Abstract

Plants have developed different signaling systems allowing for the integration of environmental cues to coordinate molecular processes associated to both early development and the physiology of the adult plant. Research on systemic signaling in plants has traditionally focused on the role of phytohormones as long-distance signaling molecules, and more recently the importance of peptides and miRNAs in building up this communication process has also been described. However, it is well-known that plants have the ability to generate different types of long-range electrical signals in response to different stimuli such as light, temperature variations, wounding, salt stress, or gravitropic stimulation. Presently, it is unclear whether short or long-distance electrical communication in plants is linked to nutrient uptake. This review deals with aspects of sensory input in plant roots and the propagation of discrete signals to the plant body. We discuss the physiological role of electrical signaling in nutrient uptake and how nutrient variations may become an electrical signal propagating along the plant.

The electrical nature of life

Pressure-drive swelling is a problem that emerged early in evolution and solved with the emergence of membrane proteins allowing for the synchronous redistribution of ionic gradients across the plasma membrane. A secondary effect of this solution is the generation a voltage drop within the membrane dielectric (Finkelstein, 1976; Armstrong, 2015). The activity of ion channels and transporters selectively regulates the passage of ions, generating transient local variations in the membrane potential while incorporating metabolites or changing membrane permeability in response to an external signal. Allowing for the synchronization of cellular processes and the communication within cellular communities, electrical sensing, and signaling develops as a wide spread mechanism at the different levels of biological organization. From bacterial biofilms (Strahl and Hamoen, 2010; Masi and Ciszak, 2014; Prindle et al., 2015) to higher plants (Sanderson, 1872; Darwin, 1897; Bose, 1907; Pickard, 1973) and animals (Galvani, 1791; Hodgkin, 1937; Cole and Curtis, 1939; Armstrong, 2007) electrical communication adopt different forms varying in its complexity from simple graduated or oscillating changes in membrane voltage to the long-range electrical signaling observed in excitable cells.

Electrical signals in animals and higher plants

It is well-established that both plants and animals utilize long-range electrical signaling to transduce environmental information to the whole body (Armstrong, 2007; Hedrich et al., 2016). In multicellular organisms, information must be conducted from detectors to the effector tissue. For the case of animals, the nervous system plays a central role in homeostasis, serving as the primary integrator for most of the relevant physiological information. The communication between epithelial tissue and excitable cells define the way animals interact with the environment, not only by taking advantage of sensory modalities such as touch, temperature, light, or sound (Frings, 2009; Julius and Nathans, 2012) but also by integrating internal processes such as hormonal discharge, gut physiology, and immune system development (Zhang and Zhang, 2009; Bellono et al., 2017; Clemmensen et al., 2017).

Molecular detectors found in sensory epithelia are activated by environmental cues, triggering (directly or indirectly) the opening of an ion channel conductance that changes the local transmembrane potential (Martinac, 2008). In non-excitable cells, such as epithelial cells in the gut or lung, electrogenic transport orchestrates nutrient uptake, controls pH, and modulates water secretion (Boyd, 2008; Beumer and Clevers, 2017; Clemmensen et al., 2017). For the case of epithelia, the absence of suitable voltage-dependent channels (i.e., Cav, Nav) impedes the propagation of the initial depolarization over long distances. In excitable cells, depolarization provides the necessary energy to induce the opening of voltage-gated channels (i.e., Cavs, Navs, and Kvs) (Bezanilla, 2008; Catterall et al., 2017). Propagation speed, the shape of the propagated potential, and the frequency of the electrical message are determined by the cable properties of the cell, which are defined by both the geometry of each particular cell type and the ion channel set available. In animals, this type of communication extends to the multicellular organism when a released substance from a given cell exert an effect in a post synaptic cell (Gerber and Südhof, 2002; Jackson, 2006; Catterall and Few, 2008). As described originally in Aplysia by E. Kandel (Castellucci and Kandel, 1976), excitable cells modify their behavior in response to stimulation. Considering that the control of expression, localization, and activity of cellular receptors and ion channels represent the molecular grounding of non-associative learning in animals (Kandel, 2001), it is tempting to question how plants modulate the different ion fluxes and which are the elements conferring plasticity to plant's learning.

Action potentials have been reported in algae and higher plants (Pickard, 1973; Trebacz and Zawadzki, 1985; Kateriya et al., 2004; Fromm and Lautner, 2007; Hegenauer et al., 2016). As foreseen by Davies (1987), nowadays it is widely accepted that electrical signaling plays a major role in inter- and intra-cellular communication of plants. However, in contrast to detailed knowledge of the molecular and cellular mechanisms that governing electrical signaling in animals, the identity of the cellular sensors and effectors, and their exact distribution within the plant, is still unclear (Ward et al., 2009; Hedrich, 2012; Hedrich et al., 2016). Moreover, lacking the sophisticated cellular wiring developed by metazoans to transmit their long-range electrical signals, it seems that plants developed an architecture allowing them to shape—or forcing them to adapt—electrical communication differently. Simple questions emerge from this reasoning, how exactly plants wire up? How electrical signals move through the cellular network? How these signals work together connecting environmental sensing, gene expression, nutrient uptake, gas exchange, water balance, energy production, and waste storing? In this review we are not aiming to answer such ambitious questions but rather to put in perspective the different elements that might contribute to the generation and propagation of the electrical message in the root of land plants.

The ability to navigate is an attribute of animals and imposes fundamental problems to solve such as (i) multiplex sensory input at high frequencies, (ii) the rapid integration of these signals, and (iii) to deliver the computed command with exquisite cellular precision, allowing a coherent body response. Unicellular green algae, ancestors of land plants, have navigation capabilities and coincidentally present a different set of ion channels when compared to their descendants, expressing essential elements important in shaping the electrical response of excitable cells in animals (Merchant et al., 2007; Wheeler and Brownlee, 2008). Among these are voltage-activated calcium and sodium channels, TRP channels, and the ryanodine receptor, all absent in modern land plants (Wheeler and Brownlee, 2008; Ward et al., 2009; Fromm and Lautner, 2012; Taylor et al., 2012; Arias-Darraz et al., 2015; Edel et al., 2017). Trapped in the same natural world, animals, and plants share a large set of environmental stress factors. Nevertheless, they have clearly adopted different ways for solving basic problems such as reproduction and self-preservation. Likely the quest for food, mating, and the need for waste disposal cued animals to develop signaling mechanisms that are tuned to navigate. On the other hand, plants not only manufacture their own carbohydrates but also importantly store their waste. Therefore, the sessile nature of land plants demands for robust adaptation mechanisms instead. Accordingly, cellular and molecular sensors are constantly feeding the plant with useful environmental information that has to be distributed through out the body (Karban, 2015). Recent studies suggests that Arabidopsis efficiently organize their three dimensional planning to optimize nutrient supply (Conn et al., 2017), strengthening the idea that plant's architecture is controlled by a management mechanism in charge of the trading between total length of the branches and nutrient distribution. Such mechanism must be associated to the nature and propagation properties of electrical signals generated at the root and leafs, tissues where minerals and water are absorbed, carbohydrates produced, and byproducts stored. Further experimental work on intact living plants, using suitable models allowing for simultaneous electrical and imaging recordings are needed to evaluate the impact of electrical signals on food distribution along the plant (Kanchiswamy et al., 2014; Salvador-Recatalà et al., 2014; Gunsé et al., 2016; Candeo et al., 2017).

The conducting plant

Missing not only the cellular architecture but also the ion channel set encoding the electrical message in animals (Ward et al., 2009; Hedrich, 2012), there is no reason to suggest that the sensory input in plants is either integrated or processed in a similar way. It has been proposed that the plant phloem forms a single conducting cable, the equivalent of an axon in a single metazoan neuron (Hedrich et al., 2016). Different cell types including companion cells and sieve elements form the phloem. Unlike other plant cell types, sieve elements cells do not present discontinuities in their permeability due to the presence of sieve plates, enabling a continuous transport of solutes between different organs of the plant and providing a low-resistance, high capacitance conduit that allows for the propagation of relatively slow electrical signals. Decades of theoretical and experimental evidence put forward the concept that the phloem would be the principal conduit, able to electrically couple roots and aerial tissues (Brenner et al., 2006; Fromm et al., 2013; Hedrich et al., 2016). Still, the information detected at epidermal cells of the root must propagate through the cortex's cellular network, integrate, and reach the phloem to be transduced all over the plant's body. Conversely, the signal should exit the phloem to have an impact on cells in the aerial tissue. To accomplish this complex task, vascular plants have an inter-connected extracellular space between the plasma membrane and the cell wall (i.e., the apoplastic space) and direct cellular connectivity via plasmodesmata (Sattelmacher and Horst, 2007; Lee, 2015). These peculiarities serve to different signaling functions in the plant, allowing not only the passage of soluble signals but also defining the electrical coupling between cells and the modulation of specific signals associated to the calcium response that comes together with the detection of diverse environmental cues (Zebelo et al., 2012; Nawrath et al., 2013; Lee, 2015; Choi et al., 2016; Edel et al., 2017).

Two major types of long-distance electrical signals have been described in plants, action potentials (APs), and variation potentials (VPs) (Bose, 1907; Pickard, 1973; Fromm and Lautner, 2007, 2012). The former are induced by voltage depolarization, exhibit a threshold potential, follow an all-or-nothing principle, and travel at constant velocity and amplitude, very much like APs observed in the animal kingdom (Zawadzki et al., 1991; Jackson, 2006; Armstrong, 2007; Yang et al., 2016). In contrast, VPs have shown to be induced by a rapid increase in the internal pressure of the xylem, and appear as slow waves of depolarization of variable sizes (Fromm and Lautner, 2007, 2012). A third mode of electrical signal dubbed system potentials (SPs), consisting of hyperpolarization that propagates over medium range distances has also been described (Zimmermann et al., 2009). While VPs depend on the inactivation of P-type H+-ATPase, SPs seems to be caused by the activation of the pump. From the early works of Burdon-Sanderson it is known that rise times for plant APs are in the order of about 0.1 s, with durations of about 1 s and rates of propagation of in the order of few hundreds of mm s−1 (Sanderson, 1872; Pickard, 1973). These electrical signals not only differ in their shape and magnitude but also in their propagation speed ranging from 1 to 60 mm s−1 for APs to several minutes per centimeter in VPs. System potentials are triggered by depolarization, do not have an all-or-nothing character, self-propagate at a constant velocity of about 0.5–2 mm s−1, and their magnitude is proportional to the input stimuli (Zimmermann et al., 2009). Interestingly, SPs resemble animal's receptor potentials, self-propagating simultaneously over sensory epithelia. The leaf of arabidopsis, beans, and barley exhibits self-propagating electrical activity, caused by wounding, restricted to leaf-to-leaf communication, and associated to the expression of glutamate receptor-like genes (Zimmermann et al., 2009; Mousavi et al., 2013; Salvador-Recatalà et al., 2014; Salvador-Recatalà, 2016a). In this case, the type of wound seems to be related to distinct types of depolarization. It has been suggested that the anatomy of the tissue will be of importance to define the connectivity between the surface tissue and the phloem (Salvador-Recatalà, 2016a).

