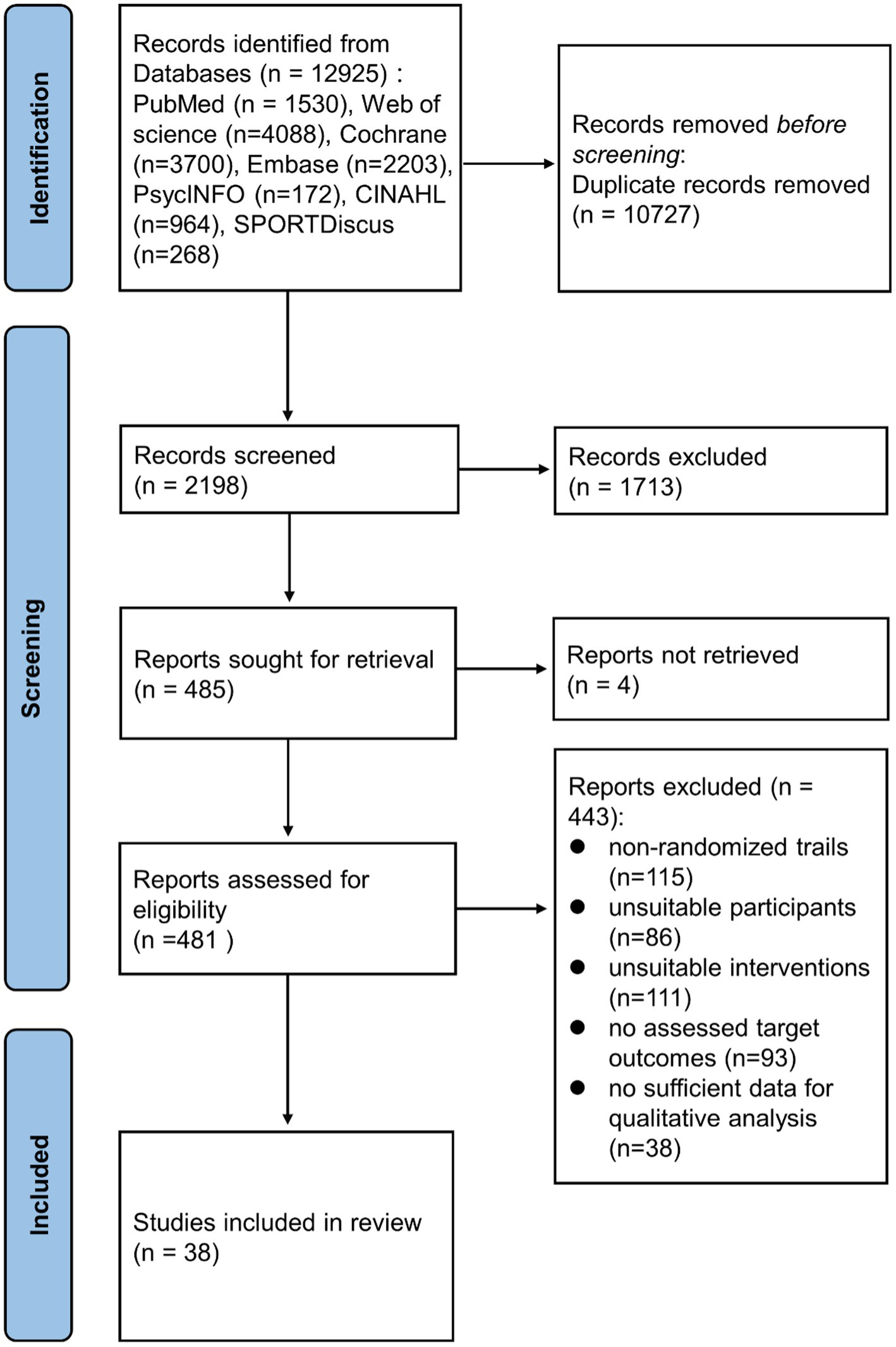

The flowchart depicting the study selection procedure is shown in Figure 1. Initially, 12,925 publications were retrieved, but after excluding the duplicates and screening the titles and abstracts, only 481 articles were left for full-text review. A further 443 articles were eliminated for the following reasons: 115 articles did not involve RCT design, participants of 86 studies were not healthy, 111 articles had improper intervention or control, assessable target outcomes were not reported in 93 articles, and 38 articles lacked sufficient data for quantitative analysis. Finally, 38 studies (Campbell et al., 2008; Nicklas et al., 2008; Levinger et al., 2009; Donges et al., 2010; Martins et al., 2010; Phillips et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2012; Libardi et al., 2012; So et al., 2013; Beltran Valls et al., 2014; Forti et al., 2014; Olesen et al., 2014; Rodriguez-Miguelez et al., 2014; Azizbeigi et al., 2015; Nishida et al., 2015; Strandberg et al., 2015; Alghadir et al., 2016; Buyukyazi et al., 2017; Lira et al., 2017; Ihalainen et al., 2018; Paolucci et al., 2018; Sloan et al., 2018; Tomeleri et al., 2018; Cunha et al., 2019; Ihalainen et al., 2019; Meyer et al., 2019; Urzi et al., 2019; Bagheri et al., 2020; Masala et al., 2020; Ward et al., 2020; Biesek et al., 2021; Dani et al., 2021; Kirk et al., 2021; Nikniaz et al., 2021; Omar et al., 2021; Qi et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2021; Griffen et al., 2022) involving 2,557 participants were included in the final meta-analysis.

Figure 1

A flowchart showing the procedure used for study selection.

Qualities of included studies and outcome measure evidences by GRADE system

The quality of the methodology of three studies (Olesen et al., 2014; Dani et al., 2021; Griffen et al., 2022) was rated as excellent according to the PEDro scale (scores ≥9), while the remaining 35 studies were rated as good quality (6–8 scores) mainly due to lack of blinding (Table 1). According to the GRADE system, the quality of evidence for IL-6, CRP were moderate, and TNFα was low (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 1

| Study | Design | Country | Subject | Comparators | Interventions | Duration of intervention | Biomarkers Outcomes | Qualitya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alghadir et al. (2016) | RP | Saudi Arabia | Healthy subjects (N = 100) | Control (N = 50): Not described | Aerobic Exercise (N = 50): stretching exercises and walking (5–10 min); treadmill, bicycle, and stair training (45–60 min). Intensity: 30–45% of VO2max Frequency: 3 times / wk | 24 wk | CRP | Good |

| Azizbeigi et al. (2015) | RP | Iran | Male physical education students (N = 30) | Control (N = 10): Not described | Resistance Exercise (N = 20): upper body and lower body exercises: chest press, lat pull down, leg extension and flexion, biceps and triceps curls, squats, and sit-ups. Intensity: 65–70% (moderate intensity group, N = 10) / 85–90% (high intensity group, N = 10) of 1RM. Frequency: 3 times / wk. | 8 wk | IL-6, TNFα | Good |

| Bagheri et al. (2020) | RP | Iran | overweight middle-aged men (N = 30) | Control (N = 15): Not described | Aerobic Exercise (N = 15): circuit training, fast walking or jogging. Intensity: moderate intensity (40–59% of the heart rate reserve). Frequency: 3 times / wk | 8 wk | IL-6, CRP, TNFα | Good |

| Biesek et al. (2021) | RP | Brazil | pre-frail older women (N = 72) | Control (N = 36): Not described | Multicomponent Exercise (N = 36): The training was divided into a warm-up (10 min), neuromotor exercises (10 min), resistance exercises (20 min), and a cool-down (10 min). exergames training (N = 18), exergames combined with protein supplementation (N = 18). Intensity: moderate intensity Frequency: 2 times / wk. | 12 wk | IL-6 | Good |

| Buyukyazi et al. (2017) | RP | Turkey | Pre-menopausal women (N = 30) | Control (N = 8): Non exercising | Aerobic Exercise (N = 22): warm-up (5 min); walking (30–50 min); cool-down (5 min). Intensity: 50–55% (moderate tempo walking group) / 70–75% (brisk walking group) of HR reserve Frequency: 3 days / wk | 8 wk | IL-6 | Good |

| Campbell et al. (2008) | RP | United States | Sedentary men and women (N = 188) | Control (N = 97): Not to change their exercise habits | Aerobic Exercise (N = 91): 60 min / d Intensity: 60–85% of HRmax Frequency: 6 days / wk | 48 wk | CRP | Good |

| Cunha et al. (2019) | RP | Brazil | untrained older women (N = 48) | Control (N = 23): Maintain daily activities | Resistance Exercise (N = 25): The exercises were performed in the following order: chest press, horizontal leg press, seated row, knee extension, preacher curl (free weights), leg curl, triceps pushdown, and seated calf raise. Intensity: / Frequency: 3 times / wk | 12 wk | CRP | Good |

| Dani et al. (2021) | RP, Db | Brazil | healthy elderly women (N = 19) | Control (N = 9): consumed 400 mL of grape juice per day | Multicomponent Exercise (N = 10): resistance and aerobic training (60 min each session). Intensity: moderate intensity Frequency: 2 times / wk | 4 wk | IL-6 | Excellent |

| Donges et al. (2010) | RP | Australia | Sedentary subjects (N = 102) | Control (N = 26): Maintained sedentary lifestyle and dietary patterns | Resistance Exercise (N = 35): warm-up (5 min); pulley-weight machine exercises (30–50 min); stretching (5 min). Intensity: 70–75% of 10RM Frequency: 2–3 sessions / wk. Aerobic Exercise (N = 41): warm-up (5 min); cycling exercise (30–50 min); stretching (5 min). Intensity: 70–75% of HRmax Frequency: 2–3 sessions / wk | 10 wk | IL-6、CRP | Good |

| Forti et al. (2014) | RP | Belgium | Elderly volunteers (N = 40) | Control (N = 20): Maintain daily activity levels | Resistance Exercise (N = 20): warm-up; progressive strength training; muscle stretching (60 min). Intensity: 50–80% of 1RM Frequency: 3 sessions / wk | 12 wk | IL-6 | Good |

| Griffen et al. (2022) | RP, Db | United Kingdom | Healthy older men (N = 36) | Control (N = 18): not alter their habitual diet or physical activity levels | Resistance Exercise (N = 18): 5-min warm up, followed by 3 sets of leg press, lateral row, hamstring curl, chest press, leg extension and shoulder press (in that order) on fixed RE machines Intensity: 60(first 4 weeks)-80% of 1RM Frequency: 2 sessions / wk | 12 wk | IL-6, CRP, TNFα | Excellent |

| Ihalainen et al. (2018) | RP | Finland | Healthy young men (N = 49) | Control (N = 18): Keep their dietary intake constant | Multicomponent Exercise (N = 31): cycle ergometer (30–50 min); resistance training (30–50 min). Intensity: low to high Frequency: 2–3 (aerobic and resistance training consecutively in the same training session group, N = 16) / 4–6 (on alternating days group, N = 15) days / wk | 24 wk | IL-6, CRP, TNFα | Good |

