- 1Institute of Chinese Materia Medica, Dazhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Dazhou, China

- 2Chongqing Key Laboratory of Traditional Chinese Medicine Resource, Endangered Medicinal Breeding National Engineering Laboratory, Chongqing Academy of Chinese Materia Medica, Chongqing, China

Epimedium L. is a taxonomically complex genus comprising 68 species worldwide, yet its mitochondrial genome (mitogenome) remains unexplored. The complete genomes of Epimedium pubescens, Epimedium wushanense, and Epimedium sagittatum were assembled using Illumina and Nanopore sequencing. The Epimedium mitogenomes displayed diverse structural variation, including a single circular molecule in E. sagittatum (324,345 bp), two circular molecules in E. wushanense (281,026 and 72,800 bp), and a multipartite structure with three circular chromosomes (171,784, 76,915, and 71,519 bp) and one linear chromosome (26,149 bp) in E. pubescens. Each species contained 58 unique genes, including 36 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 19 transfer RNAs (tRNAs), three ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), and abundant repetitive elements [77–89 simple sequence repeats (SSRs) and 169–380 dispersed repeats]. A total of 642 cytidine (C)-to-uridine (U) RNA editing sites were predicted across 35–36 PCGs, with experimentally validated edits generating start and stop codons, revealing species-specific editing profiles. Nine mitochondrial plastid DNA (MTPT) fragments (4.4–7.5 kb) were identified per species, containing six to nine complete genes. Three Epimedium species and related taxa exhibited conserved mitogenome regions alongside extensive gene rearrangements and inversions. Phylogenetic analysis based on 29 conserved PCGs strongly supported a monophyletic Epimedium clade (100% bootstrap), with E. sagittatum and E. pubescens forming a sister group to E. wushanense. This study provides the first comprehensive view of Epimedium mitogenome architecture, RNA editing, and evolutionary relationships, enriching our understanding of its mitochondrial evolution and taxonomy.

1 Introduction

Epimedium L., the largest herbaceous genus within the Berberidaceae, encompasses approximately 68 species distributed mainly across temperate mountainous regions from East Asia to Northwest Africa (Stearn, 2002). China represents the modern center of Epimedium diversity, harboring 58 species (57 of which are endemic) (Stearn, 2002; Ying, 2002; Zhang et al., 2007). Additionally, four species are distributed in the Mediterranean and Western Asian regions (Epimedium alpinum, Epimedium pubigerum, Epimedium pinnatum, and Epimedium perralderianum), while five other species (Epimedium koreanum, Epimedium grandiflorum, Epimedium sempervirens, Epimedium trifoliatobinatum, and Epimedium diphyllum) are distributed in Japan. Among them, E. koreanum is found in China, Korea, and Japan, reflecting a broader East Asian distribution pattern (Stearn, 2002; Ying, 2002). Furthermore, Epimedium macrosepalum and Epimedium elatum are distributed in Far Eastern Russia and Kashmir, respectively. China is recognized as the modern center of the distribution and diversity of the genus Epimedium. These endemic species hold significant economic value and have been used in traditional Chinese medicine for centuries. Several species, including Epimedium pubescens, Epimedium wushanense, Epimedium sagittatum, Epimedium brevicornu, and E. koreanum, are officially listed in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2025) and have long been used in traditional medicine for their tonic and therapeutic properties (Ma et al., 2011; Guo et al., 2022; Commission, 2025). China is the main supplier of Epimedium herbs and extractions, and to date, most Epimedium medicinal resources (such as E. pubescens, E. wushanense, E. sagittatum, E. brevicornu, and E. koreanum) are primarily harvested from the wild, with limited artificial cultivation. However, extensive exploitation of wild resources and the presence of morphologically similar species have led to confusion in species identification, inconsistent medicinal quality, and an urgent need for improved taxonomic resolution and sustainable utilization.

Taxonomic classification within Epimedium remains one of the most challenging issues in the Berberidaceae due to extensive morphological convergence and hybridization. Morphological differences among Epimedium species are often subtle and overlapping, making accurate species identification a persistent challenge. Since 1975, various taxonomic approaches have been applied, such as classical morphology (Stearn, 2002), chemical classification (Xie et al., 2010), and phylogenetic analysis based on karyotypes and molecular markers (Sun et al., 2005; Sheng et al., 2010; De Smet et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2014). In China, taxa frequently exhibit complex morphological variation despite minimal detectable genetic divergence, which complicates the application of Stearn’s widely accepted classification system (Guo et al., 2022). Many species are distinguished only by minor differences in floral or leaf characteristics. The Chinese Sect. (Diphyllon), which exhibits the highest species diversity within Epimedium, has been the source of numerous taxonomic controversies (Xu et al., 2008; Guo et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2019). Although morphological, chemical, and plastid-based phylogenetic studies have provided preliminary insights, discrepancies persist between morphological and molecular evidence, underscoring the need for additional genomic resources to refine species boundaries and evolutionary relationships.

The plant mitochondrial genome (mitogenome), generally ranging from 66 kb to 12 Mb in size (Sloan et al., 2012; Putintseva et al., 2020), is involved in multiple metabolic processes and plays a vital role in energetic metabolism, gene expression, stress response, and plant growth in many seed plants (Mackenzie and Mcintosh, 1999; Best et al., 2020). Moreover, plant mitogenomes exhibit remarkable diversity in genome size, structural organization, mutation rates of protein-coding genes (PCGs), RNA editing capacity, gene content, and recombination mediated by repeat sequences (Allen et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2023). For example, the mitogenome of Arabidopsis thaliana (Sloan et al., 2018) and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Vahrenholz et al., 1993) are typically assembled as a single circular structure and a linear structure, respectively, whereas other species, such as Stemona tuberosa (Xu et al., 2025), Stemona sessilifolia (Xie et al., 2024), and Angelica biserrata (Wang et al., 2024), display complex multi-chromosomal structures. They can exist as circular (Wang et al., 2023), linear (He et al., 2021), or branched forms (Jackman et al., 2020). The synonymous substitution rate within plant mitogenomes is several to dozens of times lower than that of plastomes and nuclear genomes, and even 50 to 100 times lower than that of mammalian mitogenomes (Wolfe et al., 1987).

Functional genes in mitogenomes show considerable variation due to post-transcriptional RNA editing, which can lead to highly divergent gene sequences (Li et al., 2022). In addition, the evolutionary stability of a species is closely related to the ability of its genes to adapt to global environmental changes, a characteristic reflected in the Guanine-Cytosine content of higher plant mitogenomes (Ye, 2018). Currently, it is widely recognized that both mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes can improve phylogenetic resolution at lower taxonomic levels, and their data are frequently used to clarify relationships among plant groups. Although plastid genome studies have provided valuable insights into the phylogeny and evolution of Epimedium (Epimedium acuminatum, Epimedium dolichostemon, Epimedium lishihchenii, and Epimedium pseudowushanense) (Guo et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2007), despite their significance, mitochondrial genomic data for Epimedium are completely lacking, limiting our understanding of its evolutionary dynamics and taxonomic framework.

Therefore, this study aimed to assemble and characterize the complete mitogenomes of three representative Epimedium species (E. pubescens, E. wushanense, and E. sagittatum) using Illumina and Nanopore sequencing technologies. Through comparative genomic and phylogenetic analyses, we sought to elucidate the structural organization, gene content, and evolutionary patterns of Epimedium mitogenomes, thereby providing new genomic evidence to support species identification, taxonomy, and evolutionary studies within the Berberidaceae.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 DNA extraction and sequencing

Three Epimedium species (E. pubescens, E. wushanense, and E. sagittatum) were collected from the Dazhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Dazhou, China. Genomic DNA was extracted from fresh, healthy leaves following the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method (Doyle and Doyle, 1987).

For Illumina sequencing, 1 ng of DNA was used to construct a short-read library (average insert size of 350 bp), which was sequenced on the DNBseq platform (California, USA). For Oxford Nanopore sequencing, sequence libraries were generated using the SQK-LSK109 ligation kit following the manufacturer’s protocols. The prepared library was then loaded onto primed R9.4 Spot-on Flow Cells and sequenced using a PromethION sequencer (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) over 48-hour runs. Base calling of the raw data was conducted using GuPPy version 1.2.0.

2.2 Mitogenome assembly, annotation, and visualization

The GetOrganelle software (version 1.7.5) was used to assemble the draft graphical mitogenome using the following parameters: -R 20 -k 21,45,65,85,105 -P 1000000 -F embplant_mt. The Bandage software (version 0.8.1) (Wick et al., 2015) was used to visualize the graphical mitogenome results, and extended fragments from the plastome and nuclear genomes were manually removed. Subsequently, the Nanopore data were aligned to the circular mitogenome using the BWA software (version 0.7.17) (Li and Durbin, 2009). These data were crucial in resolving repeat regions within the mitogenome, leading to the complete assembly mitogenome. The annotation of PCGs was conducted with Geseq (version 2.03) and IPMGA (http://www.1kmpg.cn/pmga/) (Tillich et al., 2017; Li et al., 2024b) using five mitogenomes as reference, including Aconitum carmichaelii (NC_084324.1), Aquilegia amurensis (OR818043.1–OR818045.1), Pulsatilla dahurica (NC_071219.1), Coptis omeiensis (OP466724.1–OP466725.1), and Corydalis pauciovulata (NC_081934.1). Transfer RNA (tRNA) and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) within the mitogenome were annotated using the tRNAscan-SE (version 2.0.11) (Lowe and Eddy, 1997) and BLASTN software (version 2.13.0) (Chen et al., 2015), respectively. The annotation results were manually corrected using the Apollo software (version 1.11.8) (Lewis et al., 2002). The final assembly and annotation results were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under accession numbers: E. sagittatum (PV694670), E. wushanense (PV694989–PV694990), and E. pubescens (PV695558–PV695561).