Still, it has been difficult to systematize both a theoretical model integrating whole plant electrical signaling and experimental methods to study long-range electrical communication in whole plant configuration (Goldsworthy, 1983; Davies, 1987; Pietruszka et al., 1997; Fromm and Lautner, 2007; Volkov, 2012; Fromm et al., 2013; Hedrich et al., 2016). Nevertheless, it has been established that the different organs of the plant including leaves, stem, flowers, and the root have intrinsic electrical activity (Pickard, 1973; Baldwin et al., 2006; Fromm and Lautner, 2007, 2012; Appel and Cocroft, 2014; Engineer et al., 2015; Karban, 2015; Zhou et al., 2016). Moreover, long-range electrical communication between roots, shoot, and leaves have been described (extensively reviewed in Pickard, 1973; Fromm and Lautner, 2007; Zimmermann et al., 2009; Hedrich et al., 2016). A detailed description of electrical signal transduction on roots is missing, probably due to the seemingly uncoordinated nature of root's APs (Fromm and Eschrich, 1993; Fromm et al., 1997, 2013; Masi et al., 2015; Salvador-Recatalà, 2016b).

Mapping the ion channel set in arabidopsis

Electrical properties of cells derive from the expression and control of ion channels, transporters, and pumps. These can be modulated by different stimuli such as: pressure, exogenous and endogenous ligands, temperature, light, membrane voltage, and stretch among others. The molecular machinery outlining the propagation of electrical signals in plants is not known in detail but taking into account experimental data and genetic information available we have learned that plants and animals utilize dissimilar strategies to propagate APs. While animals use voltage-sensitive Na+ and Ca2+ channels to drive depolarization (Hodgkin and Huxley, 1952; Armstrong, 2007; Catterall et al., 2017), the toxic nature of sodium makes plant cells to utilize Cl− and Ca2+ instead. While Ca2+ will cause depolarization by entering the cell, Cl− will do by leaving the cell. According to gene expression profiles, depolarization of plant cells is likely driven by ALMT/QUAC-type chloride channels and/or ion channels allowing for calcium influx such as two-pore channels (TPCs), cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (CNGCs), or glutamate receptor-like channels (GLRs) (Ward et al., 2009; Hedrich, 2012; Hedrich et al., 2016). In the chain of events defining the AP an initial raise in Ca2+ will trigger a Cl− efflux and the subsequent activation of voltage-dependent potassium channels will likely participate in repolarization (Schroeder et al., 1984; Ward et al., 2009; Hedrich et al., 2016).

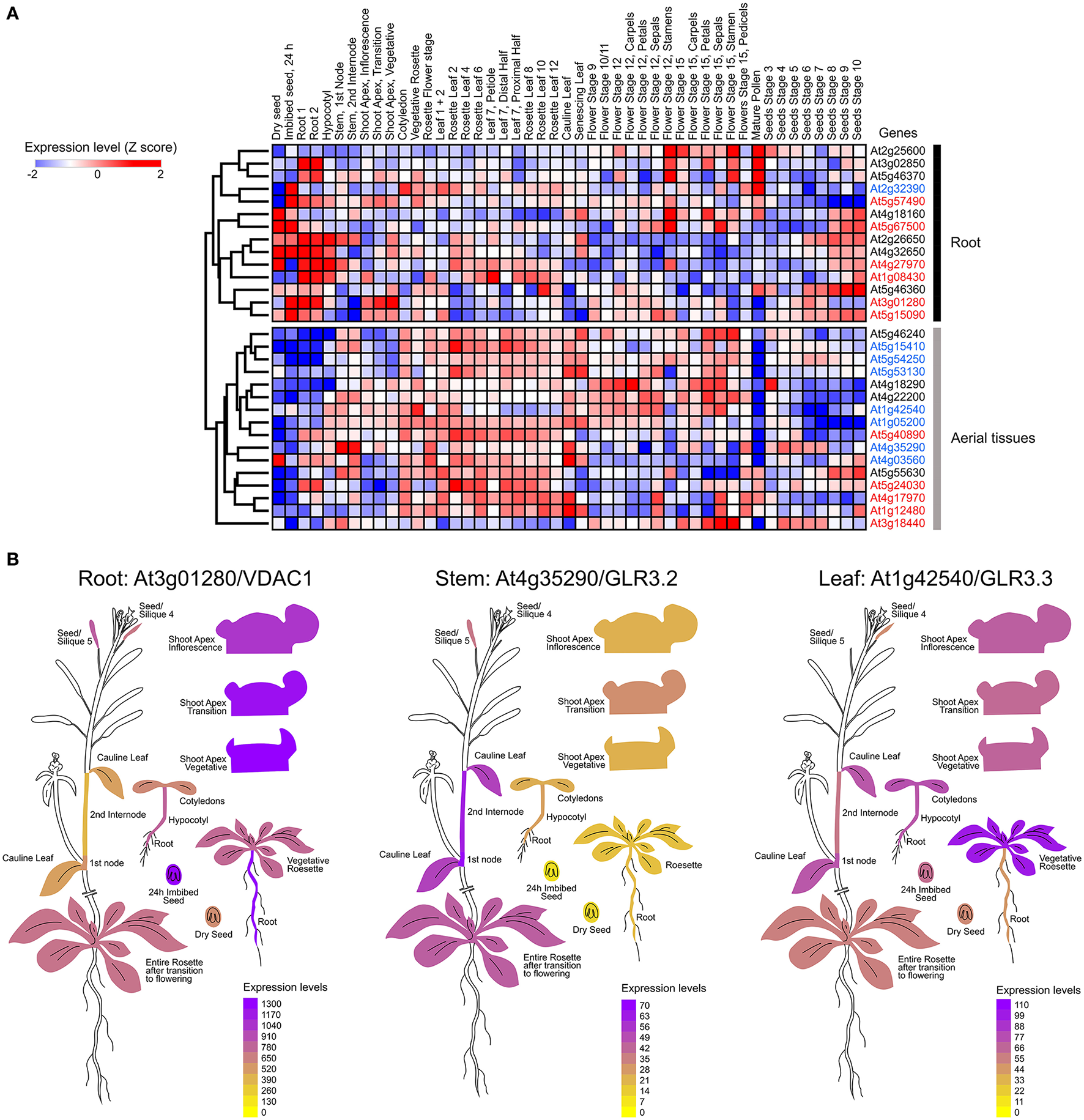

As the ability of a tissue to generate electrical signals will be determined by the ion channel set expressed in the different cell types involved in the passage of the electrical message, we mapped functionally-characterized channels and transporters that have been previously associated to electrical signaling in Arabidopsis thalina (Barbier-Brygoo et al., 2011; Hedrich, 2012) (Table 1). We performed a hierarchical clustering analysis to group these genes according to the expression profiles obtained from EPlant (Waese et al., 2017). When comparing all relevant tissues at different stages of development, we observed that the different ion channels present a characteristic pattern of expression (Figure 1A).

Table 1

| Name | Locus | Fuction | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage-gated K+ channel | KAT1 | At5g46240 | Stomatal opening | Ronzier et al., 2014 |

| KAT2 | At4g18290 | Stomatal opening | Ronzier et al., 2014 | |

| AKT1 | At2g26650 | K+ uptake from soil | Xu et al., 2006; Geiger et al., 2009 | |

| SIPK (AKT6) | At2g25600 | Pollen tube development | Mouline et al., 2002 | |

| AtKC1 | At4g32650 | Regulation AKT1 | Geiger et al., 2009 | |

| AKT2 | At4g22200 | K+ battery, stomatal movement | Szyroki et al., 2001; Gajdanowicz et al., 2011 | |

| SKOR | At3g02850 | K+ loading to xilem | Liu et al., 2006 | |

| GORK | At5g32500 | Involved in stomatal clousure, stomatal movement | Hosy et al., 2003 | |

| Voltage-independent K+ channel | TPK1 | At5g55630 | K+ homeostasis, germination, stomatal movement | Gobert et al., 2007 |

| TPK2 | At5g46370 | Unknown | Voelker et al., 2006 | |

| TPK3 | At4g18160 | Unknown | Voelker et al., 2006 | |

| TPK4 | At1g02510 | K+ homeostasis, growing tube pollen | Becker et al., 2004 | |

| KCO3 | At5g46360 | Unknown | Voelker et al., 2006; Rocchetti et al., 2012 | |

| Ca2+ channels | CNGC1 | At5g53130 | Response to pathogen, senescence | Leng et al., 1999; Ma et al., 2010; Chin et al., 2013 |

| CNGC2 | At5g15410 | Response to pathogen | Leng et al., 2002; Chin et al., 2013 | |

| CNGC4 | At5g54250 | Patogen infection | Balagué et al., 2003 | |

| GLR 3.2 | At4g35290 | Ca2+ homeostasis,ionic stress | Kim et al., 2001 | |

| GLR 3.3 | At1g42540 | Ca2+ homeostasis, wound response | Mousavi et al., 2013; Salvador-Recatalà, 2016a | |

| GLR 3.5 | At2g32390 | Ca2+ homeostasis, wound response | Salvador-Recatalà, 2016a | |

| GLR 3.6 | At3g51480 | Ca2+ homeostasis, wound response | Mousavi et al., 2013; Salvador-Recatalà, 2016a | |

| TPC1 | At4g03560 | Stomatal opening, germination | Peiter et al., 2005; Guo et al., 2016 | |

| Voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) | VDAC1 | At3g01280 | Regulate cold stress response, growth pollen | Tateda et al., 2011; Li et al., 2013 |

| VDAC2 | At5g67500 | Seedling development, energy production | Yan et al., 2009; Tateda et al., 2011 | |

| VDCA3 | At5g15090 | Germination, energy production | Tateda et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2011; Berrier et al., 2015 | |

| VDCA4 | At5g57490 | Energy production, plant growth | Tateda et al., 2011 | |

| R-type anion channel | QUAC1 (ALMT12) | At4g17970 | Involved in stomatal clousure, stomatal movement, sulfate transporter | Meyer et al., 2010; Malcheska et al., 2017 |

| AtALMT9 | At3g18440 | Stomatal opening | De Angeli et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014 | |

| S-type anion channel | SLAC1 | At1g12480 | Stomatal opening | Zhang et al., 2016 |

| SLAH3 (SLAC1 homolog 3) | At5g24030 | Stomatal opening, nitrate efflux channel | Zheng et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016 | |

| Voltage dependent Cl- | AtCLCa | At5g40890 | NO3- transporter, nitrate homeostasis | De Angeli et al., 2006 |

Functional ion channels in Arabidopsis.

Figure 1

Mapping the expression of ion channels in Arabidopsis thaliana. (A) Hierarchical clustering of normalized mRNA levels of genes coding potassium (black), calcium (red), and anion (blue) channels. Microarray data were obtained and visualized from the Arabidopsis eFP browser (Waese et al., 2017). Expression values for each gene were transformed to Z-scores across all samples in order to identify tissue-specific expression. High Z-score values (red or blue) indicate a larger deviation from the mean expression across all tissues. (B) Examples of ion channels showing tissue-specific expression.

