- Zhejiang Provincial Key Laboratory of Biometrology and Inspection and Quarantine, College of Life Sciences, China Jiliang University, Hangzhou, China

Brown planthopper (BPH) Nilaparvata lugens Stål is a serious insect pest of rice in Asian countries. Active compounds have close relationship with rice resistance against BPH. In this study, HPLC, MS/MS, and NMR techniques were used to identify active compounds in total flavonoids of rice. As a result, a BPH resistance-associated compound, Peak 1 in HPLC chromatogram of rice flavonoids, was isolated and identified as schaftoside. Feeding experiment with artificial diet indicated that schaftoside played its role in a dose dependent manner, under the concentration of 0.10 and 0.15 mg mL-1, schaftoside showed a significant inhibitory effect on BPH survival (p < 0.05), in comparison with the control. The fluorescent spectra showed that schaftoside has a strong ability to bind with NlCDK1, a CDK1 kinase of BPH. The apparent association constant KA for NlCDK1 binding with schaftoside is 6.436 × 103 L/mol. Docking model suggested that binding of schaftoside might affect the activation of NlCDK1 as a protein kinase, mainly through interacting with amino acid residues Glu12, Thr14 and Val17 in the ATP binding element GXGXXGXV (Gly11 to Val18). Western blot using anti-phospho-CDK1 (pThr14) antibody confirmed that schaftoside treatment suppressed the phosphorylation on Thr-14 site of NlCDK1, thus inhibited its activation as a kinase. Therefore, this study revealed the schaftoside-NlCDK1 interaction mode, and unraveled a novel mechanism of rice resistance against BPH.

Introduction

Brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens Stål is one of the most serious insect pests of rice (Oryza sativa L.) in Asian countries. Outbreaks of BPH can cause severe yield losses of rice and have occurred quite frequently in recent years (Bottrell and Schoenly, 2012; Hu et al., 2013). Breeding resistant rice varieties is an important strategy to control BPH, but the resistance of rice is often broken down rapidly owning to the virulence variation of this insect (Park et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2015). The interaction mechanism between rice and BPH still remained unclear, which hampers the sustainable utilization of rice resistance. Currently, controlling of BPH largely relies on extensive application of chemical insecticides, and a promising approach to search for novel insecticides is based on secondary metabolites produced by plants. Therefore, it is critical to identify some active compounds in resistant rice and explore the mechanism of interaction between the active compound and the BPH.

Plants in natural and agricultural ecosystems are constantly exposed to diverse attackers, such as herbivores, pathogens and viruses (Erb et al., 2011; Kamphuis et al., 2013). The secondary metabolites including phenolics, alkaloids, peptides and essential oils produced by plants have long been regarded important for plant defense against herbivores (Farooq et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2013). Flavonoids are a group of plant polyphenolic secondary metabolites, and these compounds consist of two benzene rings connected by a three carbon chain, forming a chemical structure with three rings (C6-C3-C6). The flavonoids can be divided into six major subtypes, which include flavones, chalcones, isoflavonoids, flavonones, anthocyanins, and anthoxanthins (Petrussa et al., 2013). Flavonoids play important roles in plant adaptation to external environments, including interaction with pests (Simmonds, 2001; Nenaah, 2013). For example, isorhamnetin-3-sophoroside-7-glucoside and kaempferol-3,7-diglucoside have been reported as feeding deterrents against Mamestra configurata (Onyilagha et al., 2004), rutin and quercetin were found toxic to Spodoptera litura larvae (Su et al., 2018), vitexin and vitexin-2-O-arabinofuranoside in Basella alba leaves impaired the growth of Spodoptera litura larvae (Aboshi et al., 2018).

Rice plants are rich in flavonoids, and some flavonoids are implicated in rice resistance to BPH. The flavonoids, tricin, can defend the rice plant against infestation by the BPH (Zhang et al., 2017). Some flavonoid glycoside compounds, such as apigenin-C-glycosides, can affect the feeding behavior of the BPH and result in death of the insect (Grayer et al., 1994; Stevenson et al., 1996; Simmonds, 2001). In our previous study, the same amount of total flavonoids extracted from different rice varieties showed different effects on the survival of BPH, indicating that some key compounds were present in total flavonoids responsible for the resistance of rice to BPH (Zhou, 2011). Since it has been estimated that the flavonoids family possess more than 10,000 members in plant kingdom (Seo et al., 2011), it is necessary to further study the flavonoids in different rice varieties and identify some active compounds. It’s also important to explore the interaction property between the identified active compound in flavonoids and the target in BPH for understanding the resistant mechanism of rice.

Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1), also called p34cdc2, plays a vital role in regulating the cell cycle as a serine/threonine kinase (Morgan, 1995). Besides, CDK1 is also involved in diverse physiological processes. For example, Cdk1 play roles in cell adaptive response to stress (Candas et al., 2013), regulation of mitochondrial preprotein translocase (Harbauer et al., 2014), and enhancing mitochondrial bioenergetics (Qin et al., 2015). Knockdown of CDK1 caused cell death in Drosophila melanogaster (Björklund et al., 2006). Some flavonoids, especifically chalcones and flavones containing nitrogen, have been reported as CDK1 inhibitors (Navarro-Retamal and Caballero, 2016). Therefore, CDK1 in BPH (NlCDK1) might be a potential target of rice flavonoids, and worthy being further studied.

Although flavonoids are abundant in rice plants, it is still uncertain whether the composition and content of flavonoids in different rice varieties are same or not, especially, the binding property of resistance-related flavonoids with NlCDK1 remains unclear. In the present work, we analyzed the flavonoids from different rice varieties by comparing the HPLC profiles, isolated and identified schaftoside as an active compound associated with BPH-resistance. We also explored the molecular mechanisms involved in the interaction between schaftoside and NlCDK1. Therefore, this research not only identified a promising compound schaftoside which might be developed as new insecticide to control BPH, but also clarified the interaction between schaftoside and NlCDK1, thus untraveled a novel mechanism of rice resistance against BPH.

Materials and Methods

Plants and Insects

Colonies of BPH were maintained on Taichung Native 1 (TN1, a variety without resistant gene to BPH) rice seedlings. Rice varieties of TN1 and Xiushui 11 (without resistance gene to BPH) are susceptible, while Mudgo (with Bph 1), ASD7 (with bph 2) and Rathu Heenati (RHT, with Bph 3) exhibit resistance to BPH of TN1 colony in the seedling bulk test. Unless otherwise stated, rice plants used in experiments were three-leaf to four-leaf stage, and test BPH were 2-3 instar nymphs. Rice plants and BPH were maintained in a phytotron at 26 ± 2°C and 75–85% RH with a 14:10 h L:D photoperiod.

Total Flavonoids Extraction and Quantification

Total flavonoids were extracted from rice plants according to previous methods (Pereira et al., 2012) with some modifications, as following: non-infested leave sheathes of rice were sampled at the tillering stage about 2 months after transplanting, blanched at 105°C for 30 min and dried at 60°C to constant weight. The dried plant material was powdered and extracted ultrasonically under an optimized condition: 70% ethanol solution, a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:25 (m/v), a power of 250 w, and an extracting time of 50 min (Zhou et al., 2011). The collected residue was extracted in the same condition for two more times. The filtrates were combined and defatted with n-hexane (1:1, v:v) for two times. The filtrates were concentrated by vacuum evaporation in rotavapor and adjusted the volume of total flavonoids to 10 mL. The prepared total flavonoids were filtered through a nylon membrane filter (0.45 μm pore size). The content of total flavonoids extracts was examined using the sodium nitrite-aluminum nitrate colorimetric method using rutin as a reference substance. A calibration curve of rutin was prepared as described by Zhou et al. (2011). Five biological replicates were analyzed for each variety, and each biological replicate includes at least 10 rice plants.

HPLC Chromatographic Condition and Quantification of the Target Compound

High performance liquid chromatography analysis was carried out on a VARIAN ProStar 240 instrument equipped with a binary pump, a PDA Varian Prostar detector. The conditions were modified as previously described (Gouveia and Castilho, 2010; Pereira et al., 2012). The wavelength range was set at 220–400 nm, monitored at 350 nm. Separation was performed using a Hypersil Gold column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm), with a sample injection volume of 10 μL. CH3CN (A) and water containing 0.1% formic acid (B) were used as chromatographic eluent, and the program for eluenting gradient was set as follows: 8–35% A (0–60 min), 95% A (61–70 min), 8% A (71–80 min). The flow rate of mobile phase was 1.0 mL min-1, and the chromatogram was recorded at 350 nm. Column temperature was controlled at 30°C.

The target compound (Peak 1) in rice total flavonoids related to BPH-resistance was selected by comparing the HPLC profiles of different rice varieties. For relative quantification of the target compound Peak 1 in rice total flavonoids, a calibration curve was obtained by diluting an original total flavonoids extract of RHT rice variety (relative concentration, 1.0) into a series solution with different concentrations (0.5, 0.25, 0.125, and 0.0625), and the calibration curve was constructed by plotting the peak-areas to the relative concentrations of the target compound Peak 1. The concentration of Peak 1 in the original total flavonoids selected is high enough, to ensure that the relative concentration of Peak 1 in all test samples will not exceed 1.0. Relative quantification for Peak 1 of different rice varieties was achieved by using the calibration curve. Five biological replicates were analyzed for each variety.

LC-ESI-MS/MS Analysis

LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis was carried out based on the method modified from Simirgiotis et al. (2013) as follows: a mass spectrometer of Esquire 4000 Ion Trap (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) was connected to an Agilent 1100 HPLC instrument (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) with ESI interface. Data acquisition of full scan was performed from m/z 50 to m/z 2000 in a negative ion mode. Nitrogen was used as nebulizer gas with electrospray needle 4500 V. Using ultrahigh pure helium as the collision gas, induced dissociation spectra were obtained with fragmentation amplitude of 1.00 V (MS/MS). HPLC analysis was carried out using the condition as above of HPLC chromatograph.

Purification of the Active Compound From Flavonoids

To obtain some pure sample for NMR analysis, the target compound of peak 1 was purified from total flavonoids extract in the following way: total flavonoids extract was firstly separated with Sephadex LH-20 medium pressure chromatography (1000 mm × 30 mm ID), the eluent is methanol/water (1/9-7/3) with a flow rate of 2.0 mL min-1, loading: 1.0 g. Sample was collected in the same conditions for 3 times. Crude extract of peak 1 in HPLC chromatogram was refined with Medium Pressure Chromatography (400 mm × 10 mm ID, Merck C18, 40–60 μm), eluent is acetonitrile (CH3CN)/water 1:9, and the flow rate is 1.0 mL min-1. By evaporating the solvent, the collected fraction was condensed to approximately 1 mL. The supernatant was removed and the precipitated material was solubilized in DMSO-d6 for following NMR analysis (Pereira et al., 2012; Simirgiotis et al., 2013).

