Abstract

Citrus tristeza is one of the most destructive citrus diseases and is caused by the phloem-restricted Closterovirus, Citrus tristeza virus. Mild strain CTV-B2 does not cause obvious symptoms on indicators whereas severe strain CTV-B6 causes symptoms, including stem pitting, cupping, yellowing, and stiffening of leaves, and vein corking. Our laboratory has previously characterized changes in transcription in sweet orange separately infected with CTV-B2 and CTV-B6. In the present study, transcriptome analysis of Citrus sinensis in response to double infection by CTV-B2 and CTV-B6 was carried out. Four hundred and eleven transcripts were up-regulated and 356 transcripts were down-regulated prior to the onset of symptoms. Repressed genes were overwhelmingly associated with photosynthesis, and carbon and nucleic acid metabolism. Expression of genes related to the glycolytic, oxidative pentose phosphate (OPP), tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) pathways, tetrapyrrole synthesis, redox homeostasis, nucleotide metabolism, protein synthesis and post translational protein modification and folding, and cell organization were all reduced. Ribosomal composition was also greatly altered in response to infection by CTV-B2/CTV-B6. Genes that were induced were related to cell wall structure, secondary and hormone metabolism, responses to biotic stress, regulation of transcription, signaling, and secondary metabolism. Transport systems dedicated to metal ions were especially disturbed and ZIPs (Zinc Transporter Precursors) showed different expression patterns in response to co-infection by CTV-B2/CTV-B6 and single infection by CTV-B2. Host plants experienced root decline that may have contributed to Zn, Fe, and other nutrient deficiencies. Though defense responses, such as, strengthening of the cell wall, alteration of hormone metabolism, secondary metabolites, and signaling pathways, were activated, these defense responses did not suppress the spread of the pathogens and the development of symptoms. The mild strain CTV-B2 did not provide a useful level of cross-protection to citrus against the severe strain CTV-B6.

Introduction

Citrus tristeza has historically been one of the most destructive and globally distributed citrus diseases and is still responsible for tremendous economic losses to the citrus industries worldwide (Bennett and Costa, 1949; Moreno et al., 2008). The disease is caused by Citrus tristeza virus (CTV), a member of the Closteroviridae, with single-stranded and positive-sense genomic RNA (gRNA) of about ~19 kb in size (Karasev et al., 1995; Moreno et al., 2008). CTV is phloem-restricted and long-distance spread of the virus is via movement of infected plants or propagation of infected buds. It is also transmitted locally by several aphid species in a semi-persistent mode, most notably by Toxoptera citricida (Kirkaldy). Strains of CTV can be classified as mild to severe based on the type and intensity of symptoms caused in different citrus hosts. Mild CTV strains do not cause symptoms on most indicators and usually do not bring about economic loss, while severe CTV strains induce distinct disease syndromes, including quick decline and death of sweet orange on sour orange rootstocks, or stem pitting (SP) of sweet orange and grapefruit scions when grown on other rootstocks, seedling yellows (SY) in sour orange, and vein clearing in “Mexican” lime seedlings (Dawson et al., 2013). Based on phylogenetic analysis of nucleotide sequences of the most variable genomic region, CTV has been divided into seven genotypes: T3, T30, T36, VT, B165/T68, RB, and HA16-5 (Dawson et al., 2015). It is interesting that complete symptoms of Tristeza disease were observed in transgenic Mexican lime plants that expressed the product of CTV ORF 11, an RNA binding protein designated p23 (Ghorbel et al., 2001).

Physiological and cellular changes caused by virus infection are accompanied by differential gene expression in plants. Understanding host responses to infection by pathogens facilitates the understanding of plant–pathogen interactions and also provides insights for new control strategies. Changes in the transcriptomes of susceptible Mexican lime (Gandía et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2013) and sweet orange (Cheng et al., 2016) and resistant trifoliate orange (Cristofani-Yaly et al., 2007) in response to the infection by mild or severe CTV strains have been well documented. Changes in gene expression in resistant, tolerant, and susceptible hosts in response to CTV were also compared to huanglongbing (HLB; Bowman and Albrecht, 2015). Citrus hosts are commonly infected with more than one CTV strain, sometimes as many as seven strains in a single tree (Roy et al., 2010). Some mild CTV strains have played an important role in protecting susceptible commercial varieties in citrus industries worldwide by cross protection (Grant and Costa, 1951), but failure is common (Roistacher and Dodds, 1993) because the presumptive protecting strain must be selected to match the genotype of the strains of CTV in the local environment (Folimonova and Achor, 2010).

Sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) is susceptible to CTV and accounts for ~60% of citrus production (Moreno et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2013). In a previous study, transcriptional changes in sweet orange separately infected with CTV-B2 and CTV-B6 revealed a disturbance of circadian rhythm and ionic homeostasis, as well as activation of defense responses including modification of cell walls. The regulation of transcription, hormone, and secondary metabolism, are also affected by infection by CTV, but with differing patterns depending on the strain of CTV (Fu et al., 2016). In this study, transcriptome data were collected from sweet orange co-infected with both mild strain CTV-B2 and severe strain CTV-B6. This provides new insight into the host response to simultaneous infection with mild and severe strains of CTV and how these changes are correlated with the host response to infection by single strains of CTV.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and inoculation with CTV

CTV mild strain B2 (T30 genotype, Florida) and severe strain B6 (mixed genotype, SY568, California; Vives et al., 2005; Ruiz-Ruiz et al., 2006) are maintained in planta as part of the Exotic Pathogens of Citrus Collection (EPCC) at the USDA-ARS Beltsville Agricultural Research Center (BARC) in Beltsville, MD. Both CTV-B2 and CTV-B6 were graft-inoculated into ten “Valencia” sweet orange seedlings simultaneously. Ten trees were mock-inoculated with their own buds as the healthy control.

Extraction of RNA and detection of CTV

Inoculated plants were tested for the presence of CTV specific amplicons by RT-PCR as described (Roy et al., 2010). RNA extracts were prepared for RNA-Seq immediately after the trees became RT-PCR positive and before any symptoms developed from three young, soft, not fully expanded leaves of uniform size. Leaves were frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at −80°C until the extraction of RNA and assessment for quantity and quality with Qubit (Thermo-Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA) and Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) instruments. Three qualified RNA replicates, each of three leaves from different plants, for CTV-B2/CTV-B6 and healthy citrus were sent to Otogenetics (Norcross, GA, USA) for paired-end sequencing with the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform.

Statistical analyses and RT-qPCR verification

Raw reads obtained by Illumina HiSeq 2500 were filtered to exclude low complexity reads. Clean reads from the nine libraries were aligned to the reference genome (Xu et al., 2013) with Bowtie (Langmead, 2010) and fold changes (log2 FC) for each transcript were evaluated by DEseq2 (Love et al., 2014). Differentially expressed transcripts (DETs) were filtered with cut-off values, Padj ≤ 0.1, |log2 FC| ≥ 1 and e-value ≤ e−5. DETs involved in pathways were enriched with Panther (Mi et al., 2009) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) data bases. A summary of gene expression patterns was visualized with MapMan software (Thimm et al., 2004). Twenty genes were selected and transcripts were amplified by RT-qPCR to validate the RNASeq analysis as described (Fu et al., 2016). Primers used for RT-qPCR were designed by Real-time PCR online tool (Integrated DNA Technology, IDT, Table S1).

In order to estimate the relative concentration of CTV-B2 and CTV-B6 genomes in co-infected plants, RNA-Seq libraries from trees co-inoculated with CTV-B2 and CTV-B6 and mock inoculated trees were searched for sequences homologous to the p23 protein of reference CTV T30 genome (AF260651) and the reference CTV T318A genome (DQ151548). The 100 bp paired end reads were mapped to the reference genomes under stringent conditions, allowing a maximum of 1 mismatch per read duo to the high homology between the p23 protein of CTV-B2 and CTV-B6.

