- 1Degree Programs in Life and Earth Sciences, Graduate School of Science and Technology, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Japan

- 2Department of Informatics, Tokyo University of Information Sciences, Chiba, Japan

- 3Institute of Biological Sciences, University of the Philippines Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines

- 4Department of Agricultural Research, Industrial Crops and Horticulture Division, Republic of the Union of Myanmar, Yezin, Myanmar

- 5Tsukuba-Plant Innovation Research Center, Institute of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Japan

Introduction: The Zingiberaceae family encompasses numerous species renowned for their significant pharmacological properties and culinary importance. Despite this value, many species remain under-utilized due to the absence of basic molecular information, which hinders effective conservation and sustainable utilization. Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR) markers are particularly suitable for genetic studies in such species, as they are highly polymorphic and do not necessitate a reference genome. Microsatellite capture sequencing (MiCAPs) presents a cost-effective solution by enriching libraries for SSR-containing fragments prior to sequencing, substantially reducing data requirements and costs for marker discovery.

Methods: MiCAPs was applied to 160 accessions, including 148 samples from 14 Zingiberaceae species and 12 samples from an outgroup (Musaceae family). SSR marker candidates were developed and evaluated via electronic-PCR (ePCR) for seven target species. Phylogenetic relationships were reconstructed using consensus sequences from MiCAPs data, and genetic similarity patterns were assessed using Polymorphic SSR Retrieval (PSR) analysis across Curcuma and Zingiber species.

Results: A total of 21.78 million raw reads were generated, from which 612 SSR marker candidates were developed. A genus-level phylogenetic tree successfully reconstructed the relationships among the 14 Zingiberaceae species. Comparative genetic diversity analysis revealed that Zingiber exhibits a relatively more conserved genetic background compared to Curcuma.

Discussion: This integrated workflow combining MiCAPs, ePCR, and PSR demonstrates a practical approach for marker development and diversity assessment in polyploid species lacking reference genomes. Despite the genetic complexities inherent in Zingiberaceae, especially potential polyploidy, our approach proved highly effective in establishing a robust phylogenetic framework and enabling comprehensive genetic diversity assessment. The novel set of 612 SSR marker candidates represents a significant resource that will facilitate future genetic studies focused on the diversity, evolutionary relationships, conservation, and sustainable utilization of valuable Zingiberaceae species

1 Introduction

Zingiberaceae, one of the most widely distributed plant families in tropical and subtropical regions, comprises ca. 50 genera and over 1,600 species. It includes a variety of species that are renowned for their pharmacological properties and traditional culinary uses (Hartati et al., 2014; Saha et al., 2020). The classification of this family was first proposed in 1889 and refined through time. The current accepted classification includes four tribes (Globbeae, Hedychieae, Alpinieae, and Zingibereae) (Kress et al., 2002). Earlier classification methods were mostly based on morphological characteristics. Later, molecular markers such as the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and plastid matK regions (Kress et al., 2002; Theerakulpisut et al., 2012), chloroplast genomes (Li et al., 2019; Liang et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2023; Xia et al., 2024), and both nrDNA and cpDNA (Ngamriabsakul et al., 2004) were introduced. These studies have provided molecular evidence for taxonomy.

Our research focuses on several species within the Zingibereae tribe, which possess value in various aspects. Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) is a widely used spice and traditional herbal medicine worldwide. Evidence from in vitro studies, animal experiments, and epidemiological research suggests that ginger and its extracts have inhibitory effects against a variety of diseases (Srinivasan, 2014; Prasad and Tyagi, 2015). Myoga (Zingiber mioga (Thunb.) Roscoe) originated in Japan and cultivated for its edible flower buds and exhibits several biological activities (Stirling, 2004; Abe et al., 2006; Chan et al., 2023). Zingiber barbatum Wall. is an underutilized medicinal species with anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties (Wicaksana et al., 2011; Wicaksana, 2012; Aung, 2016). Curcuma species, including Curcuma aromatica Salisb., Curcuma longa L., Curcuma zedoaria (Christm.) Roscoe, and Curcuma amada Roxb., are rich sources of essential oil, also widely used as food additives and for various medicinal purposes (Lobo et al., 2009; Al-Reza et al., 2010; Albaqami et al., 2022). Especially turmeric (C. longa) and its extract exhibit anti-inflammatory, anti-human immunodeficiency virus, anti-bacteria, antioxidant effects and nematocidal activities (Araujo and Leon, 2001; Ammon and Wahl, 2007). Essential oils extracted from Hedychium J. Koenig species possess anti-microbial, anti-oxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties, and some species are also cultivated as ornamental plants (Joshi et al., 2008; Van Kiem et al., 2011; Hartati et al., 2014). Kaempferia parviflora Wall. ex Baker and K. galanga L. are used as food ingredients, traditional medicine, and proved to possess anti-obesity, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergenic, and anti-cancer properties (Tewtrakul et al., 2009; Kobayashi et al., 2015; Yoshino et al., 2018; Kumar, 2020; Khairullah et al., 2021). Rhynchanthus longiflorus Hook.f. is an endangered species which is rarely reported (Prasanthkumar et al., 2005; Debnath and Vijayan, 2024).

Among these species, some are considered under-utilized, and the lack of basic molecular biological information severely hampers their conservation and utilization. Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR, also known as microsatellite) markers are particularly suitable for under-utilized species because they do not require a complete reference genome and can still provide relatively high levels of polymorphic information in even closely related samples (Grover and Sharma, 2016; Foster et al., 2020). This is especially important for Zingiberaceae species since the genome is large and complicated (Cheng et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021). Traditional SSR marker development based on Sanger sequencing is both costly and time-consuming. Although the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has significantly reduced the cost, it remains challenging for under-utilized species to secure sufficient funding for whole-genome sequencing research (Senan et al., 2014; Ramesh et al., 2020). Microsatellite capture sequencing (MiCAPs) offers a more efficient alternative for SSR detection by enriching the DNA library with SSR probes. This method requires only about 1% of the whole genome to generate sufficient SSR and flanking sequence data for marker development (Tanaka et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2024). Currently, species such as Z. mioga, Z. barbatum, and R. longiflorus lack available SSR information. Moreover, SSR markers can sometimes be unsuitable for cross-species application, further limiting their utility (Ramesh et al., 2020). With the significantly reduced cost using MiCAPs, sequencing multiple species and evaluating markers’ transferability become more possible.

Given these challenges and opportunities, the primary objectives of this study are: (i) to develop a comprehensive set of polymorphic SSR markers for under-utilized Zingiberaceae species where such resources are currently lacking; (ii) to assess the transferability of these markers across closely related species within the family; and (iii) to investigate the genetic diversity patterns and phylogenetic relationships among major genera using SSR-enriched genomic data. To address these objectives, we applied the MiCAPs approach to a total of 148 accessions representing 14 species within the Zingiberaceae family. Using the resulting data, we constructed a phylogenetic tree and developed a large set of SSR marker candidates. These efforts not only provide valuable molecular resources for future genetic and evolutionary studies but also contribute to the conservation and sustainable use of under-utilized Zingiberaceae species.

To achieve these objectives, we employed an integrated workflow combining MiCAPs for SSR enrichment, followed by bioinformatic analyses for marker development and diversity assessment, as detailed below.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant materials

In the current study, 160 accessions were collected and sequenced using the MiCAPs method. Among them, 148 accessions were from 14 Zingiberaceae species, and an additional 12 Musaceae accessions were selected as outgroups. Detailed information of all the accessions, including species name and passport data can be found in Supplementary Table S1. Species nomenclature follows Plants of the World Online (POWO, http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/, accessed on 26 October 2025) facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. The rhizome samples were obtained through SMTA (Standard Material Transfer Agreement) of FAO ITPGRFA and/or individual MTAs (Material Transfer Agreement) with the owners through the corresponding authorities.

Plants were grown in Gene Research Center, University of Tsukuba, Japan under controlled greenhouse condition. Fresh young leaf samples were collected and kept at -80°C till DNA extraction.

2.2 DNA extraction, library establishment and sequencing

The detailed experimental procedures, including library construction, SSR enrichment, and sequencing, were performed as described in our previous work (Shi et al., 2024), which followed the MiCAPs protocol developed by Tanaka et al. (2018) with minor modifications. A brief overview of the workflow is provided below; readers are referred to the original MiCAPs publication (Tanaka et al., 2018) for comprehensive methodological details, including the design of biotinylated SSR capture probes.

Genomic DNA was extracted from the frozen young leaf tissue using a modified CTAB protocol (Doyle and Doyle, 1987) supplemented with 0.02g polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) per sample. DNA quality and integrity were evaluated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA).

Subsequently, 100 ng of DNA was digested with EcoRI-HF (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and HindIII-HF (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), ligated to custom adapters, and size-selected using AMPure XP magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter, Bera, CA, USA), following the Flexible ddRAD-seq framework (Ando et al., 2018). The size-selected fragments were amplified with dual-index primers through high-fidelity PCR.

For SSR enrichment, the pooled libraries were hybridized with a biotinylated (GA)10 probe and captured using Dynabeads MyOne streptavidin C1 beads (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). It should be noted that this probe specifically captures SSR-containing fragments with GA/AG/CT/TC motifs, which limits the diversity of marker types recovered and may introduce bias in SSR density estimates across different genomic regions or species. The enriched libraries were further amplified, purified, and assessed for quality and concentration. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) to generate 2 × 300 bp paired-end reads.

