- 1Hubei Key Laboratory of Spices & Horticultural Plant Germplasm Innovation & Utilization, Yangtze University, Jingzhou, China

- 2Germplasm Resources Evaluation and Innovation Center of Phoebe Nees and Machilus Nees, College of Horticulture and Gardening, Yangtze University, Jingzhou, China

This study used Elytrigia elongata and Cynodon dactylon × C. transvaalensis ‘Tifdwarf’ as experimental materials. Flooding stress was simulated by raising the water level 2 cm above the soil surface, while the control (CK) involved conventional water management. Three treatments were applied: flooding stress alone (FS), and flooding combined with 1 mmol/L spermidine (FP). Each treatment lasted for 5, 10 and 20 days. The aim was to investigate the impact of 1 mmol/L spermidine (Spd) on the growth and physiological responses of seedlings of both species subjected to different durations of flooding stress. The results showed that applying exogenous Spd under flooding conditions significantly increased the number of epidermal cells and biomass accumulation. Spd increased photosynthetic capacity by raising chlorophyll content and gas exchange parameters while reducing antioxidant enzyme activity. This elevated free-state Spd levels and enabled the removal of accumulated reactive oxygen species (ROS). Additionally, Spd promoted the accumulation of osmoregulatory substances, alleviating oxidative damage to membrane lipids and maintaining cellular osmotic potential. Consequently, Spd mitigated the adverse effects of flooding stress on plant growth. Correlation and principal component analyses of physiological and biochemical indicators confirmed that exogenous Spd improved flooding tolerance in both species. Notably, Elytrigia elongata exhibited greater tolerance to flooding, and the mitigating effects of Spd were more pronounced in this species under the same inundation conditions. Overall, this study provides a theoretical foundation for mitigating flooding induced damage in ecological grasses and offers insights into cultivating flooding tolerant grass species.

1 Introduction

In recent years, global warming has led to increased frequency of flooding during the rainy season, subjecting plants to prolonged waterlogging stress and severely threatening ecological stability (Qiaoyu et al., 2023). Flooding induces oxygen deficiency in plant roots, disrupting normal respiration and subsequently impairing photosynthesis and other essential physiological processes (Wei, 2009). Under hypoxic conditions, the absorption of mineral nutrients from the soil is markedly reduced, causing a decline in cellular physiological functions and energy metabolism. This often results in root rot and lignification, ultimately inhibiting plant growth and development (Wei, 2009). Under waterlogging stress, the triggered oxidative burst inflicts membrane damage and lipid peroxidation, thereby activating the plant’s antioxidant enzyme system as a defense mechanism to scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Yang et al., 2015); Additionally, they adapt by forming adventitious roots and aerenchyma to facilitate internal aeration (Jackson and Colmer, 2005), and by accumulating osmoregulatory substances to reduce cellular water uptake and maintain osmotic balance (Pang et al., 2018).

Spermidine (Spd) is a naturally occurring polyamine widely present in both animals and plants (Liu et al., 2011; Cheng et al., 2010). It is a critical component of polyamines in plant tissues and plays a direct role in physiological processes such as growth, cell division, senescence, and stress responses (Mattoo et al., 2010). Among various abiotic stresses, exogenous application of Spd is indispensable for enhancing plant growth and improving resistance to environmental challenges, functioning as an important bioactive compound (Zhang et al., 2015). Specifically, Spd plays an important role in mitigating flooding stress. For example, external application of Spd enhances waterlogging tolerance in Axonopus compressus, reducing damage under flooding stress (Yang et al., 2025). In Fujian mountain cherry trees, Spd treatment increases peroxidase (POD) activity, decreases malondialdehyde (MDA), soluble sugar, and soluble protein content, thereby alleviating membrane damage caused by flooding stress (Lu et al., 2022). Similarly, Spd application improves photosynthetic capacity and waterlogging tolerance in maize leaves, resulting in increased dry matter accumulation (Cui et al., 2022). Additionally, Spd enhances antioxidant capacity and osmotic regulation in maize seedlings under flooding stress, and effectively improves physiological functions in maize roots and leaves, ultimately reducing yield losses (You et al., 2016; Seng et al., 2012a).

Elytrigia elongata, a herbaceous species in the Poaceae family and Elytrigia genus, possesses a well-developed root system, high biomass, and favorable nutritional quality (Li et al., 2022). It demonstrates strong adaptability to diverse growth conditions, exhibiting notable tolerance to saline alkaline soils, flooding, and drought, making it highly valuable for ecological environmental protection (Li et al., 2023), However, research on its physiological responses to flooding stress remains limited. Cynodon dactylon × C. transvaalensis ‘Tifdwarf’ (Xuan et al., 2005), commonly known as putting green grass due to its widespread use in golf course greens, is a hybrid of common bermudagrass and African bermudagrass (Zhou and Liu, 2016). As an evergreen perennial grass of the Poaceae family and Cynodon genus, this species exhibits vigorous growth and a suite of exceptional stress tolerances, including resistance to salt-alkali, drought, barren soil, lodging, close mowing, and wear, These combined characteristics account for its widespread application in sports fields and landscape greening (Reasor et al., 2016). This study employed Elytrigia elongata and Cynodon dactylon × C. transvaalensis ‘Tifdwarf’ as experimental materials to assess the effects of exogenous Spd on seedling growth and physiological responses under flooding stress. The results demonstrated that foliar application of Spd significantly enhanced waterlogging tolerance in both species, providing a theoretical foundation for cultivating flood resistant grasses and promoting ecological restoration.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Test materials

The experiment was conducted in 2023 within a greenhouse located at the West Campus of Yangtze University in Jingzhou District, Jingzhou City, Hubei Province (30°21′N, 112°08′E). Throughout the study, greenhouse conditions were maintained with temperatures ranging 18 to 25°C, relative humidity was 80%, and natural light provided from 8:00 to 18:00. The test materials comprised seeds of the Elytrigia elongata obtained from Crowvo (Beijing) Ecological Technology Co., Ltd., seeds of Cynodon dactylon × C. transvaalensis ‘Tifdwarf’ sourced from Shuyang Mipei Seed Industry Co., Ltd., and spermidine purchased from Sigma.

Three treatments were established for each grass species: normal moisture treatment (CK), flooding treatment (FS), and flooding combined with spermidine application (FP). Each treatment included nine replicates, with 35 plants per replicate, totaling 27 experimental units per species. In June 2023, a preliminary experiment was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of exogenous spermidine at concentrations of 0.25, 0.5, and 1 mmol/L in mitigating flooding stress on the two grass species. After 20 days of treatment, leaf yellowing and senescence were observed. Subsequently, chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and plant height were measured, followed by membership function analysis. The results ranked the treatments as follows: 1 mmol/L > 0.25 mmol/L > 0.5 mmol/L, supporting the selection of 1 mmol/L spermidine for a 20-day treatment period. After one month, seeds were disinfected and evenly sown at 50–80 seeds per plastic pot filled with substrate. When seedlings reached the three leaf stage, the main experiment commenced to assess the effects of exogenous Spd on the response of the two ecological grasses to waterlogging stress.

2.2 Experimental design

Plump and uniformly sized seeds were selected and soaked in a 500-fold dilution of Mefenoxam for 6 hours to ensure sterilization and disinfection. After treatment, the seeds were thoroughly rinsed with water and air dried for later use. Mefenoxam was sourced from Hebei Zhongnong Lvbao Crop Technology Co., Ltd. The planting substrate, composed of pond soil and river sand in a 1:1 ratio, was sterilized using a high-pressure steam autoclave (0.11 MPa, 121°C) for 2 hours to eliminate potential pathogens, weed seeds, and insects prior to sowing.

For water management, the control group (CK) was irrigated daily using the weighing method to maintain soil moisture at 60%–75%. Flooding treatments were applied using the pot immersion method, in which pots were placed in plastic basins (73 cm × 36.5 cm × 21 cm) with water maintained at 2 cm above the soil surface. During the treatment period, the CK and FS groups were watered daily between 17:00 and 18:00. The FP group received foliar applications of 1 mmol·L−1 exogenous spermidine, sprayed until the leaf surfaces were fully wetted and dripping. Sampling was conducted on days 5, 10, and 20 of the flooding treatment and designated as CK-5, FS-5, FP-5; CK-10, FS-10, FP-10; and CK-20, FS-20, FP-20, respectively. At each time point, three replicates were randomly selected for measurements of biomass, photosynthetic parameters, and root morphology. Additional plant samples were stored at –20°C for further analysis of physiological and biochemical indicators.

2.3 Leaf epidermal sections, biomass, and root morphology

Randomly select 10 leaves each from both ecological grass species subjected to 5, 10, and 20 days of flooding treatment were randomly selected. A 10 mm segment from the middle portion of the leaf was excised and fixed in FAA fixative solution (glacial acetic acid: formaldehyde: ethanol: water = 1:1:12:6) for fixation for subsequent analysis. Fixed samples were immersed in a dissociation solution composed of 30% hydrogen peroxide and 30% acetic acid (1:1, v/v) for 6 hours, then rinsed thoroughly. The upper epidermis and mesophyll were gently scraped off using a razor blade. The remaining lower epidermis was flattened with forceps, stained with 1% safranin solution, and rinsed to remove excess dye. Then observe and photograph under a microscope, and use ImageJ to count the number of epidermal cells.

After the completion of each flooding period, 10 plants per treatment group were randomly selected. Roots were gently washed to remove soil, and shoots were rinsed to remove surface dust. The above ground and belowground parts were dried with absorbent paper and weighed separately using a precision electronic balance (accuracy: 0.001 g). Root morphological parameters were assessed using an EPSON Scan v3.771 scanner (Japan) at 400 dpi resolution. The resulting root images were analyzed using WinRHIZO Pro 2007a software to determine total root length (cm).