Results

Infection and symptoms

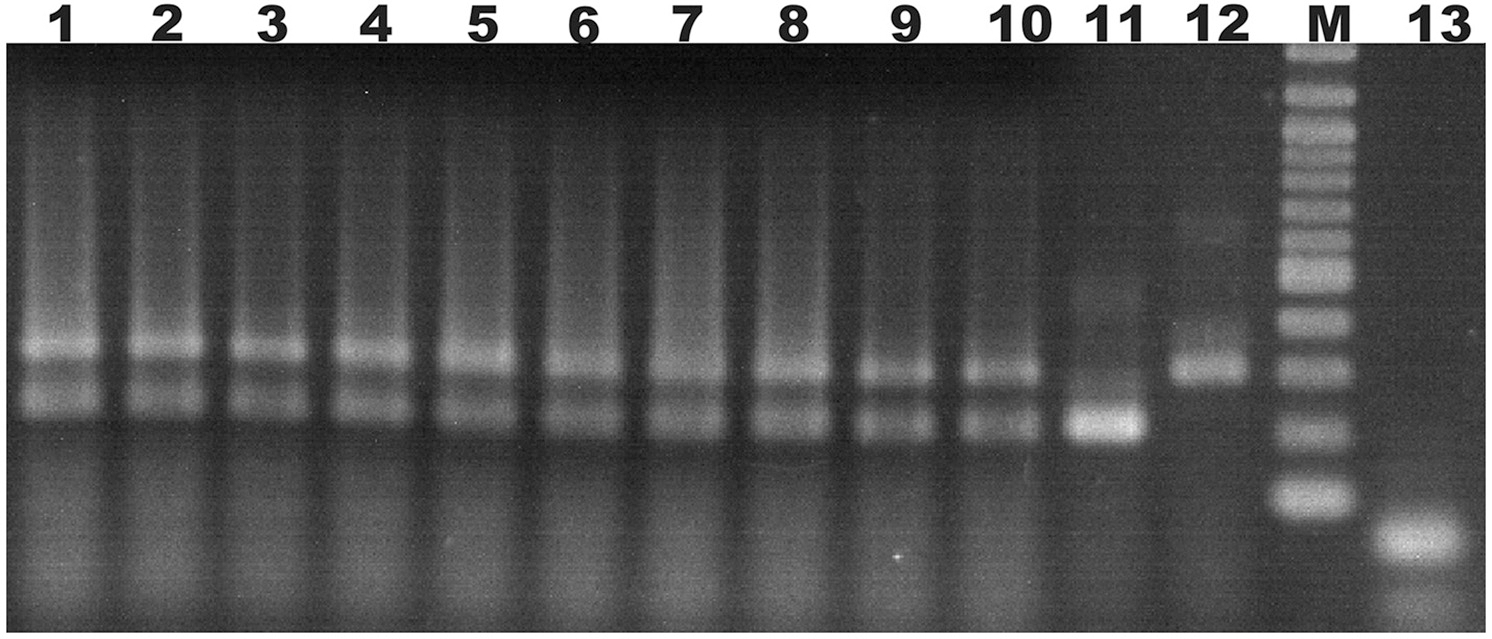

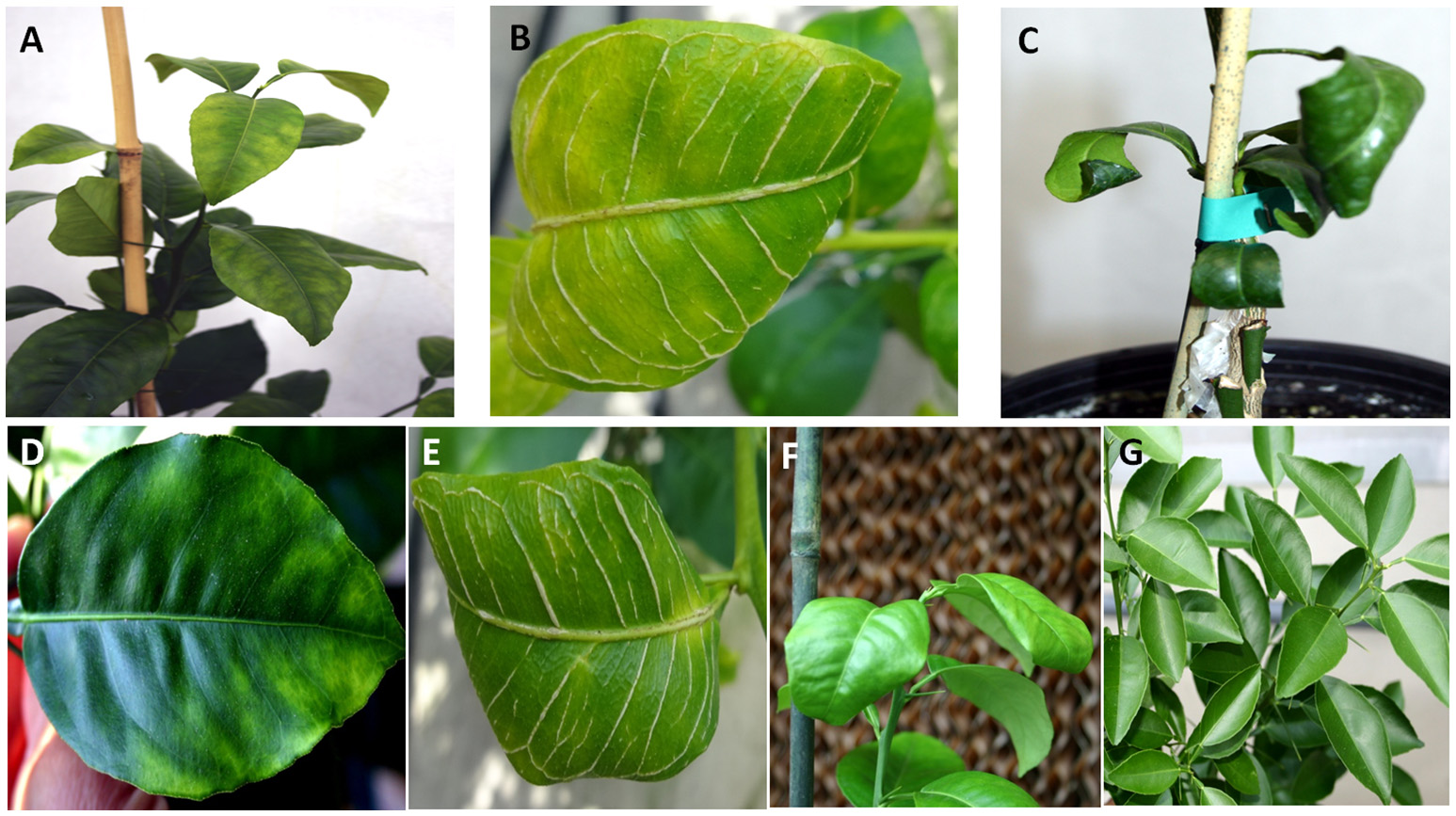

Ten doubly-inoculated trees became positive for both mild CTV-B2 and severe CTV-B6 based on RT-PCR after 2–4 months (Figure 1). Symptoms developed 5–6 months after inoculation. Trees infected with CTV-B2/CTV-B6 were much smaller and stunted than the healthy controls, with leaf chlorosis, vein corking, and vein curling (Figure 2) increasing as time passed. Symptoms of the co-inoculated plants 12 months after co-inoculation were indistinguishable from those produced by plants infected with CTV-B6 alone. In the plants co-inoculated with CTV-B2 and CTV-B6, the p23 transcript of CTV-B6 was found 300 times more frequently than the CTV-B2 homolog. Sequences homologous to p23 were not found in the mock-inoculated controls, nor when other libraries that contained only CTV-B2 or CTV-B6 were searched for the heterologous p23 sequence.

Figure 1

Agarose gel electrophoresis of products of RT-PCR of RNA extracts from sweet orange seedlings to confirm co-infection. Lanes 1–10, extracts of trees simultaneously infected with Citrus tristeza virus strains CTV-B2 and CTV-B6; 11 and 12, sweet orange seedlings inoculated with strain CTV-B2 and CTV-B6 only; M, 100 base pair ladder; 13, extracts from healthy sweet orange seedlings. Amplicons of 206 and 302 bp are specific for CTV-B2 and CTV-B6, respectively.

Figure 2

Leaf symptoms in sweet orange seedlings infected with Citrus tristeza virus strains CTV-B2 and CTV-B6 together and separately. (A–C) Seedlings co-infected with CTV-B2 and CTV-B6, (D–F) seedlings infected with CTV-B6 alone, (G) seedlings infected with CTV-B2 alone, (A,D) chlorosis; (B,E) vein corking; (C,F) leaf curl; (G) no symptoms.

