- 1College of Biological Science and Engineering, Ningde Normal University, Ningde, China

- 2The Engineering Technology Research Center of Characteristic Medicinal Plants of Fujian, Ningde Normal University, Ningde, China

Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Miq.) Pax (P. heterophylla) is a perennial medicinal herb in which heterophyllin B (HB) serves as one of the primary bioactive compounds. Identifying genes associated with HB accumulation is crucial for breeding high-HB cultivars. In this study, we performed HPLC quantification and high-throughput RNA sequencing on three P. heterophylla accessions with differential HB content. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) of the assembled transcriptome identified HB accumulation-associated modules, followed by qRT-PCR validation of candidate genes. HPLC quantification revealed significant variation in HB content among three samples (59.48 - 369.63 μg/g), with the sample ZS2 (a provincial-certified cultivars) identified as an HB-deficient genotype (t-test, p < 0.01 for all pairwise comparisons). De novo transcriptome assembly using Trinity generated a reference sequence comprising 114,625 transcripts, achieving 89.96 - 92.37% clean read mapping rates across samples. WGCNA clustered expressed genes into 55 modules, among which the yellow module (3,240 genes) showed the strongest positive correlation with HB accumulation. Gene Significance (GS) and Module Membership (MM) evaluation further identified 278 high-confidence candidate genes within this module. qRT-PCR validation using 180-day tissue-cultured samples confirmed one gene (g3166_i1) exhibiting perfect positive correlation with HB variation (kendall’s τ = 1). This study delineates transcriptomic signatures underlying HB divergence in P. heterophylla and provides actionable genetic targets for molecular breeding of high-HB cultivars.

1 Introduction

Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Miq.) Pax ex Pax et Hoffm. (P. heterophylla) is a perennial herb with well-known medicinal value (Li et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2003), primarily cultivated for its dried tuberous roots in China, Korea, and neighboring regions (Choi and Pak, 2000; Liu et al., 2017). In China, P. heterophylla is predominantly cultivated in Fujian, Guizhou, Jiangsu, and Shandong provinces (Kang et al., 2016). With over a century of clinical application history (Hu et al., 2019), it has been traditionally used to treat fatigue, spleen deficiency, anorexia, post-illness debility, and dry cough induced by lung dryness (Xiao et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2024). Its mild pharmacological properties make it particularly suitable for pediatric use, earning it the vernacular name “Hai Er Shen” (phonetically akin to the Chinese word for “children”) in Chinese. Heterophyllin B (HB) is one of the trace active components in P. heterophylla as a medicinal material (Wang et al., 2013). According to the 2022 standards (Standard number: YBZ-PFKL-2022046) issued by the Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission, each gram of P. heterophylla formula granules should contain 0.3 mg to 0.65 mg of HB. Currently, due to long-term reliance on vegetative propagation (Gu et al., 2025), P. heterophylla has limited cultivated varieties (Xu et al., 2023), and most exhibit HB content only marginally above the standard threshold. Therefore, there is an urgent need to breed P. heterophylla cultivars with high HB content to provide reliable plant materials for more effective exploitation and utilization of this medicinal resource.

Plant cyclic peptides (CPs) represent a major class of small-molecule metabolites, typically formed through the cyclization of 2–37 proteinogenic and non-proteinogenic amino acids (usually L-amino acids) via peptide bonds (Burman et al., 2010; Kaleem et al., 2012). These bioactive peptides are widely distributed in various tissues of higher plants, including stem bark, leaves, seeds, and roots (Condie et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2012). Cyclic peptides isolated from P. heterophylla exhibit relatively simple structures compared to those from other plant species, primarily categorized into two structural types: heterophyllin-type peptides and pseudostellarin-type peptides (Yang et al., 2025; Daly and Wilson, 2021). Among them, HB, a cyclic octapeptide, consists of eight L-amino acids linked by peptide bonds to form a single cyclic structure (Jia et al., 2006). In China, HB was first adopted as one of the quality control markers for P. heterophylla in 2010 (Zhao et al., 2015). Current research has demonstrated that HB exhibits significant pharmacological efficacy, particularly in anti-inflammatory (Yang et al., 2018), blood glucose regulation (Liao and Tzen, 2022), and memory enhancement applications (Yang et al., 2021; Deng et al., 2022). However, the metabolic pathways underlying HB biosynthesis remain poorly characterized. Identifying the genes involved in HB production is therefore critical for understanding the molecular mechanisms governing HB accumulation in P. heterophylla. Such research would enable efficient development of high-HB cultivars through molecular breeding strategies.

In molecular breeding research, correlating phenotypic data with transcriptomic data enables rapid identification of candidate genes associated with target traits. Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) is a genetic methodology that analyzes gene-gene correlations using large-scale gene expression profiles (Ruan et al., 2010; Fuller et al., 2011). This approach clusters tens of thousands of genes from transcriptomic datasets into dozens of gene modules and associates these modules with specific traits or phenotypes, thereby reducing the complexity of functional gene selection (Stuart et al., 2003). Particularly suitable for investigating relationships between functional modules and phenotypic traits across multiple samples, WGCNA has been successfully applied in various plant species including rice (Wang et al., 2022), maize (Ma et al., 2021), and tea plant (Xu et al., 2025) as an effective method for detecting co-expression modules and genes related to target phenotypes. In this study, we therefore adopted this WGCNA-based strategy to systematically identify genes associated with HB accumulation.

Herein we cultivated and examined three P. heterophylla samples exhibiting differential HB accumulation, and generated their transcriptome profiles using next-generation sequencing. This study aims to (1) quantify inter-sample HB variation in 180-day-old plants through HPLC analysis; (2) construct a WGCNA from RNA-seq data to identify HB-associated expression modules; (3) identify key genes within the modules that are associated with target traits, providing a reliable basis for future breeding of high-HB P. heterophylla varieties.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant materials

Three types of P. heterophylla (‘ZS1’, ‘ZS2’, and ‘ZS5’) were selected for this study. Samples ‘ZS1’ and ‘ZS2’ were provincially certified cultivars, whereas ‘ZS5’ represented a farmer-preferred landrace.

For long-term preservation, the plant materials were maintained in two forms: (1) asexually propagated clones housed at the Engineering Technology Research Center for Characteristic Medicinal Plants, Fujian, Ningde Normal University, and (2) field-grown plants cultivated at the P. heterophylla Breeding Base (Yingshan Township, Zherong County, Fujian, China). For field-grown plants, newly generated tuberous root tissues were harvested at 180 days post-transplantation for transcriptome sequencing. For tissue-cultured samples, we collected mature micro-tuberous root after 180 days of primary culture for qPCR validation experiments.

2.2 HB extraction, HPLC analysis and calibration curve construction

For accurate HB quantification, HPLC analysis was performed. The tuberous roots were ground into powder, and 2.0 g of powder was extracted with 50.0 mL methanol by ultrasonication (250 W, 30 kHz) for 45 min. After cooling and filtration, 25.0 mL filtrate was transferred to a round-bottom flask and concentrated to dryness using a rotary evaporator. The residue was dissolved in methanol and diluted to 10.0 mL as the test solution.

Chromatographic separation was performed on an Agilent 1200 system (Agilent, USA) equipped with a C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm). The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile (A) and aqueous phosphoric acid (0.2%, B) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min (isocratic elution). Detection was at 203 nm with the column maintained at 30°C and injection volume of 20.0 μL.

An HB reference standard (100.0 mg) was dissolved in methanol and diluted to 1000.0 mL to prepare a stock solution (100 μg/mL). Standard solutions (10-60 μg/mL, at 10 μg/mL intervals) were prepared by serial dilution. After filtration (0.22 μm), 20.0 μL of each solution was injected, with methanol as blank. The calibration curve was generated by plotting peak area (y-axis) versus concentration (x-axis), and the regression equation was calculated.

2.3 RNA extraction, library preparation, and high-throughput sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from P. heterophylla tuberous root tissues using a column-based plant RNA extraction kit (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). RNA purity and concentration were determined using a Nanodrop-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and the samples were stored at -80°C until further analysis. The cDNA library construction and high-throughput sequencing were performed by Tsingke Biotechnology (Beijing, China) on an MGI sequencing platform.

2.4 Transcriptome data processing, construction of WGCNA, candidate gene identification

Raw sequencing reads were quality-assessed using FastQC, followed by filtering to remove low-quality sequences (Q-score < 30). Due to the absence of a reference genome for P. heterophylla, clean reads were de novo assembled into reference transcripts using Trinity. Processed reads were then aligned to the assembly using HISAT2 (Guo et al., 2022), and transcript abundances were quantified with StringTie (Pertea et al., 2015). Based on TMM-normalized expression values, principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted to evaluate inter-sample variation and replicate consistency.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis was performed using R v4.4.1 (wgcna package) (Langfelder and Horvath, 2008). A soft-thresholding power (β, with a scale-free topology fit index > 0.8) was applied to construct unsigned networks. Genes were clustered into modules (mergeCutHeight = 0.25, minModuleSize = 30). To evaluate co-expression relationships between modules and HB content, an eigengene adjacency matrix was calculated based on their correlation coefficients. Heatmap visualization was performed to assess module-trait associations, enabling identification of HB-related key candidate modules for subsequent critical gene selection.

Key candidate genes were selected from target modules using stringent criteria: gene significance for HB content (|GS| > 0.9), module membership (MM > 0.9), p value of GS < 0.00001.

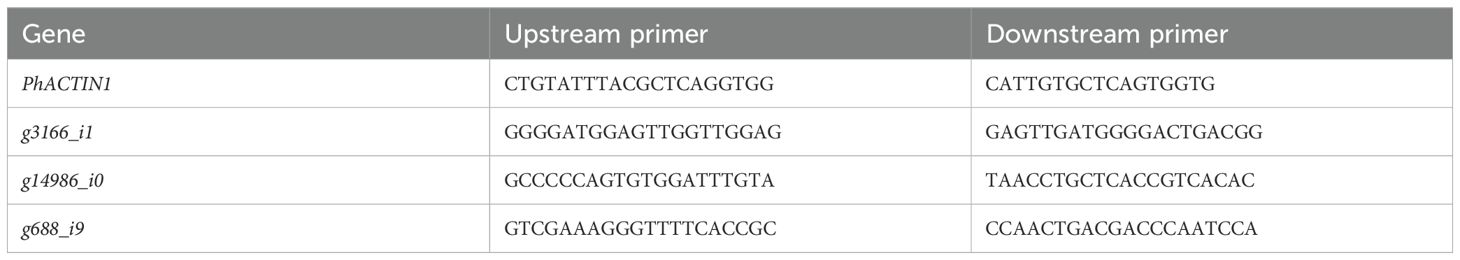

2.5 Validation and quantitative real-time PCR of candidate genes

We verified WGCNA-identified candidate genes by measuring HB content and performing qRT-PCR analysis in tuberous root tissues of three field-grown samples (‘ZS1’, ‘ZS2’, and ‘ZS5’). Total RNA was extracted from tuberous roots using the Column-based Plant RNA Extraction Kit (Sangon Biotech, China). The extracted RNA was then treated with MightyScript plus Master Mix (Sangon Biotech, China) for gDNA removal and cDNA synthesis. Gene-specific primers were designed using Primer-BLAST (Table 1). Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was carried out on a QuantStudio 3 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with 2× HyperScript SYBR Green Master Mix (Sangon Biotech, China) under the following conditions: (1) initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec; (2) 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 30 sec; (3) melt curve analysis. P. heterophylla Actin1 (PhACTIN1, Table 1) served as the internal control. Gene expression was quantified via the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) with three biological replicates (each with three technical replicates). Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test (p<0.05) in R v4.4.1 (stats package), with significance visualized via ggplot2 package (*p<0.05, **p<0.01) (Wickham, 2011).

