- 1School of Minerals Processing and Bioengineering, Central South University, Changsha, China

- 2Key Laboratory of Biometallurgy of Ministry of Education, Central South University, Changsha, China

- 3School of Biology and Environmental Science, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

- 4The Administrative Centre for China's Agenda 21, Beijing, China

- 5Key Laboratory of Forest Ecology and Environment of State Forestry Administration, Institute of Forest Ecology, Environment, and Protection, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Beijing, China

Taxus chinensis is a rare and endangered shrub, highly sensitive to temperature changes and widely known for its potential in cancer treatment. How gene expression of T. chinensis responds to low temperature is still unknown. To investigate cold response of the genus Taxus, we obtained the transcriptome profiles of T. chinensis grown under normal and low temperature (cold stress, 0°C) conditions using Illumina Miseq sequencing. A transcriptome including 83,963 transcripts and 62,654 genes were assembled from 4.16 Gb of reads data. Comparative transcriptomic analysis identified 2,025 differently expressed (DE) isoforms at p < 0.05, of which 1,437 were up-regulated by cold stress and 588 were down-regulated. Annotation of DE isoforms indicated that transcription factors (TFs) in the MAPK signaling pathway and TF families of NAC, WRKY, bZIP, MYB, and ERF were transcriptionally activated. This might have been caused by the accumulation of secondary messengers, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and Ca2+. While accumulation of ROS will have caused damages to cells, our results indicated that to adapt to low temperatures T. chinensis employed a series of mechanisms to minimize these damages. The mechanisms included: (i) cold-enhanced expression of ROS deoxidant systems, such as peroxidase and phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase, to remove ROS. This was further confirmed by analyses showing increased activity of POD, SOD, and CAT under cold stress. (ii) Activation of starch and sucrose metabolism, thiamine metabolism, and purine metabolism by cold-stress to produce metabolites which either protect cell organelles or lower the ROS content in cells. These processes are regulated by ROS signaling, as the “feedback” toward ROS accumulation.

Introduction

Taxus chinensis is a woody shrub, which belongs to the Genus Taxus and Family Taxaceae. Members of the genus Taxus are particularly well-known for their important biological compounds such as taxol and paclitaxel—effective drugs used in many cancer therapies (Hao et al., 2008). The species in the Taxus genus are rare and endangered species and are highly sensitive to temperature changes including low temperature. The limited resources call for a study into the species' cold transcriptomic response. Cold stress is a very important abiotic stress limiting plant growth, productivity, and distribution. Significant economic losses have resulted from unusual sudden temperature changes in winter and later cold spring events (Yadav, 2010). Cold stress inhibits plant development directly and, indirectly, through osmotic, oxidative, and other stresses (Thomashow, 1999). The oxidative stress caused by cold stress is the product of accumulation of cold stress responsive messengers—reactive species (ROS). The ROS are produced for the purpose of signaling, while they are also recognized as toxic by-products of aerobic metabolism. ROS trigger signal transduction pathways such as mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling path for specific responsive gene expressions. Excessive toxic ROS are scavenged by enzymes such as SOD, CAT, and POD (Bailey-Serres and Mittler, 2006).

Plants show a range of responses to cold stress. The responses include the changes in plasma membrane composition and transport activity, detoxification of ROS, and synthesis of cytoplasm-protectant molecules (Beck et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2013), and involve changes in the expression level of cold-responsive genes. The signaling transduction pathways from cold stress to altering the expression of cold responsive genes is crucial for the response of plants to cold stress. A generic signal transduction includes signal perception, generation of second messengers such as ROS and final transcription regulation by transcription factors (TFs) (Singh et al., 2002; Rahaie et al., 2013). The most important signaling pathway for regulation of cold responsive genes is the MAPK signaling pathway which involves several families of TFs (Pitzschke et al., 2009), second messengers (ROS and Ca2+) and plant hormones such as abscisic acid and salicylic acid and ethylene. The ROS induces expression of TFs directly or indirectly by accumulation of plant hormones, and TFs and plant hormones feedback on ROS by regulating expression of genes related to ROS scavengers, such as POD and SOD to minimize the potential damages caused by ROS (Tarkowski and Van den Ende, 2015). It is, therefore, important to investigate gene transcriptional changes to understand gene regulation mechanisms in response to cold stress.

Transcriptome sequencing or RNA-seq, was developed as a powerful tool to obtain an overall view of gene expression profiles of organisms (Ozsolak et al., 2009; Nagalakshmi et al., 2010). The transcriptome of the genus Taxus has been previously reported for gene expression profiles in leaf, stem, and root tissues using Illumina sequencing (Hao et al., 2011) and in needles using 454 pyrosequencing (Wu et al., 2011). However, information on the large-scale regulation of gene expression profiles in response to cold stress is still lacking for this temperature-sensitive genus. In the present study, we applied Illumina Miseq sequencing to study the whole transcriptome of Chinese yew (T. chinensis) under cold stressed conditions, with a particular focus on the role of ROS-related processes in the stress response. The activity of three ROS scavengers was also analyzed.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Enzyme Activity

Two to three-year old Chinese yew (T. chinensis) seedlings were grown in a green house with the settings at 12 light/12 h dark, and a temperature of 23/15°C. The relative humidity was 70% and photosynthetically active radiation at the leaf level was 250–350 μmol m−2 s−1. Before stress, stems of the control-grown seedlings were wrapped by cotton and cling film and the seedlings were transferred into the growth chamber. The stress treatment was carried out in a growth chamber, with a three-step incubation of plants at 10°C for the first 48 h, followed by 5°C for the next 48 h, and then 0°C until the samples harvest. After plants had been stressed for 12 h at 0°C, plant tissues were harvested for RNA extraction. Tissues from control seedlings and stressed seedlings were sampled from the longest leaf (leaf 5–8). Each treatment (control and cold stress) was carried out three times, resulting in three biological replicates. Collected samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately and stored at −80°C for further molecular analysis.

Activity of three enzymes, superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), and catalase (CAT) was determined in leaf tissue samples on the Epoch Microplate Reader (BioTek, USA) using an ELISA enzyme activity Kit (TianGen Inc., Beijing, China), following the manufacturers' instructions. The leaf tissue samples were harvested and enzyme activities were measured after 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h of the 0°C treatment. Enzyme activities of the control plants (control) were also measured by directly sampling leaf tissues from seedlings that were grown at normal temperature (23°C). Three biological replicates were analyzed.

RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and Sequencing

Frozen tissue samples were ground in liquid nitrogen into fine powder, which was used for RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted using the Column Plant RNAout Kit (Tiandz, Inc. Beijing, China), and genomic DNA was digested using Desoxyribonuclease I Amplification Grade (Invitrogen, San Diego, California, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. RNA concentration and purity was determined Nanodrop Spectrophotometer (ND-1000 Spectrophotometer, Nanodrop products, Wilmington, USA), and Qubit 2.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Poly(A) mRNA was enriched using magnetic beads with oligo(dT). The mRNA library was constructed using the Illumina TruSeq RNA sample prep kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) following the manufacturers' instructions. Paired-end sequencing was performed using Miseq 150 bp kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) on Illumina Miseq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Paired-end sequencing was performed using the following Illumina adapters: adapter-R1 5′-AGATCGGAAGAGCACACGTCTGAACTCCAGTCA-3′ and adapter-R2 5′-AGATCGGAAGAGCGTCGTGTAGGGAAAGAGTGT-3′. The raw data of Miseq paired-end sequencing was the fastq format.

Data Processing and Analysis

The barcodes and adapters in reads were removed before assembly, using cutadapt (Martin, 2011), and sequencing quality was checked using Fastqc. A total of 4.16 Gb clean data was obtained for all sample reads. As none genome data was available for Taxus, a de novo RNA-seq assembly was performed toward transcriptome analysis, using Trinity platform (Grabherr et al., 2011; Haas et al., 2013) following Trinity users' guild. The transcriptome was assembled from all six samples (three control samples and three cold stressed samples). The quality of the transcriptome was assessed by TrinityStats scripts and blasting the transcriptome to Swissprot database (Gasteiger et al., 2001). Before building a transcript expression matrix, transcript abundance in each sample was estimated by aligning each sample reads to the transcriptome using Trinity scripts and combined RSEM (Wang et al., 2009) and bowtie packages. To identify transcripts expressed differently, the transcript expression abundance was normalized by TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) method (Robinson and Oshlack, 2010; Dillies et al., 2012). The transcript matrix and normalized TMM matrix were used for downstream analysis such as quality check of samples and replicates and different expression (DE) analysis.

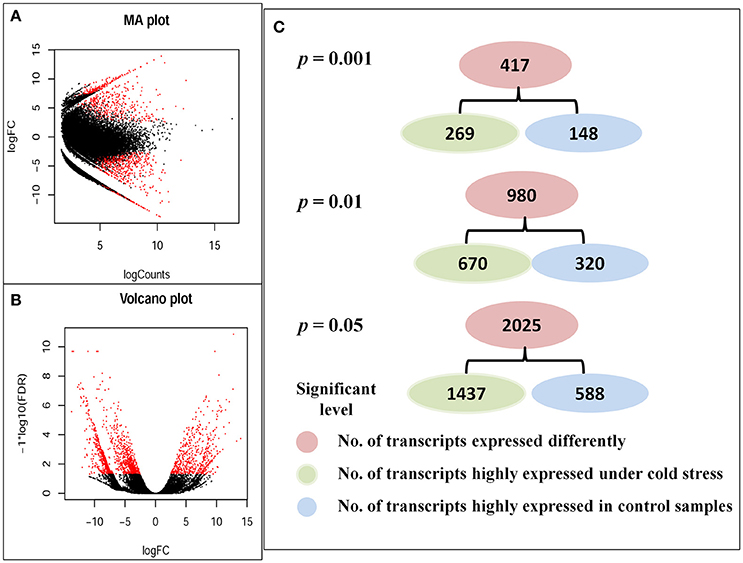

To assess the quality of replicates across all samples, the trinity PtR script was used to generate a correlation matrix (heat map) for all sample replicates using the counts-per-million (CPM) and log2 transformed data. Principal Component Analysis was also performed to explore any relationship among the sample replicates. For DE analysis, the Bioconductor R package, edgeR, was used to perform pairwise comparison between control and cold-stressed samples (Robinson et al., 2010). MA and volcano plots were generated to show transcripts that were expressed differently. Subsequently, all isoforms that were at least 2∧2 fold differently expressed and had p values at most 0.001, 0.01, and 0.05 respectively, were extracted. Heat maps were made to (i) describe the sample correlations using DE isoforms and (ii) show all isoform correlations in each sample.

Open Reading Frames (ORFs) of transcriptome and DE transcripts (both up- and down-regulated isoforms) at p = 0.05 were predicted by Transdecoder (https://github.com/TransDecoder/TransDecoder/releases). ORFs were used for function annotations. KEEG pathway annotation was performed on the KAAS (KEEG Automatic Annotation Serve) website (http://www.genome.jp/tools/kaas/). Gene Ontology (GO) annotation analyses of differently expressed isoforms was performed using BinGo (https://www.psb.ugent.be/cbd/papers/BiNGO/Home.html) by assigning the annotation to the Arabidopsis. Plant transcription factors (TFs) were predicted using PlantTFDB database (http://planttfdb.cbi.pku.edu.cn/).

The reads data has been submitted to NCBI SRA database. The accession numbers of reads data in were SRR5167062, SRR5167061, SRR5167060, SRR5167059, SRR5167058, and SRR5167057 in Bioproject PRJNA360896. Other statistical analyses were carried out using the Minitab 16.0 software (Minitab Inc.). A p-value of smaller than 0.05 was considered as significant.

RT-qPCR

RT-qPCR was carried out to validate the RNA-seq data. Digestion of genomic DNA and synthesis of cDNA were similar as in section RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and sequencing. Quantitative PCR experiments were performed on Bio-Rad iQ5 Optical System (BIO-RAD Laboratories Inc., USA) using SYBR Premix, and relative expression was calculated as described previously (Meng et al., 2016; Meng and Fricke, 2017). Primers used in the present study were designed using PrimeQuest Tools, and primer sequences are given in Table S1. A linear correlation analysis of qPCR and RNA-seq (Figure S1) showed that expression data obtained from different approaches correlated well with each other (Pearson's correlation = 0.712, and p < 0.001).

Results

Enzyme Activity

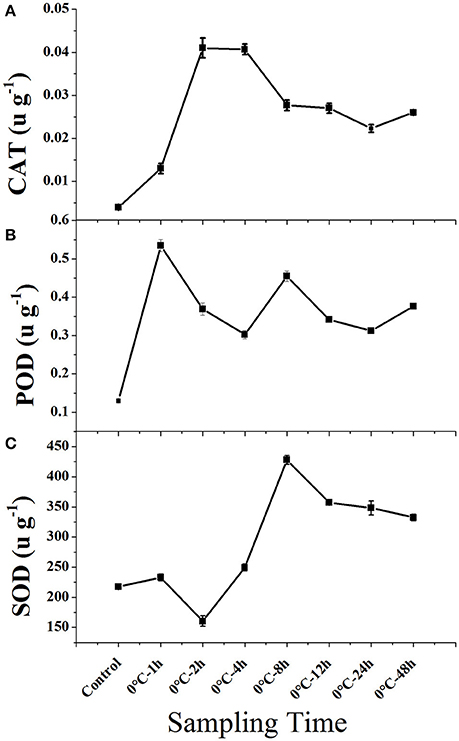

Cold stress caused a general increase in the activity of all three enzymes in leaf tissue (Figure 1). Hydroperoxidase (CAT) and peroxidase (POD) activity increased rapidly within 1–2 h when plants were exposed to 0°C and remained at a relative high level. Compare to CAT and POD, superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity increased initially slower, but increased rapidly after 2 h and remained at a high level.