| Ihalainen et al. (2019) | RP | Finland | Healthy older individuals (N = 92) | Control (N = 18): Maintain their normal physical activity | Resistance Exercise (N = 74): whole-body strength training Intensity: 70–90% 1RM Frequency: 1(N = 24) / 2 (N = 24) / 3 (N = 26) times / wk | 24 wk | IL-6, CRP | Good |

| Kirk et al. (2021) | RP | United Kingdom | Community-dwelling older adults (N = 100) | Control (N = 54): maintain their physical activity and habitual food intake | Resistance Exercise (N = 46): included leg, chest, calf, and shoulder presses; seated row; back extensions and bicep curl; and two sets to fatigue of each exercise with 3 min break Intensity: / Frequency: 3 times / wk | 16 wk | IL-6, CRP, TNFα | Good |

| Lee et al. (2012) | RP | Korea | Healthy and untrained females (N = 22) | Control (N = 7): No exercise training | Aerobic Exercise (N = 15): treadmill running (volume equated relative to kilograms of body weight). Intensity: 50% (low-intensity group, N = 8) / 70% (high-intensity group, N = 7) of VO2max Frequency: 3–5 sessions / wk | 14 wk | IL-6, CRP, TNFα | Good |

| Levinger et al. (2009) | RP | Australia | Individuals with a low number of metabolic risk factors (N = 25) | Control (N = 13): Non exercise | Resistance Exercise (N = 12): resistance training including chest press, leg press, lateral pull-down, triceps push-down, knee extension, seated row and biceps curl. Intensity: gradually increased from 40–50% of 1RM to 75–85% of 1RM Frequency: 3 days / wk | 10 wk | IL-6, CRP, TNFα | Good |

| Libardi et al. (2012) | RP | Brazil | Inactive male subjects (N = 47) | Control (N = 13): Maintain their previous nutritional patterns | Resistance Exercise (N = 11): upper and lower body exercises (60 min) Intensity: 8–10 repetition maximum Aerobic Exercise (N = 12): walking or running (60 min) Intensity: 55–85% of VO2peak Multicomponent Exercise (N = 11): performed resistance exercise (30 min) and aerobic exercise (30 min) in the same session. Frequency: 3 sessions / wk | 16 wk | IL-6, CRP, TNFα | Good |

| Lira et al. (2017) | RP | Brazil | Recreationally active men (N = 30) | Control (N = 10): Performed no intervention | Aerobic Exercise (N = 20): warm-up (5 min); 5 km run intermittently: run (1 min) + recovery (1 min) (high-intensity intermittent training group) / 5 km run continuously (steady state training group) Intensity: 100% (high-intensity intermittent training group, N = 10) / 70% (steady state training group, N = 10) of maximal aerobic speed Frequency: 3 times / wk | 5 wk | IL-6, TNFα | Good |

| Martins et al. (2010) | RP | Portugal | Women and men aged >64 years (N = 45) | Control (N = 13): Without formal exercise but maintaining their lifestyle routines |

Aerobic Exercise (N = 18): warm-up; aerobic exercise; cool-down (45 min). Intensity: from 40–50% increasing to 71–85% of HR reserve Resistance Exercise (N = 14): warm-up; strength training based on callisthenic exercises and elastics bands; cool-down (45 min). Intensity: moderate Frequency: 3 times / wk |

16 wk | CRP | Good |

| Masala et al. (2020) | RP | Italy | Post-menopausal women (N = 115) | Control (N = 58): Participants received general advice on healthy dietary and physical activity patterns |

Aerobic Exercise (N = 57): working, biking, etc. (<1 h / day). Intensity: moderate Frequency: everyday Resistance Exercise (N = 57): strenuous activity Frequency: 1 h / wk |

96 wk | IL-6, CRP, TNFα | Good |

| Meyer et al. (2019) | RP | United States | Healthy middle-aged and older adults (N = 258) | Control (N = 132): observational control | Aerobic Exercise (N = 126): cognitive behavioral concerns (1.5 h) + warm-up; aerobic exercise; cool-down (1 h) + half-day retreat. Intensity: moderate Frequency: 1 session / wk | 8 wk.,25 wk | IL-6, CRP | Good |

| Nicklas et al. (2008) | RP, Sb | United States | Non-disabled, community-dwelling men and women (N = 369) | Successful Aging (N = 186): health education; stretching (5-10 min). Frequency: 1 session / wk. (1–26 wk); 1 session/month (27–48 wk). | Multicomponent Exercise (N = 183): warm-up; combination of aerobic, strength, balance, and flexibility exercises; cool-down. Intensity: moderate Frequency: 3–5 sessions / wk | 48 wk | IL-6, CRP | Good |

| Nikniaz et al. (2021) | RP | Iran | healthy male smokers (N = 40) | Control (N = 40): follow their daily CS behavior and regular diet | Aerobic Exercise (N = 40): performed aerobic running (30 min). Intensity: 50–60%(first two weeks) to 60–70% HR max. Frequency: 3 times / wk | 4 wk | IL-6, TNFα | Good |

| Nishida et al. (2015) | RP | Japan | Healthy post-menopausal females (N = 62) | Control (N = 31): Maintain their normal lifestyle | Aerobic Exercise (N = 31): bench step exercise (10–20 min). Intensity: corresponding to lactate threshold Frequency: 3 times / day | 12 wk | IL-6, TNFα | Good |

| Olesen et al. (2014) | RC, Db | Denmark | Physically inactive healthy male subjects (N = 20) | Placebo (N = 7): Continue their habitual lifestyle | Multicomponent Exercise (N = 13): high-intensity interval spinning training (cycle ergometer); full-body circuit training. Intensity: high Frequency: 2 times / wk.; 1 time / wk. | 8 wk | IL-6, CRP, TNFα | Excellent |

| Omar et al. (2021) | RC | Malaysia | Healthy young man (N = 70) | Control (N = 34): no change in walking | Aerobic Exercise (N = 36): minimum target: 8,000 steps/day Intensity: low Frequency: everyday | 12 wk | IL-6, CRP, TNFα | Good |

| Paolucci et al. (2018) | RP | Canada | Healthy young adults (N = 55) | Control (N = 18): Remain sedentary | Aerobic Exercise (N = 37): High intensity interval training group (N = 19): warm-up (3 min); cycling at ten 60-s high-intensity intervals with ten 60-s active recovery intervals (20 min); cool-down (2 min). Intensity: 80% maximum wattage Moderate continuous training group (N = 18): warm-up (3 min); cycling at steady state (27.5 min); cool-down (2 min). Intensity: 40% maximum wattage Frequency: 3 times / wk | 6 wk | IL-6, CRP, TNFα | Good |

| Phillips et al. (2010) | RP | United States | Healthy sedentary post-menopausal women (N = 35) | Control (N = 7): Rested quietly during experimental period | Resistance Exercise (N = 28): 3 sets of 8 repetitions of resistance training; 2-min rest between sets. Intensity: 70–80% of 1RM Frequency: 3 times / wk. | 10 wk | IL-6, TNFα | Good |

| Qi et al. (2021) | RP | China | Cognitively healthy older people (N = 48) | Control (N = 26): received group-based stretching | Aerobic Exercise (N = 22): consisting of warm-up movement and nine movements involving the stretching of arms and legs, the turning of the torso, and relaxing Intensity: low Frequency: 2 times / wk. | 12 wk | IL-6 | Good |

| Rodriguez-Miguelez et al. (2014) | RP | Finland | Healthy participants (N = 26) | Control (N = 10): Followed their daily routines | Resistance Exercise (N = 16): warm-up (10 min); three resistance exercise (leg press, biceps curl, pec deck). Intensity: 60–80% of 1RM Frequency: 2 sessions / wk | 10 wk | IL-6, CRP | Good |

| Sloan et al. (2018) | RP | United States | Healthy young adults (N = 103) | Control (N = 58): Wear the step counter (so do exercise group); maintain sedentary lifestyle | Aerobic Exercise (N = 45): warm-up + cool-down (10–15 min); workout (30–40 min). Intensity: 55–75% of HRmax Frequency: 4 sessions / wk | 12 wk | IL-6, TNFα | Good |

| So et al. (2013) | RP | Korea | Healthy elderly (N = 40) | Control (N = 22): Continue their habitual lifestyle | Resistance Exercise (N = 18): One bout of training (60 min) was composed of three steps: warm-up for 15 min, exercise for 40 min, and cool-down for 5 min. Intensity: low level Frequency: 3 times / wk | 12wk | IL-6, CRP, TNFα | Good |

| Strandberg et al. (2015) | RP | Sweden | Healthy older women (N = 42) | Control (N = 21): Continue their habitual lifestyle | Resistance Exercise (N = 21): The following exercises were performed: squat, leg extension, leg press, seated row, and pull down. 5 min of core stability exercises and seven squat jumps were included. Intensity: workload of 75–85% 1 RM (8–12 reps/set) Frequency: 2 times / wk | 24 wk | CRP, TNFα | Good |

| Tang et al. (2021) | RP | China | Young adults (N = 26) | Control (N = 14): calorie restriction | Multicomponent Exercise (N = 12): 90 min a time (20 min RS plus 10 min rest, with 3 repetitions) Intensity: high Frequency: 3 times / wk | 8 wk | IL-6, CRP, TNFα | Good |

| Tomeleri et al. (2018) | RP | Brazil | Older women (N = 45) | Control (N = 23): Did not perform any type of physical exercise | Resistance Exercise (N = 22): 3 sets of 10–15 repetitions; rest between sets (1–2 min) / exercise (2–3 min) Intensity: not mentioned Frequency: 3 times / wk | 18 wk | IL-6, CRP, TNFα | Good |

| Urzi et al. (2019) | RP | Slovenia | Female nursing home (N = 20) | Control (N = 9): did not receive any placebo or treatment | Resistance Exercise (N = 11): warmup of 10 min and 35 to 40 min of 8 resistance exercisesd chair squats; band seated: biceps curl, seated row, knee extension, leg press and hip abduction; and standing behind the chair: knee flexion and calf rise. Intensity: moderate level Frequency: 3 times / wk | 12 weeks | CRP | Good |

| Beltran Valls et al. (2014) | RP | Italy | Old community-dwelling people (N = 23) | Control (N = 10): Maintained the usual lifestyle habits | Resistance Exercise (N = 13): warm-up (10 min); 3–4 sets of 10–12 repetitions; rest between sets (2 min) / exercise (3 min). Intensity: 70% of 1RM Frequency: not mentioned | 12 wk | IL-6, TNFα | Good |

| Ward et al. (2020) | RP | Sweden | Postmenopausal women (N = 55) | Control (N = 29) | Resistance Exercise (N = 26): chest press, leg press, seated row, leg curl, latissimus dorsi pull-down, leg extension, crunches and back raises. Intensity: 8 repetition-maximum (8 RM) Frequency: 3 times / wk | 15 wk | CRP, TNFα | Good |

Characteristics of included studies in this meta-analysis (38 studies).

