- 1Institute of Farmland Irrigation, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences/Key Laboratory of Crop Water Use and Regulation, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Xinxiang, China

- 2College of Natural Resources and Environment, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China

- 3College of Tropical Crops, Hainan University, Haikou, China

- 4School of Hydraulic and Civil Engineering, Ludong University, Yantai, Shandong, China

- 5College of Water Hydraulic and Architectural Engineering, Tarim University, Alar, China

Introduction: While climate change alters the balance of the terrestrial ecosystems, the impact on the soil bacterial community remains poorly understood. A field experiment was conducted to assess the effects of warming, drought, and their combination on the soil bacterial community at different growth stages of winter wheat.

Methods: Four treatments were defined for this study: warming at 1.5°C combined with full irrigation (TWS) and deficit irrigation (TWD), then ambient temperature combined with full irrigation (TNS) and deficit irrigation (TND).

Results: TWS, unlike TND, promoted nitrogen availability for plants and root exudation. The abundance and diversity of the bacterial community were more responsive to different climatic stresses at the jointing stage than at other growth stages. Chloroflexi, Firmicutes, and Bacteroidota were positively correlated with soil inorganic nitrogen, the root total organic carbon (TOC), and negatively correlated with available phosphorus (AP), available potassium (AK), soil organic carbon (SOC) under TND, while an opposite trend was observed with Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria. Furthermore, under TWS, Bacteroidota, unlike Actinobacteria, was positively correlated with NH4+, NO3-, TOC, and negatively correlated with AP, and SOC. The bacterial community network feature values were higher under TWD and lower under TNS.

Conclusion: These results indicate that the sensitivity of the rhizosphere bacterial community to the different climatic stresses varies according to the growth stage, and that the community is particularly more responsive at the jointing stage than at the later stages.

1 Introduction

Soil microbes are living organisms that perform multiple complex functions within terrestrial ecosystems. Although some of these organisms can harm plants, they play a crucial role in plant protection and growth. Microbes such as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) accelerate plant growth by improving nutritional capacity and resistance to environmental stresses and by producing growth-stimulating hormones (Lyu et al., 2019; Verma et al., 2019; Vocciante et al., 2022), which positively affect crop productivity (Kumar and Verma, 2019). The soil microbial community maintains soil quality and facilitates nutrient availability to crops by participating in nutrient mineralization processes (Rashid et al., 2019; Schloter et al., 2018). Indeed, several studies have shown the fundamental function of microorganisms in transforming organic matter, nitrogen, and phosphorus in soil (Duan et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021). Other studies have highlighted the importance of soil microorganisms in regulating greenhouse gas emissions such as carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide (Arunrat et al., 2025a; You et al., 2022; Kpalari et al., 2023). However, various environmental stresses, such as extreme climatic events, compromise the efficient functioning of the community (De Vries et al., 2018; Mekala and Polepongu, 2019).

The impact of climate change on living organisms has been a major concern for researchers in recent decades. This change manifests in various anomalies, including drought and rising atmospheric temperatures (Fawzy et al., 2020; Marengo et al., 2017). Efforts have been made in several areas to stabilize the increase in atmospheric temperature at 1.5 °C compared with pre-industrialization times (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2019; Masson-Delmotte et al., 2018). However, research continues to report a steady rise in temperature in different regions across the globe (Arnell et al., 2019; Hashimoto, 2019; Lindsey and Dahlman, 2020), and this rise could reach 4 °C by the end of this century if no action is taken to limit excessive greenhouse gas emissions (Wang et al., 2018). The increase in atmospheric temperature intensifies the risk of drought or exacerbates it in regions where both cooccur (Diffenbaugh et al., 2015; Vicente-Serrano et al., 2020). Xu et al. (2019) reported that, globally, a 1.5 °C increase in atmospheric temperature is likely to increase drought frequency by 36% and its duration by 15%.

Several studies have attempted to document the influence of warming on soil microorganisms. Previous research has suggested that an increase in atmospheric temperature has beneficial impacts on the diversity of soil microbial community (Fang et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2021a). However, this impact depends on several parameters, including the duration of the stress (Wu et al., 2022; Zheng et al., 2020) and the soil layer depth considered (Fu et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2015). Increased temperature modifies the abundance and composition of the soil microbial community by increasing the proportion of specific bacterial phyla, such as Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria, to the detriment of others (Che et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023b). Previous studies have reported positive impacts of this climatic phenomenon on soil microbial biomass (Chen et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2019) and according to Chen et al. (2021), the response of soil microbial carbon and nitrogen biomass to this thermal stress is not uniform. However, this biomass undergoes significant long-term decreases as the duration of warming increases (Xu and Yuan, 2017).

Drought is becoming an increasingly common phenomenon in different regions of the world (Dai et al., 2018), and its influence does not spare living soil organisms. Studies have shown that the unavailability or decrease in the quantity of water in the soil is likely to induce various stresses in the soil microbial community, which may result in the either death or biological adaptation (Bogati and Walczak, 2022; Schimel, 2018). Unlike global warming, drought alters the diversity (Preece et al., 2019; Siebielec et al., 2020) and biomass of the soil microbial community (Xu et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2020c). This stress disrupts the abundance and composition of the bacterial community by modifying the relative proportion of the different bacterial phyla composing it (Preece et al., 2019; Veach and Zeglin, 2020; Ochoa-Hueso et al., 2018; Kpalari et al., 2023). Bu et al. (2018) reported an increase in the relative proportions of Acidobacteria and a decrease in that of Proteobacteria under drought conditions. Other studies have also shown that water deficit reduces soil microbial diversity (Canarini et al., 2021) while destabilizing the community complexity (De Vries et al., 2018).

Temperature and precipitation are among the most influential climatic factors for the soil microbial community (Li et al., 2018). The combined impact of extreme climatic events such as drought and warming reduces the community’s abundance, composition, and functional properties (Von Rein et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2021a; Li et al., 2018). According to Sheik et al. (2011), the combination of these two climatic anomalies is capable of inducing a 50-80% reduction in the size of the soil microbial population. However, most previous studies considered only the crop maturity stage, and the impacts of climate change on the community at the different stages of crop growth remain poorly documented.

Winter wheat is one of the most widely cultivated crops in China, and its productivity depends on the various stresses it is subjected to during the different stages of its growth (Feng et al., 2020; Monteleone et al., 2023). However, this crop is highly sensitive to extreme weather events (Chandio et al., 2023; Sun et al., 2024; Shoukat et al., 2024). The main objective of this study was to simulate the impacts of different climate scenarios on the microbial community in the rhizosphere of winter wheat at different growth stages. The present study aims to (i) investigate the individual and combined effects of different climatic phenomena on the soil bacterial community and (ii) explain the community’s response to climatic stresses at different growth stages of winter wheat. We hypothesize that the response of the bacterial community to climatic stress depends on the plant growth stage.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Site description

The experiment was conducted from October 2022 to June 2023 at the Qiliying Experimental Station, Institute of Farmland Irrigation of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science (35.09°N, 113.48°E, and altitude 81 m). The trial was installed in lysimeters under the rain shelter. There were 24 lysimeters, and each measured 3.33 m×2.0 m in size, with a 1.8 m soil depth. The soil was sandy loam, with a field capacity (FC) of 29% (mass basis), bulk density of 1.45 g cm3, total nitrogen of 72.57 mg kg-1, available phosphorous of 45.25 mg kg-1, soil organic matter of 8.98 mg kg-1, soil organic carbon of 5.21 mg kg-1 and pH (H2O) of 8.54. The trial area has a continental monsoon climate with an average annual rainfall of 548 mm, an average yearly temperature of 14.5 °C, and a sunlight duration of 2398.8 hours.

2.2 Experimental design

The experimental design was identical to that used by Li et al. (2023a) (Figure 1). A randomized complete block was designed with two temperature levels and two irrigation regimes. Four treatments were defined for this study: warming combined with full irrigation (TWS) and deficit irrigation (TWD), then ambient temperature combined with full irrigation (TNS) and deficit irrigation (TND). The control treatment was TNS, and all the treatments were replicated three times. The two temperature levels were set as warming at 1.5˚C and non-warming, and the two soil moisture levels as full water supply (irrigation rate of 45 mm) and deficit water supply (irrigation rate of 33 mm). The electric infrared heater (model MRM2420, Kalglo Electronics Co., Inc., PA, USA) was used to warm the air. An infrared heater is made of an iron bracket, a far-infrared heating black-body tube (length of 1.8 m and diameter of 1.8 cm) with a power of 2,000 W, and a white stainless steel reflecting cover with dimensions of 2 m×0.2 m. Before sowing, the bracket was fixed in the soil, and an iron support held the far-infrared heating tube in place. To increase the temperature to approximately 1.5 °C, the height of the heating tube was adjusted regularly, and a manual thermometer was used to check the temperature above the canopy every morning at 8 a.m. During the winter wheat growing season, a 24-hour continuous warming mode was employed, and the effective warming area was 4 m2. A lampshade was also provided for the non-warming treatments to control and lower the error of test factors.

The winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) variety Zhoumai-22 was used in this study. Water is applied by drip irrigation when the average soil moisture between 0–80 cm depth of soil falls to 60%-65% of the field capacity. As regards fertilization, urea (46% N) calcium superphosphate (16% P2O5), and potassium sulfate (52% K2O) were applied to the crops at doses of 240 kg/ha N, 120 kg/ha P, and 120 kg/ha K based on the fertilization formulas recommended in our study area (Liu et al., 2024b).

2.3 Soil sample collection

Three soil samples were collected per treatment for the soil chemical properties analysis, and three other soil samples from the rhizosphere were collected for microbial analysis. The samples were taken at three growth stages of winter wheat: jointing, flowering, and grain-filling. For each plot, soil samples were taken between 0–10 cm soil depth and used to measure the soil acidity (pH), soil organic matter (SOM), soil organic carbon (SOC), available phosphorus (AP), available potassium (AK), total nitrogen (TN) and soil inorganic nitrogen (NO3- and NH4+). Soil within 2 mm of the root surface was considered rhizosphere soil in this study (Chen et al., 2019). After gently shaking the roots to remove loosely adhering soil clumps, rhizosphere soil samples were carefully collected by brushing the roots to remove any remaining soil and stored at -80 °C before being sent to the Shanghai Majorbio Laboratory for soil microbial community structure analysis.

2.4 Soil sample analysis

AP concentrations were determined calorimetrically (ammonium vanadate/molybdate) using spectrophotometry (540 nm, Hitachi U-2900 Double-Beam UV-Visible Spectrophotometer), while AK concentrations were measured directly in the CAL extract via flame spectrometry (Eppendorfer ELEX 6361) (Reimer et al., 2020). TN was determined by extracting soil samples for an hour using 2 M KCl (1:10) and filtering the resulting extracts using a 0.45 mm membrane. The soil pH was determined in distilled deionized water following standard procedures for soil pH measurement as described by Kome et al. (2018), SOM, and SOC by wet oxidation method (Walkley and Black, 1934). Soil NO3- and NH4+ content were determined with a continuous flow auto-analyzer as described by Ning et al. (2019).