Figure 1. Enzyme activity of CAT, POD, and CAT in leaf tissues of Taxus chinensis grown under normal and cold stress conditions. (A) Hydroperoxidase (CAT), (B) Peroxidase (POD), and (C) Superoxide Dismutase (SOD). Leaf tissues were sampled from plants grown under normal conditions and from plants that were subjected to 0°C for 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h. Results are means and SD for three replicates.

Transcriptome

The de novo assembled transcriptome had a GC content of 41.83% and included 83,963 transcripts of which 62,654 genes were identified. The median and N50 length of the transcriptome was 598 and 1,497 bp, respectively. Of all transcripts assembled, 55,135 transcripts could be annotated in reviewed Uniprot database at expectation value (e) of 1e-5, which account for 65.7% of the total transcripts. A total of 44,368 ORFs were predicted for the transcriptome by Transdecoder, of which 39,672 sequences (89.4%) could be annotated in reviewed Uniprot database at an expectation value of 1e-5.

Principal components analysis (PCA, Figure S2) of CPM showed that (i) replicates of stressed samples were well-grouped, (ii) while replicates of control samples were not as well-grouped, yet they clearly grouped different from stressed samples. Similar results were obtained by correlation matrix heat map analysis.

Different Expression (DE) Analyses

Different expression (DE) analyses revealed that 37,934 transcripts expressed differently between control and cold stressed samples at a fold-change (FC) ratio of more than 4 (|log2FC| > 2), as indicated by red dots in Volcano and MA plots (Figures 2A,B). Of all transcripts that expressed differently, 29,783 transcripts (~78.5%) were up-regulated and 8,151 (~21.5%) were down-regulated under cold stress. A fold-change of more than four (|log2FC| > 2) was shown for 417 DE transcripts at p < 0.001, 980 transcripts at p < 0.01 and 2,025 transcripts at p < 0.05 (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Differently expressed transcripts between control and cold stressed samples. (A) MA plot, (B) Volcano plot, and (C) Number of transcripts that expressed most differently at different significant levels. The red dots in MA and volcano plots indicated the transcripts that were differently expressed at least a fold change ratio of four (|log2FC| > 2) between control and cold stressed samples.

Analysis of sample correlation (Figure S3A) using differently expressed isoforms revealed a close correlation between replicates in each treatment, whereas the relationship between treatments were distant from each other. Isoform features correlation heatmap (Figure S3B) showed that DE isoforms could be partitioned into clusters with similar expression patterns.

Functional Annotation

Annotations were made for 1,437 up-regulated and 588 down-regulated transcripts under cold stress, which had a |log2FC| > 2 and a significant level of p value < 0.05. Following the prediction by Transdecoder, 1,424 ORFs were predicted from 1,437 up-regulated transcripts and 521 were predicted from 588 down-regulated transcripts.

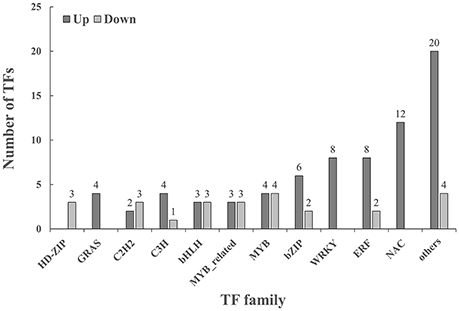

Transcription Factors (TFs) Prediction

Under cold stressed conditions, 74 TFs were up-regulated in leaf tissues of T. chinensis and 25 TFs were down-regulated as shown in Figure 3. Cold up-regulated TFs belonged to 28 TF families. The NAC, ERF, bZIP, and MYB family contained most up-regulated TFs and had 12, 8, 8, 6, and 4 TFs, respectively. Cold down-regulated TFs belonged to 12 different families, and the five most abundant families were MYB, bHLH, C2H, MYB-related, and the HD-ZIP family.

Figure 3. Classification of transcription factors (TFs) that were significant (p < 0.05 and |log2FC| > 2) changed under cold stressed conditions. Others in cold up regulated include: AP2(1), ARR-B(1) B3(1), BES1(1), Dof(1), E2F/DP(1), G2-like(1) GATA HSF(1), LBD(1), M-type MADS(1), NF-YA(1), NF-YC(1), Nin-like(1), Trihelix(1), CO-like(1), ARF(2), and TALE(2); Others in cold: DBB(1), NF-YB(1), SBP(1), and CO-like(1). Up, cold up regulated; Down, cold down regulated.

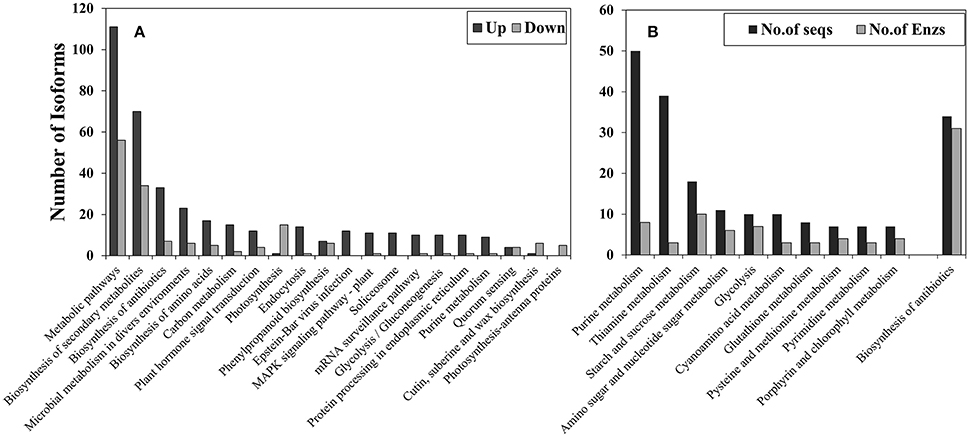

KEGG Pathway Classification

KEGG pathway classification (Figure 4A) showed that most significantly-changed transcripts belonged to metabolic pathways (111 up-regulated and 56 down-regulated) and the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (70 down-regulated and 34 down-regulated). Most of the pathways had more up-regulated transcripts than down-regulated transcripts. The only pathway which had more down-regulated transcripts was the photosynthetic pathway. In addition, KEGG annotation showed that the plant mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) signaling pathway (Ko04016) was significantly affected by cold stress, and most of the changed gene isoforms in the MAPK signaling pathway were up-regulated whereas only one isoform was down-regulated. Eleven genes were up-regulated in the MAPK signaling pathway (Figure S4), and these genes were MEKK1(K13414), MEKK9 (K20604), WRKY33 (K13424), NDPK2 (K00940), ETR/ERS (K14509), ChiB (K20547), YC2 (K13422), PYR/PYL (K14496), PP2C (K14497), CaM4 (K02183), and YODA (K20717). Most of these genes locate up-stream of MAPK signaling pathway.