Better methodological quality is indicated by a higher PEDro score (9 to 10: excellent; 6 to 8: good; 4 to 5: fair; <4: poor).

CRP, C-reactive protein; Db, double blind; kcal, kilocalories; km, kilometer; HRmax, maximal heart rate; IL-6, interleukin 6; RC, randomized crossover; RM, repetition maximum; RP, randomized-parallel; s, second; SB, single-blinded; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha; VO2max, maximal oxygen uptake; wk, week.

Characteristics of included studies

Characteristics of studies included in this meta-analysis are shown in Table 1. The final sample consisted of 2,557 participants, with the mean age ranging from 21 to 86 years. Sample sizes ranged from 19 to 369 participants, with a median size of 46. The average baseline BMI value of the participants ranged from 21.7 to 29.9. Different types of ET (aerobic exercise: 15 interventions; resistance exercise: 16 interventions; multicomponent exercise: 7 interventions) were evaluated in the studies.

Effect of long-term ET on IL-6 levels

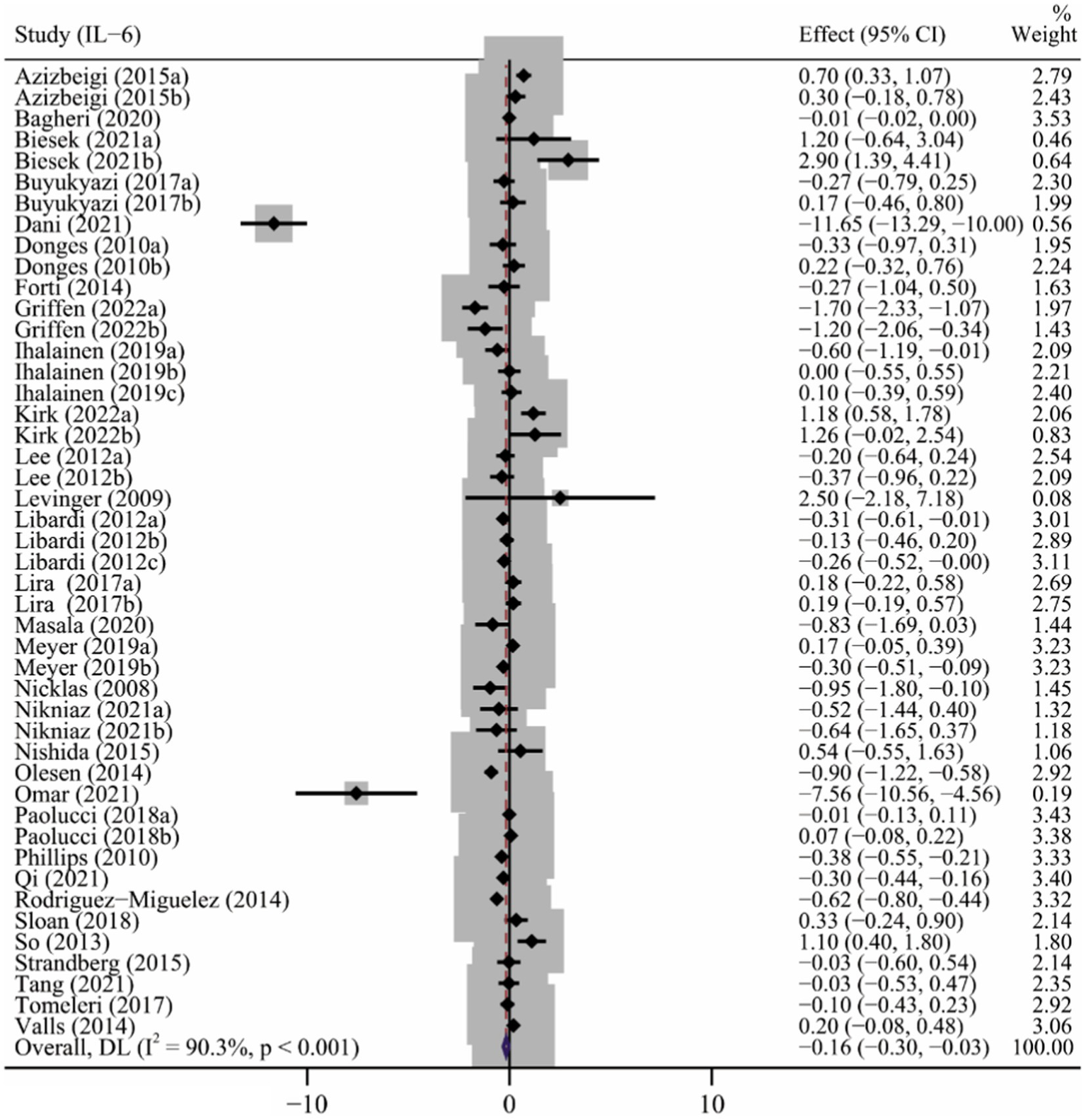

As shown in Table 2, assessments for IL-6 levels were reported in 32 articles (Nicklas et al., 2008; Levinger et al., 2009; Donges et al., 2010; Phillips et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2012; Libardi et al., 2012; So et al., 2013; Beltran Valls et al., 2014; Forti et al., 2014; Olesen et al., 2014; Rodriguez-Miguelez et al., 2014; Azizbeigi et al., 2015; Nishida et al., 2015; Strandberg et al., 2015; Buyukyazi et al., 2017; Lira et al., 2017; Ihalainen et al., 2018; Paolucci et al., 2018; Sloan et al., 2018; Tomeleri et al., 2018; Ihalainen et al., 2019; Meyer et al., 2019; Bagheri et al., 2020; Masala et al., 2020; Biesek et al., 2021; Dani et al., 2021; Kirk et al., 2021; Nikniaz et al., 2021; Omar et al., 2021; Qi et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2021; Griffen et al., 2022) involving 48 interventions. Results of the meta-analysis showed that long-term ET caused a significant decrease in IL-6 levels (SMD −0.16, 95% CI −0.30 to −0.03), although high heterogeneity was observed among the studies (p < 0.001, I2 = 90.3%) (Table 2 and Figure 2). Subgroup analysis showed that studies of baseline BMI > 25, female subjects, duration of exercise less than 12 weeks, frequency of less than three times a week, and type of multicomponent exercise were associated with PE-induced reduction in IL-6 levels (Table 2). The result of the Begg’s test (p = 0.917), Egger’s test (p = 0.091) and funnel plot (Supplementary Figure S1) indicated no significant publication bias in the primary analysis for IL-6 (Table 2).

Table 2

| Outcomes | Interventions | SMD (95% CI) | P 1 | Heterogeneity | P 3 | P 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I 2 (%) | P 2 | Begg’s value | Egger’s value | |||||

| IL-6 | ||||||||

| Overall | 48 | −0.16 (−0.30, −0.03) | 0.017 | 90.3 | <0.001 | 0.917 | 0.091 | |

| Gender | 0.303 | |||||||

| Male only | 15 | −0.19 (−0.44, 0.06) | 0.132 | 86.5 | <0.001 | |||

| Female only | 14 | −0.61 (−1.08, −0.13) | 0.013 | 94.3 | <0.001 | |||

| Age | 0.818 | |||||||

| < 45 years | 19 | −0.04 (−0.19, 0.12) | 0.653 | 79.5 | <0.001 | |||

| 45 ~ 60 years | 7 | −0.19 (−0.39, 0.02) | 0.076 | 62.1 | 0.015 | |||

| ≥ 60 years | 20 | −0.29 (−0.64, 0.07) | 0.112 | 93.7 | <0.001 | |||

| Baseline BMI | 0.431 | |||||||

| < 25 | 13 | 0.11 (−0.04, 0.26) | 0.144 | 49.9 | 0.021 | |||

| >25 | 33 | −0.30 (−0.50, −0.09) | 0.005 | 92.8 | <0.001 | |||

| Duration | 0.599 | |||||||

| 1 ~ 12 weeks | 32 | −0.19 (−0.36, −0.02) | 0.030 | 92.7 | <0.001 | |||

| > 12 weeks | 16 | −0.13 (−0.34, 0.08) | 0.240 | 63.1 | 0.001 | |||

| Frequency | 0.412 | |||||||

| <3 times/week | 13 | −0.84 (−1.37, −0.30) | 0.002 | 90.0 | <0.001 | |||

| ≥3 times/week | 34 | −0.03 (−0.22, 0.17) | 0.793 | 66.8 | <0.001 | |||

| Type of exercise | 0.474 | |||||||

| Aerobic exercise | 20 | −0.06 (−0.17, 0.05) | 0.249 | 71.9 | <0.001 | |||

| Resistance exercise | 18 | −0.05 (−0.34, 0.23) | 0.712 | 87 | <0.001 | |||

| Multicomponent exercise | 9 | −1.28 (−2.56, 0.00) | 0.050 | 97.2 | <0.001 | – | – | |

| Intensity of exercise | 0.429 | |||||||

| Low | 3 | −0.93 (−1.95, 0.09) | 0.074 | 91.2 | <0.001 | – | – | |

| Moderate | 29 | −0.17 (−0.34, 0.01) | 0.136 | 84.1 | <0.001 | |||

| High | 12 | −0.25 (−0.57, 0.08) | 0.769 | 91.6 | <0.001 | |||

| Interventions | Net change (95% CI) | P 1 | I 2 (%) | P 2 | P 3 | P 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Begg’s value | Egger’s value | |||||||

| CRP | ||||||||

| Overall | 39 | −0.18 (−0.31, −0.06) | 0.005 | 88.1 | <0.001 | 0.204 | 0.112 | |

