- 1Xinjiang Key Laboratory of Lavender Conservation and Utilization, College of Biological Sciences and Technology, Yili Normal University, Yining, Xinjiang, China

- 2School of Life Sciences, Xiamen University, Xiamen, Fujian, China

Lavender essential oils (EOs) are economically valuable, with biosynthesis linked to photosynthesis. NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductases (NDHs) play a crucial role in regulating photosynthetic processes. To better understand the functional roles and mechanisms of NDHs, we investigated Lavandula angustifolia NDHs (LaNDHs) using AlphaFold2 for structural prediction and RT-qPCR for expression analysis. Gene LaNDHs showed highest expression in leaves compared to other tissues (stems, roots and flowers), with upregulation under cadmium ion, heat, salt, and blue light. These findings suggest LaNDHs enhance stress tolerance and photosynthesis, offering potential for improving EO yield.

Introduction

Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) is an aromatic shrub cultivated for its essential oils (EOs), widely used in cosmetics and medicine (Crişan et al., 2023; de Melo Alves Silva et al., 2023; Wilson et al., 2021). The quality of lavender EOs is primarily influenced by their monoterpene composition, which predominantly features linalool, linalyl acetate, borneol, camphor, and 1,8-cineole (Prosche and Stappen, 2024; Vairinhos and Miguel, 2020; Aarshageetha et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2025b). The highest quality EOs are typically derived from the flowering tops of Lavandula angustifolia, often referred to as ‘true lavender,’ which is celebrated for its unique fragrance and has been highly valued since ancient times. Lavender EOs are extensively used in the cosmetics, hygiene, and alternative medicine industries (Hedayati et al., 2024; Khan et al., 2024; Li et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2025a; Guo and Wang, 2020). For example, EOs with elevated camphor content are employed in inhalants for treating respiratory conditions such as coughs and colds, as well as in liniments and balms for topical analgesic applications (Malloggi et al., 2021; Batiha et al., 2023; Braunstein and Braunstein, 2023; Liu et al., 2024). Furthermore, camphor has been investigated as a radiosensitizing agent to enhance tumor oxygenation prior to radiotherapy (Malloggi et al., 2021; Batiha et al., 2023; Braunstein and Braunstein, 2023; Liu et al., 2024).

EO biosynthesis depends on photosynthesis, which provides ATP/NADPH and carbon precursors for terpenes (Croce et al., 2024; Reece and Sharkey, 2020). Factors such as light intensity, spectrum, and photoperiod significantly affect the yield of lavender EOs by modulating key enzymes involved in the process (Evans, 2013). Optimal light conditions enhance both photosynthetic efficiency and the biosynthesis of monoterpenes (Li et al., 2023, 2025). Additionally, Lavandula angustifolia NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductases (LaNDHs) represent another important factor influencing the yield and quality of EOs (Croce et al., 2024; Reece and Sharkey, 2020; Dinkova-Kostova and Talalay, 2010). LaNDHs boost EOs’ yield and quality by reducing oxidative stress and stabilizing terpene biosynthesis. LaNDHs maintain redox balance, enhancing terpene synthase activity and precursor availability. Efficient LaNDHs function leads to higher the production of EOs and preserved aromatic compounds, improving overall characteristics of EOs. LaNDHs are cytosolic enzymes that catalyze the reduction of quinones and a broad range of other substrates (Pey et al., 2019). Cellular defense mechanisms against oxidative stress involve various protective pathways, with LaNDHs playing a central role (Dinkova-Kostova and Talalay, 2010). This enzyme catalyzes the two-electron reduction of quinones to hydroquinones, utilizing NADH or NAD(P)H as electron donors. This reaction prevents the formation of reactive semiquinone intermediates, thereby inhibiting the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Ross and Siegel, 2017). The NDH complex transfers electrons from LaNDHs via flavin mononucleotide and iron-sulfur centers to quinones within the photosynthetic electron transport chain, and potentially within a chloroplast respiratory chain. Plastoquinone is hypothesized to be the immediate electron acceptor for this enzyme, coupling the redox reaction to proton translocation, which in turn conserves redox energy in the form of a proton gradient. LaNDHs are vital for sustaining the biosynthesis of lavender EOs. However, no studies have yet investigated the specific roles of LaNDHs in Lavandula angustifolia.

In this study, we predicted structures using AlphaFold2, and identified their potential active site residues via GalaxyWEB. Gene expression analysis demonstrated that the LaNDHs genes (LaNDH-2, LaNDH-11, LaNDH-4L1 and LaNDH-4L2) exhibited the highest expression levels in leaves compared to other tissues (stems, roots and flowers). Expression of LaNDHs in leaves increased with higher cadmium ion (Cd2+) concentrations. Additionally, LaNDHs expression was elevated as temperature rose from 25 °C to 40 °C and as salt concentrations increased. The highest expression levels of these genes were observed under blue light compared to that under white and red light. Our results suggest that cultivating lavender varieties with enhanced tolerance to abiotic stress could optimize photosynthesis, thereby increasing both the yield and quality of lavender essential oils.

Results

Biochemical characteristics of LaNDHs

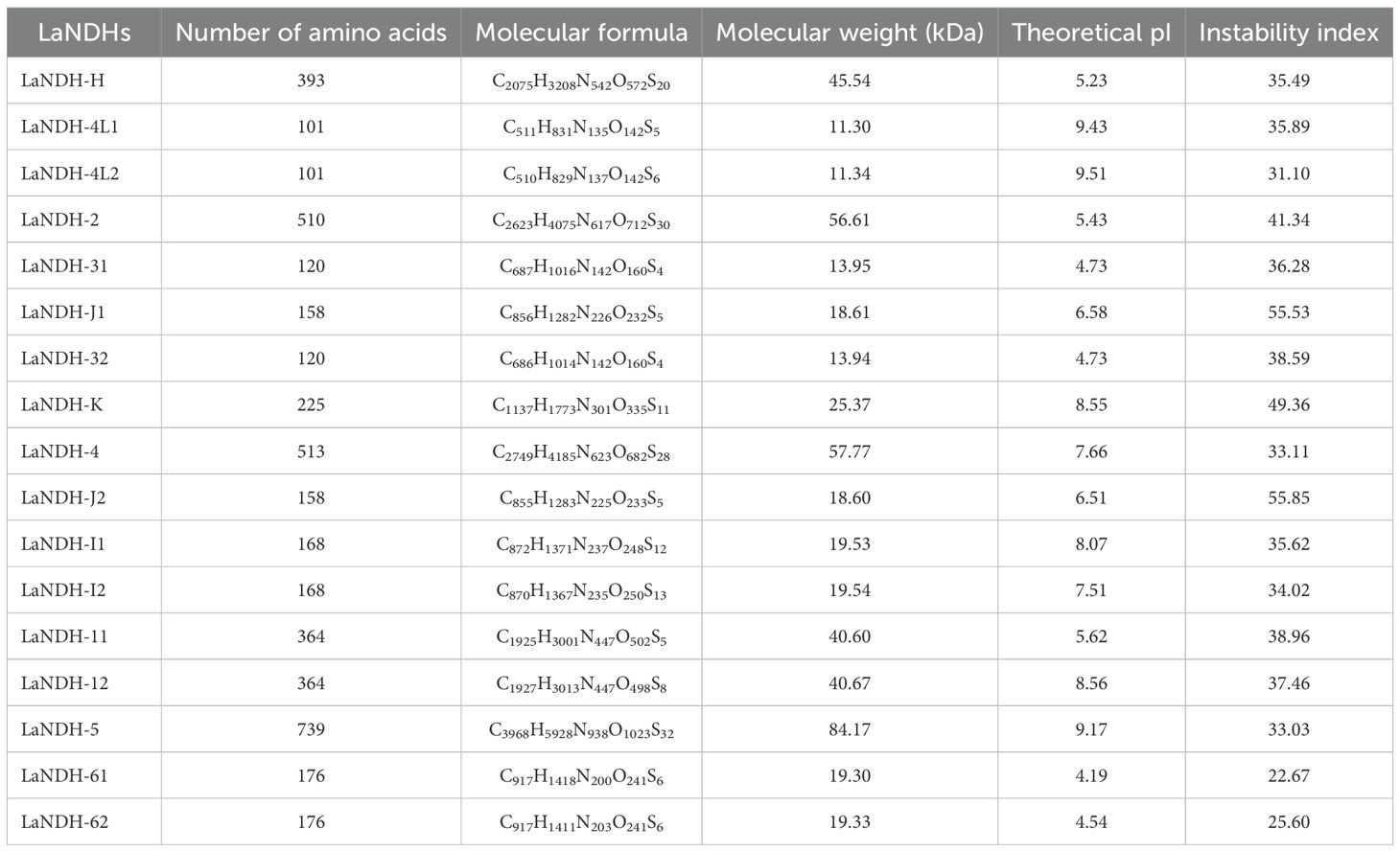

Bioinformatics analysis of Lavandula angustifolia NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductases (LaNDHs) was conducted using data obtained from the UniProt database (Supplementary Table S1). The molecular weights of these enzymes vary from 11.30 kDa to 84.17 kDa (Table 1). The number of amino acids in the LaNDHs proteins ranges from 101 to 739 (Table 1). Their isoelectric points (pI) span from 4.19 to 9.53 (Table 1). The instability index of these enzymes varies between 22.67 and 55.85 (Table 1).

