- 1Citrus Research Institute, Southwest University, Chongqing, China

- 2Citrus Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Chongqing, China

- 3Laboratory of Genetics, Wageningen University, Wageningen, Netherlands

Zinc (Zn) and iron (Fe) deficiency are widespread among citrus plants, but the molecular mechanisms regarding uptake and transport of these two essential metal ions in citrus are still unclear. In the present study, 12 members of the Zn/Fe-regulated transporter (ZRT/IRT)-related protein (ZIP) gene family were identified and isolated from a widely used citrus rootstock, trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata L. Raf.), and the genes were correspondingly named as PtZIPs according to the sequence and functional similarity to Arabidopsis thaliana ZIPs. The 12 PtZIP genes were predicted to encode proteins of 334–419 amino acids, harboring 6–9 putative transmembrane (TM) domains. All of the PtZIP proteins contained the highly conserved ZIP signature sequences in TM-IV, and nine of them showed a variable region rich in histidine residues between TM-III and TM-IV. Phylogenetic analysis subdivided the PtZIPs into four groups, similar as found for the ZIP family of A. thaliana, with clustered PtZIPs sharing a similar gene structure. Expression analysis showed that the PtZIP genes were very differently induced in roots and leaves under conditions of Zn, Fe and Mn deficiency. Yeast complementation tests indicated that PtIRT1, PtZIP1, PtZIP2, PtZIP3, and PtZIP12 were able to complement the zrt1zrt2 mutant, which was deficient in Zn uptake; PtIRT1 and PtZIP7 were able to complement the fet3fet4 mutant, which was deficient in Fe uptake, and PtIRT1 was able to complement the smf1 mutant, which was deficient in Mn uptake, suggesting their respective functions in Zn, Fe, and Mn transport. The present study broadens our understanding of metal ion uptake and transport and functional divergence of the various PtZIP genes in citrus plants.

Introduction

Zinc (Zn) and iron (Fe) are essential micronutrients for plant growth and development. As a cofactor for many enzymes and transcription factors, Zn has been involved in a wide range of cellular processes such as photosynthesis, nucleic acid and lipid metabolism, protein synthesis, and membrane stability (Broadley et al., 2007; Sinclair and Krämer, 2012). Fe functions as a catalyst for many cellular reactions such as the electron transport of photosynthesis and respiration, and chlorophyll biosynthesis (Jeong and Guerinot, 2009). Shortage or excess of Zn and Fe would cause severe nutritional disorders. To cope with this issue, plants have developed a tightly regulated cellular homeostasis system to balance the uptake, distribution and utilization of these metal ions (Clemens, 2001; Grotz and Guerinot, 2006). In this system, various members of the zinc/iron-regulated transporter (ZRT/IRT)-related protein (ZIP) family, natural resistance associated macrophage protein (NRAMP) family, cation diffusion facilitator (CDF) family, yellow stripe-like (YSL) family, major facilitator super family (MFS), P1B-type heavy metal ATPase (HMA) family, vacuolar iron transporter (VIT) family, and the cation exchange (CAX) family have been shown to play key roles (Vigani et al., 2013; Boutigny et al., 2014; Bashir et al., 2016).

The ZIP family members are thought to be important transporters for uptake and transport of Zn, Fe, Mn, and Cu (Eide et al., 1996; Zhao and Eide, 1996a,b; Guerinot, 2000; Grotz and Guerinot, 2006). The first ZIP protein, AtIRT1, has been identified in Arabidopsis thaliana, by functional expression in yeast (Eide et al., 1996). Subsequently, other plant ZIP family members were reported in tomato (Eckhardt et al., 2001), soybean (Moreau et al., 2002), A. thaliana (Milner et al., 2013), rice (Ishimaru, 2005; Yang et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2010b), Medicago truncatula (López-Millan et al., 2004), barley (Pedas et al., 2009) and maize (Li et al., 2013). In general, the ZIP proteins are consist of 309–476 amino acid residues with eight potential transmembrane (TM) domains and a similar membrane topology in which the N- and C-terminal ends of the protein are located on the outside surface of the plasma membrane. Between TM-III and TM-IV there is a variable region, which contains a potential metal-binding domain and is rich in histidine residues (Guerinot, 2000). Functionality of some AtZIP genes in mineral uptake has been demonstrated. Knockout of AtIRT1 in A. thaliana resulted in Fe deficiency, accompanied by cell differentiation defects (Henriques et al., 2002; Vert et al., 2002), while AtIRT2 expression in yeast restored the growth of Fe and Zn transport yeast mutants and enhanced Fe uptake (Vert et al., 2001). Overexpression of AtIRT3 increased the accumulation of Zn in the shoots and Fe in the roots of transgenic plants (Lin et al., 2009), while knock-out mutants of AtZIP1 and AtZIP2 exhibited defects in remobilization and translocation of Mn and Zn (Milner et al., 2013). Although the gramineous plants, unlike nongraminaceous plants, mainly depend on a mineral-chelation strategy (Strategy II) to acquire Fe (Kobayashi and Nishizawa, 2012), the ZIP genes of rice and maize, such as OsZIP4, OsZIP5, OsZIP8, ZmIRT1, and ZmZIP3, have been shown to be involved in Fe or Zn transport and distribution (Ishimaru et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2010a,b; Li et al., 2015). All these studies suggest that the expression of the most ZIPs was induced by Zn, Fe, or Mn deficiency, and that regulating the endogenous expression of ZIPs is essential to maintain cellular metal homeostasis, since these genes are involved in root metal uptake as well as metal transport and distribution among plant organs.

Because of the importance of ZIPs in metal ion uptake, transport and distribution, much research in recent years has focused on cloning and characterizing their functions in crop plants. However, there is still little information regarding ZIPs in perennial plants, such as citrus. Zn and Fe deficiencies are common in citrus trees, resulting in severe chlorosis of leaves, impaired tree vigor, and reduction of fruit set, yield, size, and quality (Fu et al., 2016). As a major rootstock, trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata L. Raf.) is directly responsible for nutrient uptake from soil; cloning and functionally analyzing ZIPs of this rootstock could facilitate significantly in the understanding of the underlying Zn and Fe uptake mechanisms. Moreover, sequencing and assembly of a citrus genome (http://citrus.hzau.edu.cn/orange/; Xu et al., 2013) provided the opportunity to identify and isolate such genes at the genome level. In the present study, we cloned 12 ZIP members of trifoliate orange and conducted detailed sequence analysis including multiple sequence alignment, phylogenetic tree construction, chromosomal location, and prediction of the transmembrane domains, gene structure, and subcellular localization. We have also characterized their expression patterns in roots and leaves under Zn, Fe, and Mn deficiency, as well as the metal selectivity and uptake activity by functional complementation of yeast mutants. The results provide us with systematic information regarding the possible functions of each of these PtZIP genes and lay the foundation for further studies.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Treatments

The outer and inner seed coats of trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata L. Raf.) seeds were removed and seeds were germinated at a temperature of 28°C and a relative humidity of 70% under darkness for 7 d. Thereafter, the germinated seedlings were transferred to a hydroponic solution composed of 2 mM Ca(NO3)2, 3 mM KNO3, 0.5 mM NH4H2PO4, 1 mM MgSO4, 20 μM H3BO3, 10 μM MnSO4, 5 μM ZnSO4, 1 μM CuSO4, 1 μM H2MoO4, and 50 μM Fe-EDTA at 25°C and 16 h photoperiod (50 μmol m−2 s−1) for 30 d of normal growth. For Zn-, Fe-, and Mn-deficient (-Zn, -Fe, and -Mn) treatments, the trifoliate orange seedlings were transferred to new hydroponic solutions without ZnSO4, Fe-EDTA, or MnSO4, respectively, and those grown in normal medium were used as a control (CK). After 7, 12, and 20 d of nutrient-deficient treatments, the roots and leaves were sampled and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, then stored at −80°C until use.

