Abstract

Diverse proteins are found modified with glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) at their carboxyl terminus in eukaryotes, which allows them to associate with membrane lipid bilayers and anchor on the external surface of the plasma membrane. GPI-anchored proteins (GPI-APs) play crucial roles in various processes, and more and more GPI-APs have been identified and studied. In this review, previous genomic and proteomic predictions of GPI-APs in Arabidopsis have been updated, which reveal their high abundance and complexity. From studies of individual GPI-APs in Arabidopsis, certain GPI-APs have been found associated with partner receptor-like kinases (RLKs), targeting RLKs to their subcellular localization and helping to recognize extracellular signaling polypeptide ligands. Interestingly, the association might also be involved in ligand selection. The analyses suggest that GPI-APs are essential and widely involved in signal transduction through association with RLKs.

Glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) Modification and GPI-Anchored Protein (GPI-AP) Biosynthesis

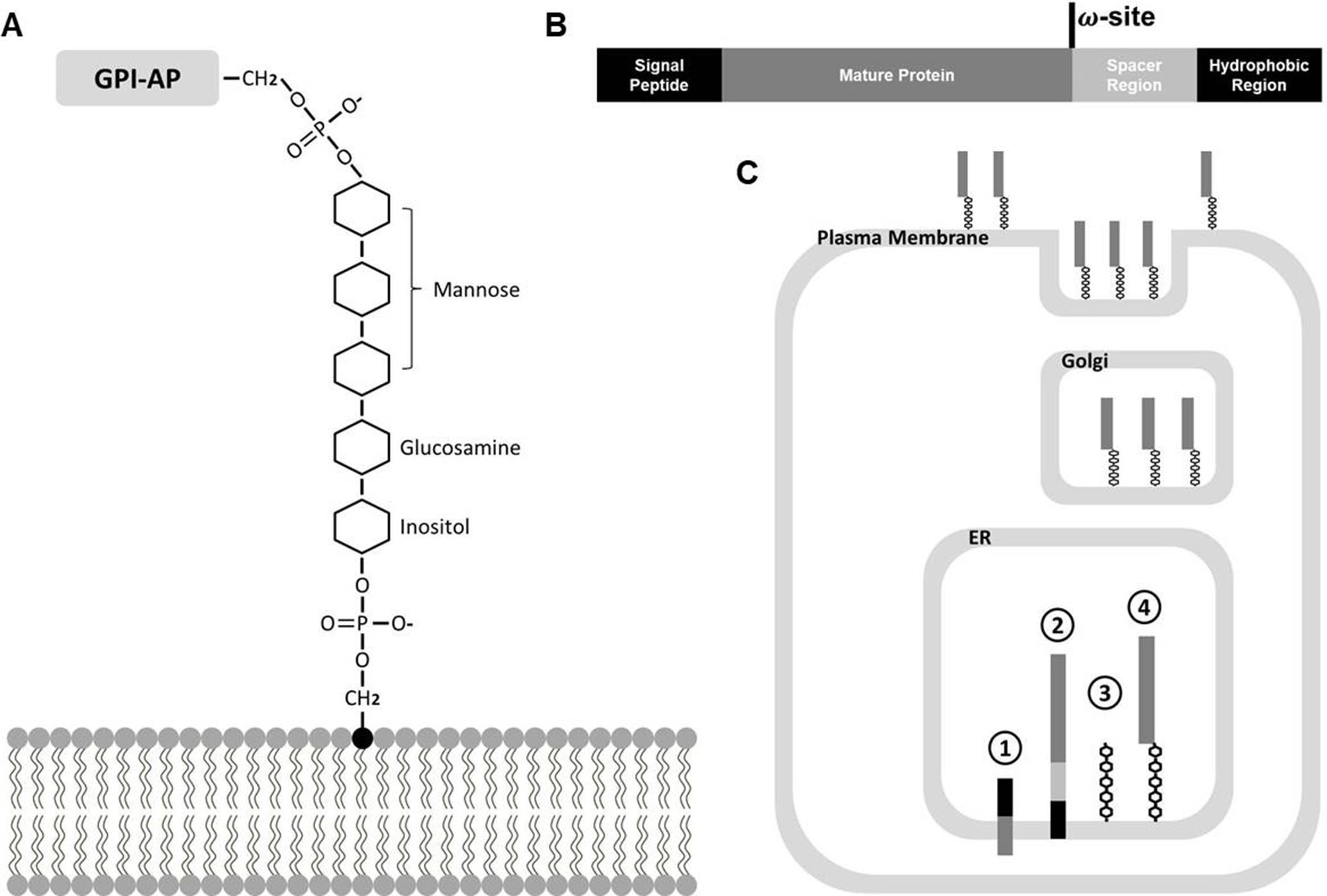

The GPI oligosaccharide structure is ubiquitous among eukaryotes with a common minimal backbone consisting of three mannoses, one non-N-acetylated glucosamine (GlcN), and inositol phospholipid, which covalently links the carboxyl terminus (C terminus) of GPI-APs to the lipid bilayer (Figure 1A) (Stevens, 1995; Oxley and Bacic, 1999; Kinoshita and Fujita, 2016). Catalyzed by a series of enzyme complexes, GPI biosynthesis starts with a lipid molecule at the rough side of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and this then flips and the synthesis is completed on the luminal side of the ER (Figure 1C) (Stevens, 1995; Takeda and Kinoshita, 1995; Kinoshita and Fujita, 2016). The typical GPI-AP precursors possess a common structure that lead them to be modified by GPI moieties inside endomembrane systems: amino-terminal (N-terminal) hydrophobic signal peptides lead them to enter the ER lumen, and during translation and maturation, C-terminal hydrophobic signals are recognized and cleaved at the ω position by a series of catalytic complexes, where the peptide bond is replaced by a bond with ethanolamine phosphate (Figures 1A–C) (Eisenhaber et al., 1998; Kinoshita, 2014a; Kinoshita and Fujita, 2016).

Figure 1

Biosynthesis of GPI moiety and GPI-AP. (A) Minimal oligosaccharide structure of GPI modification, D-Manα (1–2)-D-Manα (1–6)-D-Manα (1–4)-D-GlcN-inositol, which covalently links the C-terminus of GPI-AP and lipid molecule. (B) Common structure of GPI-AP precursor. The hydrophobic regions at the N and C termini are in black and the spacer region is in light gray. (C) Biosynthesis of GPI-APs. ① Precursor of GPI-AP enters ER, ② C terminus of GPI-AP precursor is recognized when entering ER, ③ Oligosaccharide structure of GPI modification is synthesized separately, ④ Recognized C terminus of GPI-AP is cleaved and covalently linked to the GPI moiety.

The GPI moiety allows these GPI-APs, which possess no transmembrane region, to be anchored to membrane lipid bilayers. Compared to transmembrane association, GPI anchoring has its advantages: GPI-AP shedding and release due to the presence of GPI-specific phospholipases (PLC) makes this association reversible in mammalian cells (Orihashi et al., 2012; Fujihara and Ikawa, 2016). In plants, although similar shedding and release mechanisms are indicated as various GPI-APs were identified in cell walls, thus far, no GPI-specific PLC has been identified yet (Bayer et al., 2006; Yeats et al., 2018). However, a bacterial phosphatidylinositol-specific PLC (PI-PLC) has been used for shedding GPI-APs from lipid bilayers in vitro and identifying them by further proteomic analysis in Arabidopsis (Borner et al., 2003; Elortza et al., 2003; Takahashi et al., 2016; Yeats et al., 2018).

Importance of GPI Anchoring for GPI-APs

GPI-APs and their GPI moieties were demonstrated to be crucial for diverse developmental processes in mammals and in plants, because development was found to be broadly and severely affected if GPI moiety biosynthesis is disrupted (Kawagoe et al., 1996; Gillmor et al., 2005; Kinoshita, 2014b; Bundy et al., 2016).

As the most noticeable feature, GPI anchoring was thought to be essential for the functions of GPI-APs, and their enzymatic activities or subcellular localizations could be altered by the removal of the GPI moiety (Tozeren et al., 1992; Butikofer et al., 2001; Davies et al., 2010). However, there are exceptions: the GPI anchoring of ZERZAUST and FLA4/SOS5 was shown to be dispensable for their functions in Arabidopsis (Vaddepalli et al., 2017; Xue et al., 2017).

GPI moieties also play crucial roles for driving the transient, relatively ordered membrane domains rich in sphingolipids and sterols, which are called lipid rafts or microdomains, to their target regions (Saha et al., 2016; Sezgin et al., 2017; Hellwing et al., 2018; Lebreton et al., 2018). In mammalian and yeast cells, GPI-APs are co-clustered and organized in a mixture of monomers and cholesterol-dependent nanoclusters in the same lipid raft. These exit the ER in vesicles distinct from other secretory proteins and are predominantly sorted to the apical surface to serve in protein trafficking and signaling transduction (Eisenhaber et al., 1998; Morsomme et al., 2003; Legler et al., 2005; Muniz and Zurzolo, 2014; Miyagawa-Yamaguchi et al., 2015; Sezgin et al., 2017). In Arabidopsis, although GPI modification was found essential for protein delivery from the ER to ht eplasmodesmata (Zavaliev et al., 2016), the lipid raft mechanism has not been well revealed yet.

Prediction and Identification of GPI-APs in Arabidopsis

To identify GPI-APs, various bioinformatics tools were developed, generally depending on the prediction of a specific hydrophobic region at the C terminus. Examples are big-PI Plant Predictor (http://mendel.imp.ac.at/sat/gpi/gpi_server.html) (Eisenhaber et al., 1998), PredGPI (http://gpcr2.biocomp.unibo.it/gpipe/info.htm) (Pierleoni et al., 2008), GPI-SOM (http://gpi.unibe.ch/) (Fankhauser and Maser, 2005), and fragAnchor (Poisson et al., 2007). According to the latest genomic scanning by these tools, among lower and higher eukaryotes, about 0.21% to 2.01% of total proteins from diverse families are predicted to be modified by GPI moieties, and the percentage in Arabidopsis is 0.83% (Eisenhaber et al., 2001; Poisson et al., 2007). In the meantime, proteomic assays, which depend on cleavage from membranes by bacterial PI-PLC treatment in vitro and enrichment in particular membrane fractions, were performed to compare proteomic data to bioinformatic data. To date, more than 300 GPI-APs have been identified in Arabidopsis (Borner et al., 2002; Borner et al., 2003; Elortza et al., 2003; Bayer et al., 2006; Takahashi et al., 2016).

Arabidopsis GPI-APs identified in 2003 (Borner et al., 2003; Elortza et al., 2003) and 2016 (Takahashi et al., 2016) are assembled in Tables 1 and 2 , respectively, and their functions are discussed.