3 Results

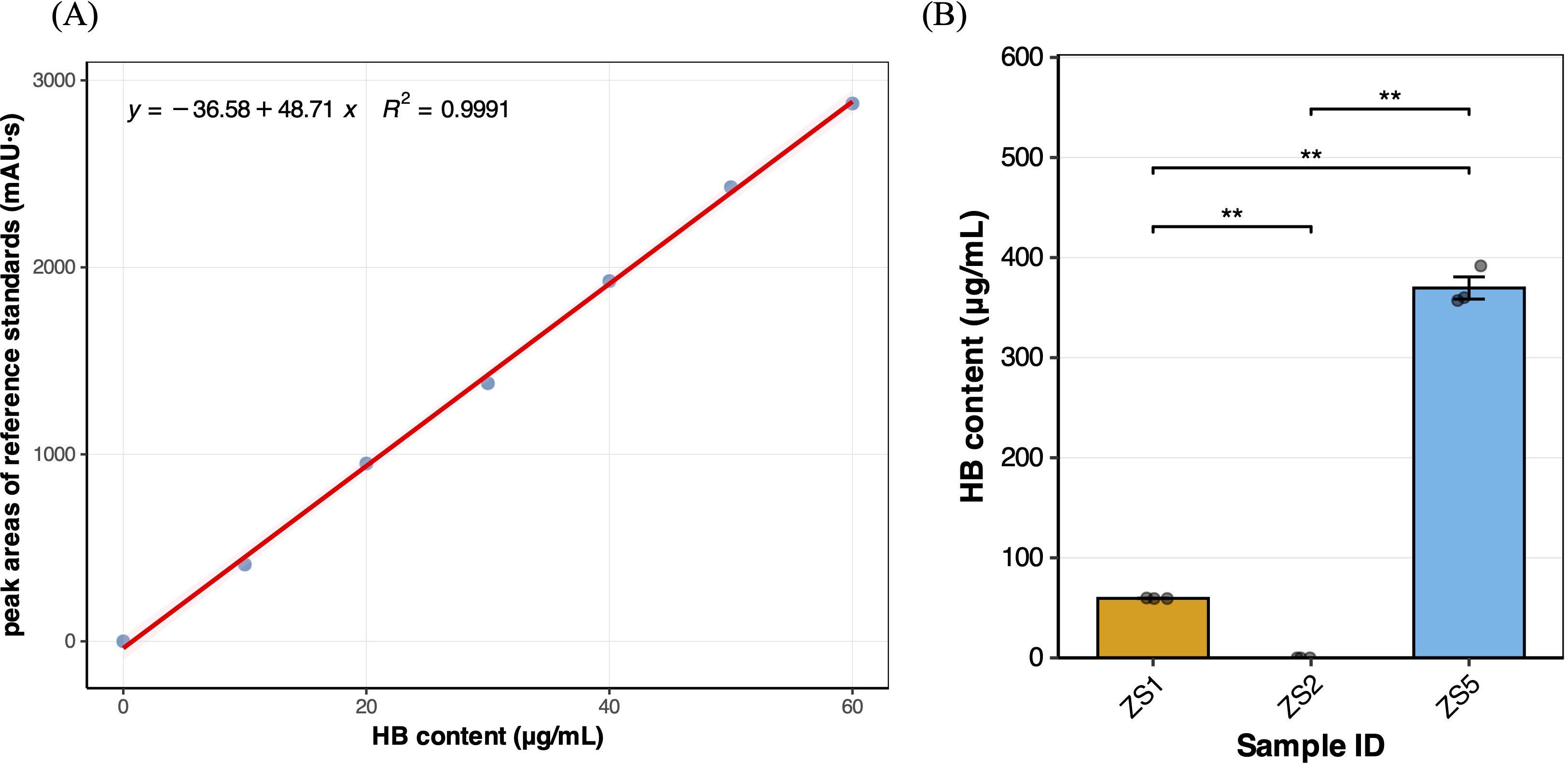

3.1 Quantification of HB in P. heterophylla tuberous roots

To assess whether significant differences in HB content existed among field-grown tuberous roots of different samples, we performed HPLC analysis on tree field-grown samples. This comparison was particularly relevant that the roots of P. heterophylla serve as the primary medicinal organs. A calibration curve (Figure 1A) was first established using HB reference standard solutions (10–60 μg/mL), which showed excellent linearity (R2 = 0.9991), demonstrating high reliability for subsequent sample quantification. HPLC analysis revealed that only ZS5 contained HB at 369.63 ± 11.09 μg/g (ZS1 only 59.48 ± 0.18 μg/g), meeting the Chinese pharmacopoeial standard (YBZ-PFKL-2022046) for drug ‘Taizishen Peifangkeli’ (> 300 μg/g). Notably, no detectable HB was observed in ZS2, suggesting it to be an HB-deficient genotype (Figure 1B). After the pairwise t-tests for significant differences, it was found that there were significant differences in the HB content among the samples (p < 0.01), which making them ideal materials for transcriptome-based identification of HB-related genes.

Figure 1. (A) Calibration curve for Heterophyllin B. (B) Heterophyllin B content variation among three field-grown samples, significant symbol “**” means the p_value < 0.01.