Structural Identification by NMR

1H and 13C NMR spectra of the purified peak 1 compound were recorded on a Bruker Avance 500 spectrometer at 500 and 125 MHz, respectively. DMSO-d6 was used as solvent. Chemical shift references were reported from the solvent resonances of DMSO-d6 at δH 2.50 and δC 39.5, relative to the internal standard tetramethylsilane TMS (Pereira et al., 2012).

Effect of Schaftoside on BPH Survival

Schaftoside (purity >98%, Chengdu Biopurify Phytochemicals Ltd., Chengdu, China) was added into the artificial diet D-97 (Fu et al., 2001) to examine its effect on BPH. The final concentrations of schaftoside were adjusted to 0.05, 0.1, and 0.15 mg/mL for different treatments. Feeding sack was made using two layers of stretched Parafilm® M film, and 20 μL artificial diet with schaftoside was sandwiched between the films. A glass chamber (2.5 cm × 15 cm), each containing 10 nymphs of 2nd instar, was covered with feeding sacks at both ends. At the same time, D-97 artificial diet without schaftoside was used as the control. The artificial diet with or without schaftoside was renewed every day to keep fresh. Insects were maintained at a temperature of 26 ± 2°C, 70% RH, and a 16:8 L:D photoperiod. Survival rates were recorded every 5 days. Ten biological replicates were analyzed for each treatment.

Preparation of Recombinant NlCDK1 Protein

The CDS for recombinant NlCDK1 protein expression were amplified by PCR, according to the NlCDK1 sequence (GeneBank: KX138392) previously submitted to NCBI databases1 by our group. The forward primer was NlCDK1-F (5′-GCGGATCCATGAATTCCTACGACATGCTTGAG-3′) containing the BamH I restriction site (underlined), and the reverse primer was NlCDK1-R (5′-GGAAGCTTTTAATCGTAGATATCAGCACCGGG-3′) containing the Hind III restriction site (underlined). The amplified fragments was digested with the corresponding restriction enzymes (BamH I and Hind III) and subcloned into vector pET32a by T4 DNA ligase overnight (for 12 h) at 16°C. The recombinant plasmid was sequenced and transformed into the Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3) for expression of recombinant protein. The proteins were induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) overnight at 15 °C. The recombinant protein with NlCDK1 was purified by ProteinIso® Ni-NTA Resin (TransGen, Beijing, China), and dialyzed against a phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH7.4). The protein samples were examined by 12% SDS–PAGE, stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250. BeyoColorTM Prestained Color Protein Marker P0076 (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was use as molecular weight markers.

Fluorescent Spectral Experiment

The fluorescent quenching spectra were used to analyze the interaction between schaftoside and NlCDK1 protein. Fluorescence was detected on a Spectrofluorophotometer RF-5301PC (Shimadzu, Japan), which is equipped with a xenon lamp source. To record the fluorescent quenching spectra, the stock solution of NlCDK1 was diluted into working solution with a concentration of 0.24 × 10-6mol L-1. Afterward, schaftoside was titrated into each working solution of NlCDK1 in the quartz cell. The mixture of schaftoside and NlCDK1 protein were excited at 281 nm, AND the fluorescent emission spectra were recorded at the wavelength of 290–500 nm.

Molecular Docking Analysis

For docking calculations, the 3D structure of NlCDK1 protein model was firstly predicted by SWISS-MODEL2 online using the crystal structure of CDK1 (PDB entry code, 4y72.1.A) as the template. Docking was performed online using DockingServer3.

Western Blot Analysis

Brown planthopper was treated with schaftoside by feeding the nymphs with artificial diet as described above. Western blot was performed according to the method modified from Hao et al. (2015). At day 10, about 25 nymphs of each biological replicate were homogenized in 1 × PBS, and then added 2 × SDS sample buffer. The lysate protein were boiled for 5 min, and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min. Protein samples of 10 μl were loaded onto the SDS gels, electrophoresis for 90 min, and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. TBST (0.1% Tween 20 in TBS) and 5% non-fat powdered dry milk (w/v) were used to block the blots for 2 h at room temperature. Primary antibody anti-phospho-CDK1 (pThr14, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, United States) at a dilution of 1:500 was then incubated with the blot for 12 h at 4°C in a TBST solution to probe pThr14 of NlCDK1. The membrane was washed with TBST for 10 min 3 times, and then incubated in the horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibody (Solarbio, Beijing, China) at a dilution of 1:1000. The membrane was washed 3 times, detected using the DAB Horseradish Peroxidase Color Development Kit (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China), and imaged with a camera equipped in a mobile phone.

Statistical Analysis

Content of total flavonoids and Peak1 (schaftoside) in different rice varieties was analyzed using one-way ANOVA and post hoc analysis with Tukey’s HSD test. Effect of schaftoside on survival rate of BPH was analyzed by Tukey’s test at each sampling time. All analysis was performed with the SPSS program (SPSS 19.0).

Results

Content of Total Flavonoids in Different Rice Varieties

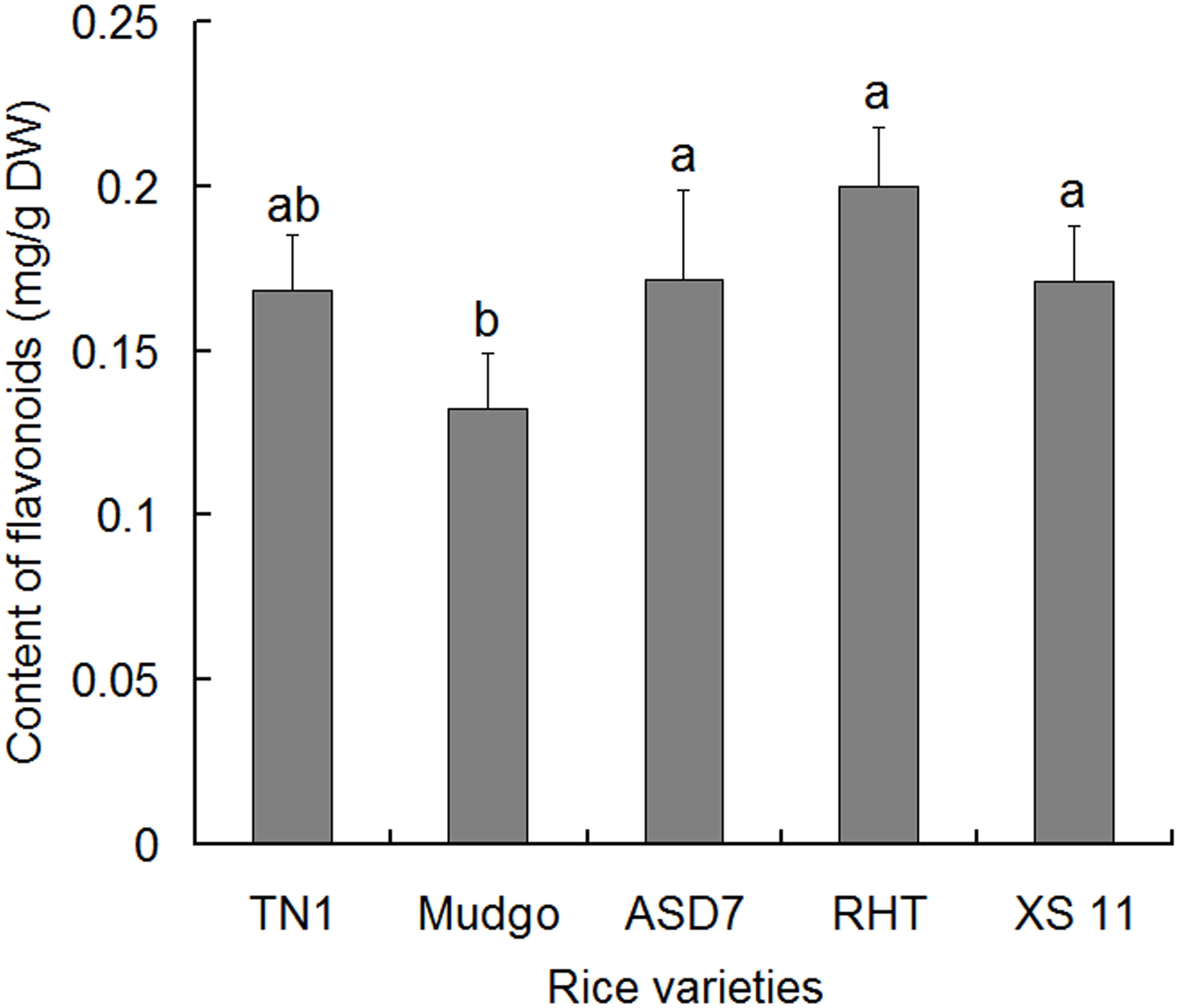

Total flavonoids were extracted from rice leaf sheathes and determined using rutin as a reference substance. In general, the content of total flavonoids between the susceptible varieties (TN1 and Xiushui 11) and the resistant varieties (ASD7 and RHT) did not show significant differences, except that the content in resistant variety Mudgo was relatively lower (Figure 1). It suggested that there was no significant correlation between the content of total flavonoids and the resistance of rice varieties. Therefore, it is necessary to further explore whether the active compounds in total flavonoids of different varieties are different in content, and contributed different resistance to rice against BPH.

FIGURE 1. Content of total flavonoids in the leaf sheathes of different rice varieties. Data were presented as means ± SD (n = 5). Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and post-hoc analysis with Tukey’s HSD test, and relative content with the same letter were not significantly different (P < 0.05). DW, dried weight.