2.5 DNA extraction and sequencing

DNA extraction was performed in 0.5 g of soil using E.Z.N.A Soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA), and purity was assessed using ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, NC, United States). DNA quality was checked by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The hypervariable region V3-V4 of the bacterial 16S rRNA was amplified using specific primers (338F: 5’-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3’; 806R: 5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’) (GeneAmp 9700, ABI, USA). The PCR amplification was performed using the following process: 27 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 30 s, and final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR mixtures contain 4 µl of 5 × TransStart FastPfu buffer, 2 µl of 2.5-mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTP), 0.8 µl of forward primer (5 µM), reverse primer (5 µM) 0.8 µl, 0.4 µl of TransStart FastPfu DNA Polymerase, and 10 ng of template DNA. The PCR products were extracted from a 2% agarose gel and quantified using a Quantus Fluorometer system (Promega, USA). Purified amplicons were pooled in equimolar and paired-end sequenced on a MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) by Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.6 Root exudation collection and analysis

Root exudates were collected at the jointing, flowering, and grain-filling stages using a modified culture-based cupping system developed specifically for collecting root exudates in the field (Phillips et al., 2008). Plants were selected randomly from each plot, and a hole was dug under each plant to isolate a few fine-branched roots of similar length and branching (2 mm average diameter with laterals) between 0–10 cm soil depth. The isolated roots were then carefully cleaned of sand and rinsed with deionized water (Ulrich et al., 2022). The roots were then placed in tubes containing sterile 2 mm diameter glass beads to simulate soil porosity and mechanical impedance in a carbon-free matrix. The beads covering the roots were moistened with a dilute sterile carbon-free nutrient mixture (0.5 mM NH4NO3, 0.1 mM KH2PO4, 0.2 mM K2SO4, 0.2 mM MgSO4, 0.3 mM CaCl2) used as a culture medium. The assembly was covered with aluminum foil and re-entered into the soil to minimize photolytic degradation of the root acids (Liu et al., 2022a; Phillips et al., 2008). 48 hours after the exudate collection device was installed, the roots were rinsed three times, and the nutrient medium was renewed. The nutrient medium containing root exudates was collected 24 hours after the previous operation and filtered to remove cellular debris (Nakayama and Tateno, 2018; Leuschner et al., 2022).

The total organic carbon (TOC) contained in the root exudates was measured using a model TOC-V CHS/CSN total organic carbon analyzer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) (Karst et al., 2017; Staszel et al., 2022). The roots were then scanned and weighed to adjust the TOC analysis results.

2.7 Data analysis

The Majorbio laboratory’s online platform (www.majorbio.com, accessed on 10 August 2023), R software (version 4.3.1), and Gephi software (version 0.10) were used to analyze the data and draw the graphs. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s honest post-hoc test, was used to study the effect of different climatic stresses on the chemical parameters and alpha-diversity indices of the soil bacterial community. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA), followed by the similarity test (ANOSIM) and permutational multivariate analysis of variance (ADONIS), was used to analyze the difference in bacterial community composition under the different treatments. This method is faster for large datasets and allows for a direct interpretation of distances and explained variance compared to other methods, such as NMDS and DCA (Ramette, 2007). All tests were performed at the 5% significance level.

The data on the relative abundance of community ASVs were used to construct co-occurrence networks (relative abundance > 40%, defined after a sensitivity analysis). The data was prepared with Spearman correlation between ASVs and random matrix theory using the igraph package to maintain comparability with previous studies (Khan et al., 2025; Shen et al., 2023). The P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rates (P < 0.01), and the similarity threshold for the networks was set to 0.8. The visualization of the networks was realized using Gephi software (version 0.10) with the Fruchterman-Reingold algorithm.

Partial least squares (PLS) was conducted using the plspm package to evaluate the effect of climate, soil, and different growth stages of winter wheat on the microbial community diversity. The Pearson correlation test assessed the relationships between the abundance of bacterial phyla and environmental parameters. Redundancy analysis (RDA) with the vegan package and heatmap with the ComplexHeatmap package were used to visualize this relationship.

3 Results

3.1 Soil chemical properties and total organic carbon of root exudats under different climatic conditions

The quantities of soil nutrients and organic carbon of root exudates under the different treatments are presented in Table 1. The test of one-way ANOVA showed a significant influence of the different climatic conditions on soil chemical properties (p<0.05). Compared to TNS, TWS significantly increased the available nitrogen content of soil at the jointing and flowering stages but not at the grain-filling stage. In contrast, TND decreased the quantity of available nitrogen at the jointing stage and an increase at the flowering and grain-filling stages. The quantities of the major nutrients under TWD were relatively similar to those under control treatment (TNS) at all winter wheat developmental stages.

Table 1. Soil chemical properties and total organic carbon of root exudation under different climatic conditions.

The highest quantities of SOC and TOC were obtained under TWS at all stages. Under TWD, the quantities of these three soil parameters were identical to those under the control treatment at all stages except at the flowering stage, where an increase in SOC was observed (Table 1). The quantity of TOC under TND was also identical to that under the control treatment at all stages except at the grain-filling stage, where it significantly decreased.

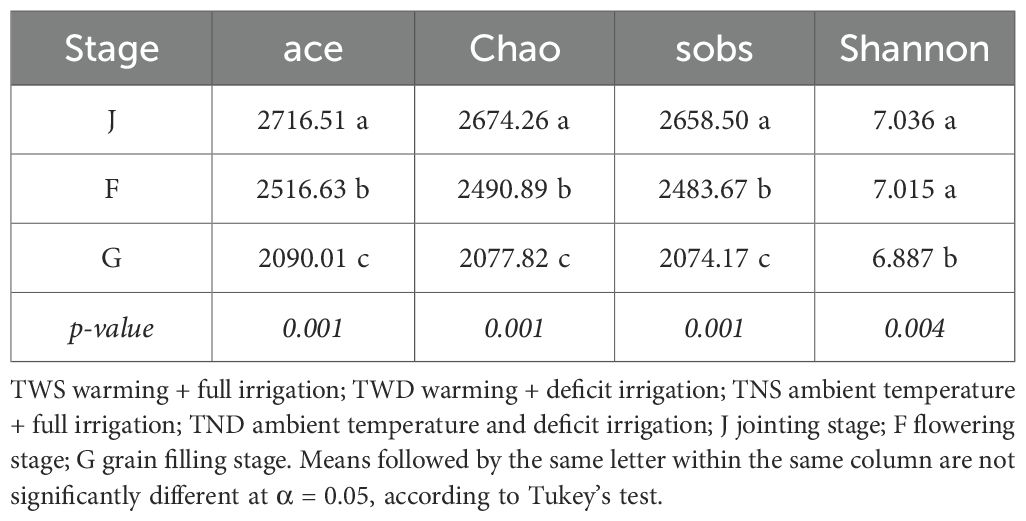

3.2 Microbial community diversity

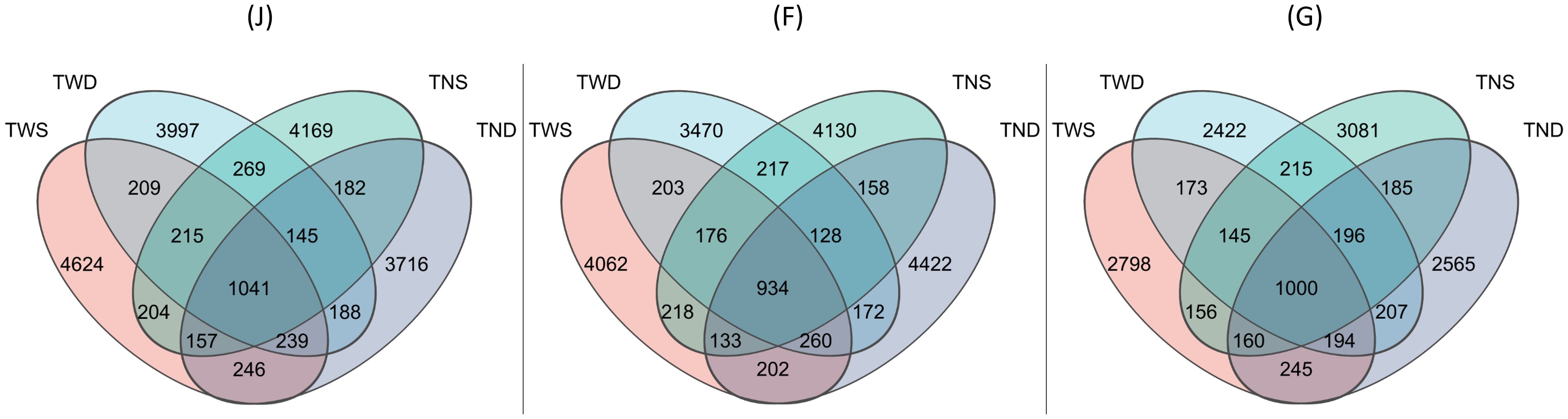

The ace, Chao, sobs and shannon diversity indices were used to assess the impact of different climatic stresses on the alpha diversity of the soil bacterial community. The ANOVA test showed that the different climatic conditions and growth stages of winter wheat had various and significant influences on the diversity of the community (p<0.05) (Tables 2, 3). Overall, the diversity indices and the number of amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) decreased as the wheat growth stage progressed (Table 3; Figure 2). At the jointing stage, diversity indices were higher under TWS and lower under TND, while at the flowering stage, indices were high under both TWS and TND (Table 2). Compared with the control treatment, TWD had no significant influence on the indices at any stage (Table 2). No significant difference was observed between the diversity indices under the different treatments at the grain-filling stage.

Figure 2. Venn diagram showing the abundance of Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) under different climatic conditions. TWS warming + full irrigation; TWD warming + deficit irrigation; TNS ambient temperature + full irrigation; TND ambient temperature + deficit irrigation; J jointing stage; F flowering stage; G grain filling stage.

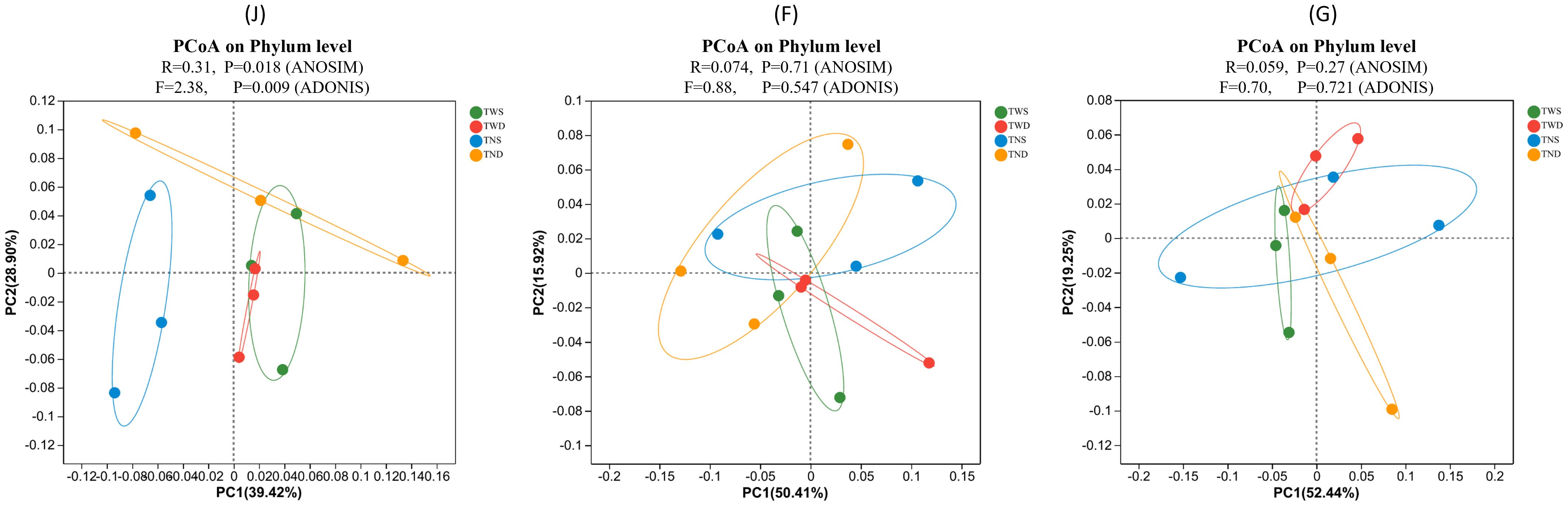

Bray-Curtis distance analysis and ANOSIM were used to assess the similarity between the bacterial communities under different climatic conditions (Figure 3). ANOSIM test revealed a significant difference (p=0.018) between the bacterial communities under the different treatments at the jointing stage. In contrast, there was no significant difference at the other stages. At the jointing stage, the bacterial community under the control treatment was distant from the communities under the other treatments, and the communities under the treatments with warming (TWS and TWD) were closer to each other.