2.3 Raw data cleaning, clustering, and phylogenetic analysis

Raw sequencing reads were initially processed using fastp v0.23.2 (Chen et al., 2018) with default parameters to remove low-quality sequences and adapters. The resulting clean paired-end reads were merged using FLASh v1.2.11 (Magoc and Salzberg, 2011) with a maximum overlap of 500 bp and a minimum overlap of 60 bp.

Subsequently, similar merged reads were clustered using CD-HIT-EST v4.6 (Li and Godzik, 2006) to reduce redundancy. SSR polymorphism was inferred based on sequence redundancy, using common sequences containing SSR motifs as reference sequences.

For polymorphism detection and phylogenetic analysis, we followed the MiCAPs protocol (Tanaka et al., 2018). Briefly, sequence data from all samples were combined and re-clustered using CD-HIT-EST to establish a reference sequence set. Individual sample reads were mapped to the reference using CLC Genomics Workbench v9.5 (Qiagen, Denmark), and consensus sequences for each sample were generated. While this consensus-based approach may collapse allelic variation in polyploid accessions, it provides a practical framework for marker development and genus-level diversity assessment without requiring specialized polyploid-aware algorithms.

SSR loci were identified from the consensus sequences using SSRIT (Temnykh et al., 2001), and polymorphism data were extracted to construct a genotype matrix. Genetic distances among samples were calculated using the distance matrix method implemented in Populations v1.2.30 (Langella, 1999). A phylogenetic tree was then constructed based on the distance matrix using the neighbor-joining method in MEGA7 (Kumar et al., 2016). To assess the robustness of the phylogenetic relationships, bootstrap analysis was performed with 1,000 replicates. The final tree was visualized in a circular layout to facilitate the interpretation of relationships among the 160 accessions and to clearly display the major phylogenetic clades within Zingiberaceae.

2.4 SSR detection, primer design and candidate marker in silico evaluation

Clustered SSR-containing reads were searched using MISA (Thiel et al., 2003; Beier et al., 2017) (MIcroSAtellite identification tool) v2.1. Definitions of unit size and min repeats were 2-6, 3-5, 4-5, 5-5, and 6-5; max interruption was 100 bp. Then, only perfect SSRs with a size between 30 and 70 nt were selected with a custom python script. Considering that library is established from AG-motif probe enriched fragments, only those SSRs containing AG, GA, TC, and CT were included.

Primer3 v.0.4.0 (Koressaar and Remm, 2007; Untergasser et al., 2012) was employed to design five primer sets for each SSR locus. These marker candidates were deduplicated with similar threshold 90% by a custom script.

In silico evaluation of these marker candidates was then conducted with ePCR (Schuler, 1997). The sts size ranged from 100 to 1000, word size set as 12, margin 3000, no mismatches or indels allowed.

2.5 Diversity analysis based on polymorphic ssr retrieval

After the establishment of a phylogenetic tree, species under Zingiber and Curcuma were given focus for a diversity analysis. The list of plants in these groups can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

Polymorphic SSR Retrieval (PSR) (Cantarella and D’Agostino, 2015) is a Perl package for identifying polymorphic SSRs from NGS data and providing quantitative information of each SSR locus for each call. For PSR analysis, individual sample reads were mapped to the reference sequences using Bowtie2 v2.3.5 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012), generating BAM (Binary Alignment Map) files that contain alignment information for each read. These BAM files, together with SSR annotations from MISA output (described above), were then processed by PSR with minimum read depth set to 3 (-t 3) and default parameters for variant calling (-p) to extract SSR genotype data, including allele sizes and copy numbers at each polymorphic locus. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on genetic distance was processed with Microsoft 365® Excel® plug-in GeneAlEx 6.503 (Peakall and Smouse, 2012; Smouse et al., 2017). From PSR output, loci present in at least 20% of the accessions were filtered for heatmap visualization. Presence/Absence heatmap of locus in each accession is drawn by a custom python script: if one locus is present in PSR output, it is marked as black, otherwise white.

To assess the distribution and transferability of SSR loci across species within each genus, presence/absence heatmaps were generated using a custom Python script. In these heatmaps, each SSR locus that passed the 20% frequency threshold is represented as a column, and each accession is represented as a row. A cell is colored black if the SSR locus is present in that accession and white if absent. To reveal the structural relationships among SSR loci and identify groups of loci with similar distribution patterns, hierarchical clustering analysis was performed on the SSR loci. Jaccard distance, which is particularly suitable for binary presence/absence data, was calculated between all pairs of loci using the scipy.spatial.distance.pdist function (Virtanen et al., 2020). Hierarchical clustering was then conducted using the average linkage method (scipy.cluster.hierarchy.linkage), which groups loci based on the average pairwise distances between members of different clusters.

3 Results

3.1 Overview of sequencing results

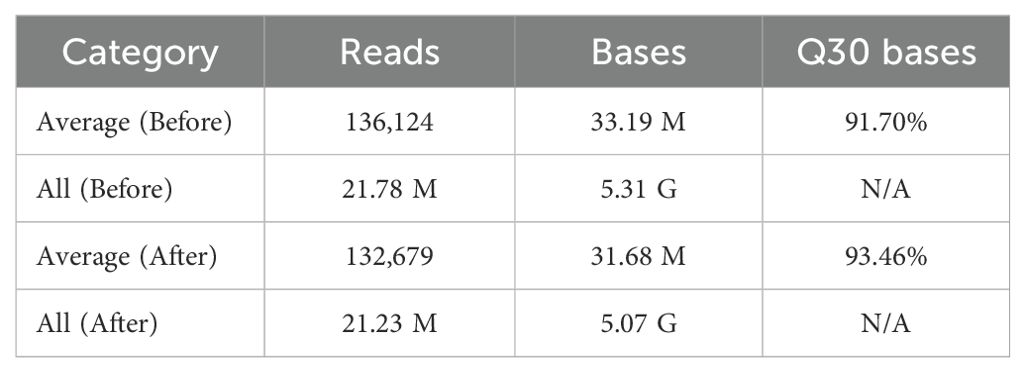

A total of 160 accessions, including 148 from Zingiberaceae and 12 from Musaceae, were subjected to MiCAPs. In total, 21.78 million raw reads were generated, corresponding to approximately 5.31 Gb of sequence data. On average, each accession yielded 136,124 reads and 33.19 Mb of raw data, with a Q30 base percentage of 91.70% (Table 1). After quality filtering using fastp, the proportion of Q30 bases increased to 93.46%, indicating good sequencing quality. The accession with the fewest sequencing bases was Z0106 (C. amada), with 12.41 Mb of bases, whereas the accession with the highest number of sequencing bases was MS3–1 from Musaceae (outgroup), with 64.77 Mb. The mean value of clean reads for each accession was 21.23 Mb (Supplementary Tables S2-S8).