Secondary structure prediction of LaNDHs

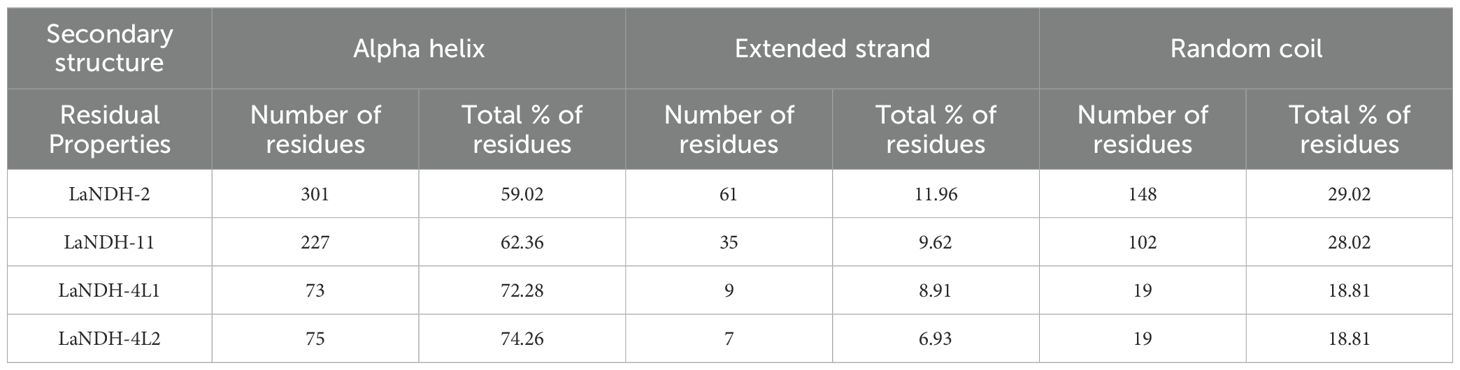

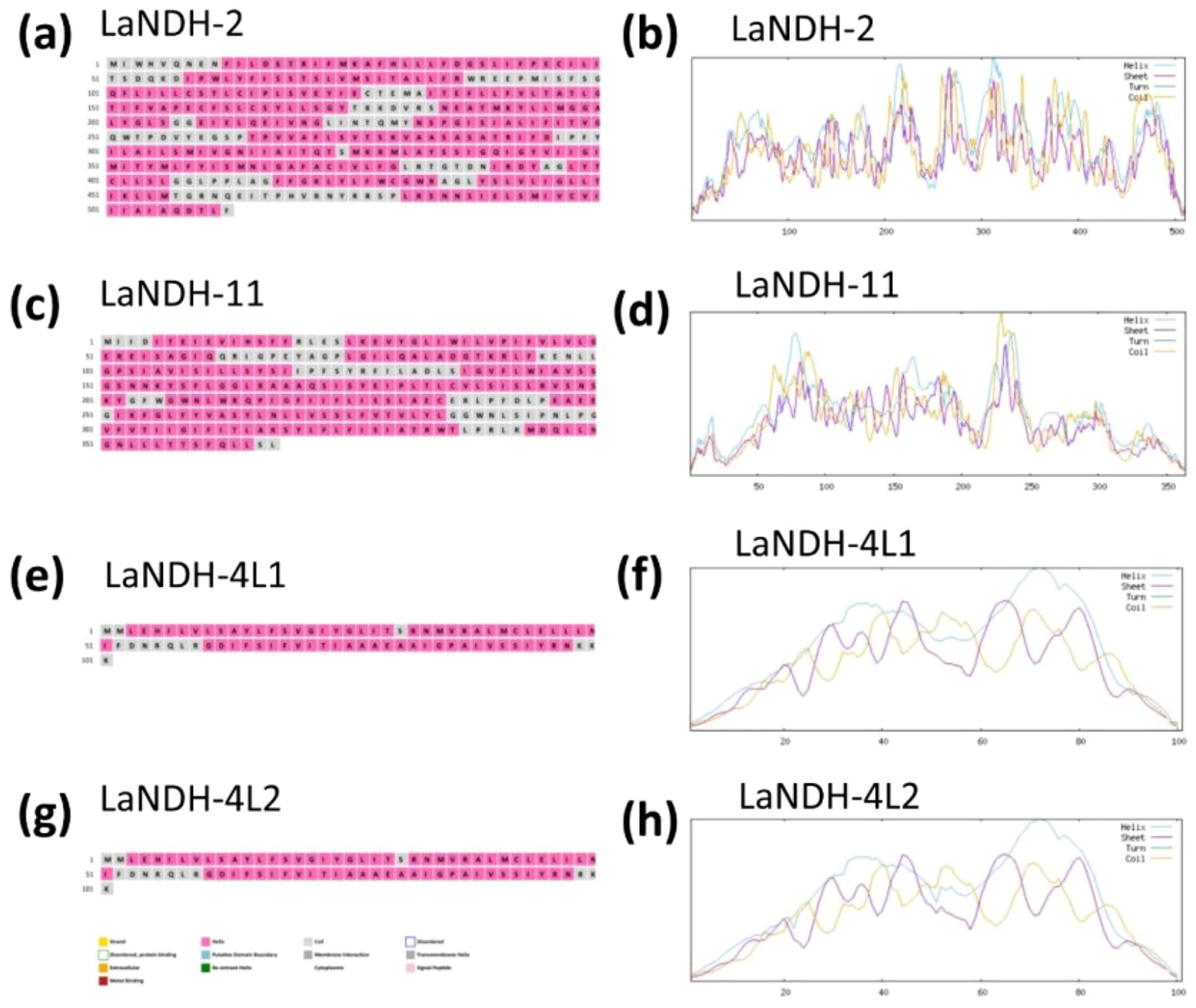

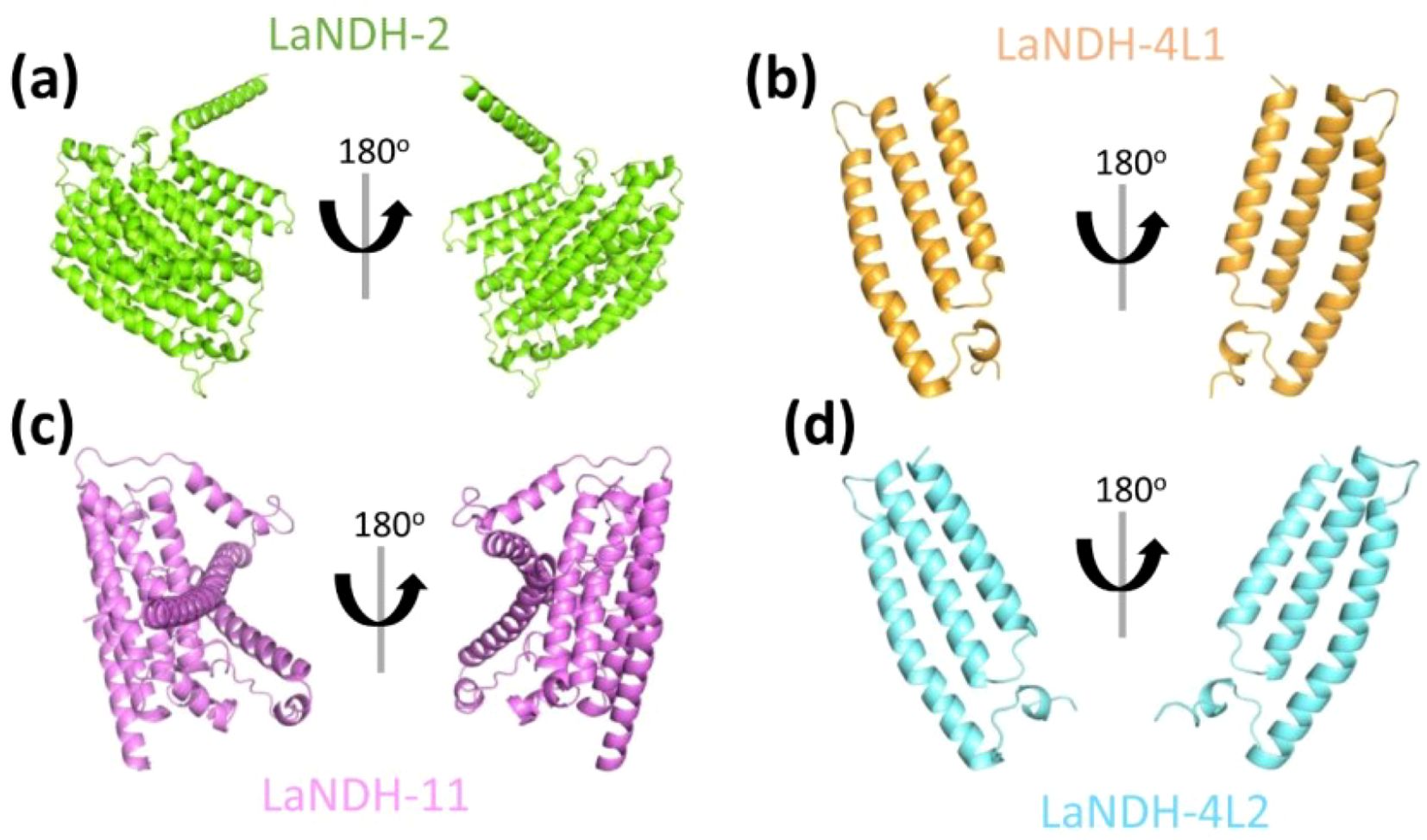

Using the amino acid sequences of LaNDH-2, LaNDH-11, LaNDH-4L1 and LaNDH-4L2 (The reasons for our choice of LaNDH-2, LaNDH-11, LaNDH-4L1, and LaNDH-4L2 can be found in the following content.), we predicted their secondary structures using the PSIPRED (Buchan et al., 2024; Jones, 1999) and NPS@ server (Combet et al., 2000) tools, respectively (Figure 1; Tables 1 and 2). The predicted secondary structures of LaNDH-2, LaNDH-11, LaNDH-4L1, and LaNDH-4L2 are predominantly composed of alpha helices, accounting for 59.02%, 62.36%, 72.28%, and 74.26% of the residues, respectively (Figure 1; Table 1). Additionally, each protein contains multiple strands and coils (Figure 1; Table 1). The number of residues in the helices for LaNDH-2, LaNDH-11, LaNDH-4L1, and LaNDH-4L2 are 301, 227, 73, and 75, respectively (Figure 1; Table 1).

Figure 1. Predicted secondary structure models of (a, b) LaNDH-2, (c, d) LaNDH-11, (e, f) LaNDH-4L1, and (g, h) LaNDH-4L2. These secondary structures were predicted using PSIPRED (a for LaNDH-2, c for LaNDH-11, e for LaNDH-4L1, g for LaNDH-4L2) and NPS@ server (b for LaNDH-2, d for LaNDH-11, f for LaNDH-4L1, h for LaNDH-4L2).

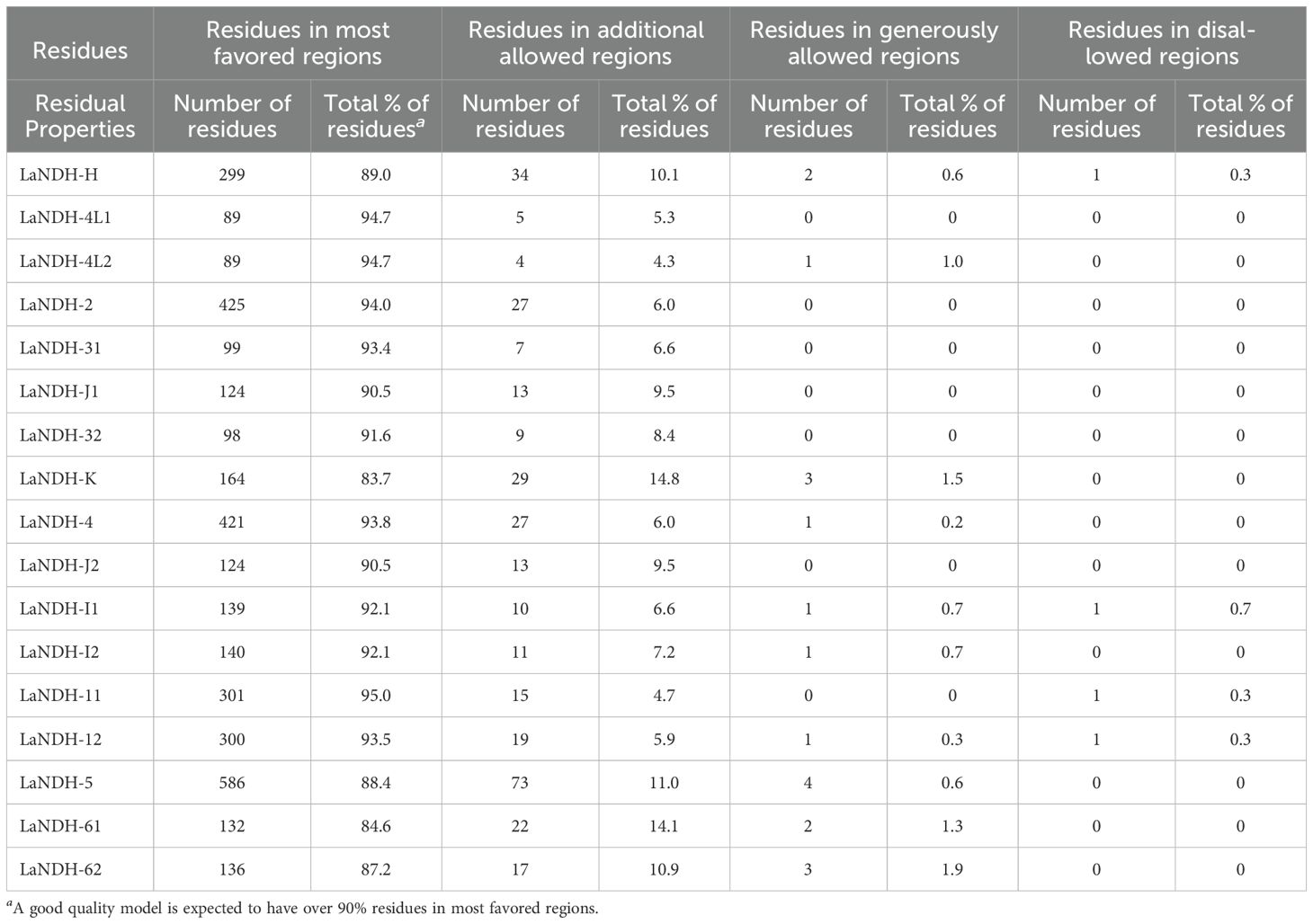

Prediction and quality assessment of structural models of LaNDHs

The three-dimensional (3D) structures of LaNDHs were predicted using AlphaFold2 (Wayment-Steele et al., 2023; Jumper et al., 2021). AlphaFold2 is a deep learning-based tool known for providing highly accurate and reliable protein structure predictions, which outperform traditional homology modeling techniques. To assess the quality of the predicted structures (Figures 2, Supplementary Figure S1), we employed the Ramachandran plot to analyze the dihedral angles of the protein backbones. These ensured they fell within acceptable regions, which indicates a valid protein conformation (Supplementary Figure S2; Table 3). A high-quality model is expected to have more than 90% of its residues in the most favored regions. In the most favored region, the residual rates of LaNDH-2, LaNDH-11, LaNDH-4L1, and LaNDH-4L2 all exceeded 94%, indicating that these models represent the highest quality structures among these LaNDHs (Table 3). Consequently, we proceeded with further analysis using LaNDH-2, LaNDH-11, LaNDH-4L1, and LaNDH-4L2.

Figure 2. Structural prediction. The three-dimensional (3D) structures of (a) LaNDH-2, (b) LaNDH-4L1, (c) LaNDH-11, and (d) LaNDH-4L2 were predicted using AlphaFold2. The predicted structures are shown as ribbon diagrams in two different orientations. The structures of LaNDH-2 (a), LaNDH-4L1 (b), LaNDH-11 (c) and LaNDH-4L2 (d) are colored in green, orange, magenta and cyan, respectively.

For LaNDH-2, 94.0% of residues were in the most favored region, 6.0% in the additionally allowed region, and none in the generously allowed or disallowed regions (Table 3). For LaNDH-11, 95.0% of residues were in the most favored region, 4.7% in the additionally allowed region, 0.3% in the disallowed region, and none in the generously allowed region (Table 3). For LaNDH-4L1, 94.7% of residues were in the most favored region, 5.3% in the additionally allowed region, and none in the generously allowed or disallowed regions (Table 3). For LaNDH-4L2, 94.7% of residues were in the most favored region, 4.3% in the additionally allowed region, 1.0% in the generously allowed region, and none in the disallowed region (Table 3).