Figure 3. Principal coordinate analysis plot based on Bray–Curtis distance under the different climatic conditions. Each circle represents the bacterial community under one treatment. The closer the circles are, the greater the similarity between the bacterial communities they represent. TWS warming + full irrigation; TWD warming + deficit irrigation; TNS ambient temperature + full irrigation; TND ambient temperature + deficit irrigation; J jointing stage; F flowering stage; G grain filling stage. R shows the degree of difference between groups, and P is the significance of the R-value at α = 0.05.

3.3 Abundance of microbial community

Proteobacteria (20-32%), Actinobacteria (17-32%), Chroroflexi (7-16%), Firmicutes (4-15%), and Acidobacteria (5-14%) were the five most dominant phyla under the different climatic conditions and at different stages of wheat growth. They represented about 80% of all the microbial taxa (Figure 4). The abundance of the bacterial community under TWS was relatively identical to that under TWD at the jointing stage but differed at the other growth stages. Compared with the other treatments, the abundance of Acidobacteria under TNS was greater at the jointing stage and lower at the other stages. A decrease in Chloroflexi and Firmicutes and an increase in Actinobacteria were observed under TND at the flowering and grain-filling stages compared with the jointing stage (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Relative abundance of soil bacteria communities at the phylum level under the different climatic conditions. Relative abundance was calculated by averaging the abundances of replicate samples. TWS warming + full irrigation; TWD warming + deficit irrigation; TNS ambient temperature + full irrigation; TND ambient temperature + deficit irrigation; J jointing stage; F flowering stage; G grain filling stage.

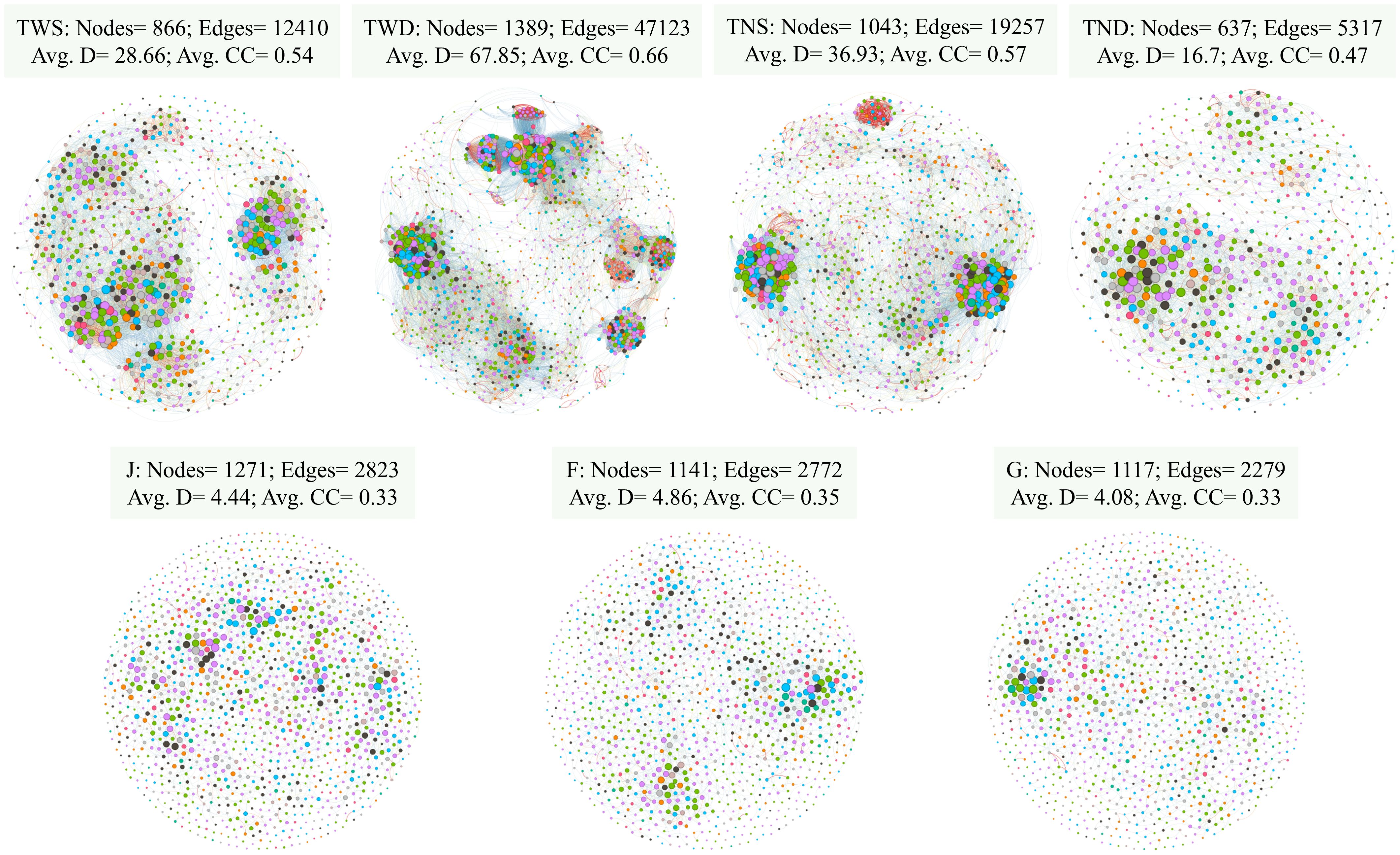

3.4 Co-occurrence network of the microbial community

The co-occurrence network of the soil bacterial community under each treatment is presented in Figure 5. Compared with the control treatment, the network feature values such as nodes, edges, average degree (Avg. D) and average clustering coefficient (Avg.CC) were higher under TWD and lower under TNS. These values under TWS were relatively close to those under the control treatment. These network features were almost identical at the different growth stages of the winter wheat.

Figure 5. The bacterial co-occurrence networks for different treatments. Each node corresponds to an ASV, and edges between nodes correspond to either positive (red) or negative (blue) correlations. ASVs belonging to different microbial phyla have different color codes. TWS warming + full irrigation; TWD warming + deficit irrigation; TNS ambient temperature + full irrigation; TND ambient temperature + deficit irrigation; J jointing stage; F flowering stage; G grain filling stage; Avg. D average degree; Avg.CC average clustering coefficient.