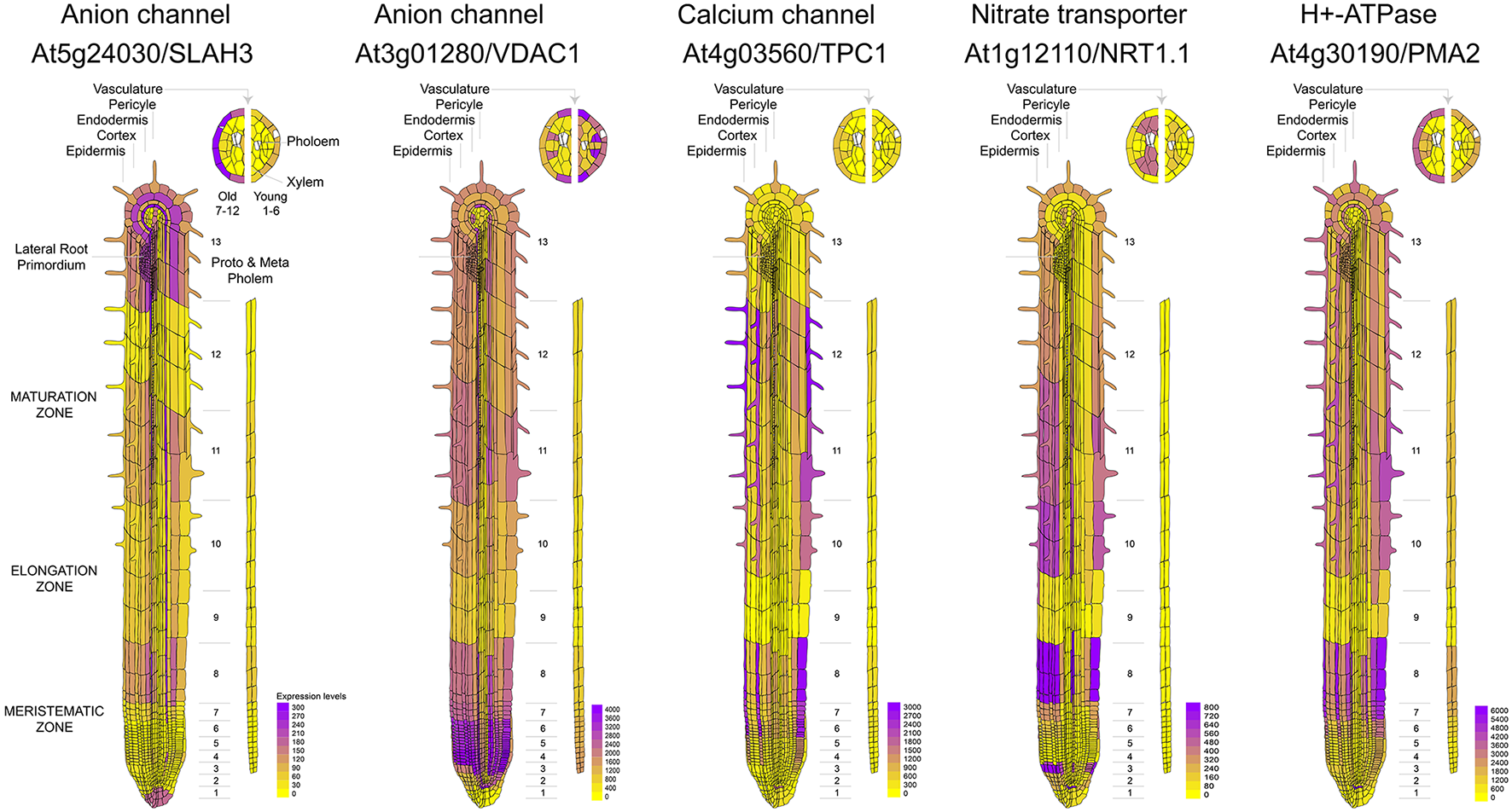

It is known that calcium signaling is important for the control of stomatal opening (Laanemets et al., 2013) and potassium channels are critical in the repolarization phase (Schroeder et al., 1984). As expected, we observed a large expression of GLR and Kv channels in the leaves (Figures 1A,B). Although genes encoding for anionic and potassium channels do not show a clear separation between the aerial part and roots (Figure 1A), we found specific genes whose expression is predominant in the roots (VDAC1), stems (GLR3.2), or leaves (GLR3.3) (Figure 1B). These tissue-specific expression profiles suggest that there are different pathways for the generation and propagation of electrical signals in plants and that these routes change during development. When observed in more detail, two root-specific anion channels, SLAH3, and VDAC1, showed different expression pattern across cell types (Figure 2). The voltage-dependent anion channel VDAC1 is strongly expressed along the root tissue. Comparatively, the expression at the meristematic zone is higher than in root hairs (Figure 2). Similarly, H+-ATPase is expressed in almost all cell types of the root. In contrast, the slow chloride conductance channel SLAH3 showed greater expression in internal root tissues such as the pericycle and the cortex, important physical barriers on the way to the phloem (Nawrath et al., 2013). While the expression of the electrogenic nitrate transporter NRT1.1 is predominantly observed in root's hairs and at the phloem closer to the stem, the vacuolar channel TPC1 is markedly expressed in root hairs of the maturation zone. Interestingly, none of these membrane proteins showed a marked expression in the phloem along the root (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Comparative expression profiles at cell-type resolution of anion channels and genes related to nitrate uptake in the Arabidopsis root. Microarray data was obtained and visualized using the Arabidopsis eFP browser (Waese et al., 2017).

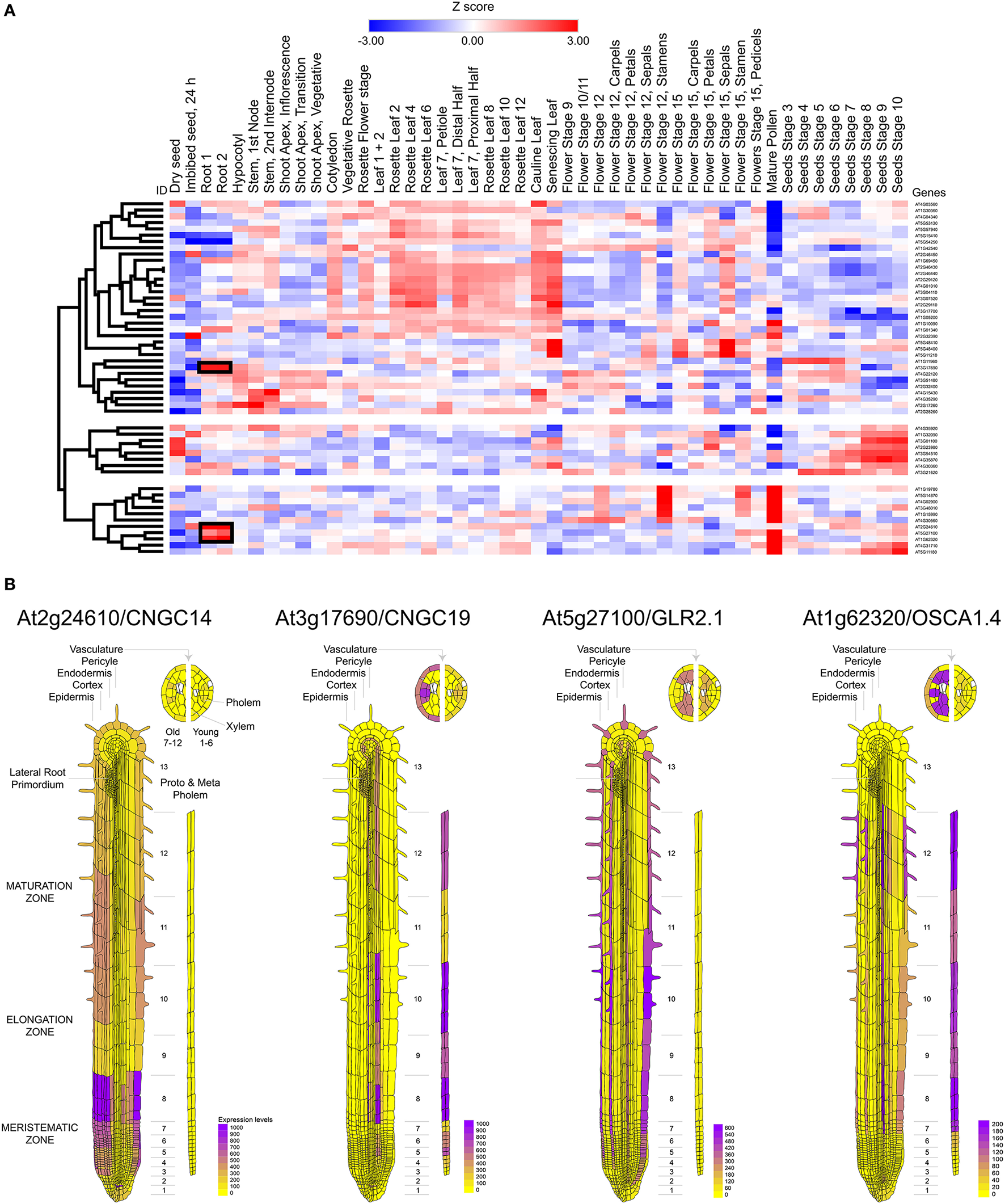

Calcium influx in response to external stimuli seems critical for the generation of the electrical signal. Nearly 50 different ion channels have been associated to Ca2+ influx in land plants. This large set of calcium channels are segregated in five different families: CNGC, GLR, TPC1, osmotic response-related channels (OSCA), and mechano-sensitive calcium channels (MCA) (Kurusu et al., 2012; Chin et al., 2013; Morgan and Galione, 2014; Edel et al., 2017) (Table 2). From these channels CNGC14, CNGC19, GluR2.1, and OSCA1.4 appear to be preferentially expressed in the root tissue (Figure 3A). The expression of these channels was also observed to be differential. CNGC14 is largely expressed at the epithelium close to the meristematic zone and to a lesser extent at the maturation zone. In contrast, the vacuolar channel CNGC19 is concentrated at the endothelium and the phloem. On the other hand, the ligand gated GLR2.1 and osmotic-related OSCA1.4 channels are preferentially expressed in root hairs. While the expression of GLR2.1 at the epithelial tissue somewhat decreases from the meristematic zone toward the maturation zone, OSCA1.4 is preferentially expressed at the maturation zone and the phloem (Figure 3B).

Table 2

| Channel family | Name | Locus |

|---|---|---|

| CGNCs | CNGC10 | AT1G01340 |

| CNGC7 | AT1G15990 | |

| CNGC8 | AT1G19780 | |

| CNGC6 | AT2G23980 | |

| CNGC14 | AT2G24610 | |

| CNGC15 | AT2G28260 | |

| CNGC3 | AT2G46430 | |

| CNGC12 | AT2G46450 | |

| CNGC19 | AT3G17690 | |

| CNGC16 | AT3G48010 | |

| CNGC13 | AT4G01010 | |

| CNGC17 | AT4G30360 | |

| CNGC9 | AT4G30560 | |

| CNGC18 | AT5G14870 | |

| CNGC2 | AT5G15410 | |

| CNGC1 | AT5G53130 | |

| CNGC4 | AT5G54250 | |

| CNGC5 | AT5G57940 | |

| GLRs | GLR3.4 | AT1G05200 |

| GLR3.3 | AT1G42540 | |

| GLR3.1 | AT2G17260 | |

| GLR2.3 | AT2G24710 | |

| GLR2.2 | AT2G24720 | |

| GLR2.9 | AT2G29100 | |

| GLR2.8 | AT2G29110 | |

| GLR2.7 | AT2G29120 | |

| GLR3.5 | AT2G32390 | |

| GLR3.7 | AT2G32400 | |

| GLR1.1 | AT3G04110 | |

| GLR1.4 | AT3G07520 | |

| GLR3.6 | AT3G51480 | |

| GLR2.4 | AT4G31710 | |

| GLR2 | AT4G35290 | |

| GLR2.6 | AT5G11180 | |

| GLR2.5 | AT5G11210 | |

| GLR2.1 | AT5G27100 | |

| GLR1.2 | AT5G48400 | |

| GLR3.1 | AT5G48410 | |

| TPC | TPC1 | AT4G03560 |

| MCAs | MCA2 | AT2G17780 |

| MCA1 | AT4G35920 | |

| OSCAs | OSCA2.2 | At1g10090 |

| OSCA1.3 | At1g11960 | |

| OSCA3.1 | At1g30360 | |

| OSCA1.8 | At1g32090 | |

| OSCA2.1 | At1g58520 | |

| OSCA1.4 | At1g62320 | |

| OSCA2.4 | At1g69450 | |

| OSCA2.3 | At3g01100 | |

| OSCA1.5 | At3g21620 | |

| OSCA2.4 | At3g54510 | |

| OSCA1.7 | At4g02900 | |

| OSCA1.1 | AT4G04340 | |

| OSCA1.6 | At4g15430 | |

| OSCA1.2 | At4g22120 | |

| OSCA4.1 | At4g35870 |

Calcium channels in Arabidopsis.

