- 1State Key Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Bio-Resources in Yunnan/Key Laboratory of Agro-Biodiversity and Pest Management of Ministry of Education, Yunnan Agricultural University, Kunming, Yunnan, China

- 2Plant Protection Research Institute, Guangxi Academy of Agricultural Science/Key Laboratory of Green Prevention and Control on Fruits and Vegetables in South China, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs/Guangxi Key Laboratory of Biology for Crop Diseases and Insect Pests, Nanning, Guangxi, China

- 3School of Breeding and Multiplication (Sanya Institute of Breeding and Multiplication), Hainan University, Sanya, China

- 4Center of Excellence in Biotechnology Research (CEBR), DSR, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Introduction: Citrus canker, caused by Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri (Xcc), is a major threat to citrus production worldwide, resulting in significant losses in yield and fruit quality. This study investigates the differential responses of endophytic microbial communities to Xcc infection in citrus cultivars with distinct resistance levels, specifically comparing the highly susceptible Citrus reticulata cv. ‘Orah’ and the more resistant Fortunella crassifolia cv. ‘Cuimi’. Through high-throughput amplicon sequencing, we characterized the bacterial and fungal communities in both cultivars before and after Xcc inoculation.

Results: The results revealed distinct shifts in microbial diversity, with bacterial community diversity largely maintained in resistant cultivars but significantly reduced in susceptible ones following Xcc infection. Conversely, fungal community richness decreased in both cultivars post-inoculation, with notable cultivar-specific changes in the relative abundance of key genera. Notably, Lysobacter emerged as the only bacterial genus that significantly increased in abundance in the resistant cultivar under pathogen pressure, highlighting its potential as a key biocontrol agent. Further, we identified several fungal genera, including Penicillium and Aspergillus, which proliferated in susceptible plants under pathogen pressure. The study also isolated and identified a Lysobacter antibioticus GJ-6 strain with potent antagonistic activity against Xcc, offering insights into its potential role in enhancing disease resistance.

Conclusions: This work provides a comprehensive understanding of how endophytic microbiomes differ between resistant and susceptible citrus cultivars, suggesting new avenues for developing sustainable biocontrol strategies to manage citrus canker. These findings underscore the potential of endophytes in mitigating plant diseases and advancing the application of microbiome-based interventions in agriculture.

1 Introduction

Citrus species are cultivated in more than 140 temperate and tropical countries worldwide. These economically vital crops are prized for their nutritional value, significant role in global trade, and diverse industrial applications across multiple sectors (Ma et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023). The citrus industry faces significant challenges from disease pressures, particularly citrus canker (Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri; Xcc), which has caused substantial production losses worldwide in recent years. This bacterial pathogen reduces fruit quality and yield while increasing management costs, creating economic burdens across the citrus value chain. The disease is caused by distinct pathotypes of Xanthomonas, with type A (X. citri subsp. citri) being the most aggressive, widespread, and economically damaging (Schaad et al., 2006). This pathotype, which is the only strain present in China, affects nearly all commercial citrus cultivars; however, the severity of the disease varies significantly among them. The pathogen affects multiple plant tissues, causing characteristic canker lesions on leaves, fruits, and stems. Severe infections lead to twig dieback, premature leaf and fruit abscission, and overall tree decline, ultimately resulting in significant yield reduction and quality deterioration (Ference et al., 2018).

Government statistics indicate that Guangxi, China, maintains 650,000 hectares of citrus cultivation, producing 1.9 billion kilograms annually, which accounts for 30% of the national output and 10% of global production as of 2023. Among the region’s key cultivars, ‘Orah’ mandarin (Citrus reticulata Blanco cv. ‘Orah’), a Temple × Dancy orange hybrid, ranks as one of China’s four major citrus varieties (Huang et al., 2022). However, this cultivar exhibits extreme susceptibility to citrus canker disease, often suffering severe yield losses and quality degradation upon Xcc infection (Qiu et al., 2022). In contrast, ‘Cuimi’ kumquat (Fortunella crassifolia Swingle cv. ‘Cuimi’), a high-value bud mutant of ‘Rongan’ kumquat indigenous to Guangxi (Liu et al., 2021b), displays notable tolerance. Although Xcc can infect all commercial citrus varieties, disease progression varies significantly among cultivars, with ‘Cuimi’ representing a rare example of partial resistance (Khalaf et al., 2011; Giraldo – González et al., 2021).

Currently, there is no complete cure for citrus canker disease. Disease control primarily relies on integrated strategies including: (1) strict quarantine measures to prevent pathogen spread, (2) removal and destruction of infected plant material, (3) cultivation of tolerant varieties, (4) chemical treatments, and (5) biological control methods (Naqvi et al., 2022). In commercial production, chemical pesticides remain the dominant control approach (Riera et al., 2018). Copper-based bactericides are widely used against various bacterial pathogens (Cervantes and Gutierrez-Corona, 1994; Izadiyan and Taghavi, 2024), while antibiotics such as streptomycin are also frequently employed (Stockwell and Duffy, 2012). Although judicious pesticide use can enhance plant disease prevention, overreliance on chemical controls poses significant risks. These include the emergence of resistant bacterial strains, phytotoxic effects on fruit surfaces, and environmental pollution (Graham et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2003; Behlau et al., 2020). Biocontrol methods for citrus canker have recently gained significant attention as an environmentally sustainable alternative to chemical treatments. These approaches offer multiple advantages, including effective disease suppression, reduced production costs, and minimized risk of pathogen resistance development (Qian et al., 2021; Ke et al., 2023).

However, critical challenges remain in achieving stable colonization and maintaining the long-term efficacy of biocontrol agents (Bonaterra et al., 2022), as identifying antagonistic microorganisms capable of thriving on the leaves of mature citrus trees has proven to be difficult (Ali et al., 2023). Endophytes, microorganisms residing within plant tissues without causing disease, are recognized as key players in plant health and pathogen resistance (Berg, 2009; Ali et al., 2023). Advances in high-throughput sequencing now allow for detailed profiling of these communities (Ahmed et al., 2025). However, the role of the entire endophytic microbiome (both bacteria and fungi) in conferring natural resistance to citrus canker remains poorly understood. While preliminary studies have identified differences in bacterial communities between asymptomatic and infected leaves (Adeleke et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2023) or noted Bacillus subtilis as a conserved species (Liu et al., 2021a), a controlled, comparative investigation of the microbiome in genetically resistant versus susceptible cultivars is lacking. Such a study is crucial for identifying microbial taxa and consortia directly associated with the host’s resistance phenotype.

Given the complex interplay of factors influencing plant endophytic communities, we hypothesized that the resistant cultivar ‘Cuimi’ would harbor a more resilient and responsive endophytic microbiome, which would undergo distinct, beneficial structural shifts upon Xcc challenge, potentially enriching for antagonistic bacteria. To test this, we employed a controlled experimental design using the susceptible ‘Orah’ and tolerant ‘Cuimi’ cultivars under uniform conditions. We systematically inoculated both cultivars with Xcc to: (1) characterize dynamic changes in leaf endophytic microbial communities pre- and post-inoculation, (2) elucidate differential responses of bacterial and fungal communities to pathogen challenge, and (3) furthermore, we aimed to isolate and identify key microbial taxa associated with the resistance phenotype, thus bridging correlation with function and providing a framework for developing targeted biocontrol strategies against citrus canke.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant material

One-year-old citrus seedlings were used in this study, including Citrus reticulata cv. ‘Orah’ (extremely susceptible cultivar) and Fortunella crassifolia cv. ‘Cuimi’ (highly tolerant cultivar). Plants were maintained in 30 × 30 cm pots containing 10 kg of soil at the experimental base of the Institute of Plant Protection, Guangxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Nanning, China (22°50’57”N, 108°14’38”E). Three weeks before experimentation, plants were pruned to synchronize young leaf development. During June 2024, plants were maintained under controlled greenhouse conditions: temperature, 28°C ± 2°C; relative humidity, 80% ± 10%; and photoperiod, 14 h light/10 h dark (Giraldo – González et al., 2021).

2.2 Bacterial strain and culture conditions

The experiment utilized strain YSPT, a highly virulent Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri (Xcc) isolated from Guangxi, which demonstrates greater virulence than the reference strain Xcc 306 (de Oliveira et al., 2016). The strain was maintained in nutrient broth (NB) medium or on nutrient agar (NA) plates (tryptone 5 g/L, sucrose 10 g/L, beef extract 3 g/L, yeast extract 1 g/L, and pH 7.0; for NA, agar 15 g/L) at 28°C (Teper et al., 2020). Liquid cultures were initiated from isolated colonies on plates and grown under shaking (160 rpm) for 24 h. After growth, the cultures were adjusted to an optical density (OD600nm) of 0.6 (108 CFU/mL) using sterile distilled water, as measured with the aid of a spectrophotometer (Saldanha et al., 2022).

2.3 Inoculation of bacterial strain, experimental conditions, and symptoms observation

Leaf inoculation was performed using a modified hand-held syringe infiltration method. For each treatment, 10 µL of either sterile NB or Xcc suspension (OD600nm = 0.6) was slowly infiltrated by pressing a needleless syringe tip against the abaxial leaf surface while applying gentle counter-pressure with a finger on the opposite side, creating a characteristic water-soaked infiltration zone. Three infiltration sites were established per leaf, one on each side of the midvein. Four experimental treatments were implemented: (1) WGC (Orah + NB control), (2) JJC (Cuimi + NB control), (3) WGT (Orah + Xcc), and (4) JJT (Cuimi + Xcc). The experimental design consisted of three biological replicates per treatment, with three plants per replicate (totaling 36 plants) and eight inoculated leaves per plant, maintaining consistent developmental stages across all samples. Disease symptoms were monitored daily following inoculation. At three days post-inoculation (3-dpi), which was determined to be the point where symptoms were fully developed and clearly distinguishable between cultivars, representative leaves from each plant and treatment were photographed.

2.4 Sample collection

Leaf samples were collected at 3-dpi when characteristic disease symptoms became apparent. This time point was selected for microbiome analysis to capture the early, dynamic shifts in the endophytic communities in direct response to pathogen challenge, before extensive tissue necrosis could irreversibly alter the microbial niche. For sequencing, four symptomatic leaves from each plant were harvested and pooled to form a single composite sample per biological replicate. These pooled samples were then subjected to a rigorous surface sterilization protocol: initial 30-second rinse in sterile distilled water, followed by sequential immersion in 70% ethanol (30 seconds), 2.5% NaClO solution containing 0.1% Tween 80 (30 seconds), and a final 70% ethanol wash (15 seconds). Between each sterilization step, leaves were thoroughly rinsed three times with sterile distilled water to remove residual disinfectants. The efficacy of the surface sterilization was validated by plating 100 µL of the final sterile distilled water rinse onto NA and potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates. No microbial growth was observed after 48–72 hours of incubation at 28°C, confirming the removal of surface epiphytes. Using sterile scissors, petioles were aseptically trimmed before placing the leaves in pre-labeled screw-cap tubes. The samples were immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C to preserve nucleic acid integrity until DNA extraction was performed. The remaining symptomatic leaves from different treatments were collected, labeled accordingly, and directly stored at 4°C for endophyte isolation.

