- 1Beijing Key Laboratory of Growth and Developmental Regulation for Protected Vegetable Crops, College of Horticulture, China Agricultural University, Beijing, China

- 2Shandong Huasheng Agriculture Co. Ltd, Shandong, China

Aluminum (Al) is present in approximately 50% of the arable land worldwide and is regarded as the main limiting factor of crop yield on acidic soil. Al-induced root malate efflux plays an important role in the Al tolerance of plants. Here, the aluminum induced malate transporter BoALMT1 (KF322104) was cloned from cabbage (Brassica oleracea). BoALMT1 showed higher expression in roots than in shoots. The expression of BoALMT1 was specifically induced by Al treatment, but not the trivalent cations lanthanum (La), cadmium (Cd), zinc (Zn), or copper (Cu). Subcellular localization studies were performed in onion epidermal cells and revealed that BoALMT1 was localized at the plasma membrane. Scanning Ion-selective Electrode Technique was used to analyze H+ flux. Xenopus oocytes and Arabidopsis thaliana expressing BoALMT1 excreted more H+ under Al treatment. Overexpressing BoALMT1 in transgenic Arabidopsis resulted in enhanced Al tolerance and increased malate secretion. The results suggested that BoALMT1 functions as an Al-resistant gene and encodes a malate transporter. Expressing BoALMT1 in Xenopus oocytes or A. thaliana indicated that BoALMT1 could increase malate secretion and H+ efflux to resist Al tolerance.

Introduction

Al is the most abundant metal and the third most abundant element, making up around 7% of the earth's crust (Tesfaye et al., 2001). When the soil pH value is lower than 5.0, the soluble aluminum in soil solutions is mostly present as the toxic Al3+, which inhibits root growth at micromolar concentrations in many species (Kochian et al., 2005). Micromole levels of Al3+ can remarkably inhibit root elongation, and impair the absorption, of water and nutrients (Kochian et al., 2005). The well-known mechanism of plant Al tolerance is the Al-induced secretion of organic acids (OA) from the root tips. The OAs chelate Al3+ and form the non-toxic compound OA-Al (Kochian et al., 2004; Horst et al., 2010; Ryan et al., 2011). The most common OAs involved in the Al detoxification process are malate, citrate, and oxalate, depending on the plant. For example, malate is used in wheat (Delhaize et al., 1993) and Arabidopsis (Hoekenga et al., 2003), citrate is secreted in maize (Pellet et al., 1995), and oxalate is used in buckwheat (Zheng et al., 2005) and tomato (Yang et al., 2008).

Wheat TaALMT1 (ALMT, for Al-activated Malate Transporter) encoding a malate transporter was the first plant gene involved in Al tolerance and the first ALMT family gene. In Al-tolerant wheat genotypes, TaALMT1 is specifically expressed in the root tips (Sasaki et al., 2004; Raman et al., 2005). Overexpression of TaALMT1 in wheat, barley, and tobacco-cell suspension increases the efflux of Al-activated malate and enhances tolerance to Al stress (Delhaize et al., 2004; Sasaki et al., 2004; Pereira et al., 2010). TaALMT1 homologs have now been isolated in Arabidopsis (Hoekenga et al., 2006), oilseed rape (Ligaba et al., 2006), rye (Collins et al., 2008), soybean (Liang et al., 2013), and Medicago sativa (Chen et al., 2013). Multi-antimicrobial extrusion (MATE) proteins are a family of proteins that function as drug/sodium or proton antiporters. MATE proteins can secrete organic anions to contribute to the Al tolerance in plants (Furukawa et al., 2007; Magalhaes et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2009). In Arabidopsis, the zinc finger transcription factor STOP1 (known as ART1 in rice) plays a critical role in plant Al tolerance by regulating the Al-inducible expression of ALMT and MATE (Liu et al., 2009). In rice, multiple genes implicated in Al tolerance, including MATE transporter family members, are regulated by the transcription factor ART1 (Yamaji et al., 2009).

Cabbage (Brassica oleracea) is one of the most important vegetable crops around the world (Wu et al., 2014). Our previous study has shown that BoMATE encodes a citrate transporter and is induced by Al and enhances aluminum tolerance in Arabidopsis (Wu et al., 2014). Here we report that cabbage BoALMT1 is located in the plasma membrane and induced by Al. A reverse genetic approach was used to characterize the functions of BoALMT1. Overexpressing BoALMT1 in Xenopus oocytes and Arabidopsis facilitated H+ efflux. Overexpressing BoALMT1 in Arabidopsis resulted in enhanced Al tolerance and increased malate secretion. These results suggested that BoALMT1 has an important role in Al tolerance in cabbage.

