- 1Molecular Biology of Vegetable Laboratory, College of Horticulture, Shenyang Agricultural University, Shenyang, China

- 2Molecular Genetics and Genomics Lab, Department of Horticulture, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Republic of Korea

- 3Dalian Modern Agriculture Development Service Center, Dalian, China

Glucosinolates (GSLs) are sulfur-rich secondary metabolites that play important roles in human health, plant defenses against pathogens and insects, and flavor. The genetic architecture of GSL biosynthesis in Brassica rapa L. remains poorly understood despite several mapping and gene prediction studies. This study conducted a conventional quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis to identify putative genes regulating GSL biosynthesis in B. rapa in two field trials. Four consensus QTL clusters were identified for various GSL compounds. Six QTLs exhibited effects of QTL–environment interactions (Q×E), reflecting the genetic variation underlying phenotypic plasticity. QTL-Cluster2 and QTL-Cluster3 on chromosome A03 represented two genetically stable regions for major aliphatic GSLs (Ali-GSLs) without Q×E effects. Interestingly, variation in the expression of BrGSL-OHa, rather than gene sequence variation, explained the association between QTL-Cluster2 and gluconapin and progoitrin accumulation in B. rapa. Further function analysis indicated that the lack of an MYB binding site in the oil-type B. rapa BrGSL-OHa promoter region represented a rare non-functional allele among B. rapa genotypes, which prevented binding with the MYB transcription factor BrMYB29b, thereby repressing BrGSL-OHa transcription and inhibiting progoitrin biosynthesis. This study provides new insights regarding the molecular regulatory mechanism of GSL biosynthesis in B. rapa.

1 Introduction

Glucosinolates (GSLs), a class of sulfur-rich secondary metabolites largely limited to the Brassicaceae crops, are known to play important roles in disease resistance, insecticide metabolism, human health, and flavor quality (Wittstock and Burow, 2001; Soundararajan and Kim, 2018). Extensive variation in GSL profiles has been detected in Brassica crops, such as pakchoi (Brassica rapa), Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L.), broccoli (Brassica oleracea), cabbage (Brassica oleracea L.), and oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.), as well as Arabidopsis (Brachi et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2022). GSLs are hydrolyzed by myrosinase to form degradation products with diverse biological activities, such as isothiocyanates, nitrile, thiocyanates, and oxazo-lidine-2-thione (Fahey et al., 2001). GSLs were initially thought to be toxic based on the 2-hydroxy-3-butenyl GSL progoitrin (PRO), which causes goiter in mammals (Kloss et al., 1996; Smolinska et al., 1997). However, the beneficial effect of 4-methylsulfinylbutyl GSL (glucoraphanin) has since been recognized due to the anti-carcinogenic activity of its degradation product (Sharma et al., 2011).

A suite of crucial structural and transcription factor genes involved in the GSL biosynthesis pathway have been identified in Arabidopsis. Genetic and functional analyses have revealed the important roles of the methylthioalkylmalate synthase (MAM) and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase (AOP) gene families in the side-chain elongation and modification of aliphatic GSLs (Ali-GSLs) (Kliebenstein et al., 2001a, b; Kroymann et al., 2001). In previous research, the GSL-OH locus was cloned and found to be a 2-oxoacid-dependent dioxygenase (2ODD) involved in the formation of PRO from the precursor gluconapin (GNA) (Hansen et al., 2008). Moreover, several R2R3-MYB transcription factors, namely, MYB28, MYB29, MYB76, MYB51, MYB34, and MYB122 have been identified as regulators for Ali-GSLs and indolic GSLs (Ind-GSLs) (Gigolashvili et al., 2007a, b; Hirai et al., 2007; Gigolashvili et al., 2008; Frerigmann and Gigolashvili, 2014). Homologs of these Arabidopsis MYB genes have been identified and characterized in various Brassica species, including B. napus, B. oleracea, and B. rapa, where they similarly orchestrate the regulation of GSL biosynthesis, albeit with increased complexity due to genome polyploidization (Liu et al., 2020; Zuluaga et al., 2019; Seo et al., 2016).

In Brassica crops, conventional quantitative trait loci (QTLs) or expression QTLs (eQTLs) are valuable approaches for dissecting the genetics of GSL synthesis. A meta-QTL analysis of GSL biosynthesis in different organs of B. oleracea uncovered the central role of the epistatic interaction of the alkenyl GSL locus (GSL-ALK) with other QTL loci (Sotelo et al., 2014). The candidate genes BoGSL-Elong (MAM) and BoGSL-ALK (AOP) have been cloned and characterized in B. oleracea (Li and Quiros, 2002, 2003). Hirani et al. (2013) developed B. rapa seeds low in 5C Ali-GSLs through replacing the A-genome functional locus with the B. oleracea non-functional GSL-ELONG locus. In B. napus and B. juncea, QTL and genome-wide association study (GWAS) analyses of GSL content have focused on seeds and several candidate genes have been identified, including GTR2a, MYB28, GSH2, MAM1, and AOP2 (Ramchiary et al., 2007; Bisht et al., 2009; Feng et al., 2012; Harper et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2014; Rout et al., 2015; Kittipol et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2021). Until recently, limited studies have reported the genetic dissection of QTLs controlling GSL accumulation in B. rapa. Lou et al. (2008) first identified 16 loci controlling the accumulation of Ali-GSLs, three loci for Ind-GSL accumulation, and three loci for aromatic GSL (Aro-GSL) accumulation. Using the same parental materials as those described by Lou et al. (2008), a doubled haploid segregation population was developed and both the metabolism QTLs and eQTLs were analyzed to elucidate the regulatory network of the GSL synthesis pathway (Pino Del Carpio et al., 2014).

Following the assembly of a whole-genome sequence for B. rapa, 102 putative GSL genes orthologous to 52 Arabidopsis GSL genes were identified in the B. rapa genome (Wang et al., 2011a). Most B. rapa GSL genes were present as two or three copies (Zang et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2011a). The genome-triplication event in the ancestor of B. rapa accounts for the greater complexity of the GSL metabolic pathway in B. rapa compared to Arabidopsis. Currently, the functional association of GSL-related genes with GSL accumulation in B. rapa, and the mechanisms responsible for the substantial variation in GSL profiles and contents among genotypes is poorly understood. Thus, it is necessary to identify functional GSL-related genes in large-scale and their underlying molecular genetic mechanisms.

This study aimed to identify and verify potential candidate genes associated with GSLs in B. rapa and their regulatory mechanisms. To unravel the genetic architecture of GSL biosynthesis and identify alleles underlying the natural variation in GSLs, conventional QTL analysis was performed using a bi-parental mapping population of B. rapa over 2 years. The results of the present study enhance the understanding of the genetic architecture of complex GSL metabolism and will contribute to the genetic improvement of GSLs in B. rapa.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Bi-parental mapping population

To map QTLs that control leaf GSL compounds, this study employed a biparental mapping population, CRF2/3, comprising 190 individuals derived from a cross between ‘Chiifu 401-42’ (hereafter Chiifu), a heading Chinese cabbage used as the reference material for the B. rapa genome sequencing project, and rapid-cycling B. rapa (RCBr) (Li et al., 2010, 2013). Two independent experiments were conducted to detect the leaf GSL content in the CRF3 population. In experiment I (2012SG), both parental lines and the CRF3 population were grown in pots from March–July 2012 in a glasshouse under a 16-h/8-h (light/dark) photoperiod at 24 °C in Daejeon, Korea. One fully expanded leaf from each of two plants per F3 family line was harvested after 40 days of growth. A second experiment (2013AF) was performed in an open field at Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Korea, from August–November 2013. Fully expanded leaves were taken and mixed from three plants per F3 family line at the four-to-five leaf stage. Leaf samples were stored at −80 °C for subsequent freeze-drying and GSL extraction.

2.2 Diverse B. rapa genetic lines

A diverse panel consisting of 85 B. rapa inbred or double-haploid lines, including heading Chinese cabbage, pakchoi, oil-type, and caixin lines, was employed for GSL compound detection and BrGSL-OHa gene sequence analysis (Supplementary Table S1). Seeds for each B. rapa line were germinated in cell trays in a glasshouse for 1 month and then transferred to an open field at Shenyang Agricultural University, China and grown from August–December in 2016. Twelve plants per line were arranged in a randomized block design with two replications. At the harvest stage, for heading Chinese cabbage lines, outer leaves were sampled and mixed with the heading leaves. For the non-heading types, two to three mature leaves were collected. For each replication, leaf samples from six plants per fixed line were collected and mixed for subsequent GSL analysis.

2.3 Glucosinolate isolation and quantification

Freeze-dried leaf samples were ground into powder using a domestic mixer, and 0.1 g of sample powder was utilized for GSL extraction with 70% methanol following the method described by Kim et al. (2013). Extraction solution desolated by sulfatase was loaded onto an ion exchange column filled by Sephadex DEAE-A25, Sigma. A high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) instrument equipped with an ultraviolet detector was employed for chromatographic analysis. The HPLC column was a C18 Atlantis water column with a particle size of 2.5 µm and a length of 150 mm. GSL compounds were detected at 229 nm and separated according to the following method: in 2% acetonitrile for 0–5 min; a 15-min gradient from 0% to 25%; and a final 10 min in 2% acetonitrile. The flow rate was 1.0 mL min−1. For mass spectrometry analysis, the eluate was directed to a quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with a positive electrospray ionization source. The spray voltage was set to 4.5 kV and the capillary temperature was maintained at 250 °C. Mass scanning was performed over a range of 100 to 700 m/z, according to the method described by Kim et al. (2013). GSLs were quantified using sinigrin (SIN, sinigrin monohydrate; Sigma-Aldrich) as an external standard. Concentrations are expressed as µmol per gram of dry weight (µmol·g-¹ DW).

2.4 Statistical and QTL analyses

The genetic map utilized for the QTL analysis of GSL compounds was updated by anchoring a small number of GSL gene-specific single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers onto a previously constructed genetic map sketch using the CRF2 mapping population. Putative GSL-related ortholog genes in the B. rapa genome were detected according to a comparative genome study by Wang et al. (2011a) and are listed in Supplementary Table S2. Information on the GSL gene-specific SNP markers is presented in Supplementary Table S3. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) between the replications of two experimental trials was conducted using GenStat.

WinQTL Cartographer version 2.5 was employed to perform QTL analysis using the composite interval mapping (CIM) function as previously described (Li et al., 2013) utilizing single-environment phenotypic data. Tests for the presence of QTLs were performed at 2-cM intervals using a window of 10 cM. Significant QTL-defining LOD (Logarithm of the odds) values were calculated with 1000 permutations for each GSL phenotypic dataset obtained in 2012 and 2013. To assess the QTL–environment interaction, a multi-environment approach (MEA) for individual GSLs was implemented following the mixed-model technique described by Boer et al. (2007). The first step was to select the variance–covariance (VCOV) model best that suited the phenotypic data across two environments. The VCOV model was employed to model the variation between genotypes both across and within environments. The entire genome was scanned using simple interval mapping and the candidate QTLs were selected as co-factors to perform a second-round composite interval mapping (CIM) scan. Finally, QTL backward selection for loci in multiple environment trails was determined and the allelic effects of QTLs in each environment and the QTL x E effect were estimated. To distinguish the QTL results obtained using this two-analysis method, a capital “E” was added following the names of the QTLs obtained using the MEA.