3.2 Transcriptome data processing

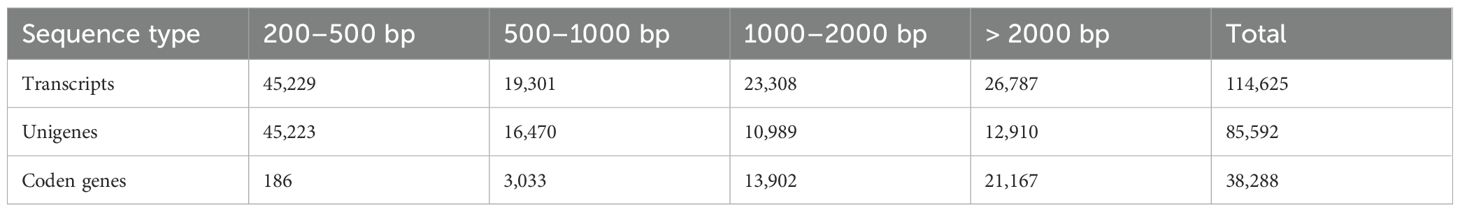

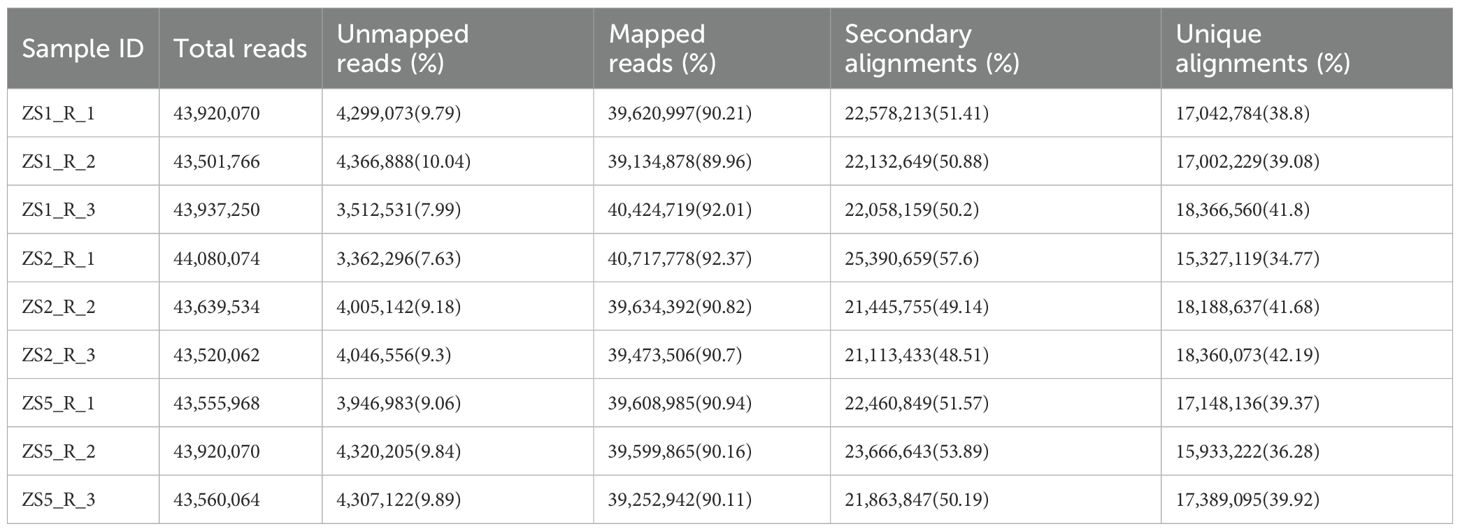

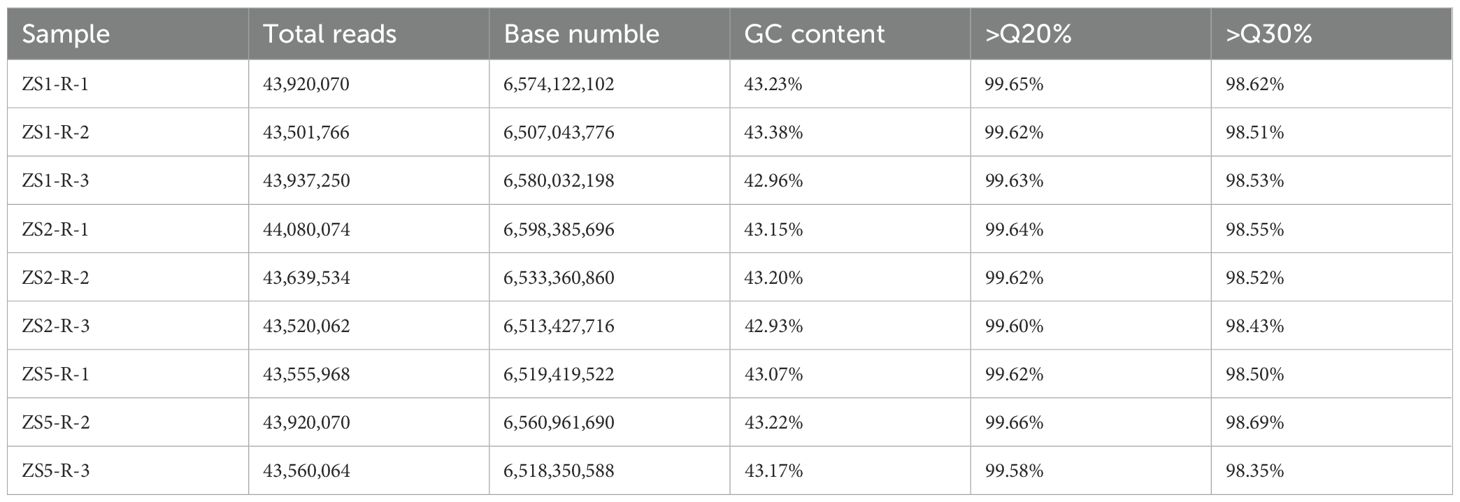

Following high-throughput sequencing, the samples exhibited original read counts ranged from 43,501,766 to 44,080,074 reads, with GC content ranging from 42.93% to 43.38% (Table 2). Quality assessment using FastQC program revealed that over 98% of reads achieved Q30 and over 99% reached Q20 quality scores. Given the absence of a reference genome for P. heterophylla or any closely related species in the same genus, we performed no-reference genome assembly using Trinity program. The assembled sequences (comprising 114,625 transcripts, 85,592 unigenes, and 38,288 coding genes) as reference sequences for subsequent read mapping and quantification across all samples (Table 3). To evaluate the assembly quality of the reference sequences, we aligned chloroplast genome-encoded genes from P. heterophylla (NCBI accession number: OQ405025.1) to the assembled transcripts using NCBI BLAST+ program (-evalue 1e-10 -word_size 30). The BLASTN alignment (Supplementary Table S1) detected 73 out of 77 expected chloroplast genes (94.81%) in the reference transcripts, confirming high assembly integrity.

Table 2. The reads information in the transcriptome for each sample after high-throughput sequencing.

Using HISAT2 program, we aligned clean reads from each sample to the reference sequences. The results showed mapping rates of 89.96-92.37% across all samples (Table 4). Additionally, unique alignments accounted for 34.77-42.19% of total mapped reads.

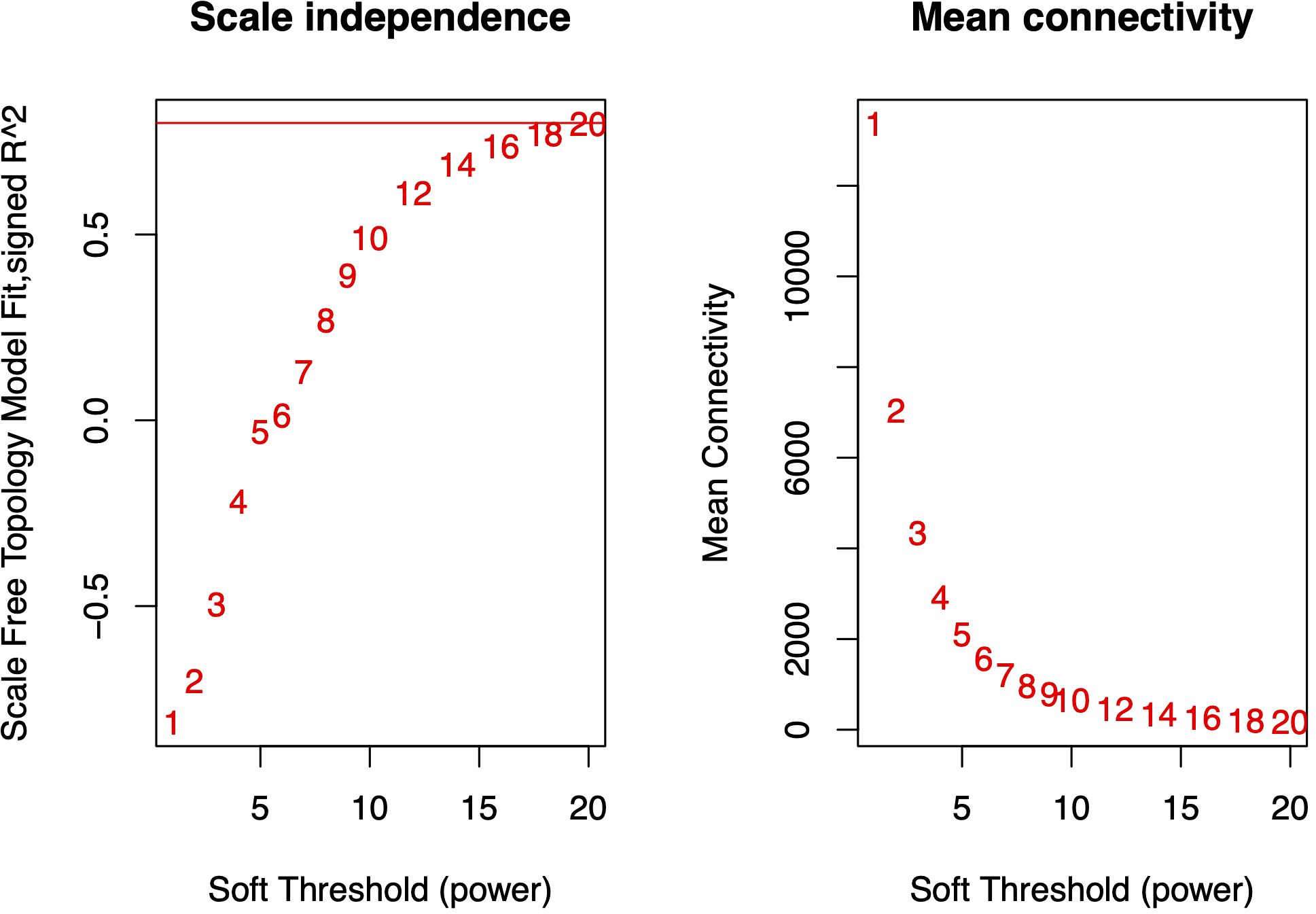

Using StringTie program, we quantified gene expression abundance (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads, FPKM) for all samples aligned to the reference sequences. All samples exhibited normally distributed FPKM values (Figure 2A). To assess inter-sample similarity and intra-sample reproducibility, we performed correlation analysis and principal component analysis (PCA), respectively. The correlation analysis revealed high reproducibility among biological replicates (r > 0.9), except for ZS2_R_1 (Figure 2B). Significant inter-sample variation was observed, with ZS5 showing distinct expression patterns. Notably, ZS2 replicates (ZS2_R_2 and ZS2_R_3) maintained moderate correlation with ZS1 (r > 0.8). PCA results corroborated these findings (Figure 2C), clearly separating the three sample groups into distinct clusters. However, ZS2_R_1 deviated substantially from its own replicates, indicating poor reproducibility. Based on these results, ZS2_R_1 was excluded from WGCNA analyses due to inconsistent reproducibility.

Figure 2. Analysis of gene expression patterns based on FPKM values. (A) Boxplot distribution of FPKM values across samples. Biological replicates are labeled as R_1 to R_3 following sample IDs. (B) Heatmap of correlation coefficients for inter-sample gene expression. The color gradient (blue to red) represents r values ranging from 0.6 to 1.0. (C) Principal component analysis (PCA) for inter-sample gene expression. Red, green, and blue points denote triplicate biological replicates of ZS1, ZS2, and ZS5, respectively.

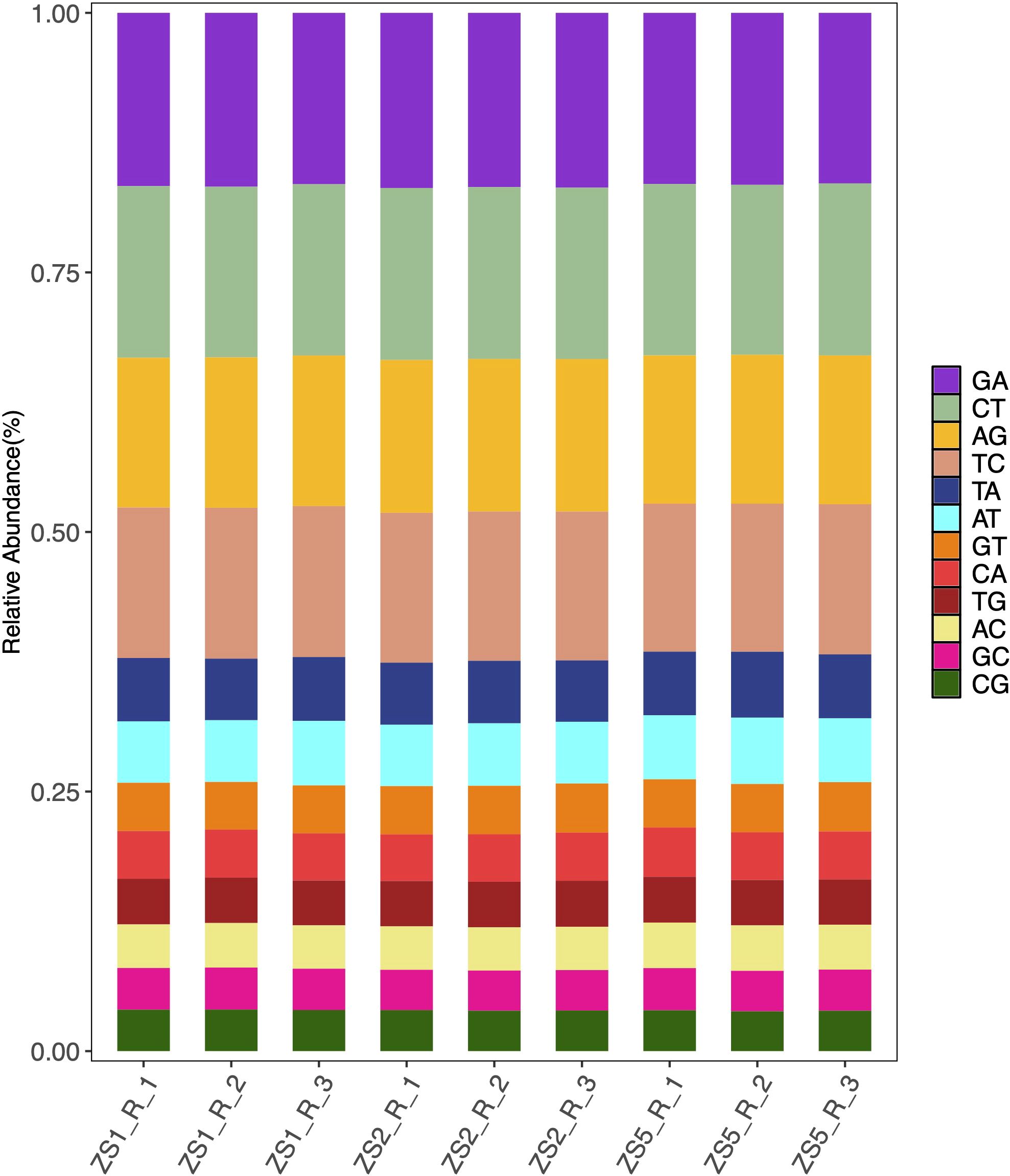

3.3 SSRs and SNPs discovery in P. heterophylla reference sequences

To facilitate genetic map construction and genome assembly for P. heterophylla, we identified SSR and SNP markers from the transcriptome sequences. A total of 2,330 SSR loci were detected within 2,053 coding genes (Supplementary Table S2), representing a 5.36% EST-SSR frequency among the 38,288 annotated coding genes. The SSR analysis revealed 1,890 loci (81.12%) contained dinucleotide or higher-order repeats, and among them, trinucleotide repeats predominated (1,222 loci, 52.45%). Alignment of all samples to the reference sequences revealed abundant SNP variants (from 76,301 to 89,726, Supplementary Table S3), with C/T (16.37 – 16.58%) and G/A (16.42 – 16.87%) transitions representing the most prevalent substitution types (Figure 3).