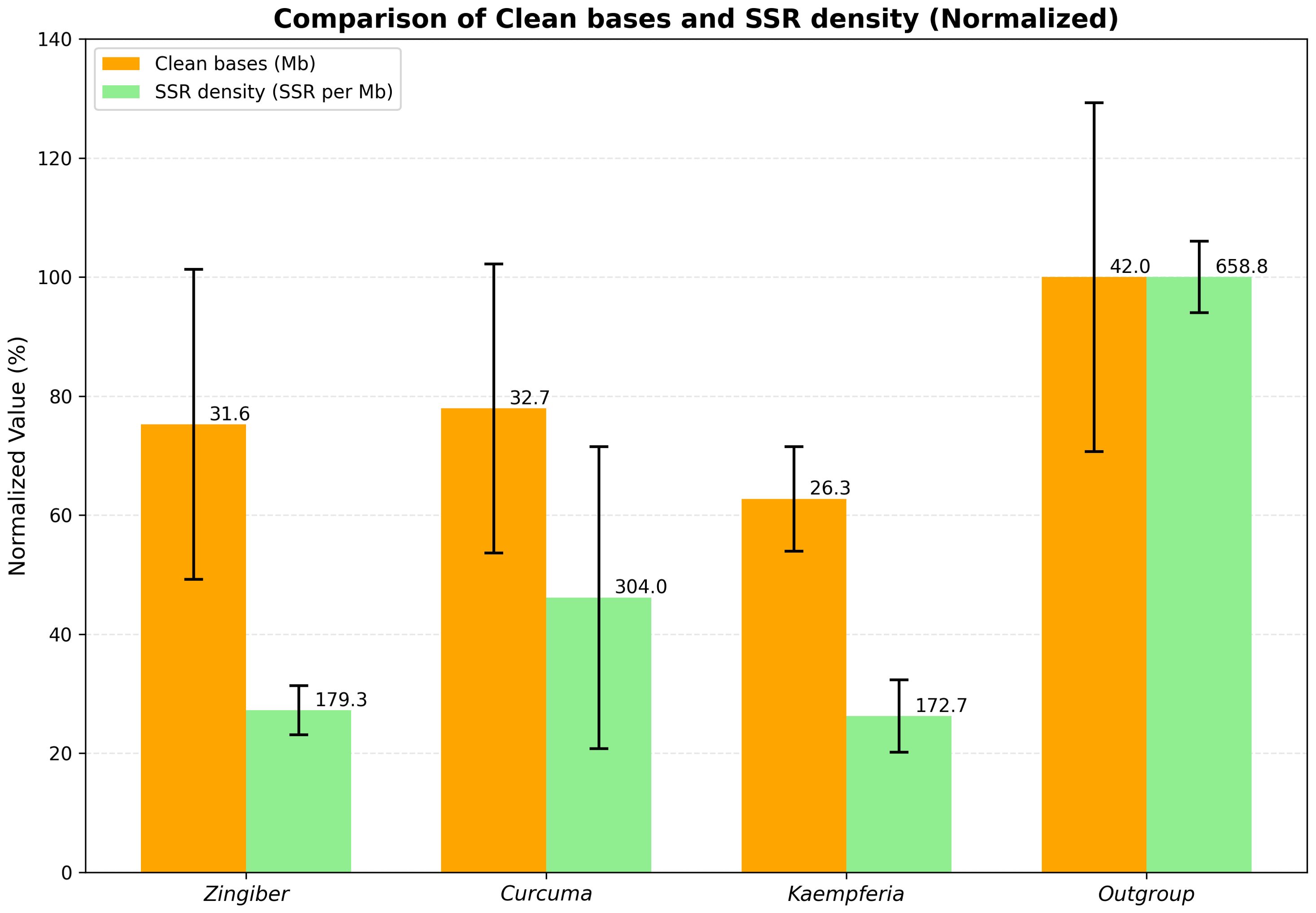

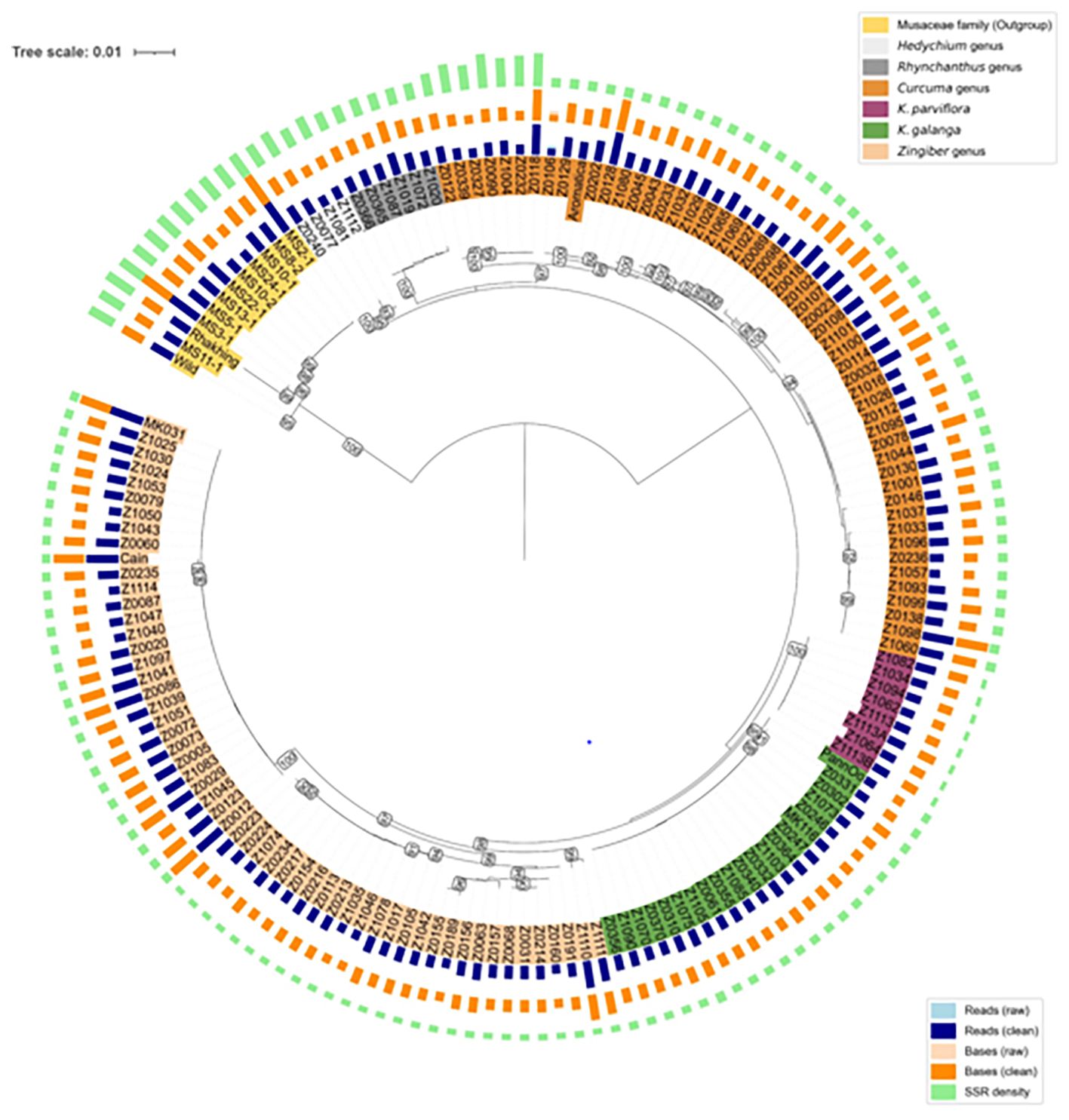

Among the three most represented genera (Zingiber, Curcuma, and Kaempferia), the clean bases showed relatively minor differences, with Zingiber and Curcuma being particularly close in their data yield (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Comparison of clean bases and SSR density across major plant groups. Clean bases and SSR density were compared among three genera (Zingiber, Curcuma, and Kaempferia) and the outgroup Musaceae. Within each dataset, the values were normalized by setting the highest value (Musaceae) to 100%, with other values scaled accordingly.

3.2 SSR mining and candidate marker development

Clustered sequences were used for SSR mining. In total, 10,414,651 sequences covering approximately 2.69 Gb of sequence data were examined, leading to the identification of 769,841 SSRs. The average SSR density was calculated to be 274.63 SSRs per Mb of sequence.

The SSR density across different groups showed substantial variation, ranging from a minimum of 108.77–188 to a maximum of 845.22 SSRs per Mb.

As shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, the SSR density differed markedly among the four groups (Zingiber, Curcuma, Kaempferia, and Musaceae), with one Curcuma branch exhibiting notably higher SSR enrichment relative to Zingiber, Kaempferia, and other Curcuma accessions.

Figure 2. Circular phylogenetic tree of 160 accessions based on SSR-enriched sequences. Branch length represents genetic distance. Bootstrap values are shown as numbers. Four concentric rings are displayed from inside to outside: accession numbers, number of reads, sequence bases, and SSR density. The color bands for accession numbers (innermost) represent the biological classification of each accession, including Outgroup Musaceae family, Hedychium genus, Rhynchanthus genus, Curcuma genus, K. parviflora, K. galanga, and Zingiber genus.

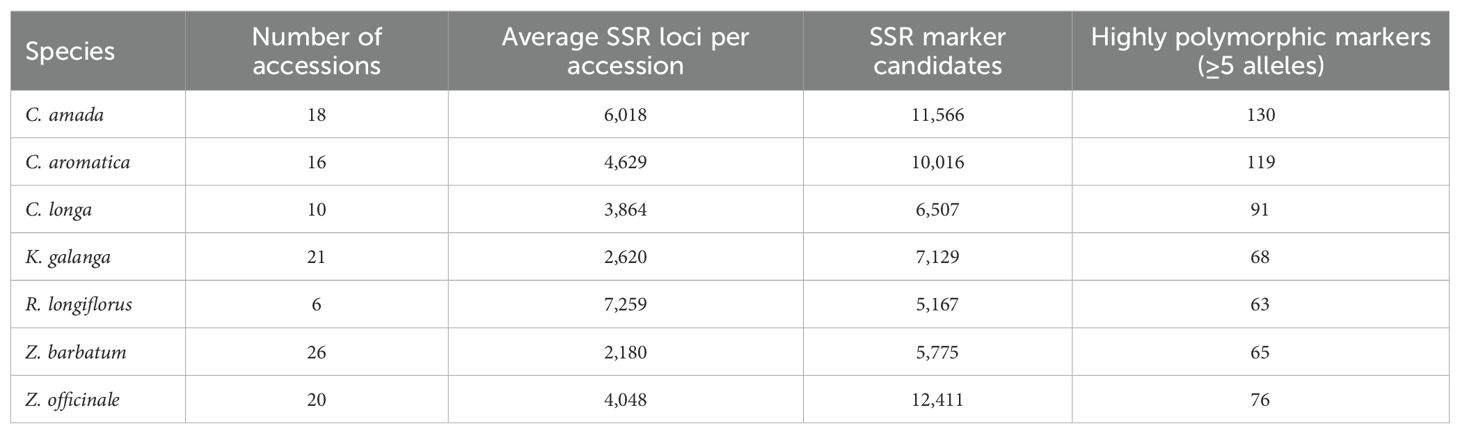

Further SSR marker development was conducted at the species level (Table 2). The number of SSR loci identified per accession varied across species, with R. longiflorus yielding the highest average (7259 SSRs per accession) and Z. barbatum the lowest (2180 SSRs per accession).

