Abstract

With the rapid development of precision agriculture, seed germination detection is crucial for crop monitoring and variety selection. Existing fully supervised detection methods rely on large-scale annotated datasets, which are costly and time-intensive to obtain in agricultural scenarios. To tackle this issue, we introduce a knowledge distillation–enhanced semi-supervised germination detection framework (KD-SSGD) that requires no pre-trained teacher and supports end-to-end training. Built on a teacher–student architecture, KD-SSGD introduces a lightweight distilled student branch and three key modules: Weighted Boxes Fusion (WBF) to optimize pseudo-label localization, Feature Distillation Loss (FDL) for deep semantic knowledge transfer, and Branch-Adaptive Weighting (BAW) to stabilize multi-branch training. On the Maize-Germ (MG) open-access dataset, KD-SSGD achieves 47.0% mAP with only 1% labeled data, outperforming Faster R-CNN (35.6%), Mean Teacher (41.9%), Soft Teacher (45.1%), and Dense Teacher (45.0%), and reaches 59.3%, 62.8%, and 65.1% mAP at 2%, 5%, and 10% labeled ratios. On the Three Grain Crop (TGC) open-access dataset, which achieves 73.3%, 75.3%, 75.6%, and 76.1% mAP at 1%, 2%, 5%, and 10% labels, surpassing mainstream semi-supervised methods and demonstrating robust cross-crop generalization. The results indicate that KD-SSGD could generate high-quality pseudo-labels, effectively transfer deep knowledge, and achieve stable high-precision detection under limited supervision, providing an efficient and scalable solution for intelligent agricultural perception.

1 Introduction

Recent advances in deep learning have made object detection a central task in modern computer vision research (Wu et al., 2020; Carion et al., 2020). Current detection approaches have achieved remarkable performance through diverse architectures, including one-stage models (e.g., RetinaNet (Lin et al., 2017b), FCOS (Tian et al., 2019)), two-stage or cascaded methods (e.g., Faster R-CNN (Ren et al., 2017), Cascade R-CNN (Cai and Vasconcelos, 2021)), and Transformer-based frameworks (e.g., Deformable DETR (Zhu et al., 2021), DAB-DETR (Liu et al., 2022)). Multi-scale feature enhancement modules, for example the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) (Lin et al., 2017a), have significantly strengthened detection performance over different object scales. However, the effectiveness of these methods is highly contingent upon comprehensive, accurately labeled datasets, whose collection is costly, particularly in domain-specific fields such as agriculture.

Seed germination detection exemplifies these challenges. Accurate identification of germination states is critical for assessing seed vigor and supporting intelligent breeding (Genze et al., 2020; Nehoshtan et al., 2021). This task requires recognizing fine-grained features—such as radicle length—from image sequences, often under challenging conditions involving small object size, ambiguous boundaries, occlusion, and severe class imbalance. These factors limit the effectiveness of conventional supervised methods in meeting the high-throughput and low-cost demands of modern agricultural applications.

To reduce reliance on labeled data, semi-supervised approaches have received increasing focus in object detection. Semi-supervised object detection (SSOD) (Chen L. et al., 2024; Fu et al., 2024a, b)commonly employs a teacher–student framework, where the supervisory signals generated from the teacher network are used to train the student branch. In agricultural applications, several studies have explored SSOD. Tseng et al (Tseng et al., 2023). constructed the smallSSD dataset and released a Python package. They further proposed a calibrated teacher–student framework that integrated data augmentation, weak teacher ensembles, and class-wise dynamic calibration to improve pseudo-label quality and robustness in agricultural environments. Zhou et al (Zhou and Shi, 2025). introduced the Perceptive Teacher framework to address small-object detection in Brassica seedlings and pest monitoring, using difficulty-adaptive learning and center distance matching, which significantly improved pseudo-label accuracy and stability under limited annotations. Yang et al (Yang et al., 2025a). combined UAV imagery with SSL for early maize seedling monitoring, constructing multi-temporal field image datasets and employing Mosaic augmentation, a pseudo-label allocator (PLA), and differentiated regression and classification losses to improve detection of critical targets. Despite progress achieved by existing methods, seed germination detection still faces challenges such as minute root tips, blurred boundaries, occlusions, and imbalanced data distributions. STAC (Sohn et al., 2020b) pioneered consistency training but relied on separate training, limiting its performance. Mean Teacher (Tarvainen and Valpola, 2017) improves stability by smoothing teacher model updates via exponential moving average (EMA), yet its heavy reliance on student predictions is prone to error accumulation and confirmation bias. Subsequent approaches are mostly variants; for instance, Soft Teacher (Xu et al., 2021) designs specific modules for two-stage detection architectures (e.g., Faster R-CNN) to refine label quality and boost performance. Dense Teacher (Zhou et al., 2022) improves dense pseudo-labeling for anchor-based detectors but remains sensitive to pseudo-label noise and lacks generalization to diverse architectures. However, such improvements lack generalizability and are difficult to transfer across different detector frameworks.

Knowledge distillation (KD) (Hinton et al., 2015; Gou et al., 2021) conveys information between a high-capacity teacher network and a compact student through soft targets, feature representations, or attention cues, thereby enhancing deployment efficiency. In agricultural computer vision, KD has been successfully applied: WD-YOLO (Yang et al., 2025) used a YOLOv10l teacher to train a lightweight student, achieving 65.4% mAP@0.5 while reducing parameters; MobileNetV3-based weeding navigation (Gong et al., 2024) incorporated CBAM attention and distilled teacher knowledge to the student, reaching 92.2% mAP at 39 FPS; hybrid ViT distillation (Mugisha et al., 2025) transferred both logits and spatial attention from a Swin Transformer teacher to MobileNetV3, achieving 92.4% accuracy with only 0.22 GFLOPs and 13 MB parameters. Most KD methods, however, rely on a two-stage training process with pre-trained teachers, which is data- and time-intensive, limiting applicability in annotation-scarce agricultural settings. To address the challenges of data dependency, error accumulation in semi-supervised Mean Teacher frameworks under extremely low annotation conditions, and the reliance of most knowledge distillation (KD) methods on pre-trained teacher models and two-stage training, while being inspired by the concept of ensemble learning Guo and Gould (2015), we propose the KD-SSGD framework. This paper presents the following major contributions:

• End-to-end knowledge distillation-based semi-supervised detection: KD-SSGD combines pseudo label learning and knowledge distillation in a cohesive end-to-end framework, extending the application of knowledge distillation in semi-supervised detection.

