- 1Division of Soil Science and Agricultural Chemistry, Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Jammu, Jammu, India

- 2Directorate of Research, Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Jammu, Jammu, India

- 3Division of Soil and Water Engineering, Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Jammu, Jammu, India

- 4Division of Vegetables, Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Jammu, Jammu, India

- 5Multidisciplinary Unit of Research on Translational Initiatives (MURTI) GITAM Deemed to be University and Department of Civil Engineering, GITAM School of Technology, Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India

- 6Department of Botany and Microbiology, College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 7Amity Institute of Biotechnology, Amity University, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

- 8Department of Plant Production, College of Food Science and Agriculture, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 9Amity Institute of Environmental Sciences (AIES), Amity University Uttar Pradesh (AUUP), Noida, India

- 10Lovely Professional University, Jalandhar, Punjab, India

- 11Indian Institute of Technology, Jammu, India

- 12Department of Physics and Earth Science, University of A Coruna, A Coruña, Spain

- 13Department of Chemistry, KLE Technological University, Hubli, Karnataka, India

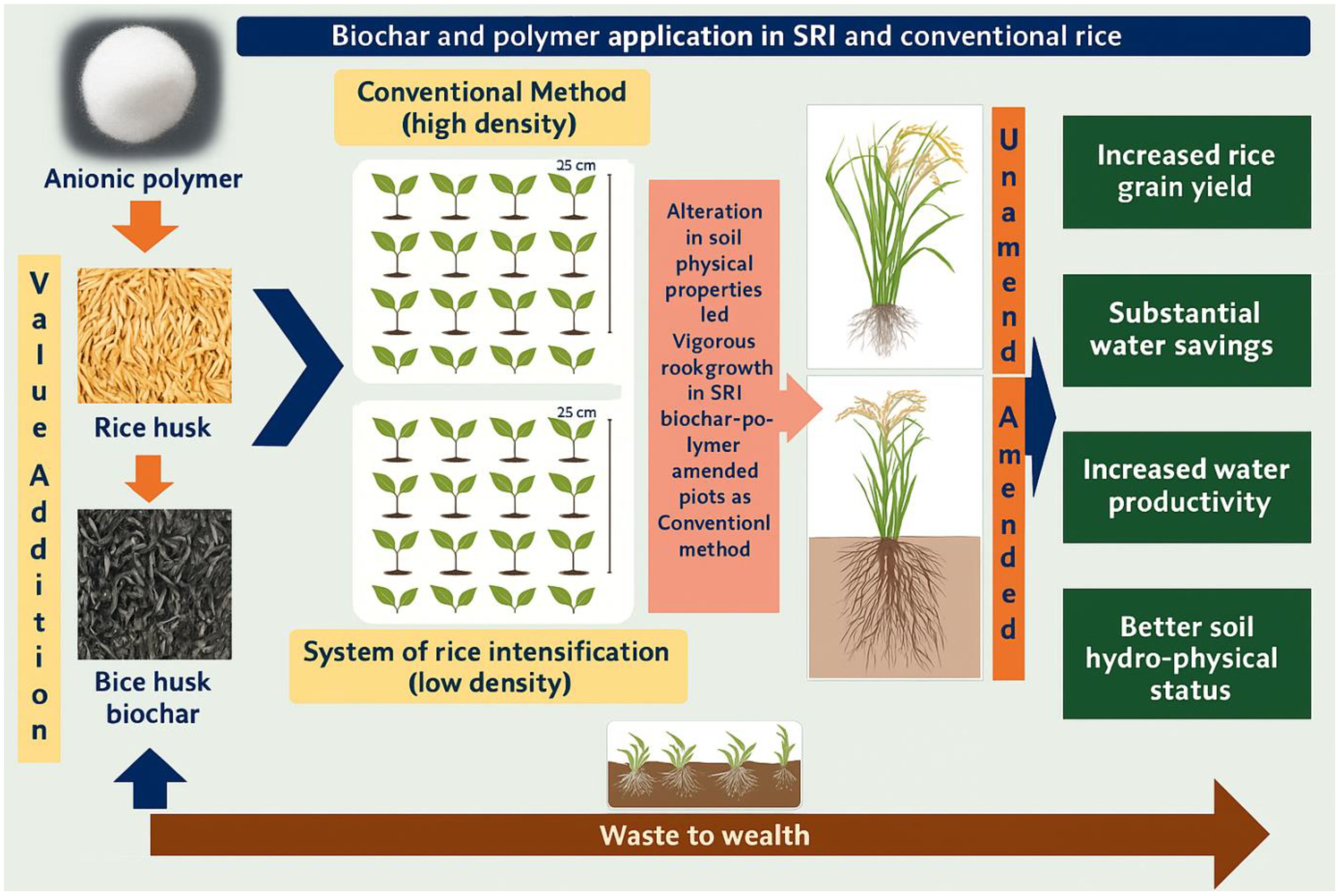

Introduction: Efficient water use while maintaining rice productivity remains a major challenge amid declining water resources. Biochar with large surface area and hydrophilic polymers, such as anionic polyacrylamide (PAM), can enhance soil moisture and nutrient retention. However, their combined effects on rice growth and soil hydro-physical properties have not been fully explored.

Methods: This study evaluated the influence of biochar and PAM on soil properties, water retention, root growth, and rice performance under two establishment methods: the System of Rice Intensification (SRI) and Conventional Method (CM). A two-year field experiment was conducted on sandy clay loam soil using a split-plot design with SRI and CM as main plots and six soil amendment treatments (control, biochar, and polymer) as subplots, replicated thrice.

Results and discussion: Results showed that SRI produced 15% higher grain yield while using 28.2% less irrigation water compared with CM. SRI also improved soil moisture (SM) content, infiltration rate (IR), hydraulic conductivity (HC), and water productivity (WP) by 6.6%, 64 5.4%, 9.0%, and 46.5%, respectively. Root length and weight densities under SRI were 1.31 and 1.62 times higher than under CM. The application of biochar (10 t ha⁻¹) and PAM (10 kg 66 ha⁻¹) significantly enhanced soil physical attributes, resulting in 1.22 and 1.27 times increases in grain yield and root length density, respectively, over the control. Integrating biochar and polymer with SRI reduced irrigation water use by 39.45% compared with CM. Overall, the combination of biochar (10 t ha⁻¹) and PAM (10 kg ha⁻¹) under SRI effectively improved soil hydro-physical properties, root development, water productivity, and rice yield in the sub-humid tropical Inceptisols of northern India.

Highlights

● Biochar and polymer amendments enhanced soil properties and crop yield.

● The SRI method achieved 15% higher rice yield with 39.5% less irrigation water.

● Combining SRI with biochar and polymer increased rice yield by 1.22-fold.

● Integrated SRI–biochar–polymer treatment reduced irrigation demand by 1.39-fold.

● Root length and weight densities improved by 1.31and 1.62-fold, respectively.

1 Introduction

Water scarcity and waste management in agriculture are primary bottlenecks in attaining the required growth in food productivity to sustain 9 billion people by 2050 (Deng et al., 2023). About 70% increase in food production is required to meet global food demands, while the water requirement for food and fiber production is projected to rise by 41.5% by 2050 (Mekonnen and Hoekstra, 2020).Agriculture alone consumes 72% of global freshwater, which is likely to escalate twice as fast as population growth (FAO, 2021). India is the world’s second-largest rice producer, followed by China, with 60% of its own consumption (Bandumula, 2018). According to a recent study, the primary rice producer country during the year 2020–2021 was China, which produced 148.30 million tonnes (Mt), followed by India (120.00 Mt), Bangladesh (35.30 Mt), Indonesia (34.90 Mt), and Vietnam (27.10 Mt) (Mohidem et al., 2022).

India contributes to 65% of the global rice production from only 20% of its cultivated land (Angha et al., 2024), wherein more than 90%of basmati rice production comes from the northwest states of India. Rice is a water-intensive staple food crop, consuming 34 – 43% of the global irrigation water and generating a considerablequantity of crop waste (Muthayya et al., 2014). On average, farmers use 3000–5000 liters of water to produce one kilogram of rice, whereas 2500 liters of water is enough to produce one kilogram of rice (Mandal et al., 2019). This highlights that 500–2500 liters of superfluous water is lost due to evapotranspiration, surface runoff, seepage, deep percolation, and the lack of adequate water-conserving techniques (Materu et al., 2018). Thus, it is imperative to develop appropriate water-conserving strategies that facilitate water retention, sustain rice yield and preserve ecological equilibrium in tropical and subtropical regions characterized by inadequate soil fertility and low water-holding capacity (Sharma et al., 2021; Saini et al., 2025).

The hydro-physical properties of soil significantly impact soil health by influencing the movement of water, root development and retention of nutrients (Blanco-Canqui et al., 2013; Abrol et al., 2024; Sharma et al., 2025b). Rice plants are traditionally cultivated by transplanting one-month-old seedlings in continuously flooded conditions. This method has several negative effects, including hindering root growth, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions, degrading soil structure (Dhanda et al., 2022; Ahmed et al., 2025), requiring a significant amount of water, and leading to low crop yields (Mandal et al., 2019; Mohapatra et al., 2023). The rice intensification (SRI) system is a novel rice cultivation technique that differs from conventional methods (Stoop et al., 2002; Mboyerwa et al., 2022). The key practices of SRI include transplanting younger plants in wider spacing, implementing alternate wetting and drying irrigation regimes, incorporating organic matter into the soil, and adopting judicious nutrient management. In addition, SRI involves soil management practices that include reduced water consumption, enhanced root development, improved soil properties through alternate wetting and drying conditions, and greatereconomic returns with higher crop yields compared to conventional methods (Thakur et al., 2013; Bagheri et al., 2021). Many researchers have also documented the adverse consequences of SRI on soil quality and crop yield (Pan et al., 2009; Sriphirom et al., 2019) and more pronounced root growth in flooded conditions compared to SRI (Suwarto et al., 2019).

Biochar is widely documented as a carbon-rich, low-cost soil amendment, adsorbent, and an alternative to agricultural waste management (Abrol et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2022; Abhishek et al., 2022; Bolan et al., 2024; Shaheen et al., 2025; Sharma et al., 2025a). In addition, incorporating biochar into soil improves soil quality by increasing soil water content, promoting soil stability, stimulating microbial activity, and retaining nutrients, thus leading to increased crop productivity (Laird et al., 2010; Abrol et al., 2016; Rawat et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2025b). Rice is cultivated in a major part of northern India under subtropical conditions that remain threatened by water scarcity due to uneven rainfall distribution, high temperature, and continuous water evaporation from flooded rice fields. Under these conditions, biochar amendment could be an effective strategy to combat these issues. Studies indicated that biochar application under water-scarce conditions in subtropical rice fields increased yield by 15-20% and enhanced water retention compared to untreated soils (Sharma et al., 2021). Furthermore, biochar aids carbon sequestration, increase crop yield and decrease toxic metal bioavailability due to its aromatic structure (Subedi et al., 2017; Kumar et al., 2018; Bolan et al., 2022; Ghani et al., 2024). Many researchers have reported an increase in root biomass with biochar application (Liu et al., 2021), while others have shown negative or no effect on root biomass (Zhu et al., 2020; Almaroai and Eissa, 2020).

Anionic polyacrylamide (PAM) is a high-molecular-weight polymer that can enhance aggregate stability, increase soil fertility, and prevent soil erosion (Sojka et al., 2007; Amiri et al., 2017; Kebede et al., 2020). Furthermore, PAM is an environmentally friendly material (Green et al., 2000), and it has been used as a soil amendment in agricultural field (Goebel et al., 2005; John et al., 2005). Many studies have shown that combining biochar with PAM improves soil structure, conserves water, and minimizes soil loss (Green et al., 2000; Abrol et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2023; Deng et al., 2023).

The synergistic impact of biochar and polymers in System of SRIand flooded rice farming has seldom been examined by any previous studies. We posited that incorporating biochar and polymer as soil amendments will modify soil physical properties, thus affect crop performance and enhance water usage efficiency. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of biochar, polymer, and their combination on soil hydraulic parameters, root development dynamics, water retention, and rice yield under conventional and SRI system approaches.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Location, climate, and soil