2.5 DNA extraction and amplicon sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted from surface-sterilized leaf samples using the E.Z.N.A.® Plant DNA isolation kit (Omega Bio-Tek) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA quality was assessed through dual approaches: concentration and purity (A260/A280 ratio) were measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific), while integrity was verified by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels (Li et al., 2025). For bacterial community analysis, the V5-V7 hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified using barcoded primers 799F (5’-barcode-AACMGGATTAGATACCCKG-3’) and 1193R (5’-ACGTCATCCCCACCTTCC-3’) (Liu et al., 2020). Fungal communities were characterized by amplifying the ITS1 region with primers ITS1F (5’-barcode-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3’) and ITS1R (5’-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3’) (Liang et al., 2020). PCR amplification was performed in triplicate 20 μL reactions containing: 4 μL 5× FastPfu Buffer, 2 μL 2.5 mM dNTPs, 0.8 μL each primer (5 μM), 0.4 μL FastPfu Polymerase, and 10 ng template DNA. The thermal cycling protocol consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 29 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s, and finally a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. PCR amplicons were size-selected on 2% agarose gels and purified using the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences). After quantification using the Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen), equimolar concentrations of uniquely barcoded amplicons (24 samples per pool) were combined for library preparation. The pooled amplicons were processed into an Illumina-compatible paired-end library following the manufacturer’s genomic DNA library preparation protocol. Final sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq platform (2 × 250 bp chemistry; Shanghai BIOZERON Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China).

2.6 Processing of sequencing data

Raw paired-end sequences obtained from Illumina MiSeq sequencing underwent rigorous quality control and processing. Initial processing included: (1) read merging using FLASH v1.2.11 with default parameters, followed by (2) quality trimming with Trimmomatic v0.36 (sliding window: 4 bp; minimum quality score: 20) (Magoč and Salzberg, 2011; Bolger et al., 2014). Chimeric sequences were identified and removed using UCHIME v8.1 through de novo detection (Edgar et al., 2011). High-quality sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a 97% similarity threshold using the UPARSE pipeline (v7.0.1090), with singletons excluded from downstream analysis (Edgar, 2013). Taxonomic classification was performed using the RDP Classifier v2.2 with Bayesian algorithm (confidence threshold: 0.8), utilizing the following reference databases: (1) SILVA release 138 for bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences, and (2) UNITE v8.2 for fungal ITS region annotation (Kõljalg et al., 2005; Quast et al., 2012). After taxonomic classification, OTUs were filtered with the “filter_pollution()” function using “microeco package” in R (v.4.2.1) to remove mitochondrial and chloroplast sequences for subsequent microbial diversity analysis.

2.7 Bioinformatics and statistical analyses

Microbial community analyses were performed using QIIME 2 to calculate alpha diversity indices (Chao1, ACE, Shannon, and Simpson) and beta diversity based on Bray-Curti’s dissimilarity matrices (Bolyen et al., 2019) (Yang et al., 2023b). Significant differences in alpha diversity among treatments were assessed using Duncan’s multiple range test (P < 0.05) implemented in the “multcomp” package (R v.4.2.1). Beta diversity patterns were statistically evaluated through permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) using the adonis() function (“vegan” package, 999 permutations) in R (Anderson and Walsh, 2013). Visualization of results was achieved using R packages: boxplots for alpha diversity indices (“ggplot2”), principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plots for beta diversity (“vegan”), and relative abundance bar plots at phylum/order levels using an R script (Ahmed et al., 2022). Rarefaction curves at the OTU level were generated to assess the adequacy of sequencing depth. Differential abundance analysis at the genus level was performed using Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.05, “multcomp” package), with results displayed as heatmaps of the top 30 species (“ggplot2”). For biomarker identification, we conducted linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) (Han et al., 2020) with a two-stage approach: (1) Kruskal-Wallis sum-rank test (P < 0.05) to detect significant abundance differences, followed by (2) linear discriminant analysis (LDA score > 2.5) to estimate effect sizes of differentially abundant taxa (Ijaz et al., 2018).

2.8 Isolation of the endophytes

According to the data analyses, key endophytic bacteria were isolated from non-inoculated regions of symptomatic leaves in the JJT (Cuimi + Xcc) treatment. The citrus leaves reserved for the isolation experiment were first rinsed with tap water, and diseased portions were removed. Next, surface sterilization was performed according to the procedure described above. After that, 5 mL of sterile water was added to a sterile mortar, and the leaves (approximately 0.5g) were processed into a homogenate, which was then kept at 28°C and 160 rpm for 30 minutes. The resulting slurry was collected and diluted into three different concentration gradients: 10−2, 10−3, and 10−4. A 100 μL sample from each dilution was spread onto King’s B (KB) medium and incubated at 28°C for 48 hours. After incubation, individual colonies with distinct morphological characteristics were picked from the plates. The strains were purified using the streak-plate technique, assigned numbers, and preserved at −20°C for later use.

2.9 Assessment of antibacterial activity of isolated bacterial strains against Xcc

The antibacterial activity of the isolated bacterial strains was evaluated against the Xcc strain 306. This well-characterized reference strain was selected for the in vitro assay to facilitate standardization and future comparisons with other studies. The assay was performed using the Oxford cup method. Initially, a 100 μL aliquot of strain 306 suspension (OD600nm = 0.5; 108 CFU/mL) was spread evenly onto NA medium Petri plates. Subsequently, 100 μL of a culture of each isolated bacterial strain (OD600nm = 0.8; 10^8 CFU/mL) was added to the Oxford cups, while NB medium served as the negative control. The plates were incubated at 28°C for 48 h in a constant-temperature incubator. After incubation, the diameter of the inhibition zones was measured.

2.10 Identification and characterization of potent endophytic bacterial strain

2.10.1 Physiological and biochemical characterization

The bacterial strain exhibiting the most potent antibacterial activity was streaked onto KB agar and incubated at 28°C for 48 h to record morphological characteristics. Colony morphology, including color, texture (e.g., mucoid, dry, or smooth), surface appearance (shiny or dull), elevation, and margin (entire, undulate, or filamentous), was recorded. A single purified colony of the strain was streaked onto Biolog universal growth (BUG) media and incubated at 28°C for 24 h. The turbidimeter was zeroed using a sterile inoculating fluid, after which bacterial cells were collected from the colony surface with a sterile cotton swab and suspended in the inoculating fluid. The bacterial suspension was thoroughly mixed and adjusted to 90-98% turbidity. Subsequently, aliquots (100 µL) of the standardized suspension were dispensed into each well of a Biolog GENIII microplate. The plate was placed in a humidity chamber with moistened gauze and incubated at 28°C for 48 h. Phenotypic characterization was performed using the Microstation™ V4.01 (Biolog, Inc.).

2.10.2 Molecular identification

The genomic DNA of the antagonistic strain was extracted using a bacterial genome extraction kit (Tiangen Biotech). The 16S rDNA region was amplified via PCR using universal primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) (Zhang et al., 2022). The PCR products were purified and sent to Qingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. for Sanger sequencing. The obtained sequences were compared with the NT database at NCBI using BLASTn. Phylogenetic identification was performed using MEGA 12 with the Maximum-Likelihood method, and clade support was assessed through 1000 bootstrap replicates (Qiu et al., 2023). The primer pair phzNO1-F1 (5′-GTCGGAAGAAGAACGCCAGA-3′) and phzNO1-R1 (5′-ATAGTCGTTGGTGCAGACCG-3′) (Zhao et al., 2016) was used to amplify a 229-bp fragment specific to Lysobacter antibioticus. PCR reaction (25 μL) was conducted three times, containing 0.5 μL genomic DNA (50 ng/μL), 0.5 μL of each primer (10 μM/μL), 12 μL 2× EasyTaq PCR Supermix (TaKaRa), and 11.5 μL ddH2O. Amplification was performed with initial denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 52°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were electrophoresed at 4 V/cm on 1.2% agarose gels stained with SYBR Green I (10,000×; Solarbio Life Sciences) and visualized under UV light.

3 Results

3.1 Disease symptom assessment

The differential resistance of the two citrus cultivars to Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri (Xcc) was unequivocally demonstrated by the distinct symptomologies observed at three days post-inoculation (dpi; Supplementary Figure S1). In the susceptible ‘Orah’ cultivar (WGT treatment), Xcc inoculation resulted in severe disease symptoms characteristic of citrus canker. Infiltration sites developed into large, raised lesions with pronounced chlorosis (Supplementary Figure S1A). In contrast, the tolerant ‘Cuimi’ (JJT treatment) exhibited a markedly reduced symptomatic response. Infiltration sites developed only unraised and water-soaking lesions (Supplementary Figure S1B). Mock-inoculated control leaves for both ‘Orah’ (Supplementary Figure S1C) and ‘Cuimi’ (Supplementary Figure S1D) remained completely asymptomatic, confirming that the developed symptoms were solely due to Xcc infection.

3.2 Sequencing and assembly

A total of 12 leaf samples were analyzed using the Illumina MiSeq platform for 16S and ITS amplicon sequencing, yielding 454,199 (average: 37,850 per sample) and 460,564 (average: 38,380 per sample) sequences, with average lengths of 378 bp and 255 bp, respectively (Supplementary Table S1). The sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% similarity for taxonomic classification, resulting in a total of 1272 bacterial and 775 fungal OTUs across the entire dataset. The sequencing data demonstrated validity and reliability for microbial diversity analysis. Rarefaction curves generated from the 12 samples confirmed that a sufficient number of reads were obtained to assess bacterial and fungal richness under all treatment conditions, indicating robust coverage of microbial communities (Supplementary Figure S2).