3.5 Relationship between soil properties and the bacterial community

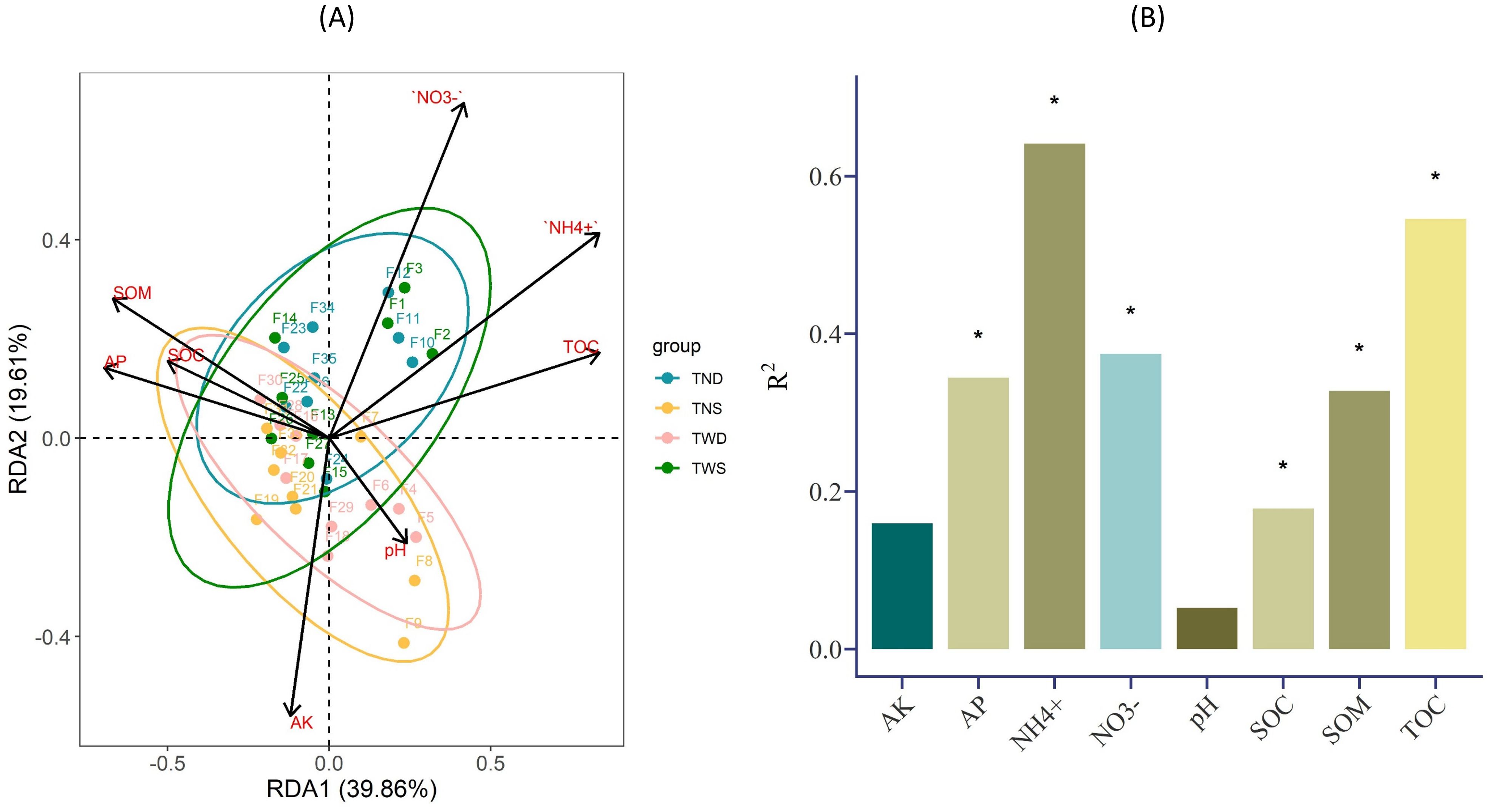

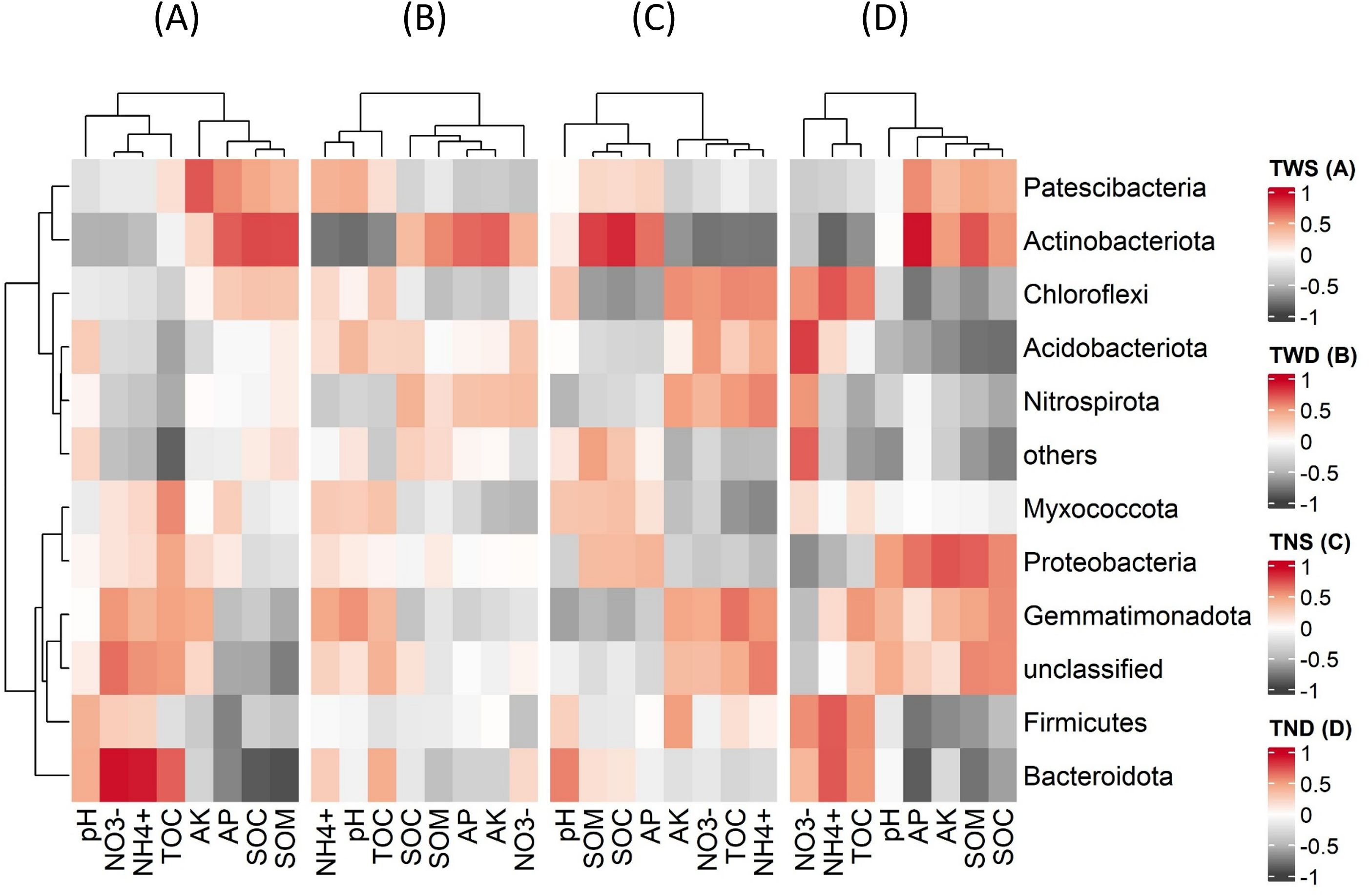

The soil chemical parameters and the TOC of root exudates were used to explain the variation in the abundance of the different bacterial phyla under different climatic conditions. Figure 6B shows that most of these parameters interacted significantly with the abundance of the soil bacterial community (p<0.05). According to Figure 6A, the bacterial community under TND and TWS interacted identically with NH4+, NO3-, and TOC, while that under TNS and TWD interacted identically with SOC, pH, and AP. Overall, the correlation between bacterial phyla and environmental parameters was weak under TWD but strong under TND (Figure 7).

Figure 6. (A) Redundancy analysis (RDA) results of soil bacterial diversity under different climatic conditions, (B) Bar plot showing the level of significance of the correlation between the abundance of the soil bacterial community and environmental parameters. TWS warming + full irrigation; TWD warming + deficit irrigation; TNS ambient temperature + full irrigation; TND ambient temperature + deficit irrigation. The sign * shows the significant difference at α =0.05. NH4+ ammonium; NO3− nitrate; AP available phosphorous; AK available potassium; pH soil acidity; SOC soil organic carbon; SOM soil organic matter; TOC total organic carbon of root exudation.

Figure 7. Pearson’s correlation between environmental parameters and bacterial abundance at the phylum level. TWS warming + full irrigation (A); TWD warming + deficit irrigation (B); TNS ambient temperature + full irrigation (C); TND ambient temperature + deficit irrigation (D). NH4+ ammonium; NO3− nitrate; AP available phosphorous; AK available potassium; pH soil acidity; SOC soil organic carbon; SOM soil organic matter; TOC total organic carbon of root exudation.

Under TND, Chloroflexi, Firmicutes, and Bacteroidota were positively correlated with NH4+, NO3-, and TOC and negatively correlated with AP, AK, and SOC, while the opposite trend was observed with Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria. Unlike Actinobacteria, Bacteroidota was positively correlated with NH4+, NO3-, and TOC and negatively correlated with AP and SOC under TWS.

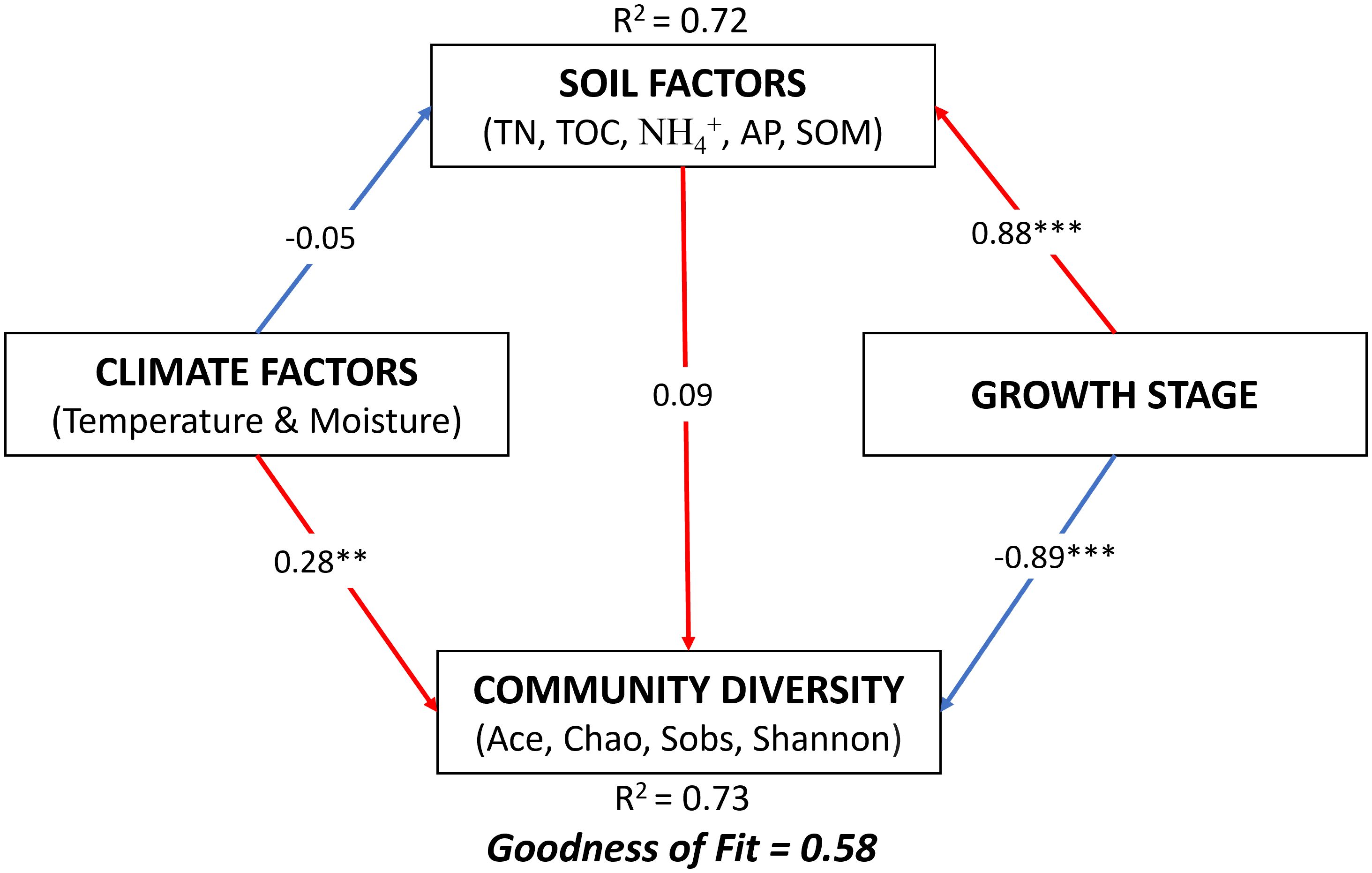

The PLS analysis revealed the direct influences of climate, soil, and growth stages on the diversity of the soil bacterial community (Figure 8). According to this analysis, the growth stage exerted a significant influence on the soil (0.88) and community diversity (-0.89). The climate also directly influenced community diversity (0.28) and soil (-0.05), but its effect on the growth stage was indirect.

Figure 8. Partial least squares (PLS) illustrating the effect of soil, climatic conditions, and winter wheat growth stages on soil microbial community diversity. Numbers at arrows are indicative of the path coefficients. Red arrows represent positive relationships, whereas blue arrows represent negative relationships. Significance levels for each predictor are **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. TN total nitrogen; TOC total organic carbon of root exudation; NH4+ ammonium; AP available phosphorous; SOM soil organic matter.

4 Discussion

4.1 Effects of different climatic stresses on soil nitrogen availability

Soil supports crops and is responsible for their defense and nutrition. Studies have shown that climate change affects the physico-chemical properties of the soil by altering the balance of the various reactions within it (Mondal, 2021; Pareek, 2017). This has repercussions on the availability of nutrients in the soil and the ability of plants to absorb them (Elbasiouny et al., 2022). The amounts of NH4+ and NO3- were high at the jointing and flowering stages and low at the grain-filling stage under warming combined with a full irrigation treatment (Table 1). This would be due to an acceleration of mineralization and nitrogen uptake. Previous studies have reported similar results (Kaštovská et al., 2022; Dai et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2017). Warming accelerates the decomposition of nutrients in the soil (Dai et al., 2020) as well as their absorption by plants (Qiao et al., 2016) through an increase in evapotranspiration (Sadok et al., 2021). In addition, these climatic conditions induce significant nitrogen losses in the form of N2O (Medinets et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2022). The availability of high quantities of nitrogen at the early stage of growth would, therefore, be due to an acceleration of mineralization activities, and the low amounts observed at the advanced stages would be due to an acceleration of their uptake by the plants and an increase in the emission of NO2 into the atmosphere.