| Gender | 0.852 | |||||||

| Male only | 10 | −0.17 (−0.43, 0.09) | 0.198 | 86.9 | <0.001 | |||

| Female only | 10 | −0.12 (0.32, 0.08) | 0.244 | 87.8 | <0.001 | – | – | |

| Age | 0.242 | |||||||

| < 45 years | 10 | −0.12 (−0.30, 0.05) | 0.177 | 92.8 | <0.001 | |||

| 45 ~ 60 years | 10 | 0.09 (−0.05, 0.23) | 0.225 | 17.9 | 0.278 | |||

| ≥ 60 years | 17 | −0.44 (−0.80, −0.09) | 0.014 | 89.7 | <0.001 | |||

| Baseline BMI | 0.474 | |||||||

| < 25 | 6 | −0.37 (−0.74, 0.01) | 0.054 | 95.5 | <0.001 | – | – | |

| >25 | 32 | −0.17 (−0.31, −0.03) | 0.017 | 83.8 | <0.001 | |||

| Duration | 0.435 | |||||||

| 1 ~ 12 weeks | 17 | −0.07 (−0.24, 0.11) | 0.439 | 82.6 | <0.001 | |||

| > 12 weeks | 22 | −0.29 (−0.49, −0.10) | 0.004 | 90.4 | <0.001 | |||

| Frequency | 0.137 | |||||||

| ≤3 times/week | 8 | 0.01 (−0.37, 0.38) | 0.977 | 76.1 | <0.001 | |||

| >3 times/week | 31 | −0.31 (−0.57, −0.05) | 0.018 | 83.7 | <0.001 | |||

| Type of exercise | 0.699 | |||||||

| Aerobic exercise | 15 | −0.23 (−0.41, −0.04) | 0.017 | 89.3 | <0.001 | |||

| Resistance exercise | 17 | 0.02 (−0.25, 0.29) | 0.890 | 78.6 | <0.001 | |||

| Multicomponent exercise | 6 | −0.27 (−0.60, 0.05) | 0.101 | 93.2 | <0.001 | – | – | |

| Intensity of exercise | 0.005 | |||||||

| Low | 3 | −1.64 (−3.89, 0.62) | 0.155 | 98.4 | <0.001 | – | – | |

| Moderate | 22 | −0.16 (−0.32, −0.01) | 0.036 | 75.2 | <0.001 | |||

| High | 8 | 0.14 (−0.05, 0.23) | 0.149 | 11.4 | 0.341 | – | – | |

| TNFα | ||||||||

| Overall | 32 | −0.43 (−0.62, −0.24) | <0.001 | 87.8 | <0.001 | 0.331 | 0.009 | |

| Gender | 0.102 | |||||||

| Male only | 15 | −0.73 (−1.14, −0.31) | 0.001 | 89.9 | <0.001 | |||

| Female only | 8 | −0.57 (−0.95, −0.20) | 0.002 | 67.6 | 0.003 | |||

| Age | 0.807 | |||||||

| < 45 years | 17 | −0.37 (−0.56, −0.17) | <0.001 | 82.5 | <0.001 | |||

| 45 ~ 60 years | 6 | −0.51 (−0.93, −0.10) | 0.015 | 11.3 | 0.343 | – | – | |

| ≥ 60 years | 9 | −0.35 (−0.90, 0.21) | 0.219 | 93.0 | <0.001 | 0.931 | – | – |

| Baseline BMI | ||||||||

| < 25 | 12 | −0.26 (−0.47, −0.06) | 0.013 | 74.4 | <0.001 | |||

| >25 | 19 | −0.45 (−0.77, −0.13) | 0.005 | 88.1 | <0.001 | |||

| Duration | 0.600 | |||||||

| 1 ~ 12 weeks | 20 | −0.48 (−0.72, −0.24) | <0.001 | 91.1 | <0.001 | |||

| > 12 weeks | 12 | −0.34(−0.66, −0.03) | 0.030 | 62.9 | 0.002 | |||

| Frequency | 0.254 | |||||||

| ≤3 times/week | 3 | −1.75 (−4.80, 1.31) | 0.262 | 94.3 | <0.001 | |||

| >3 times/week | 28 | −0.60 (−0.86, −0.35) | <0.001 | 73.3 | <0.001 | |||

| Type of exercise | 0.978 | |||||||

| Aerobic exercise | 14 | −0.24 (−0.46, −0.03) | 0.028 | 82.4 | <0.001 | |||

| Resistance exercise | 12 | −0.44 (−0.84, −0.04) | 0.031 | 78.6 | <0.001 | |||

| Multicomponent exercise | 5 | −0.38 (−0.81, 0.05) | 0.080 | 86.4 | <0.001 | – | – | |

| Intensity of exercise | 0.464 | |||||||

| Low | 2 | −4.82 (−14.21, 4.56) | 0.314 | 94.9 | <0.001 | – | – | |

| Moderate | 18 | −0.57 (−0.89, −0.24) | 0.001 | 81.2 | <0.001 | – | – | |

| High | 8 | −0.37 (−0.77, 0.04) | 0.075 | 94.2 | <0.001 | |||

Results of sensitivity analysis, subgroup analysis and publication bias stratified by study characteristics.

P 1 value for net change; P2 value for heterogeneity in the subgroup; P3 value for heterogeneity between groups with meta-regression, analyzed as categorical variables; P4 value for publication bias (conducted only when trials > 5); significant p-values are highlighted in bold prints.

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CRP, C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin 6; RC, randomized crossover; RP, randomized-parallel; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Figure 2

The forest plot of the effect of long-term ET on IL-6 levels.

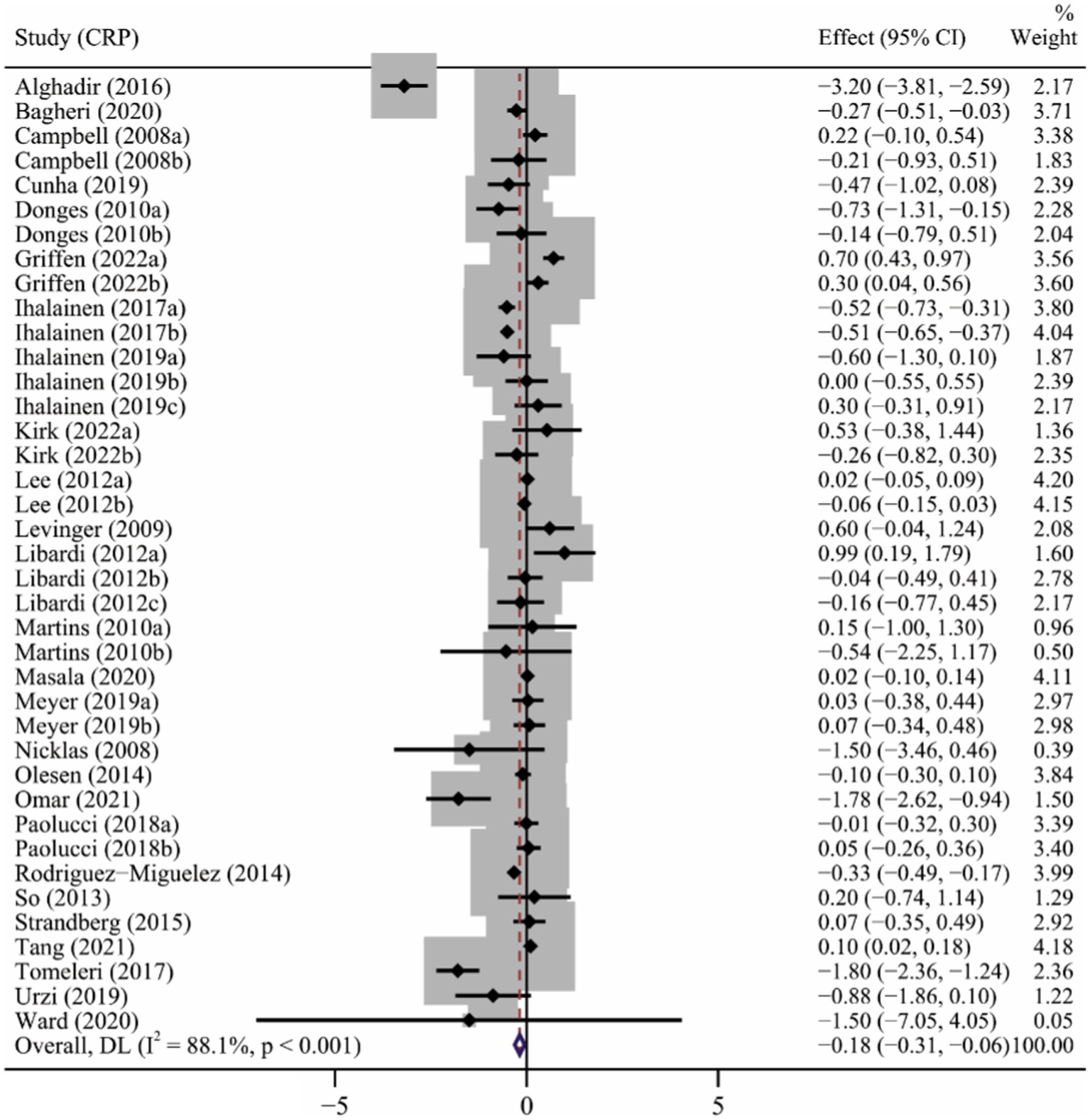

Effect of long-term ET on CRP levels

A total of 26 articles (Campbell et al., 2008; Nicklas et al., 2008; Levinger et al., 2009; Donges et al., 2010; Martins et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2012; Libardi et al., 2012; So et al., 2013; Olesen et al., 2014; Rodriguez-Miguelez et al., 2014; Strandberg et al., 2015; Alghadir et al., 2016; Ihalainen et al., 2018; Paolucci et al., 2018; Tomeleri et al., 2018; Cunha et al., 2019; Ihalainen et al., 2019; Meyer et al., 2019; Urzi et al., 2019; Bagheri et al., 2020; Masala et al., 2020; Ward et al., 2020; Kirk et al., 2021; Omar et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2021; Griffen et al., 2022) involving 39 interventions explored the effect of long-term ET on CRP levels. Long-term ET induced a significant decrease in CRP levels (SMD -0.18, 95% CI -0.31 to −0.06) compared to placebo/control groups. We found a high heterogeneity across the studies (p < 0.001, I2 = 88.1%) (Table 2 and Figure 3). Subgroup analyzes showed that studies of participants older than 60 years, baseline BMI > 25, duration of exercise greater than 12 weeks, multicomponent exercise, frequency of three or more times a week, and moderate exercise conferred to a more potent reduction in CRP levels. The result of meta-regression analysis revealed that the intensity of exercise (p = 0.005) might be a potential source of heterogeneity (Table 2), which showed that the reduction in CRP level induced by long-term ET was weakened by increasing exercise intensity.

Figure 3

The forest plot of the effect of long-term ET on CRP levels.

The result of the Begg’s test (p = 0.204), Egger’s test (p = 0.112) and funnel plot (Supplementary Figure S2) indicated no significant publication bias in the primary analysis for CRP (Table 2).