2.4 Photosynthetic pigment content and photosynthetic gas exchange parameters

On the 5th, 10th and 20th days of flooding treatment, healthy and fully expanded leaves with similar light exposure were selected to measure gas exchange parameters. Net photosynthetic rate (Pn), stomatal conductance (Gs), intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci), and transpiration rate (Tr) were measured between 13:00 and 14:00—when light intensity was at its peak—using a LI-6400 portable photosynthesis system (LI-COR Bio-sciences, USA). For each treatment, 10 plants were measured, with three readings taken per leaf (Wu, 2018); The contents of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoids were determined using the ethanol extraction method. For each treatment, 0.2 g of fresh leaf tissue was sampled, with three biological replicates performed per treatment (Wu, 2018).

2.5 Measurement of physiological indicators

Take 0.3 grams of fresh leaf tissue from each of the two ecological grass seedlings for physiological parameter measurements. Each treatment should be performed with three biological replicates. Physiological indexes were measured by spectrophotometric method (Wu, 2018) using leaves of two ecograss seedlings as samples to determine Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity、Peroxidase (POD) activity、Catalase (CAT) activity、Ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity、 Malondialdehyde (MDA) content,、free proline (Pro) content; titanium sulfate colorimetric method to determine the content of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (Liu et al., 2000); Superoxide anion radical (O2−) content was determined by the method of Wu Qiangsheng et al (Wu, 2018); soluble protein was determined by the colorimetric method of Caulmers Brilliant Blue G-250 (Wu, 2018).

2.6 Data analysis

Experimental data were organized and processed using Microsoft Office Excel 2019. Statistical analyses, including one way ANOVA and Duncan’s multiple comparison tests, were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics 20 to evaluate significant differences among treatments, with significance defined at p < 0.05. Graphical representations were generated using Origin2022. To comprehensively assess the morphological and physiological responses of the two ecological grasses to exogenous spermidine (Spd) under flooding stress, data were further analyzed using flood tolerance coefficients, principal component analysis (PCA), and membership function methods.

3 Results

3.1 Effects of exogenous Spd on epidermal cells numbers in two ecological grasses under flooding stress

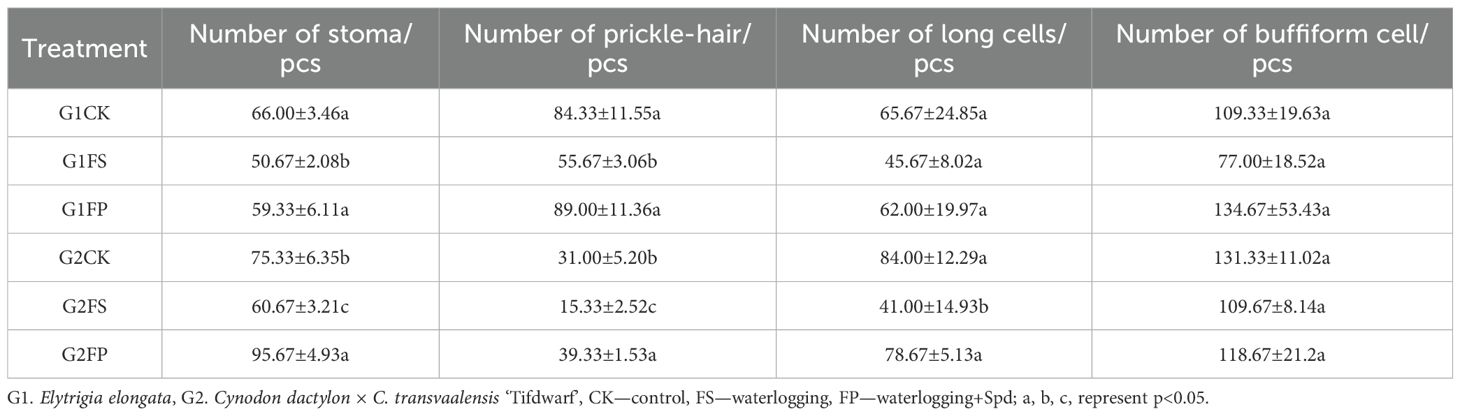

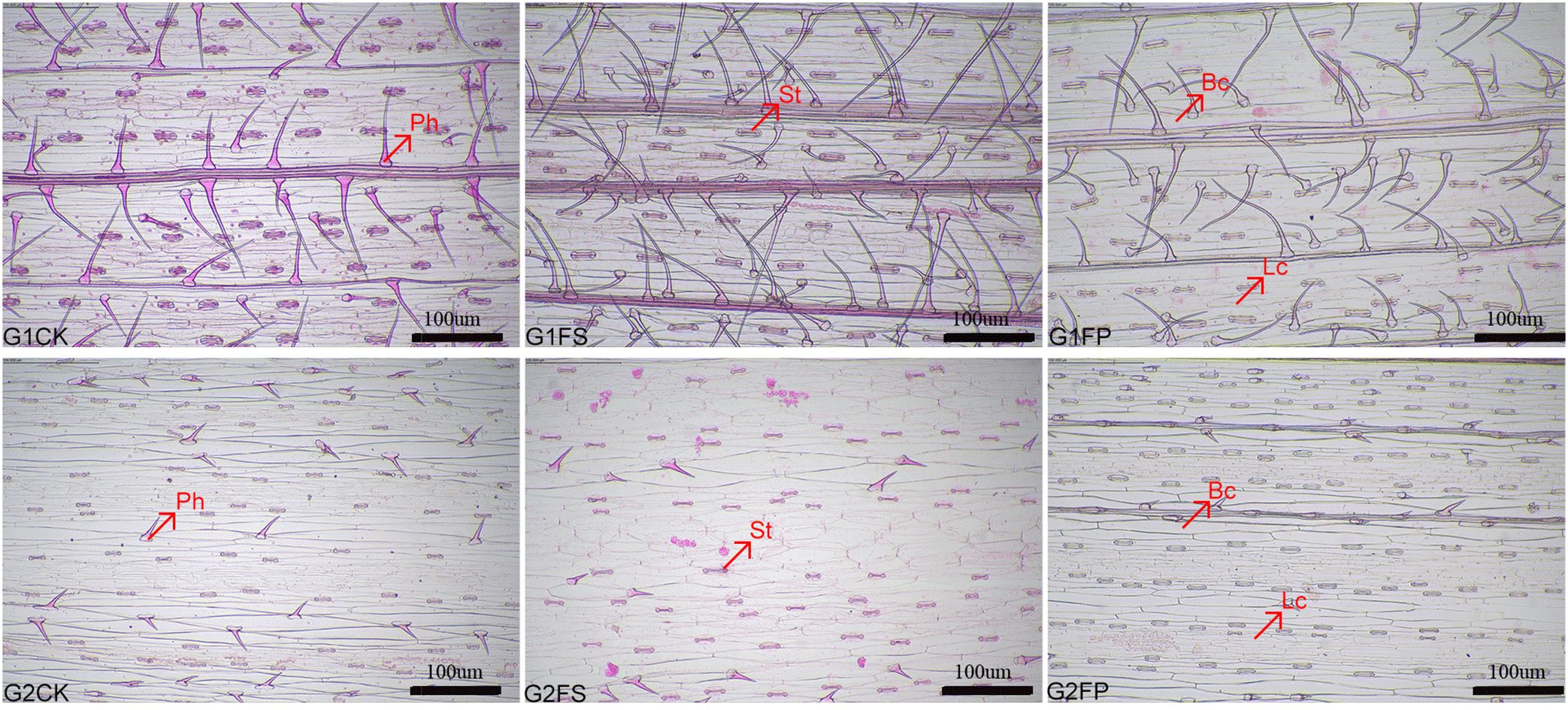

Spd influenced the number of stomata, prickle-hair, long cells, and bulliform cells in both ecological grasses (Table 1). Flooding stress significantly reduced the counts of these epidermal cell types in both species. However, application of exogenous Spd markedly increased (p < 0.05) the numbers of stomata and prickle hairs in E. elongata. In ‘Tifdwarf’, Spd treatment led to significant increases in the numbers of stomata, prickle hairs, and long cells (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Preparation of the epidermis of Elytrigia elongata and Cynodon dactylon × C. transvaalensis ‘Tifdwarf’. scale=100 μm; G1. Elytrigia elongata, G2. Cynodon dactylon × C. transvaalensis ‘Tifdwarf’; CK—control, FS—waterlogging, FP—waterlogging+Spd; Ph: Prickle-hair; St: Stoma; Lc: long cell; Bc: Buffiform cell.

