- 1Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR)-National Soybean Research Institute, Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India

- 2Jawaharlal Nehru Krishi Vishwa Vidyalaya, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India

- 3Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR)-Central Arid Zone Research Institute, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India

- 4Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR)-Indian Institute of Seed Science and Technology, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

- 5International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics, Hyderabad, Telangana, India

- 6WA State Agricultural Biotechnology Centre, Centre for Crop and Food Innovation, Murdoch University, Perth, WA, Australia

Charcoal rot is a soil- and seed-borne disease caused by a necrotrophic fungal pathogen—Macrophomina phaseolina. To understand the genetic architecture of resistance against it, a genome-wide association study (GWAS) was conducted based on a glasshouse experiment and a 3-year field experiment using 214 diverse soybean accessions. In a glasshouse experiment at the seedling stage, eight single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified: one SNP each on chromosome (chr) 8 (S8_16817767), chr 10 (S10_52066337), chr 14 (S14_50857981), chr 15 (S15_32620059), chr 17 (S17_1689021), and chr 18 (S18_9413708), while two SNPs (S16_34569104 and S16_37878937) were located on chr 16. In the case of the field experiment at the reproductive stage, 10 SNPs were identified: 1 SNP each on chr 12 (S12_14977708), chr 14 (S14_51754926), and chr 16 (S16_33491560), 2 SNPs each were identified on chr 6 (S6_41109641 and S6_41863847) and chr 10 (S10_40644409 and S10_44768495), while 3 SNPs (S18_25004105, S18_55655188, and S18_56366541) were located on chr 18. The SNP S14_50857981 associated with seedling resistance and S14_51754926 associated with adult plant resistance are present within the 1-Mb region and will be of immense importance for charcoal rot resistance breeding. The putative candidate gene analysis for identified SNPs revealed 23 genes with annotations associated with defense response pathways. Three genes encoding an NB-ARC domain associated with defense response were present near S14_50857981. The genotype PI 159923 was found to be resistant under both field and glasshouse conditions, and it will be employed as a parent in breeding for high-yielding charcoal rot-resistant genotypes. Our study provides new insights into charcoal rot resistance in soybean, identifying key SNPs and genes that can aid future breeding programs for developing climate-resilient crops.

1 Introduction

Soybean is a major oil seed crop with multi-faceted health benefits and industrial applications (Karikari et al., 2019). Though India ranks fifth in soybean production, its productivity is challenged by several biotic stresses. Among them, charcoal rot disease caused by Macrophomina phaseolina poses approximately 77% yield loss accounting for 39,200 metric tons (Wrather et al., 2010; Sharma et al., 2014). M. phaseolina is soil- and seed-borne in nature, and is a polyphagous necrotrophic fungal pathogen having a host range of approximately 500 plant species (Almeida et al., 2014; Iqbal and Mukhtar, 2020a, 2020b). This pathogen can attack soybean at any growth stage; seedlings, if infected, result in damping off, thereby affecting the plant stand. Aerial symptoms start to appear during the reproductive stage (R4–R5) (Fehr et al., 1971) where foliage starts to droop and gradually becomes yellow. The yellowing happens due to the blockage of xylem and phloem vessels by the fungal mycelia, which ultimately results in plant death (Iqbal et al., 2014; Amrate et al., 2023). The appearance of grayish-silver microsclerotia in the pith region of the stem and tap root is the diagnostic feature of this disease in soybean (Smith and Wyllie, 1999). Genomics and molecular breeding can be effective in mitigating soybean yield losses due to charcoal rot disease. Previous reports established the quantitative nature of resistance in soybean against this pathogen (Talukdar et al., 2009; Coser et al., 2017; Silva et al., 2019; Vinholes et al., 2019 and Zatybekov et al., 2023).

Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) are a potential tool in the genetic dissection of quantitative traits with high resolution. They use historical recombination in a diverse germplasm panel, evaluate a higher number of alleles per locus, and identify marker–trait associations in a short time (Susmitha et al., 2023). With the advancements in next-generation sequencing technology and single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping platforms, genomics is becoming effective in enhancing genetic gain in complex traits in crop plants. Genotype-by-sequencing (GBS) technology is a cost-effective high-throughput sequencing platform yielding simplified and uniform libraries, enabling its applicability in larger germplasm or breeding population sets (Bhat et al., 2016). This sequencing technology is being used in the identification of a large number of SNPs in a wide range of crop species to foster association mapping and genomic selection.

Association mapping relies on the linkage disequilibrium (LD) between the marker loci and functional gene governing the trait of interest. This LD can also result from the genetic relatedness in the form of population structure and kinship leading to false positives in GWASs (Kaler et al., 2020). To avoid it, several mixed linear models (MLMs) have been developed that take these two factors into consideration in identifying true associations between genetic variants and phenotypic polymorphism. However, these models are based on a single locus, and false-negative associations can occur due to overfitting (Kaler et al., 2020). To minimize this problem, several multi-locus mixed models (MLMMs) have been developed and utilized. FarmCPU (fixed and random model circulating probability unification) (Liu et al., 2016) and BLINK (Bayesian information and LD iteratively nested keyway) (Huang et al., 2019) are the two MLMMs predominantly used in GWASs across crop species including soybean (Xiong et al., 2023; Bhat et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2022). In a simulation study in soybean and maize, FarmCPU outperformed seven other models in identifying significant and true marker–trait associations (Kaler et al., 2020). In soybean, GWAS has been employed in understanding the genetic architecture and identifying loci/genes governing several traits like grain yield (Priyanatha et al., 2022), quality traits (He et al., 2021; Malle et al., 2020), abiotic stress tolerance (Sharmin et al., 2021), nutrient use efficiency (Mamidi et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2024), and Phytophthora resistance (You et al., 2024).

Given the importance of this disease in soybean, only a few attempts were made in understanding the genetics of charcoal rot resistance and in identifying the potential resistance donors (Coser et al., 2017; Vinholes et al., 2019; Zatybekov et al., 2023 and Amrate et al., 2023). Therefore, the current study was carried out (1) to identify charcoal rot resistance donors under glasshouse conditions and sick plot conditions, and (2) to identify SNP loci, haplotypes, and the putative candidate genes governing charcoal rot resistance in soybean.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Plant material

The association mapping panel (N = 214) used in the current study encompasses a diverse set of genotypes including exotic accessions (127), indigenous accessions (5), breeding lines (34), mutant lines (4), varieties (40), and unknown sources (4) (Supplementary File).

2.2 Phenotyping of soybean germplasm accessions for charcoal rot resistance at the seedling stage

The GWAS panel was phenotyped for charcoal rot resistance at the seedling stage through the cut stem inoculation technique (Twizeyimana et al., 2012). After fulfilling Kotch’s postulates, the pathogen (Jabalpur isolate—NCBI ID: OR467498) re-isolated from a susceptible genotype was used for artificial screening. The glasshouse was maintained at 28 ± 2 °C day/night temperature and at 65% relative humidity. A randomized complete block design (RCBD) was followed by replicating each genotype four times. Using a sharp sterilized lazar blade, seedlings at their V2 growth stage (completely unrolled leaf at the first node above the unifoliolate node) (Fehr et al., 1971) were cut horizontally 4 cm above the unifoliate node. A disc full of actively growing mycelia from a 4-day-old fungal culture was collected with the help of the broad end of the pipette tip (10 μL) and was kept and retained on the cut portion of the stem tip. The length of the stem necrosis (in centimeters) that progressed linearly was measured 5, 10, and 15 days after inoculation (Figure 1). Disease resistance evaluation was based on the stem necrosis length 15 days after inoculation and the area under disease progress curve (AUDPC) (Shaner and Finney, 1977).

Figure 1. Phenotyping of soybean germplasm accessions for charcoal rot resistance at the seedling stage through an artificial inoculation method.

