- 1Centre for Carbon Water and Food, University of Sydney, Brownlow Hill, NSW, Australia

- 2Institute of Agricultural Sciences, ETH Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland

- 3Chair of Bioclimatology, Georg-August University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany

Drought down-regulates above- and belowground carbon fluxes, however, the resilience of trees to drought will also depend on the speed and magnitude of recovery of these above- and belowground fluxes after re-wetting. Carbon isotope composition of above- and belowground carbon fluxes at natural abundance provides a methodological approach to study the coupling between photosynthesis and soil respiration (SR) under conditions (such as drought) that influence photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination. In turn, the direct supply of root respiration with recent photoassimilates will impact on the carbon isotope composition of soil-respired CO2. We independently measured shoot and soil CO2 fluxes of beech saplings (Fagus sylvatica L.) and their respective δ13C continuously with laser spectroscopy at natural abundance. We quantified the speed of recovery of drought stressed trees after re-watering and traced photosynthetic carbon isotope signal in the carbon isotope composition of soil-respired CO2. Stomatal conductance responded strongly to the moderate drought (-65%), induced by reduced soil moisture content as well as increased vapor pressure deficit. Simultaneously, carbon isotope discrimination decreased by 8‰, which in turn caused a significant increase in δ13C of recent metabolites (1.5–2.5‰) and in δ13C of SR (1–1.5‰). Generally, shoot and soil CO2 fluxes and their δ13C were in alignment during drought and subsequent stress release, clearly demonstrating a permanent dependence of root respiration on recently fixed photoassimilates, rather than on older reserves. After re-watering, the drought signal persisted longer in δ13C of the water soluble fraction that integrates multiple metabolites (soluble sugars, amino acids, organic acids) than in the neutral fraction which represents most recently assimilated sugars or in the δ13C of SR. Nevertheless, full recovery of all aboveground physiological variables was reached within 4 days – and within 7 days for SR – indicating high resilience of (young) beech against moderate drought.

Introduction

In trees, root growth and respiration is fuelled by a rapid transport of recent photoassimilates from leaves to roots (Brüggemann et al., 2011; Epron et al., 2012). This causal relationship between above- and belowground physiological processes – often termed aboveground to belowground coupling – has been shown by girdling and stable isotope tracer studies (Högberg et al., 2001; Kuzyakov and Gavrichkova, 2010). For beech trees, transport velocities of up to 1 m h-1 have been reported (Plain et al., 2009; Gavrichkova et al., 2011; Kuptz et al., 2011), depending on seasonality (Kuptz et al., 2011), tree height (Kuzyakov and Gavrichkova, 2010), and environmental conditions like drought (Barthel et al., 2011). In a forest ecosystem, complexity is added to the straightforward link between assimilatory and respiratory CO2 fluxes from the soil, e.g., due to different sources contributing to soil CO2 fluxes (microbial vs. plant-related), different plant species and plant ages as well as changing environmental conditions on diurnal and seasonal scales. However, as forests are an important terrestrial carbon sink (Pan et al., 2011), it is important to understand the dynamics of these opposing CO2 fluxes, especially because ecosystem perturbations are predicted to occur more frequently.

Drought is a major climatic factor determining carbon and water fluxes (Granier et al., 2007), thus productivity in forest ecosystems (Breda et al., 2006), and gains increased importance under future climatic conditions (Schär et al., 2004; Reichstein et al., 2013). Beech, an important forest tree species in Central Europe, is characterized as drought sensitive, and is predicted to suffer during extreme drought events (Granier et al., 2007), both in terms of growth and competitive ability (Gessler et al., 2007b). However, recent studies showed that beech tolerates moderate drought events, as it maintains allocation of recent photoassimilates into the roots (Blessing et al., 2015; Scartazza et al., 2015; Hommel et al., 2016). Thus, studying the effect of drought on carbon and water fluxes will provide crucial insights into the capability of European beech forests to cope with more frequent drought spells in the future.

Moreover, the drought sensitivity of beech trees will not only depend on how strongly they are affected by drought itself, but also on their ability to recover after the drought stress has been released (Zang et al., 2014), i.e., on their resilience (Grimm and Wissel, 1997). Watering beech after a drought spell showed that trees are capable to immediately utilize the supplied water (Barthel et al., 2014; Volkmann et al., 2016). A fast recovery of a plant’s water status will help to retrieve full physiological activity in form of carbon and water fluxes. However, above- and belowground carbon and water fluxes may differ in their speed and magnitude of recovery after rewetting, therefore a separate analysis of both helps to understand their impact on the ecosystem level.

Studies on the coupling of above- to belowground carbon fluxes at natural carbon isotope abundance use variations in carbon discrimination Δ13C, which is dependent on the ratio of the CO2 concentration in the intercellular air space to the atmospheric CO2 concentration (Ci/Ca) (Farquhar et al., 1982). Ci/Ca in turn is modified by environmental conditions (Cernusak et al., 2013). Multiple studies could track the imprint of Δ13C in a time lagged carbon isotope signature in stem phloem (e.g., Keitel et al., 2003; Merchant et al., 2010; Rascher et al., 2010), root phloem (Scartazza et al., 2015), soil respiration (SR; Ekblad and Högberg, 2001; McDowell et al., 2004), and ecosystem respiration (McDowell et al., 2004; Knohl et al., 2005; Werner et al., 2006; Alstad et al., 2007). These measurable changes in the carbon isotope composition of soil and ecosystem respired CO2 were detected using discrete instead of continuous isotope measurements. However, first in situ real-time measurements revealed that such conclusions are not that straightforward as Δ13C displays diurnals changes (Gentsch et al., 2014) which are not always reflected in the carbon isotope signature of SR, especially under wet conditions (Wingate et al., 2010).

A process-based understanding, both of the dynamics in the opposing ecosystem CO2 fluxes and their respective carbon isotopic signatures, cannot be attained solely by ecosystem-scale studies or by studying single ecosystem components. Therefore, simple small-scale model ecosystems may help to arrive at a better understanding of how a change in canopy assimilation confers to changes in SR, and respective carbon isotope signatures. At the same time, such systems have the advantage of providing controlled and stable conditions, helping to infer underlying processes. Here we present a drought experiment with beech saplings. We followed the coupling between above- and belowground fluxes and their carbon isotope composition at natural abundance levels also into the – often neglected – recovery period, using in situ real-time laser spectroscopy measurements in shoot and soil CO2 fluxes over about 1 month.

Using a simple controlled system, we asked the following questions:

(a) How quickly do plant physiological variables (i.e., stomatal conductance, photosynthesis, transpiration), assimilatory and respiratory CO2 fluxes recover from the induced drought spell after re-watering in our beech model ecosystem?

(b) Is the expected large change in photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination under drought and during recovery traceable to a prominent change in belowground carbon isotope composition of soil-respired CO2? And vice versa, is it feasible to draw conclusions from the carbon isotope composition of soil-respired CO2 also at natural abundance on the influence of plant physiological variables?

We focus on the short term response of our drought stressed beech model ecosystem to re-watering. Since recently fixed assimilates fuel root respiration to a high extent, we expect a prominent change in the observed carbon isotope discrimination during drought, with more 13C enriched photoassimilates imprinting on the δ13C of root and thus SR. We further expect that SR increases after re-watering and its carbon isotope signal becomes more depleted in 13C due to increased Δ13C after stress release with a delay to aboveground variables due to the transport time of photoassimilates from the leaves to the roots and back into the atmosphere.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material

Six 0.8 m tall beech saplings were enclosed individually in custom-made soil-shoot chambers that separately enclosed shoot and soil compartments of one beech sapling as described in Barthel et al. (2011). Each soil-shoot chamber was equipped with sensors for relative humidity (Hygroclip® S3C03, rotronic AG, Bassersdorf, Switzerland), soil moisture (ECH2O EC-5, Decagon Devices, Inc., Pullman, WA, USA) as well as air (Hygroclip® S3C03, rotronic AG, Bassersdorf, Switzerland), leaf (Thermocouple Type K, Omega Enginerring Inc., Stamford, CT, USA), and soil (AD 592, Analog Devices Inc., Norwood, MA, USA) temperatures. In addition, each shoot chamber was equipped with a small fan to ensure homogeneous air mixing within the shoot compartment. All six soil-shoot chambers were placed inside a climate chamber controlling the day-night cycle of 16/8 h for temperature and light intensity inside the soil-shoot chambers. Light intensity steadily increased or decreased during the first 3 and last 5 hours of the daytime period; so plants received maximal photosynthetic active radiation of about 600 μmol m-2 s-1 between 10 am and 6 pm.