HPLC Fingerprint Analysis

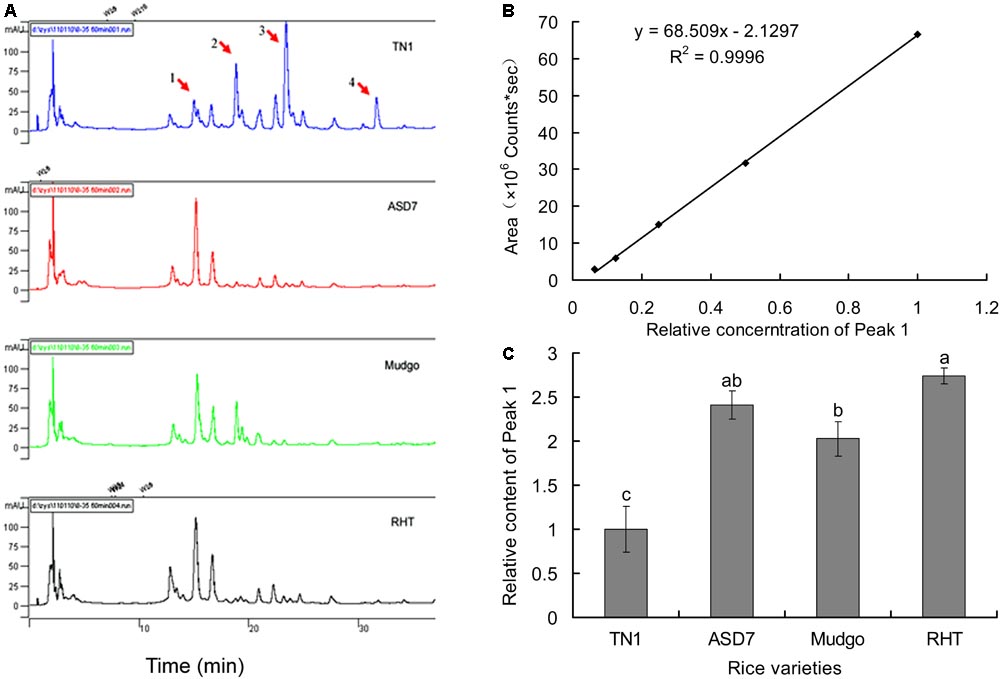

High performance liquid chromatography fingerprints of total flavonoids from different rice varieties were established to identify the active compound associated with the rice resistance against BPH. In general, four absorption peaks (Peak 1 to 4) in HPLC profiles showed obvious differences between the susceptible TN1 and resistant varieties (ASD7, Mudgo and RHT), whereas only one peak (Peak 1) had a positive correlation with the varietal resistance to BPH (Figure 2A). Therefore, Peak 1 related compound was selected as a candidate for further analysis. A calibration curve of Peak 1 was established for HPLC analysis, and the result showed that a good linearity was obtained between the peak area (y) and the relative concentration (x) of Peak 1 (Figure 2B). The relative concentration (x) of Peak 1 related compound in different rice varieties was determined according to the corresponding area (y) of Peak 1 in the HPLC chromatogram using the equation y = 68.509 x - 2.129 (R2 = 0.9996). It showed that the relative content of Peak 1 was higher in resistant varieties than that in susceptible TN1 (set as 1.0), with a variation ranging from 2.0 (Mudgo) to 2.7 (RHT). It suggested that the relative content of Peak 1 in different rice varieties were generally consistent with the resistance of rice (Figure 2C), so the Peak 1 related compound should play a key role in the resistance of rice to BPH.

FIGURE 2. Determination of Peak 1 related compound in rice flavonoids by HPLC. (A) HPLC fingerprints of flavonoids extract from different rice varieties. (B) A calibration curve constructed by plotting the peak-areas to the relative concentrations of Peak 1 related compound. (C) Relative content of Peak 1 related compound in flavonoids extract from different rice varieties, calculated according to the calibration curve in (B). Data was analyzed by ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD tests and relative content with the same letter were not significantly different (P < 0.05). Data were presented as means ± SD (n = 5).

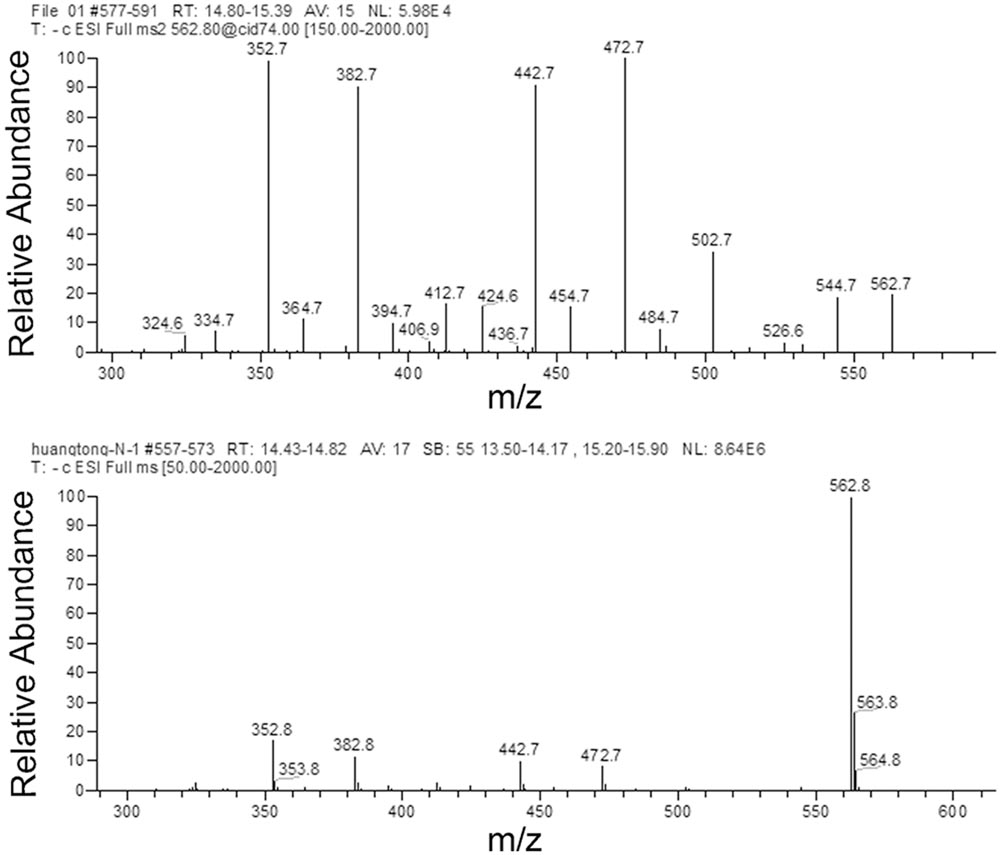

HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS-MS Identification of Peak 1 Related Compound

The flavonoids in rice leaf sheathes were investigated by HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS-MS. For MS analysis, detection of Peak 1 related compound was performed in ESI negative modes. Peak 1 with a [M-H]- ion at m/z 563 produced MS2 ions at m/z 545, 503, 473, 443, 383, and 353 (Figure 3). According to previous references (Bakhtiar et al., 1994; Ferreres et al., 2003), Peak 1 was concluded to be 6-C-arabinosyl-8-C-glucosyl apigenin or 6-C-glucosyl- 8-C-arabinosyl apigenin. However, it was still difficult to identify the exact structure of Peak 1 related compound only by HPLC-ESI-MS-MS analysis. Further elucidation by a more powerful tool, such as NMR spectroscopy was necessary in the following steps to describe an unambiguous structure about Peak 1.

In addition, three other peaks 2, 3, and 4 also showed clear difference between the susceptible rice variety TN1 and resistant varieties, but these peaks didn’t have a positive correlation with the varietal resistance of rice to BPH. Peak 2 with a [M-H]- ion at m/z 533 yielded MS2 ions at m/z 443, 473, 383, 353 and 515. Peak 3 yielded an ion at m/z 491 which produced an MS2 ion at m/z 329. Peak 4 yielded a [M-H]- ion at m/z 739 and produced MS2 ions at m/z 563, 383 and 293 (Supplementary Figures S1–S3).