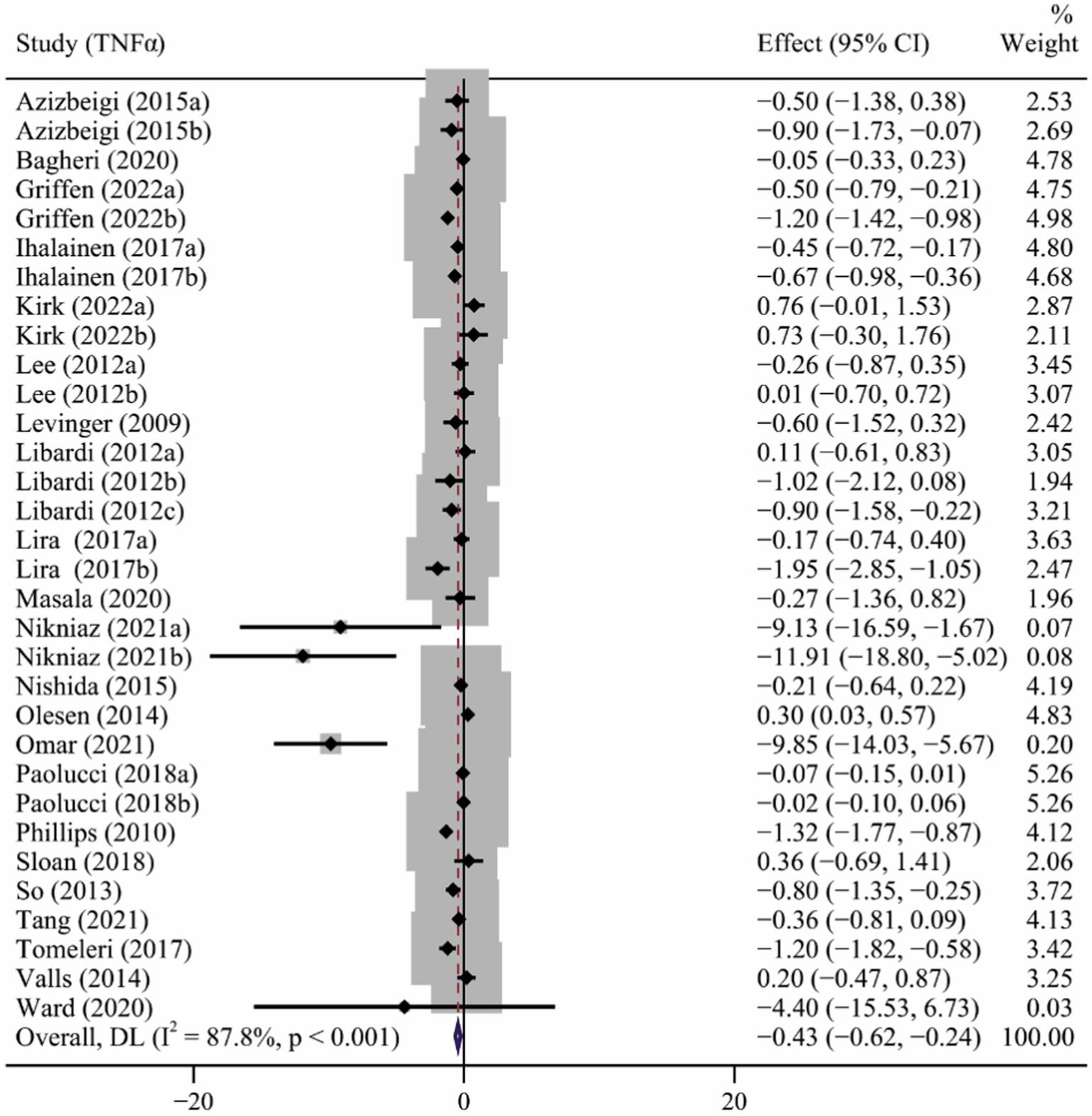

Effect of long-term ET on TNFα levels

Twenty-two studies (Levinger et al., 2009; Phillips et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2012; Libardi et al., 2012; So et al., 2013; Beltran Valls et al., 2014; Olesen et al., 2014; Azizbeigi et al., 2015; Nishida et al., 2015; Lira et al., 2017; Ihalainen et al., 2018; Paolucci et al., 2018; Sloan et al., 2018; Tomeleri et al., 2018; Bagheri et al., 2020; Masala et al., 2020; Ward et al., 2020; Kirk et al., 2021; Nikniaz et al., 2021; Omar et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2021; Griffen et al., 2022) involving 32 interventions evaluated the effect of long-term ET on TNFα levels. Results of the meta-analysis revealed that long-term ET caused a significant decrease in TNFα levels (SMD −0.43, 95% CI −0.62 to −0.24), with a high heterogeneity across the studies (p < 0.001, I2 = 87.8%) (Table 2 and Figure 4). Subgroup analyzes demonstrated that subjects with significant reduction in TNFα levels were from studies of participants younger than 60 years, those taking aerobic exercise or resistance exercise, frequency of three or more times a week, and exercise of moderate intensity. Funnel plot (Supplementary Figure S3) and Egger’s test results for TNFα (p = 0.009) revealed evidence of publication bias (Table 2).

Figure 4

The forest plot of the effect of long-term ET on TNFα levels.