Figure 4. KEGG path way annotation for transcripts that were significantly (p < 0.05) affected by cold stress and had at least a fold-change of four (|log2FC|> 2). (A) Overall classification and (B) sub-classification of metabolic pathways. Up, cold up-regulated transcripts; Down, cold down-regulated transcripts.

Sub-classification of cold-up regulated metabolic pathways (Figure 4B) showed that 50 transcripts belonged to purine metabolism, with eight enzymes being identified, 39 transcripts belonged to thiamine metabolism (three enzymes), 18 transcripts belonged to starch and sucrose metabolism (10 enzymes), and 11 transcripts in amino and nucleotide sugar metabolism (eight enzymes).

GO Annotation and Classification

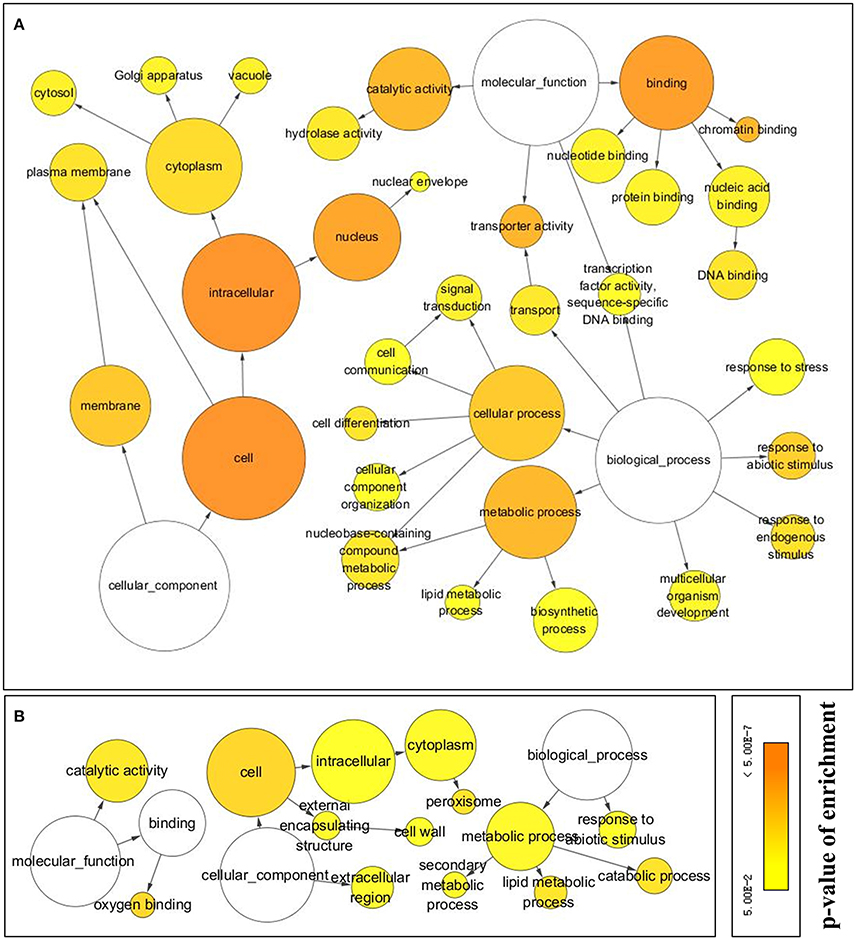

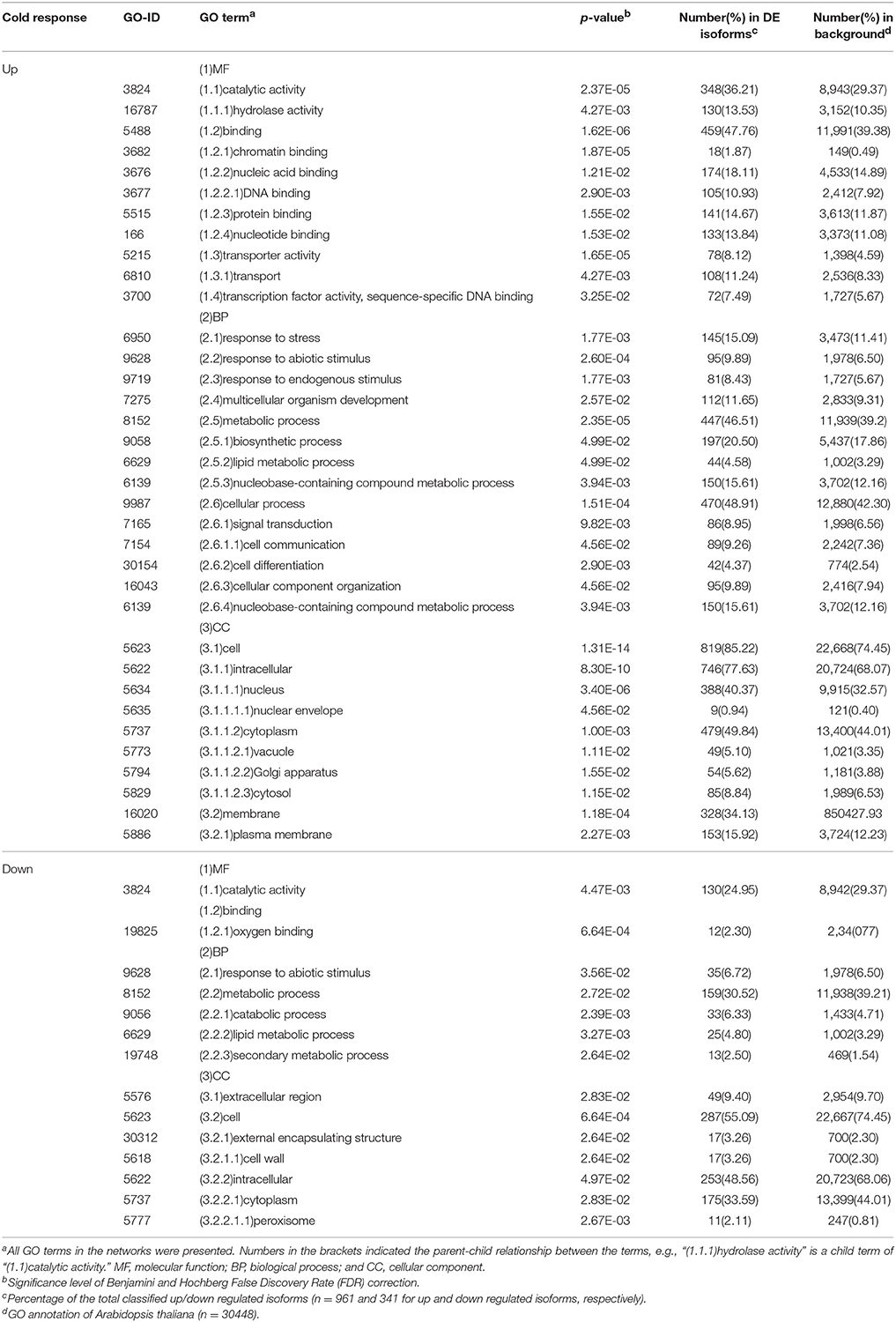

Of the 1,424 up- and 456 down-regulated ORFs, 961 and 341 were assigned to GO terms, respectively, after an annotation based on Arabidopsis homologs. Networks (Figure 5) of GO terms enriched among the DE ORFs, were constructed based on their parent-child relationships and network features were shown in Table 1.

Figure 5. Networks of GO terms enriched in DE ORFs at p < 0.05 level and had at least a 4-folderexpression ratio change (log2FC > 2) in response to cold stress. (A) GO terms enriched from cold up regulated ORFs, (B) GO terms enrichd from cold down regulated ORFs. GO enrichment analysis were carried out using BinGo after ORFs annotated to Arabidopsis. The lines between GO terms indicated their parent-child relationships. Sizes of circles represent the size of GO terms in Arabidopsis annotation. Colors indicate p-values of Benjamini and Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction. Detailed information of GO terms are list in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of gene ontology (GO) enrichment of differently expressed isoforms in Taxus chinensis in response to cold stress.

In the category “biological process,” there were three terms, “response to stress” (GO 6950, 15.09%), “response to abiotic stimulus” (GO 9628, 9.89%), and “response to endogenous stimulus” (GO 9719, 8.43%) represented in cold up-regulated ORFs, while the term “response to abiotic stimulus” (6.33%) was also represented in cold down-regulated ORFs. Protein names of cold up-regulated ORFs in the three terms are listed in Table S2.

The most abundant term enriched in cold response ORFs was the “cell” (GO 5623, 85.22 and 55.09% in up and down regulated ORFs, respectively) in the category cellular component. Its child terms “plasma membrane” (GO 5886, 15.92%), “cytoplasm” (GO 5737, 49.84%), and “nucleus” (GO 5634, 49.84%) were enriched in cold up regulated ORFs. In addition, nine up-regulated ORFs were classified into the term “nuclear envelope” (GO 5635)—a child term of “nucleus.”

In terms of the molecular function, two major terms and their child terms were enriched in cold up regulated ORFs, those were “catalytic activity” (GO 3824, 36.21%) and its child term—“hydrolase activity” (GO 16787) and “binding” (GO 5488, 47.76%) and its child terms—chromatin binding (GO 3682, 1.87%), nuclei acid binding (GO 3676, 18.11%), DNA binding (GO 3677, 10.93%), protein binding (GO 5515, 14.67%), and nucleotide binding (GO 166, 13.84%). Whereas, cold down-regulated two major molecular functions: “catalytic activity” (GO 3824) and “oxygen binding” (GO 19825) of parent “binding” term, which had 130 (24.95%), and 12 (2.30%) ORFs, respectively.