Table 1

| Group | Sub-group | Total | Gene No. | Name | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGP | Classical AGP | 17 | At1g68725 | AGP19 | AGP17-19 encode a subclass of lysine-rich AGPs, among which AGP18 was reported to be essential for the initiation of female gametogenesis both at the sporophytic and gametophytic levels, and AGP19 functions in cell division and expansion (Acosta-Garcia and Vielle-Calzada, 2004; Sun et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011a; Zhang et al., 2011b). |

| At4g37450 | AGP18 | ||||

| At2g23130 | AGP17 | ||||

| At5g14380 | AGP6 | AGP6 and AGP10 are co-expressed and co-localized in pollen grains and pollen tubes and essential for pollen grain development and pollen early germination, possibly because they are essential components of the nexine layer in pollen cell wall (Levitin et al., 2008; Coimbra et al., 2009; Coimbra et al., 2010; Costa et al., 2013; Palareti et al., 2016). | |||

| At4g09030 | AGP10 | ||||

| At3g01700 | AGP11 | Its GPI modification has been experimentally confirmed, but its function has not been characterized yet (Schultz et al., 2000). | |||

| At5g64310 | AGP1 | ||||

| At2g22470 | AGP2 | ||||

| At4g40090* | AGP3 | Shown as At4g40091 in Borner et al. (2003). | |||

| At5g10430 | AGP4/JAGGER | Essential for the degeneration of synergid cells, which guide the pollen tube attraction after acceptance of the unique pollen tube, and for prohibition of polytubey (Pereira et al., 2016a; Pereira et al., 2016b). | |||

| At1g35230 | AGP5 | ||||

| At5g65390 | AGP7 | ||||

| At2g14890 | AGP9 | ||||

| At5g18690 | AGP25 | ||||

| At2g47930 | AGP26 | ||||

| At3g06360 | AGP27 | ||||

| At4g16980* | Shown as At4g16985 in Borner et al. (2003). | ||||

| AG peptides (Schultz et al., 2004), a group of GPI-anchored arabinogalactan polypeptides | 12 | At3g13520 | AGP12 | ||

| At4g26320 | AGP13 | ||||

| At5g56540 | AGP14 | AGP14 and At3g01730 regulate root hair elongation exhibiting environmental response behavior, potentially by controlling root hair cell wall synthesis (Lin et al., 2011). | |||

| At3g01730 | |||||

| At5g11740 | AGP15 | ||||

| At2g46330 | AGP16 | ||||

| At3g61640 | AGP20 | ||||

| At1g55330 | AGP21 | ||||

| At5g53250 | AGP22 | ||||

| At3g57690 | AGP23 | ||||

| At5g40730 | AGP24 | ||||

| At3g20865 | AGP40 | ||||

| FLAs (fasciclin-like AGPs) | 16 | At5g55730 | FLA1 | Involved in lateral root initiation and shoot regeneration potentially by regulating cell-type specification (Johnson et al., 2011). | |

| At4g12730 | FLA2 | ||||

| At2g24450 | FLA3 | Specifically expressed in pollen grains and tubes and involved in microspore development potentially through the regulation of cellulose deposition (Li et al., 2010). | |||

| At3g46550 | FLA4/SOS5 | Directly associates with cell wall RLKs FEI1/2 to perceive environmental stimuli in apoplast by altering its conformation and association with FEI1/2. This complex could regulate cell wall synthesis and composition by collaborating with CESA5. Interestingly, this regulation could also be controlled by ethylene and ABA with unclear mechanism. Surprisingly, the absence of GPI anchors only affected their PM localization but not their function (Harpaz-Saad et al., 2012; Seifert et al., 2014; Basu et al., 2016; Griffiths et al., 2016; Xue et al., 2017; Turupcu et al., 2018). | |||

| At4g31370 | FLA5 | ||||

| At2g20520 | FLA6 | ||||

| At2g04780 | FLA7 | ||||

| At2g45470 | FLA8/AGP8 | ||||

| At1g03870 | FLA9 | Response to drought stress in maize and Arabidopsis (Cagnola et al., 2018). | |||

| At3g60900 | FLA10 | ||||

| At5g03170 | FLA11 | FLA11 and FLA12 affect cellulose deposition and formation of secondary cell wall composition (Ito et al., 2005; MacMillan et al., 2010). | |||

| At5g60490 | FLA12 | ||||

| At5g44130 | FLA13 | ||||

| At3g12660 | FLA14 | ||||

| At1g30800 | |||||

| At4g12950 | |||||

| Extensin related | Extensin related | 7 | At1g02405 | Proline-rich protein Proline-rich protein Proline-rich protein Proline-rich protein | |

| At1g70990 | |||||

| At4g16140 | |||||

| At5g11990 | |||||

| At3g06750 | Hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein family protein Hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein family protein | ||||

| At1g23040 | |||||

| At5g49280 | Hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein family protein | ||||

| Phytocyanins (Nersissian et al., 1998) | Stellacyanin like (Hart et al., 1996) | 4 | At5g20230 | BCB/SAG14 | Regulates lignin biosynthesis induced by oxidative stress (Ezaki et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2011; Ji et al., 2015; Tang et al., 2016). |

| At2g31050 | Copredoxin superfamily protein Copredoxin superfamily protein | ||||

| At2g26720 | |||||

| At5g26330 | Copredoxin superfamily protein | ||||

| Uclacyanin like | 8 | At1g22480 | Copredoxin superfamily protein | ||

| At1g72230 | Copredoxin superfamily protein | ||||

| At3g27200 | Copredoxin superfamily protein | ||||

| At2g32300 | UCC1 | UCC1, UCC2 and UCC3 encode copper binding proteins (Nersissian et al., 1998). | |||

| At2g44790 | UCC2 | ||||

| At3g60280 | UCC3 | ||||

| At3g60270 | Copredoxin superfamily protein | ||||

| At5g07475 | Copredoxin superfamily protein | ||||

| ENODL (early nodulin like) | 17 | At5g53870 | ENODL1 | ||

| At4g27520 | ENODL2 | Catalyzes the formation of pyroglutamic acid at the N-terminus of several peptides and proteins (Schilling et al., 2007). | |||

| At4g28365 | ENODL3 | ||||

| At4g32490 | ENODL4 | ||||

| At3g18590 | ENODL5 | ||||

| At1g48940 | ENODL6 | ||||

| At1g79800 | ENODL7 | ||||

| At1g64640* | ENODL8 | Classified as unknown/hypothetical in Borner et al. (2003). | |||

| At3g20570 | ENODL9 | Involved in starch mobilization and reproductive progresses (Khan et al., 2007). | |||

| At2g23990 | ENODL11 | ||||

| At4g30590 | ENODL12 | ||||

| At5g25090 | ENODL13 | ||||

| At2g25060 | ENODL14 | ENODL14 and ENODL15 directly interact with RLK FERONIA and regulate maternally controlled male-female communication and fertilization (Escobar-Restrepo et al., 2007; Hou et al., 2016). | |||

| At4g31840 | ENODL15 | ||||

| At3g01070 | ENODL16 | ||||

| At5g15350 | ENODL17 | ||||

| At1g08500 | ENODL18 | ||||

| COBRA family | COBRA family [all 12 COBRA members, except COBL5, was predicted to be GPI-AP (Roudier et al., 2002)] | 10 | At5g60920 | COBRA/COB | Localizes on plasma membrane polarly and regulates cell wall biosynthesis and cellulose microfibrils in Arabidopsis and tomato (Schindelman et al., 2001; Roudier et al., 2005). Its regulation responses to various stresses potentially by involving in jasmonic acid-related signaling pathway (Ko et al., 2006; Dinneny et al., 2008; Sorek et al., 2015). |

| At3g02210 | COBL1 | ||||

| At3g29810 | COBL2 | Plays a role in the deposition of crystalline cellulose in secondary cell wall structures during seed coat epidermal cell differentiation, and the regulation is independent of the FEI-SOS pathway (Ben-Tov et al., 2015; Ben-Tov et al., 2018). | |||

| At5g15630 | COBL4/IRX6 | Participates in regulating secondary cell wall biosynthesis (Taylor-Teeples et al., 2015; Niu et al., 2018). | |||

| At1g09790 | COBL6 | ||||

| At3g16860 | COBL8 | ||||

| At3g20580 | COBL10 | Crucial for pollen tube directional growth by affecting the deposition of the apical pectin cap and cellulose microfibrils of pollen tubes and might also be involved in male-female communications (Li et al., 2013). | |||

| At4g16120 | COBL7/SEB1 | ||||

| At4g27110 | COBL11 | ||||

| At5g49270 | COBL9/DER9/SHV2 | Involved in ethylene and auxin controlled root hair development (Parker et al., 2000; Ringli et al., 2005; Jones et al., 2006). | |||

| GPDL glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase like (GDPD-like) family (Cheng et al., 2011) | 6 | At1g66970 | GDPDL1/SHV3-Like2/SVL2 | Homologue of the extracellular domain of RLK GDPDL2/AT1g66980. Possesses the capacity to hydrolyze glycerophosphodiesters, which is stimulated by Ca2+ in Arabidopsis, and plays an important role in various physiological processes (Cheng et al., 2011). | |

| At3g20520 | GDPDL5 | ||||

| At4g26690 | GDPDL3/SHV3 | SHV3 and GDPDL4 are involved in primary cell wall organization, which regulates cell polar expansion by coordinating proton pumping and cellulose synthesis (Parker et al., 2000; Hayashi et al., 2008; Yeats and Somerville, 2016; Yeats et al., 2016). | |||

| At5g55480 | GDPDL4/SVL1 | ||||

| At5g58050 | GDPDL6/SVL4 | ||||

| At5g58170 | GDPDL7/SVL5 | ||||

| HIPL | 3 | At1g74790 | |||

| At5g39970 | |||||

| At5g62630 | HIPL2 | ||||

| β-1,3 Glucanas-es | 31 | At1g11830** | Does not exist | Shown in Borner et al. (2003) but could not be found in databases | |

| At1g26450 | Carbohydrate-binding X8 domain superfamily protein | ||||

| At1g64760 | ZERZAUST, ZET | Required for cell wall organization during tissue morphogenesis potentially by being mediated by RLKs. Interestingly, the presence of GPI anchor is dispensable for its function (Fulton et al., 2009; Vaddepalli et al., 2017; Vaddepalli et al., 2019). | |||

| At2g19440 | ZETH | Homolog of ZET and works redundantly with ZET (Vaddepalli et al., 2019). | |||

| At1g32860 | Glycosyl hydrolase superfamily protein | ||||

| At1g77780 | Glycosyl hydrolase superfamily protein | ||||

| At2g26600 | Glycosyl hydrolase superfamily protein | ||||

| At3g15800 | Glycosyl hydrolase superfamily protein | ||||

| At1g66250 | O-Glycosyl hydrolase family 17 protein | ||||

| At2g01630 | O-Glycosyl hydrolase family 17 protein | ||||

| At3g04010 | O-Glycosyl hydrolase family 17 protein | ||||

| At3g13560 | O-Glycosyl hydrolase family 17 protein | ||||

| At3g24330 | O-Glycosyl hydrolase family 17 protein | ||||

| At4g29360 | O-Glycosyl hydrolase family 17 protein | ||||

| At4g31140 | O-Glycosyl hydrolase family 17 protein | ||||

| At5g18220 | O-Glycosyl hydrolase family 17 protein | ||||

| At5g20870 | O-Glycosyl hydrolase family 17 protein | ||||

| At5g42720 | O-Glycosyl hydrolase family 17 protein | ||||

| At5g56590 | O-Glycosyl hydrolase family 17 protein | ||||

| At5g58090 | O-Glycosyl hydrolase family 17 protein | ||||

| At5g58480 | O-Glycosyl hydrolase family 17 protein | ||||

| At5g64790 | O-Glycosyl hydrolase family 17 protein | ||||

| At5g42100 | BG_PPAP | Regulates the gating of plasmodesmata and the palsmodesmatal transport through plasmodesmal callose degradation (Zavaliev et al., 2016). | |||

| At5g61130 | PDCB1 | PCDB1-PDCB3, At1g69295, and At3g58100 encode a subgroup of X8-domian containing GPI-APs, which localize to the plasmodesmata and predicted to bind callose (Simpson et al., 2009; Zavaliev et al., 2016). | |||

| At5g08000 | PDCB2 | ||||

| At1g18650 | PDCB3 | ||||

| At1g69295 | |||||

| At3g58100 | |||||

| At1g09460*** | At1g09460, At2g30933, At2g03505, and At4g13600 encode a subgroup of X8-domain-containing GPI-APs (Simpson et al., 2009) but not included in Borner et al. (2003). | ||||