Figure 3

Mapping the expression of calcium channels in Arabidopsis thaliana. (A) Heat map and clustering dendrograms of the expression of calcium channels among tissue types. Tissue samples are represented in columns and genes in rows. Expression values for each gene were transformed to Z-scores across all samples in order to identify root-specific expression, which is indicated with black rectangles. (B) Calcium channels showing root-specific expression.

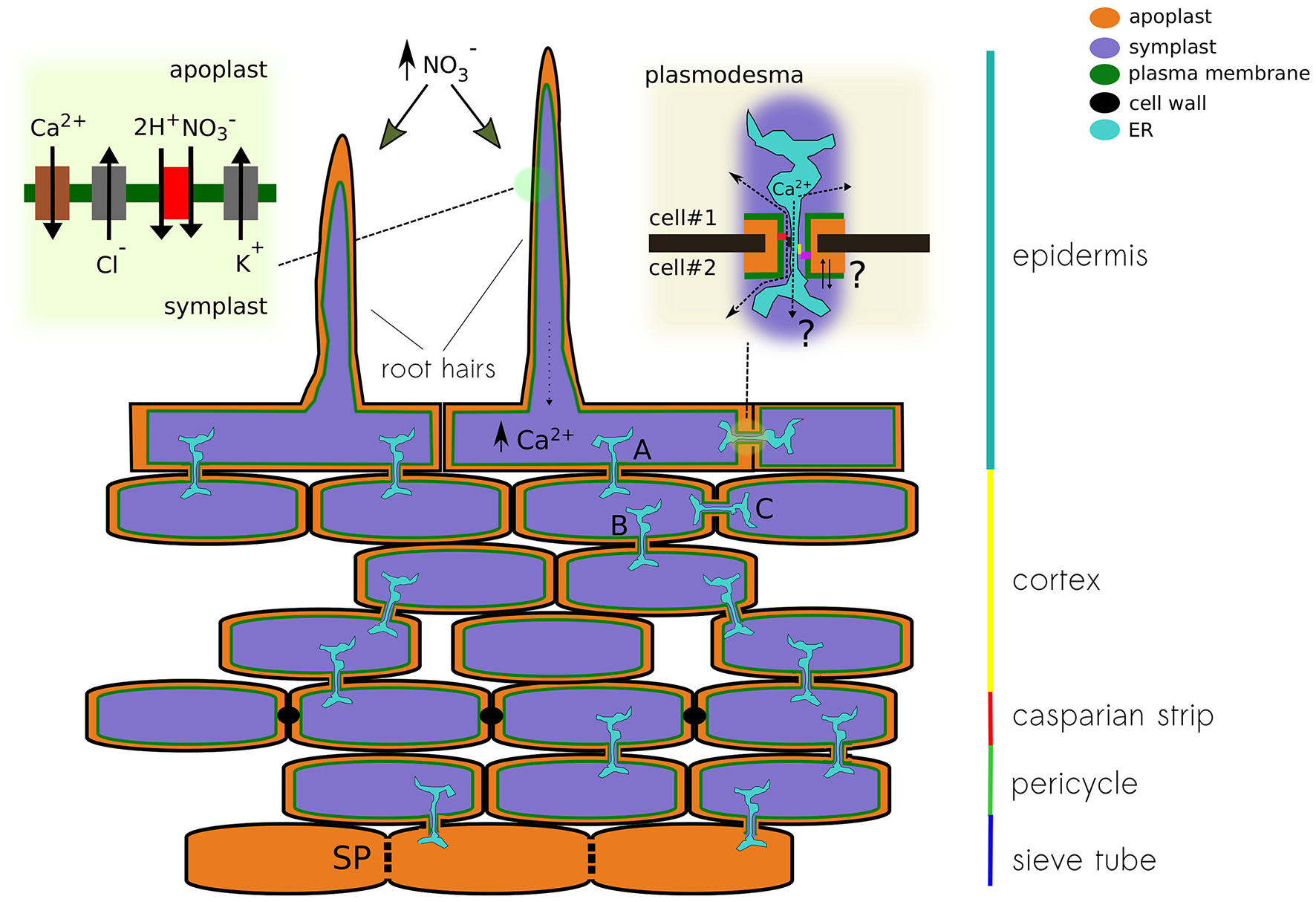

Nitrate treatments in nitrogen-starved plants induce a transient depolarization of the plasma membrane (Meharg and Blatt, 1995; Wang and Crawford, 1996; Wang et al., 1998). Likewise, it has been recently reported that nitrate treatments trigger an intracellular calcium increase, which initiates the nitrate-signaling pathway (Liu et al., 2017). Moreover, genetic evidence indicates that elevations in intracellular calcium are associated to NRT1.1. (Riveras et al., 2015). Given the observed expression profile, we may hypothesize that a nitrate uptake-induced depolarization of the epithelial cell, caused by an increase in the activity of the nitrate transporter NRT1.1, will trigger calcium influx through OSCA1.4 and/or GLR2.1, further activating a calcium or voltage-dependent chloride conductance (e.g., SLAH3 or VDAC1), allowing for the propagation of the electrical signal along the cortex toward the phloem (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Schematic representation of a plant root showing different pathways for the propagation of electrical signals. The different conducting state of plasmodesma A, B, and C will modulate the signal detected at the root hair on its way to the sieve tube. The upper left panel show the conductances that might be associated to nitrate-induced depolarization. Calcium increase in the epithelial cell modulates the activity of the plasmodesma. Both calcium levels and physical changes of the plasmodesma might modulate the activity of ion channels expressed in that region. The upper right panel pictures the cytoplasmic and reticular pathways for ions, both can be modulated by the interaction with anchoring proteins of the contact site of the pore.

Cellular connectivity as part of plant's electrical signaling

A united model connecting plant sensing and controlled behavior is needed to explain whether the stimuli detected at the boundaries of the plant body (e.g., root hairs, leafs' epithelial cells), transduce the electrical information to the phloem cable, how the signal is further integrated, and lastly how the electrical signal exits the phloem, reaching the effector tissue located in a distant epithelia (e.g., guard cells at leaf stoma). While the differential expression of the ion channel set is important to determine excitability, the plant's interconnected cellular architecture will be critical in governing the amplitude and propagation properties in three-dimensional space. Modulation of these elements in response to repetitive, acute, or chronic sensory input may confer plasticity to the plant's response and will allow for both learning and adaptation, without the need for a “brain-like” integrator or cognitive behavior as suggested in literature (Baluska et al., 2004).

One of the main structural differences between animal and plant cells is the presence of a cell wall. The plant cell wall creates an unusual extracellular environment known as the apoplast which constitutes a physical/chemical barrier that participates in cell-to-cell communication pathways including long-range electrical signaling (Sattelmacher, 2001; Fromm and Lautner, 2007; Choi et al., 2017). In plants, the extracellular concentration of ions corresponds to the apoplastic ionic concentrations, which are highly regulated. The ionic composition of the apoplast is variable and depends on both internal factors such as tissue or development stage and external factors such as nutritional stress (López-Millán et al., 2001). Ions in the apoplastic compartment are usually found in low concentrations consisting predominantly of inorganic cations and anions such as K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl−, , and (Gabriel and Kesselmeier, 1999). The apoplastic and intracellular ion concentrations together with ion permeability will define the resting potential of the root epidermal cell and has been reported to be about −120 mV, negative inside (Fromm and Eschrich, 1993). Biochemical properties of the cell wall will define the apoplastic space and nutrient permeability in the first place. In the adult plant, a high content of lignin or suberin in cell walls considerably decreases their permeability (Nawrath et al., 2013) and therefore constitutes a tight barrier to free diffusion of nutrients in and out of the plant tissue. In contrast, the structure and composition of cell walls change during root development (Somssich et al., 2016). The meristematic zone contains young cells localized close to the root tip, while the older cells are localized at the root base close to the stem. Cell walls of the meristematic zone are thin and more permeable because of a higher mitotic activity (Baluska et al., 1996). Cells from the differentiation zone are more rigid due to the accumulation of lignin associated with the development of secondary cell walls, which provides extra strength to the walls and makes them waterproof Somssich et al. (2016). Therefore, there is a longitudinal permeability gradient in primary roots determined by the differentiation degree of epidermal cells.

The equilibrium concentration of ions can be calculated from the Nernst equation of the form [X]out/[X]in = exp(VmZF/RT), were [X]out and [X]in are the external and internal concentrations of an ion X, Vm is the membrane voltage, Z is the valence of the permeable ion, F the Faraday constant, R the gas constant, and T the absolute temperature. From this equation, it is clear that variations in the extracellular concentration of a permeable charged solute will affect the membrane potential at rest. In fact, early studies have shown that both the peak of the action potential and magnitude of the inward current are dependent on the apoplastic calcium concentration (Hope, 1961a,b; Hope and Findlay, 1964). On the other hand, the activity of the H+-ATPase maintains apoplastic pH usually acidic (4.7–5) (Sattelmacher and Horst, 2007). As the resting membrane potential in plant cells is likely to be set by proton transport, therefore, one should expect a high sensitivity to variations in the activity of the proton pump (Brault et al., 2004). Considering that the apoplast occupies a relatively small volume of the plant tissues, representing less than 5% for the case of leaves (López-Millán et al., 2001) it is reasonable to expect that environmental changes might cause rapid alkalization of the apoplast that in turn will produce a local depolarization (Grams et al., 2009). Anionic nutrients such as nitrate, sulfate and phosphate are acquired passively by means of electrogenic co-transport helped by the proton gradient (Ullrich-Eberius et al., 1981; Muchhal and Raghothama, 1999). Likewise, apoplastic pH will be sensitive to the activity of phosphate and nitrate transporters (Amtmann et al., 1999). Accordingly, acute treatments with nitrate in nitrogen-starved plants induce a transient depolarization of the plasma membrane (Meharg and Blatt, 1995; Wang and Crawford, 1996). Experimental evidence suggests that 2–4 protons are co-transported during phosphate uptake (Sakano, 1990). For the case of nitrate, the stoichiometry of co-transport with protons has been calculated to be 2:1 (McClure et al., 1990; Glass et al., 1992; Wang and Crawford, 1996). Considering experimental evidence from in-vitro studies with membrane vesicles and also genetic analyses such as yeast complementation, the most probable stoichiometry for proton/sulfate co-transport would be 3:1 (Buchner et al., 2004).