3.2 Effect of exogenous Spd on biomass of two ecological grasses under flooding stress

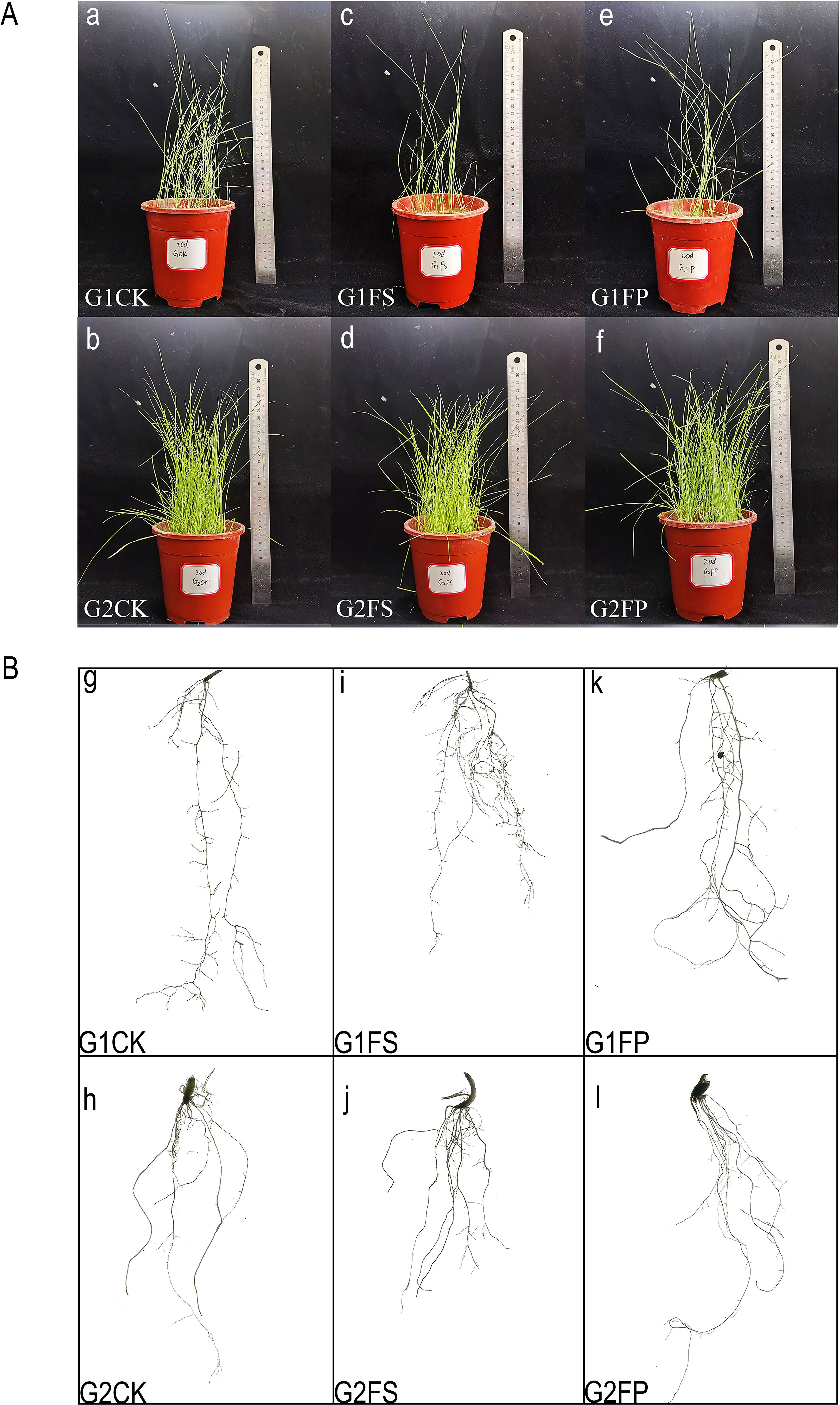

After 20 days of flooding stress, the above ground parts of E. elongata were severely affected, resulting in a reduction in plant numbers. However, exogenous application of Spd significantly increased both plant count and height compared to the FS treatment alone. In contrast, ‘Tifdwarf’ exhibited no visible adverse effects from flooding. Nevertheless, the number of plants increased following exogenous Spd application (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effect of exogenous Spd on biomass of two ecological grasses under flooding stress. (A) a~f: Growth of two Ecological grasses under different treatments after 20 days; (B) g~i: Root Scanning of Two Ecological Grasses After 20 Days Under Different Treatments; G1. Elytrigia elongata, G2. Cynodon dactylon × C. transvaalensis ‘Tifdwarf’, CK—control, FS—waterlogging, FP—waterlogging+Spd. .

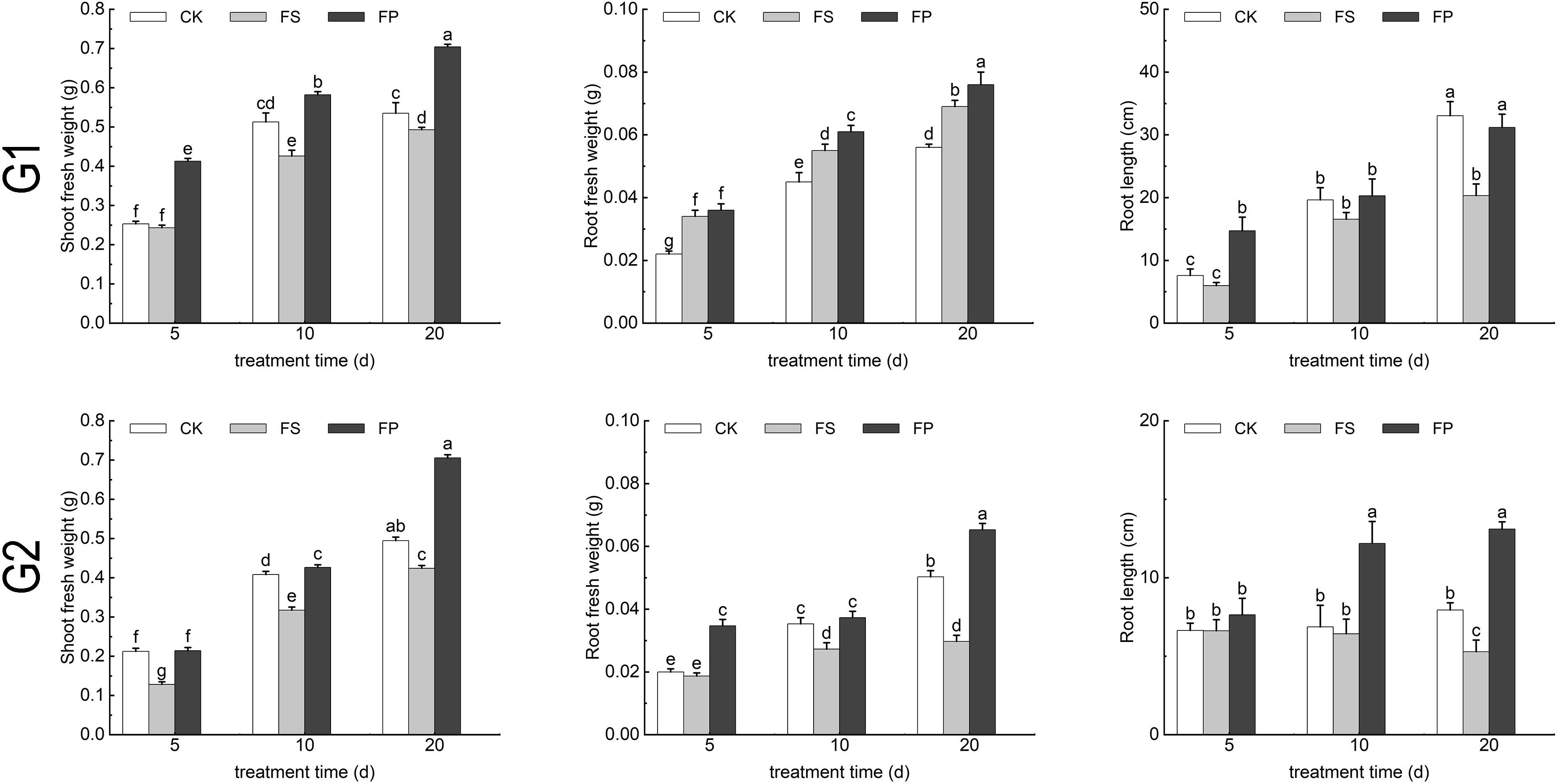

After 20 days of treatment, the application of exogenous Spd under flooding conditions (FP) promoted root length in both ecological grasses compared to flooding stress(FS) (Figure 2). Measurement of growth indicators under different treatments showed that flooding stress increased the root fresh weight of E. elongata but decreased that of ‘Tifdwarf’. In E. elongata, shoot fresh weight and root length under flooding stress (FS) were reduced compared to the control (CK) at 5, 10, and 20 days, with the greatest reduction in shoot fresh weight (16.96%) at 10 days and the largest decline in root length (38.52%) at 20 days. Exogenous spermidine (Spd) application increased shoot fresh weight and root length by 36.62% and 53.40%, respectively, compared to FS. Root fresh weight also increased with Spd treatment, showing the most significant rise (54.55%) at 5 days and a 5.88% increase at 20 days. For ‘Tifdwarf’, shoot fresh weight, root fresh weight, and root length all decreased under FS at all time points compared to CK, but these parameters were consistently improved by Spd application under flooding conditions (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Biomass of two Ecological grasses under different treatments. G1. Elytrigia elongata, G2. Cynodon dactylon × C. transvaalensis ‘Tifdwarf’, CK—control, FS—waterlogging, FP—waterlogging+Spd; different letters above the bars indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences.

3.3 Effects of exogenous spermidine on the chlorophyll content and photosynthetic parameters of two ecological grasses under flooding stress