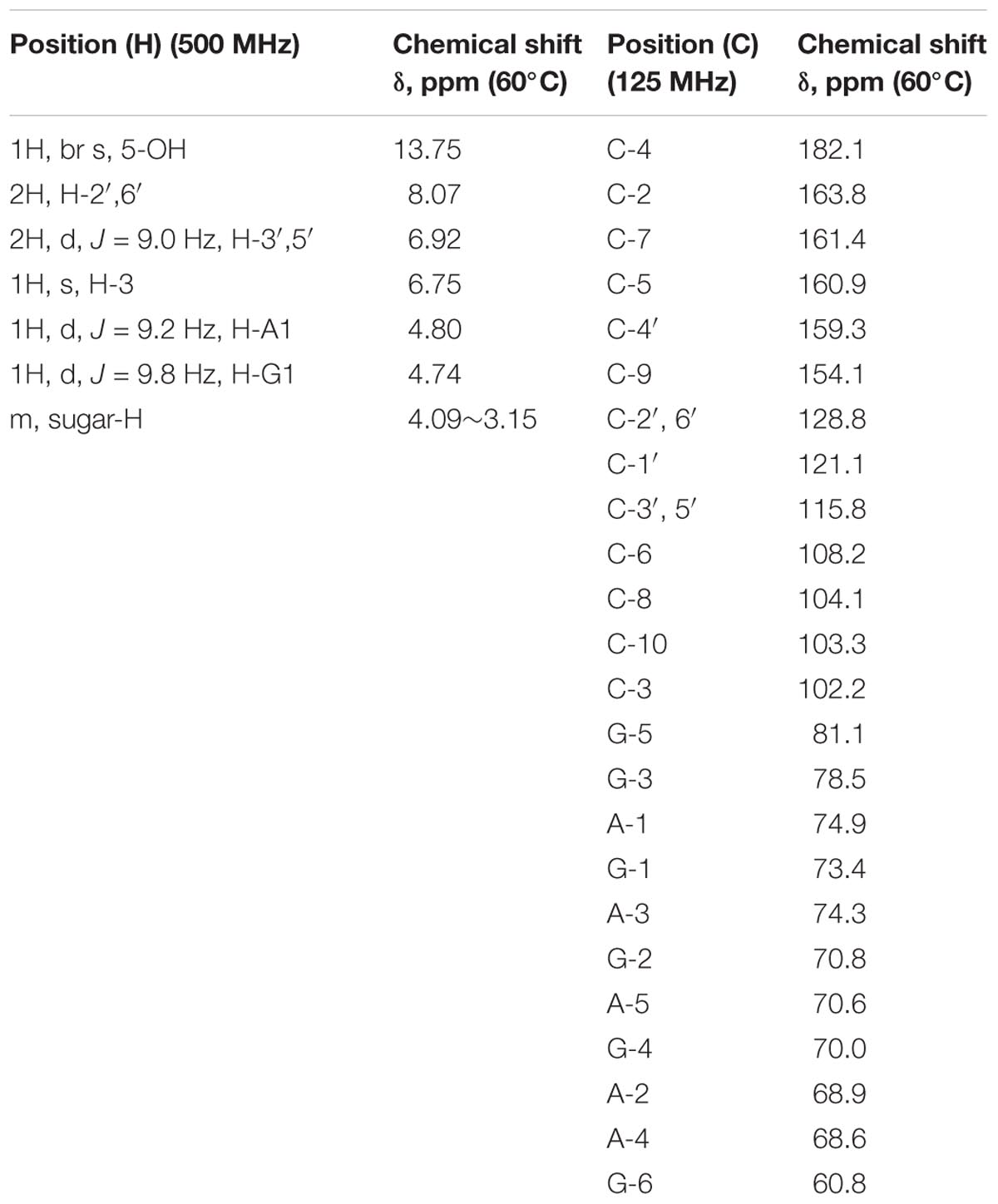

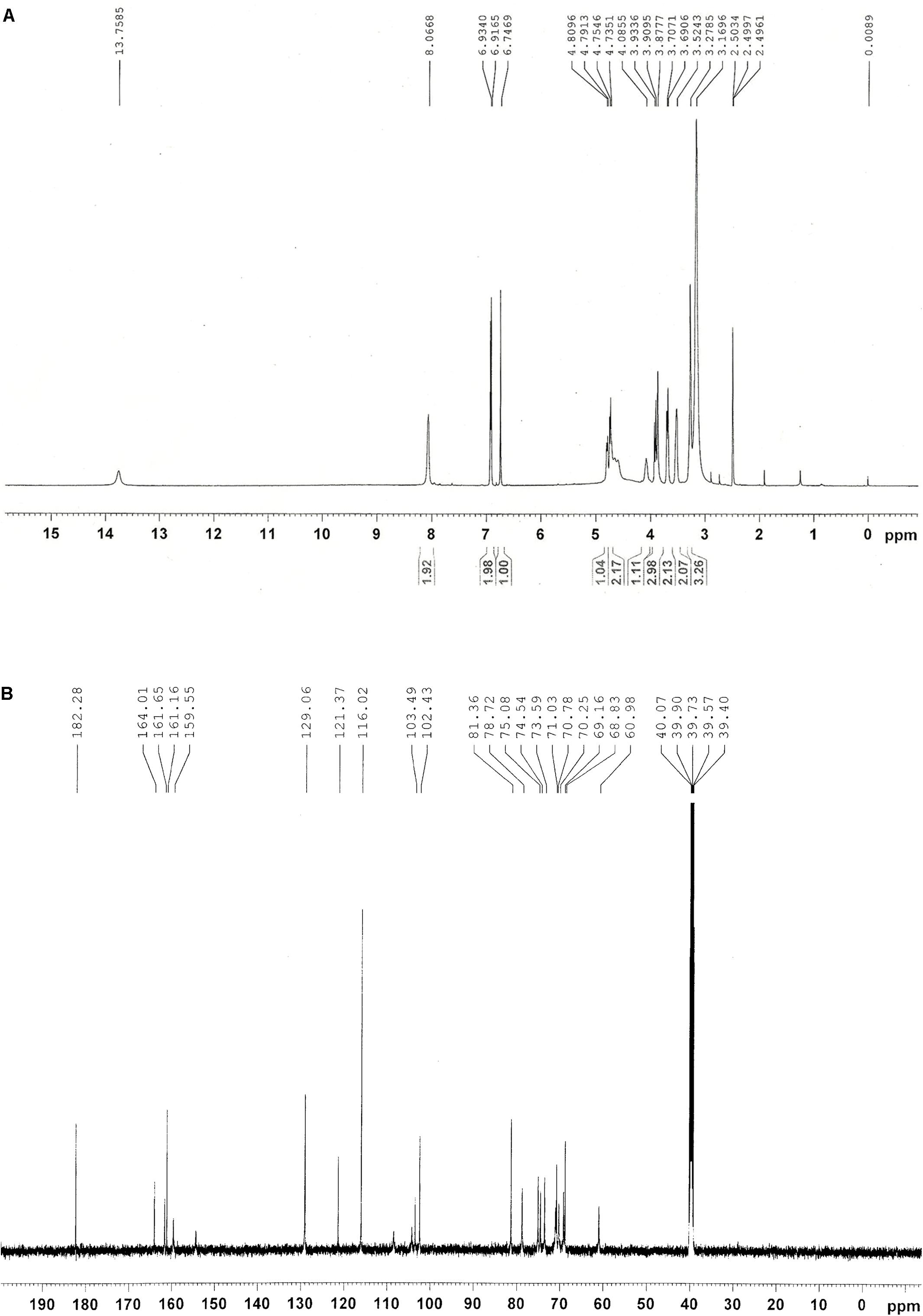

Purification and NMR Analysis of Peak 1 Related Compound

Among four HPLC peaks (Peak 1-4) of total flavonoids extract, only Peak 1 showed a positive correlation with the resistance of rice to BPH (Figure 2A), so Peak 1 related compound was separately collected and purified by HPLC. The purified compound of Peak 1 was then elucidated by NMR to identify its exact structure from two candidate compounds 6-C-arabinosyl-8-C-glucosyl apigenin and 6-C-glucosyl-8-C-arabinosyl apigenin. According to the NMR spectra of Peak 1 (Figure 4), the 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts were assigned and showed in Table 1. The 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR data totally agreed with the published data of 6-C-beta-D-Glucosyl-8-C-alpha-L-arabinosylapigenin (schaftoside), previously isolated from several plants and unambiguously elucidated by NMR spectroscopy (Xie et al., 2003; Dou et al., 2007; Simirgiotis et al., 2013).

FIGURE 4. NMR spectra of Peak 1 related compound schaftoside. (A) 1H NMR spectra; (B) 14C NMR spectra.

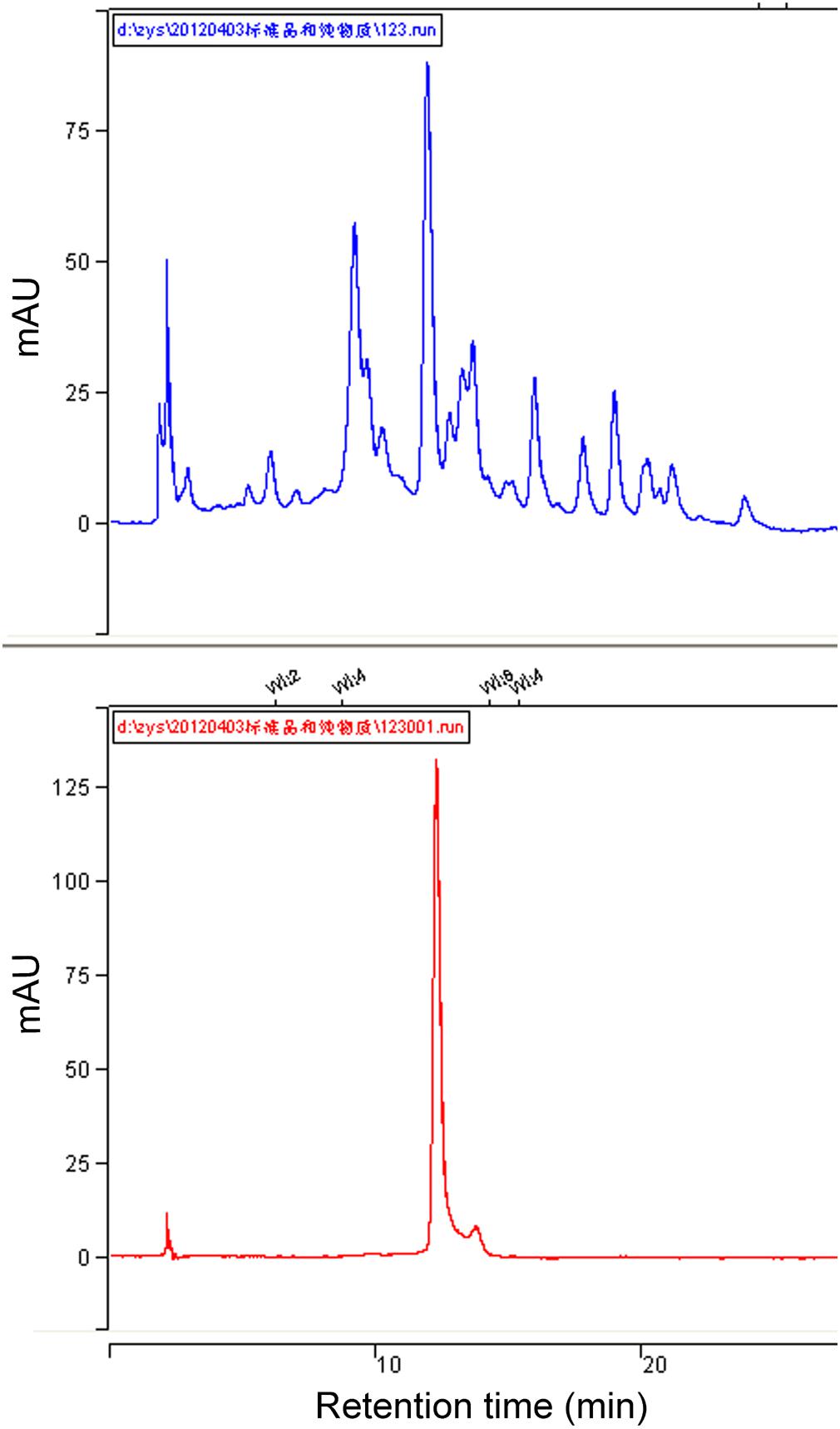

To further confirm that Peak 1 related compound was schaftoside, the standard sample of schaftoside was used as reference to compare with Peak 1 using HPLC technique. The result showed that Peak 1 related compound has same retain time with the standard sample of schaftoside (Figure 5). Therefore, Peak 1 related compound was identified as schaftoside.

FIGURE 5. HPLC chromatographs of total flavonoids and the standard sample of schaftoside. Showing the Peak 1 related compound in the flavonoids of RHT rice variety (upper) has the same retention time with the standard sample of schaftoside (lower).