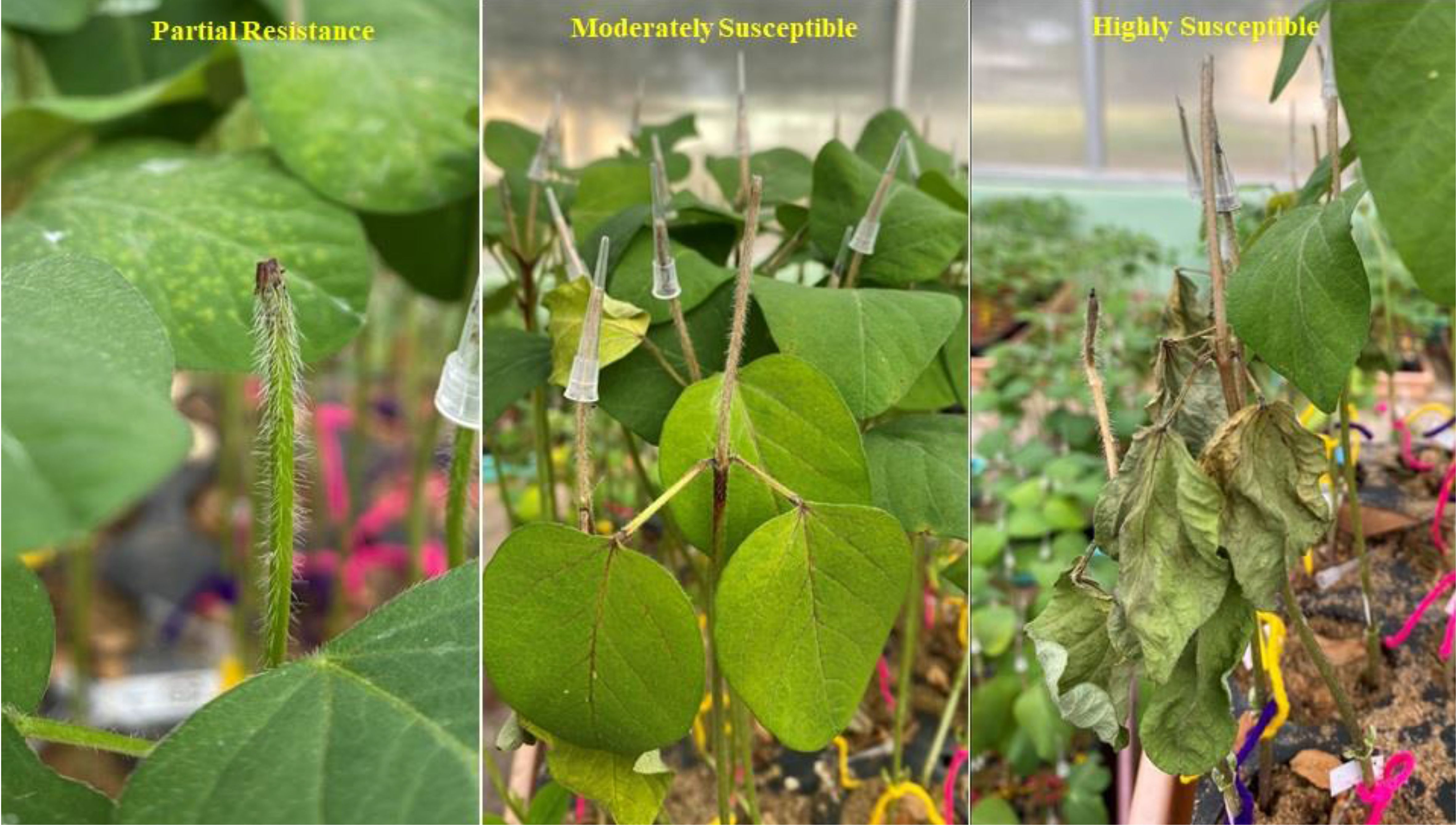

2.3 Phenotyping of soybean germplasm accessions for charcoal rot resistance at the adult plant stage

The same set of genotypes was evaluated for charcoal rot resistance under sick-plot conditions at Jawaharlal Nehru Krishi Vishwavidyalaya, Jabalpur, India, for three consecutive years: 2021, 2022, and 2023 (Figure 2). The experimental design followed was RCBD replicating each genotype three times. Seeds were hand sown in a 1-m row with 45 cm row-to-row distance and 5 cm plant-to-plant distance within the row. Two susceptible checks (JS 95–60 and JS 93-05) were sown after 10 rows every time so as to ensure uniform disease occurrence and no disease escape. Disease resistance evaluation was based on percent disease incidence (PDI) at the R7 stage (physiological maturity), AUDPC, and root stem severity (RSS) index. After 60 days of sowing, PDI was measured at an interval of every 7 days for 6 weeks and AUDPC was calculated as per the above section. For RSS, five randomly pre-tagged plants in each line were uprooted gently at the R7–R8 stage (physiological maturity–harvest maturity). Their stem and taproot portion was longitudinally split with a sharp knife and the microsclerotial density in the pith region was scored based on a 1–5 scale (Mengistu et al., 2007) (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Phenotyping of soybean germplasm accessions for charcoal rot resistance at the adult plant stage under sick plot conditions.

Figure 3. Phenotyping of germplasm accessions through the root stem severity (RSS) index. Disease rating scale (1–5) was as per Mengistu et al. (2007).

2.4 Genotyping and SNP quality control

GBS-derived SNP data of the 214 soybean accessions used in this study were obtained from study of Raghuvanshi et al. (2025). Briefly, GBS-derived FASTQ files were processed and then mapped against the soybean genome Glyma.Lee_v2.0 (Legumepedia database), and SNPs were called using the Fast-GBS.v2 pipeline (Torkamaneh et al., 2020c). K-nearest neighbor (KNN) imputations were performed in TASSEL software to fill missing genotype data. SNPs were filtered for minor allele frequency (MAF) < 0.05 and missing rate >10%, and finally a total of 66,976 SNPs distributed all over 20 chromosomes were used for association studies.

2.5 Genetic diversity and population structure analysis

A neighbor-joining tree, principal component analysis (PCA), and an LD decay plot of 214 soybean accessions using SNPs were generated using the GAPIT package (https://www.maizegenetics.net/gapit) implemented in R. Population structure was developed using STRUCTURE software (https://web.stanford.edu/group/pritchardlab/structure.html).