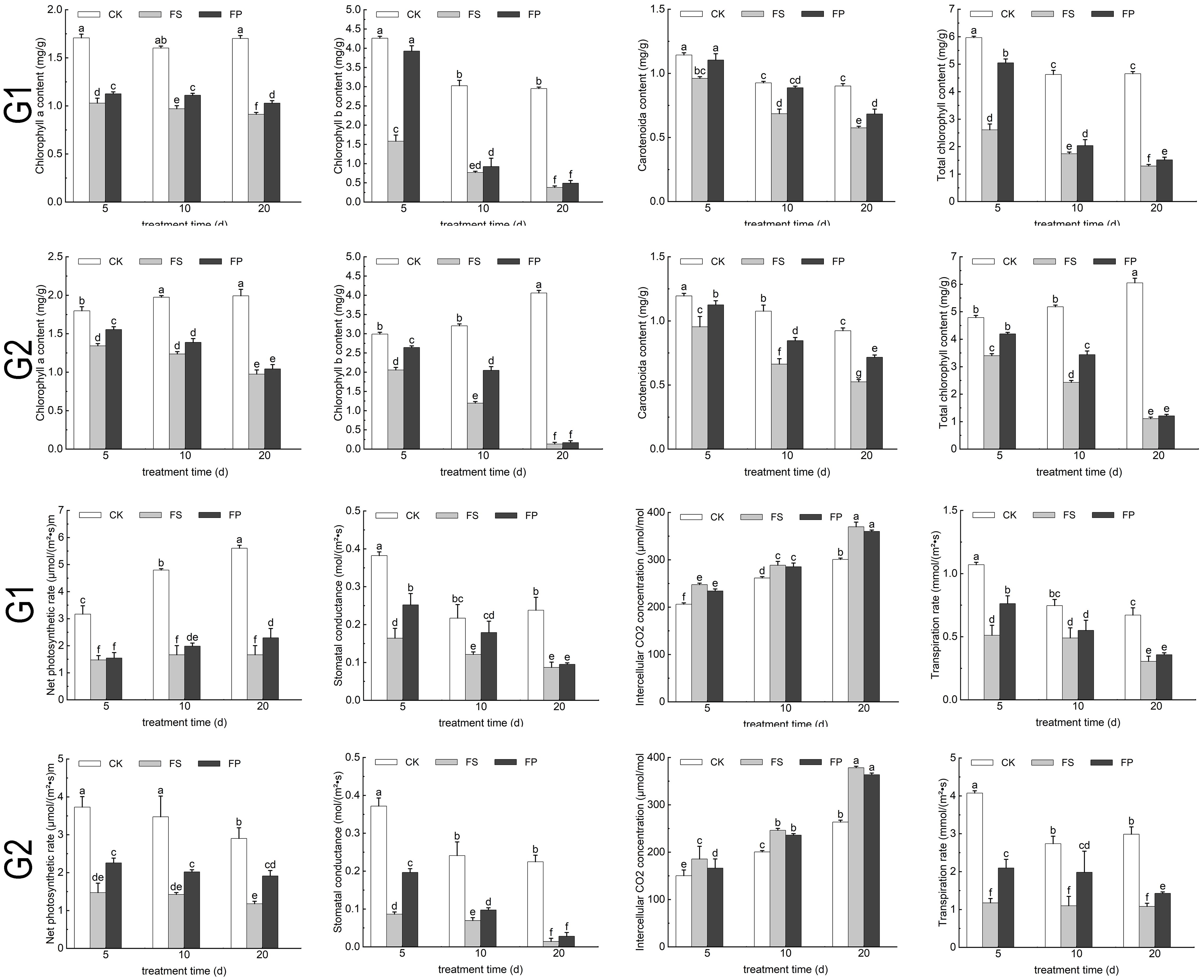

The chlorophyll content of the two ecological grasses under different treatments was determined. As shown in Figure 4, Overall, chlorophyll content followed the trend CK > FP > FS across all treatment durations. The contents of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, carotenoids and total chlorophyll in both of the two ecological grasses leaves showed a general decline under FS compared to the control, reaching their lowest levels after 20 days of treatment. However, the FP significantly increased the content of photosynthetic pigments relative to FS. Specifically, in E. elongata, chlorophyll a content under FP treatment increased by 9.53%, 14.54%, and 12.72% at 5, 10, and 20 days, respectively, compared to FS. In ‘Tifdwarf’, the corresponding increases were 15.77%, 12.27%, and 6.90%. Similar trends were observed for chlorophyll b, carotenoids, and total chlorophyll content.

Figure 4. The chlorophyll content and photosynthetic parameters of two Ecological grasses under different treatments. G1. Elytrigia elongata, G2. Cynodon dactylon × C. transvaalensis ‘Tifdwarf’, CK—control, FS—waterlogging, FP—waterlogging+Spd; different letters above the bars indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences.

As illustrated in Figure 4, leaf net photosynthetic rate (Pn), stomatal conductance (Gs), and transpiration rate (Tr) in both species exhibited the trend CK > FP > FS across all treatment durations, while intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) followed the opposite pattern (CK < FP < FS). Under FS, Pn, Gs, and Tr declined progressively with increasing flooding duration, reaching minimum values at 20 days, whereas Ci increased. The foliar application of Spd under flooding stress mitigated these declines in gas exchange parameters. After 5 days of treatment, E. elongata under FP showed increases of 4.75%, 53.66%, and 78.47% in Pn, Gs, and Tr, respectively, compared to FS (P < 0.05). ‘Tifdwarf’ exhibited even greater improvements, with increases of 53.40%, 127.55%, and 49.25%, respectively (P < 0.05). After 10 days, E. elongata showed increases of 19.23%, 47.93%, and 80.44%, while ‘Tifdwarf’ showed increases of 41.92%, 40.20%, and 12.24% in Pn, Gs, and Tr, respectively (P < 0.05). After 20 days, E. elongata exhibited increases of 37.80%, 9.20%, and 31.94%, while ‘Tifdwarf’ showed increases of 62.53%, 95.80%, and 17.30%, respectively. Although Ci values in both species under FP were lower than those under FS across all treatment durations, the differences were not statistically significant.

3.4 Effects of exogenous spermidine on the antioxidant systems of two ecological grasses under flooding stress

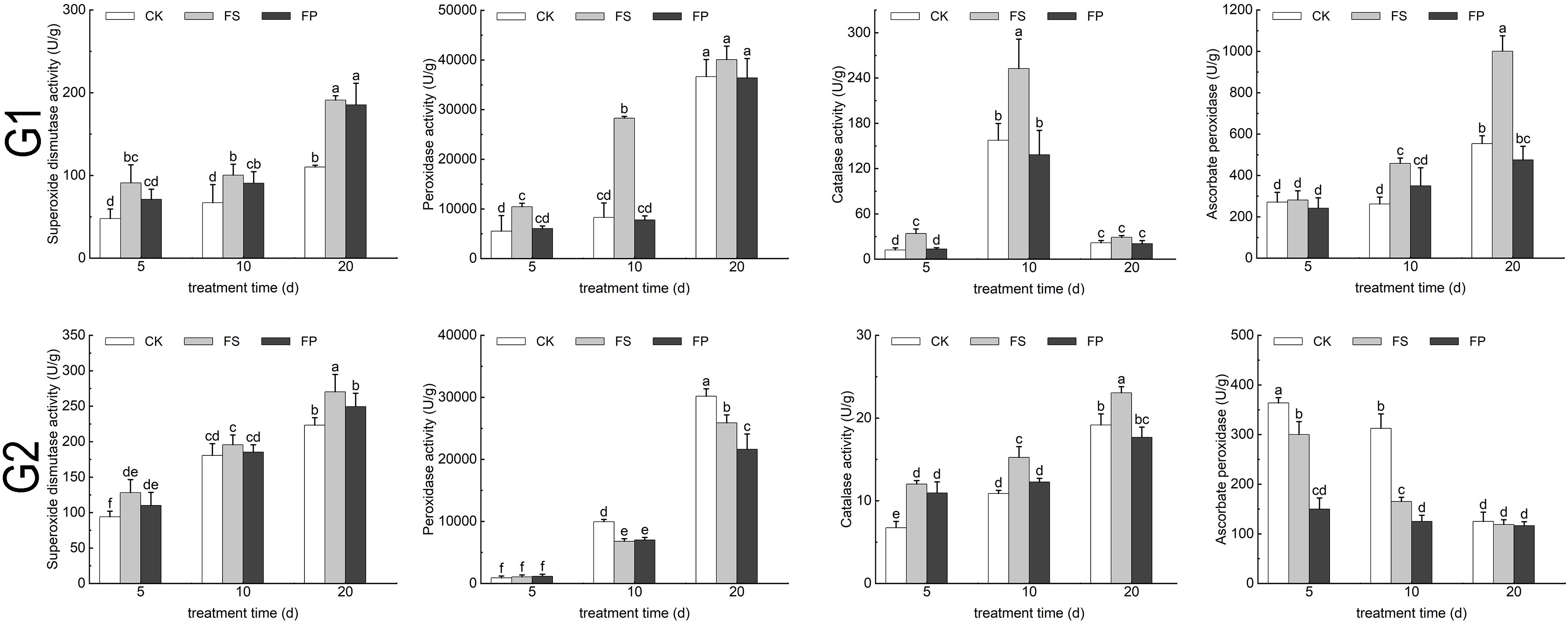

Under FS treatment, the activities of SOD and CAT in both E. elongata and ‘Tifdwarf’ exhibited a consistent trend, increasing at days 5, 10, and 20 compared to the CK. However, following exogenous Spd application, both enzyme activities decreased relative to FS (Figure 5).

Figure 5. SOD、POD、CAT、APX activity of two Ecological grasses under different treatments. G1. Elytrigia elongata, G2. Cynodon dactylon × C. transvaalensis ‘Tifdwarf’, CK—control, FS—waterlogging, FP—waterlogging+Spd; different letters above the bars indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences.

In E. elongata, the activities of peroxidase (POD) and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) increased under FS compared to CK on days 5, 10, and 20, except for a negligible change in APX activity on day 5. After Spd treatment, both POD and APX activities declined compared to FS. In ‘Tifdwarf’, POD and APX activities generally decreased under FS relative to CK at all time points, with the exception of POD activity on day 5, which remained essentially unchanged. Following Spd application, POD activity increased by 9.08% and 3.10% compared to FS on days 5 and 10, respectively, but decreased by 16.45% on day 20. APX activity showed a continuous decline after Spd application, decreasing by 50.00%, 24.37%, and 1.75% on days 5, 10, and 20, respectively (Figure 5).

3.5 Effects of exogenous spermidine on the content of malondialdehyde and reactive oxygen species in two ecological grasses under flooding stress