Effects of Schaftoside on the Survival Rate of BPH

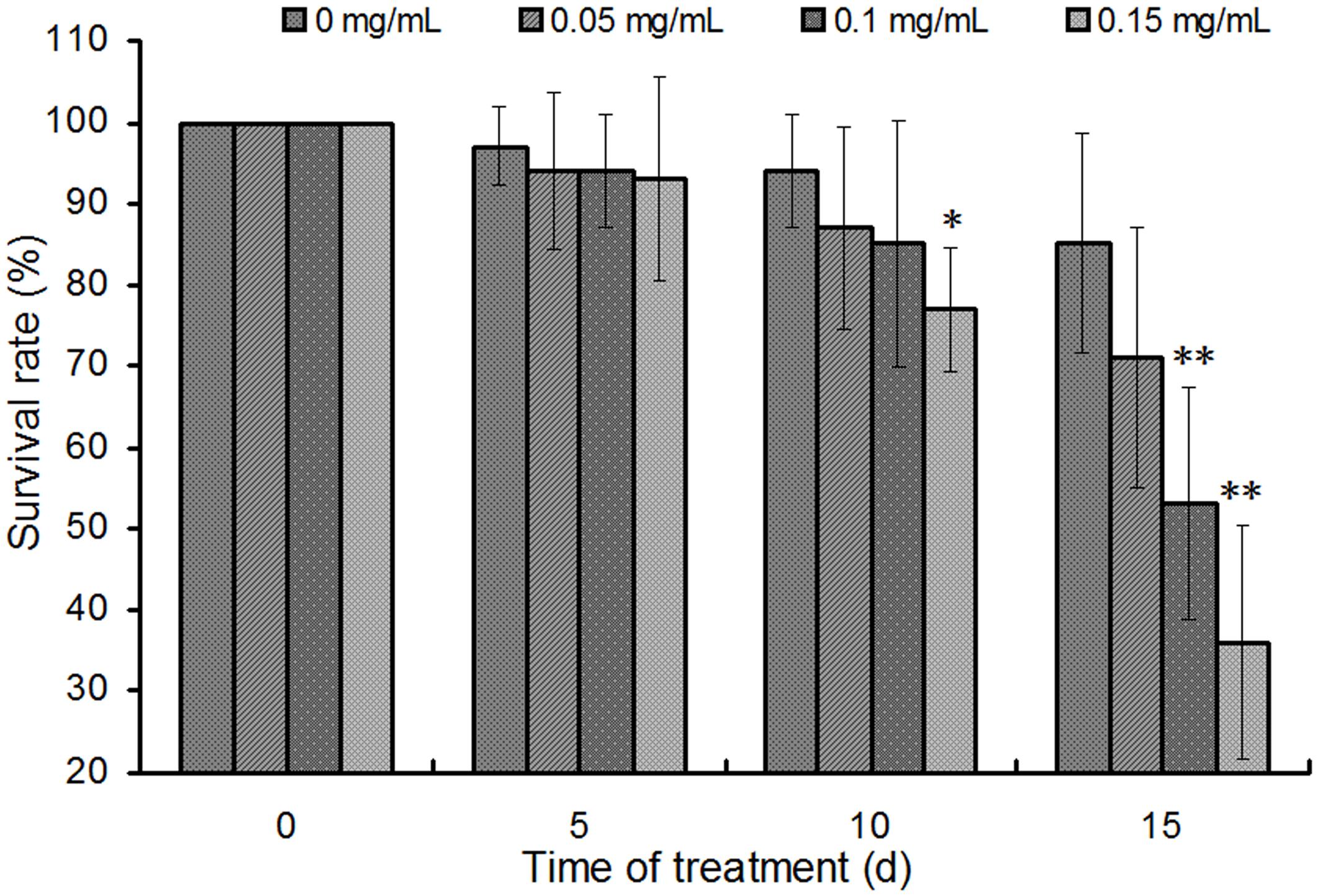

Schaftoside was dissolved in artificial diet to test its activity on BPH. Generally, survival rates of BPH showed a decline trend in schaftoside treatment groups as well as the control (0 mg mL-1) (Figure 6). The results also showed that the schaftoside affected BPH survival rate in a dose-dependent way. The treatment with 0.15 mg mL-1 schaftoside showed a significant difference at day 10 (p < 0.05), while there were no difference between the control and the treatment group of 0.05 mg mL-1 or 0.10 mg mL-1. At day 15, BPH survival rate in 0.15 mg mL-1 schaftoside treatment group showed a large decrease to 36%, while the control still remained at a higher level of 85% (Figure 6), suggesting that schaftoside had a strong lethal effect on BPH at this concentration.

FIGURE 6. Effects of schaftoside treatment on BPH. The results were expressed as the means ± SD from 10 independent experiments with 10 glass tubes (10 nymphs in each tube) examined for each treatment. The survival rates were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey HSD at each sampling time, and the asterisks on the bars indicated significant differences between the control (0 mg/mL) and the corresponding treatment group (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01).

Expression and Purification of NlCDK1

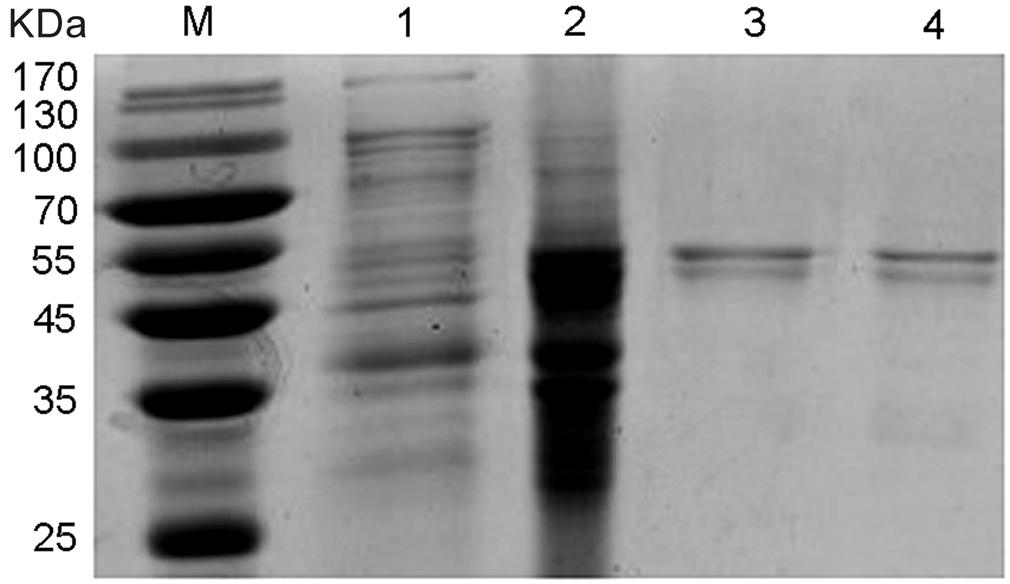

The competent E. coli BL21 (DE3) with recombinant plasmids of pET32a /NlCDK1 were induced by IPTG, and the recombinant proteins were then purified from the protein lysate using Ni2+-NTA affinity chromatography column. The purified protein, as well as the protein lysates of the crushed bacteria, was analyzed by 12% SDS–PAGE. The result showed that the target recombinant proteins with a molecular weight of about 55 kDa were obtained (Figure 7). The recombinant protein contains a fusion protein with histidine marker (about 20.4 kDa) encoded by the pET-32a(+) vector, so the molecular weight of the target NlCDK1 protein is very close to the theoretical value 34.7 kDa, indicating that NlCDK1 was successfully expressed and purified.

FIGURE 7. SDS–PAGE gel analysis of recombinant protein NlCDK1. The expression of NlCDK1 expressed in E. coli strain BL21(DE3)/pET32a was induced by 0.5 mM IPTG. The samples were analyzed in 12% SDS–PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250. M: molecular weight markers; Lane 1: total cell lysate of BL21(DE3)/pET32a prior to induction; lane 2: protein of total cells after IPTG induction for 12 h; lane 3: purified and denatured NlCDK1 protein in inclusion bodies; lane 4: purified and refolded NlCDK1 protein.

Binding Property of NlCDK1 With Schaftoside

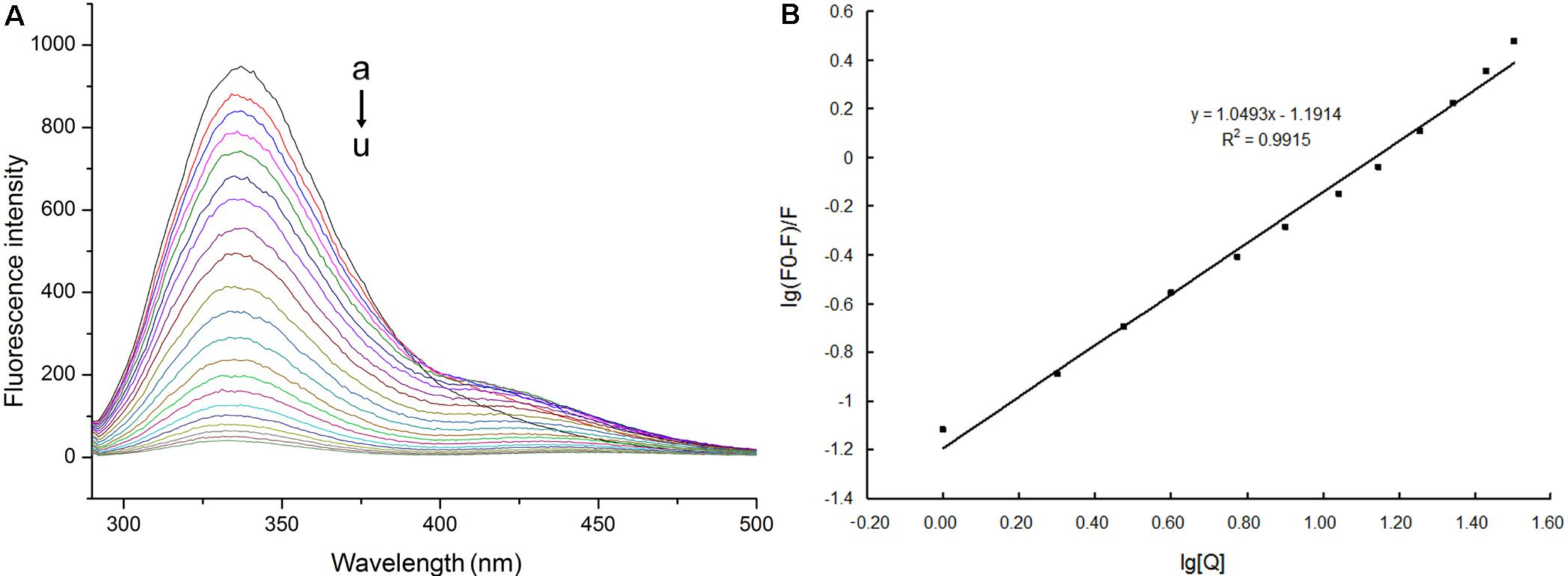

The fluorescent spectra were obtained by titrating schaftoside into the recombinant NlCDK1 protein solution. The fluorescent intensity of NlCDK1 regularly dropped at 335 nm with the titrating of schaftoside, and the emission peaks of the protein showed a very similar pattern at the different concentrations of schaftoside (Figure 8A). This reflected that non-fluorescent complexes were generated when schaftoside reached to NlCDK1 protein. Therefore, schaftoside has a strong ability to bind with NlCDK1.