Identification and Cloning of ZIP Genes in Trifoliate Orange

ZIP genes of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) were first identified by a BLASTP search of the sweet orange genome database (http://citrus.hzau.edu.cn/orange/; Xu et al., 2013) using 15 of the known A. thaliana ZIP proteins (AT3G12750.1, AT5G59520.1, AT2G32270.1, AT1G10970.1, AT1G05300.1, AT2G30080.1, AT2G04032.1, AT5G45105.2, AT4G33020.1, AT1G31260.1, AT1G55910.1, AT5G62160.1, AT4G19690.2, AT4G19680.2, and AT1G60960.1) and 12 of the known rice (Oryza sativa L.) ZIP proteins (AY302058.1, AY302059.1, AY323915.1, AB126089.1, AB126087.1, AB126088.1, AB126090.1, AY275180.1, AY324148.1, AY281300.1, AB070226.1, and AB126086.1) as query sequences. The results were filtered at the score value of ≥100 and an e ≤ e−10 (Kumar et al., 2011). After removing duplicate and overlapping genes, the remaining non-overlapping genes were further analyzed for their potential transmembrane domains using TMHMM (Krogh et al., 2001).

To clone all ZIP genes from trifoliate orange, primers were designed to amplify the full open-reading frame (ORF) according to identified ZIP sequences of sweet orange. Two Gateway recombination sites, attB1- GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTTC and attB2- GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTC, were incorporated into the 5′-end of forward and reverse primers, respectively, as described in the Gateway technology instructions (Invitrogen). The cDNAs derived from Zn- or Fe-deficient leaves and roots of trifoliate orange served as templates (see below). The amplified attB-PCR fragments were then cloned into the entry vector pDONR221 (Invitrogen) to generate entry clones by BP recombination reaction with the Gateway BP Clonase II enzyme (Invitrogen). The resulting pDONR221-ZIPs entry clones were transformed into DH5α E. coli competent cells and then sequenced at the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI, China). The ZIP genes isolated from trifoliate orange were designated PtZIP genes.

Sequence Analysis of PtZIP Genes

The putative ORFs of PtZIP genes were analyzed using NCBI ORF finder (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/). The translated PtZIP protein sequences were submitted to ExPASy (http://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/) to calculate molecular weights (MWs) and isoelectric points (pIs). Gene structure analysis was performed by using the Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS, http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) program (Guo et al., 2007). The chromosomal positions of the PtZIP genes were provided by the sweet orange genome database, and the MapInspect software (http://mapinspect.software.informer.com) was used to draw the location images. Potential transmembrane domains in each PtZIP protein were identified using TMHMM (Krogh et al., 2001). The signal peptides of PtZIPs were identified with SignalP 4.1 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/; Petersen et al., 2011). The subcellular localizations of the PtZIP proteins were predicted using the subCELlular LOcalization predictor (CELLO v.2.5; http://cello.life.nctu.edu.tw/; Yu et al., 2006) and ProtComp v. 9.0 online (http://www.softberry.com/berry.phtml?topic=protcomppl&group=programs&subgroup=proloc).

Multiple sequence alignment of the PtZIP and AtZIP proteins was performed with the ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1994) integrated in MEGA version 6 (Tamura et al., 2013). The generated files were then evaluated using MEGA 6 software to construct a phylogenetic tree based on the neighbor-joining method with 1,000 replicates of bootstrap analysis, with the other parameters set as described by Tamura et al. (2013).

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR (qPCR) Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from the leaves and roots of control (CK), -Fe, -Zn, and -Mn treated trifoliate orange seedlings using the RNAprep pure plant kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Then 1 μg of the total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis with an iScript™ cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Specific primers of PtZIP genes were designed using the online primer-blast program in the NCBI website, while Actin (Cs1g05000.1) was used as a reference gene to normalize the relative expression levels of the target genes. qPCR was performed by using a Bio-Rad CFX Connect Real-Time system. Each reaction contained 5 μL iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix dye (Bio-Rad), 1 μL cDNA, and 0.2 μM gene-specific primers in a final volume of 10 μL. The PCR condition was set up as follow: 95°C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 55°C–60°C for 30 s. Two biological replicates and three technical replicates were performed for each treatment.

Yeast Complementation

The pDONR221-PtZIP entry clones were recombined into the yeast expression vector pFL613 (Dräger et al., 2004) by an LR recombination reaction with Gateway LR Clonase II enzyme (Invitrogen). The resulting pFL613-PtZIP constructs were then transformed into three yeast strains, the Zn uptake-defective mutant zrt1zrt2 ZHY3 (MATα ade6 can1 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 zrt1::LEU2 zrt2::HIS3; Zhao and Eide, 1996b), the Fe uptake-defective mutant fet3fet4 DEY1453 (MATa/MATα ade2/+ can1/can1 his3/his3 leu2/leu2 trp1/trp1 ura3/ura3 fet3-2::HIS3/fet3-2::HIS3 fet4-1::LEU2/fet4-1::LEU2; Eide et al., 1996), and the Mn uptake-defective mutant smf1 (MATα his3 ade2 leu2 trp1 ura3 smf1::URA3ura3::TRP1; Thomine et al., 2000). The empty vector pFL613 was used as a negative control, and AtZIP4, AtIRT1, and AtZIP7 were used as positive controls for complementing zrt1zrt2, fet3fet4, and smf1, respectively (Eide et al., 1996; Assunção et al., 2010; Milner et al., 2013). In addition, the wild type strain DY1455 harboring pFL613 was used as another positive control. The complementation tests were performed using a slight modification of the method described by Milner et al. (2013). Briefly, transformed cells were selected and cultured on synthetic complete and dropout mix (without uracil) medium (SC-URA) plus 0.1 mM ZnSO4 for zrt1zrt2 or 0.1 mM Fe2(SO4)3 for fet3fet4. Then 5-μL aliquots of each yeast culture at optical densities (OD600) of 1.0, 0.1, 0.01, and 0.001 were spotted onto the specific Zn-, Fe-, and Mn-limiting media for zrt1zrt2, fet3fet4, and smf1 mutants, respectively. The Zn-limiting medium contained SC-URA plus 1.0 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, Sigma), 0.4 or 0.6 mM ZnSO4, and 10 mM MES (pH 5.0). The Fe-limiting medium contained SC-URA plus 0.01 or 0.02 mM bathophenanthroline disulphonic acid (BPDS, Sigma), and 10 mM MES (pH 6.0). The Mn-limiting medium contained SC-URA plus 10 or 20 mM ethylene glycol-bis-β-aminoethylether-N,N,N′,N′-tetreacetic acid (EGTA, Sigma) and 50 mM MES (pH 6.0). Yeast complementation was also tested by measuring the OD600 in the described Zn- (1.0 mM EDTA and 0.4 mM ZnSO4), Fe- (0.01 mM BPDS) and Mn- (10 mM EGTA) limiting liquid media. To conduct this experiment, 15 mL liquid medium was initially inoculated with a 100-μL single-colony preculture at OD600 = 1, then shaken at 200 rpm and 30°C. After 20, 32, 44, and 56 h growth, 2 mL of the 15 mL culture was utilized to measure the OD600. Three independent repeats were performed.