| At2g30933*** | |||||

| At2g03505*** | |||||

| At4g13600*** | |||||

| Polygalacturonase | 1 | At3g15720 | Pectin lyase-like superfamily protein | ||

| Pectate lyases | 3 | At3g53190 | Pectin lyase-like superfamily protein | ||

| At3g54920 | PMR6 | Required for fungal infection progress and effects cell wall composition through pectin synthesis (Vogel et al., 2002; Vogel et al., 2004). | |||

| At5g04310 | Pectin lyase-like superfamily protein | ||||

| Proteases | Aspartyl proteases | 10 | At1g05840 | ||

| At1g08210 | |||||

| At5g36260 | A36 | A36 and A39 co-localize with GPI-anchored COBL10 and involved in pollen tube germination, vitality, and pollen tube guidance (Gao et al., 2017; Gao et al., 2017). | |||

| At1g65240 | A39 | ||||

| At2g17760 | |||||

| At3g02740 | |||||

| At3g51330 | |||||

| At3g51350 | |||||

| At4g35880 | |||||

| At5g10080 | |||||

| Metalloproteases | 5 | At1g24140 | AT3-MMP | This subgroup of proteases contribute to the MAMP-triggered callose deposition in response to the bacterial flagellin peptide flg22, which suggests their involvement in the pattern-triggered immunity in interactions with necrotrophic and biotrophic pathogen (Zhao et al., 2017). | |

| At1g59970 | AT5-MMP | ||||

| At1g70170 | AT2-MMP | ||||

| At2g45040 | AT4-MMP | ||||

| At4g16640 | AT1-MMP | ||||

| Cys proteases | 1 | At3g43960 | Regulates root hair elongation (Lin et al., 2011). | ||

| LTPL (lipid transfer-like protein) | 26 | At1g05450 | |||

| At1g18280 | LTPG3 | ||||

| At1g27950 | LTPG1/LTPG | LTPG1, LTPG2, LTPG5, and LPTG6 are involved in cuticular wax export or accumulation in epidermal cells and during pathogen defense (Debono et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2013; Edstam and Edqvist, 2014; Fahlberg et al., 2019). | |||

| At3g43720 | LTPG2 | ||||

| At3g22600 | LTPG5 | ||||

| At1g55260 | LTPG6 | ||||

| At1g62790 | |||||

| At1g73890 | |||||

| At2g13830 | |||||

| At2g27130 | |||||

| At2g44290 | |||||

| At2g44300 | |||||

| At2g48130 | LTPG15 | Involved in suberin monomer export in seed coats (Lee and Suh, 2018). | |||

| At2g48140 | EDA4 | ||||

| At1g36150 | |||||

| At3g22611** | Does not exist | Shown in Borner et al. (2003) but could not be found in databases. | |||

| At3g58550 | |||||

| At4g08670 | LTPG4 | ||||

| At4g12360 | |||||

| At4g14805 | |||||

| At4g14815 | |||||

| At4g22630 | |||||

| At4g22640 | |||||

| At5g09370 | |||||

| At5g13900 | |||||

| At5g64080 | XYP1 | XYP1 and XYP2 function as mediators of inductive cell-cell interaction in vascular development (Motose et al., 2004). XYP2 was not shown in (Borner et al., 2003) due to its alternative splicing. | |||

| At2g13820*** | XYP2 | ||||

| SKU5-Similar family | 4 | At4g12420 | SKU5 | SKU5 is involved in root directional growth (Sedbrook et al., 2002), and this group of genes is redundantly essential for root development by regulating cell polar expansion and cell wall synthesis (Zhou, 2019a, Zhou, 2019b). SKS3 was not shown in Borner et al. (2003) due to alternative splicing. | |

| At4g25240 | SKS1 | ||||

| At5g51480 | SKS2 | ||||

| At5g48450*** | SKS3 | ||||

| RLP | RLK3 like (DUF26) | 5 | At1g63550 | This subgroup of RLPs homolog with the extracellular region of a group of cysteine-rich RLKs (CRKs). | |

| At1g63580 | |||||

| At5g41280 | |||||

| At5g41290 | |||||

| At5g41300 | |||||

| PRK5 like | 3 | At1g20030 | This subgroup of pathogenesis-related thaumatin superfamily proteins are similar with the extracellular region of an osmotin/thaumatin-like protein kinase PR5K (PR5-like receptor kinase) (Wang et al., 1996; Abdin et al., 2011). | ||

| At4g36010 | |||||

| At4g38660 | |||||

| Lectin like | 1 | At1g07460 | Homologue of L-type lectin receptor kinase III, 1 (LECRK-III, 1) | ||

| LysM domains | 3 | At1g21880 | LYM1/LYP2 | LYM1 and LYM3 physically interact with the major components of bacterial cell walls and peptidoglycans and work together with a LysM RLK CERK1 to mediate perception and immunity to infection (Willmann et al., 2011). | |

| At1g77630 | LYM3/LYP3 | ||||

| At2g17120 | LYM2/LYP1 | ||||

| Cf-2/Cf-5 like | 3 | At1g80080 | ATRLP17/TMM | Forms various complexes with different transmembrane RLKs from ERECTA family (ERf) and/or SERKs to recognize their ligands, such as epidermal patterning factors (EPFs) and CHAL, and then to regulate stomatal development and immune response through the activation of intracellular MAPK cascade (Bundy et al., 2016; Abrash and Bergmann, 2010; Geisler et al., 2000; Geisler et al., 1998; Jakoby et al., 2006; Jorda et al., 2016; Kobe and Kajava, 2001; Lee et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2017; Meng et al., 2015; Rasmussen et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2008; Yan et al., 2014; Bhave et al., 2009). | |

| At2g42800 | ATRLP29 | ||||

| At4g28560 | RIC7 | Interacts with a component of the vesicle trafficking machinery and acts as its linker with ROP2 (Jeon et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2010; Hwang et al., 2011; Hong et al., 2016). However, the presence of its GPI anchoring is doubted (Jeon et al., 2008; Yeats et al., 2018). | |||

| Other | 1 | At1g10375** | Does not exist | Shown in Borner et al. (2003) but could not be found in databases. | |

| At4g23180*** | Encoded by an alternative variant of CRK10, which was believed to encode a cysteine-rich RLK (Grojean and Downes, 2010). Not shown in Borner et al. (2003) due to alternative splicing. | ||||

| GPI-anchored peptides | GPI-anchored peptides | 8 | At3g01940 | ||

| At3g01950 | |||||

| At5g14110 | |||||

| At5g40960 | |||||

| At5g40970 | |||||

| At5g40980 | AT.I.24-6 | ||||

| At5g50660 | |||||

| At5g63500 | |||||

| LORELEI-like family | 4 | AT4g26466*** | LORELEI | LLG1 chaperones transmembrane RLK FERONIA from the ER to the plasma membrane, where both LORELEI and LLG1 could associate with FERONIA to recognize extracellular ligands to regulate sperm cell release during double fertilization and early seed development (Capron et al., 2008; Duan et al., 2010; Tsukamoto et al., 2010; Meng et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2012; Li C et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016; Liao et al., 2017; Stegmann et al., 2017; Feng et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2018; Yin et al., 2018). Interestingly, LLG1 was also reported to associate with RLK FLS2 and medicate PAMP recognition (Shen et al., 2017). LORELEI was not shown in Borner et al. (2003). | |

| At2g20700 | LLG2 | ||||

| At4g28280 | LLG3 | ||||

| At5g56170 | LLG1 | ||||

| PLC-like phosphodiesterases | 1 | At5g67130* | Regulates gametophytic self-incompatibility (Qu et al., 2017). Shown as At5g67131 in Borner et al. (2003). | ||

| Other | 6 | At5g07190 | SEED GENE 3 | ||

| At5g62200 | ATS3B | ||||

| At5g62210 | ATS3 | ||||

| At3g07390 | |||||

| At1g24520 | BCP1 | Active in both diploid tapetum and haploid microspores and required for pollen fertility (Theerakulpisut et al., 1991; Xu et al., 1995; Luo et al., 2000). | |||

| At4g15460 | A glycine-rich protein | ||||

| Unknown/hypothetical | 33 | At1g54860 | Identified in oil bodies purified from Arabidopsis seeds (Jolivet et al., 2004). | ||

| At3g06035 | |||||

| At5g19230 | |||||

| At5g19250 | |||||

| At1g07135 | A glycine-rich protein | ||||

| At1g09175 | |||||

| At3g04640 | A glycine-rich protein | ||||

| At3g55790 | |||||

| At1g29980 | |||||

| At2g34510 | |||||

| At5g14150 | |||||

| At3g18050 | |||||

| At4g28100 | |||||

| At3g27410 | |||||

| At5g40620 | |||||

| At1g23050 | |||||

| At1g70985 | Hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein family protein | ||||

| At5g26290 | RAMCAP | Involved in both male and female gametophytic development (Singh et al., 2017). | |||

| At5g26300 | TRAF-like protein | ||||

| At3g24518** | Natural antisense transcript overlaps with AT3G24520 | ||||

| At5g35890 | β-galactosidase-related protein | ||||

| At1g21090 | Cupredoxin superfamily protein | ||||

| At1g56320 | |||||

| At1g61900 | |||||

| At2g28410 | |||||

| At2g29660 | Zinc finger (C2H2-type) family protein | ||||

| At3g26110 | Anther-specific protein agp1-like protein | ||||

| At3g44100 | MD-2-related lipid recognition domain-containing protein | ||||

| At3g58890 | RNI-like superfamily protein | ||||

| At3g61980 | KPI-1 | Putative Kazal-type serine proteinase inhibitor, which is supposed to limit and control the spread of serine proteinase activity, and function during defense mechanism (Pariani et al., 2016). | |||

| At4g14746 | Neurogenic locus notch-like protein | ||||

| At4g28085 | |||||

| At4g38140 | RING/U-box superfamily protein | ||||

| At5g08210** | MIR834A | Encoded a microRNA of unknown function | |||

| At5g14190** | Does not exist | Shown in Borner et al. (2003) but could not be found in genomic or proteomic database actually | |||

| At5g16670** | Does not exist | Shown in Borner et al. (2003) but could not be found in genomic or proteomic database actually | |||

| At5g22430 | Pollen Olee 1 allergen and extensin family protein |

A review of predicted GPI-APs updated from (Borner et al., 2003; Elortza et al., 2003).

*Shown incorrectly in Borner et al. (2003).