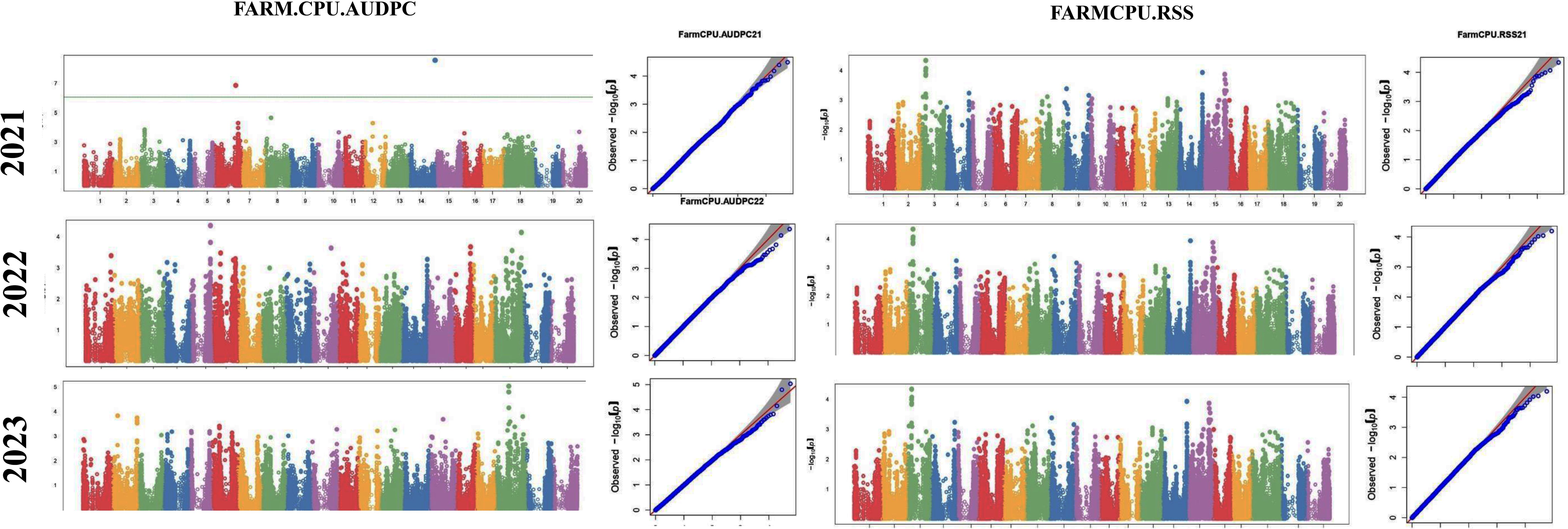

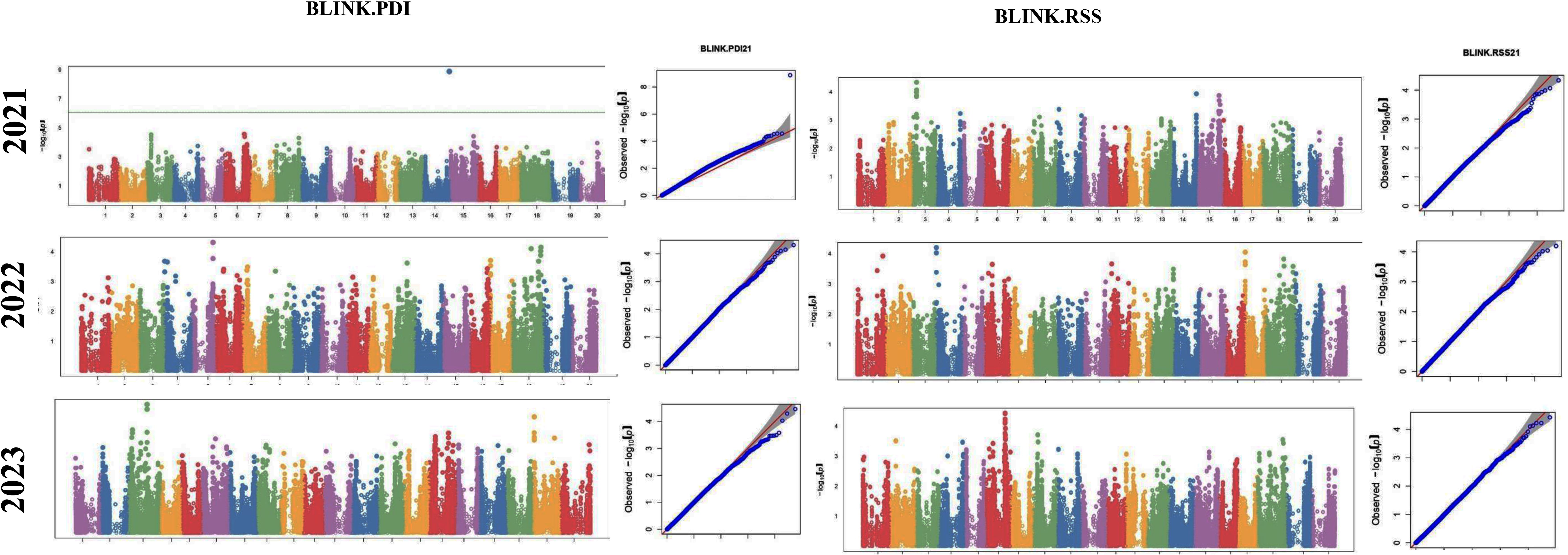

2.6 Genome-wide association studies

The analysis involved 214 diverse soybean germplasm accessions to study traits associated with charcoal rot resistance across 3 years (2021–2023). The association analysis was performed using two models—FarmCPU (Liu et al., 2016) and BLINK (Huang et al., 2019)—using the R package “GAPIT3” (Wang and Zhang, 2021). The first two principal components were included as covariates in both models. Significant SNPs were identified using an empirical significance threshold value of −Log10 p ≥ 4.0, equivalent to a p-value ≤ 0.0001, which has previously been reported to be appropriate for complex traits and has been used in previous studies (Chamarthi et al., 2021). Furthermore, to check false discovery rate (FDR), Bonferroni threshold was calculated by dividing probability level (0.05) with the total number of SNPs used, which yielded a cutoff of 7.46 e−7 (Gao et al., 2010). Those SNPs with the p-value above the cutoff were considered as “significant SNPs” while those below the cutoff were considered as “suggestive SNPs”. Manhattan plots illustrated significant markers, while quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plots compared expected versus observed p-value distributions (on a −log10 scale).

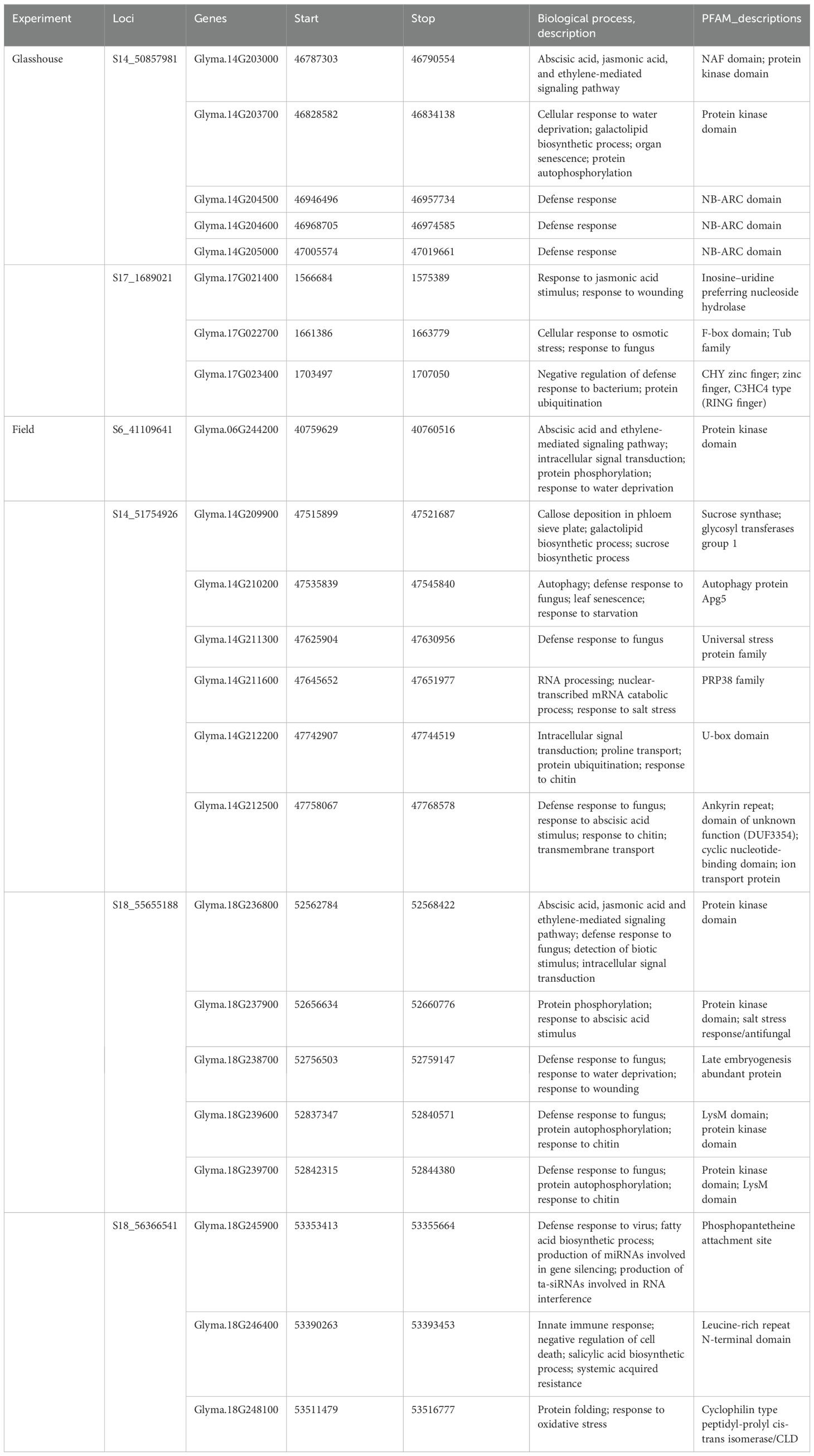

2.7 Identification of putative candidate genes

The SNPs (with p > 0.0001) identified for multiple resistance traits were further used to analyze the putative candidate gene annotation from genomic regions 200 kb upstream and downstream of these SNPs (totaling 400 kb). Gene models within these regions were downloaded, and annotation data were obtained from the corresponding locations on the Williams 82 reference genome assembly Wm82.a2.v1 from SoyBase (www.soybase.org). The genes were narrowed down by gene ontology (GO)-based biological process descriptions related to defense response and antifungal activity and PFAM descriptions for disease resistance genes.

2.8 Haplotype analysis

Haplotypes were analyzed within the LD region by using DnaSP software version 5.10 (http://www.ub.edu/dnasp/index_v5.html). To evaluate the effect of the haplotypes containing different combinations of alleles in the SNP loci associated with the putative candidate gene, the genotypes were grouped according to their haplotype in the SNP. Genotypes were grouped into independent clusters according to their specific SNP alleles, and means were compared using Tukey’s HSD (honestly significant difference) test. The average of the AUDPC in each group was calculated and represented graphically. Since all other genome regions remained randomly represented in each group, the difference in the averages of each group is a function of the fixed haplotypes in each group. Furthermore, the “t-test” was performed to determine significant differences in the mean of the AUDPC in two groups with allelic difference at the peak SNP, S14_51754926.

3 Results

3.1 SNP marker distribution across the 20 chromosomes

After filtration, a total of 66,976 polymorphic SNPs (MAF < 0.05) were retained for analysis. The highest number of SNPs was located on chromosome 18 (6,275), followed by chromosome 16 (4,326), chromosome 6 (4,237), and chromosome 13 (4,116). The least number of SNPs was located on chromosome 12 (2,071), followed by chromosome 19 (2,365) and chromosome 1 (2,442).

3.2 Population structure, genetic diversity, and linkage disequilibrium

Population structure analysis revealed that ΔK was highest when K was set at six (Figures 4A–C), indicating the grouping of the 214 germplasm accessions into six distinct subpopulations. This stratification was also supported by the neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree, which displayed six clades (Figure 4A), and was consistent with the clustering observed in the PCA (Figure 4C). Additionally, LD analysis showed that the average genome-wide LD for the diversity panel was r² = 0.471.

![Panel [A] shows a circular phylogenetic tree with colored branches representing different groups. Panel [B] features a heatmap with hierarchical clustering and a color key insert. Panel [C] includes three scatter plots displaying principal component analysis results, with different colored dots signifying data groups.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1649397/fpls-16-1649397-HTML/image_m/fpls-16-1649397-g004.jpg)

Figure 4. Genetic diversity and relatedness of the soybean germplasm accessions. (A) Neighbor-joining tree constructed using 66,976 SNP data. A total of six different clades were observed in our GWAS panel. (B) A kinship plot. A heat map of the values in the kinship matrix, showing the level of relatedness among the GWAS panel (the darker area showing a highly related genotype and also from a different origin with the rest of the population). (C) 2D principal component analysis (PCA) for the entire GWAS panel derived from SNP data.