Beech saplings grown in 7.9 l pots with potting soil (Containererde, Ökohum, Herrenhof, Switzerland) had fully developed leaves in April, when the experiment started (bud burst in February). They were irrigated daily via tubing connected to the soil chambers, replacing the amount of water lost via transpiration and via evaporation calculated from the previous day gas exchange measurements. For the experiment, the saplings were separated into two groups of three beech saplings each which experienced a different water treatment. One group served as control, for which daily irrigation was continued during the whole experiment (04 April 2009 – 05 May 2009, DOY 94–125). The other group, however, was subject to, first, reduced daily irrigation (9 April 2009, DOY 99; drought period) and, then, re-watering (26 April 2009 2:30 am, DOY 116) during the night in order to allow saturation of soil water and plant tissues (recovery period). In the following, this group is referred to as “drought-treated” saplings. The drought treatment affected both soil moisture content (SMC) and vapor pressure deficit (VPD), being dependent of the transpiration rate. We refer to DOY 116 as the first day after re-watering since re-watering took place at pre-dawn of this day. Drought-treated saplings showed significantly lower soil moisture than control saplings from 14 April 2009 (DOY 104) onward, therefore we focus on data after this day. The main drought period, during which assimilation and stomatal conductance showed a significant effect to the drought treatment, lasted from 17 April 2009 (DOY 107) until re-watering.

Continuous Gas-Exchange and Carbon Isotope Measurements with Laser Spectroscopy

The gas-tight separation between shoot and soil, realized by the combined soil-shoot chamber system, enabled independent measurements of above- and belowground gas exchange and the carbon isotopic composition of CO2. By continuously flushing the chambers with a vacuum pump (VTE 6 for soil chambers/VTL 15 for shoot chambers, Gardner Denver Inc., Quincy, IL, USA), steady-state conditions were achieved. The flow rate was adjusted according to the gas exchange of the shoot or soil during the day, to avoid condensation and to obtain sufficient differences in CO2 concentrations between inlet and outlet (shoot chamber 12–16 l min-1, soil chamber 2.1–2.3 l min-1), but then kept constant during the whole experiment. A valve system alternately directed a subsample of 0.5 l min-1 of the inlet air (surrounding air inside the climate chamber) and of the outlet air of one soil-shoot chamber for 134 and 136 s, respectively, to a pulsed quantum cascade absorption laser spectrometer (QCLAS-ISO, Aerodyne Research, Inc., Billerica, MA, USA). The laser spectrometer, located outside of the climate chamber, was used to simultaneously measure the CO2 isotopologues 12C16O2, 13C16O2, and 12C16O18O at a rate of 0.5 Hz by scanning across three spectral lines near 4.3 μm (2310 cm-1). The measurement principle is based upon two optical multipass absorption cells with stabilized pressure and temperature using a spectral ratio method (Nelson et al., 2008). Throughout the whole experiment, calibration was done every hour for 6 min in three consecutive steps, including dilution calibration, span calibration, and check for long-term calibration stability (Sturm and Knohl, 2010). The performed calibration resulted in an Allan deviation of 0.25‰ at 1 s averaging time for δ13C. Further, water vapor concentrations were measured with an infrared gas analyzer system (IRGA; Li6262, Li-Cor Biosciences Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA). Real-time data acquisition/processing and controlling of instruments, calibration units, chambers, valves, and sensors were realized by a custom-written LabVIEW program (LabVIEW, National Instruments Corp., Austin, TX, USA). The first 20 s of each sampling interval were excluded for average calculation due to the time lag after valve switching. The outlets of the shoot and the soil chambers of one sapling subjected to drought and of one control sapling were measured in alternating mode.

Leaf Sampling and δ13C Analysis

Three to five leaves per replicated beech sapling were sampled in order to determine the δ13C values of leaf material during the period of drought stress (23 April 2009, DOY 113) and at the end of the experiment during the recovery period (05 May 2009, DOY 125). Leaf samples were immediately put in liquid nitrogen after sampling and then kept frozen at -20°C until leaf material was homogenized under addition of liquid nitrogen with mortar and pestle. For δ13C analysis of bulk leaf material, a subsample was dried at 60°C for 3 days and the milled powder was weighed into tin capsules for isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) analysis (MAT DeltaplusXP, Finnigan MAT, Bremen, Germany).

For the extraction of water soluble and the neutral organic carbon fractions, 100 mg of the remaining homogenized leaf material was then suspended in 1 ml de-mineralized water and put on ice for 60 min. Afterward, samples were kept at 100°C for 3 min in order to precipitate proteins (Gessler et al., 2007a). The solution was then centrifuged at 12000 × g. A subsample was transferred into tin capsules and dried in order to analyze δ13C of the water soluble organic carbon fraction (δ13Cws). The remaining supernatant was mixed with anion and cation exchange resins (Dowex 1 and Dowex 50, VWR International AG, West Chester, PA, USA) in order to remove amino acids and organic acids (Göttlicher et al., 2006). The final solution was then pipetted into tin capsules, dried and analyzed for δ13C of the neutral organic carbon fraction (δ13Cnf). This neutral fraction represents mainly recently assimilated soluble sugars (Göttlicher et al., 2006), whereas the water soluble fraction includes also other compounds such as soluble amino acids and organic acids (Gessler et al., 2007a). IRMS analysis followed the identical treatment principle described in Werner and Brand (2001). The standard deviation of the long-term quality control standard (tyrosine) was 0.09‰ (over 9 years). In addition, on 05 May 2009 (DOY 125), all remaining leaves were collected to determine overall leaf area per plant (Li3000, Li-Cor Biosciences Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA).

Calculation of Carbon Fluxes and the Corresponding Isotope Ratios

Stomatal conductance (gs), transpiration (E), and net shoot assimilation (AN) were calculated according to von Caemmerer and Farquhar (1981), while the calculation of SR followed the calculations presented in Burri et al. (2014).

All carbon isotope values are reported on the Vienna-Pee Dee Belemnite (V-PDB) scale using the δ-notation:

where Rsample and RV -PDB denote the 13C/12C ratios of the sample and the standard, respectively. The method after Evans et al. (1986) was used to calculate on-line photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination (Δ13Cobs) as follows:

where ξ denotes the ratio of CO2 entering the chamber in relation to the photosynthetic flux [cin/(cin-cout)]. Further, δ13Cin and δ13Cout denote the respective carbon isotopic compositions of CO2 entering and leaving the chamber, respectively.

The δ13C signal of SR (δ13CSR) was calculated using an isotopic mass balance equation:

where cin and cout refer to CO2 mole fractions at chamber inlet and outlet, respectively.

Statistics

The relative effect of drought was expressed as drought effect, i.e., (100*treatment/control)-100. Full recovery from drought stress was achieved when the mean drought effect plus standard deviation exceeded 100%, and was represented in days after re-watering, with day one referring to DOY 116. Standard deviations of differences between control and drought-treated saplings are error propagated as follows:

with SDwet and SDdry representing hourly standard deviations of control and drought-treated samplings (n = 3).

The drought effect on measured plant physiological variables and isotopic signatures was tested with a linear mixed effect model using the nlme-package (Pinheiro et al., 2016) and the statistical software R [Version 3.0.3; R Development Core Team (2008–2010)], including the beech sapling as random effect in the model. If not noted otherwise, day refers to a light intensity above 500 μmol m-2 s-1, and night to a light intensity below 20 μmol m-2 s-1. As normal distribution cannot be tested based on three samples, a Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test (Wilcox test in R) was used for δ13C values of samples measured with the IRMS. The relationship between diurnal mean values of AN, E, and gs to SR (PAR > 500 μmol m-2 s-1), as well as the relationship between Δ13Cobs and δ13CSR were tested using repeated measure analysis (nlme-package).