**Shown in Borner et al. (2003) but does not exist in genomic or proteomic database or encodes non-coding RNA.

***Not shown in Borner et al. (2003) but could be predicted or studied as GPI-APs.

Table 2

| Group | Sub-group | Total | Gene No. | Name | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTPL (lipid transfer protein) | 3 | AT3g22620 | |||

| AT2g13820 | XYP2 | Functions as a mediator of inductive cell-cell interaction in vascular development (Motose et al., 2004). | |||

| AT4g22505 | Bifunctional inhibitor/lipid-transfer protein/seed storage 2S albumin superfamily protein | ||||

| β-1,3 Glucanases | 3 | AT1g11820 | O-Glycosyl hydrolase family 17 protein | ||

| AT4g34480 | O-Glycosyl hydrolase family 17 protein | ||||

| AT3g57240 | |||||

| PLC-like phosphodiesterases | 1 | AT4g36945 | |||

| RLP | 2 | AT3g17350 | Wall-associated kinase family protein | ||

| AT4g18760 | RLP51/SNC2 | Functions upstream of ankyrin-repeat transmembrane protein BDA1 to regulate plant immunity through transcriptional factor WRKY70 (Zhang et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2012). | |||

| Oligogalacturonide oxidase | 2 | AT5g66680 | DGL1 | Subunit of the oligosaccharyltransferase complex, which catalyzes N-glycosylation of nascent secretory polypeptides in the lumen of the ER (Lerouxel et al., 2005; Qin et al., 2013; Jeong et al., 2018). | |

| AT4g20830 | ATBBE20/OGOX1 | Required in plant immunity (Benedetti et al., 2018). | |||

| β-Glucuronidase | 2 | AT5g07830 | GUS2 | Contributes to the glycosylation of AGPs (Eudes et al., 2008). | |

| AT5g34940 | GUS3 | ||||

| LRR extensin | 1 | AT4g18670 | LRX5 | Physically associates with RALF peptides RALF22/23, which activate FERONIA and transduce extracellular signals to regulate plant growth and salt stress tolerance (Zhao et al., 2018). | |

| AGP | 1 | AT1g28290 | AGP31 | Involved in cell wall structure and network (Hijazi et al., 2014). | |

| Expansin | 1 | AT1g69530 | EXPA1 | Regulates stomatal opening by altering the structure of the guard cell wall (Wei et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011c). | |

| PME and PMEI proteins | PME (pectin methylesterase) | 1 | AT3g14310 | PME3 | Catalyzes the demethylesterification of pectin homogalacturonan domains in plant cell walls, and its activity could be regulated by PMEIs (Guenin et al., 2011; Senechal et al., 2015). |

| PMEI (pectin methylesterase inhibitors) | 5 | AT2g31430 | PMEI5 | A pectin methylesterase inhibitor (Muller et al., 2013). | |

| AT5g62360 | PMEI13 | Regulates root growth under cold and salt stresses (Chen et al., 2018). | |||

| AT3g62820 | Plant invertase/PMEI Inhibitor superfamily protein | ||||

| AT3g17130 | Plant invertase/PMEI inhibitor superfamily protein | ||||

| AT5g62350 | Plant invertase/PMEI inhibitor superfamily protein | ||||

| GDSL motif esterase/acyltransferase/lipase | 4 | AT4g30140 | CDEF1 | Possesses esterase activity and candidates for the unidentified plant cutinase for cutile biosynthesis (Takahashi et al., 2010). | |

| AT5g45950 | GDSL-motif esterase/acyltransferase/lipase | ||||

| AT4g01130 | GDSL-motif esterase/acyltransferase/lipase | ||||

| AT3g16370 | GDSL-motif esterase/acyltransferase/lipase | ||||

| Proteases | 3 | AT1g30600 | Subtilisin-like serine protease | ||

| AT4g21650 | SBT3.13 | Subtilisin-like serine protease | |||

| AT3g61820 | Eukaryotic aspartyl protease family protein | ||||

| Others | 25 | AT2g30700 | |||

| AT1g65870 | Disease resistance responsive | ||||

| AT5g42370 | Calcineurin-like metallophosphoesterase superfamily protein | ||||

| AT2g03530 | UPS2 | Mediates high-affinity uracil and 5-fluorouracil (a toxic uracil analogue) transport (Schmidt et al., 2004). | |||

| AT1g72610 | GLP1 | Localizes to the extracellular matrix and being considered to be involved in many physiological responses including environmental stress (Membre et al., 2000). | |||

| AT5g19240 | Glycoprotein membrane precursor GPI anchored | ||||

| AT5g04885 | BGLC3 | Possesses β-glucosidases activity and works redundantly with its homolog BGLC1 with absent GPI anchor to remove unsubstituted Glc residues from the nonreducing end of xyloglucan molecule (Sampedro et al., 2017). | |||

| AT3g05910 | PAE12 | Pectin acetyesterase 12 | |||

| AT3g47800 | Galactose mutarotase-like superfamily protein | ||||

| AT5g55750 | Hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein family protein | ||||

| AT3g53010 | Carbohydrate esterase | ||||

| AT4g29520 | SES1 | ER localized molecular chaperone and required for heat tolerance (Guan et al., 2019). | |||

| AT3g07570 | Cytochrome B561 | ||||

| AT1g75680 | GH9B7 | Glycosyl hydrolase | |||

| AT5g14030 | Translocon-associated protein beta unit (TRAPB) | ||||

| AT3g29360 | UGD2 | Products UDP-glucuronic acid, which is the common precursor for arabinose, xylose, galacturonic acid, and apiose residues in cell wall biosynthesis (Reboul et al., 2011; Siddique et al., 2012). | |||

| AT5g64620 | C/VIF2 | Inhabits both plant cell wall invertase and vacuolar invertase (Link et al., 2004). | |||

| AT1g68560 | XYL1 | Releases xylosyl residues from xyloglucan oligosaccharides at the non-reducing end, which alters xyloglucan composition and results in growth defects (Sampedro et al., 2010; Gunl and Pauly, 2011). | |||

| AT4g34180 | CYCLASE1 | A negative regulator of cell death and regulates pathogen-induced symptom development in Arabidopsis (Smith et al., 2015). | |||

| AT4g35220 | CYCLASE2 | ||||

| AT5g08260 | SCPL35 | Serine carboxypeptidase-like 35 | |||

| AT2g33530 | SCPL46 | ||||

| AT5g43600 | AAH-2/UAH | Its allantoate amidohydrolases enzymatic activity is required for nitrogen recycling from purine ring in plants (Werner et al., 2008). | |||

| AT4g15630 | CASPL1E1 | ||||

| AT4g15620 | CASPL1E2 | ||||

| Not typical GPI-Aps | |||||

| Transmembrane protein with predicted omega domain at C terminus | 8 | AT4g02420 | |||

| AT1g53210 | |||||

| AT1g55910 | ZIP11 | ||||

| AT3g48200 | |||||

| AT1g42470 | ATNPC1-1 | ||||

| AT1g70940 | PIN3 | Auxin efflux carrier family protein | |||

| AT2g01420 | PIN4 | Auxin efflux carrier family protein | |||

| AT5g55960 | |||||

| Predicted cytosol protein without signal peptide at N terminus | 13 | AT1g65820 | Microsomal glutathione S-transferase | ||

| AT2g45140 | PVA12 | ||||

| AT2g32240 | PICC | ||||

| AT5g22780 | AP-2 | Adaptin family protein | |||

| AT4g11380 | |||||

| AT5g22770 | AP2A1 | ||||

| AT3g27570 AT1g06530 | PMD2 | Sucrase/ferredoxin-like family protein | |||

| AT1g22882 | SUN3 | ||||

| AT4g32150 AT5g11150 | VAMP711 VAMP713 | VAMP711 and VAMP713 are SNARE family proteins that regulate endomembrane trafficking (Leshem et al., 2010; Ichikawa et al., 2015; Xue et al., 2018). | |||

| AT1g16240 | SYP51 | A SNARE family protein that interacts with aquaporin and regulates post-Golgi traffic and vacuolar sorting (De Benedictis et al., 2013; Barozzi et al., 2018). | |||

| AT5g16830 | PEP12/SYP21 | A SNARE family protein involved in protein sorting and plant development (Foresti et al., 2006; Silady et al., 2008; Shirakawa et al., 2010; Touihri et al., 2011). | |||

| AT5g46860 | SGR3/SYP22 | A SNARE family protein | |||

| Transmembrane RLKs | 3 | AT5g48380 | BIR1 | Functions as a negative regulator of basal immunity and cell death in Arabidopsis (Liu et al., 2016). | |

| ATIg51940 | LYK3 | Regulates the cross-talk between immunity and abscisic acid responses (Paparella et al., 2014). | |||

| AT1g63430 | Transmembrane RLK | ||||

GPI-APs identified in 2016 that not included in previous study in 2003.

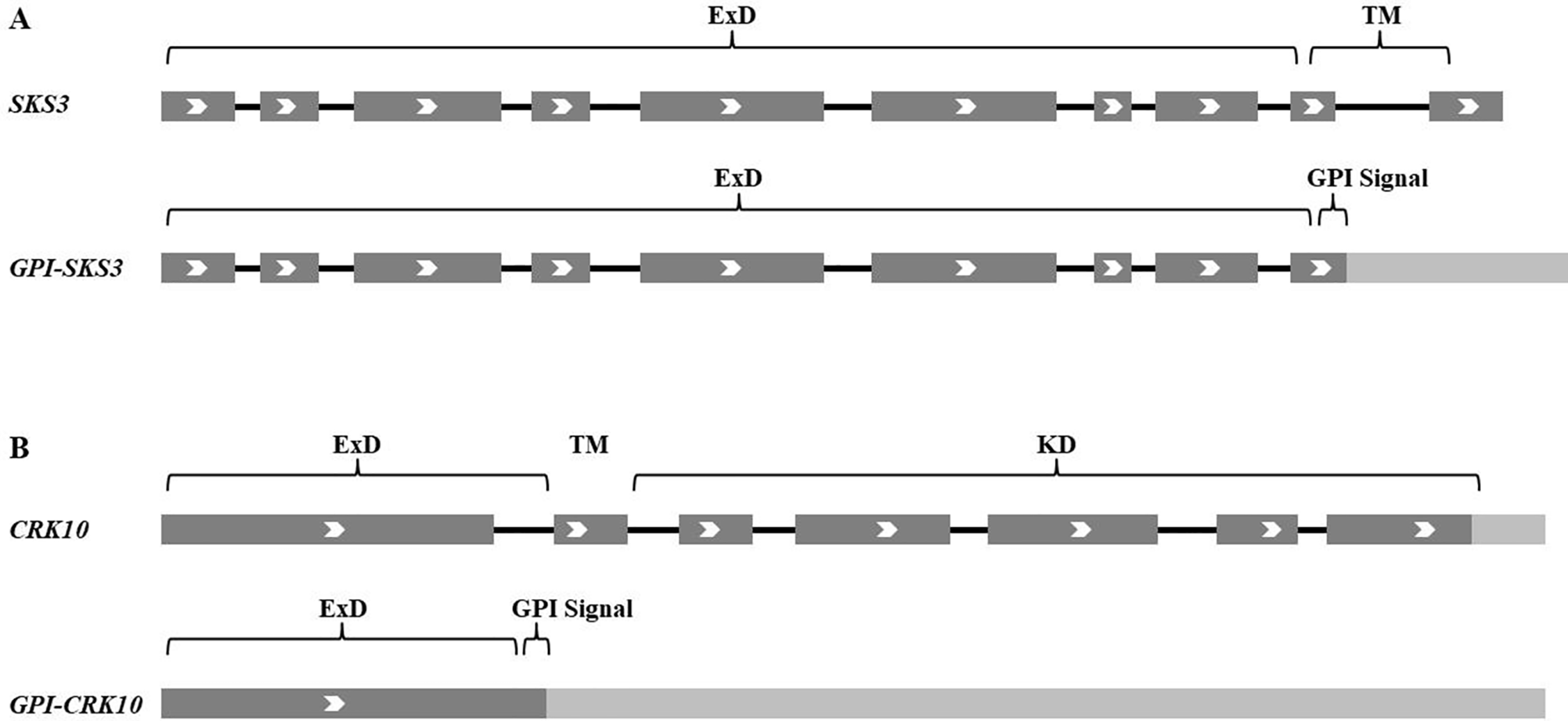

In Table 1, 248 genes predicted to encode GPI-APs in 2003 have been listed. Some corrections have been made, as some of them could not be found in databases or turned out to encode non-coding RNA. However, according to more recent experimental data, genes not included in 2003 also turned out to encode GPI-APs, such as At1g09460, At2g30933, At2g03505, and At4g13600 (Simpson et al., 2009), LORELEI (Tsukamoto et al., 2010), and XYP2 (Motose et al., 2004). Interestingly, due to recent achievements on alternative splicing, transcriptional variants of SKS3 (Zhou, 2019a) and CRK10 (Grojean and Downes, 2010) have been found to encode GPI-APs besides their ordinarily reported proteins (Figure 2). Alternative splicing largely enhanced the diversity of transcriptome and proteome, and more and more genes (up to 80% according to recent RNA-seq achievements) have been found to be alternatively spliced in Arabidopsis, which could greatly increase the abundance of GPI-APs (Wang et al., 2009; Filichkin et al., 2010; Severing et al., 2011; Reddy et al., 2013; Lee and Rio, 2015; Bush et al., 2017).

