- 1School of Agricultural Biotechnology, Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana, India

- 2Department of Soil Science, Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana, India

- 3ICAR-National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources, New Delhi, India

Limited phosphorus availability in the soil is one of the major constraints to the growth and productivity of rice across Asian, African and South American countries, where 50% of the rice is grown under rain-fed systems on poor and problematic soils. With an aim to determine novel alleles for enhanced phosphorus uptake efficiency in wild species germplasm of rice Oryza rufipogon, we investigated phosphorus uptake1 (Pup1) locus with 11 previously reported SSR markers and sequence characterized the phosphorus-starvation tolerance 1 (PSTOL1) gene. In the present study, we screened 182 accessions of O. rufipogon along with Vandana as a positive control with SSR markers. From the analysis, it was inferred that all of the O. rufipogon accessions undertaken in this study had an insertion of 90 kb region, including Pup1-K46, a diagnostic marker for PSTOL1, however, it was absent among O. sativa cv. PR114, PR121, and PR122. The complete PSTOL1 gene was also sequenced in 67 representative accessions of O. rufipogon and Vandana as a positive control. From comparative sequence analysis, 53 mutations (52 SNPs and 1 nonsense mutation) were found in the PSTOL1 coding region, of which 28 were missense mutations and 10 corresponded to changes in the amino acid polarity. These 53 mutations correspond to 17 haplotypes, of these 6 were shared and 11 were scored only once. A major shared haplotype was observed among 44 accessions of O. rufipogon along with Vandana and Kasalath. Out of 17 haplotypes, accessions representing 8 haplotypes were grown under the phosphorus-deficient conditions in hydroponics for 60 days. Significant differences were observed in the root length and weight among all the genotypes when grown under phosphorus deficiency conditions as compared to the phosphorus sufficient conditions. The O. rufipogon accession IRGC 106506 from Laos performed significantly better, with 2.5 times higher root weight and phosphorus content as compared to the positive control Vandana. In terms of phosphorus uptake efficiency, the O. rufipogon accessions IRGC 104639, 104712, and 105569 also showed nearly two times higher phosphorus content than Vandana. Thus, these O. rufipogon accessions could be used as the potential donor for improving phosphorus uptake efficiency of elite rice cultivars.

Introduction

Rice (Oryza sativa L.), one of the major staple food crops in the world, is critical to food security for billions of people around the world. Calories from rice are particularly important in Asia, especially among the poor, where it accounts for 50–80% of the daily calorie intake (http://www.gramene.org/). The estimated demand for rice in India is projected to go up to 121.2 million tons by the year 2030, 129.6 by the year 2040 and 137.3 million tons by the year 2050 as compared to 90–104 million tons being produced currently (http://www.crri.nic.in/ebook_crrivision2050_final_16Jan13.pdf). This indicates that rice production needs to be increased by 32% in the next 33 years for fulfilling the internal consumption of India. Keeping in view the situation when the area growth rate is negative and decreasing at the rate of 0.15% per year under rice, utilization of poor and problematic soils for sustaining yield requirement is one of the most promising ways.

Rice requires phosphorus to survive and thrive. It is a key element in plant metabolism, root growth, maturity, and yield. Phosphorus (P) deficiency leads to various physiological disorders in rice such as stunted growth, reduced tillering, thin and spindle stems, reduced number of grains per panicle (http://www.Knowledgebank.irri.org/phosphorus-deficiency) and ultimately leads to the reduction in the yield of rice plants. In Asia, 60% of the rain-fed lowland rice is produced on poor and problem soils that are naturally low in phosphorus or P fixing (Gamuyao et al., 2012). Phosphorus deficiency is widespread in Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Nepal, Pakistan, South China, and Vietnam (Wissuwa and Ae, 2001; Haefele and Hijmans, 2009). In India, nearly 61.02% of the soils are found low in available P, 25.89 and 13.09% are found medium and high in available P content (Hasan, 1996; Muralidharudu et al., 2011). The hurdle further increases due to the presence of a non-renewable source of phosphatic fertilizers. The indigenous deposits of rock phosphate are barely able to meet 10% of the phosphate fertilizer demand in India. For the rest of the need (90%), India depends on imports of raw materials and processed phosphatic fertilizer products (Sharma and Thaker, 2011). Large quantities of finished products of fertilizer are imported in India every year, along with raw materials and intermediates for producing different fertilizers indigenously. In 2000-01, import of finished products (on N + P2O5 + K2O nutrient basis) was 2.194 million tons, which rose to 12.208 million tons in 2010–11 (Majumdar et al., 2013). Besides, about 5 million tons of rock phosphate and 2 million tons of phosphoric acid are imported every year. The availability of rock phosphate from domestic sources is about 1.86 million tons (Majumdar et al., 2013) which is nearly one by seventh of the total demand. Further, annual outgo on fertilizer subsidy during 2013–14 was Rs. 71,251 crores, out of which Rs. 29,427 crores were shared by phosphatic and potassic fertilizers. Therefore, the development of rice varieties with sustainable productivity under the problematic soil is a valid approach toward reducing the economic burden of the country.

The wild species germplasm of rice constitutes the most important genetic resources for rice improvement. Rice belongs to genus Oryza and tribe Oryzeae of the family Gramineae (Poaceae). The genus Oryza contains 24 recognized species, of which 22 are wild species (Vaughan et al., 2003). The wild species have either 2n = 24 or 2n = 48 chromosomes representing AA, BB, CC, BBCC, CCDD, EE, FF, GG, and HHJJ genomes (Brar and Khush, 2003). Several genes and QTLs have been mined from wild species of rice for resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses and for enhancing the productivity of modern cultivars (Khush et al., 1977; Xiao et al., 1996; Moncada et al., 2001; Aluko et al., 2004; Linh et al., 2008; Rangel et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2009; Khush, 2013). In rice, the low-Pi tolerance is naturally present in wild germplasm/landraces and could be used to improve phosphorus acquisition efficiency (PAE) and phosphorus use efficiency (PUE) in modern varieties (Gamuyao et al., 2012). A major QTL for P-deficiency tolerance was mapped on chromosome 12 (Pup1) from the aus type rice variety Kasalath, explaining 70% of the variance (Wissuwa et al., 2002). Among various markers developed by Chin et al. (2010) for marker assisted breeding of phosphorus uptake efficiency, only OsPupK46-2 was found associated with the trait and later named as phosphorus-starvation tolerance 1 (PSTOL1) gene by Gamuyao et al. (2012). This gene is absent from the rice reference genome (Nipponbare) and in the genomes of other indicia varieties which are susceptible to phosphorus deficiency (Wissuwa et al., 2002). The PSTOL1 act as an enhancer of early root growth and promotes more phosphorus uptake (Gamuyao et al., 2012). Therefore, it is highly desirable to explore, utilize and transfer new alleles of PSTOL1 gene to the elite cultivars for improving their yield under low phosphorus soil conditions. Only a few reports are available on allelic diversity present among the rice wild species germplasm for the PSTOL1 gene (Pariasca-Tanaka et al., 2014; Vigueira et al., 2016). Moreover, all of the breeding programs worldwide for improving phosphorus uptake are focused on the transfer of PSTOL1 gene from Kasalath (aus type) and African rice (O. glaberrima Steud), leading to the narrowing of genetic variability. In order to deploy novel genes/alleles for improving phosphorus uptake efficiency, our primary objective is to investigate Oryza rufipogon accessions for allelic diversity at PSTOL1, its validation under the phosphorus-deficient conditions and further its transfer to elite rice indica cultivars.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials

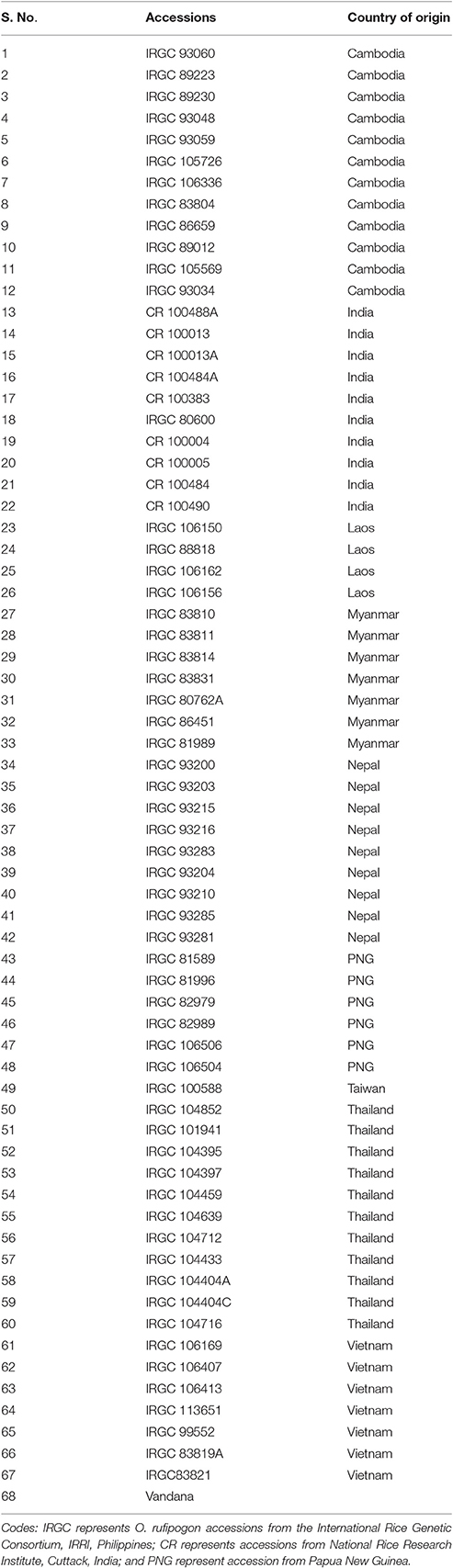

For SSR marker analysis in this study, 182 O. rufipogon accessions from 10 different countries viz. Bangladesh (n = 8), Cambodia (n = 31), Thailand (n = 24), Myanmar (n = 16), Taiwan (n = 4), Vietnam (n = 20), Nepal (n = 20), Laos (n = 8), Papua New Guinea (n = 13), and India (n = 38) were undertaken. These germplasm accessions were originally procured either from the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), Philippines or from National Rice Research Institute (NRRI), Cuttack and being actively maintained at Punjab Agricultural University (PAU), Ludhiana. The rice cultivars, Punjab Rice 114 (PR114), Punjab Rice 121 (PR121), Punjab Rice 122 (PR122), and Punjab Basmati 3 (PB3) were used as negative checks. The upland rice variety Vandana was selected as a positive control due to the presence of 90 kb of phosphorus uptake 1 (Pup1) locus. The list of accessions undertaken along with their country of origin is given in Supplementary Table S1. Out of 182 accessions, 67 were sequenced for complete coding sequences (CDS) of PSTOL1 (Table 1).

DNA Extraction and SSR Marker Analysis

Genomic DNA of 182 accessions along with cultivated varieties was isolated using modified Cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method of Saghai-Maroof et al. (1984). Eleven SSR markers comprised of 7 dominant SSR markers (Pup1-K41, Pup1-K42, Pup1-K43, Pup1-K46, Pup1-K48, Pup1-K52, and Pup1-K59) in INDEL region and 4 co-dominant (Pup1-K4, Pup1-K5, Pup1-K20, and Pup1-K29) markers located in Pup1 genomic region (Chin et al., 2010, 2011) were used for SSRs genotyping (Supplementary Table S2, Supplementary Figure S1). PCR amplification was performed in a 20 ul reaction mix with the following thermal conditions: 94°C for 4 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min and the final extension of 7 min at 72°C.

Sequencing of PSTOL1 Gene in O. rufipogon Accessions

The Oryza sativa cv. Kasalath sequence (Accession AB458444.1) from position 275,525–276,499 bp covering 975 bp CDS region of PSTOL1 was used for designing sequencing primers (PSTOL1 forward: 5′-ATAGCAGGCATTTCTGGCTCA-3′ and PSTOL1 reverse: 5′-CCATGACAGCTGATTGCCTT-3′). The amplicons were purified using Wizard® SV 96 PCR clean up/Gel extraction kit from Promega, USA, as per manufacturer's protocol. Sequencing reaction was performed using ABI Big-dye Terminator v3.1 chemistry and sequenced using ABI Sequencer 3730XL. Hi-fidelity long-read DNA polymerase (Phusion Taq) from Promega, USA, was employed to obtain the required amplicon size. A minimum of three replications was carried out for the confirmation of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs).

Haplotype Determination and Protein Prediction

For comparative sequence analysis, the PSTOL1 sequences were trimmed to remove any poor quality region at both ends. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using Clustal W of MEGA version 7.0 (Kumar et al., 2016). Kasalath sequence was used as a reference for detection and determination of SNPs position among the PSTOL1 sequences obtained from O. rufipogon accessions. The identified SNPs were manually confirmed using chromatograms. DnaSP version 5.0 and Selecton server (http://selecton.tau.ac.il/, Stern et al., 2007) were used to calculate summary statistics for nucleotide diversity (π), the number of segregating sites, non-synonymous (ka), and synonymous (ks) mutations and the ratio of ka/ks is to estimate positive/purifying selection of a given amino acid, the number of haplotype and Tajima's D test.

Bioinformatics toolkit (http://toolkit.tuebingen.mpg.de/) was used to predict protein structures of all sequences. Homology modeling approach was employed using the Modeler to determine the structure of proteins based on the known structure of template protein. Protein domains were predicted and compared using Pfam (http://pfam.xfam.org/search) and Prosite (http://prosite.expasy.org) online tools. The protein models were checked for the quality using the Ramachandran plot developed using Procheck through PDBsum (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/databases/pdbsum). The modeled protein structure was visualized and compared in UCSF Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004). All the structures were superimposed for observing structural variations.

Phylogenetic Analysis

A phylogenetic tree was generated by MEGA7.0 software using the alignment file obtained earlier. The molecular phylogeny was inferred using the Maximum Likelihood method with 1,000 bootstrap (Tamura and Nei, 1993). All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated along with other default settings of the software.