• Three collaborative mechanisms to enhance detection performance: In germination detection tasks, WBF improves pseudo-label localization accuracy, FDL enables multi-level knowledge transfer of fine-grained radicle and shoot features, and BAW balances multi-branch losses while stabilizing training, collectively boosting overall detection performance.

• Multi-crop germination detection under extremely low annotation conditions: KD-SSGD accurately detects germination targets across different developmental stages of multiple crops with very limited labeled data, consistently outperforming conventional fully supervised methods and remaining competitive with mainstream semi-supervised approaches, while demonstrating robustness and high reliability.

The subsequent sections are arranged as follows: Section 2 details the proposed methodology, including dataset partitioning and description, evaluation metrics, method overview, Weighted Box Fusion, Feature Distillation Loss, Branch Adaptive Weighting, and implementation details. Section 3 comprehensively details the experimental results and analysis, including detection performance across varying labeling ratios and critical insights from ablation studies. Concluding in Section 4, the paper discusses promising research avenues for future work.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Dataset overview and split strategy

This research conducts a comprehensive assessment of the proposed methodology using both the publicly available Maize-Germ (MG) RGB image dataset (Chen C. et al., 2024) and the Three Grain Crop (TGC) dataset (Genze et al., 2020), focusing on seed germination detection. The MG dataset comprises five annotated categories: ungerminated, germinating, germinated, primary root, and secondary root, which collectively represent the full spectrum of maize germination stages. The TGC dataset captures the germination process of three grain crops: Pennisetum glaucum (PG), Secale cereale (SC), and Zea mays (ZM), with each crop categorized into germinated and ungerminated classes.To assess the generalization capability of the proposed method, the three crop-specific subsets, each containing germinated and ungerminated classes, were combined into a single dataset comprising six labeled categories. For experimental setup, 80% of the MG dataset was used for training and 20% for validation through random splitting, while the TGC datasets followed the official training, validation, and test splits, but the validation and test sets were merged for a more comprehensive evaluation, as the original test set generally yielded higher performance. All model hyperparameter tuning and performance evaluation were conducted on independent validation sets to ensure fairness and reproducibility. Regarding data partitioning, following the semi-supervised experimental protocol proposed in MixPL (Chen et al., 2023), each training set was subsequently partitioned into labeled and unlabeled portions. Specifically, for the MG dataset (Table 1), 1%, 2%, 5%, and 10% of the train dataset were randomly chosen as labeled data, with the remainder used as unlabeled data to simulate a realistic scenario of limited annotation. For the merged TGC dataset (Table 2), the same labeled proportions were adopted, thereby systematically validating the generalization and stability of the proposed method across different crop types and data distributions.

Table 1

| Data | Labeled | Images | Ungerm. | Germin. | Germ. | Pri. root | Sec. root | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training set | – | 14500 | 119731 | 5660 | 1564 | 4101 | 13944 | 145000 |

| Validation set | – | 3625 | 30111 | 1382 | 372 | 986 | 3399 | 36250 |

| Semi-supervised | 1% | 143 | 1220 | 67 | 12 | 21 | 110 | 1430 |

| 2% | 286 | 2393 | 135 | 31 | 66 | 235 | 2860 | |

| 5% | 703 | 5852 | 281 | 61 | 175 | 661 | 7030 | |

| 10% | 1363 | 11271 | 546 | 151 | 354 | 1308 | 13630 |

Data partition and instance counts of the MG dataset at different labeled ratios.

“Ungerm.”, ungerminated seeds; “Germin.”, germinating seeds; “Germ.”, germinated seeds; “Pri. root”, primary root; “Sec. root”, secondary root.

Semi-supervised rows indicate training subsets for labeled ratios.

Table 2

| Data | Labeled | Images | PG_im | PG_el | SC_im | SC_el | ZM_im | ZM_el | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training set | – | 18884 | 24883 | 38555 | 28581 | 32219 | 46216 | 16931 | 187385 |

| Validation set | – | 4913 | 9655 | 6835 | 8144 | 8103 | 10775 | 5036 | 48548 |

| Semi-supervised | 1% | 184 | 399 | 225 | 271 | 319 | 170 | 440 | 1824 |

| 2% | 367 | 746 | 489 | 501 | 679 | 378 | 847 | 3640 | |

| 5% | 910 | 1846 | 1212 | 1308 | 1622 | 844 | 2184 | 9016 | |

| 10% | 1774 | 3503 | 2453 | 2572 | 3148 | 1516 | 4401 | 17593 |

Image and instance statistics of the merged TGC dataset with labeled ratios.

PG (Pennisetum glaucum), SC (Secale cereale), ZM (Zea mays); “ im”, ungerminated seeds; “ el”, germinated seeds. Semi-supervised rows indicate training subsets for labeled ratios.

2.2 Evaluation metrics

For a thorough assessment of the trained models’ detection capabilities, this study primarily uses the Average Precision (AP) as its key metric (Lin et al., 2014). The AP calculation relies on the Intersection over Union (IoU) between a predicted bounding box and its corresponding ground-truth box. A prediction is categorized as a true positive (TP) when its IoU score surpasses a predetermined threshold and its class label is correct. As demonstrated in Figure 1a, IoU quantifies the accuracy of localization by representing the proportion of the overlapping region to the total region of the combined boxes.

Figure 1

Key components of model performance evaluation. (A) Intersection over Union (IOU) is defined as the ratio of the overlapping area between the predicted box (PD, purple) and the ground truth box (GT, green) to their union. (B) The left panel shows the confusion matrix, representing the correspondence between predicted and actual labels, including TP, FP, FN, and TN, which are used to compute precision and recall. The right panel presents the precision–recall curve, with average precision (AP) corresponding to the area under the curve (orange shaded region).

Precision and Recall are used to evaluate seed germination detection performance. Precision represents the proportion of correctly predicted germinated seeds (TP) among all seeds predicted as germinated (TP + FP), reflecting prediction accuracy. Recall denotes the proportion of actual germinated seeds correctly detected (TP) among all ground-truth germinated seeds (TP + FN), indicating the model’s ability to identify positive instances. The definitions and relationships of TP, TN, FP, and FN are illustrated in a confusion matrix shown in Figure 1b (left panel). Figure 1b (right panel) shows the Precision–Recall (PR) curve, with AP defined as the interpolated area under the curve. For multi-class tasks, AP is computed per class and then averaged to obtain the mean Average Precision. The standard COCO metrics are reported: mAP@[0.50:0.95] (mean of class-averaged AP values at IoU thresholds from 0.50 to 0.95 in steps of 0.05), as well as mAP@0.50 and mAP@0.75, corresponding to class-averaged AP at fixed IoU thresholds of 0.50 and 0.75, respectively. In the following results, mAP@[0.50:0.95] is simply referred to as mAP.