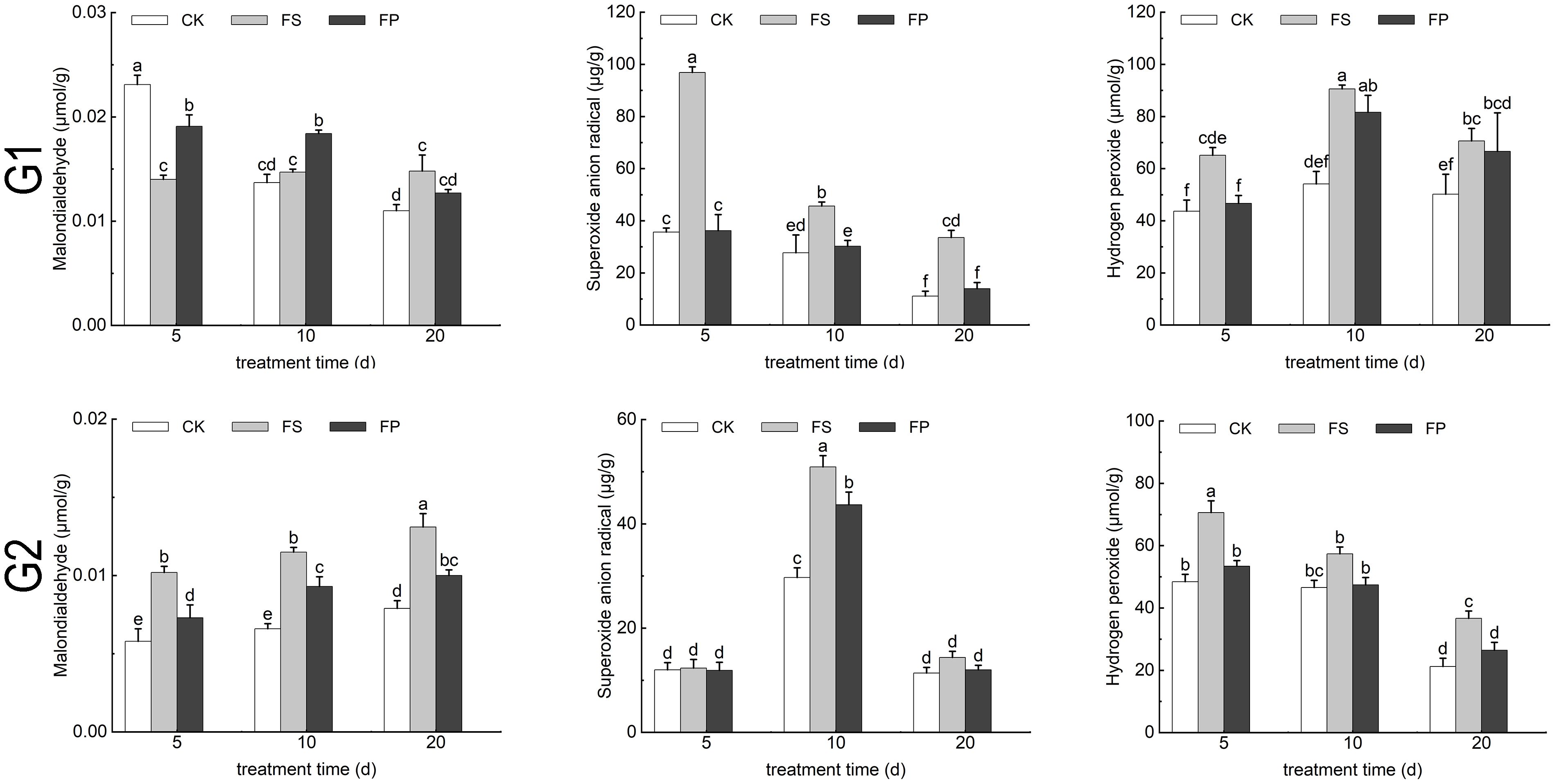

Under FS treatment, the malondialdehyde (MDA) content in E. elongata initially decreased by 39.39% at day 5 compared to the CK, then increased by 7.30% and 34.55% at days 10 and 20, respectively. Following exogenous Spd application, MDA content exhibited a transient increase of 36.43% and 25.17% at days 5 and 10 relative to FS, followed by a significant decrease of 14.19% at day 20 (p < 0.05). In contrast, ‘Tifdwarf’ displayed an overall increase in MDA content under FS compared to CK, which was reversed to a decreasing trend after Spd treatment (Figure 6).

Figure 6. MDA content and Reactive oxygen species content of two Ecological grasses under different treatment. G1. Elytrigia elongata, G2. Cynodon dactylon × C. transvaalensis ‘Tifdwarf’, CK—control, FS—waterlogging, FP—waterlogging+Spd; different letters above the bars indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences.

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and superoxide anion radical levels in both species increased under FS relative to CK at days 5, 10, and 20. These oxidative stress markers decreased following exogenous Spd application compared to FS, roughly FS>FP>CK (Figure 6).

3.6 Effects of exogenous spermidine on the contents of free proline and soluble proteins in two ecologically grasses under flooding stress

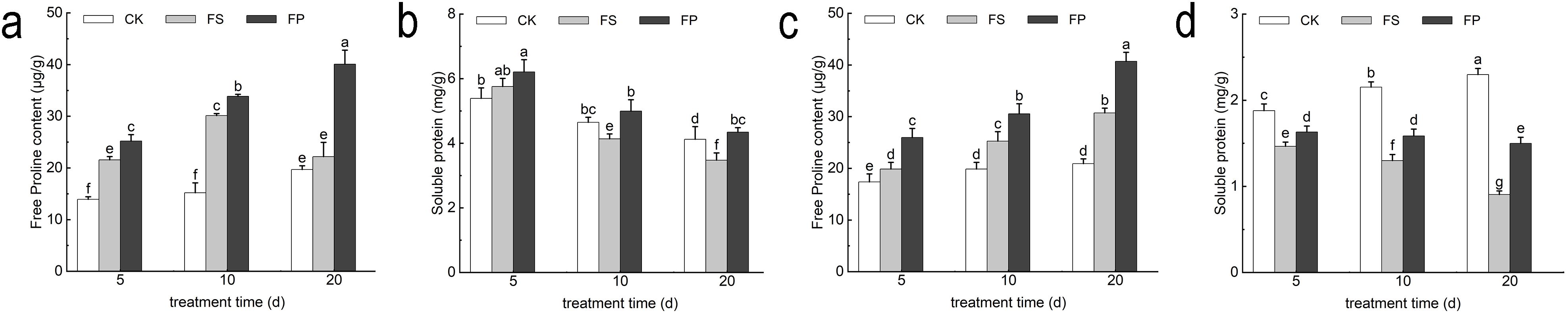

Under flooding stress (FS), the proline (Pro) content of both E. elongata and ‘Tifdwarf’ showed a consistent increasing trend compared to the CK at 5, 10, and 20 days. Furthermore, the application of exogenous Spd led to a further increase in Pro content, following the pattern FP > FS > CK across all time points. For E. elongata, the soluble protein content under FS increased slightly by 6.81% at 5 days, but declined by 10.95% and 15.68% at 10 and 20 days, respectively, compared to CK. However, foliar application of Spd (FP) resulted in an increase in soluble protein content at all three time points compared to FS, with respective increases of 7.87%, 20.78%, and 24.93%. In contrast, ‘Tifdwarf’ exhibited a substantial decrease in soluble protein content under FS treatment, with reductions of 22.01%, 39.66%, and 60.63% at 5, 10, and 20 days, respectively, relative to CK. Following Spd application, the soluble protein content increased significantly compared to FS, by 11.37%, 22.09%, and 65.58% at the corresponding time points (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Free Proline and Soluble protein content of two Ecological grasses under different treatments. (a) Elytrigia elongata free proline content; (b) Cynodon dactylon × C. transvaalensis ‘Tifdwarf’ free proline content; (c) Elytrigia elongata soluble protein content; (d) Cynodon dactylon × C. transvaalensis ‘Tifdwarf’ soluble protein content; CK—control, FS—waterlogging, FP—waterlogging+Spd; different letters above the bars indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences.

3.7 Principal component analysis and affiliation function analysis of flood tolerance coefficients of two ecological grasses

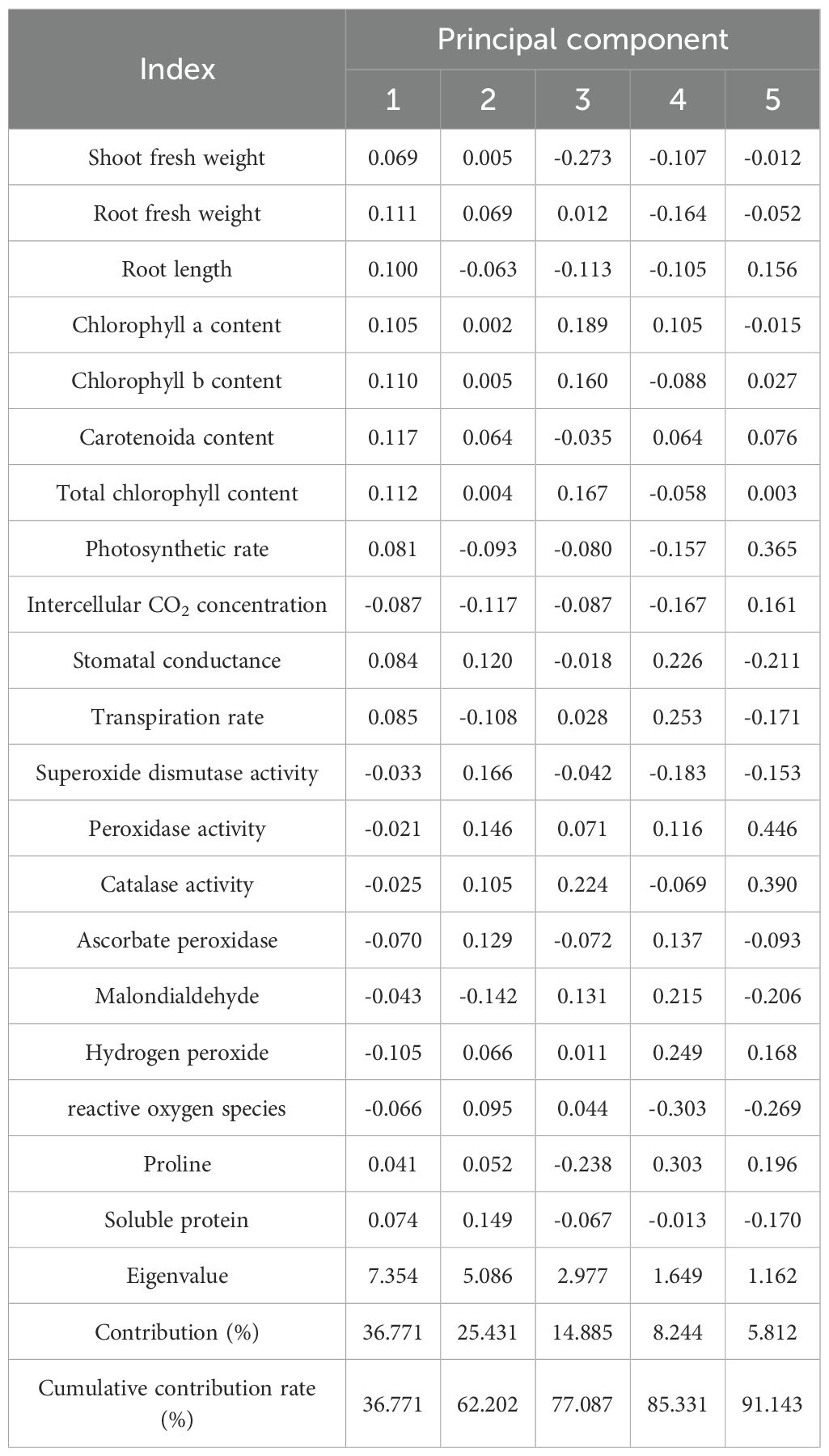

In this study, the principal component analysis was performed on the flooding tolerance coefficients of the two ecological grasses, with results summarized in Table 2. The first five principal components, explaining a cumulative variance of 91.143%, were selected for the comprehensive evaluation of flooding tolerance. Principal component 1 accounted for 36.771% of the variance and was primarily associated with chlorophyll content, as indicated by high eigenvector loadings for Carotenoid content Total chlorophyll content, shoot fresh weight and Chlorophyll b content. Principal component 2 contributed 25.431% of the variance and was mainly related to antioxidant enzyme activities, reflected by large loadings for Superoxide dismutase activity, Soluble protein content, Peroxidase activity and Ascorbate peroxidase activity. Principal component 3 explained 14.885% of the variance and was chiefly associated with osmoregulatory substances, such as shoot fresh weight and proline content (Table 2).