The number of SSR marker candidates designed for ePCR screening ranged from 5167 in R. longiflorus to 12,411 in Z. officinale. Notably, a considerable number of markers with high allelic diversity (defined as ≥5 alleles) were identified via ePCR, ranging from 63 in R. longiflorus to 130 in C. amada. Data for K. parviflora is excluded due to prior publication. The developed SSR marker candidates can be found in Supplementary Tables S2-S8.

3.3 Phylogenetic tree construction based on SSR-enriched sequences

To investigate the genetic relationships among the 160 accessions, a circular phylogenetic tree was constructed based on consensus sequences (Figure 2).

The Musaceae accessions (yellow) formed a well-supported and isolated clade (bootstrap support = 100%), serving as an outgroup relative to the Zingiberaceae species. Within Zingiberaceae, the accessions were further divided into two major clades, designated as Clade I and Clade II.

Clade I is primarily comprised of the accessions from Rhynchanthus (95%), Hedychium (100%), and Curcuma (97%), indicating strong internal consistency within these genera. Clade II mainly included accessions of K. parviflora (100%), K. galanga (95%), and Zingiber (98%), also demonstrating high bootstrap support values and clear genetic separation among these groups.

3.4 Genetic diversity on major subclades using polymorphic SSR retrieval

We continue to focus on two major subclades representing Curcuma and Zingiber genus.

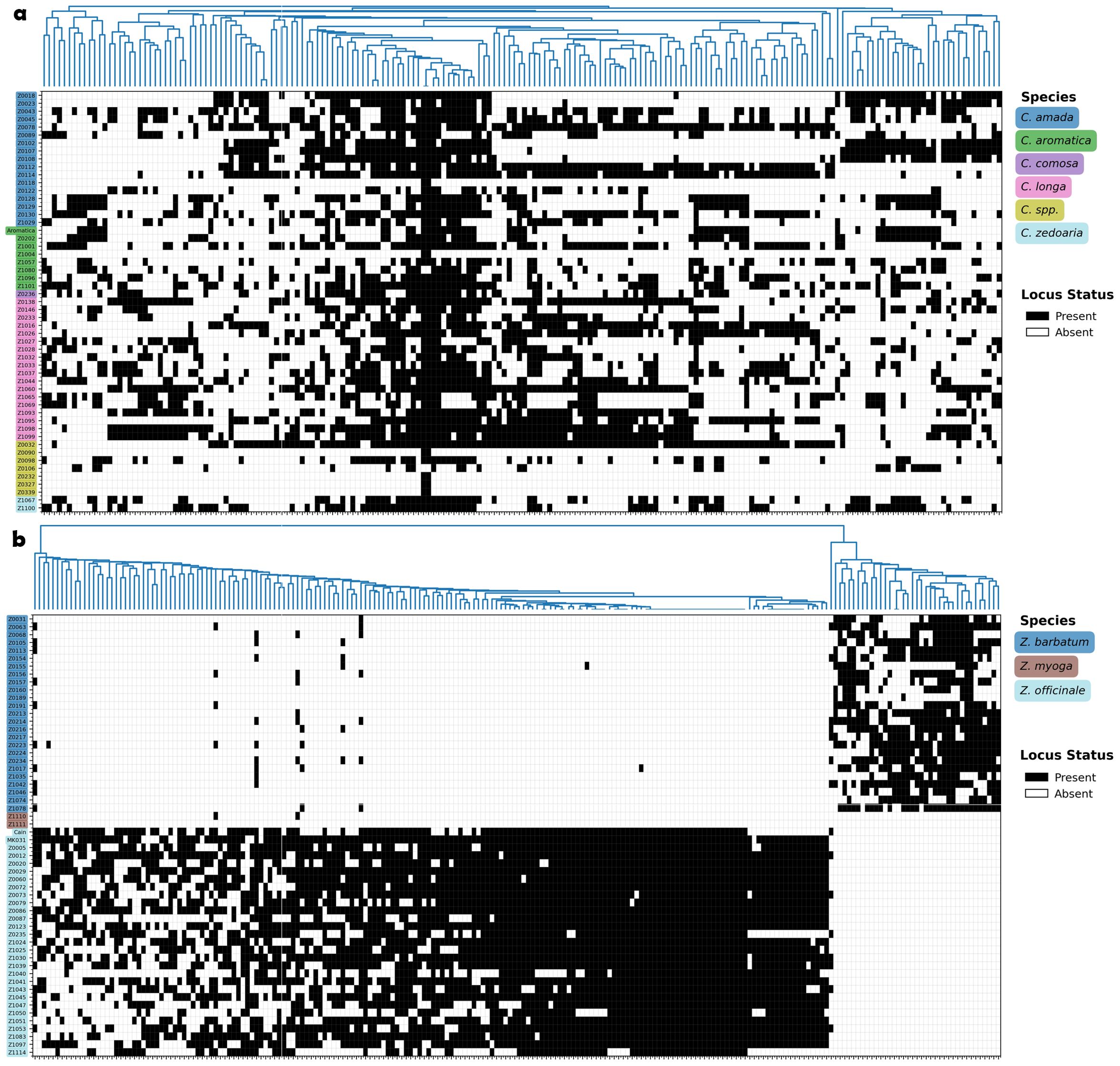

As shown in Figure 3, certain SSR loci exhibit transferability within Curcuma species, appearing simultaneously across multiple species. A total of six SSR loci were present in more than 75% of Curcuma accessions, whereas this number was zero for Zingiber. However, from another perspective, Curcuma species proved difficult to differentiate using SSR markers, while the three Zingiber species were distinctly separated from each other. This contrasting pattern suggests differential utility of SSR markers across these related genera within Zingiberaceae.

Figure 3. Presence/absence heatmap of filtered loci per accession. Loci present in at least 20% of the accessions are filtered for heatmap visualization. Black indicates presence, white indicates absence. (a) Curcuma species. (b) Zingiber species.

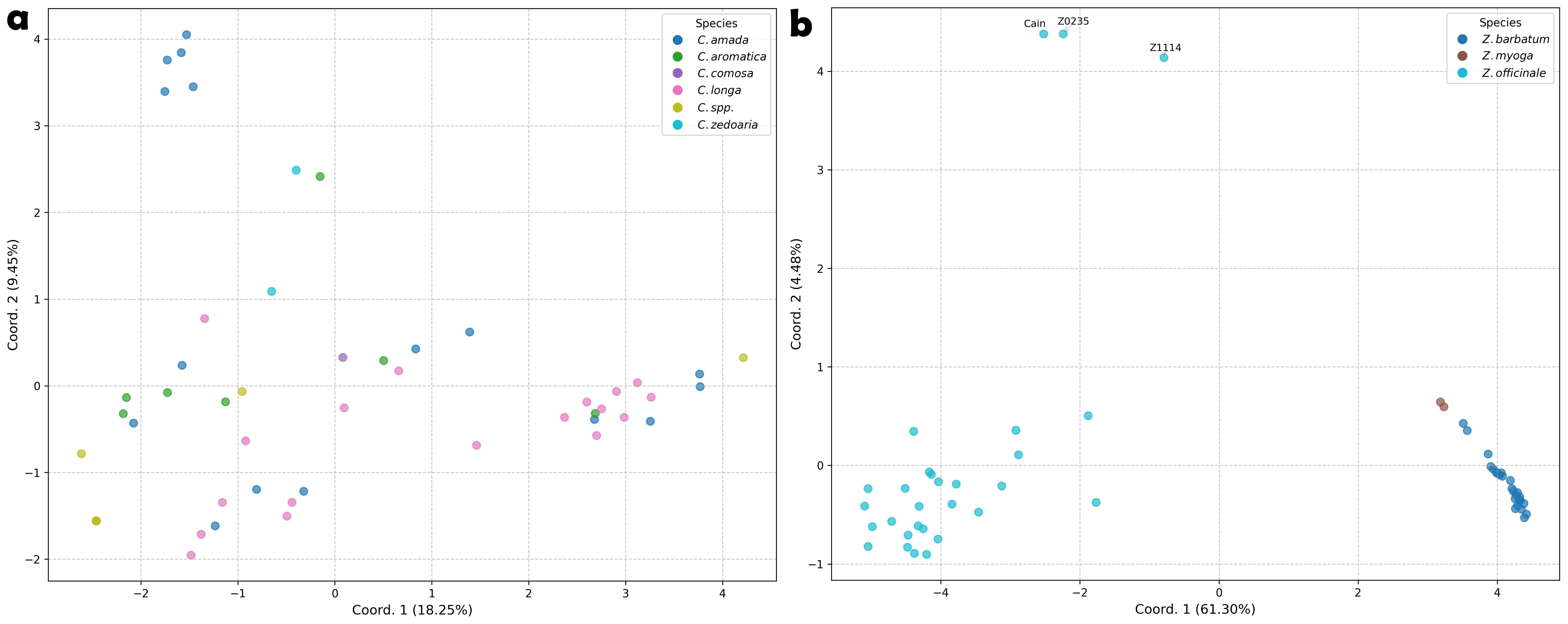

The PCoA plots based on genetic distances corroborated the heatmap and tree-based clustering findings, revealing distinct clustering patterns between genera (Figure 4). Curcuma accessions exhibited considerable admixture with no clear clustering pattern, with the first two axes explaining only a modest proportion (27.70%) of the total genetic variation. In contrast, Zingiber accessions formed three well-defined clusters that aligned precisely with their taxonomic classification. Notably, three Z. officinale accessions—Cain, Z0235, and Z1114—were positioned at considerable distance from the main cluster.