Results

Environmental Conditions

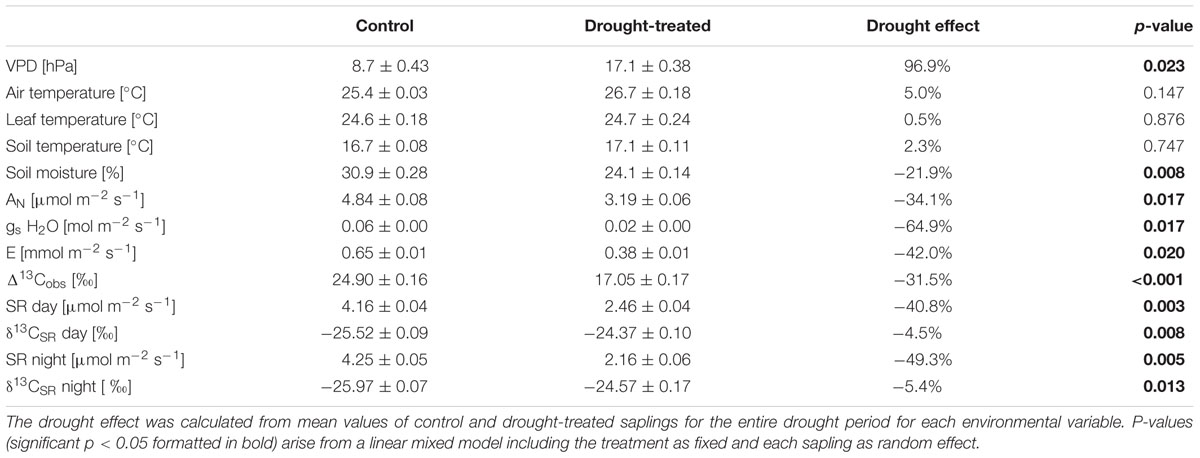

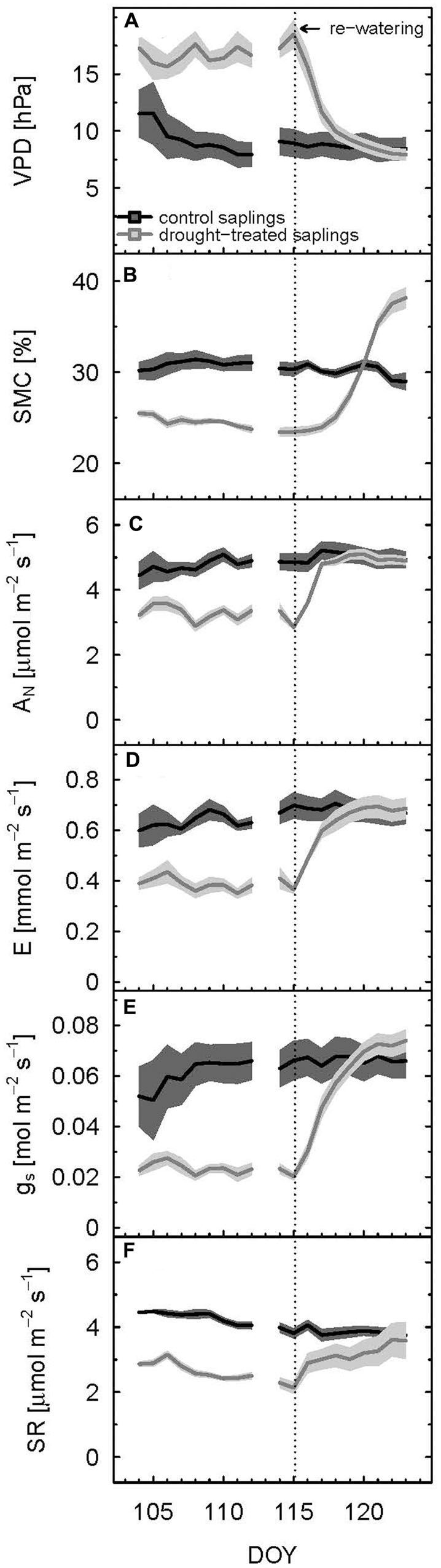

During the main drought period (DOY 107–115), VPD approximately doubled during the daytime for drought-treated compared to control plants, reaching an average of 17.1 hPa for the entire drought period (Table 1; Figure 1A). In contrast, air, leaf, and soil temperatures were not significantly affected by the drought treatment. Air temperature during the drought period was slightly lower for control saplings compared to droughttreated saplings (Figure 2B) with mean values of 25.4 and 26.7°C, respectively, and night air temperatures were 17.2 and 17.8°C, respectively. Average leaf temperatures were 1–2°C below air temperature. SMC decreased significantly from 31 to 24% for control and drought-treated saplings, respectively (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Mean values ± propagated standard deviations for environmental variables (vapor pressure deficit, air temperature, leaf temperature, soil temperature, and soil moisture), gas exchange variables (net assimilation, stomatal conductance to H2O, transpiration, and soil respiration), observed photosynthetic discrimination and the δ13C of soil-respired CO2 for day time (PAR > 500 μmol m-2 s-1) of the entire drought period (17–25 April, DOY 107–115) of the control and the drought treatment.

FIGURE 1. Diurnal means of vapor pressure deficit (VPD) (A), soil moisture content (B), net assimilation (C), transpiration (D), stomatal conductance to H2O (E), and soil respiration (F) of control and drought-treated beech saplings. Mean values were calculated for PAR > 500 μmol m-2 s-1. The shaded areas show propagated standard deviations of three replicates. Re-watering is indicated by the dashed vertical line.

After re-watering the drought-treated saplings, VPD and SMC approximated the respective values of the control saplings, and even exceeded control values for SMC (Figures 1A,B). Mean VPD in the shoot chamber of drought-treated saplings declined slightly below those of the control 5 days after re-watering (DOY 120), but stayed in a range of about 10% deviation. In contrast, SMC of drought-treated saplings exceeded that of the control by about 30% toward the end of the experiment (DOY 123), which showed that the soil of control saplings was not fully saturated. Note, this was done on purpose to avoid anaerobic soil conditions during the experiment.