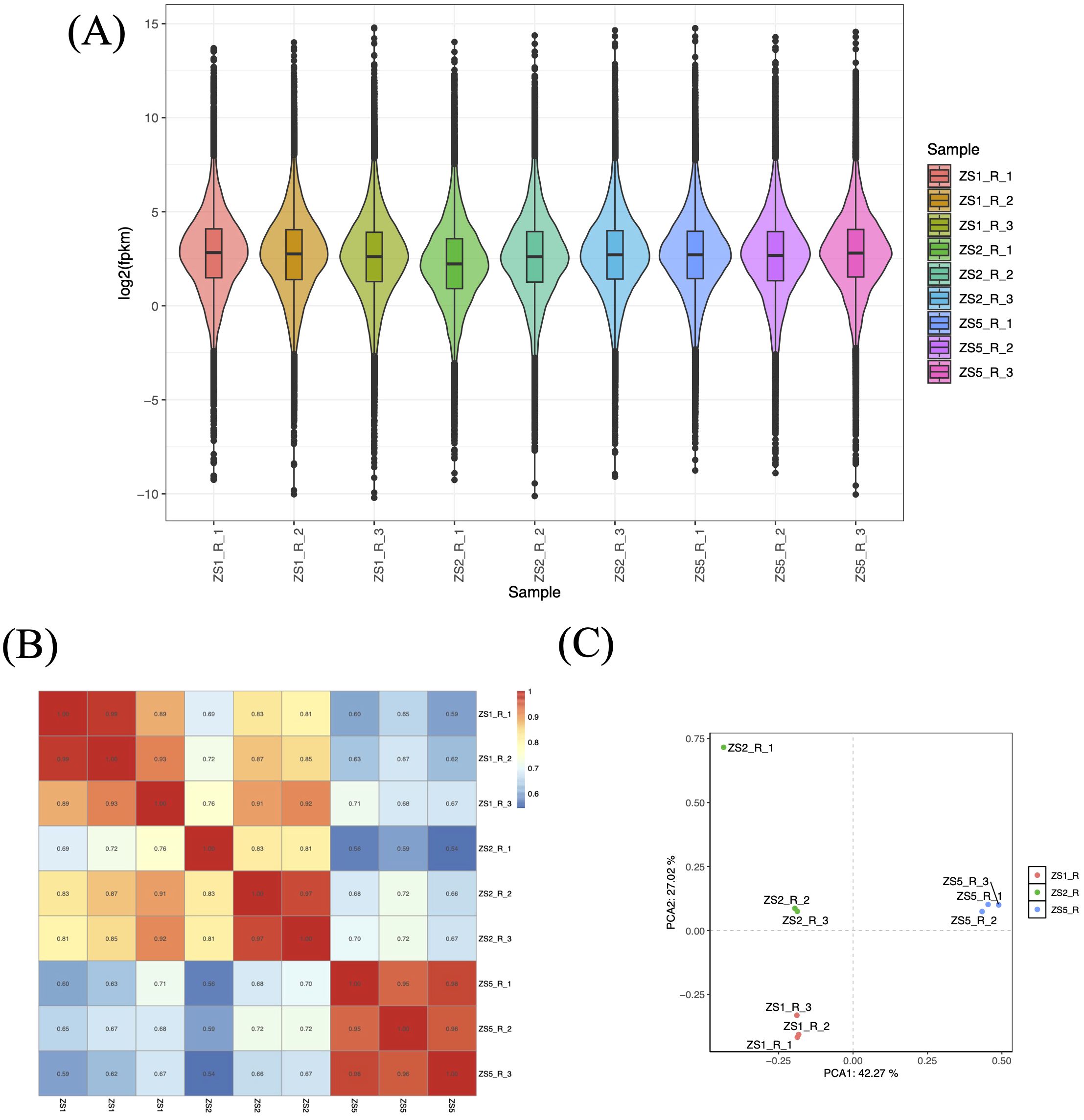

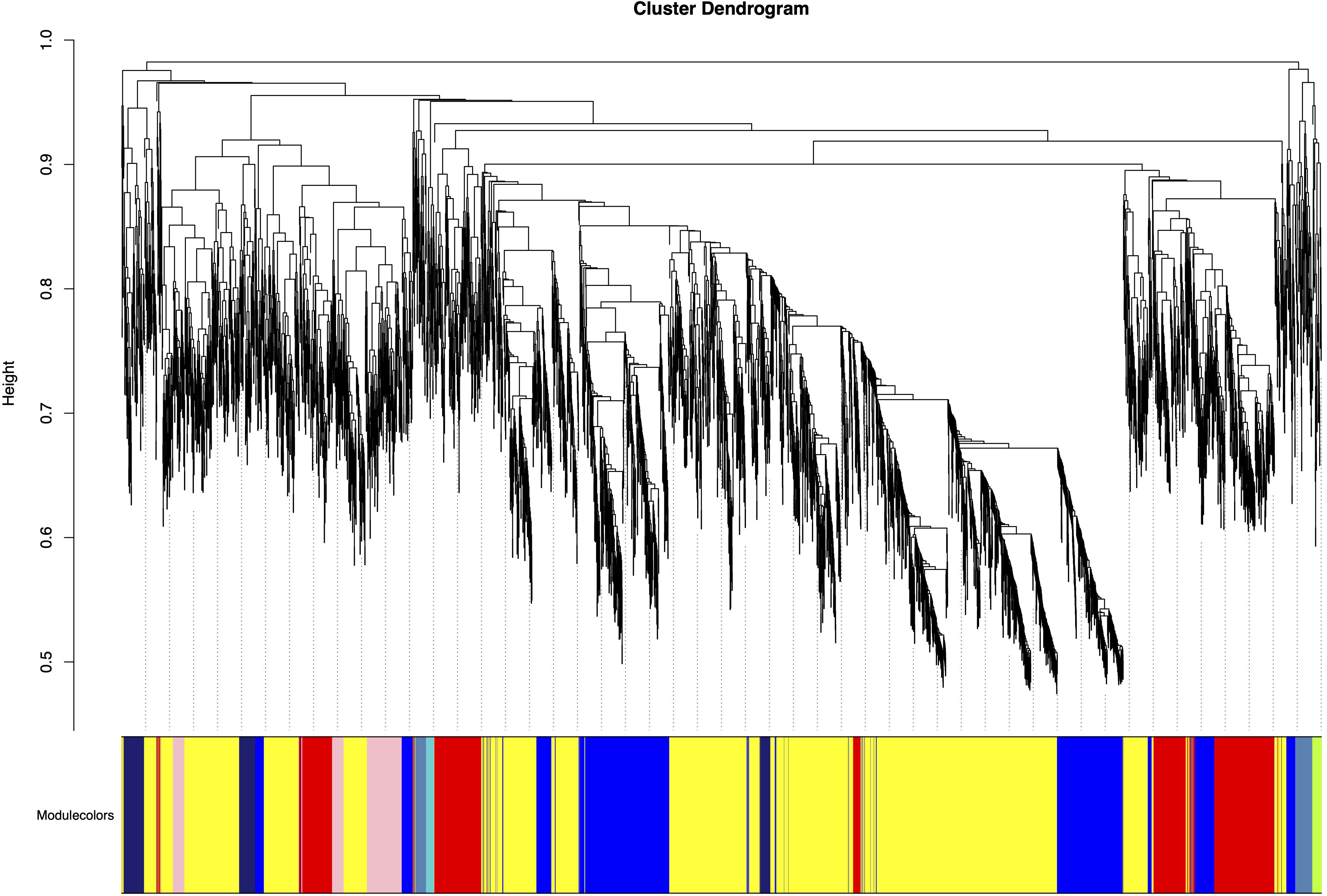

3.4 Construction of weighted gene co-expression networks and identifying modules associated with HB content

Using the gene expression abundance data (FPKM values) from Section 3.2, we constructed an expression matrix to calculate the scale-free topology fit index, which guided the selection of an appropriate soft-thresholding power. The analysis revealed that the scale-free topology fit index first exceeded 0.8 at a soft-thresholding power of 20 (Figure 4), which was subsequently adopted for network construction.The WGCNA network was built with the following parameters: minimum module size was 30 genes, module detection sensitivity with deepSplit was 2, module merging cut height was 0.25. This process ultimately generated a co-expression network comprising 55 distinct modules (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Scale-free topology fit index under varying soft-thresholding powers. The red horizontal line indicates the threshold of 0.8 for scale-free topology. At a soft-thresholding power (β) of 20, the fit index (R²) reached 0.8, suggesting the network approximates scale-free topology.

Figure 5. Gene modules identified by weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA). Modules were merged at a cut height of 0.25. Each colored row represents a distinct module, with color-coding indicating groups of highly interconnected genes. A total of 55co-expression modules was identified.