3.3 Phenotypic evaluation under glasshouse conditions

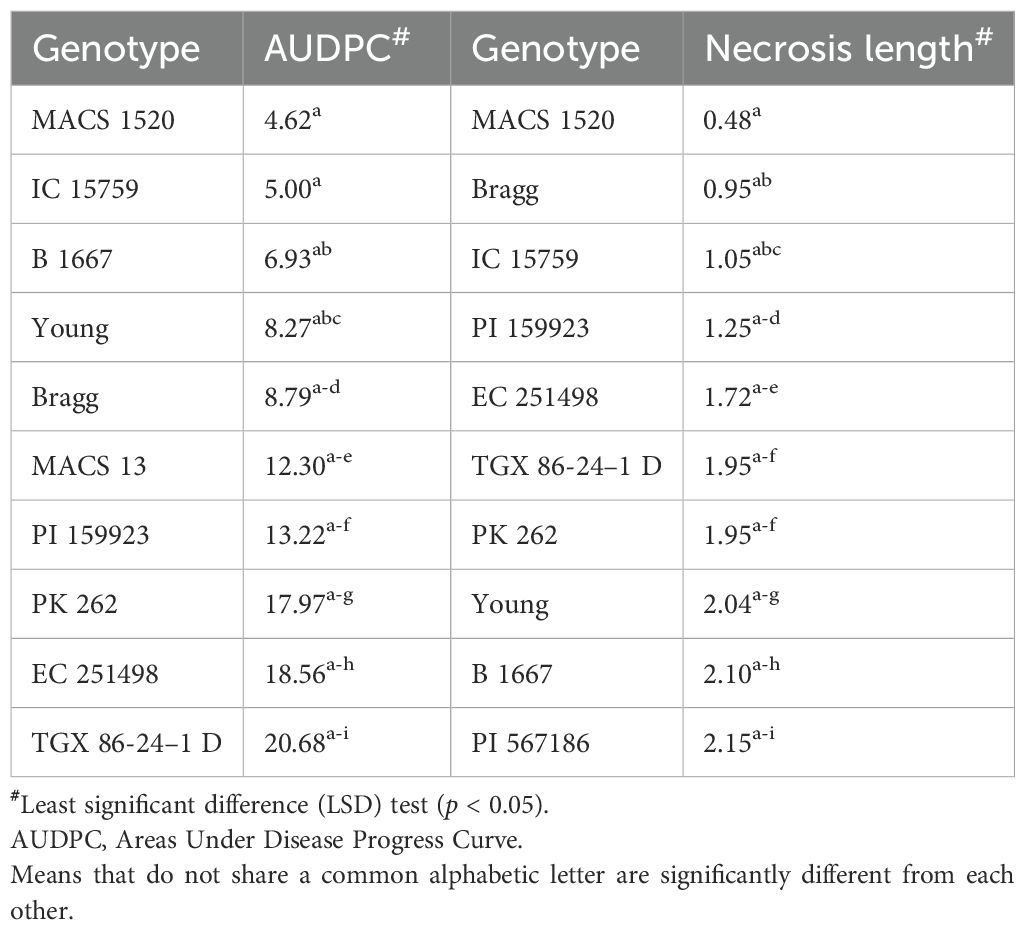

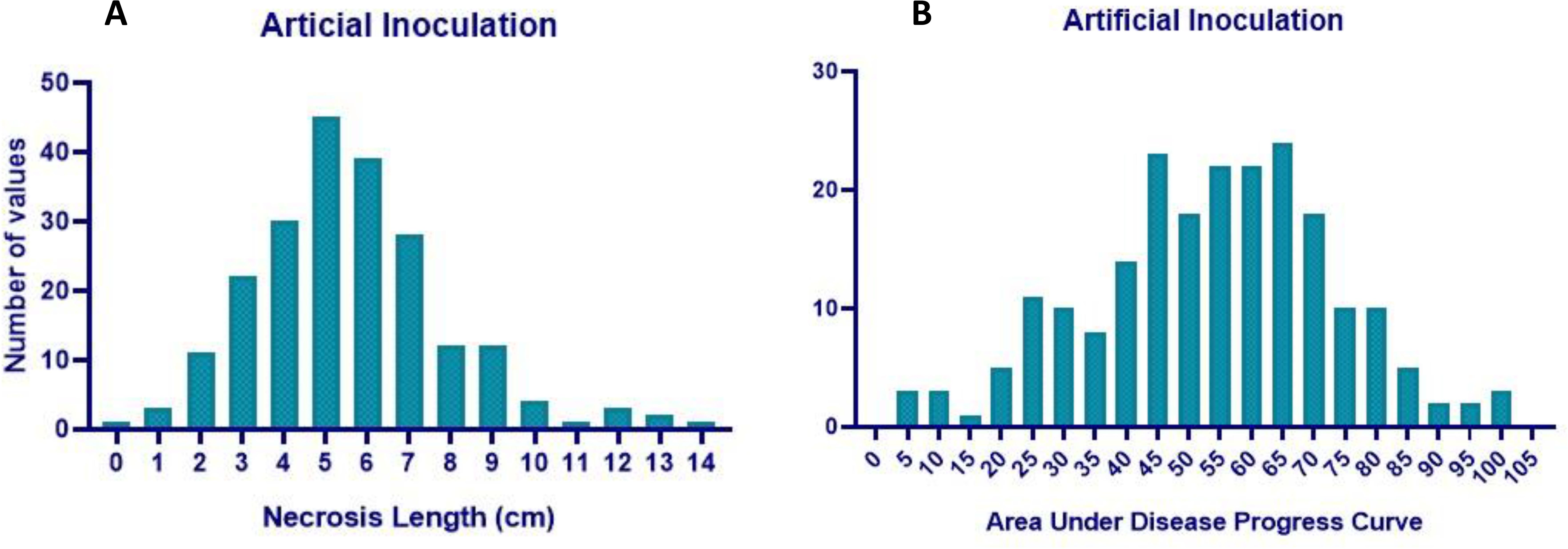

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated a significant genotypic effect for AUDPC and necrosis length. Mean AUDPC was 53.82, ranging from 4.62 to 102.27, while mean necrosis length was 5.58 cm with a range of 0.48–13.80 cm (Table 1). The top 10 best genotypes in the case of AUDPC were MACS 1520 (4.62), IC 15759 (5.00), B 1667 (6.93), Young (8.27), Bragg (8.79), MACS 13 (12.30), PI 159923 (13.22), PK 262 (17.97), EC 251498 (18.56), and TGX 86-24-1D (20.68). The top 10 best genotypes in the case of necrosis length were MACS 1520 (0.48 cm), Bragg (0.95 cm), IC 15759 (1.05 cm), PI 159923 (1.25 cm), EC 251498 (1.72 cm), TGX 86-24–1 D (1.95 cm), PK 262 (1.95 cm), Young (2.04 cm), B 1667 (2.10 cm), and EC 457305 (2.15 cm) (Table 2) The frequency distribution of the panel for necrosis length and AUDPC is depicted in Figure 5.

Table 1. Analysis of variance for the area under disease progress curve and necrosis length under the artificial inoculation experiment.

3.4 Phenotypic evaluation under sick plot conditions

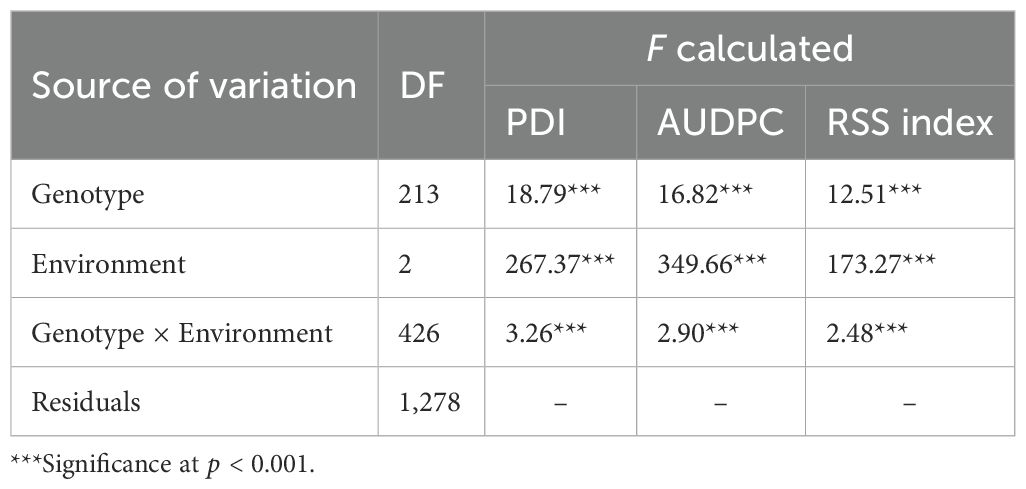

Across 3 years, the two checks (JS 95–60 and JS 93-05) showed susceptible disease reaction, indicating sufficient and uniform disease pressure in the sick plot. Pooled ANOVA revealed a significant genotype and environment effect and a significant genotype × environment interaction (p < 0.0001) (Table 3). The mean PDI was 53.83, 52.51, and 33.40 during 2021, 2022, and 2023, respectively (Table 4).