Contrary to the conditions of warming combined with full irrigation, the quantities of NH4+ and NO3- under ambient temperature combined with deficit irrigation were low at the jointing stage and high at the other stages (Table 1). This can be explained by a slowdown in nitrogen mineralization in the soil and crop uptake. Reduced soil moisture limits microbial activity and oxygen diffusion, thereby suppressing nitrification and altering denitrification pathways, which decreases net mineralization of organic nitrogen. Deng et al. (2021) reported that drought reduces soil nitrogen mineralization but increases the quantity of mineral nitrogen in the soil. Xie and Shan (2021) demonstrated that water stress significantly increases the amount of NO3- in the soil while inhibiting soil N losses. Other studies have reported the reducing effects of drought (Bista et al., 2018) and drought combined with warming (Hussain et al., 2019) on nitrogen uptake by crops. The high amount of nitrogen in the soil at the advanced stages of wheat growth would, therefore, be the consequence of its accumulation due to reduced plant uptake.

4.2 Effect of different climatic stresses on the soil organic carbon content

Root exudates mediate communication between plants and their underground environment. The results of the present study revealed an increase in the TOC content of root exudates, as well as the quantity of soil SOC under warming combined with full irrigation at all growth stages (Table 1). This suggests that elevated temperature under favorable moisture promoted greater allocation of assimilates belowground, leading to an increase in soil organic carbon. Similar trends were reported by Wang et al. (2021) and Zhang et al. (2016). Indeed, high-temperature conditions combined with full irrigation favor increased nutrient uptake (Hu et al., 2018) and biomass production by the plant (Silveira and Thiébaut, 2017). This, in turn, increases photosynthetic intensity (Liang et al., 2013; Moore et al., 2021) and consequently, the excessive release of organic compounds into the soil. The increase in the amount of SOC under warming combined with the full irrigation observed in the present study would result from the excessive release of organic carbon into the soil by winter wheat.

The TOC content under deficit irrigation combined with both ambient temperature and warming was identical to that under the control treatment at the different stages except at the grain-filling stage, where a significant drop in TOC was observed under ambient temperature combined with deficit irrigation. A decrease in SOC accompanied this decrease in TOC (Table 1). This would be due to the reduction in photosynthetic activity caused by drought and, therefore, a progressive decrease in TOC secretion by plants (Liu et al., 2018; Siddique et al., 2016). These results agree with those reported in previous studies (Karlowsky et al., 2018; Sanaullah et al., 2012).

4.3 Diversity of the soil bacterial community under different climatic stress conditions

Different climatic conditions affect the diversity of the soil microbial community in different ways. Previous studies have attempted to describe the impacts of climate change on bacterial community diversity in winter wheat fields (Preece et al., 2019; Siebielec et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2022). However, few research has considered the different growth stages of wheat. The results of the present study revealed that the influence of different climatic stresses on the alpha and beta diversity of the soil bacterial community varies with the plant growth stage (Table 3; Figures 2, 3). This result is in agreement with other previous studies that reported the impact of different plant growth stages on the diversity of the soil microbial community under different environmental conditions (Collavino et al., 2020; Fu et al., 2023b, Navarro-Noya et al., 2022). The alpha diversity and dissimilarity of the bacterial community were highest at the jointing stage under all treatments and decreased with the advancing wheat growth stage (Table 3, Figure 3). Other studies have reported similar results (Wang et al., 2023b; Chen et al., 2019). Studies on millet have also reported a decrease in the diversity of the soil bacterial community at advanced growth stages of plants (Tian et al., 2022). This result may be due to the variation in the composition of root secretions at different growth stages of the plant (Table 1) (Gransee and Wittenmayer, 2000; Zhao et al., 2021). Root exudates considerably influence the diversity of the soil bacterial community (Kozdrój and Van Elsas, 2000; Nannipieri et al., 2008). Moreover, the composition of these exudates depends on several factors, including environmental conditions (Wang et al., 2021; Yin et al., 2013a, 2013) and the growth stage of the plant (Hasibeder et al., 2015). Warming combined with full irrigation increases the alpha diversity of the soil bacterial community at all growth stages of wheat (Table 2). Similar results have been obtained by other researchers (Fang et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020; Zhai et al., 2024). However, the combined effect of warming and drought on the community’s alpha diversity remains less well understood. The present study shows that the latter climatic condition has no significant impact on the diversity of the soil bacterial community compared with the control condition (Table 2). This can be explained by the fact that drought inhibits the positive effects of higher temperatures on the soil microbial community (Liu et al., 2022b). These results contradict the work of von Rein et al. (2016), who reported adverse effects, and that of Sheik et al. (2011), who reported positive effects of the combined impact of warming and drought on the diversity of the soil bacterial community. The combined effect of these two climatic anomalies on the alpha diversity of the soil bacterial community would, therefore, depend on the intensity of warming and drought.

Several studies agree that drought alters the alpha diversity of the soil microbial community (Preece et al., 2019; Siebielec et al., 2020; Zhai et al., 2024). In the present study, the alpha diversity increased at the flowering stage compared to the jointing and the grain filling stage. These show that the effect of deficit irrigation on the community’s alpha diversity varied according to wheat’s growth stage (Table 2). These results are supported by the work of Na et al. (2019), who showed the dependence between crop growth stage and the influence of drought on soil bacterial community diversity.

4.4 Abundance and composition of the bacterial community under different climatic stress conditions

The abundance of the bacterial community under warming combined with full irrigation was relatively similar to that under warming combined with deficit irrigation at the jointing stage and different at the other growth stages of winter wheat (Figure 4). Moreover, high similarity between the bacterial communities under these two treatments was observed at the jointing stage (Figure 3). This shows that at the jointing stage, the bacterial community was more reactive to rising temperatures than to water deficit. Previous work has reported a variation in the abundance and composition of the soil bacterial community according to the growth stage of the plant (Houlden et al., 2008; Xiong et al., 2021). Wang et al. (2023a) reported significant influences of warming on the abundance of different phyla of the soil bacterial community at wheat’s tillering and jointing stage. Our findings highlight the jointing stage as the most sensitive period to warming, both in terms of soil nitrogen dynamics and rhizosphere microbial responses. This heightened sensitivity can be linked to various interconnected physiological and developmental processes because the jointing stage represents the transition from the vegetative to the reproductive stage.

The abundance of Chloroflexi and Firmicutes decreased while that of Actinobacteria increased under deficit irrigation at the flowering and grain-filling stages compared with the jointing stage (Figure 4). Previous studies have also reported a decrease in the abundance of Firmicutes (Kpalari et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2019) and Chloroflexi (Dai et al., 2019; Kang et al., 2022; Preece et al., 2019) and an increase in Actinobacteria (Kang et al., 2022; Su et al., 2020; Xue et al., 2018) under drought conditions. Other studies have also demonstrated the contribution of bacteria of the genus Bacillus, Paenibacillus, and Effusibacillus (Firmicutes) in improving plant resistance to drought (Santander et al., 2024; Arunrat et al., 2025b). Moreover, Actinobacteria is one of the bacterial phyla containing the most species that promote plant growth (Hamedi and Mohammadipanah, 2015; Palaniyandi et al., 2013; Sathya et al., 2017). Thus, the phyla Firmicutes, Chloroflexia, and Actinobacteria would play diverse but essential roles in soil under drought conditions.

4.5 Effects of different climatic stresses on co-occurrence network of bacterial community

The co-occurrence patterns of bacterial communities were more influenced by climatic conditions than the growth stages of winter wheat (Figure 5). Warming combined with deficit irrigation considerably increased the network feature values, including nodes and edges, whereas this increase was more moderate under warming combined with full irrigation. Research by Yuan et al. (2021) revealed an improvement in the stability and complexity of the microbial network under warming, but the water content of the soil used for the experiment was not specified. Other studies have also reported similar results (Yu et al., 2021b; Liu et al., 2024a). The results of the present study show that the improvement in the complexity of the bacterial network under warming depends on the water content of the soil.

In contrast to warming combined with deficit irrigation, the ambient temperature combined with deficit irrigation reduced the network feature values. This is in accordance with the work of De Vries et al. (2018), who reported a decrease in bacterial network stability under drought conditions. According to Zhang et al. (2024), drought leads to a simplification of the microbial network, which in turn promotes a reduction in its stability and soil functionality.

4.6 Influence of different climatic stresses on the relationships between the bacterial community and environmental parameters

Chloroflexi, Firmicutes, and Bacteroidota, unlike Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria, were positively correlated with NO3-, NH4+, TOC, and negatively correlated with AP, AK, SOM, and SOC under ambient temperature combined with deficit irrigation (Figure 7). This highlights the involvement of these different bacterial phyla in the transformation of macronutrients and organic matter in the soil under drought conditions. Several studies have reported positive relationships between soil organic carbon and bacteria belonging to the Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria phyla (Woolet and Whitman, 2020; Yang et al., 2021b; Yu et al., 2021a). Other studies have also shown the contributions of these two bacterial phyla to the mineralization of soil phosphorus (Soumare et al., 2021; Wei et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2021). Xiao et al. (2022) and Niu et al. (2020) reported positive correlations between Chloroflexi and nitrogen mineralization in the soil. Research into biofertilization has also shown that Bacillus-based fertilizers (Firmicutes) reduce nitrogen mineralization in the soil and their loss in the form of nitrous oxide (Sun et al., 2020a, 2020). These previous studies confirm the positive correlations observed between Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and soil organic carbon and available phosphorus and between Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Chloroflexi, and available forms of soil nitrogen. Furthermore, the results of this study show that these different bacterial phyla are the biological agents most involved in the transformation of soil nutrients under drought conditions.

Bacteroidota was negatively correlated with AP and SOC, and positively correlated with NO3-, NH4+, and TOC under warming combined with a full irrigation regime and under ambient temperature combined with deficit irrigation (Figure 7). Previous work has shown the role of Bacteroidota in mineralizing soil organic matter (Cui et al., 2023; Lan et al., 2022). Other research has also reported positive correlations between Bacteroidota, Firmicutes, and soil nitrogen mineralization (Li et al., 2023c; Sun et al., 2020b). Nevertheless, more studies are needed to better explain the behavior of these bacterial phyla under different climatic conditions.

PLS analysis showed that different growth stages had more influence on the alpha diversity of the bacterial community than climatic conditions and soil parameters (Figure 8). Other previous studies have also reported the impact of growth stage on soil microbial community diversity (Guo et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2016). These results reveal the need to consider the crop growth stages when studying factors affecting the microbial community in the crop rhizosphere.

5 Conclusion

This study evaluated the response of the soil bacterial community to different climatic stresses across different growth stages of winter wheat. These results suggest that the sensitivity of wheat’s rhizosphere bacterial community to the impact of different climatic stresses is not identical at all growth stages and that this community is more sensitive at the jointing stage than at other stages. In addition, warming combined with full irrigation, unlike drought, increases the abundance and diversity of the community, while the complexity of the community is improved by warming combined with deficit irrigation. Structural equation modeling have also revealed the importance of considering different crop growth stages when studying factors affecting the rhizosphere bacterial community. Future reseach involving other levels of warming and drought is needed to acquire all the knowledge needed to understand the impact of these two climatic phenomena on soil bacteria.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1378891.

