- 1State Key Laboratory of Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, College of Biological Sciences, China Agricultural University, Beijing, China

- 2Rice Research Institution, AnHui Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Hefei, China

- 3Department of Food and Biological Technology, College of Food Science and Nutritional Engineering, China Agricultural University, Beijing, China

Organ abscission is an important plant developmental process that occurs in response to environmental stress or pathogens. In Arabidopsis, ligand signals, such as ethylene or INFLORESCENCE DEFICIENT IN ABSCISSION (IDA), can regulate organ abscission. Previously, we reported that overexpression of AtDOF4.7, a transcription factor gene, directly suppresses the expression of the abscission-related gene ARABIDOPSIS DEHISCENCE ZONE POLYGALACTURONASE 2 (ADPG2), resulting in a deficiency of floral organ abscission. However, the relationship between AtDOF4.7 and abscission pathways still needs to be investigated. In this study, we showed that ethylene regulates the expression of AtDOF4.7, and the peptide ligand, IDA negatively regulates AtDOF4.7 at the transcriptional level. Genetic evidence indicates that AtDOF4.7 and IDA are involved in a common pathway, and a MAPK cascade can phosphorylate AtDOF4.7 in vitro. Further in vivo data suggest that AtDOF4.7 protein levels may be regulated by this phosphorylation. Collectively, our results indicate that ethylene regulates AtDOF4.7 that is involved in the IDA-mediated floral organ abscission pathway.

Introduction

Plant floral organ abscission is an important developmentally controlled process. Arabidopsis thaliana is an ideal model in which to study organ abscission (Bleecker and Patterson, 1997). In Arabidopsis, at the bases of the filaments, petals, and sepals in the floral organ, there are some small, high-density cell layers known as abscission zone (AZ), where the abscission process takes place (Patterson, 2001). The AZ cells perceive the abscission signal and subsequently activate cell wall-degrading proteins. Finally, the pectin-rich middle lamellae of AZ cell walls are dissolved, resulting in the detachment of unwanted organs from the main plant body (Patterson, 2001; Patterson and Bleecker, 2004; Niederhuth et al., 2013a).

Ethylene is thought to temporally regulate floral organ abscission (Jackson and Osborne, 1970; Niederhuth et al., 2013a). Historically, exogenous ethylene treatment has been shown to cause acceleration of abscission (Patterson and Bleecker, 2004; Butenko et al., 2006). Several key components of ethylene signaling, including ETHYLENE RESPONSE 1 (ETR1) and ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE 2 (EIN2), have been found to participate in the regulation of floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis (Chang et al., 1993; Patterson and Bleecker, 2004; Butenko et al., 2006). Both the etr1 and ein2 ethylene-insensitive mutants exhibit significantly delayed abscission.

Several reports have indicated that abscission can be regulated in an ethylene-independent manner. It was originally found that the important plant hormone auxin could regulate the differentiation of the AZ of the leaf rachis in Sambucus nigra through transportation of auxin from the organ distal to the AZ (Osborne and Sargent, 1976; Morris, 1993). In Arabidopsis, auxin negatively regulates several polygalacturonases (PGs) in the dehiscence zone (DZ) to cause a delay in cell separation (Dal Degan et al., 2001; Ellis et al., 2005). Mutation of Auxin Response Factor 2 (ARF2) can lead to a delay in floral organ abscission. Furthermore, the effect of a delay in abscission can be enhanced by mutations in ARF1, ARF2, NPH4/ARF7, and ARF19 (Ellis et al., 2005; Okushima et al., 2005), suggesting that these overlapping genes regulate auxin-mediated floral organ abscission in an ethylene-independent manner.

Other than phytohormone, signaling peptides also play important roles in the regulation of abscission. In Arabidopsis, a short peptide, INFLORESCENCE DEFICIENT IN ABSCISSION (IDA) has a key role in the regulation of floral organ abscission (Butenko et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2013). The ida single mutant fails to abscise its floral organs (Butenko et al., 2003), and constitutive expression of IDA in Arabidopsis (35S:IDA) induces premature organ abscission (Stenvik et al., 2006). Two leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinases (LRR-RLKs), HAE and HSL2, are required for organ abscission. Double mutants for these two genes display organ abscission defects (Jinn et al., 2000; Cho et al., 2008; Stenvik et al., 2008; Niederhuth et al., 2013b). As previously reported, Arabidopsis perceives and responds to environmental signals through an interaction between extracellular peptides and plasma membrane-bound RLKs (Stenvik et al., 2008). IDA may act as a ligand binding to the HAE/HSL2 RLK, which transmits the abscission signal to downstream substrates to initiate organ abscission (Cho et al., 2008; Stenvik et al., 2008).

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades play crucial roles in regulating various plant responses. There are two MEKs (MKK4 and MKK5) that are involved in floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis (Cho et al., 2008). Their downstream target substrates are MPK3 and MPK6 (Ren et al., 2002; Cho et al., 2008). MKK4 and MKK5 RNA interference (RNAi) transgenic lines show pleiotropic effects, including organ abscission deficiency, and constitutively active mutants of MKK4DD (T224D/S230D) and MKK5DD (T215D/S221D) that strongly activate endogenous MPK3 and MPK6 can restore abscission in the ida-2 and hae hsl2 mutants (Ren et al., 2002; Cho et al., 2008). Although the mpk3 and mpk6 single mutants exhibit normal organ abscission, the mpk3 mpk6 double mutant is lethal (Wang et al., 2007), while functionally inactive forms of MPK6 are expressed in mpk3 mutant plants, mpk3/MPK6KR (Lys, the key residue of phosphate transferring, mutated to Arg) or mpk3/MPK6AF (the conserved sites of phosphorylation by MKK, Thr and Tyr, mutated to Ala and Phe, respectively), survive and display loss of organ abscission (Cho et al., 2008). Furthermore, MPK6 has reduced kinase activity in hae hsl2 and ida-2 mutants. These results demonstrate that MPK6, but not MPK3, plays a dominant role in the regulation of floral organ abscission (Cho et al., 2008). In the ethylene-independent abscission pathway, IDA couples with HAE and HSL2, activating the downstream MAPK cascade to phosphorylate the substrates and initiate the separation of the AZ cells (Cho et al., 2008; Shi et al., 2011; Niederhuth et al., 2013a,b).

Generally, ethylene regulates the timing of floral organ abscission, while IDA influences the degree of abscission. The physiological process of floral organ abscission is generally divided into four stages: (1) differentiation and formation of the AZ; (2) transduction of abscission signals; (3) activation of the abscission process; and (4) post-abscission transdifferentiation (Patterson, 2001; Niederhuth et al., 2013a). The second and third stages of abscission, in which ethylene, IDA, HAE/HSL2, MAPKs and PGs play important roles, have been well-described (Niederhuth et al., 2013a). However, further investigation is needed to understand how these two stages are linked.

We previously reported that AtDOF4.7, a member of the Arabidopsis DNA binding with one finger (DOF) transcription factor family, functions as an abscission inhibitor to directly regulate the expression of ADPG2, which encodes a cell wall-hydrolyzing enzyme, to initiate cell separation (Wei et al., 2010). Nevertheless, it is still an open question whether AtDOF4.7 is a factor that acts between the second and third stage of abscission, potentially in a cascade of abscission signals that are transmitted from the second to the third stage through AtDOF4.7. In the present study, we demonstrated that AtDOF4.7 is an additional component of the IDA-mediated abscission pathway, and that it is regulated by ethylene and IDA. Our results suggest that AtDOF4.7 is regulated by both the ethylene-dependent and ethylene-independent pathways.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material

Arabidopsis thaliana (Columbia-0 ecotype) plants were grown at 22°C in a growth chamber under a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod and a light intensity of 120 μmol m-2 s-1.

The PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS line (Wei et al., 2010) was crossed with ein2-1, etr1-1, and ida-2 (SALK_133209), and 35S:AtDOF4.7 (S107; Wei et al., 2010) was crossed with 35S:IDA and GVG-MKK5DD (Ren et al., 2002). The sequencing primers used to verify hybrids are presented in online Supplementary Table S1. Kanamycin (50 μg ml-1) was employed to select the 35S:IDA and ida-2 mutant plants (Butenko et al., 2003; Stenvik et al., 2006). Hygromycin B (25 μg ml-1) was used to select plants overexpressing AtDOF4.7.