Figure 4. Principle Coordinate Analysis of Curcuma and Zingiber species based on Nei’s Genetic Distance calculated from PSR detected SSR loci. (a) Curcuma species. (b) Zingiber species.

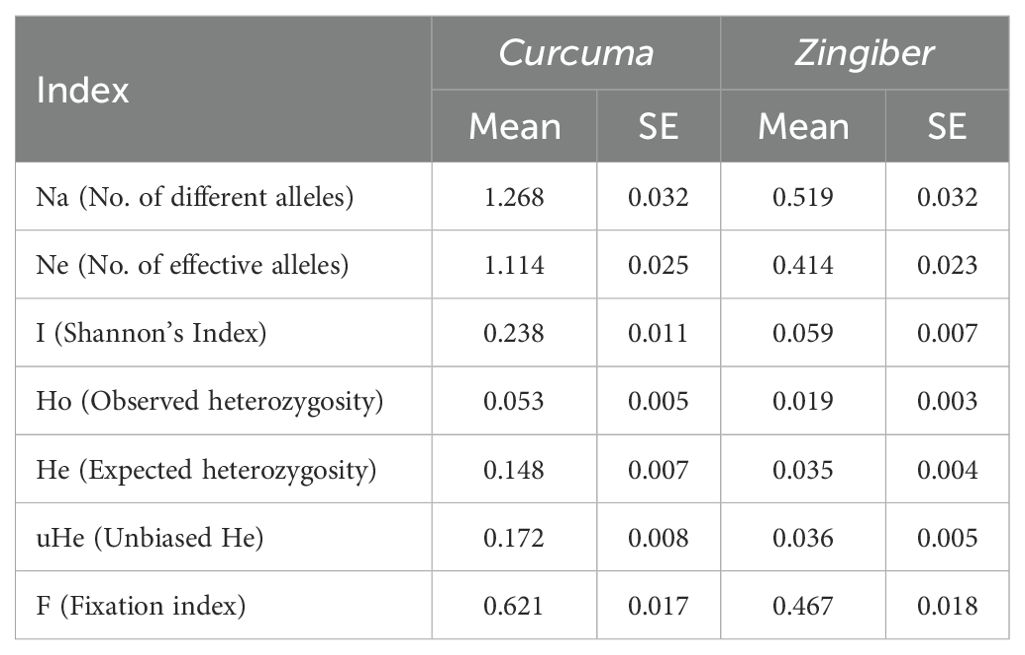

To further characterize the genetic diversity differences between the two genera, population genetic diversity indices were calculated (Table 3). Curcuma exhibited notably higher genetic diversity across multiple indices compared to Zingiber. Specifically, Curcuma showed higher values for the number of alleles (Na = 1.268 vs. 0.519), number of effective alleles (Ne = 1.114 vs. 0.414), Shannon’s information index (I = 0.238 vs. 0.059), and expected heterozygosity (He = 0.148 vs. 0.035). These quantitative measures corroborate the PCoA results and support the interpretation that Curcuma possesses greater genetic complexity, while Zingiber maintains a more conserved genetic background. The higher fixation index in Curcuma (F = 0.621) compared to Zingiber (F = 0.467) further suggests stronger population differentiation within Curcuma, consistent with its allopolyploid nature and history of hybridization.

Having established these patterns of SSR distribution, marker diversity, and genetic relationships among Zingiberaceae species, we now discuss the biological and methodological implications of these findings.

4 Discussion

4.1 SSR statistics and SSR marker candidates

In the current study, we located 769,841 SSRs with the average SSR density 274.63 SSRs per Mb of sequence. The SSR density was similar to previous study reported as 216.1–367.3 SSRs/Mb in Curcuma (Ye et al., 2024).

In our previous study, we developed and validated SSR markers for K. parviflora using the MiCAPs workflow, demonstrating its reliability (Shi et al., 2024). In the current study, we provided SSR marker candidates—validated through ePCR and PSR—for a range of Zingiberaceae species that previously lacked such resources, enabling potential future studies and applications.

The SSR-containing fragments captured and sequenced by MiCAPs account for only about 1% of the whole genome (Shi et al., 2024), significantly reducing the overall cost. This is particularly advantageous for under-utilized species. For well-studied species, the reduced cost makes it feasible to sequence multiple accessions, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of genetic variation and enabling the assessment of SSR marker transferability across closely related species.

For example, we identified six SSR loci in Curcuma that are shared among multiple Curcuma species, suggesting a degree of cross-species applicability. However, this is not always the case—among the three Zingiber species, most loci were found to be species-specific, indicating limited transferability. On the other hand, this species specificity offers a potential advantage for rapid species identification. These differential patterns of SSR distribution suggest distinct applications for the developed markers: the species-specific SSR loci identified in Zingiber are particularly suitable for germplasm authentication and species identification in breeding programs and conservation efforts, while the transferable SSR loci observed across multiple Curcuma species offer potential for comparative genetic studies and cross-species applications within this genus, which is valuable given the prevalence of hybridization and allopolyploidy in Curcuma.

At the intra-species level, when screening for SSR marker candidates, we selected perfect SSRs with repeat lengths ranging from 30 to 70 nucleotides. This size range is often associated with higher levels of polymorphism, making these SSRs particularly valuable for genetic studies (Weber, 1990; Xu et al., 2000; Temnykh et al., 2001; Patil et al., 2021). The rationale for this selection is twofold: first, SSRs of this length tend to exhibit greater allelic diversity due to higher mutation rates, facilitating the detection of fine-scale genetic differences within populations; second, they remain sufficiently short to ensure robust and reproducible PCR amplification under standard laboratory conditions. In some studies, such SSRs are also referred to as Class I (Patil et al., 2021) or HvSSR (highly variable SSR) (Singh et al., 2010), highlighting their potential for revealing significant intra-species genetic variation. These highly polymorphic SSR markers (developed from 30–70 nt perfect SSRs) therefore provide robust tools for population genetic analysis and diversity assessment in Zingiberaceae species.

The choice of MiCAPs over alternative enrichment approaches merits consideration in the context of recent phylogenomic studies in Zingiberaceae. While target capture (hybrid capture) methods have been successfully applied to obtain chloroplast genomes for phylogenetic reconstruction in this family (Li et al., 2019; Xia et al., 2024), these approaches primarily recover organellar sequences suitable for deep phylogenetic inference at family or tribe levels (Pezzini et al., 2023). In contrast, MiCAPs specifically enriches nuclear genomic regions containing SSRs, which exhibit higher mutation rates and therefore greater polymorphism levels compared to chloroplast markers (Li et al., 2020). This fundamental difference in target loci makes MiCAPs particularly advantageous for population-level studies and diversity assessment rather than deep phylogenetic reconstruction. Furthermore, the cost structure differs between approaches: while target capture requires initial investment in custom bait design, the per-sample sequencing costs can be reduced when applied to large sample sets (Pezzini et al., 2023). However, for under-utilized species with limited prior genomic resources—such as several species examined in this study—MiCAPs offers a more accessible entry point, requiring only approximately 1% genome coverage (Shi et al., 2024) to generate sufficient polymorphic markers without the need for reference genome-based bait design. These complementary methodologies serve distinct research objectives: chloroplast-based approaches excel at resolving deep evolutionary relationships, whereas nuclear SSR enrichment via MiCAPs provides the high-resolution markers necessary for intraspecific genetic diversity analysis and germplasm characterization.

4.2 Phylogenetic and diversity study of Zingiberaceae

In our phylogenetic tree (Figure 2), Hedychium, Rhynchanthus, and Curcuma are in the same cluster, while Kaempferia and Zingiber are in another. This genus-level phylogenetic relationship is concordant with previous studies based on chloroplast DNA (Cui et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021), internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions, and matK (Kress et al., 2002) sequences. While these traditional phylogenetic markers (cpDNA, ITS, matK) have proven effective for resolving higher-level taxonomic relationships, nuclear SSR markers offer complementary advantages for fine-scale diversity analysis due to their higher polymorphism levels and biparental inheritance (Kress et al., 2002; Li et al., 2020). However, we acknowledge that our neighbor-joining approach has inherent limitations, including inability to model site heterogeneity and susceptibility to long-branch attraction (Gascuel and Steel, 2006). Moreover, SSRs are biparentally inherited and multi-allelic, differing from the uniparentally inherited cpDNA commonly used in phylogenetic studies (Ellegren, 2004). We acknowledge that formal topology tests (e.g., Shimodaira-Hasegawa test) were not performed, as the primary objective of this study was a comprehensive SSR study rather than rigorous phylogenetic reconstruction. Therefore, at finer taxonomic scales—particularly within genera where hybridization and polyploidy are prevalent—our results are more appropriately interpreted as genetic similarity patterns rather than strict phylogenetic relationships. Nonetheless, the broad congruence at the genus level, supported by high bootstrap values (95–100% for major genera), suggests that SSR-based analysis can effectively capture major evolutionary relationships among Zingiberaceae genera.