Author contributions

DK: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation. YF: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SL: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. HC: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. RK: Writing – review & editing. AH: Writing – review & editing. JL: Writing – review & editing. SM: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. DL: Writing – review & editing. YG: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was funded by the Key R&D Program of Shandong Province (2023TZXD011), the China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-03–20), the Open Fund of Key Laboratory of Crop Water Use and Regulation of MARA (ZWS2023-01), and the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (ASTIP).

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Arnell, N. W., Lowe, J. A., Challinor, A. J., and Osborn, T. J. (2019). Global and regional impacts of climate change at different levels of global temperature increase. Clim. Change 155, 377–391. doi: 10.1007/s10584-019-02464-z

Arunrat, N., Sereenonchai, S., and Uttarotai, T. (2025a). Effects of soil texture on microbial community composition and abundance under alternate wetting and drying in paddy soils of central Thailand. Sci. Rep. 15, 24155. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-09843-w

Arunrat, N., Uttarotai, T., Mhuantong, W., Kongsurakan, P., Sereenonchai, S., and Hatano, R. (2025b). Soil bacterial communities in a 10-year fallow rotational shifting cultivation field and an 85-year-old terraced paddy field in Northern Thailand. Environ. Sci. Europe. 37, 95. doi: 10.1186/s12302-025-01143-4

Bista, D. R., Heckathorn, S. A., Jayawardena, D. M., Mishra, S., and Boldt, J. K. (2018). Effects of drought on nutrient uptake and the levels of nutrient-uptake proteins in roots of drought-sensitive and-tolerant grasses. Plants 7, 28. doi: 10.3390/plants7020028

Bogati, K. and Walczak, M. (2022). The impact of drought stress on soil microbial community, enzyme activities and plants. Agronomy 12, 189. doi: 10.3390/agronomy12010189

Bu, X., Gu, X., Zhou, X., Zhang, M., Guo, Z., Zhang, J., et al. (2018). Extreme drought slightly decreased soil labile organic C and N contents and altered microbial community structure in a subtropical evergreen forest. For. Ecol. Manage. 429, 18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2018.06.036

Canarini, A., Schmidt, H., Fuchslueger, L., Martin, V., Herbold, C. W., Zezula, D., et al. (2021). Ecological memory of recurrent drought modifies soil processes via changes in soil microbial community. Nat. Commun. 12, 5308. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25675-4

Chandio, A. A., Dash, D. P., Nathaniel, S. P., Sargani, G. R., and Jiang, Y. (2023). Mitigation pathways towards climate change: Modelling the impact of climatological factors on wheat production in top six regions of China. Ecol. Model. 481, 110381. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2023.110381

Che, Z., Yu, D., Chen, K., Wang, H., Yang, Z., Liu, F., et al. (2022). Effects of warming on microbial community characteristics in the soil surface layer of niaodao wetland in the qinghai lake basin. Sustainability 14, 15255. doi: 10.3390/su142215255

Chen, S., Waghmode, T. R., Sun, R., Kuramae, E. E., Hu, C., and Liu, B. (2019). Root-associated microbiomes of wheat under the combined effect of plant development and nitrogen fertilization. Microbiome 7, 136. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0750-2

Chen, S., Zhang, T., and Wang, J. (2021). Warming but not straw application increased microbial biomass carbon and microbial biomass carbon/nitrogen: importance of soil moisture. Water. Air. Soil pollut. 232, 53. doi: 10.1007/s11270-021-05029-y

Collavino, M. M., Cabrera, E. R., Bruno, C., and Aguilar, O. M. (2020). Effect of soil chemical fertilization on the diversity and composition of the tomato endophytic diazotrophic community at different stages of growth. Braz. J. Microbiol. 51, 1965–1975. doi: 10.1007/s42770-020-00373-3

Cui, H., Chen, P., He, C., Jiang, Z., Lan, R., and Yang, J. (2023). Soil microbial community structure dynamics shape the rhizosphere priming effect patterns in the paddy soil. Sci. Total. Environ. 857, 159459. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159459

Dai, A., Zhao, T., and Chen, J. (2018). Climate change and drought: a precipitation and evaporation perspective. Curr. Climate Change Rep. 4, 301–312. doi: 10.1007/s40641-018-0101-6

Dai, L., Zhang, G., Yu, Z., Ding, H., Xu, Y., and Zhang, Z. (2019). Effect of drought stress and developmental stages on microbial community structure and diversity in peanut rhizosphere soil. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 2265. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092265

Dai, Z., Yu, M., Chen, H., Zhao, H., Huang, Y., Su, W., et al. (2020). Elevated temperature shifts soil N cycling from microbial immobilization to enhanced mineralization, nitrification and denitrification across global terrestrial ecosystems. Global Change Biol. 26, 5267–5276. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15211

Deng, L., Peng, C., Kim, D.-G., Li, J., Liu, Y., Hai, X., et al. (2021). Drought effects on soil carbon and nitrogen dynamics in global natural ecosystems. Earth-Sci. Rev. 214, 103501. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103501

De Vries, F. T., Griffiths, R. I., Bailey, M., Craig, H., Girlanda, M., Gweon, H. S., et al. (2018). Soil bacterial networks are less stable under drought than fungal networks. Nat. Commun. 9, 3033. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05516-7

Diffenbaugh, N. S., Swain, D. L., and Touma, D. (2015). Anthropogenic warming has increased drought risk in California. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 3931–3936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422385112

Duan, S., Zhang, Y., and Zheng, S. (2022). Heterotrophic nitrifying bacteria in wastewater biological nitrogen removal systems: A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 2302–2338. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2021.1877976

Elbasiouny, H., El-Ramady, H., Elbehiry, F., Rajput, V. D., Minkina, T., and Mandzhieva, S. (2022). Plant nutrition under climate change and soil carbon sequestration. Sustainability 14, 914. doi: 10.3390/su14020914

Fang, J., Wei, S., Shi, G., Cheng, Y., Zhang, X., Zhang, F., Lu, Z., and Zhao, X. (2021). Potential effects of temperature levels on soil bacterial community structure. E3S Web Conf., 292, 01008 doi: 10.1051/e3sconf/202129201008

Fawzy, S., Osman, A. I., Doran, J., and Rooney, D. W. (2020). Strategies for mitigation of climate change: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 18, 2069–2094. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01059-w

Feng, P., Wang, B., Liu, D. L., Waters, C., Xiao, D., Shi, L., et al. (2020). Dynamic wheat yield forecasts are improved by a hybrid approach using a biophysical model and machine learning technique. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 285-286, 107922. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2020.107922

Fu, F., Li, J., Li, Y., Chen, W., Ding, H., and Xiao, S. (2023). Simulating the effect of climate change on soil microbial community in an Abies georgei var. smithii forest. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1189859. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1189859

Gransee, A. and Wittenmayer, L. (2000). Qualitative and quantitative analysis of water-soluble root exudates in relation to plant species and development. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 163, 381–385. doi: 10.1002/1522-2624(200008)163:4<381::AID-JPLN381>3.0.CO;2-7

Guo, Z., Wan, S., Hua, K., Yin, Y., Chu, H., Wang, D., et al. (2020). Fertilization regime has a greater effect on soil microbial community structure than crop rotation and growth stage in an agroecosystem. Appl. Soil Ecol. 149, 103510. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2020.103510

Hamedi, J. and Mohammadipanah, F. (2015). Biotechnological application and taxonomical distribution of plant growth promoting actinobacteria. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 42, 157–171. doi: 10.1007/s10295-014-1537-x

Hashimoto, K. (2019). “Global temperature and atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration,” in Global Carbon Dioxide Recycling: For Global Sustainable Development by Renewable Energy. Ed. Hashimoto, K. (Springer Singapore, Singapore).

Hasibeder, R., Fuchslueger, L., Richter, A., and Bahn, M. (2015). Summer drought alters carbon allocation to roots and root respiration in mountain grassland. New Phytol. 205, 1117–1127. doi: 10.1111/nph.13146

Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Jacob, D., Taylor, M., Guillén Bolaños, T., Bindi, M., Brown, S., et al. (2019). The human imperative of stabilizing global climate change at 1.5 C. Science 365, eaaw6974. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw6974

Houlden, A., Timms-Wilson, T. M., Day, M. J., and Bailey, M. J. (2008). Influence of plant developmental stage on microbial community structure and activity in the rhizosphere of three field crops. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 65 2, 193–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00535.x

Hu, C., Tian, Z., Gu, S., Guo, H., Fan, Y., Abid, M., et al. (2018). Winter and spring night-warming improve root extension and soil nitrogen supply to increase nitrogen uptake and utilization of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Eur. J. Agron. 96, 96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2018.03.008

Hussain, H. A., Men, S., Hussain, S., Chen, Y., Ali, S., Zhang, S., et al. (2019). Interactive effects of drought and heat stresses on morpho-physiological attributes, yield, nutrient uptake and oxidative status in maize hybrids. Sci. Rep. 9, 3890. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40362-7

Kang, E., Li, Y., Zhang, X., Yan, Z., Zhang, W., Zhang, K., et al. (2022). Extreme drought decreases soil heterotrophic respiration but not methane flux by modifying the abundance of soil microbial functional groups in alpine peatland. Catena 212, 106043. doi: 10.1016/j.catena.2022.106043

Karlowsky, S., Augusti, A., Ingrisch, J., Akanda, M. K. U., Bahn, M., and Gleixner, G. (2018). Drought-induced accumulation of root exudates supports post-drought recovery of microbes in mountain grassland. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 1593. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01593

Karst, J., Gaster, J., Wiley, E., and Landhäusser, S. M. (2017). Stress differentially causes roots of tree seedlings to exude carbon. Tree Physiol. 37, 154–164. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpw090

Kaštovská, E., Choma, M., Čapek, P., Kaňa, J., Tahovská, K., and Kopáček, J. (2022). Soil warming during winter period enhanced soil N and P availability and leaching in alpine grasslands: A transplant study. PloS One 17, e0272143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0272143

Khan, M. Z., Maron, P.-A., Dequiedt, S., Rumpel, C., and Chabbi, A. (2025). How does warming affect microbial communities in whole-soil under contrasting management? J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. doi: 10.1007/s42729-025-02598-3

Kome, G. K., Enang, R. K., and Yerima, B. P. K. (2018). Knowledge and management of soil fertility by farmers in western Cameroon. Geoderma. Reg. 13, 43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.geodrs.2018.02.001

Kozdrój, J. and Van Elsas, J. D. (2000). Response of the bacterial community to root exudates in soil polluted with heavy metals assessed by molecular and cultural approaches. Soil Biol. Biochem. 32, 1405–1417. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(00)00058-4

Kpalari, D. F., Mounkaila Hamani, A. K., Hui, C., Sogbedji, J. M., Liu, J., Le, Y., et al. (2023). Soil bacterial community and greenhouse gas emissions as responded to the coupled application of nitrogen fertilizer and microbial decomposing inoculants in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seedling stage under different water regimes. Agronomy 13, 2950. doi: 10.3390/agronomy13122950

Kumar, A. and Verma, J. P. (2019). “The role of microbes to improve crop productivity and soil health,” in Ecological wisdom inspired restoration engineering, Singapore: Springer Singapore. 249–265.