Figure 2

GPI-anchored SKS3 and CRK10 encoded by alternatively spliced transcriptional variants. (A) Alternative splicing of SKS3. (B) Alternative splicing of CRK10. ExD, extracellular domain; TM, transmembrane domain; KD, intracellular kinase domain. Exons are dark gray, introns are black lines, and untranslated transcribed regions are light gray.

In addition, 163 GPI-APs were predicted in 2016, and those not included in Table 1 are listed in Table 2. In this study, a large proportion of possible GPI-APs were discounted as typical GPI-APs in spite of being predicted to possess a GPI signal at the C terminus by various bioinformatics tools. Some of those discounted were transmembrane proteins, such as PIN3 and PIN4 and some receptor-like kinases (RLKs), and the other were cytoplasmic proteins without N-terminal secretory signal peptide, such as SNARE family proteins (listed at the end of Table 2).

Functional Diversity of GPI-APs in Arabidopsis

GPI-APs listed in Tables 1 and 2 are from diverse families, such as cell wall structure proteins, proteases, enzymes, receptor-like proteins (RLPs), lipid transfer proteins, and GPI-anchored peptides, which imply a functional diversity of GPI-APs: indeed, they were found functional in most processes, such as cell wall composition, cell wall component synthesis, cell polar expansion, stress responses, hormone signaling responses, pathogen responses, stomatal development, pollen tube elongation, and double fertilization in Arabidopsis.

Among these GPI-APs, the arabinogalactan protein (AGP) family, LORELEI family, COBRA family, and some RLPs, were better characterized. AGP family proteins are ubiquitous cell wall components anchoring on the plasma membrane throughout the Plant Kingdom and abundantly decorated at their Hyp residues by arabinogalactan polysaccharides, which make them be one of the most complex families of macromolecules in plants and play roles in various processes (Schultz et al., 2000; Ellis et al., 2010; Marzec et al., 2015; Showalter and Basu, 2016; Losada and Herrero, 2019; Palacio-Lopez et al., 2019). COBRA families were reported to be involved in various processes by regulating cell wall synthesis in plants (Hochholdinger et al., 2008; Cao et al., 2012; Niu et al., 2015; Niu et al., 2018). LORELEI family proteins associate with cell surface RLK, which is essential not only for ligand recognition but also for RLK transport (Capron et al., 2008; Duan et al., 2010; Tsukamoto et al., 2010; Meng et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016; Liao et al., 2017; Stegmann et al., 2017; Feng et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2018; Yin et al., 2018).

Involvement of GPI-APs in Signaling Transduction in Arabidopsis

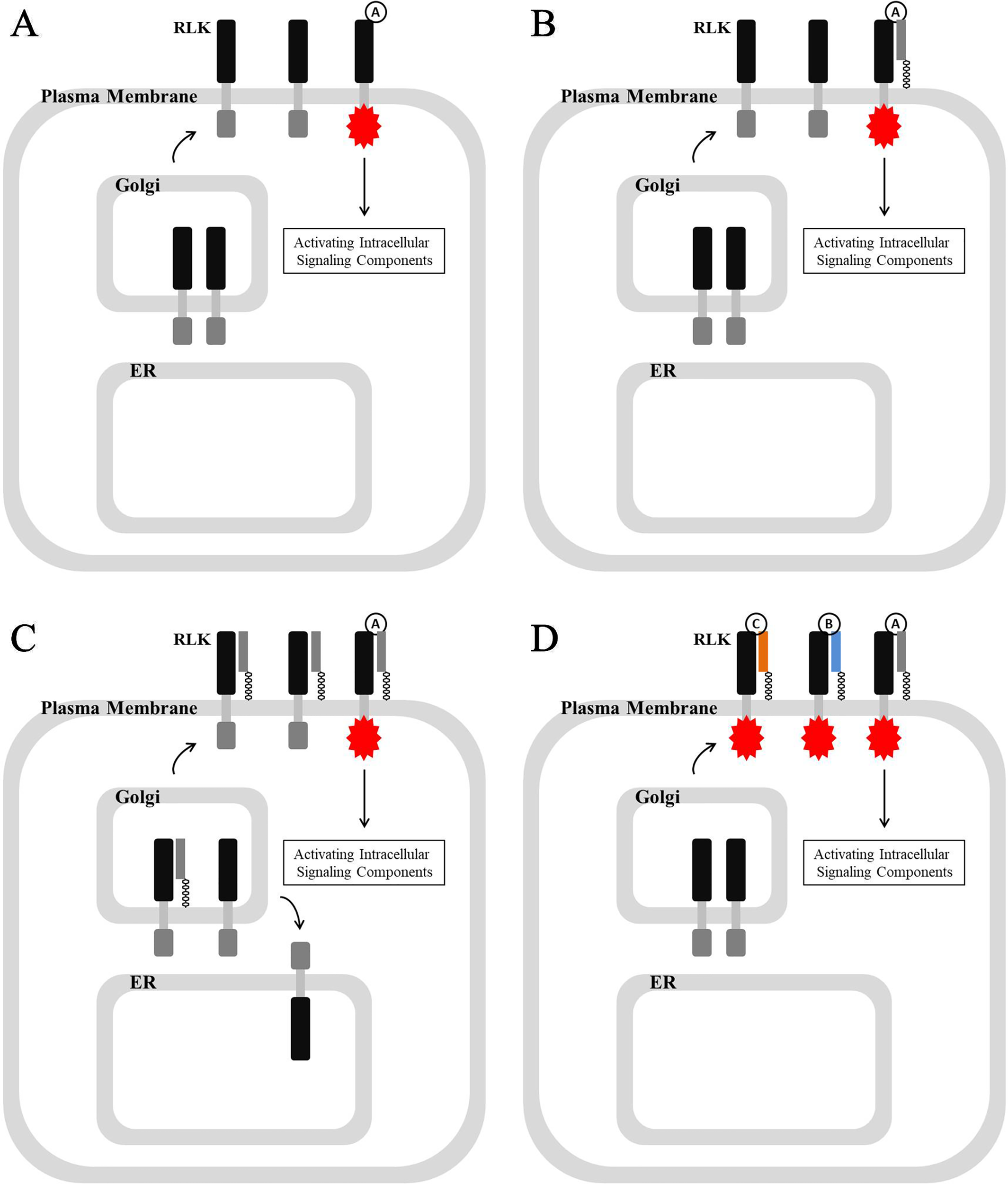

In Arabidopsis, hundreds of RLKs, which possess extracellular ligand recognition domains and intracellular kinase domains, control a wide range of processes, including development, disease resistance, hormone perception, and self-incompatibility (Shiu and Bleecker, 2001; Muschietti and Wengier, 2018; Wei and Li, 2018). Their association with extracellular ligands, including phytohormones, signaling polypeptides, and pathogen molecules, leads to the phosphorylation of the intracellular kinase domain, which consequently activate cytoplasmic signaling components and switch on response mechanisms (Figure 3A) (Pearce et al., 2001; Asai et al., 2002; Geldner and Robatzek, 2008; Murphy et al., 2012; Breiden and Simon, 2016; Yamaguchi et al., 2016; Chardin et al., 2017).

Figure 3

RLK-mediated signaling pathway and various associations between RLKs and GPI-APs. (A) Association with extracellular ligand activates and phosphorylates the intracellular kinase domain of RLK, which activates intracellular signaling components to regulate various processes. (B) GPI-AP is required for ligand recognition and its association with RLK. (C) GPI-AP is required not only for ligand recognition and its association with RLK but also for RLK localization by chaperoning its transport, and those un-chaperoned would reside in ER. (D) GPI-APs are required for ligand selection.

By summarizing the functional mechanism of those listed GPI-APs in Tables 1 and 2, a group of GPI-APs from various families was found to share a common mechanism of action involving RLK-related signal transduction (Table 3). The same mechanism has been reported in mammalian cells, for example, that GPI-anchored CD14 possessing leucine-rich repeats (LRR) region associates with not only Toll-like receptor TLR4 to perceive their polypeptide ligand lipopolysaccharide (LPS) leading them to activate mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades (Wright et al., 1990; Schumann, 1992; Zanoni et al., 2011; Li X. et al., 2015) but also TLR3 to perceive viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) leading them to activate (Vercammen et al., 2008). This common mechanism found in both animals and plants suggests that important and common roles are played by GPI-APs in signal transduction (Figure 3B).

Table 3

GPI-APs and their potential co-receptor RLKs and ligands.

*Both SKU5 and TMK1 were identified through their association with ABP1, but no direct association has been identified between TMK1 and SKU5.

Association Between GPI-AP and RLK

Interestingly, the association between GPI-AP and RLK could be involved in not only ligand recognition but also RLK transport and subcellular localization. One of the best characterized GPI-APs, LORELEI, not only participates in ligand recognition by associating with FERONIA but also plays a crucial role in chaperoning the transport of FERONIA from the ER to the plasma membrane (Capron et al., 2008; Duan et al., 2010; Tsukamoto et al., 2010; Meng et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016; Liao et al., 2017; Stegmann et al., 2017; Feng et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2018; Yin et al., 2018) (Figure 3C). This special chaperone and transport mechanism might be due to the GPI-APs becoming involved with lipid rafts, which determine distinct protein sorting and protein traffic (Eisenhaber et al., 1998; Legler et al., 2005; Miyagawa-Yamaguchi et al., 2015; Sezgin et al., 2017).

GPI-APs appear to be important not only for ligand recognition but also essential for ligand selection. For example, RLK FERONIA recognizes ligands RALF1 or RALF22/23 when associated with GPI-anchored LORELEI or LRX5, respectively (Li C et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2018). This potential GPI-AP-dependent selection mechanism could greatly enhance the ligand recognition abundance of RLK but could also mediate the cross-talk between various signaling perception and transduction (Figure 3D).

The associations between GPI-AP and RLK could be structure independent, such as SKU5-TMK1, LRE/LLGs-FERONIA, FLA4-FEI1/FEI2, ENODL14-FERONIA, and LRX5-FERONIA, or structure dependent, such as TMM and ERECTA both possessing LRR structure at the extracellular domain and LYM1/LYM3 and CERK1 both possessing LyM structure at extracellular domain in Arabidopsis. Interestingly, the same structure dependence is also present in one of the best characterized GPI-APs in mammalian cells, CD-14, and together with its partner receptor kinases TLR3 and TLR4 all possess an LRR structure.

The structure-dependent associations between GPI-APs and RLKs largely increased the curiosities of the group of GPI-anchored RLPs, which shared the same structures or sequence similarities with RLKs but lack intracellular kinase domains. They might recognize specific RLKs depending on sequence and structure similarities and form heterodimers with various RLKs in the ER or Golgi bodies and then chaperone them to specific plasma membrane regions through GPI-AP-driven lipid rafts. On arrival, they select and recognize ligands and activate the intracellular signaling components.

Whether the GPI-anchored RLKs encoded by transcriptional variants, such as GPI-CRK10 and its variant of CRK10, can form homodimers based on the same extracellular domains and play a role in RLK regulation, is a very interesting question.