The locus codes of all genes investigated or discussed in this article are listed below: AtDOF4.7, At4g38000; EIN2, At5g03280; ETR1, At1g66340; IDA, At1g68765; HAE, At4g28490; HSL2, AT5G65710; MKK4, At1g51660; MKK5, At3g21220; MPK3, At3g45640; MPK6, At2g43790; ACTIN2, At3g18780; and ADPG2, AT2G41850.

Ethylene and DEX Treatments

PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS/ein2-1 seeds were germinated on 1/2 Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium containing 5 μM ACC in the dark for 3 days to select for ethylene-insensitive mutants.

To analyze the expression pattern of AtDOF4.7 in response to ethylene, 4-weeks-old PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS plants were maintained in an air-tight growth chamber with or without ethylene at 10 ppm (10 μl l-1) for 3 days prior to the analysis.

To observe the abscission phenotype of S107/MKK5DD, siliques of S107/MKK5DD plants were treated with or without 0.02 μM DEX (Sigma, USA) for 24 h to induce MKK5DD expression. The siliques were then photographed with a Cannon G12 camera. Detached leaves from S107/MKK5DD plants were immersed in 15 μM DEX for various times prior to western blotting. Each treatment was repeated at least three times.

β-Glucuronidase (GUS) Assay

β-Glucuronidase (GUS) gene expression was analyzed by staining different flower positions along the inflorescence as described previously (Wei et al., 2010). Histochemical GUS staining in the AZ cells of siliques was observed with an Olympus SZX16-DP72 stereo microscope system.

Quantitative Real-Time and Semi-quantitative RT-PCR

For semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis, total RNA samples were extracted from Arabidopsis siliques using the RNeasy® Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany), and the RNA was reversely transcribed into cDNA with a Reverse Transcription System (Promega, USA). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR assays were run in a MJ Mini Personal Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, USA) with 25 thermal cycles. ACTIN2 (At3g18780) was employed as an internal control.

For quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis, total RNA was extracted from whole flowers and siliques, and qRT-PCR assays were run using the 7500 Real-Time PCR System (ABI, USA). After normalization to an internal control (ACTIN2; Charrier et al., 2002), the relative levels of gene expression were calculated via the Delta-Delta Ct (2-ΔΔCt) method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). All primers are given in online Supplementary Table S2. Each relative gene expression assay was repeated at least three times.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Experiment and BiFc

A yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) experiment was performed as described previously (Wei et al., 2010). Cells that had been co-transformed with the pAD-GAL4-AtDOF4.7 (Wei et al., 2010) and pBD-GAL4-MPK3/MPK6 constructs (Xu et al., 2008) were cultured and transferred to 5 mM 3-AT medium lacking Trp, Leu, His, and Ade, followed by incubation at 28°C for 3 days. Living yeast colonies were photographed with a Cannon G12 camera.

The bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFc) assay (Walter et al., 2004), co-transformation of pUC-SPYCE-MPK3/MPK6 and pUC-SPYNE-AtDOF4.7 (Miao et al., 2006) and examination of YFP fluorescence were all performed as described previously (Walter et al., 2004).

Preparation of Recombinant Proteins

Escherichia coli cells (strains BL21 and DE3) were transformed with the MPK3/6-pET30a(+)-His and MKK5DD-pET28a(+)-FLAG constructs and then incubated as described previously (Liu and Zhang, 2004). His-tagged MPK3/6 recombinant proteins and FLAG-tagged MKK5DD recombinant proteins were purified as described elsewhere (Xu et al., 2008). The AtDOF4.7 CDS was cloned into pMal-c2x (NEB, USA) in frame with the N-terminal MBP tag, and the construct was transformed into the E. coli strain Rosetta (DE3). Recombinant protein expression was induced with 0.1 mM isopropylthio-β-galactoside (IPTG) for 8 h at 18°C. The MBP-tagged protein was purified using amylose resin (NEB, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Protein Extraction and Western Blotting Assay

Total protein was extracted from Arabidopsis silique tissues as described previously (Liu et al., 2007). The protein concentration was determined with a Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, USA), using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard. For western blotting assay, total protein extracts from each sample (10 μg per gel lane) were separated on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. After electrophoresis, the proteins were electro-transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, USA). The membranes were subsequently incubated with an anti-Flag antibody (Cell Signaling, 1:10,000 dilution), washed, and then incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG as a secondary antibody (1:10,000 dilution). The resultant protein bands were visualized by treating the membrane with the ImmobilonTM Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Bands intensities in the western blots were compared using ImageJ software.

Phosphorylation of AtDOF4.7 In Vitro

Recombinant MPK3 (3.2 μg) and MPK6 proteins (5.7 μg) were activated by incubation with recombinant MKK5DD (0.36 μg) in the presence of 50 μM ATP in 50 μl of reaction buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT) at 25°C for 1 h. The activated MPK3 and MPK6 proteins were then used to phosphorylate the AtDOF4.7 protein (1.86 μg, 1:16 enzyme:substrate ratio) in the same reaction buffer containing 25 μM ATP and [γ-32P] ATP at 25°C for 30 min, according to Liu and Zhang (2014). The reaction was stopped by the addition of SDS gel-loading buffer. Using the Mini-PROTEAN® Tetra System (Bio-Rad, USA), the samples were separated via electrophoresis on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel at a constant 120 V. The gel was then dried under vacuum, and the phosphorylated AtDOF4.7 was visualized through autoradiography. Primary anti-His (TIANGEN, China) and anti-Flag (Cell Signaling Technology, USA) antibodies were used to verify the presence of the corresponding proteins in the phosphorylation buffer. Pre-stained protein markers (Fermentas, USA) were employed to calculate the molecular masses of the phosphorylated proteins.

Results

Ethylene Regulates the Expression of AtDOF4.7

A previous study indicated that overexpression of AtDOF4.7 induces abscission defects in an ethylene-independent manner, although the flowers can perceive ethylene, suggesting that AtDOF4.7 might not be a direct target of early ethylene-independent signal transduction (Wei et al., 2010). To investigate the role of AtDOF4.7 downstream of the early abscission pathway, we examined the expression pattern of PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS in the mutants with ethylene-insensitive and ethylene-independent abscission deficiencies.