Table 2. Eigenvectors and contributions to principal component analysis of flooding tolerance coefficients of two ecological grasses with various indicators.

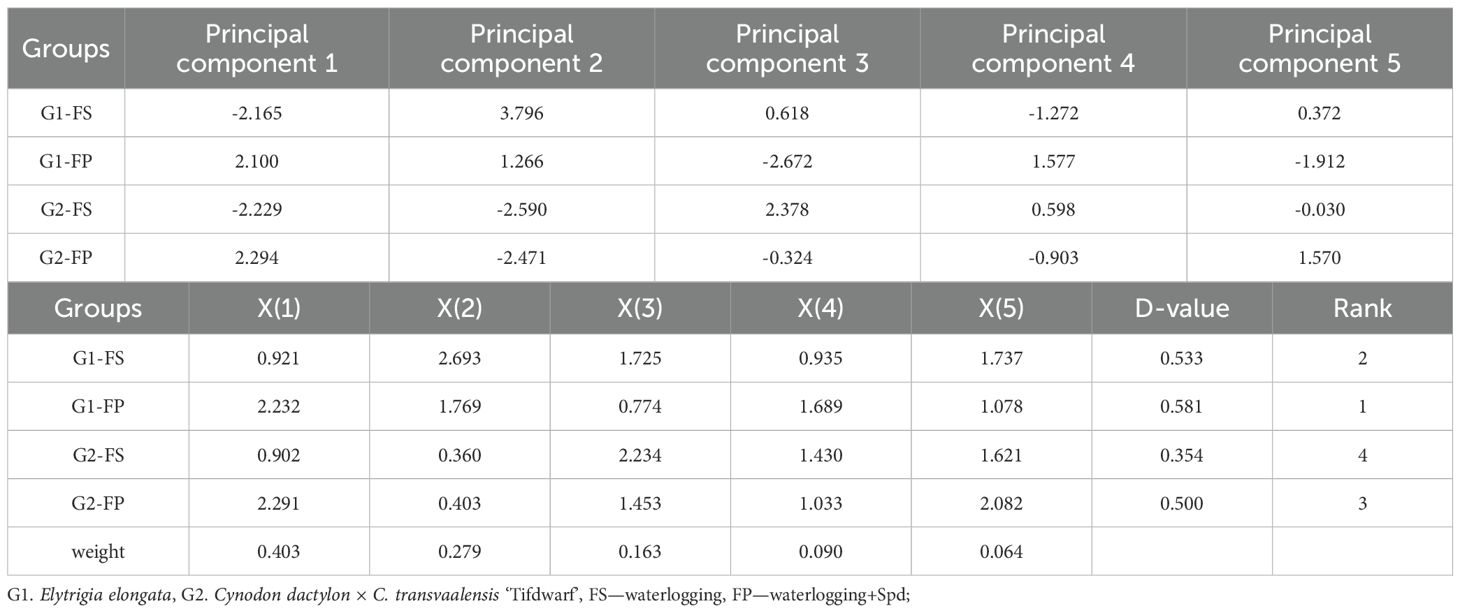

Weights for the five principal components under different flooding stress treatments were calculated using a standard formula, and composite scores (D-values) were derived to rank treatment groups (Table 3). The weights for the principal components were 0.403, 0.279, 0.163, 0.090, and 0.064, respectively. Among the four treatment groups, G1-FP ranked highest with a composite score of 0.581, followed by G1-FS (0.533), G2-FP (0.500), and G2-FS (0.354). Overall, flooding tolerance ranked as Elytrigia elongata > Cynodon dactylon × C. transvaalensis ‘Tifdwarf’ under flooding stress alone, while after exogenous spermidine (Spd) application, the ranking reversed to Elytrigia elongata > Cynodon dactylon × C. transvaalensis ‘Tifdwarf’. These results indicate that E. elongata was more tolerant to flooding under both the same inundation conditions and the inundation conditions of externally applied Spd. The external application of Spd under flooding stress effectively improves flooding resistance and mitigates stress injury in both species, with the strongest promotive effect observed in E. elongata, followed by ‘Tifdwarf’ (Table 3).

Table 3. Composite index values, weights, affiliation function values, D-values and flood tolerance rankings of the two ecological grasses.

4 Discussion

4.1 Effects of different treatments on the main growth indexes of two ecological grasses

Flooding adversely affects soil structure and gas diffusion rates, which can impair root respiration and subsequently inhibit plant growth (Dat et al., 2004). Spd plays a crucial role in plant physiological regulation and stress responses (Pan and Xue, 2012), promoting root elongation and growth by enhancing root cell division (Wei and Newton, 2005). In the present study, FS significantly reduced the shoot fresh weight, root fresh weight, and root length of both E. elongata and ‘Tifdwarf’. These reductions are likely attributable to the anoxic conditions caused by submergence, which lower the oxygen concentration around roots, restrict root respiration, and lead to the accumulation of phytotoxic substances in the soil that inhibit root development (Xin et al., 2012). However, the belowground fresh weight of E. elongata continued to increase with prolonged flooding, likely due to its inherent tolerance to waterlogging (Chen et al., 2020), Alternatively, under waterlogging stress, the plant’s root respiration may be impeded, leading to severe energy deficiency. This causes the plant to sacrifice vertical root elongation in favor of promoting the formation of lateral roots or adventitious roots (Sauter, 2013). Moreover, the exogenous application of Spd under FS significantly improved shoot fresh weight, root fresh weight, and root length in both species. These findings suggest that Spd can alleviate the detrimental effects of flooding and promote biomass accumulation, possibly through its known role in delaying senescence and maintaining cellular activity under stress conditions (Li et al., 2017).

4.2 The effects of different treatments on the chlorophyll content two ecological grasses

Flooding induces anaerobic respiration, which disrupts chlorophyll biosynthesis and reduces overall chlorophyll content in plants (Ding et al., 2020). Carotenoids play a key role in capturing and transferring light energy to chlorophyll a, serving as important accessory pigments in photosynthesis (Wang et al., 2021). Previous studies have shown that Spd can alleviate blockages in the conversion of chlorophyll precursors, such as from protochlorophyllide to uroporphyrinogen III, thereby promoting chlorophyll accumulation (Xiang et al., 2020), Furthermore, foliar application of Spd has been reported to regulate chlorophyll biosynthesis and degradation pathways, protect against oxidative stress, and improve chlorophyll stability (Sawariya et al., 2024). In this study, we found that FS stress significantly reduced the chlorophyll and carotenoid contents in both ecological grasses, aligning with physiological results reported by Yang et al. (2022). on arborvitae willow seedlings under submergence. In contrast, foliar application of Spd under FS increased chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, and carotenoid contents, likely due to Spd’s capacity to alleviate hypoxia induced degradation of photosynthetic pigments and maintain pigment stability.

4.3 The effects of different treatments on the photosynthetic gas exchange parameters of two ecological grasses

Photosynthesis is the primary driver of plant growth and biomass accumulation, providing the energy required for metabolic processes (Flexas and Carriquí, 2020). Under flooding stress, stomatal closure occurs, leading to reduced gas exchange and a consequent decline in photosynthetic rate (Nie et al., 2021). Spd has been shown to enhance photosynthetic capacity under stress conditions, thereby improving plant tolerance to flooding (Cui et al., 2022). In this study, exogenous Spd application under FS conditions reversed these trends suggesting that Spd helps maintain stomatal aperture, enhances photosynthetic activity, and contributes to flood tolerance. These findings are consistent with previous studies, such as that of Hu et al. (2021). which demonstrated that Spd improved the physiological performance of Phoebe bournei seedlings under drought stress through enhanced photosynthetic activity.

4.4 Effects of different treatments on the antioxidant response and oxidative stress of two ecological grasses

Flooding stress triggers the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to potential oxidative damage in plants (Jiang et al., 2013). In response, E. elongata activated a comprehensive enzymatic defense system, showing significantly increased activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), catalase (CAT), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) under FS, which aligns with findings in spinach and melon under similar conditions (Seymen, 2021; Diao et al., 2020). This coordinated upregulation helped maintain a dynamic ROS balance, contributing to its flooding tolerance (Sun et al., 2018). In contrast, ‘Tifdwarf’ exhibited a divergent response, with increased SOD and CAT activities but decreased POD and APX, suggesting a compensatory mechanism where ROS scavenging primarily relied on SOD and CAT (Tang et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2006).The application of exogenous Spd, FP treatment, played a decisive role in reshaping the oxidative stress response. It significantly reduced the activities of SOD, POD, CAT, and APX in both species. This downregulation was directly linked to the concurrent reduction in measured ROS levels—specifically H2O2 and superoxide anions—under FP treatment. This evidence supports the mechanism that Spd directly alleviates oxidative stress by neutralizing ROS, potentially through cation chelation or by acting as an H+ carrier and participating in disproportionation reactions that partially substitute for SOD (Jin et al., 2010; Wang, 2019). Consequently, the reduced ROS load diminished the demand for high enzymatic antioxidant activity.