Discussion

Plasma Membrane, the First Cold Signal Acceptor

The plasma membrane is the first major transport barrier of a cell which experiences environmental changes, and a sensitive cold signal receptor system at the plasma membrane would help plants to adjust to stressed conditions. GO enrichment analysis indicated significant changes in the expression of membrane related genes. Genes such as plasma membrane-associated cation-binding protein and plasma membrane proton pump were identified in the up regulated ORFs which were assigned to “response to stress” term (Table S2), indicating significant changes in plasma membrane function in response to cold stress. This caused changes in the following aspects: (a) membrane fluidity/rigidity, (b) membrane permeability of signal receptors e.g., Ca2+, and (c) membrane intrinsic protein family (Alonso et al., 1997). In the present study, the CaM4 gene of T. chinensis, was up-regulated in response to cold stress, pointing to an increased intracellular Ca2+ concentration. It suggested that membrane permeability of Ca2+ receptors was enhanced in response to cold stress to allow more Ca2+ entry into the plasma. Ca2+ influx was a very important change (initial event) in membrane during cold and (Chinnusamy et al., 2007) suggested the increase of Ca2+ influx ability may be induced by accumulation of ROS caused by cold stimulation. The intracellular Ca2+ sensors such as calmodulin (CaM) or calcium-dependent protein kinases could bind the Ca2+ and then interact with target proteins to activate a series of regulation evens (e.g., MAPK signaling path) for regulating cold-responsive gene expression (DeFalco et al., 2010). Nevertheless, genes such as Calmodulin-like protein and Calcium-dependent protein kinase were up-regulated in response to cold stress (Table S2, ORFs were annotated as AT5G66210, AT1G24620, AT2G38910, and else).

Signal Transduction and Transcription Factor (TFs) Regulation

Although the secondary messengers of ROS signaling are unknown at present, it has been suggested that ROS (i) inhibits phosphatases directly, change the membrane structure to enhance Ca2+ influx and also act as the receptors of Ca2+, (3) the unknown messengers were accepted by redox-sensitive transcription factors, e.g., MAPK signaling pathway (Miller et al., 2008). What's more, (Moller and Sweetlove, 2010) proposed oxidized peptides as the possible secondary ROS messengers that are also involved in MAPK signaling. It is commonly accepted that the plant MAPK signaling pathway plays an important role in plant abiotic stress responses (Pitzschke et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2012; Danquah et al., 2014). The secondary ROS messenger of the MAPK cascade caused indirect activation/up-regulation of cold-responsive TFs to enhance the tolerance capability to cold. One of the most effective defense response to stress is plant signal regulation by TFs, which are components of complex regulatory network in plants.