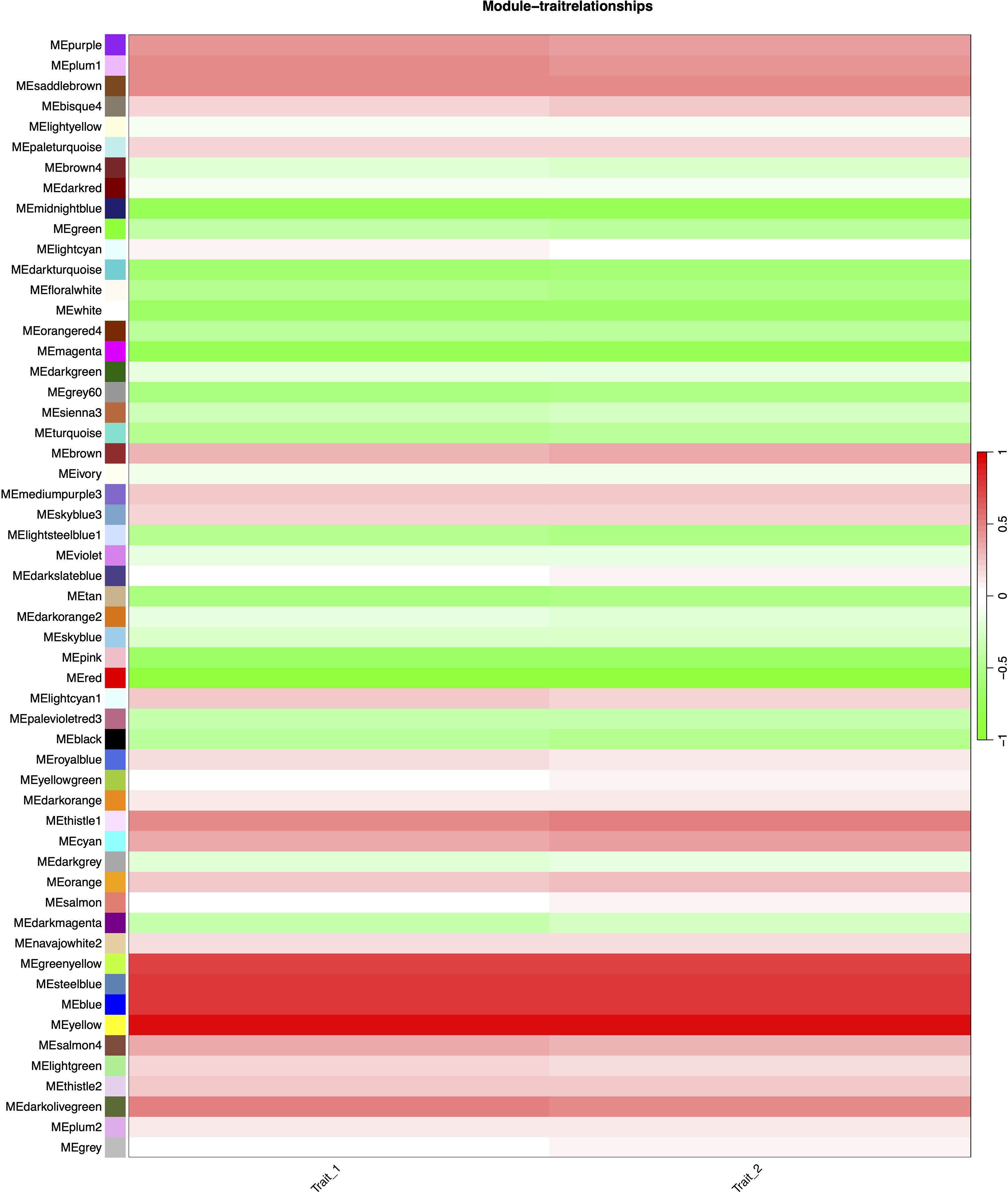

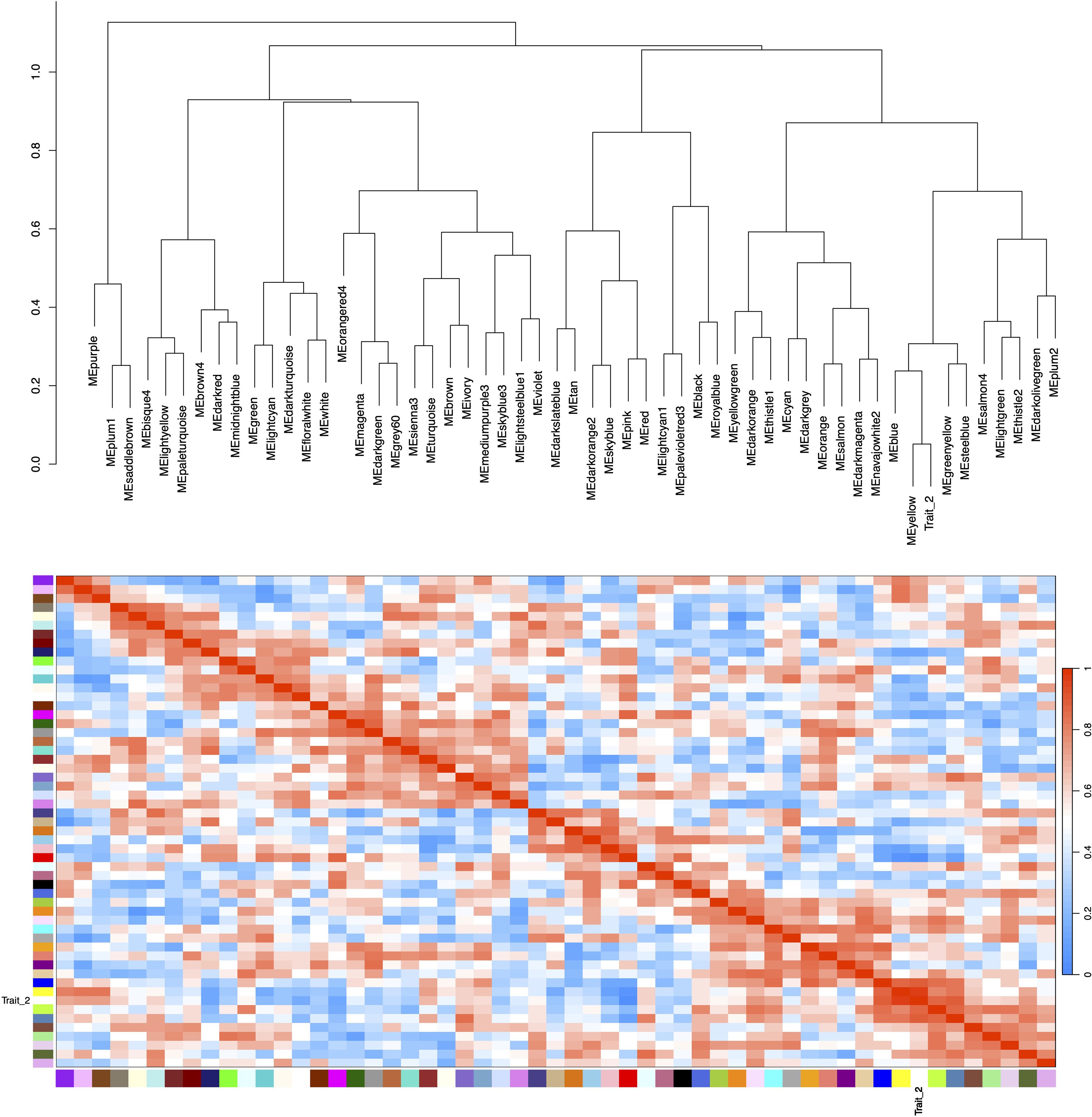

Correlation analysis between the 55 merged modules and phenotypic data revealed that the yellow module showed the strongest positive association with the target trait, while the red module exhibited the most significant negative correlation (Figure 6). Hierarchical clustering of the merged modules further divided the 55 clusters into six major groups. Notably, the yellow module co-clustered with Trait_2 (Figure 7), indicating convergent expression patterns between yellow module genes and Trait_2 phenotypic variation. Based on these findings, we identified the yellow module as key candidate module associated with HB accumulation.

Figure 6. Heatmap of module-trait correlations in WGCNA analysis. Rows represent gene modules (labeled left of each cell) and columns represent traits. The color legend (right) indicates correlation strength: red for positive (max r = 1.0), green for negative (min r = -1.0), with gradient intensity reflecting magnitude. Trait_1: HB content in tissue-cultured plants; Trait_2: HB content in field-grown plants.

Figure 7. Hierarchical clustering dendrogram and heatmap of module eigengenes. Color scale legend (right of heatmap) displays adjacency values ranging from 0 (blue) to 1.0 (red), with color gradient representing correlation magnitude. Trait_2 corresponds to HB content measured in field-grown plants. Both the dendrogram and heatmap demonstrate a strong association between the yellow module and Trait_2.

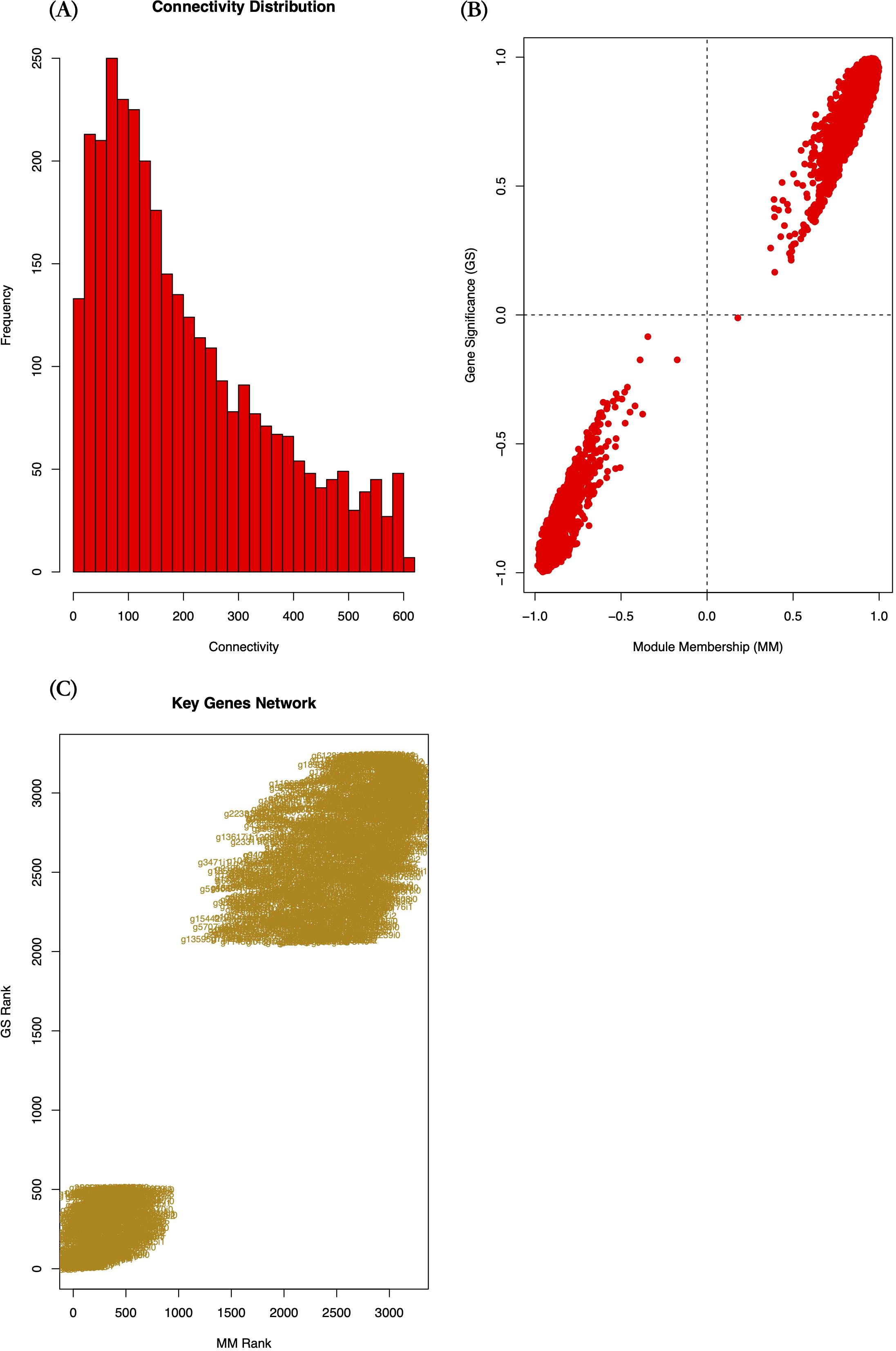

3.5 Identification and validation of trait-associated key genes in candidate module

From the candidate yellow module, we extracted 3,240 module genes. To pinpoint key genes strongly associated with the target trait, we performed Gene Significance (GS) and Module Membership (MM) analyses. Analysis revealed that intramodular connectivity of genes ranged from 1.43 to 604.13, with the majority (59.17%) exhibiting connectivity below 200 (Figure 8A). Most module genes showed |GS| and |MM| values > 0.5 (Figure 8B), indicating both conserved co-expression patterns with the module eigengene, and strong associations with the target phenotype.