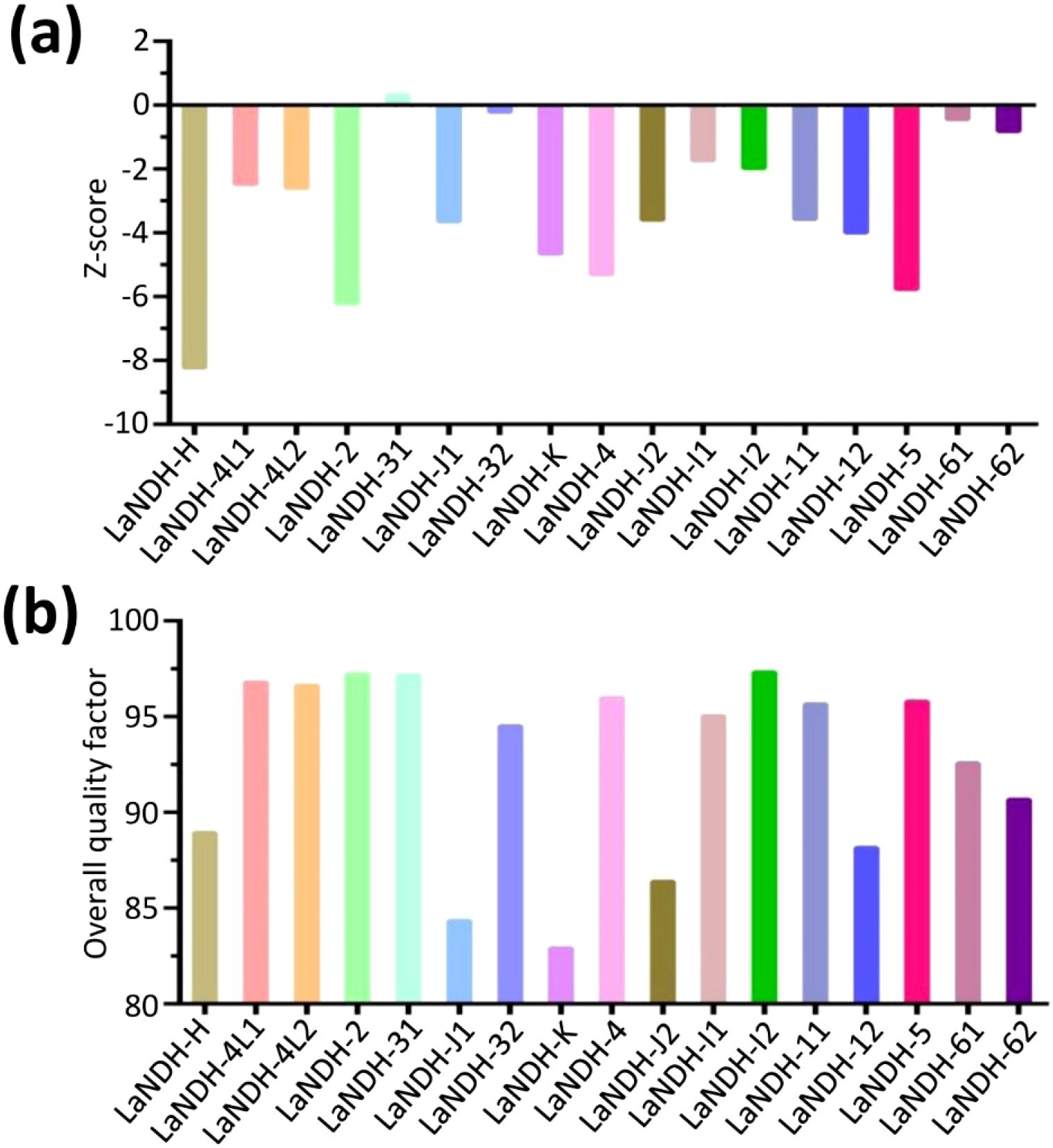

ProSA analysis of the models revealed Z-scores of -6.22, -3.58, -2.47, and -2.59 for LaNDH-2, LaNDH-11, LaNDH-4L1, and LaNDH-4L2, respectively (Figures 3a, Supplementary Figure S3). The overall quality factors of these models were 97.21, 95.66, 96.63, and 96.63, respectively (Figure 3b), further confirming the high quality of the predicted structures.

Figure 3. Structural quality assessment. (a) The reliability of the predicted models was assessed using ProSA, which calculated Z-scores to evaluate the global quality of the models. (b) Furthermore, the overall quality factor was determined to further confirm the structural integrity of the models.

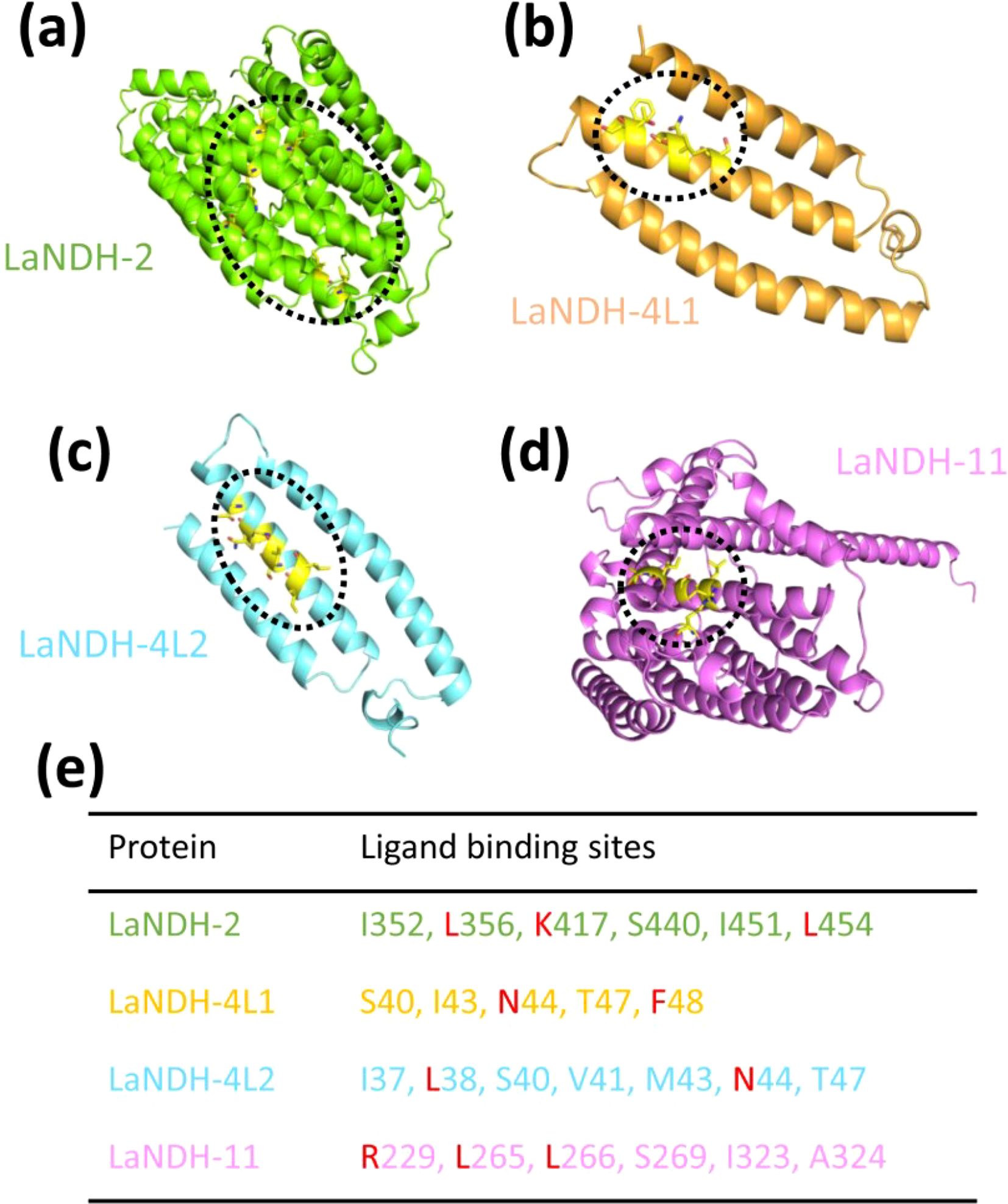

Predicting active sites of LaNDHs

Using the predicted models (Figure 2), we employed the GalaxyWEB program (Ko et al., 2012; Heo et al., 2013, 2016; Seok et al., 2021) to identify the active sites of LaNDH-2, LaNDH-11, LaNDH-4L1, and LaNDH-4L2 (Figure 4). The results revealed that the active site residues of LaNDH-2 include I352, L356, K417, S440, I451, and L454 (Figures 4a, e). For LaNDH-4L1, the active site residues were identified as S40, I43, N44, T47, and F48 (Figures 4b, e). For LaNDH-4L2, the active site residues include I37, L38, S40, V41, M43, N44, and T47 (Figures 4c, e). In the case of LaNDH-11, the active site residues consist of R229, L265, L266, S269, I323, and A324 (Figures 4d, e). These residues are highly likely to be involved in the catalytic process, potentially interacting with the substrate side chain atoms to form essential bonds.

Figure 4. Predicting (a) LaNDH-2, (b) LaNDH-4L1, (c) LaNDH-4L2 and (d) LaNDH-11 active site residues using the GalaxyWEB program. (e) The residues in the active site of LaNDH-2, LaNDH-4L1, LaNDH-4L2 and LaNDH-11. The residues (L, K, N, F and R) marked in red are evolutionarily conserved among plant NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductases.