Validation of Haplotypes under Phosphorus Starvation

For functional validation of PSTOL1 haplotypes toward phosphorus uptake efficiency, eight accessions with seven different haplotypes along with positive control Vandana and negative control PR121 were grown in replicates under low and high phosphorus conditions in the greenhouse facility following the protocol of Gamuyao et al. (2012). High and low P growth conditions were established by maintaining the NaH2PO4concentration in the hydroponic media as 100 μM and 10 μM, respectively. The eight accessions (CR 100013, CR 10013A-H2, IRGC 104639-H3, IRGC 104712-H4, IRGC 100588-H8, IRGC 105569-H9, IRGC 81989-H11, and IRGC 106506-H17) along with controls were grown in hydroponics for about 2 months. Due to poor germination of accessions representing remaining haplotypes, they were not included in the present study. The seeds were germinated on the wet filter paper, and four seedling replicates per accession were assayed for each phosphorus treatment. After 10 days of germination, seedlings were transferred to the Styrofoam trays suspended in Yoshida growth media (Yoshida et al., 1976). The nutrient media was changed at every third day. Data for the root length, shoot length, final dry root, and shoot weight were taken after 60 days in growth media. Phosphorus content in roots was measured using Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectrophotometer after digestion in a mixture of HNO3, HClO4, and H2SO4 (3:1:1) according to the protocol described by Neelam et al. (2011). The morphological data on root and shoot traits under study along with phosphorus content on dry root weight basis was subjected to the statistical analysis. Student's t-test was applied for testing the significance of differences among the means of O. rufipogon accessions and the controls.

Results

Genotyping of Pup1 Locus Using SSR Markers

The analyzed co-dominant SSR markers were found monomorphic among all the 182 O. rufipogon accessions and indica rice cultivars (PR114, PR121, PR122, PB3, and Vandana) (Supplementary Table S3). For dominant markers (Pup1-K41 to K-59), the presence of Vandana alleles was detected in the majority of the O. rufipogon accessions as well as in the modern rice cultivars except for marker K-46. Rice cultivars PR114, PR121, and PR122 did not show any amplification for K-46 marker. This indicates the specificity of K-46 marker for the assessment of phosphorus starvation tolerance.