2.3 PCR validation of graphical assembly results

Based on the graphical mitogenome results of three Epimedium mitogenomes, linkages between graphical contigs were designed using Primer BLAST (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/) (Supplementary Table S1). PCR amplification was carried out in a 50 μL reaction mixture containing 1 μL DNA template, 1 μL each of 10 μM forward and reverse primers, 25 μL of 2× EasyTaq SuperMix, and 22 μL ddH2O. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C (2 min); 35 cycles of 94°C (30 s), 58°C (30 s), and 72°C (1 min); with a final extension at 72°C (2 min). Amplification products were visualized on a 1% agarose gel, and fragment sizes were estimated using a 100–2,000-bp DNA marker (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). The target bands were subsequently sequenced via the Sanger method, and chromatograms were analyzed using the SeqMan software.

2.4 Codon usage bias and repeat element analysis

PCGs were extracted using the PhyloSuite software (version 1.1.16) (Zhang et al., 2020a) with default parameters. Codon usage bias of PCGs from three Epimedium mitogenomes was analyzed using the MEGA software (version 7.0) (Kumar et al., 2016), and relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values were calculated. For simple sequence repeat (SSR), tandem repeat, and dispersed repeat analyses, multiple tools were employed: MISA (version 2.1) (https://webblast.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/) (parameters: 1-10, 2-5, 3-4, 4-3, 5-3, and 6-3) (Beier et al., 2017), the Tandem Repeats Finder (TRF, version 4.09) (https://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.unix.help.html) (parameters: default) (Benson, 1999), and the REPuter server (parameters: default) (https://bibiserv.cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de/reputer/) (Kurtz et al., 2001), respectively. Visualization of repeat elements was accomplished using the Circos package (version 0.69.9) (Zhang et al., 2013) and Excel 2021.

2.5 Prediction and validation of RNA editing sites

RNA editing events were identified using the online tool PREPACT3 (available at http://www.prepact.de/) (Lenz et al., 2018), applying a threshold of 0.001. To validate RNA editing sites within the three Epimedium species mitogenomes, five sites of four PCGs (nad1, rps10, atp6, and rps11) were randomly selected for PCR amplification. The PCR primers for all selected PCGs were designed using Primer BLAST (Supplementary Table S2). Total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the TransScript First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix kit. Both genomic DNA and cDNA templates were then subjected to PCR amplification (same as Section 2.3). The amplified products were subsequently sequenced using the Sanger method, and chromatograms were analyzed using the SeqMan software.

2.6 Homologous sequence between organelles and collinear analysis

The chloroplast genomes of three Epimedium species (E. pubescens, E. wushanense, and E. sagittatum) were assembled using GetOrganelle (version 1.7.5) with the following parameters: -R 10; -F embplant_pt. Three chloroplast genomes were annotated using the CPGAVAS2 software (version 2.0) (Shi et al., 2019). Homologous sequences between the mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes were analyzed using the BLASTN software (version 2.13.0) with default settings, and the results were visualized using the Circos package (version 0.69.9).

The mitogenome pairwise comparison was conducted using BLASTN (parameters: -evalue 1e−5, -word_size 9, -gapopen 5, -gapextend 2, -reward 2, -penalty −3). Homologous sequences longer than 0.5 kb were used to construct conserved collinearity blocks in the multiple synteny plot, which was visualized using MCScanX (Wang et al., 2012).

2.7 Phylogenetic analysis

Twenty-three complete mitogenomes belonging to three orders (Ranunculales, Proteales, and Magnoliales) were obtained from the NCBI database (Supplementary Table S3). A total of 29 conserved PCGs were extracted using the PhyloSuite software. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using the MAFFT software (version 7.505) with parameter -auto (Katoh et al., 2002). Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using the IQ-TREE software (version 1.6.12) with the following parameters: –alrt 1000 -B 1000 (Nguyen et al., 2015). The resulting maximum likelihood tree was visualized using the ITOL software (version 4.0) (Letunic and Bork, 2019).

3 Results

3.1 Characteristics of the three Epimedium mitogenomes

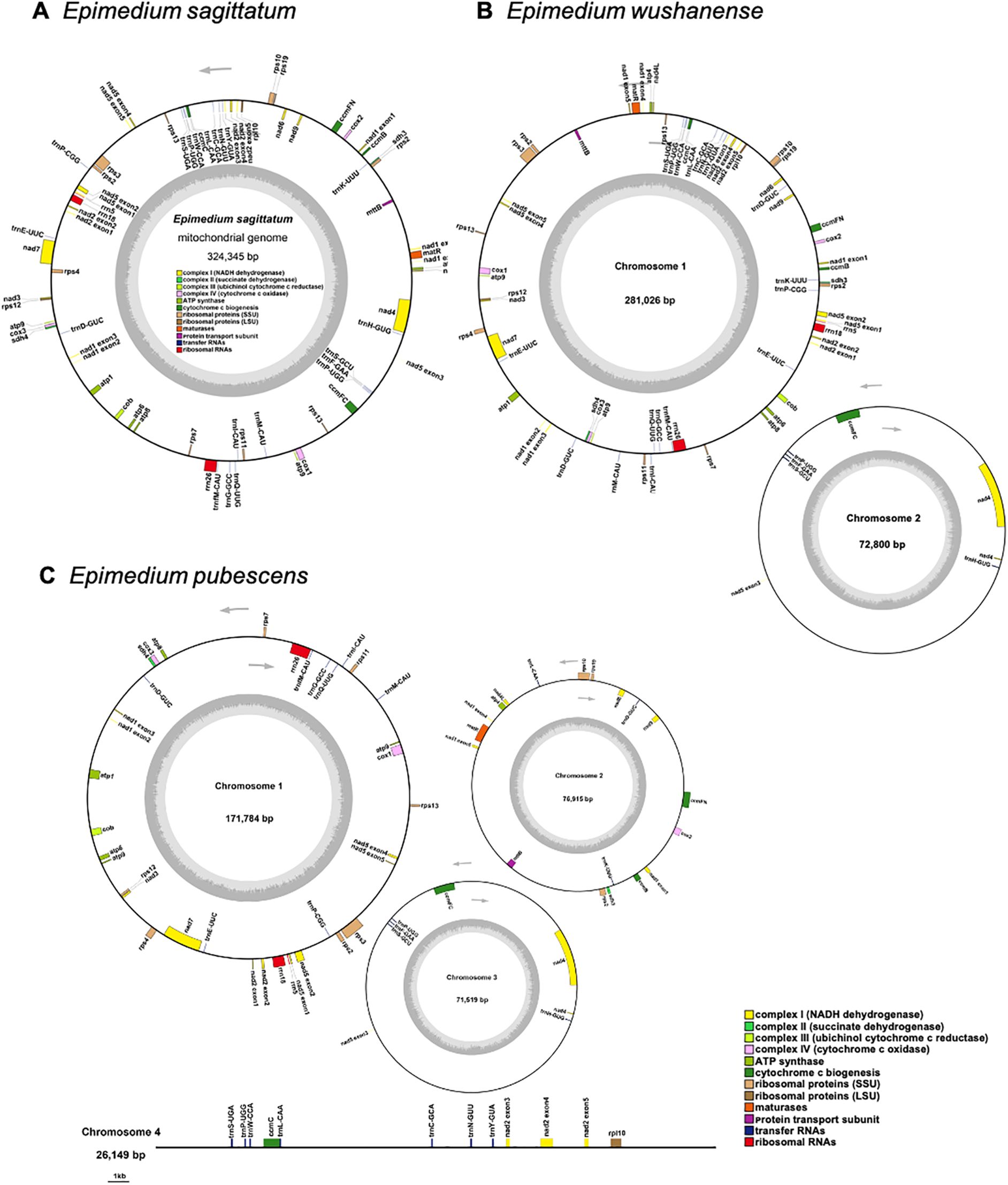

Three high-quality Epimedium mitogenomes were assembled by integrating Illumina short-read and Nanopore long-read sequencing data. The final uniting graphs consisted of six contigs in E. sagittatum, five contigs in E. pubescens (including two circular contigs), and 12 contigs in E. wushanense (with one circular contig) (Figures 1A–C). To validate the accuracy of the graphical assemblies, primers were designed at the ends of selected contigs to test the connectivity between adjacent contigs. PCR validation and subsequent Sanger sequencing confirmed eight junctions in E. sagittatum, four junctions in E. pubescens, and 16 junctions in E. wushanense (Figures 1D, F; Supplementary Figure 1). Both the PCR product sizes and Sanger sequencing results supported the graphical assembly results. Finally, the mitogenome of E. sagittatum was simplified into a single circular molecule measuring 324,345 bp with a GC content of 46.91% (Table 1; Figure 2A). In contrast, the E. wushanense mitogenome was simplified into two independent circular molecules (Table 1; Figure 2B). The total length of the E. wushanense mitogenome was 353,826 bp, with an overall GC content of 46.58%. The larger molecule was 281,026 bp in length with a GC content of 46.82%, while the smaller one measured 72,800 bp with a GC content of 45.64%. Additionally, the mitogenome of E. pubescens exhibited a complex branched structure, inferred to consist of three circular chromosomes (chromosomes 1–3) and one linear chromosome (chromosome 4), totaling 346,367 bp in length with a GC content of 46.52% (Table 1; Figure 2C). The four chromosomes exhibited variation in length and GC content: chromosome 1 was the longest at 171,784 bp with a GC content of 47.02%, followed by chromosome 2 (76,915 bp, 45.81%), chromosome 3 (71,519 bp, 45.79%), and chromosome 4 (26,149 bp, 47.36%).