Carbon Dioxide and Water Vapor Fluxes: Magnitude and Carbon Isotope Composition

Drought

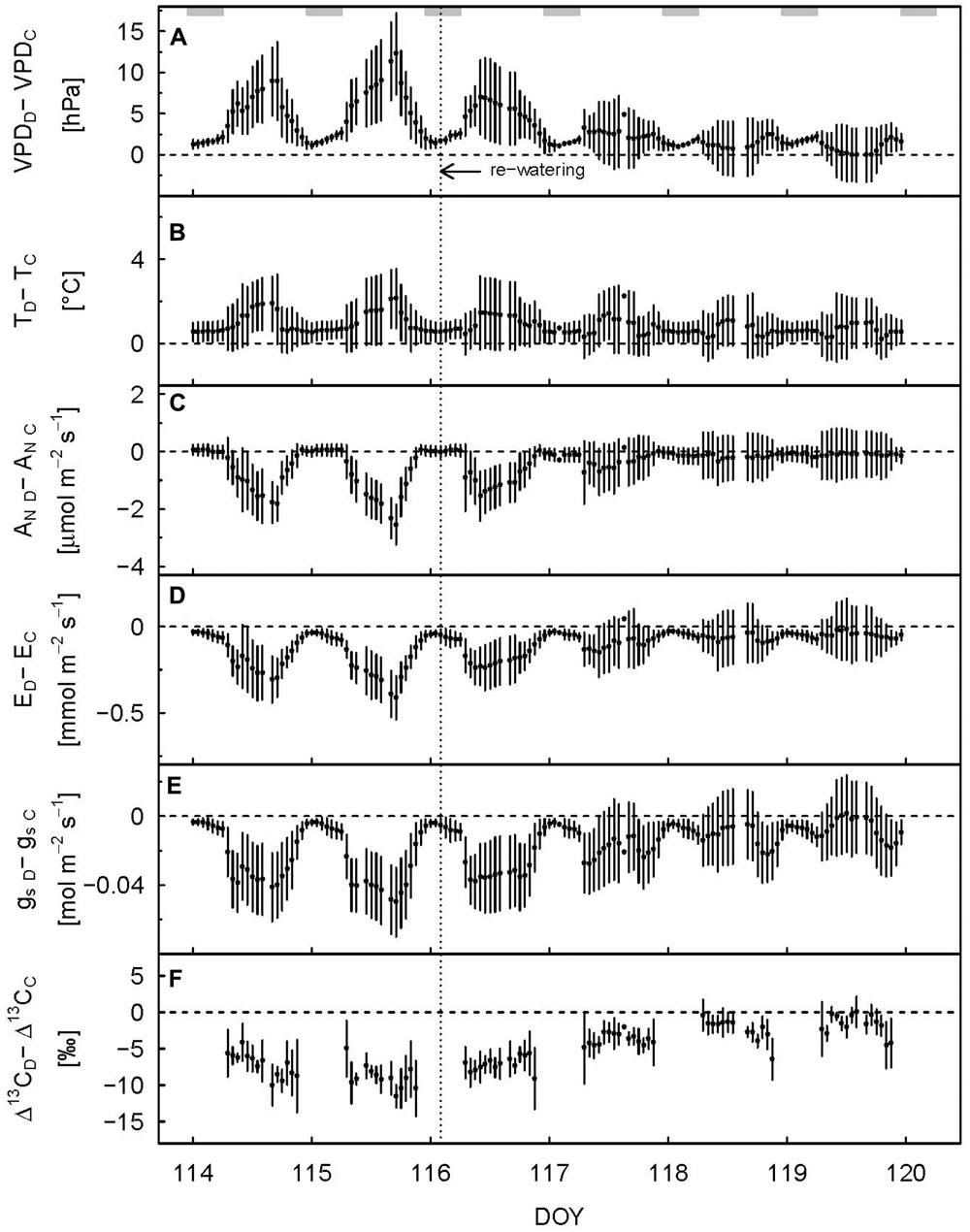

We defined the main drought period from DOY 107–115, as the drought treatment showed a significant effect on diurnal assimilation and stomatal conductance during these days (p < 0.05, linear mixed model). Stomatal conductance (gs; during the day) was most sensitive to drought stress. On average, it decreased by 65% (Table 1; Figure 1E) in drought-treated saplings compared to control saplings, while transpiration (E; Figure 1D) and net assimilation (AN; Figure 1C) decreased by 42 and 34%, respectively. While control plants showed relatively stable AN, E, and gs during full illumination (Figures 1C–E), these plant physiological variables decreased during the day in drought-treated plants, leading to an increasing difference between drought-treated and control saplings (Figures 2C–E). Simultaneously, VPD steadily increased during the day (Figure 2A).

FIGURE 2. Hourly difference in vapor pressure deficit (A), air temperature (B), net assimilation (C), transpiration (D), stomatal conductance to H2O (E), and observed photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination (F) between drought-treated (subscript D) and control (subscript C) saplings 2 days before and 4 days after re-watering. Shaded rectangles at the top indicate nighttime. Re-watering is represented by the dashed vertical line. Error bars show error propagated standard deviation, data are only shown when at least two replicates were available.

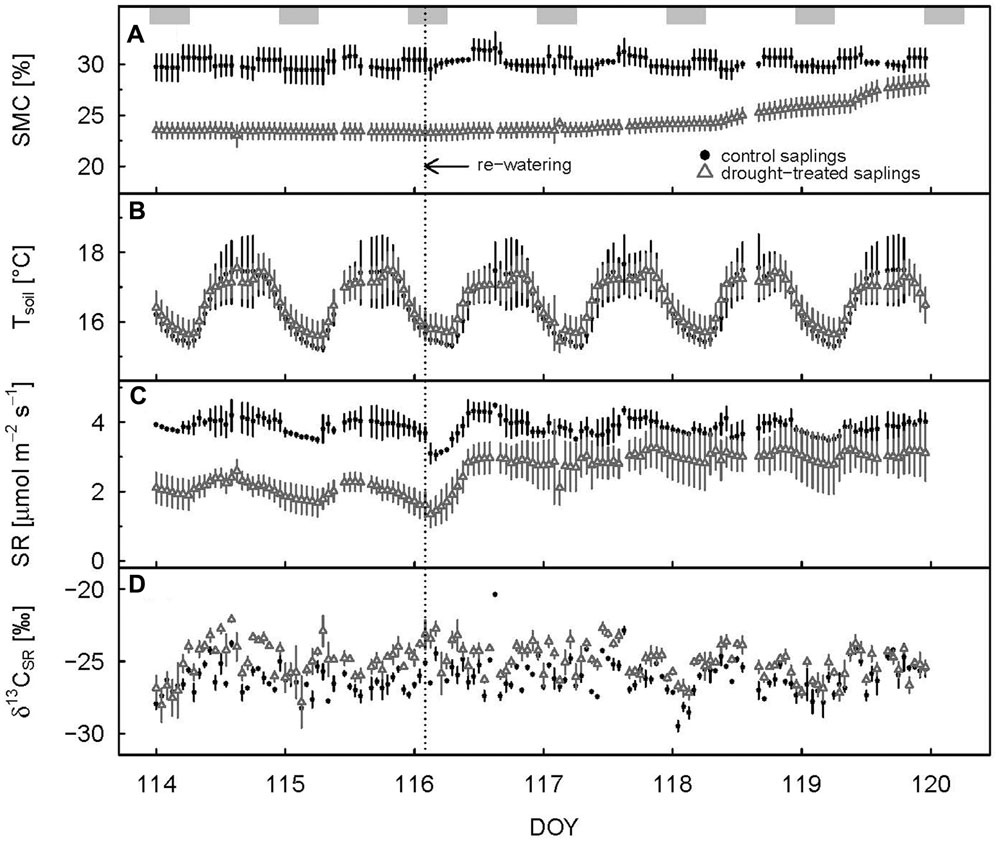

Soil respiration of drought-treated saplings was reduced between 40 and 50% compared to the control, both during day (PAR > 500 μmol m-2 s-1) and night (PAR < 20 μmol m-2 s-1; Table 1; Figure 1F). Thus, drought reduced SR more than net assimilation. During the drought period, SR of control saplings remained constantly higher than that of drought-treated saplings, with little variation between day and night (Figure 3C). Mean daytime values of SR was 4.2 and 2.5 μmol m-2 s-1 for control and drought-treated saplings, respectively, while nighttime SR was 4.3 and 2.2 μmol m-2 s-1 for control and drought-treated saplings, respectively.

FIGURE 3. Hourly mean values of soil moisture (A), soil temperature (B), soil respiration (C), and δ13C value of soil respiration (D) for control and drought-treated saplings 2 days before and 4 days after re-watering. Shaded rectangles at the top indicate nighttime. Re-watering is represented by the dashed vertical line. Error bars show the standard errors; data are only shown when at least two replicates were available.