Results

Sequence Analysis of BoALMT1 in Cabbage

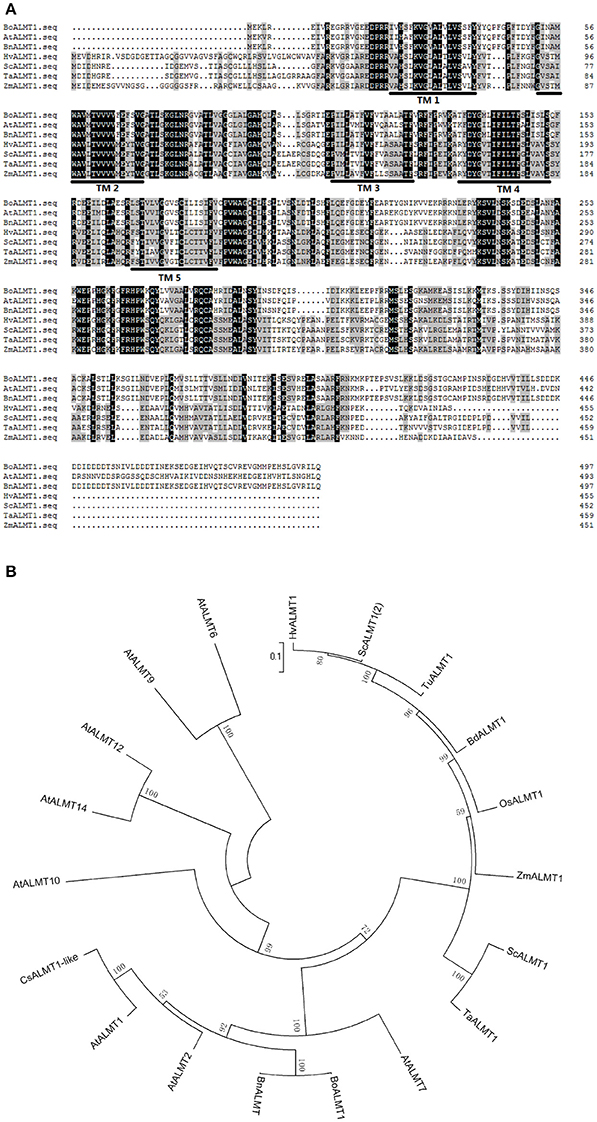

The ALMT gene was the first Al3+ tolerance gene identified in plants (Sasaki et al., 2004; Delhaize et al., 2007; Meyer et al., 2010). Membrane protein ALMTs possess 5–7 predicted transmembrane domains and a UPF0005 domain with unknown function (Delhaize et al., 2007). BoALMT1 (KF322104) cloned from cabbage contains an open reading frame of 1,497 bp, encoding a polypeptide of 498 amino acids. BLAST analysis revealed that the sequence of BoALMT1 was a 99% match to BnALMT1 from rape, 73% match to AtALMT1 from Arabidopsis, and 33% match to TaALMT1 from wheat. The HMMTOP transmembrane topology prediction server was used to predict the localization of helical transmembrane segments and the analysis indicated that BoALMT1 contained 5 predicted transmembrane domains (Figure 1A). Analysis of BoALMT1 and other reported ALMTs in plants indicated that BoALMT1 was most closely clustered with the BnALMT1 from Brassica napus (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Amino acid sequence (A) and phylogenetic (B) analysis of Brassica oleracea BoALMT1. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of cabbage BoALMT1, maize ZmALMT1, wheat TaALMT1, Arabidopsis AtALMT1, rape BnALMT1, rye ScALMT1, and Barley HvALMT1. Identical amino acids and similar amino acids were indicated by dark shading and light shading, respectively. Lines depict the 5 predicted transmembrane domains in BoALMT1 as predicted by HMMTOP. (B) Phylogenetic relationship of BoALMT1 and other known Al-activated malate transporters (ALMT). The amino acid sequences were aligned by ClustalW.

Expression Pattern of BoALMT1

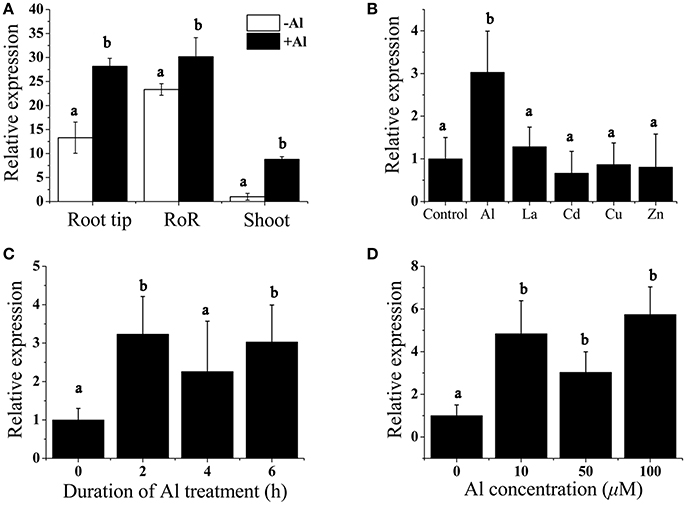

We performed real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis to measure the expression of BoALMT1 in the roots and shoots, and found that BoALMT1 expression was primarily localized to the roots (Figure 2A). Al treatment enhanced its expression in all tissues (Figure 2A). Cabbage plants were exposed to a variety of trivalent cations, and the expression of BoALMT1 was not induced by lanthanum (La), cadmium (Cd), zinc (Zn), or copper (Cu), but was severely induced by aluminum (Figure 2B). A dose-response experiment and a time-course experiment indicated that increasing the external Al concentration and treatment time did not further increase the BoALMT1 transcript level (Figures 2C,D).

Figure 2. Analysis of BoALMT1 expression in cabbage seedlings by quantitative real-time PCR. (A) Tissue-specific expression of BoALMT1. Seedlings were exposed to a 0.5 mM CaCl2 solution (pH 4.5) containing 50 μM AlCl3 for 6 h. Expression of BoALMT1 gene in the root tip, rest of root (RoR) and shoots were determined. (B) Effect of Al, La, Cd, Cu, and Zn on BoALMT1 expression. Seedlings were exposed to a 0.5 mM CaCl2 solution (pH 4.5) containing 50 μM AlCl3, 25 μM Cd, 10 μM La, 0.5 μM Cu, or 2.0 μM Zn. (C) Time-dependent expression of BoALMT1. Cabbage seedlings were exposed to a solution containing 50 μM AlCl3 for different time. (D) Dose-response expression analysis of BoALMT1 gene in cabbage roots. The roots were exposed to a 0.5 mM CaCl2 solution (pH 4.5) containing 0, 10, 50, and 100 μM AlCl 3 for 6 h. Actin expression was used as an internal control. Bars represent means ± SD of three replicates and independent experiments were performed at least three times. Different letters above the columns indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) between treatments.