3.3 Alpha diversity analysis of endophytic microbial community

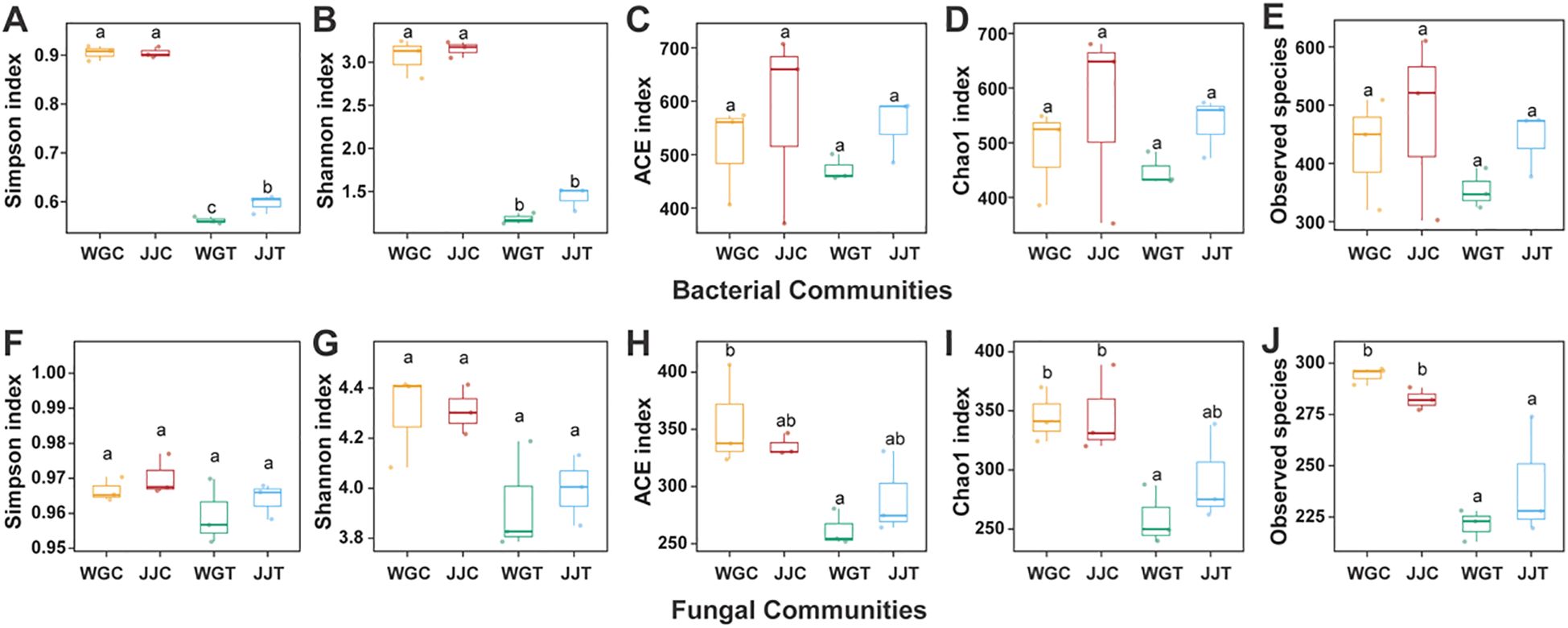

The within-sample diversity (α-diversity) of microbial communities was evaluated using Chao1, ACE, Shannon, and Simpson indices at a 97% similarity threshold across different treatments (Figure 1; Supplementary Table S2). For bacterial communities, the Shannon and Simpson indices were significantly lower in non-inoculated treatments compared to those inoculated with Xcc (WGT and JJT). Notably, the susceptible variety (WGT) exhibited a more pronounced decline in these values than the tolerant variety (JJT), with a significant difference observed in the Simpson index (Figure 1). In contrast, no significant differences were detected in Chao1 and ACE indices among treatments. Fungal communities displayed a distinct trend in α-diversity. Unlike bacteria, neither the Shannon nor the Simpson indices differed significantly across treatments (Figure 1). However, the Chao1 and ACE indices were considerably higher in non-inoculated controls (WGC and JJC) than in Xcc-inoculated treatments (WGT and JJT). Overall, the differences in endophytic bacterial communities were primarily driven by diversity metrics (Shannon and Simpson indices), whereas variations in fungal communities were mainly associated with richness indices (Chao1 and ACE).

Figure 1. Alpha diversity of leaf endophytic bacterial and fungal communities in resistant (Cuimi) and susceptible (Orah) citrus cultivars following inoculation with Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri (Xcc). Boxplots showing within-sample diversity indices for bacterial (A–E) and fungal (F–J) communities. Treatments are: WGC (C. reticulata ‘Orah’ control), JJC (F. crassifolia ‘Cuimi’ control), WGT (Orah + Xcc), JJT (Cuimi + Xcc). (A, F) Simpson index. (B, G) Shannon index. (C, H) ACE index. (D, I) Chao1 index. (E, J) Observed species. Different lowercase letters above boxes indicate statistically significant differences among treatments, as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test (P < 0.05).

3.4 Beta diversity analysis of endophytic microbial community

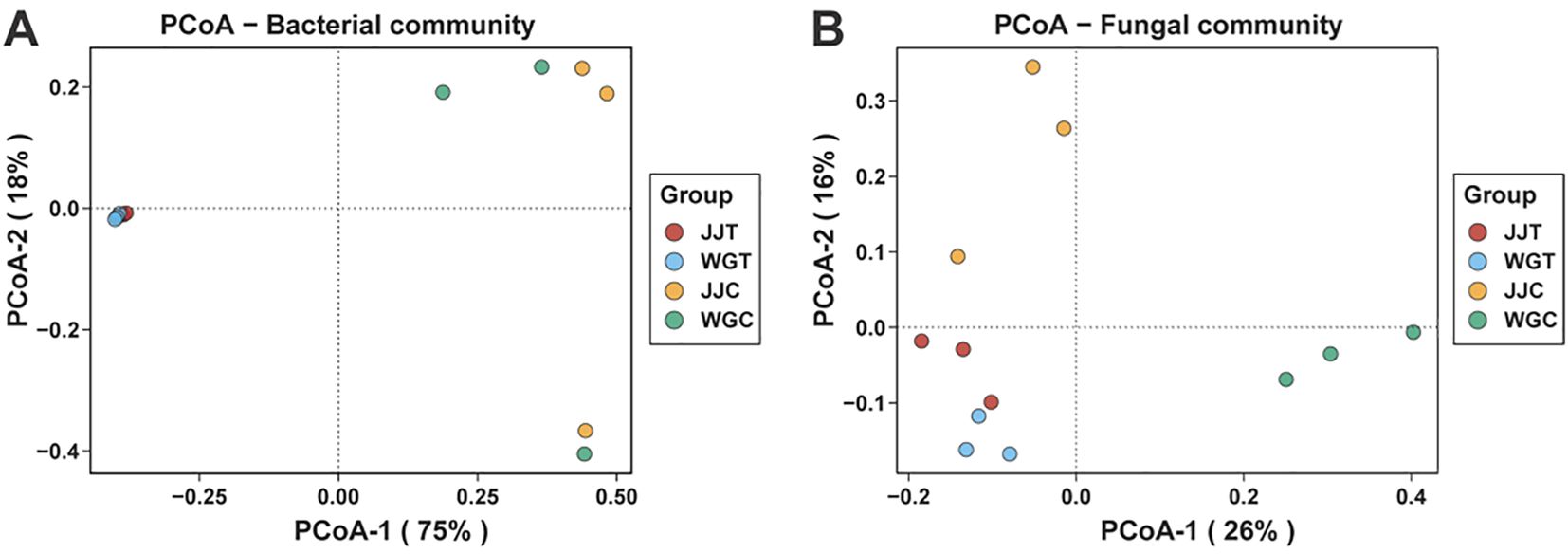

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curti’s dissimilarity was used to assess structural shifts in bacterial and fungal communities across treatments (Figure 2; Supplementary Table S3). The first two PCoA axes explained 75% (PC1) and 18% (PC2) of the variation in bacterial communities (Figure 2A), and 26% (PC1) and 16% (PC2) in fungal communities (Figure 2B). For bacterial communities, inoculated (Xcc-exposed: WGT, JJT) and non-inoculated (WGC, JJC) treatments showed clear separation (Figure 2A). The high variance explained by PC1 revealed subtle distinctions between WGC and JJC, as well as between WGT and JJT. Fungal communities exhibited pronounced dispersion across all treatments (Figure 2B). Specifically, WGT diverged from WGC along PC1, while JJT separated from JJC along PC2. PERMANOVA confirmed significant treatment effects on both bacterial (R² = 0.757, P < 0.01) and fungal (R² = 0.495, P < 0.001) community structures (Supplementary Table S3). These results demonstrate that Xcc invasion significantly alters the diversity and composition of endophytic microbiomes. Notably, bacterial and fungal communities responded differently, consistent with alpha diversity trends, suggesting distinct ecological adaptation mechanisms.

Figure 2. Beta diversity of leaf endophytic microbial communities in response to Xcc infection. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plots based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, illustrating the structural differences in bacterial (A) and fungal (B) community composition among treatments. Treatments are: WGC (C. reticulata cv. ‘Orah’ control), JJC (F. crassifolia cv. ‘Cuimi’ control), WGT (Orah + Xcc), and JJT (Cuimi + Xcc).

3.5 Differential abundance and community composition at the phylum and order level

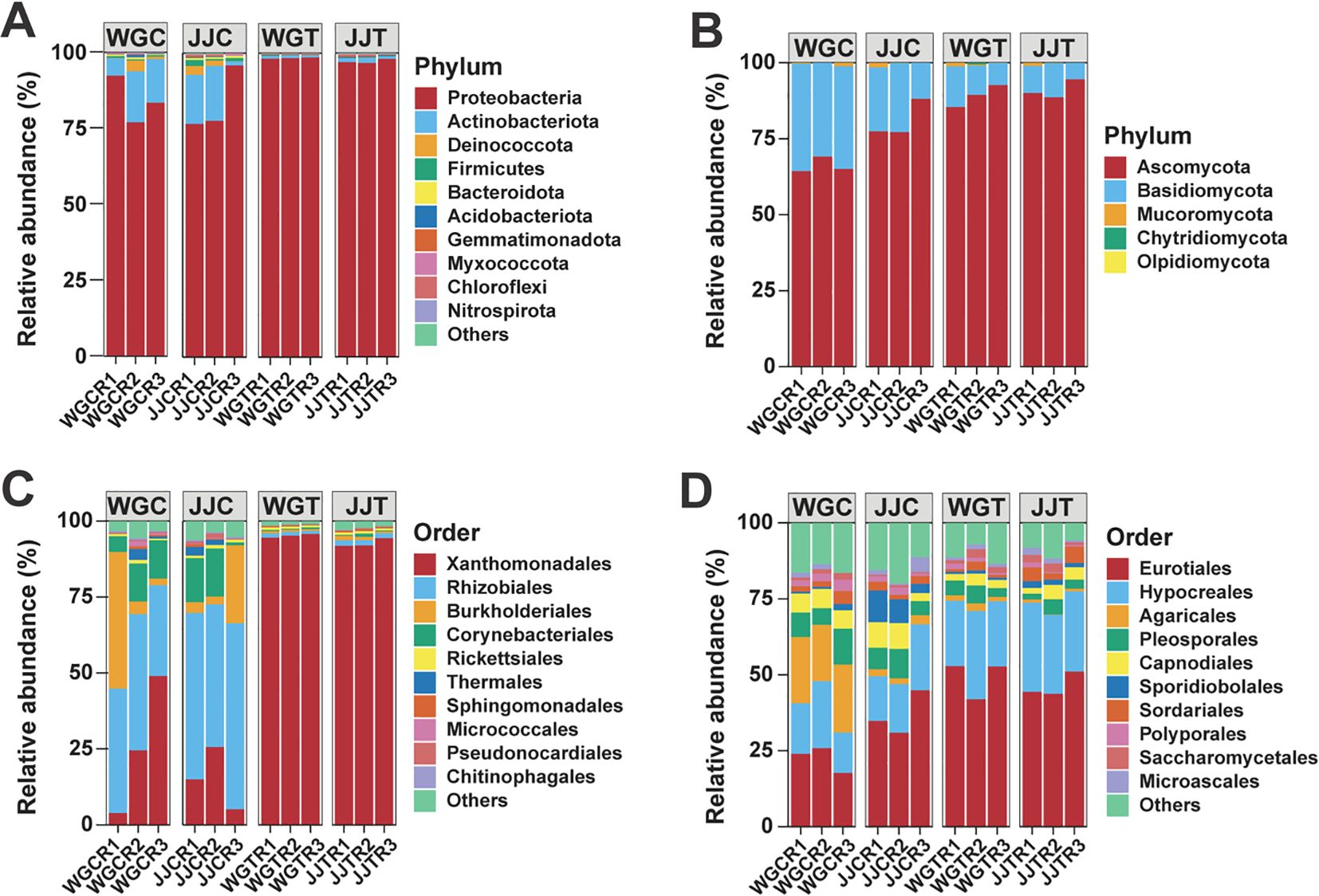

The overall structure of the endophytic communities at the phylum and order levels is shown in Figure 3. Phyla such as Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria dominated bacterial communities, while fungal communities were primarily composed of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota (Figures 3A, B; Supplementary Table S4). At the order level, Xanthomonadales, Rhizobiales, and Burkholderiales were the most abundant bacteria, and Eurotiales, Hypocreales, and Agaricales were the most abundant fungi (Figures 3C, D; Supplementary Table S5).

Figure 3. Taxonomic composition of leaf endophytic bacterial and fungal communities. Bar plots show the relative abundance of the top 10 most abundant bacterial (A) and fungal (B) phyla, and bacterial (C) and fungal (D) orders across the different treatments. Treatments are: WGC (C. reticulata cv. ‘Orah’ control), JJC (F. crassifolia cv. ‘Cuimi’ control), WGT (Orah + Xcc), and JJT (Cuimi + Xcc). All other taxa are summarized in the “Others” category. The total relative abundance of the presented taxa is indicated for each panel.