Haplotype Variations in PSTOL1 Gene

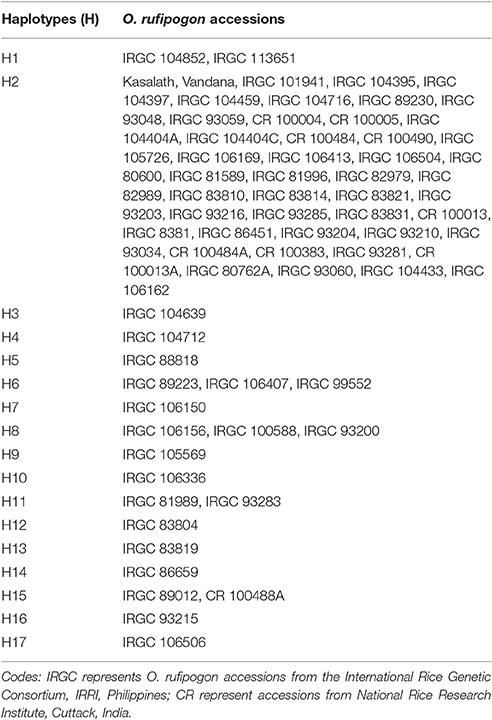

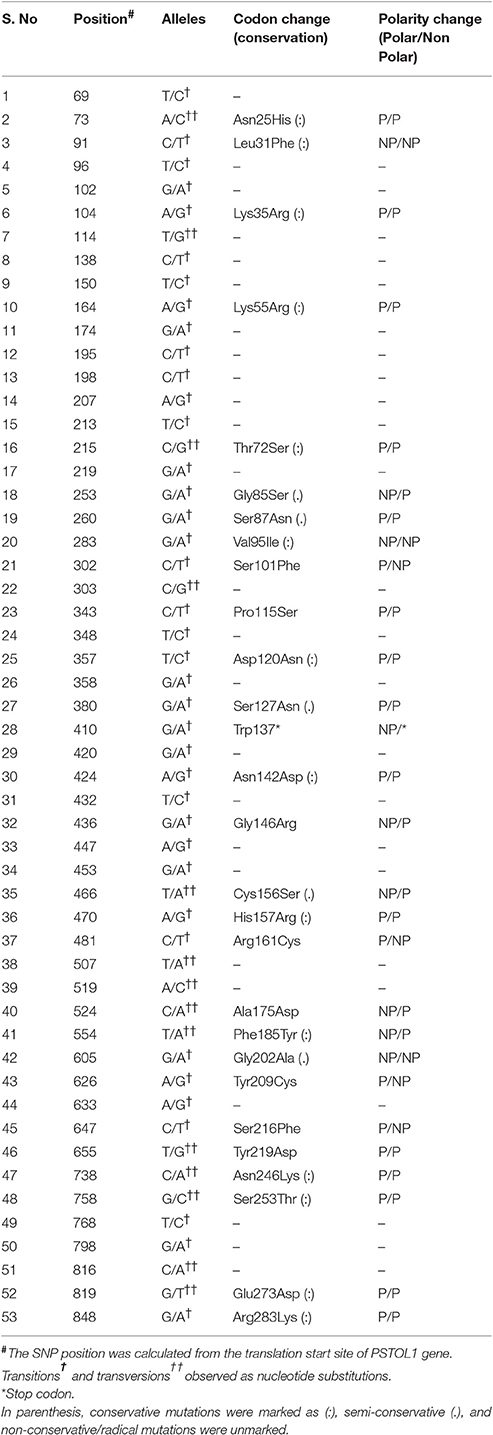

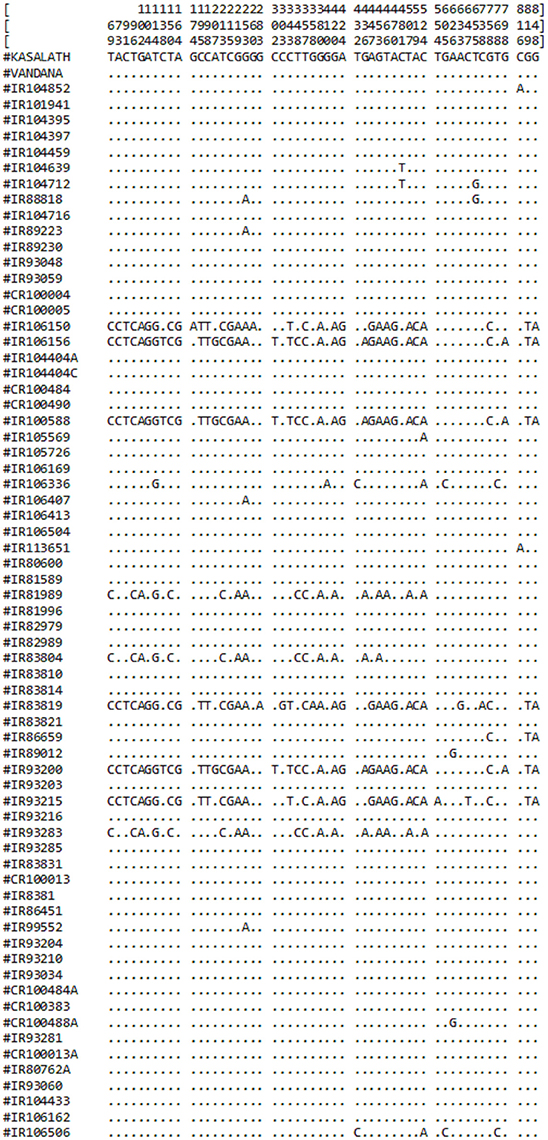

From comparative sequence analysis, 53 nucleotide changes (52 SNPs and 1 nonsense mutation) across the exon were observed (Table 2). Both types of conversions i.e., transitions (n = 39) and transversions (n = 14) were observed, while the G/A transition was most common (28.30%). Higher transitions indicated more of the synonymous substitutions were present among genotypes and hence no conformational changes in the structure of proteins were observed. Based on the nucleotide diversity present among O. rufipogon accessions, haplotypes were identified using DnaSP software v5.0. Out of 53 identified, 10 SNPs at position 174, 260, 283, 303, 358, 410, 554, 633, 647, and 738 were found as singleton whereas 43 SNPs were parsimony informative sites with a minimum frequency of occurrence in two or more O. rufipogon accessions (Figure 1). The overall nucleotide diversity (π) of the identified PSTOL1 alleles was found 0.00758, which indicates low variance in the average number of nucleotide differences per site between two sequences. The number of mutations (n = 53) and the number of segregations sites (S = 53) were same, suggesting their positive selection. The value of Tajima's D obtained is negative (−1.09788) supporting the above-said statement. Presence of fewer haplotypes was observed than the number of segregating sites indicating the lower frequency of rare alleles present in the population. A total of 17 haplotype groups was formed, revealing genotypes divergence at PSTOL1 gene among studied O. rufipogon accessions (Table 3). The haplotype H1 carried two O. rufipogon accessions, one each from Vietnam and Thailand with only one segregating site at position 816. Major haplotype group H2, harbors 44 O. rufipogon accessions along with Vandana and Kasalath indicating the sequence similarity among them. The other 16 haplotype groups had O. rufipogon accessions ranging from one to three. The haplotype H3 and H4 shares same phylogenetic clade, but having different nucleotide segregating sites. The O. rufipogon accessions (IRGC 106150, IRGC 106156, IRGC 93200, IRGC 100588, IRGC 83819, and IRGC 93215) under the smaller phylogenetic clade B grouped into different haplotype i.e., H7, H8, H13, and H16 indicating the presence of rich allelic divergence for the PSTOL1 gene in these accessions.

Table 2. The total nucleotide variations and post translational modification sites observed at PSTOL1 among O. rufipogon accessions as compared to the reference sequence.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of identified haplotypes in 67 O. rufipogon accessions along with reference sequence Kasalath and Vandana. Numerical values in vertical lines represent positions of 53 SNPs. The dots (.) represent identical nucleotide at corresponding positions among O. rufipogon accessions and the reference sequence.

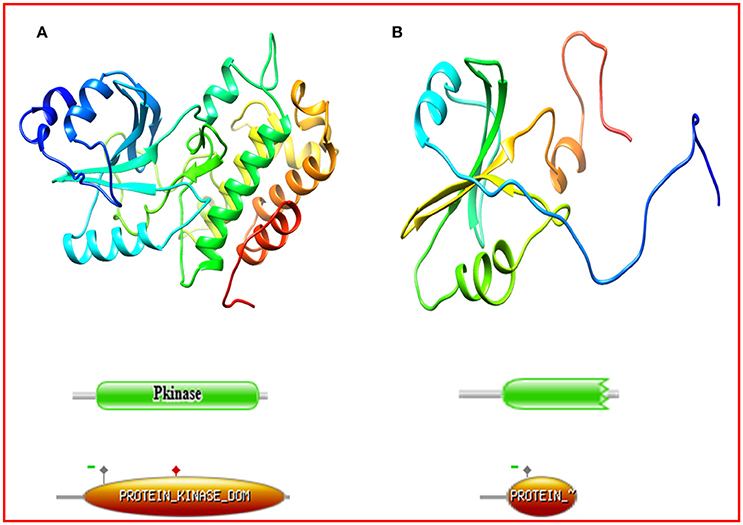

Protein Structure Prediction and Comparison

A total of 28 differences in amino acid sequences with a comparison to the variety Vandana and Kasalath were identified (Table 2). The ratio of non-synonymous/synonymous site (ka/ks) was found 1.52, suggesting that the amino acids were under positive selection and favored by the environment. The amino acids at position 25, 31, 35, 55, 72, 85, 87, 95, 101, 115, 120, 127, 142, 146, 156, 157, 161, 185, 202, 209, 216, 219, 246, 253, 273, and 283 highlighted by yellow color were under positive selection (Supplementary Figure S2).

Protein structures for Kasalath and 67 accessions of O. rufipogon belonging to different haplotype groups were superimposed and analyzed for structural differences. The non-synonymous mutations concentrate around the ATP binding site (LEU45, ARG47, GLY48, VAL53, ALA65, GLU112, MET114, TYR113, SER118, LYS168, GLN170, and LEU173). (Supplementary Figure S3). The Ramachandran plot of Kasalath revealed more than 99.3% residues were at the core and allowed region and only two residues were present in the disallowed region. Similar results were obtained for protein models of other accessions. All the accessions had a three-dimensional structure similar to the reference Kasalath except accession IRGC 106336 (Figure 2). The protein structure of Kasalath and other accessions displayed 14 helices and two beta-pleated sheets and nine strands, while accession IR 106336 showed only three helices, one sheet, and five strands. In accession IRGC 106336, the PSTOL1 sequence revealed the presence of premature stop codon at position 137 and its further domain analysis using Pfam and Prosite revealed that it encodes partial protein kinase domain instead of protein tyrosine kinase as encoded by Kasalath. The Prosite analysis for PSTOL1 protein in Kasalath predicted the features as the kinase domain from codon 39–319, nucleotide phosphate binding site (NP_BIND) at position 45–53, ATP-binding site (BINDING) at position 67 and the proton acceptor site as active site at position 166 whereas IRGC 106336 had partial protein kinase domain from 39 to 136, NP_BIND from position 45–53, ATP-binding site (BINDING) at position 67, with absence of proton acceptor site i.e., active site (Supplementary Table S4).

Figure 2. Comparison of the protein structure of (A) Kasalath, (B) Oryza rufipogon accession IRGC 106336. The Kasalath protein model represents leucine rich repeat protein kinase whereas IRGC 106336 showed tyrosine protein kinase domain. As depicted by Prosite results, the encoded structure of protein in Kasalath (green domains by Pfam E-value = 5.8e-45; orange domains by Prosite with score = 36.994) showed proton acceptor site (active site, solid red square marked on the orange domain) whereas in O. rufipogon accession IRGC 106336 (green domains by Pfam E-value = 2.4e-16; orange domains by Prosite score = 14.054) the active site was absent due premature stop codon.