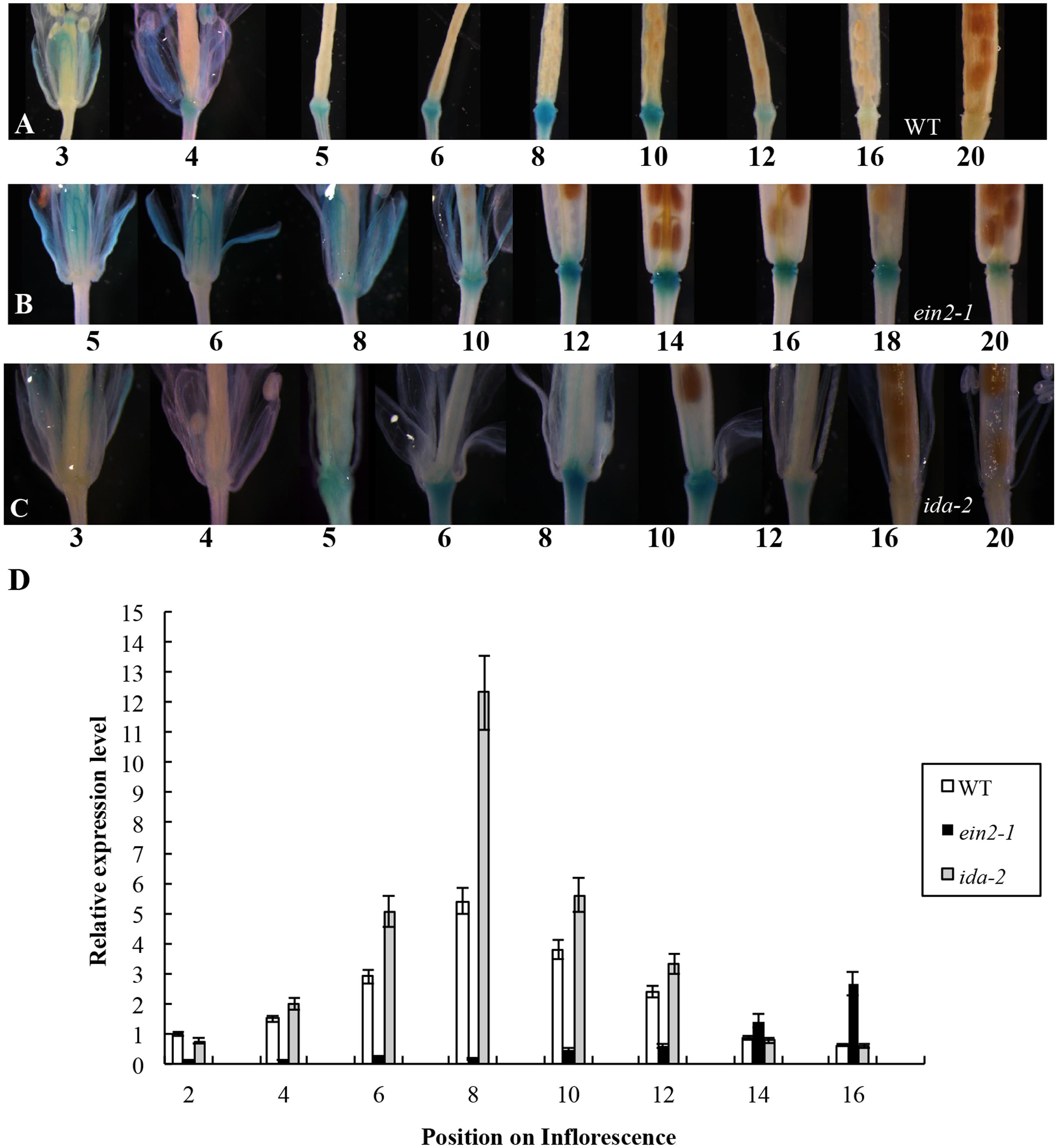

In the earlier report, the first flower showing visible white petals was referred as flower position 1 and then counted downward along the inflorescence in sequence (Wei et al., 2010). We initially crossed a plant carrying a single-copy of the PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS construct with A. thaliana Col-0 (wild-type). The GUS expression pattern in the PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS plant was similar to that reported previously (Figure 1A). GUS expression was observed in the AZ cells at flower position 4, while at position 20, GUS expression from the AtDOF4.7 promoter could scarcely be detected in the AZ cells.

FIGURE 1. Time-course of PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS expression in WT, ein2-1, and ida-2 flower AZ cells. (A) PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS expression in A. thaliana Col-0 (WT). GUS expression was first observed at flower position 4, and reached the maximum level of expression from positions 6 to 8. After flower position 10, expression was reduced, and no expression was detected from positions 16 to 20. Four-weeks-old plants were used for GUS staining. (B) PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS expression in the ein2-1 mutant. GUS staining was first observed at flower position 8, and accumulated to its maximum level from positions 12 to 14. After position 16, GUS staining declined, and little staining was observed at position 20. (C) PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS expression in the ida-2 mutant. The expression pattern was similar to that seen in WT. (D) Relative expression of AtDOF4.7 at different flower positions in WT, ein2-1 and ida-2 plants. Flower position 2 in WT was the control. The temporal expression pattern of AtDOF4.7 in WT was the same as in ida-2. However, the relative expression of AtDOF4.7 in ida-2 was higher from positions 6 to 10 than in WT. At flower positions 14 and 16, the expression level of AtDOF4.7 in the ida-2 background was similar to WT. Compared with WT, the temporal expression pattern of AtDOF4.7 was delayed in the ein2-1 mutant. The relative expression level of AtDOF4.7 in ein2-1 from positions 2 to 12 was significantly lower than in WT. After position 12, the relative expression level of AtDOF4.7 was elevated >2-fold in the ein2-1 compared with WT. Relative mRNA levels were averaged over three biological replicates and are shown with the SD (error bars).

The PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS plants were then crossed with the ethylene-insensitive mutant ein2-1. The expression pattern of PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS in the ein2-1 mutant was altered temporally (Figures 1B,D and Supplementary Figure S3B), although spatial expression was similar to that of the wild type (WT). GUS expression was first observed at position 8 and continued to accumulate until reaching its maximum level at position 14. At position 20, GUS expression was still detectable in the AZ cells (Figure 1B).

The expression pattern of PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS in the etr1-1 mutant was also examined, and we found that the temporal expression pattern was altered in this mutant as well (Supplementary Figure S1). GUS expression was detectable at later flower positions than in PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS/ein2-1 flowers and was faintly visible at position 10. Expression was clearly observed at position 20. In addition, the profile of the spatial expression of AtDOF4.7 in the etr1-1 mutant was similar to that in ein2-1 (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure S1).

Temporally, the expression of PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS in AZ cells in the ethylene-insensitive ein2-1 and etr1-1 mutants was remarkably delayed compared with that in WT. Because, flower abscission is also delayed in the inflorescences of the ein2-1 and etr1-1 mutants (Butenko et al., 2003; Patterson and Bleecker, 2004), we concluded that ethylene can influence AtDOF4.7 expression. To confirm this finding, we placed transgenic plants expressing PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS in an air-tight chamber containing 10 ppm ethylene gas, which can accelerate organ abscission. Compared with the PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS plants that were exposed to air (in the absence of ethylene), GUS expression was detected earlier at flower position 1 in the presence of ethylene (Supplementary Figure S2). The time-course of PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS expression was shortened by ethylene treatment. These experimental results indicated that ethylene can influence the timing of AtDOF4.7 expression, and the time-course of AtDOF4.7 expression could be relevant to organ abscission.

AtDOF4.7 Is a Component of the IDA-Mediated Abscission Pathway Underlying Abscission

In the IDA-mediated abscission pathway in Arabidopsis, IDA binds as a ligand to the RLKs HAE and HSL2 (Stenvik et al., 2008). Some cytoplasmic effectors, such as MKK4, MKK5, MPK3, and MPK6, function together to control cell separation during abscission (Cho et al., 2008). As reported previously, IDA can control the intensity of organ abscission (Butenko et al., 2003; Stenvik et al., 2006). To further determine whether the expression of AtDOF4.7 is regulated by IDA at the transcriptional level, we crossed a PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS transgenic plant with the ida-2 (Col-0) mutant. The temporal expression pattern of PromoterAtDOF4.7::GUS was unaltered in the AZ cells of the siliques in the ida-2 background and was similar to that of AtDOF4.7 in the WT background (Figures 1A,C). However, qRT-PCR showed that the relative expression levels of AtDOF4.7 from flower positions 6 to 10 were significantly higher in the ida-2 background that in WT (Figure 1D and Supplementary Figure S3A). These data suggested that IDA negatively regulates the expression of AtDOF4.7 at the transcriptional level.