The root is the first organ that comes in contact with water and nutrients. Therefore, when plants are deprived of nutrients, the root constitutes a primary site for detection. Comparative transcriptomic analyses between root and shoot samples showed that the plant's response to nitrate initiates at the root (Wang et al., 2003). Plants must integrate the information from the external environment and contrast it with their nutritional status. In fact, it has been reported that the balance between nitrogen and carbon is important for the control of nitrogen assimilation (Zheng, 2009). Therefore, plants require an efficient communication system between the site of nutrient perception and uptake (i.e., roots) and the metabolic center where carbon is produced (i.e., leaves) to respond adequately to changes in nutrient availability. Epidermal cells of the plant root elicit a higher permeability through a cell wall, making electrogenic transporters at the plasma membrane to face high concentrations of nutrients when they happen to get dissolved in the soil surrounding the root. The uptake of any these nutrients will produce a rapid and transient membrane depolarization of the epithelial cell in the root (Dunlop and Gradiner, 1993; Meharg and Blatt, 1995). Moreover, the diffusion of substances within the root's apoplast is internally restricted by the Casparian strip, a lignin-made hydrophobic impregnation of the primary cell wall that seal the extracellular space of endodermal cells, forcing the passage of ions, nutrients, and water through the plasma membrane of endothelial cells (Nawrath et al., 2013; von Wangenheim et al., 2017) (Figure 4).

In addition to the apoplastic communication pathway in the extracellular space, the cytoplasm of plant cells can be internally connected by cell-to-cell junctions known as plasmodesma (Lee, 2015; Kitagawa and Jackson, 2017). Intercellular communication of root tissues has been demonstrated by the rapid diffusion of fluorescent tracer molecules (e.g., propidium iodide) through plasmodesmata into inner layers of the root tissue (Nawrath et al., 2013). It has been demonstrated that the undifferentiated cells from the apical root meristem and elongation zone are dye-coupled and, therefore, are symplastically connected through plasmodesmata (Duckett et al., 1994). Ions and larger molecules can freely diffuse though the pore from one cell to the other making these cellular structures a focal point of signaling through the cortex tissue (Burch-Smith and Zambryski, 2012; Lee, 2015). Moreover, the complexity of plasmodesmata is underscored by the presence of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) passing through the pore, providing a secondary and likely more selective pathway of communication between neighbor cells. It is known that different lipids and callose, a soluble protein able to occlude the cytoplasmic pathway, tune permeation through plasmodesmata (Tilsner et al., 2016). Moreover, it has been reported that cytoplasmic calcium elevations promote the closure of the cytoplasmic pathway of the pore (Lee, 2015). Additional data is needed to determine the contribution of these ER tubes in the propagation of both calcium and electrical signals through root cortex.

In plants, direct coupling between the ER and the electrical activity at the plasma membrane is not associated to the stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) or to Orai1 calcium channels, as in animal cells. STIM-related proteins were lost at the level of single-celled algae and Orai relatives are present only up to gymnosperms (Edel et al., 2017). Nevertheless, it has been suggested that anchoring proteins, cytoskeleton elements, and lipids might modulate localization and activity of membrane proteins at the contact site between ER and plasma membrane (Lee, 2015). Thus, the differential expression and modulation of a specific set of calcium-sensitive ion channels, plasmodesmata occlusion, or the remodeling of the pore's shape at the contact site might provide amplification or suppression of the propagating electrical signal through the cortex (Figure 4).

The differentiation of root epidermal cells in Arabidopsis progressively reduces these cytoplasmic connections in such a way that become symplastically uncoupled in the last stage of their development (Duckett et al., 1994). Conversely, the cells of the hypocotyl epidermis are symplastically connected to one another regardless of their state of development (Duckett et al., 1994). Earlier evidence of electrical coupling was given by Spanswick and Costerton, who showed that when injecting current in a cell of the multicellular alga Nitella, the signal could be traced several cells away from the site of injection (Spanswick and Costerton, 1967).

Recent calcium imaging experiments using a genetically encoded ratiometric calcium indicator (i.e., Y-Cameleon 3.6), expressed in living Arabidopsis, showed how the spontaneous response originating in a root hair propagates through the root tissue in well-defined “patches” (Candeo et al., 2017). Although the authors did not comment about this patterned response, by analogy to sensory receptors in animals, it is tempting to interpret such readout as the physical dimension of the “sensory field” that correspond to a particular epithelial cell or a group of them. After the stimulation of a cell from root epidermis, an electrical signal is generated; in the example above, the influx of calcium can be directly related to cell depolarization. The generated electrical signal can be transmitted via plasmodesmata to neighbor connected cells in the root cortex. Once the signal reaches the low-resistance sieve tube in the phloem, it propagates throughout the entire plant (Figure 4). The question then is whether the phloem integrates multiple signals coming from individual receptor fields dispersed along the root's epithelia and how the network of cell-to-cell connectivity might provide plasticity, modulating the propagation of the electrical message by controlling the localization and activity of plasmodesmata (Figure 4). Moreover, diffusion experiments with fluorescent dyes showed that the communication of the hypocotyl epidermal cells ends at the base of the stem (Duckett et al., 1994). Therefore, it is likely that epidermal cells of the hypocotyl and root are electrically uncoupled, making sieve tubes the only pathway possible to propagate APs from the root to the shoot. All these physical barriers create nodes of resistive elements, useful for signal filtering not only at the exit of root tissue but also in and out of branches coming out of the stem.

It has been proposed that plants might integrate information through a “brain-like” structure, located in the root apex (Baluska et al., 2004; Brenner et al., 2006). However, the striking features of animal's brain not only come from the fact that neurons establish synapses, but rather from the ability to create complex cell-based logic circuits. A single neuron can host hundreds of cell-specific synapses, each one capable of plastic adaptation. In the absence of this kind of cellular interaction, it sounds unlikely that the integration of electrical information in the whole plant led to cognitive processing of sensory information. Moreover, recent works on unicellular organisms such as slime mold and bacteria demonstrate that there is no need for a central nervous system to spawn intelligent solutions (Nakagaki, 2001; Kotula et al., 2014).

Making a very simplistic picture of plant electrical connectivity, we observe it composed by a very inefficient cable surrounded by epithelial tissue formed by absorptive and excitable cells. In such a model epithelial hair cells of the root might function as spines in a neuron, providing signals generated by external stimuli to the cortex circuit where they are processed before reaching the phloem. At the same time, the transition from root to the stem might provide an additional filter, acting as a macroscopic version of the spine neck modulating the transit of long-range electrical signals. The number of cells in the cortex that are electrically connected define the size of the circuit's capacitor and outlines the electrical properties of the paths reaching the phloem. The presence of hypothetical “synapse-like” structures based on actin might contribute in shaping the network of cell-to-cell connectivity (Baluška et al., 2005). In this context, systemic soluble signals such as auxins might also play an important role in regulating cell-to-cell connectivity, for example by interacting with plasmodesmata (Baluska et al., 2004; Brenner et al., 2006). Furthermore, sensory input might also affect fundamental cable properties along the phloem conduit, shaping and filtering the propagated action potentials. The nature of the physical/molecular barriers (e.g., root cortex-to-phloem and phloem-to-leaf epithelia transitions) will be of mayor importance to understand the integration of sensory information in plants.

Nutrient sensing and long-range electrical signaling

Plants acquire the essential chemical components for the synthesis of biomolecules from the minerals present in the soil (Maathuis, 2009). Phosphorus, nitrogen, sulfur, potassium, magnesium, and calcium are nutrients required in greater quantities by higher plants (Kirkby, 2011). Therefore, plants must acquire these nutrients continuously to ensure suitable growth and development (Maathuis, 2009). Unlike heterotrophic organisms, plants mainly acquired nutrients in inorganic form by specific transporters localized in the roots. The expression of these nutrient transporters, as well as their activity, is regulated by nutrient availability, metabolism and environmental factors (Giehl and von Wirén, 2014). Lacking one of these essential nutrients has a direct impact on plant growth and development, especially in the case of root tissue (Gruber et al., 2013). Consequently, plants have developed sophisticated regulatory systems to ensure the uptake of these inorganic nutrients (Schachtman and Shin, 2007). In fact, the response to nutrient starvation involves complex signaling networks including sensor proteins (Ho et al., 2009), transcription factors (Rubio et al., 2001), miRNAs (Vidal et al., 2010), peptides (Ohkubo et al., 2017), and phytohormones (Kiba et al., 2011). Interestingly, these signaling pathways not only trigger short-term responses involving metabolic adjustments and/or regulation of nutrient transporters, but also induce modifications of the root system architecture.

Among macronutrients, phosphorus and nitrogen have a greater impact on the root architecture when compared to others (Gruber et al., 2013). Phosphate starvation strongly induces the development of root hairs (Péret et al., 2011), whereas the addition of nitrate causes an increase in root hair density (Canales et al., 2017). In addition, phosphate deficiency causes an important decrease of primary root growth and stimulates the development of lateral roots (Shahzad and Amtmann, 2017). In contrast, lower availability of nitrate increases the primary root growth and decreases the development of lateral roots. These opposite effects on the cellular architecture of the root suggest the presence of different signaling pathways for nitrate and phosphate, probably associated to electrical signals of different nature that do not necessarily propagates in the same way or generate in the same epithelial cell type.

Conclusion

Intracellular calcium variations in root hair cells of plant epidermis are generated by a mechanism involving a local variation in membrane potential, caused by electrogenic transport or by the direct activation of plant receptors by extracellular ligands. These local variations in membrane voltage will provide amplification of the input signal by increasing calcium permeability of the epithelial cell and further trigger action potentials by increasing the permeability of chloride conductances, followed by potassium/proton-driven repolarization. These electrical signals are initially propagated through cells in the cortex by highly regulated networks of plasmodesmata, and by taking advantage of the continuum of the apoplastic space until reaching the sieve tube of the phloem, where it get access to be transmitted throughout the plant body. Physical barriers, ion channel distribution, and cell-to-cell communication in the root are critical aspects that shape the electrical signals generated at the sensory tissue. All subject of cellular control, these elements might provide plasticity to plant response. The role of plasmodesmata in the propagation and fine-tuning of electrical signals in plant's sensory epithelia is a fundamental topic somewhat neglected and evidently requires more attention.

Statements

Author contributions

SB, JC, and CH-V wrote the paper. SB and JC prepared figures.