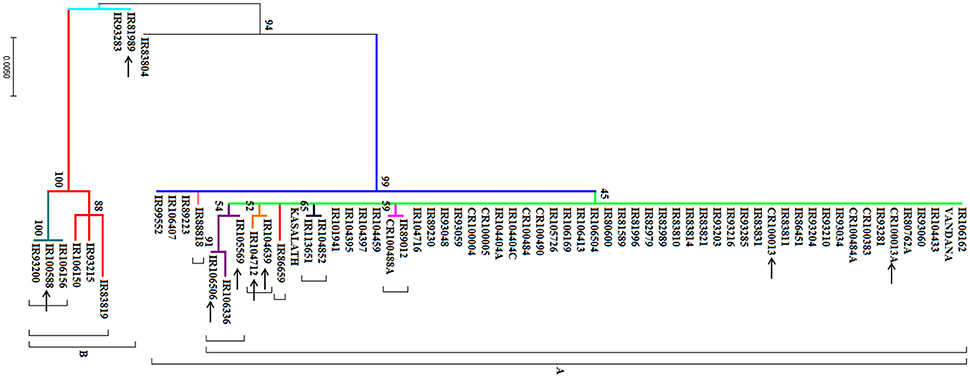

Phylogenetic Analysis

Phylogenetic analysis at PSTOL1 locus revealed divergence among O. rufipogon accessions (Figure 3). The different node colors correspond to the different mutations present in O. rufipogon accessions and vice-versa. Two major groups were observed. The clade A is consisted of 59 O. rufipogon accessions which can be further divided into 8 subgroups. Out of 59 accessions, 44 were found to have similar sequences as that of the reference sequence, whereas others having either single or more substitutions as compared to the reference. Among 44 accessions 6 are of Nepal origin, 6 are of Cambodia origin, 9 are of Indian origin, 8 are of Thailand origin, 4 are of Papua New Guinea origin, 4 are of Vietnam origin, 1 is of Laos origin, and 6 are of Myanmar origin. This indicates a common evolutionary relationship of these O. rufipogon accessions with aus type variety Kasalath. The clade B includes eight accessions, two from Laos (IRGC 106150, IRGC 106156), three from Nepal (IRGC 93200, IRGC 93215, IRGC 93283) and one each from Vietnam (IRGC 83819), Taiwan (IRGC 100588), Myanmar (IRGC 81989).

Figure 3. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Tamura-Nei model. The bootstrap consensus tree inferred from 1,000 replicates is taken to represent the evolutionary history of the taxa analyzed. Branches corresponding to partitions reproduced in less than 50% bootstrap replicates are collapsed. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood (MCL) approach, and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. The different node colors indicate the presence of different mutations as compared to the reference. The O. rufipogon accessions used for validation under phosphorus deficiency are indicated by an arrow.

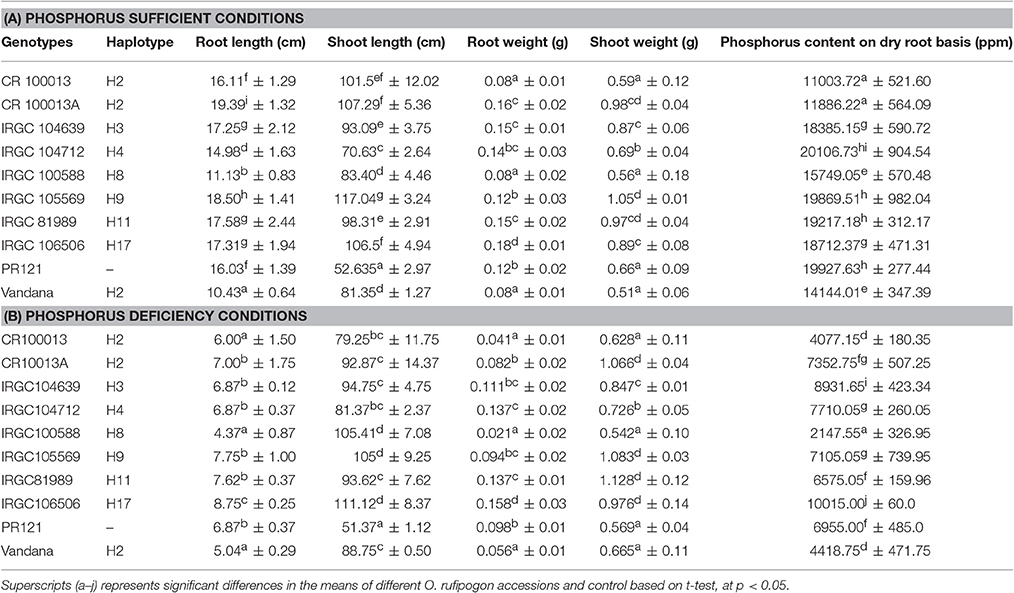

Validation of Novel Alleles under Phosphorus Deficiency

Genotypic variation for root and shoot length, dry root and shoot weight and phosphorus content on dry roots basis were examined under phosphorus sufficient and deficient conditions after 2 months of the experiment (Tables 4A,B). Genotypic differences were observed among all O. rufipogon accessions under both growing conditions. All of the genotypes under phosphorus sufficient conditions had almost double root length as compared to the deficient conditions. Though, not much difference was observed in shoot length and shoot weight for all the genotypes when compared under phosphorus sufficiency and deficiency conditions. The O. rufipogon accession IRGC 106506 (H17) showed the best root and shoot length under phosphorus-deficient conditions when compared to other genotypes and control. Among H2 haplotype O. rufipogon accession CR 100013A performed better than Vandana for all the traits studied. In terms of root and shoot weight, O. rufipogon IGCC 106506 (H17) showed the best root weight followed by IRGC 81989 from H11 haplotype. Approximately, 1.5 and 2.3 times higher phosphorus content was found in the O. rufipogon accession IRGC 106506 when compared to indica cultivar PR 121 and Vandana respectively. Other than that, O. rufipogon accession IRGC 104639 from H3 haplotype also showed 1.2 times higher phosphorus content when compared to PR121 indicating their potentiality toward improving elite cultivars for phosphorus uptake.

Table 4. Morphological data on root and shoot length, root and shoot weight and phosphorus content under phosphorus sufficient conditions (A), and phosphorus deficiency conditions (B).