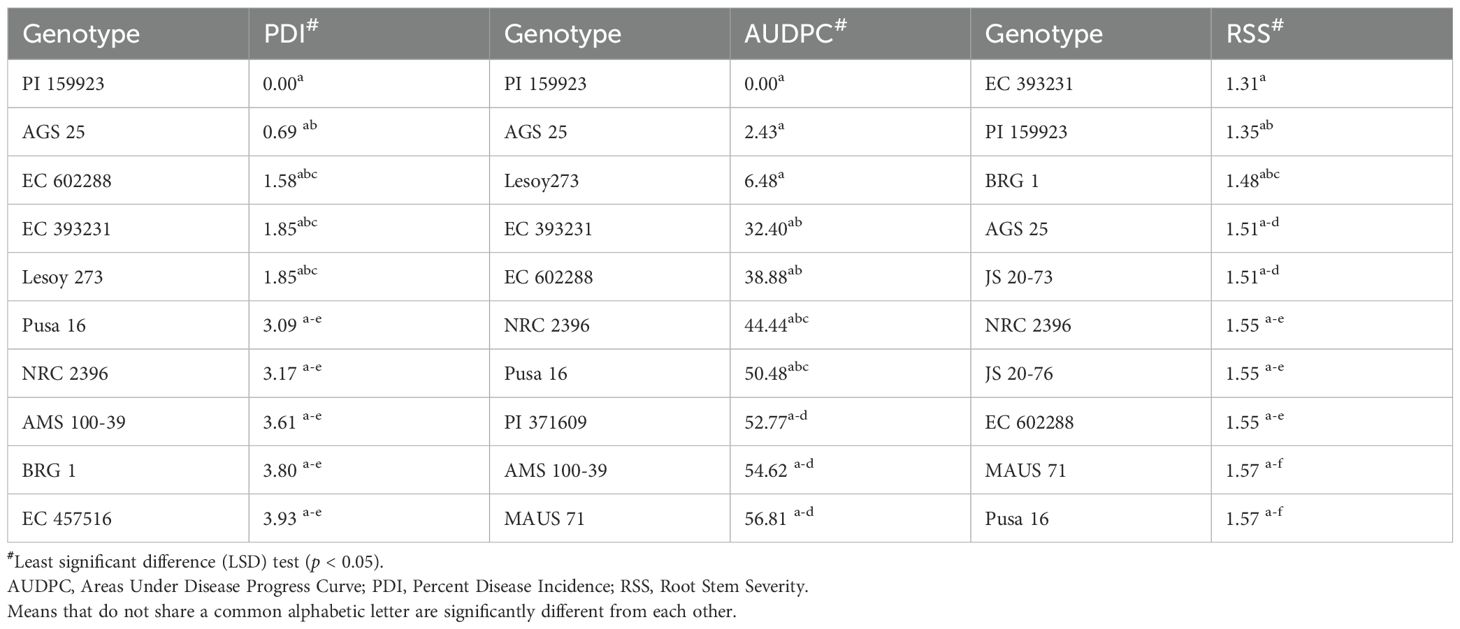

The mean RSS index was 3.07, 2.72, and 2.50 during 2021, 2022, and 2023, respectively. During 2021, the mean AUDPC was 929.02, while it was 944.18 and 481.64 during 2022 and 2023, respectively (Table 4). The 10 best-performing genotypes with respect to PDI were PI 159923 (0.0%), AGS 25 (0.69%), EC 602288 (1.58%), EC 393231 (1.85%), Lesoy 273 (1.85%), Pusa 16 (3.09%), NRC 2396 (3.17%), AMS 100-39 (3.61%), BRG 1 (3.80%), and EC 457516 (3.93%). In the case of AUDPC, the 10 best-performing genotypes were PI 159923 (0.00), AGS 25 (2.43), Lesoy 273 (6.48), EC 393231 (32.40), EC 602288 (38.88), NRC 2396 (44.44), Pusa 16 (50.48), PI 371609 (52.77), AMS 100-39 (54.62), and MAUS 71 (56.81). Genotypes EC 393231 (1.31), PI 159923 (1.35), BRG 1 (1.48), AGS 25 (1.51), JS 20-73 (1.51), NRC 2396 (1.55), JS 20-76 (1.55), EC 602288 (1.55), MAUS 71 (1.57), and Pusa 16 (1.57) were found to have the least RSS score (Table 5). The frequency distribution of the panel for PDI and AUDPC is depicted in Figure 6 and RSS is depicted in Figure 7.