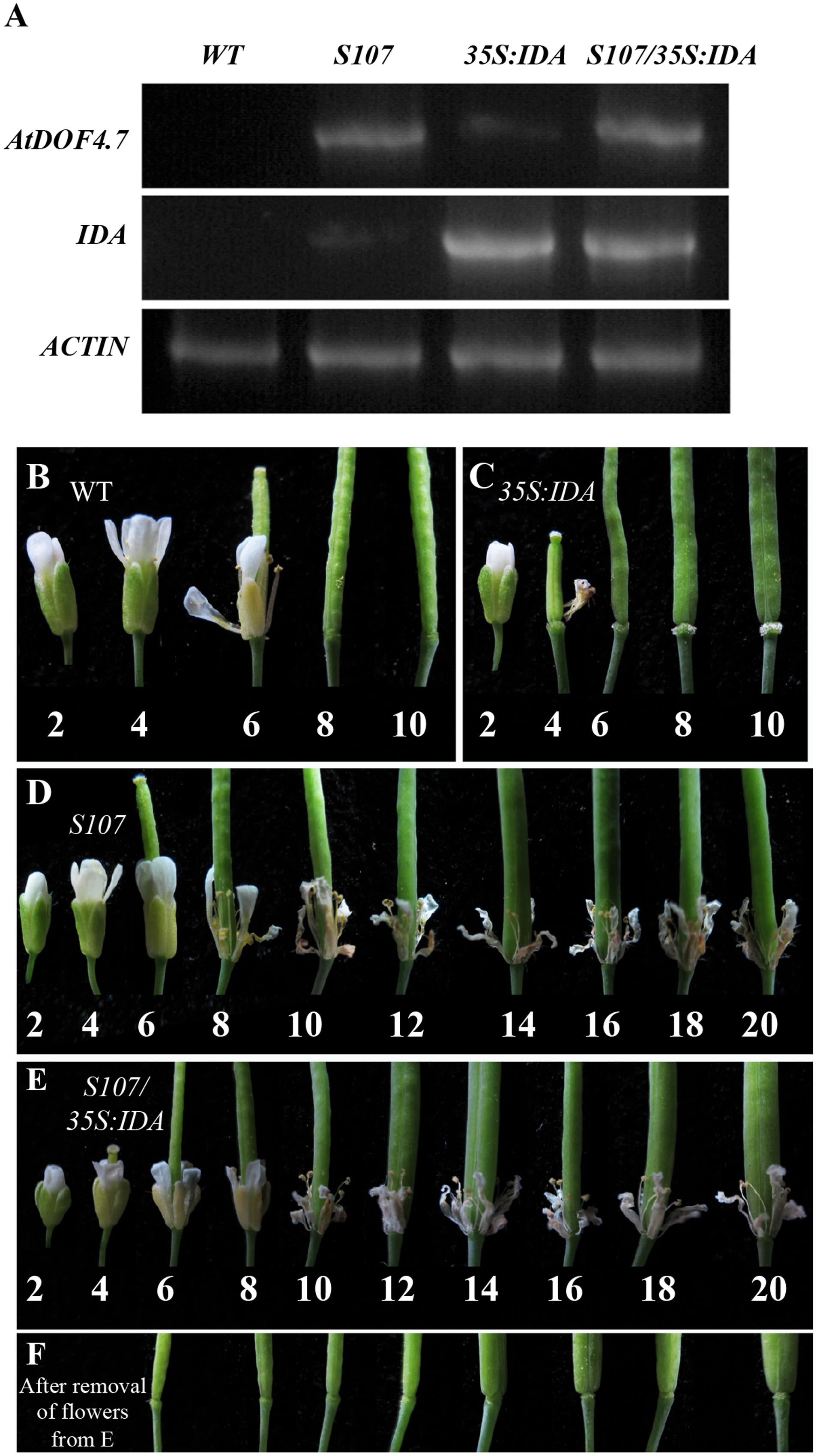

To confirm the hypothesis that IDA and AtDOF4.7 are involved in a common pathway, we crossed an AtDOF4.7-overexpressing line (S107) with 35S:IDA in the Col-0 background, which shows early abscission of the flowers at position 3 (Stenvik et al., 2006). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR demonstrated that both the AtDOF4.7 and IDA genes were overexpressed in the siliques of S107/35S:IDA plants (Figure 2A). The S107/35S:IDA lines showed that the floral organ abscission defect phenotype was similar to that in S107 plants (Figures 2D,E). Most notably, although the transcript levels of IDA were higher than that of AtDOF4.7 in S107/35S:IDA lines, from which the floral organs could not shed (Figures 2A,E). This data suggested that AtDOF4.7 might be epistatic to IDA. The flowers of WT plants exhibited normal abscission at position 6 (Figure 2B). After abscission beginning at position 6, excessive secretion of arabinogalactan protein (AGP) was observed in the AZ cells of the flowers of 35S:IDA plants (Stenvik et al., 2006; Figure 2C). However, there was no AGP observed in the AZ cells of siliques of S107/35S:IDA plants, even after the floral parts on the fruits were removed from positions 6 to 20 (Figure 2F). These results support the hypothesis that IDA and AtDOF4.7 act in a common pathway to regulate abscission, and IDA might be in the upstream abscission pathway.

FIGURE 2. S107/35S:IDA plants are deficient in floral organ abscission. (A) RT-PCR analysis of AtDOF4.7 and IDA expression in S107/35S:IDA transgenic flowers. ACTIN2 (At3g18780) was used as the internal control gene. Both AtDOF4.7 and IDA were overexpressed in S107/35S:IDA siliques. (B) Normal abscission phenotype in WT. Organ abscission began at position 6 and ended at position 8. (C) Premature abscission at position 4 in 35S:IDA flowers. After abscission, white substrate AGPs accumulated around AZ cells at position 6 and, apparently, at position 10. (D) Organ abscission defects from positions 2 to 20 in S107 flowers. (E) Organ abscission defects in S107/35S:IDA flowers from positions 2 to 20. (F) After removal of the petals and filaments in (E) from positions 6 to 20, no AGPs were detected around the AZ cells in S107/35S:IDA siliques. The abscission phenotypes of 4-weeks-old plants are shown in (B–E).