Discussion

Allelic Differences among O. rufipogon Accessions and O. Sativa with Pup1 Specific Markers

Our results with Pup1 specific markers on O. rufipogon accessions and O. sativa cultivars revealed no allelic differences for almost all markers other than K-46 and K-05 (Supplementary Table S3). Chin et al. (2010), also observed the Kasalath specific alleles for markers K-41, K-43, and K-48 in lowland/irrigated (indica, japonica, aus, and traditional or modern) rice cultivars, representing nonusefulness of these markers for marker aided selection for phosphorus uptake efficiency. Similarly, the markers K-42, and K-29 were not found linked with PUE by Sarkar et al. (2011) while assessing indica germplasm. It should be taken into consideration that Gamuyao et al. (2012) ruled out other co-dominant and INDEL markers as indicative of PUE except for K-46. This dominant marker was found useful for MAS in the progenies involving Kasalath as Pup1 donor variety and Asian lowland rice varieties (without this gene) by Chin et al. (2010, 2011) and Pariasca-Tanaka et al. (2014), supporting our results. Mukherjee et al. (2014), assessed 108 genotypes from different states of India for phosphorus acquisition efficiency with gene specific markers and closely linked SSR marker RM1261 and reported no association between markers and PUE. The same has been observed when they studied a RIL population developed from a cross between Gobindabhog (with PSTOL1 gene) and Satabdi (PSTOL1 absent). The notion that PSTOL1 specific marker was not indicative in the case of indica germplasm (Mukherjee et al., 2014) is more likely due to the complex nature of Pup1 locus and different genetic background and environment where this gene has to express.

The germplasm survey with Pup1 specific markers of Kasalath indicated entire inserted region of 90 kb among studied O. rufipogon accessions. The probable explanation for this could be a continuous gene flow between O. sativa and O. rufipogon populations throughout the history of domestication (Vaughan et al., 2008). Also, O. rufipogon accessions from South and Southeast Asia are considered as the wild progenitor of domesticated rice (Oka, 1988; Molina et al., 2011) and hence chances of recent hybridization events needs to be accounted for the phenomena. While studying allelic diversity at PSTOL1, Vigueira et al. (2016) reported presence/absence polymorphism in 12 of the O. rufipogon accessions out of 40 studied, along with the loss of function mutation in one accession and 56 synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions in 28. He explains this phenomenon as long- term balancing selection at PSTOL1 locus for maintaining both functional and non-functional alleles among the accessions of O. rufipogon and indica, aus, tropical japonica cultivars. Though, none of the alleles found conferring superior phenotype than Kasalath in their study, whereas in our case functional alleles were observed.

Phylogeography of O. rufipogon Accessions under Study

Our results on molecular diversity at PSTOL1 locus, suggests the presence of lower diversity among O. rufipogon accessions from South Asia and Southeast Asian nations. This is expected as they share common geographical boundaries. This result is in accordance with several studies conducted on the assessment of genetic diversity of Asian wild rice using RFLP, microsatellite markers, SINEs, sequence based polymorphism, ISSRs, chloroplast, and low-copy nuclear markers (Joshi et al., 2000; Cheng et al., 2002; Rakshit et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2012). In a study, conducted by Huang et al. (2012) on the phylogeography of Asian wild rice using 42 genome-wide sequence tagged sites demonstrated that O. rufipogon accessions were grouped into two genetically distinct clades (Ruf-I and Ruf-II). The O. rufipogon accessions from South Asia and Indochinese Peninsula (Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos), were clustered into one group (Ruf-II), supporting our results. The presence of few accessions from Nepal, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Myanmar into intermediate and second major clade may be interpreted as an admixture. Moreover, the humid tropical plain areas in the Indo Peninsula zone act as a transitional region for evolutionary studies is likely the reasons for observed admixture.

Haplotype Diversity at PSTOL1 and Contribution toward Phosphorus Uptake Efficiency

It is always worthwhile to look for better alleles of a gene for creating and maintaining natural genetic diversity. Our results demonstrated the presence of 17 different haplotypes within 975 bp sequence of PSTOL1 locus indicating rich nucleotide variation among studied O. rufipogon accessions. Two of the O. rufipogon accessions under H17 and H11 were found performing better than the positive control under phosphorus-deficient conditions. Functional allelic variants were observed and utilized for improving various agronomically important traits in cereal crops (Ellis and Setter, 1999; Bhullar et al., 2010; Ravensdale et al., 2012; Vasudevan et al., 2014; Ashkani et al., 2015). The wheat powdery mildew resistance gene Pm3 with 17 identified functional alleles is a remarkable example of natural variations present in GenBank accessions and can be efficiently utilized for conferring broad-spectrum disease resistance. For rice blast resistance gene, functional orthologous have been found in wild rice O. rufipogon accessions (Lv et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2014; Ashkani et al., 2015) defining their utility in widening the genetic base of cultivated rice varieties. A novel allele of PSTOL1 gene is identified in O. glaberrima (CG14) and being transferred to the NERICAs (New Rice for Africa) cultivars using allele-specific markers. In their study, they identified 3 novel alleles in 10 studied O. rufipogon accessions and also the presence of Kasalath alleles for INDEL markers which is consistent with our results. The successful efforts for the transfer of PSTOL1 were made by Gamuyao et al. (2012) through marker assisted backcross breeding to Asian rice cultivar IR74 with increased root growth and phosphorus uptake efficiency.

The presence of PSTOL1 in all O. rufipogon accessions raise the question regarding the functionality of different alleles under phosphorus deficiency. Validation of haplotype groups showed the significant difference for root and shoot length and biomass as compared to PR121 and Vandana under both phosphorus sufficient and deficient conditions. The correlation between root elongation, higher root and shoot biomass of genotypes under P-deficiency is considered as one of an important indicator of higher phosphorus uptake efficiency. A number of reports, including QTLs on P deficiency induced root elongation in plants were published (Steingrobe et al., 2001; He et al., 2003; Ma et al., 2003; Wissuwa, 2005; Li et al., 2007; Rose et al., 2013). Near isogenic line of “Nipponbare” with Pup1 QTL from “Kasalath” showed high P content, high tillering and high root growth under P-deficient upland conditions (Wissuwa and Ae, 2001; Wissuwa et al., 2002). The O. rufipogon accession IRGC 106506 showed the highest root growth under P-deficiency and thus is the best option for transferring this novel allele to elite cultivars for improving P starvation tolerance.

Conclusion

In Summary, our efforts for harnessing superior allele of PSTOL1 in O. rufipogon revealed three accessions (IRGC 106506, IRGC 81989, and IRGC 104639) from haplotypes H17, H11, and H3 with better performance under Phosphorus deficiency conditions. Though, further confirmation of identified superior alleles should be done under the phosphorus-deficient soil. Transfer and development of allele-specific markers for MAS have already been initiated at Punjab Agricultural University. Marker assisted transfer of these potential haplotypes to the indica rice cultivars would be useful to breed better rice with sustainable yield under phosphorus-deficient soil.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiment: KN, KS, and SD. Performed the experiment: KN, ST, N, and KK. Analyzed the data: KN, ST, and IY. Wrote the paper: KN and ST.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), Philippines, Manila and National Rice Research Institute (NRRI), Cuttack, India for providing wild species germplasm of rice. We are thankful to Dr. H. S. Dhaliwal for helpful suggestions and Dr. Amit Kishore for critical revision of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2017.00509/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure S1. Pup1 genomic region with positions of co-dominant and dominant markers.

Supplementary Figure S2. Evolutionary sweeps or selections of protein sequences at PSTOL1 gene: Positive selection is colored in shades of yellow, and purifying selection is colored in shades of magenta.

Supplementary Figure S3. Superimposed protein model of PSTOL1 gene of all O. rufipogon accessions using UCSF Chimera. Ball and sticks represent the mutated residues of haplotypes.