2.3 Method overview

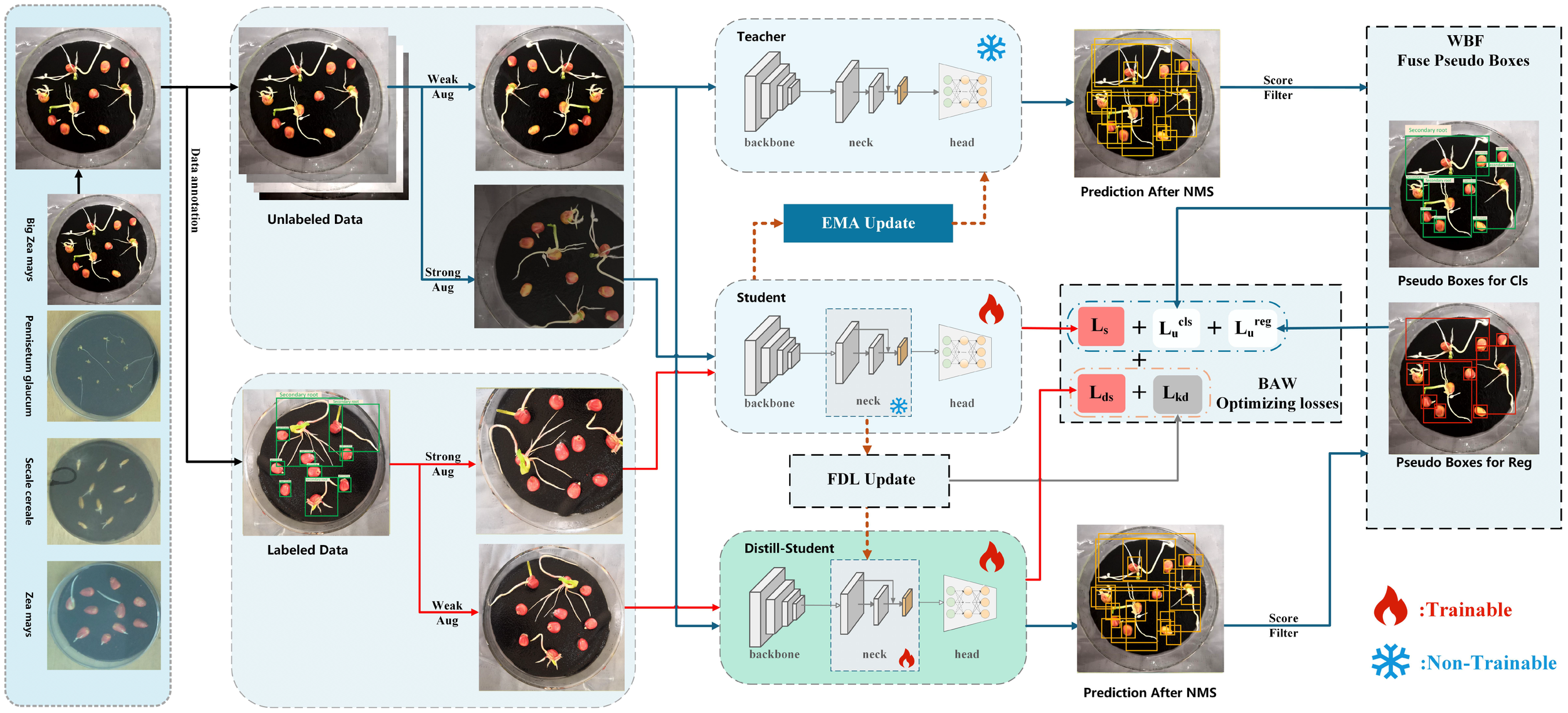

This paper proposes the KD-SSGD framework, which is built upon the classical teacher–student architecture and incorporates ensemble learning to fully exploit multi-model predictions (see Figure 2). We introduce a lightweight distilled student branch that adopts the same architecture as the student model but with a simplified backbone. The teacher model and the distilled student jointly perform inference on unlabeled images, and their predictions are first fused using WBF to generate more reliable pseudo-labels, thereby improving the semi-supervised training of germination detection in agricultural seed phenotyping. Meanwhile, the distilled student aligns its feature representations with the student model via FDL, which enhances feature expressiveness. In the multi-branch joint optimization process, we further incorporate the BAW mechanism to dynamically balance the losses across different branches, effectively improving training stability and overall performance.

Figure 2

Overview of the proposed KD-SSGD method. The model adopts a teacher–student architecture with an additional lightweight distilled student branch. During each training iteration, mixed batches containing both labeled and unlabeled images are sampled. The teacher and distilled student jointly generate predictions on unlabeled data, which are fused via Weighted Boxes Fusion (WBF) to produce robust pseudo-labels. These pseudo-labels, along with ground-truth labels, supervise the student model. Feature Distillation Loss (FDL) enables the distilled student to learn intermediate representations from the student model, while Branch-Adaptive Weighting (BAW) dynamically balances all loss terms to ensure stable training and optimal performance.

In each training iteration, we construct mixed batches containing both labeled and unlabeled samples according to a predefined ratio. Both the teacher and the distilled student models perform inference on the unlabeled data, and their outputs are combined via WBF to produce reliable pseudo-labels. The generated pseudo-labels are subsequently employed to guide the training of the student model on unlabeled data, thereby improving detection accuracy. In addition, we adopt the dual-branch augmentation paradigm from FixMatch (Sohn et al., 2020a) to enhance generalization: in the unsupervised branch, the teacher model applies weak augmentation to ensure pseudo-label stability, while the student model applies strong augmentation to encourage learning of perturbation-invariant features; in the supervised branch, the student model uses strong augmentation to fully exploit the labeled data, whereas the distilled student applies milder augmentation to maintain training stability. Meanwhile, the distilled student is further optimized through FDL, which aligns its intermediate representations with those of the student model, thereby enhancing its performance and improving the expressiveness of pseudo-labels.To coordinate optimization across branches, BAW mechanism dynamically adjusts loss weights, improving convergence stability and overall performance. The combined loss function is formulated as:

where is the supervised loss for the student model on labeled data, is the supervised loss for the distilled student model, is the unsupervised loss of the student model on unlabeled data guided by pseudo-labels, and is the knowledge distillation loss between the student and distilled student models. The hyperparameters λ1, λ2, α, β are the respective weighting coefficients. The mathematical formulations of the individual loss components are specified in Equations 2–4.

where model refers to either the student (s) model or the distilled student (ds) model. and indicate the i-th labeled and unlabeled images, respectively. and represent classification and bounding box regression losses. Nl and Nu are the numbers of labeled and unlabeled samples. fs(·) and fds(·) denote the feature mappings of the student and distilled student models, and KD(·||·) denotes the loss used for knowledge distillation.