3.5 GWAS analysis and prediction of putative candidate genes

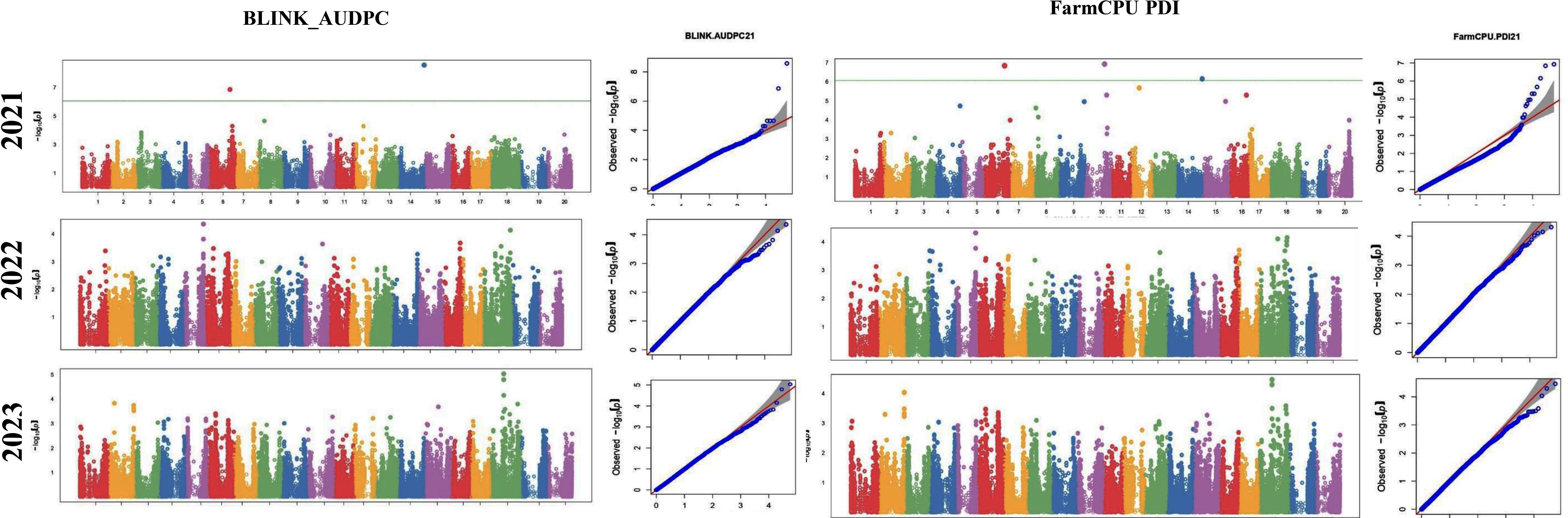

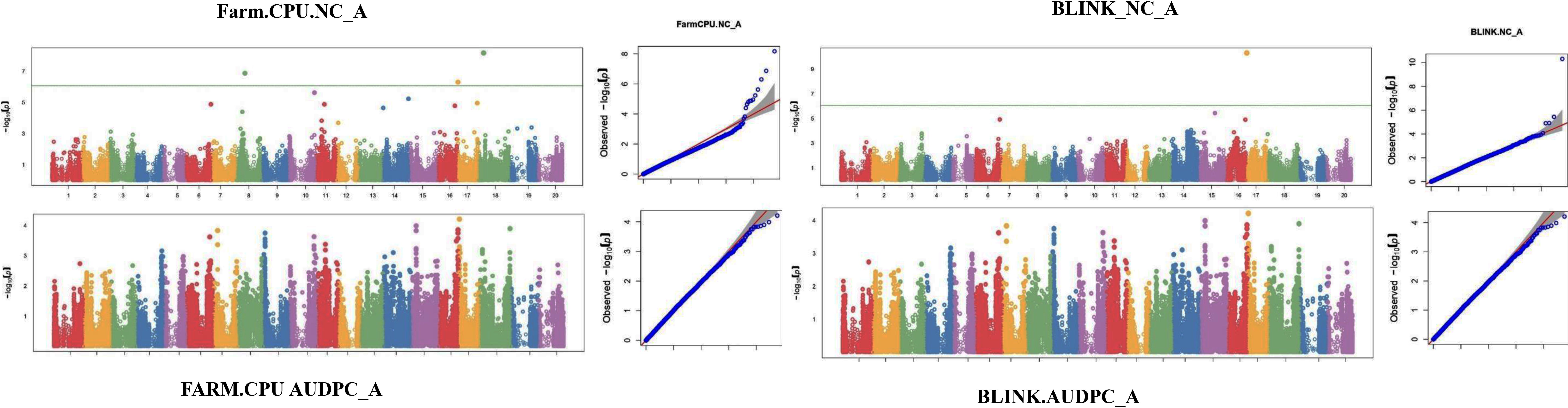

The GWAS study uncovered several SNPs associated with charcoal rot resistance traits. In the case of the glasshouse experiment, a total of eight SNPs were identified to be associated with charcoal rot resistance at the seedling stage (Table 6 and Figure 8). Of them, one SNP each was located on chromosome 8 (S8_16817767), chromosome 10 (S10_52066337), chromosome 14 (S14_50857981), chromosome 15 (S15_32620059), chromosome 17 (S17_1689021), and chromosome 18 (S18_9413708). Two SNPs—S16_34569104 and S16_37878937—were located on chromosome 16. In the case of the field experiment, 10 SNPs were found to be associated with charcoal rot resistance at the adult plant stage (Table 7 and Figures 9-11). Of them, two SNPs each were located on chromosome 6 (S6_41109641 and S6_41863847) and chromosome 10 (S10_40644409 and S10_44768495). One SNP each was identified on chromosome 12 (S12_14977708), chromosome 14 (S14_51718686), and chromosome 16 (S16_33491560), while three SNPs were located on chromosome 18 (S18_25004105, S18_55655188, and S18_56366541). The SNP S14_51754926, which was identified through both models, with a high p-value and associated with multiple resistance traits was considered for haplotype analysis.

Figure 8. Manhattan plots (left) and quantile–quantile (Q–Q plots) (right) of the genome-wide association results for stem necrosis and AUDPC generated through FarmCPU and BLINK.

Figure 9. Manhattan plots (left) and quantile–quantile (Q–Q plots) (right) of the genome-wide association results for AUDPC generated through FarmCPU and BLINK in 2021, 2022, and 2023.

Figure 10. Manhattan plots (left) and quantile–quantile (Q–Q plots) (right) of the genome-wide association results for PDI generated through FarmCPU and AUDPC through BLINK in 2021, 2022, and 2023.

Figure 11. Manhattan plots (left) and quantile–quantile (Q–Q plots) (right) of the genome-wide association results for RSS generated through BLINK in 2021, 2022, and 2023.

3.6 The putative candidate genes analysis

The putative candidate genes analysis was performed for six loci detected for multiple resistance traits. Within 400-kb genomic regions of these loci, a total of 23 genes with annotations associated with defense response pathway were identified (Table 8). Under glasshouse conditions, 5 genes (Glyma.14G203000, Glyma.14G203700, Glyma.14G204500, Glyma.14G204600, and Glyma.14G205000) were identified within the region of SNP S14_50857981, while 3 genes (Glyma.17G021400, Glyma.17G022700, and Glyma.17G023400) were identified within the region of S17_1689021, whereas under field conditions, 13 genes involved in defense response were identified. On chromosome 6, a putative candidate gene, Glyma.06G244200, was identified in the region of SNP S6_41109641. Six genes, Glyma.14G209900, Glyma.14G210200, Glyma.14G211300, Glyma.14G211600, Glyma.14G212200, and Glyma.14G212500, were identified on chromosome 14, near the peak SNP S14_51754926. Furthermore, on chromosome 18, five genes (Glyma.18G236800, Glyma.18G237900, Glyma.18G238700, Glyma.18G239600, and Glyma.18G239700) were identified within the region of S18_55655188 while three genes (Glyma.18G245900, Glyma.18G246400, and Glyma.18G248100) were identified near SNP S18_56366541. Details of the gene models and their biological functions are given in Table 8.

3.7 Haplotype analysis

Haplotype analysis was performed on the most significant locus identified in this study, located on chromosome 14, carrying a peak SNP, S14_51754926 (Figure 12A). The results identified four major haplotypes: Hap1, Hap2, Hap3, and Hap4 (Figure 12B). The data showed that Hap1 was significantly associated with a lower AUDPC, indicating a relation to charcoal resistance. In contrast, Hap3 was associated with susceptibility, as it exhibited higher AUDPC (Figure 12C). Furthermore, a significant difference was found in the mean of the AUDPC in two groups with allelic difference at the peak SNP, S14_51754926 (Figure 12D).

![Genetic analysis illustration with four panels. Panel [A] shows a linkage disequilibrium heatmap on Chromosome 14 around position 51754926 with color scale R². Panel [B] displays haplotype sequences across multiple genomic positions. Panel [C] presents a box plot comparing four haplotypes (Hap-1 to Hap-4) and their AUDPC values, highlighting a significant difference for Hap-3. Panel [D] shows a box plot of AUDPC values for genotypes G and T, indicating significance for T.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1649397/fpls-16-1649397-HTML/image_m/fpls-16-1649397-g012.jpg)

Figure 12. Haplotype analysis. (A) Significant SNPs on chromosome 14. (B) Four major haplotypes: Hap1, Hap2, Hap3, and Hap4. (C) Haplotype association with AUDPC. (D) Allelic effect on AUDPC. * - significance at p<0.05, ns - non-significance.

4 Discussion

Charcoal rot in soybean is a devastating disease that can be a threat to soybean production and sustainability. Nevertheless, very few studies have been carried out in identifying potential resistance donors and gene or loci governing the resistance. Screening for charcoal rot resistance is based on both field conditions (Coser et al., 2017; Amrate et al., 2023, 2024) and glasshouse conditions (Coser et al., 2017; Amrate et al., 2024). There are a few reports on the identification of loci governing soybean charcoal rot resistance through GWAS and bi-parental mapping (Coser et al., 2017; Silva et al., 2019; Vinholes et al., 2019 and Zatybekov et al., 2023). Previous reports are based on a glasshouse experiment and/or a single season field data. To our knowledge, this is the first report on GWAS on soybean charcoal rot resistance based on the evaluation of multiple field trials and under controlled conditions. Such studies will minimize the effect of disease escape in identifying the true associations. For example, in the current study, an SNP, S6_41109641, was found to be associated with charcoal rot resistance in 2021 and 2023 through both models.

Furthermore, no SNP was found to be associated in both seedling and adult plant resistance, indicating different defense pathways being activated at different growth stages (Coser et al., 2017). This may further be justified by the fact that the environmental conditions for both glasshouse and field experiments were different and stress induced under field conditions was gradual, whereas that of artificial inoculation was through wounding, which was acute, resulting in differential gene expressions and pathways (Coser et al., 2017). While this is plausible, alternative causes such as limited statistical power or phenotype–environment interactions cannot be ruled out. However, SNP S14_50857981 identified in artificial conditions and S14_51754926 identified in field conditions are present within a 1-Mb region and may constitute a quantitative trait locus (QTL). Such QTL will be of immense importance in breeding for seedling and adult plant resistance.

A peak SNP Gm16_36809255 was reported to be linked to charcoal rot seedling resistance in soybean (Silva et al., 2019). In our study, an SNP, S16_37878937 (position in Williams 82-36707683), which was in proximity with this reported SNP, was found to be associated with the resistance at the seedling stage. Such genomic regions should be focused for allele and gene mining for charcoal rot resistance. Furthermore, the present study identified several previously unreported novel resistance sources, which can be used for validation with the aim of using them in breeding programs for durable resistance against charcoal rot.

In addition to the identification of suggestive and significant SNPs, haplotype analysis can provide novel insights into the genetic determinants of trait (Vinholes et al., 2019). In our current study, the identified haplotype can be used in haplotype breeding for resistance against charcoal rot resistance. These haplotypes are associated with defense responsive genes—Glyma.14G209900 (callose deposition, galactolipid, and sucrose biosynthesis), Glyma.14g210200 (involved in autophagy), Glyma.14g211300 (universal stress protein), Glyma.14G211600 (PRP38 family), Glyma.14g212200 (signal transduction), and Glyma.14g212500 (PAS/PAC sensor domain). Such genes, after validation, can be used in genome editing experiments to improve charcoal rot resistance in soybean.

In case of cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L) Walp.], loci conferring charcoal rot resistance were co-localized with those of drought tolerance and there was a correspondence between M. phaseolina resistance haplotypes and drought tolerance haplotypes. Furthermore, soybean genomic regions harboring genes responsive for heat shock, sodium hypersensitivity, and calcium sensing were syntenic to the charcoal rot resistance loci identified in cowpea (Muchero et al., 2011). Late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins are attributed to the plant defense against drought stress (Chen et al., 2021). Two LEA protein-coding genes (Glyma_19G198800 and Glyma_19G198900) were reported to be involved in charcoal rot resistance in soybean (Zatybekov et al., 2023). Similarly, in our study, an LEA protein-coding gene, Glyma.18g238700, was found to be present in the locus associated with charcoal rot resistance. Such genes can be investigated for their possible role in drought tolerance and charcoal rot.