Overview of RNA-seq

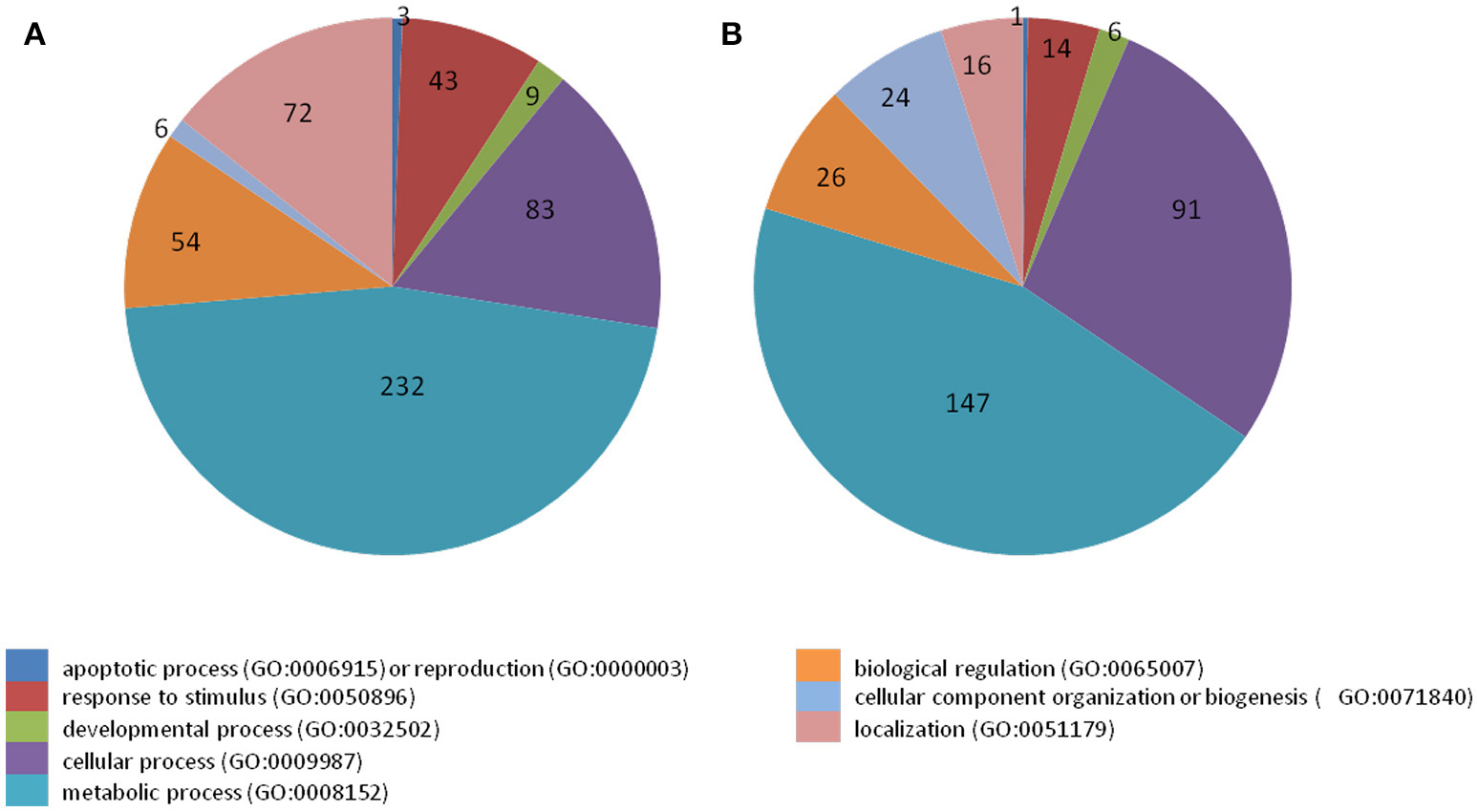

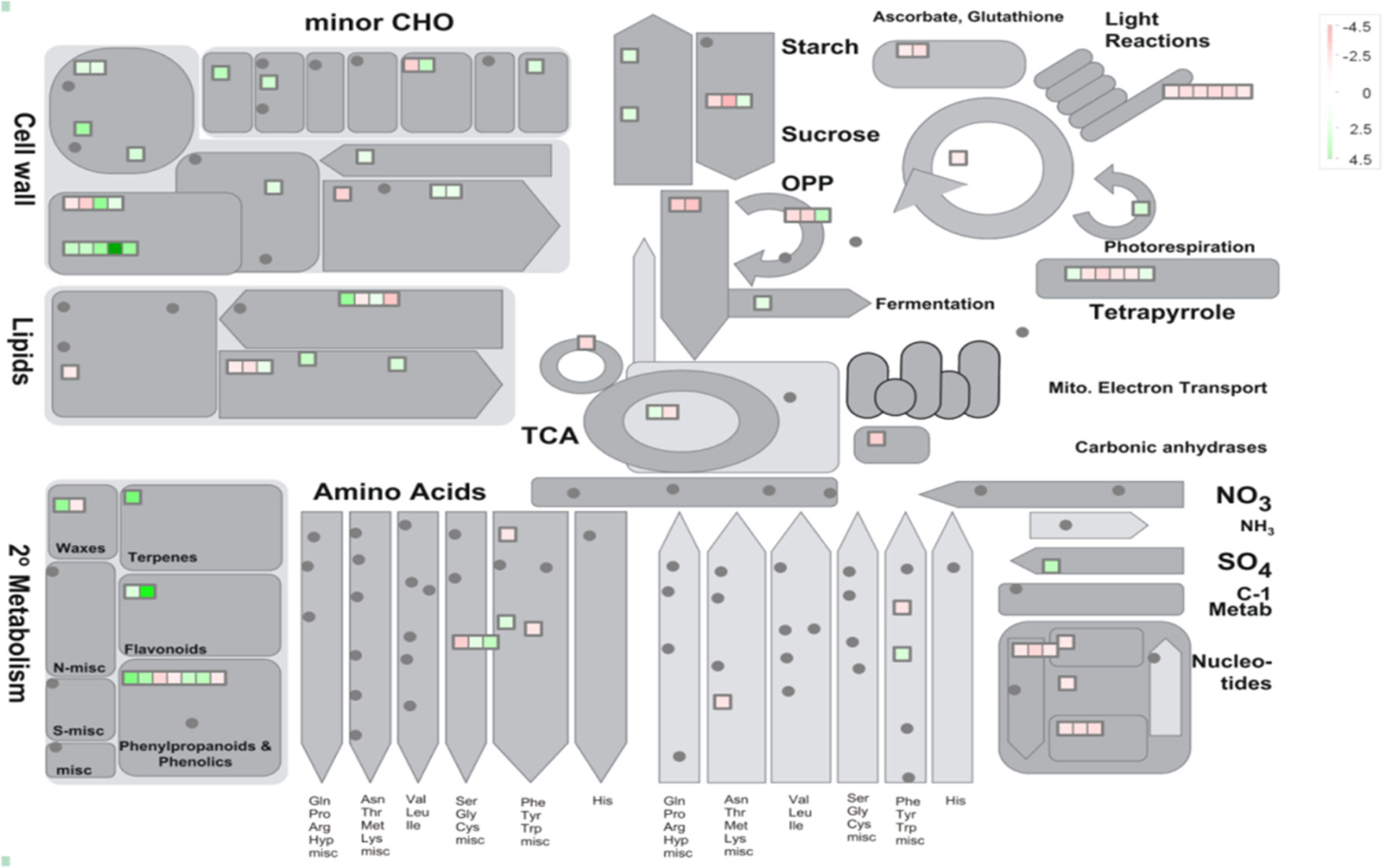

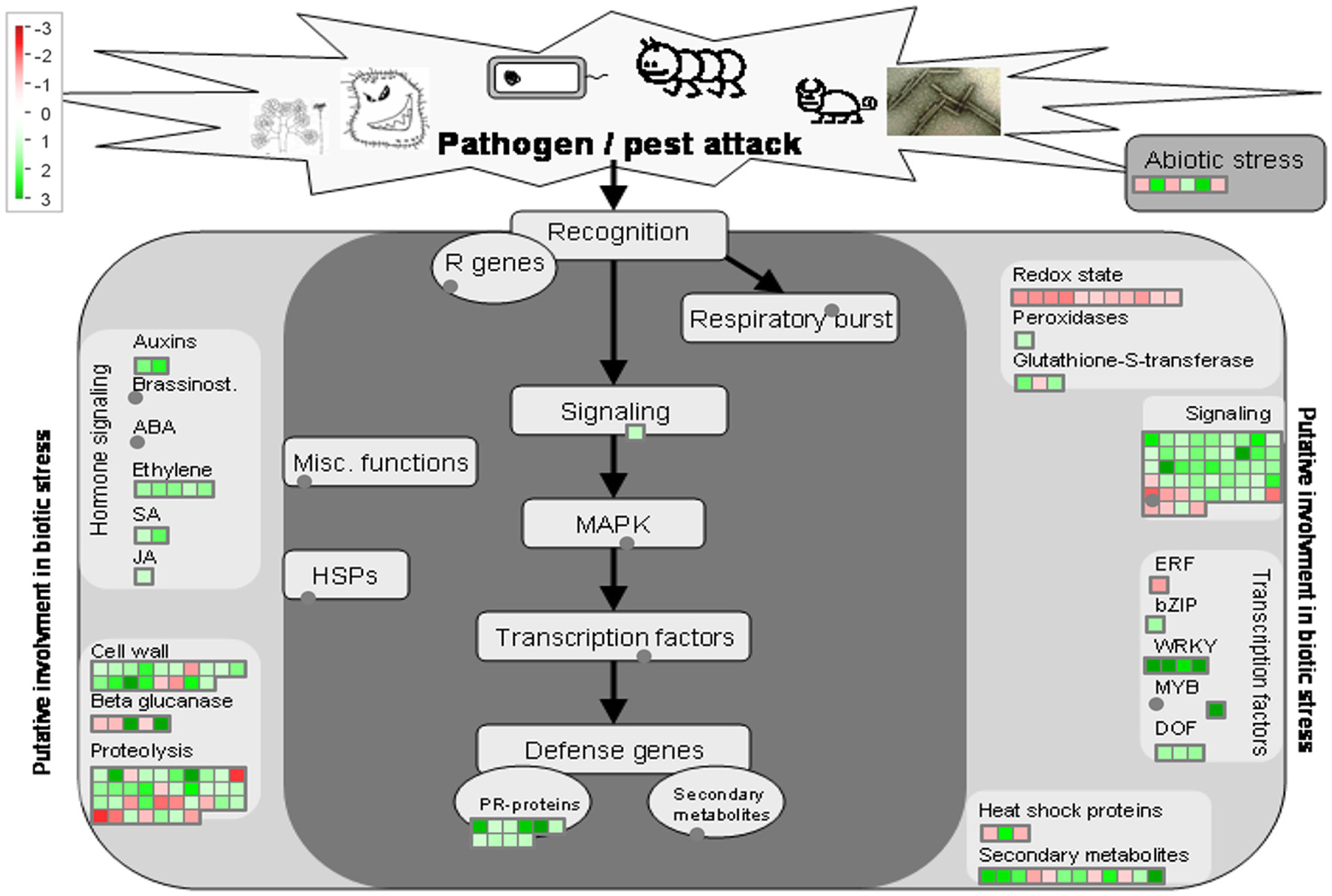

38 to 47 million raw reads were obtained from each inoculated tree with approximate 61% (average of three replicates) of these reads successfully aligned to the C. sinensis reference genome (Xu et al., 2013; Figure S1). Compared with mock-inoculated healthy trees, a total of 767 transcripts were differentially expressed: 411 were induced and 356 were repressed (Padj ≤ 0.1; Figure S2). DETs were found to be enriched for different biological processes (level 2) with Panther based on orthologs of Arabidopsis thaliana. The distribution of functional categories for up- and down-regulated genes was similar: metabolic processes, cellular processes, localization, biological regulation, and response to stimulus (Figure 3). The set of down-regulated genes had relatively more genes related to cellular component organization/biogenesis but less for localization (Figure 3). In an overview of metabolic and biotic stress pathways, genes related to light reactions, oxidative pentose phosphate (OPP), tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), tetrapyrrole synthesis, nucleotide metabolism, carbohydrate, and lipid metabolism were mostly repressed (Figure 4), whereas the genes associated with cell wall synthesis, secondary and hormone metabolism, pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins, and signaling were mostly induced (Figure 5). A full list of differentially expressed transcripts is shown in more detail (Table S2).

Figure 3

Categorization of transcripts induced or repressed in Citrus sinensis co-infected with Citrus tristeza virus strains CTV-B2 and CTV-B6 compared with the healthy control. (A) Induced transcripts; (B) repressed transcripts.

Figure 4

Metabolic overview of young asymptomatic sweet orange leaves in response to co-infection by Citrus tristeza virus strains CTV-B2 and CTV-B6. Green and red squares are shaded to represent the degree of up- and down-regulation of transcripts in response to CTV-B2 and CTV-B6 co-infection, respectively. Gray circles represent transcripts without differential expression between infected and healthy plants.

Figure 5

Overview of biotic stress pathways in young asymptomatic sweet orange leaves in response to co-infection by Citrus tristeza virus strains CTV-B2 and CTV-B6. Green and red squares are shaded to represent the degree of up- and down-regulation of transcripts in response to CTV-B2 and CTV-B6 co-infection, respectively. Gray circles represent transcripts in pathways without change between infected and healthy plants.

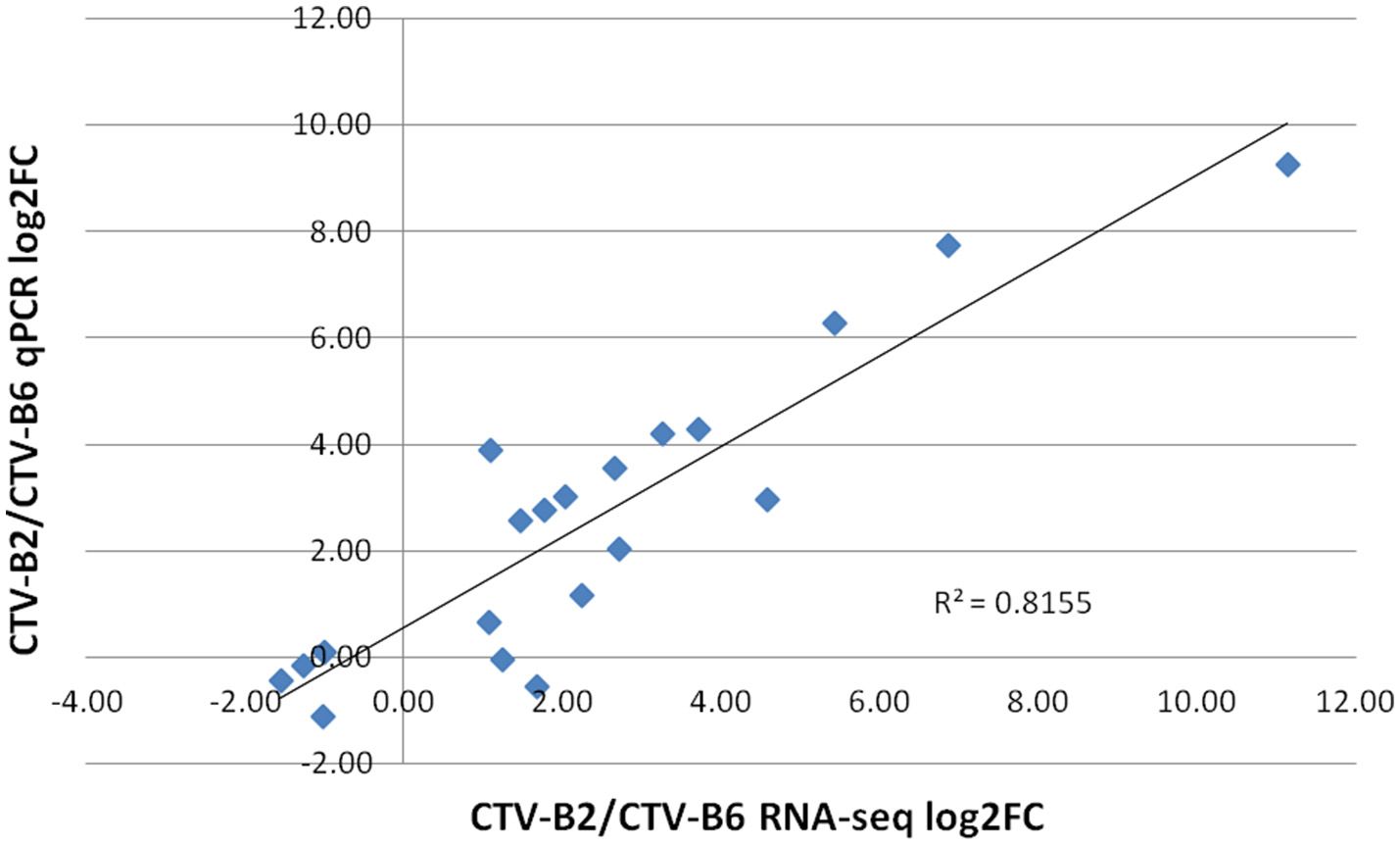

The expression levels of selected DETs ranged from −2 to 8 (log2 FC). Similar expression patterns were obtained for all evaluated transcripts by both RNA-seq and RT-qPCR techniques. The dissociation pattern and single peak obtained after RT-qPCR verified the specificity of RT-qPCR primers (Figure S3). A high Spearman's rho value (0.82) indicated good correlation of gene expression between the RNA-seq and RT-qPCR results and confirmed the reliability and accuracy of the RNA-seq data in our study (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Correlation of estimates of fold change of differentially expressed transcripts by RT-qPCR and RNA-seq. log2FC, Fold Change.

Photosynthesis, nucleic acid, and iron metabolism

The expression of several photosynthesis-related genes was down-regulated in response to CTV-B2/CTV-B6. These genes included LHCA4 (light-harvesting chlorophyll-protein complex I subunit A4), PPL1 (PsbP-like protein 1), thylakoid lumenal 20 kDa protein, PSAD-1 (photosystem I subunit D-1), photosystem II reaction center PsbP family protein, and PTAC14 (plastid transcriptionally active14; Table 1). Genes in the tetrapyrrole synthesis pathway were also repressed, including GSA2 (glutamate-1-semialdehyde 2, 1-aminomutase 2), HEMC (hydroxymethylbilane synthase), HEME2 (uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase), and HEMF1 (coproporphyrinogen oxidase; Table 1).