Supplementary Table S1. List of Oryza rufipogon accessions selected for SSR marker analysis along with countries of origin.

Supplementary Table S2. SSR primers used to study variability among O. rufipogon accessions.

Supplementary Table S3. Genotyping results of O. rufipogon accessions using eleven SSR markers of Pup 1 locus.

Supplementary Table S4. The Prosite analysis of PSTOL1 protein model of Kasalath and Oryza rufipogon accession IRGC 106336.

References

Aluko, G., Martinez, C., Tohme, J., Castano, C., Bergman, C., and Oard, J. H. (2004). QTL mapping of grain quality traits from the interspecific cross Oryza sativa x O. glaberrima. Theor. Appl. Genet. 109, 630–639. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1668-y

Ashkani, S., Yusop, M. R., Shabanimofrad, M., Azadi, A., Ghasemzadeh, A., Azizi, P., et al. (2015). Allele mining strategies: principles and utilisation for blast resistance genes in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 17, 57–74. doi: 10.21775/cimb.017.057

Bhullar, N. K., Zhang, Z., Wicker, T., and Keller, B. (2010). Wheat gene bank accessions as a source of new alleles of the powdery mildew resistance gene Pm3: a large scale allele mining project. BMC Plant Biol. 10:88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-88

Brar, D. S., and Khush, G. S. (2003). “Utilization of wild species of genus Oryza in rice improvement,” in Monograph on Genus Oryza, eds J. S. Nanda and S. D. Sharma (Enfield, NH: Science Publishers), 283–309.

Chen, Z., Hu, F., Xu, P., Li, J., Deng, X., Zhou, J., et al. (2009). QTL analysis for hybrid sterility and plant height in interspecific populations derived from a wild rice relative, Oryza longistaminata. Breed. Sci. 59, 441–445. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.59.441

Cheng, C., Tsuchimoto, S., Ohtsubo, H., and Ohtsubo, E. (2002). Evolutionary relationships among rice species with AA genome based on SINE insertion analysis. Genes Genet. Syst. 77, 323–334. doi: 10.1266/ggs.77.323

Chin, J. H., Lu, X., Haefele, S. M., Gamuyao, R., Ismail, A., Wissuwa, M., et al. (2010). Development and application of gene-based markers for the major rice QTL Phosphorus uptake 1. Theor. Appl. Genet. 120, 1073–1086. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1235-7

Chin, J. H., Gamuyao, R., Dalid, C., Bustamam, M., Prasetiyono, J., Moeljopawiro, S., et al. (2011). Developing rice with high yield under phosphorus deficiency: Pup1 sequence to application. Plant Physiol. 156, 1202–1216. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.175471

Ellis, M. H., and Setter, T. L. (1999). Hypoxia induces anoxia tolerance in completely submerged rice seedlings. J. Plant Physiol. 154, 219–230. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(99)80213-2

Gamuyao, R., Chin, J. H., Pariasca-Tanaka, J., Pesaresi, P., Catausan, S., Dalid, C., et al. (2012). The protein kinase Pstol1 from traditional rice confers tolerance of phosphorus deficiency. Nature 488, 535–539. doi: 10.1038/nature11346

Haefele, S. M., and Hijmans, R. J. (2009). Soil quality in rainfed lowland rice. Rice Today 8, 30–31.

He, Y., Lian, H., and Yan, X. (2003). Localized supply of phosphorus induces root morphological and architectural changes of rice in split and stratified soil cultures. Plant Soil 248, 247–256. doi: 10.1023/A:1022351203545

Huang, P., Molina, J., Flowers, J. M., Rubinstein, S., Jackson, S. A., Purugganan, M. D., et al. (2012). Phylogeography of Asian wild rice, Oryza rufipogon: a genome wide view. Mol. Ecol. 21, 4593–4604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05625.x

Joshi, S. P., Gupta, V. S., Aggarwal, R. K., Ranjekar, P. K., and Brar, D. S. (2000). Genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationship as revealed by inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) polymorphism in the genus Oryza. Theor. Appl. Genet. 100, 1311–1320. doi: 10.1007/s001220051440

Khush, G. S. (2013). Strategies for increasing the yield potential of cereals: case of rice as an example. Plant Breed. 132, 433–436. doi: 10.1111/pbr.1991

Khush, G. S., Ling, K. C., and Aguiero, V. M. (1977). “Breeding for resistance to grassy stunt in rice,” in Proceeding 3rd Int Congress (Canberra, ACT: SABRAO), 3–9.

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., and Tamura, K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054

Li, Z., Ni, Z., Peng, H., Liu, Z., Nie, X., Xu, S., et al. (2007). Molecular mapping of QTLs for root response to phosphorus deficiency at seedling stage in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Prog. Nat. Sci. 17, 1177–1184.

Linh, L. H., Hang, N. T., Jin, F. X., Kang, K. H., Lee, Y. T., Kwon, S. J., et al. (2008). Introgression of a quantitative trait locus for spikelets per panicle from Oryza minuta to the O. Sativa cultivar Hwaseongbyeo. Plant Breed. 127, 262–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2007.01462.x

Lv, Q., Xu, X., Shang, J., Jiang, G., Pang, Z., Zhou, Z., et al. (2013). Functional analysis of Pid3-A4, an ortholog of rice blast resistance gene Pid3 revealed by allele mining in common wild rice. Phytopathology 103, 594–599. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-10-12-0260-R

Ma, Z., Baskin, T. I., Brown, K. M., and Lynch, J. P. (2003). Regulation of root elongation under phosphorus stress involves changes in ethylene responsiveness. Plant Physiol. 131, 1381–1390. doi: 10.1104/pp.012161

Majumdar, K., Johnston, A. M., Dutta, S., Satyanarayana, T., and Roberts, T. L. (2013). Fertilizer best management practices: Concept, global perspectives and application. Indian J. Fert. 9, 14–31.

Molina, J., Sikora, M., Garud, N., Flowers, J. M., Rubinstein, S., Reynolds, A., et al. (2011). Molecular evidence for a single evolutionary origin of domesticated rice. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 8351–8356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104686108

Moncada, P., Martinez, C. P., Borrero, J., Chatel, M., Gauch, J. H., Guimaraes, E., et al. (2001). Quantitative trait loci for yield and yield components in an Oryza sativa x Oryza rufipogon BC2F2 population evaluated in an upland environment. Theor. Appl. Genet. 102, 41–52. doi: 10.1007/s001220051616

Mukherjee, A., Sarkar, S., Chakraborty, A. S., Yelne, R., Kavishetty, V., Biswas, T., et al. (2014). Phosphate acquisition efficiency and phosphate starvation tolerance locus (PSTOL1) in rice. J. Genet. 93, 683–688. doi: 10.1007/s12041-014-0424-6

Muralidharudu, Y., Reddy, K., Mandal, B. N., Subba Rao, A., Singh, K. N., and Sonekar, S. (2011). GIS Based Soil Fertility Maps of Different States of India Pp 224 All India Cordinated Project on Soil Test Crop Response Correlation. Bhopal: Indian Institute of Soil Science.