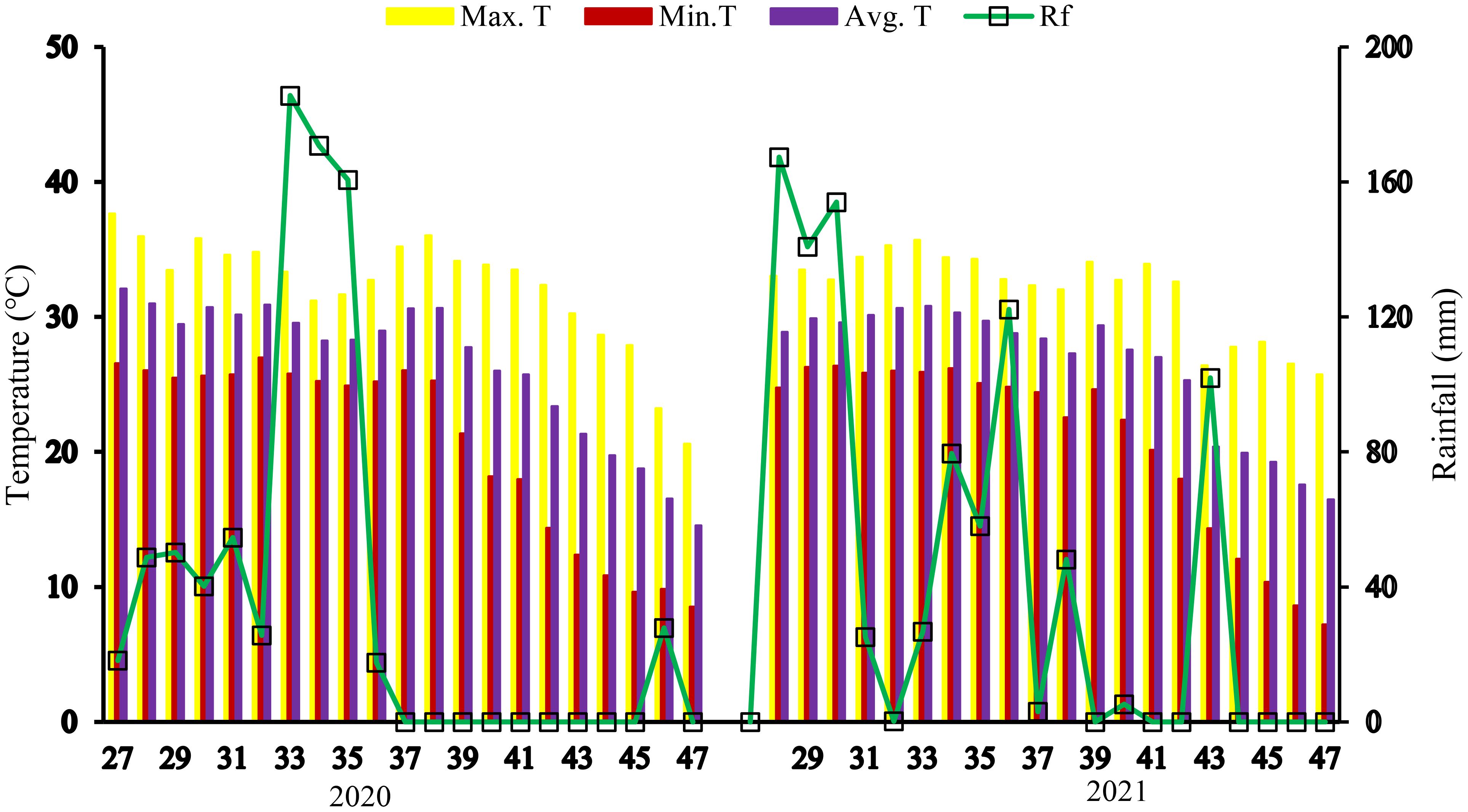

Field experiments were carried out on sandy clay loam soil during Kharif season(June-Oct) in 2020 and 2021 at Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Jammu (32° 40′ N, 74° 58′ E). The study area is subhumid tropical, with an annual rainfall of 1077.8 mm. The total amount of rainfall obtained in the first and second years of the trial was 802mm and 934.5 mm, respectively. Weather data were collected from the Agrometeorological weather station in the university (Figure 1).Soil samples were collected from a depth of 0–15 cm at the time of rice harvesting and analyzed during both Kharif seasons across successive years. The soil pH was slightly alkaline (7.5) and contained 0.44% organic carbon, low in available nitrogen (205.24 kg ha-1), medium in phosphorus (12.63 kg ha–1), and high in potassium level (138.75 kg ha–1). The EC of soil was in safer limit for crop growth.

Figure 1. Average weekly temperature and rainfall during the Kharif season (July to Oct) in 2020 and 2021.

2.2 Experimental setup

The treatments comprised two rice establishment methods, viz, system of SRI and conventional flooded method (CM), in main plots along with six soil amendments (SA) treatments (control, sole and combined application of biochar and polymer) in subplots in a split-plot design replicated thrice. The treatment detail is presented in Table 1. The experimental plot size was 4 × 3m with two-meter buffer strips between the main plots and one meter between subplots to minimize adjacent movement of water. Rice was sown in the same plots for both years of study. Two seedlings per hill of Basmati 370 were transplanted at a spacing of 20×15 cm after attaining twenty-one days of growth in the conventional method, while in SRI, twelve-day-old seedlings per hill were planted, maintaining a spacing of 25×25cm. The recommended fertilizer (N 30:P2O520:K2O10kgha–1) was applied in all the plots uniformly (100% RDF) using urea, diammonium phosphate, and muriate of potash in accordance with the package of practices. In the conventional method, 1/3 of the urea was applied during puddling and 2/3 was applied at tillering and before the panicle initiation stage. Under SRI practice, basal fertilizer application includes half the recommended nitrogen, and full dose of phosphorus and potassium, followed by a half dose of N (1/4th at twenty days after transplanting and 1/4th one week before panicle initiation).

2.3 Irrigation details

To determine the irrigation requirement, the Penman method modified by FAO was taken as illustrated in Equation 1:

where,

ETc = Crop Evapotranspiration (mmday-1)

Kc = Crop Coefficient

ET0= Reference crop evapotranspiration in mmday-1

Kc values of rice were calculated using FAO manual, and are presented in Supplementary Table 1. In CM, 1331 mm and 1096 mm irrigation depth was applied in 2020 and 2021, respectively to maintain a recommended irrigation depth of 70 mm depth. The subsequent irrigation was applied three days after the disappearance of ponded water. In the SRI, 1087 mm and 912 mm water was applied in 2020 and 2021, respectively, in irrigation depth of 25 mm after emergence of fine hair-like cracks in soil. The plots were kept at saturation from panicle initiation up to 15 days before harvesting. In both crop establishment methods, the plots were drained two weeks prior to harvesting.

Biochar was produced from rice husk by pyrolyzing it at 450°C for 2 hours in a slow pyrolysis rector and characterized for physicochemical properties as discussed in the earlier publication (Sharma et al., 2021).Before application, the biochar was crushed and sieved through 4 mm mesh manual sieve. An anionic granular polymer (A110; Cytec, Inc., North Andover, MA, USA) with a large molecular weight (12 × 106 Da) was also used for supplementation. This polymer reportedly improves soil structural stability, as reported in previous studies (Ben-Hur et al., 1992; Levy et al., 1992; Yu et al., 2003). Both soil amendments, biochar and polymer were incorporated once into the soil before the transplantation ofthe rice crop as per treatment. Specifically, the biochar and polymer were applied into the soil in a sequence of six different treatment methods: T1: No amendment, T2: 5 tonnes biochar ha-1, T3: 10 kg polymerha-1, T4: 5 tonnes biochar ha-1 + 10 kg polymerha-1, T5: 10 tonnes biochar ha-1, T6: 10 tonnes biochar ha-1 + 10 kg polymerha-1.

2.4 Data collection and analysis

Plant root samples were extracted from each plot using a 8 cm diameter and 15 cm long core sampler in both seasons and washed over a 1 mm sieve. Root dry weight was measured after drying at 65°C for 24 hrs, and root length was calculated using the Tennant method (Tennant, 1975). Root morphological attributes, and including root diameter (RD), root volume (RV), root length density (RLD) (mmcm–3), and root weight density (RWD) (gcm–3), were computed using Equations 2 and 3:

where RL is the root length (cm), RW is the root weight (g), and V is the volume of the soil core.

At harvest, soil moisture (SM) was determined at a depth of 0–15 cm by digital moisture probe. The Decagon Minidisc infiltrometer was used to measure infiltration rate and hydraulic conductivity. The soil bulk density and penetration resistance were determined withcore (Blake and Hartge, 1986) and cone penetrometer methods, respectively. Water productivity (WP) and water saving (WS) were estimated using the Equations 4 and 5:

where x is the amount of water applied in T1 in CM (m3 ha-1), and y is the amount of water applied (m3 ha-1).

Crop yield was measured for each subplot in a test area of 3m×3m, excluding border rows. At harvest, the number of effective tillers was determined for five tagged plants. The rice grain yield was determined at constant moisture content of grain of 14.5% and expressed in q ha-1.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity were verified prior to conducting statistical analyses. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of data distribution, while Levene’s test was applied to evaluate the homogeneity of variances. Accordingly, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to evaluate soil and plant parameters obtained from the split-plot design comprising rice establishment methods (main plots) and soil amendment treatments (subplots) in accordance with Gomez and Gomez (1984). Mean values of three replicates were compared using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test at a 5% probability level (p ≤ 0.05). Linear regression analyses were also performed to examine the relationships between rice yield, root growth, and soil properties. Figures in the study were prepared using Origin software version 8.5.

3 Results

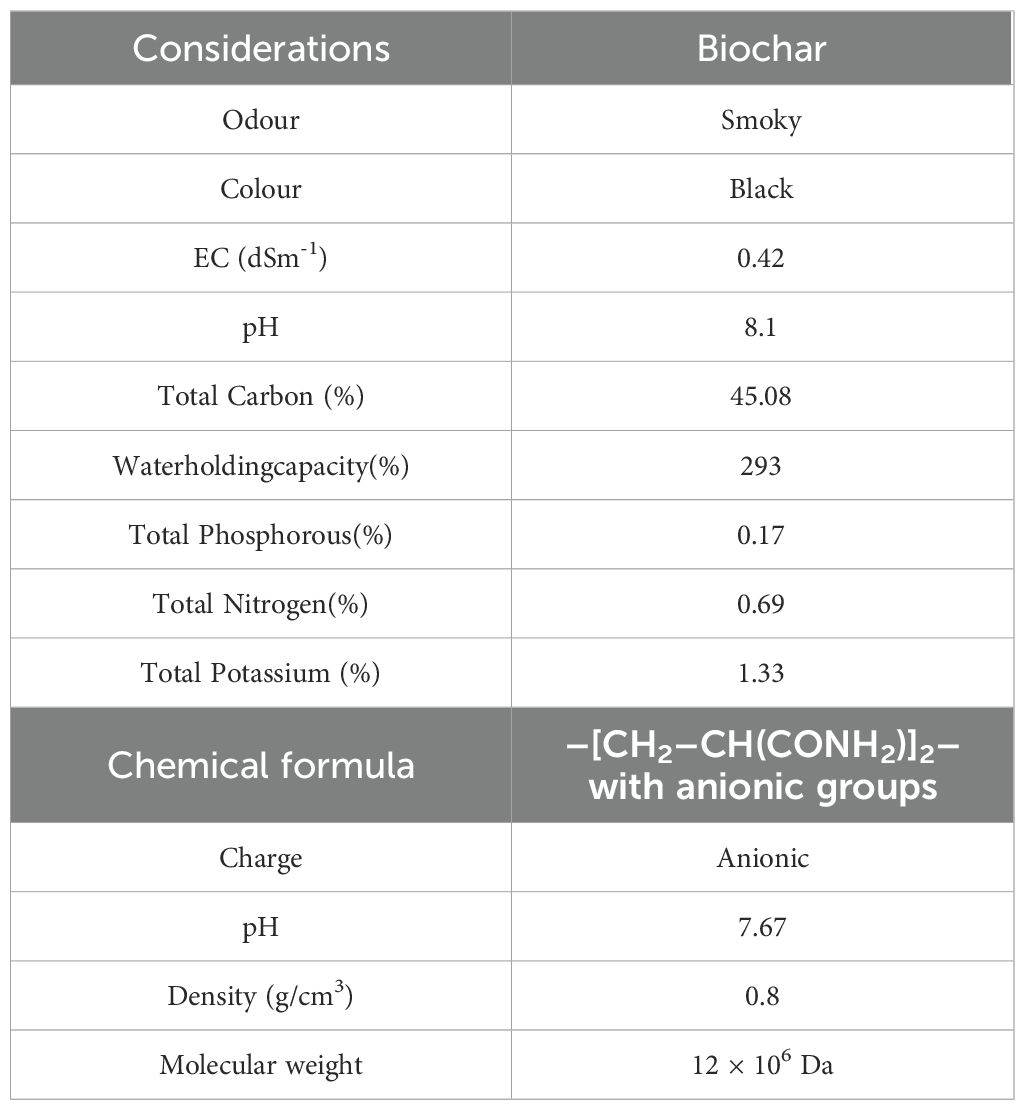

3.1 Biochar and polymer characterization

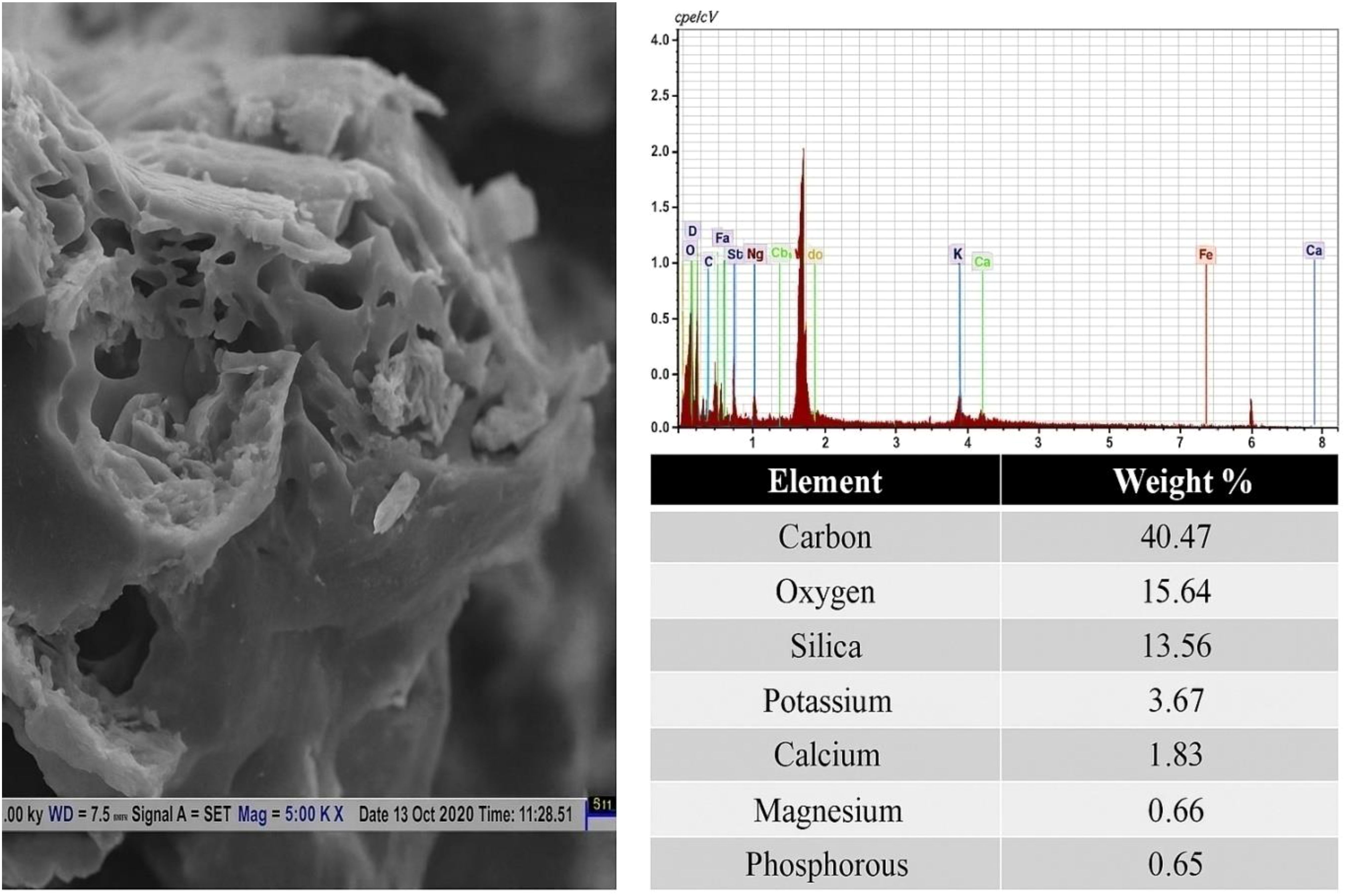

The physicochemical properties of biochar derived from rice husk and PAM are shown in Table 2. Data indicates that biochar possesses a total carbon content of 45% and exhibits alkaline properties. Biochar had a substantial water retention capacity of 293%. The nutritional analysis indicated that the biochar has total phosphorus, nitrogen, and potassium levels of 0.17%, 0.69%, and 1.33%, respectively. This signifies that the biochar possesses a comparatively low phosphorus content, moderate nitrogen levels, and a high potassium concentration. Figure 2 illustrates the Scanning Electron Microscope(SEM) and Energy-Dispersive X-ray(EDX) examination and showed that the biochar had a porous architecture characterized by both macro and micropores. The EDX analysis indicated that the biochar has approximately 40% carbon and 15.32% oxygen. Furthermore, it revealed the presence of silica oxide, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus, which are essential soil components required for plant growth. The O/C ratio, an indication of aromaticity and biochar stability in soil, was 0.28 for the biochar. Our FTIR results indicated that the biochar blend of oxygenated and aromatic surface functional groups, making it a suitable soil amendment for improving crop yield due to increased water retention capacity, nutrient retention, and better stability in the soil (Sharma et al., 2025a; Saini et al., 2025).

The Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy(FTIR) and X-ray Diffraction (XRD) analysis are illustrated in Figures 3a, b. It can be observed from Figure 3a that the biochar contains several functional groups in the wavelength range of 4000–400 cm–1. Specifically, the vibrational frequency range of 3500–3300 cm–1 ascribed to the presence of hydroxyl and phenolic functional groups (Xiao et al., 2014), 1680–1550 cm–1 linked to C=O/C=C aromatic carbon functional groups (Keiluweit et al., 2010), 1090–1020 cm–1 linked to the presence of Si-O-Si/C-O (alcoholic and silica oxide) surface functional groups (Shen et al., 2017), and 750–800 cm–1 can be ascribed to C-C aromatic functional groups (Chandra and Bhattacharya, 2019). The XRD analysis of the biochar (Figure 3b) showed the presence of various peaks at 23.20°, 28°, 40°, and 50°. The 23.20° and 28° peaks represent the amorphous carbon and silica oxide peaks (Chandra and Bhattacharya, 2019), respectively, with d-spacing of 0.382 nm and 0.316 nm, respectively. The (100) peak at 40° indicates the presence of graphitic carbon with a d-spacing of 0.223 nm. The last peak at 50° indicates the presence of a (220) plane corresponding to the silicon carbide with a d-spacing of 0.182 nm that might have formed during the pyrolysis process (Chandra and Bhattacharya, 2019).The anionic PAM polymer was directly purchased from the market and the basic properties were included with the packet as specified by the company. The basic physicochemical properties showed that the polymer possesses anionic surface characteristics, having a pH of 7.67 and a density of 0.8 g cm-3. The chemical formula (Table 2) indicates the presence of amine and carbonyl groups on the surface of the polymer.

![Two graphs analyzing rice husk biochar. Graph (a) is an infrared spectrum plot showing wavenumber versus absorption, with labeled regions for hydroxyl/phenolic, C double bond O double bond C, C-O/Si-O-Si, and aromatic groups. Graph (b) is an X-ray diffraction pattern displaying intensity peaks at positions [002], [100], [101], and [220] against angle \(2\theta\).](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1660325/fpls-16-1660325-HTML/image_m/fpls-16-1660325-g003.jpg)

Figure 3. (a) FTIR analysis of Rice husk-derived biochar, (b) XRD analysis of Rice husk-derived biochar.

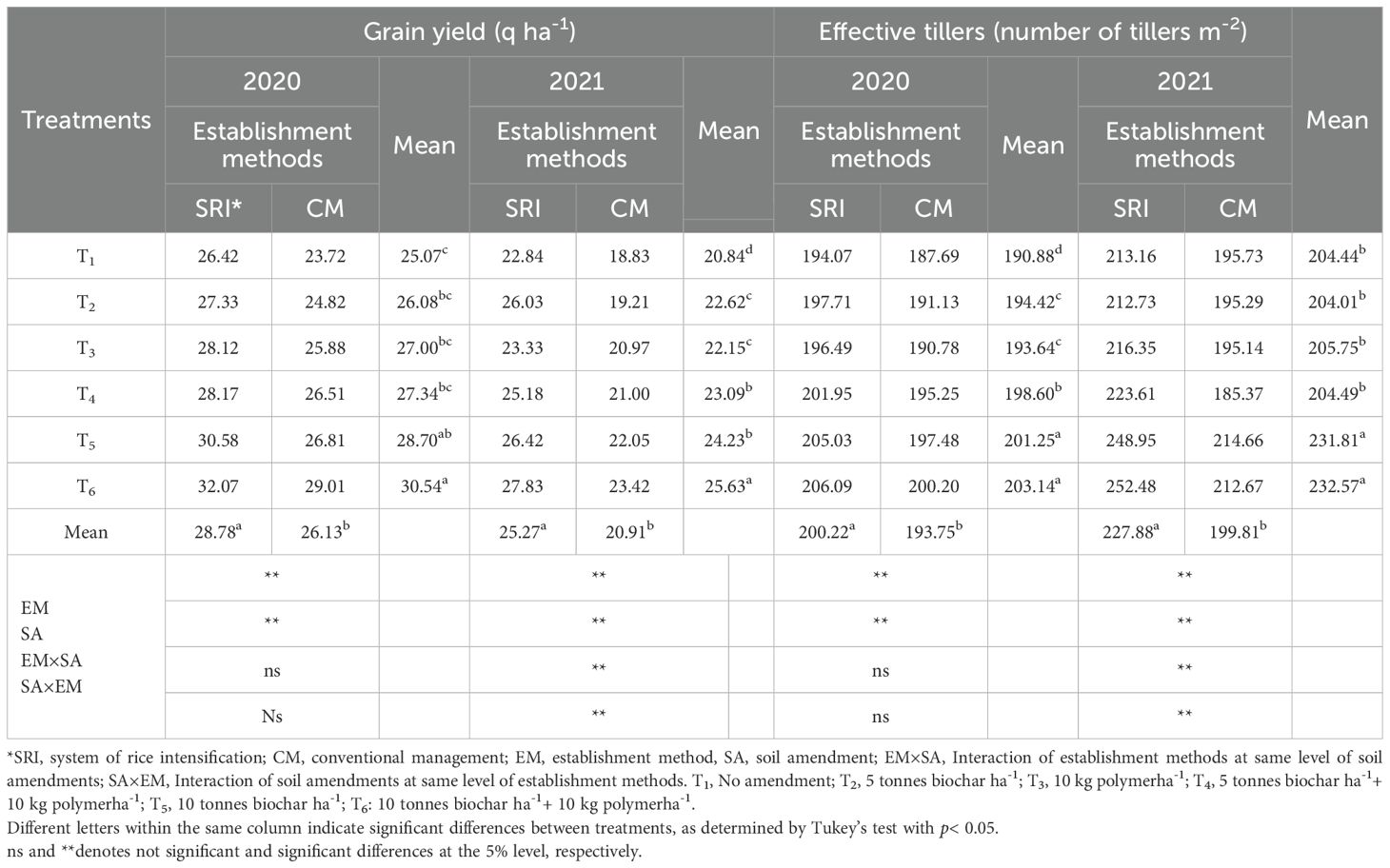

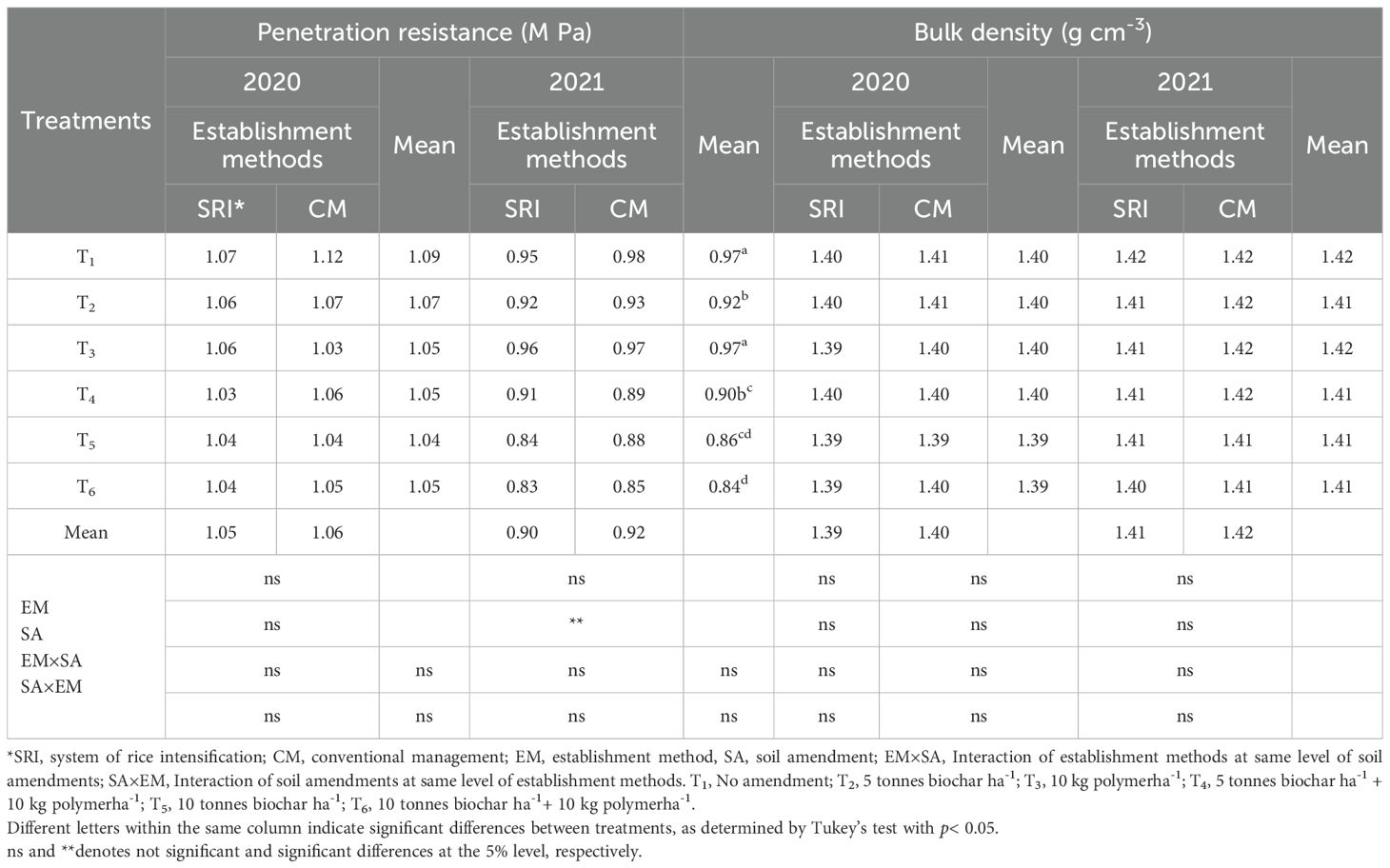

3.2 Rice crop performance

Rice establishment methods (EM) significantly affected the rice yield during the two years of experimentation (Table 3). SRI obtained significantly higher rice yield than the conventional method in both years, and the maximum average grain yield was observed in SRI (27.02 q ha-1), which was significantly higher than that of the conventional method. Among soil amendment (SA), a substantial increase in grain yield 21.8% and 23%was observed with the application of 10 tonnesbiochar ha-1 + 10 kg polymer ha-1(T6) over 100% RDF (T1) for the years 2020 and 2021, respectively. The highest average grain yield (28.08 q ha-1) was recorded in the T6 treatment, and the lowest was noticed in the control (22.95 q ha-1). The interaction effect of the planting method and soil amendments was not significant in the first year; however, it was significant in the second year, and treatment T6 × SRI had the highest mean yield (22%) compared to the control. The lowest yield was recorded in T1 (no biochar) ×CM. The magnitude of the increase in grain yield in SRI was 16.7% compared to the conventional method. In contrast,the co-application of biochar and polymer (T6) showed a 22.4% increase over the control (Figure 4).

Table 3. Effect of establishment methods and soil amendments on grain yield and effective tillers density.

Figure 4. Box and whisker plot of grain yield with respect to (a) crop establishment methods, (b) soil amendments. Solid lines indicate median and the cross signs indicate mean. The box boundaries indicate the upper and lower quartiles and the whiskers indicate the 90th and 10th percentiles. Bars indicate standard error from mean P value< 0.05. SRI, System of rice intensification; CM, Conventional management; T1, No amendment (control); T2, 5 tonnes biochar ha-1; T3, 10 kg polymer ha-1; T4, 5 tonnes biochar ha-1 + 10 kg polymer ha-1; T5, 10 tonnes biochar ha-1; T6, 10 tonnes biochar ha-1+ 10 kg polymer ha-1.

Similarly, planting methods and soil amendments (SA)significantly impacted tiller density in both years (Table 3). According to the results, the SRI system significantly enhanced the number of tillers compared to CM throughout the experiment. The mean tillers m-2 increased by 8.8% under SRI compared to CM. Among the soil amendments, the polymer and biochar (T6) combination produced more tillers m–2 than the other treatments. Across years, a significant interaction between planting method and amendments was observed in SRI × T6, resulting in an18.4% increase in tillers m-2 over the control in the second year.