Furthermore, leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinases were reported to be involved in resistance mechanism against M. phaseolina in sesame (Sesamum indicum) (Yan et al., 2021). We found three leucine rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase encoding genes (Glyma.17g019800, Glyma.06g244100 and Glyma.18g240800) associated with charcoal rot resistance. Abscisic acid (ABA), salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene were reported to be involved in the defense mechanism against different diseases in plants (Anderson et al., 2004). In the current study, several putative candidate genes involved in the ABA-mediated pathway (Glyma.14G203000, Glyma.06G244200, Glyma.14G212500, and Glyma.18G236800), SA-mediated pathway (Glyma.18G246400), JA-mediated pathway (Glyma.14G203000, Glyma.17G021400, and Glyma.18G236800), and ethylene-mediated pathway (Glyma.14G203000, Glyma.06G244200, and Glyma.18G236800) were identified as candidate genes for charcoal rot resistance. A cyclophilin protein-encoding gene, Glyma.18G248100, was found to be associated with the charcoal rot resistance under field conditions. The same gene was also previously reported to be associated with field resistance against charcoal rot disease (Coser et al., 2017).

The identification of potential resistance donors is crucial in any disease resistance breeding program. The soybean introduction, PI 159923, was found to be resistant under both field and glasshouse conditions, and such genotypes are of immense importance in deploying charcoal rot resistance in cultivars. Furthermore, this genotype was previously reported to be resistant against purple seed stain (Alloatti et al., 2015) and high SMR (stem reserve mobilization) (Satpute et al., 2020). The genotype AGS 25 identified in the current study was previously reported to carry long juvenility (Gupta et al., 2021) and such genotypes would aid in the development of wider adaptable charcoal rot-resistant genotypes/varieties. In addition, charcoal rot-resistant genotypes JS 20–76 and EC 602288 were previously reported to be water logging tolerant (Chandra et al., 2023). These genotypes will be used in breeding for multiple stress-tolerant varieties.

5 Conclusion

In the present study, 8 SNPs linked to charcoal rot resistance at the seedling stage were identified, while 10 SNPs were found to be associated with adult plant resistance. Haplotype analysis of SNP S14_51754926 revealed that out of four haplotypes, Hap1 was significantly associated with lower AUDPC, indicating a relation to charcoal resistance. The putative candidate gene analysis in genomic regions of significant SNPs identified 23 genes, with annotations associated with defense response and antifungal activity, and involved in the signaling pathway. In addition, PI 159923 was found to be resistant under both field and glasshouse conditions; such a genotype will be employed as a parent in breeding for high-yielding charcoal rot-resistant genotypes.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here: NCBI, PRJNA1367327.

Author contributions

VN: Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Supervision. PA: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation. MR: Writing – original draft, Resources. SMar: Writing – original draft, Methodology. LR: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. NA: Methodology, Writing – original draft. RR: Software, Writing – review & editing. KP: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SMan: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SMo: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. BN: Resources, Writing – review & editing. MS: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. GK: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft. VR: Writing – review & editing, Resources. SG: Writing – review & editing, Resources. AC: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. RV: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. KS: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The authors gratefully acknowledge DST-SERB (Project No. CRG/2020/002890) for funding support.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Director, ICAR-National Soybean Research Institute for supporting this investigation. The authors also acknowledge Ms. Palak Acharya for their assistance during artificial screening.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor [BNM] declared a past co-authorship with the author(s) [RKV, AC].

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1649397/full#supplementary-material

References

Alloatti, J., Li, S., Chen, P., Jaureguy, L., Smith, S. F., Florez-Palacios, L., et al. (2015). Screening a diverse soybean germplasm collection for reaction to purple seed stain caused by cercospora kikuchii. Plant Dis. 99, 1140–1146. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-09-14-0878-RE

Almeida, A. M. R., Seixa, C. D. S., Farias, J. R. B., Oliveira, M. C. N., Franchini, J. C., Debiase, H., et al. (2014). Macrophomina phaseolina em soja (Londrina: Embrapa Soja). Available online at: http://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infot eca/handle/doc/989352 (Accessed January 16, 2025).

Amrate, P. K., Nataraj, V., Shivakumar, M., Shrivastava, M. K., Rajput, L. S., Mohare, S., et al. (2024). Best linear unbiased prediction (BLUP)−based models aided in selection of high yielding charcoal rot and yellow mosaic resistant soybean genotypes. Genet. Resour. Crop Evolution. 72, 5593–5561. doi: 10.1007/s10722-024-02289-5

Amrate, P. K., Shrivastava, M. K., Bhale, M. S., Agrawal, N., Kumawat, G., Shivakumar, M., et al. (2023). Identification and genetic diversity analysis of high-yielding charcoal rot resistant soybean genotypes. Sci. Rep. 13, 8905. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-35688-2

Anderson, P. A., Badruzsaufari, E., Schenk, P. M., Manners, J. M., Desmond, O. J., Ehlert, C., et al. (2004). Antagonistic interaction between abscisic acid and jasmonate-ethylene signaling pathways modulates defense gene expression and disease resistance in arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16, 3460–3479. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.025833

Bhat, J. A., Adeboye, K. A., Ganie, S. A., Barmukh, R., Hu, D., Varshney, R. K., et al. (2022). Genome-wide association study, haplotype analysis, and genomic prediction reveal the genetic basis of yield-related traits in soybean (Glycine max L.). Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.953833

Bhat, J. A., Alim, S., Salgotra, R. K., Mir, Z. A., Dutta, S., Jadon, V., et al. (2016). Genomic selection in the era of next generation sequencing for complex traits in plant breeding. Front. Genet. 7. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2016.00221

Chamarthi, S. K., Kaler, A. S., Abdel-Haleem, H., Fritschi, F. B., Gillman, J. D., Ray, J. D., et al. (2021). Identification and confirmation of loci associated with canopy wilting in soybean using genome-wide association mapping. Front. Plant Sci. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.698116

Chandra, S., Ratnaparkhe, M. B., Satpute, G. K., Gupta, S., Kumawat, G., Rucha, K., et al. (2023). Genome wide association studies reveals genetic loci associated with water logging tolerance in Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr. J. Oilseeds Res. 40, 36–37. doi: 10.56739/jor.v40iSpecialissue.145088

Chen, J., Li, N., Wang, X., Meng, X., Cui, X., Chen, Z., et al. (2021). Late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) gene family in Salvia miltiorrhiza: identification, expression analysis, and response to drought stress. Plant Signaling Behav. 16, e1891769, 1-10. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2021.1891769

Coser, S. M., Chowda Reddy, R. V., Zhang, J., Mueller, D. S., Mengistu, A., Wise, K. A., et al. (2017). Genetic architecture of charcoal rot (Macrophomina phaseolina) resistance in soybean revealed using a diverse panel. Front. Plant Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01626

Fehr, W. R., Caviness, C. E., Burmood, D. T., and Pennington, J. S. (1971). Stage of development descriptions for soybeans, Glycine max (L.) Merrill. Crop Sci. 11, 929–931. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1971.0011183X001100060051x

Gao, X., Becker, L. C., Becker, D. M., and Starmer, J. D. (2010). Province M.A. Avoiding the high Bonferroni penalty in genome-wide association studies. Genet. Epidemiol. 34, 100–105. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20430

Gupta, S., Kumawat, G., Yadav, S., Tripathi, R., Agrawal, N., Maranna, S., et al. (2021). Identification and characterization of a novel long juvenile resource AGS 25. Genet. Resour Crop Evol. 68, 1149–1163. doi: 10.1007/s10722-020-01055-7

He, Q., Xiang, S., Yang, H., Wang, W., Shu, Y., Li, Z., et al. (2021). A genome-wide association study of seed size, protein content, and oil content using a natural population of Sichuan and Chongqing soybean. Euphytica. 217, 198. doi: 10.1007/s10681-021-02931-8

Huang, M., Liu, X., Zhou, Y., Summers, R. M., and Zhang, Z. (2019). BLINK: a package for the next level of genome-wide association studies with both individuals and markers in the millions. Gigascience. 8, 1–12. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giy154

Iqbal, U. and Mukhtar, T. (2020a). Evaluation of biocontrol potential of seven indigenous Trichoderma species against charcoal rot causing fungus, Macrophomina phaseolina. Gesunde Pflanzen 72, 195–202. doi: 10.1007/s10343-020-00501-x

Iqbal, U. and Mukhtar, T. (2020b). Inhibitory effects of some fungicides against Macrophomina phaseolina causing charcoal rot. Pakistan J. Zoology 52, 709–715. doi: 10.17582/journal.pjz/20181228101230

Iqbal, U., Mukhtar, T., and Iqbal, S. M. (2014). In vitro and in vivo evaluation of antifungal activities of some antagonistic plants against charcoal rot causing fungus, Macrophomina phaseolina. Pakistan J. Agric. Sci. 51, 689–694. Available online at: http://www.pakjas.com.pk.