Figure 8. Co-expression network features of candidate module genes. (A) Histogram of intramodular connectivity distribution, (B) Scatter plot of Gene Significance (GS) vs. Module Membership (MM) values, (C) Rank-ordered scatter plot of GS and MM values for key candidate genes. GS measures the association between gene expression and the target phenotype; MM indicates the correlation between genes and module eigengenes; Connectivity reflects the interaction strength of a gene with other module members.

Given the large number of genes in the module, we applied stringent selection criteria (|GS| > 0.9, MM > 0.9, p-value of GS < 0.00001) to identify high-confidence candidate genes. This screening yielded 278 key candidate genes (Supplementary Table S4), including 60 genes showing inverse correlation with module expression trends (downregulated with increasing HB content), 218 genes exhibiting positive correlation (upregulated with HB accumulation).

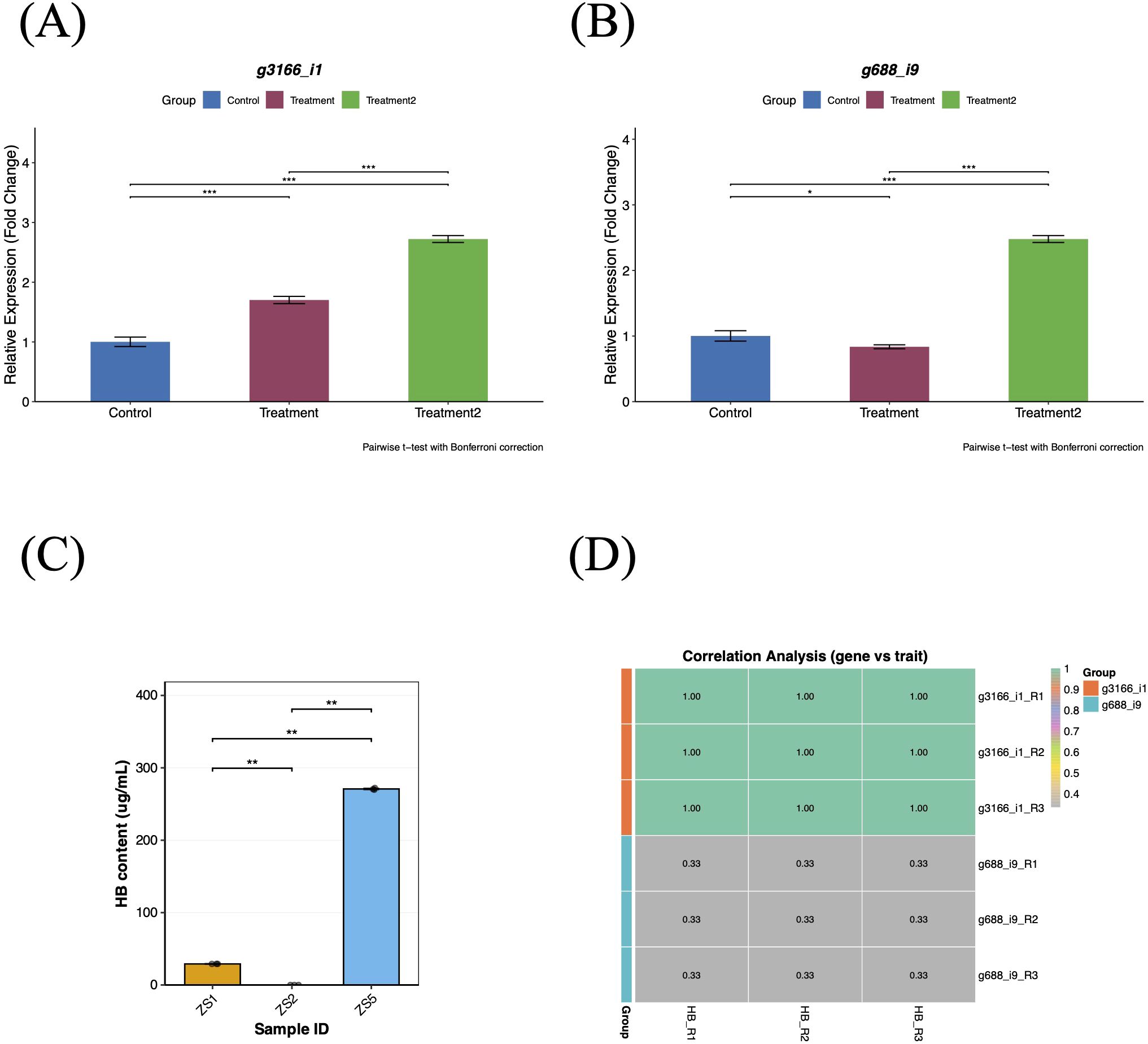

To validate the reliability of the transcriptome data, we randomly selected three genes from the top 10% (GS p-value) most significant candidate genes (Table 1) for qRT-PCR verification using tuberous root tissues of tissue-cultured plants. Candidate gene g3166_i1 showed significant upregulation in both treatment groups (p < 0.001), with significantly higher expression in ZS5 than in ZS1 (p < 0.001), consistent with the observed HB accumulation patterns (Figure 9A). In contrast, candidate gene g688_i9 exhibited downregulation in ZS1 compared to the control group (p < 0.05) but upregulation in ZS5 (p < 0.001) (Figure 9B). Since candidate gene g14986_i0 was undetectable by qRT-PCR, we performed correlation analysis (Kendall) between the relative expression levels of genes g3166_i1/g688_i9 and HB content. Gene g3166_i1 displayed a significant positive correlation with HB accumulation (Figure 9D), identifying it as a key regulator of HB biosynthesis in P. heterophylla.

Figure 9. qRT-PCR validation and correlation analysis of candidate genes. (A) Relative expression levels of candidate gene g3166_i1. (B) Relative expression levels of candidate gene g688_i9. (C) HB content variation among three tissue-cultured samples. (D) Heatmap of correlation analysis between candidate genes (g3166_i1/g688_i9) and target traits. Control group: ZS2 (HB-deficient); Treatment1: ZS1 (moderate HB); Treatment2: ZS5 (high HB). Expression levels were normalized to PhACTIN1 using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

3.6 Sequence characterization and functional annotation of gene g3166_i1

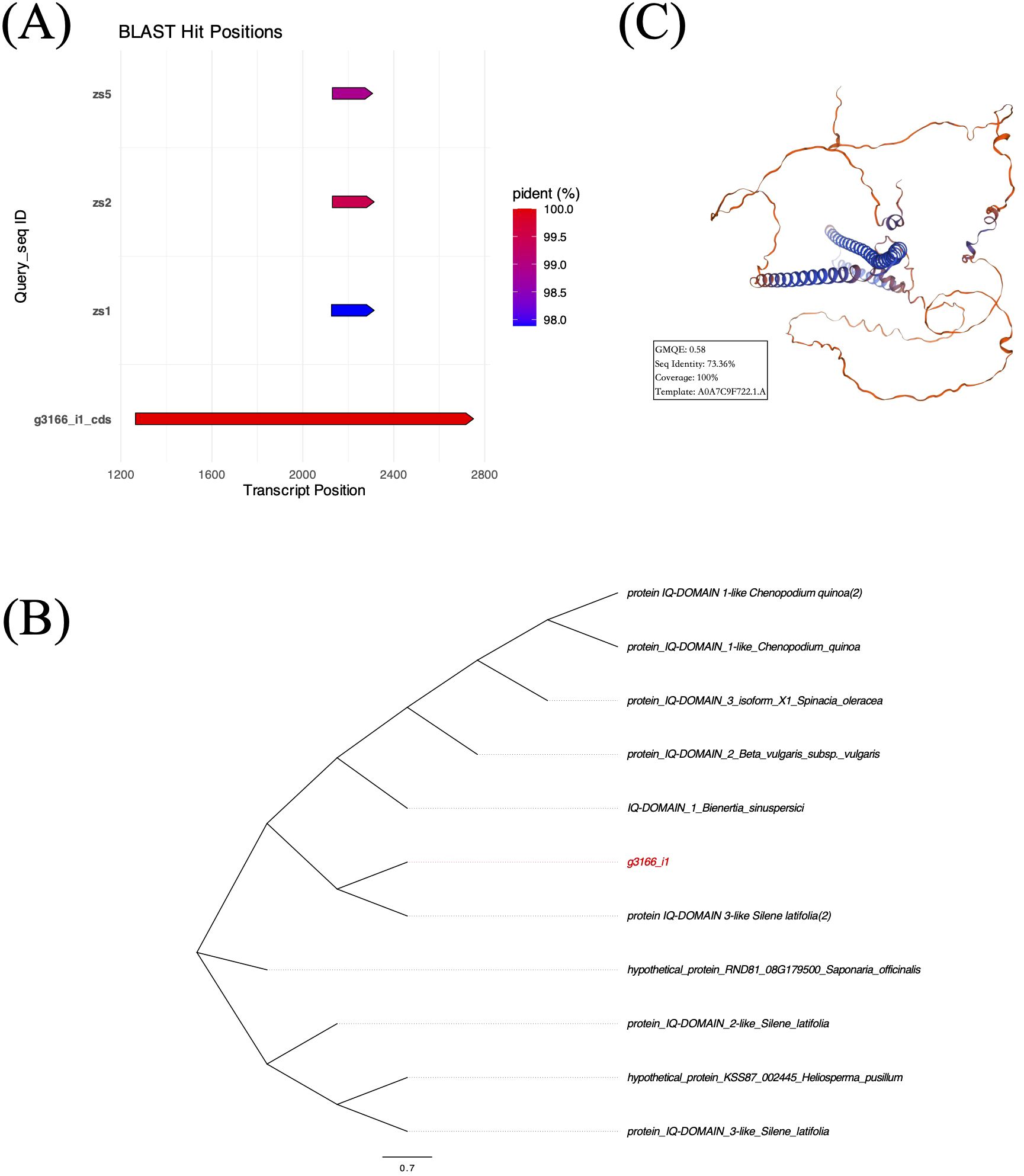

We extracted a 3,068 bp transcript sequence of g3166_i1 from the reference assembly. Open reading frame (ORF) prediction identified one coding sequence (CDS) spanning transcript 1,264 – 2,751 bp (1,488 bp). Sanger sequencing validation detected this CDS fragment in all three samples with 97.88% – 99.50% identification rates (Figure 10A), confirming its biological validity. The CDS of Gene g3166_i1 encoded a 495-amino acid protein. BLASTP analysis revealed the presence of an IQ domain (Figure 10B), consistent with functional annotations from Swiss-Prot, GO, and Pfam databases, suggesting its potential role in calcium ion signal transduction. Tertiary structure prediction using SWISS-MODEL showed 73.36% similarity to the reference protein A0A7C9F722.1.A with 0.58 GMQE value (Figure 10C).