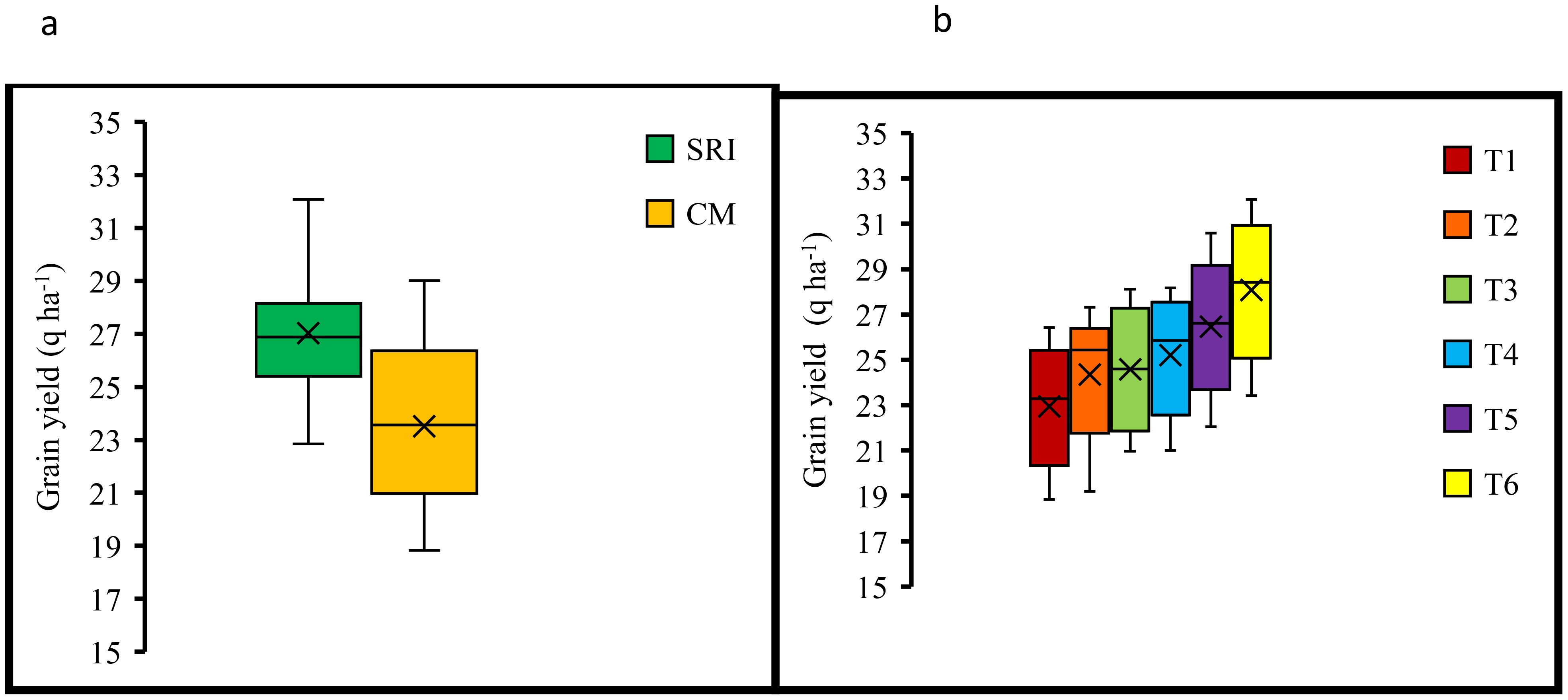

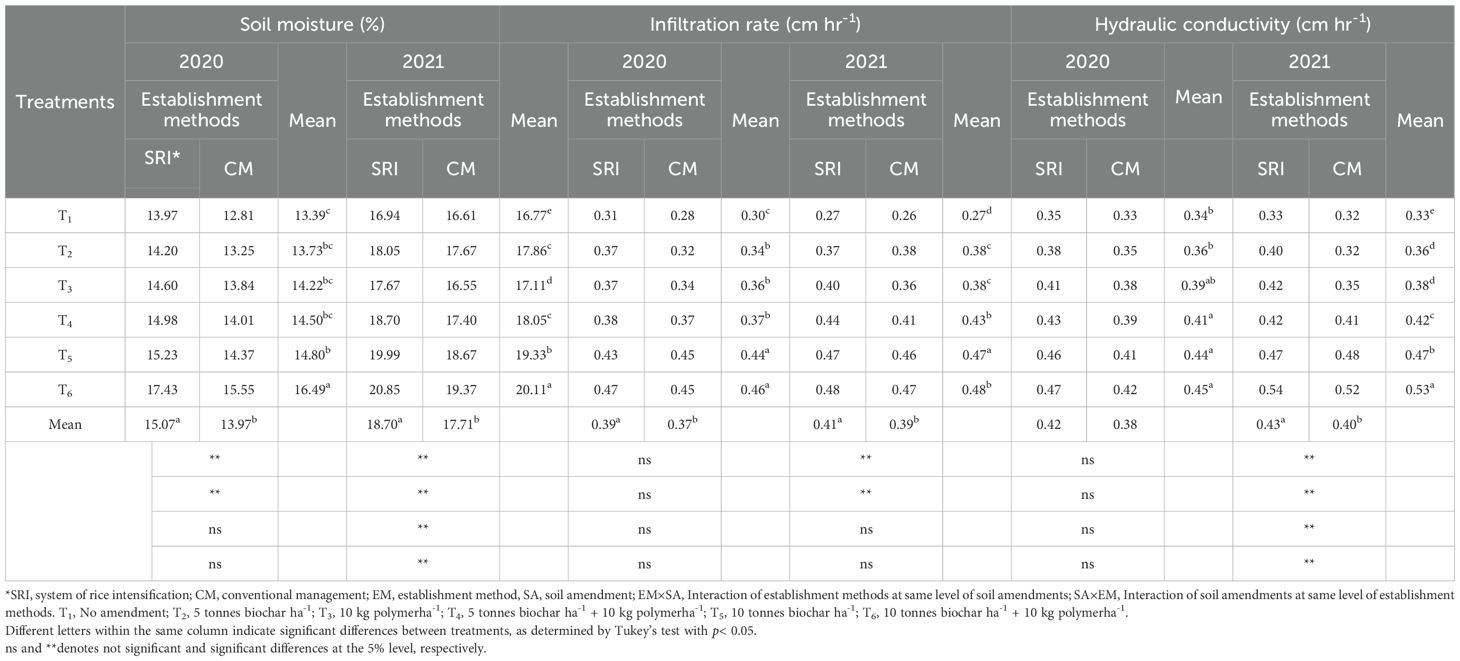

3.3 Soil hydro-physical properties

The experimental data showed that EM and SA had a significant impact on SM, HC, and IR (Table 4). However, neither the EM nor the SA altered bulk density and penetration resistance (PR) over the two years, and only significant PR was observed in the second year (Table 5). No significant differences in PR, HC, and IR were observed between SRI and the CM in the first year; however, it was significant in the second year. SRI significantly increased the average SM (6.6%), HC (3.08%), and IR (5.3%) compared to CM. The T2, T3, T4, T5 and T6 treatments increased soil moisture by 4.7%, 3.8%, 7.9%, 13.1% and 21.3%, respectively, compared to control. The combination of biochar and polymer (T6) recorded the highest increase in HC and IR, with an increase of 1.33 and 1.65 times, respectively. Gradual reductions in PR were recorded in plots amended with biochar and polymer compared to those in the control. EM and SM had significant interaction effects in terms of HC and IR in the second year. The SRI × T6 treatment resulted in the highest mean values of SM (19.14%), HC (1.5 cm h-1), and IR (0.47 cm h-1). Also, EM and SA had no interaction effect on penetration resistance in either year.

Table 4. Effect of establishment methods and soil amendments on soil moisture, infiltration rate, and hydraulic conductivity. .

Table 5. Effect of establishment methods and soil amendments on penetration resistance, infiltration rate, and hydraulic conductivity.

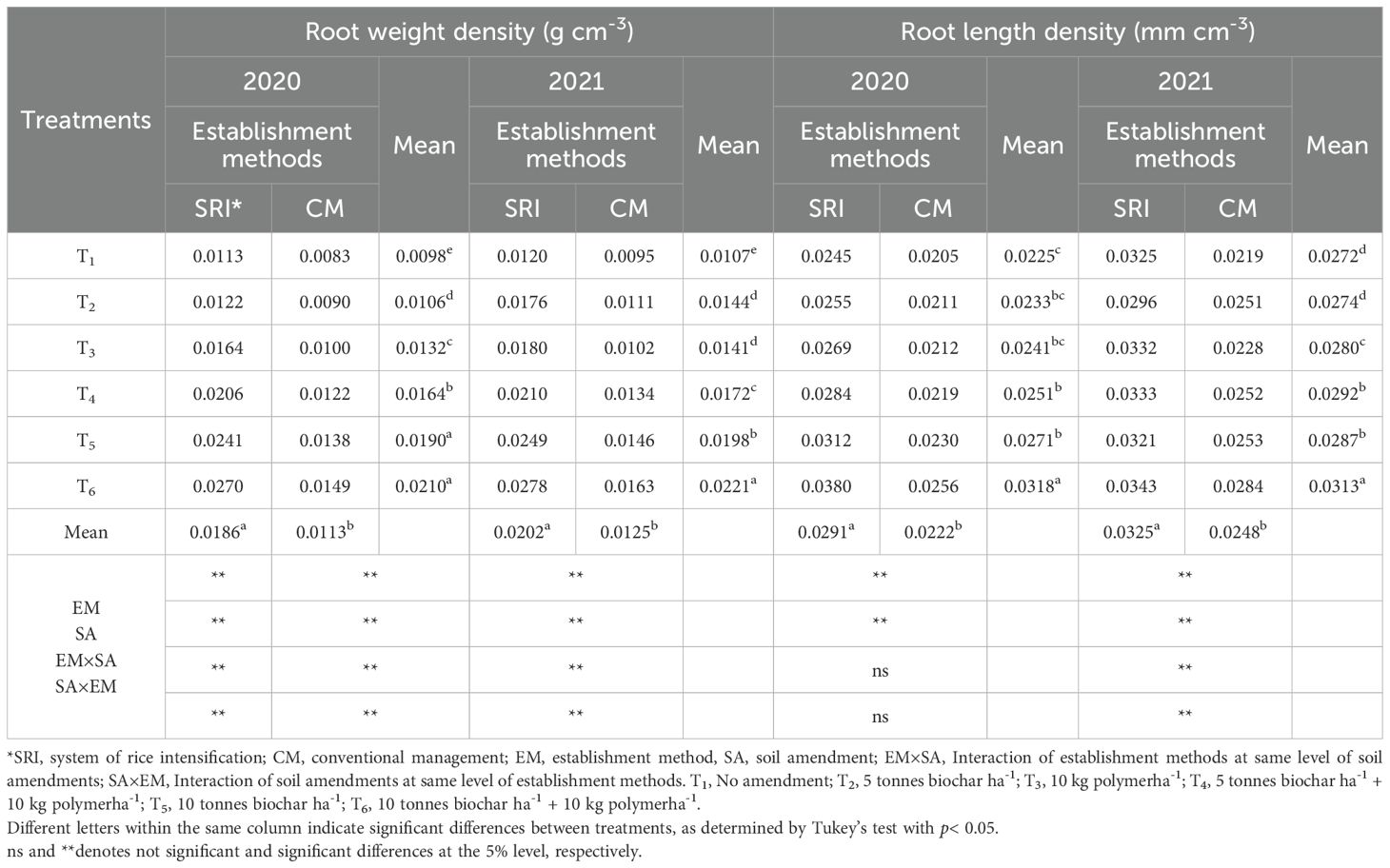

3.4 Root development

In both years, conventional and SRI practices and SA exerted substantial impacts on the RLD and RWD of basmati rice (Table 6). Irrespective of the soil amendments, the SRI yielded significantly higher average RLD (0.0308 mm cm-3) and RWD (0.0195 g cm-3) in both years than the conventional method. Under SRI, RLD and RWD increased by 31.1% and 63.8% in the first year and by 31.04% and 61.6% in the second year, respectively, compared to the conventional method. Furthermore, adding biochar and polymer increased the RLD and RWD compared to the control. Among the SA treatments, the highest RLD and RWD values were recorded for the combined application of 10 tonnes biochar ha-1 and 10 kg PAM ha-1 (T6) (0.0318 mm cm-3 and 0.021 g cm-3, and 0.0313 mm cm-3 and 0.0221 g cm-3 in 2020 and 2021, respectively), and the lowest RLD and RWD values were obtained in the control (0.0225 mm cm-3 and 0.0098 g cm-3, and 0.0272 mm cm-3and 0.0108 g cm-3 in 2020 and 2021, respectively). The magnitude of the increase in RLD and RWD over two years was 1.27 to 2.10 times greater than that in T6 treatment over RDF. In general, increasing doses of biochar and polymer markedly increased the RLD and RWD. In both years, the interaction effect of EM and SA was significant for RWD. However, for RLD, this interaction was only significant in 2021, and the greatest mean RLD (0.0343 mm cm-3) and RWD (0.02703 gm cm-3) were obtained for T6×SRI, while the lowest values were recorded for T1× CM.

Table 6. Effect of establishment methods and soil amendments on root weight density (RWD) and root length density (RLD) of Rice.