Eleven TFs in plant-MAPK signaling pathway were up-regulated by cold stresses as predicted by KEGG pathway annotation, particularly TFs that located upstream of the pathway. It has been reported that plants with over-expressed AtNDPK2 had reduced ROS levels (Moon et al., 2003), indicating the role of NDPK2 in regulating ROS scavenging-related genes. This is consistent with the present finding that the increased ROS scavenger activity in T. chinensis could be well-explained by the up-regulated NDPK2 in the MAPK signaling pathway. Two of the TFs in the MAPK pathway, ETR/ERS and CaM4 are secondary signal receptors of ethylene and Ca2+, respectively, both substances being messengers induced by stresses. It has been reported for Arabidopsis that the MAPKKK (MAP kinase kinase kinases)-MAPKK (MAP kinase kinases)-MAPK cascade could be activated by ROS, and assist plants in cold acclimation (Teige et al., 2004). Cold stress might have also activated this cascade in T. chinensis to regulate gene expression, as the MEKK1 and MKK9 members of the cascade showed significant up-regulation by cold stress. MYC2 has been reported to be an osmotic responsive gene and to be involved in ABA signaling (Abe et al., 2003) and enhance osmotic stress tolerance of transgenic plants (Gao et al., 2011). The up-regulated MYC2 in T. chinensis might have been due to the osmotic stress component of cold stress and enhanced ABA signaling caused by low temperature. Some studies have supported the idea that PP2C is an important member of the ABA signal transduction pathway and that PP2C functions as regulator of various signal transduction pathways (Rodriguez, 1998). Our observation that PP2C is up-regulated by cold stress supports the ideas that PP2C is activated by accumulated ABA.

Many of the downstream TFs in the MAPK signaling pathway were not up-regulated by cold stress by a factor of four. This may be because many other TFs fulfill “complementary” functions of those TFs. Nevertheless, many cold responsive TF families were found to be up-regulated by cold stress by a factor of more than four. Five TF families including AP2-EREBP (APETALA2/ET-Responsive Element Binding Protein), MYB (Myeloblastosis), NAC (NAM, ATAF1/2, CUC2), bHLH (basic Helix-Loop-Helix), and WRKY (named after the WRKY amino acid motif) have been shown to be involved in the cold stress response in Arabidopsis (Changsong and Diqiu, 2010). All these five families were affected by cold stress in T. chinensis, and therefore, they support a role in the Taxus cold stress response. This applies in particular to NAC, WRKY, and MYB which were the three TF families most-affected in expression by low temperature. Two of the other most numerous TF families up-regulated by cold stress in Taxus were ERF and bZIP. They have also been reported to be involved in the cold stress response in other species (Heidarvand and Maali Amiri, 2010; Mizoi et al., 2012; Calzadilla et al., 2016).

Changes in ROS Scavenging System

Almost twice as many genes (62,654 vs. 36,493) were assembled in the present study as previously reported (Hao et al., 2011). This may be due to the existence of cold activated genes, as overall, 29,783 transcripts up-regulated under cold stressed condition by a factor of 4 (|log2FC|> 2). At all significant levels, more isoforms were up-regulated than down-regulated in response to cold stresses, similar to the findings in wheat (Winfield et al., 2010), Lotus japonicas (Calzadilla et al., 2016), and Arabidopisis (Fowler, 2002).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), for example superoxide () and H2O2, play important roles in regulating plant gene expression, particularly under abiotic stress conditions (Chinnusamy et al., 2007; Heidarvand and Maali Amiri, 2010; Tamás et al., 2010; Aroca et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014). It has also been reported that ROS which accumulate under cold stress activate the membrane Ca2+ channels to increase Ca2+ flux for gene regulation signaling. The roles which ROS play are distinct (del Río et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2012). On the one hand, they are thought to play a key role in regulating stress-induced signal transduction events. On the other aspect, ROS caused many harmful effects as they inhibit proteins such as aquaporins (Knipfer et al., 2011), induce damages to DNA and lipids, and can ultimately lead to cell death. Therefore, a common problem that plants grown under stressed condition face is how to remove or detoxify ROS effectively. Genes that were assigned in the present study to GO terms “Response to abiotic stimulus,” “Response to stress,” and “Response to endogenous” are listed in Table S2. Genes of ROS scavenging enzymes, such as peroxidase (AT5G05340 and else) and phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (PHGPx, AT4G11600) were transcriptionally up-regulated in response to cold stress. It has been reported that the up-regulation of these genes inhibits cell death induced by ROS (Chen et al., 2004). Also, enzyme activity of ROS scavengers (including SOD, CAT, and POD) increased under cold stress in the present study. It has been suggested that the scavenging system responds positive to cold stress by removing the toxic ROS that are, initially, necessary for inducing cold-responsive gene expression (Bailey-Serres and Mittler, 2006). In the present study, the increase in CAT activity was the highest of the three ROS-related enzymes studied, might due to that H2O2 as a signaling factor might be the most abundant ROS and other ROS should firstly converse to H2O2 for further deoxidation. Taken together, the present data suggest that that up-regulation of the genes encoding ROS scavengers and activation of enzymes enhanced the ROS detoxification ability of T. chinensis in leaf tissues.

“Metabolism” was the most abundant category in the KEGG classification and the category most affected by cold stress. The most numerous four pathways in this classification were purine metabolism, thiamine metabolism, starch and sucrose metabolism, and amino and nucleotide sugar metabolism.

Purine metabolism is considered as a housekeeping function, however, a recent study by Watanabe et al. (2014) and Takagi et al. (2016) indicated that the purine metabolite, allantoin is involved in stress response such as ABA metabolism and jasmonic signaling, and therefore enhances plants cold tolerance. Our results showed that purine metabolism in Taxus was up-regulated. An increase in purine nucleotides in response to cold has been reported previously for plants and animals (Desautels and Himmshagen, 1979; Frischknecht and Baumann, 1985).

Up regulation of thiamine metabolism and starch and sucrose metabolism and amino and nucleotide sugar metabolism in response to cold stress may have played a role in ROS scavenging. It has been reported that thiamine (vitamin B1) is induced by the oxidative stress which accompanies cold stress rather than cold stress per se (Rapalakozik, 2011) and that thiamin inhibits lipid peroxidation and free radical oxidation of oleic acid to protect cells from ROS. Some of the carbohydrates are important components of the ROS scavenging system, function together with other components such as phenylpropanoids (Van den Ende and Valluru, 2009). Therefore, changes in starch and sucrose metabolism in response to cold stress may contribute to scavenging of excessive ROS.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study is the first insight into the transcriptome of an endangered plant, T. chinensis, under cold stress. Transcriptomic analyses revealed that 2,025 gene isoforms expressed differently at p < 0.05 and had a fold-change of at least 4; 1,437 of these genes were up-regulated and 588 were down-regulated by cold stress. Gene annotation also pointed to the signal transduction and transcription control of cold response genes of T. chinensis involving ROS.