Figure 10. (A) Prediction and validation of CDS localization within the transcript of g3166_i1. (B) Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of g3166_i1 based on top 10 BLASTP hits. (C) Predicted tertiary structure of g3166_i1-encoded protein by SWISS-MODEL database.

4 Discussion

4.1 Variation in HB accumulation among three types of P. heterophylla

Although wild resources of P. heterophylla are limited in China, cultivated populations are widely distributed across multiple provinces such as Fujian, Jiangsu, and Guizhou (Li et al., 2024). Significant variations in HB content exist among populations from different geographical origins (Sha et al., 2023). In this study, quantitative HPLC analysis of samples demonstrated undetectable HB levels in ZS2, consistent with previous reports (Zheng et al., 2019), thereby establishing its suitability as a blank control. Furthermore, considering the potential influence of environmental factors on heterophyllin B (HB) accumulation, we performed comparative HPLC analysis of field-grown and tissue-cultured materials. The results demonstrated a consistent reduction in total HB content in tissue-cultured samples (Figure 9C) compared to field-grown plants (Figure 1B), indicating that field conditions are more conducive to HB biosynthesis. However, the identical hierarchical pattern of HB accumulation across samples (ZS5 > ZS1 > ZS2) under both growth conditions suggests that the fundamental regulatory mechanism of HB variation is genotype-dependent and remains stable in field-cultured and tissue-cultured conditions. This consistency provides a rationale for utilizing tissue-cultured systems in subsequent investigations of HB accumulation mechanisms. Collectively, these three samples represent an ideal material for identifying HB-associated genes: ZS1 with moderate levels, ZS2 with undetectable HB, and ZS5 with high accumulation.

4.2 Transcriptome assembly strategy of P. heterophylla

The genomic foundation of P. heterophylla remains underdeveloped, as no reference genome for this species or the same genus plant is currently available in public databases. Consequently, most previous studies have adopted a de novo transcriptome assembly strategy (Li et al., 2016; Qin et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2016) to overcome the absence of reference genomic resources. Fortunately, the chloroplast genome sequence of P. heterophylla has been previously reported and is accessible in the GenBank database (Zhang et al., 2023). Given the high conservation of chloroplast genes within plant genera (Bu et al., 2021; Zhang and Feng, 2025), these sequences are typically useful for the identification of closely related or morphologically similar plants (Yan et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2023). In our study, we aligned the de novo assembled transcriptome sequences with the retrieved chloroplast genome. Under optimal assembly conditions, the majority or all chloroplast genes should be detectable, serving as a robust indicator of assembly completeness and accuracy. Finally, 73 chloroplast genes (94.81%) were detected in the assembled sequences. Given that the sequencing material consisted of plant tuberous roots where certain chloroplast genes may exhibit low expression or remain transcriptionally inactive. Overall, the alignment result indicates a high quality of the sequence assembly.

4.3 Functions implications of gene g3166_i1 in HB accumulation

Although HB represents a key bioactive compound in P. heterophylla, the complete metabolic pathway for its biosynthesis remains elusive. Current transcriptomic studies have identified several genes, including the precursor peptide (prePhHB) (Zheng et al., 2019), peptide cyclase (PhPCY3) (Qin et al., 2025), and prolyl oligopeptidase (PhPOP1) (Shu et al., 2025), that influence endogenous HB accumulation. In our study, the candidate gene (g3166_i1) derived from the yellow module encodes a protein annotated across multiple public databases as containing an IQ domain. In plants, five protein families (the IQD family, myosins, CAMTAs, CNGCs, and the IQ motif-containing family) possessing the calmodulin-binding IQ motif have been identified (Zhou et al., 2010). These proteins typically interact with calmodulin (CaM) in a Ca2+-independent manner, thereby participating in diverse biological processes including plant development, metabolic regulation, stress responses, and defense mechanisms (Fan et al., 2021; DeFalco et al., 2009). For instance, in Arabidopsis thaliana, AtIQM1 (IQ motif-containing protein 1) indirectly enhances the activity of jasmonic acid (JA) biosynthetic enzymes (ACX2 and ACX3) by promoting the expression of catalase 2 (CAT2), consequently increasing JA accumulation (Lv et al., 2019). Interestingly, exogenous application of methyl jasmonate (MeJA) has been confirmed to significantly enhance the expression of prePhHB, consequently promoting HB accumulation in P. heterophylla (Wu et al., 2024). We therefore propose that the candidate gene g3166_i1 may enhance HB biosynthesis and accumulation by upregulating prePhHB expression through modulation of the JA signaling pathway. Herein, we confirm that g3166_i1 exhibits significantly upregulation in both ZS1 and ZS5 compared to the control group (Figure 9A, p < 0.001). Moreover, its expression levels show a strong positive correlation with HB accumulation across all three samples (Figure 9D, τ = 1), suggesting a potential functional role in HB biosynthesis mechanisms. Our findings propose a mechanistic model in which IQM genes indirectly regulate HB accumulation in P. heterophylla by modulating the JA biosynthetic pathway, thereby revealing a previously unrecognized role of this gene family in HB metabolism within this species.

5 Conclusion

In this study, we performed high-throughput sequencing of field-grown P. heterophylla samples with contrasting HB content, generating a reference transcriptome comprising 38,288 protein-coding genes. Through WGCNA, we constructed a co-expression network containing 55 distinct modules and identified one key module (3,240 genes) significantly associated with HB accumulation. From this module, 278 key candidate genes were prioritized for further analysis. Experimental validation via qRT-PCR confirmed that the expression pattern of Gene g3166_i1, encoding an IQ domain-containing protein, strongly correlated with HB accumulation levels across different samples. These results confirm the potential role of Gene g3166_i1 in regulating HB biosynthesis in P. heterophyllla. Collectively, our findings enable systematic identification of HB biosynthesis-related genes and support molecular breeding strategies for high-HB P. heterophylla cultivars.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here: NCBI, PRJNA1311177.

Author contributions

L-YX: Validation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Software, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition. SW: Resources, Writing – original draft. Q-LX: Writing – original draft, Investigation. H-SB: Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft. Y-YW: Investigation, Writing – original draft. J-JS: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. Z-YY: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2025J011080), Fujian Provincial Regional Development Program of China (2024N3017), Scientific Research Project of Ningde Normal University (FZ202309, 2022ZX01), Student Research Program of Fujian Provincial Engineering Research Center for Characteristic Medicinal Plants (PP2024010).

Acknowledgments

We are particularly grateful to students Zhi-Ying Gu and Jing-Ting Huang for their invaluable assistance during the experimental execution.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1691269/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table 1 | Alignment results of P. heterophylla chloroplast genes to transcript sequences.

Supplementary Table 2 | Distribution of different repeat motif SSRs identified in P. heterophylla transcriptome.

Supplementary Table 3 | Distribution of SNP variants identified in P. heterophylla transcriptome.

Supplementary Table 4 | Network parameters of key candidate genes in the target module. GS measures the association between gene expression and the target phenotype; MM indicates the correlation between genes and module eigengenes; Connectivity reflects the interaction strength of a gene with other module members.

Supplementary Table 5 | The sample information of three P. heterophylla.

References

Bu, Y., Wu, X., Sun, N., Man, Y., and Jing, Y. (2021). Codon usage bias predicts the functional MYB10 gene in Populus. J. Plant Physiol. 265, 153491. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2021.153491

Burman, R., Gruber, C. W., Rizzardi, K., Herrmann, A., Craik, D. J., Gupta, M. P., et al. (2010). Cyclotide proteins and precursors from the genus Gloeospermum: Filling a blank spot in the cyclotide map of Violaceae. Phytochemistry 71, 13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.09.023

Chen, X., Li, B., and Zhang, X. (2023). Comparison of chloroplast genomes and phylogenetic analysis of four species in Quercus section Cyclobalanopsis. Sci. Rep. 13, 18731. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-45421-8

Choi, K. and Pak, J.-H. (2000). A Natural Hybrid between Pseudostellaria heterophylla and P. palibiniana (Caryophyllaceae). Acta Phytotaxonomica Geobotanica 50, 161–171. doi: 10.18942/bunruichiri.KJ00001077422

Condie, J. A., Nowak, G., Reed, D. W., Balsevich, J. J., Reaney, M. J. T., Arnison, P. G., et al. (2011). The biosynthesis of Caryophyllaceae-like cyclic peptides in Saponaria vaccaria L. from DNA-encoded precursors. Plant J. 67, 682–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04626.x

Daly, N. L. and Wilson, D. T. (2021). Plant derived cyclic peptides. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 49, 1279–1285. doi: 10.1042/BST20200881

DeFalco, T. A., Bender, K. W., and Snedden, W. A. (2009). Breaking the code: Ca2+ sensors in plant signalling. Biochem. J. 425, 27–40. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091147

Deng, J., Feng, X., Zhou, L., He, C., Li, H., Xia, J., et al. (2022). Heterophyllin B, a cyclopeptide from Pseudostellaria heterophylla, improves memory via immunomodulation and neurite regeneration in i.c.v.Aβ-induced mice. Food Res. Int. 158, 111576. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111576

Fan, T., Lv, T., Xie, C., Zhou, Y., and Tian, C. (2021). Genome-wide analysis of the IQM gene family in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plants 10, 1949. doi: 10.3390/plants10091949

Fuller, T., Langfelder, P., Presson, A., and Horvath, S. (2011). Review of Weighted Gene Coexpression Network Analysis (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg).