Through a multi-branch loss, the roles of teacher, student, and distilled-student models are exploited collaboratively. On labeled images, both the student model and the distilled student model independently perform supervised learning based on Equation 2, ensuring adequate representation capacity. On unlabeled images, the student model is optimized through the unsupervised loss defined in Equation 3, guided by pseudo-labels. Simultaneously, the distilled student model learns structural knowledge from the student model via feature distillation formulated in Equation 4, thereby enhancing its semantic modeling capability. The weighting coefficients λ1, λ2, α, β are dynamically tuned by the BAW mechanism to ensure stability and optimal final performance.

To better elucidate the mechanism of each module in the framework, detailed descriptions of WBF, FDL, and BAW are provided in the following subsections.

2.4 Weighted boxes fusion

To effectively fuse detection results from the teacher and distilled student models, we adopt WBF method (Solovyev et al., 2021) to fuse predictions and produce reliable pseudo-labels. Unlike traditional Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) (Neubeck and Van Gool, 2006) or Soft-NMS (Bodla et al., 2017), WBF does not discard overlapping boxes. Instead, it computes a confidence-weighted average of the bounding box coordinates, fully leveraging predictions from multiple models to produce more stable and accurate pseudo-labels.

Specifically, for model m, the set of predicted bounding boxes on a single image is formally defined in Equation 5:

where denotes the complete set of bounding boxes produced by model m, and Nmis the total number of predicted boxes for that model on a single image. Each bounding box consists of five elements: and indicates the positions of the top-left and bottom-right separately, and Siis the confidence score.

The spatial overlap between predicted bounding boxes is quantified using IoU to select candidates for WBF, as mathematically formulated in Equation 6:

where Biand Bjrepresent two candidate boxes from the prediction set. Candidate boxes whose IoU exceeds a predefined threshold θ (typically θ = 0.5) are grouped into the same cluster .

Within each cluster, WBF computes the fused bounding box coordinates by performing a confidence-weighted average of the bounding box coordinates, with the specific calculation method shown in Equation 7:

where refers to the confidence score assigned to the -th bounding box in cluster cluster . In Equation 8, represents the fused box confidence, accounting for both the constituent boxes' scores and the weights of the participating models:

where is the weight of the model corresponding to the -th box, denotes the set of models that participate in the fusion for cluster , is the set of all models, and is the number of boxes in the cluster.

Finally, the fused bounding box for cluster can be formulated as shown in Equation 9:

All fused boxes generated from highly overlapping clusters constitute the pseudo-label set for the current iteration. Compared with applying NMS directly on multi-model predictions, WBF effectively integrates information from multiple models, preserves high-quality predictions, refines the accuracy and robustness of pseudo-labels, leading to better outcomes in downstream semi-supervised germination detection.

2.5 Feature distillation loss

Feature distillation, a type of knowledge distillation, conveys information by matching intermediate feature representations of the teacher and student models (Liu et al., 2023). In the KD-SSGD framework, although the student model and the distilled student model share the same architecture, their backbone networks differ significantly in scale. To address this, we propose FDL as a core technique. Leveraging the student model’s internal semantic features, this approach transfers knowledge to the lightweight distilled student model, improving its ability to capture spatial layouts and semantic information. Compared with knowledge transfer methods that rely solely on the final outputs (Hinton et al., 2015), feature distillation fully exploits multi-scale semantic information from deep layers of the large model, thereby enhancing the distilled student’s ability to model complex spatial structures.

Specifically, we extract intermediate feature maps from the FPN layers of both the student and the distilled student models, and employ the Mean Squared Error with the Frobenius norm as the distance metric. To ensure spatial consistency, when the resolutions of the feature maps differ, the distilled student feature map is resized via bilinear interpolation to obtain its aligned version , which matches the spatial dimensions of the corresponding student feature map , as mathematically expressed in Equation 10:

where denotes bilinear interpolation, and are the height and width of the -th student feature map, is the original distilled student feature map, and is its aligned version.

Based on the aligned feature representations, the feature distillation loss quantifies deviations of the the distilled-student model from student model, as defined in Equation 11:

where denotes the number of channels, while and represent the height and width of the student feature map. The Frobenius norm measures the element-wise squared differences across all spatial locations and channels.

This loss strengthens the representational capacity of the distilled student model, enabling it to capture semantic and spatial patterns more effectively. Moreover, by being integrated into the overall training objective and jointly optimized with other supervised and unsupervised losses, FDL contributes to improving both the accuracy and the stability of pseudo-label generation, thereby enhancing the overall robustness of the framework.

2.6 Branch-adaptive weighting

In multi-task learning, the losses of different branches often exhibit scale discrepancies and inconsistent convergence speeds, which can adversely affect training stability and overall performance. To address this issue, previous studies have proposed dynamic weight allocation strategies. Cipolla et al (Cipolla et al., 2018). employed task uncertainty as an indicator, estimating the intrinsic noise variance of each task to adaptively adjust weights instantly. Liu et al (Liu et al., 2019). instead tracked the gradient dynamics of each loss during training to adjust task weights accordingly. Although these two approaches respectively leverage intrinsic task noise and training process signals, they can still suffer from weight adjustment lag or convergence oscillations in complex scenarios.

To enable dynamic weight adjustment for multi-branch losses, we propose a BAW mechanism. The final loss results from a weighted sum of the losses contributed by each branch as formulated in Equation 12:

where represents the weighted loss of the -th branch. To simultaneously incorporate both branch uncertainty and training dynamics, where the weighted loss is formulated as shown in Equation 13:

where is the original loss of the -th branch, is the regularization coefficient, is a learnable standard deviation representing the noise level of the branch, and denotes its logarithmic transformation, as defined in Equation 14. To further adapt to the training process in real time, the rate of change in the loss for each branch is defined as shown in Equation Equation 15:

where Li(t − 1) and Li(t − 2) denote the branch losses in the two previous iterations, respectively. The temperature hyperparameter T controls the influence of the loss change rate on weight adjustment.

By performing joint optimization, the BAW mechanism simultaneously leverages task uncertainty and real-time training dynamics to adaptively weight the influence of individual branches on the overall loss function. This effectively mitigates instability caused by scale discrepancies and inconsistent convergence speeds, thereby improving overall model performance.