3.6 Key taxonomic differences identified by LEfSe

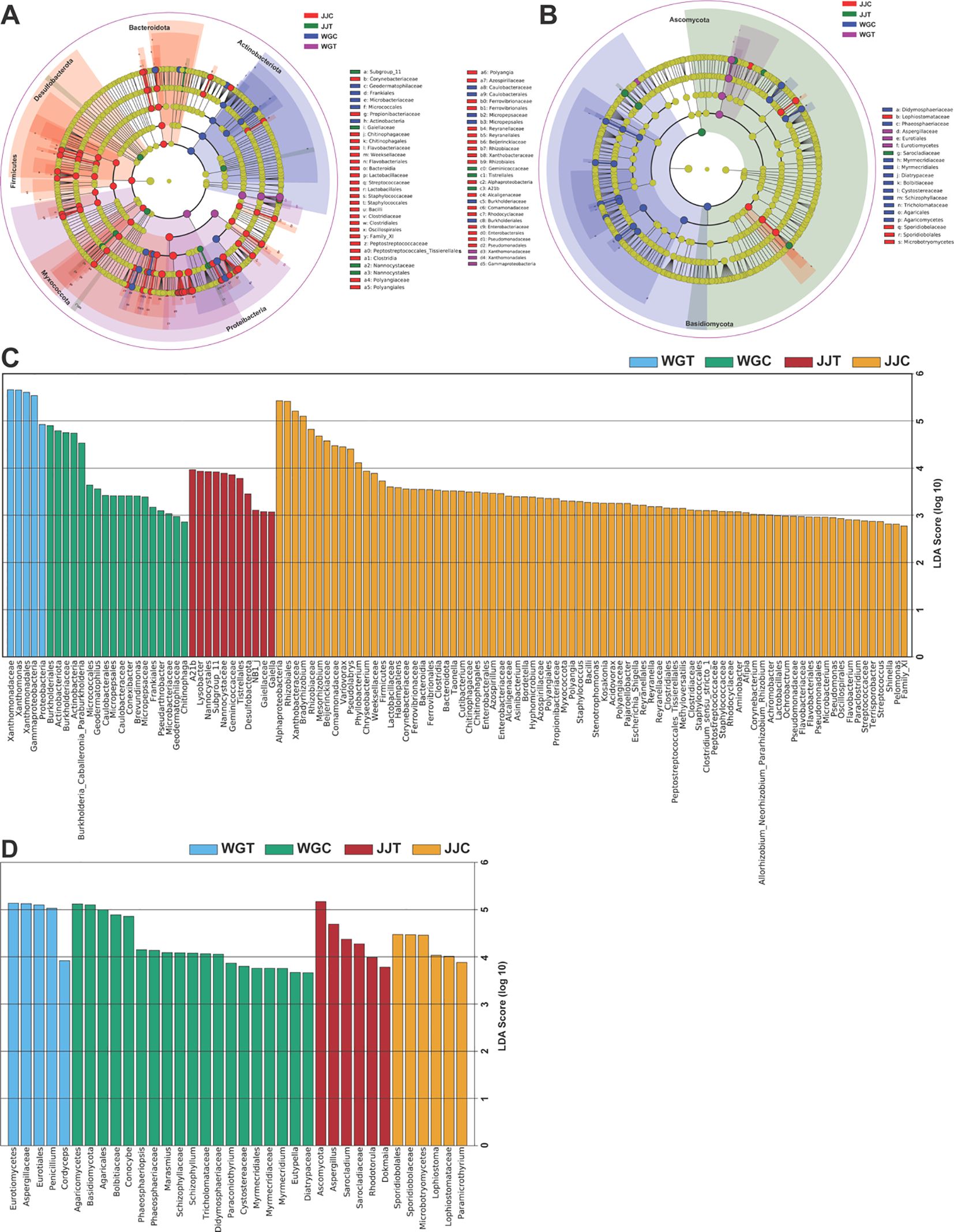

To identify the specific taxa that were statistically significant biomarkers of each treatment, we employed LEfSe analysis (Kruskal-Wallis sum-rank test, p < 0.05), with linear discriminant analysis (LDA > 2.5) quantifying effect sizes (Figure 4; Supplementary Tables S6, S7). Bacterial communities showed significant differences in 5 (WGT), 18 (WGC), 11 (JJT), and 80 (JJC) taxa (Figure 4A). In contrast, fungal communities exhibited differences in 5 (WGT), 19 (WGC), 6 (JJT), and 6 (JJC) taxa (LDA > 2.5, p < 0.05; (Figure 4B). These results demonstrate that Xcc invasion suppresses bacterial diversity in both tolerant and susceptible varieties, with the tolerant variety maintaining more biomarkers both before and after inoculation. In susceptible plants (WGT), Xcc enrichment was observed across multiple taxonomic levels (Proteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, Xanthomonadales, Xanthomonadaceae, and Xanthomonas) (Figure 4C; Supplementary Table S6). In contrast, the tolerant variety (JJT) was characterized by 11 biomarker taxa. Among these, the genus Lysobacter was identified as a key biomarker, and non-inoculated treatments were characterized by Burkholderiales (9 taxa in JJC; 3 in WGC). Fungal communities exhibited a distinct pattern. The susceptible variety (WGT) was characterized by a high-abundance consortium of biomarkers, including Penicillium and Aspergillus, whereas the tolerant variety (JJT) was primarily defined by Aspergillus alone (Figure 4D; Supplementary Table S7). Notably, the number of fungal biomarkers identified for the tolerant cultivar was consistent between its control (JJC) and inoculated (JJT) states (6 taxa each). In contrast, the susceptible cultivar showed a reduction in biomarkers post-inoculation (from 19 in WGC to 5 in WGT). This suggests a more resilient fungal community structure in the tolerant cultivar, which maintained a consistent level of taxonomic distinction despite the significant community shifts confirmed by beta diversity analysis.

Figure 4. Identification of microbial biomarkers distinguishing treatment groups using LEfSe analysis. Cladograms (A, B) and histograms of Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) scores (C, D) for bacterial (A, C) and fungal (B, D) communities. The cladograms illustrate the phylogenetic distribution of significant taxa, where colored nodes indicate taxa that are statistically significant biomarkers in the corresponding colored treatment group. Gray nodes represent non-significant taxa. The LDA score histograms (C, D) illustrate the effect size of biomarkers with an LDA score greater than 2.5 (Kruskal-Wallis test, p < 0.05) for each treatment. Treatments are: WGC (C. reticulata cv. ‘Orah’ control), JJC (F. crassifolia cv. ‘Cuimi’ control), WGT (Orah + Xcc), and JJT (Cuimi + Xcc).

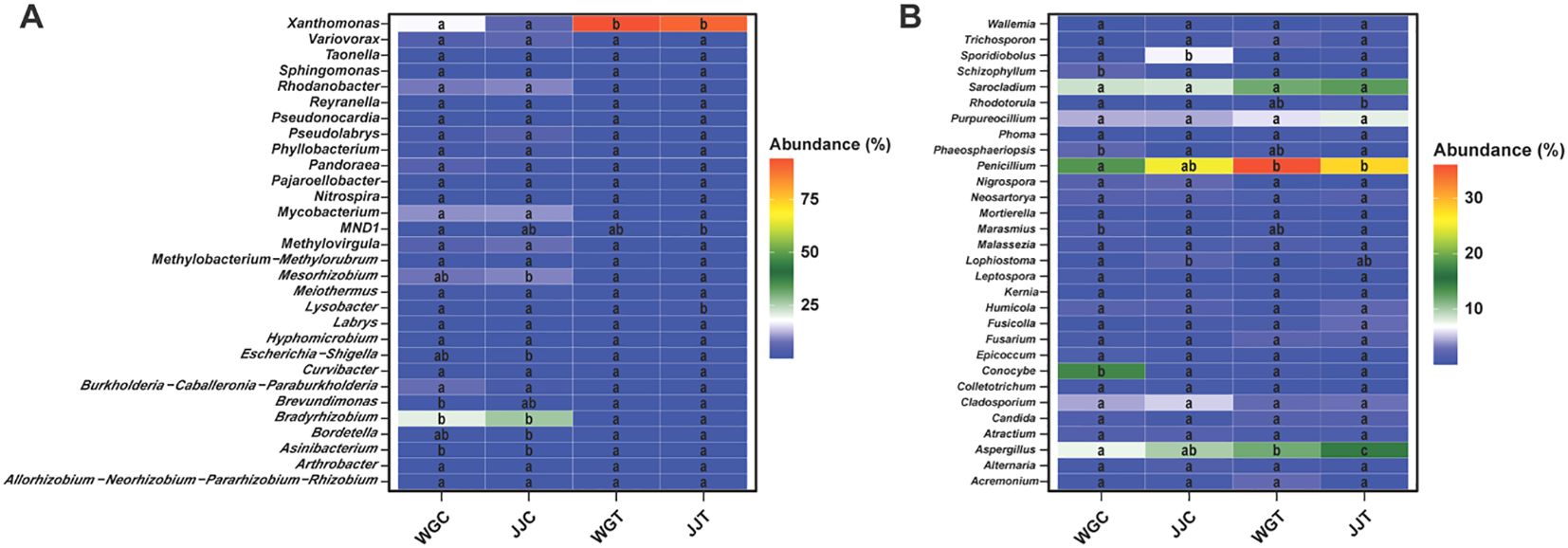

3.7 Key microbial genera differentiate treatment responses

The relative abundance patterns of the 30 most dominant genera further illustrated the community-wide reshuffling induced by Xcc invasion (Figure 5; Supplementary Tables S6, S7). The top 30 bacterial genera represented 94.66% of the total relative abundance (RA), with Xanthomonas (51.94%) and Bradyrhizobium (12.17%) being the most dominant (Supplementary Table S8). The heatmap visualization confirmed the LEfSe results, showing a massive increase in Xanthomonas RA in inoculated plants and a notable increase in Lysobacter in the tolerant JJT treatment (Figure 5A; Supplementary Table S8). Furthermore, it revealed a dramatic suppression of putative beneficial genera, such as Bradyrhizobium, Asinibacterium, and Mesorhizobium, in both cultivars following inoculation. A similar restructuring was observed in the fungal community. LEfSe identified Penicillium and Aspergillus as key biomarkers for the susceptible inoculated cultivar (WGT), while only Aspergillus was a significant biomarker for the tolerant inoculated plants (JJT). The heatmap of the top 30 fungal genera (representing 83.09% of total RA) confirmed these patterns, showing a cultivar-dependent response for Penicillium, which surged in the susceptible cultivar ‘Orah’ (WGT) but remained stable in the tolerant ‘Cuimi’ (JJT) (Figure 5B; Supplementary Table S9). In contrast, Aspergillus RA increased significantly in both cultivars under pathogen pressure. Notably, 26 of the 30 dominant fungal genera are classified as saprophytes or secondary pathogens, suggesting their proliferation may accelerate tissue senescence and indirectly promote canker progression. Collectively, these analyses demonstrate that Xcc invasion markedly reshapes endophytic community composition. The distinct, cultivar-specific responses of key genera, such as Lysobacter and Penicillium, as identified by LEfSe, underscore their potential critical roles in host-microbe interactions during pathogen challenges.

Figure 5. Heatmap analysis of dominant endophytic bacterial and fungal genera. The relative abundance (Z-score scaled) of the top 30 most abundant bacterial (A) and fungal (B) genera across the different treatments. Treatments are: WGC (C. reticulata cv. ‘Orah’ control), JJC (F. crassifolia cv. ‘Cuimi’ control), WGT (Orah + Xcc), and JJT (Cuimi + Xcc). The color gradient from blue to red indicates low to high relative abundance, respectively. Genera showing significant differences in abundance among treatments (Tukey’s HSD test, p < 0.05) are included.