Figure 1. Unitig graphs of the mitogenomes of three Epimedium species and PCR validation of their contig linkages. Assembly graphs were shown for (A) Epimedium sagittatum, (B) Epimedium pubescens, and (C) Epimedium wushanense. Corresponding PCR validation results for the contig linkage regions were presented for (D) E. sagittatum, (E) E. pubescens, and (F) E. wushanense. In the electrophoresis gel image, each band represents a junction between two contigs. For example, in panel (D), the bands correspond to the connections between contig1 and contig5 (c1c5), contig2 and contig6 (c2c6), and so on. The numbers below each band indicate the length of the PCR product.

Table 1. Basic information for the mitogenome of Epimedium sagittatum, Epimedium wushanense, and Epimedium pubescens.

Figure 2. The map of the mitogenome of (A) Epimedium sagittatum, (B) Epimedium wushanense, and (C) Epimedium pubescens. The arrows show transcriptional direction of each mitogenome. Genes with different functions are depicted using different colors.

A total of 58 unique mitochondrial genes were annotated in the three Epimedium mitogenomes, consisting of 36 distinct PCGs, 19 tRNA genes, and 3 rRNA genes (Table 2). Among the 36 unique PCGs, 24 were classified as core genes, which included five ATP synthase genes (atp1, atp4, atp6, atp8, and atp9), nine NADH dehydrogenase genes (nad1, nad2, nad3, nad4, nad4L, nad5, nad6, nad7, and nad9), four cytochrome c biogenesis genes (ccmB, ccmC, ccmFC, and ccmFN), three cytochrome c oxidase genes (cox1, cox2, and cox3), one protein transport subunit gene (mttB), one maturase gene (matR), and one cytochrome b gene (cob). The non-core genes are represented by one ribosomal protein large subunit gene (rpl10), nine ribosomal protein small subunit genes (rps2, rps3, rps4, rps7, rps10, rps11, rps12, rps13, and rps19), and two succinate dehydrogenase genes (sdh3 and sdh4). Additionally, unlike all rRNA genes, which were single-copy, certain PCGs or tRNA genes presented in double copies. Among the three Epimedium species, atp9, rps2, and trnP-UGG were consistently present in two copies. The rps13 gene was duplicated in E. sagittatum and E. wushanense, whereas trnD-GUC showed two copies in E. pubescens and E. wushanense. Additionally, trnL-CAA and trnE-UUC were duplicated in E. pubescens and E. wushanense, respectively.

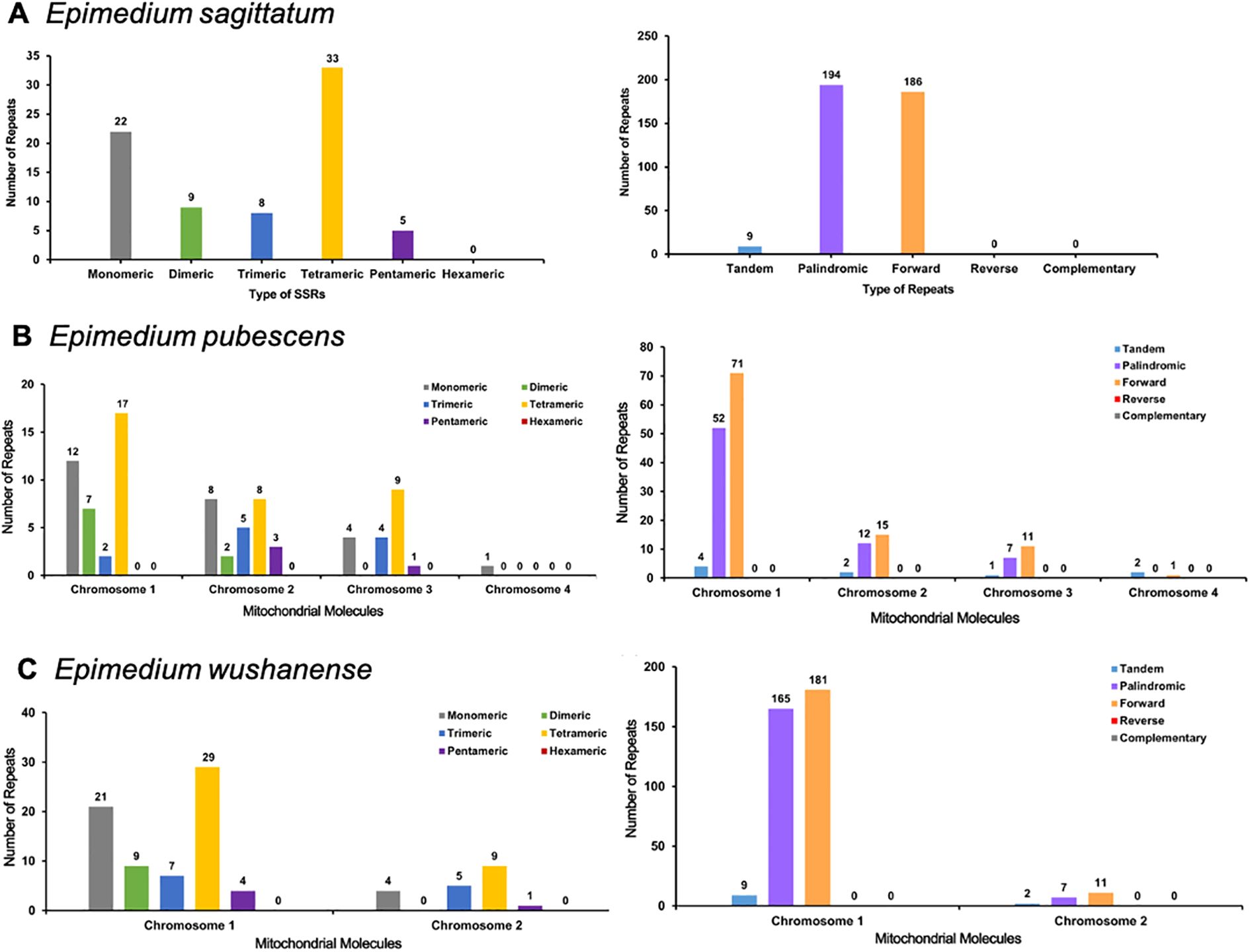

3.2 Repeat element analysis

A total of 77, 83, and 89 SSRs were identified in the E. sagittatum, E. pubescens, and E. wushanense mitogenomes, respectively (Figures 3A–C; Supplementary Table S4). Monomeric and tetrameric SSRs constituted the largest proportion of SSRs, accounting for 71.43%, 71.08%, and 70.79% in the E. sagittatum, E. pubescens, and E. wushanense mitogenomes, respectively. Notably, no hexameric repeats were found in the three Epimedium species mitogenomes. Furthermore, a total of nine, nine, and 11 tandem repeats were detected within the E. sagittatum, E. pubescens, and E. wushanense mitogenomes, respectively, displaying a variation in length ranging from 12 to 39 bp (Supplementary Table S5). Additionally, in the E. pubescens mitogenome, a total of four, two, one, and two tandem repeats, ranging from 15 to 32, 18 to 39, 12, and 29 bp, matched on chromosomes 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Moreover, in the E. wushanense mitogenome, a total of nine and two tandem repeats, ranging from 15 to 39 and 12 to 25 bp, matched on chromosomes 1 and 2, respectively. In addition to these tandem repeats and SSRs, dispersed repeats are also prevalent throughout the genome, including palindromic repeats, forward repeats, reverse repeats, and complement repeats, and their function was observed to be of equivalent significance, as supported by previous studies. Here, a total of 380, 169, and 364 dispersed repeats were identified in E. sagittatum, E. pubescens, and E. wushanense mitogenomes, respectively, and each repeat was at over or equal to 30 bp in length (Supplementary Table S6). Of these dispersed repeats, 194 palindromic repeats and 186 forward repeats, 71 palindromic repeats and 98 forward repeats, and 172 palindromic repeats and 192 forward repeats were identified in the E. sagittatum, E. pubescens, and E. wushanense mitogenomes, respectively. No reverse repeats and complement repeats were detected in the three Epimedium species mitogenomes.

Figure 3. Analysis of repeat elements in the mitochondrial genome of (A) Epimedium sagittatum, (B) Epimedium pubescens, and (C) Epimedium wushanense. Distribution and classification of repeat motifs based on SSR unit length (monomeric to hexameric) and structural types (tandem, palindromic, forward, reverse, and complementary repeats). SSR, simple sequence repeat.