The PCoA provides further insights into the genetic relationships and diversity patterns among the Curcuma and Zingiber accessions (Figure 4). Notably, the Curcuma accessions exhibited a dispersed pattern without forming distinct clusters within the PCoA plot (Figure 4a). Correspondingly, the first two principal coordinate axes explained only 27.70% of the total observed genetic variation for this genus. This lack of clear grouping and the low explanatory power of the initial axes underscore the substantial genetic complexity within Curcuma (Záveská et al., 2016; Skopalíková et al., 2023), aligning with our observation of SSR loci distribution (Figure 3a).

In striking contrast, the Zingiber accessions demonstrate a much clearer genetic structure, dividing into two well-defined major groups (Figure 4b). One cluster exclusively comprises all accessions identified as Z. barbatum and Z. mioga, while the other includes all the Z. officinale (ginger) accessions. This distinct separation suggests a more conserved genetic background or stronger reproductive barriers between these Zingiber groups compared to the pattern observed in Curcuma. Quantitative genetic diversity indices further support this interpretation (Table 3): Zingiber exhibited substantially lower values for key diversity measures including Shannon’s index (I = 0.059 vs. 0.238), expected heterozygosity (He = 0.035 vs. 0.148), and number of alleles (Na = 0.519 vs. 1.268) compared to Curcuma, corroborating the observed differences in genetic structure and complexity between the two genera.

Within these Zingiber clusters, the analysis also revealed differences in genetic diversity; the Z. officinale cluster displayed a wider dispersion, indicating greater genetic variation among the ginger accessions, whereas the Z. barbatum accessions showed lower genetic diversity within this group. Furthermore, attention was drawn to three specific ginger accessions (‘Cain’, ‘Z0235’, and ‘Z1114’) that were positioned at a considerable distance from both major Zingiber clusters, suggesting significant genetic divergence. This genetic distinctiveness could potentially indicate unique germplasm resources within Z. officinale and warrants further investigation in future breeding programs and evolutionary studies of the Zingiberaceae family.

It is important to clarify that our methodology is fundamentally based on SSR repeat number polymorphism rather than SSR-flanking sequence analysis (Tanaka et al., 2018). While this avoids complications from potentially paralogous flanking sequences, SSRs are inherently prone to homoplasy and size homoplasy (Estoup et al., 2002). However, the large number of SSR loci analyzed in this study (hundreds of polymorphic loci across the dataset) likely compensates for potential homoplasious evolution at individual loci, as the high overall variability enables robust inference of genetic relationships despite occasional convergent mutations (Estoup et al., 2002). Regarding polyploidy, our workflow simplifies complexity to facilitate marker development: consensus sequence construction may collapse allelic variation in polyploids, and PSR was applied with default diploid-like settings (Cantarella and D’Agostino, 2015). Although this simplified approach may not capture full allelic complexity, it proved effective for generating actionable SSR candidates and revealing diversity patterns without requiring specialized polyploid-aware algorithms (Rothfels, 2021). Additionally, the use of a (GA)10 biotinylated probe for SSR enrichment may introduce capture bias toward genomic regions or subgenomes enriched in GA/AG/CT/TC-type repeats, potentially affecting SSR recovery efficiency across different species or homeologous chromosomes in polyploid accessions. This bias should be considered when interpreting interspecific differences in SSR density.

4.3 Hybridization characteristics and SSR loci distribution

Each species has different genome size, and some of the accessions are polyploid within a given species classification. The chromosome number, ploidy level and genome size (2-c value or genome assembly) of some major species we used in current study that were already reported are: C. longa (2n=63; 3x or 4x; 2.60–2.85 pg) (Leong- Škorničková et al., 2007; Yin et al., 2022; Aswathi and Prasath, 2024), C. amada (2n=42; 6x; 1.82–1.88 pg) (Leong- Škorničková et al., 2007), C. aromatica (2n=42,63,86; 6x or 9x; 2.68–2.86 pg) (Leong- Škorničková et al., 2007; Shankar, 2021), Z. officinale (2n=22; 2x; 3.1Gb) (Cheng et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021), Z. barbatum (unknown; 2x, 3x or 4x; 2.90–5.98 pg) (Shukurova, 2016).

Curcuma plants display a great degree of diversity in ploidy levels with different chromosome numbers among different species (Ahmad, 2010; Chen et al., 2013; Lamo, 2017), and many of them are of allopolyploid in origin, which are therefore hybrids (Záveská et al., 2016). Hybridization within Curcuma is common in nature and is also applied in the horticultural industry (Anuntalabhochai et al., 2007; Záveská et al., 2016). This may help explain why the SSR loci in Curcuma are often shared across multiple species. Moreover, even different accessions of the same species may possess entirely distinct SSR loci (Figure 3a), a phenomenon that could be attributed to their allopolyploid nature.

Interestingly, we observed a particular branch within Curcuma (Z0122, Z0339, Z0327, Z0090, Z1004, Z0232, and Z0118) that exhibits a notably higher SSR density (Figure 2), and in heatmap they don’t share many SSR loci with other Curcuma species (Figure 3a). However, background information about this group remains limited; we were only able to identify two accessions within the cluster as C. amada and one as C. aromatica (Supplementary Table S1). The unusually high SSR density and unique SSR loci in this lineage may be related to their ploidy level and evolutionary history. Alternatively, as discussed earlier regarding probe capture bias, this elevated SSR density could simply reflect higher capture efficiency of GA-type repeats by the (GA)10 biotinylated probe in this particular lineage, rather than true genomic differences. Further investigation using flow cytometry (FCM) or whole genome sequencing will be necessary to determine exact ploidy and genetic makeup, and to distinguish between genuine genomic expansion and methodological artifacts.

In contrast, this pattern is less evident in Zingiber. Although Z. barbatum accessions used in current study are validated to be in triploid and tetraploid forms (Shukurova, 2016), neither its SSR density nor the distribution of SSR loci showed significant variation among different ploidy levels. This is also true with K. galanga, which has 4x and 5x forms (FCM data not published). This observation might be attributable to the strong reproductive isolation in these species.

In the case of K. galanga, PanOo was separated from the rest of the accessions having less SSR density. It could be attributed to its 4x ploidy level while the others are 5x (Lu et al., 2023).

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, the species investigated in this study primarily rely on vegetative propagation, and as the previous cytological studies indicated that some are regarded as allopolyploids, ordinary genetic markers could be challenging for systematic study. Compounding this, the genetic landscape is further complicated by considerable variation in genome size and the occurrence of intra-specific ploidy differences among accessions. Despite these complexities, our integrated approach employing SSR-enriched sequencing (MiCAPs) coupled with in silico SSR marker simulations (PSR) demonstrated remarkable effectiveness, particularly in efficiently generating actionable marker candidates from polyploid genomes without requiring specialized polyploid-aware algorithms. These methodologies successfully circumvented the obstacles posed by the diverse genetic complements, proving highly capable of establishing a robust phylogenetic framework across the Zingiberaceae family and facilitating a comprehensive evaluation of genetic diversity at the genus level. Furthermore, a significant outcome of this research is the development of a novel set of SSR marker candidates derived from the generated sequence data. These markers represent a valuable resource for species identification, population genetic analysis, and cross-species comparative studies, promising to significantly aid future genetic investigations focused on understanding the diversity, relationships, and conservation of under-utilized species within the Zingiberaceae family.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here: DDBJ database, accession numbers PRJDB18485 and PRJDB35866.

Author contributions

MS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KT: Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MR: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MT: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Resources. GN: Writing – review & editing. KW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. JST SPRING grant (JPMJSP2124).

Acknowledgments

The research was conducted in part by JSPS Grant-in-Aid 17H01682 and the contract research by Hirata Corporation managed by the University of Tsukuba, AKI05704 and AKI06708. Also, the research was supported in part by PTraD grant #2333 by T-PIRC, UT. MS acknowledges JST SPRING grant (JPMJSP2124). GMN and MPR thanks MEXT scholarship. GMN also acknowledges Japan Leader Empowerment Program on Global Supports towards Regional Revitalization (JLEP). Next-generation sequencer was used with the support of the NODAI Genome Research Center, Tokyo University of Agriculture.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1693622/full#supplementary-material

References

Abe, M., Ozawa, Y., Uda, Y., Morimitsu, Y., Nakamura, Y., and Osawa, T. (2006). A novel labdane-type trialdehyde from myoga (Zingiber mioga roscoe) that potently inhibits human platelet aggregation and human 5-lipoxygenase. Bioscience Biotechnology Biochem. 70, 2494–2500. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60226

Ahmad, D. (2010). Assessment of genetic and biochemical diversity of Curcuma amada from Myanmar (Tsukuba, Japan: University of Tsukuba).