Neelam, K., Rawat, N., Tiwari, V. K., Kumar, S., Chhuneja, P., Singh, K., et al. (2011). Introgression of group 4 and 7 chromosomes of Ae. peregrina in wheat enhances grain iron and zinc density. Mol. Breed. 28, 623–634. doi: 10.1007/s11032-010-9514-1

Oka, H. I. (1988). Origin of Cultivated Rice. Tokyo; Amsterdam: Japan Science Society Press; Elsevier.

Pariasca-Tanaka, J., Chin, J. H., Dramé, K. N., Dalid, C., Heuer, S., and Wissuwa, M. (2014). A novel allele of the P-starvation tolerance gene OsPSTOL1 from African rice (Oryza glaberrima Steud) and its distribution in the genus Oryza. Theor. Appl. Genet. 127, 1387–1398. doi: 10.1007/s00122-014-2306-y

Pettersen, E. F., Goddard, T. D., Huang, C. C., Couch, G. S., Greenblatt, D. M., Meng, E. C., et al. (2004). UCSF Chimera- a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084

Rakshit, S., Rakshit, A., Matsumura, H., Takahashi, Y., Hasegawa, Y., Ito, A., et al. (2007). Large-scale DNA polymorphism study of Oryza sativa and O. rufipogon reveals the origin and divergence of Asian rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 114, 731–743. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0473-1

Rangel, P. N., Brondani, R. P., Rangel, P. H., and Brondani, C. (2008). Agronomic and molecular characterization of introgression lines from the interspecific cross Oryza sativa (BG90-2) x Oryza glumaepatula (RS-16). Genet. Mol. Res. 7, 184–195. doi: 10.4238/vol7-1gmr406

Ravensdale, M., Bernoux, M., Ve, T., Kobe, B., Thrall, P. H., Ellis, J. G., et al. (2012). Intramolecular interaction influences binding of the Flax L5 and L6 resistance proteins to their AvrL567 ligands. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1003004. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003004

Rose, T. J., Impa, S. M., Rose, M. T., Pariasca-Tanaka, J., Mori, A., Heuer, S., et al. (2013). Enhancing phosphorus and zinc acquisition efficiency in rice: a critical review of root traits and their potential utility in rice breeding. Ann. Bot. 112, 331–345. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcs217

Saghai-Maroof, M. A., Soliman, K. M., Jorgensen, R. A., and Allard, R. W. (1984). Ribosomal DNA spacer length polymorphism in barley: mendelian inheritance, chromosomal location and population dynamics. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 81, 8014–8019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.24.8014

Sarkar, S., Yelne, R., Chatterjee, M., Das, P., Debnath, S., Chakraborty, A., et al. (2011). Screening for phosphorus (P) tolerance and validation of Pup-1 linked markers in indica rice. Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 71:209.

Sharma, V. P., and Thaker, H. (2011). Demand for fertilizer in India: determinants and outlook 2020. Ind. J. Agric. Econ. 66, 638–661.

Steingrobe, B., Schmid, H., and Claassen, N. (2001). Root production and root mortality of winter barley and its implication with regard to phosphate acquisition. Plant Soil 237, 239–248. doi: 10.1023/A:1013345718414

Stern, A., Doron-Faigenboim, A., Erez, E., Martz, E., Bacharach, E., and Pupko, T. (2007). Selecton 2007: advanced models for detecting positive and purifying selection using a Bayesian Inference approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 1–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm382

Tamura, K., and Nei, M. (1993). Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in human and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 10, 512–526.

Vasudevan, K., Vera Cruz, C. M., Gruissem, W., and Bhullar, N. K. (2014). Large scale germplasm screening for identification of novel rice blast resistance sources. Front. Plant Sci. 5:505. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00505

Vaughan, D. A., Lu, B. R., and Tomooka, N. (2008). The evolving story of rice evolution. Plant Sci. 174, 394–408. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.01.016

Vaughan, D. A., Morishima, H., and Kadowaki, K. (2003). Diversity in the Oryza genus. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 6, 139–146.

Vigueira, C. C., Small, L. L., and Olsen, K. M. (2016). Long-term balancing selection at the Phosphorus Starvation Tolerance 1 (PSTOL1) locus in wild, domesticated and weedy rice (Oryza). BMC Plant Biol. 16:7. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0783-7

Wissuwa, M. (2005). Combining a modelling with a genetic approach in establishing associations between genetic and physiological effects in relation to phosphorus uptake. Plant Soil 269, 57–68. doi: 10.1007/s11104-004-2026-1

Wissuwa, M., and Ae, N. (2001). Genotypic variation for tolerance to phosphorus deficiency in rice and the potential for its exploitation in rice improvement. Plant Breed. 120, 43–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0523.2001.00561.x

Wissuwa, M., Wegner, J., Ae, N., and Yano, M. (2002). Substitution mapping of Pup1: a major QTL increasing phosphorus uptake of rice from a phosphorus-deficient soil. Theor. Appl. Genet. 105, 890–897. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1051-9

Xiao, J., Grandillo, S., Ahn, S. N., McCouch, S., and Tanksley, S. D. (1996). Genes from wild rice improve yield. Nature 384, 223–224. doi: 10.1038/384223a0

Xu, J. H., Cheng, C., Tsuchimoto, S., Ohtsubo, H., and Ohtsubo, E. (2007). Phylogenetic analysis of Oryza rufipogon strains and their relations to Oryza sativa strains by insertion polymorphism of rice SINEs. Genes Genet. Syst. 82, 217–229. doi: 10.1266/ggs.82.217

Xu, X., Lv, Q., Shang, J., Pang, Z., Zhou, Z., Wang, J., et al. (2014). Excavation of Pid3 Orthologs with differential resistance spectra to Magnaporthe oryzae in rice resource. PLoS ONE 9:e93275. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093275

Keywords: rice (Oryza sativa L.), phosphorus uptake efficiency, Oryza rufipogon, allele mining, phosphorus starvation tolerance 1 (PSTOL1), SSR markers

Citation: Neelam K, Thakur S, Neha, Yadav IS, Kumar K, Dhaliwal SS and Singh K (2017) Novel Alleles of Phosphorus-Starvation Tolerance 1 Gene (PSTOL1) from Oryza rufipogon Confers High Phosphorus Uptake Efficiency. Front. Plant Sci. 8:509. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00509

Received: 25 January 2017; Accepted: 23 March 2017;

Published: 11 April 2017.

Edited by:

Raul Antonio Sperotto, Centro Universitário UNIVATES, BrazilReviewed by:

Cynthia Vigueira, High Point University, USAWalid Hassan Elgamal, Agricultural Research Center, Egypt

Nidhi Rawat, University of Maryland, College Park, USA

Copyright © 2017 Neelam, Thakur, Neha, Yadav, Kumar, Dhaliwal and Singh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kumari Neelam, a25lZWxhbUBwYXUuZWR1

Kumari Neelam

Kumari Neelam Shiwali Thakur

Shiwali Thakur Neha

Neha Inderjit S. Yadav

Inderjit S. Yadav Kishor Kumar

Kishor Kumar Salwinder S. Dhaliwal

Salwinder S. Dhaliwal Kuldeep Singh1,3

Kuldeep Singh1,3