3.3 Analysis of relative synonymous codon usage

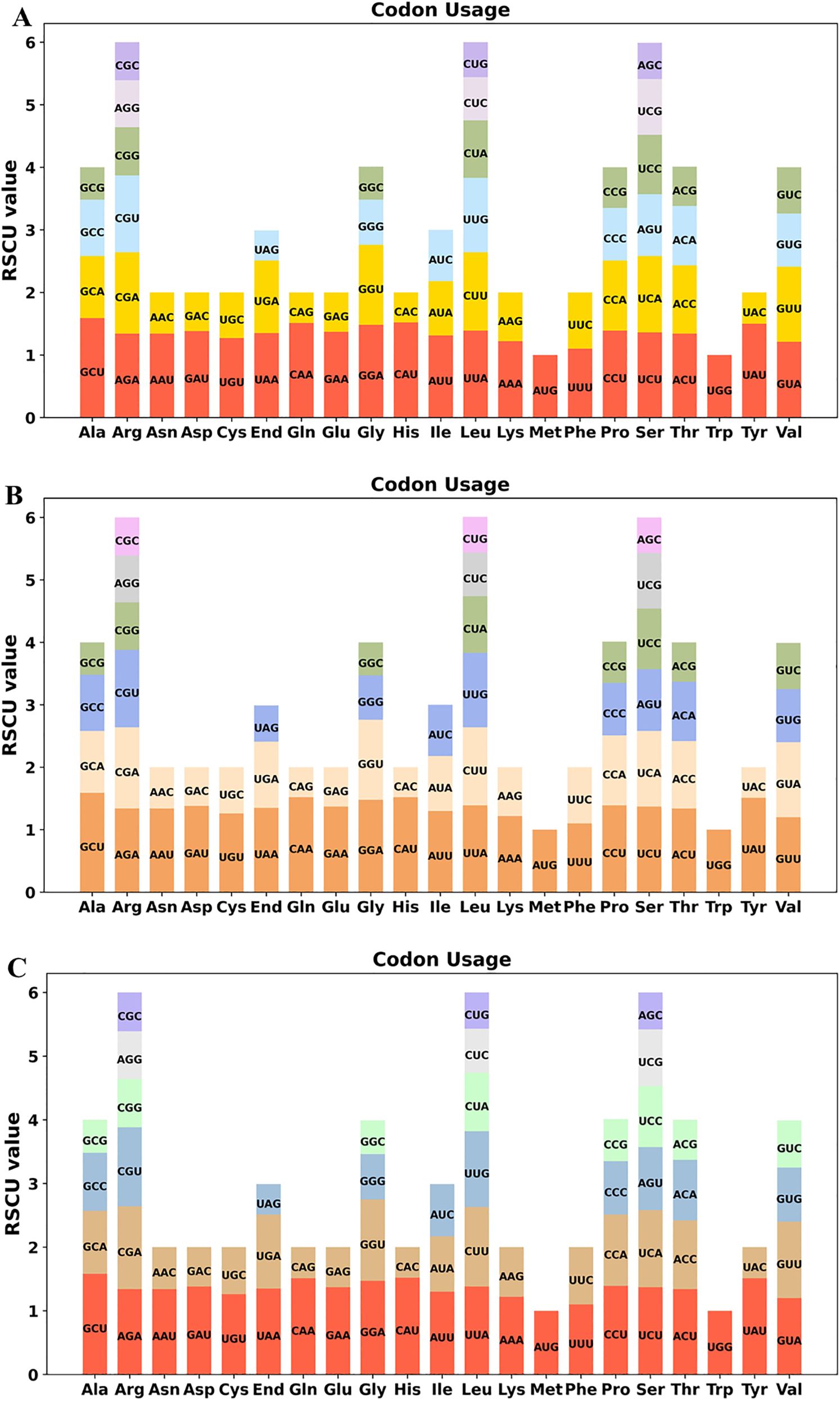

In our study, 36 unique PCGs were conducted to analyze the codon usage patterns in the three Epimedium mitogenomes (Supplementary Tables S7–S9). RSCU values exceeding 1 signify a preference for specific codons, indicating a bias toward certain amino acids, whereas values less than 1 imply the opposite. These mitogenome PCGs exhibited a general preference for codon use except for the standard AUG (Met) and UGG (Trp). For instance, alanine (Ala) exhibited a comparable highest preference for the codon GCU, with an RSCU value ranging from 1.58 to 1.59. Additionally, most amino acids were represented by at least two different codons, whereas arginine, leucine, and serine each have six associated codons (Figures 4A–C).

Figure 4. Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) in the mitochondrial protein-coding genes of three Epimedium species: (A) Epimedium sagittatum, (B) Epimedium pubescens, and (C) Epimedium wushanense. The figures illustrate RSCU values for 36 unique mitochondrial protein-coding genes, representing codon usage patterns across 20 amino acids and stop codons.

3.4 RNA editing events

Previous studies have shown that RNA editing events are pivotal in plant growth and development (Small et al., 2020). RNA editing sites were predicted in the three Epimedium species (E. sagittatum, E. pubescens, and E. wushanense), with each species exhibiting a total of 642 editing sites. These sites were distributed across 36 unique PCGs in E. sagittatum and E. pubescens and across 35 PCGs in E. wushanense (Figure 5; Supplementary Tables S10–12). All identified editing events involved cytidine (C)-to-uridine (U) conversions. nad4 harbored the highest number of editing sites (58), followed by nad7 (40). Although the overall number of RNA editing sites was consistent across most PCGs in the three Epimedium species, some PCGs exhibited notable variations. For example, predicted RNA editing sites in ccmFN were detected in E. sagittatum (29), E. pubescens (30), and E. wushanense (30). The gene rps2 had five predicted editing sites in E. pubescens, and the same number was detected in the other two species. For sdh3, one editing site was predicted in both E. pubescens and E. sagittatum, whereas no editing sites were detected in E. wushanense.

Figure 5. Predicted RNA editing sites based on protein-coding genes of (A) Epimedium sagittatum, (B) Epimedium pubescens, and (C) Epimedium wushanense. The bar chart displays the number of predicted RNA editing sites of protein-coding genes in three Epimedium species. The x-axis represents different protein-coding genes, while the y-axis indicates the number of RNA editing sites for each gene. Each bar corresponds to the number of editing sites in a gene, visually representing the distribution of editing sites across the genes.

To confirm the accuracy of predicted RNA editing events, five sites (nad1-2, rps10-2, atp6-718, rps10-331, and rps11-511) from four PCGs (nad1, rps10, atp6, and rps11) shared among the three species that generate start and stop codons were selected. For example, the following were predicted: one ACG (Thr) to AUG (Met) in the start codon of nad1 and rps10, one CAA (Gln) to UAA (End) in atp6 and rps11, and one CGA (Arg) to UGA (End) in rps10. The corresponding genomic DNA (gDNA) and complementary DNA (cDNA) were amplified using gene-specific primers, and the PCR products were subsequently sequenced via Sanger sequencing (Figure 6A). The sequencing results revealed C-to-U conversions at positions nad1–2 and rps11–511 in the cDNA compared to the gDNA, although the extent of editing varied slightly among the three Epimedium species, indicating species-specific RNA editing at these sites (Figure 6B). Overall, Sanger sequencing confirmed RNA editing at several positions in cDNA, supporting the occurrence of site- and species-specific RNA editing events within the genus Epimedium.

Figure 6. Validation of RNA editing sites in mitochondrial protein-coding genes of three Epimedium species. (A) PCR amplification of five editing sites (nad1-2, rps10-2, atp6-718, rps10-331, and rps11-511) from four mitochondrial protein-coding genes (nad1, rps10, atp6, and rps11) in genomic DNA (gDNA) and complementary DNA (cDNA) from three Epimedium species. (B) RNA editing validation at five sites (nad1-2, rps10-2, atp6-718, rps10-331, and rps11-511) in Epimedium sagittatum, Epimedium pubescens, and Epimedium wushanense. Sanger sequencing chromatograms of gDNA and cDNA show C-to-U conversions at the indicated sites. Dashed boxes highlight the edited positions.