Results

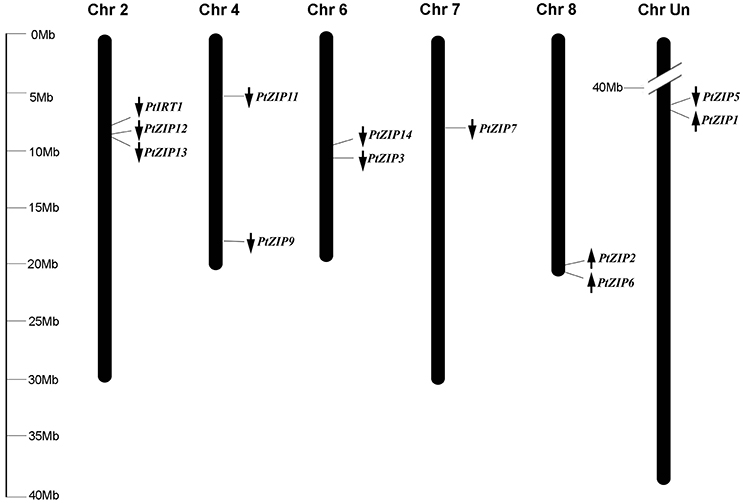

Isolation of PtZIP Genes

To genome-wide identify all ZIP genes in citrus, a BLASTP search of the sweet orange genome database was performed by using known A. thaliana and rice ZIP proteins as queries. As a result, after removal of the overlapping genes and alternative splice forms of the same gene, 13 sweet orange genes were identified, which are most similar to the ZIP sequences used as query. Further bioinformatics analysis shows that 12 of them contained transmembrane domains (TMs) and would be localized to the plasma membrane as predicted. This is consistent with known characteristics of ZIP genes. Therefore, these 12 genes were considered to be true citrus ZIP genes. Subsequently, the ZIP genes were PCR-amplified, cloned, and sequenced from trifoliate orange using sweet orange sequences as references, and were correspondingly named as PtZIPs according to the sequence and functional similarity to A. thaliana ZIPs (Table 1). The length of the PtZIPs ORF ranged from 1,005 bp (PtZIP2) to 1,260 bp (PtZIP9) with 2–4 exons, encoding 334–419 amino acids and harboring 6–9 putative TMs. The predicted MV and pI of PtZIP proteins ranged from 36.5 to 45.1 kDa and 5.5 to 8.0, respectively (Table 1).