Subcellular Localization of BoALMT1

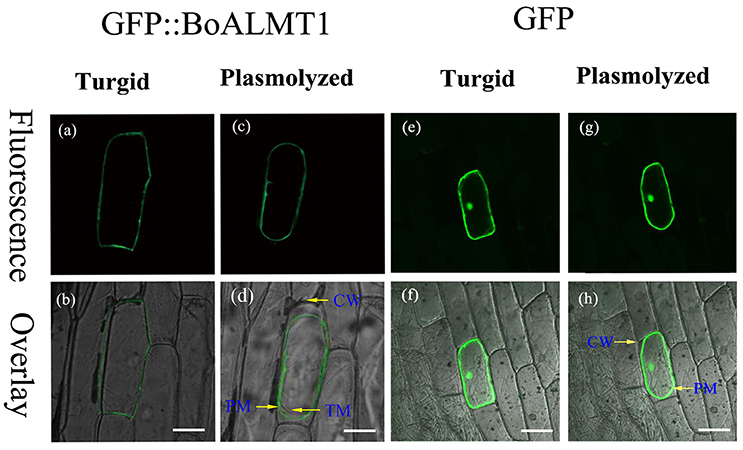

The subcellular localization of BoALMT1 was determined via localization of the GFP::BoALMT1 protein transiently expressed in onion epidermal cells (Figure 3). The GFP::BoALMT1 green fluorescence was only observed at the outer layer of the cell (Figures 3a,b), and the cells expressing GFP showed green fluorescence in the whole cell (Figures 3e,f). We induced plasmolysis by the addition of 0.8 M mannitol to distinguish localization in the plasma membrane and observed that the fluorescence of GFP::BoALMT1 was exclusively located in the plasma membrane in the plasmolysis cells (Figures 3c,d). These localization results were similar to those of some ALMTs identified in other species [TaALMT1 (Yamaguchi et al., 2005), BnALMT1 (Ligaba et al., 2006), ZmALMT1 (Piñeros et al., 2008), ZmALMT2 (Ligaba et al., 2008), and GmALMT1 (Liang et al., 2013)].

Figure 3. Cellular localization of the BoALMT1 protein by transient expression of the GFP::BoALMT1 fusion protein in epidermal onion cells. (a–d) The plasma membrane localization of BoALMT1 in onion epidermal cells before (a,b) and after cell plasmolysis with 0.8 M mannitol (c,d). (e–h) GFP protein in onion epidermal cells before (e,f) and after cell plasmolysis with 0.8M manitol (g,h). PM, CW, and TM labels denote the plasma membrane cell wall and tonoplast membrane localization, respectively. White bars = 100 μm.

Pattern of Malate Secretion

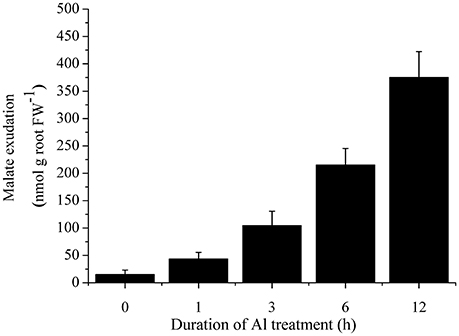

To investigate whether the secretion of malate was induced by Al treatment, we characterized malate exudation from cabbage roots. Cabbage roots secreted a low level of malate under normal conditions. After 3 h treatment with 50 μM Al, malate exudation was remarkably induced (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Time course of malate secretion after exposure of 50 μM Al in cabbage roots. Data are means ± SD (n = 5).

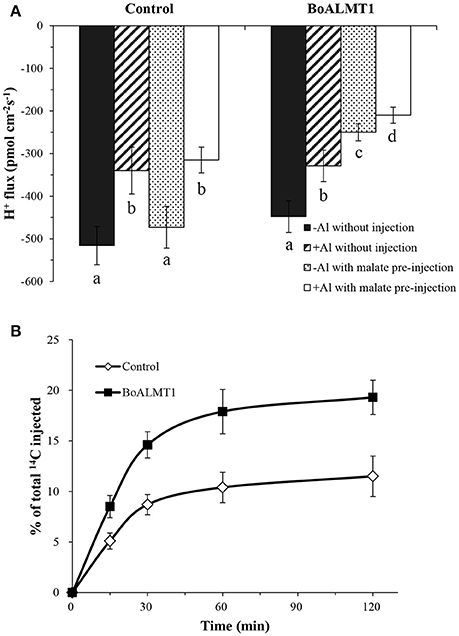

Heterologous Expression of BoALMT1 Reduced Al-Induced H+ Efflux in Xenopus Oocytes

By treated the Arabidopsis mutant with Al stress, Degenhardt et al. (1998) observed that the pH of the root surface increased, while Bose et al. (2010) further confirmed Al stress correlated with lower H+ influx. So in our study, we used the non-invasive Scanning Ion-selective Electrode Technique (SIET) system to measure H+ fluxes crossing the surface of Xenopus oocytes with or without the per-injected malate (Figure 5A). We noticed that the H+ flux had no difference in the control oocytes under the absence or the present of Al. Furthermore, compared with the control cells, BoALMT1-expressing oocytes also secreted similar amount of H+ without pretreated with malate. However, when the malate was fed, the BoALMT1-expressing oocytes secreted more H+ compared with the control oocytes under the absence or the present of Al condition (Figure 5A). To further elucidate BoALMT1 served as a malate efflux transporter, we fed the control and the BoALMT1-expressing oocytes with 14C-labeled malate and then measured the efflux of radioactively labeled malate (Figure 5B). The BoALMT1-expressing oocytes excreted more labeled malate than the control cells. These results indicated that BoALMT1 was a malate efflux transporter and enhanced the H+ efflux according to malate secretion in Xenopus oocytes.