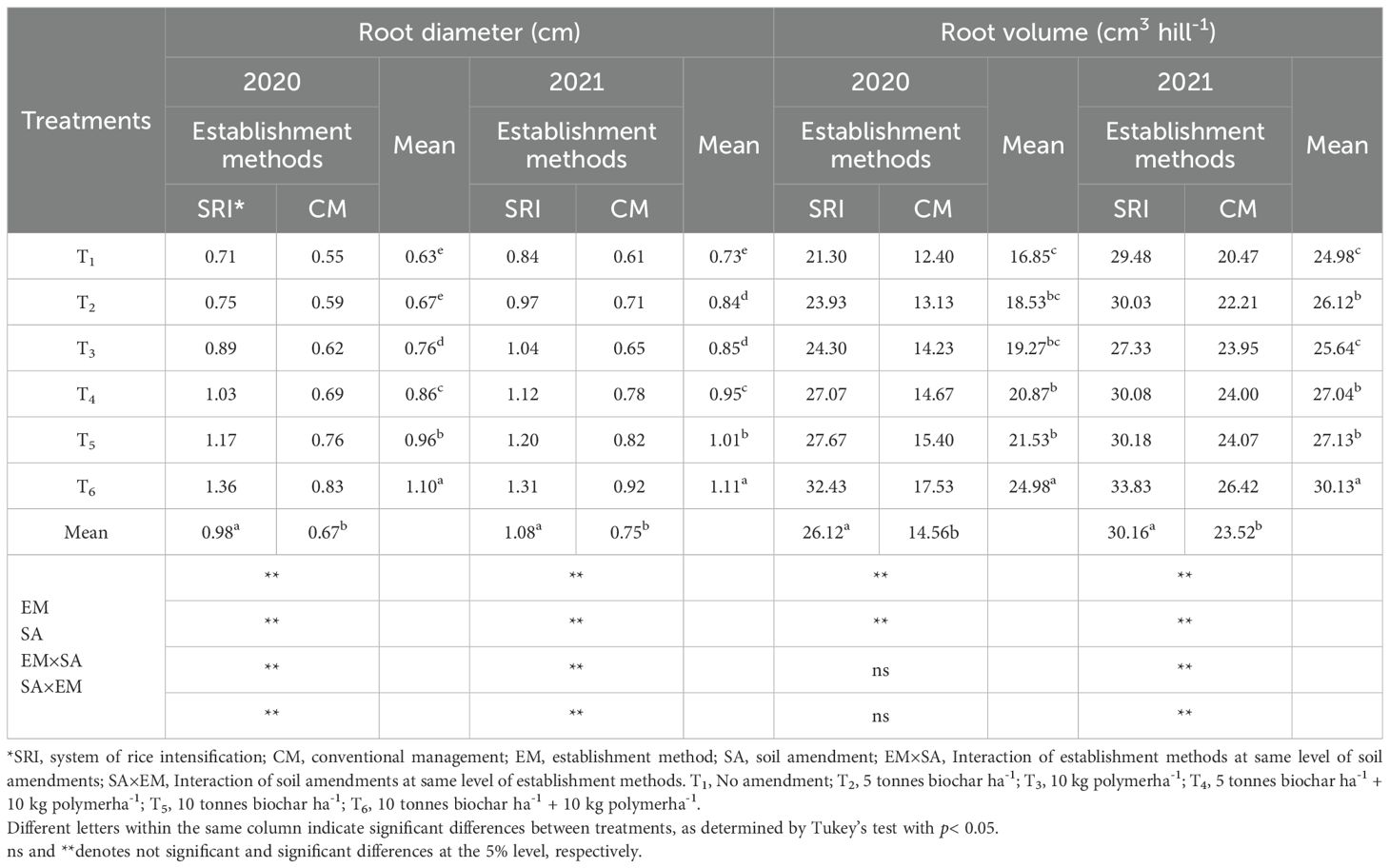

Similarly, root diameter (RD) and root volume (RV) were significantly affected by planting methods and SA (Table 7). In general, SRI recorded 45.1% and 47.8% greater RD and RV, respectively, than in CM. Among the soil amendments, T6 had the highest average RD and RV (1.10 cm, 27.55 cc hill-1), and the control evinced the lowest RD and RV. Similarly, in2020 and 2021, the root diameter and volume in the T6 treatment increased by 2.06 and 1.48 and 1.42 and 1.20, respectively, compared to the control treatment. Root morphology improved in the SRI in both years, demonstrating that SRI outperformed CM. RLD and RWD exhibited a 1.31-fold and 1.62-fold increase in SRI compared to CM.

Table 7. Effect of establishment methods and soil amendments on root diameter (RD) and root volume (RV) of rice.

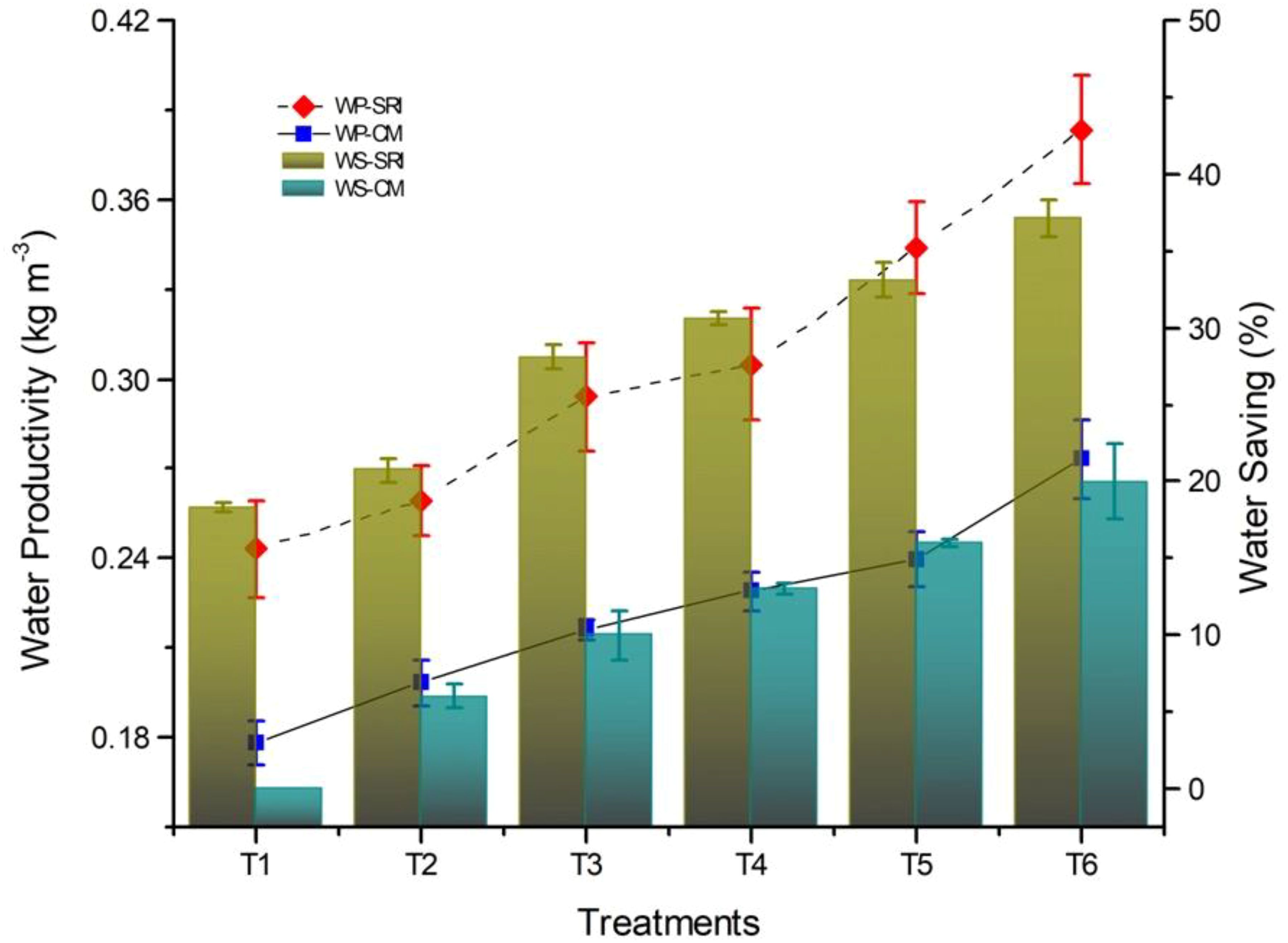

3.5 Water productivity and water savings

The EM and SA significantly impacted water productivity (WP) and water saving (WS) (Figure 5). The results indicated that SRI saved 28.2% of irrigation water compared toCM across two years. Among the soil amendments, T6 produced the highest average WS (29.45%) over the control. Similarly, for both years, the average WP in SRI was 46.5% higher than in the CM. Similarly, T6 had the highest average WP of 0.34 kg m-3. In 2020, no significant interaction was recorded between EM and SA on WS and WP. However, in 2021, SRI×T6 showed the highest values (41.81%, 0.44 kg m-3, respectively) of WS and WP, owing to the beneficial effects of biochar and polymer on soil water retention.

Figure 5. Pooled water productivity (WP) and water saving (WS) among various establishment methods and amendments. Bars indicate standard error from mean P value< 0.05. SRI, System of rice intensification; CM, Conventional management; T1, No amendment; T2, 5 tonnes biochar ha-1; T3, 10 kg polymerha-1; T4, 5 tonnes biochar ha-1+ 10 kg polymerha-1; T5, 10 tonnes biochar ha-1; T6, 10 tonnes biochar ha-1+ 10 kg polymerha-1.

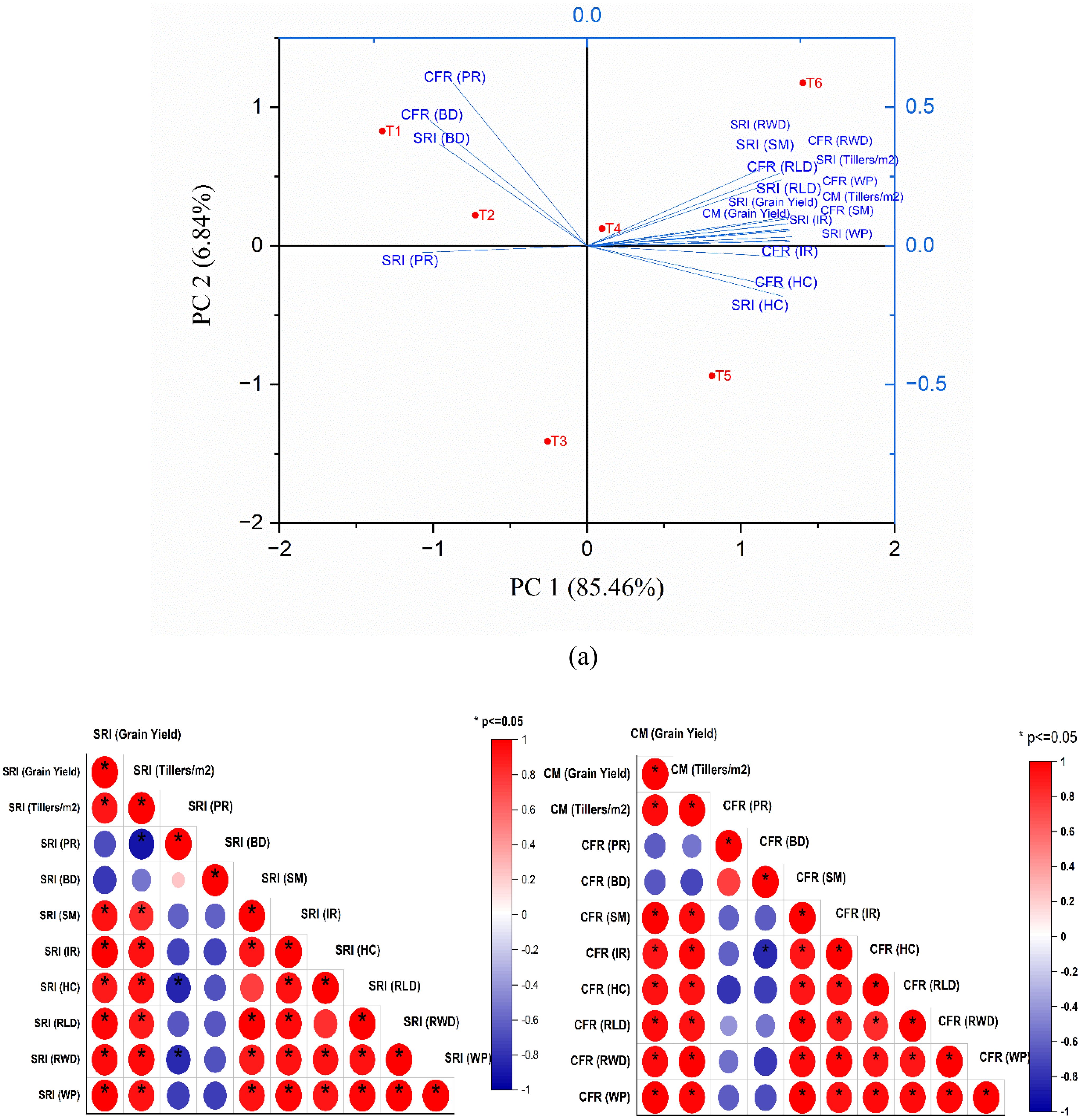

3.6 Principal component analysis and correlation matrix

Figures 6a, b display the PCA and correlation matrix, encompassing data on treatment techniques and analyzed soil and crop parameters. Figure 6a illustrates that PC1 (x-axis) accounts for 85.46% of the variation in the data, whereas PC2 (y-axis) accounts for 6.84% of the variance. Consequently, only two main components, PC1 and PC2, were used in the PCA analysis. The principal component analysis revealed that PC1 exhibited dominant loadings from variables including SRI (RWD), SRI (SM), CFR (continuous flooded rice) (RWD), SRI (Tillers m-²), CFR (WP), and CM (Grain Yield), all of which displayed the longest vector projections along the PC1 axis. This pattern indicates that PC1 primarily encapsulated the variance associated with productivity-linked agronomic traits, reflecting their strong interdependence and contribution to overall system performance. In contrast, PC2 accounted for only 6.84% of the total variability, with notable but weaker loadings from CFR (PR), CFR (BD), and SRI (BD), suggesting that these parameters exerted comparatively minor influence on the overall variance structure. The PCA biplot (Figure 6a) illustrates the directional influence and magnitude of each variable through the orientation and length of the blue vectors relative to the principal components.

Figure 6. (a) Biplot Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plot, (b) Heatmap correlation analysis diagram of treatment methods and observed parameters for rice cultivation.

Furthermore,the PCA analysis biplot depicted in Figure 6a indicates that among all treatment approaches, T6 (10 tonnes of biochar ha-1+ 10 kg of polymer ha-1) had the most significant influence, demonstrating a positive connection with PC1. Additionally, several metrics, including SRI (HC), CFR (IR), and CFR (HC), exhibited a moderate positive correlation with the T5 treatment approach (10 tonnes of biochar ha-1). CFR (PR), CFR (BD), and SRI (BD) had a significant negative correlation with treatment T1 (no modification). Ultimately, SRI (PR) had a neutral impact on any treatment modality. The biplot PCA analysis indicated that the SRI cultivation approach, utilising 10 tonnes of biochar and 10 kg of polymer amendment, yields superior outcomes compared to alternative methods. The heatmap correlation diagram presented in Figure 6b corroborates that in the SRI cultivation methodology, the treatment techniques exhibit a robust positive association with grain yield, tiller, SM, IR, HC, RLD, RWP, and WP, while demonstrating a high link with SRI PR and BD. These results align with the data obtained from PCA analysis, indicating that SRI BD and PR were negatively linked with PC1. Similarly, in the CFR approach, the treatment procedures had a positive correlation with grain yield, IR, HC, RLD, RWP, and WP, while demonstrating a negative correlation with PR and BD.