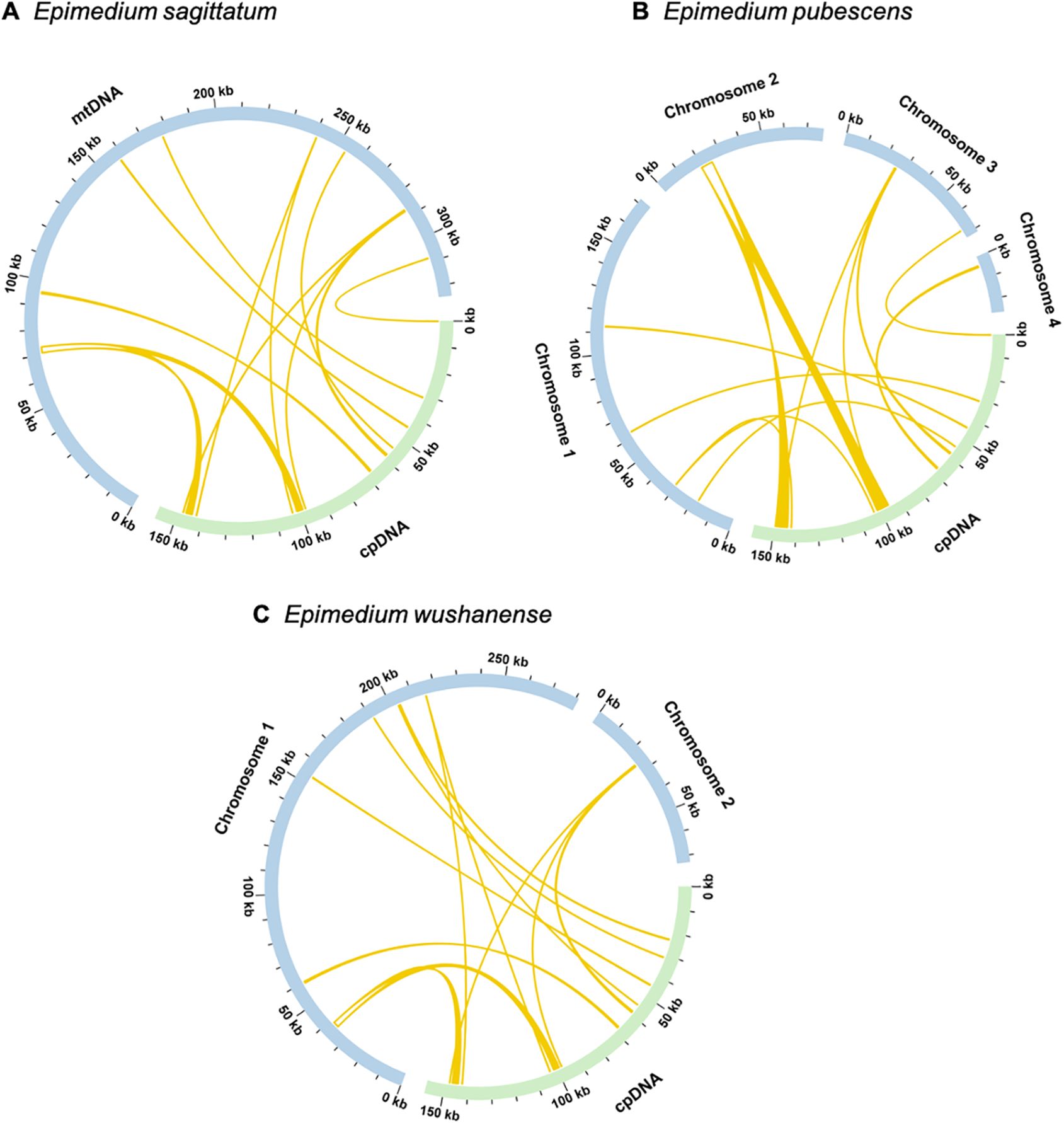

3.5 Intracellular gene transfer between chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes

Mitochondrial plastid DNAs (MTPTs) refer to specific DNA fragments of chloroplast origin that exist in the mitogenome. For the three Epimedium species, sequence alignment exhibited nine homologous fragments between the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes (Supplementary Tables S13–15). For Epimedium sagittatum, the total length of the nine homologous fragments spanned 4,394 bp (1.35% of the mitogenome), with MTPT1 being the largest at 2,400 bp in size, making it the most substantial fragment among the identified homologous sequences (Figure 7A). Subsequent annotation of these sequences unveiled the presence of seven complete genes, comprising two complete PCGs and five tRNA genes. The PCGs identified were petG and rps7. The tRNA genes included trnD-GUC, trnH-GUG, trnM-CAU, trnP-UGG, and trnW-CCA. In Epimedium pubescens, the total length of the nine homologous fragments spanned 7,505 bp (2.17% of the mitogenome), with MTPT5 as the largest at 5,505 bp, representing the most substantial fragment among the identified homologous sequences (Figure 7B). Further examination of these sequences showed that nine complete genes were present, comprising three complete PCGs and six tRNA genes. The PCGs identified were petG, rps7, and ndhB. The tRNA genes included trnD-GUC, trnH-GUG, trnM-CAU, trnP-UGG, trnW-CCA, and trnL-CAA. In Epimedium wushanense, these transfer fragments spanned 4,706 bp, comprising 1.33% of the mitogenome. Among these transfer fragments, MTPT1 was the largest, measuring 2,494 bp in size and representing the most substantial fragment among the identified homologous sequences (Figure 7C). Further annotation of these sequences showed that six complete genes were present, comprising two complete PCGs and four tRNA genes. The PCGs identified were petG and rps7, while the detected tRNA genes included trnD-GUC, trnM-CAU, trnP-UGG, and trnW-CCA.

Figure 7. Homologous analysis between mitogenome and chloroplast genome of (A) Epimedium sagittatum, (B) Epimedium pubescens, and (C) Epimedium wushanense. The blue arcs represent mitogenome, and the green arcs represent chloroplast genome. The yellow arcs inside the circle represent the homologous regions between mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes.

3.6 Collinear analysis

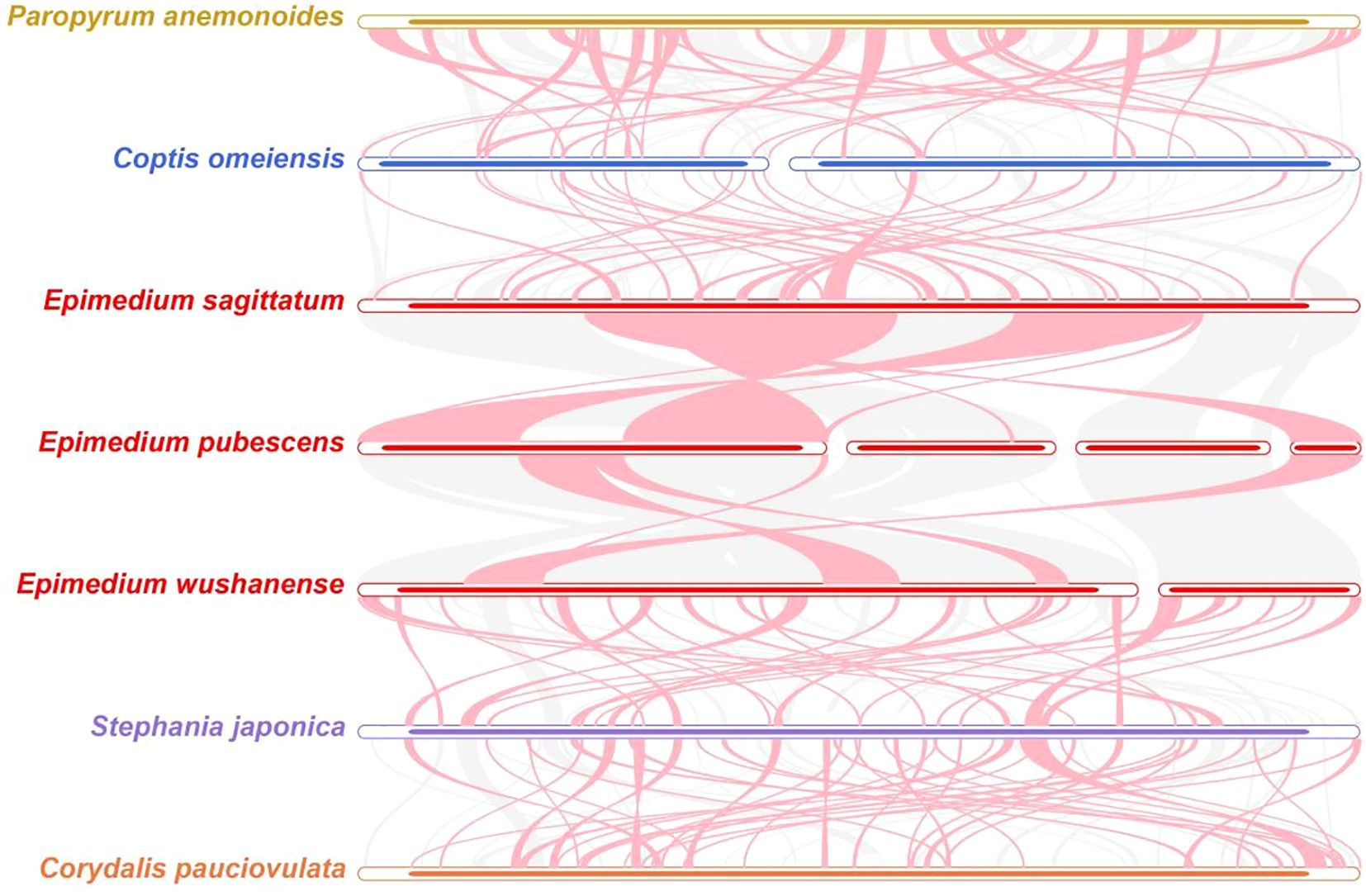

To further clarify the conservatism of mitogenome evolution in three Epimedium species and four other species (Paropyrum anemonoides, C. omeiensis, Stephania japonica, and C. pauciovulata) (Figure 8; Supplementary Table S16), collinearity analysis revealed a high degree of synteny among the three Epimedium species, with long conserved blocks—for example, chromosome 4 of E. pubescens showed substantial homologous regions in both E. sagittatum and E. wushanense, indicating its conservation during Epimedium mitogenome evolution. However, many homologous collinear blocks were relatively short, and some were missing in the compared genomes, suggesting the presence of unique regions within each mitogenome. Furthermore, the order of these collinear blocks varied among the seven species analyzed, reflecting extensive gene rearrangements. Additionally, numerous inverted regions were detected, implying a lower conservation of chromosomal structure across the mitogenomes.

Figure 8. Collinear analysis of seven species in Ranunculales. The pink curve blocks indicate regions with inversion events, the gray ones represent homologous regions, and areas lacking collinear blocks were unique to each species.

3.7 Phylogenetic analysis

To better elucidate the phylogenetic relationships of the Epimedium species with closely related species, a maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree was reconstructed based on 29 conserved PCGs shared among 26 species across three orders—Ranunculales, Proteales, and Magnoliales—with Liriodendron tulipifera (NC_021152.1) and Magnolia liliiflora (NC_085212.0) serving as outgroups (Figure 9). Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the three Epimedium species within the Pandanales order clustered clade with 100% bootstrap support. E. sagittatum and E. pubescens clustered together, indicating a close phylogenetic relationship, and this clade formed a sister group with E. wushanense. The phylogenetic tree constructed using mitochondrial PCGs effectively distinguishes Epimedium species from other taxa and exhibits a well-resolved topology that is consistent with the latest classification by the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG), supporting the reliability of mitochondrial PCGs for phylogenetic inference in plants.