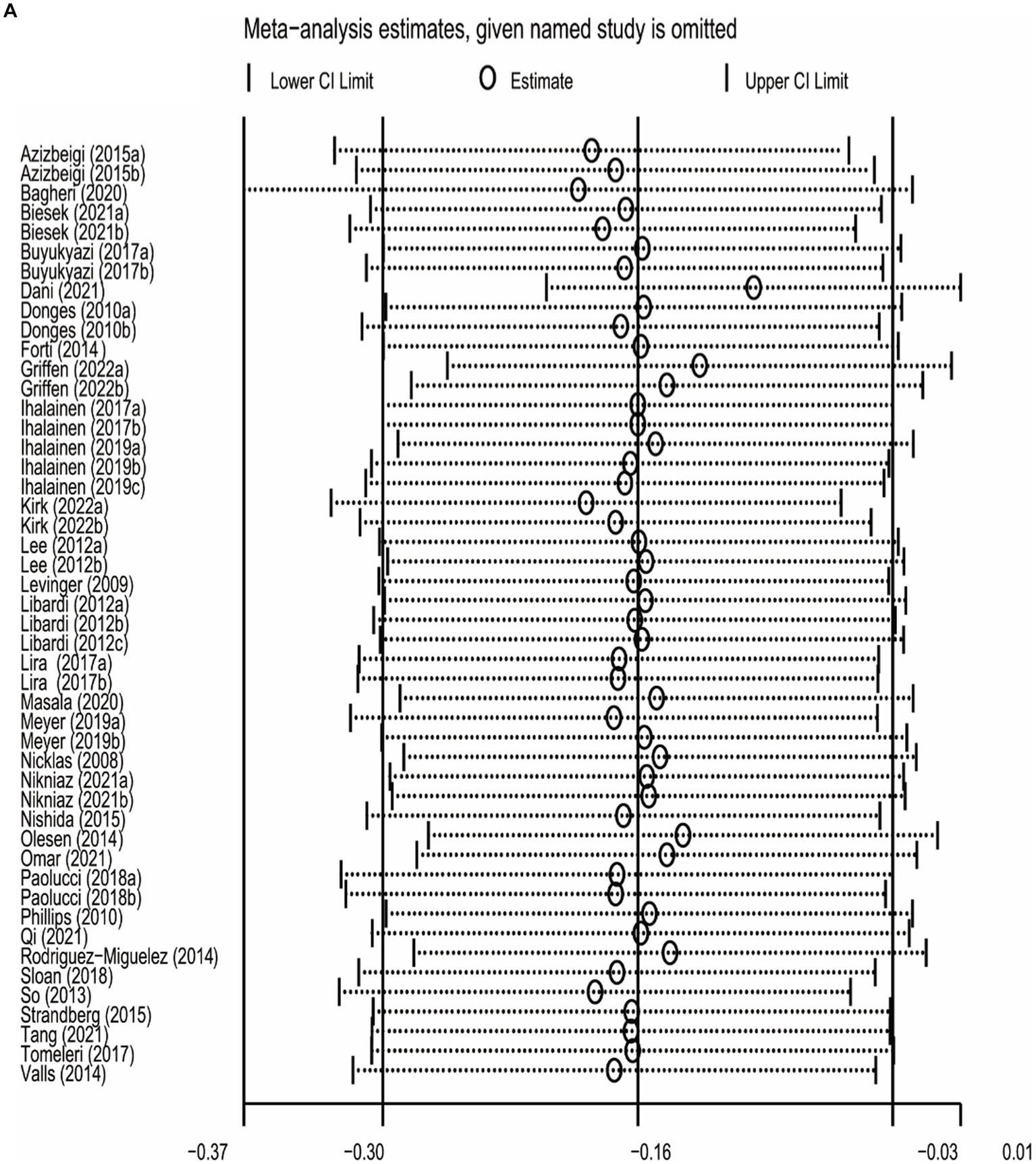

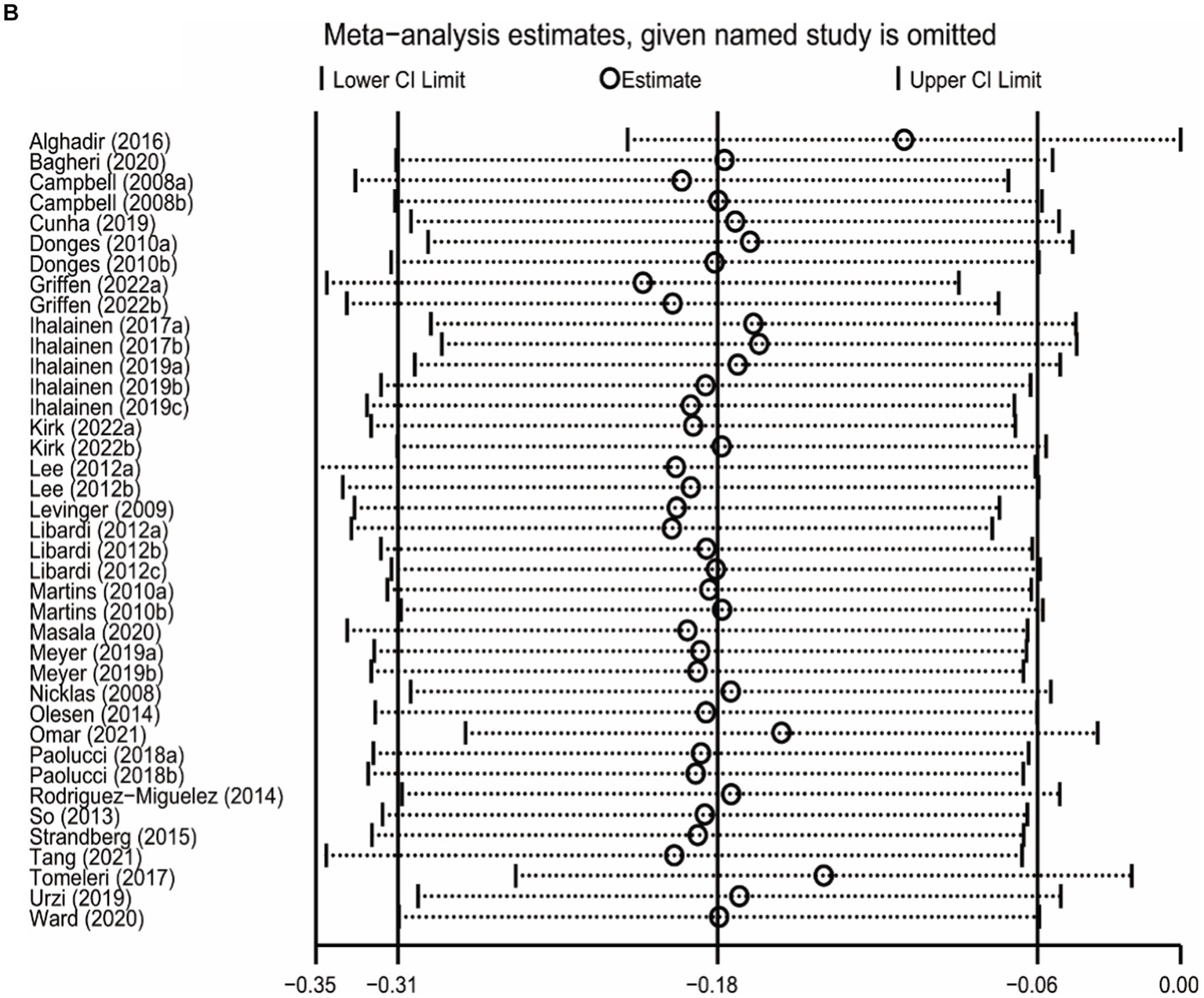

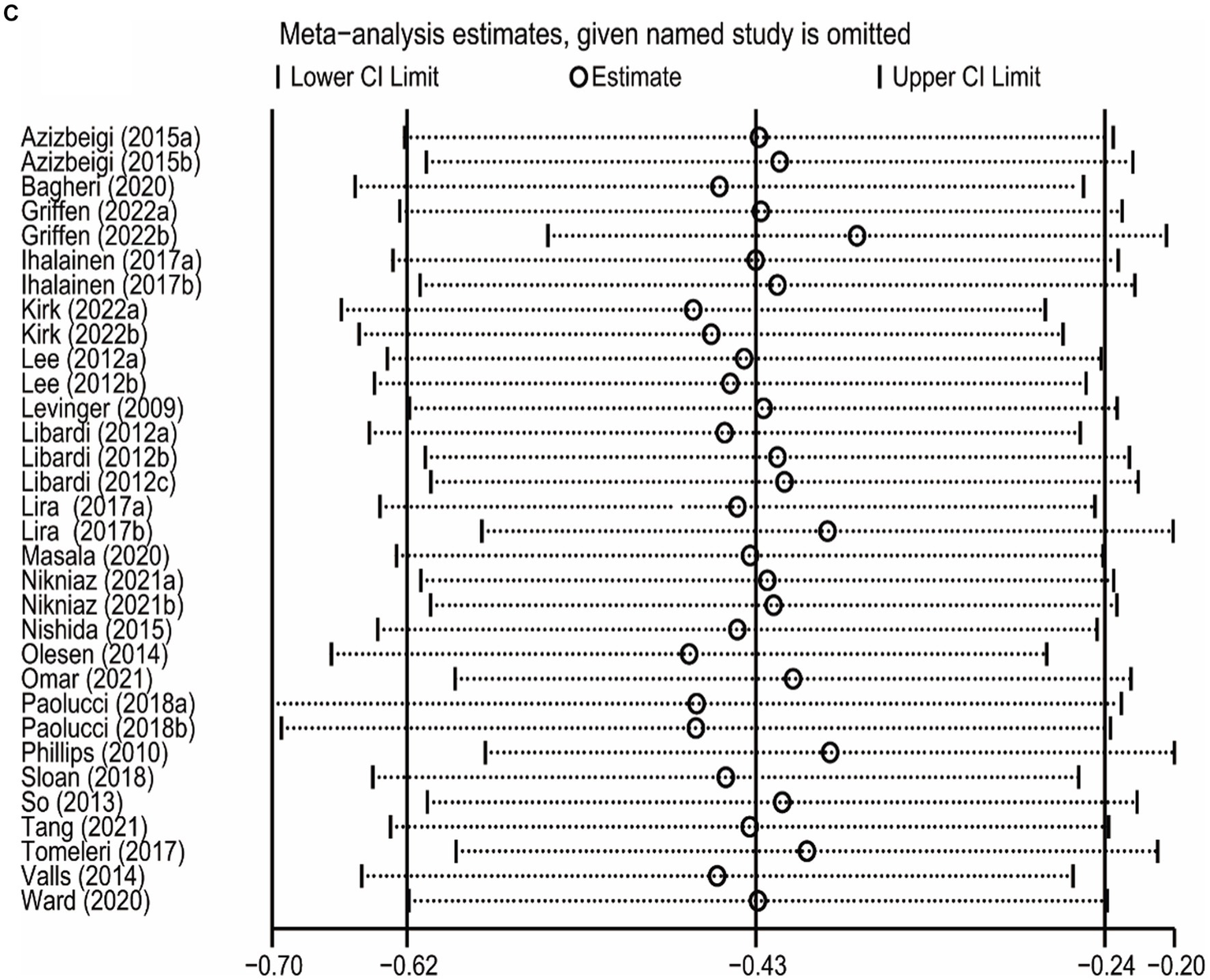

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis was carried out by leave-one-out meta-analysis (LOOM). The results of the sensitivity analysis indicated that the effect of long-term ET on IL-6 levels was unstable, suggesting that the findings should be handled with caution (Figure 5A). Long-term ET still had a stable significant impact on CRP (Figure 5B) and TNFα (Figure 5C) levels when a single trial was deleted at a time.

Figure 5

Figure 5

Figure 5

The results of leave-one-out meta-analysis on IL-6 (A), CRP (B), and TNFα (C).

Adjustment of publication bias

As shown in Table 3, results of pooling estimates indicating publication bias based on Begg’s and Egger’s tests, were recalculated using Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill method. Long-term ET still induced a significant decrease in TNFα levels (SMD −1.02, 95% CI −1.41 to −0.63).

Table 3

| Variables | Interventions (n) | Net change (95% CI) | P | Adjusted studies | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before adjusted | After adjusted | Before adjusted | After adjusted | |||

| TNFα | 32 | −0.43 (−0.62, −0.24) | −1.02 (−1.41, −0.63) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 5 |

Trim and fill adjusted analysis for outcomes with publication bias.

Significant p-values are highlighted in bold prints.

CI, confidence interval; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis from 38 RCTs to estimate the effect of long-term ET on individual biomarkers of inflammation among healthy subjects. Overall, our results revealed that long-term ET induced significant decrease in IL-6, CRP, and TNFα levels. Long-term ET-induced reduction of IL-6 was more evident in participants with a BMI >25, engaged in exercise for less than 12 weeks and engaged in type of multicomponent exercise. On the other hand, Long-term ET-induced decrease in CRP levels was associated with participants involved in exercise for more than 12 weeks and involved in aerobic exercise. Long-term ET-induced decrease in TNFα levels was associated with participants of younger than 60 years of age, involved in exercise for more than 12 weeks, and involved in exercise of moderate intensity.

Elevated levels of circulating inflammatory markers such as IL-6, TNFα and CRP, induces the development of chronic low-grade inflammation which has been identified as a risk predictor for several diseases such as T2DM (Pradhan et al., 2001) and dementia (Leonard, 2007). Our findings showed that engaging in ET for over 12 weeks effectively reduced the levels of CRP and TNFα. This is consistent with previous studies which showed that ET interventions conducted over longer durations can minimize inflammation. A meta-analysis based on elderly participants showed that resistance training alone can reduce CRP and TNFα when conducted for more than 12 weeks (Sardeli et al., 2018). It is well known that one-time exercise interferes with cell homeostasis leading to inflammation, while repeated exercise training improves immunocompetence (Scheffer and Latini, 2020). Skeletal muscle is an endocrine organ. During muscle contraction, it can produce cytokines and release them into the blood, which can systematically reduce inflammation (Furman et al., 2019). It was reported that several myokines, such as CRP, peaked at the end of exercise and returned to baseline levels within several hours (Keller et al., 2005; Fischer, 2006), which could mediate metabolic changes followed by increase anti-inflammatory cytokine (Febbraio and Pedersen, 2002), thus activate anti-inflammatory immune response. Therefore, long-term exercise may contribute to lower basal levels of inflammatory biomarkers.

Consistent with the previous studies (Scheffer and Latini, 2020), we also found that exercise of moderate intensity was more beneficial for the reduction of CRP and TNFα levels. The intensity of training has been shown to affect inflammatory markers in a dose-dependent manner (Fatouros et al., 2009). Several studies have shown that ET of moderate intensity promotes anti-inflammatory response, while ET of high intensity promotes an inflammatory response (Pinho et al., 2010; Lindsay et al., 2015). However, a recent meta-analysis based on 27 studies, including 17 studies with patients, revealed that intensity of exercise did not influence the chronic inflammatory response (Rose et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the study by Rose et al. only included studies that compared more than two different intensities of exercise, with significant heterogeneity in the exercise prescription among the studies. As a result, total exercise volume may have confounded the outcomes. Overall, our meta-analysis suggested that long-term three or more times a week of moderate intensity ET could significantly reduce the level of inflammatory biomarkers in healthy adults, and that such exercise frequency and intensity were consistent with the guidelines of the American College of Sports Medicine (Garber et al., 2011).

Aging is inherently associated with chronic increase in cytokine concentration, a condition termed as inflammaging (Franceschi and Campisi, 2014). Indeed, a meta-analysis from observational studies demonstrated that the frailty and pre-frailty in the elderly were associated with higher inflammatory parameters, especially CRP and IL-6 (Soysal et al., 2016). Therefore, the elderly are more likely to benefit from the anti-inflammatory effect of ET. Meanwhile, further studies are needed to establish the relationship between age and the anti-inflammatory effect of PE, as well as the underlying mechanisms.

There are several limitations in this study. First, there was no blinding in 34 of the 38 included studies, which may have introduced some bias. The high heterogeneity observed across studies might lead to degradation of the credibility of the results. Thus, there is need to excess caution when interpreting the results of our study. The high heterogeneity may have been due to the use of different experimental designs, particularly study samples, interventions and measures of outcome, among the different studies. Although we explored the source of heterogeneity via subgroup analysis and meta-regression, some of the results were also limited by the differences in sample size between subgroups. Furthermore, some of our results from subgroup analysis showed publication bias, which may affect the validity of the effects observed. However, most of these results remained unchanged or showed greater effect size after adjustment using the trim and fill method, thus making the results credible.

Conclusion

Taken together, long-term ET induced significant decrease in IL-6, CRP, and TNFα levels in healthy subjects compared to non-active interventions. Long-term ET of moderate intensity and conducted for more than 12 weeks induced more pronounced anti-inflammatory effects in healthy subjects. There is need for future RCTs to explore the optimum long-term ET protocol beneficial for people of different ages.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Project of Education Department of Jiangxi Province (GJJ2203217), and the Science and Technology Innovation Project of General Administration of Sport of China (22KJCX035).