2.5 Expression analysis of candidate genes using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

To confirm the expression level of the candidate gene BrGSL-OHa in the QTL-cluster region, the total RNA was extracted from 45- and 90-day-old leaf samples collected from the parental lines Chiifu and RCBr as well as selected fixed lines using the RNA-prep Pure Plant Total RNA Extraction Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). The expression levels of GSL biosynthesis-related genes in wild-type and OE-BrMYB29b transgenic Chinese cabbage lines were detected. cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg RNA for semi-quantitative and qRT-PCR in accordance with the method of Zheng et al. (2025). Internal standards using the B. rapa actin gene and gene-specific primer pairs are displayed in Supplementary Table S4.

2.6 Identification and analysis of BrGSL-OHa promoter sequences among different B. rapa genetic lines

To clone the BrGSL-OHa promoter sequences of different B. rapa materials, primers were designed according to the −1.5–2.0 kb upstream sequences of BrGSL-OHa obtained from the Chiifu reference genome. The forward primer was designed in the 5’-upstream sequence of BrGSL-OHa and the reverse primer was designed in the BrGSL-OHa coding sequence (Supplementary Table S4). DNA was isolated from the leaves of 85 B. rapa genetic lines (Supplementary Table S1). PCR was performed in a 50-ul reaction mixture containing 2 ul DNA template, 0.2 uM of each primer, and 25 ul of 2 Ex Taq Mix (Takara, Dalian, China). The PCR products were cloned into T-Vector pMD™20 (Takara, Dalian, China) for sequencing. The online tool PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) was employed for the prediction of cis-acting regulatory elements.

2.7 Heterologous expression and enzyme assays for BrGSL-OHa

The full-length cDNA of BrGSL-OHa was amplified from Chiifu and cloned into the pET30a expression vector. The constructed plasmid was expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) grown in LB (Luria-Bertan) medium to an OD600 value at 0.6. The induction of recombinant protein synthesis was initiated by adding 0.2 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside overnight at 15 °C. The expressed cells were sonicated with 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole containing 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, and 1 mM PMSF. At the same time, the Ni-IDA affinity chromatography column was balanced with 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, and 20 mM imidazole buffer. The target protein was then eluted with different concentrations of imidazole balanced buffer, and each elution component was collected for SDS-PAGE analysis. Enzyme assays were conducted as described by Zhang et al. (2015) using purified GNA as substrate. Liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization mass spectrometry was employed to detect GSL profiles (Waters ACQUITY UPLC H-Class_XEVO TQD). The mass spectrometer was operated in the positive electrospray ionization mode using the following manual optimization of the general conditions: capillary voltage: 2000 V; cone voltage: 14 V; desolvation gas flow: 1000 L/h; desolvation temperature: 650°C; scanning mode: daughter scan; collision energy: 10 V; fragment scan range: 50–330 m/z; scan time: 0.3 s.

2.8 Gene cloning, vector construction, and plant transformation

For the overexpression (OE) construct, the 1.14-kb coding sequence of BrGSL-OHa was amplified from Chiifu cDNA and cloned into the vector pBWA(V)HS driven by the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter (35Spro: BrGSL-OHachiifu). To test the effect of two promoter types on PRO synthesis, two constructs were generated. The 3.02-kb sequence fused by the 1.88-kb promoter and the 1.14-kb coding sequence of BrGSL-OHa obtained from Chiifu was amplified and cloned into the vector pBWA(V)HS to generate construct I (BrGSL-OHachiifupro: BrGSL-OHachiifu). The 2.97-kb sequence that included the 1.83-kb promoter and the 1.14-kb coding sequence obtained from oil-type B. rapa RCBr was utilized to generate construct II (BrGSL-OHaRCBrpro: BrGSL-OHaRCBr). Wild-type control plants were generated by introducing the empty vector. Chinese cabbage is quite recalcitrant to genetic transformation and is dependent on genotypes. Explants obtained from the Chinese cabbage inbred line C-24 developed in our previous study (Li et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2025), which exhibits relatively high genetic transformation efficiency, were utilized for OE construct transformation to validate BrGSL-OHa gene function. Because C-24 was difficult to utilize in resistant shoot formation when transforming constructs I and II, the constructs with combinations of the BrGSL-OHa promoter and genes were transformed into Westar, an oilseed genotype with low GSL contents and high transformation efficiency, using the Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA105-mediated method via cotyledon explants.

To further explore the regulatory role of transcription factor BrMYB29b in PRO biosynthesis, the full-length cDNA of BrMYB29b from Chiifu was cloned into pBWA(V)HS to construct the OE vector. The BrMYB29b plasmid was introduced into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 for transformation using Chinese cabbage C-24. The resulting OE Chinese cabbage transgenic plants were verified based on PCR amplification and GUS staining as described by Li et al. (2021).

2.9 Protein subcellular localization

To investigate the subcellular location of the transcription factor BrMYB29b, the coding sequence of BrMYB29b without the stop codon was amplified and cloned into the expression vector pCAMBIA 1302-GFP under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter. The subcellular localization of BrMYB29b proteins was detected by monitoring the green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression in Arabidopsis thaliana protoplast cells. Arabidopsis protoplast isolation, the transfection of plasmid DNA, and the protoplast culture protocol were performed with reference to Yoo et al. (2007). The fusion construct combined with nucleus localization protein (nls) was employed as a marker of the nucleus (Zhao et al., 2017).

2.10 Yeast one-hybrid assay

The yeast one-hybrid assay was performed as described in the Clontech PT3024-1/Yeast Protocols Handbook. BrGSL-OHa promoters obtained from the genomic DNA of Chiifu (1.88 kb) and RCBr (1.83 kb) were inserted into the pHIS2 plasmid. The full-length BrMYB28a, BrMYB28b, BrMYB28c, BrMYB29a, and BrMYB29b open reading frames were amplified from Chiifu cDNA and cloned into the pGADT7 vector (Clontech). The yeast transformants were selected on SD/−Trp/−Leu/−His medium and tested on SD/−Trp/−Leu/−His medium supplemented with various concentrations of 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole for 3 days at 30 °C.

2.11 Analysis of promoter cis-element interaction using a dual-luciferase reporter system

The full-length open reading frames of BrMYB28a, BrMYB28b, BrMYB28c, BrMYB29a, and BrMYB29b were cloned into the effector vector pCAMBIA1301S under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter. Two BrGSL-OHa promoter sequences obtained from the genomic DNA of Chiifu and RCBr were digested with HindII and BamHI and inserted into the reporter vector pGreenII0800-LUC. These plasmids were co-transformed into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 and used to infiltrate 1-month-old Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. The transient expression was analyzed following a 3-day incubation. The transcriptional activity in the infiltrated tobacco plants indicated by the ratio of firefly luciferase (LUC) to Renilla luciferase (REN) was assayed using a dual-luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega).

3 Results

3.1 Quantitative variation of leaf GSL content in the CRF2/3 population

A total of 13 GSLs were detected in the two parental materials and lines of the CRF2/3 population (Supplementary Table S5). The parental lines showed distinct GSL profiles in the 2012SG (spring, glasshouse) and 2013AF (autumn, open field) trials. GNA, a member of the aliphatic four-carbon group (Ali-4C), was the dominant GSL in the parent RCBr, with a maximum concentration of 20.76 µmol g−1 DW detected in 2013AF. In contrast, PRO, the hydroxylated product of GNA, was the dominant GSL in the parental line Chiifu, with a maximum concentration of 2.37 µmol g−1 DW observed in 2012SG. The concentrations of other Ali-GSL, Ind-GSL, and Aro-GSL compounds were generally higher in Chiifu than in RCBr but accounted for a small proportion of the total GSLs detected in both parents (Supplementary Table S5; Supplementary Figure S1).

In the CRF3 families, the contents of most individual GSLs and those of the five GSL types displayed a continuous distribution and wide variation (Supplementary Table S5), which suggests that the biosynthesis of each GSL is controlled by multiple genes in B. rapa. The CRF3 population exhibited transgressive segregation to a higher degree for most GSLs. Although the contents of glucoraphanin (GRA), glucobrassicanapin (GBN), glucobrassicin (GBS), and gluconasturtin (GNT) were relatively low in the parents, extremely high values were detected in the CRF3 family (Supplementary Table S5). As the dominant GSL compound type, Ali-GSLs contributed 56.67 and 50.51% of the total GSL content on average in the first and second trial, respectively, ranging from 5.41–91.84% and from 8.69–96.22%, respectively. Among Ind-GSLs, GBS, methoxy glucobrassicin (4ME), and neoglucobrassicin (NEO) contributed approximately 7–15% of the total GSL content in the CRF3 population, whereas 4-hydroxy glucobrassicin (4OH) made up a small percentage (0.41% in 2012SG and 0.33% in 2013AF). The significant variation in the content of each GSL in the mapping population facilitated subsequent QTL analysis.