Acknowledgments

MiNICAD is a Millennium Nucleus supported by Iniciativa Científica Milenio, Ministry of Economy, Development and Tourism, Chile. Anillo Científico ACT-1401 supports SB. SB is part of CISNe-UACh and UACh Program for Cell Biology. JC is supported by FONDECYT grant 11150070. Millennium Institute for Integrative Systems and Synthetic Biology is supported by “Iniciativa Científica Milenio,” Ministry of Economy, Development and Tourism, Chile. We thank Charlotte K. Colenso for her comments on this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

AmtmannA.JelittoT. C.SandersD. (1999). K+-Selective inward-rectifying channels and apoplastic pH in barley roots. Plant Physiol.120, 331–338. 10.1104/pp.120.1.331

2

AppelH. M.CocroftR. B. (2014). Plants respond to leaf vibrations caused by insect herbivore chewing. Oecologia175, 1257–1266. 10.1007/s00442-014-2995-6

3

Arias-DarrazL.CabezasD.ColensoC. K.Alegría-ArcosM.Bravo-MoragaF.Varas-ConchaI.et al. (2015). A transient receptor potential ion channel in chlamydomonas shares key features with sensory transduction-associated TRP Channels in mammals. Plant Cell27, 177–188. 10.1105/tpc.114.131862

4

ArmstrongC. M. (2007). Life among the axons. Annu. Rev. Physiol.69, 1–18. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.120205.124448

5

ArmstrongC. M. (2015). Packaging life: the origin of ion-selective channels. Biophys. J.109, 173–177. 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.06.012

6

BalaguéC.LinB.AlconC.FlottesG.MalmströmS.KöhlerC.et al. (2003). HLM1, an essential signaling component in the hypersensitive response, is a member of the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel ion channel family. Plant Cell15, 365–379. 10.1105/tpc.006999

7

BaldwinI. T.HalitschkeR.PascholdA.von DahlC. C.PrestonC. A. (2006). Volatile signaling in plant-plant interactions: “talking trees” in the genomics era. Science311, 812–815. 10.1126/science.1118446

8

BaluskaF.MancusoS.VolkmannD.BarlowP. (2004). Root apices as plant command centres: the unique “brain-like” status of the root apex transition zone. Biology59, 7–19.

9

BaluskaF.VolkmannD.BarlowP. W. (1996). Specialized zones of development in roots: view from the cellular level. Plant Physiol.112, 3–4.

10

BaluškaF.VolkmannD.MenzelD. (2005). Plant synapses: actin-based domains for cell-to-cell communication. Trends Plant Sci.10, 106–111. 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.01.002

11

Barbier-BrygooH.De AngeliA.FilleurS.FrachisseJ.-M.GambaleF.ThomineS.et al. (2011). Anion channels/transporters in plants: from molecular bases to regulatory networks. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol.62, 25–51. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103741

12

BeckerD.GeigerD.DunkelM.RollerA.BertlA.LatzA.et al. (2004). AtTPK4, an Arabidopsis tandem-pore K+ channel, poised to control the pollen membrane voltage in a pH- and Ca2+-dependent manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 15621–15626. 10.1073/pnas.0401502101

13

BellonoN. W.BayrerJ. R.LeitchD. B.BrierleyS. M.IngrahamH. A.JuliusD.et al. (2017). Enterochromaffin cells are gut chemosensors that couple to sensory neural pathways article enterochromaffin cells are gut chemosensors that couple to sensory neural pathways. Cell170, 1–14. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.034

14

BerrierC.PeyronnetR.BettonJ. M.EphritikhineG.Barbier-BrygooH.FrachisseJ. M.et al. (2015). Channel characteristics of VDAC-3 from Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 459, 24–28. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.02.034

15

BeumerJ.CleversH. (2017). How the gut feels, smells, and talks. Cell170, 10–11. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.023

16

BezanillaF. (2008). How membrane proteins sense voltage. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.9, 323–332. 10.1038/nrm2376

17

BoseJ. C. (1907). Comparative Electro-Physiology, a Physico-Physiological Study.London: Longmans.

18

BoydC. A. (2008). Facts, fantasies and fun in epithelial physiology. Exp. Physiol.93, 303–314. 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.037523

19

BraultM.AmiarZ.PennarunA.-M.MonestiezM.ZhangZ.CornelD.et al. (2004). Plasma membrane depolarization induced by abscisic acid in Arabidopsis suspension cells involves reduction of proton pumping in addition to anion channel activation, which are both Ca2+ dependent. Plant Physiol.135, 231–243. 10.1104/pp.103.039255

20

BrennerE. D.StahlbergR.MancusoS.VivancoJ.BaluškaF.Van VolkenburghE. (2006). Plant neurobiology: an integrated view of plant signaling. Trends Plant Sci.11, 413–419. 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.06.009

21

BuchnerP.TakahashiH.HawkesfordM. J. (2004). Plant sulphate transporters: co-ordination of uptake, intracellular and long-distance transport. J. Exp. Bot.55, 1765–1773. 10.1093/jxb/erh206

22

Burch-SmithT. M.ZambryskiP. C. (2012). Plasmodesmata paradigm shift: regulation from without versus within. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol.63, 239–260. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105453

23

CanalesJ.Contreras-LópezO.ÁlvarezJ. M.GutiérrezR. A. (2017). Nitrate induction of root hair density is mediated by TGA1/TGA4 and CPC transcription factors in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J.92, 305–316. 10.1111/TPJ.13656

24

CandeoA.DocculaF. G.ValentiniG.BassiA.CostaA. (2017). Light sheet fluorescence microscopy quantifies calcium oscillations in root hairs of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol.58, 1–12. 10.1093/pcp/pcx045

25

CastellucciV.KandelE. (1976). Presynaptic facilitation as a mechanism for behavioral sensitization in Aplysia. Science194, 1176–1178. 10.1126/science.11560

26

CatterallW. A.FewA. P. (2008). Calcium channel regulation and presynaptic plasticity. Neuron59, 882–901. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.005

27

CatterallW. A.WisedchaisriG.ZhengN. (2017). The chemical basis for electrical signaling. Nat. Chem. Biol.13, 455–463. 10.1038/nCHeMBIO.2353

28

ChinK.DefalcoT. A.MoederW.YoshiokaK. (2013). The Arabidopsis cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels AtCNGC2 and AtCNGC4 work in the same signaling pathway to regulate pathogen defense and floral transition. Plant Physiol.163, 611–624. 10.1104/pp.113.225680

29

ChoiW.-G.HillearyR.SwansonS. J.KimS.-H.GilroyS. (2016). Rapid, long-distance electrical and calcium signaling in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol.67, 287–307. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043015-112130

30

ChoiW.-G.MillerG.WallaceI.HarperJ.MittlerR.GilroyS. (2017). Orchestrating rapid long-distance signaling in plants with Ca 2+, ROS and electrical signals. Plant J.90, 698–707. 10.1111/tpj.13492

31

ClemmensenC.MüllerT. D.WoodsS. C.BerthoudH.SeeleyR. J.TschöpM. H. (2017). Gut-brain cross-talk in metabolic control. Cell168, 758–774. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.025

32

ColeK. S.CurtisH. J. (1939). Electric impedance of the squid giant axon during activity. J. Gen. Physiol.22, 649–670. 10.1085/jgp.22.5.649

33

ConnA.PedmaleU. V.ChoryJ.StevensC. F.NavlakhaS. (2017). A statistical description of plant shoot architecture. Curr. Biol.27, 2078.e3–2088.e3. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.06.009

34

DarwinC. (1897). Insectivorous Plants. ed AppletonD.. New York, NY: J. Murray.

35

DaviesE. (1987). Action potentials as multifunctional signals in plants: a unifying hypothesis to explain apparently disparate wound responses. Plant Cell Environ.10, 623–631.

36

De AngeliA.MonachelloD.EphritikhineG.FrachisseJ. M.ThomineS.GambaleF.et al. (2006). The nitrate/proton antiporter AtCLCa mediates nitrate accumulation in plant vacuoles. Nature. 442, 939–942. 10.1038/nature05013

37

De AngeliA.ZhangJ.MeyerS.MartinoiaE. (2013). AtALMT9 is a malate-activated vacuolar chloride channel required for stomatal opening in Arabidopsis. Nat Commun. 4, 1804. 10.1038/ncomms2815

38

DuckettC. M.OparkaK. J.PriorD. A. M.DolanL.RobertsK. (1994). Dye-coupling in the root epidermis of Arabidopsis is progressively reduced during development. Development3255, 3247–3255.

39

DunlopJ.GradinerS. (1993). Phosphate uptake, proton extrusion and membrane electropotentials of phosphorus-deficient Trifolium repens L. J. Exp. Bot.44, 1801–1808. 10.1093/jxb/44.12.1801

40

EdelK. H.MarchadierE.BrownleeC.KudlaJ.HetheringtonA. M. (2017). The evolution of calcium-based signalling in Plants. Curr. Biol.27, R667–R679. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.020

41

EngineerC. B.Hashimoto-SugimotoM.NegiJ.Israelsson-NordströmM.Azoulay-ShemerT.RappelW. J.et al. (2015). CO2 sensing and CO2 regulation of stomatal conductance: advances and open questions. Trends Plant Sci.21, 16–30. 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.08.014

42

FinkelsteinA. (1976). Water and nonelectrolyte permeability of lipid bilayer membranes. J. Gen. Physiol.68, 127–135. 10.1085/jgp.68.2.127

43

FringsS. (2009). Primary processes in sensory cells: current advances. J. Comp. Physiol. A Neuroethol. Sens. Neural. Behav. Physiol.195, 1–19. 10.1007/s00359-008-0389-0

44

FrommJ.EschrichW. (1993). Electric signals released from roots of willow (Salix viminalis L.) change transpiration and photosynthesis. J. Plant Physiol.141, 673–680. 10.1016/S0176-1617(11)81573-7

45

FrommJ.HajirezaeiM.-R.BeckerV. K.LautnerS. (2013). Electrical signaling along the phloem and its physiological responses in the maize leaf. Front. Plant Sci.4:239. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00239

46

FrommJ.LautnerS. (2007). Electrical signals and their physiological significance in plants. Plant Cell Environ.30, 249–257. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01614.x

47

FrommJ.LautnerS. (2012). Plant electrophysiology: signaling and responses, in Plant Electrophysiology, ed VolkovA. G. (Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag), 1–377.

48

FrommJ.MeyerA. J.WeisenseelM. H. (1997). Growth, membrane potential and endogenous ion currents of willow (Salix viminalis) roots are all affected by abscisic acid and spermine. Physiol. Plant.99, 529–537. 10.1034/j.1399-3054.1997.990403.x

49

GabrielR.KesselmeierJ. (1999). Apoplastic solute concentrations of organic acids and mineral nutrients in the leaves of several fagaceae. Plant Cell Physiol.40, 604–612. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029583

50

GajdanowiczP.MichardE.SandmannM.RochaM.CorrêaL. G.Ramírez-AguilarS. J.et al. (2011). Potassium (K+) gradients serve as a mobile energy source in plant vascular tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.108, 864–869. 10.1073/pnas.1009777108

51

GalvaniL. (1791). De viribus electricitatis in motu muscularis commentarius. Bononiensi Sci. Artium Inst. atque Acad. Comment.7, 363–418. 10.1097/00000441-195402000-00023

52

GeigerD.BeckerD.VoslohD.GambaleF.PalmeK.RehersM.et al. (2009). Heteromeric AtKC1{middle dot}AKT1 channels in Arabidopsis roots facilitate growth under K+-limiting conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 21288–21295. 10.1074/jbc.M109.017574

53

GerberS. H.SüdhofT. C. (2002). Molecular determinants of regulated exocytosis. Diabetes51, 3–11. 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.S3

54

GiehlR. F.von WirénN. (2014). Root nutrient foraging. Plant Physiol.166, 509–517. 10.1104/pp.114.245225

55

GlassA. D.ShaffJ. E.KochianL. V. (1992). Studies of the uptake of nitrate in barley: IV. Electrophysiology. Plant Physiol.99, 456–463.