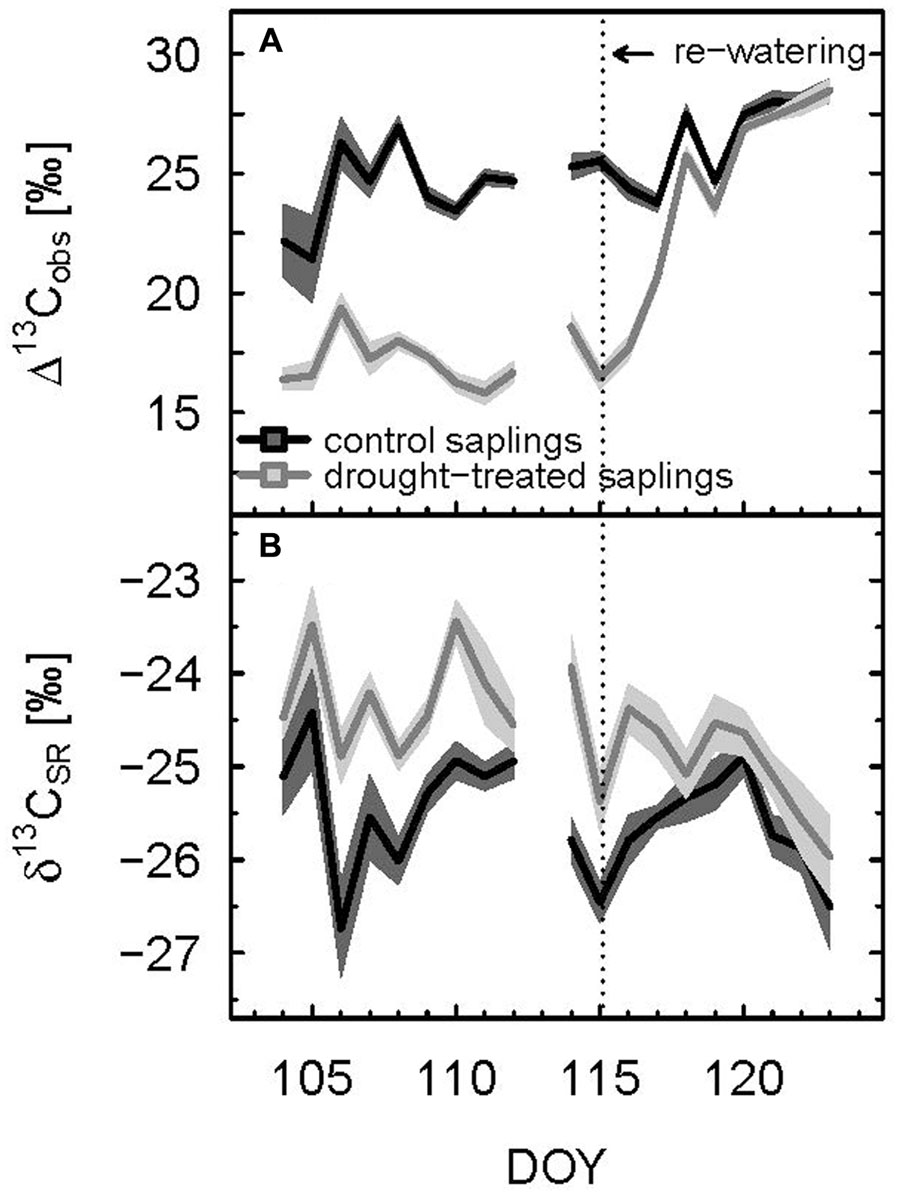

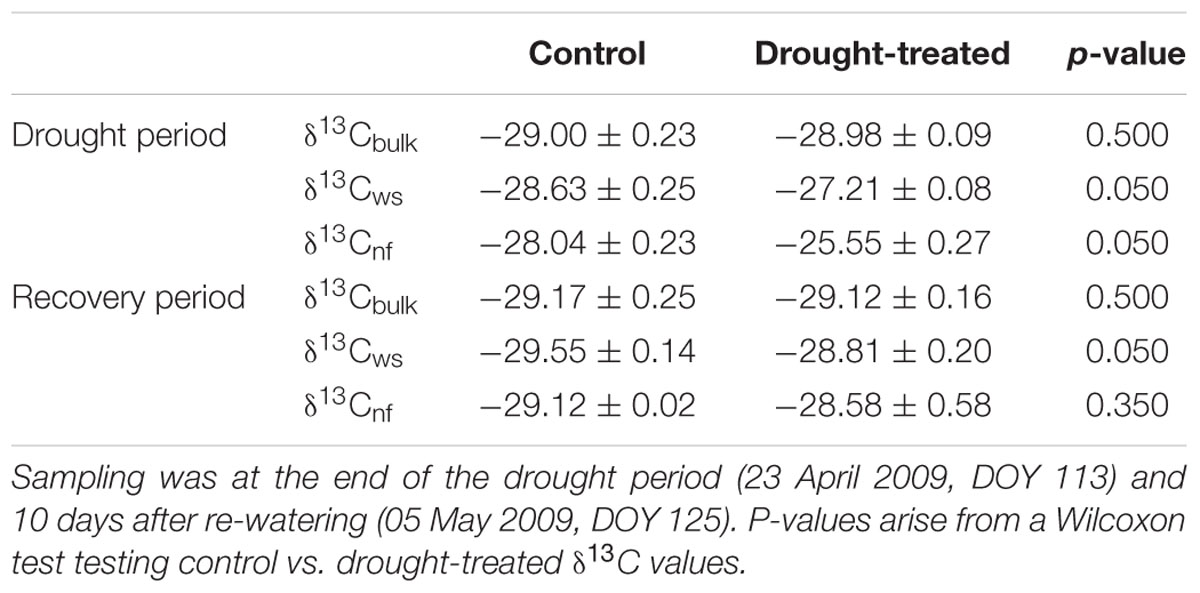

Δ13Cobs showed a relatively large day-to-day variability, even for control plants (Figure 4A) Average shoot Δ13Cobs significantly decreased from 24.9 to 17.1‰ during the drought period (p < 0.001; Table 1; Figure 4B), which resulted in a corresponding 13C enrichment of recent assimilates in leaves, i.e., larger δ13Cws and δ13Cnf during drought (p-values = 0.05; Table 2). The enrichment in 13C was larger in the neutral fraction (2.49‰) compared to the water soluble fraction (1.42‰). Bulk leaf δ13Cbulk of control and drought-treated saplings, however, did not differ (p = 0.5). The δ13C values of soil-respired CO2 (δ13CSR) of control plants were similar during day and night, with on average -25.5 and -26.0‰, respectively (Table 1). Drought caused a significant increase of δ13CSR by about 1‰ during the day and about 1.5‰ during the night (p = 0.008 for day and 0.013 for night; Table 1; Figures 3D and 4B).

FIGURE 4. Diurnal means of observed photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination (A) and δ13C value of soil respiration (B) of control and drought-treated beech saplings. Mean values were calculated for PAR > 500 μmol m-2 s-1. The shaded areas show propagated standard deviations of three replicates. Re-watering is indicated by the dashed vertical line.

TABLE 2. Mean values ± standard errors of δ13C values of leaf bulk organic material, water soluble (ws) and neutral (nf) fractions.

Recovery Period

Full recovery was achieved within a few days after re-watering for gas exchange, with AN recovering first, then gs and E, and finally SR (Figure 1). After 2 days (DOY 117), AN reached the 90% recovery level, and after 3 days (DOY 118), it was fully recovered (mean plus standard deviation > 100%) (Figure 2C). Mean recovery level of transpiration was 88% 2 days after re-watering (DOY 117) and full recovery level was reached on DOY 119 (Figure 2D). Similarly, stomatal conductance fully recovered 4 days after re-watering (DOY 119), but only recovered to 74% of the control level 2 days after re-watering (DOY 117) (Figure 2E). SR showed a strong initial recovery rate at the day of re-watering (Figures 1F and 3C), which later leveled off to a moderate recovery rate. Full recovery of SR took 7 days (DOY 122; Figure 1), during which also the amplitude of its diurnal cycle diminished (Figure 3).

Δ13Cobs reached the 90% level of recovery, which means a difference of less than 2.75‰, 3 days after re-watering (DOY 118; Figure 2F) and full recovery 7 days after re-watering (DOY 122; Figure 4A). δ13Cws values of leaf material sampled 10 days after re-watering (DOY 125) still showed a treatment effect (p-value = 0.05), in contrast to δ13C of the neutral fraction, although the standard errors for mean δ13Cnf of drought-treated saplings were much larger compared to those of control saplings (Table 2). The δ13C signal of SR approached full recovery within 3 days (DOY 118) after re-watering (Figures 3D and 4B), but due to variability between days, mean diurnal values of δ13CSR were still below control on some days afterward. Therefore, it took until DOY 122 until full recovery of δ13CSR remained for two consecutive days, thus at the same time as Δ13Cobs.

Coupling of Above and Belowground Carbon Fluxes

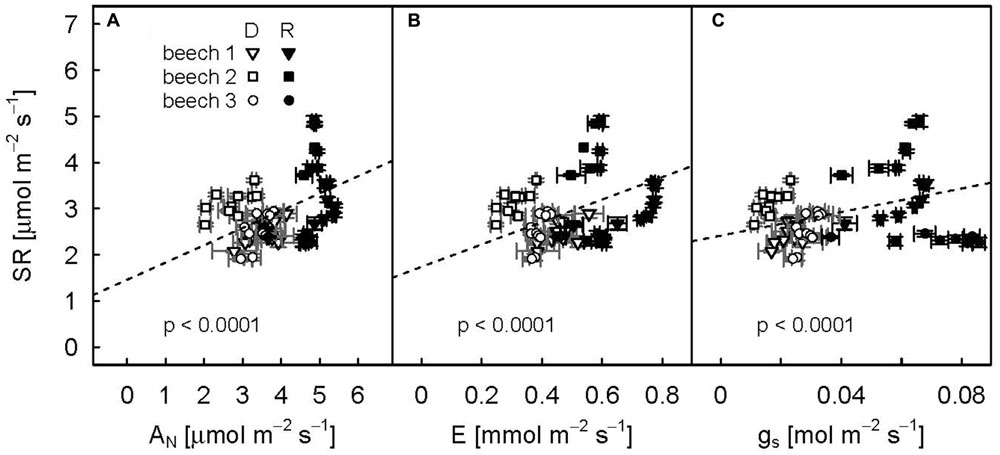

Even though SR varied considerably between individual drought-treated plants especially during the recovery period, repeated measure analysis showed a strong positive relation (p-values < 0.0001) between diurnal mean SR and aboveground plant physiological variables (Figure 5; trend lines given).