3.2 QTL identification for GSL content in leaves

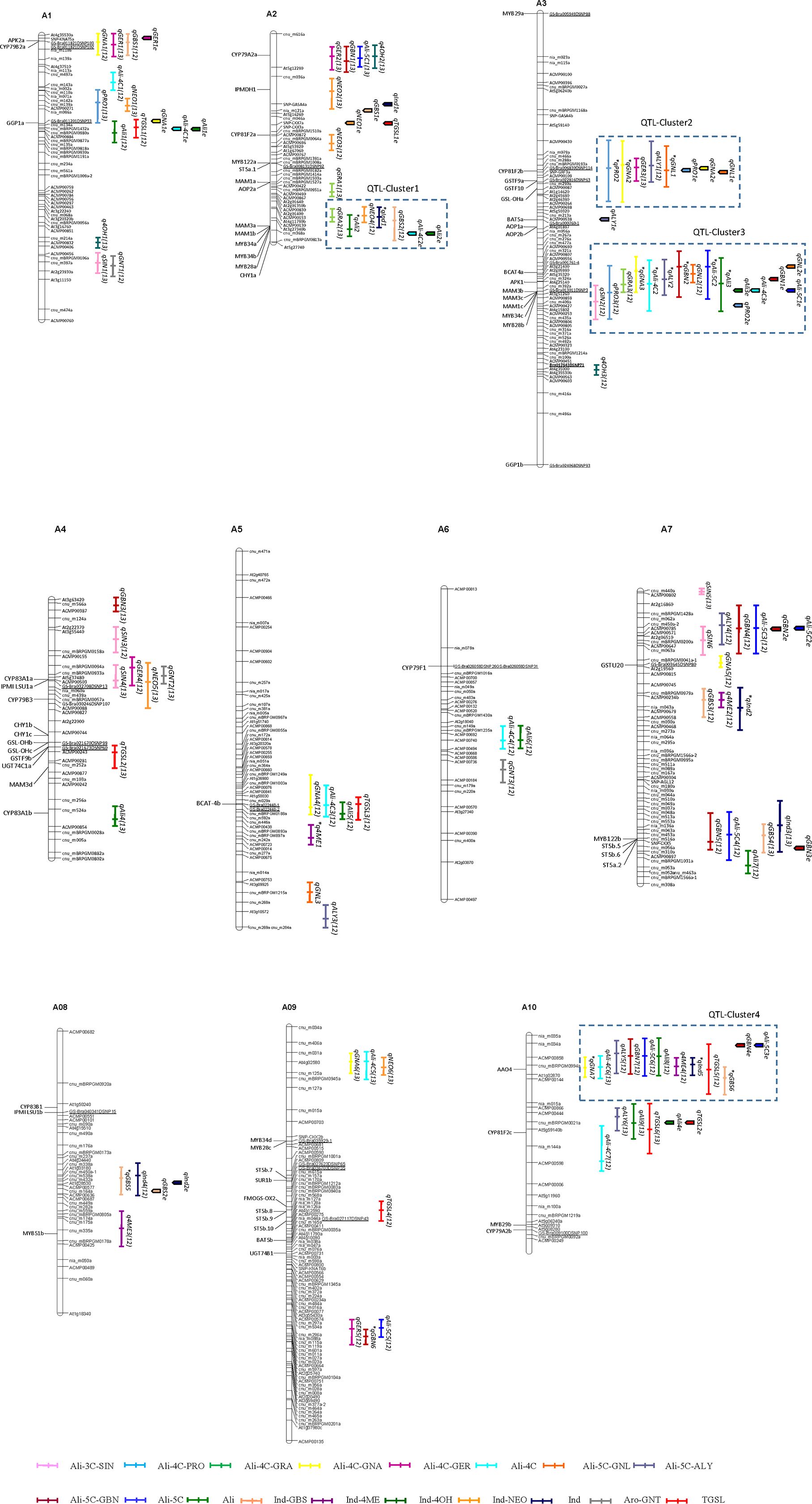

To investigate the genetic control of GSL biosynthesis in B. rapa leaves, a traditional QTL analysis was performed for 13 individual GSLs and five types of GSLs as well as the total GSL content in the CRF2/3 bi-parental mapping population in two different seasons and locations. A total of 60 QTLs for Ali-GSLs (Ali-QTLs) were identified on all chromosomes, with major loci detected on chromosomes A02 and A03 (Figure 1; Supplementary Table S6). Of the 60 Ali-QTLs, 12 were detected in both environments, while the remaining loci were detected in only a single environment. For the predominant GSL, GNA, seven QTLs were mapped, which explained 30.6 and 31.5% of the phenotypic variation in 2012AF and 2013SG, respectively. Three of these QTLs, namely, qGNA2 and qGNA3 on A03 and qGNA7 on A10, were identified in both environments. A major QTL cluster (QTL-Cluster3) on the middle-bottom of A03 was identified for gluconapin (qGNA3), glucoraphanin (qGRA3), progoitrin (qPRO3), a four-carbon side chain Ali-GSL (qAli-4C2), glucoalyssin (qALY2), glucobrassicanapin (qGBN2), gluconapoleiferin (qGNL2), a five-carbon side chain Ali-GSL (qAli-5C2), and the total Ali-GSLs (qAli3) in the two environments (2012AF and 2013SG), which accounted for 4–21.5% of the phenotypic variation (Figure 1; Supplementary Table S6). According to the physical positions of genetic markers and predicted GSL homologous genes in the B. rapa genome (Wang et al., 2011a), seven genes involved in Ali-GSL biosynthesis and regulation named BrBCAT4a, BrAPK1, BrMAM3b, BrMAM3c, BrMAM1c, BrMYB34c, and BrMYB28b were anchored in QTL-Cluster3. An additional region on A03 spanning from 50.4 to 74.8 cM (QTL-Cluster2) harbored a co-localized QTL for PRO, GNA, GER, ALY, and GNL that explained 5–20% of the phenotypic variation. Moreover, BrGSL-OHa, which is orthologous to an Arabidopsis 2ODD gene responsible for PRO formation, was found to be anchored in this region. The RCBr allele for the BrGSL-OHa locus increased the GNA content but decreased the PRO content. QTL-Cluster1, as a chromosome segment paralogous to the QTL-Cluster3 region, harbored not only Ali-QTLs (qGRA2 and qAli2) but also Ind-QTLs (qNEO4, qInd1, and qGBS2). QTL-Cluster 4 harbored both Ali-QTLs and Ind-QTLs. Of these QTLs, qGNA7 and qGBS6 were detected in the two trials, while the other QTLs were detected in one environment only (Figure 1; Supplementary Table S6).

Figure 1. Distribution of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for glucosinolate compounds in the Brassica rapa genome detected using the CRF2/3 bi-parental mapping population. QTL names are indicated by the abbreviations of individual glucosinolate names as shown in Supplementary Table S5. Numbers in parenthesis indicate the year of QTL detection. The asterisk before the name of each QTL represents a QTL detected in both trial years. Glucosinolate biosynthesis candidate genes anchored in the QTL region are shown on the left of each chromosome according to Wang et al. (2011a).

The GenStat system was employed to detect QTLs affected by the environment. A total of 29 QTLs were obtained for 13 GSL phenotypes. Except for SIN, GRA, 4OH, and GNT, these QTLs were distributed on chromosomes A01, A02, A03, A07, A08, and A10 (Figure 1; Supplementary Table S7). Among them, six QTLs for six types of GSL displayed significant QTL–environment interactions (Q×E), reflecting the genetic variation underlying their phenotypic plasticity. qGER1e, qGBN4e, qAli-5C3e, and qNEO1e exhibited Q×E effects and were co-localized with their corresponding QTLs only in the 2012SG trial (Figure 1). qPRO1e, qGNA2e, and qGNL1e exhibited no Q×E effects and were mapped to QTL-Cluster2, in which QTLs were detected for PRO, GNA, and GNL in both the 2012SG and 2013AF trials (Figure 1). Four additional QTLs that displayed no interaction effects with the environment (qAli3e, qAli-4C3e, qGBN1e, and qAli-5C1e) were mapped to the same region of QTL-Cluster 3 on chromosome A03 (Figure 1).

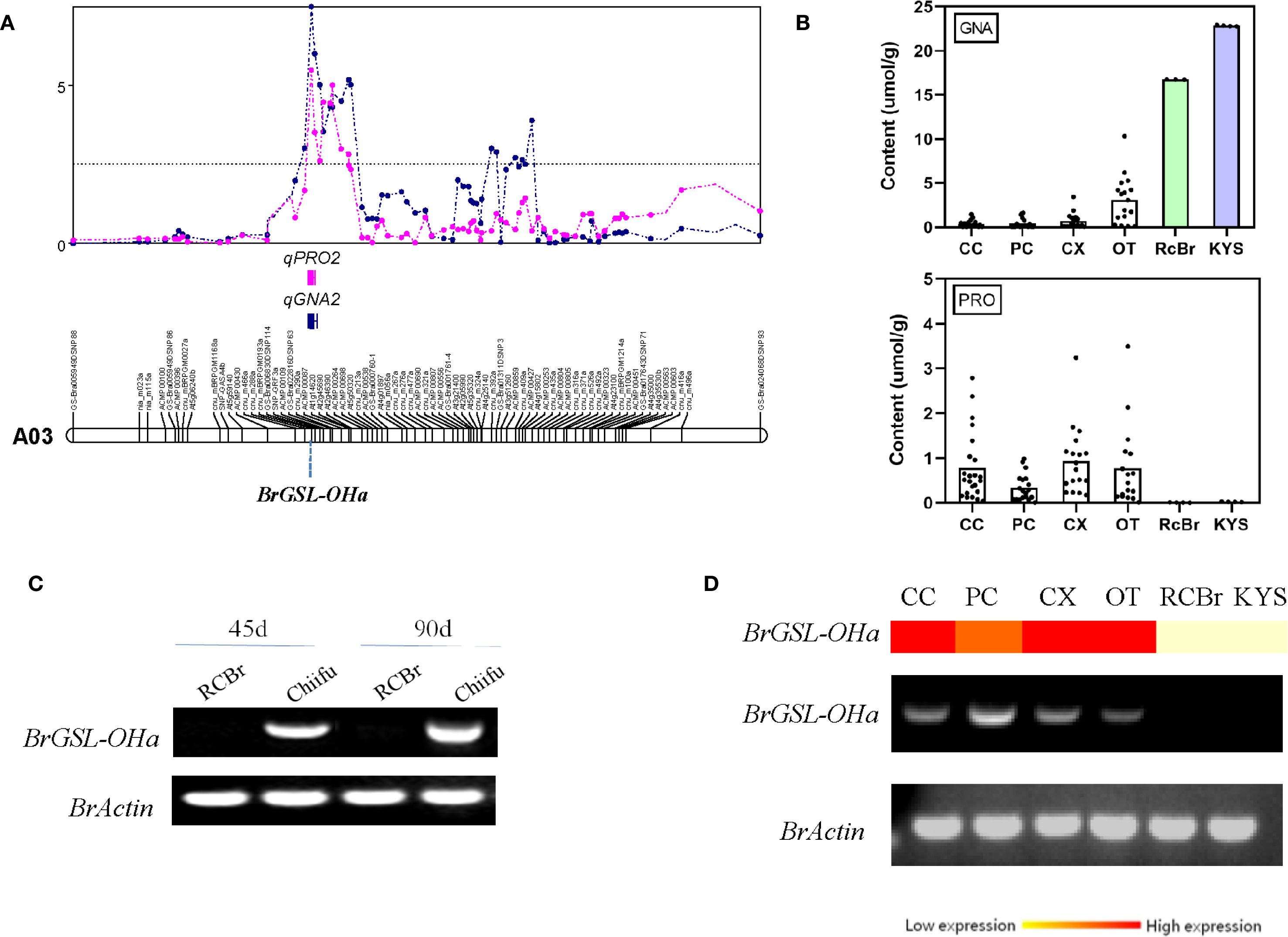

3.3 Expression variant of BrGSL-OHa contributes to the QTLs for GNA and PRO compounds

Compared with the vegetable-type B. rapa lines, the oil-type RCBr line exhibited an extreme phenotype, with high GNA content and extremely low PRO content (Supplementary Table S5; Supplementary Figure S1). In the QTL-Cluster2 region, BrGSL-OHa (Bra022920) displayed the highest amino acid sequence similarity to the Arabidopsis 2ODD gene, which is responsible for PRO transformation from GNA (Figure 2A; Supplementary Figure S2). Genomic sequencing and PCR cloning results revealed that no significant differences were detected in the BrGSL-OHa coding sequences among B. rapa. Therefore, this study compared the transcript level of BrGSL-OHa among the two parents of the CRF2/3 mapping population and a small number of selected lines representing different types of B. rapa. BrGSL-OHa showed a higher transcript level in the parent Chiifu, whereas no transcripts were detected in RCBr (Figure 2C). Among the diverse B. rapa genetic lines, BrGSL-OHa transcripts were not detected only in the oil-type line ‘KYS’, which also showed an extremely high GNA content but less PRO (Figures 2B, D). Based on these results, it was predicted that BrGSL-OHa of the oil-type RCBr and KYS was a rare non-functional allele among B. rapa species, which resulted in an inability to synthesize PRO and thus the accumulation of high GNA content.