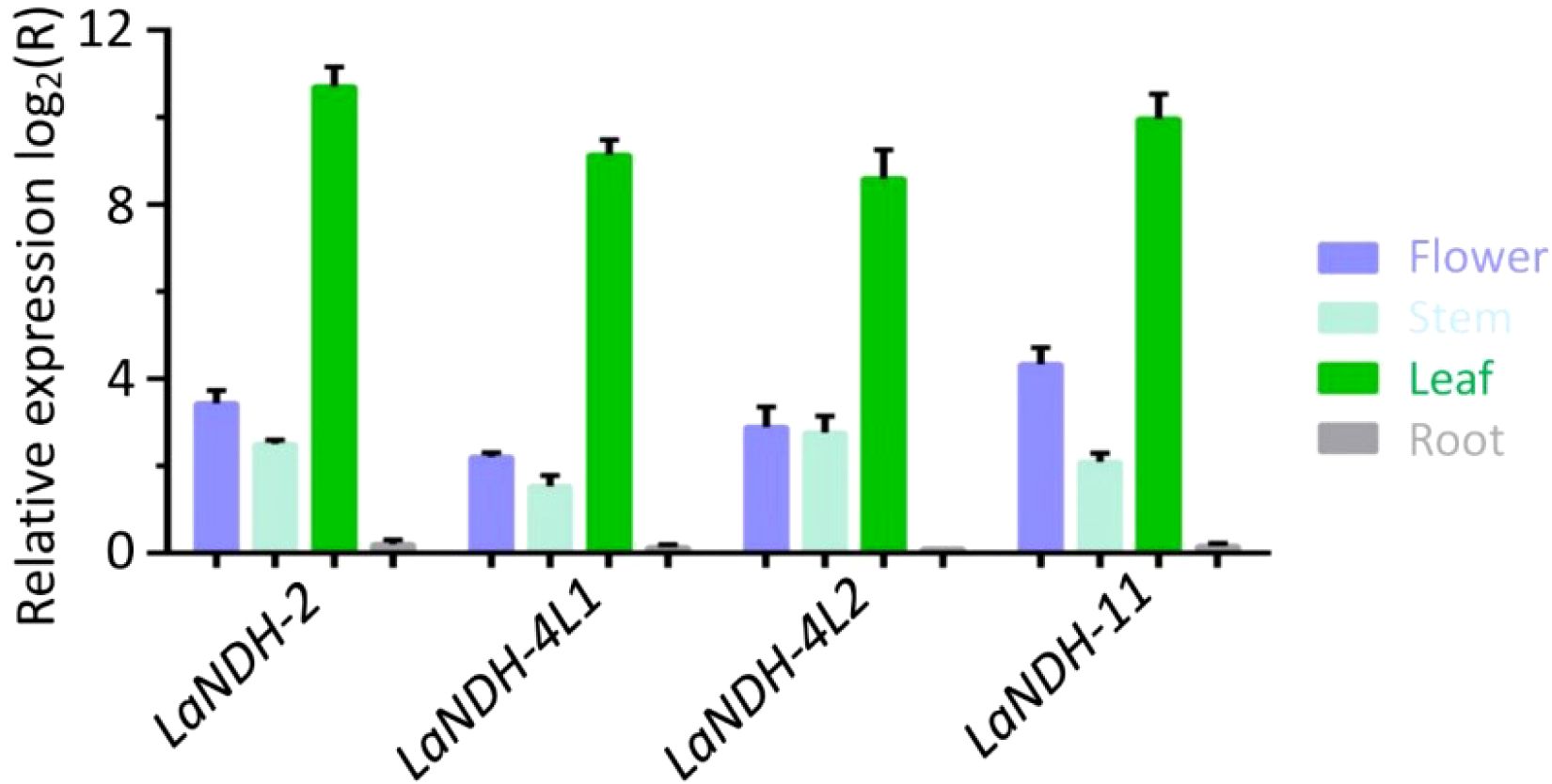

Gene LaNDHs exhibit the highest expression level in leaves among lavender tissues

To examine the expression profiles of LaNDH-2, LaNDH-11, LaNDH-4L1, and LaNDH-4L2 across various tissues (leaves, stems, flowers, and roots), we conducted real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). The results indicated that the highest expression levels of LaNDH-2, LaNDH-11, LaNDH-4L1, and LaNDH-4L2 were found in the leaves compared to other tissues (Figure 5). Specifically, the expression of LaNDH-2 was upregulated by 1663.5-fold in leaves, 10.6-fold in flowers, 5.7-fold in stems, and 1.1-fold in roots (Figure 5). LaNDH-11 expression was increased by 560.3-fold in leaves, 4.6-fold in flowers, 2.9-fold in stems, and 1.1-fold in roots (Figure 5). For LaNDH-4L1, expression was upregulated by 388.0-fold in leaves, 7.5-fold in flowers, 6.8-fold in stems, and 1.1-fold in roots (Figure 5). LaNDH-4L2 expression increased by 812.9-fold in leaves, 20.2-fold in flowers, 4.3-fold in stems, and 1.2-fold in roots (Figure 5). These results suggest that LaNDH-2, LaNDH-11, LaNDH-4L1, and LaNDH-4L2 are predominantly expressed in leaf tissue, implying their primary involvement in chloroplast-based photosynthetic processes.

Figure 5. Gene expression levels in different tissues (root, stem, leaf, and flower) using reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). Comparative analysis showed a marked increase in gene expression in leaf tissue compared to root, stem, and floral tissues. Gene expression was quantitatively assessed using the 2-ΔΔCT method, with beta-actin serving as the reference gene.

Expression profiles of gene LaNDHs under different abiotic stress conditions

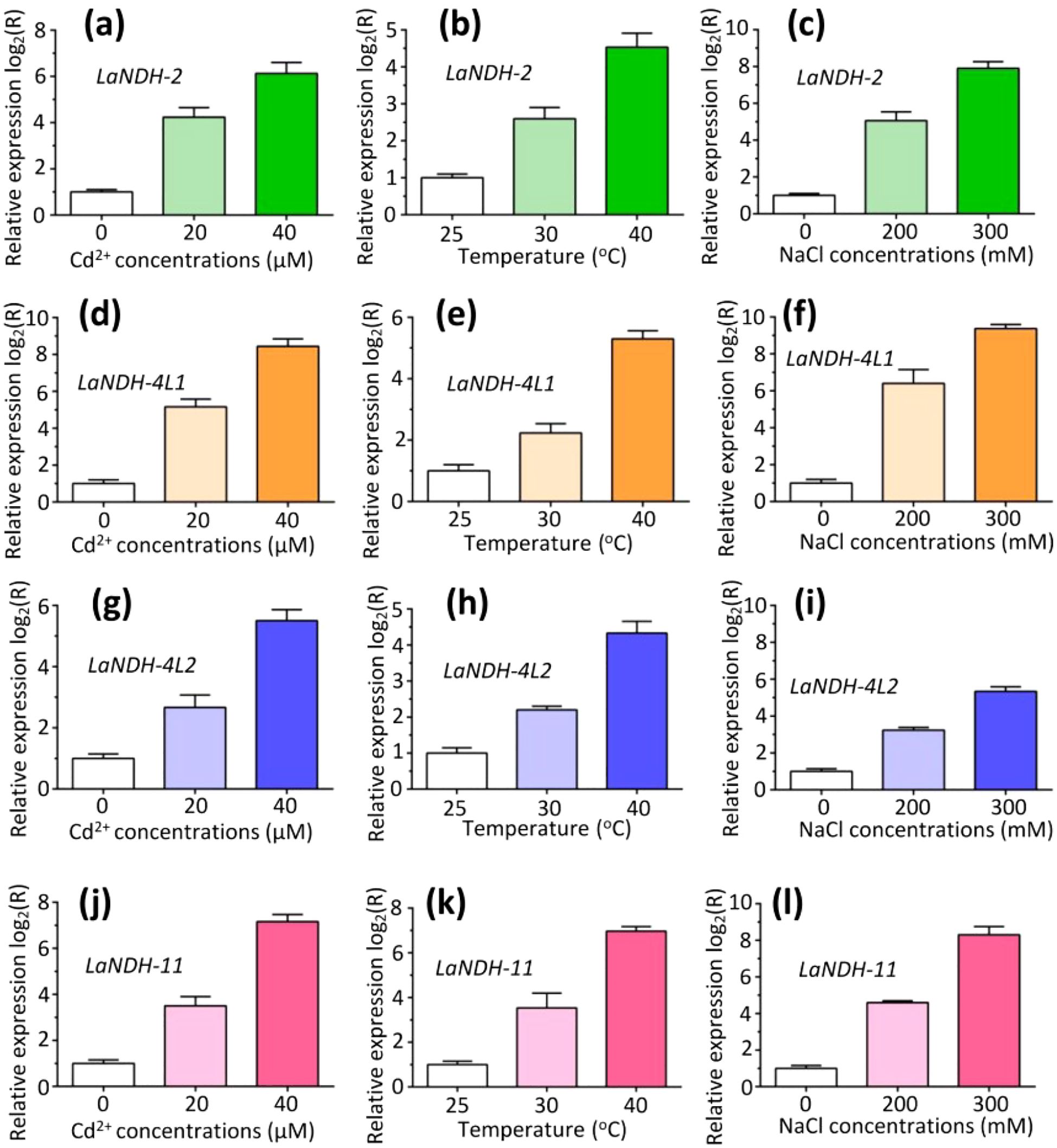

We performed RT-qPCR analysis to assess the expression levels of LaNDHs (LaNDH-2, LaNDH-11, LaNDH-4L1, and LaNDH-4L2) in response to cadmium ion (Cd2+), heat, and salt treatments in leaves (Figure 6). The results revealed that the expression of LaNDHs in leaves was positively correlated with increasing Cd2+ concentrations (Figures 6a, d, g, j). Similarly, LaNDHs expression in leaves increased as the temperature rose from 25°C to 40°C (Figures 6b, e, h, k). Additionally, LaNDHs expression in leaves was upregulated with higher salt concentrations (Figures 6c, f, i, l). These findings suggest that cadmium ion, heat and salt stress influence the photosynthetic rate in lavender, providing evidence for the association between LaNDHs genes (LaNDH-2, LaNDH-11, LaNDH-4L1, and LaNDH-4L2) and the photosynthetic process.