The mitigation of oxidative stress by Spd was further confirmed by a reduction in membrane lipid peroxidation. Malondialdehyde (MDA) content, a key indicator of membrane lipid peroxidation and is widely used to assess the extent of oxidative stress and the resilience of plant tissues (Zhao et al., 2023). increased significantly in ‘Tifdwarf’ under FS but was markedly reduced by Spd, consistent with reports by Shi et al. (2016). E. elongata displayed a biphasic MDA response under FS—decreasing initially but increasing with prolonged stress—indicating a gradual loss of protection over time (Liang et al., 2019). However, Spd application progressively counteracted this trend, ultimately lowering MDA levels, corroborating the findings of Seng et al. (2012b). The FS induced rise in H2O2 and superoxide anions, consistent with observations in rice (Ma et al., 2015), was effectively reversed by Spd, aligning with studies showing Spd’s role in suppressing anaerobic respiration and ROS accumulation (Jian et al., 2022).

4.5 Effects of different treatments on the contents of free proline and soluble protein in two ecological grasses

Free proline and soluble proteins are key osmoregulatory substances in plants, which accumulate substantially under stress to maintain cellular osmotic balance and confer protection against adverse conditions (Liu et al., 2009). The increase in proline content following flooding is often used as an indicator of plant flooding tolerance, with the timing of peak accumulation reflecting the degree of stress adaptation (Luo et al., 2007). Flooding depth also differentially influences soluble protein content. For instance, Liang et al. (2015) reported that short term shallow flooding promoted soluble protein accumulation in Phragmites australis seedlings, whereas prolonged deep flooding caused a decline. In this study, flooding stress in the present study increased proline content in both ecological grasses, aligning with results from Li et al. (2013) who examined the response of three wetland species to flooding and drought in Dongting Lake, and Song et al. (2013), who investigated flooding effects on root morphology and leaf physiology in soybean cultivars with varying flood tolerance. The soluble protein content in E. elongata initially increased and subsequently declined with extended flooding duration, whereas in ‘Tifdwarf’, soluble protein content decreased continuously, mirroring the pattern reported by Liang et al. (2015) Moreover, exogenous application of Spd enhanced the levels of proline and soluble proteins in both species, suggesting that Spd effectively regulates cellular osmoregulatory substances, stabilizes cell membranes, and maintains osmotic potential under flooding stress. These findings are consistent with those of Wang et al. (2016).

5 Conclusions

In summary, the application of 1 mmol/L exogenous Spd effectively mitigated the adverse effects of flooding stress in two ecological grass species. Under flooding conditions, Spd treatment promoted epidermal cell proliferation and biomass accumulation, enhanced photosynthetic capacity by increasing chlorophyll content and gas exchange parameters, and modulated antioxidant enzyme activity. This led to elevated levels of free-state Spd, which scavenged accumulated reactive oxygen species (ROS), while increasing osmoregulatory substances that mitigated oxidative damage to membrane lipids and helped maintain cellular osmotic balance. Consequently, Spd alleviated the inhibitory effects of flooding on the growth of two ecological grasses. Overall, this study demonstrated that flooding stress significantly impairs the growth and physiological functions of the two ecological grasses, whereas exogenous Spd application mitigates these detrimental impacts. These findings provide a theoretical basis for developing strategies to enhance flooding tolerance in grass species and support the potential use of Spd as a practical agent to improve stress resilience in ecological grasslands subjected to waterlogging.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

RS: Validation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Investigation. HH: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization. DH: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. YY: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. ZC: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. XC: Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. YF: Project administration, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Central Financial Forestry Science and Technology Extension Demonstration Fund (Grant No. E (2025)TG 30) and General Program of the Hubei Province Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 2023AFB298).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Chen, F. Y., Gu, Y. B., Bai, J. S., and Lou, Y. J. (2020). Effects of flooding and salt stress on the growth of Zizania latifolia. Chin. J. Ecology. 39, 1484–1491. doi: 10.13292/j.1000-4890.202005.037

Cheng, Z. B., Liao, Q. S., and Su, Z. F. (2010). Research progress of polyethylene-polyamine in sow milk. Feed Review., 8–11. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-0084.2010.05.003

Cui, Y. K., Kong, L. J., Zheng, F., Liu, R. X., Chen, Y. P., and Yuan, J. H. (2022). Exogenous spermidine: effect on biomass accumulation and photosynthetic capacity of maize plants under waterlogging stress. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bulletin. 38, 22–26.

Dat, J. F., Capelli, N., Folzer, H., Bourgeade, P., and Badot, P.-M. (2004). Sensing and signalling during plant flooding. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 42, 273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2004.02.003

Diao, Q. N., Jiang, X. J., Gu, H. F., Chen, Y. Y., Zhang, Y. P., and Fan, H. W. (2020). Effects of waterlogging stress and recovery on growth, physiological and biochemical indexes on different varieties of melon seedlings. Acta Agriculturae Shanghai. 36, 44–52. doi: 10.15955/j.issn1000-3924.2020.01.08

Ding, H. F., Yang, W. L., Dai, H. J., and Wang, Z. P. (2020). Effects of flooding stress on photosynthesis and root physiological characteristics of ‘Merlot’ grapevine. Sino-Overseas Grapevine Wine. 9–14. doi: 10.13414/j.cnki.zwpp.2020.02.002

Flexas, J. and Carriquí, M. (2020). Photosynthesis and photosynthetic efficiencies along the terrestrial plant’s phylogeny: lessons for improving crop photosynthesis. Plant J. 101, 964–978. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14651

Hu, S. N., Wang, B., Li, T. H., Zhang, X. Y., Li, Y. N., Yan, X., et al. (2021). Effects of spermidine on physiology of phoebe bournei seedlings under drought stress. J. Southwest Forestry Univ. (Natural Sciences). 41, 31–38. doi: 10.11929/j.swfu.202011073

Jackson, M. B. and Colmer, T. D. (2005). Response and adaptation by plants to flooding stress. Ann. Botany. 96, 501–505. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci205

Jian, S. G., Zhuang, Z. Q., Yu, H. Z., and Shun, Y. Z. (2022). Exogenous spermidine regulates the anaerobic enzyme system through hormone concentrations and related-gene expression in Phyllostachys praecox roots under flooding stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 186, 182–196. doi: 10.1016/J.PLAPHY.2022.07.002

Jiang, Y. P., Hao, T., Zou, Y. J., Zhang, Z. H., Chen, C. H., and Wang, L. J. (2013). Advance of researching into the plant growth and development as influenced by waterlogging and the plant adaptive mechanism. Acta Agriculturae Shanghai. 29, 146–149.

Jin, C. Y., Sun, J., and Guo, S. R. (2010). Effects of exogenous spermidine on growth and active oxygen metabolism in cucumber seedlings under Ca(NO3)2 stress. Acta Bot. Boreali-Occident. Sin. 30, 1627–1633.

Li, F., Qin, X., Xie, Y., Chen, X., Hu, J., Liu, Y., et al. (2013). Physiological mechanisms for plant distribution pattern: responses to flooding and drought in three wetland plants from Dongting Lake, China. Limnology. 14, 71–76. doi: 10.1007/s10201-012-0386-4

Li, H. W., Zheng, Q., Li, B., and Li, Z. S. (2022). Research progress on the aspects of molecular breeding of tall wheatgrass. Chin. Bull. Botany. 57, 792–801. doi: 10.11983/CBB22152

Li, H. W., Zheng, Q., Wang, J. L., Sun, H. Y., Zhang, K. X., Fang, H. M., et al. (2023). Industrialization of tall wheatgrass for construction of “Coastal grass belt. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 38, 622–631. doi: 10.16418/j.issn.1000-3045.20230206001

Li, W. L., Zhang, X. L., Wang, P. P., Liu, Y. P., and Kong, D. Z. (2017). Effects of exogenous spermidine on flower senescence of lotus. J. Henan Agric. Sci. 46, 95–98 + 117. doi: 10.15933/j.cnki.1004-3268.2017.04.018

Liang, B., Gao, F. L., Guo, H. Y., and Ma, C. C. (2015). Influence of different submergence gradients on growth and some physiological characteristics of Phragmites communis seedlings. Tianjin Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 35, 62–66. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-1114.2015.04.014

Liang, Q., Wang, Z. J., Lin, B. Q., and Li, C. M. (2019). Effects of flooding stress on seedling physiological indexes and leaf fluorescence char-acteristics of sorbus pohuashanensis. J. Jilin Forestry Sci. Technology. 48, 15–17. doi: 10.16115/j.cnki.issn.1005-7129.2019.04.005

Liu, J., Lv, B., and Xu, L. L. (2000). An improved method for the determination of hydrogen peroxide in leaves. Prog. Biochem. Biophys. 27, 548–551. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1000-3282.2000.05.025

Liu, Y., Wang, Y., Long, Z., Zhang, Z. Y., and Pang, X. M. (2011). Metabolic pathway of polyamines in plants: a review. Chin. J. Biotechnol. 27, 147–155. doi: 10.13345/j.cjb.2011.02.002

Liu, W. G., Yan, Z. H., Wang, C., and Zhang, H. M. (2006). Response of antioxidant defense system in watermelon seedling subjected to waterlogged stress. J. Fruit Science. 27, 860–864. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-9980.2006.06.017

Liu, S. F., Zhou, S. B., Zheng, H. Q., Zhu, X. F., and Yang, J. H. (2009). Restoration dynamics after waterlogging of Carex thunbergii on leaf physiological indexes and above-ground nutritions. Acta Prataculturae Sinica. 18, 83–88. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1004-5759.2009.02.013

Lu, R. H., Zhou, X. X., Tang, L., Xu, Q., Zhou, G. Y., Chen, C., et al. (2022). Effects of spermidine spraying on the physionlogical characteristics of Cerasus campanulata seedings under flooding stress. Hunan Forestry Sci. Technology. 49, 28–34. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-5710.2022.06.005

Luo, Q., Zhang, J. L., Hao, R. M., Xu, W. G., Pan, W. M., and Jiao, Z. Y. (2007). Change of some physiological indexes of ten tree species under waterlogging stress and comparison of their waterlogging tolerance. J. Plant Resour. Environment. 16, 69–73. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-7895.2007.01.016

Ma, L. F., Li, Z. T., Yang, K. J., Zhao, C. J., Xu, J. Y., Yang, R., et al. (2015). Effects of submergence on growth and antioxidant enzymes activities of sensitive rice (Oryza sativa) seedlings. Plant Physiol. 51, 1082–1090. doi: 10.13592/j.cnki.ppj.2015.0029

Mattoo, A. K., Minocha, S. C., Minocha, R., and Handa, A. K. (2010). Polyamines and cellular metabolism in plants: transgenic approaches reveal different responses to diamine putrescine versus higher polyamines spermidine and spermine. Amino Acids 38, 405–413. doi: 10.1007/s00726-009-0399-4

Nie, G. P., Chen, M. M., Yang, L. Y., Cai, Y. M., Xu, F., and Zhang, Y. C. (2021). Plant response to waterlogging stress: research progress. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bulletin. 37, 57–64.