Sequence Analysis of PtZIP Genes

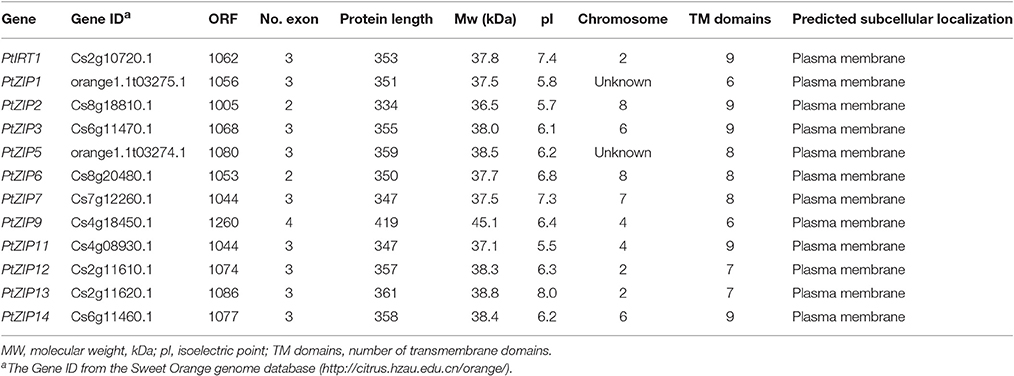

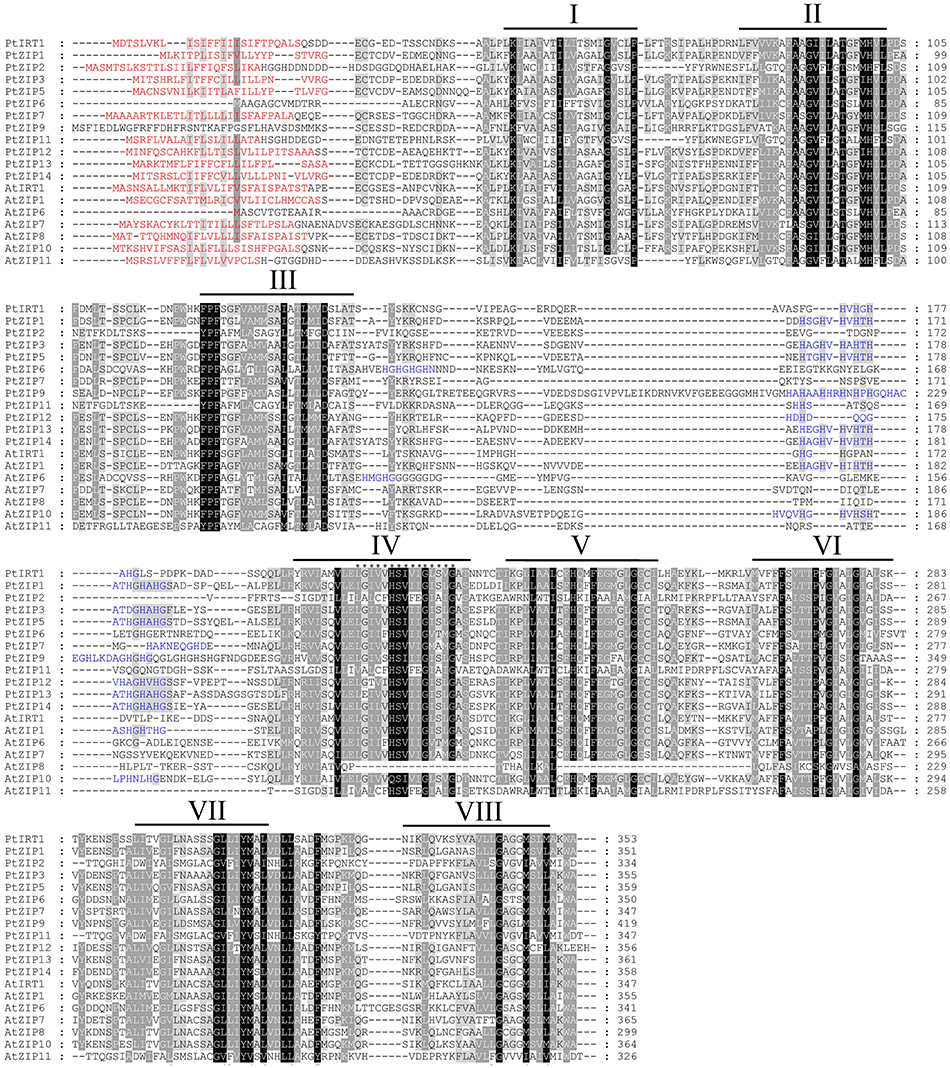

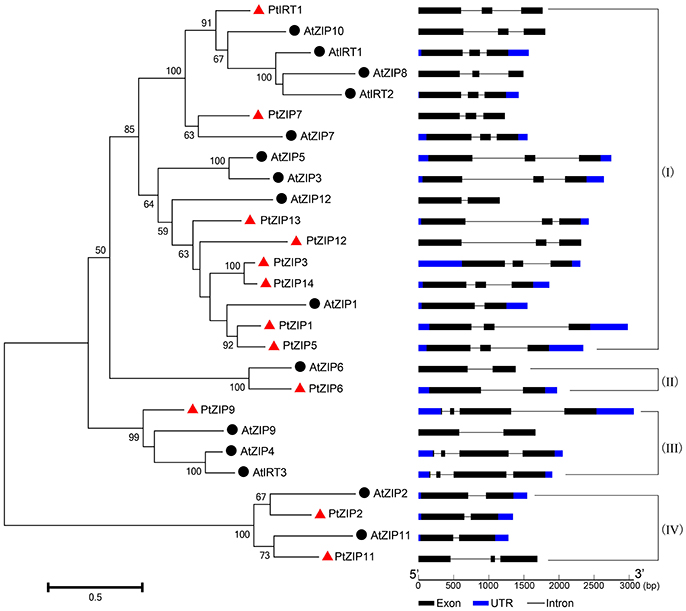

Multiple sequence alignment showed high similarity of PtZIP and AtZIP proteins, as well as a region variable in length containing a metal-binding domain rich in histidine residues between TM-III and TM-IV in all PtZIPs, except for PtZIP2 (Figure 1). Moreover, all 12 PtZIPs were predicted to be plasma membrane localized by CELLO and ProtComp predictor (Table 1), and 10 of them (excluding PtZIP6 and PtZIP9) contained a visible signal peptide for the secretory pathway at their N-terminal end (Figure 1). Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the PtZIPs were divided into four groups, the same as for AtZIPs. For nearly all AtZIPs, putative orthologues were found in trifoliate orange, except for a few closely related AtZIPs, which corresponded to only one PtZIP. The cluster with AtIRT1, AtIRT2, AtZIP8, and AtZIP10 only contained one trifoliate orange orthologue, PtIRT1. And the cluster with AtZIP4, AtZIP9, and AtIRT3, only contained PtZIP9. For the cluster containing AtZIP1, AtZIP3, AtZIP5, and AtZIP12, the closest orthologues could not be assigned, as no less than six PtZIPs resembled these four AtZIPs (Figure 2). The ZIP proteins in the same cluster often shared a similar gene structure (Figure 2). The 12 PtZIP genes could be assigned to six of the nine sweet orange chromosomes (Figure 3). The chromosomal location of two PtZIP genes could not be determined. It seems that some PtZIP genes physically cluster to very close regions, for example, PtIRt1, PtZIP12, and PtZIP13 on chromosome 2, PtZIP3 and PtZIP14 on chromosome 6, PtZIP2 and PtZIP6 on chromosome 8, and PtZIP1 and PtZIP5 on an unassigned chromosome. Of these, PtZIP12 and PtZIP13, PtZIP3 and PtZIP14, and PtZIP1 and PtZIP5 are neighboring on genome and also grouped on phylogenetic tree. It is suggested that these genes might be tandem duplicated in the evolutionary history of trifoliate orange.

Figure 1. Multiple sequence alignment of PtZIP and AtZIP proteins. Twelve PtZIP proteins isolated from trifoliate orange and seven representative AtZIP proteins from Arabidopsis were aligned using ClustalW. Similar amino acids are indicated by dark or light shading, while signal peptides in the N-terminal end are highlighted in red. Transmembrane (TM) domains were shown as lines above the sequences and numbered I to VIII. The variable region rich in histidine residues between TM-III and TM-IV is highlighted in blue. The 15 ZIP signature sequences in TM-IV domain are marked with asterisks.

Figure 2. Phylogenetic tree and gene structure of PtZIP and AtZIP proteins. Twelve of the PtZIP proteins (marked with red triangles) and 15 of the AtZIP proteins (marked with black spots) were used to construct the neighbor-joining tree. Bootstrap values above 50 and supporting a node used to define a cluster are indicated. The structures of each gene were analyzed online using the Gene Structure Display Server and displayed according to the order of the phylogenetic relationship. The black boxes, blue boxes and lines represent exons, UTRs and introns, respectively, and their lengths are shown proportionally. The proteins were divided into four groups (I to IV) according to their phylogenetic relationships.

Figure 3. Distribution of PtZIP genes on the chromosomes. The chromosomal positions of the PtZIP genes were mapped according to the information available in the sweet orange genome database. The arrows indicate transcription direction. The chromosome numbers are indicated at the top of each chromosome. The scale is in megabases (Mb).

Expression Patterns of PtZIP Genes

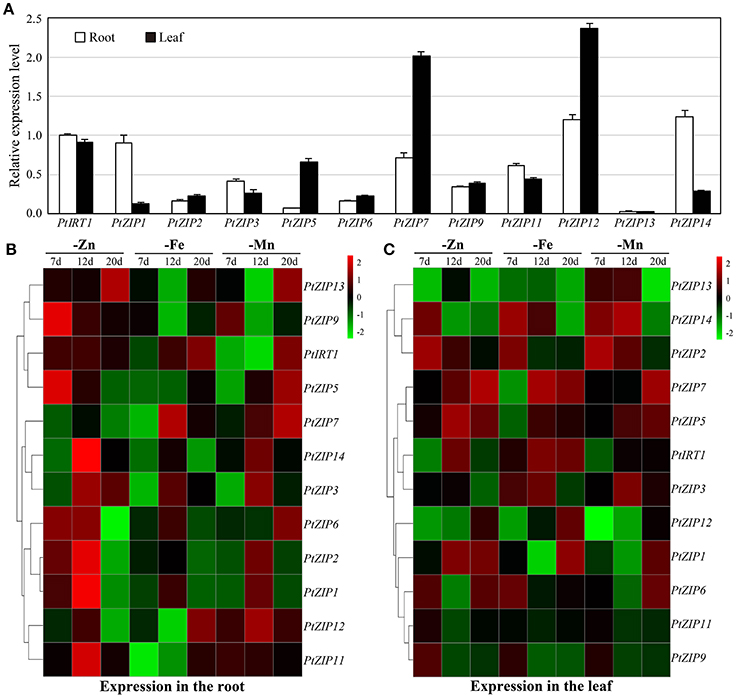

To better understand the functions of these PtZIP genes, their expression patterns were investigated under Zn-, Fe-, and Mn-sufficient and -deficient conditions in different organs (root and leaf) of trifoliate orange. Under sufficient conditions, PtIRT1, PtZIP1, PtZIP5, PtZIP7, PtZIP12, and PtZIP14 were higher expressed than the others in either roots or shoots. Expression levels of PtZIP1, PtZIP3, PtZIP11, and PtZIP14 were relatively high in roots, while PtZIP5, PtZIP7, and PtZIP12 were higher in leaves (Figure 4A). Under deficient conditions, expression of each PtZIP gene was determined at three time points (7, 12, and 20 d after treatment), and those highly expressed ( > 1) at least two times were considered as differentially induced by the treatment. As shown in Figures 4B,C, the expression of PtIRT1, PtZIP1, PtZIP2, PtZIP3, PtZIP5, PtZIP6, and PtZIP9 was significantly induced in Zn-deficient roots, while PtZIP1, PtZIP2, PtZIP5, PtZIP6, and PtZIP7 were significantly induced in Zn-deficient leaves. Additionally, the expression of PtIRT1 and PtZIP7 was significantly induced in Fe-deficient roots, while that of PtIRT1, PtZIP3, PtZIP5, PtZIP7, and PtZIP14 was significantly induced in Fe-deficient leaves. Furthermore, the expression of PtZIP7, PtZIP11, and PtZIP12 was significantly induced in Mn-deficient roots, while that of PtZIP2, PtZIP5, PtZIP13, and PtZIP14 was significantly induced in Mn-deficient leaves. Taken together, the PtZIP members exhibited very different expression profiles in different organs and in response to different metal-deficiency treatments.