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

Y-HW: Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. JT: Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. H-HZ: Data curation, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. MC: Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1253329/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Alghadir A. H. Gabr S. A. Al-Eisa E. S. (2016). Effects of moderate aerobic exercise on cognitive abilities and redox state biomarkers in older adults. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev.2016:2545168. doi: 10.1155/2016/2545168

2

Azizbeigi K. Azarbayjani M. A. Atashak S. Stannard S. R. (2015). Effect of moderate and high resistance training intensity on indices of inflammatory and oxidative stress. Res. Sports Med.23, 73–87. doi: 10.1080/15438627.2014.975807

3

Bagheri R. Rashidlamir A. Ashtary-Larky D. Wong A. Grubbs B. Motevalli M. S. et al . (2020). Effects of green tea extract supplementation and endurance training on irisin, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and adiponectin concentrations in overweight middle-aged men. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol.120, 915–923. doi: 10.1007/s00421-020-04332-6

4

Beltran Valls M. R. Dimauro I. Brunelli A. Tranchita E. Ciminelli E. Caserotti P. et al . (2014). Explosive type of moderate-resistance training induces functional, cardiovascular, and molecular adaptations in the elderly. Age (Dordr.)36, 759–772. doi: 10.1007/s11357-013-9584-1

5

Biesek S. Vojciechowski A. S. Filho J. M. Menezes Ferreira A. C. R. Borba V. Z. C. Rabito E. I. et al . (2021). Effects of Exergames and protein supplementation on body composition and musculoskeletal function of Prefrail community-dwelling older women: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health18:9324. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179324

6

Buyukyazi G. Ulman C. Çelik A. Çetinkaya C. Şişman A. R. Çimrin D. et al . (2017). The effect of 8-week different-intensity walking exercises on serum hepcidin, IL-6, and iron metabolism in pre-menopausal women. Physiol. Int.104, 52–63. doi: 10.1556/2060.104.2017.1.7

7

Campbell K. L. Campbell P. T. Ulrich C. M. Wener M. Alfano C. M. Foster-Schubert K. et al . (2008). No reduction in C-reactive protein following a 12-month randomized controlled trial of exercise in men and women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev.17, 1714–1718. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-08-0088

8

Cashin A. G. McAuley J. H. (2020). Clinimetrics: physiotherapy evidence database (PEDro) scale. J. Physiother.66:59. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2019.08.005

9

Cunha P. M. Ribeiro A. S. Nunes J. P. Tomeleri C. M. Nascimento M. A. Moraes G. K. et al . (2019). Resistance training performed with single-set is sufficient to reduce cardiovascular risk factors in untrained older women: the randomized clinical trial. Active aging longitudinal study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr.81, 171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2018.12.012

10

Dani C. Dias K. M. Trevizol L. Bassôa L. Fraga I. Proença I. C. T. et al . (2021). The impact of red grape juice (Vitis labrusca)consumption associated with physical training on oxidative stress, inflammatory and epigenetic modulation in healthy elderly women. Physiol. Behav.229:113215. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.113215

11

de Lucas R. D. Caputo F. Mendes de Souza K. Sigwalt A. R. Ghisoni K. Lock Silveira P. C. et al . (2014). Increased platelet oxidative metabolism, blood oxidative stress and neopterin levels after ultra-endurance exercise. J. Sports Sci.32, 22–30. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2013.797098

12

de Souto Barreto P. Rolland Y. Vellas B. Maltais M. (2019). Association of Long-term Exercise Training with Risk of falls, fractures, hospitalizations, and mortality in older adults: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med.179, 394–405. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5406

13

Donges C. E. Duffield R. Drinkwater E. J. (2010). Effects of resistance or aerobic exercise training on interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and body composition. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc.42, 304–313. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181b117ca

14

Duval S. Tweedie R. (2000). Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics56, 455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x

15

Egger M. Davey Smith G. Schneider M. Minder C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ315, 629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

16

Fatouros I. G. Chatzinikolaou A. Tournis S. Nikolaidis M. G. Jamurtas A. Z. Douroudos I. I. et al . (2009). Intensity of resistance exercise determines adipokine and resting energy expenditure responses in overweight elderly individuals. Diabetes Care32, 2161–2167. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1994

17

Febbraio M. A. Pedersen B. K. (2002). Muscle-derived interleukin-6: mechanisms for activation and possible biological roles. FASEB J.16, 1335–1347. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0876rev

18

Fischer C. P. (2006). Interleukin-6 in acute exercise and training: what is the biological relevance?Exerc. Immunol. Rev.12, 6–33. PMID:

19

Flynn M. G. McFarlin B. K. (2006). Toll-like receptor 4: link to the anti-inflammatory effects of exercise?Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev.34, 176–181. doi: 10.1249/01.jes.0000240027.22749.14

20

Forti L. N. Njemini R. Beyer I. Eelbode E. Meeusen R. Mets T. et al . (2014). Strength training reduces circulating interleukin-6 but not brain-derived neurotrophic factor in community-dwelling elderly individuals. Age (Dordr.)36:9704. doi: 10.1007/s11357-014-9704-6

21

Franceschi C. Campisi J. (2014). Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci.69, S4–S9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu057

22

Furman D. Campisi J. Verdin E. Carrera-Bastos P. Targ S. Franceschi C. et al . (2019). Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat. Med.25, 1822–1832. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0675-0

23

Garber C. E. Blissmer B. Deschenes M. R. Franklin B. A. Lamonte M. J. Lee I. M. et al . (2011). American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc.43, 1334–1359. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb

24

Goldet G. Howick J. (2013). Understanding GRADE: an introduction. J. Evid. Based Med.6, 50–54. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12018

25

Griffen C. Duncan M. Hattersley J. Weickert M. O. Dallaway A. Renshaw D. (2022). Effects of resistance exercise and whey protein supplementation on skeletal muscle strength, mass, physical function, and hormonal and inflammatory biomarkers in healthy active older men: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Exp. Gerontol.158:111651. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2021.111651

26

Guthold R. Stevens G. A. Riley L. M. Bull F. C. (2018). Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1·9 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health6, e1077–e1086. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(18)30357-7

27

Guthold R. Stevens G. A. Riley L. M. Bull F. C. (2020). Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health4, 23–35. doi: 10.1016/s2352-4642(19)30323-2

28

Hansson G. K. (2005). Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med.352, 1685–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430

29

Haskell W. L. Lee I. M. Pate R. R. Powell K. E. Blair S. N. Franklin B. A. et al . (2007). Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc.39, 1423–1434. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616b27

30

Heneka M. T. Carson M. J. El Khoury J. Landreth G. E. Brosseron F. Feinstein D. L. et al . (2015). Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol.14, 388–405. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(15)70016-5

31

Higgins J. P. Thompson S. G. Deeks J. J. Altman D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ327, 557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

32

Ihalainen J. K. Inglis A. Mäkinen T. Newton R. U. Kainulainen H. Kyröläinen H. et al . (2019). Strength training improves metabolic health markers in older individual regardless of training frequency. Front. Physiol.10:32. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00032

33

Ihalainen J. K. Schumann M. Eklund D. Hämäläinen M. Moilanen E. Paulsen G. et al . (2018). Combined aerobic and resistance training decreases inflammation markers in healthy men. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports28, 40–47. doi: 10.1111/sms.12906

34

Irandoust K. Hamzehloo A. Youzbashi L. Taheri M. Ben Saad H. (2022). High intensity interval training and L-arginine supplementation decrease interleukin-6 levels in adult trained males. Tunis. Med.100, 696–705. PMID:

35

Irandoust K. Taheri M. (2018). The effect of aquatic exercises on inflammatory markers of cardiovascular disease in obese women. Int. J. Health Sci.5:145. doi: 10.4103/iahs.iahs_40_18

36

Iyengar N. M. Gucalp A. Dannenberg A. J. Hudis C. A. (2016). Obesity and Cancer mechanisms: tumor microenvironment and inflammation. J. Clin. Oncol.34, 4270–4276. doi: 10.1200/jco.2016.67.4283

37

Keller C. Steensberg A. Hansen A. K. Fischer C. P. Plomgaard P. Pedersen B. K. (2005). Effect of exercise, training, and glycogen availability on IL-6 receptor expression in human skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985)99, 2075–2079. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00590.2005

38

Kirk B. Mooney K. Vogrin S. Jackson M. Duque G. Khaiyat O. et al . (2021). Leucine-enriched whey protein supplementation, resistance-based exercise, and cardiometabolic health in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. J. Cachexia. Sarcopenia Muscle12, 2022–2033. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12805

39

Lee M. G. Park K. S. Kim D. U. Choi S. M. Kim H. J. (2012). Effects of high-intensity exercise training on body composition, abdominal fat loss, and cardiorespiratory fitness in middle-aged Korean females. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab.37, 1019–1027. doi: 10.1139/h2012-084

40

Leonard B. E. (2007). Inflammation, depression and dementia: are they connected?Neurochem. Res.32, 1749–1756. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9385-y

41

Levinger I. Goodman C. Peake J. Garnham A. Hare D. L. Jerums G. et al . (2009). Inflammation, hepatic enzymes and resistance training in individuals with metabolic risk factors. Diabet. Med.26, 220–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02679.x

42

Libardi C. A. De Souza G. V. Cavaglieri C. R. Madruga V. A. Chacon-Mikahil M. P. (2012). Effect of resistance, endurance, and concurrent training on TNF-α, IL-6, and CRP. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc.44, 50–56. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318229d2e9

43

Lindsay A. Lewis J. Scarrott C. Draper N. Gieseg S. P. (2015). Changes in acute biochemical markers of inflammatory and structural stress in rugby union. J. Sports Sci.33, 882–891. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2014.971047

44

Lira F. S. Dos Santos T. Caldeira R. S. Inoue D. S. Panissa V. L. G. Cabral-Santos C. et al . (2017). Short-term high- and moderate-intensity training modifies inflammatory and metabolic factors in response to acute exercise. Front. Physiol.8:856. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00856

45

Llamas-Velasco S. Villarejo-Galende A. Contador I. Lora Pablos D. Hernández-Gallego J. Bermejo-Pareja F. (2016). Physical activity and long-term mortality risk in older adults: a prospective population based study (NEDICES). Prev. Med. Rep.4, 546–550. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.10.002

46

Maher C. G. Sherrington C. Herbert R. D. Moseley A. M. Elkins M. (2003). Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys. Ther.83, 713–721. doi: 10.1093/ptj/83.8.713

47

Majka D. S. Chang R. W. Vu T. H. Palmas W. Geffken D. F. Ouyang P. et al . (2009). Physical activity and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am. J. Prev. Med.36, 56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.031