Figure 2. Quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping for progoitrin and the expression of the candidate gene BrGSL-OHa. (A) QTL positions for progoitrin and gluconapin on chromosome A03. (B) Distribution of gluconapin (GNA) and progoitrin (PRO) contents among different types of Brassica rapa. CC, Chinese cabbage; PC, Pakchoi; CX, Caixin; OT, Oil-type. Rapid-cycling B. rapa (RCBr) and ‘KYS’ are two oil-type B. rapa varieties showing extremely high GNA content and low PRO content. (C) Semi-quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of the candidate gene BrGSL-OHa using 46-day-old and 90-day-old fresh leaves of ‘Chiifu’ and RCBr. The B. rapa actin gene was used as a control for RNA quantification. (D) Real-time and semi-quantitative PCR analysis of BrGSL-OHa among lines representing different types of B. rapa.

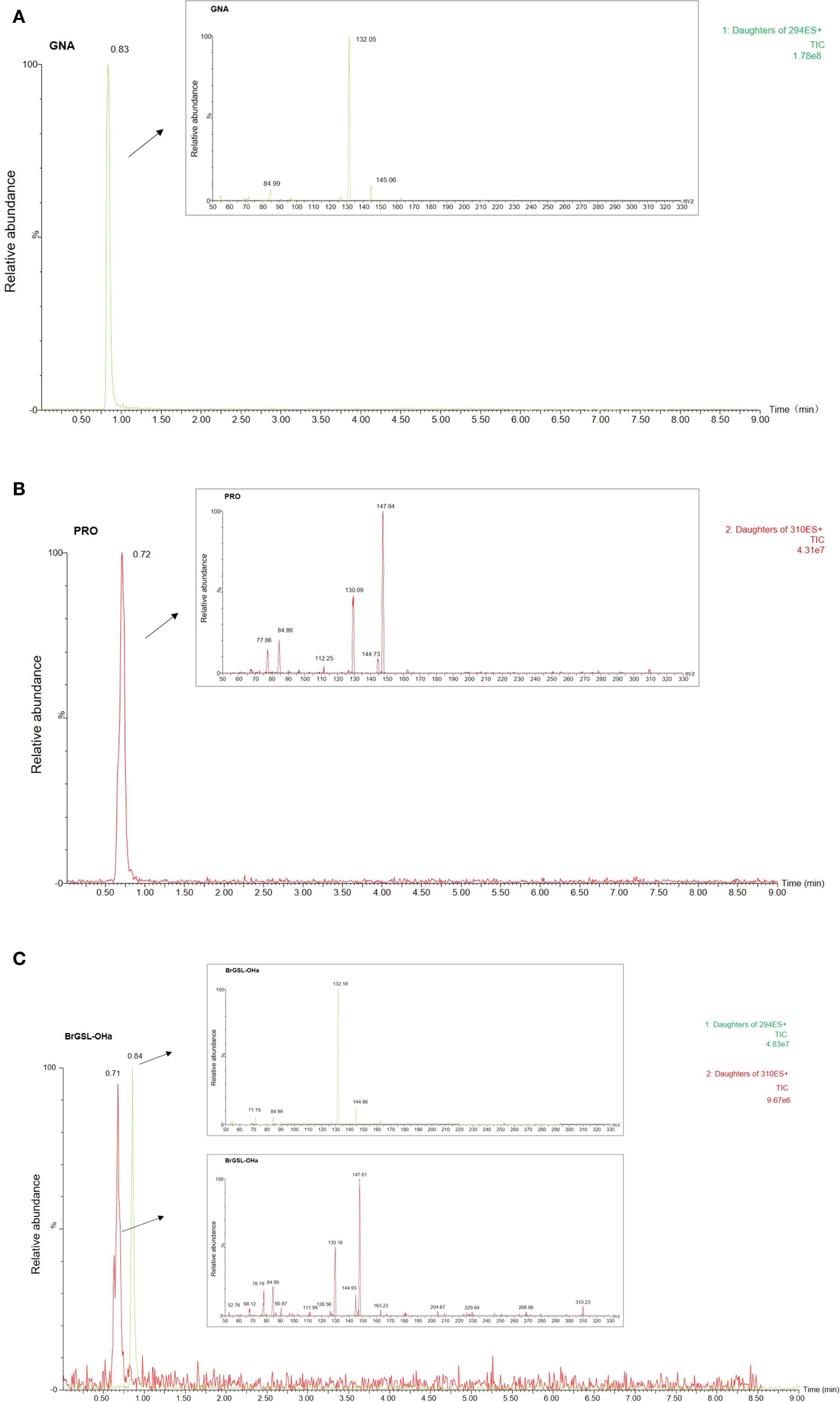

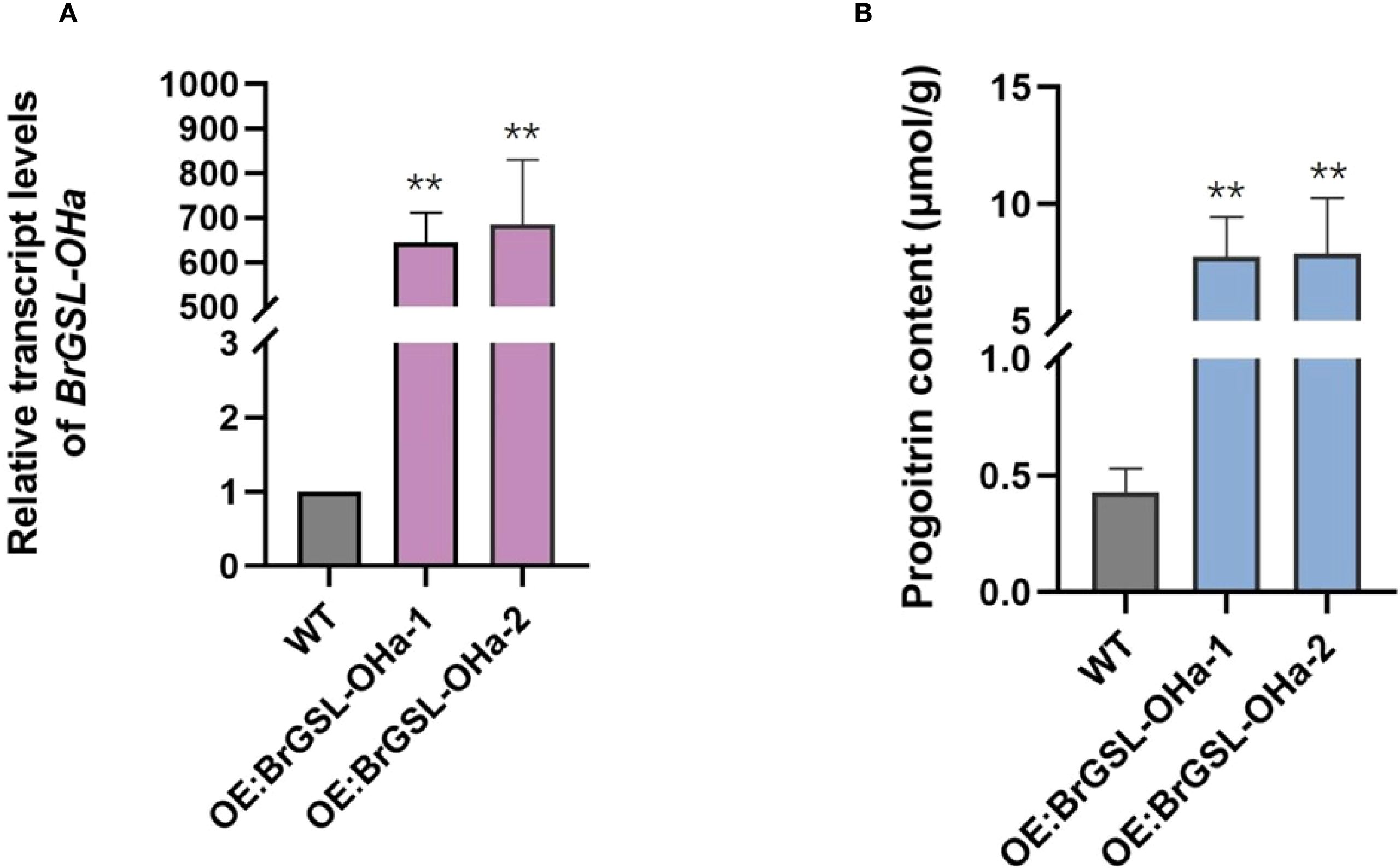

To validate the function of the predicted BrGSL-OHa for PRO biosynthesis from GNA in B. rapa, BrGSL-OHa protein was firstly heterologously expressed and purified in E. coli for enzyme catalytic activity assays (Supplementary Figure S3). As shown in Figure 3, the identities of two compounds in the sample containing GNA as substrate treated with BrGSL-OHa protein were confirmed by comparing their liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry profiles with those of GNA (Figure 3A) and PRO standards (Figure 3B). This indicated that BrGSL-OHa protein successfully catalyzed the conversion of GNA to PRO. Furthermore, BrGSL-OHa OE transgenic lines were generated for the Chinese cabbage C-24 background (Supplementary Figure S4). Compared with the wild-type C-24, two OE transgenic lines exhibited enhanced BrGSL-OHa expression levels accompanied by increased PRO content (Figures 4A, B), indicating that PRO biosynthesis was controlled by BrGSL-OHa expression.

Figure 3. Enzymatic activity of BrGSL-OHa heterologously expressed in Escherichia coli. Total ion chromatography (TIC) and product ion spectrum scanning image of (A) desulfated gluconapin (GNA) standard, (B) desulfated progoitrin (PRO) standard, and (C) desulfoglucosinolates from a sample of GNA treated with heterologously expressed BrGSL-OHa fusion protein. The x-axis of the TIC image represents the retention time and the y-axis represents the relative abundance of ions. The mother ions of GNA (294) and PRO (310) are labeled on the right side of the TIC image. Arrows indicate the product ion spectrum scanning results for the targeted peak in the TIC image.

Figure 4. BrGSL-OHa confers progoitrin biosynthesis in Brassica rapa. Relative BrGSL-OHa expression levels (A) and progoitrin content (B) in leaves from overexpression transgenic plants (OE) and wild-type Chinese cabbage C-24 (WT) The data are presented as means ± SE from three independent biological replications. Black asterisks (**) indicate a significant difference (t-test, p < 0.01).