Albaqami, J. J., Hamdi, H., Narayanankutty, A., Visakh, N. U., Sasidharan, A., Kuttithodi, A. M., et al. (2022). Chemical Composition and Biological Activities of the Leaf Essential Oils of Curcuma longa, Curcuma aromatica and Curcuma angustifolia. Antibiotics 11, 1547. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11111547

Al-Reza, S. M., Rahman, A., Sattar, M. A., Rahman, M. O., and Fida, H. M. (2010). Essential oil composition and antioxidant activities of Curcuma aromatica Salisb. Food Chem. Toxicol. 48, 1757–1760. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.04.008

Ammon, H. P. T. and Wahl, M. A. (2007). Pharmacology of curcuma longa. Planta Med. 57, 1–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960004

Ando, T., Matsuda, T., Goto, K., Hara, K., Ito, A., Hirata, J., et al. (2018). Repeated inversions within a pannier intron drive diversification of intraspecific colour patterns of ladybird beetles. Nat. Commun. 9, 3843. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06116-1

Anuntalabhochai, S., Sitthiphrom, S., Thongtaksin, W., Sanguansermsri, M., and Cutler, R. W. (2007). Hybrid detection and characterization of Curcuma spp. using sequence characterized DNA markers. Scientia Hortic. 111, 389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2006.11.008

Araujo, C. A. C. and Leon, L. L. (2001). Biological activities of Curcuma longa L. Memorias´ do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 96, 723–728. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762001000500026

Aswathi, A. P. and Prasath, D. (2024). Ploidy level variation and phenotypic evaluation of turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) diversity panel. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 71, 3541–3554. doi: 10.1007/s10722-023-01844-w

Aung, M. M. (2016). Taxonomic study of the genus Zingiber Mill.(Zingiberaceae) in Myanmar (Kochi, Japan: Kochi University).

Beier, S., Thiel, T., Münch, T., Scholz, U., and Mascher, M. (2017). MISA-web: A web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics 33, 2583–2585. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198

Cantarella, C. and D’Agostino, N. (2015). PSR: polymorphic SSR retrieval. BMC Res. Notes 8, 525. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1474-4

Chan, E. W. C., Chan, H. T., and Wong, S. K. (2023). Zingiber mioga: A perspective of its botany, uses, chemical constituents and health benefits. Food Res. 7, 251–257. doi: 10.26656/fr.2017.7(4).389

Chen, J., Xia, N., Zhao, J., Chen, J., and Henny, R. J. (2013). Chromosome numbers and ploidy levels of chinese curcuma species. HortScience. 48 (5), 525–530. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI.48.5.525

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y., and Gu, J. (2018). Fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560

Cheng, S. P., Jia, K. H., Liu, H., Zhang, R. G., Li, Z. C., Zhou, S. S., et al. (2021). Haplotype-resolved genome assembly and allele-specific gene expression in cultivated ginger. Horticulture Res. 8, 188. doi: 10.1038/s41438-021-00599-8

Cui, Y., Nie, L., Sun, W., Xu, Z., Wang, Y., Yu, J., et al. (2019). Comparative and phylogenetic analyses of ginger (Zingiber officinale) in the family Zingiberaceae based on the complete chloroplast genome. Plants 8, 283. doi: 10.3390/plants8080283

Debnath, S. and Vijayan, D. (2024). Diversity, phytogeographical distribution, endemism and conservation status of Zingiberaceae in India. Plant Sci. Today 11, 72–78. doi: 10.14719/pst.2708

Doyle, J. J. and Doyle, J. L. (1987). A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small amounts of fresh leaf material. Photochem. Bull. 19, 11–15.

Ellegren, H. (2004). Microsatellites: Simple sequences with complex evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5, 435–445. doi: 10.1038/nrg1348

Estoup, A., Jarne, P., and Cornuet, J. (2002). Homoplasy and mutation model at microsatellite loci and their consequences for population genetics analysis. Mol. Ecol. 11, 1591–1604. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01576.x

Foster, J. T., Bull, R. L., and Keim, P. (2020). “Chapter 16 - Ricin forensics: Comparisons to microbial forensics,” in Microbial Forensics, 3rd ed. Eds. Budowle, B., Schutzer, S., and Morse, S. (London: Academic Press), 241–250. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-815379-6.00016-7

Gascuel, O. and Steel, M. (2006). Neighbor-joining revealed. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 1997–2000. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl072

Grover, A. and Sharma, P. C. (2016). Development and use of molecular markers: Past and present. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 36, 290–302. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2014.959891

Hartati, R., SUganda, A. G., and Fidrianny, I. (2014). Botanical, phytochemical and pharmacological properties of Hedychium (Zingiberaceae)–A review. Proc. Chem. 13, 150–163. doi: 10.1016/j.proche.2014.12.020

Jiang, D., Cai, X., Gong, M., Xia, M., Xing, H., Dong, S., et al. (2023). Complete chloroplast genomes provide insights into evolution and phylogeny of Zingiber (Zingiberaceae). BMC Genomics 24, 30. doi: 10.1186/s12864-023-09115-9

Joshi, S., Chanotiya, C. S., Agarwal, G., Prakash, O., Pant, A. K., and Mathela, C. S. (2008). Terpenoid compositions, and antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of the rhizome essential oils of different hedychium species. Chem. Biodiversity 5, 299–309. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200890027

Khairullah, A. R., Solikhah, T. I., Ansori, A. N. M., Hanisia, R. H., Puspitarani, G. A., Fadholly, A., et al. (2021). Medicinal importance of Kaempferia galanga L.(Zingiberaceae): A comprehensive review. J. Herbmed Pharmacol. 10, 281–288. doi: 10.34172/jhp.2021.32

Kobayashi, S., Kato, T., Azuma, T., Kikuzaki, H., and Abe, K. (2015). Anti-allergenic activity of polymethoxyflavones from Kaempferia parviflora. J. Funct. Foods 13, 100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2014.12.029

Koressaar, T. and Remm, M. (2007). Enhancements and modifications of primer design program Primer3. Bioinformatics 23, 1289–1291. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm091

Kress, W. J., Prince, L. M., and Williams, K. J. (2002). The phylogeny and a new classification of the gingers (Zingiberaceae): Evidence from molecular data. Am. J. Bot. 89, 1682–1696. doi: 10.3732/ajb.89.10.1682

Kumar, A. (2020). Phytochemistry, pharmacological activities and uses of traditional medicinal plant Kaempferia galanga L.–An overview. J. Ethnopharmacology 253, 112667. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112667

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., and Tamura, K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054

Lamo, J. M. (2017). Meiotic behaviour and its implication on species inter-relationship in the genus curcuma (linnaeus, 1753) (zingiberaceae). Comp. Cytogenetics 11, 691–702. doi: 10.3897/compcytogen.v11i4.14726

Langella, O. (1999). Populations (Version 1.2.31) [Computer software]. Available online at: https://bioinformatics.org/populations/.

Langmead, B. and Salzberg, S. L. (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923

Leong- Škorničková, J., Šída, O., Jarolímová, V., Sabu, M., Fér, T., Trávníček, P., et al. (2007). Chromosome numbers and genome size variation in Indian species of curcuma (Zingiberaceae). Ann. Bot. 100, 505–526. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm144

Li, W. and Godzik, A. (2006). Cd-hit: A fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 22, 1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158

Li, D. M., Li, J., Wang, D. R., Xu, Y. C., and Zhu, G. F. (2021). Molecular evolution of chloroplast genomes in subfamily Zingiberoideae (Zingiberaceae). BMC Plant Biol. 21, 558. doi: 10.1186/s12870-021-03315-9

Li, B., Lin, F., Huang, P., Guo, W., and Zheng, Y. (2020). Development of nuclear SSR and chloroplast genome markers in diverse Liriodendron chinense germplasm based on low-coverage whole genome sequencing. Biol. Res. 53, 21. doi: 10.1186/s40659-020-00289-0

Li, H. L., Wu, L., Dong, Z., Jiang, Y., Jiang, S., Xing, H., et al. (2021). Haplotype-resolved genome of diploid ginger (Zingiber officinale) and its unique gingerol biosynthetic pathway. Horticulture Res. 8, 242. doi: 10.1038/s41438-021-00700-1

Li, D. M., Zhao, C. Y., and Liu, X. F. (2019). Complete chloroplast genome sequences of kaempferia galanga and kaempferia elegans: molecular structures and comparative analysis. Molecules 24, 474. doi: 10.3390/molecules24030474

Liang, H., Zhang, Y., Deng, J., Gao, G., Ding, C., Zhang, L., et al. (2020). The complete chloroplast genome sequences of 14 curcuma species: insights into genome evolution and phylogenetic relationships within zingiberales. Front. Genet. 11. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00802

Lobo, R., Prabhu, K. S., Shirwaikar, A., and Shirwaikar, A. (2009). Curcuma zedoaria Rosc.(white turmeric): A review of its chemical, pharmacological and ethnomedicinal properties. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 61, 13–21. doi: 10.1211/jpp.61.01.0003

Lu, J. M., Landrein, S., Song, X. Z., Wu, M., Xiao, C. F., Sun, P., et al. (2023). Polyploidy leads to phenotypic differences between tetraploid Kaempferia galanga var. latifolia and pentaploid K. galanga var. galanga (Zingiberaceae). Scientia Hortic. 307, 111527. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2022.111527

Magoc, T. and Salzberg, S. L. (2011). FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27, 2957–2963. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507

Ngamriabsakul, C., Newman, M. F., and Cronk, Q. C. B. (2004). the phylogeny of tribe zingibereae (zingiberaceae) based on its (nrdna) and trnl–f (cpdna) sequences. Edinburgh J. Bot. 60, 483–507. doi: 10.1017/S0960428603000362

Patil, P. G., Singh, N. V., Bohra, A., Raghavendra, K. P., Mane, R., Mundewadikar, D. M., et al. (2021). Comprehensive characterization and validation of chromosome-specific highly polymorphic SSR markers from Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) cv. Tunisia Genome. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 337. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.645055

Peakall, R. and Smouse, P. E. (2012). GenAlEx 6.5: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research–an update. Bioinformatics 28, 2537–2539. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts460

Pezzini, F. F., Ferrari, G., Forrest, L. L., Hart, M. L., Nishii, K., and Kidner, C. A. (2023). Target capture and genome skimming for plant diversity studies. Appl. Plant Sci. 11, e11537. doi: 10.1002/aps3.11537

Prasad, S. and Tyagi, A. K. (2015). Ginger and its constituents: role in prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal cancer. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2015, 142979. doi: 10.1155/2015/142979

Prasanthkumar, M. G., Skornickova, J., Sabu, M., and Jayasree, S. (2005). Conservation priority and phytogeographical significance of Rhynchanthus longiflorus Hook. f.(Zingiberaceae): A rare, endangered species from Mizo Hills, NE India. Curr. Sci. 88 (6), 977–980.