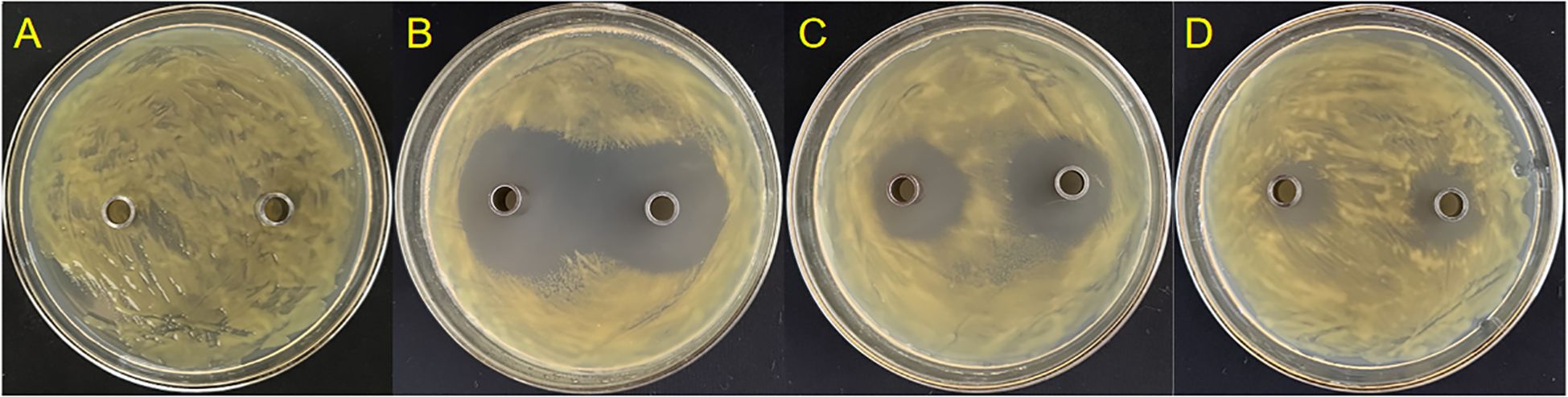

3.8 Screening of potent antibacterial strain

Three endophytic bacteria, suspected to be Lysobacter strains, were successfully isolated and purified from stored leaf samples. Strain GJ-6 exhibited the most potent antagonistic activity against Xcc. Bioassay results demonstrated that the original concentration of GJ-6 fermentation broth produced a pronounced inhibition zone, measuring 37.6 ± 0.1 mm (± SD), against Xcc, indicating superior antibacterial efficacy compared to other isolates (GJ-11 and GJ-14) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. In vitro antagonistic activity of endophytic bacterial isolates against Xcc. (A) Negative control (CK) showing no inhibition zone. (B) Strain GJ-6 exhibited a potent and clear inhibition zone (37.6 ± 0.1 mm in diameter). (C) Strain GJ-11 shows a smaller inhibition zone. (D) Strain GJ-14 shows weak or no antagonistic activity. The antibacterial activity was assessed using the Oxford cup method on nutrient agar plates. The diameter of the clear zone around the cup indicates the strength of antagonism against the lawn of Xcc strain 306.

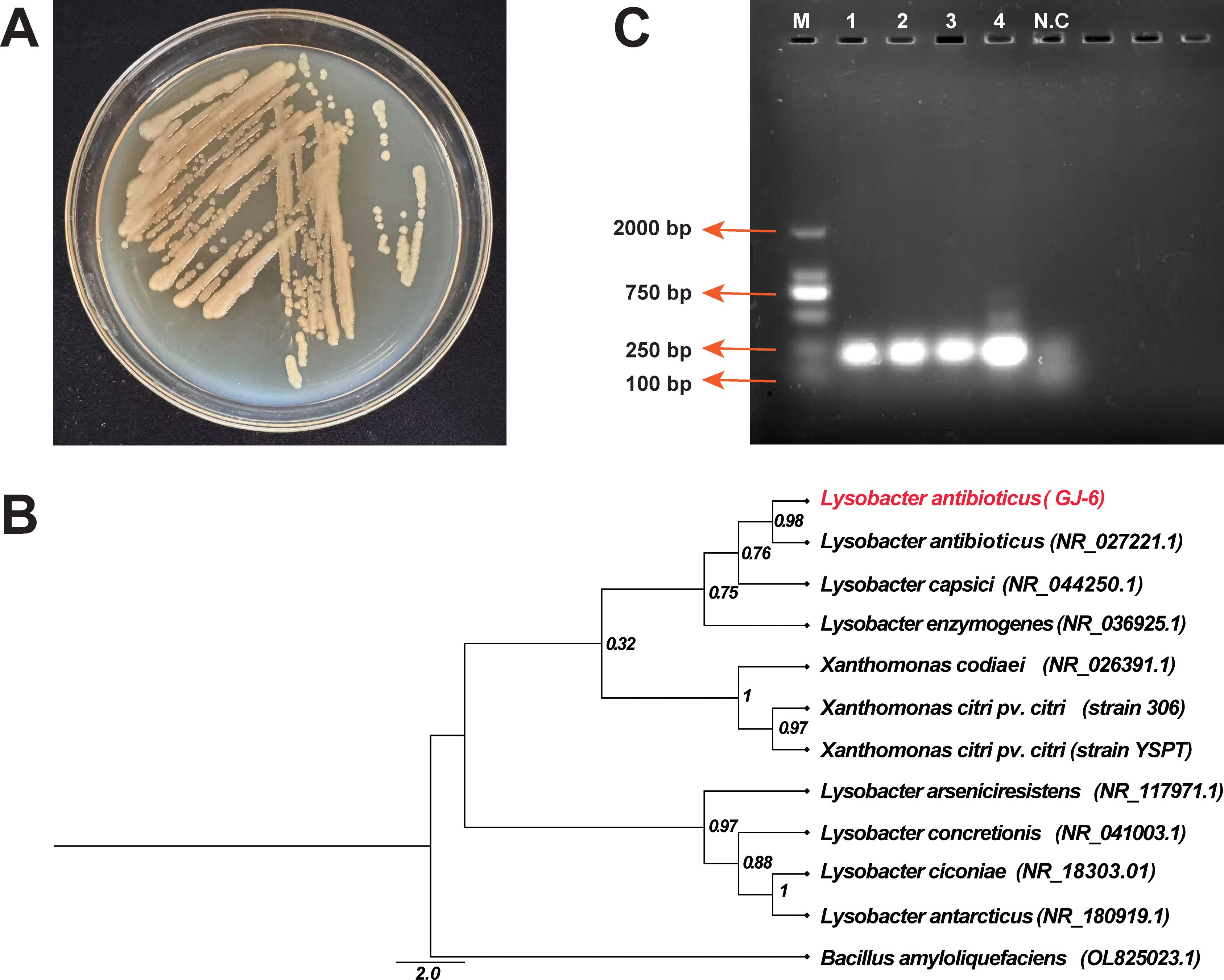

3.9 Identification and characterization of the biocontrol strain Lysobacter antibioticus GJ-6

3.9.1 Physiological and biochemical characteristics of GJ-6

After 48 hours on KB medium, strain GJ-6 formed round, light-yellow, smooth, moist, mucoid colonies with a shiny surface, central elevation, and entire margins. With further incubation, their color gradually intensified (Figure 7A). Ninety-four phenotypic traits (71 carbon/nitrogen utilization and 23 chemical sensitivity tests) were evaluated using the Biolog platform (Supplementary Table S10). The results demonstrated that GJ-6 could actively utilize 30 substrates, including D-maltose, D-trehalose, α-D-lactose, D-mannose, D-fructose, D-glucose-6-phosphate, gelatin, L-arginine, L-aspartic acid, L-glutamic acid, citric acid, L-malic acid, and acetic acid. In contrast, it showed variable utilization of 35 other substrates and was unable to metabolize six substrates, including stachyose, inosine, D-sorbitol, D-serine, p-hydroxyphenylacetic acid, and α-ketoisobutyric acid. Among the 23 chemical sensitivity tests, GJ-6 showed no inhibition in the presence of 11 agents or conditions (e.g., pH 6, 1% NaCl, 1% sodium lactate, rifamycin SV, lincomycin, vancomycin, potassium tellurite, and aztreonam). However, it was clearly inhibited by seven agents (including pH 5, 4% NaCl, fusidic acid, minocycline, Niaproof 4, and sodium bromate) and exhibited borderline sensitivity to the remaining five. These metabolic features are consistent with the known characteristics of the genus Lysobacter.

Figure 7. Identification and characterization of the biocontrol strain Lysobacter antibioticus GJ-6. (A) Colony morphology of strain GJ-6 after 48 hours of growth on King’s B agar medium. (B) Maximum-Likelihood phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences, showing the relationship of strain GJ-6 (highlighted) to closely related Lysobacter type strains. Bootstrap values (based on 1000 replicates) are shown at the nodes. The scale bar indicates the number of nucleotide substitutions per site. (C) Molecular confirmation of L. antibioticus GJ-6 using species-specific phzNO1primers. Here, M = 2000 bp marker, 1-4 = PCR product of 229 bp containing genomic DNA of strain GJ-6, and N.C = Negative control (without DNA).

3.9.2 Molecular characteristics of GJ-6

Molecular identification via 16S rDNA sequencing (amplified 1370 bp fragment using primers 27F/1492R) revealed 99.85% similarity to Lysobacter antibioticus (NR_027221.1) in the NCBI database, with phylogenetic analysis further confirming L. antibioticus as the closest relative (Figure 7B). The 16S rRNA-based phylogeny delineated three clusters: one comprising plant-associated species (L. antibioticus, L. capsici, and L. enzymogenes), all known as biocontrol agents; a distinct clade containing the pathogen Xcc, clearly separated from GJ-6; and a third cluster of environmentally derived Lysobacter species (L. antarcticus, L. ciconiae, and L. arseniciresistens). Strain-specific PCR using phzNO1 primers amplified a 229 bp fragment (Figure 7C), confirming phenazine biosynthesis genes in GJ-6 and correlating with its antimicrobial activity against Xcc, while also distinguishing L. antibioticus from related species (L. capsici, L. enzymogenes, etc.). Together, these results morphological, metabolic, phylogenetic, and genetic definitively identify strain GJ-6 as Lysobacter antibioticus and support its potential as a biocontrol agent.

4 Discussion

Citrus is a globally vital crop, with its production in China’s Guangxi Province being particularly significant to the agricultural economy. However, citrus cultivation is severely threatened by citrus canker, a devastating disease caused by Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri (Xcc) that leads to substantial economic losses (Fathi et al., 2024; Pena et al., 2024). While integrated management strategies exist, control still heavily relies on chemical pesticides, raising concerns about environmental impact, pathogen resistance, and cost. Despite the absence of complete genetic resistance in citrus, cultivars display a spectrum of susceptibility to Xcc, ranging from the highly susceptible ‘Orah’ mandarin to the partially resistant kumquat and calamondin (Chen et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2022). This variation highlights an opportunity to explore alternative control strategies. In this context, endophytes, resident plant microbes, have emerged as promising, sustainable resources for disease management (Islam et al., 2019). For instance, studies on kiwifruit canker have successfully linked distinct endophytic bacterial communities to host resistance, leading to the isolation of potential biocontrol agents like Lysobacter and Pseudomonas (Fu et al., 2024; Zheng et al., 2024). Despite these advances in other pathosystems, the role of the endophytic microbiome in conferring resistance to citrus canker remains poorly understood. Preliminary work in citrus suggests a correlation between endophytic bacteria and resistance, identifying Bacillus subtilis as a candidate (Liu et al., 2021a). However, a comprehensive understanding is lacking, particularly regarding the response of the entire microbial community, including the often-overlooked fungal endophytes, across cultivars with defined resistance phenotypes.