3.4 Promoter variation of BrGSL-OHa contributes to its expression and PRO synthesis from GNA

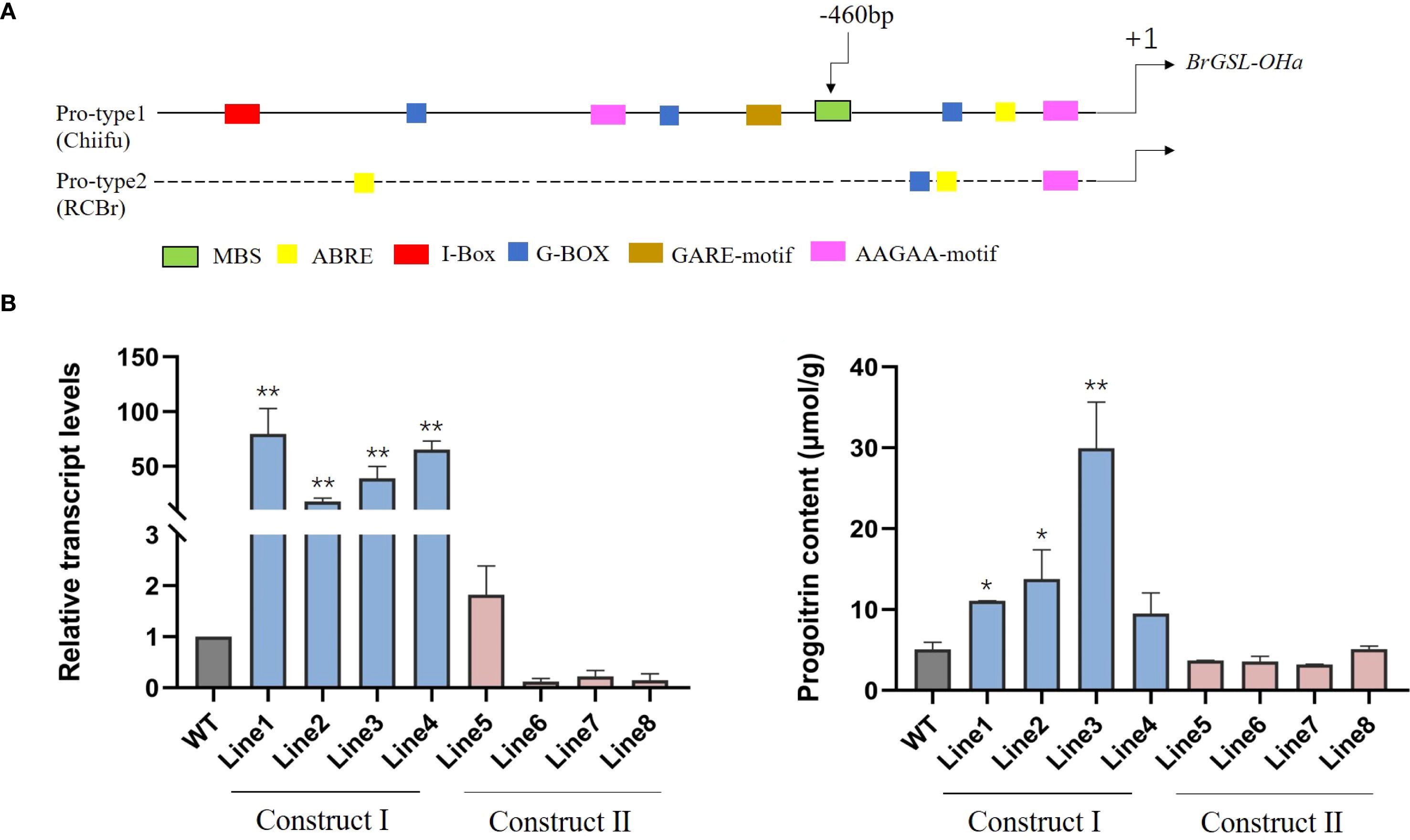

To determine whether the differential expression of BrGSL-OHa among two parental lines and B. rapa natural materials results from their promoter regions, this study cloned the promoter regions from Chiifu, RCBr, and 85 different B. rapa genotypes showing variation in GNA and PRO contents (Supplementary Table S1). The results revealed that the promoter sequences were highly conserved in B. rapa, including Chinese cabbage, pakchoi, caixin, and most oil-type B. rapa varieties, forming a Pro-type1 promoter, which was consistent with the Chiifu promoter sequence (Figure 5A). Considerable sequence differences were observed only in two oil-type B. rapa varieties, RCBr and KYS (Figure 5A). Promoter cis-element analysis demonstrated that an MYB binding site (MBS) was located at −460 bp in the Pro-type1 promoter of BrGSL-OHa, while only the RCBr and KYS varieties lacked the MBS (Figure 5A). The findings indicated that the absence of the MBS in the promoter regions of the oil-type B. rapa RCBr and KYS inhibited the expression of BrGSL-OHa, thereby blocking PRO synthesis and leading to the extreme accumulation of GNA.

Figure 5. (A) Promoter sequence variation of BrGSL-OHa among Brassica rapa was comprised of two types: Pro-type1 was found in vegetable-type B. rapa and most oil-type B. rapa, as in ‘Chiifu’; and Pro-type 2 occurred in oil-type rapid-cycling B. rapa (RCBr). Predicted cis-elements are represented by colorful boxes. Relative transcript levels (B) and progoitrin content (C) in transgenic plants expressing construct I (Lines 1–4) and Construct II (Lines 5–8) compared with the wild-type Westar genotype (WT) The data are presented as means ± SE from three independent biological replications. Black asterisks (**) indicate a significant difference (t-test, p < 0.01), Black asterisks (*) indicate a significant difference (t-test, p < 0.05).

To further demonstrate that variation in the BrGSL-OHa promoter alters its expression, this study generated transgenic plants using two types of promoters: BrGSL-OHachiifupro: BrGSL-OHachiifu (Construct I) and BrGSL-OHaRCBrpro: BrGSL-OHaRCBr (Construct II). As shown in Figures 5B, C, compared with the wild type, the transgenic lines expressing BrGSL-OHa driven by BrGSL-OHachiifupro displayed significantly enhanced BrGSL-OHa transcript levels and progoitrin contents. In contrast, the transgenic lines expressing BrGSL-OHaRCBrpro: BrGSL-OHaRCBr did not accumulate PRO to the levels compared with that in the wild type. This result suggests a natural polymorphism in the promoter of BrGSL-OHa (the MBS deletion) is responsible for the gene expression.

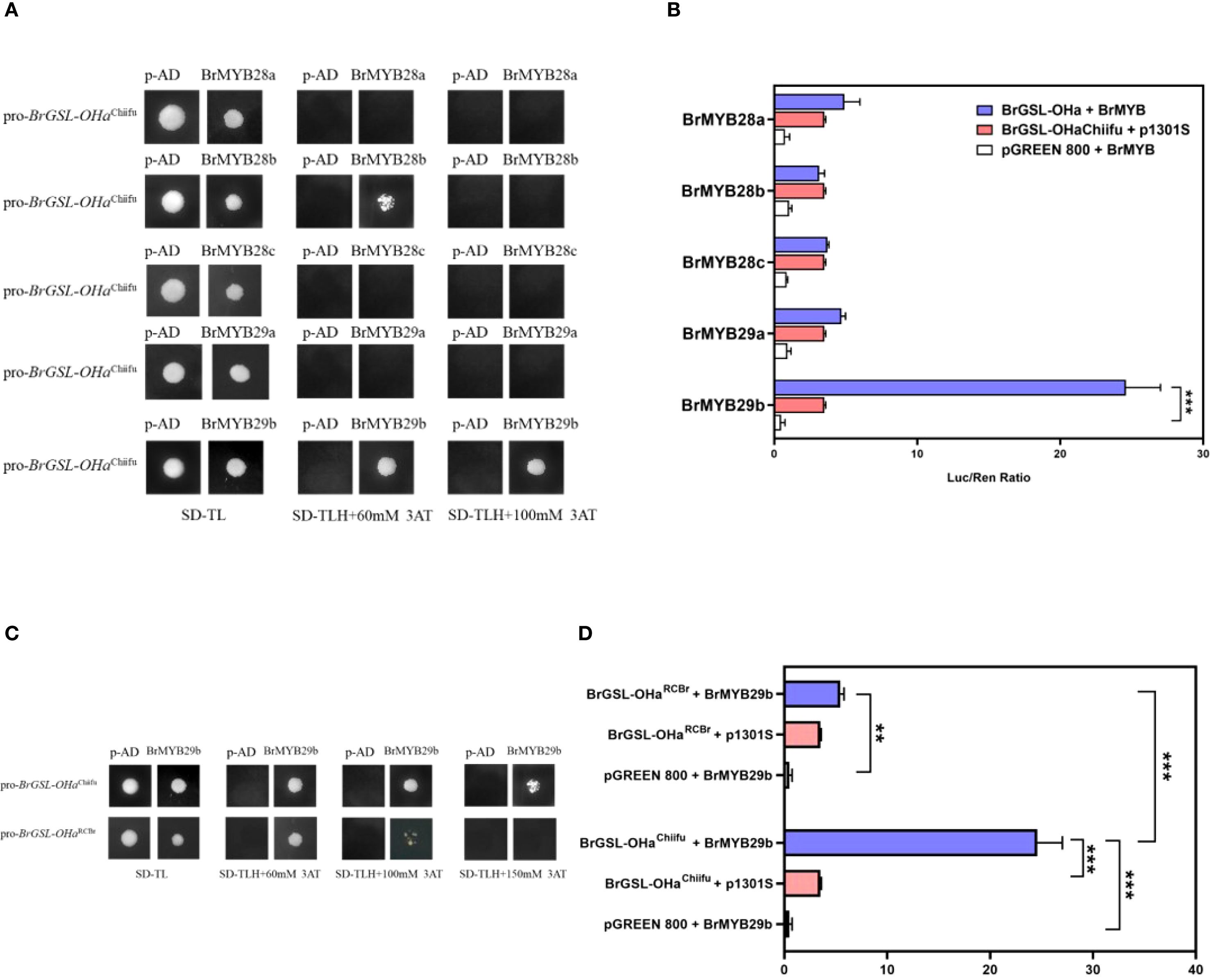

3.5 BrGSL-OHa expression is directly regulated by the transcription factor BrMYB29b in B. rapa

In Arabidopsis, three MYB transcription factors, MYB28, MYB29, and MYB76, have been shown to positively regulate a small number of structural genes in the Ali-GSL pathway (Gigolashvili et al., 2007a, 2007b, 2008; Hirai et al., 2007; Sonderby et al., 2010). In the B. rapa genome, three and two homologous genes to AtMYB28 and AtMYB29 have been identified, respectively, while no genes homologous to AtMYB76 have been reported (Wang et al., 2011a, b; Supplementary Table S2). In the present study, one MBS was detected in the type 1 BrGSL-OHa promoter, but not in KYS and RCBr, two B. rapa oil-type genotypes (Figure 5A). According to the results of yeast one-hybrid and LUC analyses, BrMYB29b (Bra009245), which is homologous to AtMYB29, is a candidate transcription factor binding to cis-elements of the BrGSL-OHaChiifu promoter (Figures 6A, B). Cells transformed with the BrGSL-OHaRCBr promoter lacking an MBS displayed less binding activity than cells transformed with the BrGSL-OHaChiifu promoter, with an increasing 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole concentration (Figure 6C). To further improve this interaction, LUC reporter constructs were generated using two BrGSL-OHa promoter sequences from Chiifu and RCBr, which either contained or lacked an MBS, respectively. As shown in Figure 6D, the use of both the BrGSL-OHaChiifu and BrGSL-OHaRCBr promoters could activate LUC signaling, but the BrGSL-OHaChiifu promoter sequence was associated with significantly higher LUC activity than that of BrGSL-OHaRCBr. These results suggest that BrMYB29b can bind directly to the BrGSL-OHa promoter and affect its expression. The absence of an MBS in the BrGSL-OHa promoter sequence of oil-type B. rapa influenced its ability to bind with BrMYB29b, thereby inhibiting its expression.