56

GobertA.IsayenkovS.VoelkerC.CzempinskiK.MaathuisF. J. M. (2007). The two-pore channel TPK1 gene encodes the vacuolar K+ conductance and plays a role in K+ homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 10726–10731. 10.1073/pnas.0702595104

57

GoldsworthyA. (1983). The evolution of plant action potentials. J. Theor. Biol.103, 645–648.

58

GramsT. E.LautnerS.FelleH. H.MatyssekR.FrommJ. (2009). Heat-induced electrical signals affect cytoplasmic and apoplastic pH as well as photosynthesis during propagation through the maize leaf. Plant Cell Environ.32, 319–326. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01922.x

59

GruberB. D.GiehlR. F. H.FriedelS.von WirénN. (2013). Plasticity of the Arabidopsis root system under nutrient deficiencies. Plant Physiol.163, 161–179. 10.1104/pp.113.218453

60

GunséB.PoschenriederC.RanklS.SchröederP.Rodrigo-MorenoA.BarcelóJ. (2016). A highly versatile and easily configurable system for plant electrophysiology. Methods3, 436–451. 10.1016/j.mex.2016.05.007

61

GuoJ.ZengW.ChenQ.LeeC.ChenL.YangY.et al. (2016). Structure of the voltage-gated two-pore channel TPC1 from Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature531, 196–201. 10.1038/nature16446

62

HedrichR. (2012). Ion channels in plants. Physiol. Rev.92, 1777–1811. 10.1152/physrev.00038.2011

63

HedrichR.Salvador-RecatalàV.DreyerI. (2016). Electrical wiring and long-distance plant communication. Trends Plant Sci.21, 376–387. 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.01.016

64

HegenauerV.FürstU.KaiserB.SmokerM.ZipfelC.FelixG.et al. (2016). Detection of the plant parasite Cuscuta reflexa by a tomato cell surface receptor. Science353, 478–481. 10.1126/science.aaf3919

65

HoC.-H.LinS.-H.HuH.-C.TsayY.-F. (2009). CHL1 functions as a nitrate sensor in plants. Cell138, 1184–1194. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.004

66

HodgkinA. L. (1937). Evidence for electrical transmission in nerve. J. Physiol.90, 183–210.

67

HodgkinA. L.HuxleyA. F. (1952). A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J. Physiol.117, 500–544.

68

HopeA. B. (1961a). Ionic relations of cells of chara australis. Aust. J. Biol. Sci.14, 312–322. 10.1071/BI9610312

69

HopeA. B. (1961b). The action potential in cells of chara. Nature191, 811–812. 10.1038/191811a0

70

HopeA. B.FindlayG. P. (1964). The action potential in Chara. Plant Cell Physiol.5, 377–380. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a079056

71

HosyE.VavasseurA.MoulineK.DreyerI.GaymardF.PoréeF.et al. (2003). The Arabidopsis outward K+ channel GORK is involved in regulation of stomatal movements and plant transpiration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 5549–5554. 10.1073/pnas.0733970100

72

JacksonM. B. (2006). Molecular and Cellular Biophysics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

73

JuliusD.NathansJ. (2012). Signaling by sensory receptors. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol.4:a005991. 10.1101/cshperspect.a005991

74

KanchiswamyC. N.MalnoyM.OcchipintiA.MaffeiM. E. (2014). Calcium imaging perspectives in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci.15, 3842–3859. 10.3390/ijms15033842

75

KandelE. R. (2001). The molecular biology of memory storage: a dialogue between gene and synapses. Science294, 1030–1038. 10.1126/science.1067020

76

KarbanR. (2015). Plant Sensing and Communication. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

77

KateriyaS.NagelG.BambergE.HegemannP. (2004). “Vision” in single-celled algae. News Physiol. Sci.19, 133–137. 10.1152/nips.01517.2004

78

KibaT.KudoT.KojimaM.SakakibaraH. (2011). Hormonal control of nitrogen acquisition: roles of auxin, abscisic acid, and cytokinin. J. Exp. Bot.62, 1399–1409. 10.1093/jxb/erq410

79

KimS. A.KwakJ. M.JaeS. K.WangM. H.NamH. G. (2001). Overexpression of the AtGluR2 gene encoding an Arabidopsis homolog of mammalian glutamate receptors impairs calcium utilization and sensitivity to ionic stress in transgenic plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 42, 74–84. 10.1093/pcp/pce008

80

KirkbyE. (2011). Introduction, definition and classification of nutrients, in Marschner's Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, 3rd Edn., ed MarschnerP. (London: Elsevier), 3–5. 10.1016/B978-0-12-384905-2.00001-7

81

KitagawaM.JacksonD. (2017). Plasmodesmata-mediated cell-to-cell communication in the shoot apical meristem: how stem cells talk. Plants6:12. 10.3390/plants6010012

82

KotulaJ. W.KernsS. J.ShaketL. A.SirajL.CollinsJ. J.WayJ. C.et al. (2014). Programmable bacteria detect and record an environmental signal in the mammalian gut. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.111, 4838–4843. 10.1073/pnas.1321321111

83

KurusuT.HamadaH.KoyanoT.KuchitsuK. (2012). Intracellular localization and physiological function of a rice Ca2+-permeable channel OsTPC1. Plant Signal. Behav.7, 1428–1430. 10.4161/psb.22086

84

LaanemetsK.BrandtB.LiJ.MeriloE.WangY.-F.KeshwaniM. M.et al. (2013). Calcium-dependent and -independent stomatal signaling network and compensatory feedback control of stomatal opening via Ca2+ sensitivity priming. Plant Physiol.163, 504–513. 10.1104/pp.113.220343

85

LeeJ. Y. (2015). Plasmodesmata: a signaling hub at the cellular boundary. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol.27, 133–140. 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.06.019

86

LengQ.MercierR. W.HuaB.-G.FrommH.BerkowitzG. A. (2002). Electrophysiological analysis of cloned cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. Plant Physiol. 128, 400–410. 10.1104/pp.010832

87

LengQ.MercierR. W.YaoW.BerkowitzG. A. (1999). Cloning and first functional characterization of a plant cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel. Plant Physiol. 121, 753–761.

88

LiZ. Y.XuZ. S.HeG. Y.YangG. X.ChenM.LiL. C.et al. (2013). The voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (AtVDAC1) negatively regulates plant cold responses during germination and seedling development in Arabidopsis and interacts with calcium sensorCBL1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 701–713. 10.3390/ijms14010701

89

LiuK.LiL.LuanS. (2006). Intracellular K+ sensing of SKOR, a Shaker-type K+ channel from Arabidopsis. Plant J. 46, 260–268. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02689.x

90

LiuK. H.NiuY.KonishiM.WuY.DuH.Sun ChungH.et al. (2017). Discovery of nitrate–CPK–NLP signalling in central nutrient–growth networks. Nature545, 311–316. 10.1038/nature22077

91

López-MillánA. F.MoralesF.AbadíaA.AbadíaJ. (2001). Iron deficiency-associated changes in the composition of the leaf apoplastic fluid from field-grown pear (Pyrus communis L.) trees. J. Exp. Bot.52, 1489–1498. 10.1093/jexbot/52.360.1489

92

MaW.SmigelA.WalkerR. K.MoederW.YoshiokaK.BerkowitzG. A. (2010). Leaf senescence signaling: the Ca2+-conducting Arabidopsis cyclic nucleotide gated channel2 acts through nitric oxide to repress senescence programming. Plant Physiol. 154, 733–743. 10.1104/pp.110.161356

93

MaathuisF. J. (2009). Physiological functions of mineral macronutrients. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol.12, 250–258. 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.04.003

94

MalcheskaF.AhmadA.BatoolS.MüllerH. M.Ludwig-MüllerJ.KreuzwieserJ.et al. (2017). Drought enhanced xylem sap sulfate closes stomata by affecting ALMT12 and guard cell ABA synthesis. Plant Physiol.174, 798–814. 10.1104/pp.16.01784

95

MartinacB. (2008). Sensing with Ion Channels. ed MartinacB.. Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer.

96

MasiE.CiszakM. (2014). Electrical spiking in bacterial biofilms. J. R. Soc. Interface12:20141036. 10.1098/rsif.2014.1036

97

MasiE.CiszakM.CompariniD.MonettiE.PandolfiC.AzzarelloE.et al. (2015). The Electrical network of maize root apex is gravity dependent. Sci. Rep.5:7730. 10.1038/srep07730

98

McClureP. R.KochianL. V.SpanswickR. M.ShaffJ. E. (1990). Evidence for cotransport of nitrate and protons in maize roots : I. Effects of nitrate on the membrane potential. Plant Physiol.93, 281–289.

99

MehargA. A.BlattM. R. (1995). NO3- transport across the plasma membrane of Arabidopsis thaliana root hairs: kinetic control by pH and membrane voltage. J. Membr. Biol.145, 49–66. 10.1007/BF00233306

100

MerchantS. S.ProchnikS. E.VallonO.HarrisE. H.KarpowiczS. J.WitmanG. B.et al. (2007). The Chlamydomonas genome reveals the evolution of key animal and plant functions. Science318, 245–250. 10.1126/science.1143609

101

MeyerS.MummP.ImesD.EndlerA.WederB.Al-RasheidK. A.et al. (2010). AtALMT12 represents an R-type anion channel required for stomatal movement in Arabidopsis guard cells. Plant J. 63, 1054–1062. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04302.x

102

MorganA. J.GalioneA. (2014). Two-pore channels (TPCs): current controversies. Bioessays36, 173–183. 10.1002/bies.201300118

103

MoulineK.VéryA.-A.GaymardF.BoucherezJ.PilotG.DevicM.et al. (2002). Pollen tube development and competitive ability are impaired by disruption of a Shaker K+ channel in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 16, 339–350. 10.1101/gad.213902

104

MousaviS. A.ChauvinA.PascaudF.KellenbergerS.FarmerE. E. (2013). GLUTAMATE RECEPTOR-LIKE genes mediate leaf-to-leaf wound signalling. Nature500, 422–426. 10.1038/nature12478

105

MuchhalU. S.RaghothamaK. G. (1999). Transcriptional regulation of plant phosphate transporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.96, 5868–5872.

106

NakagakiT. (2001). Smart behavior of true slime mold in a labyrinth. Res. Microbiol.152, 767–770. 10.1016/S0923-2508(01)01259-1

107

NawrathC.SchreiberL.FrankeR. B.GeldnerN.Reina-PintoJ. J.KunstL. (2013). Apoplastic diffusion barriers in arabidopsis. Arab. B.11:e0167. 10.1199/tab.0167

108

OhkuboY.TanakaM.TabataR.Ogawa-OhnishiM.MatsubayashiY. (2017). Shoot-to-root mobile polypeptides involved in systemic regulation of nitrogen acquisition. Nat. Plants3, 17029. 10.1038/nplants.2017.29

109

PeiterE.MaathuisF. J. M.MillsL. N.KnightH.PellouxJ.HetheringtonA. M.et al. (2005). The vacuolar Ca2+-activated channel TPC1 regulates germination and stomatal movement. Nature434, 404–408. 10.1038/nature03381

110

PéretB.ClémentM.NussaumeL.DesnosT. (2011). Root developmental adaptation to phosphate starvation: better safe than sorry. Trends Plant Sci.16, 442–450. 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.05.006

111

PickardB. G. (1973). Action potentials in higher plants. Bot. Rev.39, 172–201. 10.1007/BF02859299

112

PietruszkaM.StolarekJ. A. N.Pazurkiewicz-kocotK. (1997). Time evolution of the action potential in plant cells. J. Biol. Phys.23, 219–232.