FIGURE 5. Relationships between diurnal means of net assimilation (A), transpiration (B), and stomatal conductance (C) and soil respiration for the three drought-treated beech saplings. The drought period (DOY 104–115) is represented by open symbols, the recovery period (DOY 116–124) by filled symbols. Diurnal means and standard deviations (error bars) are calculated for PAR > 500 μmol m-2 s-1. Repeated measures analysis for all relationships were significant (p values < 0.0001, dashed line).

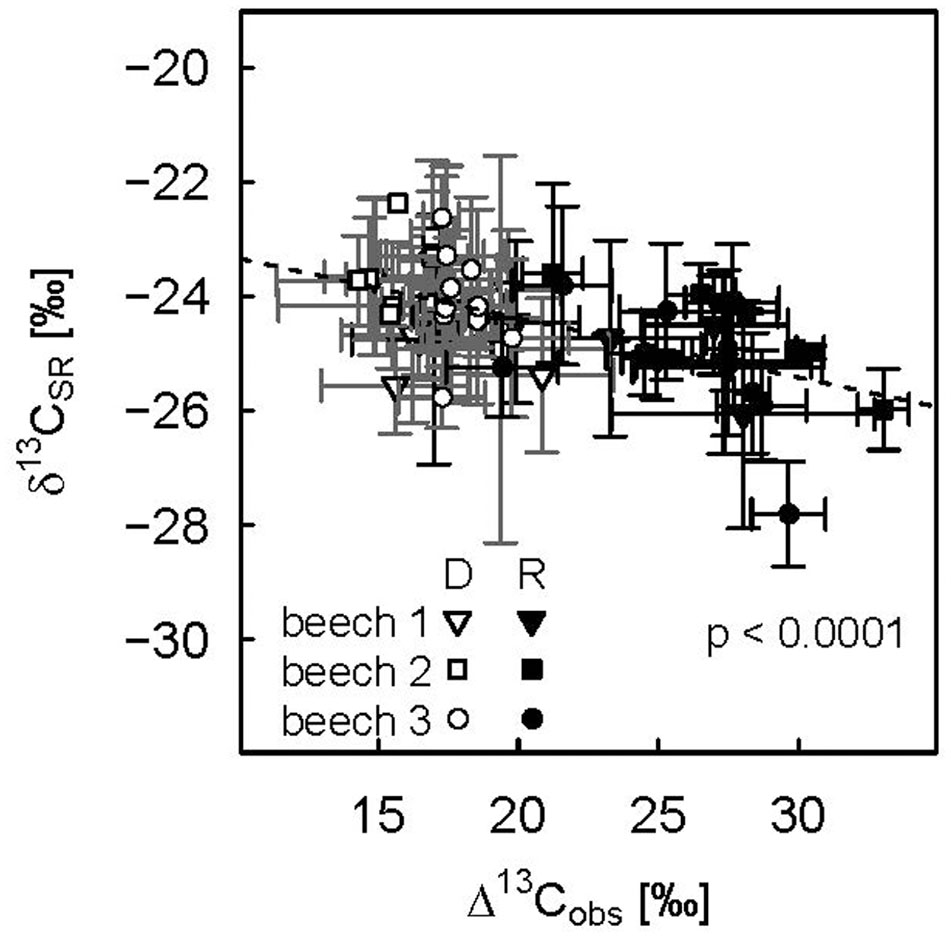

Lower Δ13Cobs indicating more 13C enriched photoassimilates during the drought period was reflected in less negative δ13CSR, while increasing Δ13Cobs during the recovery period lead to a direct decrease in diurnal mean δ13CSR (Figure 6). This dependency was reflected in a significant negative relationship between Δ13Cobs and δ13CSR of drought-treated plants. Overall, Δ13Cobs differed about 15‰ between drought and recovery periods for drought-treated plants, while δ13CSR only spanned about 2‰.

FIGURE 6. Relationship between diurnal means of photosynthetic discrimination and the δ13C value of soil respiration for the three drought-treated beech saplings. The drought period (DOY 104–115) is represented by open symbols, the recovery period (DOY 116–124) by filled symbols. Diurnal means and standard deviations (error bars) are calculated for PAR > 500 μmol m-2 s-1. Repeated measures analysis was significant (p values < 0.0001, dashed line).

Discussion

Drought Effect on Soil Respiration and δ13CSR at Natural Abundance Level

The drought-induced decrease in Δ13Cobs resulted in 13C enriched photoassimilates (higher δ13Cnf compared to control; Table 2), which in turn were transported to the roots and metabolized during SR, as seen in the increase of δ13CSR. Compared to the reduction of shoot 13Δobs by about 8‰ (i.e., about 31%) during drought, this change in daytime δ13CSR of about 1–1.5‰ (i.e., about 5%) was rather small (Figures 1 and 4; Table 1), probably caused by processes occurring during the transport of recent photoassimilates from leaves to roots. First, the isotopic signal of recently fixed assimilates is often diminished and its temporal variation dampened due to intermediate/transient storage and mixing of different carbon pools alongside their pathway from the leaves to the roots (Brüggemann et al., 2011; Gessler et al., 2014). Second, the total root carbon pool (i.e., standing biomass), into which the recently fixed assimilates are mixed, is much larger compared to the amount of carbon in assimilates supplied to the roots. Third, soil CO2 efflux is composed of several CO2 sources, amongst which root respiration is only one. In particular considering the contribution of heterotrophic respiration, the change in the isotopic signal of leaf carbon due to environmental changes should be much less expressed in the isotopic signal of soil CO2 efflux (Wingate et al., 2010; Casals et al., 2011). These combined processes probably also lead to difficulties to detect any change in δ13CSR in the field at natural isotope abundance level after drought. For example, Unger et al. (2010) found only a small increase in δ13CSR after drought using a Keeling plot approach, despite a higher relative contribution of root respiration to total soil CO2 efflux. Nevertheless, we could clearly show the effect of drought on the isotopic composition of SR – using high temporal resolution laser spectroscopy in our study under controlled environmental conditions.

Above- to Belowground Coupling

We observed a strong relationship between SR and net assimilation, transpiration and stomatal conductance for drought-treated plants during both drought and recovery periods (Figure 5). This pointed to a strong coupling of above- to belowground carbon fluxes. However, all aboveground variables were highly correlated and were all strongly related to VPD. Therefore, it was not possible to disentangle if the reduction in available carbohydrates (drought effect on AN) and/or a water-limited deceleration of carbohydrates supply to the roots due to the interaction of xylem and phloem flow rates (drought effect on gs and E, Salmon et al., 2014) limited root respiration during drought. Nevertheless, the significant increase in δ13CSR due to drought and the subsequent decrease after re-watering directly related to changes in Δ13Cobs, thus providing indirect methodological evidence that recently fixed photoassimilates rather than storage reserves drive root and rhizosphere respiration. Recent pulse-labeling studies demonstrate that beech maintains transport of recently fixed photoassimilates into the roots under moderate drought stress (Blessing et al., 2015; Hommel et al., 2016), which was suggested as strategy to support root functioning via osmotic adjustment (Hommel et al., 2016). Thus, beech saplings continue allocating carbon to the roots even under carbon limited conditions.

However, the drought effect on δ13CSR at natural isotope abundance of about 1–1.5‰ in our small-scale model ecosystems is still relatively small in order to be detected in a natural ecosystem, considering the higher level of complexity. In a forest ecosystem, different plant heights and transport velocities of recently fixed photoassimilates cause various time lags for the carbon isotope signal to be translated from above- to belowground tissues. Furthermore, different plant species may suffer from different stress levels. Wingate et al. (2010) published the only study (to the authors knowledge) in which Δ13C on a branch level were measured at high resolution simultaneously with δ13CSR in the field, confirming that time lagged correlations between the carbon isotope composition of recently fixed photoassimilates and SR might be weakly or even anticorrelated (Wingate et al., 2010).

Recovery after Re-watering

A fast recovery was observed in Δ13Cobs as well as in the carbon isotopic signatures of the neutral fraction (δ13Cnf), which represents mainly sugars. Both δ13Cnf and δ13Cws increased during the drought period for drought-treated plants compared to control plants, but after the recovery period, only the water soluble fraction (δ13Cws) representing several compounds like amino acids, organic acids, and sugars (Gessler et al., 2007a) still showed a drought signal. Since Δ13Cobs already fully recovered 7 days after re-watering (DOY 122), its isotopic signal was obviously imprinted on δ13Cnf but not (sufficiently) on δ13Cws, which integrates over longer time spans – in this study: at least 10 days (δ13Cnf and δ13Cws both sampled on DOY 125).