Figure 6. The expression profiles of genes (a-c) LaNDH-2, (d-f) LaNDH-4L1, (g-i) LaNDH-4L2, and (j-l) LaNDH-11 in leaf under abiotic stress conditions, including cadmium ion (Cd2+), heat, and NaCl exposure. For Cd2+ stress (a, d, g, j), plants were subjected to 0, 20, and 40 µM Cd2+ treatments. Heat stress (b, e, h, k) involved exposure to temperatures of 25°C, 30°C, and 40°C, respectively. Salt stress (c, f, i, l) was applied using 0, 200, and 300 mM NaCl treatments. Relative gene expression was quantified by RT-qPCR, with untreated samples normalized to a baseline value of 1.

Differential expression of gene LaNDHs under various light conditions

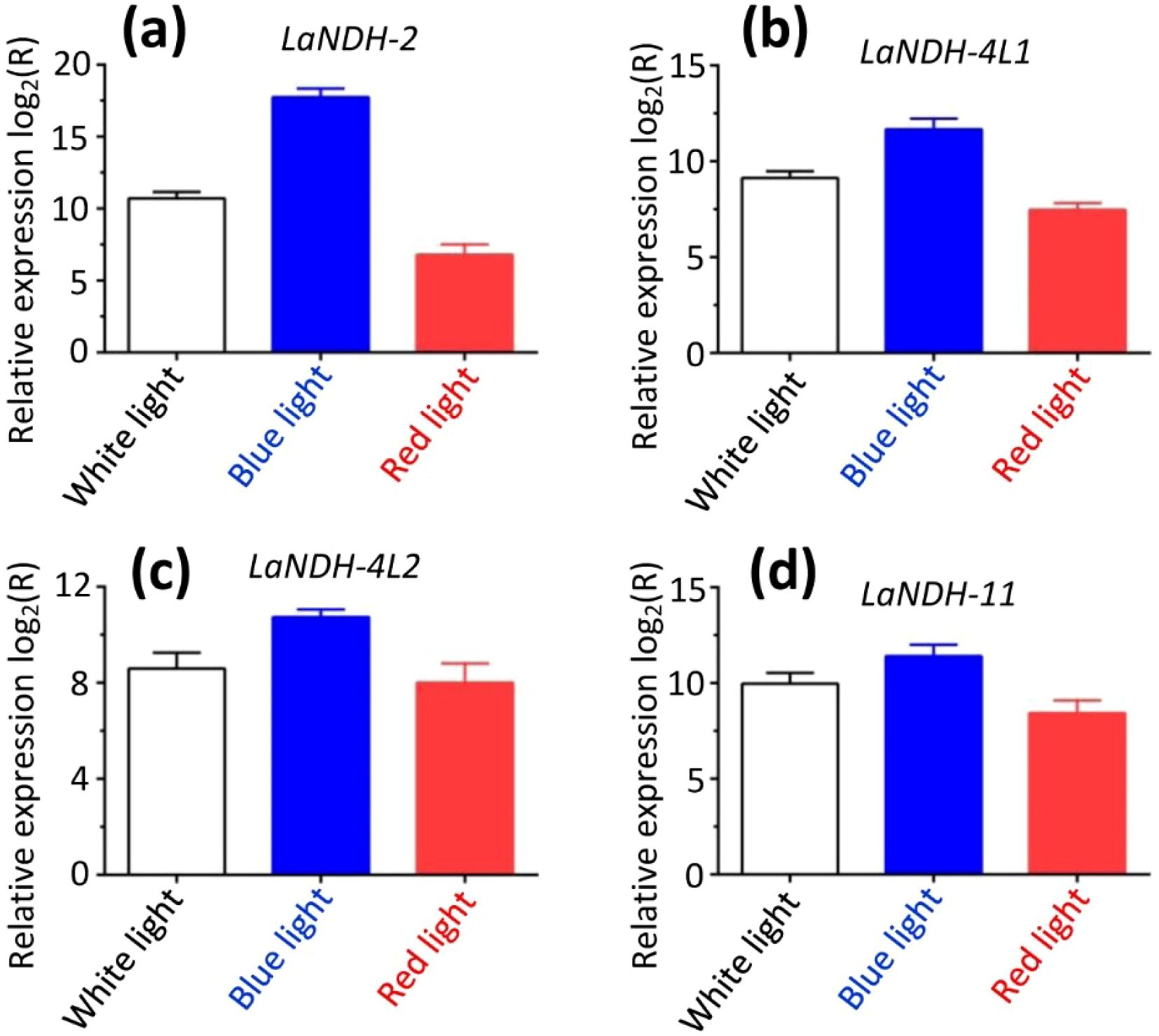

To establish a comprehensive light-responsive gene expression profile, we evaluated the expression levels of LaNDHs genes (LaNDH-2, LaNDH-11, LaNDH-4L1, and LaNDH-4L2) in leaves under various light conditions (white, red, and blue) using RT-qPCR. The results showed that the expression levels of these genes were highest under blue light compared to other light conditions (Figure 7). Specifically, for LaNDH-2, the expression was highest under blue light (217,898.9-fold), followed by white light (1,663.5-fold), and red light (111.4-fold) (Figure 7a). For LaNDH-4L1, the highest expression was observed under blue light (3,251.1-fold), followed by white light (561.6-fold), and red light (176.9-fold) (Figure 7b). For LaNDH-4L2, the expression peaked under blue light (1,702.3-fold), followed by white light (388.1-fold), and red light (256.3-fold) (Figure 7c). For LaNDH-11, the highest expression was found under blue light (2,786.4-fold), followed by white light (812.4-fold), and red light (345.7-fold) (Figure 7d). These findings underscore the significant role of light in regulating the expression of LaNDHs genes (LaNDH-2, LaNDH-11, LaNDH-4L1, and LaNDH-4L2), further supporting the connection between these genes and photosynthesis.

Figure 7. Gene expression in leaf under different light conditions (white, blue, and red light). Among the various treatments, blue light resulted in the highest expression levels of the genes (a) LaNDH-2, (b) LaNDH-4L1, (c) LaNDH-4L2, and (d) LaNDH-11. Relative gene expression was quantified by RT-qPCR, with beta-actin serving as the reference gene. Data analysis was performed using the 2-ΔΔCT method.

Discussion

In this work, we used PSIPRED and NPS@ server to predict the secondary structures of LaNDH-2, LaNDH-11, LaNDH-4L1, and LaNDH-4L2, and their structural models were generated with AlphaFold2. The GalaxyWEB program was then applied to identify potential active site residues for these proteins. Gene expression analysis showed that the LaNDHs genes (LaNDH-2, LaNDH-11, LaNDH-4L1, and LaNDH-4L2) were most highly expressed in the leaves compared to other tissues (stems, roots, and flowers). Expression levels of LaNDHs in leaves increased with higher cadmium ion (Cd2+) concentrations. Additionally, LaNDHs expression in leaves rose as the temperature increased from 25 °C to 40 °C and with higher salt concentrations. Among different light conditions (white, blue, and red), the expression levels of LaNDHs genes were highest under blue light. Given their localization in the chloroplast, these genes may be involved in lavender photosynthesis. LaNDH-4L1/4L2 could be targets for stress-tolerant lavender varieties. These findings suggest that cultivating lavender varieties tolerant to abiotic stress could enhance photosynthetic efficiency, thereby improving both the yield and quality of lavender essential oils (EOs).

LaNDHs may confer enhanced stress tolerance through multifaceted mechanisms. Functioning as a pivotal enzyme in redox homeostasis, LaNDHs mitigate oxidative damage by facilitating electron transfer from NAD(P)H to quinones, thereby scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS). LaNDHs potentially contribute to cyclic electron flow around Photosystem I, optimizing ATP/NADPH ratios and alleviating photo-oxidative stress. Notably, blue light specifically induces LaNDHs upregulation, likely mediated by specialized photoreceptors or chloroplast-derived signaling cascades. Therefore, LaNDH represents a promising genetic target for enhancing lavender stress adaptability. Potential breeding applications of LaNDHs include: (1) Genetic engineering - overexpressing LaNDH via CRISPR-Cas9 or stress-responsive promoters to bolster drought and salinity tolerance; (2) Pre-transplant conditioning - using blue light priming to pre-activate LaNDH expression in seedlings prior to field transplantation. These strategies could enhance lavender resilience to stress without compromising the yield or quality of its EOs.