Table 1

| Gene symbol | Transcript id_ Citrus sinensis | AGI | Gene description | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS AND TETRAPYRROLE SYNTHESIS | ||||

| LHCA4 | Orange1.1g025674m | AT3G47470 | Light-harvesting chlorophyll-protein complex I subunit A4 | −1.01 |

| PPL1 | Orange1.1g025977m | AT3G55330 | Psbp-like protein 1 | −1.27 |

| TLP | Orange1.1g023424m | AT3G56650 | Thylakoid lumenal 20 Kda Protein | −1.19 |

| PSAD-1 | Orange1.1g047658m | AT4G02770 | Photosystem I subunit D-1 | −1.32 |

| PTAC14 | Orange1.1g011739m | AT4G20130 | Plastid transcriptionally active14 | −1.00 |

| GSA2 | Orange1.1g011959m | AT3G48730 | Glutamate-1-Semialdehyde 2,1-Aminomutase 2 | −1.19 |

| HEMC | Orange1.1g020472m | AT5G08280 | Hydroxymethylbilane synthase | −1.38 |

| HEME2 | Orange1.1g016596m | AT2G40490 | Uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase | −1.06 |

| HEMF1 | Orange1.1g016102m | AT1G03475 | Lesion initiation 2 | −1.03 |

| ATM3 | Orange1.1g030870m | AT2G15570 | Thioredoxin M-Type 3, Chloroplast (Trx-M3) | −1.51 |

| ATM3 | Orange1.1g030784m | AT2G15570 | Thioredoxin M-Type 3, Chloroplast (Trx-M3) | −1.58 |

| ACHT5 | Orange1.1g023089m | AT5G61440 | Atypical Cys His Rich Thioredoxin 5 | −1.71 |

| ACHT4 | Orange1.1g022923m | AT1G08570 | Atypical Cys His Rich Thioredoxin 4 | −1.02 |

| FSD3 | Orange1.1g025006m | AT5G23310 | Fe superoxide dismutase 3 | −1.07 |

| TAPX | Orange1.1g016584m | AT1G77490 | Thylakoidal ascorbate peroxidase | −1.02 |

| APX6 | Orange1.1g019824m | AT4G32320 | L-Ascorbate peroxidase/Heme binding/Peroxidase | −1.23 |

| NUCLEOTIDE METABOLISM | ||||

| PYR4 | Orange1.1g020186m | AT4G22930 | Pyrimidin 4 | −1.43 |

| NDPK2 | Orange1.1g026906m | AT5G63310 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase 2 | −1.06 |

| RNR1 | Orange1.1g003561m | AT2G21790 | Ribonucleotide reductase 1 | −1.24 |

| MCM3 | Orange1.1g004502m | AT5G46280 | DNA replication licensing factor, putative | −1.04 |

| MCM2 | Orange1.1g002353m | AT1G44900 | ATP binding/DNA binding | −1.27 |

| MCM5 | Orange1.1g004862m | AT2G07690 | Minichromosome maintenance family protein | −1.43 |

| MCM7 | Orange1.1g005024m | AT4G02060 | Prolifera | −1.45 |

| FAS1 | Orange1.1g003501m | AT1G65470 | Fasciata 1 | −1.15 |

| RPA70B | Orange1.1g006973m | AT5G08020 | Rpa70-Kda subunit B | −1.64 |

| HIS H4 | Orange1.1g047769m | AT5G59970 | Histone H4 | −2.14 |

| HIS H3.2 | Orange1.1g032664m | AT4G40030 | Histone H3.2 | −2.10 |

| HTA7 | Orange1.1g032326m | AT5G27670 | Histone H2A 7; DNA binding | −2.27 |

Down-regulated transcripts in Citrus sinensis in response to infection by CTV-B2/CTV-B6.

Genes encoding enzymes for nucleotide metabolism PYR4 (pyrimidine 4), NDPK2 (nucleoside diphosphate kinase 2), and RNR1 (ribonucleotide reductase 1) were repressed. Genes related to DNA synthesis were also down-regulated, as were some genes that encode DNA repair proteins MCM2 (DNA replication licensing factor), MCM3, FAS1 (fasciata 1), RPA70B (rpa70-kda subunit B), PRL (prolifera), and genes for several histones, including H3, H4, and HTA7 (Table 1).

Alteration of ribosomal composition

A large group of genes encoding ribosomal proteins were repressed, including components of the 30S, 40S, 50S, and 60S subunits, indicating an extensive reprogramming of ribosomal synthesis (Table 2). Ribosomal proteins (RPs) play roles in metabolism, growth and cell division, but also function in developmental processes as regulatory components (Byrne, 2009).

Table 2

| Gene symbol | Transcript id_Citrus sinensis | AGI | Gene description | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPS5 | Orange1.1g021869m | AT2G33800 | Ribosomal protein S5 family protein | −1.11 |

| RPS6 | Orange1.1g027743m | AT1G64510 | Ribosomal protein S6 family protein | −1.26 |

| RPS9 | Orange1.1g042358m | AT1G74970 | Ribosomal protein S9; structural constituent of ribosome | −1.13 |

| RPS10 | Orange1.1g041275m | AT3G13120 | 30S ribosomal protein S10, chloroplast, putative | −1.35 |

| RPS17 | Orange1.1g033970m | AT1G79850 | Ribosomal protein S17; structural constituent of ribosome | −1.01 |

| RPL3 | Orange1.1g023905m | AT2G43030 | Ribosomal protein L3 family protein | −1.17 |

| RPL5 | Orange1.1g024440m | AT4G01310 | Ribosomal protein L5 family protein | −1.21 |

| RPL9 | Orange1.1g029153m | AT3G44890 | Ribosomal protein L9; structural constituent of ribosome | −1.16 |

| RPL13 | Orange1.1g026067m | AT1G78630 | Embryo defective 1473; structural constituent of ribosome | −1.07 |

| RPL13 | Orange1.1g028533m | AT1G78630 | Embryo defective 1473; structural constituent of ribosome | −1.09 |

| RPL15 | Orange1.1g024515m | AT3G25920 | Structural constituent of ribosome | −1.05 |

| RPL17 | Orange1.1g041707m | AT3G54210 | Ribosomal protein L17 family protein | −1.30 |

| RPL18 | Orange1.1g030804m | AT1G48350 | Ribosomal protein L18 family protein | −1.33 |

| RPL21 | Orange1.1g027519m | AT1G35680 | 50S Ribosomal protein L21, chloroplast/CL21 (RPL21) | −1.12 |

| RPL24 | Orange1.1g029417m | AT5G54600 | 50S Ribosomal protein L24, chloroplast (CL24) | −1.34 |

| RPL34 | Orange1.1g031306m | AT1G29070 | Ribosomal protein L34 family protein | −1.33 |

| RPS27 | Orange1.1g034124m | AT5G44710 | Molecular_function unknown | 1.01 |

| RPS21 | Orange1.1g030080m | AT3G27160 | Structural constituent of ribosome | −1.23 |

| RPL35 | Orange1.1g031865m | AT2G24090 | Ribosomal protein L35 family protein | −1.18 |

| RPS4B | Orange1.1g024793m | AT5G07090 | 40S Ribosomal protein S4 (RPS4B) | −1.05 |

| RPS20B | Orange1.1g033482m | AT3G47370 | 40S Ribosomal protein S20 (RPS20B) | −1.18 |

| RPS24B | Orange1.1g032727m | AT5G28060 | 40S Ribosomal protein S24 (RPS24B) | −1.47 |

| RPS25 | Orange1.1g033931m | AT4G34555 | 40S Ribosomal protein S25, putative | −1.01 |

| ARP1 | Orange1.1g038172m | AT1G43170 | Arabidopsis Ribosomal Protein 1 | −1.21 |

| RPL15A | Orange1.1g028730m | AT4G16720 | 60S Ribosomal protein L15 (RPL15A) | −1.11 |

| RPL37C | Orange1.1g034400m | AT3G16080 | 60S Ribosomal protein L37 (RPL37C) | −1.03 |

| * | Orange1.1g034489m | AT5G40080 | 60S Ribosomal protein-related | 1.27 |

| RPL18AA | Orange1.1g035537m | AT1G29970 | 60S Ribosomal protein L18A-1 | −1.24 |

| RPL37A | Orange1.1g044880m | AT3G10950 | 60S Ribosomal protein L37a (RPL37aB) | −1.04 |

| * | Orange1.1g026076m | AT5G38290 | Ribosomal biogenesis, peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase | −1.00 |

| * | Orange1.1g043340m | AT2G39670 | Radical SAM domain-containing protein | −1.63 |

Transcripts encoding ribosomal proteins were overwhelmingly down-regulated in Citrus sinensis in response to infection by CTV-B2/CTV-B6.

Transcripts without gene symbol.

Cell wall barriers were enhanced

The expression of a majority of genes for cell wall metabolism was up-regulated: Genes encoding CESA9 (cellulose synthase A9) and PRP4 (cell wall proline-rich protein 4), as well as XTH28 (xyloglucan endotransglycosylase) and XTH30 were all up-regulated and the expression level of EXLB3 (expansin-like B3 precursor) was up-regulated ~7 fold (Table 3).

Table 3

| Gene symbol | Transcript id_ Citrus sinensis | AGI | Gene description | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CELL WALL | ||||

| CESA9 | Orange1.1g001373m | AT2G21770 | Cellulose synthase A9 | 1.25 |

| PRP4 | Orange1.1g029350m | AT4G38770 | Proline-rich protein 4 | 1.43 |

| XTR2, XTH28 | Orange1.1g019909m | AT1G14720 | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase related 2 | 1.66 |

| XTR4, XTH30 | Orange1.1g018153m | AT1G32170 | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase 4 | 2.24 |

| EXLB1 | Orange1.1g025808m | AT4G17030 | Arabidopsis thaliana expansin-like B1 | 2.21 |

| EXLB3 | Orange1.1g032956m | AT2G18660 | Expansin-like B3 Precursor | 6.86 |

| METAL HANDLING AND TRANSPORT | ||||

| FRO6 | Orange1.1g006160m | AT5G49730 | Ferric reduction oxidase 6 | 1.38 |

| FP6 | Orange1.1g031705m | AT4G38580 | Farnesylated protein 6; metal ion binding | 1.71 |

| ZIP1 | Orange1.1g018051m | AT3G12750 | Zinc transporter 1 precursor | 11.13 |

| ZIP5 | Orange1.1g044821m | AT1G05300 | Metal ion transmembrane transporter | 5.44 |

| ZIP11 | Orange1.1g044590m | AT1G55910 | Zinc transporter 11 precursor | 1.30 |

| AAP6 | Orange1.1g011548m | AT5G49630 | Amino acid permease 6 | 1.30 |

| AAP7 | Orange1.1g012732m | AT5G23810 | Amino acid transmembrane transporter | 1.34 |

| AST56, SULTR2;2 | Orange1.1g008914m | AT1G77990 | Sulfate transmembrane transporter | 1.29 |

| AST68, SULTR2;1 | Orange1.1g006023m | AT5G10180 | Sulfate transmembrane transporter | 1.07 |

| NRT1.1 | Orange1.1g007736m | AT1G12110 | Nitrate transmembrane transporter | 1.38 |

| ABC | Orange1.1g045930m | AT1G51460 | ABC transporter family protein | 2.95 |

| DEFENSE RELATED | ||||

| TPS21 | Orange1.1g043754m | AT5G23960 | Terpene synthase 21 | 2.65 |

| CER3 | Orange1.1g006767m | AT5G57800 | Eceriferum 3 | 2.28 |

| TT4 | Orange1.1g016330m | AT5G13930 | Transparent testa 4 | 1.20 |

| AFB5 | Orange1.1g044749m | AT5G49980 | Auxin F-box protein 5 | 1.72 |

| GA5 | Orange1.1g016776m | AT4G25420 | GA5 | 1.64 |

| ERS1 | Orange1.1g005591m | AT2G40940 | Ethylene response sensor 1 | 1.63 |

| EIN4 | Orange1.1g004510m | AT3G04580 | Ethylene insensitive 4 | 1.20 |

| RLP21 | Orange1.1g021196m | AT2G25470 | Receptor like protein 21 | 1.40 |

| CHIB1 | Orange1.1g044801m | AT5G24090 | Acidic endochitinase | 3.13 |

| EDS1 | Orange1.1g007278m | AT3G48090 | Enhanced disease susceptibility 1 | 1.20 |

| NBS-LRR class | Orange1.1g046345m | AT4G27190 | Disease resistance protein | 1.17 |

| NBS-LRR class | Orange1.1g040659m | AT5G63020 | Disease resistance protein | 1.08 |

| RLP1 | Orange1.1g042603m | AT1G07390 | Protein binding | 2.03 |

| RLP6 | Orange1.1g038037m | AT1G45616 | Receptor like protein 6 | 2.43 |

| RLP15 | Orange1.1g001036m | AT1G74190 | Receptor like protein 15 | 4.48 |

| CES101 | Orange1.1g004402m | AT3G16030 | Callus expression of Rbcs 101 | 1.58 |

| IQD23 | Orange1.1g013059m | AT5G62070 | IQ-domain 23 | 2.18 |

| FRS5 | Orange1.1g002062m | AT4G38180 | Far1-related sequence 5 | 1.10 |

Up-regulated transcripts in Citrus sinensis in response to infection by CTV-B2/CTV-B6.