Figure 5. Characterization of BoALMT1 in Xenopus oocytes. (A) Mean values of H+ fluxes in the absence or presence of 50 μM Al with pretreated malate or water. Each value represents the average of at least 3 different cells, the error bars represent SD (n = 4–6). (B) Malate efflux transport activity. Control and BoALMT1-expressing oocytes injected with 14C-labeled malate were kept in OCM solution. The radioactivity in the bathing solution was measured at the indicated time points; values are expressed as a percentage of the total radioactivity injected. Data was given as means ± SD (n = 3). Different letters above the columns indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) between treatments.

Overexpressing BoALMT1 in A. thaliana Enhanced Al Tolerance

Al-activated membrane transporters, which mediate organic acid release from the root apex, are the primary physiological mechanism of plant Al tolerance (Kochian et al., 2004). Plant ALMTs that have been implicated in malate transport and Al tolerance are TaALMT1 in wheat (Sasaki et al., 2004), AtALMT1 in Arabidopsis (Hoekenga et al., 2006), BnAMLT1 and BnALMT2 in oilseed rape (Ligaba et al., 2006), GmALMT1 in soybean (Liang et al., 2013), and MsALMT1 in M. sativa (Chen et al., 2013).

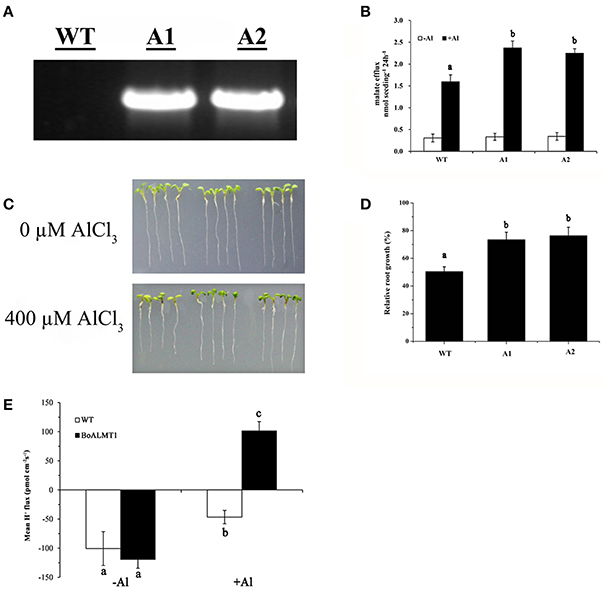

In this study, to investigate whether the overexpression of BoALMT1 enhances malate exudation and Al tolerance, we induced expression of BoALMT1 driven by the CaMV 35S promoter in Arabidopsis plants. Successful introduction of BoALMT1 in two transgenic lines, but not the control line, was confirmed by RT-PCR (Figure 6A). Root malate exudation was then measured in the plants expressing BoALMT1 and demonstrating increased Al tolerance (Figure 6B). Plants expressing BoALMT1 showed a remarkable increase in root malate exudation rates in the presence of Al, but no difference was observed in the absence of Al. When grown in in agar plates without Al, the transgenic plants expressing BoALMT1 showed root growth similar to that of wild-type (Figure 6C). When grown in agar plates with 400 μM AlCl3, root elongation of plants expressing BoALMT1 showed less root growth inhibition than that of the plants without expression (Figures 6C,D). To further determine the effect on H+ flow caused by overexpressing BoALMT1 in Arabidopsis, we performed SIET to detect the H+ flux at the root DEZ with 0 or 50 μM Al (pH = 4.5). Under low pH condition, the pattern of H+ influx exhibited no statistic difference between WT lines and BoALMT1 transgenic lines. However, treated with 50 μM Al, the H+ influx was inhibited in the WT lines, while the H+ was secreted from the roots BoALMT1 transgenic lines (Figure 6E).

Figure 6. Expression of BoALMT1 in transgenic Arabidopsis plants results in enhanced citrate release and Al tolerance. (A) BoALMT1 expression in the two transgenic lines (A1 and A2) and a control line (WT). (B) Root malate exudation in the absence and presence of 50 μM AlCl3. Experiments were repeated at least three times (n = 100). (C) Root growth of representative plants from two independent transgenic lines grown in agar medium in the absence or presence of Al for 2 days. (D) Relative root growth of the plants subjected to 400 μM Al for 2 d. Each bar represents the mean of three replicates ± SD (n = 4). (E) Comparison H+ flux at the DEZ of 4- to 5-day-old Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings in the presence and absence of Al. Data are given as means ± SD (n = 3–5). Different letters above the columns indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) between treatments.

Discussion

Al-activated malate transporters (ALMT) have been reported to be involved in Al tolerance and have been isolated from Arabidopsis, M. sativa, oil seed rape, rye, wheat, and soybean (Sasaki et al., 2004; Hoekenga et al., 2006; Ligaba et al., 2006; Collins et al., 2008; Liang et al., 2013). Here we reported that Al-induced cabbage BoALMT1 enhanced malate secretion under Al stress in Arabidopsis. BoALMT1 contains five predicted transmembrane domains (Figure 1A) and was most closely clustered with BnALMT1 (Figure 1B). The expression of BoALMT1 was rapidly induced by aluminum and was primarily localized to the root (Figure 2). Some ALMTs are Al-induced but not Al-activated, such as GmALMT1, but AtALMT1 is both induced and activated by Al (Hoekenga et al., 2006; Liang et al., 2013). If BoALMT1 is activated by Al requires further studies.