Figure 6. Identification of BrMYB29b as a transcription factor target of BrGSL-OHa. (A) Yeast-one hybrid (Y1H) assay of BrMYB29b binding to BrGSL-OHaChiifu promoter fragments among five MYB candidate genes related to glucosinolate (GSL) synthesis. (B) Dual luciferase system (LUC) detection of five MYB candidate genes binding to BrGSL-OHaChiifu promoter. The data are presented as means ± SE from three independent technical replications. Black asterisks (***) indicate a significant difference (t-test, p < 0.01), Black asterisks (**) indicate a significant difference (t-test, p < 0.05). (C) Y1H assay between BrMYB29b with BrGSL-OHaChiifu and BrGSL-OHaRCBr promoter fragments. (D) Binding of BrMYB29b with the BrGSL-OHaChiifu and BrGSL-OHaRCBr promoters according to the LUC assay results.

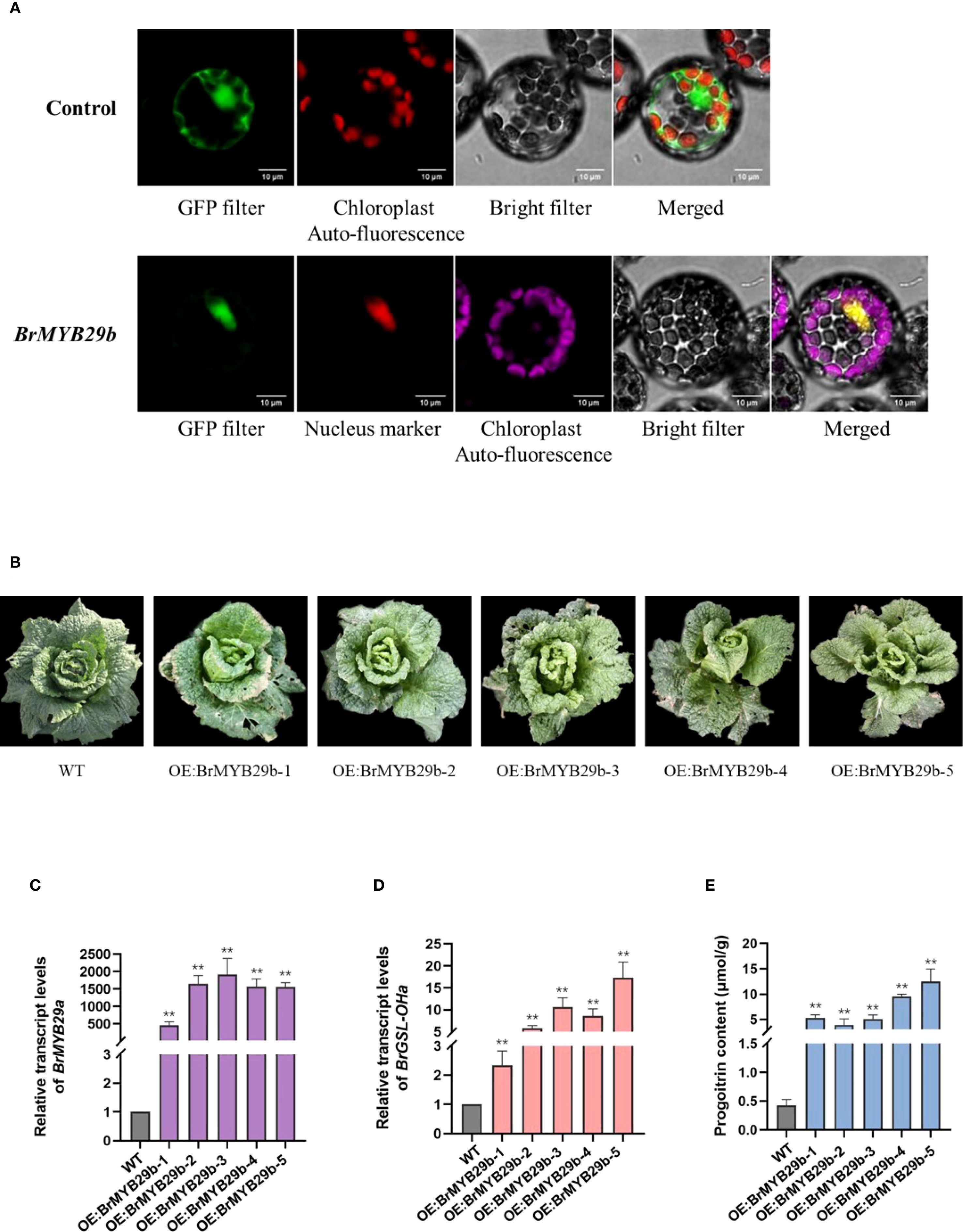

To further validate the function of transcription factor BrMYB29b in B. rapa, this study first constructed BrMYB29b-GFP fusion protein to investigate its cellular localization. The BrMYB29b-GFP fluorescence signal overlapped with a marker for the nucleus (Figure 7A). This indicated that the BrMYB29b protein was located in the nucleus, conforming to the characteristics of transcription factors. Furthermore, this study constructed a BrMYB29b OE vector and transformed it into the Chinese cabbage C-24. In successfully transformed OE transgenic plants (Figure 7B), the BrMYB29b and BrGSL-OHa transcript levels as well as the PRO concentrations were markedly enhanced compared to the wild-type C-24 plants (Figures 7C–E). These results indicate that BrMYB29b is an important transcription factor responsible for positively regulating PRO biosynthesis in B. rapa. In addition, BrMYB29b OE plants displayed 1.5- to two-fold increases in the levels of GRA, GNA, and GBN compared to the wild type, while ALY and GNL did not increase significantly (Supplementary Figure S5). In addition to the BrGSL-OHa gene, the transcript levels of several key GSL biosynthesis-related genes including MAM1 (MAM1a, b, c), AOP2 (AOP2a, b, c), and MYB28 (MYB28a, b, c) also increased (Supplementary Figure S6). In contrast, the expression level of another MYB29 paralog (MYB29a, Bra005949) was not significantly different from that of the wild type. Taken together, these findings suggest that BrMYB29b can positively control Ali-GSL synthesis, with a particular effect on PRO content in B. rapa.

Figure 7. (A) Subcellular colocalization of transiently expressed BrMYB29b-GFP fusion protein with a nucleus marker (nls) in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. (B) Phenotypes of the wild-type C-24 (WT) and BrMYB29b-overexpressing transgenic T2 plants. Relative transcript levels of BrMYB29b (C), BrGSL-OHa (D), and progoitrin content (E) in wild-type and BrMYB29b-overexpressing transgenic plants. The data are presented as means ± SE from three independent biological replications. Black asterisks (**) indicate a significant difference (t-test, p < 0.01).

4 Discussion

GSL biosynthesis is an important but complex trait in Brassica crops. Our study revealed extensive variation in GSL compounds among B. rapa varieties. Three Ali-GSLs, namely, PRO, GNA, and GBN, are dominant compounds in B. rapa leaves, which has been reported previously (Lou et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2010). RCBr plants displayed extremely high GNA content and lower PRO content compared with Chiifu Chinese cabbage. Our discovery of a major QTL cluster on chromosome A03 anchored with tandem MAM genes and MYB transcription factors controlling Ali-GSLs is consistent with meta-QTL analyses in B. oleracea, which also identified conserved hotspots on chromosomes homologous to A. thaliana chromosome 5 (Sotelo et al., 2014). Similarly, in B. napus, GWAS studies have repeatedly identified the BnaA03.MYB28 locus as a major determinant of both leaf and seed GSL content (Liu et al., 2020; Li et al., 2014), underscoring the conserved role of this genomic region across the Brassica genus. Four QTLs without Q x E effects identified using the multi-environment method were co-localized with QTL-Cluster3 for GNL, Ali-4C, GBN, and Ali-5C, suggesting that these QTLs play a stable genetic role and influence the earlier steps of the Ali-GSL biosynthesis pathway in B. rapa. Recently, Zhang et al. (2018) identified a transposon insertion of BrMAM-3 (Bra013007) in the same QTL region associated with total Ali-GSLs. Further fine-scale mapping of this QTL region, expression profiling, and the functional validation of candidate genes are necessary.

Numerous genes involved in GSL biosynthesis have been identified and characterized in Arabidopsis (Kliebenstein et al., 2001b, c; Sonderby et al., 2010). Due to ancestral genome triplication, the B. rapa genome contains duplicated or triplicated homologs of many Arabidopsis genes, including those regulating GSL synthesis (Wang et al., 2011b). This genomic complexity has resulted in multiple copies of most GSL biosynthetic genes (Wang et al., 2011a), complicating the identification of key genetic determinants underlying GSL variation. In Arabidopsis, MYB28 is a central transcription factor regulating aliphatic GSL biosynthesis (Gigolashvili et al., 2007b). Here, we found that two B. rapa homologs, BrMYB28a and BrMYB28b, colocalized with QTL-Cluster1 and QTL-Cluster3, respectively, suggesting their potential role in controlling aliphatic GSL variation. Similarly, in B. napus, four MYB28 paralogs are located near GWAS peaks for seed GSL content (Li et al., 2014), and BnaMYB28 on chromosome A03 has been associated with high leaf but low seed GSL accumulation (Liu et al., 2020). While AtMYB28 directly activates genes such as MAM, CYP79F1, and CYP83A1, functional studies in B. rapa suggest that BrMYB28 paralogs may act as negative regulators of AOP2 and positive regulators of GSL-OH—highlighting potential functional divergence from the Arabidopsis model. Thus, further investigation is needed to clarify the regulatory roles of different BrMYB28 paralogs in the GSL pathway.