Conclusion and Perspectives

Previous genomic and proteomic assays that predicted and identified GPI-APs from Arabidopsis have been listed. Due to recent experimental data and knowledge of alternative splicing, more and more GPI-APs have been identified, suggesting that GPI-APs in Arabidopsis might be more abundant than we expected.

Previous studies on those listed GPI-APs from diverse families were discussed, and they were found to be involved in diverse biological processes, including cell wall composition, cell wall component synthesis, cell polar expansion, hormone signaling response, stress response, pathogen response, stomata development, pollen tube elongation, and double fertilization. Those reports demonstrated the functional diversity and indispensability of GPI-APs in Arabidopsis.

Among these reports, direct associations were found between various GPI-APs and their partner cell surface RLKs, demonstrating not only participation in their ligand recognition but also essential roles in RLK transport and localization. Localization might due to specific protein sorting and protein traffic driven by GPI-AP-related lipid rafts. Surprisingly, GPI-APs have also been shown to participate in ligand selection, which made one RLK and its downstream intracellular target activated by various ligands. Such protein cross-reactivity greatly enhanced the ligand recognition abundance of RLKs, which can also be considered as a common mechanism of cross-talk between various ligands or various signaling pathways.

In this review, the most predicted or identified GPI-APs in Arabidopsis were listed and discussed, and a common involvement of them in signing transduction was summarized. This involvement could be very helpful for understanding the ligand-RLK signaling transduction in plants, especially for understanding the polar localization of RLKs, and the crosstalk between various ligand-RLK signaling transduction. It would be interesting to identify more associations between various GPI-APs and RLKs and study their recognition and selection of ligands and downstream intracellular signaling components in Arabidopsis.

Statements

Author contributions

KZ wrote this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

AbdinM. Z.KiranU.AlamA. (2011). Analysis of osmotin, a PR protein as metabolic modulator in plants. Bioinformation5 (8), 336–340. doi: 10.6026/97320630005336

2

AbrashE. B.BergmannD. C. (2010). Regional specification of stomatal production by the putative ligand CHALLAH. Development137 (3), 447–455. doi: 10.1242/dev.040931

3

Acosta-GarciaG.Vielle-CalzadaJ. P. (2004). A classical arabinogalactan protein is essential for the initiation of female gametogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell16 (10), 2614–2628. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.024588

4

AsaiT.TenaG.PlotnikovaJ.WillmannM. R.ChiuW. L.Gomez-GomezL.et al. (2002). MAP kinase signalling cascade in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Nature415 (6875), 977–983. doi: 10.1038/415977a

5

BarozziF.PapadiaP.StefanoG.RennaL.BrandizziF.MigoniD.et al. (2018). Variation in membrane trafficking linked to SNARE AtSYP51 interaction with aquaporin NIP1;1. Front. Plant Sci.9, 1949. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01949

6

BasuD.TianL.DebrosseT.PoirierE.EmchK.HerockH.et al. (2016). Glycosylation of a fasciclin-like arabinogalactan-protein (SOS5) mediates root growth and seed mucilage adherence via a cell wall receptor-like kinase (FEI1/FEI2) pathway in Arabidopsis. PLoS One11 (1), e0145092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145092

7

BayerE. M.BottrillA. R.WalshawJ.VigourouxM.NaldrettM. J.ThomasC. L.et al. (2006). Arabidopsis cell wall proteome defined using multidimensional protein identification technology. Proteomics6 (1), 301–311. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500046

8

BenedettiM.VerrascinaI.PontiggiaD.LocciF.MatteiB.De LorenzoG.et al. (2018). Four Arabidopsis berberine bridge enzyme-like proteins are specific oxidases that inactivate the elicitor-active oligogalacturonides. Plant J.94 (2), 260–273. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13852

9

Ben-TovD.AbrahamY.StavS.ThompsonK.LoraineA.ElbaumR.et al. (2015). COBRA-LIKE2, a member of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored COBRA-LIKE family, plays a role in cellulose deposition in Arabidopsis seed coat mucilage secretory cells. Plant Physiol.167 (3), 711–724. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.240671

10

Ben-TovD.Idan-MolakandovA.HuggerA.Ben-ShlushI.GunlM.YangB.et al. (2018). The role of COBRA-LIKE 2 function, as part of the complex network of interacting pathways regulating Arabidopsis seed mucilage polysaccharide matrix organization. Plant J.94 (3), 497–512. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13871

11

BhaveN. S.VeleyK. M.NadeauJ. A.LucasJ. R.BhaveS. L.SackF. D. (2009). Too many mouths promotes cell fate progression in stomatal development of Arabidopsis stems. Planta229 (2), 357–367. doi: 10.1007/s00425-008-0835-9

12

BornerG. H.LilleyK. S.StevensT. J.DupreeP. (2003). Identification of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins in Arabidopsis. A proteomic and genomic analysis. Plant Physiol.132 (2), 568–577. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021170

13

BornerG. H.SherrierD. J.StevensT. J.ArkinI. T.DupreeP. (2002). Prediction of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins in Arabidopsis. A genomic analysis. Plant Physiol.129 (2), 486–499. doi: 10.1104/pp.010884

14

BreidenM.SimonR. (2016). Q&A: how does peptide signaling direct plant development? BMC Biol.14, 58. doi: 10.1186/s12915-016-0280-3

15

BundyM. G.KosentkaP. Z.WilletA. H.ZhangL.MillerE.ShpakE. D. (2016). A mutation in the catalytic subunit of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol transamidase disrupts growth, fertility, and stomata formation. Plant Physiol.171 (2), 974–985. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00339

16

BushS. J.ChenL.Tovar-CoronaJ. M.UrrutiaA. O. (2017). Alternative splicing and the evolution of phenotypic novelty. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci.372 (1713). doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0474

17

ButikoferP.MalherbeT.BoschungM.RoditiI. (2001). GPI-anchored proteins: now you see ‘em, now you don’t. FASEB J.15 (2), 545–548. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0415hyp

18

CagnolaJ. I.Dumont de ChassartG. J.IbarraS. E.ChimentiC.RicardiM. M.DelzerB.et al. (2018). Reduced expression of selected FASCICLIN-LIKE ARABINOGALACTAN PROTEIN genes associates with the abortion of kernels in field crops of Zea mays (maize) and of Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Cell Environ.41 (3), 661–674. doi: 10.1111/pce.13136

19

CaoY.TangX.GiovannoniJ.XiaoF.LiuY. (2012). Functional characterization of a tomato COBRA-like gene functioning in fruit development and ripening. BMC Plant Biol.12, 211. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-211

20

CapronA.GourguesM.NeivaL. S.FaureJ. E.BergerF.PagnussatG.et al. (2008). Maternal control of male-gamete delivery in Arabidopsis involves a putative GPI-anchored protein encoded by the LORELEI gene. Plant Cell20 (11), 3038–3049. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061713

21

ChardinC.SchenkS. T.HirtH.ColcombetJ.KrappA. (2017). Review: mitogen-activated protein kinases in nutritional signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Sci.260, 101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2017.04.006

22

ChenJ.ChenX.ZhangQ.ZhangY.OuX.AnL.et al. (2018). A cold-induced pectin methyl-esterase inhibitor gene contributes negatively to freezing tolerance but positively to salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. J. Plant Physiol.222, 67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2018.01.003

23

ChengY.ZhouW.El SheeryN. I.PetersC.LiM.WangX.et al. (2011). Characterization of the Arabidopsis glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase (GDPD) family reveals a role of the plastid-localized AtGDPD1 in maintaining cellular phosphate homeostasis under phosphate starvation. Plant J.66 (5), 781–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04538.x

24

CoimbraS.CostaM.JonesB.MendesM. A.PereiraL. G. (2009). Pollen grain development is compromised in Arabidopsis agp6 agp11 null mutants. J. Exp. Bot.60 (11), 3133–3142. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp148

25

CoimbraS.CostaM.MendesM. A.PereiraA. M.PintoJ.PereiraL. G. (2010). Early germination of Arabidopsis pollen in a double null mutant for the arabinogalactan protein genes AGP6 and AGP11. Sex. Plant Reprod.23 (3), 199–205. doi: 10.1007/s00497-010-0136-x

26

CostaM.NobreM. S.BeckerJ. D.MasieroS.AmorimM. I.PereiraL. G.et al. (2013). Expression-based and co-localization detection of arabinogalactan protein 6 and arabinogalactan protein 11 interactors in Arabidopsis pollen and pollen tubes. BMC Plant Biol.13, 7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-13-7

27

DaviesA.KadurinI.Alvarez-LaviadaA.DouglasL.Nieto-RostroM.BauerC. S.et al. (2010). The alpha2delta subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels form GPI-anchored proteins, a posttranslational modification essential for function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.107 (4), 1654–1659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908735107

28

De BenedictisM.BleveG.FaracoM.StiglianoE.GriecoF.PiroG.et al. (2013). AtSYP51/52 functions diverge in the post-Golgi traffic and differently affect vacuolar sorting. Mol. Plant6 (3), 916–930. doi: 10.1093/mp/sss117

29

DebonoA.YeatsT. H.RoseJ. K.BirdD.JetterR.KunstL.et al. (2009). Arabidopsis LTPG is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored lipid transfer protein required for export of lipids to the plant surface. Plant Cell21 (4), 1230–1238. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064451

30

DinnenyJ. R.LongT. A.WangJ. Y.JungJ. W.MaceD.PointerS.et al. (2008). Cell identity mediates the response of Arabidopsis roots to abiotic stress. Science320 (5878), 942–945. doi: 10.1126/science.1153795

31

DuanQ.KitaD.LiC.CheungA. Y.WuH. M. (2010). FERONIA receptor-like kinase regulates RHO GTPase signaling of root hair development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.107 (41), 17821–17826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005366107

32

EdstamM. M.EdqvistJ. (2014). Involvement of GPI-anchored lipid transfer proteins in the development of seed coats and pollen in Arabidopsis thaliana. Physiol. Plant.152 (1), 32–42. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12156

33

EisenhaberB.BorkP.EisenhaberF. (1998). Sequence properties of GPI-anchored proteins near the omega-site: constraints for the polypeptide binding site of the putative transamidase. Protein Eng.11 (12), 1155–1161. doi: 10.1093/protein/11.12.1155

34

EisenhaberB.BorkP.EisenhaberF. (2001). Post-translational GPI lipid anchor modification of proteins in kingdoms of life: analysis of protein sequence data from complete genomes. Protein Eng.14 (1), 17–25. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.1.17

35

EllisM.EgelundJ.SchultzC. J.BacicA. (2010). Arabinogalactan-proteins: key regulators at the cell surface? Plant Physiol.153 (2), 403–419. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.156000

36

ElortzaF.NuhseT. S.FosterL. J.StensballeA.PeckS. C.JensenO. N. (2003). Proteomic analysis of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored membrane proteins. Mol. Cell. Proteomics2 (12), 1261–1270. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300079-MCP200

37

Escobar-RestrepoJ. M.HuckN.KesslerS.GagliardiniV.GheyselinckJ.YangW. C.et al. (2007). The feronia receptor-like kinase mediates male-female interactions during pollen tube reception. Science317 (5838), 656–660. doi: 10.1126/science.1143562

38

EudesA.MouilleG.TheveninJ.GoyallonA.MinicZ.JouaninL. (2008). Purification, cloning and functional characterization of an endogenous beta-glucuronidase in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol.49 (9), 1331–1341. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn108

39

EzakiB.SasakiK.MatsumotoH.NakashimaS. (2005). Functions of two genes in aluminium (Al) stress resistance: repression of oxidative damage by the AtBCB gene and promotion of efflux of Al ions by the NtGDI1gene. J. Exp. Bot.56 (420), 2661–2671. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri259