Gu, L., Qian, S., Yao, S., Wu, J., Wang, L., Mu, J., et al. (2025). Long-term effects of vegetative-propagation-mediated tuMV-ZR transmission on yield, quality, and stress resistance in pseudostellaria heterophylla. Pathogens 14, 353. doi: 10.3390/pathogens14040353

Guo, J., Gao, J., and Liu, Z. (2022). HISAT2 parallelization method based on spark cluster. J. Physics: Conf. Ser. 2179, 012038. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/2179/1/012038

Hu, D.-J., Shakerian, F., Zhao, J., and Li, S.-P. (2019). Chemistry, pharmacology and analysis of Pseudostellaria heterophylla: a mini-review. Chin. Med. 14, 21. doi: 10.1186/s13020-019-0243-z

Jia, A., Li, X., Tan, N., Liu, X., Shen, Y., and Zhou, J. (2006). Enzymatic cyclization of linear peptide to plant cyclopeptide heterophyllin B. Sci. China Ser. B 49, 63–66. doi: 10.1007/s11426-005-0204-5

Kaleem, W. A., Nisar, M., Qayum, M., Zia-Ul-Haq, M., Adhikari, A., and De Feo, V. (2012). New 14-membered cyclopeptide alkaloids from zizyphus oxyphylla edgew. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13, 11520–11529. doi: 10.3390/ijms130911520

Kang, C.-Z., Zhou, T., Jiang, W.-K., Guo, L.-P., Zhang, X.-B., Xiao, C.-H., et al. (2016). Research on quality regionalization of cultivated Pseudostellaria heterophylla based on climate factors. China J. Chin. Materia Med. 41, 2386–2390. doi: 10.4268/cjcmm20161303

Langfelder, P. and Horvath, S. (2008). WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinf. 9, 559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559

Li, J., Wang, C., Zhou, T., Jin, H., and Liu, X. (2022). Identification and characterization of miRNAome and target genes in Pseudostellaria heterophylla. PloS One 17, e0275566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0275566

Li, X., Wu, T., Kang, C., Zhang, X., Zhang, J., Yang, C., et al. (2024). Simulation of Pseudostellaria heterophylla distribution in China: assessing habitat suitability and bioactive component abundance under future climate change scenariosplant components. Front. Plant Sci. 15, 1498229. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1498229

Li, J., Zhen, W., Long, D., Ding, L., Gong, A., Xiao, C., et al. (2016). De novo sequencing and assembly analysis of the pseudostellaria heterophylla transcriptome. PloS One 11, e0164235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164235

Liao, H.-J. and Tzen, J. T. C. (2022). Investigating Potential GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Cyclopeptides from Pseudostellaria heterophylla, Linum usitatissimum, and Drymaria diandra, and Peptides Derived from Heterophyllin B for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes: An In Silico Study. Metabolites 12, 549. doi: 10.3390/metabo12060549

Liu, J., Shi, L., Song, J., Sun, W., Han, J., LIU, X., et al. (2017). BOKP: A DNA barcode reference library for monitoring herbal drugs in the Korean pharmacopeia. Front. Pharmacol. 8, 00931. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00931

Livak, K. J. and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2–ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Luo, Y., Hu, J.-Y., Li, L., Luo, Y.-L., Wang, P.-F., and Song, B.-H. (2016). Genome-wide analysis of gene expression reveals gene regulatory networks that regulate chasmogamous and cleistogamous flowering in Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Caryophyllaceae). BMC Genomics 17, 382. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2732-0

Lv, T., Li, X., Fan, T., Luo, H., Xie, C., Zhou, Y., et al. (2019). The calmodulin-binding protein IQM1 interacts with CATALASE2 to affect pathogen defense. Plant Physiol. 181, 1314–1327. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.01060

Ma, L., Zhang, M., Chen, J., Qing, C., He, S., Zou, C., et al. (2021). GWAS and WGCNA uncover hub genes controlling salt tolerance in maize (Zea mays L.) seedlings. Theor. Appl. Genet. 134, 3305–3318. doi: 10.1007/s00122-021-03897-w

Pertea, M., Pertea, G. M., Antonescu, C. M., Chang, T.-C., Mendell, J. T., and Salzberg, S. L. (2015). StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 290–295. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3122

Qin, X., Wang, F., Xie, D., Zhou, Q., Lin, S., Lin, W., et al. (2025). Identification of a key peptide cyclase for novel cyclic peptide discovery in Pseudostellaria heterophylla. Plant Commun. 6, 101315. doi: 10.1016/j.xplc.2025.101315

Qin, X., Wu, H., Chen, J., Wu, L., Lin, S., Khan, M. U., et al. (2017). Transcriptome analysis of Pseudostellaria heterophylla in response to the infection of pathogenic Fusarium oxysporum. BMC Plant Biol. 17, 155. doi: 10.1186/s12870-017-1106-3

Ruan, J., Dean, A. K., and Zhang, W. (2010). A general co-expression network-based approach to gene expression analysis: comparison and applications. BMC Syst. Biol. 4, 8. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-8

Sha, M., Li, X., Liu, Y., Tian, H., Liang, X., Li, X., et al. (2023). Comparative chemical characters of Pseudostellaria heterophylla from geographical origins of China. Chin. Herbal Medicines 15, 439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.chmed.2022.10.005

Shu, G., Zheng, W., Guo, L., Yang, Y., Yang, C., Li, P., et al. (2025). Identification and functional characterization of prolyl oligopeptidase involved in the biosynthesis of heterophyllin B in Pseudostellaria heterophylla. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 225, 109970. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2025.109970

Stuart, J. M., Segal, E., Koller, D., and Kim, S. K. (2003). A gene-coexpression network for global discovery of conserved genetic modules. Science 302, 249–255. doi: 10.1126/science.1087447

Wang, Z., Liao, S.-G., He, Y., Li, J., Zhong, R.-F., He, X., et al. (2013). Protective effects of fractions from Pseudostellaria heterophylla against cobalt chloride-induced hypoxic injury in H9c2 cell. J. Ethnopharmacology 147, 540–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.03.053

Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Liu, X., Zhou, J., Deng, H., Zhang, G., et al. (2022). WGCNA analysis identifies the hub genes related to heat stress in seedling of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Genes 13, 1020. doi: 10.3390/genes13061020

Wu, Q., Shu, G., Yang, Y., Yang, C., Guo, L., and Zhou, T. (2024). Modulation of heterophyllin B biosynthesis and transcription of key transcription factor genes in Pseudostellaria heterophylla by methyl jasmonate. Plant Growth Regul. 104, 843–854. doi: 10.1007/s10725-024-01192-4

Xiao, Q., Zhao, L., Jiang, C., Zhu, Y., Zhang, J., Hu, J., et al. (2022). Polysaccharides from Pseudostellaria heterophylla modulate gut microbiota and alleviate syndrome of spleen deficiency in rats. Sci. Rep. 12, 20217. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-24329-9

Xu, L., Li, P., Su, J., Wang, D., Kuang, Y., Ye, Z., et al. (2023). EST-SSR development and genetic diversity in the medicinal plant Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Miq.) Pax. J. Appl. Res. Medicinal Aromatic Plants 33, 100450. doi: 10.1016/j.jarmap.2022.100450

Xu, L.-Y., Su, J.-J., Zhang, C.-K., Hao, M., Zhou, Z.-W., Chen, X.-H., et al. (2025). Identification of key genes associated with anthracnose resistance in Camellia sinensis. PloS One 20, e0326325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0326325

Xu, W., Zhu, H., Tan, N., Tang, J., Zhang, Y., Cerny, R. L., et al. (2012). An in vitro system to study cyclopeptide heterophyllin B biosynthesis in the medicinal plant Pseudostellaria heterophylla. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Culture (PCTOC) 108, 137–145. doi: 10.1007/s11240-011-0022-8

Yan, M., Dong, S., Gong, Q., Xu, Q., and Ge, Y. (2023). Comparative chloroplast genome analysis of four Polygonatum species insights into DNA barcoding, evolution, and phylogeny. Sci. Rep. 13, 16495. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-43638-1

Yang, Y.-B., Tan, N.-H., Zhang, F., Lu, Y.-Q., He, M., and Zhou, J. (2003). Cyclopeptides and amides from pseudostellaria heterophylla (Caryophyllaceae). Helv. Chimica Acta 86, 3376–3379. doi: 10.1002/hlca.200390280

Yang, Y., Wen, L., Jiang, Z.-Z., Chan, B. C.-L., Leung, P.-C., Wong, C.-K., et al. (2025). Chemical properties, preparation, and pharmaceutical effects of cyclic peptides from pseudostellaria heterophylla. Molecules 30, 2521. doi: 10.3390/molecules30122521

Yang, C., You, L., Yin, X., Liu, Y., Leng, X., Wang, W., et al. (2018). Heterophyllin B ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and oxidative stress in RAW 264.7 macrophages by suppressing the PI3K/Akt pathways. Molecules 23, 717. doi: 10.3390/molecules23040717

Yang, Z., Zhang, C., Li, X., Ma, Z., Ge, Y., Qian, Z., et al. (2021). Heterophyllin B, a cyclopeptide from Pseudostellaria heterophylla, enhances cognitive function via neurite outgrowth and synaptic plasticity. Phytotherapy Res. 35, 5318–5329. doi: 10.1002/ptr.7212

Zhang, J. and Feng, M. (2025). Analysis of the codon usage bias pattern in the chloroplast genomes of chloranthus species (Chloranthaceae). Genes 16, 186. doi: 10.3390/genes16020186

Zhang, S., Kang, T., Malacrinò, A., Zhang, Z., Zhang, Z., Lin, W., et al. (2024). Pseudostellaria heterophylla improves intestinal microecology through modulating gut microbiota and metabolites in mice. J. Sci. Food Agric. 104, 6174–6185. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.13453

Zhang, W., Zhang, Z., Liu, B., Chen, J., Zhao, Y., and Huang, Y. (2023). Comparative analysis of 17 complete chloroplast genomes reveals intraspecific variation and relationships among Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Miq.) Pax populations. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1163325. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1163325

Zhao, W.-O., Pang, L., Dong, N., and Yang, S. (2015). LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis and pharmacokinetics of heterophyllin B, a cyclic octapeptide from Pseudostellaria heterophylla in rat plasma. Biomed. Chromatogr. 29, 1693–1699. doi: 10.1002/bmc.3481

Zheng, W., Zhou, T., Li, J., Jiang, W., Zhang, J., Xiao, C., et al. (2019). The Biosynthesis of Heterophyllin B in Pseudostellaria heterophylla From prePhHB-Encoded Precursor. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 01259. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01259

Keywords: medicinal plants, heterophyllin B, gene identification, weighted gene co-expression network analysis, Pseudostellaria heterophylla

Citation: Xu L-Y, Wang S, Xu Q-L, Bu H-S, Wu Y-Y, Su J-J and Ye Z-Y (2025) Identification of heterophyllin B accumulation associated genes via WGCNA in Pseudostellaria heterophylla. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1691269. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1691269

Received: 17 September 2025; Accepted: 10 November 2025; Revised: 08 November 2025;

Published: 09 December 2025.

Edited by:

Jiabao Ye, Yangtze University, ChinaReviewed by:

Roma Pandey, IILM University, IndiaMailen Ortega Cuadros, Jardin Botanico de Bogota, Colombia

Ye Wang, Institute of Traditional Chinese Medicine Health Industry, China

Copyright © 2025 Xu, Wang, Xu, Bu, Wu, Su and Ye. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Li-Yi Xu, eGx5QG5kbnUuZWR1LmNu; Zu-Yun Ye, enl5ZTA1OTNAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Li-Yi Xu

Li-Yi Xu Shuai Wang1,2

Shuai Wang1,2