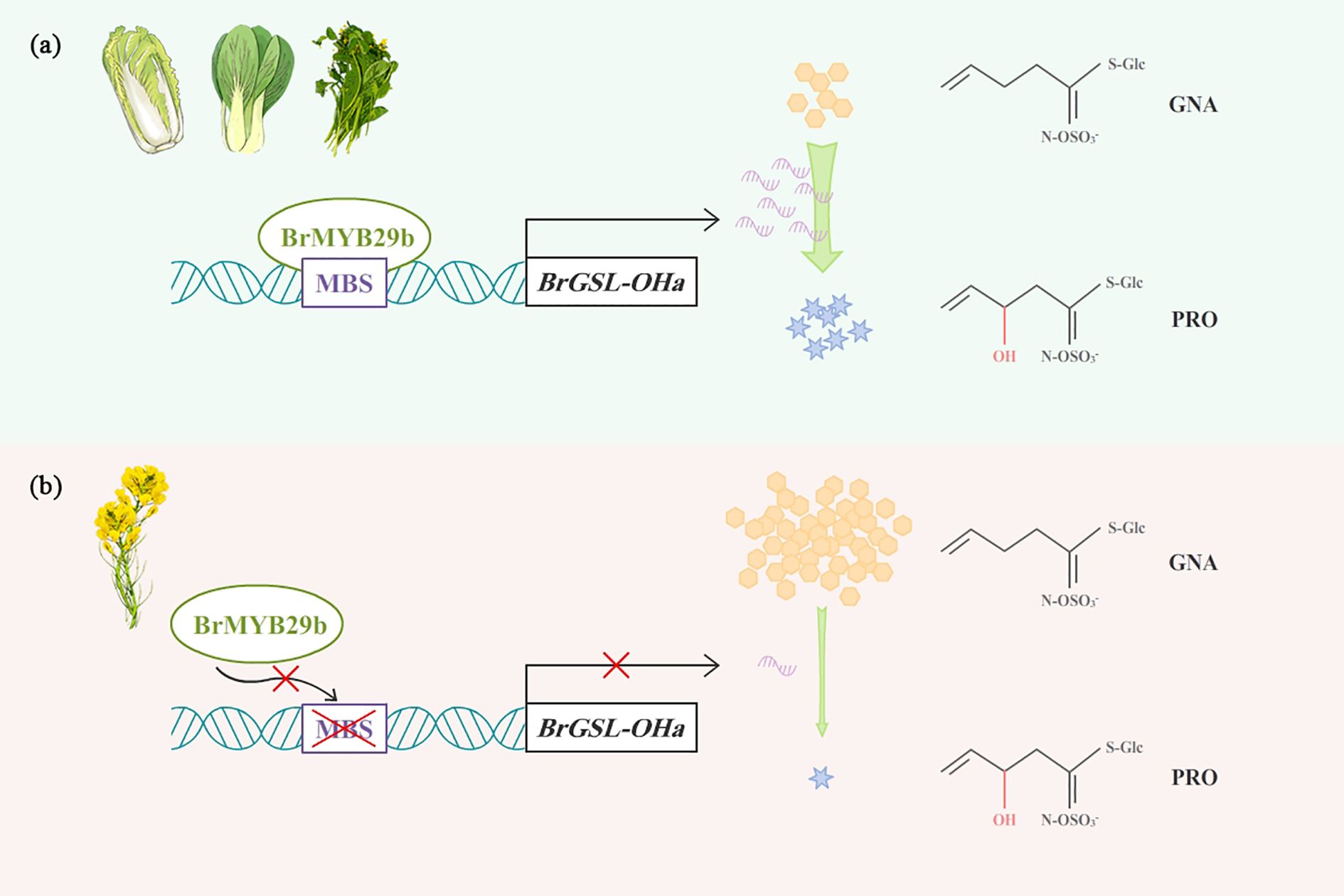

In Arabidopsis, the GSL-OH gene was detected in a strong linkage disequilibrium region associated with PRO and GNL (Brachi et al., 2015) and exerted epistatic effects on fitness with the MAM locus. In the bi-parental population employed in this study, BrGSL-OHa anchored to the hot-spot QTL region controlling GNA, PRO, and GNL contents showed no sequence variation among natural population lines, while variation in its expression may explain this QTL. Further promoter sequence analysis indicated that the lack of an MBS in oil-type RCBr and KYS influenced the interaction between the transcription factor BrMYB29b and BrGSL-OHa and inhibited the expression of BrGSL-OHa, thereby blocking PRO biosynthesis and inducing the massive accumulation of GNA, as shown in the working model (Figure 8). In Arabidopsis, Hansen et al. (2008) cloned GSL-OH loci using fine-scale mapping and found that a repeated 120-bp motif in the AtGSL-OH promoter was related to its transcript and PRO content. This stark contrast highlights that while the function of the GSL-OH enzyme in catalyzing the conversion of GNA to PRO is conserved between Arabidopsis and B. rapa (Hansen et al., 2008), the transcriptional mechanisms governing the expression of their respective genes have diverged significantly, likely reflecting the distinct evolutionary and breeding histories of these species. BrMYB29b OE resulted in increased levels of GRA, GNA, and GBN, while the PRO content increased the most dramatically; this finding demonstrated that BrMYB29b positively regulated Ali-GSLs, particularly PRO, and enhanced the BrGSL-OHa transcription level in B. rapa. The results showed that three B. rapa MYB28 paralogs (MYB28a, b, c) were all activated by the OE of BrMYB29b, which was probably caused by their interaction. Similarly, BoMYB29(2) OE in B. oleracea displayed up-regulated transcription levels of BoGSL-OH(2), BoAOP2(1), and BoMYB28(3). In contrast, Arabidopsis MYB29 was activated by MYB28, whereas MYB28 was neither strongly activated nor repressed by MYB29. Additionally, the expression level of BrMYB29a paralog showed no change in BrMYB29b OE transgenic plants compared to the wild type (Supplementary Figure S6). This demonstrated that the paralog function of BrMYB29a was independent on BrMYB29b. It is speculated that B. rapa MYB28/MYB29 paralogs exhibit functional differentiation in the GSL synthesis pathway and are probably able to activate different biosynthetic genes directly. Therefore, more work is needed to elucidate the functions and regulatory networks of these MYB transcription factors in B. rapa.

Figure 8. A proposed model for BrMYB29b binding to BrGSL-OHa promoter to regulate PRO biosynthesis in B. rapa. (A) In vegetable and most oil type B. rapa, BrMYB29b interacted with BrGSL-OHa promoter and leads to high expression of BrGSL-OHa that promotes PRO synthesis. (B) In two oil-type B. rapa, RCBr and KYS, lack of MBS in BrGSL-OHa promoter affects the binding ability with BrMYB29b, thus inhibiting BrGSL-OHa expression and PRO conversion from GNA.

Beyond elucidating a key molecular mechanism controlling GSL variation, our discovery of a rare, non-functional BrGSL-OHa allele in specific oil-type lines provides insight into potential adaptive or human-directed selection. Progoitrin is an anti-nutritional compound that diminishes the quality of oilseed meal for animal feed. The MBS deletion, resulting in low PRO and high GNA accumulation, likely represents a desirable trait that was inadvertently or deliberately selected during the breeding of these specific oil-type lineages. This allele is not widespread even among oil-types, suggesting it is a valuable, niche genetic resource rather than a universal domestication trait. Its identification enables the use of marker-assisted selection to precisely introgress this allele into elite oilseed B. rapa cultivars, aiming to improve meal quality without compromising other agronomic traits. Conversely, in vegetable-type B. rapa where certain GSLs contribute to flavor and disease resistance, the functional Pro-type1 allele would be preferred. Therefore, understanding the lineage-specificity of this mutation empowers breeders to tailor glucosinolate profiles for different end uses, balancing defense, nutrition, and consumer preference.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

JZ: Writing – original draft. SC: Writing – original draft. YJ: Writing – review & editing, Validation. WZ: Validation, Writing – review & editing. YS: Writing – review & editing, Resources. XL: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. YL: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by a National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31701930 and 32272715), a China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2016M601345 and 2019T120219), Applied Basic Research Program of Department of Science and Technology of Liaoning Province (Grant No. 2022JH2/101300169), and Scientific Research Fund project of Education Department of Liaoning Province (LJKMZ20221024). This work was also supported by Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, and Forestry (IPET) through Golden Seed Project (213006-05-4-SB110), funded by Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA), Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (MOF), Rural Development Administration (RDA) and Korea Forest Services (KFS).

Acknowledgments

We thank to Dr Wenxing Pang from Shenyang Agricultural University for sampling and field work. We thank LetPub (www.letpub.com.cn) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1654238/full#supplementary-material

References

Bisht, N. C., Gupta, V., Ramchiary, N., Sodhi, Y. S., Mukhopadhyay, A., Arumugam, N., et al. (2009). Fine mapping of loci involved with glucosinolate biosynthesis in oilseed mustard (Brassica juncea) using genomic information from allied species. Theor. Appl. Genet. 118, 413–421. doi: 10.1007/s00122-008-0907-z

Boer, M. O., Wright, D., Feng, L., Podlich, D. W., Luo, L., Cooper, M., et al. (2007). A mixed-model quantitative trait loci (QTL) analysis for multiple-environment trial data using environmental covariables for QTL-by-environment interactions, with an example in maize. Genetics 177, 1801–1813. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.071068

Brachi, B., Meyer, C. G., Villoutreix, R., Platt, A., Morton, T. C., Roux, F., et al. (2015). Coselected genes determine adaptive variation in herbivore resistance throughout the native range of Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, 4032–4037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421416112

Fahey, J. W., Zalcmann, A. T., and Talalay, P. (2001). The Chemical diversity and distribution of glucosinolates and isothiocyanates among plants. Phytochemistry 56, 5–51. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00316-2

Feng, J., Long, Y., Shi, L., Shi, J., Barker, G., and Meng, J. (2012). Characterization of metabolite quantitative trait loci and metabolic networks that control glucosinolate concentration in the seeds and leaves of Brassica napus. New Phytol. 193, 96–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03890.x

Frerigmann, H. and Gigolashvili, T. (2014). MYB34, MYB51, and MYB122 distinctly regulate indolic glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant 7, 814–828. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssu004

Gigolashvili, T., Berger, B., Mock, H. P., Muller, C., Weisshaar, B., and Flugge, U. (2007a). The transcription factor HIG1/MYB51 regulates indolic glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 50, 886–901. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03099.x

Gigolashvili, T., Engqvist, M., Yatusevich, R., Muller, C., and Flugge, U. I. (2008). HAG2/MYB76 and HAG3/MYB29 exert a specific and coordinated control on the regulation of aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 177, 627–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02295.x

Gigolashvili, T., Yatusevich, R., Berger, B., Muller, C., and Flugge, U. I. (2007b). The R2R3-MYB transcription factor HAG1/MYB28 is a regulator of methionine-derived glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 51, 247–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03133.x

Hansen, B. G., Kerwin, R. E., Ober, J. A., Lambrix, V. M., Mitchell-Olds, T., Gershenzon, J., et al. (2008). A novel 2-oxoacid-dependent dioxygenase involved in the formation of the goiterogenic 2-hydroxybut-3-enyl glucosinolate and generalist insect resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 148, 2096–2108. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.129981

Harper, A. L., Trick, M., Higgins, J., Fraser, F., Clissold, L., Wells, R., et al. (2012). Associative transcriptomics of traits in the polyploid crop species Brassica napus. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 798–802. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2302

Hirai, M. Y., Sugiyama, K., Sawada, Y., Tohge, T., Obayashi, T., Suzuki, A, et al. (2007). Omics-based identification of Arabidopsis Myb transcription factors regulating aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 6478–6483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611629104

Hirani, A. H., Zeimer, C. D., McVetty, P. B. E., Daayf, F., and Li, G. (2013). Homoeologous GSL-ELONG gene replacement for manipulation of aliphatic glucosinolates in Brassica rapa L. by marker assisted selection. Front. Plant Sci. 4. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00055

Kim, J. K., Chu, S. M., Kim, S., Lee, D., Lee, S. Y., Lim, S. H., et al. (2010). Variation of glucosinolates in vegetable crops of Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis. Food Chem. 119, 423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.08.051

Kim, Y. B., Li, X., Kim, S. J., Kim, H. H., Lee, J., Kim, H. R., et al. (2013). MYB transcription factors regulate glucosinolate biosynthesis in different organs of Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis). Molecules 18, 8682–8695. doi: 10.3390/molecules18078682