Plant microbiome homeostasis is crucial for maintaining plant health and preventing dysbiosis, a state of microbial imbalance associated with adverse outcomes (Paasch and He, 2021; Pfeilmeier et al., 2021). This equilibrium is shaped by a complex interplay of host genetics, pathogen characteristics, and environmental factors (Chen et al., 2020; Entila et al., 2024; Su et al., 2024). In our study, we standardized environmental and inoculation conditions to specifically isolate the influence of cultivar resistance on endophytic microbial responses to Xcc challenge. Furthermore, we used specific 16S rDNA primers to minimize host organelle contamination, ensuring an accurate profile of the endophytic bacteriome (Anguita-Maeso et al., 2022). Our results revealed that Xcc invasion triggered distinct responses in the bacterial and fungal communities. For bacteria, pathogen challenge significantly reduced diversity (Shannon and Simpson indices), while leaving richness (Chao1 and ACE indices) largely unaffected. This suppression of bacterial diversity is supported by PCoA, which showed clear separation between infected and non-infected plants, and aligns with previous findings in citrus canker pathosystems (Zhou et al., 2023). However, we assumed that the direct infiltration of a high Xcc biomass might be the primary driver of the bacterial community separation observed along PC1 (75% of variance). Future long-term studies are needed to determine if this effect is due solely to the high inoculum of Xcc or to Xcc ability to actively alter the host bacteriome.

In contrast, the fungal community responded differently. Pathogen invasion primarily reduced community richness, as indicated by PcoA, which revealed a distinct restructuring post-inoculation. This divergent response between the bacterial and fungal kingdoms underscores their unique ecological roles and adaptation mechanisms during pathogen stress, a phenomenon observed in other pathosystems, such as maize stalk rot (Xia et al., 2024). An important consideration in interpreting the bacterial diversity results is the method of pathogen inoculation. The syringe infiltration technique, while ensuring synchronized and high-efficiency infection for comparative purposes, introduces a substantial and immediate biomass of Xcc directly into the apoplast. This artificial input drastically alters community evenness, a key component of diversity indices such as the Shannon and Simpson indices. Therefore, the pronounced reduction in these indices in inoculated plants is likely driven by a combination of the pathogen’s biological activity and its direct physical introduction. While this method effectively standardizes infection and reveals how a massive pathogen challenge disrupts a resident microbiome, it does not fully recapitulate the more gradual, natural infection process initiated through stomata or wounds. Future studies aiming to investigate microbiome dynamics under conditions mimicking natural epidemics more closely would benefit from alternative methods, such as spray inoculation, which avoids the direct biomass confounder and allows for the observation of community shifts during the pathogen’s initial colonization and invasion phases.

Taxonomic composition analysis revealed distinct community structures for bacteria and fungi. The bacterial community was dominated by Proteobacteria (90.82%) and Actinobacteria (6.54%), primarily comprised of the orders Xanthomonadales (57.22%), Rhizobiales (23.97%), and Burkholderiales (7.34%). Fungal communities were primarily composed of Ascomycota (81.86%) and Basidiomycota (17.62%), with Eurotiales (38.73%), Hypocreales (21.52%), and Agaricales (6.45%) as the predominant orders. As expected, a marked increase in the relative abundance of Xanthomonas at the genus level directly confirmed successful Xcc colonization, validating previous culture-based findings (Teper et al., 2020). Our results revealed contrasting patterns, with genera often cited as key biocontrol agents against citrus canker (Sudyoung et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2023a). The relative abundance of Bradyrhizobium was dramatically reduced in the community profiles of both susceptible (from 20.55% to 0.53%) and tolerant (from 26.78% to 0.80%) cultivars following inoculation. However, future studies utilizing absolute quantification methods (e.g., qPCR) are needed to conclusively determine the population dynamics of Bradyrhizobium and other taxa during infection. Furthermore, other putative biocontrol genera like Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and Streptomyces were absent among the dominant taxa in our experimental setup, potentially due to the strong selective pressure of direct Xcc inoculation. Notably, Lysobacter emerged as the most prominent bacterial genus, exhibiting a significantly increased abundance in tolerant varieties under pathogen pressure. It is important to note that LEfSe identified a consortium of enriched taxa in the tolerant cultivar, with Lysobacter being the most notable at the genus level due to its well-established biocontrol function. This cultivar-specific response suggests a potential functional role in the resistance mechanism. This finding is strongly supported by well-documented evidence of Lysobacter’s biocontrol capabilities. For instance, both L. antibioticus and L. gummosus exhibit antagonism against xanthomonads (Expósito et al., 2015), and L. antibioticus is known to produce phenazine antibiotics, such as myxin, which have broad-spectrum activity against various Xanthomonas pathogens (Zhao et al., 2016). Beyond direct antagonism, L. antibioticus can also enhance plant disease resistance by modulating the associated microbiome (Chen et al., 2025). Collectively, this evidence positions Lysobacter as a critical defensive component in the tolerant citrus cultivar, likely operating through both direct pathogen inhibition and indirect plant-mediated protection.

Among the dominant fungal genera identified, a significant proportion (26 out of 30) are documented as saprophytes or pathogens associated with senescent tissues (Jayasekara et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2024). These opportunistic fungi, including Penicillium, Aspergillus, Sarocladium, Purpureocillium, and Cladosporium, exhibited distinct responses to Xcc infection. The most abundant genus, Penicillium, displayed a clear cultivar-dependent dynamic, with its relative abundance surging from 13.11% to 36.04% in the susceptible ‘Orah’ but remaining stable in the tolerant ‘Cuimi’ (25.14% to 27.95%). In contrast, Aspergillus increased significantly in both cultivars under pathogen pressure (Perrone et al., 2007; Grantina-Ievina et al., 2013). The differential behavior of these fungi highlights how host resistance modulates their proliferation during pathogen challenge. The well-documented roles of Penicillium species (e.g., P. digitatum, P. italicum) in causing postharvest rot (Bullerman, 2003), and Aspergillus (e.g., A. niger, A. flavus) as an opportunistic pathogen (Lugauskas and Stakeniene, 2002; Bamba and Sumbali, 2005; Marino et al., 2009), are consistent with our findings. We propose that these endophytic fungi are not merely present but likely exacerbate the severity of citrus canker. The cultivar-specific explosion of Penicillium in susceptible plants, coupled with the universal increase in Aspergillus, suggests they exploit the physiological weakness induced by Xcc. This likely accelerates leaf senescence and compromises tissue integrity, potentially creating a damaging feedback loop that facilitates further disease progression (Juybari et al., 2019; Nicoletti, 2019; Sadeghi et al., 2019). To identify microbial taxa associated with each treatment, we performed LEfSe analysis, which revealed distinct biomarker signatures (Liang et al., 2023). Xanthomonas, Penicillium, and Aspergillus were identified as key biomarkers for the susceptible cultivar under disease pressure. At the same time, Lysobacter and Aspergillus were identified as biomarkers for the resistant, inoculated cultivar, whereas the non-inoculated controls were characterized by Burkholderiales. This analysis provides a robust, two-dimensional validation of our findings: Penicillium is highlighted as a primary fungal indicator of susceptibility in ‘Orah’, whereas Lysobacter is strongly associated with the resistance of ‘Cuimi’ (Han et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2022). The concurrent enrichment of Aspergillus as a biomarker in both cultivars, albeit represented by distinct OTUs, suggests a universal stress response to Xcc infection within this genus. This indicates that different Aspergillus lineages, potentially with varying saprophytic or opportunistic pathogenic capabilities, proliferate in the distinct physiological environments of susceptible and tolerant hosts (Huang et al., 2023).

The biocontrol efficacy of L. antibioticus is underpinned by a diverse arsenal of antagonistic mechanisms. Beyond the production of well-characterized phenazine antibiotics, this genus also synthesizes other bioactive metabolites, such as p-aminobenzoic acid, which disrupts pathogenicity in Xanthomonas by compromising membrane integrity, inhibiting motility, and suppressing biofilm formation (Jiang et al., 2023). Our previous work has systematically detailed a multi-target mode of action for its phenazines, which includes disrupting quorum sensing, inhibiting biofilm and EPS production, impairing flagellar synthesis, and compromising cell membrane integrity (Liu et al., 2022). The optimization of fermentation processes has further enhanced the production of these inhibitory compounds, collectively establishing L. antibioticus strains as potent agents capable of suppressing pathogens through direct antimicrobial activity and virulence attenuation (Liu et al., 2021c). Successful biocontrol ultimately relies on a bacterium’s ability to achieve three key objectives: niche colonization, antimicrobial production, and/or induction of systemic resistance in the host (Bonaterra et al., 2022). Among these, the capacity to establish robust colonization within host tissues is a critical first step (Compant et al., 2010; Maurer et al., 2013). Therefore, our strategy of screening the native citrus endosphere for antagonistic strains, such as L. antibioticus GJ-6, is optimal for sustainable canker management (Poveda et al., 2021). This approach leverages microbes that are pre-adapted to the citrus environment, thereby increasing the likelihood of successful establishment and pathogen suppression while ensuring ecological compatibility. While our study provides strong correlative evidence and isolates a potent antagonistic strain, L. antibioticus GJ-6, a causal relationship between its in planta enrichment and the host’s resistance phenotype requires further validation. The logical next step to bridge this gap is a re-introduction experiment, where the susceptible ‘Orah’ cultivar is inoculated with strain GJ-6 and then challenged with Xcc. Determining whether GJ-6 can colonize the host and reduce disease severity to recapitulate a resistant phenotype is essential. Such a study, coupled with investigations into its colonization efficiency and potential to induce systemic resistance, will be critical to definitively establish causation and thoroughly evaluate the biocontrol potential of L. antibioticus GJ-6 against citrus canker.

5 Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into the differential responses of endophytic microbial communities in citrus cultivars with varying resistance to Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri infection. Our findings reveal that the pathogen significantly alters the microbial diversity in susceptible cultivars, particularly affecting bacterial and fungal communities. In contrast, tolerant cultivars exhibited less severe disruption to their microbial communities, characterized by the maintenance of bacterial diversity, including specific taxa such as Lysobacter, and a more restrained proliferation of opportunistic fungi under pathogen pressure. These shifts, observed in the context of a significantly stronger resistance phenotype in Cuimi, suggest that Lysobacter may play a pivotal role in the defense mechanisms of resistant citrus cultivars. Moreover, the study highlights the importance of endophytic microbiomes in influencing plant health and promoting pathogen resistance. The differential response of bacterial and fungal communities to Xcc infection underscores the complexity of host-microbe interactions and the potential of microbiome-based strategies for disease management. The identification of key microbial taxa associated with resistance provides a promising foundation for future research aimed at enhancing citrus resistance to X. citri through microbiome engineering or targeted biocontrol approaches. In conclusion, the results suggest that leveraging the native microbial communities in citrus could offer a sustainable alternative to chemical control methods for managing citrus canker. Further exploration of the identified taxa and their biocontrol mechanisms will be essential for developing effective, environmentally friendly strategies to combat this devastating disease.

Data availability statement

All the raw 16S and ITS sequence data can be found in the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) BioProject database with the accession numbers PRJCA047478 and PRJCA047530.