BoALMT1 was heterologously expressed in oocytes and Arabidopsis to analyze its function (Figures 5, 6). In oocytes, under the absence of Al condition, cells expressing BoALMT1 secreted more H+ compared with control cells. After Al treatment, H+ influx diminished in the wild type cells and slightly reduced in the BoALMT1-expressing cells (Figure 5A). In Arabidopsis, the BoALMT1 overexpression lines exhibited longer root elongation and more malate exudation under Al treatment compared with WT lines, but there no difference between WT and transgenic lines (Figures 6B–D). These results demonstrate that BoALMT1 increase malate secretion to resist Al tolerance in Arabidopsis. This was similar with the reported homologous ALMTs in Arabidopsis and B. napus (Hoekenga et al., 2006; Ligaba et al., 2006). In Figure 6E, compared with the low pH condition, BoALMT1 expressing plants secreted H+ form root tips while the WT plants only diminished the H+ influx. As described by Ahn and Matsumoto, the activity of H+-ATPase of Al-tolerance wheat lines was higher than that of Al-sensitive wheat under Al treatment (Ahn and Matsumoto, 2006). In faba bean, the activity of PM H+-ATPase was increased and positively associated with citrate exudation under Al stress (Chen et al., 2015). The similar results were also found in our previous study about BoMATE (Wu et al., 2014). Our results might imply that BoALMT1 mediate malate transport instead of directly mediate H+ flux, and the H+ efflux might associate with the secretion of malate (Figures 5, 6). However, the causes of these different H+ flux patterns between Xenopus oocytes and Arabidopsis are unclear. Expressing ALMTs in yeast and bacteria did not show their functions (Ryan et al., 2011). BoALMT1 may behave differently in these two heterologous expressing systems. So combining the previous studies by Wu et al. (2014) and Chen et al. (2015) with our findings, we speculated that the secretions of organic acids such as citrate and malate was associated with the activity of PM H+-ATPase to resist Al stress.

A C2H2-type zinc finger transcription factor STOP1 plays a key role in plant Al tolerance. Multiple Al-induced genes such as ALMTs and MATEs are regulated by STOP1 (Liu et al., 2009; Yamaji et al., 2009). To uncover the Al tolerance mechanism in cabbage and determine if STOP1 or a similar regulator participate in this mechanims, further studies are required.

In addition to the external Al detoxification, ALMTs may also have other uncharacterized functions. Recently, Kobayashi et al. demonstrated that ALMT1 responds to multiple signals such as abscisic acid (ABA), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), low pH, and hydrogen peroxide, but does not respond to methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid (Kobayashi et al., 2013). A few reports found that aluminum-induced malate efflux is negatively regulated by ethylene by inhibition of the expression of TaALMT1 (Tian et al., 2014), this process can be alleviated by the inhibition of ACS activity (Yu et al., 2016). Furthermore, TAA1 regulates local auxin biosynthesis and influences the aluminum-induced inhibition of root growth (Yang et al., 2014). Further work should examine the complex regulation of BoALMT1 during the resistance of multiple stresses and the mechanism by which plants can sense external Al (Kobayashi et al., 2013).

Our results illustrated that the cabbage BoALMT1 localized to the plasma membrane, and the expression of BoALMT1 was specifically induced by Al treatment. Expression of BoALMT1 in Xenopus oocytes and Arabidopsis could enhance Al tolerance. We identified that BoALMT1 can function as an Al-induced gene, and the BoALMT1 protein is involved in H+ flux in response to Al stress.

Materials and Methods

Plant Cultivars and Growth Conditions

Cabbage (B. oleracea cv. Zhonggan-11) was seeded at 25°C on moist filter paper in the dark for 2 days. The seedlings were then moved to a complete nutrient solution (Ligaba et al., 2006). After 5 days of culture, the uniform seedlings were moved to a new plastic pot wetted with 0.5 mM CaCl2 (pH 4.5) solution and pre-incubated for ~24 h. To measure the spatial expression patterns of BoALMT1 in root tips (0–1 cm), after 6 h of 50 μM Al exposure, the roots and shoots were separately collected and subjected to qRT-PCR analysis. To test the specificity of Al-induced BoALMT1 gene expression, we exposed seedlings in a 0.5 mM CaCl2 solution (pH 4.5) containing 50 μM AlCl3, 25 μM CdCl2, 10 μM LaCl3, 0.5 μM CuCl2, or 2.0 μM ZnCl2 for 6 h. To investigate the dose effects of Al on BoALMT1 expression, the seedlings were exposed to a 0.5 mM CaCl2 solution (pH 4.5) containing 0, 10, 50, or 100 μM AlCl3 for 6 h. To analyze time-course effects of Al toxicity on BoALMT1 expression, the seedlings were exposed to a 0.5 mM CaCl2 solution (pH 4.5) containing 50 μM AlCl3 for 0, 2, 4, and 6 h.

Gene Cloning and Sequencing

To clone BoALMT1, RNA was isolated from cabbage seedlings roots treated with Al. To identify cabbage BoALMT1, we performed a BLAST search with the known AtALMT1 and BnALMT1 sequences on the NCBI website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). For further amplification, two expressed sequence tags (ESTs) (DK499842 and DY012377) were selected. The two nucleotide sequences were combined to generate a full-length cDNA. The full-length cDNA of BoALMT1 was amplified with sense primer 5′-ATGGAGAAAGTGAGAGAGATAGTGAG-3′ and anti-sense primer 5′-TCAAATCTGAAGTATACGAACACCC-3′, and then constructed into the pMD18-T vector (Takara, Japan). HMMTOP was used for transmembrane protein prediction analysis. Multiple amino acid alignment was conducted by using ClustalX and MEGA4.1 software.