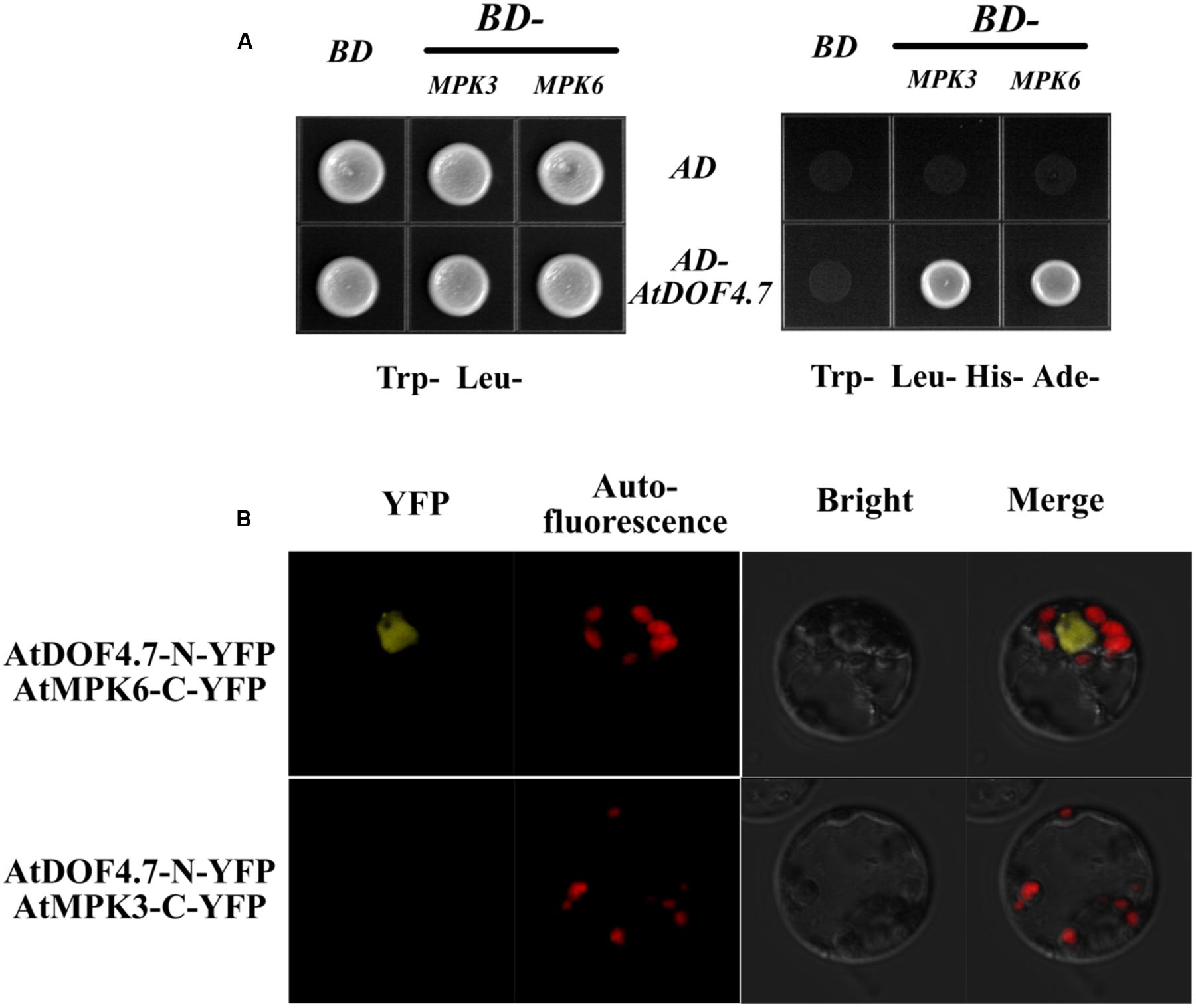

Interaction of AtDOF4.7 with MPK3 and MPK6 In Vivo and In Vitro

A previous study found that the MPK6KR/mpk3 mutant, but not mpk3 or mpk6 single mutants, showed a defective floral abscission phenotype (Cho et al., 2008). Because MPK3 and MPK6 are key components of the IDA-mediated pathway underlying abscission, to understand how AtDOF4.7 is regulated by the MAPKs, we performed yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) and BiFC assays to determine whether AtDOF4.7 interacts with MPK3 or MPK6. The Y2H experiment showed that the transformed yeast cells were able to grow on 5 mM 3-AT medium lacking Trp, Leu, His, and Ade, suggesting an interaction between pAD-GAL4-AtDOF4.7 and pBD-GAL4-MPK3/MPK6 in vivo (Figure 3A). To further confirm the interaction of AtDOF4.7 with MPK3 or MPK6, we constructed the BiFC vectors pUC-SPYNE-AtDOF4.7 and pUC-SPYCE-MPK3/6, and the two constructs were co-transformed into Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts. The cells were then observed using laser fluorescence confocal microscopy; which showed that pUC-SPYNE-AtDOF4.7 and pUC-SPYCE-MPK6 interact in the nuclei (Figure 3B). However, the yellow fluorescence could not be detected from the cells containing pUC-SPYNE-AtDOF4.7 and pUC-SPYCE-MPK3. The BiFC results strongly suggested that AtDOF4.7 and MPK6 physically interact in Arabidopsis.

FIGURE 3. Interaction of AtDOF4.7 with MPK3 and MPK6 in vivo. (A) Yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assay. Although yeast cells containing the indicated vectors could grow on Trp- Leu- medium, only cells containing the pAD-GAL4-AtDOF4.7 and pBD-GAL4-MPK3/MPK6 expression vectors could grow on medium lacking Trp, Leu, His, and Ade. (B) Bifluorescence complementation (BiFc) assay. This assay showing the colocalization of pUC-SPYNE-AtDOF4.7 with pUC-SPYCE-MPK6 in the nuclei of mesophyll protoplasts. Whereas, fluorescence was not be observed from mesophyll protoplasts containing pUC-SPYNE-AtDOF4.7 and pUC-SPYCE-MPK3.

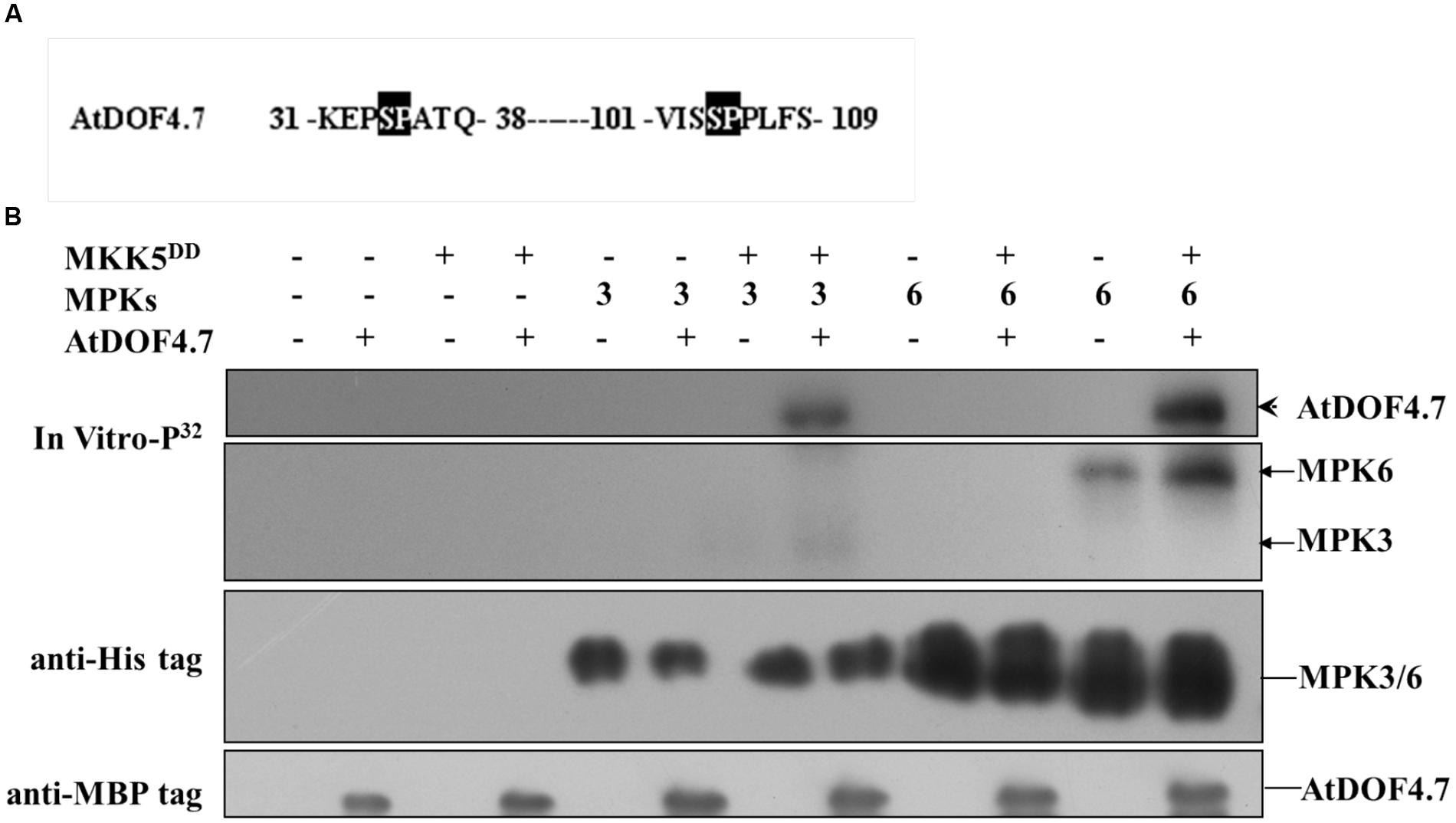

Phosphorylation of AtDOF4.7 by MPK3 and MPK6 In Vitro

Potential sites for MAPK phosphorylation are Ser/Thr residues followed by a Pro residue (Meng et al., 2013). There are two such sites in the AtDOF4.7 sequence: Ser-34-Pro and Ser-104-Pro (Figure 4A). To determine whether MPK3/MPK6 is able to carry out phosphorylation of AtDOF4.7, we obtained the recombinant proteins MBP-tagged AtDOF4.7, His6-tagged MPK3 and MPK6, and FLAG-tagged MKK5DD for phosphorylation assays. Following activation by purified FLAG-tagged recombinant MKK5DD, either His6-tagged MPK3 or MPK6 strongly phosphorylated AtDOF4.7 (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 4. Phosphorylation of AtDOF4.7 by activated MPK3 and MPK6 in vitro. (A) Partial sequences of the AtDOF4.7 protein. Black boxes indicate the conserved MAPK phosphorylation sites; (B) MPK3 and MPK6 phosphorylate the MBP-tagged AtDOF4.7 recombinant protein in vitro. The arrowhead indicates the phosphorylated AtDOF4.7 protein. Bands indicated by the arrows are MPK3 or MPK6 phosphorylated by MKK5DD. Anti-His and anti-MBP tag primary antibodies were used to detect the corresponding proteins in the phosphorylation buffer.