Cold treatment induced the accumulation of stress-responsive messengers such as the ROS and subsequently activated the TFs signaling pathway for transcription regulation. An important signaling path for regulation of cold responsive genes in T. chinensis was MAPK signaling pathway and the most abundant TF families involved in cold response were NAC, WRKY, ERF, MYB, and bZIP. ROS were supposed to be accumulated and acted as a key messenger during the signaling process, whereas, excessive ROS may have also induced damage to cells. Enzyme activity analyses suggested that the POD, SOD, and CAT are enhanced to remove excessive ROS in leaf tissues of T. chinensis. Annotation of up-regulated transcripts further confirmed the response of the ROS scavenging system in T. chinensis to cold stress. Genes such as peroxidase and PHGPx were up-regulated in response to cold stress, and other anti-oxidative defense systems, such as starch and sucrose metabolism and thiamine metabolism were enhanced in response to cold stress.

Author Contributions

YL, XL, XY, HY, DL, and HL conceived and designed the experiments. XY, XH, and LM performed the experiments. DM and LM analyzed the data. YL, HY, XL, and HL contributed reagents and materials. DM and JH wrote and revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the following grants: the National Key Technology R&D Program (2013BAC09B00-7) in China, Chinese Postdoctoral Science Foundation for DM and HL and Postdoctoral research funding plan in Hunan Province and Central South University for DM and HL. We would also like to thank Mr. Zixia Huang (PhD at University College Dublin, Ireland) for transcriptomic analyses. Great thanks to Dr. Wieland Fricke (University College Dublin, Ireland) for language corrections.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2017.00468/full#supplementary-material

References

Abe, H., Urao, T., Ito, T., Seki, M., Shinozaki, K., and Yamaguchishinozaki, K. (2003). Arabidopsis AtMYC2 (bHLH) and AtMYB2 (MYB) function as transcriptional activators in abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell 15, 63–78. doi: 10.1105/tpc.006130

Alonso, A., Queiroz, C. S., and Magalhaes, A. C. (1997). Chilling stress leads to increased cell membrane rigidity in roots of coffee (Coffea arabica L.) seedlings. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1323, 75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(96)00177-0

Aroca, R., Porcel, R., and Ruiz-Lozano, J. M. (2012). Regulation of root water uptake under abiotic stress conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 43–57. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err266

Bailey-Serres, J., and Mittler, R. (2006). The roles of reactive oxygen species in plant cells. Plant Physiol. 141:311. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.900191

Beck, E. H., Heim, R., and Hansen, J. (2004). Plant resistance to cold stress: mechanisms and environmental signals triggering frost hardening and dehardening. J. Biosci. 29, 449–459. doi: 10.1007/BF02712118

Calzadilla, P. I., Maiale, S. J., Ruiz, O. A., and Escaray, F. J. (2016). Transcriptome response mediated by cold stress in Lotus japonicus. Front. Plant Sci. 7:374. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00374

Changsong, Z., and Diqiu, Y. U. (2010). Analysis of the Cold-responsive transcriptome in the mature pollen of Arabidopsis. J. Plant Biol. 53, 400–416. doi: 10.1007/s12374-010-9129-4

Chen, S., Vaghchhipawala, Z., Li, W., Asard, H., and Dickman, M. B. (2004). Tomato phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase inhibits cell death induced by Bax and oxidative stresses in yeast and plants. Plant Physiol. 135, 1630–1641. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.038091

Chinnusamy, V., Zhu, J., and Zhu, J. K. (2007). Cold stress regulation of gene expression in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 12, 444–451. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.07.002

Danquah, A., de Zelicourt, A., Colcombet, J., and Hirt, H. (2014). The role of ABA and MAPK signaling pathways in plant abiotic stress responses. Biotechnol. Adv. 32, 40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.09.006

DeFalco, T. A., Bender, K. W., and Snedden, W. A. (2010). Breaking the code: Ca2+ sensors in plant signalling. Biochem. J. 425, 27–40. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091147

Desautels, M., and Himms-Hagen, J. (1979). Roles of noradrenaline and protein synthesis in the cold-induced increase in purine nucleotide binding by rat brown adipose tissue mitochondria. Biochem. Cell Biol. 57, 968–976. doi: 10.1139/o79-118

Dillies, M. A., Rau, A., Aubert, J., Hennequet-Antier, C., Jeanmougin, M., Servant, N., et al. (2012). A comprehensive evaluation of normalization methods for Illumina high-throughput RNA sequencing data analysis. Brief. Bioinform. 14, 671–683. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs046

Fowler, S. (2002). Arabidopsis transcriptome profiling indicates that multiple regulatory pathways are activated during cold acclimation in addition to the cbf cold response pathway. Plant Cell Online 14, 1675–1690. doi: 10.1105/tpc.003483

Frischknecht, P. M., and Baumann, T. (1985). Stress induced formation of purine alkaloids in plant tissue culture of Coffea arabica. Phytochemistry 24, 2255–2257. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)83020-4

Gao, J. J., Zhang, Z., Peng, R. H., Xiong, A. S., Xu, J., Zhu, B., et al. (2011). Forced expression of Mdmyb10, a myb transcription factor gene from apple, enhances tolerance to osmotic stress in transgenic Arabidopsis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 38, 205–211. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0096-0

Gasteiger, E., Jung, E., and Bairoch, A. (2001). SWISS-PROT: connecting biomolecular knowledge via a protein database. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 3, 47–55.

Grabherr, M. G., Haas, B. J., Yassour, M., Levin, J. Z., Thompson, D. A., Amit, I., et al. (2011). Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883

Haas, B. J., Papanicolaou, A., Yassour, M., Grabherr, M., Blood, P. D., Bowden, J., et al. (2013). De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 8, 1494–1512. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.084

Hao, D. C., Huang, B., and Yang, L. (2008). Phylogenetic relationships of the Genus Taxus inferred from chloroplast intergenic spacer and nuclear coding DNA. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 31, 260–265. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.260

Hao, D., Yang, L., and Xiao, P. (2011). The first insight into the Taxus genome via fosmid library construction and end sequencing. Mol. Genet. Genomics 285, 197–205. doi: 10.1007/s00438-010-0598-4

Heidarvand, L., and Maali Amiri, R. (2010). What happens in plant molecular responses to cold stress? Acta Physiol. Plant. 32, 419–431. doi: 10.1007/s11738-009-0451-8

Huang, G. T., Ma, S. L., Bai, L. P., Zhang, L., Ma, H., Jia, P., et al. (2012). Signal transduction during cold, salt, and drought stresses in plants. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39, 969–987. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-0823-1