Characterization of BoALMT1 Expression via qPCR

BoALMT1 expression was evaluated using quantitative real-time RT-PCR techniques. Primers for qPCR were designed using Primer 3.0. The first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed by using the Primescript reverse transcriptase (Takara, Japan). We performed real-time PCR with a SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ (perfect real time) kit (Takara, Japan) and using the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System (ABI) using a relative standard curve method with the following primers: BoALMT1, 5′-AGAGAAGGAAGGAGGGTAGGAGAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAAGACAACAACGACGGTCA-3′ (reverse); Actin (LOC106327159), 5′-TAACAGGGAGAAGATGACTCAGATCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAGATCAAGACGAAGGATAGCATGAG-3′ (reverse). Quantitative PCR was performed with conditions of 95°C for 3 min, and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Expression data were normalized to the expression level of Actin by the ΔΔCt method.

Subcellular Localization of BoALMT1

The subcellular localization of BoALMT1 was determined in onion (Allium cepa) epidermal cells. We constructed a vector as 35S:BoALMT1::GFP. The coding region of BoALMT1 was subcloned into the expression vector pCAMBIA1302 using primers: 5′-CATGCCATGGTAATGGAGAAACTGAGAGAGATAGTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGACTAGTAATCTGAAGTATACGAACACCC-3′ (reverse). We transferred the chimera by particle bombardment. The gold particles (1 μm, 1.5 mg) were coated with 5 μg of plasmid DNA in a solution of 2.5 M CaCl2 and 0.1 M spermidine (Sigma). We bombarded the epidermal onion peels at a helium pressure of 25–30 Mpa (Bio-rad, U.S.), and then incubated the tissue in MS medium at room temperature in the dark for 24 h. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (Leica DMI 6000B-CS, Germany) with a 488 nm excitation wavelength was used to detect the GFP fluorescence. We induced cell plasmolysis by adding 0.8 M mannitol for 3–5 min.

BoALMT1 Expression in Xenopus laevis Oocytes

We cloned the coding regions (cDNA) of BoALMT1 into the MCS of a pCS107 vector. According to the manufacturer's (Ambion) recommendations, we synthesized the cRNA from 1 μg of AscI-linearized plasmid DNA template. We harvested stage V–VI Xenopus laevis oocytes as described previously (Golding, 1992; Hoekenga et al., 2006). We injected 50 nl RNase-free water containing 15 ng of cRNA encoding BoALMT1 or 50 nl RNase-free water into oocytes using a micro-injector and then incubated the injected oocytes at 18°C for 2 d in oocyte culture medium, OCM; 1L OCM contains 600 ml L-15 (Sigma L4386), 400 mg BSA (Sigma A4919), 5 ml Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco 15140-122), and 400 ml H2O). Before flux measurements of H+, we preloaded malate in the Xenopus oocytes by injection of 50 nl of 0.1 M sodium malate or water. Two hours after preloading, the H+ fluxes were measured 30 μm away from X. laevis oocytes in a solution of 2 mM KCl, 96 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.3 mM MES, 1.8 mM CaCl2 with or without 0.1 mM AlCl3 and with the pH 4.5. Net H+ fluxes were measured using SIET (Xuyue Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) under steady conditions for 8–10 min to insure that no fluctuation was present. We used the OCM bath solution (pH = 4.5) to perform the 14C-labeled malate experiment as our previous study (Wu et al., 2014).

Heterologous Expression of BoALMT1 in Arabidopsis thaliana

The coding region (cDNA) of BoALMT1 was amplified with primers (5′-GCTCTAGAATGGAGAAACTGAGAGAGATAGTG-3′ and 5′-CGCCCCGGGTCAAATCTGAAGTATACGAACACCC-3′) and was cloned into pBI121. We transformed the construct into Arabidopsis using Agrobacterium tumefaciens via the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). We used RT-PCR to measure the expression level of BoALMT1 in the transgenic plants. Root malate release and Al tolerance were analyzed in two independent homozygous transgenic T3 lines as follows. Arabidopsis seeds, stratified at 4°C for 3 days, were surface-sterilized and sown onto solid MS medium for 4 days. After germination, we removed uniform seedlings to 0.5 mM CaCl2-agar plates containing 0 or 400 μM AlCl3 (pH = 4.5). The seedlings were kept on agar plates for 2 days, and then the roots were scanned and the primary root length was measured by the Image J program (Liu et al., 2009). For malate exudation assays, two transgenic Arabidopsis and wild-type lines were surface sterilized and germinated on solid MS medium for 1 week. Next, we transferred the seedlings to a 25 ml solution with 0.5 mM CaCl2 (pH 4.5) and without Al for 24 h. After this 24 h pre-incubation step, we then transfered the plants to 25 ml exudation medium (pH 4.5) with or without Al (50 μM AlCl3). We collected the sample for malate assay by capillary electrophoresis, as described by Hoekenga et al. (2006). We measured the fluxes of H+ by using the non-invasive Scanning Ion-selective Electrode Technique (SIET) (Xuyue Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) as described by Bose et al. (2010). The 4- to 5-day-old wild type and BoALMT1 expressing Arabidopsis seedlings were equilibrated in a solution (0.1 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM KCl, 0.3 mM MES, pH 4.5) with or without 50 mM Al for 5–10 min. H+ fluxes were measured 200 mm from the root tip for 6–10 min. The H+ fluxes were calculated by the JCal V3.1 (a free MS Excel spreadsheet, youngerusa.com or ifluxes.com). The H+ flux assay was replicated independently 4–6 times and the data were averaged.

Statistical Analysis

All the statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA and the t-test to determine the significance at the P < 0.05 level.