2.7 Implementation details

All experiments were carried out on an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU with 24 GB of memory. During semi-supervised training, each batch consisted of five images, using a 1:4 ratio of labeled to unlabelled data. Training was performed for 80,000 iterations. Training was carried out using AdamW, with the initial learning rate configured at 0.0002 and weight decay at 0.0001. A linear warm-up strategy was applied during the first 500 iterations with a start factor of 0.001. Subsequently, the learning rate was scheduled using the MultiStepLR policy, where it was decayed to 0.1× of its original value at the 48,000th and 60,000th iterations. The teacher model was updated using an EMA with an update interval of one iteration. For the network architecture, the distilled student branch employed a ResNet-18 backbone, while both the student and teacher branches used ResNet-50 backbones.

3 Results

3.1 Detection performance on different labeled ratios

To comprehensively evaluate the proposed KD-SSGD framework under varying levels of supervision, the evaluation was performed on the MG and TGC datasets using four labeled data ratios (1%, 2%, 5%, and 10%), simulating scenarios ranging from extremely low to moderate supervision. For an unbiased evaluation, all techniques, including the proposed KD-SSGD and representative semi-supervised baselines (Mean Teacher, Soft Teacher, and Dense Teacher)—employed the same Faster R-CNN detector, allowing direct comparison with the fully supervised counterpart.

On the MG dataset (Table 3), KD-SSGD consistently outperforms the fully supervised baseline and demonstrates significant advantages over semi-supervised methods such as Dense Teacher, Soft Teacher, and Mean Teacher. With 1% labeled data, our method achieves a mAP of 47.0%, surpassing fully supervised Faster R-CNN (35.6%) by 11.4% while outperforming Dense Teacher (45.0%), Soft Teacher (45.1%), and Mean Teacher (41.9%). Its mAP@50 and mAP@75 reached 64.3% and 57.7%, respectively, demonstrating strong performance in both overall and high-IoU object detection. With 2% labeled data, KD-SSGD’s mAP improves to 59.3%, maintaining its lead over the fully supervised baseline (47.1%) while remaining competitive against Dense Teacher (56.3%), Soft Teacher (57.5%), and Mean Teacher (58.6%). For 5% and 10% labeled data ratios, our method achieves mAP of 62.8% and 65.1%, respectively. At 5%, it slightly outperforms Dense Teacher, while at 10%, it falls slightly below Dense Teacher but still surpasses other semi-supervised methods, maintaining high performance on mAP@75.

Table 3

| Labeling ratio | Method | mAP (Δ) | mAP@50 (Δ) | mAP@75 (Δ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1%-labeled | Faster R-CNN | 35.6 | 56.5 | 39.2 |

| Mean Teacher | 41.9 (+6.3) | 57.6 (+1.1) | 50.1 (+10.9) | |

| Soft Teacher | 45.1 (+9.5) | 58.6 (+2.1) | 55.2 (+16.0) | |

| Dense Teacher | 45.0 (+9.4) | 63.1 (+6.6) | 45.0 (+5.8) | |

| KD-SSGD (Ours) | 47.0 (+11.4) | 64.3 (+7.8) | 57.7 (+18.5) | |

| 2%-labeled | Faster R-CNN | 47.1 | 66.4 | 56.7 |

| Mean Teacher | 58.6 (+11.5) | 74.4 (+8.0) | 71.8 (+15.1) | |

| Soft Teacher | 57.5 (+10.4) | 72.7 (+6.3) | 69.9 (+13.2) | |

| Dense Teacher | 56.3 (+9.2) | 72.3 (+5.9) | 60.1 (+3.4) | |

| KD-SSGD (Ours) | 59.3 (+12.2) | 74.7 (+8.3) | 72.4 (+15.7) | |

| 5%-labeled | Faster R-CNN | 57.0 | 74.4 | 69.6 |

| Mean Teacher | 60.9 (+3.9) | 76.1 (+1.7) | 73.4 (+3.8) | |

| Soft Teacher | 61.2 (+4.2) | 76.9 (+2.5) | 73.6 (+4.0) | |

| Dense Teacher | 62.1 (+5.1) | 79.3 (+4.9) | 74.0 (+4.4) | |

| KD-SSGD (Ours) | 62.8 (+5.8) | 78.1 (+3.7) | 75.5 (+5.9) | |

| 10%-labeled | Faster R-CNN | 61.7 | 78.0 | 74.0 |

| Mean Teacher | 61.9 (+0.2) | 77.3 (-0.7) | 74.4 (+0.4) | |

| Soft Teacher | 63.9 (+2.2) | 79.5 (+1.5) | 76.4 (+2.4) | |

| Dense Teacher | 66.1 (+4.4) | 82.3 (+4.3) | 77.2 (+3.2) | |

| KD-SSGD (Ours) | 65.1 (+3.4) | 80.4 (+2.4) | 77.4 (+3.4) |

Detection performance comparison on the MG validation set under different labeled ratios.

On the TGC dataset (Table 4), KD-SSGD consistently outperforms the fully supervised baseline and demonstrates competitive performance against other semi-supervised methods, including Dense Teacher. With 1% labeled data, KD-SSGD achieves a mAP of 73.3%, surpassing fully supervised Faster R-CNN (62.0%) by 11.3% and slightly outperforming Dense Teacher (71.4%), Mean Teacher (71.9%), and Soft Teacher (71.4%). Its corresponding mAP@50 and mAP@75 were 91.1% and 87.6%, respectively. At a 2% annotation rate, KD-SSGD attains an mAP of 75.3%, exceeding the fully supervised baseline (67.1%) and exhibiting comparable or superior performance to mainstream semi-supervised detection methods, such as Dense Teacher (74.3%), Soft Teacher (74.7%), and Mean Teacher (74.5%). For annotation rates of 5% and 10%, KD-SSGD achieves mAP of 75.6% and 76.1%, respectively, maintaining a clear advantage over Faster R-CNN (72.7% and 73.7%). While its performance on mAP@50 and mAP@75 metrics is slightly below Dense Teacher, it remains stable and efficient overall.