Figure 9. Phylogenetic relationships of three Epimedium species (Epimedium sagittatum, Epimedium pubescens, and Epimedium wushanense) with other 17 species in Ranunculales and four species in Proteales; two species from Magnoliales were used as outgroup. The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on concatenated sequences of conserved mitochondrial protein-coding genes from 26 species using the maximum likelihood (ML) method. Bootstrap support values from 1,000 replicates are shown at each node. The original tree with branch lengths is displayed in the upper left corner. These 29 PCGs were atp1, atp4, atp6, atp8, atp9, ccmB, ccmC, ccmFC, ccmFN, cob, cox1, cox2, cox3, matR, mttB, nad1, nad2, nad3, nad4, nad4L, nad5, nad6, nad7, rpl10, rps3, rps4, rps7, rps12, and rps13.

4 Discussion

Both the mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes are essential for energy production and cellular metabolism in plants, while they function in different aspects of cellular activity. The chloroplast genome of E. koreanum was first reported in 2016 (Lee et al., 2016), and subsequently, the chloroplast genomes of other Epimedium species were published, including E. acuminatum, E. lishihchenii, E. pseudowushanense, and E. wushanense (Sun et al., 2016b; Guo et al., 2019; Lai et al., 2022). These studies provided insights into the Epimedium chloroplast and the phylogenetic relationships of Epimedium species. However, there are no complete mitogenomes of Epimedium yet available in the public databases. The available data remain insufficient to clarify phylogenetic relationships across the genus, requiring further investigation from other genetic approaches. In our study, the complete mitogenome of three Epimedium (E. sagittatum, E. pubescens, and E. wushanense) species had been assembled and characterized. Our results showed that the three Epimedium mitogenomes displayed wide differences in structure. A configuration consisting of multiple branched molecules was observed in the E. pubescens (three circular chromosomes and one linear chromosome) and E. wushanense (two circular chromosomes) mitogenomes, rather than a single circular chromosome in the E. sagittatum mitogenome. In the graphical assembly results, two and four contigs in E. sagittatum and E. wushanense, respectively, were identified as repetitive sequences. These large repeats are known to mediate homologous recombination (Yang et al., 2022b), driving frequent genomic rearrangements and giving rise to the dynamic and multiconfigurational nature of plant mitogenomes. A similar structural diversity has also been reported in Broussonetia spp. and Saccharum spp., where different species within each genus exhibited considerable structure variation in the mitogenome (Lai et al., 2022; Li et al., 2024c). Additionally, A. biserrata, Allium cepa, and Silene conica also displayed complex multi-chromosomal structures (Alverson et al., 2011; Sloan et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2024).

During the evolutionary process in land plants, the GC content is vital for determining the amino acid composition of protein groups (Wang, 2020). The mitogenomes of the three Epimedium (E. sagittatum, E. pubescens, and E. wushanense) exhibited similar CG contents of 46.91%, 46.52%, and 46.59%, respectively, comparable to other plant species such as Punica granatum (46.09%) (Lu et al., 2023) and Corydalis saxicola (46.50%) (Li et al., 2024a). Significantly, this exceeds the GC content of the Epimedium chloroplast genome (38.8%) (Guo et al., 2019), suggesting that the GC content in angiosperm mitogenomes remains relatively stable throughout evolution.

Repetitive sequences, including tandem repeats, dispersed repeats, and SSRs, are widespread in organelle genomes and play crucial roles in shaping mitogenome architecture through rearrangements, duplications, and recombination events. For instance, in the mitogenomes of Prunus salicina, three pairs of repetitive sequences promoted genomic recombination, resulting in eight and seven distinct conformations (Fang et al., 2021). In this study, multiple types of repetitive sequences were abundantly identified in the three Epimedium mitogenomes. Specifically, 77, 83, and 89 SSRs were detected in the mitogenomes of E. sagittatum, E. pubescens, and E. wushanense, respectively, with monomeric and tetrameric motifs being the most prevalent. Notably, no hexameric repeats were found in the three Epimedium species mitogenomes. The findings are consistent with the findings in the chloroplast genome of Epimedium (Guo et al., 2019). Additionally, dispersed repeats and tandem repeats also showed variations in their distribution among different Epimedium species. A total of nine, nine, and 11 tandem repeats, displaying a variation in length ranging from 12 to 39 bp, and 380, 169, and 364 dispersed repeats were detected within the E. sagittatum, E. pubescens, and E. wushanense mitogenomes, respectively. The abundance of repetitive sequences in the mitogenome is markedly higher than in the chloroplast genome, reflecting a characteristic feature of plant mitochondria that contributes to their more complex genomic architecture. The mitogenome of E. wushanense contained a greater abundance and diversity of repetitive sequences than those of E. sagittatum and E. pubescens. This elevated repeat content reflects its enhanced recombination potential and structural complexity, resulting in a more dynamic mitochondrial genome organization. Although we have confirmed the existence of these structural variations, their specific roles within the genome still need to be further explored.

Codon usage bias, an important evolutionary feature, has been observed in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms. In the mitogenomes of the three Epimedium species, we detected a strong preference for A/U-ending codons at the third codon position. Similar findings have been reported in other species, including Elaeagnus (Li et al., 2023a), Cucumis sativus (Niu et al., 2021), and Camellia duntsa (Li et al., 2023b), which suggests that A/U-ending codon bias may be an inherent characteristic of organelle genomes. However, other species, such as S. tuberosa (Xu et al., 2025), A. biserrata (Wang et al., 2024), and Mangifera persiciformis (Niu et al., 2022), tend to favor A/T-ending codons in the third position. These results revealed that codon usage patterns in plant mitogenomes had species-specific variations.

Plant mitogenomes exhibit a high frequency of RNA editing events, which result in amino acid changes via insertions, deletions, and substitutions, thereby leading to substantial genetic diversity (Sun et al., 2016a). The number of RNA editing sites in land plant mitogenomes can exhibit substantial variation, ranging from Marchantia polymorpha (0 sites) to Selaginella moellendorffii (2,152 sites) (Zhang et al., 2020b). In the present study, 642 sites were detected in E. sagittatum, E. pubescens, and E. wushanense across 36 unique PCGs (across 35 PCGs in E. wushanense), all involving C-to-U transitions. This observation is consistent with findings from prior studies, underscoring the substantial influence of RNA editing on the functional dynamics of mitochondrial genes. Additionally, in the three Epimedium species, one RNA editing site was detected in the sdh3 gene in the E. sagittatum and E. pubescens mitogenomes, while no RNA editing sites were detected in the sdh3 gene in the E. wushanense mitogenome, suggesting a certain variability in RNA editing site distribution among different species. Sanger sequencing confirmed several predicted editing events, including modifications that restore start and stop codons, reinforcing the functional significance of these edits. The observed variation in editing efficiency among species further suggests a layer of species-specific post-transcriptional regulation in Epimedium mitochondria.

Intracellular horizontal gene transfer (IHGT) denotes the transfer of genetic sequences among the mitogenome, plastome, and nuclear genome. Among these organellar genomes, the most frequent direction is from plastome to mitogenome. The mitogenome of Salvia miltiorrhiza (Yang et al., 2022a) harbors chloroplast-derived gene fragments, serving as direct evidence for the transfer of DNA segments from chloroplasts to mitochondria. Generally, plant mitogenomes contain approximately 0.56% (M. polymorpha) to 10.85% (Phoenix dactylifera) of plastid-derived sequences (Zhao et al., 2019). In this study, MTPTs in the three Epimedium species were analyzed, and it was found that E. sagittatum (4,394 bp, 1.35%), E. pubescens (7,505 bp, 2.17%), and E. wushanense (4,706 bp, 1.33%) integrated nine MTPTs. The minimal heterogeneity in MTPT length distribution among these species suggests that plastid-derived integrations contribute only marginally to mitogenome expansion, reflecting a relatively low proportion of chloroplast-to-mitochondrion DNA transfer in Epimedium. A total of nine MTPTs were identified in each of the three Epimedium mitogenomes. Among them, several genes, including the protein-coding genes (petG, rps7, and ndhB) and the tRNA genes (trnD, trnH, trnM, trnP, and trnW), were completely transferred from the chloroplast genome. The plastid-derived tRNA genes may serve a compensatory role for lost mitochondrial tRNAs, thus maintaining essential functions required for mitochondrial translation, such as amino acid transfer (Warren et al., 2021). These findings not only deepen our understanding of plant mitogenome dynamics but also offer valuable insights into plant evolutionary processes and adaptive mechanisms. However, more analyses involving a broader range of Epimedium species are required to establish a more definitive conclusion.

Mitogenomes are less frequently employed in phylogenetic analyses of higher plants than plastid and nuclear genomes, primarily due to their relatively low mutation rates, frequent genome rearrangements, and the incorporation of foreign sequences. In this study, we constructed a phylogenetic tree based on 29 conserved PCGs from the mitogenomes of 26 species across three orders, which resolved well-supported relationships within Pandanales and were largely consistent with the APG IV system (Chase et al., 2016; Zeb et al., 2025). Notably, comparison with related families revealed that the mitogenomic data provide complementary phylogenetic signals, clarifying the placement of Epimedium within the Berberidaceae. These findings highlight the evolutionary significance of mitogenome variation, including structural rearrangements and gene content, and demonstrate its potential to refine taxonomic classification. Expanding mitogenomic sampling in future studies will further illuminate the evolutionary dynamics and phylogenetic relationships across Pandanales.

5 Conclusions

In this study, three complete Epimedium mitogenomes were assembled and characterized, revealing remarkable structural variation, abundant RNA editing sites, and evidence of mitochondrial–plastid DNA transfer. Phylogenetic analysis resolved the evolutionary relationships among E. sagittatum, E. pubescens, and E. wushanense, providing new genomic perspectives on species differentiation within the genus. These findings enrich mitochondrial genomic resources for Epimedium and offer valuable references for comparative and evolutionary studies in the Berberidaceae. Beyond expanding taxonomic and genomic knowledge, this work establishes a foundation for future research on mitochondrial genome evolution, inter-organellar communication, and the molecular mechanisms underlying plant adaptation and diversification.