Author contributions

YZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IM: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was financially supported by the Department of Science and Technology Basic Research Programs of Yunnan Province (202301AS070080), the Yunnan Academician Expert Workstation (202405AF140070), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 32460682, 32260701), Yunnan Provincial Department of Education Scientific Research (2025J0362), Science and Technology Development Fund of Guangxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences Foundation (2022JM40), and Guangxi Key Laboratory of Biology for Crop Diseases and Insect Pests Foundation (20-065-30-ST-03) and the Ongoing Research Funding program (ORF-Ctr-2025-6), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1700610/full#supplementary-material

References

Adeleke, B. S., Ayilara, M. S., Akinola, S. A., and Babalola, O. O. (2022). Biocontrol mechanisms of endophytic fungi. Egyptian J. Biol. Pest Control 32, 46. doi: 10.1186/s41938-022-00547-1

Ahmed, W., Dai, Z., Zhang, J., Li, S., Ahmed, A., Munir, S., et al. (2022). Plant-microbe interaction: mining the impact of native bacillus amyloliquefaciens WS-10 on tobacco bacterial wilt disease and rhizosphere microbial communities. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e01471–e01422. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01471-22

Ahmed, W., Wang, Y., Ji, W., Liu, S., Zhou, S., Pan, J., et al. (2025). Unraveling the mechanism of the endophytic bacterial strain pseudomonas oryzihabitans GDW1 in enhancing tomato plant growth through modulation of the host transcriptome and bacteriome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26, 1922. doi: 10.3390/ijms26051922

Ali, S., Hameed, A., Muhae-Ud-Din, G., Ikhlaq, M., Ashfaq, M., Atiq, M., et al. (2023). Citrus canker: a persistent threat to the worldwide citrus industry—an analysis. Agronomy 13, 1112. doi: 10.3390/agronomy13041112

Anderson, M. J. and Walsh, D. C. I. (2013). PERMANOVA, ANOSIM, and the Mantel test in the face of heterogeneous dispersions: What null hypothesis are you testing? Ecol. Monogr. 83, 557–574. doi: 10.1890/12-2010.1

Anguita-Maeso, M., Haro, C., Navas-Cortés, J. A., and Landa, B. B. (2022). Primer choice and xylem-microbiome-extraction method are important determinants in assessing xylem bacterial community in olive trees. Plants 11, 1320. doi: 10.3390/plants11101320

Bamba, R. and Sumbali, G. (2005). Co-occurrence of aflatoxin B 1 and cyclopiazonic acid in sour lime (Citrus aurantifolia Swingle) during post-harvest pathogenesis by Aspergillus flavus. Mycopathologia 159, 407–411. doi: 10.1007/s11046-004-8401-x

Behlau, F., Gochez, A. M., and Jones, J. B. (2020). Diversity and copper resistance of Xanthomonas affecting citrus. Trop. Plant Pathol. 45, 200–212. doi: 10.1007/s40858-020-00340-1

Berg, G. (2009). Plant–microbe interactions promoting plant growth and health: perspectives for controlled use of microorganisms in agriculture. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 84, 11–18. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2092-7

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M., and Usadel, B. (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170

Bolyen, E., Rideout, J. R., Dillon, M. R., Bokulich, N. A., Abnet, C. C., Al-Ghalith, G. A., et al. (2019). Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9

Bonaterra, A., Badosa, E., Daranas, N., Francés, J., Roselló, G., and Montesinos, E. (2022). Bacteria as biological control agents of plant diseases. Microorganisms 10, 1759. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10091759

Bullerman, L. B. (2003). “SPOILAGE | Fungi in food – an overview,” in Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 2nd ed. Ed. Caballero, B. (Academic Press, Oxford), 5511–5522.

Cervantes, C. and Gutierrez-Corona, F. (1994). Copper resistance mechanisms in bacteria and fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 14, 121–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00083.x

Chen, J., Cheng, X., Xu, G., Zhao, Y., Liu, F., and Zhao, Y. (2025). The effect of N-oxide phenazine producer Lysobacter antibioticus on bacterial leaf streak in rice and the rhizosphere microbial community. New Plant Prot. 2, e70010. doi: 10.1002/npp2.70010

Chen, T., Nomura, K., Wang, X., Sohrabi, R., Xu, J., Yao, L., et al. (2020). A plant genetic network for preventing dysbiosis in the phyllosphere. Nature 580, 653–657. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2185-0

Chen, P.-S., Wang, L.-Y., Chen, Y.-J., Tzeng, K.-C., Chang, S.-C., Chung, K.-R., et al. (2012). Understanding cellular defence in kumquat and calamondin to citrus canker caused by Xanthomonas citri subsp citri. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 79, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2012.03.001

Compant, S., Clément, C., and Sessitsch, A. (2010). Plant growth-promoting bacteria in the rhizo- and endosphere of plants: Their role, colonization, mechanisms involved and prospects for utilization. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42, 669–678. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.11.024

de Oliveira, A. G., Spago, F. R., Simionato, A. S., Navarro, M. O., Da Silva, C. S., Barazetti, A. R., et al. (2016). Bioactive organocopper compound from Pseudomonas aeruginosa inhibits the growth of Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri. Front. Microbiol. 7, 113. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00113

Edgar, R. C. (2013). UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10, 996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604

Edgar, R. C., Haas, B. J., Clemente, J. C., Quince, C., and Knight, R. (2011). UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27, 2194–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381

Entila, F., Han, X., Mine, A., Schulze-Lefert, P., and Tsuda, K. (2024). Commensal lifestyle regulated by a negative feedback loop between Arabidopsis ROS and the bacterial T2SS. Nat. Commun. 15, 456. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-44724-2

Expósito, R. G., Postma, J., Raaijmakers, J. M., and De Bruijn, I. (2015). Diversity and activity of lysobacter species from disease suppressive soils. Front. Microbiol. 6, 1243. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01243

Fathi, Z., Rezaei, R., Charehgani, H., Ghaderi, F., and Ghalavoz, M. G. (2024). Biocontrol potential of epiphytic bacteria against Xanthomonas citri pathotypes A and A. Egyptian J. Biol. Pest Control 34, 11. doi: 10.1186/s41938-024-00795-3

Ference, C. M., Gochez, A. M., Behlau, F., Wang, N., Graham, J. H., and Jones, J. B. (2018). Recent advances in the understanding of Xanthomonas citri ssp citri pathogenesis and citrus canker disease management. Mol. Plant Pathol. 19, 1302–1318. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12638

Fu, M., Chen, Y., Liu, Y.-X., Chang, X., Zhang, L., Yang, X., et al. (2024). Genotype-associated core bacteria enhance host resistance against kiwifruit bacterial canker. Horticulture Res. 11, uhae236. doi: 10.1093/hr/uhae236

Giraldo – González, J. J., De Souza Carvalho, F. M., Ferro, J. A., Herai, R. H., Chaves Bedoya, G., and Rodas Mendoza, E. F. (2021). Transcriptional changes involved in kumquat (Fortunella spp) defense response to Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri in early stages of infection. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 116, 101729. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2021.101729

Graham, J. H., Leite, R. P., Jr., Yonce, H. D., and Myers, M. (2008). Streptomycin controls citrus canker on sweet orange in Brazil and reduces risk of copper burn on grapefruit in Florida,” in Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society. 121, 118–123.

Grantina-Ievina, L., Kasparinskis, R., Tabors, G., and Nikolajeva, V. (2013). Features of saprophytic soil microorganism communities in conifer stands with or without Heterobasidion annosum sensu lato infection: a special emphasis on Penicillium spp. Environ. Exp. Biol. 11, 23–38.

Han, Q., Ma, Q., Chen, Y., Tian, B., Xu, L., Bai, Y., et al. (2020). Variation in rhizosphere microbial communities and its association with the symbiotic efficiency of rhizobia in soybean. ISME J. 14, 1915–1928. doi: 10.1038/s41396-020-0648-9

Huang, F., Ling, J., Cui, Y., Guo, B., and Song, X. (2024). Profiling of the citrus leaf endophytic mycobiota reveals abundant pathogen-related fungal groups. Journal of Fungi 10, 596. doi: 10.3390/jof10090596

Huang, F., Ling, J., Zhu, C., Cheng, B., Song, X., and Peng, A. (2023). Canker disease intensifies cross-kingdom microbial interactions in the endophytic microbiota of citrus phyllosphere. Phytobiomes J. 7, 365–374. doi: 10.1094/PBIOMES-11-22-0091-R

Huang, Q. C., Liu, J. M., Hu, C. X., Wang, N. A., Zhang, L., Mo, X. F., et al. (2022). Integrative analyses of transcriptome and carotenoids profiling revealed molecular insight into variations in fruits color of Citrus Reticulata Blanco induced by transplantation. Genomics 114, 11. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2022.110291

Ijaz, M., Ahmad, M., Zou, X., Hussain, M., Zhang, M., Zhao, F., et al. (2018). Beef, casein, and soy proteins differentially affect lipid metabolism, triglycerides accumulation and gut microbiota of high-fat diet-fed C57BL/6J mice. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2200. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02200

Islam, M. N., Ali, M. S., Choi, S.-J., Hyun, J.-W., and Baek, K.-H. (2019). Biocontrol of Citrus Canker Disease Caused by Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri Using an Endophytic Bacillus thuringiensis. Plant Pathol. J. 35, 486–497. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.OA.03.2019.0060

Izadiyan, M. and Taghavi, S. M. (2024). Diversity of copper resistant Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri strains, the causal agent of Asiatic citrus canker, in Iran. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 168, 593–606. doi: 10.1007/s10658-023-02786-w

Jayasekara, A., Daranagama, A., Kodituwakku, T., and Abeywickrama, K. (2022). Morphological and molecular identification of fungi for their association with postharvest fruit rots in some selected citrus species. Journal of Agricultural Sciences–Sri Lanka 17, 79–93. doi: 10.4038/jas.v17i1.9612

Jiang, Y. H., Liu, T., Shi, X. C., Herrera-Balandrano, D. D., Xu, M. T., Wang, S. Y., et al. (2023). p-Aminobenzoic acid inhibits the growth of soybean pathogen Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines by altering outer membrane integrity. Pest Manage. Sci. 79, 4083–4093. doi: 10.1002/ps.7608

Juybari, H. Z., Tajick Ghanbary, M. A., Rahimian, H., Karimi, K., and Arzanlou, M. (2019). Seasonal, tissue and age influences on frequency and biodiversity of endophytic fungi of Citrus sinensis in Iran. Forest Pathology 49, e12559. doi: 10.1111/efp.12559

Ke, X. R., Wu, Z. L., Liu, Y. C., Liang, Y. L., Du, M. L., and Li, Y. (2023). Isolation, Antimicrobial Effect and Metabolite Analysis of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens ZJLMBA1908 against Citrus Canker Caused by Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri. Microorganisms 11, 16. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11122928

Khalaf, A. A., Gmitter, F. G., Jr., Conesa, A., Dopazo, J., and Moore, G. A. (2011). Fortunella margarita Transcriptional Reprogramming Triggered by Xanthomonas citri subsp citri. BMC Plant Biol. 11, 159. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-159

Kõljalg, U., Larsson, K.-H., Abarenkov, K., Nilsson, R. H., Alexander, I. J., Eberhardt, U., et al. (2005). UNITE: a database providing web-based methods for the molecular identification of ectomycorrhizal fungi. New phytologist 166, 1063–1068. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01376.x

Li, Y., He, P., Ahmed, A., Liu, Y., Ahmed, W., Wu, Y., et al. (2023). Endophyte mediated restoration of citrus microbiome and modulation of host defense genes against Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2863977/v1

Li, S., Yang, L., Jiang, T., Ahmed, W., Mei, F., Zhang, J., et al. (2025). Unraveling the role of pyrolysis temperature in biochar-mediated modulation of soil microbial communities and tobacco bacterial wilt disease. Appl. Soil Ecol. 206, 105845. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2024.105845