Table 4

| Labeling ratio | Method | mAP (Δ) | mAP@50 (Δ) | mAP@75 (Δ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1%-labeled | Faster R-CNN | 62.0 | 82.9 | 74.8 |

| Mean Teacher | 71.9 (+9.9) | 90.4 (+7.5) | 86.5 (+11.7) | |

| Soft Teacher | 71.4 (+9.4) | 89.5 (+6.6) | 85.3 (+10.5) | |

| Dense Teacher | 71.4 (+9.4) | 90.6 (+7.7) | 85.6 (+10.8) | |

| KD-SSGD (Ours) | 73.3 (+11.3) | 91.1 (+8.2) | 87.6 (+12.8) | |

| 2%-labeled | Faster R-CNN | 67.1 | 85.8 | 81.6 |

| Mean Teacher | 74.5 (+7.4) | 92.5 (+6.7) | 89.4 (+7.8) | |

| Soft Teacher | 74.7 (+7.6) | 92.8 (+7.0) | 89.4 (+7.8) | |

| Dense Teacher | 74.3 (+7.2) | 92.6 (+6.8) | 88.9 (+7.3) | |

| KD-SSGD (Ours) | 75.3 (+8.2) | 92.8 (+7.0) | 89.5 (+7.9) | |

| 5%-labeled | Faster R-CNN | 72.7 | 90.6 | 87.2 |

| Mean Teacher | 74.6 (+1.9) | 92.8 (+2.2) | 89.5 (+2.3) | |

| Soft Teacher | 75.4 (+2.7) | 93.0 (+2.4) | 89.9 (+2.7) | |

| Dense Teacher | 75.2 (+2.5) | 93.6 (+3.0) | 90.1 (+2.9) | |

| KD-SSGD (Ours) | 75.6 (+2.9) | 93.0 (+2.4) | 90.0 (+2.8) | |

| 10%-labeled | Faster R-CNN | 73.7 | 91.2 | 87.4 |

| Mean Teacher | 74.5 (+0.8) | 92.3 (+1.1) | 89.6 (+2.2) | |

| Soft Teacher | 75.1 (+1.4) | 93.0 (+1.8) | 89.9 (+2.5) | |

| Dense Teacher | 75.8 (+2.1) | 94.5 (+3.3) | 91.0 (+3.6) | |

| KD-SSGD (Ours) | 76.1 (+2.4) | 93.3 (+2.1) | 90.4 (+3.0) |

Detection performance comparison on the TGC validation set under different labeled ratios.

Overall, KD-SSGD demonstrates robustness, effective utilization of unlabeled data, and stable high precision detection performance, with the most pronounced benefits observed in low-label regimes across both datasets.

3.2 Ablation study

An ablation study was performed on the MG dataset using a semi-supervised configuration with 10% labeled data to assess the contributions of WBF, FDL, and BAW to the KD-SSGD framework.

For the Teacher branch, as shown in Table 5, incorporating the WBF module increased mAP, mAP@50, and mAP@75 by 1.2%, 1.3%, and 1.2%, respectively. This demonstrates that WBF effectively improves pseudo-label localization by integrating confidence information from both Teacher and Student predictions, maintaining stable gains even at high IoU thresholds and validating the “retain rather than discard” pseudo-box strategy proposed in Section 3.2. Adding the FDL module further improved mAP to 64.3%, with additional gains of 1.1%–2.3% across all metrics, indicating that feature distillation enhances the Student model’s perception of deep multi-scale semantic information and bridges the feature extraction gap between Teacher and Student. Incorporating the BAW mechanism led to the best overall performance, with mAP reaching 65.1% and cumulative improvements of 3.2%, 3.1%, and 3.1% over the baseline. BAW dynamically adjusts the weights of multiple branch losses, adaptively balancing convergence rates and feature scale differences between Teacher and Student, significantly enhancing training stability and final detection accuracy. The Teacher model results are compared against the mean-teacher baseline to provide a reference for performance.

Table 5

| Method | WBF | FDL | BAW | mAP (Δ) | mAP@50 (Δ) | mAP@75 (Δ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (Mean Teacher) | – | – | – | 61.9 | 77.3 | 74.3 |

| KD-SSGD (Teacher) | ✓ | – | – | 63.1 (+1.2) | 78.6 (+1.3) | 75.5 (+1.2) |

| ✓ | ✓ | – | 64.3 (+2.4) | 79.6 (+2.3) | 76.8 (+2.5) | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 65.1 (+3.2) | 80.4 (+3.1) | 77.4 (+3.1) |

Ablation study of WBF, FDL, and BAW in KD-SSGD on the MG dataset (10% labeled data) —Teacher branch results.

For the Distill Student branch, all ablation experiments were conducted based on WBF (see Table 6). Starting from WBF-only results (mAP: 53.5%, mAP@50: 67.5%, mAP@75: 64.5%), adding FDL improved the metrics to 55.7%, 69.8%, and 67.1%, with gains of 2.2%, 2.3%, and 2.6%, respectively, demonstrating that feature distillation effectively enhances the semantic perception of the lightweight Student model. Further combining BAW increased mAP to 60.2%, mAP@50 to 74.7%, and mAP@75 to 71.8%, achieving cumulative improvements of 6.7%, 7.2%, and 7.3% compared to WBF-only. These results demonstrate the effectiveness and stability of multi-branch collaborative training for the Distill Student model.

Table 6

| Method | WBF | FDL | BAW | mAP (Δ) | mAP@50 (Δ) | mAP@75 (Δ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KD-SSGD (Distill Student) | ✓ | – | – | 53.5 | 67.5 | 64.5 |

| ✓ | ✓ | – | 55.7 (+2.2) | 69.8 (+2.3) | 67.1 (+2.6) | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 60.2 (+6.7) | 74.7 (+7.2) | 71.8 (+7.3) |

Ablation study of WBF, FDL, and BAW in KD-SSGD on the MG dataset (10% labeled data) —Distill Student branch results.

As shown in Figure 3, the total training loss, based on WBF, gradually decreased as FDL and BAW were added, further validating the effectiveness of each component in the KD-SSGD. Overall, WBF, FDL, and BAW synergistically contributed to improved pseudo-label quality, feature transfer, and training optimization within the KD-SSGD, ensuring consistent performance gains and enhanced generalization in semi-supervised object detection.

Figure 3

Total training loss curves of the ablation study on the MG dataset under the semi-supervised setting with 10% labeled data. Based on WBF, the total loss gradually decreased as FDL and BAW were added, validating the effectiveness of each component in the KD-SSGD.

In summary, WBF, FDL, and BAW each played a critical role in both Teacher and Distill Student branches. WBF improved pseudo-label localization, FDL enhanced feature transfer for the lightweight student model, and BAW optimized multi-branch training. For both datasets, the germination detection results are illustrated in Figure 4. These empirical findings indicate that the proposed semi-supervised seed germination detection method consistently demonstrates robust performance under different ratios of labeled data. Collectively, the three mechanisms establish a stable and efficient semi-supervised learning system, supporting continuous improvements in detection accuracy and generalization capability.

Figure 4

Visualization of germination detection on the MG and TGC datasets using the proposed KDSSGD method. (a) Ground-truth annotations and (b) detection results under the semi-supervised setting with 10% labeled data, where bounding boxes indicate the predicted outputs.