Photosynthesis is the fundamental physiological and biochemical process on Earth, underpinning plant growth, development, and the production of high yield and quality. Over ninety percent of a plant dry mass is derived from products of leaf photosynthesis (Hagemann and Bauwe, 2016; Johnson, 2016; Silveira and Carvalho, 2016). Various factors influence the efficiency of photosynthesis: Light provides the necessary energy, with its intensity and wavelength directly affecting the rate of photosynthesis. Carbon dioxide is crucial for the Calvin cycle, acting as a limiting factor when present at low concentrations (von Caemmerer and Furbank, 2016; Szechyńska-Hebda et al., 2017; Dusenge et al., 2018; Sekhar et al., 2020). Temperature impacts enzyme function, with optimal conditions typically ranging between 20–30 °C. Water availability is essential for maintaining turgor pressure and facilitating stomatal opening for gas exchange. Chlorophyll content governs the plant ability to absorb light. Additionally, oxygen competes with carbon dioxide during photorespiration, reducing yields in C3 plants. Plant adaptations, such as C4 and Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) pathways, along with leaf anatomical features, also play significant roles (von Caemmerer and Furbank, 2016; Sekhar et al., 2020; Cruz and Avenson, 2021; Guirguis et al., 2023). The overall photosynthetic rate is ultimately constrained by the slowest limiting factor.

Current research on the impact of abiotic stress on photosynthesis in lavender has primarily concentrated on drought stress, which inhibits growth and reduces photosynthetic pigment levels. These findings provide a theoretical foundation for the cultivation and industrialization of lavender in environments subject to stress (Li et al., 2023; Croce et al., 2024; Marulanda Valencia and Pandit, 2024; Shomali et al., 2024). Lavender typically thrives in temperatures ranging from 15 °C to 30 °C. Other previous studies have demonstrated that exposure to low-temperature stress (0 °C) can activate the expression of genes involved in the synthesis of protective compounds, such as fatty acid desaturases and soluble sugars, which contribute to the formation of a cold signaling regulatory network (Li et al., 2023; Croce et al., 2024; Marulanda Valencia and Pandit, 2024; Shomali et al., 2024). This network ultimately enhances lavender cold tolerance.

In summary, our study introduces a new approach to thoroughly investigate the functional mechanisms of NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductases in Lavandula angustifolia, with the objective of increasing the yield and enhancing the quality of lavender essential oils (EOs).

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics analysis

The amino acid sequences of Lavandula angustifolia NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductases (LaNDHs) (Supplementary Table S1) were analyzed using ProtParam to predict their chemical properties and physicochemical parameters (Duvaud et al., 2021; Gasteiger, 2003).

Prediction of structural models

Secondary structures were predicted using PSIPRED 4.0 (Buchan et al., 2024; Jones, 1999) and the NPS@ v2.16.0 (Combet et al., 2000). Three-dimensional structural predictions for LaNDHs were carried out with the AlphaFold2 v2.1.1 (Wayment-Steele et al., 2023; Jumper et al., 2021). Active site residues were identified using the GalaxyWEB program (Ko et al., 2012; Heo et al., 2013, 2016; Seok et al., 2021). Multiple sequence alignment was performed using the LSQKAB program within the CCP4 suite (Collaborative Computational Project N, 1994), and the root mean square deviation (RMSD) for Cα atoms was calculated. Structural visualizations were generated using PyMOL 2.3.4 (https://www.pymol.org/2/).

Quality assessment of structural models of LaNDHs

To validate the tertiary structures, Ramachandran plots for LaNDHs were generated using the PDBsum database (de Beer et al., 2014; Laskowski et al., 2017; Laskowski, 2022, 2004). This tool evaluates the quality of protein structures by detecting geometric errors, thereby enhancing the accuracy of the models. The Ramachandran plot specifically analyzes the stereochemical properties by displaying the dihedral angles of amino acid residues, identifying the allowed conformational regions, and highlighting any disallowed orientations.

On the other hand, ProSA (Protein Structure Analysis) is a commonly used tool for analyzing and validating predicted protein models (Wiederstein and Sippl, 2007). The z-score provides an overall assessment of model quality and is plotted against the z-scores of all experimentally determined protein structures in the current PDB. This plot distinguishes between structural types (e.g., X-ray, NMR) using color coding, enabling the evaluation of whether the z-score for the input structure falls within the expected range for native proteins of similar size.

Analysis of gene expression levels of LaNDHs using RT-qPCR

To quantify the expression levels of the target gene under different light conditions, real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was conducted using PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Plant tissue samples (roots, stems, leaves, and flowers) were collected, immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C for later analysis. The light treatments included white, red, and blue light, with red light having a maximum wavelength of 660 nm and blue light having a maximum wavelength of 450 nm. The light intensity was set at 100 µmol/(m·s). For cadmium ion (Cd2+) stress, concentrations of 0, 20, and 40 µM Cd2+ were applied, while temperature stress was tested at 25°C, 30°C, and 40°C. Salt stress was induced using 0, 200, and 300 mM NaCl, respectively. Total RNA was extracted using the Universal Plant Total RNA Extraction Kit (Bioteke, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA synthesis was performed with the PrimeScript 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara, Kyoto, Japan). Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S2. The PCR reaction volume was 20 μL, with the following conditions: 90°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 30 s, and a final step of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 60 s. RT-qPCR was performed using an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 5 instrument. Data were analyzed using the 2-ΔΔCT method (Hawkins and Guest, 2017; Green and Sambrook, 2018), and relative expression levels were presented as log2 values in histograms. Beta-actin gene is expressed at relatively constant levels in different tissues and cells and is used to detect changes in gene expression levels. Beta-actin was used as the reference gene, with expression normalized to untreated controls. A positive control was included for the beta-actin gene. A ratio greater than zero indicated upregulation, while a ratio less than zero indicated downregulation.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted at least in triplicate. The data were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was conducted using Origin 8.5, Microsoft Excel 2013 and SPSS 19.0. In the all statistical evaluations, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and p < 0.01 was considered high statistically significant.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

DL: Resources, Funding acquisition, Validation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Formal Analysis, Supervision, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Software, Visualization, Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology. NL: Writing – original draft, Investigation. HD: Investigation, Writing – original draft. DS: Investigation, Writing – original draft. MM: Investigation, Writing – original draft. AN: Writing – original draft, Investigation. MY: Investigation, Writing – original draft. KA: Investigation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Our research work is financially supported by grants from the third batch of the “Tianchi Talent” Young Doctoral Research Grant, Xinjiang Autonomous Region (2025QNBS001), and Start-up Fund for Doctoral Research Established by Yili Normal University (2024RCYJ08).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1661227/full#supplementary-material

References

Aarshageetha, P., Janci, P. R. R., and Tharani, N. D. (2023). Role of alternate therapies to improve the quality of life in menopausal women: A systematic review. J. Mid-life. Health 14, 153–158. doi: 10.4103/jmh.jmh_222_22

Batiha, G. E.-S., Teibo, J. O., Wasef, L., Shaheen, H. M., Akomolafe, A. P., Teibo, T. K. A., et al. (2023). A review of the bioactive components and pharmacological properties of Lavandula species. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s. Arch. Pharmacol. 396, 877–900. doi: 10.1007/s00210-023-02392-x

Braunstein, G. D. and Braunstein, E. W. (2023). Are prepubertal gynaecomastia and premature thelarche linked to topical lavender and tea tree oil use? touchREV. Endocrinol. 19, 9. doi: 10.17925/ee.2023.19.2.9

Buchan, D. W. A., Moffat, L., Lau, A., Kandathil Shaun, M., and Jones David, T. (2024). Deep learning for the PSIPRED protein analysis workbench. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W287–W293. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkae328

Collaborative Computational Project N (1994). The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallograph. Sect. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–763. doi: 10.1107/s0907444994003112

Combet, C., Blanchet, C., Geourjon, C., and Deléage, G. (2000). NPS@: network protein sequence analysis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25, 147–150. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01540-6

Crişan, I., Ona, A., Vârban, D., Muntean, L., Vârban, R., Stoie, A., et al. (2023). Current trends for lavender (Lavandula angustifolia mill.) crops and products with emphasis on essential oil quality. Plants 12, 357. doi: 10.3390/plants12020357

Croce, R., Carmo-Silva, E., Cho, Y. B., Ermakova, M., Harbinson, J., Lawson, T., et al. (2024). Perspectives on improving photosynthesis to increase crop yield. Plant Cell 36, 3944–3973. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koae132

Cruz, J. A. and Avenson, T. J. (2021). Photosynthesis: a multiscopic view. J. Plant Res. 134, 665–682. doi: 10.1007/s10265-021-01321-4

de Beer, T. A. P., Berka, K., Thornton, J. M., and Laskowski, R. A. (2014). PDBsum additions. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D292–D296. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt940

de Melo Alves Silva, L. C., de Oliveira Mendes, F., de Castro Teixeira, F., de Lima Fernandes, T. E., Barros Ribeiro, K. R., da Silva Leal, K. C., et al. (2023). Use of Lavandula angustifolia essential oil as a complementary therapy in adult health care: A scoping review. Heliyon 9, e15446. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15446