FIGURE 8. Fluorescence spectra and plots of log[(F0-F)/F] versus log[Q] for NlCDK1 binding with schaftoside. (A) C (schaftoside)/(μmol L-1): a, 0; b, 0.5; c, 1.0; d, 2.0;e, 3.0; f, 5.0; g, 7.0; h, 10.0; i, 13.0; j, 17.0; k, 21.0; l, 28.0; m, 35.0; n, 45.0; o, 55.0;p, 67.0; q, 79.0; r, 93.0; s, 107.0; t, 123.0; u, 139.0. (B) C (NlCDK1) = 0.24 × 10-6 mol L-1; pH = 7.4; ex = 281 nm. The increasing concentration of schaftoside (B) was in accordance with that in the fluorescence spectra (A) when it was titrating from a to l; log[(F0-F)/F] = logKA + nlog[Q] was presented as y = 1.0493x–1.1914.

NlCDK1 protein binding with schaftoside was further studied by the equation: log[(F0-F)/F] = logKA + nlog[Q]. F0 is the fluorescent intensity without a quencher (Q), while F stands for the fluorescent intensity at [Q] concentration of a quencher added. KA is the apparent association constant, and n stands for the number of binding sites per protein. Both KA and n were obtained once a plot of log[(F0 - F)/F] versus log[Q] was constructed (Figure 8B). In Figur 8, log[(F0-F)/F] = logKA + nlog[Q] was presented as y = 1.0493x-1.1914. According to the double logarithm equation, the apparent association constant KA for NlCDK1 binding with schaftoside is calculated as 6.436 × 103 L/mol, and the number of binding sites per protein n is 1.0493, which means that each NlCDK1 protein can bind with at least one schaftoside.

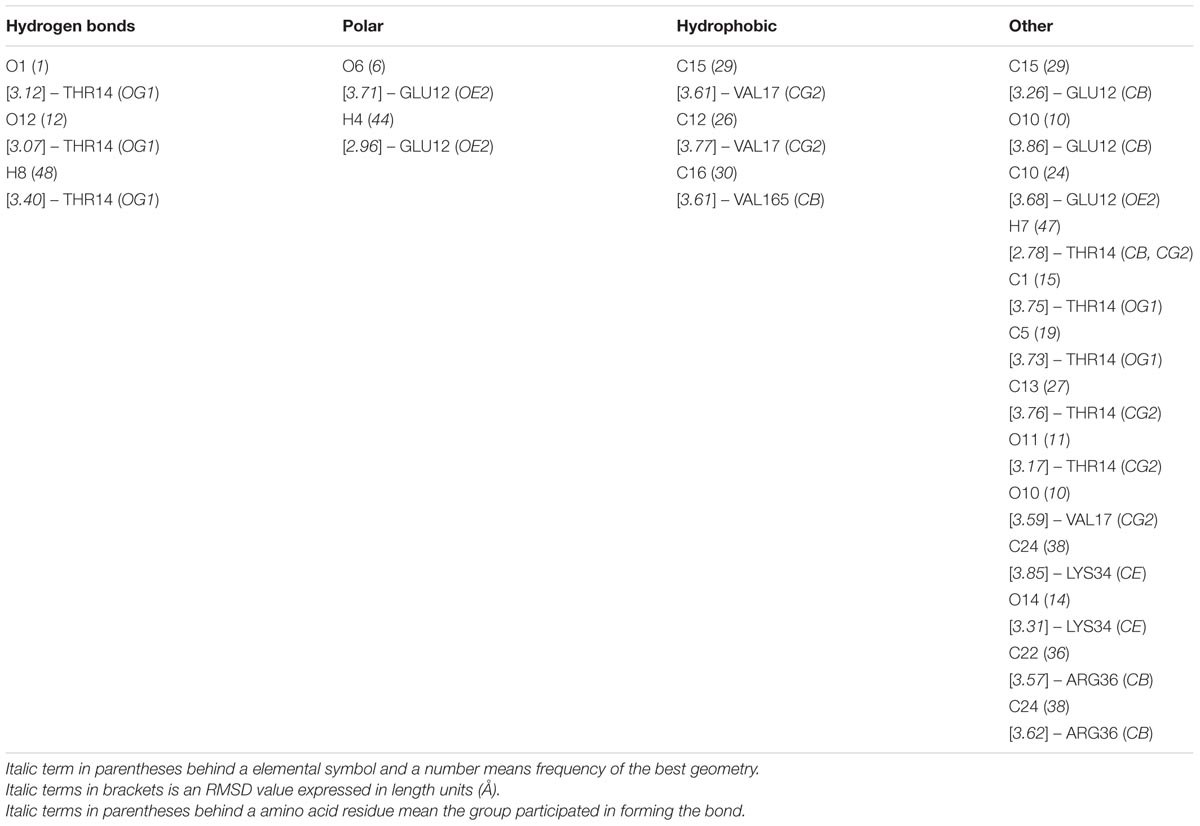

Molecular Docking

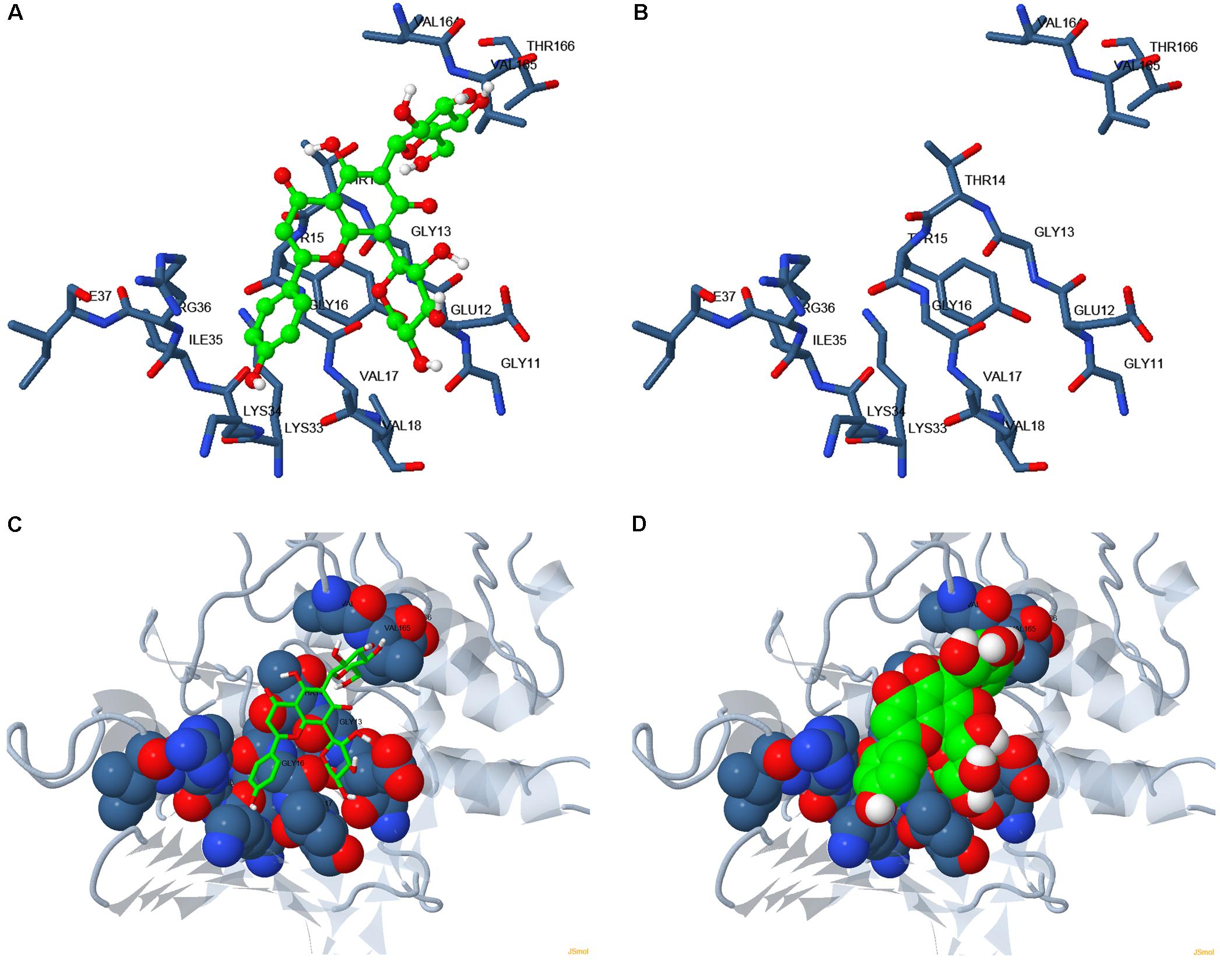

Based on the structure of CDK1 protein (PDB entry code: 4y72.1.A) available in the Protein Data Bank archive4, the tertiary structure of NlCDK was predicted by SWISS-MODEL Workspace (Supplementary Figure S4). The binding mode of schaftoside and NlCDK1 protein was predicted by molecular docking analysis using DockingServer. The docking result suggested that schaftoside strongly interacts with NlCDK1 protein, promoted by -4.61 kcal/mol (ca. -19.36 kJ/mol) free energy of binding. Hydrogen bonds, polar groups and hydrophobic interactions are main forces contributing to schaftoside binding with NlCDK1. Schaftoside binds to the region of ATP binding element GXGXXGXV (Gly11–Val18) of NlCDK1 protein, at least through interacting with 3 amino acid residues Glu12, Thr14, and Val17 (Figure 9 and Table 2). Schaftoside competed for binding to the phosphate site Thr14 by forming a strong hydrogen bond (O1-OG1), which indicated that the activation of NlCDK1 as a protein kinase should be seriously affected (Table 2). In addition, schaftoside also interacted with Lys34 and Arg36, blocking the cleft where the catalytic Lys33 located, and might affect the activity of NlCDK1 protein kinase (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure S5).