Although drought caused a stronger reduction in stomatal conductance (-65%) than in net assimilation (-34%) and transpiration (-42%), all variables fully recovered within 4 days after re-watering. Net assimilation recovered fastest, reaching full recovery already after 3 days, similar to results reported by Zang et al. (2014). Reduced stomatal conductance of drought-treated plants remained slightly lower longer into the recovery period compared to net assimilation, as reported in earlier studies (Tognetti et al., 1995; Miyashita et al., 2005; Martorell et al., 2014). The largest contributions toward full recovery in our study occurred within the day of re-watering and particularly during the following day, similar to earlier reports on other plants (kidney bean, Miyashita et al., 2005; pubescent oak, Gallé et al., 2007), which is in line with fast water uptake after re-watering (Volkmann et al., 2016). Thus, the fast initial recovery of aboveground gas exchange variables indicated that beech saplings were relatively resilient to the (moderate) drought experienced and could restore their carbon and water fluxes within a few days. Recovery of gas exchange after drought depends on the stress level (Miyashita et al., 2005), which makes it difficult to compare different studies. But also other studies (Blessing et al., 2015; Hommel et al., 2016) indicate the high resilience of beech saplings to moderate drought stress.

Conclusion

Above- and belowground CO2 fluxes were strongly coupled, both during drought and the subsequent recovery period. We showed that young beech saplings recovered within a few days from moderate drought conditions, even though they had drastically reduced stomatal conductance, and therefore, aboveground carbon and water fluxes during drought. This resilient behavior is likely to help beech in Central Europe, the area of dominance for beech in the natural vegetation (Ellenberg, 2010), particularly at young age when their root systems are not yet fully developed, coping with more frequent drought events in the future.

Author Contributions

CB processed the data. MB designed and conducted the experiment. All authors equally contributed to data interpretation, wrote, and critically revised the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this project was provided by a Marie Curie Excellence Grant from the European Commission (Project No: MEXT-CT-2006-042268). CB acknowledged financial support by the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation [Project No: C09.0159], linked to the COST Action ES0806 “Stable Isotopes in Biosphere-Atmosphere-Earth System Research (SIBAE).”

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Alexander Knohl and Patrick Sturm for their support concerning experimental design and laser spectroscopy measurements. Further, we thank Peter Plüss, Thomas Baur, and Patrick Flütsch for chamber construction and technical support, and Annika Ackermann and Roland A. Werner for IRMS sample analysis at the Isolab, ETH Zurich.

References

Alstad, K. P., Lai, C.-T., Flanagan, L. B., and Ehleringer, J. R. (2007). Environmental controls on the carbon isotope composition of ecosystem-respired CO2 in contrasting forest ecosystems in Canada and the USA. Tree Physiol. 27, 1361–1374. doi: 10.1093/treephys/27.10.1361

Barthel, M., Hammerle, A., Sturm, P., Baur, T., Gentsch, L., and Knohl, A. (2011). The diel imprint of leaf metabolism on the δ13C signal of soil respiration under control and drought conditions. New Phytol. 192, 925–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03848.x

Barthel, M., Sturm, P., Hammerle, A., Buchmann, N., Gentsch, L., Siegwolf, R., et al. (2014). Soil H218O labelling reveals the effect of drought on C18OO fluxes to the atmosphere. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 5783–5793. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru312

Blessing, C. H., Werner, R. A., Siegwolf, R., and Buchmann, N. (2015). Allocation dynamics of recently fixed carbon in beech saplings in response to increased temperatures and drought. Tree Physiol. 35, 585–598. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpv024

Breda, N., Huc, R., Granier, A., and Dreyer, E. (2006). Temperate forest trees and stands under severe drought: a review of ecophysiological responses, adaptation processes and long-term consequences. Ann. For. Sci. 63, 625–644. doi: 10.1051/forest:2006042

Brüggemann, N., Gessler, A., Kayler, Z., Keel, S. G., Badeck, F., Barthel, M., et al. (2011). Carbon allocation and carbon isotope fluxes in the plant-soil-atmosphere continuum: a review. Biogeosciences 8, 3457–3489. doi: 10.5194/bg-8-3457-2011

Burri, S., Sturm, P., Prechsl, U. E., Knohl, A., and Buchmann, N. (2014). The impact of extreme summer drought on the short-term carbon coupling of photosynthesis to soil CO2 efflux in a temperate grassland. Biogeosciences 11, 961–975. doi: 10.5194/bg-11-961-2014

Casals, P., Lopez-Sangil, L., Carrara, A., Gimeno, C., and Nogues, S. (2011). Autotrophic and heterotrophic contributions to short-term soil CO2 efflux following simulated summer precipitation pulses in a Mediterranean dehesa. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 25, 1–12. doi: 10.1029/2010gb003973

Cernusak, L. A., Ubierna, N., Winter, K., Holtum, J. A. M., Marshall, J. D., and Farquhar, G. D. (2013). Environmental and physiological determinants of carbon isotope discrimination in terrestrial plants. New Phytol. 200, 950–965. doi: 10.1111/nph.12423

Ekblad, A., and Högberg, P. (2001). Natural abundance of 13C in CO2 respired from forest soils reveals speed of link between tree photosynthesis and root respiration. Oecologia 127, 305–308. doi: 10.1007/s004420100667

Ellenberg, H. (2010). Vegetation Mitteleuropas mit den Alpen in ökologischer, dynamischer und historischer Sicht. Stuttgart: Eugen Ulmer KG.

Epron, D., Bahn, M., Derrien, D., Lattanzi, F. A., Pumpanen, J., Gessler, A., et al. (2012). Pulse-labelling trees to study carbon allocation dynamics: a review of methods, current knowledge and future prospects. Tree Physiol. 32, 776–798. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tps057

Evans, J. R., Sharkey, T. D., Berry, J. A., and Farquhar, G. D. (1986). Carbon isotope discrimination measured concurrently with gas exchange to investigate CO2 diffusion in leaves of higher plants. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 13, 281–292. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.176495

Farquhar, G. D., O’Leary, M. H., and Berry, J. A. (1982). On the relationship between carbon isotope discrimination and the intercellular carbon dioxide concentration in leaves. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 9, 121–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02518.x

Gallé, A., Haldimann, P., and Feller, U. (2007). Photosynthetic performance and water relations in young pubescent oak (Quercus pubescens) trees during drought stress and recovery. New Phytol. 174, 799–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02047.x

Gavrichkova, O., Proietti, S., Moscatello, S., Portarena, S., Battistelli, A., Matteucci, G., et al. (2011). Short-term natural δ13C and δ18O variations in pools and fluxes in a beech forest: the transfer of isotopic signal from recent photosynthates to soil respired CO2. Biogeosciences 8, 2833–2846. doi: 10.5194/bg-8-2833-2011

Gentsch, L., Sturm, P., Hammerle, A., Siegwolf, R., Wingate, L., Ogee, J., et al. (2014). Carbon isotope discrimination during branch photosynthesis of Fagus sylvatica: field measurements using laser spectrometry. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 1481–1496. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru024

Gessler, A., Ferrio, J. P., Hommel, R., Treydte, K., Werner, R. A., and Monson, R. K. (2014). Stable isotopes in tree rings: towards a mechanistic understanding of isotope fractionation and mixing processes from the leaves to the wood. Tree Physiol. 34, 796–818. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpu040

Gessler, A., Keitel, C., Kodama, N., Weston, C., Winters, A. J., Keith, H., et al. (2007a). δ13C of organic matter transported from the leaves to the roots in Eucalyptus delegatensis: short-term variations and relation to respired CO2. Funct. Plant Biol. 34, 692–706. doi: 10.1071/fp07064

Gessler, A., Keitel, C., Kreuzwieser, J., Matyssek, R., Seiler, W., and Rennenberg, H. (2007b). Potential risks for European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) in a changing climate. Trees 21, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00468-006-0107-x

Göttlicher, S., Knohl, A., Wanek, W., Buchmann, N., and Richter, A. (2006). Short-term changes in carbon isotope composition of soluble carbohydrates and starch: from canopy leaves to the root system. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 20, 653–660. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2352

Granier, A., Reichstein, M., Breda, N., Janssens, I. A., Falge, E., Ciais, P., et al. (2007). Evidence for soil water control on carbon and water dynamics in European forests during the extremely dry year: 2003. Agric. For. Meteorol. 143, 123–145. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2006.12.004