Figure 4. Expression patterns of PtZIP genes in roots and leaves under normal conditions or Zn, Fe and Mn deficiency. (A) qPCR analysis of PtZIP gene expression in roots and leaves of 40 d-old trifoliate orange seedlings grown on normal nutrient solution. Data are the means ± SE of three technical replicates. (B) Heat map showing the expression patterns of PtZIP genes following treatment to induce Zn, Fe and Mn deficiency for 7, 12, and 20 d. Relative expression levels of PtZIP genes in roots and leaves were analyzed by qPCR and normalized to Actin (Cs1g05000.1). The relative expression values in samples those grown under normal conditions for 7, 12, and 20 d were used as controls. The fold change was then calculated as (PtZIP expression under treatment)/(PtZIP expression under control). The cluster 3.0 software was then used to generate heat maps based on the data. Green and red indicates lower and higher transcriptional levels of PtZIP genes, respectively.

Complementation of PtZIP Genes in Yeast Mutants

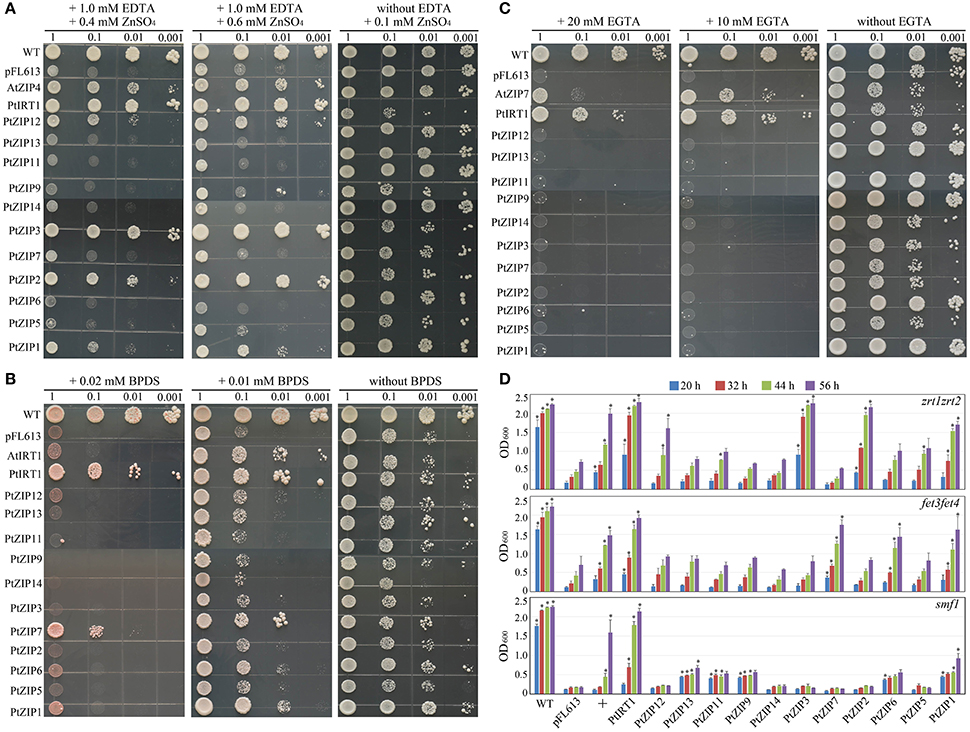

To determine the metal transport specificities of the PtZIPs, each PtZIP gene was expressed in Zn uptake-defective (zrt1zrt2), Fe uptake-defective (fet3fet4), and Mn uptake-defective (smf1) yeast mutants. As shown in Figure 5A, the zrt1zrt2 mutant transformed with PtZIP genes or the pFL613 empty vector (negative control) grew well on Zn-sufficient control medium (plus 0.1 mM ZnSO4), but on Zn-limited medium (plus 1.0 mM EDTA and 0.6/0.4 mM ZnSO4) only those transformed with AtZIP4 (positive control), PtIRT1, PtZIP1, PtZIP2, PtZIP3, and PtZIP12 showed normal growth relative to the negative control and other transformants, suggesting that these five PtZIPs are able to complement zrt1zrt2 mutant and transport Zn. Similarly, in the presence of 0.01 mM BPDS, the fet3fet4 mutant could be complemented by AtIRT1 (positive control), PtIRT1, PtZIP1, and PtZIP7 and to a lesser extent by PtZIP6 (Figure 5B). When Fe availability was more strictly limited with 0.02 mM BPDS, the PtIRT1 and PtZIP7 genes still complemented the fet3fet4 mutant (Figure 5B). Only PtIRT1 and the positive control (AtZIP7) were able to complement the smf1 mutant on Mn-limited medium (plus 10 or 20 mM EGTA; Figure 5C). To provide more evidence, the complementation experiment was also performed on liquid cultures. The OD measurements perfectly supported the drop spotting assay results as shown in Figure 5D. The zrt1zrt2 mutant transformed with PtIRT1, PtZIP1, PtZIP2, PtZIP3, and PtZIP12 had significantly higher ODs after 20, 32, 44, and 56 h of growth than the pFL613 empty vector control, which almost reach the same values as the WT at the last time point (56 h). Similarly, the ODs of fet3fet4 transformed with PtIRT1, PtZIP1, PtZIP6, and PtZIP7 and the OD of smf1 transformed with PtIRT1 were significantly higher than the OD of the negative control at all four time points. Although the OD of smf1 transformed with PtZIP1, PtZIP9, PtZIP11, and PtZIP13 were also significantly higher than the control, their OD did not increase as much as expected for full complementation after 20 h of growth.

Figure 5. Complementation of yeast metal uptake-defective mutants with PtZIP genes on selective medium. Yeast mutants defective in the uptake of Zn (zrt1zrt2), Fe (fet3fet4), and Mn (smf1) were transformed with any one of the 12 PtZIPs, the empty vector pFL613 (negative control), or the AtZIP4 (positive control for zrt1zrt2), AtIRT1 (positive control for fet3fet4) and AtZIP7 (positive control for smf1). To test the complementary ability of the genes, 5 μL of transformed yeast cells with OD600 values of 1.0, 0.1, 0.01, and 0.001 were spotted on plates containing different metal limiting medium and grown for 3–5 d at 30°C. (A) Transformed zrt1zrt2 cells on synthetic complete and dropout mix (without Uracil) medium (SC-URA) plus 0.1 mM ZnSO4 (control) or SC-URA plus 1.0 mM EDTA and 0.4/0.6 mM ZnSO4 (Zn limited with EDTA). (B) Transformed fet3fet4 cells on SC-URA without BPDS (control) or SC-URA plus 0.01/0.02 mM BPDS (Fe limited with BPDS). (C) Transformed smf1 cells on SC-URA without EGTA (control) or SC-URA plus 10/20 mM EGTA (Mn limited with EGTA). (D) Transformed yeast cells (100 μL) with an OD600 of 1.0 were initially inoculated into 15 mL liquid SC-URA medium supplemented with 1.0 mM EDTA and 0.4 mM ZnSO4 (for testing zrt1zrt2), 0.01 mM BPDS (for testing fet3fet4), and 10 mM EGTA (for testing smf1). After 20, 32, 44, and 56 h of growth at 200 rpm and 30°C, the OD600 of 2 mL from the 15 mL culture was measured. Data are the means ± SE of three independent repeats. + under the horizontal axis indicates the positive controls, AtZIP4, AtIRT1 and AtZIP7 for zrt1zrt2, fet3fet4, and smf1, respectively. * indicates the values are significantly different from those associated with pFL613 at P < 0.05 by LSD testing.