Lan, J., Wang, S., Wang, J., Qi, X., Long, Q., and Huang, M. (2022). The shift of soil bacterial community after afforestation influence soil organic carbon and aggregate stability in karst region. Front. Microbiol. 13, 901126. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.901126

Leuschner, C., Tückmantel, T., and Meier, I. C. (2022). Temperature effects on root exudation in mature beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) forests along an elevational gradient. Plant Soil 481, 147–163. doi: 10.1007/s11104-022-05629-5

Li, Q., Gao, Y., Hamani, A. K. M., Fu, Y., Liu, J., Wang, H., et al. (2023a). Effects of warming and drought stress on the coupling of photosynthesis and transpiration in winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Appl. Sci. 13, 2759. doi: 10.3390/app13052759

Li, G., Kim, S., Han, S. H., Chang, H., Du, D., and Son, Y. (2018). Precipitation affects soil microbial and extracellular enzymatic responses to warming. Soil Biol. Biochem. 120, 212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.02.014

Li, X., Wang, A., Huang, D., Qian, H., Luo, X., Chen, W., et al. (2023c). Patterns and drivers of soil net nitrogen mineralization and its temperature sensitivity across eastern China. Plant Soil 485, 475–488. doi: 10.1007/s11104-022-05843-1

Li, J., Xie, T., Zhu, H., Zhou, J., Li, C., Xiong, W., et al. (2021). Alkaline phosphatase activity mediates soil organic phosphorus mineralization in a subalpine forest ecosystem. Geoderma 404, 115376. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2021.115376

Li, W., Yuan, L., Lan, X., Shi, R., Chen, D., Feng, D., et al. (2023b). Effects of long-term warming on soil prokaryotic communities in shrub and alpine meadows on the eastern edge of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Appl. Soil Ecol. 188, 104871. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2023.104871

Liang, J., Xia, J., Liu, L., and Wan, S. (2013). Global patterns of the responses of leaf-level photosynthesis and respiration in terrestrial plants to experimental warming. J. Plant Ecol. 6, 437–447. doi: 10.1093/jpe/rtt003

Liu, J., Guo, Y., Bai, Y., Camberato, J., Xue, J., and Zhang, R. (2018). Effects of drought stress on the photosynthesis in maize. Russian J. Plant Physiol. 65, 849–856. doi: 10.1134/S1021443718060092

Liu, W., Jiang, Y., Su, Y., Smoak, J. M., and Duan, B. (2022a). Warming affects soil nitrogen mineralization via changes in root exudation and associated soil microbial communities in a subalpine tree species Abies fabri. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr., 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s42729-021-00657-z

Liu, J., Si, Z., Li, S., Wu, L., Zhang, Y., Wu, X., et al. (2024b). Effects of water and nitrogen rate on grain-filling characteristics under high-low seedbed cultivation in winter wheat. J. Integr. Agric. 23, 4018–4031. doi: 10.1016/j.jia.2023.12.002

Liu, G., Sun, J., Xie, P., Guo, C., Zhu, K., and Tian, K. (2024a). Climate warming enhances microbial network complexity by increasing bacterial diversity and fungal interaction strength in litter decomposition. Sci. Total. Environ. 908, 168444. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168444

Liu, Y., Tian, H., Li, J., Wang, H., Liu, S., and Liu, X. (2022b). Reduced precipitation neutralizes the positive impact of soil warming on soil microbial community in a temperate oak forest. Sci. Total. Environ. 806, 150957. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150957

Liu, X., Yang, Z., Lin, C., Giardina, C. P., Xiong, D., Lin, W., et al. (2017). Will nitrogen deposition mitigate warming-increased soil respiration in a young subtropical plantation? Agric. For. Meteorol. 246, 78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2017.06.010

Lyu, D., Backer, R., Robinson, W. G., and Smith, D. L. (2019). Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for cannabis production: yield, cannabinoid profile and disease resistance. Front. Microbiol. 1761. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01761

Ma, C., Liu, Y., Wang, J., Xue, L., Hou, P., Xue, L., et al. (2022). Warming increase the N2O emissions from wheat fields but reduce the wheat yield in a rice-wheat rotation system. Agricult. Ecosyst. Environ. 337, 108064. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2022.108064

Ma, Z. L., Zhao, W. Q., Liu, M., and Liu, Q. (2019). Effects of warming on microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen in the rhizosphere and bulk soil in an alpine scrub ecosystem. Ying. Yong. Sheng. Tai. Xue. Bao=. J. Appl. Ecol. 30, 1893–1900. doi: 10.13287/j.1001-9332.201906.024

Marengo, J. A., Torres, R. R., and Alves, L. M. (2017). Drought in Northeast Brazil—past, present, and future. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 129, 1189–1200. doi: 10.1007/s00704-016-1840-8

Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pörtner, H. O., Roberts, D., Skea, J., Shukla, P. R., et al. (2018). Global Warming of 1.5˚C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1. 5 C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty. Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty, 616.

Medinets, S., White, S., Cowan, N., Drewer, J., Dick, J., Jones, M., et al. (2021). Impact of climate change on soil nitric oxide and nitrous oxide emissions from typical land uses in Scotland. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 055035. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/abf06e

Mekala, S. and Polepongu, S. (2019). “Impact of climate change on soil microbial community,” in Plant biotic interactions: State of the art, Cham: Springer International Publishing. 31–41.

Mondal, S. (2021). “Impact of climate change on soil fertility,” in Climate change and the microbiome: sustenance of the ecosphere, Cham: Springer International Publishing. 551–569.

Monteleone, B., Borzí, I., Arosio, M., Cesarini, L., Bonaccorso, B., and Martina, M. (2023). Modelling the response of wheat yield to stage-specific water stress in the Po Plain. Agric. Water Manage. 287, 108444. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2023.108444

Moore, C. E., Meacham-Hensold, K., Lemonnier, P., Slattery, R. A., Benjamin, C., Bernacchi, C. J., et al. (2021). The effect of increasing temperature on crop photosynthesis: from enzymes to ecosystems. J. Exp. Bot. 72, 2822–2844. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erab090

Na, X., Cao, X., Ma, C., Ma, S., Xu, P., Liu, S., et al. (2019). Plant stage, not drought stress, determines the effect of cultivars on bacterial community diversity in the rhizosphere of broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum L.). Front. Microbiol. 10, 828. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00828

Nakayama, M. and Tateno, R. (2018). Solar radiation strongly influences the quantity of forest tree root exudates. Trees 32, 871–879. doi: 10.1007/s00468-018-1685-0

Nannipieri, P., Ascher, J., Ceccherini, M. T., Landi, L., Pietramellara, G., Renella, G., et al. (2008). “Effects of root exudates in microbial diversity and activity in rhizosphere soils,” in Molecular Mechanisms of Plant and Microbe Coexistence. Eds. Nautiyal, C. S. and Dion, P. (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg).

Navarro-Noya, Y. E., Chávez-Romero, Y., Hereira-Pacheco, S., De León Lorenzana, A. S., Govaerts, B., Verhulst, N., et al. (2022). Bacterial communities in the rhizosphere at different growth stages of maize cultivated in soil under conventional and conservation agricultural practices. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e01834–e01821. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01834-21

Ning, D., Qin, A., Duan, A., Xiao, J., Zhang, J., Liu, Z., et al. (2019). Deficit irrigation combined with reduced N-fertilizer rate can mitigate the high nitrous oxide emissions from Chinese drip-fertigated maize field. Global Ecol. Conserv. 20, e00803. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00803

Niu, Y., Zhang, M., Bai, S. H., Xu, Z., Liu, Y., Chen, F., et al. (2020). Successive mineral nitrogen or phosphorus fertilization alone significantly altered bacterial community rather than bacterial biomass in plantation soil. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 104, 7213–7224. doi: 10.1007/s00253-020-10761-2

Ochoa-Hueso, R., Collins, S. L., Delgado-Baquerizo, M., Hamonts, K., Pockman, W. T., Sinsabaugh, R. L., et al. (2018). Drought consistently alters the composition of soil fungal and bacterial communities in grasslands from two continents. Global Change Biol. 24, 2818–2827. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14113

Palaniyandi, S. A., Yang, S. H., Zhang, L., and Suh, J.-W. (2013). Effects of actinobacteria on plant disease suppression and growth promotion. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97, 9621–9636. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5206-1

Pareek, N. (2017). Climate change impact on soils: adaptation and mitigation. MOJ. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2, 136–139. doi: 10.15406/mojes.2017.02.00026

Phillips, R. P., Erlitz, Y., Bier, R., and Bernhardt, E. S. (2008). New approach for capturing soluble root exudates in forest soils. Funct. Ecol. 22, 990–999. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01495.x

Preece, C., Verbruggen, E., Liu, L., Weedon, J. T., and Peñuelas, J. (2019). Effects of past and current drought on the composition and diversity of soil microbial communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 131, 28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.12.022

Qiao, M., Zhang, Z., Li, Y., Xiao, J., Yin, H., Yue, B., et al. (2016). Experimental warming effects on root nitrogen absorption and mycorrhizal infection in a subalpine coniferous forest. Scand. J. For. Res. 31, 347–354. doi: 10.1080/02827581.2015.1080295

Ramette, A. (2007). Multivariate analyses in microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 62, 142–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2007.00375.x

Rashid, M., Kamruzzaman, M., Haque, A., and Krehenbrink, M. (2019). “Soil microbes for sustainable agriculture,” in Sustainable management of soil and environment, Cham: Springer International Publishing. 339–382.

Reimer, M., Hartmann, T. E., Oelofse, M., Magid, J., Bünemann, E. K., and Möller, K. (2020). Reliance on biological nitrogen fixation depletes soil phosphorus and potassium reserves. Nutrient. Cycling. Agroecosyst. 118, 273–291. doi: 10.1007/s10705-020-10101-w

Sadok, W., Lopez, J. R., and Smith, K. P. (2021). Transpiration increases under high-temperature stress: Potential mechanisms, trade-offs and prospects for crop resilience in a warming world. Plant. Cell Environ. 44, 2102–2116. doi: 10.1111/pce.13970

Sanaullah, M., Chabbi, A., Rumpel, C., and Kuzyakov, Y. (2012). Carbon allocation in grassland communities under drought stress followed by 14C pulse labeling. Soil Biol. Biochem. 55, 132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.06.004

Santander, C., González, F., Pérez, U., Ruiz, A., Aroca, R., Santos, C., et al. (2024). Enhancing Water Status and Nutrient Uptake in Drought-Stressed Lettuce Plants (Lactuca sativa L.) via Inoculation with Different Bacillus spp. Isolated from the Atacama Desert. Plants 13, 158. doi: 10.3390/plants13020158

Sathya, A., Vijayabharathi, R., and Gopalakrishnan, S. (2017). Plant growth-promoting actinobacteria: a new strategy for enhancing sustainable production and protection of grain legumes. 3 Biotech. 7, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0736-3

Schimel, J. P. (2018). Life in dry soils: effects of drought on soil microbial communities and processes. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. syst. 49, 409–432. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110617-062614

Schloter, M., Nannipieri, P., Sørensen, S. J., and Van Elsas, J. D. (2018). Microbial indicators for soil quality. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 54, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00374-017-1248-3

Sheik, C. S., Beasley, W. H., Elshahed, M. S., Zhou, X., Luo, Y., and Krumholz, L. R. (2011). Effect of warming and drought on grassland microbial communities. ISME. J. 5, 1692–1700. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.32

Shen, Z., Yu, B., Shao, K., Gao, G., and Tang, X. (2023). Warming reduces microeukaryotic diversity, network complexity and stability. Environ. Res. 238, 117235. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.117235