Grimm, V., and Wissel, C. (1997). Babel, or the ecological stability discussions: an inventory and analysis of terminology and a guide for avoiding confusion. Oecologia 109, 323–334. doi: 10.1007/s004420050090

Högberg, P., Nordgren, A., Buchmann, N., Taylor, A. F. S., Ekblad, A., Högberg, M. N., et al. (2001). Large-scale forest girdling shows that current photosynthesis drives soil respiration. Nature 411, 789–792. doi: 10.1038/35081058

Hommel, R., Siegwolf, R., Zavadlav, S., Arend, M., Schaub, M., Galiano, L., et al. (2016). Impact of interspecific competition and drought on the allocation of new assimilates in trees. Plant Biol. 18, 785–796. doi: 10.1111/plb.12461

Keitel, C., Adams, M. A., Holst, T., Matzarakis, A., Mayer, H., Rennenberg, H., et al. (2003). Carbon and oxygen isotope composition of organic compounds in the phloem sap provides a short-term measure for stomatal conductance of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). Plant Cell Environ. 26, 1157–1168. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2003.01040.x

Knohl, A., Werner, R. A., Brand, W. A., and Buchmann, N. (2005). Short-term variations in δ13C of ecosystem respiration reveals link between assimilation and respiration in a deciduous forest. Oecologia 142, 70–82. doi: 10.1007/s00442-004-1702-4

Kuptz, D., Fleischmann, F., Matyssek, R., and Grams, T. E. E. (2011). Seasonal patterns of carbon allocation to respiratory pools in 60-yr-old deciduous (Fagus sylvatica) and evergreen (Picea abies) trees assessed via whole-tree stable carbon isotope labeling. New Phytol. 191, 160–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03676.x

Kuzyakov, Y., and Gavrichkova, O. (2010). Time lag between photosynthesis and carbon dioxide efflux from soil: a review of mechanisms and controls. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 3386–3406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02179.x

Martorell, S., Diaz-Espejo, A., Medrano, H., Ball, M. C., and Choat, B. (2014). Rapid hydraulic recovery in Eucalyptus pauciflora after drought: linkages between stem hydraulics and leaf gas exchange. Plant Cell Environ. 37, 617–626. doi: 10.1111/pce.12182

McDowell, N. G., Bowling, D. R., Bond, B. J., Irvine, J., Law, B. E., Anthoni, P., et al. (2004). Response of the carbon isotopic content of ecosystem, leaf, and soil respiration to meteorological and physiological driving factors in a Pinus ponderosa ecosystem. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 18, GB1013–GB1013. doi: 10.1029/2003gb002049

Merchant, A., Peuke, A. D., Keitel, C., Macfarlane, C., Warren, C. R., and Adams, M. A. (2010). Phloem sap and leaf delta C-13, carbohydrates, and amino acid concentrations in Eucalyptus globulus change systematically according to flooding and water deficit treatment. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 1785–1793. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq045

Miyashita, K., Tanakamaru, S., Maitani, T., and Kimura, K. (2005). Recovery responses of photosynthesis, transpiration, and stomatal conductance in kidney bean following drought stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 53, 205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2004.03.015

Nelson, D. D., McManus, J. B., Herndon, S. C., Zahniser, M. S., Tuzson, B., and Emmenegger, L. (2008). New method for isotopic ratio measurements of atmospheric carbon dioxide using a 4.3 μm pulsed quantum cascade laser. Appl. Phys. B 90, 301–309. doi: 10.1007/s00340-007-2894-1

Pan, Y., Birdsey, R. A., Fang, J., Houghton, R., Kauppi, P. E., Kurz, W. A., et al. (2011). A large and persistent carbon sink in the world’s forests. Science 333, 988–993. doi: 10.1126/science.1201609

Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., DebRoy, S., Sarkar, D., and Team, R. C. (2016). nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. Version 3. Available at: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme

Plain, C., Gerant, D., Maillard, P., Dannoura, M., Dong, Y. W., Zeller, B., et al. (2009). Tracing of recently assimilated carbon in respiration at high temporal resolution in the field with a tuneable diode laser absorption spectrometer after in situ 13CO2 pulse labelling of 20-year-old beech trees. Tree Physiol. 29, 1433–1445. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpp072

2008–2010R Development Core Team (2008–2010). A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Development Core Team.

Rascher, K. G., Maguas, C., and Werner, C. (2010). On the use of phloem sap δ13C as an indicator of canopy carbon discrimination. Tree Physiol. 30, 1499–1514. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpq092

Reichstein, M., Bahn, M., Ciais, P., Frank, D., Mahecha, M. D., Seneviratne, S. I., et al. (2013). Climate extremes and the carbon cycle. Nature 500, 287–295. doi: 10.1038/nature12350

Salmon, Y., Barnard, R. L., and Buchmann, N. (2014). Physiological controls of the isotopic time lag between leaf assimilation and soil CO2 efflux. Funct. Plant Biol. 41, 850–859. doi: 10.1071/FP13212

Scartazza, A., Moscatello, S., Matteucci, G., Battistelli, A., and Brugnoli, E. (2015). Combining stable isotope and carbohydrate analyses in phloem sap and fine roots to study seasonal changes of source-sink relationships in a Mediterranean beech forest. Tree Physiol. 35, 829–839. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpv048

Schär, C., Vidale, P. L., Luthi, D., Frei, C., Haberli, C., Liniger, M. A., et al. (2004). The role of increasing temperature variability in European summer heatwaves. Nature 427, 332–336. doi: 10.1038/nature02300

Sturm, P., and Knohl, A. (2010). Water vapor δ2H and δ18O measurements using off-axis integrated cavity output spectroscopy. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 3, 67–77. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7714

Tognetti, R., Johnson, J. D., and Michelozzi, M. (1995). The reponse of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) seedlings from two Italian populations to drought and recovery. Trees 9, 348–354. doi: 10.1007/BF00202499

Unger, S., Maguas, C., Pereira, J. S., Aires, L. M., David, T. S., and Werner, C. (2010). Disentangling drought-induced variation in ecosystem and soil respiration using stable carbon isotopes. Oecologia 163, 1043–1057. doi: 10.1007/s00442-010-1576-6

Volkmann, T. H. M., Haberer, K., Gessler, A., and Weiler, M. (2016). High-resolution isotope measurements resolve rapid ecohydrological dynamics at the soil–plant interface. New Phytol. 210, 839–849. doi: 10.1111/nph.13868

von Caemmerer, S., and Farquhar, G. D. (1981). Some relationships between the biochemistry of photosynthesis and the gas exchange of leaves. Planta 153, 376–387. doi: 10.1007/BF00384257

Werner, C., Unger, S., Pereira, J. S., Maia, R., David, T. S., Kurz-Besson, C., et al. (2006). Importance of short-term dynamics in carbon isotope ratios of ecosystem respiration (delta C-13(R)) in a Mediterranean oak woodland and linkage to environmental factors. New Phytol. 172, 330–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01836.x

Werner, R. A., and Brand, W. A. (2001). Referencing strategies and techniques in stable isotope ratio analysis. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 15, 501–519. doi: 10.1002/rcm.258

Wingate, L., Ogee, J., Burlett, R., Bosc, A., Devaux, M., Grace, J., et al. (2010). Photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination and its relationship to the carbon isotope signals of stem, soil and ecosystem respiration. New Phytol. 188, 576–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03384.x

Keywords: carbon allocation, soil CO2 efflux, drought, beech (Fagus sylvatica), laser spectroscopy, resilience

Citation: Blessing CH, Barthel M, Gentsch L and Buchmann N (2016) Strong Coupling of Shoot Assimilation and Soil Respiration during Drought and Recovery Periods in Beech As Indicated by Natural Abundance δ13C Measurements. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1710. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01710

Received: 26 July 2016; Accepted: 31 October 2016;

Published: 17 November 2016.

Edited by:

Jean Rivoal, Université de Montréal, CanadaReviewed by:

Maren Dubbert, University of Freiburg, GermanyDaniel Epron, Université de Lorraine, France

Copyright © 2016 Blessing, Barthel, Gentsch and Buchmann. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carola H. Blessing, Y2Fyb2xhLmJsZXNzaW5nQHN5ZG5leS5lZHUuYXU=

Carola H. Blessing

Carola H. Blessing Matti Barthel2

Matti Barthel2 Lydia Gentsch

Lydia Gentsch Nina Buchmann

Nina Buchmann