Discussion

Although ZIP genes have been reported in several plant species, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically identify, clone and characterize 12 PtZIPs from trifoliate orange. The numbers of PtZIPs in trifoliate orange or citrus is the same as that in rice, but less than in A. thaliana. Sequence analysis shows that the PtZIP proteins contain several, if not all, characteristics of the known ZIP family members (Eng et al., 1998; Guerinot, 2000). Specifically, the 12 identified PtZIP genes encode polypeptides of 334–419 amino acids, all within the range of known plant ZIPs (Guerinot, 2000). All PtZIPs were predicted to be localized to the plasma membrane (Table 1) as it is known for AtIRT1, OsIRT1, HvIRT1, OsZIP4, and OsZIP5 (Bughio et al., 2002; Vert et al., 2002; Ishimaru, 2005; Pedas et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2010b). It confirms their putative role in metal ion uptake or transport. In addition, 6–9 putative TMs were identified in the PtZIP proteins, using TMHMM (Table 1). Although not all have 8 TMs as proposed by Guerinot (2000), this is closely consistent with the number of TMs found in ZmZIPs of maize (Li et al., 2013). A variable region between TM-III and TM-IV was also found in almost all PtZIPs except PtZIP2 (Figure 1). This region is predicted to be directed toward the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane and it is rich in histidine residues, thus providing a cytoplasmic metal ion binding site (Eng et al., 1998; Guerinot, 2000). PtZIP2, similar to AtZIP7, 8, and 11, MtZIP1, and MtZIP7 in M. truncatula (López-Millan et al., 2004), lacks this His-rich region between TM-III and TM-IV. Instead, it is found in their N-terminal, TM-IV, or TM-V as reported by Eng et al. (1998), indicating that these ZIPs may bind metal ions at a different site (Figure 1). PtZIP2, along with all the others, did contain the ZIP signature motif (consensus sequence: [LIVFA] [GAS] [LIVMD] [LIVSCG] [LIVFAS] [H] [SAN] [LIVFA] [LIVFMAT] [LIVDE] [G] [LIVF] [SAN] [LIVF] [GS]; Eng et al., 1998) in TM-IV (Figure 1). Taken together, all the identified characteristics of the PtZIPs suggest that they are reliable members of the ZIP family.

PtIRT1 shared 67.4% and 66.4% identity at the protein level with AtZIP10 and AtIRT1, respectively. Phylogenetic analysis also revealed that they were closely clustered together (Figure 2). PtIRT1 was also induced to a significantly greater extent in Fe-deficient roots (Figure 4) and complemented Zn, Fe, and Mn uptake-defective mutants (Figure 5), which was closely consistent with known functional characteristics of AtIRT1 (Korshunova et al., 1999; Rogers et al., 2000; Vert et al., 2002). This suggests that PtIRT1 is most likely the orthologous form of AtIRT1, so we officially name it “PtIRT1” herein. Phylogenetic analysis showed that although the closest orthologous could not be assigned, 6 PtZIPs (PtZIP1, PtZIP3, PtZIP5, PtZIP12, PtZIP13, and PtZIP14) resembled the cluster consisting of AtZIP1, AtZIP3, AtZIP5, and AtZIP12, which were mainly induced under Zn deficiency and found to be involved in Zn uptake and redistribution (Grotz et al., 1998; van de Mortel et al., 2006; Milner et al., 2013; Inaba et al., 2015). In the current results, four of them (PtZIP1, PtZIP3, PtZIP5, and PtZIP12) showed visible induction by Zn deficiency or complementation with zrt1zrt2 (Figures 4, 5), indicating that these four PtZIPs may be functional orthologous of AtZIP1, AtZIP3, AtZIP5, and AtZIP12. Among them, PtZIP1 shared the highest identity (64.0%) with AtZIP1. They also showed a similar expression pattern under Zn deficiency and Zn uptake ability (Grotz et al., 1998). PtZIP5 was induced in Zn-deficient roots and leaves but it did not complement zrt1zrt2, which was similar to the known information of AtZIP5 (van de Mortel et al., 2006; Milner et al., 2013). PtZIP3 and PtZIP12, similar to AtZIP3 and AtZIP12 (Grotz et al., 1998; Milner et al., 2013), were able to complement zrt1zrt2 but not fet3fet4 or smf1 (Figure 5), and PtZIP3 (57.8%) shared significantly closer identity with AtZIP3 than PtZIP12 did (49.7%). Based on this information, these four PtZIPs can be named PtZIP1, PtZIP3, PtZIP5, and PtZIP12, respectively. In this cluster, another two PtZIPs (PtZIP13 and PtZIP14) were neither assigned any close orthology nor found to have functional characteristics similar to those of known AtZIPs. We speculate that PtZIP13 and PtZIP14 may be previously unknown members of ZIP family in trifoliate orange relative to A. thaliana, and citrus plants may require more ZIP genes for Zn uptake or redistribution in organs, such as Zn loading in fruit. For this reason, they are here named PtZIP13 and PtZIP14, respectively. Based on phylogenetic analysis, AtZIP2, AtZIP7, AtZIP10, and AtZIP11 were clustered around only one closely related PtZIP, and the closely clustered two also shared the highest identity at protein level, for example 62.3% for PtZIP2 and AtZIP2, 67.7% for PtZIP6 and AtZIP6, 58.3% for PtZIP7 and AtZIP7, and 68.6% for PtZIP11 and AtZIP11. Thus, they are here named PtZIP2, PtZIP6, PtZIP7, and PtZIP11, respectively. For the PtZIP9, three closely AtZIPs (AtZIP4, AtZIP9, and AtIRT3) were clustered simultaneously (Figure 2). Previous studies have revealed that these three AtZIPs were visibly induced by Zn deficiency and two of them, AtZIP4 and AtIRT3, complemented zrt1zrt2 mutant (van de Mortel et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2009; Assunção et al., 2010). In the current work, PtZIP9 was also been induced in Zn-deficient roots but failed to complement zrt1zrt2, which was consistent with existing reports on AtZIP9 (van de Mortel et al., 2006; Milner et al., 2013). Thus, it is called PtZIP9. It should be noted that although we have selected an appropriate name for 12 PtZIPs according to their sequence and functional comparability to A. thaliana ZIPs, our results and existing information concerning AtZIPs are still limited, so the relationship between PtZIPs and AtZIPs still needs to be identified through further study. As mentioned in results, a tandem duplication might have happened in the evolutionary history of PtZIP family since there are three pairs of PtZIPs neighboring on genome and also clustered together on phylogenetic tree. Tandem duplication of the genes in the genome evolution is commonly existing in organisms including citrus (Zhang, 2003; Xu et al., 2013). The duplicated genes are sometimes conserved in gene function, but more outcomes are the origin of novel function (Zhang, 2003). In this study, although three pairs of PtZIPs are both phylogenetically and physically close, no obvious similarity was found in their expression pattern and yeast complementing. Thus, we believe that these genes may have evolved their own functions.