Transportation system

Transcription of genes related to transport and metal binding were largely up-regulated. These included transporters for nucleotides, sugars, amino acids, sulfate, phosphate, peptides, and oligopeptides and ABC transporters, such as, AAP6 and AAP7 (amino acid trans membrane transporter), AST56 and AST68 (sulfate transporter), NRT1.1 (nitrate transporter), ZIP1, ZIP5, and ZIP11 (zinc ion trans membrane transporter; Table 3). Transcripts encoding phloem protein PP2-B13 were somewhat down-regulated in response to co-infection with CTV-B2/CTV-B6, but were strongly down-regulated by CTV-B2 alone, whereas transcripts for PP2-B15 were slightly up-regulated by single infection with CTV-B6 (Fu et al., 2016).

Up-regulation of hormone and secondary metabolism and signaling associated defense responses

Genes involved in the synthesis of secondary metabolites and hormone metabolism were induced, such as, TPS21 (terpene synthase 21), CER3 (ceriferum 3), TT4 (transparent testa 4), AFB5 (auxin F-Box protein 5), GA5 (gibberellin 20-oxidase), EIN4 (ethylene insensitive 4), and ERS1 (ethylene response sensor 1). Genes for biotic stress associated proteins RLP21 (Receptor Like Protein 21), CHIB1 (acidic endochitinase) and EDS1 (enhanced disease susceptibility 1), and disease resistance proteins in the CC-NBS-LRR class were also induced (Table 3). Genes for receptor kinases, calcium and light related signaling were mostly induced, such as, RLP1 (receptor like protein 1), RLP6, and RLP15, CSE101 (callus expression of rbcs 101), IQD23 (IQ-domain 23) binding calmodulin, and FRS5 (FAR1-related sequence 5) binding zinc ions (Table 3).

Discussion

Infection and symptoms

Both strains of CTV were able to establish infections in the inoculated sweet orange plants, indicating that simultaneous inoculation of CTV-B2 and CTV-B6 did not prevent infection and establishment of either strain in sweet orange. We isolated RNA from the inoculated plants after infection was established but before symptoms were expressed. The assessment of gene expression prior to the onset of visible symptoms allowed identification of changes in gene expression that led to the symptoms that were subsequently observed. Symptoms of infection by strain CTV-B2 are very mild and difficult to observe. However, in our doubly inoculated plants the symptoms were extensive and severe. CTV-B6 has a complex genome based on components of several genotypes (Ruiz-Ruiz et al., 2006), and the nucleotide sequence of the p23 gene is 98.5% identical to the reference strains T318A. In our co-inoculated plant, the p23 transcript of CTV-B6 was found much more frequently than the CTV-B2 homolog, consistent with the symptoms induced in the plants (Ghorbel et al., 2001). In cases where strains are simultaneously present in sweet orange, the genotype of the severe component often becomes dominant (Sambade et al., 2007). This is evidence that CTV-B6 is the dominant strain when trees are co-infected with mild CTV-B2 and the severe, virulent CTV-B6, and that CTV-B2 is not able to protect sweet orange from CTV-B6.

Photosynthesis, nucleic acid, and iron metabolism

Genes that encode proteins that are components of both the light harvesting complex and that contribute to the assembly of tetrapyrroles and chlorophyll were down regulated. In addition to photosynthesis, tetrapyrroles play crucial roles in a broad range of biological processes including respiration and assimilation of nitrogen/sulfur in higher plants (Tanaka et al., 2011). In our study, genes associated with photosynthesis and tetrapyrrole metabolism were mostly down-regulated in response to CTV-B2/CTV-B6. HEMC, HEME2, and HEMF1 are enzyme intermediates in tetrapyrrole synthesis and their down-regulation indicates a disturbance of tetrapyrrole synthesis, as well as chlorophyll synthesis in host plants, because chlorophyll biosynthesis has been suggested to depend upon a balance between the methyl erythritol phosphate and tetrapyrrole pathways (Kim et al., 2013). The PsbP protein is indispensible for the regulation/stabilization (Ifuku et al., 2005) and photo autotrophy (Yi et al., 2007) of the PSII complex, as well as normal thylakoid membrane architecture (Yi et al., 2009) in higher plants. PsbP-like proteins (PPLs) are PsbP homologs and PPL1 is required for efficient repair of photo damaged PSII in higher plants (Ishihara et al., 2007). These alterations in gene expression patterns are consistent with altered thylakoid membrane structure and function in response to CTV infection. The decrease of several photosynthetic proteins (i.e., PSAD, PsbP, and LHCA) would also cause defects in photosynthetic performance (Romani et al., 2012). Symptoms such as, yellowing and chlorosis of leaves caused by CTV-B6 or CTV-B2/CTV-B6 may be due in part to the decrease of the PsbP andPPLs, as observed in experiments with PsbP-deficient tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) which had pale-green-colored leaves (Yi et al., 2009). The decrease in the levels of these proteins limits plant growth as there is less carbohydrate synthesized as a result of the repressed photosynthesis.

Iron metabolism was also dramatically altered in response to infection by CTV-B2 and CTV-B6, which likely contributed to the alterations photosynthetic processes observed. As we observed with infection of citrus with CTV-B2/CTV-B6, genes related to photosynthesis and tetrapyrrole metabolism were also dramatically repressed in Arabidopsis leaves in response to iron (Fe) deficiency (Rodríguez-Celma et al., 2013). Iron has crucial effects on respiration and tetrapyrrole metabolism and its deficiency compromises chlorophyll synthesis, causing chlorosis in developing leaves and decreased photosynthetic activity. The iron deficiency may be exacerbated by the decline of feeder roots induced by CTV-B6, which limit the uptake of iron from the rhizosphere.

The overwhelming down-regulation of genes related to DNA synthesis is also in concert with iron deficiency as iron is required in many enzymatic reactions in the DNA replication pathway. Hexameric mini chromosome maintenance proteins (MCMs) have important roles in DNA replication in plants (Ni et al., 2009; Herridge et al., 2014) and some of them are critical for DNA unwinding. MCM2 modulates root meristem function in Arabidopsis (Ni et al., 2009). The down regulation of MCM2 is consistent with the decline in feeder roots seen as the CTV syndrome develops. MCM2 was also down-regulated in rice with limited nutrients (Cho et al., 2008). In A. thaliana, MCM3 is present in various oligomeric forms including as a homohexamer and possesses 3′ to 5′ helicase and ATPase activities in vitro (Rizvi et al., 2015). MCM7 protein is localized in the nucleus and is required for DNA replication and cytokinesis at an early stage of Arabidopsis development (Springer et al., 2000; Holding and Springer, 2002). The repression of MCM2, MCM3, MCM5, and MCM7 was associated with viral infection previously (Choi et al., 2015), but detailed functional studies have not been carried out. The down-regulation of photosynthetic capability, tetrapyrrole and lipid metabolism and DNA replication are all associated with iron deficiency. Similar symptoms of leaf yellowing following disturbances in heavy metal metabolism are found in citrus suffering from huanglongbing (HLB). In the case of HLB, foliar sprays of nutritional supplements alleviate symptoms (Spann and Schumann, 2009; Stansly et al., 2013), and may be worthwhile in the case of severe CTV as well.

Alteration of ribosomal composition

Reduction of shoot growth and cell proliferation were found in ribosomal protein mutants (Byrne, 2009; Horiguchi et al., 2011, 2012). Many chloroplast ribosomal protein genes were strongly down-regulated in a related study in response to co-infection with CTV-B6 and “Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus,” causal agent of citrus huanglongbing (Bové, 2006; submitted), and were also greatly repressed in response to CTV-B2/CTV-B6, including RPS17, RPL9, RPL17, and RPL18 (Table 2). Gene expression in chloroplasts is primarily controlled through the regulation of translation, mediated by the ribosome. Great alterations of ribosomal composition were observed in leaves and roots of Arabidopsis in response to iron and phosphate deficiency (Rodríguez-Celma et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013). Gene expression in chloroplasts was limited and further affected the photosynthesis capacity.

Cell wall barriers were enhanced

Cellulose is the most abundant and strongest component of cell walls and it is targeted for degradation by pathogens to facilitate penetration of and movement between plant cells. Genes associated with cellulose synthase were induced by double infection with CTV-B2/CTV-B6 and by single infection with CTV-B2 but not by CTV-B6 alone (Fu et al., 2016). XTH gene expression and enzyme activity was positively associated with cell wall elongation (Shin et al., 2006) and strengthening (Antosiewicz et al., 1997). Expansin activity is most often in association with cell-wall loosening in growing cells (Lee et al., 2001), and expansin proteins are distributed throughout cell walls (Zhang and Hasenstein, 2000; Cosgrove et al., 2002). Both XTH and EXLB are also correlated with cell wall modification, which is an important aspect of plant responses to biotic and abiotic stresses, and is likely to be the relevant context in this study. The expression of EXLB3 was also up-regulated by single infection with CTV-B2 (Table 4), but not as strongly as in response to double infection with CTV-B2/CTV-B6. The stronger up-regulation of EXLB3 may be stimulated by the presence of virulent CTV-B6. The up-regulation of XTH and EXLB gene expression when under virus attack can modulate cell wall growth and equip the plant with a stronger physical barrier to deter feeding by the vector aphids. The remodeling and thickening of cell walls is also correlated with the symptoms of stiff and thickened leaves and vein corking (Figure 2).