Liang, M., Johnson, D., Burslem, D. F., Yu, S., Fang, M., Taylor, J. D., et al. (2020). Soil fungal networks maintain local dominance of ectomycorrhizal trees. Nat. Commun. 11, 2636. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16507-y

Liang, X., Wang, H., Wang, C., Yao, Z., Qiu, X., Ju, H., et al. (2023). Disentangling the impact of biogas slurry topdressing as a replacement for chemical fertilizers on soil bacterial and fungal community composition, functional characteristics, and co-occurrence networks. Environ. Res. 238, 117256. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.117256

Liu, B., Lai, J., Wu, S., Jiang, J., and Kuang, W. (2021a). Endophytic bacterial community diversity in two citrus cultivars with different citrus canker disease resistance. Arch. Microbiol. 203, 5453–5462. doi: 10.1007/s00203-021-02530-0

Liu, Y.-X., Qin, Y., Chen, T., Lu, M., Qian, X., Guo, X., et al. (2020). A practical guide to amplicon and metagenomic analysis of microbiome data. Protein Cell 12, 315–330. doi: 10.1007/s13238-020-00724-8

Liu, L., Tang, Z.-P., Li, F.-F., Xiong, J., Lü, B.-W., Ma, X.-C., et al. (2021b). Fruit quality in storage, storability and peel transcriptome analysis of Rong’an Kumquat, Huapi Kumquat and Cuimi Kumquat. Scientia Agricultura Sinica 54, 4421–4433. doi: 10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2021.20.015

Liu, Q., Yang, J., Ahmed, W., Wan, X., Wei, L., and Ji, G. (2022). Exploiting the antibacterial mechanism of phenazine substances from Lysobacter antibioticus 13–6 against Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola. J. Microbiol. 60, 496–510. doi: 10.1007/s12275-022-1542-0

Liu, Q., Yang, J., Wang, X., Wei, L. F., and Ji, G. H. (2021c). Effect of culture medium optimization on the secondary metabolites activity of Lysobacter antibioticus 13-6. Preparative Biochem. Biotechnol. 51, 1008–1017. doi: 10.1080/10826068.2021.1888298

Lugauskas, A. and Stakeniene, J. (2002). Toxin producing micromycetes on fruit, berries, and vegetables. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 9, 183–197.

Ma, G., Zhang, L., Sugiura, M., and Kato, M. (2020). “Chapter 24 - citrus and health,” in The Genus Citrus. Eds. Talon, M., Caruso, M., and Gmitter, F. G. (Woodhead Publishing), 495–511.

Magoč, T. and Salzberg, S. L. (2011). FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27, 2957–2963. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507

Marino, A., Nostro, A., and Fiorentino, C. (2009). Ochratoxin A production by Aspergillus westerdijkiae in orange fruit and juice. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 132, 185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.03.026

Maurer, K. A., Zachow, C., Seefelder, S., and Berg, G. (2013). Initial steps towards biocontrol in hops: successful colonization and plant growth promotion by four bacterial biocontrol agents. Agronomy 3, 583–594. doi: 10.3390/agronomy3040583

Naqvi, S. A. H., Wang, J., Malik, M. T., Umar, U.-U.-D., Ateeq-Ur-Rehman, Hasnain, A., et al. (2022). Citrus canker—Distribution, taxonomy, epidemiology, disease cycle, pathogen biology, detection, and management: A critical review and future research agenda. Agronomy 12, 1075. doi: 10.3390/agronomy12051075

Nicoletti, R. (2019). Endophytic fungi of citrus plants. Agriculture 9, 247. doi: 10.3390/agriculture9120247

Paasch, B. C. and He, S. Y. (2021). Toward understanding microbiota homeostasis in the plant kingdom. PloS Pathog. 17, e1009472. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009472

Pena, M. M., Martins, T. Z., Teper, D., Zamuner, C., Alves, H. A., Ferreira, H., et al. (2024). EnvC Homolog Encoded by Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri Is Necessary for Cell Division and Virulence. Microorganisms 12, 691. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms12040691

Perrone, G., Susca, A., Cozzi, G., Ehrlich, K., Varga, J., Frisvad, J., et al. (2007). Biodiversity of Aspergillus species in some important agricultural products. Stud. mycology 59, 53–66. doi: 10.3114/sim.2007.59.07

Pfeilmeier, S., Petti, G. C., Bortfeld-Miller, M., Daniel, B., Field, C. M., Sunagawa, S., et al. (2021). The plant NADPH oxidase RBOHD is required for microbiota homeostasis in leaves. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 852–864. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-00929-5

Poveda, J., Roeschlin, R. A., Marano, M. R., and Favaro, M. A. (2021). Microorganisms as biocontrol agents against bacterial citrus diseases. Biol. Control 158, 104602. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2021.104602

Qian, J., Zhang, T., Tang, S., Zhou, L., Li, K., Fu, X., et al. (2021). Biocontrol of citrus canker with endophyte Bacillus amyloliquefaciens QC-Y. Plant Prot. Sci. 57, 1–13. doi: 10.17221/62/2020-PPS

Qiu, F., Pan, Z., Li, L., Xia, L., and Huang, G. (2022). Transcriptome analysis of Orah leaves in response to citrus canker infection. J. Fruit Sci. 39, 631–643. doi: 10.13925/j.cnki.gsxb.20210475

Qiu, Y., Wei, F., Meng, H., Peng, M., Zhang, J., He, Y., et al. (2023). Whole-genome sequencing and comparative genome analysis of Xanthomonas fragariae YM2 causing angular leaf spot disease in strawberry. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1267132. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1267132

Quast, C., Pruesse, E., Yilmaz, P., Gerken, J., Schweer, T., Yarza, P., et al. (2012). The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219

Riera, N., Wang, H., Li, Y., Li, J., Pelz-Stelinski, K., and Wang, N. (2018). Induced systemic resistance against citrus canker disease by rhizobacteria. Phytopathology 108, 1038–1045. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-07-17-0244-R

Sadeghi, F., Samsampour, D., Seyahooei, M. A., Bagheri, A., and Soltani, J. (2019). Diversity and Spatiotemporal Distribution of Fungal Endophytes Associated with Citrus reticulata cv. Siyahoo. Curr. Microbiol. 76, 279–289. doi: 10.1007/s00284-019-01632-9

Saldanha, L. L., Allard, P.-M., Dilarri, G., Codesido, S., González-Ruiz, V., Queiroz, E. F., et al. (2022). Metabolomic-and molecular networking-based exploration of the chemical responses induced in Citrus sinensis leaves inoculated with Xanthomonas citri. J. Agric. Food Chem. 70, 14693–14705. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c05156

Schaad, N. W., Postnikova, E., Lacy, G., Sechler, A., Agarkova, I. V., Stromberg, P. E., et al. (2006). Emended classification of xanthomonad pathogens on citrus. Systematic and applied microbiology 29, 690–695. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2006.08.001

Sharma, A., Ference, C. M., Shantharaj, D., Baldwin, E. A., Manthey, J. A., and Jones, J. B. (2022). Transcriptomic analysis of changes in Citrus x microcarpa gene expression post Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri infection. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 162, 163–181. doi: 10.1007/s10658-021-02394-6

Stockwell, V. O. and Duffy, B. (2012). Use antibiotics Plant agriculture. Revue Scientifique et Technique - Office International des Epizooties 31, 199–210. doi: 10.20506/rst.31.1.2104

Su, P., Kang, H., Peng, Q., Wicaksono, W. A., Berg, G., Liu, Z., et al. (2024). Microbiome homeostasis on rice leaves is regulated by a precursor molecule of lignin biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 15, 23. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-44335-3

Sudyoung, N., Tokuyama, S., Krajangsang, S., Pringsulaka, O., and Sarawaneeyaruk, S. (2020). Bacterial antagonists and their cell-free cultures efficiently suppress canker disease in citrus lime. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 127, 173–181. doi: 10.1007/s41348-019-00295-9

Teper, D., Xu, J., Li, J. Y., and Wang, N. (2020). The immunity of Meiwa kumquat against Xanthomonas citriis associated with a known susceptibility gene induced by a transcription activator-like effector. PloS Pathog. 16, 28. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008886

Wang, N., Song, X., Ye, J., Zhang, S., Cao, Z., Zhu, C., et al. (2022). Structural variation and parallel evolution of apomixis in citrus during domestication and diversification. Natl. Sci. Rev. 9, nwac114. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwac114

Wei, Y., Shen, D., Lukwambe, B., Wang, Y., Yang, W., Zhu, J., et al. (2022). The exogenous compound bacteria alter microbial community and nutrients removal performance in the biofilm unit of the integrated aquaculture wastewater bioremediation systems. Aquaculture Rep. 27, 101414. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2022.101414

Xia, X., Wei, Q., Wu, H., Chen, X., Xiao, C., Ye, Y., et al. (2024). Bacillus species are core microbiota of resistant maize cultivars that induce host metabolic defense against corn stalk rot. Microbiome 12, 156. doi: 10.1186/s40168-024-01887-w

Yang, R., Shi, Q., Huang, T., Yan, Y., Li, S., Fang, Y., et al. (2023a). The natural pyrazolotriazine pseudoiodinine from Pseudomonas mosselii 923 inhibits plant bacterial and fungal pathogens. Nat. Commun. 14, 734. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36433-z

Yang, Y., Ye, C., Zhang, W., Zhu, X., Li, H., Yang, D., et al. (2023b). Elucidating the impact of biochar with different carbon/nitrogen ratios on soil biochemical properties and rhizosphere bacterial communities of flue-cured tobacco plants. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1250669. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1250669

Zhang, J., He, Y., Ahmed, W., Wan, X., Wei, L., and Ji, G. (2022). First report of bacterial angular leaf spot of strawberry caused by xanthomonas fragariae in yunnan province, China. Plant Dis. 106, 1978. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-12-21-2648-PDN

Zhang, M. K., He, Z. L., Calvert, D. V., Stoffella, P. J., Yang, X. E., and Lamb, E. M. (2003). Accumulation and partitioning of phosphorus and heavy metals in a sandy soil under long-term vegetable crop production. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 38, 1981–1995. doi: 10.1081/ESE-120022894

Zhao, Y., Qian, G., Ye, Y., Wright, S., Chen, H., Shen, Y., et al. (2016). Heterocyclic aromatic N-oxidation in the biosynthesis of phenazine antibiotics from lysobacter antibioticus. Organic Lett. 18, 2495–2498. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b01089

Zheng, W., Wang, N., Qian, G., Qian, X., Liu, W., and Huang, L. (2024). Cross-niche protection of kiwi plant against above-ground canker disease by beneficial rhizosphere Flavobacterium. Commun. Biol. 7, 1458. doi: 10.1038/s42003-024-07208-z

Keywords: citrus canker, Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri, endophytic microbiome, biocontrol agents, Lysobacter antibioticus, citrus resistance

Citation: Zhang Y, Ahmed W, Dai Z, Meng H, Li H, Moussa IM, Ma Y, Zhang J and Ji G (2025) Cultivar-specific responses of the citrus endophytic microbiome to Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri infection reveals Lysobacter as a key biocontrol taxon. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1700610. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1700610

Received: 07 September 2025; Accepted: 12 November 2025; Revised: 06 November 2025;

Published: 09 December 2025.

Edited by:

Bello Hassan Jakada, Northeast Forestry University, ChinaReviewed by:

Imran Ul Haq, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, PakistanMuhammad Awais Zahid, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Sweden

Helena Santiago Lima, Sylvio Moreira Citriculture Center, Brazil

Shazia Akram, University of Teramo, Italy