Author Contributions

LZ, X-XW, and Y-DG: designed research; X-XW, LZ, JW, CQ, XW, GW, ML, and XL: performed research; JW, X-XW, LZ, and Y-DG: analyzed the data; X-XW, LZ, JW, and Y-DG: wrote the paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. S Ren and Dr. S Weeda (Virginia State University) for critical reading of the manuscript and Prof. Q Tao (Tsinghua University, Beijing) for providing Xenopus oocytes test system. This work was supported by the grants to Y-DG (2016YFD0101007, BLVT-03) and to XL (tszy20140808).

References

Ahn and Matsumoto, H. (2006). The role of the plasma membrane in the response of plant roots to aluminum toxicity. Plant Signal. Behav. 1, 37–45. doi: 10.4161/psb.1.2.2588

Bose, J., Babourina, O., Shabala, S., and Rengel, Z. (2010). Aluminum-dependent dynamics of ion transport in Arabidopsis: specificity of low pH and aluminum responses. Physiol. Plantarum 139, 401–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2010.01377.x

Chen, Q., Kan, Q., Wang, P., Yu, W., Yu, Y., Zhao, Y., et al. (2015). Phosphorylation and interaction with the 14-3-3 protein of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase are involved in the regulation of magnesium-mediated increases in aluminum-induced citrate exudation in broad bean (Vicia faba. L). Plant Cell Physiol. 56, 1144–1153. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcv038

Chen, Q., Wu, K. H., Wang, P., Yi, J., Li, K. Z., Yu, Y., et al. (2013). Overexpression of MsALMT1, from the aluminum-sensitive Medicago sativa, enhances malate exudation and aluminum resistance in tobacco. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 31, 769–774. doi: 10.1007/s11105-012-0543-2

Clough, S. J., and Bent, A. F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x

Collins, N. C., Shirley, N. J., Saeed, M., Pallotta, M., and Gustafson, J. P. (2008). An ALMT1 gene cluster controlling aluminum tolerance at the Alt4 locus of rye (Secale cereal L.). Genetics 179, 669–692. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.083451

Degenhardt, J., Larsen, P. B., Howell, S. H., and Kochian, L. V. (1998). Aluminum resistance in the Arabidopsis mutant alr-104 is caused by an aluminum-induced increase in rhizosphere pH. Plant Physiol. 117, 19–27. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.1.19

Delhaize, E., Gruber, B. D., and Ryan, P. R. (2007). The roles of organic anion permeases in aluminium resistance and mineral nutrition. FEBS Lett. 581, 2255–2262. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.057

Delhaize, E., Ryan, P. R., Hebb, D. M., Yamamoto, Y., Sasaki, T., and Matsumoto, H. (2004). Engineering high-level aluminum tolerance in barley with the ALMT1 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 15249–15254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406258101

Delhaize, E., Ryan, P. R., and Randall, P. J. (1993). Aluminum tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.): II. Aluminum-stimulated excretion of malic acid from root apices. Plant Physiol. 103, 695–702. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.3.695

Furukawa, J., Yamaji, N., Wang, H., Mitani, N., Murata, Y., Sato, K., et al. (2007). An aluminum-activated citrate transporter in barley. Plant Cell Physiol. 48, 1081–1091. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm091

Golding, A. L. (1992). Maintenance of Xenopus laevis and oocyte injection. Method Enzymol. 207, 266–279. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)07017-I

Hoekenga, O. A., Maron, L. G., Pineros, M. A., Cancado, G. M. A., Shaff, J., Kobayashi, Y., et al. (2006). AtALMT1, which encodes a malate transporter, is identified as one of several genes critical for aluminum tolerance in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 9738–9743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602868103

Hoekenga, O. A., Vision, T. J., Shaff, J. E., Monforte, A. J., Lee, G. P., Howell, S. H., et al. (2003). Identification and characterization of aluminum tolerance loci in Arabidopsis (Landsberg erecta x Columbia) by quantitative trait locus mapping. A physiologically simple but genetically complex trait. Plant Physiol. 132, 936–948. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.023085

Horst, W. J., Wang, Y., and Eticha, D. (2010). The role of the root apoplast in aluminium-induced inhibition of root elongation and in aluminium resistance of plants: a review. Ann. Bot. 106, 185–197. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcq053

Kobayashi, Y., Sugimoto, M., Lakshmanan, V., Iuchi, S., Kobayashi, M., et al. (2013). Characterization of the complex regulation of AtALMT1 expression in response to phytohormones and other inducers. Plant Physiol. 162, 732–740. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.218065

Kochian, L. V., Hoekenga, O. A., and Pineros, M. A. (2004). How do crop plants tolerate acid soils? Mechanisms of aluminum tolerance and phosphorous efficiency. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55, 459–493. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141655

Kochian, L. V., Pineros, M. A., and Hoekenga, O. A. (2005). The physiology, genetics and molecular biology of plant aluminum resistance and toxicity. Plant Soil 274, 175–195. doi: 10.1007/s11104-004-1158-7

Liang, C., Piñeros, M. A., Tian, J., Yao, Z., Sun, L., Liu, J., et al. (2013). Low pH, aluminum and phosphorus coordinately regulate malate exudation through GmALMT1 to improve soybean adaptation to acid soils. Plant Physiol. 161, 1347–1361. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.208934

Ligaba, A., Katsuhara, M., Ryan, P. R., Shibasaka, M., and Matsumoto, H. (2006). The BnALMT1 and BnALMT2 genes from rape encode aluminum-activated malate transporters that enhance the aluminum resistance of plant cells. Plant Physiol. 142, 1294–1303. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.085233

Ligaba, A., Maron, L. G., Shaff, J., Kochian, L. V., and Piñeros, M. A. (2008). Maize ZmALMT2 is a root anion transporter that mediates constitutive root malate efflux. Plant Cell Environ. 35, 1185–1200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02479.x