Previous studies in A. thaliana, rice, soybeans, and maize have suggested the complicated expression profiles of ZIP genes in response to various metal ions and outlined their diverse functions in Zn, Fe, and Mn uptake, transport, and redistribution (Moreau et al., 2002; van de Mortel et al., 2006; Bashir et al., 2012, 2016; Milner et al., 2013; Li et al., 2015). PtZIPs also perform diverse functions in response to various metal ions. To establish these differences, it is necessary to comprehensively understand the results of the expression patterns and yeast complementation testing performed here. Results showed that PtIRT1, PtZIP1, PtZIP2, PtZIP3, PtZIP5, PtZIP6, and PtZIP9 were induced mainly in Zn-deficient roots. Meanwhile, 4 of them (PtIRT1, PtZIP1, PtZIP2, and PtZIP3) complemented zrt1zrt2 mutants visibly. This overlap suggests that at least these 4 PtZIPs may play a role in Zn uptake. Similarly, the corresponding ZIPs of A. thaliana, AtIRT1, AtZIP1, AtZIP2, and AtZIP3, were able to take up Zn (Grotz et al., 1998; Korshunova et al., 1999; Rogers et al., 2000). Under Fe deficiency, only PtIRT1 and PtZIP7 were induced mainly in roots. These two genes also strongly complemented fet3fet4 mutants even under very strictly limited Fe availability. So we expect that PtIRT1 and PtZIP7 are responsible for high Fe uptake in trifoliate oranges. The corresponding AtIRT1 has been well demonstrated in Fe uptake, but for AtZIP7 only Milner et al. (2013) provided a few evidence which indicates its Fe uptake activity via fet3fet4 complementation testing. The current findings regarding PtZIP7 are completely consistent with previous studies. For the Mn uptake, although we did not find any overlapping results among expression pattern and yeast complementation, PtIRT1 still showed prominent activity in complementing smf1. In A. thaliana, it has also been proved that AtIRT1 could complement smf1 and take up Mn (Korshunova et al., 1999; Rogers et al., 2000). We also noticed that the other four PtZIPs (PtZIP1, PtZIP9, PtZIP11, and PtZIP13) complemented growth of smf1 in the initial 20 h (Figure 5D), but they failed to grow later. It seems that these genes only weakly complemented the growth of smf1 mutant, but could not sustain proliferated yeast growth. Thus, out of the PtZIPs we identified, only PtIRT1 appears to be a Mn uptake transporter.

Conclusion

In conclusion, 12 PtZIP genes were isolated from trifoliate orange plants, and sequence analysis and prediction suggests that they all possessed the basic characteristics of members of the ZIP family. Twelve PtZIP genes were identified and named PtIRT1, PtZIP1, PtZIP2, PtZIP3, PtZIP5, PtZIP6, PtZIP7, PtZIP9, PtZIP11, PtZIP12, PtZIP13, and PtZIP14 based on the sequence and functional comparability to A. thaliana ZIPs. Comprehensively analyzing the results of expression patterns and yeast complementation tests indicates that PtIRT1, PtZIP1, PtZIP2, and PtZIP3 are responsible for Zn uptake, PtIRT1 and PtZIP7 for Fe uptake, and PtIRT1 for Mn uptake in trifoliate oranges. The present study provides essential information for citrus ZIP genes, but further work is needed to characterize the exact subcellular and tissue localization, transcriptional regulation, and functions of the PtZIP genes in the different citrus species.

Author Contributions

XF and LP conceived and designed the study. XF, XZ, FX, LL, CC, and LC performed the experiments. XF, XZ, and MA analyzed the data. XF wrote the manuscript and MA revised it. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. David Eide (Nutritional Science Program, University of Missouri, Columbia, USA) for providing the zrt1zrt2 and fet3fet4 yeast strains, Dr. Sébastien Thomine (National Center for Scientific Research, Paris, France) for providing the smf1 yeast strain, and Dr. Ute Krämer (Ruhr University, Bochum, Germany) for providing the pFL613 vector. This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31301742), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China (XDJK2016B005), the Zenith Scheme of the Netherlands Genome Initiative (93512008) and the Earmarked Fund for China Agriculture Research System (CARS-27-02A) from the Ministry of Agriculture of China.

References

Assunção, A. G., Herrero, E., Lin, Y. F., Huettel, B., Talukdar, S., Smaczniak, C., et al. (2010). Arabidopsis thaliana transcription factors bZIP19 and bZIP23 regulate the adaptation to zinc deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 10296–10301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004788107

Bashir, K., Ishimaru, Y., and Nishizawa, N. K. (2012). Molecular mechanisms of zinc uptake and translocation in rice. Plant Soil 361, 189–201. doi: 10.1007/s11104-012-1240-5

Bashir, K., Rasheed, S., Kobayashi, T., Seki, M., and Nishizawa, N. K. (2016). Regulating subcellular metal homeostasis: the key to crop improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1192. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01192

Boutigny, S., Sautron, E., Finazzi, G., Rivasseau, C., Frelet-Barrand, A., Pilon, M., et al. (2014). HMA1 and PAA1, two chloroplast-envelope PIB-ATPases, play distinct roles in chloroplast copper homeostasis. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 1529–1540. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru020

Broadley, M. R., White, P. J., Hammond, J. P., Zelko, I., and Lux, A. (2007). Zinc in plants. New Phytol. 173, 677–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.01996.x

Bughio, N., Yamaguchi, H., Nishizawa, N. K., Nakanishi, H., and Mori, S. (2002). Cloning an iron-regulated metal transporter from rice. J. Exp. Bot. 53, 1677–1682. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erf004

Clemens, S. (2001). Molecular mechanisms of plant metal tolerance and homeostasis. Planta 212, 475–486. doi: 10.1007/s004250000458

Dräger, D. B., Desbrosses-Fonrouge, A. G., Krach, C., Chardonnens, A. N., Meyer, R. C., Saumitou-Laprade, P., et al. (2004). Two genes encoding Arabidopsis halleri MTP1 metal transport proteins co-segregate with zinc tolerance and account for high MTP1 transcript levels. Plant J. 39, 425–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02143.x

Eckhardt, U., Mas, M. A., and Buckhout, T. J. (2001). Two iron-regulated cation transporters from tomato complement metal uptake-deficient yeast mutants. Plant Mol. Biol. 45, 437–448. doi: 10.1023/A:1010620012803

Eide, D., Broderius, M., Fett, J., and Guerinot, M. L. (1996). A novel iron-regulated metal transporter from plants identified by functional expression in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 5624–5628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5624

Eng, B. H., Guerinot, M. L., Eide, D., and Saier, M. H. Jr. (1998). Sequence analyses and phylogenetic characterization of the ZIP family of metal ion transport proteins. J. Membr. Biol. 166, 1–7. doi: 10.1007/s002329900442

Fu, X. Z., Xing, F., Cao, L., Chun, C. P., Ling, L. L., Jiang, C. L., et al. (2016). Effects of foliar application of various zinc fertilizers with organosilicone on correcting citrus zinc deficiency. Hortscience 51, 422–426.

Grotz, N., Fox, T., Connolly, E., Park, W., Guerinot, M. L., and Eide, D. (1998). Identification of a family of zinc transporter genes from Arabidopsis that respond to zinc deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 7220–7224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7220

Grotz, N., and Guerinot, M. L. (2006). Molecular aspects of Cu, Fe and Zn homeostasis in plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763, 595–608. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.05.014

Guerinot, M. L. (2000). The ZIP family of metal transporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1465, 190–198. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(00)00138-3

Guo, A. Y., Zhu, Q. H., Chen, X., and Luo, J. C. (2007). [GSDS: a gene structure display server]. Yi Chuan 29, 1023–1026. doi: 10.1360/yc-007-1023

Henriques, R., Jasik, J., Klein, M., Martinoia, E., Feller, U., Schell, J., et al. (2002). Knock-out of Arabidopsis metal transporter gene IRT1 results in iron deficiency accompanied by cell differentiation defects. Plant Mol. Biol. 50, 587–597. doi: 10.1023/A:1019942200164

Inaba, S., Kurata, R., Kobayashi, M., Yamagishi, Y., Mori, I., Ogata, Y., et al. (2015). Identification of putative target genes of bZIP19, a transcription factor essential for Arabidopsis adaptation to Zn deficiency in roots. Plant J. 84, 323–334. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12996

Ishimaru, Y. (2005). OsZIP4, a novel zinc-regulated zinc transporter in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 3207–3214. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri317

Ishimaru, Y., Masuda, H., Suzuki, M., Bashir, K., Takahashi, M., Nakanishi, H., et al. (2007). Overexpression of the OsZIP4 zinc transporter confers disarrangement of zinc distribution in rice plants. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 2909–2915. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm147