The PCA loading of each variable with respect to PC1 and PC2 is shown in Supplementary Table 2. The PCA outcomes demonstrate that agronomic performance and yield-related variables distinctly segregate along the two principal components, PC1 and PC2, which together account for 92.3% of the total variance.PC1 alone explains 85.46%, serving as the dominant axis of differentiation among treatments. Variables associated with WP [SRI (WP), CFR (WP)], grain yield [SRI (Grain Yield), CM (Grain Yield)], and tiller density [SRI (Tillers m-2), CM (Tillers m-2)] exhibit the highest loadings, ranging approximately from 5.1% to 5.8%, indicating their strong collective contribution to PC1. This implies that PC1 primarily represents the combined influence of yield efficiency and growth potential, where positively clustered loadings reflect mutual enhancement among these traits, thereby emphasizing their synergistic role in determining crop performance.

Additional variables such as SRI (RWD), CFR (RWD), SRI (IR), and CFR (IR) also exhibit moderate to high positive associations with PC1, reinforcing the centrality of grain and WP traits in shaping the primary axis. PC2, accounting for 6.84% of the variability, delineates a secondary but meaningful dimension, dominated by CFR (PR) (34.47%), CFR (BD) (20.35%), and SRI (BD) (13.42%), which correspond to biomass density and post-rainfall responses. This pattern suggests that PC2 captures structural or environmental variability, distinct from the yield-oriented variance encapsulated in PC1. Moderate loadings from SRI (SM) and CFR (SM) (ranging between 8.8% and 0.9%) further highlight phenological and soil-moisture interactions that complement productivity traits. Collectively, this two-axis differentiation underscores the multifactorial architecture of crop performance, wherein PC1 reflects integrated physiological and yield attributes, whilePC2 isolates environmental and biomass-related influences. This separation clarifies the relative contribution of each agronomic parameter and offers a strategic basis for optimizing management practices, aligning yield enhancement with resource efficiency and environmental adaptability.

4 Discussion

In the present study, significant improvement in soil physicochemical properties was observed in the combined application of biochar and polymer treatments compared to the sole application. Co application of biochar and polymer (T6: 10 tonnes biochar ha-1 + 10 kg polymerha-1) increased the soil moisture (1.2 times) and reduced the soil PR (1.15 times), and improved the soil water movement (IR by 1.8 and HC by 1.6 times) across the year as compared to the T1 (no amendment) in SRI practice. The SRI system increased SM by 6.6%, increased IR by 5.26%, increased HC by 3.08%, and reduced PR and BD over the CM. These findings indicate that the SRI method effectively manages soil, plants, and water in rice cultivation. Previous studies have also shown that the SRI significantly impacts water movement and soil compaction (Gathorne-Hardy et al., 2016).Studies suggest that porous nature (Figure 2) and presence of aromatic surface functional groups of biochar (Figure 3) contribute to efficient water distribution, enhanced nutrient availability, improve microbial diversity and collectively promote root development (Saini et al., 2025; Sharma et al., 2025b; Bolan et al., 2024).

The results are in line with the findings of Yu et al. (2013) and Chen et al. (2024). The O/C ratio (Figure 1) for the biochar suggests that biochar possesses a moderate level of aromaticity (resistance to microbial degradation) and stability in the soil, making it very appropriate for improving soil physicochemical qualities (Lehmann and Joseph, 2024).Finer biochar particles dissolve in irrigation water, increasing the electrolyte concentration in the soil solution as evidenced by significantly higher electrical conductivity (Supplementary Table 3), further decreasing the zeta potential. Meanwhile, the dissolved polymer assumes a coiled form rather than long linear chains (Barvenik, 1994), entrapping soil and biochar particles to create water-stable aggregates, contributing to increased water retention and higher IR and HC under high electrolyte concentration. The increased activity of the polymer is attributed to the presence of electrolytes (Yu et al., 2003). Additionally, the released electrolytes decreased the viscosity of the polymer and increased infiltration (Abrol et al., 2016). Thus, biochar was found to regulate the efficacy of the polymer. Our findings aligned with previous studies that demonstrated that the electrolytes are essential for the beneficial effect of polymer on soil water movement and that using biochar as an electrolyte source resulted in significantly higher EC values due to the release of cations in the soil solution (Abrol et al., 2013; Abrol et al., 2016).

Biochar mixed with polymer leads to a significant change in effective tillers density and rice yield, compared to sole application and control treatments (Table 3). Our findings indicate that the maximum tillers m-2 was obtained with the T6 treatment under the SRI establishment practice. Several studies confirm our results (Demeyer et al., 2001; Bagheri et al., 2021). The highest rice yield was achieved under the joint application of biochar and polymer (T6), resulting in a 22.4% increase over the control treatment under SRI (Figure 4). This difference has been attributed to the wider spacing between plants in SRI, which promotes better plant and root growth and produces more tillers than does the conventional method (Thakur et al., 2013; Bagheri et al., 2021). The yield increase was correlated with aerobic conditions in SRI relative to CM, which influenced soil physicochemical and biological properties and created a favorable environment for plant and root growth. Previous research from eight countries has also reported that SRI increased rice yields by up to 47% while using 40% less water than conventional methods (Sato and Uphoff, 2007; Africare, 2010). Our results demonstrate the positive effects of biochar and polymer amendments on rice yield. Furthermore, a substantial increase in yield was obtained when biochar was coupled with polymer as compared to their sole application. These findings suggest that the synergistic interaction between biochar and polymer improves soil structure and enhances nutrient availability during plant growth (Abdeen et al., 2023; Rafique et al., 2025). An increased in crop yield could be linked to biochar’s beneficial influence on soil physical characteristics and microbial activity (Sharma et al., 2025a; Bolan et al., 2024). Laird et al. (2010) also observed an improvement in soil physical properties and available nutrients with biochar incorporation in soil.

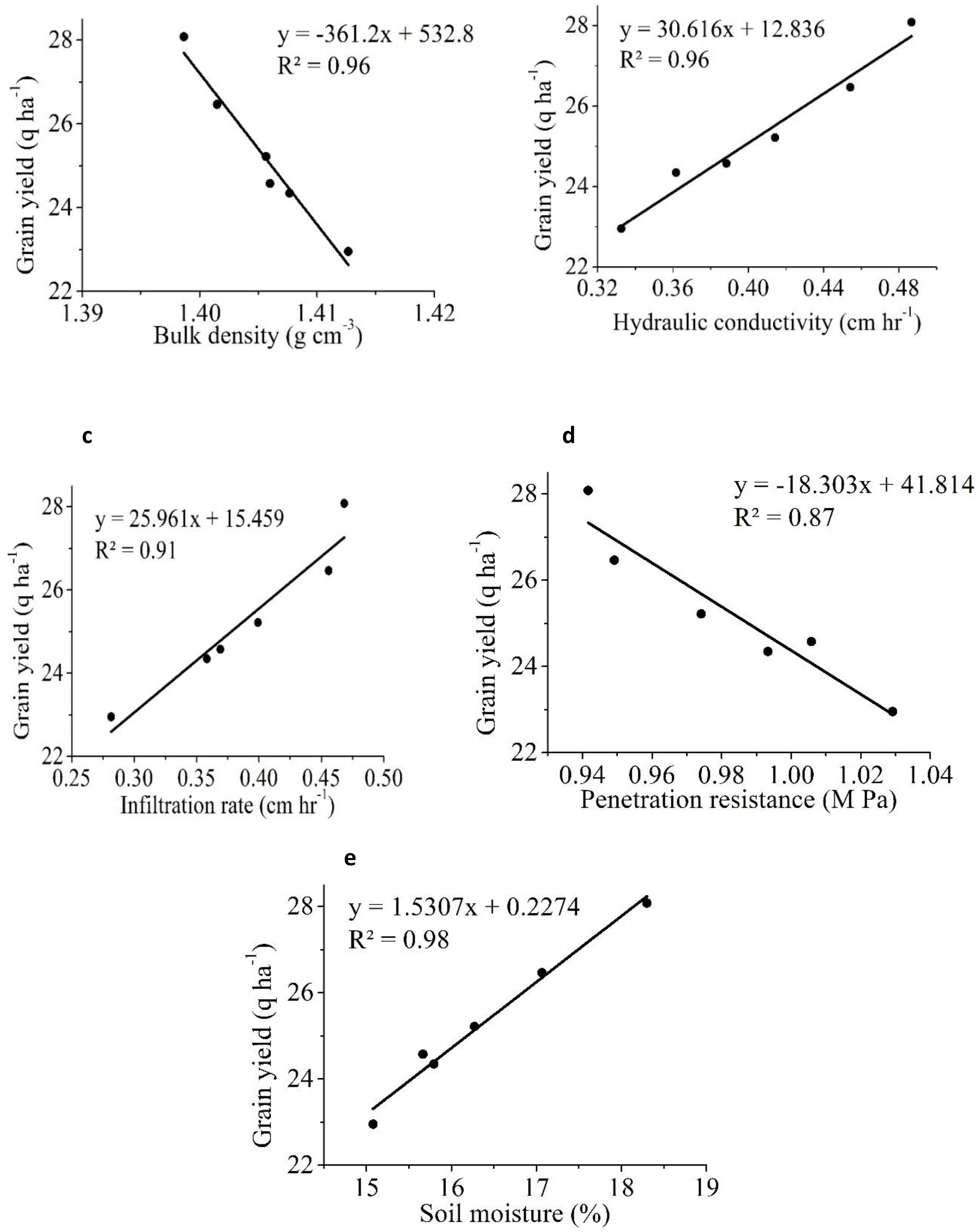

Conventional flooding conditions have an adverse impact on plant root growth because of the toxic effects of ferrous iron and manganese, which can negatively affect rice root growth (Olaleye et al., 2001). The study found that the SRI system significantly improved crop root growth by improving the soil rhizosphere environment by alternate wetting and drying, which increased oxygen supply to rice roots (Stoop et al., 2002; Ishfaq et al., 2020; Mboyerwa et al., 2022). In addition, an increase in rice yield under SRI was correlated with rapid root growth due to relatively conducive aerobic soil and increased microbial and enzymatic activity, which might have improved photosynthetic rate and, hence, crop yield (Yang et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2011; Li et al., 2016). The presence of carbon, phosphorus, nitrogen, and potassium (Table 2) in rice husk biochar provides a conducive soil environment for root growth. Phosphorus is a vital nutrient necessary for root development and energy transmission in crops, whereas nitrogen and potassium are crucial for leaf growth, water retention, and stress management, respectively (Lehmann and Joseph, 2024). The incorporation of porous and microporous biochar into the soil apparently improves its water retention and nutrient retention capabilities (Yu et al., 2013).The significant increase in rice yield and root morphology was attributable to the positive correlation between soil physical conditions (SM, IR, and HC) and the negative correlation between BD and PR (Figure 7).

Figure 7. The linear relationship between rice grain yield and different soil physical properties (a) bulk density (BD) (b) hydraulic conductivity (HC) (c) infiltration rate (IR) (d) penetration resistance (PR) (e) soil moisture (SM).