Constitutively Activated MKK5 Cannot Rescue Organ Abscission in the S107 Line

MKK4 and MKK5 are homologs found in Arabidopsis that act upstream of MPK3 and MPK6 in the regulation of floral abscission (Cho et al., 2008). Plants expressing the constitutively activated forms of MKK4 or MKK5 under the control of a steroid-inducible promoter (designated GVG-MKK4DD or GVG-MKK5DD) had a normal abscission phenotype (Ren et al., 2002; Cho et al., 2008). To assess the biological function of the phosphorylation of AtDOF4.7 by MAPK, we crossed the AtDOF4.7-overexpressing S107 line with a GVG-MKK5DD transgenic plant to obtain S107/MKK5DD. We examined the siliques of S107/MKK5DD plants at flower position 10, which is the position at which WT flowers shed completely. We observed that the organ abscission phenotype of S107/MKK5DD was not rescued; however, small parts of the flowers were shed from the siliques of S107/MKK5DD plants after dexamethasone (DEX) treatment (Figure 5). These data indicated that the two genes act in a common pathway to regulate abscission in Arabidopsis, and MKK5 may negatively regulate AtDOF4.7.

FIGURE 5. AtDOF4.7 is involved in abscission mediated by the MAPK cascade. The defective abscission defective phenotype of S107 was partly restored in S107/GVG-MKK5DD plants following DEX treatment. All representative siliques are from flower position 10 of WT, S107, GVG-MKK5DD, and S107/GVG-MKK5DD plants.

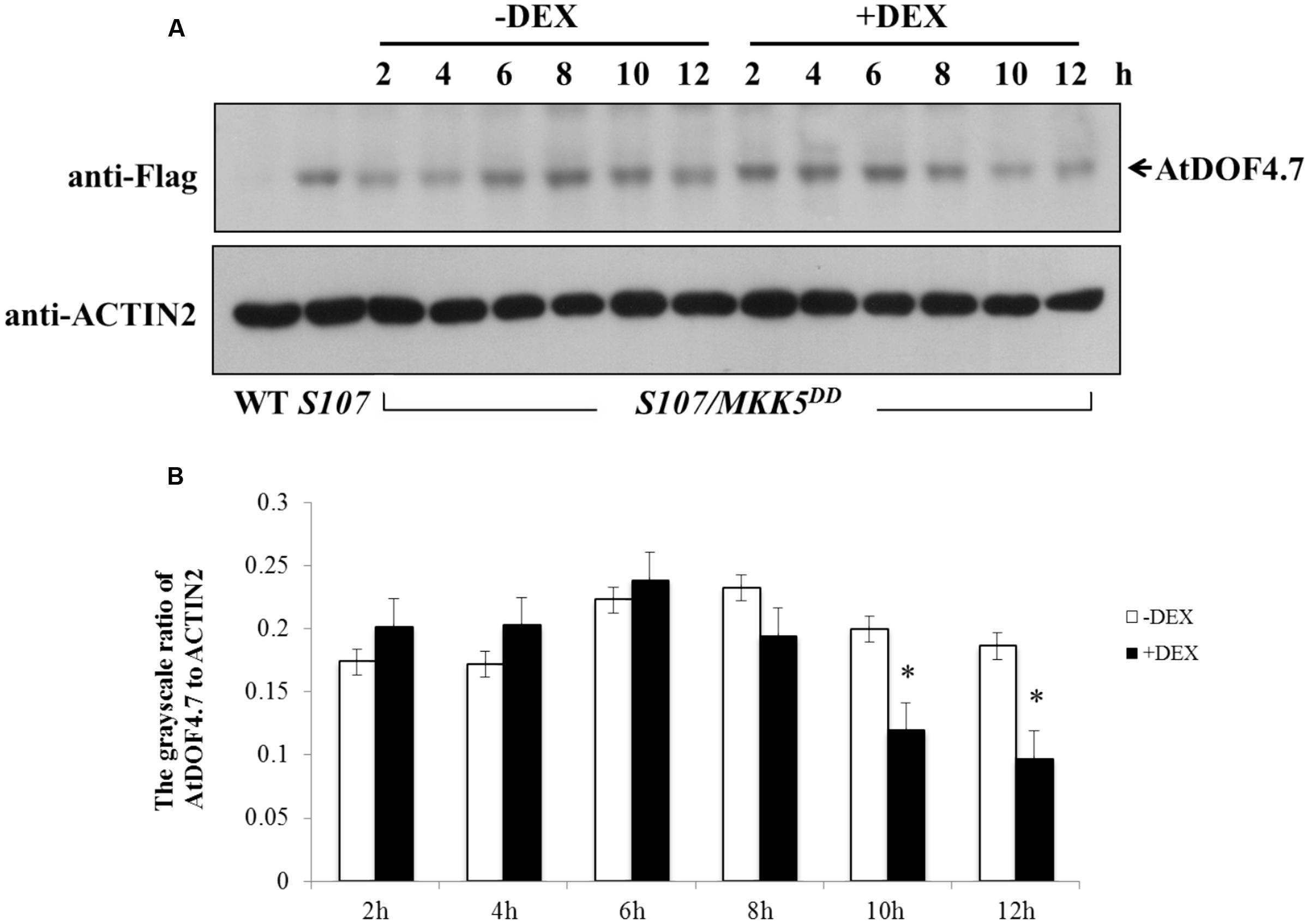

A phosphorylation-dependent mechanism is involved in protein degradation (Willems et al., 1999; Feng et al., 2004; Yoo et al., 2008). Therefore, a western blot assay was performed to determine the changes in AtDOF4.7 protein levels in S107/MKK5DD plants treated with DEX. The siliques of S107/MKK5DD at flower position 10 were induced with 15 μM DEX after 10 h, resulting in greatly decreased AtDOF4.7 protein levels (Figure 6A). The grayscale ratio of AtDOF4.7 protein bands on the western blot were measured, and the results showed that the changes in the levels of the AtDOF4.7 protein exhibited significant differences after 10 and 12 h of DEX treatment compared with the untreated control (Figure 6B). ACTIN2 was used as an internal protein control, and was detected with an anti-ACTIN2 antibody. These data suggest that activated MKK5 following DEX induction could affect AtDOF4.7 at the protein level in the S107/MKK5DD plant, providing one explanation for how organ abscission is partially recovered in S107/MKK5DD lines.

FIGURE 6. Determination of AtDOF4.7 protein levels in S107/MKK5DD siliques. (A) Without DEX treatment, the AtDOF4.7 protein levels did not change apparently over the 12 h time courses of the experiment. However, the level of the AtDOF4.7 protein appeared to be greatly decreased at the 10 and 12 h time points following DEX treatment. The bands indicated by arrows are the AtDOF4.7 protein. An anti-ACTIN2 antibody was used as the internal control. Total protein extracts from WT and S107 were used as the negative and positive controls, respectively. (B) The grayscale ratio of these bands without and with DEX treatment from (A). The asterisks indicate significant differences between DEX treatment and the control (-DEX) at the 10 and 12 h time points (t-test, P < 0.05). Grayscale measurements of each band were repeated three times.

Discussion

A recent report shows that ethylene manipulates the rate of abscission, rather than directly inducing it (Niederhuth et al., 2013a). It has been indicated that several ethylene mutants of Arabidopsis, such as those harboring the ethylene receptor ethylene-response 1 (etr1) and ethylene-insensitive 2 (ein2) point mutations, displayed a delay of floral organ abscission (Bleecker et al., 1988; Guzman and Ecker, 1990; Patterson and Bleecker, 2004), however, the formation and differentiation of the AZ cells are not affected in these ethylene-insensitive mutants. Up to now, the genetic mechanism through which ethylene regulates abscission is still unclear. Here, we suggest that ethylene accelerates organ abscission in Arabidopsis by regulating the time-course of the expression of AtDOF4.7 (Figure 1B, Supplementary Figures S1, S2, and S3B). To make a preliminary demonstration for this hypothesis, we analyzed the region 3000 bp upstream of the AtDOF4.7 promoter sequence and found that the promoter sequence of AtDOF4.7 contained three cis-acting elements in this region: a GCC box (-1702 to -1696 bp), a CRT/DRE element (-1029 to -1023 bp) and several EIN3-binding sites (EBS, ATGTA; Supplementary Figure S4). The first two elements can be recognized by Ethylene Response Factors (ERFs) in response to ethylene (GCC) and drought stress (CRT/DRE), while the last element can be recognized by EIN3. Most notably, in the ethylene signaling pathway, ERFs are critical factors responding to ethylene, which can be activated by EIN3 (Ohme-Takagi and Shinshi, 1995; Chao et al., 1997). Based on these observations, AtDOF4.7 might be a potential target gene of ERFs or EIN3 in response to ethylene. From the data presented in this study, we hypothesize that the regulation of AtDOF4.7 is related to ethylene, but it is unclear that how ethylene affecting the expression of AtDOF4.7 at the transcriptional level.