Table 4

| Gene symbol | Transcript id_ | AGI | Gene description | Fold change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrus sinensis | CTV-B2/CTV-B6 | CTV-B2a | CTV-B6a | |||

| * | Orange1.1g021031m | AT4G38690 | 1-phosphatidylinositol phosphodiesterase-related | 1.70 | 1.10 | |

| * | Orange1.1g012242m | AT3G29635 | Transferase family protein | 1.35 | 1.30 | |

| DMR6 | Orange1.1g019665m | AT5G24530 | DOWNY MILDEW RESISTANT 6 | 1.42 | 1.90 | 2.80 |

| RLP21 | Orange1.1g021196m | AT2G25470 | Receptor like protein 21 | 2.56 | 1.40 | |

| * | Orange1.1g029641m | AT1G58170 | Disease resistance-responsive protein-related | 5.97 | 1.80 | |

| * | Orange1.1g028960m | AT2G20560 | DNAJ heat shock family protein | 2.43 | 1.80 | |

| TT4 | Orange1.1g016330m | AT5G13930 | Transparent testa 4 | 3.44 | 1.20 | |

| TT7 | Orange1.1g010388m | AT5G07990 | Transparent testa 7 | 1.36 | 2.90 | 2.90 |

| RDR1 | Orange1.1g003789m | AT1G14790 | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase1 | 2.40 | 1.70 | |

| * | Orange1.1g021502m | AT1G28310 | Dof-type zinc finger domain-containing protein | 1.45 | 1.30 | |

| WRKY70 | Orange1.1g020291m | AT3G56400 | Transcription factor/transcription repressor | 3.72 | 1.80 | 3.90 |

| WRKY50 | Orange1.1g029257m | AT5G26170 | Transcription factor | 2.59 | 2.10 | |

| WRKY60 | Orange1.1g032690m | N | Rice TFs having WRKY and zinc finger domains | 3.93 | 3.20 | |

| WRKY60 | Orange1.1g033112m | N | Rice TFs having WRKY and zinc finger domains | 3.84 | 3.90 | |

| * | Orange1.1g040562m | AT1G64830 | Aspartyl protease family protein | 8.23 | 3.10 | |

| * | Orange1.1g011556m | AT5G10770 | Chloroplast nucleoid DNA-binding protein, putative | 3.46 | 2.00 | |

| CDR1 | Orange1.1g014537m | AT5G33340 | CONSTITUTIVE DISEASE RESISTANCE 1 | 5.39 | 3.90 | |

| * | Orange1.1g002533m | AT5G39000 | Protein kinase family protein | 1.07 | 1.30 | |

| FER | Orange1.1g048439m | AT3G51550 | FER (FERONIA); kinase/protein kinase | 3.17 | 1.20 | |

| BCS1 | Orange1.1g024550m | AT3G50930 | Cytochrome BC1 synthesis | 1.76 | 1.40 | |

| * | Orange1.1g021013m | AT5G25560 | Zinc finger (C3HC4-type RING finger) family protein | 1.22 | 1.60 | |

| EBF1 | Orange1.1g006749m | AT2G25490 | EIN3-binding F box protein1 | 1.52 | −1.20 | |

| ARK3 | Orange1.1g006915m | AT4G21380 | A. thaliana receptor kinase 3 | 1.35 | 1.20 | |

| PLA2A | Orange1.1g015047m | AT2G26560 | Phospholipase A 2A | 2.93 | 1.70 | |

| ZIP11 | Orange1.1g044590m | AT1G55910 | ZINC transporter 11 precusor | 2.04 | 1.10 | 1.30 |

| ZIP1 | Orange1.1g018051m | AT3G12750 | ZINC transporter 1 precursor | 11.13 | −2.50 | |

| ZIP5 | Orange1.1g044821m | AT1G05300 | Cation transmembrane transporter | 5.44 | 2.40 | |

| BAT1 | Orange1.1g010352m | AT2G01170 | Bidirectional amino acid transporter 1 | 1.23 | 1.10 | |

| ATPUP5 | Orange1.1g017963m | AT2G24220 | Purine transmembrane transporter | 1.90 | 1.10 | |

| * | Orange1.1g031629m | AT1G14870 | INVOLVED IN: response to oxidative stress | 2.87 | 1.30 | |

| * | Orange1.1g048792m | AT3G02650 | Pentatrico peptide (PPR) repeat-containing protein | 3.01 | 2.70 | |

| * | Orange1.1g021539m | AT2G23520 | Catalytic/pyridoxal phosphate binding | 1.40 | −1.10 | |

| * | Orange1.1g039041m | AT3G48770 | ATP binding/DNA binding | 2.78 | 1.90 | |

| * | Orange1.1g000623m | AT3G48770 | ATP binding/DNA binding | 2.63 | 1.90 | |

| * | Orange1.1g014290m | AT4G31980 | Unknown protein | 2.74 | 1.50 | |

| * | Orange1.1g022937m | AT3G12320 | Unknown protein | −1.19 | −1.90 | |

| * | Orange1.1g000988m | AT3G48770 | ATP binding/DNA binding | 1.43 | 1.20 | |

| PCK1 | Orange1.1g005865m | AT4G37870 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 | −1.36 | 1.10 | |

| EXLB3 | Orange1.1g032956m | AT2G18660 | Expansin-like B3 precursor | 6.86 | 1.20 | |

| * | Orange1.1g003996m | AT4G27190 | Disease resistance protein (NBS-LRR class), putative | 1.41 | 1.40 | |

| * | Orange1.1g040489m | AT2G12190 | Cytochrome P450, putative | 1.57 | 1.30 | |

Transcripts in Citrus sinensis with shared differential expression pattern when co-infected with both CTV-B2/CTV-B6 and with each virus alone.

Transcripts without gene symbol.

N, Transcripts without corresponding AGI number.

Data in columns “CTV-B2” and “CTV-B6” cited from Fu et al. (2016).

Transportation system

Induction of transporters was also observed in a previous study (Fu et al., 2016). The up-regulation of sugar, amino acid, sulfate, phosphate, and metal and oligopeptide transporters denoted a shortage of these substances and a disturbance of the transportation system in young leaves prior to the development of symptoms. SUC2 (sucrose-proton symporter 2), encoding a sucrose/proton symporter was up-regulated and is necessary for phloem loading and is also fundamental for phloem transport and plant productivity (Srivastava et al., 2009).

Ammonium is the preferred form of nitrogen for uptake by plants (Gazzarrini et al., 1999) as it requires less energy for assimilation into amino acids (Bloom et al., 1992). The assimilation of ammonium from the soil solution is regulated by ammonium transporters (AMT) and AtAMT1;1 is expressed in roots and leaves (Engineer and Kranz, 2007).

The differential down-regulation level of phloem proteins in response to co-infection with CTV-B2/CTV-B6 and single infection with CTV-B2 are consistent with the restructuring of phloem, as well as with cell-to-cell and long distance movement of viruses (Imlau et al., 1999; Gómez and Pallás, 2004).

The up-regulation of ZIP11 was also observed in response to single infections with CTV-B2 or CTV-B6 (Table 4; Fu et al., 2016). However, the expression of ZIP5, as well as ZIP1, ZIP4, and was down-regulated by CTV-B2 in a single infection (Table 4). Zinc is a key element possessing both structural and functional roles in plants and about 4% of all predicted proteins in Arabidopsis contain one or more zinc fingers (Kawagashira et al., 2001). A large number of enzymes contain zinc binding sites, such as, copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (Hacisalihoglu et al., 2003) and zinc metallo proteases (Ståhl et al., 2002). The differential expression patterns of ZIP1, ZIP4, and ZIP5 in response to co-infection by CTV-B2/CTV-B6 and infection by CTV-B2 alone is probably due to severe, virulent CTV-B6, which affects the plant profoundly, inducing chlorosis of leaves, collapse of phloem and root decline.

Iron is also an essential metal nutrient required for a number of critical cellular functions such as, the synthesis of heme and heme-dependent oxygen transport, iron-dependent enzymatic reactions, photosynthesis and ribonucleotide synthesis (Straus, 1994; Kobayashi and Nishizawa, 2012). FRO6 (ferric reduction oxidase 6) was up-regulated in response to CTV-B2/CTV-B6 infection. FRO6 is involved in metal binding/acquisition and is responsible for regulating the reduction of iron from ferric to ferrous at the plasma membrane of leaf cells in response to iron deficiency (Maynes, 2013). Compared to roots of iron-sufficient plants, very high concentrations of manganese, zinc and copper accumulated in roots of iron-deficient Arabidopsis plants (Korshunova et al., 1999; Connolly et al., 2002; Vert et al., 2002). Hence, the high up-regulation of zinc transporters may be a secondary effect of iron deficiency.

Up-regulation of hormone and secondary metabolism and signaling associated defense responses

Auxin regulates gene expression and facilitates elongation of shoot cells by activating the auxin response factor (ARF) family of transcription factors. Auxin is perceived by TIR1/AFB (transport inhibitor response1/auxin signaling F-BOX) family of F-box proteins (Salehin et al., 2015). In the presence of auxin, members of TIR1/AFB family of proteins regulate the polyubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation of Aux/IAA transcriptional repressors (Dharmasiri et al., 2005; Greenham et al., 2011). ARFs are repressed by the Aux/IAA proteins. Some of the most common symptoms produced by plant viruses are leaf curling, chlorosis, and stunting, are related to disruptions of plant hormone production, accumulation, and sensing (Jameson and Clarke, 2002; Padmanabhan et al., 2005). The auxin system has been directly disrupted by viral components in other systems. Auxin signaling was disrupted by the Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) 126 KDa replication protein via an interaction with select Aux/IAA family members (Padmanabhan et al., 2005, 2006), which are removed by auxin-induced degradation. The up regulation of AFB5 and down regulation of ARF18 and ARF19 are signs of alterations in auxin metabolism, which may be associated with disease symptoms such as, stunting and leaf curling.

Ethylene is a vital growth regulator and is also important for biotic and abiotic stress responses (Schaller, 2012). Ethylene is perceived by a family of five membrane-associated receptors (ETR1, ETR2, ERS1, ERS2, and EIN4). The ethylene receptors are involved in transcriptional as well as post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms (O'Malley et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2007; Kevany et al., 2007). The ethylene receptors function as negative regulators of ethylene responses and their function is inactivated through ethylene binding (Bleecker and Kende, 2000; Chang and Stadler, 2001). The up regulation of ERS1 and EIN4 imply enhanced ethylene production, which is an early and active response of plants to virus attack in association with the induction of defense responses (Boller, 1991).

Gibberellins are master regulators for plant growth in response to both abiotic (temperature, salt, and light) and biotic stress (Claeys et al., 2014; Colebrook et al., 2014). A giberellin-responsive pathway regulates photosynthesis (Xie et al., 2016). The up-regulation of AFB5, auxin-responsive protein, ERS1 and EIN4, and gibberellin-responsive protein are changes of hormone signaling pathways in plants under pathogen stress and lead to the induction of the following defense actions.

Terpenoids are a structurally diverse group of plant secondary metabolites and are involved in both direct and indirect plant defenses. Terpene synthases (TPSs) play an important role in the synthesis of volatile terpenes. The expression of TPS21 can be induced by gibberellin and jasmonate and the induction of TPS21 increases the emission of sesquiterpenes. The plant cuticle plays a vital role in the interactions between the plant and environment stresses, including water stress. Alkanes are prominent components of cuticular wax and the alkane-forming pathway is controlled by the co-expression of CER1/CER3 (eceriferum; Bernard et al., 2012). The increased expression of CER1/CER3 increases the amount of wax on the surface of the leaves. It is probable that increasing expression of these genes in association with hormone and signaling pathways mediated by secondary metabolites enhanced the tolerance of the plants to water stress and may deter feeding by the aphid vector of CTV.

When mild CTV-B2 and severe CTV-B6 were inoculated simultaneously, both mild and severe CTV strains successfully established in citrus plants. The sweet orange plants co-infected with both CTV strains showed symptoms typical of CTV-B6, indicating virulent CTV-B6 is the dominant strain and that neither virus affected the other's establishment in sweet orange. The failure of CTV-B2 to cross protect is likely because the two virus strains are from different genotypes (Folimonova et al., 2010; Folimonova, 2013). The photosynthetic and carbon metabolism capacities of host plants were greatly reduced, and the composition of the ribosome was greatly altered in response to co-infection. These responses may be attributed to deficiency of iron, and secondarily to zinc deficiency. Host plant metal ion transport systems were generally disturbed and ZIPs showed very different expression patterns in response to co-infection by CTV-B2/CTV-B6 and to single strain infection by CTV-B2, which was due to the presence of virulent CTV-B6.