Kaler, A. S., Gillman, J. D., Beissinger, T., and Purcell, L. C. (2020). Comparing different statistical models and multiple testing corrections for association mapping in soybean and maize. Front. Plant Sci. 10. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01794

Karikari, B., Chen, S., Xiao, Y., Chang, F., Zhou, Y., Kong, J., et al. (2019). Utilization of interspecific high-density genetic map of RIL population for the QTL detection and candidate gene mining for 100-seed weight in soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 10. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01001

Liu, X., Huang, M., Fan, B., Buckler, E. S., and Zhang, Z. (2016). Iterative usage of fixed and random effect models for powerful and efficient genome-wide association studies. PloS Genet. 12, e1005767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005767

Malle, S., Eskandari, M., Morrisson, M., and Belzile, F. (2020). Genome−wide association identifies several QTLs controlling cysteine and methionine content in soybean seed including some promising candidate genes. Sci. Rep 10, 21812. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78907-w

Mamidi, S., Lee, R. K., Goos, J. R., and McClean, P. E. (2014). Genome-wide association studies identifies seven major regions responsible for iron deficiency chlorosis in soybean (Glycine max). PloS One. 9 (9), e107469. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107469

Mengistu, A., Ray, J. D., Smith, J. R., and Paris, R. L. (2007). Charcoal Rot Disease Assessment of Soybean Genotypes Using a Colony-Forming Unit Index. Crop Sci. 47, 2453–2461. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2007.04.0186

Muchero, W., Ehlers, J. D., Close, T. J., and Roberts, P. A. (2011). Genic SNP markers and legume synteny reveal candidate genes underlying QTL for Macrophomina phaseolina resistance and maturity in cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L) Walp. BMC Genomics 12, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-8

Priyanatha, C., Torkamaneh, D., and Rajcan, I. (2022). Genome-wide association study of soybean germplasm derived from Canadian × Chinese crosses to mine for novel alleles to improve seed yield and seed quality traits. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.866300

Raghuvanshi, R., Kumawat, G., Kavishwar, R., Gupta, S., Chitikineni, A., Chandra, S., et al. (2025). Dissecting genetic architecture of flowering and maturity traits in soybean using GWAS in Indian environment. BMC Plant Biology. 25, 1426. doi: 10.1186/s12870-025-06669-6

Satpute, G. K., Arya, M., Gupta, S., Bhatia, V. S., Ramgopal, D., Ratnaparkhe, M. B., et al. (2020). Identifying drought tolerant germplasm through multiplexing polygenic traits in soybean (Glycine max L. Merrill). J. Oilseeds Res. 37, 56–57. doi: 10.56739/jor.v37iSpecialissue.139459

Shaner, G. and Finney, R. (1977). The effect of nitrogen fertilization on the expression of slowmildewing resistance in Knox wheat. Phytopathology. 67, 1051–1056. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-67-1051

Sharma, A. N., Gupta, G. K., Verma, R. K., Sharma, O. P., Bhagat, S., Amaresan, N., et al. (2014). Integrated pest management for soybean 3.

Sharmin, R. A., Karikari, B., Chang, F., Amin, G. M. A., Bhuiyan, M. R., Hina, A., et al. (2021). Genome-wide association study uncovers major genetic loci associated with seed flooding tolerance in soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 21, 497. doi: 10.1186/s12870-021-03268-z

Silva, M. P., Klepadlo, M., Gbur, E. E., Pereira, A., Mason, R. E., Rupe, J. C., et al. (2019). QTL mapping of charcoal rot resistance in PI 567562A soybean accession. Crop Sci. 59, 1–6. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2018.02.0145

Smith, G. S. and Wyllie, T. D. (1999). “Charcoal rot,” in Compendium of soybean disease, 4th edn. Eds. Hartman, G. L., Sinclair, J. B., and Rupe, J. C. (American Phytopathological Society, St. Paul), 29–31.

Susmitha, P., Kumar, P., Yadav, P., Sahoo, S., Kaur, G., Pandey, M. K., et al. (2023). Genome-wide association study as a powerful tool for dissecting competitive traits in legumes. Front. Plant Sci. 14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1123631

Talukdar, A., Verma, K., Gowda, D. S. S., Lal, S. K., Sapra, R. L., Singh, K. P., et al. (2009). Molecular breeding for charcoal rot resistance in soybeanI. Screening and mapping population development. Indian J. Genet. 69, 367–370.

Torkamaneh, D., Boyle, B., St-Cyr, J., Légaré, G., Pomerleau, S., and Belzile, F. (2020). NanoGBS: A miniaturized procedure for GBS library preparation. Front. Genet. 11. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00067

Twizeyimana, M., Hill, C. B., Pawlowski, M., Paul, C., and Hartman, G. L. (2012). A cut-stem inoculation technique to evaluate soybean for resistance to macrophomina phaseolina. Plant Dis. 96, 1210–1215. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-02-12-0126-RE

Vinholes, P., Rosado, R., Roberts, P., Borém, A., and Schuster, I. (2019). Single nucleotide polymorphism-based haplotypes associated with charcoal rot resistance in Brazilian soybean germplasm. Agron. J. 111, 182–192. doi: 10.2134/agronj2018.07.0429

Wang, J. and Zhang, Z. (2021). GAPIT version 3: boosting power and accuracy for genomic association and prediction. Genomics Proteomics Bioinf. 19, 629–640. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2021.08.005

Wang, H., Zhang, Y., Chen, Y., Ren, K., Chen, J., Kan, G., et al. (2024). The identification of significant single nucleotide polymorphisms for shoot sulfur accumulation and sulfur concentration using a genome-wide association analysis in wild soybean seedlings. Agronomy. 14, 292. doi: 10.3390/agronomy14020292

Wrather, A., Shannon, G., Balardin, R., Carregal, L., Escobar, R., Gupta, G. K., et al. (2010). Effect of diseases on soybean yield in the top eight producing countries in 2006. Plant Health Prog. 11 (1), 1535–102. doi: 10.1094/PHP-20100125-01-RS

Xiong, H., Chen, Y., Pan, Y. B., Wang, J., Lu, W., and Shi, A. (2023). A genome-wide association study and genomic prediction for Phakopsora pachyrhizi resistance in soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1179357

Yan, W., Ni, Y., Liu, X., Zhao, H., Chen, Y., Jia, M., et al. (2021). The mechanism of sesame resistance against Macrophomina phaseolina was revealed via a comparison of transcriptomes of resistant and susceptible sesame genotypes. BMC Plant Biol. 21, 159. doi: 10.1186/s12870-021-02927-5

You, H. J., Jang, I. H., Moon, J. K., Kim, J. M., Kang, S., and Lee, S. (2024). Genetic dissection of resistance to Phytophthora sojae using genome-wide association and linkage analysis in soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr. Theor. Appl. Genet. 137, 263. doi: 10.1007/s00122-024-04771-1

Yu, K., Miao, H., Liu, H., Zhou, J., Sui, M., Zhan, Y., et al. (2022). Genome-wide association studies reveal novel QTLs, QTL-by environment interactions and their candidate genes for tocopherol content in soybean seed. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.102658

Keywords: charcoal rot, genomics, oil seed, resistance, soybean

Citation: Nataraj V, Amrate PK, Ratnaparkhe MB, Maranna S, Rajput LS, Agrawal N, Raghuvanshi R, Pathak K, Mandloi S, Mohare S, Naik B, Shrivastava MK, Kumawat G, Rajesh V, Gupta S, Chitikineni A, Varshney RK and Singh KH (2025) Unveiling key genetic determinants of charcoal rot resistance in soybean via genome-wide association studies. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1649397. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1649397

Received: 18 June 2025; Accepted: 14 October 2025;

Published: 16 December 2025.

Edited by:

Babu N. Motagi, University of Agricultural Sciences, Dharwad, IndiaReviewed by:

Tariq Mukhtar, Pir Mehr Ali Shah Arid Agriculture University, PakistanAnilkumar C, National Rice Research Institute (ICAR), India

Hari Krishna, Indian Agricultural Research Institute (ICAR), India

Copyright © 2025 Nataraj, Amrate, Ratnaparkhe, Maranna, Rajput, Agrawal, Raghuvanshi, Pathak, Mandloi, Mohare, Naik K, Shrivastava, Kumawat, Rajesh, Gupta, Chitikineni, Varshney and Singh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Milind B. Ratnaparkhe, bWlsaW5kLnJhdG5hcGFya2hlQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Vennampally Nataraj

Vennampally Nataraj Pawan Kumar Amrate2†

Pawan Kumar Amrate2† Milind B. Ratnaparkhe

Milind B. Ratnaparkhe Shivakumar Maranna

Shivakumar Maranna Laxman Singh Rajput

Laxman Singh Rajput Nisha Agrawal

Nisha Agrawal Bhojaraja Naik K

Bhojaraja Naik K Manoj K. Shrivastava

Manoj K. Shrivastava Giriraj Kumawat

Giriraj Kumawat Vangala Rajesh

Vangala Rajesh Sanjay Gupta

Sanjay Gupta Rajeev K. Varshney

Rajeev K. Varshney