FIGURE 9. Binding mode of schaftoside to NlCDK1 binding sites. (A,C,D) Schaftoside binding with NlCDK1. (B) The same amino acid residues located close to the binding regions of NlCDK1 as shown in (A), without binding schaftoside. Carbon atoms in NlCDK1 and schaftoside are shown in blue and green, respectively. Colors of other atoms are as follows: oxygen (red), nitrogen (light blue). In (C,D), gray color represented for non-binding regions of NlCDK1 (local spacial structure).

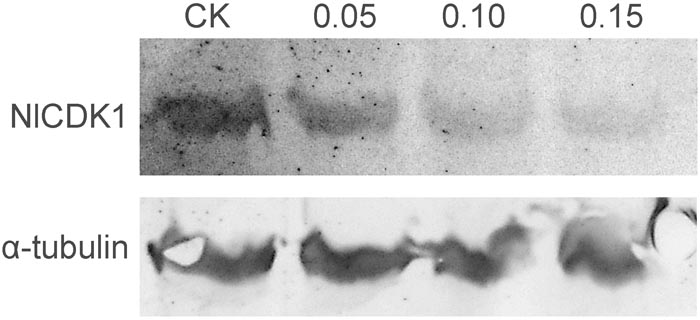

Effects of Schaftoside on the Activation of NlCDK1 Kinase

The phosphorylation level on Thr-14 of NlCDK1 was probed with anti-phospho-CDK1 (pThr14) antibody, and the result showed that phosphorylation levels on Thr-14 of NlCDK1 generally decreased with the increase of schaftoside concentrations (Figure 10). When treated with 0.15 mg/ml schaftoside, phosphorylation on Thr-14 of NlCDK1 was almost decreased to an undetectable level. Phosphorylation on Thr-14 is one of the steps for the activation of CDK1 kinase, so the decrease of the phosphorylation level on Thr-14 suggested that the activation of NlCDK1 as a protein kinase was suppressed with schaftoside treatment.

Discussion

Currently, characterization and identification of rice resistant genes against BPH have made great progress (Tamura et al., 2014). In contrast, identification of active compounds in rice against BPH are relatively weak, especially, little attention has been paid to the interaction of the active compound and its target in BPH. In this study, we identified a BPH resistance-associated compound schaftoside in rice, and found that schaftoside played its role in a dose dependent manner. The fluorescent spectra test showed that schaftoside has a strong ability to bind with NlCDK1. Docking model and western blot analysis confirmed that schaftoside treatment suppressed the phosphorylation on Thr-14 of NlCDK1, and as a result, inhibited the activation of NlCDK1 kinase. Most notably, this is the first study to our knowledge to investigate the interaction between schaftoside and NlCDK1. This study therefore unraveled a novel mechanism of rice resistance against BPH, and provided a valuable message for developing new strategy to control BPH.

In this study, total flavonoids were extracted and compared between different rice varieties. The results showed that rice plants including the susceptible varieties are rich in flavonoids. Further investigation found that the content of schaftoside is higher in resistant rice varieties than that in the susceptible, which indicates that schaftoside was implicated in rice resistance to BPH. Feeding experiments showed that schaftoside played its role in a dose dependant manner, which is similar to the previous findings using different rice lines (Grayer et al., 1994; Stevenson et al., 1996). We therefore suggested that the resistance of rice is closely related to the content of schaftoside, that is, rice varieties with low content of schaftoside are susceptible to BPH, while those with high content of schaftoside are resistant.

Fluorescent spectral experiment revealed that the concentration of schaftoside is an important element affecting the state of NlCDK1. The fluorescent intensity of NlCDK1 decreased with the increasing of schaftoside added, suggesting that more and more NlCDK1 was bound owing to the concentration of schaftoside went higher. To understand the molecular mechanism of schaftoside inaction with NlCDK1 protein, we performed molecular docking analysis, and the result suggested that schaftoside binds to the region of ATP binding element GXGXXGXV (Gly11 to Val18) of NlCDK1 protein, at least through interacting with 3 amino acid residues Glu12, Thr14, and Val17 (Figure 9 and Table 2). CDK1 activity is regulated by phosphorylation and/or dephosphorylation on Thr14, Tyr15, and Thr161 (Parker and Piwnica-Worms, 1992). The ATP binding element GXGXXGXV of NlCDK1 contains 2 phosphate sites Thr14 and Tyr15 (Figure 9 and Supplementary Figure S5), so the binding of schaftoside might affect the interacting of ATP and the regulating proteins upstream, such as wee1 and cdc25. Similarly, some flavonoids, such as chalcones and flavones, have also been reported as potent ATP competitive inhibitor of CDK1 (Navarro-Retamal and Caballero, 2016). Under a situation that schaftoside competed for binding to the phosphate site Thr14 by forming a strong hydrogen bond (O1-OG1), the activation of NlCDK1 as a protein kinase should be affected (Table 2). More importantly, western blot test using anti-phospho-CDK1 (pThr14) showed that phosphorylation levels on Thr-14 of NlCDK1 generally decreased with the increase of schaftoside concentrations, suggesting that schaftoside suppressed the activation of NlCDK1 kinase in a dose dependent manner (Figure 10). As described above, the resistant rice varieties contain more schaftoside, which indicates that BPH on resistant rice should gain more schaftoside from the plant. Therefore, with the accumulation of schaftoside ingested in BPH on resistant rice, more and more NlCDK1 would be bound and inhibited, and finally resulted in the death of BPH.

As described above, schaftoside affected the survival rate of BPH in a dose dependent manner. Molecular docking and western blot analysis strongly suggested that schaftoside suppressed the activation of NlCDK1 kinase, at least, by inhibiting the phosphorylation on Thr-14 site. Therefore, we think that higher concatenation of schaftoside would suppress more NlCDK1, and resulted in lower survival rate of BPH. Recently, we knockdown the expression of NlCDK1 using RNA interference technique, and found that NlCDK1 was required for the survival of BPH (Hao et al., 2018). However, it is still unclear how the inhibition of NlCDK1 resulted in the death of BPH. As is known, CDK1 is involved in diverse physiological processes, except for its famous role in cell cycle regulation. For example, CDK1 is also related to mitochondrial functions, including the adaptation to stress (Candas et al., 2013), regulation of mitochondrial preprotein translocase (Harbauer et al., 2014). It was also reported that CDK1 functioned in mitochondrial ATP generation, and dysfunction of CDK1 resulted in cell death (Rosenthal and Rosenthal, 2014; Li et al., 2016). Hence, a possibility is that CDK1 inhibition caused dysfunction of mitochondrial and decreases of ATP generation, and finally affected the survival of BPH. In the future, further study on how NlCDK1 inhibition affects the survival of BPH is needed, and some approaches like transcriptome or proteome analysis should be helpful in exploring the related genes, proteins, or pathways in responding to schaftoside treatment.

Conclusion

In summary, we established HPLC fingerprints of the total flavonoids extracted from different rice varieties, and identified a resistance related compound as schaftoside using HPLC, MS/MS and NMR techniques. Schaftoside showed significant lethal effect on BPH in a dose dependent manner. The fluorescent spectra test and docking model suggested that schaftoside has a strong ability to bind with NlCDK1. Western blot analysis confirmed that schaftoside treatment suppressed the phosphorylation on Thr-14 of NlCDK1 kinase, and inhibited the activation of the kinase. Therefore, this research not only clarified a new mechanism of rice resistance against BPH by revealing the schaftoside-NlCDK1 interaction mode, but also provided a valuable message for developing some strategies to control BPH. In the future, it is a potentially important strategy to develop BPH-resistant rice with higher content of schaftoside in sustainable agriculture, through breeding hybrid varieties or constructing gene modified rice. It is also possible to design new insecticides with strategies like computer-aided drug design, based on the knowledge of interaction between schaftoside and its target protein NlCDK1.

Author Contributions

P-YH and X-PY designed the research. P-YH, Y-LF, Y-SZ, YM, C-LY, X-MS, and H-LL performed the research or analyzed data. P-YH, Y-LF, Y-SZ, and X-PY prepared and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31672026, 31171860, 31772544, and 30900944), 973 Program for Key Basic Research of the Ministry of Science and Technology, China (Grant Nos. 2011CB111602 and 2012CB114100), The Research on Public Welfare Technology Application Projects of Zhejiang Province, China (Grant Nos. 2017C37092, Y3090184, and 2012C22041).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.00710/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

BPH, brown planthopper; HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography; MS, mass spectrometry; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance.