Liu, J., Magalhaes, J. V., Shaff, J., and Kochian, L. V. (2009). Aluminum-activated citrate and malate transporters from the MATE and ALMT families function independently to confer Arabidopsis aluminum tolerance. Plant J. 57, 389–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03696.x

Magalhaes, J. V., Liu, J., Guimarães, C. T., Lana, U. G., Alves, V. M., Wang, Y. H., et al. (2007). A gene in the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family confers aluminum tolerance in sorghum. Nat. Genet. 39, 1156–1161. doi: 10.1038/ng2074

Meyer, S., De Angeli, A., Fernie, A. R., and Martinoia, E. (2010). Intra- and extra-cellular excretion of carboxylates. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.10.002

Pellet, D. M., Grunes, D. L., and Kochian, L. V. (1995). Organic acid exudation as an aluminum-tolerance mechanism in maize (Zea mays L.). Planta 196, 788–795. doi: 10.1007/BF01106775

Pereira, J. F., Zhou, G., Delhaize, E., Richardson, T., and Ryan, P. R. (2010). Engineering greater aluminium resistance in wheat by over-expressing TaALMT1. Ann. Bot. 106, 205–214. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcq058

Piñeros, M. A., Cancado, G. M. A., Maron, L. G., Lyi, S. M., Menossi, M., and Kochian, L. V. (2008). Not all ALMT1-type transporters mediate aluminum-activated organic acid responses: the case of ZmALMT1, an anion-selective transporter. Plant J. 53, 352–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03344.x

Raman, H., Zhang, K., Cakir, M., Appels, R., Garvin, D. F., Maron, L. G., et al. (2005). Molecular characterization and mapping of ALMT1, the aluminium-tolerance gene of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Genome 48, 781–791. doi: 10.1139/g05-054

Ryan, P. R., Tyerman, S. D., Sasaki, T., Furuichi, T., Yamamato, Y., Zhang, W. H., et al. (2011). The identification of aluminium-resistance genes provides opportunities for enhancing crop production on acid soils. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 9–20. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq272

Sasaki, T., Yamamoto, Y., Ezaki, B., Katsuhara, M., Ahn, S. J., Ryan, P. R., et al. (2004). A wheat gene encoding an aluminum-activated malate transporter. Plant J. 37, 645–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2003.01991.x

Tesfaye, M., Temple, S. J., Allan, D. L., Vance, C. P., and Samac, D. A. (2001). Overexpression of malate dehydrogenase in transgenic alfalfa enhances organic acid synthesis and confers tolerance to aluminum. Plant Physiol. 127, 1836–1844. doi: 10.1104/pp.010376

Tian, Q., Zhang, X., Sunita, R., Matthew, G., Stephen, D. T., and Zhang, W. H. (2014). Ethylene negatively regulates aluminum-induced malate efflux from wheat roots and tobacco cells transformed with TaALMT1. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 2415–2426. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru123

Wang, J. P., Raman, H., Zhou, M. X., Ryan, P. R., Delhaize, E., Hebb, D. M., et al. (2007). High-resolution mapping of the Al locus and identification of a candidate gene HvMATE controlling aluminium tolerance in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 115, 265–276. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0562-9

Wu, X., Li, R., Shi, J., Wang, J., Sun, Q., Zhang, H., et al. (2014). Brassica oleracea MATE encodes a citrate transporter, and enhances aluminum tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 55, 1426–1436. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu067

Yamaguchi, M., Sasaki, T., Sivaguru, M., Yamamoto, Y., Osawa, H., Ahn, S. J, et al. (2005). Evidence for the plasma membrane localization of Al-activated malate transporter (ALMT1). Plant Cell Physiol. 46, 812–816. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci083

Yamaji, N., Huang, C. F., Nagao, S., Yano, M., and Sato, Y. (2009). A zinc finger transcription factor ART1 regulates multiple genes implicated in aluminum tolerance in rice. Plant Cell 21, 3339–3349. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.070771

Yang, J. L., Zhang, L., and Zheng, S. J. (2008). Aluminum-activated oxalate secretion does not associate with internal content among some oxalate accumulators. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 50, 1103–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00687.x

Yang, Z.-B., Geng, X., He, C., Zhang, F., Wang, R., Horst, W. J., et al. (2014). TAA1-regulated local auxin biosynthesis in the root-apex transition zone mediates the aluminum-induced inhibition of root growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26, 2889–2904. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.127993

Yu, Y., Jin, C., Sun, C., Wang, J., Ye, Y., Zhou, W., et al. (2016). Inhibition of ethylene production by putrescine alleviates aluminum induced root inhibition in wheat plants. Sci. Rep. 6:18888. doi: 10.1038/srep18888

Keywords: aluminum tolerance, BoALMT1, cabbage, malates, SIET

Citation: Zhang L, Wu X-X, Wang J, Qi C, Wang X, Wang G, Li M, Li X and Guo Y-D (2018) BoALMT1, an Al-Induced Malate Transporter in Cabbage, Enhances Aluminum Tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 8:2156. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.02156

Received: 24 July 2017; Accepted: 06 December 2017;

Published: 23 January 2018.

Edited by:

Wei Fan, Yunnan Agricultural University, ChinaReviewed by:

Qi Chen, Kunming University of Science and Technology, ChinaJiang Tian, South China Agricultural University, China

Copyright © 2018 Zhang, Wu, Wang, Qi, Wang, Wang, Li, Li and Guo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yang-Dong Guo, eWFndW9AY2F1LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Lei Zhang1†

Lei Zhang1† Xiaoyun Wang

Xiaoyun Wang Yang-Dong Guo

Yang-Dong Guo