Jeong, J., and Guerinot, M. L. (2009). Homing in on iron homeostasis in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.02.006

Kobayashi, T., and Nishizawa, N. K. (2012). Iron uptake, translocation, and regulation in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 63, 131–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105522

Korshunova, Y. O., Eide, D., Clark, W. G., Guerinot, M. L., and Pakrasi, H. B. (1999). The IRT1 protein from Arabidopsis thaliana is a metal transporter with a broad substrate range. Plant Mol. Biol. 40, 37–44. doi: 10.1023/A:1026438615520

Krogh, A., Larsson, B., von Heijne, G., and Sonnhammer, E. L. (2001). Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305, 567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315

Kumar, R., Tyagi, A. K., and Sharma, A. K. (2011). Genome-wide analysis of auxin response factor (ARF) gene family from tomato and analysis of their role in flower and fruit development. Mol. Genet. Genomics 285, 245–260. doi: 10.1007/s00438-011-0602-7

Lee, S., Jeong, H. J., Kim, S. A., Lee, J., Guerinot, M. L., and An, G. (2010b). OsZIP5 is a plasma membrane zinc transporter in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 73, 507–517. doi: 10.1007/s11103-010-9637-0

Lee, S., Kim, S. A., Lee, J., Guerinot, M. L., and An, G. (2010a). Zinc deficiency-inducible OsZIP8 encodes a plasma membrane-localized zinc transporter in rice. Mol. Cells 29, 551–558. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0069-0

Li, S., Zhou, X., Huang, Y., Zhu, L., Zhang, S., Zhao, Y., et al. (2013). Identification and characterization of the zinc-regulated transporters, iron-regulated transporter-like protein (ZIP) gene family in maize. BMC Plant Biol. 13:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-13-114

Li, S. Z., Zhou, X. J., Li, H. B., Liu, Y. F., Zhu, L. Y., Guo, J. J., et al. (2015). Overexpression of ZmIRT1 and ZmZIP3 enhances iron and zinc accumulation in transgenic Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 10:e0136647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136647

Lin, Y. F., Liang, H. M., Yang, S. Y., Boch, A., Clemens, S., Chen, C. C., et al. (2009). Arabidopsis IRT3 is a zinc-regulated and plasma membrane localized zinc/iron transporter. New Phytol. 182, 392–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02766.x

López-Millan, A. F., Ellis, D. R., and Grusak, M. A. (2004). Identification and characterization of several new members of the ZIP family of metal ion transporters in Medicago truncatula. Plant Mol. Biol. 54, 583–596. doi: 10.1023/B:PLAN.0000038271.96019.aa

Milner, M. J., Seamon, J., Craft, E., and Kochian, L. V. (2013). Transport properties of members of the ZIP family in plants and their role in Zn and Mn homeostasis. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 369–381. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers315

Moreau, S., Thomson, R. M., Kaiser, B. N., Trevaskis, B., Guerinot, M. L., Udvardi, M. K., et al. (2002). GmZIP1 encodes a symbiosis-specific zinc transporter in soybean. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 4738–4746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106754200

Pedas, P., Schjoerring, J. K., and Husted, S. (2009). Identification and characterization of zinc-starvation-induced ZIP transporters from barley roots. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 47, 377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2009.01.006

Pedas, P., Ytting, C. K., Fuglsang, A. T., Jahn, T. P., Schjoerring, J. K., and Husted, S. (2008). Manganese efficiency in barley: identification and characterization of the metal ion transporter HvIRT1. Plant Physiol. 148, 455–466. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.118851

Petersen, T. N., Brunak, S., von Heijne, G., and Nielsen, H. (2011). SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat. Methods 8, 785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701

Rogers, E. E., Eide, D. J., and Guerinot, M. L. (2000). Altered selectivity in an Arabidopsis metal transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 12356–12360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.210214197

Sinclair, S. A., and Krämer, U. (2012). The zinc homeostasis network of land plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823, 1553–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.05.016

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A., and Kumar, S. (2013). MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197

Thomine, S., Wang, R., Ward, J. M., Crawford, N. M., and Schroeder, J. I. (2000). Cadmium and iron transport by members of a plant metal transporter family in Arabidopsis with homology to Nramp genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 4991–4996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4991

Thompson, J. D., Higgins, D. G., and Gibson, T. J. (1994). Clustal-W - Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucl. Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673

van de Mortel, J. E., Almar Villanueva, L., Schat, H., Kwekkeboom, J., Coughlan, S., Moerland, P. D., et al. (2006). Large expression differences in genes for iron and zinc homeostasis, stress response, and lignin biosynthesis distinguish roots of Arabidopsis thaliana and the related metal hyperaccumulator Thlaspi caerulescens. Plant Physiol. 142, 1127–1147. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.082073

Vert, G., Briat, J. F., and Curie, C. (2001). Arabidopsis IRT2 gene encodes a root-periphery iron transporter. Plant J. 26, 181–189. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01018.x

Vert, G., Grotz, N., Dédaldéchamp, F., Gaymard, F., Guerinot, M. L., Briat, J. F., et al. (2002). IRT1, an Arabidopsis transporter essential for iron uptake from the soil and for plant growth. Plant Cell 14, 1223–1233. doi: 10.1105/tpc.001388

Vigani, G., Zocchi, G., Bashir, K., Philippar, K., and Briat, J. F. (2013). Cellular iron homeostasis and metabolism in plant. Front. Plant Sci. 4:490. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00490

Xu, Q., Chen, L. L., Ruan, X., Chen, D., Zhu, A., Chen, C., et al. (2013). The draft genome of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis). Nat. Genet. 45, 59–66. doi: 10.1038/ng.2472

Yang, X., Huang, J., Jiang, Y., and Zhang, H. S. (2009). Cloning and functional identification of two members of the ZIP (Zrt, Irt-like protein) gene family in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Mol. Biol. Rep. 36, 281–287. doi: 10.1007/s11033-007-9177-0

Yu, C. S., Chen, Y. C., Lu, C. H., and Hwang, J. K. (2006). Prediction of protein subcellular localization. Proteins 64, 643–651. doi: 10.1002/prot.21018

Zhang, J. Z. (2003). Evolution by gene duplication: an update. Trends Ecol. Evol. 18, 292–298. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00033-8

Zhao, H., and Eide, D. (1996a). The yeast ZRT1 gene encodes the zinc transporter protein of a high-affinity uptake system induced by zinc limitation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 2454–2458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2454

Keywords: citrus, zinc deficiency, iron deficiency, ZIP gene, yeast complementation

Citation: Fu X-Z, Zhou X, Xing F, Ling L-L, Chun C-P, Cao L, Aarts MGM and Peng L-Z (2017) Genome-Wide Identification, Cloning and Functional Analysis of the Zinc/Iron-Regulated Transporter-Like Protein (ZIP) Gene Family in Trifoliate Orange (Poncirus trifoliata L. Raf.). Front. Plant Sci. 8:588. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00588

Received: 28 January 2017; Accepted: 31 March 2017;

Published: 19 April 2017.

Edited by:

Jon Pittman, University of Manchester, UKReviewed by:

Felipe Klein Ricachenevsky, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, BrazilAnja Thoe Fuglsang, University of Copenhagen, Denmark

Copyright © 2017 Fu, Zhou, Xing, Ling, Chun, Cao, Aarts and Peng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Liang-Zhi Peng, cGVuZ2xpYW5nemhpQGNyaWMuY24=

Xing-Zheng Fu

Xing-Zheng Fu Xue Zhou

Xue Zhou Fei Xing1

Fei Xing1 Li-Li Ling

Li-Li Ling Mark G. M. Aarts

Mark G. M. Aarts