The outcome of a plant–virus interaction from antagonism to mutualism is determined by the environment, host genotype, and pathogens. Virulence is the negative impact of parasite infection on host fitness (Read, 1994; Little et al., 2010) and is determined by both the host and pathogen. Host defenses may decrease virulence through either resistance or tolerance. The former limits the multiplication of the parasite and the latter decreases damage to the host in spite of the amount of multiplication by the pathogen. C. sinensis is generally susceptible to CTV. Though defense responses, such as, strengthening of cell walls, altered hormone metabolism, increased production of secondary metabolites and signaling proteins were induced, these did not suppress the spread of the pathogens and the development of symptoms caused by CTV-B2/CTV-B6, or strain CTV-B6 alone, although they were able to induce tolerance to strain CTV-B2 (Fu et al., 2016).

Statements

Author contributions

SF: performed the laboratory experiments and drafted the manuscript; SF and JS: collected data and carried out all data analyses; JH: designed the study, oversaw the research and co-wrote the manuscript; CZ: revised the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The research was financially supported and carried out by United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS). A portion of this work was done when SF was a doctoral candidate and sponsored by China Scholarship Council (CSC) and Southwest University. The authors thank Cristina Paul, USDA ARS for skillful pathogen inoculations and plant care.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2017.01419/full#supplementary-material

References

1

AntosiewiczD. M.PuruggananM. M.PolisenskyD. H.BraamJ. (1997). Cellular localization of Arabidopsis xyloglucan endotransglycosylase-related proteins during development and after wind stimulation. Plant Physiol.115, 1319–1328. 10.1104/pp.115.4.1319

2

BennettC. W.CostaA. S. (1949). Tristeza disease of citrus. J. Agric. Res.78, 207–237.

3

BernardA.DomergueF.PascalS.JetterR.RenneC.FaureJ.-D.et al. (2012). Reconstitution of plant alkane biosynthesis in yeast demonstrates that Arabidopsis ECERIFERUM1 and ECERIFERUM3 are core components of a very-long-chain alkane synthesis complex. Plant Cell24, 3106–3118. 10.1105/tpc.112.099796

4

BleeckerA. B.KendeH. (2000). Ethylene: a gaseous signal molecule in plants. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol.16, 1–18. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.1

5

BloomA. J.SukrapannaS. S.WarnerR. L. (1992). Root respiration associated with ammonium and nitrate absorption and assimilation by barley. Plant Physiol.99, 1294–1301. 10.1104/pp.99.4.1294

6

BollerT. (1991). Ethylene in pathogenesis and disease resistance, in The Plant Hormone Ethylene, eds MatooA. K.SuttleJ. C. (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press), 293–324.

7

BovéJ. M. (2006). Huanglongbing: a destructive, newly-emerging, century old disease of citrus. J. Plant Pathol.88, 7–37. 10.4454/jpp.v88i1.828

8

BowmanK.AlbrechtU. (2015). Comparison of gene expression changes in susceptible, tolerant and resistant hosts in response to infection with Citrus tristeza virus and huanglongbing. J. Citrus Pathol.2. Available online at: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/5qt4z9c0

9

ByrneM. E. (2009). A role for the ribosome in development. Trends Plant Sci.14, 512–519. 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.06.009

10

ChangC.StadlerR. (2001). Ethylene hormone receptor action in Arabidopsis. Bioessays23, 619–627. 10.1002/bies.1087

11

ChenY.-F.ShakeelS. N.BowersJ.ZhaoX.-C.EtheridgeN.SchallerG. E. (2007). Ligand-induced degradation of the ethylene receptor ETR2 through a proteasome-dependent pathway in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem.282, 24752–24758. 10.1074/jbc.M704419200

12

ChengC.ZhangY.ZhongY.YangJ.YanS. (2016). Gene expression changes in leaves of Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck infected by Citrus tristeza virus. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol.91, 466–475. 10.1080/14620316.2016.1173523

13

ChoJ. H.KimH. B.KimH.-S.ChoiS.-B. (2008). Identification and characterization of a rice MCM2 homologue required for DNA replication. BMB Rep.41, 581–586. 10.5483/BMBRep.2008.41.8.581

14

ChoiH.JoY.LianS.JoK.-M.ChuH.YoonJ.-Y.et al. (2015). Comparative analysis of chrysanthemum transcriptome in response to three RNA viruses: cucumber mosaic virus, tomato spotted wilt virus and potato virus X. Plant Mol. Biol.88, 233–248. 10.1007/s11103-015-0317-y

15

ClaeysH.De BodtS.InzéD. (2014). Gibberellins and DELLAs: central nodes in growth regulatory networks. Trends Plant Sci.19, 231–239. 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.10.001

16

ColebrookE. H.ThomasS. G.PhillipsA. L.HeddenP. (2014). The role of gibberellin signalling in plant responses to abiotic stress. J. Exp. Biol.217, 67–75. 10.1242/jeb.089938

17

ConnollyE. L.FettJ. P.GuerinotM. L. (2002). Expression of the IRT1 metal transporter is controlled by metals at the levels of transcript and protein accumulation. Plant Cell14, 1347–1357. 10.1105/tpc.001263

18

CosgroveD. J.LiL. C.ChoH.-T.Hoffmann-BenningS.MooreR. C.BleckerD. (2002). The growing world of expansins. Plant Cell Physiol.43, 1436–1444. 10.1093/pcp/pcf180

19

Cristofani-YalyM.BergerI. J.TargonM. L. P.TakitaM. A.DortaS. D. O.Freitas-AstúaJ.et al. (2007). Differential expression of genes identified from Poncirus trifoliata tissue inoculated with CTV through EST analysis and in silico hybridization. Genet. Mol. Biol.30, 972–979. 10.1590/S1415-47572007000500025

20

DawsonW. O.Bar-JosephM.GarnseyS. M.MorenoP. (2015). Citrus tristeza virus: making an ally from an enemy. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol.53, 137–155. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080614-120012

21

DawsonW. O.GarnseyS. M.TatineniS.FolimonovaS. Y.HarperS. J.GowdaS. (2013). Citrus tristeza virus-host interactions. Front. Microbiol.4:88. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00088

22

DharmasiriN.DharmasiriS.WeijersD.LechnerE.YamadaM.HobbieL.et al. (2005). Plant development is regulated by a family of auxin receptor F box proteins. Dev. Cell9, 109–119. 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.014

23

EngineerC. B.KranzR. G. (2007). Reciprocal leaf and root expression of AtAmt1. 1 and root architectural changes in response to nitrogen starvation. Plant Physiol.143, 236–250. 10.1104/pp.106.088500

24

FolimonovaS. (2013). Developing an understanding of cross-protection by Citrus tristeza virus. Front. Microbiol.4:76. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00076

25

FolimonovaS. Y.AchorD. S. (2010). Early events of Citrus greening (Huanglongbing) disease development at the ultrastructural level. Phytopathology100, 949–958. 10.1094/PHYTO-100-9-0949

26

FolimonovaS. Y.RobertsonC. J.ShiltsT.FolimonovA. S.HilfM. E.GarnseyS. M.et al. (2010). Infection of strains of Citrus tristeza virus does not exclude superinfection of other strains of the virus. J. Virology84, 1314–1325. 10.1128/JVI.02075-09

27

FuS.ShaoJ.ZhouC.HartungJ. S. (2016). Transcriptome analysis of sweet orange trees infected with ‘Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus’ and two strains of Citrus tristeza virus. BMC Genomics17:349. 10.1186/s12864-016-2663-9

28

GandíaM.ConesaA.AncilloG.GadeaJ.FormentJ.PallásV.et al. (2007). Transcriptional response of Citrus aurantifolia to infection by Citrus tristeza virus. Virology367, 298–306. 10.1016/j.virol.2007.05.025

29

GazzarriniS.LejayL.GojonA.NinnemannO.FrommerW. B.von WirénN. (1999). Three functional transporters for constitutive, diurnally regulated, and starvation-induced uptake of ammonium into Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell11, 937–947. 10.1105/tpc.11.5.937

30

GhorbelR.LópezC.FagoagaC.MorenoP.NavarroL.FloresR.et al. (2001). Transgenic citrus plants expressing the Citrus tristeza virus p23 protein exhibit viral-like symptoms. Mol. Plant Pathol.2, 27–36. 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2001.00047.x

31

GómezG.PallásV. (2004). A long-distance translocatable phloem protein from cucumber forms a ribonucleoprotein complex in vivo with Hop stunt viroid RNA. J. Virol.78, 10104–10110. 10.1128/JVI.78.18.10104-10110.2004

32

GrantT. J.CostaA. (1951). A mild strain of the tristeza virus of citrus. Phytopathology41, 114–122.

33

GreenhamK.SantnerA.CastillejoC.MooneyS.SairanenI.LjungK.et al. (2011). RETRACTED: the AFB4 auxin receptor is a negative regulator of auxin signaling in seedlings. Curr. Biol.21, 520–525. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.02.029

34

HacisalihogluG.HartJ. J.WangY.-H.CakmakI.KochianL. V. (2003). Zinc efficiency is correlated with enhanced expression and activity of zinc-requiring enzymes in wheat. Plant Physiol.131, 595–602. 10.1104/pp.011825

35

HerridgeR. P.DayR. C.MacknightR. C. (2014). The role of the MCM2-7 helicase complex during Arabidopsis seed development. Plant Mol. Biol.86, 69–84. 10.1007/s11103-014-0213-x

36

HoldingD. R.SpringerP. S. (2002). The Arabidopsis gene PROLIFERA is required for proper cytokinesis during seed development. Planta214, 373–382. 10.1007/s00425-001-0686-0

37

HoriguchiG.Mollá-MoralesA.Pérez-PérezJ. M.KojimaK.RoblesP.PonceM. R.et al. (2011). Differential contributions of ribosomal protein genes to Arabidopsis thaliana leaf development. Plant J.65, 724–736. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04457.x

38

HoriguchiG.Van LijsebettensM.CandelaH.MicolJ. L.TsukayaH. (2012). Ribosomes and translation in plant developmental control. Plant Sci.191, 24–34. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.04.008

39

IfukuK.YamamotoY.OnoT.-A.IshiharaS.SatoF. (2005). PsbP protein, but not PsbQ protein, is essential for the regulation and stabilization of photosystem II in higher plants. Plant Physiol.139, 1175–1184. 10.1104/pp.105.068643

40

ImlauA.TruernitE.SauerN. (1999). Cell-to-cell and long-distance trafficking of the green fluorescent protein in the phloem and symplastic unloading of the protein into sink tissues. Plant Cell11, 309–322. 10.1105/tpc.11.3.309

41

IshiharaS.TakabayashiA.IdoK.EndoT.IfukuK.SatoF. (2007). Distinct functions for the two PsbP-like proteins PPL1 and PPL2 in the chloroplast thylakoid lumen of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol.145, 668–679. 10.1104/pp.107.105866

42

JamesonP. E.ClarkeS. F. (2002). Hormone-virus interactions in plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci.21, 205–228. 10.1080/0735-260291044241

43

KarasevA. V.BoykoV. P.GowdaS.NikolevaO. V.HilfM. E.KooninE. V.et al. (1995). Complete sequence of the Citrus tristeza virus RNA genome. Virology208, 511–520. 10.1006/viro.1995.1182

44

KawagashiraN.OhtomoY.MurakamiK.MatsubaraK.KawaiJ.CarninciP.et al. (2001). Multiple zinc finger motifs with comparison of plant and insect. Genome Informatics12, 368–369. 10.11234/gi1990.12.368