Ramesh, P., Mallikarjuna, G., Sameena, S., Kumar, A., Gurulakshmi, K., Reddy, B. V., et al. (2020). Advancements in molecular marker technologies and their applications in diversity studies. J. Biosci. 45, 123. doi: 10.1007/s12038-020-00089-4

Saha, K., Sinha, R. K., and Sinha, S. (2020). Distribution, Cytology, Genetic Diversity and Molecular phylogeny of selected species of Zingiberaceae – A Review. Feddes Repertorium 131, 58–68. doi: 10.1002/fedr.201900013

Schuler, G. D. (1997). Sequence mapping by electronic PCR. Genome Res. 7, 541–550. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.5.541

Senan, S., Kizhakayil, D., Sasikumar, B., and Sheeja, T. E. (2014). Methods for development of microsatellite markers: An overview. Notulae Scientia Biologicae 6, 1–13. doi: 10.15835/nsb619199

Shankar, A. (2021). Genomic Designing of Climate Smart Turmeric. Preprints. 2021110394. doi: 10.20944/preprints202111.0394.v1

Shi, M., Tanaka, K., Rivera, M. P., Ngure, G. M., and Watanabe, K. N. (2024). Developing novel microsatellite markers for Kaempferia parviflora by microsatellite capture sequencing (MiCAPs). Agronomy 14, 1984. doi: 10.3390/agronomy14091984

Shukurova, M. K. (2016). Assessment of reproductive morphology, cytology, and metabolic profiling of indigenous and under-exploited species, Zingiber barbatum (Wall.) from Myanmar (Tsukuba, Japan: University of Tsukuba).

Singh, H., Deshmukh, R. K., Singh, A., Singh, A. K., Gaikwad, K., Sharma, T. R., et al. (2010). Highly variable SSR markers suitable for rice genotyping using agarose gels. Mol. Breed. 25, 359–364. doi: 10.1007/s11032-009-9328-1

Skopalíková, J., Leong-Škorničková, J., Šída, O., Newman, M., Chumová, Z., Zeisek, V., et al. (2023). Ancient hybridization in Curcuma (Zingiberaceae)—Accelerator or brake in lineage diversifications? Plant J. 116, 773–785. doi: 10.1111/tpj.16408

Smouse, P. E., Banks, S. C., and Peakall, R. (2017). Converting quadratic entropy to diversity: Both animals and alleles are diverse, but some are more diverse than others. PloS One 12, e0185499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185499

Srinivasan, K. (2014). Antioxidant Potential of Spices and Their Active Constituents. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 54, 352–372. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.585525

Stirling, K. J. (2004). Environmental and cultural factors affecting the production of myoga (zingiber mioga roscoe) in Australia (Hobart, Australia: University of Tasmania). doi: 10.25959/23244878.v1

Tanaka, K., Ohtake, R., Yoshida, S., and Shinohara, T. (2018). “Microsatellite capture sequencing,” in Genotyping. Ed. Abdurakhmonov, I. (London: InTech). doi: 10.5772/intechopen.72629

Temnykh, S., DeClerck, G., Lukashova, A., Lipovich, L., Cartinhour, S., and McCouch, S. (2001). Computational and experimental analysis of microsatellites in rice ( Oryza sativa L.): frequency, length variation, transposon associations, and genetic marker potential. Genome Res. 11, 1441–1452. doi: 10.1101/gr.184001

Tewtrakul, S., Subhadhirasakul, S., Karalai, C., Ponglimanont, C., and Cheenpracha, S. (2009). Anti-inflammatory effects of compounds from Kaempferia parviflora and Boesenbergia pandurata. Food Chem. 115, 534–538. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.12.057

Theerakulpisut, P., Triboun, P., Mahakham, W., Maensiri, D., Khampila, J., and Chantaranothai, P. (2012). Phylogeny of the genus Zingiber (Zingiberaceae) based on nuclear ITS sequence data. Kew Bull. 67, 389–395. doi: 10.1007/s12225-012-9368-2

Thiel, T., Michalek, W., Varshney, R., and Graner, A. (2003). Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of gene-derived SSR-markers in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 106, 411–422. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1031-0

Untergasser, A., Cutcutache, I., Koressaar, T., Ye, J., Faircloth, B. C., Remm, M., et al. (2012). Primer3—new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e115–e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks596

Van Kiem, P., Thuy, N. T. K., Anh, H. L. T., Nhiem, N. X., Van Minh, C., Yen, P. H., et al. (2011). Chemical constituents of the rhizomes of Hedychium coronarium and their inhibitory effect on the pro-inflammatory cytokines production LPS-stimulated in bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Bioorganic Medicinal Chem. Lett. 21, 7460–7465. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.09.129

Virtanen, P., Gommers, R., Oliphant, T. E., Haberland, M., Reddy, T., Cournapeau, D., et al. (2020). SciPy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0686-2

Weber, J. L. (1990). Informativeness of human (dC-dA) n·(dG-dT) n polymorphisms. Genomics 7, 524–530. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90195-Z

Wicaksana, N. (2012). Characterization and diversity assessment of zingiber species with special reference to underutilized medicinal z. barbatum species from Myanmar (Tsukuba, Japan: University of Tsukuba).

Wicaksana, N., Gilani, S. A., Ahmad, D., Kikuchi, A., and Watanabe, K. N. (2011). Morphological and molecular characterization of underutilized medicinal wild ginger (Zingiber barbatum Wall.) from Myanmar. Plant Genet. Resour. 9, 531–542. doi: 10.1017/S1479262111000840

Xia, M., Jiang, D., Xu, W., Liu, X., Zhu, S., Xing, H., et al. (2024). Comparative chloroplast genome study of Zingiber in China sheds light on plastome characterization and phylogenetic relationships. Genes 15, 1484. doi: 10.3390/genes15111484

Xu, X., Peng, M., Fang, Z., and Xu, X. (2000). The direction of microsatellite mutations is dependent upon allele length. Nat. Genet. 24, 396–399. doi: 10.1038/74238

Ye, Y., Tan, J., Lin, J., Zhang, Y., Zhu, G., Nie, C., et al. (2024). Genome-wide identification of SSR markers for Curcuma alismatifolia Gagnep., and their potential for wider application in this genus. J. Appl. Res. Medicinal Aromatic Plants 42, 100572. doi: 10.1016/j.jarmap.2024.100572

Yin, Y., Xie, X., Zhou, L., Yin, X., Guo, S., Zhou, X., et al. (2022). A chromosome-scale genome assembly of turmeric provides insights into curcumin biosynthesis and tuber formation mechanism. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1003835

Yoshino, S., Awa, R., Miyake, Y., Fukuhara, I., Sato, H., Ashino, T., et al. (2018). Daily intake of Kaempferia parviflora extract decreases abdominal fat in overweight and preobese subjects: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study. Diabetes Metab. Syndrome Obesity: Targets Ther. 11, 447. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S169925

Keywords: MICAPS, SSR, microsatellite, Kaempferia, Zingiber, Curcuma, Hedychium, Rhynchanthus

Citation: Shi M, Tanaka K, Rivera MP, Thein MS, Ngure GM and Watanabe KN (2025) Comprehensive SSR study of 14 Zingiberaceae species based on microsatellite capture sequencing (MiCAPs). Front. Plant Sci. 16:1693622. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1693622

Received: 27 August 2025; Accepted: 10 November 2025; Revised: 06 November 2025;

Published: 11 December 2025.

Edited by:

Qijie Guan, Yale University, United StatesReviewed by:

Meng Li, Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences, ChinaHafiz Muhammad Wariss, University of Sargodha, Pakistan

Copyright © 2025 Shi, Tanaka, Rivera, Thein, Ngure and Watanabe. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Miao Shi, czIzMzAzMDZAdS50c3VrdWJhLmFjLmpw

Miao Shi

Miao Shi Keisuke Tanaka

Keisuke Tanaka Marlon P. Rivera

Marlon P. Rivera Min San Thein4

Min San Thein4 Godfrey M. Ngure

Godfrey M. Ngure Kazuo N. Watanabe

Kazuo N. Watanabe