Dinkova-Kostova, A. T. and Talalay, P. (2010). NAD(P)H:quinone acceptor oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), a multifunctional antioxidant enzyme and exceptionally versatile cytoprotector. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 501, 116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.03.019

Dusenge, M. E., Duarte, A. G., and Way, D. A. (2018). Plant carbon metabolism and climate change: elevated CO2 and temperature impacts on photosynthesis, photorespiration and respiration. New Phytol. 221, 32–49. doi: 10.1111/nph.15283

Duvaud, S., Gabella, C., Lisacek, F., Stockinger, H., Ioannidis, V., and Durinx, C. (2021). Expasy, the Swiss Bioinformatics Resource Portal, as designed by its users. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W216–W227. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab225

Evans, J. R. (2013). Improving photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 162, 1780–1793. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.219006

Gasteiger, E. (2003). ExPASy: the proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3784–3788. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg563

Green, M. R. and Sambrook, J. (2018). Analysis and normalization of real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) experimental data. Cold Spring Harbor Protoc. 2018, pdb.top095000. doi: 10.1101/pdb.top095000

Guirguis, A., Yang, W., Conlan, X. A., Kong, L., Cahill, D. M., and Wang, Y. (2023). Boosting plant photosynthesis with carbon dots: A critical review of performance and prospects. Small 19, 1–20. doi: 10.1002/smll.202300671

Guo, X. and Wang, P. (2020). Aroma characteristics of lavender extract and essential oil from lavandula angustifolia mill. Molecules 25, 5541. doi: 10.3390/molecules25235541

Hagemann, M. and Bauwe, H. (2016). Photorespiration and the potential to improve photosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 35, 109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.09.014

Hawkins, S. F. C. and Guest, P. C. (2017). Multiplex analyses using real-time quantitative PCR. Methods Mol. Biol. 1546, 125–133. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6730-8_8

Hedayati, S., Tarahi, M., Iraji, A., and Hashempur, M. H. (2024). Recent developments in the encapsulation of lavender essential oil. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 331, 103229. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2024.103229

Heo, L., Lee, H., and Seok, C. (2016). GalaxyRefineComplex: Refinement of protein-protein complex model structures driven by interface repacking. Sci. Rep. 6, (1). doi: 10.1038/srep32153

Heo, L., Park, H., and Seok, C. (2013). GalaxyRefine: protein structure refinement driven by side-chain repacking. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, W384–W388. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt458

Jones, D. T. (1999). Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 17, 195–202. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3091

Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A., Green, T., Figurnov, M., Ronneberger, O., et al. (2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2

Khan, S. U., Hamza, B., Mir, R. H., Fatima, K., and Malik, F. (2024). Lavender plant: farming and health benefits. Curr. Mol. Med. 24, 702–711. doi: 10.2174/1566524023666230518114027

Ko, J., Park, H., Heo, L., and Seok, C. (2012). GalaxyWEB server for protein structure prediction and refinement. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, W294–W297. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks493

Laskowski, R. A. (2004). PDBsum more: new summaries and analyses of the known 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, D266–D268. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki001

Laskowski, R. A. (2022). PDBsum1: A standalone program for generating PDBsum analyses. Protein Sci. 31, (12). doi: 10.1002/pro.4473

Laskowski, R. A., Jabłońska, J., Pravda, L., Vařeková, R. S., and Thornton, J. M. (2017). PDBsum: Structural summaries of PDB entries. Protein Sci. 27, 129–134. doi: 10.1002/pro.3289

Li, L., Liang, Y., Liu, Y., Sun, Z., Liu, Y., Yuan, Z., et al. (2023). Transcriptome analyses reveal photosynthesis-related genes involved in photosynthetic regulation under low temperature stress in Lavandula angustifolia Mill. Front. Plant Sci. 14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1268666

Li, L., Liu, Y., Jia, Y., and Yuan, Z. (2025). Investigation into the mechanisms of photosynthetic regulation and adaptation under salt stress in lavender. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 219, 109376. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2024.109376

Li, J., Zhang, X., Luan, F., Duan, J., Zou, J., Sun, J., et al. (2024). Therapeutic potential of essential oils against ulcerative colitis: A review. J. Inflamm. Res. 17, 3527–3549. doi: 10.2147/jir.s461466

Liu, D., Deng, H., and Song, H. (2025a). Insights into the functional mechanisms of the sesquiterpene synthase GEAS and GERDS in lavender. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 299, 140195. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.140195

Liu, D., Du, Y., Abdiriyim, A., Zhang, L., Song, D., Deng, H., et al. (2025b). Molecular functional mechanisms of two alcohol acetyltransferases in Lavandula x intermedia (lavandin). Front. Chem. 13. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2025.1627286

Liu, D., Song, H., Deng, H., Abdiriyim, A., Zhang, L., Jiao, Z., et al. (2024). Insights into the functional mechanisms of three terpene synthases from Lavandula angustifolia (Lavender). Front. Plant Sci. 15. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1497345

Malloggi, E., Menicucci, D., Cesari, V., Frumento, S., Gemignani, A., and Bertoli, A. (2021). Lavender aromatherapy: A systematic review from essential oil quality and administration methods to cognitive enhancing effects. Appl. Psychol.: Health Well-Being. 14, 663–690. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12310

Marulanda Valencia, W. and Pandit, A. (2024). Photosystem II subunit S (PsbS): A nano regulator of plant photosynthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 436, 168407. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2023.168407

Pey, A. L., Megarity Clare, F., and Timson David, J. (2019). NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1): an enzyme which needs just enough mobility, in just the right places. Biosci. Rep. 39, (1). doi: 10.1042/bsr20180459

Prosche, S. and Stappen, I. (2024). Flower power: an overview on chemistry and biological impact of selected essential oils from blossoms. Planta. Med. 90, 595–626. doi: 10.1055/a-2215-2791

Reece, R. and Sharkey, T. D. (2020). Emerging research in plant photosynthesis. Emerging. Topics. Life Sci. 4, 137–150. doi: 10.1042/etls20200035

Ross, D. and Siegel, D. (2017). Functions of NQO1 in cellular protection and coQ10 metabolism and its potential role as a redox sensitive molecular switch. Front. Physiol. 8. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00595

Sekhar, K. M., Kota, V. R., Reddy, T. P., Rao, K. V., and Reddy, A. R. (2020). Amelioration of plant responses to drought under elevated CO2 by rejuvenating photosynthesis and nitrogen use efficiency: implications for future climate-resilient crops. Photosynthesis. Res. 150, 21–40. doi: 10.1007/s11120-020-00772-5

Seok, C., Baek, M., Steinegger, M., Park, H., Lee, G. R., and Won, J. (2021). Accurate protein structure prediction: what comes next? Biodesign 9, 47–50. doi: 10.34184/kssb.2021.9.3.47

Shomali, A., Das, S., Sarraf, M., Johnson, R., Janeeshma, E., Kumar, V., et al. (2024). Modulation of plant photosynthetic processes during metal and metalloid stress, and strategies for manipulating photosynthesis-related traits. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 206, 108211. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.108211

Silveira, J. A. G. and Carvalho, F. E. L. (2016). Proteomics, photosynthesis and salt resistance in crops: An integrative view. J. Proteomics 143, 24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.03.013

Szechyńska-Hebda, M., Lewandowska, M., and Karpiński, S. (2017). Electrical signaling, photosynthesis and systemic acquired acclimation. Front. Physiol. 8. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00684

Vairinhos, J. and Miguel, M. G. (2020). Essential oils of spontaneous species of the genus Lavandula from Portugal: a brief review. Z. für. Naturforschung. C. 75, 233–245. doi: 10.1515/znc-2020-0044

von Caemmerer, S. and Furbank, R. T. (2016). Strategies for improving C4 photosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 31, 125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.04.003

Wayment-Steele, H. K., Ojoawo, A., Otten, R., Apitz, J. M., Pitsawong, W., Hömberger, M., et al. (2023). Predicting multiple conformations via sequence clustering and AlphaFold2. Nature 625, 832–839. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06832-9

Wiederstein, M. and Sippl, M. J. (2007). ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W407–W410. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm290

Keywords: Lavandula angustifolia (lavender), NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase, three-dimensional (3D) structures, gene expression levels, abiotic stress

Citation: Liu D, Li N, Deng H, Song D, Maimaiti M, Nuerbieke A, Yekepeng M and Aili K (2025) Structural and functional insights into NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductases in lavender: implications for abiotic stress tolerance and essential oil production. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1661227. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1661227

Received: 07 July 2025; Accepted: 11 August 2025;

Published: 28 August 2025.

Edited by:

Ahmed M. Saad, Zagazig University, EgyptReviewed by:

Mohamed T. El-Saadony, Zagazig University, EgyptAtaa Alsaber, Università degli Studi di Parma, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Liu, Li, Deng, Song, Maimaiti, Nuerbieke, Yekepeng and Aili. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dafeng Liu, ZGFmZWxpQHNpbmEuY24=; ZGFmZWxpLWRhZmVsaUBob3RtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Dafeng Liu

Dafeng Liu Na Li1†

Na Li1†