Sample collection

In compliance with ethical standards, freshly collected and cultivated specimens of three Epimedium species were obtained from the Dazhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Dazhou, China. Experimental research and plant material collection complied with all relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author contributions

DX: Writing – original draft. JH: Writing – original draft. QM: Writing – original draft. TW: Writing – original draft. ZZ: Writing – original draft. QW: Writing – original draft. ZW: Writing – original draft. ZX: Writing – original draft. XL: Writing – original draft. LF: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Sichuan Innovation Team of National Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System (SCCXTD-2025-19) and the special fund for strategic cooperation between Sichuan University and Da Zhou Municipal Government (2021CDDZ-13).

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor and the reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions on the manuscript. We thank Wuhan Benagen Technology Co., Ltd., for help in genome sequencing and the analysis of RNA editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1701895/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

PCGs, protein-coding genes; RSCU, relative synonymous codon usage; MTPT, mitochondrial plastid DNA sequence; tRNA, transfer RNA; rRNA, ribosomal RNA; APG, Angiosperm Phylogeny Group; SSRs, simple sequence repeats;IGT, intracellular gene transfer; ML, maximum likelihood.

References

Allen, J. O., Fauron, C. M., Minx, P., Roark, L., Oddiraju, S., Lin, G. N., et al. (2007). Comparisons among two fertile and three male-sterile mitochondrial genomes of maize. Genetics 177, 1173–1192. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.073312

Alverson, A. J., Rice, D. W., Dickinson, S., Barry, K., and Palmer, J. D. (2011). Origins and recombination of the bacterial-sized multichromosomal mitochondrial genome of cucumber. Plant Cell 23, 2499–2513. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.087189

Beier, S., Thiel, T., Münch, T., Scholz, U., and Mascher, M. (2017). MISA-web: a web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics 33, 2583–2585. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198

Benson, G. (1999). Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573

Best, C., Mizrahi, R., and Ostersetzer-Biran, O. (2020). Why so complex? The intricacy of genome structure and gene expression, associated with angiosperm mitochondria, may relate to the regulation of embryo quiescence or dormancy—intrinsic blocks to early plant life. Plants 9, 598. doi: 10.3390/plants9050598

Chase, M. W., Christenhusz, M. J. M., Fay, M. F., Byng, J. W., Judd, W. S., Soltis, D. E., et al. (2016). An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Botanical J. Linn. Soc. 181, 1–20. doi: 10.1111/boj.12385

Chen, Y., Ye, W., Zhang, Y., and Xu, Y. (2015). High speed BLASTN: an accelerated MegaBLAST search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 7762–7768. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv784

Commission, C. P. (2025). The pharmacopoeia of the people’s republic of China 2025 edition (China: China Medical Science Press).

De Smet, Y., Goetghebeur, P., Wanke, S., Asselman, P., and Samain, M.-S. (2012). Additional evidence for recent divergence of Chinese Epimedium (Berberidaceae) derived from AFLP, chloroplast and nuclear data supplemented with characterisation of leaflet pubescence. Plant Ecol. Evol. 145, 73–87. doi: 10.5091/plecevo.2012.646

Doyle, J. J. and Doyle, J. L. (1987). A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 19, 11–15.

Fang, B., Li, J., Zhao, Q., Liang, Y., and Yu, J. (2021). Assembly of the complete mitochondrial genome of Chinese plum (Prunus salicina): characterization of genome recombination and RNA editing sites. Genes 12, 1970. doi: 10.3390/genes12121970

Guo, M., Pang, X., Xu, Y., Jiang, W., Liao, B., Yu, J., et al. (2022). Plastid genome data provide new insights into the phylogeny and evolution of the genus Epimedium. J. Adv. Res. 36, 175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2021.06.020

Guo, M., Ren, L., Xu, Y., Liao, B., Song, J., Li, Y., et al. (2019). Development of plastid genomic resources for discrimination and classification of Epimedium wushanense (Berberidaceae). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 4003. doi: 10.3390/ijms20164003

Guo, M., Xu, Y., Ren, L., He, S., and Pang, X. (2018). A systematic study on DNA barcoding of medicinally important genus Epimedium L. (Berberidaceae). Genes (Basel) 9, 637. doi: 10.3390/genes9120637

He, T., Ding, X., Zhang, H., Li, Y., Chen, L., Wang, T., et al. (2021). Comparative analysis of mitochondrial genomes of soybean cytoplasmic male-sterile lines and their maintainer lines. Funct. Integr. Genomics 21, 43–57. doi: 10.1007/s10142-020-00760-x

Jackman, S. D., Coombe, L., Warren, R. L., Kirk, H., Trinh, E., Macleod, T., et al. (2020). Complete mitochondrial genome of a gymnosperm, Sitka Spruce (Picea sitchensis), indicates a complex physical structure. Genome Biol. Evol. 12, 1174–1179. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evaa108

Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K., and Miyata, T. (2002). MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., and Tamura, K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics Analysis Version 7.0 forbigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054

Kurtz, S., Choudhuri, J. V., Ohlebusch, E., Schleiermacher, C., Stoye, J., and Giegerich, R. (2001). REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 4633–4642. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633

Lai, C., Wang, J., Kan, S., Zhang, S., Li, P., Reeve, W. G., et al. (2022). Comparative analysis of mitochondrial genomes of Broussonetia spp. (Moraceae) reveals heterogeneity in structure, synteny, intercellular gene transfer, and RNA editing. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1052151. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1052151

Lee, J. H., Kim, K., Kim, N. R., Lee, S. C., Yang, T. J., and Kim, Y. D. (2016). The complete chloroplast genome of a medicinal plant Epimedium koreanum Nakai (Berberidaceae). Mitochondrial DNA A DNA Mapp Seq Anal. 27, 4342–4343. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2015.1089492

Lenz, H., Hein, A., and Knoop, V. (2018). Plant organelle RNA editing and its specificity factors: enhancements of analyses and new database features in PREPACT 3.0. BMC Bioinf. 19, 255. doi: 10.1186/s12859-018-2244-9

Letunic, I. and Bork, P. (2019). Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W256–W259. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz239

Lewis, S. E., Searle, S. M., Harris, N., Gibson, M., Lyer, V., Richter, J., et al. (2002). Apollo: a sequence annotation editor. Genome Biol. 3, Research0082. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-12-research0082

Li, C., Liu, H., Qin, M., Tan, Y. J., Ou, X. L., Chen, X. Y., et al. (2024a). RNA editing events and expression profiles of mitochondrial protein-coding genes in the endemic and endangered medicinal plant, Corydalis saxicola. Front. Plant Sci. 15, 1332460. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1332460

Li, C., Zhou, L., Nie, J., Wu, S., Li, W., Liu, Y., et al. (2023a). Codon usage bias and genetic diversity in chloroplast genomes of Elaeagnus species (Myrtiflorae: Elaeagnaceae). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 29, 239–251. doi: 10.1007/s12298-023-01289-6

Li, H. and Durbin, R. (2009). Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324

Li, J., Li, J., Ma, Y., Kou, L., Wei, J., and Wang, W. (2022). The complete mitochondrial genome of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus): using nanopore long reads to investigate gene transfer from chloroplast genomes and rearrangements of mitochondrial DNA molecules. BMC Genomics 23, 481. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08706-2

Li, J., Ni, Y., Lu, Q., Chen, H., and Liu, C. (2024b). PMGA: a plant mitochondrial genome annotator. Plant Commun. 6 (3). doi: 10.1016/j.xplc.2024.101191

Li, J., Tang, H., Luo, H., Tang, J., Zhong, N., and Xiao, L. (2023b). Complete mitochondrial genome assembly and comparison of Camellia sinensis var. Assamica cv. Duntsa. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1117002. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1117002

Li, S., Wang, Z., Jing, Y., Duan, W., and Yang, X. (2024c). Graph-based mitochondrial genomes of three foundation species in the Saccharum genus. Plant Cell Rep. 43, 191. doi: 10.1007/s00299-024-03277-w

Lowe, T. M. and Eddy, S. R. (1997). tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955

Lu, G., Zhang, K., Que, Y., and Li, Y. (2023). Assembly and analysis of the first complete mitochondrial genome of Punica granatum and the gene transfer from chloroplast genome. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1132551. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1132551

Ma, H., He, X., Yang, Y., Li, M., Hao, D., and Jia, Z. (2011). The genus Epimedium: an ethnopharmacological and phytochemical review. J. Ethnopharmacol 134, 519–541. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.01.001

Mackenzie, S. and Mcintosh, L. (1999). Higher plant mitochondria. Plant Cell 11, 571–585. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.4.571

Nguyen, L. T., Schmidt, H. A., Von Haeseler, A., and Minh, B. Q. (2015). IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300

Niu, Y., Gao, C., and Liu, J. (2022). Complete mitochondrial genomes of three Mangifera species, their genomic structure and gene transfer from chloroplast genomes. BMC Genomics 23, 147. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08383-1

Niu, Y., Luo, Y., Wang, C., and Liao, W. (2021). Deciphering codon usage patterns in genome of Cucumis sativus in comparison with nine species of Cucurbitaceae. Agronomy 11, 2289. doi: 10.3390/agronomy11112289