40

FahlbergP.BuhotN.JohanssonO. N.AnderssonM. X. (2019). Involvement of lipid transfer proteins in resistance against a non-host powdery mildew in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant Pathol.20 (1), 69–77. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12740

41

FankhauserN.MaserP. (2005). Identification of GPI anchor attachment signals by a Kohonen self-organizing map. Bioinformatics21 (9), 1846–1852. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti299

42

FengW.KitaD.PeaucelleA.CartwrightH. N.DoanV.DuanQ.et al. (2018). The FERONIA receptor kinase maintains cell-wall integrity during salt stress through Ca(2+) signaling. Curr. Biol.28 (5), 666–75 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.01.023

43

FilichkinS. A.PriestH. D.GivanS. A.ShenR.BryantD. W.FoxS. E.et al. (2010). Genome-wide mapping of alternative splicing in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Res.20 (1), 45–58. doi: 10.1101/gr.093302.109

44

ForestiO.SilvaL. L.DeneckeJ. (2006). Overexpression of the Arabidopsis syntaxin PEP12/SYP21 inhibits transport from the prevacuolar compartment to the lytic vacuole in vivo. Plant Cell18 (9), 2275–2293. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.040279

45

FujiharaY.IkawaM. (2016). GPI-AP release in cellular, developmental, and reproductive biology. J. Lipid Res.57 (4), 538–545. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R063032

46

FultonL.BatouxM.VaddepalliP.YadavR. K.BuschW.AndersenS. U.et al. (2009). Detorqueo, Quirky, and Zerzaust represent novel components involved in organ development mediated by the receptor-like kinase Strubbelig in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet.5 (1), e1000355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000355

47

GaoH.LiR.GuoY. (2017). Arabidopsis aspartic proteases A36 and A39 play roles in plant reproduction. Plant Signal. Behav.12 (4), e1304343. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2017.1304343

48

GaoH.ZhangY.WangW.ZhaoK.LiuC.BaiL.et al. (2017). Two membrane-anchored aspartic proteases contribute to pollen and ovule development. Plant Physiol.173 (1), 219–239. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01719

49

GeislerM.NadeauJ.SackF. D. (2000). Oriented asymmetric divisions that generate the stomatal spacing pattern in Arabidopsis are disrupted by the too many mouths mutation. Plant Cell12 (11), 2075–2086. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.11.2075

50

GeislerM.YangM.SackF. D. (1998). Divergent regulation of stomatal initiation and patterning in organ and suborgan regions of the Arabidopsis mutants too many mouths and four lips. Planta205 (4), 522–530. doi: 10.1007/s004250050351

51

GeldnerN.RobatzekS. (2008). Plant receptors go endosomal: a moving view on signal transduction. Plant Physiol.147 (4), 1565–1574. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.120287

52

GillmorC. S.LukowitzW.BrininstoolG.SedbrookJ. C.HamannT.PoindexterP.et al. (2005). Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins are required for cell wall synthesis and morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell17 (4), 1128–1140. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.031815

53

GriffithsJ. S.CrepeauM. J.RaletM. C.SeifertG. J.NorthH. M. (2016). Dissecting seed mucilage adherence mediated by FEI2 and SOS5. Front. Plant Sci.7, 1073. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01073

54

GrojeanJ.DownesB. (2010). Riboswitches as hormone receptors: hypothetical cytokinin-binding riboswitches in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biol. Direct5, 60. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-5-60

55

GuanP.WangJ.XieC.WuC.YangG.YanK.et al. (2019). SES1 positively regulates heat stress resistance in Arabidopsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.513 (3), 582–588. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.04.015

56

GueninS.MareckA.RayonC.LamourR.Assoumou NdongY.DomonJ. M.et al. (2011). Identification of pectin methylesterase 3 as a basic pectin methylesterase isoform involved in adventitious rooting in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol.192 (1), 114–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03797.x

57

GunlM.PaulyM. (2011). AXY3 encodes a alpha-xylosidase that impacts the structure and accessibility of the hemicellulose xyloglucan in Arabidopsis plant cell walls. Planta233 (4), 707–719. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1330-7

58

GuoH.NolanT. M.SongG.LiuS.XieZ.ChenJ.et al. (2018). FERONIA receptor kinase contributes to plant immunity by suppressing jasmonic acid signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr. Biol.28 (20), 3316–3324. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.078

59

GuoL.YangH.ZhangX.YangS. (2013). Lipid transfer protein 3 as a target of MYB96 mediates freezing and drought stress in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot.64 (6), 1755–1767. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert040

60

Harpaz-SaadS.WesternT. L.KieberJ. J. (2012). The FEI2-SOS5 pathway and CELLULOSE SYNTHASE 5 are required for cellulose biosynthesis in the Arabidopsis seed coat and affect pectin mucilage structure. Plant Signal. Behav.7 (2), 285–288. doi: 10.4161/psb.18819

61

HartP. J.NersissianA. M.HerrmannR. G.NalbandyanR. M.ValentineJ. S.EisenbergD. (1996). A missing link in cupredoxins: crystal structure of cucumber stellacyanin at 1.6 A resolution. Protein Sci.5 (11), 2175–2183. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051104

62

HayashiS.IshiiT.MatsunagaT.TominagaR.KuromoriT.WadaT.et al. (2008). The glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase-like proteins SHV3 and its homologs play important roles in cell wall organization. Plant Cell Physiol.49 (10), 1522–1535. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn120

63

HellwingC.SchoenigerA.RoesslerC.LeimertA.SchumannJ. (2018). Lipid raft localization of TLR2 and its co-receptors is independent of membrane lipid composition. PeerJ.6, e4212. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4212

64

HijaziM.RoujolD.Nguyen-KimH.Del Rocio Cisneros CastilloL.SalandE.JametE.et al. (2014). Arabinogalactan protein 31 (AGP31), a putative network-forming protein in Arabidopsis thaliana cell walls?Ann. Bot.114 (6), 1087–1097. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcu038

65

HochholdingerF.WenT. J.ZimmermannR.Chimot-MarolleP.da Costa e SilvaO.BruceW.et al. (2008). The maize (Zea mays L.) roothairless3 gene encodes a putative GPI-anchored, monocot-specific, COBRA-like protein that significantly affects grain yield. Plant J.54 (5), 888–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03459.x

66

HongD.JeonB. W.KimS. Y.HwangJ. U.LeeY. (2016). The ROP2-RIC7 pathway negatively regulates light-induced stomatal opening by inhibiting exocyst subunit Exo70B1 in Arabidopsis. New Phytol.209 (2), 624–635. doi: 10.1111/nph.13625

67

HouY.GuoX.CyprysP.ZhangY.BleckmannA.CaiL.et al. (2016). Maternal ENODLs are required for pollen tube reception in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol.26 (17), 2343–2350. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.06.053

68

HwangJ. U.JeonB. W.HongD.LeeY. (2011). Active ROP2 GTPase inhibits ABA- and CO2-induced stomatal closure. Plant Cell Environ.34 (12), 2172–2182. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02413.x

69

IchikawaM.NakaiY.ArimaK.NishiyamaS.HiranoT.SatoM. H. (2015). A VAMP-associated protein, PVA31 is involved in leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal. Behav.10 (3), e990847. doi: 10.4161/15592324.2014.990847

70

ItoS.SuzukiY.MiyamotoK.UedaJ.YamaguchiI. (2005). AtFLA11, a fasciclin-like arabinogalactan-protein, specifically localized in sclerenchyma cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem.69 (10), 1963–1969. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.1963

71

JakobyM. J.WeinlC.PuschS.KuijtS. J.MerkleT.DissmeyerN.et al. (2006). Analysis of the subcellular localization, function, and proteolytic control of the Arabidopsis cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor ICK1/KRP1. Plant Physiol.141 (4), 1293–1305. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.081406

72

JeonB. W.HwangJ. U.HwangY.SongW. Y.FuY.GuY.et al. (2008). The Arabidopsis small G protein ROP2 is activated by light in guard cells and inhibits light-induced stomatal opening. Plant Cell20 (1), 75–87. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054544

73

JeongI. S.LeeS.BonkhoferF.TolleyJ.FukudomeA.NagashimaY.et al. (2018). Purification and characterization of Arabidopsis thaliana oligosaccharyltransferase complexes from the native host: a protein super-expression system for structural studies. Plant J.94 (1), 131–145. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13847

74

JiH.WangY.CloixC.LiK.JenkinsG. I.WangS.et al. (2015). The Arabidopsis RCC1 family protein TCF1 regulates freezing tolerance and cold acclimation through modulating lignin biosynthesis. PLoS Genet.11 (9), e1005471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005471

75

JohnsonK. L.KibbleN. A.BacicA. (2011). Schultz CJ. A fasciclin-like arabinogalactan-protein (FLA) mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana, fla1, shows defects in shoot regeneration. PLoS One6 (9), e25154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025154

76

JolivetP.RouxE.D’AndreaS.DavantureM.NegroniL.ZivyM.et al. (2004). Protein composition of oil bodies in Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype WS. Plant Physiol. Biochem.42 (6), 501–509. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2004.04.006

77

JonesM. A.RaymondM. J.SmirnoffN. (2006). Analysis of the root-hair morphogenesis transcriptome reveals the molecular identity of six genes with roles in root-hair development in Arabidopsis. Plant J.45 (1), 83–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02609.x

78

JordaL.Sopena-TorresS.EscuderoV.Nunez-CorcueraB.Delgado-CerezoM.ToriiK. U.et al. (2016). ERECTA and BAK1 receptor like kinases interact to regulate immune responses in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci.7, 897. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00897

79

KawagoeK.KitamuraD.OkabeM.TaniuchiI.IkawaM.WatanabeT.et al. (1996). Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchor-deficient mice: implications for clonal dominance of mutant cells in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood87 (9), 3600–3606.