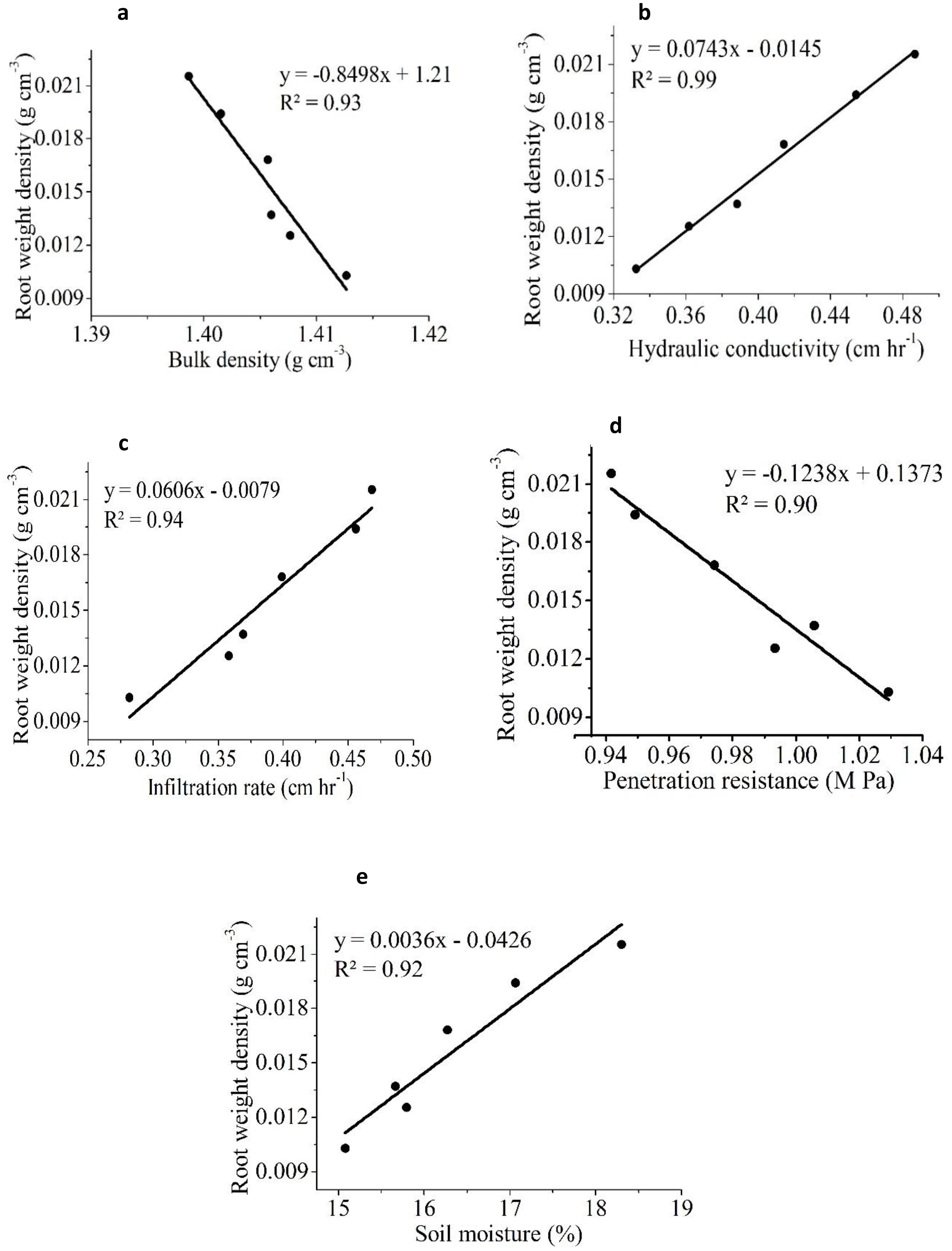

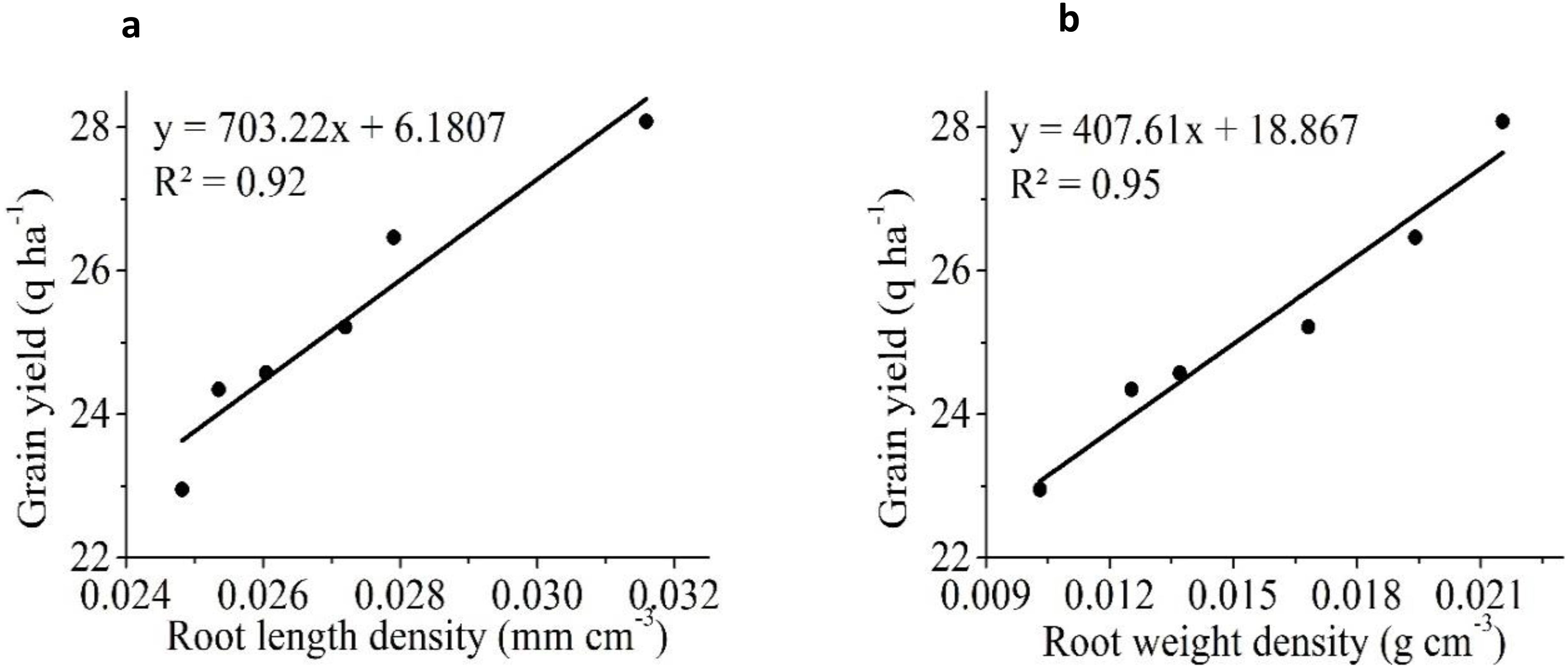

Similar results in a previous study reportedly showed a significant improvement in rice yield due to a positive change in soil properties in SRI that used less water than CM (Stoop et al., 2002; Pascual and Wang, 2016). Figure 7 shows that rice yield was significantly and positively associated with IR (R2 = 0.91), HC (R2 = 0.93), and SM (R2 = 0.98), but was negatively correlated with BD (R2 = 0.96) and PR (R2 = 0.97). The results showed that BD had the strongest negative correlation with yield, followed by PR. Several researchers have demonstrated that increased soil compaction reduces crop yield, possibly due to poor aeration and nutrient availability (Sharma et al., 2021; Tripathi et al., 2005). Similarly, RLD was positively correlated with IR, HC, and SM but negatively correlated with BD and PR (Figure 8). RWD had strong positive relationships with IR, HC, and SM (Figure 9). A significant correlation was found between the RLD (R2 = 0.92), and RWD (R2 = 0.95), which improved soil physical properties, favoring a soil environment that promoted higher crop yield (Figure 10).

Figure 8. The linear relationship between root length density (RLD) and different soil physical properties (a) bulk density (bd) (b) hydraulic conductivity (BC) (c) infiltration rate (IR) (d) penetration resistance (PR) (e) soil moisture (SM).

Figure 9. The linear relationship between root weight density (RWD) and different soil physical properties (a) bulk density (BD) (b) hydraulic conductivity (HC) (c) infiltration rate (IR) (d) penetration resistance (PR) (e) soil moisture (SM).

Figure 10. The linear relationship between rice grain yield (a) root length density (RLD) (b) root weight density (RWD).

Furthermore, the strong positive relationships of grain yield with RLD and RWD are consistent with previous findings (Blanco et al., 2013). In addition, PCA analysis demonstrated that, except BD and PR, all other parameters were influenced by the kind of amendment, regardless of the culture mode employed. Furthermore, several metrics, including SRI (RWD), SRI (SM), SRI (RLD), SRI (grain yield), SRI (Tillersm-2), and SRI (WD), exhibited a robust correlation with the T6 treatment, suggesting that optimal outcomes in rice cultivation may be attained by this strategy. The PCA analysis further validated that the T6 amendment technique yielded the most favourable outcomes compared to all other amendment methods.

Among all the treatments, SRI establishment practice with biochar and polymer (T6) showed the highest WS and WP values (41.81%, 0.44 kg m-3, respectively). The effect of biochar and polymer could be beneficial on soil water retention (Abrol et al., 2013, 2016; Alkhasha et al., 2018). Our findings suggest that it can save 39.45% of the water if the conventional planting method is replaced with SRI×T6. The results of our study suggest that biochar with polymer plays a crucial role in the improvements of soil hydraulic functions and root growth, thereby facilitating an increase in rice grain yield and WP.

5 Conclusion

This study revealed that soil additives (biochar and polymer) and rice establishment methods (SRI, traditional) substantially influenced soil hydraulic properties, water retention, root development, and rice production. A 15% increase in rice production attained using the SRI compared to CM illustrates a soil condition that promotes root development, hence enhancing the availability of water and nutrients. WP increased by 1.7 times, and irrigation water depth was reduced by 39.45%, confirming the synergistic good effects of biochar and polymer under the SRI. Therefore, implementation of SRI×T6 (10 tonnes of biochar ha-1 and 10 kg of polymer ha-1) is a potential strategy for attaining increased basmati rice yields with reduced irrigation water usage. Nevertheless, the future research should more focus on understanding the long-term impacts of biochar–polymer integration on soil microbial dynamics, nutrient cycling, and carbon sequestration across diverse soil types and climatic conditions. Additionally, further field experiments are required to observe the long-term impacts of biochar–polymer integration on different soil properties and agricultural productivity across various agroecosystems.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author contributions

PeS: Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Methodology. VA: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Resources, Conceptualization, Visualization, Project administration, Methodology. HS: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SG: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. NG: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. RaS: Writing – review & editing. SC: Writing – review & editing. OB: Writing – review & editing. SA: Writing – review & editing. PrS: Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. AH: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. AK: Writing – review & editing. EFA: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. MK: Writing – review & editing. RuS: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. VC: Writing – review & editing. ML: Writing – review & editing. LH: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The author(s) gratefully acknowledges the financial support received through the Water Technology Initiative Programme of the Department of Science and Technology, New Delhi for conducting the study. The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to Ongoing Research Funding program (ORF-2026-134), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Acknowledgments

The author (s) gratefully acknowledges the financial support received through the Water Technology Initiative Programme of the Department of Science and Technology, New Delhi for conducting the study. The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to Ongoing Research Funding program (ORF-2026-134), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1660325/full#supplementary-material

References

Abdeen, S. A., Hefni, H. H., Awadallah-F, A., and El-Rahman, N. R. A. (2023). The synergistic effect of biochar and poly (2-ethyl-2-oxazoline)/poly (2-hydroxyethylmethacarylate)/chitosan) hydrogels on saline soil properties and carrot productivity. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 10, 68. doi: 10.1186/s40538-023-00435-2

Abhishek, K., Srivastava, A., Vimal, V., Gupta, A. K., Bhujbal, S. K., Biswas, J. K., et al. (2022). Biochar application for greenhouse gas mitigation, contaminants immobilization and soil fertility enhancement: A state-of-the-art review. Sci. Total Environ., 158562.

Abrol, V., Ben-Hur, M., Verheijen, F. G., Keizer, J. J., Martins, M. A., Tenaw, H., et al. (2016). Biochar effects on soil water infiltration and erosion under seal formation conditions: rainfall simulation experiment. J. Soils Sediments 16, 2709–2719. doi: 10.1007/s11368-016-1448-8

Abrol, V., Shainberg, I., Lado, M., and Ben‐Hur, M. (2013). Efficacy of dry granular anionic polyacrylamide (PAM) on infiltration, runoff and erosion. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 64, 699–705. doi: 10.1111/ejss.12076

Abrol, V., Sharma, P., Anand, S., Chary, R., Prasad, T.N.V.K.V., Samnotra, R. K., et al. (2021). Biochar: atool for sustainable agriculture and climate change mitigation. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 10, 713–727.

Abrol, V., Sharma, P., Chary, G. R., Srinivasarao, C., Maruthi Sankar, G. R., Singh, B., et al. (2024). Integrated organic and mineral fertilizer strategies for achieving sustainable maize yield and soil quality in dry sub-humid inceptisols. Sci. Rep. 14, 27227. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-74727-4

Africare. Oxfarm America, WWF-ICRISAT Project (2010). More Rice for people, more water for planet WWF-ICRISAT Project Hyderabad India. Available online at: https://s3.amazonaws.com/oxfam-us/www/static/oa3/files/more-rice-for-people-more-water-for-the-planet-sri.pdf.

Ahmed, S., Kumar, V., Zaman, A. U., Dewan, M. R., Khatun, A., Hossain, K., et al. (2025). Dry direct-seeded and broadcast rice: A profitable and climate-smart alternative to puddled transplanted aus rice in Bangladesh. Field Crops Res. 322, 109739. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2025.109739

Alkhasha, A., Al-Omran, A., and Aly, A. (2018). Effects of biochar and synthetic polymer on the hydro-physical properties of sandy soils. Sustainability 10, 4642. doi: 10.3390/su10124642

Almaroai, Y. A. and Eissa, M. A. (2020). Effect of biochar on yield and quality of tomato grown on a metal-contaminated soil. Sci. Hortic. 265, 109210. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109210

Amiri, E., Emami, H., Mosaddeghi, M. R., and Astaraei, A. R. (2017). Investigating the effect of vetiver and polyacrylamide on runoff, sediment load and cumulative water infiltration. Soil. Res. 55, 769–777. doi: 10.1071/SR17011

Anagha, K. S., Kuttippurath, J., Sharma, M., and Cuesta, J. (2024). A comprehensive assessment of yield loss in Rice due to surface ozone pollution in India during 2005–2020: A great concern for food security. Agric. Systems 215, 103849. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2023.103849

Bagheri Novair, S., Motesharezadeh, B., and Asgari Lajayer, B. (2021). “Techniques for improving nitrogen use efficiency in rice,” in Soil Nitrogen Ecology (Springer International Publishing, Cham), 203–213.

Bandumula, N. (2018). Rice production in Asia: Key to global food security. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 88, 1323–1328. doi: 10.1007/s40011-017-0867-7

Barvenik, F. W. (1994). Polyacrylamide characteristics related to soil application. Soil Sci. 158, 235–243. doi: 10.1097/00010694-199410000-00002

Ben-Hur, M., Malik, M., Letey, J., and Mingelgrin, U. (1992). Adsorption of polymers on clays as affected by clay charge and structure, polymer properties and water quality. Soil Sci. 153, 349–356. doi: 10.1097/00010694-199205000-00002

Blake, G. R. and Hartge, K. H. (1986). Methods of soil analysis, part 1: physical and mineralogical methods. Soil Sci. Soc. America 363.

Blanco-Canqui, H., Benjamin, J. G., Logsdon, S., Berli, M., Horn, M., Madison, W. I., et al. (2013). “Impacts of soil organic carbon on soil physical behavior,” in Quantifying and Modeling Soil Structure Dynamics: Advances in Agricultural Systems Modeling, vol. 3. (Soil Sci Soc Am Inc), 11–40. doi: 10.2134/advagricsystmodel3.c2

Bolan, N., Hoang, S. A., Beiyuan, J., Gupta, S., Hou, D., Karakoti, A., et al. (2022). Multifunctional applications of biochar beyond carbon storage. Int. Mater. Rev. 67, 150–200. doi: 10.1080/09506608.2021.1922047

Bolan, S., Sharma, S., Mukherjee, S., Kumar, M., Rao, C. S., Nataraj, K. C., et al. (2024). Biochar modulating soil biological health: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 914, 169585. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169585

Chandra, S. and Bhattacharya, J. (2019). Influence of temperature and duration of pyrolysis on the property heterogeneity of rice straw biochar and optimization of pyrolysis conditions for its application in soils. J. Clean Prod. 215, 1123–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.079

Chen, Y., Sun, K., Yang, Y., Gao, B., and Zheng, H. (2024). Effects of biochar on the accumulation of necromass-derived carbon, the physical protection and microbial mineralization of soil organic carbon. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 39–67. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2023.2221155

Demeyer, A., Nkana, J. V., and Verloo, M. G. (2001). Characteristics of wood ash and influence on soil properties and nutrient uptake: an overview. Bioresour. Technol. 77, 287–295. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(00)00043-2

Deng, H., Fang, C., and Wang, Z. (2023). Synergistic effects of biochar and PAM on water conservation and soil structure improvement in rice fields. Catena 227, 107075.