Footnotes

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- ^ https://www.swissmodel.expasy.org

- ^ https://www.dockingserver.com/web

- ^ http://www.wwpdb.org

References

Aboshi, T., Ishiguri, S., Shiono, Y., and Murayama, T. (2018). Flavonoid glycosides in Malabar spinach Basella alba inhibit the growth of Spodoptera litura larvae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 82, 9–14. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2017.1406301

Bakhtiar, A., Gleye, J., Moulis, C., and Fourasté, I. (1994). Desorption chemical ionization mass spectrometry of C-glycosylflavones. Phytochem. Anal. 5, 86–89. doi: 10.1002/pca.2800050208

Björklund, M., Taipale, M., Varjosalo, M., Saharinen, J., Lahdenpera, J., and Taipale, J. (2006). Identification of pathways regulating cell size and cell-cycle progression by RNAi. Nature 439, 1009–1013. doi: 10.1038/nature04469

Bottrell, D. G., and Schoenly, K. G. (2012). Resurrecting the ghost of green revolutions past: the brown planthopper as a recurring threat to high-yielding rice production in tropical Asia. J. Asia Pac. Entomol. 15, 122–140. doi: 10.1016/j.aspen.2011.09.004

Candas, D., Fan, M., Nantajit, D., Vaughan, A. T., Murley, J. S., Woloschak, G. E., et al. (2013). CyclinB1/Cdk1 phosphorylates mitochondrial antioxidant MnSOD in cell adaptive response to radiation stress. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 166–175. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjs062

Dou, J., Lee, V. S., Tzen, J. T., and Lee, M. R. (2007). Identification and comparison of phenolic compounds in the preparation of oolong tea manufactured by semifermentation and drying processes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 55, 7462–7468. doi: 10.1021/jf0718603

Erb, M., Balmer, D., De Lange, E. S., Von Merey, G., Planchamp, C., Robert, G., et al. (2011). Synergies and trade-offs between insect and pathogen resistance in maize leaves and roots. Plant Cell Environ. 34, 1088–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02307.x

Farooq, M., Jabran, K., Cheema, Z. A., Wahid, A., and Siddique, K. H. (2011). The role of allelopathy in agricultural pest management. Pest Manag. Sci. 67, 493–506. doi: 10.1002/ps.2091

Ferreres, F., Silva, B. M., Andrade, P. B., Seabra, R. M., and Ferreira, M. A. (2003). Approach to the study of C-glycosyl flavones by ion trap HPLC-PAD-ESI/MS/MS: application to seeds of quince (Cydonia oblonga). Phytochem. Anal. 14, 352–359. doi: 10.1002/pca.727

Fu, Q., Zhang, Z., Hu, C., Lai, F., and Sun, Z. (2001). A chemically defined diet enables continuous rearing of the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens (Stål) (Homoptera: Delphacidae). Entomol. Zool. 36, 111–116. doi: 10.1303/aez.2001.111

Gouveia, S. C., and Castilho, P. C. (2010). Characterization of phenolic compounds in Helichrysum melaleucum by high-performance liquid chromatography with on-line ultraviolet and mass spectrometry detection. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 24, 1851–1868. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4585

Grayer, R. J., Kimmins, F. M., Stevenson, P. C., Harborne, J. B., and Wijayagunesekera, H. N. P. (1994). Phenolics in rice phloem sap as sucking deterrents to the brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens). Acta Hortic. 381, 391–394. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.1994.381.100

Hao, P., Ma, Y., Feng, Y., Lu, C., and Yu, X. (2018). NlCDK1 gene is required for the ovarian development and survival of the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens Stål, as revealed by RNA interference. J. Asia Pac. Entomol. 21, 316–321. doi: 10.1016/j.aspen.2018.01.013

Hao, P. Y., Lu, C. F., Ma, Y., Xu, L. B., Zhu, J. J., and Yu, X. P. (2015). Roles of NlAKTIP in the growth and eclosion of the rice brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens Stål, as revealed by RNA interference. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 22888–22903. doi: 10.3390/ijms160922888

Harbauer, A. B., Opalinska, M., Gerbeth, C., Herman, J. S., Rao, S., Schönfisch, B., et al. (2014). Cell cycle-dependent regulation of mitochondrial preprotein translocase. Science 346, 1109–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.1261253

Hu, J., Cheng, M. X., Gao, G. J., Zhang, Q. L., Xiao, J. H., and He, Y. (2013). Pyramiding and evaluation of three dominant brown planthopper resistance genes in the elite indica rice 9311 and its hybrids. Pest Manag. Sci. 69, 802–808. doi: 10.1002/ps.3437

Kamphuis, L. G., Lichtenzveig, J., Peng, K., Guo, S. M., Klingler, J. P., Siddique, K. H., et al. (2013). Characterization and genetic dissection of resistance to spotted alfalfa aphid (Therioaphis trifolii) in Medicago truncatula. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 5157–5172. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert305

Li, H. B., Wang, R. X., Jiang, H. B., Zhang, E. D., Tan, J. Q., Xu, H. Z., et al. (2016). Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L10 associates with Cyclin B1/CDK1 activity and mitochondrial function. DNA Cell Biol. 35, 680–690. doi: 10.1089/dna.2016.3271

Liu, Y., Wu, H., Chen, H., Liu, Y., He, J., Kang, H., et al. (2015). A gene cluster encoding lectin receptor kinases confers broad-spectrum and durable insect resistance in rice. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 301–305. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3069

Navarro-Retamal, C., and Caballero, J. (2016). Flavonoids as CDK1 inhibitors: insights in their binding orientations and structure-activity relationship. PLoS One 11:e0161111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161111

Nenaah, G. E. (2013). Potential of using flavonoids, latex and extracts from Calotropis procera (Ait) as grain protectants against two coleopteran pests of stored rice. Ind. Crops Prod. 45, 327–334. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.12.043

Onyilagha, J. C., Lazorko, J., Gruber, M. Y., Soroka, J. J., and Erlandson, M. A. (2004). Effect of flavonoids on feeding preference and development of the crucifer pest Mamestra configurata Walker. J. Chem. Ecol. 30, 109–124. doi: 10.1023/B:JOEC.0000013185.62475.65

Park, D. S., Lee, S. K., Lee, J. H., Song, M. Y., Song, S. Y., Kwak, D. Y., et al. (2007). The identification of candidate rice genes that confer resistance to the brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens) through representational difference analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 115, 537–547. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0587-0

Parker, L. L., and Piwnica-Worms, H. (1992). Inactivation of the p34cdc2-cyclin B complex by the human WEE1 tyrosine kinase. Science 257, 1955–1957. doi: 10.1126/science.1384126

Pereira, O. R., Silva, A., Domingues, M. R., and Cardoso, S. M. (2012). Identification of phenolic constituents of Cytisus multiflorus. Food Chem. 131, 652–659. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.09.045

Petrussa, E., Braidot, E., Zancani, M., Peresson, C., Bertolini, A., Patui, S., et al. (2013). Plant flavonoids-biosynthesis, transport and involvement in stress responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 14950–14973. doi: 10.3390/ijms140714950

Qin, L. L., Fan, M., Candas, D., Jiang, G. C., Papadopoulos, S., Tian, L., et al. (2015). CDK1 enhances mitochondrial bioenergetics for radiation-induced DNA repair. Cell Rep. 13, 2056–2063. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.11.015

Rosenthal, C. K., and Rosenthal, C. K. (2014). Cdk1 boosts mitochondrial energy production. Nat. Cell Biol. 16:511. doi: 10.1038/ncb2982

Seo, J., Kang, S. I., Kim, M., Han, J., and Hur, H. G. (2011). Flavonoids biotransformation by bacterial non-heme dioxygenases, biphenyl and naphthalene dioxygenase. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 91, 219–228. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3334-z

Simirgiotis, M. J., Schmeda-Hirschmann, G., Bórquez, J., and Kennelly, E. J. (2013). The Passiflora tripartita (Banana Passion) fruit: a source of bioactive flavonoid C-glycosides isolated by HSCCC and characterized by HPLC-DAD-ESI/MS/MS. Molecules 18, 1672–1692. doi: 10.3390/molecules18021672

Simmonds, M. S. (2001). Importance of flavonoids in insect-plant interactions: feeding and oviposition. Phytochemistry 56, 245–252. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00453-2

Stevenson, P. C., Kimmins, F. M., Grayer, R. J., and Raveendranath, S. (1996). Schaftosides from rice phloem as feeding inhibitors and resistance factors to brown planthoppers. Nilaparvata lugens. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 80, 246–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.1996.tb00928.x

Su, Q., Zhou, Z., Zhang, J., Shi, C., Zhang, G., Jin, Z., et al. (2018). Effect of plant secondary metabolites on common cutworm, Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Entomol. Res. 48, 18–26. doi: 10.1111/1748-5967.12238

Sun, X. Q., Zhang, M. X., Yu, J. Y., Jin, Y., Ling, B., Du, J. P., et al. (2013). Glutathione S-transferase of brown planthoppers (Nilaparvata lugens) is essential for their adaptation to gramine-containing host plants. PLoS One 8:e64026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064026

Tamura, Y., Hattori, M., Yoshioka, H., Yoshioka, M., Takahashi, A., Wu, J., et al. (2014). Map-based cloning and characterization of a brown planthopper resistance gene BPH26 from Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica Cultivar ADR52. Sci. Rep. 4:5872. doi: 10.1038/srep05872

Xie, C., Veitch, N. C., Houghton, P. J., and Simmonds, M. S. (2003). Flavone C-glycosides from Viola yedoensis Makino. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 51, 1204–1207. doi: 10.1002/chin.200412218

Zhang, Z., Cui, B., Yan, S., Li, Y., Xiao, H., Li, Y., et al. (2017). Evaluation of tricin, a stylet probing stimulant of brown planthopper, in infested and non-infested rice plants. J. Appl. Entomol. 141, 393–401. doi: 10.1111/jen.12353

Zhou, Y. S. (2011). Separation of Flavonoids from Rice and its Resistance to Brow Planthopper Nilaparvata lugens Stål. Master’s thesis, China Jiliang University, Hangzhou.

Zhou, Y. S., Hao, P. Y., and Yu, X. P. (2011). “Flavonoids in rice: ultrasonic extraction and its insecticidal effect on the brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens Stål,” in Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on IT in Medicine and Education, Vol. 2 (Guangzhou: Guangzhou University), 720–724.

Keywords: rice, varietal resistance, flavonoids, schaftoside, brown planthopper, CDK1 protein, interaction mechanism

Citation: Hao P-Y, Feng Y-L, Zhou Y-S, Song X-M, Li H-L, Ma Y, Ye C-L and Yu X-P (2018) Schaftoside Interacts With NlCDK1 Protein: A Mechanism of Rice Resistance to Brown Planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens. Front. Plant Sci. 9:710. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00710

Received: 10 January 2018; Accepted: 09 May 2018;

Published: 29 May 2018.

Edited by:

Wanchai De-Eknamkul, Chulalongkorn University, ThailandReviewed by:

Rensen Zeng, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, ChinaKhawar Jabran, Düzce University, Turkey

Copyright © 2018 Hao, Feng, Zhou, Song, Li, Ma, Ye and Yu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiao-Ping Yu, eXhwQGNqbHUuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Pei-Ying Hao

Pei-Ying Hao Ya-Lin Feng

Ya-Lin Feng Yi-Shen Zhou†

Yi-Shen Zhou† Xin-Mi Song

Xin-Mi Song Hong-Liang Li

Hong-Liang Li Yan Ma

Yan Ma Cheng-Long Ye

Cheng-Long Ye Xiao-Ping Yu

Xiao-Ping Yu