Shoukat, M. R., Wang, J., Habib-Ur-Rahman, M., Hui, X., Hoogenboom, G., and Yan, H. (2024). Adaptation strategies for winter wheat production at farmer fields under a changing climate: Employing crop and multiple global climate models. Agric. Syst. 220, 104066. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2024.104066

Siddique, Z., Jan, S., Imadi, S. R., Gul, A., and Ahmad, P. (2016). Drought stress and photosynthesis in plants. Water Stress Crop Plants.: Sustain. Approach. 1, 1–11. doi: 10.1002/9781119054450.ch1

Siebielec, S., Siebielec, G., Klimkowicz-Pawlas, A., Gałązka, A., Grządziel, J., and Stuczyński, T. (2020). Impact of water stress on microbial community and activity in sandy and loamy soils. Agronomy 10, 1429. doi: 10.3390/agronomy10091429

Silveira, M. J. and Thiébaut, G. (2017). Impact of climate warming on plant growth varied according to the season. Limnologica 65, 4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.limno.2017.05.003

Soumare, A., Boubekri, K., Lyamlouli, K., Hafidi, M., Ouhdouch, Y., and Kouisni, L. (2021). Efficacy of phosphate solubilizing Actinobacteria to improve rock phosphate agronomic effectiveness and plant growth promotion. Rhizosphere 17, 100284. doi: 10.1016/j.rhisph.2020.100284

Staszel, K., Lasota, J., and Błońska, E. (2022). Effect of drought on root exudates from Quercus petraea and enzymatic activity of soil. Sci. Rep. 12, 7635. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-11754-z

Su, X., Su, X., Zhou, G., Du, Z., Yang, S., Ni, M., et al. (2020). Drought accelerated recalcitrant carbon loss by changing soil aggregation and microbial communities in a subtropical forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 148, 107898. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2020.107898

Sun, B., Bai, Z., Bao, L., Xue, L., Zhang, S., Wei, Y., et al. (2020a). Bacillus subtilis biofertilizer mitigating agricultural ammonia emission and shifting soil nitrogen cycling microbiomes. Environ. Int. 144, 105989. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105989

Sun, Y., Chen, H. Y., Jin, L., Wang, C., Zhang, R., Ruan, H., et al. (2020c). Drought stress induced increase of fungi: bacteria ratio in a poplar plantation. Catena 193, 104607. doi: 10.1016/j.catena.2020.104607

Sun, B., Gu, L., Bao, L., Zhang, S., Wei, Y., Bai, Z., et al. (2020b). Application of biofertilizer containing Bacillus subtilis reduced the nitrogen loss in agricultural soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 148, 107911. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2020.107911

Sun, H., Wang, Y., and Wang, L. (2024). Impact of climate change on wheat production in China. Eur. J. Agron. 153, 127066. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2023.127066

Tian, L., Yu, S., Zhang, L., Dong, K., and Feng, B. (2022). Mulching practices manipulate the microbial community diversity and network of root−associated compartments in the Loess Plateau. Soil Tillage. Res. 223, 105476. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2022.105476

Ulrich, D. E., Clendinen, C. S., Alongi, F., Mueller, R. C., Chu, R. K., Toyoda, J., et al. (2022). Root exudate composition reflects drought severity gradient in blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis). Sci. Rep. 12, 12581. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-16408-8

Veach, A. M. and Zeglin, L. H. (2020). Historical drought affects microbial population dynamics and activity during soil drying and re-wet. Microbial. Ecol. 79, 662–674. doi: 10.1007/s00248-019-01432-5

Verma, M., Mishra, J., and Arora, N. K. (2019). Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria: Diversity and Applications. In: Environmental Biotechnology: For Sustainable Future. Singapore: Springer Singapore 129–173. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-7284-0_6

Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Quiring, S. M., Pena-Gallardo, M., Yuan, S., and Dominguez-Castro, F. (2020). A review of environmental droughts: Increased risk under global warming? Earth-Sci. Rev. 201, 102953. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2019.102953

Vocciante, M., Grifoni, M., Fusini, D., Petruzzelli, G., and Franchi, E. (2022). The role of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) in mitigating plant’s environmental stresses. Appl. Sci. 12, 1231. doi: 10.3390/app12031231

Von Rein, I., Gessler, A., Premke, K., Keitel, C., Ulrich, A., and Kayler, Z. E. (2016). Forest understory plant and soil microbial response to an experimentally induced drought and heat-pulse event: the importance of maintaining the continuum. Global Change Biol. 22, 2861–2874. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13270

Walkley, A. and Black, I. A. (1934). An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 37, 29–38. doi: 10.1097/00010694-193401000-00003

Wang, J., Chen, S., Sun, R., Liu, B., Waghmode, T., and Hu, C. (2023a). Spatial and temporal dynamics of the bacterial community under experimental warming in field-grown wheat. PeerJ 11, e15428. doi: 10.7717/peerj.15428

Wang, Q., Chen, L., Xu, H., Ren, K., Xu, Z., Tang, Y., et al. (2021). The effects of warming on root exudation and associated soil N transformation depend on soil nutrient availability. Rhizosphere 17, 100263. doi: 10.1016/j.rhisph.2020.100263

Wang, X., Jiang, D., and Lang, X. (2018). Climate change of 4 C global warming above pre-industrial levels. Adv. Atmospheric. Sci. 35, 757–770. doi: 10.1007/s00376-018-7160-4

Wang, Y., Ma, A., Chong, G.-S., Xie, F., Zhou, H., Liu, G., et al. (2020). Effect of simulated warming on microbial community in glacier forefield. Huan. Jing. Ke. Xue= Huanjing. Kexue. 41 6, 2918–2923. doi: 10.13227/j.hjkx.201911157

Wang, P., Nie, J., Yang, L., Zhao, J., Wang, X., Zhang, Y., et al. (2023b). Plant growth stages covered the legacy effect of rotation systems on microbial community structure and function in wheat rhizosphere. Environ. Sci. pollut. Res. 30, 59632–59644. doi: 10.1007/s11356-023-26703-0

Wang, J., Xue, C., Song, Y., Wang, L., Huang, Q., and Shen, Q. (2016). Wheat and rice growth stages and fertilization regimes alter soil bacterial community structure, but not diversity. Front. Microbiol. 7. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01207

Wei, X., Hu, Y., Razavi, B. S., Zhou, J., Shen, J., Nannipieri, P., et al. (2019). Rare taxa of alkaline phosphomonoesterase-harboring microorganisms mediate soil phosphorus mineralization. Soil Biol. Biochem. 131, 62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.12.025

Woolet, J. and Whitman, T. (2020). Pyrogenic organic matter effects on soil bacterial community composition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 141, 107678. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2019.107678

Wu, L., Zhang, Y., Guo, X., Ning, D., Zhou, X., Feng, J., et al. (2022). Reduction of microbial diversity in grassland soil is driven by long-term climate warming. Nat. Microbiol. 7, 1054–1062. doi: 10.1038/s41564-022-01147-3

Xiao, R., Man, X., Duan, B., Cai, T., Ge, Z., Li, X., et al. (2022). Changes in soil bacterial communities and nitrogen mineralization with understory vegetation in boreal larch forests. Soil Biol. Biochem. 166, 108572. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2022.108572

Xie, T. and Shan, L. (2021). Water stress and appropriate N management achieves profitable yields and less N loss on sandy soils. Arid. Land. Res. Manage. 35, 358–373. doi: 10.1080/15324982.2020.1868024

Xiong, C., Singh, B. K., He, J.-Z., Han, Y.-L., Li, P.-P., Wan, L.-H., et al. (2021). Plant developmental stage drives the differentiation in ecological role of the maize microbiome. Microbiome 9, 171. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01118-6

Xu, L., Chen, N., and Zhang, X. (2019). Global drought trends under 1.5 and 2 C warming. Int. J. Climatol. 39, 2375–2385. doi: 10.1002/joc.5958

Xu, S., Geng, W., Sayer, E. J., Zhou, G., Zhou, P., and Liu, C. (2020). Soil microbial biomass and community responses to experimental precipitation change: A meta-analysis. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2, 93–103. doi: 10.1007/s42832-020-0033-7

Xu, W. and Yuan, W. (2017). Responses of microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen to experimental warming: A meta-analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 115, 265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.08.033

Xue, P.-P., Carrillo, Y., Pino, V., Minasny, B., and Mcbratney, A. B. (2018). Soil properties drive microbial community structure in a large scale transect in South Eastern Australia. Sci. Rep. 8, 11725. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30005-8

Yang, S., Jansen, B., Absalah, S., Kalbitz, K., Castro, F. O. C., and Cammeraat, E. L. (2022). Soil organic carbon content and mineralization controlled by the composition, origin and molecular diversity of organic matter: a study in tropical alpine grasslands. Soil Tillage. Res. 215, 105203. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2021.105203

Yang, Y., Li, T., Wang, Y., Cheng, H., Chang, S. X., Liang, C., et al. (2021a). Negative effects of multiple global change factors on soil microbial diversity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 156, 108229. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2021.108229

Yang, Y., Liu, H., Dai, Y., Tian, H., Zhou, W., and Lv, J. (2021b). Soil organic carbon transformation and dynamics of microorganisms under different organic amendments. Sci. Total. Environ. 750, 141719. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141719

Yin, H., Li, Y., Xiao, J., Xu, Z., Cheng, X., and Liu, Q. (2013a). Enhanced root exudation stimulates soil nitrogen transformations in a subalpine coniferous forest under experimental warming. Global Change Biol. 19, 2158–2167. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12161

Yin, H., Xiao, J., Li, Y., Chen, Z., Cheng, X., Zhao, C., et al. (2013b). Warming effects on root morphological and physiological traits: The potential consequences on soil C dynamics as altered root exudation. Agric. For. Meteorol. 180, 287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2013.06.016

You, X., Wang, S., Du, L., Wu, H., and Wei, Y. (2022). Effects of organic fertilization on functional microbial communities associated with greenhouse gas emissions in paddy soils. Environ. Res. 213, 113706. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113706

Yu, Y., Liu, L., Wang, J., Zhang, Y., and Xiao, C. (2021b). Effects of warming on the bacterial community and its function in a temperate steppe. Sci. Total. Environ. 792, 148409. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148409

Yu, H., Wang, F., Shao, M., Huang, L., Xie, Y., Xu, Y., et al. (2021a). Effects of Rotations with legume on soil functional microbial communities involved in phosphorus transformation. Front. Microbiol. 12, 661100. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.661100

Yuan, M. M., Guo, X., Wu, L., Zhang, Y., Xiao, N., Ning, D., et al. (2021). Climate warming enhances microbial network complexity and stability. Nat. Climate Change 11, 343–348. doi: 10.1038/s41558-021-00989-9

Zhai, C., Han, L., Xiong, C., Ge, A., Yue, X., Li, Y., et al. (2024). Soil microbial diversity and network complexity drive the ecosystem multifunctionality of temperate grasslands under changing precipitation. Sci. Total. Environ. 906, 167217. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.167217

Zhang, R., Chen, L., Niu, Z., Song, S., and Zhao, Y. (2019). Water stress affects the frequency of Firmicutes, Clostridiales and Lysobacter in rhizosphere soils of greenhouse grape. Agric. Water Manage. 226, 105776. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2019.105776

Zhang, B., Chen, S., Zhang, J., He, X., Liu, W., Zhao, Q., et al. (2015). Depth-related responses of soil microbial communities to experimental warming in an alpine meadow on the Q inghai-T ibet P lateau. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 66, 496–504. doi: 10.1111/ejss.12240