Pan, L. and Xue, L. (2012). Plant physiological mechanisms in adapting to waterlogging stress: A review. Chin. J. Ecology. 31, 2662–2672. doi: 10.13292/j.1000-4890.2012.0393

Pang, H. D., Hu, X. Y., Hu, W. J., Zhou, W. C., and Wang, X. R. (2018). Effects of waterlogging stress on the physiological and biochemical characteristics of three tree species. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 38, 5–20. doi: 10.14067/j.cnki.1673-923x.2018.10.003. 26.

Qiaoyu, L., Huichun, X., Zhi, C., Yonggui, M., Haohong, Y., Bing, Y., et al. (2023). Morphology, photosynthetic physiology and biochemistry of nine herbaceous plants under water stress. Front. Plant science. 14. doi: 10.3389/FPLS.2023.1147208

Reasor, E., Brosnan, J., Trigiano, R., Elsner, J., Henry, G., and Schwartz, B. (2016). The genetic and phenotypic variability of interspecific hybrid Bermudagrasses (Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. × C. transvaalensis Burtt-Davy) used on golf course putting greens. Planta. 244, 761–773. doi: 10.1007/s00425-016-2573-8

Sauter, M. (2013). Root responses to flooding. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16, 282–286. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.03.013

Sawariya, M., Yadav, N., Kumar, A., Mehra, H., Kumar, N., Devi, S., et al. (2024). Effect of spermidine on reproductive, seed quality and bio-physiological characteristics of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) genotypes under salt stress. Environ. Res. Commun. 6, 035005. doi: 10.1088/2515-7620/ad2948

Seng, S. S., Wang, Q., Li, C. H., Liu, T. X., and Zhao, L. F. (2012a). Difference in root structure and respiration metabolism between two maize cultivars under waterlogging stress. Scientia Agricultura Sinica. 45, 4141–4148. doi: 10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2012.20.003

Seng, S. S., Wang, Q., Zhang, Y. E., Li, C. H., Liu, T. X., Zhao, L. F., et al. (2012b). Effects of exogenous spermidine on physiological regulatory of maize after waterlogging stress. Tso Wu Hsueh Pao. 38, 1042–1050. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1006.2012.01042

Seymen, M. (2021). How does the flooding stress occurring in different harvest times affect the morpho-physiological and biochemical characteristics of spinach? Scientia Horticulturae. 275. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109713

Shi, W. W., Liu, R. R., Fu, T. T., and Song, J. (2016). Interactive effects of salinity and waterlogging on growth and physiological index in sugarbeet seedlings. Sugar Crops China. 38, 8–11. doi: 10.13570/j.cnki.scc.2016.02.003

Song, X. H., Teng, Z. L., Xiao, C. L., Li, D. M., Li, W. B., and Zhang, D. P. (2013). Effect of waterlogging on root morphology and foliar physiological indexes of soybean varieties. Soybean Sci. 32, 130–132. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-9841.2013.01.030

Sun, X. Y., Chen, M., Li, Y. Q., Wu, Z. X., Zong, Y. D., and Yu, F. Y. (2018). Variations in physiological and biochemical responses in clones of Liriodendron tulipifera under flooding stress. Plant Physiol. 54, 473–482. doi: 10.13592/j.cnki.ppj.2017.0310

Tang, Y. X., Liu, Y. Q., Wu, M., Tang, J., and Li, Y. J. (2008). Effects of flooding stress on the activity of cell defensive enzymes of populus deltoides clones. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 28, 1–5. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-923X.2008.03.001

Wang, S. K. (2019). Effects of polyamines and their synthetic inhibitors on the activities of SOD, POD and CAT in leaves of prunus L. Seedlings under drought stress. J. Shandong Agric. Univ. (Natural Sci. Edition). 50, 388–392. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-2324.2019.03.007

Wang, Y. W., Chang, Y. X., Luo, C. P., Liu, Q. M., Zhou, L., and Hu, B. Y. (2016). Effects of exogenous spermidine on root physiological property of sesame seedling under waterlogging stress. J. Henan Agric. Sci. 45, 29–33. doi: 10.15933/j.cnki.1004-3268.2016.12.006

Wang, Z. X., Li, J. J., Yu, X. D., Cai, Z. P., Luo, J. J., and Xu, Q. H. (2021). An overview of carotenoids biosynthesis in higher plants. Mol. Plant Breeding. 19, 2627–2637. doi: 10.13271/j.mpb.019.002627

Wei, Y. N. (2009). Hazards of waterlogging stress on plants. Modern Agric. Res. 17. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-0653.2009.08.020

Wei, T. and Newton, R. J. (2005). Polyamines promote root elongation and growth by increasing root cell division in regenerated Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana Mill.) plantlets. Plant Cell Rep. 24, 581–589. doi: 10.1007/s00299-005-0021-5

Wu, Q. S. (2018). Experimental guidance of plant physiology experiments (Beijing: China Agriculture Press).

Xiang, L. X., Hu, L. P., Meng, S., and Zou, Z. R. (2020). Effects of foliar-spraying spermidine on chlorophyll synthesis metabolism of tomato seedlings under heat stress. Acta Bot. Boreali-Occident. Sin. 40, 846–851. doi: 10.7606/j.issn.1000-4025.2020.05.0846

Xin, J. L., Huang, B. F., Yang, Z. Y., Yuan, J. G., and Xu, Y. X. (2012). Physiological Responses of Indigofera spicata to different flooding stress. Acta Prataculturae Sinica. 21, 177–183.

Xuan, J. P., Guo, A. G., Liu, J. X., Zhou, J. Y., Guo, H. L., Zhu, X. H., et al. (2005). Study on Induced Breeding of Warm Turfgrass II. Analysis on Morphological Variation of mutants of Cynodon dactylon × C. transvaalensis cv. “Tifdwarf” Induced by Colchicine. J. Grassland Forage Science., 45–47. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-8403.2005.05.016

Yang, J., Du, Y. W., Li, Y. X., Dai, Y. H., Liu, G. Y., Chen, Y., et al. (2022). Effects of submergence stress on the phenotype and physiological indexes of the cuttings from 13 arbor willow varieties. J. Northwest Forestry University. 37, 95–104. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-7461.2022.03.14

Yang, L., Hu, H., Cheng, Z. H., and Fei, Y. J. (2025). The Effects of Exogenous Spermidine on the Morphology and Physiology Characteristics of Axonopus compressus under Flooding Stress. Chin. J. Grassland. 47, 72–84. doi: 10.16742/j.zgcdxb.20240127

Yang, M., Zhang, Y. L., Xu, Z. D., Liu, G., and Fei, Y. J. (2015). Effects of water stress on seedlings growth and physiological characteristics of Lindera megaphylla Hemsl.and Cinnamomum camphora (L.) Presl. J. South. Agriculture. 46, 1449–1454. doi: 10.3969/j:issn.2095-1191.2015.08.1449

You, D. L., Zhang, X., Yu, K. K., Li, C. H., and Wang, Q. (2016). Effect of exogenous spermidine on growth and physiological properties of maize seedling under waterlogging stress. Yu Mi K’o Hsueh. 74-80, 87. doi: 10.13597/j.cnki.maize.science.20160113

Zhang, F., He, E. P., Wang, G. Y., and Yan, H. W. (2015). Research progress on effect of extrinsic spermidine on resistance of organism. Chem. Bioengineering. 32, 1–4. 21. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-5425.2015.07.001

Zhao, X. Y., Han, L. X., and Zhang, G. X. (2023). Physiological Characteristics and Leaf Structure of Chionanthus virginicus Seedlings under Flooding Stress. Acta Bot. Boreali-Occident. Sin. 43, 410–420. doi: 10.7606/j.issn.1000-4025.2023.03.0410

Keywords: flooding stress, waterlogging tolerance, exogenous spermidine, Elytrigia elongata, Cynodon dactylon × C. transvaalensis ‘Tifdwarf’

Citation: Sun R, Hu H, Hu D, Yang Y, Cheng Z, Chen X and Fei Y (2025) Effects of exogenous spermidine on the morphology and physiology of two ecological grasses under flooding stress. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1683739. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1683739

Received: 11 August 2025; Accepted: 13 November 2025; Revised: 17 October 2025;

Published: 09 December 2025.

Edited by:

Klára Kosová, Crop Research Institute (CRI), CzechiaReviewed by:

Ansar Mehmood, University of Poonch Rawalakot, PakistanJuan Pablo Rodriguez, Julius Kühn-Institut, Germany

Lindamir Pastorini, State University of Maringa, Brazil

Copyright © 2025 Sun, Hu, Hu, Yang, Cheng, Chen and Fei. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yongjun Fei, ZnlqMjAxMEAxNjMuY29t

Rui Sun

Rui Sun Hui Hu1,2

Hui Hu1,2 Yujie Yang

Yujie Yang Yongjun Fei

Yongjun Fei