4 Discussion and conclusion

This study proposes KD-SSGD, a semi-supervised germination detection framework enhanced by knowledge distillation, designed to address the challenges of limited annotations and complex seed germination morphology in agricultural scenarios. The framework introduces a lightweight distilled student branch together with three core modules: WBF, FDL, and BAW. These components sequentially enhance pseudo-label quality, enable effective multi-scale knowledge transfer, and stabilize multi-branch optimization. Comprehensive experiments on the Maize-Germ (MG) and Three Grain Crop (TGC) datasets demonstrate that KD-SSGD consistently outperforms mainstream semi-supervised methods under various annotation ratios, while maintaining high accuracy and robustness even with extremely sparse labels (1% and 2%). These results highlight its potential to substantially reduce annotation costs and provide a scalable solution for intelligent agricultural perception. Moreover, as shown in Table 7, training efficiency comparisons indicate that KD-SSGD achieves superior accuracy while incurring only minor additional computational overhead compared to baseline methods, thereby confirming its computational feasibility and practicality for real-world deployment.

Table 7

| Dataset | Method | Training time (h:min) | Avg. iteration time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MG | Mean Teacher | 17:24 | 0.78 |

| Soft Teacher | 18:21 | 0.83 | |

| Dense Teacher | 18:13 | 0.82 | |

| KD-SSGD | 19:02 | 0.86 | |

| TGC | Mean Teacher | 11:47 | 0.53 |

| Soft Teacher | 15:48 | 0.71 | |

| Dense Teacher | 15:04 | 0.67 | |

| KD-SSGD | 15:11 | 0.68 |

Comparison of training time and per-iteration cost for different methods on the MG and TGC datasets.

Results are reported under a single GPU (1 × RTX 3090) and a single training task with 10% labeled data. All methods were trained for 80,000 iterations.

Despite these advantages, KD-SSGD still faces several challenges. The current framework models only single-frame information, which limits its capacity to track the temporal dynamics of germination. It also relies solely on RGB imagery, which remains sensitive to illumination changes and occlusion in complex field conditions. In addition, the framework requires training from scratch on each dataset, leading to considerable computational cost and limited scalability.

Future work will therefore focus on three promising directions. First, incorporating temporal modeling could enable the framework to capture germination dynamics by leveraging growth trajectories and radicle emergence patterns, thereby yielding more biologically meaningful predictions (Adak et al., 2024). Second, the integration of multimodal fusion (e.g., hyperspectral or multispectral data) may provide complementary cues to improve robustness under diverse environmental conditions (Yang et al., 2025b). Third, applying transfer learning can enhance adaptability across different crops and imaging environments, while simultaneously improving detection accuracy and reducing computational cost (Hossen et al., 2025). Collectively, these extensions will further strengthen KD-SSGD’s accuracy, stability, and applicability in real-world agricultural scenarios.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. DL: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. TP: Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. XW: Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. RF: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. KG: Formal Analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. HY: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China, Young Scientist Fund (32501793). Liaoning Provincial Department of Education University Basic Research Program Youth (JYTQN2023078). Shenyang Aerospace University Talent Research Initiation Fund Project(23YB05). Liaoning Provincial Department of Education University Basic Research Program Youth (2024061101). Sub-project of the National Key R&D Program (2022YFD200160202). Jilin Provincial Science and Technology Innovation Base (Platform) Construction Project (YDZJ202502CXJD006). Thanks for the support of CCF Young Computer Scientists & Engineers Forum of Shenyang and Shenyang Key Laboratory of Computer Software Defined. Intelligent Collaboration.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Adak A. Murray S. C. Washburn J. D. (2024). Deciphering temporal growth patterns in maize: integrative modeling of phenotype dynamics and underlying genomic variations. New Phytol.242, 121–136. doi: 10.1111/nph.19575

2

Bodla N. Singh B. Chellappa R. Davis L. S. (2017). “ Soft-nms — improving object detection with one line of code,” in 2017 IEEE international conference on computer vision (ICCV) ( IEEE, Venice), 5562–5570. doi: 10.1109/ICCV.2017.593

3

Cai Z. Vasconcelos N. (2021). “ Cascade r-cnn: High quality object detection and instance segmentation,” in IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, Los Alamitos, CA, USA: IEEE Computer Society43, 1483–1498. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2019.2956516

4

Carion N. Massa F. Synnaeve G. Usunier N. Kirillov A. Zagoruyko S. (2020). “ End-to-end object detection with transformers,” in In Computer Vision – ECCV, vol. 12346 . Eds. VedaldiA.BischofH.BroxT.FrahmJ. M. ( Springer, Cham), 213–229. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-58452-813

5

Chen C. Bai M. Wang T. Zhang W. Yu H. Pang T. et al . (2024). An rgb image dataset for seed germination prediction and vigor detection - maize. Front. Plant Sci.15. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1341335

6

Chen L. Tang H. Wen Y. Chen H. Li W. Liu J. et al . (2024). Collaboration of teachers for semi-supervised object detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.13374. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2405.13374

7

Chen Z. Zhang W. Wang X. Chen K. Wang Z. (2023). Mixed pseudo labels for semi-supervised object detection. arXiv, 2312.07006. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2312.07006

8

Cipolla R. Gal Y. Kendall A. (2018). Multi-task Learning Using Uncertainty to Weigh Losses for Scene Geometry and Semantics. 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (Salt Lake City, UT, USA: IEEE) 7482–7491. doi:–10.1109/CVPR.2018.00781

9

Fu R. Chen C. Yan S. Wang X. Chen H. (2024a). Consistency-based semi-supervised learning for oriented object detection. Knowledge-Based Syst.304, 112534. doi: 10.1016/j.knosys.2024.112534

10

Fu R. Yan S. Chen C. Wang X. Heidari A. A. Li J. et al . (2024b). S2o-det: A semisupervised oriented object detection network for remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf.20, 11285–11294. doi: 10.1109/TII.2024.3403260

11

Genze N. Bharti R. Grieb M. Schultheiss S. J. Grimm D. G. (2020). Accurate machine learning-based germination detection, prediction and quality assessment of three grain crops. Plant Methods16, 157. doi: 10.1186/s13007-020-00699-x

12

Gong H. Wang X. Zhuang W. (2024). Research on real-time detection of maize seedling navigation line based on improved yolov5s lightweighting technology. Agriculture14, 124. doi: 10.3390/agriculture14010124

13

Gou J. Yu B. Maybank S. J. Tao D. (2021). Knowledge distillation: A survey. Int. J. Comput. Vision129, 1789–1819. doi: 10.1007/s11263-021-01453-z