Dhanda, S., Yadav, A., Yadav, D. B., and Chauhan, B. S. (2022). Emerging issues and potential opportunities in the rice–wheat cropping system of North-Western India. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 832683. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.832683

FAO. (2021). The state of the world’s land and water resources for food and agriculture – Systems at breaking point. Synthesis report 2021. Rome. doi: 10.4060/cb7654en

Gathorne-Hardy, A., Reddy, D. N., Venkatanarayana, M., and Harriss-White, B. (2016). System of Rice Intensification provides environmental and economic gains but at the expense of social sustainability - A multidisciplinary analysis in India. Agric. Syst. 143, 159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2015.12.012

Ghani, M. I., Ahanger, M. A., Sial, T. A., Haider, S., Siddique, J. A., Fan, R., et al. (2024). Almond shell-derived biochar decreased toxic metals bioavailability and uptake by tomato and enhanced the antioxidant system and microbial community. Sci. Total Environ. 929, 172632. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.172632

Goebel, M. O., Bachmann, J., Woche, S. K., and Fischer, W. R. (2005). Soil wettability, aggregate stability, and the decomposition of soil organic matter. Geoderma 128, 80–93. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2004.12.016

Gomez, K. A. and Gomez, A. A. (1984). Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research (New York: John Wiley and Sons).

Green, V. S., Stott, D. E., Norton, L. D., and Graveel, J. G. (2000). Polyacrylamide molecular weight and charge effects on infiltration under simulated rainfall. Soil Sci. Soc Am. J. 64, 1786–1791. doi: 10.2136/sssaj2000.6451786x

Ishfaq, M., Farooq, M., Zulfiqar, U., Hussain, S., Akbar, N., Nawaz, A., et al. (2020). Alternate wetting and drying: A water-saving and ecofriendly rice production system. Agric. Water Manage. 241, 106363. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2020.106363

John, B., Yamashita, T., Ludwig, B., and Flessa, H. (2005). Storage of organic carbon in aggregate and density fractions of silty soils under different types of land use. Geoderma 128, 63–79. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2004.12.013

Kebede, B., Tsunekawa, A., Haregeweyn, N., Mamedov, A. I., Tsubo, M., Fenta, A. A., et al. (2020). Effectivenessof polyacrylamide in reducing runoff and soil loss under consecutive rainfall storms. Sustainability 12, 1597.

Keiluweit, M., Nico, P. S., Johnson, M. G., and Kleber, M. (2010). Dynamic molecular structure of plant biomass-derived black carbon (biochar). Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 1247–1253. doi: 10.1021/es9031419

Kumar, M., Ambika, S., Hassani, A., and Nidheesh, P. V. (2022). Waste to catalyst: Role of agricultural waste in water and wastewater treatment. Sci. Total Environ., 159762.

Kumar, A., Elad, Y., Tsechansky, L., Abrol, V., Lew, B., Offenbach, R., et al. (2018). Biochar potential in intensive cultivation of Capsicum anuum L. (sweet pepper): Crop yield and plant protection. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 98, 495–450. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.8486

Laird, D. A., Fleming, P., Davis, D. D., Hortonne, R., Wang, B., Karlen, D. L., et al. (2010). Impact of biochar amendments on the quality of a typical Midwestern agricultural soil. Geoderma 158, 443–449. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2010.05.013

Lehmann, J. and Joseph, S. (Eds.) (2024). Biochar for environmental management: science, technology and implementation (Taylor & Francis).

Levy, G. J., Levin, J., Gal, M., Ben‐Hur, M., and Shainberg, I. (1992). Polymers' effects on infiltration and soil erosion during consecutive simulated sprinkler irrigations. Soil Sci. Soc Am. J. 56, 902–907. doi: 10.2136/sssaj1992.03615995005600030037x

Li, X., Zeng, R., and Liao, H. (2016). Improving crop nutrient efficiency through root architecture modifications. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 58, 193–202. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12434

Liu, X., Wang, H., Liu, C., Sun, B., Zheng, J., Bian, R., et al. (2021). Biochar increases maize yield by promoting root growth in the rainfed region. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 67, 1411–1424. doi: 10.1080/03650340.2020.1796981

Mandal, K. G., Thakur, A. K., and Ambast, S. K. (2019). Current rice farming, water resources and micro-irrigation. Curr. Sci. 116, 568–576. doi: 10.18520/cs/v116/i4/568-576

Materu, S. T., Shukla, S., Sishodia, R. P., Tarimo, A., and Tumbo, S. D. (2018). Water use and rice productivity for irrigation management alternatives in Tanzania. Water 10, 1018. doi: 10.3390/w10081018

Mboyerwa, P. A., Kibret, K., Mtakwa, P., and Aschalew, A. (2022). Rice yield and nitrogen use efficiency with system of rice intensification and conventional management practices in mkindo irrigation scheme, Tanzania. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6, 802267. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.802267

Mekonnen, M. M. and Hoekstra, A. Y. (2020). Blue water footprint linked to national consumption and international trade is unsustainable. Nat. Food. 1, 792–800. doi: 10.1038/s43016-020-00198-1

Mohapatra, K. K., Nayak, A. K., Patra, R. K., Tripathi, R., Swain, C. K., Moharana, K. C., et al. (2023). Multi-criteria assessment to screen climate smart rice establishment techniques in coastal rice production system of India. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1130545. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1130545

Mohidem, N. A., Hashim, N., Shamsudin, R., and Che Man, H. (2022). Rice for food security: Revisiting its production, diversity, rice milling process and nutrient content. Agriculture 12, 741. doi: 10.3390/agriculture12060741

Muthayya, S., Sugimoto, J. D., Montgomery, S., and Maberly, G. F. (2014). An overview of global rice production, supply, trade, and consumption. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1324, 7–14. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12540

Olaleye, A. O., Tabi, F. O., Ogunkunle, A. O., Singh, B. N., and Sahrawat, K. L. (2001). Effect of toxic iron concentrations on the growth of lowland rice. J. Plant Nutr. 24, 441–457. doi: 10.1081/PLN-100104971

Pan, G., Zhou, P., Li, Z., Smith, P., Li, L., Qiu, D., et al. (2009). Combined inorganic/organic fertilization enhances N efficiency and increases rice productivity through organic carbon accumulation in a rice paddy from the Tai Lake region, China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 131, 274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2009.01.020

Pascual, V. J. and Wang, Y. M. (2016). Impact of water management on rice varieties, yield, and water productivity under the system of rice intensification in Southern Taiwan. Water 9, 3. doi: 10.3390/w9010003

Rafique, M. I., Al-Wabel, M. I., Al-Farraj, A. S., Ahmad, M., Aouak, T., Al-Swadi, H. A., et al. (2025). Incorporation of biochar and semi-interpenetrating biopolymer to synthesize new slow release fertilizers and their impact on soil moisture and nutrients availability. Sci. Rep. 15, 9563. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-90367-8

Rawat, J., Saxena, J., and Sanwal, P. (2019). “Biochar: a sustainable approach for improving plant growth and soil properties,” in Biochar- An imperative amendment for soil and the environment. Eds. Abrol, V. and Sharma, P. (Intech Open, London). doi: 10.5772/intechopen.82151

Saini, A. K., Abrol, V., Sharma, P., Srinivasarao, C., Parmar, A. S., Lado, M., et al. (2025). Nitrogen-fortified nanobiochar impacts soil properties, root growth and basmati rice yield. Biochar 7, 102. doi: 10.1007/s42773-025-00503-w

Sato, S. and Uphoff, N. (2007). “A review of on-farm evaluations of system of rice intensification methods in Eastern Indonesia,” in CABI Reviews, 12. doi: 10.1079/PAVSNNR200720

Shaheen, S. M., Ullah, H., Wu, Y., Mosa, A., Fang, Y., Shi, Y., et al. (2025). Remediation of emerging inorganic contaminants in soils and water using pristine and engineered biochar: a review. Biochar 7, 34. doi: 10.1007/s42773-024-00407-1

Sharma, P., Abrol, V., Kumar, S., Sharma., R., Maanik, Shabir, H., et al. (2025a). Efficiency of biochar and compost on soil bio-chemical properties and yield of knol-khol (Brassica oleracea L.). Pl. Sci. Tod. doi: 10.14719/pst.3358

Sharma, P., Abrol, V., Nazir, J., Samnotra, R. K., Gupta, S. K., Anand, S., et al. (2025b). Optimizing soil properties, water use efficiency, and crop yield through biochar and organic manure integration in organic soil. J. Environ. Manage. 373, 123673. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.123673

Sharma, P., Abrol, V., Sharma, V., Chaddha, S., Rao, C. S., Ganie, A. Q., et al. (2021). Effectiveness of biochar and compost on improving soil hydrophysical properties, crop yield and monetary returns in inceptisol subtropics. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 28, 7539–7549. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.09.043

Shen, Z., Zhang, Y., McMillan, O., Jin, F., and Al-Tabbaa, A. (2017). Characteristics and mechanisms of nickel adsorption on biochars produced from wheat straw pellets and rice husk. Environ. Sci. pollut. Res. 24, 12809–12819. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-8847-2

Sojka, R. E., Bjorneberg, D. L., Entry, J. A., Lentz, R. D., and Orts, W. J. (2007). Polyacrylamide in agriculture and environmental land management. Adv. Agron. 92, 75–162. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2113(04)92002-0

Sriphirom, P., Chidthaisong, A., and Towprayoon, S. (2019). Effect of alternate wetting and drying water management on rice cultivation with low emissions and low water used during wet and dry season. J. Clean Prod. 223, 980–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.03.212

Stoop, W. A., Uphoff, N., and Kassam, A. (2002). A review of agricultural research issues raised by the system of rice intensification (SRI) from Madagascar: opportunities for improving farming systems for resource-poor farmers. Agric. Syst. 71, 249–274. doi: 10.1016/S0308-521X(01)00070-1

Subedi, R., Bertora, C., Zavattaro, L., and Grignani, C. (2017). Crop response to soils amended with biochar: expected benefits and unintended risks. Ital. J. Agron. 12, 161–173. doi: 10.4081/ija.2017.794

Susanto, U., Rohaeni, W. R., and Sasmita, P. (2019). Root growth dynamics and grain yield of ten new plant type of rice lines under aerobic and flooded condition. IOP. Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 250, 012082.

Tennant, D. (1975). A test of a modified line intersects method of estimating root length. J. Ecol., 995–1001. doi: 10.2307/2258617

Thakur, A. K., Rath, S., and Mandal, K. G. (2013). Differential responses of system of rice intensification (SRI) and conventional flooded-rice management methods to applications of nitrogen fertilizer. Plant Soil. 370, 59–71. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1612-5

Tripathi, R. P., Sharma, P., and Singh, S. (2005). Tilth index: an approach to optimize tillage in rice-wheat system. Soil tillage Res. 80, 125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2004.03.004

Wang, X., Suo, Y., Feng, Y., Shohag, M. J. I., Gao, J., Zhang, Q., et al. (2011). Recovery of 15 N-labeled urea and soil nitrogen dynamics as affected by irrigation management and nitrogen application rate in a double rice cropping system. Plant Soil. 343, 195–208. doi: 10.1007/s11104-010-0648-z

Xiao, X., Chen, B., and Zhu, L. (2014). Transformation, morphology, and dissolution of silicon and carbon in rice straw-derived biochars under different pyrolytic temperatures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 3411–3419. doi: 10.1021/es405676h

Yang, C., Yang, L., Yang, Y., and Ouyang, Z. (2004). Rice root growth and nutrient uptake as influenced by organic manure in continuously and alternately flooded paddy soils. Agric. Water Manage. 70, 67–81. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2004.05.003

Yu, J., Lei, T. W., Shainberg, I., Mamedov, A. I., and Levy, G. J. (2003). Infiltration and erosion in soils treated with dry PAM and gypsum. Soil Sci. Soc Am. J. 67, 630–636. doi: 10.2136/sssaj2003.6300

Yu, O. Y., Raichle, B., and Sink, S. (2013). Impact of biochar on the water holding capacity of loamy sand soil. Int. J. Energy Environ. Eng. 4, 1. doi: 10.1186/2251-6832-4-44

Zhang, H., Xue, Y., Wang, Z., Yang, J., and Zhang, J. (2009). An alternate wetting and moderate soil drying regime improves root and shoot growth in Rice. Crop Sci. 49, 2246–2260. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2009.02.0099

Zhou, W., Chen, Y., and Li, W. (2023). Improving soil water retention with biochar-PAM mixtures under high-temperature conditions. Soil Tillage Res. 233, 105632.

Keywords: biochar, polymer, soil hydraulic properties, system of rice intensification (SRI), root growth, water saving

Citation: Sharma P, Abrol V, Shabir H, Gupta SK, Gupta NK, Samnotra RK, Chandra S, Bashir O, Amjid S, Singh P, Hashem A, Kumar A, Abd_Allah EF, Kumar M, Sandhu R, Chembolu V, Lado M and Hublikar LV (2025) Biochar and anionic polyacrylamide modulated soil hydraulic functions catalyze water saving, root development and yield of basmati rice. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1660325. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1660325

Received: 05 July 2025; Accepted: 20 November 2025; Revised: 10 November 2025;

Published: 11 December 2025.

Edited by:

Hanmi Zhou, Henan University of Science and Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Krishan K. Verma, Guangxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences, ChinaHermes Pérez Hernández, Agriculture and Livestock Research (INIFAP), Mexico

Copyright © 2025 Sharma, Abrol, Shabir, Gupta, Gupta, Samnotra, Chandra, Bashir, Amjid, Singh, Hashem, Kumar, Abd_Allah, Kumar, Sandhu, Chembolu, Lado and Hublikar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vikas Abrol, YWJyb2x2aWNzQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==; Manish Kumar, bWFuaXNoa3VtYXIuYnRAZ21haWwuY29t

Peeyush Sharma1

Peeyush Sharma1 Vikas Abrol

Vikas Abrol Owais Bashir

Owais Bashir Abeer Hashem

Abeer Hashem Ajay Kumar

Ajay Kumar Elsayed Fathi Abd_Allah

Elsayed Fathi Abd_Allah Manish Kumar

Manish Kumar Rubby Sandhu

Rubby Sandhu Vinay Chembolu

Vinay Chembolu Leena V Hublikar

Leena V Hublikar