48

Marcell T. J. McAuley K. A. Traustadóttir T. Reaven P. D. (2005). Exercise training is not associated with improved levels of C-reactive protein or adiponectin. Metabolism54, 533–541. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.11.008

49

Martins R. A. Neves A. P. Coelho-Silva M. J. Veríssimo M. T. Teixeira A. M. (2010). The effect of aerobic versus strength-based training on high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in older adults. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol.110, 161–169. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1488-5

50

Masala G. Bendinelli B. Della Bella C. Assedi M. Tapinassi S. Ermini I. et al . (2020). Inflammatory marker changes in a 24-month dietary and physical activity randomised intervention trial in postmenopausal women. Sci. Rep.10:21845. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78796-z

51

Meyer J. D. Hayney M. S. Coe C. L. Ninos C. L. Barrett B. P. (2019). Differential reduction of IP-10 and C-reactive protein via aerobic exercise or mindfulness-based stress-reduction training in a large randomized controlled trial. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol.41, 96–106. doi: 10.1123/jsep.2018-0214

52

Neefkes-Zonneveld C. R. Bakkum A. J. Bishop N. C. van Tulder M. W. Janssen T. W. (2015). Effect of long-term physical activity and acute exercise on markers of systemic inflammation in persons with chronic spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.96, 30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.07.006

53

Nicklas B. J. Hsu F. C. Brinkley T. J. Church T. Goodpaster B. H. Kritchevsky S. B. et al . (2008). Exercise training and plasma C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 in elderly people. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc.56, 2045–2052. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01994.x

54

Nieman D. C. Wentz L. M. (2019). The compelling link between physical activity and the body's defense system. J. Sport Health Sci.8, 201–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2018.09.009

55

Nikniaz L. Ghojazadeh M. Nateghian H. Nikniaz Z. Farhangi M. A. Pourmanaf H. (2021). The interaction effect of aerobic exercise and vitamin D supplementation on inflammatory factors, anti-inflammatory proteins, and lung function in male smokers: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil.13:102. doi: 10.1186/s13102-021-00333-w

56

Nishida Y. Tanaka K. Hara M. Hirao N. Tanaka H. Tobina T. et al . (2015). Effects of home-based bench step exercise on inflammatory cytokines and lipid profiles in elderly Japanese females: a randomized controlled trial. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr.61, 443–451. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2015.06.017

57

Olesen J. Gliemann L. Biensø R. Schmidt J. Hellsten Y. Pilegaard H. (2014). Exercise training, but not resveratrol, improves metabolic and inflammatory status in skeletal muscle of aged men. J. Physiol.592, 1873–1886. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.270256

58

Omar N. O. Ahmad R. A. Mohd Shah M. S. Aminuddin A. A. Chellappan K. C. (2021). Amelioration of inflammation in young men with cardiovascular risks participating pedometer-based walking programme. Med J Malaysia76, 375–381. PMID:

59

Ozemek C. Lavie C. J. Rognmo Ø. (2019). Global physical activity levels - need for intervention. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis.62, 102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2019.02.004

60

Page M. J. McKenzie J. E. Bossuyt P. M. Boutron I. Hoffmann T. C. Mulrow C. D. et al . (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

61

Paolucci E. M. Loukov D. Bowdish D. M. E. Heisz J. J. (2018). Exercise reduces depression and inflammation but intensity matters. Biol. Psychol.133, 79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2018.01.015

62

Pedersen B. K. Febbraio M. A. (2008). Muscle as an endocrine organ: focus on muscle-derived interleukin-6. Physiol. Rev.88, 1379–1406. doi: 10.1152/physrev.90100.2007

63

Pedersen B. K. Steensberg A. Schjerling P. (2001). Exercise and interleukin-6. Curr. Opin. Hematol.8, 137–141. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200105000-00002

64

Petersen A. M. Pedersen B. K. (2005). The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985)98, 1154–1162. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00164.2004

65

Phillips M. D. Flynn M. G. McFarlin B. K. Stewart L. K. Timmerman K. L. (2010). Resistance training at eight-repetition maximum reduces the inflammatory milieu in elderly women. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc.42, 314–325. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181b11ab7

66

Pinho R. A. Silva L. A. Pinho C. A. Scheffer D. L. Souza C. T. Benetti M. et al . (2010). Oxidative stress and inflammatory parameters after an ironman race. Clin. J. Sport Med.20, 306–311. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3181e413df

67

Pradhan A. D. Manson J. E. Rifai N. Buring J. E. Ridker P. M. (2001). C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA286, 327–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3.327

68

Qi D. Wong N. M. L. Shao R. Man I. S. C. Wong C. H. Y. Yuen L. P. et al . (2021). Qigong exercise enhances cognitive functions in the elderly via an interleukin-6-hippocampus pathway: a randomized active-controlled trial. Brain Behav. Immun.95, 381–390. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.04.011

69

Rapa S. F. Di Iorio B. R. Campiglia P. Heidland A. Marzocco S. (2019). Inflammation and oxidative stress in chronic kidney disease-potential therapeutic role of minerals, vitamins and plant-derived metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21:263. doi: 10.3390/ijms21010263

70

Ritter B. Greten F. R. (2019). Modulating inflammation for cancer therapy. J. Exp. Med.216, 1234–1243. doi: 10.1084/jem.20181739

71

Rodriguez-Miguelez P. Fernandez-Gonzalo R. Almar M. Mejías Y. Rivas A. de Paz J. A. et al . (2014). Role of toll-like receptor 2 and 4 signaling pathways on the inflammatory response to resistance training in elderly subjects. Age (Dordr.)36:9734. doi: 10.1007/s11357-014-9734-0

72

Rose G. L. Skinner T. L. Mielke G. I. Schaumberg M. A. (2021). The effect of exercise intensity on chronic inflammation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sci. Med. Sport24, 345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2020.10.004

73

Sardeli A. V. Tomeleri C. M. Cyrino E. S. Fernhall B. Cavaglieri C. R. Chacon-Mikahil M. P. T. (2018). Effect of resistance training on inflammatory markers of older adults: a meta-analysis. Exp. Gerontol.111, 188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2018.07.021

74

Scheffer D. D. L. Latini A. (2020). Exercise-induced immune system response: anti-inflammatory status on peripheral and central organs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. basis Dis.1866:165823. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165823

75

Schwingshackl L. Missbach B. Dias S. König J. Hoffmann G. (2014). Impact of different training modalities on glycaemic control and blood lipids in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetologia57, 1789–1797. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3303-z

76

Shinkai S. Konishi M. Shephard R. J. (1998). Aging and immune response to exercise. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol.76, 562–572. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-76-5-562

77

Sloan R. P. Shapiro P. A. McKinley P. S. Bartels M. Shimbo D. Lauriola V. et al . (2018). Aerobic exercise training and inducible inflammation: results of a randomized controlled trial in healthy, young adults. J. Am. Heart Assoc.7:e010201. doi: 10.1161/jaha.118.010201

78

So W. Y. Song M. Park Y. H. Cho B. L. Lim J. Y. Kim S. H. et al . (2013). Body composition, fitness level, anabolic hormones, and inflammatory cytokines in the elderly: a randomized controlled trial. Aging Clin. Exp. Res.25, 167–174. doi: 10.1007/s40520-013-0032-y

79

Soysal P. Stubbs B. Lucato P. Luchini C. Solmi M. Peluso R. et al . (2016). Inflammation and frailty in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev.31, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.08.006

80

Steven S. Frenis K. Oelze M. Kalinovic S. Kuntic M. Bayo Jimenez M. T. et al . (2019). Vascular inflammation and oxidative stress: major triggers for cardiovascular disease. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev.2019, 7092151–7092126. doi: 10.1155/2019/7092151

81

Strandberg E. Edholm P. Ponsot E. Wåhlin-Larsson B. Hellmén E. Nilsson A. et al . (2015). Influence of combined resistance training and healthy diet on muscle mass in healthy elderly women: a randomized controlled trial. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985)119, 918–925. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00066.2015

82

Tang Z. Ming Y. Wu M. Jing J. Xu S. Li H. et al . (2021). Effects of caloric restriction and rope-skipping exercise on Cardiometabolic health: a pilot randomized controlled trial in young adults. Nutrients13:3222. doi: 10.3390/nu13093222

83

Tomeleri C. M. Souza M. F. Burini R. C. Cavaglieri C. R. Ribeiro A. S. Antunes M. et al . (2018). Resistance training reduces metabolic syndrome and inflammatory markers in older women: a randomized controlled trial. J. Diabetes10, 328–337. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12614

84

Urzi F. Marusic U. Ličen S. Buzan E. (2019). Effects of elastic resistance training on functional performance and Myokines in older women-a randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc.20, 830–834.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.01.151

85

Voss M. W. Soto C. Yoo S. Sodoma M. Vivar C. van Praag H. (2019). Exercise and hippocampal memory systems. Trends Cogn. Sci.23, 318–333. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2019.01.006

86

Wan X. Wang W. Liu J. Tong T. (2014). Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med. Res. Methodol.14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135

87

Wannamethee S. G. Lowe G. D. Whincup P. H. Rumley A. Walker M. Lennon L. (2002). Physical activity and hemostatic and inflammatory variables in elderly men. Circulation105, 1785–1790. doi: 10.1161/hc1502.107117

88

Ward L. J. Nilsson S. Hammar M. Lindh-Åstrand L. Berin E. Lindblom H. et al . (2020). Resistance training decreases plasma levels of adipokines in postmenopausal women. Sci. Rep.10:19837. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76901-w

89

Wu L. Liu Y. Wu L. Yang J. Jiang T. Li M. (2022). Effects of exercise on markers of inflammation and indicators of nutrition in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Urol. Nephrol.54, 815–826. doi: 10.1007/s11255-021-02949-w

90

Xing H. Lu J. Yoong S. Q. Tan Y. Q. Kusuyama J. Wu X. V. (2022). Effect of aerobic and resistant exercise intervention on Inflammaging of type 2 diabetes mellitus in middle-aged and older adults: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc.23, 823–830.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2022.01.055

Summary

Keywords

long-term exercise training, inflammation, interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor alpha, meta-analysis

Citation

Wang Y-H, Tan J, Zhou H-H, Cao M and Zou Y (2023) Long-term exercise training and inflammatory biomarkers in healthy subjects: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Psychol. 14:1253329. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1253329

Received

05 July 2023

Accepted

11 August 2023

Published

30 August 2023

Volume

14 - 2023

Edited by

Fang Fu, Fudan University, China

Reviewed by

Khadijeh Irandoust, Imam Khomeini International University, Iran; Laisa Liane Paineiras-Domingos, Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), Brazil

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Wang, Tan, Zhou, Cao and Zou.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Meng Cao, caomeng123@szu.edu.cnYu Zou, zouyuzy@zju.edu.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.