Auxin, as an antagonist of ethylene, negatively regulates the cell wall-degrading enzymes, leading to a delay in cell separation via an ethylene-independent mechanism. Additionally, the AZ patterning is not affected in arf2 mutants (Ellis et al., 2005). It has been reported that auxin may regulate IDA and HAE/HSL2 to control cell separation (Kumpf et al., 2013; Niederhuth et al., 2013a). Thus, we can put forward the hypothesis that both ethylene and auxin may be involved in the regulation of AtDOF4.7 expression.

Previous data indicated that the delay of abscission caused by AtDOF4.7 overexpression could not be accelerated by exogenous ethylene, suggesting the potential involvement of ethylene-independent regulation. Therefore, we investigated the relationship between IDA and AtDOF4.7 in this study. In the mutant of IDA, the expression pattern of AtDOF4.7 promoter was not significantly altered (Figure 1C), while the transcript level of AtDOF4.7 was found to be up-regulated at the same flower positions in the ida-2 mutant (Figure 1D). IDA is involved in the regulation of ADPG2 expression in the AZ to control cell separation during floral organ abscission (González-Carranza et al., 2002, 2007; Ogawa et al., 2009; González-Carranza et al., 2012), and its expression is suppressed by overexpression of AtDOF4.7 in the regulation of abscission (Wei et al., 2010). Our results indicated that the overexpression of AtDOF4.7 could inhibit the early abscission caused by IDA overexpressing lines (Figure 2). Therefore, this result provides a hint that AtDOF4.7 might participate in the regulation of PGs by IDA. It has been well-established that MAPK cascades (mainly MKK4/MKK5-MPK3/MPK6 pathway) are involved in downstream of IDA-mediated abscission pathway. Thus, the relations between the MAPKs and AtDOF4.7 were also investigated. First, we found two abscission-related MPKs, MPK3 and MPK6, could interact with AtDOF4.7 in yeast. The in vitro assay indicated that both MPK3 and MPK6 could phosphorylated AtDOF4.7, and the signal of MPK6 was apparently stronger than that of MPK3. This is consistent with the stronger in vivo interaction between MPK6 and AtDOF4.7, suggesting MPK6 may play more important role in the regulation of abscission. Second, our results indicated that the AtDOF4.7-induced abortion of abscission could be partially rescued by MKK activation (Figure 5), and the protein level of AtDOF4.7 is down-regulated following the MKK5 activation. Thus, it is reasonable to speculate that the AtDOF4.7 may act as a direct target of MPKs in the abscission regulation. Taken together, our results suggested that the AtDOF4.7 should also involved in downstream of the IDA-MAPK-mediated abscission pathway.

Conclusion

AtDOF4.7, as a negative regulator in floral organ abscission, is regulated by the ethylene-dependent and ethylene-independent abscission pathways. It is suggested that AtDOF4.7 might be regulated by ethylene, and also by IDA, which represses expression of AtDOF4.7. Nevertheless, the relationship between phosphorylation and ethylene signaling remains unclear. A previous study showed that phosphorylated MPK3/6 activated by MKK4/5 further phosphorylates ERF6 to regulate defense gene induction and fungal resistance ((Meng et al., 2013). Therefore, it is worthwhile to explore whether the phosphorylation of ERFs by MPK3/6 in the regulation of AtDOF4.7 occurs in response to ethylene. Further detailed biochemical and genetic analyses will allow us to gain a better understanding of the importance of AtDOF4.7 phosphorylation and ethylene responses in plant organ abscission.

Author Contributions

G-QW, P-CW, FT, MY, and X-YZ performed the research; G-QW, P-CW, FT, Q-JC, and X-CW analyzed the data; G-QW, P-CW, and X-CW designed the research, G-QW and X-CW wrote the article with contributions from G-QW, P-CW, FT, and MY.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Basic Research Program of China [No.2012CB114204], the National Natural Science Foundation of China [No.31100216], and the Ministry of Agriculture Transgenic Major Project [No.2009ZX08009020-002].

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Ming Yuan and Prof. Dong-Tao Ren (China Agricultural University, China) for critical reading of this manuscript. We thank Prof. Dong-Tao Ren for providing the seeds of GVG-MKK5DD (Col), the pBD-GAL4-MPK3/MPK6 yeast-two hybrid vectors and the MKK5DD FLAG-tagged and MPK3/MPK6 His-tagged fusion proteins, Reidunn B. Aalen (University of Oslo, Norway) for providing the seeds of ida-2 (Col) mutant and 35S:IDA (Col), and Michael Walter (Universität Tübingen, Germany) for providing the BiFc vectors.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.00863

References

Bleecker, A. B., Estelle, M. A., Somerville, C., and Kende, H. (1988). Insensitivity to ethylene conferred by a dominant mutation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 241, 1086–1089. doi: 10.1126/science.241.2869.1086

Bleecker, A. B., and Patterson, S. E. (1997). Last exit: senescence, abscission, and meristem arrest in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 9, 1169–1179. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.7.1169

Butenko, M. A., Patterson, S. E., Grini, P. E., Stenvik, G. E., Amundsen, S. S., Mandal, A., et al. (2003). Inflorescence deficient in abscission controls floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis and identifies a novel family of putative ligands in plants. Plant Cell 15, 2296–2307. doi: 10.1105/tpc.014365

Butenko, M. A., Stenvik, G. E., Alm, V., Saether, B., Patterson, S. E., and Aalen, R. B. (2006). Ethylene-dependent and -independent pathways controlling floral abscission are revealed to converge using promoter::reporter gene constructs in the ida abscission mutant. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 3627–3637. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl130

Chang, C., Kwok, S. F., Bleecker, A. B., and Meyerowitz, E. M. (1993). Arabidopsis ethylene-response gene ETR1: similarity of product to two-component regulators. Science 262, 539–544. doi: 10.1126/science.8211181

Chao, Q., Rothenberg, M., Solano, R., Roman, G., Terzaghi, W., and Ecker, J. R. (1997). Activation of the ethylene gas response pathway in Arabidopsis by the nuclear protein ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and related proteins. Cell 89, 1133–1144. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80300-1

Charrier, B., Champion, A., Henry, Y., and Kreis, M. (2002). Expression profiling of the whole Arabidopsis shaggy-like kinase multigene family by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. Plant Physiol. 130, 577–590. doi: 10.1104/pp.009175

Cho, S. K., Larue, C. T., Chevalier, D., Wang, H., Jinn, T. L., Zhang, S., et al. (2008). Regulation of floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 15629–15634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805539105

Dal Degan, F., Child, R., Svendsen, I., and Ulvskov, P. (2001). The cleavable N-terminal domain of plant endopolygalacturonases from CLADE B may be involved in a regulated secretion mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 35297–35304.