Putintseva, Y. A., Bondar, E. I., Simonov, E. P., Sharov, V. V., Oreshkova, N. V., Kuzmin, D. A., et al. (2020). Siberian larch (Larix sibirica Ledeb.) mitochondrial genome assembled using both short and long nucleotide sequence reads is currently the largest known mitogenome. BMC Genomics 21, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12864-020-07061-4

Sheng, M.-Y., Wang, L.-J., and Tian, X.-J. (2010). Karyomorphology of eighteen species of genus Epimedium (Berberidaceae) and its phylogenetic implications. Genet. Resour Crop Evol. 57, 1165–1176. doi: 10.1007/s10722-010-9556-6

Shi, L., Chen, H., Jiang, M., Wang, L., Wu, X., Huang, L., et al. (2019). CPGAVAS2, an integrated plastome sequence annotator and analyzer. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W65–W73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz345

Sloan, D. B., Alverson, A. J., Chuckalovcak, J. P., Wu, M., Mccauley, D. E., Palmer, J. D., et al. (2012). Rapid evolution of enormous, multichromosomal genomes in flowering plant mitochondria with exceptionally high mutation rates. PloS Biol. 10, e1001241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001241

Sloan, D. B., Wu, Z., and Sharbrough, J. (2018). Correction of persistent errors in Arabidopsis reference mitochondrial genomes. Plant Cell 30, 525–527. doi: 10.1105/tpc.18.00024

Small, I. D., Schallenberg-Rüdinger, M., Takenaka, M., Mireau, H., and Ostersetzer-Biran, O. (2020). Plant organellar RNA editing: what 30 years of research has revealed. Plant J. 101, 1040–1056. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14578

Stearn, W. T. (2002). Genus epimedium and other herbaceous berberidaceae (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press).

Sun, T., Bentolila, S., and Hanson, M. R. (2016a). The unexpected diversity of plant organelle RNA editosomes. Trends Plant Sci. 21, 962–973. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.07.005

Sun, Y., Fung, K. P., Leung, P. C., and Shaw, P. C. (2005). A phylogenetic analysis of Epimedium (Berberidaceae) based on nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet Evol. 35, 287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.12.014

Sun, Y., Moore, M. J., Zhang, S., Soltis, P. S., Soltis, D. E., Zhao, T., et al. (2016b). Phylogenomic and structural analyses of 18 complete plastomes across nearly all families of early-diverging eudicots, including an angiosperm-wide analysis of IR gene content evolution. Mol. Phylogenet Evol. 96, 93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.12.006

Tillich, M., Lehwark, P., Pellizzer, T., Ulbricht-Jones, E. S., Fischer, A., Bock, R., et al. (2017). GeSeq - versatile and accurate annotation of organelle genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W6–w11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx391

Vahrenholz, C., Riemen, G., Pratje, E., Dujon, B., and Michaelis, G. (1993). Mitochondrial DNA of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: the structure of the ends of the linear 15.8-kb genome suggests mechanisms for DNA replication. Curr. Genet. 24, 241–247. doi: 10.1007/BF00351798

Wang, Y. R. (2020). Mitochondrial genome of Selaginella Sinensis (Desv.) Spring (Lycophyte). Master’s thesis. (Hainan University, Haikou, Hainan Province).

Wang, Y., Chen, S., Chen, J., Chen, C., Lin, X., Peng, H., et al. (2023). Characterization and phylogenetic analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome sequence of Photinia serratifolia. Sci. Rep. 13, 770. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-24327-x

Wang, L., Liu, X., Xu, Y., Zhang, Z., Wei, Y., Hu, Y., et al. (2024). Assembly and comparative analysis of the first complete mitochondrial genome of a traditional Chinese medicine Angelica biserrata (Shan et Yuan) Yuan et Shan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 257, 128571. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128571

Wang, Y., Tang, H., Debarry, J. D., Tan, X., Li, J., Wang, X., et al. (2012). MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1293

Warren, J. M., Salinas-Giegé, T., Triant, D. A., Taylor, D. R., Drouard, L., and Sloan, D. B. (2021). Rapid shifts in mitochondrial tRNA import in a plant lineage with extensive mitochondrial tRNA gene loss. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 5735–5751. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab255

Wick, R. R., Schultz, M. B., Zobel, J., and Holt, K. E. (2015). Bandage: interactive visualization of de novo genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 31, 3350–3352. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv383

Wolfe, K. H., Li, W. H., and Sharp, P. M. (1987). Rates of nucleotide substitution vary greatly among plant mitochondrial, chloroplast, and nuclear DNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 9054–9058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9054

Xie, Y., Liu, W., Guo, L., and Zhang, X. (2024). Mitochondrial genome complexity in Stemona sessilifolia: nanopore sequencing reveals chloroplast gene transfer and DNA rearrangements. Front. Genet. 15, 1395805. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2024.1395805

Xie, P. S., Yan, Y. Z., Guo, B. L., Lam, C. W., Chui, S. H., and Yu, Q. X. (2010). Chemical pattern-aided classification to simplify the intricacy of morphological taxonomy of Epimedium species using chromatographic fingerprinting. J. Pharm. BioMed. Anal. 52, 452–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2010.01.025

Xu, Y., Li, Z., and Wang, Y. (2008). Fourteen microsatellite loci for the Chinese medicinal plant Epimedium sagittatum and cross-species application in other medicinal species. Mol. Ecol. Resour 8, 640–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.02029.x

Xu, Y., Liu, L., Liu, S., He, Y., Li, R., and Ge, F. (2019). The taxonomic relevance of flower colour for Epimedium (Berberidaceae), with morphological and nomenclatural notes for five species from China. PhytoKeys 27, 33–64. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.118.30268

Xu, D., Wang, T., Huang, J., Wang, Q., Wang, Z., Xie, Z., et al. (2025). Comparative analysis of mitochondrial genomes of Stemona tuberosa lour. reveals heterogeneity in structure, synteny, intercellular gene transfer, and RNA editing. BMC Plant Biol. 25, 23. doi: 10.1186/s12870-024-06034-z

Yang, H., Chen, H., Ni, Y., Li, J., Cai, Y., Ma, B., et al. (2022a). De novo hybrid assembly of the Salvia miltiorrhiza mitochondrial genome provides the first ervidence of the multi-chromosomal mitochondrial DNA structure of Salvia species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 14267. doi: 10.3390/ijms232214267

Yang, Z., Ni, Y., Lin, Z., Yang, L., Chen, G., Nijiati, N., et al. (2022b). De novo assembly of the complete mitochondrial genome of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas [L.] Lam) revealed the existence of homologous conformations generated by the repeat-mediated recombination. BMC Plant Biol. 22, 285. doi: 10.1186/s12870-022-03665-y

Ye, N. (2018). Study on mitochondrialgenome of Ginkgo biloba. Master’s thesis. (NanJing Forestry University, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province).

Ying, T. S. (2002). Petal evolution and distribution patterns of Epimedium L. (Berberidaceae). Acta Phytotaxonomica Sin. 40, 481–489. doi: 10.7523/j.issn.2095-6134.2002.6.001

Zeb, U., Aziz, T., Sun, W.-J., Haleem, A., Guan, G.-Q., Meng, L.-J., et al. (2025). Recent innovations in Grifola frondosa polysaccharides: production, properties, and their biological activity. Food Bioscience 69, 106765. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2025.106765

Zhang, J., Fu, X. X., Li, R. Q., Zhao, X., Liu, Y., Li, M. H., et al. (2020b). The hornwort genome and early land plant evolution. Nat. Plants 6, 107–118. doi: 10.1038/s41477-019-0588-4

Zhang, D., Gao, F., Jakovlić, I., Zou, H., Zhang, J., Li, W. X., et al. (2020a). PhyloSuite: An integrated and scalable desktop platform for streamlined molecular sequence data management and evolutionary phylogenetics studies. Mol. Ecol. Resour 20, 348–355. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13096

Zhang, H., Meltzer, P., and Davis, S. (2013). RCircos: an R package for Circos 2D track plots. BMC Bioinf. 14, 244. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-244

Zhang, M. L., Uhink, C. H., and Kadereit, J. W. (2007). Phylogeny and biogeography of Epimedium/Vancouveria (Berberidaceae): Western North American - East Asian Disjunctions, the origin of European Mountain Plant Taxa, and East Asian species diversity. Systematic Bot. 32, 81–92. doi: 10.1600/036364407780360265

Zhang, Y., Yang, L., Chen, J., Sun, W., and Wang, Y. (2014). Taxonomic and phylogenetic analysis of Epimedium L. based on amplified fragment length polymorphisms. Scientia Hortic. 170, 284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2014.02.025

Keywords: Epimedium L., mitochondrial genome, comparative analysis, gene transfer, RNA editing events

Citation: Xu D, Huang J, Ma Q, Wang T, Zhang Z, Wang Q, Wang Z, Xie Z, Liu X and Fu L (2025) Comparative analysis of mitochondrial genomes of Epimedium L. reveals heterogeneity in structure, synteny, intercellular gene transfer, and RNA editing. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1701895. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1701895

Received: 09 September 2025; Accepted: 07 November 2025; Revised: 28 October 2025;

Published: 24 November 2025.

Edited by:

Khurram Shahzad, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Xu, Huang, Ma, Wang, Zhang, Wang, Wang, Xie, Liu and Fu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: De Xu, MTUwODY3MzY4MzFAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Liang Fu, ZnVsaWFuZ3JhaW5AMTI2LmNvbQ==; Xue Liu, bGl1MDkwNnh1ZUAxNjMuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally in this work

De Xu

De Xu Juan Huang1†

Juan Huang1† Xue Liu

Xue Liu