Knipfer, T., Besse, M., Verdeil, J. L., and Fricke, W. (2011). Aquaporin-facilitated water uptake in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) roots. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 4115–4126. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err075

Li, G., Santoni, V., and Maurel, C. (2014). Plant aquaporins: roles in plant physiology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1840, 1574–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.11.004

Martin, M. (2011). Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 17, 10–12. doi: 10.14806/ej.17.1.200

Meng, D., and Fricke, W. (2017). Changes in root hydraulic conductivity facilitate the overall hydraulic response of rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars to salt and osmotic stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 113, 64–77. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.02.001

Meng, D., Walsh, M., and Fricke, W. (2016). Rapid changes in root hydraulic conductivity and aquaporin expression in rice (Oryza sativa L.) in response to shoot removal - xylem tension as a possible signal. Ann. Bot. 118, 809–819. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcw150

Miller, G., Shulaev, V., and Mittler, R. (2008). Reactive oxygen signaling and abiotic stress. Physiol. Plant. 133, 481–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2008.01090.x

Mizoi, J., Shinozaki, K., and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. (2012). AP2/ERF family transcription factors in plant abiotic stress responses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1819, 86–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.08.004

Moller, I. M., and Sweetlove, L. J. (2010). ROS signalling–specificity is required. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 370–374. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.04.008

Moon, H., Lee, B., Choi, G., Shin, D., Prasad, D. T., Lee, O., et al. (2003). NDP kinase 2 interacts with two oxidative stress-activated MAPKs to regulate cellular redox state and enhances multiple stress tolerance in transgenic plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 358–363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252641899

Nagalakshmi, U., Waern, K., and Snyder, M. (2010). RNA-Seq: a method for comprehensive transcriptome analysis. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. Chapter 4:Unit 4.11.1-13. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb0411s89

Ozsolak, F., Platt, A. R., Jones, D. R., Reifenberger, J. G., Sass, L. E., Mcinerney, P., et al. (2009). Direct RNA sequencing. Nature 461, 814–818. doi: 10.1038/nature08390

Pitzschke, A., Schikora, A., and Hirt, H. (2009). MAPK cascade signalling networks in plant defence. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12, 421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.06.008

Rahaie, M., Xue, G.-P., and Schenk, P. M. (2013). The role of transcription factors in wheat under different abiotic stresses. Development 2:59. doi: 10.5772/54795

Rapalakozik, M. (2011). Vitamin B1 (Thiamine): a cofactor for enzymes involved in the main metabolic pathways and an environmental stress protectant. Adv. Bot. Res. 58, 37–91. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386479-6.00004-4

del Río, L. A., Sandalio, L. M., Corpas, F. J., Palma, J. M., and Barroso, J. B. (2006). Reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species in peroxisomes. production, scavenging, and role in cell signaling. Plant Physiol. 141, 330–335. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.078204

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J., and Smyth, G. K. (2010). edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616

Robinson, M. D., and Oshlack, A. (2010). A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 11, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r25

Rodriguez, P. L. (1998). Protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) function in higher plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 38, 919–927. doi: 10.1023/A:1006054607850

Singh, K., Foley, R. C., and Oñate-Sánchez, L. (2002). Transcription factors in plant defense and stress responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5, 430–436. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00289-3

Takagi, H., Ishiga, Y., Watanabe, S., Konishi, T., Egusa, M., Akiyoshi, N., et al. (2016). Allantoin, a stress-related purine metabolite, can activate jasmonate signaling in a MYC2-regulated and abscisic acid-dependent manner. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 2519–2532. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw071

Tamás, L., Mistrík, I., Huttová, J., Halušková, L., Valentovičová, K., and Zelinová, V. (2010). Role of reactive oxygen species-generating enzymes and hydrogen peroxide during cadmium, mercury and osmotic stresses in barley root tip. Planta 231, 221–231. doi: 10.1007/s00425-009-1042-z

Tarkowski, L. P., and Van den Ende, W. (2015). Cold tolerance triggered by soluble sugars: a multifaceted countermeasure. Front. Plant Sci. 6:203. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00203

Teige, M., Scheikl, E., Eulgem, T., Doczi, R., Ichimura, K., Shinozaki, K., et al. (2004). The MKK2 pathway mediates cold and salt stress signaling in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cell 15, 141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.023

Thomashow, M. F. (1999). PLANT COLD ACCLIMATION: freezing tolerance genes and regulatory mechanism. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 50, 571–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.571

Van den Ende, W., and Valluru, R. (2009). Sucrose, sucrosyl oligosaccharides, and oxidative stress: scavenging and salvaging? J. Exp. Bot. 60, 9–18. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern297

Wang, X., Zhao, Q., Ma, C., Zhang, Z., Cao, H., Kong, Y., et al. (2013). Global transcriptome profiles of Camellia sinensis during cold acclimation. BMC Genomics 14:415. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-415

Wang, Z., Gerstein, M., and Snyder, M. (2009). RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2484

Watanabe, S., Matsumoto, M., Hakomori, Y., Takagi, H., Shimada, H., and Sakamoto, A. (2014). The purine metabolite allantoin enhances abiotic stress tolerance through synergistic activation of abscisic acid metabolism. Plant Cell Environ. 37, 1022–1036. doi: 10.1111/pce.12218

Winfield, M. O., Lu, C., Wilson, I. D., Coghill, J. A., and Edwards, K. J. (2010). Plant responses to cold: transcriptome analysis of wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 8, 749–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00536.x

Wu, Q., Sun, C., Luo, H., Li, Y., Niu, Y., Sun, Y., et al. (2011). Transcriptome analysis of Taxus cuspidata needles based on 454 pyrosequencing. Planta Med. 77, 394–400. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1250331

Keywords: Taxus chinensis, transcriptome, DE isoforms, cold stress, ROS, cold response

Citation: Meng D, Yu X, Ma L, Hu J, Liang Y, Liu X, Yin H, Liu H, He X and Li D (2017) Transcriptomic Response of Chinese Yew (Taxus chinensis) to Cold Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 8:468. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00468

Received: 11 December 2016; Accepted: 17 March 2017;

Published: 28 April 2017.

Edited by:

Ruth Grene, Virginia Tech, USAReviewed by:

Dong-Ha Oh, Louisiana State University, USAUmesh K. Reddy, West Virginia State University, USA

Copyright © 2017 Meng, Yu, Ma, Hu, Liang, Liu, Yin, Liu, He and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xianghua Yu, d2VhbGwyMDAwQDEyNi5jb20=

Delong Meng

Delong Meng Xianghua Yu1,2*

Xianghua Yu1,2* Jin Hu

Jin Hu Huaqun Yin

Huaqun Yin