Ellis, C. M., Nagpal, P., Young, J. C., Hagen, G., Guilfoyle, T. J., and Reed, J. W. (2005). AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR1 and AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR2 regulate senescence and floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 132, 4563–4574. doi: 10.1242/dev.02012

Feng, J., Tamaskovic, R., Yang, Z., Brazi, D. P., Merlo, A., Hess, D., et al. (2004). Stabilization of MDM2 via decreased ubiquitination is mediated by protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 35510–35517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404936200

González-Carranza, Z. H., Elliott, K. A., and Roberts, J. A. (2007). Expression of polygalacturonases and evidence to support their role during cell separation processes in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 3719–3730. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm222

González-Carranza, Z. H., Shahid, A. A., Zhang, L., Liu, Y., Ninsuwan, U., and Roberts, J. A. (2012). A novel approach to dissect the abscission process in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 160, 1342–1356. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.205955

González-Carranza, Z. H., Whitelaw, C. A., Swarup, R., and Roberts, J. A. (2002). Temporal and spatial expression of a polygalacturonase during leaf and flower abscission in oilseed rape and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 128, 534–543. doi: 10.1104/pp.010610

Guzman, P., and Ecker, J. R. (1990). Exploiting the triple response of Arabidopsis to identify ethylene-related mutants. Plant Cell 2, 513–523. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.6.513

Jackson, M. B., and Osborne, D. J. (1970). Ethylene, the natural regulator of leaf abscission. Nature 225, 1019–1022. doi: 10.1038/2251019a0

Jinn, T. L., Stone, J. M., and Walker, J. C. (2000). HAESA, an Arabidopsis leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase, controls floral organ abscission. Genes Dev. 14, 108–117. doi: 10.1101/gad.14.1.108

Kumpf, R. P., Shi, C. L., Larrieu, A., Sto, I. M., Butenko, M. A., Peret, B., et al. (2013). Floral organ abscission peptide IDA and its HAE/HSL2 receptors control cell separation during lateral root emergence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 5235–5240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210835110

Liu, B., Butenko, M. A., Shi, C. L., Bolivar, J. L., Winge, P., Stenvik, G. E., et al. (2013). NEVERSHED and INFLORESCENCE DEFICIENT IN ABSCISSION are differentially required for cell expansion and cell separation during floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 5345–5357. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert232

Liu, H., Wang, Y., Xu, J., Su, T., Liu, G., and Ren, D. (2007). Ethylene signaling is required for the acceleration of cell death induced by the activation of AtMEK5 in Arabidopsis. Cell Res. 18, 422–432. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.29

Liu, Y., and Zhang, S. (2004). Phosphorylation of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase by MPK6, a stress-responsive mitogen-activated protein kinase, induces ethylene biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16, 3386–3399. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.026609

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Meng, X., Xu, J., He, Y., Yang, K. Y., Mordorski, B., Liu, Y., et al. (2013). Phosphorylation of an ERF transcription factor by Arabidopsis MPK3/MPK6 regulates plant defense gene induction and fungal resistance. Plant Cell 25, 1126–1142. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.109074

Miao, Y., Lv, D., Wang, P., Wang, X. C., Chen, J., Miao, C., et al. (2006). An Arabidopsis glutathione peroxidase functions as both a redox transducer and a scavenger in abscisic acid and drought stress responses. Plant Cell 18, 2749–2766. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.044230

Morris, D. A. (1993). The role of auxin in the apical regulation of leaf abscission in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). J. Exp. Bot. 44, 807–814. doi: 10.1093/jxb/44.4.807

Niederhuth, C. E., Cho, S. K., Seitz, K., and Walker, J. C. (2013a). Letting go is never easy: abscission and receptor-like protein kinases. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 55, 1251–1263. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12116

Niederhuth, C. E., Patharkar, O. R., and Walker, J. C. (2013b). Transcriptional profiling of the Arabidopsis abscission mutant hae hsl2 by RNA-Seq. BMC Genomics 14:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-37

Ogawa, M., Kay, P., Wilson, S., and Swain, S. M. (2009). ARABIDOPSIS DEHISCENCE ZONE POLYGALACTURONASE1 (ADPG1), ADPG2, and QUARTET2 are polygalacturonases required for cell separation during reproductive development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21, 216–233. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.063768

Ohme-Takagi, M., and Shinshi, H. (1995). Ethylene-inducible DNA binding proteins that interact with an ethylene-responsive element. Plant Cell 7, 173–182. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.2.173

Okushima, Y., Mitina, I., Quach, H. L., and Theologis, A. (2005). AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 2 (ARF2): a pleiotropic developmental regulator. Plant J. 43, 29–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02426.x

Osborne, D. J., and Sargent, J. A. (1976). The positional differentiation of abscission zones during the development of leaves of Sambucus nigra and the response of the cells to auxin and ethylene. Planta 132, 197–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00388903

Patterson, S. E. (2001). Cutting loose. Abscission and dehiscence in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 126, 494–500. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.2.494

Patterson, S. E., and Bleecker, A. B. (2004). Ethylene-dependent and -independent processes associated with floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 134, 194–203. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.028027

Ren, D., Yang, H., and Zhang, S. (2002). Cell death mediated by MAPK is associated with hydrogen peroxide production in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 559–565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109495200

Shi, C. L., Stenvik, G. E., Vie, A. K., Bones, A. M., Pautot, V., Proveniers, M., et al. (2011). Arabidopsis class I KNOTTED-like homeobox proteins act downstream in the IDA-HAE/HSL2 floral abscission signaling pathway. Plant Cell 23, 2553–2567. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.084608

Stenvik, G. E., Butenko, M. A., Urbanowicz, B. R., Rose, J. K., and Aalen, R. B. (2006). Overexpression of INFLORESCENCE DEFICIENT IN ABSCISSION activates cell separation in vestigial abscission zones in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18, 1467–1476. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.042036

Stenvik, G. E., Tandstad, N. M., Guo, Y., Shi, C. L., Kristiansen, W., Holmgren, A., et al. (2008). The EPIP peptide of INFLORESCENCE DEFICIENT IN ABSCISSION is sufficient to induce abscission in Arabidopsis through the receptor-like kinases HAESA and HAESA-LIKE2. Plant Cell 20, 1805–1817. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.059139

Walter, M., Christina, C., Katia, S., Oliver, B., Katrin, W., Christian, N., et al. (2004). Visualization of protein interactions in living plant cells using bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Plant J. 40, 428–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02219.x

Wang, H., Ngwenyama, N., Liu, Y., Walker, J. C., and Zhang, S. (2007). Stomatal development and patterning are regulated by environmentally responsive mitogen-activated protein kinases in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19, 63–73. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048298

Wei, P. C., Tan, F., Gao, X. Q., Zhang, X. Q., Wang, G. Q., Xu, H., et al. (2010). Overexpression of AtDOF4.7, an Arabidopsis DOF family transcription factor, induces floral organ abscission deficiency in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 153, 1031–1045. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.153247

Willems, A. R., Goh, T., Taylor, L., Chernushevich, I., Shevchenko, A., and Tyers, M. (1999). SCF ubiquitin protein ligases and phosphorylation-dependent proteolysis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 354, 1533–1550. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0497

Xu, J., Li, Y., Wang, Y., Liu, H., Lei, L., Yang, H., et al. (2008). Activation of MAPK KINASE 9 induces ethylene and camalexin biosynthesis and enhances sensitivity to salt stress in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 26996–27006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801392200

Keywords: abscission, abscission zone, DOF, ethylene, IDA, MAPK, phosphorylation

Citation: Wang G-Q, Wei P-C, Tan F, Yu M, Zhang X-Y, Chen Q-J and Wang X-C (2016) The Transcription Factor AtDOF4.7 Is Involved in Ethylene- and IDA-Mediated Organ Abscission in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 7:863. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00863

Received: 13 January 2016; Accepted: 01 June 2016;

Published: 17 June 2016.

Edited by:

Péter Poór, University of Szeged, HungaryReviewed by:

Brad M. Binder, University of Tennessee-Knoxville, USAPeter Ulvskov, Copenhagen University, Denmark

Copyright © 2016 Wang, Wei, Tan, Yu, Zhang, Chen and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xue-Chen Wang, eGN3YW5nQGNhdS5lZHUuY24=

Gao-Qi Wang

Gao-Qi Wang Peng-Cheng Wei

Peng-Cheng Wei Feng Tan1

Feng Tan1 Man Yu

Man Yu Xiao-Yan Zhang

Xiao-Yan Zhang Qi-Jun Chen

Qi-Jun Chen Xue-Chen Wang

Xue-Chen Wang