113

PrindleA.LiuJ.AsallyM.LyS.Garcia-OjalvoJ.SüelG. M.et al. (2015). Ion channels enable electrical communication in bacterial communities. Nature527, 59–63. 10.1038/nature15709

114

RiverasE.AlvarezJ. M.VidalE. A.OsesC.VegaA.GutiérrezR. A. (2015). The calcium ion is a second messenger in the nitrate signaling pathway of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol.169, 1397–1404. 10.1104/pp.15.00961

115

RocchettiA.SharmaT.WulfetangeC.Scholz-StarkeJ.GrippaA.CarpanetoA.et al. (2012). The putative K(+) channel subunit AtKCO3 forms stable dimers in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 3:251. 10.3389/fpls.2012.00251

116

RonzierE.Corratgé-FaillieC.SanchezF.PradoK.BrièreC.LeonhardtN.et al. (2014). CPK13, a noncanonical Ca2+-dependent protein kinase, specifically inhibits KAT2 and KAT1shaker K+ channels and reduces stomatal opening. Plant Physiol. 166, 314–326. 10.1104/pp.114.240226

117

RubioV.LinharesF.SolanoR.MartínA. C.IglesiasJ.LeyvaA.et al. (2001). A conserved MYB transcription factor involved in phosphate starvation signaling both in vascular plants and in unicellular algae. Genes Dev.15, 2122–2133. 10.1101/gad.204401

118

SakanoK. (1990). Proton/phosphate stoichiometry in uptake of inorganic phosphate by cultured cells of Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don. Plant Physiol.93, 479–83.

119

Salvador-RecatalàV. (2016a). New roles for the Glutamate Receptor-Like 3.3, 3.5, and 3.6 genes as on/off switches of wound-induced systemic electrical signals. Plant Signal. Behav.11:e1161879. 10.1080/15592324.2016.1161879

120

Salvador-RecatalàV. (2016b). The AKT2 potassium channel mediates NaCl induced depolarization in the root of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signal. Behav.11:e1165381. 10.1080/15592324.2016.1165381

121

Salvador-RecatalàV.TjallingiiW. F.FarmerE. E. (2014). Real-time, in vivo intracellular recordings of caterpillar-induced depolarization waves in sieve elements using aphid electrodes. New Phytol.203, 674–684. 10.1111/nph.12807

122

SandersonJ. B. (1872). Note on the electrical phenomena which accompany irritation of the leaf of Dionaea muscipula. Proc. R Soc. Lond.21, 495–496. 10.1098/rspl.1872.0092

123

SattelmacherB. (2001). The apoplast and its significance for plant mineral nutrition. New Phytol.149, 167–192. 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2001.00034.x

124

SattelmacherB.HorstW. J. (2007). The Apoplast of Higher Plants: Compartment of Storage, Transport and Reactions: The Significance of the Apoplast for the Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants.Dordrecht: Springer.

125

SchachtmanD. P.ShinR. (2007). Nutrient Sensing and Signaling: NPKS. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol.58, 47–69. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.103750

126

SchroederJ. I.HedrichR.FernandezJ. M. (1984). Potassium-selective single channels in guard cell protoplasts of Vicia faba. Nature312, 361–362. 10.1038/312361a0

127

ShahzadZ.AmtmannA. (2017). Food for thought: how nutrients regulate root system architecture. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol.39, 80–87. 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.06.008

128

SomssichM.KhanG. A.PerssonS. (2016). Cell Wall heterogeneity in root development of Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci.7:1242. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01242

129

SpanswickR. M.CostertonJ. W. F. (1967). Plasmodesmata in Nitella translucens : structure and electrical resistance. J. Cell Sci.2, 451–464.

130

StrahlH.HamoenL. W. (2010). Membrane potential is important for bacterial cell division. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 12281–12286. 10.1073/pnas.1005485107

131

SzyrokiA.IvashikinaN.DietrichP.RoelfsemaM. R. G.AcheP.ReintanzB.et al. (2001). KAT1 is not essential for stomatal opening. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 2917–2921. 10.1073/pnas.051616698

132

TatedaC.WatanabeK.KusanoT.TakahashiY. (2011). Molecular and genetic characterization of the gene family encoding the voltage-dependent anion channel in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 4773–4785. 10.1093/jxb/err113

133

TaylorA. R.BrownleeC.WheelerG. L. (2012). Proton channels in algae: reasons to be excited. Trends Plant Sci.17, 675–684. 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.06.009

134

TilsnerJ.NicolasW.RosadoA.BayerE. M. (2016). Staying tight: plasmodesmal membrane contact sites and the control of cell-to-cell connectivity in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol.67, 1–28. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043015-111840

135

TrebaczK.ZawadzkiT. (1985). Light-triggered action potentials in the liverwort Conocephalum conicum. Physiol. Plant.64, 482–486. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1985.tb08526.x

136

Ullrich-EberiusC. I.NovackyA.FischerE.LüttgeU. (1981). Relationship between energy-dependent phosphate uptake and the electrical membrane potential in lemna gibba G1. Plant Physiol.67, 797–801.

137

VidalE. A.ArausV.LuC.ParryG.GreenP. J.CoruzziG. M.et al. (2010). Nitrate-responsive miR393/AFB3 regulatory module controls root system architecture in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.107, 4477–4482. 10.1073/pnas.0909571107

138

VoelkerC.SchmidtD.Mueller-RoeberB.CzempinskiK. (2006). Members of the Arabidopsis AtTPK/KCO family form homomeric vacuolar channels in planta. Plant J. 48, 296–306. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02868.x

139

VolkovA. G. (2012). Plant Electrophysiology. ed VolkovA. G.. Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer.

140

von WangenheimD.GohT.DietrichD.BennettM. J. (2017). Plant biology: building barriers… in roots. Curr. Biol.27, R172–R174. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.060

141

WaeseJ.FanJ.PashaA.YuH.FucileG.ShiR.et al. (2017). ePlant: visualizing and exploring multiple levels of data for hypothesis generation in plant biology. Plant Cell29, 1806–1821. 10.1105/tpc.17.00073

142

WangR.CrawfordN. M. (1996). Genetic identification of a gene involved in constitutive, high-affinity nitrate transport in higher plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.93, 9297–9301.

143

WangR.LiuD.CrawfordN. M. (1998). The Arabidopsis CHL1 protein plays a major role in high-affinity nitrate uptake. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. A.95, 15134–15139.

144

WangR.OkamotoM.XingX.CrawfordN. M. (2003). Microarray analysis of the nitrate response in Arabidopsis Roots and shoots reveals over 1,000 rapidly responding genes and new linkages to glucose, trehalose-6-phosphate, iron, and sulfate metabolism. Plant Physiol.132, 556–567. 10.1104/pp.103.021253

145

WardJ. M.MäserP.SchroederJ. I. (2009). Plant ion channels: gene families, physiology, and functional genomics analyses. Annu. Rev. Physiol.71, 59–82. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163204

146

WheelerG. L.BrownleeC. (2008). Ca2+ signalling in plants and green algae - changing channels. Trends Plant Sci.13, 506–514. 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.06.004

147

XuJ.LiH.-D.ChenL.-Q.WangY.LiuL.-L.HeL.et al. (2006). A protein kinase, interacting with two calcineurin B-like proteins, regulates K+ transporter AKT1 in Arabidopsis. Cell125, 1347–1360. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.011

148

YanJ.HeH.TongS.ZhangW.WangJ.LiX.et al. (2009). Voltage-dependent anion channel 2 of Arabidopsis thaliana (AtVDAC2) is involved in ABA-mediated early seedling development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 10, 2476–2486. 10.3390/ijms10062476

149

YangW.NagasawaK.MünchC.XuY.SatterstromK.JeongS.et al. (2016). Mitochondrial sirtuin network reveals dynamic SIRT3-dependent deacetylation in response to membrane depolarization. Cell0, 14447–14452. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.016

150

YangX. Y.ChenZ. W.XuT.QuZ.PanX. D.QinX. H.et al. (2011). Arabidopsis kinesin KP1 specifically interacts with VDAC3, a mitochondrial protein, and regulates respiration during seed germination at low temperature. Plant Cell23, 1093–1106. 10.1105/tpc.110.082420

151

ZawadzkiT.DaviesE.BziubinskaH.HtkbaczK.CharacteristicsK. (1991). Characteristics of action poteetials in Helianthus annuus. Physiol. Plant.83, 601–604.

152

ZebeloS. A.MatsuiK.OzawaR.MaffeiM. E. (2012). Plasma membrane potential depolarization and cytosolic calcium flux are early events involved in tomato (Solanum lycopersicon) plant-to-plant communication. Plant Sci.196, 93–100. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.08.006

153

ZhangA.RenH.-M.TanY.-Q.QiG.-N.YaoF.-Y.WuG.-L.et al. (2016). S-type anion channels SLAC1 and SLAH3 function as essential negative regulators of inward K+ channels and stomatal opening in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell28, 949–965. 10.1105/tpc.16.01050

154

ZhangJ.MartinoiaE.De AngeliA. (2014). Cytosolic nucleotides block and regulate the Arabidopsis vacuolar anion channel AtALMT9. J. Biol. Chem.289, 25581–25589. 10.1074/jbc.M114.576108

155

ZhangX.ZhangY. (2009). Neural-Immune Communication in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Host Microbe5, 425–429. 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.003

156

ZhengX.HeK.KleistT.ChenF.LuanS. (2015). Anion channel SLAH3 functions in nitrate-dependent alleviation of ammonium toxicity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 38, 474–486. 10.1111/pce.12389

157

ZhengZ.-L. (2009). Carbon and nitrogen nutrient balance signaling in plants. Plant Signal. Behav.4, 584–591. 10.4161/psb.4.7.8540

158

ZhouW.BrockmöllerT.LingZ.OmdahlA.BaldwinI. T.XuS. (2016). Evolution of herbivore-induced early defense signaling was shaped by genome-wide duplications in Nicotiana. eLife5:e19531. 10.7554/eLife.19531

159

ZimmermannM. R.MaischakH.MithöferA.BolandW.FelleH. H. (2009). System potentials, a novel electrical long-distance apoplastic signal in plants, induced by wounding. Plant Physiol.149, 1593–1600. 10.1104/pp.108.133884

Summary

Keywords

nutrient transport, action potential, ion channels, apoplast, plasmodesma, sensory epithelia

Citation

Canales J, Henriquez-Valencia C and Brauchi S (2018) The Integration of Electrical Signals Originating in the Root of Vascular Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 8:2173. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.02173

Received

03 October 2017

Accepted

12 December 2017

Published

10 January 2018

Volume

8 - 2017

Edited by

Vicenta Salvador Recatala, Ronin Institute, United States

Reviewed by

Taku Takahashi, Okayama University, Japan; Frantisek Baluska, University of Bonn, Germany

Updates

Copyright

© 2018 Canales, Henriquez-Valencia and Brauchi.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sebastian Brauchi sbrauchi@uach.cl

This article was submitted to Plant Physiology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Plant Science