14

Guo J. Gould S. (2015). Deep cnn ensemble with data augmentation for object detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:1506.07224. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1506.07224

15

Hinton G. Vinyals O. Dean J. (2015). Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. NeurIPS 2014 Deep Learning Workshop. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1503.02531

16

Hossen M. I. Awrangjeb M. Pan S. Mamun A. A. (2025). Transfer learning in agriculture: a review. Artif. Intell. Rev.58, 97. doi: 10.1007/s10462-024-11081-x

17

Lin T.-Y. Dollár P. Girshick R. He K. Hariharan B. Belongie S. (2017a). “ Feature pyramid networks for object detection,” in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR) (Honolulu, HI, USA: IEEE), 936–944. doi: 10.1109/CVPR.2017.106

18

Lin T.-Y. Goyal P. Girshick R. He K. Dollar P. (2017b). “ Focal loss for dense object detection,” in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) (Venice, Italy: IEEE), 2980–2988. doi: 10.1109/ICCV.2017.324

19

Lin T.-Y. Maire M. Belongie S. Hays J. Perona P. Ramanan D. et al . (2014). “ Microsoft coco: Common objects in context,” in European conference on computer vision (ECCV) (Cham, Switzerland: Springer) 8693, 740–755. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-10602-1_48

20

Liu S. Johns E. Davison A. J. (2019). “ End-to-end multi-task learning with attention,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (Long Beach, CA, USA: IEEE), 1871–1880. doi: 10.1109/CVPR.2019.00197

21

Liu D. Kan M. Shan S. Chen X. (2023). Function-consistent feature distillation. arXiv2304.11832. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2304.11832

22

Liu S. Li F. Zhang H. Yang X. Su H. Zhu J. et al . (2022). “ DAB-DETR: Dynamic anchor boxes are better queries for DETR. arXiv, 2201.12329. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2201.12329

23

Mugisha S. Kisitu R. Tushabe F. (2025). Hybrid knowledge transfer through attention and logit distillation for on-device vision systems in agricultural iot. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.16128. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2504.16128

24

Nehoshtan Y. Carmon E. Yaniv O. Ayal S. Rotem O. (2021). Robust seed germination prediction using deep learning and rgb image data. Sci. Rep.11, 22030. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-01712-6

25

Neubeck A. Van Gool L. (2006). Efficient non-maximum suppression. In 18th Int. Conf. Pattern Recognition (ICPR’06). vol.3, 850–855. doi: 10.1109/ICPR.2006.479

26

Ren S. He K. Girshick R. Sun J. (2017). Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell.39, 1137–1149. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031

27

Sohn K. Berthelot D. Carlini N. Zhang Z. Zhang H. Raffel C. A. et al . (2020a). “ Fixmatch: Simplifying semi-supervised learning with consistency and confidence,” in Advances in neural information processing systems (Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc) 33, 596–608.

28

Sohn K. Zhang Z. Li C.-L. Zhang H. Lee C.-Y. Pfister T. (2020b). A simple semi-supervised learning framework for object detection. arXiv, 2005.04757. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2005.04757

29

Solovyev R. Wang W. Gabruseva T. (2021). Weighted boxes fusion: Ensembling boxes from different object detection models. Image Vision Computing107, 104117. doi: 10.1016/j.imavis.2021.104117

30

Tarvainen A. Valpola H. (2017). “ Mean teachers are better role models: Weight-averaged consistency targets improve semi-supervised deep learning results,” in Advances in neural information processing systems (Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc) 30.

31

Tian Z. Shen C. Chen H. He T. (2019). “ Fcos: Fully convolutional one-stage object detection,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision (ICCV) (Seoul, Korea (South): IEEE), 9627–9636. doi: 10.1109/ICCV.2019.00972

32

Tseng G. Sinkovics K. Watsham T. Rolnick D. Walters T. C. (2023). “ Semi-supervised object detection for agriculture,” in Proceedings of the 2nd AAAI workshop on AI for agriculture and food systems. Available online at: https://openreview.net/forum?id=AR4SAOzcuz.

33

Wu X. Sahoo D. Hoi S. C. (2020). Recent advances in deep learning for object detection. Neurocomputing396, 39–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2020.01.085

34

Xu M. Zhang Z. Hu H. Wang J. Wang L. Wei F. et al . (2021). “ End-to-end semi-supervised object detection with soft teacher,” in In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) (Montreal, QC, Canada: IEEE) 3060–3069. doi: 10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.00305

35

Yang R. Chen M. Lu X. He Y. Li Y. Xu M. et al . (2025a). Integrating uav remote sensing and semi-supervised learning for early-stage maize seedling monitoring and geolocation. Plant Phenomics7, 100011. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphe.2025.100011

36

Yang X. Wang H. Zhou Q. Lu L. Zhang L. Sun C. et al . (2025). A lightweight and efficient plant disease detection method integrating knowledge distillation and dual-scale weighted convolutions. Algorithms18, 433. doi: 10.3390/a18070433

37

Yang Z.-X. Li Y. Wang R.-F. Hu P. Su W.-H. (2025b). Deep learning in multimodal fusion for sustainable plant care: A comprehensive review. Sustainability (2071-1050)17, 5255. doi: 10.3390/su17125255

38

Zhou H. Ge Z. Liu S. Mao W. Li Z. Yu H. et al . (2022). “ Dense teacher: Dense pseudo-labels for semi-supervised object detection,” in Computer vision – ECCV 2022 (Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Nature Switzerland), 35–50. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-20077-9_3

39

Zhou C. Shi F. (2025). Perceptive teacher: Semi-supervised small object detection of brassica chinensis seedlings and pest infestations. Comput. Electron. Agric.229, 109956. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2025.109956

40

Zhu X. Su W. Lu L. Li B. Wang X. Dai J. (2021). “ Deformable detr: Deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. arXiv2010.04159. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2010.04159

Summary

Keywords

semi-supervised object detection, knowledge distillation, germination detection, ensemble learning, deep learning

Citation

Chen C, Luo D, Pang T, Wang X, Fu R, Gou K and Yu H (2025) KD-SSGD: knowledge distillation-enhanced semi-supervised germination detection. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1688792. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1688792

Received

19 August 2025

Revised

16 October 2025

Accepted

10 November 2025

Published

08 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Zhiwei Ji, Nanjing Agricultural University, China

Reviewed by

Zhenguo Zhang, Xinjiang Agricultural University, China

Fengkui Zhao, Nanjing Forestry University, China

Bishal Adhikari, Mississippi State University, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Chen, Luo, Pang, Wang, Fu, Gou and Yu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Helong Yu, yuhelong@jlau.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.