45

KevanyB. M.TiemanD. M.TaylorM. G.CinV. D.KleeH. J. (2007). Ethylene receptor degradation controls the timing of ripening in tomato fruit. Plant J.51, 458–467. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03170.x

46

KimY.LimJ.YeomM.KimH.KimJ.WangL.et al. (2013). ELF4 regulates GIGANTEA chromatin access through subnuclear sequestration. Cell Rep.3, 671–677. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.02.021

47

KobayashiT.NishizawaN. K. (2012). Iron uptake, translocation, and regulation in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol.63, 131–152. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105522

48

KorshunovaY. O.EideD.ClarkW. G.GuerinotM. L.PakrasiH. B. (1999). The IRT1 protein from Arabidopsis thaliana is a metal transporter with a broad substrate range. Plant Mol. Biol.40, 37–44. 10.1023/A:1026438615520

49

LangmeadB. (2010). Aligning short sequencing reads with Bowtie. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics Chapter 11:Unit 11.7. 10.1002/0471250953.bi1107s32

50

LeeY.ChoiD.KendeH. (2001). Expansins: ever-expanding numbers and functions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol.4, 527–532. 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00211-9

51

LittleT. J.ShukerD. M.ColegraveN.DayT.GrahamA. L. (2010). The coevolution of virulence: tolerance in perspective. PLoS Pathog.6:e1001006. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001006

52

LiuY.WangG.WangZ.YangF.WuG.HongN. (2012). Identification of differentially expressed genes in response to infection of a mild Citrus tristeza virus isolate in Citrus aurantifolia by suppression subtractive hybridization. Sci. Hortic.134, 144–149. 10.1016/j.scienta.2011.11.022

53

LoveM. I.HuberW.AndersS. (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol.15, 1–21. 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8

54

MaynesM. E. (2013). Characterization of the Role of FRO6 in Metal Homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Master's thesis, Biological Sciences, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC.

55

MiH.DongQ.MuruganujanA.GaudetP.LewisS.ThomasP. D. (2009). PANTHER version 7: improved phylogenetic trees, orthologs and collaboration with the gene ontology consortium. Nucleic Acids Res.38, D204–D210. 10.1093/nar/gkp1019

56

MorenoP.AmbrosS.Albiach-MartíM. R.GuerriJ.PenaL. (2008). Citrus tristeza virus: a pathogen that changed the course of the citrus industry. Mol. Plant Pathol.9, 251–268. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00455.x

57

NiD. A.SozzaniR.BlanchetS.DomenichiniS.ReuzeauC.CellaR.et al. (2009). The Arabidopsis MCM2 gene is essential to embryo development and its over-expression alters root meristem function. New Phytol.184, 311–322. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02961.x

58

O'MalleyR. C.RodriguezF. I.EschJ. J.BinderB. M.O'DonnellP.KleeH. J.et al. (2005). Ethylene-binding activity, gene expression levels, and receptor system output for ethylene receptor family members from Arabidopsis and tomato. Plant J.41, 651–659. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02331.x

59

PadmanabhanM. S.GoregaokerS. P.GolemS.ShiferawH.CulverJ. N. (2005). Interaction of the Tobacco mosaic virus replicase protein with the Aux/IAA protein PAP1/IAA26 is associated with disease development. J. Virol.79, 2549–2558. 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2549-2558.2005

60

PadmanabhanM. S.ShiferawH.CulverJ. N. (2006). The Tobacco mosaic virus replicase protein disrupts the localization and function of interacting Aux/IAA proteins. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact.19, 864–873. 10.1094/MPMI-19-0864

61

ReadA. F. (1994). The evolution of virulence. Trends Microbiol.2, 73–76. 10.1016/0966-842X(94)90537-1

62

RizviI.ChoudhuryN. R.TutejaN. (2015). Arabidopsis thaliana MCM3 single subunit of MCM2-7 complex functions as 3′ to 5′ DNA helicase. Protoplasma253, 467–475. 10.1007/s00709-015-0825-2

63

Rodríguez-CelmaJ.PanI. C.LiW.LanP.BuckhoutT. J.SchmidtW. (2013). The transcriptional response of Arabidopsis leaves to Fe deficiency. Front. Plant Sci.4:276. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00276

64

RoistacherC. N.DoddsJ. A. (1993). Failure of 100 mild Citrus tristeza virus isolates from California to cross protect against a challenge by severe sweet orange stem pitting isolates, in Proceeding 12th Conference of International Organization of Citrus Virologists,, eds MorenoP.da GracaJ. V.TimmerL. W. (Riverside, CA, IOCV), 100–107.

65

RomaniI.TadiniL.RossiF.MasieroS.PribilM.JahnsP.et al. (2012). Versatile roles of Arabidopsis plastid ribosomal proteins in plant growth and development. Plant J.72, 922–934. 10.1111/tpj.12000

66

RoyA.AnanthakrishnanG.HartungJ. S.BrlanskyR. (2010). Development and application of a multiplex reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction assay for screening a global collection of Citrus tristeza virus isolates. Phytopathology100, 1077–1088. 10.1094/PHYTO-04-10-0102

67

Ruiz-RuizS.MorenoP.GuerriJ.AmbrosS. (2006). The complete nucleotide sequence of a severe stem pitting isolate of Citrus tristeza virus from Spain: comparison with isolates from different origins. Arch. Virol.151, 387–398. 10.1007/s00705-005-0618-6

68

SalehinM.BagchiR.EstelleM. (2015). SCFTIR1/AFB-based auxin perception: mechanism and role in plant growth and development. Plant Cell27, 9–19. 10.1105/tpc.114.133744

69

SambadeA.AmbrosS.LopezC.Ruiz-RuizS.Hermoso de MendozaA.FloresR.et al. (2007). Preferential accumulation of severe variants of Citrus tristeza virus in plants co-inoculated with mild and severe variants. Arch. Virol.152, 1115–1126. 10.1007/s00705-006-0932-7

70

SchallerG. E. (2012). Ethylene and the regulation of plant development. BMC Biol.10:9. 10.1186/1741-7007-10-9

71

ShinY.-K.YumH.KimE.-S.ChoH.GothandamK. M.HyunJ.et al. (2006). BcXTH1, a Brassica campestris homologue of Arabidopsis XTH9, is associated with cell expansion. Planta224, 32–41. 10.1007/s00425-005-0189-5

72

SpannT. M.SchumannA. W. (2009). The role of plant nutrients in disease development with emphasis on citrus and huanglongbing. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 122, 169–171. Available online at: http://swfrec.ifas.ufl.edu/hlb/database/pdf/00001871.pdf

73

SpringerP. S.HoldingD. R.GrooverA.YordanC.MartienssenR. A. (2000). The essential Mcm7 protein PROLIFERA is localized to the nucleus of dividing cells during the G(1) phase and is required maternally for early Arabidopsis development. Development127, 1815–1822. Available online at: http://dev.biologists.org/content/127/9/1815

74

SrivastavaA. C.DasguptaK.AjierenE.CostillaG.McGarryR. C.AyreB. G. (2009). Arabidopsis plants harbouring a mutation in AtSUC2, encoding the predominant sucrose/proton symporter necessary for efficient phloem transport, are able to complete their life cycle and produce viable seed. Ann. Bot.104, 1121–1128. 10.1093/aob/mcp215

75

StåhlA.MobergP.YtterbergJ.PanfilovO.von LöwenhielmH. B.NilssonF.et al. (2002). Isolation and identification of a novel mitochondrial metalloprotease (PreP) that degrades targeting presequences in plants. J. Biol. Chem.277, 41931–41939. 10.1074/jbc.M205500200

76

StanslyP. A.ArevaloH. A.QureshiJ. A.JonesM. M.HendricksK.RobertsP. D.et al. (2013). Vector control and foliar nutrition to maintain economic sustainability of bearing citrus in Florida groves affected by huanglongbing. Pest Manag. Sci.70, 415–426. 10.1002/ps.3577

77

StrausN. A. (1994). Iron deprivation: physiology and gene regulation, in Molecular Biology Cyanobacteria, Advances in Photosynthesis, Vol 1, ed BryantD. A. (Dordrecht: Springer), 731–750.

78

TanakaR.KobayashiK.MasudaT. (2011). Tetrapyrrole metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Arabidopsis Book9:e0145. 10.1199/tab.0145

79

ThimmO.BläsingO.GibonY.NagelA.MeyerS.KrügerP.et al. (2004). Mapman: a user-driven tool to display genomics data sets onto diagrams of metabolic pathways and other biological processes. Plant J.37, 914–939. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02016.x

80

VertG.GrotzN.DédaldéchampF.GaymardF.GuerinotM. L.BriatJ.-F.et al. (2002). IRT1, an Arabidopsis transporter essential for iron uptake from the soil and for plant growth. Plant Cell14, 1223–1233. 10.1105/tpc.001388

81

VivesM. C.RubioL.SambadeA.MirkovT. E.MorenoP.GuerriJ. (2005). Evidence of multiple recombination events between two RNA sequence variants within a Citrus tristeza virus isolate. Virology331, 232–237. 10.1016/j.virol.2004.10.037

82

WangJ.LanP.GaoH.ZhengL.LiW.SchmidtW. (2013). Expression changes of ribosomal proteins in phosphate-and iron-deficient Arabidopsis roots predict stress-specific alterations in ribosome composition. BMC Genomics14:783. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-783

83

XieJ.TianJ.DuQ.ChenJ.LiY.YangX.et al. (2016). Association genetics and transcriptome analysis reveal a gibberellin-responsive pathway involved in regulating photosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot.67, 3325–3338. 10.1093/jxb/erw151

84

XuQ.ChenL.-L.RuanX.ChenD.ZhuA.ChenC.et al. (2013). The draft genome of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis). Nat. Genet.45, 59–66. 10.1038/ng.2472

85

YangF.WangG.-P.JiangB.LiuY.-H.LiuY.WuG.et al. (2013). Differentially expressed genes and temporal and spatial expression of genes during interactions between Mexican lime (Citrus aurantifolia) and a severe Citrus tristeza virus isolate. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol.83, 17–24. 10.1016/j.pmpp.2013.03.001

86

YiX.HargettS. R.FrankelL. K.BrickerT. M. (2009). The PsbP protein, but not the PsbQ protein, is required for normal thylakoid architecture in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett.583, 2142–2147. 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.05.048

87

YiX.HargettS. R.LiuH.FrankelL. K.BrickerT. M. (2007). The PsbP protein is required for photosystem II complex assembly/stability and photoautotrophy in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem.282, 24833–24841. 10.1074/jbc.M705011200

88

ZhangN.HasensteinK. H. (2000). Distribution of expansins in graviresponding maize roots. Plant Cell Physiol.41, 1305–1312. 10.1093/pcp/pcd064

Summary

Keywords

Citrus sinensis, transcriptome, host–pathogen interaction, defense response, closterovirus

Citation

Fu S, Shao J, Zhou C and Hartung JS (2017) Co-infection of Sweet Orange with Severe and Mild Strains of Citrus tristeza virus Is Overwhelmingly Dominated by the Severe Strain on Both the Transcriptional and Biological Levels. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1419. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01419

Received

06 June 2017

Accepted

31 July 2017

Published

31 August 2017

Volume

8 - 2017

Edited by

Vitaly Citovsky, Stony Brook University, United States

Reviewed by

Donato Gallitelli, Università degli studi di Bari Aldo Moro, Italy; Zonghua Wang, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2017 Fu, Shao, Zhou and Hartung.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: John S. Hartung john.hartung@ars.usda.gov

This article was submitted to Plant Microbe Interactions, a section of the journal Frontiers in Plant Science

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.