Kittipol, V., He, Z., Wang, L., Doheny-Adams, T., Langer, S., and Bancroft, I. (2019). Genetic architecture of glucosinolate variation in Brassica napus. J. Plant Physiol. 240, 152988. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2019.06.001

Kliebenstein, D. J., Gershenzon, J., and Mitchell-Olds, T. (2001a). Comparative quantitative trait loci mapping of aliphatic, indolic and benzylic glucosinolate production in Arabidopsis thaliana leaves and seeds. Genetics 159, 359–370. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.1.359

Kliebenstein, D. J., Kroymann, J., Brown, P., Figuth, A., Pedersen, D., Gershenzon, J., et al. (2001b). Genetic control of natural variation in Arabidopsis glucosinolate accumulation. Plant Physiol. 126, 811–825. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.2.811

Kliebenstein, D. J., Lambrix, V. M., Reichelt, M., Gershenzon, J., and Mitchell-Olds, T. (2001c). Gene duplication in the diversification of secondary metabolism: tandem 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases control glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 13, 681–693. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.3.681

Kloss, P., Jeffery, E., Tumbleson, M., Zhang, Y., Parsons, C., and Wallig, M. (1996). Studies on the toxic effects of crambe meal and two of its constituents, 1-cyano-2-hydroxy-3-butene (CHB) and epi-progoitrin, in broiler chick diets. Br. Poult. Sci. 37, 971–986. doi: 10.1080/00071669608417928

Kroymann, J., Textor, S., Tokuhisa, J. G., Falk, K. L., Bartram, S., Gershenzon, J., et al. (2001). A gene controlling variation in Arabidopsis glucosinolate composition is part of the methionine chain elongation pathway. Plant Physiol. 127, 1077–1088. doi: 10.1104/pp.127.3.1077

Li, F., Chen, B., Xu, K., Wu, J., Song, W., Bancroft, I., et al. (2014). Genome-wide association study dissects the genetic architecture of seed weight and seed quality in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). DNA Res. 21, 355–367. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsu002

Li, X., Li, H., Zhao, Y., Zong, P., Zhan, Z., and Piao, Z. (2021). Establishment of a simple and efficient Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation system to Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). Hortic. Plant J. 7, 117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.hpj.2021.01.006

Li, G. and Quiros, C. F. (2002). Genetic analysis, expression and molecular characterization of BoGSL-ELONG, a major gene involved in the aliphatic glucosinolate pathway of Brassica species. Genetics 162, 1937. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.4.1937

Li, G. and Quiros, C. F. (2003). In planta side-chain glucosinolate modification in Arabidopsis by introduction of dioxygenase Brassica homolog BoGSL-ALK. Theor. Appl. Genet. 106, 1116–1121. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1161-4

Li, X., Ramchiary, N., Choi, S. R., Van Nguyen, D., Hossain, M. J., Yang, H. K., et al. (2010). Development of a high density integrated reference genetic linkage map for the multinational Brassica rapa Genome Sequencing Project. Genome 53, 939–947. doi: 10.1139/G10-054

Li, X., Ramchiary, N., Dhandapani, V., Choi, S. R., Hur, Y., Nou, I. S., et al. (2013). Quantitative trait loci mapping in Brassica rapa revealed the structural and functional conservation of genetic loci governing morphological and yield component traits in the A, B, and C subgenomes of Brassica species. DNA Res. 20, 1–16. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dss029

Liu, S., Huang, H., Yi, X., Zhang, Y., Yang, Q., Zhang, C., et al. (2020). Dissection of genetic architecture for glucosinolate accumulations in leaves and seeds of Brassica napus by genome-wide association study. Plant Biotechnol. J. 18, 1472–1484. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13314

Lou, P., Zhao, J., He, H., Hanhart, C., Del Carpio, D. P., Verkerk, R., et al. (2008). Quantitative trait loci for glucosinolate accumulation in Brassica rapa leaves. New Phytol. 179, 1017–1032. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02530.x

Lu, G., Harper, A. L., Trick, M., Morgan, C., Fraser, F., O’Neill, C., et al. (2014). Associative transcriptomics study dissects the genetic architecture of seed glucosinolate content in Brassica napus. DNA Res. 21, 613–625. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsu024

Pino Del Carpio, D., Basnet, R. K., Arends, D., Lin, K., De Vos, R. C. H., Muth, D., et al. (2014). Regulatory network of secondary metabolism in Brassica rapa: insight into the glucosinolate pathway. PloS One 9, e107123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107123

Ramchiary, N., Bisht, N. C., Gupta, V., Mukhopadhyay, A., Arumugam, N., Sodhi, Y. S., et al. (2007). QTL analysis reveals context-dependent loci for seed glucosinolate trait in the oilseed Brassica juncea: importance of recurrent selection backcross scheme for the identification of ‘true’ QTL. Theor. Appl. Genet. 116, 77–85. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0648-4

Rout, K., Sharma, M., Gupta, V., Mukhopadhyay, A., Sodhi, Y. S., Pental, D., et al. (2015). Deciphering allelic variations for seed glucosinolate traits in oilseed mustard (Brassica juncea) using two bi-parental mapping populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 128, 657–666. doi: 10.1007/s00122-015-2461-9

Seo, M. S., Jin, M., Chun, J. H., Kim, S. J., Park, B. S., and Shon S.H. and Kim, J. S. (2016). Functional analysis of three BrMYB28 transcription factors controlling the biosynthesis of glucosinolates in Brassica rapa. Plant Mol. Biol. 90, 503–516. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0437-z

Sharma, C., Sadrieh, L., Priyani, A., Ahmed, M., Hassan, A. H., and Hussain, A. (2011). Anti-carcinogenic effects of sulforaphane in association with its apoptosis-inducing and anti-inflammatory properties in human cervical cancer cells. Cancer Epidemiol. 35, 272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2010.09.008

Smolinska, U., Morra, M. J., Knudsen, G. R., and Brown, P. D. (1997). Toxicity of Glucosinolate degradation products from Brassica napus seed meal toward aphanomyces euteiches f. sp. pisi. Phytopathology 87, 77–82. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1997.87.1.77

Sonderby, I. E., Burow, M., Rowe, H. C., Kliebenstein, D. J., and Halkier, B. A. (2010). A complex interplay of three R2R3 MYB transcription factors determines the profile of aliphatic glucosinolates in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 153, 348–363. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.149286

Sotelo, T., Soengas, P., Velasco, P., Rodriguez, V. M., and Cartea, M. E. (2014). Identification of metabolic QTLs and candidate genes for glucosinolate synthesis in Brassica oleracea leaves, seeds and flower buds. PloS One 9, e91428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091428

Soundararajan, P. and Kim, J. (2018). Anti-carcinogenic glucosinolates in cruciferous vegetables and their antagonistic effects on prevention of cancers. Molecules 23, 2983. doi: 10.3390/molecules23112983

Wang, X., Wang, H., Wang, J., Sun, R., Wu, J., Liu, S., et al. (2011b). The genome of the mesopolyploid crop species Brassica rapa. Nat. Genet. 43, 1035–1039. doi: 10.1038/ng.919

Wang, H., Wu, J., Sun, S., Liu, B., Cheng, F., Sun, R., et al. (2011a). Glucosinolate biosynthetic genes in Brassica rapa. Gene 487, 135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.07.021

Wittstock, U. and Burow, M. (2001). Glucosinolate breakdown in arabidopsis. Arabidopsis. Book. 8, e0134. doi: 10.1199/tab.0134

Yang, J., Wang, J., Li, Z., Li, X., He, Z., Zhang, L., et al. (2021). Genomic signatures of vegetable and oilseed allopolyploid Brassica juncea and genetic loci controlling the accumulation of glucosinolates. Plant Biotech. J. 19, 2619–2628. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13687

Yoo, S. D., Cho, Y. J., and Sheen, J. (2007). Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1565–1572. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.199

Zang, Y. X., Kim, H. U., Kim, J. A., Lim, M.H., Jin, M., Lee, S.C., et al. (2009). Genome-wide identification of glucosinolate synthesis genes in Brassica rapa. FEBS J. 276, 3559–3574. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07076.x

Zhang, Y., Jiang, M., Ma, J., Chen, J., Kong, L., Zhan, Z., et al. (2025). Metabolomics and transcriptomics reveal the function of trigonelline and its synthesis gene BrNANMT in clubroot susceptibility of Brassica rapa. Plant. Cell Environ., pce.15474. doi: 10.1111/pce.15474

Zhang, J., Liu, Z., Liang, J., Wu, J., Cheng, F., and Wang, X. (2015). Three genes encoding AOP2, a protein involved in aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis, are differentially expressed in Brassica rapa. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 6205–6218. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv331

Zhang, J., Wang, H., Liu, Z., Liang, J., Wu, J., Cheng, F., et al. (2018). A naturally occurring variation in the BrMAM-3 gene is associated with aliphatic glucosinolate accumulation in Brassica rapa leaves. Hortic. Res. 5, 69. doi: 10.1038/s41438-018-0074-6

Zhao, F., Zhao, T., Deng, L., Lv, D., Zhang, X., Pan, X., et al. (2017). Visualizing the essential role of complete virion assembly machinery in effificient hepatitis C virus cell-to-cell transmission by a viral infection-activated split-intein-mediated reporter system. J. Virol. 91, e01720–e01716. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01720-16

Zheng, J., Zhou, Y., Sun, Y., and Li, X. (2025). Brassica-specific orphan gene CROG1 confers clubroot resistance in Arabidopsis via phenylpropanoid pathway activation. Plants 14, 2683. doi: 10.3390/plants14172683

Zhu, B., Liang, Z., Zang, Y., Zhu, Z., and Yang, J. (2022). Diversity of glucosinolates among common Brassicaceae vegetables in China. Hortic. Plant J. 9, 365–380. doi: 10.1016/j.hpj.2022.08.006

Keywords: Brassica rapa, glucosinolates, QTL, BrGSL-OHa, BrMYB29b

Citation: Zheng J, Choi SR, Jing Y, Zhang W, Sun Y, Li X and Lim YP (2025) A naturally occurring promoter variation of BrGSL-OHa contributes to the conversion of gluconapin to progoitrin in Brassica rapa L. leaves. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1654238. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1654238

Received: 26 June 2025; Accepted: 08 September 2025;

Published: 24 September 2025.

Edited by:

Ryo Fujimoto, Kobe University, JapanReviewed by:

Nadia Raboanatahiry, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, ChinaFeng Liu, Shihezi University, China

Shuanghua Wu, Hunan Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS), China

Copyright © 2025 Zheng, Choi, Jing, Zhang, Sun, Li and Lim. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaonan Li, Z3JhY2VzbGVleG44M0BzeWF1LmVkdS5jbg==; Yong Pyo Lim, eXBsaW1AY251LmFjLmty

†Present address: Yong Pyo Lim, Department of Smart Farming, Konyang University, Nonsan, Republic of Korea

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work

Jingyi Zheng

Jingyi Zheng Su Ryun Choi

Su Ryun Choi Yue Jing1

Yue Jing1 Xiaonan Li

Xiaonan Li Yong Pyo Lim

Yong Pyo Lim