80

KhanJ. A.WangQ.SjolundR. D.SchulzA.ThompsonG. A. (2007). An early nodulin-like protein accumulates in the sieve element plasma membrane of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol.143 (4), 1576–1589. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.092296

81

KimD. S.KimJ. B.GohE. J.KimW. J.KimS. H.SeoY. W.et al. (2011). Antioxidant response of Arabidopsis plants to gamma irradiation: genome-wide expression profiling of the ROS scavenging and signal transduction pathways. J. Plant Physiol.168 (16), 1960–1971. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.05.008

82

KimH.LeeS. B.KimH. J.MinM. K.HwangI.SuhM. C. (2012). Characterization of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored lipid transfer protein 2 (LTPG2) and overlapping function between LTPG/LTPG1 and LTPG2 in cuticular wax export or accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol.53 (8), 1391–1403. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs083

83

KinoshitaT. (2014a). Enzymatic mechanism of GPI anchor attachment clarified. Cell Cycle13 (12), 1838–1839. doi: 10.4161/cc.29379

84

KinoshitaT. (2014b). Biosynthesis and deficiencies of glycosylphosphatidylinositol. Proc. Jpn. Acad., Ser. B, Phys. Biol. Sci.90 (4), 130–143. doi: 10.2183/pjab.90.130

85

KinoshitaT.FujitaM. (2016). Biosynthesis of GPI-anchored proteins: special emphasis on GPI lipid remodeling. J. Lipid Res.57 (1), 6–24. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R063313

86

KoJ. H.KimJ. H.JayantyS. S.HoweG. A.HanK. H. (2006). Loss of function of COBRA, a determinant of oriented cell expansion, invokes cellular defence responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot.57 (12), 2923–2936. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl052

87

KobeB.KajavaA. V. (2001). The leucine-rich repeat as a protein recognition motif. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol.11 (6), 725–732. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(01)00266-4

88

LebretonS.ZurzoloC.PaladinoS. (2018). Organization of GPI-anchored proteins at the cell surface and its physiopathological relevance. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol.53 (4), 403–419. doi: 10.1080/10409238.2018.1485627

89

LeeY.RioD. C. (2015). Mechanisms and regulation of alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Annu. Rev. Biochem.84, 291–323. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034316

90

LeeS. B.SuhM. C. (2018). Disruption of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored lipid transfer protein 15 affects seed coat permeability in Arabidopsis. Plant J.96 (6), 1206–1217. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14101

91

LeeJ. S.HnilovaM.MaesM.LinY. C.PutarjunanA.HanS. K.et al. (2015). Competitive binding of antagonistic peptides fine-tunes stomatal patterning. Nature522 (7557), 439–443. doi: 10.1038/nature14561

92

LeeJ. S.KurohaT.HnilovaM.KhatayevichD.KanaokaM. M.McAbeeJ. M.et al. (2012). Direct interaction of ligand-receptor pairs specifying stomatal patterning. Genes Dev.26 (2), 126–136. doi: 10.1101/gad.179895.111

93

LeglerD. F.DouceyM. A.SchneiderP.ChapatteL.BenderF. C.BronC. (2005). Differential insertion of GPI-anchored GFPs into lipid rafts of live cells. FASEB J.19 (1), 73–75. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1338fje

94

LerouxelO.MouilleG.Andeme-OnzighiC.BruyantM. P.SevenoM.Loutelier-BourhisC.et al. (2005). Mutants in defective glycosylation, an Arabidopsis homolog of an oligosaccharyltransferase complex subunit, show protein underglycosylation and defects in cell differentiation and growth. Plant J.42 (4), 455–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02392.x

95

LeshemY.GolaniY.KayeY.LevineA. (2010). Reduced expression of the v-SNAREs AtVAMP71/AtVAMP7C gene family in Arabidopsis reduces drought tolerance by suppression of abscisic acid-dependent stomatal closure. J. Exp. Bot.61 (10), 2615–2622. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq099

96

LevitinB.RichterD.MarkovichI.ZikM. (2008). Arabinogalactan proteins 6 and 11 are required for stamen and pollen function in Arabidopsis. Plant J.56 (3), 351–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03607.x

97

LiS.GeF. R.XuM.ZhaoX. Y.HuangG. Q.ZhouL. Z.et al. (2013). Arabidopsis COBRA-LIKE 10, a GPI-anchored protein, mediates directional growth of pollen tubes. Plant J.74 (3), 486–497. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12139

98

LiX.WangD.ChenZ.LuE.WangZ.DuanJ.et al. (2015). Galphai1 and Galphai3 regulate macrophage polarization by forming a complex containing CD14 and Gab1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.112 (15), 4731–4736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503779112

99

LiC.WuH. M.CheungA. Y. (2016). FERONIA and her pals: functions and mechanisms. Plant Physiol.171 (4), 2379–2392. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00667

100

LiC.YehF. L.CheungA. Y.DuanQ.KitaD.LiuM. C.et al. (2015). Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins as chaperones and co-receptors for FERONIA receptor kinase signaling in Arabidopsis. eLife4. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06587

101

LiJ.YuM.GengL. L.ZhaoJ. (2010). The fasciclin-like arabinogalactan protein gene, FLA3, is involved in microspore development of Arabidopsis. Plant J.64 (3), 482–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04344.x

102

LiangX.DingP.LianK.WangJ.MaM.LiL.et al. (2016). Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G proteins regulate immunity by directly coupling to the FLS2 receptor. eLife5, e13568. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13568

103

LiaoH.TangR.ZhangX.LuanS.YuF. (2017). FERONIA receptor kinase at the crossroads of hormone signaling and stress responses. Plant Cell Physiol.58 (7), 1143–1150. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcx048

104

LinW. D.LiaoY. Y.YangT. J.PanC. Y.BuckhoutT. J.SchmidtW. (2011). Coexpression-based clustering of Arabidopsis root genes predicts functional modules in early phosphate deficiency signaling. Plant Physiol.155 (3), 1383–1402. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.166520

105

LinG.ZhangL.HanZ.YangX.LiuW.LiE.et al. (2017). A receptor-like protein acts as a specificity switch for the regulation of stomatal development. Genes Dev.31 (9), 927–938. doi: 10.1101/gad.297580.117

106

LinkM.RauschT.GreinerS. (2004). In Arabidopsis thaliana, the invertase inhibitors AtC/VIF1 and 2 exhibit distinct target enzyme specificities and expression profiles. FEBS Lett.573 (1–3), 105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.062

107

LiuY.HuangX.LiM.HeP.ZhangY. (2016). Loss-of-function of Arabidopsis receptor-like kinase BIR1 activates cell death and defense responses mediated by BAK1 and SOBIR1. New Phytol.212 (3), 637–645. doi: 10.1111/nph.14072

108

LosadaJ. M.HerreroM. (2019). Arabinogalactan proteins mediate intercellular crosstalk in the ovule of apple flowers. Plant Reprod.32, 291–305. doi: 10.1007/s00497-019-00370-z

109

LuoH.LyznikL. A.GidoniD.HodgesT. K. (2000). FLP-mediated recombination for use in hybrid plant production. Plant J.23 (3), 423–430. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00782.x

110

MacMillanC. P.MansfieldS. D.StachurskiZ. H.EvansR.SouthertonS. G. (2010). Fasciclin-like arabinogalactan proteins: specialization for stem biomechanics and cell wall architecture in Arabidopsis and Eucalyptus. Plant J.62 (4), 689–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04181.x

111

MarzecM.SzarejkoI.MelzerM. (2015). Arabinogalactan proteins are involved in root hair development in barley. J. Exp. Bot.66 (5), 1245–1257. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru475

112

MembreN.BernierF.StaigerD.BernaA. (2000). Arabidopsis thaliana germin-like proteins: common and specific features point to a variety of functions. Planta211 (3), 345–354. doi: 10.1007/s004250000277

113

MengX.ChenX.MangH.LiuC.YuX.GaoX.et al. (2015). Differential function of Arabidopsis SERK family receptor-like kinases in stomatal patterning. Curr. Biol.25 (18), 2361–2372. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.068

114

MengX.WangH.HeY.LiuY.WalkerJ. C.ToriiK. U.et al. (2012). A MAPK cascade downstream of ERECTA receptor-like protein kinase regulates Arabidopsis inflorescence architecture by promoting localized cell proliferation. Plant Cell24 (12), 4948–4960. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.104695

115

Miyagawa-YamaguchiA.KotaniN.HonkeK. (2015). Each GPI-anchored protein species forms a specific lipid raft depending on its GPI attachment signal. Glycoconj. J.32 (7), 531–540. doi: 10.1007/s10719-015-9595-5

116

MorsommeP.Prescianotto-BaschongC.RiezmanH. (2003). The ER v-SNAREs are required for GPI-anchored protein sorting from other secretory proteins upon exit from the ER. J. Cell Biol.162 (3), 403–412. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212101

117

MotoseH.SugiyamaM.FukudaH. (2004). A proteoglycan mediates inductive interaction during plant vascular development. Nature429 (6994), 873–878. doi: 10.1038/nature02613

118

MullerK.Levesque-TremblayG.BartelsS.WeitbrechtK.WormitA.UsadelB.et al. (2013). Demethylesterification of cell wall pectins in Arabidopsis plays a role in seed germination. Plant Physiol.161 (1), 305–316. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.205724

119

MunizM.ZurzoloC. (2014). Sorting of GPI-anchored proteins from yeast to mammals—common pathways at different sites? J. Cell Sci.127 (Pt 13), 2793–2801. doi: 10.1242/jcs.148056

120

MurphyE.SmithS.De SmetI. (2012). Small signaling peptides in Arabidopsis development: how cells communicate over a short distance. Plant Cell24 (8), 3198–3217. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.099010

121

MuschiettiJ. P.WengierD. L. (2018). How many receptor-like kinases are required to operate a pollen tube. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol.41, 73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.09.008

122

NersissianA. M.ImmoosC.HillM. G.HartP. J.WilliamsG.HerrmannR. G.et al. (1998). Uclacyanins, stellacyanins, and plantacyanins are distinct subfamilies of phytocyanins: plant-specific mononuclear blue copper proteins. Protein Sci.7 (9), 1915–1929. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070907

123

NiuE.FangS.ShangX.GuoW. (2018). Ectopic expression of GhCOBL9A, a cotton glycosyl-phosphatidyl inositol-anchored protein encoding gene, promotes cell elongation, thickening and increased plant biomass in transgenic Arabidopsis. Mol. Genet. Genomics293 (5), 1191–1204. doi: 10.1007/s00438-018-1452-3

124

NiuE.ShangX.ChengC.BaoJ.ZengY.CaiC.et al. (2015). Comprehensive analysis of the COBRA-Like (COBL) gene family in Gossypium identifies two COBLs potentially associated with fiber quality. PLoS One10 (12), e0145725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145725

125

OrihashiK.TojoH.OkawaK.TashimaY.MoritaT.KondohG. (2012). Mammalian carboxylesterase (CES) releases GPI-anchored proteins from the cell surface upon lipid raft fluidization. Biol. Chem.393 (3), 169–176. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2011-0269

126

OxleyD.BacicA. (1999). Structure of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor of an arabinogalactan protein from Pyrus communis suspension-cultured cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.96 (25), 14246–14251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14246

127

Palacio-LopezK.TinazB.HolzingerA.DomozychD. S. (2019). Arabinogalactan proteins and the extracellular matrix of charophytes: a sticky business. Front. Plant Sci.10, 447. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00447

128

PalaretiG.LegnaniC.CosmiB.AntonucciE.ErbaN.PoliD.et al. (2016). Comparison between different D-Dimer cutoff values to assess the individual risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism: analysis of results obtained in the DULCIS study. Int. J. Lab. Hematol.38 (1), 42–49. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12426

129

PaparellaC.SavatinD. V.MartiL.De LorenzoG.FerrariS. (2014). The Arabidopsis LYSIN MOTIF-CONTAINING RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASE3 regulates the cross talk between immunity and abscisic acid responses. Plant Physiol.165 (1), 262–276. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.233759

130

ParianiS.ContrerasM.RossiF. R.SanderV.CoriglianoM. G.SimonF.et al. (2016). Characterization of a novel Kazal-type serine proteinase inhibitor of Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochimie123, 85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2016.02.002

131

ParkerJ. S.CavellA. C.DolanL.RobertsK.GriersonC. S. (2000). Genetic interactions during root hair morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell12 (10), 1961–1974. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.10.1961

132

PearceG.MouraD. S.StratmannJ.RyanC. A.Jr. (2001). RALF, a 5-kDa ubiquitous polypeptide in plants, arrests root growth and development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.98 (22), 12843–12847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201416998

133

PereiraA. M.LopesA. L.CoimbraS. (2016b). JAGGER, an AGP essential for persistent synergid degeneration and polytubey block in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal. Behav.11 (8), e1209616. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2016.1209616

134

PereiraA. M.NobreM. S.PintoS. C.LopesA. L.CostaM. L.MasieroS.et al. (2016a). “Love Is Strong, and You’re so Sweet”: JAGGER is essential for persistent synergid degeneration and polytubey block in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant9 (4), 601–614. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.01.002

135

PierleoniA.MartelliP. L.CasadioR. (2008). PredGPI: a GPI-anchor predictor. BMC Bioinformatics9, 392. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-392

136